Albion’s Seed

AMERICA

A CULTURAL HISTORY

VOLUME I: ALBION’S SEED

VOLUME II: AMERICAN PLANTATIONS

Oxford University Press

Oxford New York

Athens Auckland Bangkok Bombay

Calcutta Cape Town Dar es Salaam Delhi

Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madras Madrid Melbourne

Mexico City Nairobi Paris Singapore

Taipei Tokyo Toronto

and associated companies in

Berlin Ibadan

Copyright © 1989 by David Hackett Fischer

First published in 1989 by Oxford University Press, Inc.,

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 1991

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fischer, David Hackett, 1935-

Albion’s seed: four British folkways in America/

David Hackett Fischer.

p. cm. (America, a cultural history; v. 1)

Bibliography: p. Includes index.

ISBN-13 978-0-19-506905-1

1. United States—Civilization—To 1783.

2. United States—Civilization—English influences.

I. Title. II. Series: Fischer, David Hackett, 1935-

America, a cultural history, v. 1.

E169.1.F539 vol. 1 [E162] 973 s-dc20 [973] 89-16069 CIP

23 25 27 29 30 28 26 24

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

For Robert and Patricia Blake

PREFACE

An Idea of Cultural History

History is culturally ordered, differently so in different societies … The converse is also true: cultural schemes are historically ordered.

—Marshall Sahlins, 1985

THIS BOOK is the first in a series, which will hopefully comprise a cultural history of the United States. It is cultural in an anthropological rather than an aesthetic sense—a history of American folkways as they have changed through time.

Each volume (five are now in draft) centers on a major problem in American historiography. The first volume, Albion’s Seed, is about the problem of cultural origins. The second volume, American Plantations, studies the problem of culture and environment in the colonial era. The third volume examines the coming of independence as a cultural movement. Volume four takes up the problem of cultural change in the early republic, and volume five is about the Civil War as a cultural conflict. Other volumes will follow if the author is allowed to complete them.

This project has grown from an intellectual event that happened in the 1960s—a revolution in the writing of history, very much like the thought-revolutions described in Thomas Kuhn’s essays on the history of science, and Michael Foucault’s studies of social thought. Three generations ago, there was an established “paradigm” or “episteme” of historical knowledge. A writer had only to call his book a history in order to announce what sort of work it was, for history books were very much the same. History was about the past. It was a narrative discipline—a story-telling art. The stories that it told were about the organization of power and authority. Not all historians wrote political history, but most were interested in the politics of the subjects they studied. Labor historians wrote about labor leaders; historians of eduction studied school systems and the men who ran them; historians of women wrote about suffrage leaders and reform elites. Large masses of less eminent people also passed through the history books, or loitered in the wings like armies of anonymous extras on a Hippodrome stage. But the leading actors were small and highly individuated power-elites.

Historians studied these people through documentary sources. The results were organized as narratives and presented in the form of testimony—sometimes with specific citations, but for the most part historians testified to their readers, “I have steeped myself in the sources, and here is what I believe to have happened,” and they were believed, for this was a time when scholars were gentlemen, and a gentleman was as good as his word.

All of this activity created a coherent and plausible idea of history, which was at once a body of knowledge about the past and also a way of knowing it. Its masters were the great “narrative” historians such as Macaulay, Michelet, Ranke and Parkman. The last of this breed in America were Allan Nevins and Samuel Eliot Morison, who are both in their graves.

Early in the twentieth century, this paradigm of history began to come apart. Its ethical framework disintegrated. Suddenly, there were many new interests and problems that no longer seemed to fit. Anomalies were found; young scholars were promoted primarily for finding them. For two generations, historians became hunters after the anomalous fact. Each of their successes was a blow against the old synthesis, which was soon reduced to something like a ruin.

Some scholars struggled to repair it. Others attempted to replace it with a new synthesis. In the United States, the work of Turner, Beard, Parrington, Hofstadter, Boorstin and Hartz might be understood as a series of highly tentative paradigm sketches. But nobody could put the pieces together again. This was the period (1935-60) when historical relativism came into fashion, and every convention of the American Historical Association became an organized expression of professional Angst.

Then, in the decade of the 1960s, something new began to happen. Young scholars in Europe and America were inspired by the French school of the Annales to invent a new kind of history which differed from the old paradigm in all of the characteristics mentioned above. This new history was not really about the past at all, but about change—with past and present in a mutual perspective. It was not a story-telling but a problem-solving discipline. Its problematiques were about change and continuity in the acts and thoughts of ordinary people—people in the midst of others; people in society. The goal of this new social history was nothing less than an histoire totale of the human experience. To that end, the new historians drew upon many types of evidence: documents, statistics, physical artifacts, iconographic materials and much more. They also presented their findings in a new way—not as testimony but as argument. An historian was required not only to make true statements but also to demonstrate their truthfulness by rigorous methods of logic and empiricism. This epistemic revolution was the most radical innovation of the new history. It was also the most difficult for older scholars to understand.

In its early years, the new social history claimed to be not merely a new subdiscipline of history but the discipline itself in a new form. It promised to become a major synthesizing discipline in the human sciences—even the synthesizing discipline. Unhappily, these high goals were not reached. The new social history succeeded in building an institutional base, and also in exploring many new fields of knowledge. But in Fernand Braudel’s words, it was overwhelmed by its own success. Instead of becoming a synthesizing discipline, it disintegrated into many special fields—women’s history, labor history, environmental history, the history of aging, the history of child abuse, and even gay history—in which the work became increasingly shrill and polemical. Moreover, too many important subjects were excluded from the new history—politics, events, individuals, even ideas—and too many problems were diminished by materialist explanations and “modernization models.” By the 1980s the new social history had lost much of its intellectual momentum, and most of its conceptual range. It had also lost touch with the larger purposes that had called it into being.

From this mixed record of success and failure, a question inevitably arises. What comes after the new history? How can we continue to move forward? How might we strengthen the weakened hand of synthesis in an analytic discipline? What larger intellectual and cultural purposes might an historian seek to serve?

To those questions, this series offers an answer in its organizing idea of cultural history. Briefly, it seeks to find a way forward by combining several elements which the old and new histories have tended to keep apart. In terms of substance, it is about both elites and ordinary people, about individual choices and collective experiences, about exceptional events and normative patterns, about vernacular culture and high culture, about the problem of society and the problem of the state. To those ends, it tries to keep alive the idea of histoire totale by employing a concept of culture as a coherent and comprehensive whole.

In causal terms, this inquiry searches for a way beyond reductive materialist models (of both the left and the right) which are presently in fashion among historians in the United States and Britain, where materialism became a cultural mania during the Reagan and Thatcher years. Without denying the importance of material factors in history, one might assert that they are only a part of a larger whole, and that claims for their priority are rarely grounded in empirical fact. This inquiry seeks to place them in their proper context.

In terms of epistemology, this work tries to find a way forward in yet another way. The old history was idealist in its epistemic assumptions. Its major findings were offered as “interpretations” which tended to be discovered by intuition and supported by testimony. The new social history aspired to empiricism, but the epistemic revolution was incomplete—and something of the old interpretative sweep was lost in the process. This work tries to combine the interpretative thrust of the old history with the empiricism of the new—interpretative sails and empirical anchors, so to speak.

In its temporal aspect, this inquiry seeks a new answer to an old problem about the relationship between the past and the present. Many working historians think of the past as fundamentally separate from the present—the antiquarian solution. Others study the past as prologue to the present—the presentist solution. This work is organized around a third idea—that every period of the past, when understood in its own terms, is immediate to the present. This “immediatist” solution cannot be discussed at length here; it must be defined ostensively by the work itself, and especially by the conclusion. Suffice to say that the temporal problem in this volume is to explore the immediacy of the earliest period of American history without presentism, and at the same time to understand the cultures of early America in their own terms without antiquarianism.

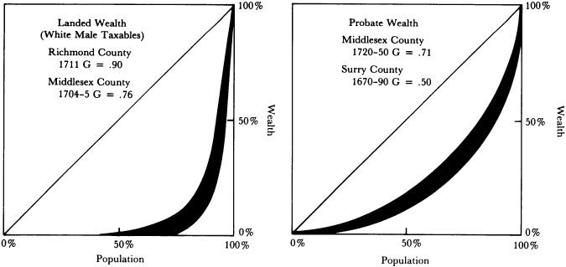

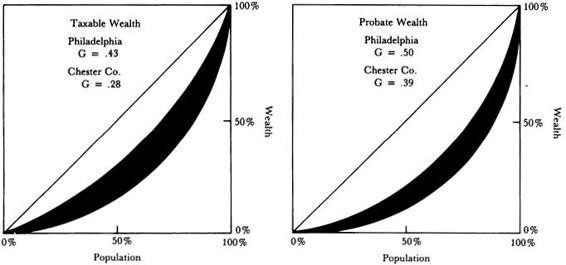

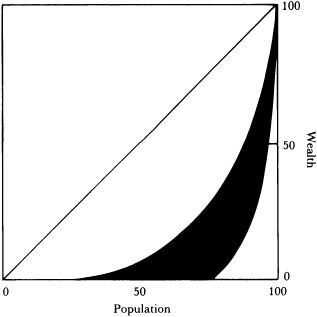

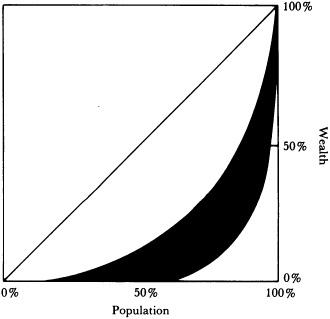

An immediatist idea of a relationship between the past and present might also support a more spacious relationship between history and other fields of knowledge. The old history was conceived as an autonomous discipline. The new history was more interdisciplinary—but its efforts consisted mainly of borrowings from other fields. This work is meant to suggest that major problems in many disciplines are insoluble without the application of historical knowledge. A case in point is the problem of wealth distribution; this work will argue, for example, that the distribution of wealth is determined not merely by timeless economic laws but by the interplay of cultural values and individual purposes which are rooted in the past.

Such an approach to the relationship between past and present might also help to enlarge historical inquiry in its ethical dimension. This work, for example, tries to apply new empirical methods and findings to old problems about the history of freedom in the world. It suggests that the problem of liberty cannot be discussed intelligently without a discrimination of libertarianisms which must be made in historical terms. Empirical knowledge of the past is not merely useful but necessary to an understanding of our moral choices in the present.

Finally, in terms of rhetoric, a problem has arisen from the empirical requirements of the new history, which have destroyed the possibility of simple story-telling in original scholarship without changing the narrative nature of the writing that historians do. This series seeks to combine story-telling and problem-solving in a “braided narrative” of more complex construction.

In all of those many ways, this idea of cultural history rests upon an assumption that the old and the new history are not two disciplines but one. The progress of historical knowledge is best served by their creative integration.

Old Headington, Oxford

Wayland, Massachusetts

D.H.F.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Drawings

by Jennifer Brody

ew England’s Transatlantic Elite |

uritan Ministers in the Great Migration |

Puritan Physician in the Great Migration |

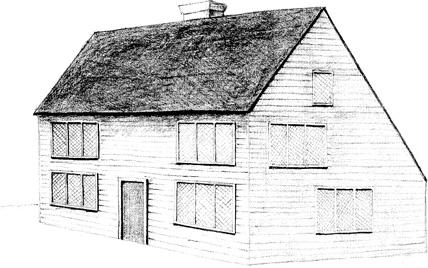

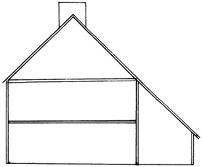

he Salt Box House in Old and New England |

he Gabled Box in Essex, England and Essex County, Massachusetts |

he Apparatus of Courtship in Puritan New England |

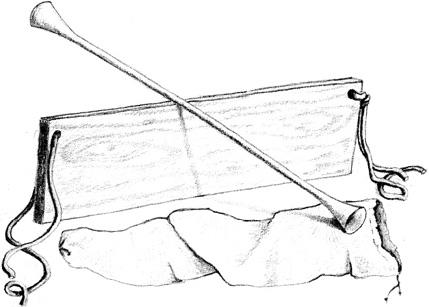

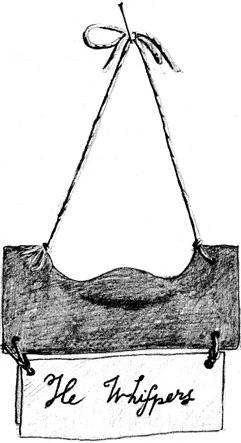

The Technology of Will Breaking: Whispering Sticks |

The Iconography of Old Age in New England: Mistress Anne Pollard |

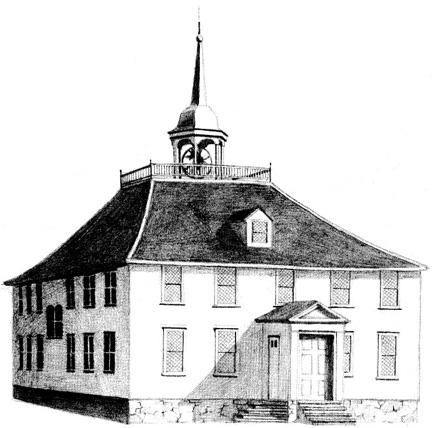

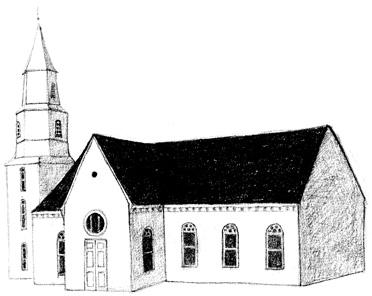

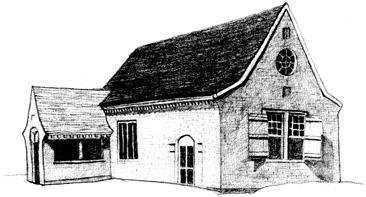

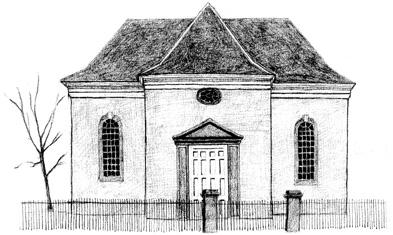

A New England Meeting House |

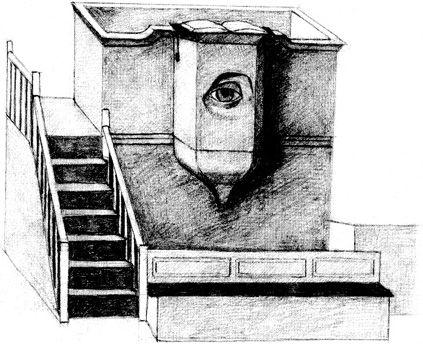

Pulpit Eye and Elder Bench |

Spirit Stones in Massachusetts |

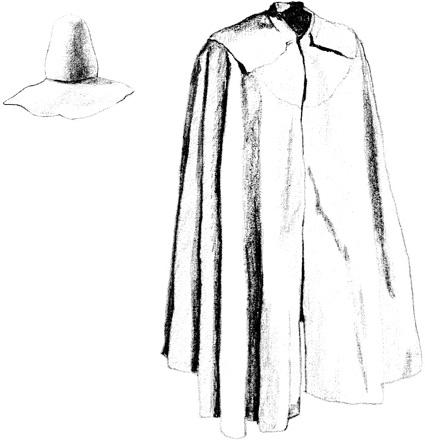

Steeple Hats and “Sadd Colors” |

The Swing Plow in New England and East Anglia |

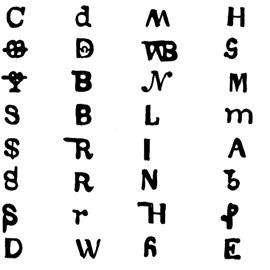

Symbols of Belonging: “Towne Marks” in Massachusetts |

John Winthrop’s Little Speech on Liberty |

Sir William Berkeley and Charles I |

Colonel Richard Lee |

Anna Constable Lee |

Norborne Berkeley, Lord Botetourt |

Tenant Farmers in Oxfordshire |

Virginia’s First Great House: Sir William Berkeley’s Green Spring |

Stratford |

The Hall-and-Parlor House in Virginia |

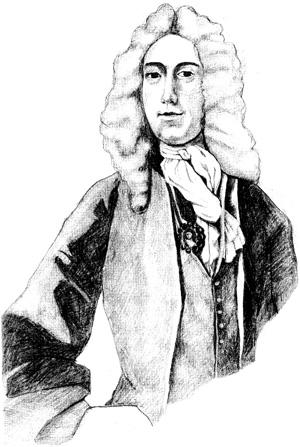

William Byrd II |

Lucy Parke Byrd |

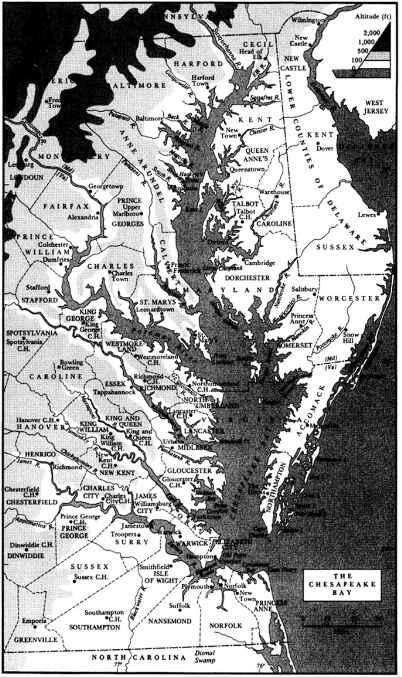

Virginia’s “Spirited She-Britons”: Sarah Harrison |

Colonel Daniel Parke |

Bruton Church, Williamsburg, Virginia |

Yeocomico Church, Westmoreland County, Virginia |

Christ Church, Lancaster County, Virginia |

Slashed Sleeves |

The Iconography of Deference |

A Freeborn Gentleman of Virginia: Thomas Lee |

William Penn in Youth |

William Penn in Maturity |

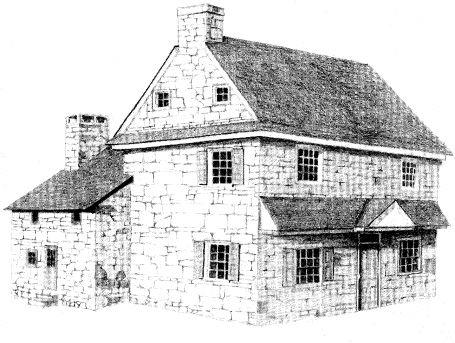

Vernacular Architecture in Pennsylvania |

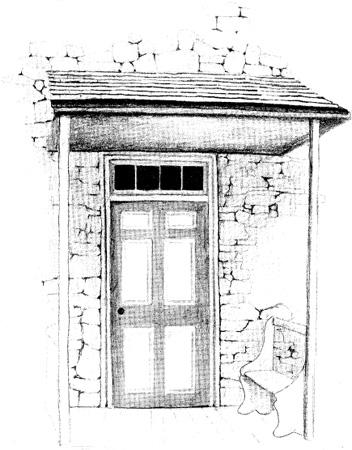

Pent Roofs and Door Hoods |

A Quaker Woman Preaching |

Quaker Meetinghouses |

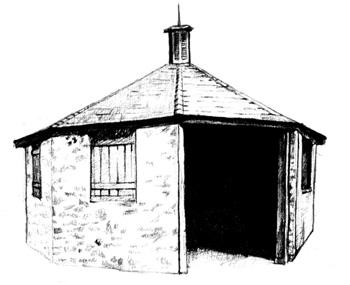

A Hexagonal Quaker Schoolhouse |

A Quaker Wedding Dress |

Quaker Outbuildings |

The Great Quaker Bell |

Penrith Beacon |

Andrew Jackson |

James Knox Polk |

John Caldwell Calhoun |

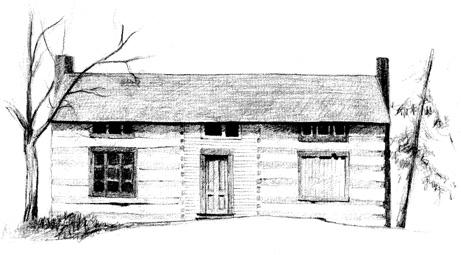

Cabin Architecture in the Borderlands and Backcountry |

The Abduction of Rachel Donelson |

Age and Authority in the Backcountry |

Crackers, Rednecks, Hoosiers |

Patrick Henry |

Maps

by Andrew Mudryk

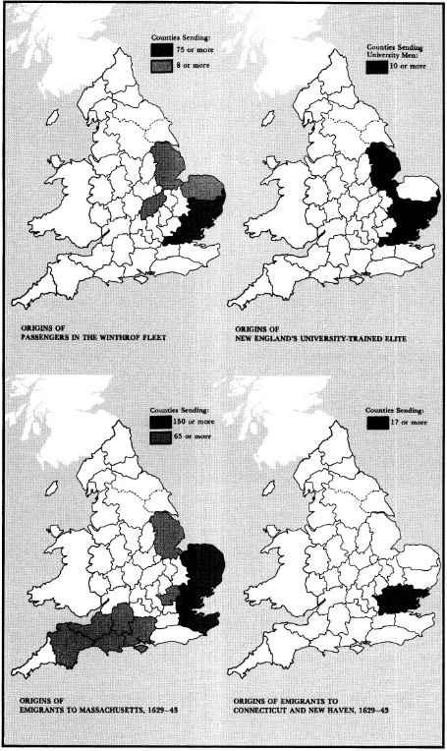

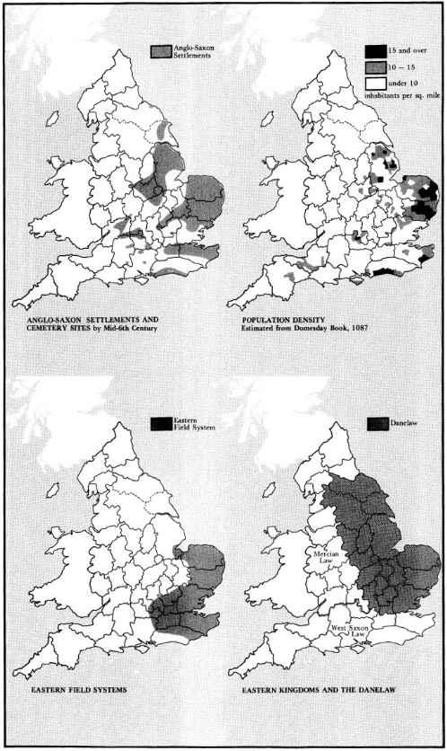

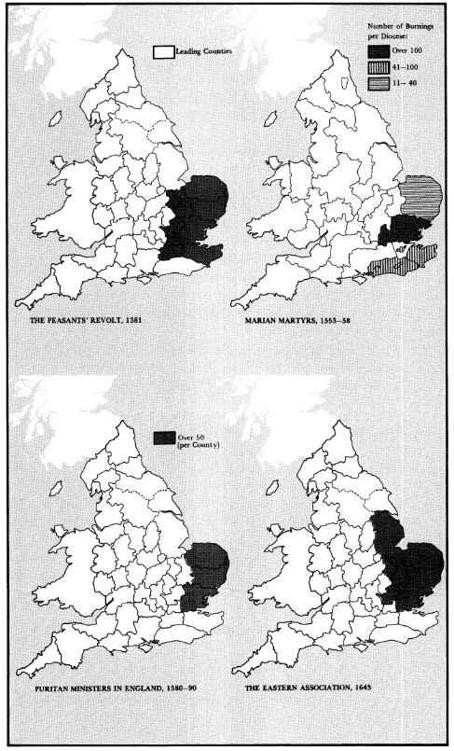

English Regional Origins of the Puritan Migration |

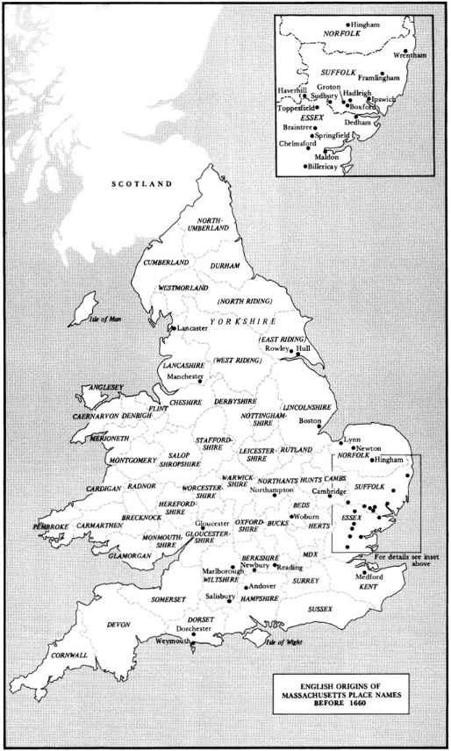

English Origins of Massachusetts Place Names |

The Regional Culture of Eastern England |

The Tradition of Dissent in Eastern England |

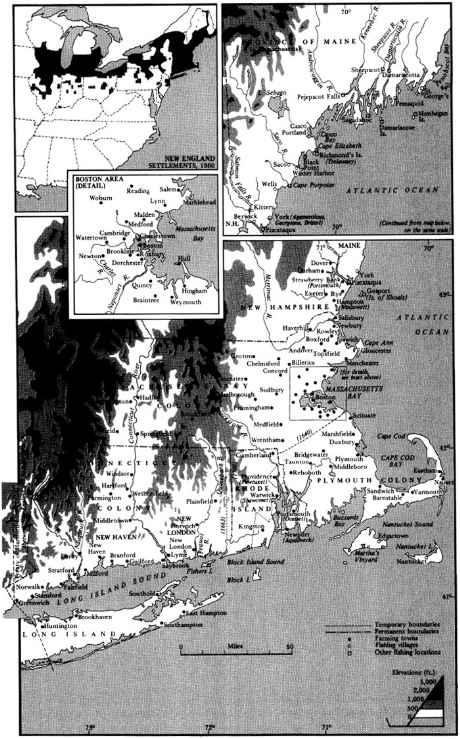

Town Founding in New England |

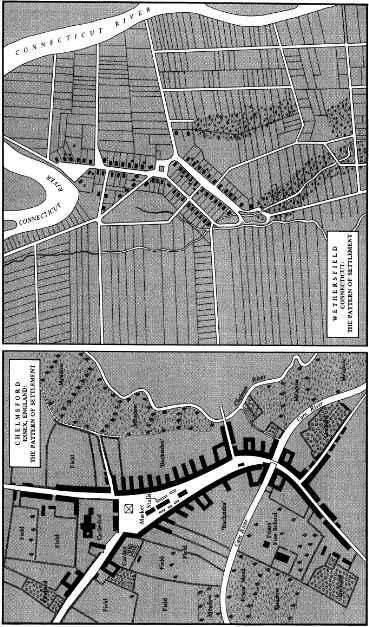

Patterns of Settlement in East Anglia and Massachusetts |

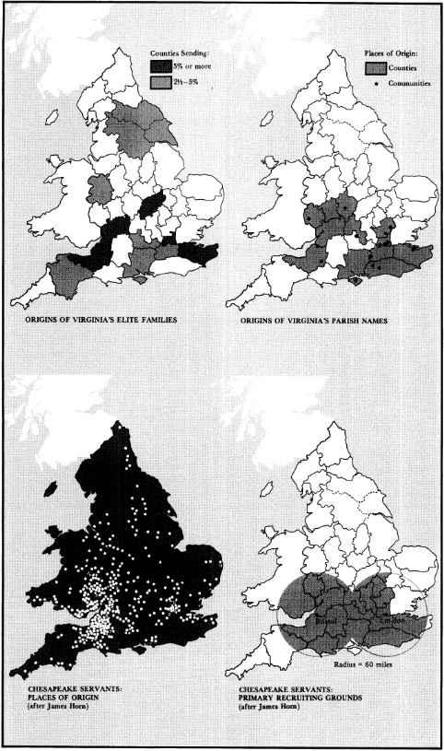

English Regional Origins of Virginia’s Great Migration |

The South of England |

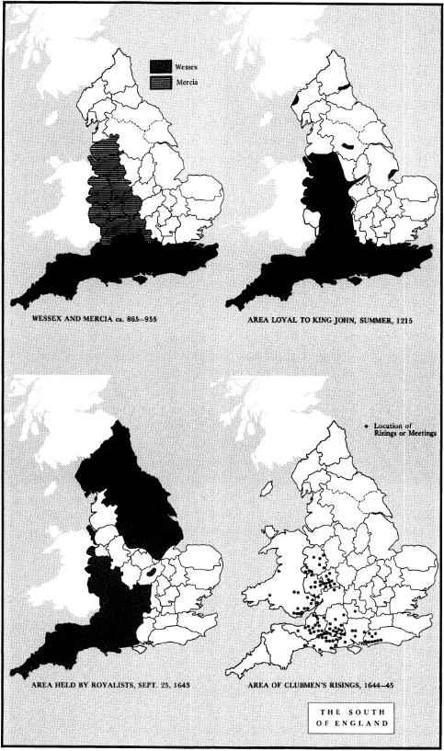

The Chesapeake Region |

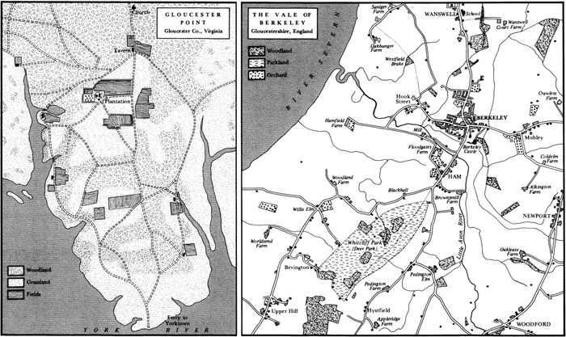

Patterns of Settlement: Gloucestershire, England |

Patterns of Settlement: Gloucester County, Virginia |

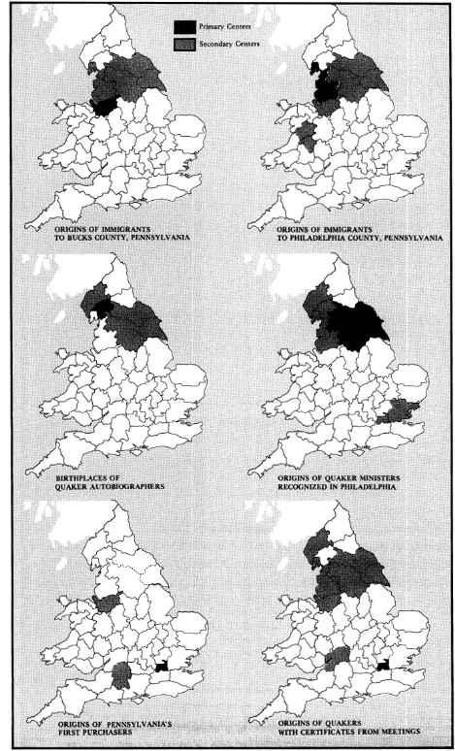

English Regional Origins of the Friends’ Migration |

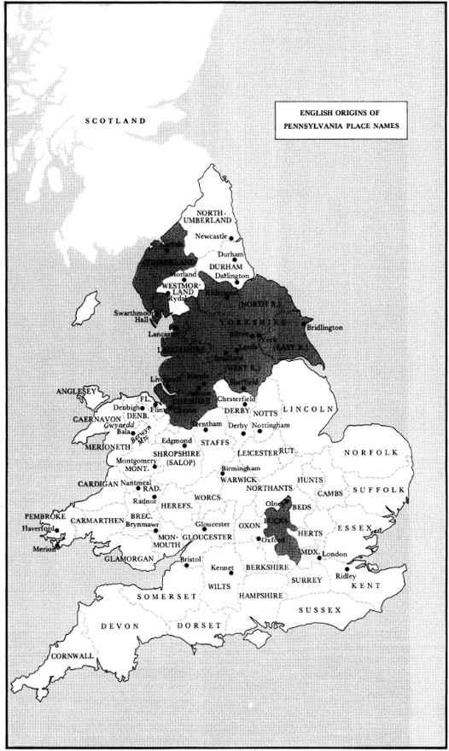

English Origins of Pennsylvania Place Names |

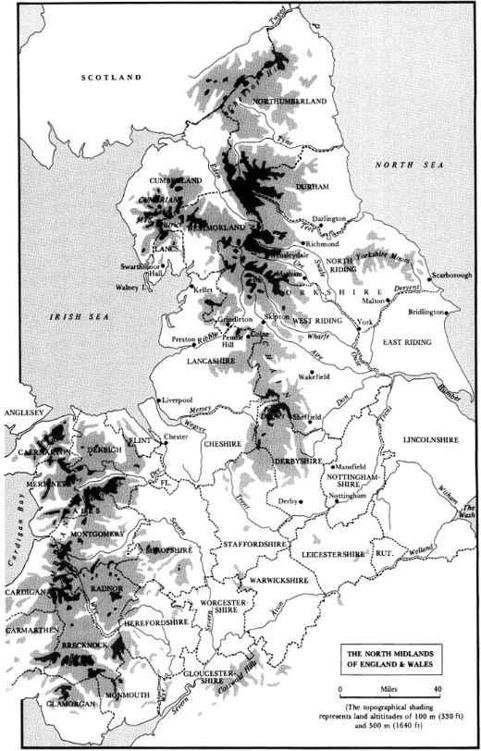

The North Midlands of England |

The Quaker Heartland |

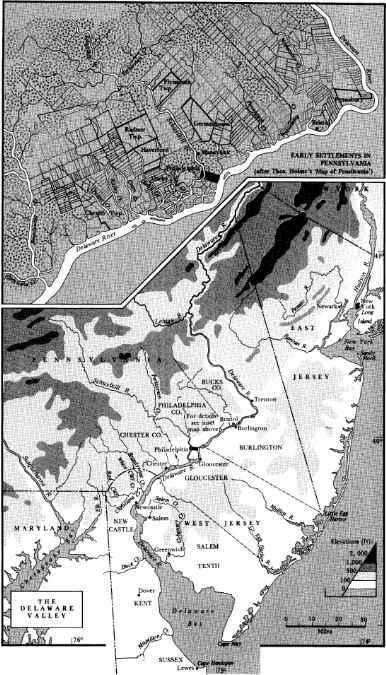

The Delaware Valley |

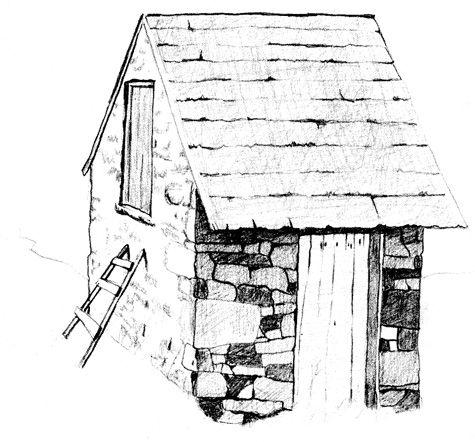

Patterns of Settlement in Pennsylvania |

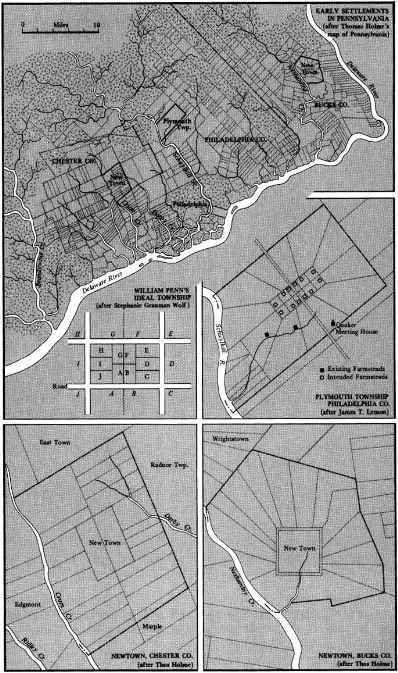

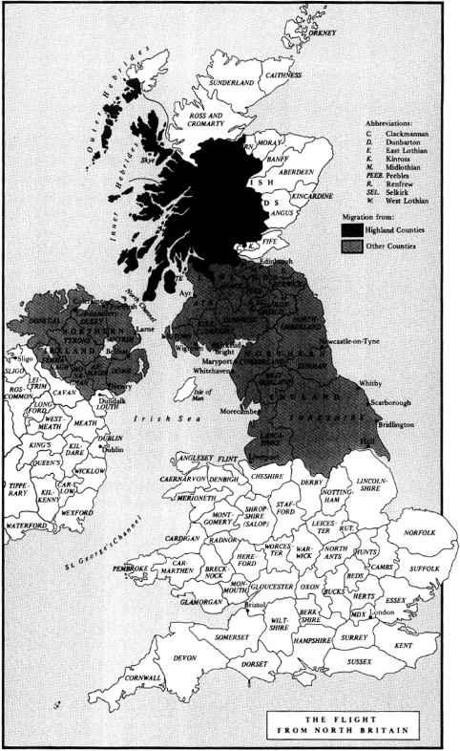

The Flight from North Britain |

Scotland and Northern Ireland |

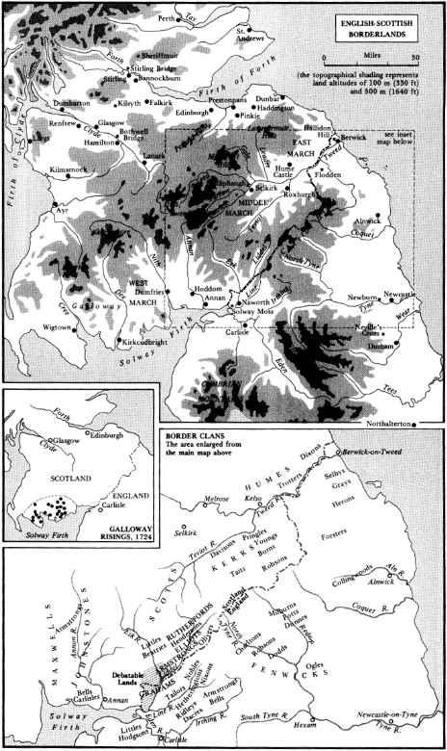

The Borderlands |

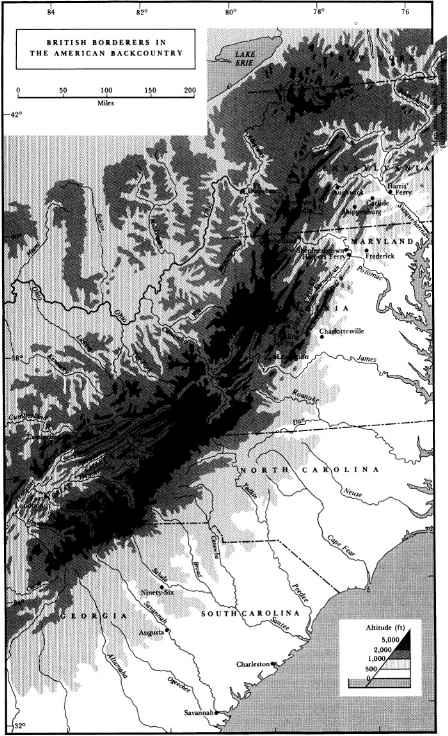

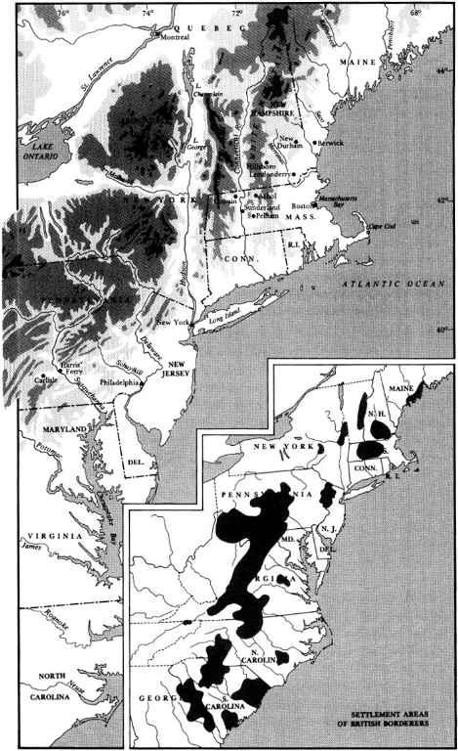

British Borderers in the American Backcountry |

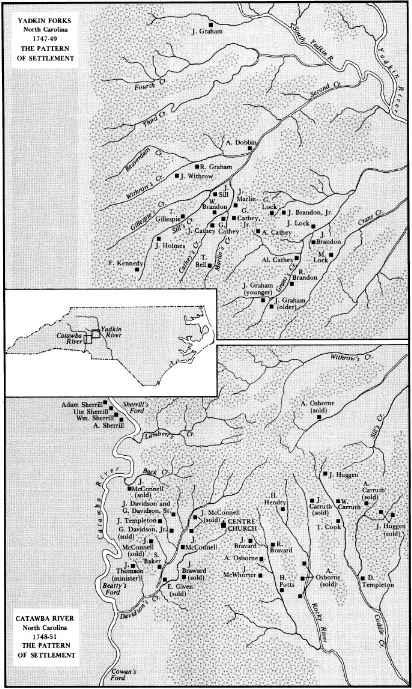

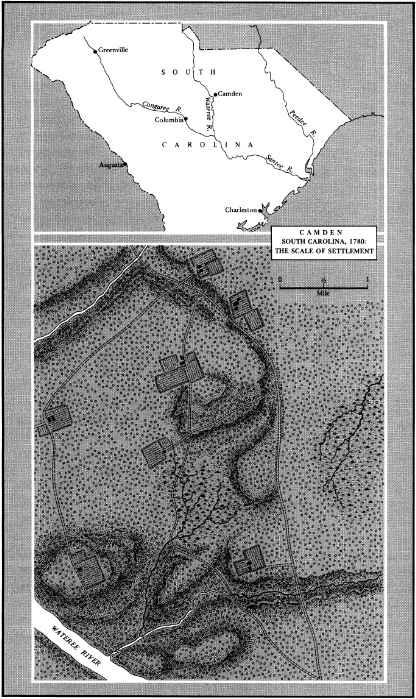

Patterns of Settlement in the Backcountry |

The Scale of Settlement in the Backcountry |

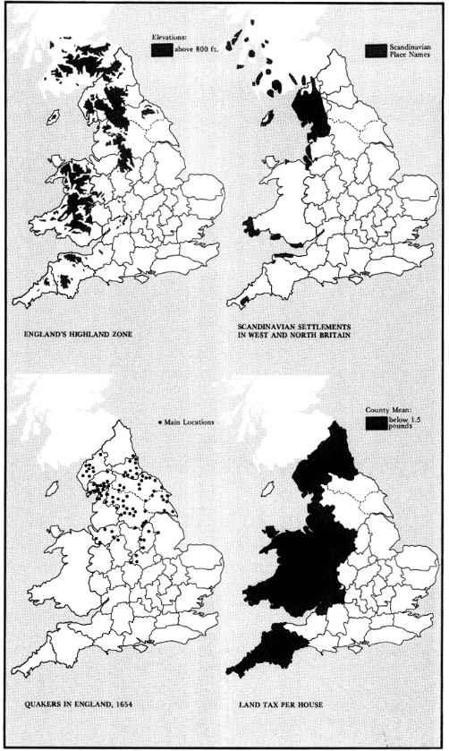

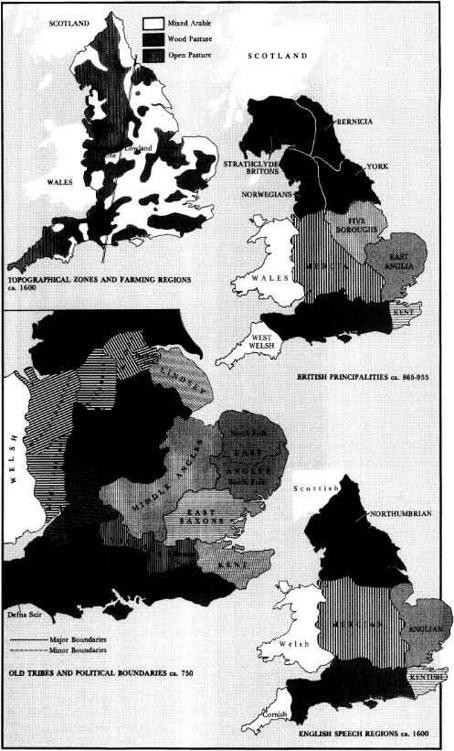

Regional Taxonomies in British History |

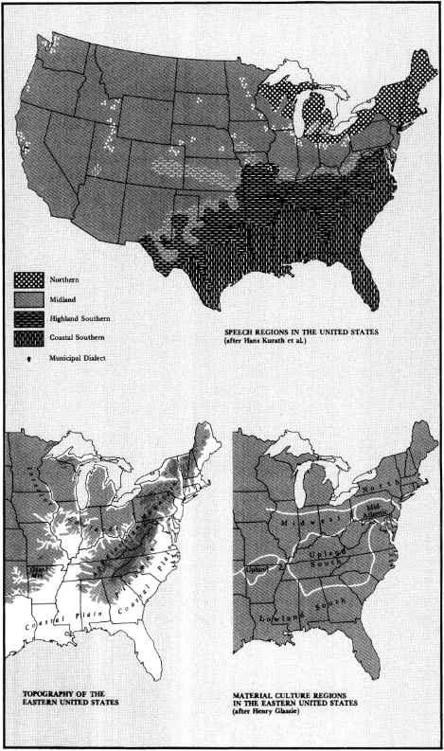

Speech and Culture Regions in the United States |

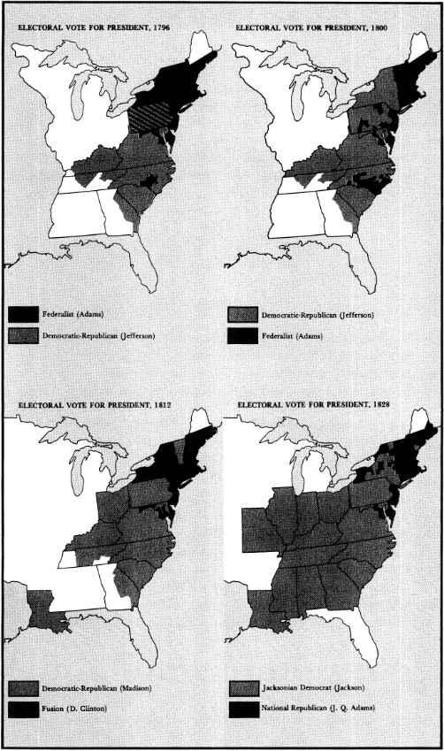

Regional Voting in the Early Republic, 1796-1832 |

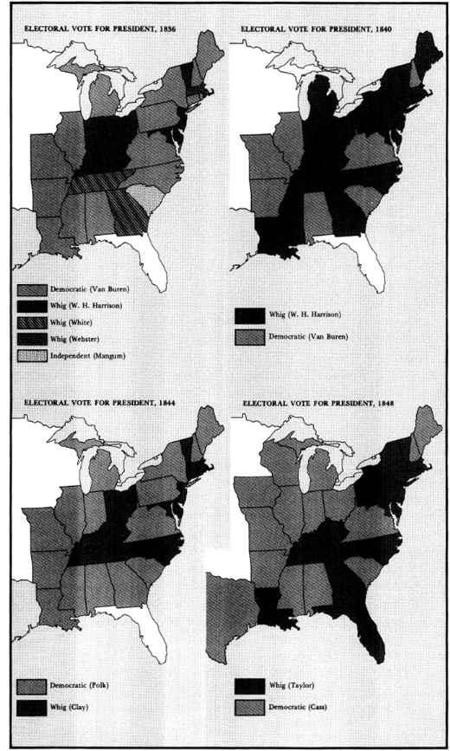

The Eclipse of Region: The Second Party System, 1840-52 |

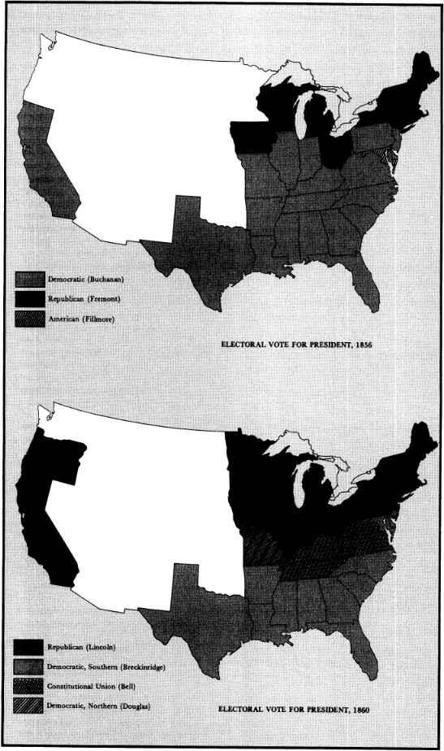

From Region to Section: The Republican Coalition, 1856-60 |

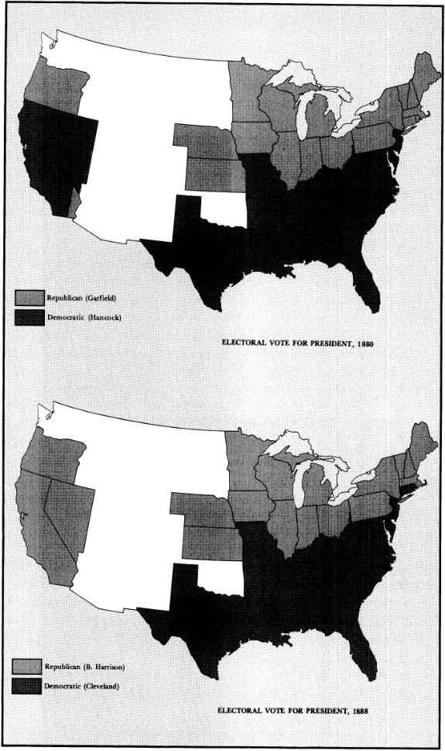

The Republican Coalition versus the Solid South, 1880-88 |

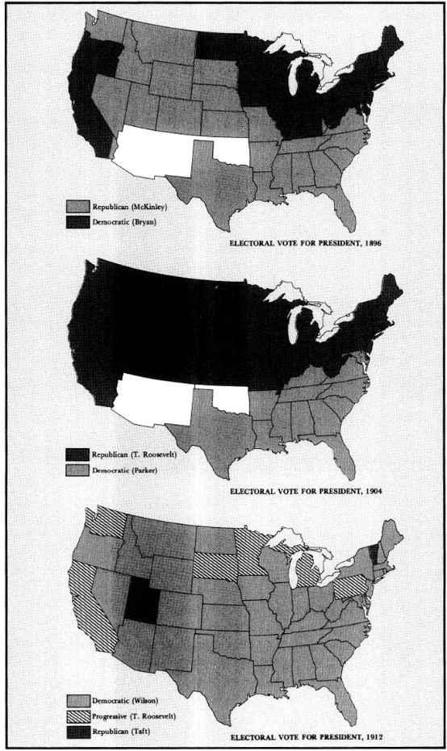

Region and Reform, 1896-1912 |

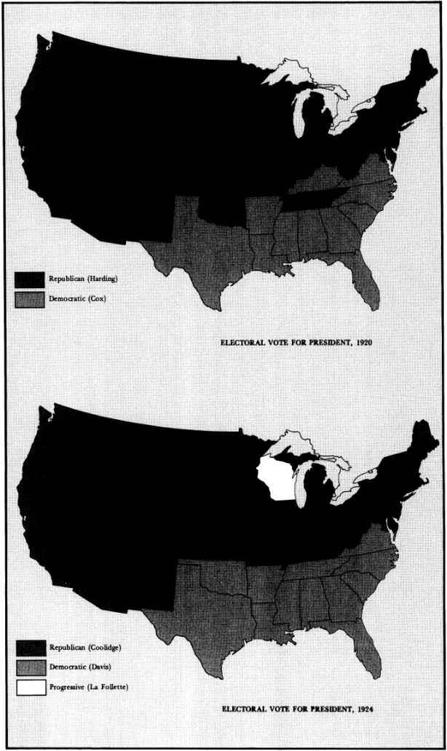

The High Tide of Sectionalism, 1920-24 |

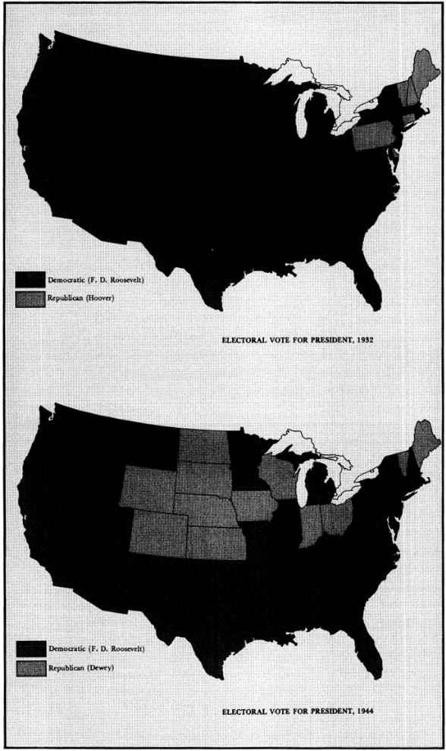

Regional Alliances in the New Deal Coalition, 1932-44 |

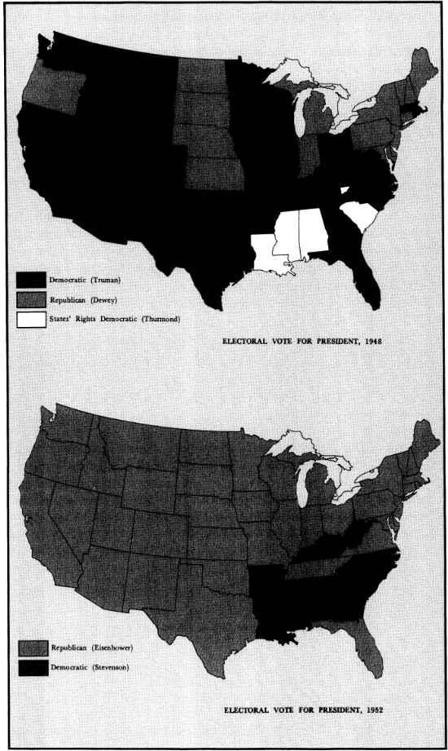

The Regional Revival, 1948-56 |

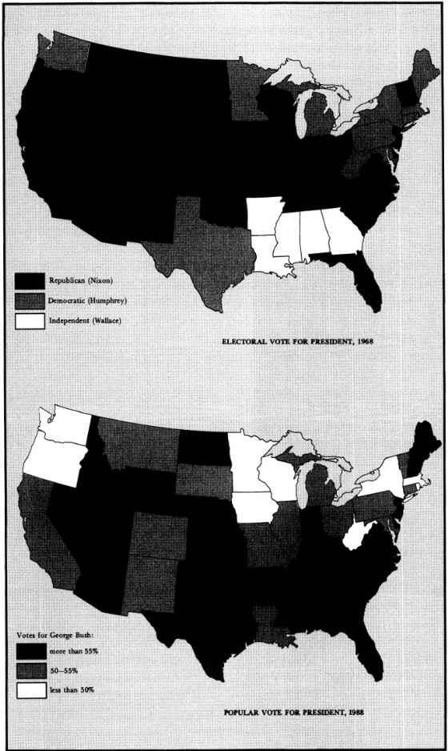

The Regional Revolution in American Politics, 1968-88 |

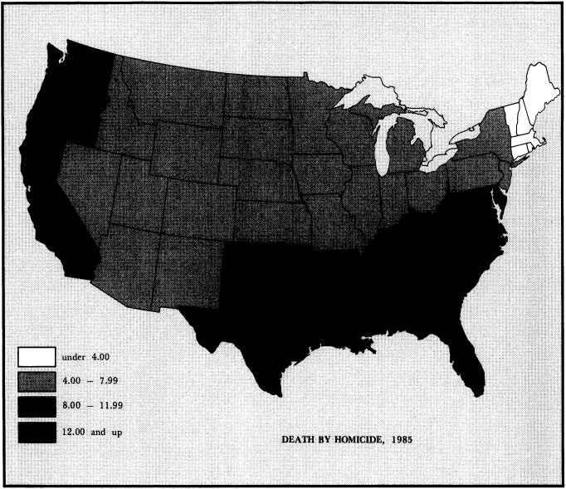

Regional Patterns of Violence in America |

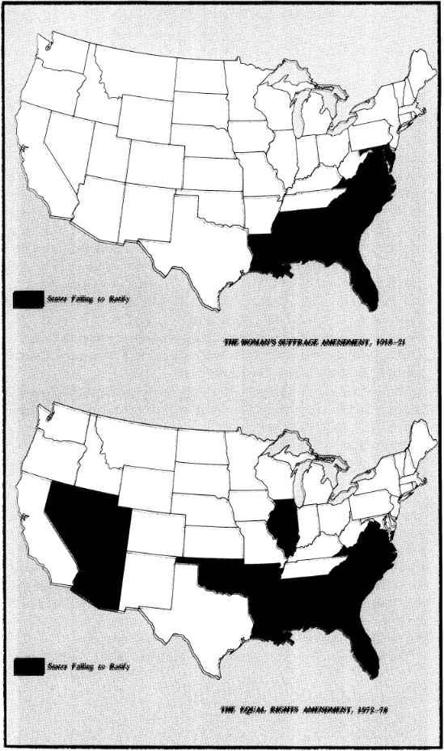

Regional Attitudes toward the Rights of Women |

Tables

Cultural Indicators Used in This Work |

Religion and the Great Migration: Church Members in New England |

Gender and Age Composition in the Great Migration |

Occupations in the Great Migration: Five Studies |

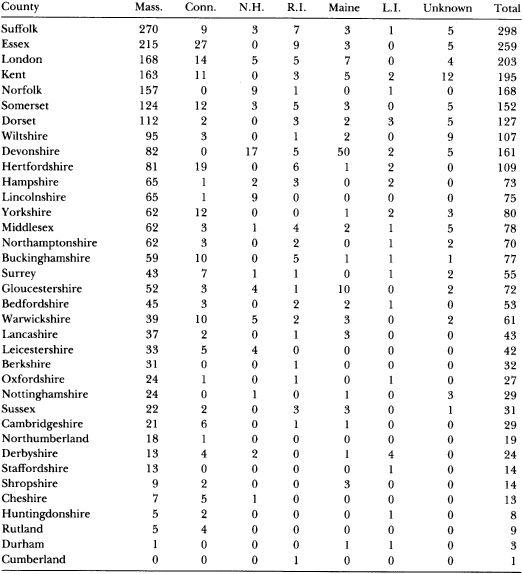

English Origins of the Great Migration |

English Origins of Town Names in Massachusetts |

English Residence of University Men in New England |

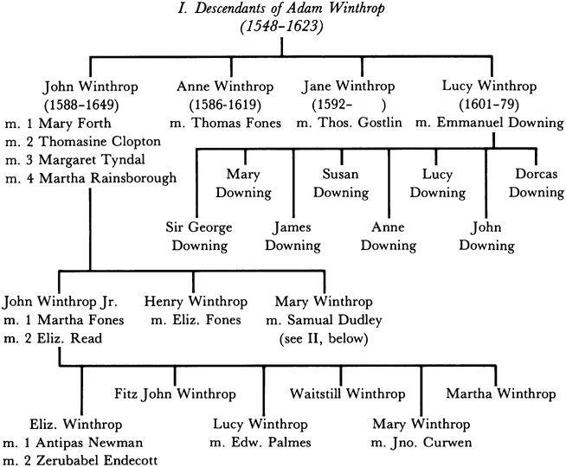

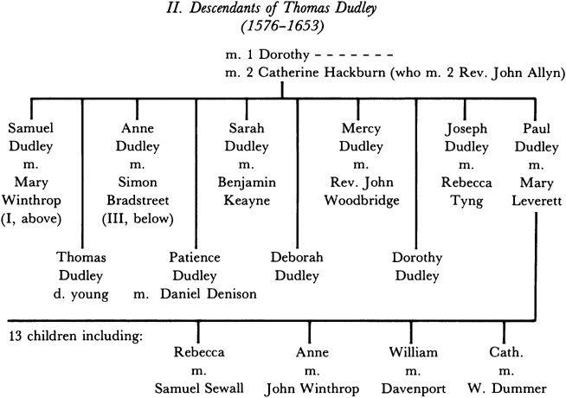

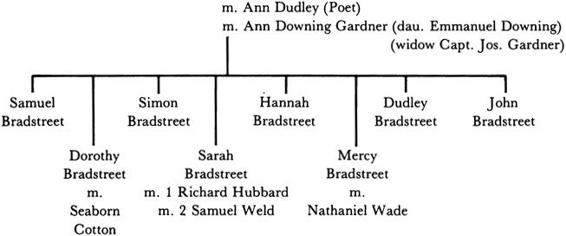

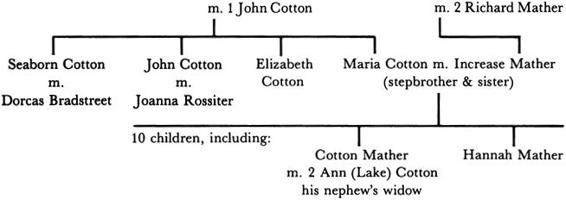

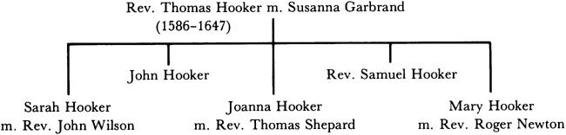

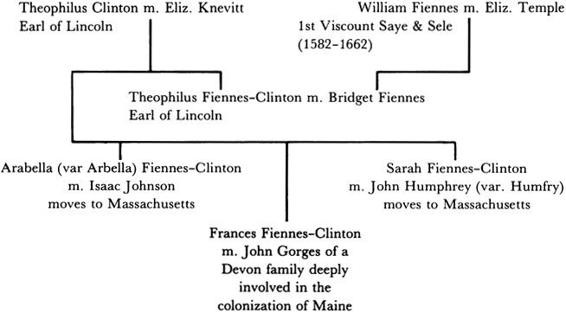

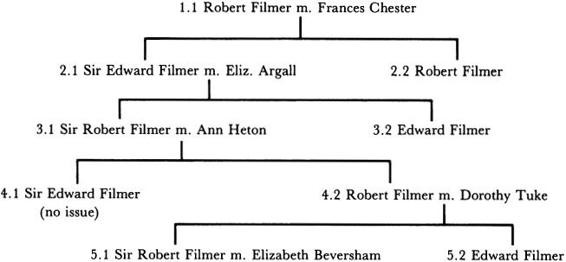

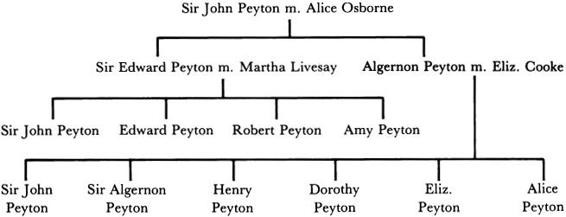

New England’s Puritan Elite: Genealogical Links |

Puritan Ministers in England before 1590 |

Completed Family Size in New England: Eleven Studies |

Age at Marriage in New England: Twenty Studies |

Prenuptial Pregnancy in Massachusetts: Nine Studies |

Illegitimacy Ratios by English Region |

“Sending Out” in Massachusetts and East Anglia |

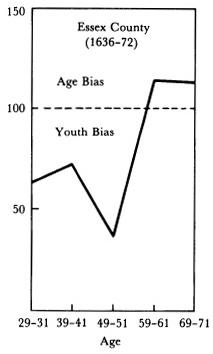

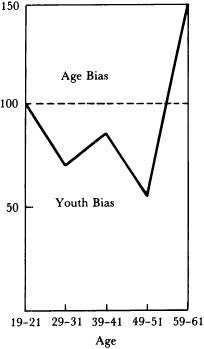

Age Bias in New England: Four Studies |

Witchcraft Prosecutions in England and America: Six Studies |

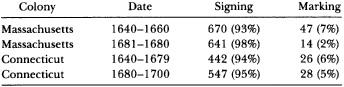

Literacy in New England and East Anglia: Five Studies |

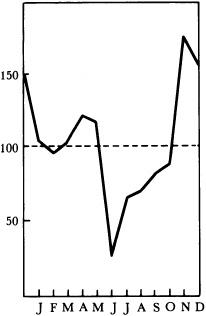

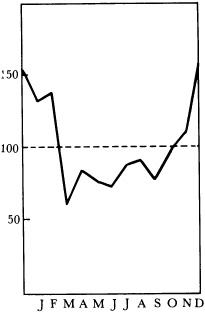

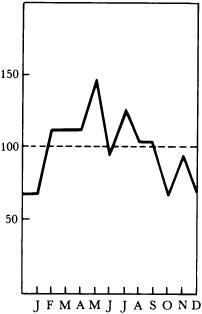

Season of Marriage in New England |

Size of Land Grants in Billerica, Massachusetts |

Wealth Distribution in Hingham, Norfolk and Hingham, Mass. |

Wealth Distribution in New England Towns and English Parishes |

Wealth Distribution in New England: Twenty-Six Studies |

Rates of Persistence in New England: Eight Studies |

Crime Statistics by State, 1790-1827 |

Criminal Prosecutions in Massachusetts: Three County Studies |

Criminal Prosecutions in Massachusetts and South Carolina |

Voter Participation in Massachusetts: Ten Town Studies |

Virginia’s Elite: Dates of Immigration |

Virginia’s Elite: Social Rank in England |

Virginia’s Elite: English Counties of Origin |

Virginia’s Elite: Genealogical Links |

Population Growth in Virginia & Other Colonies |

Occupation of Virginia Servants: Four Studies |

Religion in Virginia: Patterns of Church Attendance |

English Origins of Families, Isle of Wight, Virginia |

English Origins of Virginia Servants and Bristol Apprentices |

English Origins of Place Names in Virginia and Maryland |

Completed Family Size in the Chesapeake: Four Studies |

Age at Marriage in the Chesapeake: Seven Studies |

Prenuptial Pregnancy in the Chesapeake: Four Studies |

Illegitimacy in the Chesapeake: Two Studies |

Chesapeake Onomastics |

Descent of Names, Virginia and New England |

Age Bias in the Chesapeake |

Literacy of Europeans in Virginia |

Literacy of Africans in Virginia |

Literacy by Social Rank in Virginia |

Kitchen Equipment in England and the Chesapeake |

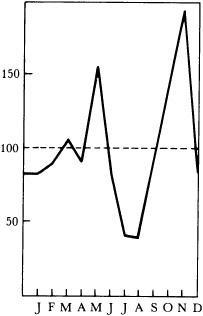

Season of Marriage in the Chesapeake |

Season of Conception in the Chesapeake |

Population by Social Rank in Virginia |

Wealth Distribution in Virginia |

Size of Land Grants in Virginia |

Tenancy in Virginia: Seven Studies |

African Population in the Colonies |

Rates of Persistence in Surry and Northampton Counties, Va. |

Rates of Persistence in Northamptonshire, England |

Criminal Prosecutions in the Chesapeake: Five County Studies |

Voter Participation in Virginia: Sixteen Studies |

The Growth of Population in the Delaware Valley |

Quakers in Derby Meeting |

Churches in Early America |

Ethnic Composition of Pennsylvania Population, 1726-90 |

Religious Composition of Pennsylvania Legislature, 1729-55 |

Occupation of Immigrants to Philadelphia and Bucks Co., 1682-87 |

Geographic Origins of Immigrants to Philadelphia and Bucks County |

Geographic Origins of Quaker “Ministers” |

Geographic Origins of Quaker Autobiographers |

Geographic Origins of Quakers with Certificates from Meetings |

Geographic Origins of Pennsylvania’s “First Purchasers” |

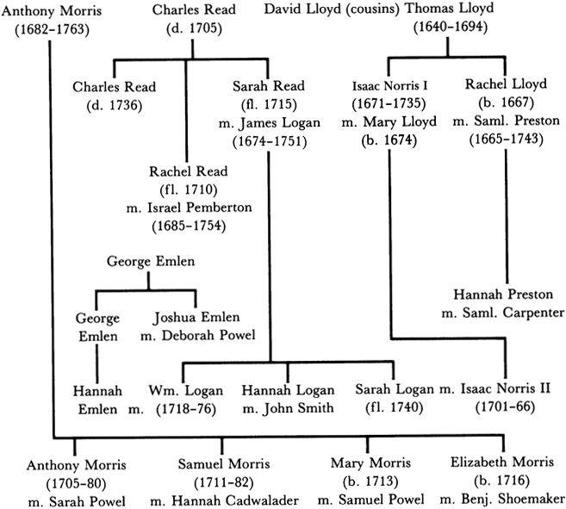

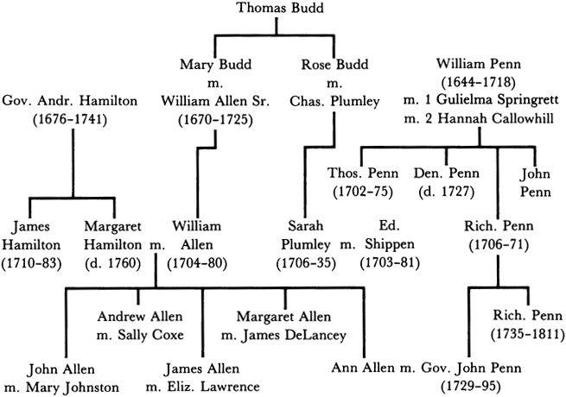

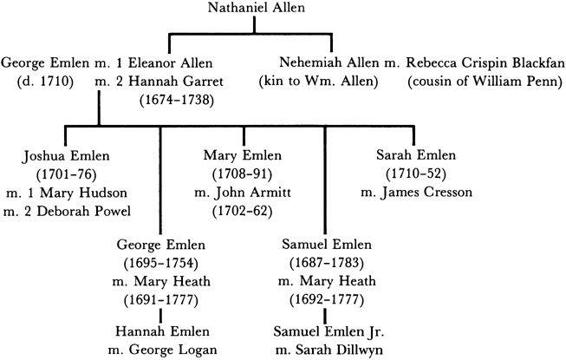

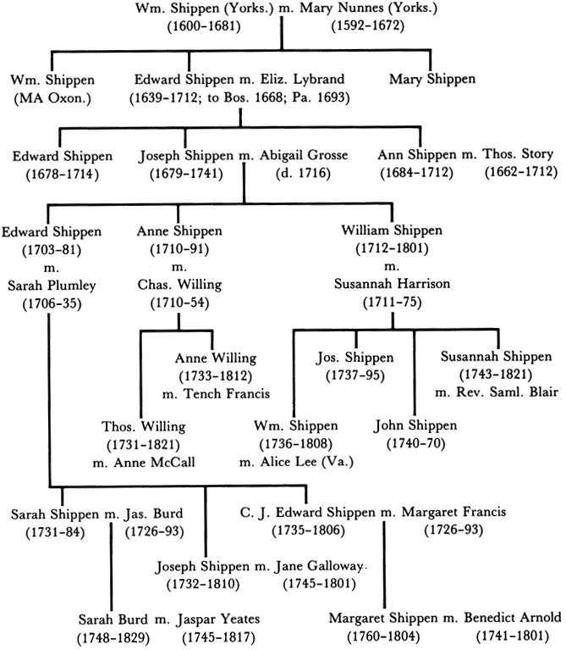

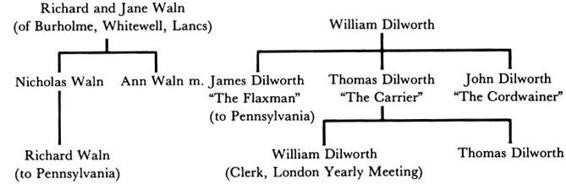

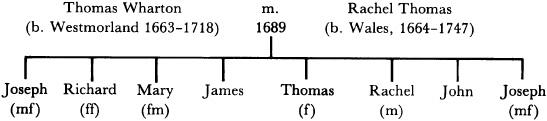

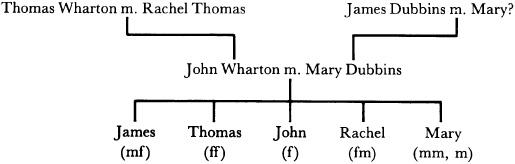

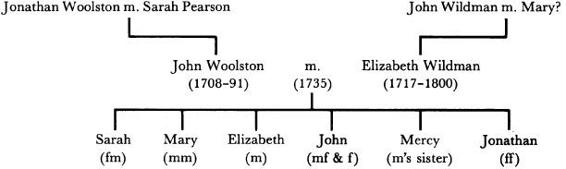

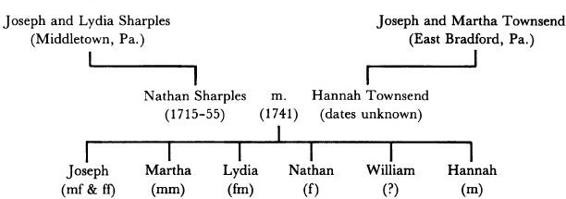

The Delaware Elite: Genealogical Links |

English Regional Speechways |

Completed Family Size in the Delaware Valley: Six Studies |

Age at Marriage in the Delaware Valley: Seven Studies |

Descent of Names in Quaker Families |

Quaker Onomastics in England and America |

Literacy in Pennsylvania: Two Studies |

Season of Marriage and Conception in the Delaware Valley |

Distribution of Wealth in the Delaware Valley: Two Studies |

Rates of Persistence in Chester and Lancaster Counties, Pa. |

Rates of Persistence in Nottinghamshire, England |

Criminal Prosecutions in Chester County, Pa. |

Voter Participation in the Delaware Valley: Six Studies |

Scotch-Irish Emigration to America before 1775: Six Studies |

Emigration from Scotland: Four Estimates |

Family Status of North British Emigrants: Four Studies |

Gender of North British Emigrants |

Age Distribution of North British Emigrants |

Motives for Migration from North Britain: Six Surveys |

Occupations of North British Emigrants |

Scottish and Irish Surnames in the Census of 1790: Two Studies |

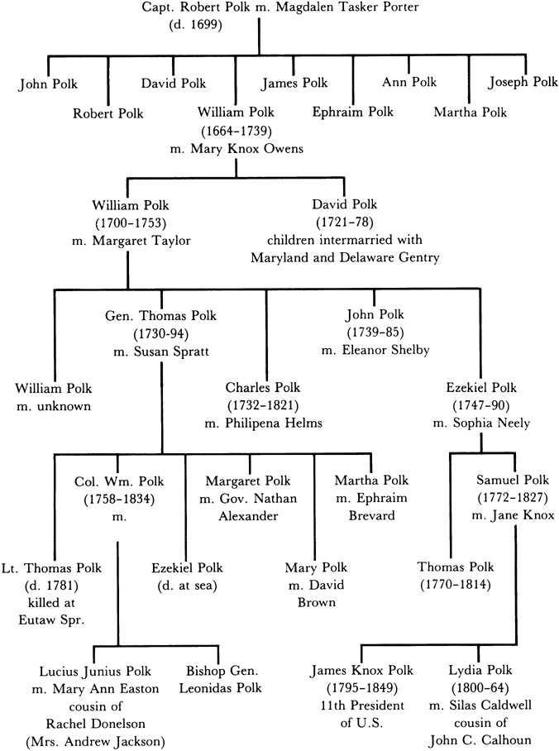

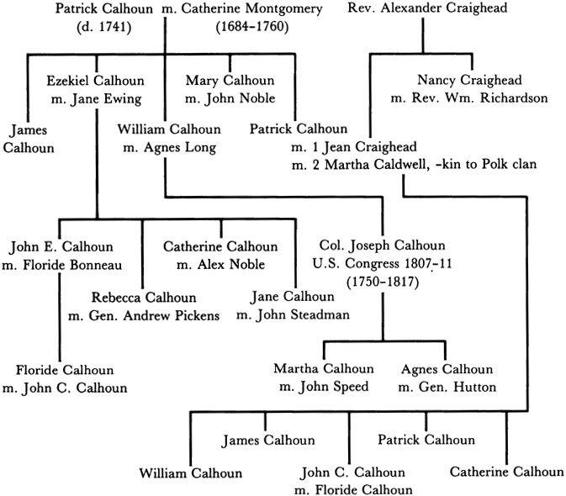

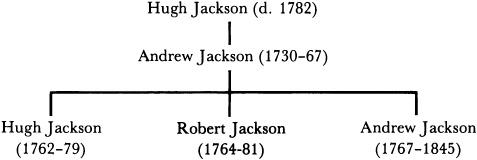

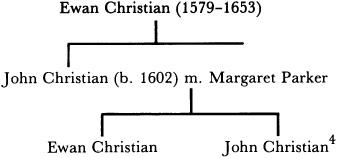

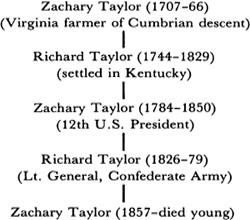

Backcountry Elites: Genealogical Links |

Backcountry Elites: Origins of Officers at Kings Mountain |

Age at Marriage in Three Backcountry Districts |

Illegitimacy in North Britain |

Backcountry Onomastics |

Descent of Names in the Backcountry |

Age Bias in the Backcountry, 1776 |

Rates of Literacy in North Britain |

Season of Marriage in the Backcountry: Augusta County, Va. |

Wealth Distribution in North Carolina and Tennessee before 1800: Eight Counties |

Wealth Distribution in Kentucky before 1800: Eleven Counties |

Rates of Persistence in the Borderlands and Backcountry |

Criminal Prosecutions in the Backcountry: Ohio County, Va. |

Voter Participation in the Backcountry: Four County Studies |

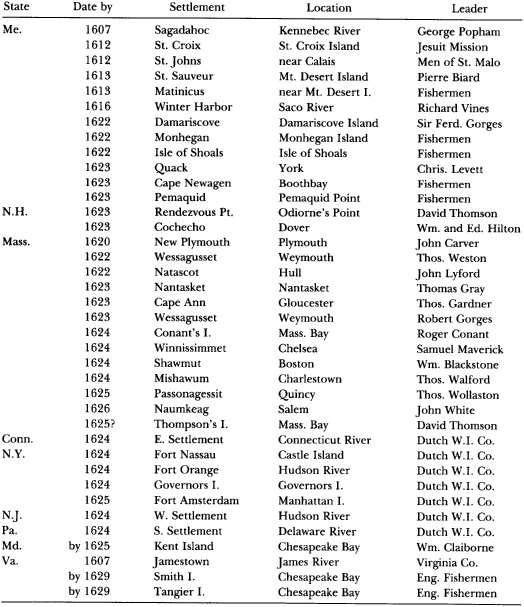

Settlements in British America before the Great Migrations |

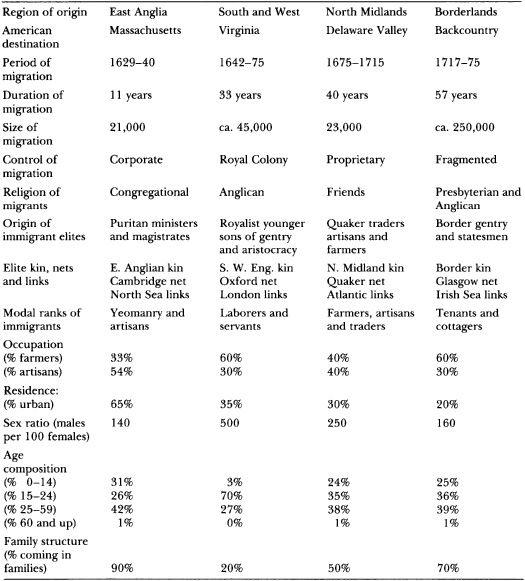

Four British Folk Migrations: Modal Characteristics |

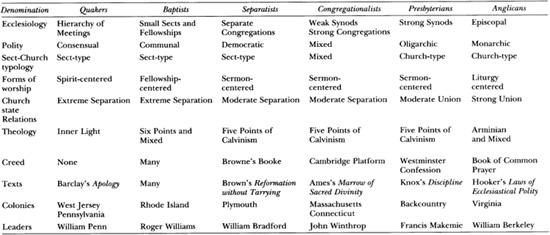

British Protestantism in the Seventeenth Century |

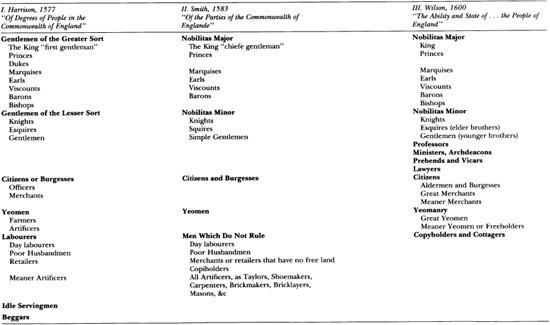

Taxonomies of Social Rank in England, 1577-1600 |

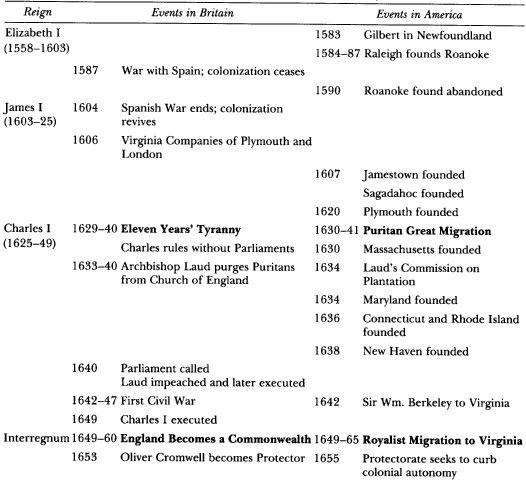

Chronology of Anglo-American History, 1558-1760 |

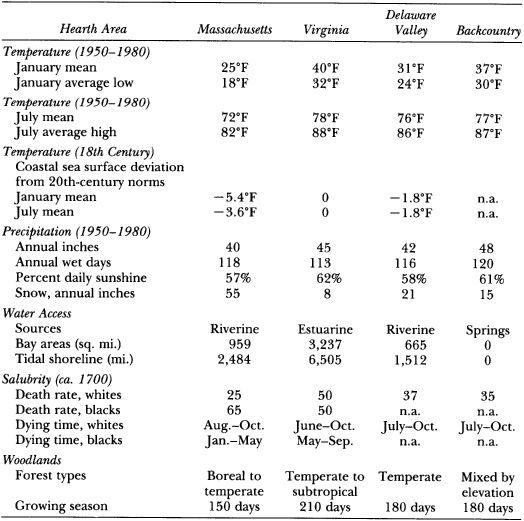

Four Regions in Early America: Environment |

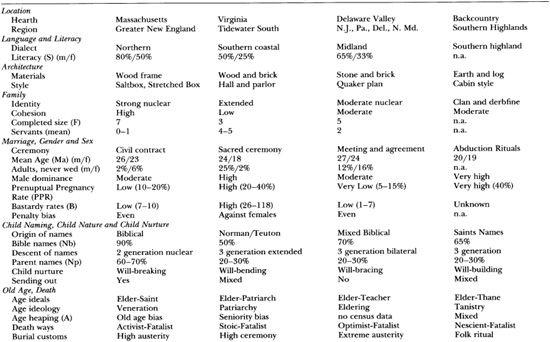

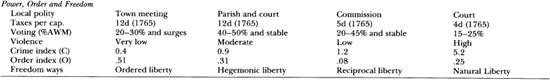

Four Regions in Early America: Culture |

Regional Voting on Jay’s Treaty, 1796 |

Region of Origin and Voting in New York and Ohio, 1840-46 |

Region of Origin and Voting in New York and Ohio, 1856-60 |

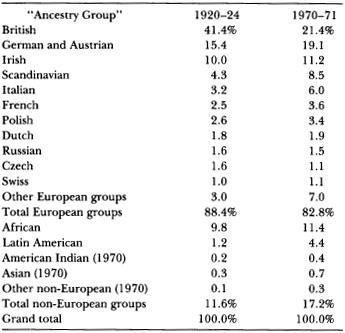

Ethnic Composition of the American Population, 1820-71 |

Regional Voting for Richard Nixon |

Albion’s Seed

INTRODUCTION

The Determinants of a Voluntary Society

Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going?

—Paul Gauguin, 1897

IN BOSTON’S MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, not far from the place where English Puritans splashed ashore in 1630, there is a decidedly unpuritanical painting of bare-breasted Polynesian women by Paul Gauguin. The painting is set on a wooded riverbank. In the background is the ocean, and the shadowy outline of a distant land. The canvas is crowded with brooding figures in every condition of life—old and young, dark and fair. They are seen in a forest of symbols, as if part of a dream. In the corner, the artist has added an inscription: “D’ou venons nous? Qui sommes nous? Ou allons nous?”

That painting haunts the mind of this historian. He wonders how a Polynesian allegory found its way to a Puritan town which itself was set on a wooded riverbank, with the ocean in the background and the shadow of another land in the far distance. He observes the crowd of museumgoers who gather before the painting. They are Americans in every condition of life, young and old, dark and fair. Suddenly the great questions leap to life. Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going?

The answers to these questions grow more puzzling the more one thinks about them. We Americans are a bundle of paradoxes. We are mixed in our origins, and yet we are one people. Nearly all of us support our republican system, but we argue passionately (sometimes violently) among ourselves about its meaning. Most of us subscribe to what Gunnar Myrdal called the American Creed, but that idea is a paradox in political theory. As Myrdal observed in 1942, America is “conservative in fundamental principles … but the principles conserved are liberal and some, indeed, are radical.”1

We live in an open society which is organized on the principle of voluntary action, but the determinants of that system are exceptionally constraining. Our society is dynamic, changing profoundly in every period of American history; but it is also remarkably stable. The search for the origins of this system is the central problem in American history. It is also the subject of this book.

The Question Framed

The organizing question here is about what might be called the determinants of a voluntary society. The problem is to explain the origins and stability of a social system which for two centuries has remained stubbornly democratic in its politics, capitalist in its economy, libertarian in its laws, individualist in its society and pluralistic in its culture.

Much has been written on this subject—more than anyone can possibly read. But a very large outpouring of books and articles contains a remarkably small number of seminal ideas. Most historians have tried to explain the determinants of a voluntary society in one of three ways: by reference to the European culture that was transmitted to America, or to the American environment itself, or to something in the process of transmission.

During the nineteenth century the first of these explanations was very much in fashion. Historians believed that the American system had evolved from what one scholar called “Teutonic germs” of free institutions, which were supposedly carried from the forests of Germany to Britain and then to America. This idea was taken up by a generation of historians who tended to be Anglo-Saxon in their origins, Atlantic in their attitudes and Whiggish in their politics. Most had been trained in the idealist and institutional traditions of the German historical school.2

For a time this Teutonic thesis became very popular—in Boston and Baltimore. But in Kansas and Wisconsin it was unkindly called the “germ theory” of American history and laughed into oblivion. In the early twentieth century it yielded to the Turner thesis, which looked to the American environment and especially to the western frontier as a way of explaining the growth of free institutions in America. This idea appealed to scholars who were middle western in their origins, progressive in their politics, and materialist in their philosophy.3

In the mid-twentieth century the Turner thesis also passed out of fashion. Yet another generation of American historians became deeply interested in processes of immigration and ethnic pluralism as determinants of a voluntary society. This third approach was specially attractive to scholars who were not themselves of Anglo-Saxon stock. Many were central European in their origin, urban in their residence, and Jewish in their religion. This pluralistic “migration model” is presently the conventional interpretation.4

Other explanations have also been put forward from time to time, but three ideas have held the field: the germ theory, the frontier thesis, and the migration model.

This book returns to the first of those explanations, within the framework of the second and third. It argues a modified “germ thesis” about the importance for the United States of having been British in its cultural origins. The argument is complex, and for the sake of clarity might be summarized in advance. It runs more or less as follows.

The Argument Stated

During the very long period from 1629 to 1775, the present area of the United States was settled by at least four large waves of English-speaking immigrants. The first was an exodus of Puritans from the east of England to Massachusetts during a period of eleven years from 1629 to 1640. The second was the migration of a small Royalist elite and large numbers of indentured servants from the south of England to Virginia (ca. 1642-75). The third was a movement from the North Midlands of England and Wales to the Delaware Valley (ca. 1675-1725). The fourth was a flow of English-speaking people from the borders of North Britain and northern Ireland to the Appalachian backcountry mostly during the half-century from 1718 to 1775.

These four groups shared many qualities in common. All of them spoke the English language. Nearly all were British Protestants. Most lived under British laws and took pride in possessing British liberties. At the same time, they also differed from one another in many other ways: in their religious denominations, social ranks, historical generations, and also in the British regions from whence they came. They carried across the Atlantic four different sets of British folkways which became the basis of regional cultures in the New World.

By the year 1775 these four cultures were fully established in British America. They spoke distinctive dialects of English, built their houses in diverse ways, and had different methods of doing much of the ordinary business of life. Most important for the political history of the United States, they also had four different conceptions of order, power and freedom which became the cornerstones of a voluntary society in British America.

Today less than 20 percent of the American population have any British ancestors at all. But in a cultural sense most Americans are Albion’s seed, no matter who their own forebears may have been.5 Strong echoes of four British folkways may still be heard in the major dialects of American speech, in the regional patterns of American life, in the complex dynamics of American politics, and in the continuing conflict between four different ideas of freedom in the United States. The interplay of four “freedom ways” has created an expansive pluralism which is more libertarian than any unitary culture alone could be. That is the central thesis of this book: the legacy of four British folkways in early America remains the most powerful determinant of a voluntary society in the United States today.

The Problem of Folkways

Before we study this subject in detail, several conceptual problems require attention. All are embedded in the word “folkways.” This term was coined by American sociologist William Graham Sumner to describe habitual “usages, manners, customs, mores and morals” which he believed to be practiced more or less unconsciously in every culture. Sumner thought that folkways arose from biological instincts. “Men begin with acts,” he wrote, “not with thoughts.”6

In this work “folkway” will have a different meaning. It is defined here as the normative structure of values, customs and meanings that exist in any culture. This complex is not many things but one thing, with many interlocking parts. It is not primarily biological or instinctual in its origins, as Sumner believed, but social and intellectual. Folkways do not rise from the unconscious in even a symbolic sense—though most people do many social things without reflecting very much about them. In the modern world a folkway is apt to be a cultural artifact—the conscious instrument of human will and purpose. Often (and increasingly today) it is also the deliberate contrivance of a cultural elite.

A folkway should not be thought of in Sumner’s sense as something ancient and primitive which has been inherited from the distant past. Folkways are often highly persistent, but they are never static. Even where they have acquired the status of a tradition they are not necessarily very old. Folkways are constantly in process of creation, even in our own time.7

Folkways in this normative sense exist in advanced civilizations as well as in primitive societies. They are functioning systems of high complexity which have actually grown stronger rather than weaker in the modern world. In any given culture, they always include the following things:

—Speech ways, conventional patterns of written and spoken language: pronunciation, vocabulary, syntax and grammar.

—Building ways, prevailing forms of vernacular architecture and high architecture, which tend to be related to one another.

—Family ways, the structure and function of the household and family, both in ideal and actuality.

—Marriage ways, ideas of the marriage-bond, and cultural processes of courtship, marriage and divorce.

—Gender ways, customs that regulate social relations between men and women.

—Sex ways, conventional sexual attitudes and acts, and the treatment of sexual deviance.

—Child-rearing ways, ideas of child nature and customs of child nurture.

—Naming ways, onomastic customs including favored forenames and the descent of names within the family.

—Age ways, attitudes toward age, experiences of aging, and age relationships.

—Death ways, attitudes toward death, mortality rituals, mortuary customs and mourning practices.

—Religious ways, patterns of religious worship, theology, ecclesiology and church architecture.

—Magic ways, normative beliefs and practices concerning the supernatural.

—Learning ways, attitudes toward literacy and learning, and conventional patterns of education.

—Food ways, patterns of diet, nutrition, cooking, eating, feasting and fasting.

—Dress ways, customs of dress, demeanor, and personal adornment.

—Sport ways, attitudes toward recreation and leisure; folk games and forms of organized sport.

—Work ways, work ethics and work experiences; attitudes toward work and the nature of work.

—Time ways, attitudes toward the use of time, customary methods of time keeping, and the conventional rhythms of life.

—Wealth ways, attitudes toward wealth and patterns of its distribution.

—Rank ways, the rules by which rank is assigned, the roles which rank entails, and relations between different ranks.

—Social ways, conventional patterns of migration, settlement, association and affiliation.

—Order ways, ideas of order, ordering institutions, forms of disorder, and treatment of the disorderly.

—Power ways, attitudes toward authority and power; patterns of political participation.

—Freedom ways, prevailing ideas of liberty and restraint, and libertarian customs and institutions.

Every major culture in the modern world has its own distinctive customs in these many areas. Their persistent power might be illustrated by an example. Consider the case of wealth distribution. Most social scientists believe that the distribution of wealth is determined primarily by material conditions. For Marxists the prime mover is thought to be the means of production; for Keynesians it is the process of economic growth; for disciples of Adam Smith it is the market mechanism. But to study this subject in a comparative way is to discover that the distribution of wealth has varied from one culture to another in ways that cannot possibly be explained by material processes alone. Another powerful determinant is the inherited structure of values and customs which might be called the “wealth ways” of a culture.

These wealth ways are communicated from one generation to the next by many interlocking mechanisms—child-rearing processes, institutional structures, cultural ethics, and codes of law—which create ethical imperatives of great power in advanced societies as well as primitive cultures. Indeed, the more advanced a society becomes in material terms, the stronger is the determinant power of its folkways, for modern technologies act as amplifiers, and modern institutions as stabilizers, and modern elites as organizers of these complex cultural processes.8

The purpose of this book is to examine those processes at work in what is now the United States, where at least four British folk cultures were introduced at an early date. Their variety makes them unusually accessible for study, as William Graham Sumner himself was one of the first to observe. He found his leading example of folkways not in primitive tribes but in the regional culture of New England. Sumner wrote:

The mores of New England, however, still show deep traces of the Puritan temper and world philosophy. Perhaps nowhere else in the world can so strong an illustration be seen, both of the persistency of the spirit of mores, and their variability and adaptability. The mores of New England have extended to a large immigrant population, and have won control over them. They have also been carried to the new states by emigrants, and their perpetuation there is an often-noticed phenomenon.9

The same historical pattern appears in the American south. However different that region may be from New England, it also has preserved its own distinctive folkways through many generations. Something similar also happened in the American midlands, and in the American west. Throughout all four of these broad areas we find the same processes of cultural persistence, variability and adaptability that William Graham Sumner observed in New England. Even as the ethnic composition of these various regions of the United States has changed profoundly, regional cultures themselves have persisted, and are still very powerful even in our own time. All of them derive from folkways that were planted in the American colonies more than two centuries ago.

If these folkways are to be understood truly, they must be described empirically—that is, by reference to evidence which can be verified or falsified. In this work, descriptive examples are presented in the text for illustrative purposes, and empirical indicators are summarized in the notes.10 Not all of these folkways can be treated empirically, but the work of many scholars has produced a broad range of historical evidence for each of the four major cultures in British America. Let us begin with Puritan New England, which was founded by the first great migration, and take up the others in chronological order.

EAST ANGLIA TO MASSACHUSETTS

The Exodus of the English Puritans, 1629-1641

You talk of New England; I truly believe

Old England’s grown new and doth us deceive.

I’ll ask you a question or two, by your leave:

And is not old England grown new?

New fashions in houses, new fashions at table,

The old servants discharged, the new are more able;

And every old custome is but an old fable!

And is not old England grown new? …

Then talk you no more of New England!

New England is where old England did stand,

New furnished, new fashioned, new womaned, new manned

And is not old England grown new?

—Anonymous verse, c. 16301

ON A BLUSTERY MARCH MORNING in the year 1630, a great ship was riding restlessly at anchor in the Solent, near the Isle of Wight. As the tide began to ebb, running outward past the Needles toward the open sea, a landsman watching idly from the shore might have seen a cloud of white smoke billow from the ship’s side. A few seconds later, he would have heard the sharp report of a cannon, echoing across the anchorage. Another cannon answered from the shore, and on board the ship the flag of England fluttered up its halyard—the scarlet cross of Saint George showing bravely on its field of white. Gray sails blossomed below the great ship’s yards, and slowly she began to move toward the sea. The landsman might have observed that she lay deep in the water, and that her decks were crowded with passengers. He would have noticed her distinctive figurehead—a great prophetic eagle projecting from her bow. And he might have made out her name, gleaming in newly painted letters on her hull. She was the ship Arbella, outward bound with families and freight for the new colony of Massachusetts Bay.2

Arbella was no ordinary emigrant vessel. She carried twenty-eight great guns and was the “admiral” or flagship of an entire fleet of English ships that sailed for Massachusetts in the same year. The men and women who embarked in her were also far from being ordinary passengers. Traveling in the comfort of a cabin was Lady Arbella Fiennes, sister of the Earl of Lincoln, in whose honor the ship had received her name. Also on board was her husband, Isaac Johnson, a rich landowner in the county of Rutland; her brother Charles Fiennes; and her friend the future poet Anne Dudley Bradstreet, who had grown up in the household of the Earl of Lincoln. Other berths were occupied by the Earl’s high stewards Simon Bradstreet and Thomas Dudley; by an English gentleman called Sir Richard Saltonstall; and by a Suffolk lawyer named John Winthrop who was destined to become the leader of the colony.3

Most of Arbella’s passengers were families of lesser rank, but very few of them came from the bottom of English society. Their dress and demeanor marked them as yeomen and artisans of middling status. Their gravity of manner and austerity of appearance also said much about their religion and moral character.

Below decks, the great ship was a veritable ark. Its main hold teemed with horses, cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, dogs, cats and dunghill fowl. Every nautical nook and cranny was crowded with provisions. In the cabin were chests of treasure which would have made a rich haul for the Dunkirkers who preyed upon Protestant shipping in the English Channel.4

The ship Arbella was one of seventeen vessels that sailed to Massachusetts in the year 1630. She led a great migration which for size and wealth and organization was without precedent in

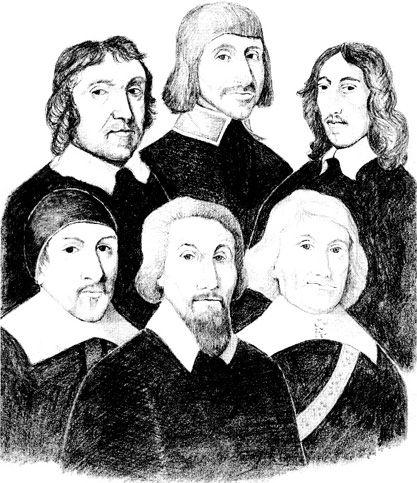

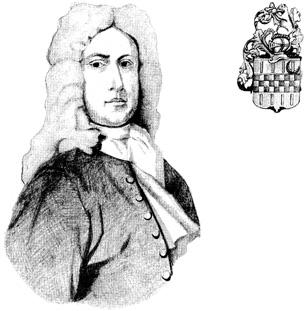

These Puritan leaders personified the spiritual striving that brought the Bay colonists to America. John Winthrop (center front) was a pious East Anglian lawyer who became governor of Massachusetts. His son John Winthrop, Jr. (center rear) was governor of Connecticut, entrepreneur, and scientist, much respected for what Cotton Mather called his “Christian qualities … studious, humble, patient, reserved and mortified.” Sir Harry Vane (right rear) was briefly governor of Massachusetts at the age of 24. He was reprimanded for long hair and elegant dress, but was so rigorous in his Puritanism that he believed only the thrice-born to be truly saved. Sir Richard Saltonstall (right front) founded Watertown and colonized Connecticut, but dissented on toleration and returned to England. William Pynchon (left front) founded Springfield and wrote a book on atonement that was ordered burned in Boston. Hugh Peter (left rear) was minister in Salem, a founder of Harvard and an English Parliamentary leader who was executed in 1660. The original portraits are in the Am. Antiq. Soc., Essex Institute, Mass. Hist. Soc., Queens College (Cambridge) and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

England’s colonization of North America. Within a period of eleven years, some 80,000 English men, women and children swarmed outward from their island home. This exodus was not a movement of attraction. The great migration was a great flight from conditions which had grown intolerable at home. It continued from 1629 to 1640, precisely the period that Whig historians called the “eleven years’ tyranny,” when Charles I tried to rule England without a Parliament, and Archbishop William Laud purged the Anglican church of its Puritan members. These eleven years were also an era of economic depression, epidemic disease, and so many sufferings that to John Winthrop it seemed as if the land itself had grown “weary of her Inhabitants, so as man which is most precious of all the Creatures, is here more vile and base than the earth they tread upon.”5

In this time of troubles there were many reasons for leaving England, and many places to go. Perhaps 20,000 English people moved to Ireland. Others in equal number left for the Netherlands and the Rhineland. Another 20,000 sailed to the West Indian islands of Barbados, Nevis, St. Kitts, and the forgotten Puritan colony of Old Providence Island (now a haven for drug-smugglers off the Mosquito Coast of Nicaragua). A fourth contingent chose to settle in Massachusetts, and contributed far beyond its numbers to the culture of North America.6

The seventeen vessels that sailed to Massachusetts in 1630 were the vanguard of nearly 200 ships altogether, each carrying about a hundred English souls. A leader of the colony reckoned that there were about 21,000 emigrants in all. This exodus continued from 1630 to the year 1641. While it went on, the North Atlantic Ocean was a busy place. In the year 1638, one immigrant sighted no fewer than thirteen other vessels in midpassage between England and Massachusetts.7

After the year 1640, New England’s great migration ended as abruptly as it began. The westward flow of population across the Atlantic suddenly stopped and ran in reverse, as many Massachusetts Puritans sailed home to serve in the Civil War. Migration to New England did not resume on a large scale for many years—not until Irish Catholics began to arrive nearly two centuries later.8

The emigrants who came to Massachusetts in the great migration became the breeding stock for America’s Yankee population. They multiplied at a rapid rate, doubling every generation for two centuries. Their numbers increased to 100,000 by 1700, to at least one million by 1800, six million by 1900, and more than sixteen million by 1988—all descended from 21,000 English emigrants who came to Massachusetts in the period from 1629 to 1640.

The children of the great migration moved rapidly beyond the borders of Massachusetts. They occupied much of southern New England, eastern New Jersey and northern New York. In the nineteenth century, their descendants migrated east to Maine and Nova Scotia, north to Canada, and west to the Pacific. Along the way, they founded the future cities of Buffalo, Cleveland, Chicago, St. Paul, Denver, Seattle, San Francisco and Salt Lake City. Today, throughout this vast area, most families of Yankee descent trace their American beginnings to an English ancestor who came ashore in Massachusetts Bay within five years of the year 1635.

Religious Origins of the Great Migration

For these English Puritans, the new colony of Massachusetts had a meaning that is not easily translated into the secular terms of our materialist world. “A letter from New England,” wrote Joshua Scottow, “ … was venerated as a Sacred Script, or as the writing of some Holy Prophet. ‘Twas carried many miles, where divers came to hear it.”1

The great migration developed in this spirit—above all as a religious movement of English Christians who meant to build a new Zion in America. When most of these emigrants explained their motives for coming to the New World, religion was mentioned not merely as their leading purpose. It was their only purpose.2

This religious impulse took many different forms—evangelical, communal, familial and personal. The Massachusetts Bay Company officially proclaimed the purpose of converting the natives. Its great seal featured an Indian with arms beckoning, and five English words flowing from his mouth: “Come over and help us.” However bizarre this image may seem to us, it had genuine meaning for the builders of the Bay Colony.3

A very different religious motive was expressed by many leaders of the Colony, who often declared their collective intention to build a “Bible Commonwealth” which might serve as a model for mankind. The classical example was John Winthrop’s exhortation which many generations of New England schoolchildren have been made to memorize: “We shall be as a City upon a Hill, the

Ninety Puritan ministers came to New England in the Great Migration. They were a close-knit cultural elite, strong in their spiritual purposes, and highly respected for intellect and character. John Cotton (front center) was a leading theologian of the Congregational middle way and minister in Boston, a leader much loved for his piety and wisdom. Richard Mather (front left) became minister in Dorchester, and architect of the Cambridge Platform (New England’s system of church discipline). John Eliot (left rear) served as minister in Roxbury and Indian missionary who founded the “praying town” of Natick and translated the Bible into Algonkian. Peter Bulkeley (right rear) was minister in Concord, and a gentleman of old family and large fortune which he devoted to God’s work in America. John Davenport (front right) was a Londoner who founded New Haven, the most conservative and purse-proud colony in New England. Their portraits are owned by the American Antiquarian Society, Peter Bulkeley Brainerd, the Connecticut Historical Society, Harvard University and the Huntington Library.

eyes of all people are upon us. … we shall be made a story and a byword throughout the world.”4

But most emigrants did not think in these terms. They were not much interested in converting heathen America, and had little hope of reforming Christian Europe. Mainly they were concerned about the spiritual condition of their own families and especially their children. Lucy Downing, the Puritan wife of a London lawyer, wrote to her brother in New England on the eve of her own sailing:

If we see God withdrawing His ordinances from us here, and enlarging His presence to you there, I should then hope for comfort in the hazards of the sea with our little ones shrieking about us … in such a case I should [more] willingly venture my children’s bodies and my own for them, than their souls.5

Many others embarked upon entirely personal errands. A tailor named John Dane explained that he “bent myself to come to New England, thinking that I should be more free here than there from temptations.” His parents did not approve, but agreed to settle the question by consulting the Bible. Dane wrote afterwards:

To return to the way and manner of my coming: … My father and mother showed themselves unwilling. I sat close by a table where there lay a Bible. I hastily took up the Bible, and told my father if, where I opened the Bible, there I met with anything either to encourage or discourage, that should settle me. I, opening of it, not knowing no more than the child in the womb, the first I cast my eyes on was: “Come out from among them, touch no unclean thing, and I will be your God and you shall be my people.” My father and mother never more opposed me, but furthered me in the thing, and hastened after me as soon as they could.

John Dane and his family did not emigrate to escape persecution. Even that motive, which we call “religious” in our secular age, was more worldly than his own thinking. He never wrote in grand phrases about a “city on a hill,” and showed no interest in saving any soul except his own. John Dane’s purpose in coming to New England was to find a place where he could serve God’s will and be free of temptation. The New World promised to be a place where he would “touch no unclean thing.” In that respect, he was typical of the Puritan migration.6

Most immigrants to Massachusetts shared this highly personal sense of spiritual striving. Their Puritanism was not primarily a formal creed or reasoned doctrine. In Alan Simpson’s phrase it was the “stretched passion” of a people who “suffered and yearned and strived with an unbelievable intensity.”7

That “stretched passion” was shared by the great majority of immigrant families to Massachusetts. This truth has been challenged by materialist historians in the twentieth century, but strong evidence appears in the fact that most adult settlers, in most Massachusetts towns, joined a Congregational church during the first generation. This was not easy to do. After 1635, a candidate had to stand before a highly skeptical group of elders, and satisfy them in three respects: adherence to Calvinist doctrines, achievement of a godly life, and demonstrable experience of spiritual conversion.8

These requirements were very rigorous—more so than in the Calvinist churches of Europe. Even so, a majority of adults in most Massachusetts towns were willing and able to meet them. In the town of Dedham, for example, 48 people joined the church by 1640–25 women and 23 men, out of 35 families in the town. Most families included at least one church member; many had two. By 1648, Dedham’s church members included about 70 percent of male taxpayers and an even larger proportion of women.9 That pattern was typical of country towns in Massachusetts. In Sudbury, 80 were admitted out of 50 or 60 families. In Watertown, 250 were in “church fellowship” out of 160 families. In Rowley, we are told that “a high percentage of men” joined the church—and probably a higher percentage of women—despite local requirements that were even more stringent than in the Colony as whole.10

Church membership was not as widespread in seaport towns such as Salem or Marblehead. But even in Salem more than 50 percent of taxable men joined the church in the mid-seventeenth century. Those who did not belong were mostly young men without property.11

This pattern of church membership reveals a vital truth about New England’s great migration. It tells us that the religious purposes of the colony were not confined to a small “Puritan oligarchy,” as some historians still believe, and that the builders of the Bay Colony did not come over to “catch fish,” as materialists continue to insist. The spiritual purposes of the colony were fully shared by most men and women in Massachusetts. Here was a fact of high importance for the history of their region.12

The religious beliefs of these Puritans were highly developed before they came to America. Revisionist historians notwithstanding, these people were staunch Calvinists. Their spiritual leader John Cotton declared, “I have read the fathers and the schoolmen, and Calvin too; but I find that he that has Calvin, has them all.” Many other ministers agreed.13

Without attempting to describe their complex Calvinist beliefs in a rounded way, a few major doctrines might be mentioned briefly, for they became vitally important to the culture of New

England. These Puritan ideas might be summarized in five words: depravity, covenant, election, grace, and love.14

First was the idea of depravity which to Calvinists meant the total corruption of “natural man” as a consequence of Adam’s original sin. The Puritans believed that evil was a palpable presence in the world, and that the universe was a scene of cosmic struggle between darkness and light. They lived in an age of atrocities without equal until the twentieth century. But no evil ever surprised them or threatened to undermine their faith. One historian remarks that “it is impossible to conceive of a disillusioned Puritan.” They believed as an article of faith that there was no horror which mortal man was incapable of committing. The dark thread of this doctrine ran through the fabric of New England’s culture for many generations.15

The second idea was that of the covenant. The Puritans founded this belief on the book of Genesis, where God made an agreement with Abraham, offering salvation with no preconditions but many obligations. This idea of a covenant had been not prominent in the thinking of Luther or Calvin, but it became a principle of high importance to English Puritans. They thought of their relationship with God (and one another) as a web of contracts. As we shall see, the covenant became a metaphor of profound importance in their thought.16

A third idea was the Calvinist doctrine of election—which held that only a chosen few were admitted to the covenant. One of Calvinism’s Five Points was the doctrine of limited atonement, which taught that Christ died only for the elect—not for all humanity. The iron of this Calvinistic creed entered deep into the soul of New England.

A fourth idea was grace, a “motion of the heart” which was God’s gift to the elect, and the instrument of their salvation. Much Puritan theology, and most of the Five Points of Calvinism, were an attempt to define the properties of grace, which was held to be unconditional, irresistible and inexorable. They thought that it came to each of them directly, and once given would never be taken away. Grace was not merely an idea but an emotion, which has been defined as a feeling of “ecstatic intimacy with the divine.” It gave the Puritans a soaring sense of spiritual freedom which they called “soul liberty.”17

A fifth idea, often lost in our image of Puritanism, was love. Their theology made no sense without divine love, for they believed that natural man was so unworthy that salvation came only from God’s infinite love and mercy. Further, the Puritans believed that they were bound to love one another in a Godly way. One leader told them that they should “look upon themselves, as being bound up in one Bundle of Love; and count themselves obliged, in very close and Strong Bonds, to be serviceable to one another.” This Puritan love was a version of the Christian caritas in which people were asked to “lovingly give, as well as lovingly take, admonitions.” It was a vital principle in their thought.18

These ideas created many tensions in Puritan minds. The idea of the covenant bound Puritans to their worldly obligations; the gift of grace released them from every bond but one. The doctrine of depravity filled their world with darkness; the principle of election brought a gleam of light. Puritan theology became a set of insoluble logic problems about how to reconcile human responsibility with God’s omnipotence, how to find enlightenment in a universe of darkness, how to live virtuously in a world of evil, and how to reconcile the liberty of a believing Christian with the absolute authority of the word.

For many generations these problems were compressed like coiled springs into the culture of New England. Long after Puritans had become Yankees, and Yankee Trinitarians had become New England Unitarians (whom Whitehead defined as believers in one God at most) the long shadow of Puritan belief still lingered over the folkways of an American region.

Social Origins of the Puritan Migration

The builders of the Bay Colony thought of themselves as a twice-chosen people: once by God, and again by the General Court of Massachusetts. Other English plantations eagerly welcomed any two-legged animal who could be dragged on board an emigrant ship. But Massachusetts chose its colonists with care. Not everyone was allowed to settle there. In doubtful cases, the founders of the colony actually demanded written proof of good character. This may have been the only English colony that required some of its immigrants to submit letters of recommendation.1

Further, after these immigrants arrived, the social chaff was speedily separated from Abraham’s seed. Those who did not fit in were banished to other colonies or sent back to England. This complex process of cultural winnowing created a very special population.2

To a remarkable degree, the founders of Massachusetts traveled in families—more so than any major ethnic group in American history. In one contingent of 700 who sailed from Great Yarmouth (Norfolk) and Sandwich (Kent), 94 percent consisted of family groups. Among another group of 680 emigrants, at least 88 percent traveled with relatives, and 73 percent arrived as members of complete nuclear families. These proportions were the highest in the history of American immigration.3

The nuclear families that moved to Massachusetts were in many instances related to one another before they left England. A ballad of the great migration commemorated these ties:

Stay not among the Wicked,

Lest that with them you perish,

But let us to New-England go,

And the Pagan people cherish …

For Company I fear not,

There goes my cousin Hannah,

And Reuben so persuades to go

My Cousin Joyce, Susanna.

With Abigail and Faith,

And Ruth, no doubt, comes after;

And Sarah kind, will not stay behind;

My cousin Constance daughter.4

From the start, this exceptionally high level of family integration set Massachusetts apart from other American colonies.

Equally extraordinary was the pattern of age distribution. America’s immigrants have typically been young people in their teens and twenties. A distribution which is “age-normal” in demographic terms is decidedly exceptional among immigrant populations. But more than 40 percent of immigrants to the Massachusetts Bay Colony were mature men and women over twenty-five, and nearly half were children under sixteen. Only a few migrants were past the age of sixty, but in every other way the distribution of ages was remarkably similar to England’s population in general.5

Also unusual was the distribution of sexes, which differed very much from most colonial populations. The gender ratio of European migrants to Virginia was four men for every woman. In New Spain it was ten men for every woman; in Brazil, one hundred men for every Portuguese woman. Only a small minority of immigrants in those colonies could hope to live in households such as they had left behind in Europe. But in the Puritan migration to Massachusetts, the gender ratio was approximately 150 males for every 100 females. From an early date, normal family life was not the exception but the rule. As early as 1635, the Congregational churches of New England had more female than male members. Our stereotypical image of the Puritan is a man; but the test of church membership tells us that most Puritans were women. One historian infers from the gender ratio that “many Puritans brought their wives along”; it would be statistically more correct to say that many Puritans led their husbands to America.6

In terms of social rank, most emigrants to Massachusetts came from the middling strata of English society. Only a few were of the aristocracy. Two sisters and a brother of the Earl of Lincoln settled in Massachusetts, but all were gone within a few years. The gentry were rather more numerous; as many as 11 percent of male heads of households in the Winthrop fleet were identified as gentlemen.7 Many New England towns attracted a few “armigerous” families whose coats of arms were on record at the College of Heralds in London. This elite, as we shall see, contributed much to the culture of Massachusetts, but comparatively little to its population.8

The great majority were yeomen, husbandmen, artisans, craftsmen, merchants and traders—the sturdy middle class of England. They were not poor. A case in point was Benjamin Cooper, an emigrant who died on the way to America in the Ship Mary Anne (1637). He had modestly described himself as “husbandman” in the passenger list. But when his estate was settled he was found to be worth £1,278. This was a large fortune in that era, much above the usual idea of a “husbandman’s” condition.9

Remarkably few of these migrants came from the bottom of English society, to the surprise of some immigrants themselves. “It is strange the meaner people should be so backward [in emigrating],” wrote Richard Saltonstall in 1632. But so they were. On three occupational lists, less than 5 percent were identified as laborers—a smaller proportion than in other colonies.10 Only a small minority came as servants—less than 25 percent, compared with 75 percent in Virginia. Most New England servants arrived as members of household, rather than as part of a labor draft as in the Chesapeake.11

The leaders of the great migration actively discouraged servants and emigrants of humble means. Thomas Dudley, for example, urged the Countess of Lincoln to recruit “honest men” and “godly men” who were “endowed with grace and furnished with means.” But he insisted that “they must not be of the poorer sort.” When John Winthrop’s son asked permission to send a servant named Pease, the governor replied: “people must come well provided, and not too many at once. Pease may come if he will, and such other as you shall think fit, but not many and let those be good, and but few servants and those useful ones.”12

As a result of this policy, nearly three-quarters of adult Massachusetts immigrants paid their own passage—no small sum in 1630. The cost of outfitting and moving a family of six across the ocean was reckoned at £50 for the poorest accommodation, or £60 to £80 for those who wished a few minimal comforts. A typical English yeoman had an annual income of perhaps £40 to £60. A husbandman counted himself lucky to earn a gross income of £20 a year, of which only about £3 or £4 cleared his expenses. Most ordinary families in England could not afford to come to Massachusetts.13

The social status of these people also appeared in their high levels of literacy. Two-thirds of New England’s adult male immigrants

Dr. John Clark was a Puritan physician in the Great Migration. Trained in England as a specialist in “cutting for the stone,” he sailed to Massachusetts in 1638 and became more generally employed as a physician, surgeon, apothecary, merchant, landowner, distiller, inventor, magistrate in Essex County, and representative in the General Court. His left hand holds a crown saw which was used to trepan skulls, an operation he may have been the first to perform in New England. Behind the skull is a Hey’s saw, another tool of his trade. Clark’s wealth was subtly displayed by a small finger ring which was painted with actual gold dust. His Puritan faith appears in his physiognomy, dress and demeanor. This drawing follows a portrait (1664), the earliest dated in New England, which hangs in the Countway Library of the Harvard Medical School.

were able to sign their own names. In old England before 1640, only about one-third could do so. By this very rough “signature-mark test,” literacy was nearly twice as common in Massachusetts as in the mother country.14

These colonists were also extraordinary in their occupations. A solid majority (between 50 and 60%) had been engaged in some skilled craft or trade before leaving England. Less than one-third had been employed primarily in agriculture—a small proportion for a seventeenth-century population. The ballads of the great migration remarked upon this fact:

Tom Taylor is prepared,

And th’ Smith as black as a coal;

Ralph Cobler too with us will go.

For he regards his soul;

The Weaver, honest Simon …

Professeth to come after.

That lyrical impression was solidly founded in statistical fact.15

This was mainly an urban migration. Approximately one-third of the founders of Massachusetts came from small market towns in England. Another third came from large towns—a much greater proportion than in the English population as a whole. Less than 30 percent had lived in manorial villages, and a very small proportion had dwelled on separate farms.16

In summary, by comparison with other emigrant groups in American history, the great migration to Massachusetts was a remarkably homogeneous movement of English Puritans who came from the middle ranks of their society, and traveled in family groups. The heads of these families tended to be exceptionally literate, highly skilled, and heavily urban in their English origins. They were a people of substance, character, and deep personal piety. The special quality of New England’s regional culture would owe much to these facts.

Regional Origins of the Puritan Migration

Another important fact about the founders of Massachusetts was their region of origin in the mother country. When one examines the ship lists in these terms, the first impression is one of extreme diversity. One “sample” of 2,885 emigrants to New England came from no fewer than 1,194 English parishes. Every county was represented except Westmorland in the far north and Mon-mouth on the border of Wales.1

But closer study shows that some counties contributed more than others, and that one region in particular accounted for a majority of the founders of Massachusetts. It lay in the east of England. We may take its geographic center to be the market town of Haverhill, very near the point where the three counties of Suffolk, Essex and Cambridge come together. A circle drawn around the town of Haverhill with a radius of sixty miles will circumscribe the area from which most New England families came.2 That great circle (or semicircle, for much of it crosses the North Sea) reached east to Great Yarmouth on the coast of Norfolk, north to Boston in eastern Lincolnshire, west to Bedford and Hertfordshire, and south to the coast of East Kent. This area of approximately 7,000 square miles (about 8% of the land area of Britain today) roughly included the region that was defined in 1643 as the Eastern Association—Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Huntingdonshire and Lincolnshire—plus parts of Bedfordshire and Kent.

Approximately 60 percent of immigrants to Massachusetts came from these nine eastern counties. Three of the largest contingents were from Suffolk, Essex and Norfolk. Also important was part of east Lincolnshire which lay near the English town of Boston, and a triangle of Kentish territory bounded by the towns of Dover, Sandwich and Canterbury. These areas were the core of the Puritan migration.3

On the periphery of New England’s primary recruiting ground lay the great city of London. Less than 10 percent of emigrants to Massachusetts came from the metropolis. London was an important meeting place and shipping point for the builders of the Bay Colony, but it was not their English home. Those who had lived in the capital tended not to be native Londoners, but transplanted East Anglians to whom London seemed a foreign place, more alien even than the American wilderness. An example was Lucy Winthrop Downing, a Puritan lady who had moved from East Anglia to London because of her husband’s business. In 1637, Lucy Downing was expecting the birth of a child. She wrote her brother in New England that she wanted to have her baby in Massachusetts rather than in London. “I confess could a wish transport me to you,” she declared, “I think, as big as I am, I should rather bring an Indian than a Cockney into the world.”4

The Puritan migration also drew from other parts of England, but often it did so through East Anglian connections. Throughout England, there were scattered parishes where charismatic ministers led their congregations to Massachusetts. But these leaders were themselves often East Anglians. A case in point was the parish of Rowley in Yorkshire, whence the Reverend Ezekiel Rogers brought a large part of his congregation to Massachusetts, where they founded another community called Rowley in the New World. Rogers was himself an East Anglian, born at Wethersfield in Essex, educated at Christ’s College, Cambridge, and for twelve years a chaplain at Hatfield Broad Oak. He had moved to Yorkshire as a Puritan missionary, “in the hope that his more lively ministry might be particularly successful in awakening those drowsy corners of the north.”5

It would be a mistake to exaggerate the role of the eastern counties in the peopling of New England. A large minority (40%) came from the remaining thirty-four counties of England. An important secondary center of migration existed in the west country, very near the area where the counties of Dorset, Somerset and Wiltshire came together.6 But many of these West Country Puritans did not long remain in the Bay Colony. They tended to move west to Connecticut, or south to Nantucket, or north to Maine. Diversity of regional origins became a major factor in the founding of other New England colonies.7

The concentration of Puritans from East Anglia, and from the county of Suffolk, was especially great in the Winthrop Fleet of 1630.8 In the New World, their hegemony became very strong in the present boundaries of Suffolk, Norfolk, Essex and Middlesex counties in Massachusetts. This area became the heartland of its region; its communities are called “seed towns” in New England because so many other communities were founded from them. Most families in these seed towns came from the east of England. The majority was highly concentrated in its regional origin while the minority was widely scattered. As a consequence, the East Anglian core of New England’s population had a cultural importance greater even than its numbers would suggest.9

Regional Origins: Names on the New Land

The same pattern of regional origins also appeared in English place names that were given to the new settlements of Massachusetts. The first counties in the Bay Colony were called Suffolk, Essex, Norfolk and Middlesex. Three out of four received East Anglian names.

Town names showed a similar tendency. A few Massachusetts communities were named after natural features (Marblehead, Watertown). Others expressed the social ideals of their founders. Salem took its name from the Hebrew word for peace—Shalom. The first town in the interior was named Concord. The town of Dedham wanted to call itself Contentment, but that idea caused such rancor in the General Court that it had to be given up. Only one town in Massachusetts (Charlestown) was named for any member of the royal family during the first generation—a striking exception to the monarchical rule in most British colonies

throughout the world, from the sixteenth to the twentieth century.1

Every other Massachusetts town founded before 1660 was named after an English community. Of thirty-five such names, at least eighteen (57%) were drawn from East Anglia and twenty-two (63%) from seven eastern counties. Most were named after English towns within sixty miles of the village of Haverhill.2

As the Puritans moved beyond the borders of New England to other colonies, their place names continued to come from the east of England. When they settled Long Island, they named their county Suffolk. In the Connecticut Valley, their first county was called Hartford. When they founded a colony in New Jersey, the most important town was called the New Ark of the Covenant (now the modern city of Newark) and the county was named Essex. In general, the proportion of eastern and East Anglian place names in Massachusetts and its affiliated colonies was 60 percent—exactly the same as in genealogies and ship lists.3

Origins of the Massachusetts Elite

This predominance of England’s eastern counties was even stronger among the Puritan elite. Of 129 university-trained ministers and magistrates in the great migration, 56 percent had lived in the seven eastern counties of Suffolk, Essex, Norfolk, Lincolnshire, Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire and Kent before sailing to America. Only 9 percent were Londoners. The rest had been widely scattered through many parts of England.1

This statistic refers only to their last known addresses in England. Many more had some other connection with the eastern counties, and with East Anglia in particular. Altogether, 78 percent of New England’s college-trained ministers and magistrates had been born, bred, schooled, married, or employed for long periods in seven eastern counties.2

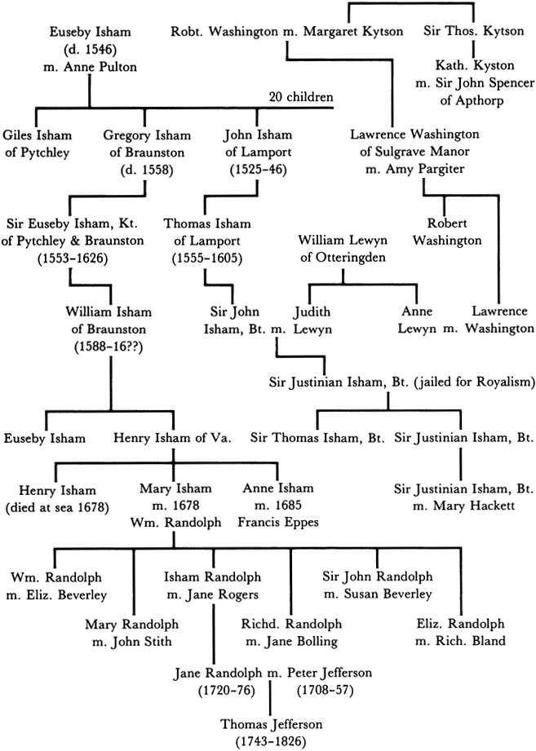

This little elite was destined to play a large role in the history of New England. Its strength developed in no small degree from its solidarity. Many of its members had known one another before coming to America. They had gone to the same schools. Nearly half had studied in three Cambridge Colleges—Emmanuel, Magdalen and Trinity. Approximately 30 percent had attended Emmanuel alone. They intermarried with such frequency that one historian describes the leading Puritan families of East Anglia as a “prosopographer’s dream.”3

Several of these genealogical connections were especially important in the history of New England. One centered on the county of Suffolk and included the families of Winthrop, Downing, Rainborough, Tyndal and Fones. A second connection had its base in Emmanuel College and united a large number of eminent Puritan divines, including Samuel Stone, Thomas Hooker,

Thomas Shepard, John Wilson and Roger Newton, all of whom came to New England. These men had known each other at Cambridge. Most had held livings in East Anglia and had been removed for their Puritan beliefs. They were often related by marriage or other ties of kinship.4

A third group had its seat in the household of the Earl of Lincoln. It included two of the Earl’s sisters and a younger brother, all of whom came to Massachusetts. Also in this connection were Thomas Dudley and Simon Bradstreet, stewards of the Earl of Lincoln; and Thomas Leverett and Richard Bellingham, alderman and recorder of the town of Boston in Lincolnshire.

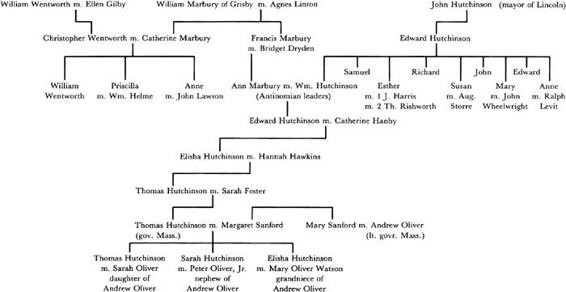

A fourth connection had its home in the parish of Alford, Lincolnshire. This was a small settlement six miles from the sea, in the “fat marsh” country that ran many miles across east Lincolnshire from the Humber to the Wash. Alford sent three families who loomed large in the history of Massachusetts: the Hutchinsons (an armigerous family of county gentry), the Storres or Storys (prosperous yeomen), and the Marburys (a clerical family). These three groups were linked to many other families in the surrounding countryside, including the Coddingtons, Wentworths, Quincys and Rishworths, who would also play prominent parts in New England and Old Providence Island.

The spiritual leader of this flock was the Reverend John Cotton, vicar of Boston’s St. Botolph’s church—the largest parish church in England. Its tremendous tower called Boston Stump, 272 feet high, served mariners as a seamark, and the Puritans as a spiritual beacon. On Sundays the Marburys and Hutchinsons traveled twenty miles through the Lincoln fens toward Boston Stump where they heard John Cotton preach from the beautiful pulpit that still stands in the church.5

In Massachusetts, these various Puritan connections were soon united in a single cousinage. Genealogists have remarked upon “the vast number of unions between the members of the families of Puritan ministers.” One commented that “it seemed to be a law of social ethics that the sons of ministers should marry the daughters of ministers.” Mathers, Cottons, Stoddards, Eliots,

The East-Anglian Puritan Elite of Massachusetts

The Winthrop-Downing-Dudley-Endecott-Bradstreet-Cotton-Mather Connection

I. Descendants of Adam Winthrop (1548-1623)

II. Descendants of Thomas Dudley (1576-1653)

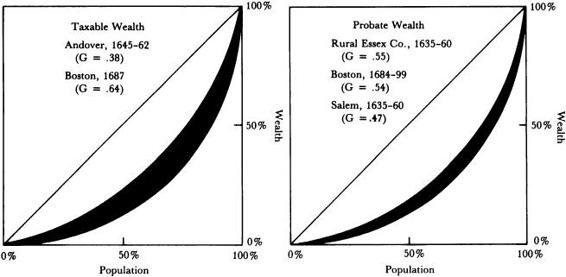

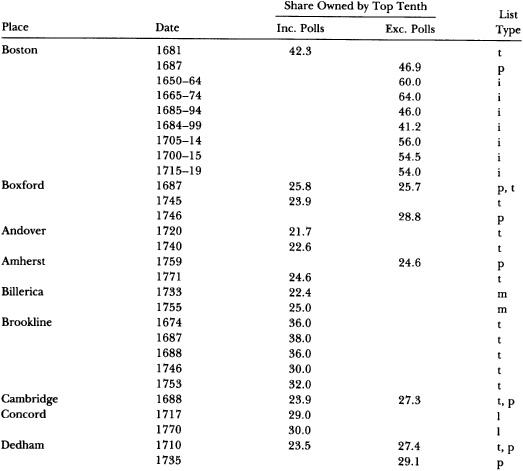

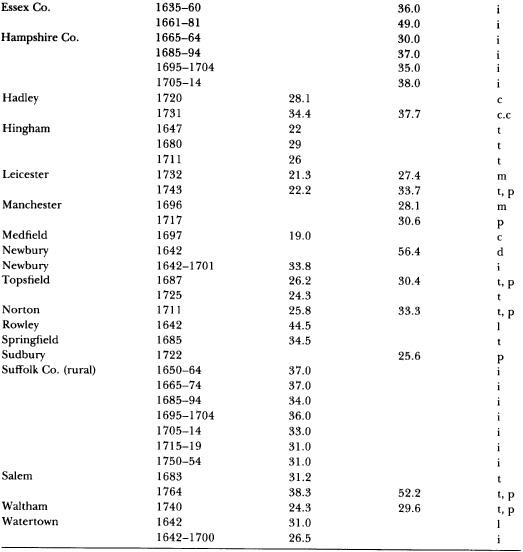

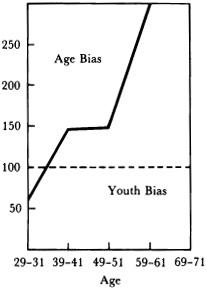

III. Descendants of Simon Bradstreet