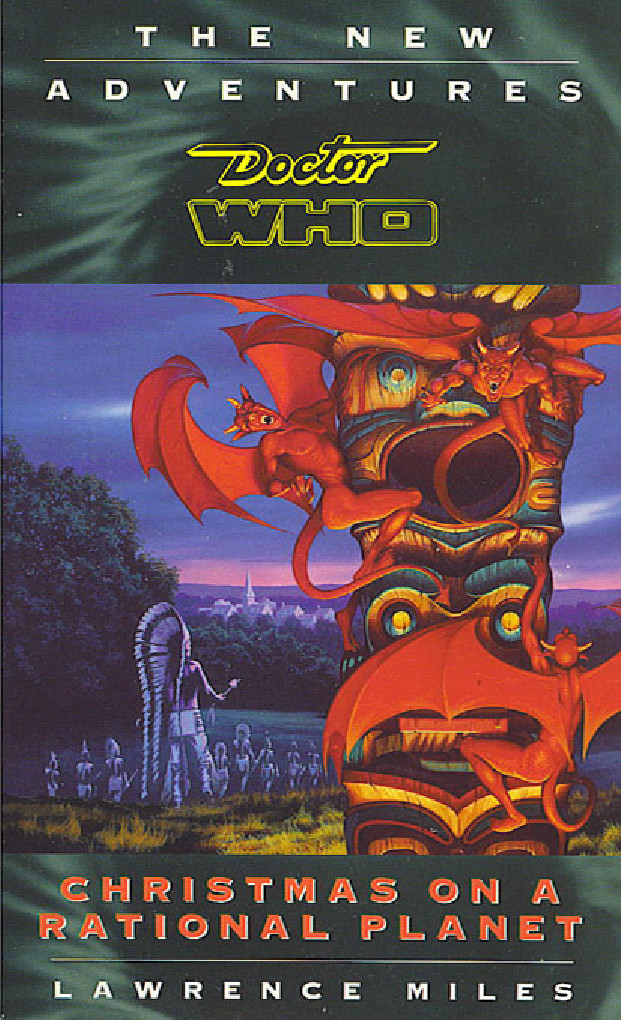

CHRISTMAS ON A

RATIONAL PLANET

Lawrence Miles

First published in Great Britain in 1996 by Doctor Who Books

an imprint of Virgin Publishing Ltd

332 Ladbroke Grove

London W10 5AH

Copyright © Lawrence Miles 1996

The right of Lawrence Miles to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

’Doctor Who’ series copyright © British Broadcasting Corporation 1996

Cover illustration by Mike Posen

ISBN 0 426 20476 X

Typeset by Galleon Typesetting, Ipswich

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Mackays of Chatham PLC

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior written consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Contents

PART ONE - STATE OF INDEPENDENCE

3 - Thought About Saving the World, Couldn’t Be Bothered

PART TWO - MADNESS, MADNESS, THEY CALL IT

6 - Non-Interventionist Policy (Yeah, Sure)

8 - Various Gods Out of Assorted Machines

10 - Obligatory Chapter Named After Pop Song

An Epilogue: - One Way or Another, the World Will Be Saved

Dedicated to the usual suspects.

‘All great myths are inspired by the organic life-cycle. The hero’s quest to find his perfect mate, his struggle to build a better world for his children, his willingness to give up his life for the next generation... but Time Lords do not reproduce organically, and all their young are born from the gene-looms.

What other conclusion can we draw? Time Lords have no understanding of myths, no understanding at all. And they have very little time for fairy-tales.’

– Gustous Thripsted, Genetic Politics Beyond the Third Zone, appendix LXXVII

A Prologue

Necessary Secrets

There were two kinds of darkness. It was one of those things that children always forgot, the moment they were old enough and big enough to reach the light-switch.

The ordinary kind, the dull kind, came and went night-by-night; just a backcloth, big and black and wet, colouring in the sky and framing the city lights outside the bedroom window. It was the other kind you had to watch out for, the kind that lived at the back of the cupboard and in the mystical dimension behind the sofa, the kind that kept secrets, that swallowed lost toys and hinted at futures you could only ever half-understand.

True darkness. Monster darkness.

And when Roslyn Forrester looked up, that was the colour of the sky.

There was a sun, somewhere up there, but it was black, an impossible fluorescent black, turning the desert into a great bruise-coloured shadow that stretched all the way to the horizon and vanished over the edge of the world. Only under the rocks, where the sun couldn’t reach, was there any kind of illumination. Pools of sticky yellow light.

The world’s been turned inside out, she thought. Shadows where the light should be, light where the shadows should be.

Arizona. That was the last place – the last real place – she remembered. After the TARDIS had left Mars, the Doctor had started poking and prodding at the console, as if that’d make the machine go faster. There were things to do, he’d said.

‘Yemaya,’ he’d added.

‘What about it?’

‘Loose ends. After we paid our last respects to SLEEPY, Bernice asked if we should pop back and see how the whole thing started. SLEEPY ‘s progenitor had telekinetic powers.

He vanished just after you dropped in on him. All research records of the Dione-Kisumu Company spontaneously erased themselves once we’d left Yemaya 4. An impressive feat, even for the most influential of corrupt megalomaniacal corporations.’

Roz had raised a quiet eyebrow ‘What are you suggesting?’

The Doctor had waved his hands in an agitated fashion.

‘Nothing. But I hate loose ends. I hate feeling that there are things I don’t know about going on behind my back ‘

‘Liar,’ Roz had mumbled.

So he’d kept on prodding, and had spent the next few days shifting the TARDIS from one end of creation to the other, looking for leads no one else would have recognized. Showing his face at seances, having tea with black magicians, poking his nose into the psychic nooks and crannies of human history.

He’d had an audience with Madame Blavatsky, and shuffled through Nostradamus’s drawers while the great man had been out on the razz.

‘He won’t mind,’ the Doctor had assured Roz. ‘I’ll leave a note for his wife. She’s the practical one in the household, you know.’

Finally, they’d visited Arizona during the last days of the American empire, where the Doctor had expected to find a convention of half-crazed telepathic UFO abductees. But there had been no convention. Just a desert. Not like this one. A normal desert. A proper desert.

With a body in it.

Then she heard it, the sound of raw, wet flesh grinding against rock, and realized that the creature – the alien – the monster – was following her up out of the ravine. She’d hoped that it wasn’t capable of climbing, but by the sound of it (and she wasn’t going to look back to make sure), it had scaled the ravine wall faster than she had.

She kept running

She remembered the first time she’d seen one of the creatures, as a corpse, lying out in the Arizona sun; the Doctor stumbling across it, standing over its body like the judge of the dead, a look of disapproval erupting across his face.

Roz looked up, squinting at the landscape ahead of her, and felt something sharp and ugly scratch her optic nerve. Looking at the sun was like staring into an eclipse. She gritted her teeth.

Nothing up ahead, no buildings, no exits, definitely no TARDIS. Just a few rocks, nightmare-coloured sand and the occasional gully. She heard the thing slipping over the dust at her heels, and tried not to think about what it looked like.

She failed totally.

It had just lain there, pockmarked and sand-blown, its big, bloated body expanding and contracting, like a sea creature washed up on a beach and gasping for water. Quite dead, the Doctor had insisted, though he couldn’t tell the cause. Its movement had been some kind of automatic function, the thing constantly adjusting and re-adjusting its shape even after death, still uncertain of the exact form it should take.

He’d poked it with the end of his walking-cane – he’d been trying to wean himself off the umbrella – and the body had split open like a ripe peach.

There was no sign of the Doctor now. She was on her own again, by accident or design, with just the Doctor’s parting gift for company. She glanced down at the little shining sphere, cradled in her left hand. The amaranth. Goddess, why didn’t they give these things proper names? ‘Blasters’, ‘Tenser guns’,

‘neuro-whips’... you knew where you were with that kind of technology. What the hell was an ‘amaranth’ supposed to do?

‘Useful,’ the Doctor had said, five minutes before the world had opened up and dragged her down into its shadow. Just that, as he’d pressed the sphere into her hands. ‘Useful.’

Cwej had been fascinated by the alien corpse, of course.

Sure, he’d made ‘yeuch’ noises, but underneath it all he had a kind of morbid curiosity that a fourteen-year-old would’ve been proud of. Roz had glanced into the split in the thing’s body, but only briefly. Coils, cords, knotted tissues, liquid pathways. It had been like looking into the workings of a visceral computer, but the patterns wouldn’t stay still, the connections constantly splitting and rearranging, breaking off to form new circuits and new systems.

‘Is it an android?’ Cwej had asked, eager to be part of the Doctor’s investigation. Roz had rolled her eyes. It hadn’t looked like an android at all, no face or hands or joints, nothing to identify it as the work of a humanoid species.

The Doctor had shaken his head. ‘Gynoid.’

‘Gynoid?’

Roz stumbled as she made her way down a slope, regaining her balance but feeling something twist and pop in her ankle.

The thing was gaining on her. Had to be.

‘Did you ever stop to think about the word "android"?’

he’d said, addressing himself as much as anyone else. ‘Did you ever stop to think about what it means?’

Cwej had shrugged. ‘Robot. Machine that looks like a man, right?’

‘No.’ The Doctor had turned away, and the split skin of the dead thing had sealed itself up in seconds. ‘Android. From the Greek "Ana-, Andros", meaning "man". "Oid", meaning

"like".’

Cwej had looked confused, which was hardly a novelty. ‘A machine that’s like a man. That’s what I said.’

‘You said a machine that looks like a man. There’s a difference.’

‘Er, what?’

There was a moment’s silence as the thing hit the bottom of the slope behind her, and for a moment Roz wondered if it had broken its neck; but a second more and it was whispering to her again, bright coppery syllables that licked at the nerves along her spine. Should’ve known better, she thought.

Gynoids probably don’t even have necks. ‘Gynoid’. Stupid name. Like a make-believe alien out of an Imperial propaganda simcord. ‘Earth Versus the Gynoid Menace!’

Goddess, it’ll look bloody awful on my headstone.

And then, with almost cinematic timing, she tripped.

‘... the witch-skulls of Peking, a perfect pentagram burned into the forehead of every one. Our investigators believe that their owners were still alive when the marks were made, no doubt being involved in some long-forgotten pagan rite. Here, the Clockwork Fantastique, found in the ruins of an eleventh-century village, yet inexplicable even today. And here, a set of Egyptian manuscripts, found by our own Cardinal Scarlath, describing a world built by one-eyed supernatural horrors...’

Absently, Cardinal Catilin realized that he should have been enjoying this more. In all the years he’d been custodian of the Collection, this was the first time he’d had the opportunity to show the curiosities to anyone from outside the church; at the very least he should have been showing off his encyclopaedic knowledge of the ‘exhibits’, explaining the Satanic rituals described in the Borianu tapestries, pointing out the heretical hidden messages in the da Vinci portrait of John the Baptist... but the French woman seemed unresponsive, somehow unconcerned, as if she’d seen it all before.

Which wasn’t very likely, Catilin reflected.

The woman stopped in front of one of the larger glass-fronted cases, and Catilin risked a good long look at her. She was a tall woman, her body not so much thin as somehow pained, her spidery limbs cloaked by a mud-coloured chemise, dark hair trickling down her back Her sharp, wide-eyed face had that haunted (some would say ‘scared’) look that Catilin had noticed in many survivors of the French Revolution, the skin interrupted by a circular red mark set into her left cheek.

Catilin briefly wondered what had happened to her. The mark looked like a burn, about the same shape and width as a decent-sized coin. A thin layer of make-up just failed to disguise it.

He was about to turn away when he noticed the way she was standing, back curiously crooked, fingertips against the glass. She looked like she was in pain.

‘Mademoiselle? Mademoiselle Duquesne?’

The woman snapped into an upright position.

‘Cardinal? There is, ahhh, a problem?’

‘You look... unwell. If there’s anything wrong...?’

‘No. No, not at all. Please, continue. It’s all most interesting. Please.’

She attempted a smile, and Catilin noticed her hand reach for the base of her spine, as if to scratch it. Something about the movement was familiar –

Ah. Of course.

‘If I might ask a question, Mademoiselle,’ he said, before he had a chance to think about what he was saying, ‘were you at all familiar with, ah, Cardinal Roche?’

‘Roche. No. No, I don’t believe so.’

‘The previous custodian of the Collection of Necessary Secrets. My predecessor here.’ Catilin indicated the hall around him, moving his small and crumpled frame in a complete circle, as if to embrace the whole of its undusted majesty. ‘Cardinal Roche was... "gifted", shall we say. He possessed a certain "gift" which he believed to be a boon from the Higher Orders of Creation. A blessing, perhaps.’

He caught Duquesne’s eye. ‘I believe that pagan peoples would call it "The Sight",’ Catilin went on. ‘A sense, a sixth sense one might say, for the uncanny and the improper. To me, the Collection is merely a building full of oddities. To Roche, it was much more. He claimed he felt a burning in his spine whenever he grew close to certain objects, as though his body could sense the very strangeness of them. He once told me that he could often hear whispers from the skeletons and the fossils, and wondered if they wished to relate their peculiar histories to him.’

He’d been watching Duquesne as he spoke, and he’d seen her hand involuntarily shoot back to her spine. That was it.

The woman was sensitive, just as old Roche had been.

Probably the only reason why her employers had sent her here.

The French weren’t in the habit of using women as agents.

‘How fascinating,’ she said, flatly.

‘Indeed,’ said Catilin, deciding not to tell her that Roche had gone quite mad and cut his own throat open with one of the Collection’s sharper ‘exhibits’.

‘What do men do?’ the Doctor had asked, turning his back on them.

The question had been directed at Cwej, which was a pity, as Roz had thought of about half a dozen smart answers in no time at all. ‘Er,’ Cwej had said. ‘Er, give up.’

‘The same things as women,’ Roz had muttered. ‘But without wiping the sick off the furniture afterwards.’

There was a furrow, a tiny indentation in the ground, and Roz had run right into it, catching the toe of her boot against the lip and losing her balance. Instinctively she threw her arms out in front of her, realizing that it probably didn’t make much difference how you fell if there was an alien monster breathing down your neck. She felt the amaranth slip out of her grasp.

‘No. Not the same at all.’ The Doctor had paused, as if he had difficulty getting to grips with this subject himself ‘The male and female of the species, of every humanoid species, have completely different psychologies. Evolution made sure that their brains were suited to very different tasks. Usually the two perspectives lock together, and no one even notices the join. Nobody spots the difference. Usually, that’s how civilizations are made.’

Roz had folded her arms impatiently, wondering what this had to do with dead aliens, and Cwej had looked like he hadn’t been following any of it.

‘Men build,’ the Doctor had continued, his Gaelic inflection becoming more noticeable by the second. ‘Their fundamental purpose is to act as architects. Towers. Pillars.

Bridges. All men’s things. In a man’s world, everything has to be defined, named, planned with precision. Things have to be conquered, not accepted. No patch of earth is complete until it has a building on it. An orderly, precise, geometrically exact building.’

Roz rolled as she hit the ground, and realized that she was on top of another slope. Fine by her. She pushed herself over the edge, picking up momentum as she spun downhill. Once in every 360-degree roll, she could see the gynoid as a grey blur framed against the unnatural black of the sky. There was something else, too, a flash of gold, somewhere nearby.

The amaranth. Obviously.

‘Towers and pillars. Right.’ Roz had remembered an Academy lecture on Freudian symbolism in the psychology of the serial killer, and remembered that she hadn’t listened to most of it. Routine procedure when faced with a serial killer was to blow his kneecaps off, so she’d never understood what his psychology had to do with anything. And women?’

‘Different instincts. The female psyche has no need to construct, no need to control –’

Cwej had giggled, but they’d ignored him.

‘– no need to define. The female psyche is adaptable, mutable. That’s why little boys dream of killer robots and little girls dream of faerie queens. A generalization, of course. In many cultures, men tend to see that difference as a weakness, which is probably why killer robots are always in fashion and faerie queens get such a bad press.’

‘They don’t see it as a weakness,’ a voice had said. ‘They see it as a threat.’

There had been a moment of shocked silence. It had been Cwej’s voice, but Roz couldn’t believe that it had been Cwej speaking. This was Chris Cwej, for Goddess’ sake, Chris Cwej who’d had a bedroom full of toy anti-grav starfighters, Chris Cwej who’d once spent six hours in the TARDIS wardrobe trying on every single pair of sunglasses in the Doctor’s collection until he’d found the ones he thought were ‘neatest’.

He’d been having these moments of inspiration ever since Yemaya, Roz had noticed, but where the hell had that little pearl of wisdom come from?

The Doctor had looked as if he’d just been dealt a killing blow, as if the comment had been a personal attack on him.

‘Perhaps,’ he’d conceded.

Her back slammed into something, and Roz realized that she’d rolled into a large rock, positioned right at the bottom of the slope. Whichever god or goddess put that there, she thought as the pain crackled up her spine, should be making Tom and Jerry cartoons. But the whispering was getting closer, and she looked up, towards the advancing gynoid, determined to face death head-on.

It was a pathetic gesture, but it was the best she could do at short notice.

"Android",’ the Doctor had repeated. ‘Meaning "manlike".

Not because it looks like a man, but because it’s just like a man. Even if it looked like a woman, or a tiger, or a hairy monotreme, or a shapeless green blob, it would still be a man’s machine. Perfectly ordered artificial life. The ultimate creation of the masculine psyche. Whereas, by contrast...’

... and he’d pointed his cane at the corpse of the gynoid.

The blur was rolling down the slope towards her, new orifices opening in its quicksilver skin every second. The whispers spilled into Roz’s ears until they filled every avenue in her head and turned the world into static.

She and Cwej had both glanced back at the dead thing, still quivering in the sun. ‘Gynoid,’ Cwej had said, apparently back to normal. ‘It’s Greek, right? "Gyno". Like "woman". ‘

‘Yes.’ There’d been a strain in the Doctor’s voice, and he’d just failed to disguise it. And it shouldn’t be here.’

‘Uh-huh. You mean, they don’t build them round this part of the galaxy?’ Yeah, that was Cwej. Chief Inspector Cwej, determined to be on top of the case.

‘You weren’t listening.’ The Doctor had scowled, though not at anyone in particular ‘Gynoids aren’t "built". Only androids are "built". Gynoids just are.’

They just are, Roz thought. Yeah, right. And now one of them just is about to bite my legs off.

Then there was something else, a high-pitched chiming, as the amaranth hit the rock next to her and rang like a bell. Even without looking, she could tell that it was spinning in the dust, making the same sound a glass makes when you run your finger around the rim. Louder, though, loud enough to make her eardrums ache. The gynoid raised its many voices, trying to make itself heard above the screeching, and just for a moment Roz could almost tell what it was trying to say... then the yellow light under the rock crept out into the darkness, folded itself around her, and blotted out the world.

The skeleton within the case was that of a huge, lizard-like creature, a row of dagger-shaped spines punctuating its back.

Catilin wondered if the woman was really looking at it, or just using it as an excuse not to catch his eye again.

‘The bones were discovered in the great deserts of the New World,’ Catilin told her. ‘As you can see, they belonged to some behemoth which no longer walks the Earth. My fellow cardinals insist that its species was destroyed during the great flood, though there is, as always, talk of God releasing unto them a great fire from Heaven.’

Duquesne nodded. ‘And His Holiness... God rest his soul...

refused to let the skeleton be exhibited in public?’

‘God rest his soul. Yes. We have many skeletons like this one, or fragments of them. Shortly before his passing, His Holiness decided that all such relics should be interred here upon their discovery. The Collection is, after all, a repository for those things which we feel it would be... inappropriate ...

for the general public to see. The discoverers of the bones are usually easy to pay off, their treasures brought here from around the world.’

‘I do not quite understand.’ The woman’s voice was strained, and Catilin guessed that she was trying to keep her

‘sensitivity’ under control. ‘Why such secrecy? Why should you keep such things from the eyes of the people?’

Catilin frowned. ‘Those few men of reason who have examined them claim that the bones are older than one might expect. More than six thousand years old, which, according to the holy scripture, would seem to be older than the age of the Earth, as created by our Lord. In death, then, these creatures accuse the scripture of fraud. Naturally, it does not do for such accusations to be made public.’

Duquesne was silent for a while, and Catilin wondered if he should continue with his half-hearted guided tour. And then;

‘This will not last forever,’ she said.

‘Mademoiselle?’

‘The Vatican cannot be in every place at once. Discoveries will soon be made that your "fellow Cardinals" will overlook.

The public will see all these things, which you have hidden from them for so long. Reason dictates it.’

‘Perhaps. Though even reason would fail to answer many of the mysteries in the Collection, I’m sure. There is a skeleton of a man in our vaults that was found side-by-side with one of these great reptiles, while Cardinal Roche claimed to have seen the corpse of a creature that was halfway between man and fish, refuting both science and the book of Genesis.’

Catilin nodded contemplatively. ‘However, if there’s one thing I refuse to argue with, it’s the Age of Reason. At least, not with the French.’

‘A good Catholic not arguing with reason? Unthinkable!’

Catilin had asked for that, of course, but he let out a loud sniff anyway, as if mortally offended. She’d touched a nerve, it was true. The Vatican couldn’t hold off the Age of Reason for much longer. Since His Holiness had died, the Church had been under the thumb of the bastard conqueror Bonaparte, and the world knew it; that was why the woman was here, come to survey the Collection for the ‘little Emperor’, just as they’d survey all the Vatican’s secret treasures, from the Library of St John the Beheaded in London to the living specimens of the Crow Gallery in Southern Africa. Something vast and raw and new was forcing its way into the world, Catilin reflected, ripping up the traditions and the establishments, replacing monarchies with revolutionaries and revolutionaries with short French megalomaniacs. New rulers. New religions. A new century on its way.

Catilin suddenly noticed that the woman had moved on and was standing, frozen, in front of an ancient scrap of parchment, covered with tiny dancing figures.

‘Primitive art,’ Catilin told her. ‘Hundreds of years old, though the fabric is of unknown manufacture. The illustration is of Shango, a god of lightning. Thought to be the only pictorial representation of the deity in existence –’

But Duquesne wasn’t listening. Her eyes had become glass baubles, her face flushed red as if she were about to burst into flames, her attention fixed on the little figure of Shango as he danced in front of the oblong ‘magic box’ with which, according to the parchments, he travelled a mystic triangle between the Earth, the sky, and the future.

‘ Caillou,’ Duquesne said, her voice reduced to a croak.

Catilin opened his mouth to ask her what she meant.

But she’d fainted dead away.

PART ONE

STATE OF INDEPENDENCE

‘The first century began with the year 1 AD and ended with the year 100 AD. Hence, the twentieth century began on January 1st 1901 and will end on December 31st 2000 AD.

The first day of the twenty-first century and the "Third Millennium" will be the first day of 2001 AD, not the first day of 2000 AD as is commonly thought [...] yet when discussing such ideas as "millennial rites" and "thousand-year shifts", astrologers and numerologists consider December 31st 1999

to be the crucial date of change, thus getting their calculations wrong by a whole year. The conclusion is obvious. The actual dates are unimportant; it is our perception of the dates that matters. So-called "end-of-the-century fever" has more to do with human hysteria than with astrological significance... ‘

– James Rafferty, Portents and Pathways (1978)

‘When we get piled upon one another in large cities, as in Europe, we shall become corrupt as in Europe, and go to eating one another as they do there.’

– Thomas Jefferson (1787)

1

Waifs and Strays

New York State was celebrating. But that didn’t mean it was happy.

The festivities had spread across the East Coast like a pox, taking Manhattan first, then Brooklyn, then Richmond; the smaller towns had been the last to fall to the fever, and when they’d fallen, they’d fallen with a kind of grudging contempt.

When the garlands and the banners and the polished wooden angels had gone up in Woodwicke – a town the world in general had never really noticed, and probably never would –

their colours were garish and aggressive, the people unwilling to celebrate without a snarl. During the War most of them had been loyal to the losing side, and even now, even after history had given them a hundred and one other things to be unhappy about, they still seemed to want a rematch. Christmas bled from the windows, dripped reluctantly out of the storefronts.

The eighteenth century was in its dying days, and Woodwicke was a town that knew exactly what the President could do with his ‘new age of freedom’s glory’.

But of course, the ‘attractions’ had opened for business even there. The craftsmen, the performers, the novelties; stalls run by middle-aged businessmen pretending to be gypsies and second-rate medicine peddlers masquerading as miracle-workers. Mystics and stargazers, showmen who turned the black arts into an almost-but-not-quite acceptable form of entertainment.

So when Isaac Penley entered the fortune-teller’s tent on Eastern Walk, he instinctively glanced around to make sure no one was watching him. It was the very evening before Christmas Day, and for Isaac – esteemed member of the local council and upstanding pillar of the community, as he’d readily tell anyone who bothered listening to him – the holy festival was about to be laced with a touch of necromancy.

‘Sit down,’ said the witch-woman, and Isaac sat.

The woman was a Negro (Negress, Isaac corrected himself), but she was alone in the tent, unsupervised and unattended. Her face didn’t seem to fit what he knew about the black species; the slave-ships that occasionally docked at Woodwicke carried creatures whose faces all seemed identical to Isaac, pitch-dark and lifeless, but this woman could almost have been fashioned from an entirely different material. Her skin was tinged with ash, her hair streaked with full-moon grey, and her bearing seemed almost aristocratic.

Once, in New Orleans, Isaac had visited a carnival far grander than any that had ever been seen in Woodwicke. At one of the sideshows there had been a huge leather-skinned Negro on a great wooden throne, his half-naked body covered with smudges of red and yellow paint. The Negro’s attendants had informed the audience that this was Konga-Tchin, fearsome warrior-king of darkest Africa, who had slain tigers with his bare hands and destroyed entire armies on the battlefield. The audience had paid good money to hear the tales of Konga-Tchin, the attendants translating the answers he gave to their questions (’Have you ever wrestled a crocodile?’

‘Is it true you eat people in Africa?’). There had been something about his bearing, as well, a kind of nobility; as if he were lost in this land, but still determined to hold on to the memory of his past life and the dignity it afforded him.

Except, of course, that Konga-Tchin had turned out to be a fake. A runaway slave, employed by a showman with a flair for the exotic.

‘Abracadabra, shalom-shalom,’ growled the Negress. Isaac found himself distracted by her costume, a rough shawl covering smoother, tighter garments that he couldn’t quite identify. ‘I see into the mists of time and stuff, blah blah blah.

Anything in particular you wanted to know?’

There was, but he couldn’t find the words, so he just shook his head. ‘Erm, no. Nothing. In particular. Um, the future?’

The Negress leaned back in her seat, and Isaac got the impression that she really didn’t give a damn about anyone’s future but her own. ‘Yeah, well, there’s a lot of it, the universe is still in red shift. There’s a couple of good wars coming up, if you like that kind of thing. I can give you some dates, if you want. People are going to get born. They’ll go through the usual interpersonal shit. They’ll kill each other.’

She shrugged.

‘Works for me,’ she said.

‘Well, yes.’ Isaac nodded seriously, as if to prove that he wasn’t confused by such profound thoughts. ‘But I was thinking of something a little more... personal?’

‘Personal?’

‘Personal. Um. My future.’

The woman sighed. ‘What’s your name?’

‘What?’ Isaac had a sudden vision of some monstrous jungle-god, scratching his name into the book of the damned.

‘Um, I’d rather not...’

‘ Name? ’

He cleared his throat. ‘Penley,’ he mumbled. ‘Isaac Penley.’

‘Right. You’re not going to achieve anything of note in your entire life. If you were important, the Doctor would’ve claimed to have met you by now. He’s claimed to have met just about everyone else. Henry the Eighth. Cyrano de Bergerac. Everyone.’

Isaac opened his mouth to ask who the Doctor was, then imagined a half-naked witch-doctor dancing before the jungle-god, talking with the spirits of the famous dead. His jaw snapped shut again.

‘All right,’ said the woman, misreading his expression. ‘I’ll tell you what you want to know. You’ll lead a happy, prosperous life, move out to the plains, buy yourself a nice big house and a nice big flitter, or horse-and-cart, or whatever it is you have here, and your children’ll grow up to be lawyers or generals or something. You still won’t achieve anything much, and you’ll die of old age, probably in your sleep. Happv?’

She didn’t so much say the last word as bite a word-shaped hole out of the air. Isaac nodded, for the simple reason that he couldn’t think of anything else to do.

‘Good. Any other questions?’

Any other questions?

Yes, thought Isaac. Oh, yes. Questions about the shape the world is being twisted into, questions about the mumblings I hear from the town and all the wars they seem to want to start, questions about Church and State and Heaven and Hell and politics and anarchy and everything in between. Questions that I can’t even fit into proper sentences.

And he felt a series of words slide onto his tongue, and prayed that this would be it, that this would be the one question he desperately needed to ask, that just the right letters would fall from his lips and the Negress would understand what he really wanted and give him all the answers.

He opened his mouth.

‘Is it true you eat people in Africa?’ he heard himself say.

There was a silence as big as all outdoors. The woman’s expression was unreadable.

‘No,’ she said, emotionlessly. ‘But that isn’t going to stop me biting your face off.’

Erskine Morris stared at the thing that was floating near the top of his drink, sniffed it, swore at it, then swallowed it anyway. He had no idea whether it was a vital ingredient of the cocktail or just a piece of flotsam that had accidentally fallen into his glass, but the liquid was powerful enough to make sure that his taste-buds never found out for certain.

Besides, he was three glasses past caring.

‘ Naturellement, I find the writings of Monsieur Jefferson most interesting,’ Tourette was saying on the other side of the pub. ‘His thoughts on liberation are most liberating. A-hahhah.

Hah-hah.’

‘Hellfire and buggery,’ Erskine growled, and downed the rest of the drink.

His chair made an ugly cracking sound under his weight.

Erskine Morris was a big man; not fat, not muscular, just big, in some vague and indefinable way that the world’s furniture-makers were obviously unprepared for. When he sat, his legs would spill awkwardly across the floor, and his elbows would topple any table that was unlucky enough to be in the vicinity.

Furniture ‘disagreed’ with him.

‘As we say in my own country, gentlemen; liberté, égalité, fraternité.’ Tourette spread his arms wide, as if he’d just said something terribly profound and was waiting for a round of applause. His audience – three unfortunate members of the Society who’d been unable to escape the idiot Frenchman’s attentions – nodded dumbly, not knowing where to look.

By all the sodomized choirboys of Pope Pius VI, thought Erskine, things are going from bad to worse around here. Back when he’d joined the New York Renewal Society, there’d been an unshakeable code of conduct. The Society had been a group of Deists, atheists and rationalists, with three principle aims: to advance the cause of reason; to annoy the hell out of the damned Papists; and to experiment with every alcoholic concoction known to science. But now?

Erskine let his eyes wander around the old King George, getting used to the gaslight that lit the hollow shell of the building. There were men standing around in their Sunday bests, looking like blubbery children in stiff shirts, discussing a hundred and one half-cocked philosophies that were probably all the rage in Paris or Rome or London. Erskine’s gaze settled on one man in particular, surrounded by a small audience that seemed a good deal more interested than Tourette’s had been. The man was hard to miss. His shapeless, powder-pale face was hardly a face at all, just a collection of features looking for somewhere to happen, while his thin grey hair looked as though it had been painted onto the top of his head.

Matheson Catcher. The worst of the lot.

‘Many primitive races worshipped nature’s tyranny,’

Catcher was saying, his voice a constant throb-throb-throb that made Erskine think of someone turning the handle of a music box. ‘The so-called goddesses of the druids, the sickly cults of Hecate and Astarte. But the architects of Peru understood the true horror of the natural world. Consider their greatest constructions, gentlemen, built in defiance of the jungle’s chaos. An example to the world. We are not primitives, we are men of Reason. We have a duty, a responsibility, to hold back the chaos of our own age in the same manner.’

‘By building pyramids,’ Erskine grunted under his breath.

‘Bloody stargazer.’

Catcher paused for a moment, giving Erskine the irrational feeling that he’d heard. ‘There is a nobility in architecture, gentlemen. Architecture is purity itself, the triumph of the rational mind over the terrible Cacophony of nature. Only through this purity can we know the Wa...’

Catcher tailed off, like a man who’d just caught himself giving away a secret.

‘...can we know God,’ he finally concluded.

Erskine winced at the G-word, and cast a critical eye over the man’s audience. Certain members of the Society (weak-willed, pox-brained members, naturally) were incapable of staying away from Catcher. Erskine had become convinced that ‘unofficial’ Society meetings were going on somewhere, just Catcher and his ‘inner circle’ of hangers-on. If this goes on, thought Erskine, we’ll be no better than the damned Freemasons. There were even half-serious rumours that Catcher and his gullible friends had summoned up Baalzebub, rumours which the man had no doubt started himself in order to appear more interesting. Erskine had made several loud jokes about Catcher sprouting horns and drinking blood, but no one had thought they were funny, and even Isaac Penley –

a humpty-dumpty little man who usually laughed at everyone’s jokes, and only seemed to have joined the Renewalists because he didn’t have anything better to believe in – had just turned away, embarrassed.

Then Erskine became aware of a sound, a ticking, clicking sound; and, with a start, he realized that Catcher was staring directly at him from across the old pub. Catcher’s eyes were little grey pebbles. Little grey pebbles that blinked once every eight seconds – precisely, Erskine had timed them – as if there were a mechanism of clockwork inside his head.

Ticking.

Clicking.

‘Hellfire and sodomy,’ Erskine exclaimed, then realized that he’d actually shouted it out at the top of his voice.

When Roslyn Forrester slouched back to the house on Burr Street – at about 19:30 hours, by her reckoning – someone was waiting for her on the stoop.

‘Want any help?’ he said.

He was, by local standards, a boy. Sixteen, maybe seventeen, with the kind of face that would have found him a good role in a spaghetti western, had he been born two hundred years later. There were no teenagers here, Roz remembered. There were boys, and there were men, with nothing in between but wet dreams and bad complexions. The boy’s clothes fitted so badly that they could only have been stolen.

‘What did you have in mind?’ she asked, not trusting him an inch.

The boy shrugged. ‘Can’t be easy, looking after the house by yourself. Me, I’m ready to work cheap. Just naturally generous, that’s me. So I got to thinking, well, give the woman a chance, let her know she should get me now ‘fore I’m in demand.’ He gave her a grin that wasn’t entirely unpleasant, except for the fact that it was yellow.

Roz just scowled. He didn’t react, meaning that she was too tired even to scowl properly.

‘You know anything about temporal engineering?’ she asked.

‘Say again?’

‘Restructuring local space–time in order to facilitate movement through the fourth dimension. Know anything about it?’

The boy nodded thoughtfully. ‘Haaaahhh. Well, I can put shoes on horses. Don’t know if you could get them through your fourth dimension. Maybe you’d have to give ‘em a push.’

Roz scowled again, reminding herself that sarcasm wasn’t exclusive to her own century. She failed to think of any witty or half-intelligent response, so she just told him to piss off.

‘Right,’ said the boy, as if it were perfectly normal for people to talk to him like that. He gangled to his feet. ‘Can I ask you a question?’

‘It’d better be a good one.’

‘You some kind of lunatic?’

‘I’m the best kind of lunatic. Dementus futurus, the lesser–

spotted ranting bloody psychopath. Now get lost.’

The boy shrugged. ‘Your loss,’ he said, and sulked off around a corner.

Roz unlocked the front door with a carefully placed kick, and dragged herself into the main hall of the house. The hall was large but mostly empty, ringed with columns of fake marble that made no difference to the way the roof stayed up.

There were a lot of houses like that in Woodwicke. America had just worked out that it was an expanding empire, so the architects had decided to make every building look like a Roman ruin. A cheap, tasteless, badly furnished Roman ruin, in this case.

It wasn’t much of a house, Roz told herself, but it was home. Not her home, obviously, and the owner would get a hell of a shock if he unexpectedly came back to it, but it was the only place she’d been able to find, and even that had been a fluke. As far as she’d been able to figure out, the owner was some kind of second-rate businessman who’d waltzed off to Asia to deal in commodities that no one wanted to talk to her about; he wasn’t due back until spring, which gave her about two months more to pretend to be the housekeeper. Slave.

Whatever.

Six weeks, she’d been here now. Six weeks of sneaking and scraping that made a survival training course on Ponten Luna Sierra look like an all-expenses-paid holiday on Disneyplanet.

Six weeks of very little sleep and even less food.

Six weeks of looking for the TARDIS.

As for the time before that... just random images. Arizona had opened up and swallowed her, Chris telling her to get out of the crukking way as she’d been sucked through a crack in the world. Then she was running, she was trying not to look back at the gynoid, she was falling, the sphere was spinning...

And then she was here. Here in New York State. Here in 1799.

At Christmas.

Lost.

As lost as you can get, in fact, with no way of letting the others know where she was or how to find her. There were no organizations here that might know the Doctor, no LONGBOWs or PROBEs, and no way of sending out any kind of distress call. The one possible means of communication she’d had – the damned amaranth that had presumably brought her here – had got itself lost. It had got itself lost. She was quite adamant that she hadn’t lost it. When she’d woken up in this timezone, finding herself lying in a puddle of frost and dirty water in the woods on the edge of town, there’d been no sign of the thing. She imagined it trundling away of its own accord, looking for a more interesting owner than Roslyn Inyathi Forrester.

Ah yes, Roslyn Inyathi Forrester. Professional fortune-teller and small-town oddball. A bitter, cynical woman who seriously believed that she used to travel to the stars with a diminutive magician, and who spent her poor, wasted life trying to find her way back to the delusion. Dementus futurus.

The best kind of lunatic.

Which is why she’d had to develop her own escape plan, why she’d spent the last two weeks planning, waiting and brooding, and why there was now something heavy and metallic and probably illegal nestling in her pouch. She’d only survived this long by setting herself up as an ‘attraction’, her tent supplied by showmen who took most of what she made as payment, but there was a limit to the time she could go on telling false futures for failed businessmen and using the same stories and answering the same questions and Goddess oh Goddess I have to get out of here this place is killing me I said this place is killing me.

It was half past eight on Christmas Eve when Daniel Tremayne heard the call. Of course, as far as Daniel was concerned, the time was just ‘night’ and the date was just

‘today’.

He was on Hazelrow Avenue when it started, standing in the shadow of the grey house on the corner, slipping into the dark spaces behind the porch pillars whenever a carriage rolled past. Making sure he wasn’t seen. No particular reason for that; Daniel Tremayne just didn’t like being seen. The people who lived in towns like this – the soft people, the ones who could stay in one place till the end of the world came for them, the farmers and the lawyers and the storekeepers – had built this world out of their queer politics, out of weird rituals like ‘Christmas’ and ‘Day of Independence’, and Daniel lived in the cracks of that world. Seventeen-and-a-half years of hiding in alleys. A lifetime of not being noticed.

The house looked ugly in the moonlight, uglier than he’d remembered it. The windows weren’t lit, and there were pools of darkness around the top-floor balconies, so it looked like the roof was being held up by shadows. The house had been kind-of-square, once, but the owner had stripped it down and rebuilt it so often that the place just looked like a shape, now, instead of being any shape in particular. Passers-by looked away when they walked past it, like they were embarrassed or something. The other buildings on Hazelrow Avenue were fine, all pearl-white pillars and marbled walls and cosy gas-lit windows, but the house on the corner... Daniel remembered the soldiers who’d fought the Revolution, men who’d been out in the snow so long that their arms and legs had twisted and turned black. The house was like that, like the town’s dead limb

Daniel Tremayne climbed up onto the stoop and stood there awhile, getting ready to knock. Rehearsing.

Mr Catcher? Don’t know if you remember me...

No. Catcher was too formal for that kind of thing. Last time Daniel had been through Woodwicke, the man had hired him to work on the cellars and the attics of the house, tearing out timbers and ripping up floorboards. Daniel hadn’t asked why, because he knew better than to ask questions, but Catcher had told him anyway. Something about the purity of the architecture, something Daniel hadn’t understood.

Sir, regarding the circumstances of our previous dealings...

Oh God, this was awful. Talking to Catcher was like talking to a clock; you could almost hear the ticking going on inside him, but you couldn’t expect him to smile, or frown, or do anything that might make him look half-human. Daniel was only here because he was desperate. A day and a half he’d been in Woodwicke, and he hadn’t found a single place that wanted him. He hadn’t even been needed at the McClellan house, where the new slave had asked about space–time engineering (hahh?), then told him to ‘piss off’ in a voice that made her sound like an English noblewoman. He’d spent the previous night in the ruins of an old pub, staying half-awake in case the watchmen turned up, because everyone knew what watchmen did to vagrants and wanderers and itinerants.

Mr Catcher, sir, I was just wondering...

And that was when he first heard the call, from somewhere on the other side of the door. Like a humming, like a hissing, noises twisted out of shape by half a dozen walls or more.

Call? What kind of a call? Nothing important, Daniel Tremayne, nothing that’s any of your business. You’ve lived seventeen-and-a-half years by keeping your head down and not getting mixed up in other people’s fights, and it’s not a call, it’s just a noise, that’s all. Who’d be calling you, anyhow?

But he was already hopping down off the stoop, checking the street – instinctively – to make sure no one was watching him, and creeping around the corner of the building, because Daniel Tremayne crept everywhere, whether he needed to or not. The shadows at the side of the house were thick enough to hide him from the eyes of any passers-by, and there was another door set into the brickwork there, in the narrow channel between the main building and the shithouse. An entrance for servants, salesmen and anyone else who was too poor to use the front door, Daniel guessed. He crept between the piles of junk and firewood that had built up around the entrance, listening for the call. The noise was stronger here, like a pulse, like a Negro rhythm. Or maybe it was just the thought of a noise, a kind of feeling you couldn’t pin down, like the way you could tell a storm was coming before it arrived?

‘ This is none of your business, Daniel Tremayne, ’ someone squealed, and he almost started to run before he realized that he’d said it himself.

The door was locked. Daniel wondered how he knew that, then remembered that he’d just tried to open it, without even noticing what he was doing.

‘This is none of your business,’ he insisted, and the lock clicked open. Daniel knew maybe half a dozen ways of opening locks, but if anyone had asked him which he’d used, he wouldn’t have been able to say. Burgling. Didn’t they still hang you for that, in this town? You trying to get yourself killed all of a sudden, Daniel Tremayne?

But the call was telling him to open the door, and the hinges were squeaking, and the sound was already rushing out of the darkness and going for his throat.

‘Catcher!’

During his forty-three years on the planet Earth, many opinions had been formed about the temper of Erskine Morris.

Some – mainly his close family, admittedly – claimed that his loud, aggressive nature was just a façade that hid a deeply lovable ‘inner self’, while others just wished that he’d keep the noise down. Even Erskine had to admit that, from time to time, his perpetually foul mood was a social drawback.

Now, however, he had cause to be very, very glad of it.

Because although he would never have admitted it – not even to the holy bastard son of Galileo, by Christ – right now, it was the only thing stopping him from being utterly terrified.

‘Catcher! For the sake of Saint Peter and all his baby catamites, man, you’ve got thirty seconds to show yourself or I’ll rip your damned heart out!’

It had all started at the meeting, of course. Erskine had finally snapped, looking into Catcher’s blinking pebble-eyes and accusing him of any number of things, from being an irrational mystic to bringing the Society into disrepute.

Catcher had taken it all remarkably well, except possibly for the ‘irrational’ part. He’d frowned, just for a second, the first time Erskine had seen that happen.

‘Are you a rational man?’ he’d asked, with deadly seriousness.

Erskine had laughed once, loudly, and tried to ignore the funny looks he was getting from the other Society members.

‘Of course I’m a bloody rational man. Jesus Christ and his big Negro brother, Catcher, what kind of doughy-eyed stargazer do you take me for?’

Catcher had nodded, and Erskine could almost have heard the cogs and wheels turning in his head. ‘Good,’ the man had said, humourlessly. ‘Good.’

And he’d promptly invited Erskine to his house.

It had taken Erskine a while to realize that he was being formally invited to a meeting of Catcher’s ‘inner circle’. Well, how could he refuse an invitation like that? He’d get to the bottom of the man’s madness, ohhh yes, even if he had to walk through the blistering gates of Hell to do it.

But then it had all started to go wrong. When he’d arrived at the man’s disgusting house, Catcher and his little band of followers had been waiting in ambush. They’d blindfolded him – or rather, drawn some kind of cowl over his head – then tied his hands behind his back and led him, protesting in words of four letters or less, around more corners than he could count.

‘Catcher! Catcher! ’

He’d been right, all the time. Catcher was no better than a buggering Freemason. He’d heard the stories of the rituals the Masons put each other through, humiliation and symbolic execution, vows made until death, gullible idiots blindfolding each other and swearing to slaughter those who crossed them with fish-gutting knives –

– oh, damnation.

‘I’m warning you, man! If all this ends with my good self tied naked with a spit up my arse, I’ll chew every inch of skin off your body!’

No good. He was alone now, he was sure of it, no doubt locked in Catcher’s cellar or some such vile locale. Erskine felt his arm brush against something solid, a pillar or a door-frame. He rubbed his head against the shape, pushing the hood up over his forehead until it fell away from his face.

The first thing he saw was a column, like something out of an ancient Greek temple. Not cheap-looking, though, not like those ghastly mock-classical houses on Burr Street. Erskine squinted. Beyond the column was another, then another, then another...

With a start, he realized that he was in a corridor, lined with pillars on both sides. The walls looked like marble, shot through with veins of some unrecognizable foreign material.

He turned his head. The passage stretched as far as the eye could see in both directions, occasionally branching off into side-tunnels. The corridor was longer than Catcher’s entire house.

Where in the name of sodomy was he?

Io Ordo Io Io Ordo, a voice whispered in his ear.

Erskine Morris felt the muscles in his legs begin to grind together, and noticed – almost as if it were happening to someone else – that he was moving, stumbling down the passage with his hands still bound. He had absolutely no idea where he was going. In fact, he had absolutely no ideas at all.

Something cold and hard shifted inside Roz’s pouch. She tried to ignore the illusion that the shape was alive and impatient.

Her stomach started singing protest songs when she came within sight of the church on Paris Street, so she drifted into the nearby general store and wasted the morning’s earnings on a pocketful of something edible and vegetable-based, hoping this would be the last time she’d need local currency. The shop was swamped with the usual festive decorations, the owner intent on pushing the local laws of commerce to their very limits and staying open right up until the dawn of Christmas Day.

‘Not just celebrating Christmas,’ he told her from behind his polished counter, speaking slowly as if talking to a child.

‘It’s the anniversary.’

‘Really,’ she growled.

‘Ten years since they signed the Constitution. Give or take a few months.’

‘I’m happy for you,’ she said.

‘ And sixteen years since we beat the shite out of the British.’

She stuffed some of the food into her mouth, half-noticing that it tasted like apricots. ‘Sixteen. Not the kind of anniversary you normally celebrate. Ten, yeah. Fifteen, maybe. But sixteen...?’

The man stared at her as if she’d just admitted to being a baby-eating devil-worshipper.

‘It’s usual enough in these parts,’ he said pointedly.

She decided not to argue. These people just needed a reason to celebrate. Any reason, whether they agreed with the principle behind it or not. It’d been one of those centuries.

Like that little fat-faced man, Isaac someone-or-other, who’d come to her tent just to ask if there was a future at all. End-of-the-century blues. There’s always someone who thinks the world’s going to end.

Roz continued along the street until she came to the church, and squatted on the steps, concentrating on the building opposite. One of a dozen stone-faced pseudo-mansions on Paris Street, with narrow windows and whitewashed walls, fronted by a porch made up of unconvincing classical archways. She’d come here a lot, the past few days, watching the house from the church steps, concentrating on the routine of the man who lived there and trying to look like she was just a poor dumb foreigner basking in the glory of this fine monument to the Protestant faith. Just another stake-out, she’d tell herself.

In her pouch, the cold thing pushed against her leg expectantly. She rested her hand on the lump.

The house was owned by a man called Samuel Lincoln, who’d visited her tent a fortnight ago. She’d told him he’d have a fine family, offspring that’d go far in the world of politics, and he hadn’t believed a word of it. Well, that was his mistake, seeing as it was probably her one accurate prediction.

Lincoln. She’d recognized the name almost immediately. And she’d known. She’d just known, that was all. Call it time-traveller’s instinct, call it whatever.

Samuel would turn out to be the father of the legendary Abraham, the President who’d blah blah blah something about Civil War blah blah blah fathers of democracy blah blah blah wore a big hat and got shot...

Roz had been born nearly a millennium after the fall of the United States, so her knowledge of Great American Heroes was based entirely on the historical simcord dramas that the Empire would show whenever they wanted to make a point about the proud heritage of the human race. But her certainty that Samuel was one of the President’s ancestors wasn’t based on her knowledge of history. Yeah, call it time-traveller’s instinct. That, and the fact that the TARDIS crew always seemed to end up around important people and events, for some reason even the Doctor didn’t seem to understand properly. There must’ve been hundreds of Lincolns, even in a half-grown nation like this, but she would have bet her sister’s fortune that she’d ended up in the same town as the most significant one.

Besides, Lincoln senior had Abraham’s nose. A dead give-away.

And the moment she’d met him in that tent, and he’d chuckled at her predictions, she’d known. She’d started to figure out the one way to get out of this God-forsaken millennium. She had a plan. She had an escape route. And Samuel Lincoln was the key.

‘ Io Ordo Io Ordo Ordo. ’

Daniel Tremayne had been in Catcher’s cellar before, but back then it had just been a louse-ridden lumber-room, made up of stale air and splinters. Now it was different. He was sure it was bigger, for one thing. The walls looked like they’d been covered with marble, and there was some kind of platform in the middle of the baby-arse-smooth floor, muddy light glinting off the crystals that had been pushed into its surface. Daniel briefly wondered how much the thing was worth.

‘ Ordo Ordo Io Ordo Io Io... ’

He didn’t recognize the words the men were chanting.

Chanting, or whispering, or something between the two. There were half a dozen of them, standing ten, twenty feet away; their clothes were ordinary, shirts and jackets and shoes and pants, but their heads were hidden under crude sackcloth hoods, crumpled grey faces with tiny slits for eyes. Daniel should’ve been alarmed – alarmed, hah, was that all? – but the words that were spilling from their throats wrapped themselves around his spine, soothing his nerves until, God, what was the point of worrying? He must have stood there for ten minutes or more, tucked out of sight in the shadows around the cellar entrance. Just staring. Just listening.

‘ Io Ordo Ordo ... ’

And in the middle of it all was Catcher, the only one whose face wasn’t hidden, standing next to the platform in his dull grey shirt and his high-collared jacket; and now Daniel looked at the thing in the middle of the floor, didn’t it remind him of an altar? He thought of the stories he’d heard around New York, about the warlocks and the diabolists who got together in old crypts and graveyards, summoning up the children of Hell itself, spilling unholy blood on Christian altars and defecating in churches (whatever ‘defecating’ meant)...

Hah. But these weren’t witches, were they? In Dill Village, someone had once told Daniel that there were people in the world who did even stranger things than the Satanists.

Freethinkers and scientists, not witch-doctors and mad monks.

‘Like Freemasons,’ he’d been told, but he hadn’t understood the word. He’d even heard that the ones who ran the world, the Presidents and the Prime Ministers and the mad Englishmen, belonged to groups like that. The news hadn’t surprised him at all.

That was it, then. Catcher and his friends weren’t talking to bug-a-boos and hobgoblins. They were doing something else, something more modern, something scientific. Like what?

And what are you doing here, Daniel Tremayne, down in the belly of the beast? Coming out of the cracks and getting yourself noticed. Just like the soft Revolutionaries, sticking their heads up so that the English could blow their brains out.

‘Listen,’ said Catcher. And the men fell silent, and there was a moment’s quiet –

– no there wasn’t. Daniel could hear a kind of echo in the room, like parts of their words had stopped dead in mid-air, like they’d got stuck in the muddy light. ‘ Ordo Io. Ordo Io Ordo Ordo. ’

‘O,’ said the echo. ‘O.’

‘ Io Ordo Io Io Ordo,’ said Catcher.

‘I O I I O,’ said the echo.

One. Nought. One. One. Nought.

Daniel Tremayne wanted to cover his ears, but couldn’t.

Was this what he’d heard outside, the call, the thing that had dragged him here by the scruff of the neck? Was it just calling to him, or to Catcher, or to all of them?

‘ Ordo Io. Ordo Io Io.’

Nought one. Nought one one. Daniel Tremayne looked up, and saw that everything – colours, shapes, everything – was turning into the bastard numbers, blinking from nought to one and back again, Catcher’s words reshaping the world, giving the whole of creation a new program, chanted in ‘O’s and ‘I’s and noughts and ones. And somehow Daniel knew exactly what was going to happen, and in that brief moment of revelation he understood what had been calling him, and why he was here, and what it was he had to do, but a second passed and the thought was gone, pushed out of his head by ‘Io’s and

‘Ordo’s.

I-SAID-WHAT-ARE-YOU-DOING-HERE-DANIEL

TREMAYNE?

‘ Ordo Io,’ said Catcher, and the words became the world, the world became the words, the air spasmed like it was giving birth and something arrived.

It was a dead end. Erskine Morris uttered the second most obscene word he knew – he was keeping the worst until he was face-to-face with Catcher – and turned around, trying not to notice that his legs were trembling like Englishmen in a whorehouse. He could still hear words being hissed into his ear, and still had no idea where they were coming from. He was sure they were being spoken by human tongues – thunder and fornication, what other kind could speak? He was letting this charade get to him, by Christ – but it was hard to say where the whispers ended and the low humming of the corridor began.

‘Catcher!’ he called out, stumbling back along the passage.

‘It’s no use hiding there, man, I can see you! Come out and show yourself!’

That was a lie, of course. Erskine could only see flickers in the dim light, irritating shapes that lurked on the edges of his vision, hiding around the corners like giggling children.

Finally, one of the shadows decided to step forward.

Erskine Morris whirled around to face it, almost losing his balance and cracking his shoulder against a pillar.

‘ Io Ordo Io,’ the shape said.

‘Hellfire and shite!’ Erskine immediately recognized the man from his clothes and his slightly portly frame; Monroe, the fool’s name was, one of Catcher’s arse-lickers from the Renewal Society. Monroe’s face was obscured, though, covered by a crude grey sackcloth mask which – in Erskine’s view – improved his appearance no end. ‘Good grief, man, do you not know that there are laws against this kind of thing?’

‘ Ordo Ordo Ordo Io Ordo,’ said Monroe, no doubt coating the inside of his cowl with a layer of blustering spittle.

‘And you can stop that, as well –’ Erskine broke off in mid-complaint as he noticed several other forms, breaking away from the shadows and stepping out in front of him. Most of them were immediately recognizable, despite their hoods, as spineless and unimportant members of the Society. Men who couldn’t even hold a bottle and a half of Wilkeson’s and stand up straight. Catcher wasn’t among them.

‘All right, where is he? Where is the odious little absurdity?’

‘ Ordo Io Io Ordo Io,’ the men told him

‘Damnation!’ Erskine took a few steps towards them, hoping that his sheer size would intimidate them, but they didn’t even flinch. ‘Enough of this. Where’s Catcher?’

‘ Ordo Ordo Io. ’

In fact, not only were they not moving away, but they were moving towards him. Erskine felt himself take an involuntary step back.

‘ Io Io Io Ordo Io Ordo Ordo. ’

‘Of all the childish, irrational...’

Another step back.

‘ Ordo Io. ’

‘Damnation!’

And another.

‘ Io Io Io Io Io Io Io Io -’

Erskine Morris turned on his heel, and stalked away down another roundelled corridor. He refused to look back over his shoulder, telling himself that it wasn’t important whether the idiots followed him or not. They were trying to rattle him, that was all. Trying to stop him asking questions about their poxy

‘inner circle’. As if they could. Hah! As if.

He asked himself why he was walking so quickly, and couldn’t think of a decent answer. Imbeciles and mystics.

Nothing a good, sound, rational mind couldn’t deal with. And now that good, sound, rational mind just had to find the exit, a drink, and Matheson Catcher, in that order.

Then he turned the next corner, and walked right into something large, alive, and impossible.

The night she’d met Samuel Lincoln, Roz had dreamt of spinning golden spheres, of stovepipe hats and civil wars and witch-doctors and flowers that never died. By the time she’d woken up, every detail of the escape plan had been considered, calculated, and filed in her memory.

The only way out of this place. The only way to let the Doctor know where she was. The only way to summon a Time Lord.

The hardest part of the plan had been getting hold of the gun. There were simpler weapons, easier ways of killing someone, but a gun just seemed right, the only tool for the job.

It was like preparing a magic ritual, thought Roz, where all the pieces had to be in place for the plan to work, and all the right props had to be used. Time-traveller’s voodoo.

She’d mingled with the people from the other ‘attractions’, drifting from whisper to whisper until she’d found someone who knew where to get hold of firearms, no questions asked. It had reminded her of one of the undercover operations she’d been involved in during her former life, and their unwillingness to talk reminded her that she’d never been any good at them then. The job had taken her the best part of a week.

The arms dealer had been a middle-aged man with vaguely Latin features, who seemed to talk to people without really noticing they were there. He’d struck Roz as the type who’d make a good narcotics dealer, a thousand years in the future, but the people of Woodwicke didn’t seem to understand the concept of ‘controlled substances’. Cocaine was legal, caffeine was legal, marijuana was not only legal but apparently used by the President – who did inhale – and vraxoin wouldn’t be discovered for another two hundred years (when some idiot junkie out on the Cygnus Rim would get wasted one night and say to himself, the way only a junkie could: ‘Hey, I know!

Let’s snort dead alien!’).

The gun had cost her everything she owned – which she had to admit was pretty damn cheap – plus a few odds and ends she’d taken from the house. It was a clumsy piece of machinery, even by eighteenth-century standards. ‘Army surplus’, she’d been told, a relic from the War of Independence. She’d spent some time practising out in the woods, using up most of what little ammunition she’d been able to afford, getting a feel for the weapon, learning how to fire the damned thing without being killed by the recoil.

She’d also spent some time hanging around the Lincoln house, an address that had taken her several days to worm out of the locals. There, she’d found the convenient little alleyway that opened up directly opposite the building, right by the church. The perfect site. Not only did the alley give her good cover, it also had an excellent view of the drawing– room window.

The clock in the church tower struck nine, listlessly, perhaps aware that no one cared about the time this close to Christmas.

No one was around on Paris Street. Roz Forrester crouched in the alley, slipped the gun out of her pouch, and prepared to shoot Samuel Lincoln.

2

A Fistful of Timelines

Daniel Tremayne was running. At last, he was running.

Saw the alleyways flash past, saw the lights on Paris Street turn into yellow smears, saw a corner where he’d once been attacked by a drunken priest and a store where he’d stolen a whole pineapple, slipping it under his coat-of-rags, thinking, they don’t even notice me when I’ve got something this size bulging out of my shirt. Daniel Tremayne, running through the places he’d been before, and all of them he recognized, and none of them made sense. It was like something –

– the thing hadn’t entered the basement, or even appeared in a magical puff of smoke. It had been born into Catcher’s house, kicking its way out of the very stuff of creation –

– like something had reached into his head and pulled away all the strings that held his memories together. People were on Eastern Walk, people who stared, people who noticed him. He thought about calling out to them, warning them about the thing that was filling up Catcher’s house, but his head was already full of the whispers, and there was no room in there for putting words together any more.

Saw that the stones of the street were closer to his face than they should have been. Didn’t think it mattered much. He kind-of-remembered feeling something under his foot, tripping up on some piece of garbage at the entrance to an alley. The pain that cracked across his forehead when he hit the ground might as well have been happening to someone else, and the splintering noise might as well have come from somewhere a hundred miles away.

Suddenly he could see a picture of dirt-shrouded men in a field of snow, and Daniel recognized it as a memory, knocked out of the back of his skull and into the space behind his eyes.

There was the sound of music, shot through with gunfire, like he was listening to the carnival at the end of the world.

– he’d seen a million futures, worlds held together by webs of machines, mapping out civilization as a tapestry of noughts and ones. Everything in the known universe, converted into the simplest of pulses, on-off on-off –

All the sounds and all the pictures had melted down into the noughts and the ones. There was nothing else, except for something big and black and empty, but Daniel Tremayne didn’t know the word ‘unconscious’ so he didn’t know what to call it.

Marielle Duquesne lashed out against the machine, jamming her fist into its cheek, and it was only when her knuckles failed to bleed that she knew she was dreaming. The cracks she’d made in the thing’s head formed a near-perfect circle, a flower of chipped plaster against the smooth surface of its face.

‘Knock knock,’ grinned the machine.

Duquesne hesitated, fists still clenched.

‘Do I take it that this is my cue to wake up?’ she asked.

‘Knock knock,’ it repeated, and the dream fell to pieces.

‘Come in,’ said Duquesne, rubbing her eyes.

Even before the cabin door opened, she knew the caller had to be her contact in America, the sentinel – some would say

‘spy’ – that her employers had set to watch over New York.

She guessed it was nine o’clock, or thereabouts. She’d meant to sleep for only an hour or so after dinner, readying herself for her first trip into the towns, but the dream had pulled her deeper into sleep than she’d wanted to go.

‘My lady,’ said Tourette, removing his hat with an unnecessary flourish.

She considered offering him her hand, then decided that he’d probably think she was flirting, and just sat up with the bedsheet wrapped around her torso. Tourette’s body was thin and angular, with a face to match, his chiselled features leading him to the false conclusion that he had some kind of regal charm about him. His wardrobe had obviously been designed to reflect this, his bright velvet jacket and oversized cravat making him the most conspicuous agent Duquesne had ever been forced to work with.

‘Good evening, Monsieur Tourette,’ she said, mechanically, as she slid out of the bed. Tourette didn’t seem at all intimidated by the fact that she was only half-dressed, which irked her slightly. He obviously felt that morality was for the peasants. ‘You bring news from the towns?’

‘I do, my lady, I do indeed.’ Tourette bowed extravagantly, and for no immediately obvious reason. ‘For strange things are afoot there, and those of superstitious and irrational demeanours are claiming devilry is at work. These past nights, there have been dreams both weird and unfathomable amongst the townsfolk. A sensation of unease has swept across these harbours, like a great wind of... er... unease.’

Duquesne gritted her teeth. The colonies were littered with idiot agents like Tourette, ‘expendables’ who knew nothing but were led to believe that they knew everything. Duquesne politely turned her back on him as she dragged her chemise over her shoulders. ‘Your last dispatch to the Directory mentioned the Renewal Society...?’

‘Indeed, my lady. And since that time, I have infiltrated the local lodge of that group, in the hope of hearing some rumour amongst the enlightened. My cover is faultless, as one might expect from an agent of my experience, and they have accepted me as a man of great learning and philosophical insight.’

‘I don’t doubt it, Monsieur Tourette.’ Duquesne tried to smile sweetly as she crossed the cabin floor, barefoot on the splintered boards.

‘Even amongst the rationalist minds of the Society, there are feelings of ill-omen,’ Tourette continued. ‘Many members have begun to discuss ancient and absurd magics as if they were founded in science, and secret meetings are held that smack of Freemasonry. Some in the town suspect the rationalists of being the cause of their ill-feeling, though they cannot seem to explain why. I, myself, have been spat at in the street.’

‘Ah, good.’

‘My lady...?’

‘Good that you have so, ah, successfully infiltrated the Society. But these secret meetings...’

‘I have not yet been invited to any of them, my lady.’

‘I see.’

Tourette looked crestfallen, like the dog that had failed to bring back the bone. ‘But it is only a matter of time, my lady, I assure you. I have the trust of the Society.’

Duquesne stepped out through the cabin door and on to the deck of the ship, Tourette at her heels. ‘I’m sure you do,’ she said, lips still forced into a smile. ‘I’m sure you do.’

No one else on the street. No witnesses, thought Roz, crouching in the alley by the church. The nearest human sounds came from around the corner, where the man from the general store was having a loud argument with someone about the legality of his opening hours.

Quiet enough.

Abraham Lincoln. Born in the United States of America in... what was the year? Eighteen-hundred-and-something, going by the Empire’s version of history. Lincoln. Focus on that name, Forrester. Something about all men being created equal. Something to do with Civil War. Remember those simcords? Full of blood and guts and triumph and glory. Not the way the Empire would pay tribute to a loser. One of history’s heroes, then. Someone significant.

Two minutes since the clock had struck nine, and Roz hadn’t breathed out since. She knew the routine by now.

Samuel Lincoln would appear in the drawing-room window every night at around this time, cross the room, sit at his desk...

But if Samuel Lincoln was going to die, then little Abraham would never exist. No more Civil War, whatever it had been about. No more Presidents with warts, no more simcord dramas. One bullet, one careful shot. Thick black marker-pen over the pages of history. ‘Roz Forrester was here.’

Killing time. A mystic ritual to summon a Time Lord, involving the sacrifice of an innocent on the altar of history.

Four-dimensional voodoo. The same method the Hellenic Atlanteans used to summon the Chronovores, but how the Sheol do you know a thing like that, Roslyn Forrester? What are you, psychic or something?

She unexpectedly remembered her botched attempt to kill SLEEPY on Yemaya 4, and wondered what her subconscious could possibly be trying to tell her.

A shadow appeared behind the drawing-room curtain, a human shape framed against the orange lamplight. Sitting target, she thought. Practice, she thought. She checked that everything was in place, that the ammunition was loaded properly, that there was no safety-catch she hadn’t noticed.

One shot. No different from any other. She’d shot at people before. Mostly she’d missed, but this was different. Sitting target. Practice. No problem.

The shadow of Samuel Lincoln moved across to his desk, and – presumably – opened one of the drawers. Roz levelled the gun. The American Way; remember when the Empire terraformed Mogar and Murtaugh and the Prion system? How they wanted everyone to remember the spirit of the frontier, showing westerns where the cowboys looked suspiciously multi-cultural and the Indians looked suspiciously non-terrestrial? The ghost of the Wild West, the spirit of liberty and gun-law nesting down in the foundations of the USA. Just another killing, just one of many.

One bullet.

One careful shot.

Samuel Lincoln sat down at his desk, putting his head directly in her line of fire.

Roz Forrester’s second-to-last thought before she pulled the trigger was: shoot first and ask questions later.

Roz Forrester’s last thought before she pulled the trigger was: shoot first and don’t ask questions.

Then her vision was filled with something huge and white, bigger than the flash of the gun-barrel, bigger than she could even imagine, filling up the whole universe and blotting out every sense she had.

It was –

It was just –

Erskine Morris closed his eyes, and his vision was filled with a dozen fluorescent scratches and swirls that danced across the insides of his eyelids. He could feel something wrapping itself around his shoulders, and it was warm to the touch. He closed his eyes tighter, making the shapes leap and crackle like straws in a fire.

A word was growing in his belly, like a magical incantation that would send the damned monster back to Hell, but however hard he strained he couldn’t force it up into his mouth. Astonishingly, he began to walk forward, feeling his face push against the beast’s soft underbelly. Trying to prove that it couldn’t possibly be there, perhaps. He felt liquid skin ripple in front of him, and heard the sound of gently tearing flesh, the layers of the thing’s body opening up for him Revolting notion. Ridiculous notion.

It was just –

It was just that –

And he could have sworn that the flesh was closing up again behind him, the creature sealing him into its carcass.

Absurdly, it was only now that he truly began to panic, and the whispering flooded into his ears. Music, like carnival music. A voice? A woman’s voice?

It was just that it didn’t make sense.

And finally, the word in his belly erupted out through his throat.

‘Buggery!’ he shrieked.