A Malazan Book of the Fallen Collection 2 – Read Now and Download Mobi

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 9781409092421

Version 1.0

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Steven Erikson is an archaeologist and anthropologist and a graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop. The first six novels in his Malazan Book of the Fallen sequence – Gardens of the Moon, Deadhouse Gates, Memories of Ice, House of Chains, Midnight Tides and The Bonehunters – have met with widespread international acclaim and established him as a major voice in the world of fantasy fiction. The thrilling seventh instalment in this remarkable story, Reaper's Gale, is now available from Bantam Press. Steven Erikson lives in Canada.

www.rbooks.co.uk/stevenerikson

Acclaim for Steven Erikson's

The Malazan Book of the Fallen:

'Steven Erikson is an extraordinary writer . . . My advice to anyone who might listen to me is: treat yourself'

Stephen R. Donaldson

'Give me the evocation of a rich, complex and yet ultimately unknowable other world, with a compelling suggestion of intricate history and mythology and lore. Give me mystery amid the grand narrative ... Give me the world in which every sea hides a crumbled Atlantis, every ruin has a tale to tell, every broken blade is a silent legacy of struggles unknown. Give me in other words, the fantasy work of Steven Erikson ... a master of lost and forgotten epochs, a weaver of ancient epics' Salon.com

'I stand slack-jawed in awe of The Malayan Book of the Fallen. This masterwork of the imagination may be the high watermark of epic fantasy' Glen Cook

'Truly epic in scope, Erikson has no peer when it comes to action and imagination, and joins the ranks of Tolkien and Donaldson in his mythic vision and perhaps then goes one better' SF Site

'Rare is the writer who so fluidly combines a sense of mythic power and depth of world with fully realized characters and thrilling action, but Steven Erikson manages it spectacularly' Michael A. Stackpole

'Like the archaeologist that he is, Erikson continues to delve into the history and ruins of the Malazan Empire, in the process revealing unforeseen riches and annals that defy expectation ... this is true myth in the making, a drawing upon fantasy to recreate histories and legends as rich as any found within our culture' Interzone

'Gripping, fast-moving, delightfully dark . . . Erikson brings a punchy, mesmerizing writing style into the genre of epic fantasy, making an indelible impression. Utterly engrossing' Elizabeth Hayden

'Everything we have come to expect from this most excellent of fantasy writers; huge in scope, vast in implication and immensely, utterly entertaining'

alienonline

'One of the most promising new writers of the past few years, he has more than proved his right to A-list status'

Bookseller

'Erikson's strengths are his grown-up characters and his ability to create a world every bit as intricate and messy as our own' J. V. Jones

'An author who never disappoints on delivering stunning and hard-edged fantasy is Steven Erikson ... a master of modern fantasy' WBQ magazine

'Wondrous voyages, demons and gods abound ... dense and complex ... ultimately rewarding' Locus

'Erikson ... is able to create a world that is both absorbing on a human level and full of magical sublimity ... A wonderfully grand conception ... splendidly written ... fiendishly readable' Adam Roberts

'A multi-layered tale of magic and war, loyalty and betrayal. Complexly drawn characters occupy a richly detailed world in this panoramic saga' Library Journal

'Epic in every sense of the word ... Erikson shows a masterful control of an immense plot ... the worlds of mortals and gods meet in what is a truly awe-inspiring clash' Enigma

By Steven Erikson

GARDENS OF THE MOON

DEADHOUSE GATES

MEMORIES OF ICE

HOUSE OF CHAINS

MIDNIGHT TIDES

THE BONEHUNTERS

REAPER'S GALE

Table of Contents

- Copyright Page

- About the Author

- Acclaim for Steven Erikson's The Malazan Book of the Fallen

- By the Same Author

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

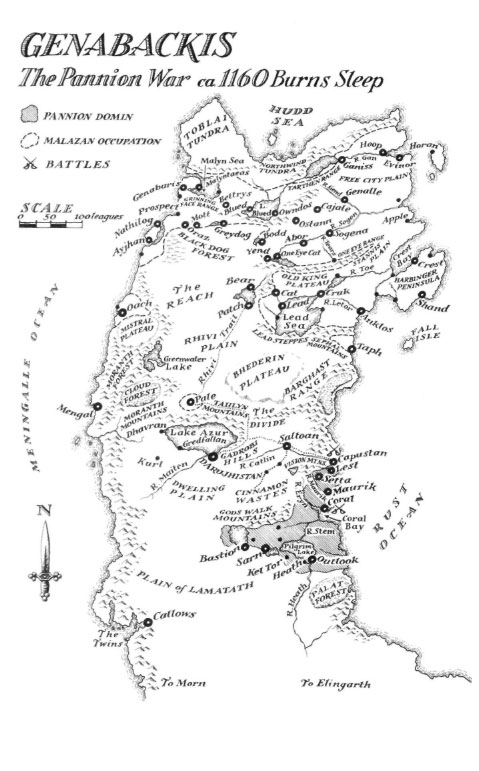

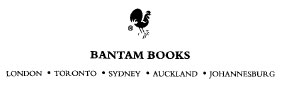

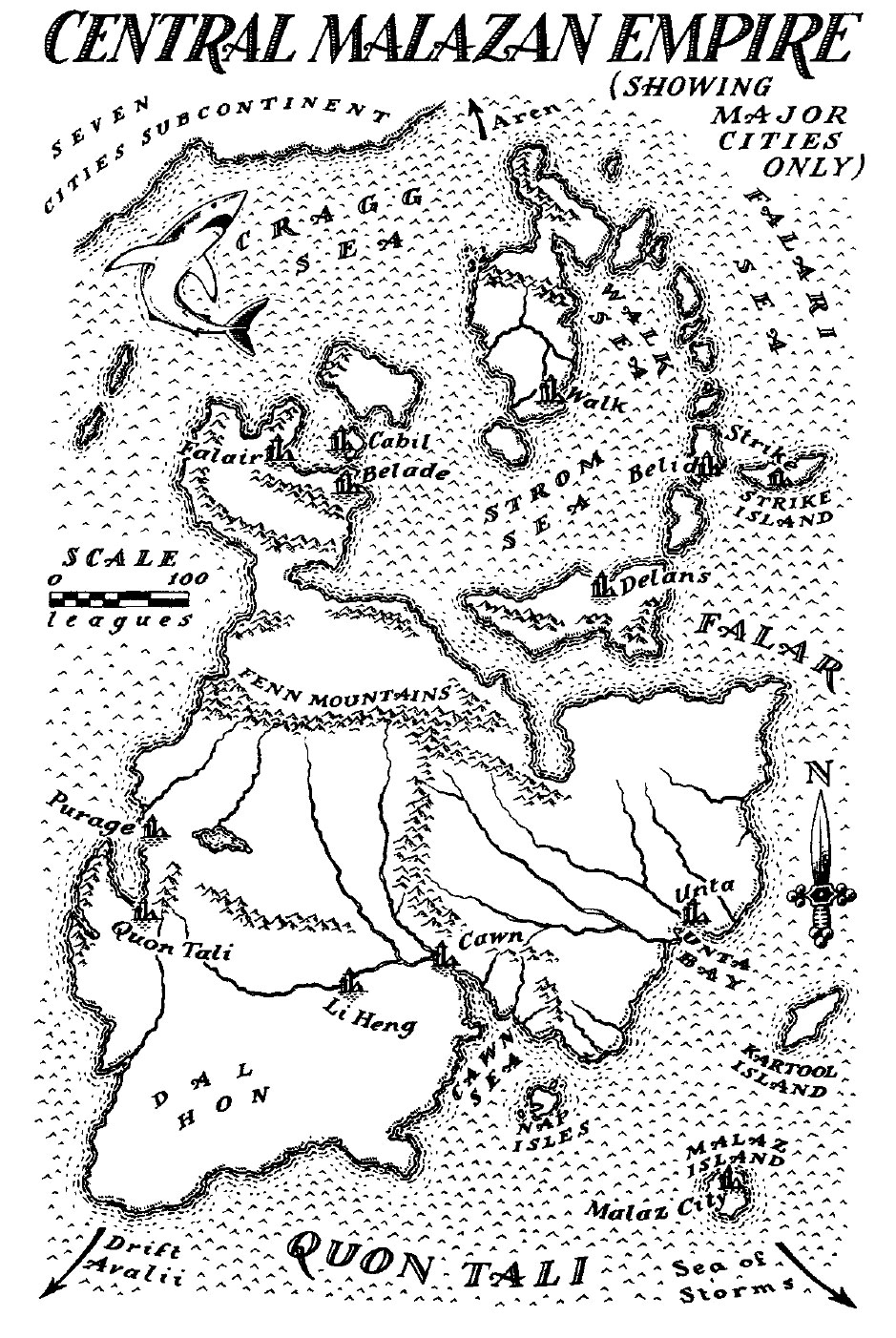

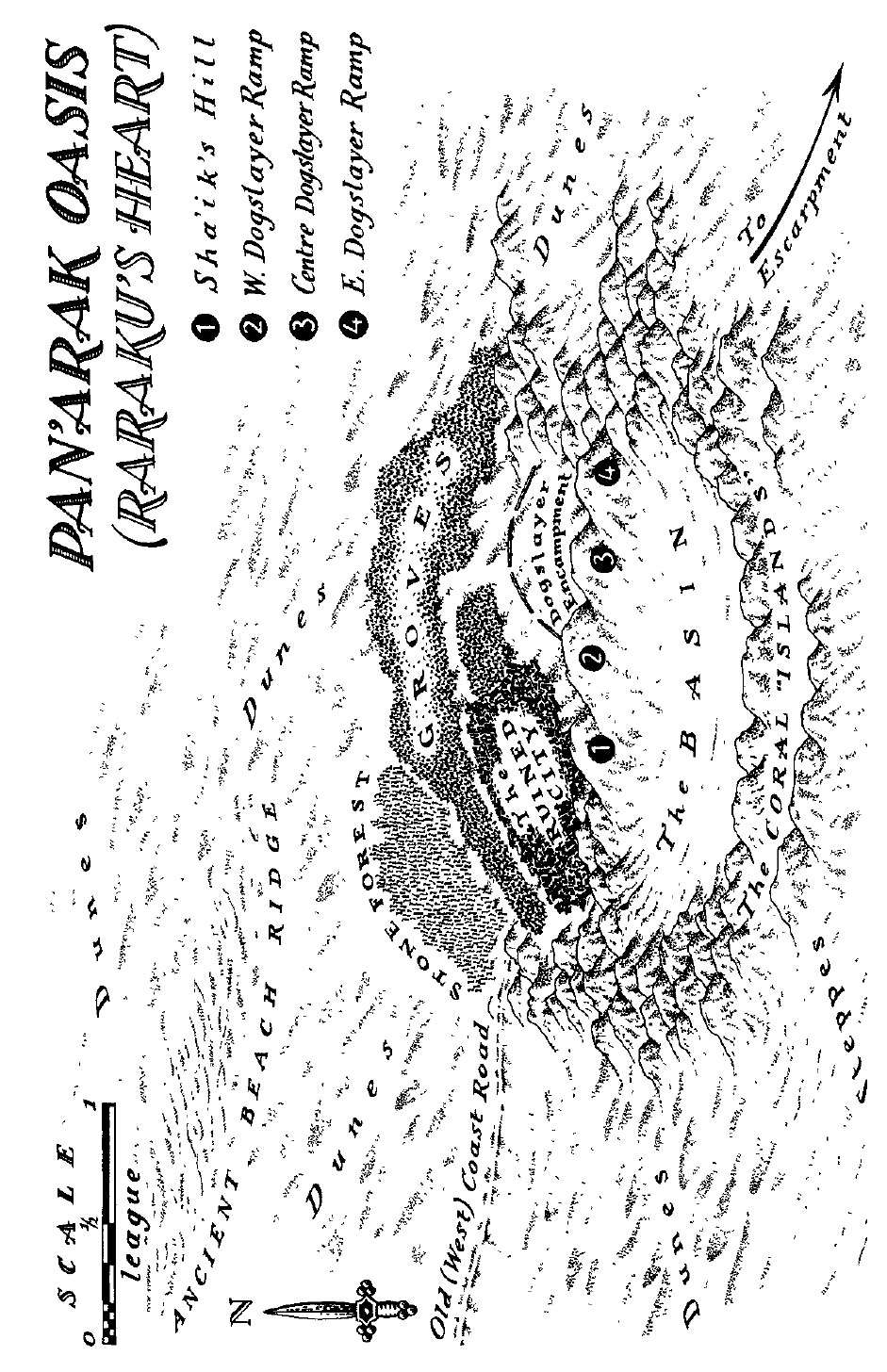

- GENABACKIS

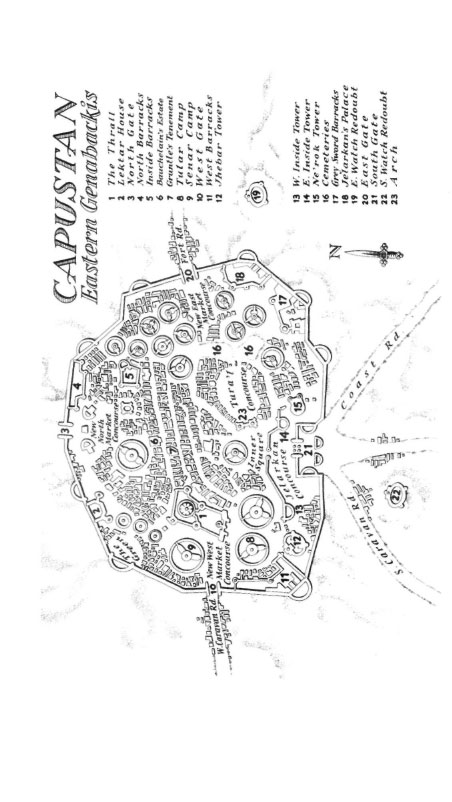

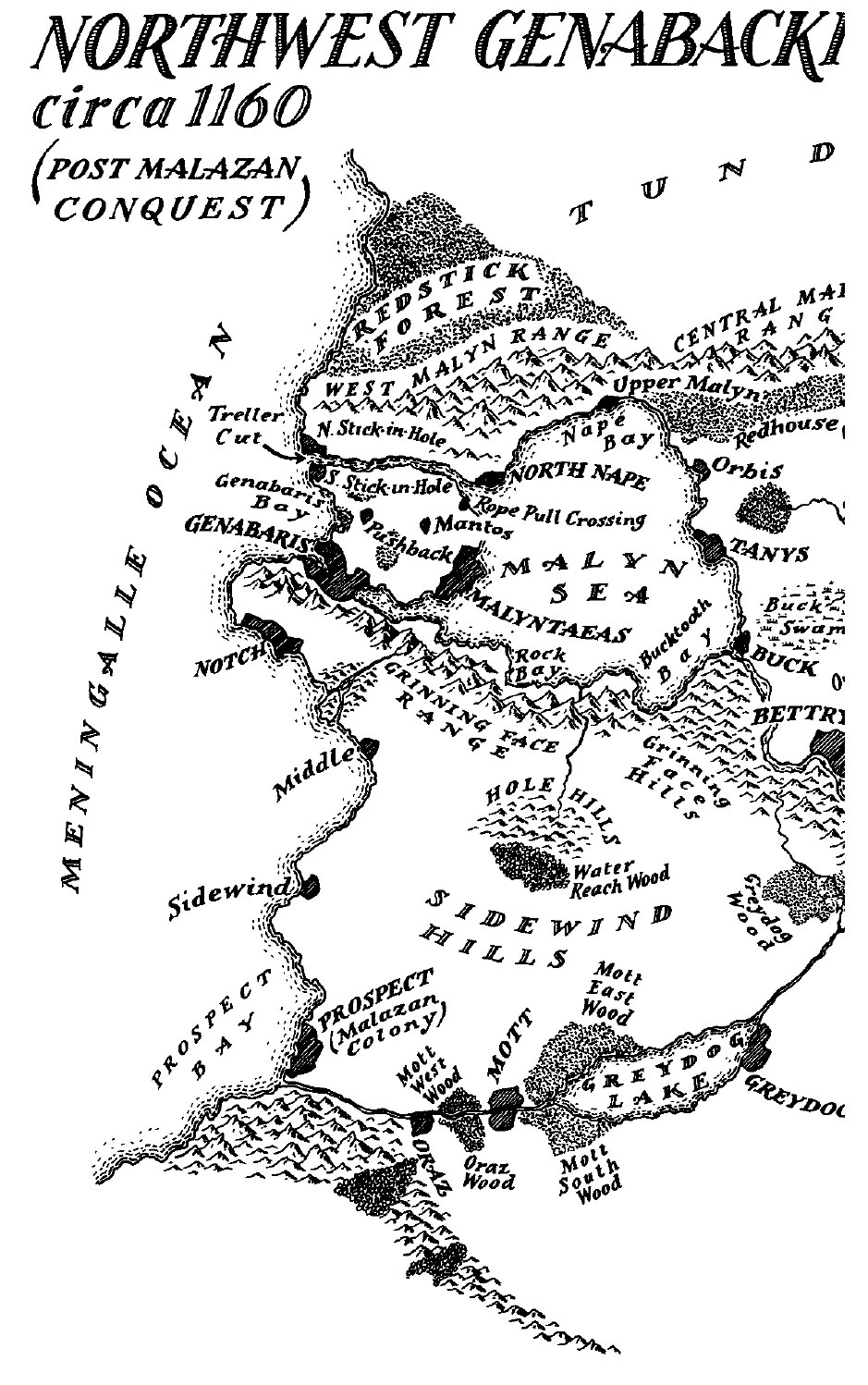

- CAPUSTAN

- DRAMATIS PERSONAE

- Prologue

- BOOK ONE: THE SPARK AND THE ASHES

- BOOK TWO: HEARTHSTONE

- BOOK THREE: CAPUSTAN

- BOOK FOUR: MEMORIES OF ICE

- Epilogue

- Glossary

- Extract: House of Chains

- HOUSE OF CHAINS

- GARDENS OF THE MOON

- DEADHOUSE GATES

- MIDNIGHT TIDES

- THE BONEHUNTERS

- NIGHT OF KNIVES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I extend my gratitude to the following for their support and friendship: Clare, Bowen, Mark, David, Chris, Rick, Cam, Courtney; Susan and Peter, David Thomas Sr and Jr, Harriet and Chris and Lily and Mina and Smudge; Patrick Walsh and Simon and Jane. Thanks also to Dave Holden and his friendly staff (Tricia, Cindy, Liz, Tanis, Barbara, Joan, Nadia, Amanda, Tony, Andi and Jody) of the Pizza Place, for the table and the refills. And thanks to John Meaney for the disgusting details on dead seeds.

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

THE CARAVANSERAI

Gruntle, a caravan guard

Stonny Menackis, a caravan guard

Harllo, a caravan guard

Buke, a caravan guard

Bauchelain, an explorer

Korbal Broach, his silent partner

Emancipor Reese, a manservant

Keruli, a trader

Marble, a sorcerer

IN CAPUSTAN

Brukhalian, Mortal Sword of Fener's Reve (the Grey Swords)

Itkovian, Shield Anvil of Fener's Reve (the Grey Swords)

Karnadas, Destriant of Fener's Reve (the Grey Swords)

Recruit Velbara (the Grey Swords)

Master Sergeant Norul (the Grey Swords)

Farakalian (the Grey Swords)

Nakalian (the Grey Swords)

Torun (the Grey Swords)

Sidlis (the Grey Swords)

Nilbanas (the Grey Swords)

Jelarkan, prince and ruler of Capustan

Arard, prince and ruler in absentia of Coral

Rath'Fener (Priest of the Mask Council)

Rath'Shadowthrone (Priest of the Mask Council)

Rath'Queen of Dreams (Priestess of the Mask Council)

Rath'Hood (Priest of the Mask Council)

Rath'D'rek (Priest of the Mask Council)

Rath'Trake (Priest of the Mask Council)

Rath'Burn (Priestess of the Mask Council)

Rath'Togg (Priest of the Mask Council)

Rath'Fanderay (Priestess of the Mask Council)

Rath'Dessembrae (Priestess of the Mask Council)

Rath'Oponn (Priest of the Mask Council)

Rath'Beru (Priest of the Mask Council)

ONEARM'S HOST

Dujek Onearm, commander of renegade Malazan army

Whiskeyjack, second-in-command of renegade Malazan army

Twist, commander of the Black Moranth

Artanthos, standard-bearer of renegade Malazan army

Barack, a liaison officer

Hareb, a noble-born captain

Ganoes Paran, Captain, Bridgeburners

Antsy, sergeant, 7th Squad, Bridgeburners

Picker, corporal, 7th Squad, Bridgeburners

Detoran, soldier, 7th Squad

Spindle, mage and sapper, 7th Squad

Blend, soldier, 7th Squad

Mallet, healer, 9th Squad

Hedge, sapper, 9th Squad

Trotts, soldier, 9th Squad

Quick Ben, mage, 9th Squad

Aimless (Bridgeburner corporal)

Bucklund (Bridgeburner sergeant)

Runter (Bridgeburner sapper)

Mulch (Bridgeburner healer)

Bluepearl (Bridgeburner mage)

Shank (Bridgeburner mage)

Toes (Bridgeburner mage)

BROOO'S HOST

Caladan Brood, warlord of liberation army on Genabackis

Anomander Rake, Lord of Moon's Spawn

Kallor, the High King, Brood's second-in-command

The Mhybe, matron of the Rhivi Tribes

Silverfox, the Rhivi Reborn

Korlat, a Tiste Andii Soletaken

Orfantal, Korlat's brother

Hurlochel, an outrider in the liberation army

Crone, a Great Raven and companion to Anomander Rake

THE BARCHAST

Humbrall Taur, warchief of the White Face Clan

Hetan, his daughter

Cafal, his first son

Netok, his second son

DARUJISTAN ENVOYS

Coll, an ambassador

Estraysian D'Arle, a councilman

Barak, an alchemist

Kruppe, a citizen

Murillio, a citizen

THE C'LAN IMASS

Kron, ruler of the Kron T'lan Imass

Cannig Tol, clan chief

Bek Okhan, a Bonecaster

Pran Chole, a Bonecaster

Okral Lom, a Bonecaster

Bendal Home, a Bonecaster

Ay Estos, a Bonecaster

Olar Ethil, the First Bonecaster and First Soletaken

Tool, the Shorn, once First Sword

Kilava, a renegade Bonecaster

Lanas Tog, of Kerluhm T'lan Imass

THE PANNION DOMIN

The Seer, priest-king of the Domin

Ultentha, Septarch of Coral

Kulpath, Septarch of the besieging army

Inal, Septarch of Lest

Anaster, a Tenescowri Child of the Dead Seed

Seerdomin Kahlt

OTHERS

K'rul, an Elder God

Draconus, an Elder God

Sister of Cold Nights, an Elder Goddess

Lady Envy, a resident of Morn

Gethol, a Herald

Treach, a First Hero (the Tiger of Summer)

Toc the Younger, Aral Fayle, a Malazan scout

Garath, a large dog

Baaljagg, a larger wolf

Mok, a Seguleh

Thurule, a Seguleh

Senu, a Seguleh

The Chained One, an unknown ascendant (also known as the Crippled God)

The Witch of Tennes

Munug, a Daru artisan

Talamandas, a Barghast sticksnare

Ormulogun, artist in Onearm's Host

Gumble, his critic

Haradas, a Trygalle Trade Guild caravan master

Azra Jael, a marine in Onearm's Host

Straw, a Mott Irregular

Sty, a Mott Irregular

Stump, a Mott Irregular

Job Bole, a Mott Irregular

Prologue

The ancient wars of the T'lan Imass and the Jaghut saw the world torn asunder. Vast armies contended on the ravaged lands, the dead piled high, their bone the bones of hills, their spilled blood the blood of seas. Sorceries raged until the sky itself was fire ...

Ancient Histories, Vol. I

Kinicik Karbar'n

I

Maeth'ki Im (Pogrom of the Rotted Flower), the 33rd Jaghut War

298,665 years before Burn's Sleep.

Swallows darted through the clouds of midges dancing over the mudflats. The sky above the marsh remained grey, but it had lost its mercurial wintry gleam, and the warm wind sighing through the air above the ravaged land held the scent of healing.

What had once been the inland freshwater sea the Imass called Jaghra Til – born from the shattering of the Jaghut ice-fields – was now in its own death-throes. The pallid overcast was reflected in dwindling pools and stretches of knee-deep water for as far south as the eye could scan, but none the less, newly birthed land dominated the vista.

The breaking of the sorcery that had raised the glacial age returned to the region the old, natural seasons, but the memories of mountain-high ice lingered. The exposed bedrock to the north was gouged and scraped, its basins filled with boulders. The heavy silts that had been the floor of the inland sea still bubbled with escaping gases, as the land, freed of the enormous weight with the glaciers' passing eight years past, continued its slow ascent.

Jaghra Til's life had been short, yet the silts that had settled on its bottom were thick. And treacherous.

Pran Chole, Bonecaster of Cannig Tol's clan among the Kron Imass, sat motionless atop a mostly buried boulder along an ancient beach ridge. The descent before him was snarled in low, wiry grasses and withered driftwood. Twelve paces beyond, the land dropped slightly, then stretched out into a broad basin of mud.

Three ranag had become trapped in a boggy sinkhole twenty paces into the basin. A bull male, his mate and their calf, ranged in a pathetic defensive circle. Mired and vulnerable, they must have seemed easy kills for the pack of ay that found them.

But the land was treacherous indeed. The large tundra wolves had succumbed to the same fate as the ranag. Pran Chole counted six ay, including a yearling. Tracks indicated that another yearling had circled the sinkhole dozens of times before wandering westward, doomed no doubt to die in solitude.

How long ago had this drama occurred? There was no way to tell. The mud had hardened on ranag and ay alike, forming cloaks of clay latticed with cracks. Spots of bright green showed where windborn seeds had germinated, and the Bonecaster was reminded of his visions when spirit-walking – a host of mundane details twisted into something unreal. For the beasts, the struggle had become eternal, hunter and hunted locked together for all time.

Someone padded to his side, crouched down beside him.

Pran Chole's tawny eyes remained fixed on the frozen tableau. The rhythm of footsteps told the Bonecaster the identity of his companion, and now came the warm-blooded smells that were as much a signature as resting eyes upon the man's face.

Cannig Tol spoke. 'What lies beneath the clay, Bonecaster?'

'Only that which has shaped the clay itself, Clan Leader.'

'You see no omen in these beasts?'

Pran Chole smiled. 'Do you?'

Cannig Tol considered for a time, then said, 'Ranag are gone from these lands. So too the ay. We see before us an ancient battle. These statements have depth, for they stir my soul.'

'Mine as well,' the Bonecaster conceded.

'We hunted the ranag until they were no more, and this brought starvation to the ay, for we had also hunted the tenag until they were no more as well. The agkor who walk with the bhederin would not share with the ay, and now the tundra is empty. From this, I conclude that we were wasteful and thoughtless in our hunting.'

'Yet the need to feed our own young...'

'The need for more young was great.'

'It remains so, Clan Leader.'

Cannig Tol grunted. 'The Jaghut were powerful in these lands, Bonecaster. They did not flee – not at first. You know the cost in Imass blood.'

'And the land yields its bounty to answer that cost.'

'To serve our war.'

'Thus, the depths are stirred.'

The Clan Leader nodded and was silent.

Pran Chole waited. In their shared words they still tracked the skin of things. Revelation of the muscle and bone was yet to come. But Cannig Tol was no fool, and the wait was not long.

'We are as those beasts.'

The Bonecaster's eyes shifted to the south horizon, tightened.

Cannig Tol continued, 'We are the clay, and our endless war against the Jaghut is the struggling beast beneath. The surface is shaped by what lies beneath.' He gestured with one hand. 'And before us now, in these creatures slowly turning to stone, is the curse of eternity.'

There was still more. Pran Chole said nothing.

'Ranag and ay,' Cannig Tol resumed. 'Almost gone from the mortal realm. Hunter and hunted both.'

'To the very bones,' the Bonecaster whispered.

'Would that you had seen an omen,' the Clan Leader muttered, rising.

Pran Chole also straightened. 'Would that I had,' he agreed in a tone that only faintly echoed Cannig Tol's wry, sardonic utterance.

'Are we close, Bonecaster?'

Pran Chole glanced down at his shadow, studied the antlered silhouette, the figure hinted within furred cape, ragged hides and headdress. The sun's angle made him seem tall – almost as tall as a Jaghut. 'Tomorrow,' he said. 'They are weakening. A night of travel will weaken them yet more.'

'Good. Then the clan shall camp here tonight.'

The Bonecaster listened as Cannig Tol made his way back down to where the others waited. With darkness, Pran Chole would spiritwalk. Into the whispering earth, seeking those of his own kind. While their quarry was weakening, Cannig Tol's clan was yet weaker. Less than a dozen adults remained. When pursuing Jaghut, the distinction of hunter and hunted had little meaning.

He lifted his head and sniffed the crepuscular air. Another Bonecaster wandered this land. The taint was unmistakable. He wondered who it was, wondered why it travelled alone, bereft of clan and kin. And, knowing that even as he had sensed its presence so it in turn had sensed his, he wondered why it had not yet sought them out.

She pulled herself clear of the mud and dropped down onto the sandy bank, her breath coming in harsh, laboured gasps. Her son and daughter squirmed free of her leaden arms, crawled further onto the island's modest hump.

The Jaghut mother lowered her head until her brow rested against the cool, damp sand. Grit pressed into the skin of her forehead with raw insistence. The burns there were too recent to have healed, nor were they likely to – she was defeated, and death had only to await the arrival of her hunters.

They were mercifully competent, at least. These Imass cared nothing for torture. A swift killing blow. For her, then for her children. And with them – with this meagre, tattered family – the last of the Jaghut would vanish from this continent. Mercy arrived in many guises. Had they not joined in chaining Raest, they would all – Imass and Jaghut both – have found themselves kneeling before that Tyrant. A temporary truce of expedience. She'd known enough to flee once the chaining was done; she'd known, even then, that the Imass clan would resume the pursuit.

The mother felt no bitterness, but that made her no less desperate.

Sensing a new presence on the small island, her head snapped up. Her children had frozen in place, staring up in terror at the Imass woman who now stood before them. The mother's grey eyes narrowed. 'Clever, Bonecaster. My senses were tuned only to those behind us. Very well, be done with it.'

The young, black-haired woman smiled. 'No bargains, Jaghut? You always seek bargains to spare the lives of your children. Have you broken the kin-threads with these two, then? They seem young for that.'

'Bargains are pointless. Your kind never agree to them.'

'No, yet still your kind try.'

'I shall not. Kill us, then. Swiftly.'

The Imass was wearing the skin of a panther. Her eyes were as black and seemed to match its shimmer in the dying light. She looked well fed, her large, swollen breasts indicating she had recently birthed.

The Jaghut mother could not read the woman's expression, only that it lacked the typical grim certainty she usually associated with the strange, rounded faces of the Imass.

The Bonecaster spoke. 'I have enough Jaghut blood on my hands. I leave you to the Kron clan that will find you tomorrow.'

'To me,' the mother growled, 'it matters naught which of you kills us, only that you kill us.'

The woman's broad mouth quirked. 'I can see your point.'

Weariness threatened to overwhelm the Jaghut mother, but she managed to pull herself into a sitting position. 'What,' she asked between gasps, 'do you want?'

'To offer you a bargain.'

Breath catching, the Jaghut mother stared into the Bonecaster's dark eyes, and saw nothing of mockery. Her gaze then dropped, for the briefest of moments, on her son and daughter, then back up to hold steady on the woman's own.

The Imass slowly nodded.

The earth had cracked some time in the past, a wound of such depth as to birth a molten river wide enough to stretch from horizon to horizon. Vast and black, the river of stone and ash reached southwestward, down to the distant sea. Only the smallest of plants had managed to find purchase, and the Bonecaster's passage – a Jaghut child in the crook of each arm – raised sultry clouds of dust that hung motionless in her wake.

She judged the boy at perhaps five years of age; his sister perhaps four. Neither seemed entirely aware, and clearly neither had understood their mother when she'd hugged them goodbye. The long flight down the L'amath and across the Jagra Til had driven them both into shock. No doubt witnessing the ghastly death of their father had not helped matters.

They clung to her with their small, grubby hands, grim reminders of the child she had but recently lost. Before long, both began suckling at her breasts, evincing desperate hunger. Some time later, the children slept.

The lava flow thinned as she approached the coast. A range of hills rose into distant mountains on her right. A level plain stretched directly before her, ending at a ridge half a league distant. Though she could not see it, she knew that just the other side of the ridge, the land slumped down to the sea. The plain itself was marked by regular humps, and the Bonecaster paused to study them. The mounds were arrayed in concentric circles, and at the centre was a larger dome – all covered in a mantle of lava and ash. The rotted tooth of a ruined tower rose from the plain's edge, at the base of the first line of hills. Those hills, as she had noted the first time she had visited this place, were themselves far too evenly spaced to be natural.

The Bonecaster lifted her head. The mingled scents were unmistakable, one ancient and dead, the other ... less so. The boy stirred in her clasp, but remained asleep.

'Ah,' she murmured, 'you sense it as well.'

Skirting the plain, she walked towards the blackened tower.

The warren's gate was just beyond the ragged edifice, suspended in the air at about six times her height. She saw it as a red welt, a thing damaged, but no longer bleeding. She could not recognize the warren – the old damage obscured the portal's characteristics. Unease rippled faintly through her.

The Bonecaster set the children down by the tower, then sat on a block of tumbled masonry. Her gaze fell to the two young Jaghut, still curled in sleep, lying on their beds of ash. 'What choice?' she whispered. 'It must be Omtose Phellack. It certainly isn't Tellann. Starvald Demelain? Unlikely.' Her eyes were pulled to the plain, narrowing on the mound rings. 'Who dwelt here? Who else was in the habit of building in stone?' She fell silent for a long moment, then swung her attention back to the ruin. 'This tower is the final proof, for it is naught else but Jaghut, and such a structure would not be raised this close to an inimical warren. No, the gate is Omtose Phellack. It must be so.'

Still, there were additional risks. An adult Jaghut in the warren beyond, coming upon two children not of its own blood, might as easily kill them as adopt them. 'Then their deaths stain another's hands, a Jaghut's.' Scant comfort, that distinction. It matters naught which of you kills us, only that you kill us. The breath hissed between the woman's teeth. 'What choice?' she asked again.

She would let them sleep a little longer. Then, she would send them through the gate. A word to the boy – take care of your sister. The journey will not be long. And to them both – your mother waits beyond. A lie, but they would need courage. If she cannot find you, then one of her kin will. Go then, to safety, to salvation.

After all, what could be worse than death?

She rose as they approached. Pran Chole tested the air, frowned. The Jaghut had not unveiled her warren. Even more disconcerting, where were her children?

'She greets us with calm,' Cannig Tol muttered.

'She does,' the Bonecaster agreed.

'I've no trust in that – we should kill her immediately.'

'She would speak with us,' Pran Chole said.

'A deadly risk, to appease her desire.'

'I cannot disagree, Clan Leader. Yet ... what has she done with her children?'

'Can you not sense them?'

Pran Chole shook his head. 'Prepare your spearmen,' he said, stepping forward.

There was peace in her eyes, so clear an acceptance of her own imminent death that the Bonecaster was shaken. Pran Chole walked through shin-deep water, then stepped onto the island's sandy bank to stand face to face with the Jaghut. 'What have you done with them?' he demanded.

The mother smiled, lips peeling back to reveal her tusks. 'Gone.'

'Where?'

'Beyond your reach, Bonecaster.'

Pran Chole's frown deepened. 'These are our lands. There is no place here that is beyond our reach. Have you slain them with your own hands, then?'

The Jaghut cocked her head, studied the Imass. 'I had always believed you were united in your hatred for our kind. I had always believed that such concepts as com-passion and mercy were alien to your natures.'

The Bonecaster stared at the woman for a long moment, then his gaze dropped away, past her, and scanned the soft clay ground. 'An Imass has been here,' he said. 'A woman. The Bonecaster—' the one I could not find in my spiritwalk. The one who chose not to be found. 'What has she done?'

'She has explored this land,' the Jaghut replied. 'She has found a gate far to the south. It is Omtose Phellack.'

'I am glad,' Pran Chole said, '1 am not a mother.' And you, woman, should be glad I am not cruel. He gestured. Heavy spears flashed past the Bonecaster. Six long, fluted heads of flint punched through the skin covering the Jaghut's chest. She staggered, then folded to the ground in a clatter of shafts.

Thus ended the thirty-third Jaghut War.

Pran Chole whirled. 'We've no time for a pyre. We must strike southward. Quickly.'

Cannig Tol stepped forward as his warriors went to retrieve their weapons. The Clan Leader's eyes narrowed on the Bonecaster. 'What distresses you?'

'A renegade Bonecaster has taken the children.'

'South?'

'To Morn.'

The Clan Leader's brows knitted.

'The renegade would save this woman's children. The renegade believes the Rent to be Omtose Phellack.'

Pran Chole watched the blood leave Cannig Tol's face. 'Go to Morn, Bonecaster,' the Clan Leader whispered. 'We are not cruel. Go now.'

Pran Chole bowed. The Tellann warren engulfed him.

The faintest release of her power sent the two Jaghut children upward, into the gate's maw. The girl cried out a moment before reaching it, a longing wail for her mother, who she imagined waited beyond. Then the two small figures vanished within.

The Bonecaster sighed and continued to stare upward, seeking any evidence that the passage had gone awry. It seemed, however, that no wounds had reopened, no gush of wild power bled from the portal. Did it look different? She could not be sure. This was new land for her; she had nothing of the bone-bred sensitivity that she had known all her life among the lands of the Tarad clan, in the heart of the First Empire.

The Tellann warren opened behind her. The woman spun round, moments from veering into her Soletaken form.

An arctic fox bounded into view, slowed upon seeing her, then sembled back into its Imass form. She saw before her a young man, wearing the skin of his totem animal across his shoulders, and a battered antler headdress. His expression was twisted with fear, his eyes not on her, but on the portal beyond.

The woman smiled. 'I greet you, fellow Bonecaster. Yes, I have sent them through. They are beyond the reach of your vengeance, and this pleases me.'

His tawny eyes fixed on her. 'Who are you? What clan?'

'I have left my clan, but I was once counted among the Logros. I am named Kilava.'

'You should have let me find you last night,' Pran Chole said. 'I would then have been able to convince you that a swift death was the greater mercy for those children than what you have done here, Kilava.'

'They are young enough to be adopted—'

'You have come to the place called Morn,' Pran Chole interjected, his voice cold. 'To the ruins of an ancient city—'

'Jaghut—'

'Not Jaghut! This tower, yes, but it was built long afterward, in the time between the city's destruction and the T'ol Ara'd – this flow of lava which but buried something already dead.' He raised a hand, pointed towards the suspended gate. 'It was this – this wounding – that destroyed the city, Kilava. The warren beyond – do you not understand? It is not Omtose Phellack! Tell me this – how are such wounds sealed? You know the answer, Bonecaster!'

The woman slowly turned, studied the Rent. 'If a soul sealed that wound, then it should have been freed ... when the children arrived—'

'Freed,' Pran Chole hissed, 'in exchange!'

Trembling, Kilava faced him again. 'Then where is it? Why has it not appeared?'

Pran Chole turned to study the central mound on the plain. 'Oh,' he whispered, 'but it has.' He glanced back at his fellow Bonecaster. 'Tell me, will you in turn give up your life for those children? They are trapped now, in an eternal nightmare of pain. Does your compassion extend to sacrificing yourself in yet another exchange?' He studied her, then sighed. 'I thought not, so wipe away those tears, Kilava. Hypocrisy ill suits a Bonecaster.'

'What...' the woman managed after a time, 'what has been freed?'

Pran Chole shook his head. He studied the central mound again. 'I am not sure, but we shall have to do something about it, sooner or later. I suspect we have plenty of time. The creature must now free itself of its tomb, and that has been thoroughly warded. More, there is the T'ol Ara'd's mantle of stone still clothing the barrow.' After a moment, he added. 'But time we shall have.'

'What do you mean?'

'The Gathering has been called. The Ritual of Tellann awaits us, Bonecaster.'

She spat. 'You are all insane. To choose immortality for the sake of a war – madness. I shall defy the call, Bonecaster.'

He nodded. 'Yet the Ritual shall be done. I have spirit-walked into the future, Kilava. I have seen my withered face of two hundred thousand and more years hence. We shall have our eternal war.'

Bitterness filled Kilava's voice. 'My brother will be pleased.'

'Who is your brother?'

'Onos T'oolan, the First Sword.'

Pran Chole turned at this. 'You are the Defier. You slaughtered your clan – your kin—'

'To break the link and thus achieve freedom, yes. Alas, my eldest brother's skills more than matched mine. Yet now we are both free, though what I celebrate, Onos T'oolan curses.' She wrapped her arms around herself, and Pran Chole saw upon her layers and layers of pain. Hers was a freedom he did not envy. She spoke again. 'This city, then. Who built it.'

'K'Chain Che'Malle.'

'I know the name, but little else of them.'

Pran Chole nodded. 'We shall, I expect, learn.'

II

Continents of Korelri and Jacuruku, in the Time of Dying 119,736 years before Burn's Sleep (three years after the Fall of the Crippled God)

The Fall had shattered a continent. Forests had burned, the firestorms lighting the horizons in every direction, bathing crimson the heaving ash-filled clouds blanketing the sky. The conflagration had seemed unending, world-devouring, weeks into months, and through it all could be heard the screams of a god.

Pain gave birth to rage. Rage, to poison, an infection sparing no-one.

Scattered survivors remained, reduced to savagery, wandering a landscape pocked with huge craters now filled with murky, lifeless water, the sky churning endlessly above them. Kinship had been dismembered, love had proved a burden too costly to carry. They ate what they could, often each other, and scanned the ravaged world around them with rapacious intent.

One figure walked this landscape alone. Wrapped in rotting rags, he was of average height, his features blunt and unprepossessing. There was a dark cast to his face, a heavy inflexibility in his eyes. He walked as if gathering suffering unto himself, unmindful of its vast weight; walked as if incapable of yielding, of denying the gifts of his own spirit.

In the distance, ragged bands eyed the figure as he strode, step by step, across what was left of the continent that would one day be called Korelri. Hunger might have driven them closer, but there were no fools left among the survivors of the Fall, and so they maintained a watchful distance, curiosity dulled by fear. For the man was an ancient god, and he walked among them.

Beyond the suffering he absorbed, K'rul would have willingly embraced their broken souls, yet he had fed – was feeding – on the blood spilled onto this land, and the truth was this: the power born of that would be needed.

In K'rul's wake, men and women killed men, killed women, killed children. Dark slaughter was the river the Elder God rode.

Elder Gods embodied a host of harsh unpleasantries.

The foreign god had been torn apart in his descent to earth. He had come down in pieces, in streaks of flame. His pain was fire, screams and thunder, a voice that had been heard by half the world. Pain, and outrage. And, K'rul reflected, grief. It would be a long time before the foreign god could begin to reclaim the remaining fragments of its life, and so begin to unveil its nature. K'rul feared that day's arrival. From such a shattering could only come madness.

The summoners were dead. Destroyed by what they had called down upon them. There was no point in hating them, no need to conjure up images of what they in truth deserved by way of punishment. They had, after all, been desperate. Desperate enough to part the fabric of chaos, to open a way into an alien, remote realm; to then lure a curious god of that realm closer, ever closer to the trap they had prepared. The summoners sought power.

All to destroy one man.

The Elder God had crossed the ruined continent, had looked upon the still-living flesh of the Fallen God, had seen the unearthly maggots that crawled forth from that rotting, endlessly pulsing meat and broken bone. Had seen what those maggots flowered into. Even now, as he reached the battered shoreline of Jacuruku, the ancient sister continent to Korelri, they wheeled above him on their broad, black wings. Sensing the power within him, they were hungry for its taste.

But a strong god could ignore the scavengers that trailed in his wake, and K'rul was a strong god. Temples had been raised in his name. Blood had for generations soaked countless altars in worship of him. The nascent cities were wreathed in the smoke of forges, pyres, the red glow of humanity's dawn. The First Empire had risen, on a continent half a world away from where K'rul now walked. An empire of humans, born from the legacy of the T'lan Imass, from whom it took its name.

But it had not been alone for long. Here, on Jacuruku, in the shadow of long-dead K'Chain Che'Malle ruins, another empire had emerged. Brutal, a devourer of souls, its ruler was a warrior without equal.

K'rul had come to destroy him, had come to snap the chains of twelve million slaves – even the Jaghut Tyrants had not commanded such heartless mastery over their subjects. No, it took a mortal human to achieve this level of tyranny over his kin.

Two other Elder Gods were converging on the Kallorian Empire. The decision had been made. The three – last of the Elder – would bring to a close the High King's despotic rule. K'rul could sense his companions. Both were close; both had been comrades once, but they all – K'rul included – had changed, had drifted far apart. This would mark the first conjoining in millennia.

He could sense a fourth presence as well, a savage, ancient beast following his spoor. A beast of the earth, of winter's frozen breath, a beast with white fur bloodied, wounded almost unto death by the Fall. A beast with but one surviving eye to look upon the destroyed land that had once been its home – long before the empire's rise. Trailing, but coming no closer. And, K'rul well knew, it would remain a distant observer of all that was about to occur. The Elder god could spare it no sorrow, yet was not indifferent to its pain.

We each survive as we must, and when time comes to die, we find our places of solitude ...

The Kallorian Empire had spread to every shoreline of Jacuruku, yet K'rul saw no-one as he took his first steps inland. Lifeless wastes stretched on all sides. The air was grey with ash and dust, the skies overhead churning like lead in a smith's cauldron. The Elder God experienced the first breath of unease, sidling chill across his soul.

Above him the god-spawned scavengers cackled as they wheeled.

A familiar voice spoke in K'rul's mind. Brother, I am upon the north shore.

'And I the west.'

Are you troubled?

'I am. All is ... dead.'

Incinerated. The heat remains deep beneath the beds of ash. Ash ... and bone.

A third voice spoke. Brothers, I am come from the south, where once dwelt the cities. All destroyed. The echoes of a continent's death-cry still linger. Are we deceived? Is this illusion?

K'rul addressed the first Elder who had spoken in his mind. 'Draconus, I too feel that death-cry. Such pain ... indeed, more dreadful in its aspect than that of the Fallen One. If not a deception as our sister suggests, what has he done?'

We have stepped onto this land, and so all share what you sense, K'rul, Draconus replied. I, too, am not certain of its truth. Sister, do you approach the High King's abode?

The third voice replied, I do, brother Draconus. Would you and brother K'rul join me now, that we may confront this mortal as one?

'We shall.'

Warrens opened, one to the far north, the other directly before K'rul.

The two Elder Gods joined their sister upon a ragged hilltop where wind swirled through the ashes, spinning funereal wreaths skyward. Directly before them, on a heap of burnt bones, was a throne.

The man seated upon it was smiling. 'As you can see,' he rasped after a moment of scornful regard, 'I have ... prepared for your arrival. Oh yes, I knew you were coming. Draconus, of Tiam's kin. K'rul, Opener of the Paths.' His grey eyes swung to the third Elder. 'And you. My dear, I was under the impression that you had abandoned your ... old self. Walking among the mortals, playing the role of middling sorceress – such a deadly risk, though perhaps this is what entices you so to the mortal game. You've stood on fields of battles, woman. One stray arrow ...' He slowly shook his head.

'We have come,' K'rul said, 'to end your reign of terror.'

Kallor's brows rose. 'You would take from me all that I have worked so hard to achieve? Fifty years, dear rivals, to conquer an entire continent. Oh, perhaps Ardatha still held out – always late in sending me my rightful tribute – but I ignored such petty gestures. She has fled, did you know? The bitch. Do you imagine yourselves the first to challenge me? The Circle brought down a foreign god. Aye, the effort went... awry, thus sparing me the task of killing the fools with my own hand. And the Fallen One? Well, he'll not recover for some time, and even then, do you truly imagine he will accede to anyone's bidding? I would have—'

'Enough,' Draconus growled. 'Your prattling grows wearisome, Kallor.'

'Very well,' the High King sighed. He leaned forward. 'You've come to liberate my people from my tyrannical rule. Alas, I am not one to relinquish such things. Not to you, not to anyone.' He settled back, waved a languid hand. 'Thus, what you would refuse me, I now refuse you.'

Though the truth was before K'rul's eyes, he could not believe it. 'What have—'

'Are you blind?' Kallor shrieked, clutching at the arms of his throne. 'It is gone! They are gone! Break the chains, will you? Go ahead – no, I surrender them! Here, all about you, is now free! Dust! Bones! All free!'

'You have in truth incinerated an entire continent?' the sister Elder whispered. 'Jacuruku—'

'Is no more, and never again shall be. What I have unleashed will never heal. Do you understand me? Never. And it is all your fault. Yours. Paved in bone and ash, this noble road you chose to walk. Your road.'

'We cannot allow this—'

'It has already happened, you foolish woman!'

K'rul spoke within the minds of his kin. It must be done. I will fashion a ... a place for this. Within myself.

A warren to hold all this? Draconus asked in horror. My brother—

No, it must be done. join with me now, this shaping will not be easy—

It will break you, K'rul, his sister said. There must be another way.

None. To leave this continent as it is ... no, this world is young. To carry such a scar ...

What of Kallor? Draconus enquired. What of this ... this creature?

We mark him, K'rul replied. We know his deepest desire, do we not?

And the span of his life?

Long, my friends.

Agreed.

K'rul blinked, fixed his dark, heavy eyes on the High King. 'For this crime, Kallor, we deliver appropriate punishment. Know this: you, Kallor Eiderann Tes'thesula, shall know mortal life unending. Mortal, in the ravages of age, in the pain of wounds and the anguish of despair. In dreams brought to ruin. In love withered. In the shadow of Death's spectre, ever a threat to end what you will not relinquish.' Draconus spoke, 'Kallor Eiderann Tes'thesula, you shall never ascend.'

Their sister said, 'Kallor Eiderann Tes'thesula, each time you rise, you shall then fall. All that you achieve shall turn to dust in your hands. As you have wilfully done here, so it shall be in turn visited upon all that you do.'

'Three voices curse you,' K'rul intoned. 'It is done.'

The man on the throne trembled. His lips drew back in a rictus snarl. 'I shall break you. Each of you. I swear this upon the bones of seven million sacrifices. K'rul, you shall fade from the world, you shall be forgotten. Draconus, what you create shall be turned upon you. And as for you, woman, unhuman hands shall tear your body into pieces, upon a field of battle, yet you shall know no respite – thus, my curse upon you, Sister of Cold Nights. Kallor Eiderann Tes'thesula, one voice, has spoken three curses. Thus.'

They left Kallor upon his throne, upon its heap of bones. They merged their power to draw chains around a continent of slaughter, then pulled it into a warren created for that sole purpose, leaving the land itself bared. To heal.

The effort left K'rul broken, bearing wounds he knew he would carry for all his existence. More, he could already feel the twilight of his worship, the blight of Kallor's curse. To his surprise, the loss pained him less than he would have imagined.

The three stood at the portal of the nascent, lifeless realm, and looked long upon their handiwork.

Then Draconus spoke, 'Since the time of All Darkness, I have been forging a sword.'

Both K'rul and the Sister of Cold Nights turned at this, for they had known nothing of it.

Draconus continued. 'The forging has taken ... a long time, but I am now nearing completion. The power invested within the sword possesses a ... a finality.'

'Then,' K'rul whispered after a moment's consideration, 'you must make alterations in the final shaping.'

'So it seems. I shall need to think long on this.'

After a long moment, K'rul and his brother turned to their sister.

She shrugged. 'I shall endeavour to guard myself. When my destruction comes, it will be through betrayal and naught else. There can be no precaution against such a thing, lest my life become its own nightmare of suspicion and mistrust. To this, I shall not surrender. Until that moment, I shall continue to play the mortal game.'

'Careful, then,' K'rul murmured, 'whom you choose to fight for.'

'Find a companion,' Draconus advised. 'A worthy one.'

'Wise words from you both. I thank you.'

There was nothing more to be said. The three had come together, with an intent they had now achieved. Perhaps not in the manner they would have wished, but it was done. And the price had been paid. Willingly. Three lives and one, each destroyed. For the one, the beginning of eternal hatred. For the three, a fair exchange.

Elder Gods, it has been said, embodied a host of unpleasantries.

In the distance, the beast watched the three figures part ways. Riven with pain, white fur stained and dripping blood, the gouged pit of its lost eye glittering wet, it held its hulking mass on trembling legs. It longed for death, but death would not come. It longed for vengeance, but those who had wounded it were dead. There but remained the man seated on the throne, who had laid waste to the beast's home.

Time enough would come for the settling of that score.

A final longing filled the creature's ravaged soul. Somewhere, amidst the conflagration of the Fall and the chaos that followed, it had lost its mate, and was now alone. Perhaps she still lived. Perhaps she wandered, wounded as he was, searching the broken wastes for sign of him.

Or perhaps she had fled, in pain and terror, to the warren that had given fire to her spirit.

Wherever she had gone – assuming she still lived – he would find her.

The three distant figures unveiled warrens, each vanishing into their Elder realms.

The beast elected to follow none of them. They were young entities as far as he and his mate were concerned, and the warren she might have fled to was, in comparison to those of the Elder Gods, ancient.

The path that awaited him was perilous, and he knew fear in his labouring heart.

The portal that opened before him revealed a grey-streaked, swirling storm of power. The beast hesitated, then strode into it.

And was gone.

Five mages, an Adjunct, countless Imperial Demons, and the debacle that was Darujhistan, all served to publicly justify the outlawry proclaimed by the Empress on Dujek Onearm and his battered legions. That this freed Onearm and his Host to launch a new campaign, this time as an independent military force, to fashion his own unholy alliances which were destined to result in a continuation of the dreadful Sorcery Enfilade on Genabackis, is, one might argue, incidental. Granted, the countless victims of that devastating time might, should Hood grant them the privilege, voice an entirely different opinion. Perhaps the most poetic detail of what would come to be called the Pannion Wars was in fact a precursor to the entire campaign: the casual, indifferent destruction of a lone, stone bridge, by the Jaghut Tyrant on his ill-fated march to Darujhistan . . .

Imperial Campaigns (The Pannion War)

1194–1195, Volume N, Genabackis

Imrygyn Tallobant (b. 1151)

CHAPTER ONE

Memories are woven tapestries hiding hard walls—tell me, my friends, what hue your favoured thread, and I in turn, will tell the cast of your soul . . .

Life of Dreams

Ilbares the Hag

1164th Year of Burn's Sleep (two months after the Darujhistan Fete)

4th Year of the Pannion Domin

Tellann Year of the Second Gathering

The bridge's Gadrobi limestone blocks lay scattered, scorched and broken in the bank's churned mud, as if a god's hand had swept down to shatter the stone span in a single, petty gesture of contempt. And that, Gruntle suspected, was but a half-step from the truth.

The news had trickled back into Darujhistan less than a week after the destruction, as the first eastward-bound caravans this side of the river reached the crossing, to find that where once stood a serviceable bridge was now nothing but rubble. Rumours whispered of an ancient demon, unleashed by agents of the Malazan Empire, striding down out of the Gadrobi Hills bent on the annihilation of Darujhistan itself.

Gruntle spat into the blackened grasses beside the carriage. He had his doubts about that tale. Granted, there'd been strange goings on the night of the city's Fete two months back – not that he'd been sober enough to notice much of anything – and sufficient witnesses to give credence to the sightings of dragons, demons and the terrifying descent of Moon's Spawn, but any conjuring with the power to lay waste to an entire countryside would have reached Darujhistan. And, since the city was not a smouldering heap – or no more than was usual after a city-wide celebration – clearly nothing did.

No, far more likely a god's hand, or possibly an earthquake – though the Gadrobi Hills were not known to be restless. Perhaps Burn had shifted uneasy in her eternal sleep.

In any case, the truth of things now stood before him. Or, rather, did not stand, but lay scattered to Hood's gate and beyond. And the fact remained, whatever games the gods played, it was hard-working dirt-poor bastards like him who suffered for it.

The old ford was back in use, thirty paces upriver from where the bridge had been built. It hadn't seen traffic in centuries, and with a week of unseasonal rains both banks had become a morass. Caravan trains crowded the crossing, the ones on what used to be ramps and the ones out in the swollen river hopelessly mired down; while dozens more waited on the trails, with the tempers of merchants, guards and beasts climbing by the hour.

Two days now, waiting to cross, and Gruntle was pleased with his meagre troop. Islands of calm, they were. Harllo had waded out to a remnant of the bridge's nearside pile, and now sat atop it, fishing pole in hand. Stonny Menackis had led a ragged band of fellow caravan guards to Storby's wagon, and Storby wasn't too displeased to be selling Gredfallan ale by the mug at exorbitant prices. That the ale casks were destined for a wayside inn outside Saltoan was just too bad for the expectant innkeeper. If things continued as they did, there'd be a market growing up here, then a Hood-damned town. Eventually, some officious planner in Darujhistan would conclude that it'd be a good thing to rebuild the bridge, and in ten or so years it would finally get done. Unless, of course, the town had become a going concern, in which case they'd send a tax collector.

Gruntle was equally pleased with his employer's equanimity at the delay. News was, the merchant Manqui on the other side of the river had burst a blood vessel in his head and promptly died, which was more typical of the breed. No, their master Keruli ran against the grain, enough to threaten Gruntle's cherished disgust for merchants in general. Then again, Keruli's list of peculiar traits had led the guard captain to suspect that the man wasn't a merchant at all.

Not that it mattered. Coin was coin, and Keruli's rates were good. Better than average, in fact. The man might be Prince Arard in disguise, for all Gruntle cared.

'You there, sir!'

Gruntle pulled his gaze from Harllo's fruitless fishing. A grizzled old man stood beside the carriage, squinting up at him. 'Damned imperious of you, that tone,' the caravan captain growled, 'since by the rags you're wearing you're either the world's worst merchant or a poor man's servant.'

'Manservant, to be precise. My name is Emancipor Reese. As for my masters' being poor, to the contrary. We have, however, been on the road for a long time.'

'I'll accept that,' Gruntle said, 'since your accent is unrecognizable, and coming from me that's saying a lot. What do you want, Reese?'

The manservant scratched the silvery stubble on his lined jaw. 'Careful questioning among this mob had gleaned a consensus that, as far as caravan guards go, you're a man who's earned respect.'

'As far as caravan guards go, I might well have at that,' Gruntle said drily. 'Your point?'

'My masters wish to speak with you, sir. If you're not too busy – we have camped not far from here.'

Leaning back on the bench, Gruntle studied Reese for a moment, then grunted. 'I'd have to clear with my employer any meetings with other merchants.'

'By all means, sir. And you may assure him that my masters have no wish to entice you away or otherwise compromise your contract.'

'Is that a fact? All right, wait there.' Gruntle swung himself down from the buckboard on the side opposite Reese. He stepped up to the small, ornately framed door and knocked once. It opened softly and from the relative darkness within the carriage's confines loomed Keruli's round, expressionless face.

'Yes, Captain, by all means go. I admit as to some curiosity about this man's two masters. Be most studious in noting details of your impending encounter. And, if you can, determine what precisely they have been up to since yesterday.'

The captain grunted to disguise his surprise at Keruli's clearly unnatural depth of knowledge – the man had yet to leave the carriage – then said, 'As you wish, sir.'

'Oh, and retrieve Stonny on your way back. She has had far too much to drink and has become most argumentative.'

'Maybe I should collect her now, then. She's liable to poke someone full of holes with that rapier of hers. I know her moods.'

'Ah, well. Send Harllo, then.'

'Uh, he's liable to join in, sir.'

'Yet you speak highly of them.'

'I do,' Gruntle replied. 'Not to be too immodest, sir, the three of us working the same contract are as good as twice that number, when it comes to protecting a master and his merchandise. That's why we're so expensive.'

'Your rates were high? I see. Hmm. Inform your two companions, then, that an aversion to trouble will yield substantial bonuses to their pay.'

Gruntle managed to avoid gaping. 'Uh, that should solve the problem, sir.'

'Excellent. Inform Harllo thus, then, and send him on his way.'

'Yes, sir.'

The door swung shut.

As it turned out, Harllo was already returning to the carriage, fishing pole in one massive hand, a sad sandal-sole of a fish clutched in the other. The man's bright blue eyes danced with excitement.

'Look, you sour excuse for a man – I've caught supper!'

'Supper for a monastic rat, you mean. I could inhale that damned thing up one nostril.'

Harllo scowled. 'Fish soup. Flavour—'

'That's just great. I love mud-flavoured soup. Look, the thing's not even breathing – it was probably dead when you caught it.'

'I banged a rock between its eyes, Gruntle—'

'Must have been a small rock.'

'For that you don't get any—'

'For that I bless you. Now listen. Stonny's getting drunk—'

'Funny, I don't hear no brawl—'

'Bonuses from Keruli if there isn't one. Understood?'

Harllo glanced at the carriage door, then nodded. 'I'll let her know.'

'Better hurry.'

'Right.'

Gruntle watched him scurry off, still carrying his pole and prize. The man's arms were enormous, too long and too muscled for the rest of his scrawny frame. His weapon of choice was a two-handed sword, purchased from a weapon-smith in Deadman's Story. As far as those apish arms were concerned, it might be made of bamboo. Harllo's shock of pale blond hair rode his pate like a tangled bundle of fishing thread. Strangers laughed upon seeing him for the first time, but Harllo used the flat of a blade to stifle that response. Succinctly.

Sighing, Gruntle returned to where Emancipor Reese stood waiting. 'Lead on,' he said.

Reese's head bobbed. 'Excellent.'

The carriage was massive, a house perched on high, spoked wheels. Ornate carvings crowded the strangely arched frame, tiny painted figures capering and climbing with leering expressions. The driver's perch was canopied in sun-faded canvas. Four oxen lumbered freely in a makeshift corral ten paces downwind from the camp.

Privacy obviously mattered to the manservant's masters, since they'd parked well away from both the road and the other merchants, affording them a clear view of the hummocks rising on the south side of the road, and, beyond it, the broad sweep of the plain.

A mangy cat lying on the buckboard watched Reese and Gruntle approach.

'That your cat?' the captain asked.

Reese squinted at it, then sighed. 'Aye, sir. Her name's Squirrel.'

'Any alchemist or wax-witch could treat that mange.'

The manservant seemed uncomfortable. 'I'll be sure to look into it when we get to Saltoan,' he muttered. 'Ah,' he nodded towards the hills beyond the road, 'here comes Master Bauchelain.'

Gruntle turned and studied the tall, angular man who'd reached the road and now strode casually towards them. Expensive, ankle-length cloak of black leather, high riding boots of the same over grey leggings, and, beneath a loose silk shirt – also black – the glint of fine blackened chain armour.

'Black,' the captain said to Reese, 'was last year's shade in Darujhistan.'

'Black is Bauchelain's eternal shade, sir.'

The master's face was pale, shaped much like a triangle, an impression further accented by a neatly trimmed beard. His hair, slick with oil, was swept back from his high brow. His eyes were flat grey – as colourless as the rest of him – and upon meeting them Gruntle felt a surge of visceral alarm.

'Captain Gruntle,' Bauchelain spoke in a soft, cultured voice, 'your employer's prying is none too subtle. But while we are not ones to generally reward such curiosity regarding our activities, this time we shall make an exception. You shall accompany me.' He glanced at Reese. 'Your cat seems to be suffering palpitations. I suggest you comfort the creature.'

'At once, master.'

Gruntle rested his hands on the pommels of his cutlasses, eyes narrowed on Bauchelain. The carriage springs squeaked as the manservant clambered up to the buckboard.

'Well, Captain?'

Gruntle made no move.

Bauchelain raised one thin eyebrow. 'I assure you, your employer is eager that you comply with my request. If, however, you are afraid to do so, you might be able to convince him to hold your hand for the duration of this enterprise. Though I warn you, levering him into the open may prove something of a challenge, even for a man of your bulk.'

'Ever done any fishing?' Gruntle asked.

'Fishing?'

'The ones that rise to any old bait are young and they don't get any older. I've been working caravans for more than twenty years, sir. I ain't young. You want a rise, fish elsewhere.'

Bauchelain's smile was dry. 'You reassure me, Captain. Shall we proceed?'

'Lead on.'

They crossed the road. An old goat trail led them into the hills. The caravan camp this side of the river was quickly lost to sight. The scorched grass of the conflagration that had struck this land marred every slope and summit, although new green shoots had begun to appear.

'Fire,' Bauchelain noted as they walked on, 'is essential for the health of these prairie grasses. As is the passage of bhederin, the hooves in their hundreds of thousands compacting the thin soil. Alas, the presence of goats will spell the end of verdancy for these ancient hills. But I began with the subject of fire, did I not? Violence and destruction, both vital for life. Do you find that odd, Captain?'

'What I find odd, sir, is this feeling that I've left my wax-tablet behind.'

'You have had schooling, then. How interesting. You're a swordsman, are you not? What need you for letters and numbers?'

'And you're a man of letters and numbers – what need you for that well-worn broadsword at your hip and that fancy mail hauberk?'

'An unfortunate side effect of education among the masses is lack of respect.'

'Healthy scepticism, you mean.'

'Disdain for authority, actually. You may have noted, to answer your question, that we have but a single, rather elderly manservant. No hired guards. The need to protect oneself is vital in our profession—'

'And what profession is that?'

They'd descended onto a well-trodden path winding between the hills. Bauchelain paused, smiling as he regarded Gruntle. 'You entertain me, Captain. I understand now why you are well spoken of among the caravanserai, since you are unique among them in possessing a functioning brain. Come, we are almost there.'

They rounded a battered hillside and came to the edge of a fresh crater. The earth at its base was a swath of churned mud studded with broken blocks of stone. Gruntle judged the crater to be forty paces across and four or five arm-lengths in depth. A man sat nearby on the edge of the rim, also dressed in black leather, his bald pate the colour of bleached parchment. He rose silently, for all his considerable size, and turned to them with fluid grace.

'Korbal Broach, Captain. My ... partner. Korbal, we have here Gruntle, a name that is most certainly a slanting hint to his personality.'

If Bauchelain had triggered unease in the captain, then this man – his broad, round face, his eyes buried in puffed flesh and wide full-lipped mouth set slightly downturned at the corners, a face both childlike and ineffably monstrous – sent ripples of fear through Gruntle. Once again, the sensation was wholly instinctive, as if Bauchelain and his partner exuded an aura somehow tainted.

'No wonder the cat had palpitations,' the captain muttered under his breath. He pulled his gaze from Korbal Broach and studied the crater.

Bauchelain moved to stand beside him. 'Do you understand what you are seeing, Captain?'

'Aye, I'm no fool. It's a hole in the ground.'

'Amusing. A barrow once stood here. Within it was chained a Jaghut Tyrant.'

'Was.'

'Indeed. A distant empire meddled, or so I gather. And, in league with a T'lan Imass, they succeeded in freeing the creature.'

'You give credence to the tales, then,' Gruntle said. 'If such an event occurred, then what in Hood's name happened to it?'

'We wondered the same, Captain. We are strangers to this continent. Until recently, we'd never heard of the Malazan Empire, nor the wondrous city called Darujhistan. During our all too brief stay there, however, we heard stories of events just past. Demons, dragons, assassins. And the Azath house named Finnest, which cannot be entered yet, seems to be occupied none the less – we paid that a visit, of course. More, we'd heard tales of a floating fortress, called Moon's Spawn, that once hovered over the city—'

'Aye, I'd seen that with my own eyes. It left a day before I did.'

Bauchelain sighed. 'Alas, it appears we have come too late to witness for ourselves these dire wonders. A Tiste Andii lord rules Moon's Spawn, I gather.'

Gruntle shrugged. 'If you say so. Personally, I dislike gossip.'

Finally, the man's eyes hardened.

The captain smiled inwardly.

'Gossip. Indeed.'

'This is what you wanted to show me, then? This ... hole?'

Bauchelain raised an eyebrow. 'Not precisely. This hole is but the entrance. We intend to visit the Jaghut tomb that lies below it.'

'Oponn's blessing to you, then,' Gruntle said, turning away.

'I imagine,' the man said behind him, 'that your master would urge you to accompany us.'

'He can urge all he likes,' the captain replied. 'I wasn't contracted to sink in a pool of mud.'

'We've no intention of getting covered in mud.'

Gruntle glanced back at him, crooked a wry grin. 'A figure of speech, Bauchelain. Apologies if you misunderstood.' He swung round again and made his way towards the trail. Then he stopped. 'You wanted to see Moon's Spawn, sirs?' He pointed.

Like a towering black cloud, the basalt fortress stood just above the south horizon.

Boots crunched on the ragged gravel, and Gruntle found himself standing between the two men, both of whom studied the distant floating mountain.

'Scale,' Bauchelain muttered, 'is difficult to determine. How far away is it?'

'I'd guess a league, maybe more. Trust me, sirs, it's close enough for my tastes. I've walked its shadow in Darujhistan – hard not to for a while there – and believe me, it's not a comforting feeling.'

'I imagine not. What is it doing here?'

Gruntle shrugged. 'Seems to be heading southeast—'

'Hence the tilt.'

'No. It was damaged over Pale. By mages of the Malazan Empire.'

'Impressive effort, these mages.'

'They died for it. Most of them, anyway. So I heard. Besides, while they managed to damage Moon's Spawn, its lord remains hale. If you want to call kicking a hole in a fence before getting obliterated by the man who owns the house "impressive", go right ahead.'

Korbal Broach finally spoke, his voice reedy and high-pitched. 'Bauchelain, does he sense us?'

His companion frowned, eyes still on Moon's Spawn, then shook his head. 'I detect no such attention accorded us, friend. But that is a discussion that should await a more private moment.'

'Very well. You don't want me to kill this caravan guard, then?'

Gruntle stepped away in alarm, half drawing his cutlasses. 'You'll regret the attempt,' he growled.

'Be calmed, Captain.' Bauchelain smiled. 'My partner has simple notions—'

'Simple as an adder's, you mean.'

'Perhaps. None the less, I assure you, you are perfectly safe.'

Scowling, Gruntle backed away down the trail. 'Master Keruli,' he whispered, 'if you're watching all this – and I think you are – I trust my bonus will be appropriately generous. And, if my advice is worth anything, I suggest we stride clear and wide of these two.'

Moments before he moved beyond sight of the crater, he saw Bauchelain and Korbal Broach turn their backs on him – and Moon's Spawn. They stared down into the hole for a brief span, then began the descent, disappearing from view.

Sighing, Gruntle swung about and made his way back to the camp, rolling his shoulders to release the tension that gripped him.

As he reached the road his gaze lifted once more, south-ward to find Moon's Spawn, hazy now with distance. 'You there, lord, I wish you had caught the scent of Bauchelain and Korbal Broach, so you'd do to them what you did to the Jaghut Tyrant – assuming you had a hand in that. Preventative medicine, the cutters call it. I only pray we don't all one day come to regret your disinterest.'

Walking down the road, he glanced over to see Emancipor Reese, sitting atop the carriage, one hand stroking the ragged cat in his lap. Mange? Gruntle considered. Probably not.

The huge wolf circled the body, head low and turned inward to keep the unconscious mortal within sight of its lone eye.

The Warren of Chaos had few visitors. Among those few, mortal humans were rarest of all. The wolf had wandered this violent landscape for a time that was, to it, immeasurable. Alone and lost for so long, its mind had found new shapes born of solitude; the tracks of its thoughts twisted on seemingly random routes. Few would recognize awareness or intelligence in the feral gleam of its eye, yet they existed none the less.

The wolf circled, massive muscles rippling beneath the dull white fur. Head low and turned inward. Lone eye fixed on the prone human.

The fierce concentration was efficacious, holding the object of its attention in a state that was timeless – an accidental consequence of the powers the wolf had absorbed within this warren.

The wolf recalled little of the other worlds that existed beyond Chaos. It knew nothing of the mortals who worshipped it as they would a god. Yet a certain knowledge had come to it, an instinctive sensitivity that told it of ... possibilities. Of potentials. Of choices now available to the wolf, with the discovery of this frail mortal.

Even so, the creature hesitated.

There were risks. And the decision that now gnawed its way to the forefront had the wolf trembling.

Its circling spiralled inward, closer, ever closer to the unconscious figure. Lone eye fixing finally on the man's face.

The gift, the creature saw at last, was a true one. Nothing else could explain what it discovered in the mortal man's face. A mirrored spirit, in every detail. This was an opportunity that could not be refused.

Still the wolf hesitated.

Until an ancient memory rose before its mind's eye. An image, frozen, faded with the erosion of time.

Sufficient to close the spiral.

And then it was done.

His single functioning eye blinked open to a pale blue, cloudless sky. The scar tissue covering what was left of his other eye tingled with a maddening itch, as if insects crawled under the skin. He was wearing a helm, the visor raised. Beneath him, hard sharp rocks dug into his flesh.

He lay unmoving, trying to remember what had happened. The vision of a dark tear opening before him – he'd plunged into it, was flung into it. A horse vanishing beneath him, the thrum of his bowstring. A sense of unease, which he'd shared with his companion. A friend who rode at his side. Captain Paran.

Toc the Younger groaned. Hairlock. That mad puppet. We were ambushed. The fragments coalesced, memory returning with a surge of fear. He rolled onto his side, every muscle protesting. Hood's breath, this isn't the Rhivi Plain.

A field of broken black glass stretched away on all sides. Grey dust hung in motionless clouds an arm's span above it. Off to his left, perhaps two hundred paces away, a low mound rose to break the flat monotony of the landscape.

His throat felt raw. His eye stung. The sun was blistering overhead. Coughing, Toc sat up, the obsidian crunching beneath him. He saw his recurved horn bow lying beside him and reached for it. The quiver had been strapped onto the saddle of his horse. Wherever he'd gone, his faithful Wickan mount had not followed. Apart from the knife at his hip and the momentarily useless bow in his hand, then, he possessed nothing. No water, no food. A closer examination of his bow deepened his scowl. The gut string had stretched.

Badly. Meaning I've been . . . away . . . for some time. Away. Where? Hairlock had thrown him into a warren. Somehow, time had been lost within it. He was not overly thirsty, nor particularly hungry. But, even if he had arrows, the bow's pull was gone. Worse, the string had dried, the wax absorbing obsidian dust. It wouldn't survive retightening. That suggested days, if not weeks, had passed, though his body told him otherwise.

He climbed to his feet. The chain armour beneath his tunic protested the movement, shedding glittering dust.

Am I within a warren? Or has it spat me back out? Either way, he needed to find an end to this lifeless plain of volcanic glass. Assuming one existed ...

He began walking towards the mound. Though it wasn't especially high, he would take any vantage point that was available. As he approached, he saw others like it beyond, regularly spaced. Barrows. Great, I just love barrows. And then a central one, larger than the rest.

Toc skirted the first mound, noting in passing that it had been holed, likely by looters. After a moment he paused, turned and walked closer. He squatted beside the excavated shaft, peered down into the slanting tunnel. As far as he could see – over a man's height in depth – the mantle of obsidian continued down. For the mounds to have showed at all, they must be huge, more like domes than beehive tombs. 'Whatever,' he muttered. 'I don't like it.'

He paused, considering, running through in his mind the events that had led him to this ... unfortunate situation. The deathly rain of Moon's Spawn seemed to mark some kind of beginning. Fire and pain, the death of an eye, the kiss that left a savagely disfiguring scar on what had been a young, reputedly handsome face.

A ride north onto the plain to retrieve Adjunct Lorn, a skirmish with Ilgres Barghast. Back in Pale, still more trouble. Lorn had drawn his reins, reviving his old role as a Claw courier. Courier? Let's speak plain, Toc, especially to yourself. You were a spy. But you had been turned. You were a scout in Onearm's Host. That and nothing more, until the Adjunct showed up. There'd been trouble in Pale. Tattersail, then Captain Paran. Flight and pursuit. 'What a mess,' he muttered.

Hairlock's ambush had swatted him like a fly, into some kind of malign warren. Where I . . . lingered. I think. Hood take me, time's come to start thinking like a soldier again. Get your hearings. Do nothing precipitous. Think about survival, here in this strange, unwelcome place ...

He resumed his trek to the central barrow. Though gently sloped, it was at least thrice the height of a man. His cough worsened as he scrambled up its side.

The effort was rewarded. On the summit, he found himself standing at the hub of a ring of lesser tombs. Directly ahead, three hundred paces beyond the ring's edge yet almost invisible through the haze, rose the bony shoulders of grey-cloaked hills. Closer and to his left were the ruins of a stone tower. The sky behind it glowed a sickly red colour.

Toc glanced up at the sun. When he'd awoken, it had been at little more than three-quarters of the wheel; now it stood directly above him. He was able to orientate himself. The hill lay to the northwest, the tower a few points north of due west.

His gaze was pulled back to the reddish welt in the sky beyond the tower. Yes, it pulsed, as regular as a heart. He scratched at the scar tissue covering his left eye-socket, winced at the answering bloom of colours flooding his mind. That's sorcery over there. Gods, I'm acquiring a deep hatred of sorcery.

A moment later, more immediate details drew his attention. The north slope of the central barrow was marred by a deep pit, its edges ragged and glistening. A tumble of cut stone – still showing the stains of red paint – crowded the base. The crater, he slowly realized, was not the work of looters. Whatever had made it had pushed up from the tomb, violently. In this place, it seems that even the dead do not sleep eternal. A moment of nervousness shook him, then he shrugged it off with a soft curse. You've known worse, soldier. Remember that T'lan Imass who'd joined up with the Adjunct. Laconic desiccation on two legs, Beru fend us all. Hooded eye-sockets with not a glimmer or gleam of mercy. That thing had spitted a Barghast like a Rhivi a plains boar.

Eye still studying the crater in the mound's flank, his thoughts remained on Lorn and her undead companion. They'd sought to free such a restless creature, to loose a wild, vicious power upon the land. He wondered if they'd succeeded. The prisoner of the tomb he now stood upon had faced a dreadful task, without question – wards, solid walls, and armspan after armspan of compacted, crushed glass. Well, given the alternatives, I imagine I would have been as desperate and as determined. How long did it take? How malignly twisted the mind once freed?

He shivered, the motion triggering another harsh cough. There were mysteries in the world, few of them pleasant.

He skirted the pit on his descent and made his way towards the ruined tower. He thought it unlikely that the occupant of the tomb would have lingered long in the area. I would have wanted to get as far away from here and as fast as was humanly possible. There was no telling how much time had passed since the creature's escape, but Toc's gut told him it was years, if not decades. He felt strangely unafraid in any case, despite the inhospitable surroundings and all the secrets beneath the land's ravaged surface. Whatever threat this place had held seemed to be long gone.

Forty paces from the tower he almost stumbled over a corpse. A fine layer of dust had thoroughly disguised its presence, and that dust, now disturbed by Toc's efforts to step clear, rose in a cloud. Cursing, the Malazan spat grit from his mouth.

Through the swirling, glittering haze, he saw that the bones belonged to a human. Granted, a squat, heavy-boned one. Sinews had dried nut-brown, and the furs and skins partially clothing it had rotted to mere strips. A bone helm sat on the corpse's head, fashioned from the frontal cap of a horned beast. One horn had snapped off some time in the distant past. A dust-sheathed two-handed sword lay nearby. Speaking of Hood's skull...

Toc the Younger scowled down at the figure. 'What are you doing here?' he demanded.

'Waiting,' the T'lan Imass replied in a leather-rasp voice.

Toc searched his memory for the name of this undead warrior. 'Onos T'oolan,' he said, pleased with himself. 'Of the Tarad Clan—'

'I am now named Tool. Clanless. Free.'

Free? Free to do precisely what, you sack of bones? Lie around in wastelands?

'What's happened to the Adjunct? Where are we?'

'Lost.'

'Which question is that an answer to, Tool?'

'Both.'

Toc gritted his teeth, resisting the temptation to kick the T'lan Imass. 'Can you be more specific?'

'Perhaps.'

'Well?'

'Adjunct Lorn died in Darujhistan two months ago. We are in the ancient place called Morn, two hundred leagues to the south. It is just past midday.'

'Just past midday, you said. Thank you for the enlightenment.' He found little pleasure in conversing with a creature that had existed for hundreds of thousands of years, and that discomfort unleashed his sarcasm – a precarious presumption indeed. Get back to seriousness, idiot. That flint sword ain't just for show. 'Did you two free the Jaghut Tyrant?'

'Briefly. Imperial efforts to conquer Darujhistan failed.'

Scowling, Toc crossed his arms. 'You said you were waiting. Waiting for what?'

'She has been away for some time. Now she returns.'

'Who?'

'She who has taken occupation of the tower, soldier.'

'Can you at least stand up when you're talking to me.' Before I give in to temptation.

The T'lan Imass rose with an array of creaking complaints, dust cascading from its broad, bestial form. Something glittered for the briefest of moments in the depths of its eye-sockets as it stared at Toc, then Tool turned and retrieved the flint sword.

Gods, better I'd insisted he just stay lying down. Parched leather skin, taut muscle and heavy bone . . . all moving about like something alive. Oh, how the Emperor loved them. An army he never had to feed, he never had to transport, an army that could go anywhere and do damn near anything. And no desertions – except for the one standing in front of me right now.

How do you punish a T'lan Imass deserter anyway?

'I need water,' Toc said after a long moment in which they simply stared at each other. 'And food. And I need to find some arrows. And bowstring.' He unstrapped his helmet and pulled it clear. The leather cap beneath it was soaked through with sweat. 'Can't we wait in the tower? This heat is baking my brain.' And why am I talking as if I expect you to help me, Tool?