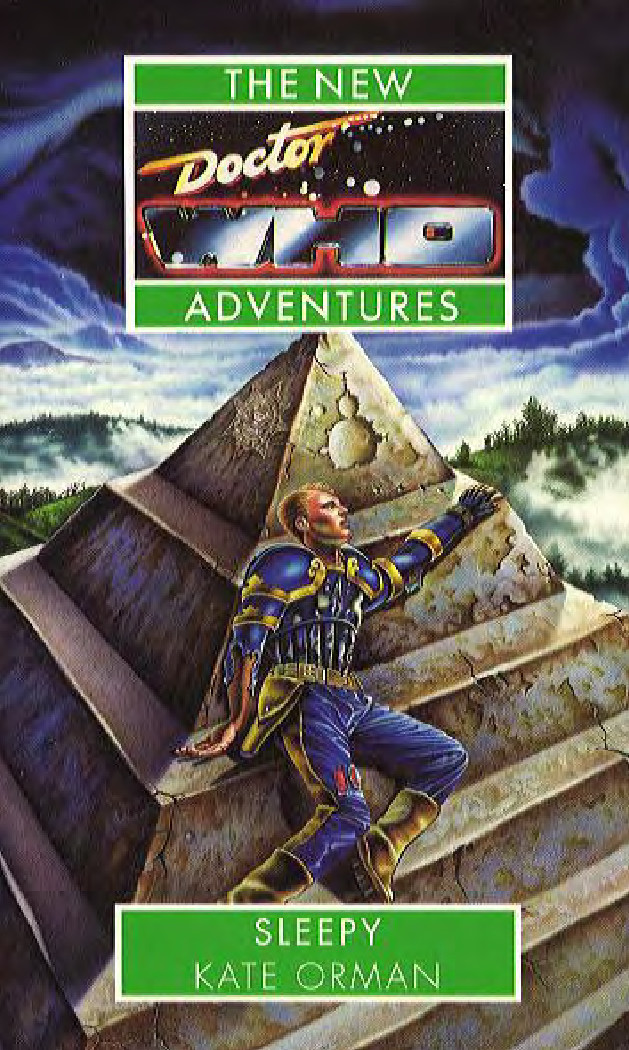

SLEEPY

KATE ORMAN

First published in Great Britain in 1996 by Doctor Who Books

an imprint of Virgin Publishing Ltd

332 Ladbroke Grove

London W10 5AH

Copyright © Kate Orman 1996

The right of Kate Orman to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

‘Doctor Who’ series copyright © British Broadcasting Corporation 1996

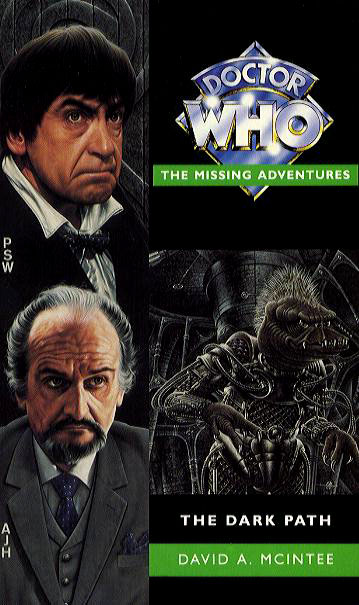

Cover illustration by Mark Wilkinson

Internal illustrations by Jason Towers

ISBN 0 426 20465 4

Typeset by Galleon Typesetting, Ipswich

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Mackays of Chatham PLC

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any Resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior written consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

For Paul Cornell, who made it all seem possible Thanks to everyone for their help and encouragement, especially Nancy Catherine Bernadski and Jason Towers (and a belated thanks to Ben Aaronovitch for his help with the last one.)

A round of applause, ladies and gentlemen, for the read-through team! Put your hands together for Todd Beilby, Nathan Bottomly, Steven Caldwell (discover of the Milton Principle), David Carroll, Mel and Sarah Fitzsimmons-Groenewegen, Stephen Groenewegen, Neil Hogam. Andrew Orman, Fiona Simms and Kayla Ward.

The quote from the Good News Bible on page 83 is used with the kind permission of the Bible Society in Australia.

Beware the fury of a patient man. (John Dryden, Absalom and Achitophel)

Part One

The Voice of the Turtle

Parmi les morts, it y en a toujours quelques-uns qui désolent les vivants.

(Among the dead there are those who still trouble the living.) (Denis Diderot, Le Neveu de Rameau)

1 Home by the Sea

The Doctor was having a nightmare.

He collided with a metal surface, the breath whooshing out of his lungs. Someone pushed him against the curved wall, leaning on him with their weight, while someone else pulled his arms behind his back.

He twisted his head around, awkwardly, trying to catch his breath, and looked right into Roz Forrester's eyes. Her mouth was drawn into a tight line. There was no mercy in her face.

She pulled him away from the wall. ‘What are you doing?’ he gasped, realizing that his wrists had been cuffed behind him.

Chris Cwej was a huge silhouette in front of the sun. The Doctor squinted into the hot alien light. Everything was intense and blurry at once. ‘We’re not going to hurt you,’

rumbled the big man.

‘You are hurting me,’ protested the Doctor, as Forrester dragged him awkwardly backwards. ‘Where are we going?’

Forrester didn’t answer. Cwej followed, chewing on his lip, as she pulled her captive along.

There was a door in the wall. The noonday sun was glinting fiercely from solar cells on the roof of the habitat dome. Cwej did something to a control by the door.

‘No,’ said the Doctor.

A great wave of panic caught him, and he yelled. He tried to pull out of Forrester’s grasp, kicking against the metal wall.

If he went inside the dome he was going to die — he would die, his friends were going to kill him...

‘For Goddess’ sake!’ shouted Forrester. The Doctor snapped his head backwards and upwards, but only managed to bounce his skull off her chin. They both yelped.

Cwej reached down and took the Doctor’s face in his hand, firmly. The Time Lord felt the points of Cwej’s nails pressing into his skin. ‘Stop it,’ he said. ‘We’re not going to hurt you.’

It took both of them to drag him through the door.

Inside someone was waiting with a trolley — no, a gurney: there were straps on it. He tried to fight, but they were both holding his arms now, pulling him across the floor.

If only he could stop panicking, if only he could think of what to say, but all he could do was roar with fury, kicking and struggling.

The woman by the trolley was wearing a tattered, shapeless green jumper. The detail of stitches and holes held his eyes, keeping them away from the spray hypo she clutched in one hand. ‘No,’ said Forrester. ‘No drugs.’

They tipped the gurney until it was almost upright, and pushed him backwards against it. There was a strap that went around his ankles, and another that went over his throat. He stopped struggling when he felt the cold fabric across his neck.

Forrester pushed him up. The strap cut into his throat.

She unclipped the cuffs, threw them away. She and Cwej took an arm each and tied him down. They tilted the gurney back on its hinge until the Doctor was staring up at the ceiling, at their faces looking down at him.

‘Why are you doing this?’ he gasped.

Cwej looked as if he was about to burst into tears.

Forrester elbowed him out of the way and started pushing the gurney, fast. The others had to scurry to keep up with her.

He wanted to fight, but he was choking against the strap.

Anyway, you could never move or run in nightmares. ‘Are you sure we shouldn’t sedate him?’ said the green woman. She was naggingly familiar. Someone he’d once met? What random piece of his subconscious did she represent?

‘We don’t know which of your drugs are safe for him,’

said Forrester. ‘Anyway, he’s not going anywhere.’

He shouted as the gurney crashed through a pair of metal doors. He couldn’t turn his head to get a proper look. It wasn’t an operating theatre. Some sort of lab? A computer lab, much of the machinery as old and banged-up as the woman’s jumper.

The gurney slid to a halt. Forrester booted its kickstand, locking it in place. Someone was waiting in the room.

‘Bernice!’ He almost sobbed with relief. ‘Help me, Benny.’

She came up to the gurney. She took his hand. ‘I’ll stay with you. No matter what happens.’

‘Why are you doing this?’ he asked again. The green woman pushed cold metal against his skin, turned his head to get at his other temple. ‘Have I done something terrible?’

he said to the opposite wall. He shook his head, but the electrodes wouldn’t dislodge. ‘Tell me what I’ve done!’

Benny’s voice: ‘I’ll stay with you.’ She squeezed his hand, fiercely.

The green woman: ‘We’re ready.’

Forrester: ‘Get on with it!’

The sound of a machine warming up. An electric sensation in his temples.

The panic hit him again, and he wrenched against the straps and screamed.

He sat bolt upright in bed, yelling, catapulted back into wakefulness.

He flopped back down against the pillow, breathing hard, making himself relax, to wait for the nightmare feeling to drain away, for his breathing and heartsbeat to quieten.

It was just dawn. White curtains were moving in a soft cool breeze, glowing with the early light. The ceiling seemed strangely far away, the window too high up.

On one of the bedroom’s wooden walls, a clock ticked backwards, the numbers reversed around its face. He folded his arms behind his head, breathed out a sigh, and relaxed back onto the futon.

The beach house...

He hadn’t been here for... decades, at least decades.

Decorated the place himself, which had meant dragging some of the centuries’ accumulated junk out of the TARDIS

and scattering the knick-knacks about at random. If he wasn’t mistaken, there was a half-read paperback of Flaubert’s Parrot in the study. Maybe he’d finish reading it after breakfast, if he could find something else to prop up the desk’s leg.

When he got downstairs, breakfast was ready. Two butter croissants were waiting for him on a tray in the kitchen, along with a mug of cocoa and a single boiled egg.

He extracted a clean paisley handkerchief from his pocket, tucked it under his chin. He pulled off a bit of croissant and dipped it in the cocoa. Then he allowed himself to think back over the dream.

Nasty. The usual themes — betrayal, captivity, revenge, all the usual self-flagellatory flotsam from the depths of his mind. Jung had called dreams a theatre ‘...in which the dreamer is himself the scene, the player, the prompter, the producer, the author, the public and the critic,’ he said out loud, tapping absently at the top of the egg. There was a piece of toast beside it, neatly sliced in three. He dipped one slice into the egg, breaking the sticky yolk. It felt lonely to be having breakfast by himself, as though the whole universe had disappeared behind the Sunday newspaper.

There was a sudden flick of movement on one of the walls. He glanced around, but it-was gone. Probably a gecko; they got into the house all the time.

He’d bought the beach house when he was having the place at Allen Road painted. Everything there had been covered in dusty sheets, and the air was thick with chemical smells. So he’d flown to Sydney (with Mel in tow, if he remembered correctly) and driven a rented VW up the coast until they found the place, set back from the dunes in a shorn patch of thick scrub. Isolated. Quiet, except for the constant growling of the sea.

Very quiet. Where was everyone else? The place had seven bedrooms. They were probably sleeping in. Lucky he hadn’t woken them all up, shouting like that.

The book wasn’t under the desk leg.

He went out onto the beach in his shirt sleeves, with a pair of dark glasses and some zinc cream. There was a haze of heat over the ocean. The water hissed and sucked at the shore. He walked along in the beery fizz of the surf for a while, watching the seagulls and looking for interesting shells, and finally had to admit that he couldn’t remember how on earth he’d come to be here.

He stuck his hands in his pockets and jutted out his lower lip. Amnesiac episodes like this always disturbed him. Or at least he assumed they did. But with his lifestyle the odd swim in the Lethe was an occupational hazard.

He was probably recovering from something or other. He might have been asleep for days. His companions would probably be delighted to see him. He hadn’t had a chance to say thank you for breakfast.

He spun around. A movement, out of the corner of his eye — no, it was just the gulls. Or an illusory sense of being watched. The nightmare feeling wouldn’t go away.

He wanted someone to talk to.

Back at the house, the lights were on, but no-one was home. He snapped off the fluorescent tube in the guest bedroom, wandered from room to room. There was no sign of his companions.

In the kitchen, the breakfast things had been tidied away.

He puffed out his cheeks. There was intelligent life around somewhere, then.

He moped at himself in the bathroom mirror. Nothing ached, he couldn’t see any obvious scars, signs of damage.

It was, of course, possible that he had deliberately locked his own memory away, for whatever reason. Anyway, an enemy was hardly going to throw him into the briar patch like this.

He sighed. Always enemies in the shadows. His holiday plans attracted them like magnets.

He looked back at the mirror. Something looked back out at him.

‘That’s a cheap trick,’ he said.

The thing in the mirror didn’t respond.

‘Well?’ he asked, reaching out a finger to touch the smooth glass.

Skin, said the thing in the mirror. Flesh hate skin hate flesh you can’t trust it gets sick it corrodes it ages and it dies when you least expect it.

The Doctor watched as his palm slid down the mirror.

The glass was startlingly cold in the warm noon. He tried to pull his hand away.

Abruptly, he was smashing the mirror. Nasty skin wicked skin hate skin hate flesh. He smacked his hand against the glass until it splintered, shouted as the slivers bit into the thick skin of his palm.

He lost his balance, grabbing at the sink that held the mirror, but hitting it, hitting it. Hate skin hate you hate you.

Hate you.

When he woke up again it was evening. The wind hissed through the scrub. The purple sky was already breeding stars, glittering harshly in the cold, clean air.

Pieces of mirror were lying all over the floor, spattered with blood. He was lucky the cuts hadn’t been worse. He rummaged in a drawer for bandages and things, bound his hand up, scowling.

The something in the mirror... he hadn’t seen anything but his own reflection, but it had been there. And the feeling of being watched was back again. It was the rainforest feeling, knowing that tiny creatures were peeking at you from the trees.

But no-one had come to his rescue in the hours he’d spent in a daze on the bathroom floor. He was alone here.

Someone had laid the evening meal out on the kitchen table.

He stood in the doorway, eyeing it. Had breakfast been drugged? Something in the food that suppressed memories?

Made him homicidal with regard to looking-glasses?

He circled warily around the food, pulling open drawers and peeping in cupboards. The old Chinese crockery still in its boxes, the chipped mugs purloined from the UNIT

cafeteria. Nothing was — out of its place. Alien. Except him.

He remembered his companions’ faces from the dream.

Chris scared and trying to be professional, Roz stern and cold, Benny shattered and trying not to show it. He wished he could see them now. Talk to them.

Tomorrow he would go into town. Talk to someone. But now, he was suddenly, overwhelmingly tired, and his hand hurt. So he went to bed, and dreamed about Benny.

She was sitting in a chair. She had fallen asleep sitting up, shoulders hunched. She was wearing one of her more tattered denim jackets, over a T-shirt that said Keep the Leap. Her trousers were ex-army khaki, an Aboriginal flag patch sewn over one knee.

He was so pleased to see her that he just watched her sleep for a while. Her dark fringe hung down into her face.

There were fine lines around her eyes, and her skin was tanned from the sunlight of a hundred worlds.

He tried to imagine thirty years from now. She’d make a fabulous old lady, full of stories and laughter. Maybe with some grandchildren. He’d visit, teach them origami and stargazing.

‘I’m getting sentimental in your old age,’ he said aloud.

She startled awake, trying to pull herself together, be ready for action. But he wasn’t struggling or yelling, just lying there, watching her. The air was still, only the machines disturbing the quiet, humming like insects. Out of a window, he could see a night sky.

In this version of the nightmare, there was no strap around his neck. He lifted his head, looked around the room.

It was a cybernetics lab, probably one dredged up from an ancient memory. Goodness knew he tried to edit his memories, keep the clutter in his little brain attic down to a minimum, but there were always more. And besides, you never knew which snippet of information might be useful.

‘Twenty-third century,’ he said hoarsely. ‘Looks like a colonial set-up.’

‘Are you thirsty?’ said Benny. She was carefully checking a series of monitors. He was aware of the electrodes on his temples and behind his ears, the weight of their short antennae tugging as he moved his head.

He nodded, so she brought him a squeeze-bulb of water.

As nightmares went, this one was very calm and simple.

Tedious, even. A Hoothi would probably come in through the wall in a minute.

When she took the straw out of his mouth, he said, ‘Have you ever thought about having children?’ She almost dropped the water. ‘Sorry,’ he said.

She hovered. ‘Cinnabar says it would be a bad idea to talk to you.’

‘Cinnabar? The moth or the mineral?’ Benny didn’t answer.

Some authoritarian symbol or other, no doubt. ‘I’m sorry.

I just can’t motivate the action in this nightmare while I’m tied to this trolley.’

‘Everything’s going to be all right,’ she whispered, sitting back down in the chair.

‘Can’t you let me up? Even for a moment?’ He pulled against the bonds around his wrists. ‘I’m very uncomfortable.’

‘Are you in pain?’

‘No. I just want you to untie me. Please.’

‘Stop it,’ said Benny.

‘I’ll die here!’ He thrashed against the straps, shouting.

‘You’re killing me!’ It didn’t sound like his voice — panic wasn’t his style. But she was grabbing his head to stop him smacking it against the trolley. She was crying; people were running in. ‘Don’t you understand? I’ll die here!’

The electrodes fizzed against his scalp. He convulsed as they tightened their cold grip on his brain. ‘Benny,’ he hissed through his clenched teeth. ‘Help me.’

‘Get her out of here,’ said someone, taking Benny by the arm.

‘No,’ she said. ‘I’ll stay with him.’

When he woke there was a lump in his throat, and he was still alone.

Breakfast was cold cereal and milk. He crunched on it despondently. ‘Company, that’s what you need,’ he told himself. ‘Before you start talking to yourself.’

He washed and dressed, buttoning a paisley waistcoat over his shirt. Judging by the haze over the ocean, it would be a warm day. He changed the bandage on his hand. The cuts were healing nicely.

He stopped at the upstairs bathroom. The floor was still covered in broken glass. So room service was limited to meals.

Gingerly, he picked up one of the larger pieces, an inch across. It glinted in the morning light, its surface lightly spattered with his blood. Let me out hate you, it said. He wrapped it in a handkerchief, put it in his pocket. It muttered to itself, irritably.

He rolled up his trouser legs and splashed through the surf again. The tide had left thick banks of seaweed to cook in the sunlight. He didn’t find any interesting shells. It should take less than an hour to walk into town.

After three hours he sat down on a rock.

A memory flashed into his mind: making this journey with Mel, to buy milk and ice creams. She’d striped her nose and cheeks with fluorescent-coloured zinc cream, given him a lecture about sunburn. The recollection was as clear as if it had been yesterday. Which, given his current state of mind, admittedly wasn’t saying much.

The horizon was remarkably clear, sun and sky sliced in two with a line that was almost geometric. The tide had come up the beach, soaking the ends of his trousers. It was hot.

Even the seagulls must be sleeping somewhere; the bright sky was empty of wheeling dots and hungry cries.

He had a sudden vision of Wells’s time traveller, looking at a bloated sun across a steaming ocean, utterly alone at the end of the world. Could this bit of Australia have become an island since he’d last visited? Had he simply been walking around its circumference? Had hundreds of years passed?

Thousands? And if they had, why hadn’t his house been swept away with the passing time?

Reluctantly, he took the piece of mirror out of his pocket and unwrapped it.

He dipped it into the water around the rock with his unbandaged hand, rubbing off the clinging blood with his hanky. The silver backing caught the sunlight in a blinding flash.

The piece of mirror looked up at him from the palm of his hand.

He sighed. ‘Who are you?’

You sound like you don’t want to know.

‘Look,’ said the Doctor. ‘We have something in common.

You’re trapped in that bit of glass. And I’m — I’m trapped on this island.’ He squinted at the fragment. ‘Did you bring me here? Trap me here?’

The thing in the mirror laughed. Tiny cracks spread across the glass with a tinkling sound.

The Doctor was about to toss it into the surf when he thought better of it. That could give someone a nasty cut. He wrapped it up again, pushed it back into his pocket. At least it was someone to talk to.

That evening, the piece of glass watched him from the table as he peered at one of the kitchen walls, nose an inch from the wood.

What are you doing?

‘Looking for cracks,’ said the Time Lord.

Oh yes?

‘Specifically,’ said the Doctor, ‘I want to see if the pattern of the wood has been determined by a fractal algorithm.’

The piece of mirror laughed. You think this is a virtual reality!

The Doctor glanced at it. ‘It’s on my list of possibilities.

Or, rather, was on my list.’

What makes you think this isn’t real?

‘Pieces of mirror,’ said the Doctor, ‘don’t generally talk to me. And then there’s the omelette.’ He waved at the half-eaten meal. ‘It tastes like cardboard. The Chardonnay’s like water. You sometimes get that effect in a simulation when the batteries are running down.’

What else, what else?

‘I thought I might be dreaming. But my nightmares aren’t like this. There’s too much sunshine, the surroundings are too familiar.’

What else?

‘Someone might have stranded me on an Earthlike planet. It wouldn’t take much effort to create the house from my memories. But the seagulls are a superfluous touch.’

What else?

‘I might have finally gone around the twist.’

What else?

‘Purgatory,’ said the Doctor shortly.

The mirror’s laughter was like light-bulbs underfoot.

Coming apart at the seams who’ll be trapped and who’ll be free?

‘You’re trapped here too.’ The Doctor leaned over the piece of glass, gripping the edge of the table. ‘You’re trapped too. Do you know a way out?’

When everything comes apart at the seams.

‘Is it this world that’s changing? Or my perception of it?’

You’ll be trapped and who’ll be free?

The Doctor thumped the table, infuriated. The wineglass tumbled off the table, shattered on the floor tiles. The sound was muffled, indistinct.

There was something watching him from outside the window.

He bolted to the sink, peered outwards into the gathering dusk. Nothing. He ran out of the door. Still nothing. ‘Show yourself!’ he shouted. ‘Talk to me!’

He sat on the rock, watching the tide come in.

It wasn’t computer-generated. He’d tried three different tricks to spot the programming. He’d wanted so much for it to be a VR. It couldn’t be real — it couldn’t be.

Unless, of course, he was coming apart at the seams.

His best guess right now was that he had been deliberately marooned here. Judging by the house, the menu, he very much suspected he had done it himself.

He might have been here for years. Decades. Centuries.

Long enough that the days blurred into one another, the little events of daily living lost their focus, until his memory was worn smooth as old stone.

There weren’t many stars tonight. He stared at them, willing the sky to get darker, willing them to come out. Willing the surf to sound louder, the sand to regain its texture, its warmth. Even the feeling of being watched was gone.

But why? In the nightmare, he’d asked again and again,

‘What have I done?’ It might be a clue. He might be enduring some punishment. A life sentence. The dream suggested an arrest, a trial. But, if anyone had passed judgment, it would have been him.

What had most probably happened was that he’d gone mad. Not merely insane. Mad. Tumbled down into mental spaces a human being couldn’t even imagine, turning corners only a Time Lord could turn.

Goodness knew what he might have done.

Leaving him alone in some quiet corner of the universe would have been the only safe thing to do. ‘Heaven left him at large to his own Dark Design,’ he whispered, ‘that with reiterated crimes he might heap on himself damnation.’

Absolutely nothing he did now would matter. It would take him a lot of years to die.

The grip started with his ankles.

Of course he tried to get up and run, but something had his feet, and shortly it had his legs as well.

‘No,’ he said, but the grip ran up his body, clutching muscles and skin. He felt it in his elbows and running through his hair, invisible fingers taking hold of his body, the way they had taken his hand and used him to break the mirror.

They went down to the surf together, the thing in the glass and the Time Lord. There were no stars, no horizon.

The water was invisible, just white noise licking at the beach.

‘You were right,’ said the Doctor. ‘It is coming apart at the seams.’ He hovered at the edge of the surf in the darkness, the water licking at his feet. ‘You’re unravelling it all, aren’t you?’

He heard that tinkling laughter again. The fingers were inside his skin, cold and sizzling, eroding him from the inside out.

He lunged for the water.

The grip inside him tightened, angrily, making him thrash in the hungry surf. The water dragged him away from the land, sucked him under.

‘For God’s sake, hold him down!’

The thing in the mirror screamed with rage as he tried to breathe ocean. His arms and legs jerked as it tried to force him back to the surface, back to the beach. But there was no beach. The water rolled on and on.

Someone was shining a brilliant light into his eyes. He flinched, squinted, tasted salt.

The static sound of the ocean hissed in his ears.

The light was overhead, on the ceiling. Something was holding his head down, pushing down on his arms, trying to stop the violent movement of his body.

The thing in the mirror roared with fury. He screamed with its rage, thrashed with its terror, and then, at last, it slid back into the water and was gone.

‘Work!’ he gasped hoarsely. ‘Did it work?’

Benny relaxed her grip on his head. She looked over at Cinnabar, who nodded fiercely. ‘All the scans are clear.’

He relaxed, exhausted. Chris and Roz let go of their death-grip on his arms. Benny pulled the straps away from him with almost feverish urgency. But he was too tired to do much more than roll onto his side, stretching cramped muscles. His hand stung. He looked at it. Deep white lines crisscrossed the palm.

‘Are you all right?’ said Roz, peering at him. ‘Is that thing gone?’

‘Yes,’ he breathed. ‘We’ll talk in the morning.’

He blew out a long sigh and went to sleep.

2 ESP is Catching

The Doctor opened his eyes and shut them again, quickly.

Cinnabar and Byerley were having a quick kiss against a bench of medical equipment. He waited until he heard them part before he yawned and stretched.

‘Good morning,’ said Cinnabar Flynn.

‘Don’t you ever wear anything besides that jumper?’ he asked.

She patted at the baggy green garment. ‘It’s my favourite. It’s the only thing I brought from Earth. How do you feel?’

‘I’m fine. Now.’

Byerley came over to the bed. ‘Doctor.’

‘Doctor.’

The man waved a printout at him. ‘Your viral count has dropped to zero. I wanted to test you for antibodies too...’

‘You won’t be able to match my blood against the human samples. How many infections are we up to now?’

Cinnabar and Byerley exchanged glances. ‘Number forty-seven was reported this morning. That’s nearly ten per cent of the colonists.’

‘Then I don’t have time to be lying about here.’ He sat up, pushed the covers aside.

Sometime during the night, they’d moved him into the infirmary. Probably because the night shift in cybernetics couldn’t stand the snoring. There was an office area behind a desk, a door with a sign saying ‘The Other Room’ taped to it.

Sunlight was streaming in through a plastic window,

‘Breakfast,’ he said.

His companions were eating in the common area, a huge, circular room with a skylight at the very centre of the main habitat dome. They formed a haggard little triangle at the end of one of the long benches.

Two weeks ago, when they’d first come to Yemaya 4, this room was always full of people — eating, or making or mending things, or playing small instruments and singing.

Now there was hardly anyone here, just a family eating despondently in the corner and a group of kids throwing their modelling clay around while a tired-looking teacher watched.

His companions looked up as one, startled, like conspirators caught in the act. Bernice opened her mouth and closed it.

At last, Roz Forrester said, ‘Well?’

‘Yes, thanks.’ He beamed at them, saw Chris and Bernice relax as he sat down. But Roz was still peering at him, as if expecting the monster to surface again.

‘There’s no trace of the virus?’

‘It’s gone?’ said Benny. ‘Completely?’

The Doctor nodded. ‘There aren’t many microorganisms which my immune system can’t deal with, given time.’

‘You’re not infectious, then,’ said Roz.

‘Hey!’ Benny glared at the Adjudicator across the table, but the Doctor drummed his fingers to get their attention.

‘What I am,’ he said, ‘is ravenous.’

Roz pushed her untouched plate across to him. Ration cubes and slices of tomatoes grown in Yemaya’s own soil.

He stabbed at the stuff with a plastic fork.

Chris said, ‘So what do we do now?’

‘There’s more going on here than I thought,’ said the Doctor, around a mouthful of cheese-flavoured rations. ‘Much more.’

Bernice leaned back in her chair, watching something the Playgroup were doing. ‘The virus had a completely different effect on you,’ she said.

‘Well, you are... I mean...’ Chris looked at Roz and stumbled; . that is, your biology is . .

‘ Alien is the word you’re looking for,’ said the Doctor. ‘It shouldn’t have affected me at all. But it did.’

Chris and Roz followed Bernice’s gaze. One of the kids, a girl in overalls, was backed up against the wall, trying not to cry. The teacher was getting food from the counter, her back to the group. The other children, in their temporary freedom, were lobbing chunks of clay at the girl.

‘Now, a virus designed to alter human genes can hardly do anything to me,’ the Doctor continued, oblivious. ‘But memory sequences, that’s another thing. My metabolism is capable of interpreting human memory RNA, producing the Gallifreyan equivalent.’

He noticed that none of them were listening to him. Saw the bits of clay arcing towards the girl, jerking back, as if they were bouncing off an invisible shield a foot from her body.

‘That’s forty-eight,’ he said softly.

‘Odds are,’ said Roz, ‘one of us is going to be infected.’

‘One of us already has been,’ muttered Chris. The tall blonde’s boots sank into the grass as he followed her.

‘I meant the humans,’ said Roz sourly. ‘You, me or Benny might suddenly become telepathic. Or psychokinetic.’

The colonists digging and planting looked up as they passed. Chris found himself nervous under their eyes. He could imagine what Roz was thinking. Here, like everywhere else, they were the aliens.

Yemaya 4 was ideal for colonization — a large temperate zone, gentle seasons, biochemistry not too different from Earth’s. Thick forests, rushing rivers, no large predators. The gravity was slightly lower, which leant a spring to Chris’s step as he hurried after the short black woman. From here, the cluster of domes were distant bumps, the big silver habitat dome surrounded by storage sheds.

The colonists had been here for two months. They had started accelerated gardens around the habitat dome almost immediately, and now they were busily turning some of the surrounding meadows into farms. The Doctor said that their ecological plan was exceptionally good — they were going to be able to use several Yemayan native plants as crops, and planetfall had been timed to allow almost immediate planting of Terran seed stock. Until one or the other crop came up, they’d be living on a combination of rations and veggies from the garden. It would be more than a year before they could think about unfreezing the animals.

The whole colonization had been proceeding like clockwork when the first infections occurred. Someone’s kid had fallen in the fast-running river nearby, and, when the mother couldn’t reach the boy with a tree limb, she’d pulled him out with her mind.

The next day, her husband told Doctor St John he thought he was going insane. Hearing voices. Byerley had checked him with a standard telepathic potential test, and the results had been off the scale.

It had taken Byerley a week to isolate an unknown virus from their blood. In that time, there were a dozen more cases. The day after that, the TARDIS had plonked down in a field next to the habitat dome, and the Doctor had poked his nose right in.

It had been the Time Lord who had isolated human genes from the virus. The bug was travelling to the brain and releasing its payload: psychic powers. There was even a pyrokinetic and a couple of psychometrists. There didn’t seem to be a pattern to who got what.

Chris caught Roz up. ‘Would it be so bad if one of us did get some kind of power? It could be useful. Imagine smashing a Dalek up inside its shell by thinking about it.’

‘Imagine smashing up someone’s brain inside their skull by thinking about it.’ Roz stopped still and looked out across the field, where Cinnabar’s green jumper was visible against the fluorescent bulk of a hovertractor. ‘Why do you think the Gifted were registered back home, Chris?’

‘I thought it was because they needed training to use their powers safely.’ Chris found himself trailing behind her again as she cut across the field. ‘What do they do with them in this century?’

‘Nothing at all, apparently. They just let them run loose.’

‘Hey there, hi there, ho there,’ said Cinnabar, wiping sweat from her forehead with a grimy hand. ‘Either of you any good at fixing tractors?’

Chris shrugged. The hovertractor was stuck in the ground at an angle, looking as if it had swerved and crashed.

‘What happened to it?’

‘ I did, I’m afraid.’ A skinny black kid came from around the back of the tractor. ‘I was... well, I was...’

‘He tried to drive it psychokinetically,’ said Cinnabar. ‘It’s all right, Cephas, you just made a mistake, that’s all.’

The boy withered under Roz’s glare. ‘I was just trying to get the hang of it,’ he said. ‘If I’m going to be stuck like this for the rest of my life..

‘You’re not,’ snapped Roz. ‘Plan on being cured. Shortly.’

The boy’s mouth drew into a line. ‘It’s okay for you. You can leave any time...’

‘What can I do for you folks?’ said Cinnabar, half disappearing into the tractor’s engine.

‘Oh, we’ve been sent to get more soil bacteria samples,’

sighed Chris. ‘The Doctor wants some bugs from the tilled areas, in case anything got dug up. Hey,’ he added, ‘that’s new, isn’t it?’ Cinnabar stuck her head out and looked where he was pointing across the field. A small dome had been set up, almost a kilometre from the habitat dome.

‘That’s the SmithSmiths,’ murmured Cinnabar. ‘Haven’t you seen them, going around with their masks on?’

‘The filter masks?’ said Roz. ‘I thought they must be working with chemicals.’

‘Nope. They’re trying not to let themselves get infected.

They stay in their own dome most of the time. The kids never come out.’

‘Paranoia.’

‘It’s something religious, I think. I don’t know them too well. Given we still don’t know the source of the infections, maybe they’ve got the right idea.’

Cephas said, ‘No. If we’re going to sort this out, we’re going to have to do it together.’ He turned big eyes on Chris and Roz. ‘My sister said they might make us leave the colony. Before we could infect anyone else.’

‘That’s not going to happen,’ said Chris.

‘It might make sense,’ said Roz. ‘Slow the rate of new infections.’

‘Possibly,’ said Cinnabar. ‘But for all we know the bug’s in the soil or the air. Cephas is right. We’re not going to solve this by splitting up. Pass me the bluminator, will you?’

The boy knelt by the tool kit. His hand hovered over the device. Then he flicked it up into the air, watching it hover in front of his face. It shook in his invisible grip.

He let it drift up, past Roz’s scowl, into Cinnabar’s outstretched hand. She grinned.

Bernice came with him when he took the girl to the infirmary.

‘Psychokinesis,’ said the Doctor, as he lifted the sobbing child onto a bench.

Doctor Byerley St John abandoned the genetic sequence he was working on and strode across to them. He sat down on the bench beside the little girl, and took her hand. ‘You’ll be all right, sweetheart,’ he said. ‘Lots of people have caught the same germ you have, but it doesn’t hurt. You won’t even feel sick.’

Next to the crying six-year-old, Byerley was huge. He was muscular, with the frame of a dancer rather than a bodybuilder, with serious eyes and dark hair.

‘I want my daddy,’ she sobbed. ‘Are you going to send me away?’

‘No-one’s going to send you anywhere, honey.’

‘But my teacher said that all the people with the germ will have to go and live somewhere else.’

‘Not if I have anything to say about it. I’m going to call your daddy, and then I’m going to prick your finger to take a drop of blood, okay? Then you can have a jelly bean.’ She nodded, sniffling. There was clay in her hair, sticking it to her forehead. Byerley got up to get his equipment.

The Doctor was stalking about the lab, peering at machines and reports. Benny patted the girl on the head, awkwardly. ‘When I was your age,’ she said, ‘I used to wish I had magical powers all the time. I used to wish I could fly, so that instead of getting into fights, I would just fly away.’ The girl just shook her head. ‘Look, Doctor, if you’ve got any new insights...’

‘It can’t be Yemayan,’ said the Doctor, pacing. ‘And if...

but then, the colonists’ gene pool was deliberately diverse.

It’s not...’ He trailed off into an inaudible mumble as Byerley came back into the room, putting down his equipment on the bench.

‘Your daddy will be here in a couple of minutes. Okay?’

The girl nodded again. ‘Then I’ll take this sample, and you can go home. Doctor, will you come with me?’

The Time Lord, still muttering to himself, followed Byerley into the storeroom. Byerley waved a hand in front of his face.

‘Doctor.’

‘Doctor.’

‘Have you been able to draw any conclusions from your own infection?’

The Doctor leaned on a shelf, folding his arms. ‘There’s obviously a second payload in the virus. Not just DNA, but memory RNA. But whose RNA? Where did it come from in the first place?’

‘I still think it’s something native. It has to be. What are the odds of the virus’s protein coat matching that of Yemayan soil viruses?’

‘No, no. We’ve been over this. The protein’s Yemayan, the genes are Terran. Could it be a natural hybrid?’

‘Then how did it overcome our inoculation programme? It has to be manufactured.’

‘Not necessarily. There are some naturally occurring microorganisms which can affect psi ability.’

‘I wish more was known about the genetics,’ said Byerley. ‘Back on Earth, the only research is being done by big business, and that’s all kept under wraps. Listen, no-one else had symptoms like yours. I still don’t quite understand what that was all about.’

‘My own memories and personality were being overwritten by the viral memory RNA,’ said the Doctor.

‘You were being taken over?’

‘Not exactly. You couldn’t store an entire personality inside a virus. But the viral RNA was replicating itself out of control, probably as a result of my brain cells trying to make sense out of it, integrate it. If Cinnabar hadn’t plugged me into her computer, given me a chance to find the viral sequences and eliminate them, it would have driven me mad and then killed me.’

Byerley nodded gravely. ‘You should be immune now, at least.’

‘I should have been immune in the first place.’ The Doctor squinted, as though trying to see something in the distance. ‘Just as the inoculated colonists should have been.

After all the work we’ve done, all the research, I should have an idea of what’s going on here. I feel as if it’s on the tip of my mind...’ He shook his head. ‘My brain cells are probably still shaken up. It’ll come to me.’

‘Doctor,’ said Byerley, ‘if it does come to you, do you think we’re going to be able to cure it?’

The Doctor looked back through the door, where Bernice was trying to comfort the girl and her dismayed father. ‘Some people would consider these powers a miracle. They’d think we were looking a gift horse in the mouth.’

‘Most of these people are just plain terrified. They don’t even want to know what’s going on — they just want an easy solution. But it’s more complicated than we think, isn’t it?’

The Doctor nodded. ‘And we can’t do anything about virus or powers until we find out what’s really going on.’

‘You smell something burning?’ asked Chris.

Roz sniffed the air and shook her head. She was leaning on the tree he was sitting against, watching a gaggle of kids improvising a game with a saggy football. The trees here looked like gigantic celery stalks, dark green at the base and shading upwards to fiery orange at the top. Tiny, harmless creatures crawled over the succulent bark.

‘Look,’ said Chris. ‘They’ve worked it into the game.’ He pointed. ‘The tall girl with the black hair, she’s telepathic. She has to guess where the other person will throw the ball next.’

Roz saw the girl lunge sideways suddenly, snatching the ball out of the air. ‘And the red-headed twins are both psychokinetic. They’ve been throwing the ball around without their hands.’

‘They do seem to have pretty good control, for learners,’

said Roz. ‘So long as they don’t start throwing one another around.’

Chris shrugged. ‘It all looks pretty harmless to me.’

‘Don’t let your guard down,’ she told him. ‘You know how fast things can get out of control.’

‘So, urn... if one of us does become infected,’ said Chris,

‘what do we do about it?’

‘The Doctor will find a cure for the psi powers,’ said Roz.

‘What you really want to know is, what do we do if one of us is... possessed, the way that he was?’

Chris wished he could tell what she was thinking. ‘Maybe it only does that to aliens.’

‘Look,’ Roz said, ‘we just don’t know enough, all right?

We don’t know where the virus came from or what it’s for, and, until the Doctor finds that out, we can’t make any assumptions. All we can do is wait.’

Abruptly, she turned and smacked an armoured fist into the tree trunk, showering him with splinters.

‘Sorry,’ she said, as he flapped his fingers in his hair, looking startled. ‘I hate monsters that are too small to shoot.’

Benny found the Doctor in Byerley’s microbiology lab, sleeves rolled up, arms sheathed in long latex gloves. She sat down on a stool across the room, waited until he finished streaking the bacterial samples he was working on.

‘How’s it going?’

‘Our current theory,’ said the Doctor, snapping off the gloves, ‘is that the virus is symbiotic with the soil bacteria. It’s nonsense, unfortunately. I’m fine.’

Benny laughed. ‘You are, aren’t you?’

‘I am now. Thanks for watching over me.’ The Doctor washed his hands, rolled his sleeves back up. ‘Come on, let’s go and steal some of Byerley’s coffee.’

They lounged about in the colony doctor’s office, drinking the medic’s special blend, smuggled from Earth in his luggage. ‘Can I ask you something?’ said Bernice.

The Doctor nodded.

‘Why did you ask me about having children?’

‘Did I?’ He closed his eyes, trying to bring the moment back. ‘I really have no idea.’

‘Well, I’m not planning on it.’

The Doctor nodded, looking uncomfortable. ‘It would be difficult.’

Benny put down her cup. ‘I thought about it. After you asked. I realized I had no idea how I felt. But then we brought that little girl here this morning. And I suddenly knew I wasn’t going to have any kids.’

‘Oh,’ said the Doctor. ‘You mean, not while you’re travelling with me?’

She shook her head. ‘The poor thing could be turned into a fungus one week, taken over by aliens the next... I couldn’t stand it.’

‘It’s bad enough,’ said the Doctor gravely, ‘having to watch it happen to your friends.’

Benny hugged him suddenly, almost making him spill the coffee. ‘Gack,’ he said.

He put down the cup carefully, put his hands on her shoulders. ‘If you’re serious about this,’ he said, ‘we can drop you off somewhere.’

‘Maternity leave?’ She shook her head. ‘Something else I realized. I’m not ready to lose you yet.’

They pushed their foreheads together. ‘I just wish there was something more I could do here,’ whispered Benny.

‘We’ve been to so many worlds. But this world is so new, so fragile. Like a new child. Can’t we help them?’

‘We will,’ said the Doctor softly, ruffling her hair. ‘And I know something you could do.’

Later. He stood alone in Cinnabar’s cybernetics lab. He picked up the end of the gurney’s neck-strap, rolled the fabric between his fingers contemplatively.

He hadn’t worried about the needlestick at all. It had been careless of him — not concentrating on one thing at once, that was always his problem in laboratories. But there shouldn’t have been anything in human blood that could affect him.

The memories had started surfacing a few hours later.

Just flashes, tiny moments. Someone else’s memories.

Infuriatingly, he couldn’t remember any of them now. But he remembered how they’d kept repeating over and over, like a melody he couldn’t get out of his mind.

Roz had been the first person he had told. He knew that she’d do whatever was necessary, without hesitating.

Byerley had taken it all in his stride — both the fact that there were viral particles in the Doctor’s blood, and that his new patient just looked human. In this time period, ‘alien’ still meant scaly and green. But, when the Time Lord had asked Byerley to keep it to himself, he’d looked at him long and hard and then agreed.

It had grown steadily worse. He would be so caught up in the foreign memories that he forgot where he was for minutes at a time. That was when he and Forrester had talked about the gurney.

The idea had been to create a ‘reality’ that could keep the viral personality busy, while the Doctor ferreted out its memories and erased them, the same way he edited his own memories from time to time. Of course, the ‘reality’ would have to keep the Doctor’s conscious mind just as busy... a cyberspace wouldn’t do it, he’d have realized what it was too quickly.

The memories had swollen, taking up more of his mind, making it impossible to concentrate from minute to minute.

When he’d disappeared, Chris and Roz had gone to bring him back. They’d found him in the forest, talking nonsense.

The beach house had been a pocket of his own mind, monitored and stabilized by Cinnabar’s computer link. She and Byerley had also been monitoring the levels of virus in his blood, the changes to the memory RNA in his brain.

He’d given up so easily, so quickly, accepting that he’d gone mad. Perhaps, on a subconscious level, he’d been waiting for that to happen for a long time.

The question now was: whose memories had they been?

For that matter, why had they been packaged into the viruses? Why hadn’t they emerged in the minds of the infected humans? Why the psi powers in any case? Why... ?

He let go of the strap, sat on the trolley, folding his arms.

He was so close to the solution. So close. He hoped he hadn’t erased it along with the foreign personality. He needed the answer, before the colony’s tensions became worse. No-one had been hurt yet; they were scared, confused, but they hadn’t started to turn on one another.

If there was violence, it wouldn’t last long. There just weren’t that many of them. And now, some of them would be able to kill you by thinking about it.

Chris wandered in. ‘We’ve got you that dirt.’ He stopped, seeing that he’d caught the Time Lord in the middle of a train of thought.

‘If we don’t help these people soon,’ said the Time Lord in a low voice, ‘there’s the very real possibility that we’re going to find ourselves in the middle of a miniature civil war.

We’ve got to find a cure.’ He banged himself in the forehead.

‘If I could just work out where the infection had come from in the first place!’

‘Inoculations,’ said Chris.

The Doctor looked up at him.

Chris coloured. ‘They were all vaccinated before they came here, weren’t they?’

‘Great jumping gobstoppers!’ The Doctor hopped down off the gurney. ‘Why didn’t I think of that?’

3 Looking for Things

‘Byerley!’ said the Doctor, almost running into the lab.

‘We’ve been coming at this from completely the wrong angle!’

The medic was filling a cup from his coffee machine. He spun around so fast that he sent a spoonful of sugar flying.

‘Listen,’ said the Doctor. ‘We’ve been assuming that the virus causes the psi powers.’

‘Well, everyone who’s been infected has developed powers...’

‘No. It’s the other way around.’ The Doctor waved his hands about, agitatedly. ‘We’ve tested everyone who developed powers. But we haven’t tested everyone else.

What if the virus only affects certain people?’

‘I do have two asymptomatic cases on record,’ said Byerley. He sat down, almost involuntarily, behind his desk.

‘Do you mean that...?’

The Doctor perched on a corner of the desk. ‘Everyone’s infected. We assumed that the virus was carrying the genes for the psi powers. But what if those genes are already present in some brains?’

Byerley leaned across the desk. ‘The viral code is switching on the latent genes in those individuals,’ he said.

‘The same way some cancer viruses switch on growth genes.’

‘And it would explain why different people have developed different powers, rather than everyone getting the same power.’

‘It’s too specific,’ breathed Byerley. ‘Something that specific couldn’t possibly be natural. But I thought, if it were manufactured, there’d be a serial number in the chromosomes...’

‘The standard procedure for this century is for a full biological survey to be done before anyone sets foot on the planet, correct?’

Byerley nodded. ‘Robots take samples of bacteria and viruses. Anything that might be pathological is used to develop a vaccine and — oh my God, that’s what you mean, isn’t it! There was something in the inoculations themselves!

Oh my God, the bastards — they’ve been using us as guinea pigs!’

The Doctor put a hand on Byerley’s arm before he spilt his coffee. ‘Not necessarily. Who was responsible for the vaccinations?’

‘DKC,’ said Byerley. ‘The Dione-Kisumu Company. They provided most of the medical technology.’ He gestured around the lab with his cup, angrily.

‘I’ve heard of them,’ said the Doctor.

‘We came here in a DKC colony ship. You’ve met Captain Kamotja, haven’t you? She flew the thing. The crew took it back, and she stayed on to oversee the initial stages.’

The Doctor nodded. ‘The Company made quite a profit during this century’s push for colonization.’

‘Doctor,’ said Byerley, ‘I need to ask you about that.’

‘About Dione-Kisumu? They were Kenyan, weren’t they?’

‘No. About you — and Benny and Chris and Forrester.

About why you’re here.’

‘All right.’ The Doctor folded his arms. ‘We knew from future history that an outbreak of psi powers occurred on Yemaya 4 in the year 2257. But there was very little information about it. As though someone deliberately covered up the records. I wanted to see for myself what happened here.’

‘Believing that you’re not human is much easier than believing that you come from the future. How — how far in the future?’

‘We travel,’ said the Doctor, ‘a lot.’

‘Why us?’ said Byerley. ‘Why this colony? Yemaya doesn’t have any strategic significance. The geological survey was completely run-of-the-mill.’ He shook his head.

‘Why is all this happening to us?’ He pointed at the Doctor.

‘You must know.’

‘You may have just been in the wrong place at the wrong... Time moves in mysterious ways.’

‘What the hell are they trying to do?’ Byerley let him go, sat down behind his desk, despondent. ‘We came here to get away from all of that sort of thing. From the companies and corporations. Do you know where I was working before I came here?’

The Doctor shook his head. ‘Sydney,’ said Byerley.

‘Downstream from the nuclear plant. There are kids there living in a rubbish tip.’ He raised his hands, as if to shield himself from the memory. ‘There was a little boy that the others kept blindfolded. He made weapons for them, by touch.’

‘I didn’t think anyone still lived in Sydney,’ said the Doctor softly. Not in this epoch.’

‘When I — when I took the blindfold off, his eyes were like a pair of loose grey eggs. They rolled and pulsed as though someone was inside his head, trying to push their fingers out... and I just walked away. Just gave him his antibiotic shot and walked out of there.’ He reached out blindly for his coffee, knocked the cup over. ‘I can’t get away from it,’ he whispered. ‘Even here...’

The Doctor picked up the cup. The cold liquid formed a neat pool on Byerley’s desk, surface tension holding it in place. ‘No,’ he said. ‘You can’t. You can only do the same thing you were doing in Sydney.’

Byerley looked at him.

‘You can fight back,’ said the Doctor.

‘Fight?’ said Byerley. ‘I’ll kill those bastards. Wait till I get on the communications link. The Colonial Commission...’

‘No,’ said the Doctor sharply. Not yet. We don’t want them to know that we know. In fact, we should keep this between the two of us for as long as we can.’

The sun was going down when they reached the waterfall.

Benny’s mind had been in neutral for an hour, empty of everything except the wind through the trees and the distant hissing of the water.

Zaniwe and Jenny had made the trip twice before, leaving beacons behind in the forest. They navigated partly by memory, partly by tracking the beacons, short poles with a red bulb of radio equipment on top. They looked like matchsticks poking out of the undergrowth.

There was a wide clearing at the waterfall’s base. The air was cool, a fine spray of droplets forming a mist around the rocky pool at the bottom of the cliff. They pulled off their backpacks, dropped them on the ground. Benny lay flat on her back and made a face. ‘Argh,’ she said. ‘I don’t suppose I could get you two to carry me the rest of the way.’

Zaniwe laughed, as Jenny rummaged in her backpack.

‘Really, it’s only another hour,’ she said. ‘It’s a very nice walk in the morning light.’

Benny shut her eyes, listened to the roar of the water, feeling its distant rhythm through the soil beneath her.

They’d set out from the domes in the morning. There had been four more infections reported during the night. But the Doctor had had a glint in his eye, which meant he was onto the solution. He hoped to have confirmed the source of the bug by the time they got back. Maybe even to have found a cure.

In the meantime, he’d suggested she investigate the local ruins. Jenny was the colony’s xenobiologist; they would have made it to the waterfall more quickly, if she hadn’t insisted on rushing off into the trees every half-hour to take photos of the wildlife.

Benny couldn’t even see the wildlife, but Jenny would point excitedly to some tiny creature half hidden in a tree while snapping a dozen holograms of it. The biggest creature they’d seen since entering the forest was the size of a cat, a slender-necked, dappled thing grazing on the undergrowth. It had blinked its single eye at them and bolted before she could take its picture.

The couple were pulling bedding and equipment out of their packs. They never seemed to do anything if it wasn’t together. They were Africans, like most of the colonists —

people who could afford to break away from Earth and look for a new life. Originally they were from whatever country South Africa was part of these days, the United African Confederacy or something or other.

They’d been flying a hoverskimmer over the forest on a survey run when they’d discovered the temple. Benny dragged her backpack over and pulled out the sheaf of photos. They were slightly distorted without the hologram viewer, but they were still striking — the forest like an ocean of trees, different shades of green and yellow. And the clearing in the centre, the ruins stark silvery grey against the green of the undergrowth.

They were clearer in the later photos, Jenny holding the skimmer in place while Zaniwe hung out of the window, snapping away. At first glance, they could be mistaken for recent dwellings; Jenny said she’d nearly crashed the skimmer when she saw them. But the closer shots showed weather-worn stone, huts open to the sky, thick growth around and on the buildings.

Benny rolled over, holding the best picture in a stray beam of late-afternoon sunlight. The central building dwarfed the others. It reminded her of a Mayan temple, a steep ziggurat with a flat top. The other buildings were clustered around it at a respectful distance.

It was a shame they couldn’t have flown the skimmer here, but there simply wasn’t anywhere to land it. The trees came right up to the edge of the huts and stopped there, as if they were just as timid as the little buildings about getting close to the temple.

If it was a temple. Benny knew only too well how dangerous it was to play guessing-games about alien cultures. Make no assumptions, that was the rule; avoid the just-like’ fallacy.

But in this case the only danger was of being roasted in the archaeological journals. These aliens were long, long gone.

Benny wasn’t sure whether the Doctor had sent her out here because he wanted her safely out of the way, because he thought she was feeling bored and useless, or because he thought the ruins might actually have something to do with what was happening to the colonists. From what he’d been saying this morning about the inoculation programme, that didn’t seem likely.

Zaniwe and Jenny had got their tent together already.

Benny scrambled up, knocking twigs and dirt off her denim gear.

‘So what did you find on the last couple of tries?’ she asked, dragging stuff out of her pack.

‘Very little,’ said Jenny. ‘We do not have the equipment to date the buildings, but they may have been there more than a thousand years. We didn’t want to damage the site by digging. If there are tools or potsherds or other artifacts, a proper archaeologist should search for them.’

‘And that’s you,’ said Zaniwe, dumping an armload of firewood in the centre of the camp.

‘The initial planetary surveys didn’t find anything, did they?’

Zaniwe shook her head. ‘Nope. Unless someone was fudging — there’s no way they’d allow colonists on the planet if there was evidence of an alien civilization. Even just remains.’ ‘You mean someone might have found the temple, but kept it quiet so the colonization could proceed?’ ‘This happened on Nephelokokkugian two years ago,’ said Jenny.

‘There was a furore.’

Benny had become completely tangled up in her tent.

She threw the half-folded thing down on the ground in disgust. ‘Any inscriptions?’

‘Not much,’ said Zaniwe. ‘A few symbols on the temple, or they might just be illustrations. I’m surprised Professor SmithSmith even let us come out here again. She thinks this is all a waste of time.’

Benny aimed a kick at her tent. ‘I wonder what they were like...’

Couldn’t get the canopy open.

‘Are you ill?’

Chris looked at Roz in surprise. ‘No, no, I’m fine!’

The small, hot sun was just starting to disappear into the trees. They were walking through a field, along a track in the grass made by passing machinery. Their boots squelched in the damp soil.

‘You’re very quiet.’

‘I was just thinking. That’s all.’

‘What about?’

‘Stuff,’ he said. ‘It occurred to me that if you had a gene for psi powers, you’d probably know about it.’

The sun was behind him, making her squint up at him.

‘What?’

‘Wouldn’t your family pedi... um, history mention something like that?’

‘It doesn’t,’ she said shortly. ‘But think about it. These genes are recessive, and rare. Like one-in-a-million rare.

They could be passed down through a family for generations before they showed up in someone.’

‘They can’t be all that rare. The Doctor says that the proportion of affected colonists is levelling out around fourteen per cent.’

‘Makes you wonder about how they selected them, doesn’t it?’ Roz shrugged. ‘I don’t know a damned thing about abnormal genetics.’

‘I don’t know if that’s the right word,’ mumbled Chris, and suddenly he had drawn his blaster and was pointing it at a bush. ‘Come out of there!’ he yelled.

Roz was half a second behind him ( Damn, that was fast! ), in time to train her weapon on the tiny creature who emerged from the foliage. Terrified eyes above a hideous black snout. She shivered when she realized it was a little girl. Even she could have burned the kid from this distance.

They lowered their weapons. The child hovered for a moment, then bolted, running up the path towards a small silver dome.

‘She can lose the filter mask,’ said Chris, looking shaken.

‘Don’t these people read their e-mail?’

‘Let’s see if we can convince Mummy and Daddy.’ Roz strode up the path after the girl.

There was a forcefield around the dome, marked with small flashes of light at eye level at two-metre intervals. They looked like tiny candle flames circling the house, warding off evil spirits.

Roz found a comm screen outside the forcefield. She tapped at its call button for a couple of minutes.

‘There’s no sign of the kid,’ said Chris, who’d jogged around the house.

‘Nobody home,’ said Roz, giving the comm screen a final thump. ‘They’ve made a run for it.’

‘No,’ said Chris, ‘they’re here...’ He squinted at the house, as though in intense concentration.

‘Are you trying to have an idea?’ said Roz dryly.

‘We just need to get their attention.’ Cwej drew his blaster again, and pumped a single shot into the forcefield.

It absorbed the shot, sent its energy spinning around the field as flashes of blue and violet light. He waited for the blast to dissipate, and was raising his gun for a second shot when the comm screen bleeped.

‘What? What?’ shouted a man, his face distorted by the flat surface of the screen. He was very blond. A filter mask hung around his neck.

‘Mr SmithSmith?’ said Roz.

‘Don’t try to breach the forcefield,’ he said. ‘I’m willing to defend my home with deadly force.’

Roz rolled her eyes at Chris. ‘Mr SmithSmith, have you received the message from Doctor St John?’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘Then why is your daughter wearing an air-filter mask?’

‘There’s nothing the matter with taking additional precautions,’ said Mr SmithSmith.

‘I understand you have religious concerns,’ said Roz.

‘But the masks and the forcefield aren’t going to help you.

You ought to come back to the habitat dome for tests.’

‘“Religious concerns?”’ said SmithSmith. ‘We’re pretty tired of people making us out to be weirdos.’

‘Mr SmithSmith,’ said Roz, with infinite patience, ‘your Personal beliefs are none of my business. I’ve been asked to Come here to make sure you understand the medical facts of the situation. You obviously do. Now it’s up to you.’

She snapped off the comm screen. ‘Weirdo,’ she muttered.

Chris was staring off into the forest. She tugged on his arm until he looked down at her. ‘Let’s leave them to it,’ she said. ‘They’re the last ones who haven’t been tested.’

Chris said, ‘Except us.’

‘We don’t need to be tested,’ said Roz. ‘No inoculations, remember?’

‘Oh, come on, it’s just a little pinprick.’ He held up a finger in front of her face. ‘Right here. You’ll hardly feel it.’

‘Chris, what’re you talking about?’

He shrugged. ‘I just thought... well, there’s no sense in taking chances...’

Sometimes you’re such an idiot, she thought irritably. He turned away, his brow wrinkling. She punched him on the arm.

‘We’ll see what the Doctor says. Come on.’

‘The Doctor says,’ said the Doctor, ‘that he’s busy right now, and you ought to let Cinnabar take you home and feed you.’

The Doctor and Byerley had been muttering and clattering in the small lab for hours. Now it was getting crowded. Cinnabar had turned up, her shift in cybernetics complete. And Cwej and Forrester always took up a lot of room when they were wearing their armour. Chris had folded his arms tightly, as though worried that he would be asked to buy anything he broke.

‘Begone,’ said the Doctor. ‘This is going to take hours.’

‘What is it you’re doing?’ Roz insisted, as Byerley clattered past with an incubator tray full of blood samples.

‘We’re sequencing ten different strains of the virus.’

‘Sequencing?’ said Cinnabar.

Byerley said, ‘Working out the sequence of base pairs in the DNA. Decoding the genes.’

‘You’re decompiling it?’

‘Yes,’ said the Doctor. ‘Or we would be if it weren’t for all these sightseers. Scat.’

‘Once we have the sequence, we can work out what each of the genes is supposed to do,’ said Byerley. ‘There’s a lot more to this bug than just the powers.’

‘Crackers sometimes hide their names in the code of their computer viruses,’ said Cinnabar. Will the sequence give you some idea of where the virus came from?’

‘Very probably,’ said the Doctor. ‘ Exeunt.’

Cinnabar sighed. ‘Ration cubes?’ she asked the Adjudicators.

Byerley and Cinnabar lived in a single room at the edge of the habitat dome. Chris had to fold himself up to get under the door lintel, and sit on the single piece of furniture that doubled as bed and lounger. He tugged at the catches on his armour, awkwardly, yawning. Roz leaned back against the wall, shutting her eyes, pretending to be comfortable, even when he kept banging her breastplate with his elbow.

‘We’re both hopeless in the kitchen.’ Cinnabar grinned.

‘Such as it is. I think we’re lucky to be stuck with ration cubes, for a while at least.’ She started heating up some of the ubiquitous slabs of processed food. ‘Though we’re not going to lure anyone else to Yemaya on a diet like this.’

‘I’m surprised there are so few of you to start with,’ said Roz.

Cinnabar sat cross-legged on the floor, next to the low stove unit. ‘We’re the pioneers, the ground-breakers. Well, really, we’re a sort of test.’ She tugged absently on a loose thread in her jumper. ‘The idea is that a few hundred highly skilled people and their families are planted here. If we make a success of the place, if we manage to raise a crop and we don’t get eaten by alien monsters, then more colonists are sent.’

‘What happens if it goes wrong?’ said Chris.

‘We get taken home again. Unless they decide for a second try, but that doesn’t often happen. They’ll just strip-mine the place and then use it as a prison colony.’ The stove pinged, and she pulled the cubes out. Earthlike planets are a dime a dozen. And too many colonies have been wiped out.

Better to risk a relatively small group at first.’

She handed Roz a cube and a utensil. Chris took his plate awkwardly, still trying to struggle out of his breastplate.

The Older woman said, ‘What will you and Byerley do?’

‘I don’t know.’ Cinnabar put her plate down, suddenly. I just don’t have any idea.’ She pushed her face into her hands. ‘I don’t think anyone knows.’

Benny blinked awake and wriggled her hand out through the tent opening. It wasn’t just raining, it was pelting down.

She rolled over, and sloshed.

‘Holy tents, Batman!’ There was an inch of water in the tent. She pulled her torch out from inside the sleeping-bag and shone it around. Yep, there it was — a long rip in the side of the tent, probably created by her desperate fumbling with it earlier in the day.

She wriggled out of the narrow plastic tube, the torch beam swinging around in the blackness. Zaniwe was sticking her head out of the other tent. ‘What’s up?’

‘My tent’s awash!’ Benny shone the torch on the rip.

‘You’d better grab your stuff and come in here then!’

shouted the black woman over the rain.

‘You’re sure that’s okay?’

‘Of course! Get in here before you drown!’

Benny knelt on the wet rocks in front of her tent, rummaging inside. Most of her stuff was safely tucked away in the backpack. She threw in her boots and a soggy National Geographic, zipped the bag up, and dived for cover.

It was a tight squeeze, even though Zaniwe’s and Jenny’s tent was much larger than Benny’s. Several moments of giggling, wriggling and fumbling with a lantern followed. Finally Jenny got the light to work, and Benny discovered she was wedged upside down between them on top of their sleeping-bag.

‘This is a little intense.’ Zaniwe groaned. ‘Sorry, folks,’

said Benny, wriggling.

‘We have been awake for some time in any case,’ said Jenny, sitting up on one elbow. ‘Talking about Cinnabar and Byerley.’

Benny unzipped her pack, got out her big coat and started tugging it on. ‘Oh yes?’

‘About their wedding, actually,’ said Zaniwe. ‘Did they tell you about it? Just before you turned up.’

Benny shook her head. ‘Cinnabar mentioned they’d had to stop the ceremony partway through.’

‘Yep. It was a catastrophe. They should have done it before coming here. We did it before coming here.’

‘It is possible that they would not have been ready before coming here,’ said Jenny.

Zaniwe flapped her hands about. ‘We were the bridesmaids,’ she said. ‘Cinnabar’s family is Reformed Independent Neo-Anglican, so she wanted the ceremony done properly. They had to improvise a bit, though. Captain Kamotja stood in for the father of the bride and was best man, or woman, or whatever.’

‘We cut some of the coloured plants from the undergrowth to substitute for flowers,’ said Jenny. ‘The Chaplain was astonished when he discovered the chapel was full of them.’

‘Everybody crammed in there. Cinnabar and Byerley had borrowed a couple of uniforms from the crew. They looked great.’

‘We got about as far as “Dearly beloved” when one of the kids started crying.’

‘Don’t tell me,’ said Benny.

‘She was only four,’ said Jenny. ‘She was levitating. It terrified her.’

‘We had to stop everything while Byerley got her down from the ceiling and took her to the lab.’

‘A catastrophe,’ repeated Jenny.

‘So, when are they planning another try?’ said Benny, trying to make herself narrower as she snuggled down between them.

‘Dunno.’ Zaniwe yawned. ‘They’re probably waiting for all of this to resolve itself before they try again.’ She reached over and put the lantern out.

‘There’s something I’ve been meaning to ask,’ said Benny sleepily. ‘Why didn’t the Captain call off-world for a medical team? Byerley’s good, but he could use some help.’

‘We came here because we believed we could look after ourselves,’ said Jenny. ‘It would be a mark of failure to ask for assistance now.’

‘Eep,’ said Benny. ‘I hope this doesn’t mean our help is a sort of insult.’

‘Don’t be ridiculous.’ Zaniwe elbowed her in the back.

‘Go to sleep.’

Couldn’t get the canopy open.

Chris was dreaming that he was walking through the forest. In the dream, he was wading through water that was almost knee deep, struggling to move his legs and keep his eyes open, the way you do in dreams.

Got caught in the blast.

It became harder and harder to keep battling along in the darkness. He banged his foot onto something and tripped over.

When he woke up, he was astonished to find himself actually in the forest.

‘Whoa,’ he said out loud. ‘Brain check.’

He flinched at the volume of his voice. It was nearly pitch black; the tops of the trees were defined by the stars they blocked out.

Finagle’s nostrils! Where was he? And what was he doing out here? Sleepwalking? He couldn’t remember ever having done that before. How long had he been wandering about like this?

His bare feet were soaked with dew, and he was freezing cold. He was just wearing the stuff he’d gone to sleep in, a Jets T-shirt with a huge hole under one arm and a pair of old tracksuit pants. The last thing he remembered was muttering

‘Lights off’. They’d been staying in the TARDIS, for once; the colony just didn’t have room for them.

Chris squinted. Was that a glimmer of light through the trees? It must be the habitat dome, or one of the surrounding buildings. The TARDIS was parked barely fifty metres from the base, an odd blue bump in the even field. He set off in the general direction of the light.

He jumped back as a low-hanging frond brushed against his face. He reached out to the celery-stick tree, leaned against it while he got his balance back.

A flash of heat so huge it went right through him, from one side to the other. Flame blossomed across his skin as his fur kindled. He tried to scream, but his mouth was full of fire.

He ought to be safe in the TARDIS. Safe from anything.

If he had to, he’d just stay there. There was no point in making a fuss about it. He might not be much use to anyone, but he’d just stay inside.

Chris!

He whirled around, fingernails raking at the juicy bark of the tree. ‘Who’s there?’ he yelled, like a frightened kid.

But there wasn’t anyone there. He frowned.

‘There’s no point in making a fuss about it,’ he told himself, and set off for the TARDIS.

Benny poked her head out of the tent. ‘It’s stopped raining,’

she said.

Zaniwe and Jenny muttered and stretched as the archaeologist climbed out, glad of her big coat. The ground was soaked, the stones slick with water. The waterfall had swollen, sending great clouds of spray into the air. The morning light was refracted through the drifting droplets.

She unzipped the front of her tube tent. Water rushed out in a puddle around her boots. She looked down in disgust.

‘D’you think it’s fixable?’ said Zaniwe, wriggling free of the tent. ‘No offence, but I don’t think I want to play sardines again...’

Benny grimaced, kneeling down by the side of the tube.

‘I’ve got a patch kit, but they’re not very large. I’ll try putting a couple on.’

‘Wait until after breakfast,’ said Zaniwe, yawning hugely.

‘Ration cubes once more,’ said Jenny, emerging.

‘Scrumplicious,’ said Zaniwe, sticking out her tongue.

‘We can heat them up a bit, I guess.’

‘Can we eat any of the native plants without our heads exploding?’ said Benny, dragging her sodden sleeping-bag out of the tent.

‘We don’t have the list of edible species with us,’ said Jenny shortly. ‘Ration cubes it is.’

Benny hung her sleeping-bag over a tree branch to dry while Zaniwe cranked up the portable electric stove. If only a soggy sleeping-bag and an unappetizing breakfast were the worst problems on the planet.

She tugged at the tube tent’s support lines. Maybe this was the reason the Doctor had asked her to come out here

— nothing more sinister than realizing she needed a bit of a break. A spot of fresh air and a bit of rummaging about in some interesting alien ruins. She could get back to worrying about the colonists when she got back to the colony.

Heck, she hadn’t even brought any booze.

‘I’ve even got the knack of this bloody tent,’ she said out loud, pushing it back from the opening at the front. It obligingly accordioned back until it was only a foot long, leaving the rip still visible. She picked it up, tipped it to get the last of the water out, and hung it on the tree.

Zaniwe handed her a lukewarm cube, still in its wrapper.

She tugged at the plastic, and a small burst of spinach-flavoured steam escaped into the chilly morning air.

‘So what’s a nice girl like you doing on a frontier world like this?’ said Zaniwe.

‘Oh, we just dropped in,’ Benny obfuscated. ‘We travel a lot. And the Doctor’s always poking his nose into other people’s business.’

‘I am glad you are here.’ Jenny was perched on a rock, breaking off little pieces of crumbly cube in her fingers. ‘It is just surprising to encounter travellers this far out.’

Change the subject. ‘What made you decide to come here?’

Zaniwe laughed. ‘We were bored. It’s very boring being stuffed into a three-metre-by-three-metre flat. It’s very very boring to have a degree in xenobiology and no aliens to study.’

Jenny said, ‘We have a plan. It is not legitimate to name a species after oneself. Therefore, as we classify Yemaya’s flora and fauna, we will name them after one another.’

Benny giggled. ‘You could really make it big,’ she said, ‘if you can study the planet’s previous inhabitants.’ A sudden thought hit her. ‘You don’t suppose they’re not previous at all...’

Jenny looked around at the trees. Zaniwe shook her head. ‘Come on, those ruins are ruins. Even from the photos, it’s obvious that they haven’t been in use for a long, long time.’

Make no assumptions.

‘I’d better try and patch up this tent.’

As she walked back to the tree, her boot collided with something. She looked down, then squatted.

It was a long, sharp rock, sticking up like a blunt shark’s fin from the soil. ‘I think,’ she said, fingering the edge, ‘I’ve found out how my tent got holed.’

There was something odd about the rock. She tugged at it, and it came away from the soil easily. It was heavier than she’d expected.

And there was writing on it.

Benny stared at the red shapes behind the dirt. She brushed at the stone with her fingers, trying to make it out more clearly. This was going to be one of the easier archaeological discoveries ever made.

‘What is it?’ said Jenny, coming over to take a look.

‘Ye gods and little fishes,’ said Benny aloud.

Jenny peered at the piece of rock. No. The piece of metal.

It said, in faded letters, DO NOT.

4 The Queen’s Temple

The Doctor had been awake all night, but that was normal for him. One good night’s sleep could last him a couple of weeks.

Byerley was not so fortunate. Cinnabar had dispatched Cwej and Forrester to remove her fiancé bodily from the lab and bring him home. Now she was watching the Doctor finish off their research, typing so fast on the little medical computer that she could barely follow.

‘Do you think you’re going to be able to find a cure?’ she said.