Contents

History, Politics &

Foreign Affairs

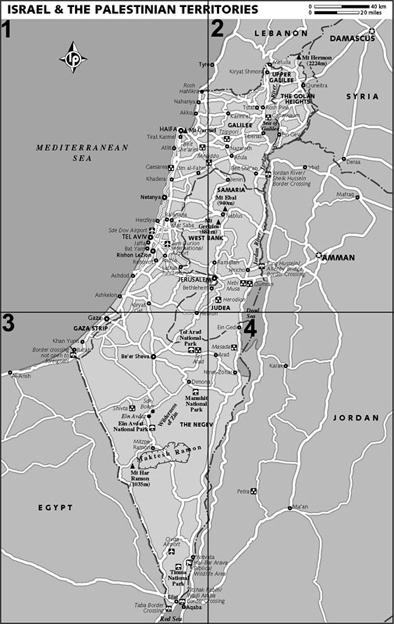

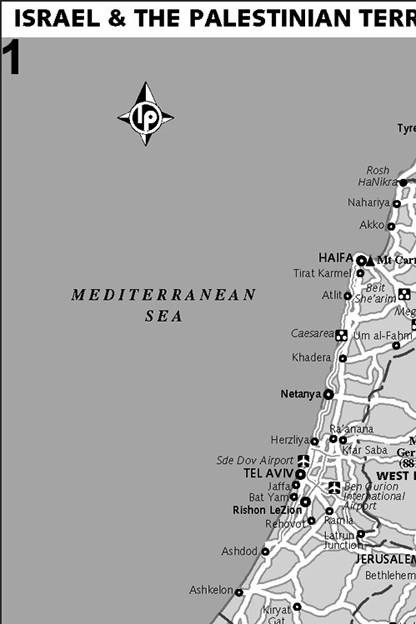

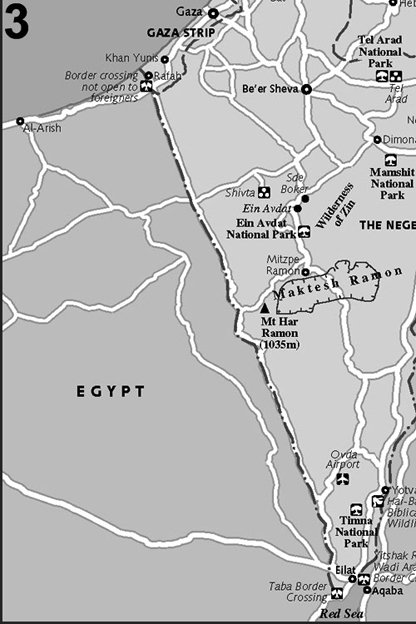

Israel & the Palestinian Territories

Destination Middle East

The Middle East is one of history’s grand epics in the making. Once the cradle of civilisation, now a region where modern human history is daily being written upon the stones of the past, the Middle East is where the lines between history’s story and the magic of the travel experience are forever being blurred.

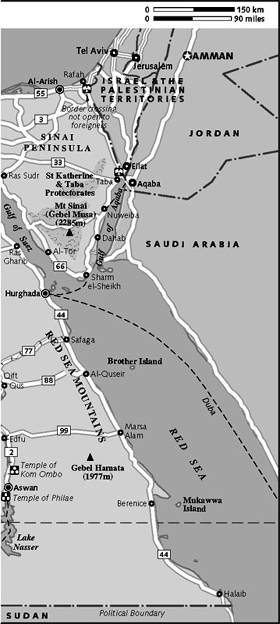

Few places in the world can match the Middle East’s roll-call of ancient ruins, landscapes of rare beauty and extraordinary cities whose personalities seem to spring from the tales of The Thousand and One Nights. More than that, the unforgettable travel moments that the Middle East has to offer are almost as diverse as the stunning backdrops in which to enjoy them. You’ll never forget the wide-eyed wonder of that first time you dip below the surface of the Red Sea and discover an underwater world of dazzling colour and otherworldly coral. Or the feeling of well-being as you sit by the feet of the Middle East’s last storyteller in Damascus and he weaves an intricate web of fact and fable worthy of Sheherezade. Or the spiritual stirrings in your soul the first time you hear the haunting call to prayer carried by the wind through the lanes of old Jerusalem.

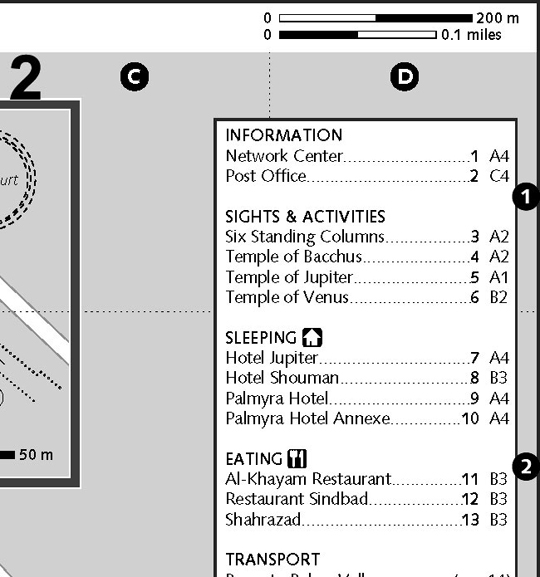

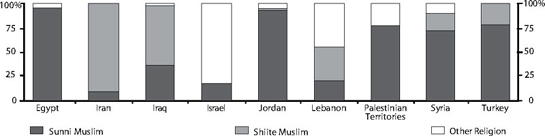

Israel has the highest GDP per capita in the region (US$25,500), while the lowest is in the West Bank and Gaza Strip (US$1100). Otherwise, on average Turks earn US$12,900, Lebanese US$11,300, Egyptians US$5500, Jordanians US$4900,

Syrians US$4500 and oil-rich Iraqis US$3600.

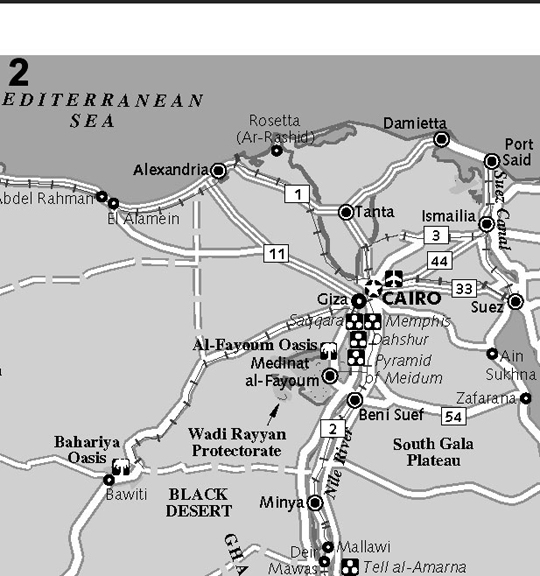

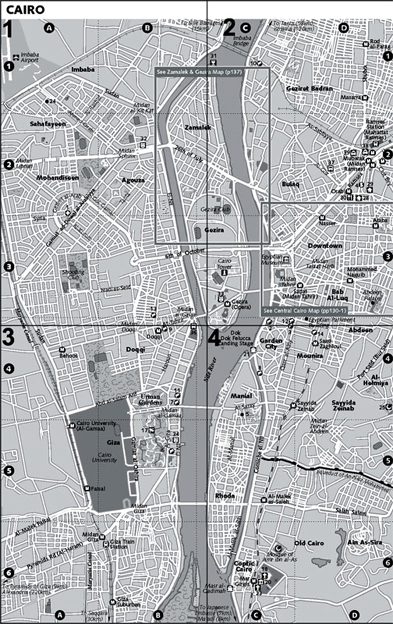

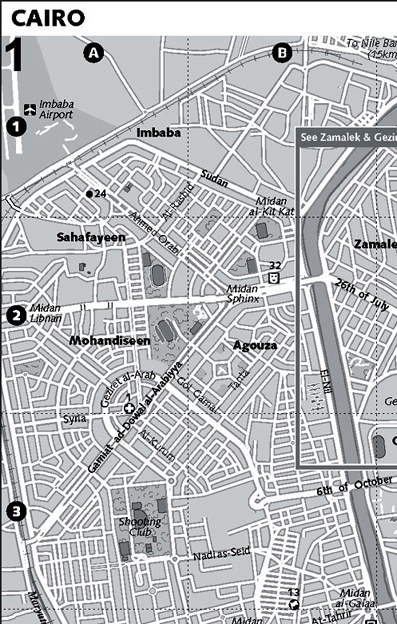

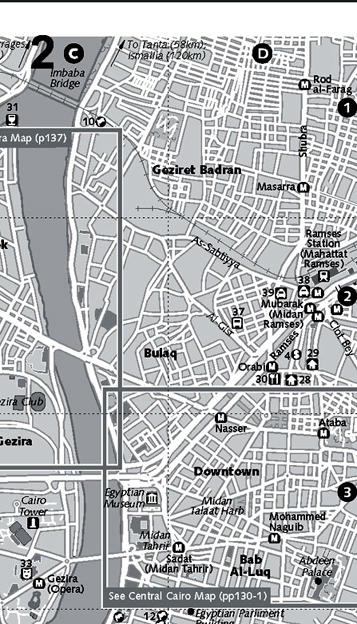

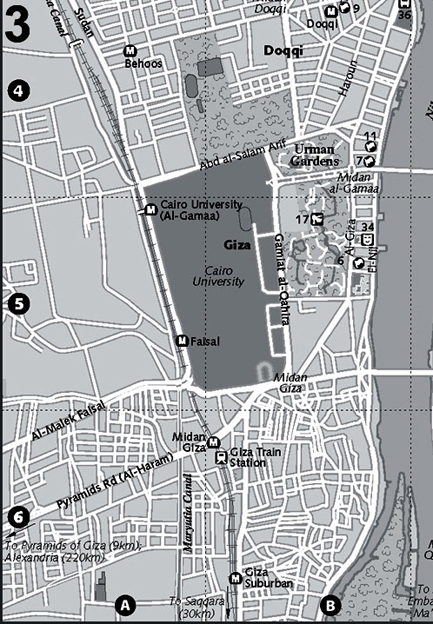

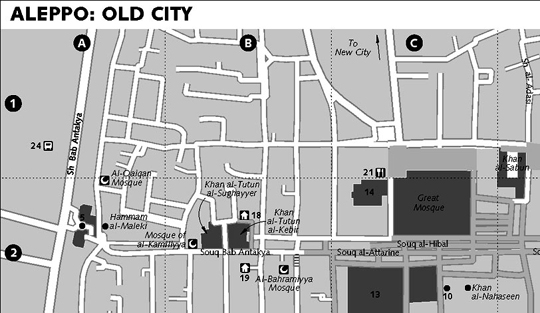

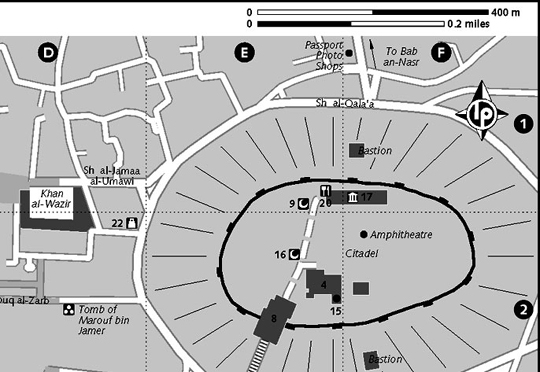

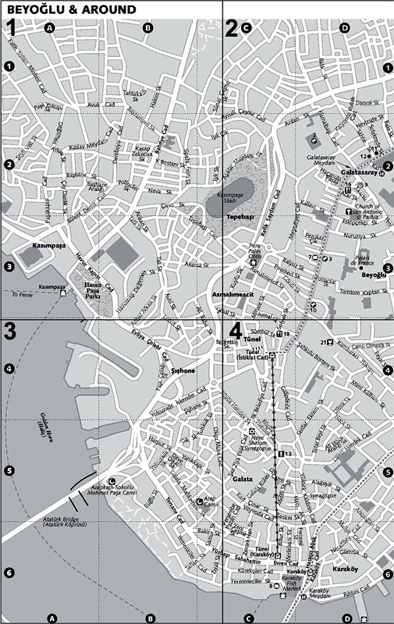

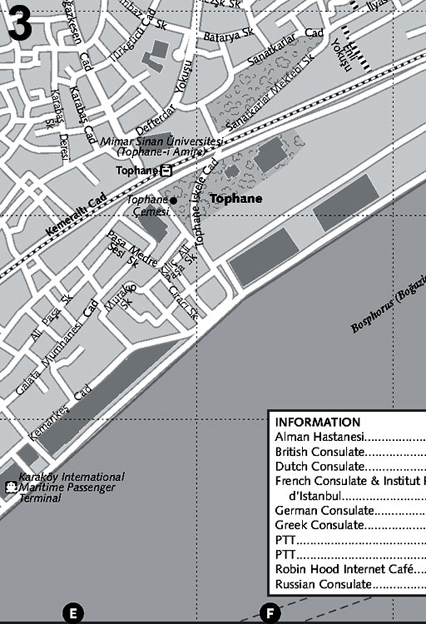

Many travellers fall irretrievably in love with the region in its cities. Cairo is known as ‘the mother of the world’; it is a clamorous cultural hub for the Middle East, not to mention the home of the Pyramids of Giza. There’s also something special about Damascus with its compelling claim to be the world’s oldest continuously inhabited city (at least four other cities, all in the Middle East, make a similar claim); it is a place where the layers of history infuse every aspect of daily life. Call it what you like – Byzantium, Constantinople or İstanbul – but Turkey’s most beguiling city is simply splendid, providing a bridge, in more ways than one, between Europe and the Middle East amid so many jewels of its Ottoman past. And then there’s Jerusalem, a city sacred to almost half the world’s population. If a whiff of the exotic is your thing, the souqs of Aleppo have no rivals. If pulsating nightlife gets you on your feet, Tel Aviv and Beirut rock deep into the night.

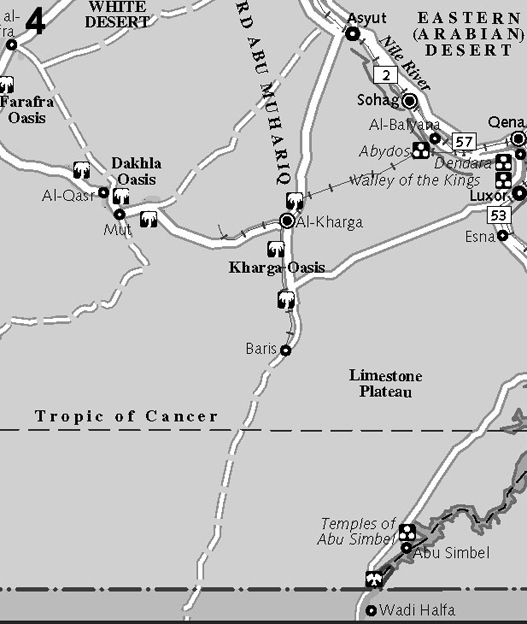

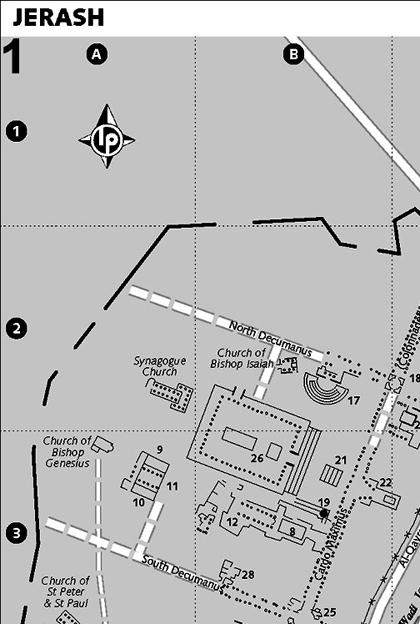

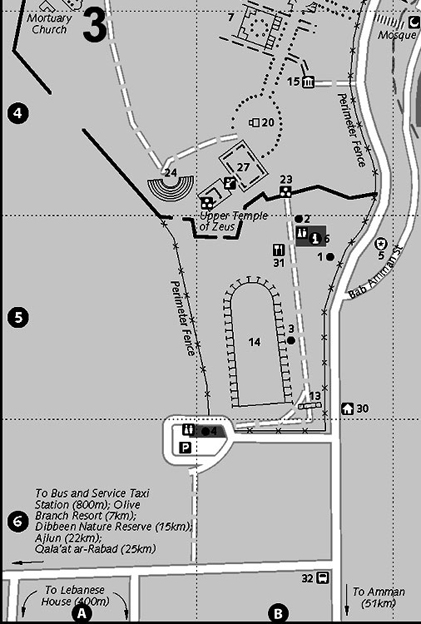

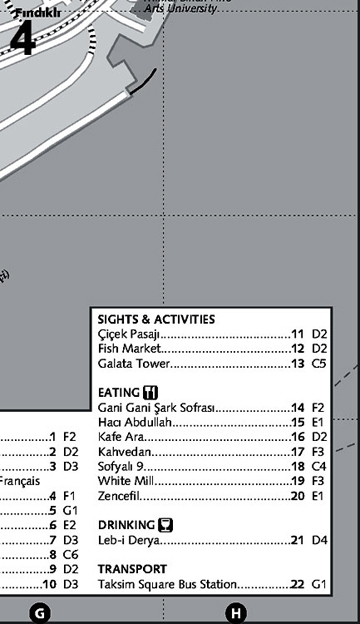

Cities have always been essential to the fabric of Middle Eastern life and no other spot on the globe can match the Middle East for the extant glories of its ancient world. There are no more stirring ruins than Petra (Jordan), that most magical landmark of antiquity where the only suitable response is awe. Not far away, the wonders of ancient Egypt, from the Pyramids to the valleys of kings and queens that sit across the Nile from Luxor, similarly leave all who see them spellbound by the wisdom of the ancients. The Romans also left their mark across the region; in the

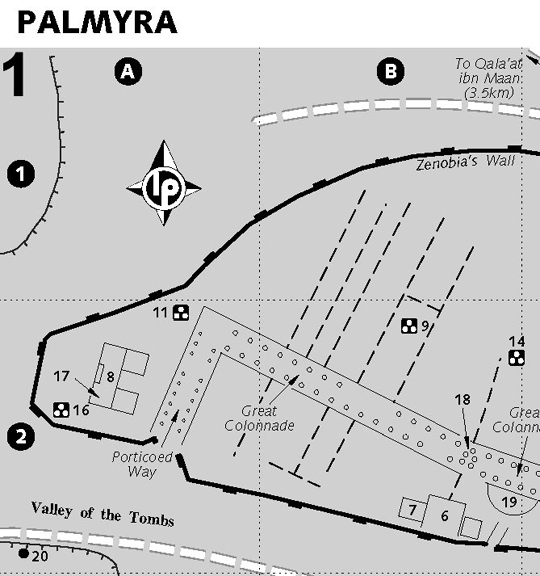

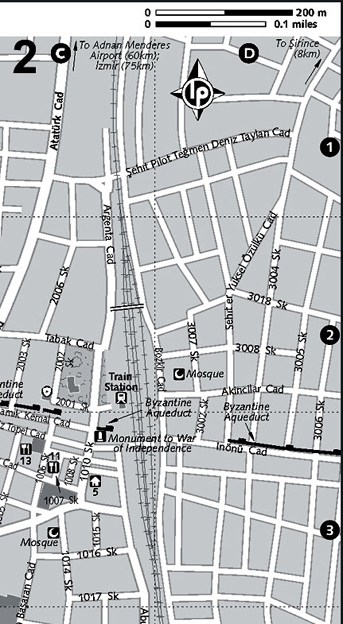

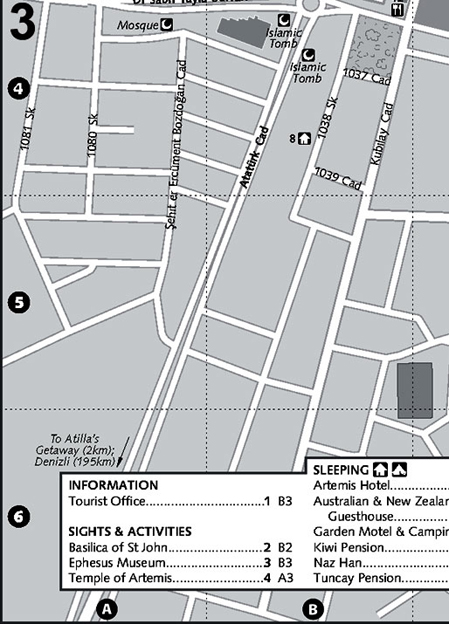

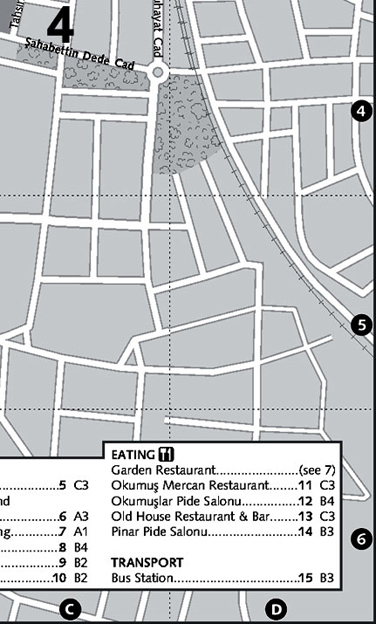

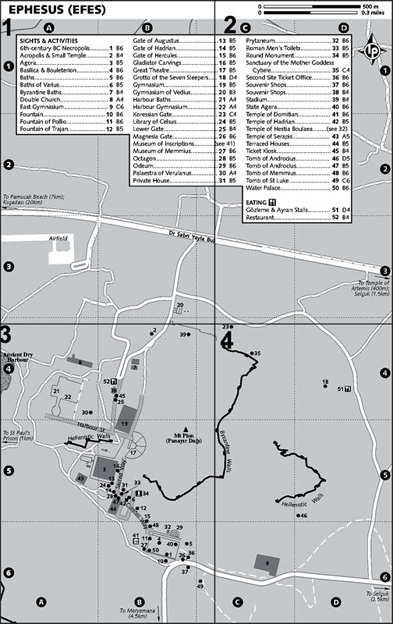

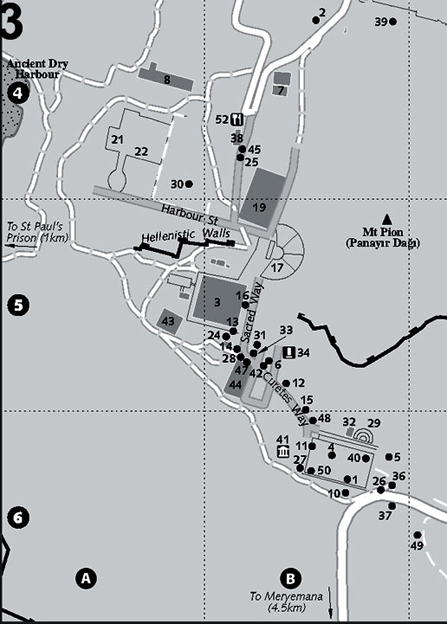

ruined cities of Ephesus (Turkey), Baalbek (Lebanon), Jerash (Jordan) and Palmyra, Apamea and Bosra (Syria) you’ll stroll down great colonnades and enter ancient theatres so wonderfully preserved that the

extravagance of the Roman Empire seems within your grasp.

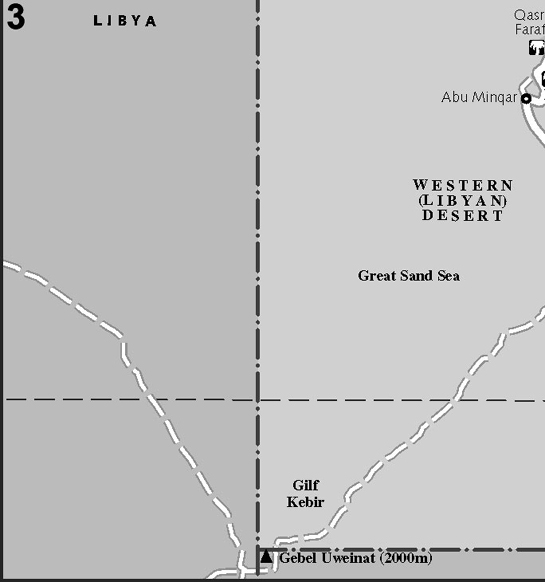

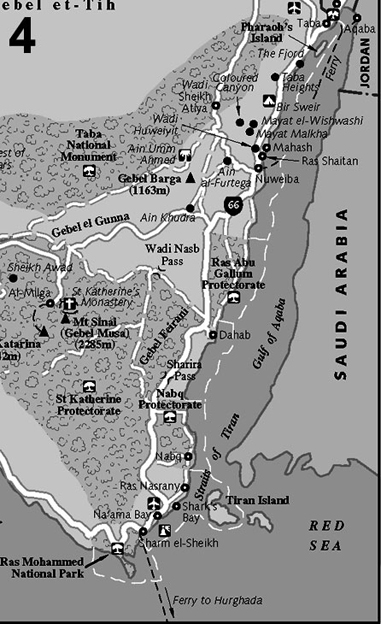

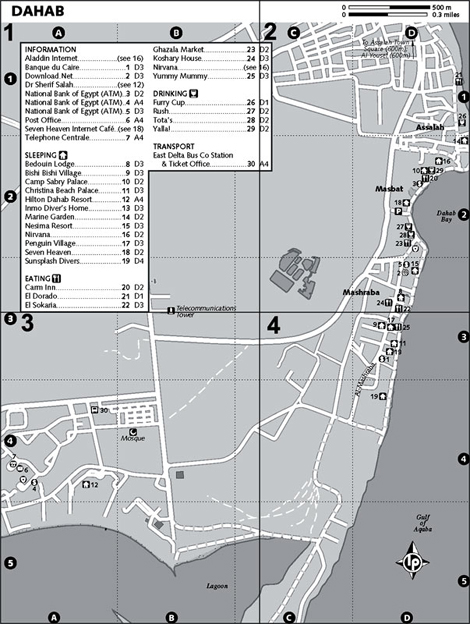

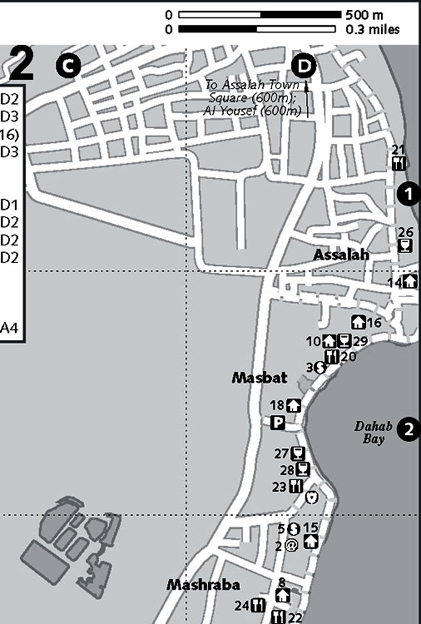

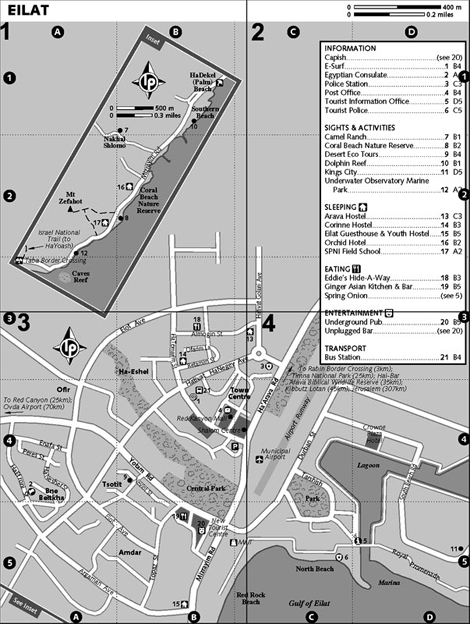

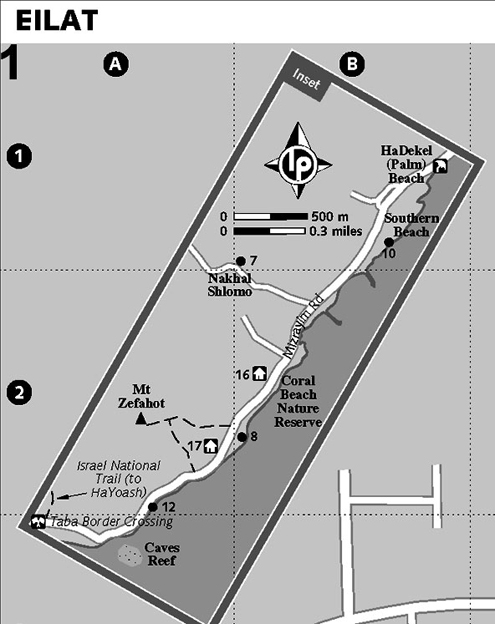

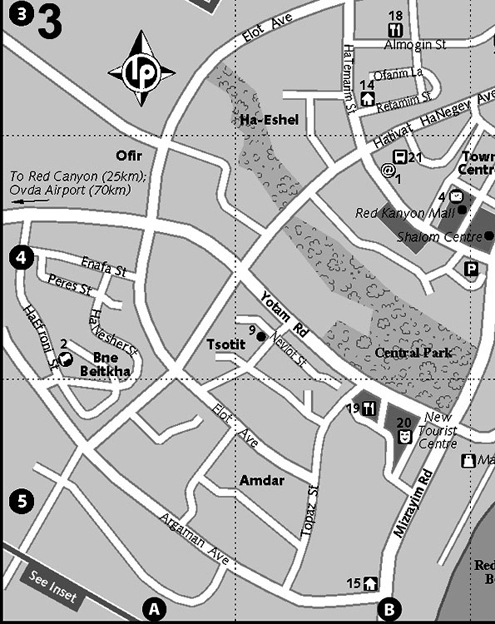

If your ideal travel day extends beyond a diet of coffeehouses and old stones to making your own discoveries and leaving the madding crowds behind, the range of activities on offer can seem endless. Diving and snorkelling in the Red Sea – from Egypt, Jordan and, to a lesser extent, Eilat in Israel – is the ultimate aim for diving connoisseurs and beginners alike; combining this with lazy days along the Dahab shoreline could conceivably occupy weeks of your time. Sharing the desert with the soulful Bedouin in the extraordinary red sands of Wadi Rum with their echoes of Lawrence of Arabia, or leaving behind the last outpost of civilisation and losing yourself in the White and Black Deserts of the Egyptian Sahara, are also experiences with an almost spiritual dimension of solitude and silence. Hikers who take to the hills of Jordan invariably make a similar claim.

Such are the headline attractions of the Middle East. And yet it’s the people of the region who will leave the most lasting impression. We’ve lost count of the number of times that we’ve received invitations to take tea, to pass the time in conversation or to eat in people’s homes. The art of hospitality, with its strong roots in the desert cultures of Arabia and in Islam, is one of the most enduring constants in Middle Eastern life. ‘Ahlan wa sahlan’ (‘You are welcome’) is a phrase you’ll hear again and again because many Middle Easterners treat every encounter with guests in their country as a gift from their god.

This warmth that you’ll experience often on your travels through the region is all the more remarkable given that life is a daily struggle for many people in the Middle East. Poverty and a lack of freedom are quotidian concerns for millions of people here. With the flawed exceptions of Turkey, Israel and Lebanon, political freedoms are heavily circumscribed and people chafe under the old guard of leaders who have, by some standards, singularly failed to better the lives of their citizens. Armed conflict and terrorism are rarer and more isolated in the Middle East than the mainstream Western media would have you believe, but they still darken the horizon of many, especially in Iraq and Gaza.

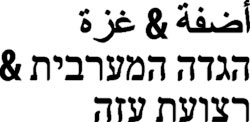

Far more paralysing are the conflicts over land that seem frozen in time and no nearer to a solution than they were six decades ago. Like a separation wall between historical conflict and a peaceful future, the enduring inability of Israel, the Palestinians, Syria and Lebanon to make peace with each other continues to cast a shadow over the region, hindering its economic growth and maintaining almost perpetual uncertainty for many.

All of these issues may be why nine out of 10 people polled will probably tell you the Middle East is too dangerous to visit (one of these nine will, most likely, be your mum). The Middle East does indeed have its problems and dangers. They are, however, far fewer than the prevailing stereotypes suggest. They’re also far more likely to affect the people of the Middle East rather than travellers, for whom the risks are extremely small. You will come across relatively minor inconveniences, such as not being able to cross between Lebanon and Israel, or finding that an Israeli entry stamp in your passport means you cannot visit Syria or Lebanon. But we cannot emphasise it more strongly than this: many parts of the Middle East are safe to travel to.

To put it another way, the Middle East is a destination for discerning travellers, for those looking for the story behind the headline. It’s the story of a region with its feet firmly planted on three continents, of a warm and hospitable people standing at the crossroads of history. And it’s a story that, having visited the Middle East once, you’ll find yourself returning to over and over again.

Getting Started

There’s one question that every traveller to the Middle East wants answered: is it safe? The short answer is yes, as long as you stay informed. For the longer answer, turn to the boxed text, Click here. Show it to your mum. Show it to all those friends who told you that you were crazy for travelling to the Middle East. Once you’ve realised that the region’s reputation as a place that cannot be travelled to comes almost solely from people who’ve never been there, you can get down to the fun part of pretrip planning – tracking down a good read, surfing the net to learn other travellers’ tales and renting a few classic Middle Eastern movies. And if the idea of scuba diving in the Red Sea, sleeping under the desert stars or skiing (yes, skiing in the Middle East) sounds like your kind of holiday, we recommend that you see Activities, Click here) so that you can start dreaming. For the ultimate at-a-glance guide to planning your trip, see the Travel Planner, Click here.

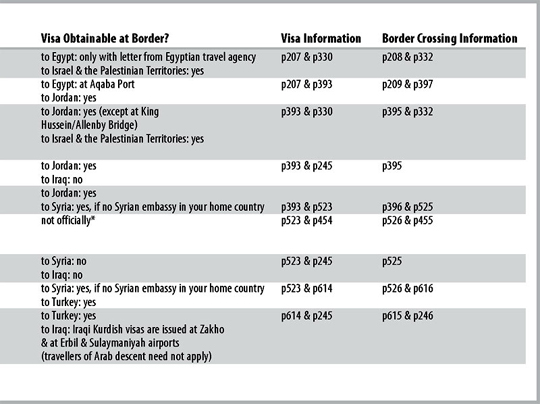

There are, of course, a few logistical matters that you should consider before setting out; primary among these is the question of visas. Although you can get visas on arrival in most countries, Syria could provide a road block if you don’t plan ahead. For more information, Click here. You should also consult the Visa sections of the Directory in each individual country chapter, or for a general overview, see the table on Click here.

DON’T LEAVE HOME WITHOUT…

- Checking the latest travel advisory warnings (see the boxed text, Click here)

- Travel insurance (Click here) – accidents do happen

- Driving licence, car documents and appropriate car insurance if bringing your own car (Click here)

- Checking the status of border crossings in the region (see the boxed text, Click here)

- A big appetite (Click here)

- Warm clothes for winter – the Middle East can be cold; desert nights can be freezing

- A universal bathplug – you’ll thank us when you emerge from the desert

- An MP3 player – the desert can be beautiful but there are days when epic distances and empty horizons can do your head in

- Mosquito repellent – that unmistakeable high-pitched whine in the ear is death to sleep

- A small size-three football – a great way to meet locals

- A Swiss Army knife with a bottle and/or can opener – you never know when you might need it

- Photocopies of your important documents – leave a copy at home or email them to yourself before leaving

- Ear plugs – wake-up calls from nearby mosques can be very early

- Contraceptives – some local condoms have a distressingly high failure rate

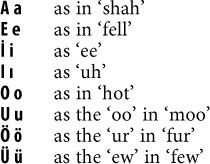

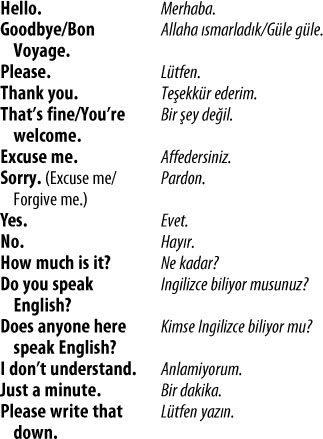

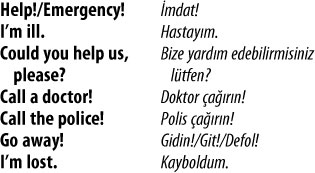

- A phrasebook – an ‘al salaam ‘alaykum’, or ‘peace be upon you’, works wonders in turning suspicion to a smile

- Checking the status of visa rules for travel between Lebanon and Syria (see the boxed text, Click here)

- A chic outfit if you’re planning a night out in Beirut, İstanbul or Tel Aviv

- Hiking boots if you intend to get too far off the beaten track

- Patience – most things do run on time, but the timetable may be elusive to the uninitiated

If you’re planning to visit Israel and the Palestinian Territories, remember that any evidence in your passport of a visit to Israel will see you denied entry to Syria, Lebanon and possibly Iraq. For advice on how to avoid this problem, see the boxed text, Click here.

Return to beginning of chapter

WHEN TO GO

Although the timing of your trip may owe less to personal choice and more to the caprices of your employer back home, there’s nothing worse than arriving in the Middle East to discover that it’s Ramadan and stinking hot.

Climate

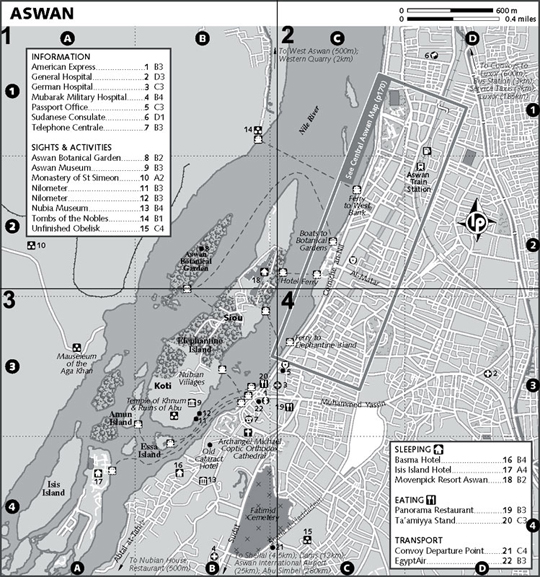

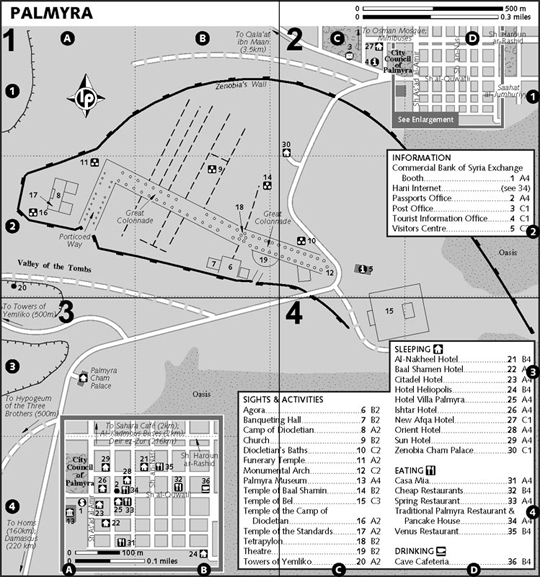

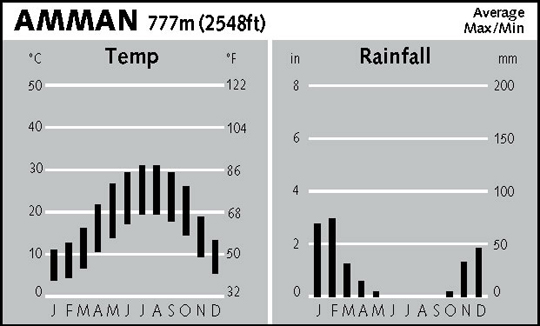

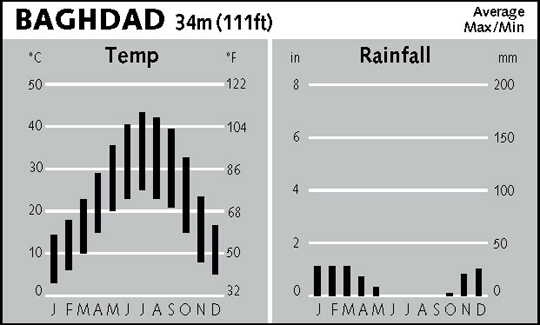

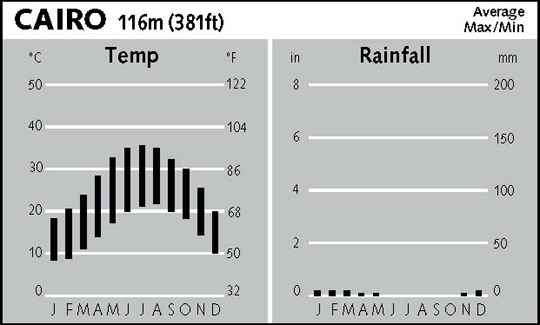

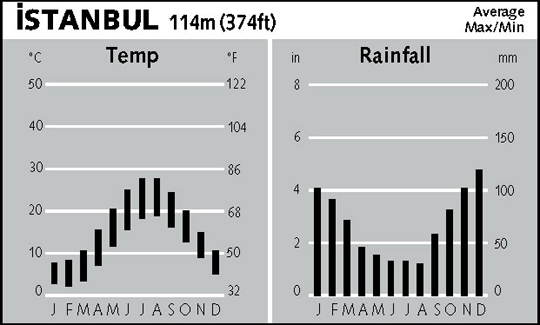

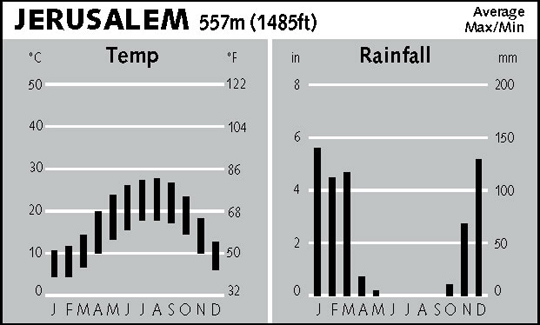

The best time to visit the Middle East is autumn (September to November) or spring (March to May). December and January can be fairly bleak and overcast in the region. Any time from October through to March can see overnight temperatures plummet in desert areas. Unless you’re like the ancient Egyptians and worship the sun, or you’re a watersports freak, the summer months of June through to September may be too hot for comfort. In July and August visitors to the Pharaonic sites at Aswan and Luxor in Egypt, or to Palmyra in Syria, are obliged to get up at 5am to beat the heat. Don’t even think of an expedition into the desert in summer.

The most obvious exceptions to these rules are the mountain areas. The northeast of Turkey before May or after mid-October can be beset by snow, perhaps even enough to close roads and mountain passes.

For more details on weather conditions, see the Climate section in each individual country chapter and Click here.

Religious Holidays & Festivals

Although non-Muslims are not bound by the rules of fasting during the month of Ramadan, many restaurants and cafés throughout the region will be closed, those who are fasting can be understandably taciturn, transport is on a go-slow and office hours are erratic to say the least. If you’re visiting Turkey, Kurban Bayramı, which lasts a full week, can be an uplifting experience, but careful planning is required as hotels are jam-packed, banks closed and transport booked up weeks ahead. In Israel and the Palestinian Territories quite a few religious holidays, such as Passover and Easter, cause the country to fill with pilgrims, prices to double and public transport to grind to a halt.

On the positive side, it’s worth trying to time your visit to tie in with something like Eid al-Adha (the Feast of Sacrifice, which marks the Prophet’s pilgrimage to Mecca) or the Prophet’s Birthday, as these can be colourful occasions. Both of these religious holidays can be wonderful opportunities to get under the skin of the region and enjoy the festive mood. Remember, however, to make your plans early, especially when it comes to public transport and finding a hotel. Click here for the dates of these and more Islamic festivals.

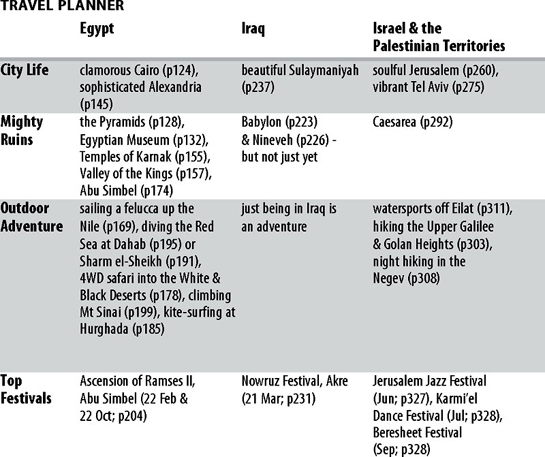

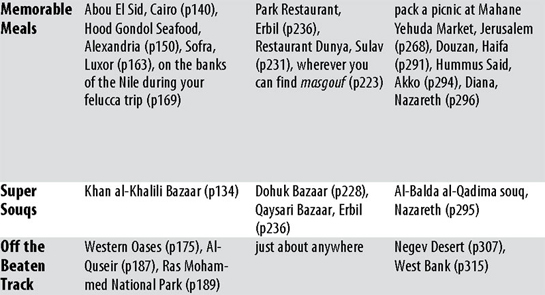

For a snapshot of the Middle East’s best festivals, see the Travel Planner Click here.

Return to beginning of chapter

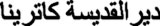

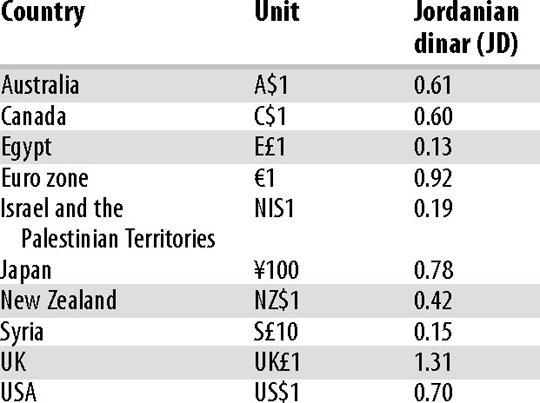

COSTS & MONEY

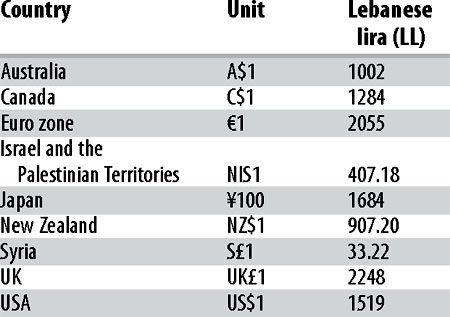

The Middle East is in the midst of an inflationary spiral driven by rising oil prices and it’s difficult to predict how far it will go. Previously cheap countries such as Jordan, Egypt and Syria (where prices have almost doubled since we were last there) remain cheap by Western standards and travel staples – accommodation, meals and transport – are generally affordable for most travellers. The gap is, however, narrowing. The gap between prices in the West and Lebanon, Turkey and Israel and the Palestinian Territories long ago narrowed, and don’t be surprised to pay the same for your latte in Beirut, Tel Aviv or İstanbul as you would at home. Indeed, in many places, midrange and especially top-end travellers may find themselves paying prices on a par with southern Europe. Budget travellers should still, however, be able to travel economically in most countries of the Middle East.

‘some of the best travel experiences cost nothing’

Although it’s dangerous to generalise, if you’re on a really tight budget, stay at cheap hotels with shared bathrooms, eat street food and carry a student card with you to reduce entry fees at museums, you could get by on around US$20 to US$25 a day. Staying in comfortable midrange hotels, eating at quality restaurants to ensure a varied diet, the occasional private taxi ride and some shopping will push your daily expenses up to between US$40 and US$60. In Lebanon, US$25 a day is the barest minimum, while US$45 is more realistic. In Israel and the Palestinian Territories, budget travellers could keep things down to $US40 per day if they really tried hard, while a more comfortable journey would require up to US$65.

When estimating your own costs, take into account extra items such as visa fees (which can top US$50 depending on where you get them and what your nationality is), long-distance travel and the cost of organised tours or activities, such as desert safaris and diving. And remember, some of the best travel experiences cost nothing: whiling away the hours taking on the locals at backgammon in Damascus, sleeping under the desert stars in the Sahara or watching the sun set over the Mediterranean.

For advice on the pros and cons of carrying cash, credit cards and/or travellers cheques, check out the Money section in the Directory of each individual country chapter. In general, we recommend a mix of credit or ATM cards and cash (Click here), but the situation varies from country to country.

Return to beginning of chapter

READING UP

Books

Lonely Planet has numerous guides to the countries of the Middle East, including Egypt, Turkey, Jordan, Cairo & the Nile and Syria & Lebanon. There’s also a city guide to İstanbul, a World Food guide to Turkey, as well as phrasebooks for Arabic, Farsi, Hebrew and Turkish.

TRavel Literature

In From the Holy Mountain, William Dalrymple skips lightly but engagingly across the region’s landscape of sacred and profane, travelling through Turkey, Syria and Israel and the Palestinian Territories in what could be an emblem for your own journey.

The 8:55 to Baghdad: From London to Iraq on the Trail of Agatha Christie and the Orient Express, by Andrew Eames, is a well-told tale retracing Agatha Christie’s journey from Britain to archaeological digs in Iraq.

Travels with a Tangerine, by Tim Mackintosh-Smith, captures a modern journey in the footsteps of Ibn Battuta, a 13th-century Arab Marco Polo. The book begins in Morocco and takes in several countries of the Middle East.

Syria Through Writers’ Eyes is one in a series of anthologies that brings together the best travel writing about the region down through the centuries. There are similar titles for Egypt, Persia and the Turkish coast.

The famous march to Persia by the Greek army, immortalised in Xenophon’s Anabasis, has been retraced some 2400 years later by Shane Brennan in his fabulous tale, In the Tracks of the Ten Thousand: A Journey on Foot Through Turkey, Syria and Iraq.

Johann Ludwig (also known as Jean Louis) Burckhardt spent many years in the early 19th century travelling extensively through Jordan, Syria and the Holy Land. His scholarly travelogue Travels in Syria and the Holy Land is a great read.

ONWARD TRAVEL: IRAN, SAUDI ARABIA & THE GULF STATES

If you can’t bear your Middle Eastern journey to end and you’ve got Iran in your sights, pick up a copy of Lonely Planet’s Iran guide. For Saudi Arabia, Oman, the UAE, Yemen, Bahrain, Kuwait and Qatar, see Oman, UAE & Arabian Peninsula, which features a special chapter for expats headed to the Gulf states. If Africa awaits, Lonely Planet’s Africa covers the entire continent, while Libya and Ethiopia & Eritrea may also appeal.

Mark Twain’s The Innocents Abroad is still many people’s favourite travel book about the region. Twain’s sharp humour and keen eye make the story still relevant 140 years after the fact.

Other Great Reads

Nine Parts of Desire, by Geraldine Brooks, takes our fascination with the life and role of women in the Middle East and gives it the depth and complexity the subject deserves, but all too rarely receives. It includes interviews with everyone from village women to Queen Noor of Jordan.

In the Land of Israel, by one of Israel’s most acclaimed writers, Amos Oz, introduces you to the people of Israel in all their glorious diversity. Letting ordinary people speak for themselves, Oz paints a rich, nuance-laden portrait of Israelis and the land they inhabit.

Once Upon a Country: A Palestinian Life, by Sari Nusseibeh, was described by the New York Times as ‘a deeply admirable book by a deeply admirable man’. It’s a personal journey through 60 years of history by one of the Palestinians’ most eloquent voices.

You won’t want to carry Robert Fisk’s The Great War for Civilisation in your backpack (it’s a weighty tome), but there has been no finer book written about the region in recent years.

You’ve seen the movie, now read the book – Seven Pillars of Wisdom by TE Lawrence. Not only was Lawrence one of the Middle East’s most picaresque figures, he was also a damn fine writer.

The Thousand and One Nights resonates with all the allure and magic of the Middle East and its appeal remains undiminished centuries after its tales were first told with Cairo, Damascus and Baghdad playing a starring role.

Websites

For specific country overviews, the lowdown on travel in the region and useful links head to Lonely Planet’s website (www.lonelyplanet.com), which includes the Thorn Tree, Lonely Planet’s online bulletin board.

The following websites are an excellent way to get information about the Middle East.

- Al-Ahram Weekly (http://weekly.ahram.org.eg) Electronic version of Egypt’s weekly English-language newspaper.

- Al-Bab (http://www.al-bab.com) Portal that covers the entire Arab world with links to dozens of news services, country profiles, travel sites, maps, profiles and more. A fantastic resource.

- Al-Bawaba (http://www.albawaba.com) A good mix of news, entertainment and phone directories, with everything from online forums to kids’ pages.

- Al-Jazeera (http://english.aljazeera.net/news/middleeast/) The CNN of the Arab world provides an antidote to Western-driven news angles about the Middle East.

- Al-Mashriq (http://www.almashriq.hiof.no) A terrific repository for cultural information from the Levant (Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestinian Territories, Syria, Turkey). Some of the information is a bit stale but its range of articles, from ethnology to politics, is hard to beat.

- Arabnet (http://www.arab.net) Excellent Saudi-run online encyclopaedia of the Arab world, collecting news and articles plus links to further resources that are organised by country.

- Bible Places (http://www.bibleplaces.com) Interesting rundown on biblical sights in Jordan, Egypt, Turkey and Israel and the Palestinian Territories.

- BBC News (http://www.news.bbc.co.uk) Follow the links to the Middle East section for comprehensive and excellent regional news that’s constantly updated.

- Great Buildings Online (http://www.greatbuildings.com) Download then explore digital 3D models of the Pyramids of Giza and İstanbul’s Aya Sofya, plus lots of other info and images of monuments throughout the Middle East.

- Jerusalem Post (http://www.jpost.com) Up-to-the-minute news from an Israeli perspective. Sections include a blog page, tourism news and a link to the 24-hour Western Wall webcam.

Return to beginning of chapter

MUST-SEE MOVIES

The Middle East is so much more than a backdrop for Western-produced blockbusters such as Lawrence of Arabia, the Indiana Jones series and a host of biblical epics. For more on Middle Eastern film Click here. The following movies are likely to be available in your home country or online.

Lawrence of Arabia (1962) may be clichéd and may give TE Lawrence more prominence than his Arab peers, but David Lean’s masterpiece captures all the hopes and subsequent frustrations for Arabs in the aftermath of WWI.

Yilmaz Güney’s Yol (The Way; 1982) is epic in scale but at the same time allows the humanity of finely rendered characters to shine through as five Turkish prisoners on parole travel around their country. It won the coveted Palme d’Or in Cannes.

West Beirut (1998) begins on 13 April 1975, the first day of the Lebanese Civil War, and is Ziad Doueiri’s powerful meditation on the scars and hopes of Christian and Muslim Lebanese. This is the film about the Lebanese Civil War.

Savi Gabizon’s Nina’s Tragedies (2005) begins with a Tel Aviv army unit telling a family that their son has been killed in a suicide bombing and ends with a disturbing but nuanced look at the alienation of modern Israel as it struggles for peace.

Palestinian director Hany Abu-Assad’s Paradise Now (2005) caused a stir when it was nominated for the Best Foreign-Language Film Oscar in 2005. It’s a disturbing but finely rendered study of the last hours of two suicide bombers as they prepare for their mission.

The average age of people living in the Gaza Strip is 16.2 years, while for the West Bank it’s 18.7. Iraq (20.2) and Syria (21.4) also have young populations. Turkey (29), Israel (28.9) and Lebanon (28.8) have the highest average ages. The average age in the UK is 39.9 years.

The Yacoubian Building (2006), an onscreen adaptation of the best-selling Egyptian novel by Alaa al-Aswany, is a scathing commentary on the modern decay of Egypt’s political system. Its release marked the rebirth of Egyptian cinema.

Caramel (2007) is a stunning cinema debut for Lebanese director Nadine Labaki. It follows the lives of five Lebanese women struggling against social taboos in war-ravaged Beirut.

The biggest budget Egyptian film in decades, Baby Doll Night (2008) is at once a thriller with the threat of terrorism at its core and a thoughtful evocation of the complexities in relations between the Muslim world and the West.

Return to beginning of chapter

TRAVELLING RESPONSIBLY

Tourism has the potential to change for the better the relationship between the Middle East and the West, but the gradual erosion of traditional life is mass tourism’s flipside. Sexual promiscuity, public drunkenness among tourists and the wearing of unsuitable clothing are all of concern. For more coverage on the impact of tourism in the Middle East, Click here. For a list of Middle Eastern businesses and sights that engage in sustainable environmental practices, see the GreenDex.

Try to have minimal impact on your surroundings. Create a positive precedent for those who follow you by keeping in mind the following:

- Don’t hand out sweets or pens to children on the streets, since it encourages begging. Similarly, doling out medicines can encourage people not to seek proper medical advice and you have no control over whether the medicines are taken appropriately. A donation to a project, health centre or school is a far more constructive way to help.

- Buy your snacks, cigarettes, bubble gum etc from the enterprising grannies trying to make ends meet, rather than state-run stores. Also, use locally owned hotels and restaurants and buy locally made products.

- Try to give people a balanced perspective of life in the West. Try also to point out the strong points of the local culture, such as strong family ties and comparatively low crime.

- Make yourself aware of the human-rights situation, history and current affairs in the countries you travel through.

- If you’re in a frustrating situation, be patient, friendly and considerate. Never lose your temper as a confrontational attitude won’t go down well and for many Arabs a loss of face is a serious and sensitive issue. If you have a problem with someone, just be polite, calm and persistent.

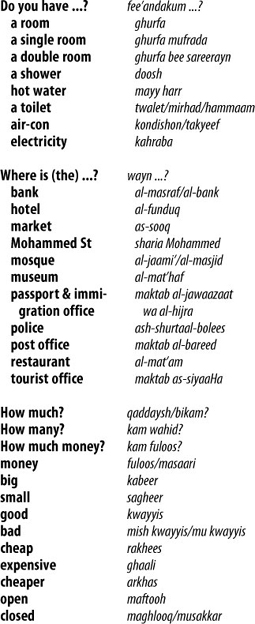

- Try to learn some of the standard greetings (Click here) – it will make a very good first impression.

- Ask before taking photos of people. Don’t worry if you don’t speak the language – a smile and gesture will be appreciated. Never photograph someone if they don’t want you to. If you agree to send someone a photo, make sure you follow through on it.

- Be respectful of Islamic traditions and don’t wear revealing clothing; loose lightweight clothing is preferable.

- Respect local etiquette. Men should shake hands when formally meeting other men, but not women, unless the woman extends her hand first. If you are a woman and uncomfortable with men extending their hand to you (they don’t do this with local women), just put your hand over your heart and say hello.

- Public displays of physical affection are almost always likely to be misunderstood. Be discreet.

- Choose environmentally sustainable transport options (eg train, renting a bike, or sailing up the Nile) where they exist and support ecotourism initiatives and local environmental organisations (see the boxed text, Click here).

- Consider offsetting the carbon emissions of your flights (see the boxed text, Click here).

- Try not to waste water. Switch off lights and air-con when you go out.

- When visiting historic sites, consider the irreparable damage you inflict upon them when you climb to the top of a pyramid, or take home an unattached artefact as a souvenir.

- Do not litter.

All countries of the Middle East have literacy levels above 80%, except for Iraq (74.1%) and Syria (79.6%). The highest literacy rates are for men in Israel (98.5%) and the Palestinian Territories (96.7%), while lowest are women in Egypt (59.4%).

For more specific advice in relation to diving responsibly, see the boxed text, Click here, while hikers should check out the boxed text, Click here.

A British organisation called Tourism Concern ( in the UK 020-7133 3330; www.tourismconcern.org.uk; Stapleton House, 277-281 Holloway Rd, London N7 8HN) is primarily concerned with tourism and its impact upon local cultures and the environment. It has a range of publications and contacts for community organisations, as well as advice on minimising the impact of your travels.

in the UK 020-7133 3330; www.tourismconcern.org.uk; Stapleton House, 277-281 Holloway Rd, London N7 8HN) is primarily concerned with tourism and its impact upon local cultures and the environment. It has a range of publications and contacts for community organisations, as well as advice on minimising the impact of your travels.

Middle East Stories

Telling stories is an age-old tradition in the Middle East. Although public storytelling is a dying art form in the region, every traveller to the Middle East will return home with a bag full of unforgettable experiences. As Lonely Planet authors, we have been criss-crossing the region for years, listening to the ordinary people of the Middle East (the region’s real storytellers), setting out on adventures, then returning home to write our own stories. What follows are some of our favourites.

Return to beginning of chapter

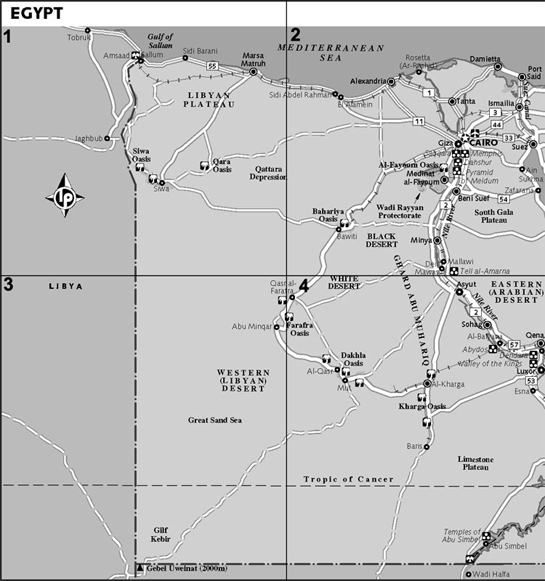

EGYPT

Diving the Mighty Thistlegorm

Though other bubble-blowing pundits may be chafing at the bit to disagree, I stand by my conviction that Egypt’s SS Thistlegorm is the premiere wreck dive in the world. This steam-powered, 126.5m-long British armed freighter was on her way to restock army supplies in Tobruk (Libya) when she was sunk in the northern Red Sea by German bombers in 1941. The ship was packed to the brim with cargo – munitions, trucks, armoured cars, motorcycles, uniforms, aircrafts and even locomotives. Now resting just 30m below sea level, the famed freighter is surrounded by the clear waters of the Red Sea with her full payload intact.

The site is 3½ hours by boat from Sharm el-Sheikh, so when diving the Thistlegorm I normally arrange a trip on an overnight live-aboard from Dahab or Sharm. Due to the sheer size of the wreck and the amount of well-preserved paraphernalia on board, the site is usually explored over two dives, though having said that, I have done half-a-dozen dives on this wreck and have yet to see all it has to offer. On our first dive, we circumnavigated the outside of the ship. Everything down here lies preserved exactly as it was when it sank, encrusted in a thick film of algae and barnacles. Fish teem all over the wreck, darting in and out of the deck’s cabins, around the long barrels of heavy-calibre machine guns and deep in the bowels of the cargo hold. Lying a few hundred metres away from the ship on the sandy floor is a locomotive that was thrown off the deck during the original bombing raid. It is one thing to see a sunken ship lying underneath the sea, but the odd sight of a train wreck brings a whole new surreal edge to the dive. Along the top deck we swim through the captain’s cabin and over the dismembered cargo hold where the fateful bombs hit. The highlight of the dive is rounding the stern to see the massive 2m brass propeller, which completely dwarfs the divers as they fin their way around it.

The SS Thistlegorm is just one of hundreds of dive sites scattered the length and breadth of the Red Sea. Pick up a copy of Lonely Planet’s Diving & Snorkeling the Red Sea for detailed descriptions of more than 80 of the best dive sites in the area.

The second dive is where the adrenaline kicks in, as we penetrate the twisted bowels of the cargo hold. Using torches to find our way, we grapple along from one section of the ship’s hold to another. Most of the original supplies are still found here: boots, lorries, munitions and more. The most impressive sight is the Bedford trucks, all lined up in a row and each with three perfectly preserved BSA motorcycles mounted on the back. Up close, you can make out the individual details of these 65-year-old relics – from the motorcycle handbrakes to the tachometers on truck dashboards. There are so many details to discover in this living museum of WWII artefacts that one tank of air is barely enough to skim the surface. Before too long we must make our ascent, most of us vowing before we even break the surface that we will return to one the world’s greatest underwater war memorials.

Rafael Wlodarski

A Little Sheesha on the Sidelines

Ahh sheesha, my one weakness. My Achilles heel if you will. In every nook and cranny of the country, in any town of any size, you will always find a café of some description serving shai (tea) and catering to the archaic tradition of smoking tobacco from a sheesha, or water pipe. In Cairo, I love nothing more than plonking myself down on a makeshift table outside one of the thousands of cafés that line that city’s maze of streets and alleys. Partaking in the daily sheesha ritual feels like I am part of the club – an initiated member of the puffing galabeya-clad contingent that sit here pondering the events of the world. As our tobacco smoke is languidly inhaled the soothing soundtrack of bubbles wafts through the air. Upon exhalation, each plume of the sweet-smelling haze is charged with the quiet whispers of political debate and friendly gossip. A small cup of sweetly brewed tea is always within arm’s reach; the diligent staff rarely allow it to stay empty for long. For me this is the best way to experience Cairo – by taking time out of the city’s hectic schedule to sit, rest, converse with friends and watch the world through a lethargic mist of blue tobacco clouds.

Rafael Wlodarski

For a unique insight into Cairo – its politics, personalities and gossip – pick up a copy of Khalid Al Khamissy’s Tales of Rides, which is a fascinating collection of personal stories from Cairene taxi drivers.

Return to beginning of chapter

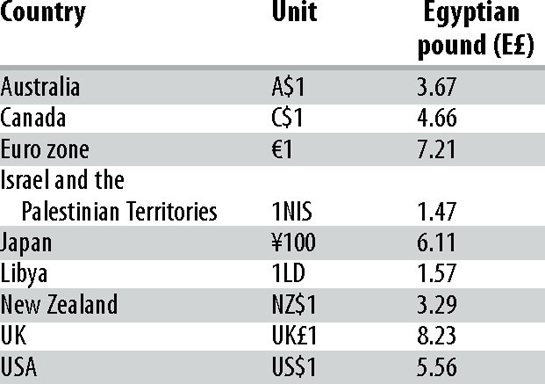

IRAQ

Backpacking Iraq

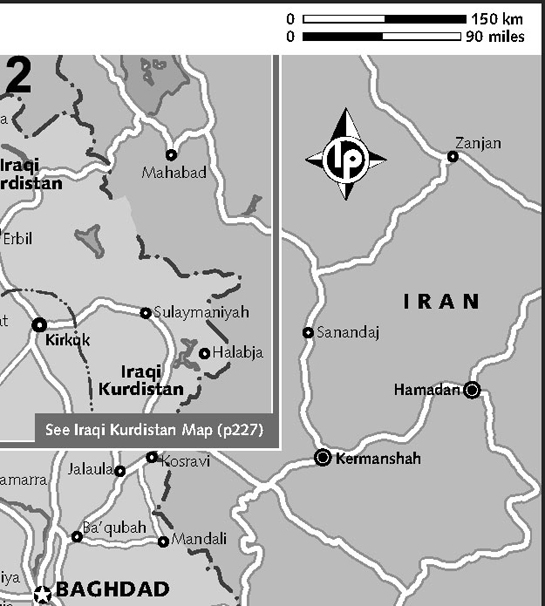

It’s not everyday that Iraqi Kurds see American backpackers traipsing through their countryside. In some places, I was simply a curious anomaly. But in rural areas where America is considered to be the Kurdish peoples’ liberator, we Yanks were practically treated to a hero’s welcome.

Late one afternoon, my mate Chase and I – both Americans – arrived in the hillside town of Akre. We had just begun hiking up the steep town to look for a hotel when a Kurdish Peshmerga soldier armed with an AK-47 rifle ran over to us, glanced at our rucksacks and cameras, and demanded to know who we were. ‘We are tourists,’ I said. ‘Em geshtiyar in,’ Chase repeated in Kurdish. The dumbstruck soldier took us to his boss, Peshmerga Commander Ayoub, a round, jovial man with a friendly face, who was even more incredulous. We were the first Western visitors they had ever seen, American or otherwise. With a big grin and outstretched arms, Commander Ayoub welcomed us with steaming cups of hot tea and promptly assigned two of his soldiers to escort us on a sightseeing trip through town. ‘Americans good,’ Ayoub exclaimed with a thumbs-up sign, ‘President Bush VERY good!’

In 1928, New Zealand engineer Sir AM Hamilton was commissioned to build a road from Erbil to Haji Omaran through some of the most inhospitable terrain in the world. He recounted his successful mission in his 1937 travelogue, Road Through Kurdistan. It remains a timeless, travel-writing classic and a wonderful insight into the psyche of Iraqi Kurdish people.

The pro-American hospitality would be repeated several times during my journey. In Haji Omaran, a local English teacher insisted I stay overnight with his family as a guest of the village. In Choman, a college student and his grandmother dragged me to their home and fed me a lunch fit for a king. In Gali Ali Beg, a family of Iraqi Kurds whipped out their cell phones and insisted on having their photographs taken with me. And in Shaqlawa, hotel manager Karim kept us up until the wee hours to chat politics over mugs of cold Heineken beer. ‘We may not necessarily agree with American policies,’ he said, ‘but we love American people!’

César Soriano

War Correspondents Invade Iraq

By February 2003 the US-Iraq war seemed like a foregone conclusion. At the time, I was working as an entertainment and celebrity reporter for USA Today. Because I was a US Army veteran I was tasked to be one of 800 civilian journalists who would be ‘embedded’ with military forces for a front seat to war. In early March, I flew to Bahrain and hopped a puddle jumper to USS Constellation, an aircraft carrier with a crew of 5000 that would be my home for the next month. As embedded journalists, we lived, slept, ate and worked alongside young sailors and marines and followed them anywhere they went, even into combat. We floated around the Gulf for several weeks of sheer boredom and anxiety, waiting for war. On 19 March the war began with a volley of air strikes and missile attacks that were dubbed ‘shock and awe’.

It Seems Ridiculous, But I’m Really Enjoying Iraq Tony Wheeler

In this condensed extract from his book Tony Wheeler’s Bad Lands: A Tourist on the Axis of Evil, Lonely Planet founder Tony Wheeler crosses the border from Turkey into Iraq. The year is 2006…

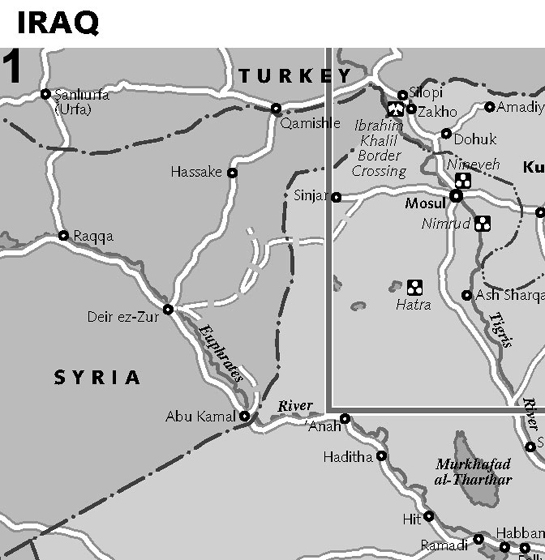

The border is a chaotic, muddy mess and it’s raining solidly again. Husni seems to know exactly which door to head for, which window to bang on, which queue to barge to the front of and exactly whom to bribe. I spot him slipping a note into my passport before he hands it over to one official. Nevertheless it takes over an hour of zigzagging from one ramshackle building to another before we make the short drive across the bridge that conveys us into Iraq.

Arriving in Iraq is like a doorway to heaven. Suddenly I’m sitting in a clean, dry, mud-free waiting room being served glasses of tea while we wait for the passports to be processed – Husni’s too. The officials decide to put me through hoops, however, and I have to spend 20 minutes explaining why I want to visit Iraq and what I do for a living. Finally they relent, hand my passport over, and welcome me to Iraq. I’ve already been welcomed by half a dozen Peshmerga soldiers, photographed with two of them and had a chat, in French, with one.

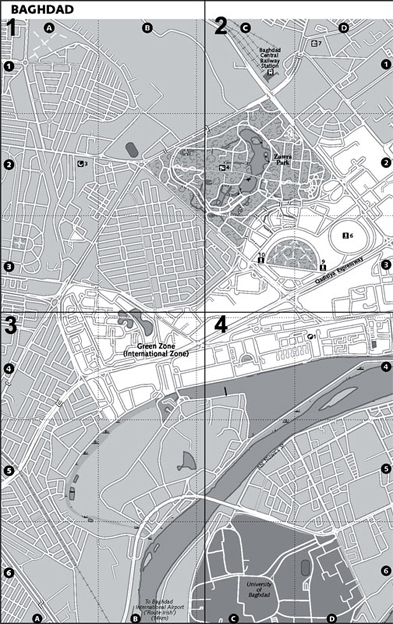

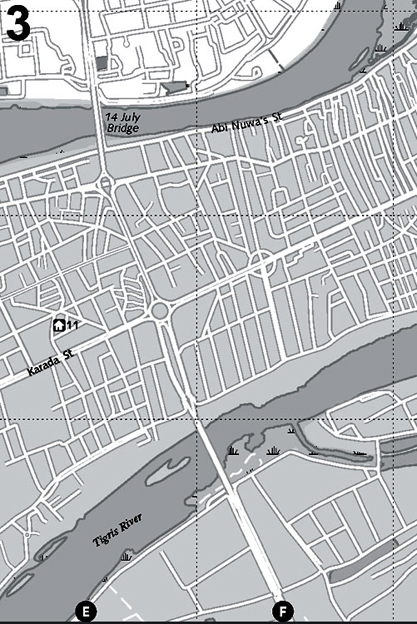

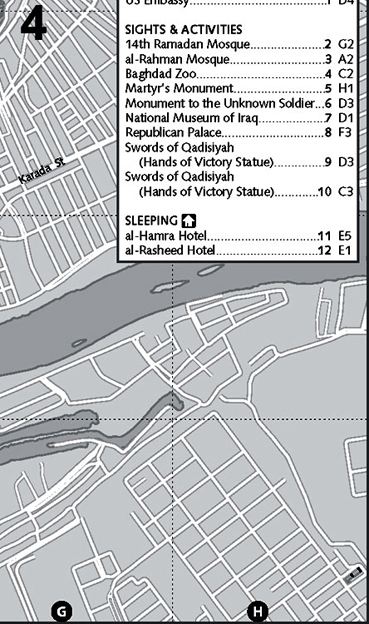

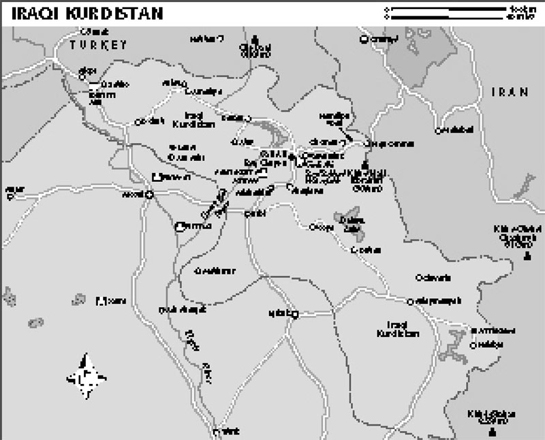

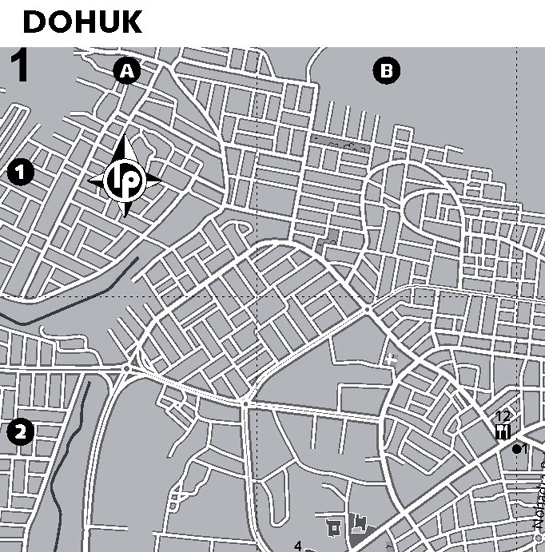

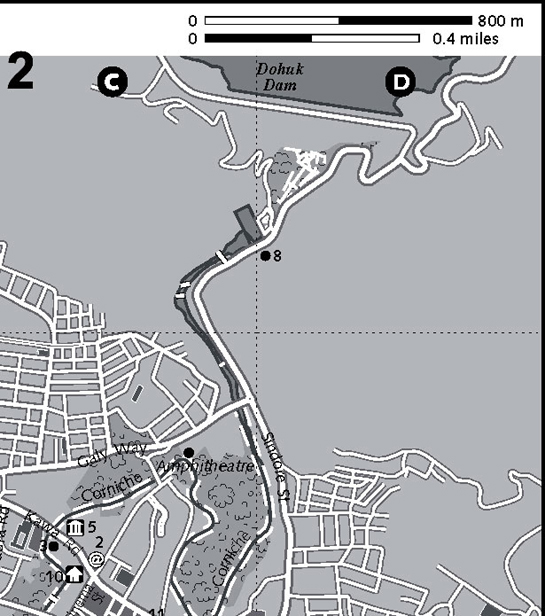

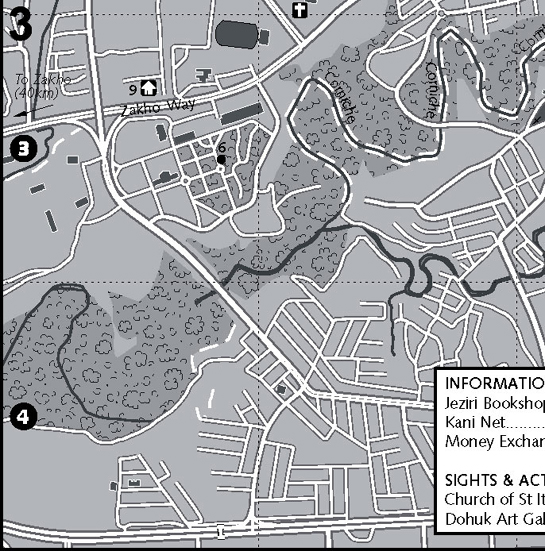

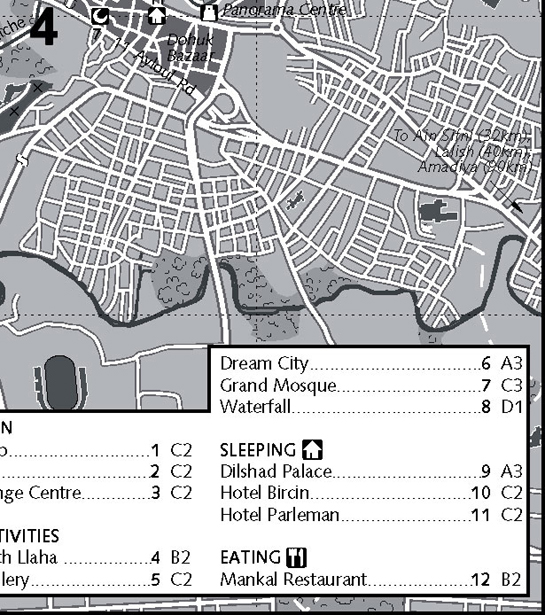

Husni drops me in a car park, and I take a taxi to Zakho to look at the town’s ancient bridge before continuing on to Dohuk for the night. As we drive in to the centre there are a surprising number of hotels. I take an instant liking to Dohuk. It’s bright, energetic and crowded and has lots of fruit-juice stands. I wander around the town, try out an internet café – it had such a tangle of wires leading in to the building, I concluded it had to be the centre of the World Wide Web – search inconclusively for Dohuk’s bit of decaying castle wall, look in various shops in the bazaar, check out the money-changing quarter (there are no ATMs that work and credit cards don’t function either) and take quite a few photographs. Everybody is very enthusiastic about being photographed, a sure sign that there aren’t many tourists around.

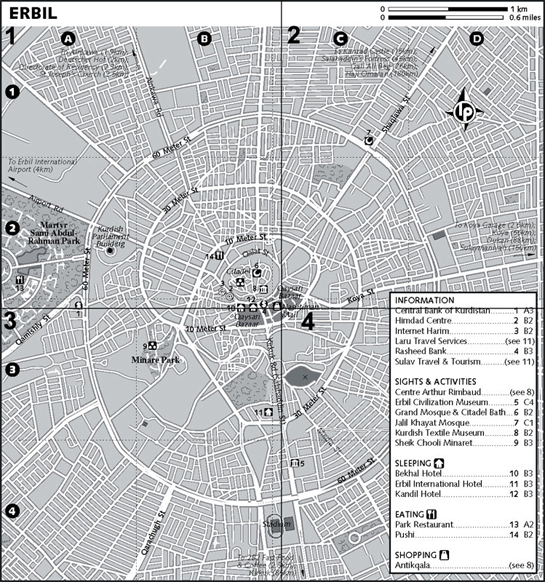

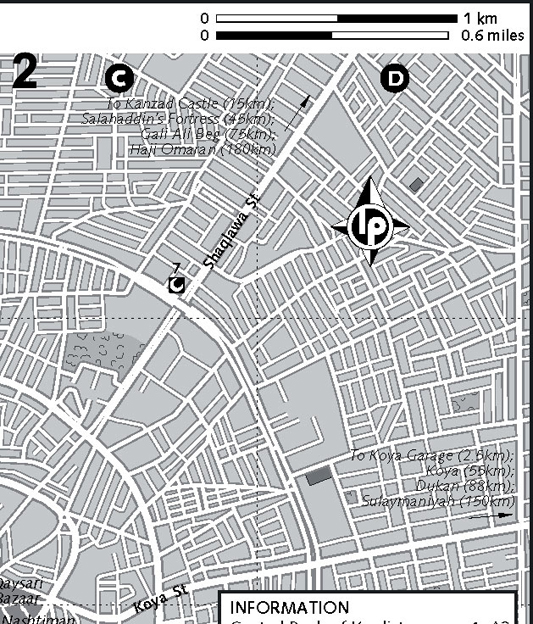

Erbil is a delight as well. A sign announces the Kurdish Textile Museum. Recently opened and very well presented, the museum displays an eclectic collection of carpets, kilims, saddle bags, baby carriers and other local crafts along with well-presented displays and information about the Kurdish people and nomadic tribes. Lolan Mustefa, who established the museum, is a mine of information on Erbil and the surrounding region. I’m enormously impressed that he has put so much effort into creating an excellent tourist attraction when Iraq today has so very few tourists.

From the museum I continue to the citadel’s mosque, visit the hammam (or bathhouse) and enjoy the view over the city from the citadel walls on the other side. Back down below the citadel walls I explore the bazaars, inspect the kilim shops, joke with the shoeshine guys, check the selection of papers on sale at the newsstands, photograph the photographers waiting for customers outside the citadel, snack on a kebab and drop in to a fruit-juice stand for an orange juice. It seems ridiculous, but I’m really enjoying Iraq.

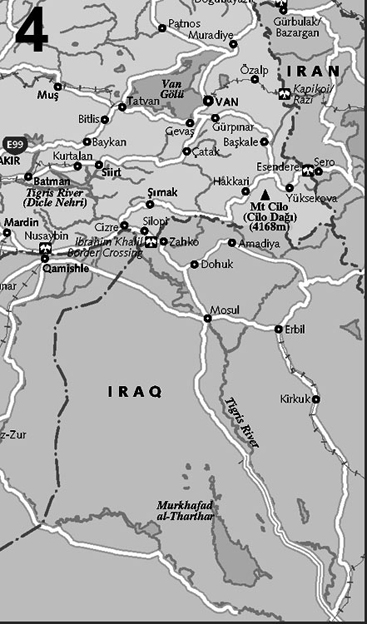

What’s Changed? César Soriano

I retraced Tony’s steps in 2008 while researching this guidebook. Thankfully, the Ibrahim Khalil border crossing isn’t as chaotic anymore – it took less than 45 minutes to get from Silopi (Turkey) to Zakho, including customs and immigration processes (for information on the crossing, Click here). Like Tony, I took an instant liking to Dohuk; it’s a wonderfully addictive town with a youthful feel and growing tourism industry. Iraq is still a cash country, but some places, including Erbil’s Kurdish Textile Museum, now accept credit cards. ATMs are also popping up, but at the time of writing they only worked for Iraq-held accounts. In late 2006, the citizens of Erbil’s citadel were controversially paid off and evicted from the ancient mound to make way for redevelopment; most of the citadel is now a ghost town. Thankfully, the tasty fruit-juice stands are still common throughout Iraqi Kurdistan.

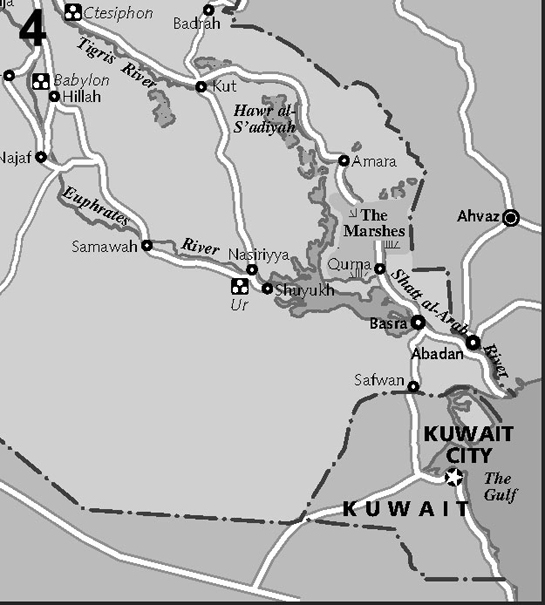

Itching to get to the front lines, I made my way to the Kuwait Hilton, where many journalists were assembling to cover the biggest story on the planet. On 9 April, Baghdad fell to US forces. Still, I hitched a ride with several journalists to Basra. With no guards or customs officials at the border, we strolled into Iraq easily, occasionally passing British and American troops. In Basra, Richard Leiby (Washington Post journalist) and I hired a taxi to the capital. No armed guards, no weapons, just two guys and a taxi on the road to Baghdad. We arrived late at night to find hundreds of other journalists encamped at the famous Palestine Hotel. By then, the invasion was over, but little did we know that the war was just beginning.

Imperial Life in the Emerald City: Inside Iraq’s Green Zone by Washington Post reporter Rajiv Chandrasekaran is a blunt, often hilarious account at America’s attempt at nation building after the 2003 US-led invasion. It leaves many a reader laughing, crying and furious. A film adaptation by director Paul Greengrass will be released in 2009.

Over the next several years, I returned to Iraq many times, occasionally embedding with other US forces including the US Marine Corps and US Army. Because of the ongoing violence, being embedded is often the only safe way for reporters to work and travel around Iraq, but it’s also the most restrictive. Contrary to popular belief, most journalists working in Iraq are not embedded or hunkered down in the Green Zone. These ‘unilaterals’, to use military parlance, live and work alongside Iraqi civilians, sharing their lives and the danger.

Since 2003, more than 130 journalists have been killed covering the war in Iraq.

César Soriano

Return to beginning of chapter

JORDAN

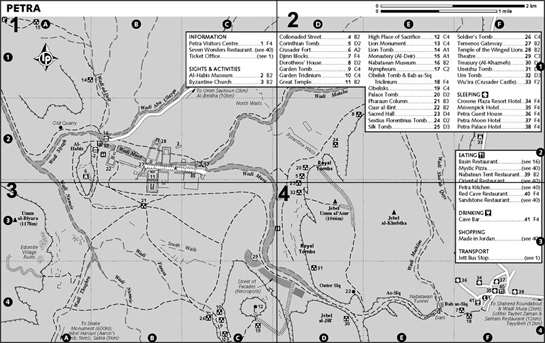

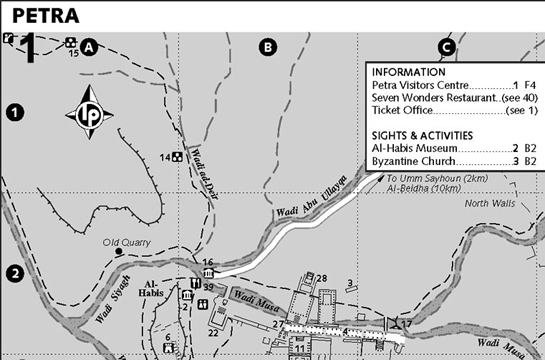

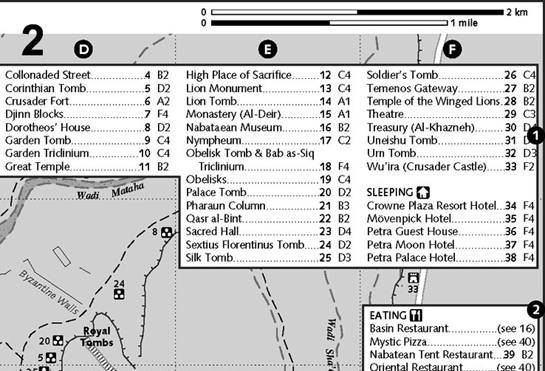

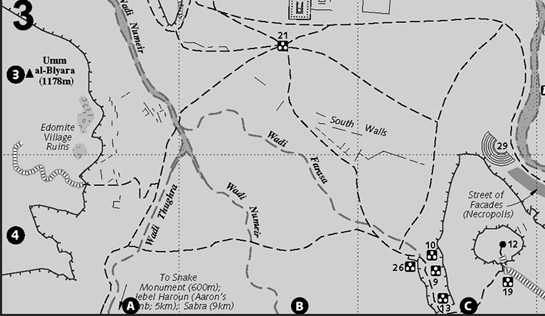

Vertigo on Horseback

She didn’t look capable of much when I slipped into the saddle but I should have known better than to underestimate a glossy chestnut Arab with a star on her nose. ‘You can ride, no?’ asked Mahmoud as we edged the horses uphill in the opposite direction to the Siq. Odd time to be asking the question, I thought as we broke into a trot on the makeshift bridlepath out of town.

I hadn’t intended to go riding but when offered a different way to reach Petra’s Treasury I hopped into the saddle without a second thought. ‘You first person ever to say yes,’ said Mahmoud, pointing his horse in the direction of a distant plateau, ‘you must be crazy woman!’ It was breathtakingly beautiful, high above the stone turrets of Petra, the crisp winter sun drawing the colours from the rocky outcrops like a magnet.

Suddenly we reached the edge of the plateau and the horses lurched immediately from a canter into a gallop, snorting breath into the cut-glass air. I just about remembered to lift out of the saddle, leaning forward as one whole, magnificent horsepower urged at full speed across the slight rise. Caught somewhere between fear and exhilaration, I noticed the plateau was large…but not that large, and that it was surrounded on three sides by the end of the world. It was towards this aerial vacancy that we were now charging at full speed.

The path narrowed, the vague outline of Petra’s tortured rock formations passed below on either side of us and the edge loomed terrifyingly into view. ‘Stop. Stop! Sto…!’ The last ‘p’ disappeared over the rim of the plateau, together with heart, lungs and stomach. The rest of me came to a perfectly poised four-legged tiptoe on the vertical edge. We dismounted. ‘Come,’ said Mahmoud, ‘let me show you my Petra.’ Flattened out against the rock and gingerly looking down, I spotted two climbers below us on the opposite ledge. They too were looking down. Somewhere in the dark end-of-day gloom, a trail of tiny figures marched in single file up through the gap in the rock. ‘I said I’d bring you to the Treasury,’ said Mahmoud, triumphantly dangling over the ledge, high above the monument. ‘Coming down?’

Jenny Walker

For an intimate picture of the ways that the Bedouin, like Mahmoud, make Petra their own, read Married to a Bedouin by Marguerite van Geldermalsen. The author met her husband in 1978 while backpacking around Jordan and spent the next two decades living near his extended family within the ancient city, raising three children and running the local clinic.

Careful Handling in Wadi Rum

We gripped the frosty rails of Vehicle Number 1 and headed for a sandy rise, safe in the hands of our Bedouin driver. Having written our own off-road guide, we knew exactly what he would be thinking – is it the right speed for the incline? Will the engine cope? Can we reverse downhill if necessary? But today it wasn’t our responsibility, so when Vehicle Number 1 ground to a halt, spraying sand from all four wheels independently, we just laughed.

Time for Vehicle Number 2: a stranger bundled us into his cosy pickup and sailed competently over the dune, finding time with one hand to wrap me in a goat-hair blanket while answering his mobile with the other. He was ‘on business’ at a nearby camp but detoured to unload us into Vehicle Number 3.

Number 3 was a work of art – dashboard padded with sheepskin, dangling talismans against the evil eye, a door attached with masking tape and an absent handbrake. Unfortunately, there was an absence of petrol too and so we unwrapped our picnic, resigned to a long wait. One bite into a cow-cheese triangle and Vehicle Number 4 arrived, backfiring like a mule on chilli. Five minutes aboard this bucking bronco and it sneezed out the drive shaft.

The sun sank behind great auburn pillars of sandstone and it was mind-numbingly cold so we were pleased when a whistle produced Vehicle Number 5 – with its 14-year-old driver. With superb skill he delivered us to base and drove off without waiting for thanks.

Our memorable journey was a seamless display of care. None of the drivers asked us for money; they simply delivered us hand-over-hand into safety. The Bedouin don’t pay lip service to ‘hospitality’ – they live it.

Jenny Walker

TE Lawrence didn’t have the luxury of mechanised transport in the desert but he did document the extraordinary hospitality (not to mention irascibility and stubbornness) of the Howeitat of Wadi Rum in Seven Pillars of Wisdom. This epic account of the Arab Revolt, in which he took part, remains the most intimate account of this region ever written in English.

Return to beginning of chapter

ISRAEL

A Hard day at the beach

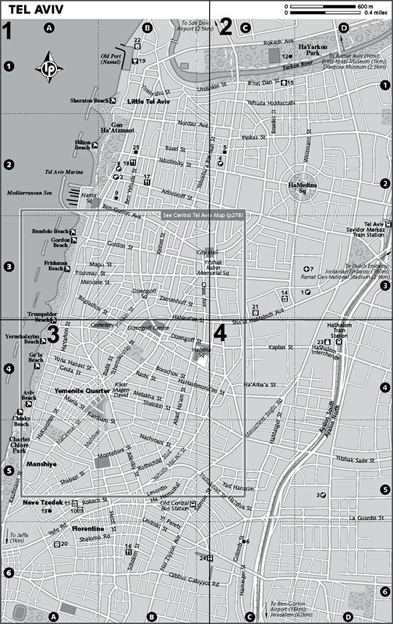

There’s no better a day in Israel than one spent on the beach in September. The weather’s perfect – hot but not blistering; breezy but not sand-blinding – and the Mediterranean’s warm and glassy as a soothing bath. The crowds of international tourists have gone home, the Israeli kids are back at school, and the local, vocal lifeguards have closed their megaphones for the season, leaving vast swathes of sparkling sand for the rest of us to relish.

Our usual lazy location is a beach just north of Tel Aviv, since there’s safe paddling for the children and a strong line in passionfruit margaritas for the grown-ups. We pick a shady spot, strip our tribe of toddlers down to the bare essentials, and settle in for sandcastles, sun and snacks. It’s the most mellow day out you could hope for in the midst of the Middle East.

Today, I’ve brought along a British friend’s two little children to play with our gang of four. Armed with buckets and spades, I head down the steps to the beach in sole charge of my group of six blonde-haired, blue-eyed under-4s, constantly counting the numbers to ensure no one’s gone AWOL.

‘French fries, everyone,’ I call, as the legion of little children trots eagerly along behind me all the way to the waterfront. At this time of year, the beach’s usual crowds have been replaced by a regular clientele of squawking old ladies, gossiping, smoking and playing cards beneath their parasols. I walk. The children follow. A hush descends among the ranks of pensioners. Mouths gape as the children parade past them like a gaggle of ducklings. ‘They can ’ t all be hers…can they?’ I hear the crowd whispering. ‘What hard work it must be!’ It’s very rare you see blonde toddlers in Israel. It’s even rarer to see so many old ladies so quiet.

For a great beach read, pick up Israeli author David Grossman’s novel, The Zigzag Kid, which tells the story of a 12-year-old boy’s trials and adventures on the eve of his Bar Mitzvah. Grossman is one of Israel’s most successful authors in translation and has also published several children’s books.

We reach the shoreline and I sink my toes into the sand. The ladies resume their squawking, I stretch out in my sarong and the children head for the open sea. A bronzed waiter appears. ‘Chips for six, please,’ I smile. He raises an eyebrow. ‘And a margarita for their hard-working mother.’

Amelia Thomas

Return to beginning of chapter

PALESTINIAN TERRITORIES

A Light in the Darkness

On the road as a Lonely Planet author and journalist in the West Bank and Gaza, it often seems that the scales are balanced precariously between the good and the bad. There was the Christmas tree–lighting ceremony in Bethlehem’s Manger Sq, beneath a magical snow flurry. The time, during Israel’s Gaza disengagement of 2005, when I found myself holed up with a group of armed Jewish militant settlers inside an abandoned old hotel. An afternoon spent with the head of the militant Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigade in restive Jenin refugee camp. The cold beers sipped at Taybeh Brewery’s happy hilltop Oktoberfest. The hours I queued pregnant at the Erez checkpoint after researching the Gaza Strip, hoping I wouldn’t go into labour before complacent soldiers allowed me back into Israel.

Sometimes, when the scales seem to be tilting in favour of the bad, I remember a trip I took into the scruffy Aida Refugee Camp, on the outskirts of Bethlehem, where one determined man has made a difference to a generation of children’s lives.

‘Welcome!’ Abdelfattah Abu Srour greeted me with a grin. ‘Come on in!’

In Aida camp it’s hard to imagine that anyone spends much time smiling. Immured behind Israel’s ‘security wall’ and subjected to frequent military incursions, it’s a place of concrete, curfews and barbed wire. But Abdelfattah has pledged to make life better for the kids of the camp, creating the Al Rowwad theatre centre as a stage on which to set free their everyday frustrations.

Get hold of a copy of Growing Up Palestinian: Israeli Occupation and the Intifada Generation by Laetitia Bucaille, for a glimpse into the lives of young Palestinians who have never experienced the world outside their refugee-camp homes.

That afternoon I wandered its small rooms watching children rehearsing a new play, with Abdelfattah their diligent director. Other kids were taking music lessons, working on computers and surfing the internet. The centre is a blazing light in an otherwise dark world, providing hope and happiness for dozens of Palestinian children. We drank a cup of coffee. I listened to Abdelfattah’s dreams for the centre’s future and I knew that while people like him are hard at work ensuring children can continue to dream, the scales haven’t tipped too far in the wrong direction.

Amelia Thomas

Return to beginning of chapter

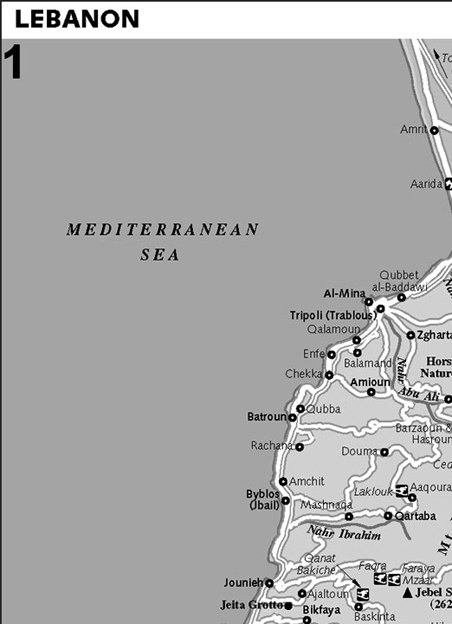

LEBANON

Breakfast on mt Lebanon

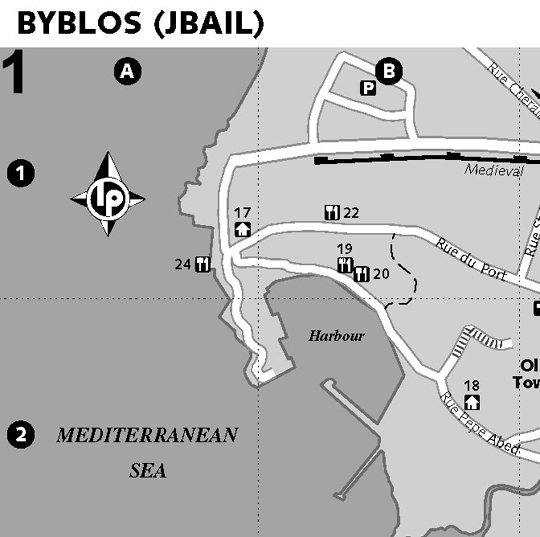

It’s early morning in the Mt Lebanon Ranges and I’m standing in a forgotten field that’s full of ancient Greek ruins, en route to the ancient Lebanese port town of Byblos. Gunshots ring out in the clear morning air, echoing through ancient temple archways as I pick my way across the desolate, rock-studded site. Not another soul is in sight. Bang. Bang, bang. The volley is getting louder. Lebanon is a relatively peaceful place just now; I’ve picked a lull between political assassinations, Palestinian gun battles and Hezbollah upheavals. But still, I’m five months pregnant and in Lebanon you never know what’s lurking around the corner. Bang. Bang. I hurry across grass crisp with frost towards the gatekeeper’s hut, which was unmanned when I entered. The gatekeeper appears, grinning, with a rifle over his shoulder. ‘Rabbits,’ he declares, ‘for breakfast.’ He gazes at my tummy. ‘Coffee?’ He produces a battered kettle. ‘Strong and sweet. Good for the baby.’

Amelia Thomas

Waxing Lyrical in Deir al-Qamar

Waxworks have never really been my cup of tea, so it seemed unfortunate that one of Lebanon’s favourite national pastimes appeared to be traipsing around musty halls filled with the slightly skewed features of long-dead politicians, national heroes, and the odd tragic British princess or George Bush Sr. Everywhere I went in Lebanon, there was yet another waxworks – big, small, or downright bizarre – just waiting for me to step intrepidly inside, and Deir al-Qamar was no different.

Lebanon’s contradictory nature – a place overshadowed by the threat of extreme violence, but offering relentlessly warm hospitality – is captured in all its tragic humanity in Robert Fisk’s Pity the Nation: Lebanon at War, though unlike my morning in the mountains, he was often dodging real bullets.

We arrived back in the small, picturesque town – Lebanon’s prettiest – after a long day trekking the trails of the vast Chouf Cedar Reserve. The late afternoon light was fading from pink to russet and bats were emerging from the eaves of ancient buildings surrounding the town square. The small grocery stores were closing their doors for the night, the café on the square was full of locals and tourists winding down over ice-cold beers, and yet, to my chagrin, the waxworks was still open, with reception lights blazing.

‘Come in, come in!’ the ticket clerk cried, as I peered reluctantly into the lobby.

‘I wouldn’t want to bother you if you’re about to…’

‘Nonsense! Our guide is honoured to show you our collection.’ On cue, an ancient, near-deaf man in a dirty baseball cap stepped grinning eagerly from the shadows, ‘Come in!’

I took a deep breath, assumed my most fascinated expression and put my best foot forward.

‘Jumblatt…Jumblatt Junior…Senior…Senior’s Father…Headless Jumblatt!’ the old guide barked, in English and then in French, as he frogmarched us into our third long gallery, this one filled with weird wax renditions of the powerful Druze chieftain clan.

‘Why is he headless?’ I ventured.

‘Quoi?’ he yelled, cupping a hand to his ears and continued on regardless.

A full and excruciating 30 minutes later, the tour concluded with a final quick-fire bilingual round of 20 obscure historical figures and one hoarse old tour guide. We applauded with relief as he came to the end of his spiel. He bowed proudly.

‘Mademoiselle,’ he confided, leaning forward, ‘it has been a pleasure to meet someone who appreciates beauty.’

‘Well, I…’ I began.

‘So much so,’ he seemed not to hear me, ‘that there’s a little something extra you might be interested to see.’

My heart sank. Visions of a hidden Albert Hall of wax dummies filled my mind.

‘Allons-y,’ he shuffled off, ‘follow, please.’

Outside, night had closed in and bright strings of fairy lights illuminated the town square. I looked over with envy at the terrace café, where crowds sat listening to a local musician. The old man beckoned, producing a fistful of keys and fumbling with the lock in a heavy wooden door. I sighed and followed.

Up on the roof of the once-grand, abandoned summer palace, the view of the town was something from a dream. Low clouds rolled gently across the rooftops, mingling with woodsmoke from crooked chimneys. The lights on the square below twinkled. An owl hooted and swept by in a feathery hush. I surveyed the fairytale rooftop scene, reflected a thousand times in the broken window panes of the once-grand hall of the summer palace. This was well worth 30 minutes of morose, melting mannequins.

‘It’s beautiful,’ I whispered to myself.

‘Oui, mademoiselle,’ the old man’s hearing was suddenly sharp as a shard of broken window, ‘almost as beautiful as the waxworks.’

Amelia Thomas

Deir al-Qamar seems to have changed little in the last century or so. For a strong evocation of 19th-century Lebanon, delve into The Rock of Tanios by journalist Amin Maalouf, which tells a compelling tale of murder and mystery in a Lebanese village.

Return to beginning of chapter

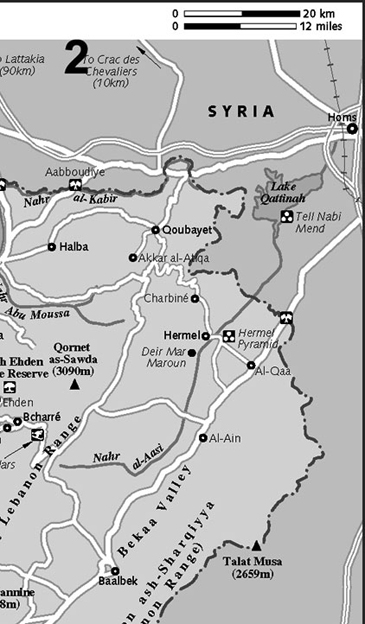

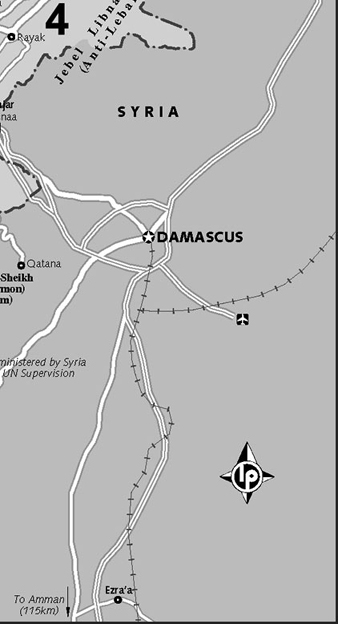

SYRIA

Damascus Nights

It was almost 10 years to the night since I had first walked down the steps behind the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus and through the doors of Al-Nawfara Coffee Shop. It was like coming home. For three months back in 1998, I had spent almost every evening here, arriving a couple of hours before the sunset call to prayer to find a quiet corner to write and chat with the locals before Abu Shady, the resident hakawati (storyteller), took his throne. Occasionally, in the manner of all live acts, his performance fell flat. But when it worked there was magic in the air as he wove fabulous tales, berated his audience and slammed down his sword for dramatic effect. In the time that I had been away from the Al-Nawfara Coffee Shop I had been drawn to the art of storytelling around the world. One time in particular, in the southern Spanish city of Granada, I had entered a tea room in the old Albaicín quarter and been assailed with apple-scented tobacco and the memories of stories told in Damascus.

But this time was different. The popularity of storytelling, that most noble of Middle Eastern art forms, is waning, displaced by gyrating pop divas beamed live from Beirut. Abu Shady had been one of my heroes. He was not a young man when I saw him last. That he was now the last heir to the Sheherezade throne had me worried – would I find him still telling tall tales?

I pulled up a chair in the corner of the shop, inhaled deeply and looked around. There in the corner, in the same seat that he has occupied for the past 10 years and probably longer, Mohammed was drawing long and hard on his nargileh. When I introduced myself and asked if he remembered me (he clearly didn’t), he exhaled and said without hesitation, ‘Yes, and you still owe me money.’ I looked around at the other faces, most of which were lined with the passing years but unmistakeably the same. And there in the corner sat Abu Shady, chain-smoking and reminiscing about old times with his friends. When he donned his waistcoat and planted his tarboosh atop his head and climbed his throne, I felt a frisson of excitement. And then, with the manner of a kindly grandfather, with all the passion of an angry imam, he began to tell the story of the star-crossed lovers of Anta and Abla. The years melted away. When he was finished Abu Shady shuffled off into the night, leaving me to draw long draughts of reassurance from my nargileh.

In Damascus Nights, Rafik Schami, the exiled Damascene writer, tells the marvellous story of Salim the coachman, a storyteller in Damascus who loses his voice and only the seven stories of seven friends can bring it back. In its sense of magic, rambling digressions and larger-than-life characters, it’s just like a night spent at Al-Nawfara Coffee Shop.

By interviewing Abu Shady for this book, I came to know a man with a passion for stories, a greengrocer by day who devours the classic works of world literature in his spare time, a man who believes that although he is one of the world’s last storytellers, the tradition will never die. The world will, he assured me, always need stories, then he introduced me to his son, Shady, who promised that he stands ready to continue the tradition when his father retires.

Anthony Ham

Hospitality’s Generation Next

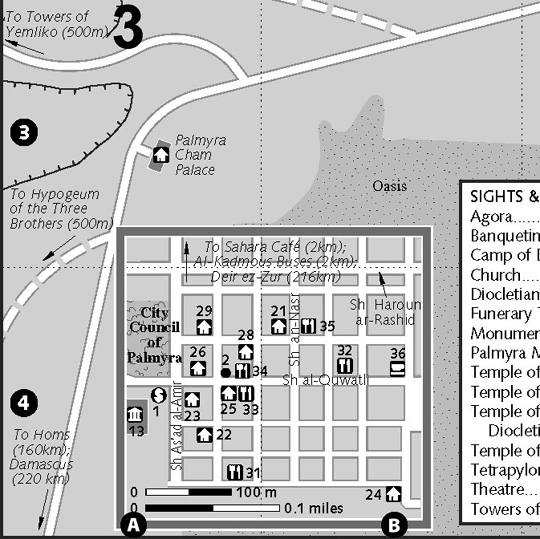

As I picked my way through the ruins of Palmyra, I became accustomed to men with camels, men with portable eskies and men with ‘old Roman coins, very cheap’. But Hamid, a local Bedouin boy, was different – he asked for nothing more than a coin to add to his collection. Finally, he settled on a 50¢ coin, forsaking the more-valuable €1 and €2 coins on offer because he already had them. He handed me a set of dusty postcards. Keep the postcards and the coin, I told him. Suddenly serious-faced, he gave back the coin, assuring me that he had never accepted money for nothing and didn’t intend to start now.

To understand the Syrian love of hospitality at a deeper level, read Damascus: Taste of a City by Marie Fadel and Rafik Schami, while the lives of children across the region take centre stage in the enlightening Children in the Muslim Middle East, by Elizabeth Warnock Fernea.

A few weeks later, outside the citadel in Aleppo, I found Abdul lingering in my shadow. This quiet, gentle boy became my silent companion as I wandered through the souqs, translating for me when my Arabic wasn’t up to it, always polite, never asking for anything in return. Later again, this time in the courtyard of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, a young girl named Fatima began by playing with my daughter and ended by inviting us to her family’s home for a meal. I had long ago grown used to friendliness at every turn and gracious hospitality in Syria. I just wasn’t expecting it to start so young.

Anthony Ham

Return to beginning of chapter

TURKEY

Divriği’s Divine Doors

It was a typical start to a Turkish journey. I took a taxi to the Sivas otogar, where the men shook their şapkas (hats) and said the next dolmuş to the southeast left in a few hours. As I had more than 350km to cover that day, I decided to tear up the thrifty traveller’s rulebook and commandeer the taxi. The driver’s eyes bulged behind his glasses, but he rapidly recovered and calculated the charge. We negotiated and haggled and bartered and frowned and, eventually, smiled and shook hands. Woohoo!

Bircan (the driver and I were now on first-name terms) steered us out of town. The rolling hills had one-mosque villages in their folds and stickmen shepherds on their ridges. Our first stop was Kangal, announced by a statue of a black-faced, pale-bodied, spiky-collared canine. Kangal dogs, originally bred to protect sheep from wolves and bears, are now man’s best friend across Turkey.

Another type of creature had drawn me to this remote service town and I soon came face to scaly face with it at the Balıklı Kaplıca health spa. The warm water is inhabited by ‘doctor fish’, underwater ticklers that nibble fingers, toes and any other body part you offer them. The fish supposedly favour psoriasis-inflicted skin and the spa attracts patients from all over the world, but the school happily gets stuck into any patch of flesh. It’s wonderfully therapeutic to dangle your feet in the water and feel nature giving you a thorough pedicure.

Shirking the recommended three-week treatment, we returned to the taxi. As the dry brown hills turned into snow-capped mountains, the road began to resemble a rollercoaster and Bircan’s driving became increasingly inventive. Luckily, he was paying a rare visit to the right side of the white lines when we arrived at the military checkpoint.

Bircan’s English was as lousy as my Turkish, but we always managed to communicate the important things. When the soldiers had examined our IDs and waved us on, he explained, ‘PKK…terror!’ The years of widespread insurgency in Kurdish southeastern Anatolia are over, but the area’s fearsome reputation endures, as do military operations against the PKK (Kurdistan Workers Party).

Our last stop before taking the Big Dipper home was Divriği, a town dominated by Alevi Muslims in a valley between 2000m-plus mountains. It had a tense feel, but there was a good reason to come here. Three reasons, in fact. The Ulu Cami mosque and medrese (Islamic seminary), built in 1228 and named on the Unesco World Heritage list, has a trio of doorways carved in mind-boggling detail. Each door is decorated with a stone starburst of flowers, medallions, interlinking geometric forms and Arabic inscriptions.

When Bircan had finished praying, I asked him if he was glad I’d dragged him all this way. He smiled. The doors were so intricately carved, he said, that their craftsmanship proved the existence of God.

James Bainbridge

Andrew Eames recounts his journey to ancient sites in The 8.55 to Baghdad. On the eve of the Iraq War, he retraced the British crime writer Agatha Christie’s life-changing train journey through the Balkans and the Middle East to Ur, Iraq. A chapter covers his Turkish adventures.

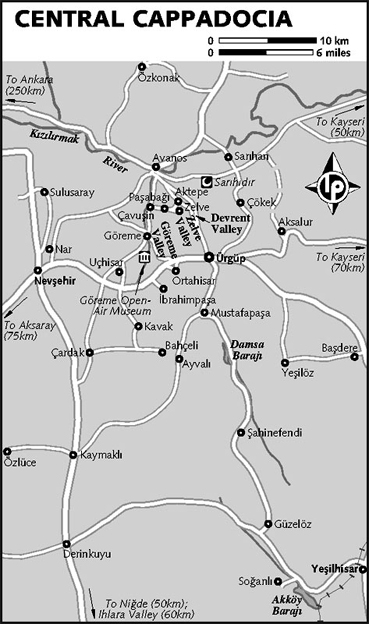

Above the Fairy Chimneys

Morning! For the first time in my life, I was happy to get up at 5am. I was taking a balloon flight over Cappadocia’s unique landscape of fairy chimneys (rock formations). With 10 other passengers, I clambered into the basket and took a deep breath of crisp country air as we left the ground crew far below.

The valleys housing the chimneys looked as remarkable, if not as snigger-inducing, as the often-phallic formations; the wavy tuff (compressed volcanic ash) resembled a mound of wobbly blancmange. With the balloon’s bulbous shadow falling on the curvy cliff faces, it was a symphony of surreal shapes.

Some 28 balloons fly most mornings and the multicoloured craft dotted the blue sky. The pilot was able to control the balloon’s height to within a few centimetres, allowing us to descend into a valley to pinch some breakfast from an apricot tree in a secret garden. Around us, the rock was riddled with pigeon houses, traditionally used to collect the birds’ droppings for fertilising the fields. As we used the katabatic currents of cool air to surf down the valleys, or rose on a warm anabatic wind, the only sound was the flame shooting into the balloon.

Former Lonely Planet author Tom Brosnahan’s memoir, Turkey: Bright Sun, Strong Tea, begins high above the Atlantic Ocean, as the US writer-to-be flies to Turkey at the end of the ‘Summer of Love’, to work for the Peace Corps in İzmir.

Leaving the fairy chimneys, we climbed almost 1000m and admired Erciyes Dağı (Mt Erciyes), which formed Cappadocia when it erupted. I had to pinch myself to check I hadn’t overslept: moving effortlessly through the air above those flowing valleys was just like dreaming.

James Bainbridge

History, Politics &

Foreign Affairs

THE CRUSADES & THEIR AFTERMATH

The Middle East is history, home to a roll-call of some of the most important landmarks in human history. Mesopotamia (now Iraq) was the undisputed cradle of civilisation. Damascus (Syria), Aleppo (Syria), Byblos (Lebanon), Jericho (Israel and the Palestinian Territories) and Erbil (Iraq) all stake compelling claims to be the oldest continuously inhabited cities on earth. And it was here in the Middle East that the three great monotheistic religions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – were born. Fast forward to the present and the great issues of the day – oil, religious coexistence, terrorism and conflicts over land – find their most compelling expression in the Middle East. It remains as true as it has for thousands of years that what happens here ripples out across the world and will shape what happens next in world history.

Five out of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World were within the boundaries of the modern Middle East: the Temple of Artemis (Turkey), the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus (Turkey), the Hanging Gardens of Babylon (Iraq), Pharos of Alexandria (Egypt) and the Pyramids of Giza (Egypt).

This section sketches out the broadest sweeps of Middle Eastern history – for further details see the more-specific history sections in the individual country chapters throughout this book.

CRADLE OF CIVILISATION

The first human beings to walk the earth did just that: they walked. In their endless search for sustenance and shelter, they roamed the earth, hunting, foraging plants for food and erecting makeshift shelters as they went. The world’s first nomads, they carried what they needed; most likely they lived in perfect harmony with nature and left next to nothing behind for future generations to write their story. It was a difficult life, always on the move and vulnerable to predators and the elements. Increasingly, when they found a spot they liked, they stayed a little longer, either in caves or in shelters that would last long beyond the next morning. By observing the plants that bore food, they planted their first rudimentary crops and began to develop stone tools. Thus it was that they began to put down roots.

The Great Pyramid of Khufu (built in 2570 BC) remained the tallest artificial structure in the world until the building of the Eiffel Tower in 1889.

The first signs of agriculture, arguably the first major signpost along the march of human history, grew from the soils surrounding Jericho in what is now the West Bank, around 8500 BC. Forced by a drying climate and the need to cluster around known water sources, these early Middle Easterners added wild cereals to their diet and learned to farm them. In the centuries that followed, these and other farming communities spread east into Mesopotamia (a name later given by the Greeks, meaning ‘Between Two Rivers’), where the fertile soils of the Tigris and Euphrates floodplains were ideally suited to the new endeavour. For some historians, this was a homecoming of sorts for humankind: these two rivers are among the four that, according to the Bible, flowed into the Garden of Eden. At around the same time, the enduring shift from nomadism to more sedentary, organised societies was gathering pace in the Nile River valley of ancient Egypt.

THE MIDDLE EAST’S INDIGENOUS EMPIRES AT A GLANCE

Few regions can match the Middle East for its wealth of ancient civilisations, all of which have left their mark upon history.

Sumerians (4000–2350 BC) Mesopotamia’s first great civilisation developed advanced irrigation systems, produced surplus food and invented the earliest form of writing.

Egyptians (3100–400 BC) This most enduring of ancient empires was a world of Pharaonic dynasties, exquisite art forms, the Pyramids and royal tombs. The monumental architecture of the empire reached new heights of aesthetic beauty.

Babylonians (1750–1180 BC) This empire further developed the cuneiform script and was one of the first civilisations to codify laws to govern the Tigris-Euphrates region from the capital at Babylon, one of the great centres of the ancient world.

Assyrians (1600–609 BC) Conquerors of territories far and wide and shrewd administrators of their domains from their exquisite capital at Nineveh, the Assyrians also developed the forerunners of modern banking and accounting systems. Their heyday was the 9th century BC.

Persians (6th–4th centuries BC) The relatively short-lived dynasties begun by Cyrus the Great ruled from India to the Aegean Sea and produced the stunning ancient city of Persepolis.

Ottomans (1300s–1918) The last of the great indigenous empires to encompass most of the Middle East. From the opulent capital in Constantinople, they governed from Iraq to North Africa before the decadence of Ottoman rule (and the ungovernable size of their realm) got the better of them.

In the 6th century BC, a culture known as Al-Ubaid first appeared in Mesopotamia. We know little about it, largely because it was soon supplanted by the Sumerians who were the first to build cities and to support them with year-round agriculture and river-borne trade. In the blink of a historical eye, although almost 2000 years later in reality, the Sumerians invented the first known form of writing: cuneiform, which consisted primarily of pictographs and would later evolve into alphabets on which modern writing is based. With agriculture and writing mastered, the world’s first civilisation had been born.

The Penguin Guide to Ancient Egypt, by William J Murnane, is one of the best overall books on the lifestyle and monuments of the Pharaonic period, with illustrations and descriptions of the major temples and tombs.

Elsewhere across the region, in around 3100 BC, the kingdoms of Upper and Lower Egypt were unified under Menes, ushering in 3000 years of Pharaonic rule in the Nile Valley. The Levant (present-day Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Israel and the Palestinian Territories) was well settled by this time, and local powers included the Amorites and the Canaanites.

Return to beginning of chapter

BIRTH OF EMPIRE

With small settlements having grown into city-states, and with these city-states drawing outlying settlements into their orbit, civilisations were no longer content to mind their own business. The moment in history when civilisations evolved into empires is unclear, but by the 3rd century BC, the kings of what we now know as the Middle East had listened to the fragmented news brought by traders of fabulous riches just beyond the horizon.

The Cyrus Cylinder, which is housed at the British Museum with a replica at the UN, is a clay tablet with cuneiform inscriptions, and is widely considered to be the world’s first charter of human rights.

The Sumerians, who were no doubt rather pleased with having tamed agriculture and inventing writing, never saw the Akkadians coming. One of many city-states that fell within the Sumerian realm, Akkad, on the banks of the Euphrates southwest of modern Baghdad, had grown in power, and, in the late 24th and early 23rd centuries BC, Sargon of Akkad conquered Mesopotamia and then extended his rule over much of the Levant. The era of empire, which would convulse the region almost until the present day, had begun.

Although the Akkadian Empire would last no more than a century, his idea caught on. The at-once sophisticated and war-like Assyrians, whose empire would, from their capital at Nineveh (Iraq), later encompass the entire Middle East, were the most enduring power. Along with their perennial Mesopotamian rivals, the Babylonians, the Assyrians would dominate the human history of the region for almost 1000 years.

The 7th century BC saw both the conquest of Egypt by Assyria and, far to the east, the rise of the Medes, the first of many great Persian empires. In 550 BC, the Medes were conquered by Cyrus the Great, usually regarded as the first Persian shah (king).

In 333 BC, Persian Emperor Darius, facing defeat by Alexander, abandoned his wife, children and mother on the battlefield. His mother was so disgusted she disowned him and adopted Alexander as her son.

Over the next 60 years, Cyrus and his successors Cambyses (r 525–522 BC) and Darius I (r 521–486 BC) swept west and north to conquer first Babylon and then Egypt, Asia Minor and parts of Greece. After the Greeks stemmed the Persian tide at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC, Darius and Xerxes (r 486–466 BC) turned their attention to consolidating their empire.

Egypt won independence from the Persians in 401 BC, only to be reconquered 60 years later. The second Persian occupation of Egypt was brief: little more than a decade after they arrived, the Persians were again driven out of Egypt, this time by the Greeks. Europe had arrived on the scene and would hold sway in some form for almost 1000 years until the birth of Islam.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, written in 2700 BC and one of the first works of world literature, tells the story of a Sumerian king from the ancient city of Uruk (which gave Iraq its name).

Return to beginning of chapter

HERE COME THE GREEKS

The definition of which territories constitute ‘the Middle East’ has always been a fluid concept. No-one, least of all the Turks, can decide whether theirs is a European or Middle Eastern country. And some cultural geographers claim that the Middle East includes all countries of the Arab world as far west as Morocco. But most historians agree that the Middle East’s eastern boundaries were determined by the Greeks in the 4th century BC.

THE PHOENICIANS

The ancient Phoenician Empire (1500–300 BC), which thrived along the Lebanese coast, may have been the world’s first rulers of the sea, for their empire was the Mediterranean Sea and its ports, and their lasting legacy was to spread the early gains of Middle Eastern civilisation to the rest of the world.

An offshoot of the Canaanites in the Levant, the Phoenicians first established themselves in the (now Lebanese) ports of Tyre and Sidon. Quick to realise that there was money to be made across the waters, they cast off in their galleys, launching in the process the first era of true globalisation. From the unlikely success of selling purple dye and sea snails to the Greeks, they expanded their repertoire to include copper from Cyprus, silver from Iberia and even tin from Great Britain.

As their reach expanded, so too did the Phoenicians’ need for safe ports around the Mediterranean rim. Thus it was that Carthage, one of the greatest cities of the ancient world, was founded in what is now Tunisia in 814 BC. Long politically dependent on the mother culture in Tyre, Carthage eventually emerged as an independent, commercial empire. By 517 BC, the powerful city-state was the leading city of North Africa, and by the 4th century BC, Carthage controlled the North African coast from Libya to the Atlantic.

But the nascent Roman Empire didn’t take kindly to these Lebanese upstarts effectively controlling the waters of the Mediterranean Sea, and challenged them both militarily and with economic blockades. With Tyre and Sidon themselves severely weakened and unable to send help, Carthage took on Rome and lost, badly. The Punic Wars (Phoenician civilisation in North Africa was called ‘Punic’) between Carthage and Rome (264–241 BC, 218–201 BC and 149–146 BC) reduced Carthage, the last outpost of Phoenician power, to a small, vulnerable African state. It was razed by the Romans in 146 BC, the site symbolically sprinkled with salt and damned forever.