Irrational Economist: Making Decisions in a Dangerous World – Read Now and Download Mobi

Comments

Table of Contents

RELIGION AND SUPERSTITION

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 2 - Berserk Weather Forecasters, Beauty Contests, and Delicious Apples ...

BERSERK WEATHER FORECASTERS

THE BEAUTY CONTEST AND DELICIOUS APPLE METAPHORS

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 3 - Subways, Coconuts, and Foggy Minefields

THE FAILURE OF DECISION THEORY

TWO TYPES OF UNCERTAINTY

COMMIT ONLY AS FAR AS YOU CAN PREDICT

FROM AIRPLANES TO FOGGY MINEFIELDS

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 4 - The More Who Die, the Less We Care

BACKGROUND AND THEORY: THE IMPORTANCE OF AFFECT

FACING CATASTROPHIC LOSS OF LIFE

THE DARFUR GENOCIDE

AFFECT, ANALYSIS, AND THE VALUE OF HUMAN LIVES

THE PSYCHOPHYSICAL MODEL

THE COLLAPSE OF COMPASSION

THE FAILURE OF MORAL INTUITION

WHAT TO DO?

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 5 - Haven’t You Switched to Risk Management 2.0 Yet?

MANAGING AND FINANCING EXTREME EVENTS: A NEW ERA CALLS FOR A NEW MODEL

A NEW RISK ARCHITECTURE IS STILL TO BE DEFINED

WHY BEING SELFISH TODAY MEANS TAKING CARE OF OTHERS . . .

RECOMMENDED READING

PART TWO - ARE WE ASKING THE RIGHT QUESTIONS? ECONOMIC MODELS AND RATIONALITY

WHAT IS EXPECTED UTILITY?

NORMATIVE DEBATES

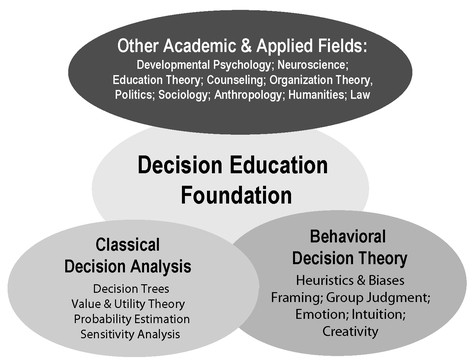

WHAT IS BEHAVIORAL DECISION THEORY?

LIMITS OF THE RATIONAL MODEL

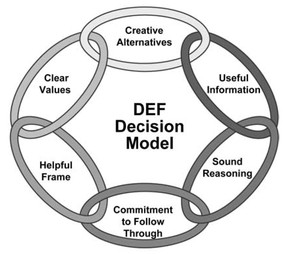

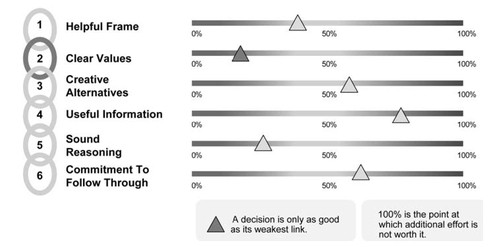

A PRACTICAL CASE FOR TEENAGERS: DECISION EDUCATION FOUNDATION

IN CLOSING: A SPORTS ANALOGY

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 7 - Constructed Preference and the Quest for Rationality

WHAT CHOICES ARE WISE?

CONSTRUCTED CHOICE

RATIONALITY IN THE CONTEXT OF CONSTRUCTED CHOICE

RATIONALITY IN FLUX

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 8 - What If You Know You Will Have to Explain Your Choices to Others Afterwards?

INDIVIDUAL DECISION MAKING AND LEGITIMATION

LEGITIMATION AND DECISION MAKING

A CONTEMPORARY CHALLENGE: CLIMATE CHANGE AND SUSTAINABILITY

WHAT TO DO?

CONCLUSION

RECOMMENDED READING

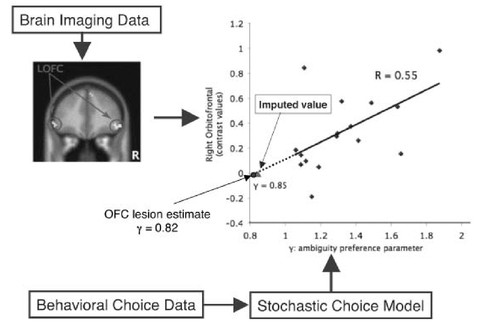

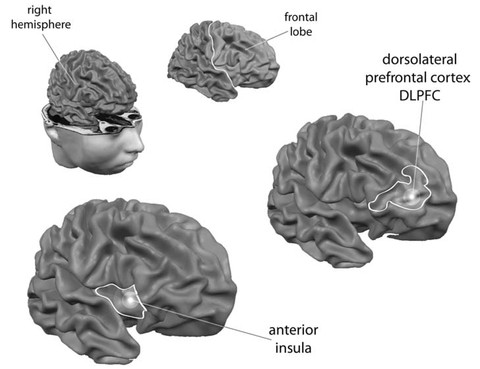

THE GOAL OF NEUROECONOMICS

AN APPLICATION: EYE-TRACKING AND BACKWARD INDUCTION IN BARGAINING GAMES

WHAT CAN NEUROECONOMICS DO FOR ECONOMICS?

RECOMMENDED READING

SHAKING THE (IR)RATIONALITY TREE: WELCOME TO “EMO-RATIONALITY”

THE CURIOUS CASE OF PHINEAS GAGE

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE MARRIAGE OF ECONOMICS AND NEUROSCIENCE?

FROM LABORATORY EXPERIMENTS TO DECISIONS IN EVERYDAY LIFE

NEUROECONOMICS AND BEYOND

RECOMMENDED READING

PART THREE - INDIVIDUAL DECISIONS IN A DANGEROUS AND UNCERTAIN WORLD

Chapter 11 - Virgin Versus Experienced Risks

INTRODUCTION

THE INABILITY TO USE BAYESIAN UPDATING IN EVERYDAY PRACTICE

UPDATING AS A FUNCTION OF PREVIOUS EXPERIENCE AND PREVIOUS CONTEMPLATION

CONCLUSION

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 12 - How Do We Manage an Uncertain Future?

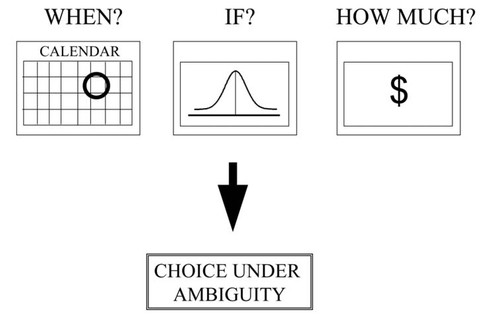

AMBIGUOUS CHOICES

ATTITUDES TOWARD AMBIGUITY

AMBIGUITY AND THE FUTURE

CONCLUSION

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 14 - Dreadful Possibilities, Neglected Probabilities

DEMONSTRATING PROBABILITY NEGLECT

CONCLUSION

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 15 - Why We Still Fail to Learn from Disasters

WHEN GOOD DECISION PROCESSES PRODUCE BAD CONSEQUENCES

THE COMPOUNDING ROLE OF POOR MENTAL MODELS

THE COUNTERPRODUCTIVE EFFECTS OF KNOWLEDGE

THE AGENCY PROBLEM

POSTSCRIPT: CAN LEARNING BE IMPROVED?

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 16 - Dumb Decisions or as Smart as the Average Politician?

INTRODUCTION

AVERSION TO DEDUCTIBLES

CONSUMER WARRANTIES

THE NONPOOR HEALTH UNINSURED

INSURANCE AND A TRANQUIL LIFE

CONCLUSION: WHEN RATIONAL AND BEHAVIORAL DECISION MAKING COMPLEMENT EACH OTHER

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 17 - The Hold-Up Problem

THE CASE OF FLOOD INSURANCE DECISIONS

BEHAVIORAL CONSIDERATIONS

WHY WAS NEW ORLEANS, STILL HIGHLY EXPOSED TO FUTURE HURRICANES, REBUILT IN THE ...

THE HOLD-UP PROBLEM

POLICIES TO FOSTER ADEQUATE SELF-PROTECTION AND INSURANCE

RECOMMENDED READING

PART FOUR - MANAGING AND FINANCING EXTREME EVENTS

Chapter 18 - The Peculiar Politics of American Disaster Policy

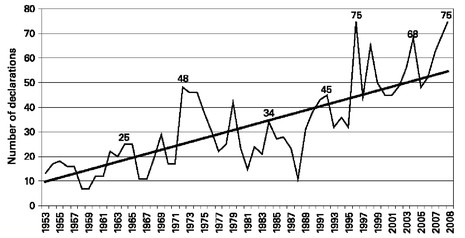

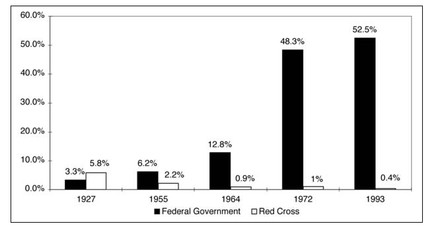

A BRIEF HISTORY OF FEDERAL DISASTER RELIEF

RELIEF OVER INSURANCE: A PROBLEM OF CONCENTRATED BENEFITS AND DIFFUSE COSTS?

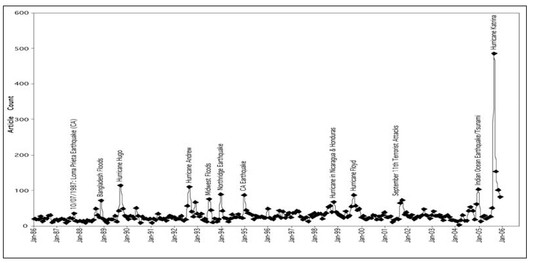

AN ALTERNATIVE EXPLANATION: THE POWER OF THE PRESS IN SHAPING DISASTER POLITICS

CONCLUSION: REFRAMING THE DISCUSSION AS A PREREQUISITE FOR REFORM

Chapter 19 - Catastrophe Insurance and Regulatory Reform After the Subprime ...

INTRODUCTION

LESSONS LEARNED FROM CATASTROPHES AND GOVERNMENT CATASTROPHE INSURANCE

RE-REGULATING LOAN MARKETS IN THE AFTERMATH OF THE SUBPRIME CRISIS

GOVERNMENT REINSURANCE FOR MUNICIPAL BOND INSURANCE

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 20 - Toward Financial Stability

UNDERSTAND WHY THIS HAPPENED: TWO DIVERGENT VIEWS

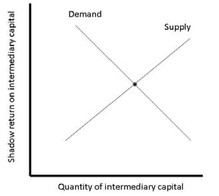

SOME PARALLELS WITH THE CATASTROPHE RISK MARKET

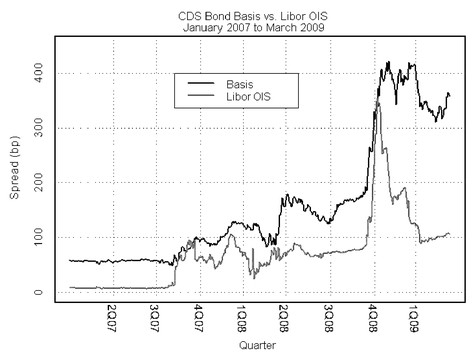

UNDERSTANDING THE 2008-2009 FINANCIAL CRISIS

THREE LESSONS ON MARKET BEHAVIORS

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 21 - Economic Theory and the Financial Crisis

GENERAL EQUILIBRIUM AND CREDIT INSTRUMENTS

GENERAL EQUILIBRIUM UNDER UNCERTAINTY

LIMITED INFORMATION OF ECONOMIC AGENTS

INFORMATION AS A COMMODITY

INEFFICIENT INCENTIVES: AN ENDEMIC PROPERTY OF CAPITALISM?

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 22 - Environmental Politics

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 23 - Act Now, Later, or Never?

THE PROBLEM OF DISCOUNTING THE DISTANT FUTURE

THE PROBLEM OF DYNAMIC RISK MANAGEMENT

IN CLOSING

RECOMMENDED READING

INTRODUCTION

CLIMATE CHANGE AS A COMPOUND LOTTERY

ALTERNATIVE DISPOSITIONS OF STAGE 1 RISK

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS ON INSURER SOLVENCY

Chapter 25 - International Social Protection in the Face of Climate Change

“A TRULY INTERNATIONAL ENDEAVOUR”

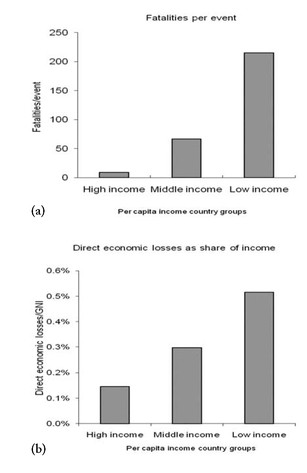

WEATHER EXTREMES: WHY THE POOR SUFFER THE MOST

INSURANCE FOR THE POOR AS SECURITY AGAINST WEATHER DISASTERS

BENEFITS, COSTS, AND CHALLENGES OF INSURANCE INSTRUMENTS

INTERNATIONAL SUPPORT FOR INSURANCE: EFFICIENCY AND EQUITY

CONCLUSION: A ROLE FOR THE ECONOMIST

RECOMMENDED READING

PART FIVE - WHAT DIFFERENCE CAN WE MAKE?

Chapter 26 - Are We Making a Difference?

UNREASONABLE FRIENDS AND ENEMIES

OUR PROGRAM?

REINVENTING OUR PROGRAMS

REINVENTING OUR INSTITUTIONS

CHANGING THE TALK—AND PERHAPS THE WALK

THE SCIENCE AND PRACTICE OF DECISION MAKING

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 27 - Thinking Clearly About Policy Decisions

INTRODUCTION

ARTICULATING AND UNDERSTANDING VALUE JUDGMENTS

UNDERSTANDING THE STRUCTURE OF POLICY DECISIONS

ASSESSING, UNDERSTANDING, AND COMMUNICATING ABOUT UNCERTAINTY

THE AMPLIFICATION OF RISK

EDUCATING POLICY MAKERS ABOUT DECISION SCIENCES CONCEPTS

RECOMMENDED READING

A WIDER SCOPE FOR THE DECISION SCIENCES

SOME OF MY DISAPPOINTMENTS

THE INTERDEPENDENCY OF SURPRISE BAD OUTCOMES

A PARADIGM SHIFT FOR ACADEMICS: FROM PROBLEM SOLVERS TO PROBLEM INVENTORS

A FINAL WORD, TO THE NEW GENERATION

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 29 - Influential Social Science, Risks, and Disasters

ARE ACADEMIC SOCIAL SCIENTISTS MAKING A DIFFERENCE?

RISK MANAGEMENT AND DISASTER RESEARCH

DISASTER RESEARCH AND PUBLIC POLICY ON MITIGATION AND RECOVERY

SUPPORT FOR RISK MANAGEMENT AND DISASTER RESEARCH AT THE NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION

RECOMMENDED READING

Chapter 30 - Reflections and Guiding Principles for Dealing with Societal Risks

REFLECTIONS OF THINGS PAST

GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR MANAGING SOCIETAL RISK PROBLEMS

GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR YOUNG RESEARCHERS

RECOMMENDED READING

ec·o·nom·ics (ĕk‘ə-nŏm’ĭks) - noun

1. a study of mankind in the ordinary business of life (Alfred Marshall, 1890)

2. the social science that analyzes human behavior as a relationship between the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

NOTE TO THE READERS

There is a clear tendency to view our own thoughts, words, and actions as rational and to see those who disagree as irrational.

Introduction

An Idea Whose Time Has Come

ERWANN MICHEL-KERJAN AND PAUL SLOVIC

All the forces in the world are not so powerful as an idea

whose time has come.

—Victor Hugo

OUR DANGEROUS AND INTERDEPENDENT WORLD

At a time of immensely consequential choices, it has never been more important to make the right decisions. But how can we be sure we are not making fatal mistakes? How can we be sure we can trust the tools, models, and methods we use to make our decisions?

The Irrational Economist aims to shed light on some important developments in decision making that have occurred in economics and other social sciences over the past few decades, including some of the most recent discoveries. Quite surprisingly, much of the knowledge developed in these fields has yet to be translated from research into actionable decisions in the real world. Our goal in this book is simple: to provide this knowledge in a condensed fashion to help people make better decisions in a world that seems to become more and more uncertain—if not more dangerous—as time passes.

This last statement may seem controversial. Conventional wisdom holds that crises and catastrophes are not new and that the world has seen many great dangers before. The twentieth century alone witnessed one of the deadliest five-year periods in human history: Between 1914 and 1918, World War I killed over 15 million people. And as the war ended, the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic (commonly referred to as the Spanish flu) spread to nearly every part of the world. The flu killed over 50 million, more than the toll of the Black Death in the fourteenth century. Wars and natural disasters have indeed devastated many parts of the world throughout history. Since the industrial revolution, new types of technological risks and deadly weapons have also emerged.

But one of the hallmarks of the twenty-first century will likely be more and more unthinkable events, previously unseen contexts, and pressure to react extremely quickly, even when we cannot predict the cascading impact our actions might have.

That is because the world has been evolving at an accelerating speed. Physical frontiers between economies are disappearing, as described by Thomas Friedman in his best-selling book, The World Is Flat. Increasingly widespread social and economic activities have turned our planet into an interdependent village. Communication costs are close to zero, goods and people travel faster and more cheaply than ever before, and knowledge is shared with unprecedented ease on the Internet and through emerging social networks. There are many benefits to this process.

Yet the flip side of this extraordinary transformation has been somewhat underappreciated: Actions taken or risks materializing 5,000 miles away can affect any of us very soon thereafter. Viruses fly business class, too! The financial turmoil that started in 2008 is another example; this blew up the theory of decoupling long supported by many theorists who thought a reduction in the United States’ or China’s economic growth would not severely affect the rest of the world. Well, as we now know, it did—with profound consequences. We are all interconnected.

The litany of global interdependent risks is almost endless. Events that have surfaced prominently on the social, economic, and political fronts in many countries just since the beginning of 2001 are eye-opening: terrorist attacks; financial crises; global warming; scarcity of water and other resources; hurricanes, floods, tsunamis, heat waves, droughts, earthquakes, and wildfires unprecedented in scale and recurrence;1 failures of our aging critical infrastructures; 2 repeated genocides and local wars; nuclear threats; pandemics and new illnesses.

This list is long but hardly exhaustive: We trust that if you think for a moment about what is going wrong today, what you are afraid of, or you simply watch news TV, you shall soon add to this list. And as challenging as it is today on a planet with nearly 7 billion people, it is likely to be even more so as the population continues to grow; ever greater concentrations of people and assets at risk set the stage for truly devastating events to happen.

At the heart of the work that led to this somewhat unusual book is this question: Is the series of untoward events that have occurred since 2001 an omen of what the twenty-first century has in store for us? If so—as we believe—it is time to think about the future in a fundamentally different way. What does this mean for us, as individuals and families, private companies, government authorities, and organizations? How might we behave in this new, uncertain, and more dangerous environment? Will our actions be rational or irrational? And what does this last question actually mean?

ARE WE RATIONAL ACTORS OR RATIONAL FOOLS?

We sought the answer to these questions from a group of internationally recognized experts who had worked with or were influenced by the economist Howard Kunreuther, who pioneered the field of decision making and catastrophe management (see the Acknowledgments section). Their work in The Irrational Economist examines human decision making from a variety of perspectives and documents the rich and subtle complexities of the concept “rationality.” These contributors’ perspectives are the result of an important evolution in theory and applied research that has occurred during the past half-century and is now accelerating.

Many mainstream economists in the second part of the twentieth century developed sophisticated mathematical treatments that attempted to model human behavior. But most of these were founded on a very simplistic concept of rationality. Indeed, early views on rationality were dominated by the concept of homo economicus: The idea here is that we can all be represented by an economic man who is assumed to be completely informed, perfectly responsive to economic fluctuations, and rational in the sense of having stable-over-time , orderly preferences that maximize economic well-being and are independent of the actions and preferences of others.

Slowly, psychologists and other behavioral scientists began testing this presumption of rationality, which, as noted by Herbert Simon, one of the most influential social scientists of the twentieth century, permitted economists to make “strong predictions . . . about behavior without the painful necessity of observing people.”3

Simon, both an economist and a psychologist, drew upon empirical research on human cognitive limitations to challenge traditional assumptions about the motivation, omniscience, and computational capacities of “economic man.” He introduced the notion of “bounded rationality,” which asserts that cognitive limitations force people to construct simplified models of how the world works in order to cope with it. To predict behavior “we must understand the way in which this simplified model is constructed, and its construction will certainly be related to man’s psychological properties as a perceiving, thinking, and learning animal.”4

About the same time that Simon was documenting bounded rationality in the 1960s and 1970s, another psychologist, Ward Edwards, began testing economic theories through controlled laboratory experiments to examine how people process information central to “life’s gambles.” Early research confirmed that people often violate the assumptions of economic rationality and are guided in their choices by noneconomic motivations. For example, one series of studies showed that slight changes in the way choice options are described to people or in the way they are asked to indicate their preferences can result in markedly different responses. In short, we behave very differently depending on how the information is presented to us, on the nature of the decision-making environment, even on what period of life we are in. Moreover, in many important situations we do not really know what we prefer; we must construct our preferences “on the spot.”5

Not surprisingly, as often happens with new ideas, economists of the 1960s and 1970s were divided on how to interpret them. Many, rather than trying to understand the psychology, embarked on studies designed “to discredit the psychologists’ work as applied to economics.”6 Evidence against the rationality of individual behavior tended to be dismissed by those economists on the grounds that in the competitive world outside the laboratory, rational agents would survive at the expense of others. In this way, the study of irrationality could be downplayed as the study of transient phenomena.

At the same time, and despite very important advances in economic theory that were made possible by the traditional view of economic man,7 there was a growing sense of unease among the general public and other social scientists as well as among policy makers that many economists had been unrealistic in their attempts to always rationalize how people, enterprises, and markets function.

Fortunately, the story did not stop there. Stimulated by creative conceptual, methodological, and empirical work by the more senior authors in The Irrational Economist and many others, including Amos Tversky, Daniel Kahneman, and Richard Thaler, the trickle of studies challenging traditional economic assumptions of rationality became a torrent. Nobel prizes in economics awarded to Herbert Simon in 1978, to George Akerlof in 2001, and to Daniel Kahneman and Vernon Smith in 2002 for their contributions toward understanding the behavioral dynamics of economic decisions further contributed to what has become a revolution in thinking.

Today, young scholars, and even those not so young, have become convinced that the secret to improving economic decision making lies in the careful empirical study of how we actually make decisions. New multidisciplinary fields have now emerged—many represented in this book by those who pioneered them—including behavioral economics, economic psychology, behavioral finance, decision sciences, and neuroeconomics, to integrate theories and results from economics, psychology, sociology, anthropology, biology, and brain sciences. Applied fields such as management, marketing, finance, public policy, and risk management and insurance are using this new knowledge today in significant ways.

We now recognize that the question “Are people rational or irrational?” is ill-formed. As human beings, we have intuitive and analytic thinking skills that work beautifully, most of the time, to help us navigate through life and achieve our goals, individually and collectively. But sometimes our thinking skills fail us.

The very modes of thought that are highly rational most of the time can get us into big trouble when the nature of the environment surrounding us, or the time horizon on which we make decisions, changes. We are also fundamentally influenced by short-term rewards, by what others do, and by what is at stake and how we feel when we make these decisions. Our emotions (known to economists as “affective feelings” or “affects”), including fear, anxiety, love, trust, and confidence, all of which help us assess risk and reward, are processed swiftly in our minds. These feelings form the neural and psychological substrate of what is important to us and guide many decisions, what economists refer to as “utility.” In this sense, reliance on feelings enables us to be rational actors in many important situations. For instance, if you were to see a venomous snake on your vacation trip, you would not pause to calculate the mathematical utility of all the possible harmful consequences multiplied by their associated probability (hard to calculate anyway) in order to decide what to do. Upon seeing the snake, you would act rationally: You would move away fast.

More generally, reliance on our gut feelings works when our experience enables us to anticipate accurately the consequences of our decisions—that is, when we have a good knowledge of the situation and (think we) fully understand our reactions today and in the future. But it fails miserably when the consequences turn out to be very different from what we expected—which is likely to happen quite often in an uncertain world. In the instance of surprise, the rational actor often becomes, to borrow the words of 1998 Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen,8 the rational fool.

This brings us back to two of our original questions: How might we behave in this new, uncertain, and more dangerous environment? Will our actions be rational or irrational? Our answer is: It depends. Part One of this book—“Irrational Times”—addresses a series of behaviors that many might consider irrational. Yet, when we look at them more closely and try to understand the rationale behind them, they often make sense: Our actions are driven by our feelings, incentives, and the nature of the environment in which we make decisions.

The challenge before us now is to better understand when and how rationality fails in this modern world. The chapters in Part Two—“Are We Asking the Right Questions? Economic Models and Rationality”—consider the growing menu of tools we have at our disposal today to meet this challenge. Part Three—“Individual Decisions in a Dangerous and Uncertain World”—looks at the individual decision processes that arise when people are confronted with small and catastrophic risks, and at how experience, uncertainty, and different time horizons can radically threaten rationality. By understanding these processes and thus avoiding the failures of rationality that sometimes result, people can make better decisions for themselves, and also better decisions for others in our society. Part Four—“Managing and Financing Extreme Events”—analyzes how individual behavior can translate into very good or very poor collective decisions by enterprises, markets, and governments. Natural disasters, climate change, terrorism threats, and financial crises are cited as illustrative examples of uncertain and dangerous environments.

WHAT ROLE FOR THE ECONOMIST? FROM THE IVORY TOWER TO THE CIRCLE OF POWER

In many ways, the transformation of economics as a discipline that now includes more realistic behavioral models is similar to what happened over the course of several centuries in physics, chemistry, biology, and medicine. Established paradigms evolve with new knowledge, the discovery of which is fueled, at least in part, by the collective desire to explain more accurately the world we live in, and by the aspiration to make it better. Economics is still a young discipline. To mature, it needs to transform itself into one that not only can better represent human behavior in the real world (the normative approach) but also can propose better remedies to societal issues the world faces (the prescriptive approach).

This leads us to ask: What should be the role of those who study or have a special knowledge of economics and other social sciences in ensuring the success of this transformation? Many pioneers of economics not only were advocates of specific theoretical programs but also participated directly in government. One example is Adam Smith, often cited as the father of modern economics. His work on self-interest was largely prompted by a critique of mercantilism and adherence to a moderate free-market policy (even though his earlier work focused on a morality based on sympathy and benevolence).9 But he was also one of the leading customs commissioners in Scotland appointed in 1778. Another is James Mill, who made significant contributions to classical British economic theory and was also a high-ranking official of the East India Company that governed India. During the 1830s, he was an influential leader in Parliament. A third is David Ricardo, tutored by Mill; after writing his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation in 1817 he entered Parliament as well. And influential laissez-faire economist Michel Chevalier negotiated the free-trade agreement between the U.K. and France in 1860—the same year he became a senator in the French Congress.

This long history of prominent economists influencing policy has continued. For instance, the Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto made important contributions to the study of income distribution and the analysis of individuals’ choices; but he was also a militant laissez-faire liberal who battled for free trade. And of course John Maynard Keynes, the very influential British economist, served in several key government posts during the twentieth century. Keynes would spearhead a revolution in economic thinking that was essentially pragmatic, rather than theoretical. He wanted his ideas to work in the world.

It is for the same reason that in a rare moment of collective awareness for our profession, Part Five of this book addresses the ultimate question “What Difference Can We Make?” If we are right in saying that the world is becoming more interconnected, that the potential for catastrophes is more widespread than ever before, and that the effects of any single person or group may be, like the proverbial flap of the butterfly’s wing, amplified across the world with potentially vast consequences, then an accurate appreciation of the science of decision making and of catastrophe risk management cannot remain within the ivory towers of universities and specialist institutes. Indeed, this knowledge must be shared—with industries, governments, nongovernmental organizations, philanthropic foundations, investors, the media, and, last but by no means least, all individuals who care to make the best-informed choices to safeguard themselves and their families in this fast-moving, ever-thrilling world that may challenge them with deep adversity and extreme events. This is the goal of The Irrational Economist.

As a way of ensuring that this knowledge is shared and used more broadly, we hope to see more and more behavioral scientists being asked to provide top decision makers with their views, or even to take on high-level positions in the public and private sectors. In doing so, they will assume this dual role of researchers/teachers and influential players in the power circles of business and public policy, as other great minds in economics have done before. But this time, not quite as purely rationally.

PART ONE

IRRATIONAL TIMES

IN THESE FIVE OPENING CHAPTERS, the authors contemplate a patchwork of situations where decisions can be viewed as irrational (i.e., deviating from what economic rationality would seem to dictate). Each chapter, each anecdote, each piece of evidence provides a touch of color representing an aspect of human behavior either in daily life or during extraordinary times. Together, they provide a mosaic of ideas, integral parts of a surprising painting, that will be discussed in detail in the rest of the book.

For example, why don’t many hotels have a thirteenth floor? Or planes a thirteenth row? Should our believing in supra-human forces (superstition and religion) be considered irrational? If so, how do economists study the ways in which it affects human behavior? A cast of remarkable characters—weather forecasters and beautiful people—unexpectedly help us better understand how (misaligned) incentives on Wall Street pushed us into financial chaos. This section will also consider how decisions can be made today about career choices for the next thirty years, given the increasing uncertainties that come with our rapidly changing world. Part One ends with an ounce of behavioral observation about our dangerous world. We ask how compassionate we really are when it comes to helping others in profound distress . . . and learn that caring does not increase proportionally with the number of victims, as economic rationality would suggest, but rather goes in the opposite direction. All the anecdotes and evidence highlighted in Part One give us a sense of how we really make decisions—a consideration that is all the more important to appreciate and acknowledge as we contemplate the extraordinary times that lie ahead. The new risk architecture that is now unfolding brings complex interdependencies among nations, companies, and individuals all over the world. How others behave should matter more to you today than ever: Directly or indirectly, you are linked to them, as they are to you.

1

Superstition

A Common Irrationality?

THOMAS SCHELLING

The night before the conference honoring Howard Kunreuther’s birthday I stayed in a Philadelphia Hotel. Riding up the elevator I noticed there was no thirteenth floor.

Walking up Madison Avenue in New York recently, for about twenty blocks, I counted more than twenty fortune tellers on one side of the street. I remember that the wife of a president of the United States was reported to have consulted some kind of seer who resided in California. I’ve been told by what I thought a reliable source that air traffic is below normal on a Friday the thirteenth. Several airlines have no thirteenth row. (What could happen to a passenger in the thirteenth row that would not occur in the fourteenth, I can’t imagine.)

And this morning’s newspaper carried this advice in the horoscope for (my birth month) Aries:

Old problems surface. Make progress in this regard so you can avoid sharing the all-too-familiar chorus of your discontent. That tune is tired and loved ones will thank you for not playing it.

I recall that the oracle at Delphi had a reputation for prophecies sufficiently ambiguous to avoid her being proved wrong. (Now that I think of it, I’ve never checked whether the horoscopes in different newspapers provide similar advice, or whether they are sufficiently specific that their similarity can be judged.)

Before many states succumbed to the temptation to use lotteries to enhance their revenue, illegal lotteries, known as “numbers rackets,” met the demand and were able to charge higher prices for “lucky” numbers—particular numbers that, unlike one’s birth date, were not peculiar to an individual but were widely regarded as somehow blessed.

There is a well-known, and much-studied, “gamblers’ fallacy”—actually two of them. One is that if a tossed coin comes up heads four times in a row, it has “exhausted” its heads inventory and is likely to come up tails. The other is that it’s on a “roll,” and is likely to come up heads again. (If the experimenter pulls a new coin out of his pocket, after the four heads, the new coin is viewed as neutral, offering a 50-50 chance.) My statistically sophisticated colleagues dismiss these expectations with the rhetorical question, “Does the coin remember, does the coin care?” I think the believers must answer, “Someone up there does!”

Many years ago, while driving a son to school with the radio on, I would hear the advertisement of the Massachusetts Lottery Commission urging us to consider that if we concentrated hard enough we might just do better than chance with our ticket. I never knew whether the Commission meant we might predict the winning numbers or we might determine the winning numbers. (Not all of us, I’m sure, because not all of us could concentrate on the same number!) I marveled that the Commonwealth of Massachusetts would promote extrasensory perception to sell tickets. The market analysis must have led the Commission to believe that some of us could be conned. (Or did the Commissioners believe it themselves; did they even buy tickets themselves and concentrate?)

There are experiments in which people given a modest gift, a coffee mug or a sweatshirt, decline to trade it for some equally “valuable” gift that they might instead have been given. Something happens to “attach” the gift to the recipient. Similarly, people who receive lottery tickets at the door to some event have been found unwilling to trade their tickets for “equally” valuable tickets. (See the work of Ellen Langer, psychologist, Harvard University.) One explanation is that if it’s “their” day to win, they don’t want to confuse the decision by switching tickets!

In the Theory of Games it is held that in “games against nature,” such as deciding whether the weather will turn cold, or rain may ensue, nature is neutral, in contrast to games with human subjects who will act strategically. My impression is that for many people nature is not neutral. I’ve known someone whose auto collision insurance expired while he was traveling, and he wouldn’t drive until his renewed insurance was confirmed. I asked him how many collisions he’d had in some decades of driving, and the answer was none. What’s the expected value of the risk of auto damage if you drive, I asked, thinking he could give a statistical answer that would contradict his decision not to drive. Instead he smiled and said, “That’s just the day that I’d have the accident!” I think the same goes for driving without one’s license: “That’s the day I’d get stopped by a cop!”

(Maybe it is not a truly superstitious belief that if I drive without a license I’ll be stopped by an officer. It may be that if I drive without a license I cannot stop thinking I have no license, and cannot stop looking in the mirror for a police car. It’s my imagination I cannot control, not my logic.)

We’ve been taught by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky that many people are innocent of statistical sampling, that many get “anchored” by a randomly produced number, that many are seduced by “representativeness,” and many don’t understand “regression to the mean.” You walk into a public library in the suburb of a large city and see a man, dressed in tie and jacket, reading Thucydides; you have already learned that he is either a concert violinist or a truck driver. Which do you guess he is? Considering that there are 10,000 concert violinists in the country and 2 million truck drivers, if 1 in 200 truck drivers is as likely as any single concert violinist to read Thucydides in the public library dressed in jacket and tie, you should guess truck driver, but you (and I) usually don’t.

RELIGION AND SUPERSTITION

An article in the magazine of the American Association of Retired People on the prevalence of belief in miracles reported that among 1,300 people over 45 years of age 80 percent believed in miracles. Fully 37 percent said they had actually witnessed one. The article defined a miracle as “an incredible event that cannot be scientifically explained.” (What about credible events that cannot be scientifically explained? Believers must find miracles credible, else they’d not believe in them.)

The American Heritage Dictionary defines miracle as “an event that appears unexplainable by the laws of nature and so is held to be supernatural in origin or an act of god.” It defines superstition as “a belief, practice, or rite irrationally maintained by ignorance of the laws of nature or by faith in magic or chance.” (Emphasis added.) If magic is supernatural, these definitions are distinguished mainly by the somewhat superfluous adjective irrationally.

Of course, what is in accordance with the laws of nature can be somewhat ephemeral. Isaac Newton believed in the transmutation of elements; alchemy was not yet against the laws of nature. Eventually the laws of nature made the transformation of one element into another not possible. Then, in the twentieth century, it proved possible to convert Uranium 238 into Plutonium 239 by irradiation.

In 1997, a religious organization called Heavensgate believed that a space vehicle was hidden on the far side of the Hale Bopp comet and could be accessed by the devout if they would commit communal suicide. Seventy-five followers killed themselves. Was their belief “against the laws of nature”? Most of us don’t believe they made it to the other side of Hale Bopp but many of us do believe in heaven and hell, which “appear unexplainable by the laws of nature.” As miracles go, the Heavensgate project is not uniquely unimaginable, but the media treated it as superstition.

During the New Hampshire Republican primary campaign George H. W. Bush shouted at Ronald Reagan, “That’s Voodoo economics!” (I couldn’t tell whether he capitalized voodoo.) I doubt whether anyone would dare to say, in a New Hampshire primary campaign, “That’s Mormon economics” or “That’s Seventh Day Adventist economics” or “That’s Jehovah’s Witnesses economics.” There might be a Mormon, or an Adventist, or a Witness in the audience but probably not someone from Haiti registered to vote.

Most people I encounter appear willing to dismiss Voodoo as superstition, are amusedly patronizing of Native American theology, but respectful of monotheisms whether or not they subscribe to one.

All three of the world’s great monotheisms entail prayer, “a reverent petition made to a deity or other object of worship” (American Heritage Dictionary ). It is no insult to those who pray to observe that a response to a reverent petition would be a miracle as defined above, “an event that appears unexplainable by the laws of nature and so is held to be supernatural in origin or an act of god.”

I doubt whether the authenticity of prayer can be experimentally disproven. Prayer certainly has been shown to have a placebo effect. Whether the prayer itself can be deemed responsible for the success of the petition depends on whether the outcome can be identified with any certainty as not due to natural causes. Any negative results in an experiment designed for the purpose of testing the deity’s responsiveness would surely violate the Third Commandment and could be discarded on that account.

If we have now arrived at the junction of myth, superstition, and religion, it’s time for me to close.

P.S. A couple of months after Howard’s celebration my wife and I were in the security line at Copenhagen airport and realized that I had no wallet. We cancelled our flight, retrieved our luggage, returned to our hotel, cancelled my credit and ATM cards, talked to all the cab drivers, went back to the airport for a late flight to Warsaw. Our luggage didn’t arrive. On checking out of our hotel five days later, we needed to verify the date of our arrival. It turned out to have been Friday the thirteenth!

RECOMMENDED READING

Kahneman, Daniel, Paul Slovic, and Amos Tversky, eds. (1982). Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky, eds. (2000). Choices, Values, and Frames. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Langer, Ellen J. (1982). “The Illusion of Control.” In Daniel Kahneman, Paul Slovic, and Amos Tversky, eds. Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schelling, Thomas (1996). “Coping Rationally with Lapses from Rationality,” Eastern Economic Journal (Summer): 251-269. Reprinted in Thomas Schelling, Strategies of Commitment and Other Essays (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.)

2

Berserk Weather Forecasters, Beauty Contests, and Delicious Apples on Wall Street

GEORGE A. AKERLOF AND ROBERT J. SHILLER

No one has ever made rational sense of the wild gyrations in financial prices, such as stock prices.1 These fluctuations are as old as the financial markets themselves. And yet these prices are essential factors in investment decisions, which are fundamental to the economy. Corporate investment is much more volatile than aggregate GDP, and it appears to be an important driver of economic fluctuations. If we recognize these facts, we are left once again with more evidence that animal spirits are central to the ups and downs of the economy.

The real value of the U.S. stock market rose over fivefold between 1920 and 1929. It then came all the way back down between 1929 and 1932. The real value of the stock market doubled between 1954 and 1973. Then the market came all the way back down. It then lost half of its real value between 1973 and 1974. The real value of the stock market rose almost eightfold between 1982 and 2000. Then it lost nearly 60 percent of its value between 2007 and early 2009, before rebounding again.2

The question is not just how to forecast these events before they occur. The problem is deeper than that. No one can even explain why these events rationally ought to have happened even after they have happened.

One might think, from the self-assurance that economists often display when extolling the efficiency of the markets, that they have reliable explanations of what has driven aggregate stock markets, which they are just keeping to themselves. They can of course give examples that justify the stock price changes of some individual firms. But they cannot do this for the aggregate stock market.3

Over the years economists have tried to give a convincing explanation for aggregate stock price movements in terms of economic fundamentals. But no one has ever succeeded. They do not appear to be explicable in terms of changes in interest rates, subsequent dividends or earnings, or anything else.4

“The fundamentals of the economy remain strong.” That cliché is repeated by authorities as they try to restore public confidence after every major stock market decline. They have the opportunity to say this because just about every major stock market decline appears inexplicable if one looks only at the factors that logically ought to influence stock markets. It is practically always the stock market that has changed; indeed, the fundamentals haven’t.

How do we know that these changes could not be generated by fundamentals? If prices reflect fundamentals, they do so because those fundamentals are useful in forecasting future stock payoffs. In theory, the stock prices are the predictors of the discounted value of those future income streams, in the form of future dividends or future earnings. But stock prices are much too variable. They are even much more variable than those discounted streams of dividends (or earnings) that they are trying to predict.5

BERSERK WEATHER FORECASTERS

To pretend that stock prices reflect people’s use of information about those future payoffs is like hiring a weather forecaster who has gone berserk. He lives in a town where temperatures are fairly stable, but he predicts that one day they will be 150° and on another they will be -100°. Even if the forecaster has the mean of those temperatures right, and even if his exaggerated estimates are at least accurate in calling the relatively hot days and the relatively cold days, he should still be fired.

He would make more accurate forecasts on average if he did not predict that there would be any variation in temperature at all. For the same reason, one should reject the notion that stock prices reflect predictions, based on economic fundamentals, about future earnings. Why? Because the prices are much too variable.

Even this fact, blatant as it is, has not convinced efficient-markets advocates that their theory is wrong. They point out that the movements in stock prices could still be rational. They say that such movements could be reflecting new information about some possible major event affecting fundamentals that by chance did not happen in the past century, or the century before that either. In this view the stock market is still the best predictor of those future payoffs. Its gyrations are occurring because something might have happened to fundamentals. They maintain that the mere fact that the major event did not happen cannot be taken to mean that the market was irrational. Maybe they are right. One cannot decisively prove that the stock market has been irrational. But in all of this debate no one has offered any real evidence to think that the volatility is rational.6

The price changes appear instead to be correlated with social changes of various kinds. Andrei Shleifer and Sendhil Mullainathan have observed the changes in Merrill Lynch advertisements. Prior to the stock market bubble, in the early 1990s, Merrill Lynch was running advertisements showing a grandfather fishing with his grandson. The ad was captioned: “Maybe you should plan to grow rich slowly.” By the time the market had peaked around 2000, when investors were obviously very pleased with recent results, Merrill’s ads had changed dramatically. In one of these was a picture of a computer chip shaped like a bull. The caption read: “Be Wired . . . Be Bullish.” After the subsequent market correction, Merrill went back to the grandfather and the grandson. They were again patiently fishing. The caption advertised “Income for a lifetime.”7 Of course, the marketing professionals who concoct such ads believe they are closely tracking public thinking as it changes dramatically over time. Why should we regard their professional opinion as less worth listening to than the professional opinion of finance professors and efficient-markets advocates?

THE BEAUTY CONTEST AND DELICIOUS APPLE METAPHORS

In his 1936 book Keynes compared the equilibrium in the stock market to that of a popular newspaper competition of his time. Competitors were asked to pick the six prettiest faces from a hundred photographs. The prize was awarded to the competitor whose choices came closest to the average preferences of all of the competitors as a group. Of course, to win such a competition one should not pick the faces one thinks are prettiest. Instead, one should pick the faces that one thinks others are likely to think the prettiest. But even that strategy is not the best, for certainly others are employing it too. It would be better yet to pick the faces that one thinks others are most likely to think that others think are the prettiest. Or maybe one should even go a step or two further in this thinking.8 Investing in stocks is often like that: Just as with the beauty contest, in the short run one wins not by picking the company most likely to succeed in the long run but, rather, by picking the company most likely to have high market value in the short run.

The Delicious Apple offers another metaphor for much the same theory. Hardly anyone today really likes the taste of the varietal now called Delicious. And yet these apples are ubiquitous. They are often the only choice in cafeterias, on lunch counters, and in gift baskets. Delicious Apples used to taste better, back in the nineteenth century when an entirely different apple was marketed under this name. The Delicious varietal had become overwhelmingly the best-selling apple in the United States by the 1980s. When apple connoisseurs began shifting to other varietals, apple growers tried to salvage their profits. They moved the Delicious Apple into another market niche. It became the inexpensive apple that people think other people like, or that people think other people think other people like. Most growers gave up on good taste. They cheapened the apple by switching to strains with higher yield and better shelf life. They cheapened it by clear-picking an entire orchard at once, no longer choosing the apples as they ripened individually. Since Delicious Apples are not selling based on taste, why pay extra for taste? The general public cannot imagine that an apple could be so cheapened. Nor does it imagine the real reason these apples are ubiquitous despite their generally poor taste.9

The same kind of phenomenon occurs with speculative investments. Many people do not appreciate how much a company with a given name can change through time, or how many ways there are to debase its value. Stocks that nobody really believes in but that retain value are the Delicious Apples of the investment world.

RECOMMENDED READING

Allen, Franklin, Stephen Morris, and Hyung Song Shin (2002). “Beauty Contests, Bubbles, and Iterated Expectations in Asset Markets.” Unpublished paper, Yale University.

Barberis, Nicholas, and Richard Thaler (2003). “A Survey of Behavioral Finance.” In George Constantinides, Milton Harris, and René Stulz, eds. Handbook of the Economics of Finance. New York: Elsevier Science.

Campbell, John Y., and Robert J. Shiller (1987). “Cointegration and Tests of Present Value Models.” Journal of Political Economy 97, no. 5: 1062-1088.

Higgins, Adrian (2005). “Why the Red Delicious No Longer Is.” Washington Post, August 5, p. A1.

Jung, Jeeman, and Robert J. Shiller (2005). “Samuelson’s Dictum and the Stock Market.” Economic Inquiry 43, no. 2: 221-228.

Keynes, John Maynard. (1936/2009). The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Kindle: Signalman Publishing.

LeRoy, Stephen, and Richard Porter (1981). “Stock Price Volatility: A Test Based on Implied Variance Bounds.” Econometrica 49: 97-113.

Marsh, Terry A., and Robert C. Merton (1986). “Dividend Variability and Variance Bound Tests for the Rationality of Stock Prices.” American Economic Review 76, no. 3: 483-498.

Shiller, Robert J. (1981). “Do Stock Prices Move Too Much to Be Justified by Subsequent Changes in Dividends?” American Economic Review 7, no. 3: 421-436.

Shiller, Robert J. (1986). “The Marsh-Merton Model of Managers’ Smoothing of Dividends.” American Economic Review 76, no. 3: 499-503.

Shiller, Robert J. (2000). Irrational Exuberance, 1st ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Shleifer, Andrei, and Robert W. Vishny (1997). “The Limits of Arbitrage.” Journal of Finance 52, no. 1: 33-55.

3

Subways, Coconuts, and Foggy Minefields

An Approach to Studying Future-Choice Decisions

ROBIN M. HOGARTH

“Future-choice” decisions are decisions that have three important sources of complexity.

First, actions taken today can have unknown consequences at future horizons that are difficult to specify.

Second, decisions imply complex inter-temporal tradeoffs.

And, third, it is problematic to specify relevant states of the world, let alone to assess their probabilities.

Consider, for example, making decisions today that will affect the layout of a city. How far into the future should such decisions look? What volumes of traffic are likely to develop on alternative highways? What unknown technological advances could change costs and benefits? Will public preferences remain stable? What are the possibilities of different natural or social disasters? And so on. The list of possibilities and complications is endless. Imagine further a 23-year-old who is planning a career and ways of acquiring capital across her life. How can she evaluate different career paths? How can she know today what expertise will be in demand in ten or twenty years? How can she predict changes in her personal situation as well as her health?

Today, the standard economic model for dealing with these situations is the discounted utility model. This has the advantage of reducing the net benefits of each alternative stream of actions to a single number so that “rational” comparisons can be made. However, achieving these single numbers implies a series of heroic assumptions that exceed most mortals’ capabilities.

In thinking about these issues, I first want to salute the considerable advances made in our understanding due to decision theory. In so doing, however, we need to keep clearly in mind just what decision analysis can and cannot take into account.

Second, I will go on to distinguish two types of uncertainty that characterize decisions labeled “subway” and “coconut” uncertainty, respectively.

Third, the presence of coconut uncertainty essentially implies the breakdown of decision-theoretic and forecasting models and demands a new approach for future-choice decisions. Whereas I cannot offer a new approach yet—or an intellectual breakthrough—I can suggest a heuristic principle and metaphor that may help us deal with some of the issues. Perhaps by considering their advantages and disadvantages, we might illuminate some of the problems of future-choice decisions and, at the least, set an agenda for future research.

THE FAILURE OF DECISION THEORY

Like many graduate students of my generation, I was totally seduced by statistical decision theory. But statistical decision theory never really became the universal tool that many imagined it would.

Nor do I believe that decision theory has been handicapped by the fact that many of its axioms are violated by people’s choices. Indeed, it is precisely “violations” of this sort that illustrate why a good theory is necessary.

My belief is that statistical decision theory fails in many important problems—particularly future-choice problems—because humans are incapable of characterizing the uncertainties of the world in which they operate. Decision theory applies only to well-defined “small worlds” (Savage, 1954).

In addition, although there can be no doubt that the ability to predict many phenomena has been an important element of human development, when it comes to predicting events in the socioeconomic domain the human predictive track record is, frankly, dismal.

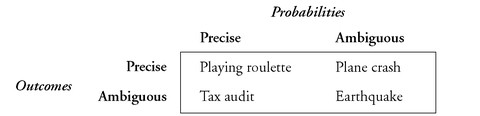

TWO TYPES OF UNCERTAINTY

I think that what really hampers the use of formal analytical techniques for future-choice decisions is that uncertainty can take two forms. In a new book (Makridakis, Hogarth, and Gaba, 2009), my co-authors and I refer to these as “subway uncertainty” and “coconut uncertainty,” respectively.

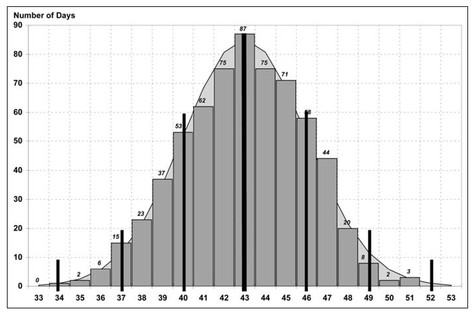

FIGURE 3.1 Klaus’s Travel Time to Work (in minutes) Source: Makridakis, Hogarth, and Gaba (2009).

In explaining these concepts, we cite the example of a mythical and obsessive character called Klaus who every day charts his commuting times to and from work (using the subway) so that, over a certain period, he accumulates a statistical representation of his travel times in the form of what is essentially a normal distribution—as shown in Figure 3.1. Indeed, assuming that nothing systematic disturbs the statistical pattern observed, Klaus can use the characteristics of the normal distribution to calculate the probability that his arrival time on any given day will fall within specified limits based on past history. Moreover, he can actually validate his model’s predictions every day when he goes to work.

By “subway uncertainty,” then, we mean a source of uncertainty whereby the statistical properties are well known and future “surprises” fall within well-specified limits. This kind of uncertainty—or approximations thereof—can be well handled within our decision-theoretic and forecasting models.

By “coconut uncertainty” we mean something quite different. Imagine you are sitting under a palm tree on a South Seas island and a coconut happens to fall on your head, causing considerable distress. Now, there are many disasters that you can imagine in life, but being hit on the head by a coconut when you are on vacation is probably not one of them (until you read this story, at least). In other words, by realizations of coconut uncertainty we mean events that you probably never even imagined could occur—there are so many different ones and you don’t know which particular one will happen. Indeed, you might not even have a good handle on the class of events that could be described as coconuts.1

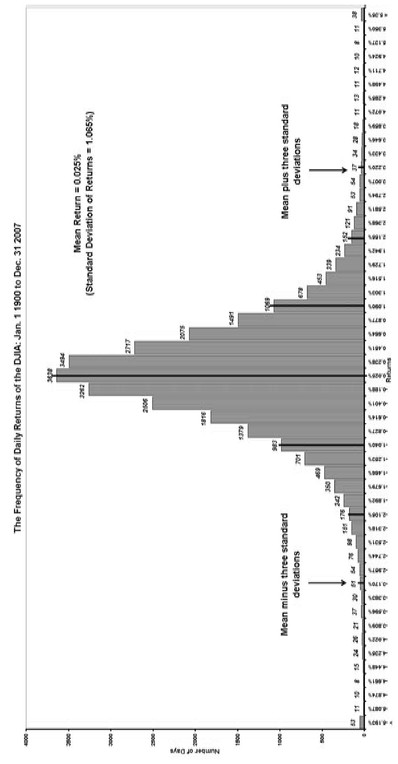

Interestingly, although there is a history of coconuts in some domains, people are still surprised by their occurrence. Daily returns on the stock market provide a case in point. Figure 3.2 shows the distribution of daily returns of the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) for the period from January 1, 1900, to December 31, 2007. As you can see, many observations lie outside the plus-or-minus-three-standard-deviations limits, and this graph does not even contain the observations for the wild market movements that occurred in 2008 and 2009. Parenthetically, if you look at the same data as a time series, there are periods—mainly at “crisis” times (e.g., October 1987 or 2001)—during which there seems to be dependence in the size of fluctuations, rather like the pre- and after-shocks that accompany earthquakes. In principle, in considering the stock market and other financial data one could always model some coconuts; but for some reason, many practitioners fail to do this and inevitably suffer the consequences—as evidenced by the worldwide financial crisis of 2008.

This observation is not limited to the financial markets, however. My point is that for future-choice decisions many variables are inherently unknowable. We cannot characterize the uncertainty because, if we are honest, we cannot even specify the events that might or might not occur. Consider, for example, how few people at the beginning of the 1980s foresaw the widespread use of personal computers and the development of the Internet. If you had been given correct forecasts for these developments at the time, would you have believed them? My contention is that you probably would not have known how to evaluate the forecasts.

What developments will occur over the next twenty-five years? I believe that we are all quite blind with respect to the future—and, moreover, that if we simply extrapolate past trends, huge errors will ensue. The path of social and economic development follows an evolutionary trail and, as is well known, although evolution provides a good story for explaining the past, it makes no predictions.

FIGURE 3.2 Dow Jones Industrial Average from January 1, 1900, to December 31, 2007

Source: Makridakis, Hograrth, and Gaba (2009)

COMMIT ONLY AS FAR AS YOU CAN PREDICT

It would be wonderful to come up with a “good” or “amended” discounted utility model that could be used for long-term future-choice decisions. However, the complexities are such that I think this is not practicable. Instead, I would like to suggest a different strategy: Formulate a number of simple decision rules, or heuristics, that people can use to guide their actions when facing future-choice decisions. Whereas we must accept that no rule can be a guarantee, we could at least test such rules through simulation techniques and get some sense of their possibilities and limitations. Thus the rules would depend on more than just common sense.

The essence of the rule I wish to suggest here is to “commit only as far as you can predict.” The rationale for this rule was suggested to me by the old joke about a Japanese Airlines pilot who ditched his aircraft in the bay at the San Francisco airport after a flight from Tokyo. “Why did you miss the airport by 200 yards?” a journalist asked. “Well,” replied the pilot, “considering I came all the way from Tokyo, 200 yards was not much of an error.”

The insight provided by this story is that, normally, when making commitments (here, where to land), a person should match actions with the level of uncertainty that can be managed. Thus, when leaving Tokyo, the pilot was foolish to commit to the precise parameters for landing in San Francisco; all he should have done was to select a path that could be adapted as conditions changed. When close to San Francisco, however, he could commit to a particular landing spot because at this proximity there would be considerably less uncertainty about the specific parameters. In short, the level of commitment should be matched to the level of uncertainty.

What are the implications of this pilot metaphor for future-choice decisions? First, many future-choice decisions have a temporal structure—similar to that of the Tokyo-San Francisco flight path—that can be broken down into several segments. Consider, for example, the many scenarios involved in urban planning or career development. However, in contrast to the Tokyo- San Francisco flight, which has a precise goal (i.e., arrival at a specific spot in San Francisco), the end-states of these future-choice decisions are not necessarily well defined. On the other hand, they undoubtedly are driven by a “direction” or values (e.g., creation of a viable city, achievement of personal and professional success). The important point here is that the time line of all these decisions can be broken down into periods for which it is reasonable to make commitments that can be evaluated.

FROM AIRPLANES TO FOGGY MINEFIELDS

Although it makes this point, the pilot metaphor is too simple for many realistic future-choice decisions. So, instead, I would like to introduce the metaphor of traveling across a minefield in a fog. The general goal—as in life—is to get across the field in good shape, and let’s assume that in crossing the field there are various positive rewards that you can collect. But at the same time, your ability to see where you are going is restricted—randomly—by the density of the fog so that, whereas you might be able to see quite far in some cases, this is not always going to be the case. The mines, too, are distributed randomly around the field and vary in terms of how much damage they can inflict. In other words, whereas some are “coconuts,” others might be quite containable. Let’s say you also have some diagnostic mine-detecting equipment but this is not 100 percent reliable and may be biased for some types of mines.2

In the foggy minefield, the goal cannot be precise—it’s just to get to the other side in the best possible condition. As for sub-goals, these are going to vary considerably depending on the state of the fog when you make any particular commitment. How, then, should one act?

It should be clear that decision making in the foggy minefield cannot be modeled easily by, say, some form of dynamic programming. The reason is that the characteristics of the environment are not known in advance but are only revealed as you advance. (Sure, you can have some intuitions about how the field is structured, but there will still be events you cannot even imagine.) My contention is that many future-choice decisions are like foggy minefields and, thus, that determining how to handle such environments is an important research agenda.

What research can be done on this topic? I argue that a good starting point would be to take a rule like the one described above—“commit only as far as you can predict”—and see how it performs in simulations that model different variations of the foggy-minefield paradigm. My suspicion—based on the work being done on simple decision rules in conventional environments3—is that heuristics that “work well” will be those that match the environment in critical ways.

As an example of such a simulation, imagine the following videogame, which I shall simply call “life.” You start with an endowment that has to be allocated across a portfolio of assets, and the goal is to cross a foggy minefield and reach the other side with a portfolio that has increased substantially in value. The assets in your portfolio differ in their characteristics. One, which simulates your health, decreases over time, but you can invest resources to reduce the speed of decrease. If this asset hits a specified value, you are out of the game (i.e., you die). The other assets are income-producing but differ in their rates of return and in how much you can invest. These variations are hard to predict—because of the fog. Some, for example, are more predictable than others (i.e., they are less affected by the fog). In the game, time is conceptually continuous but is represented by discrete periods: If you don’t make a specific decision during a given period to manage a specific asset, the asset will remain under the influence of the last time you made a decision concerning it. (This assumption is quite realistic; we all know that there are many things in our lives that will not change unless we decide to act upon them. If we delay our decision to act, things simply remain “as usual”—that is, the same as they were the last time we decided to change them.) And, of course, there are potential dangers in the form of mines that can explode and destroy your assets. You can, however, spend part of your resources to get some (imperfect) information.

Clearly, there are many issues involved in setting up the parameters of foggy minefields, including not only the one just described but also technical matters pertaining to creation of the actual simulation. However, in my opinion, the most interesting issue to investigate is the question of which decision rules, or heuristics, work effectively in foggy-minefield situations, as well as in variations of the game. How would different operational versions of the “commit only as far as you can predict” heuristic perform, and how sensitive would these be to changes in the game’s parameters? What other rules might experts in decision making suggest?

Finally, going beyond research, it would make sense to have such a game played systematically at schools (from kindergarten up to our elite universities). After all, and as we know too well, our children and grandchildren will also grow up facing the vagaries of foggy minefields and thus will need to know how to handle both subway and coconut uncertainty.

RECOMMENDED READING

Hogarth, R. M., and N. Karelaia (2007). “Heuristic and Linear Models of Judgment: Matching Rules and Environments.” Psychological Review 114, no. 3: 733-758.

Makridakis, S., R. M. Hogarth, and A. Gaba (2009). Dance with Chance: Making Luck Work for You. Oxford: Oneworld Publications.

Savage, L. J. (1954). The Foundations of Statistics. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Taleb, N. N. (2007). The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. New York: Random House.

Winter, S. G., G. Cattani, and A. Dorsch (2007). “The Value of Moderate Obsession: Insights from a New Model of Organizational Search.” Organization Science 18, no. 3: 403-419.

4

The More Who Die, the Less We Care

PAUL SLOVIC

A defining element of catastrophes is the magnitude of their harmful consequences. To help society prevent or mitigate damage from catastrophes, immense effort and technological sophistication are often employed to assess and communicate the size and scope of potential or actual losses.1 This effort assumes that people can understand the resulting numbers and act on them appropriately.

However, recent behavioral research casts doubt on this fundamental assumption. Many people do not understand large numbers. Indeed, large numbers have been found to lack meaning and to be underweighted in decisions unless they convey affect (feeling). As a result, there is a paradox that rational models of decision making fail to represent. On the one hand, we respond strongly to aid a single individual in need. On the other hand, we often fail to prevent mass tragedies such as genocide or take appropriate measures to reduce potential losses from natural disasters. I think this occurs, in part, because as numbers get larger and larger, we become insensitive; numbers fail to trigger the emotion or feeling necessary to motivate action.

I shall address this problem of insensitivity to mass tragedy by identifying certain circumstances in which it compromises the rationality of our actions and by pointing briefly to strategies that might lessen or overcome this problem.

BACKGROUND AND THEORY: THE IMPORTANCE OF AFFECT

Risk management in the modern world relies upon two forms of thinking. Risk as feelings refers to our instinctive and intuitive reactions to danger. Risk as analysis brings logic, reason, quantification, and deliberation to bear on hazard management. Compared to analysis, reliance on feelings tends to be a quicker, easier, and more efficient way to navigate in a complex, uncertain, and dangerous world. Hence, it is essential to rational behavior. Yet it sometimes misleads us. In such circumstances we need to ensure that reason and analysis also are employed.

Although the visceral emotion of fear certainly plays a role in risk as feelings, I shall focus here on the “faint whisper of emotion” called affect. As used here, affect refers to specific feelings of “goodness” or “badness” experienced with or without conscious awareness. Positive and negative feelings occur rapidly and automatically; note how quickly you sense the feelings associated with the word joy or the word hate. A large research literature in psychology documents the importance of affect in conveying meaning upon information and motivating behavior. Without affect, information lacks meaning and will not be used in judgment and decision making.

FACING CATASTROPHIC LOSS OF LIFE

Risk as feelings is clearly rational, employing imagery and affect in remarkably accurate and efficient ways; but this way of responding to risk has a darker, nonrational side. Affect may misguide us in important ways. Particularly problematic is the difficulty of comprehending the meaning of catastrophic losses of life when relying on feelings. Research reviewed below shows that disaster statistics, no matter how large the numbers, lack emotion or feeling. As a result, they fail to convey the true meaning of such calamities and they fail to motivate proper action to prevent them.

The psychological factors underlying insensitivity to large-scale losses of human lives apply to catastrophic harm resulting from human malevolence, natural disasters, and technological accidents. In particular, the psychological account described here can explain, in part, our failure to respond to the diffuse and seemingly distant threat posed by global warming as well as the threat posed by the presence of nuclear weaponry. Similar insensitivity may also underlie our failure to respond adequately to problems of famine, poverty, and disease afflicting large numbers of people around the world and even in our own backyard.

THE DARFUR GENOCIDE

Since February 2003, hundreds of thousands of people in the Darfur region of western Sudan, Africa, have been murdered by government-supported militias, and millions have been forced to flee their burned-out villages for the dubious safety of refugee camps. This has been well documented. And yet the world looks away. The events in Darfur are the latest in a long list of mass murders since World War II to which powerful nations and their citizens have responded with indifference. In her Pulitzer Prize-winning book A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide, Samantha Power documents in meticulous detail many of the numerous genocides that occurred during the past century. In every instance, American response was inadequate. She concludes: “No U.S. president has ever made genocide prevention a priority, and no U.S. president has ever suffered politically for his indifference to its occurrence. It is thus no coincidence that genocide rages on” (Power, 2003, p. xxi).

The UN general assembly adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in 1948 in the hope that “never again” would there be such odious crimes against humanity as occurred during the Holocaust of World War II. Eventually some 140 states would ratify the Genocide Convention, yet it has never been invoked to prevent a potential attack or halt an ongoing massacre. Darfur has shone a particularly harsh light on the failures to intervene in genocide. As Richard Just (2008) has observed, “we are awash in information about Darfur. . . . [N]o genocide has ever been so thoroughly documented while it was taking place . . . but the genocide continues. We document what we do not stop. The truth does not set anybody free. (p. 36) . . . [H]ow could we have known so much and done so little?” (p. 38).

AFFECT, ANALYSIS, AND THE VALUE OF HUMAN LIVES

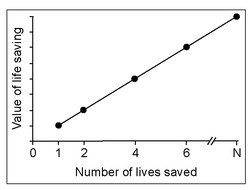

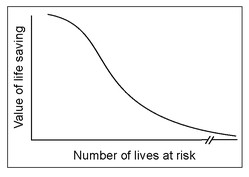

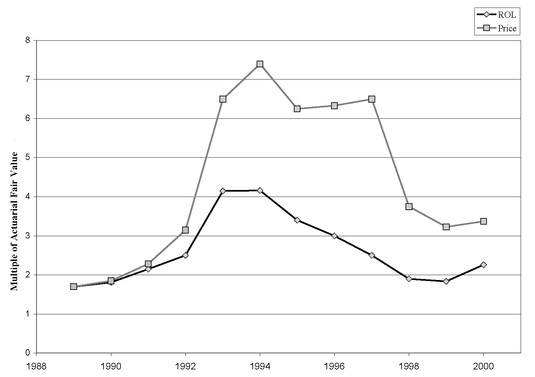

This brings us to a crucial question: How should we value the saving of human lives? An analytic answer would look to basic principles or fundamental values for guidance. For example, Article 1 of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights asserts that “[a]ll human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” We might infer from this the conclusion that every human life is of equal value. If so, then—applying a rational calculation—the value of saving N lives is N times the value of saving one life, as represented by the linear function in Figure 4.1.

FIGURE 4.1 A Normative Model for Valuing the Saving of Human Lives (Every Human Life Is of Equal Value)

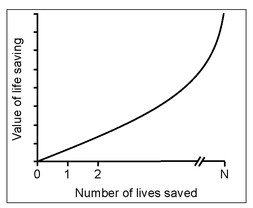

FIGURE 4.2 Another Normative Model (Large Losses Threaten the Viability of the Group or Society)

An argument can also be made for judging large losses of life to be disproportionately more serious because they threaten the social fabric and viability of a group or community (see Figure 4.2). Debate can be had at the margins over whether one should assign greater value to younger people versus the elderly, or whether governments have a duty to give more weight to the lives of their own people, and so on, but a perspective approximating the equality of human lives is rather uncontroversial.

How do we actually value human lives? Research provides evidence in support of two descriptive models linked to affect and intuitive thinking that reflect values for lifesaving profoundly different from those depicted in the normative (rational) models shown in Figures 4.1 and 4.2. Both of these descriptive models demonstrate responses that are insensitive to large losses of human life, consistent with apathy toward genocide.

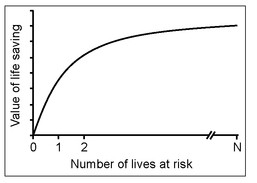

FIGURE 4.3 A Psychophysical Model Describing How the Savingof Human Lives May Actually Be Valued

THE PSYCHOPHYSICAL MODEL

There is considerable evidence that our affective responses and the resulting value we place on saving human lives follow the same sort of “psychophysical function” that characterizes our diminished sensitivity to changes in a wide range of perceptual and cognitive entities—brightness, loudness, heaviness, and wealth—as their underlying magnitudes increase.

As psychophysical research indicates, constant increases in the magnitude of a stimulus typically evoke smaller and smaller changes in response. Applying this principle to the valuing of human life suggests that a form of psychophysical numbing may result from our inability to appreciate losses of life as they become larger. The function in Figure 4.3 represents a value structure in which the importance of saving one life is great when it is the first, or only, life saved but diminishes as the total number of lives at risk increases. Thus, psychologically, the importance of saving one life pales against the background of a larger threat: We may not “feel” much difference, nor value the difference, between saving 87 lives and saving 88.

My colleagues David Fetherstonhaugh, Steven Johnson, James Friedrich, and I demonstrated this potential for psychophysical numbing in the context of evaluating people’s willingness to fund various lifesaving interventions. In a study involving a hypothetical grant-funding agency, respondents were asked to indicate the number of lives a medical research institute would have to save to merit receipt of a $10 million grant. Nearly two-thirds of the respondents raised their minimum benefit requirements to warrant funding when there was a larger at-risk population, with a median value of 9,000 lives needing to be saved when 15,000 were at risk (implicitly valuing each life saved at $1,111), compared to a median of 100,000 lives needing to be saved out of 290,000 at risk (implicitly valuing each life saved at $100). Thus respondents saw saving 9,000 lives in the smaller population as more valuable than saving more than ten times as many lives in the larger population. The same study also found that people were less willing to send aid that would save 4,500 lives in Rwandan refugee camps as the size of the camps’ at-risk population increased.

In recent years, vivid images of natural disasters in South Asia and the American Gulf Coast, and stories of individual victims there, brought to us through relentless, courageous, and intimate news coverage, unleashed an out-pouring of compassion and humanitarian aid from all over the world. Perhaps there is hope here that vivid, personalized media coverage featuring victims could also motivate intervention to prevent mass murder and genocide.

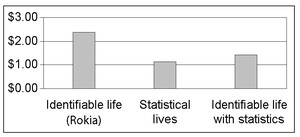

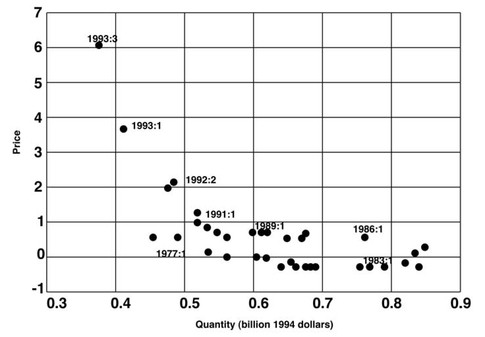

Perhaps. Research demonstrates that people are much more willing to aid identified individuals than unidentified or statistical victims. But a cautionary note comes from a study in which my colleagues and I gave people who had just participated in a paid psychological experiment the opportunity to contribute up to $5 of their earnings to the charity Save the Children. In one condition, respondents were asked to donate money to feed an identified victim, a 7-year-old African girl named Rokia, of whom they were shown a picture. They contributed more than twice the amount given by a second group who were asked to donate to the same organization working to save millions of Africans (statistical lives) from hunger. Respondents in a third group were asked to donate to Rokia, but were also shown the larger statistical problem (millions in need) shown to the second group. Unfortunately, coupling the large-scale statistical realities with Rokia’s story significantly reduced contributions to Rokia (see Figure 4.4).

Why did this occur? Perhaps the presence of statistics reduced the attention to Rokia essential for establishing the emotional connection necessary to motivate donations. Alternatively, recognition of the millions who would not be helped by one’s small donation may have produced negative feelings that inhibited donations. Note the similarity here at the individual level to the failure to help 4,500 people in the larger refugee camp. The rationality of these responses can be questioned. We should not be deterred from helping 1 person, or 4,500, just because there are many others we cannot save!

In sum, research on psychophysical numbing is important because it demonstrates that feelings necessary for motivating lifesaving actions are not congruent with the normative/rational models in Figures 4.1 and 4.2. The nonlinearity displayed in Figure 4.3 is consistent with the devaluing of incremental loss of life against the background of a large tragedy. It can thus explain why we don’t feel any different upon learning that the death toll in Darfur is closer to 400,000 than to 200,000. What it does not fully explain, however, is apathy toward genocide, inasmuch as it implies that the response to initial loss of life will be strong and maintained, albeit with diminished sensitivity, as the losses increase. Evidence for a second descriptive model, better suited to explain apathy toward large losses of lives, follows.

FIGURE 4.4 Mean Donations

Source: Reprinted from Small et al. (2006), copyright 2006, with permission from Elsevier.

THE COLLAPSE OF COMPASSION