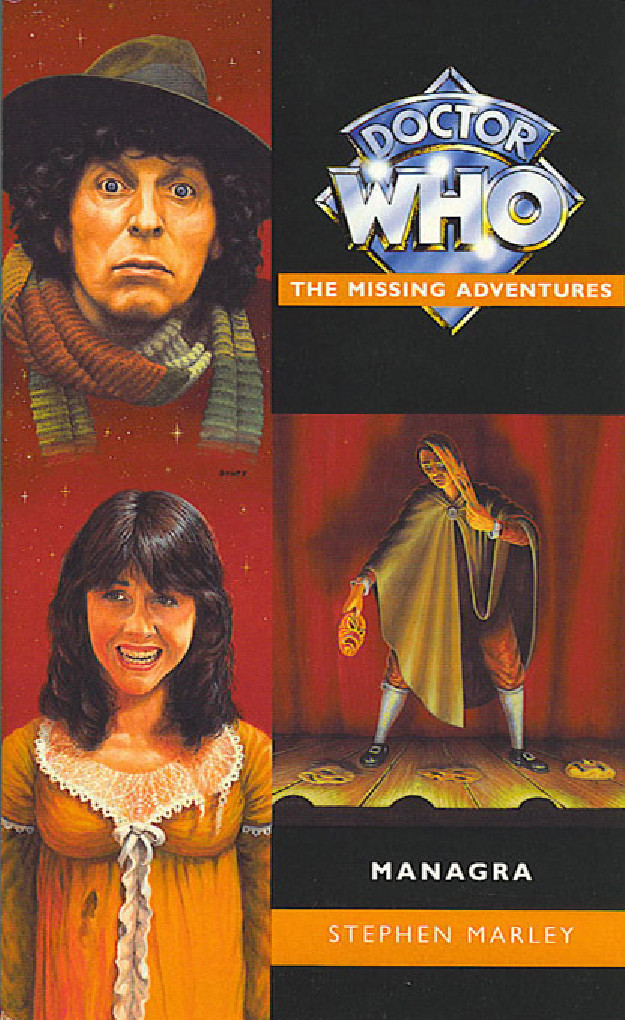

M A N A G R A

AN ORIGINAL NOVEL FEATURING THE FOURTH DOCTOR

AND SARAH JANE SMITH.

‘EUROPA IS INFESTED BY GHOSTS, VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, GHOULS AND OTHER GROTESQUES SPAWNED FROM OLD

EUROPEAN FOLKLORE. I THINK

WE’RE IN A SPOT OF BOTHER, SARAH JANE.’

Europa, designed by lunatics a thousand years in the future, is a resurrected Europe that lives in an imaginary past.

In Europa, historical figures live again: Lord Byron combats Torquemada’s Inquisition, Mary Shelley is writing her sequel to Frankenstein, and Cardinal Richelieu schemes to become Pope Supreme while Aleister Crowley and Faust vie for the post of Official Antichrist.

When the Doctor and Sarah Jane arrive, they are instantly accused of murdering the Pope. Aided only by a young vampire hunter and a revenant Byron, they must confront the sinister Theatre of Transmogrification in their quest to prove their innocence.

This adventure takes place between the television stories PLANET

OF EVIL and PYRAMIDS OF MARS.

Stephen Marley is a well-established writer of dark fantasy. He is the author of Spirit Mirror, Mortal Mask, Shadow Sisters,

Judge Dredd – Dreddlocked and Judge Dredd – Dredd

Dominion.

ISBN 0 426 20453 0

MANAGRA

Stephen Marley

First published in Great Britain in 1995 by Doctor Who Books

an imprint of Virgin Publishing Ltd

332 Ladbroke Grove

London W10 5AH

Copyright © Stephen Marley 1995

The right of Stephen Marley to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

‘Doctor Who’ series copyright © British Broadcasting Corporation 1995

ISBN 0 426 20453 0

Cover illustration by Paul Campbell

Typeset by Galleon Typesetting, Ipswich

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Mackays of Chatham

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior written consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

CONTENTS

For Anita, for reasons known by few.

And for Tom Baker, for reasons known by everybody.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Peter Darvill-Evans, Rebecca Levene (the long-suffering) and Andy Bodle, noble souls all. Thanks also to Desmond and Sonja for – whatever, and Jim Newcombe for the videos and slim volume. To Paul Campbell, for his superb cover illustration, I owe a debt of gratitude (which I may or may not pay). And a nod to Andy Lane, for reasons which will be revealed in a month or so. Above all, my regards to all those readers who have (preferably) bought this book and (hopefully) got round to reading it.

Prologue

London: 29 June 1613

The reddest of flames licked the bluest of skies.

The Globe Theatre’s first staging of Will Shakespeare’s Henry VIII had turned out to be its last performance. Gone up in smoke, bracket and beam, stage and balconies.

The squat wooden tower of the Globe was a column of fire, disgorging a terrified multitude. Crammed in the gateway, the crowds that had flocked to witness Shakespeare’s farewell play now jostled and trampled one another in a stampede to flee the blaze.

It had been a full house, the theatre packed to its two-thousand capacity.

‘’Tis a pity,’ Francis murmured under his breath. ‘But it had to be done.’

Francis stood on the Southwark bank, an easy pebble’s toss from the bridge, and watched the inferno at a hefty stone’s throw distance. He stepped to one side as a merchant rushed past, wreathed in flames, and dived into the Thames, disappearing in a splash and wisp of steam. Others, their garb a fiery flamboyance, soon dived in his wake.

London’s towers tolled their bells, a carillon of alarm, the air percussive with fear.

Francis kept his eyes fixed on the mighty conflagration.

Inside the burning theatre was his tinder-box, evidence, if any should find it, of his guilt in starting the fire. But the act of arson had been planned meticulously: no one had spotted him switch the flame from his tobacco pipe to the paper and straw he’d crumpled under the bench.

The tinder-box that created the fire would be consumed in the fire it created.

‘I think that’s dramatic irony,’ he mumbled, frowning his uncertainty, then he caught sight of a bowed figure standing nearby, draped in the makeshift cloak of a scorched blanket.

Wincing in the mounting blast of heat and clouds of smoke, he strode up to the distraught man, took him gently by the arm.

‘Will...’

Will Shakespeare looked all of his forty-nine years as he raised smoke-smudged features to Francis. Then the playwright shook his head, turning desolate eyes on the blazing theatre and terrified crowds. ‘God,’ he groaned.

‘God...’

Francis shifted his hand from Will’s elbow and gripped him tight by the shoulder. ‘Remember your own lines from Richard II, Will?’ He took a deep breath before declaiming:

‘His rash fierce blaze of riot cannot last, For violent fires soon burn out themselves...’

Shakespeare, absorbed in the fiery catastrophe, wasn’t listening. Blank-eyed, he continued to shake his head. He shuddered, and swerved a piercing glance at Francis, quoting from the first scene of Henry VIII:

‘Heat not a furnace for your foe so hot

That it do singe yourself.’

Then he stared back at the inferno, lost in grief.

Disturbed by the aptness of the quotation, Francis let fall his hand and left the dramatist to his distress. He’d taken barely ten paces when the chorus of screams intensified, underscored by low, bestial growls. He squinted into the billows of smoke and drifting cinders, and saw shambling shapes emerge.

A shadow, bulging from night into light

‘’S’blood!’ he swore, backing away, as much bedevilled by the shadowy phantom in his head as frightened of the approaching silhouettes. Then the silhouettes hardened into clarity and the dark devil fled his mind at the prospect of a more immediate threat. The menace wore fur and padded on four legs and bellowed fit to burst.

Bears were on the loose, the pelts of some flickering with flames. The fiery bears were not in the best of moods. Either the beasts had broken out of the bear pit adjoining the theatre or the keeper had set them free. Accident or folly, burning bears were on the loose...

Moments after Francis took to his heels, he spotted a smoke-blinded woman running straight into the path of one of the enraged creatures. A blistering paw swiped the side of her head and spun the wretch clean off her heels, her neck a snapped stalk.

Running along the Southwark shore, he tried to blank out the horrors at his back, struggled to smother the upsurge of guilt. He had created this disaster. He was responsible for the suffering.

The author of all their woes.

‘Author of all their woes,’ he mumbled, staring into the dregs of his tenth cup of sour wine.

He lifted bleary eyes to rove the squalid interior of the Black Boar Tavern, one of the lowlier drinking dens in the stinking slum known as the Stews. The tavern had few customers this evening. Most of the regulars had joined the vast crowd gathered to watch the bonfire of the Globe light up the evening. The bears, it was reported, had been laid low by infantry musket-balls.

Heat not a furnace for your foe so hot –

All over London the bells were still tolling. For Francis, the peals had a funereal tone.

‘I had to do it,’ he whispered, returning his abstracted gaze to the wine cup. ‘I had good reason. It had to be done. But no one will ever understand.’

Kelley and Bathory, they’re to blame. If it wasn’t for them...

A dark memory skimmed across his mind. A shadow, bulging from night to light. Hard to grasp...

A croaky tone dispersed the elusive memory. ‘Good e’en to you, Francis. Fancy a bit of a tumble in a bed made for tumblin’?’

He glanced up and scowled at the swollen bulk of Alice, two score years and ten with a wart for every year. Her tongue wiggled suggestively.

‘A doxy with the pox,’ he sneered. ‘I’d sooner stick my head in a piss-pot.’

She spat at him and hurled a stream of colourful insults as he shouted for another flask of wine.

The flask was duly delivered and Alice eventually withdrew to a corner, muttering to herself.

Francis downed three cupfuls inside a minute. ‘Must be getting drunk,’ he said. ‘This slop doesn’t taste like bilge-water any more.’

A pot-bellied behemoth of a tavern-keeper glared in his direction. ‘King James himself has praised my wines!’ he bellowed, shaking a meaty fist.

‘That’s what you always say,’ Francis responded dully, gulping another draught. ‘Besides, yon canny Scots king has no liking for strong drink – or is it tobacco?’ He reeled in his chair. ‘Well, something like that... wrote a book...

Counterblast... or suchlike –’

Something had happened to his head. He felt as though there were a hole in it, and his liquefying brains were gushing out.

I had to do it. I had good reason.

Time dissolved into the stale wine. Past and future acquired a fluid quality. He swam in it.

He blinked twice, and between one blink and the next he composed an epic poem. He blinked again, and forgot every word of it.

For several aeons, he wandered in Arcadia. A rare delight it was – until he walked into a waterfall.

Spluttering, he swam up into a lamplit room that was vaguely familiar. He was soaked in some foul liquid. He stared up at the raftered ceiling for a long moment before he realized that he was lying on the floor. Faces loomed over him, guffawing.

He put a name to one of the laughing faces: Alice. She waved a metal bowl in front of his eyes. ‘Sooner stick your head in a piss-pot, would you, Master Francis? Your wish has been granted, from my very own pot.’

Wiping the rank liquid from his face with the back of his sleeve, he heaved himself on to his elbows. ‘Now I know where the tavern wine comes from. Just as well I’ve no intention of paying,’ he heard himself say. His voice seemed to issue from inside his boots.

From a prone position he found himself suddenly yanked upright, feet dangling above the rush-strewn floor. He heard his doublet tear in the tavern-keeper’s grip as the burly man shoved his bearded face up close. ‘Not – paying?’ the beard-fringed mouth snarled. A gust of foul breath hit Francis in the face. His nose wrinkled in revulsion.

‘I’m the author of all our woes,’ he croaked.

A meat-slab of a fist put paid to any further ramblings. He felt himself sailing through the air to land with a thump.

He was dimly aware of the next couple of punches and kicks, then the sweet waters of Lethe washed over him and he sank into blessed oblivion.

After several ages of the world, or a fleeting second, he opened an eye. Closed it again. Opened it once more.

Time and place were askew; it took some effort to slot them back into position.

At length, he managed to take in his surroundings. It was night. He was sprawled in a greasy alley in the Stews, his body battered, skin and clothes steeped in Alice’s urine and his own blood. Inside his ruined physique, he could sense the fatal seepage from damaged organs.

He might as well give up the ghost. His ambitions had foundered. His plans had unravelled. He’d been betrayed.

‘Betrayed,’ he wheezed, then broke into a harsh spasm of coughing.

There was a rosy glow above the rooftops. The Globe Theatre was still providing London with a lusty bonfire. His handiwork. The last act of a desperate man, whose motives would be known and understood by nobody.

Roused by sudden rage, Francis forced himself to his feet –

or rather, to one foot; the limp left leg was well and truly broken. Swaying to keep balance, he shook a fist at the frost of stars.

‘You betrayed me! Edward Kelley, Elizabeth Bathory, you betrayed me! Damn you to the sulphurous pit of Hell!’

‘ Hell...’ echoed an immense voice.

Francis’s heart drummed in his shattered rib-cage.

Night congealed into what might have been a shape and walked towards him down the thin alley. A shadow, bulging from night –

His befuddled wits couldn’t cope with what he was seeing.

A coagulated darkness, prowling between the leaning houses.

The sight of it convinced him that either the world was insane for containing such a thing, or he was insane for imagining it.

‘Who are you?’ he wheezed.

‘ Who are you?’ boomed the advancing spectre.

Losing his equilibrium, Francis toppled to the cobblestones.

‘Christ protect me,’ he moaned softly.

‘ Christ protect me,’ the voice repeated.

The nonsense shape of night leaned over him, a cold, starry twinkle in its eye.

‘I’m damned,’ Francis sobbed.

‘ I’m damned,’ came the vast echo.

It was close now, close as breath. Essence of dark filtered into Francis’s shrinking pores. He looked the nightmare nonsense in its impossibility of a face.

He felt as though a cat had licked his heart.

‘I know you,’ he gasped as the darkness seeped into the red life in his veins. The invading dark worked a spiritual alchemy. A transmutation. A merging of souls.

‘ I know you.’

‘You’re the Devil.’

‘ You’re the Devil,’ the voice mimicked.

Francis’s mouth opened, then froze in a rictus. His body lay quiet and rigid as a corpse on the slab.

A long silence of deepest night was finally broken by a vast whisper.

‘ WE ARE THE DEVIL.’

Castle Ludwig: the Black Forest, Bavaria Tomb night.

Skull moon.

The scenery and theatrical props were in place, the scene was set, the audience of two settled in their thronelike chairs, and the actors awaited the cue of a raised curtain.

A fanfare of trumpets.

The red velvet curtains parted, revealing a stage-set that resembled the interior of a spacious tomb, or the most austere of bedchambers. A skull-featured moon peered in through a wide crack in the upper wall. Centre-stage, on a bed of stone, lay a man in white robes, his head crowned with the papal tiara that proclaimed him Pope Supreme of the Catholic Church Apostolic.

Enter the Archangel Michael, stage left. The warrior angel, attired in silver armour, hoisted a long spear.

Enter Lord Byron, stage right, sabre in hand.

The drama had begun.

As the scene unfolded, one of the two spectators – a young sybarite dressed as a late eighteenth-century fop – turned to the man at his side. ‘May I speak, Doctor?’ While posing the question, he nervously stroked a pink poodle nestled in his lap.

‘You will be silent, Prince Ludwig.’ The speaker’s voice was mellifluous, his smile broad, his face hard and white as marble.

Prince Ludwig held his tongue. The stroking of the poodle became brisk and insistent, an expression of frustration.

Finally, Ludwig moved his mouth close to the poodle’s fluffy pink ear. ‘Did you hear that, Wagner?’ he whispered under his breath. ‘The Doctor orders the Prince to keep silent.

And after all we’ve done for him, placing Castle Ludwig at his disposal.’ His delicate hand weaved in a circle, indicating the soaring, gloomy arches, the stained-glass windows, the ranks of gargoyles, the general neo-Gothic extravagance of the castle’s Chimera Hall. ‘A melancholically magnificent setting for a drama of fear.’

‘I told you to be silent,’ the Doctor said, the smile fixed on his rigid features.

Trembling, Ludwig inclined his head to the sinister Doctor, astonished that the man at his side could have heard so faint a whisper. ‘Forgive me. It’s just that I am a Prince of the House Glockenstein, and – and –’ He tried not to stutter. ‘Th-this is my castle. Much as I admire your drama of f-fear –’

The perpetual smile imprinted on his mouth, the Doctor rose to his feet, carefully adjusting the black folds of his full-length opera cloak. ‘I will show you fear, and not in a handful of dust. And I will teach you to be silent.’

A quivering Ludwig hugged the poodle tight as his gaze followed the tall man’s fluent movements. The Doctor placed long, manicured fingernails under his chin, and deftly peeled off his smiling face.

Aghast, Ludwig crushed the poodle to his breast as though to absorb its warmth and comfort. ‘Uh – uh –’

The Doctor brandished his white face from an outstretched hand. On the front of his head was a blank, pink oval, framed by long, auburn hair. Smooth and featureless as an egg, the non-face paralysed Ludwig with a horror of – well, the faceless.

The white mask spoke from the man’s hand, its smiling lips murmuring satin-soft words. ‘I have shown you fear. Now I will teach you silence.’ The arm stretched forwards, and pressed the mask to the prince’s face. The white lips greeted his with a kiss. Sealed them with a kiss.

Ludwig’s fingers flew to his mouth – and contacted only smooth skin. A flat expanse of smooth skin from nose to chin.

Where is my mouth? he tried to scream, but had no mouth for screaming.

With a graceful gesture, the Doctor replaced the mask over the pink blank of his face. ‘Now, Prince Ludwig,’ he said, resuming his seat. ‘Let us watch the play – in silence.’

Bathed in the hot sweat of fear, the prince watched the drama, hardly daring to blink lest the Doctor blind his eyes with another kiss.

Onstage, the performance was gathering momentum. There was blood on Byron’s sword, and blood on the Archangel Michael’s spear.

Ludwig barely caught the Doctor’s faint whisper: ‘The play’s the thing...’

Part One

Crimes at Midnight

Crimes at midnight would wail

If torn tongue could tell the tale

In this castle incarnadine

With rare juice, heart’s wine.

Pearson’s The Blood, the Horror, and the Countess One

he pope is dead.’

‘T Cardinal Agostini flickered open his eyes at the panicked words, tilted his head on the pillow and, under lowered lids, studied the intruder who had presumed to invade his bedroom. The portly figure of Father Rosacrucci hovered beside the cardinal’s bed, dithering hither and thither, rosary beads rattling.

‘What was that about the pope?’ growled Agostini, pulling back the monogrammed silk covers.

‘His Holiness Pope Lucian has – has been taken to the bosom of Christ,’ Rosacrucci spluttered. He leaned close, his plump face sheened in sweat that glistened in the muted torchlight. ‘There is evidence of – foul play.’

The cardinal glowered at the priest. ‘Have you been overdoing the flagellation again, Rosacrucci? If this is another of your visions –’

‘It’s true, your eminence. The Enclave is gathering in the papal night-chamber and the Camerlengo urgently desires your attendance.’

Agostini pursed his lips, then nodded. ‘Tell him I’m on my way.’

Father Rosacrucci backed away across the spacious bedchamber, bowing until he reached the bronze double doors and slipped quietly through.

Observing the priest’s departure, Agostini leaned back on his pillow and surveyed the fresco that adorned the ceiling.

The painted expanse depicted the Sufferings of the Damned in a tangle of tormented limbs, howling heads, and demons rampant. The fresco had acquired an additional figure overnight: a fresh recruit to the company of the damned. The new lost soul in Hell bore the unmistakable features of Pope Lucian.

‘So it’s true,’ the cardinal whispered. His gaze descended to the crossed-keys papal insignia above the door. ‘ Sic transit gloria mundi.’

Expelling a short breath, he eased his tall, chunky frame out of the bed. His bedchamber was on the upper level of the Apostolic Palace, thirty paces down the corridor from the papal apartments. If he hurried, he’d be there before the rest of the Enclave. On the spot, ready to take action.

As Cardinal Agostini dressed, he kept his stare fixed upward on the Sufferings of the Damned. Pope Lucian glared down at him from his heights of woe.

Clad in red robes and a gold pectoral cross, Agostini finally lowered his gaze as he crossed the marble floor.

‘So it begins,’ he murmured. ‘It begins.’

Miles Dashing stalked Bemini’s colonnades bordering St Peter’s Square, wondering whether he was supposed to be somewhere else. The rendezvous was in Vatican City, he was sure of that, but was it St Peter’s Square or St Peter’s Basilica?

Blast it – if only he could remember...

Miles swept back the long, blond fringe from his youthful face with one hand as his other kept a tight grip on his épée.

The twenty-year-old ex-Earl of Dashwood was in enemy territory, and every muscle of his tall, lithe figure was on the alert.

At any moment a prelate or military guard of the Exalted Vatican might step from the shadows and discover Miles for the interloper he was. Then there would be much sounding of alarms and much rousing of Vatican minions. A prudent man would make a run for it right now, rendezvous or no rendezvous.

Miles swished his blade and swirled his black opera cloak.

Miles Dashing of Dashwood was not one to fail an appointment with a comrade, even if he was having problems finding him. And find him he would, or perish in the attempt.

‘Now,’ he whispered, ‘Square or Basilica? Or was it the Apostolic Palace? I know it was at stroke of midnight.’ His brow furrowed. ‘Or was it at first stroke past midnight?’

Épée in hand, black cloak billowing in the rising breeze, Miles Dashing continued to stalk the colonnades of St Peter’s Square.

Giovanni Giacomo Casanova lay in bed with his latest conquest, a comely wench of sixteen, and stared through the open windows of the balcony at the star-haunted night above Venice, resonant with the amorous songs of gondoliers.

Casanova turned to the sleeping girl at his side. What was her name? Maria... something. He’d ask her when she awoke; he liked to keep a full account of his affairs.

He glanced at the sword by the bed, and his thin lips formed a wry twist. Tonight, if he had put duty before passion, that sword would be in his hand and he would be far from here, in the shadow of St Peter’s. Casanova, despite his reputation, set great store in keeping his word, fulfilling an honourable duty. But Maria-something had been so exquisite, so beguilingly innocent, and passion had won out over duty.

He exhaled a slow breath and closed his eyes, head sinking back to the pillow. His comrade would have to make do without him.

‘Forgive me, Byron,’ he murmured regretfully.

‘A sorrowful moment, eminence,’ acknowledged the Camerlengo, Cardinal Maroc, as Agostini entered the papal bedchamber. Maroc, like Agostini, struggled to suppress his emotions at the grim spectacle laid out on the bed.

‘A sorrowful moment for us all, eminence,’ Agostini solemnly greeted, echoing Maroc’s formality of address. He noted, with disapproval, that the dumpy figure of Torquemada was standing at the side of the tall, austere Camerlengo.

Agostini had hoped to be first on the scene.

His gaze moved to the papal bed. The pontiff, in full pontifical regalia, was sprawled face down on the sheets.

Above his prone figure was an inverted statue of St Michael the Archangel, three metres long from upended feet to helmeted head. The spear gripped in the silver-plated St Michael’s hand was lodged in Pope Lucian’s back, pinning him to the mattress. A glance under the bed revealed that the spear had been driven clean through the mattress to bury its point in the tiled floor.

‘Skewered,’ Cardinal Maroc said. ‘Like a lamb on a spit. It would take several strong men to hoist the statue above Pope Lucian and drive it down with such force.’

‘Either that,’ Torquemada said in his silky tone, ‘or some deviltry has been at work. I smell the warted hand of Lucifer in this unholy deed.’

Agostini shook his head. ‘Lucifer works most often through human hands. The Heretic Alarm must be sounded and the guard mobilized.’

Cardinal Maroc raised a Gothic eyebrow. ‘Should we not wait for all members of the Enclave to arrive before taking action?’

‘While we wait, the perpetrators escape. As Camerlengo, the papal chamberlain, you must take the role of acting pope, and must act accordingly.’

Maroc deliberated a moment, then inclined his head. ‘The alarm will be sounded.’

Stroking his heavy jowl, Agostini studied Pope Lucian’s body. ‘There was a rumour,’ he mused. ‘I paid scant heed to it at the time...’

The Camerlengo’s brows contracted. ‘What rumour?’

‘Well – it may be nothing, but there was a whisper in the corridors that His Holiness planned a secret meeting with Lord Byron this very night.’

‘Byron!’ Torquemada spat out the word like a dose of poison. ‘The devil incarnate, cloven-hoofed. If that degenerate was here, then I have no doubt who committed this sacrilegious murder.’

‘He would have needed assistance,’ Agostini said, pointing at the massive metal statue. ‘But still, we can proceed on the assumption that Byron was the ringleader. Any henchmen –’

‘Why was His Holiness dressed in full regalia at this time of night?’ Torquemada interrupted, his normally smooth brow creased in puzzlement.

Agostini lifted burly shoulders. ‘More proof that he was meeting someone in his formal role as head of the Catholic Church Apostolic, perhaps?’

‘Someone like Byron,’ Torquemada grunted.

Agostini studied the skewered pontiff. ‘There’s no one like Byron.’

Mad, bad, and dangerous to know.

That’s how that titled doxy, Lady Caroline Lamb had described him. He was the first to admit that the lady had a point. George Gordon, Lord Byron had few illusions about himself.

His present predicament was indubitably mad, bad and dangerous, and he was in great part the author of it.

Prowling through the baroque labyrinth of the Apostolic Palace, blood on his bared sabre, Lord Byron – poet, satirist, politician, pugilist, swordsman, marksman, seducer, adventurer and general hell-raiser – was in peril of his life: the taste of danger had a distinct relish.

The hue and cry had just gone up, resounding from deserted halls and galleria. Ah, so they’d found the pope’s body, and were after blood. One sight of Byron, and the Vatican prelates would know whose blood they sought. Already the Vatican guard might be on the scent.

Catching the pounding of booted feet up ahead, signalling the approach of the heavily armed Switzia Guardians, he ducked into a side-chapel and hid behind the wrought-iron grille of a rood-screen.

He peered through the grille as the military guard stormed past, their barbed halberds glinting in the flicker of wall-mounted flambeaux. He counted seven halberds raised above seven gleaming helmets. At a pinch, and in different circumstances, he might have taken them on with a blade in hand and an apt quotation on his lips, but tonight was a night for stealth and flight.

The rumble of booted feet receded down the corridor.

He sat down in a pew and ran strong fingers through his red-brown hair as he considered his situation. His co-conspirators had let him down: Miles Dashing and Casanova had failed to appear for the rendezvous in St Peter’s Basilica.

The pox on the both of them for leaving him in the lurch, alone in the middle of a hostile Vatican City. With alarms screeching all over the Vatican, and the Apostolic Palace sealed off by now, he was in a spot as sticky as a dead man’s gore.

The line of his mouth hardened. ‘Well, the son of Mad Jack and grandson of Admiral Foul-weather Jack is no wee, sleekit, cow’rin tim’rous beastie to be caught in a trap.’ A smile bent his lips as he glanced at the blood on his sword.

The shriek of the alarm stopped as abruptly as it started.

That boded ill, implying that his whereabouts had already been located.

He scanned a row of incongruous gargoyles on one wall.

The Gothic additions to the baroque chapel served more than a decorative purpose but, for the moment, the stone faces seemed nothing more than ornamentation. The gargoyles, however, could stir to life in the blink of an eye...

Jumping to his feet, he studied the shrine, whose paintings and statuary had a twitchy shadow-and-shine life of their own in the dance of candle-and torchlight. His attention centred on the altar, above which loomed a marble statue of St Anne.

The front of the altar was decorated with a rococo riot of imagery in bas-relief, purportedly telling the tale of the Virgin Mary’s birth. The eyes of all the figures were hollow. Byron smiled as he recognized a cryptic pattern in the bas-relief.

Sheathing his sabre, he knelt down and pressed his fingertips in the hollows of the eyes in a sequence according to a basic Baconian code. He was rewarded with a click and a low humming sound as the altar rose from its base and ascended two metres, revealing the black square of a portal in the chapel’s back wall.

A secret door to a secret passage. The Vatican was honeycombed with hidden tunnels, and a man with such sharp wits as Lord Byron needed no Ariadne’s thread to weave his way through the maze.

He stepped towards the white marble frame of the portal.

And leaped back as the doorway filled with Switzia Guardians, halberds jabbing, teeth bared as they chorused:

‘HERETIC!’

Unsheathing the sabre and whipping out a dagger, Byron stood his ground, bellowing words of defiance from his own Childe Harolde’s Pilgrimage: ‘War, war is still the cry, War even to the knife!’

Sharp steel sliced the air. Hot splashes of red decorated white marble.

Two

he fresco of The Last Judgement blazed electric blue.

T A burst of electromagnetic frenzy illuminated the painted wall of the barrel-vaulted hall. Displaced air fled down the hall with a rush as supercharged ions unleashed a manic dance of crazed lightning. A flamboyant novelty was arriving with a flash and a bang.

The lightning fizzled out and the luminosity dimmed as a blue object intruded itself upon the candlelit expanse with a noise like an asthmatic tank engine afflicted by grating gears.

At first more phantom than substance, the intruder phased from image to solidity. In seconds, a blue police box stood on the marble floor.

It stood there for some time, quiet and still, devoid of pyrotechnics, behaving as a proper police box should.

Its door began to open. ‘No need to check the screens, Sarah,’ a cheery male tone announced from inside. ‘Sorry about the tricky touchdown, but this time I’ve landed us right on a Shalonarian beach.’

‘That’s what you said last time,’ muttered a woman’s voice, loaded with irony.

The door opened wide and a tall man stepped out, hands thrust in the pockets of a brown overcoat, a brown fedora planted on the coppery bramble of his hair. An inordinately long multi-coloured scarf swung down from his neck and scraped his shoes. From head to toe, he was the essential bohemian, and his toothy grin exuded bonhomie.

‘Sun and sands,’ he declared.

He pulled to an abrupt halt and confronted the dark, vaulted spaces, the light and shadow of the frescoed hall.

His pale blue eyes bugged and his mouth fell open. ‘Ah...’

A young woman, almost a foot shorter than her companion, emerged from the box. She was dressed in a black bikini, her heart-shaped face adorned with sunglasses, a towel in one hand, a bottle of sun-tan lotion in the other. Slowly, deliberately, she placed the towel and lotion bottle on the floor and pushed her shades to the top of her head, revealing hazel eyes and a peeved look.

He bent an apologetic smile in her direction. ‘Ah...’

‘This doesn’t look like a sun-drenched shore of Shalonar,’

she said dryly.

‘Just a teeny bit off course,’ he conceded. ‘But what’s a couple of centuries and a few light-years between friends, eh, Sarah? Sarah?...’

Sarah Jane Smith pursed her lips. ‘Don’t – don’t tell me you’ve landed us in "a spot of bother" again. I still haven’t recovered from the last one.’

‘Yes, that was a bit of a rum do, of somewhat apocalyptic proportions, in which I played a not insignificant role, if I say so myself,’ he said, taking several strides to a baroque altar fronting the near wall.

Sarah heaved an exasperated breath and tracked his steps.

‘Doctor,’ she said in a warning tone, ‘if you start exploring again I’ll –’

‘Jelly baby?’ offered the Doctor, cutting her off in mid-threat as he whisked a paper bag from a pocket while simultaneously pointing at the immense fresco. ‘The end of the story,’ he murmured, gaze roving the depiction above the candlelit altar. ‘A graphic story. What does it tell you?’

Ignoring the proffered bag of sweets, Sarah’s mouth formed a moue as she studied the fresco. She’d recognized the spacious chapel almost at first glance; she’d visited it on a tour back in 1971. But she was in no mood to play the Doctor’s games, not with a bikini barely covering the necessary on her goose-pimpling skin she wasn’t. ‘Why don’t you tell me a graphic tale,’ she said, all wide-eyed innocence.

The Doctor, however, had lapsed into a thoughtful silence.

His features, although partially shaded by the wide-brimmed hat, betrayed a hint of uneasiness as he scanned the painting.

Despite accompanying the Time Lord through two of his incarnations, Sarah still found much of his character a giant question mark, but she’d learned to pick up on the little signals of content or anxiety. Something troubled him now, as he studied the images on the wall. ‘Eschatology isn’t what it used to be,’ he mumbled to himself.

Curiosity aroused, she examined the fresco. It was familiar from a hundred popular reproductions: The Last Judgement, Michelangelo’s towering nightmare in paint. Her stare was drawn to the stern, Grecian Christ hovering high above the altar. His athletic physique seemed to move in the light-and-shadow-play of the flickering altar candles. Christ brandished his right arm at the cascade of lost souls tumbling down to Charon the Ferryman who waited to ship them off to Hell. The damned were suitably horror-struck. But then, even the faces of the blessed appeared less than ecstatic as their souls were sucked into Heaven.

A macabre picture, but Sarah couldn’t spot what was bothering the Doctor. She glanced over her shoulder at the murky chapel, sparsely patched with the illumination of flambeaux and the candles of side-altars. If the scene was intended to evoke reverence and awe, it didn’t succeed. It was downright spooky: she could almost imagine a painted Renaissance spectre stepping off a wall.

‘Astounding!’

The Doctor’s loud exclamation made her heart do the hop-skip-and-jump. She darted a glance at his animated expression: a near-childlike excitement had got the better of him. You could always rely on the Doctor to be erratic.

He was engrossed in the portrait of St Benedict. ‘Look,’ he said, indicating Benedict’s aged hand. ‘The attention to detail is remarkable.’

She already knew what to look for; she was educated, she was an astute journalist: besides, she’d read the guide books.

Michelangelo had painted his own features into the wrinkled flesh on the back of the saint’s hand. A neat little touch, sure, but what was so amazing about it?

She gave an indifferent shrug. ‘Just a portrait in wrinkles.

Michelangelo’s face.’

‘Do you recognize Michelangelo?’

How the blazes was she supposed to identify the Renaissance artist in a maze of wrinkles? ‘No,’ she said in a flat tone. ‘Sorry. Don’t recognize him at all.’

He peered closer at the painted hand. ‘Neither do I, Sarah.

Neither do I. Most curious.’

Puzzled by his remark, she was about to pose a question when he spun on his heel and marched swiftly down the hall, his arms spreading expansively. His energetic tone boomed in the cavernous space as he hurled his personality in all directions. ‘You know where we are, Sarah Jane? I’ll give you a clue: there’s no place like Rome.’

Cursing under her breath, she ran after him, the soles of her rope sandals slapping on the marble. By the time she drew alongside his gangling figure she’d traversed more than half the length of the floor.

‘Of course I know,’ she snorted. ‘We’re in the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel. Judging by the wall-torches, sometime before the mid-nineteenth century. And, if you hadn’t noticed, I’m strolling around the Vatican in a skimpy bikini.’

His pace didn’t slacken as he headed for the far wall.

‘Hmm... The TARDIS has materialized inside the Sistine Chapel – makes a change from the cargo hold of an alien spacecraft.’ Momentarily, there was a distant glint in his stare.

‘Inside the Sistine Chapel, within the Vatican.’

‘Yes, so, this is the Sistine Chapel. What of it?’

He flashed one of his disarming grins. ‘A rose is a rose is a rose – and if you believe that, you’ll believe anything.’

‘You call that an answer?’

‘No, but at least it’s a point of view.’

They’d reached the far wall to confront the first of the nine panels portraying the narrative of Genesis: the Separation of Light and Darkness. The Doctor’s gaze moved up the wall, then travelled along the frescoes of the vaulted ceiling.

‘What neurotic splendour!’ he marvelled. ‘Rather like Michelangelo himself, in fact. He didn’t want to do all this, you know. Pope Julius II badgered him into it. But then, Michelangelo chose the subject – the Bible, from Creation to the Last Judgement, a graphic story from beginning to end.’

As he was speaking he walked to a side-altar, beckoning his companion to follow.

She stood her ground. ‘Doctor, if this is turning into another of your investigations I’ll nip into the TARDIS and slip into something more – uncomfortable.’ She nodded in the direction of the time-travelling police box that contained a mini-universe. ‘Let’s face it, I’m not in suitable attire for a Vatican visitor.’

He pointed a finger at the ceiling, indicating the depiction of the Creation of Eve. ‘You’re more fully clad than Eve,’ he said.

‘Tell that to any passing cardinal.’

‘This won’t take more than a few seconds, Sarah, I promise.’ He held out a hand. ‘Please?’

She did her best to muffle a smile as she joined him by the altar. ‘Oh, OK. You always know how to get round me. Too fond of you by half, that’s my trouble.’

‘Really? I’m terribly fond of you, Sarah, and I don’t find it any trouble at all.’ Beaming genially, he nodded at the lighted altar candles. ‘Try putting one of the candles out.’

She raised a quizzical eyebrow, but stepped up to the altar and slammed a hand down on a candle. Her eyes widened as she witnessed the flame flickering through her hand. There wasn’t the slightest sensation of heat. Light without warmth.

Sarah glanced questioningly at the Doctor. ‘A holoflame,’

he informed, ‘like the fires on the wall-torches. The programmed flicker is an absolute give-away.’

She withdrew her hand. ‘Puts paid to my guess about the century. OK, you’ve had your little demonstration. Let’s get back to the TARDIS and head for the sun-kissed beaches of –’

‘The face.’

The Doctor’s incisive tone and remote aspect silenced her.

In an instant, all trace of the clown and prankster had vanished from his features. In the blue of his inward gaze was the light of an alien world, exposing his habitual tomfoolery for what it was, the froth on the surface of the ocean.

He looked a young forty going on eternity.

At times like these, mercifully rare, she felt as small as a mouse.

‘What about the face?’ she heard herself whisper.

His baritone thrilled right through her. ‘The image on St Benedict’s hand was a composite face. Faces within faces. I thought I recognized the pattern – from long ago.’

The moment of abstraction lengthened, then he shook his head and broke into a smile as he pulled out a yo-yo and put it into play. The froth was back on the ocean, obscuring the depths.

‘A composite face?’ she said.

‘Oh, heed me no heed,’ he grinned, performing a figure-of-eight with the yo-yo. ‘A little trot down memory lane to a door I never opened, into the rose garden.’

Quicker than she could blink, the yo-yo was back in his pocket. He raised his arms and circled on his heels, taking in the surroundings. ‘Impressive. A near-perfect reconstruction.

The artificial ageing is particularly noteworthy. However, the patterning of the marble floor is distinctly anachronistic, to say nothing of those gargoyles up there.’

She frowned. ‘A reconstruction? This is the Vatican, isn’t it?’

‘It’s a Vatican.’

She scratched her head. ‘Just how many are there?’

‘Oh, very few. In fact –’ His hand flew to his mouth. ‘Oh dear.’

‘What’s wrong?’

‘We’re on Earth.’

‘Is that bad?’

‘It is if I got the time co-ordinates right for Shalonar - AD

3278. Vatican City was remodelled in the 31st century by colonists from the Overcities, signalling the inception of the Europan era. If this is the Europa of 3278, or even a century either way...’ He grabbed her arm. ‘Quick, Sarah, back in the TARDIS. I’ll be right behind you.’

She didn’t need any more prompting to take to her heels as fast as her flip-flops would allow. Her sprinting strides devoured the distance to the vehicle, the Doctor’s heavier steps thumping close at her back.

Something was about to go seriously wrong, she just knew it.

But only a few more paces to the open door of the police box. Inside, safety.

Almost there...

The police box dropped clean through the floor.

Sarah skidded to a halt at the rim of an empty black square where the TARDIS had stood an instant earlier.

She spun round to confront the Doctor’s dismayed expression. ‘What happened?’ she demanded, heart thudding.

‘Don’t tell me you managed to land the TARDIS right on top of a trapdoor.’

‘A drop-slab,’ he responded. ‘I thought the patterning of the floor was peculiar – interlocking squares. Any one of them can function as a drop-slab. Should have realized that at first glance.’

A low rumble resounded from the square-framed pit as a slab of marble slammed up and slotted back into place, leaving the floor intact as before, minus the TARDIS. Sarah stared forlornly at the spot where the TARDIS wasn’t.

‘Somebody knows we’re here,’ she said bleakly.

‘Yes.’ The Doctor’s tone was sepulchral. ‘They must have known it from the moment we arrived.’ For a moment, he wore a woebegone expression, then switched from the funereal to the happy-go-lucky. ‘Oh well, that wily old girl of a TARDIS must have had one of its “tendencies”, depositing us here for some jolly good reason. After all, the TARDIS is a sort of extension of my psyche. No doubt, deep in my unconscious, I intended to come to this space-time co-ordinate. And so – here we are...’

Sarah closed her eyes and counted to five before speaking.

‘Do you actually believe that?’

‘Not a word of it,’ he said. ‘But a fool who persists in his folly becomes wise, as a friend of mine once said on Brighton sands. Mind you, he thought he was talking to Moses at the time...’ He straightened abruptly, snapping to attention. ‘No time for chit-chat. Must get the TARDIS back. Bothersome thing is, you left the door wide open.’

‘ I left the door wide open?’ she snorted, hands on hips.

He raised a hand in absolution. ‘Don’t blame yourself, Sarah. A mistake anyone could make.’

On the verge of delivering a barbed retort, she bit her lip.

‘Are you trying to rile me so I forget to be scared?’

He appeared genuinely baffled. ‘Am I? Oh well, if you say so.’

‘Tell me, just what should I be scared of? Dropping through the floor like the TARDIS? Being attacked by a mob of demented monks? What do you know about – what did you call it – Europa?’

‘Its reputation,’ he said darkly.

‘Oh, come on. You can tell me more than that.’

He scratched his brambly hair, as if trying to tease memories from his head. ‘Not much more. I’ve never visited Europa. All I know is a little something I picked up once from the TARDIS data banks. Europa is an area reconstructed on the site of the original Europe – East and West, and – er, this is slightly embarrassing...’

‘Go on, be embarrassed.’

‘Whatever you say. Well, how shall I put it – Europa is infested by ghosts, vampires, werewolves, ghouls and other grotesques spawned from old European folklore. I think we’re in a spot of bother, Sarah Jane.’

She gave a slow shake of the head. ‘I don’t think I want to hear this...’

The Doctor breezed on regardless. ‘And the whole kit and caboodle is ruled by the Inquisition under a renegade branch of the Catholic Church. The official papal seat is, I believe, situated in the Betelgeuse system during this era.’ The Doctor’s grin broadened into a crescent that was positively devilish. ‘If you want an idea of what it’s like travelling through Europa, imagine running scared in the Black Forest under a bad moon.’

‘But you’re talking about that old, black magic!’ she protested. ‘Has science just got ditched out the window?’

He twitched his shoulders. ‘Someone once said that advanced science becomes indistinguishable from magic, or words to that effect. Besides, I’m only quoting the data banks, which are not immune to the occasional gremlin. Perhaps this era has developed highly sophisticated psionics and – oh, never mind.’ He started to move away. ‘Now, Sarah, let’s introduce ourselves to the local ecclesiastic dignitaries before they introduce themselves to us.’

Breaking into a brisk stride, he made for a pair of imposing double doors. With a philosophical shrug, she tracked his long paces. At the doorway, he paused, and shot up a finger. ‘Take me to your pontiff! How does that sound as an introduction?’

‘Ho hum,’ she responded. ‘Although it has a resounding ring. The ringing tone of a ham actor. Lead on, Macduff.’

Pushing open the doors, he gave her a conspiratorial wink.

‘That’s the spirit, Sarah. I do so admire a plucky journalist.’

She scowled. ‘I hate it when you call me that.’ The scowl faded. ‘Or are you deliberately riling me again?’

‘Am I?’ he said, his bugging eyes the soul of innocence.

‘Hard to tell.’

A rumble from the floor startled the pair. Alternate drop-slabs had plunged out of sight, leaving the floor resembling a chess board with empty gaps for black squares.

‘Time to run?’ Sarah urged.

He raised a hand. ‘I don’t think so. Better wait and see what happens.’

Bare seconds passed before the slabs ascended back into place. On each slab stood a man garbed in livery reminiscent of the Swiss Guards, a score in all, bearing cruelly barbed halberds.

The nearest soldier, whose insignia marked him out from the rest, jabbed an accusatory finger at the time-travellers.

‘Protestant heretics!’ he roared. ‘Captain Emerich of the Switzia Guardians places you under arrest for the murder of Pope Lucian!’

‘You were right, Sarah,’ the Doctor confided out the corner of his mouth. ‘Time to run.’

Three

he sabre slashed as halberds jabbed in the chapel of St An

T ne.

Byron, blade streaking fast as thought, dispensed with poetic quotes and saved his breath for battle. Two Switzia Guardians had felt the edge of his keen steel and been split wide open, spilling their hot life on to cold marble. Five more to go.

The poet’s sabre flashed across a throat. Four to go.

In a blur of thrust, counterthrust and parry, Byron bedazzled his adversaries, spinning their wits. The sabre ripped through one man’s chest as the knife drove into another’s heart.

‘He’s a fiend!’ shrieked the foremost of the two surviving guards.

‘One of the devil’s own crew,’ the Englishman snarled, booting the man in the stomach and stabbing between the ribs.

A final swing of the sword severed the remaining man’s head from his shoulders. No enemies left standing: the way to the secret passage was clear.

He jumped over the heaped bodies, some still twitching, and cast a backward look at the chapel. His feet froze in mid-stride.

A granite gargoyle was turning its demonic head on a chapel wall. Its scaly neck craned towards him, stony eyes fixing the lord with a baleful glare.

Breaking free of the gargoyle’s dire spell, he sprang into the portal’s shadows.

‘Now they know where I am,’ he muttered under his breath.

‘Hell’s teeth.’

‘St Anne’s chapel,’ Agostini announced as a picture formed on a stained-glass window, obliterating the coloured glass depiction of Christ’s Harrowing of Hell. Framed by the window’s Gothic arch, the scene of slaughter in the chapel was revealed in three-dimensional detail, transmitted by a Gargoyle Vigilant. The assembled members of the Enclave caught a glimpse of Byron before he disappeared into the secret passage.

‘The ringleader,’ Agostini pronounced, then switched his attention to another window which displayed the interlopers in the Sistine Chapel. ‘And two of his accomplices. The accomplices are in our hands. Their leader may prove more elusive if he’s gleaned knowledge of the hidden maze.’

‘He’ll not last long,’ Cardinal Maroc stated confidently.

‘Who can outwit us in our own labyrinth?’

Agostini’s stare swept over the other six members of the Enclave, the innermost cabal of Vatican City, gathered in the circular Chapel of Witness beneath the Apostolic Palace. The faces of Inquisitor General Torquemada, Cardinals Maroc, Borgia, Richelieu, Altzinger and Francisco met his stare, unspeaking.

‘The murderers of Pope Lucian must be brought swiftly to punishment,’ he declared. ‘Europa must be left in no doubt of the fate awaiting those who dare strike against the Church Apostolic.’

Torquemada, exuding his customary aura of oily saintliness, uplifted his hands to heaven. ‘The apprehension of murderous heretics must be swift,’ he said. ‘But the punishment must be slow.’

Six heads nodded in accord.

He was all at sevens and sixes on this piggledy-higgledy night.

Miles Dashing sneaked out of St Peter’s Basilica and resumed lurking in the shadows of Bernini’s colonnade, perplexed and undecided.

No sign of Byron anywhere. Miles was mortified by the prospect of letting down his poetical comrade – despite the fellow being a bit of a scallywag – but what to do? Either it was the wrong place or the wrong time or maybe the whole thing had been called off. Come to think of it, where was Casanova? Wasn’t he supposed to be here too?

What to do? What to do?

‘Alack, unhappy night,’ he groaned, covering his exquisite features in a long-fingered hand.

Ashamed of his momentary lapse, Miles straightened his shoulders, flicked back his long blond hair, and determined to resolve his predicament. If neither Byron nor Casanova was here, it stood to reason that they were probably somewhere else. Well, yes, that was blindingly obvious, now he thought about it. So where else should he go? If not St Peter’s Square in Vatican City...

‘Yes!’ He snapped his fingers. ‘Casanova. There’s a clue.

And where does that saucy scoundrel live – Venice. St Mark’s Square in Venice.’

Decision reached, Miles Dashing raced from the piazza, his long, athletic legs taking him to the brink of – nothing.

Beyond the entrance to St Peter’s Square, Vatican City ended in a rim which overlooked the Roman hills two kilometres below, the moonlit vista puffed with cumulus cloud. Tonight, the Vatican was Exalted, hovering high above the earth.

Miles sheathed his sword and leaped off the edge of Vatican City.

Sarah didn’t need the Doctor to tell her it was time to run.

She’d already kicked off her sandals and was speeding down the corridor to the Borgia Apartments.

The Doctor delayed his flight, standing in the doorway to cover Sarah’s escape. Captain Emerich led the charge, halberd lowered. ‘Apostate necromancer!’ the captain screeched, froth speckling his blubbery lips.

With the prestidigitation of a conjurer, the Doctor drew the yo-yo from his pocket and unleashed its spinning disc to impact at lightning velocity between the captain’s eyes. The man’s onrush continued for a second from its own momentum, then he toppled, pole-axed.

The yo-yo was whisked back into the Doctor’s hand an instant after braining Captain Emerich, ready for a repeat performance.

The Switzia Guardians skidded to a stop, mouths agape.

‘Ah-hah!’ the Doctor chuckled wickedly, giving a convincing portrayal of a desperado. It was evident that these men were unaccustomed to defiance. ‘Are you ready to surrender?’ he demanded imperiously.

They were impressed. But not that impressed. The onslaught was resumed with redoubled intensity. ‘Heretic!

Pagan! Blasphemer!’

‘Now you’ve asked for it!’ the Doctor thundered, lashing out again with the yo-yo, downing two assailants in a fleet figure-of-eight. ‘Beware the Flashing Lemniscate!’ he boomed, whipping the yo-yo in another figure-of-eight, disposing of a couple more guards. ‘Devastation to flesh and bone!’

Two more soldiers hit the floor, senseless.

The Switzia Guardians finally faltered, unable to make rhyme or reason of the bizarre weapon launched at them, then dropped their halberds and executed a swift about-turn, beating a panicked retreat.

The Doctor was already hot on Sarah’s tracks the instant the guardians turned their backs. By the time the men had replenished their meagre stock of courage he’d be long gone.

‘Ah,’ he murmured. ‘But gone where?’

Sarah raced from the grandiose Borgia Apartments on to the seemingly interminable Lapidary Gallery skirting the Court of the Belvedere. The night sky was just visible above the far side of the grassy court.

She gave a breath of relief at the distinctive sound of the approaching paces.

‘What took you so long?’ she said as the Doctor rushed round the corner.

‘Just keep running.’

‘Where to?’ she gasped, legs pumping as she pushed herself to the limit.

‘Keep running down the corridor and I’ll think of something.’

They’d covered hardly thirty paces when a figure in black darted from the right, a sabre glinting in his hand.

‘Stand, or be chopped up fit for the butcher and baker!’

The Doctor grabbed Sarah’s arm and slowed her to a halt.

They confronted the stranger, who was dressed in a black velvet suit over a flared white shirt. Reddish-brown curls framed a saturnine face. An imperious air belied the man’s medium height.

‘George!’ the Doctor exclaimed. ‘It’s a small universe. But what are you doing a millennium or so out of your time?’ He threw a glance at Sarah. ‘I told you I’d think of something.

Meet George, an old friend.’

‘Lord Byron to you,’ the man scowled, although lowering his sword.

Sarah gazed, awestruck. Byron. Mad, bad and dangerous to know. The roistering poet whom no self-respecting career woman should look up to. But – she couldn’t help it – her skin tingled as Byron’s gaze roved her bikini-clad body. Besides, she was in a tight corner, and the mad, bad poet was a good man to have on your side in tight corners.

‘Good to meet you,’ she smiled, feeling thoroughly naked under his probing stare.

A wicked grin bent the lord’s lips. ‘Running near-nude through the Vatican. A shameless Diana of the chase. An honest slut. I approve.’

‘Don’t call me a slut, you male chauvinist pig!’ she exploded, sensual thoughts dispersed with a word.

‘A filly with spirit too,’ observed Byron. ‘If we find the time, I shall enjoy the taming. So shall you. On second thoughts... I couldn’t be bothered.’

‘George,’ interposed the Doctor before Sarah could hurl a well-chosen insult. ‘I’m the Doctor. We once sat by the Parthenon and I gave you a critique of a poem you hadn’t yet written. I know I look different now, but surely you remember that little episode with the five oranges and the purple handkerchief and the misplaced nostrum?’

The lord’s brow furrowed. ‘I remember nothing of the kind.

Your wits are obviously addled.’

The Doctor stroked his chin in meditation. ‘Hmm...

curious.’

‘Doctor!’ Sarah implored. ‘We’re up to our eyebrows in trouble. No time for reminiscences. We’ve got to –’

‘Are you the assassins who sent Pope Lucian to his Maker?’ Byron cut in.

The Doctor darted a glance down the passage. ‘The Switzia Guardians seemed to think so.’

Byron snorted. ‘They’re also saying it was me. I’ve been hunted through every hall and gallery in the Apostolic Palace.’

He stared deep into the Doctor’s eyes, then gave a small, knowing nod. ‘You’re no assassin.’

Without waming, he sped past them in the direction of the Borgia Apartments, a flick of the hand indicating a farewell.

‘No, not that way!’ the Doctor warned.

‘Adieu,’ Byron called out as he ran speedily, despite a slight limp, to the near end of the corridor.

‘Good riddance,’ sniffed Sarah, but with less conviction than she felt at the loss of a potentially valuable ally.

‘Shame about him running off like that,’ the Doctor murmured. ‘I find his amnesia about our meeting quite baffling. And why’s he in this epoch? Pope Lucian...’

He thumped his head. ‘Pope Lucian. Of course! Now it’s coming back to me. It is the year AD 3278, or very close. That means we’re bang in the middle of the High Dogmatic period.’

A low sigh. ‘We really are in a spot of bother, Sarah Jane.’

‘This is news?’ Despite her affection for the Doctor, he certainly took the biscuit for driving her clean up the wall.

‘Let’s get out of here. Fast!’

‘Absolutely right,’ he said, launching into a sprint down the gallery. ‘Follow me.’

The precise instant she resumed running the walls came alive. Faces grew out of them. Stone faces. From floor to ceiling, the full length of the corridor, gargoyles sprouted from the masonry, stony tongues flicking from their gaping mouths.

The myriad gargoyles screamed the same refrain, a high-pitched, eardrum-drilling shriek, incessantly repeated:

‘HERETICS...’

Sarah’s pulse accelerated its tempo to panic stations. ‘What in God’s name’s going on?’ she gasped.

The Doctor glanced over his shoulder. ‘Heretic Alarm, I suppose. Don’t let those ugly mugs on the wall worry you.

They’re just a type of plasmic extrusion – I think. Anyway, I find the mixture of Gothic and Baroque elements decidedly unaesthetic.’

Sarah couldn’t resist a smile. You had to give it to the Doctor for bare-faced insouciance in the middle of bedlam.

‘Bare-faced cheek, more like it,’ she said under her breath.

Ignoring the strident gargoyles, she focused her attention on the Doctor’s back and told her legs to run, run and run. The metres flashed by, and she forgot about her thumping heart and strained limbs. Run like the devil with a bigger devil at your back.

Her gaze still focused on the Doctor, his overcoat swirling, ludicrous scarf flying, she gave an extra push to draw alongside.

It was then she noticed something untoward about him.

Sarah couldn’t identify the wrongness at first. Her mind shifted several notches out of kilter when she realized that she could see through him. In a few blinks of the eye, he was becoming transparent. A phantom.

‘Doctor!’

His fading silhouette elongated, twisted out of shape. A thin cry of pain issued from the distorted spectre: ‘ Sarah... ’

The cry fled into the distance and the contorted residue of the Doctor vanished.

The corridor stretched ahead, empty and limitless. Her heart turned to lead and sank. ‘No!’ she railed. ‘No!’

She fell to her knees and thumped the mosaic floor with her fist, biting back the tears. A corner of her mind registered that the gargoyles had fallen silent. She didn’t care one way or the other. The Doctor was gone.

She had no idea how many minutes passed while she knelt on the floor. At length, she told herself not to give up, give out, give in. The Doctor wouldn’t have wanted that. Keep going, mourn later.

When she raised reddened eyes on the way ahead, she could see no end to the corridor. She rose to her feet and peered into the distance. The Lapidary Gallery lost itself in some unguessable vanishing point. The gallery had put space on the rack and stretched it beyond the limits.

‘Oh well, start moving.’ Her voice was weak and small.

She started forward. And stayed put. She looked down at her feet planted on the marble, the soles stuck fast. What the hell? Sarah shook her head in bemusement. What was doing this to her, and why?

As she gazed around helplessly, she noticed that the light of the holo-torches was dimming. As the illumination lowered, a chant rose, mounting wave by wave.

It was Gregorian chant, the discordant voices souring the natural beauty of the harmony. The Latin phrases clanged like funeral bells in the air:

Dies irae, dies illa,

Solver saeclum in favilla...

She mentally translated the familiar words: Day of wrath, day of mourning, Heaven and Earth in ashes burning...

‘Who’s the requiem for?’ she muttered. ‘Me?’

Her sense of balance suddenly went haywire.

The rapid forward motion was so abrupt that she reeled backwards, arms flailing. It took a few seconds for her senses to reorientate. When they did, she groaned aloud.

Her feet were still glued to the floor, but the floor was moving. The walls slid past at some ten miles an hour.

Inexorably, the speed increased until the gargoyles streaked by, mere smears in the shadows. She was racing along at fifty miles an hour, minimum, and the velocity kept on increasing.

Sarah was on an express conveyor belt whisking her to an unknown destination at a rate of knots.

‘What’s happening?’ she yelled. Then the acceleration escalated to a point where the breath was forced from her lungs.

At that point she saw the end of the corridor hurtle towards her. Rubbing water from her eyes, she made out a black door that blocked out the entire corridor.

The door enlarged in moments, glinting metallically. End of the line. A terminal full stop.

Sarah slammed into it at killing speed with a despairing scream: ‘DOCTOR!’

Four

lad in the hooded robes of Convocation Extraordinary, the dignitaries of the E

C

nclave sat in the seven thrones of the

Crypt of the Seven Sleepers. Each of the fabled Sleepers, dreaming or otherwise, was entombed behind an icon set in the granite walls.

In front of the Altar Ipsissimus, flanked by congregations of holocandles and a small group of mechanical monks, rested the two-metre-high blue box taken from the two intruders in the Sistine Chapel. Although the object’s door was open, no one had yet succeeded in entering the outlandish container.

Fidgeting on his throne, Torquemada folded his arms and glared. ‘What is this infernal, heathenish machine? What sorcery obstructs us from walking through an open door? And what is the diabolic meaning of the legend on its crest: Police Public Call Box? And the rest of its words of witchcraft on the side: police telephone free for use of public –’

‘The point, surely,’ said Richelieu, ‘is that the entrance is invisibly barred.’

Agostini, accepting a proffered glass of wine from a mechanical monk, ushered the cowled robot away before flicking a hand at the box’s open door. ‘Whatever force prevents access, we’ll circumvent it.’

‘It is the gate to Satan’s domain,’ Torquemada insisted.

Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia waved a lazy arm at the Spanish Inquisitor General. ‘You’re so naive, Tomas.’ Ignoring the bristling Torquemada, he continued in a robust tone. ‘It’s merely a device, like an Angelus or viewing gargoyle or mechanical horse. Like all devices, when mastered, it will serve a purpose.’

‘I beg to differ,’ Agostini said. ‘There are forms of technology which undermine the dominance of the Catholic Church Apostolic and the Holy Inquisition. This contraption here may be a product of just such technological expertise.’

He glanced across at Torquemada. ‘The intruders must be interrogated as to the nature of this – this apparatus. I trust the man and his shameless female companion are secure in Hell?’

The Inquisitor General bent a pious smile, small eyes brimming with anticipation. ‘Yes, indeed – interrogated – in Hell.’ The words were honey on his tongue.

Maroc raised a hand. ‘The candidature for the papacy has not been decided. In my capacity as Camerlengo, I must deal with this matter without delay. Rodrigo Borgia would seem the obvious choice –’

The Borgia cardinal nodded vigorously.

Agostini gave a firm shake of the head. ‘Until the identity of the pope’s assassins is irrefutably established, it would be unwise to institute a papal election. Many out there in Europa would be only too willing to believe that the murder was arranged – in Vaticano. There is, after all, a long history of ambitious cardinals disposing of popes in order to ascend the Throne of Peter and wear the Fisherman’s Ring.’

‘Why are you looking at me?’ Cardinal Borgia rumbled, glaring under his bushy eyebrows.

‘I wasn’t,’ Agostini replied wearily. ‘Until this matter is settled, a cloud hangs over the entire Vatican Curia. In short, Lord Byron and his two accomplices must be sentenced to an auto-da-fé. Justice must be seen to be done. The arts of the inquisitor will ensure a satisfactory outcome in that area, I have no doubt.’

‘You may count on it, eminence,’ Torquemada said.

‘As regards this puzzling device,’ said Agostini, indicating the police box. ‘The dungeons of the Inquisition will supply us with answers from Byron’s co-conspirators.’ He looked around for confirmation. ‘Agreed?’

One by one, heads inclined.

‘Excellent.’ Agostini leaned back in the throne. ‘Then, Torquemada, I suggest you introduce the two accused to the torments of Hell.’

‘The Pit and the Pendulum,’ chuckled Rodrigo Borgia.

‘Oh no, eminence,’ Torquemada purred. ‘That would be too great a mercy.’

Sarah recalled a phrase from Milton: darkness visible.

The dark pressed in on her with all the force of a sentient presence, intimating the blackest of revelations. She wondered if she’d died and gone to Hell. There were no pits of lurid fire, no sulphurous smoke, no gibbering demons with pitchforks at the ready. This was a cold, night Hell. Hovering weightless in this nothingness, aware of neither up nor down, she recalled the metal door she’d seemed to slam into at fatal speed.

Had it been an illusion of the dying, or had her rapid forward acceleration altered into an abrupt downward tilt? For all she knew, she might have been plucked from the gallery and deposited in a psionically engineered Pit somewhere in the Vatican.

To keep terror at bay – and terror was damn near breathing down her throat – she cast her mind back to childhood. Think back to the happy days.

Behind her eyes, she resurrected the streets of South Croydon, the tiny playing field of her primary school where she frequently lost her ball over the blue railings. And there was Julie with her mass of freckles, always laughing. And Billy, forever giving her the wink, while she thumbed her nose at the tow-haired scamp. Coming home, satchel swinging in one hand, choc-ice in the other, socks collapsed round her ankles. Home to Mum and Dad.

Until that day when Mum and Dad weren’t there. She’d wandered the too-empty house for an hour, then the phone rang. The caller was Aunt Lavinia, ringing from Morton Harewood. There’d been a car accident. Mum and Dad hadn’t suffered. It had all been very quick. Quick and painless...

The darkness visible bored back into her. With an effort, she thrust it away. Recall a face, a voice...

Aunt Lavinia.

After the car accident came the sharp transition to Morton Harewood and the slow tempo of village life. Aunt Lavinia had done her best to be father and mother to the orphan under her roof, but nobody’s best would have been enough. Sarah’s parents had been the best in the world. She still believed that.

When she moved back to South Croydon, it was chiefly the memory of Mum and Dad that prompted the return. She’d always ensured the grave was kept tidy...

The past images deliquesced like water-colours in the rain.

The darkness visible was back in full intensity, driving out each light-and-life recollection.

She wasn’t a child any more, nor a teenager. And she wasn’t in the London suburbs. She was either dead and damned, or alive and in a hell contrived by a pseudo-Vatican.

The only fixed point left was the Doctor. When she first met him in his third incarnation as a crease-featured, grey-haired man, apparently in late middle age, she almost came to look on him as a father-figure.

Father-figure? She’d kidded herself back then. For all that he was a Time Lord from the mysterious planet of Gallifrey, he just didn’t measure up. No one could stand in her Dad’s shoes.

But with the Doctor’s regeneration into a younger man with hair like an exploding Brillo pad, the father-figure issue never arose. The Fourth Doctor was her idea of a mad uncle, and she’d always wanted a mad uncle. Gifted by the experience of his seven-hundred-whatever years, he still looked like he’d come down with the last shower.

If he was dead...

No, she refused to accept that. Many times, when she thought him dead and done for, up he popped again like a jack-in-the-box. She even believed him capable of negotiating an escape clause from the Last Judgement.

She needed him now. Needed his tomfoolery, his clown’s wisdom.

The darkness visible lapped over the fringes of her mind, threatening to swamp all the memories in the locked cupboards and cabinets – her parents, Aunt Lavinia, the Doctor, steeped in oblivion.

Terror, no longer at bay, leapt like a tiger, ravenous to devour her, piece by piece.

Of one thing Sarah was sure; living or dead, she was in Hell.

The Doctor hung in the middle of a black void, arms folded, feet crossed, body leaning against a metaphorical lamp-post.

He had tried shouting out for Sarah, but the muffling dark all but swallowed up his voice, and he caught no response from his companion. Oh well, if whoever put him here had decided to keep him alive, the chances were good that they’d done the same for Sarah. If they hadn’t, they’d answer to him.

Whoever they were, they possessed considerable skill in the field of somatic transmatography. He had been phased from the Lapidary Gallery to – wherever he was – with ruthless efficiency. The transdimensional distortions, warping his physique during transit, were decidedly uncomfortable.

Where exactly was he? Limbo? No, that was a catch-all name, another way of admitting that you hadn’t a clue where you were. It wasn’t E-space – or N-space for that matter.

Lifting his battered hat, he scratched his head, trying to solve the puzzle.

‘Hmm...’ he mused.

Miles Dashing plummeted three metres from the brink of the Exalted Vatican City and landed in the seat of his Draco, the golden hover-scooter fashioned in the likeness of a stylized dragon, wings partially unfurled.

‘Must check it’s still hovering in the same spot I left it before I jump next time,’ he muttered.

Releasing the camouflage device that disguised the craft as an Angelus, one of the Vatican’s air vehicles, he sped north towards Venice. As the kilometres raced below, his native melancholy reasserted itself. Two hours to Venice at full Draco speed. About half that time to Florence, where his beloved dwelt – his divinity in female form.

‘ Beatrice...’ he sighed soulfully. ‘Beatrice Florentino.’

He had glimpsed her first as he stood on the Ponte Vecchio over the River Arno that wound through Florence’s glorious cityscape. In that one look, he had become her worshipper, her idolater. For a time he worshipped his goddess from afar, then he made his reckless move, made mad by all-consuming adoration.

A rose gripped between his teeth, he swung in through her open window in the depths of the Florentine night –

– and discovered it was the wrong window. He landed on top of Beatrice’s mother where she slept in bed. There followed a session of screams and gunshots and unseemly language, culminating in his expulsion from the villa with the tidings ringing in his ears that his divine Beatrice had fled her home on the very eve of his importunate entrance. He set off in quest of his Queen of Heaven, scouring the numerous Dominions of Europa.

He found her at last in the Demi-monde area west of the Wall in Franco-Berlin. She had grown very fat and exceedingly common in that brothel in the Demi-monde. No longer the radiant idol of his youth (well, of nine months earlier), she stubbornly refused to leave the house of ill-repute, speaking in the most foul-mouthed manner of ‘good money’

and ‘liking ‘em rough’. Oft-times he beseeched the fallen lady to turn from her sorry state and take up residence with him in a small but serviceable castle in one of Bohemia’s Black Forests, but ever she spurned him with unladylike scorn until he desisted and rode away on his mechanical horse, wracked with sorrow and steeped in irredeemable gloom.

‘A sad tale, but mine own,’ he sighed mournfully to the wind. Then, slowly, the importance of his mission dawned on him. Enough of past regrets and tristesse, no matter how deeply lodged in his wounded heart. He had a duty to fulfil, and a gentleman always did his duty.

Miles Dashing’s obligation now was to Byron – wherever he may be. The poetic lord was involved in some kind of deal with the pope that would advance the cause of the Dominoes and diminish the flourishing power of the Inquisition. A high, noble ambition.

‘If only I could play my part,’ Miles muttered, brow troubled with a frown. ‘I hope Byron’s in Venice. At least, there’s a good chance that Casanova will be there.’

The torchlights of Florence came into sight on the horizon.

‘Oh, my lost Beatrice,’ Miles Dashing moaned soulfully.

‘What the –’

Casanova flung back the sheets and blankets and rubbed his pounding head. His vision gradually focused on the tall, aristocratic figure standing by the bed. Taking in the heroic posture, the tragic aura, the flowing blond hair and outrageously good-looking features, he gave a low groan. ‘Oh

– it’s you.’

Miles Dashing gave a curt bow. ‘Miles Dashing of Dashwood, at your service.’

Casanova yawned, still partly in his dreams. ‘I thought the name was Miles Dashwood.’

‘I had to adopt a pseudonym, for political purposes.’

‘You’re hardly likely to pass incognito with a minor alteration like that, are you?’ Casanova said, blinking sleep from his eyes.

Miles politely waved aside the sardonic observation. ‘You may not be acquainted with my reasons for secrecy, but two years ago, the nobly born but vampiric Mindelmeres, owners of an estate neighbouring Dashwood House, attacked my family while I was elsewhere engaged in a duel over a lady’s honour –’

Casanova was now fully awake, despite the throbbing in his skull from too much wine. ‘Oh, wait, you’ve told me all this before, several times –’

Miles, however, was in full flood. ‘Little was I to know, as I passed the gloomy fastnesses of the Mindelmere estates, what horrors that foul brood had visited upon the Dashwood family. Yet, a curious despondency and chill foreboding settled on my spirit as the lofty towers of Dashwood House loomed into view –’

‘Yes, we’re all familiar with your family tragedy and very sympathetic, but –’

‘Hesitating a moment at the threshold of my family home, strangely hushed in the spectral gloom, I summoned my courage and entered, sword in hand –’

Casanova buried his head in his hands. ‘Oh God,’ he moaned.

‘I was soon to discover that my sword would serve me naught, for my family had become – vampires. They advanced upon me, fangs bared, eager to bestow the bloody kiss of the undead. “Avaunt!” I cried at the ghastly sight, and reached for my stake-gun –’

‘And staked the lot of them,’ Casanova broke in, ‘which led to the charge of kin-slayer being laid at your door, chiefly through the influence of the Mindelmeres, forcing you to escape execution by fleeing Regency Britannia, since when you’ve wandered through the Europan Dominions with a price on your head.’

Miles’s graceful eyebrows arched in surprise. ‘Oh, I see.

I’ve told you all this before.’

‘And about bloody Be–’ Casanova checked himself. ‘And about Beatrice,’ he concluded lamely.

Miles averted his elegant profile. ‘Yes, but that was all long, long ago.’

Casanova sat up. ‘Anyway, what did you want?’

Pulling himself together with a mighty effort, Miles squared his shoulders and flung back his head. ‘Plans are afoot and the Dominoes are on the march. The ignoble alliance between the Inquisition and Cardinal Richelieu is about to be sabotaged. But I must locate Lord Byron for the first blow to be struck. Would you happen to know his whereabouts?’

The Venetian shrugged and sprawled crossways on the bed.

‘I’d like to know Maria Fiore’s whereabouts. I arranged a tryst with her last night. She didn’t turn up.’ He grunted. ‘Sleeping alone is best left to when one is in one’s coffin.’

‘You slept alone,’ Miles remarked in a tactful tone.

‘It has been known,’ Casanova retorted. ‘Anyway, about Byron – he’s not here. I should try Britannia if I were you.’

‘Which one?’

‘Either of the two main ones.’

Miles rubbed his finely chiselled chin. ‘Hmm... You don’t think he’d be in the Vatican then? I was under the impression that you also had a meeting with him in the Exalted City.’

‘Are you joking? That’s hardly likely, is it? No, if I were you, I’d try Regency Britannia first, or – wait a moment – I heard rumour of Byron taking up residence in the Villa Diodati again.’

Giving a resigned lift of the shoulders, Miles exhaled a short breath. ‘The Villa Diodati would seem the most probable choice.’ He swirled the opera cloak around him. ‘Adieu.’

An instant later he leaped through the open window.

Casanova slumped back on the disordered pillows, and mulled over Dashing’s strange visit. Then he thumped his head, and winced at the pain it caused.