American Language – Read Now and Download Mobi

BOOKS BY H·L·MENCKEN

THE AMERICAN LANGUAGE

THE AMERICAN LANGUAGE: Supplement I

THE AMERICAN LANGUAGE: Supplement II

A NEW DICTIONARY OF QUOTATIONS

TREATISE ON THE GODS

CHRISTMAS STORY

A MENCKEN CHRESTOMATHY (with selections from the Prejudices series, A Book of Burlesques, In Defense of Women, Notes on Democracy, Making a President, A Book of Calumny, Treatise on Right and Wrong, with pieces from the American Mercury, Smart Set, and the Baltimore Evening Sun, and some previously unpublished notes)

MINORITY REPORT: H. L. MENCKEN’S NOTEBOOKS

THE BATHTUB HOAX and Other Blasts and Bravos from the Chicago Tribune

LETTERS OF H. L. MENCKEN, selected and annotated by Guy J. Forgue

H. L. MENCKEN ON MUSIC, edited by Louis Cheslock

THE AMERICAN LANGUAGE: The Fourth Edition and the Two Supplements, abridged, with annotations and new material, by Raven I. McDavid, Jr., with the assistance of David W. Maurer

H. L. MENCKEN: THE AMERICAN SCENE, A READER, selected and edited, with an introduction and commentary, by Huntington Cairns

These are BORZOI BOOKS, published by ALFRED A. KNOPF in New York

Copyright 1919, 1921, 1923, 1936 by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. Copyright renewed 1947, 1949, 1950 by H. L. Mencken. Copyright renewed 1963 by August Mencken and Mercantile-Safe Deposit and Trust Company. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

PUBLISHED March, 1919

REVISED EDITION published December, 1921

THIRD EDITION again revised published February, 1923

FOURTH EDITION corrected, enlarged, and rewritten

Published April, 1936

Reprinted Twenty-six Times

Twenty-eighth Printing, May 2006

eISBN: 978-0-307-80879-0

v3.1

PREFACE

TO THE FOURTH EDITION

The first edition of this book, running to 374 pages, was published in March, 1919. It sold out very quickly, and so much new matter came in from readers that a revision was undertaken almost at once. This revision, however, collided with other enterprises, and was not finished and published until December, 1921. It ran to 492 pages. In its turn it attracted corrections and additions from many correspondents, and in February, 1923, I brought out a third edition, revised and enlarged. This third edition has been reprinted five times, and has had a large circulation, but for some years past its mounting deficiencies have been haunting me, and on my retirement from the editorship of the American Mercury at the end of 1933 I began to make plans for rewriting it. The task turned out to be so formidable as to be almost appalling. I found myself confronted by a really enormous accumulation of notes, including hundreds of letters from correspondents in all parts of the world and thousands of clippings from the periodical press of the British Empire, the United States and most of the countries of Continental Europe. Among the letters were many that reviewed my third edition page by page, and suggested multitudinous additions to the text, or changes in it. One of them was no less than 10,000 words long. The clippings embraced every discussion of the American language printed in the British Empire since the end of 1922 — at all events, every one that the singularly alert Durrant Press-Cutting Agency could discover. Furthermore, there were the growing files of American Speech, set up in October, 1925, and of Dialect Notes, and a large number of books and pamphlets, mostly in English but some also in German, French and other foreign languages, including even Japanese. It soon became plain that this immense mass of new material made a mere revision of the third edition out of the question. What was needed was a complete reworking, following to some extent the outlines of the earlier editions, but with many additions and a number of emendations and shortenings. That reworking has occupied me, with two or three intervals, since the beginning of 1934. The present book picks up bodily a few short passages from the third edition, but they are not many. In the main, it is a new work.

The reader familiar with my earlier editions will find that it not only presents a large amount of matter that was not available when they were written, but also modifies the thesis which they set forth. When I became interested in the subject and began writing about it (in the Baltimore Evening Sun in 1910), the American form of the English language was plainly departing from the parent stem, and it seemed at least likely that the differences between American and English would go on increasing. This was what I argued in my first three editions. But since 1923 the pull of American has become so powerful that it has begun to drag English with it, and in consequence some of the differences once visible have tended to disappear. The two forms of the language, of course, are still distinct in more ways than one, and when an Englishman and an American meet they continue to be conscious that each speaks a tongue that is far from identical with the tongue spoken by the other. But the Englishman, of late, has yielded so much to American example, in vocabulary, in idiom, in spelling and even in pronunciation, that what he speaks promises to become, on some not too remote tomorrow, a kind of dialect of American, just as the language spoken by the American was once a dialect of English. The English writers who note this change lay it to the influence of the American movies and talkies, but it seems to me that there is also something more, and something deeper. The American people now constitute by far the largest fraction of the English-speaking race, and since the World War they have shown an increasing inclination to throw off their old subservience to English precept and example. If only by the force of numbers, they are bound to exert a dominant influence upon the course of the common language hereafter. But all this I discuss at length, supported by the evidence now available, in the pages following.

At the risk of making my book of forbidding bulk I have sought to present a comprehensive conspectus of the whole matter, with references to all the pertinent literature. My experience with the three preceding editions convinces me that the persons who are really interested in American English are not daunted by bibliographical apparatus, but rather demand it. The letters that so many of them have been kind enough to send to me show that they delight in running down the by-ways of the subject, and I have tried to assist them by setting up as many guide-posts as possible, pointing into every alley as we pass along. Thus my references keep in step with the text, where they are most convenient and useful, and I have been able to dispense with the Bibliography which filled 32 pages of small type in my third edition. I have also omitted a few illustrative oddities appearing in that edition — for example, specimens of vulgar American by Ring W. Lardner and John V. A. Weaver, and my own translations of the Declaration of Independence and Lincoln’s Gettsyburg Address. The latter two, I am sorry to say, were mistaken by a number of outraged English critics for examples of Standard American, or of what I proposed that Standard American should be. Omitting them will get rid of that misapprehension and save some space, and those who want to consult them will know where to find them in my third edition.

I can’t pretend that I have covered the whole field in the present volume, for that field has become very large in area. But I have at least tried to cover those parts of it of which I have any knowledge, and to indicate the main paths through the remainder. The Dictionary of American English on Historical Principles, now under way at the University of Chicago under the able editorship of Sir William Craigie, will deal with the vocabulary of Americanisms on a scale impossible here, and the Linguistic Atlas in preparation by Dr. Hans Kurath and his associates at Brown University will similarly cover the large and vexatious subject of regional differences in usage. In the same way, I hope, the work of Dr. W. Cabell Greet and his associates at Columbia will one day give us a really comprehensive account of American pronunciation. There are other inquiries in progress by other scholars, all of them unheard of at the time my third edition was published. But there are still some regions into which scholarship has hardly penetrated — for example, that of the vulgar grammar —, and therein I have had to disport as gracefully as possible, always sharply conscious of the odium which attaches justly to those amateurs who, “because they speak, fancy they can speak about speech.” I am surely no philologian, and my inquiries and surmises will probably be of small value to the first successor who is, but until he appears I can only go on accumulating materials, and arranging them as plausibly as possible.

In the course of the chapters following I have noted my frequent debt to large numbers of volunteer aides, some of them learned in linguistic science but the majority lay brothers as I am. My contacts with them have brought me many pleasant acquaintanceships, and some friendships that I value greatly. In particular, I am indebted to Dr. Louise Pound, professor of English at the University of Nebraska and the first editor of American Speech, whose interest in this book has been lively and generous since its first appearance; to Mr. H. W. Seaman, of Norwich, England, whose herculean struggles with the chapter on “American and English Today” deserve a much greater reward than he will ever receive on this earth; to Dr. Kemp Malone, professor of English at the Johns Hopkins, who was kind enough to read the chapter on “The Common Speech”; to the late Dr. Robert Bridges, Poet Laureate of England and founder of the Society for Pure English, who was always lavish of his wise and stimulating counsel; to Professor Dr. Heinrich Spies of Berlin, who published a critical summary of my third edition in German, under the title of “Die amerikanische Sprache,” in 1927; and to the late Dr. George Philip Krapp, professor of English at Columbia, who allowed me the use of the manuscript of his excellent “History of the English Language in America” in 1922, and was very obliging in other ways down to the time of his lamented death in 1934. Above all, I am indebted to my secretary, Mrs. Rosalind C. Lohrfinck, without whose indefatigable aid the present edition would have been quite impossible. The aforesaid friends of the philological faculty are not responsible, of course, for anything that appears herein. They have saved me from a great many errors, some of them of a large and astounding character, but others, I fear, remain. I shall be grateful, as in the past, for corrections and additions sent to me at 1524 Hollins street, Baltimore.

Baltimore, 1936

H. L. M.

Contents

1. The Earliest Alarms

2. The English Attack

3. American “Barbarisms”

4. The English Attitude Today

5. The Position of the Learned

6. The Views of Writing Men

7. The Political Front

8. Foreign Observers

II. THE MATERIALS OF THE INQUIRY

1. The Hallmarks of American

2. What is an Americanism?

III. THE BEGINNINGS OF AMERICAN

1. The First Loan-Words

2. New Words of English Material

3. Changed Meanings

4. Archaic English Words

1. A New Nation in the Making

2. The Expanding Vocabulary

3. Loan-Words and Non-English Influences

1. After the Civil War

2. The Making of New Nouns

3. Verbs

4. Other Parts of Speech

5. Foreign Influences Today

1. The Infiltration of English by Americanisms

2. Surviving Differences

3. English Difficulties with American

4. Briticisms in the United States

5. Honorifics

6. Euphemisms

7. Forbidden Words

8. Expletives

VII. THE PRONUNCIATION OF AMERICAN

1. Its General Characters

2. The Vowels

3. The Consonants

4. Dialects

1. The Influence of Noah Webster

2. The Advance of American Spelling

3. The Simplified Spelling Movement

4. The Treatment of Loan-Words

5. Punctuation, Capitalization, and Abbreviation

1. Outlines of its Grammar

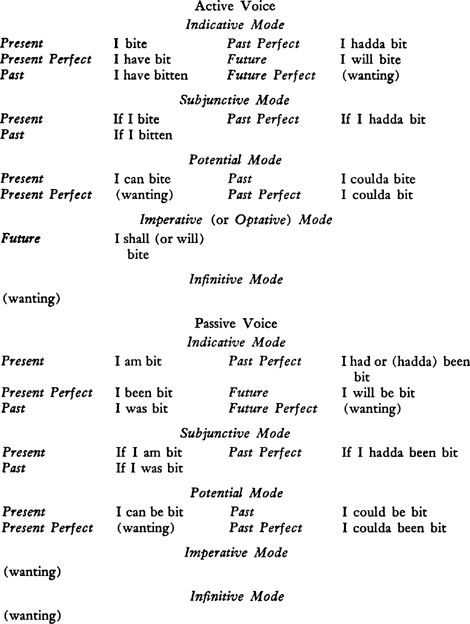

2. The Verb

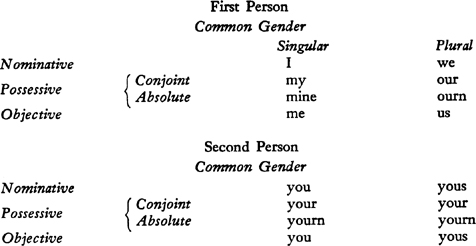

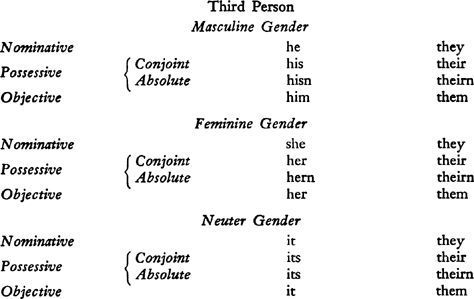

3. The Pronoun

4. The Noun

5. The Adjective

6. The Adverb

7. The Double Negative

8. Other Syntactical Peculiarities

1. Surnames

2. Given-Names

3. Place-Names

4. Other Proper Names

1. The Nature of Slang

2. Cant and Argot

XII. THE FUTURE OF THE LANGUAGE

1. The Spread of English

2. English or American?

APPENDIX. NON–ENGLISH DIALECTS IN AMERICA

1. Germanic

a. German

b. Dutch

c. Swedish

d. Dano-Norwegian

e. Icelandic

f. Yiddish

2. Latin

a. French

b. Italian

c. Spanish

d. Portuguese

e. Rumanian

3. Slavic

a. Czech

b. Slovak

c. Russian

d. Ukrainian

e. Serbo-Croat

f. Lithuanian

g. Polish

4. Finno-Ugrian

a. Finnish

b. Hungarian

5. Celtic

a. Gaelic

6. Semitic

a. Arabic

7. Greek

a. Modern Greek

8. Asiatic

a. Chinese

b. Japanese

9. Miscellaneous

a. Armenian

b. Hawaiian

c. Gipsy

I

THE TWO STREAMS OF ENGLISH

I. THE EARLIEST ALARMS

The first American colonists had perforce to invent Americanisms, if only to describe the unfamiliar landscape and weather, flora and fauna confronting them. Half a dozen that are still in use are to be found in Captain John Smith’s “Map of Virginia,” published in 1612, and there are many more in the works of the New England annalists. As early as 1621 Alexander Gill was noting in his “Logonomia Anglica” that maize and canoe were making their way into English.1 But it was reserved for one Francis Moore, who came out to Georgia with Oglethorpe in 1735, to raise the earliest alarm against this enrichment of English from the New World, and so set the tone that English criticism has maintained ever since. Thus he described Savannah, then a village only two years old:

It stands upon the flat of a Hill; the Bank of the River (which they in barbarous English call a bluff) is steep, and about forty-five foot perpendicular.2

John Wesley arrived in Georgia the same year, and from his diary for December 2, 1737, comes the Oxford Dictionary’s earliest example of the use of the word. But Moore was the first to notice it, and what is better to the point, the first to denounce it, and for that pioneering he must hold his honorable place in this history. In colonial times, of course, there was comparatively little incitement to hostility to Americanisms, for the stream of Englishmen coming to America to write books about their sufferings had barely begun to flow, and the number of American books reaching London was very small. But by 1754 literary London was already sufficiently conscious of the new words arriving from the New World for Richard Owen Cambridge, author of “The Scribleriad,” to be suggesting3 that a glossary of them would soon be in order, and two years later the finicky and always anti-American Samuel Johnson was saying, in a notice of Lewis Evans’s “Geographical, Historical, Political, Philosophical, and Mechanical Essays,”4 substantially what many English reviewers still say with dogged piety:

This treatise is written with such elegance as the subject admits, tho’ not without some mixture of the American dialect, a tract [i.e., trace] of corruption to which every language widely diffused must always be exposed.

As the Revolution drew on, the English discovered varieties of offensiveness on this side of the ocean that greatly transcended the philological, and I can find no record of any denunciation of Americanisms during the heat of the struggle itself. When, on July 20, 1778, a committee appointed by the Continental Congress to arrange for the “publick reception of the sieur Gerard, minister plenipotentiary of his most christian majesty,” brought in a report recommending that “all replies or answers” to him should be “in the language of the United States,”5 no notice of the contumacy seems to have been taken in the Motherland. But a few months before Cornwallis was finally brought to heel at Yorktown the subject was resumed, and this time the attack came from a Briton living in America, and otherwise ardently pro-American. He was John Witherspoon (1723–94), a Scottish clergyman who had come out in 1769 to be president of Princeton in partibus infidelium.

Witherspoon took to politics when the war closed his college, and was elected a member of the New Jersey constitutional convention. In a little while he was promoted to the Continental Congress, and in it he sat for six years as its only member in holy orders. He signed both the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation, and was a member of the Board of War throughout the Revolution. But though his devotion to the American cause was thus beyond question, he was pained by the American language, and when, in 1781, he was invited to contribute a series of papers to the Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser of Philadelphia, he seized the opportunity to denounce it, albeit in the politic terms proper to the time. Beginning with the disarming admission that “the vulgar in America speak much better than the vulgar in England, for a very obvious reason, viz., that being much more unsettled, and moving frequently from place, they are not so liable to local peculiarities either in accent or phraseology,” he proceeded to argue that Americans of education showed a lamentable looseness in their “public and solemn discourses.”

I have heard in this country, in the senate, at the bar, and from the pulpit, and see daily in dissertations from the press, errors in grammar, improprieties and vulgarisms which hardly any person of the same class in point of rank and literature would have fallen into in Great Britain.

Witherspoon’s mention of “the senate” was significant, for he must have referred to the Continental Congress, and it is fair to assume that at least some of the examples he cited to support his charge came from the sacred lips of the Fathers. He divided these “errors in grammar, improprieties and vulgarisms” into eight classes, as follows:

1. Americanisms, or ways of speaking peculiar to this country.

2. Vulgarisms in England and America.

3. Vulgarisms in America only.

4. Local phrases or terms.

5. Common blunders arising from ignorance.

6. Cant phrases.

7. Personal blunders.

8. Technical terms introduced into the language.6

By Americanisms, said Witherspoon,

I understand an use of phrases or terms, or a construction of sentences, even among people of rank and education, different from the use of the same terms or phrases, or the construction of similar sentences in Great Britain. It does not follow, from a man’s using these, that he is ignorant, or his discourse upon the whole inelegant; nay, it does not follow in every case that the terms or phrases used are worse in themselves, but merely that they are of American and not of English growth. The word Americanism, which I have coined for the purpose, is exactly similar in its formation and significance to the word Scotticism.

Witherspoon listed twelve examples of Americanisms falling within his definition, and despite the polite assurance I have just quoted, he managed to deplore all of them. His first was the use of either to indicate more than two, as in “The United States, or either of them.” This usage seems to have had some countenance in the England of the early Seventeenth Century, but it had gone out there by Witherspoon’s day, and it has since been outlawed by the schoolmarm in the United States. His second caveat was laid against the American use of to notify, as in “The police notified the coroner.” “In English,” he said somewhat prissily, “we do not notify the person of the thing, but notify the thing to the person.” But to notify, in the American sense, was simply an example of archaic English, preserved like so many other archaisms in America, and there was, and is, no plausible logical or grammatical objection to it.7 Witherspoon’s third Americanism was fellow countrymen, which he denounced as “an evident tautology,” and his fourth was the omission of to be before the second verb in such constructions as “These things were ordered delivered to the army.” His next three were similar omissions, and his remaining five were the use of or instead of nor following neither, the use of certain in “A certain Thomas Benson” (he argued that “A certain person called Thomas Benson” was correct), the use of incident in “Such bodies are incident to these evils,” and the use of clever in the sense of worthy, and of mad in the sense of angry.

It is rather surprising that Witherspoon found so few Americanisms for his list. Certainly there were many others, current in his day, that deserved a purist’s reprobation quite as much as those he singled out, and he must have been familiar with them. Among the verbs a large number of novelties had come into American usage since the middle of the century, some of them revivals of archaic English verbs and others native inventions — to belittle, to advocate, to progress, to notice, to table, to raise (for to grow), to deed, to locate, to ambition, to deputize, to compromit, to appreciate (in the sense of increase in value), to eventuate, and so on. Benjamin Franklin, on his return to the United States in 1785, after nine years in France, was impressed so unpleasantly by to advocate, to notice, to progress and to oppose that on December 26, 1789 he wrote to Noah Webster to ask for help in putting them down, but they seem to have escaped Witherspoon. He also failed to note the changes of meaning in the American use of creek, shoe, lumber, corn, barn, team, store, rock, cracker and partridge. Nor did he have anything to say about American pronunciation, which had already begun to differ materially from that of Standard English.

Witherspoon’s strictures, such as they were, fell upon deaf ears, at least in the new Republic. He was to get heavy support, in a little while, from the English reviews, which began to belabor everything American in the closing years of the century, but on this side of the ocean the tide was running the other way, and as the Revolution drew to its victorious close there was a widespread tendency to reject English precedent and authority altogether, in language no less than in government. In the case of the language, several logical considerations supported that disposition, though the chief force at the bottom of it, of course, was probably only national conceit. For one thing, it was apparent to the more astute politicians of the time that getting rid of English authority in speech, far from making for chaos, would encourage the emergence of home authority, and so help to establish national solidarity, then the great desideratum of desiderata. And for another thing, some of them were far-sighted enough to see that the United States, in the course of the years, would inevitably surpass the British Isles in population and wealth, and to realize that its cultural independence would grow at the same pace.

Something of the sort was plainly in the mind of John Adams when he wrote to the president of Congress from Amsterdam on September 5, 1780, suggesting that Congress set up an academy for “correcting, improving and ascertaining the English language.” There were such academies, he said, in France, Spain and Italy, but the English had neglected to establish one, and the way was open for the United States. He went on:

It will have a happy effect upon the union of States to have a public standard for all persons in every part of the continent to appeal to, both for the signification and pronunciation of the language.… English is destined to be in the next and succeeding centuries more generally the language of the world than Latin was in the last or French is in the present age. The reason of this is obvious, because the increasing population in America, and their universal connection and correspondence with all nations will, aided by the influence of England in the world, whether great or small, force their language into general use, in spite of all the obstacles that may be thrown in their way, if any such there should be.8

Six years before this, in January, 1774, some anonymous writer, perhaps also Adams, had printed a similar proposal in the Royal American Magazine. That it got some attention is indicated by the fact that Sir John Wentworth, the Loyalist Governor of New Hampshire, thought it of sufficient importance to enclose a reprint of it in a dispatch to the Earl of Dartmouth, Secretary of State for the Colonies, dated April 24. I quote from it briefly:

The English language has been greatly improved in Britain within a century, but its highest perfection, with every other branch of human knowledge, is perhaps reserved for this land of light and freedom. As the people through this extensive country will speak English, their advantages for polishing their language will be great, and vastly superior to what the people of England ever enjoyed. I beg leave to propose a plan for perfecting the English language in America, thro’ every future period of its existence; viz: That a society for this purpose should be formed, consisting of members in each university and seminary, who shall be stiled Fellows of the American Society of Language; That the society … annually publish some observations upon the language, and from year to year correct, enrich and refine it, until perfection stops their progress and ends their labor.9

Whether this article was Adams’s or not, he kept on returning to the charge, and in a second letter to the president of Congress, dated September 30, 1780, he expressed the hope that, after an American Academy had been set up, England would follow suit.

This I should admire. England will never more have any honor, excepting now and then that of imitating the Americans. I assure you, Sir, I am not altogether in jest. I see a general inclination after English in France, Spain and Holland, and it may extend throughout Europe. The population and commerce of America will force their language into general use.10

In his first letter to the president of Congress Adams deplored the fact that “it is only very lately that a tolerable dictionary [of English] has been published, even by a private person,11 and there is not yet a passable grammar enterprised by any individual.” He did not know it, but at that very moment a young schoolmaster in the backwoods of New York was preparing to meet both lacks. He was Noah Webster. Three years later he returned to Hartford, his birthplace, and brought out his “Grammatical Institute of the English Language,” and soon afterward he began the labors which finally bore fruit in his “American Dictionary of the English Language” in 1828.12 Webster was a pedantic and rather choleric fellow — someone once called him “the critic and cockcomb-general of the United States” —, and his later years were filled with ill-natured debates over his proposals for reforming English spelling, and over the more fanciful etymologies in his dictionary. But though, in this enlightened age, he would scarcely pass as a philologian, he was extremely well read for his time, and if he fell into the blunder of deriving all languages from the Hebrew of the Ark, he was at least shrewd enough to notice the relationship between Greek, Latin and the Teutonic languages before it was generally recognized. He was always at great pains to ascertain actual usages, and in the course of his journeys from State to State to perfect his copyright on his first spelling-book13 he accumulated a large amount of interesting and valuable material, especially in the field of pronunciation. Much of it he utilized in his “Dissertations on the English Language,” published at Boston in 1789.

In the opening essay of this work he put himself squarely behind Adams. He foresaw that the new Republic would quickly outstrip England in population, and that virtually all its people would speak English. He proposed therefore that an American standard be set up, independent of the English standard, and that it be inculcated in the schools throughout the country. He argued that it should be determined, not by “the practise of any particular class of people,” but by “the general practise of the nation,” with due regard, in cases where there was no general practise, to “the principle of analogy.” He went on:

As an independent nation, our honor requires us to have a system of our own, in language as well as government. Great Britain, whose children we are, and whose language we speak, should no longer be our standard; for the taste of her writers is already corrupted,14 and her language on the decline. But if it were not so, she is at too great a distance to be our model, and to instruct us in the principles of our own tongue.… Several circumstances render a future separation of the American tongue from the English necessary and unavoidable.… Numerous local causes, such as a new country, new associations of people, new combinations of ideas in arts and sciences, and some intercourse with tribes wholly unknown in Europe, will introduce new words into the American tongue. These causes will produce, in a course of time, a language in North America as different from the future language of England as the modern Dutch, Danish and Swedish are from the German, or from one another: like remote branches of a tree springing from the same stock, or rays of light shot from the same center, and diverging from each other in proportion to their distance from the point of separation.… We have therefore the fairest opportunity of establishing a national language and of giving it uniformity and perspicuity, in North America, that ever presented itself to mankind. Now is the time to begin the plan.15

What Witherspoon thought of all this is not recorded. Maybe he never saw Webster’s book, for he was going blind in 1789, and lived only five years longer. Webster seems to have got little support for what he called his Federal English from the recognized illuminati of the time;16 indeed, his proposals for a reform of American spelling, set forth in an appendix to his “Dissertations,” were denounced roundly by some of them, and the rest were only lukewarm. He dedicated the “Dissertations” to Franklin, but Franklin delayed acknowledging the dedication until the last days of 1789, and then ventured upon no approbation of Webster’s linguistic Declaration of Independence. On the contrary, he urged him to make war upon various Americanisms of recent growth, and perhaps with deliberate irony applauded his “zeal for preserving the purity of our language.” A year before the “Dissertations” appeared, Dr. Benjamin Rush anticipated at least some of Webster’s ideas in “A Plan of a Federal University,”17 and they seem to have made some impression on Thomas Jefferson, who was to ratify them formally in 1813;18 but the rest of the contemporaneous sages held aloof, and in July, 1800, the Monthly Magazine and American Review of New York printed an anonymous denunciation, headed “On the Scheme of an American Language,” of the notion that “grammars and dictionaries should be compiled by natives of the country, not of the British or English, but of the American tongue.” The author of this tirade, who signed himself C, displayed a violent Anglomania. “The most suitable name for our country,” he said, “would be that which is now appropriated only to a part of it: I mean New England.” While admitting that a few Americanisms were logical and necessary — for example, Congress, president and capitol —, he dismissed all the rest as “manifest corruptions.” A year later, a savant using the nom de plume of Aristarcus delivered a similar attack on Webster in a series of articles contributed to the New England Palladium and reprinted in the Port Folio of Philadelphia, the latter “a notoriously Federalistic and pro-British organ.” “If the Connecticut lexicographer,” he said, “considers the retaining of the English language as a badge of slavery, let him not give us a Babylonish dialect in its stead, but adopt, at once, the language of the aborigines.”19

But if the illuminati were thus chilly, the plain people supported Webster’s scheme for the emancipation of American English heartily enough, though very few of them could have heard of it. The period from the gathering of the Revolution to the turn of the century was one of immense activity in the concoction and launching of new Americanisms, and more of them came into the language than at any time between the earliest colonial days and the rush to the West. Webster himself lists some of these novelties in his “Dissertations,” and a great many more are to be found in Richard H. Thornton’s “American Glossary”20 — for example, black-eye (in the sense of defeat), block (of houses), bobolink, bookstore, bootee (now obsolete), breadstuffs, buckeye, buckwheat-cake, bull-snake, bundling and buttonnjoood, to go no further than the b’s. It was during this period, too, that the American meanings of such words as shoe, corn, bug, bureau, mad, sick, creek, barn and lumber were finally differentiated from the English meanings, and that American peculiarities in pronunciation began to make themselves felt. Despite the economic difficulties which followed the Revolution, the general feeling was that the new Republic was a success, and that it was destined to rise in the world as England declined. There was a widespread contempt for everything English, and that contempt extended to the canons of the mother-tongue.

2. THE ENGLISH ATTACK

But the Jay Treaty of 1794 gave notice that there was still some life left in the British lion, and during the following years the troubles of the Americans, both at home and abroad, mounted at so appalling a rate that their confidence and elation gradually oozed out of them. Simultaneously, their pretensions began to be attacked with pious vigor by patriotic Britishers, and in no field was the fervor of these brethren more marked than in those of literature and language. To be sure, there were Englishmen, then as now, who had a friendly and understanding interest in all things American, including even American books, and some of them took the trouble to show it, but they were not many. The general tone of English criticism, from the end of the Eighteenth Century to the present day, has been one of suspicion, and not infrequently it has been extremely hostile. The periods of remission, as often as not, have been no more than evidences of adroit politicking, as when Oxford, in 1907, helped along the graceful liquidation of the Venezuelan unpleasantness of 1895 by giving Mark Twain an honorary D.C.L. In England all branches of human endeavor are alike bent to the service of the state, and there is an alliance between society and politics, science and literature, that is unmatched anywhere else on earth. But though this alliance, on occasion, may find it profitable to be polite to the Yankee, and even to conciliate him, there remains an active aversion under the surface, born of the incurable rivalry between the two countries, and accentuated perhaps by their common tradition and their similar speech. Americanisms are forcing their way into English all the time, and of late they have been entering at a truly dizzy pace, but they seldom get anything properly describable as a welcome, save from small sects of iconoclasts, and every now and then the general protest against them rises to a roar. As for American literature, it is still regarded in England as somewhat barbaric and below the salt, and the famous sneer of Sydney Smith, though time has made it absurd in all other respects, is yet echoed complacently in many an English review of American books.21

There is an amusing compilation of some of the earlier diatribes in William B. Cairns’s “British Criticisms of American Writings, 1783–1815.”22 Cairns is not so much concerned with linguistic matters as with literary criticism, but he reprints a number of extracts from the pioneer denunciations of Americanisms, and they surely show a sufficient indignation. The attack began in 1787, when the European Magazine and London Review fell upon the English of Thomas Jefferson’s “Notes on the State of Virginia,” and especially upon his use of to belittle, which, according to Thornton, was his own coinage. “Belittle!” it roared. “What an expression! It may be an elegant one in Virginia, and even perfectly intelligible; but for our part, all we can do is to guess at its meaning. For shame, Mr. Jefferson! Why, after trampling upon the honour of our country, and representing it as little better than a land of barbarism — why, we say, perpetually trample also upon the very grammar of our language, and make that appear as Gothic as, from your description, our manners are rude? — Freely, good sir, will we forgive all your attacks, impotent as they are illiberal, upon our national character; but for the future spare — O spare, we beseech you, our mother-tongue!” The Gentleman’s Magazine joined the charge in May, 1798, with sneers for the “uncouth … localities” [sic] in the “Yankey dialect” of Noah Webster’s “Sentimental and Humorous Essays,” and the Edinburgh followed in October, 1804, with a patronizing article upon John Quincy Adams’s “Letters on Silesia.” “The style of Mr. Adams,” it said, “is in general very tolerable English; which, for an American composition, is no moderate praise.” The usual American book of the time, it went on, was full of “affectations and corruptions of phrase,” and they were even to be found in “the enlightened state papers of the two great Presidents.” The Edinburgh predicted that a “spurious dialect” would prevail, “even at the Court and in the Senate of the United States,” and that the Americans would thus “lose the only badge that is still worn of our consanguinity.” The appearance of the five volumes of Chief Justice Marshall’s “Life of George Washington,” from 1804 to 1807, brought forth corrective articles from the British Critic, the Critical Review, the Annual, the Monthly, and the Eclectic. The Edinburgh, in 1808, declared that the Americans made “it a point of conscience to have no aristocratical distinctions — even in their vocabulary.” They thought, it went on, “one word as good as another, provided its meaning be as clear.” The Monthly Mirror, in March of the same year, denounced “the corruptions and barbarities which are hourly obtaining in the speech of our transatlantic colonies [sic],” and reprinted with approbation a parody by some anonymous Englishman of the American style of the day. Here is an extract from it, with the words that the author regarded as Americanisms in italics:

In America authors are to be found who make use of new or obsolete words which no good writer in this country would employ; and were it not for my destitution of leisure, which obliges me to hasten the occlusion of these pages, as I progress I should bottom my assertation on instances from authors of the first grade; but were I to render my sketch lengthy I should illy answer the purpose which I have in view.

The British Critic, in April, 1808, admitted somewhat despairingly that the damage was already done — that “the common speech of the United States has departed very considerably from the standard adopted in England.” The others, however, sought to stay the flood by invective against Marshall, and, later, against his rival biographer, the Rev. Aaron Bancroft. The Annual, in 1808, pronounced its anathema upon “that torrent of barbarous phraseology” which was pouring across the Atlantic, and which threatened “to destroy the purity of the English language.” In Bancroft’s “Life of George Washington” (1808), according to the British Critic, there were “new words, or old words in a new sense,” all of them inordinately offensive to Englishmen, “at almost every page,” and in Joel Barlow’s “The Columbiad” (1807; reprinted in England in 1809) the Edinburgh found “a great multitude of words which are radically and entirely new, and as utterly foreign as if they had been adopted from the Hebrew or Chinese,” and “the perversion of a still greater number of English words from their proper use or signification, by employing nouns substantive for verbs, adjectives for substantives, &c.” The Edinburgh continued:

We have often heard it reported that our transatlantic brethren were beginning to take it amiss that their language should still be called English; and truly we must say that Mr. Barlow has gone far to take away that ground of reproach. The groundwork of his speech, perhaps may be English, as that of the Italian is Latin; but the variations amount already to more than a change of dialect; and really make a glossary necessary for most untravelled readers.

Some of Barlow’s novelties, it must be granted, were fantastic enough — for example, to vagrate and to ameed among the verbs, imkeeled and homicidious among the adjectives, and coloniarch among the nouns. But many of the rest were either obsolete words whose use was perfectly proper in heroic poetry, or nonce-words of obvious meaning and utility. Some of the terms complained of by the Edinburgh are in good usage at this moment — for example, to utilize, to hill, to breeze, to spade (the soil), millenial, crass, and scow.23 But to the English reviewers of the time words so unfamiliar were not only deplorable on their own account; they were also proofs that the Americans were a sordid and ignoble people with no capacity for prose, or for any of the other elegances of life.24 “When the vulgar and illiterate lose the force of their animal spirits,” observed the Quarterly in 1814, reviewing J. K. Paulding’s “Lay of the Scottish Fiddle” (1813), “they become mere clods.… The founders of American society brought to the composition of their nation few seeds of good taste, and no rudiments of liberal science.” To which may be added Southey’s judgment in a letter to Landor in 1812: “See what it is to have a nation to take its place among civilized states before it has either gentlemen or scholars! They have in the course of twenty years acquired a distinct national character for low and lying knavery; and so well do they deserve it that no man ever had any dealings with them without having proofs of its truth.” Landor, it should be said, entered a protest against this, and on a somewhat surprising ground, considering the general view. “Americans,” he said, “speak our language; they read ‘Paradise Lost.’ ” But he hastened to add, “I detest the American character as much as you do.”

The War of 1812 naturally exacerbated this animosity, though when the works of Irving and Cooper began to be known in England some of the English reviewers moderated their tone. Irving’s “Knickerbocker” was not much read there until 1815, and not much talked about until “The Sketch-Book” followed it in 1819, but Scott had received a copy of it from Henry Brevoort in 1813, and liked it and said so. Byron mentioned it in a letter to his publisher, Murray, on August 7, 1821. We are told by Thomas Love Peacock that Shelley was “especially fond of the novels of Charles Brockden Brown, the American,” but Cairns says there is no mention of the fact, if it be a fact, in any of Shelley’s own writings, or in those of his other friends. “Knickerbocker” was published in 1809, the North American Review began in May, 1815, Bryant’s “Thanatopsis” was printed in its pages in 1817, and Paulding’s “The Backwoodsman,” with an American theme and an American title, came out a year later, but Cooper’s “Precaution” was still two years ahead, and American letters were yet in a somewhat feeble state. John Pickering, so late as 1816, said that “in this country we can hardly be said to have any authors by profession,” and Justice Story, three years later, repeated the saying and sought to account for the fact. “So great,” said Story, “is the call for talents of all sorts in the active use of professional and other business in America that few of our ablest men have leisure to devote exclusively to literature or the fine arts.… This obvious reason will explain why we have so few professional authors, and those not among our ablest men.” In 1813 Jefferson, anticipating both Pickering and Story, had written to John Waldo:

We have no distinct class of literati in our country. Every man is engaged in some industrious pursuit, and science is but a secondary occupation, always subordinate to the main business of life. Few, therefore, of those who are qualified have leisure to write.

Difficulties of communication hampered the circulation of such native books as were written. “It is much to be regretted,” wrote Dr. David Ramsay, of Charleston, S. C., to Noah Webster in 1806, “that there is so little intercourse in a literary way between the States. As soon as a book of general utility comes out in any State it should be for sale in all of them.” Ramsay asked for little; the most he could imagine was a sale of 2,000 copies for an American work in America. But even that was apparently beyond the possibilities of the time. It would be a mistake, however, to assume that the Americans eschewed reading altogether; on the contrary, there is some evidence that they read many English books. In 1802 the Scot’s Magazine reported that at a book-fair held shortly before in New York the sales ran to 520,000 volumes, and that a similar fair was projected for Philadelphia. Six years before this the London bookseller, Henry Lemoine, made a survey of the American book trade for the Gentleman’s Magazine.25 He found that very few books were being printed in the country, and ascribed the fact to the high cost of labor, but he encountered well-stocked bookstores in New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore, and plenty of customers for their importations. He went on:

Their sales are very great, for it is scarcely possible to conceive the number of readers with which every little town abounds. The common people are on a footing, in point of literature, with the middle ranks in Europe; they all read and write, and understand arithmetic. Almost every little town now furnishes a small circulating-library.… Whatever is useful sells, but publications on subjects merely speculative, and rather curious than important, controversial divinity, and voluminous polemical pieces, as well as heavy works on the arts and sciences, lie upon the importer’s hands. They have no ready money to spare for anything but what they find useful.

But other visitors were much less impressed by the literary gusto of the young Republic. Henry Wansey, who came out in 1794, reported in his “Excursion to the United States of North America”26 that the American libraries were “scanty,” that their collections were “almost entirely of modern books,” and that they were deficient in “the means of tracing the history of questions,… a want which literary people felt very much, and which it will take some years to remedy.” And Captain Thomas Hamilton, in his “Men and Manners in America,”27 said flatly that “there is … nothing in the United States worthy of the name of library. Not only is there an entire absence of learning, in the higher sense of the term, but an absolute want of the material from which alone learning can be extracted. At present an American might study every book within the limits of the Union, and still be regarded in many parts of Europe — especially in Germany — as a man comparatively ignorant. Why does a great nation thus voluntarily continue in a state of intellectual destitution so anomalous and humiliating?” According to Hamilton, all the books imported from Europe for public institutions during the fiscal year 1829–30 reached a value of but $10,829.

But whatever the fact here, there can be no doubt that the Americans were quickly aware of every British aspersion upon their culture, whether it appeared in a book or in one of the reviews. If nothing else was read, such things were certainly read, and they came with sufficient frequency, and were couched in terms of sufficient offensiveness, to keep the country in a state of indignation for years. The flood of books by English visitors began before the end of the Eighteenth Century, and though many of them were intended to be friendly, there was in even the friendliest of them enough of what Cairns calls “the British knack for saying gracious things in an ungracious way” to keep the pot of fury boiling. At the other extreme the thing went to fantastic lengths. The Quarterly Review, summing up in 1814, accused the Americans of a multitude of strange and hair-raising offenses — for example, employing naked colored women to wait upon them at table, kidnapping Scotsmen, Welshmen and Hollanders and selling them into slavery, and fighting one another incessantly under rules which made it “allowable to peel the skull, tear out the eyes, and smooth away the nose.” In this holy war upon the primeval damyankee William Gifford, editor of the Anti-Jacobin in 1797–98, and after 1809 the first editor of the Quarterly, played an extravagant part,28 but he was diligently seconded by Sydney Smith, Southey, Thomas Moore and many lesser lights. “If the [English] reviewers get hold of an American publication,” said J. K. Paulding in “Letters From the South” in 1817, “it is made use of merely as a pretext to calumniate us in some way or other.” There is an instructive account of the whole uproar in the fifth volume of John Bach McMaster’s “History of the People of the United States From the Revolution to the Civil War.” McMaster says that it was generally believed that the worst calumniators of the United States were subsidized by the British government, apparently in an effort to discourage emigration. He goes on:

The petty annoyances, the little inconveniences and unpleasant incidents met with in all journeys, were grossly exaggerated and cited as characteristic of daily life in the States. Men and women met with at the inns and taverns, in the stage-coaches and far-away country towns, were described not as so many types, but as the typical Americans. The abuse heaped on public men by partisan newspapers, the charges of corruption made by one faction against the other, the scandals of the day, were all cited as solemn truth.

Even the relatively mild and friendly Captain Hamilton condescended to such tactics. This is what he had to say of Thomas Jefferson:

The moral character of Jefferson was repulsive. Continually puling about liberty, equality, and the degrading curse of slavery, he brought his own children to the hammer, and made money of his debaucheries.29

Such violent assaults, in the long run, were bound to breed defiance, but while they were at their worst they produced a contrary effect. “The nervous interest of Americans in the impressions formed of them by visiting Europeans,” says Allan Nevins,30 “and their sensitiveness to British criticism in especial, were long regarded as constituting a salient national trait.” The native authors became extremely self-conscious and diffident, and the educated classes, in general, were daunted by the torrent of abuse: they could not help finding in it an occasional reasonableness, an accidental true hit. The result was uncertainty and skepticism in native criticism. “The first step of an American entering upon a literary career,” said Henry Cabot Lodge, writing of the first quarter of the century,31 “was to pretend to be an Englishman in order that he might win the approval, not of Englishmen, but of his own countrymen.” Cooper, in his first novel, “Precaution,” (1820) chose an English scene, imitated English models, and obviously hoped to placate the English critics thereby. Irving, too, in his earliest work, showed a considerable discretion, and his “Knickerbocker” was first published anonymously. But this puerile spirit did not last long. The English libels were altogether too vicious to be received lying down; their very fury demanded that they be met with a united and courageous front. Cooper, in his second novel, “The Spy” (1821), boldly chose an American setting and American characters, and though the influence of his wife, who came of a Loyalist family, caused him to avoid any direct attack upon the English, he attacked them indirectly, and with great effect, by opposing an immediate and honorable success to their derisions. “The Spy” ran through three editions in four months, and was followed by a long line of thoroughly American novels. In 1828 Cooper undertook a detailed reply to the more common English charges in “Notions of the Americans,” but he was still too cautious to sign his name to it: it appeared as “by a Travelling Bachelor.” By 1834, however, he was ready to apologize formally to his countrymen for his early truancy in “Precaution.” Irving, who was even more politic, and suffered moreover from Anglomania in a severe form, nevertheless edged himself gradually into the patriot band, and by 1828 he was brave enough to refuse the Quarterly’s offer of a hundred guineas for an article on the ground that it was “so persistently hostile to our country” that he could not “draw a pen in its service.”

The real counter-attack was carried on by lesser men — the elder Timothy Dwight, John Neal, Edward Everett, Charles Jared Ingersoll, J. K. Paulding, and Robert Walsh, Jr., among them. Neal went to England, became secretary to Jeremy Bentham, forced his way into the reviews, and so fought the English on their own ground. Walsh set up the American Review of History and Politics, the first American critical quarterly, in 1811, and eight years later published “An Appeal From the Judgments of Great Britain Respecting the United States of America.” Everett performed chiefly in the North American Review (founded in 1815), to which he contributed many articles and of which he was editor from 1820 to 1824. Wirt published his “Letters of a British Spy” in 1803, and Ingersoll followed with “Inchiquin the Jesuit’s Letters on American Literature and Politics” in 1811. In January, 1814 the Quarterly reviewed “Inchiquin” in a particularly violent manner, and a year later Dwight replied to the onslaught in “Remarks on the Review of Inchiquin’s Letters Published in the Quarterly Review, Addressed to the Right Honorable George Canning, Esq.” Dwight ascribed the Quarterly diatribe to Southey. He went on:

Both the travelers and the literary journalists of [England] have, for reasons which it would be idle to inquire after and useless to allege, thought it proper to caricature the Americans. Their pens have been dipped in gall; and their representations have been, almost merely, a mixture of malevolence and falsehood.

Dwight rehearsed some of the counts in the Quarterly’s indictment — that “the president of Yale College tells of a conflagrative brand,” that Jefferson used to belittle, that to guess was on the tongues of all Americans, and so on. “You charge us,” he said, “with making some words, and using others in a peculiar sense.… You accuse us of forming projects to get rid of the English language; ‘not,’ you say, ‘merely by barbarizing it, but by abolishing it altogether, and substituting a new language of our own.’ ” His reply was to list, on the authority of Pegge’s “Anecdotes of the English Language,” 105 vulgarisms common in London — for example, potecary for apothecary, chimly for chimney, saace for sauce, kiver for cover, nowheres for nowhere, scholard for scholar, and hisn for his — to accuse “members of Parliament” of using diddled and gullibility32 and to deride the English provincial dialects as “unintelligible gabble.”

But in this battle across the ocean it was Paulding who got in the most licks, and the heaviest ones. In all he wrote five books dealing with the subject. The first, “The Diverting History of John Bull and Brother Jonathan” (1812) was satirical in tone, and made a considerable popular success. Three years later he followed it with a more serious work, “The United States and England,” another reply to the Quarterly review of “Inchiquin.” The before-mentioned “Letters From the South” came out in 1817, and in 1822 Paulding resumed the attack with “A Sketch of Old England,” a sort of reductio ad absurdum of the current English books of American travels. He had never been to England, and the inference was that many of the English travelers had never been to America. Finally, in 1825, he resorted to broad burlesque in “John Bull in America, or The New Munchausen.”33 Now and then some friendly aid came from the camp of the enemy. Cairns shows that, while the Quarterly, the European Magazine and the Anti-Jacobin were “strongly anti-American” and “deliberately and dirtily bitter,” three or four of the lesser reviews displayed a fairer spirit, and even more or less American bias. After 1824, when the North American Review gave warning that if the campaign of abuse went on it would “turn into bitterness the last drops of good-will toward England that exist in the United States,” even Blackwood’s became somewhat conciliatory.

3. AMERICAN “BARBARISMS”

But this occasional tolerance for things American was never extended to the American language. Most of the English books of travel mentioned Americanisms only to revile them, and even when they were not reviled they were certainly not welcomed. The typical attitude was well set forth by Captain Hamilton in “Men and Manners in America,” already referred to as denying that the United States of 1833 had any libraries. “The amount of bad grammar in circulation,” he said, “is very great; that of barbarisms [i.e., Americanisms] enormous.” Worse, these “barbarisms” were not confined to the ignorant, but came almost as copiously from the lips of the learned.

I do not now speak of the operative class, whose massacre of their mother-tongue, however inhuman, could excite no astonishment; but I allude to the great body of lawyers and traders; the men who crowd the exchange and the hotels; who are to be heard speaking in the courts, and are selected by their fellow-citizens to fill high and responsible offices. Even by this educated and respectable class, the commonest words are often so transmogrified as to be placed beyond recognition of an Englishman.

Hamilton then went on to describe some of the prevalent “barbarisms”:

The word does is split into two syllables, and pronounced do-es. Where, for some incomprehensible reason, is converted into whare, there into thare; and I remember, on mentioning to an acquaintance that I had called on a gentleman of taste in the arts, he asked “whether he sheiv (showed) me his pictures.” Such words as oratory and dilatory are pronounced with the penult syllable long and accented: missionary becomes missionary, angel, ângel, dânger, danger, etc.

But this is not all. The Americans have chosen arbitrarily to change the meaning of certain old and established English words, for reasons they cannot explain, and which I doubt much whether any European philologist could understand. The word clever affords a case in point. It has here no connexion with talent, and simply means pleasant or amiable. Thus a good-natured blockhead in the American vernacular is a clever man, and having had this drilled into me, I foolishly imagined that all trouble with regard to this word, at least, was at an end. It was not long, however, before I heard of a gentleman having moved into a clever house, of another succeeding to a clever sum of money, of a third embarking in a clever ship, and making a clever voyage, with a clever cargo; and of the sense attached to the word in these various combinations, I could gain nothing like a satisfactory explanation.…

The privilege of barbarizing the King’s English is assumed by all ranks and conditions of men. Such words as slick, kedge and boss, it is true, are rarely used by the better orders; but they assume unlimited liberty in the use of expect, reckon, guess and calculate, and perpetrate other conversational anomalies with remorseless impunity.

This Briton, as usual, was as full of moral horror as of grammatical disgust, and put his denunciation upon the loftiest of grounds. He concluded:

I will not go on with this unpleasant subject, nor should I have alluded to it, but I feel it something of a duty to express the natural feeling of an Englishman at finding the language of Shakespeare and Milton thus gratuitously degraded. Unless the present progress of change be arrested by an increase of taste and judgment in the more educated classes, there can be no doubt that, in another century, the dialect of the Americans will become utterly unintelligible to an Englishman, and that the nation will be cut off from the advantages arising from their participation in British literature. If they contemplate such an event with complacency, let them go on and prosper; they have only to progress in their present course, and their grandchildren bid fair to speak a jargon as novel and peculiar as the most patriotic American linguist can desire.34

All the other English writers of travel books took the same line, and so did the stay-at-homes who hunted and abhorred Americanisms from afar. Mrs. Frances Trollope reported in her “Domestic Manners of the Americans” (1832) that during her whole stay in the Republic she had seldom “heard a sentence elegantly turned and correctly pronounced from the lips of an American”: there was “always something either in the expression or the accent” that jarred her feelings and shocked her taste. She concluded that “the want of refinement” was the great American curse. Captain Frederick Marry at, in “A Diary in America” (1839) observed that “it is remarkable how very debased the language has become in a short period in America,” and then proceeded to specifications — for example, the use of right away for immediately, of mean for ashamed, of clever in the senses which stumped Captain Hamilton, of bad as a deprecant of general utility, of admire for like, of how? instead of what? as an interrogative, of considerable as an adverb, and of such immoral verbs as to suspicion and to opinion. Marryat was here during Van Buren’s administration, when the riot of Americanisms was at its wildest, and he reported some really fantastic specimens. Once, he said, he heard “one of the first men in America” say, “Sir, if I had done so, I should not only have doubled and trebled, but I should have fourbled and fivebled my money.” Unfortunately, it is hard to believe that an American who was so plainly alive to the difference between shall and will, should and would, would have been unaware of quadrupled and quintupled. No doubt there was humor in the country, then as now, and visiting Englishmen were sometimes taken for rides.

Captain Basil Hall, who was here in 1827 and 1828, and published his “Travels in North America” in 1829, was so upset by some of the novelties he encountered that he went to see Noah Webster, then seventy years old, to remonstrate. Webster upset him still further by arguing stoutly that “his countrymen had not only a right to adopt new words, but were obliged to modify the language to suit the novelty of the circumstances, geographical and political, in which they were placed.” The lexicographer went on to observe judicially that “it is quite impossible to stop the progress of language — it is like the course of the Mississippi, the motion of which, at times, is scarcely perceptible; yet even then it possesses a momentum quite irresistible. Words and expressions will be forced into use, in spite of all the exertions of all the writers in the world.”

“But surely,” persisted Hall, “such innovations are to be deprecated?”

“I don’t know that,” replied Webster. “If a word becomes universally current in America, where English is spoken, why should it not take its station in the language?”

To this Hall made an honest British reply. “Because,” he said, “there are words enough already.”

Webster tried to mollify him by saying that “there were not fifty words in all which were used in America and not in England” — an underestimate of large proportions —, but Hall went away muttering.

Marryat, who toured the United States ten years after Hall, was chiefly impressed by the American verb to fix, which he described as “universal” and as meaning “to do anything.” It also got attention from other English travelers, including Godfrey Thomas Vigne, whose “Six Months in America” was printed in 1832, and Charles Dickens, who came in 1842. Vigne said that it had “perhaps as many significations as any word in the Chinese language,” and proceeded to list some of them — “to be done, made, mixed, mended, bespoken, hired, ordered, arranged, procured, finished, lent or given.” Dickens thus dealt with it in one of his letters home to his family:

I asked Mr. Q. on board a steamboat if breakfast be nearly ready, and he tells me yes, he should think so, for when he was last below the steward was fixing the tables — in other words, laying the cloth. When we have been writing and I beg him … to collect our papers, he answers that he’ll fix ’em presently. So when a man’s dressing he’s fixing himself, and when you put yourself under a doctor he fixes you in no time. T’other night, before we came on board here, when I had ordered a bottle of mulled claret, and waited some time for it, it was put on the table with an apology from the landlord (a lieutenant-colonel) that he fear’d it wasn’t properly fixed. And here, on Saturday morning, a Western man, handing his potatoes to Mr. Q. at breakfast, inquired if he wouldn’t take some of “these fixings” with his meat.35

In another letter, written on an Ohio river steamboat on April 15, 1842, Dickens reported that “out of Boston and New York” a nasal drawl was universal, that the prevailing grammar was “more than doubtful,” that the “oddest vulgarisms” were “received idioms,” and that “all the women who have been bred in slave States speak more or less like Negroes.” His observations on American speech habits in his “American Notes” (1842) were so derisory that they drew the following from Emerson:

No such conversations ever occur in this country in real life, as he relates. He has picked up and noted with eagerness each odd local phrase that he met with, and when he had a story to relate, has joined them together, so that the result is the broadest caricature.36

Almost every English traveler of the years between the War of 1812 and the Civil War was puzzled by the strange signs on American shops. Hall couldn’t make out the meaning of Leather and Finding Store, though he found Flour and Feed Store and Clothing Store self-explanatory, albeit unfamiliar. Hamilton, who followed in 1833, failed to gather “the precise import” of Dry-Goods Store, and was baffled and somewhat shocked by Coffin Warehouse (it would now be Casketeria!) and Hollow Ware, Spiders, and Fire-Dogs. But all this was relatively mild stuff, and after 1850 the chief licks at the American dialect were delivered, not by English travelers, most of whom had begun by then to find it more amusing than indecent, but by English pedants who did not stir from their cloisters. The climax came in 1863, when the Very Rev. Henry Alford, D.D. dean of Canterbury, printed his “Plea for the Queen’s English.”37 He said:

Look at the process of deterioration which our Queen’s English has undergone at the hands of the Americans. Look at those phrases which so amuse us in their speech and books; at their reckless exaggeration and contempt for congruity; and then compare the character and history of the nation — its blunted sense of moral obligation and duty to man; its open disregard of conventional right when aggrandisement is to be obtained; and I may now say, its reckless and fruitless maintenance of the most cruel and unprincipled war in the history of the world.

It will be noted that Alford here abandoned one of the chief counts in Sydney Smith’s famous indictment, and substituted its exact opposite. Smith had denounced slavery, whereas Alford, by a tremendous feat of moral virtuosity, was now denouncing the war to put it down! But Samuel Taylor Coleridge had done almost as well in 1822. The usual English accusation at that time, as we have seen, was that the Americans had abandoned English altogether and set up a barbarous jargon in its place. Coleridge, speaking to his friend Thomas Allsop, took the directly contrary tack. “An American,” he said, “by his boasting of the superiority of the Americans generally, but especially in their language, once provoked me to tell him that ‘on that head the least said the better, as the Americans presented the extraordinary anomaly of a people without a language. [Allsop’s italics] That they had mistaken the English language for baggage (which is called plunder in America), and had stolen it.’ ” And then the inevitable moral reflection: “Speaking of America, it is believed a fact verified beyond doubt that some years ago it was impossible to obtain a copy of the Newgate Calendar, as they had all been bought up by the Americans, whether to suppress the blazon of their forefathers, or to assist in their genealogical researches, I could never learn satisfactorily.”38

4: THE ENGLISH ATTITUDE TODAY

Smith, Alford and Coleridge have plenty of heirs and assigns in the England of today. There is in the United States, as everyone knows, a formidable sect of Anglomaniacs, and its influence is often felt, not only in what passes here for society, but also in the domains of politics, finance, pedagogy and journalism, but the corresponding sect of British Americophils is small and feeble, though it shows a few respectable names. It is seldom that anything specifically American is praised in the English press, save, of course, some new manifestation of American Anglomania. The realm of Uncle Shylock remains, at bottom, the “brigand confederation” of the Foreign Quarterly, and on occasion it becomes again the “loathsome creature,… maimed and lame, full of sores and ulcers,” of Dickens. In the field of language an Americanism is generally regarded as obnoxious ipso facto, and when a new one of any pungency begins to force its way into English usage the guardians of the national linguistic chastity belabor it with great vehemence, and predict calamitous consequences if it is not put down. If, despite these alarms, it makes progress, they often switch to the doctrine that it is really old English, and search the Oxford Dictionary for examples of its use in Chaucer’s time, or even in the Venerable Bede’s;39 but while it is coming in they give it no quarter. Here the unparalleled English talent for discovering moral obliquity comes into play, and what begins as an uproar over a word sometimes ends as a holy war to keep the knavish Yankee from undermining and ruining the English Kultur and overthrowing the British Empire. The crusade has abundant humors. Not infrequently a phrase denounced as an abominable Americanism really originated in the London music-halls, and is unknown in the United States. And almost as often the denunciation of it is sprinkled with genuine Americanisms, unconsciously picked up.

The English seldom differentiate between American slang and Americanisms of legitimate origin and in respectable use: both belong to what they often call the American slanguage.40 It is most unusual for an American book to be reviewed in England without some reference to its strange and (so one gathers) generally unpleasant diction. The Literary Supplement of the London Times is especially alert in this matter. It discovers Americanisms in the writings of even the most decorous American authors, and when none can be found it notes the fact, half in patronizing approbation and half in incredulous surprise. Of the 240 lines it gave to the first two volumes of the Dictionary of American Biography, 31 were devoted to animadversions upon the language of the learned authors.41 The Manchester Guardian and the weeklies of opinion follow dutifully. The Guardian, in a review of Dr. Harry Emerson Fosdick’s “As I See Religion,” began by praising his “telling speech,” but ended by deploring sadly his use of the “full-blooded Americanisms which sometimes make even those who do not for a moment question America’s right and power to contribute to the speech which we use in common wince as they read.”42 One learns from J. L. Hammond that the late C. P. Scott, for long the editor of the Guardian, had a keen nose for Americanisms, and was very alert to keep them out of his paper. Says Hammond:

He would go bustling into a room, waving a cutting or a proof, in which was an obscure phrase, a preciosity, or an Americanism. “What does he mean by this? He talks about a final showdown? An Americanism, I suppose. What does it mean? Generally known? I don’t know it. Taken from cards? I never heard of it.”43

This war upon Americanisms is in progress all the time, but it naturally has its pitched battles and its rest-periods between. For months there may be relative quiet on the linguistic Western front, and then some alarmed picket fires a gun and there is what the German war communiqués used to call a sharpening of activity. As a general thing the English content themselves with artillery practise from their own lines, but now and then one of them boldly invades the enemy’s country. This happened, for example, in 1908, when Charles Whibley contributed an extremely acidulous article on “The American Language” to the Bookman (New York) for January. “To the English traveler in America,” he said, “the language which he hears spoken about him is at once a puzzle and a surprise. It is his own, yet not his own. It seems to him a caricature of English, a phantom speech, ghostly yet familiar, such as he might hear in a land of dreams.” Mr. Whibley objected violently to many characteristic American terms, among them, to locate, to operate, to antagonize, transportation, commutation and proposition. “These words,” he said, “if words they may be called, are hideous to the eye, offensive to the ear, meaningless to the brain.” The onslaught provoked even so mild a man as Dr. Henry W. Boynton to action, and in the Bookman for March of the same year he published a spirited rejoinder. “It offends them [the English],” he said, “that we are not thoroughly ashamed of ourselves for not being like them.” Mr. Whibley’s article was reprinted with this counterblast, so that readers of the magazine might judge the issues fairly. The controversy quickly got into the newspapers, and was carried on for months, with American patriots on one side and Englishmen and Anglomaniacs on the other.

I myself once helped to loose such an uproar, though quite unintentionally. Happening to be in London in the Winter of 1929–30, I was asked by Mr. Ralph D. Blumenfeld, the American-born editor of the Daily Express, to do an article for his paper on the progress of Americanisms in England since my last visit in 1922. In that article I ventured to say:

The Englishman, whether he knows it or not, is talking and writing more and more American. He becomes so accustomed to it that he grows unconscious of it. Things that would have set his teeth on edge ten years ago, or even five years ago, are now integral parts of his daily speech.… In a few years it will probably be impossible for an Englishman to speak, or even to write, without using Americanisms, whether consciously or unconsciously. The influence of 125,000,000 people, practically all headed in one direction, is simply too great to be resisted by any minority, however resolute.

The question whether or not this was sound will be examined in Chapters VI and XII. For the present it is sufficient to note that my article was violently arraigned by various volunteer correspondents of the Express and by contributors to many other journals. One weekly opened its protest with “That silly little fellow, H. L. Mencken, is at it again” and headed it “The American Moron,” and in various other quarters I was accused of a sinister conspiracy against the mother-tongue, probably political or commercial in origin, or maybe both. At this time the American talkie was making its first appearance in England, and so there was extraordinary interest in the subject, for it was obvious that the talkie would bring in far more Americanisms than the silent movie; moreover, it would also introduce the hated American accent. On February 4, 1930 Sir Alfred Knox, a Conservative M.P., demanded in the House of Commons that the Right Hon. William Graham, P.C., then president of the Board of Trade, take steps to “protect the English language by limiting the import of American talkie films.” In a press interview he said:

I don’t go to the cinema often, but I had to be present at one a few days ago, when an American talkie film was shown. The words and accent were perfectly disgusting, and there can be no doubt that such films are an evil influence on our language. It is said that 30,000,000 [British] people visit the cinemas every week. What is the use of spending millions on education if our young people listen to falsified English spoken every night?44

There had been another such uproar in 1927, when an International Conference on English was held in London, under the presidency of the Earl of Balfour. This conference hardly got beyond polite futilities, but the fact that the call for it came from the American side45 made it suspect from the start, and its deliberations met with unconcealed hostility. On June 25, 1927, the New Statesman let go with a heavy blast, rehearsing all the familiar English objections to Americanisms. It said:

It is extremely desirable, to say the least, that every necessary effort should be made to preserve some standard of pure idiomatic English. But from what quarter is the preservation of such a standard in any way threatened? The answer is “Solely from America.” Yet we are asked to collaborate with the Americans on the problem; we are to make bargains about our own tongue; there is to be a system of give and take.… Why should we offer to discuss the subject at all with America? We do not want to interfere with their language; why should they seek to interfere with ours? That their huge hybrid population of which only a small minority are even racially Anglo-Saxons should use English as their chief medium of intercommunication is our misfortune, not our fault. They certainly threaten our language, but the only way in which we can effectively meet that threat is by assuming — in the words of the authors of “The King’s English”46 that “Americanisms are foreign words and should be so treated.”