A Unified Theory of a Law – Read Now and Download Mobi

A Unified Theory of a Law

By: John Bosco

Online: <http://cnx.org/content/col10670/1.106>

This selection and arrangement of content as a collection is copyrighted by John Bosco.

It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Collection structure revised: 2011/03/25

For copyright and attribution information for the modules contained in this collection, see the "Attributions" section at the end of the collection.

A Unified Theory of a Law

Table of Contents

5. The Formation of a Lawmaker's Opinion

6. The Externalization of a Lawmaker's Opinion

7. The Three Permutations of a Law

14. The Periodic Table of the Elements of a Law

15. Glossary of a Unified Theory of a Law

16. Test Your Legal Literacy by Answering One Question

17. Hohfeld, The Two Meanings of Power and Toxic Derivatives

18. The Nature and Structure of a Legal Argument

19. An Application of the Theory: Thanatology

20. An Application of the Theory: Evidence Part 1

21. An Application of the Theory: Evidence Part 2

22. The Technology that Makes Legal Understanding Instantaneous and Transportable

A Unified Theory of a Law

By: John Bosco

Online: <http://cnx.org/content/col10670/1.106>

This selection and arrangement of content as a collection is copyrighted by John Bosco.

It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Collection structure revised: 2011/03/25

For copyright and attribution information for the modules contained in this collection, see the "Attributions" section at the end of the collection.

Chapter 1. Opening Statement*

An invasion of armies can be resisted, but not an idea whose time has come. (Victor Hugo)

HOW DO YOU UNDERSTAND A LAW?

Everyone can understand a law - to a greater or lesser degree. My question to you is how do you do it? Articulate for me how you understand a law. Legal meaning is dynamic not static. It moves from mind to mind over a definite path. The path can be described as follows:

We dismount legal meaning from its vehicle and import it into our minds

We process it

We mount legal meaning onto a vehicle and export it to others.

Do you have a 'system' that imports, processes and exports legal meaning? The emphasis is on the word, 'system'. Or does legal meaning wander into and out of your mind randomly without any rhyme or reason like a drunk on a pub crawl?

THE BLACK BOX

Most have never given the slightest thought to how they import, process and export legal meaning. They cannot articulate how they do it. It seems to happen magically like the sudden appearance of a magician on stage in a puff of smoke. But, let me disabuse you of the notion that magic is at work. Whether you realize it or not, in your head is a "black box" that holds a mechanism that imports, processes and exports legal meaning. The mechanism consists of

a model of a law that mirrors the laws that exist outside our heads in the world and

a toolkit of techniques that, using the model, do the actual importing, processing and exporting of legal meaning.

The model of a law is akin to a noun and the techniques in the toolkit are akin to verbs. How well we import, process, and export legal meaning depends on

the fidelity between the model of a law inside our heads and the laws that exist outside our heads in the world and

on whether the techniques in our tool kits are well-defined or poorly defined.

A high fidelity black box generates a fair and accurate representation of our laws. A low fidelity black box generates only a poor approximation of our laws.

THE FAILURE OF OUR LAW SCHOOLS TO UPGRADE THE BLACK BOXES OF THEIR STUDENTS

Our "black boxes" ought to opened and the mechanism therein inspected, tinkered with and upgraded while students are still in law school. Yet, our law schools do not do this. Their current approach toward upgrading the 'black boxes' of their students is indirect, unscientific and a manifestation of wishful thinking. Judicial opinions, statutes and other laws are thrown at law students in the hope that the load placed on their black boxes will somehow and in someway cause them to magically upgrade themselves. It is a sink or swim method of pedagogy. Students are thrown off the pier into the maelstrom of laws in the hope that exigency teaches the students to swim. A few teach themselves to swim well; most teach themselves to swim poorly; many just sink to the bottom. The effectiveness of the sink-or-swim method of legal pedagogy is doubtful. Why allow even one student to drown in the maelstrom of laws when there is a way to teach all students to become clear legal thinkers? A direct approach is necessary. A student's "black box" needs to be opened, the low fidelity, untutored mechanism within ripped out and replaced with a new, refined, high fidelity model that unfailingly generates legal understanding. Unfortunately, to borrow the motto of my alma mater, I am a lone voice in the desert. The need for a change in legal pedagogy is recognized by few. (I am being generous to myself in using the word, 'few'). The momentum of the sink or swim method of legal pedagogy keeps the minds of law schools closed to an alternative approach to teaching students how to understand a law. It may be uncharitable and harsh but I am haunted by the line from the Katha Upanishad that goes "Abiding in the midst of ignorance, thinking themselves wise and learned, fools go aimlessly hither and thither, like blind led by the blind"

HOHFELD'S BLACK BOX

Professor Wesley Newcomb Hohfeld attempted to establish a framework within which legal understanding could take place. Many law professors, lawyers and jurists, however, have only a surface familiarity with his doctrine. They recognize his words, 'right', 'no-right', 'duty' and 'privilege'. Unfortunately, the words alone, not their meaning, measure the depth of their understanding. Hohfeld discovered a system of jural opposites and correlatives. However, he derived them by induction from examples of judicial reasoning. He did not deduce them from a theory. Although his jural opposites and correlatives are themselves quite simple and straightforward, his derivation of them is somewhat obtuse and difficult to understand.

OPENING HOHFELD'S BLACK BOX TO SEE HOW IT WORKS

When I was given the opportunity to teach law to a class of high school students. I knew that I would share Hohfeld with them. However, upon thinking about how to do so I realized that teaching Hohfeld to high school students would be impossible without a theory. Merely telling them that jural opposites and correlatives exist would not be enough. I needed a theory to explain why they exist. The reason for the existence of a fact is often as important and interesting as the fact itself. Christopher Columbus is celebrated for discovering that the world is round. Yet, he did not discover why the world is round. Someone else did. Thus, the exigency of teaching drove me to reverse engineer Hohfeld's doctrine. I took him apart and put him back together again. In the process, I had a number of legal epiphanies. In A Unified Theory of a Law, I wish to share them with you. A Unified Theory of a Law is the missing theory that gives the body of Hohfeld's doctrine legs.

THE MECHANISM IN A BLACK BOX CALLED A UNIFIED THEORY OF A LAW

A Unified Theory of a Law attempts to make our model of a law more accurate and to define a toolkit of techniques that, using the upgraded model, better import, process and export legal meaning. It is powered by the insight that legal fission is possible. The physics of legal fission postulate that a law can be split into two components 1) its words and 2) its structure. They exist independently of each other. Together they constitute a law. While many have taken notice of the words of a law, knowledge of the structure of a law is still rare. The words, like ornaments, adorn the structure of a law. The words change; but the structure stays the same. Like the DNA of a cell, the structure of a law repeats itself over and over again in every instance of a law. To generate a law's meaning, both its words and its structure cooperate. Anyone who wishes to push meaning into or pull meaning out of a law must be mindful of a law's structure. Any failure to respect the structure of a law generates inscrutable legalese and legal misunderstanding.

A UNIFIED THEORY OF A LAW LEVELS THE PLAYING FIELD MAKING THE ORDINARY LEGAL THINKER EQUAL TO THE LEGAL GENIUS

Anyone of ordinary intelligence even the high school and college student can learn A Unified Theory of a Law, and by doing so, elevate his or her understanding of a law to the level of the legal genius. Do not pass this point by without grasping its full significance. Its import is not small. I am making a claim that, on its face, seems preposterous in its extravagance. Yet, I tell you, my claim is true. How is this possible? A law can be likened to a cow that gives the same quantity of milk no matter who does the milking. A legal genius can milk a law for no more meaning than the ordinary legal thinker who understands A Unified Theory of a Law. A law, when properly understood, has only a finite amount of meaning to give. The boundaries that define our knowledge of a law have been discovered, explored and mapped. A Unified Theory of a Law is the map.

A UNIFIED THEORY OF A LAW CAN BE LEARNED IN FEWER THAN THREE HOURS

Give A Unified Theory of a Law no more than three hours of your time, and, in return, your legal understanding shall be perfected.

CONCLUSION

The first commandment of understanding holds that the finite is easier to understand than the infinite. The infinite is simply too big for us to wrap our minds around. Therefore, the trick to understanding anything is to make anything finite. Number and name it and you can understand it. A Unified Theory of a Law applies this commandment to the study of a law. The framework of a law consists of finite number of building blocks. They all have been counted, numbered and named. The number of building blocks is finite and few - a mere handful. Anyone can understand a small number of ideas especially when they are not random and disorganized but arranged systematically into a coherent legal ideology. A Unified Theory of a Law is a safe harbor that keeps us from becoming confused when buffeted by the dizzying storms of meaningless legalese that rumble and flash all too often across the legal landscape. Physicists have struggled in vain for years to discover a unified theory of everything; lawyers, however, have had better success. We now have A Unified Theory of a Law . It teaches that a law is simple, its behavior is regular, and its boundaries have been discovered, explored and mapped. A Unified Theory of a Law is the map. Take it with you as you journey through the legal world.

John Bosco Project Director The Legal Literacy Project

Chapter 2. The Facts*

Although the number of facts is infinite, A Unified Theory of a Law teaches that the best way to arrange them is according to the following principles: The subject of a law is conduct. Conduct flows. It flows from a Source to a Recipient. Conduct that reaches a Recipient is called consequences. Furthermore, a flow of conduct from Source to Recipient is done in circumstances. Circumstances are the context through which conduct flows. Hence, a flow of conduct from Source to Recipient through circumstances is the factual aspect of a law. The factual mantra of A Unified Theory of a Law is conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances. Repeat it over and over again until it falls trippingly from the tongue.

Moreover, conduct flowing from Source to Recipient through circumstances has two important characteristics:

It is mono-directional. It always flows from a Source to a Recipient. The Source is upstream; the Recipient is downstream. Conduct never flows the other way.

Furthermore, it has polarity. The flow is either on or off. When on, a flow of conduct is described as being “affirmative”. When off, as “negative”. There is absolutely no difference between affirmative conduct and negative conduct other than its polarity. The function of the word, 'not' in A Unified Theory of a Law is simply to reverse the polarity of conduct. 'Not' turns affirmative conduct into negative conduct.

Direction and polarity are the two significant properties of conduct as it flows from Source to Recipient through circumstances.

What proof do we have that the subject of a law is conduct? Have you ever wondered why, in general, there are only two types of litigant in a court of law? Why only a plaintiff and a defendant? Why not more? Why not less? There are two types of litigant in a court of law because the focus of a court a law is conduct and conduct has only two ends. On one of its ends is the Source of conduct - who, in a court, is called a defendant; on the other end is the Recipient of conduct - who, in a court, is called a plaintiff. If conduct had one end or three ends instead of two, the number of litigants would be a number other than two.

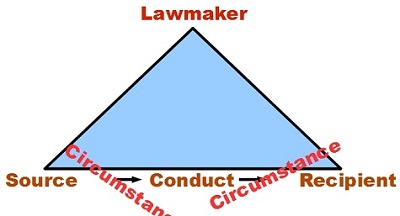

A Unified Theory of a Law has developed a graphic to help you organize the legal ideology being taught. The graphic is called the Triangle of Law. As we progress, it is helpful to keep it in mind. There are three relationships in A Unified Theory of a Law one of which is factual and two of which are legal. Hence, the geometric shape of a triangle whose three sides represent the three relationships found in A Unified Theory of a Law. The factual relationship is depicted at the base of the Triangle of Law. The process of making a law is simple. A Lawmaker perched at the acme of the Triangle of Law despises conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances and picks one of the three core permutations of a law to apply to it rejecting the other two.

John Bosco Project Director The Legal Literacy Project

Chapter 3. The Focus of a Lawmaker*

The focus of a Lawmaker at the acme of The Triangle of Law shifts as she despises conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances at its base. The focus shifts in three ways:

A Lawmaker can focus on the Source doing conduct. (a Source Focused Lawmaker) (this is represented by one of the two legs of the Triangle of a Law),

A Lawmaker can focus on the Recipient receiving conduct. (a Recipient Focused Lawmaker) (this is represented by one of the two legs of the Triangle of a Law), or,

A Lawmaker can be out of focus neither concentrating upon the Source doing conduct nor the Recipient receiving conduct. (a Neither Focused Lawmaker)

In observing the process of making a law, it is important to take notice of the focus of a Lawmaker. Legal discourse is always clearer when everyone is focusing upon the same thing. Confusion arises when participants in legal discourse do not share the same focus.

John Bosco Project Director The Legal Literacy Project

Chapter 4. The Metaphor of Lawmaking*

A metaphor helpful to understand the process of making a law is the image of the hands of a Lawmaker grabbing conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances. Hands grabbing conduct - picture them in your mind. A "hands on" Lawmaker grabs conduct, pushes it from a Source and pulls it to a Recipient through circumstances. A "hands on" Lawmaker interferes and does not leave a flow of conduct alone. A "hands off" Lawmaker does not grab conduct as it flows from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances. There is no pushing or pulling. A "hands off" Lawmaker leaves a flow of conduct alone. A "hands on" Lawmaker regulates; a "hands off" Lawmaker deregulates. Commands are "hands on"; push and pull are present. Permissions are "hands off"; push and pull are absent. A duty pushes; a right pulls; a no-duty (a privilege) does not push; a no-right does not pull.

John Bosco Project Director The Legal Literacy Project

Chapter 5. The Formation of a Lawmaker's Opinion*

THE TWO STAGES OF THE PROCESS OF MAKING A LAW

The process of making a law takes place in two stages: 1) Formation and 2) Externalization. During formation, a Lawmaker forms an opinion about conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances. During externalization, the opinion of the Lawmaker is conveyed. This chapter is about the first stage of the process of making a law, i.e., Formation.

A LAWMAKER'S OPINION ARISES FROM THE FACTS

Conduct flows from a Source to Recipient through circumstances. These are "the facts". They are depicted at the base of The Triangle of Law. A Lawmaker, at the acme of The Triangle of Law, despises "the facts" below and forms an opinion about them. What is the nature of the opinion that a Lawmaker forms about conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances?

LIKE, NEUTRALITY, DISLIKE AND THE SPECTRUM OF OPINIONS

The opinion formed by a Lawmaker about conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances is no different than the opinion that we form about anything.

We like it,

We dislike it or

We just don't care.

Furthermore,

When a Lawmaker likes conduct, a desire to turn on the flow of conduct arises.

When a Lawmaker dislikes conduct, a desire to turn off the flow of conduct arises.

When a Lawmaker is indifferent to conduct, harboring neither like nor dislike, no desire with regard to the polarity of conduct arises.

These are the opinions that a Lawmaker forms about conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances. Like results in a desire for affirmative conduct. Dislike results in a desire for negative conduct. With indifference, however, neither a desire for affirmative conduct nor a desire for negative conduct arises. Because indifference is about both affirmative conduct and negative conduct, we can sever it in twain and treat it as two separate opinions instead of one opinion. Moreover, after indifference is severed in twain to produce two separate opinions, we can reorder our list of opinions so the two opinions dealing with turning off the flow of conduct and the two opinions dealing with turning on the flow of conduct are grouped together. Thus, we can rewrite the opinions of a Lawmaker as follows:

When a Lawmaker likes conduct, a desire to turn on the flow of conduct arises.

When a Lawmaker does not like conduct, a desire to turn on the flow of conduct does not arise.

When a Lawmaker does not dislike conduct, a desire to turn off the flow of conduct does not arise.

When a Lawmaker dislikes conduct, a desire to turn off the flow of conduct arises.

Instead of organizing the opinions of a Lawmaker vertically into a list, they can be organized horizontally onto a spectrum. The spectrum of opinions looks like this: Presence of like --- Absence of like --- Absence of dislike --- Presence of dislike. Of the four opinions, the toughest to understand -- and when understood, the toughness dissipates -- are the two opinions in the middle of the spectrum of opinions. Why? They represent the absence of a thing. The absence of a thing is harder to understand than the presence of a thing. With presence, a thinker needs only to understand the thing itself. With absence, a thinker needs to understand the thing itself and then overlay it with the concept of absence. The two opinions in the middle of the spectrum of opinions are negations. They negate the two opinions at the ends. A negation has two functions: 1) it excludes and 2) it points. A negation excludes the opinion negated from our consideration and, because the number of opinions in the universe of a Lawmaker's opinions is only four, points us to the other two opinions. Please note that the other two opinions are always about the opposite polarity of conduct. When a legal thinker encounters either of the two negation opinions, they tell the legal thinker not to look over here at this polarity of conduct but to look over there at the opposite polarity of conduct. Let me inject a word of warning here. Legal thinkers fall into the trap who think that negation points to only one other opinion. The number of opinions in the universe of opinions available to a Lawmaker is four. When one opinion negates another opinion, two are used up - the negation and the opinion negated - and two are available to the Lawmaker - the two opinions dealing with the opposite polarity of conduct. A Lawmaker who does not like conduct, either dislikes it or does not dislike. A Lawmaker who does not dislike conduct, either likes it or does not like it.

CREATING FOUR HANDLES TO MAKE IT EASIER TO CARRY THE FOUR OPINIONS AROUND

Sometimes the opinions of a Lawmaker are difficult to lift into and out of our understanding. By assigning a number and polarity to each of the four opinions we can build "handles" that make it easier for us to pick them up and carry them around. Borrowing from the binary language of computers, let us assign the number, 0, to represent an opinion where like or dislike are absent. 1 will represent an opinion where like or dislike are present. To indicate whether the opinion is about affirmative conduct or about negative conduct, let us use a + sign to indicate affirmative conduct and a - sign to indicate negative conduct. Hence, affirmative conduct has two opinions: +1 and +0. Negative conduct has two opinions: -1 and -0. The 1 opinions are at the ends of the spectrum of opinions and the 0 opinions are at the middle. 0 is used to represent an absence. 1 is used to represent a presence. A 0 opinion of the same polarity as a 1 opinion simply excludes the 1 opinion from our consideration and points to the other two opinions of the opposite polarity.

+1 = When a Lawmaker likes conduct, a desire to turn on the flow of conduct arises.

+0 = When a Lawmaker does not like conduct, a desire to turn on the flow of conduct does not arise.

-0 = When a Lawmaker does not dislike conduct, a desire to turn off the flow of conduct does not arise.

-1 = When a Lawmaker dislikes conduct, a desire to turn off the flow of conduct arises.

IT TAKES TWO OPINIONS TO MAKE ONE PERMUTATION OF A LAW

The four opinions of a Lawmaker constitute the three permutations of a law. A permutation of a law arises from the opinions of a Lawmaker. Let me again inject a word of warning. A trap lurks in the path of a legal thinker who does not give the concept of polarity its due. A Lawmaker's opinion has two components: 1) affirmative conduct and 2) negative conduct. To clearly understand a permutation of a law, a legal thinker must consider both affirmative conduct and negative conduct not just one or the other. Many legal thinkers have yet to realize that IT TAKES TWO OPINIONS TO MAKE ONE PERMUTATION OF A LAW. Like the double helix of DNA, a pair of opinions constitutes a permutation of a law.

| -1 | -0 | +0 | +1 |

| Negative Regulation | Deregulation or Affirmative Regulation | Deregulation or Negative Regulation | Affirmative Regulation |

| Negative Conduct | Affirmative Conduct | ||

| A Lawmaker dislikes the conduct | A Lawmaker does not dislike the conduct | A Lawmaker does not like the conduct | A Lawmaker likes the conduct |

| Focus is on neither Source nor Recipient | |||

| A Lawmaker desires that the flow of conduct be turned off | A Lawmaker does not desire that the flow of conduct be turned off | A Lawmaker does desire that the flow of conduct be turned on | A Lawmaker desires that the flow of conduct be turned on |

| Focus is on the Source | |||

| A Lawmaker desires a Source to not do the conduct. | A Lawmaker lacks a desire for a Source to not do the conduct. | A Lawmaker lacks a desire for a Source to do the conduct. | A Lawmaker desires a Source to do the conduct. |

| Focus is on the Recipient | |||

| A Lawmaker desires a Recipient to not receive the conduct. | A Lawmaker lacks a desire for a Recipient to not receive the conduct. | A Lawmaker lacks a desire for a Recipient to receive the conduct. | A Lawmaker desires a Recipient to receive the conduct. |

THE THREE PERMUTATIONS OF A LAW ARISE FROM THE PAIRING OF TWO OF THE FOUR OPINIONS OF A LAWMAKER

The chart above entitled the Spectrum of Opinions from which The Three Permutations of a Law Arise consists of four columns entitled, -1, -0, +0, and +1. Negative Regulation results from a combination of the opinions in column -1 and the opinions in column +0. In negative regulation, a Lawmaker reserves the decision whether or not in engage in a course of negative not affirmative conduct to herself and does not delegate it to a Source of conduct. Deregulation results from a combination of the opinions in column -0 and the opinions in column +0. In deregulation, a Lawmaker delegates the decision whether or not in engage in a course of negative conduct or affirmative conduct to its Source and does not reserve it to herself. Affirmative Regulation results from a combination of the opinions in column +1 and the opinions in column -0. In affirmative regulation, a Lawmaker reserves the decision whether or not in engage in a course of affirmative not negative conduct to herself and does not delegate it to a Source of conduct. When the opinions of a Lawmaker is combined to make a permutation of a law, understanding is better when all legal thinkers are on the same page, that is, focusing on the same thing. Therefore, combine opinions that share the same focus.

AMBIGUITY AND COEXISTENCE

Because the absence of a desire for a polarity of conduct is one of the two opinions that appears in both Regulation and Deregulation, it is ambiguous alone and tells us nothing about the governing permutation of a law. When only one permutation is examined and the absence of a desire is detected, the opinions of a Lawmaker toward the other polarity of conduct must be looked at to determine the governing permutation. Not so when the presence of a desire for a polarity of conduct is detected. When the presence of a desire for a polarity of conduct is detected, the permutation of a law is immediately known. It is either affirmative regulation or negative regulation. The opinion of a Lawmaker with regard to the opposite polarity is always an absence of a desire because the presence of desires toward both polarities of conduct cannot co-exist. The pairing of a +1 opinion with a -1 opinion is irrational existing only in theory but not in the real world. A Lawmaker cannot want you to do something and want you to not do something simultaneously. Furthermore, none of the permutations of a law can coexist with each other with regard to the same flow of conduct from Source to Recipient through circumstances. A Lawmaker picks one permutation and rejects the other two. Why? The pair of opinions that underlie each permutation of a law are different for each permutation of a law.

THE CONJUNCTIONS OF LAWMAKING

Because a Lawmaker, during the process of making a law, takes into account both polarities of conduct, it is helpful to take notice of the conjunctions used to join the two polarities of conduct together in a permutation of a law. The conjunction of Regulation is the word, 'not' and the conjunction of Deregulation is the word, 'or'. The opinion of a Lawmaker engaged in affirmative regulation is 'I want affirmative conduct not negative conduct'. The opinion of a Lawmaker engaged in negative regulation is 'I want negative conduct not affirmative conduct'. The opinion of a Lawmaker engaged in deregulation is 'I don't care whether affirmative conduct or negative is done.' In Regulation, the polarity of conduct desired by a Lawmaker is typically the only one expressed. The polarity of conduct not desired is implied. The same is true in Deregulation wherein, typically, only one polarity is expressed and the other implied. This habit is a potential pitfall because it obfuscates the fact that a Lawmaker takes into account both polarities of conduct in each permutation of a law. The habit of expressing only one polarity of conduct and implying the other arises because our view of a legal dispute is often through an adversarial lens. One side takes up one polarity of conduct in their advocacy of a permutation of a law and the other side takes up the opposite polarity. Proponents of 'Thou shall not kill' (See, the chapters on Vehicles and The Nature and Structure of a Legal Arguments) are met by opponents who advocate either 'Thou may kill' or 'Thou shall kill'. In this legal argument, the negative polarity of conduct is pitted against the affirmative polarity.

Synecdoche

Be advised that my usage of the word, 'opinion', is slippery. Technically, a Lawmaker has one opinion about the two polarities of conduct. Each opinion has two components: 1) an affirmative conduct component and 2) a negative conduct component. At times I use the word, opinion, to refer to the opinion itself and at times I use the word, opinion, to refer to its components. Greek rhetoricians, if I am not mistaken, called this synecdoche, referring to the whole by reference to a part and referring to a part by reference to a whole. As long as you are aware of what is being done, however, this mixed usage does not put understanding at risk.

A LAGNIAPPE WITH COMMENTS

As a lagniappe thrown in to make a baker's dozen is a table using just the symbolic shorthand. As a test for your understanding of the opinions of a Lawmaker, determine whether or not you understand what the table and the comments mean. The use of symbolic shorthand consisting of a limited vocabulary of just four words, +1, +0, -0, and -1, brings mathematical precision to the understanding of the opinions that make up the permutations of a law.

| AFFIRMATIVE CONDUCT | NEGATIVE CONDUCT | PERMUTATION OF A LAW |

| +1 | -0 | Affirmative Regulation |

| +0 | -0 | Deregulation |

| +0 | -1 | Negative Regulation |

The opinions available to a Lawmaker are four in number: +1, +0, -0, -1.

+1 equals like and a desire to turn the flow of conduct on

-1 equals dislike and a desire to turn the flow of conduct off

+0 equals an absence of like and an absence of a desire to turn the flow of conduct on

-0 equals an absence of dislike and an absence of a desire to turn the flow of conduct off

(+1 or +0) plus (-1 or -0) equals a permutation of a law. This is the equation that makes a permutation of a law

(+1) plus ( -0) equals affirmative regulation

(+0) plus ( -1) equals negative regulation

(+0) plus ( -0) equals deregulation

In the three permutations of a law more 0 opinions than 1 opinions are found so an understanding of the 0 opinion is important

There is a 0 opinion in every permutation of a law

There is a two 0 opinions in 1 of the 3 permutations of a law

There is a 1 opinion in 2 of the 3 permutations of a law

There is either a 0 or a 1 for each polarity of conduct

The 1 opinions occupy the ends of the spectrum of opinions and the 0 opinions occupy the middle.

-0 excludes -1 and points to +0 and +1

-0 means not -1 but either +0 and +1

+0 excludes +1 and points to -0 or -1

+0 means not +1 but either -0 or -1

+1 and -1 is an irrational pair of opinions

a +1 and a -1 cannot coexist

a +1 only coexists with a -0

a -1 only coexists with a +0

a -0 can coexist with a +0 or a +1

a +0 can coexist with a -0 or a -1

+0 is an opinion found in both negative regulation and deregulation

-0 is an opinion found in both affirmative regulation and deregulation

+0 alone is ambiguous with regard to the permutation of a law

-0 alone is ambiguous with regard to the permutation of a law

+1 alone is unambiguous with regard to the permutation of a law

-1 alone is unambiguous with regard to the permutation of a law

-1 is an opinion only found in negative regulation

+1 is an opinion only found in affirmative regulation

John Bosco Project Director The Legal Literacy Project

Chapter 6. The Externalization of a Lawmaker's Opinion*

THE TWO STAGES OF THE PROCESS OF MAKING A LAW

The process of making a law takes place in two stages:

Formation and

Externalization.

During formation, the opinion of the Lawmaker is formed. During externalization, the opinion is conveyed. This chapter is about the second stage of the process of making a law, i.e., Externalization.

WHAT IS EXTERNALIZATION?

Externalization deals with the vehicles that convey the opinions of a Lawmaker. Onto a vehicle the opinions of a Lawmaker are mounted to convey them to the citizenry. Upon arrival, the opinions are dismounted from their vehicles so the citizenry can learn what their Lawmaker thinks about conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN OPINIONS , VEHICLES AND PERMUTATIONS OF A LAW

Available to a Lawmaker are four opinions. A pair of them make up any single permutation of a law. There is not a vehicle for each opinion. There is a vehicle for each permutation of a law. Actually, there are three vehicles for each permutation of a law when the focuses (foci) of a Lawmaker are taken into account.

The Regulation of Affirmative Conduct

The vehicles that convey the opinion of a Lawmaker at each of the three focuses (foci) for Affirmative Regulation are

A Command for affirmative conduct. This vehicle conveys the opinion that a Lawmaker wants to turn on a flow of conduct. The Lawmaker wants affirmative not negative conduct. The "hands on" Lawmaker grabs the affirmative conduct, pushes it and pulls it.

A duty to do affirmative conduct. This vehicle conveys the opinion that a Lawmaker wants a Source to do affirmative conduct. The "hands on" Lawmaker grabs the affirmative conduct and pushes it from a Source to a Recipient.

A right to receive affirmative conduct. This vehicle conveys the opinion that a Lawmaker wants a Recipient to receive affirmative conduct. The "hands on" Lawmaker grabs the affirmative conduct and pulls it to a Recipient from a Source.

Deregulation

The vehicles that convey the opinion of a Lawmaker at each of the three focuses (foci) for Deregulation are

A Permission for affirmative or negative conduct. This vehicle conveys the opinion that a Lawmaker lacks a desire to turn on a flow of conduct and lacks a desire to turn off a flow of conduct. The Lawmaker lacks a desire for either polarity of conduct. The "hands off" Lawmaker does not grab the conduct, does not push it and does not pull it. The Lawmaker lets the conduct alone.

A no-duty to do affirmative or negative conduct. This vehicle conveys the opinion that a Lawmaker lacks a desire for a Source to do affirmative conduct and lacks a desire for a Source to do negative conduct. The "hands off" Lawmaker does not grab either polarity of conduct and does not push it from a Source to a Recipient. The Lawmaker lets the conduct alone.

A no-right to receive affirmative or negative conduct. This vehicle conveys the opinion that a Lawmaker lacks a desire for a Recipient to receive either polarity of conduct. The "hands off" Lawmaker does not grab the conduct and does not pull it to a Recipient from a Source. The Lawmaker lets the conduct alone.

The Regulation of Negative Conduct

The vehicles that convey the opinion of a Lawmaker at each of the three focuses (foci) for Negative Regulation are

A Command for negative conduct. This vehicle conveys the opinion that a Lawmaker wants to turn off a flow of conduct. The Lawmaker wants negative not affirmative conduct. The "hands on" Lawmaker grabs the flow of conduct, pushes it and pulls it.

A duty to do negative conduct. This vehicle conveys the opinion that a Lawmaker wants a Source to do negative conduct. The "hands on" Lawmaker grabs the negative conduct and pushes it from a Source to a Recipient.

A right to receive negative conduct. This vehicle conveys the opinion that a Lawmaker wants a Recipient to receive negative conduct. The "hands on" Lawmaker grabs the negative conduct and pulls it to a Recipient from a Source.

The Marriage of an Opinion and a Vehicle

The pair of opinions is the definition of the vehicle that conveys them. Do not divorce one from the other. Divorce leads to misunderstanding.

Warning

Often only one polarity of conduct is expressed in a vehicle. This tends to make us forget that there are two opinions in every permutation of a law. Be forewarned.

John Bosco Project Director The Legal Literacy Project

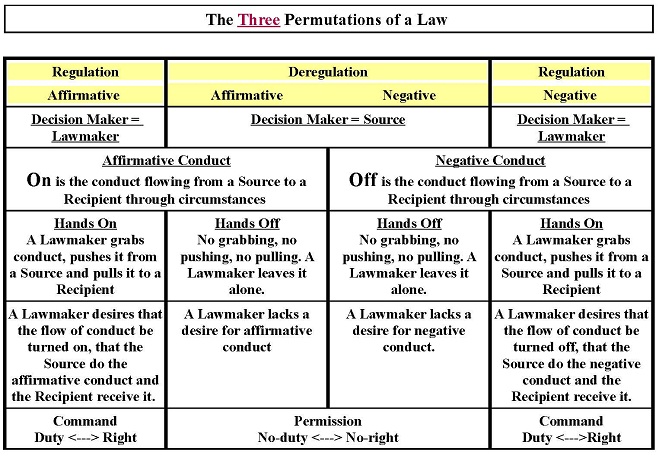

Chapter 7. The Three Permutations of a Law*

A SYSTEM

As proof that the ideas of A Unified Theory of a Law systematically arrange themselves into a coherent legal ideology, a table has been created showing the connections amongst the three permutations of a law, who decides whether or not to engage upon a course of conduct, the two polarities of conduct, the metaphors that help us understand the opinions of a Lawmaker, the opinions of a Lawmaker themselves, and the vehicles that convey the opinions.

THE CURRENCY OF A LAWMAKER

An analogy helpful to understand what a Lawmaker does in the process of making a Law is currency. The currency that a Lawmaker gets to "spend" during the process of making a law consists of three (3) coins. The names of the three (3) coins are:

Affirmative Regulation

Deregulation and

Negative Regulation

Each coin has three sides: two outsides and a middle. The coins have three sides because a Lawmaker has three focuses (foci). One side is for a Lawmaker who focuses on the Source doing conduct. Another side is for a Lawmaker who focuses on the Recipient receiving conduct. The middle is reserved for a Lawmaker whose focus is amorphous on neither or both the Source nor the Recipient. Each side holds 1) a Lawmaker's opinion, 2) the vehicle used by the Lawmaker to convey the opinion and 3) the metaphor that helps explain the opinion. A Lawmaker engages in lawmaking by "applying" one of the three coins to conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances. The three (3) coins are the only things that a Lawmaker can "spend" in making a law. Hence, it is helpful to keep these four objects in mind. Three coins and one instance of conduct flowing from Source to Recipient through circumstances. The process of Lawmaking involves these four objects.

OCCAM'S RAZOR AND THE LAWMAKING PROCESS

The doctrine of Occam’s Razor holds that the simplest solution is often the best solution. Therefore, if three (3) coins are sufficient to give our minds a high fidelity model of the lawmaking process then there is no need for any more. In short, any additional "coins" would be counterfeit.

John Bosco Project Director The Legal Literacy Project

Chapter 8. The Decision Maker*

Who decides? The Lawmaker or the Source of conduct. The primary characteristic of the process of making a law is who gets to make the decision about whether or not to engage in a course of conduct. Sometimes, a Lawmaker wants to make the decision for the Source. This is called regulation. With regulation, the Source has no choice but the Lawmaker's. The Lawmaker substitutes his decision for the Source's. At other times, a Lawmaker does not want to regulate either the affirmative conduct or the negative conduct. When there is an absence of intervention by a Lawmaker in both affirmative and negative conduct, a Lawmaker is allowing the Source of conduct to make the decision. This is called deregulation. In deregulation, the Source has autonomy, liberty and freedom. It is up to the Source to decide. You cannot tell whether or not a Lawmaker has put the decision whether or not to engage in conduct into the hands of a Source of conduct or reserved it to himself without looking at the pair of opinions a Lawmaker forms about each polarity of conduct. It is only when a Lawmaker desires not to intervene with regard to both polarities that the decision whether or not to engage in conduct is the Source's to make.

Legality versus Illegality

Conduct is legal in two ways but illegal in only one. Conduct is legal if it is done or not done in accordance with a permission or a command. Conduct is illegal only if it is done or not done contrary to a command. It is legal for a motorist to drive through a green traffic light not because a Lawmaker has permitted a motorist to do so but because a Lawmaker has required a motorist to do so.

John Bosco Project Director The Legal Literacy Project

Chapter 9. Matter and Antimatter*

Matter and Antimatter annihilates each other. So does a permission and a command. Although it is legal for a motorist to drive through a green light. It is legal because it is mandatory not because it is permissible. Why is it not both? Why can it not be said that a Lawmaker issues a permission allowing a motorist to drive through a green light and a command ordering a motorist to drive through a green light? Why cannot "Thou may drive through a green light" and "Thou shall drive through a green light" coexist? Driving through a green light is the affirmative polarity of conduct. Viewing this affirmative polarity of conduct in the 'context' of the METAPHOR of Lawmaking, a Lawmaker can be either "hands on" or "hands off" with regard to it. A Lawmaker cannot be "hands on" and "hands off" at the same time. Holding the opinion that a motorist is both commanded and permitted to drive through a green light is saying that a Lawmaker can be "hands on" and "hands off" at the same time. Impossible. Viewing this affirmative polarity of conduct in the 'context' of the OPINION of a Lawmaker, a Lawmaker either possesses a desire that the affirmative conduct be done or lacks a desire that the affirmative conduct be done. A Lawmaker cannot possess and lack a desire simultaneously. Holding the opinion that a motorist is both commanded and permitted to drive through a green light is saying that a Lawmaker can both harbor a desire and lack a desire at the same time. Impossible. Viewing this affirmative polarity of conduct in the 'context' of the VEHICLES a Lawmaker uses to convey her opinion, a Lawmaker either issues a command that the affirmative conduct be done (Affirmative Regulation) or issues a permission allowing the doing of the affirmative conduct and the doing of the negative conduct (Deregulation). Holding the opinion that a motorist is both commanded and permitted to drive through a green light is saying that a Lawmaker can issue both a command and a permission with regard to the same polarity of conduct. Impossible. A Lawmaker always addresses both polarities of conduct in any permutation of a law. Those who maintain that "Thou may drive through a green light" and "Thou shall drive through a green light" can coexist, ignore this principle. There is no such thing as a half permission. Either a Lawmaker delegates the decision whether to go or stop at a green light to a Source doing conduct via Deregulation or reserves the decision for herself via Regulation. There is no in between. There is a real difference between a command and a permission. A permission is not a command and a command is not a permission. Sadly, our law schools do not make this distinction clear and, hence, many lawyers do not fully understand the difference.

John Bosco Project Director The Legal Literacy Project

Chapter 10. Extrapolation*

The relationships of A Unified Theory of a Law can be depicted on The Triangle of Law because its three main characters - Lawmaker, Source and Recipient - give rise to three relationships, two of which are legal and one of which is factual. A Lawmaker exists solely in the legal world. A Source and a Recipient can exist in both the factual and the legal world. They enter the legal world when a Lawmaker binds a token to them. Before a lawmaker binds a token to them, they exist solely in the factual world. When a lawmaker binds a legal token - a duty, privilege (no-duty), right or no-right - to someone other than a Source or a Recipient, the lawmaker is engaged in extrapolation. Beware of Extrapolation. It is usually pathological. The legal situation can often be reinterpreted to conform to the doctrine of A Unified Theory of a Law instead of warping it. One example of a legal thinker trying to warp the doctrine of A Unified Theory of a Law occurs when an attempt is made to disconnect a Source from a Recipient in a flow of conduct. A flow of conduct from a Source to a Recipient in circumstances is implacable. Therefore, it is factually impossible to disconnect its Source and Recipient. Hence, when a legal thinker wants to give the Source a duty to do the affirmative conduct but give the Recipient a no-right to receive the affirmative conduct, A Unified Theory of a Law tells us that this is impossible. A Lawmaker can either turn the flow of conduct on, or turn it off or not care whether it is on or off. A Lawmaker cannot make the flow of conduct do a U turn. [Note: when the flow of conduct is itself reflexive a U turn is possible but not because a Lawmaker is making it so] A Lawmaker who wants a Source to do affirmative conduct also wants a Recipient to receive affirmative conduct whether the Lawmaker likes it or not. A Lawmaker who does not care whether or not a Source does either polarity of conduct also does not care whether or not a Recipient receives either polarity of conduct, whether the Lawmaker likes it or not. A Lawmaker who wants a Source to do negative conduct also wants a Recipient to receive negative conduct whether the Lawmaker likes it or not. With regard to the same flow of conduct from Source to Recipient through circumstances, a Lawmaker cannot simultaneously issue a command to turn on the flow, a command to turn off the flow and a permission allowing the flow to be on or off. This would be a conflict of laws. Only one permutation can exist at a time. King Cnut , a lawmaker of old, knew that some things were impossible.

John Bosco Project Director The Legal Literacy Project

Chapter 11. Expression*

When it comes to legal expression, it is often best to use a sentence with three clauses:

a main clause,

an if clause, and

an even though clause.

In the main clause is expressed the command or permission and hence, one of the legal tokens, i.e., the right, duty, no-right or privilege. In the if clause is placed any circumstance necessary and sufficient to trigger the main clause. In the even though clause is placed any unnecessary circumstances.

John Bosco Project Director The Legal Literacy Project

Chapter 12. Evaluation*

After A Unified Theory of a Law is employed to visualize the three permutations of a law available to a Lawmaker with regard to any particular instance of conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances, the real debate begins. What are the merits and demerits of each permutation of a law? Why prefer one permutation over another? Why is a permutation good? Why is a permutation bad? What will a permutation of a law accomplish? What won't it accomplish? The evaluation of the permutations of a law for their virtues and vices is where energy ought to be expended. These are the hard questions that A Unified Theory of a Law cannot answer.A Unified Theory of a Law makes the issue clear. Only our hearts and souls can provide the answers to the hard questions.

Chapter 13. Closing Statement*

"The poet's eye, in a fine frenzy rolling, doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven; And, as imagination bodies forth the forms of things unknown, the poet's pen turns them to shapes, and gives to airy nothing a local habitation and a name." Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream" (5.1.7-12)

The imagination of legal scholars over the centuries has bodied forth, to paraphrase Shakespeare, the forms of legal things unknown. In A Unified Theory of a Law, they are given a local habitation and a name. A Unified Theory of a Law does not present them to you randomly floating independently in a hodgepodge of disorganized ideas. A Unified Theory of a Law organizes them and then presents them to you as parts of a coherent legal system.

The system that is A Unified Theory of a Law is well-defined. Please do not pass blithely over the word, 'system', as though it is unimportant. It is very important. Ask yourself, "What system do you use to import, process and export legal meaning?" In all likelihood, you do not have a system. Your law school left a gaping hole in your legal education that the proverbial truck can be driven through. Instead of taking umbrage at my exposing the hole in your legal education, fill the hole with A Unified Theory of a Law or any alternative doctrine - if you can find it - that systematically imports, processes and exports legal meaning.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the Danish author, Hans Christian Andersen, wrote a story called, “The Emperor’s New Clothes”. Anderson told a tale of a king and a kingdom who deceived themselves into thinking that an imaginary set of clothes were real. When a guileless boy, upon seeing the king dressed in the imaginary set of clothes, exclaimed, “But he hasn't got anything on", the bubble of belief was burst and the illusion shattered. Andersen’s story is an allegory for lawyers. Too many of the laws that govern us are naked of meaning. Yet, we have convinced ourselves otherwise. A Unified Theory of a Law opens your eyes like the guileless boy in Anderson's story so you won't fool yourself into thinking that the meaningless is meaningful.

An invasion of armies can be resisted,but not an idea whose time has come.Victor Hugo

John Bosco Project Director The Legal Literacy Project

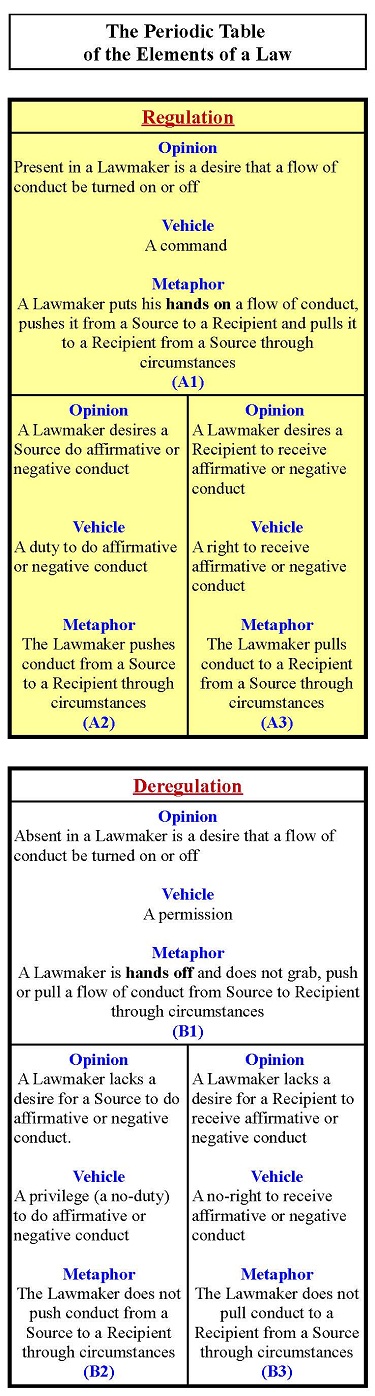

Chapter 14. The Periodic Table of the Elements of a Law*

Chapter 15. Glossary of a Unified Theory of a Law*

ACME

The acme of the Triangle of a Law is the perch from which a Lawmaker despises conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances at the base below. It is the top of the Triangle of a Law. Below at the corners of the base are a Source doing conduct and a Recipient receiving conduct.

AFFIRMATIVE

Conduct is affirmative when its flow is on.

BASE

The base of the Triangle of a Law is where the facts are located. The optimal arrangement of the facts in A Unified Theory of a Law is as conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances. At he base of the Triangle of a Law, the Source doing conduct is at one end and at the other end is a Recipient receiving conduct. The conduct flows from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances.

BENEFIT AND BURDEN

Conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances can carry to a Recipient benefits and burdens. A Recipient has a right when a Lawmaker wants a Recipient to receive conduct regardless of whether the conduct carries a benefit or a burden to the Recipient. In other words, the factual benefit or burden of a flow of conduct is irrelevant to the definition of a command, duty, right, permission, privilege (no-duty) and no-right. A Lawmaker who wants a Recipient to receive conduct carrying horrible consequences still bestows a right upon the Recipient.

BINDING

Binding occurs when a Lawmaker gives one of the four tokens - a duty, a privilege (no-duty), right or no-right - to a Source or to a Recipient. Think of a general pinning a medal onto the tunic of a soldier.

CIRCUMSTANCES

Circumstances are the facts that surround a flow of conduct from a Source to a Recipient. They are the context in which conduct flows. Conduct flows through them.

COMMAND

A command is a vehicle that carries a Lawmaker's opinion to the citizenry. It is used when the focus of a Lawmaker is broad upon all of the conduct flowing from Source to Recipient through circumstances. It is synonymous with a duty and a right, which are vehicles used when a Lawmaker narrows her focus. A command, duty and a right are the three vehicles of Regulation. It means that a Lawmaker holds a desire for affirmative conduct or a Lawmaker holds a desire for negative conduct.

CONDUCT

At one end of a flow of conduct is a Source; at the other end is a Recipient. In short, conduct has two ends. This is mirrored in a Court by a Plaintiff and a Defendant. The Defendant is the Source and the Plaintiff is the Recipient. Conduct flows. It is the thoughts, words and deeds that flow from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances. The flow of conduct has the property of polarity. It is either flowing or not flowing. When the flow of conduct is on, the conduct is affirmative. When the flow of conduct is off, the conduct is negative. Conduct also possess the property of direction. The flow of conduct is mono-directional. It always flows from a Source to a Recipient. The Source is upstream; the Recipient downstream. When we talk about a particular instance of conduct, we use the gerundial form of the verb e.g. driving.

CONJUNCTIONS OF REGULATION AND DEREGULATION

'OR' is the conjunction of Deregulation and 'NOT' the conjunction of Regulation. They join together affirmative conduct and negative conduct. 'OR' indicates that both permutations of conduct are available to a Source doing conduct. 'NOT' indicates the permutation of conduct that a Lawmaker does not desire. These conjunctions are important because they emphasize the fact that each permutation of a law is made from a Lawmaker's opinion about both polarities of conduct. In other words, it takes two opinions to make one permutation of a law.

CONSEQUENCES

Conduct that arrives at a Recipient is known as consequences.

DECISION TO ENGAGE IN A COURSE OF CONDUCT

The hallmark of the process of making a law is who decides whether or not to engage on a course of conduct: the Lawmaker or the Source. A Lawmaker either reserves the decision to himself or delegates it to the Source. Regulation occurs when a Lawmaker reserves the decision to himself. Deregulation occurs when a Lawmaker delegates the decision to a Source.

DEREGULATION

Deregulation is one of the three permutations of a law. The other two are Affirmative Regulation and Negative Regulation. A Lawmaker applies one of the three permutations of a law to any single instance of conduct flowing from Source to Recipient through circumstances. In Deregulation a Lawmaker lacks a desire for affirmative conduct and lacks a desire for negative conduct. The vehicles that convey Deregulation are a permission, privilege (no-duty) and no-right. A Lawmaker issues a permission and binds a privilege (no-duty) to a Source doing conduct and a no-right to a Recipient receiving conduct. In Deregulation a Lawmaker is "hands off". There is no pushing of conduct from a Source. There is no pulling of conduct to a Recipient. The Lawmaker leaves the conduct alone. In Deregulation, the Source doing conduct decides whether to engage in a course of conduct. The Lawmaker delegates the decision to the Source doing conduct. The Lawmaker does not reserve the decision to himself.

Warning

Every permutation of a law consists of two opinions. The presence of a desire toward one polarity of conduct discloses the permutation of a law. However the absence of a desire toward one polarity of conduct is ambiguous. It does not disclose the permutation of a law. When an absence of a desire is detected both polarities of conduct must be examined to determine the permutation of a law.

DESIRE FOR AFFIRMATIVE CONDUCT - ABSENT

In the process of making a law, a Lawmaker forms opinions about both polarities of conduct flowing from a Source to Recipient through circumstances. One of the four opinions is the absence of a desire for affirmative conduct. Narrowing the focus of a Lawmaker to the Source we can phrase this by saying that a Lawmaker lacks a desire for a Source to do affirmative conduct. Narrowing the focus of a Lawmaker to the Recipient we can phrase this by saying that a Lawmaker lacks a desire for a Recipient to receive affirmative conduct. It takes two opinions to constitute a permutation of a law. Both polarities of conduct must be consider by a Lawmaker who is making a law. When a desire for affirmative conduct is absent it is impossible to tell the permutation of a law. The absence of a desire is ambiguous. The other polarity of conduct must be examined. If the absence of a desire for affirmative conduct is coupled with the absence of a desire for negative conduct, a Lawmaker is engaged in Deregulation. If the absence of a desire for affirmative conduct is coupled with the presence of a desire for negative conduct, a Lawmaker is engaged in Negative Regulation.

DESIRE FOR AFFIRMATIVE CONDUCT - PRESENT

In the process of making a law, a Lawmaker forms opinions about both polarities of conduct flowing from a Source to Recipient through circumstances. One of the four opinions is the presence of a desire for affirmative conduct. Narrowing the focus of a Lawmaker to the Source we can phrase this by saying that a Lawmaker desires a Source to do affirmative conduct. Narrowing the focus of a Lawmaker to the Recipient we can phrase this by saying that a Lawmaker desires a Recipient to receive affirmative conduct. It takes two opinions to constitute a permutation of a law. Both polarities of conduct must be consider by a Lawmaker who is making a law. The presence of a desire, however, is unambiguous. The presence of a desire for affirmative conduct is accompanied only by an absence of a desire for negative conduct. When a desire for affirmative conduct is present, the Lawmaker is engaged in Affirmative Regulation.

DESIRE FOR NEGATIVE CONDUCT - ABSENT

In the process of making a law, a Lawmaker forms opinions about both polarities of conduct flowing from a Source to Recipient through circumstances. One of the four opinions is the absence of a desire for negative conduct. Narrowing the focus of a Lawmaker to the Source we can phrase this by saying that a Lawmaker lacks a desire for a Source to do negative conduct. Narrowing the focus of a Lawmaker to the Recipient we can phrase this by saying that a Lawmaker lacks a desire for a Recipient to receive negative conduct. It takes two opinions to constitute a permutation of a law. Both polarities of conduct must be consider by a Lawmaker who is making a law. When a desire for negative conduct is absent it is impossible to tell the permutation of a law. The absence of a desire is ambiguous. The other polarity of conduct must be examined. If the absence of a desire for negative conduct is coupled with the absence of a desire for affirmative conduct, a Lawmaker is engaged in Deregulation. If the absence of a desire for negative conduct is coupled with the presence of a desire for affirmative conduct, a Lawmaker is engaged in Affirmative Regulation.

DESIRE FOR NEGATIVE CONDUCT - PRESENT

In the process of making a law, a Lawmaker forms opinions about both polarities of conduct flowing from a Source to Recipient through circumstances. One of the four opinions is the presence of a desire for negative conduct. Narrowing the focus of a Lawmaker to the Source we can phrase this by saying that a Lawmaker desires a Source to do negative conduct. Narrowing the focus of a Lawmaker to the Recipient we can phrase this by saying that a Lawmaker desires a Recipient to receive negative conduct. It takes two opinions to constitute a permutation of a law. Both polarities of conduct must be consider by a Lawmaker who is making a law. The presence of a desire, however, is unambiguous. The presence of a desire for negative conduct is accompanied only by an absence of a desire for affirmative conduct. When a desire for negative conduct is present, the Lawmaker is engaged in Negative Regulation.

DESPISE

Take away the negative connotation and despise signifies that a Lawmaker looks down from his perch at the acme of the Triangle of a Law to the conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances at its base. One can imagine how the meaning of despise acquired its negative connotation when one thinks about the arrogance of many Lawmakers who prefer to place burdens on others and not upon themselves.

DIRECTION

Direction is a property of a flow of conduct from Source to Recipient through circumstances. The flow of conduct is one way, i.e., mono-directional. The Source is upstream; the Recipient is downstream.

DUTY

A duty is a vehicle that carries a Lawmaker's opinion to the citizenry. it is used when the focus of a Lawmaker is upon a Source. A Lawmaker binds a duty onto a Source. It is synonymous with a command and a right. A duty, command and right are the three vehicles of Regulation. It means that a Lawmaker wants a Source to do either affirmative or negative conduct.

EVEN THOUGH CLAUSE OF A THREE PART SENTENCE

The even though clause of a three part sentence holds facts that are irrelevant for the main clause of a three part sentence to operate. The other parts of a three part sentence are a main clause and an if clause.

EXTERNALIZE

Externalization is one of the two stages of the process of making a law. Having formed an opinion with regard to the polarities of a flow of conduct in the first stage of the process of making a law, a Lawmaker externalizes the opinion formed by placing it on a vehicle that carries them to the citizenry. Externalization deals with the vehicles that carry a Lawmaker's opinion to the citizenry. Regulation and Deregulation have their own vehicles and the number of them is three. The vehicles of Regulation are synonymous with each other; the vehicles of Deregulation are also synonymous with each other. There are three because the focus of a Lawmaker is three, that is, there is a vehicle for each of the focuses (foci) of a Lawmaker. Command, duty, right are the vehicles of Regulation. Permission, privilege (no-duty) and no-right are the vehicles of Deregulation.

EXTRAPOLATION

Extrapolation occurs when a Lawmaker binds a right, duty, no-right or privilege (no-duty) to someone other than a Source or a Recipient.

FACTS

Although the number of facts is infinite, the best way to arrange them is as conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances.

FLOW

Conduct flows from a Source to Recipient through circumstances. In other words, conduct is dynamic not static. It is either on or off. When on, conduct is affirmative; When off, conduct is negative.

FOCUS

Focus is the target of scrutiny of a Lawmaker who despises conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances. From the acme of The Triangle of Law, a Lawmaker focuses upon a Source doing conduct or a Recipient receiving conduct. These focuses (foci) are represented by the legs of The Triangle of Law. The focus of a Lawmaker, however, may not be concentrated on a Source or a Recipient. It may be broader, more amorphous. It may try to take in conduct in its entirety as it flows from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances. In short, the focus of a Lawmaker shifts from Source, to Recipient, to neither Source nor Recipient. Three, therefore, is the number of focuses (foci) of a Lawmaker.

"HANDS OFF" LAWMAKER

A METAPHOR helps us to understand what a Lawmaker does and does not do in Regulation and Deregulation. The image of the metaphor involves the hands of a Lawmaker and conduct. A "hands off" Lawmaker leaves conduct alone. A "hands off" Lawmaker does not grab conduct. There is no pushing of conduct from a Source. There is no pulling of conduct to a Recipient. A "hands off" Lawmaker is engaged in Deregulation. See also, "hands on" Lawmaker.

"HANDS ON" LAWMAKER

A METAPHOR helps us to understand what a Lawmaker does and does not do in Regulation and Deregulation. The image of the metaphor involves the hands of a Lawmaker and conduct. A "hands on" Lawmaker grabs the throat of conduct, pushes it from a Source and pulls it toward a Recipient. A "hands on" Lawmaker does not leave conduct alone. A "hands on" Lawmaker is engaged in Regulation. See also, "hands off" Lawmaker.

IF CLAUSE OF A THREE PART SENTENCE

The if clause of a three part sentence holds facts that are necessary and sufficient for the main clause of a three part sentence to operate. The other parts of a three part sentence are a main clause and an even though clause.

ILLEGALITY

Conduct is legal in two ways but illegal in only one. Conduct is legal if done or not done in accordance with a permission or a command. In other words, conduct is legal if the conduct is mandatory or if the conduct is permissible. Being mandatory and being permissible are two entirely different things. Conduct is illegal if done or not done contrary to a command.

A LAW

A Law is the fruit of a process in whose first stage a Lawmaker forms an opinion about the two polarities of conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances and in whose second stage the opinion formed is externalized by loading it onto a vehicle for conveyance to the citizenry. A Law with regard to any particular instance of conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances comes in any of three permutations: 1) Affirmative Regulation, 2) Deregulation and 3) Negative Regulation.

LAWMAKER

A Lawmaker is the person who picks one permutation of a law from a total of three and applies it to conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances. A Lawmaker is perched at the acme of the Triangle of a Law and despises the facts at its base.

LAWMAKING

The process of making a law consists of a Lawmaker forming an opinion about the two polarities of conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances and, having formed an opinion, externalizing it by loading it onto a vehicle for conveyance to the citizenry. The process boils down to a Lawmaker picking one of the three permutations of a law and applying it to the facts. A legal thinker needs to be mindful of the following in trying to understand a law:

the OPINION of a Lawmaker (four are possible and two - one for each polarity - are needed to constitute a permutation of a law),

the VEHICLES that convey the opinion of a Lawmaker (there are three for Regulation and three for Deregulation),

the METAPHOR helping us to understand what a Lawmaker does and does not do in Regulation and Deregulation and

the FOCUS of a Lawmaker on conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances (there are three).

A law can be discussed within any of these four "contexts" and it is helpful to the legal thinker to know in which context she is located when talking about a law.

LEAVE IT ALONE

A METAPHOR helps us to understand what a Lawmaker does and does not do in Regulation and Deregulation. The image of the metaphor involves the hands of a Lawmaker and conduct. Leaving it alone explains what a Lawmaker is not doing during Deregulation. During Deregulation the Lawmaker leaves the conduct alone. There is no push. There is no pull. The Lawmaker is "hands off". A Lawmaker lacks a desire for affirmative conduct and lacks a desire for negative conduct.

LEGALITY

Conduct is legal in two ways but illegal in only one. Conduct is legal if done or not done in accordance with a permission or a command. Conduct is illegal if done or not done contrary to a command. In other words, conduct is legal if the conduct is mandatory or if the conduct is permissible. Being mandatory and being permissible are two entirely different things.

LEGAL DISCOURSE, RECOMMENDATIONS

Talking about a law is different than talking about a cheese or talking about a car. Although a law is simple, its nature is different than a cheese or a car. Therefore, it is recommended that the legal thinker be mindful of the "context" of any legal discourse. All legal discourse that takes place within four "contexts":

the OPINION of a Lawmaker (four are possible and two - one for each polarity - are needed to constitute a permutation of a law),

the VEHICLES that convey the opinion of a Lawmaker (there are three for Regulation and three for Deregulation),

the METAPHOR helping us to understand what a Lawmaker does and does not do in Regulation and Deregulation and

the FOCUS of a Lawmaker on conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances (there are three).

It is important for a legal thinker to be aware of the "context" of a legal discussion. All too often, participants blunder from one context to another context haphazardly. For instance, one participant in legal discourse may be focusing on the Source doing conduct while another upon the Recipient receiving conduct. This leads to confusion. Shifting from context to context is fine if it is done purposefully.

LEGAL FISSION

A Unified Theory of a Law is powered by the insight that legal fission is possible. The physics of legal fission postulate that a law can be split into two components: 1) its words and 2) its structure. They exist independently of each other. Together they constitute a law. While many have taken notice of the words of a law, knowledge of the structure of a law is still rare. The words, like ornaments, adorn the structure of a law. The words change; but the structure stays the same. Like the DNA of a cell, the structure of a law repeats itself over and over again in every instance of a law. To generate a law's meaning, both its words and structure cooperate. Anyone who wishes to push meaning into or pull meaning out of a law must be mindful of a law's structure. Any failure to respect the structure of a law generates inscrutable legalese and legal misunderstanding.

LEGAL THINKER

A Legal Thinker observes the process of making a law.

LEGS

The legs of the Triangle of a Law represent the relationships between a Lawmaker and a Source doing conduct and a Lawmaker and a Recipient receiving conduct. They illustrate two of the three focus (foci) of a Lawmaker. The focus of a Lawmaker can be upon 1) the Source doing conduct, 2) the Recipient receiving conduct or 3) imprecisely on neither or both of these.

LOOPHOLE

A loophole is a circumstance that, when added to the mix, changes one permutation of a law into another.

THE MAIN CLAUSE OF A THREE PART SENTENCE

The main clause of a three part sentence holds "the law". In it is a command, a permission, a right, a duty, a no-right or a privilege (no-duty). The other parts of a three part sentence are an if clause and an even though clause.

MAP

The boundaries that define a law have been discovered, explored and mapped. A Unified Theory of a Law is the map. Take it with you on your journey through the legal world.

MAY

The word, 'may', is a helping verb. It appears in sentences that are permissions and indicates what grammarians call the permissive mood. It is a clue to Deregulation.

METAPHOR FOR THE PROCESS OF MAKING A LAW

The image of the hands of a Lawmaker and conduct is a helpful metaphor for understanding the process of making a law. A Lawmaker is either "hands on" or "hands off". A "hands on" Lawmaker has her hands around conduct. She pushes conduct from a Source. She pulls conduct to a Recipient. A "hands on" Lawmaker is a Lawmaker who is regulating. A "hands on" Lawmaker does not leave conduct alone. A "hands off" Lawmaker leaves conduct alone. There is no push. There is no pull. A "hands off" Lawmaker is a Lawmaker who is deregulating.

MODEL OF A LAW

In our heads is a model of law. We use it to makes sense of the laws we meet in the world. A high fidelity model gives us a fair and accurate representation of a law. A low fidelity model gives us only a poor approximation. A Unified Theory of a Law attempts to upgrade your model of a law. Note: the model of a law is akin to a noun and the techniques in the toolkit are akin to verbs.

NEGATIVE

Conduct is negative when its flow is off.

NOT

The word, 'not', changes the polarity of conduct to off from on. 'Not' also is a conjunction of Regulation joining together affirmative conduct and negative conduct and indicating the permutation not desired by a Lawmaker.

NO-DUTY

A no-duty is a vehicle that carries a Lawmaker's opinion to the citizenry. it is used when the focus of a Lawmaker is upon a Source. A Lawmaker binds a no-duty onto a Source. It is synonymous with a permission and a no-right. A no-duty, permission, and a no-right are the three vehicles of Deregulation. It means that a Lawmaker lacks a desire for a Source to do affirmative and lacks a desire for a Source to do negative conduct. Another word for a privilege is a privilege.

NO-RIGHT

A no-right is a vehicle that carries a Lawmaker's opinion to the citizenry. It is used when the focus of a Lawmaker is upon a Recipient. A Lawmaker binds a no-right onto a Recipient. It is synonymous with a permission and a privilege (no-duty). A no-right, permission and a privilege (no-duty) are the three vehicles of Deregulation. It means that a Lawmaker lacks a desire that a Recipient receive affirmative and lacks a desire that a Recipient receive negative conduct.

OPINION

The first stage of the process of making a law consists of a Lawmaker forming an opinion with regard to conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances. The Lawmaker forms an opinion about both polarities of a flow of conduct. A broad focused Lawmaker can form the following opinions:

holds a desire for affirmative conduct

lacks a desire for affirmative conduct

lacks a desire for negative conduct

holds a desire for negative conduct

The opinions can be rewritten if the focus of the Lawmaker narrows to a Source doing conduct or a Recipient receiving conduct. If the focus of a Lawmaker is narrowed to a Source, the opinions would look like

holds a desire for a Source to do affirmative conduct

lacks a desire for a Source to do affirmative conduct

lacks a desire for a Source to do negative conduct

holds a desire for a Source to do negative conduct

If the focus of a Lawmaker is narrowed to a Recipient, the opinions would look like

holds a desire for a Recipient to receive affirmative conduct

lacks a desire for a Recipient to receive affirmative conduct

lacks a desire for a Recipient to receive negative conduct

holds a desire for a Recipient to receive negative conduct

To have a permutation of a law, a Lawmaker must form an opinion about each of the polarities of conduct. A desire for affirmative conduct and a lack of desire for negative conduct constitute Affirmative Regulation. A lack of desire for affirmative conduct and a lack of desire for negative conduct constitute Deregulation. A desire for negative conduct and a lack of desire for affirmative conduct constitute Negative Regulation. A legal thinker looks at both permutations of a law serially, i.e., first one then the other. The detection of the presence of a desire when looking at the first permutation is unambiguous. It definitively indicates Regulation. Why? A desire for one polarity of conduct and a desire for the other polarity of conduct cannot coexist. They are like matter and anti-matter. A Lawmaker cannot want you to do something and simultaneously want you to not do something. The absence of a desire, however, is ambiguous. The absence of a desire can coexist with both the presence of a desire and the absence of a desire for the opposite polarity. Hence, both polarities must be scrutinized when an absence of desire is first detected in order to determine the permutation of a law.

OR

'OR' is a conjunction of Deregulation joining together affirmative conduct and negative conduct and indicating that both permutations of conduct are available to a Source doing conduct.

PERMISSION

A permission is a vehicle that carries a Lawmaker's opinion to the citizenry. It is used when the focus of a Lawmaker is broad upon all of the conduct flowing from Source to Recipient through circumstances. It is synonymous with a privilege (no-duty) and a no-right, which are vehicles used when a Lawmaker narrows her focus. A permission, a privilege (no-duty) and a no-right are the three vehicles of Deregulation. It means that a Lawmaker lacks a desire for affirmative conduct and a Lawmaker lacks a desire for negative conduct.

PERMUTATION

Available to a Lawmaker with regard to any single instance of conduct flowing from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances are three permutations of a law: 1) Affirmative Regulation, 2) Deregulation or 3) Negative Regulation. A Lawmaker picks one of the three permutations of a law and rejects the other two during the process of making a law. There are not sixteen permutations; there are not six permutations; only three. Each permutation of a law consists of a combination of two opinions out of a total of four opinions. A Lawmaker can 1) hold a desire for affirmative conduct, 2) lack a desire for affirmative conduct, 3) lack a desire for negative conduct, 4) hold a desire for negative conduct. Opinions 1 and 3 constitute Affirmative Regulation. Opinions 2 and 3 constitute Deregulation. Opinions 4 and 2 constitute Negative Regulation.

Warning

A Lawmaker can form any of four opinions. However, there are only three permutations of a law.

POLARITY

Polarity is the property of a flow of conduct from a Source to a Recipient through circumstances. The flow is binary either off or on. If on, the polarity of a flow of conduct is said to be affirmative. If off, the polarity of a flow of conduct is said to be negative.

Note

The word, 'not', changes the polarity of conduct from affirmative to negative.

PRIVILEGE

A privilege is a vehicle that carries a Lawmaker's opinion to the citizenry. it is used when the focus of a Lawmaker is upon a Source. A Lawmaker binds a privilege onto a Source. It is synonymous with a permission and a no-right. A privilege, permission, and a no-right are the three vehicles of Deregulation. It means that a Lawmaker lacks a desire for a Source to do affirmative and lacks a desire for for a Source to do negative conduct. Another word for a privilege is a no-duty.

PROCESS OF MAKING A LAW

The process of making a law consists of two stages. In the first stage, a Lawmaker forms an opinion about the polarities of conduct flowing from a Source to Recipient through circumstances. In the second stage, a Lawmaker externalizes the opinion by loading it onto a vehicle for conveyance to the citizenry.

PULL