Catherine Price – Read Now and Download Mobi

101

PLACES

NOT

TO SEE

before you die

Catherine Price

For my grandmother

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Introduction

Chapter 1 - The Testicle Festival

Chapter 2 - An Underpass in Connaught Circle, New Delhi, at the Moment When Someone Puts a Turd on Your Shoe

Chapter 3 - Euro Disney

Chapter 4 - Ibiza on a Family Vacation

Chapter 5 - The Beijing Museum of Tap Water

Chapter 6 - A Bathtub Filled with Beer

Chapter 7 - An Overnight Train in China on the First Day of Your First Period

Chapter 8 - Grandpa and Grandma, Koh Samui, Thailand

Chapter 9 - The Winchester Mystery House

GUEST ENTRY: The Worst Places in the Encyclopedia—A. J. Jacobs

Chapter 10 - Hell

Chapter 11 - A Buzkashi Match

Chapter 12 - Your Boss’s Bedroom

Chapter 13 - An Overnight Stay at a Korean Temple

Chapter 14 - Pamplona, from the Perspective of a Bull

Chapter 15 - The Gloucester Cheese Rolling Competition

GUEST ENTRY: The Worst Meal in Barcelona—Michael and Isaac Pollan

Chapter 16 - Wall Drug

Chapter 17 - Bart

Chapter 18 - A Stop on Carry Nation’s Hatchetation Tour

Chapter 19 - The Third Infiltration Tunnel at the DMZ

Chapter 20 - Rush Hour on a Samoan Bus

GUEST ENTRY: The Tupperware Museum—Mary Roach

Chapter 21 - An Outdoor Wedding During the 2021 Emergence of the Great Eastern Cicada Brood

Chapter 22 - (Tr)Action Park

Chapter 23 - A Giant Room Filled with Human Crap

Chapter 24 - Kingman Reef

Chapter 25 - Naked Sushi

Chapter 26 - Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument

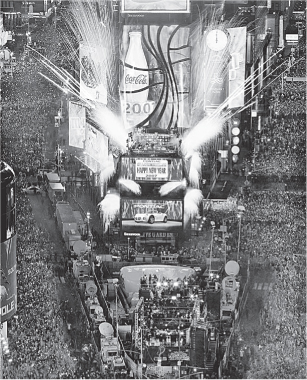

Chapter 27 - Times Square on New Year’s Eve

Chapter 28 - The Double Black Diamond Run at Powderhouse Hill

Chapter 29 - The Double Black Diamond Run at Corbet’s Couloir

Chapter 30 - The Beast

Chapter 31 - The Grover Cleveland Service Area

Chapter 32 - The Room Where Spam Subject Lines Are Created

Chapter 33 - Anywhere Written About by Nick Kristof

GUEST ENTRY: Experiences That Nick Kristof Does Not Think Are Worth Having Before You Die—Nick Kristof

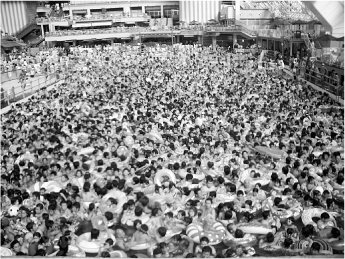

Chapter 34 - The Tokyo Summerland Wave Pool, August 14, 2007, 3 P.M.

Chapter 35 - Mid-January in Whittier, Alaska

Chapter 36 - Onondaga Lake

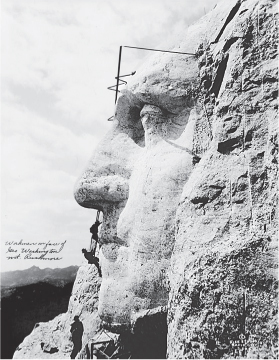

Chapter 37 - Mount Rushmore

Chapter 38 - Amateur Night at a Shooting Range

Chapter 39 - Ciudad Juárez

Chapter 40 - The World’s Skinniest Buildings

Chapter 41 - The Great Pacific Garbage Patch

GUEST ENTRY: The Customs Office at the Buenos Aires Airport—Rebecca Solnit

Chapter 42 - Any Hotel That Used to Be a Prison

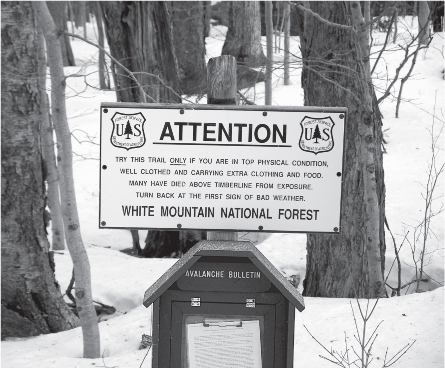

Chapter 43 - The Top of Mount Washington in a Snowstorm

Chapter 44 - The Bottom of the Kola Superdeep Borehole

Chapter 45 - The Inside of a dB Drag Racer During Competition

Chapter 46 - Shangri-La

Chapter 47 - Body Farms

Chapter 48 - An AA Meeting When You’re Drunk

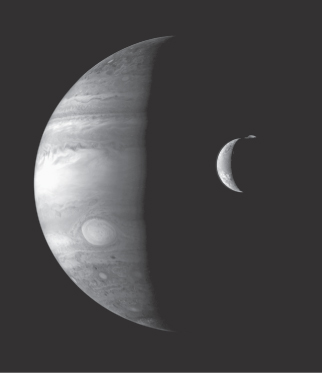

Chapter 49 - Jupiter’s Worst Moon

GUEST ENTRY: Splitting the Czech—J. Maarten Troost

Chapter 50 - Picher, Oklahoma

Chapter 51 - Tierra Santa Theme Park

Chapter 52 - A Vomitorium

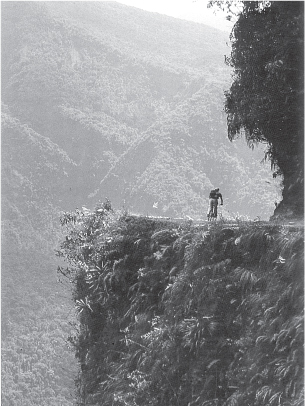

Chapter 53 - Medinat al-Fayoum, Egypt, Accompanied by Your Own Security Detail

Chapter 54 - The Steam Room at the Russian & Turkish Baths

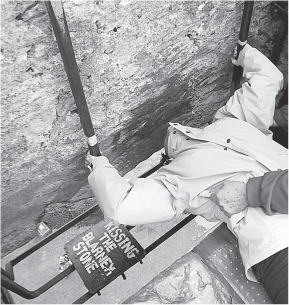

Chapter 55 - The Blarney Stone

GUEST ENTRY: Mexico City on the First Day of the Swine Flu Outbreak—Michael Baldwin

Chapter 56 - The Wiener’s Circle

Chapter 57 - The Top of Mount Everest

Chapter 58 - Garbage City

Chapter 59 - Stonehenge

Chapter 60 - The Khewra Salt Mines Mosque

Chapter 61 - Anywhere on a Yamaha Rhino

Chapter 62 - Chacabuco, Chile

Chapter 63 - The New South China Mall

GUEST ENTRY: Sumqayit, Azerbaijan—Lisa Margonelli

Chapter 64 - An Island off Germany’s East Coast, January 16, 1362

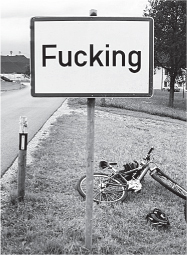

Chapter 65 - Fucking, Austria

Chapter 66 - The White Shark Café While Dressed as an Elephant Seal

Chapter 67 - The Sidewalk Outside the Roman Coliseum During the Crazy Gladiator’s Shift

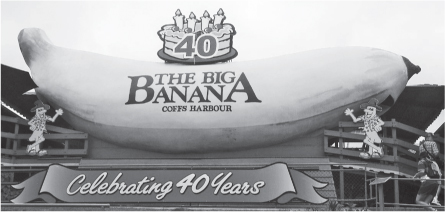

Chapter 68 - Any Place Whose Primary Claim to Fame Is a Large Fiberglass Thing

Chapter 69 - The Path of an Advancing Column of Driver Ants

Chapter 70 - The Road of Death

GUEST ENTRY: Adventure of the Beagle, the Musical—Eric Simons

Chapter 71 - Cusco, If You Are Albino

Chapter 72 - Manneken Pis

Chapter 73 - An Old Firm Derby While Wearing the Wrong Color T-Shirt

Chapter 74 - The Annual Poison Oak Show

Chapter 75 - The Inside of a Chinese Coal Mine

Chapter 76 - The Seattle Gum Wall

Chapter 77 - Varrigan City

Chapter 78 - The Inner Workings of a Rendering Plant

Chapter 79 - An Airplane After It Has Been Stranded on the Runway for Eight Hours

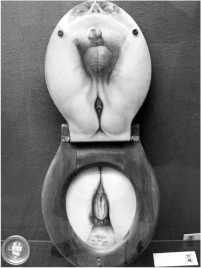

Chapter 80 - The Amsterdam Sexmuseum

Chapter 81 - The Next Eruption of the Yellowstone Supervolcano

Chapter 82 - The Shores of Burundi’s Lake Tanganyika When Gustave Is Hungry

Chapter 83 - Ancient Rome on or Around the Night of July 18, 64 A.D.

Chapter 84 - Nevada

GUEST ENTRY: Fan Hours at the Las Vegas Porn Convention—Brendan Buhler

Chapter 85 - The World Bog Snorkelling Championships

Chapter 86 - Your College Campus Four Months After You Graduate

Chapter 87 - A North Korean Gulag

Chapter 88 - Disaster City

Chapter 89 - The Inside of a Spotted Hyena’s Birth Canal

Chapter 90 - Gropers’ Night on the Tokyo Subway

Chapter 91 - The Yucatán Peninsula When a Giant Asteroid Hit the Earth

Chapter 92 - Monday Morning at the DMV

Chapter 93 - Black Rock City

GUEST ENTRY: Burning Man—Jennifer Kahn

Chapter 94 - The Bottom of a Pig Lagoon

Chapter 95 - Sohra, India, 10 A.M., During Rainy Season

Chapter 96 - The Thing

Chapter 97 - Four Corners

Chapter 98 - Russia’s Prison OE-256/5

Chapter 99 - A Bikram Yoga Studio

Chapter 100 - The Traveling Mummies of Guanajuato

Chapter 101 - The Top of the Stari Grad Bell Tower

Acknowledgments

Index

Copyright

About the Publisher

There are a lot of things I need to do before I die.

Or at least that’s what my local bookstore is telling me. Every time I visit, I’m faced with a shelf’s worth of guides listing things to accomplish, from 100 Places to See in Your Lifetime to 101 Things to Do Before You’re Old and Boring. I appreciate the idea behind Patricia Schultz’s 1,000 Places to See Before You Die, the inspiration for this genre of books, but its offspring stresses me out.

There are lists of jazz albums I need to listen to, foods I must taste, paintings I have to see, walks I’m required to take—my own father has a book of 1,001 gardens I can’t die without visiting. How am I supposed to conquer 1,001 movies while simultaneously reading 1,001 books and traveling to 1,001 historic sites—not to mention making it to the 500 places I must see before they disappear? By the time I found a copy of 101 Places to Have Sex Before You Die, I was tempted to swear off travel books, grab a selection of the 1,001 beers I have to drink, and head to one of the 1,001 spots where I’m supposed to escape.

I am a person who routinely writes lists of things I’ve already done, just to make myself feel more accomplished. Like many people, I already spend too much time coming up with arbitrary things I “should” be doing, keeping myself so busy that it’s hard to separate one moment from the next. The last thing I need to read is a book that pits my desire for adventure against the time pressure of mortality—especially in the form of 1,001 places I’m supposed to play golf.

So I decided to create an antidote: a list of places and experiences that you don’t need to worry about missing out on. I called upon travel-loving friends, family members, and, in some cases, complete strangers to tell me about overhyped tourist sites, boring museums, stupid historical attractions, and circumstances that can make even worthwhile destinations miserable.

Some entries on the list are unquestionably unappealing, like a field strewn with decomposing bodies or fan hours at the Las Vegas porn convention. Some depend on context—Pamplona’s a very different city from the perspective of a bull. Some are just good stories, albeit ones that are more fun to read about than to experience firsthand.

As I gathered suggestions, I came across a characteristic common among frequent travelers: a reluctance to define anything as bad. “I have a soft spot for underdog places and a perverse need to find even the worse stuff a source of delight and titillation,” wrote one friend about her inability to hate on Uzbekistan or, for that matter, Detroit. She’s right, of course—the worse something is in the moment, the better the story when you get home. So for those people who look at a warehouse full of rotting human sewage and see an interesting way to spend an afternoon, I also included some places that would be impossible to visit even if you were intent on finding the bright side in everything, like the Yucatán Peninsula sixty-five million years ago or the bottom of the Kola Superdeep Borehole. It might seem pointless to say that you shouldn’t go to a place like Io, Jupiter’s least hospitable moon, but look at it this way: when someone publishes 1,001 Places in Space to See Before You Die, the pressure will be off.

No matter what type of traveler you are, I invite you to take a break from your other to-do lists and spend a moment being grateful for some of the things you’re not doing. Then, when you’re ready to hit the road, leave behind your list of 1,001 Places You Must Pee* and give yourself a chance to come up with some experiences of your own. Travel should be an adventure, not an assignment, and if you spend your vacations armed with too many checklists, you’re missing the point of leaving home.

Forget apple pie. Few foods are as uniquely American as the Rocky Mountain oyster, a euphemism that refers not to a high-altitude mollusk but to the testicles of a bull. Also known as cowboy caviar and Montana tendergroin, these balls can be boiled, sautéed, or even eaten raw, but they’re usually treated more like chicken—breaded and deep-fried.

There are also few things more American than eating competitions, so it should come as no surprise that each summer offers opportunities to prove your manhood by stuffing your face with gonads. I appreciate the pun of the Nuts About Rocky Mountain Oysters competition that occurs annually in Loveland, Colorado. But the award for Best in Show goes to the Testicle Festival, held each year at the Rock Creek Lodge near Missoula, Montana. Started in 1982, it is America’s premier venue to chow down on balls.

When the festival first began, it drew about three hundred people. But these days the crowd has grown to fifteen thousand, and the debauchery has expanded to a weekend full of wet T-shirts, impromptu nudity, and an Indy 500–inspired race called the “Undie 500”—all natural evolutions of an event whose tagline is “Come Have a Ball.” Try your hand at Bullshit Bingo, a larger-than-life—and quite literal—game of chance where every time a bull defacates on a giant bingo card, someone wins $100. Or support the event’s alternate title—the Breasticle Festival—by signing up for the Biker Ball-Biting Competition, where girls riding on the backs of Harleys race to snag a Rocky Mountain oyster off a string without using their hands. There are belly shots. There’s No Panty Wednesday. And, of course, there are the Rocky Mountain oysters themselves—more than fifty thousand pounds of them—greasy, salted, and USDA-approved.

Jim Kleeman

An Underpass in Connaught Circle, New Delhi, at the Moment When Someone Puts a Turd on Your Shoe

Imagine this scene: you’re walking through an underpass in Connaught Circle, a mess of traffic where twelve of New Delhi’s roads converge, and all of a sudden a voice calls out of the crowd.

“Excuse me, friend,” it says. “You’ve got feces on your shoe.”

Several weeks in India have made you realize that when people yell at you on the street, it’s usually best to ignore them. So at first you pay no attention. But something in this man’s voice is different, believable. He repeats himself, and you slowly lower your eyes.

And there it is: a flattened turd sitting on the top of your shoe.

Your first reaction is disbelief—you’ve had shit on the bottom of your shoe, sure. But the top? How can this be? There aren’t any birds around, or monkeys. Disgusted, you lean down to inspect it. Still moist and glistening, it gives off a familiar fecal smell.

You consider throwing up, but before your gag reflex can kick in, a voice pipes up. “Don’t worry, I will clean it for you.” It is your new friend, who now is standing next to you with a shoe-shining kit. Well, will you look at that! Here you are, caught in the one moment in your life where you need an emergency shoe cleaning, and this kind man pops out of nowhere to help you. What are the odds?

Before you have a moment to actually calculate the odds of this happening coincidentally, the man has escorted you off to the side of the passageway where, with a flourish, he rids your shoe of the offending turd. Then, as you reach into your wallet for a tip, he announces the price for a shit-shine special—and it’s more than most New Delhi residents earn in a week.

If you think about it, the scam is brilliant. The service has already been rendered, and besides, who wants to walk around with a turd perched on his shoe?

So you pay him—not his asking price, but still enough to make it worth his while to continue smearing poop on the footwear of passersby. If you’re a victim, feel free to get pissed off. But at least the shit scheme isn’t as bad as the loogie-on-your-shoulder trick. In that one, you don’t even have the chance to give a tip—someone smears a wad of spit on your jacket while a second guy steals your wallet.

I’ve never liked Disney World. As a child who was terrified of mimes, Santa Claus, and any larger-than-life stuffed animal, I hated the giant mice that roamed the streets of the Magic Kingdom, holding children hostage until their parents took a photograph. Huge, unblinking eyes; garish smiles; swollen, cartoon hands—this was the stuff of nightmares. When my parents brought me to a special event called “Breakfast with the Characters,” I took one look at Pinocchio and dove under the table.

So perhaps I was biased against Euro Disney from the start. But really, who wasn’t? Opened in 1992, it was an attempt to bring Mickey Mouse to Europeans—an audience that tends to be skeptical of American culture to begin with, especially when it tries to steal the hearts and minds of its children. Convinced that parental disapproval was no match for their offspring’s love of The Little Mermaid, Disney pushed forward with its plans and eventually settled on a spot in the rural town of Marne-la-Vallée. An easy train ride from Paris, the location was estimated to be less than a four-hour drive for sixty-eight million people.

Controversy soon followed. Assuming that there must be a direct connection between Euro Disney and the U.S. government, French farmers blockaded its entrance with their tractors to protest European and American agricultural policies. A Parisian stage director named Ariane Mnouchkine called Euro Disney a “cultural Chernobyl,” and while she quickly moved on to making other exaggerated comparisons to nuclear disasters (“Television seems to me to be a much more menacing cultural Chernobyl,” she told the New York Times in July 1993), the classification stuck.

And then there were tactical errors: Euro Disney opened, for example, in the middle of a European recession. It offended would-be workers with a strict dress code forbidding long nails and requiring “appropriate undergarments” for women, which prompts the question of why a Disney employee would be showing her undergarments to begin with. As a primarily outdoor attraction, it didn’t take into account the fact that France, unlike Florida and Southern California, actually has a winter. The restaurants in the park also didn’t serve alcohol, a policy that didn’t go over well with Europeans used to enjoying a glass of wine with lunch. By July 1993—a little over a year after the park opened—Euro Disney had debts of about $3.7 billion.

Wikipedia Commons

But despite the challenges of translating Americana into every European language (in Italian, Cattleman’s Chili is Pepperoncino alla Cowboy) Euro Disney kept fighting. The park posted its first profits in 1995 and has done so intermittently since then. Scarred by the negative connotations of “Euro Disney,” it also changed its name to “Disneyland Paris.” Former Disney CEO Michael Eisner says this title was chosen to identify the park with “one of the most romantic and exciting cities in the world,” but this seems like an odd association—the place is so quintessentially American that it has an Aerosmith-themed roller coaster.

First settled by the Phoenicians over twenty-five hundred years ago, the Spanish island of Ibiza wasn’t always a party town. Back in the day (and by “day,” I mean Carthaginian rule), the club capital of the world was best known for its exports of dye, salt, and wool. Sure, the islanders dabbled in garum, a pungent condiment made from fermented fish, but in those days, who didn’t? If people really wanted to party, they went to Rome.

Times have changed. Today Ibiza is known not for its fish sauce but for clubbing, promiscuity, and an abundance of illicit drugs. A favorite holiday destination for the world’s horniest youth, Ibiza’s flesh-baring clientele and encouragement of casual sex have earned it the nickname “Gomorrah of the Med.”

Until recently, the government was happy to bear the responsibility for a few extra STDs in exchange for the purchasing power of thousands of hormonally fueled visitors. But then, after some thirty years of tolerance, it closed several prominent clubs for part of the 2007 season, citing evidence of illegal drug use. Among its arguments: one of the clubs had telephone booths that contained traces of cocaine, snorting tubes, bloody tissues, and, incidentally, no phones. But with possible sexual partners on all sides anyway, who would have needed to place a call? When the clubs eventually reopened, it was with limitations: the government banned clubs from operating past 6 in the morning (they used to stay open all day), and is now trying to actively push Ibiza as a family vacation destination.

Considering that Ibiza has thousands of years’ worth of archaeological remains—not to mention several UNESCO World Heritage Sites—this isn’t entirely preposterous. And yet, I still find it difficult to imagine a family vacation in the midst of an Ibizan summer. Where would you take the kids first? Amnesia, a giant club famous for its foam parties? Or Es Paradis, where every night thousands of ample-bosomed girls wearing white T-shirts are sprayed with a fire hose?

Pick your poison, but don’t let the kids leave Ibiza without an outing to Privilege, the world’s largest club. With a capacity for ten thousand people, its airplane hangar–size space offers something for everyone: you and your spouse can gyrate with thousands of sweaty partiers next to the indoor pool while a stranger teaches your five-year-old how to spell “ecstasy” and your teenager samples ketamine in the bathroom. Just make sure that if your family gets separated, no one tries to find a phone.

The Beijing Museum of Tap Water

When you’re dealing with two languages as different as Chinese and English, it’s inevitable that some things get lost in translation. Handicapped bathrooms are occasionally referred to as “Deformed Man End Places.” In Dongda, the proctology center used to be known as the Hospital for Anus and Intestine Disease. Occasionally, a place receives a title that’s both bizarre-sounding and mundane. Case in point: the Beijing Museum of Tap Water.

The history of Beijing’s tap water dates back to 1908, when the Empress Dowager Cixi supported a plan to build a water system for Beijing. The museum, however, is a recent addition—it’s the result of a 2001 edict requiring that 150 new museums open in Beijing by 2008. As any curator can attest, 150 is an awful lot of new museums to build in seven years. The result: in addition to tap water, Beijing also now has museums devoted to honeybees, red sandalwood, and goldfish.

Housed in a former pump house, the tap water museum starts with the founding of Beijing’s first water company, the Jingshi Tap Water Co., and features artifacts like vintage water coupons and a stethoscope used to listen for water leaks. It also boasts not just 130 “real objects,” but 110 pictures, 40 models, and a miniature tap water filtration system. Step aside, Forbidden City.

The weirdest thing about the museum, though, is that the substance it’s meant to commemorate—clean tap water in Beijing—doesn’t actually exist. Yes, in 2007 Beijing was the first Chinese city whose water officially passed a test for 106 contaminants. But thanks to the condition of the pipes transporting it from stations to people’s taps, it’s still unsafe to drink.

Molly Loomis

In the realm of teenage male fantasies, taking a bath in beer is right up there with doing body shots off Megan Fox. But for people who would rather drink their hops than bathe in them, the idea is less sexy than sticky.

If you fall into the latter camp, skip the Chodovar brewery in the Czech Republic. Billed as “Your beer wellness land,” it offers hops-crazed visitors the chance to soak their cares away in bathtubs full of their favorite beverage. Complete with warm mineral water and a “distinct beer foam of a caramel color,” the brewery’s special dark bathing beer contains active beer yeast, hops, and a mixture of crushed herbs. But the fun doesn’t end with the bath: afterward, guests are led to a relaxation area where they are wrapped in a blanket in a dim room with pleasant music and given one of several complimentary drinks.

“The procedures have curative effects on the complexion and hair, relieve muscle tension, warm up joints, and support immune system of the organism,” says Dr. Roman Vokaty, the spa’s official balneologist, in response to the obvious question of why a beer bath is a good idea. One could argue that the combination of a post-bath massage and the bottles of Chodovar’s lager consumed while the organism soaks in the tub might have just as much, if not more, of an impact on the organism’s well-being than the beer’s carbon dioxide and ale yeasts. But then, I’m not a balneologist.

If you like the idea of wasting a perfectly good drink, check out some of Europe’s other beer spas: Starkenberg in Austria, for example, has been known to fill an entire swimming pool with Pilsner, and the Landhotel Moorhof in Franking, Austria, offers a brewski facial made from ground hops, malt, honey, and cream cheese. According to one survivor, it “smells remarkably like breakfast.”

An Overnight Train in China on the First Day of Your First Period

June 16, 1991, was Father’s Day. It was also the day I got my period for the first time, and it occurred right in the middle of a family vacation to China—a three-week self-guided journey with my parents and my mom’s seventy-year-old friend, Betty.

I was mortified. To make things worse, the hotel we were in didn’t have sanitary supplies, and in China at the time it was difficult to find a store opened to foreigners at all, let alone one with Western toiletries. Had we been in America, the next step would have been for us to go to a drugstore together where I, too embarrassed to pick out sanitary products myself, would inspect the toothbrush display as my mother yelled questions from the next row over like “Scented or non-scented?” and “Do you want wings?” Instead, my mother convinced me to allow her to tell Betty; the two conferred in hushed tones, and when back in my room, Betty rummaged through her toiletry bag and presented me with a Depends.

Wearing an adult diaper as a twelve-year-old added insult to the injury of menstruation, and our itinerary only made things worse. Presumably if we’d been sticking around at our hotel, we would have been able to find maxi-pads somewhere in the city before Betty’s supplies ran out. However, my parents, eager for an authentic, self-guided China experience, had arranged for us to get on a train to a city twenty-three hours away. No sooner had we left for the station than my body, unsatisfied with the humor of me simply menstruating on a Chinese train, broke out in hives. My mother gave me two extra-strength Benadryl. I stumbled to the train platform with my parents and woke up three hours later on an upper bunk in a moving train, in a car with vomit stains on the carpet and circles at the end of each bed where people’s heads had wiped away the dirt. My parents and Betty were giggling on the bunks below me as they played bridge and drank “tea” they’d brewed from water and Johnny Walker Black. I needed to use the bathroom.

I slid off the top bunk and unlatched the door to our cabin to find the toilet, but my mother stopped me before I could leave.

“It’s clogged,” she said. “Betty and I tried to use it, and it smells so bad, we almost threw up.”

“What am I supposed to do?”

“Do what we did,” said my mother, which was greeted by tipsy laughter from Betty and my father. “Pee in this.”

My mother then handed me a Ziploc bag.

What bothered me about this was not so much the fact that my mother was telling me to urinate into a freezer bag, but rather, how I could do so with my father in the room. Holding the empty bag, I glared at my mother, glanced at my father, and then glared at her again until she realized what I was trying to communicate.

“Richard, go out in the hall. Catherine needs some privacy.”

With my mother and Betty playing cards in front of me, I squatted down, pulled down my pants, pushed aside my diaper, and peed into the bag, trying my best to keep my balance on my heels as the train rocked back and forth.

“I don’t want it,” my mother said when I tried to hand it to her. “Give it to your father.” I slid the door open and found him standing in the hallway watching rice paddies out the window. A childhood polyps operation gone awry left him with no sense of smell, so he took the bag when I offered it and carried it down the hall to the bathroom. He stuffed the bag down the toilet with a hanger, it burst upon the tracks, and he returned to our cabin to finish his tea.

When we arrived at our hotel in Beijing the next day, my family’s first destination was the Summer Palace. My first destination was the bathroom, a squat building a short, urine-scented walk away from the park entrance. Inside, a long row of waist-high, doorless stalls subdivided a porcelain trough pitched slightly toward one end of the room, over which women squatted on their heels, bottoms bared to the world. Some read magazines; most held tissues clamped to their noses to keep out the stench. Driven by the pressure of my bladder and the presence of my Depends, I ignored the smell and forged ahead toward the end of the room, picking the last stall so that I would be exposed to the fewest number of people possible. I glanced around to see if anyone was watching and yanked my pants to my knees, realizing only when I looked down that my stall was downstream from the other seven.

The second thing I noticed was that my period had stopped—apparently it had decided that two and a half days was sufficient for a first-time visit. This filled me with joy until I realized that, now that I had begun to ovulate, it would return once a month for the rest of my child-bearing years. When I looked up to the ceiling in a “Why, God?” moment, my eyes were stopped halfway by a third realization: despite my attempts at seclusion, the other women in the room had seen me enter. Curious about what a Caucasian twelve-year-old would look like while urinating, several had walked up to where I was squatting and were standing next to my stall, giggling behind their tissues as they stared at my naked backside. I felt self-conscious enough simply being an American in China, but being watched in a bathroom while wearing a diaper was as embarrassing as going bra shopping with my father. I pulled my pants up and they scattered back to their places in line as I pushed past them, ashamed. If this was what it meant to be a woman, I wanted to go home.

Postscript: I returned to China in the summer of 2002 and am happy to report that train travel has remarkably improved. Unfortunately, however, my bottom is still considered a tourist attraction—when my friend and I visited a public squat toilet, we looked up to find a group of women taking photographs.

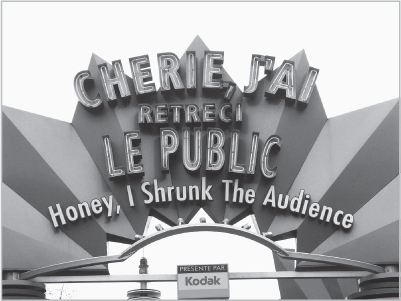

Grandpa and Grandma, Koh Samui, Thailand

If I suggested that you visit the Grandpa and Grandma Rocks on Thailand’s Lamai Beach, what would you expect to see? The silhouettes of two aged lovers? A piece of granite resembling wrinkled hands intertwined? No and no. Grandma and Grandpa are rock formations that look like genitalia.

When I first heard about these rocks—referred to locally as Hin Ta and Hin Yai—I thought that seeing genitalia in the rocks might require effort, like how it takes a certain degree of creativity to find Jesus in your toast. But these grandparents aren’t subtle. Granddad is clearly a large, erect penis. And Grandma has spread her legs open to the sea, positioned so that she’s caressed by every wave that hits the shore.

When you see the rocks, you will probably wonder whether people in Thailand have a very different relationship with their grandparents from what we have in America. Perhaps, but in this particular case, the nickname comes from a legend—Ta Kreng and Yai Riem, an elderly couple, were on their way to try to procure a bride for their grandson from a family to the north when their boat got caught in a storm. They drowned. And then, as so often befalls seafaring grandparents, they were turned into rocks representing their respective naughty bits.

These days, it’s probably best not to bother visiting unless you enjoy fighting your way through street vendors selling phallic souvenir T-shirts just so that you get a picture of yourself perched on Grandma’s thigh. The beach isn’t particularly good for swimming, and you’ll be surrounded by people who decided that, of the many attractions Thailand has to offer, all they really wanted to see was a granite penis.

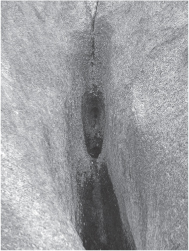

Grandpa

Benjamin Thomas

Grandma

Sigrid Georgescu and Alex Falls

Some people might argue that San Jose, California, is itself a place not worth visiting before you die. Fair enough. But if you do find yourself driving its wide, traffic-clogged streets, you may be tempted to stop at the Winchester Mystery House. It’s impossible to drive in or out of San Jose without coming across a billboard advertising the bizarre 160-room mansion built by Sarah Winchester, heiress to the fortune of the Winchester Repeating Arms Company.

But please, resist the urge.

The story of the Winchester Mystery House—or, rather, the legend—is as follows: after her infant daughter and husband passed away, Sarah Winchester visited a psychic who told her that her loved ones’ deaths were caused by the souls of the people who had been killed by the Winchester repeating rifle (tagline: “The Gun That Won the West”). If she didn’t take drastic action, said the psychic, Sarah Winchester could be next. The psychic supposedly told her that the only way to appease the angry spirits was to go west and build a house—not too difficult a task for a woman who had an income of about $1,000 a day in the late 1800s. But there was one catch: the house could never be completed. If construction ever stopped, the spirits would seek their revenge once more.

And so Sarah Winchester moved from Connecticut to San Jose, bought an unfinished eight-room farmhouse, and started construction. She hired shifts of men to work around the clock, seven days a week, 365 days a year. From the day she began until her death thirty-eight years later, the workers never stopped. Every evening, legend has it, Sarah Winchester would retreat to a special séance room in the middle of the house to commune with lost souls and, while she was at it, figure out the next day’s construction plans.

The result is a sprawling mansion that gives a sense of what happens when a multimillion-dollar fortune and a belief in the paranormal are combined in a woman with no architectural training. There are stairs that lead to the ceiling, chimneys that stop a foot and a half short of the roof, cabinets that are actually passageways, and a second-story “door to nowhere” that opens fifteen feet above the ground outside. Throughout the house are touches of grandeur—hand-inlayed floors, Tiffany glass windows—and bizarre architectural elements, like custom-designed window panes in the shape of spider webs and a preoccupation with the number thirteen.

The house has been open to the public, in one form or another, since soon after Winchester’s death in 1922. But unfortunately for anyone intrigued by her story, its legend is more interesting than the tour itself. Part of the problem is that Winchester left all of her furniture, household goods, pictures, and other artifacts to her niece, the alliterative Mrs. Marian Merriman Marriott, who wasted no time in clearing out the house and selling them off. This was no doubt profitable for Mrs. M, but it means that aside from a few rooms that have been refurnished with period-appropriate decor, the gigantic house is empty. What’s more, despite the legend of the house—the séances, the spirits, the psychic—no one really knows for certain why Sarah Winchester built her house the way she did. Maybe the story is true; maybe she was just participating in an early-twentieth-century version of Extreme Home Makeover. Or maybe she was just bat-shit crazy.

Regardless, like all good tourist traps, the opportunities to spend money at the Winchester House don’t end with the tour. In addition to an arcade offering 1980s video games, there’s an antique products museum featuring Winchester flashlights, Winchester roller skates, and Winchester wrenches, and a display titled WINCHESTER HOUSE IMMORTALIZED IN GINGERBREAD. The nearby gift shop is a warehouse-size collection of Winchester House shot glasses, tote bags, T-shirts, and specialty wine, all sharing shelf space with butterfly-shaped wind chimes, novelty dishtowels, and magnets announcing that “STRESSED” IS “DESSERTS” SPELLED BACKWARDS.

The effect of all this—the gift shop, the mile-long tour through endless empty rooms, the near total lack of concrete facts—is to leave you feeling as if you’d just binged on McDonald’s: full, and yet, surprisingly empty. In fact, the only justification for the house’s popularity as a tourist attraction is its size—whereas usually one would balk at the prospect of paying $26 to tour a crazy lady’s empty home ($5 more if you want to see the plumbing system), the Winchester House is so large that with some creative math, it’s almost justifiable: each of its 110 rooms costs less than 25 cents to see.

But still, one question remains: who signs up for the annual pass?

Nota bene: The Winchester Mystery House is not to be confused with the pirate-themed haunted house that opens in Fremont, California, every Halloween. That is totally different—though, incidentally, also not worth seeing.

A. J. JACOBS

The Worst Places in the Encyclopedia

Paris in 1871

During the famous Siege of Paris, food was hard to come by. The residents resorted to “rat paté.” Or, if they were lucky and had connections, they got to eat the giraffes and elephants from the Paris zoo. Not a place you want to visit unless you have an extremely adventurous palate.

The Emperor’s Court in China, Twelfth Century

It’s hard to pick the most evil ruler in the encyclopedia, but among the top ten was probably Emperor Chou. To please his concubine, Chou built a lake of wine and forced naked men and women to chase one another around it. Also, he strung the forest with human flesh.

The Eighth Circle of Hell

In Dante’s book The Divine Comedy, the ninth circle of hell is traditionally considered the worst. In this circle, betrayers are stuck in a frozen lake for eternity, their tears making blocks of ice on their eyes. But personally, I think the eighth circle sounds worse. This one has a river of human excrement that submerges flatterers. To me, ice sounds pretty good next to that.

The North End of Boston on January 15, 1919

This may be a stretch for this list, but I try to mention the Great Molasses Flood in everything I write. And it really was a bad place to be. It occurred when a giant molasses storage tank exploded and sent a fifteen-foot wave of molasses through the streets of Boston. Twenty-one people were drowned in the sticky stuff. Trains were lifted off their tracks and horses were submerged in the strangest and sweetest disaster in history.

A. J. JACOBS is the author of The Know-It-All: One Man’s Humble Quest to Become the Smartest Person in the World.

Regardless of which circle you deem the worst, I think we can all agree that hell is not a great place to visit. Whether you choose to stop by the Greek and Roman Tartarus or the horrible O le nu’u-o-nonoa of Samoan mythology, you’re likely to be treated to some blend of fire, ice, and demons. Oh, and pain. Lots and lots of pain.

The many variations of hell are a testament to humans’ ability to invent unusual methods of torture. But when it comes to specifics, you have to hand it to Zoroastrianism. Its version of hell includes precise punishments for everything from approaching fire or water when you’re menstruating to unlawfully slaughtering a sheep.

If I had to pick a hell to visit, I’d probably go with the one in Michigan. Complete with a fictional nonaccredited college that offers “signed, sealed and singed diplomas,” Hell, Michigan, is a small town about twenty-five miles by car northwest of Ann Arbor that focuses more on puns than on punishments. Eager to capitalize on its name, the town has a part-time post office (for people who get their thrills through postmarks) and a tagline—“A little town on its way up.” And, for couples whose definition of romance includes fire and brimstone, Hell also has a wedding chapel.

How to play buzkashi:

1 Kill a goat.

2 Behead it.*

3 Disembowel it.

4 Soak it in cold water for twenty-four hours to toughen it up.

5 Give it to crazed men on horseback to play a violent, gruesome game.

6 Barbecue!

An Afghani tradition, buzkashi is an animal-rights advocate’s nightmare: a sport in which three teams of horsemen compete to score goals with the body of a dead, headless goat.

But that makes it sound too easy. In order to score goals, horsemen first have to grab the goat and carry the seventy-pound carcass around a small post. Then they gallop seventy-five yards down the field and hurl the goat into a small chalk circle. All this happens while they and their horses are being beaten, whipped, punched, and otherwise attacked by the other players, who can do anything, save tripping a horse, to prevent the other teams from scoring. Few games end without a horse trampling at least one rider or, for that matter, a spectator—buzkashi fields don’t have boundaries.

Dexter Filkins, a war correspondent for the New York Times, witnessed a near disaster when a player rode his horse directly into the crowd. “Spectators scattered and screamed as the horses thundered close,” he wrote. “The referee reached for his Kalashnikov, then thought better of it.

‘ “Run!’ a boy squealed. ‘Ha! Ha! Ha! Run!’ ”

When the game ends—which can take days, since there’s no official time limit or set number of goals—the winning team gathers for the traditional end of the game: barbecuing the goat. Buzkashi means goat-pulling, after all, and according to a hungry old man interviewed by Filkins, “All that pulling and stretching makes it very tender.”

Note the goat

Gideon Tsang/Wikipedia Commons

This does not count as corporate team building.

An Overnight Stay at a Korean Temple

In theory, an overnight stay at a Korean temple sounds like the perfect activity for anyone struggling to escape the pressures of modern life. You’ll meditate, you’ll learn about Buddhism, you’ll go vegetarian. Concerns and cares will slip away as you drift into a blissful state of conscious awareness.

Unfortunately, that’s not what it’s like.

I signed up for one of these sleepovers through a program called Templestay. Created in 2002 by the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism—the largest Buddhist order in Korea—the Templestay program aims to allow visitors to “sample ordained lifestyle and experience the mental training and cultural experience of Korea’s ancient Buddhist tradition.” In other words, it’s a chance to test-drive life as a monk.

The meditation center I visited, about two hours from Seoul on Ganghwa Island, seemed like the sort of place that could inspire calm. The grounds are nestled between rice paddies and a leafy forest, and the center’s brightly painted temple sits several stone steps up from a gentle brook and a small pond stocked with lotus flowers and koi.

When my friend and I arrived—several hours late, thanks to trouble reading the bus schedule—the Templestay coordinator introduced herself in fluent English and led us to the room where we’d be staying. It was empty except for sleeping pads, blankets, and small pillows stuffed with plastic beads (see nurdles, p. 101). After we’d dropped off our bags, she handed us our clothes for the weekend: two identical extra-large sets of baggy gray pants and vests, along with sun hats and blue plastic slippers. We looked like we’d stepped out of a propaganda poster for Maoist China.

I’d assumed that most temple life involved sitting still and cultivating enlightenment, but instead our first activity was community work time. Clad in our Mao suits, we followed the coordinator to the garden, where eight other Templestay guests squatted between raised rows of dirt, piles of potatoes scattered around them. They gave us hostile glances as we approached—thanks to our late arrival, they’d been forced to harvest potatoes for three hours in eighty-

degree heat. I couldn’t blame them for their animosity; if I’d been

digging in the dirt while some assholes took the slow route to Ganghwa Island, I’d be pretty pissed off too. But such negativity seemed to go against the spirit of the retreat. I adjusted my sun hat and joined them in the field.

After we’d assumed our squatting positions, the coordinator explained that we were supposed to sort the potatoes into piles of small, medium, and large—and then left without demonstrating what the Buddhist definition of “small” was. After a half hour spent tossing any potato smaller than a golf ball into a nearby box, I looked up to find a monk standing above me, examining my work. I smiled. Expressionless, he picked up my box and emptied it onto the ground.

It was time for meditation.

Once we’d learned the correct way to arrange our shoes outside the temple door, the Templestay coordinator demonstrated how to prostrate according to the Korean Buddhist tradition: kneel down, touch your forehead to the floor, and rest your hands, palms upward, on the ground. Then do it all in reverse, like a movie playing backward. Repeat, ideally several hundred times.

To me, the main value of the prostration practice was as a quadriceps exercise, but any improvement in the shape of my thighs was mitigated by the pain it caused in my arthritic knees. I had plenty of time to reflect on this discomfort when we followed our prostrations with a meditation: sitting in silence for a half hour, a slight breeze blowing through the open doors at our back as if beckoning us to escape.

After a slow walking meditation through the temple grounds, a vegetarian dinner, calligraphy practice, and a discussion on meditation led by the temple’s head monk (I spent most of the time killing mosquitoes and then feeling guilty about the karmic implications), we were sent back to our rooms to get rest before our 3:30 A.M. wake-up call. Lying on the floor, still dressed in my Mao suit, I fidgeted till 1:30.

Two hours later, the sound of the mokt’ak—a wooden percussion instrument played every morning to start the temple’s day—jolted me awake. I pulled myself up from my floor mat and stumbled through the predawn darkness to the temple, where pink lotus lanterns illuminated a small group of people inside, creating the kind of picture you would send home to friends to make them feel jealous about the exotic experiences you had while on vacation.

There is a difference, however, between postcards and reality. For example, no one sends postcards at 3:30 in the morning. Nor do most people’s vacation plans involve getting out of bed in the middle of the night to sit for a half hour in silence with their eyes closed. I watched through cracked eyelids as the Templestay coordinator repeatedly jerked herself awake just before tipping over, like a commuter on an early-morning subway train. I was close to succumbing to the same fate myself when I noticed something that kept me awake: a gigantic beetle crawling on a lotus lantern hanging above my head. This beetle was easily the size of a large fig; having it fall on my head would have been the equivalent of being smacked by a mouse. I began to focus my attention entirely on the beetle, sending prayers into the ether for its secure footing.

My prayers worked—the beetle remained aloft, and we were eventually allowed to go back outside. After sneaking a cup of instant coffee with a Venezuelan couple, I pulled myself through another walking meditation and followed the other participants to the main room for a Buddhist meal ceremony. A highly choreographed process of place-setting, serving, and eating, it included a final inspection by a head monk to see if our bowls were clean. “You do not want to disappoint him,” said the coordinator. “Doing so would reflect poorly.”

She then walked us through what would take place during the meal ceremony, including a final cleansing: we were to take a piece of pickled radish and use it to swab our dishes. This caught the attention of a young Canadian woman.

“I’m sorry to interrupt,” she said. “But how is wiping my bowl with a radish going to make it clean? What about germs?”

“We fill the bowls with very hot water,” said the coordinator, sidestepping the question. “So when you use the radish, the bowl is already very clean.”

“Is it, like, a hygienic radish?” asked the Canadian woman.

“Yes,” said the coordinator. “It is a hygienic radish.”

Things went downhill from there. Exhausted and cranky, one by one we began refusing to play monk. If one of the whole points of Buddhism was to cultivate acceptance, why, I asked, did we have to go through such an elaborate meal ceremony? The Venezuelan couple went a step further: they left.

Wishing that we had the same kind of courage, my friend and I instead counted down the hours until we returned to Seoul, and upon arrival treated ourselves to a bottle of wine. Several days later, the Templestay coordinator e-mailed the weekend’s participants and invited us to a workshop to perform three thousand prostrations to “inspire yourself into practice.” The idea sounded horrifying, but it reminded me how difficult it would be to live like a monk. Which, as the coordinator suggested, may have been the point.

Pamplona, from the Perspective of a Bull

Your day starts precisely at 8 A.M. when, standing in the pitch darkness of your temporary corral, you hear the sound of people singing. “A San Fermín pedimos, por ser nuestro patrón, nos guíe en el encierro dándonos su bendición,” they chant, asking a guy named Saint Fermín to give them his blessing as they participate in something called an “encierro.”

“What’s an ‘encierro’?” you ask yourself, still sleepy from your long journey from your farm the day before. But before you get any answers, a gun goes off and someone presses a Taser to your skin, prodding you from complete darkness into total, blinding sunlight. Confused and frightened, you trip over your own hooves as you try to figure out what is going on. Your eyes adjust just in time to see a crowd of people, all dressed in white with silly red neckerchiefs, start to… hit you with rolled up newspapers? What the hell is this? And why are all the other bulls running so fast?

I’ll tell you why: because those jerks with the newspapers are now chasing you down the street, whooping and hollering and poking you with their papers. “Really?” you think, hooves skittering on cobblestones as you force yourself around a corner. “Are you really trying to outrun a bull?”

It’s enough to make you want to gore them, but there’s no time—you’ve now reached a large ring and are surrounded by a different group of people, who force you into a new corral and give you some food. It tastes good, but man, it’s making you sleepy. You haven’t been this tired since that breakfast they gave you the day you left the farm. Maybe you’ll just lie down for a little nap…

Suddenly it’s 6:30 in the evening and you’re being prodded back into that big circle, where thousands of people are staring down at you from the stands. Several men come up to you on horseback, but before you can figure out why the horses are wearing blindfolds, the men take sharp lancets and twist them into your neck and back muscles. What are they doing, trying to kill you? You try to raise your head to gore them, but the lancets are making it hard to move. You’re still really sleepy, the blood is flowing freely down your legs, a different man just came in and stuck a harpoon point in your back, and now some asshole is standing in front of you with a red cape.

www.andysimsphotography.com

This is officially the worst day ever.

Editor’s note: In addition to the Running of the Bulls/subsequent nightly bullfights that occur in Pamplona during the eight days of the Fiesta de San Fermín, watch out for the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals protest that occurs the day before the festival begins. Formerly known as the Running of the Nudes, it involves hundreds of naked people parading through the streets smeared with fake blood—and is a total buzzkill for anyone looking forward to the sight of drugged, wounded bulls being brutally slaughtered in front of a live audience.

The Gloucester Cheese Rolling Competition

Certain activities make me question how the human race survives. For example, the Cheese Rolling Competition, a yearly festival in which scores of people gather at Cooper’s Hill near Gloucester, England, for the chance to chase a piece of cheese off a cliff. Bones are broken. Joints are dislocated. Contestants are carried off the field on stretchers. This might be understandable for a sufficiently large prize, but in this particular contest, runners are risking life and limb for the glory of winning a seven-pound round of Double Gloucester cheese.

Fans of the Cheese Rolling Competition will accuse me of oversimplifying things, so let me take a step back. The proud tradition of cheese rolling dates back some two hundred years (diehard fans insist it comes from the Romans) and follows a strict order of proceedings. First, competitors line up on the top of Cooper’s Hill, a rugged, uneven pitch so steep that from the top of the slope, it appears concave. A master of ceremonies, wearing a white coat and a silly hat, escorts a guest “roller”—the person responsible for releasing the cheese—to the edge of the hill. On the count of three, the roller releases the cheese; on the fourth count, the runners throw themselves down the hill after it. Originally the point was to try to catch the cheese, but given that it can travel more than seventy miles per hour and has a one-second head start, the winner is usually just whoever crosses the finish line first.

It’s a painful race to watch. Most people lose their footing almost immediately and begin violently tumbling down the hill, bouncing onto shoulders, ankles, and heads, occasionally landing back on their feet before being thrown forward again. Lucky runners make it to the bottom intact, where volunteer rugby players known as catchers try to intercept them before they crash into the safety barrier of hay bales. Unlucky contestants are taken away by ambulance.

The 2009 competition alone saw fifty-nine injuries, of which only thirty-five were competitors. The rest were catchers and spectators, some trampled, some wounded when hit by the wayward cheese. One particularly unfortunate man held up the entire contest when he fell out of a tree.

But regardless of its inherent dangers, history dictates that the competition must continue. When World War II rationing forbade using a real round of cheese, contest organizers fashioned a cheese-shaped piece of wood with a token piece of Gloucester stowed inside. And even when the contest itself has been canceled, as it was during the foot-and-mouth scare of 2001 and again in 2003 when the contest’s volunteer Search and Rescue Assistance in Disasters teams were called off to help victims of an Algerian earthquake, organizers rolled a single piece of cheese off the hill anyway—a symbolic act to ensure that the tradition would remain unbroken. If only the same were true for contestants’ bones.

MICHAEL AND ISAAC POLLAN

The Worst Meal in Barcelona

It’d be hard to pinpoint the best meal in Barcelona, a city known for its excellent Catalonian food. But on a recent trip there, our family had no trouble identifying the worst: a frozen, microwaveable paella—basically, a Spanish TV dinner—available in low-end eateries near tourist destinations. A true paella is a delicious thing, a saffron-infused concoction of meats, vegetables, or seafood cooked with rice in a two-handled pan over an open flame until the ingredients are tender and the bottom has formed a savory crust. Unfortunately, however, the dish does not stand up well in the microwave.

We had ours one hot afternoon after leaving the Park Güell, Gaudi’s weirdly wonderful garden on a hill overlooking the city. We left the park around 4 P.M., famished, and could find no other place willing to serve lunch; the kitchens were closed. But not the microwaves at the place near the trinket shop. There they offered several versions of traditional foods—various tapas and raciónes and, of course, my fateful paella. I placed my order, and in the kitchen, out of sight, someone slipped it into the microwave. Several minutes later, my Spanish meal was served.

What possessed me to order it? A desire to have something indigenous, I suppose. But there was nothing indigenous about the substance on the steaming plate before me: it was a solid clump of mushy rice punctuated with dubious chunks of sausage and a few world-weary prawns.

I should have gone with the hot dog.

MICHAEL POLLAN is the author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals and In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto.

Before heading to Barcelona, my parents and I had received lists from many esteemed culinary minds as to where to spend each bite in the tapas capital of the world. But these lists did us no good when, walking back to the Metro from Park Güell, the three of us were simultaneously struck by pangs of late-afternoon hunger. I knew what this meant: far from any foodie destination, we would have to venture into a restaurant unexplored by our gourmand guides. There would be no Alice Waters in the back of our heads recommending the “ever-

so-simple” tomato breads and the Iberico ham, or Dan Barber advising us to try the fried artichokes with the lemon aioli, or even my grandmother suggesting the Pimientos de Padrón. We were truly on our own.

The restaurant we found was so bland that it didn’t even have a name. And yet this was our only choice; it was siesta, and the other shops we passed were closed. Except, of course, for this anonymous hole in the wall, which we staggered into upon spying paella on the crookedly taped menu in the front window.

As we entered we were quickly greeted and ushered to a table that was squeezed so tightly into a corner that it reminded me of a Tetris piece. I sat down and immediately noticed three ominous things: the tableware and chairs (all plastic), the fact that there was not a single Spaniard in the entire establishment, and the bathroom. Oh, the bathroom. It wasn’t politely located down the hall or in the back; no, it sat in the corner across from our table, in the dining room itself. Consisting of three small walls erected to form a box the size of a small airport bathroom stall, it leaked both smells and sounds.

But despite all of this, the actual items on the menu did not seem too nauseating. My parents, emboldened by their hunger, ordered the surf and turf paellas. I stuck to the strictly turf. After placing our order with a middle-aged and chipper man, we waited for five, ten, twenty minutes, our stomachs growling louder and louder until I was sure the entire restaurant could hear the symphony of our gastric tracts. Then, finally, the food arrived, delivered in three matching oval plastic plates with slightly elevated walls.

I stared, crestfallen at the sight of my dish. It was a large lump of brown-black gooeyness, with indecipherable chunks jutting out from the sludge. Upon the first bite, which required me to cram my plastic fork as hard as possible into the slightly crusty edges of the dish, I came to the conclusion that my paella had been frozen for a very, very long time. Perhaps the delay in service was due to the time it took our server to find an ice pick to extricate the dish from the bottom of his freezer.

But while disgusting, no one could accuse my paella of being simple. After a top note of freezer burn came the lovely astringent taste of gamy meat and mushy carrot. The rice was even more complex: clumped and congealed, certain bites were reminiscent of leather-hard slabs of clay. Others were mushy beyond recognition, saturated with a drool-like substance released from the meat that created an effect of heavily burnt oatmeal.

I’ve never seen my father so happy to pay the bill.

—ISAAC POLLAN

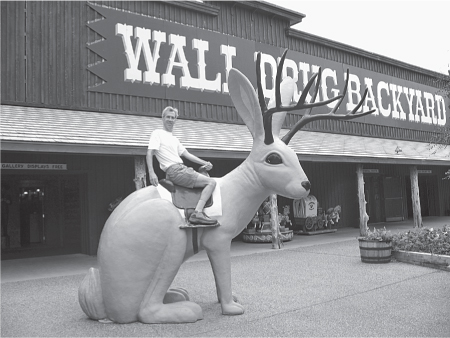

If you’ve taken a cross-country road trip, chances are you’ve seen the signs. At its peak in the 1960s, Wall Drug—a roadside attraction in South Dakota that has become synonymous with American kitsch—was advertised on over three thousand billboards around the country. HAVE YOU DUG WALL DRUG? FREE COFFEE AND DONUT FOR VETERANS: WALL DRUG. T-REX: WALL DRUG.

The signs were so relentless that Wall Drug became a tautology of a tourist trap: a place worth visiting only because of the billboards claiming it was worth visiting. Adding to the circularity, the advertisements themselves are now considered campy artifacts in their own right, and have sprung up in places as far away from South Dakota as Moscow, the Taj Mahal, Afghanistan, and even the South Pole.

These days the actual Wall Drug advertises itself as a “76,000 square foot wonderland of free attractions” including both a life-size tyrannosaurus rex head and the world’s second-largest fiberglass jackalope. But it wasn’t always this glamorous: when the original Wall Drug opened in 1931, Wall was a tiny prairie town with fewer than four hundred residents. Wall Drug’s founders, Ted Hustead and his wife, Dorothy, liked the town because it had a drugstore for sale and a Catholic church. Their families, however, were not as easily convinced, and insisted on having a prayer circle to see if it was really a good idea. Luckily for lovers of American roadside attractions, God approved.

It takes a while, though, to go from a small family-run pharmacy to an internationally known destination, and for a while, business was slow—really slow. So slow that even five years after they’d opened—Dorothy and Ted’s self-imposed deadline to turn things around—it still was virtually nonexistent. And then one hot summer day Dorothy, watching passing carloads of sweaty travelers, stumbled upon a gimmick that, in retrospect, was genius: Wall Drug should give away free ice water.

Dorothy even came up with a slogan: “Get a soda… Get a root beer… Turn next corner… Just as near… To Highway 16 & 14… Free Ice Water… Wall Drug.” Skeptical but supportive, Ted got a kid to help him paint the slogan on a bunch of wooden signs, then spent a weekend nailing them up on the side of the road, spaced out so that travelers could read them sequentially as they drove. According to legend, by the time he got back to the store, people were already lining up for ice water.

Julie Mangin

That Wall Drug still exists is a testament to how few manmade tourist attractions there are in South Dakota (cf., Mount Rushmore, p. 92). But it’s also a testament to clever advertising and ice cubes. Seventy-something years since Ted and Dorothy opened their shop, Wall Drug now is a sprawling cowboy-themed mall with restaurants, gift shops, a chapel, an art museum, and attractions that include a

piano-playing gorilla and an eighty-foot-tall apatosaurus. You can buy boot spurs or a “freedom pistol,” watch some singing cowboy dolls, or take a photo of your kids on the jackalope. Wall Drug still offers free ice water and 5-cent cups of coffee, but that’s about all that is recognizable from the original tiny store. It’s grown so large that it is no longer simply an attraction—Wall Drug has swallowed the town.

Let’s start with the carpet. Why would Bay Area Rapid Transit, one of the country’s busiest commuter rail systems, decide it was a good idea to upholster the floor?

The result is Eau de BART, the stomach-turning scent that hits you in the face every time you board a train to San Francisco. It’s a blend of spilled coffee, greasy hair, body odor left by vagrants who take naps on its blue cloth seats, and the aroma that arises from substances trapped on thousands of commuters’ shoes. Thankfully, there’s a movement afoot to rip up the rug from some of the cars, but this still leaves the question of the fabric seats unresolved. Perhaps my allegiance to the New York subway system makes me biased, but I believe that all public transportation systems should be built with materials that can be hosed down with bleach.

BART was honored as one of the Top Ten Public Works Projects of the Century by the American Public Works Association. But despite this accolade, its problems don’t end with its odor—or with the questionable decision to refer to a major public transportation system with an acronym that rhymes with “fart.” BART is the main transit link between the East Bay and San Francisco, and yet its trains don’t run between 12 and 4 A.M. Berkeley residents looking for a night on the town therefore find themselves in a public transportation version of Cinderella—except when the clock strikes midnight, BART doesn’t turn into a pumpkin; it disappears entirely.

If you do manage to get on a train, be prepared to ponder several engineering questions such as: why did no one predict that thanks to some unfortunate confluence of acoustics and friction, BART cars would emit an ear-piercing shriek for their entire 3.6-mile passage underneath the water through the Transbay Tube? Or, alternatively, what would happen in an earthquake? The BART Earthquake Safety Program has identified areas that are particularly vulnerable if the ground starts to shake: the Transbay Tube, the stations, and the aerial guideways that prop up the tracks when the train emerges above ground. In other words, pretty much all of it. One can only hope that if and when the big one comes, it does so between the hours of midnight and 4 A.M.

A Stop on Carry Nation’s Hatchetation Tour

Born in 1846, Carry Nation didn’t come from the stablest of backgrounds. Her maternal grandmother, aunt, uncle, and cousin all had dementia, and her mother suffered from delusions that she was Queen Victoria. Not to be outdone, Nation directed her own mental energy toward religion; she claimed to have frequent chats with Jesus.

Apparently, Jesus had a lot to say about alcohol. After her first husband drank himself to death, Nation remarried and joined the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which closed all liquor-selling establishments in Medicine Lodge, Kansas, except for one stubborn drugstore. The other women considered this a success, but it wasn’t enough for Nation, who grabbed a sledgehammer, stormed into the shop, and smashed a keg of whiskey. The druggist, terrified, left soon thereafter, and Nation had found herself a cause.

After following a voice in her head that told her to destroy saloons in nearby Kiowa, Nation returned to Medicine Lodge and bought a hatchet. She then began what she called a “hatchetation” tour across the eastern half of the United States, bursting into saloons and destroying bottles with an enthusiastic chant of “Smash! Smash! For Jesus’ sake, smash!” Nation soon developed such a formidable reputation that when she arrived in New York City, bartenders locked their doors. Who could blame them? The woman was nearly six feet tall, a muscular 175 pounds, armed, and crazy.

Luckily, Nation kept her rampages focused on inanimate objects like bottles, kegs, and cash registers; her reign of terror ended when she ran out of money and was reduced to supporting herself by selling souvenir hatchets and reenacting saloon smashes at local carnivals. But her legacy lived on—and across the United States, bartenders posted signs in her honor. ALL NATIONS SERVED, they said. EXCEPT CARRY.

Carry Nation with bible, hatchet

Wikipedia Commons

The Third Infiltration Tunnel at the DMZ

Advertised by tourist brochures as the “most fortified border on Earth that only Korea can offer,” the demilitarized zone is anthropologically fascinating, not to mention one of the world’s only active battle lines to have its own gift shop. (Sample souvenirs: DMZ key chains, child-size camouflage suits, duty-free alcohol.) There is a welcome center; there is a movie theater. Concerned about providing fodder for North Korean propaganda photos, the DMZ even has its own dress code; visitors are forbidden from wearing flip-flops, tank tops, or shorts that “expose the buttocks.” It is not entirely clear what the people who wrote the dress code have against leather riding chaps, but they’re not kidding: wear the wrong thing, and you’re not going on the tour.

Providing that your pants meet protocol, you’ll sign a release acknowledging that you could get shot, watch a slideshow presentation and briefing, and eventually be led to the Joint Security Area, which is the only area in the DMZ where North and South Korean troops stand face-to-face.

The border in this section is less Berlin Wall than it is sidewalk curb: a half foot tall and straddled by a group of squat, powder-blue UN buildings. These were originally designed as neutral spots for negotiations. But since visitors are allowed to go inside, most of the negotiations going on these days are among members of large tour groups figuring out where in the building they need to stand to get a picture of themselves in what is technically North Korea. Like most of the DMZ tour, this comes highly recommended. But do not bother with the Third Infiltration Tunnel.

That’s not because it is uninteresting. The Third Infiltration Tunnel—or the Third Tunnel of Aggression, as it’s more poetically known—is the third discovered underground passageway (of an estimated dozen or so) that North Korea’s Kim Jong Il ordered to be blasted from North to South Korea in preparation for a potential invasion. When South Korea found this particular tunnel in 1978, North Korea claimed that it was merely a coal mine—even going so far as to have part of the granite walls painted black. Unconvinced, the South blocked the tunnel with three barricades and then, as a capitalist “screw you,” opened it as a tourist site.

The resulting experience is not for claustrophobics, people prone to panic attacks, or anyone with an aversion to being buried alive. First, you’re led to a train platform and told to put all your belongings into a small cubby. Next, you’re given a hard hat and herded onto a small trolley. That’s probably the part where you should start asking questions, like: why are you on a train? Or, more important, where are you going? But most tourists, lulled into complacence by the

trolley’s similarity to those in Disneyland’s “It’s a Small World,” don’t think to be inquisitive.

Instead, the claustrophobic visitor will experience an unexpected rush of terror as the train begins a 240-foot descent underground through a narrow tunnel blasted out of solid rock. As your little train chugs lower and lower, you wonder how the giggling tourists around you can seem so oblivious to the lack of emergency exits and escape hatches built into the suffocating walls pushing in on you from all sides. Several horrible minutes later, the trolley finally reaches the bottom and you’re given several minutes to walk to the tunnel’s main attraction—the barricade between North and South Korea. (Spoiler alert: it looks like a wall.) The good part about the tunnel is that, at 6½ by 6½ feet, it’s slightly less oppressive than the train ride, but the extra headroom isn’t worth the panic attack it took to get

there.

Your opinion toward bus travel in Samoa is likely to depend on one important variable: whether or not you mind being close with strangers. And when I say close, I’m not talking about having your face smushed into people’s armpits during rush hour. I’m talking about sitting on their laps.

In Samoa, buses are small, seating is limited, and nobody’s supposed to stand. So drivers are left with two options: leave people in the road, or assume the passengers will find a place for them to sit. Etiquette dictates the latter, and so whenever a bus picks up

someone—which could be anywhere, since Samoa has few predetermined bus stops—the passengers engage in a round of quiet shuffling to make space on someone’s lap for the new arrival. Whose lap you sit on depends on your status in the social hierarchy—elderly people get the front, then come women with children, then women with no children, and finally a throng of men at the back.

If you have a loose definition of personal boundaries, this lap sitting can actually be a fun cultural experience, not to mention provide a welcome layer of padding on rough roads. But be careful: according to the World Health Organization, in Samoan urban areas, over 75 percent of adults are obese. Ending up on the wrong side of a lap could mean a very painful ride.

Also worth noting: After years of driving on the right, Samoans recently were forced to start driving on the left, a transition that not only increases the risk of head-on collisions, but means that many bus doors now open directly into oncoming traffic.

MARY ROACH

The Tupperware Museum

America has an enduring passion for highly specific and unnecessary food storage receptacles. It was created, almost single handedly, by Earl Tupper, the man whose Orlando empire has given us, over the years, the Garlic Keeper and the specially designed pickle storage container, never minding that the Vlasic jar has a screwable lid. I once wrote a magazine article about Tupperware, partly because I was fascinated by Mr. Tupper and his wares, but also because I had long harbored a desire, unfathomable even to me, to visit the Tupperware Museum of Historical Food Containers. Could anything be duller? (Possibly. There’s a Needle Museum somewhere in England.)

As the afternoon at Tupperware HQ wound down and my host from the public relations office began moving us toward the door, I asked to be directed to the museum. She replied that it had closed some years back and that the contents were—are you ready?—in storage.

Years later, I found a photograph of the museum. Its dullness surpassed even my imagination: brown carpeting and case after case of drab, unimaginatively displayed crockery, amphoras, vats. It appeared that the whole point of the museum had been to make pre-Tupperware food storage seem sad and boring, to foster a yearning for festively colored Wonderlier bowls and stackable sandwich-fixings holders. Nonetheless, my disappointment lingers, as though for all these years it had been stored in a virtually airtight, just-right Disappointment Keeper.

MARY ROACH is the author of Spook: Science Tackles the Afterlife.

An Outdoor Wedding During the 2021 Emergence of the Great Eastern Cicada Brood

First, let’s clear something up: cicadas are not locusts. Locusts, which are related to grasshoppers, enjoy swarming, eating everything in their paths, and bragging about the good old days of their biblical plague. Cicadas, on the other hand, feed only on tree sap, can’t fly well, and are too dumb to organize. If locusts are ravenous sociopaths, cicadas are more like frat boys—clumsy, loud, and obsessed with sex.

There are cicadas around every year, but the number of annual cicadas is nothing compared to their periodical counterparts, which are the longest-living insects in North America and only exist in the eastern United States. These periodical cicadas spend most of their lives underground, but every thirteen or seventeen years, depending on the species, entire broods of cicadas push their way out of the dirt and climb into trees to mate. Scientists don’t know how cicadas synchronize their appearance—it might be related to soil temperature—

but the result is striking: millions of cicadas can come out of the ground in a single night.

Once above ground, cicadas devote themselves to one thing: finding another cicada. Newly emerged cicadas, still nymphs, climb up on whatever woody structures they can find and quickly molt into adults, leaving behind amber-colored, creepy-looking sheaths that are great for practical jokes. Then the males start singing, joining together in chirping choruses that can reach up to 100 dB. Females respond by coyly flicking their wings, and about ten days of nonstop noise later, they mate. Females cut slits in twigs, lay eggs, and then die, their carcasses dropping from trees to form a thick, crunchy carpet. Six or seven weeks later, tiny white ant-like nymphs hatch, fall to the ground, burrow into the dirt, and the cycle begins again.

So let’s get to the wedding: the Great Eastern Brood, also known as Brood X, is the farthest-reaching cicada brood in the northeastern United States—and it’s set for a reemergence in 2021. Sometime early that summer—probably in the heat of wedding season—millions of cicadas will tunnel their way toward open air and, if you plan things poorly, your wedding site. Imagine it: your vows being drowned out by the singing of thousands of horny cicadas, insects falling onto your guests’ heads, the crunch underfoot of countless abandoned shells.

Dave Allen Photography/daveallenphotography.com

The upside is that cicadas are harmless—they don’t bite or sting, and they’re not even attracted to human food. But at 1½ inches long with large wings and bright red eyes, they’re definitely noticeable, especially given their tendency to fly into things. If your wedding site has seen cicadas in the past, consider renting a tent.

Action Park—also known as Traction Park, Class Action Park, and Death Park—was an amusement park in Vernon Township, New Jersey. Responsible for at least six deaths and countless accidents, it inspired so many personal injury lawsuits that in 1996, it was forced to shut down.

The park was built as an off-season moneymaker for the Vernon Valley/Great Gorge ski area, and featured rides so obviously dangerous that they call into question the sanity of the person who designed them. Take, for example, the Alpine Slide. Built into the ski slope, it sent visitors zooming down the hillside on a concrete and fiberglass track in sleds equipped with poorly maintained brakes. There were two speeds available: very slow or extremely fast. Extremely fast meant risking having your sled jump the rails (a frequent occurrence), suffering abrasions and burns when you hit the track, and being hurled into a bale of hay at the bottom of the hill. Very slow, on the other hand, put you in danger of being rear-ended by the extremely fast person behind you. In 1984 and 1985, state records show that the ride resulted in at least fourteen fractures and twenty-six head injuries. It was also responsible for the park’s first death.

But the accidents didn’t stop there. Employees—mostly under twenty years old and often inebriated—souped up the Super Go Karts so that guests could play bumper cars at fifty miles per hour. The Super Speedboats, which visitors often rammed into one another, shared a pond with a healthy population of water snakes. The Tidal Wave Pool—nicknamed the “Grave Pool”—required twelve full-time lifeguards, who reported rescuing as many as thirty people per day on busy summer weekends. The Tarzan Swing dropped people into a pool of water so cold that in 1984, it’s said to have triggered a man’s fatal heart attack. The Aqua Scoot gave people head lacerations. The Diving Cliffs were positioned above a pool whose swimmers didn’t know they existed. The Kayak Experience’s submerged electric fans killed the park’s second victim: a twenty-seven-year-old man who was electrocuted when his boat tipped over and he stepped out to right it.

And then there was the Cannonball Loop slide—an enclosed waterslide that ended with a roller coaster-esque loop-de-loop. Based on the faulty premise that a wet bathing suit would provide the slickness and momentum necessary to carry a person up and around a 360-degree loop, the ride was closed after only a month.

Gone are the days of Action Park’s treacherous rides, untrained employees, and copious beer stands. It’s now the Mountain Creek Waterpark and is, by all accounts, much, much safer. But the morbidly nostalgic can still catch a glimpse of past dangers—underneath the route of the modern-day gondola lies the abandoned track of the Alpine Slide.

A Giant Room Filled

with Human Crap

Imagine a room filled with human shit—huge, steaming piles of it, arranged in rows in a dimly lit, windowless space the size of a parking garage. Actively rotting, the piles give off a fog so thick that, on particularly humid days, the machinery operators can’t actually see the ground.