How We Believe: Science and the Search for God – Read Now and Download Mobi

“This is an important book, which is at the same time a great read. Michael Shermer digs into the American religious psyche with devastating logic and intensity … . Too often politeness (or cowardice) prevents people from asking questions or from expressing dissent. No such barriers stand in the way of Shermer’s acute intellect, the more powerful since he so obviously cares about the issues on which he writes. I love his discussions of God and morality and when I disagree, I simply want to argue the more.”

—Michael Ruse, author of Taking Darwin Seriously and professor of philosophy and zoology, University of Guelph

“Those who approach this intriguing and informative book with a receptive mind will come away with a much deeper appreciation for the wonderful interplay of biology and culture that makes us who we are—perhaps unique creatures in the universe.”

—Donald Johanson, director of the Institute of Human Origins and author of From Lucy to Language

“The book will convince and delight all who are not chronically averse to opening their minds and thinking for themselves.”

—Richard Dawkins, author of Unweaving the Rainbow

To Stephen Jay Gould

For examining God, religion, and myth as Spinoza would have it: not to ridicule, not to bewail, not to scorn, but to understand.

Happy is the man who finds wisdom, and the man who gets understanding, for the gain from it is better than gain from silver and its profit better than gold. She is more precious than jewels, and nothing you desire can compare with her. Long life is in her right hand; in her left hand are riches and honor. Her ways are ways of pleasantness, and all her paths are peace. She is a tree of life to those who lay hold of her; those who hold her fast are called happy.

—Proverbs 3:13-18

Table of Contents

Epigraph

Title Page

Epigraph

PREFACE - The God Question

INTRODUCTION TO THE PAPERBACK EDITION - The Gradual Illumination of the Mind

Part I - GOD AND BELIEF

Chapter 1 - DO YOU BELIEVE IN GOD?

A LEAP OF FAITH

A BREACH IN THE FAITH

THE ART OF THE INSOLUBLE

WHAT IS GOD?

THE FAITH OF THE FLATLANDERS

Chapter 2 - IS GOD DEAD?

GOD IN THE 1960s

TIME AND GOD

GOD’S RESURRECTION

SUPPLY-SIDE RELIGION AND THE SECULARIZATION OF THE WORLD

SOCIAL INDICATORS OF GOD

SACRED SCIENCE

Chapter 3 - THE BELIEF ENGINE

THE PATTERN-SEEKING ANIMAL

THE MEDIEVAL BELIEF ENGINE

THE MODERN BELIEF ENGINE

TALKING TWADDLE WITH THE DEAD

Chapter 4 - WHY PEOPLE BELIEVE IN GOD

SEEING THE PATTERN OF GOD

IS BELIEF IN GOD GENETICALLY PROGRAMMED?

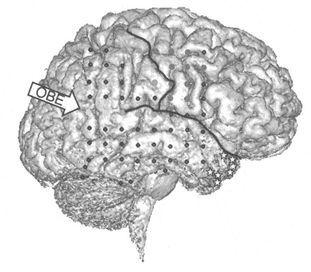

IS THERE A GOD MODULE IN THE BRAIN?

GOD AS MEME

SCIENTISTS’ BELIEF IN GOD

WHY PEOPLE BELIEVE IN GOD

INTELLECTUAL AND EMOTIONAL REASONS TO BELIEVE

ALL’S RIGHT WITH GOD IN HIS HEAVEN

Chapter 5 - O YE OF LITTLE FAITH

PHILOSOPHICAL ARGUMENTS FOR GOD

SCIENTIFIC ARGUMENTS FOR GOD

THE NEW COSMOLOGY

THE NEW CREATIONISM

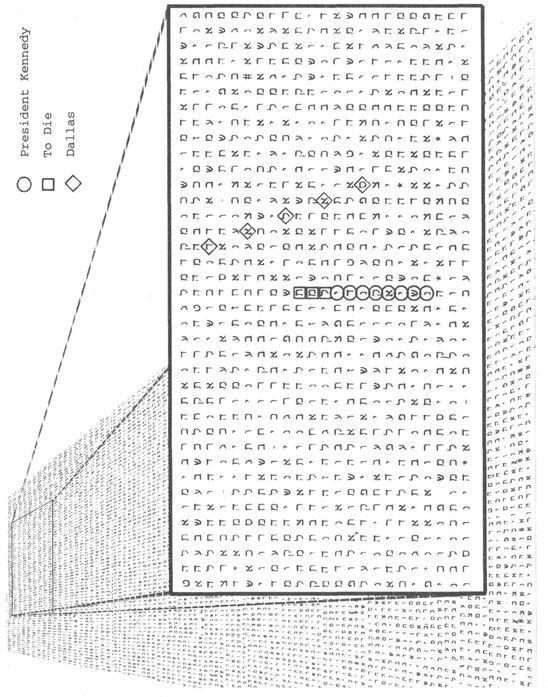

THE BIBLE CODE

THE REAL MEANING OF ARGUMENTS FOR GOD

Part II - RELIGION AND SCIENCE

Chapter 6 - IN A MIRROR DIMLY, THEN FACE TO FACE

A THREE-TIERED MODEL OF RELIGION AND SCIENCE

MORAL COURAGE AND NOBILITY OF SPIRIT

Chapter 7 - THE STORYTELLING ANIMAL

THE HOW AND THE WHY: IN SEARCH OF DEEPER ANSWERS

FROM PATTERN-SEEKING TO STORYTELLING

FROM STORYTELLING TO MYTHMAKING

FROM MYTHMAKING TO MORALITY

FROM MORALITY TO RELIGION

FROM RELIGION TO GOD

Chapter 8 - GOD AND THE GHOST DANCE

THE GHOST DANCE AS MYTHMAKING

THE 1890 GHOST DANCE

THE ETERNAL, RETURN OF THE GHOST DANCE

THE CARGO CULT GHOST DANCE

JESUS AS MESSIAH MYTH

WHY THE MESSIAH MYTH RETURNS

Chapter 9 - THE FIRE THAT WILL CLEANSE

WHAT IS THE MILLENNIUM?

WHEN PROPHECY FAILS—A.D. 1000

WHEN PROPHECY FAILS—A.D. 2000

THE LURE OF THE MILLENNIUM

HEAVEN ON EARTH

SECULAR HEAVENS

HOLDING THE CENTER

Chapter 10 - GLORIOUS CONTINGENCY

IF THE TAPE WERE PLAYED TWICE

THE MISMEASURE OF CONTINGENCY

CONTINGENT-NECESSITY

GLORIOUS CONTINGENCY: A LITTLE TWIG CALLED HOMO SAPIENS

THE FULL IMPACT OF CONTINGENCY

CONTINGENCY AND FREEDOM

IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE

FINDING MEANING IN A CONTINGENT UNIVERSE

AFTERWORD TO THE SECOND EDITION - God on the Brain

APPENDIX I - What Does It Mean to Study Religion Scientifically? Or, How Social Scientists “Do” Science

APPENDIX II - Why People Believe in God—The Data and Statistics

A Bibliographic Essay on Theism, Atheism, and Why People Believe in God

NOTES

CREDITS

INDEX

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Copyright Page

The God Question

A Moral Dilemma for Dr. Laura

Not long after I set out to write this book, I received a fax from a subscriber to the magazine I publish. Skeptic, who had just finished reading the most recent issue (Vol. 5, No. 2) devoted to “The God Question.” This volume of the magazine addressed the various theological, philosophical, and scientific arguments for God’s existence, Einstein’s views on God, skeptic Martin Gardner’s belief in God, arguments for and against immortality, and the decline of atheism in America. The correspondent, however, was not writing about any specific article, but about the qualifications of one of the members of Skeptic’s board of advisors. “I would love to know what qualifies a person to be on your editorial board,” the letter began. “If he were interested would Rev. Pat Robertson qualify? I consider myself to be an atheist, a skeptic, and a semiprofessional talk show listener. In the latter capacity I have had many occasions to listen to one Dr. Laura Schlessinger, a member of your board.” The letter went on to chronicle Schlessinger’s reliance on the Bible as her authority for resolving moral dilemmas presented to her by her callers on her radio program. “I didn’t know that skeptics relied on authority to settle disagreements over morality,” the letter concluded.

This was not the first correspondence we received concerning Laura Schlessinger’s position on our board of advisors. Throughout 1996 and 1997 we were sent a couple of dozen critical letters, faxes, and e-mails, and for a couple of weeks in mid-1997, on a skeptics Internet discussion group, a debate ensued about Schlessinger’s involvement in the skeptical movement. We explained that membership or involvement in any capacity with the Skeptics Society and Skeptic magazine is not exclusionary. We could not care less what anyone’s religious beliefs are. In fact, at least two of our more prominent supporters—the comedian and songwriter Steve Allen and the mathematician and essayist Martin Gardner—are believers in God. Other members of the board may believe in God as well. I do not know. I have never asked.

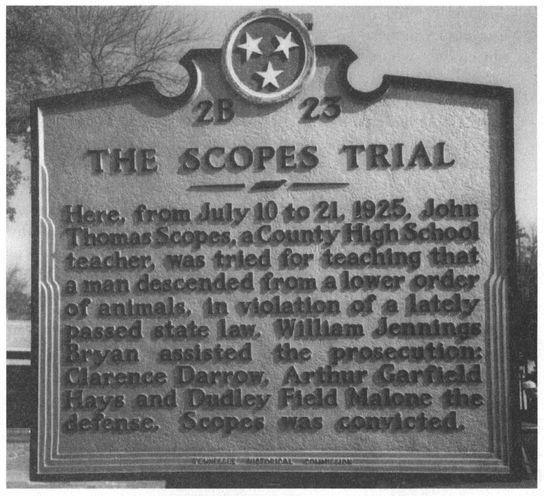

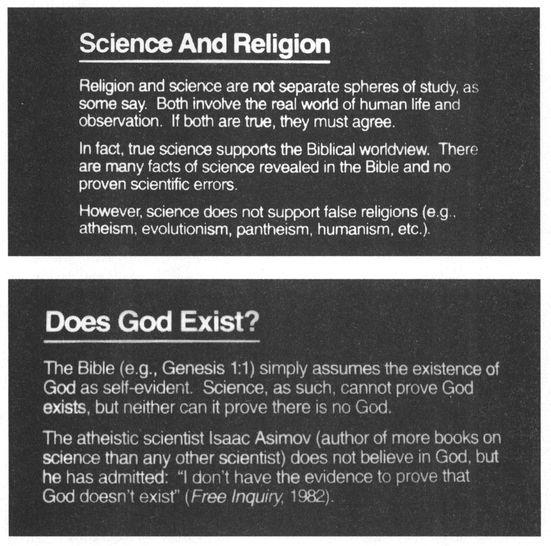

The primary mission of the Skeptics Society and Skeptic magazine is the investigation of science and pseudoscience controversies, and the promotion of critical thinking. We investigate claims that are testable or examinable. If someone says she believes in God based on faith, then we do not have much to say about it. If someone says he believes in God and he can prove it through rational arguments or empirical evidence, then, like Harry Truman, we say “show me.” Some Christians claim that the Shroud of Turin proves that Jesus lived and was crucified and resurrected. But the shroud was carbon-14 dated and found to be a fourteenth-century hoax (some are now claiming that the dating process was contaminated and that the shroud may be older still, but these claims have never been corroborated in peer-reviewed journals). Some creationists claim that geology proves that the Earth was created only 10,000 years ago. But strict scientific dating techniques show that the Earth is billions of years old. Similarly, some physicists and cosmologists claim that the laws of nature, the configuration of atoms, and the structure of the universe prove it was all created by a supernatural being. But science continues to show that everything from the simplest atoms to the most complex galaxies is explicable by natural laws, historical contingencies, and rules of self-organized complexity.

If, in the process of learning how to think scientifically and critically, someone comes to the conclusion that there is no God, so be it—but it is not our goal to convert believers into nonbelievers. From considerable personal experience I can attest to the futility of trying to either prove or disprove God (see Chapter 5). In any case, the process would seem inherently impossible since, by admission of nearly all religions, belief in God rests on faith and means suspending the requirements of proof and logic. When people say they believe in God because it comforts them, because they have faith, because of personal revelation, or just because it “works” for them, I have no qualms with these reasons. But when others say they can prove God, prove that their religion is the right one, prove that we cannot be moral without God, and so forth, such claims demand a scientific and rational analysis. Of course, if the answers to these arguments are as obvious and clear-cut as both theists and atheists think, then why do such debates continue, even in the hallowed halls of theological seminaries and universities, where presumably the question of God’s existence would have been resolved by now? It has not. That fact alone tells us something about the nature of the subject. So, I would have thought that any member of the Skeptics Society would be aware that God’s existence, from a scientific and rational perspective, remains an open question—it cannot be “proved” one way or the other. But I also would have imagined that Schlessinger, who is both highly intelligent and well educated, would have been equally aware and sensitive to this issue.

For those who may still be unfamiliar with her, Laura Schlessinger, best known as “Dr. Laura,” is the star and host of the top-rated nationally syndicated radio talk show program, running neck and neck with Rush Limbaugh for the number-one spot. She is in virtually every radio market in America, has millions of listeners, receives on average upwards of 60,000 calls per day, and in 1997 her program was sold for a staggering $71 million. Her books, Ten Stupid Things Women Do to Mess Up Their Lives, Ten Stupid Things Men Do to Mess Up Their Lives, How Could You Do That?, and The Ten Commandments, were all national bestsellers in both hardback and paperback. She draws huge crowds for her speaking engagements. “Dr. Laura” mugs, T-shirts, and newsletters are promoted daily through the radio program and an ever-growing mailing list of fans. She has been featured on several national newsmagazine and morning programs, and was even satirized in Playboy magazine. This is all to say that Laura Schlessinger is hugely influential. When she speaks, people listen.

We invited Laura to be on our board of advisors in 1994 when she took a skeptical stance about the recovered-memory movement and other “victimization” groups. We admired her courage to make a public statement against what in hindsight turned out to be a bad chapter in the history of psychology. At the time it was a very dangerous thing to denounce. (The “recovery” of distant memories of childhood sexual abuse usually turns out to be nothing more than the planting of “false” memories in patients by well-meaning but irresponsible therapists.) We invited Laura to speak for the Skeptics Society at Caltech. For nearly three hours (and without notes) she paced back and forth across the stage, educating and entertaining a sizeable audience. She was brilliant and funny. Most of all she was controversial. Schlessinger promotes critical thinking, independence of thought, self-reliance, and other attributes certainly admired by most free thinkers, humanists, and skeptics. Although she publicly ratcheted up the intensity of her religious convictions through 1996 and 1997 (when she converted to Judaism), and critical letters came pouring into Skeptic’s office, we continued to defend her because as a general principle we do not believe in excluding people from organizations based on their religious beliefs.

Imagine my surprise, then, when we received another fax four days later from Laura Schlessinger herself, who had just finished reading the issue of Skeptic entitled “The God Question.” The fax read:

Please remove my name from your Editorial Board list published in each of your Skeptic Magazine issues immediately. Science can only describe what; guess at why; but cannot offer ultimate meaning. When man’s limited intellect has the arrogance to pretend an ability to analyze God, it’s time for me to get off that train.

A voice-mail message followed, reinforcing the seriousness of her resignation. Amazed at this conjunction of ironic events, I called Laura at her home that same morning and spoke with her at length. She made it clear and in no uncertain terms (as Laura does with such effectiveness on her radio show) that she was “offended” by our issue and that God was off limits to human reason and inquiry. There is a God. Period. End of discussion. I pointed out that we had gone out of our way not to offend, and that, in fact, the arguments and critiques that we presented came from some of the greatest theologians and philosophers over the past two thousand years. Arrogant all, she responded. God is not open for analysis. But Which God, I inquired? There is only one God, she explained—the God of Abraham (she clarified this to mean monotheism—Christianity and Islam included—not just Judaism). But what about the Problem of Evil and the Problem of Free Will, I asked. Laura’s rapid-fire answers to these timeless problems of theology told me that this was not the first time she had spoken about them.

Our conversation wove in and out of a number of deep philosophical and moral issues—issues Laura had clearly contemplated for much of her adult life. In her twenties, she admitted, she was an atheist, not unhappy but certainly not a fulfilled individual. But now she is a theist and claims to have found not only greater happiness but also completeness as an individual. She said she can now stand on moral terra firma, the very basis of her radio success. In fact, she has essentially shifted her radio show emphasis from psychological advice to moral counseling—callers are now instructed to preface their question with “my moral dilemma is this … .” Laura then helps them resolve the dilemma, often with sage advice from the good book.

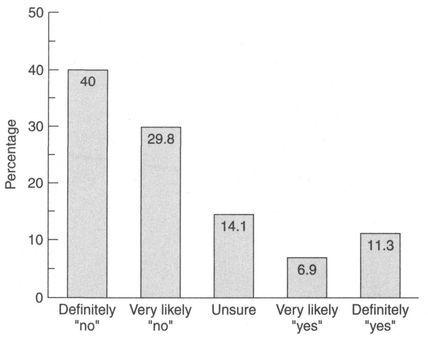

Dr. Laura believes in God. More than that, she knows God exists. Her level of doubt must be as close to zero as a belief system can get. And she is not alone. In fact, most believers in God stand very firm in the conviction of their belief. Why?

GENESIS TO REVELATION

Why people believe in God is a specific subject I address to get at a deeper one: how we believe. If this were just a generic book on the psychology of belief systems, however, there would be little concern for controversy or emotional reaction. But this book is more than that, a lot more. So my moral dilemma is this: How can we have a dialogue about the God Question and keep our emotions in check? As I will explain in the next chapter, I am an agnostic who has no ax to grind with believers, and I hold no grudge against religion. My only beef with believers is when they claim they can use science and reason to prove God’s existence, or that theirs is the One True Belief; my only gripe with religion is when it becomes intolerant of other peoples’ beliefs, or when it becomes a tool of political oppression, ideological extremism, or the cultural suppression of diversity. I am unabashedly interested in understanding how and why any of us come to our beliefs, how and why religion evolved as the most powerful institution in human history, and how and why belief (or lack of) in God develops and shapes our thoughts and actions. One prominent scientist told me “you have a rather conciliatory attitude toward religion,” and after reading an early draft of this book noted: “You seem to be saying it is okay for people to believe in God.” Of course, whether I say it is okay for people to believe in God or not, they will believe (or not) regardless. My primary focus in addressing readers is not whether they believe or disbelieve, but how and why they have made their particular belief choice. Within the larger domain of how we believe, I am mainly interested in three things: (1) Why people believe in God; (2) the relationship of science and religion, reason and faith; and (3) how the search for the sacred came into being and how it can thrive in an age of science.

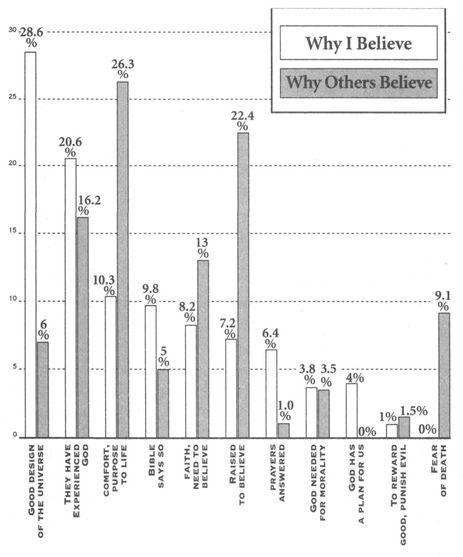

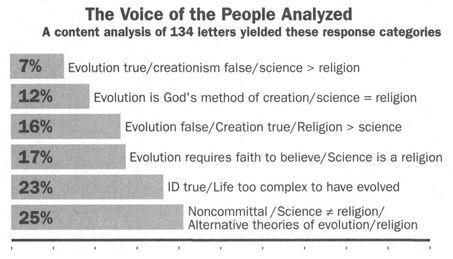

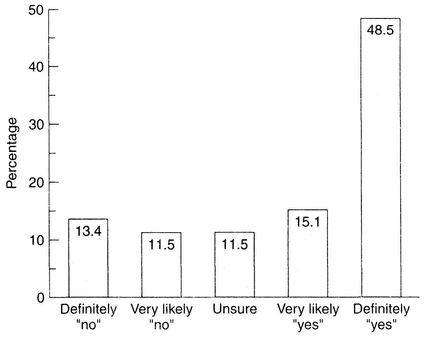

The intellectual and spiritual quest to understand the universe and our place in it is the foundation of the God Question, the various answers to which are explored in the first chapter of this book, including theist, agnostic, nontheist, and atheist, along with the differences these positions make in our thinking about the question. At the beginning of the twentieth century social scientists predicted that belief in God would decrease by the end of the century because of the secularization of society. In fact, as the second chapter shows, the opposite has occurred. Never in history have so many, and such a high percentage of the population, believed in God. Not only is God not dead, as Nietzsche proclaimed, but he has never been more alive. To find out why, the “Belief Engine” is considered in the third chapter as the mechanism by which any of us come to believe in anything, including and especially the magical thinking that leads millions of people to believe in psychics and mediums who claim that they can talk to the dead in heaven. To get at the core of the God Question and why people believe, the fourth chapter presents the results of an empirical study that asked a random sampling of the population that very question. The results were most enlightening, not only in the reasons people give for belief in God (made especially poignant when contrasted with why we think other people believe in God) but also in the quality and depth of the answers given (often in multipage, single-spaced typed letters), showing that the God Question is one of the most compelling any of us can ask ourselves.

It turns out that the number-one reason people give for why they believe in God is a variation on the classic cosmological or design argument: The good design, natural beauty, perfection, and complexity of the world or universe compels us to think that it could not have come about without an intelligent designer. In other words, people say they believe in God because the evidence of their senses tells them so. Thus, contrary to what most religions preach about the need and importance of faith, most people believe because of reason. So the fifth chapter reviews the various proofs of God, from those presented by medieval philosophers to those proffered by modern creationists, and considers what these arguments, and their employment in the service of religious belief, tell us about faith.

This relationship between science and religion, reason and faith, the subject of the sixth chapter, has once again emerged to the forefront of cultural importance due to a conjuncture of events, including the millennium that beckons us to reconsider the meaning of the past and future and the relative roles of science and religion in history; the discovery by physicists that the universe is more finely tuned and delicately balanced than we ever realized; the magnificent photographs of the universe made by the Hubble Space Telescope revealing an almost spiritual beauty of the cosmos as never seen before; and the issuance by the Pope of two statements, one acknowledging the validity of the theory of evolution and the other endorsing the successful marriage of fides et ratio, faith and reason.

Because humans are storytelling animals, a deeper aspect of the God Question involves the origins and purposes of myth and religion in human history and culture, the subject of the seventh, eighth, and ninth chapters. Why is there an eternal return of certain mythic themes in religion, such as messiah myths, flood myths, creation myths, destruction myths, redemption myths, and end of the world myths? What do these recurring themes tell us about the workings of the human mind and culture? What can we learn from these myths beyond the moral homilies offered in their narratives? What can we glean about ourselves as we gaze into these mythic mirrors of our souls?

Not only are humans storytelling animals, we are also pattern-seeking animals, and there is a tendency to find patterns even where none exists. To most of us the patterns of the universe indicate design. For countless millennia, we have taken these patterns and constructed stories about how our cosmos was designed specifically for us. For the past few centuries, however, science has presented us with a viable alternative in which we are but one among tens of millions of species, housed on but one planet among many orbiting in an ordinary solar system, itself one among possibly billions of solar systems in an ordinary galaxy, located in a cluster of galaxies not so different from billions of other galaxy clusters, themselves whirling away from one another in an expanding cosmic bubble that very possibly is only one among a near-infinite number of bubble universes. Is it really possible that this entire cosmological multiverse exists for one tiny subgroup of a single species on one planet in a lone galaxy in that solitary bubble universe? The final chapter explores the implications of this scientific worldview and what it means to fully grasp the nature of contingency—what if the universe and the world were not created for us by an intelligent designer, and instead is just one of those things that happened? Can we discover meaning in this apparently meaningless universe? Can we still find the sacred in this age of science?

To help me answer these questions a number of people have been highly influential in my thinking and writing, both directly and indirectly. The ultimate genesis of my beliefs, as it is for all of us of course, is parental, so I thank my mother, Lois, my stepfather, Dick, my late father, Richard, and my stepmother, Betty, for raising me in an atmosphere open and uncritical toward both religious and secular beliefs; I truly had a free choice in the matter, as it should be for all children. For introducing me to Christianity in my youth I thank the Oakleys: George, Marilyn, George, and Joyce (though they are not to be blamed for my subsequent fall from grace). At Glendale College Professor Richard Hardison was especially effective in helping me think clearly about philosophy and theology, particularly with regard to reason and faith; and at Pepperdine University Professor Tony Ash’s courses on Jesus the Christ and the writings of C. S. Lewis awakened me to the depth and seriousness of Christian theology and apologetics. The primary credit (or blame, depending on your perspective) for my turn toward science and secular humanism in graduate school goes to Professors Bayard Brattstrom, Meg White, and Doug Navarick at the California State University—Fullerton, whose passion for science made me realize that no religion could come close to the epic narratives told by cosmologists, evolutionary biologists, and social scientists about the origins and evolution of the cosmos, life, behavior, and civilization.

Over the past two decades countless conversations with hundreds of people have helped me sort out some answers to these deep religious and philosophical questions, but those most directly affecting the development of this book include Skeptic magazine editors and board members David Alexander, Tim Callahan, Napoleon Chagnon, Gene Friedman, Nick Gerlich, Penn Jillette, Gerald Larue, Bernard Leikind, Betty McCollister, Tom McDonough, Sara Meric, Richard Olson, Donald Prothero, Vincent Sarich, Jay Snelson, Carol Tavris, Teller, and Stuart Vyse. As always I acknowledge the support of the Skeptics Society and Skeptic magazine provided by Dan Kevles, Susan Davis, and Chris Harcourt at the California Institute of Technology; Larry Mantle, Ilsa Setziol, Jackie Oclaray, and Linda Othenin-Girard at KPCC 89.3 FM radio in Pasadena; Stan Hynds and Linda Urban at Vroman’s bookstore in Pasadena; as well as those who help at every level of our organization, including Jane Ahn, Jaime Botero, Jason Bowes, Jean Paul Buquet, Bonnie Callahan, Cliff Caplan, Randy Cassingham, Amanda Chesworth, Shoshana Cohen, John Coulter, Brad Davies, Clayton Drees, Janet Dreyer, Bob Friedhoffer, Jerry Friedman, Sheila Gibson, Michael Gilmore, Tyson Gilmore, Steve Harris, Andrew Harter, Laurie Johansen, Terry Kirker, Diane Knudtson, Joe Lee, Tom McIver, Dave Patton, Rouven Schaefer, Brian Siano, and Harry Ziel.

I am especially grateful for the additional input provided by my agents Katinka Matson and John Brockman, my editor John Michel and my publicist Sloane Lederer at W. H. Freeman and Company (as well as Diane Maass, Peter McGuigan, and all the folks in production at this fine publishing house); as well as Louise Ketz and Simone Cooper; and for taking the time to read individual chapters or provide valuable feedback on my thinking I thank Richard Abanes, Michele Bonnice, Richard Dawkins, Jared Diamond, Richard Elliott Friedman, Ursula Goodenough, Alex Grobman, Donald Johanson, Elizabeth Knoll, J. Gordon Melton, Massimo Pigliucci, Michael Ruse, Eugenie Scott, Nancy Segal, Frank Tipler, Bob Trivers, Edward O. Wilson, and Rabbi Edward Zerin. Bruce Mazet and Frank Miele both went above and beyond the call of duty to both critique and support my efforts to grasp the deeper meaning of the God Question; and James Randi, as always, serves as inspiration requiring perspiration to keep up with his tireless efforts to keep us on our intellectual toes.

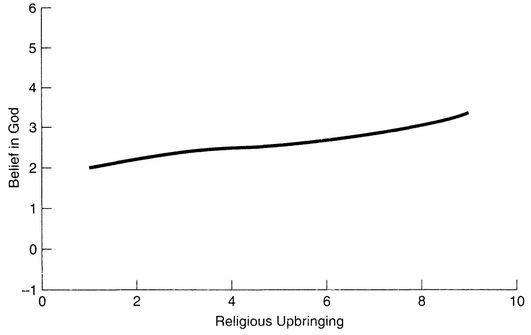

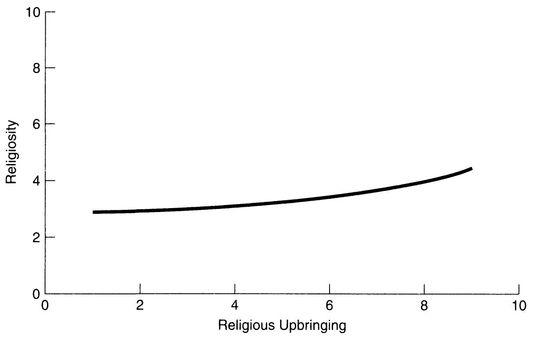

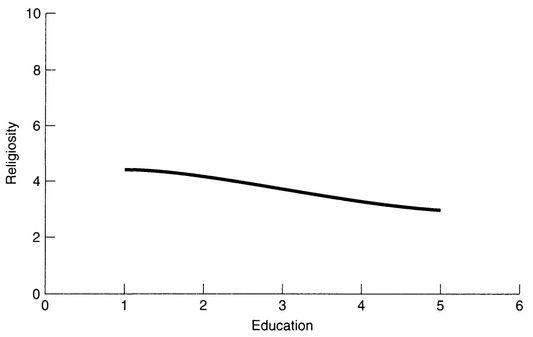

The influence of Frank Sulloway on my thinking is immeasurable, but not his effect on this book, especially Chapter 4 and our corroboration on the study of religious attitudes, which can be measured precisely and significantly at three sigmas above the mean. I am also deeply appreciative of my Skeptics Society partner Pat Linse, not only for her brilliant artwork and design of Skeptic magazine and for preparing all of the illustrations for this book, but also for the conversations on God and religion that have kept in check my occasional paroxysms of irritations with religion.

Finally, I thank Kim for being my wife, confidante, and best friend who has refereed the countless wrestling matches that go on in my mind about the timeless questions that concern us all; and Devin (although she had no choice in the matter) for being my daughter, joy, and source of mind-cleansing play so necessary to get rid of the cognitive clutter that goes with research and writing.

When we began the Skeptics Society and Skeptic magazine in 1992 we adopted a quote from the seventeenth-century philosopher and religious thinker Baruch Spinoza: “I have made a ceaseless effort not to ridicule, not to bewail, not to scorn human actions, but to understand them.” When it comes to religion it is especially difficult for any of us to apply this principle consistently. But if we do, the moral dilemma of how to discuss the God Question without offense may be resolved. As my friend and colleague Stephen Jay Gould told me: “You cannot understand the human condition without understanding religion or religious arguments.”

I hope that this book in some small way adds to our understanding of the human condition.

INTRODUCTION TO THE PAPERBACK EDITION

The Gradual Illumination of the Mind

Reconsiderations and Recapitulations on the God Question

It appears to me (whether rightly or wrongly) that direct arguments against christianity and theism produce hardly any effect on the public; and freedom of thought is best promoted by the gradual illumination of men’s minds which follows from the advance of science.

—Charles Darwin

In the first edition of this book I wrote on page xv of the Preface: “Of course it is okay for people to believe in God; moreover, people will believe regardless of what I say or think.” The second part of this sentence can be verified, since God’s ratings have not slipped in the polls one iota since How We Believe was first released in October 1999. In fact, a March 2000 poll from Gallup shows that, as always, belief in God remains potent, not only in America but worldwide:

—Belief in God: Even when Gallup added the option for respondents that they “don’t believe in God, but believe in a universal spirit or higher power,” only eight percent chose that response with 86 percent saying that they believe in God. Gallup added: “In fact, only five percent of the population choose neither of these choices and thus claim a more straightforward atheist position.”

—Church Attendance: Although less than the percentage of people who believe in God, “about two-thirds of the population claim to attend services at least once a month or more often,” Gallup said, while “thirty-six percent say they attend once a week.” By contrast, only 8 percent say they never attend religious services, while 28 percent report that they “seldom” go.

—Church Membership: Matching the figures for church attendance, two-thirds of Americans say they are members of a church or some other religious institution. “Only nine percent of the public respond with ‘none’ when asked to identify a religious affiliation or preference,” Gallup concluded.

—Importance of Religion: Americans match people in other countries in ranking religion as very or fairly important in their lives. In a joint study between Gallup International and the London-based Taylor Nelson Sofres marketing firm covering 60 countries, 87 percent said that they consider themselves to be part of some religion. In America 60 percent say that religion is “very important in their life,” with another 30 percent saying that it is “fairly important.”

—God and Politics: Since 2000 is a presidential election year, Gallup found that 52 percent of voters surveyed “would be more likely to vote for a candidate for president who has talked about his or her personal relationship with Jesus Christ during debates and news interviews.” As anyone who watched the presidential debates knows, all the candidates went on public record to extol their Christian beliefs, including the Democratic candidate Al Gore, not exactly known for his conservatively religious views. On the Republican side, George W. Bush announced that he considered Jesus to be the most influential philosophical thinker in his life.

SKEPTICISM AS A VIRTUE

Is it okay for people to believe in God? A number of atheists objected to this statement. One wrote me: “Religion is a bad idea. Belief in god is a bad idea. These ideas should be self-evident to any rationalist. That religion/belief is common is not a reason to avoid such statements. That religion/belief will perhaps always be with us is not a reason. That religion/belief is old is not a reason. That religion/belief may at times do some good is not a reason. None of these statements are reasons to avoid clearly stating the truth. Anything less is duplicitous, disingenuous, appeasing—and ultimately, helps the other side by providing approval where disapproval should instead be offered.”

“The other side.” What a revealing way to phrase a critical attitude toward religion, whose long history of dividing the world between “our side” and the “other side” is a notoriously bloody one. Should nonbelievers really ape this most nonsalubrious side of the system of belief from which they so often distance themselves? Clearly religion has no monopoly here. The very propensity to cleave nature into unambiguous yeses and noes may very well be an evolutionary by-product whose ultimate outcome could result in the extinction of the species (and a further indication that not everything in evolution can be explained by its adaptive significance).

Another friend who objected to my “okay to believe” statement spelled it out even clearer: “I won’t let anyone who believes in god in my home. I won’t sleep with them and I have none in my social circle. But I can do more.” What “more” shall we do? What more can we do? Should we evangelize against Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and the other systems of religious belief? Since I am a libertarian in more ways than just political, I am disinclined to tell people what they should or should not be doing with their personal lives and beliefs. Nevertheless, I am a scientific and skeptical activist (not just a dispassionate onlooker from the intellectual sidelines), so I am forced on a daily basis to attempt to dissuade people from their less rational beliefs. How to reconcile these competing motives? Through a positive push-forward program instead of a negative push-back agenda. Evangelize for science rather than rail against religion. Don’t curse the darkness; light a candle. Charles Darwin, who renewed the science-religion debate nearly a century and a half ago, expressed this position well in the epigraph above.

Nevertheless please note that in this edition of the book I changed the phrase to read that it is okay not to believe in God. By this statement I am speaking to those atheists, nontheists, and nonbelievers of all stripes as a form of validation from a fellow free-thinker; I am also reaching out to theists and believers of all faiths who, occasionally or even frequently, doubt their faith. Doubt is good. Questioning belief is healthy. Skepticism is okay. It is more than okay, in fact. Skepticism is a virtue and science is a valuable tool that makes skepticism virtuous. Science and skepticism are the best methods of determining how strong your convictions are, regardless of the outcome of the inquiry. If you challenge your belief tenets and end up as a nonbeliever, then apparently your faith was not all that sound to begin with and you have improved your thinking in the process. If you question your religion but in the end retain your belief, you have lost nothing and gained a deeper understanding of the God Question. It is okay to be skeptical.

In light of Darwin’s wise advice, why, one may ask, do I devote an entire chapter (2) to a head-on confrontation of the alleged proofs of God’s existence? The reason is that my laissez-faire attitude toward other people’s religious beliefs ends when they use, misuse, and abuse reason and science in the service of faith and religion. As even libertarians will admit, your freedom to swing your fist ends at my nose. Claims that religious tenets can be proved through science require a response from the scientific community. Making evidentiary claims puts religion on science’s turf, so if it wants to stay there it will have to live up to the standards of scientific proof. This is not an archaic academic or philosophical issue. As I show in Chapter 4, the scientistically based “design argument” is the most common one made. People say they believe in God because of the evidence of their senses and their understanding of how the world works. In other words, they give reasons for their beliefs. What are those reasons? If they are good reasons shouldn’t we all become believers?

GOD AND THE INTELLIGENTLY DESIGNED UNIVERSE

The hottest area in the search for scientific support of God’s existence can be found in the so-called “new creationism” that deals in “irreducible complexity” and especially “Intelligent Design” (ID as it is known among its adherents). Although I discuss these at length in Chapter 5, they continue to generate so much attention that it is worth expanding on it more here. It is rapidly becoming the strongest scientistic argument for believers. For example, I participated in two scientific debates on ID in 2000, a number of new books on it have been released by Christian publishers since my book came out, and an entire issue of the Christian magazine Touchstone was devoted to Intelligent Design, “a new paradigm in science that could revolutionize the way we view creation, the cosmos, and ourselves.”

Much is made of the fact that the universe is grandly complex, intricate, and apparently delicately balanced for carbon-based life forms such as ourselves. It is here where science and religion meet, say believers who wish to graft the findings of science onto 4,000-year-old religious doctrines. And they have no difficulty in finding observations from leading scientists that seemingly support their contention that the universe does not just look designed, it is designed. “It is not only man that is adapted to the universe,” John Barrow and Frank Tipler proclaim in The Anthropic Cosmological Principle, “The universe is adapted to man. Imagine a universe in which one or another of the fundamental dimensionless constants of physics is altered by a few percents one way or the other? Man could never come into being in such a universe. That is the central point of the anthropic principle. According to the principle, a life-giving factor lies at the center of the whole machinery and design of the world.” For theists, of course, that life-giving factor is God.

The Templeton Foundation has spent tens of millions of dollars promoting a reconciliation between science and religion, including the grant of the single largest cash prize in history for “progress in religion.” On the day I wrote this introduction, in fact, it was announced that physicist Freeman Dyson won the prize valued at $964,000, for such works as Disturbing the Universe, one passage of which is often quoted by ID theists: “As we look out into the universe and identify the many accidents of physics and astronomy that have worked to our benefit, it almost seems as if the universe must in some sense have known that we were coming.” Mathematical physicist Paul Davies also won the Templeton prize, and we can understand why in such passages as this from his 1999 book The Fifth Miracle:

In claiming that water means life, NASA scientists are … making—tacitly—a huge and profound assumption about the nature of nature. They are saying, in effect, that the laws of the universe are cunningly contrived to coax life into being against the raw odds; that the mathematical principles of physics, in their elegant simplicity, somehow know in advance about life and its vast complexity. If life follows from [primordial] soup with causal dependability, the laws of nature encode a hidden subtext, a cosmic imperative, which tells them: “Make life!” And, through life, its by-products: mind, knowledge, understanding. It means that the laws of the universe have engineered their own comprehension. This is a breathtaking vision of nature, magnificent and uplifting in its majestic sweep. I hope it is correct. It would be wonderful if it were correct.

Indeed, it would be wonderful. But not any more wonderful than if it were not correct. If life on Earth is unique, or at least exceptionally rare (and in either case certainly not inevitable, as I demonstrate in the final chapter), how special is our fleeting Mayfly-like existence; how important it is that we make the most of our lives and our loves; how critical it is that we work to preserve not only our own species, but all species and the ecosystem itself. Whether the universe is teaming with life or we are alone, whether our existence is strongly necessitated by the laws of nature or it is highly contingent, whether there is more to come or this is all there is, either way we are faced with a worldview that is equally breathtaking and majestic in its sweep across time and space.

In the Touchstone issue on Intelligent Design, Whitworth College philosopher Stephen Meyer argues that ID is not simply a “God of the gaps” argument to fill in where science has yet to give us a satisfactory answer. It is not just a matter of “we don’t understand this so God must have done it” (although to me, and to all scientists I have spoke to about ID, this is how these arguments always appear). ID theorists like Meyer and Phillip Johnson, William Dembski, Michael Behe, and Paul Nelson (all leading IDers and contributors to this issue) say they believe in ID because the universe really does appear to be designed. “Design theorists infer a prior intelligent cause based upon present knowledge of cause-and-effect relationships,” Meyer writes. “Inferences to design thus employ the standard uniformitarian method of reasoning used in all historical sciences, many of which routinely detect intelligent causes. Intelligent agents have unique causal powers that nature does not. When we observe effects that we know only agents can produce, we rightly infer the presence of a prior intelligence even if we did not observe the action of the particular agent responsible.” Even an atheist like Stephen Hawking can be found to present cosmological arguments seemingly supportive of scientistic arguments for God’s existence:

Why is the universe so close to the dividing line between collapsing again and expanding indefinitely? In order to be as close as we are now, the rate of expansion early on had to be chosen fantastically accurately. If the rate of expansion one second after the big bang had been less by one part in 1010, the universe would have collapsed after a few million years. If it had been greater by one part in 1010, the universe would have been essentially empty after a few million years. In neither case would it have lasted long enough for life to develop. Thus one either has to appeal to the anthropic principle or find some physical explanation of why the universe is the way it is.

That explanation, at the moment, is a combination of a number of different concepts revolutionizing our understanding of evolution, life, and cosmos, including the possibility that our universe is not the only one. We may live in a multiverse in which our universe is just one of many bubble universes all with different laws of nature. Those with physical parameters like ours are more likely to generate life than others. But why should any universe generate life at all, and how could any universe do so without an intelligent designer? The answer can be found in the properties of self-organization and emergence that arise out of what are known as complex adaptive systems, or complex systems that grow and learn as they change. Water is an emergent property of a particular arrangement of hydrogen and oxygen molecules, just as consciousness is a self-organized emergent property of billions of neurons. The entire evolution of life can be explained through these principles. Complex life, for example, is an emergent property of simple life: simple prokaryote cells self-organized to become more complex units called eukaryote cells (those little organelles inside cells you had to memorize in beginning biology were once self-contained independent cells); some of these eukaryote cells self-organized into multi-cellular organisms; some of these multi-cellular organisms self-organized into such cooperative ventures as colonies and social units. And so forth. We can even think of self-organization as an emergent property, and emergence as a form of self-organization. How recursive. No Intelligent Designer made these things happen. They just happened on their own. Here’s a bumper sticker for evolutionists: Life Happens. In The Life of the Cosmos, cosmologist Lee Smolin explains how this property of emergence and self-organization out of complexity works:

It seems to me quite likely that the concept of self-organization and complexity will more and more play a role in astronomy and cosmology. I suspect that as astronomers become more familiar with these ideas, and as those who study complexity take time to think seriously about such cosmological puzzles as galaxy structure and formation, a new kind of astrophysical theory will develop, in which the universe will be seen as a network of self organized systems. Many of the people who work on complexity … imagine that the world consists of highly organized and complex systems but that the fundamental laws are simply fixed beforehand, by God or by mathematics. I used to believe this, but I no longer do. More and more, what I believe must be true is that there are mechanisms of self-organization extending from the largest scales to the smallest, and that they explain both the properties of the elementary particles and the history and structure of the whole universe.

There may even be a type of natural selection at work among many universes, with those whose parameters are like ours being most likely to survive. Those universes whose parameters are most likely to give rise to life occasionally generate complex life with brains big enough to achieve consciousness and to conceive of such concepts as God and cosmology, and to ask such questions as Why?

REASONS TO BELIEVE

Self-organization, emergence, and complexity theory form the basis of just one possible natural explanation for how the universe and life came to be the way it is. But even if this explanation turns out to be wanting, or flat-out wrong, what alternative do Intelligent Design theorists offer in its stead? If ID theory is really a science, as they claim it is, then what is the mechanism of how the Intelligent Designer operated? ID theorists speculate that four billion years ago the Intelligent Designer created the first cell with the necessary genetic information to produce all the irreducibly complex systems we see today. But then, they tell us, the laws of evolutionary change took over and natural selection drove the system, except when totally new and more complex species needed creating. Then the Intelligent Designer stepped in again. Or did He (She? It?)? They are not clear. Did the Intelligent Designer—let’s call it ID—create each genus and then evolution created the species? Or did ID create each species and evolution created the subspecies? ID theorists seem to accept natural selection as a viable explanation for microevolution—the beak of the finch, the neck of the giraffe, the varieties of subspecies found in most species on earth. If ID created these species why not the subspecies? And how did ID create the species? We are not told. Why? Because no one has any idea but you can’t just say, “God did it.”

I presented all these challenges to the leading Intelligent Design theorists at a June 2000 conference at Concordia University (Wisconsin) on “Intelligent Design and Its Critics.” Although there were some critics there, both on stage and in the audience, it was mostly populated by ID supporters. The conference was partially sponsored by the Templeton Foundation, and was clearly structured to make it appear that there is a real scientific debate ongoing about Intelligent Design. However, as I pointed out in my opening remarks, the conference was being held at a Lutheran college and just before I was introduced they announced what time chapel was the next morning and how we can obtain transportation to it. Virtually every ID supporter turns out to be a born-again Christian. Can this really be a coincidence? For these remarks I was later accused of committing the “genetic fallacy,” where one attacks the person rather than their arguments. Nevertheless, my participation at this conference was a debate in which I did address many of their points.

It is not coincidental that ID supporters are almost all Christians. It is inevitable. ID arguments are reasons to believe if you already believe. If you do not, the ID arguments are untenable. But I would go further. If you believe in God, you believe for personal and emotional reasons (as I show in Chapter 4), not out of logical deductions. But this chapter also shows that highly educated believers, especially men who were raised religious, have a strong tendency to defend their beliefs with rational arguments. And looking out over an auditorium of about 250 ID supporters at this debate it was overwhelmingly educated males.

ID theorists also attack scientists’ underlying bias of “methodological naturalism.” That is, they feel it is not fair to forbid supernaturalism from the equation as it pushes them out of the scientific arena on the basis of nothing more than a rule of the game. But if we change the rules of the game to allow them to play, what would that look like? How would that work? What would we do with supernaturalism? ID theorists do not and will not comment on the nature of ID. They wish to say only “ID did it.” This is not unlike the famous Sidney Harris cartoon with the scientists at a chalkboard filled with equations: an arrow points to a blank spot in the series and denotes “Here a miracle happens.” Although IDers eschew any such “god of the gaps” style arguments, that is precisely what it all amounts to. They have simply changed the name from GOD to ID.

Let’s assume for a moment, though, that ID theorists have suddenly become curious about how ID operates. And let’s say that we have determined that certain biological systems are indeed irreducibly complex and intelligently designed. As ID scientists who are now given entree into the scientific stadium with the new set of rules that allows supernaturalism, they call a time-out during the game to announce “Here ID caused a miracle.” What do we do with supernaturalism in the game of science? Do we halt all future experiments? Do we continue our research and say “Praise ID” every couple of hours? The whole system collapses in a risible game of semantics.

GLADLY WOLDE WE LEARNE

If there is a God, He has yet to provide incontrovertible evidence of His existence, leaving belief in Him instead to lie in the realm of faith, or emotional preference, which is the very basis of the theological position known as fideism. Because I see this as the most tenable of all theistic possibilities, I have explored it further since I first wrote this book. As Martin Gardner, a fideist and believer in God, noted in his 1983 book The Whys of a Philosophical Scrivener: “If ‘evidence’ means the kind of support provided by reason and science, there is no evidence for God and immortality.” Gardner rejects the flood story (“even as a myth it is hard to admire the ‘faith’ of a man capable of supposing God could be that vindictive and unforgiving”), does not believe that God asked Abraham to kill his son (“Abraham appears not as a man of faith, but as a man of insane fanaticism”), and finds wanting most of the stories in the Bible: “The Old Testament God, and many who had great ‘faith’ in him, are alike portrayed in the Bible as monsters of incredible cruelty.”

If, as I argue in Chapter 4, beliefs are based on emotion rather than evidence, personality instead of reason, upbringing more than arguments, it would seem to vindicate Gardner’s fideism as the most honest of all the reasons to believe in God. In a personal aside, Gardner confesses that he does have some faith:

Let me speak personally. By the grace of God I managed the leap when I was in my teens. For me it was then bound up with an ugly Protestant fundamentalism. I outgrew this slowly, and eventually decided I could not even call myself a Christian without using language deceptively, but faith in God and immortality remained. The original leap was not a sharp transition. For most believers there is not even a transition. They simply grow up accepting the religion of their parents, whatever it is.

Gardner is, if nothing else, refreshingly honest about his faith: “The leap of faith, in its inner nature, remains opaque. I understand it as little as I understand the essence of a photon. Any of the elements I listed earlier as possible causes of belief, along with others I failed to list, may be involved in God’s way of prompting the leap. I do not know, I do not know!”[12] We do not know either, but we ought to be able to respect this honest appraisal of how and why you believe, and especially acknowledge what Gardner, as one of the chief teachers of science and skepticism, have offered us for enlightenment on the problem. As the clerk of Oxenford in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales proclaimed: “gladly wolde he lerne, and gladly teche.”

GOD AND BELIEF

R. Buckminster Fuller

Sometimes I think we’re alone.

Sometimes I think we’re not.

In either case, the thought is quite staggering.

DO YOU BELIEVE IN GOD?

The Difference in Our Answers and the Difference It Makes

The word God is used in most cases as by no means a term of science or exact knowledge, but a term of poetry and eloquence, a term thrown out, so to speak, as a not fully grasped object of the speaker’s consciousness,—a literary term, in short; and mankind mean different things by it as their consciousness differs.

—Matthew Arnold, Literature and Dogma, 1873

In my senior year of high school I accepted Jesus as my savior and became a born-again Christian. I did so at the behest of a close and trusted friend, who assured me this was the road to everlasting life and happiness. It was a Saturday night and we were sitting, ironically, at my father’s monkey-wood bar, fully equipped to allow a number of guests to imbibe just about any mixed drink their imaginations could create. We read John 3:16 (now infamous for its appearance on handprinted signs at nationally televised sporting events): “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.” At the moment of my conversion coyotes began howling outside. We took it as a sign that Lucifer was unhappy at the loss of another soul from Sheol.

The next day I attended church services with my friend and his family, and when the minister called for anyone to come forward to be saved, I went up to make it official. My friend assured me that I did not need to be saved twice, but I figured maybe it was more official at a church than at a bar. From that moment on everything seemed neatly explained by the Christian paradigm. Anytime something good happened, it was God’s will and a reward for good behavior; anytime something bad happened, it was part of God’s larger plan, and even though I did not at present understand the long-term benefits, these would become clear in due time. Either way it was a neat and tidy worldview—everything in its place and a place for everything.

The whole process was premised on faith. With faith in Jesus, I now had eternal life. With faith in God, I was saved. I had found the One True Religion, and it was my duty—indeed it was my pleasure—to tell others about it, including my parents, brothers and sisters, friends, and even total strangers. In other words, I “witnessed” to people—a polite term for trying to convert them (one wag called it “Amway with Bibles”). Of course, I read the Bible, as well as books about the Bible. I regularly attended youth church groups, one in particular at a place called “The Barn,” a large red house in La Crescenta, California, at which Christians gathered a couple of times a week to sing, pray, and worship. I got so involved that I eventually began to put on Bible study courses myself.

In my sophomore year at Glendale College I read Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth. The front cover of the book pronounced “AMAZING BIBLICAL PROPHECIES ABOUT THIS GENERATION!” (with “OVER 2,000,000 COPIES IN PRINT!”), while the back cover asked provocatively, “IS THIS THE ERA OF THE ANTICHRIST AS FORETOLD BY MOSES AND JESUS?” My Christian friends and I began reading the newspapers to watch the millennial drama unfold as Lindsey said the Bible had predicted. I recall taking a political science course in which the professor was talking about the possibility of a European Common Market, and comparing his take on this event to Lindsey’s, who claimed this is a reincarnation of the Roman Empire as prophesied in Daniel and the Book of Revelation: “We believe that the Common Market and the trend toward unification of Europe may well be the beginning of the ten-nation confederacy predicted by Daniel and the Book of Revelation.” Following this there will be “a revival of mystery Babylon,” and the rise of “a man of such magnetism, such power, and such influence, that he will for a time be the greatest dictator the world has ever known. He will be the completely godless, diabolically evil ‘future fuehrer.’” Skeptics beware, says Lindsey: “If this sounds rather spooky, bring your head out from under the skeptical covers and examine with us in a later chapter the Biblical basis and the current applications.” I threw the covers off and devoured the book with great credulity. So did millions of others: Through the 1970s The Late Great Planet Earth sold 7.5 million copies, making it, according to the New York Times Book Review (April 6, 1980), the bestselling nonfiction book of the decade. By 1991, notes the Los Angeles Times (February 23, 1991), the book had reached an almost unimaginable figure of 28 million copies sold in 52 languages worldwide. Prophecy sells, especially prophecies of biblical proportions.

Taking all this fairly seriously, I transferred to Pepperdine University (affiliated with the Church of Christ) with the intent of majoring in theology. I took courses in the Old and New Testaments, on the history of the Bible, the writings of C. S. Lewis, and the historical Jesus. I stayed after class to talk to professors and visited them in their offices. I went to chapel several times a week (students were required to go twice and attendance was taken) and prayed regularly. I even told one coed that I “loved” her—in the Christian sense of loving everyone—but I am afraid she took it the wrong way. (She needn’t have worried—students were prohibited from visiting the dorm rooms of members of the opposite sex, and such sin-provoking activities as dancing were forbidden.)

There were problems with my conversion from the beginning, however, and I think deep down on some level I must have known it. First, my motives for converting, while sincere later, were not quite as pure at the time—my friend had a sister that I wanted to get to know better and I figured this might help. On reflection, howling coyotes are not exactly unusual, since my parents’ home is nestled high up in the San Gabriel mountains of Southern California where coyotes routinely come down from the hills to rummage through trash cans. More importantly, there were chinks in the armor: Another friend at my high school told me I had chosen the wrong path and that his faith, Jehovah’s Witnesses, was the One True Religion, making me wonder how another religion could be as certain it had the truth as my newfound one did. I was generally uncomfortable witnessing to people, especially strangers. And the normal sexual urges that overwhelm teenagers created intense conflict and frustration.

There were philosophical problems as well. I recall spending an afternoon with a Presbyterian minister whose deep wisdom I greatly respected, going over and over what is known as the “Problem of Free Will”: If God is omniscient (all knowing) and omnipotent (all powerful), then how can we be held responsible for making “choices” we could not possibly have made? If we do have free will, does this mean God is limited in knowledge or power? And if God is limited, what else can He not do? The minister, who had a Ph.D. in theology, did his best to address the problem but it all seemed like labyrinthine word games and obfuscating analogies to me. For example: “Imagine history as one long film, which God has already seen but we, the characters in the film have not, so our actions ‘seem’ free even though they are predestined.” Or: “God is outside of space and time so the normal laws of cause and effect do not apply to Him.”

Similarly, with one of my Pepperdine professors I grappled with what is known as the “Problem of Evil”: If God is omnibenevolent (all good) and omnipotent, then why is there evil in the world? If He allows evil, then He is not all good. If He cannot help but allow evil, then He is not all powerful. The best book I have read on this problem is Harold Kushner’s When Bad Things Happen to Good People, but his solution—“God can’t do everything, but he can do some important things”—is not how most people conceive of the “almighty.”

To this day I have not heard an answer to the Problem of Evil that seems satisfactory. As with the Problem of Free Will, most answers involve complicated twists and turns of logic and semantic wordplay. One answer, for example, is based on a fundamental assumption of logic that no set may have itself as its own subset—God cannot create a stone so heavy that He cannot lift it. Likewise, God cannot be encompassed in the subset of evil. Evil, like heavy stones, exists independently of the larger set of God, even though remaining within that set. Another riposte involves explaining specific historical evils, like the Holocaust, where one answer is that “humans committed these evil acts, not God.” But all this avoids the problem altogether: Either God allowed Nazis to kill Jews, in which case He is not omnibenevolent, or God could not prevent Nazis from killing Jews, in which case He is not omnipotent. In either case God is not the plenipotent Yahweh of Abraham, the King of Kings and Lord of Lords Sovereign of the Universe. Or, in explaining the death of innocent children from cancer or automobile accidents, one rejoinder is that “God has a bigger plan for us and we shall grow and learn from this experience.” The problem here is that no matter what happens—good things or bad things—God’s intentions can be inferred. Everything that happens is attributed to God, and this just puts us back to where we started with God either unable or unwilling to take action or prevent the evil.

At Glendale College I challenged my philosophy professor (and now my friend) Richard Hardison, to read The Late Great Planet Earth, believing he would see the light. Instead he saw red and hammered out a two-page, single-space typed list of problems with Lindsey’s book. I still have the list, folded and tucked neatly into my copy of the book. Hardison took no prisoners. For example, where Lindsey writes, “When a prophet speaks in the name of the Lord, if the word does not come to pass or come true, that is a word which the Lord has not spoken,” Hardison notes that this creates an “inevitable precision, since we disregard those prophesies that don’t occur.” On page 40 Lindsey explains that when reading the Bible we should “take every word at its primary, ordinary, usual, literal meaning,” yet on page 50 Lindsey says that “the bones coming together and sinews and flesh being put upon them” really means “the regathering of the people into a physical restoration of a national existence in Palestine. Isn’t it fascinating how graphic this physical analogy is?” Lindsey cannot have it both ways. On pages 55—56, Lindsey commits another logical fallacy: “Peter considered the certainty and relevance of the prophetic word to be the most important thing. He even warned that in ‘the latter times’ men posing as religious leaders would rise from within the Church and deny, even ridicule, the prophetic word (II Peter 2:1–3; 3:1–18) If you pass this book around to many ministers you’ll find how true this prediction has become.” Hardison notes that “denial of Lindsey’s position is thus impossible without proving oneself to be among those misguided persons that Peter warns about. This becomes a device to make Lindsey’s position nondisprovable.” Hardison concluded his analysis with this biting statement:

Of all Lindsey’s statements, the one I most want to quarrel with is found in the introduction: “There are many students who are dissatisfied with being told that the sole purpose of education is to develop inquiring minds. They want to find some of the answers to their questions—solid answers, a certain direction.” I think I can offer some possible explanations for this “egregious” development. But even more, I feel impelled to propose that such a student is dead.

Hardison’s analysis shook me up. I did not want to be a “dead” student in only my second year of college. So I continued reading what the great minds in history had to say about God. It was an illuminating experience that got me thinking about the concept of “believing” in God. What does it mean to believe in God or not to believe in God? Are these great questions about God’s existence answerable from a scientific perspective? Can reason alone help us arrive at solutions to the moral dilemmas of our lives? In short, does religion present us with soluble problems to be analyzed with the tools of observation and logic, or are these questions too subjective and too personal for us to come to a collective agreement on a solution?

The British Nobel laureate Sir Peter Medawar once described science as the “art of the soluble.” “No scientist is admired for failing in the attempt to solve problems that lie beyond his competence,” Medawar opined. “If politics is the art of the possible, research is surely the art of the soluble.” If science is the art of the soluble, religion is the art of the insoluble. God’s existence is beyond our competence as a problem to solve.

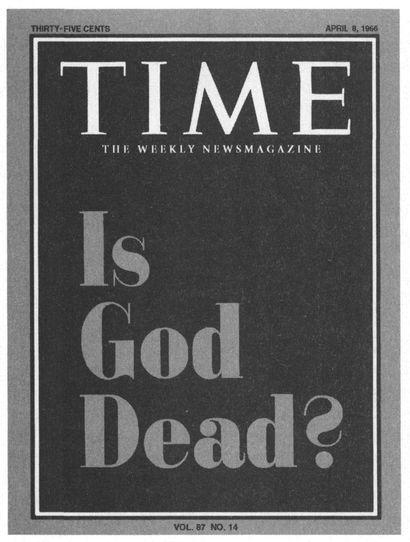

This is what Thomas Huxley meant when he coined the term agnostic in 1869: “When I reached intellectual maturity and began to ask myself whether I was an atheist, a theist, or a pantheist … I found that the more I learned and reflected, the less ready was the answer. They [believers] were quite sure they had attained a certain ‘gnosis,’—had, more or less successfully, solved the problem of existence; while I was quite sure I had not, and had a pretty strong conviction that the problem was insoluble.” In the now-classic 1966 Time magazine cover story, “Is God Dead?,” the editors came to the same conclusion after spending a year conducting more than 300 interviews with leading theologians from around the world:

For one thing, every proof seems to have a plausible refutation; for another, only a committed Thomist [a follower of the theology of St. Thomas Aquinas] is likely to be spiritually moved by the realization that there is a self existent Prime Mover [a first being that moves all others but itself does not need to be moved—see Chapter 5]. “Faith in God is more than an intellectual belief,” says Dr. John Macquarrie of Union Theological Seminary: “It is a total attitude of the self.”

One either takes the leap of faith or does not. Faith is the art of the insoluble.

There are many positions one can take with regard to the God Question (see the Bibliographic Essay at the end of this book for suggested readings on both the theist and atheist positions). The Oxford English Dictionary (OED), our finest source for the history of word usage, defines theism as implying “belief in a deity, or deities” and “belief in one God as creator and supreme ruler of the universe.” Atheism is defined by the OED as “disbelief in, or denial of, the existence of a God.” And agnosticism as implying “unknowing, unknown, unknowable.” At a party held one evening in 1869, Huxley further clarified the term agnostic, referencing St. Paul’s mention of the altar to “the Unknown God” as: “one who holds that the existence of anything beyond and behind material phenomena is unknown and so far as can be judged unknowable, and especially that a First Cause and an unseen world are subjects of which we know nothing.” Belief in God is the art of the insoluble.

To clarify this linguistic discussion it might be useful to distinguish between a statement about the universe and a statement about one’s personal beliefs. As a statement about the universe, agnostic would seem to be the most rational position to take because by the criteria of science and reason God is an unknowable concept. We cannot prove or disprove God’s existence through empirical evidence or deductive proof. Therefore, from a scientific or philosophical position, theism and atheism are both indefensible positions as statements about the universe. Thomas Huxley once again clarified this distinction:

Agnosticism is not a creed but a method, the essence of which lies in the vigorous application of a single principle. Positively the principle may be expressed as, in matters of the intellect, follow your reason as far as it can carry you without other considerations. And negatively, in matters of the intellect, do not pretend the conclusions are certain that are not demonstrated or demonstrable. It is wrong for a man to say he is certain of the objective truth of a proposition unless he can produce evidence which logically justifies that certainty.

Martin Gardner, mathematician, former columnist for Scientific American, and one of the founders of the modern skeptical movement, is a believer who admits that the existence of God cannot be proved. He calls himself a fideist, or someone who believes in God for personal or pragmatic reasons, and defended this position to me in an interview: “As a fideist I don’t think there are any arguments that prove the existence of God or the immortality of the soul. Even more than that, I agree with Unamuno that the atheists have the better arguments. So it is a case of quixotic emotional belief that is really against the evidence and against the odds.” Credo consolans, says Gardner—I believe because it is consoling. Fideism is the art of the insoluble.

As for my part, I used to be a theist, believing that God’s existence was soluble. Then I became an atheist, believing that God’s nonexistence was soluble. I am now an agnostic, believing that the issue is insoluble. Ever since I made my position known in the pages of Skeptic magazine many years ago, I have received a large volume of correspondence, much of it from atheists who accuse me of copping out or being wishy-washy in using the term agnostic. One wrote: “I, sir, am a plain unqualified atheist. Would you like to hear my reason? Okay, ‘there is no God.’ That’s my reason.” Most skeptics and atheists would agree and argue that there are really only two positions on the God Question: you either believe in God or you do not believe in God—theism or atheism. What’s this agnosticism nonsense, they ask?

If by fiat I had to bet on whether there is a God or not, I would bet that there is not. Indeed, I live my life as if there is no God. And if the common usage of the term atheism was nothing more than “no belief in a God,” I might be willing to adopt it. But this is not the common usage, as we saw in the OED. (And we would do well to remember that dictionaries do not give definitions, they give usages.) Atheism is typically used to mean “disbelief in, or denial of, the existence of a God” (not to mention its pejorative permutations). But “denial of a God” is an untenable position. It is no more possible to prove God’s nonexistence than it is to prove His existence. “There is no God” is no more defensible than “there is a God.” The problem with the term agnostic, however, is that most people take it to mean that you are unsure or have yet to make up your mind, so the term nontheist might be more descriptive.

Belief or disbelief in God is clearly a decision of considerable personal importance. But making this decision is not a science. For thousands of years the greatest minds of every generation have worked diligently to prove the existence of God, and for thousands of years equally great minds have produced valid refutations of those proofs. The problem may be in the meaning of the word prove. Drawing upon the OED once again, to “prove” means: “to make trial of, put to the test.” How could you possibly put God to the test? There is no conceivable experiment that could confirm or disconfirm God’s existence. There comes a time in the history of an idea when it seems reasonable to conclude that the problem is beyond the human mind to solve. God is insoluble.

Although it is almost certainly not possible to define God in any concise way, it would seem remiss not to at least try in any discussion such as this. Studies show that the vast majority of people in the Industrial West who believe in God associate themselves with some form of monotheism, in which God is understood to be all powerful, all knowing, and all good; who created out of nothing the universe and everything in it with the exception of Himself; who is uncreated and eternal, a noncorporeal spirit who created, loves, and can grant eternal life to humans. Synonyms include Almighty, Supreme Being, Supreme Goodness, Most High, Divine Being, the Deity, Divinity, God the Father, Divine Father, King of Kings, Lord of Lords, Creator, Author of All Things, Maker of Heaven and Earth, First Cause, Prime Mover, Light of the World, Sovereign of the Universe, and so forth.

Many scientists, however, feel that such discussions about the nature of and belief in God are meaningless, tantamount to asking, as anthropologist Donald Symons did, “Do you believe [fill in any three letters] exists?” Symons explained:

You have to know more about what’s in the brackets and how its existence or nonexistence might be determined or, at /east. what kinds of evidence might potentially bear on the question. If you find out that the questioner has essentially no ideas about the characteristics of the [ ] (such as, for example, whether it is made of matter), and, more importantly, states that no conceivable observation could have any bearing on the existence/nonexistence question, then to me the original question is meaningless, or incoherent, or empty, or some similar concept.

Vince Sarich, another anthropologist, feels that the God Question “may be one of those I have tended to term a ‘wrong question’; that is, one that wrongly assumes there is an answer in a form defined by the question.” In what way is it the wrong question? “Gods that live only in people’s heads are far more powerful than those that live ‘somewhere out there’ for the simple reasons that (1) there aren’t any of the latter variety around, and (2) the ones in our heads actually affect our lives and, of course, the lives of those we interact with and everything else we touch.” Therefore, Sarich concludes, “the whole God Question—atheist, agnostic, theist, whatever—is irrelevant.” How so?

What difference does it, or can it, make? Who cares? Who should care? Indeed, who even should care about anyone else’s answer to that particular question? That answer will in no sense begin to define what feelings you will have in any particular situation, nor even more important, what actions you will take on behalf of those feelings. The fact is that you will have, indeed you must have, a belief system that has moral and ethical dimensions, while you may, or may not justify that belief system, implicitly or explicitly, in terms of a God or gods. I believe that gods exist to the extent that people believe in them. I believe that we created gods, not the other way around. But that doesn’t make God any less “real.” Indeed, it makes God all the more powerful. So, yes, I believe in, and, maybe, to some extent fear, the God in your head, and all the gods in the heads of believers. They are real, omnipresent, and something approaching omnipotent.

This is what makes the God Question one of the most potent we can ask ourselves, because whether God really exists or not is, on one level, not as important as the diverse answers offered from the thousands of religions and billions of people around the world. To an anthropologist these differences are scientifically interesting in trying to understand the cultural causes of the diversity of belief. But from a believer’s perspective, the differences are emotionally significant because they tell us something about our personal values and commitments.

An even more extreme position with regard to the God question is that of Paul Tillich: “The question of the existence of God can be neither asked nor answered. If asked, it is a question about that which by its very nature is above existence, and therefore the answer—whether negative or affirmative—implicitly denies the nature of God. It is as atheistic to affirm the existence of God as it is to deny it. God is being-itself, not a being.” The God question cannot even be asked.

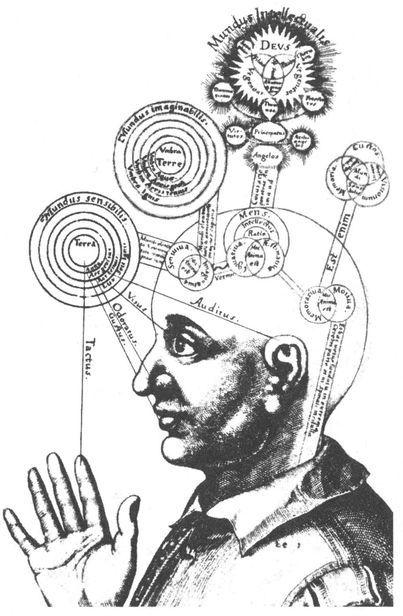

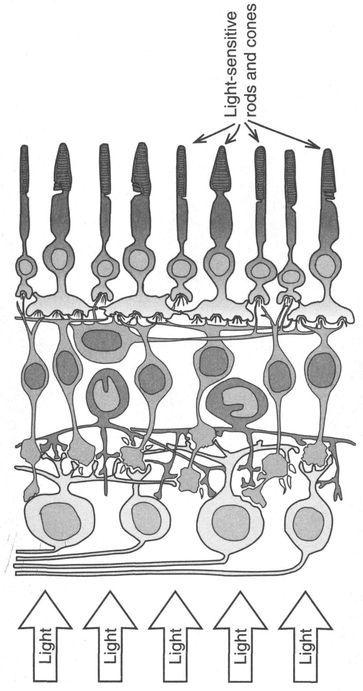

One problem with arguing God through a series of logical definitions and syllogisms is the impossibility of finding spiritual or emotional comfort in such a rational process. For most people God is not found in the sixth place after the decimal point. Another problem is the impossibility of comprehending something that is, by definition, incomprehensible. Whatever God is, if there is a God, He would be so wholly Other that no corporeal, time-bound, three-dimensional, nonomniscient, nonomnipotent, nonomnipresent being like us could possibly conceive of an incorporeal, timeless, dimensionless, omniscient, omnipotent, omnipresent being like God. It would be like a two-dimensional creature trying to grasp the meaning of three-dimensionality, an analogy a nineteenth-century Shakespeare scholar named Edwin Abbott put into narrative form in the splendid 1884 mathematical tale, Flatland. The story powerfully illuminates the insolubility of God’s existence and why faith instead of reason, religion instead of science, is the proper domain of God.

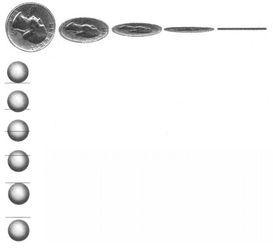

A human being trying to understand God is like a two-dimensional being trying to understand the third dimension. In his classic tale Flatland, Edwin Abbott describes such an existence, where a circle would only be perceived as a line. Watching a three-dimensional object such as a sphere pass through Flatland, a resident would see only a point and then a succession of circles growing larger at first and then smaller as it returns to a point before vanishing.

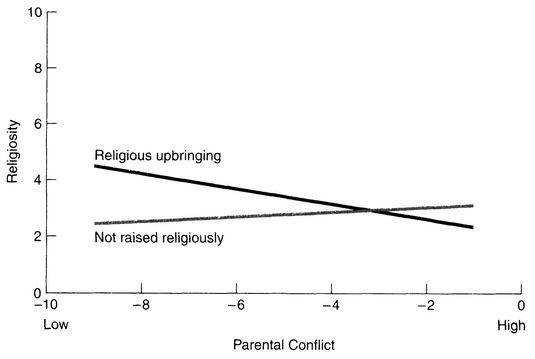

Abbott’s surrealistic story begins in a world of two dimensions, where the inhabitants—geometrical figures such as lines, triangles, squares, pentagons, hexagons, and circles—move left and right, forward or backward, but never “up or down.” Looking at a coin you can see the shapes within the circle, much like you could see the inhabitants of Flatland from Spaceland looking down; but if you turn the coin on its side, the interior disappears and you only see a straight line. This is what all geometrical shapes look like to Flatlanders.