It Chooses You – Read Now and Download Mobi

CANONGATE

Edinburgh • London • New York • Melbourne

Published in Great Britain in 2012 by Canongate Books Ltd,

14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

Copyright © Miranda July, 2011

The moral right of the author has been asserted

First published in the USA in 2011 by McSweeney’s, San Francisco

Photographs on page 209 are by Aaron Beckum.

The interviews and sequences within have been edited for length, coherence, and clarity.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on

request from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 85786 254 9

eISBN 978 0 85786 283 9

This digital edition first published by Canongate in 2011

Join the discussion:

#itchoosesyou or follow Miranda July on @Miranda_July

FOR JOE AND CAROLYN PUTTERLIK

CONTENTS

I slept at my boyfriend’s house every night for the first two years we dated, but I didn’t move a single piece of my clothing, a single sock or pair of underwear, over to his place. Which meant I would wear the same clothes for many days, until I found a moment to go back to my squalid little cave, a few blocks away. After I changed into clean clothes I’d walk around in a trance, mesmerized by this time capsule of my life before him. Everything was just as I’d left it. Certain lotions and shampoos had separated into waxy layers, but in the bathroom drawer there were still the extra-extra-large condoms from the previous boyfriend, with whom intercourse had been painful. I had thrown away some foods, but the nonperishables, the great northern beans and the cinnamon and the rice, all waited for the day when I would remember who I really was, a woman alone, and come home and soak some beans. When I finally put my clothes in black plastic bags and drove them over to his house, it was with a sort of daredevil spirit – the same way I had cut off all my hair in high school, or dropped out of college. It was impetuous, sure to end in disaster, but fuck it.

I’ve now lived in the boyfriend’s house for four years (not including the two years I lived there without my clothes), and we’re married, so I’ve come to think of it as my house. Almost. I still pay rent on the little cave and almost everything I own is still there, just as it was. I only threw out the extra-extra-large condoms last month, after trying hard to think of a scenario in which I could safely give them to a large-penised homeless person. I kept the house because the rent is cheap and I write there; it’s become my office. And the great northern beans, the cinnamon, and the rice keep the light on for me, should anything go horribly wrong, or should I come to my senses and reclaim my position as the most alone person who ever existed.

This story takes place in 2009, right after our wedding. I was writing a screenplay in the little house. I wrote it at the kitchen table, or in my old bed with its thrift-store sheets. Or, as anyone who has tried to write anything recently knows, these are the places where I set the stage for writing but instead looked things up online. Some of this could be justified because one of the characters in my screenplay was also trying to make something, a dance, but instead of dancing she looked up dances on YouTube. So, in a way, this procrastination was research. As if I didn’t already know how it felt: like watching myself drift out to sea, too captivated by the waves to call for help. I was jealous of older writers who had gotten more of a toehold on their discipline before the web came. I had gotten to write only one script and one book before this happened.

The funny thing about my procrastination was that I was almost done with the screenplay. I was like a person who had fought dragons and lost limbs and crawled through swamps and now, finally, the castle was visible. I could see tiny children waving flags on the balcony; all I had to do was walk across a field to get to them. But all of a sudden I was very, very sleepy. And the children couldn’t believe their eyes as I folded down to my knees and fell to the ground face-first, with my eyes open. Motionless, I watched ants hurry in and out of a hole and I knew that standing up again would be a thousand times harder than the dragon or the swamp and so I did not even try. I just clicked on one thing after another after another.

The movie was about a couple, Sophie and Jason, who are planning to adopt a very old, sick stray cat named Paw Paw. Like a newborn baby, the cat will need around-the-clock care, but for the rest of his life, and he might die in six months or it might take five years. Despite their good intentions, Sophie and Jason are terrified of their looming loss of freedom. So with just one month left before the adoption, they rid their lives of distractions – quitting their jobs and disconnecting the internet – and focus on their dreams. Sophie wants to choreograph a dance, and Jason volunteers for an environmental group, selling trees door-to-door. As the month slips away, Sophie becomes increasingly, humiliatingly paralyzed. In a moment of desperation, she has an affair with a stranger – Marshall, a square, fifty-year-old man who lives in the San Fernando Valley. In his suburban world she doesn’t have to be herself; as long as she stays there, she’ll never have to try (and fail) again. When Sophie leaves him, Jason stops time. He’s stuck at 3:14 a.m. with only the moon to talk to. The rest of the movie is about how they find their souls and come home.

Perhaps because I did not feel very confident when I was writing it, and because I had just gotten married, the movie was turning out to be about faith, mostly about the nightmare of not having it. It was terrifyingly easy to imagine a woman who fails herself, but Jason’s storyline confounded me. I couldn’t figure out his scenes. I knew that in the end of the movie he would realize he was selling trees not because he thought it would help anything – he actually felt it was much too late for that – but because he loved this place, Earth. It was an act of devotion. A little like writing or loving someone – it doesn’t always feel worthwhile, but not giving up somehow creates unexpected meaning over time.

So I knew the beginning and the end – I just had to dream up a convincing middle, the part when Jason’s soliciting brings him in contact with strangers, perhaps even inside their homes, where he has a series of interesting or hilarious or transformative conversations. It was actually easy to write these dialogues; I had sixty different drafts with sixty different tree-selling scenarios, and every single one had seemed truly inspired. Each time, I was convinced I had found the missing piece that completed the story, hilariously, transformatively. Each time, I had chuckled ruefully to myself as I proudly emailed the script to people I respected, thinking, Phew, sometimes it takes a while, but if you just have faith and keep trying, the right thing will come. And each of those emails had been followed by emails written a day, or sometimes even just an hour, later – “Subject: Don’t read the draft I just sent you!! New one coming soon!!”

So now I was past faith. I was lying in the field staring at the ants. I was googling my own name as if the answer to my problem might be secretly encoded in a blog post about how annoying I was. I had never really understood alcohol before, which was something that had alienated me from most people, but now I came home from the little house each day and tried not to talk to my husband before I’d had a thimbleful of wine. I’d been vividly in touch with myself for thirty-five years and now I’d had enough. I discussed alcohol with people as if it were a new kind of tea I’d discovered at Whole Foods: “It tastes yucky but it lowers your anxiety, and it makes you easier to be around – you have to try it!” I also became sullenly domestic. I did the dishes, loudly. I cooked complicated meals, presenting them with resentful despair. Apparently this was all I was capable of now.

I tell you all this so you can understand why I looked forward to Tuesdays. Tuesday was the day the PennySaver booklet was delivered. It came hidden among the coupons and other junk mail. I read it while I ate lunch, and then, because I was in no hurry to get back to not writing, I usually kept reading it straight through to the real estate ads in the back. I carefully considered each item – not as a buyer, but as a curious citizen of Los Angeles. Each listing was like a very brief newspaper article. News flash: someone in LA is selling a jacket. The jacket is leather. It is also large and black. The person thinks it is worth ten dollars. But the person is not very confident about that price, and is willing to consider other, lower prices. I wanted to know more things about what this leather-jacket person thought, how they were getting through the days, what they hoped, what they feared – but none of that information was listed. What was listed was the person’s phone number.

On one hand was my fictional problem with Jason and the trees, and on the other hand was this telephone number. Which, normally, I would never have called. I certainly didn’t need a leather jacket. But on this particular day I really didn’t want to return to the computer. Not just to the script, but also the internet, its thrall. So I picked up the phone. The implied rule of the classifieds is you can call the phone number only to talk about the item for sale. But the other rule, always, is that this is a free country, and I was trying hard to feel my freedom. This might be my only chance to feel free all day.

In my paranoid world every storekeeper thinks I’m stealing, every man thinks I’m a prostitute or a lesbian, every woman thinks I’m a lesbian or arrogant, and every child and animal sees the real me and it is evil. So when I called I was careful to not be myself; I asked about the jacket in a voice borrowed from The Beav on Leave It to Beaver. I was hoping for the same kind of bemused tolerance that he received.

The person who answered was a man with a hushed voice. He wasn’t surprised by my call – of course he wasn’t, he had placed the ad.

“It’s still for sale. You can make an offer when you see it,” he said.

“Okay, great.”

There was a pause. I sized up the giant space between the conversation we were having and the place I hoped to go. I leaped.

“Actually, I was wondering if, when I come over to look at the jacket, I could also interview you about your life and everything about you. Your hopes, your fears…”

My question was overtaken by the kind of silence that rings out like an alarm. I quickly added: “Of course, I would pay you for your time. Fifty dollars. It’ll take less than an hour.”

“Okay.”

“Okay, great. What’s your name?”

“Michael.”

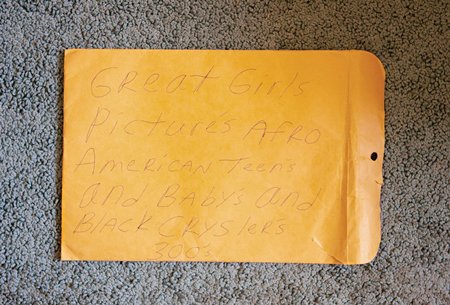

MICHAEL

–

LARGE BLACK LEATHER JACKET

$10

–

HOLLYWOOD

–

It was wonderful to have this opportunity to leave my cave. I packed a bag with yogurt, apples, bottles of water, and a little tape recorder. It was the kind that used mini-tapes; I’d gotten it when I was twenty-six in order to listen to the tapes the director Wayne Wang sent me after he recorded our conversations about my sexual history as part of his research for a movie he was making. I had always thought of this as a rather creepy exercise that I’d participated in for the money and because I liked to talk about myself. But now, putting the tape recorder in my purse, I felt a little more sympathetic. Maybe Mr. Wang had just wanted to talk to someone he hadn’t made up. Maybe it was a casualty of the job.

I drove to Michael’s with a photographer, Brigitte, and my assistant, Alfred. Brigitte had met all my family and friends, but I hadn’t known her very long, or very well – she was our wedding photographer. Her photographic equipment legitimized this outing in my mind; maybe I was a journalist or a detective – who knew? Alfred was there to protect us from rape.

The address was a giant old apartment building on Hollywood Boulevard, the kind of place where starlets lived in the ’30s, but now it was the cheapest sort of flophouse. It’s not that my world smells so good – my house, the houses of my friends, Target, my car, the post office – it’s just that I know those smells. I tried to pretend this too was a familiar smell, the overly sweet note combined with something burning on a hotplate thirty years ago. I also tried to appreciate small blessings, like that when we pressed 3 on the elevator, it went up and opened on a floor with a corresponding number 3.

The door opened and there was Michael, a man in his late sixties, burly, broad-shouldered, a bulbous nose, a magenta blouse, boobs, pink lipstick. Before he opened the door completely he quietly stated that he was going through a gender transformation. That’s great, I said, and he asked us to please come in. It was a one-bedroom apartment, the kind where the living room is delineated from the kitchen area by a metal strip on the floor, joining the carpet and the linoleum. He showed us the large leather jacket and I felt a little starstruck: here it was, the real thing. I touched its leather and immediately got a head-rush. This sometimes happens when I’m faced with actualities – it’s like déjà vu, but instead of the sensation that this has happened before, I’m suffused with the awareness that this is happening for the first time, that all the other times were in my head.

We murmured admiration for the jacket, which was entirely ordinary, and I asked if I could turn on the tape recorder. Michael settled into a medical-looking chair and I perched on the couch. I glanced at my questions, but now they seemed beside the point.

Miranda: | When did you begin your gender transformation? |

Michael: | Six months ago. |

Miranda: | And when did you know that you – |

Michael: | Oh, well, I knew it when I was a child, but I’ve been in the closet all my life. I came out in 1996 and then went back in the closet again, but this time I’m not going to go back in the closet. I’m going to complete the transformation. |

Miranda: | So the first time you came out must have been hard. You must not have had a good experience? |

Michael: | It wasn’t hard. I just decided to do it, and I don’t know why I went back in the closet. It’s one of those psychological things that I’m going to a psychologist to work out. |

Michael spoke softly and with a sort of evenness that made me wonder if he was a little bit drugged. Nothing crazy, maybe just some muscle relaxers to take the edge off. The thought calmed me – I was glad there was some padding between him and my invasive questions. I wished I was on muscle relaxers too.

Miranda: | What was your life like before you came out? |

Michael: | I was trying to be the same as every other man, and hiding the fact that inside I felt like a woman. I knew that when I was a child, but I had this strong fear of coming out for a long time. The movement for gay people to come out helped me realize that I shouldn’t do that. |

Miranda: | What did you do for a living? |

Michael: | I ran my own business as an auto mechanic. |

Miranda: | What do you do now? |

Michael: | Now I’m retired. |

Miranda: | What are you living on? |

Michael: | On Social Security benefits. This is a Section 8 building, so rent is very reasonable. And before this building I lived in the cheapest rooming house in Hollywood. |

Miranda: | And how do you spend your days? |

Michael: | I go shopping and watch television, and I go for walks for my health. |

Miranda: | What shows are your favorites? |

Michael: | The Price Is Right and the news. |

Miranda: | And do you feel like you have a community here? |

Michael: | I do have a community. I’m going to Transgender Perceptions meetings every Friday at the Gay and Lesbian Center on McCadden, and there’s a bunch of other transgender people that go. Male-to-female, female-to-male. There’s two I met there that had their major surgeries forty years ago. |

I asked if we could look around his apartment and he said sure. Michael stayed seated and watched us as we walked around, quietly peering at everything.

It reminded me of being at a garage sale, the rude feeling of surveying someone’s entire life in one greedy glance. Every few seconds I raised my eyebrows with reassuring interest, but Michael was not concerned.

Miranda: | Can I look at your movie collection? |

Michael: | Oh, that’s all pornography. |

I nodded and smiled warmly to indicate how okay I was with pornography.

Michael: | You can look through it. |

I knelt down and studied the tapes. They were all of women, or what seemed to be women. I did one of those modern calculations: male-to-female + porn for straight men = he wants to be lesbian?

Miranda: | Is it women that you like? |

Michael: | Well, there’s straight pornography and there’s trans pornography. There’s also some pornography with she-males too. And that’s about it. |

This answer just created more questions, but I was too shy to ask them. I took my pre-written questions out of my pocked.

Miranda: | Have you ever had a computer? |

Michael: | No, I’ve never had any computers. I may get one someday. I use the computer at the library. |

Miranda: | Is there anything you want that you worry you’ll never have? |

Michael: | No, not at this age. |

Miranda: | You feel like you’ve come to peace with things? |

Michael: | Yeah. The only thing left is my completed transition; that’s the only thing left that I’m desiring. I’m waiting for that. |

Miranda: | And what would you say has been the happiest time in your life so far? |

Michael: | Oh, I just enjoy living. I’m always happy. I can’t say between one or the other which is the happiest time. I never thought about that. |

Miranda: | Not everyone enjoys living – is that just part of the spirit you were born with, or do you think your parents instilled that? |

Michael: | No. It’s part of my spirit that I was born with. I was never taught that idea. |

I threw a question mark at Brigitte and she nodded yes, she’d photographed everything. So we said goodbye to Michael, nervously heaping on parting graces, and silently rode the elevator back down to the first floor. We stepped out onto sunny Hollywood Boulevard, a street I drive down every day. Now when I drove past this building I would always know that Michael was in there, living on Social Security benefits, enjoying life and desiring only one last thing – to transform into a woman. His conviction ignited me. I felt light and alert. Evidence of his faith in this almost-impossible challenge was everywhere: the pink blouse, the makeup littering the bathroom, the handmade dildo-esque wig stand. These were not signals of defeat. This was not someone who was getting sleepy at the end of his journey; in fact, everything he had lived through made him certain of what mattered now.

I had become narrow and short-sighted at my desk. I’d forgotten about boldness, that it was even an option. If I couldn’t write the scenes, then I should really go all the way with not writing them. I decided to remove myself from my computer and the implication that I might be on the verge of a good idea. I would meet with every PennySaver seller who was willing. I would make myself do this as if it were my job. I would get a better tape recorder and drive all over Los Angeles like an untrained, unhelpful social worker. Why? Exactly. This was the question that my new job would answer.

I had to force myself each time I dialed a stranger’s number, but I made myself do it, because this was the end of the road for me; not calling would be the beginning of not doing a lot of other things, like getting out of bed. I started with the first item for sale (a pair of matching silver champagne flutes engraved with the year 2000, twenty dollars) and made my way down the list. Most people didn’t want to be interviewed, so when someone said yes I felt elated, as if they had said, “Yes, and after you pay me fifty dollars for the interview, I’ll pay you one-point-five millon dollars to finance your movie.” Because that was the other problem I was now having. In the time it had taken me to write the movie, the economy had turned to dust. Suddenly all the companies that had been so excited to meet me a year ago were not financing anything that didn’t star Natalie Portman. Which kind of brought out the Riot Grrrl in me – I walked out of polite meetings in Beverly Hills with visions of turning around and walking back in, naked, with something perfect scrawled across my stomach in black marker. But what was the perfect response to logical, cautious soulessness? I didn’t know. So I kept my clothes on and drove to the home of someone who had said yes to me, sight unseen. A woman selling outfits from India for five dollars each.

PRIMILA

–

OUTFITS FROM INDIA

$5 EACH

–

ARCADIA

–

I had presumed that very wealthy people didn’t use the PennySaver, but as we drove up to a house with turrets and perhaps even balustrades, depending on what those are, I reconsidered my presumption. And as I listened to the long tones of Primila’s musical doorbell, I considered reconsidering everything – my sexuality, my profession, my friends; they were all up in the air for as long as the chimes pealed. Was this what church sounded like? What if I became born-again right now? I crossed my arms to keep this from happening and reminded myself to be attentive to mysterious advice and coded messages. In any vision quest–type scenario, one had to be very alert; I was keeping an ear out for something like “The trees have eyes.” It would make no sense at the time, but later it would save my life.

A middle-aged Indian woman opened the door. She wasn’t wearing an outfit from India, just a normal suburban-mom outfit. She held a flyswatter and warmly welcomed us inside while savagely slapping flies.

Miranda: | Thank you so much for having us here. |

Primila: | So do you want to tell me again a little bit more about what this is for? Do you have any brochure or write-up on things that you do, or your company? |

Miranda: | I’m just interviewing people. I’m really interested in just getting a portrait of the person and what they’re interested in, and a sense of their life story. I’m a writer and I usually write fiction, but this is – you know, I’m always curious about people. So this is a chance to – |

Primila: | You write fiction? Do you have any particular themes or any commission or fashion? |

Miranda: | They’re – I mean, gosh. They’re usually about people trying to connect in one way or another and the importance of that. And the different ways people sort of make that harder than it needs to be. |

Primila: | I’m just curious, because out of the blue – |

Miranda: | I know, I know. So, I know you told me a little bit on the phone, but now that I’m recording, what led to you putting – what are you selling in the PennySaver? |

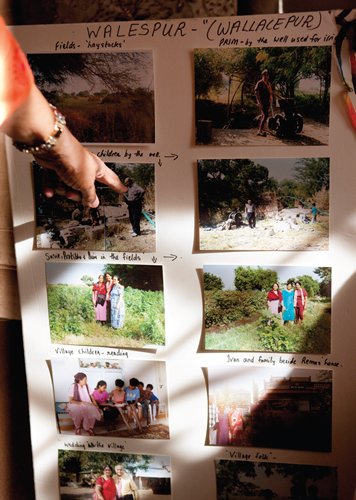

Primila: | What I’m selling are some outfits from India. I have quite a few of them. I’m trying to do two things. One is get them to people who would probably appreciate it who normally wouldn’t have a chance to have this kind of ethnic costume. But the whole thing started, I think it was a year ago in July. We had gone to India, and we went to a village. My husband has a special interest in that place because his grandmother hailed from that village. Of late, because of the lack of rainfall and because of all that, the crops have been failing. These people from the village said, “Can you help us and send us money? We need a motorized irrigation system.” |

| So I had an open house and sold all these Indian outfits that I brought from India. I did that for two days, two Saturdays, and I raised about… I think it was a few hundred, and I sent it all there, and they got this motorized pump. |

| In April my husband went back, and they’re very happy with the irrigation system but now they want to expand their fields. I thought, Let me put an ad in the PennySaver and maybe I will reach people who want to buy the stuff. One lady came, and she got a lot because she works as an extra in the movies and she’s a Latino lady. She said sometimes they want her to dress up as an Indian lady. So she loved that. |

Miranda: | Where in India are you from? |

Primila: | Bombay. My dad was a meteorologist at the Bombay airport. So we built a house right near the airport. A huge, big three-story house. |

Miranda: | And can you tell me your earliest memory? |

Primila: | Yes. I was two years old. I was traveling on a ship from Bombay to England. It was like a big doll’s house. In those days people didn’t fly, they went by cruise liners. I was just two and I can remember so clearly. My name is Primila, but I would tell everyone my name is Mrs. Haggis. I don’t know why or how. My mom tells the story of how this little girl – I had ringlets – there would be a group around me saying, “What’s your name, little girl?” And I’d say, “Mrs. Haggis.” I insisted that was my name. I’d never even eaten haggis, so I don’t know where it – or maybe I’d heard about haggis and I thought, you know, that’s an English dish. |

Primila showed me around her house. It was immaculate and girlish, with white carpet and arrangements of large dolls dressed in frilly dresses. And though she knew I wasn’t a reporter or anyone of consequence, she began to tell me about herself the way Michael had, as if this interview really mattered. It occurred to me that everyone’s story matters to themselves, so the more I listened, the more she wanted to talk.

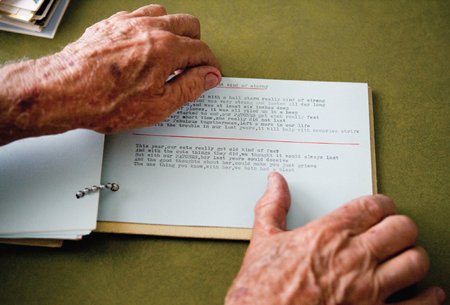

Primila: | I write poems with a theme or a message. “Each Day Is a Gift” was a theme. Then after Thanksgiving I wrote “Ten Reasons to Be Thankful.” There’s another one, “Look for the Rainbow” – because I’ve had so many things happen and I try always to still be upbeat and positive, no matter what. I lost my sister very tragically to cancer years ago. She had fourth-stage colon cancer. She was thirty-five years old with four little kids. They wouldn’t give her the visa to come to America, and she was in the last month. I talked to the embassy in India and every time it was no, no, because they didn’t believe it – she looked so healthy and so they didn’t believe. |

| It was Thanksgiving here in America. So the next day I woke up and I said I’m going to call the top official. His name was Tom Fury, I still remember. And they’d never let you through. It was all this hierarchy of people. Finally he came on the phone and I said, “Mr. Fury, I just want to tell you one thing. If my sister doesn’t make it, I’ll be at peace because I’ve done everything I can. And she knows how much we love her.” But I said, “Whoever has been instrumental in denying her this last opportunity will have to live with that for the rest of their lives and will have to answer for that on the Day of Reckoning.” That’s all I said, and “Thank you so much.” And this had been going on for three months, not granting the visa. |

| At 2 a.m. the phone rang. It was my mom in India. “Primila, you won’t believe this. The embassy called. They’ve granted the visa to the whole family.” And when my brother went down to get the visa, they said this had never happened before in the history of the embassy. |

| She passed away on December 24. We buried her on December 31 at Forest Lawn. Then I kept her children and raised them. So whatever happens, I always try to share things that we can learn from what happens in our lives, how we can help others. |

Miranda: | And what do you do for a living? |

Primila: | I’m director of rehabilitation at a hospital. I’ve worked there twenty-three years. I’m so passionate about my work that in twenty-three years I’ve never had an unscheduled absence. I never picked up and said, “I’m not coming in today.” But today I locked my door – I always lock my bedroom door when my husband’s in India – and I realized my purse was still inside with the car key. I didn’t know what to do. I went up and I shook the door. It wouldn’t open. So I thought, What do I do? Let me call my son. My son tells me, “Mom, you’ve never called in sick. I’m busy. Maybe today’s the first time in your life – you have a reason: you don’t have a car.” I said, “Are you kidding? I would never do that.” The day I drop dead I won’t show up at work. So I went up again and I just shook the door and I managed to budge it. |

Miranda: | You broke down the door? |

Primila: | Yes. |

Primila took us upstairs and showed us the door, hanging off its hinges, and then she pointed out two places in the house where a tiny square of wall had been removed. She asked me to guess what these holes were for, but I said I couldn’t even begin to imagine.

Primila: | Okay, I’ll tell you because it’s a funny story. One day I was at work and my nephew Benny calls me and he says, “Auntie, I’m hearing voices from the wall. Not from the roof, but from the actual wall.” I said, “What nonsense.” But when I came home I listened, and sure enough, in the closet, behind the wall – in the wall – there was a little meow meow. So my son-in-law cut a hole in the closet wall and he put a little food there. Then in the morning there was the cutest little black and white kitten, just two weeks old. |

| And then a week or two later, just behind the water heater, he calls me up and says, “Auntie, there’s another meow going on there.” And sure enough, we cut a hole there and another kitten came out. And then it happened again! There was a tree that had grown over our wall, so the cat from there had climbed up, made a hole in our roof, and got into our attic to have her kittens. And then they were falling through the insulation. My daughters are married and I’m waiting for grandchildren, but the joke is that the stork brings only four-legged babies to my house. |

Before we left, she showed me how to wear a sari properly. As she wound the fabric around my hips I realized I would join the Latina actress when Primila told her story about people who had answered the ad. I had thought of myself as outrageously forward, but PennySaver sellers weren’t hung up about inviting strangers into their homes. So I didn’t have to be so nervous — I could drop the Leave It to Beaver voice and focus on the secret clues each person was trying to convey to me.

That night I wrote down: (1) Each day is a gift, and, (2) Look for the rainbow. Gift. Rainbow. Primila was a hellcat, breaking down doors and threatening officials with eternal damnation. She had adopted four kids and had three four-legged grandchildren. I crossed out clues one and two. These were obviously decoy messages. Of course the truth wouldn’t be sweetly concealed in a motto, because I wasn’t Hansel or Gretel. My inquiry was open-ended, but it wasn’t pretend, I wasn’t in a fairytale or a fable. I shut my eyes and absorbed the silent whoomp that always accompanies this revelation. It’s the sound of the real world, gigantic and impossible, replacing the smaller version of reality that I wear like a bonnet, clutched tightly under my chin. It would require constant vigilance to not replace each person with my own fictional version of them.

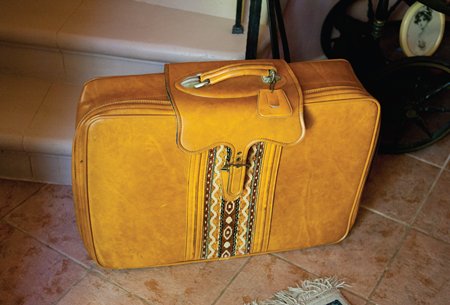

PAULINE & RAYMOND

–

LARGE SUITCASE

$20

–

GLENDALE

–

Pauline had been eager on the phone; she’d begun telling me about her life even before I asked the question or offered the fifty dollars. She lived in a pretty part of Glendale, my ex-boyfriend’s neighborhood. As I exited at the familiar exit, I thought what if it was the same street, the same house, what if it was him selling the suitcase, what if the suitcase was mine, something I’d forgotten, and what if I bought it and inside there was myself as a child or my dad as a child, or my child as a child, the one I hadn’t found time to have yet? But my ex-boyfriend’s name wasn’t Pauline, so we drove right past his street and parked on one a few blocks away. The house was big and grand, again. Pauline was in her seventies, and she immediately began showing me pictures and telling me stories about her amateur singing group, the Mellow Tones.

Pauline: | We sang “Two Sleepy People,” “Hello Dolly”… |

Miranda: | What’s this photo where you’re holding the gun? |

Pauline: | Oh, that’s me – oh, yeah. Well, in other words, you could call me a ham. That’s my Cohan medley – I forgot the name of what I sang. “Hello My Honey,” I guess. I can still sing but I had an operation on my ear because of a little growth and it turned out to be two cancer cells. So they had to dig harder. And somewhere along the line, I lost some of my hearing and so it comes out foggy for me. I don’t know what I sound like. So I dropped out of the singing groups I was in. |

Miranda: | So it’s your suitcase that you’re selling through the PennySaver? |

Pauline: | The suitcase? Oh, yes, I have it in the hallway. Do you want to see it? |

Miranda: | Maybe we should see it. |

Pauline: | Of course, that’s what you came for. |

I nodded but shrugged, to suggest that my reasons for coming were ever-evolving and expanding.

Miranda: | Why are you selling it? |

Pauline: | Well, when my daughter and grandson moved in, a lot of things had to be sold. She said, “Where are you going to make room for my stuff?” So I had to get rid of a lot of my books and condense everything. I’ve sold sheets – bedsheets – and mattresses. I’ve sold paintings. What else did I sell? The bed. |

Miranda: | How do you place the ads? Do you have a computer? |

Pauline: | I call it in. I write up an ad – there’s a special way of doing it, you get only so many words. The PennySaver will advertise your item for free if it’s under a hundred dollars. So that’s a big boost. But to sell one item at a time, it takes forever. |

Miranda: | And so when did your daughter and grandson move in? |

Pauline: | About two or three years already. Or four? |

Raymond: | Seven years. |

This was Pauline’s grandson – he had appeared out of nowhere. He was in his mid-thirties and wore a hearing aid. A very skinny dog wearing a striped rugby shirt followed him into the room.

Pauline: | Seven years? You’re joking. Oh, no. Where has the time gone? |

Raymond: | I started working a year later. |

Miranda: | Where do you work? |

Raymond: | I’m a driver for a company. I deliver mannequins. |

Miranda: | You deliver mannequins? |

Pauline: | Naked mannequins. |

Miranda: | Naked ones. And what company is that? |

Raymond: | United Galleria. We make them, we sell them, and we rent them. And repair them. |

Pauline: | He’s met a few people, too, haven’t you? |

Raymond: | I’ve met a lot of people. |

Pauline: | Celebrities. |

Raymond: | Not very many. |

Pauline: | You could name a few. |

Raymond: | I’ve met a few. Cameron Diaz – I met her, and Mark Jenkins. |

Miranda: | Neat. Do you have any pictures of you with mannequins? |

Raymond: | I have a mannequin upstairs. |

Miranda: | Okay, maybe we’ll go up there. |

Raymond: | I can bring it down. |

Miranda: | We can go up there. I don’t want you to have to bring it down. |

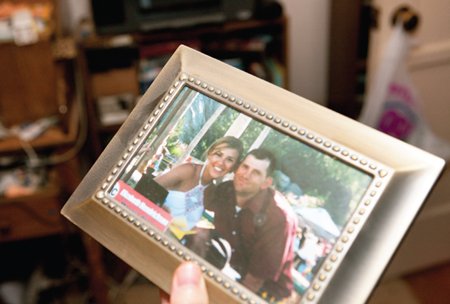

As we climbed the stairs, I began to realize the grandeur of the house was an illusion. These were the poor relations of the former owner. The mother and grandson both kept food and small refrigerators in their rooms, living in them like tiny studio apartments with a shared kitchen and bathroom. Before we looked at the mannequin, Raymond showed me a picture of himself with the actress Elizabeth Hendrickson from All My Children.

Raymond: | I met her at Disneyland. We had to get in line and we had to wait two hours. |

Miranda: | What is she like? What do you like about her? |

Raymond: | She’s friendly. And she’s beautiful, she’s pretty. |

Then he showed me the mannequin. It looked just like Elizabeth Hendrickson.

Miranda: | So this – I mean, it kind of looks like her. Why does it look so much like her? |

Raymond: | I took this from this picture here. |

Miranda: | So did you make her face? |

Raymond: | My boss. |

Miranda: | Oh, your boss. |

Raymond: | Yeah, he made her. |

Miranda: | From the picture. And did he do that just for you? |

Raymond: | Yeah. |

Miranda: | Oh, that’s nice. |

Raymond: | He put it in the mold. |

Miranda: | Is that expensive? I mean, did you have to buy that? |

Raymond: | If a regular person would buy it, it would probably be about fifteen hundred dollars. He gave me a discount. |

Miranda: | I see you have two computers. What do you do on your computers? |

Raymond: | I email. I email my friends. Sometimes I email my sister if I have a question. And I download music. |

Miranda: | What kind of music? |

Raymond: | Dido. |

Miranda: | She’s cool. |

Raymond: | It’s too bad Michael Jackson passed away. |

Miranda: | Yeah. |

Raymond: | I’m heartbroken because of it. |

Miranda: | Right before his big tour. |

Raymond: | That’s my generation. |

Miranda: | How old are you? |

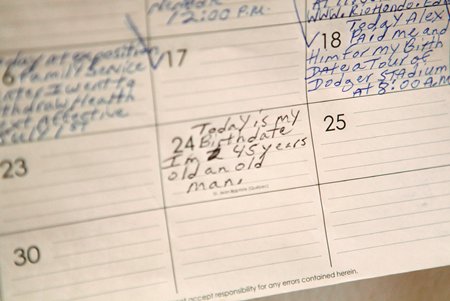

Raymond: | I’m thirty-nine. |

Miranda: | I’m thirty-five. |

Raymond: | So it’s our generation. |

Miranda: | Right. |

It was a relief, meeting someone whom I had anything at all in common with. Michael and Primila and Pauline had exhausted me with their openness and their quaint inefficiency, but Raymond and I were the same generation; we both knew how to click on things, we both had a version of our name with @ in it. As I left his room I said something like “Maybe I’ll see you around,” as if our generation all liked to congregate at one coffee shop.

But the moment I got back in my car I knew I would never see him again, ever. It suddenly seemed obvious to me that the whole world, and especially Los Angeles, was designed to protect me from these people I was meeting. There was no law against knowing them, but it wouldn’t happen. LA isn’t a walking city, or a subway city, so if someone isn’t in my house or my car we’ll never be together, not even for a moment. And just to be absolutely sure of that, when I leave my car my iPhone escorts me, letting everyone else in the post office know that I’m not really with them, I’m with my own people, who are so hilarious that I can’t help smiling to myself as I text them back.

Not that I was meeting one kind of person though the PennySaver, or that they all sold things for the same reason. Michael was poor, Pauline was lonelier than she was poor, Primila was just old-fashioned. But so far there was one commonality, something so obvious it had taken me a moment to notice. In the process of trying to reassure the people I was calling, I would occasionally mention that I was somewhat established – not a student, but a published writer. Google “Miranda July,” I’d suggest (I do it all day long!). But they weren’t googlers. People who place ads in the print edition of the PennySaver don’t have computers – of course they don’t, or they’d just use Craigslist.

And as I circled and crossed out ads, the newsprint booklet itself began to seem like some vestigial relic. On one future Tuesday the number of computerless people would become too small, and the booklet would simply not arrive. This made me a little anxious, so I called up PennySaver headquarters and asked them if they would be around forever. “The PennySaver in concept will be here forever,” said Loren Dalton, the president of PennySaver USA (which actually serves only California), “but not necessarily in print. That’s why we’ve made pretty heavy investments on the digital side – internet, mobile, we’re getting ready to do some things with the iPad.” But he assured me that nothing would happen right now, not during the recession. The PennySaver has always been strongest when the economy is the weakest; the first issue was printed during the Great Depression in someone’s garage. The word was never trademarked, so the PennySaver Maryland is unaffiliated with PennySaver Florida and PennySaver Nevada. They’ve all started online versions of themselves in the last decade, and the print versions of all of them will be discontinued within the next decade.

So this recession was perhaps the last hurrah for the PennySaver. The internal slogan of the company in 2009 was “Now Is Our Time.” This seemed like a pretty upbeat approach to the crisis. Just claim it! Own it. Dibs on the recession! The PennySaver catered to people for whom ten dollars was worth some trouble – people who saved pennies. Which, right now, was a lot of people.

ANDREW

–

BULLFROG TADPOLES

$2.50 EACH

–

PARAMOUNT

–

Now when friends asked me about how my script was going, I responded with the good news about my new job as a reporter for a newspaper that didn’t exist, interviewing people I found through a soon-to-be-extinct piece of junk mail. And because I was refused by the majority of people I called, the ones I met with did not feel random – we chose each other.

Paramount was completely outside my understanding of LA. I just did what the GPS told me to, and then I was there. It was hotter than where I lived; the blinding new pavement barely concealed the desert. I was much too early, so I drove up and down the streets, past rows of identical new houses. I could picture the man who’d built them, a hammer in one hand and the other hand hitting his forehead for the thousandth time as he stepped back from his newest creation and saw that it was, once again, exactly like the last house he’d built, the one next door. I hate it when I keep having the same bad idea, so I could empathize with him. It seemed like a tough neighborhood for a bullfrog that was just getting started, a tadpole. I hurried back to the address, now late. I’m always late and it’s always because I get there too early.

Andrew turned out to be a seventeen-year-old with three ponds in his backyard. Teenage boys never really made sense to me, and I’ve pretty much avoided them since high school. But Andrew was the one kind of teenage boy I was familiar with: the sweet, curious loner. My brother had also built ponds in high school. Andrew’s ponds were thick with water hyacinths and the special fish that eat mosquito eggs. Actual lily pads floated in the sun and the frogs seemed happy, as suburban frogs go.

Miranda: | How’d you make this? |

Andrew: | I just dug. |

Miranda: | Did you read about ponds, or how did you figure it out? |

Andrew: | I didn’t really read about it. People just told me. Everything ended up working out little by little. |

Miranda: | What do you like about it? |

Andrew: | I don’t know. It’s just relaxing. Watching all this, it relaxes me a lot. |

I nodded, pretending I was relaxed. I watched the sunlight sparkling on the water and practiced mind-body integration for a few seconds by quietly hyperventilating.

Miranda: | Had you ever put an ad in the PennySaver before? |

Andrew: | I never really tried it. It arrives every Wednesday or Thursday. I just started looking at it and said, “Let me try that.” I just wanted to try it out to see. It actually kind of did work out. |

Miranda: | Oh, really? Have people bought the tadpoles? |

Andrew: | Yeah. People enjoy them. They were kind of shocked, because nobody could really find a bullfrog tadpole. |

Miranda: | So the tadpoles are here? |

Andrew: | Let me take this plant out and you’ll see. |

He lifted a pile of dripping plants and scooped up a tadpole in a handful of water.

Miranda: | Wow, they’re really getting pretty froglike. I thought they’d be smaller. It must be kind of exciting, because suddenly you’re going to have a lot of – I mean, how quickly is this happening? |

Andrew: | The transformation? |

Miranda: | Yeah. |

Andrew: | It’s pretty fast. I’d say there are a couple of weeks left for this one. |

Miranda: | Am I picturing the right kind, with the big white thing that’ll make a noise like – well, I’m not gonna make the noise. |

Andrew: | Yeah. |

Miranda: | So that’ll be kind of amazing – you’ll have this sound. |

Andrew: | Everywhere, yeah. It’s really loud. |

Miranda: | That’ll be kind of surprising in the neighborhood. |

Andrew watched carefully as a pigeon tried to decide where to land and then nervously perched next to the pond.

Andrew: | Look at the pigeon. I’ve never seen that before. The pond attracts wildlife. It attracts all kinds of animals. |

Miranda: | Like what other kinds? |

Andrew: | Lizards too. |

Miranda: | I guess most of the city must not seem very welcoming for an animal, so this is like a little… |

Andrew: | Yeah, their habitat. |

Miranda: | What if, as we stand here, like, lions and antelopes start to come? |

Andrew: | That’d be crazy. |

Miranda: | And what do your parents do? Are they at work now? |

Andrew: | My dad just got laid off from the district. He used to work in Buena Park next to Knott’s Berry Farm. He was a custodian. He got laid off, so now he’s at home. We’re spending more time with him now. My mother, she works at Kaiser. |

I was burning in the sun, so we went inside, tip-toeing past the father watching TV and into Andrew’s room. I instinctively shut the door behind us, because what teenager leaves their bedroom door open, ever? But then that seemed weird – I was a total stranger – so I reopened it a crack.

Miranda: | Do your parents have ideas of what you should do now that you’ve graduated? Do you have a plan? |

Andrew: | Go to college, get a good education, get a career started. |

Miranda: | Where are you going to go? |

Andrew: | Long Beach. I already registered. I have the booklets and stuff. |

Miranda: | And what do you want to study? |

Andrew: | I want to get into engineering with airplanes and stuff, work with the engine or something like that. I don’t know. Something using my hands, like a mechanic. |

Miranda: | And, besides a job, besides school and then a job, what things do you picture in your future? |

Andrew: | Picture? |

Miranda: | What do you imagine? |

Andrew: | Like in the future? |

Miranda: | Yeah, anything. |

He looked at the ceiling, summoning a vision as if I had asked him to actually see his own future.

Andrew: | I probably imagine myself, I guess, being in the forest and stuff like that – in the mountains, something like that, around wildlife. |

Miranda: | So maybe not here. |

Andrew: | No, not here. |

Something moved in Andrew’s terrarium; I thought it was a turtle but then I looked again.

Miranda: | Whoa. |

Andrew: | Yeah. That’s my pet spider. |

Miranda: | Is it a tarantula? |

Andrew: | Yeah. He doesn’t bite. It’s all right. |

Miranda: | Okay. Good to know there’s a tarantula behind me. Okay, what’s been the happiest time of your life so far? |

Andrew: | The happiest time? I would have to say it was the graduation party my mom and my father had for me. |

Miranda: | I bet they were really proud. |

Andrew: | Yeah. They’re proud. One of my goals was getting out of high school. |

Miranda: | Was it hard? |

Andrew: | Well, to me it wasn’t really that hard. I was in Special Ed, so the teachers don’t try to take out effort from you. It’s easy. |

Miranda: | Was it too easy? |

Andrew: | Too easy. It could’ve been harder. They don’t try to teach you, because they think you won’t be able to pick up the information they’re giving you. |

Miranda: | Do you know why you’re in Special Ed? |

Andrew: | No. I’ve been in it since 2000. |

Miranda: | So… since you were eight. |

Andrew: | Yeah. They just gave me my paperwork, and on the paper it says it’s because I’m slow in remembering. |

Miranda: | Is that true? |

Andrew: | It says supposedly when I’m in class I’m daydreaming. I guess the teacher must think that because I don’t really talk to people in my classes, because I don’t know them. I just sit there and do my work and I don’t talk to nobody. I guess the teacher must think I daydream because I’m not interacting with other people. |

Miranda: | What do you wish you’d learned more about? |

Andrew: | Probably science. In my science class we weren’t able to do experiments. If you give some of the Special Ed kids a knife or something, they’ll play around, and I guess they didn’t really trust all of us so they’d rather not give us materials to be able to do experiments and stuff. I kind of got mad at that part. We weren’t able to do experiments where the other kids would do projects and stuff. We never had the chance to do that. |

Andrew: | Probably science. In my science class we weren’t able to do experiments. If you give some of the Special Ed kids a knife or something, they’ll play around, and I guess they didn’t really trust all of us so they’d rather not give us materials to be able to do experiments and stuff. I kind of got mad at that part. We weren’t able to do experiments where the other kids would do projects and stuff. We never had the chance to do that. |

Miranda: | And you would’ve been so good at biology and – |

Andrew: | All that stuff. It’s crazy. |

Miranda: | It’s making me mad. |

Andrew: | It made me mad. |

Miranda: | Not many people your age build a whole pond and keep everything alive. I wonder how much your college will look at those papers or if you can get kind of a fresh start. |

Andrew: | They’re going to look at them. My counselor, she told me to turn in all that information to Special Ed services or something like that. |

Miranda: | It seems like it could be just as easy to be a park ranger or something like that as to work on airplanes – I mean, if you had the choice. |

Andrew: | I don’t know, because people say it’s hard. And I’m not really good with all that stuff. When I want to do something I want to know that I can accomplish it, but if I start thinking that in the long run it’s going to be super hard, I kind of take a step back. |

Miranda: | Well, especially if you’ve had people telling you that you’re not good at that, it’s a hard thing to learn to finish. At least you’re almost an adult – there are some good things about that. In high school you don’t have any real rights, but at least in college… |

Andrew: | Yeah. It’s all on me now. |

It was tempting to jump in with some advice – I was about two seconds away from offering him an internship at my brother’s workplace, restoring wetlands. But it seemed be a tendency of mine to look for each person’s problem and then overlook all the other things about them. So I tried to see what else he was, besides lost in the system. Andrew was a little angry, but more than that, he was proud. So I changed my approach; I said the opposite of what I felt, and it was more true.

Miranda: | So we caught you at a kind of exciting time in your life. |

Andrew: | Yeah, pretty much at a good time. |

Miranda: | This is corny, but you’re kind of like the tadpole about to transform. |

Andrew: | Yeah. It’s true. |

Miranda: | You’re one of the big ones that have only a couple weeks left. |

Andrew: | You could say that, a tadpole. |

For a moment I could feel time the way he felt it – it was endless. It didn’t really matter that his dreams of wildlife were in the opposite direction from the airplane hangar where he was headed, because there was time for multiple lives. Everything could still happen, so no decision could be very wrong.

That was exactly the opposite of how I was feeling now, at thirty-five. I drove home from Paramount feeling ancient, like the characters in my script

Sophie: | We’ll be forty in five years. |

Jason: | Forty is almost fifty, and after fifty the rest is just loose change. |

Sophie: | Loose change? |

Jason: | Like not quite enough to get anything you really want. |

I knew this wasn’t really true, but that was the paralyzing sensation. There wasn’t time to make mistakes anymore, or to do things without knowing why. And each thing I made had to be more impossibly challenging than the last, which was hair-raising, since I had been out of my depths from the very start.

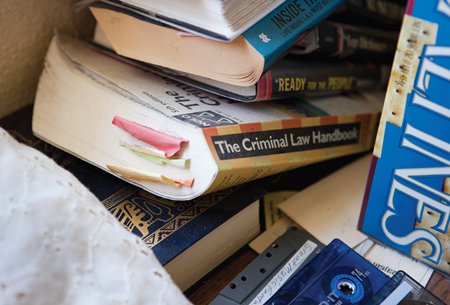

The first thing I ever made professionally – that is, for the ostensible public – was a play about my correspondence with a man in prison. I started writing to Franko C. Jones when I was fourteen. I’d found his address in (where else?) the classifieds, in a section that doesn’t seem to exist anymore called “Prison Pen Pals.” When I was younger, my dad had read The Minds of Billy Milligan to me before bed, the true story of a robber and rapist with multiple personality disorder (my father’s preference was to read me books that he himself was interested in). So my sympathy for imprisoned men was sort of a family tradition; I may even have written my first letter to Franko because I wanted to do something my dad would think was interesting. But then I kept writing to him for three years, every week.

The gap between a thirty-eight-year-old murderer serving his eighteenth year in Florence, Arizona, and a sixteen-year-old prep-school student in Berkeley, California, is lyrical in scale, like the size of the ocean or outer space. Bridging it seemed like one of the few things I could do that might be holy or transcendent. I’ve been trying for so long now, for decades, to lift the lid a little bit, to see under the edge of life and somehow catch it in the act – “it” being not God (because the word God asks a question and then answers it before there is any chance to wonder) but something along those lines. We wrote about grades, prison riots (Franko tape-recorded the sounds of one), my friends (Johanna, Jenni), his friends (Lefty, One-Eye), and everything else in our lives, except for sex, which I said at the start was off-limits.

I wrote the play because I couldn’t explain the relationship; conversations about it ended badly and I longed to be understood on a grand scale. I put a casting call in the free weekly newspaper, and I held auditions in a reggae club. I cast a drug-and-alcohol counselor in his thirties as Franko, and the character based on me was played by a Latina woman in her early twenties named Xotchil. (I thought I would be taken more seriously as a director if I didn’t also act in it – something I keep forgetting these days.) We practiced in my attic and performed the play, The Lifers, at 924 Gilman Street, a punk club. I rented chairs from a church and sat in them with my friends and family and my family’s friends and a few bewildered punk rockers. Together we watched this enactment of my improbable friendship and its clumsy spiritual yearning. I was so electrified with simultaneous shame and pride that two-thirds of the way through the play I got out of my seat and crept up to the side of the stage. I’m not sure what I planned to do from there – perhaps stop the show or redirect it as it happened. The drug-and-alcohol counselor gave me a hard look from the stage and I slunk back to my seat. I would simply have to endure it.

BEVERLY

–

BENGAL LEOPARD BABY

CALL FOR PRICES

–

VISTA

–

Movies are the only thing I make that puts me at the mercy of financiers, which is partly why I make other things too. Writing is free, and I can rehearse a performance in my living room; it may turn out that no one wants to publish the book or present the performance, but at least I’m not waiting for permission to make the thing. Having a screenplay and no money to make it would almost be worse than not having a screenplay and maintaining the dream of being wanted. At times it seemed that I was only pretending the script wasn’t finished, to save face, to give myself some sense of control. And on a more superstitious level, I secretly believed I would get financing when I had completed my vision quest, learned the thing I needed to know. The gods were at the edges of their seats, hoping I would do everything right so they could reward me.

I had been avoiding Beverly because Vista, on the map, seemed dangerously far away. But I was becoming more intrepid, or else my time was seeming less valuable. If, worst-case scenario, I couldn’t find my way home from Vista, I could just live there. So I called Brigitte and Alfred and we set out in the morning. In between the towns and cities in California are straw-covered hills that sometimes burst into flames. Beverly lived on one of these brown hills, which made sense; you could keep a suitcase or a jacket in the city, but Bengal leopard babies would need more room.

The road was dirt, the house was surrounded by abandoned furniture and equipment, and Beverly, who met us in the lawn, was painfully lacerated. She had told me on the phone that she didn’t want her face photographed because she’d just had an accident involving a shovel. The wounds were still spinning their scabs.

Beverly: | Come on, I’ll take you in the house and show you the cats first, and then we’ll go from there. You know what this is? |

She pointed to something on the wall. It had eyes.

Miranda: | Yes. |

Beverly: | What? What is it? |

Miranda: | That’s the butt of something. |

Beverly: | Yes – very good! Excellent! |

Miranda: | Of what, though? |

Beverly: | A deer. And this bone came from Vietnam. Some man there carves it. Isn’t that incredible? |

Miranda: | Amazing, yeah. |

Beverly: | It’s all hand-carved. Come on. These are fish. This was from a volcano. |

It was like a very questionable natural-history museum; each thing might be a million years old or it might have been made in the late ’70s. But I was learning to assess people quickly, and Beverly wasn’t crazy, just very glad to see us and in a hurry to get the party started. There was so much to see and do.

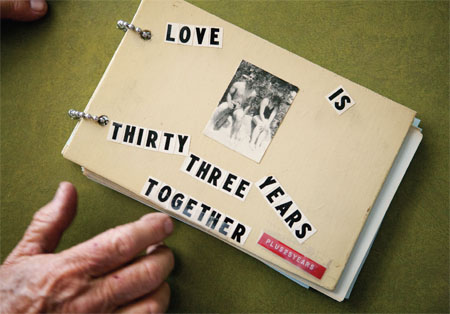

Beverly: | Oh, and this one is dinosaur poop. And you know what this is? That’s a dinosaur tooth – no, a mammoth tooth, but it’s pre-mammoth. This is a picture of my second marriage. My first husband died. We were married forty years – forty and a half – and he died of cancer. It was horrible. |

Miranda: | I’m sorry. How long have you been with your current husband? |

Beverly: | Eight years. |

Miranda: | That’s like two lives. |

Beverly: | Yeah, it is – two entirely different ones. This is our love. |

By “love” she meant the leopards; we had just entered a fenced-off kitchen crawling with baby leopards.

Beverly: | These are the girls, and I don’t allow them on the table and they know better. She’s a real lover, that one. This is Bonnie Blue, and she’s in heat, so that’s why she does a lot of yelling. Different, aren’t they? |

I nodded, but at first they did not seem very different or very much like leopards. Weren’t leopards massive and deadly? These looked more like cute kittens. Then one of them suddenly jumped in the air to the height of my face. Two more began wrestling, slamming each other against the wall with violent cracks. They were small, but they no longer seemed cute; there was a strong man inside of each one. I tried to contemplate breeds and cross-breeds, but my knowledge was thin and I had to supplement it with what I knew about Spiderman and Frankenstein. And the Incredible Hulk.

Beverly: | I started this twenty years ago – 1988. Twenty-one years, I guess. These cats are bred with a British Shorthair, because the leopard itself is only eight to ten pounds – a tiny little leopard. So they’re bred with a British Shorthair to give them some macho, some heavy. |

Beverly took us outside to show us the bigger cats in their cages, who shared a wall with an aviary full of screaming birds.

Miranda: | Does it drive the cats crazy that there are all these birds next door? |

Beverly: | Oh, they love it! It’s their entertainment center. |

I was fine with admiring the coop from the outside, but Beverly told me to hurry in before one flew out. Dozens of birds swarmed around our heads. The squawking and chirping were deafening.

I thought about my dad’s bird phobia and how unenjoyable he would find this. Then I breathed in and out slowly and pretended I was a rebellious teenager trying to differentiate myself from my parents, and in this way I was able to stay in the aviary and continue the interview.

Miranda: | What kind of bird is this? |

Beverly: | Isn’t that beautiful? And they’re rare. That’s a green-winged dove. There’s also a bird in here called a bobo. It’s black and white and it has a red beak – look for that. It sings like a canary in the morning, and it’s from Africa. And the finch is so doggoned cute. |

Miranda: | Yeah. Really loud, isn’t it? |

Beverly: | You get used to it after a while. Look at the colors. Our creator just has an unbelievable imagination. |

The sound and smell and the wings beating around my face began to make me feel slightly hysterical, like I might cry. I also couldn’t stop smiling. I should go to Mexico, I thought. Not that Beverly was Mexican, just that I’d always meant to go there. She took a baby bird out of its nest and held it in her palm. It looked like an embryo.

Beverly: | See the way the tongue goes side to side? They have little polka dots in the mouth, and that’s what attracts the mother to feed them. This has just been born. |

Miranda: | Maybe it should go back in the nest. |

Beverly: | Let me give you guys some eggs. You guys can take these with you. |

Miranda: | Really? Will they hatch? |

Beverly: | Only if you sit on them for thirty days! And now we have a surprise – come on. |

She hurried us out of the aviary and over to a field, where we were quickly surrounded by massive sheep. I am not that familiar with sheep, so it took me a moment to notice that these ones had many, many horns, horns growing out of horns, all of them curly.

Beverly: | These are the oldest breed known to man. They’re from Israel and they’re actually in the Bible. They’re in Genesis 28 to 30 – they’re Jacob’s. Very, very special. They have anywhere from two to six horns. |

Miranda: | Yeah, they really do have a lot of horns. |

Three dogs came rushing up to the fence.

Beverly: | Her name is Raspberry, and then the black one’s Squooshy, and the big one is Puppy-Puppy. If you hand-feed them they’re wonderful, but they’re wild if you don’t. |

Miranda: | Were these ones hand-fed? |

Beverly laughed, so I laughed. I suggested we go inside, so I could interview her away from the sound of the birds. We went in the kitchen and she prepared the kittens’ lunch while we talked.

Miranda: | Give me a sense of your history. |

Beverly: | I started off with one female. |

Miranda: | Okay. And you’re from? |

Beverly: | I’m from Huntington Beach. |

Miranda: | How long have you lived here? |

Beverly: | Let’s see – thirty-seven years? Since ’72. |

Miranda: | How do you make an income? |

Beverly: | The cats. The birds are not cutting it right now – they’re just not. |

Miranda: | Do you notice the economy? Does that affect it at all? |

Beverly: | Oh, yeah. They’re not buying like they used to. |

Miranda: | Do you have a computer? |

Beverly: | I do, but I don’t use it. |

Miranda: | So no online selling – none of that. |

Beverly: | Uh-uh. And that’s a down thing too, because everybody does it by computer now. I’m hurting my own self, but I don’t have the time or the energy. I just don’t. I’m not interested in computers. |

Miranda: | You’ve got a lot else to keep you busy. Do you feel like you have a community here or are you pretty isolated? What’s it like in this area? |

Beverly: | People-wise? Yeah, I’m isolated. |

Miranda: | What’s been the strangest part of your life so far? |

Beverly: | Losing my husband was the worst. |

Miranda: | Would you say he was the love of your life? |

Beverly: | Yeah. |

Miranda: | How old were you when you met him? |

Beverly: | Sixteen. |

Miranda: | So how did you meet him? |

Beverly: | At church. A very handsome man. Blue eyes, six foot two, six foot three – really sharp. |

Miranda: | And do you have pictures? |

Beverly: | I do, but I’m embarrassed. My husband, Fernando – I would feel bad for him. |

Miranda: | I understand. |

I felt a little ashamed to have asked. And yet it would have been more romantic if she had pulled a picture of the blue-eyed husband, the one I had just suggested was the love of her life, out of her blouse. Two lives, one after the other, but the second life can never compare…

Beverly: | I planned a surprise for you. His name is Sebastian, and he won’t be here till four thirty. |

Miranda: | Oh, well, you know what – we have another interview at four thirty. |

Beverly: | Oh no. |

Miranda: | Sorry, I didn’t realize that. |

Beverly: | I’m really sorry you can’t see Sebastian. He’s thirty-five pounds. He’s double what we’ve got here. And she walks him on a leash like a dog, and it’s just the darnedest thing you ever saw in your whole life. And the thing of it is she does drum rolls on him – hard. She gets in there and just pounds and he just takes it all – I don’t know how, but he does. Look what I made you guys. |

Beverly pulled a giant bowl of fruit salad out of the fridge. It was the kind with marshmallows; they’d melted into the juice, turning it milky. I started to make a polite noise of regret, but seeing her face fall, I realized refusing was the opposite of polite. I squeezed my iPhone in my pocket. Would it be weird to check my email right now? Or maybe read the news? I had an overwhelming desire to take a little time-out. One option was a bathroom break.

Miranda: | Wow, that’s a lot of chopping. Could you point me toward the – |

Beverly: | Yeah – took me all morning. I can send a cup with you home on the road. |

She had bought an enormous amount of fruit and spent all morning chopping it. She’d asked her husband to herd the biblical sheep toward us at the exact moment we exited the aviary; she’d invited Sebastian, the thirty-five-pound leopard. The least I could do was eat the salad.

Miranda: | Okay, give us a cup, that would be great. |

Beverly: | I can also do a bowl. Or cups – which would you prefer? |

Miranda: | A bowl’s good. Just one bowl and we’ll – |

Beverly: | Oh no! You each get one! Would you like some crackers to go with it? We like soda crackers with ours, crumbled on top, but it’s up to you. |

We held the dripping bowls in the car and drove to the gas station. I made us each eat one piece of pineapple before we threw them in the trash. It tasted fine. I moved some newspaper over the bowls, because what if Beverly went to get some gas and threw something away and saw? Nothing could be worse than that. We had gone to the place where all living things come from; it was fetid and smelly and cloyingly sweet, filled with raw meat and curling horns, her face was smashed, everything was breeding and cross-breeding, newborn or biblical. And I couldn’t take it. The fullness of her life was menacing to me – there was no room for invention, no place for the kind of fictional conjuring that makes me feel useful, or feel anything at all. She wanted me to just actually be there and eat fruit with her.

I went home and immediately fell asleep, as if fleeing from consciousness. I woke up three hours later and, instead of going online, I tried to pretend I was Beverly, that I was so caught up in living things I that didn’t have “the time or the energy” for a computer. The PennySaver didn’t have quite the allure it once did, but I sat down with the latest issue and a pen to circle new listings. Andrew’s ad was still in there; the tadpoles had probably transitioned this week. It seemed Michael had sold the leather jacket; he was ten dollars closer to womanhood. Everything was changing, except me. I was sitting in my little cave, trying to squeeze something out of nothing. I couldn’t just conjure a fiction – the answers to my questions about Jason had to be true, wrought from life, like all the other parts of the story.

Each character in the movie had been wrestled into existence, quickly or slowly, usually slowly and then all at once. A year earlier I had been suffering through a fruitless week when I told myself, Okay, loser, if you really are incapable of writing, then let’s hear it. Let’s hear what incapable sounds like. I made broken, inhuman sounds and then tried to type them, with sodden, clumsy hands. I wrote the pathetic tale of Incapable. It was long and irrelevant to my story about Sophie and Jason. Who would talk like this? Not a man or woman, no one fit for a movie.

I shut my computer gratefully at the sound of my husband’s car outside. I waved from the porch as he parked, and then, with growing horror, I watched our dog jump out of the car, chasing a cat into the street as a speeding car approached. The car swerved to avoid hitting the dog, and hit the cat instead. It had happened so quickly – one moment I was writing about Incapable, and in the next moment I was putting a dead cat in a bag. He was an old, bedraggled stray, one I had seen around. I felt as though we were all complicit – me, my husband, and the driver. All of us had been careless, if not today then on another day, and all this carelessness had culminated in the death of a stranger.

When the cat was buried I finally sat back down to work and re-read the broken monologue. I felt more tenderly toward the inhuman voice now; it wasn’t really incapable, just very alone, and tired, and unwanted – a stray. I named him Paw Paw and swore I would avenge his death. He was part of the script now.

It took me a long time to figure out this cat’s place in the story. Again and again it was respectfully suggested to me that I cut Paw Paw’s monologue. But I couldn’t kill him twice, and I thought his voice might be the distressing, ridiculous, problematic soul of what I was trying to make. Not that my conviction protected me; it’s always embarrassing to pin a tail onto thin air, nowhere near the donkey. It might be wrong, it sure looks like it is – but then again, maybe the donkey’s in the wrong place, or there are two donkeys, and the tail just got there first.

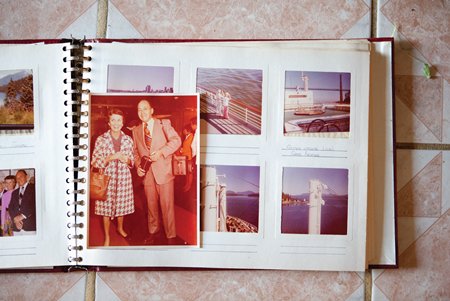

PAM

–

PHOTO ALBUMS

$10 EACH

–

LAKEWOOD

–

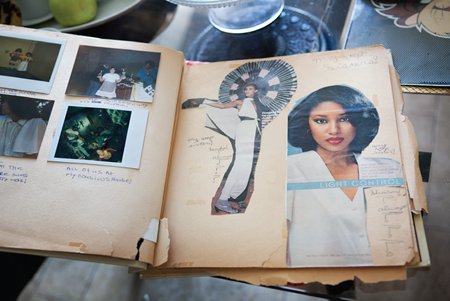

Pam could not believe we were seeing her house when it was such a mess. We assured her that it looked very clean, which it did – clean and chaotically filled with art. Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy, The Hunt of the Unicorn, and various other familiaresque images had been meticulously re-created in needlepoint, by Pam, over the years. We settled ourselves around a large stack of albums and I lifted one onto my lap.

Miranda: | Where did these come from? |

Pam: | One of my friends, he has a friend, and that friend have a big sale. I keep looking at the first album and the second one, and I said, “Oh my god, that’s interesting. I wish I could go on vacation like this lady here.” |

As she talked I flipped though the album, and then another one. They were all filled with pictures of the same wealthy white couple – beginning with their wedding in the ’50s and ending with the last of their cruises.

Pam: | These people, they are going all over the world. To Greece and Italy and Japan, and it is gorgeous wherever. It really is nice, and someday maybe I wish I can go, but no money this time. My life, I get married so young and I have no time for vacation. And I say, Well, I can look at this pictures – is better than no vacation. |

Miranda: | So you don’t know these people? |

Pam: | No, I don’t know the people, but I don’t want the albums to be thrown away. I keep almost like ten years actually, in my house. |

I glanced at her, wondering if she was a bit of a hoarder. She wore a pink sleeveless top, not unlike Michael’s, and her baroque decorating style made her seem older than she was. I guessed she was forty-eight. An exhausted forty-eight.

Miranda: | What do you imagine their life was like? |

Pam: | I think they have very, very good life. Nice, happy life, actually, if you living that long. |

Miranda: | Yeah, they’re pretty old in some of these. |

Pam: | Yeah, is very, very old, and is nice not only that they go, but it is nice to see them be happy with each other. Look at him, and he is just smiling, and it’s nice. I always feel so good to see somebody really happy. |

Miranda: | Do you think they died pretty old? |

Pam: | Yeah, I think the lady is like ninety-five and the guy ninety, yeah. |

Miranda: | I’m surprised their kids wouldn’t have taken these. Wouldn’t you think – |

Pam: | They don’t have kids, yeah. They don’t have kids. |

Miranda: | So when did you move from Greece? How old were you? |

Pam: | I was seventeen. I got married and I come here, and then after I had three kids. |

Miranda: | Right away? |

Pam: | Yeah, after a year. |

Miranda: | So you were eighteen. And what did you do? |

Pam: | We work in restaurants, fixing food. |

Miranda: | So you had a restaurant? |

Pam: | Yeah. Twenty years one, and thirteen years another one. |

Miranda: | Wow – so twenty-three years. |

Pam: | Yeah, thirty-three years. |

Pam: | Right, thirty-three. What would you do in the restaurant? What was your job? |

Pam: | My job was waitress, service, cashier – talk to the people, you know. |

Miranda: | Do you have a computer? |

Pam: | No. I don’t know computer. I wish to know it, but I don’t know. |

Pam opened another album, and as we looked at pictures of the rich, white strangers on a boat, I had the queasy feeling that I was Pam, in reverse. She’d invented all kinds of happiness for these people who seemed boring to me, while her immigrant story struck me as inherently poignant and profound. And probably neither of us was entirely wrong; it’s just that we were, more than anything, sick of our own problems.

Miranda: | Have you ever run another ad in the PennySaver? |

Pam: | No. |

Miranda: | And why do you think you decided to do this now? |

Pam: | Because you know what, I need the room. |

Miranda: | And has anyone called about the albums to buy them? |

Pam: | Yeah, a lot of people, but – |

Miranda: | But they don’t buy them. |

Pam: | Yeah. But I can’t throw them out. I used to have one customer in the restaurant, she was like ninety-five years old. Her name was Meg. She was so sweet. She come in every day at eleven o’clock and she eat. And this lady, she’s doing a job kind of like your job, she goes to people and takes pictures and talks to somebody. And then after she’s like sixty-five years old, you know what she does? She takes pictures of herself every day. And she goes home, and she puts them in the scrap album. She was so careful – three rooms like this high, thick, thick with albums. And then one day she passed away. And the son-in-law, he take all the albums and put everything in the dumpster. It’s so sad. That’s why I took these albums, so they wouldn’t get thrown in a dumpster, you know? That’s sad to me. |

At age sixty-five, an age so far past young as to be almost unfeminine, a woman had decided to photograph herself every single day. It was immediately one of my favorite works of art, all the more significant because she wasn’t Sophie Calle or Tracey Emin. She knew no one would clamor for the three rooms’ worth of albums; their value was entirely self-defined. And though of course I wished I had somehow saved the albums, the performance had to end with her dying and the collection being thrown into the dumpster. It was the ending that really made you think.

I bought a few of Pam’s albums, and when I got home I forced myself to look at the pictures of the couple posing at alumni functions and tourist attractions. The moral of these people was clear to me: if you spend your life endlessly cruising around the world, never stopping to plant children on dry land, then when you die some Greek woman you don’t even know will become the steward of your legacy. And when she wants more room in her house, she sells your legacy in the PennySaver. And no one wants it.

I’d been waiting for the perfect movie title, but finally I decided to just name it. It had to be short, a very familiar, short word. I looked up the most commonly used nouns. The number one most common noun was time. Which made me feel less alone; everyone else was thinking about it too. Number two was person. Number three was year. Number 320 was future. The Future.

I didn’t set out planning to write a script about time, but the longer I took to write it and get it made, the more time became a protagonist in my life. At first my boyfriend and I thought we’d get married after our movies were made, but after about six months of trying to get the films financed we thought better of this plan and set a date, come what may. Nothing came, we got married. And then, right around the time I started blindly meeting PennySaver sellers, it began to dawn on me that not only was I now old enough to have a baby, I was almost old enough to be too old to have a baby. Five years left. Which is not very long if an independent movie takes at least one year to finance, one year to make, and throw in a year or two for unforeseen disasters. (And I couldn’t make the movie while pregnant, even if I wanted to, because I was in it.)

So all my time was spent measuring time. While I listened to strangers and tried to patiently have faith in the unknown, I was also wondering how long this would take, and if any of it really mattered compared to having a baby. Word on the street was that it did not. Nothing mattered compared to having a baby.