A DELL TRADE PAPERBACK

Published by

Dell Publishing

a division of

Random House, Inc.

1540 Broadway

New York, New York 10036

Quotations taken from Golf in the Kingdom by Michael Murphy, copyright © 1972 by Michael Murphy, all rights reserved, are reprinted by permission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Books USA, Inc.

Copyright © 1990 by Marlin M. Mackenzie

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law.

The trademark Dell® is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

eISBN: 978-0-307-79673-8

v3.1

To my brother,

Ken, for auld lang syne.

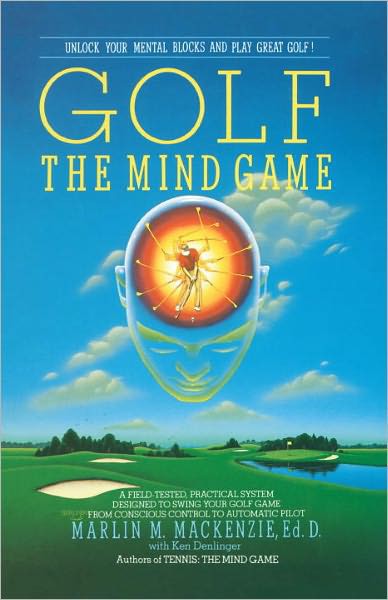

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1 Teeing It Up

2 The Sherlock Holmes Exercise: Discover How Your Mind Regulates Your Golf Shots

3 Anchoring: Tapping Your Inner Resources

Part 2 • Metaskills Techniques

4 Just-Right State: Concentration

5 Just-Right State: Confidence

6 Just-Right State: The “Zone”

7 The Pro Within: Your Instructional Mind

8 Swing Effort: The Short Game

9 Self-hypnosis: Tapping the Power of Your Unconscious Mind

10 Mind and Body: Generating Energy, Controlling Pain, and Hastening Healing

Selected References: Neuro-Linguistic

Programming

Appendix A Uptime Cues

Appendix B Sensory Awareness

Appendix C Guide to Selecting Metaskills

Techniques

Lots of people shared directly and indirectly in the development of this book—athletes from many sports, my students, my agent, my collaborating author, my editor, and most of all my wife, Edna.

Several dozen outstanding golfers were exceedingly helpful because they allowed me to rummage around in their brains to find out how their minds work. And they provided the true test of the validity of my techniques when they actually performed better after using them.

My graduate students at Teachers College, Columbia University, contributed as they constantly challenged me to clearly describe and justify what I did with my clients. Their analytical minds and healthy skepticism enabled me to refine and expand my techniques.

My collaborator, Ken Denlinger, a good golfer in his own right, was a constant source of humor, understanding, encouragement, practicality, and skepticism.

My agent, Faith Hornby Hamlin, had the insight and confidence to recognize that my earliest draft of a book for athletes in general contained the seeds of a publishable book; and she obviously convinced others to agree with her.

My editor, Jody Rein, with the force of her logical analysis and organization, and with her interest in the uniqueness of my approach, guided my collaborator and me in transforming our original manuscript into a better organized and more succinct piece of work.

Edna, my wife and companion on and off the golf course, deserves a hearty hug and unmeasurable thanks for her emotional support and for her hours of careful editing of draft after draft after draft of this book. She demanded clarity, logic, and good grammar without imposing upon me her own ideas about competition and play, about hitting a golf ball, or about mental processes.

To all of these people I say “Thanks.” To the golfers among them, I say “Have a good time, and hit ’em long and straight. ”

MMM

Washingtonville, New York

July 1989

People pay dearly to play golf. They wear the most expensive shoes in their closet, and they kill grass with implements that can run over a thousand dollars a set. Some pay a small fortune to determine where to play golf—and with whom. At those prices the civilized sport becomes an investment. Yet nearly all golfers, from humble hackers to elite touring pros, in dogged pursuit of enjoyment—and par—rarely invest as much as a thought on what will help them more than any hunk of high-tech equipment:

Their own minds.

I propose to change that. In this book I explain the ways your mind, more marvelous than any computer, can be tapped to improve your golf. Wouldn’t you prefer feeling the ball jump from the sweet spot on your club, flying long, high, and straight rather than short, skidding dubs? Wouldn’t you prefer more matches won and fewer payoffs at the 19th hole? Sure you would.

What I offer is a practical, down-to-earth system that uses the mind and emotions to regulate skills in golf—and it works, whether you’re a weekend enthusiast or a world-class professional, a 30-handicapper playing from the white tees or a scratch player. The system works because it quiets the conscious mind and engages your unconscious resources. An active conscious mind acts like the hazards on the golf course—trapping, drowning, or blocking balls from their flight to the cup because you’re thinking too much about your swing while playing. My techniques get you to do all your thinking about your swing on the practice tee so that your mind stays out of your way as you swing on the course.

Although golf is a complex mind game, it’s also supposed to be fun. So are the exercises in this book. In Part 1 I describe the fundamentals of the mind game—how your mind operates, how to deepen awareness of your mental processes, and how to improve your game by capitalizing on your inner resources.

Part 2 contains descriptions of specific techniques, about thirty in all, that can be applied to your method of thinking and the unique way you respond emotionally to competition. These techniques are designed to help you achieve better concentration, heightened motivation, consistency of performance, increased self-confidence, recovery of lost skills, and more enjoyment. A few of them focus on the mobilization of energy when tired, faster healing after injury, and pain control.

I’ve coined a word that describes my perspective of how the mind works—Metaskills. It refers to the interaction between emotions and thoughts that regulate skillful athletic performance, most of which are out of conscious awareness. After years of coaching and thinking about the unity of mind and body, I became dissatisfied with the methods of coaching that stressed conscious thought. The methods are okay up to a point, but they don’t fully represent what superb athletes really do in their minds to control their behavior.

To eliminate my dissatisfaction I studied psychology and counseling in a search for knowledge that I knew existed although I did not know exactly where to look. Finally, I decided to go to the source. I asked athletes directly how they used their minds and emotions to develop and control their skills. My training as a master practitioner in Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) provided me with the knowledge to ask the right questions and the refined skills to uncover their conscious and unconscious processes.

I then created counseling techniques out of what the athletes told me. I combined their information with what I’d learned from psychology and from my coaching experience. To refine my metaskills techniques I worked directly with eighty elite athletes (male and female, ages eight to thirty-five) in eleven sports over a two-year period. The model that evolved has been working successfully for about seven years with all kinds of athletes. This book contains those techniques that are most appropriate for golfers.

The psychological perspective that I emphasize is one of understanding how golfers, at every level, regulate their performance, not why they don’t play well. Believe it or not, you already possess all the necessary internal resources for playing better golf. The trick is to uncover them and put them to work. Trying to figure out the reasons why you don’t hit the ball well is counterproductive. This kind of thinking taps and reinforces negative stuff in your mind, the stuff that makes you continue to swing badly and feel worse.

The mind games in this book were designed to swing your golfing mind from conscious control to automatic pilot. The ultimate goal is to have your unconscious mind in complete control during competition, except for conscious planning of each shot before addressing the ball. Seldom will there be a need for conscious application of any metaskills techniques while playing a match. If you’ve learned them well, they’ll “kick in” automatically, just as your golf swing automatically follows a grooved pattern.

While this is not a workbook, it nonetheless should be a learning companion when practicing the skills taught to you by your golf pro. For quite a while don’t leave home for the driving range without it. Treat it as a learning manual to help you use your mind and emotions to get what you want. Read Part 1 carefully and do the exercises presented there. This will make the rest of the book more meaningful. After doing the Sherlock Holmes Exercise and learning how to “anchor” your internal resources, read Part 2 casually. Then study and use the appropriate techniques in Part 2 when something in your game, or temperament, needs to be retuned or cleared up.

Not every lesson is for you. The final chapter, “The 19th Hole,” contains information about how to identify your outcomes and guides you in selecting appropriate metaskills techniques to achieve them. However, I encourage you only to pay attention to the crucial elements of your swing you want to improve. I’m a firm believer in the notion, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. ”

Setting aside mental-practice time is essential for learning my metaskills techniques. Merely reading this book is not enough to determine its effectiveness. Do only one exercise at a time. Learn how it works and determine if it fits your mental style. Judge for yourself the validity of a technique in relation to the quality of your performance and the degree to which you achieve each specific outcome.

My writing partner, whose love of golf once compelled him to play nine holes in Scotland while waiting for a rental car, experienced brainlock trying to use too many of my exercises at once. He learned, the hard way, the importance of exploring one technique at a time. The less you think about while swinging, the better your performance.

What eventually became useful for Ken was the concept of effort control described in Chapter 8. He applies that concept to lag-putting and those short putts which, when missed, can result in putters flying through the air like helicopter blades. The most valuable parts of the book for him were the ones that dealt with performance expectations and mood changes.

Which ones will be most useful for you? Happy exploring.

Learning how your mind works, how to make it work more efficiently, and how to tap your internal resources are the first steps to master in the golfer’s mind game. The initial part of this book is as fundamental as learning how to set your stance, grip the club, and swing it. Not until the fundamentals are learned will you be able to swing your mind so that you swing the club with effortless effort and mindless concentration.

Settle back into an easy chair now and put your point of view about hitting a golf ball aside. In this first part of the book I’ll tee up some basic ideas about the mind and about how to run your brain. Then I’ll have you become your own investigator to explore how your mind actually swings your club. After exploring how the pros use their minds while playing, I’ll provide you with special exercises to expand your mental capacities. Finally, you’ll learn a special way to uncover and anchor internal resources that are useful for playing golf.

Ted Jackson was an eighty-two-year-old golfer with a problem as common—and frustrating—as a cold. He would maneuver his shots well enough until the cup was about the length of a football field away. From ninety-plus yards his ball was an unguided missile, skittering into deep rough, thwacking off trees, flying every which way but straight.

A few years ago Ted uttered two words familiar to me and to everyone else for whom sport has gone sour: “What’s wrong?”

Answering a question like that isn’t very useful because it can reinforce his mistakes. So I focused on the solution instead of on the problem.

I asked him, “Have you ever in your life hit a ninety-yard pitch shot well?” Of course, he had.

I told him to recreate that beautifully played shot in as much detail as possible. Was the day pleasant or overcast? How did the swing look and feel? Could he recall the sound of the click as he connected with the ball? Then I put him through a series of exercises, on the practice range and on the course, designed to train his unconscious mind to perform automatically.

Ted had known all along how to hit that shot. I was helping him realize that—and also never again to misplace it. I find that once a skill is locked in the mind, it can be retrieved, appropriately enough, with a key. Ted found that key rather quickly, and now uses it before routinely hitting splendid pitch shots.

Ted’s key was a metaphor, the thought—of all the craziest things—of a flying red goose. It was a metaphor that integrated his thoughts and body and allowed his unconscious mind to swing the club so that the ball would consistently plop close to the flagstick.

How Ted created his metaphor will be fully explained in a subsequent chapter. For now, it’s only important to realize that all the mind games in this book reflect Ted’s experience. They are unusual and fun; and they work.

They’re based on a couple of very simple and basic ideas: the unity of mind and body and the power of the unconscious mind.

Mind-Body Unity

The fundamental principle underlying my perspective of human behavior in general, and athletic performance in particular, is that mind, body, and emotion are integrated—inextricably interwoven. It’s sort of like having your two hands pressed together as one, gripping the club.

Thought influences feelings and performance; feelings affect thought and performance; and performance affects thought and feelings. Specifically, the quality and consistency of an athlete’s performance depends upon how he thinks and how he feels emotionally.

The metaskills techniques presented in this book are designed to affect your thought processes and emotional states, with only minimal attention to the content of your thoughts.

The Unconscious Mind in Sports

Think about thinking. It’s usually detrimental in sports because it destroys concentration, a goal of most golfers. As in Zen meditation, the ideal state of concentration is to pay attention to nothing. This is also true when swinging a golf club. But this is an extremely difficult task. The next best way of thinking is to pay attention to only one thing. It might be watching the ball, feeling your grip, hearing a phrase in your head, or seeing an image in your mind’s eye, whatever works for you.

For instance, if airborne Mary Lou Retton had to mentally process every bit of information necessary to execute that perfect-vaulting ten in the 1984 Olympics—feet together at takeoff … hands exactly so to get into the twist … knees bent at a precise moment in the air—she would never have landed on a Wheaties box.

Instead, Mary Lou tied every bit of complex movement into a single anchor. That anchor was one word: stick. She knew unconsciously what was necessary, in the air, to achieve perfection, to “stick” a ten and to “stick” to the mat after a flawless trip. That word triggered her unconscious mind, which automatically guided her body to achieve Olympian power and grace.

I know the paramount role the unconscious mind has in affecting human behavior. Superb athletic performance is regulated with little or no conscious thought given to purpose and mechanics. The clichés that reinforce this are numerous: “paralysis by analysis,” “playing in the zone,” and “It’s like I wasn’t there. ”

Conscious processing is entirely too slow and results in confusion. You don’t think about hitting a baseball; you just do it. If you thought about how to connect with a slider, low and outside, the umpire would have his thumb jerked in the air for strike three before the bat got off your shoulder.

The more refined the athlete’s performance, the more the unconscious mind is in control. While conscious attention to performance is most important during learning and practice, mindless (unconscious) processes regulate exquisite execution of skills already mastered.

Neuro-Linguistic Programming

During the past fifteen years a new psychotechnology has emerged on the scene. It’s called Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), and was created by Richard Bandler and John Grinder. It is essentially a multipurpose technology of communication that is used to identify how people actually regulate their behavior with their minds. It is used to help people change their behavior rather quickly by changing mental processes. NLP is one of the bases of my work, along with cognitive psychology.

In my opinion NLP is one of the most useful, and perhaps the most powerful psychological tool for helping people change. It’s state-of-the-art theory and practice based on verbal and nonverbal communication processes. Increasing numbers of psychologists and psychiatrists are coming to recognize its usefulness. In case you’re interested, there’s a selected list of references in the back of the book.

The elements of the NLP model that apply to golf are information processing, mental strategies, emotional states, and beliefs and values.

Information Processing and Mental Strategies

Let’s look a little closer at the way your golfing mind works. How does someone know how to swing a golf club, drive a car, or do anything, for that matter? By reproducing in his mind the sights, sounds, feelings, smell, and tastes associated with how he did it in the past.

In a span of two or three seconds—the time it takes to swing a golf club—we will unconsciously process as many as a hundred bits of patterned, or programed, sensory information—sights, sounds, and feelings—to control our behavior. This programed information, or strategy, fires off just nanoseconds in advance of a behavior such as sinking a seven-foot putt. If the golfer’s putting program is wrong or is interrupted, he gets the “yips.”

The mental programing we’ve developed for ourselves over a lifetime is much more sophisticated than anything that could be put on a floppy disk. And the nice thing about our programs is that they’re flexible. We can change them at a moment’s notice when we sense, consciously or unconsciously, that they ought to be altered for our own best interests.

We often find several separate strategies in operation to regulate a number of different behaviors at the same time. For example, consider a figure skater who falls while doing her free-skating program. First, she must initiate her decision-making strategy to determine if she will continue skating. If she decides to continue, her motivation strategy is energized to carry out that decision.

Since the present situation (falling) is not exactly like any previous instance, she sets her creativity strategy in motion to put together the necessary movements to get her back in time with the music and the planned routine. Knowing where she ought to be in the planned program also requires that her memory strategy be set off. To actually perform the new movements that will get her back to a point where she can move her body and limbs to match the movements of her program, she activates her performance strategy.

Whew!

Within several seconds, or much less time that it took you to read this, she triggered five separate strategies: decision-making, motivation, creativity, memory, and performance. Each strategy was somewhat dependent upon the others. Unconscious thought, that which is out of awareness, was much more significant for her athletic performance than conscious thought. And the more streamlined the mental process, the faster her reaction time—or that of any athlete.

Although golfers have more time to think about their shots, they, too, go through the same kinds of mental processes quickly, and often unconsciously, when they prepare to hit a ball. Consider an errant shot that strays into the woods and becomes ensnarled in twigs and leaves under a low-hanging branch. Under these conditions the golfer must: decide how to stand and swing, based on his memory of similar shots and his ability to create the appropriate stance for the situation at hand; motivate himself to hit the ball with deep concentration; and then actually perform, executing the shot as planned.

This complex form of mentally regulating human behavior is called a cybernetic system. Feed-forward and feedback mechanisms are constantly in operation as the athlete performs, usually out of conscious awareness. The internal regulatory systems of the body are constantly comparing ongoing internal and external sensory data with the output of the muscles that bring about our intended behavior, like hitting a golf ball.

Let’s say you’re standing on the tee of a par 3, 175-yard hole with about 160 of those yards across a pond. Information about where you would like the ball to land, how you want to be set up to the ball, and how to swing is fed forward into the entire operation of planning and executing the tee shot. Information about how the club actually feels in your hands, the actual alignment of the club face, the stability of your stance, the smoothness of the swing itself, and certain important environmental information, like the wind, is constantly being fed back to your mind, either in or out of your awareness.

Comparisons are continuously and rapidly being made in your brain, consciously and unconsciously, between information that is fed forward and information that is fed back. When the comparisons match, no change in the operation of the system is initiated. Voilà! You tee up the ball, plan the shot over the pond, make a silky pass, and the ball lands five feet from the pin. Your unconscious mind is so sensitive, it makes your reaction and adjustment during takeaway to an unexpected breeze a breeze.

Metaskills techniques are designed to affect the basic elements of the golfer’s mental strategies, especially the internal comparison processes he uses to evaluate his swing. The techniques are designed to change or stabilize a golfer’s performance by changing how he thinks—how he processes sights, sounds, feelings, smells, and tastes in his mind.

Just-Right Emotional State

Although people’s programed mental strategies for hitting golf balls are different, what’s common to all of us is the fact that we must be in an appropriate mood or emotional state for a particular strategy to be activated. And each of us has unique just-right states for accomplishing different tasks. When you are in the just-right state for a particular task, the patterned sequence of all of the auditory, visual, and kinesthetic information that represents your experience of having done that task before is automatically and unconsciously fired off before and during the execution of that task. However, if you’re not in the right state, the strategy for the task will be defective because key elements in it will be missing.

I’m sure you know that the state you want to be in while going for a six-foot downhill breaking putt on a slick green will be much different from the state you want to be in when you take that 175-yard drive over water. On the one hand you want a delicate touch; on the other you want to muster the power needed to prevent a splash.

Because of the centrality of the emotions, many of my metaskills techniques are based on identifying and anchoring the appropriate internal states for hitting different golf shots. When they’re properly anchored, the swing will be executed automatically. Getting into those just-right states is part of what this book is about.

Beliefs and Values

Golfers can’t leave their beliefs and values behind when they head out to the course. A belief is something accepted as true without certainty of proof; a value is something important to each individual, and serves as a guide to making decisions. They are at work during every golf game, affecting the golfer’s moods from moment to moment. Since moods influence mental strategies, beliefs and values either facilitate or intrude on what could be very pleasurable.

Compare the emotional responses of two different golfers when down three holes with four to play. One golfer values winning and perfection and believes victory should be based on expert performance. If he has made a lot of bad shots, his emotional response will most probably be dejection; he thinks he doesn’t deserve to win, playing as badly as he has.

Another player, however, might respond positively to the same situation; his attitude could be that here is an unprecedented chance to learn what has prevented him from playing up to his potential. The first player is controlled by values pertaining to perfection and winning; the second, in exactly the same context, is influenced by his belief in the value of any experience being an opportunity to learn and change.

The first player is dejected, the second curious and optimistic. The chances of the second player winning the match are certainly higher than for the first player because his emotional state, influenced by his beliefs and values, is more conducive to good play.

In many instances changing beliefs and reordering your values can affect your performance. This book will help you do just that.

Communication and Change

The techniques in this book are forms of communication that are intended to change your behavior. They are designed to influence your mental strategies, emotional states, and your beliefs and values. My instructions are deliberately intended to affect the way you perceive the environment and the way you communicate with yourself—the way you run your brain. Your attention will be limited to how you process relevant sights, sounds, and feelings, not to how you address, swing, and hit the ball. My techniques do not teach you the proper physical mechanics of addressing the ball and of holding and swinging the club; that’s the golf pro’s job. However, while you are learning the mechanics of golf, or after you have learned them, my mental techniques will help you execute them better.

Self-hypnosis

Some of my exercises are based on hypnosis because it is a mental state that permits the golfer to access important information within himself about hitting golf balls and because a hypnotic state is a mental characteristic of fine performance. Although highly sophisticated daydreaming might be as good a way to describe some of what actually happens during a hypnotic state, my work is Walter Mitty stuff, nothing scary. Most athletes, in fact, are in a trance, a profound altered state, when they perform superbly.

Admit it, now. You’ve transformed yourself, perhaps at a traffic light or at the office, to the 18th tee at Augusta National, needing only a routine par for Jack Nicklaus to help you slip into something worthy of a legend. Make that green jacket a 44 regular! In your mind you see the flawless swing that just might get that accomplished, the one that made you most proud on your home course.

Growing up, you watched Sandy Koufax, Arnold Palmer, Billie Jean King, and other wondrous athletes. Later you tried to mimic their seemingly unique motions in your mind—and then scooted outside and worked on duplicating them. What surely never entered your mind at the time is that you were using a kind of self-hypnosis. I have techniques that use that concept, one of which can make your putting stroke seem a whole lot like Ben Crenshaw’s.

I was working one afternoon with George Burns, the touring pro, at his club. He has been playing so long, there are few situations where he can’t recall having hit a fine shot somewhere in similar circumstances. But on one hole George couldn’t remember ever having been faced with a particular shot. So I said, “Have you ever seen anyone else hit one like that?”

Out of thin air he grabbed a golfing god.

“Nicklaus. I saw Nicklaus hit that shot.”

We then began a process I’ll explain in full later, in which George pictured Nicklaus hitting the shot. And then, in his mind, he pictured himself hitting the shot as if he were Nicklaus. Finally, George struck the ball, and it landed a few feet from the pin. That process took no more than five minutes, and George was in an altered state during much of that time.

What Will This Book Do for You?

The metaskills techniques will improve your golf game by changing the way you think and feel. You’ll learn how your mind regulates your golf swing. You’ll learn how to expand and modify your sensory apparatus so your thinking is changed. You’ll learn how your emotions can be controlled so your mind can work smoothly and unconsciously; you’ll learn how to use self-hypnosis to identify your mental resources. In short, you’ll learn to have more choices about how to hit a golf ball so that your golf game improves and your sense of enjoyment is enhanced.

If you’re a 90-shooter, these techniques won’t get you an invitation to the Masters. Still, they’ll get you out of bunkers more quickly, if that’s a goal, or get you to hit higher and longer shots off the fairway. Using them will make you as fine at specific skills as your ability allows, and better able to cope with such miseries as knee-knocker putts.

This book will help you get in the just-right state so your mental golf-shot programs will take over. You’ll learn to get your conscious mind out of the way, stop talking to yourself, stop doing anything, and just let go when you swing.

How to Use This Book

Use this book to supplement the work of your golf pro whose job it is to teach you the actual mechanics of golf. You can read it whenever you have a spare moment and refer to it during your practice sessions.

The time frame for learning any one of the techniques can range from half an hour to a few weeks. It all depends on what you want, and how much energy you give to getting it. Practice for the mind also takes time.

I can’t emphasize often enough that the best way to learn my techniques is to experience them first hand while doing something—lag putting, for instance, or regulating your swing tempo—something very precise that you would like to improve. First find out what happens to the way you play golf; analyze and evaluate the usefulness of a technique in terms of your improvement, not in terms of whether my approach fits existing psychological theory.

The goal is to have your unconscious mind in complete control during competition. Seldom will there be a need for conscious application of any metaskills techniques while playing a match. If you’ve learned them well, they’ll take over automatically, just as your ideal golf swing follows a grooved pattern.

The essence of my approach and the way I want you to use this book was best expressed in Golf in the Kingdom by Michael Murphy:

“But this is the thing,” he raised his hand and shook a finger at me, “ye can only know wha’ it is by livin’ into it yersel’—not through squeezin’ it and shovin’ it the way they do in the universities and laboratories. Ye must go into the heart o’ it, through yer own body and senses and livin’ experience, level after level right to the heart o’ it. Ye see, Michael, merely shootin’ par is second best. Goin’ for results like that leads men and cultures and entire worlds astray. But if ye do it from the inside ye get the results eventually and everythin’ else along with it. So ye will na’ see me givin’ people many tips about the gowf swings lik’ they do in all the ‘how-to’ books. I will na’ do it. Ye must start from the inside, lik’ I showed ye there.”*

Controlling your golf swing, indeed, comes from the inside out, first consciously, then unconsciously. Your beliefs and values, your emotions and your thought processes, regulate the quality of your swing and the extent of your enjoyment. My metaskills techniques are based on tapping your unconscious resources through your senses—going “right to the heart o’ it”—and getting your conscious mind out of your way.

Let’s get started.

* Published by the Viking Press (New York, 1972), pp. 85-86; reprint Delta Books (New York: Dell Publishing, 1973).

This is a must-read chapter; it’s fundamental to everything that follows. Practically all of the techniques in this book deal with “going inside” and retrieving past experiences. These remembered experiences are resources to be used to refine your game. How to go about doing that is what you’ll learn in this chapter.

Be Sherlock Holmes for a while and discover the important elements of your setup and swing. Knowing about them will help you become more consistent, if you’re already a sweet swinger. Being able to find them, on command, is essential to playing my unique mind games.

All you have to think about is being wonderful, in your own mind, at least. As Sherlock you’ll be searching for clues that make your performance so special. It’s important that you go to a quiet place to do this exercise. When you do, you will recall when you played a particular shot exceptionally well and relive it in exquisite detail. You’ll think about a very specific shot, not an entire round, or even a whole hole. Out of the hundreds or thousands of shots you’ve struck, you’ll simply select one shot that made you proud. Maybe it was a tee shot that split the fairway, or an approach hit stiff to the pin, or a long, breaking putt that dropped for a birdie.

The idea is to uncover some of the crucial elements of the mental sequence, or strategy, that regulates your movements. That strategy contains a series of representations of sensory cues—sights, sounds, and feelings. I use the letters V, A, and K to signify those cues; V is for visual, A is for auditory, and K is for kinesthetic—muscle and joint feelings, feelings on the surface of your body, and the bodily sensations associated with emotions.

During the execution of a three-second golf swing, from take-away to follow-through, your mind processes as many as one hundred bits of sensory information with machine-gun rapidity. Just a few of those sensory representations are in your conscious awareness. The rest are processed unconsciously because of the speed of the swing.

Sensory information consists of specific internal sights, sounds, and feelings representing specific, past experiences of swinging the golf club along with ongoing, internal and external sights, sounds, and feelings that are occurring as you swing.

Here’s how I want you to think about that specific golf shot. First, just do a general, overall review of it, like watching a sound movie. See the course where you were playing, the lie of the ball, the distance to the pin. Notice the light and shadows and the brightness of the colors. See the images that were in your mind as you were taking that shot. Maybe you were imagining the flight of the ball.

Hear again what you heard then, both on the outside and inside your mind. Perhaps you heard the whoosh of your club and the sound of your own voice giving yourself instructions. Pay attention to the loudness and pitch and tempo of those sounds. As you see and hear those things, feel again what you felt then during your setup and swing—the coordinated movements of your body and the tension and relaxation of your muscles. Also, become aware of the mood or emotional state you were in as you were swinging and hitting the ball.

Now it’s time to get out Holmes’s magnifying glass and ear trumpet and pay more attention to the details of what you saw, heard, and felt back then, on the outside and inside your mind. The main questions to ask yourself as you relive that shot again and again in detail are these: What were the things you saw, the things you heard, and the things you felt that let you know when and how to swing the club? What did you see, hear, and feel that let you know that your movements were either okay or needed to be corrected?

You’re looking for clues in this exercise, details that control what you already know how to do, but may not know that you know. Sometime during the exercise, for instance, you might notice that you took the club all the way back to parallel. That is a clue. The more clues you can gather, the better your swing will become.

Forget about spectators and forget about what your playing partners did. Just pay attention to the sensory clues—what you saw, heard, and felt—that regulated your shot. Those clues could be related to your alignment, stance, grip, or swing and the mood or state you were in.

Make mental notes of your clues as you go along. At the end of the search you can write down what’s important.

The way you watch your past performance, the way you listen to the sounds associated with it, and the kind of bodily sensations that you pay attention to will determine your success as Sherlock Holmes. The more thorough you are, the better clues you will uncover.

Identifying the V’s—the Sights

First pay attention to what you saw on the outside as if you were right there on the course, standing over the ball and making that shot. I call these images “regular” pictures. Then shift your way of watching so that you see yourself hitting the golf ball. It might be helpful to imagine stepping out of your body, walking a few paces, and then turning to gaze upon a piece of athletic magic about to unfold from your favorite athletic star—you.

From this visual perspective, called the “meta position,” take the role of Sherlock Holmes and search for something that you didn’t know you knew that made your golf shot so good.

As you watch yourself perform, change the image of yourself—the meta picture—to color if it is black and white; change it to black and white if it is in color. If the picture is bright, make it dull; if it is dull, make it bright. If the picture is sharply defined, make it fuzzy; if fuzzy, make it defined. Notice what happens to the quality of your performance as you vary the internal images this way; your performance may get better or worse. Does your swing get better or worse as you vary the color, brightness, focus, and size of the images? Make mental notes about the kinds of images that made your performance good.

Now make regular pictures of your setup and swing, no longer watching yourself. See again what you saw while setting up and swinging. Vary the color, brightness, and definition of what you saw as you were striking the ball. Continue to search for the important clues that let you know when and how to swing. Look for the clues that let you know whether your movements were okay or needed to be changed. Notice what happens to the quality of your swing as you vary the images. Does it improve or deteriorate?

Now take a moment to become aware of the internal images, the ones you had in your mind then, when you were swinging the club. What were they, if any? For example, did you see an image of the proper grip? Did you see an imaginary line in front of the ball directing you to the target? How were these internal images helpful?

Identifying the A’s—the Sounds

While watching your past performance, using either regular or meta pictures, hear again what you heard then. Listen to the sounds directly associated with setting up and swinging. Listen to the sounds in the surrounding environment and the sounds in your mind. For instance, on the outside you might hear your spikes striking the ground as you set up to the ball, or the breeze in nearby trees. On the inside, in your mind, you might hear silence or your own voice giving yourself instructions.

If the sounds were loud, make them barely audible; if hardly heard, turn up the volume. If they were high-pitched tones, make them low; if low-pitched, make them high. If they were harmonious, make them discordant and unpleasant; if unpleasant, make them harmonious. If the tempo of the sounds was an even beat, make it irregular; if irregular, make it even. And while you’re varying the sounds, notice if the quality of your performance improves or deteriorates. Continue, as Sherlock Holmes, to listen for the important clues that were present when your movements were just like they were supposed to be. Are some sounds more important than others? Make a mental note of your discoveries.

Identifying the Ks—the Bodily Sensations

As you relive hitting the shot over and over again, pay close attention to: (1) the feelings of your coordinated movements, (2) the feelings of certain parts of your body that were essential to setting up and swinging, (3) the amount of energy and tension you felt in your muscles, and (4) the bodily feelings that represented the mood you were in while you were hitting the ball.

There might be a number of things you could feel as you do this exercise. For instance, you might feel the turn of your shoulders on the backswing, or the strength of your grip on the club, or the lifting of your forward heel toward the end of the backswing.

Now, in your mind, vary the way you moved. If your movements were quick, slow them down; if slow, speed them up. If you were exerting a lot of energy and pressure, relax the effort; if you weren’t, increase the tension of your muscles. While varying those feelings, notice what happens to the quality of your performance. Does your swing get better or worse? As Sherlock Holmes, continue to identify and make mental notes of the feelings that made your performance so good.

Equally as important as the muscular feelings that were associated with setting up and swinging the club are the emotional feelings you had while, not after, you were actually hitting the ball. Those bodily sensations represent the mood or state you were in. Feel them again. Perhaps they were feelings of lightness, fluttering, tingling, warmth, tension, or pulsing that were present in parts of your body. Vary the intensity of these emotional feelings and find out what happens to the quality of the shot. Does it get better or worse when you increase or decrease the intensity? What is the amount of intensity that is just right for making that shot the best possible?

Putting It All Together

After you’ve gone through seeing, listening, and feeling, have some fun with reliving that past performance. Pretend you’ve got a videotape of it, and watch it while using the variable speed and direction buttons on the video control.

First, run the tape twice as fast as normal, then four times as fast, and then bring the speed back to normal. In addition, slow the tape down to half speed and then to one frame at a time. Be sure to bring the tape back up to normal speed. With each variation in speed carefully pay attention, as before, to discovering new visual, auditory, and kinesthetic clues that were essential for hitting the ball so well.

Now run the tape in reverse—in normal, slow, and fast motion—again looking for clues. Finish up by running the tape forward again, analyzing and evaluating your performance in light of what you’ve discovered.

Before reading any further, go through the entire Sherlock Holmes Exercise now.

SHERLOCK HOLMES EXERCISE

- Go to a quiet room. With experience you’ll be able to do it out on the practice range or course.

- Remember a specific shot that you hit during a round.

- See everything you can see about the shot; hear everything you can hear about the shot; feel everything you can feel about the shot.

- Vary what you see (from color to black and white, from fuzzy to clear); change the sounds (from loud to soft, from pleasant to unpleasant); alter your feelings from relaxed to tense).

- Remember the details. Write them down if it’ll help. Judge what seems most important.

Reactions to the Sherlock Holmes Exercise

Although there are some typical sensory cues that most golfers pay attention to while they’re making a shot, each person has his or her own way of processing and giving meaning to sensory information. There are no right or wrong sensory cues for playing golf. It’s what you do with them that’s important.

To help you understand how professional golfers process information, I’ll share with you what I learned from some of them when they did the Sherlock Holmes Exercise. Their mental processes are often unusual and quite sophisticated.

What the Pros See—the Internal V’s

Former U.S. Open and PGA Champion David Graham sees images of past shots as he decides how to make the shot facing him.

Touring pro Danny Edwards checks his setup as if he is facing himself. For a second or two he mentally steps outside his body, almost into the gallery, and looks back. When Danny is convinced that everything about his setup is okay from that perspective, he hops back inside and lets the ball fly. Lon Hinkle, another PGA Tour professional, makes pictures of himself properly set up and swinging from behind the ball. He then walks up to the ball and “steps into” his created pictures.

When Bill Burgess, 1987 Nissan Classic Champion and head club professional at Areola Country Club in Paramus, New Jersey, played investigator, he found he had an image of strings that connect his ball with the target. He described it “as if there were strings out there, lines. And it felt like everything matched up to the lines, so all I had to do was swing the club. I can’t always do it. But when I can get the strings and feel the lines, I always hit good shots.”

All pros that I’ve talked to imagine the actual trajectory they want the ball to follow before striking it. They know precisely where they want the ball to come to rest, either in the fairway, or in the hole on putts.

What the Pros Hear—the Internal As

The internal auditory information of professional golfers almost always consists of short, positive statements or commands. Peter Jacobsen routinely says to himself, “Knock it close.” David Graham says, “Rhythm,” as he approaches the ball, and he repeats the phrase “Good shot” throughout his backswing.

Mike Davis, a colleague of Bill Burgess at Areola, quickly calls off in his mind a checklist of the key elements of his setup and swing as a part of his preshot mental routine. Mike Sparks, an assistant pro at Ridgewood Country Club in New Jersey, listens to music in his head when he’s in his best playing mood.

“I never realized it,” he said, “but when I replayed my shot and heard what was in my head, I learned I sing a song to myself. Before I hit shots, I get in a mode where I kind of do my own deal and don’t pay attention to people. Maybe it’s a tune I’ve heard in the car on the way to the course that day.”

Bill Loeffler, a former PGA Tour professional, and Mike McCullough, currently on tour, both “hear” silence as a positive indication that they’re ready to hit the ball well.

What the Pros Feel—the Internal Ks

The way golfers feel emotionally on the inside is absolutely crucial for playing golf consistently well. As you might expect, Sherlock Holmes revealed that the emotional state most conducive for good play varies from person to person and from time to time. Mike Davis says he feels relaxed when he plays well. Bill Burgess says, “Instead of feeling relaxed like Mike, I feel slightly juiced up in my legs and arms. When I get turned up a notch, I really play better. ”

Another touring craftsman, George Burns, says, “I have a feeling of freedom in my chest, belly, arms, and shoulders when I’m on my game.” And Bill Adams, head pro at Ridgewood, has “a feeling of eagerness” in his forearms that lets him know that it’s time to putt, and a “loosey-goosey feeling” when he’s ready to chip.

Identifying the just-right states—the emotional K’s—for hitting various golf shots is perhaps the most important set of internal clues that you can identify; and the ability to quickly generate that state at will is undoubtedly the most important skill you can learn. Chapters 4, 5, and 6 are devoted to this important process.

External, or “Uptime” Cues

The kinds of sensory cues that pros identified while doing the Sherlock Holmes Exercise have been, up to this point, “internal” cues—what they saw, heard, and felt inside of themselves; I refer to them as “downtime” cues. Now I want to briefly identify what the pros saw, heard, and felt on the outside—the important sensations that come directly from the environment or are associated directly with the movements that control their golf swings. As you might expect, I refer to these environmental and movement sensations as “uptime” cues. An extensive list of what good golfers consider to be the most important “uptime” cues can be found in Appendix A.

Uptime visual cues that pros attend to are familiar to you, I’m sure, because most golfers are sensitive to them. They include: location of the target and intervening hazards, out-of-bounds markers, contours of the fairway and green, alignment of the body with respect to the target, and, of course, the lie of the ball.

The significant uptime auditory cues that pros listen to are: the wind, the whoosh of the club on the downswing, the click of the ball coming off the club head, and their breathing. Chip Beck, one of the elite golfers on the PGA Tour, uses the sound of his spikes as he walks up to the ball. This helps him determine how big a divot he wants to take on approach shots. He combines this with the feel of the grass underfoot to make that decision.

The most important uptime kinesthetic cues of most pros are associated with the grip, stance, and swing mechanics. Lee Trevino feels his grip on the club as if he’s holding a bird in his hands. Bob Tosky, a master golf teacher, has the sensation of accelerating the clubhead speed at the bottom of the swing. Mike Davis feels increased tension in his hands and wrists when his club head is about a foot from the ball on the downswing.

Some Important Questions and Answers

Since the price of this book does not include me, I’ve anticipated some of the questions the Sherlock Holmes Exercise might inspire.

Q. What am I supposed to see, hear, and feel?

A. Whatever you do see, hear, and feel. Each one of us has developed our own set of clues that regulate our behavior; some have more clues to good performance than others. Also, some people become so involved as Sherlock, they think they’re actually on the course. So don’t go into this exercise with preconceived ideas.

Q. How come you had me change what I saw, heard, and felt so often? Why change colors to black and white and then back? Why change the tension in my muscles? Why change the volume of the sound?

A. Technically, I’m dealing with what we call sensory submodalities. Modalities are seeing, hearing, and feeling. As you know, there are also the modalities of smelling and tasting, but they’re of little consequence for our purposes. Submodalities are the refined elements of seeing, hearing, and feeling such as color, volume, and tension. Without getting too complex, mentally varying the submodalities of sight, sound, and feeling is when learning—and change—occur. Trust me.

Q. Was I in a trance?

A. You could call it that. You changed into a different state when you were asked to relive a past shot. Most athletes are in a trance—a profound altered state—when they perform superbly.

Q. Will I be learning hypnosis?

A. Actually, you know how to do it already. I’ll be telling you how to use self-hypnosis in Chapter 9.

Now that you know how to retrieve the details of past experience, let’s start playing some of my mind games so your golf game improves. If after doing the Sherlock Holmes Exercise you have difficulty with generating images in your mind, with making internal sounds, or with feeling a variety of physical sensations, you can use the questions and exercises in Appendix B to expand or refine your sensory awareness. The better that is, the easier it will be for you to apply metaskills techniques.

This chapter is your guide to making the most of your past experience. Here you’ll learn how to identify the kinds of internal mental and emotional resources you have within you to play better golf, and then how to make them automatically available for eventual application on the golf course.

As you know, golf is essentially a mental game, because there’s so much time to think in between shots. The actual act of setting up to the ball and striking it takes twenty-five to thirty seconds. If you play a round in par, it means that you’re spending about thirty minutes out of four and a half hours actively playing the game. Thirteen minutes per hole is spent walking or riding, talking, and, of course, thinking between shots.

It’s those between-shot periods that can jump up and jostle a golfer’s mind. They can tense the muscles, decrease concentration, cause forgetfulness, reduce confidence, and eventually produce inconsistent shots—unless he or she knows how to keep focused on the here and now.

What is needed, then, is a way to keep yourself in the proper frame of mind between shots; that is, to be in the appropriate emotional state when you’re ready to hit the ball. The appropriate states of mind needed to play good golf vary from person to person and situation to situation, depending perhaps upon the lie of the ball, your score, and the pace of play.

Not only do conditions on the course affect your state, but whatever is on your mind—your business, your school, your family, or your social life—also affects your game. The capacity to leave outside interests out of your mind while playing is crucial if you want to play well consistently. The states you generate on the course that keep you attentive to the present moment are what count.

There are three underlying states of mind that are essential to playing well consistently. They are concentration, confidence, and a sense of mind-body unity. As you probably know, playing good golf requires riveted concentration on the shot at hand. When not concentrating, many golfers get ahead of themselves, imagining that they are on the next tee or in the clubhouse having shot a preconceived score. They forget that they still have a shot to make and more holes to play.

Confidence of your ability to execute a planned shot well is necessary if you want to play to your handicap or better. While in this state you know that a shot will be good even before you strike the ball. But if there’s doubt in your mind, shots start to fly all over the place.

As a result of concentration and confidence, you will develop an inner sense of unity. This state of mind has elements of resonance and harmony, rhythmic energy, and grooved coordinated movement that feels effortless. When in this state—some call it a “zone”—golfers sense that their mind, mood, and movement are all-of-a-piece, resulting in shots that are “pure.”

As you will see in Chapters 4, 5, and 6, there are a variety of metaskills techniques that facilitate the development and maintenance of these three states. But for now we will focus on general procedures to identify and retrieve specific internal resources that will make for more consistent play.

Your Inner Resources

You’ve done a lot of living and have all sorts of experiences stored in your memory that can be used to generate appropriate states of mind for playing good golf. These “resource states” include, among others, optimism, eagerness, determination, calmness, inventiveness, hopefulness, acceptance, patience, friendliness, sensitivity to nature, and a lot more. Optimism helps you to think positively about your shots; eagerness and determination keep you focused on the shot at hand; calmness keeps your swing fluid; inventiveness and hope are needed to create new shots to get out of trouble; patience and friendliness allow you to overlook the slowness and perhaps golfing ignorance of your playing partners; and sensitivity to the beauty of nature around you can be a counterpoint to much of the anxiety in your life, on or off the course.

Other useful resources include past experiences related to learning all sorts of physical skills; embedded in these experiences are the basic resources for playing golf well, such as balance, power, strength, energy, rhythm, coordination, and effort control. Finally, your past experiences of making good golf shots contain unconscious mental strategies, the resources that directly control your game.

Identifying the Right Resources

By now you’ve probably assumed that you’re about to learn to put yourself into the right frame of mind—confident, optimistic, patient—at will. But first you must decide which resource to call up from your past experience. You’ll know this by answering two basic questions: (1) “Specifically, what kind of shots do I want to make?” and (2) “What stops me from hitting the ball the way I want to hit it or the way I’m capable of hitting it?” Let’s look at the answers to these two questions, one at a time.

To answer the first question, knowing what you want comes from having alternatives in mind. These alternatives include remembering precisely when and how you’ve hit similar shots in the past, remembering how other good golfers have executed similar shots, or recalling instructions from your pro. This means knowing what you would have to see, hear, and feel for the shot to be good. Then you can transfer pertinent information to the shot facing you at the moment.

Frequently, the answer that some people give to the second question, “What stops me?” is “I don’t know. If I did, I’d do something about it.” Yet there are ways to uncover the answer to this question. One way is to guess. By guessing, you’ll be tapping into your unconscious mind; and frequently guesses turn out to be quite accurate.

If you have no good guesses, take another approach. Replay in your mind what you’re doing incorrectly and compare it to the way you want to swing, using your own past performance or someone else’s performance as a standard for comparison. When you identify the differences between how you mentally regulate what you’re doing and how you mentally regulate what you want to do, you’ll have some important clues as to what’s stopping you.

Frequently, it’s your emotional state that stops you from playing good golf. If you change to a just-right emotional state, your grooved swing will return. By paying close attention to the mood you’re in, you may have the answer to what’s stopping you. Perhaps you have been annoyed, impatient, skeptical, despairing, feeling hopeless, whatever. After identifying this stopper state, all that’s necessary is to replace it with its opposite.

This isn’t always as easy as it might seem. Sometimes it may be impossible to discover all the factors that keep you from achieving your outcomes. You may need the help of a golf professional to refine the mechanics of your swing, or you may need the help of a skilled counselor to deal with unconscious conflicts; such conflicts could interfere with maintaining the mood you need to play well.

Nonetheless, knowing how to identify and use your internal resources is a valuable process in itself; so let’s look at it now.

Accessing Internal Resources

Fortunately, NLP has formalized the normal human process of tapping past experiences and making them automatically available for use in present situations. The Sherlock Holmes Exercise is part of this process; you already know it. By reliving past experiences in full detail, you’ll be pleasantly surprised to discover that you have more resources for playing better golf than you thought you had. When you discover this, you’ll trust yourself more and you will build your self-confidence.

Anchoring is the part of the process which makes your internal resources—your past experiences and feelings, still available to you in your subconscious—automatically available to play better golf in spite of conditions that conspire to make the game difficult. Anchors keep your resources stabilized so your game can become more consistent and enjoyable. Let’s turn to the process of anchoring in general. Later you’ll learn how to use a variety of anchors for specific aspects of your game.

What Is an Anchor?

An anchor is either an internal or actual external sight, sound, feeling, smell, or taste—a stimulus—that triggers the sensory details associated with a particular past experience. For example, when you see an old photograph of yourself as a child, it usually stirs up memories of that time in your life. Similarly, when you see azaleas and dogwoods, you could think of the Augusta National. It’s the same with a special song.

It’s a fact that our conscious and unconscious thoughts—what we see, hear, feel, smell, and taste internally—directly affect our moods or internal emotional states. Consequently, we can become conditioned to respond emotionally in the same way over and over again whenever we generate a particular thought or whenever a particular stimulus is experienced. You vaguely remember hearing this from someone else, don’t you? Yes, it was Pavlov who got the dog to salivate simply by ringing a bell.

Our lives are full of anchors, some of which have powerful effects. The sight of the American flag or the sound of “America the Beautiful” inspires deep feelings of patriotism in some people. Seeing a snake or spider can evoke intense fear in those who are phobic. The smell of popcorn stirs up the just-right kind of feelings in Peter Carruthers, 1984 Olympic pairs skater, that he says makes him skate his best. The thought of a past event—like sinking an eagle approach shot—can evoke the same feelings associated with it in the here and now.

Golfers have more anchors than the Sixth Fleet. Unfortunately, most of them are negative, similar to phobias. Teeing up on the first tee, for instance, is enough to create intense anxiety in many golfers. Even the thought of participating in a tournament can evoke discomfort in some people or arouse excited anticipation in others. Water hazards seem to evoke gloom or fear in some golfers, resulting in golf balls drowned with regularity. All an uncertain golfer has to do is to look at the water and splash, in goes an old substitute ball.

Other anchors consist of some form of compulsive, superstitious behavior. Superstitious anchors range from wearing certain pieces of jewelry or clothing for good luck to believing in a “trusty” club that is expected to produce a good shot every time, even though another club would be more suitable for the shot at hand.

All of these uncontrollable phobic responses and compulsive, ritualistic behaviors override the ability to make intelligent choices about your actions. Ritualistic behaviors create internal pressure and can distract you from absorbing important external information, such as the distance to the pin, the strength of the wind, or the contour of the fairway and green. Moreover, they interfere with the internal state that is most appropriate for executing a well-hit golf shot.

On the other hand, metaskills anchors automatically evoke good feelings, without the need for conscious thought; they will utilize your talents and emotional states so that you play well consistently. This will free you to enjoy the game, the scenery, and your playing companions.

Retrieving Past Experiences

Let’s see how we can use the Sherlock Holmes Exercise to retrieve past experiences so they can be anchored for practical use while playing golf. In that exercise you learned how to go inside your mind and retrieve or remember a past experience. You learned how to run your brain by modifying sights, sounds, and feelings. And you identified the condition or state of consciousness when your mental thoughts, emotions, and muscles conspired to create as fine a golf shot as you had ever made.

This process of “going inside”—actively remembering what you saw, heard, and felt during a particular past experience—is, as I’ve said, central to practically all of my mind games, because it’s there, in your brain and muscles, where you have all the resources you need to play golf as well as your physical condition and skills will allow, or to do anything else worth doing.

Sherlock Holmes Revisited

Let’s revisit the Sherlock Holmes Exercise as a way to learn how to anchor. Quickly reread the instructions on this page of Chapter 2. When you’ve finished reading, go inside and go back to that wonderful shot that you examined as Sherlock Holmes before. See, hear, and feel again what you saw heard, and felt when you hit that shot. Be sure to make regular pictures, not meta pictures, because regular pictures elicit stronger feelings. Especially feel the emotions you felt while you were hitting it. Pay attention to the bodily sensations of that emotional state. Perhaps it’s a tingling feeling, goose bumps, warmth, a rush of blood, a feeling of energy or power in some part of your body, or whatever.

Intensify these sensations until they’re as strong as you can make them. As they get stronger, press one finger against any one specific part of your body. Increase the amount of finger pressure as the intensity of the emotional sensations increases; as they subside, reduce the amount of finger pressure. That’s the anchor—a K-anchor—the pressure of your finger on a specific part of your body. The central idea is to associate the anchor with the emotional feeling.

When the emotional feeling is at its most intense level, let one, and only one, internal image associated with the shot flash spontaneously in your mind; then let one sound associated with the shot spontaneously pop into your head. The image and sound are also anchors—a V-anchor and an A-anchor. They should be directly and specifically related to the shot and not to golf in general.

Now let your mind go blank and come back to the present. Take a five- or ten-minute break from reading this book and do something else to distract your mind from what you have been reading. At the end of the break return to this place where you are presently reading.

Welcome back. Take a moment to determine the nature of the state you’re in right now. After that press your finger on the exact same spot on your body when you were Sherlock. Hold the finger pressure for a full sixty seconds without reading any further than the end of this paragraph. Just pay attention to what happens inside, nothing else, and then return to the book when the sixty seconds are up.

Welcome back again. Are you thinking about the past good shot? Do you now see or hear what you saw or heard then? Do you now feel the same emotions you felt when you hit that shot? I’d be surprised if you aren’t aware of some aspect of the shot, assuming you followed my instructions. If you reactivated some of the same feelings, images, or sounds associated with the shot, you have experienced how an anchor works. Within sixty seconds you changed your state.

Now, reflect on the meaning of this experience. Do you realize that you can change your state quickly, and therefore don’t have to stay stuck in a lousy state? With a properly established anchor you have more choices about the way you want to feel, and you can activate any state automatically if your anchor is “contextualized.”

Contextual Anchors

If an anchored resource is to be useful on the golf course, it must be contextualized; that is, the anchor should fire automatically without conscious thought in the context of a special situation when a particular resource is needed, not just at any old time or in any situation. If anxiety normally takes over on the first tee, then a confidence anchor could be triggered automatically just before you approach the teeing ground. If you want to keep your cool when duffers are ahead, then a calmness anchor could be activated automatically when you first see the duffers hacking around. If a delicate putt is required, then the anchored feeling of having a fine touch could be fired automatically as you study the line and distance to the cup.

When you contextualize an anchor, it’s important to select either a movement, an external visual cue, or an external auditory cue that is always present on the golf course to serve as an anchor. Only one cue is necessary. For example, tying the laces of your golf shoes, a K-anchor, could be an anchor for generating the resource of determination; and looking at a tee marker, a V-anchor, could be used to get into the right state for making a tee shot.

Your ingenuity is all that’s necessary to identify an anchor. Using a habitual movement that occurs in a particular situation or context as an anchor is most effective, since it already is unconsciously automatic. Habitual movements could include: the unique manner in which you squat when you line up a putt, the way you hold a club as you study and prepare for a shot, a gesture of a hand or arm as you approach the ball, taking a club out of the bag.

The only limitation on your choice of an anchor is that it be “clean”—not already associated with an experience on or off the golf course. For example, looking at a wedding ring would not be a good V-anchor because it’s already connected to very powerful emotional experiences.

Making Anchors Work Automatically

To fully establish these anchors so they’ll be useful later on, it’s necessary to “fire” them consciously three or four times a day for a week or two until the anchored emotional state can be activated within a few seconds. Then forget about conscious anchoring, letting the process become part of your unconscious mind. The conscious act of firing an anchor consists of deliberately looking at the external visual cue, or listening to the external sound cue or moving in an habitual way, while associating the cue or movement with the actual emotional feeling of a resourceful state.

If you would like to establish the finger-pressing anchor related to the good shot which you identified as Sherlock, press your finger on the specific part of your body and consciously see the internal image and hear the internal sound that were part of the remembered shot. The finger pressure should be maintained until you feel the return of the full force of the emotional sensations you had while hitting that past shot. Repeat this process several times each day for the next week or two. With this anchor-firing practice you’ll eventually be able to reactivate the emotional state associated with the past shot very quickly—in a matter of seconds.

If you want to contextualize the anchor for that past good shot, select either a habitual movement, an external visual cue, or an external auditory cue that is always present on the golf course to serve as a new substitute anchor. Practice firing this new anchor three or four times a day for several weeks until it works as well as the finger pressure; this may be done on or off the course. When off the course just think about the external cue or make the habitual movement until the emotional state can be produced in a few seconds.

One professional golfer looks at the printed logo on his golf bag; it’s his V-anchor for generating determination. Another golfer looks at the end of the grip on his clubs; this is his V-anchor to activate a state of concentration. A third golfer listens to the rhythmic sound of his clubs rattling in the bag as he walks between shots; this A-anchor returns him to a feeling of calmness after he makes a poor shot.

Each of these golfers used finger pressure on some part of their body when they first identified and anchored their resource state during the Sherlock Holmes Exercise. They fired the finger-pressure anchor on the golf course to regenerate the desired state. Then they transferred the feeling anchored by the finger pressure to a new A-, V-, or K-anchor that is always present on the course.

The golfers practiced firing these new anchors both on and off the course. When at home or in the office, they imagined they were on the course. Then they saw, heard, or felt their particular anchor, and consciously generated their desired emotional state. After they were able to generate the desired state in association with a particular anchor within a matter of seconds, they stopped formal practice and allowed their unconscious minds to take over—just the way hearing a certain song can automatically generate a feeling of love for a special person.

ANCHORING

- Identify the resource (the emotional or physical state from your past) needed to accomplish a particular outcome or to execute a particular shot.

- Remember a time in your life when you had an experience during which that resource was used successfully.

- “Go Inside” and see, hear, and feel again what you saw, heard, and felt during that past resourceful experience.

- Intensify the internal emotional feelings that were present during (not after) the time when you were actively involved in accomplishing a particular outcome or executing a particular shot.

- Anchor the internal emotional feelings or state with finger pressure and with an image and sound that were directly associated with that past experience.

- Contextualize the anchor to a sight, sound, touch, or habitual movement that will always be present in the golf environment.

- Practice “firing” the anchor four or five times per day for about two or three weeks so that the internal emotional feelings can be regenerated within a matter of a few seconds.

Now that you know how to anchor a resource, you’ll learn the practical uses of anchors in subsequent chapters.

Now that you are aware of your mental-detective skills—the tools of sensory awareness—you’re ready to uncover your internal resources and apply them to improve your golf game. The metaskills mind games in this part of the book are designed to: (1) identify and stabilize in your mind and body the just-right states that make for consistent play; (2) discover how to take advantage of the pro within yourself; (3) develop a refined sense of effort regulation so that you know how hard to strike the ball during the short game; (4) expand your ability to use the power of self-hypnosis; and (5) learn how to control pain, unleash stored energy, and speed up healing so you can play at your physical best. In short, you’ll be learning specific mind games to control your golf game.

Read leisurely through this section of the book. When you discover a technique that fits a goal you have in mind, put it to work. Follow the instructions precisely. Evaluate the effectiveness of the technique in terms of whether or not you achieve a desired outcome.

If you’re not sure about the application of a particular technique, go to “The 19th Hole,” the final chapter. This chapter, along with Appendix C, will help you select appropriate techniques.

There’s a 15th club in golf. You don’t hit the ball with it, or even see it, for that matter. Call it mood, the emotional state you bring to the course, or to a shot, that determines how you use the other tools at your command. That mood can change as quick as lightning, depending on your values and how your mind works, consciously and unconsciously.

Some days you’re hot. The ball flies so true, it’s as though someone were standing far down the fairway with a large magnet in hand; frequently trees uproot themselves and step in front of the few badly struck shots, bumping the ball out of harm’s way; the four-inches-in-diameter cup all of a sudden seems crater wide.

On other days it’s hot of a different sort. You’re hot under the collar. Glaciers hustle along faster than the gang ahead; somehow, blades of grass on the fairway turn into steel and redirect a solidly struck ball into a jungle jail. You don’t know whether, as the country song goes, to shoot yourself or go bowling.

Mood swings are as important as the golf swing; and your mind controls both. Fortunately, you don’t have to be the victim of your not-so-good states; you can either maintain a good state or quickly change it from lousy to just right. You can learn to make all the between-shot time work to quiet your mind during each shot and to have all the necessary mental and physical resources readily and automatically available for making good shots. If you don’t, golf might regress into Mark Twain’s description of it as “a good walk spoiled. ”

In Part 1 you learned how to use your mind to access your inner resources. This and the next two chapters deal with the process of how to use your mind and inner resources to control and swing your moods, since they dramatically affect the swing of your club. If you’re a scratch player, say, and take a quadruple bogey on the second hole, I have a way to keep that instant anger from making the remaining 16 holes almost as miserable. I’ll teach you how to uncover and remain in touch with your feelings of confidence so that you can perform comfortably at the peak of your capacity when the chips are down. In essence, you’ll learn how to get into the just-right states that are conducive to hitting all sorts of shots well, using the anchoring process described in the previous chapter.

A few golfers I know use a natural, unconscious process of anchoring just-right states. For example, David Graham unconsciously repeats to himself the rhyming phrase “Low and slow” as an auditory anchor to activate the proper form and mood to regulate taking away his club on tee shots. Whenever he approaches a tee in tournament play, Peter Jacobsen automatically looks at the gallery as a visual anchor, and in some way absorbs spectators’ energy as a means to get more power into his tee shots. My wife, Edna, says to herself, “Let the clubhead fly,” just before take-away as a way to generate the feeling of hitting the ball with zip at impact.

In each of the three cases David, Peter, and Edna “fire” their anchors automatically, without conscious thought. They just find themselves doing it. And I’ll bet that you have an anchor or two tucked away in your unconscious mind that work for you.

I have developed several step-by-step anchoring processes that you can use to get and keep yourself in the just-right state for hitting each shot facing you at the moment. These anchors evolved from my systematic study of what athletes in many different sports do to generate and stabilize their moods. I refer to them generally as just-right anchors.