MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL: An Interactive Guide to the World of Sports – Read Now and Download Mobi

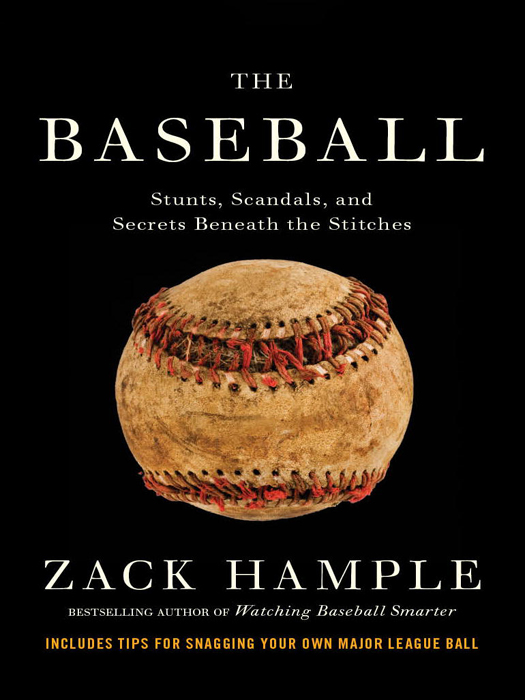

ZACK HAMPLE

THE BASEBALL

Zack Hample is a baseball fan best known for having snagged 4,662 baseballs (and counting) from 48 different major league stadiums. Hample has been featured in hundreds of newspapers and magazines, including Sports Illustrated, People, Men’s Health, Maxim, Playboy, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and USA Today. He has also appeared on NPR, ESPN, FOX Sports, CNN International, The Rosie O’Donnell Show, the CBS Evening News with Katie Couric, and The Tonight Show with both Jay Leno and Conan O’Brien. Hample’s first book, How to Snag Major League Baseballs, was published in 1999 when he was 21 years old. His last book, Watching Baseball Smarter, was published in 2007 and is currently in its 16th printing. Hample, a New York City native, runs a business called “Watch With Zack” through which he takes people to games and guarantees them at least one ball. He also snags baseballs to raise money for the charity Pitch In For Baseball and writes a popular blog called The Baseball Collector.

ALSO BY ZACK HAMPLE

Watching Baseball Smarter

How to Snag Major League Baseballs

AN ANCHOR SPORTS ORIGINAL, MARCH 2011

Copyright © 2011 by Zack Hample

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Anchor Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Anchor Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hample, Zack, 1977–

The baseball : stunts, scandals, and secrets beneath the stitches / by Zack Hample.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-74208-7

1. Baseball—United States—History. 2. Baseball—Social aspects— United States. I. Title. GV863.A1H36 2011

796.3570973—dc22

2010043551

Cover design by Base Art Co.

Cover photograph © Don Hamerman

v3.1

This one’s for my dad.

CONTENTS

PART ONE BASEBALLS IN THE NEWS

“Ball Grabbers, Read This” • Steve Bartman • Jeffrey Maier • Red Sox World Series Balls • Barry Bonds Home Run Balls • Hank Aaron’s Final Home Run • Sammy Sosa’s 62nd Home Run of 1998 • Ryan Howard’s 200th Career Home Run • Big Money Opportunities

Consecutive Foul Balls • Lightning Strikes Twice • Nice “Catch” • Heckle This! • Don’t Mess with Cal Ripken Jr. • Lynyrd Skynyrd • Banned from Baseball • Great Balls of Fire • Happy Mother’s Day • Family Affair • That Ball Is … Gone!

Dangerous Game • Ray Chapman • Mike Coolbaugh • Fan Fatalities • Fowl Balls

Such Great Heights • Knocking the Cover Off the Ball • Punk’d by Pete Rose • Outer Space • The Motorcycle Test • Does a Curveball Really Curve? • The Brass Glove Award • Just Say No

CHAPTER 5 FOUL BALLS IN POP CULTURE

Movies and TV Shows • Celebrity Ballhawks

PART TWO HISTORICAL AND FACTUAL STUFF

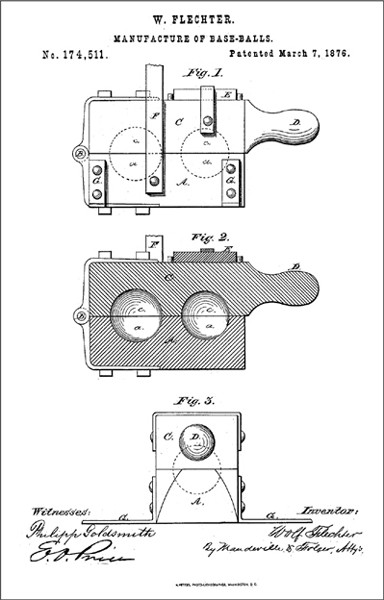

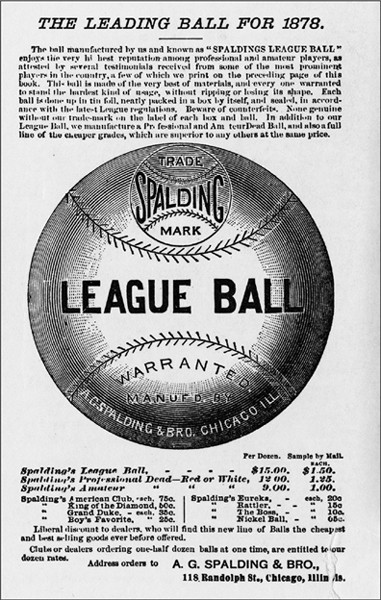

CHAPTER 6 THE EVOLUTION OF THE BALL

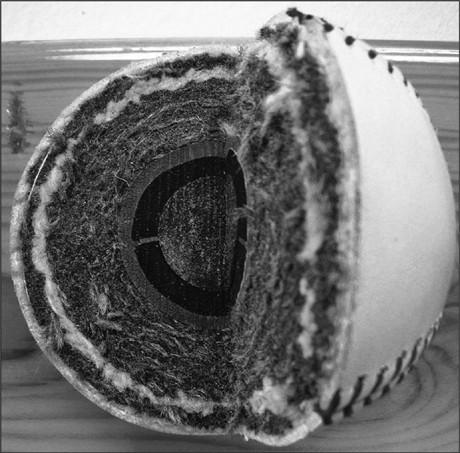

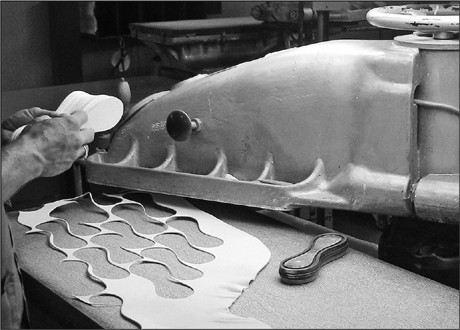

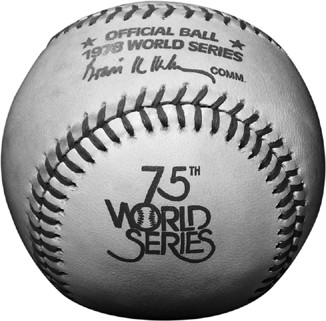

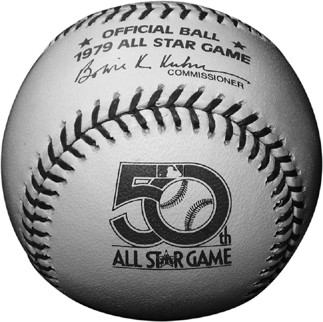

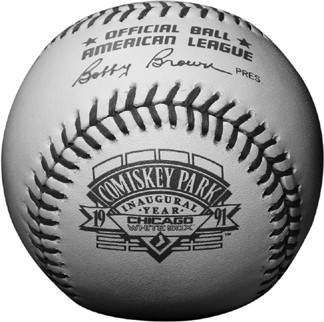

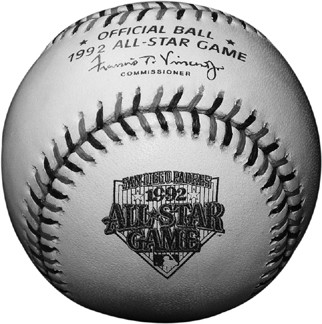

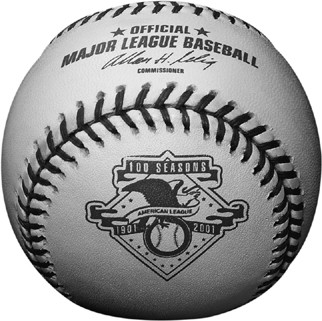

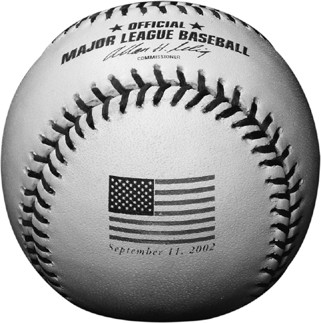

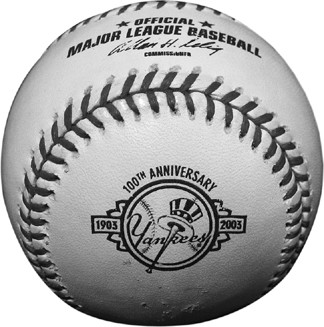

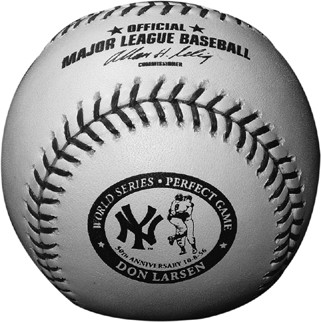

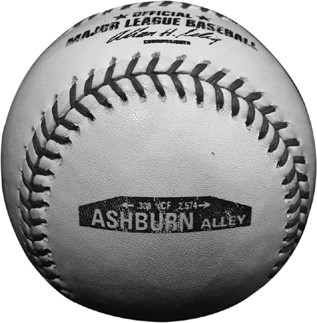

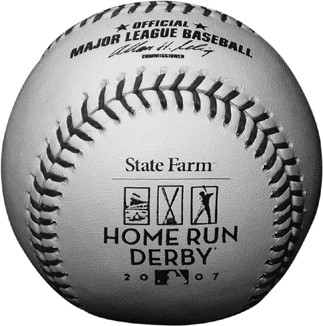

(De)constructing the Ball • The Pill • Mission: Impossible • The Winding Room • The Cowhide • The Stitching Process • Finishing Touches • Commemorative Balls

CHAPTER 8 STORAGE, PREPARATION, AND USAGE

Striving for Uniformity • Lena Blackburne Rubbing Mud • Equipment Managers

PART THREE HOW TO SNAG MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALLS

CHAPTER 9 BEFORE YOU ENTER THE STADIUM

Luck versus Skill • Choosing a Game • Stadium Security • Buying Tickets • What to Bring • When to Arrive

The First 60 Seconds • General Advice on Positioning • Left Field versus Right Field • Home Run Balls • Ground Balls • The Glove Trick (and Other Devices)

CHAPTER 11 HOW TO GET A PLAYER TO THROW YOU A BALL

Dress for Success • A Mishmash of Strategies • Don’t Be Annoying • Tailor Your Request to the Situation • Where to Go and When to Be There • If It Rains

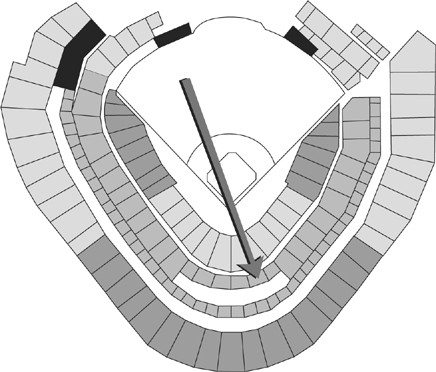

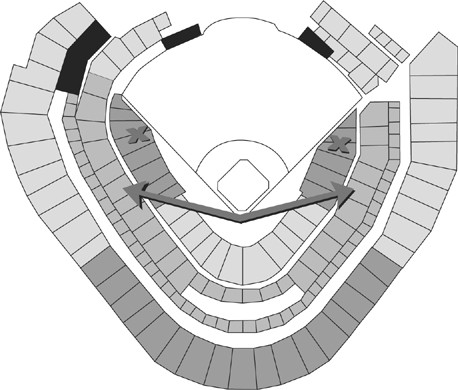

What Are the Odds? • Foul Ball Theory • Game Home Runs • Nice Catch! Now What? • Third-Out Balls and Other Tosses • After the Final Out

CHAPTER 13 TOP 10 LISTS AND OTHER THINGS OF INTEREST

Top 10 Ballhawks of All Time • Top 10 Memorable Ballhawking Moments • Top 10 Stadiums for Ballhawking • Spring Training, Home Run Derby, and the Postseason • Ballhawking Etiquette • Documenting Your Collection

Photo and Illustration Credits

INTRODUCTION

I know this might be asking a lot, but can we forget about steroids for a moment? And while we’re at it, can we stop griping about instant replay and ticket prices and everything else? Baseball is still the national pastime, and whether you’re just a regular fan or a multimillionaire A-list celebrity, catching a foul ball—or better yet, a home run—might be the ultimate American experience. Ask Charlie Sheen. Back in April 1996, he bought 2,615 outfield seats at an Angels game to increase his odds of snagging a home run ball.

It didn’t work.

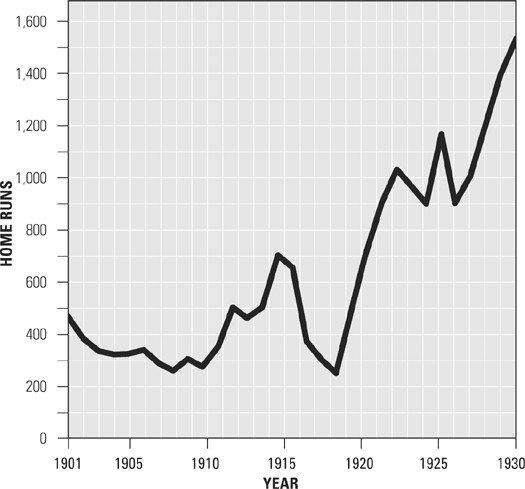

As hard as it might seem (particularly for Sheen) to leave the stadium with a souvenir, it used to be much harder. At the turn of the 20th century, fans weren’t even allowed to keep balls. Teams typically used just a few balls per game, so whenever one landed in the seats, a stadium employee retrieved it and put it back into play. Naturally, by the end of each game the balls were so dirty and discolored that they were tough to see, especially at dusk. No one thought much about this until 1920—more than two decades before teams started wearing helmets—when a batter named Ray Chapman was fatally hit in the head by a pitch that he barely saw. Soon after, umpires were instructed to keep new, clean balls in play.

The tradition of keeping foul balls, while impossible to trace back to one particular moment, got a major boost the following season when a 31-year-old New York Giants fan named Reuben Berman refused to return a ball, got kicked out of the Polo Grounds, sued the team for mental anguish, and won. Now, nearly a century later, catching and keeping balls is such a big part of the game that some fans enjoy this pursuit as much as the game itself.

I know because I’m one of them.

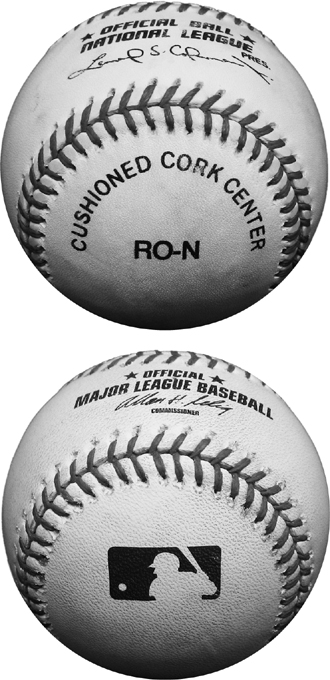

Since 1990 I’ve snagged 4,662 baseballs at 48 different major league stadiums. Of course, when I first started going to games, I didn’t know what I was getting myself into. There weren’t any blogs about snagging baseballs. I didn’t know what a so-called ballhawk was. The whole thing was a mystery, and I just wanted to catch one ball. But now that I’ve reeled in thousands of them and had some time to reflect, I’ve discovered that the ball is more than just a five-ounce sphere of cork, rubber, yarn, and cowhide. It’s a major source of history and controversy and hilarity. Did you know that Babe Ruth once tried to catch a ball that was dropped from an airplane? Or that several NASA astronauts have thrown ceremonial first pitches from outer space? (See “Stunts.”) Remember when Kramer got hit in the head by a foul ball on Seinfeld? Or when Carrie snagged a ball on Sex and the City? (See “Foul Balls in Pop Culture.”) Do you know how many fans have been killed by balls at major league games? Or the story about Dave Winfield nearly getting thrown in jail after killing a bird with a ball in Toronto? (See “Death by Baseball.”) Are you aware that Rawlings uses nearly one thousand feet of yarn and thread inside every ball? Or that the balls get stamped with invisible ink that only shows up under a black light? (See “The Rawlings Method.”) Did you know that the juiced-ball controversy dates back to the 1860s? Or that the cover of the ball used to be made of horsehide that was purchased from dog food companies? (See “The Evolution of the Ball.”)

Gathering these facts was lots of fun—it helped to have Rawlings, Major League Baseball, and the Hall of Fame on my side—but when I first started doing the research, explaining the book to people was oddly difficult.

“It’s about baseballs,” I’d say.

“You’re writing a baseball book?”

“No … I mean … yes. I mean, it’s about base-balls … you know? The ball—the actual baseball itself.”

(Cue the awkward silence.)

“Oh, like, how the ball is made?”

Yeah, how the ball is made—but this book covers so much more. I’m still not quite sure how to describe it, but if there’s one thing I’ve learned from going to hundreds of games and snagging thousands of balls and meeting tens of thousands of fans, it’s that there’s something about baseballs that makes people crazy. This book is a celebration of the ball—and of those people.

Base ball fans—the radicals—are so anxious to get a base ball that has history attached to it, that they willingly risk arrest for petty theft. They are willing to fight amongst themselves for such a ball, if necessary. A blackened optic or a busted breezer, in their opinion, is a mere incident—if they only can get that pellet.

—Sporting Life magazine, July 22, 1916

CHAPTER 1

THE SOUVENIR CRAZE

“BALL GRABBERS, READ THIS”

Way back in 1915, a first-class stamp cost two cents, a gallon of gas went for a quarter, and a game-used baseball fetched three bucks. At least, that was the going rate at the Polo Grounds when a Yankee fan named Guy Clarke snagged one in the left-field bleachers, got arrested for refusing to return it, and had to pay a $3 fine. That was a lot of money back then, but we’re not talking about any old ball. It was a ninth-inning home run hit by Yankees shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh against the Boston Red Sox. Considering what that ball would sell for today, it was totally worth it. The editors at the New York Times, however, didn’t see it that way, and on May 8, 1915—one day after the incident—the paper ran a short article called “Ball Grabbers, Read This.” It was a warning, and the message was clear: if you steal a baseball, you’re gonna get busted.

This was old news.

And it wasn’t entirely true.

Clarke was just one of the unlucky few who got prosecuted; fans had been snapping up baseballs for years, and by 1915 more than two dozen balls were disappearing at the Polo Grounds each week. Yeah, these balls were expensive—owners were paying $15 per dozen—but beyond the financial burden, it didn’t really matter. If a few balls were lost here and there, the home plate umpire simply replaced them.

That’s not how things worked when the National League formed in 1876. High-quality balls were so scarce that each one was expected to last an entire game, and if the ball went missing, the players went looking for it. As a result, fans policed themselves whenever a ball landed in the crowd and made sure that it was returned. It had to be. There was no room for debate. But when foul balls flew completely over the grandstand and landed outside the ballpark, they were much harder to recover. These balls were often grabbed by little kids who didn’t have enough money to buy tickets, so teams came up with a solution: anyone who returned a ball got to watch the game for free.

This reward system was effective at first, but kids eventually began to value the ball more than the opportunity to watch grown men play with it. (Can you blame them?) On June 1, 1887, Toronto World reported that “fifteen balls were knocked over the left field fence at Buffalo Monday and were stolen by bad boys.”1 In other words, teams weren’t just losing balls during games; kids were taking them during batting practice as well. What began as a nuisance—a missing ball every once in a while—was turning into an epidemic.

On May 1, 1897, The Sporting News declared that “the souvenir craze” was affecting games in the South. In 1899 the Washington Senators hired a group of boys to retrieve baseballs. By 1901 teams were spending so much money on balls that the National League Rules Committee suggested penalizing batters who fouled off good pitches. On May 2, 1902, the Detroit Free Press said, “Baseballs that go into the stands at St. Louis are hopelessly lost, the man who first gets his hands on the flying sphere clinging to it.” Sometime around 1903, it was rumored that on one occasion when a fan at the Polo Grounds refused to return a ball, John McGraw, the Hall of Fame manager of the New York Giants, retaliated by stealing the guy’s hat.

Major League Baseball took action the following season by officially giving teams the right to retrieve balls that were hit into the stands. This new measure worked in some cases, but for the most part all it did was piss off the fans and make them more determined than ever not to cooperate.

In 1905 a Cubs fan named Samuel Scott was arrested in Chicago after catching a foul ball and refusing to hand it over to an usher. Cubs president James Hart personally confronted him and signed a larceny complaint, but the charges were dropped the next day when Scott, a member of the Board of Trade, threatened to sue for assault and false arrest.

Things got progressively worse from there.

“Brooklynites seem to prize highly balls which go into the bleachers,” reported the New York Tribune in 1908.

“Women are as bad as men about stealing baseballs; they aren’t so skillful in hiding them,” said baseball manufacturer Tom Shibe in 1911.

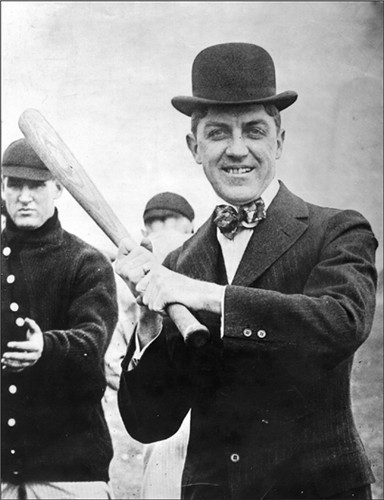

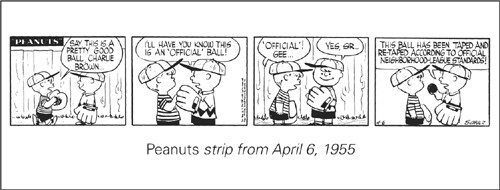

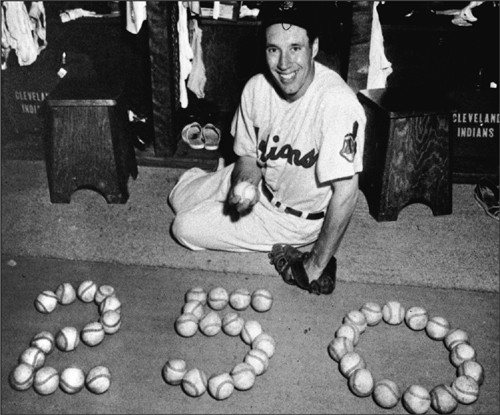

Charles Weeghman, an unsung hero among modern-day ballhawks, was the first owner to let fans keep foul balls. (Photo Credit 1.1)

“The practice of concealing balls fouled into the grandstand or bleachers has reached disgusting proportions in New York,” claimed Sporting Life magazine in 1915.

Cubs owner Charles Weeghman felt otherwise. He recognized the foul ball frenzy as a business opportunity—a chance to bring more folks to the ballpark—and on April 29, 1916, he began letting fans keep the balls they caught. Two and a half months later, the Phillies’ business manager billed Weeghman for eight baseballs that were hit into the stands during BP, but that was the price of good PR. The October 1916 issue of Baseball magazine praised Weeghman in a lengthy staff editorial. “The charm of novelty, of possible gain might lure far more spectators than enough to pay for the lost balls,” it said. “At any rate, Mr. Weeghman evidently thinks so. For he has recently inaugurated this common-sense policy in his park at Chicago.”

Other owners just didn’t get it.

“Why should a man carry away an object worth $2.50 just because he gets his hands on it?” asked Colonel “Cap” Huston, part-owner of the Yankees. “When people go to a restaurant, do they take the dishes or silverware home for souvenirs?”

Most teams generously donated used balls to servicemen during World War I, but continued bullying the regular fans.

Enter Reuben Berman.

On May 16, 1921, Berman, a 31-year-old stockbroker from Connecticut, caught a foul ball during a Reds-Giants game at the Polo Grounds, and when the ushers demanded that he return it, he responded by tossing it deeper into the crowd. Berman was whisked away by security personnel, taken to the team offices, threatened with arrest, and ejected from the stadium. Giants management figured that was the end of it, but nearly three months later Berman’s attorney served the team with legal papers, claiming that his client had been unlawfully detained and had suffered mental anguish and a loss of reputation. The case was tried in New York’s Supreme Court, and Berman was awarded $100—far less than the $20,000 sum originally sought by his attorney, but the message was delivered.

“Reuben’s Rule” (as it came to be known) was the real turning point, although change didn’t happen all at once. Several owners still refused to give in, and as a result, there were a few more high-profile clashes between fans and security personnel. The most outrageous incident took place in 1923, when an 11-year-old boy named Robert Cotter was arrested and thrown in jail for pocketing a ball at the Baker Bowl in Philadelphia. The following day he was released by a sympathetic judge who said, “Such an act on the part of a boy is merely proof that he is following his most natural impulses. It is a thing I would do myself.”

Seven years later in Chicago, with Weeghman long gone as Cubs owner, there was another ugly incident involving a young fan. Arthur Porto, age 17, caught a Hack Wilson foul ball and brawled with stadium security when they tried to take it from him. He and his two friends, who had joined the scuffle, were booked for disorderly conduct. The next day in court the judge dismissed the charges and ruled that a ball hit into the crowd belongs “to the boy who grabs it.”

There were still a few more altercations in the 1930s, and during World War II teams once again donated balls to the armed forces. During that time fans were asked to return whatever they snagged, but that was the end of it. Ballhawking bliss, along with a whole new set of controversies, was about to begin.

STEVE BARTMAN

Steve Bartman is responsible for the biggest ball-related controversy in history. Most sports fans know his name, but few are aware of the entire wacky aftermath. The original incident occurred on October 13, 2003—Game 6 of the National League Championship Series at Wrigley Field. It was the top of the eighth inning. One out. Runner on second base. The Cubs were beating the Marlins, 3–0, and needed just five more outs to advance to the World Series. They hadn’t been there since 1945. They hadn’t won it since 1908. Momentum was finally on their side—until Luis Castillo lofted a seemingly harmless fly ball down the left-field line. Cubs left fielder Moises Alou ran into foul territory and probably would’ve made the catch had a certain fan not reached out of the stands and deflected it.

That fan was Steve Bartman.

Alou flung his glove in disgust, and the crowd directed its wrath at Bartman, who had to be escorted out by stadium security for his own safety. When play resumed, the Marlins rallied for eight runs and put the game away.

Poor Bartman. Not only did half a dozen police cars have to gather outside his home that night to protect him and his family, but things got worse the next day after the Cubs blew their lead in Game 7 and failed to reach the World Series. Bartman became an instant scapegoat for generations of disgruntled Cubs fans, received death threats, had to change his phone number, and was forced into hiding. Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich suggested that he enter the witness protection program, while Florida governor Jeb Bush offered him asylum. Bartman proceeded to turn down interview requests and endorsement deals, and he eventually rejected a $25,000 offer to autograph a photo of himself at a sports memorabilia convention.

Here’s where it gets weird.

Several months later, a successful restaurateur named Grant DePorter bought the infamous foul ball at an auction for $113,824. DePorter, hoping to rid the Cubs of their curse, recruited Michael Lantieri, an Academy Award–winning special effects expert, to blow up the ball at Harry Caray’s restaurant. The stunt was covered live on CNN, ESPN, and MSNBC and was written up by more than 4,000 newspapers. Then, a year later, at a much less publicized event, DePorter used the remnants of the ball to make a dish he named “Foul Ball Spaghetti.” What remained of the ball was boiled; the steam was captured and distilled and added to the recipe.

JEFFREY MAIER

Jeffrey Maier was the most infamous baseball fan before Bartman, and he attained his notoriety by doing the same thing: reaching out of the stands and interfering with a ball that was still in play. Luckily for Maier, who was just 12 years old at the time, he was treated as a hero because his interference happened to help the home team. And not just any team—the New York Yankees.

It was October 9, 1996—Game 1 of the American League Championship Series. The Yankees were trailing the Baltimore Orioles, 4–3, with one out in the bottom of the eighth, when Derek Jeter spanked a deep drive toward the short porch in right field. Orioles right fielder Tony Tarasco reached the blue padded wall as the ball was descending and leaped to make the catch—but he never got the chance because Maier stuck out his glove and deflected the ball back into the stands.2 Right-field umpire Rich Garcia ruled it a home run, prompting Tarasco and Orioles manager Davey Johnson to argue like mad. And they were right—slow-motion replays indicated that the ball would not have cleared the wall if not for Maier—but the bad call stood, and the Yankees won the game (and eventually the World Series) in extra innings. The Orioles filed an official protest, and even though Garcia admitted that there was fan interference, the protest was denied by American League president Gene Budig. Maier appeared on national talk shows and was given the key to New York City by Mayor Rudy Giuliani.

RED SOX WORLD SERIES BALLS

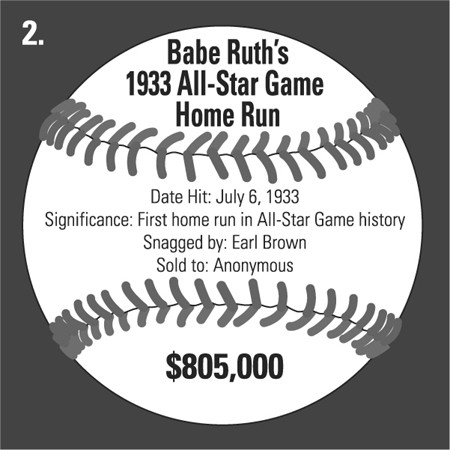

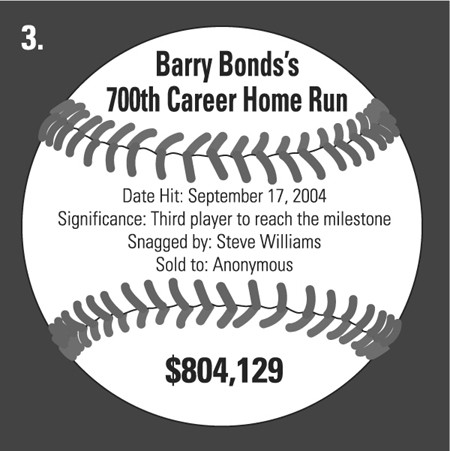

When Red Sox first baseman Doug Mientkiewicz caught the final out of the 2004 World Series, he found an extra way to get his name in the papers: by deciding to keep the ball for himself. Mientkiewicz, a former Gold Glove winner who had entered the game as a defensive replacement for David Ortiz in the bottom of the seventh, felt that he deserved to keep it since he caught it. Red Sox fans and management disagreed. Their team had finally overcome “the Curse of the Bambino”3 and won its first championship in 86 years. In their minds, this was one of the most important balls in the history of the sport, and it belonged in the team’s museum. Mientkiewicz held out, and as the negative media attention intensified, he joked to a Boston Globe reporter that the ball was his “retirement fund.” Or was he joking? On the same day he caught it, Barry Bonds’s 700th career home run ball sold for $804,129 through an online auction.

How did the Mientkiewicz saga end? It was easy. First the Red Sox traded him to the Mets for a minor leaguer. Then they filed a lawsuit against him. Then they dropped the charges when he agreed to let an independent mediator settle the dispute. Finally he lent the ball to the Sox for a year and then donated it to the Hall of Fame.

When Boston won the World Series again in 2007, a whole new controversy erupted over the final-out ball. This time it ended up in the hands of catcher Jason Varitek, who initially said he planned to return it to the team, but later admitted that he gave it to reliever Jonathan Papelbon. When the team asked Papelbon for the ball, he claimed that his dog ate it.

“He plays with baseballs like they are his toys,” said the pitcher of his bulldog, Boss. “He jumped up one day on the counter and snatched it. He likes rawhide. He tore that thing to pieces.”

Papelbon vowed to keep what was left of the ball, but later told the New England Sports Network that he’d thrown it out. “It’s in the garbage in Florida somewhere,” he said.

Team officials took his word and did not file charges.

BARRY BONDS HOME RUN BALLS

It wasn’t just the steroids that caused controversy for Barry Bonds. On four separate occasions, it was the product of his alleged steroid use—the home run balls themselves—that created a buzz.

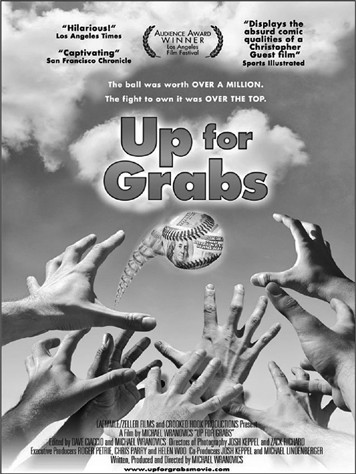

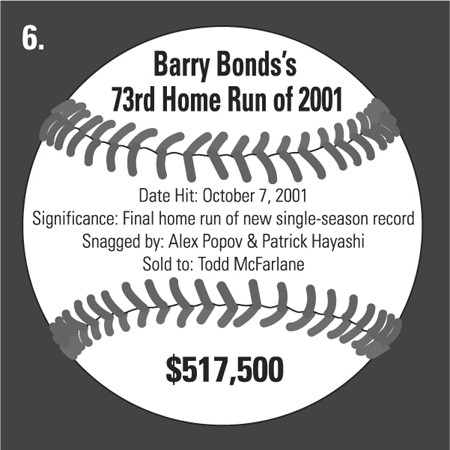

73RD HOME RUN OF 2001 When Mark McGwire hit 70 home runs in 1998 to break the single-season record, his final home run ball sold for more than $3 million. Three years later, when Bonds surpassed him by hitting 73 homers, the final ball ended up in court. Video replays showed a fan making the catch in the tip of his glove, but after the ensuing melee in the right-field stands of what was then called Pacific Bell Park, a different fan held up the ball and was quickly escorted to safety by security personnel. The first fan, Alex Popov, sued the other fan, Patrick Hayashi, for ownership of the ball, claiming that Hayashi had stolen the prized souvenir from him. Fourteen months after number 73 had been hit, the judge ordered the men to sell the ball and split the money. Comic book mogul Todd McFarlane (who had bought the McGwire ball) paid $517,500 for it—far less than Popov needed to cover his legal costs. Hayashi’s lawyers went pro bono, and a full-length documentary called Up for Grabs was made about the whole ordeal.

700TH CAREER HOME RUN Six months before Bonds hit his 700th career homer, a fan in Los Angeles purchased every ticket in the right-field pavilion for two of the season’s last three Giants games at Dodger Stadium—6,458 tickets in all. The fan, a 28-year-old investment banker named Michael Mahan, hoped that Bonds would hit the historic blast during one of those contests, but unfortunately for him, the Giants slugger connected two weeks too soon. Unfortunately for the Dodgers, who had offered a reduced group rate on the seats, Mahan resold thousands of the tickets for a profit.

Up for Grabs is the best documentary ever made about a baseball. (Photo Credit 1.2)

On September 17, 2004, when Bonds connected on number 700, the milestone ball landed in the left-center-field bleachers in San Francisco. Steve Williams, the man who snagged it, had two separate lawsuits filed against him by fans who claimed that he’d stolen it from them during the scrum. One of those fans, an accomplished Bay Area ballhawk named Alex Patino, insisted that he had possession of the ball after sitting on it. Because of the lack of evidence (and perhaps the absurdity of the claim), the judge dismissed the charges and allowed Williams to sell the ball.

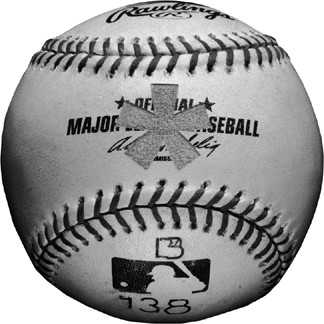

Barry Bonds’s 756th home run ball was “branded” with an asterisk carved into the cowhide. (Photo Credit 1.3)

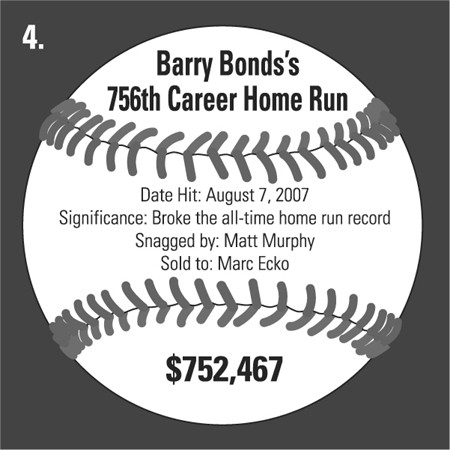

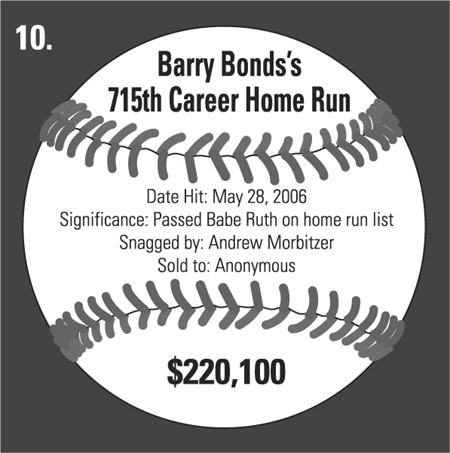

756TH CAREER HOME RUN On August 7, 2007, Bonds launched his record-breaking 756th home run toward the right-center-field bleachers at San Francisco’s AT&T Park, sparking such a wild melee for the ball that a fan in a wheelchair was knocked over and an usher nearly died from an asthma attack. Fashion designer Marc Ecko ended up buying the ball for $752,467 and creating a website where fans could vote for its fate. Eight days and 10 million votes later, the public decided to “brand” the historic ball with an asterisk and send it to the Hall of Fame. (The other two options included sending the ball sans brand to the Hall or putting it on a rocket and launching it into space.) Bonds responded by threatening to boycott his own induction if the Hall accepted the branded ball. Gilbert Arenas, an All-Star point guard on the NBA’s Washington Wizards, offered to buy the ball from Ecko for $800,000. Ultimately Ecko branded the ball and donated it to Cooperstown after a lengthy negotiating process.

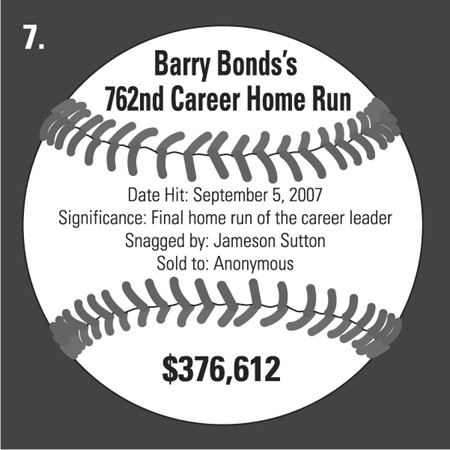

762ND CAREER HOME RUN Ever since an FBI sting in the mid-1990s nabbed dozens of high-profile memorabilia counterfeiters, specially marked balls, often with invisible infrared markings, have been used whenever a player has approached a major record or milestone. On September 5, 2007, Bonds hit his final major league home run—number 762—against the Rockies at Coors Field, but the historic ball was unmarked. Still, under normal circumstances it could have been authenticated on the spot, but because two fans each emerged from the scuffle with a ball in their hands, Major League Baseball officials wanted nothing to do with it.

It turned out that when Bonds stepped to the plate, one of the fans was already holding a ball that he’d caught during pregame warm-ups. That ball, which the fan wisely dropped in order to grab the real home run, was subsequently snagged by a 58-year-old season-ticket holder named Robert Harmon. At the time, there were three weeks remaining in the season; everyone assumed that Bonds would hit at least a few more homers, so no one made a big deal about number 762 or the unnamed fan who grabbed it—until the regular season ended. Then the official manhunt began. One media outlet even issued an all-points bulletin for the owner of the ball to come forward, prompting five phony claims and a follow-up story two months later reporting that the real owner was still at large.

Jameson Sutton, an unemployed 24-year-old from Boulder, Colorado, finally came out of hiding and revealed that he had snagged the controversial ball. Then, thanks to Harmon’s unlikely admission that his own ball was a fake, Sutton sent his ball to auction, where it sold for $376,612—money he desperately needed to pay for his ailing father’s medical bills. (There was one twist: Sutton had pulled a Jeffrey Maier by reaching out of the stands and interfering with the ball. The play should not have been ruled a home run. Good thing the umpires blew the call.)

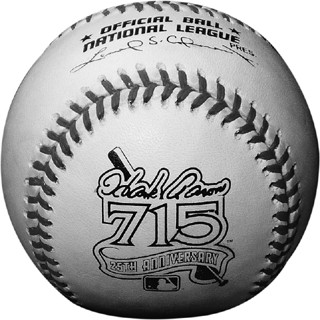

HANK AARON’S FINAL HOME RUN

On July 20, 1976, in an otherwise meaningless game between two last-place teams in Milwaukee, Hank Aaron belted his 755th career home run. At the time, no one gave it much thought because there were still two and a half months remaining in the season. The man who snagged the ball even offered to return it to Aaron—for free—under one condition: that he be allowed to meet the future Hall of Famer and hand it over himself. Given the fact that this man, a 29-year-old named Richard Arndt, worked for the Brewers as a part-time groundskeeper, his request could have easily been granted. Well, not only did the Brewers refuse to let Arndt meet Aaron, and not only did they fire him the next day for refusing to return the meaningful item, but the team also docked him $5 from his final paycheck for the cost of the ball. After the season ended, Aaron tried to buy it from Arndt, who declined the offer, moved to Albuquerque, tucked the ball in a safety deposit box, and wasn’t heard from for more than two decades.

At some point in the late 1990s, Arndt snuck the ball into a baseball card show and handed it to an unsuspecting Aaron, who autographed it and handed it right back. Soon after, as the ball was headed to auction, Aaron’s representatives contacted Arndt and made a lowball offer. Arndt once again refused, ended up selling the ball to a private collector for $650,000, and donated 25 percent of the proceeds to Aaron’s charitable foundation.4

SAMMY SOSA’S 62ND HOME RUN OF 1998

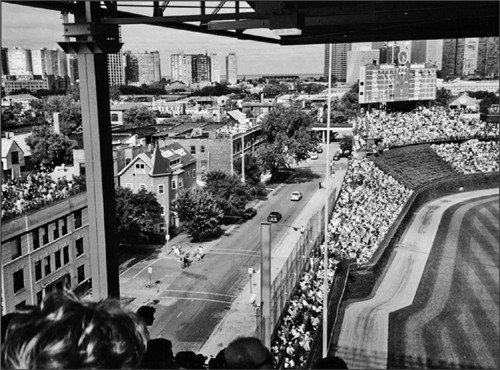

Before Mark McGwire bashed all those home runs in 1998, the single-season record belonged to Roger Maris, who went deep 61 times in 1961. Luckily for McGwire, his record-breaking 62nd home run ball was returned to him by a groundskeeper in St. Louis. Five days later, when the red-hot Sammy Sosa eclipsed Maris with a 480-foot blast onto Chicago’s Waveland Avenue, the precious ball went to court. What set this case apart from other ball-related disputes was that the plaintiff was a legendary ballhawk named Moe Mullins.

Mullins, a 47-year-old truck driver who had reeled in more than 3,100 baseballs over the previous three decades, insisted that he had Sosa’s homer in his possession before it was ripped out of his hands by a violent mob. Numerous witnesses backed up his claim, and several local residents painted the number “62” in their driveway along with the slogan, “Give it to Moe.” Still, there was no way to prove that the fan who ended up with the ball had acquired it illegally. That fan, a mortgage broker named Brendan Cunningham, said he simply found himself in a pile of people and reached down for the ball when it rolled near him. Mullins dropped the lawsuit two weeks later when Cunningham vowed to return the ball to Sosa.

Waveland Avenue, seen here in the late 1990s, saw far more home runs before the bleacher expansion of 2006. (Photo Credit 1.4)

RYAN HOWARD’S 200TH CAREER HOME RUN

This wasn’t your typical lawsuit. No one disputed the fact that Jennifer Valdivia snagged Ryan Howard’s 200th career home run ball, but when the Phillies reportedly used shady tactics to get the ball back from her, they ended up getting sued.

Valdivia was only 12 years old when she grabbed the milestone ball on July 16, 2009, at Land Shark Stadium.5 Because of its additional historical significance—Howard hit 200 homers in the fewest number of games—Valdivia was approached by a Marlins representative and taken to the Phillies’ clubhouse with her 17-year-old brother. Once they got there, she was told that if she handed over the ball, Howard would autograph it for her later and that she could come back and meet him after the game.

That never happened.

When Valdivia returned after the Phillies’ 4–0 victory, Howard wasn’t there, and she was given a different (brand-new) ball with his signature. And when Valdivia’s mother was told by her coworkers the following day just how special number 200 was, she took action. First she called the Phillies and asked them to return it, and when the team refused she got a lawyer. The lawyer called the Phillies. The Phillies told him to contact Howard’s agent. The agent rebuffed him. So the family filed a lawsuit, and wouldn’t you know it? The ball was returned two days later with a letter of authenticity.

BIG MONEY OPPORTUNITIES

In April 2001, when Reds first baseman Sean Casey hit the first home run ever at Pittsburgh’s PNC Park, the ball bounced back onto the field and was then absentmindedly tossed back into the crowd by Pirates center fielder Adrian Brown. A month later, the fan who grabbed that ball sold it for $9,400.

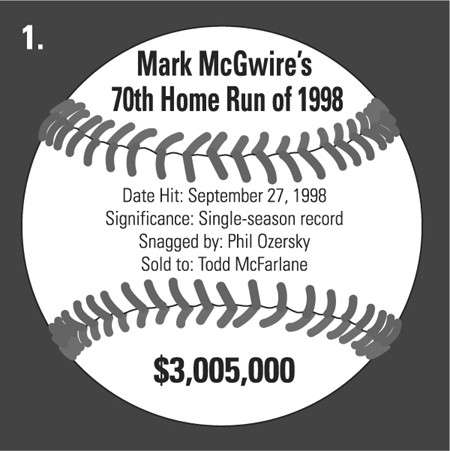

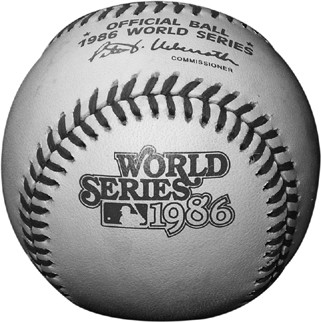

Not bad. But it was nothing compared to a ball that had made history 15 years earlier. You’ve probably seen the replays a thousand times. It was Game 6 of the 1986 World Series at Shea Stadium. Bottom of the 10th inning. Two outs. Winning run on second. Mookie Wilson hit a weak grounder down the first-base line, and the ball trickled through Bill Buckner’s legs. Mayhem. Heartbreak. Jubilation. Right-field umpire Ed Montague retrieved the ball, then handed it to a Mets employee named Arthur Richman, who gave it to Wilson—who signed it and gave it back. Six years later, Richman sent the ball to auction, where actor Charlie Sheen bought it for $93,500.6 At the time, it was the most that anyone had paid for a baseball, but now it wouldn’t even crack the top 10:

1 The Buffalo Bisons were a National League team from 1879 to 1885. They moved to the International League in 1886 and have been a minor league franchise ever since.

2 Let the record show, once and for all, that Maier did not “catch” the ball. Not only was he glorified for breaking a rule, but the media mistakenly credited him with having athleticism.

3 If you don’t know what this is, pick up a copy of Watching Baseball Smarter and turn to page 203.

4 Arndt claimed he was pressured into donating the money by Aaron’s representatives—that if he didn’t make the contribution, Aaron himself was going to challenge the ball’s authenticity. Arndt initially agreed to donate 42.5 percent, but Aaron accepted the smaller amount after the ball failed to meet its $850,000 reserve price at auction.

5 Home of the Florida Marlins, previously known as Dolphin Stadium, Dolphins Stadium, Pro Player Stadium, Pro Player Park, and Joe Robbie Stadium—and now named Sun Life Stadium. (And the name will probably change three more times by the time you read this.)

6 Sheen outbid Keith Olbermann, who walked away at $85,000.

CHAPTER 2

FOUL BALL LORE

CONSECUTIVE FOUL BALLS

In the 19th century, foul balls weren’t sexy like they are today. For the most part, in fact, they were just plain annoying. Not only were fans forced to return them, and not only was the game delayed each time a foul ball had to make its way back to the field, but the action itself was meaningless. Foul balls were essentially non-events because they didn’t count as strikes. As a result, carefree batters intentionally hit fouls in order to wear out the opposing pitcher and wait for pitches they could hammer.

In 1901 the National League made a dramatic attempt to curtail this practice by instituting a rule that turned foul balls into strikes—and it worked. Batters weren’t nearly as eager to hit foul balls, and pitchers regained some of their much-needed advantage.1 The American League adopted the foul-strike rule two years later.

Although foul ball stats were not consistently documented until pitch counts began ruling the sport, there are several known cases of extreme fouls—not surprisingly, from before the foul-strike rule took effect. During a game in 1897, Hall of Famer Billy Hamilton, then a member of the Boston Beaneaters, hit 29 in a row. Later that season, Hamilton led off a game against Cy Young by hitting the first three pitches foul. Young responded by walking toward Hamilton and telling him, “I’m putting the next pitch right over the heart of the plate. If you foul it off, the next one goes right in your ear.”

Roy Thomas, a 13-year veteran who began his career with the Phillies in 1899, supposedly fouled off 22 pitches during one plate appearance, but it remains unknown if he hit them consecutively. Jack Dittmer, a second baseman for the Milwaukee Braves in the mid-1950s, is also believed to have fouled off 22 during a single turn at bat. The 21st-century record belongs to Dodgers second baseman Alex Cora, who fouled off 14 straight pitches on May 12, 2004, and punctuated his effort with a home run. But the true master of the mis-hit—the Duke of Deflection, the Sultan of Slap—was Hall of Famer Luke Appling.

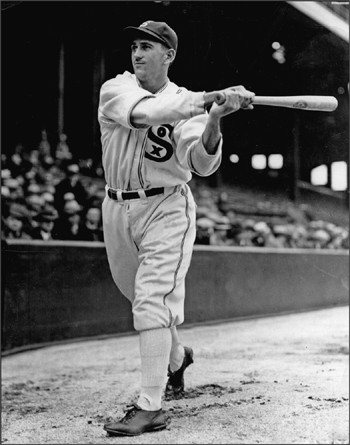

“No batter could ever frustrate a pitcher more than ol’ Luke,” said Dizzy Trout, whose Detroit Tigers faced Appling’s White Sox more than 200 times in the 1940s. “He would stand there and nonchalantly foul off your best pitches—10, 12, or more—until he finally got the one he was waiting for.” One time, after Appling fouled off a dozen of Trout’s 0-2 pitches, Trout threw his glove at him and yelled, “Hit that foul!”

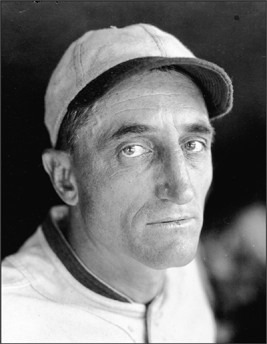

Luke Appling was a foul ball–hitting machine. (Photo Credit 2.1)

On another occasion, Appling hit two dozen balls into the crowd to get even with his own team. Why he did it, however, is unclear. One account suggests he was angry because the owner wouldn’t provide free tickets for his friends; a different (and better) story claims Appling took his course of action because the team wouldn’t give him baseballs to autograph and hand out to the fans. According to the latter version, Appling’s requests for baseballs were never denied again.

Appling himself claimed to have hit foul balls at least once for his own amusement. During a game against the Yankees in 1940, the White Sox were so far behind that Appling decided to mess with Red Ruffing, the opposing pitcher. “I started fouling off his pitches,” he said. “I took a pitch every now and then. Pretty soon, after 24 fouls, old Red could hardly lift his arm, and I walked. That’s when they took him out of the game, and he cussed me all the way to the dugout.”

And then there was the peanut vendor who made the mistake of laughing at a fan who had gotten hit by one of Appling’s foul balls. “I’ll fix him,” Appling declared, then stepped back into the batter’s box and drilled the guy in the head with the next foul. The vendor had to be carried out of the stadium.

LIGHTNING STRIKES TWICE

Hall of Famer Richie Ashburn was so good at hitting foul balls that a teammate once approached him with an odd (and rather disturbing) request to use his batting skills. The teammate was angry at his own wife, who was sitting in the left-field stands, and asked Ashburn to hit her with a foul ball. Ashburn refused to do it, but on another occasion he accidentally sent a different female fan to the hospital.

That fan was Alice Roth, the wife of Earl Roth, sports editor of the Philadelphia Bulletin. On August 17, 1957, she took her two young grandsons to a game at Connie Mack Stadium and made the mistake of momentarily looking away from the action to fix one of the boys’ caps. At that very instant, Ashburn fouled off a ball that whacked her in the face and broke her nose—but that was just half of Mrs. Roth’s ordeal. As she was being tended to by medical personnel and carried off on a stretcher, Ashburn stepped back into the box and fouled off another ball that hit her again.

“I didn’t mean to do it,” insisted Ashburn. “When I saw what happened, I felt terrible.”

Ashburn felt so bad about it that he visited Roth in the hospital, and the team gave her grandsons free tickets and a clubhouse tour. Back then, people didn’t sue when they got hit by a ball, and in the end all was forgiven.

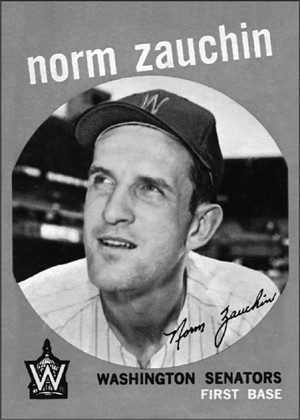

Norm Zauchin hit 18 home runs for the Senators from 1958 to 1959. (Photo Credit 2.2)

NICE “CATCH”

Norm Zauchin, a hulking first baseman for the Boston Red Sox and Washington Senators in the 1950s, might not be a household name, but he made the great-est “catch” of all time on a foul ball. It was a Sunday afternoon in 1950—the year before his major league debut—and Zauchin was playing for the Birmingham Barons at Rickwood Stadium. At one point in the middle innings, Zauchin ran into foul territory to chase a pop-up, reached far over the railing to make a catch, and tumbled into the crowded front row. He happened to land in the lap of a pretty young woman named Janet Mooney, whose parents knew the usher in their section.2 Back in those days, it was customary for families to welcome players into their homes for Sunday dinner, so the usher finagled an invitation for Zauchin. He and Janet started dating, and the two were married the following season.

HECKLE THIS!

According to Joe Cronin, Red Sox manager from 1935 to 1947, Ted Williams once tried to silence a heckler by hitting foul balls at him. Williams later admitted it in his autobiography—the notorious incident taking place in 1942—but there was a discrepancy in the two men’s tales. Cronin claimed that Williams hit 17 foul balls at the fan and never missed by more than six feet. Williams said he “aimed three or four fouls in this spot behind third, but never got close enough.”

Who’s telling the truth? Who cares? If the heckler had brought a glove, Williams would’ve been doing him a favor.

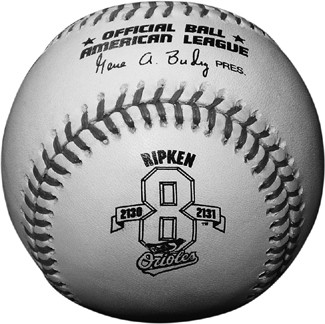

DON’T MESS WITH CAL RIPKEN JR.

Toward the end of his celebrated career, Cal Ripken Jr. drew heavy criticism whenever he fell into a slump. The future Hall of Famer was in the process of playing in a record 2,632 consecutive games, and lots of people believed that the streak was wearing him out. One of his critics was Baltimore Sun columnist Ken Rosenthal, who suggested that Ripken voluntarily take a day off for the good of his team. (The Orioles were actually sort of almost in contention at the time.)

Not long after the column ran, Ripken responded with his bat, sending a foul ball flying back toward Rosenthal in the press box at Camden Yards. Rosenthal ducked out of the way, but the ball smashed and destroyed his laptop.

LYNYRD SKYNYRD

In 1964 a teenager named Ronnie Van Zant stepped up to the plate in a youth baseball game and ripped a foul ball down the first-base line. Two of his schoolmates were in attendance, one of whom got hit in the head by the ball and was briefly knocked unconscious. The kid’s name was Bob Burns. His friend was Gary Rossington. Van Zant didn’t know them well at the time, but the unnerving incident brought them closer together. All three of them, it turned out, were aspiring musicians, each playing in various garage bands, and in the following days they got together for some jam sessions.

Later that summer, Van Zant and Rossington formed their own band called The Noble Five. The following year, Burns joined them, and they changed their name to My Backyard. The band, which included other members, ultimately became known as Lynyrd Skynyrd. Van Zant was the lead singer (until his untimely death in 1977), Burns was the drummer (until he quit in 1974), and Rossington played the guitar. The group was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2006.

BANNED FROM BASEBALL

Forget about Pete Rose and the 1919 Black Sox. The most outrageous gambling scandal in the history of professional baseball (as far as this book is concerned) involves an ex–major leaguer named Joe Tipton, who got banned for life from the minor leagues for hitting foul balls.

In the late 1950s, speculation arose that numerous players in the Class AA Southern Association were intentionally hitting fouls to help gamblers. (Gamblers had an easier time convincing individual players to hit harmless foul balls than paying off entire teams to throw games. The gamblers then sat in the stands and bet with the fans at just the right time that the batter would hit the next pitch foul.) An investigation was launched, and everyone who was questioned denied involvement—everyone except Tipton, who admitted that while playing for the Birmingham Barons in 1957 he had accepted two payments—one for $50 and another for $75—to hit foul balls. Tipton had appeared in his final major league game three years earlier, and he’d already retired from the minors by the time he confessed, yet he still received a lifetime ban.

In the 1960s it was revealed that the gamblers’ foul ball scheme had infiltrated the sport decades earlier. Wally Kimmick, a major league infielder whose career had ended in 1926, recalled a bizarre incident in which a fan he vaguely recognized asked him if he could hit foul balls. Kimmick insisted that he could, but when the guy doubted him he was compelled to prove himself. “I could hit 10 in a row,” Kimmick told the man. “Naturally I wouldn’t try it if there were men on base, but if I come up with nobody on, you just watch.” Kimmick found out later that the man made $10,000 betting he’d hit foul balls, and he never saw the man again.

GREAT BALLS OF FIRE

It figures that a guy named Burns was responsible for a foul ball that started a fire. In August 1915, Tigers first baseman George Burns worked a full count against Red Sox starter Dutch Leonard and fouled the next pitch into the stands. As the fans jockeyed for position to make the catch, the ball hit a man’s coat and ignited a box of matches in his pocket. Then, when the fire began to spread, a soft drink vendor rushed over, opened up a bottle of soda, and poured it on the guy to douse the flames.

HAPPY MOTHER’S DAY

Mother’s Day 1939 didn’t turn out the way Bob Feller had envisioned it. His family made the trip from their home in Iowa to watch him pitch against the White Sox at Comiskey Park, and he arranged for them to sit in box seats along the first-base side. The seats were particularly close to the action, and in the bottom of the third inning things went horribly awry. Sox pinch hitter Marv Owen slashed a vicious foul ball into the crowd that hit Feller’s mother in the face, broke her glasses, and opened a deep cut over her right eye that required six stitches. Feller, who had thrown the pitch, raced over to the stands and discovered that although his mother was bleeding and in serious pain, she was at least conscious.

“I felt sick,” he later recalled. “I saw the police and ushers leading her out of the stands so they could take her to the hospital.… There wasn’t anything I could do, so I went on pitching.”

Feller, incredibly, not only stayed in the game but went the distance for a 9–4 victory. The Hall of Famer then visited the hospital, and his mother ended up making a full recovery.

FAMILY AFFAIR

It wasn’t Mother’s Day, and no one went to the hospital. It didn’t even involve a future Hall of Famer, but at a game at Camden Yards in 2006 a foul ball nonetheless left a family up in arms. Orioles designated hitter Jay Gibbons fouled one straight back over the protective screen and into the family section, where it smashed his own wife in the ribs. Fortunately, she wasn’t seriously hurt, but Gibbons was furious. As the team’s player representative, he had asked Orioles management to raise the screen long before she got hit—he and his teammates felt it wasn’t tall enough to provide adequate protection for their families—but his request was denied. Management had claimed that a taller screen would disrupt the sight lines of fans sitting behind the plate, but team officials finally relented and raised the screen in 2007.3

THAT BALL IS … GONE!

It sounds impossible, but this story, reported by Sergeant A. D. Hawkins, a Marine Corps combat correspondent during World War II, comes straight from the archives of the Hall of Fame. The featured foul, as you might already be guessing, wasn’t hit at a major league stadium, and in fact this incident didn’t even take place during a game. The ball was hit during batting practice in the South Pacific by a player on a First Marine Division regimental team, so you know it had to be something special.

Marine Private First Class George E. Benson Jr., a 20-year-old soldier from Dawson, Iowa, yanked a high foul ball that sailed behind third base and smashed through the windshield of a small Grasshopper airplane that was gliding 40 feet off the ground toward a nearby airstrip. But that’s not all the ball did. It broke the pilot’s jaw and briefly knocked him unconscious. Marine Corporal Robert J. Holm, a passenger with no flying experience, instinctively pulled back on the dual controls and prevented the plane from crashing, and when the pilot recovered he took over and landed safely at another airfield 15 miles away.

Benson had seen the impact after following the flight of the ball, but a few of his teammates hadn’t noticed and went looking for it.

“Once I broke a high school window with a foul ball,” he said, “but I never thought this would happen to me.”

Grasshopper airplanes were not designed for combat—or for absorbing the impact of foul balls. (Photo Credit 2.3)

1 In 1894 the mound was moved back more than 10 feet to its current distance of 60 feet, 6 inches, and the National League’s batting average increased 29 points to .309. By 1900 the leaguewide average had dropped to .279, and in 1901, the first season of the foul-strike rule, the average plummeted an additional 12 points to .267.

2 As the story goes, it was love at first sight.

3 Gibbons isn’t the only player to have struck a member of his own family with a foul ball. During a Spring Training game in 2010, Twins outfielder Denard Span sliced a wicked liner that hit his mother in the chest. (Don’t worry. She was okay.)

CHAPTER 3

DEATH BY BASEBALL

DANGEROUS GAME

Remember that scary moment during the 1999 American League Division Series when Kenny Lofton dove violently into first base and dislocated his shoulder? Or the regular-season game in 1995 when Ken Griffey Jr. crashed into the center-field wall and broke his wrist? Or the incident during the 2001 All-Star Game when the 73-year-old Tommy Lasorda got knocked on his ass by a flying broken bat? Fortunately, Lasorda was okay, but the fact remains that there are many ways to get hurt on a baseball field. In addition to the obvious, waiting-to-happen accidents like catchers getting bowled over while blocking the plate, shortstops getting spiked while covering second base, or first basemen falling down the dugout steps while chasing foul pop-ups, there are unexpected hazards everywhere. Players don’t necessarily have to dive headfirst or slam into walls to land on the disabled list. After a Cubs victory in 2009, Ryan Dempster broke his right big toe and missed three weeks after tripping over the dugout railing in an attempt to run out onto the field with his celebrating teammates.

What do all these misfortunes have in common? None of them are directly linked to the ball. Sure, the bat that hit Lasorda had been broken by the ball—and it was the ball that Griffey had hoped to catch when making his fateful dash to deep center field—but these guys were not hurt by the ball itself. Ball-related injuries are a whole other story. There’ve been enough to fill an encyclopedia, and with all due respect to Mariners reliever Josias Manzanillo, who needed testicular surgery in 1997 after taking a 107-mile-per-hour Manny Ramirez liner to the groin, any discussion of them needs to start with Indians pitcher Herb Score.

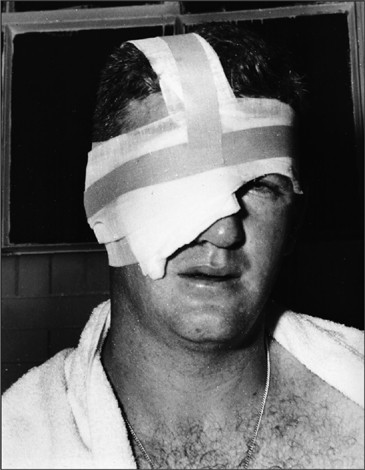

Herb Score was never the same after getting hit in the face by a line drive. (Photo Credit 3.1)

A 23-year-old phenom in 1957, Score was struck in the right eye by a wicked line drive off the bat of Yankees shortstop Gil McDougald. The impact broke several bones in his face, permanently affected his vision, and ruined what was shaping up to be a Hall of Fame career. Score had been named the minor league player of the year in 1954 and was voted the American League Rookie of the Year in 1955. The following season he won 20 games while striking out 263 batters and posting a 2.53 ERA. In the five years that Score pitched after his injury, he won a total of 17 games and had a forgettable 4.43 ERA.

Because Score was so young and gifted, and because he played during baseball’s golden age, he remains the poster boy for devastating injuries—even though Cardinals right fielder Juan Encarnacion suffered one that proved to be much worse. On August 31, 2007, while standing in the on-deck circle at Busch Stadium, Encarnacion got hit in the face by a foul ball that shattered his left eye socket and caused severe trauma to his optic nerve. The Cardinals’ head physician said it was the worst injury he’d ever seen on a baseball player’s face and compared the mangled socket to a disintegrated eggshell. Fifteen months later, the St. Louis Post Dispatch reported that Encarnacion had “not yet recovered enough vision in his left eye to drive, let alone attempt to play baseball again.” And sure enough, his career was over.

There’ve been lots of other notable ball-related injuries over the years. In Game 4 of the 2001 American League Division Series, A’s right fielder Jermaine Dye fouled a ball off his leg that shattered his fibula. During batting practice in 1988, Mets first baseman Keith Hernandez yanked a foul ball that ricocheted off the batting cage and broke his nose. In Game 7 of the 1960 World Series, Yankees shortstop Tony Kubek suffered a bruised larynx when a ground ball took a bad hop and hit him in the throat. Prior to the 2007 season, Giants catcher Mike Matheny was forced to retire because of all the concussions he’d suffered from getting whacked by foul tips. During a regular-season game in 1996, home plate umpire Ed Rapuano sustained a broken collarbone and was taken off the field on a stretcher after getting struck by a foul ball. On Opening Day in 1954, Hall of Fame baseball writer H. G. Salsinger lost his vision in one eye after being nailed by a foul ball in the Briggs Stadium press box.4

Then there are the untold number of batters who have sustained serious injuries from being hit in the face or on the head, the most notorious cases including Tony Conigliaro, Dickie Thon, Andre Dawson, Kirby Puckett, Ron Santo, Joe Medwick, and Hall of Famer Mickey Cochrane, who in 1937—four years before batting helmets were first used—suffered a fractured skull, remained unconscious for 10 days, and never played again. Incredibly, in the history of Major League Baseball, only one player has ever died from being hit by a pitch. That player was Ray Chapman.

RAY CHAPMAN

Raymond Johnson Chapman was born in Beaver Dam, Kentucky, in 1891. He made his major league debut with Cleveland in 1912 and quickly established himself as the team’s everyday shortstop. If there had been All-Star Games back then, Chapman probably would’ve played in a few; in 1915 he hit 17 triples and scored 101 runs, in 1917 he stole 52 bases and hit 67 sacrifice bunts (a single-season record that still stands), and in three of his last four seasons he batted .300 or higher.

That final season was cut short by tragedy.

The date was August 16, 1920. The Indians were in New York, facing Yankees superstar pitcher Carl Mays, a fiery competitor who exploited a batter’s fear as well as anyone. Not only had he led the American League in hit batsmen just three years earlier, but his repertoire included an erratic spitball, and his submarine-style delivery made all of his pitches tough to see.

By the time Chapman stepped to the plate in the top of the fifth inning, he faced two additional challenges that reduced his visibility. First, the late-afternoon sun was casting shadows on the field, and second, the ball itself was dirty. Very dirty. In 1920—the season before Reuben Berman’s successful lawsuit—the same ball would be put back into play repeatedly, batter after batter, even inning after inning, until it was scuffed, misshapen, and discolored. But it wasn’t just the routine wear and tear that darkened the ball; pitchers often spat tobacco juice on it and rubbed it with dirt to make the horsehide as dark as possible.

No one’s sure what type of pitch did Chapman in. It might’ve been a spitter, it might’ve been a fastball, but whatever it was, he didn’t see it. He didn’t even flinch as the ball cracked him on the left temple. The sound of the impact was so loud that Mays thought the ball had hit Chapman’s bat, so he fielded it and threw it to first base. Chapman, meanwhile, was sprawled on the ground with a fractured skull and blood pouring out of his ear. He was rushed to the hospital and died 12 hours later. The spitball, along with other doctored pitches, was banned the following season, and umpires were instructed to take dirty baseballs out of play.5

MIKE COOLBAUGH

Back in the old days, ballplayers were more concerned with being tough than being safe. Thus, after Chapman’s death, it took 21 years before a major league team was willing to experiment with batting helmets—and then it took an additional three decades for helmets to become mandatory. But change came about much sooner after a wayward line drive struck and killed minor league first-base coach Mike Coolbaugh in 2007. Starting the following season (with predictable resistance from a handful of old-school guys), every first- and third-base coach in professional baseball was made to wear a helmet.

Coolbaugh, a former major league third baseman, was hired on July 3, 2007, by the Tulsa Drillers, the Rockies’ Double-A affiliate. Nineteen days later, while standing in the first-base coach’s box during a game in Arkansas, he was hit in the neck by a line drive off the bat of Drillers catcher Tino Sanchez. The impact crushed Coolbaugh’s left vertebral artery and caused a severe brain hemorrhage that killed him almost instantly.

The incident was particularly tragic because Coolbaugh left behind a pregnant wife and two young boys, who had prompted him to take the coaching job because they loved seeing him in uniform on a baseball field. Later that season the family got a much-needed boost, both emotionally and financially, when the Rockies clinched the National League Wild Card and unanimously voted to give Coolbaugh’s widow a full share of their playoff money. That bounty rose to $233,505.18 as the Rockies swept the Phillies and then the Diamondbacks to reach the World Series.

FAN FATALITIES

When the National League was founded in 1876, none of the ballparks had protective screens in place to shield fans from foul balls—and guess what? It didn’t really matter. Back then, the pitcher’s job was simply to help start the action by giving the batter an easy pitch to hit; pitchers were forced to throw underhand, and batters could request a high or low pitch. It wasn’t hard for batters to hit the ball into fair territory, nor was there any strategic advantage in wasting pitches by intentionally hitting them foul. But over the next few seasons, as the rules evolved and pitchers gained the right to throw hard, there was a surge in the number of foul balls and fan injuries. The section of the grandstand located directly behind home plate became known as the “slaughter pens” because of all the injuries that were taking place there, and in 1878 the Providence Grays became the first team to do something about it. They put up a screen in their home ballpark, the Messer Street Grounds, and by the turn of the century most ballparks offered similar protection.

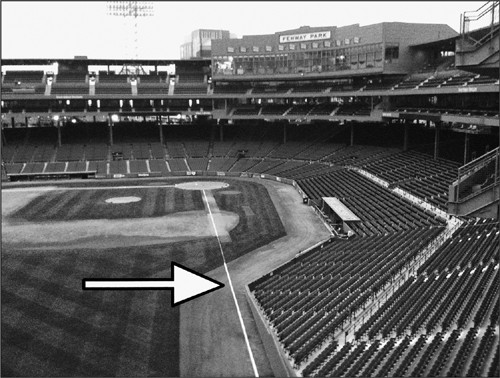

Nowadays, despite the fact that protective screens are a given and fans get warned repeatedly about the danger of foul balls, there are still a disturbingly large number of injuries at professional baseball games—more than 300 every season that are severe enough to send fans to hospitals. Most of these accidents take place in the minor leagues (where there are more games and where fans sit closer to the field), but there’ve been plenty of gruesome injuries at the major league level. There was a two-year span when Tigers fans were hit especially hard—in 1999 at Tiger Stadium a woman lost her left eye after getting struck in the face by a foul ball,6 and in 2000 at Comerica Park a young boy suffered a fractured skull and developed a life-threatening hematoma after getting drilled by a line drive—but every team’s fan base has fallen victim to the ball. One of the best-known incidents took place in 1982 at Fenway Park, when a six-year-old boy sitting behind the dugout was literally saved by Hall of Famer Jim Rice after a foul ball fractured his skull. While everyone in the stands waited helplessly for medical personnel to arrive, Rice stepped out of the dugout, reached into the crowd, cradled the boy in his arms, and rushed him to the trainer’s room inside the clubhouse.

Incredibly, with all the stadiums and teams and games and defensive two-strike swings, only one fan in the history of Major League Baseball has ever been killed by a foul ball. That fan was a 14-year-old boy named Alan Fish, who was hit behind and above the left ear by a Manny Mota line drive on May 16, 1970, at Dodger Stadium. The impact knocked Fish unconscious and caused a hairline fracture, which in turn caused an intracerebral hemorrhage—part of his skull was pushed into his brain and caused it to bleed—but no one realized the severity of his injury at the time. That’s because Fish regained consciousness after a minute, and although he was disoriented at first, he said he felt okay and stayed in his seat. Then, when he was taken to a first aid station later in the game, the doctor examined him quickly, gave him two aspirins, and sent him on his way. Fish felt fine for the rest of the game and even chased another foul ball at one point, but by the time he got home he was feeling dizzy and shaky. His parents (who had not attended the game) rushed him to the hospital, where his condition quickly deteriorated. It was only then that he was properly diagnosed, but the emergency surgery was too late to save him, and he died several days later.

The only other ball-related death in major league history was the result of an errant throw from a player who probably shouldn’t have been in the majors in the first place.7 On September 29, 1943, in the first game of a twi-night doubleheader at Griffith Stadium, Senators third baseman Sherry Robertson fielded a routine grounder and airmailed Mickey Vernon across the diamond. (Robertson was a mediocre hitter and an even worse fielder, but he lasted in the major leagues for a decade as the nephew of team owner Clark Griffith.) The ball sailed into the front row of the stands and hit a man named Clarence D. Stagemyer on the head. Stagemyer, a 32-year-old Civil Aeronautics Administration employee, initially shook off the injury but was convinced by the Senators’ physician to go to the hospital. It turned out that he had suffered a concussion and a fractured skull, but it was too late to save him, and he died the next day.

While flying baseballs pose a constant threat, far more fans have been killed in fights or by falling off escalators or—as was frighteningly common in the old days when ballparks were made of wood and overcrowding was prevalent—by entire sections of the grandstand collapsing. Just as players have to deal with an array of safety hazards, the same is true for fans. There has even been a case of a fan getting hit and killed by a car outside a stadium. Granted, it wasn’t a major league stadium—it happened in March 1988 at the Pirates’ Spring Training facility in Bradenton, Florida—but the tragic event still deserves an honorable mention because the man, a 42-year-old named Daniel McCarthy, was hit while chasing a foul ball that had flown out of the stadium.

FOWL BALLS

On June 11, 2009, the outcome of the Royals-Indians game at Progressive Field was determined by a bird. With runners on first and second, a flock of seagulls dawdling in shallow center field, and the score tied at 3–3 in the bottom of the 10th inning, Cleveland’s Shin-Soo Choo ripped a line drive up the middle that deflected off one of the birds and skipped past center fielder Coco Crisp to plate the winning run. Everyone was able to laugh about it later because the stunned gull had managed to fly away, but there’ve been several other games in which birds were not as lucky.

The incidents that have caused the least uproar involved pigeons that were killed by batted balls. That’s because it was always assumed to be an accident and—let’s face it—because no one likes pigeons, at least not in New York City, where the birds lurk everywhere and poop on everything. It was in New York that a pigeon was famously killed in 1987 by an otherwise routine fly ball hit by Atlanta’s Dion James. As Mets shortstop Rafael Santana gingerly picked up the carcass and handed it to the ball girl, the only thing upsetting to Mets fans was that the bird had caused the ball to drop in front of left fielder Kevin McReynolds, allowing James to motor into second base with a double. There’ve been other pigeon fatalities, including one at Fenway Park in 1974 thanks to a foul ball hit by Tigers left fielder Willie Horton, but again, no one really cared. You want uproar? Enter Dave Winfield.

It was August 4, 1983. Winfield, then playing center field for the Yankees, was just finishing his fifth-inning warm-ups in Toronto, and when he fired the ball back in, it struck and killed a seagull that had been walking across the field. Yankees manager Billy Martin later joked about it, saying it was the first time that his outfielder had hit the cutoff man all year, but it was no laughing matter to the peaceful people of Canada. Many of the 36,684 fans in attendance believed that Winfield had done it on purpose and immediately began pelting him with debris. After the game, Winfield was arrested for animal cruelty, a charge that could’ve brought a six-month jail sentence had it not been dropped the next day.

Twenty years later, during batting practice at a minor league stadium in Daytona Beach, Florida, a teenaged pitcher named Jae Kuk Ryu intentionally threw several balls at an osprey that was perched on a utility crossbar above the field. Witnesses claimed that Ryu hit the bird on his fourth attempt, causing it to plummet onto the warning track 25 feet below. The bird was blinded in one eye and died six days later. Ryu received numerous death threats and was demoted to the lowest level of the minor leagues; he turned his career around, however, and earned a major league call-up in 2006.

Then there was the unfortunate dove that crossed paths with a Randy Johnson fastball. (There are video clips of the incident online; do a search for “randy johnson bird” and you’ll find them.) It happened on March 24, 2001, during the seventh inning of a Spring Training game in Tucson, Arizona. Just after Johnson unleashed a mid-90s heater, the bird swooped in front of catcher Rod Barajas, took a direct hit, and exploded in a puff of white feathers. The ball (in addition to the bird) was called dead, and the play was ruled “no pitch.”

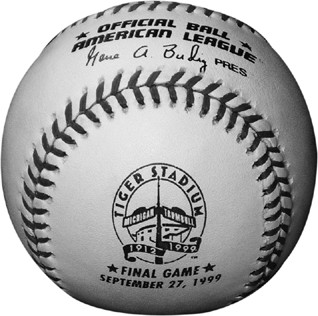

4 Tiger Stadium, home of the Tigers from 1912 to 1999, was named Briggs Stadium from 1938 to 1960. The ballpark was known as Navin Field before that.

5 The 17 pitchers who had depended on the spitball in 1920 were allowed to continue throwing it for the remainder of their careers. The list of grandfathered pitchers included three future Hall of Famers: Stan Coveleski, Red Faber, and Burleigh Grimes, who threw the last legal spitball in 1934.

6 She was reaching for her boyfriend’s popcorn and didn’t see the ball coming. She later sued the Tigers for $10 million, but because of the “assumption of risk” and printed disclaimer on the back of her ticket stub, she collected just $5,000—the maximum amount that the Tigers’ insurance policy permitted. Injured fans often sue, but rarely win.

7 No, this is not a story about Yankees second baseman Chuck Knoblauch, who hit Keith Olbermann’s mother in the face with a bad throw in 2006. (She survived.)

CHAPTER 4

STUNTS

SUCH GREAT HEIGHTS

During Spring Training in 1915, Brooklyn Robins1 manager Wilbert Robinson attempted a feat that was thought to be impossible: catching a baseball dropped out of an airplane. He might have succeeded if not for the fact that a grapefruit was dropped from the plane instead.

Aviation pioneer Ruth Law made the historic flight and circled her biplane hundreds of feet above the field—that much we know—but there are two different versions of the grapefruit portion of the story. It has been widely reported that Casey Stengel, then an outfielder with the team, made the fruity substitution, either as a practical joke or to protect his manager from the destructive force of a rock-hard baseball. Some historians, however, claim that Stengel wasn’t even in camp at that point, and Law herself stated years later that no one had put her up to the switcheroo—she simply dropped the grapefruit because she had forgotten to take a ball. Regardless, as the speeding grapefruit descended, its force became so great that it splattered all over Robinson and knocked him on his back.

“Help me, lads!” shouted Robinson. “I’m covered with my own blood!”

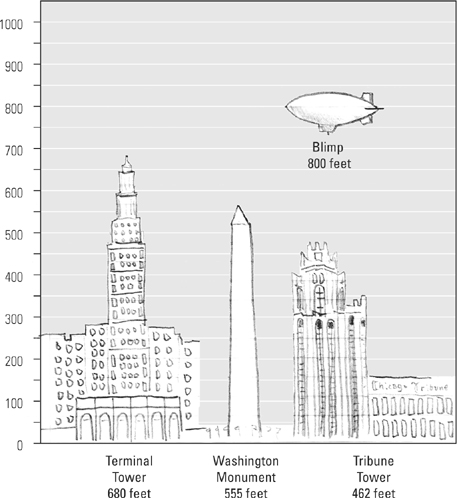

Even after discovering that his body was intact, Robinson still wasn’t happy because he’d lost his chance to enter the record books. In 1908 Senators catcher Gabby Street had become the first person to catch a ball dropped from the top of the Washington Monument—555 feet above the ground. Never mind that Street was 25 years old and still needed 13 attempts to make the catch (in large part because the wind blew the balls all over the place); the overweight, 51-year-old Robinson was inspired by the stunt and wanted to one-up him.

After Street earned his place in baseball lore, he said, “The ball I caught hit my mitt with terrific force, much greater than any pitched ball I have ever caught, and I have caught some pitchers who are given credit for having wonderful speed. Though my mitt is three or four inches thick, the force of the ball benumbed my hand.”

According to a story published the following day in the New York Times, it was estimated that the ball had been traveling “slightly over 140 feet a second,” or a shade above 95 miles per hour, when Street caught it—an estimate, given the lack of technology at the time, that was remarkably precise. More than 80 years later, in his seminal book The Physics of Baseball, Yale University’s Sterling Professor of Physics Robert K. Adair proved, among many other things, that “the terminal velocity of a ball dropped from a great height is but 95 mph.”

Street wasn’t the first person to attempt to catch a ball dropped from a great height, and Robinson wasn’t the last. Paul Hines, an outfielder who debuted in 1872 with the Washington Nationals, could have become the first to catch a ball dropped off the Washington Monument, but he chickened out (perhaps because baseball gloves were not yet in vogue) shortly before the stunt was supposed to take place in 1885. Nine years later, Chicago Colts catcher Pop Schriver made an unpublicized attempt to catch a ball dropped from the Monument, but was quickly chased away by police after two failed tries. For years after the fact, there were inconsistent reports that Schriver had made the catch, but his teammate and accomplice, Clark Griffith, who had dropped the balls from high above, eventually admitted that they had not succeeded.

In 1910 White Sox catcher Billy Sullivan caught several balls that had been dropped and thrown from the top of the Washington Monument, although it took two dozen attempts before he snagged the first one. In 1925 another White Sox catcher, named Ray Schalk, caught a ball dropped from the newly constructed 462-foot Tribune Tower in downtown Chicago. The following summer, in a stunt that took place at an army aviation field in New York, Babe Ruth caught a ball that was dropped from an airplane flying at an altitude of 250 feet and a speed of 100 miles per hour. (Can you imagine Derek Jeter attempting this?) In 1930 Cubs Hall of Fame catcher Gabby Hartnett bested Ruth and set a record that still stands: catching a baseball dropped from the greatest height. The Cubs were in Los Angeles for a preseason game when Hartnett grabbed a ball that was tossed from a blimp 800 feet above the field. In 1938 Frankie Pytlak and Hank Helf—both catchers on the Indians—caught balls dropped from Cleveland’s Terminal Tower at a height of approximately 680 feet. They still hold the record for catching balls dropped from the highest structure.

Among all the successful attempts, there’ve been numerous failures, but none worse than that of Joe Sprinz in 1939. A former catcher whose brief career had ended with the Cardinals six years earlier, Sprinz agreed to participate in a publicity stunt at the World’s Fair in San Francisco. The baseball was supposed to be dropped from an airplane flying more than 1,000 feet high, but it ended up being released from a blimp at 800 feet instead. Sprinz, to his credit, managed to get his glove on it, but the force of the ball smashed his glove into his face. The impact broke his jaw, knocked out several teeth, severely cut his lips, and caused him to drop the ball—and to make matters worse, the mishap discouraged future generations from attempting anything similar.

Why did Sprinz agree to do it in the first place?

“All the other players refused and walked off the field,” he recalled. “But I said to myself, ‘God hates a coward.’ ”

KNOCKING THE COVER OFF THE BALL

Ever since Robert Redford’s character in the 1984 movie The Natural literally knocked the cover off a baseball, people have wondered if such a feat is actually possible. Twenty-three years later, a TV show on the Discovery Channel called Mythbusters attempted to find out once and for all.

The two hosts, Jamie Hyneman and Adam Savage, tested the myth by firing balls at a “static bat” from an air cannon. In other words, the bat wasn’t being swung; it was held in place by a mechanical arm. And therein lay the first of two problems: the experiment, as interesting as it was, degenerated into an exercise in bunting the cover off the ball.

As Hyneman and Savage increased the speed at which the balls were fired, something unexpected happened at the 200-mile-per-hour threshold. The bat snapped in half, but the ball remained intact.

“It’s obvious to me,” said Hyneman to his co-host, “that knocking the hide off a ball is way beyond the capability of a human pitcher or batter.” (Even guest star Roger Clemens.)

The test concluded with Hyneman and Savage cranking up the cannon full blast and shooting a brand-new ball 437 miles per hour into a padded backdrop. That did the trick and caused the cowhide cover to fly off the twiny core—but that’s where the second problem arose. There were several unanswered questions: What’s the slowest speed at which the ball would’ve broken apart? What exactly made the cover rip off at top speed? Was it the jolt of 150 pounds per square inch from deep inside the cannon’s long barrel? Or was it the air resistance once the ball escaped?

The most important question might be: would it have been possible to knock the cover off an old and slightly worn-out ball, like the one used in The Natural? Probably not, but the circumstances were favorable. The scene took place in 1939, when umpires weren’t nearly as anal about discarding used balls—and in the moments before Redford unleashed his sensational swing, a close-up of the ball in the pitcher’s hand revealed a small imperfection on the stitches.

Still, Hyneman and Savage are probably right: myth busted.

PUNK’D BY PETE ROSE

Pete Rose did not perform well in All-Star Games. He played in 16 of them and batted just .212 (7-for-33), but at the 1978 contest in San Diego he used a different approach to help the National League.

Long before the game took place, Rose devised a plan to psych out the American League. He knew that Japanese baseballs travel farther than major league balls because they’re made smaller and wound tighter, so he secretly arranged for Mizuno to ship dozens of balls to the stadium.

“I brought the balls in for the National League’s batting practice,” said Rose. “It was all for psychological warfare.”

With his teammates in on the trick, Rose visited the American League clubhouse and convinced a bunch of players to watch BP.

“Everyone was hitting them out of the park,” recalled Phillies second baseman Larry Bowa.2 “I even hit a couple out in BP—something I never did before. It made me feel like Babe Ruth.”

Rose and Bowa and the rest of the National League All-Stars put on quite a show, then made sure to gather every ball before clearing the field and watching the American League take their cuts.

“They were just barely hitting them to the outfield wall,” said Bowa. “It was normal stuff, but after the way our balls were flying way up into the stands, the American Leaguers looked like Little Leaguers.”

Rose’s plan worked. The National League beat the American League, 7–3, for its seventh straight win.

OUTER SPACE

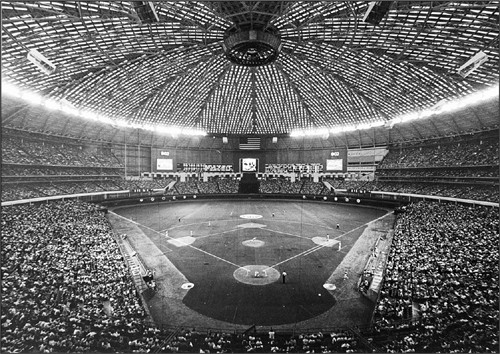

Ceremonial first pitches have come a long way since President Taft started the tradition in 1910. There’ve been comical first-pitch mishaps, like the time Olympian Carl Lewis made an inconceivably wimpy throw that nosedived 30 feet in front of the mound and rolled to home plate, or when Cincinnati mayor Mark Mallory flung one so far off the plate that one of the umpires jokingly ejected him, but there’ve also been historical triumphs. In 1995, before Game 5 of the World Series got under way at Cleveland’s Jacobs Field, NASA astronaut Ken Bowersox became the first person to throw a first pitch from outer space. His antigravity toss inside the space shuttle Columbia was transmitted via satellite to the scoreboard at the stadium and viewed by a national audience on ABC-TV. The seven-member crew, spending time in space to conduct a microgravity research mission, had taken two baseballs aboard the shuttle—one from each league—and then signed them after the mission. One of the balls was sent to the Hall of Fame. The other was displayed at the NASA Glenn Visitor Center.

Michael Lopez-Alegria, a member of Bowersox’s crew, teamed up with a fellow astronaut (and die-hard Red Sox fan) named Suni Williams in 2007 to throw the second ceremonial first pitch from space. This time it took place at the International Space Station before a regular-season Yankees–Red Sox game at Fenway Park. One year later, as the same two teams prepared to face off in the Bronx, NASA astronaut (and lifelong Yankee fan) Dr. Garrett Reisman threw another ceremonial first pitch at the space station.

THE MOTORCYCLE TEST