© 2003 by Peter Reinhart

Except as otherwise noted, photography © 2003 by Maren Caruso. Shot on location at Pizzetta 211, San Francisco.

Photos on 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, and 1.6 by Peter Reinhart.

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.tenspeed.com

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Reinhart, Peter.

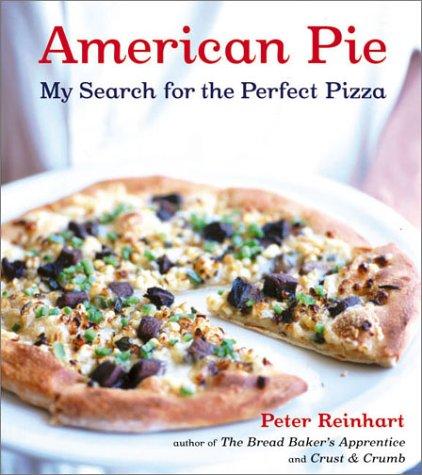

American pie : my search for the perfect pizza / Peter Reinhart.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-60774-090-2

1. Pizza. 2. Italy—Description and travel. 3. United States—Description and travel. I. Title.

TX770.P58.R45 2003

641.8’248—dc22

2003019597

Book design by Nancy Austin

v3.1

Contents

Liguria ** Florence ** Rome ** Naples ** New York City ** New Haven ** San Francisco Bay Area ** Los Angeles ** Sardinia in Dallas and Croatia in Bellevue ** Providence ** Chicago ** Pizzeria Bianco ** Philadelphia and Mama’s ** Postscript

Napoletana Pizza Dough ** Roman Pizza Dough ** Neo-Neapolitan Pizza Dough ** New York–Style Pizza Dough ** Pizza Americana Dough ** Prebaked Freezer Dough ** Sourdough Pizza Dough ** Grilled Pizza Dough ** Chicago Deep-Dish Pizza Dough ** Sardinian Carta di Musica Dough ** Focaccia Dough ** Focaccia col Formaggio and Greek Pita Dough

Crushed Tomato Sauce ** All-Purpose Marinara Pizza Sauce

Pesto alla Genovese

Balsamic Syrup ** Herb Oil ** Spicy Oil ** Caramelized Garlic Purée and Whole Cloves and Garlic Oil ** White Sauce ** Smoked Eggplant Purée ** Sweet-and-Sour Onion Marmalade ** Sautéed Mushrooms ** Butternut Squash Purée ** Dill and Chive Sauce ** Crab and Cream Cheese Topping ** Tapenade ** Roasted Eggplant, Tomato, and Lemon Topping

Pizza Margherita ** Pizza alla Marinara ** Pizza Quattro Stagioni ** Pizza alla Pugliese ** Pizza con Acciughe ** Pizza Quattro Formaggi ** Pizza Vesuvio ** Pizza con Rucola ** Pizza Rosa al Bianco

FIRST GENERATION NEO-NEAPOLITAN PIZZAS

Sauce and Mutz Pizza ** White Clam Pizza

SECOND GENERATION NEO-NEAPOLITAN PIZZAS

New York–Style Sauce and Cheese Pizza ** New York–Style White Pizza ** Pepperoni Pizza Americana ** Three Cheese Pizza with Roasted Eggplant, Tomato, and Lemon

THIRD GENERATION NEO-NEAPOLITAN PIZZAS

Candied Figs, Pecans, Andouille, and Goat Cheese Pizza ** Onion Marmalade, Walnuts, and Blue Cheese Pizza ** Smoked Eggplant Pizza ** Cream Cheese and Crab Pizza ** Smoked Salmon, Dill Sauce, and Onion Pizza ** Folded Greek Salad Pizza

Pizza alla Romana con Salumi ** Pizza al Taglio, Rosa e Bianca

Classic Deep-Dish Pizza

SARDINIAN CARTA DI MUSICA PIZZA

Pizza alla Pescatora ** Pizza con le Sarde

Focaccia alla Genovese ** Potato Rosemary Focaccia ** Focaccia with Onion Marmalade, Blue Cheese, and Walnuts ** Raisin Focaccia ** Grape Focaccia ** Focaccia col Formaggio di Recco

Prasopita

Introduction

For a long time, I thought the best pizza in the country was from Mama’s in Bala Cynwyd, just outside of Philadelphia. And then something happened.

I grew up on Mama’s, even worked there briefly as a delivery boy, and found warm comfort in its stringy cheese and crisp, yet floppy crust whenever I’d been rejected for a date, lost a basketball game, or got together with high-school friends for a Saturday-night poker game. My family was equally hooked, and we often picked up a Mama’s pizza for dinner when my mom wanted a break from cooking, especially if going out for Chinese food, our other favorite pastime, seemed like too much trouble. We knew the owners of Pagano’s Pizzeria in West Philadelphia and often went there when we wanted an actual restaurant experience to go along with our pizza, pasta, and broasted chicken (they were pioneers in this now rarely seen pressurized frying system). But as good as Pagano’s pizza was, it never measured up to Mama’s for deeply felt satisfaction, a culinary balm of Gilead. More than forty years after eating my first Mama’s pizza, almost always made by Paul Castelucci (though I never knew his last name when I worked as a delivery boy), the business is still in the family, and the pizzas are now supervised, but not made, by Paul Jr., Paul’s son. Mama’s is still extremely popular, with long waiting times not only for pizza, but also for fabulous stromboli, hoagies, and cheese steaks.

My brother Fred, who now lives forty-five minutes from Mama’s instead of the five minutes of our childhood, continues to make the pilgrimage whenever he needs a fix. He brought us a Mama’s pizza when my wife, Susan, and I were in Philadelphia for a big food event. Susan had sprained her ankle at the airport just after we landed, forcing us to cancel our dinner plans so she could keep her foot on ice. When I called Fred to explain our plight, he said, “No problem, I’ll pick up a pizza and some cheese steaks at Mama’s and we’ll eat in.” I loved the idea. It had been years since my last Mama’s pizza.

The pizza arrived ninety minutes later, accompanied by Fred and his wife, Patty. I rushed through the greetings—hug, hug, “great to see you”—while Patty comforted Susan. I was captivated by the aroma of the pizzas and cheese steaks, and my mind floated away to distant times. It was like a long-lost friend, triggering painful and joyful memories that were flashing like a deck of cards rifled in front of my eyes. I’d deal with those later. For now, as far as I was concerned, it was about opening the pizza box, unwrapping the butcher paper from the cheese steaks, and getting everyone to stop talking and start eating. We divvied up the cheese steaks, which tasted even better than I remembered them to be, and then, at last, passed around slices of the pizza. I took a bite and stopped, the pleasant image-streaming of food memories suddenly interrupted by a mental disconnect. I shook it off and took another bite expecting an automatic memory flash to kick in so I could resume my forty-year flavor retrospective. Instead, I got a blast of “Whoa!”

There was definitely something amiss. The words just came out without forethought. “Fred, they’ve changed the crust.”

“No they haven’t.”

“Yes they have.”

“No, they haven’t. Maybe it’s you.”

“I don’t think so. The crust is thicker and there are no air bubbles in the lip. Definitely not the Mama’s I grew up with.”

“I think it’s you.”

“No, it isn’t.”

Fred took another bite. “Well, it does seem a little thicker than usual. I heard they were breaking in a new pizza guy. But, I gotta tell you, it’s still pretty close to usual.”

“Maybe it is me,” I thought. It wasn’t just that the crust was a little different. The cheese and sauce certainly still resonated with old memories, and even if it wasn’t the best Mama’s, it was close enough that it should have elicited, within my usually tolerant margin-for-error forgiveness code, at least a sigh of pleasure. But something had changed within me. My expectations, an internal bar of standards that is both conscious and subconscious, had been violated. A slow wave of realization set in, one that I couldn’t suppress even though I tried.

“Maybe,” I said to myself, “it was never as good as I thought it was, just the best I’d been exposed to during my sheltered youth.” I knew it was something I couldn’t say out loud because Fred and Patty still lived here, while I was going back to Providence and might not have another Mama’s pizza for years. Yet I couldn’t shake the thought.

Since 1990, when I left the communal setting of a religious order in which everyone lived a vow of poverty and thus had limited restaurant experience, I have had the privilege of teaching and writing about food, especially bread. I’ve traveled around the country and beyond, belatedly pursuing knowledge about my taste passions. These passions are simple, not of the great gourmand type. I have learned that one of my inherent gifts is the ability to recognize flavors and textures of universal appeal and show people how to reproduce them. As a result of this gift, I have carved out a career as an educator, writer, and product developer. Which brings me back to pizza.

I have had a steady stream of students who have their own sets of childhood food associations that have driven them to the gates of learning. Food memories, as James Beard and M.F. K. Fisher have shown us, are powerful and compelling forces. Wherever I teach, if I want to get a lively conversation going, I need only ask, “Where do I find the best pizza around here?” Nearly everyone has a pizza story and a strong opinion. Pizza, it seems, lives in everyone’s hall of fame.

In 1976, I worked in Raleigh, North Carolina, as a houseparent in a home for what we euphemistically called undisciplined teenagers; in other words, juvenile delinquents. There was a pizzeria on Hillsborough Street called Brothers Pizza, and although I barely remember the details of the place, I do remember the experience of it. I took the kids there whenever we needed to decompress from the latest dramatic event in our house, and there were always, always dramas. That pizza, and only that pizza among all the pizza shops in town, was a panacea, our emotional salve. It had a crispy, crackly crust, like hot buttered toast, comforting and satisfying. It was perfect. The cheese was stringy and slightly salty. Was it the best pizza I’d ever had? No, but it was “perfect” pizza, a peerless match of textures and flavors that fed more than our stomachs and palates. But if I had it now, all these years later, I imagine it would be like having a Mama’s now. It would be good, perhaps the same as it always was, but it wouldn’t be the pizza of 1976, when teenage boys and girls from shattered families, with broken hearts and raging hormones, felt safe enough to confess their fears to me and to one another as they ate their pizza. That pizza, out of that context, could never be that perfect again.

So here I was, years after Raleigh, in Philadelphia, realizing that I was caught in a nature versus nurture situation. Was it me or was it the pizza that had changed, or was it a little bit of both? I’m pretty sure that when I asked myself that question, I set this whole pizza quest in motion.

Pizzeria Bianco

A few years before what I now refer to as my “Mama’s awakening,” a student of mine at the California Culinary Academy in San Francisco told me about a guy named Chris Bianco, who owned Pizzeria Bianco, in Phoenix, Arizona. She had worked at his restaurant prior to coming to school and raved about his pizza. By a happy coincidence, I was headed to Phoenix for the annual conference of the International Association of Culinary Professionals, which is always held in a different city. Most of us went to Phoenix expecting to experience a blitz of great Southwest cuisine, and we weren’t disappointed. But the restaurant that had the biggest buzz of all was Pizzeria Bianco, located just a short walk from the convention center in downtown Phoenix.

I was scheduled to make a presentation on bread-baking techniques at one of the conference workshops, so prior to leaving San Francisco, I asked my Phoenix student to recommend a bakery that I could partner with for making my workshop breads. She said there weren’t any good bread bakeries, but that Chris Bianco made his own bread for his pizzeria, and it was easily the best in town. I called him and we arranged to bake bread together.

When I got to town, I walked over to Pizzeria Bianco with Steve Garner, a friend of mine who hosts a radio food show in Santa Rosa, California, and John Ash, one of the great chefs of America who also cohosts the show with Steve. It was three o’clock in the afternoon and the restaurant wasn’t scheduled to open for another two hours. My idea was that we’d talk and plan out our bread baking, but Chris insisted on making us a couple of pizzas first.

“Okay,” I said without resistance, hoping, but doubtful, that they would live up to their reputation. A few minutes later, two perfect, I mean perfect, pizzas landed on our table, a classic Margherita and a white pizza with arugula and onions, and all thought of bread baking vanished for the moment. Steve and John immediately kicked into their radio-interview mode and began grilling Chris about his pizzas. We learned that as a young man with cooking talent he had gone to Naples from the Bronx, his hometown, to learn how to make true Neapolitan pizza. When his family moved to Phoenix, he decided to make his culinary statement by trying to create the best pizza in the world. He made his own mozzarella cheese and grew his own basil and lettuce behind the restaurant. He and his brother, Marco, made their own rustic Italian bread (similar to ciabatta) from the pizza dough, and their mother came in to make the three desserts on the menu. Chris served five types of pizza (no substitutes, please), house salad, an appetizer course, beverages, and dessert. There was no pasta course on the menu, nor any other entrée. It was just a pizzeria, but with haute cuisine attitude. I asked him why no pasta.

“I think I actually could make the best pasta in town, and if we served it people would love it,” he explained. “But then I’d have my attention divided and the pizzas might suffer. So I decided my true goal is to make the best pizza in the world. If I ever want to do pasta, I’ll open a different restaurant and do it there.”

Did he have plans to do just that? He smiled sheepishly and said, “No, not really. You’ve got to understand, I love making pizza.”

We talked for quite awhile and I realized it was almost five o’clock. A crowd had been gathering outside the front door for over an hour—hot, anxious people hoping to be in the first wave to grab one of the forty-two seats and not have to wait for the second seating. (I soon learned that this is a daily ritual at Bianco.)

Chris anticipated my question and said, “I don’t do takeout. Can’t keep up. Besides, I want them to eat the pizza the way it’s meant to be eaten, right out of the oven. It’s just not the same out of the box. But even so, a wood-fired oven can only handle so many pies and that’s that.” He excused himself to get ready for dinner.

Now we were getting dirty looks from some of the people peering through the window, wondering why we were on the inside, eating pizza, while they had to wait until the doors opened at five. More to the point, probably, they were worried our three precious seats might not be available when the doors opened. So, we made our exit, and a collective sigh of relief rose from the line.

The next morning I returned to make my bread dough and watched Chris make his pizza dough. “I don’t use a mixer, just a big bowl and my hands,” he said. Sure enough, he combined about fifty pounds of flour (specially flown in from the Giusto’s mill in San Francisco) with salt, yeast, and water. Unlike most American pizza makers, he used no oil, true to the Neapolitan rule.

“It’s really all about feel,” he explained. “I have to make it by hand because it’s the only way to really know when it’s right. I can just feel what adjustments are needed and when it’s ready.”

Twenty minutes later we had finished mixing our respective doughs. Mine, using a new technique I had just learned in France, had to be chilled, but Chris’s dough stayed out, covered in the bowl, to ferment slowly. Hours later he divided it into smaller pieces for either pizza or bread, shaped his loaves, and again allowed the dough to ferment, chilling the evening pizza dough in the refrigerator and leaving the bread pieces out for Marco to bake off later. The rest of the time he and his crew did all the prep, making the sauces, picking lettuce and basil from the garden, and readying themselves for the rush of people gathered at the still-locked door.

Watching Chris work helped me to realize how much I still had to learn about that simple yet complex substance called dough and, more importantly, about how dough is transformed, in the hands of a skilled pizzaiolo (pizza maker) into pizza. A few years passed and I got deeper and deeper into the intricacies of bread making, trying to figure out how, as I described it, to evoke the full potential of flavor from the grain. In developing pizza dough for several companies, I gradually came to understand what causes some dough to be better than others. I ate a lot of pizza along the way and tasted many toppings and, more important, heard many pizza philosophies. Whenever the subject of great pizza came up, I mentioned Bianco. At first I was met with laughter and disbelief. The idea of great pizza in Phoenix just didn’t compute. But then I ran into people who knew about Pizzeria Bianco, either from experience or from reading or hearing about it.

It had been a while since I’d tasted the pizza at Pizzeria Bianco, so I began to doubt my memory. Shortly after the “Mama’s awakening,” I ran into one of my favorite food writers, Jeffrey Steingarten, and he asked me who I thought made the best pizza. “I used to think it was Mama’s in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania,” I told him, “but now I think it might be Pizzeria Bianco in Phoenix.”

He hadn’t been there but had heard of it. “How can you call it the best if you haven’t tried Frank Pepe’s or Sally’s in New Haven, or John’s or Grimaldi’s in New York City?” he asked.

Of course he was right. Pizzeria Bianco might have been the best I’d ever had, but there were so many other legendary places still to try. So I did go to Pepe’s, Sally’s, Grimaldi’s, John’s, and many other places. I went to Genoa and then to Naples, into the belly of the beast, to the source, and then returned to America to immerse myself in pizza of all types: classic, modern, avant-garde, you name it. I was searching for the perfect slice. That meant I had to discover what perfection, at least pizza perfection, really is. Along the way I went back to Pizzeria Bianco in Phoenix to find out if my memory held true, or if it was to be another Mama’s moment, surpassed by even better pizza found elsewhere.

In the pages that follow, I recount the journey that took place between my two visits to Phoenix, plus some trips that followed it. (This is a journey with no clear endpoint; it doesn’t begin or end with Pizzeria Bianco or Mama’s, but is merely signposted by them.) I had become a hunter of sorts, a pizza hunter, and I enlisted others to join me on the hunts. With Mama’s no longer the benchmark, and with the memory of Pizzeria Bianco serving as a temporary beacon and standard, I sought out great pizza everywhere I traveled, and I traveled to seek out great pizza.

Some of the numerous pizza excursions I choreographed were thwarted by circumstances: trip cancellations, a restaurant Closed sign, logistical mix-ups. But almost every time something went wrong, something else occurred to make it all right. In fact, Plan B was often better than Plan A could ever have been. As result I came up with the Reinhart Pizza Hunter’s Credo, a sound axiom for anyone who decides to adopt it: It’s all about the adventure, not the pizza. The pizza is just grace.

Sometimes my fellow pizza hunters made the hunt itself a more memorable adventure than the pizza did. I had so many interesting conversations around a pizza, on the way to get a pizza, or in anticipation of a pizza, that the pizza itself became the excuse for the hunt. But every now and then, the quality of the pizza transcended the hunt, stopped all conversation and refocused everything on itself, the object and subject, and the thrill of the hunt fulfilled itself in the quarry. When that happened it was magical, and all that mattered again was pizza.

So, I followed the trail wherever it led. And where it inevitably led, to no one’s surprise, was Italy.

Those who have traveled to Naples, or to Genoa and its surrounding Ligurian coast, know that American pizza and focaccia (the northern Italian version of pizza) are not always the same as what we call Neapolitan, or Napoletana, pizza or Ligurian focaccia. There are a number of reasons for this difference, and it is not necessarily a bad thing that ours are different from theirs. Pizza is, and has always been, a work in progress.

My Greek friends insist that pizza isn’t even originally Italian, but Greek, brought to Naples by Peloponnesians escaping the Ottomon Turks or, much earlier, by Trojans fleeing the builders of that famous horse. Indeed, most Greeks are happy to take credit for contributions from both eras and like to connect nearly everything in Italy to their famous ancestors, Odysseus and Aeneas. In relation to pizza, their reasoning may be accurate. Naples, originally called Neapolis, was founded in the sixth century B.C. by Greek colonists from the even earlier nearby settlement of Cumae. We also know that the ancient Greeks made a flatbread with toppings called placenta.

But here’s the pith of it: Pizza evolved from one of the most basic food concepts—bread and topping, specifically dough cooked over or in a fire, finished off with sauce, oil, cheese, whatever was at hand. Did the Greeks invent it? Why not the Egyptians? Or the Indians? Forget about who invented pizza. The real question is where was it perfected, where was it elevated from a simple peasant food to the craft, to the art form we appreciate today? You do not have to be an Italian or even an Italian American to know the answer to that one. When Gennaro Lombardi brought pizza to New York City’s Lower East Side in 1905, he brought it from Italy; his influence was the pie of Naples. But the fuel in New York was coal, not the wood of southern Italy, so from the moment pizza hit the shores of America, modification and adaptability were inevitable. Thus began the evolution (some would say the devolution) of pizza as we now know it.

I knew I would have to visit the surviving great early pizzerias of America, not only for the pleasure of their pies, but also to back my response to the inescapable challenge, “How can you say Pizzeria Bianco is the best if you haven’t been to —?” But even more important, I knew I would have to (would want to, would love to) visit the original role models, the pizzerias of Naples and the focaccerie of Liguria, to understand what they had fostered on this side of the Atlantic. In other words, I would have to go to Italy.

LIGURIA

I began my search for the roots of pizza in the port city of Genoa, the commercial heart of the northwest region of Liguria. Susan and I settled into a hotel room just around the corner from the statue of Christopher Columbus near the central train station, and then set out to explore this hardworking harbor town known as the epicenter of focaccia alla genovese. The people of Genoa are as proud of their focaccia as the Neapolitans are of their pizza. Some variation of it is served at most meals. Focaccerie, similar to the pizza-by-the-slice shops of New York City, are found every few blocks in this colorful, maritime town, which meant that freshly baked focaccia was never more than a few minutes away, no matter where we found ourselves.

In my brief sampling, I came to the following conclusion: focaccia is not automatically extraordinary just because it is made in Genoa. Like pizzas everywhere, focaccia can be great, good, or forgettable. Whether topped with cheese, onions, potatoes, cured meats, or pesto or another sauce, the bread itself is usually good but seldom outstanding, mind-numbing, conversation stopping, or otherwise memorable.

One thing I learned during two previous trips to Italy is that while Italians love bread, you won’t find great bread everywhere in the country. The ratio of world-class bread to average bread is about the same as in the United States. Even so, Italians are loyal to their local bread products, regardless of outside opinion. For instance, while visiting Bologna, I encountered the manino, a roll shaped to look like a hand. The locals raved to me about how special this bread was, and I found I had to hide my disappointment when I finally tried some. What was special was that the Bolognans had grown up with this unusually shaped bread. What was a bit perplexing was how these food-savvy people could be so deluded about their dry, overly starchy bread that had no discernible special property other than its shape. This is not an unusual circumstance. People are notoriously—and naturally—chauvinistic to the point of delusion about many of the things they have known since childhood. I myself am that way—or once was—about Mama’s pizza.

The focaccia of Genoa was certainly better than the manino of Bologna. But would I make a return trip for it? No. The focaccia in San Francisco’s North Beach, from the aptly named Liguria Bakery, is as good. The focaccia-like pizza at Sullivan Street Bakery in Manhattan is substantially better. The focaccia my culinary students make is actually as good or better than anything I had in Genoa.

“Well, do you think we should still go to Recco?” Susan asked.

“We’ve got nothing to lose,” I replied, trying to remain hopeful that something new and different awaited us there.

We bought train tickets for the forty-five-minute ride to Recco, a small town just south of Genoa. Carol Field, author of The Italian Baker among other classics, and Johanne Killeen and George Germon, owners of the Al Forno Restaurant in Providence had all said we must go to try the local focaccia col formaggio di Recco. Once on the train, Susan asked me what I thought about the focaccia in Genoa. Our conversation went something like this:

“Well, focaccia is just bread with something on it or in it. So if it’s going to be memorable, the bread has to be really, really good. The breakfast focaccia at the hotel, plain with just a little salt and aniseed on top, was good. It was flavorful, the bread was moist and not dry—I liked it. But will I dream about it? Will I crave it when we get home and regret not being able to find anything like it? I doubt it. The pesto focaccia from the shop near our hotel was good. The sauce was wonderful, which I would expect here in Genoa since pesto, focaccia, and Christopher Columbus are the three things for which the city is famous.”

“So what’s the big deal then about focaccia?” Susan asked.

“The potential for greatness is always there, but I think focaccia is like most things that have been around for a while: bakers settle into a routine until someone comes along and pushes the envelope. As long as people buy it at this level, most bakers have no incentive to take it to another level. I’m sure there are focaccerie that do it better than what we’ve sampled, and bakers who know there are ways to make the bread better. That said, I do appreciate one thing about all Genoa focaccia: the thickness. In the States, focaccia is usually too thick—more than an inch and sometimes even two inches tall—so that it becomes too much about the bread and not enough about the topping. Here, it’s just right, about a half inch thick, and even though it looks like it’s going to be dry, it stays moist and creamy. That’s the most valuable thing I saw in Genoa.”

As we pulled into our stop, Susan sighed, “Well I hope this Recco focaccia is better than what we’ve had so far.” We would soon discover that she had just uttered the understatement of the trip.

The train station stood at the top of a hill, and the street that led away from it spiraled down to sea level and the Via Roma, the main street of Recco. According to Ed Behr, who reported on Recco in his wonderful journal, The Art of Eating, the town had been heavily bombed during World War II and then rebuilt. That explains its rather modern feel, which is reminiscent of a small East Coast beach community in America. As we wound our way down to the town, its charm began to grow on us.

We were in search of the most famous restaurant in Recco, Manuelina, the purported early-twentieth-century birthplace of the legendary focaccia col formaggio di Recco. Ed Behr’s research seemed to suggest that it was probably Manuelina Capurra’s marketing skills that earned her the credit for inventing something that was already being served in many towns along the coast (and in similar permutations in Greece under the generic category “pita”). The civic fathers of Recco realized well before their neighbors the value in “owning” a celebrated product. The town had once been known for its watch factory, but that was long gone. So it latched onto dough and cheese, established an annual focaccia col formaggio festival, and pulled off a coup that would make any chamber of commerce proud. Recco claimed focaccia col formaggio as its own, and the town had the franchise by fiat.

Almost every restaurant we passed proudly listed this item in its window display, but only a select few have become renowned for it. We had been given a street address for Manuelina on Via Roma, so we kept walking until we came to it, about a mile down the road. It was closed.

“This can’t be happening,” I moaned.

Susan responded more philosophically, proposing “Maybe this is one of those times when, you know, if a door closes, a window opens.”

I groaned as I knocked on the door. Amazingly, it was unlocked and opened slowly. We went in, hoping that our American audaciousness would result in us finding someone who would tell us that even though the restaurant was closed on Wednesdays, and this was Wednesday, the staff would cook for us. The restaurant was beautiful and I wanted to eat there. We heard someone walking toward us. It was the cleaning woman, and even though she did not speak English, a series of desperate hand gestures prompted her to lead us across the alley into a pleasant hotel and to a woman who seemed to be in charge. I explained that we had come all the way from the United States to experience the focaccia col formaggio di Recco at Manuelina and how distressed we were to find the restaurant closed.

“Ah yes,” she said in good English, “It is our restaurant, but it is closed every Wednesday. I am so sorry.”

I put on my saddest face and asked, “Are any of the cooks around? Is there any chance?”

“Ah no,” she said. “But I have an idea. About sixty meters down the road is another restaurant, Da Vittorio. They also make the focaccia and theirs is,” and at this point she whispered, “as good as ours.”

“Really?”

“Well, almost as good. But it is very good and they are open and we are not.”

She pointed us back toward the train station and we walked until we came to Da Vittorio. It looked like a Swiss chalet, less fancy than Manuelina, but charming in its own way. Like Manuelina, it seemed to be a combination hotel and restaurant. The doors were open and we saw movement inside, so we went in. Two men were at work in the room, setting things up for the lunch hour. They both looked up and smiled as we entered. They were identical twins. We approached one of them and explained our plight. He nodded, gestured with the international wait-a-second motion, and then returned with the other twin.

“I am Giovanni, and this is my twin brother, Vittorio. We are the Bisso brothers. I speak English but he does not.”

So I again explained our mission, how we discovered that Manuelina was closed after traveling all the way from the United States to eat there, but that we had heard that their restaurant was equally good. He especially liked the last point and translated it for his brother, who smiled and nodded.

A focaccia col formaggio di Recco, just out of the oven, made by focacciaiolo Fabio, and Da Vittorio co-owner Giovanni Bisso. (photo credit 1.1)

“Yes, there are three such famous places in Recco, and we are one of them. We will take good care of you.”

Those were the magic words I had been waiting all day to hear.

Giovanni, whose nickname is Gian, guided us into the kitchen where we were surrounded by bubbling pots of fish stock and an active little community of three cooks calmly but busily making sauces, fresh pasta, and, in its own little corner of the kitchen, focaccia col formaggio. We moved to the very back of the room where we met the focacciaiolo, Fabio, who generously demonstrated for us the simple art of Recco’s gift to the culinary lexicon.

I had never had focaccia col formaggio di Recco, so I had no idea that it was unlike all the other focaccia I had seen in Genoa. It is made from unyeasted dough—just flour, water, and a bit of salt. Fabio first rolled it out and then stretched it by hand into a larger and larger disk that was so paper-thin that it was almost translucent, much like strudel or phyllo dough. He draped the disk over a large copper pan about twenty-four inches in diameter with a half-inch lip around the edge, and then tucked it in to eliminate any air pockets. Next, he topped it with dollops of creamy stracchino, a fresh cheese that looked like a rich ricotta but was more like mascarpone or soft cream cheese. He then shaped a second piece of the dough just like the first one, used it to cover the top of the “pie” (for that was what it had now become), and crimped the edges of the two disks together. Finally, he poked four or five holes in the top, pulled them out slightly to create vents, drizzled the entire surface with olive oil, sprinkled on a little salt, and slid the pan into the oven (after a little awkward translation, we decided it was heated to the equivalent of 500 degrees). Fabio told us to come back in about eight minutes.

This is what a focaccia col formaggio di Recco looks like just before the top crust covers all that luscious stracchino cheese. (photo credit 1.2)

Gian then took us up a short flight of stairs to his pasta shop, where we met Renato, who was making trofie (or troffie) and pansotti from a simple dough of flour, water, and salt—no eggs, no oil. To make the trofie, Renato cut off small snippets of dough and rolled them into little corkscrewed twigs with the edge of his hand. He showed me how to do it and was a little surprised, and pleased, that I was able to pick up the technique fairly quickly. Within a few minutes he had, with the addition of my few pieces, created a large pile of trofie, ready to be boiled. Some of the remaining dough was rolled into small disks, about the size of a silver dollar, and then pressed with a small wooden stamp that imprinted a design. These decorative, delicate pastas were called corzetti stampati. Gian explained that the stamps came in many patterns, some personal and some of general interest, ranging from abstract lines and geometric shapes to more representational pastoral scenes and figures.

By this time the focaccia col formaggio was ready to be pulled from the oven. It had turned a deep golden color with caramelized splotches that were dark brown. Gian quickly escorted us to our table in the dining room. A couple at the table across the aisle from us were sipping some white wine. We were brought a bottle of the same local wine, and the pan of focaccia that we had watched Fabio make was placed next to our table. The waiter sliced it into squares, not wedges as with pizza, and lifted a few pieces onto each of our plates. He did the same for the couple across the aisle. It looked like a lot of pie, larger than what we think of as an extra-large pizza, but because the dough was so thin, it was not a lot of food. As soon as we finished our servings, Susan and I realized that we could have easily devoured the entire pie without the help of the other couple. I even felt pangs of resentment toward them. I wanted more.

But we didn’t get more. Gian had taken charge of our dining experience, and it was time for the definitive Genoese pasta experience, trofie col pesto. Those toothsome little pasta twigs that we had twisted in the kitchen had been boiled for just a few minutes and were now served in a sauce of fresh basil, garlic, pine nuts, olive oil, and Parmesan. We had had pasta with pesto before, of course, but there is something to be said for being served this dish by people who are proud of what they do and of what their region has contributed to the culinary vocabulary. Gian and Vittorio both had the appearance of hosts content with fulfilling their appointed purpose in life. They were bringing us pleasure and they were doing it through total immersion in their heritage. The Bisso brothers’ pesto was excellent, brightly colored and flavored. It was perhaps not the best I had ever eaten, but given the context, it was certainly the most memorable.

The trofie was followed by the pansotti served in salsa di noce, a rich béchamel-like cream sauce with walnuts, garlic, marjoram, pine nuts, and some kind of fresh, creamy cheese which Gian casually referred to as formagita. What remains in my memory about both the trofie and the pansotti is not the sauce, but the texture of the pasta, one of slightly chewy resistance that just gave way under the tooth, complemented by the sauce but not really dependent on it.

By the time the fish stew was served, we were so sated we were practically hanging onto our chairs. I have no idea what we had for dessert, though I remember that it was very good; my mind was still rapt with thoughts, cravings, for focaccia col formaggio di Recco. Gian sat with us as we collected ourselves, telling us nostalgic stories of his region. I remember little bits of what he said, like how the term blue jeans was named after the blue trousers of Genoese sailors; that the flag of London was based on the flag of Genoa; that the patron saints of the area are Mary the Suffering, Saint John the Baptist, and Saint George (of dragon fame); and that Vitturin, Manuelina, and La Barachetta di Biagio were other restaurants where you can find excellent focaccia col formaggio di Recco. Some places, he told us, don’t bake it in copper pans but directly on the stone hearth. Opinion is divided on the matter of which method is best, and we didn’t have another day to stick around to find out, but I wondered, “How could it get any better than this?”

As we prepared to leave, Vittorio, who is named after his grandfather, the original owner of Da Vittorio, took us to a large urn and indicated that we should choose something from it. Gian explained, “He wants you to take a wooden pasta stamp as a souvenir of your time here.”

We pulled one of the stamps from the bowl. It had a simple design on it, but the pattern did not matter. It was a touching moment. We had been treated to true Ligurian hospitality, and even though this scene may have been repeated countless times with other visitors, we felt that for a few hours we had been adopted, maybe even initiated, into a special private society.

As we walked back to the train station, I said, “You know, even if nothing else remarkable happens on this trip, it will all have been worth it just for this experience.”

Then I remembered Susan’s optimistic comment about serendipity, and officially adopted the credo that informed the next few months of pizza discovery: it’s all about the adventure.

FLORENCE

The bookends of our Italian pizza hunting were Genoa and Naples, but there were two important stops between them, Florence and Rome. Faith Willinger lives in Florence. A New Yorker married to an Italian businessman, her heart now belongs to Italy. She has carved out an important niche in the city, taking people on market and vineyard tours and teaching them how to cook in her home kitchen with the things they bring back. Faith is a star among the chefs in Italy; everyone knows her and she, in turn, seems to know everyone. When I told her we were coming to town, she invited us over for lunch, choreographed our visit to Florence, and also helped us plan out our time for Rome and Naples.

Faith even recommended our hotel, Palazzo Castiglione, which was only a ten-minute walk from her house and was located in a wonderful old palazzo, with a different hotel occupying each floor. Indeed, everything in Florence seemed like a ten-minute walk from everything else. We spent much of our time doing the typical first-time-in-Florence things, such as being overwhelmed by Michelangelo’s David, visiting various museums, buying jewelry on the Ponte Vecchio, and exploring the many narrow streets and alleys in search of the best gelateria. Faith arranged for us to have lunch at Cibrèo, one of the finest restaurants in Florence, where the flavors were so fresh and perfectly balanced that we just sighed and, as in Recco, let go. All of these things would have been enough to make our stay perfectly satisfying. We were not expecting to find great pizza in Florence. After all, the city is not known for it. But we got lucky on our final evening.

Just up the block from our sweet little hotel was a pizzeria we had walked past a number of times. It took the recommendation of an Australian chap, a handyman at our hotel, to give us the nudge we needed to check out the place.

“If it’s pizza you want, you won’t do any better than that Antica place just a few doors up the street,” he said. That was enough for us.

We were greeted at Antica Pizzeria dell’Arte by the first of two Salvatores. This one was the headwaiter and he would turn out to be the only employee we met who was not one of the three sons of the owners, Ciro Urbano and his wife, Palma (who was also the pastry chef). It was a warm, not-too-muggy night, so we decided to eat outside. In a scene that was to repeat itself many times, sometimes in English and sometimes through a fractured, though practiced, Italian phrase, Susan explained to the waiter that I was a writer of cookbooks (“Buongiorno. Mi chiamo Susan Reinhart. Mio marito Peter Reinhart è un autore dei libri della cucina.”), that I was doing a book on pizza, and that we’d heard that the pizza here was very good (that part was always in English).

“Not just good but the best,” Salvatore, the proud waiter, told us. “Come, I will show you.”

He beckoned us inside where the pizzaiolo, the other Salvatore (son of Ciro), was happily stationed in front of the forno, a beehivelike brick oven fueled by hardwood logs that we could see glowing through the oven’s open mouth. As I held up my camera to show that I wanted to take pictures of him making a pizza, Salvatore I explained to Salvatore II who we were. He smiled and nodded. I asked Salvatore II what his best pizza was, and Salvatore I translated his response. He thought that we should order a Margherita, the most famous style, but that we should also try a special pizza that he had invented. As Salvatore I repeated that advice, I saw a proud smile appear on the second Salvatore’s face, and then he said something else in Italian.

“He says he has, how do you say, marked this, registered this pizza.”

“You mean trademarked it?” I asked.

Big smile, nods all around, “Yes, like that. He calls it his Vesuvio pizza. It is very good, you will see.”

He explained that it was made with the famed mozzarella di bufala, and also black truffles and tomatoes, to which I reprised my usual, “Bring it on.”

More nods, more smiles. I took pictures of Salvatore II making the pizzas as Salvatore I filled in more of the story. He asked if we had been to Naples, and I explained that we were headed there in a few days. He said we should go to Pizzeria Brandi, where the pizza Margherita was invented and also where Salvatore II had learned to make authentic DOC pizza.

“You know DOC?” he asked, pronouncing the word “dock,” not as three initials.

“Yes, I know DOC,” I replied. DOC, which stands for Denominazione di Origine Controllata, is a government system that regulates the standards for some Italian foods and beverages, primarily cheeses and wines. But in this instance the designation means that a pizza is made according to strict guidelines established by the Associazione della Vera Pizza Napoletana.

“We’re DOC here,” he told me.

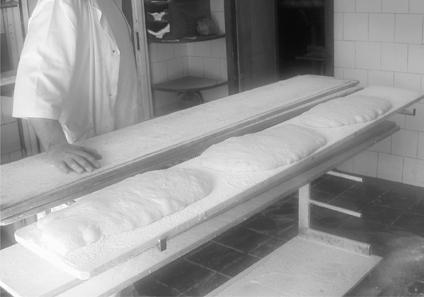

A pizza marinara about to go in the forno for its 60-second bake at about 800 degrees. (photo credit 1.3)

So I watched Salvatore II make our first official pizza napoletana. It was not a flashy process—there was no tossing of a disk into the air—but rather a brisk working of the dough into a circle on a floured counter, followed by a swift knuckling of it by one hand to stretch it a bit further, about ten inches across. He placed it on a floured wooden peel, spread it with a small amount of sauce made from fresh-looking crushed tomatoes, arranged four large basil leaves on top, and then scattered shredded fresh cow’s milk mozzarella, known as fior di latte, over the surface. Salvatore II told us that mozzarella di bufala, the prized fresh cheese made from the milk of the water buffalo, was saved for special pizzas, while most of the fresh mozzarella used on everyday pizzas, like the Margherita he was making, was fior di latte because it was less expensive and not as puddly when melted. (This is actually stretching the DOC rules, but we did not know that at the time.) He finished off the pizza with a small dusting of grated Parmesan cheese, and slid it into the oven. Then he put a small amount of what looked like sawdust or fine wood shavings on the peel and flicked them over the hot coals. They flared like a swarm of lightning bugs and created a burst of smoke. Salvatore II looked over at us with a satisfied smile.

Next, he began to work on the pizza Vesuvio, stretching the dough and then laying it on the wooden peel as he had just done for the Margherita, stopping his work after exactly sixty seconds to remove the first pizza from the oven. He returned to the dough, laying a bed of chopped fresh tomatoes on it, and then placing a small ball of mozzarella di bufala in the center, but only after first cradling it in his hands with a gentle, affectionate rocking motion. My heart leapt as he opened a jar of black paste that released an earthy pungency into the air. It was, of course, chopped black truffle, and he spooned out a healthy dollop of it, balancing it on top of the ball of cheese. He quickly flattened a second ball of dough, cut off strips, and then laid them on top of the pizza from the rim to the center, like spokes on a wheel. He pinched the ends of the strips together on top of the now thoroughly truffled mozzarella ball, and slid the pizza into the oven. He suggested we go back to the table, where our first pizza was waiting for us.

The Margherita was truly wonderful, especially since it was the first supposedly official DOC pizza we had eaten, and we didn’t really have anything with which to compare it. The dough puffed around the edge, creating what Salvatore I called the cornicione. The edge had the texture of ciabatta, but the pie was thin toward the center. At first the slice seemed crisp, but it quickly softened. Somewhere along the journey we had been told to eat Neapolitan-style pizzas with a knife and fork and not to try to pick up the slices as you would an American-style pizza. I cut a wedge and rolled it back from the pointy nose to the cornicione, like a jelly roll. Then I sliced off a portion and ate it with my fork, working confidently as if I knew what I was doing.

The pizza Vesuvio soon arrived, and it was a fantastic sight. The strips of dough running across the top and rising toward the center gave it its namesake look. The ball of fresh mozzarella had melted into a semiliquid state, and the black truffle paste running through it in rivulets was reminiscent of molten lava. The chopped tomatoes brought some acidity and liveliness to the flavors, while the top crust, although not solid, gave the pizza the quality of a calzone. In the end, I thought the dough strips took away from the overall flavor of the pie, diluting the impact of the amazing truffled flavor that flowed from the “volcano.” I’m ashamed to admit I had the terribly vain thought, “This is really good, but I think I can make it even better.”

As our meal wound down, I became lost in my own musings. I was thinking about the tweaks I might make to the Vesuvio, until I suddenly shook myself free of such thoughts, aware that I was beginning to step on sacred pizza turf. I quickly tempered my irreverence by adding the thought, “Well, maybe it will be more perfect when we get to Naples.” But first we had to go through Rome.

ROME

An American we met on the train to Rome told us we should go to Da Baffetto for the best Roman-style pizza, and since it was a mere ten-minute walk from our hotel we did, passing numerous other pizzerias along the way. There is something liberating about having a recommended place, even if it comes from a stranger. It fit the spirit of the hunt, and it didn’t hurt that it was also on a published list of best pizzerias in Rome that someone else had given us.

Da Baffetto had a tiny interior, but it had a lot of picnic tables along the side of the building, and the tables were full, always a good sign. We sat at the only empty bench. Almost immediately another couple was assigned to the two vacant seats next to us by the rough-and-tumble-but-heart-of-gold-looking host. I almost always, automatically, impulsively, imagine a backstory for interesting-looking waiters or restaurant workers. At Da Baffetto, the entire crew was backstory worthy; they all looked like motley sailors, pirates really, who, without warning, could break into “Blow the Man Down,” or its Italian equivalent. They were all smiling, especially the two pizzaioli, who were working as a team. One guy shaped the dough, stretching it thin and flat, into a circle larger than the Neapolitan-style pizza we had had in Florence. He laid it out on a large wooden peel, and then the other man sauced it, topped it, and slid it into a brick oven, where it baked for two or three minutes. It emerged as a thin pizza with a nice char around the edge and even on the cheese. The crust was nearly cracker crisp with very little air in it, and without the puffed edge of a Naples pizza.

The young couple seated next to us were Americans, and they seemed familiar with the menu. I asked them if they’d been to Da Baffetto before.

“We discovered this place on our first night here, three days ago, and have eaten here every night since,” the husband said. “I don’t know if it’s just because were are in Rome, or maybe because we haven’t had great pizza before, or maybe even because this is our honeymoon, but this is the best pizza I’ve ever had in my life.”

I would never discount the “aah Roma” factor in falling in love with a place, but whenever I hear the words, “The best I’ve ever had,” I take them seriously. So I asked, “Well, do you have any good pizza where you live?”

They looked at each other, trying to recall, and then he said, “Well, actually, we do have a couple of places we like. We used to think they were good, but now …,” and they drifted off into the kind of semiswoon that happens only when lovers are caught in the thrall of finding their own special place. Our dining companions definitely had a contented “we’ll always have Da Baffetto” look. It’s nice to be around that look.

Susan and I were hoping to have our own bonding moment, but when our Margherita and prosciutto pizzas came, we knew by the first bite that as good as they were, and they were good, this was not going to be an “our place” moment. The sauce of crushed tomatoes, the fresh and dry cheeses, the char—they were all great. Both pizzas were executed, in their style, about as well as I could imagine they could be done. But there was something about the ultrathin crust that didn’t work for either of us. It was as if it was too slight when matched up against the bold flavors of the toppings.

Would I go back to Da Baffetto? Absolutely. We had other pizzas in this same style while in Rome and none was as tasty. But is it one of my favorites of all time? I can only say that the style itself precludes it from making my hall of fame. I am, after all, a bread baker and love an undulating, holey cornicione. So I learned this much: the Roman crackerlike crust is not my favorite style, but within that style, there are some excellent versions.

Don’t be fooled by the unassuming exterior of Antico Forno. Inside, treasures abound for the long line of customers waiting to indicate how big a piece of pizza bianca or pizza rossa they would like sliced from the 7-foot “plank.” (photo credit 1.4)

I thought that would end my Roman pizza tasting, but then I remembered a place that Faith Willinger had told us was a must-see. Called Antico Forno, it was a bakery located in Campo dei Fiori, a large square in central Rome that is the site of a farmers’ market each morning. Only two kinds of pizza are made there: bianca, topped only with olive oil and salt, and rossa, brushed with a red sauce. Similar versions in other places are called by at least two names, pizza al taglio (by the slice) and pizza al metro (by the meter). Basically this is a long pizza, over two meters, and it’s fun to watch it being made, which they let you do at Antico Forno. In a room adjacent to the sales shop, with its own door open to the outside, a team of bakers rolls out balls of dough into lengths of about seven feet and about one-quarter inch thick. This is done in a couple of stages, as the dough must relax a few times along the way before it will yield to the baker’s final push to its full length. But it would be difficult to slide a seven-foot banner of dough into the oven, so the bakers (and this is the part that Faith enthused over) scrunch the dough back accordion style until it is about three feet long and then jiggle it off the peel, carefully extending it to its full length on the oven deck. It bakes for five to seven minutes and comes out of the oven golden brown and crisp. The bakers transfer the pizzas to a rack, from which the man at the cash register retrieves them for sale.

Three pieces of dough ready to be transformed into seven-foot-long pizzas at Antico Forno in the Campo dei Fiori section of Rome. (photo credit 1.5)

Early one morning while Susan slept in, I visited Antico Forno and watched the bakers create plank after plank, snapping pictures with my camera, much to their delight. I couldn’t wait to try some. When it was time to place my order, I imitated those who had gone before me and held my hands out to indicate a piece about eighteen inches long. Pretending to know what I was saying, I said, “Uno rouge et uno bianca.”

The cash register guy asked, “One red and one white?”

I smiled, nodded, and, I think, blushed.

When I returned to the hotel, I had only six inches of each type left, which I vowed to save for Susan. She finally woke up and I gave her what remained of the two pizzas, now just four inches of each. She devoured them.

“This is really good. I like it much better than the focaccia in Genoa. Is that all you got?” she asked.

“Afraid so,” I replied quietly. “But we could go back and get some more.”

NAPLES

When hearing about the pizza of Naples from a person who has just been there, one can easily be convinced that real pizza doesn’t exist in the United States. Send an American to Naples and it is as if he or she has seen the burning bush—that person’s pizza world has been rocked and will never be the same again, or so it seems. The once-hallowed pizza americana (my catchall term for mainstream American pizza) is suddenly perceived as an abomination; even the neighborhood Naples-style pizzeria back home, no matter how authentic, is seen as a pretender. It was clear I had to go to Naples myself to find out if I too would become a pizza napoletana zealot.

The next day we took the train from Rome to Naples. Friends had warned us to the point of paranoia about the seedy side of the city, so we did our best impression of seasoned travelers, brushing off the many drivers offering us cheap taxi rates and heading for the first car that had a visible meter. Our driver, Ciro, was a nice young man who proudly told us that he took Naples’s bad reputation personally. It wasn’t long before we let down our guard, seduced by the rhythms and charms of the bustling coastal city.

We checked into the Hotel Majestic, took a walk around the neighborhood, and then decided to go to Mattozzi for our first authentic Naples pizza. Recommended by Ciro and seconded by the hotel clerk, it proved to be the perfect introduction to the joyous Neapolitan spirit. After some antipasti and a salad, Susan ordered her usual, a pizza Margherita, and I ordered a caprese, which is like a Margherita except that it uses small grape-sized tomatoes from Capri instead of crushed San Marzano tomatoes. The pizzas were very good, a little puffier than the DOC version we had in Florence and clearly made with fior di latte (cow’s milk mozzarella) and not the mozzarella di bufala of a DOC vera pizza napoletana. I didn’t mind and they didn’t apologize. I learned that you must ask for the DOC version, and be prepared to pay a little more for it. This stop turned out to be a good way to tiptoe up to the real-deal Neapolitan pizza, especially since Mattozzi was not considered the best pizzeria in town.

The waiter took Susan and me back to meet Maurizio, the pizzaiolo, who gave me a quick shaping lesson, pressing out the petola, or disk, of dough in a circular motion, but not lifting or spinning it, which, as was becoming apparent, is an American technique. The cornicione was fairly thick, and the disk itself was not stretched as far or as thin as Salvatore’s in Florence. By keeping the dough a little smaller and thicker, Maurizio was also able to apply more sauce than Salvatore had. I soon realized Maurizio was making a pizza alla marinara, not a pizza Margherita, as it had no cheese and the sauce was topped with a sprinkle of oregano and a few basil leaves. It took exactly sixty seconds to bake in the beautiful ceramic-tiled forno.

As we watched the pizza show, owner Alfonso Mattozzi came into the kitchen to see the cause of all the hubbub. Since he didn’t speak English, our waiter, Gennaro, acted as translator, explaining who I was based on Susan’s usual icebreaker: “Buongiorno, mi chiamo Susan Reinhart. Mio marito Peter Reinhart è un autore dei libri della cucina.” Everyone seemed fascinated by my background as a teacher of bread making, and Alfonso asked if I knew some of his friends in America, especially one at Café Milano in Washington. I gave him my Johnson & Wales card, and he added it to a large pile of American contacts.

Then I learned the reason behind his excitement about my bread background. He asked Maurizio to slide a pizza disk without any toppings on it into the oven. In less than a minute, it rose dramatically, ballooning and then splitting through the center into two even-sided bread walls. When it charred to the same degree as a pizza, Maurizio pulled it from the deck and Alfonso split it open, revealing long strands of gluten dangling like stalactites and stalagmites. Then he stuffed the center with what looked like prosciutto, a slice of mozzarella, and a handful of arugula. He sliced it into wedges and gave one piece to Susan and another one to me.

“Do you think this would be well received in America?” he asked.

“Yes, would you like to come over and make them?” I answered quickly.

“Oh yes,” he responded just as quickly, and his eyes took on a wistful look as he stared into the distance for, maybe, three seconds, and then he quickly came back to the present. He smiled and nodded at his sandwich creation, pleased that we liked it.

When we returned to our table, shots of ice-cold limoncello, the wondrous, sweet lemon liqueur from the Amalfi coast, were waiting for us. We were very content and very full.

The next day I was hungry again, but first we took a tour to the volcanic ruins of Pompeii, just a few dozen miles southeast of Naples. There I posed for a scrapbook picture in the town bakery, and kept an eye on nearby Vesuvius to make sure it was docile. I flashed back to Florence and that truffled pizza Vesuvio that I couldn’t wait to try to make.

As the tour bus returned us to town, we asked our guide, Maria, if we would pass near Da Michele, probably the most recommended pizzeria on our list. When we explained our interest, Maria and the bus driver got excited for us and assumed the roles of co-conspirators, detouring the bus to Via Cesare Sersale and our destination. Maria jumped off first, ran inside, and came out with a piece of paper with a number on it. She explained to us that everyone had to wait outside until their numbers were called, but that she had told the man inside who we were and he promised to watch out for us. Then she pointed to an intersection about two blocks away and said we could catch a taxi home there.

“If you go there, it is very safe,” she said, “but not so much there,” as she pointed to just about everywhere else. “So go there when you are ready to return to your hotel. It will be okay. Ciao.” And she jumped back on the bus and waved good-bye.

We waited for about twenty minutes in the middle of a wildly diverse crowd. There were nicely dressed men and women, some shadier-looking characters, young lovers, older folks—all types really. We were the only Americans, but nobody seemed to notice or care. Then our number was called and we were escorted inside, past an old poster with a love poem to the noble pizza printed on it. I took a photo and everyone looked up at once, smiled, and then returned to their conversations and their pizzas.

What I loved about Da Michele is that only two kinds of pizza are made, the Margherita and the marinara (though you can ask for extra cheese on the Margherita and also for a special larger size), yet the place is always busy. We ordered one of each type. On the way to the table I noticed the pizzaiolo cranking out his wares, and I could see that he spread his dough into a circle larger than what we had seen elsewhere. The dough overhung the peel as it was maneuvered into the forno, requiring great dexterity on the part of the pizzaiolo to avoid getting it stuck. The pizzas came out of the oven puffy at first, and then immediately settled down to beautiful, flat disks nearly twelve inches in diameter. They were perfect.

We struck up a conversation with the people at the next table. They were two brothers, one of whom lived and worked in Sardinia as a merchant marine. Anytime he came to visit Naples, the brothers would meet at Da Michele to catch up on family news. I asked what kind of pizza they liked and one answered Margherita, the other marinara. When I asked what was the best place to eat a true Neapolitan pizza, I was told that we were sitting in it.

“But where else do you go?” I pressed.

“Only here. We go nowhere else but here.”

Two girls sitting at a nearby table started giggling and said something to one of the brothers. He explained, “She says my English is very funny.”

So I asked the girls if this was true. “Oh yes, he speaks bad English, but it is also cute, or, maybe, funny.”

By now everyone in the room, about thirty people, was aware of us, all of them wanting to be in my pictures as I snapped away at the walls and the oven and shot close-ups of the pies. Then, as if on cue, an older fellow entered the room playing “Sorrento,” a Neapolitan classic, on the accordion. The place had turned into a festival and the pizzas were among the best I had ever eaten, and still among the best I have had since. There was not one thing that could be done to them to make them better. The crust had all the properties I crave—the snap, the sweetness, the smoky char—the cheese and the sauce were impeccable, and I even found I appreciated the pizza alla marinara, despite the absence of cheese. I didn’t realize it at the time, but this was to be the summer I learned to like pizza without cheese.

Meanwhile, the two brothers had shifted their conversation to the girls next to them. But we hardly noticed. Our pizzas took all our attention.

When we tried to leave, the owner, Michele Condurro (descendant of Michele Gargivolo, who opened the original Da Michele in 1900) embraced us and brought us over to the oven to meet Luigi, the pizzaiolo. I took pictures of Luigi making pizzas and promised to stay in touch.

We walked to the intersection that Maria had pointed out and waited for a taxi. One appeared within seconds and we were whisked back to our hotel, amazed at how perfectly the day was going. We took a long walk around the neighborhood and then down to the marina, trying to work off lunch so that we could keep our appointment at Ciro a Santa Brigida for dinner. We still had research to do.

The restaurant was also only a short walk from the hotel, and we were becoming accustomed to the narrow, winding, bustling streets peopled mainly by young, nicely dressed Neapolitans. The reason we needed to go to Ciro a Santa Brigida is because the owner, Antonio Pace, is the president of the Associazione della Vera Pizza Napoletana and has become the point man, the grand protector, of the DOC status. I wanted to meet him and to see if his pizzas were as good as his marketing skills. The answer: almost but not quite. Perhaps it was because we felt we had touched the top of the Neapolitan pizza pyramid at lunch, or maybe because we spent too much time enjoying the antipasti, but the pizza was not as satisfying as I’d hoped. Antonio Pace is as genuinely committed to the purity of his city’s pizza as anyone on earth, but I realized that I was now forming a set of criteria that, right or wrong, was beginning to narrow my focus. Even within the rules, subtle shadings of quality and execution exist, and my preference had definitely shifted to the Da Michele style: larger, thinner, cheesier.

Signore Pace was very kind to us, however, and through Mauro, our waiter and translator, he explained the brief history of the associazione and how he and others felt it was important to establish the key principles that set la vera pizza napoletana apart from all other pizzas before the phrase lost its meaning. For instance, when you order a DOC pizza, he explained, it should always be made with mozzarella di bufala, not fior di latte. The dough should always be of a high standard, following preordained mixing and fermentation rules. He noted that although American pizza is influenced by Neapolitan pizza, it has become its own kind of pie and should not be called Napoletana, or Neapolitan, but, maybe, “in the style of pizza napoletana.”

The next day we took a trip to Capri, and while on a small, motorized shuttle boat to visit the Blue Grotto—the single most touristy, yet obligatory, destination in southern Italy—we met a young American couple from Massachusetts, Susanna and Mark. As soon as they heard about my pizza research, they told me about a place called Tony’s Pizza in Springfield. “But there are a few Tony’s,” Mark called out after Susan and I transferred to a little gondolier-propelled rowboat for our entrance into the grotto. Just as I was ducking to prevent my head from getting bashed on the low-hanging rock at the cave door, I heard Mark yell, “So be sure it’s the one in Springfield.”

Later that same day, on the ferry back to the mainland, we met another American couple, this time from San Jose, California. At the mention of pizza research, they told us about a place called Dante’s in State Park, Pennsylvania, where they had gone to college. “Or check out Highway Pizza—it’s owned by the same guy. They have the best sauce, plus a double-crusted, two-level pie.”

Pizza hunters, they’re everywhere.

That evening we got all dressed up, not because the restaurant was fancy, but to celebrate our last Naples pizza. We were headed the next day to Positano, a little slice of paradise farther down the Amalfi coast, just past Sorrento, for three days of, well, nothing. While the whole trip was an adventure, these three days were our official vacation, and the only food I really wanted to see at Positano was one of my other passions—sweet, little Mediterranean clams and, maybe, some mussels.

Pizzeria Brandi had very good pizza, almost as good as the pizza at Da Michele. It was my second favorite pizza on the trip. The reason we went there was because Brandi owns the bragging rights to the invention of the pizza Margherita. The story of how Raffaele Esposito made three types of pizza for King Umberto and Queen Margherita of Savoy is well documented. Apparently, the pair had once lived in Naples and, upon returning to their palace, wanted some pizza. Esposito was invited to prepare the pizza and made, or so it goes, a marinara pizza with anchovies; a bianca, or white pizza, with lard, provolone or creamy caciocavallo cheese, and basil; and a pizza with tomatoes, mozzarella, and basil—red, white, and green in honor of the Italian flag. The queen flipped for the latter, and when Esposito received a note of thanks from the monarch, he dedicated the pizza to her, calling it pizza Margherita. In her book Pizza Napoletana!, author Pamela Sheldon Johns explains that Esposito’s pizzeria was called Pietro il Pizzaiolo when he prepared pizzas for Queen Margherita, but was later renamed Pizzeria Brandi. Just as Antonio Pace and his associazione grabbed the vera pizza napoletana franchise and the town of Recco grabbed the focaccia col formaggio franchise, Brandi grabbed the Margherita franchise. Based on our visit, I’d say the tradition is in good hands.

As we sat on the balcony of the pizzeria, with the sun slowly setting on the Mediterranean, we ate a pizza Margherita and watched the evening street activity below. Franco, our waiter, had responded in the usual helpful fashion to our routine (“Buongiorno, mi chiamo Susan Reinhart …”), which added to an already wonderful night. We laughed our way through dinner and then raised our glasses in a final toast to pizza napoletana and to a series of indelible memories.

* * *

We returned to the United States, where we slowly emerged from the glow of our Italian pilgrimage. Then, gradually feeling the tug of the hunt, I embarked on an intensive summer of pizza hunting, which turned into twelve months. I ate at dozens of New York City pizzerias; trekked through the streets of New Haven in search of coal-fired pizza; picked up knife and fork to compare deep-dish pizzas in Chicago; consumed across the spectrum of so-called California-style pizza in the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles; gobbled up dozens of slices of conventional college town–style pizza around universities in five cities; tracked down American attempts at duplicating the DOC pizzas of Naples in Washington, D.C., and Manhasset, New York (where the restaurant Naples 22 actually imports its water from Naples); tasted pizza from over thirty pizzerias in the Providence area; stumbled upon Sardinian pizza in Dallas, Texas, and Croatian pizza in Bellevue, Washington; fell in love again and again with grilled pizza in Providence; tested many brands of frozen pizza; read numerous books and scoured countless websites containing pizza facts and emotional opinions (including www.pizzatherapy.com, my favorite); interviewed the editors of three pizza publications; and went on dozens of pizza hunts with chefs, writers, childhood friends, colleagues from work, total strangers, and pretty much anyone who said, “Let’s get some pizza.” I ate more pizza in that single year than I had eaten in my entire life, and even though I often got sick of it, I found myself craving it within a week. So I would set out again.

NEW YORK CITY

Jeffrey Steingarten warned me that he was not a pizza ecumenist when we went on our hunt. “You need to know,” he told me, “that I judge pizzas this way: the crust I judge on a scale of one to ten, the sauce and toppings on a scale of one to two.”

“So you’re telling me that the crust is at least five times more important than the sauce and toppings?” I asked.

“At least, but probably more.”

“I have no problem with that,” I said. I too consider myself a crust guy first and foremost. But I saw the problem this can cause when we shared a pizza in Brooklyn at DiFara’s Pizzeria on Avenue J. We had gone there on the recommendation of my boyhood friend Joel Kostman, who is a writer and, more important, also a locksmith. Because of the latter profession, Joel knows the fastest way to get anywhere in New York City. He is also a great storyteller, so I asked him if he would join us on the hunt as a sort of urban safari guide. We left Jeffrey’s apartment in Manhattan’s Flatiron District at about two o’clock in the afternoon, and Joel got us to Brooklyn’s Midwood neighborhood in less than thirty minutes, narrating the rationale behind his road choices and providing some historical perspective on pizza as we traveled (“… and over to the left, there’s the Original Ray’s that a lot of people think is the actual Original Ray’s, but it really isn’t; at least it’s not worth going into, not like the one on Prince Street, which is much better …”).

I loved the sauce and cheese pizza we had at DiFara’s. On the wall is a photo of owner Domenico DeMarco taken forty years ago, picturing him standing in the exact position where he stood making our pizza. He imports his fresh mozzarella from the town where he grew up, and he has a window box where he grows thyme, oregano, and hot peppers. This is his world and has been for a long time. I made a sentimental connection within seconds of arriving, giving the place strong emotional perfection points before even tasting the pizza. DiFara’s is a classic neighborhood pizzeria, the kind of place that would be there in your childhood and then follow you into adulthood. This kind of emotional hit, plus my admiration for Domenico’s longevity and soulfulness, may have clouded my judgment, but I simply loved the pizza, even though the crust was not as crisp as I like it. I was willing to overlook this shortcoming because the tomato sauce was about the best I’d tasted outside of Naples. It was slightly acidic, but sweet at the same time, and herbed modestly, with no one flavor dominating another. Domenico’s sauce has probably been this good from day one, and it will hopefully continue to be this good.

I learned that the sauce is a combination of canned San Marzano tomatoes, the pride and joy of Campania, and chopped fresh tomatoes, and includes snippets of herbs from the pizzeria’s window box, among other seasonings. It was one of the few times—Da Michele was another—that I noticed the sauce as an equal player with the cheese and crust. In this case it was the best part, though I also liked the hand-shredded full-fat mozzarella from the Grande Cheese Company (one of the better domestic brands, from Wisconsin) mixed with ample amounts of fresh mozzarella. (Domenico said the blend was 75 percent mozzarella di bufala from Casapulla, near Caserta, just outside Naples, and 25 percent Grande mozzarella.) Then he topped the whole thing off with some grated grana padano to salt things up a bit. The flavors were so fresh and balanced that I was willing to overlook the tender but slightly underbaked crust. (The tenderness, which I liked, is a result of Domenico’s choice of flour. Unlike most American pizzerias, which use all high-gluten flour, DiFara’s uses a mix of 75 percent Italian “00” flour and 25 percent American high-gluten flour. As for the underbaked crust, I learned of a solution two weeks later when I came across a website that recommended always buying DiFara’s pizza by the slice, not the whole pie, because the crust crisps up perfectly when it is reheated to serve.)

Jeffrey was not so forgiving. On the ride home, he went into great depth on how and why the crust was not to his liking: too limp, too thick, not the proper snap, and so on. When I asked him how he liked the sauce, he said, “The crust bothered me so much that I can barely remember the sauce.” And then, in a moment of conciliation, he added, “Since you liked it so much, maybe I should have paid more attention to the sauce, but I just couldn’t get past that crust.”

I can respect that kind of honesty. There are very few rules while on the hunt other than respecting each other’s criteria. I knew that Jeffrey’s included a five-to-one focus on the crust, and I learned that, on rare occasions like at DiFara’s, I am capable of loosening up my own crust-to-sauce bias, but the sauce had better be exceptional. I’m actually kind of proud of the flexibility I discovered and displayed on that particular hunt, even though I also discovered what a sentimental pushover I am.

* * *

Pizza in New York is not Neapolitan, but a hybrid of the Naples influence and the coal-fired reality of late-nineteenth-century New York. Like an Abrahamic patriarch, Gennaro Lombardi gets due credit for establishing the first formal pizzeria in 1905. It in turn begat Totonno’s on Coney Island and then John’s in the Village, which begat Patsy’s in Harlem, Grimaldi’s in Brooklyn, Angelo’s in Midtown, and Nick’s in Queens. Unlike Naples, which founded its pizza heritage on hardwood-fired ovens, New York City fueled its first pizzerias with bituminous coal, a soft, tarry substance rich in hydrocarbons that burns with an intense, bright yellow flame and heats up ovens to 1,200 degrees. Coal changed everything about pizzas; it made it possible to heat large, brick bread ovens efficiently and bake many pizzas at one time. These made-in-America pies, though assembled with similar ingredients, were also much larger than the individual pizzas of Naples. Coal eventually gave way to gas and electric heat, but the style of the pies remained the same. Now the predominant pizza genre in the world, this style is generally called neo-Neapolitan, with subsets such as Newyorkapolitan, coined by food writer David Rosengarten, and, on a national level, what I call pizza americana.

One day, I took a train to Manhattan from Providence and had lunch with my nephew Rudy and good friend Hal Robinson, an actor who was understudying for Hal Linden in Cabaret at the time. We went to two different Ray’s Pizzerias on the Upper West Side, both of which said “Famous” and “Original,” but neither of which is. Nor are they related to each other. We ordered a variety of slices at each place; Hal told us some backstage stories about life on Broadway; and Rudy summed up the pizza for all of us: “Pretty typical New York style, but definitely not the best.” All Ray’s outlets are not created equal, but it’s still possible to get a serviceable slice of pizza at most of them. Of course, the one on Prince Street, as Joel the locksmith pointed out, is clearly better.