MISSION MONGOLIA

Two men, One Van… No Turning Back

David Treanor

MISSION MONGOLIA

Copyright © David Treanor 2010

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, nor transmitted, nor translated into a machine language, without the written permission of the publishers.

The right of David Treanor to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Condition of Sale

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher.

Summersdale Publishers Ltd

46 West Street

Chichester

West Sussex

PO19 1RP

UK

eISBN: 978-1-84953-414-8

Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Summersdale books are available to corporations, professional associations and other organisations. For details contact Summersdale Publishers by telephone: +44 (0) 1243 771107, fax: +44 (0) 1243 786300 or email: [email protected].

Acknowledgements

Thanks to my family, Tricia, Emma and Sarah for their belief and support, Rick for his advice, and Jen, Dave,

Chris, Ben and all at Summersdale for making it happen.

About the Author

David Treanor was a BBC journalist for more than 25 years, editing news bulletins for the Today programme and Radio 4's Six O'clock News. The journey was made in support of the charity Save the Children.

Chapter One

Good to Gobi

The email from senior management confirmed the rumours. The BBC was to make big job cuts – 3,000 in all. It was hoped these could be achieved through voluntary redundancies, but, if not… well, people would be told their services were no longer needed. Geoff and I were fifty-four and in our prime – prime candidates to take whatever was on offer and go. Younger colleagues with big mortgages and small families eyed us hopefully – a sacrifice was going to have to be made and they hoped we were it.

This was not an unreasonable expectation. Both of us had spent almost thirty years working day and night newsroom shifts and they were getting harder to handle. A glance in the mirror at nine in the morning after three twelve-hour nights provided convincing evidence that this was no occupation for old men. Indeed, if we wanted to live to be old men it was probably time to have no occupation. At lunchtime, along with some of the younger members of the team, we headed to the BBC Club on the fourth floor at Television Centre. At the door, the younger ones turned left for the gym while Geoff and I turned right, for the bar.

The barman saw us coming and pulled two pints of Young's. We took our glasses and headed to our usual perch in the corner.

'Are you going to go for it?' I asked. There was no need to specify exactly what. Redundancy had been dominating conversation in the newsroom.

'I suppose so.' Geoff seemed less than fully committed. 'I don't know what I'd do, though.'

We drank in unison. I stayed silent, mainly because I didn't have any idea of what I'd do either. Escape seemed the first priority; once under the wire it was a case of keep running and hope for the best.

Geoff went to the bar for a couple of refills. I picked up a newspaper discarded by an earlier drinker. When he came back, I had our plan.

'We're going to Mongolia,' I said, ignoring his look of exaggerated scorn. 'A road trip for charity, a group called Go Help. They're looking for people who'll buy an old van or pickup, drive to Mongolia any route you feel like, hand it over to the locals on arrival, they auction it to raise some cash to help local children and, hopefully, someone gets a useful vehicle. And we raise more cash for children's charities before we go.' I tapped the newspaper. 'Piece about it in here.'

Geoff glanced at the article. 'It says they don't provide any backup.'

'That's true,' I admitted, relieving him of the paper before he got to the bit about extreme temperatures, bandits and driving across rivers.

'When did you last look under the bonnet of your car?' he inquired.

This was something of an embarrassment. My car had refused to start a couple of weeks ago, and not only had I failed to find the cause, I had failed even to release the catch which held the bonnet down. The AA man had been polite and hadn't even smirked. I suppose they go on training courses entitled 'Staying Impassive When Faced With Almost Total Ignorance'.

'It'll be fine. We'll get it serviced before we go. Anyway, you know about engines and stuff.'

'Dave,' said Geoff, the scornful look returning, 'I might know more than you, but being able to top up the oil and check the water level in the windscreen washer bottle does not really qualify me for the job of expedition mechanic.'

'Oh, I don't know,' I said, encouraged by this admission of A-level mechanical skills.

'How far is it anyway?' asked Geoff.

I consulted the newspaper. 'Says here, at least eight thousand miles, maybe more depending on which route you choose. You can take as long as you like, though, it's up to you. Deserts, mountain ranges, off-road driving, sounds brilliant.'

'We'd have to get a four-wheel drive van.'

'Of course.'

'And get it properly prepared by someone who knew what they were doing.'

'Naturally.'

'And when do you have to set off?'

'You can go any time you like. You sign up to the charity, let them know when you're starting and they arrange the import papers.'

Geoff went silent. I could see a mental struggle going on between the common sense half of his brain and the part which hankered after a bit of adventure. It was a close call. He gulped down another large swig of his beer.

'Yeah OK.'

We clinked glasses. Some of our colleagues walked past from the gym, freshly showered and ready for the afternoon's work.

'Time for one more to celebrate?' I suggested.

'I think we have just cause,' agreed Geoff. I felt we would make a good team.

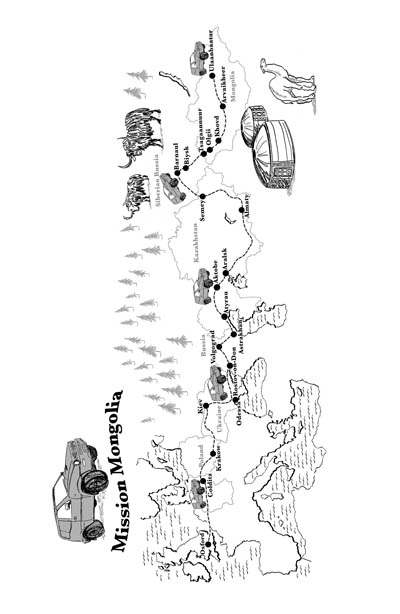

Back in the newsroom, I wandered over to the foreign desk and borrowed their very large atlas of the world and flicked through the pages tracing a putative route with my finger. After France, Germany and Poland came Ukraine, the names of the cities familiar from past bulletins – Lviv and Kiev, scenes of big demonstrations in support of the Orange Revolution which brought Viktor Yushchenko to power, his pock-marked poisoned face evidence of how rough politics can be in the former Soviet states. Then down to Odessa – hadn't there been a song written about that city? I put the question to Adam, a bookish journalist with a first class degree in Law from Cambridge but, more importantly, a Google-sized knowledge of pop music.

He paused from preparing the next hour's news summary. 'Indeed there has,' he confirmed. 'The Bee Gees, 1969. It was the title track off the album and, to be precise was called 'Odessa', open brackets, 'City on the Black Sea', close brackets. As I recall there were some strange lyrics, including stuff about moving to Finland and loving the vicar.'

Adam returned to his keyboard. I was going to miss being around such extraordinary knowledge. My finger moved on, crossing into Russia and reaching Volgograd – Stalingrad as it was known when it was the scene of the most epic battle of World War Two – then down to the Caspian, turn left and into Kazakhstan. Thanks to the comedian Sacha Baron Cohen the words 'Kazakhstan' and 'Borat' are inextricably linked. Which, if you are Kazakh, must be extremely irritating. In the atlas, it looked to be a huge country, about the size of Western Europe with a great deal of desert and very few roads. I followed a route across to the east, close to the border with China. I was now entering an area where the names of the cities might have given the BBC pronunciation unit pause for thought. They all seemed to feature lots of 'z's and 'y's.

I followed a road up to the north and back into Russia, the Siberian region, turning right for Mongolia. The contours of the mountains became more densely packed, with figures above 10,000 feet common. Then, once over the border, it looked about a thousand miles to Ulaanbaatar across a big, empty country. I emailed Geoff an outline of the route.

'Big Country, Adam, anything known, m'lud?'

'Frontman Stuart Adamson, who came from Dunfermline,' said Adam continuing to type. The deadline for the next summary was only a few minutes away. 'They found a rather novel way of making their guitars sound like bagpipes. Most famous song was "In a Big Country", which, I'm fairly certain, was their only US top forty hit. The summary is ready for you to check through.'

I stopped my dreaming of big countries far away and concentrated on a spot of work. More economic gloom, violence in Iraq, an inquiry announced into a case where social workers had failed to spot child abuse, a survey showing a rather disturbing thirty-four per cent of people questioned believed evidence of UFOs was being hidden from the public by the government and, near the bottom, another news item which caught my eye – police in southern Russia were searching for a gang of men who hijacked a van which had been driven from Germany, and forced the driver to lie by the side of the road while they drove over his legs to prevent him raising the alarm. Nasty. And just the sort of news item to put Geoff off the suggested route I had just emailed him.

'This Russian hijack story Adam, where has that come from?'

'On Reuters a few hours ago – I was just doing a quick trawl back to find something to vary the mix a bit. Do you think it doesn't quite make it?'

'Well, maybe not quite. If it had been a Brit driver, of course, that would have been fine. But a German? And they didn't actually kill him. Maybe it would be best to drop it and put back in that story about the Government minister who wants compulsory health checks for skinny models.'

'OK, will do. You're right. Probably doesn't quite cut it. And it's a long way away.' Adam made the changes and sprinted down to the studio with the summary.

A few weeks later came the news from the Human Resources Department, as personnel is now called in big organisations, that our redundancy applications had been approved. It was winter, and I pencilled in a date at the end of April for us to set off, giving us a few months' preparation. I reckoned this would be the ideal time – we'd reach Mongolia before the rains in July and August and we could cross deserts in Mongolia and Kazakhstan before the high summer temperatures, which can, in Kazakhstan at least, hit 50°C and more. From Geoff's point of view this scenario had one big downside – we'd be travelling on our own. If we left a couple of months later we could set off with others who were taking part in an official Mongolia charity rally, giving the prospect of some company en route and perhaps some help if things went wrong.

He had already been open about his worries – 'Whenever I think about it, the prospect just seems so daunting that I start to feel queasy' he told me. This feeling wasn't eased when he began some detailed research on Mongolia, majoring in Deadly Diseases. He rang me with some of his findings.

'Have you heard of TBE?' he inquired. I confessed ignorance.

'Tick-borne encephalitis,' he explained. 'Very common in Mongolia. Basically, you're camping, this tick which lives in the grass nips out and bites you, your brain swells up you go into a coma, then you die.'

'There's probably a jab we can get,' I replied, optimistically.

'There is,' said Geoff. 'I've looked into it. Trouble is, it's only ninety per cent effective.'

'That sounds pretty good,' I told him encouragingly. 'That's practically a hundred per cent.'

'Dave, it isn't a hundred per cent. It's ninety per cent. That means out of every ten people who have the jab and get bitten, one is going to die. It's a sort of Mongolian roulette. Given that the stakes are so high, those are not great odds.'

Well, put like that I had to concur, although I did feel that Geoff's pessimistic side was kicking in.

'Then there's rabies,' he continued.

'Everywhere has rabies except Britain. France has rabies and you're not going to stop going to Calais to stock up on wine are you?'

'We are not talking about a few foxes living in the forest. We are talking one in ten dogs. And that includes family pets. Although "pets" isn't quite the right word to describe the dogs kept by most Mongolians. I've been reading up about them. They're big, they're vicious and their chief function is to fend off attacks by wolves. In the absence of wolves, they like to practise a bit on strangers.'

I patted the head of my golden retriever, Humphrey, who was sitting in his usual position at my feet. He seemed a long way removed from his Mongolian relations, terrorised as he was by our cats and, in truth, not one to put up much of a fight against a daddy-long-legs in a bad mood. I tried to look on the positive side.

'Well, that means nine out of ten aren't infected! And, again, I'm sure there's an injection you can get.'

Geoff gave what writers of popular fiction sometimes call a hollow laugh. 'You can. And there's one big downside. Even if you've had the jab, once you get bitten, or even just slobbered on, you have twenty-four hours to get to a hospital. Outside of the capital, Ulaanbaatar, hospitals are fairly thin on the ground in Mongolia. And from the border to the capital is about a week's driving.'

'So the message is, if you're going to get bitten by a rabid dog, leave it until the last day or so!'

Geoff ignored me and pressed on. He'd been saving the worst until last.

'And then there's the plague.'

'What plague? Locusts? Bees? Flying ants?'

'The bubonic sort. Otherwise known as the Black Death. The plague which wiped out nearly half the population of Britain in around 1350. Interestingly, it's thought to have originated in the Gobi Desert in Mongolia and was carried to Europe by the invading Mongol army. I have some facts to hand.'

There was the sound of paper being rustled.

'First recorded instance in Europe in 1347 in the Crimea. The city of Caffa was under siege. The Mongol army decided to catapult infected corpses over the city walls. You might say the first example of biological warfare.'

'And they still have it?' Interesting as the history lesson was, I had to admit that my tenner would have be placed on the plague dying out worldwide sometime during the last couple of centuries.

'Oh yes. Carried by fleas on marmots. A very common rodent in Mongolia, often found in the cooking pot. It likes to get its own back occasionally.'

'And I don't suppose there's a jab against that?' I already knew what the answer would be.

'Not as such.'

'So the message seems to be avoid ticks, don't pat any dogs and keep clear of marmots and everything should be tickety-boo, as it were. Perhaps we could just drive across Mongolia and not get out of the van.'

'No, that's no good. The guide book warns that if you drive over a dead marmot the fleas which carry the plague are released into the vehicle's ventilation system.' His voice had risen a couple of octaves as he contemplated the perils which lay ahead.

'Well all I can suggest is that we drive round them. And you'd better make sure your will is in order.' I chuckled. Geoff didn't.

'I already have,' he replied.

The more Geoff researched the trip, the more his concerns piled up. 'I'm beginning to lose my nerve,' he emailed. 'I know you're keen to go early, but I'm already losing sleep over the prospect of tackling it alone. Strength in numbers and all that! If you're not convinced, what about taking the tarmac approach through Russia then a sharp right down to UB. Pathetic I know, but I'm just too old to ignore what seem to me like potentially big problems.'

I was now genuinely fearful that the whole thing might fall apart. I won't pretend I didn't have worries of my own – chief among them encountering a ferocious and possibly rabid dog. But I began to feel that I had underestimated Geoff's anxieties and had bounced him into agreeing to a trip that in his heart he really didn't want to do. I admired his honest approach – but for me, to keep the trip to a tarmac drive through Russia and only a little of Mongolia went against the spirit of the adventure. I rang him. It was time for openness from both of us, and there would be no hard feelings if we agreed our visions of what we wanted were just too different to achieve. Geoff insisted there was no way he wanted to back out; I was relieved because the Geoff I'd known for years was easy-going, calm in a crisis and sociable. But there was little I could offer in the way of practical reassurance. He would be travelling with someone who could rustle up a half decent curry, but skill with a frying pan would be no use at all if the van gave up the ghost in the Gobi.

'It'll be fun,' I told him, lamely.

'That's all I wanted to hear,' he replied. The trip was on. The search for a vehicle could begin in earnest.

We found out that the Mongolian authorities had brought in new rules on what could be imported without paying tax – motorbikes were fine, but I hadn't ridden anything on two wheels since I sold my Lambretta with my name on the flyscreen back in 1971. Cars, even rugged four-wheel drives, had to pay tax but commercial vehicles, such as lorries, pickup trucks and vans, were exempted provided they were less than ten years old.

I took advice from Dave West at Risboro 4x4, the man who has looked after my Subaru for the past five years. When it comes to my mechanical knowledge there are no secrets between us – Dave knows better than anyone the depth of my ignorance. I outlined our plans.

'How far is it to Mongolia?' he asked.

'Depends on which route we take, but about eight thousand miles, maybe more.'

I thought I detected Dave wincing slightly. 'And the roads are likely to be pretty bad, I suppose.'

'Off-road tracks, deserts and mountains for about half of it,' I confirmed cheerfully.

'And the weather?'

'Well, we're planning to go end of April, so we'll get some quite hot stuff by the time we get to the deserts but there'll still be snow in Siberia.'

Dave bit his bottom lip, which was strange because I'd never seen him do that before. 'But the other chap you're going with, he knows about vehicles and engines, right?'

'Weeeell, not really. A little bit maybe. More than me certainly,' I said, trying to sound encouraging.

This information seemed to do little to brighten his mood. 'So when you break down…'

I noticed that Dave said 'when' rather than 'if' but I let it go. 'Oh, we'll be OK, we'll just find someone to fix it,' I replied airily with a dismissive wave of the hand.

'OK,' said Dave, slowly and with the air of a man who had just been faced with a choice between the burning deck or the ocean, 'and how much have you got to spend on this vehicle that's going to take you there?'

'About a thousand pounds each.'

Dave stayed silent.

'Two thousand pounds in total,' I added, in case his maths was as weak as mine and not wanting him to think we were trying to do this on the cheap.

'Jeez.'

'And we'd like you to prepare it for us. Anything you'd recommend?'

'Staying at home.'

I made a mental note never to introduce Dave to Geoff. 'How about a Land Rover Freelander van?' I suggested, trying to move the conversation onto more positive territory.

'Got to be a diesel version,' said Dave, concentrating now on the practical side of things. 'I wouldn't even contemplate a trip like that in a petrol Freelander. They've got no guts. A diesel is a much better bet, more solid. And the more modern ones have got BMW engines. Plus, of course, if you're going to be driving through water there are no spark plugs or leads to get wet.'

'Yes,' I agreed, 'I'd been thinking that myself.'

This was, of course, a lie, and from the look Dave gave me I suspected he'd seen right through me.

I relayed this information to Geoff and we scoured Internet ads. There, in Wigan, about two hundred miles to the north of where I lived, was a vehicle which sounded like it might fit the bill. A diesel Freelander van, nine years old, 82,000 miles on the clock and £2,400. A little over budget but perhaps with a bit of negotiation, close to our price range. We made an appointment to view and set off in buoyant mood.

On the outskirts of Wigan, Geoff reached into his pocket and produced a small screen with a wire attached. He removed the cigarette lighter, plugged it in, fixed it to the windscreen and tapped in some numbers and letters. The screen lit up and a female voice, attractive but with a note of command, ordered me to take the second exit at the next roundabout. Now I know that for the rest of the country satnavs have been commonplace for years. Everyone, except probably me and a Welsh hill farmer named Ivor who drives only to the local village on market day, has used one. But think back to your first time. Everyone must remember it. That sense of wonder that a device about a couple of inches square could know where you were and give you instructions. How could it possibly work? My brain started to hurt with the effort of trying to work that one out, so I gave up and did as I was told and took the second exit.

A few minutes later the voice told me I had reached my destination. We stopped and looked round. We were in the middle of an industrial estate with nothing bearing the legend 'Mick Simms Autos' which we'd been told to look out for. Geoff rang Mick on his mobile phone. He arrived and led us to a locked and anonymous unit. Opening the door, he motioned us inside to where a dozen or so unwanted cars stood parked in a row. Several still bore on their windscreens the inflated prices of the original garages which had failed to sell them. Ours, I noticed, had been on offer for £500 more. Mick started it up and drove it outside.

'Well it starts anyway,' Geoff observed, assuming his role as lead mechanic.

I nodded sagely and kicked a tyre as I had seen people do on Minder.

'Has it got any history?' I asked Mick. I wasn't really sure what this meant but it was a phrase I had heard used in similar circumstances.

'It's here,' said Mick, passing me a book. I opened it and after several minutes study managed to translate the unfamiliar letters and numbers. It seemed the van had done 82,000 miles but its last service had been at 40,000. Even I knew that this was Not a Good Thing. We opened the back and peered in. Yup, it was a van. Mick opened the bonnet. There didn't seem to be an engine, just a large plastic box. Geoff explained that this was how diesels looked. I saw something I assumed was an oil dipstick and knew the correct form was to examine this and 'tut' several times. With Mick watching I tried to remove it. It seemed stuck. I tried twisting it and pulling it but it was in no mood to budge so I stepped back and said 'Hmmmmm' in what I hoped was a deeply meaningful way.

Mick offered to let us have a drive, so I naturally deferred to Geoff who took it out first. He came back looking not too happy.

'Very odd knocks and bangs,' he observed. 'See what you think.'

I took the wheel with Mick at my side and we set off. It all seemed fine to me.

'I can't hear anything odd,' I told Mick.

He looked at me pityingly. I could sense a mental struggle – whether to agree with me and suggest Geoff must have been mistaken or to admit the truth. It seemed a close call but in the face of such touching naivety, truth won. 'You have to go over a few bumps,' he explained, in the measured tones one would use when addressing a rather slow child.

'Oh OK,' I said, accelerating over a speed hump and hearing the distinct clunks which confirmed Geoff had indeed been right.

Back at the lock-up, we decided to adjourn for lunch and talk things over.

We walked to the centre of Wigan and looked in at the first pub we came to, but that had only one person in it and he was the barman. We took that as a bad sign and walked on. Across the square we spotted another bar. From the menu, Geoff ordered a cheeseburger and I plumped for a beef baguette with onions. I thought these might be some raw red onions, or perhaps a few caramelised versions. I hadn't expected them to be swimming in a warm and rather splodgy gravy which rested perilously at the top of the bread. Geoff's cheeseburger, on the other hand, was accompanied by a good quantity of crisp and light brown chips.

'You'll have to eat far worse in Mongolia,' said Geoff, collecting our glasses and going to the bar for a refill. I felt this was a rather unsympathetic approach, so stole several of his chips while his back was turned, before picking up the baguette delicately. Not delicately enough, though, as the gravy spurted lava-like from both sides, trickled over my fingers and bounced from the plate to my jeans. I managed to suck some of the excess from the bread, wiped my beard with the back of my hand and chewed thoughtfully on a piece on beef.

I was still chewing on the same piece when Geoff arrived back with the drinks several minutes later.

'Not good, huh?' he inquired. 'And perhaps a touch messy.'

There was a long pause before I answered as the beef was proving a tough opponent. 'Gravy's not too bad. Just a surprise that anyone thought filling a bread roll with it was a good idea.'

'Well I've got plenty of chips, help yourself,' he offered, generously.

'Thanks very much,' I replied, taking a handful.

Once we'd finished eating, we discussed the van. It was a long way home empty handed, but if the van was clunking over a few speed bumps in Wigan, it would be making far worse noises by the time we were halfway through the trip. We set the satnav for the M6 and headed back south.

Over the next few weeks, we criss-crossed the country, visiting vans in Torquay, Birmingham, Aylesbury and Bristol, sometimes together, sometimes on our own. Each time there seemed a good reason not to buy. But we were becoming disheartened so it was time to give the search for a vehicle a rest and concentrate on other preparations. In particular, the need to face the needle, or rather, in my case, look away with eyes closed tight as a nurse jabbed my arm full of various things that my body never thought it would need.

Geoff took all this in his stride. He gives blood. He can look on while a jar fills with the stuff which only moments before has been coursing though his veins. He can do this without fainting or even going just a little bit weak at the knees.

I, on the other hand, avoid doctors like, er, the plague. Which, of course, was one of the things we couldn't have jabs for, as the nurse at my local clinic confirmed after she'd given me a Travel Risk Assessment Form to fill out, with its discouraging questions such as 'How far will you be at any one time from emergency medical treatment?'. I put down several thousand miles and hoped that would do.

I also noticed that one of the questions asked 'Do you feint at the sight of needles?' I know I should have ignored this. I know that it was an irritating and pedantic thing to cross it out and write 'faint' above it in pencil. I should have learned my lesson when I failed in my campaign to get my local supermarket to change 'ten items or less' to 'ten items or fewer'. But I'd had decades of being a language pedant and old habits die hard. The nurse, however, was not amused.

'It's the American spelling,' she suggested.

'I don't think it is,' I said, rolling up a sleeve. 'It means to make a deceptive movement, often used in fencing.'

She glared at me.

'Actually,' I said, trying to dig myself out of the hole I had created, 'you could argue it's a rather appropriate use of the word. I expect lots of people feint when they see a needle heading towards them. Ha ha.'

She didn't laugh. 'We don't have time here to check spellings,' she told me, coldly, breaking a second needle out of its box. 'Roll up both sleeves. I think you'd better have two injections today.'

While I wondered which sore arm to rub first, the nurse consulted the long list of vaccinations still to come and filled out an appointment card.

'The trip is to raise money for charity, you say?' she asked. I confirmed that we were raising cash for Save the Children before we set off, and that the van itself would be donated to raise more money for local children's charities once we were there.

'These inoculations are quite expensive,' said the nurse, scrolling down the list of charges. 'What did you say your occupation was?'

'Well, I've just retired but I suppose I'm still a journalist.'

'About to become a bat handler, you say? Well that is interesting work. And, of course, you will be aware that, as a bat handler, you are entitled to these rabies jabs without charge.'

She smiled and gave me a broad wink.

'Ah, yes, of course,' I replied. 'Some people might consider bat handling an unusual choice for a second career, but I believe I'll find it most satisfying work.'

She smiled again. 'Excellent. Well, I'll see you in two weeks' time for the next jabs. Let me know if there are any side effects.'

We now turned our attention to some more detailed planning of the route and how long to allow. Geoff had been won over by the argument that it was better to avoid heat and travel alone, so we met at his house with maps, guidebooks and the foreign office advice on the countries which we were to visit. Geoff had printed this out and highlighted the worrying passages with a marker pen. There was a lot of yellow on the pages.

I have some sympathy with the Foreign Office – they have to err on the side of extreme caution, otherwise when something goes wrong and a Brit ends up in trouble abroad, some hack looks up what the official travel advice is and uses it as a stick with which to beat them. But to take all the Foreign and Commonwealth Office's warnings to heart would probably mean travelling no further than the neighbouring English county. Take Ukraine, for example. We were planning to drive across from Lviv in the west, to Kiev, down to Odessa and out at the Russian border near Mariupol. The Foreign Office is discouraging: 'You should avoid driving outside urban areas,' it cautions. 'Driving standards are poor and roads are of variable quality. There are a high number of traffic accidents, including fatalities. Take extra care.'

Our guidebook was even more gloomy, adopting an apocalyptic tone: 'There aren't enough pages in this book to list the reasons you should not want to drive in Ukraine,' it warned.

As for Russia, the main threat seemed to be violent robbery after making new 'friends' in bars. OK, that one was easy to avoid.

So if we didn't buy drinks for strangers and got through Russia unscathed, there was Kazakhstan to come. About three thousand miles of it. The FCO's advice didn't sound too promising. I skimmed through it:

'Service stations and petrol/water access can be limited outside the main cities. Make sure you take all you need for your journey… a significant proportion of cars are not safely maintained… in some remote parts of Kazakhstan animals can be seen regularly on the roads and can be especially difficult to see in the dark… driving can be erratic… many roads are poorly maintained…' And so on.

Then it would be back to Russia where we would have to cross the semi-autonomous republic of Altai. The main problem here seemed to be the FSB – the successors to the KGB – who had been put in charge of security. They were very keen to make it as difficult as possible for foreigners to visit, and travel blogs reported that they kept a helicopter on standby to whisk away those who didn't have the correct papers. That would include us, as the procedure for getting them seemed too cumbersome to contemplate.

'It'll be fine,' I assured Geoff. 'We'll just be transiting through. We won't need all that paperwork. Bureaucratic nonsense. The FSB won't worry about people like us.'

Geoff sighed deeply and pushed the FCO's pages on travelling in Mongolia across the table.

'If you are planning to travel into the countryside, you should consider carrying a Global Positioning System and emergency communications, such as a satellite phone… extreme temperatures… weather can change without warning… standard of driving very poor… many fatal accidents… '

Added to that, our guidebook suggested the first Mongolian phrase every traveller should learn was 'hold the dog'.

I wrote down 'Things to Buy' on a blank sheet of paper, then number one: 'Stout walking stick'.

I couldn't immediately think of a number two, so started a new sheet of paper, which I headed 'The Schedule'.

We spread out our maps on Geoff's dining room table. The Western European section was easy to estimate, Ukraine and Russia less so but at least we knew they had tarmac roads, even if the quality was variable. The tricky bit started in Kazakhstan.

'That's a red road there, must be OK,' I asserted confidently, my index finger moving swiftly across a few inches of map which represented about eight hundred miles. 'I reckon two days to do that stretch. Then, let's say three to do there to there, another two would get us up to there.'

My finger jabbed at another unpronounceable town. 'That looks doable.'

I could see Geoff had his doubts from the way that he just kept shaking his head, and repeating 'Well, maybe' but in the land of the ignorant the blusterer is king. I jotted down our estimates: 'Right, let's say Western Europe two days; Eastern Europe five days; Russia, four days should be plenty; then Kazakhstan, that's a bit more tricky, two weeks, maybe a bit less, I'll put down thirteen days, hope that's not unlucky; then we've got Siberia and Altai, three days and Mongolia, let's say a week to cross it, that means leave on Thursday, April the thirtieth and arrive,' I used my fingers to help with the complicated calculation, 'on June the first. Job done. '

We'd agreed our wives, Tricia and Jackie, would arrive on Friday, 5 June, so that gave us three days 'spare' in case things went wrong. Not a lot, but I felt confident we could achieve it. Indeed, I convinced myself I'd been pretty generous with the time allowed and that – apart from the couple of 'rest days' I'd built in – there would be plenty of time for a bit of sightseeing as well.

'Right, that's that sorted,' I said brightly, folding away the maps before Geoff had a chance to check through the figures. 'Let's see what Jackie's left us for lunch.'

The dates and route set, it was time to put some more renewed effort into finding a vehicle. Rather in the manner of an estate agent, Geoff kept emailing me details of attractive, but ever more expensive vehicles which were always that bit too much outside our budget.

Then he unearthed a gem. Not a Land Rover, but a Nissan Terrano van – short, but chunky like a Tonka toy. And four-wheel drive. And offered at a fiver under £2,000. It was for sale in Lincoln and a date was set to visit – the day, it turned out, that the winds turned, the weather changed and southern England ground to a halt under a thick and unfamiliar coating of snow. I turned on the weather forecast – more was on the way, warned the forecaster, followed by the usual irritating instruction that no one should venture out of doors unless their journey was absolutely necessary and they were accompanied at all times by a team of huskies.

There was a knock at the front door. Through the blizzard, I could make out a frosted figure on the step.

'Geoff?' I asked. The figure managed to nod its head, then, walking stiffly, stepped inside and started to melt in the hall. Once his teeth had stopped chattering, he explained that he'd had to abandon his car – a large Volvo – down the road nearby as he couldn't make it up the lane to my house. I told him he had brought shame on Swedish car owners everywhere but he protested that I had no idea what it was like, he'd taken three hours to do sixty miles, there were drifts ten feet high and if we tried to set off for Lincoln there was every chance of getting stuck and becoming a statistic on the evening news while weather forecasters everywhere said 'Told you so, but you just wouldn't listen'.

I sat him down and made him a cup of tea and a bacon sandwich while I went to check out the road conditions and the latest forecast online. It was not good at all. The M40 just to the north of me was closed completely, the nearby A40 was clogged with abandoned vehicles, and the snow was set to continue to fall thickly for hours. This was no time for the brutal truth.

'It's all looking good,' I told Geoff cheerily when I returned to the kitchen. 'Snow's about to stop falling and in the east they've hardly seen a flake. Probably best, on balance, to avoid the motorway but I've worked out a cross-country route. We'll be fine. Eat up and we'll get underway.'

I patted him on a soggy shoulder then, a little more roughly as he seemed disinclined to move, pulled him to his feet and we set off with me at the wheel. Five hours later, we arrived in Lincoln just before the banks closed and I nipped inside to withdraw a large wad of cash. It had been a tough journey, but I was optimistic. This van was feeling like it might be 'The One'.

'Right,' I said to Geoff, 'what's the address?'

'Glebe Farmhouse,' he replied, fishing in his pocket for his satnav.

'That's unusual,' I replied, 'a farmhouse in a city. I suppose it must be in the old part. Probably built centuries ago.'

Geoff keyed in the postcode. It came up with a destination thirty miles away. Thirty miles almost straight back in the direction we had just come.

'Try it again,' I suggested. 'It must have made a mistake.' I frowned at the satnav and tapped its irritating screen.

Geoff did as he was bidden. It was the same result. Glebe Farmhouse was not situated in a suburb of Lincoln but a small village in Lincolnshire.

'OK,' I said, trying to sound brightly cheerful and falling some way short, 'nothing for it. Let's get going. If we're quick we might make it before it goes dark.'

We pulled out of the car park. 'Turn left,' said the satnav. I did as I was told. 'Turn right, then take the next turning on the left.' I followed the instructions precisely and came to a halt behind a large wagon in Sainsbury's loading bay. We returned to the last junction and switched on the satnav again. Ten minutes and a whole series of instructions later, we arrived in the car park of the local magistrates' court. It was time for old-fashioned technology. I got the map out and worked out the route while Geoff made excuses for his toy along the lines that the town must have introduced a new one-way system and no one had let the satnav people know. I tried not to glare at him, but it was hard and I think I failed.

An hour later and we were bouncing down the muddy, potholed track to Glebe Farm. There, parked outside, was the vehicle we had come to see. We knocked on the farm door. There was no reply. We tried again. There was the sound of movement inside, then a teenage youth appeared looking slightly out of breath.

'Is it my dad?' asked a female voice from within.

'No just someone about the van,' he called, over his shoulder. It seemed we had disturbed their afternoon's peace.

He produced the key to the van and left us to it, telling us to feel free to take it for a test drive. His father, who owned it, was out but would be back later.

Geoff assumed his rightful role of expedition mechanic and took the key. The van started first time. A little noisily, perhaps, but it was a diesel after all. Geoff selected first gear. There was a grating noise. First, it seemed, was off the menu. As was second. And reverse.

'Let me try,' I said, impatiently. We hadn't driven all this way to be beaten by a dodgy clutch. I pumped the pedal hard, went for first and met determined resistance. I tried again. And failed. I gripped the gear lever hard and aimed for second. With much protest, the van engaged gear and we were off. I got it up to third, but when I tried to return to second, the van was having none of it. Brute force failed, so, revving hard to get going, we kept it in third and returned to the farmhouse. The youth was summoned to explain.

He shrugged his shoulders. 'It's fine once it's warmed up,' he insisted. 'I've driven it loads. Bit sticky at first, but just let it warm up and it's no problem.'

'A bit sticky?' repeated Geoff, indignantly. 'The clutch is completely knackered. Probably the gearbox as well. When was it last serviced?'

'Ah, there you've got me,' admitted the youth. 'You'll have to ask my dad.'

We all knew there was no point. The van was a mistreated specimen and doomed to an early resting place in the local scrapyard.

We walked silently back to my car in the gathering gloom, a state of affairs which exactly matched our mood.

'Let's get some food,' I suggested. Neither of us had eaten since the bacon sandwich in my kitchen. 'There was a pub we passed in the village down the road. Looked OK.'

We entered and asked for the menu.

'Chef's night off,' said the barmaid, cheerily. 'We've got peanuts.'

We ordered a packet each and two pints of bitter to wash them down.

'Beer's off, I'm afraid,' said the barmaid. 'We should have had a delivery today, but they couldn't get through the snow.'

We settled unhappily for two bottles of lager and ate and drank in silence. Our journey, I reflected, hadn't been essential at all. I should have listened to the weatherman.

After the Fiasco in the Fens we returned home with promises to forget about trying to buy a van for a few days. But sitting at my keyboard the next morning I thought it was worth just one more Internet search. Page one revealed nothing. Nor did pages two, three, four, five or six. But there on page seven was a short one line ad which had possibilities. I felt like a gold mining prospector who gets a glimpse of a nugget at the bottom on his pan amid all the dirt and grit.

'Nissan Terrano van four-wheel drive 52 reg, fsh, 74,000 miles, drives well, will part-ex. £2,200.'

I rang the Ipswich number given. 'Hello, I'm interested in the van.'

'Yeaah?' A cautious response, uttered slightly defensively. 'Interested in what way?'

'Interested in buying it.'

His tone changed. 'Oh, right, well yeh, it's a beauty. Goes like a dream. Real bargain.'

'The thing is,' I continued, 'a friend and I are planning a charity drive to Mongolia in it. We've had a lot of wasted journeys criss-crossing the country looking at vans which turn out to be totally unsuitable. The last one we couldn't even get into gear. So to save us a wasted trek, just tell me if there are any big faults which we'd have to put right.'

The voice took on an offended tone. 'Would I sell a van with faults? Me? I've serviced it myself and it comes with my personal guarantee. I wouldn't let you drive away if there was anything wrong. I couldn't take your money.'

I felt he was going to add 'on my mother's grave' but he stopped just short.

'And cos it's for charity,' he went on, 'I'll knock £200 off. Cos I like to support a good cause.'

His sales pitch had done little to reassure me, but, on the face of it, the van was just what we were looking for and a bargain. The voice, who said his name was Nick, confirmed he would be around the next day if we wanted to come and view it.

I rang Geoff. The next day, a Saturday, wouldn't be any good for him. Crystal Palace were at home to Barnsley and he had tickets. Now, to many people, an excuse to get out of going to see Crystal Palace against Barnsley might be something to be seized. I do not share that view. Supporting an underachieving football team through thick and, more often, very thin times is a sign of good character. The only advice about men I have ever given my daughters is to be suspicious of someone who supports a top side, unless it can be shown their grandfather was a season ticket holder, or they were born round the corner from the ground. Following a team that never wins anything prepares a person for life's inevitable disappointments and setbacks. It instils virtues of loyalty and fortitude. And compared with my own team, Tranmere Rovers, Crystal Palace have at least tasted life at the top.

Geoff rang Nick and a time on Sunday was agreed. We met at a motorway junction and set off, Geoff driving along roads free of snow, which still lay thick in the fields around. And this time he had taken the precaution, which I should have done myself, of asking Nick where he lived. So, with the aid of that wonderful and simple invention, a map, we could see it was a village about forty miles from Ipswich. The satnav grumbled occasionally and demanded we turn left or right where we didn't want to, but we ignored it and it fell into a silent sulk.

We arrived and spotted the van parked outside a bungalow. A head popped up over the fence next door. It introduced itself as Nick and said he'd just been having a cup of tea with the neighbours. The van, in white, with the names of its previous owners, Anglian Water, faded but still visible on the side, looked the business. Upright, eager, ready to go. It started first time and Geoff set off with Nick at the wheel.

While they were gone, I had a wander around. Glancing through the window of the bungalow, where Nick said he lived, I noticed there was a slightly suspicious absence of any furniture. And in the garden was a 'To Let' sign. Still, I thought, maybe he'd just split up with his wife and was preparing to move out. And the van did look very nice. Geoff arrived back, reasonably happy with the way it had gone, but a touch disappointed that Nick hadn't let him drive it on the grounds that he might not be insured and, as a cautious man, he couldn't take the risk. The bonnet was opened and we peered in, Geoff doing excellent work firing a series of quickfire questions to Nick in the manner of John Humphrys in the Mastermind chair.

'Nick your specialist subject is this Nissan Terrano van, can you tell me when it last had an oil change?'

'Err, last week. Last month. No, wait a minute, I'm about to do it. I've bought the oil and everything.'

'And how long are the service intervals?

'Ten thousand miles. Fifteen thousand miles. Every year whether it needs one or not.'

Nick clearly hadn't grasped the concept that he was only allowed one answer. In another life, he could have had a successful career in politics. The questioning went on and a thin film of perspiration appeared on his upper lip.

Eventually, we had gleaned as much as we were going to and had a quick confab. We agreed Nick was about as trustworthy as a Manchester United supporter from Maidstone, but, well, the van seemed OK, and if we could get a bit more off the price, then that would give us some cash in hand to do any repairs. And, in truth, we both wanted to believe in it. It would be a relief just to have a vehicle even if it needed bit of attention. Geoff went to work on the hard bargaining and, with protestations that there was now hardly any profit in it for him, Nick shook hands on £1,850. We handed over the notes and set off to find a pub. The nearest one was a busy, friendly place and it sold proper beer. We took that as a good omen and clinked glasses.

'Cheers!'

'By the way,' I asked Geoff, 'did you get a receipt?'

He paused, glass halfway to his lips. 'No,' he replied, 'I thought you had.'

I shook my head and we fell into a rather uncomfortable silence while we contemplated the fact that we had committed a series of textbook errors from Chapter One of the How Not to Buy a Car Guide.

'Never mind,' I said sipping the excellent Adnams, a beer always calculated to induce optimism and well-being. 'I'm sure it'll be fine.'

The vehicle bought, we could concentrate on supplies; broadly speaking, Geoff bought things for the van – spare wheels, couple of jacks, a tow rope, etc. – while, as self-appointed expedition cook, I stocked up on the camping stoves and enough food to make sure we didn't go hungry if supplies were hard to come by.

I also made sure we weren't going to be short of loo rolls, scattering several dozen among our ever-growing pile of equipment. I also constructed a 'desert dumper' out of a wooden chair and a toilet seat. This, I was convinced, would be an essential piece of kit. We each allowed the other some indulgences – I bought some expensive but excellent Cretan extra virgin olive oil for what I was convinced would be our many leisurely lunchtime picnics and dinners of fresh local ingredients cooked on a couple of gas stoves.

Geoff invested in a dashboard compass, a GPS system and a fire extinguisher.

'We don't need that,' I told him. 'I've been driving for nearly forty years and never had a fire in a car.'

'Look at it this way,' Geoff retorted, 'if your walking stick fails to deter a large and rabid hound, what are you going to do? With a fire extinguisher you have a fall back line of defence. Your can see it off with a jet of foam.'

It was a winning argument.

'I'd really like to take a satellite phone,' said Geoff, clearly feeling he was on a roll. 'We've no idea what mobile reception will be like, and even if we get a signal in major towns there are huge distances in between when there'll be nothing.'

'The thing is,' I replied. 'If you take a satphone, and we break down, who are we going to ring?'

Geoff considered this reasoning for a moment and admitted defeat. The satphone was struck from the list.

We made some half-hearted efforts to get sponsorship, writing to Arsenal, Chelsea and Manchester United in the hope that they might have some small merchandise – perhaps an out-of-date range of souvenirs – that we could give to children in extremely poor parts of the world, where the names of those famous clubs were nevertheless known by every youngster who kicked a football.

Arsenal sent a signed photo of Arsene Wenger which we could sell to raise cash, and some club brochures. Chelsea sent a letter of apology, pointing out they had a great many such requests and couldn't accede to them all. Manchester United didn't reply.

What did genuinely surprise and touch us was the generosity of friends, former colleagues and, in some cases, people we barely knew to our Save the Children appeal. We'd set a target of £1,000, and Geoff had opened a Just Giving page. I'd felt this was an optimistic total, and that, although we were covering all our own costs and giving away the van at the end of it, most people would regard the trip as a bit of a jolly. I was wrong. Hugely generous donations and messages of support began to come in – £1,000 was quickly achieved, then £2,000 until by the end we weren't far short of £3,000.

The van now insured and taxed, it was time to return to Dave West. I parked outside and went into his workshop.

'Good news, Dave, we've bought a van. There's a few weeks before we set off, so just time for you to give it a quick once over and make sure it's good enough to get us there.'

Dave did not look like a man who had just been given good news. His expression was more of someone whose lottery numbers had come up the week he'd decided not to bother entering.

'Here it is,' I told him proudly, leading him outside by the elbow. 'A bargain. All ready for the rough stuff.'

The weight of responsibility seemed to cause his shoulders to sag. Dave had already generously offered to do any necessary work at cost as it was a charity venture. Now the full implications of the undertaking were kicking in.

'Leave it with me,' he replied, taking the key gingerly as if fearful of what horrors might be revealed once he started the engine. 'I'll give you a call.'

The call, once it came, brought mixed news.

'I've checked the van over and its basically sound. The engine's good and the body's solid. Clutch and gearbox OK, I've relined the brakes and put a new battery on, changed all your lubricants, new filters etc. I've also ordered you four new tyres, good off-road ones, won't cost you too much as I've got a good deal for you.'

So far so good, but I felt a 'but' was lurking.

'But I'm afraid we might have a problem with the diff.'

Dave might as well have said 'We might have a problem with the scrottle manifold'. I had no idea what he was talking about. But I wasn't going to admit it.

'Oh dear,' I said. 'Could be a big job, huh?'

'Of course. Potentially. Thing is I was checking the oil in the diff and I noticed there were bits of metal in it.'

'Doesn't sound too good,' I asserted, confidently.

'Well they shouldn't be there, that's for sure. I'm going to have to get it opened up and have a look.'

Dave sounded like a surgeon who had spotted something nasty on an X-ray. An operation would be necessary. 'Could be maybe just a couple of cogs have splintered. Could be more. I'll let you know.'

I put the phone down and entered 'vehicle diff' into Google. It instantly produced a number of sites offering explanations of what one was. One suggested that the job of the diff – or differential – was 'to act as the final gear reduction in the vehicle, slowing the rotational speed of the transmission one final time before it hits the wheels'. Well, that made everything clear, then. Another offered that the job of the diff was 'to transmit the power to the wheels allowing them to rotate at different speeds'. This was even more confusing. I had always assumed a vehicle's wheels went round at the same speed. Not so, it seemed. I didn't really understand how they could go at different speeds without coming to grief, but that didn't matter. What the sites made clear was that the differential was pretty damn important. And a big – and costly – job to replace.

I rang Geoff: 'Looks like we might have a problem with the diff.' He understood the significance immediately and without having to resort to an Internet search.

'Christ, that could be expensive. What's wrong with it?'

I relayed Dave's information. Geoff took comfort from the fact that Dave was being so thorough that the problem had been uncovered and I promised to ring him back when there was further news. When it came it wasn't good. A good proportion of the cogs which go to make up a differential were chewed and broken. It was greatly excessive wear for a van of that age and mileage. I asked how it could have happened. Dave speculated that it could have been caused by two of the van's wheels being in mud and the other two on tarmac – and the driver gunning it hard and repeatedly in an attempt to free it. It was going to be a costly job to put right.

'So how long do you think it would have lasted?' I asked Dave.

'Hard to put an exact figure on it. Could have gone before you reached the Channel or could have lasted for a couple of months. Best guess, about two thousand miles. Then it would have seized up.'

That would probably have meant somewhere in Ukraine. Whatever the cost, it was indeed good to have the problem uncovered now rather than coming to a grinding halt in an Eastern European roadside trying to work out the Ukrainian for 'Can I have a tow please?'.

But there was more bad news to come. Dave made inquires and rang again to say Nissan no longer made new differentials for vans the age of ours – it was too old by a year. And the replacement unit for the newer models were of a slightly different axle size. It seemed that with only days to go before we planned to be on the road, we might have to start looking for another vehicle.

After more phone calls, however, Dave called back sounding more hopeful – the axle units were indeed the wrong size, but the cogs inside weren't. He could get a replacement unit and fillet it for the right parts. We were back in business.

'I'm fed up with all the planning and worrying,' said Geoff when I told him the news. 'I'll be glad just to be on our way.'

He spoke for us both. Much as it's often said that work expands to fill the time available, so it seemed planning for a trip like this did the same. And perhaps as we were both retired we'd had too much time. But now we could order the ferry tickets. We were ready to go, and, as in so many times in the past in the newsroom, we'd hit our deadline – just.

Chapter Two

Fire Up the Terrano

Start day, 30 April, up at half five to be away by six. Sadly for my family, my wife Tricia and daughters Emma and Sarah, that meant they had to be up too. But they gamely gathered to say goodbye with hugs and expressions of good luck. Tricia pressed a sausage sandwich wrapped in tinfoil into my hands and I was away, driving through leafy Oxfordshire lanes to the motorway. I set the milometer to zero. If we reached Ulaanbaatar it would read at least 8,000 – a year's mileage for many people. I had always brushed aside Geoff's worries with a dismissive wave and an insistence that 'It'll be fine'. Now the journey was underway I was a little less blasé, listening keenly to the van's engine note, accelerating smoothly and changing gear gently. Everything seemed in order. The van was running sweetly, no suspicious rattles or clunks. Dave West had done his job well.

I relaxed and turned on the radio. The weather forecaster promised another warm, sunny day, with temperatures well above normal for the time of year. It should be a smooth Channel crossing.

To celebrate, I decided to break open my sausage sandwich. It was still warm and I bit into it enthusiastically. Tomato sauce spurted out from both sides and landed in large blobs on my freshly ironed polo shirt. I carried on eating, then did my best to clean up the mess with some wet wipes. Ten minutes into the trip and I was already dipping into supplies intended for more remote places than the M40. It wasn't wholly successful. Dark stains betrayed me. The more I rubbed at them, the more ingrained they appeared. Normally this wouldn't have worried me. I am a messy eater. Not intentionally, of course, it just happens. When the waiter clears the plates in a restaurant, mine is always the place with the ring of food stains on the tablecloth.

By contrast, Geoff was a man who could eat a croissant without making crumbs and would, I knew, be immaculately turned out. A shame if I turned up looking like I'd had a heavy night in a burger joint.

I took another handful of wet wipes, squeezed them over the offending area and hoped the large wet patch would dry by the time I reached East Grinstead in Sussex.

Geoff was outside when I arrived and keen to be away. He was, I noticed, dressed in a white T-shirt, which I felt was just showing off. He said nothing, but I saw his eyes drawn to the Impressionist-style stains that decorated the front of my shirt.

'That would be tomato sauce,' I explained. 'And possibly a little sausage fat. I have half a sandwich left if you'd like it.'

'I've had some muesli,' Geoff confessed, and I gave him a sympathetic look. It seemed to me that a bowl of muesli was no way to prepare for a regular day, never mind an 8,000-mile cross-continental drive.

I opened the back of the van and helped him with his bags. One seemed especially heavy, as if a few half bricks had been slipped in for ballast.

'What the heck have you got in here?' I asked.

'Batteries,' Geoff replied. 'For the GPS,' he added, seeing my puzzled look. 'When I've been testing it, it seemed to run down quite quickly and I didn't want us to run out.'

Using both hands, I heaved the bag into the little remaining space in the back of the van. Several twelve-pack A4s, extra-long life, tumbled out from a side pocket.

'There's more in the bag,' said Geoff, concerned lest I think that he might be risking a flat GPS. As it was, I felt we had enough batteries to power it round the clock for at least a couple of years.

The bags packed, we turned our attention to the jerry cans. All five of them. They stood in a neat line, nozzles facing the same way, as if waiting to be loaded. I looked at them and sighed. The plan had been to buy two jerry cans, one for water, one for fuel. Geoff had returned with five, on the grounds that he'd got a much better price for buying in bulk.

'We can't leave them behind,' he said, looking at the cans fondly, as if they were refugees, or perhaps his children.

'They can't all come, there's just no space,' I said, brutally.

Geoff winced, fearing perhaps that the cans would understand that, for some of them, it was to be an empty life.

'We can try, dammit,' he said approaching the van with a can in each hand. 'Maybe if we just shuffle stuff around a bit.'

We shuffled, and repacked, and pressed bags into unnatural shapes and after about twenty minutes had fitted in four of the cans.

'That's it, that's the lot,' I said, firmly, and began shutting the door. Geoff threw the final can through the gap and slammed the door shut before it had chance to fall out.

'There,' he said, triumphantly. 'I knew there was room.'

It was at this point that we realised we had forgotten to pack the tents. To open the rear door would have invited a cascade of cans, so the tents were squeezed snugly behind the seats. Geoff said his farewells to his family, waved to his neighbours who had turned out to watch our departure and we were on our way.

A smooth run down to Dover and an equally smooth ferry crossing. We sipped coffee and watched a despairing teacher try to control a school party of teenage boys whose mission seemed to be to empty the onboard shop of strong lager. There would be trouble ahead and we congratulated ourselves on having chosen journalism as a career rather than teaching.

Our van, with its London–Ulaanbaatar stickers, attracted some attention as we waited to disembark.

'You guys going all the way to Mongolia?' asked an incredulous American voice.

'We hope so. Where are you headed for?'

'Bruges,' came the reply, which made us feel like rather superior world travellers. A few hours later we felt a little less superior as a wrong exit out of a petrol station on the edge of Brussels found us headed for the middle of that traffic-clogged city rather than scooting round the bypass.

'I think I can get us out of this,' I told Geoff, with a wholly misplaced confidence.

'Turn left at the next lights, straight on for a bit, then look for another left turn. That should do the trick. Be on the bypass in no time.'

Geoff did as he was bidden. The traffic seemed as thick as ever. We then passed a building which I thought, uneasily, looked rather familiar. It did to Geoff, too.

'I'm sure we passed that building earlier,' he observed. We had plenty of time to study it. We now weren't moving at all.

'Possibly,' I agreed. 'Not sure how that happened. Well, better take a right, rather than a left.'

Geoff took a right turn. Several of them. Half an hour later there was no doubt – we were back at the same spot and running out of options.

'Straight on then,' I instructed. 'If we just keep heading straight we have to hit the ring road eventually.'

Geoff breathed slightly heavily but said nothing. An hour of going straight on brought us finally to the ring road, which was by now doing a passable imitation of conditions on the M25 just after a new set of road works had been put in place.

Hopes of reaching a campsite in Cologne – which we had pencilled in as our first stop – were beginning to fade.

'I suppose,' I suggested cautiously, 'we could always just head to the city centre when we get to Cologne and find a hotel.'

Geoff and I are men of iron resolve. Rusted, rather brittle iron.

'Excellent plan,' he agreed instantly. 'Not our fault we hit this traffic. Would have been camping otherwise.'

That was agreed then. Our good resolutions to spend most of the trip under canvas had lasted for half a day. Our tents, one of which Geoff had warned was thirty years old and no longer waterproof, could be left untested behind the seats.

Encouraged by the prospect of a comfortable bed, we pressed on, crossing the border into Germany and, taking advantage of the relaxed German attitude to speed limits, pushing the van up to an unfamiliar ninety miles an hour. The fuel gauge started to drop noticeably quickly, but the two-point-seven-litre diesel engine, more commonly found powering London taxis, chugged along as if it were a born motorway cruiser.

On the edge of the city, we followed the wide, brown Rhine to the centre and parked near the station. A basic hotel nearby had a twin room available, many times the cost of a campsite, but we lied to each other that this was just a special treat. We dumped our bags and headed out.

Cologne suffered from Allied bombing in World War Two. There were more than 250 raids, including the first raid by 1,000 Allied planes. But its towering cathedral – the largest in Germany – remained intact. The cathedral has been declared a World Cultural Heritage site, and lovers of Gothic majesty will feel that its architecture is as good as it gets. For the casual tourist, however, the effect has been somewhat spoiled by the recently renovated and very visible public toilets rights outside. Strangely, these seem to be a matter of some pride for the city: when they were reopened, an official ceremony was held at which they were blessed with holy

water by the Archbishop of Cologne.

But we had time only for the most cursory sightseeing – our priorities were food and beer, but not in that order. Round the corner, we found a brewery tavern which looked quite jolly, a large crowd having gathered, with tables set for dinner. We ordered beef stroganoff and the local lager which arrived, disappointingly, in sherry-sized glasses. We looked around. Everyone seemed to be drinking in the same mean measure.

Geoff, who had told me he'd studied German to A-level standard, took charge of the situation.

'Entschuldigen sie mich, could we have zwei big ones, bitte?'

The waiter looked unimpressed. I matched him, look for look.

'I thought you said you could speak German,' I said, accusingly.

'It was a long time ago,' said Geoff. 'Amazing how much you forget.'

It was clear Geoff's language skills weren't up to the job, so we left in search of a bar where an understanding of English and bigger measures were the norm.

We found it in a nearby square which was picture-postcard pretty. Brightly coloured buildings, most four storeys high and with sharply angled roofs, were clustered together, giving the impression of having been crammed in so they could all enjoy the view. More importantly, several were bars with tables and chairs outside, so their customers could enjoy the warm, late spring evening. We ordered a jug of lager and settled back in our chairs.

'Hello there boys, and what brings you to this town?'

An Irish voice from a table nearby. It belonged to a man in his late thirties, long blonde hair parted in the middle, a glass of beer with a spirit chaser in front of him. His friend – similar age but with short dark hair – nodded a greeting.

'We're just passing through,' we replied, not wanting to launch straight away into a long explanation of our trip.

'Ah that's what I said five years ago and I've been here ever since. My advice. Don't get tangled up with any of the local women. They might be good-lookers, but they'll have you trapped. I ended up marrying one of them. Divorced now of course. But still here.'

They joined our table and introduced themselves. Damon, from County Cork, and his friend Andy from London. They were both chefs on a day off. And they'd spent it drinking. All of it. And they were in no mood to stop.

'So passing through to where?' Damon wasn't going to let us get away with English reticence. We told them about the trip. Andy winced.

'You've done it now,' he said in a mock serious tone. 'Damon will be in the back of the van with you.'

Damon confirmed that the trip was an interesting prospect.

'That's amazing,' he said. 'Just amazing. Fantastic.'

Actually, he punctuated that sentence with a number of expletives to emphasise just how fantastic he thought it was. More drinks were ordered.

'Will you leave that ugly man of yours and move in with me?' he inquired of the barmaid as the next round was brought. She indicated that there was little chance of that happening.

'That's it then boys. She won't have me, so I'm chucking it all in here and coming with you. Cheers.' He grinned amiably and raised his glass to his lips.

'You've got trouble now,' observed Andy.

'Trouble? Me? I'm no trouble. I'm…' Damon paused and searched for the right word. His large intake of alcohol meant that he had trouble finding it.

'I'm a dolphin,' he exclaimed for no apparent reason, moving seat so he could put his arm round Geoff. 'I'm a dolphin. That's what I am. Cheers.'

He downed whatever spirit had been in his shot glass. 'What time do we leave?'

'It's a very small van and it's full of our gear,' said Geoff, politely, trying to free himself from Damon's arm that was now firmly round his shoulders.

'Ah, and aren't I only small meself?' asked Damon, rhetorically.

And then, in one of those bizarre moments that would seem so unlikely as to be beyond reasonable coincidence, he asked: 'And what do you boys do anyway? Do you work for the BBC?'

We exchanged bemused glances and confirmed that, up until recently, that had indeed been the case.

'You see,' said Damon. 'I'm a dolphin.'

Dolphins, it seemed, were animals possessed of psychic powers. It was shaping up to be a long session and it was looking increasingly like unless we wanted an additional travelling companion it might be time to make our excuses and leave. Damon seemed unsurprised and took our departure in his stride.

'Ah well, you've missed your chance to have a dolphin travelling with you,' he observed shaking our hands. 'I wish you good luck boys. You're going to make it though, I can tell you that.'

As we left he was explaining to the barmaid that it was her lucky day because he'd be staying after all.

Our hotel bedroom was stuffy and I lay awake for a while. It was then that I made a terrible discovery about the sleeping habits of my travelling companion, one that cast a black shadow when I contemplated the next five weeks together. Geoff snored. Loudly. Rather like waves breaking upon a shore, they seemed to follow a set pattern. There would be half a dozen small, grunting snores then one mighty shuddering snort which seemed to end mid-breath. It seemed inevitable that this final snore would wake him up. But no. He slept on. There would then be silence for, perhaps, two minutes in which my hopes rose that he might have stopped, then the sequence would start again. I lay awake while this pattern was repeated over and over until, with dawn showing through a gap in the curtains, I drifted off myself.

At breakfast there was a slightly uncomfortable silence between us. I wondered how to broach the subject or, indeed, whether to mention anything at all. It was tricky.

'Sleep OK?' I inquired eventually.

'Bit mixed,' he replied. 'What about you?'

'Not too bad. I suppose. Once I'd managed to get off. Took a while.'

He didn't ask why, so the matter rested there. I consoled myself with the thought that we'd probably be in separate tents from now on, so it wouldn't really be a problem.

We checked out and walked back to the van, our spirits lifted by another morning of blue skies and sunshine. A youth approached me, scruffily dressed, unshaven. Even though he spoke in German, the meaning was clear enough, he wanted some money. This was an easy one to bat away.

'Sorry,' I told him, 'I'm English. I'm afraid I don't understand.'

'Ah, English,' he replied instantly. 'Well let me explain. My wallet has been stolen and I have lost my train ticket and all my money. I am trying to get home to Berlin. I wonder if you could help me by making a donation.'

I felt this said something for the German education system when even beggars who slept on the street were perfectly bilingual. However, I had a general rule of always giving to buskers and never to beggars, even those with advanced language skills, so I turned him away and he approached another target with the same story.

After a couple of false starts, we found the right road out of Cologne and headed for the motorway. We were aiming for Colditz Castle, in the state of Saxony, about forty miles from Dresden, in what had been East Germany up until reunification in 1990. The castle is best known as a maximum security prison in World War Two, when it was called Oflag 1V-C, and designated to hold high-profile allied prisoners, in particular those who were prone to escape attempts.

We reached the castle in late afternoon. It sits just above the village which bears its name, close to the Mulde River. For people of my generation, it was brought to life by the 1970s TV series, Escape from Colditz, in which British officers displayed their derring-do by plotting frequent escape attempts. Irritatingly, in real life the first three successful escapes were by French officers and, less irritatingly, the next four by Dutchmen, but the Brits eventually got themselves organised with 'home runs' of their own.

Such was the popularity of the series that it spawned a board game and many books.

We were expecting a grim, rather forbidding place, but in recent years Colditz Castle has been renovated and now, on a sunny afternoon and with a fresh coat of white paint, the turrets and thick stone walls looked more welcoming than threatening and far from the brooding building we had been expecting. Part of it is in use as a youth hostel, and on the day we arrived the village was holding its May Day festival in the lower courtyard. There were stalls similar to those found at any English village fete, and a stage on which local singers could show Colditz had talent. It was all very jovial and carried the added advantage that the castle was open without charge, so we wandered at will, down stone stairwells and along narrow passages, finding the spot below the chapel where the remains of an escape tunnel could be seen.

The main courtyard was decorated with life-sized wooden cut-outs of some of the famous prisoners – including Airey Neave, the first British officer to escape, later an MP and a close ally of Margaret Thatcher when she became Conservative Party leader, who was to die in an Irish National Liberation Army car bomb at the Commons in 1979.

Some of the cut-outs showed the prisoners in their escape attempt disguises – a fake electrician posed next to the real electrician he was imitating in an attempt to walk to freedom. Another showed a rather butch French officer disguised as a woman. This one failed which, surely, must have been no surprise to the other prisoners.

'Ow do I look, Francois?'

'Lovely Pierre, that colour really suits you.' (Crosses fingers behind his back.)

Pierre smoothes down skirt and does a twirl in front of the mirror.

'You do not think it should be a little 'igher, I av' very good knees. Or so I've been told.' (Lifts skirt up and pirouettes around bunk bed).

Sadly, he didn't get past the main gate.

The weather was warm with the promise of a long evening. If we were going to camp there would never be a better time. We spotted signs to a site on the edge of town and followed them. Unfortunately, they led straight into a wood where the track grew increasingly narrow.

'This is what four-wheel drive was invented for,' I told an apprehensive-looking Geoff as I steered the van further into the trees. The track narrowed to a footpath and then narrowed again, and with the branches of the trees beating angrily against the windscreen, I had to admit defeat. Reversing, we retraced our steps and eventually found the tarmac route to the site.

Geoff erected the tents while I assembled our folding table, chairs and cooking implements. All we needed now were some beers, and the camp shop provided them well-chilled from the fridge. Perfect. I knocked up some pasta and a beef casserole, which was thirsty work in the heat, while Geoff enjoyed a well-earned drink after his efforts with the tents. Our beer supplies, which had seemed ample when we bought them, ran out rather more quickly than we were expecting. I staggered off in the falling light to stock up but found the shop shuttered and bolted. Rattles at the door produced no response. There was only one thing to do in the circumstances – break open our 'emergency rations' box which Tricia had packed for when times got tough. I knew that this contained a bottle of Scotch. It wasn't quite the tough conditions that Tricia had intended, but, well, it was a lovely evening and it seemed there would never be a better time to perhaps have a nightcap before bed.

'But I don't drink whisky,' said Geoff, as I uncorked the malt. 'Well, perhaps just a small one then.'

A small one, as is the way at these times, led inexorably to another slightly bigger one, then a very large one indeed.

'I told you I done drink wishky. Don't like tayshte,' said Geoff, slurring the words all together, shaking his head, and holding out his glass at the same time.

To my amazement, after I had refilled us both, the bottle appeared to be empty. Clearly, some of it must have spilled somewhere.

It was now pitch dark, the rest of the camp was asleep, and it was certainly bedtime for both of us. We stood, rather uncertainly, and I headed for my tent. This involved a route past the five jerry cans, which sat piled up by the side of the van, having spilled out as soon as I opened the rear door. I approached them cautiously, swaying to the left, then the right. The cans swayed too, making navigation somewhat tricky. I waited until they stopped moving, then made a dash for it. The cans repositioned themselves and there was no time to take evasive action. I stumbled into them, sending them crashing in all directions.