Also by William Fotheringham

Put Me Back on My Bike: In Search of Tom Simpson

Roule Britannia: A History of Britons in the Tour de France

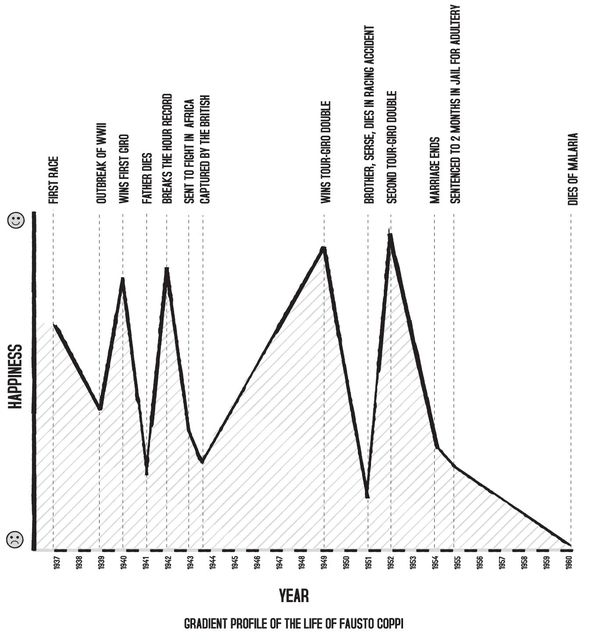

Fallen Angel: The Passion of Fausto Coppi

A Century of Cycling

Fotheringham’s Sporting Trivia

Fotheringham’s Sporting Trivia:

The Greatest Sporting Trivia Book Ever II

Design and layout: www.carrstudio.co.uk

First published in the United Kingdom by Yellow Jersey Press in 2010

This substantially revised American edition published in 2011 by Chicago Review Press

Copyright © William Fotheringham 2010, 2011

All rights reserved

Illustrations copyright © Telegramme Studio 2010

All rights reserved

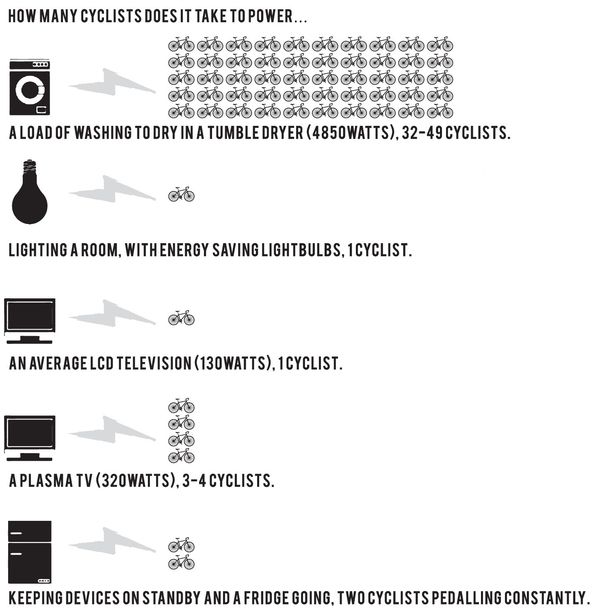

We are grateful to BBC Focus magazine for permission to use the pedal-power data first published in the October 2009 issue.

Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago IL 60637

ISBN 978-1-56976-817-4

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

Table of Contents

Also by William Fotheringham

Title Page

Copyright Page

PREFACE

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

Y

Z

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PREFACE

The particular joy of cycling is in its infinite variety, its seemingly boundless history. Get on a bike and you can go anywhere, literally and metaphorically. Unlike a football or a tennis racket, a bike has multiple uses. It is simultaneously a piece of high-tech sports gear, a means of transportation to work or the store, a way of discovering the world, an escape to solitude and nature, a social network that beats any of the virtual variety, and a means of discovering your personal limits, whether by crawling up an Alpine pass or shredding your nerves downhill on a mountain bike. Over the last 150 years cycling has helped to change the world and it may yet help to save it from environmental catastrophe. Bikes have carried politicians, soldiers, explorers, suffragettes, socialists, artists, and artisans. Yet as cyclists we tend to exist in our own bubbles. We race, we ride to work, we may fret over whether to buy carbon fiber or titanium, we pedal off to picnics, we find new places. For whatever reason we ride our bikes, and whatever the depth of our personal passion, there will be sides of cycling, its history, its culture, that we don’t even know exist. There isn’t time to go everywhere and the signposts are not always there in the first place. And that is where this book may just be able to help, by giving some idea of the multiplicity of areas—social, technical, sporting, cultural, historical—to which two wheels can transport us.

There is one proviso. This book cannot help but reflect my personal views on a world in which I have been immersed for two-thirds of my life, over 30 years. No one will agree with everything they find here, but that is how it should be. The aim of this book is simply to offer some signposts toward what cycling has to offer, and some guidance through a world of never-ending possibilities. If, after reading it, you want to try something new, go to a race, or buy a book or DVD that you might not have known about, it will have served its purpose.

Enjoy the ride.

William Fotheringham,

July 2010

A

ABDUZHAPAROV, Djamolidin

(b. Uzbekistan, 1964)

Squat, tree-trunk thighed sprinter from Uzbekistan who was one of the biggest stars to emerge from the Eastern bloc after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Abdu’ first came to prominence in the British MILK RACE, winning three stages in 1986, but it was in the 1991 TOUR DE FRANCE where his unique style grabbed world headlines: he put his head down low over the front wheel—a style later adopted to great effect by MARK CAVENDISH—and zigzagged up the finish straight, terrifying opponents and onlookers.

He took two stages in the 1991 Tour but came to grief in dramatic style as a third win beckoned on the Champs-Elysées: after colliding with an oversized cardboard Coke can standing against the barriers he somersaulted over the bars and rolled down the road. He had to be helped over the line, and was eventually awarded the points winner’s green jersey three months later. This led to him being nicknamed the Terminator, because he got back up each time he was knocked down.

He went on to have a memorable feud with Italian sprinter Mario Cipollini—“send him back to Russia” was Cipo’s line—and won a total of nine stages and three green points jerseys in the Tour. His career came to an end in 1997 after he tested positive for Bromantan, a drug used by Russian air force pilots; he retired to live on Lake Garda, where he tends pigeons.

(SEE NICKNAMES FOR OTHER BIZARRE CYCLING MONICKERS, AND EASTERN EUROPE FOR MORE INFO ON THE ORIGINS OF ABDU’ AND HIS PEERS)

AERODYNAMICS If the strength of any cyclist is a given on a particular day, several key variables determine how fast he or she can travel: friction (resistance within the bearings and chain), the rolling resistance of the tires on the road, gravity, and air resistance. Of the four, air resistance is the hardest to overcome and has the greatest effect.

Air or wind resistance increases as a square of a cyclist’s velocity; for every six miles per hour faster a cyclist travels, he must double his energy output. It is estimated that over 15 mph, overcoming wind resistance can account for up to 90 percent of energy output. Estimates vary as to how much a contrary wind can affect speed: some say it slows a cyclist down by half the windspeed (e.g., 2 mph for a 4 mph wind). Roughly a third of air resistance is encountered by the bike, roughly two-thirds by the rider.

The most obvious way to counter air resistance is by sheltering, be it merely by riding close to the hedge when the wind blows or choosing valley roads on a windy day. Riding in the slipstream of another cyclist uses up about 25 percent less energy depending on the size of the rider in front (team pursuit squads look for four cyclists about the same height and width to take advantage of this) and is the key to most of the tactical niceties of road and track racing. A bunch of cyclists riding together offers even greater shelter, as does a pacing motorbike such as a DERNY. Before motor vehicles got too quick, cyclists like FAUSTO COPPI would go “truck-hunting” to get in speed training.

Changing handlebar position produces immediate results; riding with the hands on the “drops,” not the brake levers, flattens the torso and increases speed by between 0.5 and 1.25 mph. Tucking in any loose clothing helps as well. Shaving the legs produces negligible benefits (see HAIR for other shaggy-cyclist stories), but wearing an aerodynamic teardrop-shaped helmet helps considerably, as does wearing a one-piece skinsuit rather than separate jersey and shorts, and putting covers over the shoes.

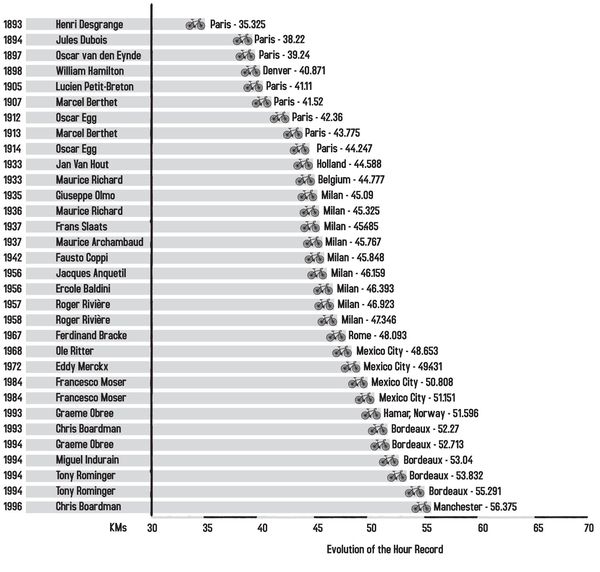

So much for the basics. Most recent aerodynamic developments can be traced back to FRANCESCO MOSER and his attempts on the HOUR RECORD in 1982. The Italian used a Lycra hat, shoe-covers, a plunging frame to lower the angle of his torso and reduce the profile of the bike, and solid disc wheels. All became widely accepted ways of reducing air resistance.

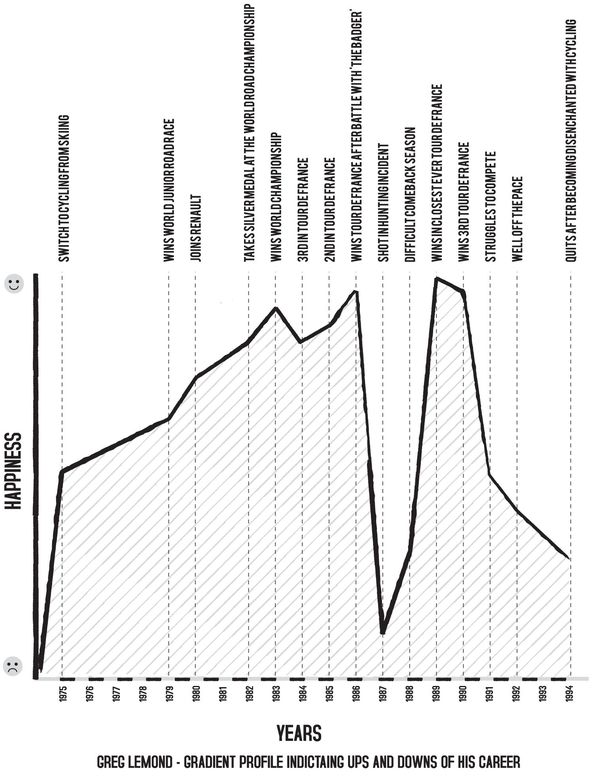

Tri-bars, so-called because they were first used by triathletes in the US in the 1980s, were the next major development. They provided the most dramatic recent illustration of the power of aerodynamics when GREG LEMOND used a pair to overturn a 50 second deficit in the final time trial of the 1989 TOUR DE FRANCE. The loser, LAURENT FIGNON, was not riding the extensions, which allow the user to flatten the torso and push the arms forward along the lines of a downhill skier’s tuck.

Perhaps the ultimate tri-bar position was achieved by CHRIS BOARDMAN in the mid-1990s. He said of his work in the windtunnel at the Motor Industry Research Assocation in Birmingham, England: “They discovered that if I folded up my body position and tucked in my elbows the drag would be considerably reduced. What I learned was to reduce my frontal area. I have my handlebars about four or five centimeters lower than anybody else.” As a result, if you drove behind Boardman when he was riding a time trial, all that could be seen of him was his backside: his front end was completely flat, or pointing down slightly to minimize air resistance.

Percentage of drag in the following:

BODY: 80%

WHEELS: 4%

FRAME: 5%

Ways to improve aerodynamics:

TRIATHLON BARS: 10%

DEP. ON BODY SIZE + SHAPE

TEAR-DROP HELMET: 2%

ONE-PIECE SKINSUIT: 2%

SHOE COVERS: 1%

SMOOTHED OUT CARBON FRAME: 2%

DISC WHEELS: 2% DEP. ON WIND DIRECTION

The boundaries were pushed further by GRAEME OBREE in the build-up to his Hour attempt in 1993, when the Scot experimented with a tuck position with his arms up close to his chest. Together with his coach Peter Keen, Boardman ran tests on the Manchester velodrome, riding in various positions and using POWER CRANKS to ensure his power output was relatively constant. Under these controlled conditions, Obree’s tuck gave better airflow than either riding on the drops on a conventional bike or using triathlon handlebars. Obree later devised a stretched position known as “Superman”; both this and the tuck were eventually banned.

In the 1990 and 1991 Tours, LeMond rode Drop-In bars, which brought the tri-bar idea to road-racing bars; they had a lowered central section enabling him to get flatter and make his elbows more narrow than on conventional drops (they were also a handy location to put stickers advertising his bar-makers, Scott, for head-on television pictures); in the mid-1990s there was a brief craze for short triathlon-type extensions such as Cinelli’s Spinaci bars, which could be fitted to the middle of road racing bars, again enabling the rider to lower his profile. They were banned from 1998 by the UCI; Cinelli are still campaigning for the ban to be lifted.

The wind and the drag coefficient of the cyclist and the bike are not the only factors affecting aerodynamics. Air resistance decreases as altitude is gained, because there are fewer molecules in the atmosphere for the cyclist to push through; traveling at 30 mph at 2,000 m above sea level should take about 20 percent less effort. Hence the choice of Mexico City and La Paz for record attempts by riders like CHRIS HOY and EDDY MERCKX.

Air temperature matters too, with air resistance reducing by about 1 percent for every increase of three degrees Celsius. It has been known for track meeting organizers to keep the doors closed before the home team rides a qualifier in an event such as the team pursuit, so they benefit from a higher temperature. They then open the doors shortly before their main rival goes to lower the temperature by a few degrees. Barometric pressure has an effect as well: the ideal weather conditions for recordbreaking are a high temperature combined with low pressure.

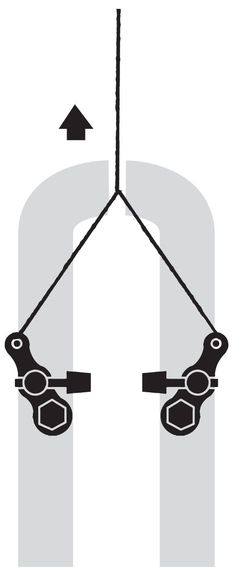

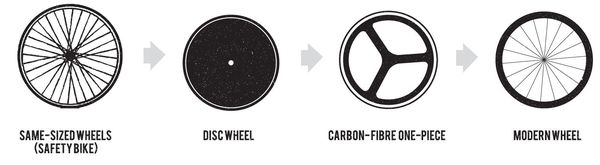

After tri-bars, the most efficient way to improve the aerodynamic profile of a bike is to fit disc wheels. These eliminate the drag produced by a conventional wheel with spokes, which have an uneven drag profile because as they come forward at the top of the wheel rotation they are going at twice the bike’s forward speed.

Aerodynamic frame tubes also play a part: they should be teardrop-shaped, but three and a half times as long as they are round to be most efficient. “If a tube is too round, instead of flowing round the tube, the air bounces off it and creates mini vortexes that actually increase drag,” says Boardman. Every part of the bike pulls on the air; hence the British Olympic team’s return to the drawing board before the Beijing Games when their technicians—led by Boardman and the carbon frame specialist Dimitris Katsanis—assessed every last part of their carbon-fiber bikes. The result was smoothed-out handlebars, produced as a single element with the stem; even the wheelnuts were reconfigured to save an estimated 0.005 percent of drag coefficient.

(SEE BURROWS, RECUMBENTS, OLYMPIC GAMES)

AFRICA Cycling is a vital means of transport here and, in addition, cycle racing goes on in places and ways that few outside the continent know about. To take one example, in Eritrea the influence of Italian colonists from the early 20th century means that cycling is the national sport, with some 800 registered racers in the capital Asmara. The Giro di Eritrea was founded in 1946 and relaunched in 2001, eight years after the end of war with Ethiopia. There are said to be about 100 professionals in the country earning several times the average wage. An Eritrean cyclist, Daniel Teklehaimanot, finished 50th in the time trial in the 2009 world under-23 road race championships.

Italian and French colonial influence brought bike racing to the North African coast, and the sport is also strong in other former French colonies such as Burkina Faso and Mali. The Italian Marco Pastonesi interviewed Burkinabe cyclists for his 2007 book The Craziest Race in the World; they told him that cycling is the most popular sport in the country. The TOUR DE FRANCE organizers ASO recognize this by running the annual Tour du Faso each autumn. Cycle racing in Burkina Faso goes back to the postwar era, when FAUSTO COPPI came to race there in a series of criteriums in the capital, Ouagadougou, to celebrate the country’s independence (it was then known as Upper Volta); after one of the races, Coppi caught the malaria which was to end his life.

Colonialism was also responsible for bringing the first African to the Tour de France: Abdel Kader Zaaf was an Algerian who became French national champion in 1942 and 1947, and rode the Tour in 1950 for a North Africa team. Zaaf was involved in a legendary episode when he was riding 16 minutes ahead of the bunch on a baking hot stage in the South of France and was given a bottle of wine by a spectator; the alcohol affected him so badly that he ended up riding the wrong way down the road.

More recently, in 2007, the South African team Barloworld became the first squad from the continent to race the Tour, when Robbie Hunter—already the first South African to start the Tour, in 2001—was the first stage winner from the country at Montpellier (see CAPE TOWN to read about the biggest bike race in Africa and the world). The best African races figure on the UCI’s Africa Tour that includes events in Cameroon, Tunisia, Ivory Coast, Morocco, Gabon, Egypt, and Libya. The 2008–9 winner was Dan Craven, a Namibian riding with British squad Rapha-Condor.

In 2009, there were projects under way to turn cyclists in both Rwanda and Kenya into world-class roadmen. The Rwanda project was headed by Jonathan Boyer, the first American to finish the Tour de France. One of his riders, Leonard, was spotted when he kept pace with the team while carrying 150 pounds of potatoes on his bike. The project was set up by Tom Ritchey, one of the founding fathers of the MOUNTAIN BIKE, who set up a race, the Wooden Bike Classic, on which Rwandans could race the basic machines they used to carry coffee from the fields. The project in Kenya, backed by a French hedge fund, aims to transfer to cycling the endurance skills the Kenyans have shown in running.

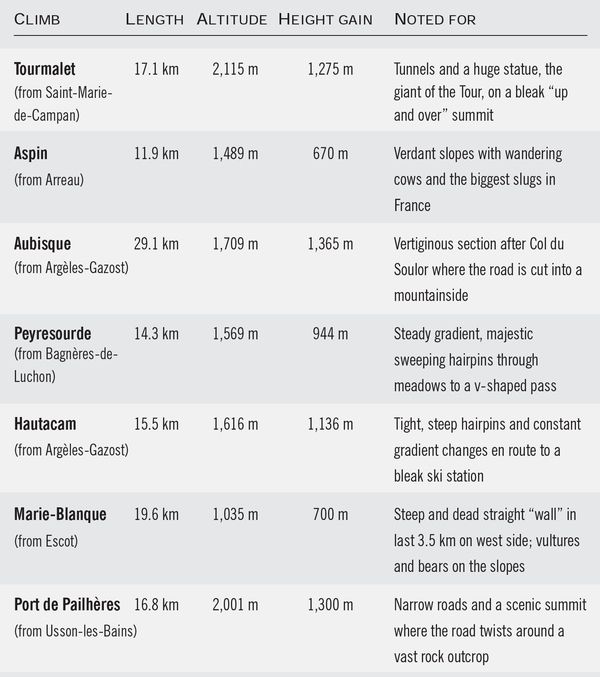

ALPS When the Alps were added to the TOUR DE FRANCE route in 1911, the idea of riding a bike over summits such as the 2,646 m high Col du Galibier seemed outlandish: such tracks connecting one mountain village with another were barely passable on foot, even in summer. When the Tour went over that July, the Galibier was still covered in vast snowdrifts and the road was a dirt track deeply rutted with streams of melt water. The road has been improved, but cycling to an altitude of nearly 9,000 ft remains an immense challenge.

Then, the Alps fitted perfectly with Tour founder HENRI DESGRANGE’s aim of producing cycling supermen to captivate the readers of his paper L’Auto. Desgrange wanted to set his cyclists seemingly impossible tasks to perform amid epic backdrops, to make the most dramatic copy possible for his paper. Now, however, the mountains are accessible to ordinary cyclists thanks to better roads and the organization of a huge range of mass-participation events (see CYCLOSPORTIVES). In these events, the attraction lies in facing the same challenges as the stars of cycling, at a different speed.

The highest paved pass in the Alps is the Cime de la Bonette, sometimes known as the Bonette-Restefonds. It actually consists of two roads, one of which crosses the Col de Restefonds at an altitude just below that of the Col d’Iseran; to create the highest pass in Europe, the local council added a loop up around the black shale scree slopes of the Bonette peak, which is where the Tour goes.

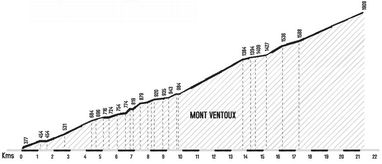

Opinions vary, naturally, as to the toughest climb in the Alps: the north face of the Galibier, as climbed by the Tour in 1911, is a contender, because of the length of the ascent from Valloire over the Col du Télégraphe before the steepest part actually begins. Another contender is the Joux-Plane between Cluses and Morzine in the northern Alps, which is unremittingly steep, but toughest of all is probably Mont Ventoux. This peak lies a little south of the main Alpine massif. It is longer than the Joux-Plane but almost as steep, with extreme conditions—heat or cold—occurring frequently on the summit. (see TOM SIMPSON to read the story of his death here).

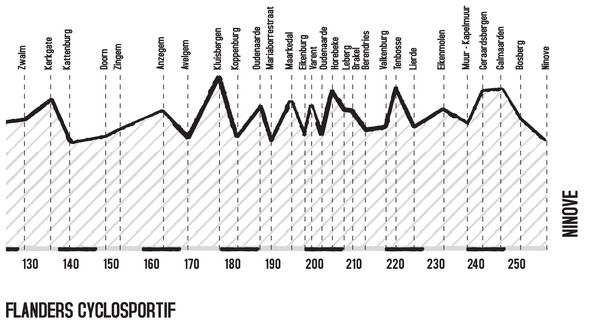

The great Alpine climbs are used by CYCLOSPORTIVE events, of which the best-known is the Marmotte, which has been run for over 30 years. The 174 km course begins in Bourg d’Oisansand goes over the Croix de Fer and Galibier before finishing up l’Alpe d’Huez. La Ventoux ascends the Ventoux at the end of a 170 km loop. On some of the great climbs, local tourist offices run informal timed events up the climbs, so that amateurs can measure their times against the professionals—at l’Alpe d’Huez, for example, this takes place every Monday through the summer.

There are two Raids Alpines run along the lines of the better-known RAID PYRENEAN. These are informal challenges run by the cycling club in Thonon-les-Bains. One route takes cyclists from Lake Geneva to the Mediterranean Coast at Antibes over 43 passes with a total of 18,187 m climbing during the 740 km journey; the other travels from Thonon to Trieste, taking in 44 cols for a total of 22,131 m climbing in the 1,180 km route.

The passes in the southeastern section of the Alps, over the Italian border from France, are a key element in the GIRO D’ITALIA, with their own cycling history: see DOLOMITES for more details.

Further reading: Tour Climbs, Chris Sidwells (Collins, 2008).

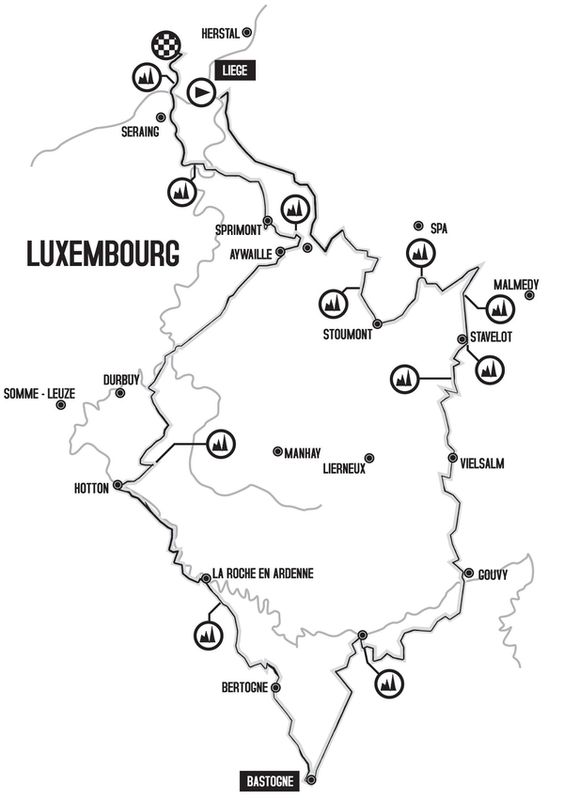

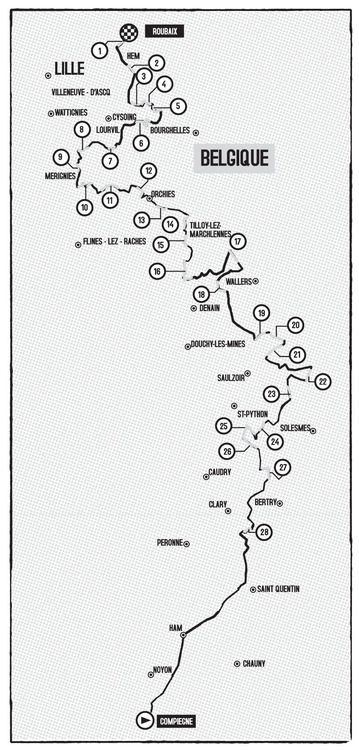

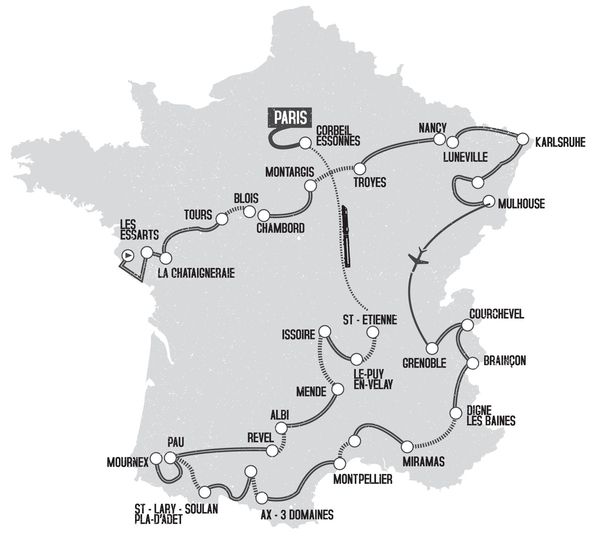

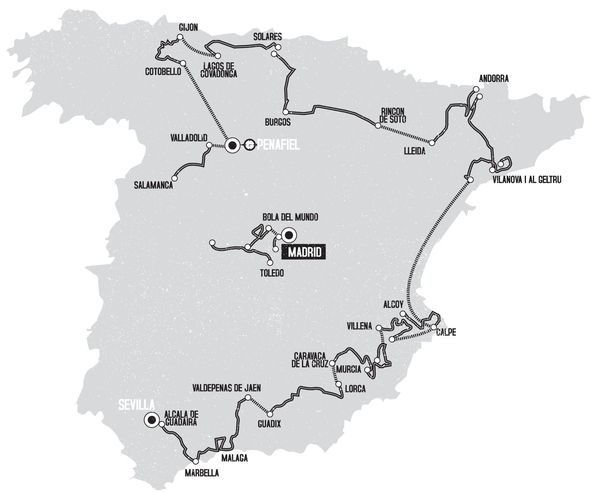

AMAURY SPORT ORGANISATION (ASO) The world’s leading cycle race organizer, responsible for the TOUR DE FRANCE, LIÈGE–BASTOGNE–LIÈGE and PARIS–ROUBAIX, and other races (see right) which make up the bulk of the French calendar. Based in Paris, the company also owns 49 percent of the Vuelta a España, and has partnerships with Tour of California. In early 2010 it took over the Dauphiné Libéré, giving it a near monopoly on French races.

ASO’s lineage goes back to the newspaper L’Auto, which ran the first Tour de France. Under HENRI DESGRANGE and his successor Jacques Goddet, the paper organized the race until the outbreak of war in 1940. During the war, Goddet continued to publish, which meant that after liberation, L’Auto could no longer appear as all publications that had printed under the Germans were shut down. After the war, the paper and its editor were charged with collaboration, but cleared, and Goddet was given charge of L’Equipe, a new paper that was in essence L’Auto under a different name. He then ran the race jointly with Émilien Amaury’s Le Parisien Libéré, with Félix Lévitan as codirector. Amaury bought L’Equipe in 1965 and created a multimedia promotional and publishing empire that included venues such as the Parc des Princes stadium in Paris.

The ASO Roster

=

TOUR DE FRANCE

PARIS–ROUBAIX (PRO AND UNDER-23)

LIÈGE–BASTOGNE–LIÈGE

PARIS–TOURS (PRO AND UNDER-23)

FLÈCHE–WALLONNE (PRO AND WOMEN)

CRITÉRIUM INTERNATIONAL

PARIS–NICE

DAUPHINÉ LIBÉRÉ

TOUR DE PICARDIE

ÉTAPE DU TOUR

TOUR DE L’AVENIR

TOUR OF QATAR (PRO AND WOMEN)

TOUR DU FASO

PARIS–DAKAR MOTOR RACE

PARIS MARATHON

FRENCH GOLF OPEN

Later the group’s cycling promotions were split off into a separate company, the Société du Tour de France; early in the 21st century this was merged into ASO, covering all Amaury’s sports promotions. Goddet remained in charge of the STF’s races until his retirement in 1989, when the former journalist Jean-Marie Leblanc took over. ASO grew rapidly during the 1990s, from less than 50 employees in 1992 to well over 200 in 2008, running 16 sports events including the Paris–Dakar rally, athletics, golf, and equestrianism.

After the 1998 doping scandal involving the Festina team, ASO became aware of the dangers that drugs posed to its races. The problem was that as race organizers, its options were limited: Leblanc tried refusing entry to those the race considered to be suspect, but he had limited support from the UCI, and in any case it was impossible to tell who was suspect and who wasn’t. Leblanc retired in 2005; since then the Tour has been run by former television journalist Christian Prudhomme. (See section on the UCI for how ASO fell out with cycling’s governing body between 2005 and 2008.)

The Tour is ASO’s main source of income, estimated to bring in 70 percent of its profits.

ANDERSON, Phil (b. England, 1958)

Australian cycling’s second great pioneer, after Sir HUBERT OPPERMAN. A whole new antipodean audience became aware of cycling thanks to Anderson’s achievements in the 1980s, most notably his two stints in the Tour de France’s yellow jersey in 1981 and 1982. Neither a truly great time triallist, sprinter, or climber, Anderson epitomized the battling Aussie, winning races through grit and racecraft.

An early member of the FOREIGN LEGION, he was a young pro with PEUGEOT when he hung on to BERNARD HINAULT at the Pla d’Adet climb in the 1981 Tour to become Australia’s first wearer of the maillot jaune. Anderson went on to win two Tour stages (Nancy 1982, Quimper 1991) and finished in the Tour’s top 10 five times, once while fighting the pain from a broken sternum. He also won two one-day CLASSICS (Amstel Gold 1985, Créteil–Chaville 1986); he was a member of two iconic teams, Peugeot and Panasonic, and together with GREG LEMOND helped to drag European cycling into the modern world.

Anderson was one of the first riders to arrive at a contractual meeting with a lawyer in tow (“I couldn’t read French but that was the language of the contract so I turned up with a solicitor from Paris. He said it wasn’t worth the paper it was written on,” he said in Rupert Guinness’s Aussie Aussie Aussie Oui, Oui, Oui). In addition, his relationship with 7-Eleven SOIGNEUR Shelley Verses in the late 1980s broke the long standing taboo over SEX in cycling. He was also a legendary hardman who late in his career suffered from a loose shoulder-joint that would dislocate when he crashed; Anderson would simply put it back in by the roadside and get back on his bike.

ANQUETIL, Jacques

Born: Mont-St-Aignan, France, January 8, 1934

Died: Rouen, November 18, 1987

Major wins: Tour de France 1957, 1961–64, 16 stage wins; Giro d’Italia 1960, 1964, six stage wins; Vuelta a España 1963, one stage win; Liège–Bastogne–Liège 1966; Ghent–Wevelgem 1964; Bordeaux–Paris 1965; GP des Nations 1953–58, 1961, 1965–66; world hour record 1956

Nickname: Master Jacques

Interests outside cycling: cards, alcohol, cigarettes, farming, women (especially close family members)

Further reading: Sex, Lies and Handlebar Tape, Paul Howard (Mainstream, 2008)

A single image of the Norman strawberry-grower’s son is forever etched on France’s national consciousness. The elbow-to-elbow battle between “Monsieur Jacques” and Raymond POULIDOR (nicknamed PouPou) on the Puy-de-Dôme mountaintop finish in the 1964 TOUR DE FRANCE remains French cycling’s equivalent of the Stanley Matthews Cup Final. The RIVALRY between the pair was one of the greatest that French sports has ever seen.

Blond-haired and with chilly blue eyes, Anquetil made his name in 1956 aged only 22, by breaking the HOUR RECORD, which had been held by FAUSTO COPPI for 14 years; like the Italian, he won the Tour at his first attempt. Coppi was his early model in his approach to cycling, and like the CAMPIONISSIMO, he was a master of cycling style: always well dressed, with immaculately slicked-back hair, and with his glamorous wife, Jeanine, gracing his arm. He was respected rather than loved by French cycling fans, who found him clinical and unemotional; the less successful PouPou remains their favorite.

Anquetil was the first man to win five Tours, his best victories coming in 1963, when he took both major mountain stages, and in 1964, when his duel with Poulidor reached its climax on the extinct volcano in the Massif Central. There, knowing he had to gain time on Anquetil before the final time trial, PouPou attacked repeatedly and Monsieur Jacques hung on for grim death. Just before the finish, he cracked, but held the yellow jersey—and the psychological whiphand—by just 14 seconds. Their rivalry was never personal, as Anquetil later said: “Of course I would like to see Poulidor win in my absence. I have beaten him so often that his victory would only add to my reputation.”

Anquetil managed the Giro–Tour DOUBLE that year, but his most audacious feat came in 1965, when he took back-to-back wins in the Dauphiné Libéré stage race and the now defunct motorpaced Bordeaux–Paris (see CLASSICS for more on this event). The Dauphiné is eight days of racing through the Alps; the 560 km “Derby” lasted 15 hours. The stage race finished at 5 PM; Bordeaux— Paris began at two o’clock the following morning. Legend has it that Anquetil spent the time between the two races playing poker, but what is certain is that he was flown from the Alps to Bordeaux in a government jet with the blessing of General de Gaulle and then braved bone-chilling rain to win in Paris, having raced 2,500 km in nine days.

Anquetil was a supreme time triallist, winning 65 solo races in his career. He could churn massive gears in immaculate style, thanks to motorpaced training, and an efficient aerodynamic position. He made a point of ignoring conventional wisdom about diet—champagne, oysters, and whisky were among his favorites—posed for cigarette ads, and was notoriously open about his use of DRUGS, which he viewed as being no more than what it took to do the job he was paid to do. He refused a drug test after his second hour record—which was not ratified—and led a riders’ strike against drug tests in 1966. His domestic life was also unconventional (see SEX).

A television commentator and gentleman farmer in retirement, as well as director of the Paris–Nice stage race, he died of stomach cancer in 1987 and is remembered with an ornate gravestone in the cemetery in his home village of Quincampoix, just outside Rouen.

(SEE ALSO MEMORIALS)

ANTARCTICA Not the most hospitable of cycling environments, but during Sir Ernest Shackleton’s abortive attempt to cross the continent in 1914–15 one of the more eccentric members of his crew, Thomas Orde-Lees, got on a bike and rode on the pack ice while the expedition’s ship Endurance was frozen in the Weddell Sea.

APPAREL

Team apparel, a selection of the good, the bad, and the ugly:

Bic: gloriously simple, amazingly orange, to set off the brooding Hispanic looks of Luis Ocana, not to mention JACQUES ANQUETIL.

Brooklyn: Yankee stars and white stripes on a deep blue backdrop, and CLASSICS specialist ROGER DE VLAEMINCK to wear it.

Z: moldbreakingly bonkers comic-book “kapow splash” on a blue background. Crazy sponsor, crazy money for GREG LEMOND.

ONCE: dramatic yellow with “blind man” logo (or was it a lottery winner taking a leak?); the pink design for the Tour never worked that well.

EMI: one for the connoisseur, black diamond amid black and white hoops, worn by ace climber Charly Gaul, the “Angel of the Mountains.”

St. Raphael: twirly lettering and the glamour of Jacques Anquetil and TOM SIMPSON.

La Vie Claire: groundbreaking Mondrian-style interlocking rectangles that took team jersey design away from the “name on colored background” template when BERNARD HINAULT began wearing it in 1984.

Saeco: the uniform itself was routine red, but the crazy variants created for wacky sprinter Mario Cipollini were unique, perhaps fortunately. Green with a peace symbol for Peace in Ireland, Julius Caesar’s “veni vidi vici,” tiger stripes, “X-ray” showing internal organs, and so on. Impactful yes, tasteful no.

Carrera Jeans: basic blue-shoulders-on-white design that was simplicity itself and was fine in its first incarnation worn by STEPHEN ROCHE. But then the company decided to bring in “denim” shorts complete with fake pockets and rivets.

Le Groupement: a psychedelic nightmare of red, yellow, green, purple, and blue splotches worn inter alia by ROBERT MILLAR. A merciful deliverance when the pyramid sales group went bust in July 1995.

Great Britain, 1997: who can forget the green snot color that replaced good old blue with red shoulders. It certainly made the point that GB had broken with the past when lottery funding started (see GREAT BRITAIN).

Scotland, 1998: tartan shorts no less. Nationalists dreamed this one up, aesthetes just covered their eyes.

(SEE SPONSORS FOR A LIST OF WEIRD AND WONDERFUL CYCLING BACKERS; TEAMS FOR HOW THEY DEVELOPED PLUS SOME OF THE ICONIC NAMES AND THEIR COLORS)

ARMSTRONG, Lance

Born: Dallas, Texas, September, 18, 1971

Major wins: Tour de France 1999–2005, 22 stage wins; world road race championship 1993; San Sebastian Classic 1995, Flèche Wallonne 1996

Nicknames: Big Tex, Mellow Johnny, Le Boss

Further reading: It’s Not About the Bike, Lance Armstrong and Sally Jenkins, Berkley Trade, 2000; Lance Armstrong’s War, Daniel Coyle, Harper Paperbacks, 2006; Lance: The Making of the World’s Greatest Champion, John Wilcockson, Da Capo Press, 2010; Comeback 2.0: Up Close and Personal, Lance Armstrong with Elisabeth Kreutz, Touchstone, 2009

There are two sides to the record winner of the Tour de France: a hero to cancer survivors worldwide and a highly divisive figure within his sport. Armstrong will always be defined by his comeback from severe testicular cancer, diagnosed in September 1996 when he was only 25, but he had already won a world championship (1993), a brace of one-day CLASSICS, and a stage in the 1995 TOUR DE FRANCE. With lesions in his lungs, stomach, and brain as well as one testicle, he was told he had a 40 percent chance of survival but in fact the doctors did not expect him to come through.

Vicious courses of chemotherapy followed, but there was never any doubt about whether he would return to cycling, as his first thought when he was diagnosed had been for his sport. “When they told me about the cancer I can’t remember which hit me first: I might die, or I might lose my cycling career.” But while he was in remission, no team would gamble on signing him as they were worried his comeback would end in failure.

Armstrong eventually signed for the relatively small US Postal Team and remained bitterly angry with the European managers who had rejected him. By spring 1998 he was racing again, and in 1999 he won the Tour, sealing victory with a crushing mountaintop win at the Italian ski resort of Sestrière. Suddenly, he was cycling’s biggest ever star: his autobiography It’s Not About the Bike topped the bestseller lists, by 2002 his earnings were estimated at $7.5 million, and presidents Clinton and Bush jumped on the bandwagon.

To complete the dream story, Armstrong married his fiancée, Kristin Richards, and they had three children, conceived in vitro from sperm he had banked before his chemotherapy began. His cancer charity Livestrong was a rapid success, with its most successful promotion a distinctive yellow wristband launched in May 2004 and retailing at one dollar. Over 70 million have been snapped up to date, with up to 10,000 sold on a single day in the 2009 Tour de France.

Dominating the Tour in the early years of the new century, Armstrong took cycling to a new audience worldwide and particularly in the USA, popularizing the sport to the extent that a time trial up l’Alpe d’Huez in his seventh successive victorious Tour, 2005, was shown live on a big television screen in Times Square. By then, however, his private life had unraveled: he had divorced from Kristin in 2003 and would subsequently date rock singer Sheryl Crow and various Hollywood starlets before starting a second family with Anna Hansen in June 2009. His story brought the Tour onto the celebrity circuit: as well as Crow, comedian Robin Williams and actor Jake Gyllenhaal came in Armstrong’s wake. Damien Hirst customized a bike for him, while George W. Bush put him on a cancer commission.

For all the celebrity sheen, Armstrong can be vindictive toward anyone who crosses him: journalists, officials, former teammates, and other cyclists, as his exchanges with Alberto Contador after the 2009 Tour showed. During his run of seven Tour wins, a team press officer kept a blacklist of media “trolls,” and he crossed swords regularly with the WADA head Dick Pound over the latter’s views on doping. In the 2004 Tour the Texan waged a personal campaign against the Italian Filippo Simeoni, because he had testified against their trainer MICHELE FERRARI in a drugs trial.

Armstrong was accused of DOPING on several occasions. In his first Tour win, 1999, traces of corticosteroids were found in his urine, but a prescription indicated it came from a skin cream. In 2000, French police investigated packaging and bloodied compresses dumped by personnel from his team, but found nothing. When samples from the 1999 Tour de France were tested retroactively for EPO during research in 2005, several allegedly showed traces of the drug, but an inquiry concluded that no action should betaken. Questions were frequently asked about his close working relationship with Ferrari. He also won a case brought by the insurance company that guaranteed his win bonuses, alleging he had used banned practices to take his Tour wins. His response was consistently the same: he was the most tested athlete in the world and had nothing to hide. In 2005 on his retirement, standing on the winner’s podium on the Champs-Elysées, he bitterly attacked those who had doubted his probity and that of his colleagues.

Armstrong returned to competition in 2009 after three seasons out. It was a lively year: a team of French drug testers claimed that Armstrong had breached protocol by taking a shower before a random test; the Texan boycotted the press during the Tour of Italy after falling out with the organizers, and when the equally combative five-times Tour winner BERNARD HINAULT questioned his comeback, the Texan responded on his Twitter feed that the Badger was a “wanker.” In the background, as well, were constant doubts about the financial status of the backer Astana, a consortium of companies based in Kazakhstan. When money failed to turn up to pay the riders, Armstrong responded by riding in a jersey with none of the Kazakh sponsors’ names visible on it. Shortly before the Tour, the team was within hours of being declared financially unviable.

The 2009 Tour was dominated by Armstrong’s battle for leadership within Astana with Alberto Contador, the 2007 Tour winner. The Spaniard had the legs; Armstrong had the experience, the backing of team manager Johan Bruyneel, and the ability to wage psychological war. Although Contador ended up the winner, Armstrong became one of the oldest cyclists to get on the podium when he finished third. At the end of the season he and Bruyneel quit Astana to start their own team, sponsored by Radioshack.

Team Radioshack won the 2010 Tour de France team prize, although Armstrong placed 23rd, in part due to a serious crash on stage 8. He announced that after the January 2011 Tour Down Under, he would confine his racing to the United States. In the meantime, the FDA is investigating whether Armstrong was involved in an organized doping operation as a member of the US Postal Service team between 1999 and 2004.

(SEE ALSO UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, CHARITIES, LONGEVITY, RIVALRIES)

ART The best-known cycling work of art is probably La Chaine Simpson, a poster produced by the cycling mad impressionist Henri de TOULOUSE-LAUTREC in 1896, while bikes are also featured in the work of Salvador Dali and Picasso. The Catalan impressionist painter Ramon Casas y Carbo (1866–1932) produced images similar to those of Toulouse-Lautrec. The Repair perfectly captures the moment when a cyclist bends down to his or her wheel to adjust a nut or a valve. Woman on a bike is a cartoon of a lady tricyclist;

ART FACTOID

At the end of 2009 six bikes decorated by contemporary artists for Lance Armstrong to ride during his comeback season were auctioned at Sotheby’s in aid of the Texan’s Livestrong charity. A Damien Hirst machine decorated with butterflies sold for $500,000.

4

The Tandem shows two hirsute, muscly men—a self-portrait of Casas and his fellow artist Pere Romeu—in full flight. Dali, for his part, produced an official postcard for the 1959 Tour de France—which no one seems able to locate today—and produced several works featuring cyclists, such as Sentimental Conversation (1944), in which a host of deathly figures on bikes ride across the canvas past a grand piano.

There are also a host of cycle specialist artists active today. For example, in the United States, Brooklyn-based artist Taliah Lempert has been exhibiting since 1996 and is well known for her paintings, sketches, and prints of bicycles of all kinds: racers, shopping bikes, kids’ playbikes, and classic Bianchis and Masis. Some of her work uses oils on large canvases containing a single bicycle against a semi-neutral background, with the emphasis on the machine as a work of art in itself, akin to a sculpture with its graded lines. Other works feature details of cut-out lugs and individual items such as waterbottles. In a 1999 interview, Lempert said she does not work from photographs or slides, but only from original bikes, which she rides in order to get a feel for the character of the machine: worn, shiny, pristine, etched with street grime. Lempert’s work includes tangled piles of bikes such as might have been found outside a velodrome in the halcyon days of the sport, and “blind drawings,” loosely drawn and impressionistic in style; she described these in an interview with thewashingmachinepost. net as an “explosion of color and lines, there’s lots of movement.”

In Great Britain, Cornish artist Peg Jarvis has produced a body of work featuring track cyclists including the award-winning etching Pursuit 3. “I particularly love the track; it reminds me of Roman chariot racing—the excitement, the sound, the fact that you can see everyone and everything. I need to see the cyclists at work, warming up, warming down. As an artist, you need to draw something 100 times before it sinks into the memory; on the road, they go past so quickly that they are no use to me.”

Jarvis has moved from drawings to etching, in some cases manipulating photographic negatives and shining them onto light sensitive metal plates, in others simply sitting by the trackside and scratching onto huge metal plates. More recently she has used watercolors; she is particularly proud of a painting that used the photofinish image of Olympic cyclist Jason Kenny’s crash in Manchester as its starting point. The photo was blown up, manipulated, and subdivided into sections that included artifacts such as parking tickets and stamps in order to illustrate its interaction with her own life.

Jarvis cites among her influences Italian and Russian futurists, for the way they attempted to capture speed and power: the best-known images of this kind include Umberto Boccioni’s Dynamism of a Cyclist (1913) and Au Velodrome by the cubist Jean Metzinger, which includes cut-outs of words from newspapers glued onto the walls of the track.

The British artist Frank Patterson (1871–1952) has a devoted following for his pen-and-ink drawings of cyclists and the British landscape that appeared in the pages of Cycling magazine and the CTC journal The Gazette from 1893. Patterson was hugely prolific, working for other magazines owned by Temple Press, which published Cycling; his total number of drawings was estimated at about 26,000 in his 59-year career.

Pattersons are beautifully and precisely drawn, with an element of the draftsman to them. They are bucolic, romantic, occasionally humorous, and now look distinctly old-fashioned and even mannered, with their clubmen smoking pipes and wearing plus fours, bicycles leaning against a convenient tree while they admire the view. There is a timeless and very British charm about them.

ASO See AMOURY SPORT ORGANISATION.

AUDAX The term is used to denote long group rides covered in a set time in a single day and dates back to a group of Italian cyclists who rode from Rome to Naples—230 km—in June 1897. The newspapers referred to those who completed the distance as audace—audacious—and when Neapolitan cyclists made the return trip they formed a club for riders who could do over 200 km in a day; the newspaper term was translated into Latin, audax, and the group called itself Audax Italiano. The rides are called Randonnées—a French term meaning an outing using any means of transport—and the riders randonneurs.

The notion of group rides within a certain time, halfway between leisure and pure competition, gained pace internationally when the TOUR DE FRANCE’s father, HENRI DESGRANGE, founded a French body in 1904. Desgrange’s paper L’Auto—organizer of the Tour—ran the first Audax event in which medals and certificates were awarded to finishers; yellow, the color of L’Auto’s pages and the leader’s jersey in the Tour, remains the color of 200 km medals.

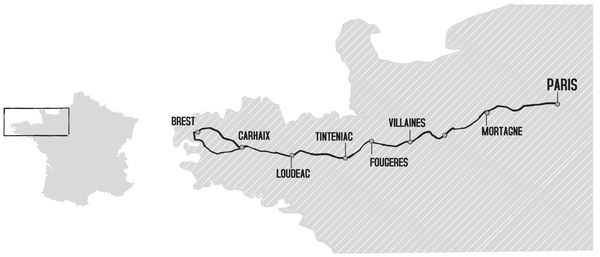

Audax rides differ from the more recently invented CYCLOSPORTIVES such as L’ÉTAPE DU TOUR in that in theory their events have to be ridden at a predetermined average speed—this was 18 kph until 1945—and there may be a “ride leader” who cannot be overtaken. The idea is to discourage racing. In practice there has been a rift in the movement and this is not universally followed. PARIS–BREST–PARIS, the largest and oldest Audax Randonnée, is not run on this basis; unlike cyclosportives, however, riders are set a minimum time, which means that superfast cyclists may have to wait for controls to open. Additionally, while some ’sportives have assistance cars and are fully signposted, Audaxes emphasise self-sufficiency.

Today, Audaxes are run over the set distances of 200, 400, and 600 km; qualification for major events such as Paris–Brest–Paris depends on completion of a certain number of distance rides, which is checked by reference to the rider’s brevet book, which is stamped by the organizers. Events are thus sometimes also known as brevets.

AUSTRALIA The bicycle has a long history here, beginning with its use in the 1880s by gold prospectors in the bush. Cycles were also used for early postal services and by groups of itinerant sheep-shearers. Track racing began early in Australia with the Austral run in 1887 by the Melbourne Bicycle Club at the MCG over two miles; the discipline would remain important for the next 120 years.

The first Australian cycling star was a SIX-DAY rider in the heyday of the American events, Reggie MacNamara, known as the Iron Man. He moved to the US in 1912 and rode 115 of the events. His was one of the longest pro careers ever: he did not retire until 1939 when he was 50 years old. By then he had made a fortune but he ended his days penniless, working as a doorkeeper at Madison Square Garden, his stomach so damaged by the lifestyle and the drugs that he could not keep food down for more than half an hour.

The first road race in the Southern Hemisphere was Warrnambool—Melbourne, first run in 1895 and now the longest one-day race in the world at 299 km, as well as the second oldest. By 1909, the Australasian road championship was drawing over 500 entries. But Australia enjoyed only a sporadic international presence, simply because it was so far from the European heartland. In 1920, for example, the sprinter Bob Spears, son of a sheep farmer, became world champion in the discipline and made headlines at French tracks for giving boomerang lessons in between races.

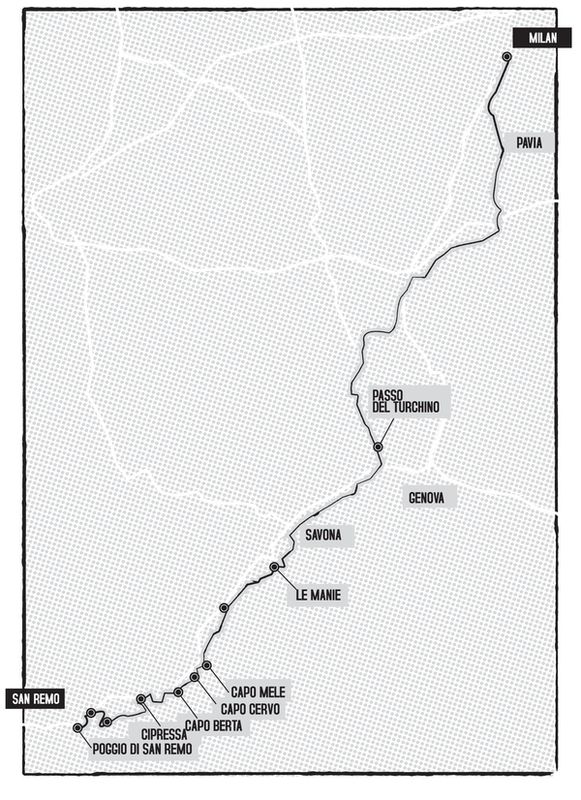

Professionals Don Kirkham and Snowy Munro did manage to finish the Tour in 1914, having spent the season racing in Europe as part of an Australian squad, riding classics such as Milan–San Remo and Paris–Roubaix. Kirkham and Munro rode the Tour as domestiques to the Frenchman Georges Passerieu; no Australian would again attempt the race until SIR HUBERT OPPERMAN made headlines in Europe and back home in the 1930s.

Australia continued to produce talented track riders such as Russell Mockridge, who won the Olympic kilometer title in 1952 and finished the Tour three years later, but internationally, the turning point came in the 1980s. In 1981 PHIL ANDERSON wore the yellow jersey briefly in the TOUR DE FRANCE, while in 1987 under the guidance of Charlie Walsh the Australian Institute of Sport began a cycling program that churned out droves of fine track racers—who dominated racing at the 2004 OLYMPIC GAMES—and guided their riders to the road through the formation of a European academy in Tuscany, and a pro team sponsored by GIANT.

Australian Cycle Racing at a Glance

=

Biggest race: Tour Down Under

Biggest star: Phil Anderson

First Tour stage win: Anderson, Nancy, 1982

Tour overall wins to 2010: none

Australia has given cycling: Cadel Evans, sprinters on road and track, a sunny start to the professional season, and Mulga Bill’s Bike (see BANJO PATERSON for this contribution to cycling culture)

Further reading: Aussie Aussie Aussie Oui, Oui, Oui by Rupert Guinness (Random House Australia, 2003)

Anderson had already been followed to Europe by talented racers such as Allan Peiper (a member of the FOREIGN LEGION), Stephen Hodge, and Neil Stephens, but the AIS program produced so much talent that by the late 1990s and early years of the 21st century, Australia was a stronger presence—certainly in performance terms, and sometimes even numerically—in the Tour de France than traditional cycling nations such as Belgium and Holland.

Robbie McEwen twice won the Tour’s most prestigious stage finish, on the Champs-Elysées (1999 and 2002) and won the green jersey in the latter year; Stuart O’Grady managed two spells in the yellow jersey (1998 and 2001), while Brad McGee landed the prologue time trial in 2003. An Australian event of truly international stature came onto the calendar in 2005 with the promotion of the Tour Down Under, which opens the UCI’s ProTour calendar in January.

With Cadel Evans, meanwhile, Australia finally found a rider capable of challenging for overall titles in major Tours. Evans began racing as a mountain-biker, winning the World Cup in 1998 and 1999 before transferring to the road with Saeco and Mapei then T-Mobile.

He is a volatile character not exactly popular with the media, who were hardly charitable to him as he came close to winning both the 2007 and 2008 Tours de France: his moodiness earned him the nickname “Cuddles.” Late 2009 saw him truly make history with a late solo attack to win Australia’s first world title in the men’s elite race at Mendrisio (see DOGS to learn how his love for his pet colored his relations with the media).

B

BAHAMONTES, Federico

(b. Spain, 1928)

Spain’s first TOUR DE FRANCE winner, and one of the finest mountain climbers the sport has ever produced. The “Eagle of Toledo” was the first rider to be crowned King of the Mountains in all three major Tours, a feat emulated only by LUIS HERRERA of Colombia. He won the best-climber award in the Tour de France six times, a record that stood for 40 years. He is also one of the few cyclists to race the Vuelta, Giro, and Tour in the same year, finishing 6th, 17th, and 8th in the three events in 1958.

Bahamontes is celebrated as the rider who would race away from the field on the Tour’s great passes, then would stop and eat an ice cream at the top. That’s actually one of the race’s great myths, a one-off incident, as Bahamontes explained in an interview: “one of my spokes broke on the way up [the Galibier], so I attacked so that the repair could be done at the top. But the team car with the spare was stuck behind the bunch, so I bought an ice cream to pass the time.”

Bahamontes turned to cycling as a way of escaping starvation during the Spanish civil war, won his first race at 17, and was King of the Mountains in the Tour at his first attempt in 1954. He was received by the dictator General Franco after winning the Tour in 1959. His victory came partly thanks to a stalemate in the French team, which had two leaders, JACQUES ANQUETIL and Roger Rivière, neither of whom would work with the other. Bahamontes was a nervous, irrritable man who threw his bike into a ravine in the 1954 Tour because he was fed up and once chased a rival through the peloton brandishing a pump. After retirement he ran a bike shop in his home town.

(SEE ALSO SPAIN, WAR, POLITICS)

BALLANTINE, Richard

Contender for the title of cycling’s biggest-selling author, Ballantine introduced generations of Britons and Americans to cycling as a lifestyle through his million-selling Richard’s Bicycle Books series, which have been market-leaders since the first one was launched in 1972. Ballantine was an adept trend reader, founding the UK’s first glossy cycling magazine for the general market—Bicycle Magazine in 1981—and importing some of the first MOUNTAIN BIKES to the UK.

Prompted by the 1970s oil crisis, Ballantine was an early advocate of cycling as part of a green lifestyle, arguing strongly against the universal use of motor vehicles and suggesting that cycling was life-enhancing and liberating. The Bicycle Book, a practical guide to cycling for the novice, has been compared to Alex Comfort’s Joy of Sex for the way it changed mindsets and established a whole new market. Its great strengths are the accessible way that essential cycling knowledge is presented and Ballantine’s passion and humor about everything two-wheeled—one section in the Commuting chapter is simply labelled “Joy.”

It also includes a robust section on dealing with DOGS, a guide to the dangers of cars, and argues strongly for DEFENSIVE CYCLING. Ballantine’s latest work is City Cycling, which caters for the fast-growing cycle-commuter market.

BARTALI, Gino

Born:Ponte a Ema, Italy, July 18, 1914

Died: Ponte a Ema, Italy, May 5, 2000

Major wins: Tour de France 1938, 1948, 12 stage wins; Giro d’Italia 1936–7, 1946, 17 stage wins; Milan–San Remo 1939–40, 1947, 1950; Giro di Lombardia 1936, 1939–40; Championship of Zurich 1946, 1948; Tour of Switzerland 1946–7

Nicknames: the Pious One, the Iron Man, the Old One

The Italian remains the oldest man to win the TOUR DE FRANCE in the postwar era, triumphing in 1948 at the age of 34, 10 years after his first victory in the event. His career was one of cycling’s longest, 19 years spanning three decades; he won his first Italian national title in 1935, his last in 1952 (see LONGEVITY for other durable cyclists).

Bartali was famed for his epic RIVALRY with FAUSTO COPPI and for his fervent CATHOLICISM—he had a private chapel in his home in Tuscany and famously attended mass before stage starts in the Tour and Giro. He was also said never to have sworn once in seven years, and to disapprove of fellow cyclists urinating during races. Bartali was courted by Benito Mussolini’s fascists—Il Duce put pressure on him to ride the 1937 Tour—but he refused to wear the party insignia.

Like Coppi he lost the best years of his career to the Second World War. During the conflict he carried letters and forged documents hidden in his bike; he appeared to be merely training but was in fact acting as a courier for a Catholic network that was smuggling Jews out of Italy. The material was used to forge passports.

Postwar he became friendly with the Christian Democrat Italian prime minister Alcide de Gasperi. Bartali’s victory in the Tour in 1948 came as Italy descended into chaos and near revolution following the attempted murder of the Communist party leader Palmiro Togliatti. Before the critical stage through the ALPS, de Gasperi called Bartali at his hotel in Cannes and asked him to win for his country.

He broke away through the Alps to win the critical mountain stage, and the revolution was averted. Although historians contend that the tumult in Italy might well have died away whether or not Bartali had triumphed in the Tour, he has become celebrated as the man who prevented a revolution by winning it.

(SEE ALSO WAR, POLITICS)

BAUER, Steve (b. Canada, 1959)

While Alex Stieda has the honour of being the first Tour de France yellow jersey wearer from CANADA, Bauer blazed a lone trail as the country’s Tour de France star through the late 1980s and early 1990s, spending a total 14 days in the maillot jaune, and achieving Canada’s highest Tour finish of fourth in 1988. He was also Canada’s first CLASSIC winner, taking the Championship of Zurich in 1989, and his career at the highest level lasted from his silver medal ride in the 1984 OLYMPIC GAMES road race at Los Angeles to the 1996 Games in Atlanta, the year he retired.

Bauer turned professional for the La Vie Claire team alongside BERNARD HINAULT in 1985, and won the first stage of the 1988 Tour de France riding for the Helvetia team run by Hinault’s old manager Paul Koechli; he then wore the yellow jersey for five days. Later that year he was involved in one of the most controversial incidents seen in any WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS, when he and Claude Criquielion of Belgium collided while sprinting for the finish of the pro road race in Ronsse, Belgium. Criquielion sued Bauer for assault and the case dragged on for three years before going Bauer’s way.

In 1990 Bauer was on the wrong end of perhaps the closest finish to PARIS–ROUBAIX, coming second to Eddy Planckaert by a few millimeters, but later that year he was one of four riders who gained 10 minutes in the first stage of the Tour de France, and he ended up in the yellow jersey for nine days before eventually finishing 27th overall. In 1993, riding for Motorola, Bauer turned up at Paris–Roubaix on one of the strangest bikes ever seen there—an Eddy Merckx machine with a drastically relaxed seat angle nicknamed the stealth bike. It had a massively long wheelbase, a lengthened chain, and a special saddle with a raised back.

BBAR (British Best All Rounder) The BBAR is the mainstay of British TIME TRIALLING, a season-long contest to decide the best endurance specialist of the year. The rankings are decided according to average speeds set over three disciplines—50 and 100 miles and 12 hours for men, and 25, 50, and 100 miles for women. Men who achieve an average of over 22 mph are given certificates; for women the cutoff is 20 mph. There are also team and veteran rankings and competitions for school-age boys and girls over shorter distances. Individual clubs also run their own BBAR contests.

The BBAR was founded by the magazine Cycling in 1930, and the first winner was Frank Southall, who went on to win the contest four times in a row. After the war, the time trialling governing body, the Road Time Trials Council, took over the contest; until 1976, the average speed calculations were made by a Manchester cyclist named Tom Barlow using a slide rule. The women’s contest was dominated for a quarter of a century by the late BERYL BURTON, a record that stands out in all sports.

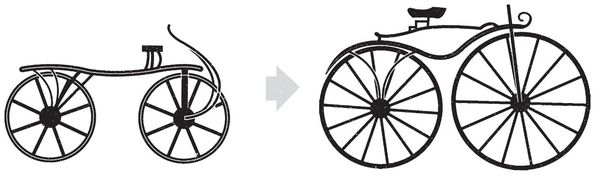

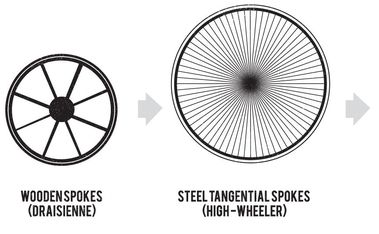

BICYCLE From the Latin “two wheels.” Although there are claims that LEONARDO DA VINCI dreamed up a bike, the earliest two-wheeled human-powered machines were produced at the start of the 19th century—first the DRAISIENNE or HOBBY HORSE, which didn’t have any pedals, and later the BONESHAKER, which did. What followed was a constant search for improvement in any area where mechanics came into play, from industry to personal transport, and a wide variety of cycle designs were patended, many for tricycles and quadricycles, none of which caught on.

In the early 1840s KIRKPATRICK MACMILLAN and the Frenchman Alexandre Lefebvre both produced rear-wheel-driven machines that never became popular; instead the HIGH-WHEELER took over before the first SAFETY BICYCLES were produced in the 1880s, with the definitive pattern set by JAMES STARLEY’s Rover in 1885.

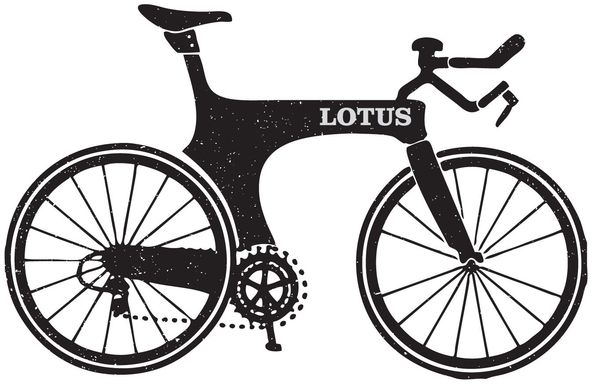

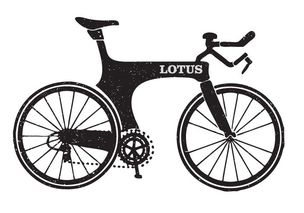

Radical variations on this basic bike design, truly established at the end of the 19th century, have been relatively rare. The Moulton small-wheeler from the 1960s is one departure that has enjoyed enduring popularity. The BMX bike and rear-suspended cross-country mountain bike are others, while MIKE BURROWS’s Lotus monocoque and GRAEME OBREE’s cross-beamed frame are reminders that we should never be content with the status quo.

(SEE MOULTON, OBREE, PEDERSEN FOR INVENTORS WHO TRIED TO BREAK THE MOLD; BRAKES, GEARS, WHEELS, TIRES, FRAMES FOR HOW THESE COMPONENTS DEVELOPED)

BICYCLE LANES Famously crap, except in HOLLAND (go to that country’s section to find out why this is the case). The first cycle lane in Britain opened in 1934, alongside the A40 in West London and was two and a half miles long and 2.5 m wide on either side of the road. Even then cyclists were complaining of a lack of investment in facilities and things have hardly improved since. Every urban cyclist has their own horror story of cars parked where they shouldn’t be, lanes that lead onto main thoroughfares and stop just when they are most needed, and lanes that last, oh, two meters if you are lucky. The phenomenon was significant enough that it generated its own pocket novelty book, Crap Cycle Lanes. We read it and wept.

BINDA, Alfredo

Born:Cittiglio, Italy, August 11, 1902

Died: March 30, 1986

Major wins: World road title 1927, 1930, 1932; Giro d’Italia 1925, 1927–9, 1933, 41 stages; Milan–San Remo 1929, 1931; Giro di Lombardia 1925–7, 1931

Nickname: Mona Lisa

One of the CAMPIONISSIMO, the first professional world champion, a great team manager, and the only man to be paid not to ride the Giro d’Italia, because he was so good that the organizers were worried he would kill off any interest in the race. By curious coincidence, he was also the first man to be offered start money to ride the TOUR DE FRANCE.

Binda began working life as a bricklayer and developed his sprinting speed with track racing when he was young. From 1927 to 1930 he was almost unbeatable, taking the inaugural professional world road race title on the Nürburgring in Germany ahead of the other campionissimo of the time, Costanta Girardengo. He won the Giro in 1925 and from 1927 to 1929, with 12 stage wins in the 1929 race, but was discreetly requested not to start the 1930 race and given the equivalent of first prize, six stage wins, and the bonus he would have won. “My best Giro,” he said later. “I consider I won it five and a half times.”

At that year’s Tour de France, on the other hand, HENRI DESGRANGE badly needed him to lend some luster to the event, being run for the first time with national rather than trade teams. Binda was paid a daily rate, won two stages, and quit so he could prepare to win a second world title. He was sworn to silence over the fee—Desgrange had been adamant he would never pay start money—and the secret emerged only in 1980.

After retirement in 1936, Binda became Italian national team manager, with the task of keeping FAUSTO COPPI and GINO BARTALI from falling out when their rivalry was at its height. He led the elaborate negotiations to ensure the pair would ride the 1949 Tour under Italian colors, then was responsible for persuading Coppi to stay in the race after he crashed on the stage to Saint-Malo and became convinced he should quit. He also had to deal with little matters like his deputy (Coppi’s trade team manager) failing to provide Bartali with a feed bag, and the fact that on the decisive day in the ALPS, neither would cooperate with the other.

Binda also oversaw Coppi’s second Tour win, in 1952, and guided Italy to world titles with Coppi and Ercole Baldini in 1953 and 1958. Later, he ran a company that made shoes, which was best known for producing toestraps, the universal way of attaching cycling shoes to pedals until ski-type bindings became popular in the late 1980s.

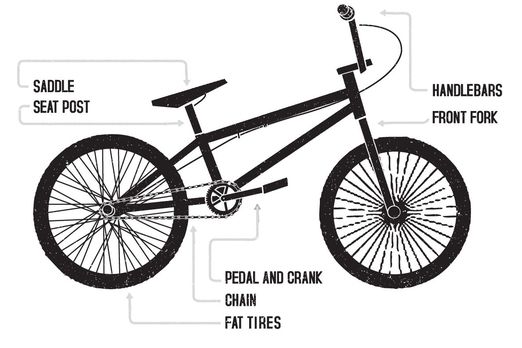

BMX Bicycle motocross entered the mainstream in 2008 when it was part of the program at the Beijing OLYMPIC GAMES. The hackles of traditionalists were raised, because the event it ousted, the kilometer time trial, was one of the classic disciplines. But the appeal was obvious. Run over short obstacle courses using scaled-down bikes, BMX is accessible, spectator friendly, and spectacular for television viewers. It’s also indelibly imprinted in the minds of anyone who watched the science fiction film E.T. “It’s a power sport that calls for skills and nerve as well,” says the British world champion Shanaze Reade. “You get a real rush of adrenaline when the start gate drops because you have only got 45 seconds to get everything out.”

BMX began in the 1970s in California when kids used to mess around on dirt tracks, inspired by the skill and speed of motocross racers. Today, races consist of heats for up to eight riders over a short purpose-built course (300–400m) including banked curves (berms), humps, and jumps. The riders line up with their wheels against a start gate that drops to launch them down a start ramp. Usually this ramp is only a few meters high, but at the Olympic Games, to make it a livelier spectacle for television, riders flew down a vertiginous eight-meter-high ramp with a slope of 33 percent. That meant the riders hit the course at over 30 mph, enabling them to get up to five meters into the air over the jumps.

BIZARRE BMX FACTOID

Nicole Kidman had her first starring role in the 1983 film BMX Bandits in which she played a bouffant-haired, crime-fighting, BMX-riding teenager. See FILMS for other two-wheeled movies.

4

Crashing is an ever-present risk so the riders wear loose-fit clothing and full motorcycle-style helmets. Bikes are small-wheeled—20 or 24 inches—with one brake and fat tires, and are small-framed with a huge amount of clearance between seat and saddle so that the riders can throw the bike about more easily.

Basic techniques include wheelies, bunnyhops, and manualing—when the rider lifts the front wheel of the bike over a jump with the back wheel still on the ground—as well as slide braking, in which the bike is pushed sideways around the corner, with the rider on the very edge of losing control. Contact is important as well, because on track the riders fight for position going into and out of the bends.

World championships have been held in BMX since 1982, while Freestyle BMX—doing tricks on the bike along the lines of skateboarding or snowboarding—is a staple at the annual extreme sports X Games. But the sport really gained credibility when it became part of the Olympic program in 2008. To assist Reade in her build-up for gold, the GREAT BRITAIN team built her a course in Manchester that included an extremely steep Olympic standard start ramp. Unfortunately she crashed out when going for gold; the inaugural Olympic champions were Anne-Caroline Chausson, a former MOUNTAIN-BIKE downhiller from France, and Maris Strombergs of Latvia.

Former BMX champions who have made it in other disciplines include: Robbie McEwen, Australian road sprinter who won the green jersey at the 2002 Tour de France; CHRIS HOY, Scottish track sprinter who took three gold medals at the 2008 Olympics; and Jamie Staff, BMX world champion who won Olympic gold on the track in 2008.

BOARDMAN, Chris

Born: Hoylake, England, August 26, 1968

Major wins: Olympic pursuit gold 1992; Olympic time trial bronze 1996; world time trial gold 1994; world pursuit champion 1994, 1996; world hour records 1993, 1996; three stage wins in Tour de France; MBE 1992

Further reading/viewing: Chris Boardman, the Complete Book of Cycling, Partridge Press, 2000; DVDs: Battle of the Bikes; The Final Hour

The first British Olympic cycling gold medalist of the modern era and one of the men behind the sport’s great revival in GREAT BRITAIN in the 21st century, Boardman is mildly dyslexic, with an investigative brain and amazing mind for detail. His interest in cycling stemmed purely from a love of competition rather than the act of riding a bike. “I’m not a cyclist,” he said. “I rode bikes. Ninety percent of me said ‘I don’t believe I’m here,’ 10 percent said I had to do it. I was a visitor, which was a shame because [cycling] is a lovely sport.”

Boardman began his career as a British TIME-TRIALLING champion—winning the 25-mile and hill-climb titles—then targeted the individual pursuit at the Barcelona Olympics, where his gold was the first by a British cyclist since 1920. To some extent, the feat was overshadowed by the fact that he won the pursuit on a radical aerodynamic bike with a carbon-fiber monocoque frame made by Lotus and designed by MIKE BURROWS; Boardman won the race, but the bike grabbed the headlines.

While his time-trialling RIVALRY with GRAEME OBREE made news in Britain he and his trainer, Peter Keen, turned their attention to the HOUR RECORD, which he broke in 1993, earning a professional contract with the French team GAN. In his first Tour de France, in 1994, his time-trialling skill secured him the yellow jersey when he won the prologue time trial. He also took the opening stage in 1997 and 1998, but crashed out of the Tour four times in six starts.

In 1994 Boardman won the inaugural time trial world championship and in 1996 he won an Olympic bronze medal at the discipline, then set what is now the definitive distance at the hour with 56.375 km. After the rules governing the hour record were changed, he decided to end his career with an attempt under the new system and managed to beat EDDY MERCKX’s 1972 distance of 49.431 km by a mere 10 m.

Boardman was unlucky to race at a time when DOPING was rampant; he found out late in his career that he suffered from a hormone deficiency that causes osteoporosis and that it could only be treated with injections of testosterone, a banned drug. Following the Festina doping scandal of 1998 the authorities did not feel they could let him use the drug, so he could only take up the treatment after retirement. He is perhaps the only cyclist to quit racing in order to use banned drugs.

Boardman and Keen had been highly inventive in their approach to training, using a treadmill to simulate mountain climbs and focusing on quality not volume. After a few years in retirement, Boardman went to work on the British Lottery-funded Olympic track racing program founded by Keen. When not devoting time to extreme scuba diving—his personal obsession—and his large family, Boardman mentored gold medalists such as BRADLEY WIGGINS, devised coach management systems, became one of the program’s core management quartet, and was one of the “secret squirrels” who researched aerodynamic uniforms in the run-up to the Beijing Games of 2008.

(SEE ALSO AERODYNAMICS, GREAT BRITAIN, OLYMPIC GAMES)

BOBET, Louison

Born: St Méen le Grand, France, March 12, 1925

Died: Biarritz, France, March 13, 1983

Major wins: World road race, 1954; Tour de France 1953–55, 11 stage wins; King of the Mountains 1950; Milan–San Remo 1951; Tour of Flanders 1955; Paris–Roubaix 1956; Giro di Lombardia 1951; Bordeaux–Paris 1959

Nickname: the Baker of St. Meen

Further reading: Tomorrow We Ride, Jean Bobet, Cordee, 2008

First man to win the TOUR DE FRANCE in three consecutive years (1953—55); the Breton was a tenacious cyclist who learned his trade alongside FAUSTO COPPI in Italy and was also capable of major one-day wins such as MILAN– SAN REMO (1951), the TOUR OF LOMBARDY (1951), PARIS–ROUBAIX (1956), and the world road title (1954).

Bobet is also famous for a curious episode in the 1955 Tour when he refused to put on the yellow jersey because it was made of synthetic material; he was worried it might irritate his skin. Perhaps his nerves were understandable: he completed the Tour with a severe saddle boil, which was operated on after the race; he came back to competition too soon and was never the same again (see SADDLE SORES for other nether nasties).

Bobet was celebrated for his determination and ended his career with perhaps the bravest final act cycling has seen. In the 1959 Tour he was ill and suffering but forced himself to complete much of the race, finally riding to the top of the highest pass in the event, the Col de l’Iséran (see ALPS to find out how high and hard this one is relative to other cols). There he climbed off his bike, never to race again.

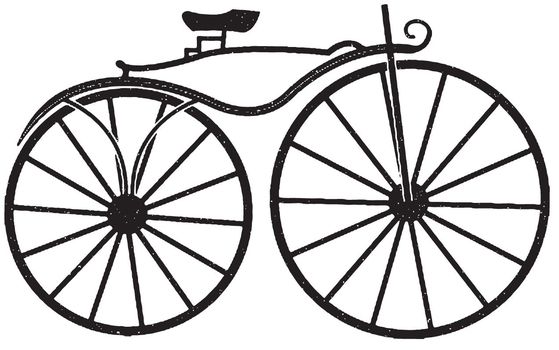

BONESHAKER Generic term for early front-wheel bicycle similar to the machines invented in 1861 by the Frenchman Pierre Michaux and his son Ernest, not dissimilar to the DRAISIENNE, but it was powered by pedals on the axle of the front wheel, “like the crank handle of a grindstone” as Pierre put it; in 1865 his company turned out 400 of the things in their workshop near the Champs-Elysées. They were unforgiving and hard to steer, but they were also simple to use and speedy compared to walking.

Michaux understood the value of publicity; he supplied a bike to the French head of state Napoleon III and supplied JAMES MOORE with one for the first official cycle race in 1868. With some outside investment from Olivier Brothers, his company pushed up production to 200 a day; there were by now 60 other boneshaker makers in the capital and upmarket models were being made with steel frames, ebony wheels, and ivory grips on the handlebars.

In November 1869 the first cycling magazine, Le Vélocipede Illustré, and Olivier Brothers ran the Paris–Rouen race, won by Moore (see ROAD RACING) using the machines. By now race meetings were drawing up to 300 competitors, including women, and as many as 10,000 spectators. The vogue for the machines spread rapidly, to Switzerland, Belgium, Holland, Germany, Britain, and the US. In France, however, velocipede use stuttered with the onset of the Franco–Prussian war in 1870, and the political turmoil that followed.

In Britain the Midlands, and Coventry in particular, rapidly became the center for velocipede production. Gradually, the design changed: the unpowered back wheel of the Michaux-type machines was shrunk, to save weight, frames became more nimble, and the front wheel grew, to a limit set by the inside leg of the rider. The boneshaker disappeared, and the HIGH-WHEELER was born.

BOOKS—FICTION

A subjective selection in no particular order

The Wheels of Chance, H.G. Wells

Hard-to-find turn-of-the-century novel in which Wells’s hero, Hoopdriver, undertakes a 10-day cycle tour of Britain’s South Coast and falls in love with a fellow cyclist, one of many women given freedom by their newfound mobility. Beautiful portrait of cycling in the formative years of the pastime, with acute observation of the blurring of class distinctions the bicycle brought with it.

Cat, Freya North

Since its publication in 1999 this chick-lit tale of bedhopping on the Tour (as the author puts it, “big egos and bigger bulges in the lycra shorts”) is probably the biggest selling cycling fiction work ever: 10 years later, almost every British thrift store and teenage female babysitter seem to have a copy. Tour journos who were on the 1998 race when La North was researching the work are known to scrutinize the book closely trying to figure who is who. Trivia lovers note: there is a William Fotheringham in the pages, but he’s sports editor of the Guardian. We emphasize that it is fiction.

Bad to the Bone, James Waddington

Surreal novel published by happy coincidence in 1998, the year of the Festina scandal, in which top cyclists in the TOUR DE FRANCE are offered a Faustian pact by a sports doctor: a wonder drug which will make them unbeatable, but which has horrendous side effects. It’s fiction. Honest. Pro cyclists would never go so far—would they?

The Rider, Tim Krabbe

Cult novella with a popular English translation from 2002. Goes inside one rider’s mind during a fictional race somewhere hilly in the South of France—the only issue being that if any cyclist actually thought that much he’d be too distracted to compete. Totally compulsive: you either love it or it leaves you cold.

The Yellow Jersey, Ralph Hurne

Possibly the least politically correct cycling work ever, what with the big-breasted, topless lady (alongside the Condor bike) on the Pan paperback, and the constant references to potential sexual partners as “it.” Get past that and this 1973 novel is a hilarious, racy, suspenseful gem: you can’t help but get drawn in as Terry Davenport,jaded ex-pro and womanizer, gears up for one last Tour and suffers like hell in the process. The bit where the top five riders in the race all test positive is amusingly prescient. Written with two endings, one for the British market, one for the US.

The Big Loop, Claire Huchet Bishop

Published in 1955, offering a Parisian teenager’s view of a cycling career from aspirant without a bike to Tour winner. It has a certain charm as a portrait of French cycling in the glory days of Bobet and Robic, but is unlikely to cut much ice with the PlayStation generation.

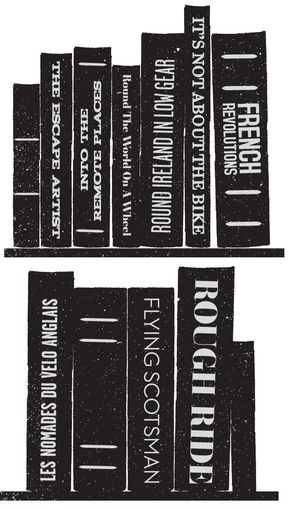

BOOKS—NONFICTION

The Great Bike Race, Geoff Nicholson

Masterly history of the Tour de France crafted around the 1976 race, oozing humor and glorious detail without a hint of self.

Nicholson, God rest his soul, was a writer who topped the Galibier while the others were toiling up the Télégraphe. His sequel, Le Tour, did not quite hit these heights.

Wide-Eyed and Legless, Jeff Connor

No journalist will ever get as close to a team as Connor got to ANC-Halfords in the 1987 Tour de France, and no squad will want them to, given the stuff he picked up thanks to his inimitable eye for detail. The gradual implosion of the first British trade team to ride the Tour is dissected in all its quarrelsome, anarchic glory. Connor’s attempt to ride a Tour stage is the hilarious high point.

Lance Armstrong’s War, Daniel Coyle

The best way to learn about LANCE ARMSTRONG and 21st century pro cycling, through the eyes of a wry outsider given inside access to Planet Lance. Brilliantly observed, hilariously written, but above all dispassionate, neither for nor against the controversial Texan.

Read and judge Le Boss for yourself.

Major Taylor, Andrew Ritchie

Ritchie set the standard for cycling biography with this account of the life of one of America’s first nonwhite sports stars. Impeccable research and a lively re-creation of cycling’s HEROIC ERA.

Kings of the Road, Robin Magowan and Graham Watson

This 1985 opus is the best integrated words-and-pictures book about professional cycle racing. Some of the content is dated but GRAHAM WATSON’s photos and the pen-portraits of ROBERT MILLAR, SEAN KELLY, PHIL ANDERSON, and GREG LEMOND are timeless.

Kings of the Mountains, Matt Rendell

Exhaustive and intense investigation into cycling in COLOMBIA. Like Ritchie’s Major Taylor, it extends way beyond things two-wheeled and offers a superb insight into a controversial, colorful nation.

Greg Lemond: The Incredible Comeback, Samuel Abt

The best work from one of the great cycling writers of the last quarter-century. This 1990 account of LeMond’s return from near-death to win the best Tour de France ever is as good at it gets.

Sean Kelly: A Man for All Seasons, David Walsh

The definitive account of the great man’s rise in the early 1980s; Walsh is superbly observant, can work out the deals his fellow Irishman is striking, and benefits from unlimited access. Those were the days.

BOOKS—MEMOIRS/AUTOBIOGRAPHY

It’s Not About the Bike, Lance Armstrong

Love or loathe Lance Armstrong, you can’t ignore one of the biggest-selling cycling books ever, because of the visceral emotions it brings. The detail is telling, most notably the scene where Armstrong has to masturbate into a cup so that he can bank sperm before his testicular cancer operation. A key element in the Big-Tex myth.

Flying Scotsman, Graeme Obree

For my money the rawest and best cycling autobiography. Graeme Obree tells his story uncut, without the intermediary of a ghost writer, and tells of sexual abuse and attempted suicide with not a hint of self-pity. Alongside this the film of the same name is distinctly insipid.

Rough Ride, Paul Kimmage

As with Armstrong, you swoon or swear at this up and (let’s face it, mainly) down account of Paul Kimmage’s career as a pro in the mid-1980s. Great inside stuff, but his drug “revelations” seem timid now, though at the time they were scandalous. No one describes suffering on a bike quite so well; brutally debunked the “glamour” of pro life, even if it is a bit Gone with a Whinge.

The Escape Artist, Matt Seaton

Elegiac telling of Matt Seaton’s discovery of cycling against a background of serious “stuff of life,” namely his wife’s death of cancer. Beautifully written, elegantly crafted, tugs at the heartstrings, and sums up why we all ride bikes.

A Dog in a Hat, Joe Parkin

The life and times of a mediocre American pro in Belgium is one of the most compelling memoirs of its time, mainly because of Parkin’s sheer love of Flandrian cycling culture and the pure weirdness of pro racing. The high point comes early on, when Parkin reads the lyrics to “Jumping Jack Flash” handwritten on Bob Roll’s tires.

MEMOIRS A brief selection:

| For the Love of Jacques | Sophie Anquetil | 2004 |

| Glory Without the Yellow Jersey | Raymond Poulidor | 1977 |

| Boy Racer | Mark Cavendish | 2009 |

| Cycling Is my Life | Tom Simpson | 1966, 2009 |

| The Fastest Bicycle Racer in the World | Major Taylor | 1928 |

| In Pursuit of Glory | Bradley Wiggins | 2008 |

| Personal Best | Beryl Burton | reiss. 2008 |

| Le Peloton des Souvenirs | Bernard Hinault | 1988 |