Gaslight Grimoire: Fantastic Tales of Sherlock Holmes – Read Now and Download Mobi

Comments

Gaslight Grimoire

Fantastic Tales of Sherlock Holmes

Edited by

J.R. Campbell & Charles Prepolec

E-Book Edition

Published by

EDGE Science Fiction and

Fantasy Publishing

An Imprint of

HADES PUBLICATIONS, INC.

CALGARY

Notice

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. It may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each reader. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of the author(s).

* * * * *

This book is also available in print

* * * * *

Ghosts May Apply

David Stuart Davies

Arthur Conan Doyle was an accomplished practitioner of the supernatural tale and created some classic narratives in the genre. ‘The Ring of Thoth’, for example, was very influential within the realm of mummy stories. The idea of an ancient Egyptian achieving immortality and the setting of a museum after closing time became the essential ingredients of the 1932 movie, The Mummy, starring a very desiccated Boris Karloff. Other Doylean horror gems include ‘The Brazilian Cat’, ‘The Terror of Blue John Gap’, ‘The Leather Funnel’ and ‘The Nightmare Room’, to name a few — stories which are particularly chilling and memorable.

It must therefore have been a little frustrating for Doyle not to be able to involve his detective hero Sherlock Holmes in this mysterious and frightening world. What exciting scenes, puzzling scenarios and scary moments he could have created if he had allowed himself this guilty pleasure. But he had established Sherlock Holmes as a purely rational detective investigating real crimes with logical solutions. He knew that he would be weakening Holmes’ appeal and powers if he involved him with ghosts and other creatures from beyond the grave where logicality had no foothold. As Holmes memorably observed in ‘The Sussex Vampire’, ‘This Agency stands flat-footed upon the ground and there it must remain. This world is big enough for us. No ghosts need apply.’

Nevertheless, Doyle did tease his readers with suggestions of supernatural interventions in two of Holmes’ cases. In the aforementioned ‘The Sussex Vampire’ it was implied that a bloodsucking fiend was at work in the Ferguson household; and in The Hound of the Baskervilles, for some time the reader is unsure whether the phantom beast of the title really does exist. Even at the climax of the novel, when the hound finally makes its appearance — ‘Fire burst from its open mouth, its eyes glowed with a smouldering glare, its muzzle and hackles and dewlap were outlined in flickering flame’ — we are still not absolutely certain that the thing is of flesh and blood and not a spectre from the pit. It is only when the creature howls with pain after Holmes has shot it several times that we are assured that the beast is mortal.

Despite these deceptive forays into the realms of the unknown Doyle actually stopped short of presenting the Great Detective with a real supernatural mystery. Other writers, perhaps seeing a niche gap in the market, took advantage of Doyle’s reticence and around the end of the nineteenth century there was a rack of ghost detectives materializing in print. 1898 saw the first appearance of Flaxman Low in Pearson’s Magazine. Low was a sleuth cast clearly in the Holmes mould: clever, well read, possessing strong deductive powers with the ability to discern clues where others failed to do so. The marked difference between Low and his Baker Street counterpart was that he specialized in solving problems of a supernatural nature. Low was the joint creation of Kate Prichard and her son Hesketh who published the tales under the pen name of E. and H. Heron. Hesketh was a friend and admirer of Conan Doyle and the Holmes influence on the stories is marked, especially in the two final cases where Low encounters the Moriarty-like figure of Kalmarkane. This collection brings Low and Holmes together as an intriguing double act in ‘The Things That Shall Come Upon Them’.

Other spook sleuths followed in Low’s wake. Most notably there was Algernon Blackwood’s John Silence, who first appeared in 1908, and Carnacki the Ghost Finder penned by William Hope Hodgson. Carnacki, who made his debut in 1910, is of particular interest because not all his cases turned out to be supernatural ones. On occasion human agencies were at the root of the various upheavals. Usually there is a chamber or a specific location that needs to be examined and carrying his trusty electric pentacle, Carnacki approaches the scene in very much the same way that Holmes does in many of his cases, with a close observation of the area searching for clues. You can observe how these two sleuths fare together in ‘The Grantchester Grimoire’, one of the tales in this volume.

As the twentieth century rolled on other psychic detectives followed in the footsteps of Low, Silence and Carnacki. There was Alice and Claude Askew’s Aylmer Vance, Dion Fortune’s Dr. Taverner, A. M. Burrage’s Francis Chard and Seabury Quinn’s Jules de Grandin to name but a few. None really achieved the notoriety of Silence and Carnacki and certainly none approached the success of earth-bound Sherlock Holmes. Maybe the reason for their failure to catch the imagination of the mainstream reader is that these fellows not only believed in, but embraced the idea of the supernatural. They did not need convincing that there was a goblin in the cupboard, a vampire in the cellar or an ogre up the chimney. There was no surprise for them when they faced their demons … literally. The appeal then of these stories falls into two camps: the unusual nature of the haunting or supernatural event and the strange methods used by the psychic sleuth to alleviate the problem. These methods of course for the main part are invented by the author and have no roots in reality. This fanciful approach tends to rob the stories of suspense.

What is appealing about the prospect of Sherlock Holmes facing and battling the dark forces is that he is not a believer. The supernatural world is a fairy tale to him. No ghosts need apply because to his mind there are no such things.

When I wrote my first Holmes novel I took the brave or foolhardy step of pitting Holmes against Count Dracula, the king of all vampires. I don’t do things by half measures. However, the novel began with Holmes holding exactly the same opinions as he did in ‘The Sussex Vampire’, decrying the idea that such fantastic nocturnal creatures exist:

‘It should be clear, even to the most elementary of scientific brains, that the explanation of such beliefs lies not in the supernatural, but in the acceptance of weird folk-tales as factual occurrences. For the simple mind, the line between reality and fantasy is blurred, but the educated brain should reject any such nonsense without hesitation.’

And, indeed, Holmes continues to reject any such nonsense until he encounters one of these blood-sucking fiends himself and then is schooled by Van Helsing in vampire lore. I believe that Holmes’ gradual and reluctant acceptance of the supernatural world and his understanding that certain rationalities can still apply to it is one of the interesting aspects of this exercise in Sherlockian fiction. The fact that Holmes approaches any problem which may have supernatural connotations with scepticism and doubt adds extra interest and tension to the narrative, which is missing from those tales featuring ghost detectives. It is a subtle difference but it adds a richer and more engrossing element to the story.

Sherlock Holmes has always been a supremely gothic character with a strange costume, emerging himself like a ghost from the eerie fog and investigating bizarre crimes which take place in various ancient houses. The scenario of ‘The Speckled Band’ with bells ringing in the night, an unstable step father and a snake slithering down the bell rope are all elements that could have been plucked from one of Edgar Allan Poe’s nightmare tales. Consider also the conclusion of ‘The Creeping Man’ (a good ghost story title if there ever was one) where we have a respectable academic turned into a libidinous monkey, swinging through the trees. Is this any less believable than one of Carnacki’s poltergeists?

The point I am making is that in reality it is not too giant a step to take Holmes and Watson into the twilight world of the supernatural — Doyle brought them close to it on several occasions. As long as Holmes can still function as a detective, surprising Watson and others with his deductions, the introduction of a werewolf or an avenging spirit adds an extra frisson to the Baker Street scenario.

Doyle had to defend himself when critics observed that the stories in his final collection, The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes, lacked the freshness and ingenuity of the earlier tales. He explained that in repeating the basic formula of the stories there was bound to be a sense of deja vu about them, a certain tiredness which was inevitable. If that was the case with Doyle, think how much more apposite it is to all the pastiches which have followed in the wake of the great man’s work. In an attempt to replicate Doyle’s style and approach, so many pastiches end up being pale imitations with that awful sense of repetition. ‘Great heavens,’ Watson will cry, ‘How did you know I’ve just been to the tailors/been playing billiards/had a romantic liaison with Irene Adler/just shot your brother Mycroft.’ Holmes will smirk and say, ‘Elementary, Watson, you’re wearing a new waistcoat/there is billiard chalk on the index finger of your left hand/there is lipstick on your earlobe, the hue of which is peculiar to Miss Adler/I saw a bullet with Mycroft’s name on your dressing room table this morning.’ We’ve read that kind of stuff a hundred times before. The formula needs perking up. And maybe giving Holmes a taste of the supernatural is just the fillip needed. Of course it has been tried before. In recent years there’s been a volume of the Lovecraftian extravaganzas, Shadows over Baker Street (2003), Caleb Carrs’s ghostly stab at Holmes in The Italian Secretary (2005) and a collection called Ghosts in Baker Street (2006). However in general these stories were penned by writers who, for want of a better expression, were having a go at a Holmes tale unlike the authors featured in this volume who are very well-versed in the world of Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson and so can effectively blend the world of Baker Street with the world of the unknown. I can guarantee you a good time here. Expect a few shivers along the way.

How will Holmes cope with things that go bump in the night? Well you’ll have to read the stories to find out, but let me leave you with this thought. What better detective is there to delve into the unpredictable and frightening world of the supernatural than the one whose motto has always been: ‘When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains however improbable must be the truth.’

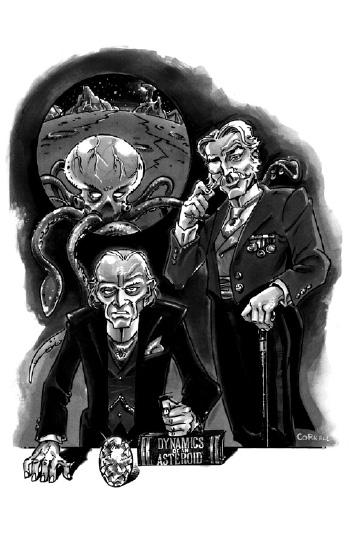

him, the thin-lipped leering countenance of the author of The Dynamics of an Asteroid.

“I have, I think, made my point,” said Professor Moriarty. “And you, Stent, have finally learned your lesson.”

Introduction

An Introductory Rumination on Stories for Which the World Is Not Yet Prepared

Charles V. Prepolec

Never underestimate the impact of the fantastic on an impressionable child, be it in print, film or television. You never quite know where it may lead, or when it might

bite you on the ass. In my case, it eventually led to the creation of Gaslight Grimoire: Fantastic Tales of Sherlock Holmes, so feel free to hold the likes of Alfred Hitchcock, Homer (the Greek chap, not Simpson), Alexander Korda, Stan “The Man” Lee, Lester Dent, Ray Harryhausen, Creature Feature presentations on Saturday afternoon television, Otto Penzler, Hammer Films and, of course, Arthur Conan Doyle accountable for the book you now hold in your hands. Although, to be perfectly fair, H. G. Wells, Jules Verne, R. L. Stevenson, Bram Stoker, and Greek myth in general should probably shoulder some of the blame too, but for now we’ll stick to the shortlist. You see, as an only child, I spent a lot of time exploring fantasy worlds wherever I could find them — and quite frankly, I found them everywhere!

Hitchcock’s Three Investigators (okay, Hitch himself is off the hook since he didn’t write a one of them) were probably my first exposure to slightly scary mysteries. Well, at least some of the covers were sort of scary. One that had a glowing disembodied head on it had to be safely put away before the lights went out in my bedroom each night. My thanks to those fine folks at Scholastic Books (the same fine folks who, if memory serves, were inexplicably responsible for making me aware of Sawney Bean while I was still under ten years of age) for messing with my young mind! Right about the same time, through a chunky paperback book found in my school library, Greek myth popped into my life with Jason and the Argonauts, which in turn led to a far too early reading of Homer’s Odyssey. Jason, Hercules, and the clever Odysseus became early heroes. My sense of heroic fantasy, heroes and their heroic deeds, was forming, although a strange fear of cannibals was lurking in there somewhere too. Thank you again Scholastic. At about the same time I also had my first brush with Sherlock Holmes. I found myself reading

The Hound of the Baskervilles, but at the time I didn’t find it terribly engaging and didn’t finish it. Anyhow, that Greek myth interest was further fuelled when Ray Harryhausen’s Jason and the Argonauts turned up on television. Harryhausen’s stop-motion animation gave magical life to creatures that had previously only existed in my imagination. In short order I was begging to be taken to see his Sinbad films (for the record, Kali has always been my favorite Harryhausen creation), which indirectly took me back to Alexander Korda’s The Thief of Bagdad. Now that was the mother load for skewing this kid’s idea of fantasy. It was the most magical thing I had ever seen, and it had the best villain ever in Conrad Veidt’s Jaffar! He made

Tom Baker’s Prince Koura seem like a boy scout by comparison. What kid wouldn’t want to be Sabu?

So with a major itch for heroic fantasy, I did what most geeky kids would do, start reading comic books and developing the first stages of ‘collector’s mania’. The Mighty Thor, Iron Man, Dr. Strange, Tomb of Dracula, the Uncanny X-men, and on and on went the list of Marvel comics. Stan Lee had a lot to answer for when he had the idea to infuse the tired superhero books of the 1950s with the soap opera antics of romance comics. Can you say addiction? I knew you could. It was all the perfect fodder to fuel my fascination with heroic fantasy figures. It also led me to discover the world of pulp heroes in a roundabout way. At the time, the mid-1970s, Marvel was producing a line of black and white magazine sized comics and amongst them was Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze. Incidentally, there was also a two-part adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles in Marvel Preview, which was my second brush with Sherlock Holmes. The pictures helped, but I still wasn’t terribly impressed. Through that Doc Savage magazine I discovered the near perfect heroic fantasy character. Doc Savage combined the best of everything I’d encountered up to that time. He was built like a hero from Greek myth, with bronzed skin and freaky gold eyes, blessed with a brilliant mind, surrounded by a band of lesser heroes, each with their own scientific specialty and had adventures that almost always had a huge fantasy element. Suddenly used bookstores entered my life as part of the quest to accumulate as many of the Doc Savage paperback reprints that I could get my hands on. It became an all-consuming passion. I must have been driving my poor parents nuts with my obsession, but they thought reading was good for me (can’t imagine what they would have made of the Bond books or John Norman’s Gor series I was also reading at the time) and so indulged me in my interests. I can vividly recall successfully convincing them to drive me some 300 kilometers north just so that I could scour the virgin territory of Edmonton’s used bookshops. I eventually managed to accumulate about 102 of the paperback reprints, before moving on to another obsession, but not before reading Phil Farmer’s curious Doc Savage bio Doc Savage: His Apocalyptic Life and being introduced to the inbred wonders of his Wold-Newton family tree. Suddenly there was a thread, however tenuous; tying together all these fantastic fictional heroes, and look, there on a low branch is that Sherlock Holmes guy again. I also discovered The Avenger, The Spider and, of course, The Shadow! Like Doc Savage, I first encountered The Shadow in comic books, although the fact they were published by DC bothered me no end! Still, Denny O’Neil’s stories and more importantly Mike Kaluta’s unsurpassed artwork did the trick. “Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men?” became my catchphrase. Rarely got an answer to that one, but what did I know about ‘evil’ or ‘the hearts of men’? I was a twelve year old kid and The Shadow was cool. So cool that when I spotted him in a book called The Private Lives of Spies, Crime Fighters, and Other Good Guys by Otto Penzler, and discovered there were films with The Shadow, I simply had to have it! While The Shadow chapter was pretty thin, I was introduced to a whole new genre that captured my imagination, however fleetingly. The detective in print and film had entered my life … and there was that Sherlock Holmes guy again. I can recall being quite taken with a photo of John Barrymore as Holmes holding a gun on the grotesquely featured Gustav Von Seyffertitz as Moriarty, but little else.

Unfortunately my detective interest was immediately sidetracked by another book, Alan Frank’s The Movie Treasury: Monsters and Vampires with a garish cover image of Christopher Lee being staked. Suddenly I wanted to see monster movies, and lots of them. Happily every Saturday afternoon there was a Creature Feature program on television to feed that particular craving. More importantly it had the added benefit of sending me back to the literature. I ended up reading Dracula, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, The Picture of Dorian Gray, The House on the Borderland, Carnacki the Ghost Finder, The War of the Worlds, The Invisible Man and who knows how many horror anthologies edited by the late Peter Haining. My interest in fantasy had shifted away from the bright and shiny, clean cut heroes of childhood and drifted down the dark gaslit alleys of the macabre. Comic books grew less important and gave way to somewhat more esoteric reading materials. Yup, you guessed it; puberty had begun to work its own peculiar magic! Sexual repression seemed to be the order of the day as my fantasy worlds began to take on a distinctly Victorian tinge. It seemed to me that the era was simply one big heavily populated playground for monsters, madmen and murderers, and thanks to Hammer Films on television, apparently they all looked an awful lot like either Christopher Lee or Peter Cushing.

While my reading interests went all over the map at that point, bloody 80’s horror, trashy true crime thrillers, Herbert’s Dune series, Tolkein’s The Lord of the Rings, Anne McCaffrey’s Pern, and God knows what else, the concept of an almost homogenous Victorian nightmare world remained firmly lodged at the back of my mind. My teen years came to an end and on a fateful day in 1986 I found myself in a comic shop. Browsing the racks I was drawn to the brightly painted image of Sherlock Holmes standing in a graveyard. It was the cover of the first issue of Renegade Press’ Cases of Sherlock Holmes. The text was Conan Doyle’s “The Beryl Coronet”, but it was accompanied by the wonderfully atmospheric black and white artwork of Dan Day. Was that Peter Cushing’s face staring out at me? Yes, it was, although in the next panel it was Basil Rathbone’s, and in the one after that John Barrymore. Hmm, that Victorian playground concept was flashing back into my mind so I picked it up, went home and read it. Here was that Sherlock Holmes guy that I kept running across, but largely ignored, throughout my childhood. Sherlock Holmes, turned out to be calm, cool, insightful, larger than life fantastic hero and best of all, he lived in my Victorian fantasyland. By the next day I was in a used bookstore looking for a copy of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. I found myself reading the words “To Sherlock Holmes she was always the woman”, and considering I was floundering after a bad break-up with my girlfriend, I was utterly and completely hooked. By the weekend I had Peter Haining’s The Sherlock Holmes Scrapbook and discovered there was a whole world of Sherlock Holmes related material out there, including something called a pastiche. Back to the used bookshops I went. Fred Saberhagen’s The Holmes-Dracula File fell into my hands, Loren D. Estleman’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Holmes followed suit, then Manly Wade Wellman’s Sherlock Holmes’s War of the Worlds, and oh look, Phil Farmer’s Wold-Newtonry was back in my life with The Adventure of the Peerless Peer. Apparently I wasn’t the only one who thought the Victorian era was a literary fantasyland, but best of all, my new hero, a classic one that seemed to embody the best qualities of all my childhood interests, served as a guide through this nightmare world. To be sure, some of it was truly dire in terms of quality writing, but it was the most fun I’d had in a lifetime of reading, and fun is the key to entertainment.

Flash forward some 20-odd years and here I am, still having fun in my Victorian fantasyland and exploring the ever-expanding world of Sherlock Holmes. From the distance an early 21st century vantage point provides, the idealized Victorian and Edwardian world Sherlock Holmes inhabits is to the modern reader, in its own way, as strongly realized and alien a fantasy setting as Tolkien’s Middle Earth or Baum’s Oz and just as much fun! Gaslight Grimoire: Fantastic Tales of Sherlock Holmes will, I hope, communicate some of that sense of fun that I’ve been enjoying all these years.

Throughout this rambling rumination I’ve made mention of a number of Conan Doyle’s contemporaries and successors who worked the rich vein of fantasy fiction. In the stories ahead you will perhaps find echoes from some of their works or their characters. The connection may be very subtle or it may come through loud and clear as it does in Barbara Hambly’s “The Lost Boy”, a bittersweet tale of Sherlock Holmes and J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan. Considering Conan Doyle’s one-time collaboration and longtime friendship with Barrie, it is a perfect starting point for our collection. Christopher Sequeira’s “His Last Arrow” is a cautionary tale, possibly inspired by Sir Richard Francis Burton’s translation of The Book Of The Thousand Nights And A Night, which drives home the adage that you should be careful what you wish for as Watson appears to have brought home more than a war-wound from his time in Afghanistan. Barbara Roden’s “The Things That Shall Come Upon Them” contains our first pairing of Holmes with a classic ‘psychic detective’, in this case Hesketh-Prichard’s groundbreaking Flaxman Low. Holmes and Low both find themselves investigating, from decidedly different perspectives, strange occurrences in a house that is sure to be familiar to readers of M. R. James’ “The Casting of the Runes”. The Flaxman Low stories are a perfect example of Conan Doyle’s direct influence on a contemporary, as the Low stories began appearing in Pearson’s Magazine in 1898, less than a year after Hesketh-Prichard met Conan Doyle at a writer’s dinner. Another, earlier, writer’s dinner was also a meeting point for Arthur Conan Doyle and Oscar Wilde, who’s The Picture Of Dorian Gray, seems to have an echo in M. J. Elliott’s “The Finishing Stroke”, a grisly tale of art gone wrong. Martin Powell brings in Conan Doyle’s other great creation Professor George Edward Challenger in a Boy’s Own/pulp styled two-fisted adventure tale that could only be called “Sherlock Holmes in the Lost World”. In Rick Kennett and A. F. (Chico) Kidd’s “The Grantchester Grimoire”, Holmes meets his second ‘psychic detective’. In this case it is arguably the best known, and certainly best loved, example of the breed, William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki the Ghost Finder. Kennett and Kidd have previously collaborated on a highly recommended collection of Carnacki pastiche available under the title No. 472 Cheyne Walk (Ash-Tree Press 2002). In “The Strange Affair of the Steamship Friesland”, a direct follow-up to “The Five Orange Pips”, journalist Peter Calamai presents Holmes with a unique method of correcting an early failure after consulting a certain familiar doctor with an address in South Norwood. Lewis Carroll’s Alice may have disappeared into another world, but any comparison with J. R. Campbell’s “The Entwined” stops right there, as the girl in this story dreams of nothing that could be described as a Wonderland. An aging Watson finds himself faced with the horrific power of strong remembrances when Chris Roberson delves into the untold tale of “Merridew of Abominable Memory”. When a private investigator on the mean streets of 1940s Los Angeles finds himself faced with a corpse that won’t stay down he turns to the greatest detective still living for help, bringing together influences as widely removed as Bram Stoker and Dashiell Hammett in Bob Madison’s humorous and hardboiled story “Red Sunset”. Our final entry takes a decidedly different turn in that Sherlock Holmes is nowhere to be found; instead Kim Newman has Professor Moriarty, along with Colonel Moran, waging a highly personal and often hilarious War Of The Worlds in “The Red Planet League”.

At the beginning of this long-winded and wandering introduction I wondered what the impact of fantastic fiction on an impressionable child, might be? Well, now you know, in my case it eventually led to the creation of the book you hold in your hands. A little horror, a little pulp-style thriller, a little comic book adventure, a little ghostly spook story, a little bit mystery and hopefully a whole lot of fun. Not your traditional selection of Sherlock Holmes stories by any means, but what is the fun of that? After all, as Watson noted in The Speckled Band “…he refused to associate himself with any investigation which did not tend towards the unusual and even the fantastic…” so why should we?

Enjoy!

Charles Prepolec, 2008

The Lost Boy

The Lost Boy

by Barbara Hambly

When the Darling children disappeared without a trace from their nursery one night, their father took the case at once to Mr. Sherlock Holmes.

Mrs. Darling came to me.

“You know how George is,” she said, when the first spate of anguish, of terror, of speculations both probable and grotesque had been talked out over tea. I had been in the Darling night nursery innumerable times, listening to the tales Meg Darling — Meg Speedwell she had been, when first I knew her at Mrs. Clegg’s dreary boarding school in the north of England — would tell small Wendy, smaller John, and baby Michael of pirates, mermaids, red Indians and the fairies that dwell in Kensington Gardens.

I knew the distance from that high window to the street below, and that the drainpipe was at the back, not the front, of that narrow brick mansionette in its row of identical dwellings. I knew how big a dog Nana was, and the sturdy Newfoundland’s ferocity where the children were concerned.

“George says—” Meg began, and then stopped. For a time she sat turning her saucer round and round, forty-five degrees at a time, a habit she’d had when we were girls, and she was thinking about how best to say something that the adults had told us we shouldn’t say or even think.

And I knew then that what — or who — she was thinking about, was Peter Pan.

“Do you remember Peter Pan?” she asked, after a long, long time, in the small voice one usually only hears late at night, when the other girls in the bleak cold dormitory have gone to sleep.

I nodded. I didn’t say, How could I forget? I think Peter Pan was the reason that I didn’t kill myself when I was seven or eight — and it’s a mistake adults make, to think that children who are sufficiently unhappy don’t want to try to end their own lives. Mostly we just don’t know how. That I’d lived through Mrs. Clegg’s ideas of how to operate a girls’ school was entirely because I learned to dream, and in those dreams I’d met Peter Pan.

It was what we called him, Meg and I, because Meg dreamed about him, too. We both knew he had another name, a real name, and that other children had called him other things over the years. We both knew — the way you do in dreams — that he was more than he appeared to be, and more than he himself realized he was much of the time. We were both certain that it was possible for him to cross through the film that separates the Neverlands from the damp chilly world of girls’ schools, and account-books that don’t add up, and bleak London streets, and knowing one is going to die.

Meg had told me once back then — and I believed her — that she had seen him do so.

Now she said — and I believed her — “I saw him in the night-nursery, a week ago.” She watched my face as she said it, knowing of course that John — my John, after whom her own seven-year-old son was named — was a doctor, and fearing that my immediate conclusion would be that she was mad.

When I said nothing, she went on softly, “It was only for a moment. I dreamed he had rent the film, that separates the Neverlands from us—” That was what we’d called them, Meg and I: those endless skerries of islands, where children go when they dream. “I dreamed the children peeked through, and saw. I woke, and he was there still, looking just as he always did.” She shook her head, at the shared memory of that shock-headed child clothed in skeleton leaves, smiling his ageless brilliant smile.

“Did the children see him?” I asked, and she hesitated, calling the scene back to her mind.

“I think so,” she said slowly. “I screamed, and he flew away through the window, like a swallow flies—”

How well I remembered — though I had not until she said it — the motion of his flight, a darting swoop, the tiny lights of whatever fairies he had with him just then flicking in his wake.

She whispered, “He left his shadow behind.”

John came home early that evening, though he had stopped at Baker Street to visit with Mr. Holmes. I was ill a great deal that year, and though John kept closer to home than he had before, he also saw a good deal more of Holmes. He would stop at Baker Street for a half an hour on his way back from his rounds. Though I would take a Bible oath that he never so much as mentioned to Holmes his fears for me, nor did Holmes offer so much as a shred of a reassurance that he would have disdained as illogical, still, John would come home comforted, and full of the details of whatever case occupied his friend’s keen mind.

Thus that evening I heard all about George Darling’s visit to Holmes. “Old George kept his head remarkably,” John said, as he stirred cocoa for us both in a little pan on the bedroom hearth, while I lay among my pillows sorting through his medical notebook. It was my duty always to keep track of his patients, and tot up the bills which half the time John then left uncollected. “Holmes could not have done better. George knew the height of the window-sill from the pavement, the names of the cab-men at the corner of the road; before he came to Holmes, he went through the whole of the rear yard examining the ground there, and found no marks of a ladder, nor smudges on the window-sill, nor signs on the drain-pipe that it had been climbed. Of course Holmes returned to the house with him in any case, but he found nothing, either.”

I nodded, and the part of me that had years since ceased to believe in that small, shining boy with the wonderful smile wept with sickened shock, that the three children John and I loved as if they were our own might at that moment be dead. Or if not dead, in the hands of the human horrors that he and I both knew too well populated the adult world.

John wrapped his hand around mine as he handed me my cocoa. “They’ll be all right, Mary,” he said, looking into my eyes. “Holmes will find them. They’ll come to no harm.”

I whispered, “I know.”

The medicine I was taking then was bitter and strong. Though it gave me the sleep I needed, it also sent dreams, more vivid than I had known in adult life. In dreams that night I walked in Kensington Gardens, leaving the paths that John and I followed on our summer afternoon strolls and seeking the tree-hidden stillness along the far end of the Lake, where the fireflies’ reflection played above water like black onyx. This was where the fairies lived, Meg had whispered to me when we were children. This was where Meg herself had disappeared one evening when Mrs. Clegg had brought the lot of us down to London for I forget what occasion — it wasn’t a treat for us, that was all I knew — and had not reappeared for almost two days. Mrs. Clegg had hushed it up, of course, and pretended that it hadn’t been more than a few hours. But though we were quite small — five or six — I remembered it clearly.

It had been two days.

And Meg had told me, that she had been in the Neverlands, with Peter Pan, for what seemed to her then to have been many weeks. She was never quite the same after that. Happier, as if she carried in her heart the assurance that things would all come right in the end.

I knew, too, from conversations with Martha Hudson, that Mr. Holmes’ logic and studies extended far beyond what people like John — bless his kindly, literal heart! — regard as the Real World.

Thus I wasn’t at all surprised to see Mr. Holmes in Kensington Gardens, walking quietly in the cool blackness barred with moonlight, not only listening but touching the tree-bark, the grass-blades, the dew upon the leaves as he passed. I couldn’t imagine how he knew about Kensington — Mrs. Clegg had certainly never reported that long-ago disappearance of her charge to the police — but he moved like a man who knew the place well, and knew what he sought. When a fairy darted in a sparkling skim of pale-blue light across the lake-surface he only stopped, as it swooped up before him, hung in the darkness a yard in front of him for the space of a second or two, then whipped away.

Whether Mr. Holmes carried something in his pockets that signaled the fairies of his benign intent — and I think he must have — I did not know. But they flickered from the woods, followed him thicker and thicker, as he walked unerringly toward the belvedere that only exists in the park sometimes, usually after the sun goes down: the rest of the time you cannot find it, no matter how systematic your search. But Holmes went straight towards it, coming out of the circle of willows to see it standing in its little meadow, with the fairies hovering around it like dragonflies above standing water in the darkness.

And as he came into the open, about thirty feet from the ghostly circle of marble pillars, he met Peter Pan.

Or, rather, Peter seized Holmes by the sleeve and dragged him back into the willows: “Hist! Beware!” His dagger wrought of meteor-iron, its handle carved of dragon’s bone, caught the moonlight in his other hand.

Holmes dropped at once to one knee at the child’s side, so that their eyes were nearly level; followed his gaze toward the open meadow, the belvedere. “What is it?”

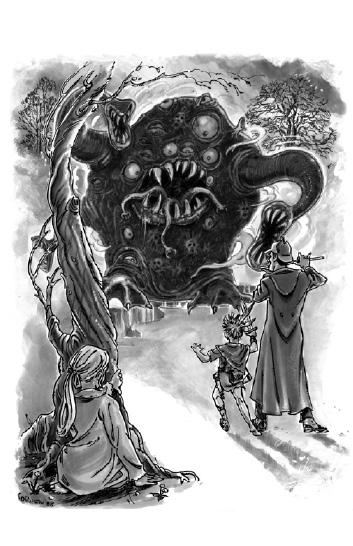

“It’s the Gallipoot,” whispered the child. “The Thing Cold and Empty. It haunts the zone of shadow between your world and the Neverlands. It waits for the veil to open, so that it can slip through and hunt.”

“What does it hunt?” asked Holmes.

“Souls on this side,” Peter replied. “Dreams on the other. It slices them up and swallows them, and all the little pieces of them wave shrieking about it like bloody flags in agony, forever.” His eyes burned somberly. It was hard to tell from where I stood, half-hidden among the willows, whether Peter was pretending or not, because he did pretend … only the things that he pretended often came to pass. “I’ve sought to drive it back through the belvedere into the zone of shadow, but it’s eluded me, and I dare not call upon my henchmen, for it would make short work of them.”

Holmes took a flute from his pocket — an ivory one he’d acquired in Tibet — and said, “Will it come to the music of souls?”

Peter nodded.

“I will stand before the opening into the zone of shadow,” said Holmes, “and play. When it lunges at me, I will leap out of the way, and you must drive it through with your weapon.”

The child nodded again, trying not to look impressed — I couldn’t remember whether Peter could play the flute himself or not. Holmes and Peter walked toward the belvedere together, and I noticed that all the fairies had disappeared. The air of the summer night grew cold, and strange, directionless movements seemed to stir the darkness, with a smell of sulfur and mould. Far, far off, as if at the end of an endless corridor, I could hear shrieking, as of the bleeding fragments of a thousand souls.

I did not know whether at that moment I qualified as a soul or a dream. All I knew was that this was real, this was happening in Kensington Gardens, even as I lay deep in sleep at John’s side not many streets away. If it caught my soul, I would never wake up.

I had thought Holmes would play one of those strange airs that he learned in Tibet, or the weird gypsy music that he sometimes coaxed from his violin. But he played the air from Vivaldi’s Concerto in D Major for Lute, and the Gallipoot drew closer — I could smell it, hear the trapped souls screaming, feel its nearness in the bone-hurting cold. When it broke from the trees I tried to cry out in my sleep, tried to scream so that John would wake me, but I couldn’t. It was well I didn’t, for I realized a moment later that if I screamed it would become aware of me, come for me…

It rolled, oozed, surged toward the belvedere, and the exquisite melancholy song of the flute didn’t waver, though the screaming of the trapped and devoured souls rose like the wail of storm-wind. Through its darkness the marble pillars glimmered, then vanished, and I felt in my bones the wrenching of the fabric of the world as it struck.

A shriek like a thunderclap pierced my skull like lightning, and in the blackness that swallowed the moonlight, I saw the flash of Peter’s knife—

Then Holmes was stepping down the shallow platform of the belvedere, the world normal again and as it should be, tucking his bone flute into his pocket with one hand.

In the other hand, he held Peter’s knife.

“Give that back!” Peter came leaping out of the belvedere, grabbed for Holmes’ arm.

Holmes sidestepped him like a dancer. “When the Darling children return to their home, you shall have your knife back.”

“Who are the Darling children?”

Peter doesn’t always remember things.

“Wendy, and John, and Michael,” said Holmes. “The children who went away with you to the Islands last night.” I don’t know how he learned this — perhaps he’d only guessed it, until he actually encountered Peter — but then, as I said, Holmes studied extensively the writings concerned with other realities than those of the material earth. Someone, at some time, must have written about the Neverlands — or the Islands, as they were apparently also called, and they had other names as well. Certainly Meg was not the only child who had inexplicably disappeared, without any traceable sign of human agency, in Kensington Gardens or elsewhere.

Peter said, “They’re my friends. Wendy is to be my mother, and take care of me, and look after my Lost Boys in a secret house below the ground.”

Holmes nodded gravely. “You are renowned for looking after your friends,” he said, as one recalling a legend — or a set of instructions, as to what one must say to a dragon or a fairy — “in the face of any and all danger to yourself.”

Peter smote his chest proudly. “I am.” Peter never could resist renown.

“Then promise me this,” said Holmes. “When the Darling children return home — as return they will, one day — promise me that you will see to it, that they will do so on the day after they departed. That way,” he added, “you will have your knife back in only two days.”

The fairies were gone, and the moon sinking, as Holmes walked back toward the paths of the more populated parts of the Gardens. In the shadows of the willow circle he stopped, as if at a sound, and turning his head his eyes met mine. He had encountered the fairies, and Peter — not to mention the fearsome Gallipoot — without a blink, but now his eyes widened, first startled, then filled with shocked grief. “Mrs. Watson?” he asked softly.

I know that we do not look the same to others, when we encounter them in dreams.

I put my finger to my lips, and slipped away.

Holmes and Peter met a number of times that summer, usually in Kensington Gardens, where Holmes would go walking when all of London slept. Peter did get his knife back within two days, for as Holmes understood from those strange — and sometimes very ancient — accounts of mysteriously-appearing children over the centuries, time spent in that other world is notoriously elastic, and bears no relation to the seasons by which we live.

As my illness ran its course I would dream of them, when sleeping under the influence of my medicines. Holmes taught Peter boxing and single-stick on the fringes of the lake by moonlight, and the intricacies of baritsu throws, in exchange for whatever Peter could tell him of the worlds that lie beyond our own. Peter, for his part, was fond of displaying his knowledge. Though his accounts varied wildly from interview to interview, still I think Holmes gleaned sufficient information to unlock certain clues in those cases that he never told John about. I know that it was from Peter that he learned the secret behind the events at Rowson Priory, and the riddle that saved his life and John’s, years later, during the affair of the Covyng Stones.

But about such matters as Red Indians and pirates, Peter found Holmes shockingly obtuse. And Holmes had enough of Peter in himself, to take umbrage when a boy who didn’t quite come up to his elbow scoffed at his researches into the habits of the Cherokee and Sioux. “They’re not Sioux, they’re Indians,” Peter almost shouted at him. “And they’ll scalp any white man who comes in their midst!” I think they finally parted over Holmes’ contention that the giant ants that lived on one island of the Neverlands archipelagoes could not exist because it was scientifically impossible for them to breathe. “You’re wrong,” cried Peter. “You’re wrong, I’ve seen them — I’ve slain one with my knife!”

He stamped his foot, and the impact launched him glittering into the air. He was gone before Holmes could speak.

I think Peter would have cheerfully made up the quarrel, had he remembered to go back to the Gardens, but he didn’t. Peter does forget things, and people, too, alas. Nearly a year went by, in which Holmes would patiently walk the byways of Kensington Gardens, looking for the paths that had once led him to the belvedere beyond the willow circle — paths that were no longer there and never had been. Holmes continued elsewhere his education in the lore of the Beyond Realms through other connections in London: through a strange young antiquarian who had a house on the Embankment, and the white-haired proprietor of a junk-yard at the end of Fetter Lane.

It was Peter who came to me, for help in finding Holmes again.

I was delighted to see him again. My illness weighed heavily on me just then, made worse by the fact that I knew John was nearly frantic, between the costs of caring for me, and fear that I wouldn’t pull out of it, and the sheer insanely mundane burden of running a house. I had dreamed more and more of the Neverlands, hearing in the distance the pounding of the surf on their shores, and the singing of the mermaids among the rocks, but this was the first time Peter appeared in one of the dreams. It wasn’t in the Neverlands, either, but in my own bedroom — John had taken to sleeping on the couch in his study, for fear of disturbing me — and when Peter swooped in through the window I could see he was almost incandescent with rage.

“Mary, where’s Holmes?” he demanded, as if it hadn’t been decades since we’d parted. He grabbed my hand, and as he pulled me to my feet I was as we all are in dreams, perfectly healthy and much younger than in real life. “You have to show me where he lives. I need him.”

He was as he had always been. I was as well, the long blonde hair that had been cut off with my illness (that’s how sick I was) now lying intact again in pigtails on the shoulders of my white nightgown, and my nails chewed off short. (I’d quit biting them the minute I left Mrs. Clegg’s).

Of course I said yes immediately, and being Peter, he completely forgot about putting fairy-dust on me to fly until we were standing on the window-sill, and then Ten Stars had to remind him: Ten Stars was the fairy he flew with by that time, and much less jealous by nature than her predecessor. Tinker Bell would never have bothered to keep a human — dreaming or not — from crashing to the pavement. To do her justice I don’t think Tink ever really understood why it wasn’t funny.

We flew over London, something I had always wanted to do. And it was as glorious as I had always known it would be.

It was not so very late: Big Ben was striking eleven in the distance as we stepped through the window at 221B Baker Street. We entered through the bedroom that had been John’s, now crammed almost floor-to-ceiling with Mr. Holmes’ books and souvenirs. I could hear the strains of Mr. Holmes’ violin from the parlor, smell strong shag tobacco with an intensity I hadn’t experienced since I was a child. By the sudden chill on my bare ankles I knew that Peter and I had stepped from dream into reality, and panic filled me at this thought. Peter, still keeping a grip on my hand, barged through the parlor door saying “Holmes!” but I hung back in the shadows, suddenly shy of meeting, in my changed dream-state, a man I knew as an adult in the cold adult world.

Holmes had already started up from his chair and the violin was out of his hands — I think he had a pistol tucked behind the chair-cushion — but he saw it was Peter and his eyebrows went up with astonished delight. The next second his glance went to me, still half-hid in the dark bedroom doorway, and his expression changed, but before he could speak, Peter jabbed a finger at him and snapped,

“You have to help me, Holmes. I am being accused of kidnapping — kidnapping! — and you must help me clear my name!”

The boy’s name was Robert Lewensham and his father was the Earl of Wylcourt. Peter didn’t know these things, of course; Holmes looked them up while I poured us all out tea. Peter’s account was only that Bobbie had come with him to the Neverlands twice — “He’s a tremendous sport and the Black Knight of Ravensmire lives in terror of his blade,” — after first meeting him in the bleak fells of Yorkshire, where one of Ten Stars’s relatives had gotten lost and Peter went to find her.

“This last time, he didn’t get back home,” Peter said. “It isn’t my fault. Bobbie knew the way. Only now his father’s hired men — wizards, some of them quite wicked — to find him, and the King of Dreams is saying, that this kind of thing can not be tolerated, and that if need be he will shut the Gates of Horn and Ivory that lie between this world and the Neverlands, so that no one may cross. He’s always saying things like that,” Peter added sulkily. It was the first time I’d ever heard him mention the King of Dreams. “And it isn’t fair.”

“It isn’t,” I added, a little timidly. “What about all those children who’ve never gone to the Neverlands, Mr. Holmes? What becomes of them?”

Holmes glanced across at me, the line between his brows telegraphing his uncertainty. In the shadows he had thought he’d recognized me, but sitting on his sofa before the fire — where so many times I’d sat in my adult life, all dressed up in proper gray delaine with a corset, bustle and husband — I could see he didn’t know why he’d thought so, or who he’d imagined I might be.

“What indeed?” Holmes remarked dryly, and turned back to Peter, who was devouring biscuits left over — like the contents of the teapot — from Holmes’ own tea earlier that evening. “Might your friend have been seized by something that haunts the space between the worlds, like the Gallipoot? There are other things as well—”

Peter waved impatiently with a biscuit. “We can get away from them,” he boasted — by we, I assume he meant, himself and his Lost Boys. “The Gallipoot only eats people like pirates and Red Indians and black knights.”

“Does it, indeed?” Holmes had crossed the room to the most recent of his scrapbooks, and the newspapers piled on top of it, sorting through the headlines of the past week with swift sureness, as if he knew exactly what he sought, which indeed he did. “I thought this sounded familiar,” he remarked in a moment, and extricated the York Evening Star from three-quarters of the way down the stack. “Robert Lewensham, Viscount Mure — h’rm — heir to the Earl of Wylcourt — born 1885 — police are seeking gypsies — believed to have vanished on the Yorkshire fells three miles from the village of Kethmure — bird-watching — blue jacket, blue cap — A shocking paucity of detail.” He plucked out another newspaper, handed it to me, got another for himself.

I’d worked with John enough to know what Holmes sought, and located the follow-on article without trouble. “They add little,” I ventured, after scanning the columns. “They do say, Bobbie disappeared on the ninth—” I looked at the date of the paper in my hands, then turned, shocked, to Holmes. “Is the paper you have the day before this one?”

Holmes nodded, regarding me again with that questing speculation in his eyes. “So the papers — and presumably, the police — didn’t learn of it until the twelfth. Either the boy’s guardians are singularly neglectful, or they had some reason to believe him safely elsewhere for two days. This last time, did Bobbie say he’d been visiting anywhere?”

“Bobbie never visits anywhere,” replied Peter promptly. “He goes to school in the city, and when he’s at his home he’s alone.” For the first time since I’d known him, Peter’s voice had a note of real distress in it, of concern, not that he, Peter, was being accused of kidnapping children from the real world, but that his friend was somewhere in trouble. And that his friend lived the sort of life that he, Peter, had all his existence fled.

When he’s at home he’s alone. There was a dismal world of Mrs. Cleggery in those six words.

“Most interesting.” Holmes pulled another scrap-book from the overflowing shelves. “Do the fairies often get lost on the fells?”

Peter nodded. “Mostly they find their way back at dawn. Ten Stars’s cousin Cloverberry’s just a little fairy, though, barely more than a bud, and you know how fairies are. Ow—!” he added, because Ten Stars, who was sitting on Holmes’ desk blotter, indignantly threw a collar-button at him. “I met him when I was looking for Cloverberry.”

“And is this place near a ring of stones?” From between the pages of the scrap-book Holmes extracted one of his vast collection of Ordnance Survey maps, and spread it on the desk. Craning to look over his shoulder, I saw Wylcourt Hall marked, and the village of Kethmure.

“In the middle of one,” affirmed Peter. He couldn’t keep out of his voice the awed surprise of one who sees magic done. A small circle within two miles of Wylcourt Hall was labeled, Stone Circle — Fairies’ Dance.

“And the boy’s father has hired wizards to find him. Well, well.” From the bottom drawer of his desk — the locked one where he keeps certain poisons and lists of names — Holmes brought out a thick, much-dog-eared notebook with a scribbled paper label on it, SPIRITUALISTS — THEOSOPHISTS. Prior to his journey to Tibet, Mr. Holmes had compiled a catalog of known frauds and fake adepts in matters occult, the way he compiled catalogs of every other sort of criminal and confidence trickster he heard of: details cross-referenced in his mind.

Yet he had returned from those years of travel with a different outlook than he had taken out of England with him. And he had never, even when I first met him, been a close-minded man. I knew — not from John, to whom he never mentioned it, but from Martha Hudson — that Holmes had continued his catalog with the names given him by his various contacts in that portion of knowledge that lies along the boundary between the world we know and the multitude of worlds that we do not, and it was in this rear section of the book that he now searched.

“Tell me, Peter,” he said after a time, with his long forefinger resting on a column of names, “is there an ill wizard in the Neverlands, who commands a group of black knights? Faceless knights,” he added, seeing Peter’s hesitant frown. Black Knights are as common as black birds, in the Neverlands, and come in all sizes and varieties. “Knights who do not bleed, when stabbed by a foe.”

Peter’s eyes widened again. Then he quickly readjusted his features, as if he realized how much like a very little boy he looked, a little boy the first time a birthday-party magician produces a penny from behind his ear. Casually, he replied, “That would be Nightcrow. He has a dreadful fortress at the farthest end of the Neverlands. He seldom ventures forth, but sometimes one sees him—”

Peter’s voice sank. It was the first time I’d seen him troubled: not frightened, because Peter doesn’t frighten easily, but deeply uneasy. “His island lies within the realm of nightmares. Even the pirates won’t go near it, and they’ll sail just about anywhere.”

“So I thought,” said Holmes. Looking over his shoulder, I saw — as well as I could make out his strong but nearly illegible handwriting — the entry on the notebook page: Krähnacht, Jakob — 37 Barsham Lane, Deptford — followed by a long series of notations in Holmes’ personal shorthand, which as far as I know only Martha can make out.

Hesitantly, I asked, “Why would this Mr. Krähnacht wish to kidnap Bobbie, even if he did know where he would come out of the Neverlands? Surely there are children in London—”

“Obviously,” said Holmes as he drew a half-sheet of paper to him and picked up a pencil, “he was paid to do so. By whom, can be deduced fairly easily once we have the boy himself back safe. Can you bring Peter to this place,” he asked, turning round to me the sketch-map he’d made, “in three hours? It’s down-river a good ways, but I can be there by then in a cab.”

Mischievously, I said, “Why don’t you fly with us, Mr. Holmes? I’m sure Peter and Ten Stars could fix you up.”

Peter’s eyes flamed with delight at the thought of Mr. Holmes, Inverness flapping like some vast cinder-hued bird, soaring through the night sky in a trail of fairy-dust. But Holmes shook his head and said primly, “I shall take a cab. Like most adults, I do not travel — at least in this instance — without baggage. I shall see you in Deptford at three.”

He laid emphasis on these words and met my eye with a look that said, Can you make sure he gets there?

I gave a tiny shrug and a grimacing nod: I’ll do my best.

It came to me that he knew Peter as well as I did.

Barsham Lane lay on the far side of Deptford, far enough back from the river to be half in the countryside still. Number 37 was part of no ribbon-development, but rather lay apart, in its own grounds and about three-quarters of a mile from the last of the suburban villas. It took Peter and me exactly three hours and ten minutes to get there, and we swooped down out of the sky just as Mr. Holmes’ cab was disappearing into the thickness of the river mist, leaving him standing by Number 37’s iron gate.

As we came down through the fog I asked Peter softly, “Did you know Mr. Holmes before?”

“Of course I did, silly.” Peter dove in a circle around me, to pull my pigtail. “He helped me slay the dreadful Gallipoot, that haunted Kensington Gardens. You were there.”

I hadn’t thought Peter had seen me. “I mean before that.”

“Look,” said Peter, pointing, “there he is. D’you think he’s brought some more of those biscuits in that carpetbag?” For Holmes did indeed have a large carpetbag at his feet. He wasn’t looking at his watch, but into the fog above him, as if he knew we would take just as long to arrive as he did.

“Tell him to save me one,” added Peter, and flashed away over the wall in the direction of the house, Ten Stars like a glittering comet-tail behind him. The mud of the drive was very cold and nasty between my toes, and the gravel hurt my feet. I waved to Mr. Holmes but came down on the other side of the gate, lifting the bar there that was heavy to my child’s strength.

Holmes whispered, “Good girl, Mary,” as he slipped through, and shut the gate behind us. He stood for a moment looking down at me — he stood many inches taller than even my adult, real-world self — and though the fog made it too dark to see more than his outline against the dim reflection from his dark-lantern, when he spoke again I could hear the concern in his voice. “Can you find your way back to your home without Peter?” he asked quietly. “You know that you are not dreaming now—”

“I know.” I reached out, took his hand — cold, the way they always were, even through his gloves — and pinched his wrist with my fingernails, hard. His hand jerked back and I grinned up at him, then sobered again, when I saw that in my swift smile he almost recognized me. “But I’m not really real, either — or perhaps I’m more real than I’ve been in many years. And I know the danger is real. If something happens to me…”

I hesitated, not knowing what would become of me — where my self, my true self, whatever that true self was, would go.

“Peter,” I went on hesitantly, “doesn’t understand. He’s never really lived in this world, not since he was a tiny baby…”

I glanced back toward the house, invisible in the absolute blackness, save for the swift-moving foxfire glow that was Peter Pan, scouting every window, chimney, and door for signs of occupancy.

Then I went on, “But we can’t let the King of Dreams… It isn’t just about finding Bobbie Lewensham, you know, though of course he must be rescued. But if indeed some mage in this world has found the way through to the world of dreams — or even through to the borderlands that lie between them — he must be stopped. Even for the good mages of this world to go tampering on its borders is … dangerous. Too many of us need the Neverlands, to let the King of Dreams close its gates.”

Holmes whispered, “Yes.” I thought he would say something else, but after an intake of breath, he was after all silent.

Peter came whipping back in a shower of brightness that lit up the fog around him like diamonds. “Cravens! The house is deserted!”

“Excellent.” Holmes picked up his carpetbag. “Krähnacht is presumably still back in Yorkshire, in whatever place he breached through to the Nightmare Castle when he ambushed our young Viscount upon his emergence from the Neverlands. Whatever that entrance is — almost certainly close by the stone-circle — the Fairies’ Dance — where you first met Bobbie Lewensham, Peter — it will be heavily guarded. But Krähnacht has been in and out of the Neverlands before.”

“The Wizard Nightcrow!” I cried excitedly. And when Peter looked blank, I said, “Krähnacht is German for…”

“I knew that,” said Peter loftily. “I’d just forgot.”

Holmes gave me the lantern to carry (of course Peter sees like a cat in the dark), and, when we drew near the house, the carpetbag as well. “It’s very heavy,” he warned, uncoiling from it a good twenty-five feet of insulated wire, at the end of which was rigged what I recognized as a crude electromagnetic coil. “But whoever doesn’t carry it has to get near them, and I’d rather that were me.”

“Get near who?” I asked, hoisting the unwieldy burden and staggering under its weight.

“The Black Knights,” Holmes said, “of course.”

Ten Stars — who was tremendously helpful and obliging (unlike some other fairies I could name) — lit on the corner of the bag like a butterfly, and smeared it with fairy-dust, which made carrying it much easier, although it did develop a tendency to want to travel in its own direction and had to be pulled fairly firmly. Still, that was better than carrying fifteen or twenty pounds of electrical batteries all by myself.

Jakob Krähnacht had his laboratories on the ground floor, strange rooms filled with crystals and mirrors, and a workshop with a small forge. There was a conservatory creeping with foul-smelling plants, and all the carpets and wallpaper stank of smoke and worse things. Much worse things. Ten Stars refused to go in, when Holmes picked the lock on the side door, but Peter walked just ahead of Holmes in the darkness, calling out softly, “Bobbie? Bobbie, it’s Peter…”

The darkness thickened, and thickened, until the rays of the lamp couldn’t pierce it, as if a hand of invisibility were slowly closing around the light-source, crushing the glow back in. Peter’s voice ahead of us suddenly sounded a vast distance away, dimming down a long corridor. “Bobbie? We’re here to save you—”

Holmes stopped. What little light remained showed me a wall ahead of us, dark and seemingly soot-stained. Holmes put out his hand to touch it, yet I could hear Peter on the far side of it, his voice fading, “Bobbie—”

I said, “We can go through. We only think it’s there.” I’d encountered such walls in the Neverlands. Evil Wizards use them all the time. “Close your eyes—”

I set the carpetbag down — and it settled with a metallic rattle to the floor — and closing my eyes, walked forward, hands outstretched.

After perhaps a dozen steps, I could hear the sound of the breakers, far off on Neverland’s shores.

I turned around, and Holmes was gone.

I was in the blackness of a dungeon, cold rock under my feet. By the taste of the air, the smell of horror and damp, I knew I was in the Nightmare Realm somewhere, and I knew there was evil close-by. Peter darted up beside me, his face grim in the tiny glow shed by Ten Stars — goodness knows where she’d come from — and his knife in his hand. “Did they get him?” he whispered. “The Black Knights. They’re everywhere…”

I shook my head, grieving and very frightened, at least in part because I suspected that Peter did not hold the power here in these realms that he had in the kindlier skerries of dreams. “He can’t come through,” I whispered. “He doesn’t remember the way. Mr. Holmes!” I called, as loudly as I dared. “Mr. Holmes, just close your eyes! Walk forward!”

We stood for what felt like an eternity — what could have been eternity, I was well aware, for this realm was neither in the real world nor the Neverlands themselves, like a pocket of darkness in the curtain that separates them. An old pocket, filled with the smell of things that belong in no child’s dreams.

“Holmes!” Peter cried, a little louder, and somewhere in the dark behind us, I heard the soft, deadly whisper of metal on metal, the distant clicking of machinery, like a dozen vile clocks.

I kept my voice steady with an effort. “Mr. Holmes,” I said. “Mr. Holmes, if you can hear me… What was the first song you learned to play?”

I listened hard in the darkness, in my mind and my heart, but heard nothing from him.

Peter whispered, “It was this one.” He took from his pocket (the only pocket he had, hanging from the belt where he carried his knife) his pipes, and played: it was an Irish tune that I’d heard Mr. Holmes weave into fantasias of melody on his violin. Yet it was very simple, the kind of thing a boy might whistle, when he’s been locked in his room for seeing too clearly, and for making deductions about his elders from what he sees.

Behind us the clicking grew louder, and by the glow of Ten Stars’ fairy-light I could see them, at the far end of the corridor. Four Black Knights, towering and identical. Faceless, as Holmes had said, only through their helmets’ visors I could see the cold glitter of something moving steadily, mechanically. Peter’s eyes widened, but he kept playing, playing as he and I slowly backed from them, until we reached the wall at the end of the corridor, trapped by that pocket of blackness. The lead knight raised its hand, and I could see that instead of a hand it had glittering steel blades coming straight out of its wrist, blades that whacked back and forth like saw-toothed scissors.

In panic, in despair, my adult self somewhere in dreaming cried, John—!

Then Holmes was beside us, stepping out of what looked like a pocket of still-deeper blackness by the wall. Ten Stars flickered, dove about him as he dropped the heavy carpetbag, dug from it a second electromagnetic rod. “We’ll only have current for a moment,” he warned as he handed it to Peter. “Mary, when I yell Now—”

“—throw the switch,” I finished, because there was a switch among the neat maze of wires and batteries visible in the bag. “Is it a magnet?” I called after them, as they went striding, gray-clothed man and green-clothed boy, trailing wires down the corridor toward those faceless dark shapes, those whirling blades. The corridor was narrow, the Black Knights crowded one another, jostling, two behind two as they lifted their deadly slashing hands.

Holmes said, “Absolutely,” and lunged like d’Artagnan, thrusting the rod into the center of the metal attacker’s breastplate at the same instant that Peter thrust his. “Now!”

There was a blazing shower of white sparks, a flash of lightning when whatever was still trying to power the clockwork mechanism of the attacking knights imploded as metal fused to metal. The second pair of knights, running into the first pair, magnetized from them and also froze in a shower of blue sparks.

Peter’s eyes shone blue and wild, brighter than the lightning with delight. “Super!” he breathed.

The Black Knights completely blocked the corridor, so Peter put his shoulder to the nearest one, sending all four crashing. “That tears it,” said Holmes, kneeling to wrap up his electrical rods and batteries. “We must find Bobbie and flee, for Nightcrow will come, and he won’t make the mistake again, of using the technology of the real world in this realm.”

Peter whispered confidently, “This way.”

We found the boy Bobbie Lewensham in a stone cell, its barred door standing open to the dank blackness of the corridor. His head was pillowed on his rolled-up blue coat and his little blue cap; he was profoundly asleep. Holmes tried to wake him, and then Peter, to no avail. I stood looking down at that thin, peaky-looking little face — he was very young, no older than John Darling. What is it that you were fleeing, Bobbie, that opened your heart so fully to the realm of dreams? ‘Bobbie never visits anywhere,’ Peter had said. ‘When he’s at home, he’s alone…’

Alone with at least one person who knew or guessed about the Neverlands, and knew where to hire a kidnapper who would hide him in the other world forever.

“He’s been drugged.” Holmes scooped the boy up in his arms as if he were a kitten. “Drugged or a spell. Peter, listen. Can you keep him in the Neverlands with you for another two days? It will take me that long to find the man who hired Krähnacht — Nightcrow — and make sure he’s not in a position to make a second attempt on the boy.”

“He’ll be safe with me.” Peter inclined his head like a young king. He always liked to turn orders or suggestions around so that they were actually his idea.

And behind us, the barred door clanged.

We all whirled. And there he stood in the corridor, the nightmare wizard Nightcrow: a chubby gray-bearded man in the sort of tweeds you see hikers wear in the countryside — he had, of course, been in Yorkshire. And behind his spectacles, the coldest blue eyes I had ever seen.

“A mortal man,” he said thoughtfully, regarding Holmes with those awful eyes. “A dream-child—” He looked at me, as if I were a butterfly in a net who’d make an interesting addition to some tray in a library. “And…” He looked at Peter. “And what have we here?”

“We have here your doom, Nightcrow!” trumpeted Peter, striding to the bars. “I am Peter Pan, and I have come here armed with spells for your destruction! Holmes, play your magic flute!”

“Holmes?” Nightcrow’s salt-and-pepper eyebrows ascended; he wasn’t in the least disconcerted. “So old Wylcourt’s hired occultists have given up trying to find the Gate I opened, and he’s hired Mr. Sherlock Holmes, eh? Now, that is a piece of news.”

Holmes laid Bobbie back on the stone bench where we’d found him and said coldly, “I have nothing to say to you, Herr Krähnacht, except that I advise you to flee as fast as you can. For you are indeed doomed.” Then, when Nightcrow only folded his arms with the air of a man expecting to see an interesting show in complete safety, Holmes sat down on the edge of the bench, turned his back on Nightcrow, took his flute from his pocket, and began to play the air from Vivaldi’s Concerto in D Major. Peter flung up his arms, uttered a long wailing “Oooo-oo-ooo-ah-ah-ah-ooo-ooo-ooo,” and began to chant a string of nonsense syllables, coils of fairy-light (courtesy of Ten Stars, hiding prudently behind his back) ribboning from his outstretched fingers.

I realized what was going on, and began to hop around Peter in the best imitation I could contrive of my friend Delphine Tremlow’s Ancient Grecian Dances that she teaches shop-girls.

“Fascinating,” Nightcrow murmured, not disconcerted in the least. “You can’t do a thing to me, you know. We are neither in reality nor the dream world, and this enclave has its own laws. I look forward, Holmes, to observing you here over the next several years. As for Peter Pan — the Peter Pan — Well! I have a number of experiments I am eager to try—”

“Silence, fiend.” Peter paused in his chanting. “I am weaving your Doom.”

“I await it,” smiled Nightcrow sarcastically, “with bated breath. I’ve heard about you, of course — Did you come because young Viscount Mure was calling for you? He did, you know. For years now I’ve sought the secrets that lie within the realm of Dreaming, and now they’re within my grasp. My dear young lady, I hope your parents…”

At that point, summoned by Holmes’ piping, the terrible Gallipoot emerged from the darkness behind Nightcrow in a rush of sulfur stench and the wailing of a thousand chewed-up fragments of souls, and devoured him down to the last morsel. When the Thing Cold and Empty rolled, surged, oozed away down the corridor and vanished once again, all that was left of Nightcrow was his spectacles, his watch, and the key to the cell, lying on the stone floor a few inches outside the bars, in a puddle of Gallipoot slime.

“You did tell him to run away,” said Peter, in a satisfied voice. He knelt to retrieve the key. “Grown-ups never listen, do they?”

“Never,” lamented Holmes.

There is a crossroads on the borders of the ocean of sleep, a tiny islet of rock and sand in the vast archipelagoes of the Neverlands that stretch into eternity, and from there I could see, far away across the darkness, my bedside lamp burning low, and John asleep in a chair beside my bed.

If I turned my head I could see the other way, toward the Neverlands, world after world of forests and rainbows, of mermaid lagoons and pirate ships, of castellated islands and magic horses and caves full of enchanted books. Peter and Bobbie stood hand in hand where the gray arm of the crossroad led in that direction: “I’ll have him back at the stone circle in two days,” said Peter. I guessed that if Peter forgot, the King of Dreams would remind him.

“It was Mr. Gower, you know,” said Bobbie to Holmes. “Mr. Gower’s our business manager — Father’s, I mean. I never liked him — he was always asking questions about the fairies, and the Neverlands. When I came back through at the stone circle last time, he was there, he and Nightcrow…”

“He shall be dealt with,” promised Holmes, with grim quiet. “He will be gone, by the time you return.”

“If we see the King of Dreams,” said Bobbie, “I’ll tell him you’ve taken care of the problem.”

“You’re sure you won’t come with us?” asked Peter, looking up at Holmes. “Your tree’s still there, and Old Chief Walking Wolf would love to see you again.”

Holmes smiled, and shook his head. “I have to go deal with Mr. Gower,” he said. “To make sure that the Neverlands will still be open, the next time Bobbie — or your friends Wendy and John and Michael — wish to come through. But do indeed give my regards to the Chief, and to Melegriance the White Wizard, and to the Evil Queen of the Night Island, and all the others. And thank you.” He held out his hand, and Peter shook it, very man-to-man.

Peter said, “Any time,” though Holmes and I both knew how quickly he would forget.

After Peter and Bobbie had gone, I asked softly, “Were you one of Peter’s Lost Boys?”

Holmes gave me a sidelong look. “Certainly not. How would I have come to be Lost in the Neverlands?”

“How does anyone?” I asked. “Will you be able to get rid of this Mr. Gower when you get back? He’s obviously studied occult matters, the same as you have, to guess about Bobbie and the stone-circle and the fairies and the Neverlands, and to know to hire Mr. Krähnacht. If he’s their business manager, must he not have been speculating with the Earl’s money, while the old Earl’s been sick? That’s why he wanted to hide Bobbie in another world — so no one would find a body. It would be years before he’d have to be accountable for money he’d lost.”

Holmes smiled down at me. “I see you’ve grasped my methods, Mary. Since the matter is one of financial peculation, it should be easy enough to bring home to him, and to put him out of the way. Even had I not spoken to Bobbie, the culprit would have been simple to find. Quite elementary, my dear…”

The word stopped on his lips, and his face changed, in the starry twilight of that crossroads, as he recognized me at last. First enlightened, then filled with a rush of comprehension, as he understood at last why I had come to be so free within the Neverlands, followed by pity and grief. And it seemed to me that I no longer looked up so far at him, though as I’ve said he was always far taller than I. But it seemed to me that I was as he saw me, not my child self, nor even the woman I’d been when first we’d met, but a gaunt and shorn-haired invalid in the final stages of consumption.

“My dear.” He put out his hand, and where once it had felt cold against the healthy heat of my child-hand in dreaming, now his was the warm one.

“Don’t worry,” I said gently. “I’ll be returning to John, at least for a short while.”

In his face I saw his knowledge, of how short that time would be.

“Take care of him,” I said, simple and matter-of-fact.

“Of course.”

“It’s been good to have an adventure with you,” I said. “I always wanted to. They never let girls.”

Holmes opened his mouth to reply — almost certainly with some sentence beginning, The female of the species … then thought about the words, and closed it again. At length he said, “That has been my loss.”

We were silent, on that crossroads island, the dark bridge that led back toward my own room — and to Baker Street, for him — disappearing into the star-sprinkled gloom before our feet. In the other direction I could still see the Neverlands, sparkling in sunlight and joy.

Holmes asked, “Will you be all right?”

“Oh, yes. Peter will look after me, and go with me the first part of the way. It is the one thing he always does.”

He nodded, knowing this to be true. “Until we meet again, then, Mary.”

And we went our separate ways.

His Last Arrow

His Last Arrow

by Christopher Sequeira

The following is transcribed exactly as it appears on many handwritten sheets of paper. The original document itself was the sole contents of a plain brown envelope that had at one time been sealed with wax, which was found amongst a large selection of items in a house in Crowborough, East Sussex, in England. The envelope and many items of value were believed to have been stolen property, accumulated by a gang of burglars who were apprehended after successfully robbing several houses in the vicinity. Some of the goods the thieves had taken appeared to have come from the home of the late Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, however, when the brown envelope was proffered to the late author’s family, and it was noted that the seal was broken, a legal representative of the Doyle family examined the documents and announced the papers had never at any time been in the possession of the family, and then took the unusual step of expressing the view in writing that any attempts to claim otherwise would meet with legal action.

In 1894 I had returned to Baker Street following the failure of my marriage. I had concealed the full ignominy of my situation by revising the beginning of a story that was just about to see print in The Strand magazine so that the tale began with a contemporary reference to the ending of the union as a ‘bereavement’. This was artistic sophistry, of course, for the woman I had married was still on this earth, she had simply decided she could tolerate no more of my involvement in the activities of my friend, Sherlock Holmes. What my other friends and acquaintances, as well as my readers had no appreciation of, however, was how well I knew this deception would take on a life of its own, and surely enough, it did. Within months old friends like Thurston, Murray and Stamford were speaking of my former wife as if she had passed from this world.