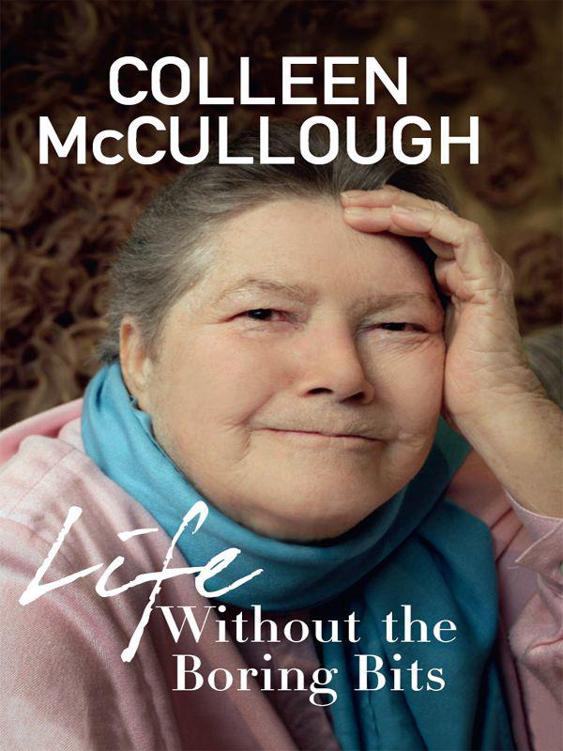

Life Without The Boring Bits – Read Now and Download Mobi

Dearest Anthony,

This is for you because we go back such an enormously long way, to days when you stuck your publishing neck out for me and began a friendship as deep as platonic, as enduring as chequered.

Thank you too for giving me the only title this present work can possibly sustain, for if it isn’t life without the boring bits, what is it?

With much love, always loyal, Col.

CONTENTS

Cover

Dedication

1. FREAKING AT THE CONTROLS

2. THE CRUCIFIXION

3. MIDSOMER NO MISNOMER

4. UNELECTED POWER

5. POP GOES THE PUSSYCAT

6. PORTRAIT OF A COLONIAL OVERLORD

7. ANTHROPOMORPHISM

8. HANDSOME IS AS HANDSOME DOES

9. TIME

10. THE SEPIA BLUES

11. BELITTLING BILL

12. COL ON THE WRITING OF HER BOOKS

List of published works

13. ETERNAL STATES

14. POPULATE AND PERISH

15. ONE, POTATO, TWO, POTATO

16. ON WOOD AND WARS

17. JIM

18. LAURIE

Other Books by Colleen McCullough

Copyright

Freud divided people into two kinds: those with “oral” fixations and those with “anal” fixations. Pray understand that I merely parrot the undoubtedly inaccurate generalizations that represent the good doctor’s output in the public’s mind. And onward and upward! Oral people are untidy and methodically slapdash, see the grand picture and overall purpose of a plan or a scheme, but dismiss minor details as irrelevant. Anal people are tidy and meticulously organized, see every last and most trivial detail of a plan or a scheme, but fail to grasp its overall purpose or design. Naturally there are fusions of both types, as well as one type adulterated by the veriest drop of the other, and all the various shades of grey.

I am a fusion of both types, though the anal can appear to dominate; this happens in persons who exist on a higher plane than mixtures of the two types. I speak, of course, of that most irritating of all types: the control freak. This is another term open to misinterpretation; people tend to think of control freaks as persons who want to rule the world, or their work place, or their home — putting the verb “to rule” first in importance. Such is not the case. “Control” need not mean “rule.” Control implies a judgement. Can he drive this car competently? Yes, he can, so I can sit back and relax. Can he sedate this cat without being scratched to bits? No, he can’t, so I’d better do it for him. Control is about controlling a given situation, not ruling anything — unless it’s being done badly, or, worse, incompetently.

Apropos Freud, has it ever occurred to anyone that the good doctor built a whole theory on toilet training infants/toddlers back in the days when diapers were revolting things had to be cleaned, then washed, dried, and used over and over again? A mommy couldn’t wait to sit the kid on a potty productively. Now, who cares if the kid wears a disposable diaper until it’s four? If, that is, the wallet can afford it. Kids toilet train themselves. And though world prosperity has pinnacled and is now on the decline, I predict that many domestic sacrifices will be made before the disposable diaper is abandoned. Interesting.

Okay, I have established that I am a fusion of oral and anal, and a control freak to boot. I am also an incorrigible nit-picker.

In my Yale days, I watched a neurology resident writing a report on a plain yellow pad.

“Since you can’t keep a natural margin,” I said when I had either to speak or to explode, “why don’t you draw one before you start? And your tabulations are so untidy! Do you want to enclose your numbers in parentheses or circles?”

He put his pen down and looked up at me with mild interest. “I bet you get migraines,” he said.

That’s the perfect way to squash a nit-picker flat.

The trouble is, nit-pickers can’t help themselves. There is an element of pure agony involved when, for instance, I look at sloppily presented work. I itch to write it out again for its author in glorious neatness, balm for my nit-picking soul.

Watching movies can drive me quite mad. It’s said of directors that if they get the cars in a film right, they don’t need to worry about getting anything else right. I believe it’s because film directors tend to be men, and in adolescence the only thing that matters more than girls are cars. Men love cars, that’s why the director gets them right. His accuracy also pleases the male segment of his audience. Ric will be snoozing gently through a film, then suddenly jerk and sit up straight. “There’s a 1953 De Soto! I had one of those when I was a kid.” The car drives off-screen, and he goes back to sleep. At the end of the session he’ll vote it a good film. In the meantime I’ve noticed that the guy with the gammy leg can never remember which leg is supposed to be gammy; the redhead is suddenly a blonde, and then goes back to red again without any reason; the plants in the ducal conservatory are wrong; and Hitler’s army in Russia is bogged down in mud and pouring rain, yet the sky is blue.

Roman films are money for jam to a nit-picker with knowledge of the period. They couldn’t even get the name of the hero right in Gladiator! He had a cognomen for a praenomen, a praenomen for a nomen, and a nomen for a cognomen — three out of three wrong. Even the BBC made mistakes in I, Claudius, though it was a good effort. They had the famous bronze statue of the Tuscan wolf in the Senate House, and that was correct, but the lupine old girl was suckling Renaissance twins, added later. Cicero remarks in passing to Atticus that lightning struck the suckling Romulus — the Tuscan wolf hadn’t nursed two babes, just the one who founded Rome. My favorite fluff out of this wonderful series illustrates a tragedy, despite its humor. A hefty Brian Blessed (Augustus) pins a willowy John Castle (Postumus) against a wall that bows and buckles dangerously — it’s made of cardboard! I guess they didn’t have the money for another take, so it stayed in. There’s the real rub! Those who would genuinely try for historical accuracy are on a shoe-string budget, whereas those with money to burn don’t give a tuppenny bumper anent historical accuracy. Sod’s Law in action.

Here’s one I must have seen half a hundred times over the decades: the cup of tea poured from the coffee pot. Directors clearly played hookey from a very early age, as they don’t seem to remember the rhyme about the teapot — short and stout. Coffee pots are tall and slender, designed to pour anything from pea water to unwatered pee. There is no grille of holes at the base of the spout to block the onward progress of some of the tea leaves. But, as I have always said, God gave us teeth to strain the tea leaves. I’m sure the residents of Boston knew that.

I remember reading Baroness Orczy’s series of novels about the Scarlet Pimpernel when I was ten years old. Quite why, I do not know, but the nuclear story became one of the most re-made of all beloved tales. I think my count on DVD is six versions of The Scarlet Pimpernel, starting with Leslie Howard and Merle Oberon, and going through mostly TV recreations. Perhaps it appeals to the British, who can’t say they hate the French any more, but love anything that sees a Brit shove one up a Frog. And the Scarlet Pimpernel, safely back in the early l790s, is ideal one-up-the-Frogs material. Impeccably historic, ahem.

Yet in every version they make the same mistakes, chiefly to do with knitting. Knitting, you say? But to knit is to knit! Not so. The Brits and the Frogs knit differently. What is more, the Frog way of knitting is faster and easier than the Brit. In the Frog method, one needle and the yarn do most of the work, which grows at the rate of one metre per guillotined head. The Brit method uses both needles on the yarn equally, so limps along at the rate of an inch per guillotined head.

Perhaps because Leslie Howard came from Czechoslovakia, he knitted the correct way, the Frog way, but no British actor since has got it right. Why is this so important? Because the Scarlet Pimpernel disguises himself as a crone at least as noisome as Madame Defarge and sits in the front row of crones watching the aristo heads fall into the basket. Knitting, knitting, knitting.

I want to see a version in which the crones whizz along Frog-style knitting, and thoroughly bored with counting aristo heads.

One crone says to the Scarlet Pimpernel, “Ma foi! Zis twenty denier yarn, she is incroyable for les turning of ze ’eels aftaire les jambons zey are feeneeshed, non?”

The S.P. leers at her evilly, sucks on his pipe. “Sure is, you reeking old crone! Excuse me, I’ll lose count — knit one, purl one, knit one, slip one, pass the slipped stitch over.”

The crone jumps, shocked clear out of her sabots. “Sacre bleu! Zat kneeting, she is not le kneeting of la Belle France! Ze yarn she is ’undred denier et les niddles zey go flic-flic, flic-flic, à l’Anglais! En avant, citoyens, en avant! ’Ere ees le Pimpernel Rouge! Keel ’eem! Keel, keel!”

A dozen men wearing the tricolored cockade in their hats dive on top of Richard E. Grant/Anthony Andrews and, boom-boom, ’ees ’ead, she ees dans le basket — a basket case, we say.

My favorite continuity disaster concerns a disaster. In Series 5 of Spooks some terrorists hold London to ransom by threatening to destroy the Thames Barrier.

I have a very soft spot for Prince Charles, for two reasons that spring immediately to mind. One is that he adores the Goon Show, which won’t mean anything to anybody, but he and I both adore it. The second reason is that he detests what modern architecture has done to London, and he’s spot-on right. When one goes to Brasilia or Pamplona, or any other of dozens of places, modern architecture is thrilling. But in London it’s a complete fuck-up of a grand old city that should have remained respectably old, in its architecture at least. I admire Prince Charles for speaking out when royalty isn’t supposed to. Well, bugger that. Someone needs to say it! Though the damage is done: the Ferris wheel is an eyesore, the Millennium Dome worse — but who gave the go-ahead to that awful little skyscraper made of colored glass shaped like an anal suppository? If I knew who was responsible, I’d have a go at shoving it right up where it belongs.

Off the soap box, Col! The Thames Barrier has a definite purpose, so it’s hard to criticise, but yellow like businesses trying to catch the eye? It should have been river-colored to blend in, not silvery-white and acid-drop yellow.

Anyway, to make a soap box go somewhere, these terrorists are threatening the Thames Barrier, which was built, as I understand it, to minimize the impact of floodwaters rushing down the Thames while simultaneously a king tide is rushing up the Thames. This particular disaster has happened before, and it can happen again; if left to its liquid fate, London would be submerged under feet of water.

We learn that the king tide peaks at 5 p.m. and the barrier has to be activated on the dot of 5 p.m. But don’t king tides do what other tides do, and rise gradually? Or is 5 p.m. the leading edge of the sine, so to speak? Spooks is not very specific. And why aren’t the super spies doing their thing clad in gumboots, macintoshes and sou’westers while the rain pours down? Against newsflashes of Oxfordshire under ghastly floods? I know that in Hertford and Hereford hurricanes hardly ever happen, but the plot surely calls for one. We may safely ignore the Hampshire weather.

Instead, the camera shows the sun shining and the Thames as placid as the wee in granny’s potty. Can this be why a tsunami is suddenly added to the plot? But can the North Sea at the Thames Estuary really generate anything like a tsunami? Tsunamis are oceanic phenomena that occur when a seismically triggered wave suddenly strikes a very wide continental shelf, which is why most earthquakes don’t cause damaging tsunamis.

The episode finishes at the beginning of Series 6, but I’m not holding my breath or rushing out to buy Series 6. It’s a perfect illustration of a scriptwriter dumped on by the trillion-ton floodwaters of his too-fertile imagination.

I am never sure whether this kind of television torment is cynically inflicted on its audience, or in true ignorance of how bad it actually is. Are scriptwriters overpaid, or underpaid? I know Jerry Bruckheimer has an Outer Mongolia for his stable of scriptwriters — CSI Miami it’s called. But whereabouts would Kudos/BBC send an erring Spooks scriptwriter? Composing the teleprompter weather for BBC Scotland? All I know about the matter is one thing: there is always an Outer Mongolia.

Control freaks don’t really want much out of life. A perfectly organized, perfectly run world will do for starters. Having organized and run a couple of weeny worlds in my day, I can testify to the fact that once people get used to method and order, they absolutely love it. “Everything has a home!” I would snarl, advancing menacingly upon a shivering professor, and waving a jar holding two chimpanzee testicles under his nose. “You know where things live — put them there, or it’s soprano time!” At first they hated this merciless treatment, but after they’d learned to put things in their homes — oh, it was so wonderful to be able to lay their hands on them immediately. If order and method weren’t among life’s necessities, control freaks wouldn’t exist. But, as some NASA and other red faces can bear witness, it helps to have nit-pickers and control freaks around. Then billions don’t get wasted for the want of a screw, or the difference between metric and imperial. Imperial is better for mensuration — stick to it!

I will tell you a true story that happened to me in another incarnation — no, no, I don’t believe in reincarnation! I use it in the sense of doing a different job wearing a different hat.

I was marking time in England for six months, and working as a temp/sec in a little city that shall be nameless. It was a precision engineering works, and the engineers loved to grab me to type their specifications because I didn’t make mistakes and would even query their calculations from time to time, thus saving the engineer a red face later on. But the pace of work in that office, which had a large pool of typists, was desperately slow; I always seemed to have time on my hands. The period, I must add, was prior to the computer age — mid 1970s will do.

One of the oldest engineers in terms of staff longevity was a man I’ll call Bob, who was responsible for the factory’s parts. For some years he had been working on a catalogue of every last part the factory contained, down to the tiniest washer. His list was long finished, but he couldn’t persuade a typist to type it for him. This wasn’t an ordinary typing job. Its object was to create a typed description on a sheet of mylar, using a sheet of yellow carbon paper in the mix as well as a carbon ribbon in the IBM machine, which had a phenomenal roller to accommodate the mylar sheet. Typewriters were massive then anyway, but the roller on this special machine was 27 inches in length. Each mylar sheet had been pre-printed into rectangular boxes that allowed for a full description of each part, each name, its code number, parts number, source — in all, I think each part had six or seven boxes across the two-foot width of a sheet. Then each sheet held the details of thirty different parts.

When Bob asked me if I would be willing to type his parts sheets in my spare time, I said yes, of course; it looked like the perfect job for a nit-picker. Bob himself was neat, precise, and ideally suited for his job. My answer was greeted with joy; I settled down with my gigantic typewriter and a parts list that ran over ten thousand items. How I loved it! The other typists could not believe that anyone could do the work and stay sane. Whereas what had driven me insane was twiddling my fingers and giggling over gossip. I pounded away with the yellow carbon reversed so it haloed the dense black print with yellow, and it was amazing how quickly I ploughed through the items. Within a month I had finished it, and done other work as well. It’s my power to concentrate; absolutely nothing impinges on the work.

Bob was so overcome that he took a cartload of mylar sheets up to the general manager’s office and showed them off, praising me to the skies. And the manager, not a tactful man, summoned the typists together (apparently the engineers had also been singing my praises) and harangued them about their lack of a work ethic. Using as his example of the work ethic my typing of the parts catalogue. Mercifully I wasn’t asked to attend, any more than I had known of Bob’s trip upstairs, but the filthy looks and cold shoulder treatment said it all.

Here I should say that Bob was a very elderly man, probably past retirement, working for interest’s sake. He was paraplegic, couldn’t move from the waist down, and spent his waking life in a wheelchair. A really pleasant man, he never complained.

I suppose he behaved a little as if he had just had the most exciting birthday present ever, but seeing his list done at last meant a lot to him.

That was a Friday. When we came in to work on Monday, we found that someone had taken a razor-sharp blade to the huge stack of mylar sheets and slashed them to ribbons. All my work had gone for nothing, reduced to shreds littering the office floor. Which wasn’t the worst. That poor old man broke down and cried as if his heart were broken, and I suppose in a way it was. A paraplegic in a wheelchair! How deep can the poison run in some people, to do that, but especially to do it to someone who can’t stand on his own two legs and fight back?

I wasn’t without friends in the office. We dried Bob’s tears and I promised to re-type his list, which I did. But at night, every single night, we locked the sheets in a safe, and when the job was finished for the second time, Bob kept them in a safe permanently.

To this day I think that unknown person’s venom remains the most appalling, terrifying demonstration of sheer evil I have ever encountered. It was so personal. One of the faces I saw every day — and I honestly do not know which one — was capable of destroying a crippled old man’s dream, a crippled old man she knew, spoke to, probably joked with. All because a fellow worker had shown her up. What she hadn’t counted on was my willingness to do the same job all over again.

The crux of the matter is that nit-pickers and control freaks can’t help what they are, and if that means they work harder and/or faster and/or more accurately than others, it’s a fact of life. I am just glad that when the mylar sheets were finished for the second time, I moved on and never went back.

A true story, one I haven’t embroidered in the least. It isn’t necessary to embroider something so horrible.

Now here am I in a wheelchair, not paraplegic, but walking is a pain in the arse, literally. As well as a pain in the hips, the legs and the feet. I can walk a little way pushing a wheeled walker, but it’s standing kills me. Not to mention that I’ve lost depth perception in my vision, so I don’t see steps, or jogs and humps in a flat surface. Therefore when I leave the familiar contours of my house, it’s wheelchair time.

And no, I’m not whining. That is the prelude to explaining a fate worse than death for a control freak — losing control. I am at someone else’s mercy most of the time. Ric’s, most of the time. The best egg that ever was, but it is just awful not to be in control of one’s own locomotion! The ordeal isn’t too bad while I’m being pushed forward, but when he turns my chair around and pulls rather than pushes, my heart doesn’t know whether to rocket out the top of my head or thump through the soles of my feet. What won’t Ric let me see? It’s a cockroach! A cockroach, it’s got to be a cockroach! And if it is a cockroach, I’m stuck in this ruddy chair! It’s a cockroach! I know it’s a cockroach, he says it isn’t but he’s got that I-won’t-tell-her-about-the-cockroach tone in his voice — it’s a cockroach! Oh, please, puh-lease, Ric, don’t let the cockroach get me! It’s a cockroach!

This essay has been a long time in the writing, and gone through many drafts. Unless a subject be lighthearted or lightweight, I put what I deem a satisfactory draft into a drawer for weeks or months, then look at it anew with a dispassionate eye. And finally, it seems to me, I have shorn away the pretensions that marred the fleece of scholarship sufficiently to view my subject with a true detachment: the detective’s conclusions based on scanty evidence.

When I began to amass knowledge of the history of the late Roman Republic and the early Imperium, a question popped into my mind that never seems to occur to those of us nurtured in a largely Christian society: Why did Jesus Christ die the death of a slave?

Later on in the Imperium, particularly after its administration passed into the hands of Greek freedmen and other non-Roman civil servants, crucifixion was levied upon free men as well as upon slaves, though it was always a capital criminal’s death. No Roman citizen or foreign citizen could be crucified; the common death sentence for Roman and non-Roman alike was beheading.

During the period in which Jesus Christ lived, crucifixion was strictly limited to two kinds of men: slaves and pirates.

Rome did have one exception to this: a Roman convicted of perduellio treason. After a ponderous trial heard in the Centuries, a man found guilty was crucified “tied to an unlucky tree” — that is, a tree that had never borne fruit. It was an archaic process of the early Republic, long fallen out of use by the late Republic, but Julius Caesar ran a case for it in the Centuries against one Rabirius Postumus; the trial was abruptly terminated before the vote was fully taken. Caesar used it as a political device to prove a political point. No later case of perduellio was ever heard, and Caesar’s employment of it was called frivolous.

During the relevant period two instances of mass crucifixion are recorded in the ancient sources. Marcus Licinius Crassus hung 6,600 rebellious Spartacan slaves on crosses along the Via Appia all the way from Capua to Rome. Julius Caesar crucified a large number of pirates on the river flats below Pergamum against orders from the Governor, who wanted to sell them as slaves. Both acts were done to show slaves what would happen to them if they rose against Rome or preyed on Roman shipping.

These parameters didn’t change under the emperors Augustus and Tiberius. There are a few other, unconnected instances of crucifixion of inviduals, but nothing that basically affects the reality of the time: crucifixion was the death of a slave.

Why Jesus Christ received the death of a slave is a mystery. Not one thing that has come down to us suggests that Christ was in fact a slave, including his being hied before the Roman prefect for permission to execute him. Were he in truth a slave, his master had no need to apply to anyone for permission to kill him.

The charges laid against Jesus Christ were of treason against Rome; the Prefect of Judaea, one Pontius Pilatus (we do not know his praenomen, or first name), dismissed the charges and ordered the prisoner released. Whereupon the members of the Jewish Sanhedrin proceeded to bully and browbeat Pontius Pilatus into reversing his decision and passing a sentence of death by crucifixion on Christ after he had been exonerated!

Every fact contradicts other facts, and all of it ran counter to Roman law and practice. Above all, the Romans were in love with their law as well as extremely litigious-minded. Nor were governors or their prefects prone to be intimidated unless their province stood in danger of imminent war or rebellion.

The history of the period in southern Syria was turbulent. To understand the political climate when Christ was sentenced, it is necessary to go back to 69 BC, when Alexandra, the widow of King Alexander Jannaeus, died. The old Queen’s two sons, Hyrcanus and Aristobulus, were the last Hasmonaean kings. Alexandra had favored Hyrcanus, whom she made both High Priest and King of the Jews. The sovereignty was not over a land, but a people; even if the land dwindled to nothing, the King’s realm was no smaller. Despite which, Judaea was the ancient homeland and Jerusalem the Holy City.

Aristobulus and his sons disputed the succession, provoking revolt and hugely annoying Pompey the Great right at the moment when Pompey was looking forward to spending the winter in Damascus, reputedly a delightful place to spend the winter. Instead, he had to lay siege to Jerusalem, a city he loathed. The result of Pompey’s irritation horrified the Jews, but it was too late to retrieve Aristobulus’s blunders. Pompey annexed the whole of Syria into a Roman province and made sure the two legions garrisoning it kept a severe eye on Judaea. Rome was suddenly a presence that would not go away.

In 57 BC the Governor of Syria, Aulus Gabinius, literally dismembered Judaea, seeing this as the best way out of his troubles there. He split it into five tiny, geophysically unconnected districts: Jerusalem, Gazara, Jericho, Amathus and Galilaean Sepphora. Each had a Jewish governor, called a tetrarch.

Relations between Rome and the Jews passed into the hands of a crafty, brilliant Idumaean nobleman named Antipater, who had an Arab wife, Cypros, and three sons deemed Arabs under matrilineal law, a Semitic characteristic. Antipater set himself up as the “expert” on Jewish matters to the Roman greats marching through the region in pursuit of civil war; Julius Caesar and Cassius used him and liked him as a man who got the job done.

Antipater’s second eldest son, Herod, was an unscrupulous, cruel, murdering individual who, despite his Arab status, set out to become King of the Jews. Further to that end, he married the Hasmonaean princess Mariamne and sired matrilineally Jewish sons. One of the best crawlers of all time, Herod wormed his way upward through Marcus Antonius and then Octavianus, who became the first Roman emperor, Augustus, in 27 BC. Augustus took some of Herod’s sons to live with him in Rome to receive a “proper education” — that is, to Romanize them.

Always full of himself, Herod took the title Herod the Great and managed to have Gabinius’s five tiny districts joined together again, with the addition of Samaria, Idumaea and the Greek cities of the Decapolis. Alas, a paper tiger! Herod’s chief duty was to collect the taxes and tributes for Rome. The only way he hung onto his throne was by murdering any among his relatives, even his sons, who seemed a threat. He was a notorious voluptuary, a characteristic despised by Jews and Romans alike.

Jewish intransigence continued unabated. In 6 AD Augustus gave the Jews a Roman head of state physically present within Jerusalem: the Prefect of Judaea. This executive was junior to the Governor of Syria, but to no one else; by birth he was a Roman nobleman and a member of the Senate. Modern usage, particularly pertaining to schoolchildren, has tended to diminish modern perception of the prefect’s importance and power: he had military and civil teeth, and within his sphere his word was law, enforced by the legions and by a cohort of troops permanently garrisoned in his capital — in this case, Jerusalem, possessed of a formidable fortress called the Antonia.

With the Kingdom of the Parthians on the far bank of the Euphrates River, Syria was of vital military importance, and Judaea a perpetual Roman headache. Its prefect was always a very capable, carefully chosen man.

Here I introduce the hypothesis of an impressive classical scholar of the 1920s and 1930s, Robert Graves. Nowadays Graves is best known to the public as the author of two novels, I, Claudius and Claudius the God. Among many other works in a serious vein is a book entitled King Jesus that postulates that Jesus Christ really was the King of the Jews, and that the Sanhedrin knew it.

Graves contended that Christ’s mother, Mary, was a slave in the Great Temple and was the heiress of the House of David. The phrase “temple slave” may be true or, in our eyes, a misnomer; to the Jews of that time, an irrelevancy. Mary was resident in the temple precinct as a person of high honor. The reason for her detention was to keep her out of the clutches of Herod, who wanted to marry her, sire sons who were by Davidian blood rightfully entitled to the throne. Whereas the Sanhedrin had another choice for husband: one Joseph, a widower and Mary’s kinsman. If he were indeed our Joseph, he was from her village, her blood relative, of suitable social status, and with Pharisaical leanings.

Mary was probably all of fourteen years old when Herod’s senior son, Herod Antipater, abducted her and fathered her firstborn, the male child we know as Jesus Christ. Herod Antipater was typical of his house: vain, amoral, merciless, hugely ambitious, and intensely jealous of his near male relatives. Poor little girl! She would have married at fifteen, but only after careful preparation and much support from her female kin. This hinted at rape.

What no one seems to have taken into account were Herod Antipater’s brazen brand of atheism and his reckless daring. To the Sanhedrin, residence in the Great Temple made Mary safe. It stopped Herod the Great, but not his senior son.

By Graves’s telling, the whole business was furtive — had to be, to avoid the wrath both of the old King and the Sanhedrin. Eventually came the flight into Egypt; the entire scheme fell to pieces. Herod the Great murdered his son Herod Antipater and Mary returned with her infant son to Nazareth, where she married Joseph.

Under matrilineal law the husband’s duty was to bring both additional wealth and prestige to the woman carrying the bloodline. Which, if one follows Graves’s reasoning, would make Joseph an important man of some affluence; he was probably the Sanhedrin’s original choice. A widower getting on in years (he is said to have had two grown sons, which would put him in his forties) was not frowned upon as a matrimonial partner for a young girl; he was a made man rather than a man in the making. If Joseph’s business was carpentry, it didn’t have to be a humble workshop. Certainly Mary seems to have had other children by Joseph, both girls and boys.

When the Emperor Augustus heard of Herod Antipater’s murder he was angry and grief-stricken; Herod Antipater had lived in Rome as Augustus’s guest when a child, and Augustus had loved him. An imperial command went out to Herod the Great that stopped him in his tracks: there were to be no further reprisals of any kind.

Herod Antipas, a far different man from his stormy elder brother, now moved upward. When old Herod died, he assumed the title King of the Jews and “ruled” — but not in Jerusalem. His Roman title was Tetrarch of Galilaea, where at Sepphora he built a luxurious palace and cavorted far from the jaundiced eyes of the Roman Prefect and the Sanhedrin.

While the historical substrate and some of the events told in the Christian Gospels are accurate, the above on Mary is Robert Graves’s hypothesis, one attempt at solving the contradictions inherent in the life of Jesus Christ the man: he was the true King of the Jews.

By this, I hope, the reader has concluded that I am not concerned with the godhead of Jesus Christ, a state of being that has no place in this essay. Like Graves, I am attempting to solve a factual conundrum: I am asking why Christ was crucified rather than beheaded?

Curiously, there had been a worldwide frisson of excitement that had begun in about 35 BC and was to continue until about 65 AD — a total of 100 years.

It was said that a Chosen Child would be born to herald in a Golden Age. For the Romans it began at a time when they were exhausted by a long series of devastating civil wars; the stimuli were the pregnancies of Octavia, Augustus’s sister, by Marcus Antonius, and Scribonia by Augustus himself. Virgil hymned it for one. But when both babies were girls — oh, darn! Neither Antonia the Elder nor Julia was hailed as the Chosen Child, but the rumors did not die down. The Chosen Child and the Golden Age were still coming. Gaius Caligula believed himself the Chosen Child.

It took three generations for the talk to die away. The Hellenized (Greek-influenced) world expected the New Dionysus, who would change water into wine and make every day an unadulterated orgy of joy and pleasure. Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra cashed in on this. Jewish anticipation was of the Messiah, not by the Sanhedrin, but in regions like Galilaea, a hotbed of Messianic rumors, and other rural districts.

The Jews at this time were not entirely religiously united. Most Jews appear to have had Pharisaical inclinations, among them a belief in a life after death, angels, and a Jewish nation. However, there were many Sadducees; as they pinned their hopes on prosperity in this life, up to and including gentile habits, they did not believe in a life after death or a Jewish nation. The common folk were Pharisaical, especially in rural areas, but both sects contained persons of liberal mind as well as conservative and orthodox persons. The Sanhedrin was dominated by Pharisees who tended to be orthodox and conservative.

Though Samaria was a Jewish land, its interpretation of sacred scriptures was so different from the Jerusalem line that Samaritan Judaism was deemed a schism — a state of religious being that gave it some clout. Whereas up-country Galilaean beliefs were scattier and regularly produced wild men, prophets and hermits who proclaimed themselves the Messiah or the trumpet sounding the clarion of his arrival. The result was deemed a heresy and had no clout at all.

I gain an impression of a vital, vigorous, ancient religion, sternly monotheistic, that was often debated and always in a state of flux. All the more interesting, then, that the arrival of Jesus Christ on the religious scene inspired such opposition. Galilaea was the home of heretics, and presumably these men made little impact upon society beyond Galilaea: what then was so different about Jesus Christ? Did his importance lie in his heretical teachings, or was it because he was believed by many to be the rightful King of the Jews? Or did he also claim to be the Messiah?

It is difficult to decide whether at this stage I should go on to discuss Jesus Christ the man himself, or whether I ought first to discuss early Christianity. My previous efforts have dealt with the man and his crucifixion first, so here I will take the other tack and discuss the rise of Christianity. If the reader knows the genesis of the new religion, it may be easier to reach warming conclusions about the man and his death, however inadequate.

I must be one of very few from the Christian world to have walked the long, wildflower-strewn grasses of an utterly deserted place in far northeastern Turkey named Ani. It lies on the lip of a great gorge; far below flows the river the ancients called the Araxes, and on the far side (at the time of my visit) there bristled fences of barbed wire, guard towers and soldiers. For the far side of the gorge was Russian Armenia. A lone army helicopter clattered down the gorge, then vanished to leave Ani to the whirring peace of birds and insects.

Ani is the oldest purely Christian community extant, though no one has lived in it for centuries. Its brick buildings stand as shells, some still vaulted by roofs; some are humble, some more imposing. Almost every interior of every building is adorned by wonderful frescoes that depict early Christianity, an illustrated story whose predominant color takes the breath away — a rich, intense, vivid ultramarine blue. I presume that there was a deposit of lapis lazuli in the neighborhood that, ground to pigment, provided the artists with the chief glory of their palette.

But there is tragedy, too. In obedience to the laws of Islam, every face has been gouged off every human or angelic or godly figure, leaving its blue draperies and the flesh tones of hands and feet. Haloes and remnants of hair survive, and all the non-human details, but no face has escaped. When one religion infringes the tenets of another, there will always be man-made demonstrations of the power of one god over the other; east of the sources of the Euphrates is a fundamental world.

In the Roman mind, Christianity was inevitably entangled with Judaism. From time to time the Imperium was shaken by fears of a pan-Jewish uprising, for no part of the Roman sphere of influence was without a fairly large Jewish population, and the two cultures were at ideological loggerheads. Because of their religion’s Judaic roots, early Christians were all too often lumped in with Jews willy-nilly, though after the death of Jesus Christ and his contemporaries, Christianity ceased to have any attraction for Jews. In fact, quite the opposite. Most Jews avoided it as one more burden. This, combined with Roman belief that Christians and Jews were one and the same, only served both to increase and diversify antisemitism, a great tragedy.

Christianity was never a religion of enlightenment. It was a religion of revelation for the abjectly poor designed to help them bear their unenviable lot. They could neither read nor write. Thus for the first two generations at least the religion was orally disseminated to believers; what was written down by a very few was vestigial and read aloud to gatherings. The importance of the Epistles cannot be over-emphasized, as their writers knew well how unlearned the congregations were.

A hierocracy is natural to a system of beliefs wherein few have learning; those who had it gradually became known as bishops, responsible for instructing more junior ministers, the priests.

However, I don’t wish to discuss the Christian hierocracy any further: it is not germane.

There are great differences of opinion upon the date when the four Gospels were formally written down. Many scholars argue for a time as close to Christ’s death as thirty or forty years. However, one large group opts for a date after the first third of the second century AD as their very earliest; circa 133 AD, a century after the crucifixion. The hypothetical “Q” is said to be at least a generation earlier — if there ever was a Q. The four Gospels, apparently teaching aids aimed at new converts, were written in Greek, an indication to me that if this date is right, it reveals an upward trend in converts toward those who were literate. Q is said to have been written in Aramaic, a pan-Syrian semitic language, but to me Greek sounds more logical for the early Christian writers. It was the lingua franca of the eastern Mediterranean, and the earliest Christians seem to have been Greek-speaking.

What is known is that Christianity made great strides, that its adherents multiplied rapidly, and that by the time Constantine spent his childhood among the barbarian Picts and Scots, they also were converting to Christianity. Jesus Christ’s simple credo, with its emphasis on the life hereafter and its promise of a happiness eternal, was perfect for its time.

That today it is dwindling is due to such gargantuan changes in the human condition, at least for western peoples, that its simplicity and promise are deemed antiquated, unappealing rubbish.

Its greatest appeal remains among those peoples who are abjectly poor, under-educated, and politically oppressed. However, there are some prosperous peoples who have found vigorous versions of Christianity robust enough still to offer spiritual comfort. I am not wrong. Godlessness is growing in the Christian world.

Back now to the life of Jesus Christ the man.

The problem is that absolutely nothing about him was written during his lifetime or for a generation after. He lived and died unrecorded in the contemporary annals of either Rome or Jerusalem; the little we know comes from the Epistles, the Gospels, and Josephus, and is not very helpful, for they were not concerned with the man per se. Using these sources, Christ was a Jew from Galilaea who seems from his teachings not to have had much time for the finer points of Judaic religious law, inextricably bound up with Jewish government as it then was. He seems not to have hated Rome or viewed it as anything but a temporal power. He preached tolerance and was not a bigot. He believed in Satan, demons, angels and archangels, in living by the rules of goodness and decency, and, above all, by love. He had a kind word to say about almost everyone, and taught that the most hardened of sinners could be redeemed. His preferred method of teaching was the parable. It was a benign, inoffensive credo that made some inroads in Galilaea and other rural regions. A man of thirty, he commenced three years of fairly limited walks and wanders, often attended by large crowds. Only at the very end of his career did he go to Jerusalem.

Why then did he die? And why was he sentenced to the death of a slave?

Already condemned by a trial before the Sanhedrin, he was hied before the Prefect of Judaea as a traitor to Rome. And, since slaves didn’t need Roman permission to be killed, it would seem as a free man. Whereupon the Prefect examined the evidence, pronounced it spurious, and dismissed the charges. After which the Sanhedrin, present, created such a furore that Pilatus Praefectus actually recanted his verdict and authorized Christ’s death by crucifixion.

None of it makes a scrap of sense.

The text of the four Gospels as they exist today is so non-specific that various and different assumptions may be made.

The first is that Jesus Christ really was a slave, an assumption I dismiss. If in truth he were a slave, the Sanhedrin was not obliged to ask Rome’s permission to crucify him. Whereas only the Roman governor or his prefect could sentence a free man to death, be he a Roman citizen or a citizen of his nation.

Under Roman law any free man, Roman or other, was in full ownership of his slaves, and at complete liberty to kill them arbitrarily. Slaves were as cattle, they had no rights at law.

The second is that Jesus Christ had committed capital murder. This fits better legally, even if he had no criminal history prior to committing capital — premeditated — murder.

Even so, I dismiss it. Nothing in Christ’s career as we know it indicates a capital crime. Nor did the Prefect pass a death sentence; he debunked the charges as patently ridiculous. Only fierce and remorseless bullying by the Sanhedrin caused him to reverse his original decision.

Apropos Pontius Pilatus’s craven crumbling, Jerusalem had been a nucleus of sedition and rebellion for years by 33 AD, the commonest date attributed to the crucifixion. Pompey the Great’s siege was seventy years in the past, but fresh Roman insults to the Jewish homeland came hard on the heels of each revolt, and after 6 AD never were the Jews of Jerusalem without a resident overlord. A son of Aristobulus named Antigonus had even ruled Judaea as a Parthian puppet; there were still Jews known to favor Parthian to Roman rule. If the legion of southern Syria was not in Jerusalem’s vicinity during that Passover of 33 AD, Pilatus may well have thought the cohort (600 men) garrisoning the city was not militarily capable of putting down open revolt. I imagine the sheer violence of the Sanhedrin’s reaction to his decision came as a terrific shock to Pilatus, and, for all he pitied this poor wretch, he wasn’t prepared to risk a fragile peace. That at least is feasible and understandable.

What if Jesus Christ really was the genuine King of the Jews?

Robert Graves’s treatise fascinated me from the time of first reading forty years ago; it was one answer to some of the most puzzling questions as to why Jesus Christ had to die — and why the title King of the Jews was bruited during the hearing before Pilatus — and why Pilatus tried to defuse the situation by holding Christ up as a figure of fun — and why a note was fixed to the top of Christ’s cross announcing that here hung the King of the Jews, a slave with grand pretensions.

When Christ entered Jerusalem riding on a donkey he was hailed as King of the Jews, and even by some as the Messiah. If his mother was the heiress of the House of David, her firstborn son, no matter who his father, could claim to be the King of the Jews. If Graves is followed, the identity of his father was known, increasing his claim, but anathema to the Sanhedrin. If they had to have a Herod, better by far to have the torpid Antipas, as apolitical as he was corrupt.

At this distance in time, it isn’t possible to know without better evidence how word of Christ’s regal identity would have reached the ordinary residents of Jerusalem, but according to the Gospels he was met by cheering crowds who strewed the path of the King with palm leaves. Since his entry into Jerusalem seems to have been a public announcement of his kingly status, he may have worn purple — of which, more anon.

Because Graves’s answer is the only one makes real sense to me, I am going to postulate that it is true.

Following this line, the treason charges laid against Christ to Pilatus were that he plotted to have himself made King of the Jews and foment rebellion against Rome. The Sanhedrin’s argument failed to carry weight with Pilatus, who, if one looks at what is known objectively, seems to have regarded Christ as a crazy man whose lunacy he tried to debunk by flogging, a crown of brambles and a broken reed in one hand as a sceptre. Relevant to later events that will be mentioned in due course, the lash appears not to have broken the skin, nor the crown caused typical copious bleeding of the scalp. “Behold the King of the Jews, ha ha ha!” But the Sanhedrin didn’t laugh; to them, this was no joking matter. Whichever way one looks at it, this hearing was not Pilatus’s finest hour. Only one thing was going to pacify the Sanhedrin: the death sentence of a slave.

Certainly Jesus Christ seems to have become a threat only after he entered Jerusalem; no important Jew seems to have taken any notice of him during his three years of wanderings outside the city. The reaction among the general populace of Jerusalem must then have come as a shock, particularly if he wore the purple.

If one considers Christ’s career as an orchestrated bid to spread his heretical ideas to the people, thus offering them a gentler, more unbiased kind of code that made room for the humble, the poor and the powerless in the scheme of things, then his entry into Jerusalem marked a change. It increased his importance immeasurably, and was perhaps the first step in a peaceful bid for the throne. If he could trace his lineage back to David, he himself would have seen nothing incendiary anent his claim. As a Galilaean Jew, his political thinking was probably naive, at least to some extent; the power plays and intrigues among those at the top of the urban social mix would have been foreign to him.

Religious leaders are rarely done to death at the beginning of their careers; only after they have stirred up the political ant heap do they court extirpation. And in Judaea two thousand years ago politics and religion were intermingled, further complicated by a political overlord in Rome that ran counter to Jewish autonomy of all kinds. Did Christ have kingly plans, they would not have been out of character for the man as I see him: he just wanted a simpler, less materialistic, more tolerant attitude to life and living, which, good Jew that he was, he knew stemmed from God. He disliked theologians and didacticians, religious leaders who interpreted God as rigid, intolerant of human frailty. Christ’s view was that all human beings were frail, and God loved them anyway.

Jesus Christ as King of the Jews was extremely dangerous to the established Jewish religious governors, the Sanhedrin. If the Sanhedrin plus Herod Antipas comprised Christ’s body of accusers, then there were seventy-two men involved.

Christian leaders throughout the ages have thrown up men who blame the Jews for the crucifixion: a manifest injustice. Equally unjust is the retaliatory allegation that the Romans were to blame. The truth is in the Gospels, at least as we have them: including the Roman prefect, seventy-three men exclusive to that time and that place were responsible. No one else.

One, the Roman prefect, acquiesced unwillingly, yet still he acquiesced, while the other seventy-two would not be cheated of their death even at the possible price of provoking the prefect to a military solution. It wasn’t necessary. Pilatus backed down — but were they sure he would? All considered, it reads to me as if they were willing to dare everything to achieve Christ’s crucifixion.

Pontius Pilatus had been Prefect of Judaea for six years by 33 AD, and, given the Emperor Tiberius’s known policy of keeping nobly born, wealthy Romans on foreign duty for many years, he expected to remain in Judaea for more years to come. As indeed proved to be the case. He was not recalled to Rome until three years after the crucifixion, which negates the contention of some Christians that he was recalled to answer for crucifying Jesus Christ — a ridiculous assertion. Why would Tiberius, senile and living on Capri for a decade by this — or his Greek freedman bureaucrats — care about the death of three Jewish slaves, entered in the books of the Antonia fortress and then forgotten?

Such things were not reported to Rome. No doubt Pilatus wrote a report on the matter of Jesus Christ to his boss in the capital, Antioch — the Governor of Syria. He would have described a potentially explosive incident nipped in the bud at the price of one Jewish life. That accomplished, it appears the Sanhedrin settled down.

By all accounts a severe and dour man, Pontius Pilatus would have couched the matter in a factual light, neither spared nor praised himself, merely informed the Governor that though his decision had been a prudent one at odds with Roman law, it did the trick: threats of an uprising faded away.

It is not astonishing that we hear no more of Pilatus upon his return to Rome. Within a year of that, Tiberius was dead and Gaius Caligula emperor. My feeling is that a man who, on the whole, had successfully governed a notoriously difficult people for ten years, would have had great sense and remarkable antennae for trouble. The motion pictures that portray him as an effete nonentity are far from the mark.

On the ascension of Gaius Caligula, Pilatus may well have retired to his estates, kept his head down and lived out the rest of his days in peace and quiet. In fact, were it not for the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, Pontius Pilatus’s name would have been entered on the fasti and utterly forgotten otherwise. I find it a pity that he is almost universally vilified; to him, in that place at that time, to give in must have seemed the best course of action. A goodly proportion of the few Jews he knew personally would have been members of the Sanhedrin, which would have given him a basis for his decision. He knew they meant it, it was written on their faces, in their eyes, their very bodies.

I have come to think that it was Christ’s entry into Jerusalem, home of the Great Temple, lies at the bottom of that death by crucifixion. Given the paucity of our sources, it is the most logical possibility. How could the Jewish heads of state defuse the situation Christ had provoked? Clearly the ordinary people knew of him through his preaching and approved of his message, which is best summarized in the Sermon on the Mount — a radical departure from the sterner orthodoxy of the Sanhedrin, and from the traditional concept of a rather unforgiving God. So when Christ entered the city, his reception badly alarmed the Sanhedrin, whom I acquit of worldly motives for their hatred.

In their eyes Jesus Christ was apostate and had to be put down. But how? How could seventy-one men deal with what they had seen on that day of palms? By achieving Christ’s death, yes, absolutely, but in such a way that his teachings died with him. These men were wise in the ways of men, even if they were not exactly stuffed with common sense. Social disgrace rather than apostacy had to seem the reason for his death, and the Roman prefect its author.

The Sanhedrin was more than a religious government; it was also the Jewish court of justice, and empowered to hear charges against fellow Jews. Also to levy sentence, save for death, the province of Rome alone. But death by sword or axe was the death of a free man: it would not answer. Crucifixion would. If this man who was thought the rightful King of the Jews was deemed a slave and went to a slave’s death, he was branded a pariah — especially if he had pretended to be free, and gathered many ardent followers.

Someone thought of it, but who? And what did they need Judas Iscariot for? Identification of Christ’s person doesn’t wash; after his triumphant entry into Jerusalem, his face was known. Was it Judas’s function to testify before the Prefect that Christ had openly boasted of setting himself up as King of the Jews in a war against Rome? Did Judas testify that he was actively courting the Parthians as allies?

He was paid thirty “pieces of silver” for his services — denarii, I imagine. Not a big sum of money, save perhaps to an impoverished upcountry Galilaean who counted his wealth in mere sesterces, three or four at a time. Maybe he had a small gambling debt; there are faint suggestions that he may have been a gambler. Or perhaps he secretly hankered for the fleshpots? We will never know, beyond the fact that thirty denarii were enough to buy a despicable betrayal. Gaius Trebonius springs to mind: a man who had been superbly honored by his superior, Julius Caesar, and in gratitude amassed envy, resentment, feelings of impotence. All Caesar’s assassins were men he had advanced, and they had hated him for his power to do so. Perhaps Judas Iscariot was that kind of man. Such men hate sourly, implacably, even coldly.

What is certain is that the Sanhedrin needed Judas to further their ends, not identify a face. What, you think every member of the Sanhedrin stayed home that Palm Sunday refusing to set eyes upon a sudden enemy? That’s not human nature. They were there, in the crowd.

Crucifixion as a slave it was going to be, and so it was. It’s the best of the possible solutions to the mystery, and detracts not in the slightest from the eventual structure that grew out of Christ, his life and slave’s death: Christianity.

What kind of man was Jesus Christ, as distinct from his message? Nobly born, that seems evident, but he had one superlative gift that is indeed God-given — charisma. He drew people to himself nigh effortlessly, and once he had them, they remained his. Perhaps uniquely in a misogynistic time, he treated women as his equals, permitted them to follow him, had them among his closest friends, and respected their opinions.

There is nothing in the Gospels that indicates Christ was a poor man, though he abrogated wealth. The two are not the same. Carpenters are not poor men, they have a trade that amounted to a skill, for it included what now would be called cabinet making and the crafting of elegant furniture. Joseph’s workshop may have been a large one employing a number of craftsmen. When Christ quit his trade to wander he seems never to have wanted for money, accommodation, sustenance. Whether or not he worked miracles is beyond the scope of this essay, nor does his declaration of his godhead depend for proof upon the ability to work miracles. It is an article of faith, and faith alone.

Were Christ abjectly poor, he would not have presented such a threat to the Sanhedrin; his declaration of kingship would have been dealt with in other ways than a slave’s death. If he was in truth of the House of David and backed by a wealthy family having considerable power, the threat was urgent. He had to be dealt with immediately, before the family could rally.

When Christ was crucified, the eight legionaries who made up an octet in a century threw dice for his garments. If that is true, it speaks volumes.

First of all, he seems to have been given no opportunity to change his clothes between his sentence and his execution. Why was that? The most logical answer is that a crucifixion death had already been scheduled for two slave criminals. The Romans were very efficient; crosses they had, stored in the Antonia. A third cross came out for Jesus Christ, detained overnight in the Antonia without opportunity to see anyone or send any messages. No doubt the Sanhedrin used the time to spread the “truth” — Jesus Christ was a slave going to a slave’s death. Certainly those who had cheered him and laid palm fronds before him were not present at his crucifixion; that was a small crowd, his nearest relatives from his mother to his brothers and sisters, some of his close friends, men and women.

If he had no opportunity to change his clothes, he cannot have been flogged hard enough to break the skin and ruin his tunic with blood. There were no enzyme laundry powders in existence, nor even soap; clothing was washed in a fountain or stream and pounded with stones to loosen the dirt. Nor could the thorns in his crown have done much damage; the blood, flowing profusely from scalp wounds, would have dripped on to his tunic.

Secondly, his clothing — loincloth, tunic and stola — must have been worth having to a legionary. The garb of a man going to crucifixion soaked in blood would have been incinerated as unwearable, unsellable. Legionaries were paid, they weren’t poor.

Whether Christ’s clothing was that he wore for his hearing before Pilatus or a new, fresh set, it was expensive and unmarked.

Thirdly, it was possible that Christ’s clothing was purple in color. When they existed, Roman sumptuary laws were directed at Tyrian purple, so dark it was almost black, yet shot with rich, plummy highlights. Not a color a Roman legionary would find very eye-catching, whereas ordinary purple he would love.

Fourthly, the tunic would have needed to be properly cut and tailored to appeal — darts to define the waist and set-in sleeves — the stola capacious — and the loincloth made, as they were, with some resemblance to modern underpants. They would have been of wool, not unenviable linen; weavers in an ancient era could produce exquisitely fine woollen fabrics, semi-transparent or as sleek to the feel as modern top quality suiting. Sheep kept for wool wore supple kidskin jackets to keep the wool creamy-white in color and free from burrs and detritus.

There is a Christian tendency to regard the casting of lots for Christ’s garments as evidence of Roman depravity; whereas the truth is that much of a legionary’s life was boring in the extreme; as indeed would this unusual duty have been. I imagine few crucifixions happened. This day’s may have been the year’s total to date. Dice were the best way to while away the time. Not many gambled their pay; most dice were cast out of natural curiosity as to how the ivory cubes would fall, and who had the luck that day. The pot was as likely to be pebbles. To have the chance to play for something worth winning was rare, so Christ’s clothing was an unexpected bonus. No matter what its color, that says it was fine, not the garb of a poor man. Nor ruined by blood.

I discount the story of Barabbas as apocryphal. Pontius Pilatus was a Roman governor, and such men did not turn a solemn event into a crowd-pleasing circus; there were games for that.

It is also highly likely that once Jesus Christ left his audience chamber, Pilatus had nothing more to do with his death. It was more likely to be up to his subordinates to decide when and how Christ would die, and if there were other slaves scheduled for death, the tidy bureaucratic mind saw the solution immediately: all together, as scheduled for the other two.

The Gospels were written in Greek for a Greek-speaking congregation that had no love for either Romans or Jews. Orally transmitted events by definition cannot be rigidly policed; the early Church was rife with doctrinal argument and more influenced in the main by Paul than by Jesus Christ the man. The Gospels were an attempt at the history of Jesus Christ the man, whose life was, unfortunately, not appreciated as the product of its times.

A hundred years down the road, crucifixion was a commoner death and not confined to slaves — the reason why, in all likelihood, the slave question never arose. Converts were not only more numerous, but also of a higher social status, and the interpretation of Christ’s teachings was becoming more intellectual. Some parts of the Gospels received scant theological attention, as they neither affected nor influenced the thinking of Christian bishops, beginning to thrust out feelers toward debate on Transubstantiation and the Trinity as well as what Christian living should consist of in terms of ceremony and ritual.

Why weren’t Christ’s legs broken? Who decreed it?

Under ordinary circumstances those who were crucified begged to have their legs broken, as it hastened death by literal days. A man tied to a cross by his arms was provided with a small, blocklike shelf on which he could rest his feet, thus taking the bulk of his weight on his feet. What killed him eventually were thirst and exposure to the elements. Perhaps three days. But if his legs were broken, all his weight subsided into his trunk and he was unable to expand his lungs sufficiently to breathe. What killed him was suffocation. Perhaps three hours.

It seems to me that the Sanhedrin would infinitely have preferred broken legs; they had no reason to want an articulate Jesus Christ on their hands for several days. Yes, he would cease to speak lucidly at the end, but he was a man in the full flower of his strength, and he wouldn’t give in to death easily. But once the Roman machine took over, the Sanhedrin had no power to influence the grinding of its wheels. They could intimidate the Prefect, yes, but had no leverage whatsoever with his minions, unknown to them. One has to presume that Christ himself chose not to have his legs broken — but whom did he ask? I inclined to think it was Pilatus, but after long thought, I believe it was a choice could only be made at Golgotha, of the head legionary. The man probably thought him mad, but if that was what he wanted — well and good.

Though Christ couldn’t fight against his death sentence, if he still had the use of his tongue after he was hung upon his cross, Christ could speak out. Not against the Sanhedrin or Herod Antipas, but to voice the ideas he conceived and perceived as absolutes: in his death he could die for all humanity did he have the breath to proclaim it. His suffering would be to atone with God for the sins of men, and thereby save them.

This he did — but only for three hours. Either in fact his legs were broken and he died exactly on time, which didn’t get a mention in the Gospels, or at Roman instigation his life was terminated on time by a pilum spear thrust through the chest wall. This termination most likely came as the decision of the chief legionary, either fed up with this duty or moved by pity, as was his right as supervisor of the triple crucifixion. Who was to gainsay him? The weather had turned bad, there was a minor earth tremor, and it had been a tedious day, garments notwithstanding.

But Jesus Christ had lived on his cross long enough.

The small crowd was docile and well behaved. And those who were present carried his last messages faithfully as they disseminated to hold aloft the torch he had lit. Inspired, they proved effective and ardent torch bearers. Peter must have spoken good Greek, to have traveled as far as he did if indeed Christian history is right. So must others among them. They were not untutored oafs, bucolic ignoramuses. The pity of it is that as time went on women were subtracted from the Christian equation, though Christ had treated them as equals. The virgin birth held sway only because it turned Mary into a non-woman, a femunculus. Enough said. The place of women in religions is a sore point with me.

Outside every locus of population larger than a village was the necropolis, in the least intrusive corner of which were the lime pits. In these the bodies of those who could not afford to pay for a funeral were thrown, to be covered with quicklime and soil. And there the bodies of Jesus Christ’s two fellow condemned were tossed. To go to the lime pits was an appalling fate: as a result, all sorts of lowly, including slaves, contributed a coin or two every so often to a burial club. It was one of the earliest examples of a time-payment contract.

Such was not the fate of Jesus Christ. His body was given, probably on the tendering of a paper, to some persons, including women, who wrapped it in a fine shroud and interred it in the costly private sepulchre belonging to one Joseph of Arimathaea. Three days later the women found the stone sealing the tomb rolled off, and the tomb itself empty. Soon it was spreading at an incredible rate that Christ had been seen alive, walking and talking. At the end of forty days he disappeared, not to be seen thereafter.

The truth or otherwise of this doesn’t matter. Christianity is a religion of blind faith, not to be questioned in its essence, for all that ostensibly good Christians have been questioning its essence for two thousand years. Did they not, there would be but one kind of Christianity, whereas the kinds are legion.

To me, it is of no moment whether Jesus Christ the man lived in the knowledge of his godhead with every nanosecond of that life already cemented in his mind, or whether he seized what came with no foreknowledge, just like the rest of us. Immaterial.

What set me off was a valid question: why was Jesus Christ given the death of a slave?

How real the Sanhedrin’s fears about Jesus Christ were is hard to tell two thousand years later, but certainly their behavior during the hearing before Pontius Pilatus says that they were terrified of a living, breathing Christ. For all we know today, Christ’s power and influence over the common people may have been formidable indeed; seen from the ivory tower of seventy-one men entrenched in their function and implacably opposed to change, a living Christ loomed as disaster. Were they correct in regarding him thus? To their way of thinking, yes.

He had to be put down. If in putting him down they could simultaneously discredit him, all the better.

I have concluded that the reasons behind Christ’s crucifixion death were threefold: religious, political, and social. An impressive Judaic heresy was a religious threat; a man believed to be the King of the Jews was a political threat; and that man’s popularity among the common people was a social threat.

What more effective device to achieve the Sanhedrin’s ends in Jerusalem in 33 AD was there than the death of a slave?

Why on earth is Midsomer Murders so successful? In a fabulous British whodunit world that includes series as brilliant as Dalziel & Pascoe and Lewis and Waking the Dead to name but three out of many, M.M. has labored plots and unbelievable characters. It’s a box of chocolates. Yet for longevity and loyal fans, it puts even the CSI series in the shade, rolling on year after year after year. I am way behind at Series 10, but I have no trouble casting my mind forward to Series 49, released in 2040.

Scene: What looks like Anne Hathaway’s cottage in spring. A large camera crew is positioned behind the hollyhocks and a decapitated body lies on the doormat; its head sits on the letterbox.

From a cute little shed made of wattled withies emanates a soft “Brrr-clank! Brrr-clank!” noise.

A man in frayed clothes rushes down the pebbled path between heart’s-ease, monk’s-hood and baby’s-breath, and reaches the cute little shed, panting painfully.

“He’s dead this time, Mr. True-May, sir, honest he is! He has fallen off the twig, he is no more, he’s gone to that big cop shop in the sky, he’s an ex-policeman! What do I do?”

The producer thrusts his head farther out of the bionic iron lung in which he lives; it has enabled him to survive for 183 years, and he’s still going. The cute little shed hides the bionic iron lung and has been designed to fit in no matter what outdoor location M.M. might be using for a shoot.

“Put the facsimile plastic mask on him, 137, blow him up with helium, and use the new kid with the great Nettles voice,” True-May orders between the “Brrrclank!”s of his apparatus.

“Sir, even dead he’s past it! Whatever the oncologist did on his last visit, Superintendent Barnaby’s joints have locked stiffer than a dicky on a double dose of Dynamix.”

“Oh, bugger! Send on his doppelganger.”

“Sir, I can’t! He died of old age last Tuesday.”

“Shit!”

One-three-seven looks suddenly inspired. “Sir, sir! Mr. True-May, I’ve found the answer!”

“What answer, young whipper-snapper 137?”

“A perfect Barnaby, sir, only ninety-nine years old.”

“Splendid, 137, splendid! You’ll get an extra tuppence in your pay packet this year. Walk him through the scene.”

“Um — wheelchair him through, sir. He’s gaga.”

“So’s Barnaby, that’s perfect. Expect an extra fourpence.”

It really does begin to trigger weeny fantasies like the above. Our Joyce Barnaby looks a lot sourer than she used to, and in Series 10 it’s obvious that sex is off the Barnaby marital menu — if it were ever on, that is. Joyce has started to wear Tom’s pajamas, supplemented by ear plugs and an eye mask. Her waist is disguised by a jacket, but she’s spending more on pricier clothes. The daughter, Cully, grows older, no thinner on the hips and thighs but scrawnier in the face, and the viewer rather gathers that Cully’s acting career has foundered, in which case she is a drain on the government by living on Welfare. However, Series 10 sees a serious boyfriend — the manager of a rock ’n’ roll band, yet. Where did Joyce and Tom go wrong as parents?

As for Tom Barnaby — um, well … He’s been a chief inspector for ten years, so a promotion to superintendent must be just around the corner. Unless that too requires a written examination, and Tom keeps failing it?

Q. How do you deal with a recalcitrant sergeant? Be thorough.

Q. How many murders a day do you solve? Be honest.

Q. How many murders a day do you think you could solve? Be as ambitious as you like, but don’t forget the corpse in the field between Midsomer Mere and Midsomer Marshmallow.

Q. Draw in the location of all public toilets in Causton on a freehand map. Be specific. Extra marks will be awarded for artistic ability but cartography will get you nowhere.

I’m getting ahead of myself.

What distinguishes M.M. from its rivals is its relatively huge American audience, but there are reasons for that. Brian True-May, who retains the title of producer against all comers, nutted out the correct formula, something no one at the BBC was smart enough or egalitarian enough to do.

First item on the True-May list: no thick regional accents and, by and large, good diction. This means Americans can understand most of what is said. You can’t hope for that with Dalziel, though Lewis, with the extraordinary Laurence Fox as sidekick, would succeed were it not so intellectual. Big TV success demands low-brow, no matter what the nationality. The second item Mr. True-May stipulated, I speculate, was some degree of Americanization, so that the cast say “Yeah!” and “Hi!” and call a torch a flashlight. There are times, I add, when this leads to fluffs that must have the Americans in fits of laughter.

Sometimes I think that a great deal of the problem is due to the Americans involved, who, I speculate, belong to a tight little klatch of L.A. television moguls. And L.A. television moguls are utterly ignorant of how a native of Tennessee or North Dakota or Vermont lives, let alone any Britisher. So when we non-Americans watch an American program, it is essential that we keep the ignorance of the producers about their own country firmly in mind. Vermonters or Tennesseeans must grow furious.

I digress. Mr. True-May moved from his verbal to his visual approach, and declared a theme of English village life as remote from a real English village as L.A. is from Waterbury, Connecticut. A decision having every advantage. No filming in big cities. A signpost amid thick trees at night turns the location into anywhere from Hong Kong to the foothills of the Himalayas. PUDONG AIRPORT 3K and it’s Shankers. KHYBER PASS 10K and it’s dangerously close to the Taliban. I adored the Chinese touch at the PUDONG AIRPORT 3K sign: two small men pedaling bicycles. But ninety-nine per cent of the locations are the villages of Midsomer, a fictitious county stuffed with thatch, half-timber, stone and Georgian red brick as its architectural theme. In Midsomer, it’s charming if it can’t be pretty, but usually it’s both. The difference between a town and a village? Easy! In a town, the village green has been tarred over and transformed into a huge and very ugly parking lot.

Now, Mr. True-May obviously reasoned, what would Americans most love to see? And top of his list is at least one shot of people riding horses with tiny English saddles: kids riding fat ponies, women riding fat hacks, men riding fat hunters. And oh, please, as often as possible, a horse-and-hounds cross-country hunt! As the fox is now protected, hunts are permissible. Do they use an electric fox, like the electric rabbit at a greyhound track? A Japanese prototype robot fox? A toddler in a fox suit?

Village greens must be enlivened by a cricket match, of course. Hint: always a match, never a game. Games are against, matches are between.

Mansions in parklands, sadly devoid of verdure around the house itself, which must be seen. Thatched cottages galore, with gardens in bloom. Pubs, pubs, and more pubs. Social activities having an Olde Worlde feel, from World War II dances to drama society Shakespeare or Shaffer. Receptions at the Big House. And — how could one forget them? — fairs, fetes and festivals on the village greens or in the grounds of a manor.

The plot, Mr. True-May surely decided, was best kept utterly implausible. Who wants to be reminded of reality, equally bitter on both sides of the Atlantic? Therefore, over-the-top situational plots replete with larger-than-life characters are the thing.

The characters are either stock, or wildly eccentric. You know from his or her occupation and appearance what the personality is going to be. A farmer, for example, is foul-tempered, boozy and irascible, and may have a totally intimidated son. His scenes are always shot in a horribly primitive kitchen to show the American viewers how primitive a kitchen can be. At the other end of the scale is the execrable cook Joyce Barnaby’s kitchen, wasted on her. Few British kitchens are so fine.

Everything thus far is mere window dressing.

Window dressing? you ask. Yes, window dressing for the dead bodies, almost all of whom have been murdered.

A boring episode features two miserable corpses, whereas a real rip-snorter of an episode will have up to five or six corpses, including one or two you prayed feverishly wouldn’t die. I best remember the poor woman who was left utterly alone in the world, even her beloved son murdered — and in such a cavalier way that you know the silly scriptwriter forgot there was a dead son. I detest the persons who perish screaming in hellish flames, and wish the scriptwriters were less addicted to this most horrible of all deaths.

It does occur to me from time to time that the death rate in Midsomer County should prompt a socialist government at least to call for a Royal Commission, after which it could declare the soil of Midsomer County toxic, and evacuate the Midsomerians to Welsh Snowdonia or Scots Orkneys and set them up in a cottage industry, Murder Inc., provided their victims are not too close to home. I can see some valuable export figures if the project were managed with True-Mayan efficiency.

It’s on about the fourth episode and the nineteenth corpse that the viewer realizes the ultimate purpose of everything: to harbor a dead body. Village greens are for dumping dead bodies on or around — poor material compared to woods, wherein schoolkids can take short cuts to discover dead bodies, couples can frolic nude to discover dead bodies, couples can have sex on blankets and wind up dead bodies, as well as hang, strangle, stab or shotgun blast other people into dead bodies. Streams are wonderful — lots of trout fishing as well as dead bodies. Ponds and lakes allow skinny dipping and serenely sailing swans as well as dead bodies. Tumbledown barns are more than just picturesque: they contain disused farm equipment to reward the viewers with the grisliest dead bodies. Someone drove a car full tilt into a tractor trailer loaded with logs. Occasionally horses are framed for heavy, hoofy murders that were done by the village blacksmith with his hammer and/or anvil. That nightmare booth called Punch & Judy can hide more than police puppets.

However, the best venue for murder is undoubtedly the lovely old Norman village church, God’s gift to a scriptwriter befogged by plotter’s block. The belfry is useful for chucking persons off of, or donging to death with a bell, or squashing by the two-ton bell, or strangling with a bell rope, or breaking the neck in a fall down the winding stairs. Either apse or aisle is ideal for a blunt instrument death or flaming phosphorus or being suspended from the rafters in a copycat The Silence of the Lambs murder.

And when all else fails, there is always the baptismal font for drowning in, as they are the size of bath tubs. Nowadays they’re mostly kept empty and have a dinky wee basin in their bottoms for the babies; however, if someone demands the full Henrician immersion, it can be done: just fill the font.

Which led to Episode 3,708 of Series 23, the only case that DCI Barnaby never solved. The worst of it was that in the very next episode, 3,709, he got his promotion to superintendent by drawing England, Scotland and Wales freehand and marking in every public toilet from Peebles to Lower Slaughter.