ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

With heartfelt thanks to my agent, Luigi Bonomi, to my editors Harriet Evans and Bill Massey, and to Jane Heller. Also to Amanda Preston, Amelia Cummins, Vanessa Forbes, Gaia Banks, Jenny Bateman and Catherine Cobain. To the many friends, colleagues and institutions who have helped make my fieldwork such an adventure over the years, and have made real archaeology as exciting as fiction. To Ann Verrinder Gibbins, who took me to the Caucasus and Central Asia, and then provided the perfect haven for writing. To Dad, Alan and Hugh, and to Zebedee and Suzie. To Angie, and to our lovely daughter Molly, who arrived when this book was just an idea and has seen me through it.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, institutions, places and incidents are creations of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual or other fictional events, locales, organizations or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. The factual backdrop is discussed in the author’s note at the end.

“A mighty empire once ruled the larger part of the world. Its rulers lived in a vast citadel, up against the sea, a great maze of corridors like nothing seen since. They were ingenious workers in gold and ivory and fearless bullfighters. But then, for defying Poseidon the Sea God, in one mighty deluge the citadel was swallowed beneath the waves, its people never to be seen again.”

PROLOGUE

The old man shuffled to a halt and raised his head, as awestruck as he had been the first time he stood before the temple. Nothing like this had yet been built in his native Athens. High above him the monumental doorway seemed to carry all the weight of the heavens, its colossal pillars casting a moonlit shadow far beyond the temple precinct into the shimmering expanse of the desert. Ahead loomed rows of huge columns, soaring into the cavernous antechamber, their polished surfaces covered with hieroglyphic inscriptions and towering human forms scarcely visible in the spluttering torchlight. The only hint of what lay beyond was a whispering, chilling breeze which brought with it the musty odour of incense, as if someone had just opened the doors of a long-sealed burial chamber. The old man shuddered in spite of himself, his philosophical demeanour momentarily giving way to an irrational fear of the unknown, a fear of the power of gods whom he could not placate and who had no interest in the well-being of his people.

“Come, Greek.” The words hissed out of the darkness as the attendant lit his torch from one of the doorway fires, its leaping flame revealing a lithe, wiry physique clad only in a loincloth. As he padded ahead, the bobbing flame was the only mark of his progress. As usual he stopped at the entrance to the inner sanctum and waited impatiently for the old man, whose stooped form followed behind through the antechamber. The attendant had nothing but contempt for this hellenos, this Greek, with his bald head and unkempt beard, with his endless questions, who kept him waiting in the temple every night far beyond the appointed hour. By writing on his scrolls, the Greek was performing an act properly reserved for the priests.

Now the attendant’s contempt had turned to loathing. That very morning his brother Seth had returned from Naucratis, the busy port nearby where the brown flood-water of the Nile debouched into the Great Middle Sea. Seth had been downcast and forlorn. They had entrusted a batch of cloth from their father’s workshop in the Fayum to a Greek merchant who now claimed it was lost in a shipwreck. They were already full of suspicion that the wily Greeks would exploit their ignorance of commerce. Now their foreboding had hardened to hatred. It had been their last hope of escaping a life of drudgery in the temple, condemned to an existence little better than the baboons and cats that lurked in the dark recesses behind the columns.

The attendant peered venomously at the old man as he approached. Lawmaker, they called him. “I will show you,” the attendant whispered to himself, “what my gods think of your laws, you Greek.”

The scene within the inner sanctum could not have been in greater contrast to the forbidding grandeur of the antechamber. A thousand pinpricks of light, like fireflies in the night, sprang from pottery oil lamps around a chamber hewn from the living rock. From the ceiling hung elaborate bronze incense burners, the wispy trails of smoke forming a layer of haze across the room. The walls were set with recesses like the burial niches of a necropolis; only here they were filled not with shrouded corpses and cinerary urns but with tall, open-topped jars brimming over with papyrus scrolls. As the two men descended a flight of steps, the reek of incense grew stronger and the silence was broken by a murmur that became steadily more distinct. Ahead lay two eagle-headed pillars which served as jambs for great bronze doors that opened towards them.

Facing them through the entrance were orderly rows of men, some sitting cross-legged on reed mats and wearing only loincloths, all hunched over low desks. Some were copying from scrolls laid out beside them; others were transcribing dictations from black-robed priests, their low recitations forming the softly undulating chant they had heard as they approached. This was the scriptorium, the chamber of wisdom, a vast repository of written and memorized knowledge passed down from priest to priest since the dawn of history, since even before the pyramid builders.

The attendant withdrew into the shadows of the stairwell. He was forbidden from entering the chamber, and now began the long wait until the time came to escort the Greek away. But this evening, instead of whiling away the hours in sullen resentment, he took a grim satisfaction in the events planned for the night.

The old man pushed past in his eagerness to get on. This was his final night in the temple, his last chance to fathom the mystery that had obsessed him since his previous visit. Tomorrow was the beginning of the monthlong Festival of Thoth, when all newcomers were barred from the temple. He knew that an outsider would never again be granted an audience with the high priest.

In his haste the Greek stumbled into the room, dropping his scroll and pens with a clatter which momentarily distracted the scribes from their work. He muttered in annoyance and glanced around apologetically before collecting together his bundle and shuffling between the men towards an annexe at the far end of the chamber. He ducked under a low doorway and sat down on a reed mat, his previous visits giving him the only intimation that there might be another seated in the darkness before him.

“Solon the Lawmaker, I am Amenhotep the high priest.”

The voice was barely audible, little more than a whisper, and sounded as old as the gods. Again it spoke.

“You come to my temple at Saïs, and I receive you. You seek knowledge, and I give what the gods will impart.”

The formal salutations over, the Greek quickly arranged his white robe over his knees and readied his scroll. From the darkness Amenhotep leaned forward, just enough for his face to be caught in a flickering shaft of light. Solon had seen it many times before, but it still sent a shudder through his soul. It seemed disembodied, a luminous orb suspended in the darkness, like some spectre leering from the edge of the underworld. It was the face of a young man suspended in time, as if mummified; the skin was taut and translucent, almost parchment-like, and the eyes were glazed over with the milky sheen of blindness.

Amenhotep had been old before Solon was born. It was said that he had been visited by Homer, in the time of Solon’s great-grandfather, and that it was he who told of the siege of Troy, of Agamemnon and Hector and Helen, and of the wanderings of Odysseus. Solon would have dearly loved to ask him about this and other matters, but in so doing he would be violating his agreement not to question the old priest.

Solon leaned forward attentively, determined not to miss anything in this final visit. At length Amenhotep spoke again, his voice no more than a ghostly exhalation.

“Lawmaker, tell me whereof I spoke yesterday.”

Solon quickly unravelled his scroll, scanning the densely written lines. After a moment he began to read, translating the Greek of his script into the Egyptian language they were now speaking.

“A mighty empire once ruled the larger part of the world.” He peered down in the gloom. “Its rulers lived in a vast citadel, up against the sea, a great maze of corridors like nothing seen since. They were ingenious workers in gold and ivory and fearless bullfighters. But then, for defying Poseidon the Sea God, in one mighty deluge the citadel was swallowed beneath the waves, its people never to be seen again.” Solon stopped reading and looked up expectantly. “That is where you finished.”

After what seemed an interminable silence, the old priest spoke again, his lips scarcely moving and his voice little more than a murmur.

“Tonight, Lawmaker, I will tell you many things. But first let me speak of this lost world, this city of hubris smitten by the gods, this city they called Atlantis.”

Many hours later the Greek put down his pen, his hand aching from continuous writing, and wound up his scroll. Amenhotep had finished. Now was the night of the full moon, the beginning of the Festival of Thoth, and the priests must prepare the temple before the supplicants arrived at dawn.

“What I have told you, Lawmaker, was here, and nowhere else,” Amenhotep had whispered, his crooked finger slowly tapping his head. “By ancient decree we who cannot leave this temple, we high priests, must keep this wisdom as our treasure. It is only by command of the astrologos, the temple seer, that you are able to be here, by some will of divine Osiris.” The old priest leaned forward, a hint of a smile on his lips. “And, Lawmaker, remember: I do not speak in riddles, like your Greek oracles, but there may be riddles in what I recite. I speak a truth passed down, not a truth of my own devising. You have come for the last time. Go now.” As the deathly face receded into the darkness Solon slowly rose, hesitating momentarily and looking back one last time before stooping out into the now empty scriptorium and making his way towards the torchlit entranceway.

Rosy-fingered dawn was colouring the eastern sky, the faint glow tinting the moonlight which still danced across the waters of the Nile. The old Greek was alone, the attendant having left him as usual outside the precinct. He had sighed with satisfaction as he passed the temple columns, their palm-leaf capitals so unlike the simple Greek forms, and glanced for the last time at the Sacred Lake with its eerie phalanx of obelisks and human-headed sphinxes and colossal statues of the pharaohs. He had been pleased to leave all that behind and was walking contentedly along the dusty road towards the mud-brick village where he was staying. In his hands he clutched the precious scroll, and over his shoulder hung a satchel weighed down by a heavy purse. Tomorrow, before leaving, he would make his offering of gold to the goddess Neith, as he had promised Amenhotep when they first spoke.

He was still lost in wonderment at what he had heard. A Golden Age, an age of splendour even the pharaohs could not have imagined. A race who mastered every art, in fire and stone and metal. Yet these were men, not giants, not like the Cyclops who built the ancient walls on the Acropolis. They had found the divine fruit and picked it. Their citadel shone like Mount Olympus. They had dared defy the gods, and the gods had struck them down.

Yet they had lived on.

In his reverie he failed to notice two dark forms who stole out from behind a wall as he was entering the village. The blow caught him completely unawares. As he slumped to the ground and darkness descended, he was briefly aware of hands pulling off his shoulder bag. One of the figures snatched the scroll from his grasp and tore it to shreds, throwing the fragments out of sight down a rubbish-strewn alley. The two figures disappeared as silently as they had come, leaving the Greek bloodied and unconscious in the dirt.

When he came to he would have no memory of that final night in the temple. In his remaining years he would rarely speak of his time in Saïs and never again put pen to paper. The wisdom of Amenhotep would never again leave the sanctity of the temple, and would seem lost for ever as the last priests died and the silt of the Nile enveloped the temple and its key to the deepest mysteries of the past.

I’VE NEVER SEEN ANYTHING LIKE IT BEFORE!”

The words came from a dry-suited diver who had just surfaced behind the stern of the research vessel, his voice breathless with excitement. After swimming over to the ladder, he removed his fins and mask and passed them up to the waiting barge chief. He hauled himself laboriously out of the water, his heavy cylinders causing him momentarily to lose balance, but a heave from above landed him safe and sound on the deck. His dripping shape was quickly surrounded by other members of the team who had been waiting on the dive platform.

Jack Howard made his way down from the bridge walkway and smiled at his friend. He still found it amazing that such a bulky figure could be so agile underwater. As he negotiated the clutter of dive equipment on the aft deck he called out, his mocking tone a familiar part of their banter over the years.

“We thought you’d swum back to Athens for a gin and tonic beside your father’s pool. What’ve you found, the lost treasure of the Queen of Sheba?”

Costas Kazantzakis shook his head impatiently as he struggled along the railing towards Jack. He was too agitated even to bother taking off his equipment. “No,” he panted. “I’m serious. Take a look at this.”

Jack silently prayed that the news was good. It had been a solo dive to investigate a silted-up shelf on top of the submerged volcano, and the two divers who had followed Costas would soon be surfacing from the decompression stop. There would be no more dives that season.

Costas unclipped a carabiner and passed over an underwater camcorder housing, pressing the REPLAY button as he did so. The other members of the team converged behind the tall Englishman as he flipped open the miniature LCD screen and activated the video. Within moments Jack’s sceptical grin had given way to a look of blank amazement.

The underwater scene was illuminated by powerful floodlights which gave colour to the gloom almost one hundred metres below. Two divers were kneeling on the seabed using an airlift, a large vacuum tube fed by a low-pressure air hose which sucked up the silt covering the site. One diver wrestled to keep the airlift in position while the other gently wafted sediment up towards the mouth of the tube, the action revealing artefacts just as an archaeologist on land would use a trowel.

As the camera zoomed in, the object of the divers’ attention came dramatically into view. The dark shape visible upslope was not rock but a concreted mass of metal slabs laid in interlocking rows like shingles.

“Oxhide ingots,” Jack said excitedly. “Hundreds of them. And there’s a cushioning layer of brushwood dunnage, just as Homer described in the ship of Odysseus.”

Each slab was about a metre long with protruding corners, their shape resembling the flayed and stretched hide of an ox. They were the characteristic copper ingots of the Bronze Age, dating back more than three and a half thousand years.

“It looks like the early type,” one of the students on the team ventured. “Sixteenth century BC?”

“Unquestionably,” Jack said. “And still in rows just as they were laden, suggesting the hull may be preserved underneath. We could have the oldest ship ever discovered.”

Jack’s excitement mounted as the camera traversed down the slope. Between the ingots and the divers loomed three giant pottery jars, each as tall as a man and over a metre in girth. They were identical to jars that Jack had seen in the storerooms at Knossos on Crete. Inside, they could see stacks of stemmed cups painted with beautifully naturalistic octopuses and marine motifs, their swirling forms at one with the undulations of the seabed.

There was no mistaking the pottery of the Minoans, the remarkable island civilization that flourished at the time of the Egyptian Middle and New Kingdoms but then disappeared suddenly, around 1400 BC. Knossos, the fabled labyrinth of the Minotaur, had been one of the most sensational discoveries of the last century. Following close on the heels of Heinrich Schliemann, excavator of Troy, the English archaeologist Arthur Evans had set out to prove that the legend of the Athenian prince Theseus and his lover Ariadne was as grounded in real events as the Trojan War. The sprawling palace just south of Heraklion was the key to a lost civilization he dubbed Minoan after their legendary king. The maze of passageways and chambers gave extraordinary credence to the story of Theseus’ battle with the Minotaur, and showed that the myths of the Greeks centuries later were closer to real history than anyone had dared think.

“Yes!” Jack punched the air with his free hand, his normal reserve giving way to the emotion of a truly momentous discovery. It was the culmination of years of single-minded passion, the fulfillment of a dream that had driven him since boyhood. It was a find that would rival Tutankhamun’s tomb, a discovery that would secure his team front place in the annals of archaeology.

For Jack these images were enough. Yet there was more, much more, and he stood transfixed by the screen. The camera panned down to the divers on a low shelf below the clump of ingots.

“Probably the stern compartment.” Costas was pointing at the screen. “Just beyond this ledge is a row of stone anchors and a wooden steering oar.”

Immediately in front was an area of shimmering yellow which looked like the reflection of the floodlights off the sediment in the water. As the camera zoomed in, there was a collective gasp of astonishment.

“That’s not sand,” the student whispered. “That’s gold!”

Now they knew what they were looking at, the image was one of surpassing splendour. In the centre was a magnificent golden chalice fit for King Minos himself. It was decorated in relief with an elaborate bullfighting scene. Alongside lay a life-sized golden statue of a woman, her arms raised in supplication and her headdress wreathed in snakes. Her bare breasts had been sculpted from ivory, and a flickering arc of colour showed where her neck was embellished with jewels. Nestled in front was a bundle of golden-handled bronze swords, their blades decorated with fighting scenes made from inlaid silver and blue enamel.

The most brilliant reflection came from the area just in front of the divers. Each waft of the hand seemed to reveal another gleaming object. Jack could make out gold bars, royal seals, jewellery and delicate diadem crowns of intertwined leaves, all jumbled together as if they had once been inside a treasure chest.

The view suddenly veered up towards the ascent line and the screen abruptly went blank. In the stunned silence that followed, Jack lowered the camera and looked at Costas.

“I think we’re in business,” he said quietly.

Jack had staked his reputation on a far-flung proposal. In the decade since completing his doctorate he had become fixated on discovering a Minoan wreck, a find that would clinch his theory about the maritime supremacy of the Minoans in the Bronze Age. He had become convinced that the most likely spot was a group of reefs and islets some seventy nautical miles north-east of Knossos.

Yet for weeks they had searched in vain. A few days earlier their hopes had been raised and then dashed by the discovery of a Roman wreck, a dive Jack expected to be his last of the season. Today was to have been a chance to evaluate new equipment for their next project. Once again Jack’s luck had held out.

“Mind giving me a hand?”

Costas had slumped exhausted beside the stern railing on Seaquest, his equipment still unbuckled and the water on his face now joined by rivulets of sweat. The late afternoon sun of the Aegean drenched his form in light. He looked up at the lean physique that towered over him. Jack was an unlikely scion of one of England’s most ancient families, his easy grace the only hint of a privileged lineage. His father had been an adventurer who had eschewed his background and used his wealth to take his family away with him to remote locations around the world. His unconventional upbringing had left Jack an outsider, a man most at ease in his own company and beholden to nobody. He was a born leader who commanded respect on the bridge and the foredeck.

“What would you do without me?” Jack asked with a grin as he lifted the tanks off Costas’ back.

The son of a Greek shipping tycoon, Costas had spurned the playboy lifestyle which was his for the asking and opted for ten years at Stanford and MIT, emerging as an expert in submersible technology. Surrounded by a vast jumble of tools and parts that only he could navigate, Costas would routinely conjure up wondrous inventions like some latter-day Caractacus Pott. His passion for a challenge was matched by his gregarious nature, a vital asset in a profession where teamwork was essential.

The two men had first met at the NATO base at Izmir in Turkey when Jack had been seconded to the Naval Intelligence School and Costas was a civilian adviser to UNANTSUB, the United Nations anti-submarine warfare research establishment. A few years later Jack invited Costas to join him at the International Maritime University, the research institution which had been their home for more than ten years now. In that time Jack had seen his remit as director of field operations at IMU grow to four ships and more than two hundred personnel, and despite an equally burgeoning role in the engineering department, Costas always seemed to find a way to join Jack when things got exciting.

“Thanks, Jack.” Costas slowly stood up, too tired to say more. He only stood as high as Jack’s shoulders and had a barrel chest and forearms inherited from generations of Greek sponge fishermen and sailors, with a personality to match. This project had been close to his heart as well, and he was suddenly drained by the excitement of discovery. It was he who had set the expedition in train, using his father’s connections with the Greek government. Although they were now in international waters, the support of the Hellenic Navy had been invaluable, not least in keeping them supplied with the cylinders of purified gas which were vital for trimix diving.

“Oh, I almost forgot.” Costas’ round, tanned face broke into a grin as he reached into his stabilizer jacket. “Just in case you thought I’d faked the whole thing.”

He extracted a package swaddled in protective neoprene and handed it over, a triumphant gleam in his eye. Jack was unprepared for the weight and his hand momentarily dropped. He undid the wrapping and gasped in astonishment.

It was a solid metal disc about the diameter of his hand, its surface as lustrous as if it were brand new. There was no mistaking the deep hue of unalloyed gold, a gold refined to the purity of bullion.

Unlike many of his academic colleagues Jack never pretended to be unmoved by treasure, and for a moment he let the thrill of holding several kilogrammes of gold wash through him. As he held it up and angled it towards the sun, the disc gave off a dazzling flash of light, as if it were releasing a great burst of energy pent up over the millennia.

He was even more elated when he saw the sun glint off markings on the surface. He lowered the disc into Costas’ shadow and traced his fingers over the indentations, all of them exquisitely executed on one convex side.

In the centre was a curious rectilinear device, like a large letter H, with a short line dropping from the crossbar and four lines extending like combs from either side. Around the edge of the disc were three concentric bands, each one divided into twenty compartments. Each compartment contained a different symbol stamped into the metal. To Jack the outer circle looked like pictograms, symbols that conveyed the meaning of a word or phrase. At a glance he could make out a man’s head, a walking man, a paddle, a boat and a sheaf of corn. The inner compartments were aligned with those along the edge, but instead contained linear signs. Each of these was different but they seemed more akin to letters of the alphabet than to pictograms.

Costas stood and watched Jack examine the disc, totally absorbed. His eyes were alight in a way Costas had seen before. Jack was touching the Age of Heroes, a time shrouded in myth and legend, yet a period which had been spectacularly revealed in great palaces and citadels, in sublime works of art and brilliantly honed weapons of war. He was communing with the ancients in a way that was only possible with a shipwreck, holding a priceless artefact that had not been tossed away but had been cherished to the moment of catastrophe. Yet it was an artefact shrouded in mystery, one he knew would draw him on without respite until all its secrets were out.

Jack turned the disc over several times and looked at the inscriptions again, his mind racing back to undergraduate courses on the history of writing. He had seen something like this before. He made a mental note to email the image to Professor James Dillen, his old mentor at Cambridge University and the world’s leading authority on the ancient scripts of Greece.

Jack passed the disc back to Costas. For a moment the two men looked at each other, their eyes ablaze with excitement. Jack hurried over to join the team kitting up beside the stern ladder. The sight of all that gold had redoubled his fervour. The greatest threat to archaeology lay in international waters, a free-for-all where no country held jurisdiction. Every attempt to impose a global sea law had ended in failure. The problems of policing such a huge area seemed insurmountable. Yet advances in technology meant that remote-operated submersibles, of the type used to discover the Titanic, were now little more expensive than a car. Deep-water exploration that was once the preserve of a few institutes was now open to all, and had led to the wholesale destruction of historic sites. Organized pillagers with state-of-the-art technology were stripping the seabed with no record being made for posterity and artefacts disappearing for ever into the hands of private collectors. And the IMU teams were not only up against legitimate operators. Looted antiquities had become major currency in the criminal underworld.

Jack glanced up at the timekeeper’s platform and felt a familiar surge of adrenaline as he signalled his intention to dive. He began carefully to assemble his equipment, setting his dive computer and checking the pressure of his cylinders, his demeanour methodical and professional as if there were nothing special about this day.

In truth he could barely contain his excitement.

MAURICE HIEBERMEYER STOOD UP AND wiped his forehead, momentarily checking the sheen of sweat that was dripping off his face. He looked at his watch. It was nearly noon, close to the end of their working day, and the desert heat was becoming unbearable. He arched his back and winced, suddenly realizing how much he ached from more than five hours hunched over a dusty trench. He slowly made his way to the central part of the site for his customary end-of-day inspection. With his wide-brimmed hat, little round glasses and knee-length shorts he cut a faintly comic figure, like some empire builder of old, an image that belied his stature as one of the world’s leading Egyptologists.

He silently watched the excavation, his thoughts accompanied by the familiar clinking of mattocks and the occasional creak of a wheelbarrow. This may not have the glamour of the Valley of the Kings, he reflected, but it had far more artefacts. It had taken years of fruitless search before Tutankhamun’s tomb had been discovered; here they were literally up to their knees in mummies, with hundreds already revealed and more being uncovered every day as new passageways were cleared of sand.

Hiebermeyer walked over to the deep pit where it had all begun. He peered over the edge into an underground labyrinth, a maze of rock-cut tunnels lined with niches where the dead had remained undisturbed over the centuries, escaping the attention of the tomb robbers who had destroyed so many of the royal graves. It was a wayward camel that had exposed the catacombs; the unfortunate beast had strayed off the track and disappeared into the sand before its owner’s eyes. The drover had run over to the spot and recoiled in horror when he saw row upon row of bodies far below, their faces staring up at him as if in reproach for disturbing their hallowed place of rest.

“These people are in all likelihood your ancestors,” Hiebermeyer had told the camel drover after he had been summoned from the Institute of Archaeology in Alexandria to the desert oasis two hundred kilometres to the south. The excavations had proved him right. The faces which had so terrified the drover were in reality exquisite paintings. Some were of a quality unsurpassed until the Italian Renaissance. Yet they were the work of artisans, not some ancient great master, and the mummies were not nobles but ordinary folk. Most of them had lived not in the age of the pharaohs but in the centuries when Egypt was under Greek and Roman rule. It was a time of increased prosperity, when the introduction of coinage spread wealth and allowed the new middle class to afford gilded mummy casings and elaborate burial rituals. They lived in the Fayum, the fertile oasis which extended sixty kilometres east from the necropolis towards the Nile.

The burials represented a much wider cross-section of life than a royal necropolis, Hiebermeyer reflected, and they told stories just as fascinating as a mummified Ramses or Tutankhamun. Only this morning he had been excavating a family of cloth-makers, a man named Seth and his father and brother. Colourful scenes of temple life adorned the cartonnage, the plaster and linen board that formed the breastplate over their coffins. The inscription showed that the two brothers had been lowly attendants in the temple of Neith at Saïs but had experienced good fortune and gone into business with their father, a trader in cloth with the Greeks. They had clearly profited handsomely to judge from the valuable offerings in the mummy wrappings and the gold-leaf masks that covered their faces.

“Dr. Hiebermeyer, I think you should come and see this.”

The voice came from one of his most experienced trench supervisors, an Egyptian graduate student who he hoped one day would follow him as director of the institute. Aysha Farouk peered up from the side of the pit, her handsome, dark-skinned face an image from the past, as if one of the mummy portraits had suddenly sprung to life.

“You will have to climb down.”

Hiebermeyer replaced his hat with a yellow safety helmet and gingerly descended the ladder, his progress aided by one of the local fellahin employed as labourers on the site. Aysha was perched over a mummy in a sandstone niche only a few steps down from the surface. It was one of the graves that had been damaged by the camel’s fall, and Hiebermeyer could see where the terracotta coffin had been cracked and the mummy inside partly torn open.

They were in the oldest part of the site, a shallow cluster of passageways which formed the heart of the necropolis. Hiebermeyer fervently hoped his student had found something that would prove his theory that the mortuary complex had been founded as early as the sixth century BC, more than two centuries before Alexander the Great conquered Egypt.

“Right. What do we have?” His German accent gave his voice a clipped authority.

He stepped off the ladder and squeezed in beside his assistant, careful not to damage the mummy any further. They had both donned lightweight medical masks, protection against the viruses and bacteria that might lie dormant within the wrapping and be revived in the heat and moisture of their lungs. He closed his eyes and briefly bowed his head, an act of private piety he carried out each time he opened a burial chamber. After the dead had told their tale he would see that they were reinterred to continue their voyage through the afterlife.

When he was ready, Aysha adjusted the lamp and reached into the coffin, cautiously prising apart the jagged tear which ran like a great wound through the belly of the mummy.

“Just let me clean up.”

She worked with a surgeon’s precision, her fingers deftly manipulating the brushes and dental picks which had been neatly arranged in a tray beside her. After a few minutes clearing away the debris from her earlier work she replaced the tools and edged her way towards the head of the coffin, making room for Hiebermeyer to have a closer look.

He cast an expert eye over the objects she had removed from the resin-soaked gauze of the mummy, its aroma still pungent after all the centuries. He quickly identified a golden ba, the winged symbol of the soul, alongside protective amulets shaped like cobras. In the centre of the tray was an amulet of Qebeh-sennuef, guardian of the intestines. Alongside was an exquisite faience brooch of an eagle god, its wings outstretched and the silicate material fired to a lustrous greenish hue.

He shifted his bulky frame along the shelf until he was poised directly over the incision in the casing. The body was facing east to greet the rising sun in symbolic rebirth, a tradition which went far back into prehistory. Below the torn wrapping he could see the rust-coloured torso of the mummy itself, the skin taut and parchment-like over the ribcage. The mummies in the necropolis had not been prepared in the manner of the pharaohs, whose bodies were eviscerated and filled with embalming salts; here the desiccating conditions of the desert had done most of the job, and the embalmers had removed only the organs of the gut. By the Roman period even that procedure was abandoned. The preservational characteristics of the desert were a godsend to archaeologists, as remarkable as waterlogged sites, and Hiebermeyer was constantly astonished by the delicate organic materials that had survived for thousands of years in near perfect condition.

“Do you see?” Aysha could no longer contain her excitement. “There, below your right hand.”

“Ah yes.” Hiebermeyer’s eye had been caught by a torn flap in the mummy wrapping, its ragged edge resting on the lower pelvis.

The material was covered with finely spaced writing. This in itself was nothing new; the ancient Egyptians were indefatigable record-keepers, writing copious lists on the paper they made by matting together fibres of papyrus reed. Discarded papyrus also made excellent mummy wrapping and was collected and recycled by the funerary technicians. These scraps were among the most precious finds of the necropolis, and were one reason why Hiebermeyer had proposed such a large-scale excavation.

At the moment he was less interested in what the writing said than the possibility of dating the mummy from the style and language of the script. He could understand Aysha’s excitement. The torn-open mummy offered a rare opportunity for on-the-spot dating. Normally they would have to wait for weeks while the conservators in Alexandria painstakingly peeled away the wrappings.

“The script is Greek,” Aysha said, her enthusiasm getting the better of her deference. She was now crouched beside him, her hair brushing against his shoulder as she motioned towards the papyrus.

Hiebermeyer nodded. She was right. There was no mistaking the fluid script of ancient Greek, quite distinct from the hieratic of the Pharaonic period and the Coptic of the Fayum region in Greek and Roman times.

He was puzzled. How could a fragment of Greek text have been incorporated in a Fayum mummy of the sixth or fifth century BC? The Greeks had been allowed to establish a trading colony at Naucratis on the Canopic branch of the Nile in the seventh century BC, but their movement inland had been strictly controlled. They did not become major players in Egypt until Alexander the Great’s conquest in 332 BC, and it was inconceivable that Egyptian records would have been kept in Greek before that date.

Hiebermeyer suddenly felt deflated. A Greek document in the Fayum would most likely date from the time of the Ptolemies, the Macedonian dynasty that began with Alexander’s general, Ptolemy I Lagus, and ended with the suicide of Cleopatra and the Roman takeover in 30 BC. Had he been so wrong in his early date for this part of the necropolis? He turned towards Aysha, his expressionless face masking a rising disappointment.

“I’m not sure I like this. I’m going to take a closer look.”

He pulled the angle-lamp closer to the mummy. Using a brush from Aysha’s tray, he delicately swept away the dust from one corner of the papyrus, revealing a script as crisp as if it had been penned that day. He took out his magnifying glass and held his breath as he inspected the writing. The letters were small and continuous, uninterrupted by punctuation. He knew it would take time and patience before a full translation could be made.

What mattered now was its style. Hiebermeyer was fortunate to have studied under Professor James Dillen, a renowned linguist whose teaching left such an indelible impression that Hiebermeyer was still able to remember every detail more than two decades after he had last studied ancient Greek calligraphy.

After a few moments his face broke into a grin and he turned towards Aysha.

“We can rest easy. It’s early, I’m sure of it. Fifth, probably sixth century BC.”

He closed his eyes with relief and she gave him a swift embrace, the reserve between student and professor momentarily forgotten. She had guessed the date already; her master’s thesis had been on the archaic Greek inscriptions of Athens and she was more of an expert than Hiebermeyer, but she had wanted him to have the triumph of discovery, the satisfaction of vindicating his hypothesis about the early foundation of the necropolis.

Hiebermeyer peered again at the papyrus, his mind racing. With its tightly spaced, continuous script it was clear this was no administrative ledger, no mere list of names and numbers. This was not the type of document which would have been produced by the merchants of Naucratis. Were there other Greeks in Egypt at this period? Hiebermeyer knew only of occasional visits by scholars who had been granted rare access to the temple archives. Herodotus of Halicarnassos, the Father of History, had visited the priests in the fifth century BC, and they had told him many wondrous things, of the world before the conflict between the Greeks and the Persians which was the main theme of his book. Earlier Greeks had visited too, Athenian statesmen and men of letters, but their visits were only half remembered and none of their accounts had survived first-hand.

Hiebermeyer dared not voice his thoughts to Aysha, aware of the embarrassment that could be caused by a premature announcement which would spread like wildfire among the waiting journalists. But he could barely restrain himself. Had they found some long-lost lynchpin of ancient history?

Almost all the literature that survived from antiquity was known only from medieval copies, from manuscripts painstakingly transcribed by monks in the monasteries after the fall of the Roman Empire in the west. Most of the ancient manuscripts had been ruined by decay or destroyed by invaders and religious zealots. For years scholars had hoped against hope that the desert of Egypt would reveal lost texts, writings which might overturn ancient history. Above all they dreamed of something that might preserve the wisdom of Egypt’s scholar priests. The temple scriptoria visited by Herodotus and his predecessors preserved an unbroken tradition of knowledge that extended back thousands of years to the dawn of recorded history.

Hiebermeyer ran excitedly through the possibilities. Was this a firsthand account of the wanderings of the Jews, a document to set alongside the Old Testament? Or a record of the end of the Bronze Age, of the reality behind the Trojan War? It might tell an even earlier history, one showing that the Egyptians did more than simply trade with Bronze Age Crete but actually built the great palaces. An Egyptian King Minos? Hiebermeyer found the idea hugely appealing.

He was brought back to earth by Aysha, who had continued to clean the papyrus and now motioned him towards the mummy.

“Look at this.”

Aysha had been working along the edge of the papyrus where it stuck out from the undamaged wrapping. She gingerly raised a flap of linen and pointed with her brush.

“It’s some kind of symbol,” she said.

The text had been broken by a strange rectilinear device, part of it still concealed under the wrapping. It looked like the end of a garden rake with four protruding arms.

“What do you make of it?”

“I don’t know.” Hiebermeyer paused, anxious not to seem at a loss in front of his student. “It may be some form of numerical device, perhaps derived from cuneiform.” He was recalling the wedge-shaped symbols impressed into clay tablets by the early scribes of the Near East.

“Here. This might give a clue.” He leaned forward until his face was only inches away from the mummy, gently blowing the dust from the text that resumed below the symbol. Between the symbol and the text was a single word, its Greek letters larger than the continuous script on the rest of the papyrus.

“I think I can read it,” he murmured. “Take the notebook out of my back pocket and write down the letters as I dictate them.”

She did as instructed and squatted by the coffin with her pencil poised, flattered that Hiebermeyer had confidence in her ability to make the transcription.

“OK. Here goes.” He paused and raised his magnifying glass. “The first letter is Alpha.” He shifted to catch a better light. “Then Tau. Then Alpha again. No, scratch that. Lamna. Now another Alpha.”

Despite the shade of the niche the sweat was welling up on his forehead. He shifted back slightly, anxious to avoid dripping on the papyrus.

“Nu. Then Tau again. Iota, I think. Yes, definitely. And now the final letter.” Without letting his eyes leave the papyrus he felt for a small pair of tweezers on the tray and used them to raise part of the wrapping that was lying over the end of the word. He blew gently on the text again.

“Sigma. Yes, Sigma. And that’s it.” Hiebermeyer straightened. “Right. What do we have?”

In truth he had known from the moment he saw the word, but his mind refused to register what had been staring him in the face. It was beyond his wildest dreams, a possibility so embedded in fantasy that most scholars would simply disown it.

They both stared dumbfounded at the notebook, the single word transfixing them as if by magic, everything else suddenly blotted out and meaningless.

“Atlantis.” Hiebermeyer’s voice was barely a whisper.

He turned away, blinked hard, and turned back again. The word was still there. His mind was suddenly in a frenzy of speculation, pulling out everything he knew and trying to make it hold.

Years of scholarship told him to start with what was least contentious, to try to work his finds into the established framework first.

Atlantis. He stared into space. To the ancients the story could have occupied the tail end of their creation myth, when the Age of Giants gave over to the First Age of Men. Perhaps the papyrus was an account of this legendary golden age, an Atlantis rooted not in history but in myth.

Hiebermeyer looked into the coffin and wordlessly shook his head. That could not be right. The place, the date. It was too much of a coincidence. His instinct had never failed him, and now he felt it more strongly than he ever had before.

The familiar, predictable world of mummies and pharaohs, priests and temples seemed to fall away before his eyes. All he could think about was the enormous expenditure of effort and imagination that had gone into reconstructing the ancient past, an edifice that suddenly seemed so fragile and precarious.

It was funny, he mused, but that camel may have been responsible for the greatest archaeological discovery ever made.

“Aysha, I want you to prepare this coffin for immediate removal. Fill that cavity with foam and seal it over.” He was site director again, the immense responsibility of their discovery overcoming his boyish excitement of the last few minutes. “I want this on the truck to Alexandria today, and I want you to go with it. Arrange for the usual armed escort, but nothing special as I do not want to attract undue attention.”

They were ever mindful of the threat posed by modern-day tomb robbers, scavengers and highwaymen who lurked in the dunes around the site and had become increasingly audacious in their attempts to steal even the smallest trifle.

“And, Aysha,” he said, his face now deadly serious. “I know I can trust you not to breathe a word of this to anyone, not even to our colleagues and friends in the team.”

Hiebermeyer left Aysha to her task and grappled his way up the ladder, the extraordinary drama of the discovery suddenly compounding his fatigue. He made his way across the site, staggering slightly under the withering sun, oblivious to the excavators who were still waiting dutifully for his inspection. He entered the site director’s hut and slumped heavily in front of the satellite phone. After wiping his face and closing his eyes for a moment he composed himself and switched on the set. He dialled a number and soon a voice came over the headphone, crackly at first but clearer as he adjusted the antenna.

“Good afternoon, you have reached the International Maritime University. How may I help you?”

Hiebermeyer quickly responded, his voice hoarse with excitement. “Hello, this is Maurice Hiebermeyer calling from Egypt. This is top priority. Patch me through immediately to Jack Howard.”

THE WATERS OF THE OLD HARBOUR LAPPED gently at the quayside, each wave drawing in lines of floating seaweed that stretched out as far as the eye could see. Across the basin, rows of fishing boats bobbed and shimmered in the midday sun. Jack Howard stood up and walked towards the balustrade, his dark hair ruffled by the breeze and his bronzed features reflecting the months spent at sea in search of a Bronze Age shipwreck. He leaned against the parapet and gazed out at the sparkling waters. This had once been the ancient harbour of Alexandria, its splendour rivalled only by Carthage and Rome itself. From here the grain fleets had set sail, wide-hulled argosies that carried the bounty of Egypt to a million people in Rome. From here, too, wealthy merchants had despatched chests of gold and silver across the desert to the Red Sea and beyond; in return had come the riches of the east, frankincense and myrrh, lapis lazuli and sapphires and tortoiseshell, silk and opium, brought by hardy mariners who dared to sail the monsoon route from Arabia and far-off India.

Jack looked down at the massive stone revetment ten metres below. Two thousand years ago this had been one of the wonders of the world, the fabled Pharos of Alexandria. It was inaugurated by Ptolemy II Philadelphus in 285 BC, a mere fifty years after Alexander the Great had founded the city. At one hundred metres it towered higher than the Great Pyramid at Giza. Even today, more than six centuries after the lighthouse had been toppled by an earthquake, the foundations remained one of the marvels of antiquity. The walls had been converted into a medieval fortress and served as headquarters of the Institute of Archaeology at Alexandria, now the foremost centre for the study of Egypt during the Graeco-Roman period.

The remains of the lighthouse still littered the harbour floor. Just below the surface lay a great jumble of blocks and columns, their massive forms interspersed with shattered statues of kings and queens, gods and sphinxes. Jack himself had discovered one of the most impressive, a colossal form broken on the seabed like Ozymandias, King of Kings, the toppled image of Ramses II so famously evoked by Shelley. Jack had argued that the statues should be recorded and left undisturbed like their poetic counterpart in the desert.

He was pleased to see a queue forming at the submarine port, testimony to the success of the underwater park. Across the harbour the skyline was dominated by the futuristic Bibliotheca Alexandrina, the reconstituted library of the ancients that was a further link to the glories of the past.

“Jack!” The door of the conference chamber swung open and a stout figure stepped onto the balcony. Jack turned to greet the newcomer.

“Herr Professor Dr. Hiebermeyer!” Jack grinned and held out his hand. “I can’t believe you brought me all the way here to look at a piece of mummy wrapping.”

“I knew I’d get you hooked on ancient Egypt in the end.”

The two men had been exact contemporaries at Cambridge, and their rivalry had fuelled their shared passion for antiquity. Jack knew Hiebermeyer’s occasional formality masked a highly receptive mind, and Hiebermeyer in turn knew how to break through Jack’s reserve. After so many projects in other parts of the world, Jack looked forward eagerly to sparring again with his old tutorial partner. Hiebermeyer had changed little since their student days, and their disagreements about the influence of Egypt on Greek civilization were an integral part of their friendship.

Behind Hiebermeyer stood an older man dressed immaculately in a crisp light suit and bow tie, his eyes startlingly sharp beneath a shock of white hair. Jack strode over and warmly shook the hand of their mentor, Professor James Dillen.

Dillen stood aside and ushered two more figures through the doorway.

“Jack, I don’t think you’ve met Dr. Svetlanova.”

Her penetrating green eyes were almost level with his own and she smiled as she shook his hand. “Please call me Katya.” Her English was accented but flawless, a result of ten years’ study in America and England after she had been allowed to travel from the Soviet Union. Jack knew of Katya by reputation, but he had not expected to feel such an immediate attraction. Normally Jack was able to focus completely on the excitement of a new discovery, but this was something else. He could not keep his eyes off her.

“Jack Howard,” he replied, annoyed that he had let his guard down as her cool and amused stare seemed to bore into him.

Her long black hair swung as she turned to introduce her colleague. “And this is my assistant Olga Ivanovna Bortsev from the Moscow Institute of Palaeography.”

In contrast to Katya Svetlanova’s well-dressed elegance, Olga was distinctly in the Russian peasant mould. She looked like one of the propaganda heroines of the Great Patriotic War, thought Jack, plain and fearless, with the strength of any man. She was struggling beneath a pile of books but looked him full in the eyes as he offered his hand.

With the formalities over, Dillen ushered them through the door into the conference room. He was to chair the proceedings, Hiebermeyer having relinquished his usual role as director of the institute in deference to the older man’s status.

They seated themselves round the table. Olga arranged her load of books neatly beside Katya and then retired to one of the chairs ranged along the back wall of the room.

Hiebermeyer began to speak, pacing to and fro at the far end of the room and illustrating his account with slides. He quickly ran through the circumstances of the discovery and described how the coffin had been moved to Alexandria only two days previously. Since then the conservators had worked round the clock to unravel the mummy and free the papyrus. He confirmed that there were no other fragments of writing, that the papyrus was only a few centimetres larger than had been visible during the excavation.

The result was laid out in front of them under a glass panel on the table, a ragged sheet about thirty centimetres long and half as wide, its surface densely covered by writing except for a gap in the middle.

“Extraordinary coincidence that the camel should have put its foot right in it,” Katya said.

“Extraordinary how often that happens in archaeology.” Jack winked at her after he had spoken and they both smiled.

“Most of the great finds are made by chance,” Hiebermeyer continued, oblivious to the other two. “And remember, we have hundreds more mummies to open. This was precisely the type of discovery I was hoping for and there could be many more.”

“A fabulous prospect,” agreed Katya.

Dillen leaned across to take the projector remote control. He straightened a pile of papers which he had removed from his briefcase while Hiebermeyer was speaking.

“Friends and colleagues,” he said, slowly scanning the expectant faces. “We all know why we are here.”

Their attention shifted to the screen at the far end of the room. The image of the desert necropolis was replaced by a close-up of the papyrus. The word which had so transfixed Hiebermeyer in the desert now filled the screen.

“Atlantis,” Jack breathed.

“I must ask you to be patient.” Dillen scanned the faces, aware how desperate they were to hear his and Katya’s translation of the text. “Before I speak I propose that Dr. Svetlanova give us an account of the Atlantis story as we know it. Katya, if you will.”

“With pleasure, Professor.”

Katya and Dillen had become friends when she was a sabbatical fellow under his guidance at Cambridge. Recently they had been together in Athens when the city had been devastated by a massive earthquake, cracking open the Acropolis to reveal a cluster of rock-cut chambers which contained the long-lost archive of the ancient city. Katya and Dillen had assumed responsibility for publishing the texts relating to Greek exploration beyond the Mediterranean. Only a few weeks earlier their faces had been splashed over front pages all round the world following a press conference in which they revealed how an expedition of Greek and Egyptian adventurers had sailed across the Indian Ocean as far as the South China Sea.

Katya was also one of the world’s leading experts on the legend of Atlantis, and had brought with her copies of the relevant ancient texts. She picked up two small books and opened them at the marked pages.

“Gentlemen, may I first say what a pleasure it is for me to be invited to this symposium. It is a great honour for the Moscow Institute of Palaeography. Long may the spirit of international co-operation continue.”

There was an appreciative murmur from around the table.

“I will be brief. First, you can forget virtually everything you have ever heard about Atlantis.”

She had assumed a serious scholarly demeanour, the twinkle in her eye gone, and Jack found himself concentrating entirely on what she had to say.

“You may think Atlantis was a global legend, some distant episode in history half remembered by many different cultures, preserved in myth and legend around the world.”

“Like the stories of the Great Flood,” Jack interjected.

“Exactly.” She fixed his eyes with wry amusement. “But you would be wrong. There is one source only.” She picked up the two books as she spoke. “The ancient Greek philosopher Plato.”

The others settled back to listen.

“Plato lived in Athens from 427 to 347 BC, a generation after Herodotus,” she said. “As a young man Plato would have known of the orator Pericles, would have attended the plays of Euripides and Aeschylus and Aristophanes, would have seen the great temples being erected on the Acropolis. These were the glory days of classical Greece, the greatest period of civilization ever known.”

Katya put down the books and pressed them open. “These two books are known as the Timaeus and the Critias. They are imaginary dialogues between men of those names and Socrates, Plato’s mentor whose wisdom survives only through the writings of his pupil.

“Here, in a fictional conversation, Critias tells Socrates about a mighty civilization, one which came forth out of the Atlantic Ocean nine thousand years before. The Atlanteans were descendants of Poseidon, god of the sea. Critias is lecturing Socrates.

“There was an island situated in front of the Straits which are by you called the Pillars of Hercules; the island was larger than Libya and Asia put together. In this island of Atlantis there was a great and wonderful empire which had rule over the whole island and several others, and over parts of the continent, and, furthermore, the men of Atlantis had subjugated the parts of Libya within the Columns of Hercules as far as Egypt, and of Europe as far as Tyrrhenia. This vast power, gathered into one, endeavoured to subdue at a blow our country and yours and the whole of the region within the Straits.”

Katya took the second volume, looking up briefly. “Libya was the ancient name for Africa, Tyrrhenia was central Italy and the Pillars of Hercules the Strait of Gibraltar. But Plato was neither geographer nor historian. His theme was a monumental war between the Athenians and the Atlanteans, one which the Athenians naturally won but only after enduring the most extreme danger.”

She looked again at the text.

“And now the climax, the nub of the legend. These final few sentences have tantalized scholars for more than two thousand years, and have led to more dead ends than I can count.

“But afterwards there occurred violent earthquakes and floods; and in a single day and night of misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea.”

Katya closed the book and gazed quizzically at Jack. “What would you expect to find in Atlantis?”

Jack hesitated uncharacteristically, aware that she would be judging his scholarship for the first time. “Atlantis has always meant much more than simply a lost civilization,” he replied. “To the ancients it was a fascination with the fallen, with greatness doomed by arrogance and hubris. Every age has had its Atlantis fantasy, always harking back to a world of unimagined splendour overshadowing all history. To the Nazis it was the birthplace of Überman, the original Aryan homeland, spurring a demented search around the world for racially pure descendants. To others it was the Garden of Eden, a Paradise Lost.”

Katya nodded and spoke quietly. “If there is any truth to this story, if the papyrus gives us any more clues, then we may be able to solve one of the greatest mysteries of ancient history.”

There was a pause as the assembled gathering looked from one to the other, anticipation and barely repressed eagerness on their faces.

“Thank you, Katya.” Dillen stood up, obviously more comfortable speaking on his feet. He was an accomplished lecturer, used to commanding the full attention of his audience.

“I suggest the Atlantis story is not history but allegory. Plato’s intention was to draw out a series of moral lessons. In the Timaeus, order triumphs over chaos in the formation of the Cosmos. In the Critias, men of self-discipline, moderation and respect for the law triumph over men of pride and presumption. The conflict with Atlantis was contrived to show that Athenians had always been people of resolve who would ultimately be victorious in any war. Even Plato’s pupil Aristotle thought Atlantis never existed.” Dillen put his hands on the table and leaned forward.

“I suggest Atlantis is a political fable. Plato’s account of how he came by the story is a whimsical fiction like Swift’s introduction to Gulliver’s Travels, where he gives a source which is plausible but could never be verified.”

Dillen was playing devil’s advocate, Jack knew. He always relished his old professor’s rhetorical skills, a reflection of years spent in the world’s great universities.

“It would be useful if you could run over Plato’s source,” Hiebermeyer said.

“Certainly.” Dillen looked at his notes. “Critias was Plato’s great-grandfather. Critias claims that his own great-grandfather heard the Atlantis story from Solon, the famed Athenian lawmaker. Solon in turn heard it from an aged Egyptian priest at Saïs in the Nile Delta.”

Jack did a quick mental calculation. “Solon lived from about 640 to 560 BC. He would only have been admitted to the temple as a venerated scholar. If we therefore assume he visited Egypt as an older man, but not too old to travel, that would place the encounter some time in the early sixth century BC, say 590 or 580 BC.”

“If, that is, we are dealing with fact and not fiction. I would like to pose a question. How is it that such a remarkable story was not known more widely? Herodotus visited Egypt in the middle of the fifth century BC, about half a century before Plato’s time. He was an indefatigable researcher, a magpie who scooped up every bit of trivia, and his work survives in its entirety. Yet there is no mention of Atlantis. Why?”

Dillen’s gaze ranged around the room taking in each of them in turn. He sat down. After a pause Hiebermeyer stood up and paced behind his chair.

“I think I might be able to answer your question.” He paused briefly. “In our world we tend to think of historical knowledge as universal property. There are exceptions of course, and we all know history can be manipulated, but in general little of significance can be kept hidden for long. Well, ancient Egypt was not like that.”

The others listened attentively.

“Unlike Greece and the Near East, whose cultures had been swept away by invasions, Egypt had an unbroken tradition stretching back to the early Bronze Age, to the early dynastic period around 3100 BC. Some believe it stretched back even as far as the arrival of the first agriculturalists almost four thousand years earlier.”

There was a murmur of interest from the others.

“Yet by the time of Solon this ancient knowledge had become increasingly hard to access. It was as if it had been divided into interlocking fragments, like a jigsaw puzzle, then packaged up and parcelled away.” He paused, pleased with the metaphor. “It came to reside in many different temples, dedicated to many different gods. The priests came to guard their own parcel of knowledge covetously, as their own treasure. It could only be revealed to outsiders through divine intervention, through some sign from the gods. Oddly,” he added with a twinkle in his eye, “these signs came most often when the applicant offered a benefaction, usually gold.”

“So you could buy knowledge?” Jack asked.

“Yes, but only when the circumstances were right, on the right day of the month, outside the many religious festivals, according to a host of other signs and auguries. Unless everything was right, an applicant would be turned away, even if he arrived with a shipload of gold.”

“So the Atlantis story could have been known in only one temple, and told to only one Greek.”

“Precisely.” Hiebermeyer nodded solemnly at Jack. “Only a handful of Greeks ever made it into the temple scriptoria. The priests were suspicious of men like Herodotus who were too inquisitive and indiscriminate, travelling from temple to temple. Herodotus was sometimes fed misinformation, stories that were exaggerated and falsified. He was, as you English say, led up the garden path.

“The most precious knowledge was too sacred to be committed to paper. It was passed down by word of mouth, from high priest to high priest. Most of it died with the last priests when the Greeks shut down the temples. What little made it to paper was lost under the Romans, when the Royal Library of Alexandria was burnt during the civil war in 48 BC and the Daughter Library went the same way when the emperor Theodosius ordered the destruction of all remaining pagan temples in AD 391. We already know some of what was lost from references in surviving ancient texts. The Geography of Pytheas the Navigator. The History of the World by the emperor Claudius. The missing volumes of Galen and Celsus. Great works of history and science, compendia of pharmaceutical knowledge that would have advanced medicine immeasurably. We can barely begin to imagine the secret knowledge of the Egyptians that went the same way.”

Hiebermeyer sat down and Katya spoke again.

“I’d like to propose an alternative hypothesis. I suggest Plato was telling the truth about his source. Yet for some reason Solon did not write down an account of his visit. Was he forbidden from doing so by the priests?”

She picked up the books and continued. “I believe Plato took the bare facts he knew and embellished them to suit his purposes. Here I agree in part with Professor Dillen. Plato exaggerated to make Atlantis a more remote and awesome place, fitting for a distant age. So he put the story far back in the past, made Atlantis equal to the largest landmass he could envisage, and placed it in the western ocean beyond the boundaries of the ancient world.” She looked at Jack. “There is a theory about Atlantis, one widely held by archaeologists. We are fortunate in having one of its leading proponents among us today. Dr. Howard?”

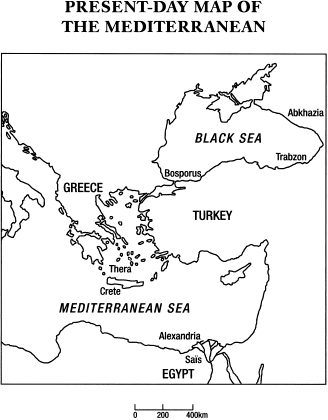

Jack was already flicking the remote control to a map of the Aegean with the island of Crete prominently in the centre.

“It only becomes plausible if we scale it down,” he said. “If we set it nine hundred rather than nine thousand years before Solon we arrive at about 1600 BC. That was the period of the great Bronze Age civilizations, the New Kingdom of Egypt, the Canaanites of Syro-Palestine, the Hittites of Anatolia, the Mycenaeans of Greece, the Minoans of Crete. This is the only possible context for the Atlantis story.”

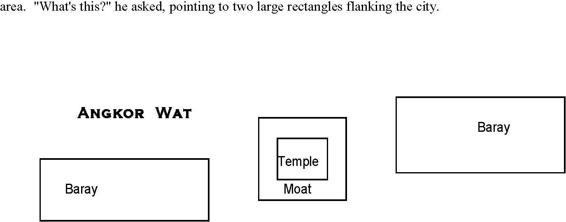

He aimed a pencil-sized light pointer at the map. “And I believe the only possible location is Crete.” He looked at Hiebermeyer. “For most Egyptians at the time of the Pharaohs, Crete was the northerly limit of their experience. From the south it’s an imposing land, a long shoreline backed by mountains, yet the Egyptians would have known it was an island from the expeditions they undertook to the palace of Knossos on the north coast.”

“What about the Atlantic Ocean?” Hiebermeyer asked.

“You can forget that,” Jack said. “In Plato’s day the sea to the west of Gibraltar was unknown, a vast ocean leading to the fiery edge of the world. So that was where Plato relocated Atlantis. His readers would hardly have been awestruck by an island in the Mediterranean.”

“And the word Atlantis?”

“The sea god Poseidon had a son Atlas, the muscle-bound colossus who carried the sky on his shoulders. The Atlantic Ocean was the Ocean of Atlas, not of Atlantis. The term Atlantic first appears in Herodotus, so it was probably in widespread currency by the time Plato was writing.” Jack paused and looked at the others.

“Before seeing the papyrus I would have argued that Plato made up the word Atlantis, a plausible name for a lost continent in the Ocean of Atlas. We know from inscriptions that the Egyptians referred to the Minoans and Mycenaeans as the people of Keftiu, people from the north who came in ships bearing tribute. I would have suggested that Keftiu, not Atlantis, was the name for the lost continent in the original account. Now I’m not so sure. If this papyrus really does date from before Plato’s time, then clearly he didn’t invent the word.”

Katya swept her long hair back and gazed at Jack. “Was the war between the Athenians and the Atlanteans in reality a war between the Mycenaeans and the Minoans?”

“I believe so,” Jack looked keenly back at her as he replied. “The Athenian Acropolis may have been the most impressive of all the Mycenaean strongholds before it was demolished to make way for the buildings of the classical period. Soon after 1500 BC Mycenaean warriors took over Knossos on Crete, ruling it until the palace was destroyed by fire and rampage a hundred years later. The conventional view is that the Mycenaeans were warlike, the Minoans peaceable. The takeover occurred after the Minoans had been devastated by a natural catastrophe.”

“There may be a hint of this in the legend of Theseus and the Minotaur,” Katya said. “Theseus the Athenian prince wooed Ariadne, daughter of King Minos of Knossos, but before taking her hand he had to confront the Minotaur in the Labyrinth. The Minotaur was half bull, half man, surely a representation of Minoan strength in arms.”

Hiebermeyer joined in. “The Greek Bronze Age was rediscovered by men who believed the legends contained a kernel of truth. Sir Arthur Evans at Knossos, Heinrich Schliemann at Troy and Mycenae. Both believed the Trojan wars of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, written down in the eighth century BC, preserved a memory of the tumultuous events which led to the collapse of Bronze Age civilization.”

“That brings me to my final point,” Jack said. “Plato would have known nothing of Bronze Age Crete, which had been forgotten in the Dark Age that preceded the classical period. Yet there is much in the story reminiscent of the Minoans, details Plato could never have known. Katya, may I?” Jack reached across and took the two books she pushed forward, catching her eye as he did so. He flicked through one and laid it open towards the end.

“Here. Atlantis was the way to other islands, and from those you might pass to the whole of the opposite continent. That’s exactly how Crete looks from Egypt, the other islands being the Dodecanese and Cycladic archipelagos in the Aegean and the continent Greece and Asia Minor. And there’s more.” He opened the other book and read out another passage.

“Atlantis was very lofty and precipitous on the side of the sea, and encompassed a large mountain-girt plain.” Jack strode over to the screen which now displayed a large-scale map of Crete. “That’s exactly the appearance of the southern coast of Crete and the great plain of the Mesara.”

He moved back to where he had left the books on the table.

“And finally the Atlanteans themselves. They were divided into ten relatively independent administrative districts under the primacy of the royal metropolis.” He swivelled round and pointed at the map. “Archaeologists believe Minoan Crete was divided into a dozen or so semi-autonomous palace fiefdoms, with Knossos the most important.”

He flicked the remote control to reveal a spectacular image of the excavated palace at Knossos with its restored throne room. “This surely is the splendid capital city halfway along the coast.” He advanced the slides to a close-up of the drainage system in the palace. “And just as the Minoans were excellent hydraulic engineers, so the Atlanteans made cisterns, some open to the heavens, others roofed over, to use in winters as warm baths; there were the baths for the kings and for private persons and for horses and cattle. And then the bull.” Jack pressed the selector and another view of Knossos appeared, this time showing a magnificent bull’s horn sculpture beside the courtyard. He read again. “There were bulls who had the range of the temple of Poseidon, and the kings, being left alone in the temple, after they had offered prayers to the god that they might capture the victim which was acceptable to him, hunted the bulls, without weapons but with staves and nooses.”

Jack turned towards the screen and flicked through the remaining images. “A wall painting from Knossos of a bull with a leaping acrobat. A stone libation vase in the shape of a bull’s head. A golden cup impressed with a bull-hunting scene. An excavated pit containing hundreds of bulls’ horns, recently discovered below the main courtyard of the palace.” Jack sat down and looked at the others. “And there is one final ingredient in this story.”

The image transformed to an aerial shot of the island of Thera, one Jack had taken from Seaquest’s helicopter only a few days before. The jagged outline of the caldera could clearly be seen, its vast basin surrounded by spectacular cliffs surmounted by the whitewashed houses of the modern villages.

“The only active volcano in the Aegean and one of the biggest in the world. Some time in the middle of the second millennium BC that thing blew its top. Eighteen cubic kilometres of rock and ash were thrown eighty kilometres high and hundreds of kilometres south over Crete and the east Mediterranean, darkening the sky for days. The concussion shook buildings in Egypt.”

Hiebermeyer recited from memory from the Old Testament: “ ‘And the Lord said unto Moses, stretch out thine hand toward heaven, that there may be darkness over the land of Egypt, even darkness which may be felt. And Moses stretched forth his hand toward heaven; and there was a thick darkness in all the land of Egypt three days.’ ”

“The ash would have carpeted Crete and wiped out agriculture for a generation,” Jack continued. “Vast tidal waves, tsunamis, battered the northern shore, devastating the palaces. There were massive earthquakes. The remaining population was no match for the Mycenaeans when they arrived seeking rich pickings.”

Katya raised her hands to her chin and spoke.

“So. The Egyptians hear a huge noise. The sky darkens. A few survivors make it to Egypt with terrifying stories of a deluge. The men of Keftiu no longer arrive with their tribute. Atlantis doesn’t exactly sink beneath the waves, but it does disappear forever from the Egyptian world.” She raised her head and looked at Jack, who smiled at her.

“I rest my case,” he said.

Throughout this discussion Dillen had sat silently. He knew the others were acutely aware of his presence, conscious that the translation of the papyrus fragment may have unlocked secrets that would overturn everything they believed. They looked at him expectantly as Jack reset the digital projector to the first image. The screen was again filled with the close-set script of ancient Greek.

“Are you ready?” Dillen asked the group.

There was a fervent murmur of assent. The atmosphere in the room tightened perceptibly. Dillen reached down and unlocked his briefcase, drawing out a large scroll and unrolling it in front of them. Jack dimmed the main lights and switched on a fluorescent lamp over the torn fragment of ancient papyrus in the centre of the table.

THE OBJECT OF THEIR ATTENTION WAS REVEALED in every detail, the ancient sheet of writing almost luminous beneath the protective glass plate. The others drew their chairs forward, their faces looming out of the shadows at the edge of the light.

“First, the material.”

Dillen handed round a small plastic specimen box containing a fragment removed for analysis when the mummy was unwrapped.

“Unmistakably papyrus, Cyperus papyrus. You can see the criss-cross pattern where the fibres of the reed were flattened and pasted together.”

“Papyrus had largely disappeared in Egypt by the second century AD,” Hiebermeyer said. “It became extinct because of the Egyptian mania for record-keeping. They were brilliant at irrigation and agriculture but somehow failed to sustain the reed beds along the Nile.” He spoke with a flush of excitement. “And I can now reveal that the earliest known papyrus dates from 4000 BC, almost a thousand years before any previous find. It was discovered during my excavations earlier this year in the temple of Neith at Saïs in the Nile Delta.”

There was a murmur of excitement around the table. Katya leaned forward.

“So. To the manuscript. We have a medium which is ancient but could date any time up to the second century AD. Can we be more precise?”

Hiebermeyer shook his head. “Not from the material alone. We could try a radiocarbon date, but the isotope ratios would probably have been contaminated by other organic material in the mummy wrapping. And to get a big enough sample would mean destroying the papyrus.”

“Obviously unacceptable.” Dillen took over the discussion. “But we have the evidence of the script itself. If Maurice had not recognized it we would not be here today.”

“The first clues were spotted by my student Aysha Farouk.” Hiebermeyer looked round the table. “I believe the burial and the papyrus were contemporaneous. The papyrus was not some ancient scrap but a recently written document. The clarity of the letters attests to that.”

Dillen pinned the four corners of his scroll to the table, allowing the others to see that it was covered with symbols copied from the papyrus. He had grouped together identical letters, pairs of letters and words. It was a way of analysing stylistical regularity familiar to those who had studied under him.

He pointed to eight lines of continuous script at the bottom. “Maurice was correct to identify this as an early form of Greek script, dating to no later than the high classical period of the fifth century BC.” He looked up and paused. “He was right, but I can be more precise than that.”

His hand moved up to a cluster of letters at the top. “The Greeks adopted the alphabet from the Phoenicians early in the first millennium BC. Some of the Phoenician letters survived unaltered, others changed shape over time. The Greek alphabet didn’t reach its final form until the late sixth century BC.” He picked up the light pointer and aimed at the upper right corner of the scroll. “Now look at this.”

An identical letter had been underlined in a number of words copied from the papyrus. It looked like the letter A toppled over to the left, the crossbar extending through either side like the arms of a stick figure.

Jack spoke excitedly. “The Phoenician letter A.”

“Correct.” Dillen drew his chair close to the table. “The Phoenician shape disappears about the middle of the sixth century BC. For that reason, and because of the vocabulary and style, I suggest a date at the beginning of the century. Perhaps 600, certainly no later than 580 BC.”

There was a collective gasp.

“How confident are you?” asked Jack.

“As confident as I have ever been.”

“And I can now reveal our most important dating evidence for the mummy,” Hiebermeyer announced triumphantly. “A gold amulet of a heart, ib, underneath a sun disc, re, together forming a symbolic representation of the pharaoh Apries’ birth name Wah-Ib-Re. The amulet may have been a personal gift to the occupant of the tomb, a treasured possession taken to the afterlife. Apries was a pharaoh of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty who ruled from 595 to 568 BC.”