The Dirt on Clean – Read Now and Download Mobi

NATIONAL BESTSELLER

FINALIST FOR THE NEREUS WRITERS’ TRUST NON-FICTION PRIZE

NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY “BEST BOOK”

Praise for The Dirt on Clean

“A terrific history of personal hygiene… Ashenburg has produced a wonderfully interesting and amusing book.”

—Daily Mail

“Utterly charming… Ashenburg’s achievement in this book is to put the daily shower in historical context, and not by chance show us that clean is always relative.”

—The Vancouver Sun

“Ashenburg is a lively and entertaining guide… A sparkling, discursive and witty history: good, clean fun.”

—New Statesman

“A smart gallop… Katherine Ashenburg has unearthed marvellously jaw-dropping material in her research… This is a rich, messy stew of a subject, often irresistibly yucky, and Katherine Ashenburg does it proud. The Dirt on Clean is stuffed to bursting with highly memorable stories and characters.”

—Literary Review of Canada

“The only possible complaint about Ashenburg’s exceptionally enjoyable book is that, being beautifully designed and illustrated, it is not suitable for reading in the bath.”

—The Sunday Times

“Brimming with lively anecdotes, this well-researched, smartly paced and endearing history of Western cleanliness holds a welcome mirror up to our intimate selves, revealing deep-seated desires and fears spanning two thousand-plus years.”

—Publishers Weekly

“With significant research and well-placed examples, Ashenburg outlines just how notions of cleanliness have changed and where they intersect with sexuality, social movements, and of course, hygiene… The book successfully lays bare the fact that our idea of cleanliness is a haphazard construction. By the end, you’ll look at your bathroom a little differently.”

—Quill & Quire

“Katherine Ashenburg has a real gift for making the abhorrent utterly irresistible… We shouldn’t be surprised by her ability to wring eloquence out of something as foul as perspiration, soot and plain old grime.”

—Toronto Star

“Ashenburg rolls up her sleeves and takes us on an engaging tour of hygiene through the ages. Her masterful mix of erudition and anecdote makes this a fascinating, fast-paced read… More than just a witty insight into washing, her book confronts our obsession with preening, plucking and perfuming our bodies so that we smell less like humans and more like exotic fruits… Thought-provoking, charming and great fodder for dinner party chat, this is a memorable read.”

—Time Out

For Kate and John,

who love their bath,

and for Alberto,

always immaculate

ONE

The Social Bath: Greeks and Romans

THREE

A Steamy Interlude: 1000–1550

FOUR

A Passion for Clean Linen: 1550—1750

FIVE

The Return of Water: 1750—1815

SIX

Baths and How to Take Them: Europe, 1815—1900

SEVEN

Wet All Over at Once: America, 1815—1900

NINE

The Household Shrine: 1950 to the Present

“BUT DIDN’T THEY SMELL?”

For the modern, middle-class North American, “clean” means that you shower and apply deodorant each and every day without fail. For the aristocratic seventeenth-century Frenchman, it meant that he changed his linen shirt daily and dabbled his hands in water but never touched the rest of his body with water or soap. For the Roman in the first century, it involved two or more hours of splashing, soaking and steaming the body in water of various temperatures, raking off sweat and oil with a metal scraper, and giving himself a final oiling—all done daily, in company and without soap.

Even more than in the eye or the nose, cleanliness exists in the mind of the beholder. Every culture defines it for itself, choosing what it sees as the perfect point between squalid and over-fastidious. The modern North American, the seventeenth-century Frenchman and the Roman were each convinced that cleanliness was an important marker of civility and that his way was the royal road to a properly groomed body.

It follows that hygiene has always been a convenient stick with which to beat other peoples, who never seem to get it right. The outsiders usually err on the side of dirtiness. The ancient Egyptians thought that sitting a dusty body in still water, as the Greeks did, was a foul idea. Late-nineteenth-century Americans were scandalized by the dirtiness of Europeans; the Nazis promoted the idea of Jewish uncleanliness. At least since the Middle Ages, European travellers have enjoyed nominating the continent’s grubbiest country—the laurels usually went to France or Spain. Sometimes the other is, suspiciously, too clean—which is how the Muslims, who scoured their bodies and washed their genitals, struck Europeans for centuries. The Muslims returned the compliment, regarding Europeans as downright filthy.

Most modern people have a sense that not much washing was done until the twentieth century, and the question I was asked most often while writing this book always came with a look of barely contained disgust: “But didn’t they smell?” As St. Bernard said, where all stink, no one smells. The scent of one another’s bodies was the ocean our ancestors swam in, and they were used to the everyday odour of dried sweat. It was part of their world, along with the smells of cooking, roses, garbage, pine forests and manure. Twenty years ago, airplanes, restaurants, hotel rooms and most other public indoor spaces were thick with cigarette smoke. Most of us never noticed it. Now that these places are usually smoke-free, we shrink back affronted when we enter a room where someone has been smoking. The nose is adaptable, and teachable.

The North American reader, schooled on advertisements for soap and deodorants, is likely to protest at this point: “But body odour is different from smoke. Body odour is innately disgusting.” My own experience tells me that isn’t true. For the first seven years of my life, I spent countless hours with my maternal grandmother, who came from Germany. She lived only a few houses down the street from us in Rochester, New York, and she often took care of us grandchildren. She was a cheerful, hard-working woman, perpetually cooking, cleaning, sewing, crocheting or knitting. Two smells bring my grandmother vividly to mind. One is the warm amalgam of yeast and linen, from the breads she shrouded in tea towels and set to rise on her dining-room radiators. The other smell came from my grandmother herself. As a child, it never occurred to me to describe it or wonder what it was—it was just part of my grandmother. Whom I loved, so the smell never troubled me.

When I married, my husband and I went to Germany on our honeymoon, staying in bed and breakfasts in small, clean-swept Bavarian towns. There, unexpectedly, memories of my grandmother came flooding back. The industrious Bavarian women who cleaned our rooms and made our breakfasts didn’t just act like my grandmother; they smelled like her. By then, as an adult raised in cleaner-than-clean North America, I knew what the smell was—the muffled, acrid odour of stale sweat—and for the first time, I consciously connected my grandmother’s characteristic smell to its cause. She cleaned her house ferociously but not her body, or not very often. (It was a northern European habit I would later read about, when travellers from other European countries, as far back as the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, would marvel at the cleanliness of Swiss, German and Dutch houses and even streets, but note that it did not extend to their bodies.)

I had to learn that my grandmother’s smell was not “good,” as determined by twentieth-century North American standards. My natural, uncultivated reaction was that it was neutral or better. Similarly, there are tribes that consider the odour of menstrual blood pleasant because it signifies fertility; others that find it repulsive, because their taboos include blood or secretions; and still other tribes that remain indifferent to it. When it comes to feelings about our bodies or those of other people, much depends on the assumptions of our group.

To modern Westerners, our definition of cleanliness seems inevitable, universal and timeless. It is none of these things, being a complicated cultural creation and a constant work in progress. My grandmother kept her Old Country notions of cleanliness until she died, in the late 1970s. Her daughter, my mother, left Germany when she was six, in 1925. Growing up in Rochester, she went to college and became a nurse. She also became an American, watching with the immigrant’s ever vigilant eye as her adopted country ratcheted up the cleanliness standards in the 1930s and ’40s.

She remembered the advertising campaigns, launched by razor manufacturers, inculcating the novel idea that women’s hairy legs and underarms were bad and, in the case of underarms, encouraged body odour. She remembered when she first heard of a newfangled product known as deodorant and when she realized that something called shampoo worked better than the boiled-down soap her mother produced for washing hair. She never wore perfume because, as she liked to say, “That’s what Europeans use instead of soap.” (Not that perfume had ever touched her no-nonsense mother’s body.) Her own regime involved plenty of soap and Mitchum’s, a clinically packaged deodorant “for problem perspiration.”

In my generation, standards reached more absurd levels. The idea of a body ready to betray me at any turn filled the magazine ads I pored over in Seventeen and in Mademoiselle in the late 1950s and early ’60s. The lovely-looking girls in those pages were regularly baffled by their single state or their failure to get a second date or their general unpopularity, and all because their breath, their hair, their underarms or—the worst—their private parts were not “fresh.” A long-running series of cartoon-style ads for Kotex sanitary napkins alerted me to the impressive horrors of menstrual blood, which apparently could announce its presence to an entire high school.

The most menacing aspect of the smells that came with poor-to-middling hygiene was that, as we were constantly warned, we could be guilty of them without even knowing it! There was no way we could ever rest assured that we were clean enough. For me, the epitome of feminine daintiness was the model who posed on the cover of a Kotex pamphlet about menstruation, titled You’re a Young Lady Now. This paragon, a blue-eyed blonde wearing a pageboy hairdo and a pale blue shirtwaist dress, had clearly never had a single extraneous hair on her body and smelled permanently of baby powder. I knew I could never live up to her immaculate blondness, but much of my world was telling me I had to try.

While ads for men told them they would not advance at the office without soap and deodorant, women fretted that no one would want to have sex with them unless their bodies were impeccably clean. No doubt that’s why the second-most-frequent question I heard during the writing of this book—almost always from women—was a rhetorical “How could they bear to have sex with each other?” In fact, there’s no evidence that the birth rate ever fell because people were too smelly for copulation. And although modern people have a hard time accepting it, at least in public, the relationship between sex and odourless cleanliness is neither constant nor predictable. The ancient Egyptians went to great lengths to be clean, but both sexes anointed their genitals with perfumes designed to deepen and exaggerate their natural aroma. Most ancient civilizations matter-of-factly acknowledged that, in the right circumstances, a gamy, earthy body odour can be a powerful aphrodisiac. Napoleon and Josephine were fastidious for their time in that they both took a long, hot, daily bath. But Napoleon wrote Josephine from a campaign, “I will return to Paris tomorrow evening. Don’t wash.”

Early in my reading about the history of cleanliness, I began talking one day at a lunch about some of the extremes, in both directions, that I was discovering. Another guest, a journalist, was astonished. “I just assume everyone is like me,” she said, “showering every single day, no more, no less.” Her assumption, even about educated North Americans like her, is not true, but most people are loath to admit that they deviate from the norm. As I went on reading about cleanliness, people began taking me aside and confessing things: several didn’t use deodorant, just washed with soap and water; some didn’t shower or bathe daily. Two writers told me separately that they had a washing superstition: as the end of a long project neared, they stopped washing their hair and didn’t shampoo until it was finished. One woman confided that her husband of some twenty years takes long showers at least three times a day: she would love, she said wistfully, to know what he “really” smells like, as opposed to deodorant soap.

Something similar happened during the writing of my last book, which was about mourning customs. Most of the traditional customs were obsolete and considered primitive or sentimental—or both—by a world interested in “moving on” as quickly as possible. But while I worked on that book, people would tell me privately about a mourning observance that was acutely important for them, even if it didn’t seem quite right in the twenty-first century—how they wore their father’s old undershirts, for example, or had long talks with their dead wife. Now that people were confiding their washing eccentricities—usually on the side of less scrupulosity rather than more—I was amused. Is a failure to meet the standards of the Clean Police as bizarre as full-blown mourning in the modern world? The surreptitious way people revealed their deviations to me indicates how thoroughly we have been conditioned: to risk smelling like a human is a misdemeanour, and the goal is to smell like an exotic fruit (mango, papaya, passion fruit) or a cookie (vanilla, coconut, ginger). The standard we read about in magazines and see on television is a sterilized and synthetic one, “as if we’re not on this earth,” a male friend remarked, but it takes some courage to disregard it.

What could be more routine and apparently banal than taking up soap and water and washing yourself? At one level and almost by definition, personal cleanliness is superficial, since it involves only the surface. At the same time it echoes, and links us to, some of the most profound feelings and impulses we know. In almost every religion, water and cleansing are resonant symbols—of grace, of forgiveness, of regeneration. Worshippers around the world wash themselves before prayer, whether literally, as the Muslims do, or more metaphorically, as when Catholics dip their fingers in holy-water fonts at the entrance to the church.

The archetypal link between dirt and guilt, and cleanliness and innocence, is built into our language—perhaps into our psyches. We talk about dirty jokes and laundering money. When we step too close to something morally unsavoury at a business meeting or a party, we say, “I wanted to take a shower.” Pontius Pilate washed his hands after condemning Jesus to death, and Lady Macbeth claims, unconvincingly, “A little water clears us of this deed,” after persuading her husband to kill Duncan.

Baths and immersions also have a natural kinship with rites of passage, the ceremonies that mark the transition from one stage of life to the next—from being an anonymous infant to a named member of the community, from singlehood to marriage, from life to death. Being submerged in water and emerging from it is a universal way of declaring “off with the old, on with the new.” (My writer friends who finally shampoo when their projects are finished are signalling that a passage has been accomplished.) Brides, and often grooms, from ancient Greece to modern-day Africa, have been given a celebratory prenuptial bath; young women in Renaissance Germany made a “bath shirt” for their husbands-to-be, a token of this custom. The Knights of the Bath were so called because they took a ritual bath the night before their formal investiture, as do men and women in many religious orders on the night before their final vows.

One of the most widespread rites of passage involves bathing the dead, an action that serves no practical purpose but meets deep, symbolic ones. The final washing given to Jewish corpses is a solemn ceremony performed by the burial society, in which the body is held upright while twenty-four quarts of water are poured over it. Other groups—the Japanese, the Irish, the Javanese—enlist the family and close neighbours to wash the dead. All have a sense that respect for the dead means that he or she must be clean for the last journey, to the last resting place. This is a ritual whose power is by no means exhausted: in one of the most moving episodes in the television series Six Feet Under, the mother and brother of Nate Fisher wash his corpse, slowly and methodically, in the family funeral parlour in twenty-first-century Los Angeles.

Rites of passage and religion are not the only domains in which washing extends its reach beyond the bathroom. Until the late nineteenth century, therapeutic baths played a significant part in the Western medical repertoire, and they still do in eastern Europe. Observers often connect a culture’s cleanliness to its technological muscle. It’s true that plumbing and other engineering feats have made our modern standard of cleanliness possible, but technology usually follows from a desire rather than leads it: the Roman bathhouses had sophisticated heating and water-delivery systems that no one cared to imitate for centuries because washing was no longer a priority.

Climate, religion and attitudes to privacy and individuality also affect the way we clean ourselves. For many in the modern West, few activities demand more solitude than washing our naked bodies. But for the ancient Romans, getting clean was a social occasion, as it can still be for modern Japanese, Turks and Finns. In cultures where group solidarity is more important than individuality, nudity is less problematic and scrubbed, odourless bodies are less necessary. As these values shift, so does the definition of “clean.”

Because this book is a history of Western cleanliness, it only glances at the rich traditions of other cultures, usually as they revealed themselves to astonished European travellers, missionaries or colonizers. Before the twentieth century, Europeans usually found that prosperous Indian, Chinese and Japanese people washed themselves far more than was usual in the West. (In the case of Japan, every social level was well washed.) For their part, Indians and Asians considered Westerners puzzlingly dirty. To some extent, it was a matter of merocrine sweat glands, which Caucasians have in profusion while Asians have few or none. (Because of this, they can still find even clean Westerners very smelly.) Partly it was that Christianity’s emphasis on the spirit encouraged a certain neglect and disparagement of the physical side of life, and Christian teachings, unlike those of Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam, ignored hygiene. And partly the difference between West and East was that much of Europe took a long hiatus when it came to regular washing, roughly from the late Middle Ages to the eighteenth or nineteenth century, and non-Westerners who encountered Europeans in those centuries were often stunned by their abysmal hygiene.

The story of that hiatus was the germ of this book. Until a few years ago, I had a vague notion that after the Roman baths petered out, everyone was more or less filthy until perhaps the end of the nineteenth century. The world I imagined was very like Patrick Süskind’s description of eighteenth-century Paris in his novel Perfume, except that it went on unchanged for fifteen hundred or so years—an overwhelming, rank palimpsest of rotten meat, sour wine, grimy sheets, excrement and, above all, the look and smell of dirty human flesh. Then, one day in the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, I paused in front of a picture of an eighteenth-century crowd. The caption underneath read, “The aristocrats in this picture are as dirty as the peasants. Press the button and learn more.”

That seemed to confirm my assumptions about the history of cleanliness, but I was willing to learn more, so I pressed the button. The story turned out to be more complicated than I had imagined. The aristocrats were dirty, according to the audiotape, because of an undulating chain of events that began in the eleventh century. When the Crusaders returned from the East, they brought with them the news of Turkish baths, and for a few centuries medieval people enjoyed warm water, communal baths and plentiful opportunities for sexual hijinks. Although ecclesiastical disapproval and the threat of syphilis cast a shadow over the bathhouses, it was the devastating plagues of the fourteenth century that closed their doors in most of Europe. The French historian Jules Michelet called the years that followed “a thousand years without a bath”—in fact, four hundred years without a bath would be more accurate. At least until the mid-eighteenth century, Europeans from the lowliest peasant to the king shunned water. Instead, they convinced themselves that linen had admirable cleansing properties, and they “washed” by changing their shirts.

For me, the medieval interlude of cleanliness and its end were startling and absorbing news. Personal cleanliness, even during the relatively few centuries detailed in the museum’s audiotape, suddenly had ups and downs I had never suspected, and it connected to far more than soap and water. I needed to know more about all the tentacles—social, intellectual, scientific, political and technological—that found their way in and out of a condition we call “clean.” Following those twists and turns led me from Homer’s Greece to the American Civil War, from Hippocrates to the germ theory, and through a handful of revolutions—French, Industrial and the sexual one of the 1960s and ’70s. Cleanliness played a part in all of them.

The evolution of “clean” is also a history of the body: our attitudes to cleanliness reveal much, occasionally too much, about our most intimate selves. Benjamin Franklin said that to understand the people of a country, he needed only to visit its graveyards. While there’s truth in that, I suggest a smaller and likelier place. Show me a people’s bathhouses and bathrooms, and I will show you what they desire, what they ignore, sometimes what they fear—and a significant part of who they are.

THE SOCIAL BATH

GREEKS AND ROMANS

Odysseus, his wife, Penelope, and their son, Telemachus, were a notably well-washed family, and the reasons would have been obvious to the first audience of The Odyssey. Greeks in the eighth century B.C. had to wash before praying and offering sacrifices to the gods, and Penelope frequently prays for the return of her wandering husband and son. A Greek would also bathe before setting out on a journey, and when he arrived at the house of strangers or friends, etiquette demanded that he first be offered water to wash his hands, and then a bath. This is a book full of departures and arrivals, as Odysseus struggles for a decade to return home to Ithaca after the Trojan War, and Telemachus searches for his father. Their journeys are the warp and weft of this great adventure story.

Washing in Greece, fifth century B.C. The young woman is about to pour water into the labrum, or washstand.

When Odysseus visits the palace of King Alcinoos, the king orders his queen, Arete, to draw a bath for their guest. Homer describes it in the deliberate, formulaic terms reserved for important customs: “Accordingly Arete directed her women to set a large tripod over the fire at once. They put a copper over the blazing fire, poured in the water and put the firewood underneath. While the fire was shooting up all round the belly of the copper, and the water was growing warm … the housewife told him his bath was ready.”

Let not your hands be unwashed when you pour a libation

Of flaming wine to Zeus or the other immortal gods.

—Hesiod, Works and Days

Then the housekeeper bathes Odysseus, probably in a tub of brass or polished stone, rubbing his clean body with oil when he steps out of the tub. Here it is the head servant who washes the stranger, but when the guest was particularly distinguished, one of the daughters of the house might do the honours. When Telemachus travels to the palace of King Nestor, his youngest daughter, Polycasta, bathes him and massages him with olive oil. Telemachus emerges from her ministrations “as handsome as a young god.”

SYBARITIC STEAM

The Sybarites, a luxury-loving people who lived in southeastern Italy from around 720 to 510 B.C., are credited with inventing the soup spoon, the chamber pot and the steam bath.

More than the most lyrical copywriter extolling the wonders of a modern bathroom, Homer stresses the transforming power of the bath—partly because The Odyssey is a tall tale but partly because travellers in the wilds of ancient Greece did no doubt look remarkably better after soaking in hot water. Not only does a bath turn nice-looking young men into near-divinities, but Odysseus gains height, strength and splendour when his old nurse bathes him. With his clean hair curling like hyacinth petals, he too “came out of the bathroom looking more like a god than a man.”

The most poignant transformation achieved by a bath in The Odyssey happens at the end of the book. Odysseus, who has been away from home for twenty years, comes upon his old father, Laertes, digging in his vineyard. Laertes’ clothes are dirty and patched, and “in the carelessness of his sorrow,” as Homer puts it, he is wearing a goatskin hat, an emblem of rustic poverty. Before he reveals his identity, Odysseus tells his father that he looks like a man who deserves better—namely, “a bath and a good dinner and soft sleep.” Laertes explains that his son is missing, probably devoured by fishes or beasts, and “a black cloud of sorrow came over the old man: with both hands he scraped up the grimy dust and poured it over his white head, sobbing.” It is a potent image of desolation, one repeated by mourners from many cultures—dirtying oneself, whether by daubing one’s face with mud or covering one’s head, as Laertes does, with dust. Misfortune and dirtiness are natural companions, as are cleanliness and good fortune.

MURDER IN THE BATH

In Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, Agamemnon’s wife, Clytemnestra, kills him in the bath by striking him twice with an axe.

At this point, Odysseus reveals his identity and takes an overjoyed Laertes back to his house. The neglected old man has a bath, which once again works its magic: “Athena stood by his side and put fullness into his limbs, so that he seemed stronger and bigger than before. When he came out of the bathroom his son was astonished to see him like one come down from heaven, and he said in plain words: ‘My father! Surely one of the immortal gods has made a new man of you, taller and stronger than I saw you before!’”

The ancient Greeks cleaned themselves for the reasons we do: to make themselves more comfortable and more attractive. They also bathed for reasons of health, since soaking in water was one of the major treatments in their physicians’ limited arsenal. Hippocrates, the great fifth-century doctor, was a champion of baths, believing that a judicious combination of cold and hot immersions could bring the body’s all-important humours, or constituent liquids, into a healthy balance. Warm baths also prepared the body, by softening it, to receive nourishment and supposedly helped a variety of ailments, from headaches to the retention of urine. Those suffering from painful joints were prescribed cold showers, and female ills were treated with aromatic steam baths.

HIPPOCRATES ON BATHING

“The person who takes the bath should be orderly and reserved in his manner, should do nothing for himself, but others should pour the water upon him and rub him.”

The world’s earliest known bathtub—painted terra cotta—dates from about 1700 B.C. and was found in the queen’s apartments at the Palace of Knossos on Crete.

As The Odyssey makes clear, washing was a necessary prelude to prayer and libations. Sanctuaries normally had fonts of water at their entrances—not that intercourse with the gods required greater cleanliness than with humans, but the Greeks believed that any respectful relationship demanded neatness and cleanliness.

And, like almost all peoples, they bathed as part of a rite of passage. The first bath of the newborn and his mother was an important event, with the water sometimes brought from a propitious spring. Both the Greek bride and groom took a ceremonial bath on the eve or the morning of the wedding, washing off their single state and preparing to take on a married identity. And when someone died, not only was the body formally washed and anointed, but the chief mourners and attendants on the dead also needed purifying, and they washed after the funeral. Contact with the dead and with grief made you dirty, always symbolically and sometimes actually. When Achilles, in The Iliad, hears that his friend Patroclus has been killed, he acts out that connection: “Taking grimy dust in both his hands he poured it over his head, and befouled his fair face.” He refuses to wash until Patroclus has received a proper funeral.

With an abundant coastline, long, sunny summers and mild winters, the Greeks must have bathed in the sea from the time they first settled in the southeastern tag end of Europe, around four thousand years ago. As early as 1400 B.C., they had invaded Crete, an advanced civilization with running water, drains and (at least in the royal palace at Knossos) bathtubs. No doubt Crete influenced their bathing customs, as did the other, more shadowy cultures they met in the course of their trading and colonizing, which extended into North Africa and Asia Minor.

DIRT AND GRIEF

“It is not only the widows that remain, either theoretically or practically unwashed; all the mourners do. The Ibibios seem to me to wear the deepest crape in the form of accumulated dirt.”

—Mary Kingsley, Travels in West Africa, 1894

By the Athenian golden age, in the fifth century B.C., the bathing habits the Greeks had forged from native and foreign sources were in place. An upper-middle-class or patrician Greek—let us call him Pittheus—could clean himself in various ways. His house would probably have a bathroom, more accurately a washing room, next to the kitchen. The essential equipment was a washstand, called a labrum, rather like a big birdbath on a base, positioned roughly at hip height. A servant would be sent to the household cistern or the nearest well for water and might be enlisted to pour it over Pittheus or his wife. The room might also include a terra cotta hip bath—big enough for the bather to sit in with legs extended, but not to lie down. The bath was set into the floor and drained by a channel to the outside. Pittheus gave himself a speedy, stand-up wash in the morning and reserved the time before dinner for a more thorough cleansing.

“Eureka!” (“I have found it!”) cried the Greek scientist Archimedes in the third century B.C., jumping naked from a public bath and running exultantly through the streets of Syracuse. What he’d discovered in his bath— by noting that the water level rose when he entered it— was the formula needed to measure the volume of King Hieron II’s crown.

A poor man without a bathroom at home might use the nearest well for a daily wash and make an occasional visit to the public bath. Some of these baths were run by the government, others by private businessmen; they either were free or had a very low admission price. Water was warmed over a fire, as in The Odyssey, and the rooms were heated, when necessary, with braziers. At its most lavish, the public bath had separate rooms for cold, warm and steam baths—basic by later Roman standards but more than the prosperous Pittheus had at home. He, as well as his wife, patronized the public bath—for the steam bath, perhaps, or for the primitive showers, in which streams of water from spouts mounted on the wall doused his head and shoulders. (A servant on the other side of the wall poured the water into the spouts.) There were no hard and fast rules about the frequency of bathhouse visits; some customers appeared daily, others once or twice a month.

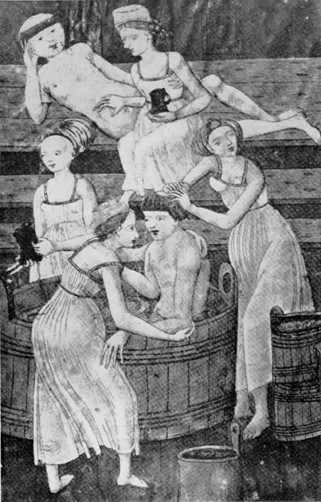

The sociable Greek public bath, with individual hip baths arranged in a circle.

Another advantage of the public bath was its sociability. Pittheus bathed there in an individual hip bath, one of up to thirty arranged around the perimeter of a circular room. (It’s an odd image, more like the bathing room of an orphanage or an infirmary than one intended for healthy adults.) The bath assistant, or bath man, provided customers with a cleansing substance, wood ashes or the absorbent clay called fuller’s earth. Pittheus, who could afford it, brought his own, perfumed cleansers. Games such as dice or knucklebones were available, as were wine and probably snacks. What was to become unimaginably sumptuous in the Imperial baths of Rome was modest and intimate in Pittheus’s bathhouse, but the essentials—baths in a variety of temperatures in a public, recreational setting—were here.

HERODOTUS ON THE EGYPTIANS IN THE FIFTH CENTURY B.C.

“They always wear freshly washed linen clothes. They make a special point of this. They have themselves circumcised for reasons of cleanliness, preferring cleanliness to a more attractive appearance. Priests shave their bodies all over every day to keep off lice or anything else dirty.”

In addition to home and bathhouse, Pittheus had a third place in which to wash—the gymnasium. One of the central Athenian institutions, the gymnasium was intended primarily as a place for middle- and upper-class young men to develop their physical strength and for older men to maintain it. Its rooms were arranged around an outdoor exercise field, with a running track nearby. Either after exercise or instead of it, men used the rooms and nearby groves (the original gymnasiums were outside the town centre) for discussions and lectures. The motto mens sana in corpore sano—a sound mind in a sound body—is Roman, but the Greeks were even more passionately devoted to the cult of the well-trained body and mind. To us it sounds incongruous that Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum, two of the earliest schools of philosophy, both founded in the fourth century, were part of working gymnasiums, but to the Greeks it was a natural combination.

In the gymnasium, bathing was a humble adjunct to exercise. Greek athletes, who exercised in the nude—gymnasium literally means “the naked place”—first oiled their bodies and covered them with a thin layer of dust or sand to prevent chills. After wrestling or running or playing ball games, the men and boys removed their oil and dust, now mingled with sweat, with a curved metal scraper called a strigil. After using the strigil, athletes could wash, either standing up at a basin or in a shower or a tub. Although hot water would have made their oil and grit much easier to remove, there is no evidence that the gymnasiums offered hot water before the Roman period. The manly rigour of cold-water bathing suited the gymnasium’s spirit and reassured those Athenians who brooded about the weakening and feminizing effects of hot water.

And brood they did. The playwright Aristophanes makes fun of the perennial tug-of-war between austerity and luxury in his fifth-century comedy The Clouds. Strepsiades, an older man who remembers fondly his sloppy youth in the countryside—then there was “no bother about washing or keeping tidy”—has fallen under the sway of Socrates and the philosophers. Strepsiades likes the fact that they never shave, cut their hair or wash at the baths. He prefers their ways to those of his citified son, Phidippides, who is “always at the baths, pouring my money down the plug-hole.” A character called Fair Argument agrees with the father, harking back to the good old days when boys sang rousing military melodies, sat up straight and would have scorned to cover their bodies in oil. That kind of no-frills upbringing, he insists, produced the hairy-chested men who fought at the battle of Marathon. These days, boys who indulge in hot baths shiver in the cold and waste their time gossiping like sissies.

A Greek’s position on hot-water bathing spoke volumes about his values, and one of the most enduring debates in the history of cleanliness centres on the merits of cold versus hot water. Edward Gibbon, the eighteenth-century chronicler of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, was convinced that hot baths were one of the principal reasons Rome weakened and fell. Victorian men, influenced by their classical Greek studies, believed that the British Empire was built on the bracingly cold morning bath. It’s a prejudice with staying power, as indicated by the modern German expression for a man short on masculinity—a Warmduscher, or warm-showerer. Plato, who in The Laws reserves hot baths for the old and ill, would have sympathized with those judgments. But, in spite of Plato, young and healthy men became accustomed to warm water at the bathhouses, if not in the gymnasiums.

Young and healthy Athenians, that is, but not the militaristic, ascetic Spartans, who bathed their newborns in wine (perhaps with some sense that it acted as an antiseptic) but took baths infrequently after that. The biographer Plutarch tells the story of a Spartan who watched in disbelief as a slave drew water for the bath of Alcibiades, the Athenian general, and commented that he must be exceedingly dirty to need such a quantity of water. (That remark, always attributed to people who saw little need for washing, surfaces again and again over the centuries.) The Spartans’ ninth-century lawgiver Lycurgus ordered the Spartans to eat in public mess halls in order to avoid dining at home on couches. If they grew accustomed to that self-indulgence, he warned, they would soon be in need of “long sleep, warm bathing, freedom from work, and, in a word, of as much care and attendance as if they were continually sick.” Warm bathing keeps company in Lycurgus’ list with the other mollycoddling tendencies he saw as threatening his city state’s military severity. Spartan self-discipline remained uncompromised by hot water, and Lycurgus’ grim forecast never came true.

Theophrastus was an Athenian philosopher whose most enduring legacy is The Characters, a collection of thirty merciless portraits of irritating types, such as Pretentiousness, Officiousness and Buffoonery. Through them we get a keen sense of grooming standards at the beginning of the Hellenistic period, near the end of the fourth century B.C., as well as a satirical sketch of a society still rough and ready in many ways. Nastiness, for example, typifies “a neglect of the person which is painful to others” and goes about town in stained clothes, “shaggy as a beast,” with hair all over his body. The parts not covered with hair display scabs and scaly deposits. His teeth are black and rotten. He goes to bed with his wife with unwashed hands (hands were to be washed after supper, which was eaten without forks or spoons), and when the oil he takes to the baths is rancid and thickened, he spits on his body to thin it.

Repulsive as Nastiness is, Theophrastus is no more fond of his foppish opposite, Petty Pride, who gets his hair cut “many times in the month,” uses costly unguent for oil and has white teeth (a rarity and considered over-fussy). The middle way between the extremes of slovenliness and vanity, Theophrastus suggests, is best. (So do the arbitrators of almost every period, at least in theory, but that prized middle ground shifts considerably.)

Public baths have always been a godsend to painters—lots of naked flesh and water—and to satirists—ample opportunity for bad behaviour. The baths as Theophrastus describes them are a flourishing institution with well-defined rules, all the better for unsocialized types to flout. Water and resonant surfaces must have been as tempting to the bathroom baritone 2,300 years ago as they are now, but it takes an oaf like Boorishness to give in to the temptation to sing in the bathhouse. It goes along with his other loutish, attention-seeking behaviour, such as confiding too much in servants and wearing shoes with clattering hobnails on the soles.

Disingenuously, Meanness complains that the oil his slave has brought to the baths is rancid, so that he can help himself to another man’s. The Unconscionable, or tight-fisted, man is similar, always trying to get something for nothing. That includes the drenching at the baths, for which the bath man was customarily paid. Unconscionable grabs the ladle, dips it into the cauldron of water, douses himself and runs off, shouting to the infuriated bath man, “I’ve had my bath, and no thanks to you for that!”

The Greeks appreciated water, but the Romans adored it. In their gymnasiums, the Greeks bathed as a necessary conclusion to exercise. The Romans reversed the priorities: they exercised because it made their baths even more enjoyable. “Hedonist” and “sybarite” come to us from the Greek—perhaps because the Greeks so distrusted those types—but the terms were better suited to the Romans, who inspired and enjoyed the over-the-top luxuries of the great Imperial baths.

But first, the characteristic Roman bath—heated and communal, as opposed to cold and individual—had to be born. It probably evolved in the region of Campania, in southern Italy on the Tyrrhenian Sea, sometime in the third century B.C. The area was a lively meeting place for Greek, Etruscan, Italian and Roman influences, and it was here that the Greek bath mingled with local and imported traditions. By the second century B.C., the Roman bath had become an ordinary, expected part of everyday life. As Roman customs insinuated themselves into the Hellenistic world, the Roman-style bath triumphed even in Greece. By the first century B.C., gymnasiums, the symbols of stoic Greek athleticism, were adding hot water.

“Baths, wine, and sex ruin our bodies, but they are the essence of life—baths, wine, and sex.”

—Epitaph on the tomb of Titus Claudius Secundus, first century A.D

The oldest more-or-less intact Roman baths are the Stabian Baths at Pompeii, dating from around 140 B.C. Pompeii had a population of 20,000 when Vesuvius erupted in A.D. 79, so the Stabian’s small-windowed, cave-like changing room must have been crowded during peak hours. Here the bather stored his street clothes in one of the cubicles, to be guarded either by a personal slave or a member of the bathhouse staff. (Even so, theft was common.) Outside the changing room is the exercise yard, a big grassy space ringed on three sides by a portico. In this space, which was not for women, male bathers, oiled and usually naked, would work up a light sweat playing ball, wrestling or running.

After his exercise, the bather would proceed to a moderately warm room, where he continued to perspire. Usually in the warm room, he would scrape off the accumulated oil, dirt and perspiration with his strigil. An attendant or fellow bather would strigil his back. In the next chamber, the hot room, he might plunge into a pool of hot water or might just sprinkle water on himself from a basin on a pedestal. Finally came a room with a shockingly cold plunge pool. That could be followed by another oiling, a massage and a final scraping with the strigil. Oils and perfumes are frequently mentioned as accessories to the bath, but not soap. In any case, a thorough scraping of oiled and sweaty skin with a strigil and a rinse with hot water probably removed as much dirt as would soap and warm water.

Rather than using soap and a washcloth, the Greeks and Romans scraped oil and sweat off their bodies with a metal implement called a strigil. The small canister held oil.

“Swiftly, safely, sweetly” was the motto of Asclepiades of Bithynia, who popularized Greek medicine in Rome in the first century B.C. and who preferred bathing his patients to bleeding them—hence his motto. He was a great advocate of cold baths in particular and was known as “the Cold Bather.”

With its waters of contrasting temperatures, the Roman bath has more than a passing likeness to another social bath, the Finnish sauna, where the sauna takers alternately sweat and cool down with hot air, cold water and, in season, snow. The Roman bath and the hamam, or Turkish bath, have an even closer family resemblance since, as we shall see, the hamam descends directly from its Roman parent.

A basic Roman bathhouse needed a warm room, hot room and cold room. More elaborate ones might include a chamber with intense dry heat, and a separate chamber for oiling and massage. A special scraping room and an open-air swimming pool were also possibilities, but these were frills. In theory (and unlike the Greeks’ baths, which followed no special order), a Roman bath proceeded from warm to hot to icy cold, with exercise at the start and at least one scraping. In reality, the bather could modify the order as he wished. The architecture of the later, Imperial baths reflected the ideal progression. But in the more modest bathhouses of the Roman republic, up to the end of the first century B.C., rooms were added haphazardly as a new treatment became popular or as the clientele grew.

Roman men adopted the Greek habit of bathing after work, which meant about two or three in the afternoon, corresponding to the eighth or ninth hour in the Roman time scheme. (The Roman workday began early in the morning, certainly by six o’clock, and was effectively over by mid-afternoon.) In the Republic, when the sexes were more reliably segregated for bathing than they were in the Empire, women would have either separate bath chambers or separate hours, usually in the morning. Slaves and servants, too, often bathed in the morning so they would be available to escort their masters to the bathhouse in the afternoon. The typical price for men was the smallest copper coin, called the quadrans, a quarter of a cent. Women might pay twice that amount, but children, soldiers and sometimes slaves were admitted free of charge.

Close to the Stabian Baths was Pompeii’s biggest brothel. The combination of warm water, nudity and relaxation meant that baths and brothels tended to be near neighbours; sometimes prostitutes offered their services on the second floor of a bath. In another Pompeiian bathhouse, the Suburban Baths, the link between bathhouses and sex is literally painted on the wall. In the intimate, ochre-coloured changing room of these first-century A.D. baths, the wooden compartments where bathers left their clothes are long gone. But on the wall above where they stood are eight unblushingly bawdy frescoes—a woman, brandishing a fish, about to be penetrated by a man; women giving and receiving oral sex; a threesome (two men and a woman) locked in close conjunction; and other similarly frisky scenes. They may be advertising services available nearby, or perhaps they were simply meant to contribute to the baths’ pleasure-loving, sensuous atmosphere. The frescoes, dashed off with charm and style, are disarmingly direct—and utterly unlike our idea of suitable decoration for a commercial building used by men, women and probably children.

THE STORY OF SOAP, PART I

A mixture of animal fats and ashes sounds neither clean nor pleasant, but that is how soap was made for most of human history. Clay cylinders dating from about 2800 B.C., discovered during excavations in Babylon, contain a soapy substance, and the writing on the cylinders confirms that fat and ashes were boiled together to produce it. What actually got washed with soap is less clear. The Egyptians, whose soap contained milder, vegetable oils as well as animal fats, used it for washing their bodies. The Greeks and Romans did not: they preferred coating themselves with sand and oil and scraping it off with a strigil. Although soap, probably made with olive oil, was a regular part of the Turkish bath, or hamam, that aspect of washing did not travel to Europe when the bath returned in the Middle Ages. Europeans were still boiling animal fats and ashes together to make a soap that was used to wash clothes and floors but was too harsh for bodies. Toilet soap, made from olive oil, was manufactured in small batches in pioneering soap businesses in Marseilles, Italy and Spain (where the soap made in Castile was so prized that eventually all fine white soap made with olive oil was called Castile soap), but it was a luxury and beyond the budgets of most people in the Middle Ages. They made do with plain water, to which they sometimes added herbs believed to have cleansing or medicinal qualities.

The Romans considered cleanliness a social virtue. (Up to a point, so did the Greeks, as Theophrastus makes clear, but the Romans were more preoccupied with grooming, and they raised the bar when it came to hygienic standards.) The Latin word for “washed” or “bathed” is lautus, which became by extension the adjective for a refined, grand or elegant person. And more and more, as the daily bath was knitted tightly into their schedules, cleanliness—achieved their way—became a Roman virtue. Modern-day Japanese people report that what they miss most when living abroad is not familiar food or language or people: it is the Japanese bath, with its particular protocol of pre-washing before a communal soaking in extraordinarily hot water. Similarly, the Roman bath became one of the defining marks of Roman-ness, one of the central ways they separated themselves from outsiders, and one of the first civilities with which they welcomed conquered peoples into the far-flung Roman family. When Agricola became governor of cold, foggy Britain in A.D. 76, he knew what the shaggy and unkempt natives needed. He introduced them, in short order, to public buildings, togas, Latin and baths. It was the essential shortcut to Romanization.

FIRST-CENTURY A.D. GRAFFITI

“Two companions were here and, since they had a thoroughly terrible attendant called Epaphroditus, threw him out on the street not a moment too soon. They then spent 105½ sesterces most agreeably while they fucked.”

—At the Suburban Baths, Herculaneum, in a room off the vestibule (possibly a brothel)

As in Greece, some of the baths of the Roman Republic were private enterprises and some were owned by the city. The unassuming Republican bath was a beloved institution but no marvel. The Imperial bath, a grandiose pleasure palace built and maintained by the government, left even jaded Romans slack-jawed with awe. The great age of Imperial baths began around 25 B.C., when Agrippa, the designated successor of Augustus, opened the baths that bore his name. Set in gardens that included an artificial lake and a canal, the Baths of Agrippa were notable for their size (the buildings measured at their largest 120 metres by 100 metres) and their splendour. When Agrippa died in 12 B.C., he left the baths to the people of Rome. All this—scale, grandeur and the bequest to the Romans—was new, and it set the standard for the Imperial baths to come. Agrippa’s were the first thermae, as the dazzling, multi-functional Imperial baths came to be called, to distinguish them from a balneum, a plainer, more workaday bathhouse.

At the same time as the thermae grew more and more extravagant, the satirist Juvenal coined the phrase “bread and circuses” to describe the government’s attempts to buy the people’s favour with cheap food and mindless entertainment. Vastly more expensive than bread and circuses—they required not only building but costly maintenance—the thermae were like them on some levels but, to the Roman mind, far more substantial. Becoming lautus, or bathed, was essential to a person’s self-respect, as well as his health.

BATHROOM BARITONE

“Then he sat back as though exhausted, and enticed by the acoustics of the bath, he opened his drunken mouth as wide as the ceiling, and began to murder the songs of Menecrates—or so those who could catch the words said.”

—Petronius, Satyricon

An emperor would usually build his thermae at the start of a dynasty or after a civil war to signal his magnanimity and his ability to provide the best of Roman lives for his people. Nero built ambitious thermae, famous for their very hot water, around A.D. 60. Impressive as they were, it was only in 109, when the Baths of Trajan were built, that successive emperors began to pull out all the stops. In the Baths of Trajan, the central bath block was surrounded by a perimeter of buildings that included club rooms, libraries, lecture halls and exercise rooms. It was a virtual village, the most complete bath domain Rome had seen.

The two biggest thermae, the Baths of Caracalla (216–17) and the Baths of Diocletian (298–306), were reckoned among the wonders of Rome and the fate of their remains gives some idea of their magnificence. When Pope Paul III ransacked the Baths of Caracalla in the sixteenth century to decorate his Farnese Palace, the spoils—marbles, medals, bronzes and bas-reliefs—were enough to furnish a museum (the Farnese Collection, now mainly in the Naples Archaeological Museum). In the twentieth century, the ruins of the hot room alone housed productions of Verdi’s opera Aida that included chariots, horses and camels, as well as the cast and audience. Even more colossal, Diocletian’s thermae were estimated to hold three thousand bathers. In 1561, Michelangelo converted the cold room into the nave of the Basilica Santa Maria degli Angeli. The ruins of the thermae are now home as well to the National Roman Museum and the Oratory of Saint Bernard.

A nineteenth-century recreation of the Baths of Diocletian, the many-splendoured Imperial bath, which also functioned as a gymnasium, club and town square.

As baths and their facilities grew more elaborate, Romans often spent most of their leisure hours there. With pools, exercise yards, gardens, libraries, meeting rooms and snack bars, the bath became a multi-purpose meeting point, a place to make connections, do business, flirt, talk politics, eat and drink. Prostitutes, healers and beauticians often had premises in the bath complex or in the shops around its perimeter, so it was possible to have sex, a medical treatment and a haircut as part of a regular visit. Although well-born men used their favourite bath as English aristocrats would later use their London club, the bathhouse was also the most democratic Roman institution. Unlike the Greek gymnasium, which was limited to middle-class and upper-class men, the Roman bath accommodated men and women, slaves and freedmen, rich and poor. A Roman, at least by the first century B.C., when there were 170 baths in the capital, had plentiful choice but usually settled on one as a regular haunt. It was common, when meeting a man, to ask where he bathed.

The purposes that cafés, town squares, clubs, gymnasiums, country clubs and spas served in other societies, including ours, were fulfilled here. Imagine a superbly equipped YMCA that covered some blocks, with gyms, pools, ball courts and meeting rooms. Then add onto it the massage and treatment rooms of a fancy spa and the public rooms and grounds of a resort. Finally, give it a fee structure that would allow the poorest people to use its facilities. That approximates, but does not equal, an Imperial bathhouse.

BATHHOUSE CAMARADERIE

“Skinship” is the approving Japanese expression for the close relationship that is built by bathing together. In Japan, work groups often bathe communally as part of a professional retreat. In Finland, where the sauna is a national institution, when government leaders cannot agree on an issue, they continue their discussion in the sauna.

Although the emperors had lavish baths in their palaces, most of them bathed in one of the bathhouses occasionally, if only for the sake of public relations. The most famous anecdote about an emperor at the bathhouse involves Hadrian, in the second century A.D. One day, the story goes, he recognized an old army crony in the hot room. The veteran was rubbing himself up against the marble wall, and when Hadrian asked why, he explained that he lacked the money to hire an attendant to strigil him. Hadrian immediately gave him money and slaves. The next day, when the bathers heard that the emperor was in the baths, a number of them began rubbing themselves ostentatiously against the walls. Hadrian suggested that they take turns strigiling each other.

The rosy-coloured vision of the baths in which slave and emperor soak side by side before consulting the bathhouse libraries and discussing philosophy in the lecture rooms, called exedrae, is largely wishful thinking. The libraries and exedrae were smaller and less frequented than the ball courts. The baths were notorious (some more than others) for the stealing, drunkenness and unsavoury sex that went on under their roofs. Social distinctions naturally persisted there, in that the rich could pay extra for the use of particular rooms or services. They could and did flaunt their wealth, swanning in with a retinue of servants bearing costly flagons and perfume dispensers, finely wrought strigils and sumptuous towels.

GROOMING ADVICE FOR MEN

Keep your nails pared, and dirt-free; Don’t let those long hairs sprout In your nostrils; make sure your breath is never offensive, Avoid the rank male stench That wrinkles noses.

—Ovid, Art of Love

But for the men and women who lived in Rome’s dark apartment blocks, without water or toilets or much space, an afternoon at the bathhouse was a delight. Even the relatively modest quarters of a Republican bath were luxurious to them, while the huge, light-filled Imperial baths gave them an intimate experience of Rome at its most splendid. Besides, poverty was not always a disadvantage at the baths. Far from making everyone equal, nudity imposed its own hierarchy, one that frequently favoured the toned body of the poorest freedman or slave over that of the indulged, unexercised rich man.

The accumulated sweat, dirt and oil that a famous athlete or gladiator strigiled off himself was sold to his fans in small vials. Some Roman women reportedly used it as a face cream.

BEHIND THE GREAT THERMAE

Three technological innovations allowed the sturdy Republican bath to evolve into the sybaritic Imperial one. The early baths obtained their water from wells, cisterns and springs, but by 100 B.C., nine aqueducts provided each Roman with 300 gallons of water a day, four times the average consumed by a modern North American. The baths were among the aqueducts’ most demanding and privileged users, served from mains connected to the bottom of the tank, where the water flowed with greatest force.

From the bath’s reservoir, water was sent, by means of pumps and lead pipes, to the furnace and then to the bath’s various chambers. The pools and the rooms were heated by the second innovation, a system called a hypocaust. Developed at the end of the second century B.C., the hypocaust heated a hollow space underneath the floors and behind the walls with hot air generated from a furnace. The floor, supported over the cavity by short piles of bricks or tiles, could become so hot that bathers needed sandals to protect their feet. The bath’s hottest rooms were positioned directly over the furnace, with the cold room and the dressing room placed farthest away.

An early bath could be made of squared stones. By the first century B.C., the invention of Roman concrete, an amalgam of brick fragments and stones in a mortar of lime, sand and volcanic dust, made increasingly large, sophisticated buildings possible. The development of the concrete vaulted roof, in particular, led to the untrammelled spaces that made a visit to the Imperial baths such an impressive experience.

Prosperous Romans also built private baths in their townhouses and, more frequently, in their country villas. Although lodged in private houses, these too were public, in that family and guests bathed together in a suite of rooms that usually included tepid, hot and cold chambers. Far from being a private hideaway, the bath suite was often positioned near the main entrance of the villa—a reception room as public as the dining room.

A bath at home had obvious advantages, but a family that owned one would also use the public baths for their greater size and variety of facilities. Pliny the Younger had baths in his Laurentine villa, but he was pleased that the nearest village had three public baths, “which is a great convenience if you arrive unexpectedly, or if you are staying such a very short time that you do not feel inclined to have the fires in your own bath lit.” Few Romans wanted to deprive themselves of the convivial fun of the public bath. After his outrageous, wine-sodden dinner party, Trimalchio and his guests, in Petronius’ novel Satyricon, retreat to his private baths to sober up, but before dinner, he had gone, as usual, to the public baths.

GROOMING ADVICE FOR WOMEN

I was about to warn you against rank goatish armpits And bristling hair on your legs, But I’m not instructing hillbilly girls from the Caucasus…

—Ovid, Art of Love

A bathhouse in the first century A.D. appealed to all the senses—the smell of the oils and perfumes as well as of the bathers before and after their baths; the feel of the waters, the strigil, the massage, the towels; the taste of the wine, oysters, anchovies, eggs and other foods that were for sale; the sight of the architecture, with its arches, domes and endless spaces lined with marble and works of art, as well as of the humans, either nude or decked out to impress the crowds. As for the noise, Seneca’s famous account of the bathhouse hubbub brings its cacophony to life.

I live over a public bathhouse. Now imagine to yourself every type of sound which can make you sick of your ears: when hearty types are exercising by swinging dumbbells around—either working hard at it or pretending to—I hear their grunts, and then a sharp hissing whenever they let out the breath they’ve been holding. Or again, my attention is caught by someone who is content to relax under an ordinary massage and I hear the smack of a hand whacking his shoulders, the sound changing as the hand comes down flat or curved. If on top of all that there is a game-scorer beginning to call out the score, I’ve had it! Then there’s the brawler, the thief caught in the act, the man who likes the sound of his voice in the bath, the folk who leap into the pool with an enormous splash. Besides those whose voices are, if nothing else, natural, think of the depilator constantly uttering his shrill and piercing cry to advertise his services: he is never silent except when plucking someone’s armpits and forcing him to yell instead. Then there are the various cries of the drink-seller; there’s the sausage seller and the pastry-cook and all the eating-house pedlars, each marketing his wares with his own distinctive cry.

The scene at Seneca’s balneum sounds like a vivid human comedy but not necessarily a decadent one. Still, the anxieties about effeminacy and softness that dogged the Greeks worried the Romans too. Writers in the Empire often looked back nostalgically to the Republic, when manly men would have scorned a hot bath that stole hours out of every day. Seneca visited the seaside villa of Scipio Africanus, the general who had defeated Hannibal and the Carthaginians in the Second Punic War, some 250 years earlier. The letter in which he describes the war hero’s bath contrasts Scipio’s hardy habits with the self-indulgent preciousness of his own time.

The baths of Seneca’s Rome glistened with vaulted glass roofs, silver faucets and marble finishes imported from Egypt and Africa. Scipio, who was dirty from the plowing and other farm work he did when not at war, cleaned himself in a narrow, dark bath, designed to conserve heat. “Who is there nowadays who could bear to bathe in such a place?” Seneca asks.

Some people nowadays condemn Scipio as being extremely uncouth because he did not let the daylight into his hot water tub through wide windows, because he did not boil himself in a well-lit room, and because he didn’t linger in the hot tub until he was stewed. “What an unfortunate man!” they say. “He didn’t know how to live well. He bathed in water which was unfiltered, which in fact was often murky and, after a heavy rain, was almost muddy.” But it didn’t matter much to Scipio whether he bathed in murky water, because he came to the baths to wash off sweat, not oily perfumes!

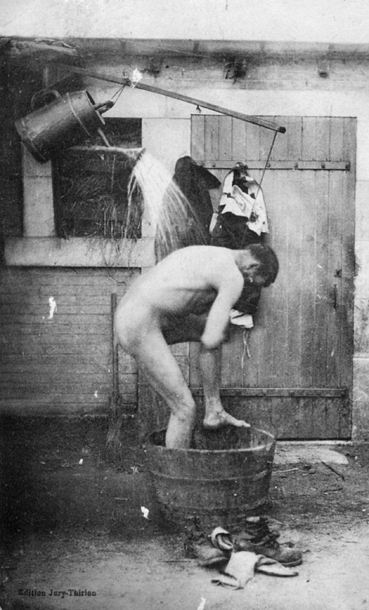

Even more unsavoury to Seneca’s contemporaries, Scipio didn’t take a daily bath. In his time, people washed their arms and legs, which got dirty from farm labour, every day, and their whole bodies only once a week. “Of course,” Seneca continues, “someone will at this point say, ‘Sure, but they were very smelly men.’ And what do you think they smelled of? Of the army, of farm work, and of manliness!’”

The poet Martial was a few generations younger than Seneca, born in about A.D. 40, and less inclined to berate his era for self-indulgence. He’s an unflaggingly racy guide to the baths, with his own satirical hobbyhorses—chiefly social climbing and sex, the latter of which often involves descriptions of the physical attributes of his fellow bathers. As they did for Theophrastus four centuries earlier, the baths afforded Martial excellent views of people’s foibles and peccadilloes. His portrait of Aper is typically etched in acid. Before he inherited money, Aper decried the drinking of wine in the baths. A bow-legged slave carried his towel there and a “a one-eyed old crone” guarded his clothes in the changing room. Now that he’s rich, the formerly abstemious man leaves the baths drunk every night. And the homely servants are a thing of the past: Aper insists on handsome slaves and delicately chased gold cups.

Above all, the bath for Martial is a place to meet people, cadge a dinner invitation or offer one, and judge others as they do the same things. Poor pathetic Selius, one of Martial’s targets, would do anything rather than dine at home. He darts from fashionable shops to the temple of Isis to no fewer than seven baths, all the while angling for a dinner invitation. Another man is equally assiduous in his invitation-seeking efforts:

A MINORITY VIEW

“What is bathing when you think of it—oil, sweat, filth, greasy water, everything revolting.”

—Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

I defy you to escape him at the baths.

He’ll help you arrange your towels;

While you’re combing your hair, scanty as it may be,

He’ll remark how much you resemble Achilles;

He’ll pour your wine and accept the dregs;

He’ll admire your build and spindly legs,

He’ll wipe the perspiration from your face,

Until you finally say, “Okay, let’s go to my place.”

Because the baths took up so much of a Roman’s day, vignettes from the bathhouse appear again and again in Martial’s poems—anecdotes of ladies bathing with their male slaves, of drunken bathing parties, of persistent worries about the cleanliness of the bathwater, of the dinner one Aemilius made at the baths, including lettuce, eggs and lizard-fish. When the poet gripes about a too-demanding friend, one of his offences is to expect an exhausted Martial to accompany him to the Baths of Agrippa at the tenth hour, or later, even though Martial regularly bathes earlier, at the Baths of Titus. In one of Martial’s funniest protests, addressed to his friend Ligurinus, who is “too much of a poet,” we meet a man who can’t stop reading his work to his friends—while they’re running, while they’re walking, while they’re using the latrine or sitting in the dining room. “I fly to the warm baths,” Martial sighs, “you buzz in my ear; I make for the swimming bath: I am not allowed to swim.”

The intimate, revealing work of caring for one’s body is made to order for Martial’s satirical purposes. Take poor Thais, who smells dreadful and tries to cover her “reek” with other odours. Stripped, she enters the bath “green with depilatory, or is hidden behind a plaster of chalk and vinegar, or is covered with three or four layers of sticky bean-flour [to remove wrinkles].” It’s to be hoped that Thais stays out of plunge and swimming baths when she is so bedaubed, but in any case, when it comes to her unfortunate odour, it is all fruitless: “Thais, do what she will, smells of Thais.”

The baths are also a fine place to assess the other patrons’ physical attributes. A well-endowed man is cause for comment:

It’s easy to tell

by the roar of applause

in which of the baths

Maron is bathing.

To some extent, nudity was optional when men and women bathed together in Martial’s day, but he complains when a woman is clothed. When he compliments Galla on her hands and legs, she promises him, “Naked I shall please you more.” Still, she resists bathing with him, and he asks, “Surely you are not afraid, Galla, that I shall not please you?” Similarly, Saufeia says she wants to have a liaison with him but shies away from a bath. He wonders, do her breasts sag, is her belly lined with furrows, or is there some other imperfection? Or, worst of all, is she beautiful—and, hence, stupid?

The old strictures against men and women bathing together in the nude seem to have retained some latent force, even if they were often not honoured. Martial writes teasingly to a matron that, up to this point, his book has been written for her. But now, he warns her, he’s writing for himself: “A gymnasium, warm baths, a running ground are in this part of the book; depart, we are stripping; forbear to look on naked men.” Then he says, mischievously, that he knows he’s piqued her interest.

Martial’s voice is usually cynical and ironical. But his famous definition of the good life is sincere. He needs, he writes, “a taverner, and a butcher and a bath, a barber, and a draught-board and pieces, and a few books—but to be chosen by me—a single comrade not too unlettered, and a tall boy and not early bearded, and a girl dear to my boy—warrant these to me, Rufus, even at Butunti, and keep to yourself Nero’s warm baths.”

The needs of the body come first—the means to drink, eat, bathe (at a balneum) and be barbered. Then, social and mental life—a game, books and a compatible friend. With these and a servant boy and girl, he is content, even in Butunti, an obscure town in Calabria. The two words Martial uses for “bath” are significant: Nero’s grandiose thermae count for nothing, compared with his necessary and beloved balneum, a humble, non-Imperial, neighbourhood bathhouse. Martial’s unpretentious balneum was in a tradition that stretches back to the Greeks’ simple bathhouses, while the thermae were bravura demonstrations of the Romans’ mechanical skill and taste for luxury. Luckily for Martial, he died around A.D. 103 without realizing that the days of both kinds of bath were numbered.

A larger, even more unimaginable future event was the end of the mighty Roman Empire, as well as the appearance of an obscure Galilean preacher who became the founder of a world religion. The decline of the baths was due more directly to the fall of Rome than to the rise of Christianity, but there is no denying that the three events—one apparently mundane, but close to the heart of Roman civilization, and two with vast, long-term consequences—were intertwined.

BATHED IN CHRIST

200–1000

An Arab gardener in A Thousand and One Nights accounted quite simply for the dirtiness of the Christians: “They never wash, for, at their birth, ugly men in black garments pour water over their heads, and this ablution, accompanied by strange gestures, frees them from all obligation of washing for the rest of their lives.” Of course, the Arab’s claim that baptism absolved Christians from further cleansing was partly a joke, but it suggests how Christians were seen by medieval Muslims.

Outsiders to the Christian tradition have frequently been puzzled by what they see as its indifference to cleanliness. When the twentieth-century English writer Reginald Reynolds was in India, an observant Hindu once asked him about the Christian teaching on personal hygiene. Reynolds answered that there was no such thing. The Hindu protested that that was impossible:

“He who has bathed in Christ has no need of a second bath.”

—St. Jerome

For every religion has a code for the closet, how cleansing is to be performed, when and in what manner the hands shall be washed, also concerning baths and the cleaning of teeth. Nevertheless, I told him … we have none such. How so, then, says he, have you no teachings at all in these matters? To which I replied that our priests taught theology, but left hygiene to the individual conscience.

The Hindu’s surprise was justified, for Christianity’s unconcern with cleanliness is unusual among world religions. There is no single, obvious reason for that omission. The first Christians were Jews, people who were expected to be clean for reasons of health as well as out of respect for others. But their laws were much more specific about ritual purity than about physical cleanliness. Jews were obliged to wash away in a ritual bath the pollution caused by immoral acts, such as adultery, homosexuality and murder, as well as by innocent activities and conditions such as sexual intercourse with their spouse, contact with the dead, genital discharges and childbirth. During the time of Christ, that web of obligatory purifications was tightening and expanding.

MORE MURDER IN THE BATH

“Odious to himself and to mankind, Constans [ca. A.D. 323–50] perished by domestic, perhaps by episcopal, treason in the capital of Sicily. A servant who waited in the bath, after pouring warm water on his head, struck him violently with the vase. He fell, stunned by the blow and suffocated by the water; and his attendants, who wondered at the tedious delay, beheld with indifference the corpse of their lifeless emperor.”

—Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

The Jesus who appears in the gospels was either rebellious or indifferent when it came to some of the most important of these impure states. In the course of his healing, he touched the dead, as well as people with leprosy-like conditions and a woman with a “bloody issue” (vaginal discharge)—all forbidden. He scandalized the Pharisees, one of the strictest groups when it came to ritual purification, by belittling one of their central practices, washing their hands before eating. Mark’s gospel describes their dismay when Jesus’ disciples eat bread with unwashed hands: “For the Pharisees, and all the Jews, except they wash their hands oft, eat not, holding the tradition of their elders” (Mark 7:1–23). In Luke’s version of the story, it is Jesus who sits down to eat without washing, shocking his Pharisee host (Luke 11:37–54). Jesus’ response in both accounts is to belittle the custom and accuse the Pharisees of hypocrisy. A man is not defiled by what goes into him, he says in Mark’s gospel, only by what comes out of him. “Now do ye Pharisees make clean the outside of the cup and the platter,” he retorts in Luke’s account, “but your inward part is full of ravening and wickedness” (Luke 11:39). It’s the familiar Christian dichotomy between outer and inner, between flesh and spirit, between the letter of the law and its essence, applied to ritual handwashing. The handwashing stories were traditionally read by Christians as examples of the Pharisees’ badgering Jesus with the minutiae of the law, but they also point to what became a telling separation between Judaism and Christianity.

Detail from The Birth of the Virgin, by Pietro Lorenzetti. Bathing a newborn baby, whether the Virgin Mary, Jesus or a saint, was a favourite theme in medieval religious painting.

Scholars have advanced various reasons to explain Jesus’ indifference to ritual purity. His thinking may have been influenced by his origins in a rural, Galilean branch of Judaism that was relatively unconcerned with ritual purity. His teachings on morality may also have inclined him away from ritual cleansing, for he does not seem to have believed that the innocently “impure,” menstruating women or men with a discharge, for example, needed purification. Nor were the morally culpable absolved, in Jesus’ view, by immersing themselves in a ritual pool—they also had to repent. As a further complication, the speech and actions of the Jesus we meet in the gospels may well have been doctored to suit the attitudes of the early Church.

St. John baptizes Jesus. Baptism is one of Christianity’s rare ritual washings, and until the seventh century it involved a full immersion. Because pagan rituals marking the summer solstice often included water and immersion, the Church Christianized them by celebrating the feast of St. John the Baptist near the solstice, on June 24.

So the reasons behind Jesus’ attitude to ritual purification remain stubbornly opaque. And whatever they were, they do not lead in a straight line to a Christian devaluation of cleanliness. Ritual purity is not the same as cleanliness. You can be physically clean and ritually impure, just as you can be physically dirty and ritually pure. But it is mostly anthropologists who place ritual purity and physical cleanliness in watertight containers. To the average person, purity, which was good, simply felt more like cleanliness than like uncleanliness; impurity, on the other hand, almost inevitably had connotations of uncleanliness. Also, since people emerged from a ritual immersion or even a ritual handwashing cleaner than before, there was a natural connection between the symbolic act and the physical result.

Jesus’ indifference to ritual purity accorded with what became a wider Christian distrust or neglect of the body. Somewhat paradoxically, the Jewish purity laws, especially at the time of Christ, emphasized the body’s importance: the purity or impurity of the body at any given moment was a significant matter. Within a few hundred years of Christ’s death, Christianity had gone in a different direction. It discounted the body as much as possible, devaluing the flesh so as to concentrate on the spirit.