Flight of the Reindeer: The True Story of Santa Claus and His Christmas Mission – Read Now and Download Mobi

Comments

FLIGHT OF THE REINDEER, 15TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION

THE TRUE STORY OF SANTA CLAUS AND HIS CHRISTMAS MISSION

ROBERT SULLIVAN

Copyright © 2010 by ROBERT SULLIVAN Book design by J PORTER

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles.

All inquiries should be addressed to

SKYHORSE PUBLISHING,

555 Eighth Avenue, Suite 903, New York, NY 10018.

SKYHORSE PUBLISHING books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 555 Eighth Avenue, Suite 903, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

9781616081515

Printed in China

Dedication

TO MY PARENTS,

who first taught me about Santa Claus—R.S.

TO LILLIE AND SARAH,

who make it easy to believe—G.W.

TO MARGIT,

who showed me that reindeer really do fly—J. P.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

DEEPEST THANKS AND BEST CHRISTMAS WISHES are extended to my partners, artist Glenn Wolff and designer J Porter. Merry Christmases go, as well, to the experts and Helpers who shared their knowledge regarding The Mission. Special appreciation is extended to literary agent Jeannie Hanson, and to our talented and sympathetic editor at Macmillan, John Michel. The author, illustrator and designer would like to acknowledge the patience, support and inspiration afforded by their wives while they were off chasing reindeer. They would also like to recognize assistance graciously given by the following individuals and institutions: Doreen Means; Adrienne Aurichio; Dave Ziarnowski; Hank Dempsey; The Potter Park Zoo in Lansing, Michigan; the Michigan State University Museum; Baker Library and the Institute of Arctic Studies at Dartmouth College; The Roger Williams Park Zoo in Providence, Rhode Island; Joe Mehling; Jim Brandenburg; Doug Mindell; Tim Hanrahan; Erick Ingraham; Tonia Means; Craig Neff; the Grose family; Doug Meyerhoff, Paul Traudt, Mary Anne Spiezio and Quad Graphics.

Final thanks to Dan Okrent and all colleagues at LIFE magazine for allowing the time to pursue this project.—R.S.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Acknowledgments

INTRODUCTION - The Reindeer by the River

PART ONE - The Echo of Hooves

PART TWO - The North Pole Today

PART THREE - The Miracle of Reindeer Flight

PART FOUR - Eight Tiny Reindeer (Plus One)

AFTERWORD - Like Down on a Thistle, Evermore

The End

Credits

INTRODUCTION

The Reindeer by the River

It Was a Wondrous Thing

AS A BOY, I knew with certainty that reindeer could fly. As I grew older, I had my doubts. But now—matured and sound of mind—I know again that reindeer can fly. Surely, it is strange. It is strange and marvelous and altogether phenomenal that these deer can spring from the earth and, snouts high and antlers back, mount to the sky.

IT SEEMS NOTHING SHORT OF MIRACULOUS, but miracles do happen, and that this miracle serves mankind at Christmas seems to lend it all some sense. Reindeer do fly. Many have seen it happen, and you yourself may one day.

I have seen it happen—once. I think I may have seen it happen twice.

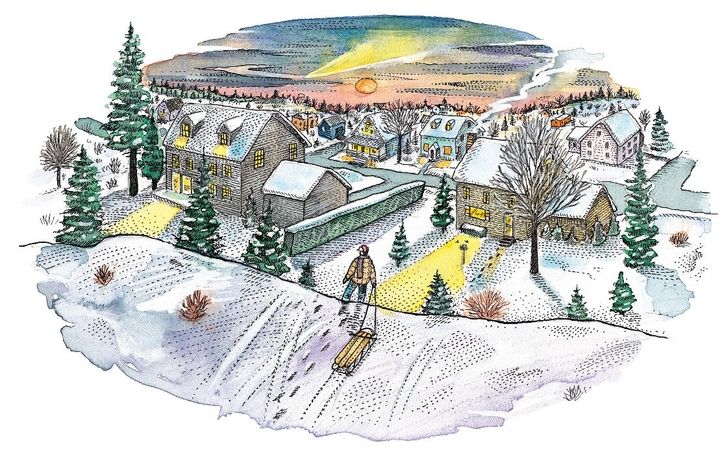

I grew up in New England in a time when our countryside filled with snow each winter, when the golds and reds of autumn always, always yielded to an ice-blue, frosted-windows tableau. The snow would be ankle deep, then knee deep, then hip deep, ever deeper, deeper, deeper. It doesn’t snow like that anymore, not most years.

I loved the winter, and I loved snow. I was an all-afternoon sledder as a kid, schussing the hillsides in back of our old white-clapboard house until each evening’s sun had set. Then I would trudge home with my trailing sled, heading for the yellow warmth of the distant kitchen. In the finger-aching cold of five o’clock, I felt most alive. My mind would race, and I found myself wondering about all sorts of things.

Are all snowflakes truly unalike? Is there even more snow farther north? What’s it like at the North Pole?

Towards December I would wonder as any kid wonders : Do reindeer really fly?

One evening, making my way slowly home after an exhausting session of sledding, I saw something undeniably unusual. It was awfully cold, and the northern lights were at play. Suddenly, silhouetted against those greens and blues, I saw something. . . a very large bird, I thought, flying very fast—not too, too far away. As I peered intently, I could have sworn I saw legs dangling from the underbelly. The bird disappeared into the shadows of the horizon.

On my way home I saw something very strange.

Or was it a bird? Was it even there? Had I seen anything at all?

I didn’t dwell on what I’d seen. But neither was I able to remove the memory from my mind.

IN 1984 I WAS, IN MY GROWN-UP JOB as a nature writer, researching an article on Rangifer tarandus—the reindeer family. I had already learned whatever I could from books—“Reindeer are Arctic and sub-Arctic deer, the North American species of which is called caribou. They are characterized by the possession of antlers by both sexes, they have large lateral hooves and hairy muzzles, and a curious type of antler with the brow-tine directed downwards. The compact, dense coat is usually clove-brown in color above and white below, with a white tail-patch. . .”—I had read all that kind of thing. And now I wanted to go north to see for myself, to watch the animal in its native habitat, to observe its behavior.

So I made my way to a small Inuit village in far northern Canada called Kuujjuaq. Ever since, it has lived in my mind as a place of great import, a village of wisdom, grace and even magic.

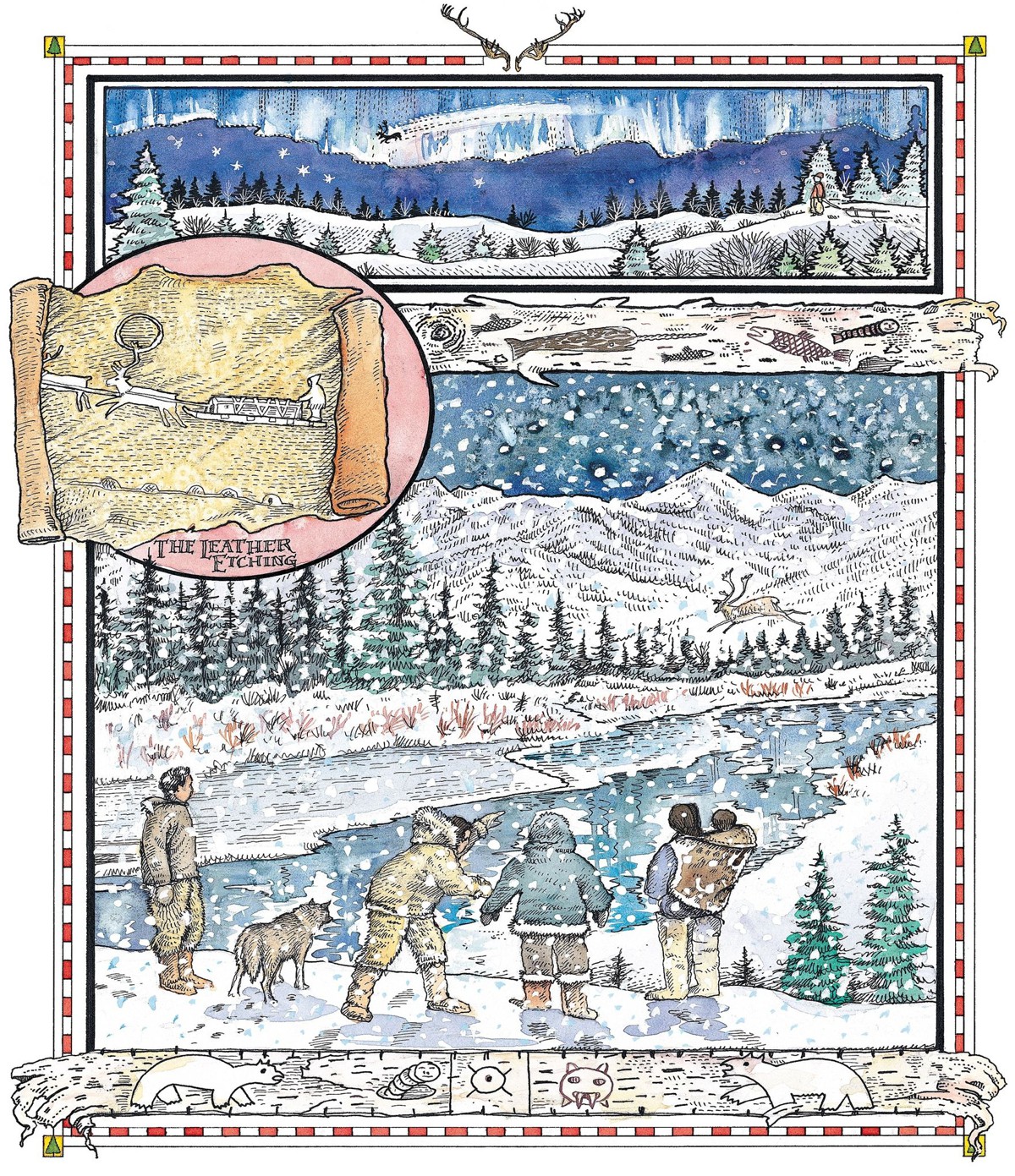

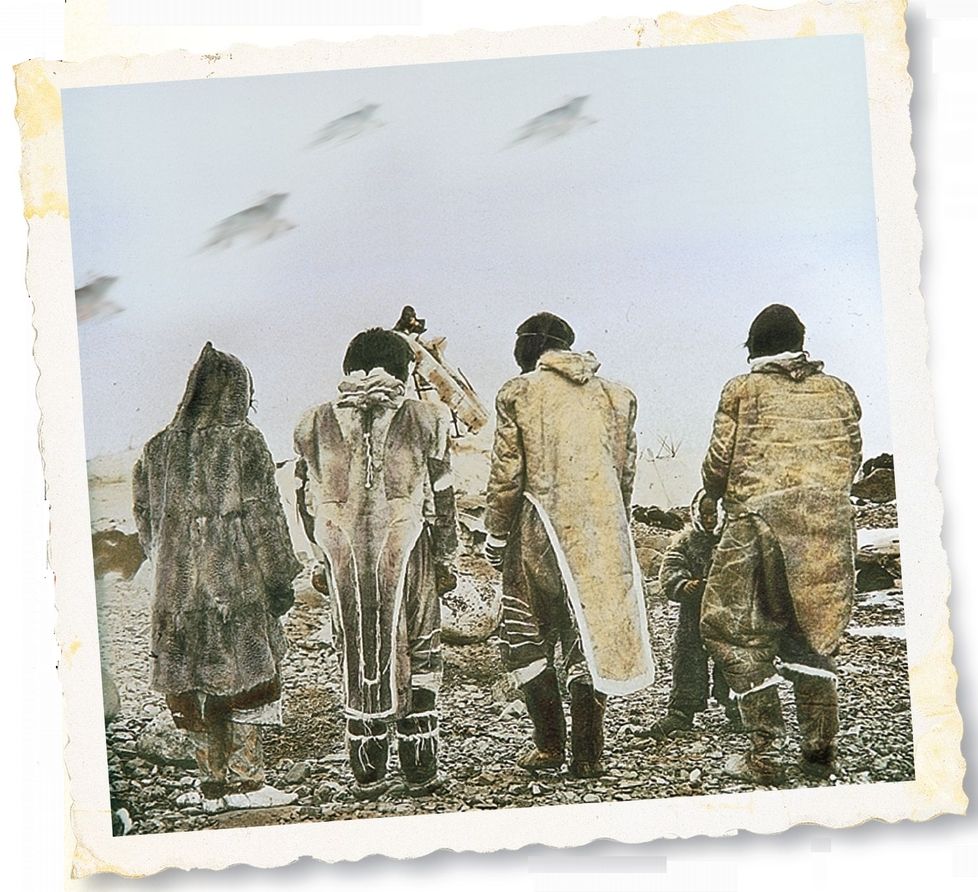

I STAYED WITH AN INUIT FAMILY, very gentle, quiet and good-humored folks.1 I learned a great deal about reindeer by watching several species in their natural surroundings at Un  ava Bay, and I became aware of Inuit customs, too. I learned about Inuit traditions and Inuit religion. Some of the people’s beliefs were steeped in a northern mythology. Much of it seemed pretty strange to me—legends of singing fish, whales with horns like unicorns, ghost bears. Most of the traditions had to do with animals.

ava Bay, and I became aware of Inuit customs, too. I learned about Inuit traditions and Inuit religion. Some of the people’s beliefs were steeped in a northern mythology. Much of it seemed pretty strange to me—legends of singing fish, whales with horns like unicorns, ghost bears. Most of the traditions had to do with animals.

The Inuit were not at all insulted when I appeared surprised by some of their stories and superstitions. They would often laugh quietly among themselves. “Yes,” my hostess once said. “I have never seen the ghost bear, and I never expect to see him either!” But the Inuit were adamant on the subject of reindeer. They believed, beyond any doubt, that reindeer could fly.

The fervor with which my hosts talked of flying reindeer made an impression on me. This wasn’t a singing fish, this was something else. They just wouldn’t hear a discouraging word on the subject. “The reindeer fly,” my host once told me. “It is simple. It is like the moon. Like fire. It is hard to understand, but it just is.”

Their passion on this single and singular assertion led me to wonder.

WONDER, YES, but certainly not believe. I kept expressing doubt, mildly and politely, but emphatically. They would just shake their heads and say, “Of course it is true.” Sometimes they would smile, but they weren’t laughing with me on this one. They were laughing at me.

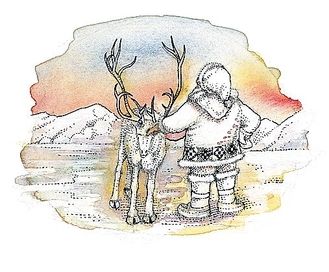

The Inuit seem to regard the one we call “Santa Claus” not only as a miracle worker but also as a friend and neighbor.

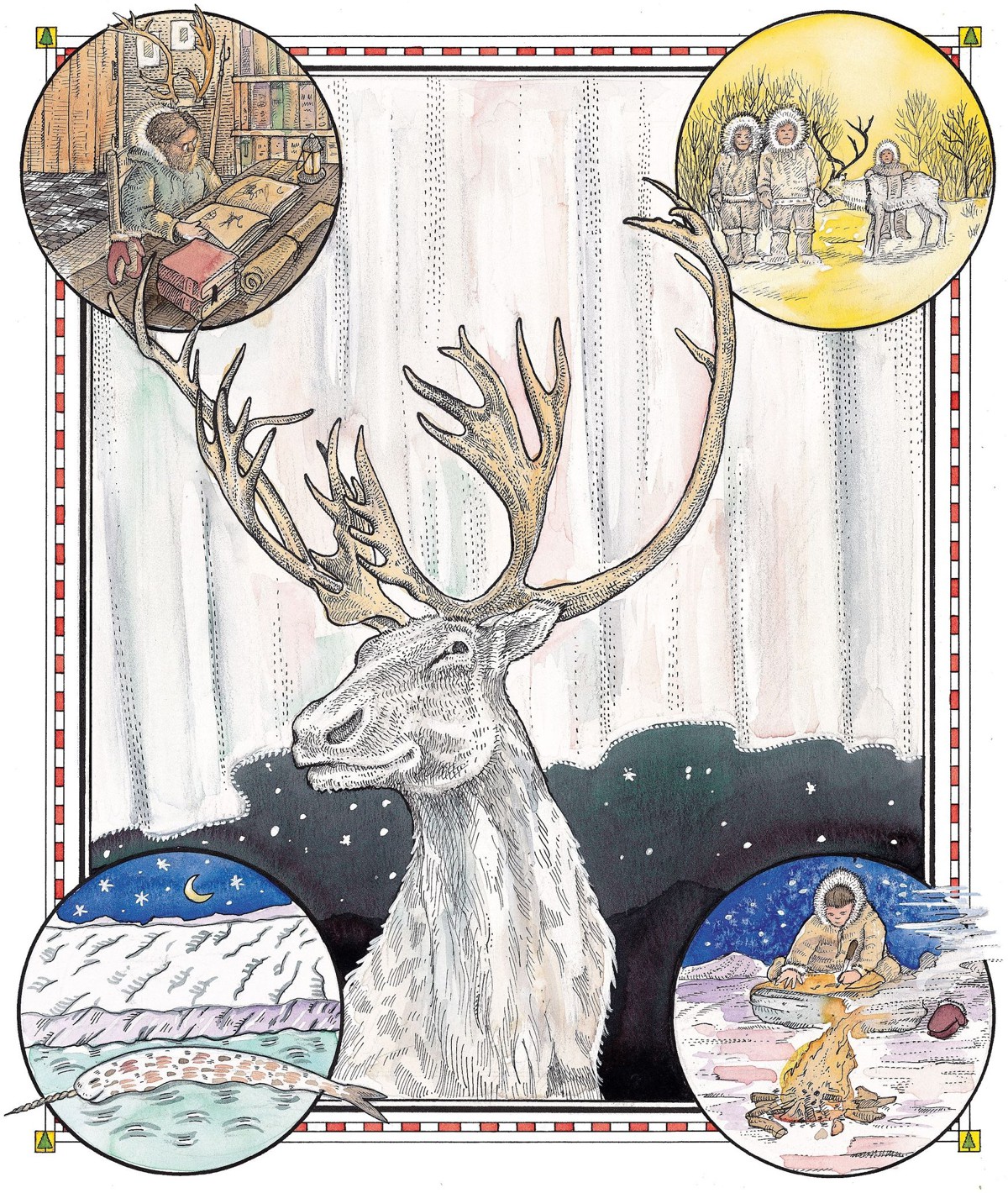

On a cold, gray day in November, my host and hostess took me down to the village’s “museum,” which was actually just a shack, way out at the end of a winding, lonely, little-used dirt road. I brought my camera, and I have since congratulated myself for remembering it.

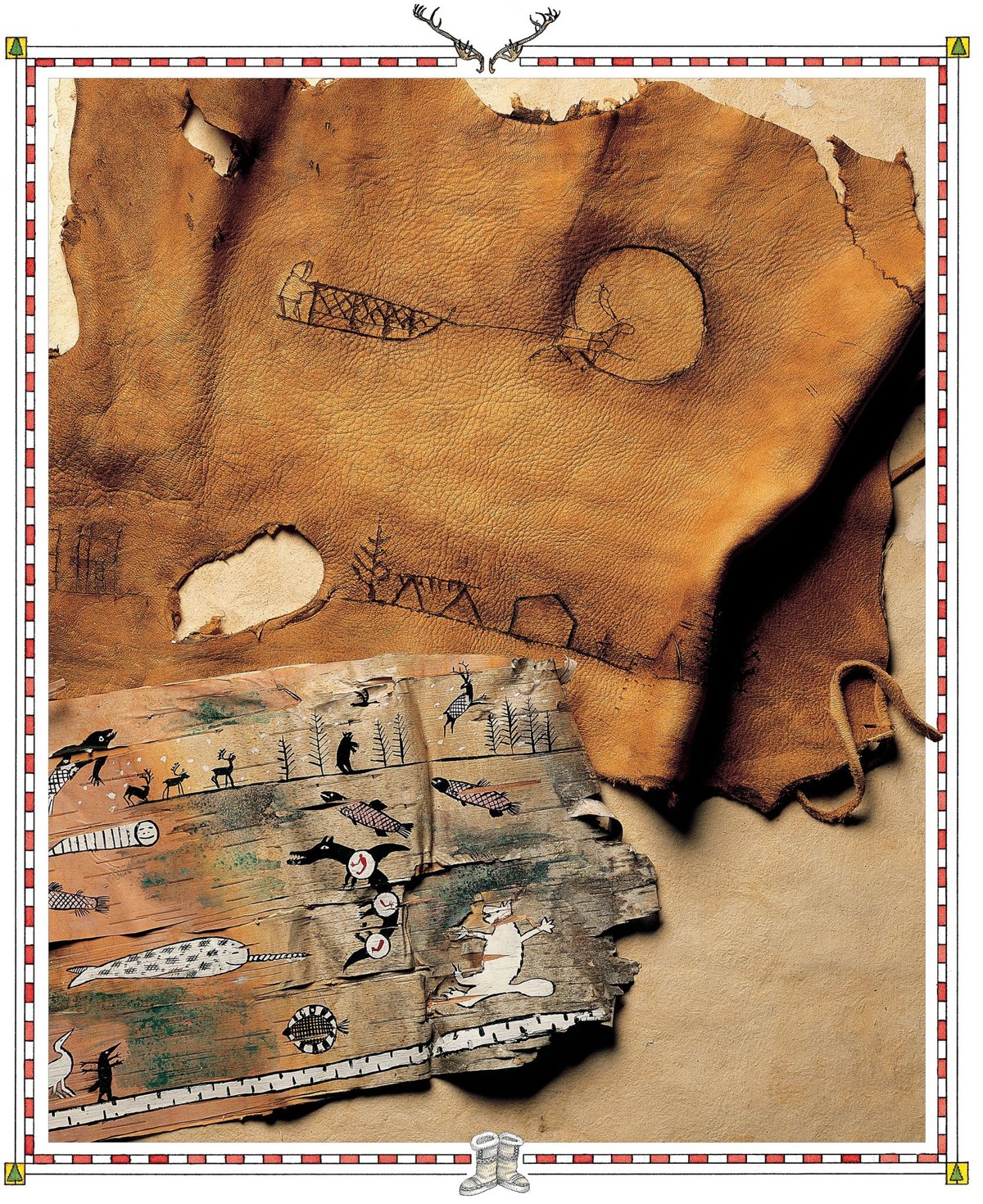

Inside the shack there were all these old—I guess you’d call them scrapbooks. They lay scattered and uncatalo  ued on shelves of unpainted wood. The room was lit only by our lantern; it was not a particularly pleasant place, that museum. But there were those books that my friends insisted I see. I took several of them to the dusty wood table in the center of the museum’s single room. I sat down on a rickety wooden chair.

ued on shelves of unpainted wood. The room was lit only by our lantern; it was not a particularly pleasant place, that museum. But there were those books that my friends insisted I see. I took several of them to the dusty wood table in the center of the museum’s single room. I sat down on a rickety wooden chair.

The pages of the first book were made of leather. Between these heavy leaves were etchings on birch bark, scraps of very old writings, knife drawin  s—all kinds of things. The illustrations were of animals that were supposed to be walking, talking and, yes, flying. Many of these animals were reindeer. These weren’t exactly funny sketches—they certainly weren’t intended to be—but if they had been, you might have said they had been drawn by an ancient, Inuit Dr. Seuss.

s—all kinds of things. The illustrations were of animals that were supposed to be walking, talking and, yes, flying. Many of these animals were reindeer. These weren’t exactly funny sketches—they certainly weren’t intended to be—but if they had been, you might have said they had been drawn by an ancient, Inuit Dr. Seuss.

I asked my host if the illustrations existed simply because Inuit believed reindeer had a sacred aspect. Maybe the ancient artists were likening reindeer to angels? My host insisted this was not the case. “They fly,” was all he said.

There was one item. . . I’d call it a drawing. It was an etching on leather, done with the point of a knife. It obviously showed a deer pulling a sled, seen in front of a full moon. I asked the Inuit if this was supposed to be Santa Claus. “Who is Sand in Claws?” my hostess asked. I soon discovered that Inuit ideas of who delivers the gifts on December 25th are quite different from ours. The man we know as Saint Nicholas does indeed have a place among the Inuit, but he is no red-suited, ho-ho-ho ball of fun to them. He’s an Inuit saint, a man of great seriousness and firm intent. They claim to know him as an ancestor. “He came this way one thousand years ago,” said my host. “He lived to the east, some five hundred miles. But only for a very short time. And then he went north. He left behind many small deer.”

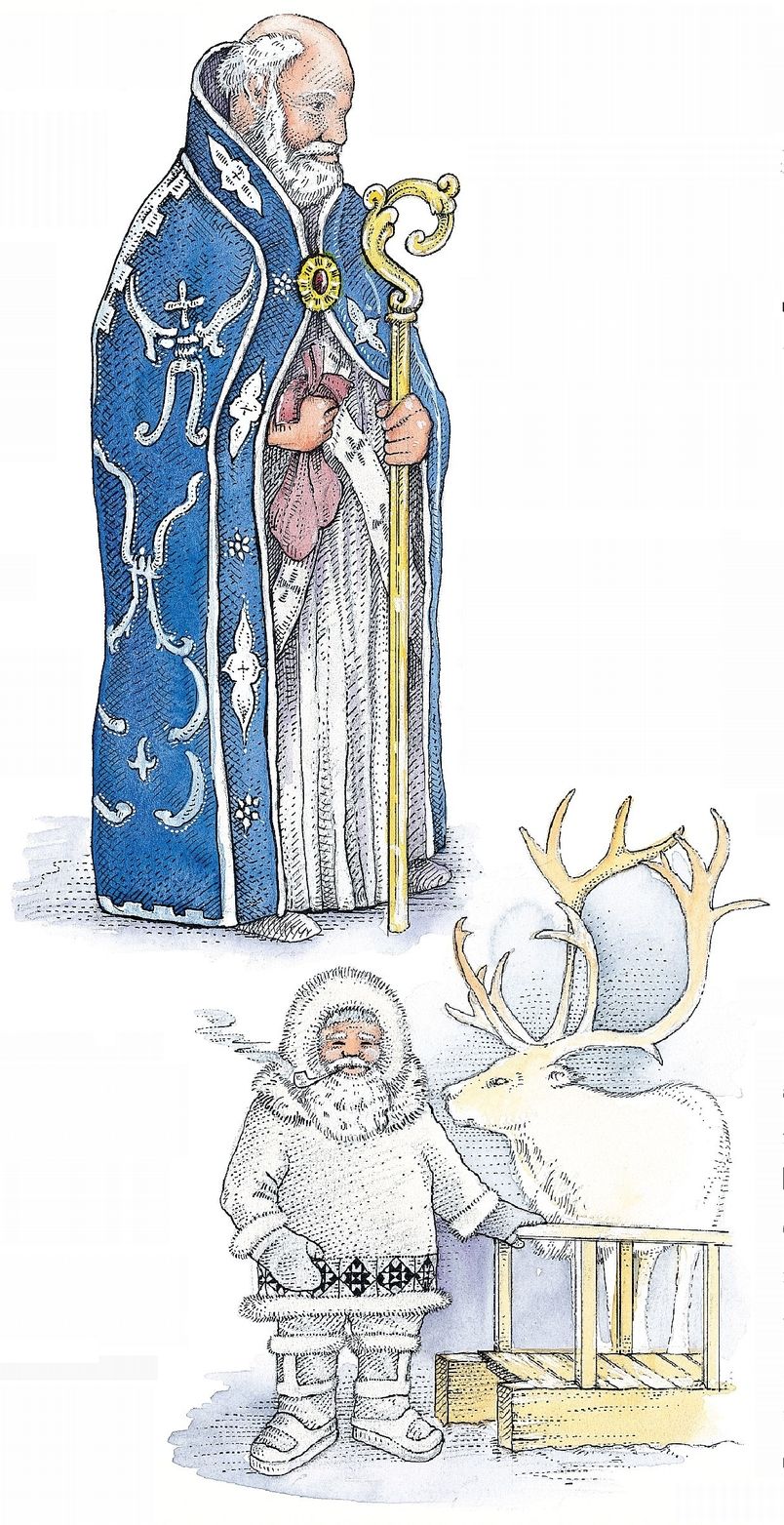

In the north, a reindeer represents a noble spirit as well as a source of food and even a means of transport.

As we left the museum, my Inuit friends could tell that I still didn’t accept the idea of flying deer. I was trying to be agreeable, but they could tell.

THEY DISCUSSED their next step at a community council to which I was not invited. Then, just before I was to leave Kuujjuaq, I was escorted by a party of Inuit from the village to a riverbank not far from town. The north-flowin Caniapiscau River enters Un

Caniapiscau River enters Un  ava Bay just above Kuujjuaq, and that’s where we went, to the mouth of the Caniapiscau, where the big stream flattens and grows wide. The Inuit elders—the tribal leaders—obviously had decided that this field trip was an acceptable thing to do. And so, while I sensed some slight hesitancy about unveiling whatever secret was going to be unveiled, our little party made its way through the trees to the river.

ava Bay just above Kuujjuaq, and that’s where we went, to the mouth of the Caniapiscau, where the big stream flattens and grows wide. The Inuit elders—the tribal leaders—obviously had decided that this field trip was an acceptable thing to do. And so, while I sensed some slight hesitancy about unveiling whatever secret was going to be unveiled, our little party made its way through the trees to the river.

When we arrived at the Caniapiscau, we pushed aside the brush, and there before us, as if made to order, was a mammoth deer. He weighed, I would say, about six or perhaps even seven hundred pounds. He was very big for a reindeer. He was one of the extensive St. George’s herd, the herd I had traveled to Kuujjuaq to learn about.

He was browsing at the edge of the forest. As I say, you come across reindeer everywhere up there—the St. George’s herd comprises 300,000 deer, spread all over northeastern Canada. So it was nothing unusual to find this big fellow munching lichen by the river. I had been watching him and his brethren deer move alone or in groups for nearly a month, and I felt I had come to understand them. I felt, in my arrogance, that I knew just about everything there was to know about them.

And then. . .

And then it happened. Suddenly this enormous buck stopped, turned, took a short run and—after a soft grunt and a forceful liftoff—he soared across the water. It was astonishing: two hundred yards in a single bound! He was in the air forever, it seemed.

He was flying.

I gasped, then shivered. I was too stunned to snap even one picture.

The Inuit said that this was nothing compared with what “the little ones” could do. “The little ones that live farther north,” one man said. “Those are the real fliers.”

EVER SINCE MY EXPERIENCE in the far north I have spent whatever free time I have had investigating this flying-deer phenomenon, and how it applies to Santa Claus’s annual Mission. I had gone to Kuujjuaq to investigate the biology and physiology that govern the earthbound lives of reindeer. I came away determined to unravel a far greater mystery.

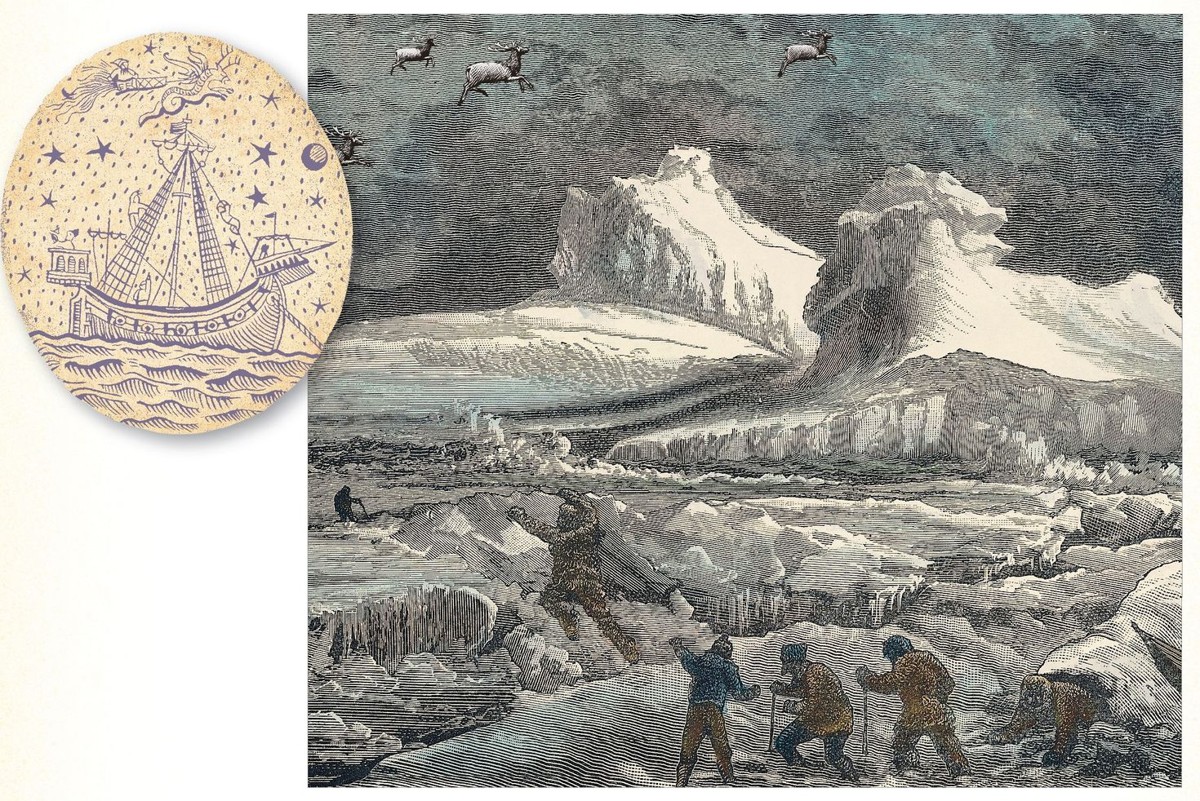

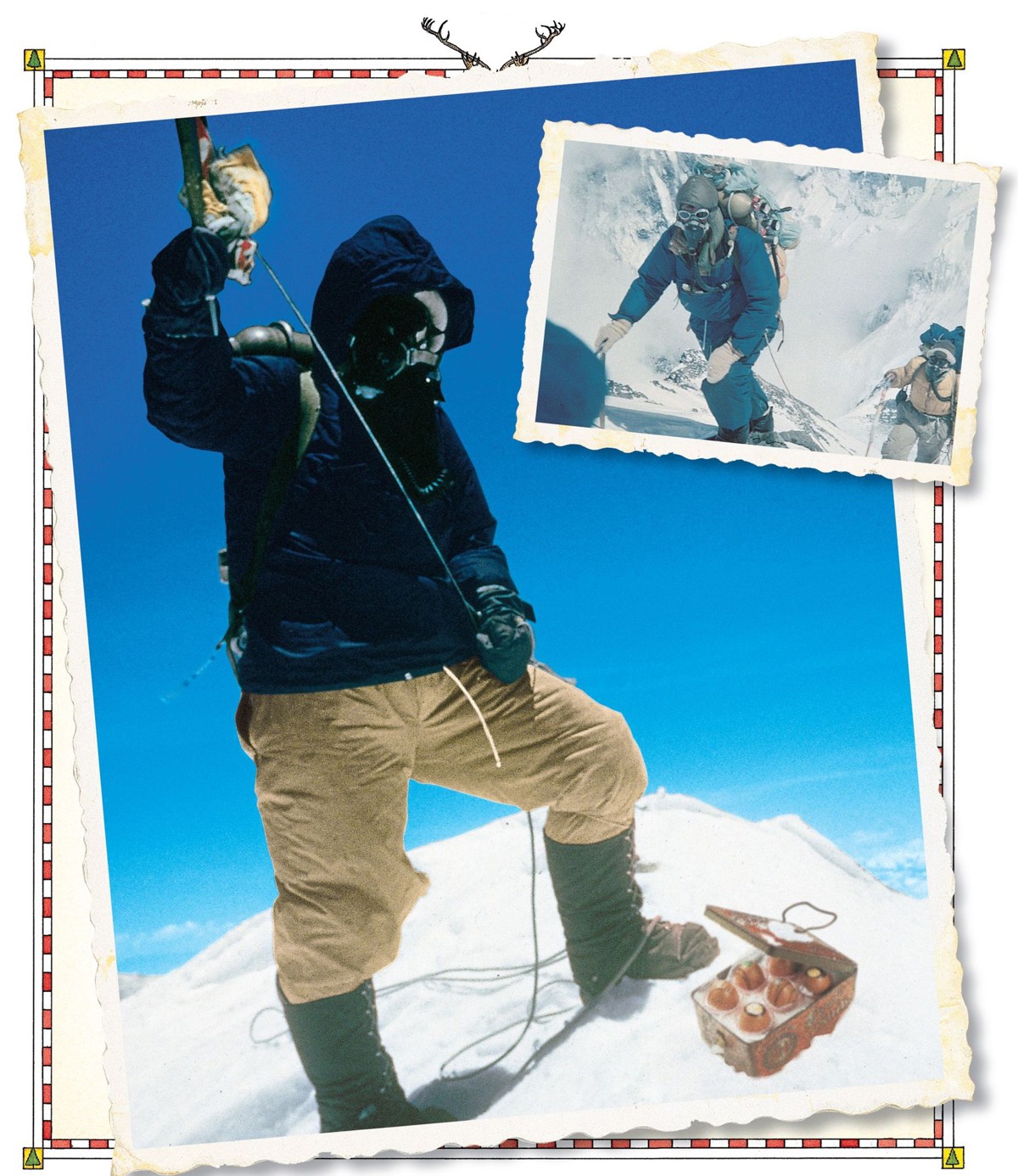

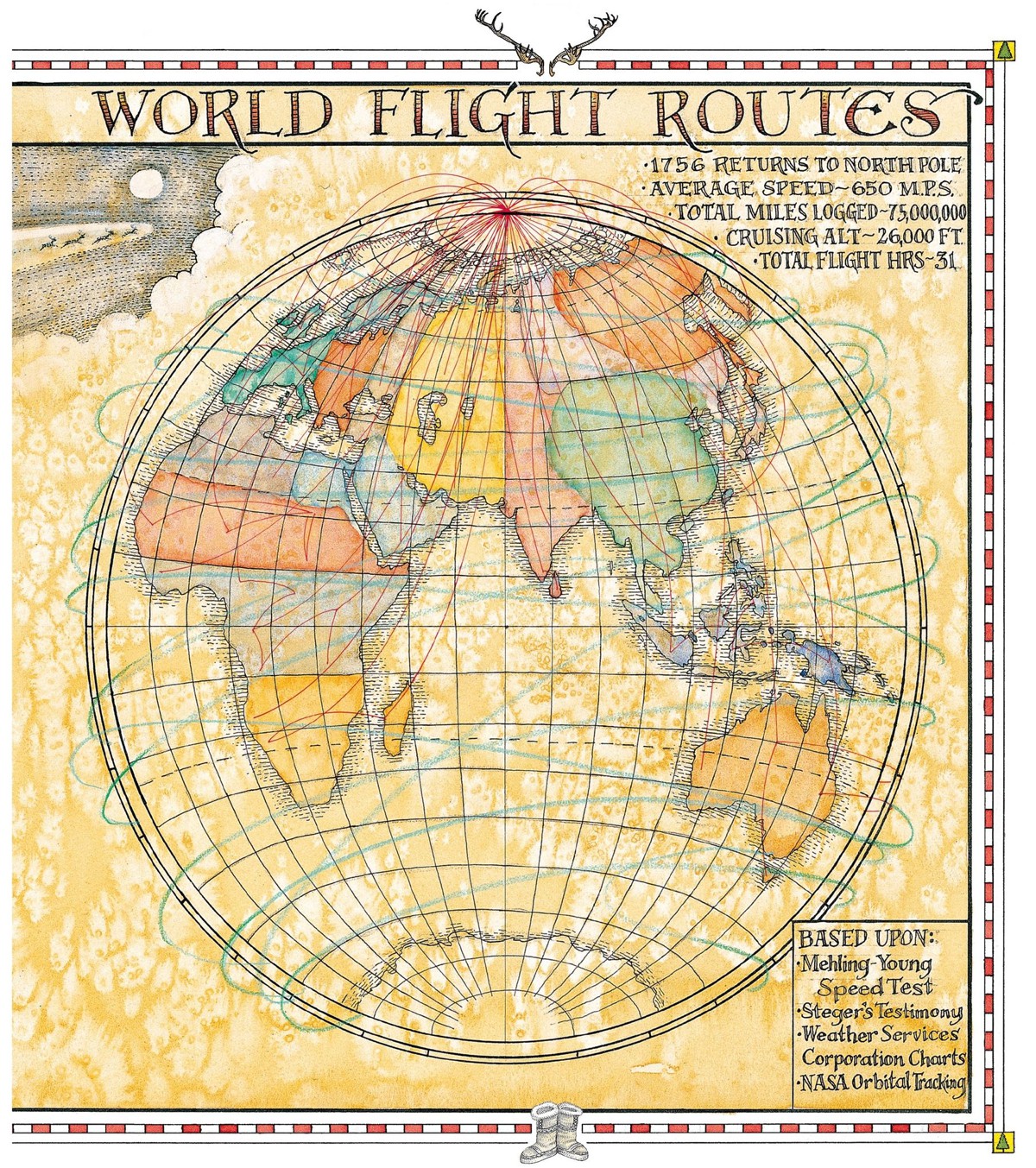

When poring over photographs in one collection of Arctic artifacts, I was astonished to find this image—undated, unsined but wholly real.

I have, by now, read dozens of books—both old and new—on reindeer and caribou: books of natural history and books of pure mythology. I have found a clue here and a clue there, a possible source here and another there—I’ve even found an old photograph of Inuit looking skyward, at what seem to be flying deer. I have learned of several people who have first- or second-hand information concerning Santa Claus and his tremendous undertaking. It turns out there is a small network of people around the world that helps the great elf, and I have been fortunate in gaining the confidence of this network.

I promised that I would never try to exploit or in any way intrude upon Santa Claus and his Christmas Mission. But, I said, I needed to understand some things. And I added that I was sure others wanted to understand as well. An interesting discovery: As I reached deeper into this marvelous story, I learned that although Santa Claus feels strongly that he and his elves must live and toil in isolation, he is not at all reluctant to have us know certain facts about his Mission. In fact, he seems to want us to know. In 1986 he told Will Steger—the Minnesota adventurer who is the only person alive to have ventured into Claus’s North Pole camp—that he is happy to divulge how he does what camp—that he is happy to divulge how he does what he does. “Because,” he told Steger, “then maybe people will understand why I do it.”

I HOPED to come to some better understanding of this “why.” But to get there, I realized I needed to figure out the “what” and the “how”—What did Santa Claus do each year, and how did he do it? What I needed to know about was this: There was once an Inuit somewhere in Canada—a hunter who lived long, long ago. On a midnight, moonlight hunt, something strange and wonderful had happened in the sky, and he had seen it. He had been moved by it, and he had set it down in an old leather book. What was it? What had he seen?

What did it mean? Did it have anything to do with that nonbird “bird” I had seen, years before, beyond the far fields and forests of a New England landscape?

You see, I already knew with absolute certainty, deep in my soul, that there was an ancient Inuit who had seen, one December night long ago, a sleigh being pulled by deer and silhouetted against the moon. Fascinated by this vision, he had scratched out a picture with his knife on a piece of leather. This had been saved in a dark little shack on the outskirts of a village named Kuujjuaq. In an old, tattered scrapbook sits a hunter’s picture of Santa Claus and a flying reindeer. It is a wondrous thing.

Two items in the museum intrigued me, so I photographed them. In the upper righthand corner of the birch painting, reindeer can be seen taking flight. The leather etching speaks for itself. But what tale does it tell?

PART ONE

The Echo of Hooves

Searching for Yesteryear’s Deer

HOW OLD IS the jolly old man? Unless he chooses to tell us-and it is exceedingly unlikely that he will, for he is a lovely but reticent man—we will never know. That is to say, we’ll never know how old he is in the way that we count the years. Surely he is immortal in a spiritual sense.

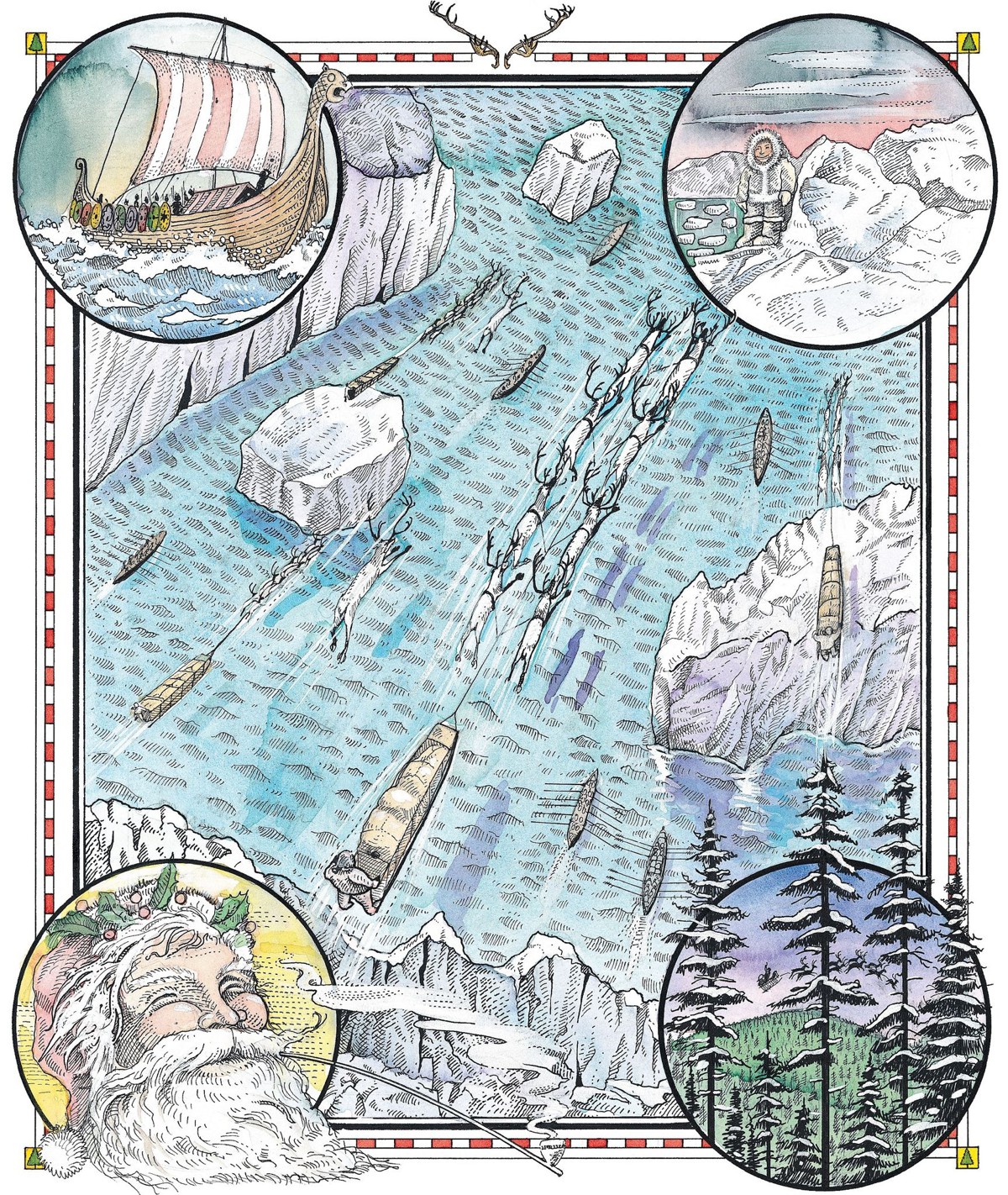

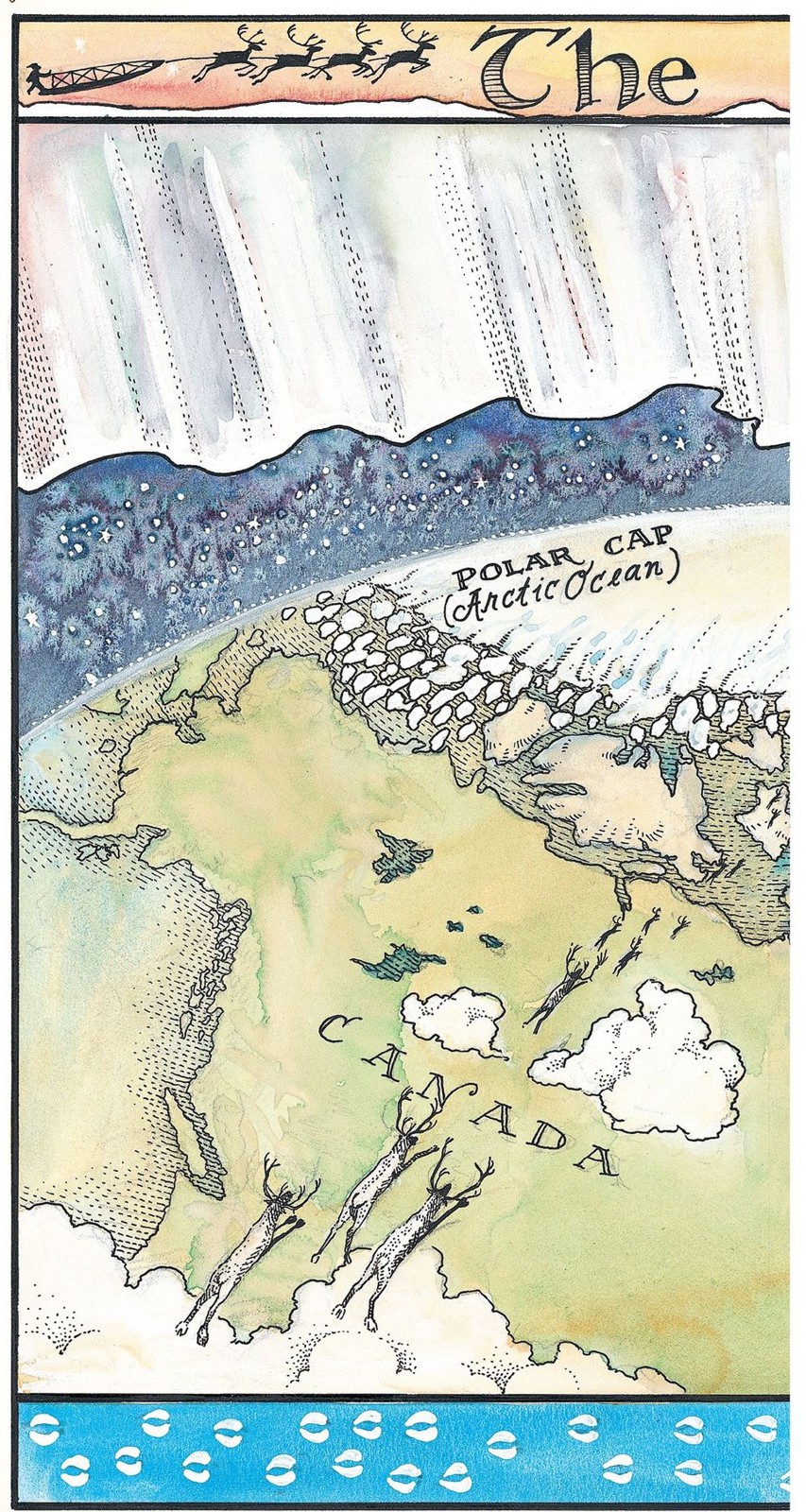

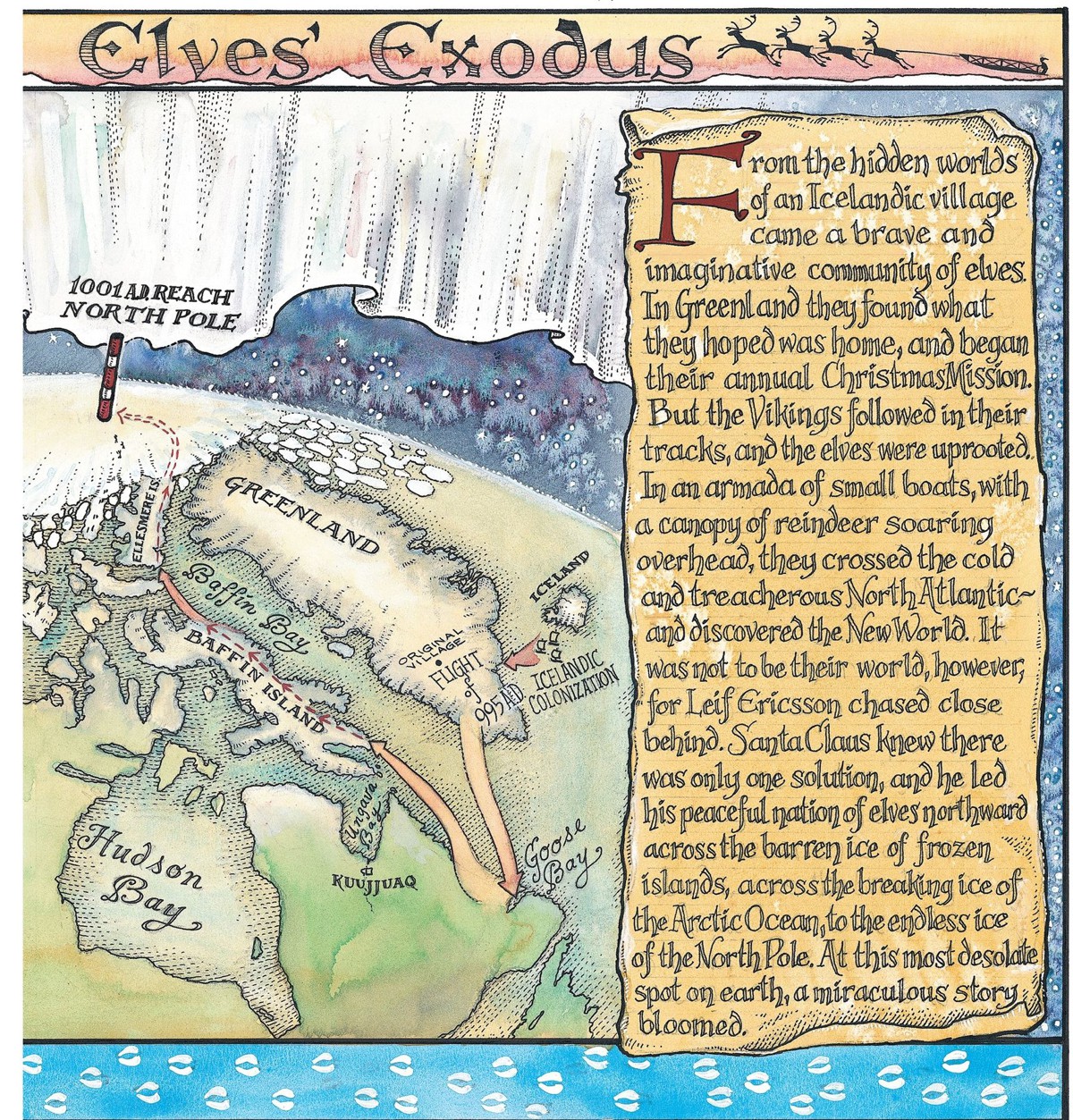

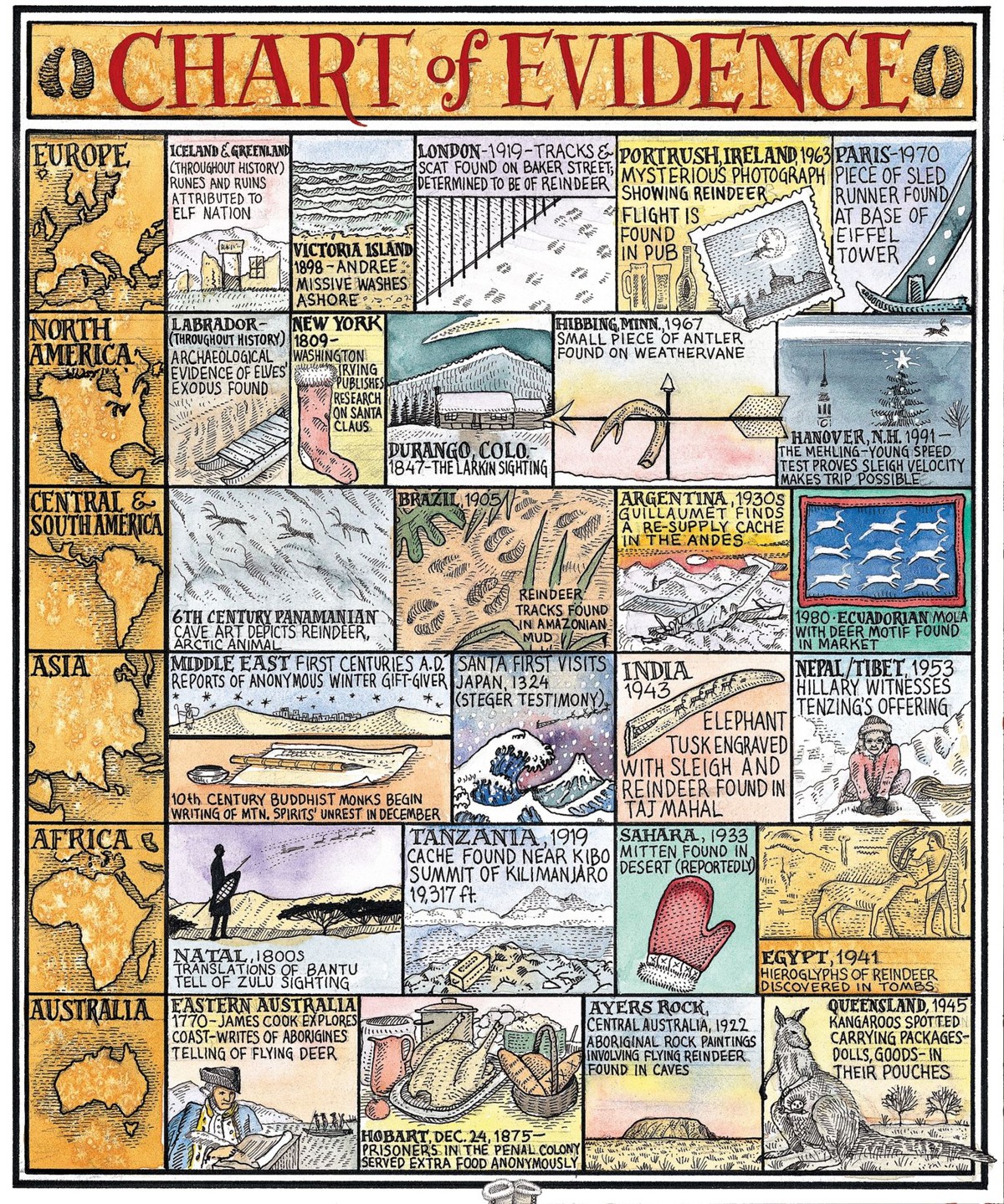

AND SURELY HE IS LONG-LIVED in any sense because we do know that he has been on the job for nearly two thousand years. There are records of children in northern Africa getting mysterious presents as long ago as that. There are stories of strange midwinter visitations made to Native Americans that long ago. There are aboriginal traditions in Australia that speak of a flying man from the north. There are reports of a curious Arctic city of elves that date that far back. There is even firm support for the claim of those Inuit of Kuujjuaq: Yes, indeed, Santa Claus did pass through their land a thousand years ago. He and his community settled for a short while just to the east, and then—exactly as the Inuit said—they uprooted themselves and went north.

“ By reading histories, we can trace the origins of Santa’s nation far beyond its establishment at the North Pole.”

– PHILIP N. CRONENWETT, librarian of Arctic studies and authority on northern civilizations

“If you look at the evidence—and I mean evidence, not legend—then you arrive at a few pieces of certain knowledge,” says Philip N. Cronenwett. “Piece Number One: Santa Claus opened shop two millennia ago, give or take a decade. Piece Number Two: He has been in business every year since, although some years, it is clear, were difficult for him—very hard indeed for him to deliver during those years. Piece Number Three: He has modified his approach, he has gotten better at what he does. Piece Number Four, and this is a tangent to Piece Number Three: He has had to change his location. He did not start all this activity at the North Pole. That’s something I find fascinating.”

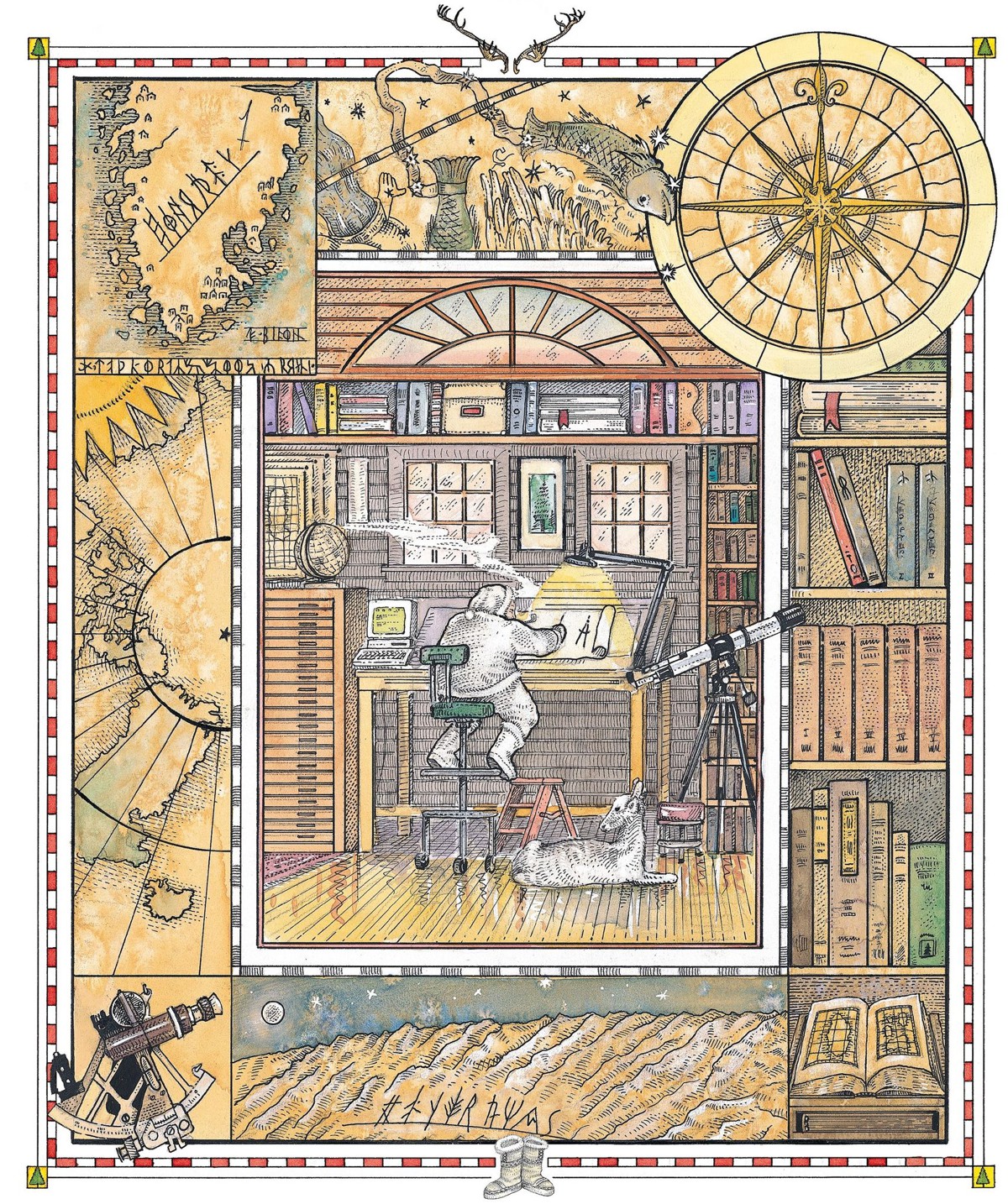

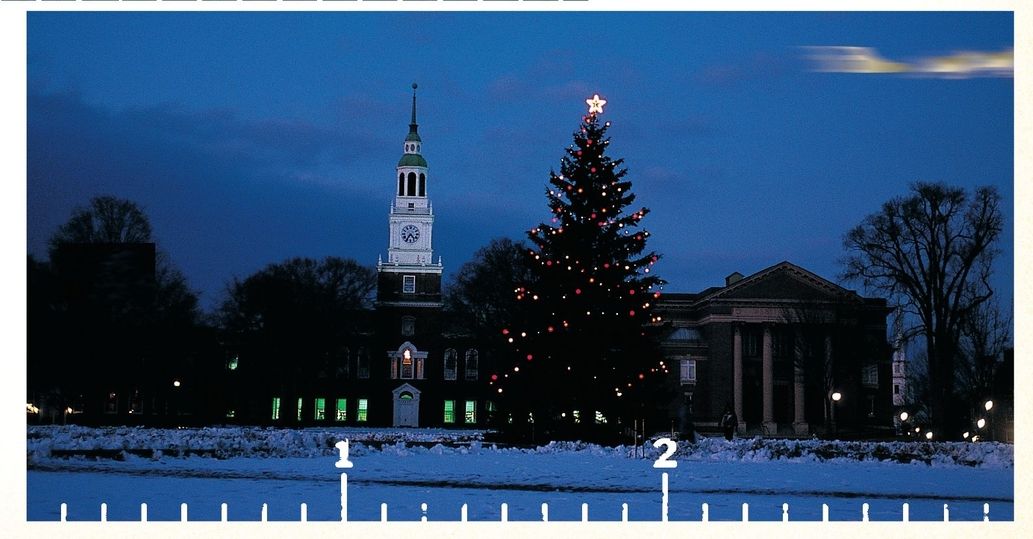

Who is Philip N. Cronenwett, and how does he know these things with such certainty? He is the director of Special Collections at Dartmouth College’s Baker Library in New Hampshire. Baker’s is, perhaps, the finest collection of Arctic artifact and literature in the country. Cronenwett’s office is just off the dark, oiled-wood Treasure Room, where the library’s most valuable books are kept under lock and key. Cronenwett has read those books, all of them. He has put together the pieces.

“Santa Claus is two things indisputably—he is an elf, and he is a good man,” says Cronenwett as he leans back in his chair. “I have never been able to learn where he was born, but I do know that his. . . his ‘village’ was originally situated in south-central Greenland. Makes sense, when you think about it, that he used to live somewhere else. I mean, why would anyone choose to live at the North Pole?”

To support his theories, Cronenwett can cite chapter and verse from great antiquated volumes. ”We have writings from eleventh century Iceland,” he says, not a little proudly. “We have books depicting cave art from eleventh century Canada—or, rather, the region we now call Canada.”

Cronenwett sketches a chronology of dramatic events: A vast community of elves, led by the one who would come to be known as Saint Nicholas or, more commonly, Santa Claus, was established in Greenland untold centuries ago. It was quite near what is now a small town known as Holsteinborg, and the citizens of Holsteinborg have found many relics from Claus’s first settlement.

This, of course, fits well with established histories of elfin communities, none of which suggest elves emigrated south from the Pole. In fact, elves probably originated in Iceland, then quite quickly spread to Greenland, Ireland and the northern reaches of the European continent. If you are looking for an elfin Eden—a place of origin for little people—you’d do well to look at the Icelandic town of Hafnarfjördur. Relics found there indicate a veritable beehive of “hidden worlds.” On the outskirts of town, angelic beings are said to dwell on the Hamarinn Cliff and all up and down Mount Asfjall. In town, some twenty different types of elf live (or have lived in past generations). In the western sector, the conical houses of elves proliferate, and in the Tjarnargata district there is a dense community of dwarves. “We have known for a long time of another society coexistent with our human one, a community concealed from most people with its dwellings in many parts of town and in the lava and cliffs that surround it,” says Ingvar Viktorsson, mayor of Hafnarfjördur. “We are convinced that the elves, hidden people and other beings living there are favorably disposed towards us and are as fond of our town as we are.”

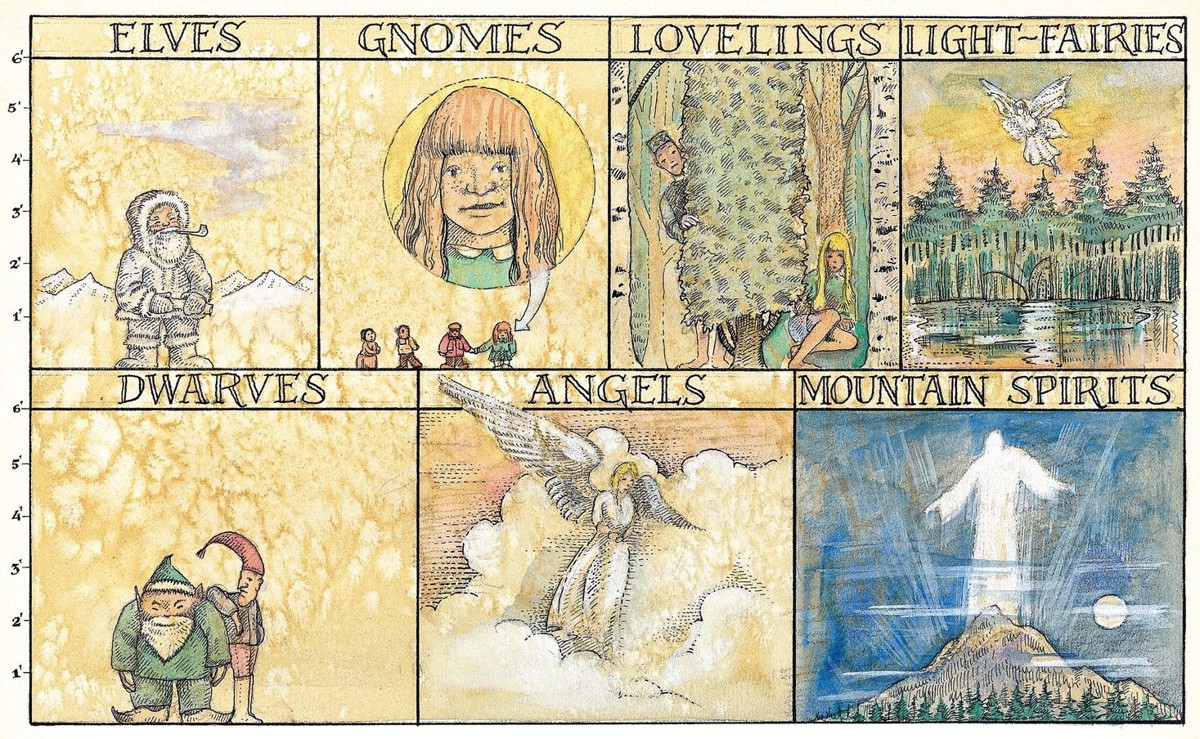

A catalog of hidden beings: In Iceland, all manner of them abound—animal and spiritual.

The variety and number of souls throughout Hafnarfjördur suggest that here is where it might have started for all the world’s small ones—and that here, indeed, is where Santa Claus’s forebears probably once dwelled. In the Town Hall there are records of who is suspected of living where, and in an afternoon’s visit you can put together an extraordinary census for Hafnarfjördur:

Elves (in Icelandic, alfar), some twenty types;

Elves (in Icelandic, alfar), some twenty types;

Gnomes (jarodvergar), related to elves but no more than seven inches tall, four types;

Gnomes (jarodvergar), related to elves but no more than seven inches tall, four types;

Lovelings (ljuflingar), the size of ten-year-old children, usually live behind hedgerows and in woodlands, at least two types;

Lovelings (ljuflingar), the size of ten-year-old children, usually live behind hedgerows and in woodlands, at least two types;

Light-fairies (ljosalfar), resembling angels but tinier, dwelling near lakes, one type;

Light-fairies (ljosalfar), resembling angels but tinier, dwelling near lakes, one type;

Dwarves (dvergar), squat creatures the size of three-year-old humans, six types including the temperamental beings and the sweet-natured ones;

Dwarves (dvergar), squat creatures the size of three-year-old humans, six types including the temperamental beings and the sweet-natured ones;

Angels (englar), as many as a dozen types, to the very highest illuminations;

Angels (englar), as many as a dozen types, to the very highest illuminations;

Mountain Spirits (tivar), one type—but this one, living on Asfjall, is said by those who’ve seen it to be the most radiant anywhere in the world.

Mountain Spirits (tivar), one type—but this one, living on Asfjall, is said by those who’ve seen it to be the most radiant anywhere in the world.

Clearly, Hafnarfjördur has long been a fertile, nurturing place for what some call “the wee people.” A last point to be made, before returning to the community led by Santa Claus, is this: The citizens of Hafnarfjördur, hidden and nonhidden, have longstanding traditions of good community relations, serenity, generosity and industriousness. These are, of course, qualities often associated with Santa Claus generally, and specifically with The Christmas Mission.

WE DON’T KNOW WHEN the Claus clan emigrated from Iceland to Greenland, but we do know that Santa Claus’s “village” in Greenland was a thriving town, and that its main concentration was manufacturing. For nearly a thousand years, from the earliest period A.D. until the turn of the first millennium, the centerpiece of this society was its annual Mission, a fantastic one-night global voyage, the intent of which was, from the first, to bring cheer to the world’s least fortunate. “We know of this intent from the testimony Will Steger brought back from the North Pole in 1986,” says Cronenwett. “What an extraordinary thing—a first-hand interview with Claus. A meeting with the elves! A tour of the village. I’ve always been deeply envious.”

Steger tells us—because Santa Claus told him—that near the end of the first millennium the elves fled Greenland.

History tells us why.

In the 10th century, human beings—Inuit, Sami, Lapp—started to drift onto Greenland from Iceland, Labrador and elsewhere. Whether their presence was of any concern to Claus’s elf community is unclear, but it seems Santa Claus has always been less wary of northernfolk than of Europeans, for whatever reasons.

In the year 982 a Viking chieftain in Iceland named Eric the Red was convicted of certain crimes, and was sent into exile for three years. His banishment took him to Greenland. On returning to his homeland, he began to sing the praises of this other, larger isle. He urged colonization, and in the spring of 986, twenty-five ships headed across the Greenland Sea laden with fowl, farm animals and 750 Icelanders. The passage was treacherous, and only fourteen ships survived. But a foothold had been gained, and in the next few years thousands of Icelanders joined their Norse kinfolk in the Osterbygd, or “eastern settlement.”

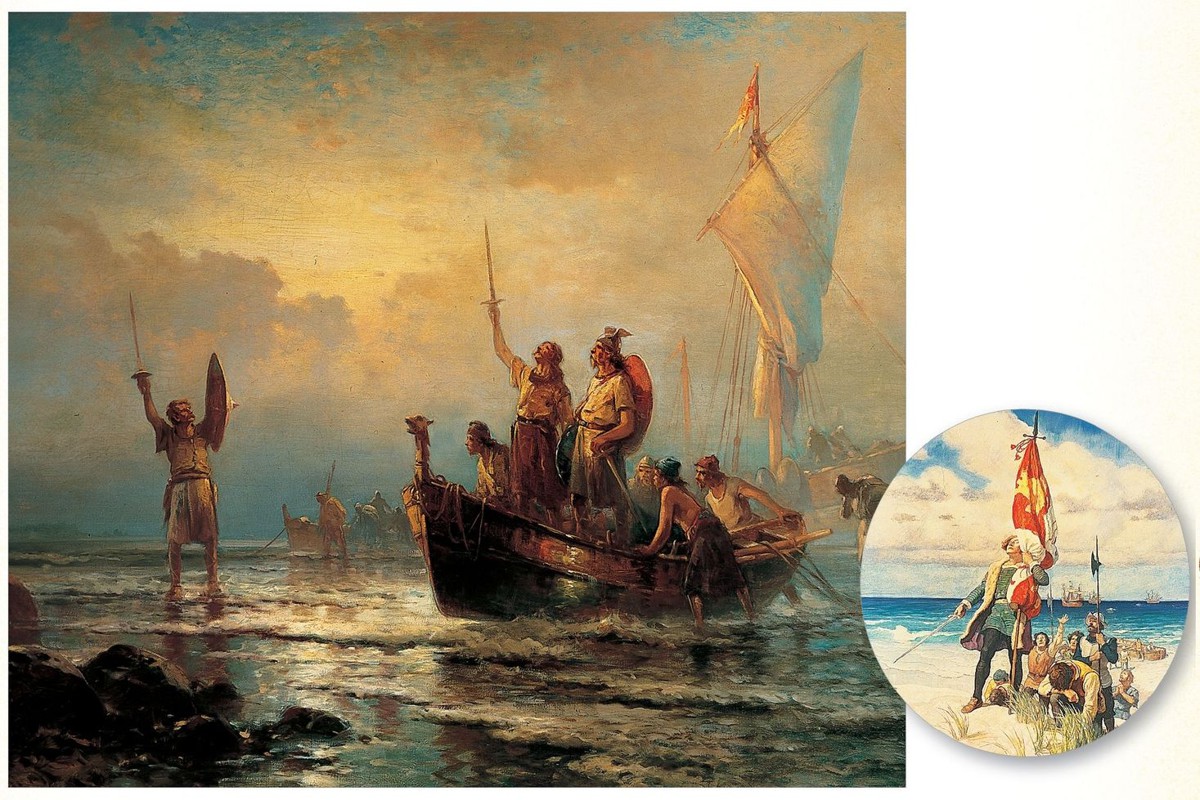

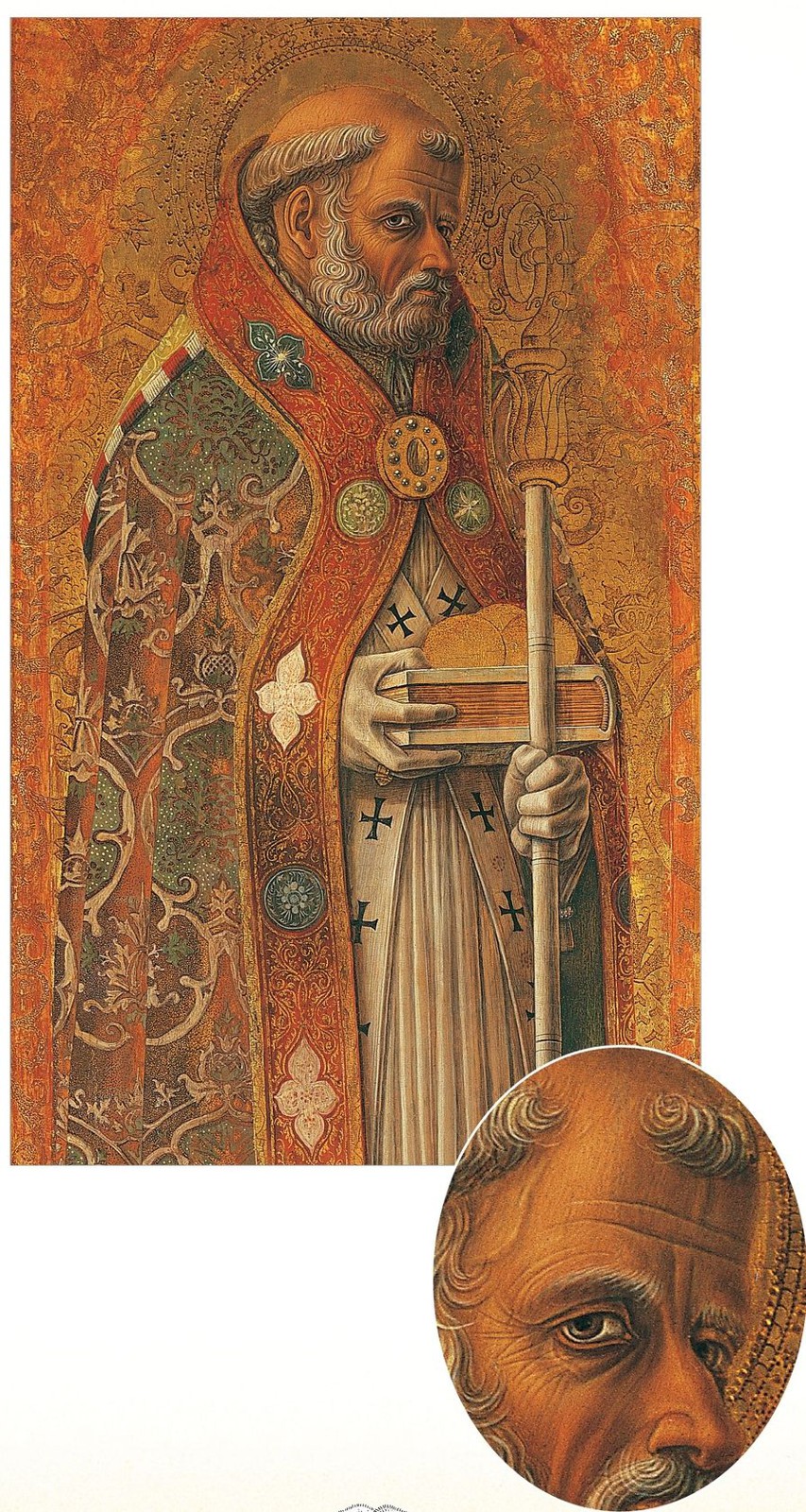

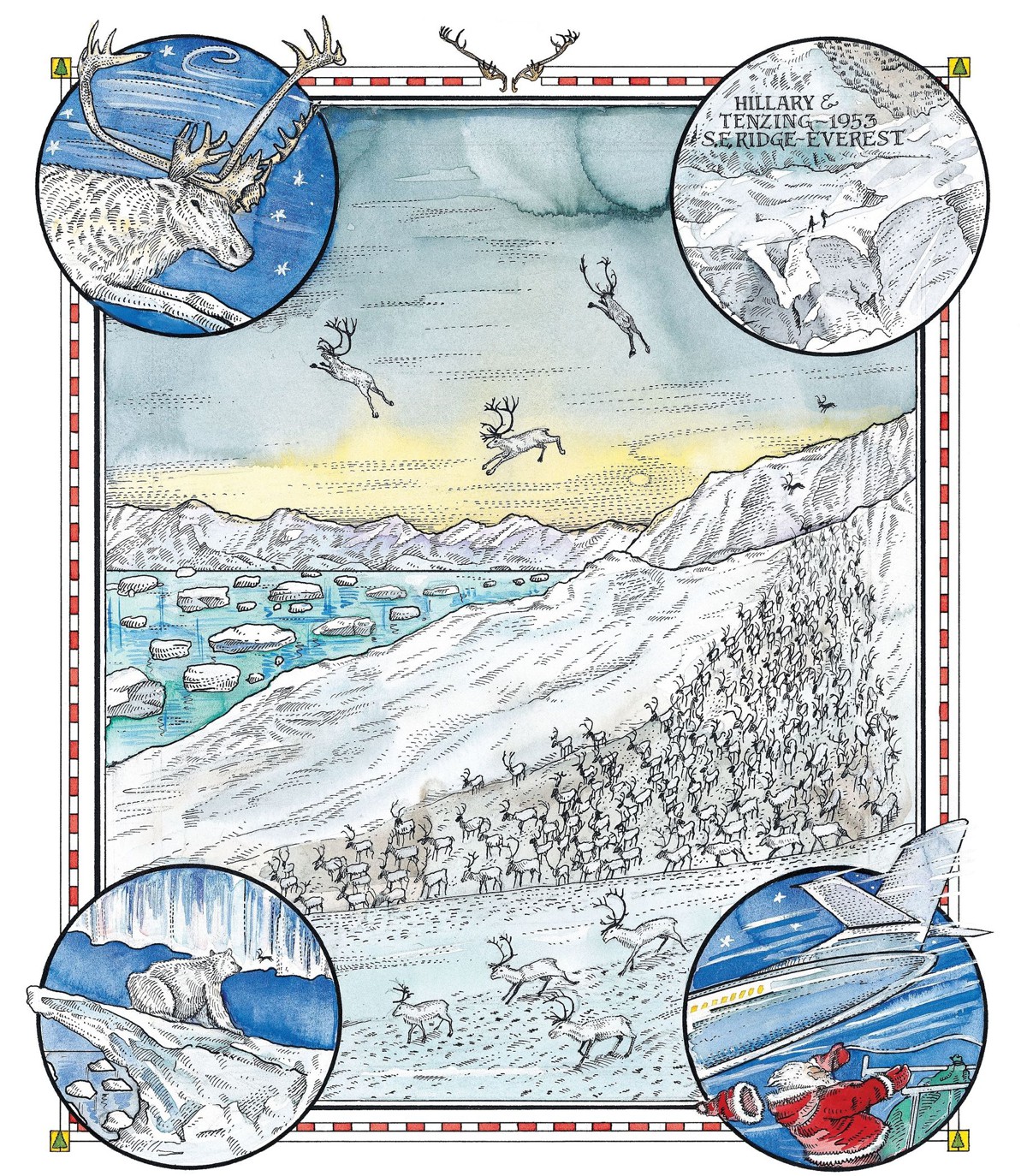

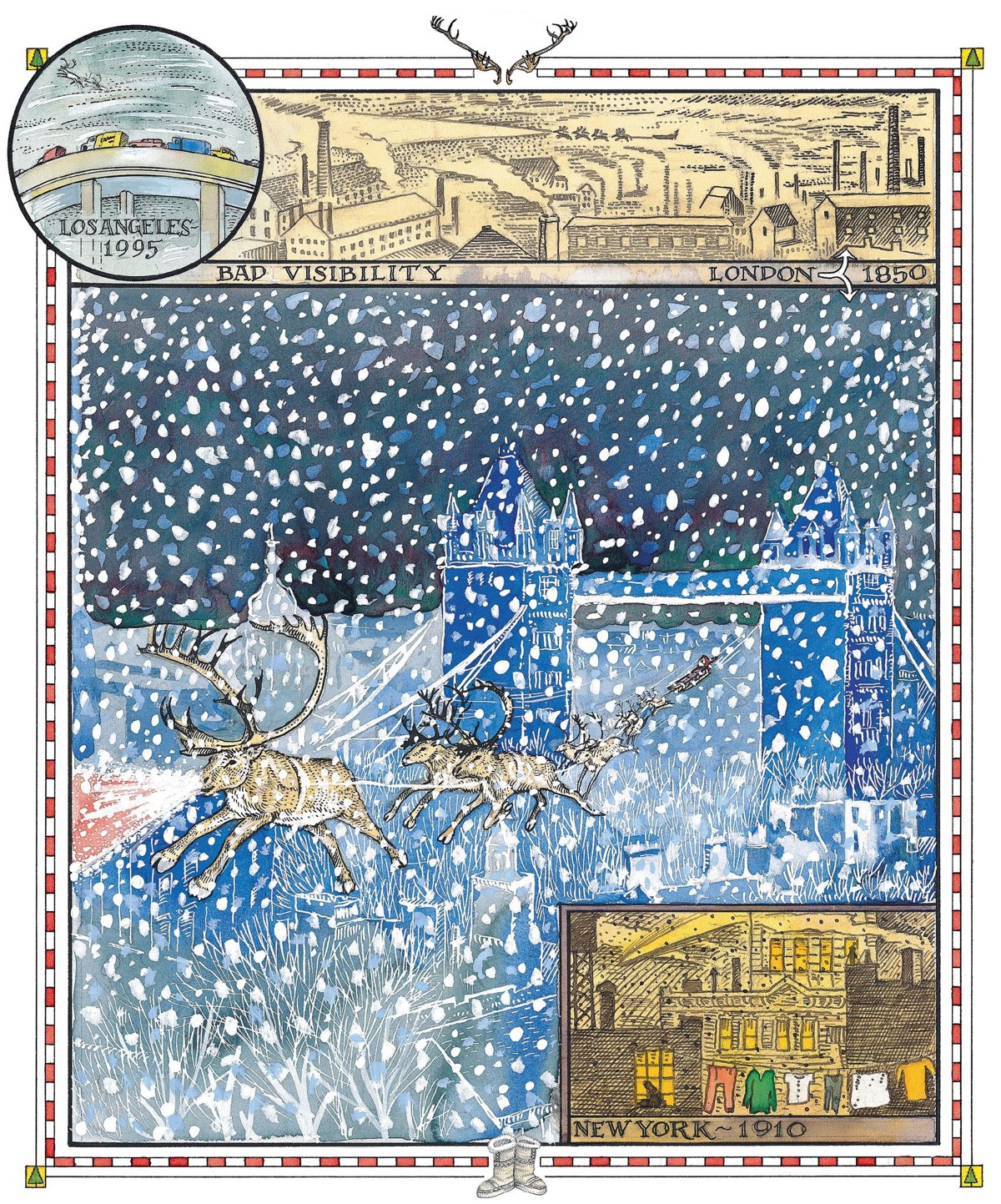

In European art, flying animals are prevalent. The Italian woodcut, circa 1500, shows a dragon pulling a sleigh, while the 19th century Norwegian print depicts men stunned by deer.

Word of this seeped inland, and Santa Claus decided that his own small nation had to be moved. Elves can live five thousand years, but only if they are left unharmed. They are so small and so docile by nature that they present no match for humans.

Claus acted quickly and forcefully when he learned of a European presence on the island, says Cronenwett. He moves from his office into the Treasure Room where, from a glass case, he takes two mammoth volumes bound in leather—Journals of the Osterbygd. “Look here,” he says as he leafs through the ancient pages. “You can’t read the words because they’re in Old Icelandic, but in translation this page recounts, ‘Activity to the west. . . Eskimo? Elves?. . . Night movement sighted by scouting parties?’ And over here. . .” He turns several more pages. “This says, in translation, that the Vikings found an intact, absolutely abandoned city of five miles square, a city that would have housed people less than half their own size. You see? I think what this means is, Eric’s men found Santa’s first village! But they were too late. The whole Claus nation was able to beat it out of there before the Vikings swooped down. It’s one of the great reconnaissances in history.”

Einar Gustavsson, a native of the northern Iceland village of Siglufjördur and an expert translator of Old Icelandic, has read the ancient texts and has worked hard to visualize this first escape of Santa Claus. In relating the tale, he propounds an extraordinary thesis, one that instantly alters what we know of western history. “They traveled overland by dogsled, then oversea by boats,” says Gustavsson during an interview in Reykjavik, the capital of Iceland. “This is not to mention overhead, via scores of provision-packed sleds pulled by the flying reindeer. The entire village simply pulled up stakes—poof!—and fled westward. Santa Claus was then, as he is today, the most knowledgeable navigator on earth. It’s clear that he plotted every latitude and longitude from the air centuries before any Europeans got around to mapping the face of the earth—that amazing route map they found in Norway in 1654 proves it. Therefore, he knew exactly where he was going. His people made landfall in what is now Labrador in Canada, then went south and set up an elfin city in what is now called Goose Bay. It’s interesting that this was the only time Santa Claus ever headed south—he’s certainly a north-bearing man. But what I find much more interesting is this: If you consider Santa Claus a European, as we Icelanders do, then you must consider him—not Leif Ericsson and certainly not Christopher Columbus—to be the very first from the Old World to discover the New!”

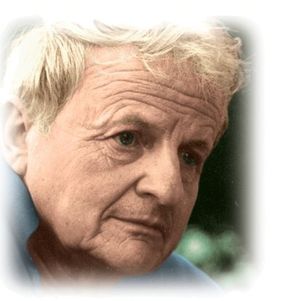

Two runners-up: Leif Ericsson (left) thought he was the first European in the New World when he came ashore at Baffin Island in 1001, and Christopher Columbus (below) thought he was first when he reached the Bahamas in 1492.

LEIF WOULD NOT BE FAR BEHIND. Eric the Red’s son became, in the year 1000, the first Viking to view the mainland of North America. And to be viewed in turn. From the harbor where his commune was taking root, Santa Claus saw Ericsson’s ships. He knew what he had to do.

“Leaving Labrador for the Arctic was the only option available,” says Cronenwett. “He must have known the only place in the whole world where he would be left alone was on the polar ice cap. And he knew that his elves were the only beings on the planet who could survive where there was no place to grow food—no ground, no soil, nothing. How? The flying deer would allow them to establish an operation that imported food! My guess is that Santa knew that whatever provisions they needed in those difficult early years could be scavenged at night throughout Europe, Asia and North America by reindeer-riding elves, who would then fly back to the Pole. In a way, they were the original homeless people of the northern world. Until they got the village up and running, they basically lived on scraps.”

“Elves are tiny, their reindeer are tiny, their city is tiny. This is why they’re so seldom seen.”

– ORAN YOUNG, Arctic Institute director and hiddenworld historian

The exodus of elves to the North Pole was a difficult one, over the windswept hills of Baffin and Ellesmere Islands, and finally to the Arctic cap. There, in the late spring of 1001, the elves saw the great ice of the far northern Atlantic start to break up behind them, giving way to open, frigid, impassable water. Fatal water. They looked back from their new, eternally floating homeland on the ice and knew that they had severed ties forever with all earthly continents.

Except. . . They hadn’t. For decades they came each night for food. And, of course, once a year, every year, they—or at least he—returned to carry out the extraordinary Mission that was theirs and theirs alone. The assignment—given to them by God knows who—was to provide Christmas each 24th and 25th of December. Through struggle and courage they found the one perfect place in the wide world from which to do it.

CERTAINLY, Claus could not have made good his flight were it not for a number of factors peculiar to him and his people. First, they’re very small.2 And elfin communities are known to be as stealthy as any the world has ever produced—stealthier by far than societies of gnomes or dwarves. Claus’s people, in particular, seem blessed with an uncanny ability to travel largely undetected (which is not to say unseen) and to leave few tracks. “Now you glimpse ’em, now you don’t,” says Oran Young, a colleague and good friend of Cronenwett’s at Dartmouth and head of the college’s Institute of Arctic Studies. “All northernfolk know they’re up there. There’s mountains and mountains of circumstantial evidence, and tons of lore that borders on fact. But if you say to the Inuit or the Sami, ‘Prove it!’ not many of them can. They say, ‘Well, I saw this,’ or ‘I saw that,’ but not a lot of them will say, ‘Look at this here elf’s cap!’ Claus and his colleagues are superb at covering their footprints. The only reason we can speak of them with any certainty is the cumulative record built over two millennia, and bits of first-hand evidence like Steger’s.”

The elves’ size is advantageous in other ways as well. They have a unique metabolism, and need precious little food to generate enormous amounts of energy; Santa Claus certainly factored this in when he made the hard choice to head for the barren, foodless North Pole. Still, they eventually would have starved without the big factor. We’re refering to flight, of course.

Flight is the salient point, the essential ingredient. Santa Claus’s was the first of all the world’s communities to be gifted with the ability to fly. Were it not for their tiny reindeer, they couldn’t have reached the Pole, they couldn’t have thrived at the Pole. Were it not for the reindeer, all that we know about Santa Claus would be contained in weathered Norse history books. Were it not for the reindeer, the elf nation that brings us Christmas might have ended long ago in Greenland.

But it did not—because of Santa Claus, because of his people’s courage. And because of the reindeer.

“ There is reindeer cave art in Australia, in Africa, in South America. You tell me how it got there! ”

– CARLTON PLUMMER, art professor emeritus and collector of cave paintings

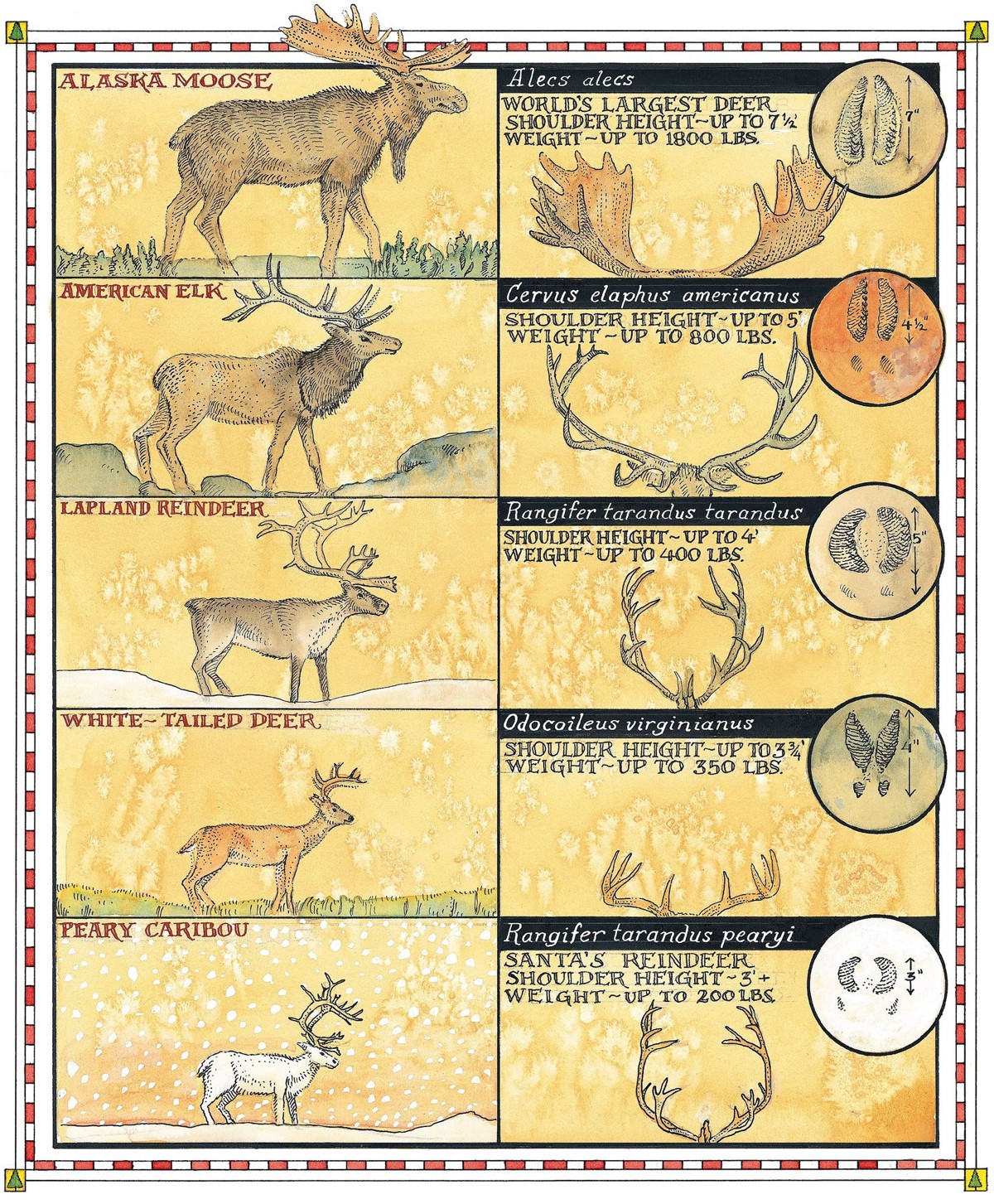

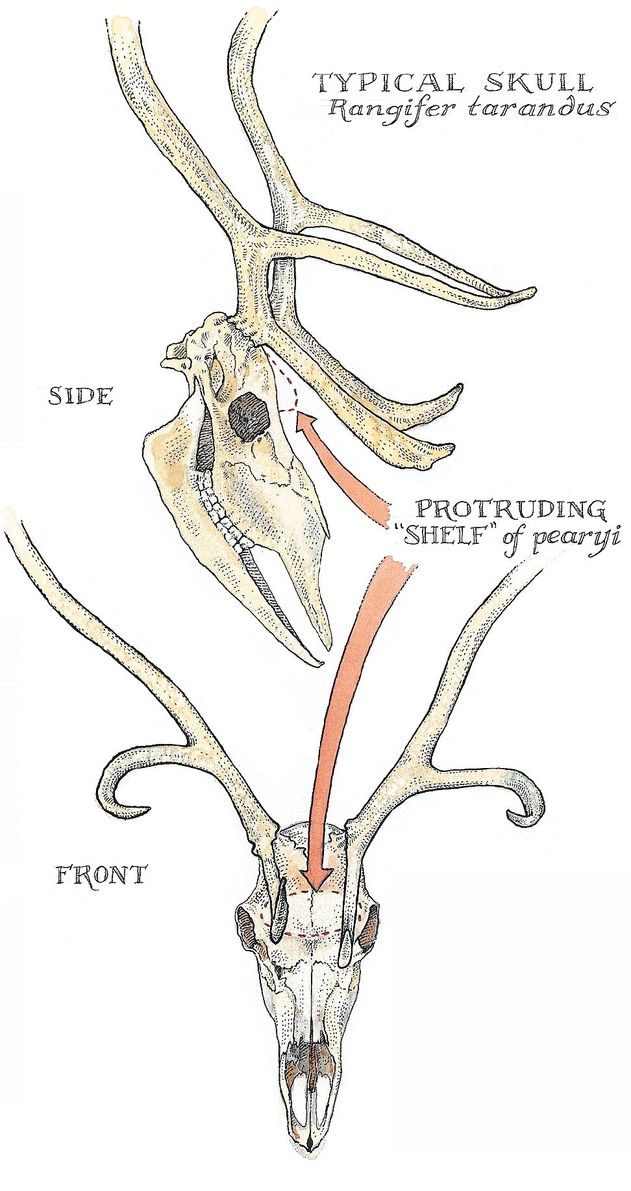

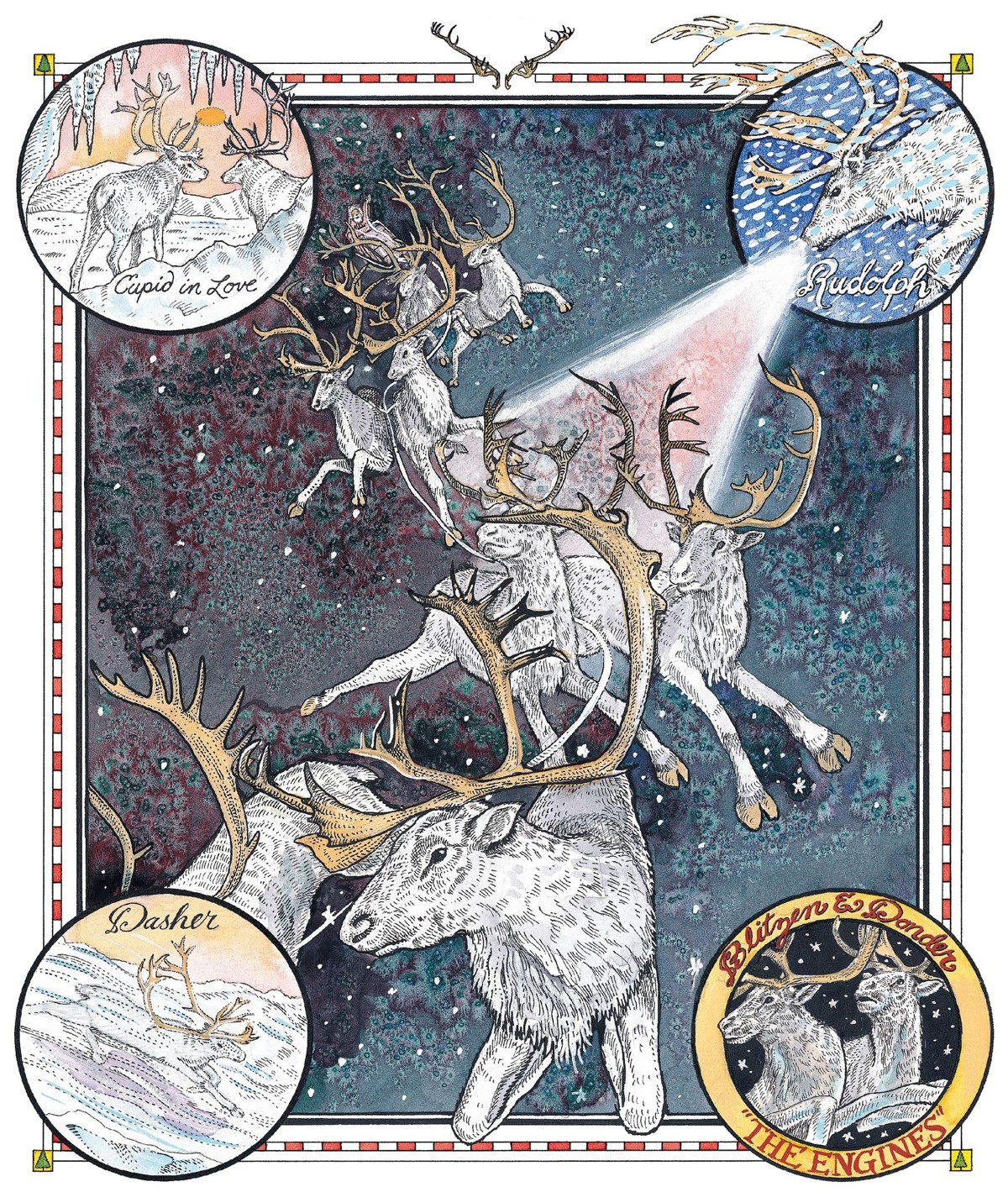

NOT JUST ANY REINDEER. The deer in question is a certain species, Rangifer tarandus pearyi—the Peary caribou. These are “the little ones” spoken of by the Inuit of Kuujjuaq.3

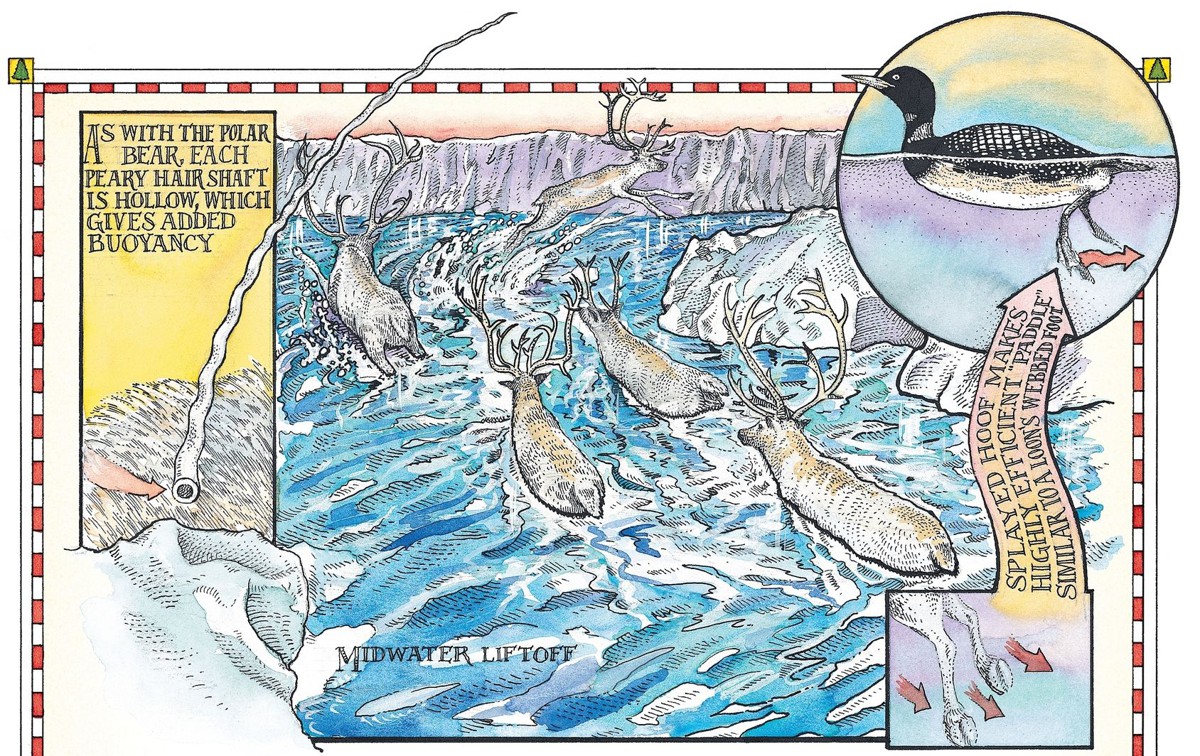

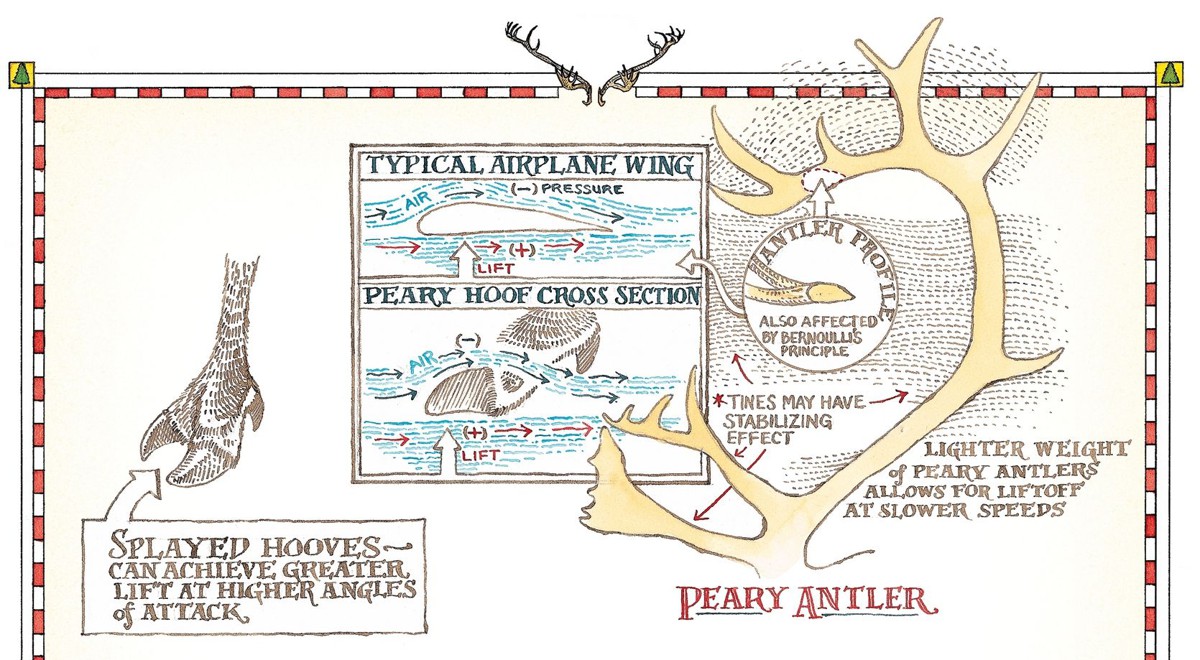

First, we must understand that caribou and reindeer are essentially the same animal. The Old World reindeer is the same as the New World caribou, genetically speaking. There are woodland and barren-ground reindeer, and there are several subspecies of each. The biggest woodland animals stand about as high as a man’s shoulder and weigh 600 pounds or more; the smallest barren-ground reindeer look like big dogs with horns and weigh only about 150 pounds. Most reindeer have coats that are brown on top and white on the underbelly, but one particular subspecies is snow-white in color. These are the smallest, most northern, most purely white reindeer on the face of the earth. And while other reindeer can fly, it is these that fly best, farthest, fastest.

How old is the Peary? That’s impossible to say. The first deer of any kind appeared about ten million years ago in the Pliocene Epoch, but whether Peary were among the early species is uncertain. “Mankind has been on the earth for only several thousand years,” says Bil Gilbert, the esteemed natural history writer. “We know the Peary is much older than man. More we cannot say. But he’s a feisty animal, compact, hard to see and hard to hunt—not least because he can just take off and fly away. So I would suspect he’s probably been around and thriving for a good long while.”

Gilbert, relaxing by the stream that passes behind his ranch in Fairfield, Pennsylvania, continues: “The Peary is a fine, peaceful animal—a credit to the plan-et. Humankind, throughout our own brief history, has always related positively to the Peary in particular, and to all reindeer generally. You can tell from all the cave art.” Indeed, in his definitive book Prehistoric Cave Paintings, Max Raphael writes of drawings made many centuries ago in Les Combarelles, France: “The horses are repeatedly represented as hostile to the bison and bulls: the reindeer as friendly to mammoths. . . . Everywhere the reindeer live a bright cheerful idyll, just as the bison live a stormy drama.” The images in Raphael’s book show buoyant reindeer that look to be dancing or, perhaps, flying.

“Sure, there’s all sorts of iconography indicating reindeer flight,” says Carlton Plummer, professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell. Plummer is a painter himself, and an expert on primitive art. “But what you have to do is separate representations of myth from realistic interpretations. Were those ancient people in France drawing what they truly saw, or just what they believed? Were they journalists or mythmongers?” He pauses, then adds quietly, “Of course, there have been many, many flying-reindeer finds in the Southern Hemisphere too, and that’s the rub. The reindeer is an Arctic animal—strictly Northern Hemisphere—so how would people down there have known of it back in ancient times? I mean, of course, unless they saw one. And how could they have seen one, unless . . . . Well, unless one had flown over!”

A reindeer on a rock wall in southwestern France, painted by the Lascaux artists sometime between 12,000 and 30,000 years ago, clearly shows the animal in an attitude of liftoff.

LET US BE CONSERVATIVE and say that, on the evidence of cave paintings, man has been thinking about flying reindeer for at least 5,000 years. That’s fine, because our interest is in the Santa Claus story, and that is a story which, it appears, extends back only 2,000 years. So by the time Claus and his people started making their efforts known to the rest of the planet, reindeer flight was a commonly regarded phenomenon.

And then, suddenly, in the earliest years A.D., gifts started falling from the sky. “It’s almost a footnote to history,” says Forrest Church, pastor of All Souls Church in New York City and author of Everyday Miracles and several other books about religion. “This is the mysterygifts phenomenon that occurred in Africa and southwestern Asia back then. Those were the only cultures on Earth with reliable chroniclers, and when you read their reports about these strange visitations, you develop an odd impression—that this was just an incidental thing to these writers, a very small thing.”

He picks up a piece of paper from his cluttered desk. “Here, I’ll quote from one. This one was found somewhere in Palestine, and my translation is pretty rough, but it reads as follows: ‘And in a strange situation, it appears the poorest of the poor were visited Tuesday last, and were given bread and wine. Of the same night, several children of our settlement were visited as well, and given trinkets.’ It goes on, but not much longer. It wasn’t news, really, it was just a curiosity—this gift-giving. Why wasn’t it a bigger deal? Well, you see, it was a time of great turmoil in the civilized world, and obviously there were more pressing things to talk about than these unconfirmed stories about children and peasants being given tokens by some wandering stranger.”

Church pauses. “And also,” he says, being playful, as though offering a riddle. “Think about it—there’s another reason why it wasn’t big news. No one could have known that it was global.”

Church continues with a smile, enjoying the moment: “You see, a kid in Rome wakes up on December 25th and finds a gift, and the same thing happens in Athens on the same day. But who could’ve put two and two together? It was local news, minor neighborhood gossip. There was no quick communication between settlements, between towns, between regions. It is only with hundreds of years of hindsight, and ten thousand excavations, that we can see what was going on. We add this report here to that one from over there, and soon we see the truth—on the same night, in places all over the world, charity was being offered. Why? We don’t know. We’ve never known. But we do know one thing. We can tell from the local histories that it happened once and only once each year. Year after year after year. It was an annual signal to us—an anniversary, a reminder.

“Of what? Well, to be charitable, maybe. To think about the least fortunate. To be generous. To live each day as if you would deserve such a reward as this. I can’t say for sure, though I wish I could.”

“Saint Nicholas was an exemplar y human being. Santa Claus is an exemplary elf. What’s the problem?”

– FORREST CHURCH, minister, theologian, historian

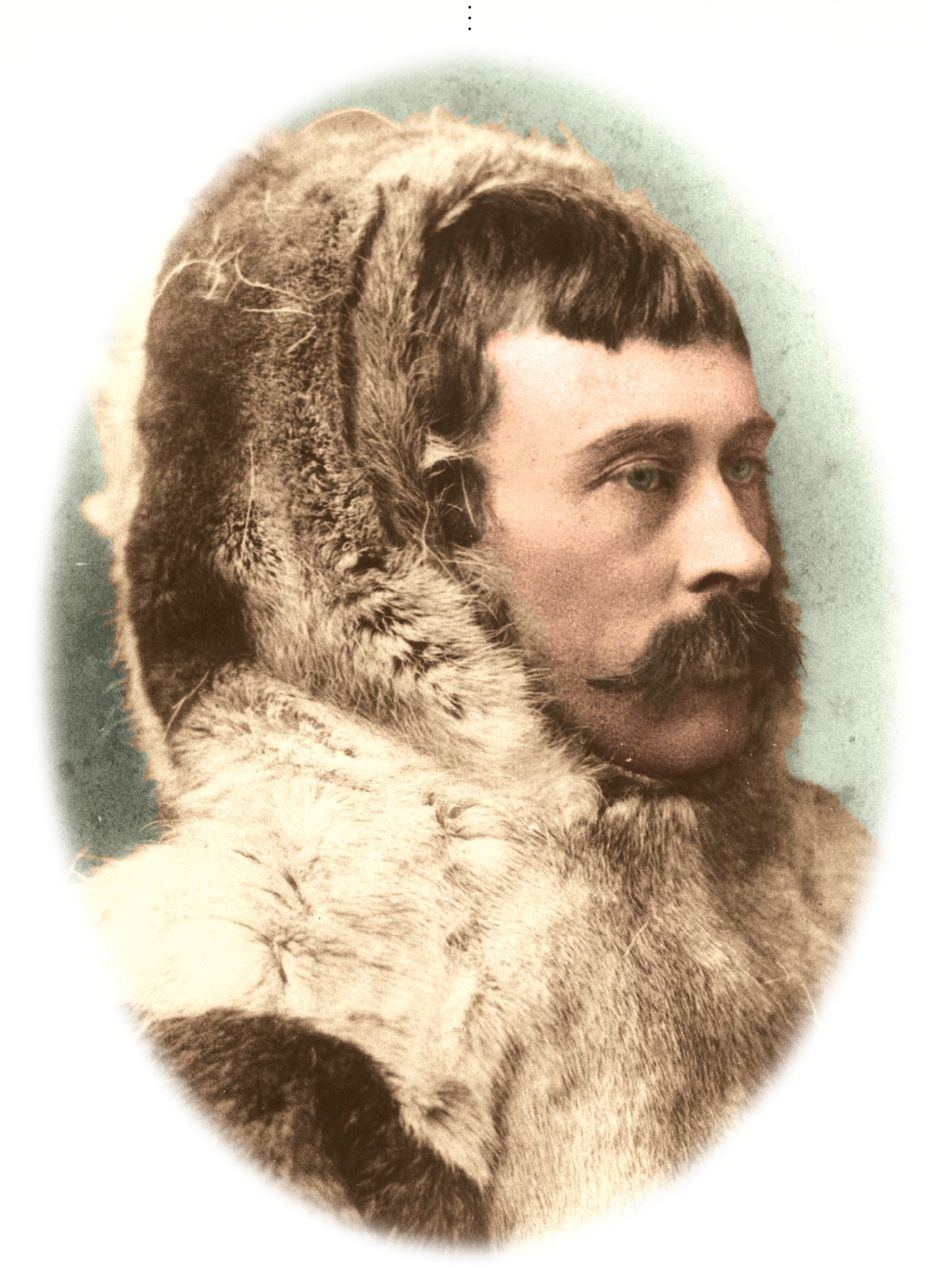

BACK IN THOSE EARLY YEARS of Santa Claus’s visits, not only was the elf’s reindeer not called the Peary but the elf wasn’t called Santa Claus. “He answers to that now,” says Will Steger, the famous adventurer from Ely, who actually asked Claus about this. “All the kids of the world call him Santa, so it’s fine with him. But his elves know him as something else. It has many syllables, and it really sings—La-la-flayah- something. I tried to pronounce it, and simply could not do it. That was strange. I just couldn’t make the words come out of my mouth.”

When the name-change occurred is hard to pinpoint, but it had to have happened in the 4th century A.D. or later. “Yes, absolutely, he worked for at least three hundred years under his real name, whatever it is,” says Church, who is equal parts scholar and Unitarian minister. “You could say ‘Santa Claus’ is his Christian name, because he got it when people started confusing him with a famous and very popular Christian saint—a man, not an elf. The confusion was natural because the North Pole elf and the very human man, Saint Nicholas, were both famous, principally, for their charity and gift-giving. The confusion started sometime in the Middle Ages, and slowly the two figures grew into one—at least in the mind of the world’s children.”

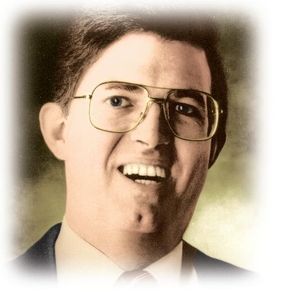

WHO WAS THIS SAINT Nicholas? He was a man born late in the 3rd century in Patara, which used to be a city in what is now Turkey. He was a devout and serious child, and as a boy he made a pilgrimage to Palestine, seeking knowledge. He entered a monastery and became a priest when he was only nineteen years old. He was known as a loving minister. There is a tempera painting on wood panel (facing page) done many years after his death by Carlo Crivelli that shows a stern Saint Nicholas. But look closely at the forehead, at the eyes: There is kindness there, for those who are good.

Nicholas became Bishop of Myra in Lycia on the coast of what was then Asia Minor. There is a legend that he was imprisoned during Diocletian’s persecution, then released under Constantine the Great—but much about this man is uncertain. He may never have been imprisoned, may never have needed release.

A serious Nicholas is depicted in this painting, executed by Crivelli in 1472 and now on display at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

There is one tale, however, that makes its way to our time having been told over and over again. It takes on the air of truth because so many believe it. It is this:

Nicholas came to know a poor man with a large family. The man had three daughters, each of them personable, intelligent and altogether companionable. But no man would marry any of the daughters because the father could not provide a dowry. The father grew saddened, the daughters despondent. Then, one December night, Nicholas passed by the family’s house. He threw three bags of money through an open window. (Who does that sound like?) Each of the girls now had a dowry, each of them married, and the legend of Saint Nicholas as a secret gift-giver was born.

But not only as a gift-giver.

As “One who helps the poor.”

As “One who understands.”

As one who sees bright futures for the young, inspiring them to always be at their best.

After his death, Nicholas was credited with having performed many miracles. He was beatified, and came to be considered the patron saint of sailors, travelers, bakers, scholars, merchants, of all of Russia—but most importantly, of children. He became famous throughout the world, and by the Middle Ages traditions were springing up that were associated with him. His feast day was celebrated on December 6th. In many European countries this became a day of celebration and gift-giving.

IT’S EASY TO SEE how the confusion started, what with the saint having an annual day in his honor—during which gifts were exchanged—and the elf making his surreptitious visits in the same season. From the year 1000 until approximately 1500, the images blurred further, with the saint getting more and more credit for the elf’s work, with the elf taking on the saint’s name in country after country, with the saint taking on elfin characteristics in certain cultures, with the elf starting to look more and more like a man.

On one level, it seems odd that the elf was confused with a man at least twice his size.

As for the name, it came by way of Holland. Of all the places where Saint Nicholas was popular, he was most beloved in the Scandinavian countries and in the Netherlands. The Dutch for “Saint Nicholas” is Sinterklass, and when this term made its way to the English-speaking world, “Santa Claus” was born. Because of various pictures of the human saint that were available, the winter visitor from the North Pole acquired a physical image that would not be corrected until the 1800s. For centuries, most people thought “Claus” was a tall man who wore bishop’s robes and rode a white horse. Children throughout Europe would leave carrots and hay for the horse on the special eve, and must have wondered why only the carrots—a vegetable that Peary caribou adore—were gone the next morn.

Not all countries called the mysterious visitor Santa Claus or even Saint Nicholas. In Germany he was Knecht Ruprecht, or Servant Rupert. In Italy he—or, rather, she—was Le Befana, a kindly old witch. In England he was Father Christmas, and on this point—if few others—France agreed with England, calling him Pêre Noel.

Why all the variation? Because no one was sure. No one could pin him down precisely. Those who came closest were those who were geographically and spiritually nearest to him: the Scandinavians. Swedish children, it was said, received gifts from the elf Jultomten, and Danes and Norwegians were visited by an elf they called Julenissen. “We know they found evidence of Santa’s elves—that map, for instance—since they lived way up there near the Pole,” says Young of the Institute of Arctic Studies. “I’ve always figured that’s why their version of Santa Claus is closest to the real thing.” It was in the early 1800s that Americans started to know the real thing better. The writer Washington Irving played a large part in this. He spent much of the first decade of the century researching traditions concerning the Christmas holiday and its famous present-bearer. In 1809 Irving published the fruits of his labor. To give an idea of the portrait he painted, there is this, concerning a visit by the elf to New York state: “And lo, the good Saint Nicholas came riding over the tops of the trees, in that selfsame wagon wherein he brings his yearly presents to children, and he descended hard by where the heroes of Communipaw had made their late repast. And he lit his pipe by the fire, and sat himself down and smoked; and as he smoked the smoke from his pipe ascended into the air and spread like a cloud overhead. . . . And when Saint Nicholas had smoked his pipe, he twisted it in his hat-band, and laying his finger beside his nose, gave the astonished Van Kortlandt a very significant look, then mounting his wagon he returned over the treetops and disappeared.” And later: “Thus, having quietly settled themselves down, and provided for their own comfort, they bethought themselves of testifying their gratitude to the great and good Saint Nicholas. . . . At this early period was instituted that pious ceremony, still religiously observed in all our ancient families of the right breed, of hanging up a stocking in the chimney on Saint Nicholas eve; which stocking is always found in the morning miraculously filled; for the good Saint Nicholas has ever been a great giver of gifts, particularly to children.”

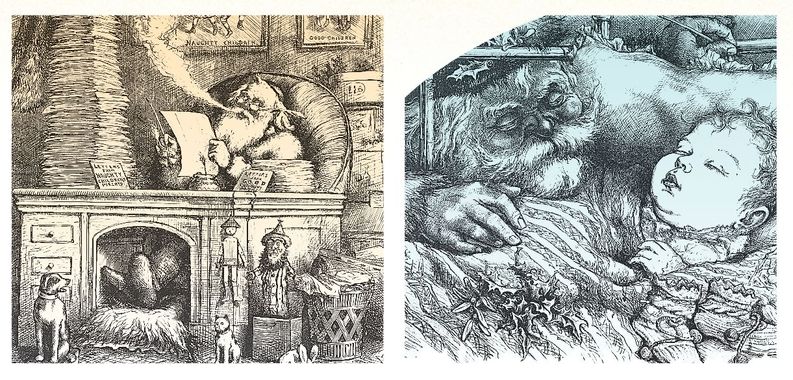

In the 19th century, Nast’s illustrations (top) and the word portraits of Irving (seated) gave us an accurate picture of the elf.

With these words America’s first great man of letters was codifying a vision of the December visitor: the most accurate description of Claus yet presented anywhere in the world. Substitute “sleigh” for “wagon”—and what historian might not suffer a trivial mistake like that?—and it becomes evident that Irving’s was a remarkable achievement.

“Irving was a brilliant man,” says Regina Barreca, professor of English at the University of Connecticut and an expert on British and American literature. “Careful, thoughtful, thorough. He was just as great a biographer as he was a writer of fiction. When he turned to biography, he didn’t choose to write about just anyone. He liked to deal with the true giants—the biggest of the big. He gave us masterful portraits of George Washington, of Shakespeare and, of course, of Santa Claus.”

What was Irving’s source material? “I presume Irving found copies of the Greenland journals, and there were also several Scandinavian histories concerning elves published right about that time,” says Dartmouth’s Cronenwett. “We have some of them on our shelves, though we certainly didn’t have them back then. Irving would have been able to acquire them because he was one of the first American authors to travel extensively in England and Europe. He spent an awful lot of time in London doing research, and these books, which would not have made their way to the U.S. until much later, would have been available there.”

“Without the good, honest reporting of Irving, Moore and others, it would be much harder to believe in Santa.”

– REGINA BARRECA, literature professor and Santa Claus scholar

IRVING’ S VERSION of Santa Claus was confirmed and elaborated on throughout the remainder of the 19th century. There were many reported sightings, of which the 1847 group sighting in Durango, Colorado, is perhaps the most famous. From The Durango Nugget, December 26, 1847: “Mike and Janice Larkin were hosting their annual ‘Dark Night Dance’ at their cabin on the mountain Friday night when a noise was heard and all the guests made for the porch. ‘Sounded like dynamite, ’ Larkin said. ‘But who would be blasting at that time of night? So we went to see and, I swear, a flash of light just zoomed up over the far hills, it looked like a star flying by, but closer. It was weird, son, real weird.’ Larkin’s guests confirmed this account.”

There were the visual interpretations of Thomas Nast in several issues of Harper’s Weekly from 1863 to 1890. There was Clement Clark Moore’s famous 19th century poem “An Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas” that enlarged and embellished the Irving Santa. It is interesting and a bit sad to note that this poem, which begins with the famous line “Twas the night before Christmas,” may not have been written by Moore at all, but by a man named Henry Livingston. Moore was credited because, as a renowned scholar, he was believed more capable of insight into Claus’s character than was Livingston, a land surveyor by trade.

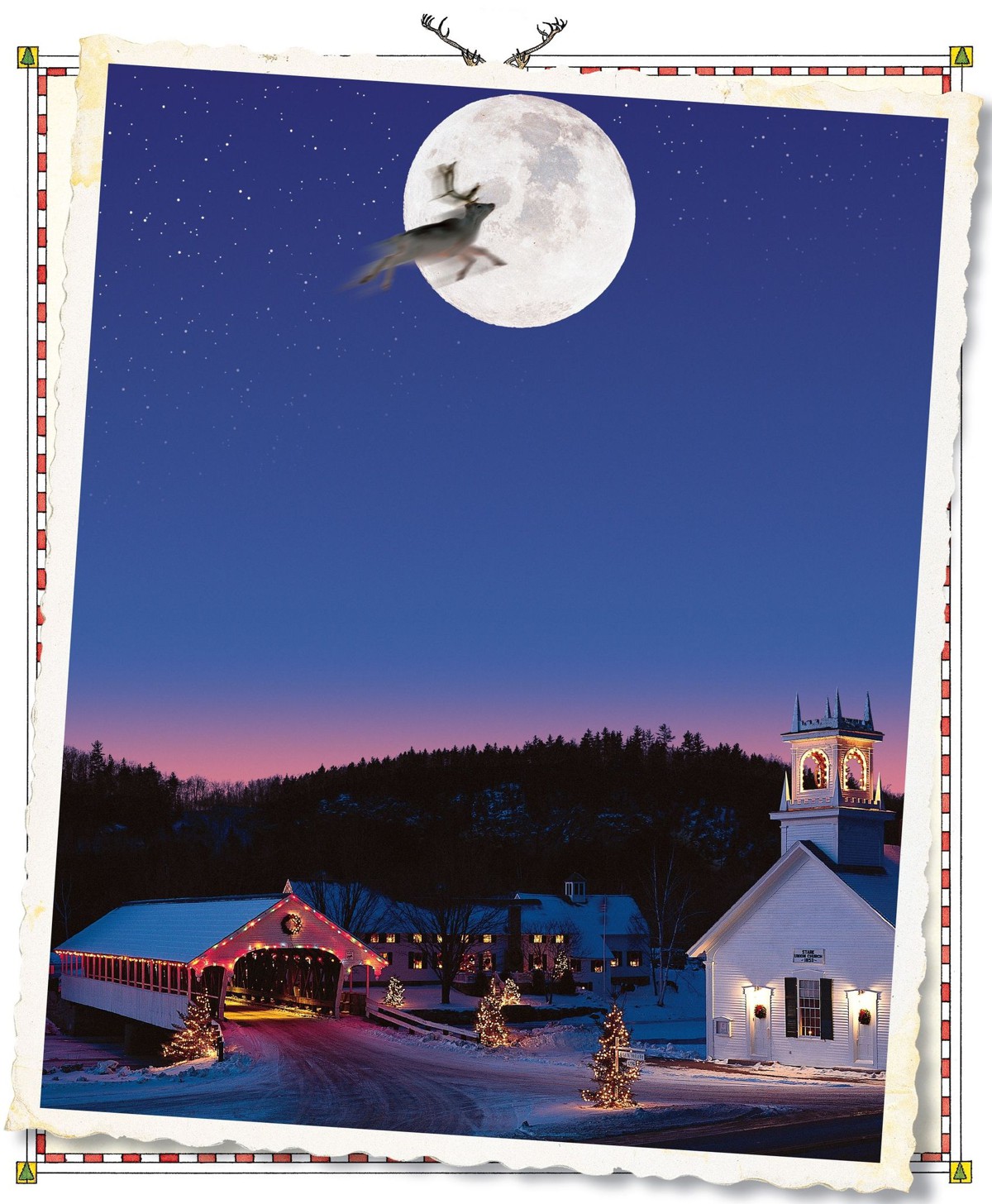

There were even those strange photographs of unidentified flying objects. Many remain unexplained. Some people think they’re spaceships, others insist they are merely photographic illusions. Undeniably, a few of these photos are taunting in the extreme. Look hard at Bill Johnson’s famous image taken in far northern New Hampshire, in a tiny village with the cold and lonely name of Stark (population, 350). Yes, sure, it could have been a speck on Johnson’s lens as he turned his camera toward the moon late one night in December. Or it could have been a reindeer, flying. Imagine it: He is traveling slowly—slowly enough to forge a distinct image on film, instead of just a blur—as he heads back to the North Pole following a workout. The Stark Image beguiles and bedevils us.

There were these things and others to lead us closer to an understanding of Santa Claus—who he was and what he did.

But, still. . .

No one had yet met him.

No one had gone north to the Pole.

No one had seen the village.

No one knew the secrets behind the miracle.

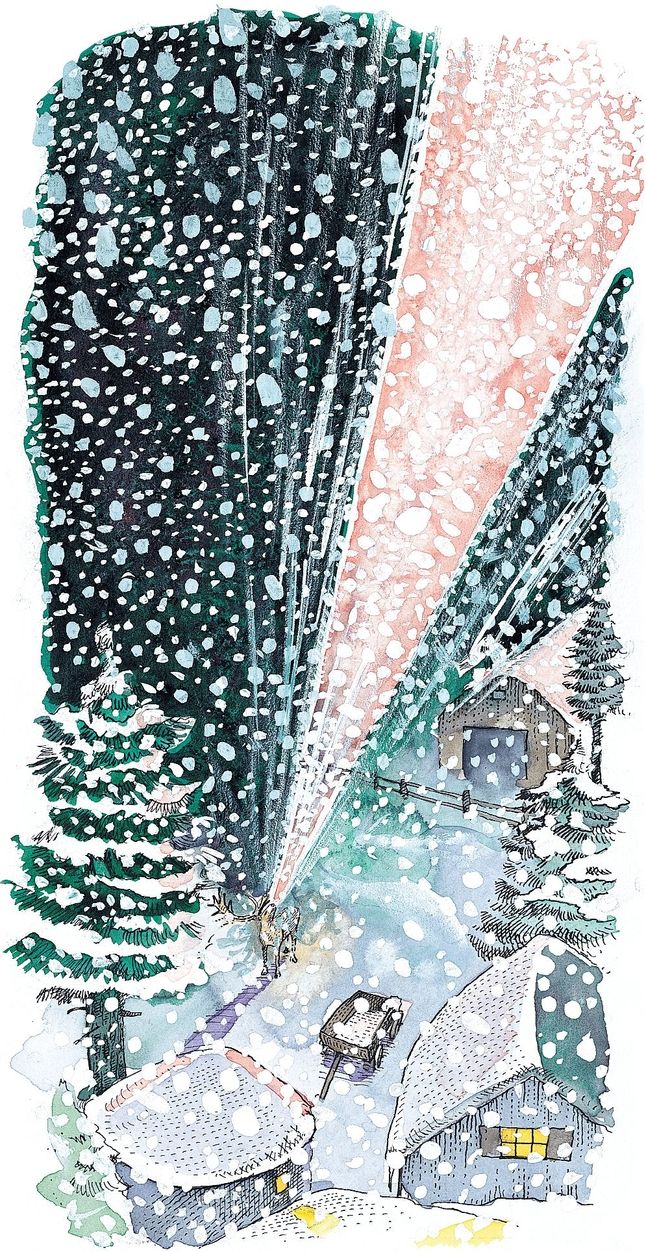

Johnson remembers: “The covered bridge at Stark never looked lovelier than it did on that night. The air was frigid and I was absolutely alone. Then, suddenly, in front of the moon—There it was!”

PART TWO

The North Pole Today

On the Roof of the World

NOT A CONTINENT, not a country. It is solid but it is liquid. Nothing grows there and almost no one goes there. It is never in precisely the same place that it was only a moment ago. It is always in flux, shifting and floating. All ice, not a bit of earth beneath it, it is the roof of the world. It is the North Pole.

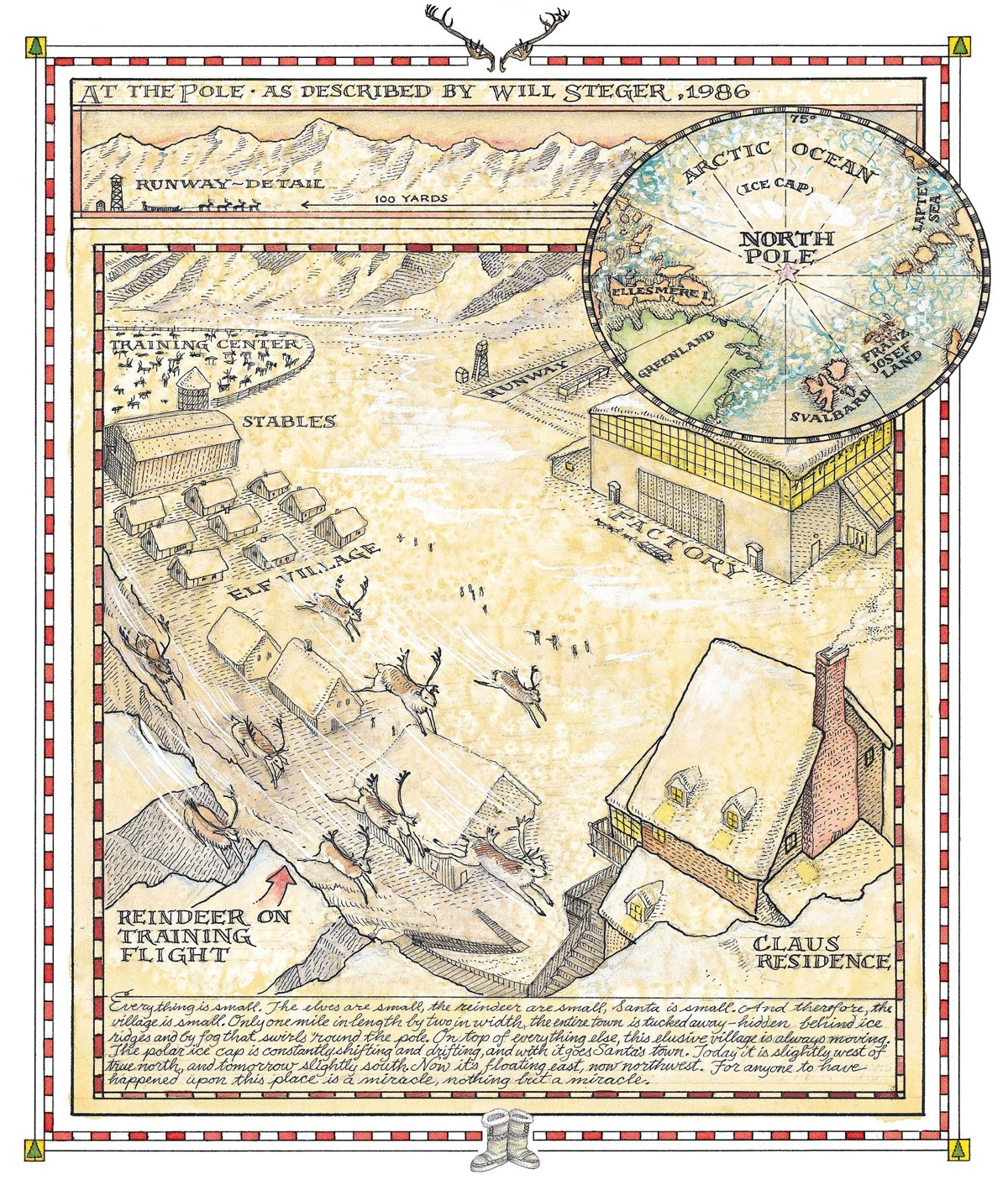

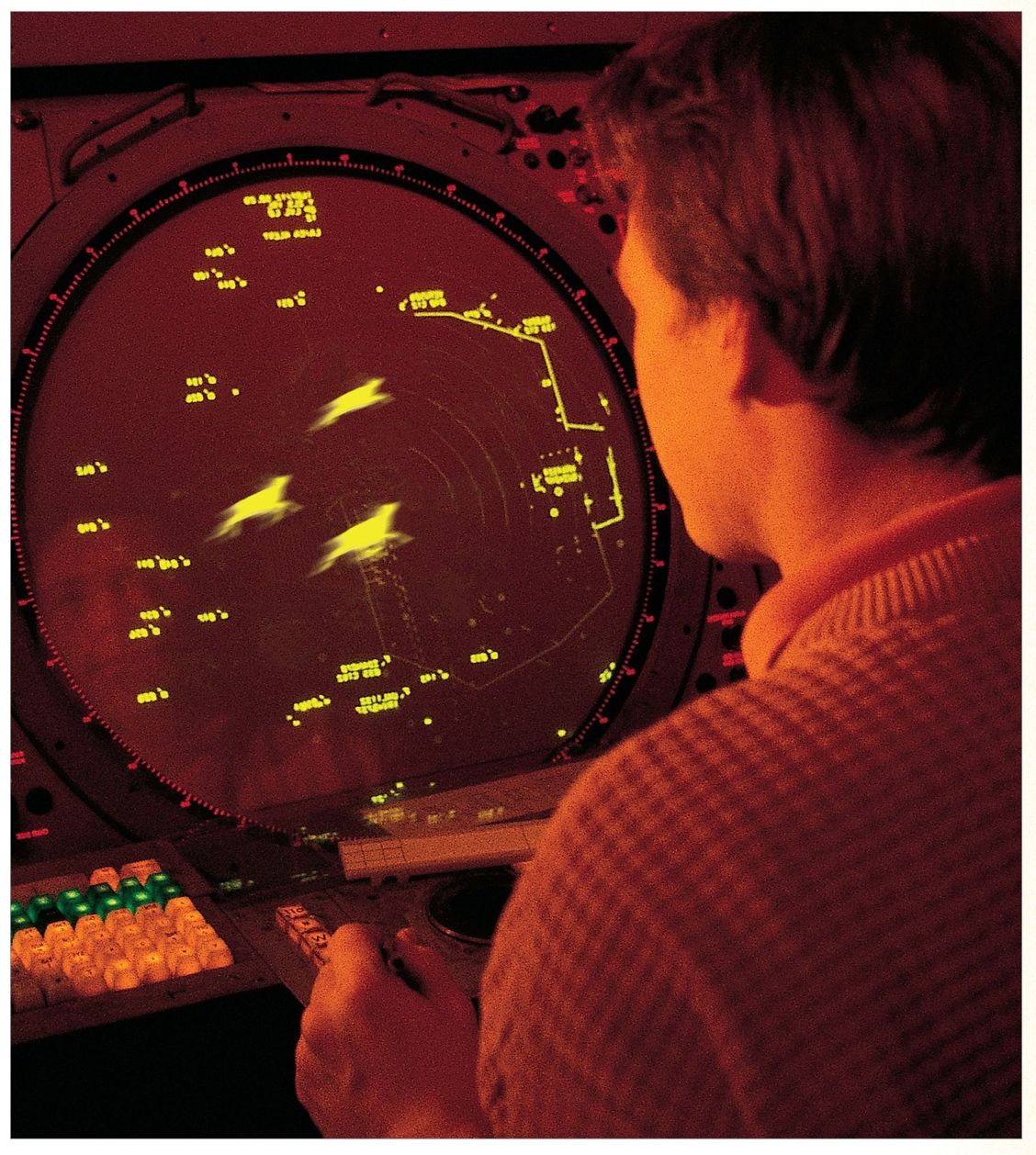

I’VE STUDIED THE NORTH POLE, and I can tell you—it’s a very mysterious, almost eerie place,” says Dartmouth’s Oran Young, who is also vice-president of the International Arctic Science Committee. “There’s often fog, and there are these mountains of ice all around. There’s absolutely no way Santa Claus and the entire village could be so seldom seen if they were anywhere else on the globe. Every other location is fixed in space and time. Plus, the way the ice floats—swirling and sailing like it does—well, the huge ice ridge that you saw in the west yesterday can be in the north tomorrow, and it can be east the day after that. You start to think your compass is going crazy. It makes Santa’s village nearly impossible to locate. It’s the only town in the entire world that does not lie at a specific latitude and longitude. It moves.”

“Of course we wondered whether we might see him. But you can’t count on much that far north. ”

– WILL STEGER, adventurer and the only man to have visited the village

THOSE WHO HAVE SEEN the tiny village have literally stumbled upon it. They have been tourists, glimpsing it through a cloud bank as their airplane flew over the Pole. Or they have been explorers, seeing something as they gained the summit of a sheltering ridge of ice. Will Steger is one of the latter, although to say he saw merely “something” is a gross understatemnt. In 1986 Steger went north with his dog team and, near the very top of the planet, realized that he was among the blessed few. “I was driving my team up this ice ridge,” he remembers, as he sits by the shore of a lake in back of his rustic cabin in far northern Minnesota. He gazes at the water, and his eyes glisten. “The sled crested, and at that moment the fog blew away. There it was, below us. The whole village. The reindeer. The small sleds being pulled all over the place by deer and elves. The moment I saw it, I was sure it wasn’t true. I figured I was getting delirious, that the cold and fatigue were finishing me off. I mean, that’s an ice world up there. Nothing can live there, right? But I rubbed my eyes, and the village did not vanish. I wondered if I had died, and was maybe in some kind of Arctic heaven.”

“Some kind of heaven”—Steger was more right than he realized. He was in an otherworldly kingdom, a place of magic, miracles, nonmortal things. He was in a place humankind had been trying to reach forever.

Some history: The North Pole has always been considered a grail; man has always wanted—needed—to understand the place and those who live there. The ancients believed that there existed a happy region, Boreas, that lay north of the north wind, a place where the sun always shone and the Hyperboreans led a peaceful and productive existence. The Greek Pythias went in search of this happiness in 325 B.C., proceeding northward along Europe’s western coast. He made it to Norway, which he called Thule, but he probably didn’t reach the Arctic Circle. In the 9th century a group of Irish monks also quested northward, eventually settling in Iceland; people were getting closer. There were many, many thrusts north throughout the years, most of these by English,

Scandinavian and eventually American explorers. But before this century, each effort was stymied by the horrible weather and the various dangers of the polar cap. The ice up there is never smooth; it is thrust up into terrifying ridges with knife-edge peaks. How could anyone travel in such a land?

But the pull of True North was great, and eventually a contest of sorts developed: Who would reach it first? The Englishman David Buchan tried to find the Pole in 1818 and came nowhere near. Nine years later his countryman William Edward Parry also went north via Spitzbergen, and also came back south in disappointment. In 1871 Charles Hall’s third try came to tragedy: He died, and on their attempted return to England half of his crew became stranded on the ice during a storm. They drifted on the frigid sea for six months before being rescued by a whaling boat.

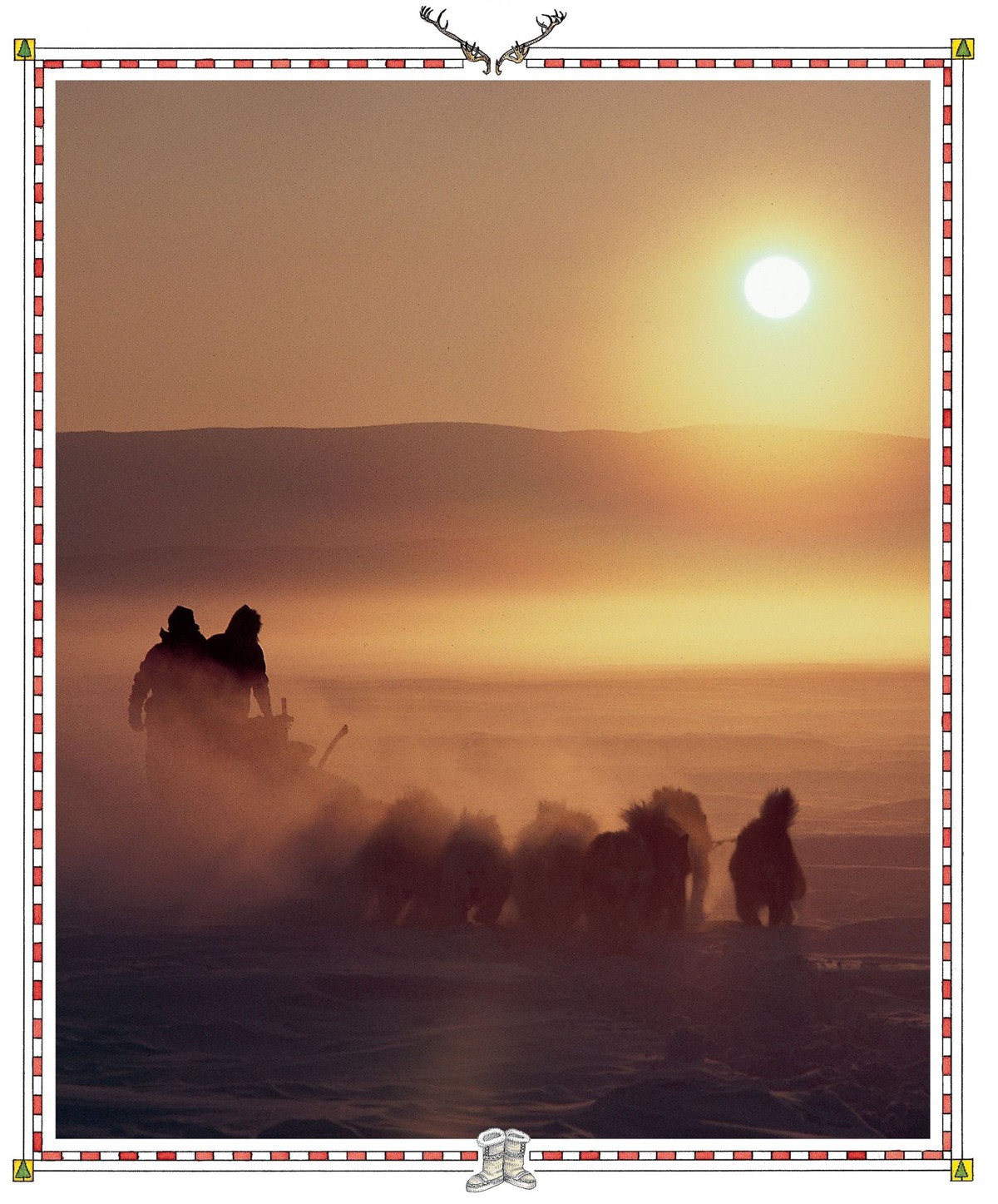

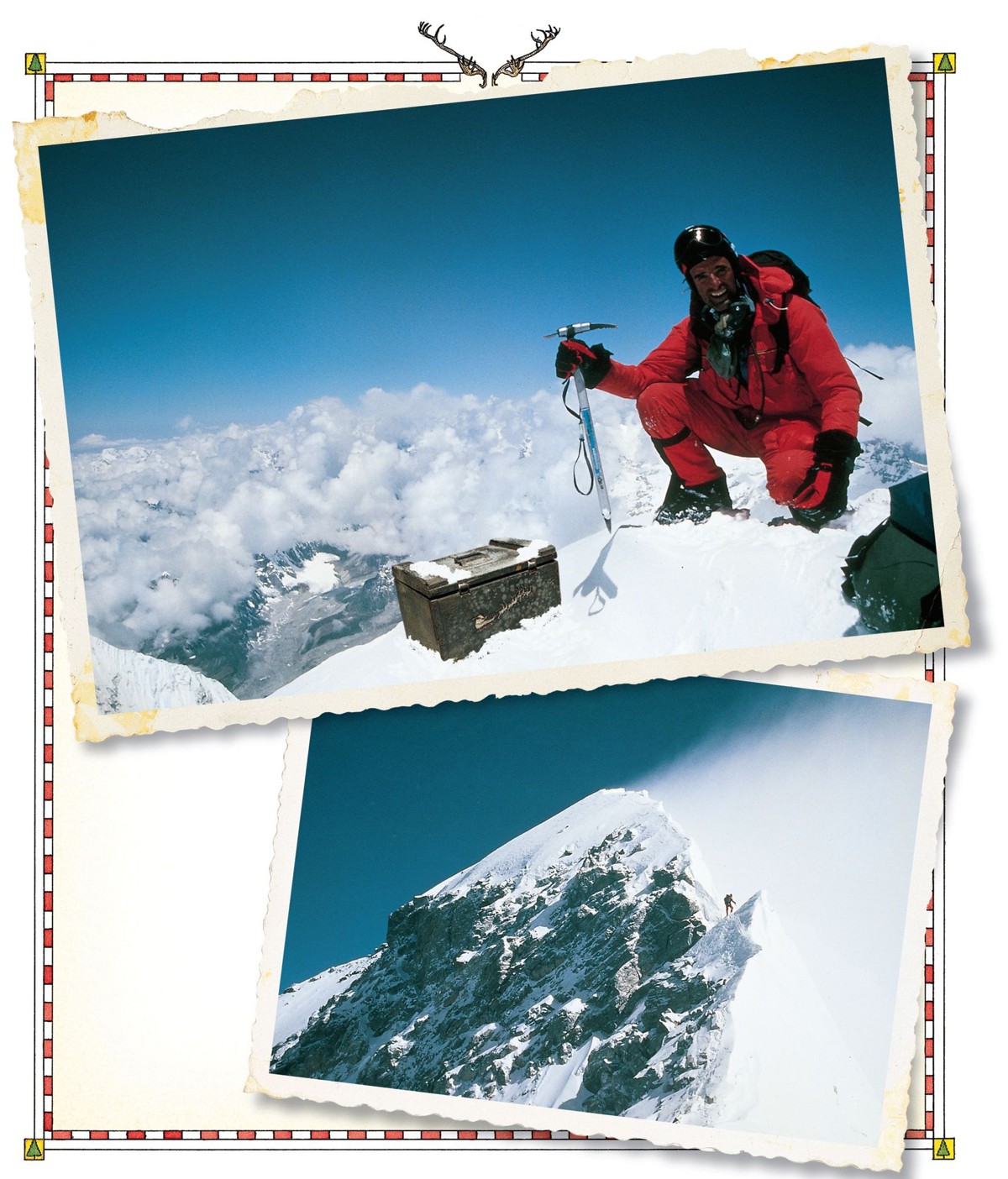

Steger’s team was only the latest in a very long line that have followed the midnight sun toward True North.

In 1875 British naval officer George Nares failed. In 1882 the U.S. Navy’s Lt. George Washington De Long also failed. In 1884 American Brig. Gen. Adolphus Washington Greely led an expedition up the length of Ellesmere Island, and his junior officer, Lt. Lockwood, established a new Farthest North point. But Greely, too, ultimately failed, and six of his twenty-four men died.

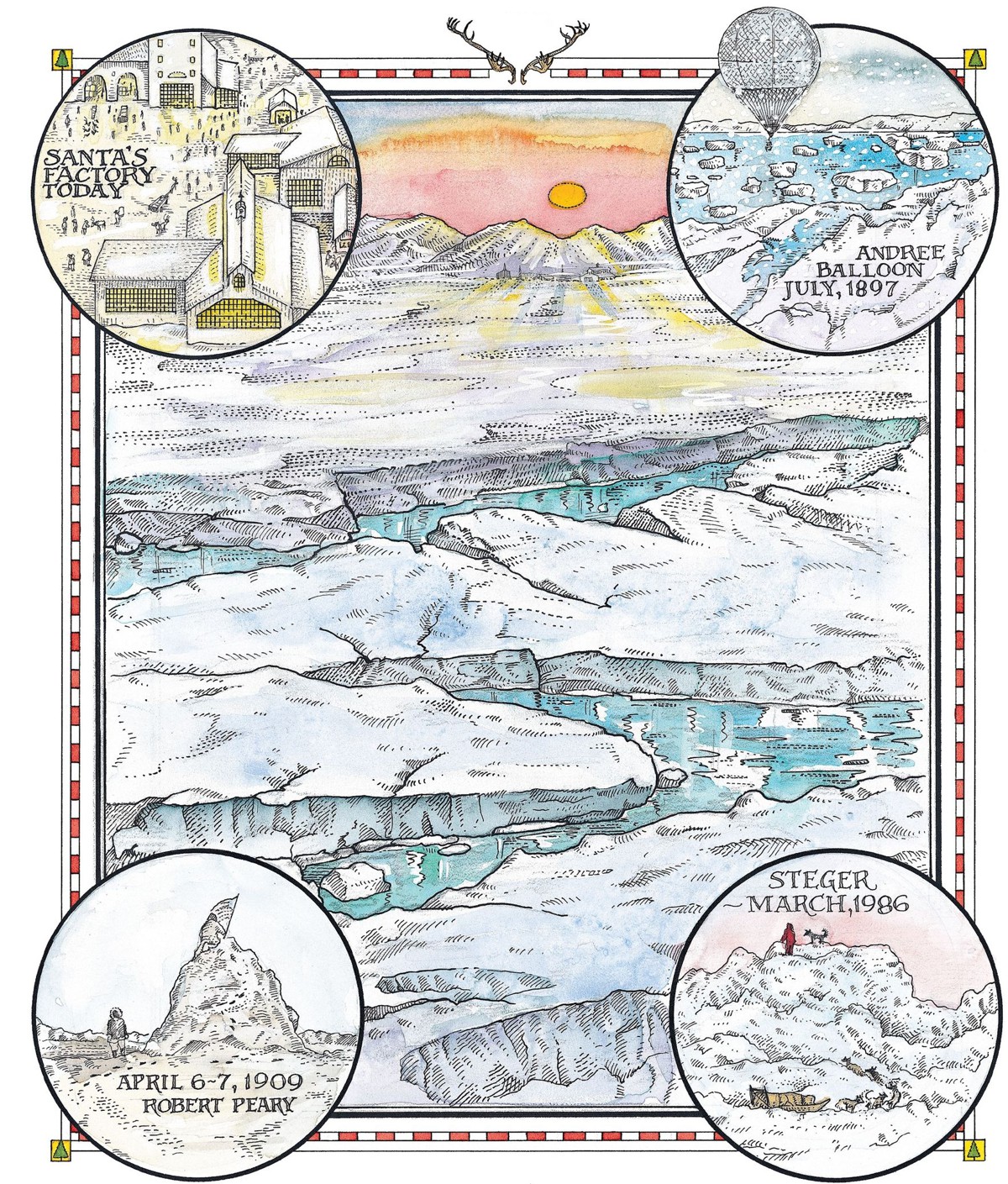

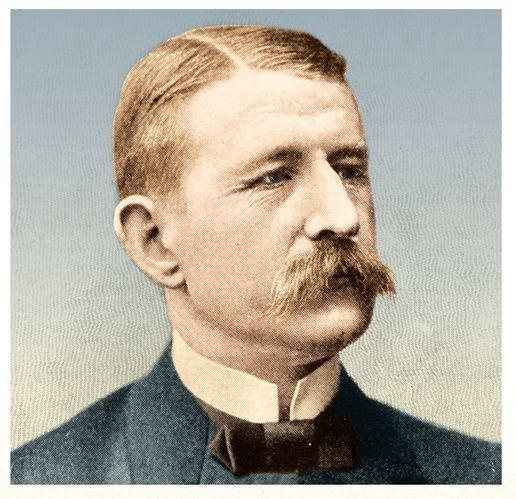

Andree was 42 years old and an explorer with ten years’ polar experience when he announced his daring flight. No previous exploration generated the keen anticipation that his did.

IN THE LAST DECADE of the last century, the zeal for getting to the Pole (and to insights about Santa Claus) became feverish. In 1897, a charismatic Scandinavian named Salomon

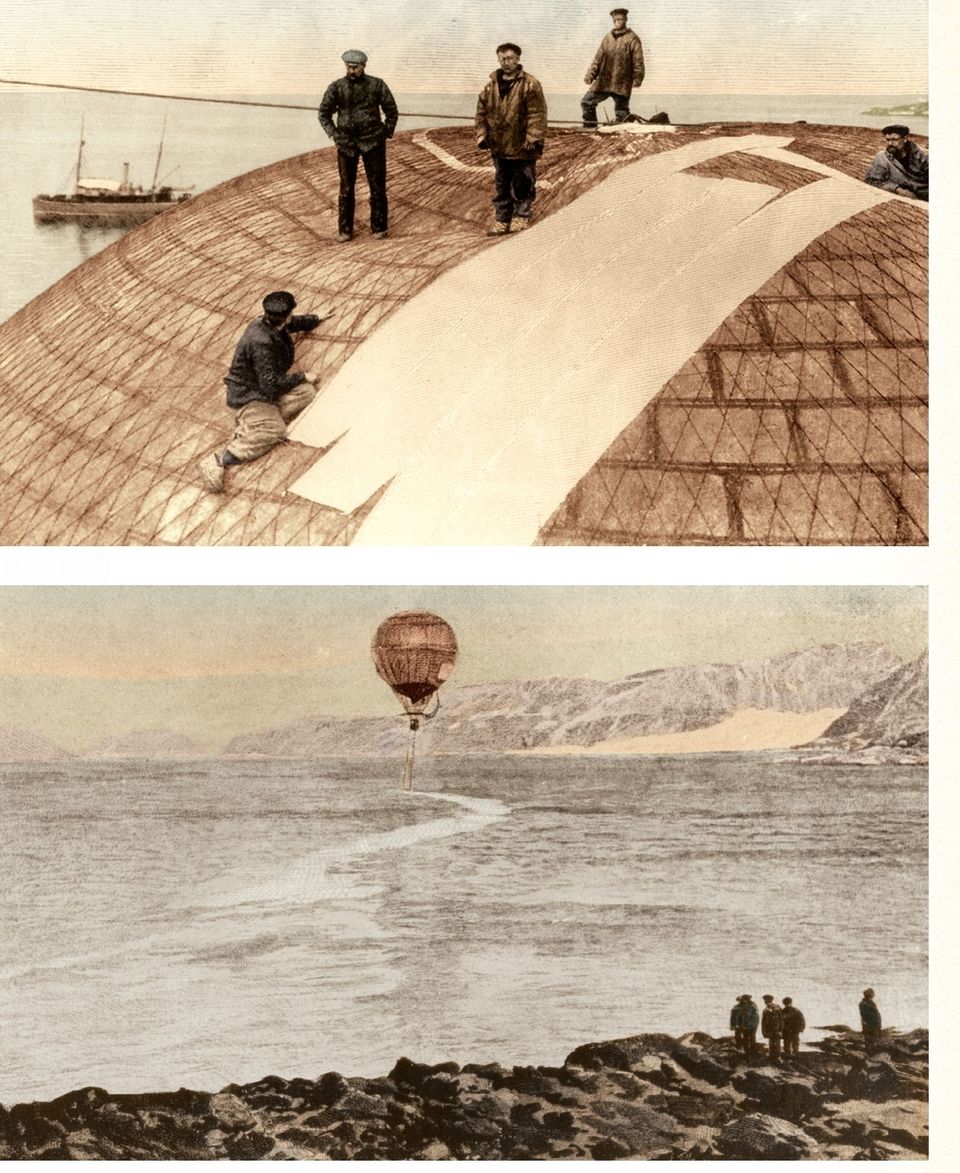

Andree—scientist, athlete, airman—electrified the world and shocked the competition: He would try to reach the Pole in a balloon. The earth’s citizens held their breath as Andree and two comrades made their way to the northern coast of Spitzbergen and, on a windy July 11th, lifted off dramatically. “The balloon is now traveling straight to the north; it goes along swiftly,” wrote Alexis Machuron, a member of the base party who was present at the launch. “If it keeps up this initial speed and the same direction, it will reach the Pole in less than two days. The way to the Pole is clear, no more obstacles to encounter; the sea, the ice-field, and the Unknown!”

It was Andree’s intention to fly to the Pole, land there, then travel back over the ice by sled; he had brought equipment and provisions in the basket of his balloon. It is sad to say, but must suffice: He was never seen alive again. Vilhjálmur Stefánsson, the renowned Arctic explorer and historian, author of The Northward Course of Empire, Unsolved Mysteries of the Arctic and many other books, theorized that Andree stayed aloft for three days before crash-landing on the ice at 83 degrees north latitude. Stefánsson recounted how Andree and his fellow adventurers made their way to White Island over the course of three arduous months. There, finally, they died during the brutally harsh winter of 1897 – 98. Stefánsson

based his account on the diaries, logbooks and tentsite relics that were found years later on the island.

And he based his tale on the messages of doves.

Andree, an able technician, oversaw the design of his mammoth balloon, the patching of its surface in the hangar at Spitzbergen and, of course, its northward launch.

ANDREE HAD CARRIED thirty-six homing pigeons aloft with him. Their job was to transport news back to Norway. We’ll never know with certainty how many birds he released during his twoday flight, but it seems that there were at least three. Some experts contend that only one was found. Others insist: All three were.

The first to be located was picked up by a ship traveling north from the Barents Sea. Sure enough, there was a message in the canister attached to the bird’s leg, and it read: “July 13, 12:30 midday. . . good speed to east. . . all well on board. This is the third pigeon-post.”

Stefánsson wrote of the two “lost” doves: “Reports came in that natives had killed a bird unknown to them (i.e., a pigeon) that they had eaten the bird and destroyed or lost a message which had been fastened to it. The excitement about the pigeons spread far and wide.”

As well it might have, for stories began to circulate among the natives of Spitzbergen, Iceland and northern Norway and Sweden of an inexplicable discovery—a discovery nowhere mentioned in Stefánsson’s careful writing. In Scandinavian histories written by indigenous people, the Sami, there is evidence that the second message was not “destroyed or lost” but in fact found months later on a Swedish beach. The extraordinary memorandum in that canister read (in translation): “July 11, 12:01 midnight. fast to north. . . fantastic sight, large mammals in flight . . . deer?. . . a hundred or more. This is the first pigeon-post.”

Stefánsson was one of the century’s most distinguished explorer-scientists, and ventured into the Arctic many times before his death in 1962.

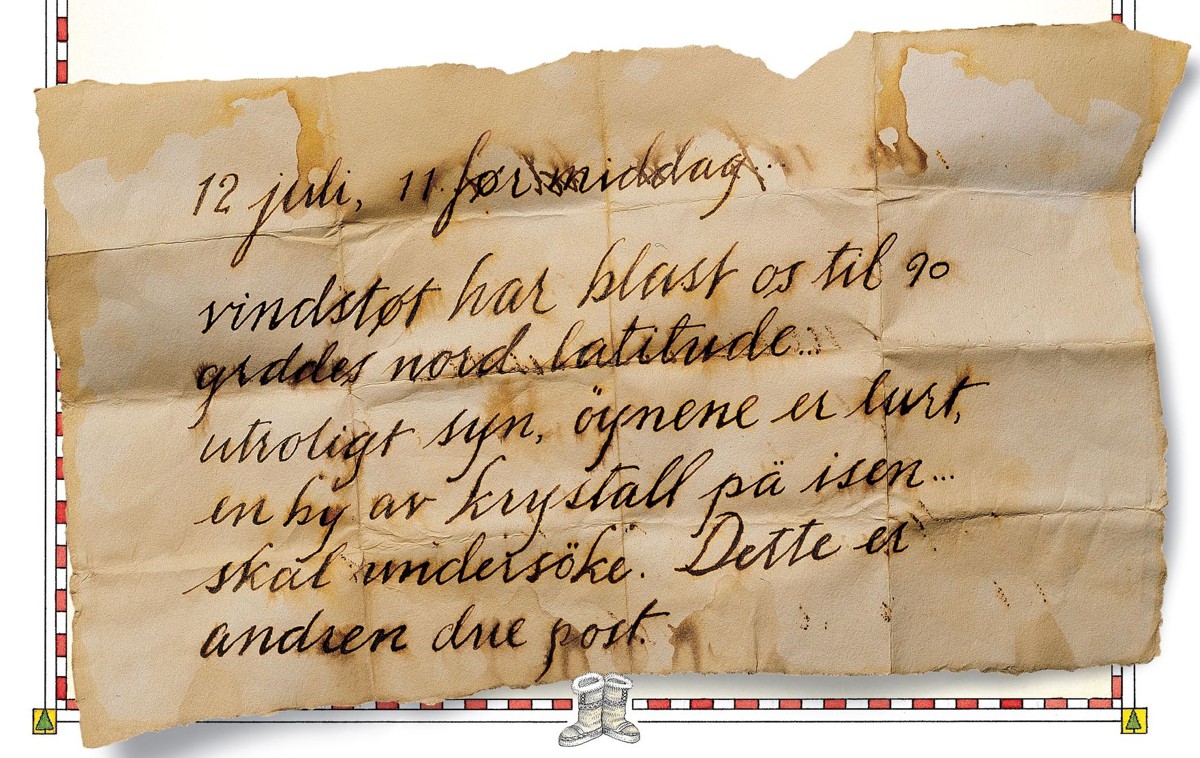

A full year after Andree’s balloon had taken off, another dead pigeon washed ashore at Victoria Island. It bore even more stunning information, as a tattered note now in the possession of the Artic Institute proves: “July 12, 11:00 midday. . . gust has blown us to 90 degrees north latitude. . . incredible vision, eyes are deceived! A crystal city below on the ice!. . . Shall investigate. This is the second pigeon post.”

Although the messages were ignored at the time—not least because competitive English and American explorers didn’t want to admit that Andree might have been the first to fly over the Pole—the facts were recorded in scores of northern histories. These frank, unamazed narratives are not unlike the ones in the Inuit museum of Kuujjuaq.

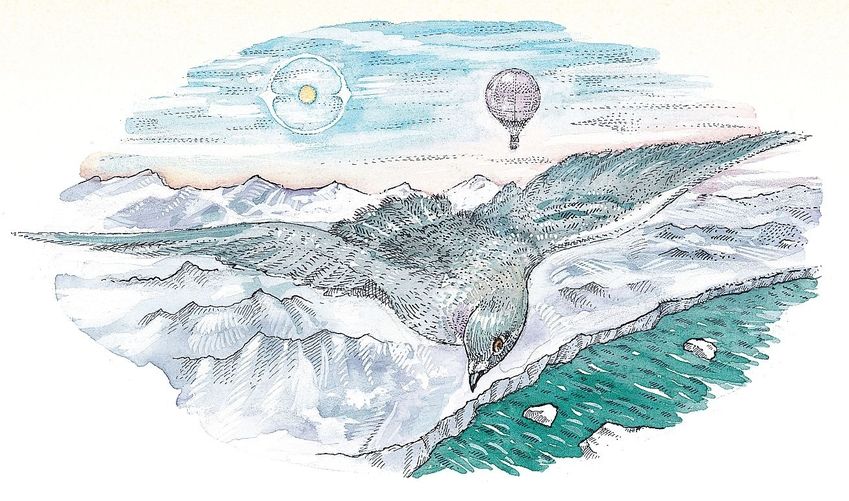

“Again,” says Oran Young, “we’re the ones who are always astonished by this news of elves and other Arctic phenomena. The natives up there live with them and know them as neighbors. To them, this was no big deal. Elves and the flying deer, it’s part of their daily culture. Want proof? Just look at old northern European paintings—not just the Inuit, Sami or other native stuff, either. You can see flying beasts in the distance just as surely as there are birds in American scenics. Why not? The deer were in training constantly, so of course they had become part of the landscape.”

Just so. But as an historical item, the conclusions regarding Andree remain a very big deal to all of humankind. Think of it: Salomon Andree and his compatriots were the first men ever to view not only the North Pole but also Santa Claus’s kingdom. Had they been able to land their balloon in those whirling winds above True North, they might have been the first men to make contact. As it was, all Andree was able to leave us was that alluring description, “a crystal city below on the ice!”

It’s all but certain that the American adventurer Robert E.

Peary knew of Andree’s sighting when he became the first man to reach the North Pole in 1909. After all, he had many Sami and Eskimos as members of his expedition, and they surely told him of Andree’s two strange, suppressed messages. But just as surely, Peary himself saw nothing of Santa Claus. Peary was an ambitious man who sought fame as much as achievement itself. Had he discovered any sign of the elf nation, he unquestionably would have trumpeted the news. His silence remains the best evidence that he saw nothing.

“But Santa saw him,” says Will Steger. “He told me so.”

Northerners say the second dove bore a missive from the balloon that eventually was found. The “July 12, 11:00 midday” note at the Arctic Institute bears them out.

Steger, as far as is known, was the first person to actually venture into the elves’ village, and remains the only person alive to have enjoyed this privilege. It is possible that an Inuit citizen or a Scandinavian adventurer also made his way into the sanctum, then kept the news largely to himself. There are legends of such things, particularly in the northern communities. But there is nothing written. And, most reliably, Steger reports that Santa Claus himself feels that his community has stayed a closed nation during its millennium on the Arctic ice. “Santa said I could talk about this when I returned to Minnesota,” Steger says reflectively. “He said there were certain things it would be good for people to know.

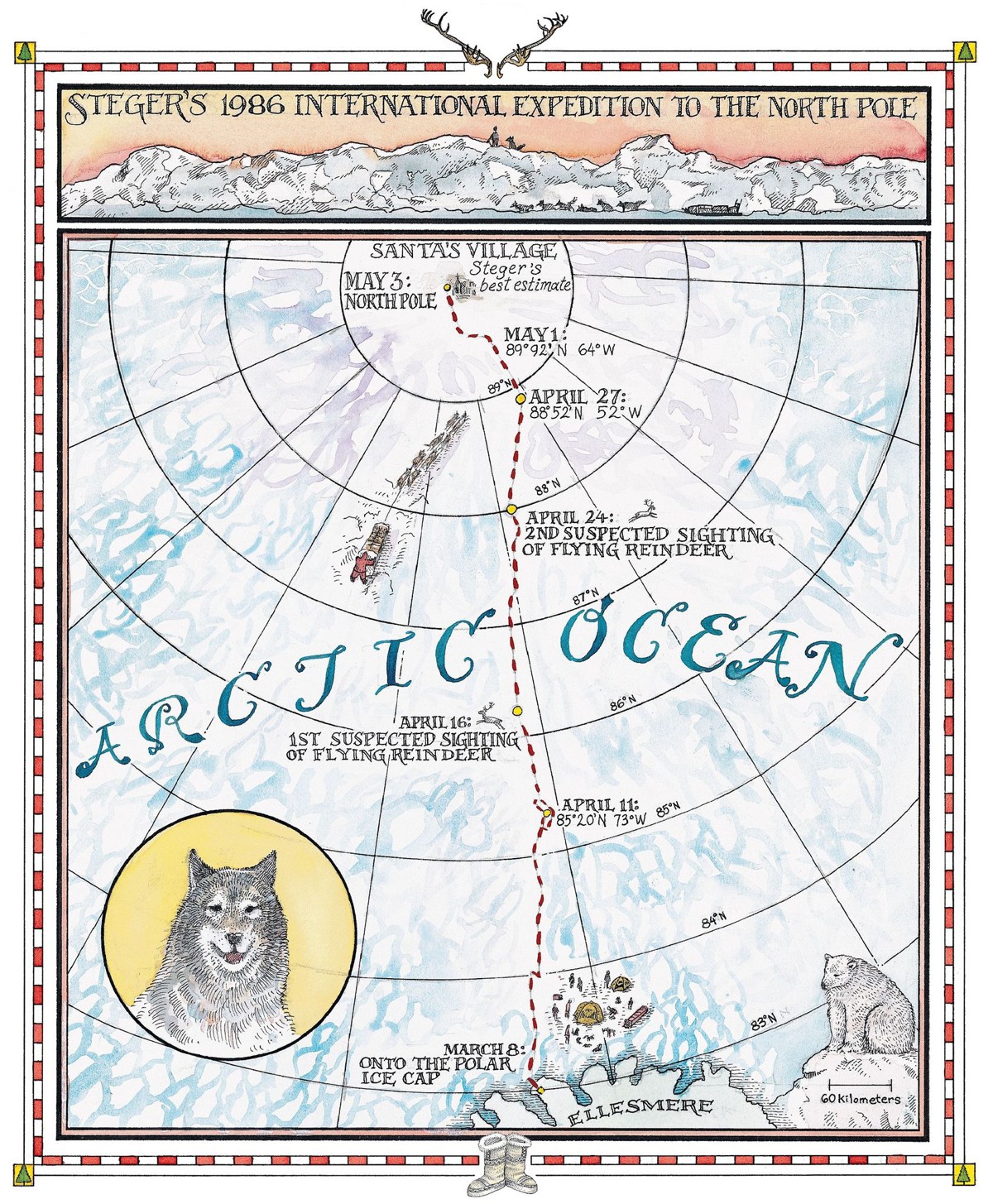

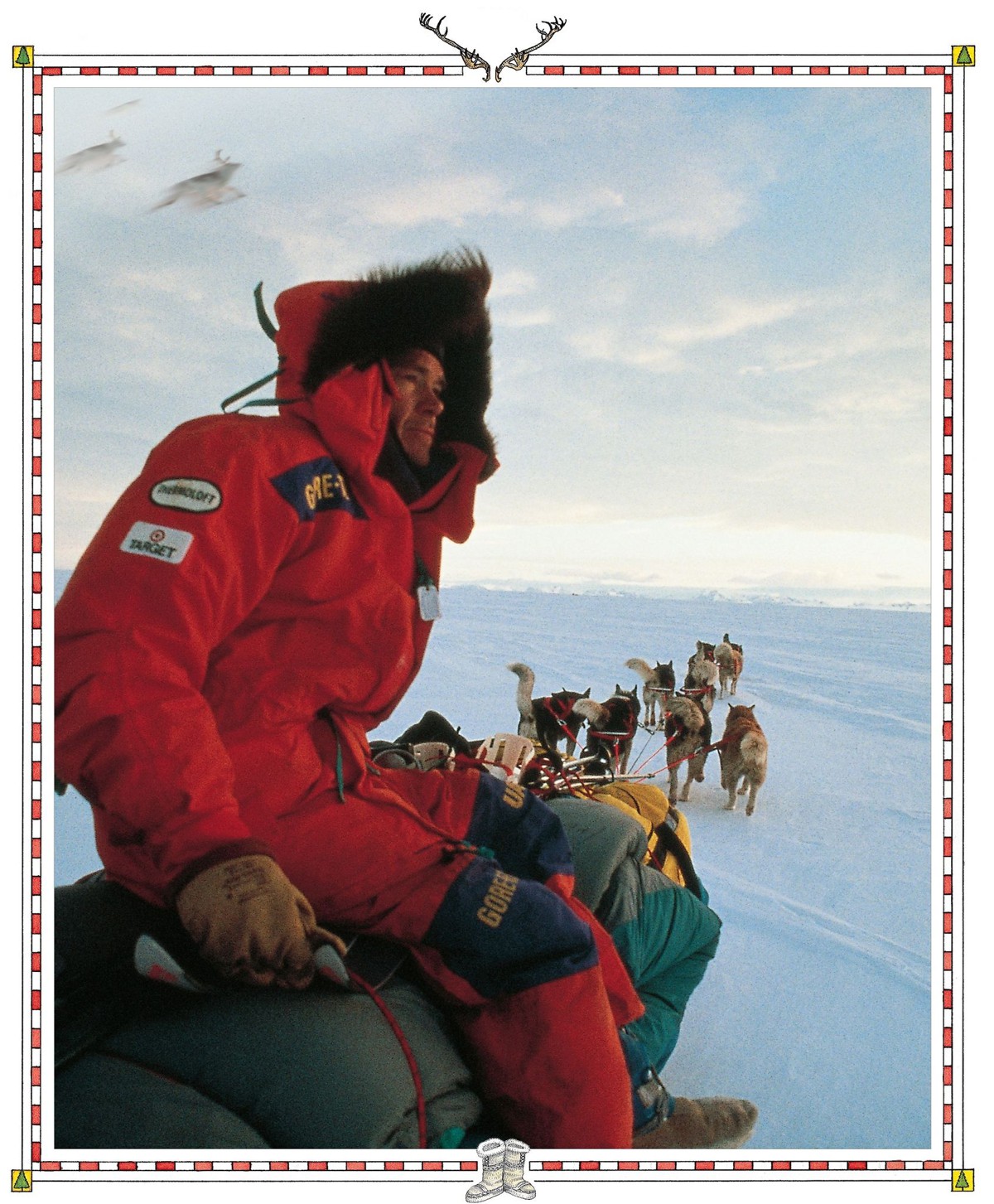

“Where to start?” he continues. “Well, as I say, it was 1986 and eight of us were trying to get to the Pole by dogsled. We were attempting to be the first ones to do it by carrying our own supplies with us. On March eighth we went north onto the frozen polar sea from Drep Camp on the north coast of Ellesmere. Santa joked about that. He said he had taken the same route, a long, long time ago.”

The same route pioneered by Peary (above) in 1909 was followed by Will Steger years later (opposite).

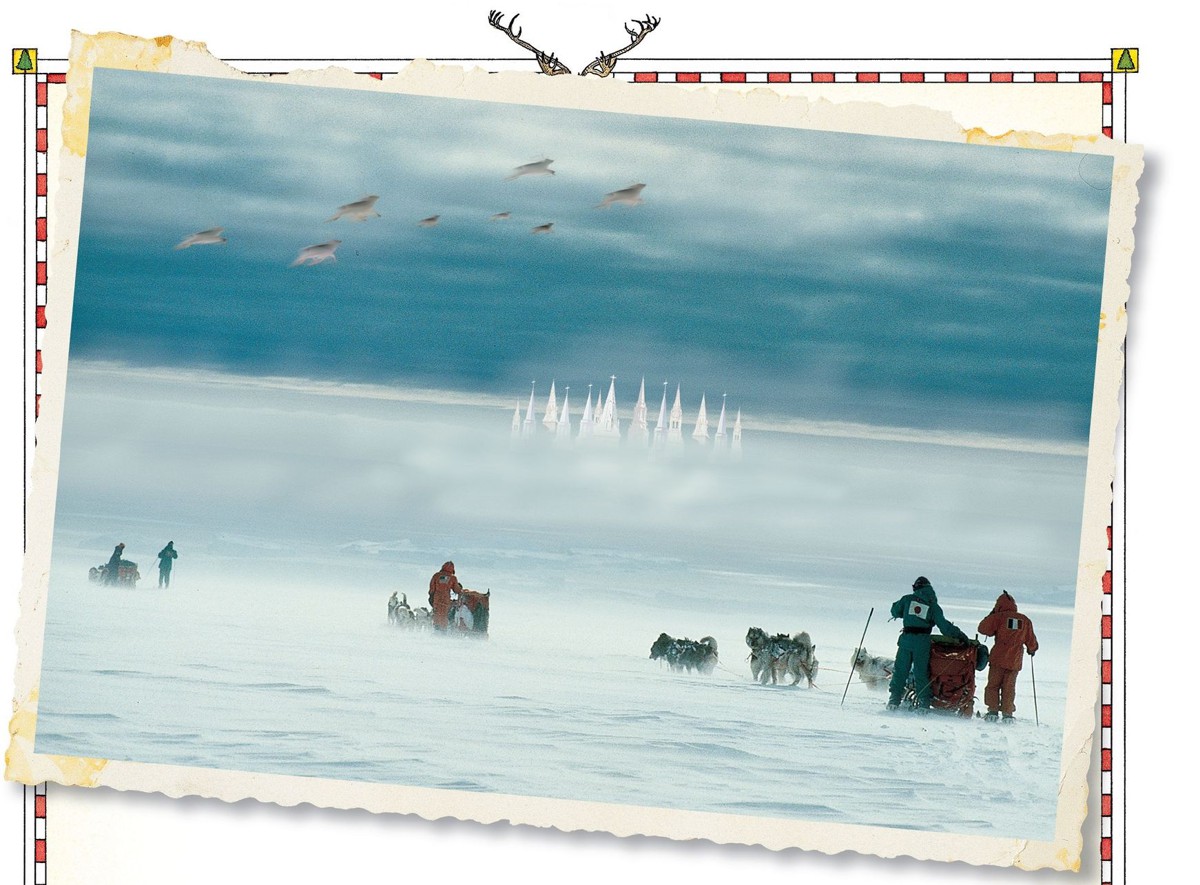

Steger remembers, “The first weeks were awful. The blocks of blue ice rose fifty feet or more, aligned like a series of huge frozen waves, and we had to climb each of these ridges with our tremendous loads. By the time we were nearing the Pole, in April, the ice was getting really weak and shifty—dangerous. After fifty days or so we were only a few miles from the top of the world, and things started getting strange. We heard odd noises, we hallucinated at times. This is to be expected in extreme conditions, but the things that we were thinking we saw. . .

“Once, it seems, the sky was filled with birds. They were so far off in the distance, yet we could see them. One of my teammates said, ‘How could they be that big? We shouldn’t be able to see an eagle from here!’ He shot some photos, hoping the animals could be identified later.

“Another time, I swore I saw man-made structures beyond an ice ridge. I shot some photos quickly, but by the time I had taken the camera down from my eye, whatever I had seen had vanished, like a mirage. ‘Probably the shifting of the ice,’ I said to myself.

“As we neared the Pole there was so much of that—moving ice, sudden loud cracks in the ice—that it was getting hazardous to travel fast as a team. We started scouting the safest routes individually, then doubling back to get the others. That’s how the strangest, most wonderful day of my life began. It had warmed up to about minus-twenty, and there was a constant fog over the ice—very eerie and mysterious—and it was my turn to scout. I went out with Zap, my lead dog, and a team of eight, pulling a light sled—I wanted to travel nimbly over the ridges. We were making our way through this skim-milk haze, and every now and then a wind would blow an opening in the fog and I could see blue sky.

“Suddenly, I saw something. It was crazy. I saw this ice ridge ahead and what looked like a pinnacle above it, like a steeple. And then, just as suddenly as it had appeared, the fog enveloped it again.

“Now, in the Arctic, you can have visions all the time. I figured I had just had one. I said to myself, ‘Will, it’s the cold. It’s been fifty days on the ice. You’re seeing things.’ I shook my head to get the cobwebs out, and drove the dogs toward the ice ridge, which wasn’t a very high one. Maybe ten or fifteen feet tall.

“Zap started barking, just going nuts. He was making a racket all the way up the ridge, and soon all the other dogs started yapping too. I couldn’t shut them up until Zap got to the top, and the minute he did he just stopped barking. Stopped cold. I had never seen that before—he always keeps barkin’ when he senses something. But not this time. Zap was just struck dumb, and all the other dogs stopped too. So I’m pushing the sled up behind them and I’m shouting ‘What’s wrong, boy? What’s up? What do you see?’ Then I got to the top, and just as I did the fog blew away.

“There, below me, was heaven. It was Oz. It was the village itself.”

STEGER STOPS TALKING and rises slowly. He goes down to the edge of the lake and looks out over the surface of the water. He walks back up the bank and slowly resumes his story, as he sits down again on a tree stump. As he talks, he continues to gaze out over the lake and struggles, briefly, to regain his composure.

The pressure ridges, which sometimes climbed to fifty feet, made Steger’s progress slow and exhausting.

“It was certainly the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen. The loveliest. The strangest, of course, and. . . well, obviously it was the most unexpected.” He smiles at this, then picks up steam. “It was both huge and small, if you can imagine that. A whole kingdom, and yet compact. A city of carefully sculpted snow and white-wood buildings that were all packed in tight, one against another. It was a booming metropolis, but it was just a village. It was a nation, but just a community. It was maybe three square miles, yet it was home to thousands—I could see them, scurrying around in the streets. It was overwhelming.”

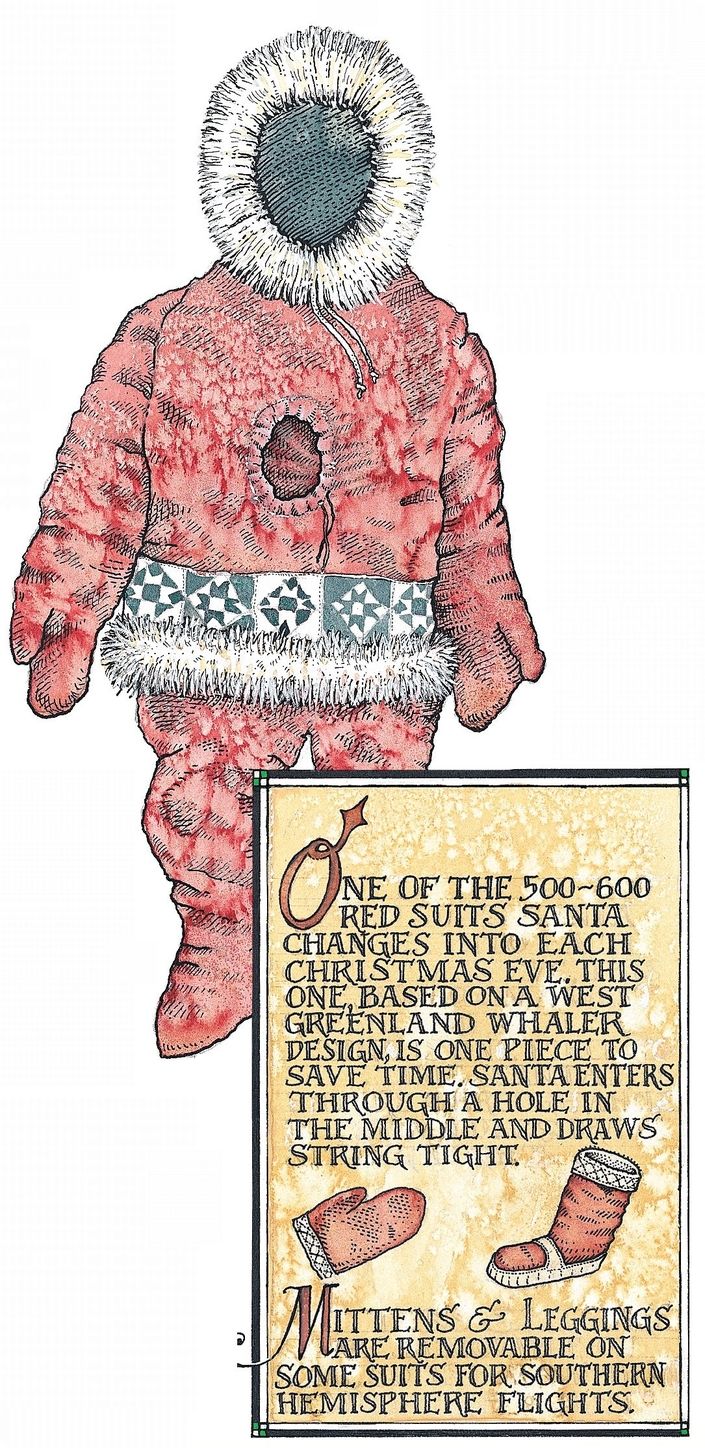

Steger says the village was “white—all white, pure white. The snow castles are white, the wooden factory is white, the streets aren’t paved or shoveled because all travel is, of course, by reindeer. The reindeer are white! All the elves wear white. From December 26th until the following December 24th, Santa Claus himself wears white. ‘The reason should be pretty obvious, pretty obvious,’ this little elf told me.”

It wasn’t until weeks later, when film was developed, that some of Steger’s wildest notions of what he might have seen were confirmed.

Steger digresses briefly: “Well, they’re all little, but this one was particularly short. His name sounded like Morluv, and he was the first one I met. ‘Pretty obvious, pretty obvious, pretty obvious,’ he kept saying—in English, once he had figured out which language I spoke. He speaks dozens of them. ‘Pretty obvious, pretty obvious. I mean, well, it should be obvious. It’s camouflage, you see. How do you hide in a tree? You do a green thing. In the desert? You do a brown thing. In the snow? You do a white thing! Voila—Here it is, here we are, the whitest white thing in the world! White on white on white on white on white!’

“He had surprised me,” Steger continues. “He was up near the ridge, about a half mile from the village. He’d snuck up on me because he was as curious about me as I was about this amazing vision I had stumbled onto. He actually broke a law, I found out later. It’s a rule in the village that if you see anything coming—anything at all—you’re supposed to hide. But this Morluv was a fun-loving sort and really excitable. Hiding was the last thing on his mind. I guess he hadn’t broken a law, exactly, because he wasn’t punished—not while I was there. They just have these rules, and everybody obeys them. ‘That way,’ Santa told me later, ‘everybody lives happily.’ He then said, ‘Tell your friends that. It works fine if you try.’ ”

“Zap went through the whole range of emotions that day. He was afraid, he was exited, he was joyous. So was I. ”

– WILL STEGER, referring to his longtime lead husky

STEGER PAUSES AGAIN, picks a piece of grass from the bankside and starts chewing it. Now, the gleam of humor comes into his eyes. “I was there only a few hours, and Morluv became a great friend. They insinuate themselves into your affections, these elves. In ten minutes you feel like you’ve known them ten years. Morluv was a little crazy and a whole lot of fun. He was about two feet tall and said he was four hundred years old, more or less. ‘In your human years,’ he said, making it sound like dog years. He said four hundred was young, considering where he lived.

“Did you know,” asks Steger, “that elves—or any animals, for that matter—live much longer at the Pole? It’s true. It’s the elf’s physique and biology, and also the temperature. They’re very small and efficient, and their metabolism slows down to almost nothing because of the cold. Every minute that you live in New York City, an elf could do a full day’s work. Every carrot they eat is roughly equivalent to three square meals for us.

“But anyway—I’m getting away from my story.

“He was about two feet tall, and he stunned me—I jumped a mile. He comes up and starts going crazy in elf language, elfese, or whatever—then tries French, German, Gaelic and about twenty other things on me before I hear him going ‘Who’re you? Who’re you? Who’re you???’ And I say I’m Will Steger from Minnesota, and this doesn’t mean too much to him, apparently. But he says this guy he knows—and then he gives the weird, elfin name for Santa—he says this guy must hear about this, and he puts his hand on the sled like he’s going to guide it down into the village—like I’m a prisoner. And I’m thinking, ‘This elf’s two feet tall!’ So I yank the sled away, even though I obviously want to go to the village. And you know what? The sled doesn’t budge. Not a half-inch. I yank again. Nothing. The elf’s two feet tall, maybe four hundred years old, and as strong as an ox. Ten oxen!

“So I mumble, ‘Let’s go.’ He hops aboard, and we slide down into the village.

“At one point, Zap looked back and snarled at Morluv. Morluv smiled and went ‘zzzzzzz.’ Zap went quiet immediately, and seemed to like Morluv from that moment on. I learned while I was there that the elves have an uncommon, even uncanny way with animals. They love them, and are loved in return. It’s principally between them and the reindeer, since that’s the animal up there. But I’ll tell you—my dogs didn’t want to leave.”

NEITHER DID I, really, after what I saw up there,” Steger continues. “And heard. And experienced. And learned. In two hours I got the most phenomenal education that you can imagine. My eyes were open wide, and I learned what the world can be. “No, wait. What the world is. At its best place, right now.”

Steger’s thoughts return to the village: “What happened was, Morluv took me down into town, and I was walking down these narrow ice streets, watching all the elves go about their chores—their lives are nothing but chores, yet they love the chores.” Steger smiles at the remembrance. “They’re constantly grinning, and they always seem in an incredible hurry. They carry huge loads, and they hurry along. The streets are clogged with reindeer, too—the white ones, the Peary. They’re everywhere, never harnessed. And the elves will be carrying loads of stuff, and they’ll is hop on a Peary and say, ‘Heeeee!’ and the thing will just bound out of sight. Incredible leaping ability! They just spring into the air, and disappear over the tops of these thin, icewalled buildings.

“The most amazing thing about my visit was this—no one stared at me! No one cared about this ‘man’—this man who was twice as big as any of them—walking down the street. They had jobs to do, places to get to. They smiled at me, and I tried to smile back. I was just so stunned by the whole experience, I couldn’t be sure if I was smiling or laughing or crying.

“All the elves patted Zap and the other dogs as we walked down the main avenue. They said something that in the elfin tongue probably means dog. It sounded like ‘Veeezaa.’

Morluv the elf, based upon a detailed description by Steger

Morluv was holding my hand as we went. He kept pointing out this and that, but he was excited too, and he kept slipping into elf language or Chinese or Spanish or something other than English. But finally I realized he was saying, ‘Show you the place, show you the place!’ ”

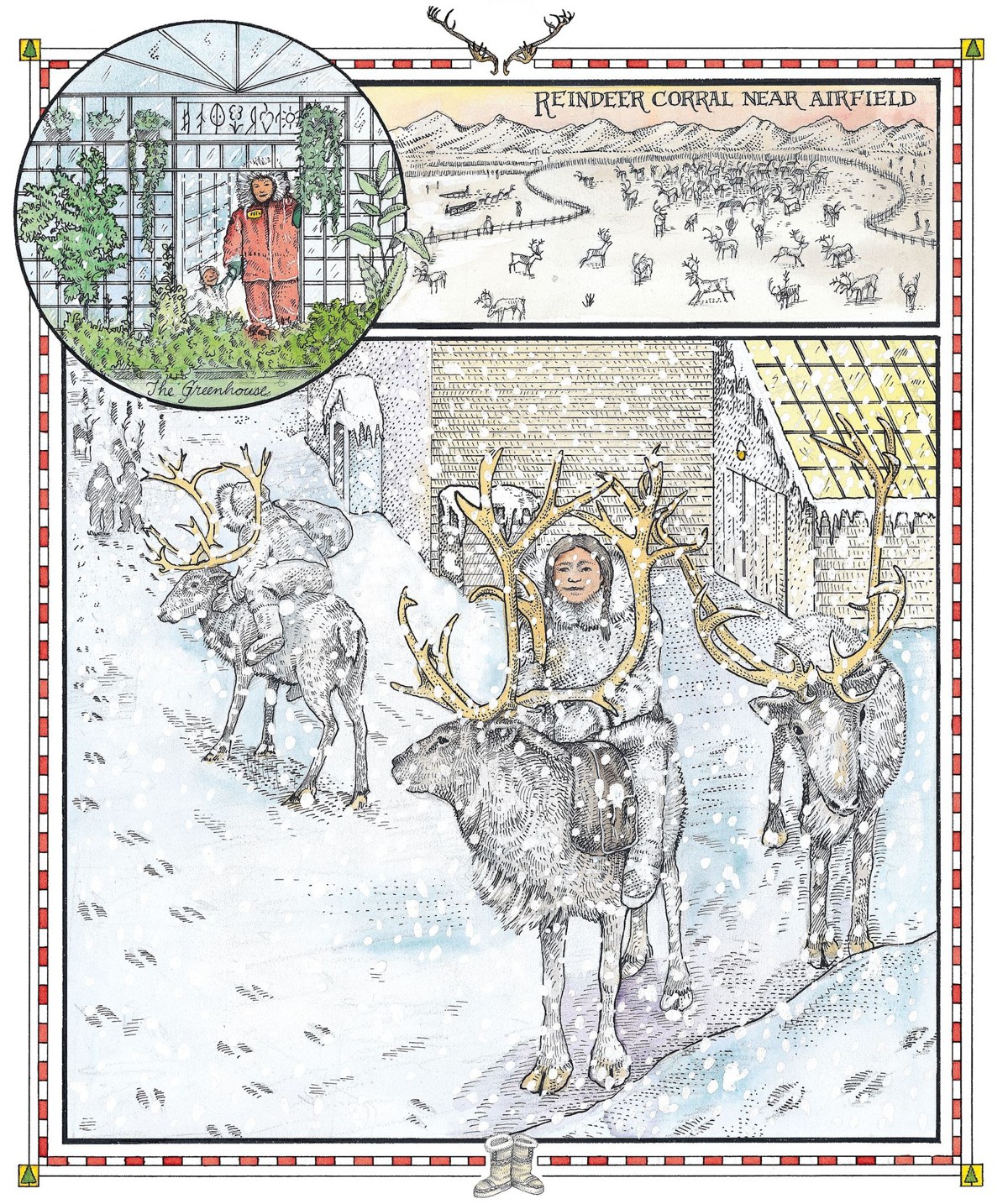

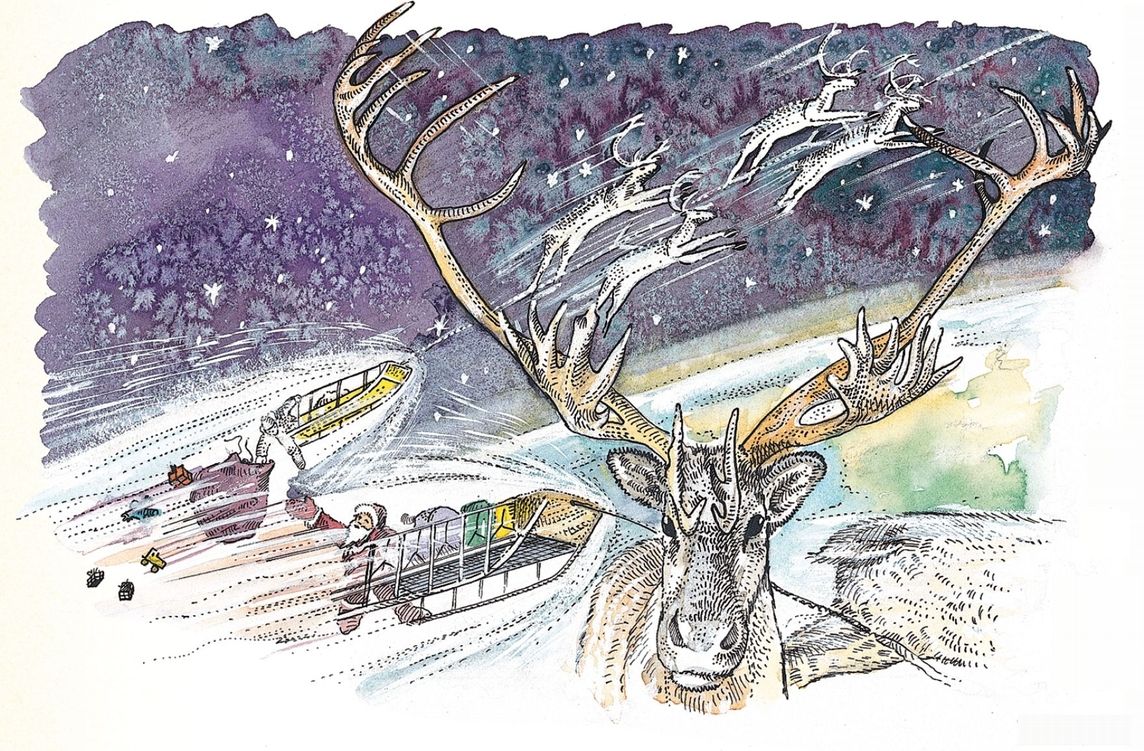

The place was on the outskirts, “It was out by the farthest factory, which is beyond the farthest ice fields. The place was,” Steger pauses. “Well, I would call it Reindeerland. There were hundreds of Peary out there, in stables and just roaming the ice. Some were feeding over by the greenhouses—the only non-white buildings up there because they’re translucent. Other reindeer were out at the ‘runway, ’ a hard-packed stretch of solid ice. At the runway, Peary were taking off, one after another. They would start, then they would be a blur as they went down the runway—a speck you could barely see, a spark shooting along. And then there was a flash of light, and you saw the spark disappear into the blue sky. One after another they went. So fast, so fine. I’ll admit it—it brought tears to my eyes.

“Above us, gliding, were a hundred reindeer—two hundred, five hundred! They coated the sky. They were cruising, then sprinting, then—whoooooosh!—going into overdrive. You can recognize them as reindeer only when they coast through the sky. When they really fly, they just look like a flash of light. They seemed so fast to me, but Morluv kept saying, ‘Those aren’t the good ones. Those aren’t the good ones. Those aren’t the good ones.’ ”

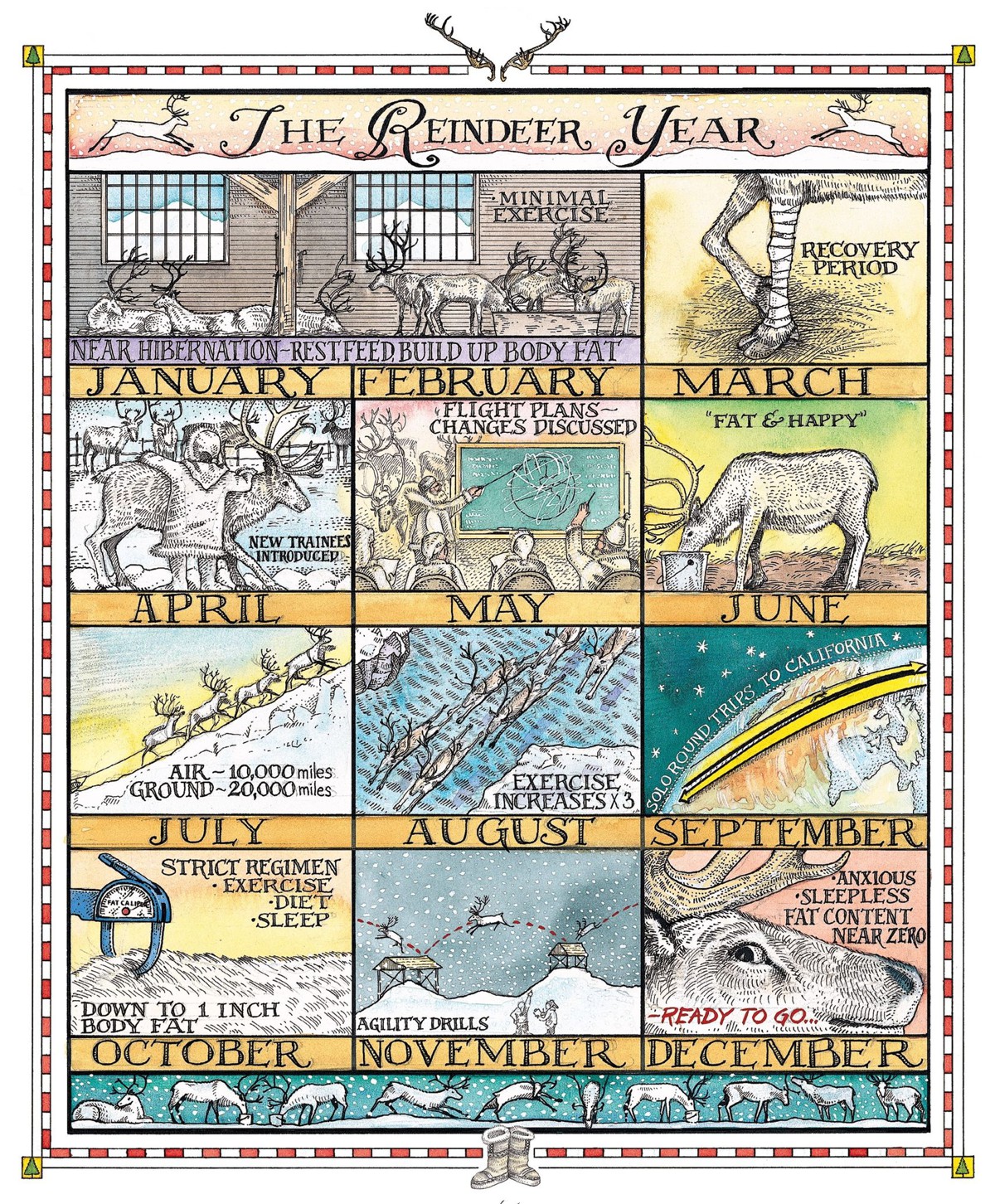

The “good ones,” the ones that we know—Dasher, Dancer and the gang—were in a grand stable behind the runway, Steger reports. “They were attended by a hundred elves, bringing corn and carrots from the greenhouses,” he says. “Seemed to me they were really pampered. They have this nice, cushy, kind of regal stable—and all the other deer sleep outside. I asked if the good ones were in the stable just then, and Morluv nodded vigorously. ‘Resting, resting, resting,’ said Morluv, ‘resting, resting.’

“It was spring, of course, when I was there. As I was soon to learn—from Santa himself, in fact—the nine deer who make the annual journey must rest a full four months before they start to train for the next year’s Mission. The short of it is, they burn out. They go so hard for one night, and then just collapse. Time is just different up there, that’s all there is to it. They’re different animals, living in the same world as us but living by their own rules. To them, it all makes sense.”

Steger adds: “Morluv and I left the reindeer training grounds and headed back into the village. I had so many questions to ask, when Morluv stunned me by saying, ‘Want to meet? Want to meet? Want to meet?’ I asked, ‘Who?’ He said, ‘Him,’ and then he said that weird fa-la-la name. I said, ‘Santa?’ He laughed uncontrollably, nodding up and down like a maniac. ‘Yesyesyesyesyesyes,’ he said. ‘Sandra Claus! Him you call Sandra Claus!!’

“He took my hand, turned me around once more and led me on.”

“I can say unequivocally that the villagers are the most industrious people on earth. I mean, elves on earth.”

– EINAR GUSTAVSSON, Icelandic scholar and elf historian

STEGER STOPS FOR A MOMENT, and looks at the sky. He is thinking. He looks at the ground, and says slowly, “Santa said I could relate certain things, and others I should not tell. I was surprised by how open he was, and how much information he wanted me to bring back. He seemed to want to seize this rare opportunity—as I did, of course. He said I could say that the village is peaceful, that the village is unarmed, that the village is there for the good of all mankind, that the village loves all countries and all the children of all the countries, that the village will never perish, that the village will never desert us. He added that the village is movable, but there was a twinkle in his eye, and I didn’t know how to take that. I’m not sure what he meant.”

Steger continues: “He lives in a house—not a castle—out by the reindeer grounds. He does have a wife, yes, and, interestingly, they have two children.”