Elementals – Read Now and Download Mobi

Table of Contents

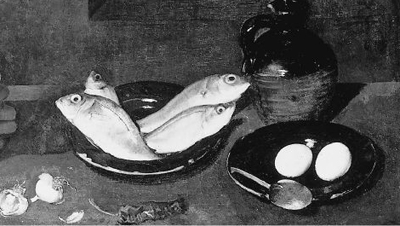

Christ in the House of Martha and Mary

For Claus Bech

ACCLAIM FOR A. S. BYATT’S

Elementals

“[Byatt’s] prose has a lustrous yet exacting shimmer that answers to Keats’s injunction that poetic language should ‘surprise by a fine excess.’”

—The Boston Globe

“Energetic and magisterial . . . full of light and life.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“Sparkling. . . . [Byatt’s] vivid prose leaps and pirouettes, shimmies and shivers.”

—The Wall Street Journal

“Harnesses a brilliant new power. . . . Byatt has reached back to legend and fairy tale, elements of storytelling as basic and combustive as fire and ice.”

—Los Angeles Times Book Review

“A collection of richly imagined stories etched in such vivid color, sensuousness, and language that they seem like art objects. . . . A delight.”

—Richmond Times-Dispatch

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my Norwegian editor, Birgit Bjerck, for telling me about the one tree, and for information about Peer Gynt. I am also grateful to David Perry for commissioning the ekphrastic tale about Velasquez. My husband, Peter, gave me a central idea about Jael, and Helen Langdon found several images of Jael that were most illuminating. I am, as always, grateful to Jenny Uglow, best of readers, for patience and inspiration. And also, as always, to Gill Marsden for order out of chaos.

The author and publishers are grateful for permission to reproduce the following illustrations:

Nîmes crocodile: from The Crocodile of Nîmes by W. Froehner, Paris, 1872; Sirène by Henri Matisse: from Ronsard’s Florilège des Amours. Collection Musée Matisse. © Succession H. Matisse/DACS 1999; Façon de Venise goblet: © Sotheby’s Picture Library; Jael and Sisera, School of Rembrandt: Kent County Council, from the Kent Master Collection; detail from Kitchen Scene with Christ in the House of Martha and Mary by Velázquez: © National Gallery, London.

Crocodile Tears

Le Crocodile de Nîmes

Crocodile Tears

Patches of time can be recalled under hypnosis. Not only suppressed terrors but those flickering frames of the continuum that, even at the time, seem certain to be forgotten, pleasantly doomed to nonentity. So they have sunk into our brains after all, are part of us. Patches of time is a mild metaphor, mixing time and space, mildly appropriate in art galleries, where time is difficult to deal with. How do you decide when to stop looking at something? It is not like a book, page after page, page after page, end. You give it your attention, or you don’t. The Nimmos spent their Sundays in those art galleries that had the common sense to open on that dead day. Not the great state galleries, but little ones, where some bright object or image might be collected. They liked buying things, they liked simply looking, they were happily married and harmonious in their stares, on the whole. They engaged a patch of paint and abandoned it, usually simultaneously, they lingered in the same places, considering the same things. Some they remembered, some they forgot, some they carried away to keep.

That Sunday, they were in the Narrow House Gallery, which specialised in minor English art, drawings, prints of flowers, birds, angels, hand-screen landscapes and pop art posters. It was higgledy-piggledy, with real plums in the duff, Tony Nimmo used to say. The Gallery was in Bloomsbury, in what had been an eighteenth-century private house; it went up and up, with small rooms opening off a turning stair, which was also hung with stags and sunsets, garden gates, watering cans and silver lakes with swans on. They always had a good pub lunch on these Sundays. This one was a sunny Sunday in early May, a really sunny Sunday that narrowed the eyes in the light, that warmed the skin, even through glass. Patricia ate prawn salad; she was watching her figure. Tony ate a robust beef and ham platter with pickles and onions. Then he had brandy syllabub. And two pints of Special. He was a large man, with a bald crown above fine dark hair. His face was peacefully reddened, a pale poppy flush. They were in their middle fifties. Patricia wore a butter-yellow suit, nipped in at the waist, and a bronze silk scarf. Her hair was bronze too, fanning up and out. She had good big breasts and a generous bottom, solid and lively. On the top floor of the Narrow House, they had one of their rare disagreements.

The disagreement was about a work called The Windbreak. It was small; about two feet long and one foot deep, framed in a deep, polished dark wooden frame, with brass nails. It was part collage, part oil painting. It was a seaside scene, an English seaside scene, with a blue-grey sea, flecked with dirty white, stretching to meet a pewter sky with livid oily blue patches. These took up the top two-thirds of the work. The beach had real sand scattered on a fawn surface, and tiny real shells and bits of seaside plastic reconstituted into tiny windmills and buckets and spades, sugar-pink, turquoise-blue, poster-red. Much of the left part of the beach was taken up with the windbreak. This was made up of painted cloth, in rainbow stripes, stretched on wooden pegs, representing stakes. There was also a coloured ball, Day-Glo orange with green stars on it. Patricia’s indifferent glance slid over this object; she had seen, in other patches of time, hundreds more or less like it; she moved on to contemplate a delicate six-inch-square dandelion clock on a cobalt-blue ground. Tony, however, was taken with The Windbreak. He went up to it, and peered into its glass box. He stood back and stared. He smiled. Patricia, when he called her, turned back from the dandelion, and saw him smiling.

‘I like this,’ said Tony. ‘I really like this. It isn’t much.’

‘You can’t like that, darling. It’s banal.’

‘No, it’s not. I can see how you might think it was. But it’s not. It’s just simple and it reminds you of things, of whole – of whole – oh, of all those long days of doing nothing on beaches, you know, the mixture of misery and being out in the air and sort of free – of being a child.’

‘Banal, as I said.’

‘Look at it, Pat. It’s a perfectly good complete image of something important. And the colours are good – all the natural things dismal, all the man-made things shining – ’

‘Banal, banal.’ Patricia did not know why she was so irritable. It had been a good lunch. She could even, secretly, see what the memory-box would look like to her if she had liked it, as opposed to disliking it. Tony and the unknown artist shared an emotion, shared a response to the conventional images that evoked that emotion. She didn’t, or if she did, it provoked opposition.

‘I like it,’ said Tony. ‘I’ll buy it, it can go in my study, in that space by the window.’

‘It’s a complete waste of money. You’ll go off it in no time. I don’t want a thing like that in the house. Look at the dreadful predictability of those colours.’

‘Don’t be so snooty. It’s about the dreadful predictability of those colours. About sad English attempts to cheer up sad English landscapes.’

‘They don’t have to be sad. Not the English, not the colours, not the landscapes. It’s a dreadful cliché.’

‘Clichés are moving.’

‘I don’t want it.’

‘I do.’

‘I can’t stop you,’ said Patricia, walking away, past a green maze, past a departing galleon, past a hunt in full cry. She was upset; the good Sunday was threatened by Tony’s bad taste. She turned round to tell him that it didn’t really matter, that of course he should buy the windbreak if he wanted it, and found that she was alone in the upper room. She could hear his heavy tread winding down the stairwell. She would make it up later. Leave a space, make it up later. She turned back to the walls – a blown sheep on moorland, a huge black bull, staring furiously out of the canvas, a fragile bunch of teasels. Later all this would come back, without hypnosis.

It was perhaps half an hour before she went downstairs. She was wearing high-heeled sandals, so she went very carefully round the turns of the stairs, holding on to the banister. There was a noise downstairs, of doors, of voices; she could hear no words, but she could hear agitation. There were thuds, there was hurry. Outside, there was a siren. Cautiously, she turned the last corner. She saw the backs of a tight group of people bending over something at the bottom of the stairs. A man in a green sweater, who had been kneeling, stood up. He was holding a stethoscope. ‘Dead,’ he said. ‘I’m afraid. Instantly. A massive infarct, I suppose. No hope, I’m afraid.’ Outside, a stretcher was being carried in from an ambulance. The group split, and stood back, and Patricia saw Tony, lying on his back, on the carpet, below a large painting of an avalanche. His red face was ivory. The doctor had closed his eyes but he did not look peaceful. His jacket and shirt were opened; the grey hairs on his chest were springy. His belly was a proud mound. His shoes were splayed. Patricia stood by the banister. The ambulance-men came in with the stretcher. As the group gathered again, Patricia walked quickly behind them, and out of the open door, into the street. She walked away, quick, quick, with her head up. She stood beside the flowing traffic on New Oxford Street. A taxi came past with a gold light in a black frame. She waved, it stopped, she got in. She gave her home address, which was in Wimbledon. The driver said something, which she did not hear. She sat, clenching both fists on her handbag. It was quick.

Inside her own house she walked from room to room in the May light, and then went upstairs and packed a small suitcase. She was an efficient woman, and she packed for a business trip – a nightdress, cheque-books, the usual pharmacopoeia, uncrushable trousers and tunics, slippers. Washing things, make-up, lap-top, mobile phone. Universal adaptor. Passport. Then she looked round her bedroom, their bedroom, and left it. She called a taxi, and looked round the drawing-room. A few photographs smiled at her: Tony in tennis things on the bookshelf, the children twenty years ago. She turned these face down. The phone began to ring. She did not answer, and after a time, it stopped. Then it began again. The taxi came. She went out, leaving it ringing. In the taxi, she realised that she should have changed out of her sandals, and nearly burst into tears. She told the taxi-driver to go to Waterloo. At Waterloo she walked from the main station to the Eurostar terminal, covering her tracks perhaps, and bought a ticket to Paris. It was smooth, it was easy, there was a train in half an hour. She flowed with the crowd onto the platform, carrying her little bag, and at the top of the escalator, catching sight of her dim reflection in the train window, she nearly began to weep again because of the memorable brightness of her yellow suit.

She found some dark glasses in the pocket of her case, and leaned back in her seat, staring out at fields and hedges. She refused food, refused newspapers. She slept. She woke in the dark tunnel, in a swaying space, and for a moment did not know who or where she was, only that something had happened. Then she began to worry about money. How to have money without being traced? She had money, she was the founder and managing director of a chain of shops, Anadyomene, that specialised in bathrooms. The question was, how to have money where she was going, without being traced. She had thought about this before. Vanishing without trace was an idea that had teased her through all the happy years of her married life, her working life. The idea that it was possible to vanish, that there was nothing ineluctably necessary about her work, or her home, was a condition of her pleasure in those things.

She did not think, at this point, about who might trace her. She had a daughter, Megan, and a son, Benjamin, Ben, Benjie, both grown-up and married, but they were not the pursuers she figured to herself.

She did not know where she was going.

They brought champagne in little tub-like tumblers, and this she accepted. She felt a light-headed pleasure in the fact that she did not know where she was going. It could be anywhere at all, anywhere at all. How many people was that ever true of? The train came out of the tunnel.

She had booked to Paris, but she got out at Lille. She bought a ticket to Nice, and climbed into a TGV, going south. It was now evening. Lille station was darkening. She remembered early versions of the imagined escape. The young bride’s version, standing solitary on the heaving deck of the cross-Channel steamer, a vision complete with wake, spray, crying gulls, and the moving troughs on the surface of the salt deeps under which she had just shot, sitting in her dark glasses by her brightly lit window. The successful woman’s version, the rising nose of the aircraft breaking through the white froth of cloud into clear blue and sunlight, the space of creamy-curded water-vapour, the silver purr. Anywhere, at the end of it. Anywhere, nowhere, somewhere. The train was without shock. But quick. The darkening fields flung past, unreadable indicators hissed past, the sky went turquoise, Prussian blue, indigo, rusty black in the lights of the way. She slept. She dreamed, and when she woke, remembered that she had dreamed something she didn’t want to remember. Her mind ran loose and nauseous, for a moment, and then she began to worry about credit cards, about whether they could or would trace credit cards. The world was small now, which was good, you could move in it with ease. But everything was linked to every other thing, and that wasn’t good.

She got out at Avignon, several hours later, and took a train to Montpellier and Barcelona. Shortly after Avignon, the train stopped at Nîmes, and there she got out, it was perhaps the coincidence, the almost coincidence, of the names, Nîmes, Nimmo, that decided her. It wasn’t a city she knew anything about. No one would look for her there, for that reason. She set off, in the warm southern darkness, on the high-heeled sandals in which she had come down that staircase, carrying her bag. The city has big boulevards, with plane trees, and she kept to these, walking briskly, past cafés spilling light on to dark pavements, past squares, past alleys. She followed signs to ‘Jardin de la Fontaine’ because that sounded like a refuge, and thus found herself outside the Hôtel Impérator Concorde, which looked, and was, large and comfortable. She went in, and booked a room. The room was curtained and shuttered. There was a large bed, with a sprigged Provençal quilt, rose and gold on cream, to match the curtains, which she pulled back, revealing tall, sun-blistered shutters and a small balcony. She looked out; below was a walled garden, full of trees, cypresses and olives, and with a fountain bubbling in golden light in a pale green-blue pool. She closed the shutters again. She found she had a semicircular bath in tawny pink, tiled round with eighteenth-century birds in pink on white glaze. She bathed, and put on her nightdress. She put out the lights and got into the large bed. She remembered briefly, the windbreak and the painted avalanche, broken trees and dislodged rocks in the arrested crush of carefully painted snow. She thought she would move money, tomorrow, out of the Jersey account, and then move it again, and then move it again. The bed was like a nest, the pillows frilled, the sheets crisp. She was afraid of not sleeping, but slept. In the morning there were bright needle-stripes of light in the shutters. When she opened them, there was the blue sky, full of pale yellow light.

Breakfast was on a terrace, sheltered by a glass wall, under a canopy. Beyond the terrace was the walled garden, with sandy paths, the bubbling fountain in its stone-rimmed pool, and a huge stone bowl overflowing with ivy-leaved geraniums, scarlet, crimson, pink. There were tall cedars and pointed yews; there was a group of silver olives, and cypresses. There was bright light, shade. It was the South. Under one of the cedars a man was writing at a folding table. He was a blond man, with a head of glittering pale curls. His long legs encompassed the little table. He wore white trousers, and a pale, blue-green linen jacket.

After breakfast Patricia went out. The hotel looked across the Quai de la Fontaine to the Jardin de la Fontaine, a landscaped eighteenth-century space, with orderly terraces, stone stairs, balustrades and carved fauns and nymphs. The houses along the quai are dignified, heavy, eighteenth-century, barred and shuttered. A wide channel of green water runs under bridges, under high plane trees, along the quai. In the distance a fountain rose and shone in a high foaming spray. Patricia turned the other way, into the narrow streets, crossing a wide boulevard. The buildings are close together, made of warm cream and gold stone, with roofs of overlapping terracotta tiles. Patricia walked. She walked between heat and shade, from cool stony courts to sudden bright squares, between heavy carved doorways into white spaces where she blinked and saw water. She saw many fountains, pouring from huge stone mouths, trickling over stones, bubbling in circular pools around bronze figures or flowing along channels. Once she saw a high sculpted crested monumental spout in the centre of a grassy place she did not cross, turning back into the small streets. She began also to notice crocodiles on bronze studs in the streets, the reptile chained to a palm tree. The same motif was repeated in windows, on street signs. A life-sized bronze monster crawled over the edge of a fountain in a quiet square. She sat beside the water, under a parasol, and ordered a coffee. She was a girl, a girl on her first solitary trip abroad. She stared at the energetic bronze claws and curving tail, as she had stared at the golden stones and the blue sky and the shadows, curious and indifferent. ‘Your serpent of Egypt is bred now of your mud by the operation of your sun: so is your crocodile.’ He had played Lepidus. He had wanted to play Antony but had had to be content with Lepidus. She remembered, with her fingertips, smoothing artificial sun-tan into his white English tennis-playing thighs, sinewy and pale. She remembered the toga. She stood up again, leaving her coffee untouched, and began to walk. She stepped lightly, like a girl.

She shopped. She bought a pair of flat white sandals, two pairs of linen trousers, and some floating dresses in airy cotton, painted with dark purple grapes on a yellow that was French, a mustardy ochre-yellow, not like the daffodil-yellow of the bright suit she had travelled in. In the Rue de l’Aspic she found an elegant bathroom boutique and spent time in front of mirrors holding up lawn nightshirts printed with seashells, gowns sprigged with mimosa on glazed cotton, a classical column of falling white silk jersey pleats, which she bought, adding a pretty pair of golden slippers, and a honeycomb cotton robe, in aquamarine. These things gave her pleasure. She told the proprietor, an elegant young woman with dark hair and eyes, and a Roman nose, that she herself was in the business. She spoke a slow, clear, grammatical French. She had meant to be a theatre designer; they had all been theatre-mad, at university; but she had made a success of Anadyomene instead. She admired a treasure-cavern full of translucent beakers in sand-blasted glass, rosy, nacreous, powder-blue, duck-egg. She bought a gold-and-silver striped toothbrush. She went out and walked. She went back to the hotel, and ate lunch on the terrace, in the dappled garden, listening to the steady plash of the fountain. She went upstairs, arranged her purchases in cupboards and drawers, closed out the afternoon heat with the heavy shutters, and slept, curled on the counter-pane. In the evening she took a bath, dressed in her new dress, and went down to dine on the terrace. There were stars and a new moon in an indigo sky. The fountain was lit from underneath, like a moving cube of glass or ice, white with blue shadows. An owl called. She had a floating candle on her table in a tall-stemmed glass cup. She saw these things with the pleasure of a post-war girl. She ate a salad of avocados and fruits de mer, arranged like an open flower; she ate loup de mer, a small silver square of fish criss-crossed with golden lines, on a bed of melting fennel; she ate red berries in a bitter chocolate cup; she drank Pouilly-Fumé. There was an excess of pleasure in the simplicity: stars, flames, water, the scent of cedars and burned fennel, the salt of olives, the juicy flakes of the fish, the gold wine, the sweet berries, the sharp chocolate, the warm air. She ate ceremoniously. There were other murmuring diners. At the other end of the terrace was the long man with the mass of blond hair. He was bent at an angle, holding a book to the light of his candle. She thought: tomorrow I will get a book. She thought slowly: getting a book was a pleasure proposed, like the purchase of the nightdress. After dinner, she went upstairs, bathed again, slowly, in the circular bath with its Provençal sprigged curtains, put on the pleated nightdress, and slept. A crocodile slipped through a dream, and went under the surface as she woke. She breakfasted on the terrace, and went out again to walk in the little streets.

The next few days she repeated. She ate, she slept, she walked, she shopped. She learned the little streets, and arrived from many narrow openings at the heavy, high pile of the Arènes. It was a closed golden cylinder, made of tiers of immense arches. She avoided it. She swung back into the narrow streets. They brought her out to the Maison Carrée, a severe cube with tall pillars, ancient in its sunny space, and to its elegant shadow, the Carré d’Art, a vanishing and beautiful series of cubes of silver metal and grey-green glass. She went into neither. In a bookshop she bought a guide to Nîmes, a town plan, a dictionary and the three Pléiade volumes of A la recherche du temps perdu, in French. It would be her project. She began to read in the after-lunch hush, and soon saw that her dictionary was inadequate. She returned to the bookshop, and bought their largest. Her French was not good enough to read Proust. She had to look up twenty or thirty words on each page, so that she pieced together the world of the novel in slow motion, like a jigsaw seen through thick, uneven glass, the colours and shapes hopelessly distorted, the cutting lines of the pieces the only clear image. This difficulty encouraged her to persist. She would learn good French, and then she would see Proust. She could not, she thought, sustain an interest in anything easy, a detective story or anything like that. A project was good. She bought a notebook and made a patient and lengthening list of words she couldn’t understand in Proust. She sat in the walled garden of the Hôtel Impérator Concorde, under the cedars, at a wrought-iron table. Scented gum dropped on the pages of Du côté de chez Swann. Mosquitoes hummed like wires. Under another tree the blond man read and wrote furiously. His wrist-movements were ungainly. He rocked the table as he wrote.

She had her hair cut. Her English waves became a close shining cap. ‘I am reading Proust,’ she told the hairdresser, a young man in black, with the Roman nose of the Nîmois. ‘That will take a very long time,’ he observed. In the little guidebook, studied over coffee in the Place de l’Horloge, and the Place d’Assas, she had discovered that the ubiquitous emblem of the crocodile chained to the palm tree derived from an Augustan coin, dug up in the Renaissance, with crocodile, palm and the phrase, COL NEM, Colonia Nemausis. It was believed that Nîmes had been peopled by Augustus’s legionaries, to whom he had given the land in gratitude for their victory over Antony and Cleopatra, on the Nile. François I of France had granted the city the same coat of arms, in perpetuation of the myth. The guidebook said there was no reason to believe the story. Patricia, sitting by the solid and gleaming bronze crocodile in the Place de l’Horloge, had a sudden vision of Tony in a toga, white against the white light and the white spray of the fountain. They had met through student theatre, a classical world of greasepaint and sewn sheeting and Shakespearean rhythms and clarity and ferocity. He had been Lepidus, and she had sewn and fitted the sheets. Later he had graduated to Hector in Tiger at the Gates, and she had made him a scarlet cloak and a crested Trojan helmet; she had fitted thonged sandals round those stalwart legs. The student theatre was a dark, hot box, peopled by flitting ghosts, too puny for their lines, but fiery, all the same. It was hard to remember, here in this square, where the stones were Roman stones, the spotlit flaring passion of that imaginary wooden box. He had called her Patra, and she had called him Antony, in those days, in secret. Large, kind Tony, through whom Shakespeare’s lines spoke strong and clear, and to her. They had whispered them to each other. ‘I’ll set a bourn how far to be belov’d.’ ‘Then must you needs find out new heaven, new earth.’ They had appropriated what many had appropriated. He wanted passionately to be an actor, for a year or two, and then gave up the idea, quite suddenly. So that the singing words and the brighter light of the dark box became less interesting than the complicated light of common day, so that the drama of international negotiation took over from the eloquent simplicities of love and death and power. But he could always make her smile by calling her Patra. It was a joke and not only a joke. All this she acknowledged and did not acknowledge, seeing and not seeing the lines of Hector’s harness, the folds of Lepidus’s toga on thin air and trickling water, beyond the dark crocodile.

She was getting thinner. She ate, but she got thinner. Other guests came and went, but she stayed. So did the blond man in the blue-green jacket. He had bought a straw hat, like the hat in which Van Gogh painted himself in the days of his madness in the fields of light around Arles. The hats were sold around the Arènes, by itinerant pedlars, woven domes ending in ragged spikes of reeds. It perched on his tough blond curls without denting them. She began to lose her sense of the businesswoman she had been, was. She walked the streets more purposefully as her sense of purpose wavered. Her French was improving rapidly. She would stop and read the local newspaper, the Midi Libre, which was set out on polished wooden rods, in the hotel salon. Most of the contents of this paper concerned bull-fighting. She realised slowly that she was in a bull-fighting hotel; on the walls of the bar were photographs of Hemingway and Picasso who had stayed here to admire the skills of the shining pigtailed dolls, with their braid and gilt and cockades. Later she noticed that the bar itself was called the Bar Hemingway. In the newspaper also were accounts of other kinds of combat, in which the heroes were the bulls, whose more complex rushes were rewarded with standing ovations and renderings of Carmen. There was almost no foreign news in this journal; what there was was North African, bombs in Algiers, tourists attacked in Egypt. And local news: school concerts, the building of cisterns, the pollution of rivers. She read it all, for the French language. One evening she sat on a sofa in the shade and worked her way through it. ‘Yet another traffic accident on the road to Uzès. A man was killed by a speeding car, as he stood on the edge of a vineyard. His body was found by a cyclist. From the marks on the road it was clear that the killer had made off immediately, without stopping to offer help, or to ascertain whether his victim was dead. This is the third such accident in the region this year. The police are searching . . . ’

Patricia began to weep. She thought of the unknown dead man in the road, and tears poured down her face. She moved no other muscles; she sat on the camel-coloured sofa, a dignified ageing woman, with the newspaper in her lap, and her tears splashed on to it, darkening the newsprint, the grainy dark photographed bulls, the catalogue of accidents. She could not move. She could not see. She could not imagine a moment when the tears would stop, or she would be able to stand. She suppressed all sounds; not a whiffle, not a sniff, not a whimper. Just salt water.

After a long time, certainly a very long time, she heard a voice.

‘Excusez-moi, madame, est-ce que je peux vous aider?’ She did not move. The tears ran.

He knelt at her feet, in his blue linen coat, clumsy on one knee. His French accent was clumsy, too. He changed to English, the excellent English of the Scandinavian North.

‘Please forgive me, I think you need help.’

‘No.’ Her voice came from far away. She was not even sure she had spoken.

‘Maybe I can help you to your room? Bring you a drink, perhaps. I cannot watch – I cannot watch – I should like to help.’

‘You are kind,’ she said, and swayed. His words were kind, but his voice was a harsh voice, a cold voice.

‘You have a great grief,’ he said, still harshly. She heard it harshly.

‘It doesn’t matter. I must. I should.’

He put a hand under her elbow and helped her to stand.

‘I know your room,’ he said. ‘Come. We will go there, and then I will send for a drink. What would you like? Tea? Coffee? Something stronger, for the shock? Cognac, perhaps?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Come.’

He supported her to the lift. He called it. It was a gold-barred lift, an old, creaking, handsome lift, like a bird-cage. He managed the doors, he held her elbow, he led her to her room, he supported her. He sat her in her armchair, with its rosy chintz frill, and looked into her swollen eyes. His face swayed before her, a white face, with ledged blond brows, a large ugly nose, blue, blue eyes in deep hollows above jutting cheekbones, a wide, thin mouth with a white-blond moustache.

‘Thank you,’ she said.

‘Let me call for a drink. I think cognac would be best.’

She inclined her head. He used her phone, he called room service. He said:

‘You have a great grief, I see.’

‘My – someone – is dead.’

‘Ah. I am sorry.’

She could think of no answer. She put her head back and closed her eyes. She could feel him standing at a respectful distance, watching her until the waiter knocked. He opened the door, and left with the waiter. She gulped the cognac, shuddering, and went to bed.

When she passed him at breakfast the next day, she nodded silently, acknowledging him. They did not speak, and she thought she was pleased. Over dinner that night, they smiled coolly again, from opposite ends of the terrace, inexpressive northerners. She was surprised therefore, at the end of the meal, to find him bending over her table. He wondered, he said, if she would take a digestif with him, in the bar. He did not mean to take up much of her time. She thought of saying no. There was an awkwardness in his acknowledgement that she might not want to speak to him. She said yes, because she owed him something for his kindness, and because there was no warmth, no pressure, in his invitation. The Bar Hemingway is a glass box, which juts from the terrace into the garden. It is full of warm, deep yellow light. On the walls are photographs of the matadors who have slept in the hotel, who have put on their embroidered waistcoats, their sculpted breeches, their long sashes, in its shuttered rooms, and gone out to dance their absurd deathly dance with cloak and sword.

They sat, side by side, looking out at the dancing blue cube of water in the dark garden. He ordered eau-de-vie Mirabelle, with ice, and she ordered the same, indifferent. He said:

‘My name is Nils Isaksen. I am from Norway.’

‘My name is Patricia Nimmo. I am English.’

The drinks arrived, sweet, white, glistening liquid over shattered fragments of ice. The taste was fire and air, a touch of heat, an after-space of emptiness. And the mere ghost of a fruit. She would have liked to say something banal, to keep communication to a safe minimum, and could think of nothing at all.

‘I am here to write a book. I am an ethnologist. I am studying the relations between certain Norse beliefs and customs, and those in the South.’

It was a prepared little speech. He raised his glass to her. She said:

‘I am on holiday.’

‘I have never been able to spend an extended time in the South. It was always my dream. I, too, have lost someone, Mrs Nimmo. My wife died, after a long illness, a very long illness. I find myself – detached – and – and – well off, you would say? I wanted no longer to see Tromsø. So I work here.’

‘I am sorry. About your wife. I have just lost my husband.’

‘And you do not wish to speak of this. I understand. I do not intend to speak of Liv. Do you find much to interest you in Nîmes, Mrs Nimmo?’

‘I somehow haven’t done the things one should do. I haven’t walked in the Jardin de la Fontaine. I haven’t been into the Maison Carrée, or the Carré d’Art.’

‘Or the Arènes?’

‘Or the Arènes. I find that rather horrifying. I don’t like the idea of it.’

‘I don’t like it either. But I go there, often. I sit there, in the sun, and think. It is a good place to think, for a man from the north who is starved of sun. The sun pours into it, like a bowl.’

‘I still don’t think I’ll go. I find all this – ’ she gestured at the photographs of bulls, matadors, Hemingway and Picasso – ‘simply unpleasant. The English do.’

‘You are temperate people. I, too, find it unpleasant. But it needs to be understood, I find. Why does an austere Protestant city go mad every year, for blood and death and ritual?’

He bent his pale head towards her. His pale blue eyes shone. His bony white hands were still on the table, on each side of his ice-misted glass. She said:

‘I hope you do come to understand it. I shan’t try.’

After this they had several more brief drinks together, in the evenings, which were getting hotter, and heavier. Patricia did not think she liked Nils Isaksen, and also felt that this simply did not matter. The nerve-endings with which she had once felt out the shape of other people’s feelings were severed or numbed. She got no further than acknowledging to herself that he was in some way a driven man. His reading and his writing were extravagant, his concentration theatrical, his covering of the paper – wrong somehow, too much, or was it that she felt that any effort, any energy, was too much? The pleasure was going out of A la recherche, though she persisted, and her French improved. They talked about Nîmes. He told her things she hadn’t wanted to know, hadn’t been at all anxious about, which nevertheless changed her ideas. He told her that the city and the water of the fountain, Fons Nemausis, were one single thing; that this closed, walled collection of golden houses with red-tiled roofs in a dustbowl in the garrigue had been built because of the presence of the powerful source. That the god of the town, Nemausus, was the god of the source. That under and beyond it were gulfs, caverns, galleries of water in the hill. That there had been a nunnery on the hill above the fountain, around the temple of Diana, from the year 1000 to the Renaissance, whose abbesses had claimed ownership of the water. He spoke of excavations, of pagan antiquities, of religious wars of resistance to Simon de Montfort, to Louis XIV, to the Germans. He spoke of the guillotine in the Revolution, and the gibbet in the Second World War. Patricia listened, and then went shopping, or wandering. She thought, if he talked much more, or overstepped some boundary, she would have to move on. But she did not know where she would go. The weather was getting hotter. The weather-map on the television in her room showed that Nîmes was almost invariably the hottest city in France, uncooled by coastal breezes, or mountain winds, a city on a plain, absorbing heat and light. She took longer walks, for variation. She went into the Jardin de la Fontaine in the midday heat, stared into the green troubled depths, climbed the unshaded, formal staircase with its balustrades, observed a crocodile made of bronze-leaved plants in a bed of rose and white flowers, curving its tail over its back, yawning vegetably, in the dancing bright air. Nils Isaksen told her she shouldn’t go out without a hat. She wanted to reply that she didn’t care. She said ‘I know’ but did not buy a hat. Let it bake her brain, something said.

One evening Nils Isaksen broke his cautious bounds. Patricia was very tired. She had taken three eaux-de-vie Mirabelle, instead of one, and saw the cedars shifting across the too spangling stars.

‘I should be happy,’ said Nils Isaksen, ‘if you would come with me to the ethnological museum. I should like to show you . . . ’

‘Oh, no.’

‘I should like to show you the tombstones of the gladiators. So young. We can read the life of a city, in its monuments – ’

‘No, no – ’

‘Forgive me, I think you should make some change. I am impertinent. When I first lost Liv, I wished the whole world to be dead, too. Frozen stiff, I wished everything to be. But I exist. And you, forgive me, you exist.’

‘I don’t need company, Mr Isaksen. I don’t need to be – entertained. I have – I have things to do.’

Before his intervention, something had been going on, in the silence. He had spoiled it. She stared angrily at him.

‘Forget I spoke, please. I am in need of speech, from time to time, but that is nothing to do with you, as I can understand.’

The dreadful thing was that her refusal had made more of an event, had brought them closer together.

The next day she decided, as she walked along the Boulevard Victor-Hugo, that she would certainly leave Nîmes. She kept in the shelter of the plane trees, like a southerner. She decided that, since she was leaving, she would do the city the courtesy of going to the Maison Carrée. Ezra Pound had said it was a structure of ideal beauty. She had read the guidebook. It was made of the local pierre de Lens, shining white when quarried in the garrigue, turning golden with time and sunlight. It was tall, high on a pedestal, with Corinthian columns ornamented with acanthus leaves, and a frieze of fruits and heads of bulls or lions. It had been the centre of the Roman forum, part of a Franciscan monastery, owned and embellished and pierced by Visigoths, Moors and monks. Staircases had been raised and razed round it. In 1576 the Duchess of Uzès had decided to transform it into a mausoleum for her dead husband, but the City Fathers had resisted. It had been a place of sacrifice according to Nils Isaksen, who had a Viking bloodthirstiness under his bloodless skin.

She climbed the high steps of the portico, and looked out between the columns at the human space around the ancient house. She could see the discreet, vanishing gleam of the Carré d’Art, across the place. The guidebook told her that the square house was now a museum for the city’s archaeology, the endlessly unearthed Pans and nymphs, dancers and gladiators. But the guidebook was out of date. There was nothing there but red ochre paint, and a few informative placards. What do you do in a dark red space, full of stony art? Patricia walked along, around, and across. She remembered wondering when it made sense to stop looking – at a pictured dandelion, a windbreak, a frozen avalanche. She went out of the Maison Carrée in a dreamy rush, across the portico and down the steps. Between the place and the narrow maze of little streets runs a cobbled lane, along which cars and motorcycles run, occasionally and unexpectedly. The heat and the light dazzled her. She blinked at the dark, bright blue, at the burning white. She narrowed her eyes, and plunged forward. Several things happened. A screaming – brakes and a bystander – a grip like a claw on her wrist, twisting and dragging. She was on her knees in front of the square house, looking up at the violet form of Nils Isaksen’s face above her, framed by his white-gold curls, and the spiky rim of his hat. Somewhere beyond, a dark driver, with the Nîmois nose, was making a speech of mingled reproach and regret.

‘You cannot make him an accomplice – that is to say, responsible –’ said Nils.

‘Don’t be absurd. I was dazzled.’

‘You looked neither to right nor to left. I saw. You threw yourself under his wheels.’

‘I did not. I could not see. The sun dazzled me, after the dark.’

‘I saw you. You threw yourself.’

‘And how did you come to be there?’ asked Patricia, one human being to another. She stood up, wiping dust and blood from her knees and the palms of her hands like a schoolgirl. She bowed to the driver, and made a gesture of abasement with her head and arms. ‘How?’ she said, to Nils Isaksen.

‘I was passing by. I thought I would ask you to have lunch with me. I stepped forward to do that, and you plunged. So I was able to take hold.’

‘Thank you.’

They ate lunch under an ivory-coloured parasol, next to the fountain with the unmoving energetic crocodile. Patricia had quails’ eggs in aspic, pale little spheres in translucent coffin-shapes of jelly, flecked with sprigs of herbs. Her palms and her knees were stinging as they had not stung since school playgrounds. The sunlight packed down, dense and brilliant. The canvas was not enough protection. Sweat ran along her upper lip, between her breasts, in the crook of her elbow. Nils Isaksen had an angry red line between his hair and his shirt collar. Blood pulsed beside his Adam’s apple, ruddy where it should have been pale. He asked if she liked her aspic. He had chosen barquettes of brandade de morue. A northern fish, he said, the codfish. It seemed illicit and unnatural, made into a paste, would she say? – a purée? – with olive oil. And garlic. Excuse me, he said, you have dust on your cheeks, from your fall. May I? He touched her cheekbone with his napkin. All the same, he said, you took a plunge. I will say no more. But I was watching. You launched yourself, so to speak, from the plinth of the Maison Carrée. I would like to be able to help.

‘Help,’ she said. ‘I don’t believe in help. I believe . . .’

‘Yes?’

‘I believe in indifference,’ said Patricia Nimmo. ‘The flow of things. Anything. One thing, then another thing. Crocodile fountains. Dust. Sun. Eggs in aspic. I’m talking nonsense. The sun’s moved. It’s in my eyes.’

‘We could change chairs. I have dark glasses. I have a hat. Please – ’

They stood up. They changed places. Nils Isaksen said:

‘I understand you. You will think I don’t, but I think I do. To me indifference is a temptation, fatally easy. You will say that he is insensitive, he has understood nothing, he is a fool, everybody believes indifference is bad, but I, Patricia Nimmo, have secret wisdom, I know there is good in it. That is what you think, don’t you? Whereas, Mrs Nimmo, I dare to offend you by saying I have been there, I have tried indifference, it is a good station for changing trains, then it becomes – cement. Cement. You did not launch yourself into the path of that Corvette out of indifference.’

‘Out of the purest indifference. If it was a launch, it was out of indifference.’

‘We are in deep.’

‘Talking does no good.’

‘I should like to recommend curiosity. You must take an interest. Curiosity and indifference, Mrs Nimmo, are opposites, you will say. But not truly. For both are indiscriminate. You may sit there, glass-eyed while things slip past, what did you say, eggs in aspic, crocodile fountains, the stones of this city. Or you may look with curiosity, and live. I am trying to learn this city. It is not a trivial undertaking. I am learning these stones. You are right, in part, I believe it is a matter of indifference what you learn – or rather, it is a matter of blind fate, which has a creepy way of looking like destiny. But you must be curious, you must take an interest. This is human.’

The truth was, Patricia thought, with a trace of her old wit, he looked dreadfully inhuman as he said this, staring like a gargoyle, his pale skin flaking in patches, his yellow-white curls sweat-streaked, his lips stretched with evangelical fervour. He did not create curiosity about himself, by no means.

‘I take an interest in you,’ he said, plucking off his dark glasses and turning a dazzled blue stare on her.

‘I don’t want a guardian angel, I’m afraid,’ said Patricia, pushing back her chair.

‘Afraid?’

‘I’m sorry. I don’t want, that is what I mean, I don’t want – ’ She stood up and walked away in the white-gold air.

Because she forgot to pay for her lunch and also because she possibly owed him her life, she went with him two days later to the museum. The building stood, almost Roman, around an inner courtyard, round whose walls, in a kind of cloister, were partly ordered rows and heaps of ancient burial stones, dignitaries, priestesses, warriors, some with effigies, portly matrons with heavy heads of hair, noseless busts in togas. Inside were more stones, much older, menhirs with strange whiskered faces and fine-fingered pointy hands, a sabre-toothed tiger, the skull of a Stone Age survivor of one trepanning who had died at the second attempt. Patricia walked briskly, and Nils walked slowly, calling her to look at choice objects. ‘My favourite,’ said Nils Isaksen, ‘fresh with life, look here, the Roman flower-seller from Vic-le-Fesc.’

It was a white stone, carved deep.

NON VENDO NI

SI AMANTIBUS

CORONAS

He translated: ‘I do not sell my crowns, except to lovers.’

‘I can read Latin. Thank you.’

He took her to see the gladiators. Lucius Pompeius, net-fighter, put to combat nine times, born in Vienna, dead at 25 years, rests here. Optata, his wife, with his money, made this tomb. Colombus, myrmillon from Severus troop, 25. Sperata, his wife. Aptus, Thracian, born in Alexandria, dead at 37, buried by Optata his wife. Quintus Vettius Gracilis, a Spaniard, thrice-crowned, dead at 25. Lucius Sestius Latinus, his teacher, gave this tomb. There were only replicas in the glass case in the museum. Nils said he had hoped to be able to work on the tombs of these dead fighters. Three or four centuries, he said, of dead young men, swordsmen and net-throwers, from all over the Empire and beyond, buried now under cafés and cinemas, pâtisseries and churches. Ten or so had got turned up by accident, he said, over the centuries, out of the thousands. He hoped to find a northman, perhaps.

‘Why?’ asked Patricia, without curiosity.

‘A buried berserker, with his amulets. It has been known.’

‘He would have done better not to come here,’ said Patricia. ‘Hypothetically.’

‘Do you know,’ said Nils, ‘that there is a theory that Valhall, in the Grimnismal, was based on the Roman Colosseum? Valhall was described with 640 doors – a circular place where the spirits of warriors fought daily and the dead were daily revived to feast on hydromel and the flesh of the magic boar, until the last battle, when they would go out to fight, eight hundred at a time, through the 640 doorways. The northern paradise is perhaps linked to these stone rings here. We were fighters.’

‘Tant pis,’ said Patricia. ‘They died long ago. Leave them in peace.’

‘Peace –’ began Nils. But she had walked away from stones and bones, along a corridor, up a stair.

In a long narrow dim room, she came face to face with two stuffed bulls. They faced the doorway, balancing trim muscular bodies on delicate hoofs, pointing sharp horns, staring from liquid brown glass eyes. They had been reconstructed with anatomical intelligence, with respect. They had been killed a century apart, ‘Tabenaro’ in September 1894, ‘Navarro’ in 1994 at the centenary corrida for the Granaderia Pablo Romero from which both came. Their hides were both glossy and dusty, Tabenaro pied, Navarro a flea-bitten iron grey. Both skins were slashed, ripped and stitched together like patchwork quilts, flaps reconstructed round the wounds of pic, of banderillas, of the sword. Behind them, along a central island trudged a dusty procession of beasts, a sample of rejects from the Ark, some wearing their reconstituted fur and skin, some standing bleached and bony. A wild boar, Sus scrofa, and five striped piglets; a Siberian bear; a musk bull and calf; two differing deer; a looming derelict moose; a young dromedary, its ears frayed to bare holes, but its eyelashes long, tufted and curving; behind this dusty beast the bone-cages of a giraffe and a llama; behind these a Camarguais calf, a very small Camarguais foal, and the skeleton of a Camarguais horse; behind these the huge bony head of a whale beached in 1874 at Les-Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer.

Round the walls of the long room were other beasts in cages: monkeys and sloths, weasels and beavers, spotted cats and a polar bear, orang-utan and gorilla. In one glass case were curiosities, two-headed sheep, a monster with one gentle face and two bodies trailing eight woolly legs.

And the reptiles. An amphisbaena, leathery-brown, long harmless local snakes, asps in jars. Aspic commun. Vipère aspic, vipera aspic, Lin. And mummies of crocodiles from Egyptian tombs, boneless, long, leathery parcels, Nîmois.

‘Le crocodile, animal sacré des anciens prêtres égyptiens, était embaumé après sa mort. On le trouve en abondance dans les tombes.’

Nils Isaksen loomed behind her. He pointed out, to please her, that the text engraved above the roof-arch was English, from Francis Bacon, 1626.

Interprète et ministre de la nature L’homme ne peut la connaître Qu’autant qu’il l’observe.

‘Curiosity,’ said Nils Isaksen. ‘You see.’

A very large cayman was rampant on the wall behind him, not discreetly tubular like the Egyptian mummy, but clawed and brightly glazed.

‘We are the only people here. The dust makes me want to sneeze. The poor beasts should have been let die decently.’

‘Look at the love, in the pose of those bulls, in the stitches.’

‘Love?’

‘Of a sort.’

‘Horrible.’

‘Interesting.’

That night, as usual, they dined separately, and then drank together in the bar. Patricia was disinclined to speak. The glass angle of the bar was brightly lit in the shadowed garden. The fountain bubbled and splashed. Nils Isaksen said he had something he would like to show her. He emptied out the pockets of his blue-green linen jacket on the glass table between them. There was a scattering of stones – one or two mosaic tesserae, a fragment of the golden Lens stone, a sphere of black shiny stone, a handful of sunflower seeds, a crudely carved amulet of an iron hammer on a ring.

‘I found it in an antique shop,’ said Nils Isaksen. ‘In a tray of little things dug up by workmen, bottles and coins and beads. I know what it is. It is Thor’s hammer. It is Mjölnir. It will have come from a grave, maybe of my berserker gladiator. They were everywhere in those days, these little hammers. In marriage-beds and graves. To help the spirit on its way to Valhalla, perhaps. Or perhaps to prevent the ghost from rising to stalk the living. Maybe there are more under this pavement. Maybe.’

‘Are you sure it is so old?’

‘Decidedly. It is my profession.’

Patricia picked up the little dark ball. When she turned it in the candlelight it sparked with a blue fire that ran in veins and flakes in its glossy substance.

‘Pretty,’ she said.

‘Labradorite,’ said Nils Isaksen. ‘A kind of feldspar.’ He hesitated. ‘When I put up the tombstone of my wife, Liv, I made it of a single slab of labradorite. It is a costly stone. It flashes like the Northern Lights in the land of the Northern Lights. I wrote on the stone only her name, Liv, which is to say, Life. She was my life. And her dates, because she was born, and died. It is in a small churchyard, surrounded by bare space. It is too cold for trees or bushes, mostly. I put a hammer in the grave with her, Mjölnir, as my ancestors would have done. Thor was the god of lightning. There is lightning in the labradorite.’

Patricia put the stone down, quickly. Nils Isaksen stared through the glass at the cedars and olives and flouncing water.

‘In the town beyond my own, towards the Arctic Circle, there is a single tree. Those towns, you know, are as far from Oslo as Rome is. Further than Nîmes. Every winter, people wrap the tree, they shroud it against the cold. The sun does not rise for months, we live in the dark, with our shrouded tree. We imagine the south.’

He pushed his stones, his seeds, and his amulet around the glass table-top, like counters in a game.

Patricia slept deeply, at first. She woke suddenly, from a confused dream of long corridors, lined with high glass cases. She went to the window. The square pane framed the huge liquid ball of the moon’s light, a full moon. The sky was spangled with stars. The light poured from the moon on to garden walls, and the great stone bowl of geraniums, fiery in daylight, now silver-rose. The air-conditioning cranked and hummed. She put her forehead on the glass. A rhythm struggled to be remembered. ‘This case of that huge spirit now is cold.’ She moved her lively golden toes in the soft carpet and rubbed her face on the almost-cold glass. When she opened the window, the night air was warm on her skin, though the moonlight was cold.

She ordered breakfast in her room. She slipped out early: even so, the air was like a hot bath as soon as she was beyond the shadow of the Impérator Concorde. She went to the Carré d’Art. It is a beautiful building, discreet, ghostly, absent, a space of grey glass cubes on fine matt steely pillars, taller than the Maison Carrée but deferring to it, with a kind of magnified geometrical repetition and transformation of the proportions of its elegant solidity. Inside, up the wide, steep staircase, in the calm muted light was an exhibition of the work of a German, Sigmar Polke. Patricia’s attention was churning, like water boiling in a jug, a stream of rising currents, a troubled, jagged surface, a downdraught, a bubbling up. She floated from room to room, her sandalled feet soundless, her lavender muslin skirt wafting round her cool knees. Sigmar Polke is strong and witty and various. The old Patricia would have been delighted. There was a wall of images of watch-towers at the corner of barbed-wire fences. There was a room full of gay, charming images of the French Revolution. A pile of parcels, a triangle, two cubes, a diagonal, brightly spattered with tri-coloured motifs, a flower, a Gallic cock, which resolved itself into the blade, ladder and basket of the guillotine. Two eighteenth-century mannikins playing in an Arcadian field with a ball which turns out to be a severed head. In another room, a blown-up drawing of Mother Holle shaking out snow from her feather-bed in the clouds. A high room full of huge, romantic, stained sheets of colour, labelled Apparizione. Gilded puddles, seas of cobalt and lapis, floating milky and creamy clouds and vapours, forked mountains, blue promontories, crevasses and fjords of swirling indigo, pendent rocks hanging over crimson and russet lakes with dragonish jaws or long fingers of purple and bleached bone clutching froth, veiled norns and mocking ghouls, drowning white birds and crumbling citadels. The text beside these visionary expanses emphasised vanishing and danger. Polke paints with currently discarded pigments that are poisons, orpiment, Schweinfurt green, lapis. He mixes unstable chemicals: aluminium, iron, potassium, manganese, zinc, barium, turpentine, alcohol, methanol, smoke black, sealing wax and corrosive lacquers. His surfaces shift and dislimn, the stains change, become indistinct, no shapes hold, no colours are constant. The world of these apparitions is ghastly and lovely. Patricia stared. Here were beauty and danger, flat on a wall. She said in her head, ‘What shall I do? What can I do?’ She stared at the falling veils of melting snow, of curdled cream. How do you decide when to stop looking at something? It is not like a book, page after page, page after page, end. How do you decide?

On the top floor of the Carré d’Art, behind the stair, is a balcony. You can step out there, and suddenly there is no smoky glass between you and the heat and the light, you can look over the city, the intricate circling of red-tiled roofs, like flattish cones. You can see the Tour Magne on the skyline. Patricia went out. The hot air was as solid as the glass. You could touch it with your finger. She floated over to the balustrade, and looked out and down at Nîmes. She leaned back in a corner, she leaned back, and stared at the dark bright blue. She was light, she was insubstantial, in her shadowy lavender dress. She leaned out. Out. The heat fizzed in her eyes and ears. Her feet left the ground, she balanced, she leaned. A hand took her wrist and dragged. Nils Isaksen grasped her other wrist for good measure. His face loomed craggy in the shadow of his Van Gogh hat. It was a very angry face. His feet were planted like lead and his knees pressed against hers as he dragged her back into the box of the balcony.

‘Leave me alone.’

‘How can I?’

‘Very easily. Go away.’

‘I think not. Not yet.’

They walked in hostile silence out of the gallery and faced each other in the hot sun on its steps.

‘Please,’ said Patricia, English and icy, ‘just leave me alone.’

‘I think I should – ’

‘I am going to have to leave this town because of you. Because of your interference in my life.’

‘Because of my interference in your death,’ said Nils Isaksen.

Patricia began to walk away, brisk and furious. She did not look behind to see what he was doing or not doing. In the Place d’Assas there is no shade. There are many modern fountains, carved in the gold stone – a huge head spewing clear water into a long narrow channel, a naked pair of youth and maiden, in bronze, catching water from a columnar structure in a pale aquamarine circular pool. Patricia came to the middle of the square and began to shake. She stumbled towards the pale blue under the dark bright sky and fell on her face towards the water, like a desert traveller in a film. Her stomach heaved. The sun clanged in the sky like a gong. Tears squeezed between her hot lids. She fell forwards to drown in two inches of warm water. And the large bony fingers of Nils Isaksen gripped again, pulling her back by her shoulders. Between the sun and her eyes he was no more than a black space, a shadow carved with spikes. He pulled her to her feet and she fell into his arms, gulping and staggering. He put his arms round her for a moment, and then transferred the Van Gogh hat from his white curls to her bronze cap. She clutched him.

‘Come in,’ he said. ‘Out of the sun.’

They sat together in her bedroom, Patricia in the chintz chair, Nils Isaksen gawky on the pretty desk chair. The air-conditioning groaned. It was only the second time he had been in her room. He wiped her face with a cold flannel, and poured her a glass of water from the minibar. He said:

‘This cannot go on.’

‘It is not what you think.’

‘I will tell you a story. In Norwegian it is called Følgesvennen. In French it is Le Compagnon. The Companion? It is about a young man, who dreams of a beautiful princess and when he wakes, sells all he has and sets out in search of her. And when he has walked far, and farther than far, for months, in the deep winter, he comes to a church. And outside the church is a block of ice. And in the ice is a dead man, standing upright. And when the priest comes out of the church, the young man asks him what the man is doing in the ice. And the priest replies that he is a great sinner who has been put to death, and stands there to be spat at. And it would take more money than anyone is prepared to spend on such a sinner to lay him in the ground. So he just stands there.

‘When I think of you, walking up and down in the heat with no hat,’ said Nils Isaksen, ‘I think of the block of ice.’

‘How does it go on?’

‘Oh, the young man asks what the dead man’s sin was. He was a butler, says the priest, who watered the wine. Not so terrible, says the young man and gives the remains of his savings for the dead man to be chipped out of the ice and decently buried. So then he has nothing and goes on his way. And that night a man comes to him, and proposes to be his servant, and the young man says he has nothing left to pay a servant. So the other says he will come for fellowship. So he comes, as a companion. And they have many adventures. They meet three old women – troll women – in three caves. Each hag invites the young man to sit in a stone chair. Each time the Companion insists that the old woman herself sits there, and she cannot refuse, and the chairs do their work, and seize them, and will not let them go. And from each old hag the Companion takes a treasure in return for the promise of her release – a sword, and a thread, and a magic hat of invisibility. But then he leaves them sitting there and breaks the bargain. I have observed,’ said Nils Isaksen, ‘that Norwegian heroes are particularly given to bargain-breaking. They make compacts with trolls, and think nothing of cheating.’

‘It is not what you think,’ said Patricia.

‘What is not what I think?’

‘The body in the ice. I am not the dead man. I left him.’

She told Nils Isaksen then, more or less, the story of the day in the Narrow House, and of Tony’s fall, and of how she had left her life behind and come to Nîmes.

‘So you see,’ she finished. ‘You buried your wife, under that stone, and I – I walked away. I did not see why I should not walk away.’

There was a long silence. Patricia was filled with dread, that was the word, by the uncanny aptness of the man in the ice. She told Nils Isaksen how she had fled; she expected, perhaps hoped for, judgement. But he appeared to be struck dumb by her story.

‘I did not think I did wrong,’ she said. ‘I loved him, and he died, and that was an end. Enough of an end. But it feels wrong, terribly wrong. Not to the children, which is what you might think, leaving them to – look after – things. But to him. I left him.’

Nils sat looking out of the window.

‘What happened, in the rest of the story?’

‘The princess was found. In one of those castles with a fence where the skulls of past suitors are on every post. She set the young man three tasks – things to keep safe overnight, a pair of gold scissors, a ball of gold thread – which she stole back. She was bewitched, she was the lover of a troll to whom she flew every night on the back of a ram. But the Companion made himself invisible, and followed, and seized the scissors and thread, and returned them, so in the morning the boy triumphed after all. So then she said, bring me tomorrow what I am thinking of at this moment. And he said, how can I know that? And he despaired. But the Companion followed again, he followed again, and heard her tell the ugly troll, it was his beloved head she was thinking of. So of course, the Companion decapitated the troll with the magic sword, and brought back his head. And the next day, the boy threw it down before her. And then she had to marry him. And then the spell had to be broken, with alternate baths in milk and in ashes, I remember, certainly with bathing her skin. And then she became his good wife. And the Companion went away, and after five years returned to claim his reward. So the young king gave him half of everything he had. And the Companion said, there is one thing more, born since I left. And the young king and queen brought out their son, and the young king raised his sword to divide the boy, as justice required. And the Companion held back his hand, and said, no, you owe me nothing, for I am the spirit of that man who was frozen in the block of ice. And now I may go to my rest in peace. It is a dark story, Mrs Nimmo.’

‘Not altogether.’

‘You are right, Mrs Nimmo. You have done wrong. To the living, and to the dead. It can be set right, I think. You can return and set it right.’

‘Thank you,’ said Patricia gravely. And kissed his cool, bony cheek.

She did not sleep, that night, but lay awake, still and calm, visited by hypnagogic moons and stars and waves lapping on seashores, or skies lit with flaring curtains of blue and crimson light, as though she had stepped, or fallen, into some world of mythical absolutes. When she came down in the morning, Nils Isaksen was nowhere to be seen. The hotel lobby and dining-room were full of people and life. It was the time of the corrida, and the matadors and their retinues were moving into the Impérator Concorde. Two or three photographers lounged against pillars. Dark Spanish faces nodded ceremoniously to each other, as bundles of bright cloth and weapons went into the gilded lift-cage. Patricia paid them little attention. She went out and walked through the morning, fluid and automatic, from fountain to fountain, crocodile to clocktower, Memnon’s head to the naïf bronze lovers. She avoided the Arènes, as usual. In the evening the town was packed with crowds of festive Nîmois; there were bursts of music and fireworks. Patricia avoided it all. She was not in that world. She looked in the restaurant and the garden for Nils Isaksen, and he was nowhere to be seen. On the first day she thought easily that she could wait – time had become a coloured cave of light in which planets rolled like plates, and fish leaped, and toothed reptiles floated and paddled. On the second day she thought once or twice that she saw him at street-corners, but it was always other tall men in straw hats or linen jackets. She tried sitting in the garden, but that too was full of aficionados, drinking cocktails, discussing faenas, moving naked bronzed shoulders gracefully under the great linen parasols. On the second evening she saw Nils Isaksen, but he did not see her. He was quarrelling with the receptionist. It might have been the kind of quarrel guests have, when they have been politely requested to pay bills they cannot pay. The old Patricia, sharp as a needle, would have picked up a clue from an intonation, or a gesture. The new one, floating largely in some other dimension, registered the quarrelling with difficulty, and was about to approach Nils, to whom she needed to speak, to whom she now needed very much to speak, when she registered dimly that he was drunk. His arms and legs and head were not working together, his voice was loud and uncontrolled, his face was hot. She backed away. She went up in the lift, and lay on the bed. She ordered supper through room service, and it took a long time to come, because of the eddying tauromanic crowds in the body of the hotel. On the third evening of the corrida she made her way past the Bar Hemingway to see whether Nils was on the terrace, or alternatively whether there was a quiet table where she could sit and watch the fountain. The fountain had been turned up, perhaps in honour of the matadors. What used to be a bubbling aquamarine cube of suspended liquid was now a high spraying column, flailing a little in the air, like a turning horsetail, throwing bright droplets and white shoots of wet over the grass. At the far end of the terrace, she saw, through the real glass wall of the Bar Hemingway and the molten glass cocoon of her own consciousness, a struggle round one of the dinner tables. She could hear shouting, but no words. There was a group, like Laocoön and the serpents, one figure rising above a mass, holding above his head what seemed to be a silver buckler, and a flashing bottle. It was Nils Isaksen, his blue-green jacket stained with what could have been blood, or could have been red wine, his hair dishevelled and his mouth open in a roar, fighting off a cohort of white-aproned waiters led by the maître d’hôtel in his uniform. One or two dark Spaniards stood close, involved but not active. The mass of men swayed this way and that; the plume of water swayed this way and that in the dark garden; Nils Isaksen felled the maître d’hôtel with what Patricia could now clearly see to be a heavy silver dishcover, and was himself brought down, more or less pinioned with napkins and tablecloths, and half-led, half-carried, still struggling, into the hotel. Patricia turned to the barman, and ordered an eau-de-vie framboise, on ice. She sat down, inside the glass wall, and stared at the cubes of ice. The barman was explaining the disturbance to a young couple.

‘Nothing serious. No, no. He criticised the spectacle. Not a wise thing to do in Nîmes, certainly not during the f te.

te.

‘What displeased him?’ asked the young husband, laughing, his arm round his wife’s silky brown shoulder. ‘The quality of the bulls, or the art of the torero?’

‘The mise à mort,’ said the barman. ‘He comes out of the North, somewhere. They don’t understand the death of the bulls.’

The young couple laughed again, easily.

‘The culture is different in the Mediterranean,’ said the barman. He saw Patricia listening, and changed the subject, easily, deftly, to the beauty of the night, the brilliance of the moon, the prevalence of shooting stars in this season.

Patricia made no attempt to find out what had happened to Nils Isaksen. She did not see him again until the Fiesta was over, and the toreadors had ceremoniously driven away in their polished old limousines, with their acolytes, their strapped trunks, their bright capes and swords.

When she saw him it was in the street, in the Rue de l’Aspic. He was looking into a shop window, his hat pushed forward over his knobbed brow, his skin spangled with unshaven gold bristles. Before she reached him, he loped away, ungainly and hurried. She followed. She followed even when he crossed to the entrance of the Arènes, bought a ticket, and went in. She waited a little, and then bought a ticket herself, and stepped into the circle.

The Arènes is not a labyrinth. It is an orderly structure of tunnels, colonnades, staircases, rising, diminishing rings of stone seats, open to the sky. At first, having gone in, Patricia walked round in the cavernous arched dark of the ground-level circuit. It smelled of musty stone, and stale urine, the urine of frightened beasts, partly masked with eau de Javel. The silence in it is numb and dumb. There were Coca-Cola machines and bins of empty champagne bottles. She made one and a half circuits in the gloom and then plunged at random under an archway and up a stair, coming out suddenly perhaps four tiers up from the sanded circular arena, with its intricate raked pattern, its red-painted wooden screens behind which men sprang or scrambled out of the way of the plunging horns. The bottom tier was very close to the ground. She had read in the guidebook that it was not thought that there had been wild-beast fighting, because the barrier was too low for safety. Only men ingeniously slaughtering men, and men ingeniously, elegantly, dancing the great beasts on their delicate hoofs, to standstill, shuddering, and the knife. Over all those centuries, people had come there to sit together, festive, and watch death.

She found it hard to see, in the light. She looked around and could see neither Nils Isaksen nor anyone else. She ducked back under her archway, made another segmented progress, climbed another stone stair, reached an upper open gallery and walked round. From the height of the heavy stone cylinder she looked down, and saw a straw hat, and a patch of innocent Norse blue-green, across the great space of the circle. So she went on, round and down, and sat on the warm stone, shaped roughly to hold her, beside him. The silence was at the same time the stony silence of monuments and the airy hot silence of midday in open spaces. It was hot, very hot, the stone was hot to touch. Below, the patterns in the swept sand were pretty and sinister. She sat still for a time, and he sat, his head in his hands, and did not move. Black birds wheeled over, high up, in their own circles.

‘Nils.’

‘I have nothing to say to you.’

‘Are you in trouble?’

‘Why should you think I am in trouble? Yes, I am in trouble. Now leave me alone, please, Mrs Nimmo.’

‘I saw you fighting.’

‘I was berserk.’ With a certain gloomy self-approbation.

‘I saw. Why?’

‘Because of what you told me. And because I came here, to see the bull-fighting.’

Patricia was silent, not understanding. She stared round the white rim of the circle. He said, into his hands, ‘I thought it would be a mystery. And it was simply disgusting.’

‘I could have told you that, without needing to come,’ she said, taut and English.

He said something in Norwegian.

‘What was that?’

‘ “Jeg er redd jeg var død longe førenn jeg døde.” I was a dead man long before I died. Peer Gynt. The great liar. The great Norwegian folk-hero. A tissue of lies and old tales and boasting. I lied to you, Mrs Nimmo. You did not lie to me, and in the end you told me – what you told me. And I took it upon myself to be judge and confessor. But my lies are worse. What I have done is much worse.’

‘I should like to know,’ said Patricia, although mostly she did not want to know, and feared vaguely that the dead wife had been killed, that she was to be forced to hear something unspeakable.

‘I am not an ethnologist, Mrs Nimmo. I am, or was, a junior schoolteacher. I don’t know archaeology. I never married. My wife is a lie, and the labradorite stone is a lie. All lies.’

‘And the town with the one tree?’

‘That is true. I lived there. I lived there with my mother and my aunt, and taught school, until I had to give up. Three years ago, my mother died. She was eighty-six. I inherited the house, and her savings.’

Patricia waited. The black birds circled.

‘She had not known who I was for five years. I did everything. I washed her. I clothed her. My aunt sat and smiled and sang. Sometimes she cried. Then she too – deteriorated. I had to give up my teaching because I had two old women in wheelchairs in one house, nodding and babbling, and shouting too, they could get very angry, they got very angry with each other . . . Then my mother died. My aunt and I buried my mother in the churchyard. The labradorite stone is a story I told myself, when I found a little piece in a shop, and it reminded me of the North.’

‘And then your aunt died?’

‘No. Then, Mrs Nimmo, I packed suitcases, and sold the house, and wheeled my aunt on to the train and went south to Oslo. And from there I took her to Stockholm. There is a famous clinic there, a neurological clinic. I took her in there, Mrs Nimmo. I had not made any appointment. We were not particularly remarkable. The clinic was full of people like us. We met nurses in the corridors, and my aunt raised her hand to them, like a queen, and they smiled. I walked up and down, quite quickly, looking for a long line of people. There was one outside the pharmacy, everyone waits there. I put my aunt in her chair, in this queue, in the hospital corridor. She was smiling at everyone, she usually did, she was a nicer woman than my mother. Then I left, Mrs Nimmo. I had premeditated my act like a criminal. There is nothing in my aunt’s clothing, or her handbag, to say who she is, or that she came from the North. Then I came here. By hazard, as you did, as you told me you did. I got on trains and travelled south. Europe is one, now, my movements were unremarkable. I had all my money with me. It was very premeditated, Mrs Nimmo.’

‘But understandable. You were at the end – at the end – under terrible strain.’

‘It was wrong. We both know that. I had a Calvinist upbringing. I burn already,’ said Nils Isaksen, gaunt and hunched under the fiery disc of the Mediterranean sun over the stone skeleton of the amphitheatre.

‘I think perhaps you did the best you could – ’

‘I did not tell you this sorry story in order to hear you say that, Mrs Nimmo. I told it to hear it told aloud. Now, if you will excuse me, I have things to do.’

He stood.

‘Will you be all right?’

‘It is no concern of yours. But thank you. And yes, I shall be all right.’

He walked away, into the tunnelled arch, not looking back.

That night, she dreamed. She was in the arena, sitting where she had sat with Nils Isaksen (who had not been at dinner, or in the bar). The sky was black night, and starry, in the dream, but the sand of the arena was shining with sunlight. In its closed bright circle, two men fought. They wore unbleached white canvas or linen suits, like professional fencers, and wore also fencing masks. They had an extraordinary arsenal of weapons heaped around them. Trident, the retiarius’s weighted net, short swords, long swords, heavy long swords, stilettos, poniards, mace and battle-axe. They went at each other, gracelessly and doggedly, with all these things in turn, inflicting dreadful dints, and savage thrusts, so that the canvas became crisscrossed with slits, and great gouts and gashes of blood spouted from both hidden bodies and soaked into the cloth and into the bright surrounding sand. Blood poured, too, out of the blank wire faces of the masks. First one, and then the other, were beaten to their knees, and hacked at horribly from above and below. It all took a very long slow time, and Patricia was not permitted to turn her eyes away, or leave her stony seat, or speak, or wake. When they were at a standstill, a strange thing happened. All the red blood, in which terrible strips and slivers of flesh, external and internal, floated and stuck, turned back. All the carnage flowed back, quickly, into the two men, peeling off the sand, shrinking and vanishing in stains on the buckram, so that they were again fit, pale figures, surrounded by gleaming pristine blades. And then they bowed to her, turned somersaults in the swept sand, and began all over again, hacking, thrusting, bleeding.

She noticed, in the way of dreams, that someone was sitting next to her, had perhaps been there all the time. It was Tony, looking solid and well, leaner than on that last day, and smiling. He did not speak. The bloody men had been real and inescapable. She wanted Tony to stay. She was dreadfully happy to see his living face, the wrinkles at the corner of his eyes, the kink in his left brow, the warm lips. She knew then that this very real man was not real, and felt anguish. He would go, and she would wake. She said:

‘Why are they doing that?’

He smiled, as though the slaughter was normal and agreeable. He did not speak. He put a warm hand on her knee. This made her cry, and she woke.

The next day, she saw Nils Isaksen in his usual corner on the breakfast terrace. She walked straight over to him. He did not stand to greet her. She asked him if she could sit down, and he made a grudging gesture of assent. She said: