Table of Contents

- Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- PART 1 – I'VE A GOOD MIND TO WRITE A LETTER

- PLEASE KEEP OFF THE MUD

- THIS JAGUAR LOOKS A BIT HALF-BAKED TO ME

- BRITAIN'S SURFACE INDUSTRY FAILS TO DELIVER

- MY CUP RUNNETH OVER AND INTO THE CENTRE CONSOLE

- BROWN'S GREEN TAX – A BIT OF A GREY AREA

- ANY COLOUR YOU LIKE AS LONG AS IT'S AVAILABLE FROM DULUX

- PORSCHE OUTPERFORMS DESKTOP PRINTER – SHOCK

- MEN, RISE UP AND EMBRACE THE WHEELBRACE

- HOW THE PEACE AND QUIET OF ENGLAND WAS RUINED BY THE NOISE OF PEOPLE COMPLAINING

- IN CASE YOU'RE READING THIS ON THE BOG, HERE ARE SOME EQUATIONS OF MOTION

- IT'S A CAR, JIMMY, BUT NOT AS WE KNOW IT

- PART 2 – THE FUZZY EDGE OF AUTOMOTIVE UNDERSTANDING

- CHARLES DARWIN MAY BE ON TO SOMETHING

- NAKED MOTORCYCLE PORN SHOWING NOW

- SOME OBSERVATIONS ON REAR-END HANDLING

- THE FUTURE OF IN-CAR ENTERTAINMENT

- THE TECHNICAL REVOLUTION IN THE TOYSHOP

- THE BEST DRIVING SONG IN THE WORLD EVER

- HOW TO DEAL WITH VAN DRIVERS

- BE AFRAID. BE VERY AFRAID. BUT ONLY OF THE SIZE OF THE BILL.

- I'M GAY, BUT NOT THAT GAY

- THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF THE CAR OF THE FUTURE

- THIS IS PERSONAL

- IS IT A CAR? IS IT A BIKE? NO. AND NO.

- IF HE KNOWS, HE'S NOT SAYING ANYTHING

- PART 3 – THESE ONES ARE ACTUALLY ABOUT CARS, SORT OF

- HOW GREAT CARS COME TO BE ABANDONED IN OLD BARNS

- BREAKING DOWN IS NOT SO HARD TO DO

- LAMBORGHINIS ARE GREAT. YOU SHOULD HAVE ONE.

- PIOUS PORSCHE PEDDLES PATHETIC PEDAL-POWERED PRODUCT

- THE FOLLY OF TRYING TO SAVE FUEL

- JEREMY CLARKSON RUINED MY DREAM CAR

- THE RANGE ROVER OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY

- POETRY ON MOTION

- ONLY THE FRENCH WOULD BUILD A CAR DESIGNED TO BREAK DOWN

- THESE MODERN SUPERCARS ARE ALL BLOODY RUBBISH YOU KNOW

- TRACK DAYS, OR THE FUTILITY OF GOING NOWHERE

- CLASSIC CARS – YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED

- ACHTUNG! BENTLEY!

- THE VAUXHALL VECTRA, A REPRESENTATIVE VIEW

- I'VE NEVER FELT SUCH A SPANNER

- PART 4 – THE THRILL OF THE OPEN ROAD (AT LEAST UNTIL THE PHOTOGRAPHER WANTS TO STOP AND TAKE A PICTURE)

- SOURCES

- INDEX

NOTES FROM THE HARD

SHOULDER

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 9780753520789

Version 1.0

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in

2007 by

Virgin Books Ltd

Thames Wharf Studios

Rainville Road

London

W6 9HA

Copyright © James May 2007

The right of James May to be identified as the Author of this

Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

This electronic book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

A catalogue record for this book is available from

the British Library.

ISBN: 9780753520789

Version 1.0

To Pullin and Green, for the

opportunity

PART 1 – I'VE A GOOD MIND TO WRITE A LETTER

PLEASE KEEP OFF THE MUD

It is time, now that someone has raised the truly preposterous notion of congestion charging in our national parks, to acknowledge a few painful realities about the countryside. There is a feeling at large that cars somehow do not belong in the countryside; I now put it to you that in fact the countryside belongs to the car.

Before anyone writes in with a volume of Rupert Brooke, I should make it clear that I understand perfectly the position occupied by the rural idyll in the English national consciousness; how its gently swaying fields of corn are instantly evoked by thoughts of home when abroad; how the memory of England endures not as a shopping centre or theme park but as an endless Arcadian vista who gave her flowers to love etc. But how are we to enjoy all this, if not from the car?

You could go for a walk, say some, but have you seen the size of the place? It would take me two days to reach the edge of it from where I live, and even then there would be a few golf courses to negotiate before I arrived in the other Eden. Cycling? Civilised bicycles only work on the road, and the road is only there because of cars. If you try off-roading on one of these so-called 'mountain' bikes, farmers will shoot at you. And I have to say that if I were a farmer, and you rode across my field with an inverted polystyrene fruit bowl on your head astride £2,000-worth of unobtanium, I'd shoot at you as well.

No – the problem is not that people keep driving through the countryside, it's that people keep living there.

If you're a farmer, tilling manfully on the land to produce the things I love to eat, then that's fine. Likewise a gamekeeper or some old toff, since they're not safe in the city. Also fine is running a country pub, as that's where I like to stop for a pie. But the rest of you – and especially those of you who think a two-inch-high ribbon of tarmac is somehow 'ruining the countryside' – can bugger off, because your houses are spoiling the view from my Porsche.

If, for example, you're a merchant banker working in the City, you should live in the City near the bank. If you're the manager of a country bank, you should live in the flat above it or in a windowless bothy alongside. Similarly, working for a software consultancy and living in the sticks is as absurd as turning up for work at a software consultancy in a straw hat singing ee-aye-ee-aye-oh. I don't want to escape to the countryside in my car to be rewarded with an endless rolling panorama of Barratt Homes. It's the ruin of England.

Everyone I know who lives in the cuds is, in terms of their demands, aspirations and general lifestyle, exactly the same as my neighbours in London. They are separated from me by nothing more than a very, very big garden. They drive into the town every day and complain about congestion, without stopping to think for long enough to realise that the road isn't there so that they can come in, it's there so I can get out in something with a flat six and enjoy a world as Adam would have known it.

The harsh truth is that cod country living is a privilege bequeathed entirely by the roads and motor transport. So if you live in Chodford and despise all things automotive, you should live as I imagine country folk did before the car was invented. That is, like a chicken; in your own poo, driven mad by blight and at the mercy of wild animals. You should ride a donkey, and the road to your damp dwelling should be a rough track beset by bandits and deranged inbreds with huge hands and one eye in the middle of their faces.

Actually, I'd go further than that. You should not be allowed anything in life that is in any way dependent on road transport. So no fresh shiitake mushrooms from the charming deli in the village, because they arrived in a van. You'll have to bake your own bread in the little cubby holes at the side of your Aga – the ones with the red-hot handles. And no reading the Daily Telegraph, because it isn't really a telegraph at all. It comes in a van as well.

Anti-car sentiment is nowhere as incongruous as it is in the countryside. In fact, the beauty of the countryside in modern times is that you can drive through it, look at it and then leave it alone. Its principal function is for the growing of carrots, but after that, it's what sports cars were invented for.

THIS JAGUAR LOOKS A BIT HALF-BAKED TO ME

I've now been sitting here for some hours looking at a picture of the Jaguar X-Type estate fitted with the maker's optional 'Sports Collection' body styling package. And I have to say, I'm just not sure about it.

To explain why, we have to go back a few weeks to an idle evening when I decided that I would make a Chinese meal. And I don't mean one contrived from a packet sauce and a tin of water chestnuts. I mean the real thing, like that bloke Ken Whatsit would do.

Now, I don't really rate myself as a chef. Anything outside the orbit of the old school favourites – shepherd's pie, cheesy pasta – is frankly a bit of a mystery. But that doesn't matter, because you can buy sets of instructions for clever cooking and the picture on the front is usually so good it's tempting just to eat the book.

I did everything properly. I went to a Chinese supermarket for the ingredients and I borrowed a wok from a neighbour. The preparation time amounted to many hours of careful chopping and straining.

But then it started to go wrong. I've heard a theory that oriental cooking is the way it is because of a historical shortage of fuel, so everything is cut up small and it's all cooked together in one very thin utensil that becomes blindingly hot in seconds. It all happened far too quickly.

I think the word that best sums up my Szechuan double-cooked pork with chow mein is 'grey'.

Undeterred, I decided to try an Indian instead, since the cooking process would then be much more leisurely. I visited a proper Indian food shop and started from scratch with raw spices, ghee, basmati rice and what have you. I ground, roasted, made pastes, marinated things overnight – in fact, my chicken tikka bhuna with peas pilau took almost two days to complete. It could best be described as 'brown'.

As a result of all this I have decided to abandon any ridiculous pretence of being multi-culti and acknowledge that if I fancy a Chinese or an Indian, I'll find some Chinese or Indian people to make it for me. There are several within a few hundred paces of my house, as it happens, and they are much, much better at this sort of thing than I am because they are steeped in the appropriate culture and traditions; rather in the way that I know, almost instinctively, what to do with Spam.

Similarly, I may have spent many hours as a boy sketching supercars in the back of my geometry exercise book with my Oxford Mathematical Instruments set, but I will still recognise that real car designers are better. So if I buy a car that I think looks good, I'll leave it alone. I don't order a butter chicken from the Light of Nepal and then start adding some extra ingredients I brought along from home.

In fairness to Jaguar, the 'Sports Collection' body package is the work of the factory, so presumably all the bits will fit properly. But I can't help wondering why, if it looks so good, they don't just make it like that in the first place. And in what other arena of sporting endeavour is weight added for no performance gain? This is like an Olympic sprinter thinking he'd be better off if he was a bit fatter.

Car manufacturers are developing an unhealthy appetite for mucking about with things that were already right. I've just driven a new and extra-sporty version of the Audi TT, which has a harder suspension, ridiculous bucket seats that feel like, well, buckets, daft alloy wheels that stick out further than the tyres and which you will kerb on the way home from the showroom and, worst of all, a black roof. They've completely ruined it. It was a seminal and much-trumpeted bit of automotive design, but somebody imagined it could be improved with a tin of Humbrol enamel. Even the Subaru Impreza Turbo, which comes sort of pre-kitted, looks better left alone.

I know the modifled-car scene is a huge and vibrant one. I've examined the work of the lads who are into it and a lot of it is really exquisitely done and bought at the expense of still living at home with mum. Good for them. But I still don't believe I've ever seen a modified Citroen Saxo or Vauxhall Corsa that looked better than the ones Citroen and Vauxhall came up with.

So here's a tip. If you open the fridge tonight and find that it contains, like mine, a pork chop, some potatoes and a sprig of broccoli, have pork chop with potatoes and broccoli for dinner.

BRITAIN'S SURFACE INDUSTRY FAILS TO DELIVER

Last year, the main road that runs perpendicular to the little road I live on was resurfaced. And I know what you're expecting me to say next.

That it's now worse than it ever was, is covered in nasty grit that destroys underseal, and has already been dug up by the GPO to lay some new telephone cables. But no. This was by far the most professional, efficient and well-managed civil engineering project I've ever witnessed at close quarters.

The work began at around 10 o'clock one night, when all the traffic had died down. The whole road was closed, and an army of stout men turned up with a gigantic fire-belching engine, a sort of mechanical version of that Norwegian cheese slicer, the one that you use to put parmesan shavings on the top of your salad if people are coming round for dinner.

This thing, moving at a speed so imperceptible that in the time it took me to drink three pints and have a game of darts it had travelled only about 30 yards, removed exactly three inches from the top of the road surface while somehow avoiding the drains and manhole covers. Once the pub had shut, and because I had no one left to talk to, I went to watch the miracle unfold and have a ride on the iron horse.

The next morning, just before the rush-hour started, the bollards, the security tape, the cheese slicer and the workers' tea tent thing were all removed and the road was opened again. It wasn't very good, because each manhole cover now assumed the proportions of Ayers Rock and the grooves left by the skimming machine tended to steer one's motorcycle into the path of oncoming traffic. But it was open.

The next night, it was closed again. Now another roaring inferno worthy of Hieronymus Bosch himself turned up to lay the new surface, inching along the street and dispensing the gleaming, sweet-smelling blacktop of hope in its wake. By morning it was finished, and this little corner of UK PLC was back in business, thanks largely to some blokes from Poland.

And the results were – and there really is no other word for this – perfect. People were on their hands and knees at the kerb examining the road and searching vainly for flaws. Small children were riding up and down on bicycles, marvelling at its smoothness. People in shops could be heard saying, 'Have you driven on the new road yet?' There had not been such a collective sense of wonderment since the invention of radio.

Even now, a year on, I can find only two small patches that have been disturbed, and these have been mended almost invisibly. It really is a pleasure to arrive home by car.

So can someone explain the appalling Horlicks that's been made of the side road running parallel to mine? It was closed and excavated for the purposes of installing a new water main, although for the most part it was simply closed. The job is now complete, and in fairness the contractor has made good the road, in the sense that I don't actually fall down a hole when I'm making my way home from the pub at night. But, God in heaven, it's unsightly. The new tarmac is the wrong colour, the wrong texture, and it isn't flush with the old stuff.

How can I portray the sheer horror of these road repairs? Let me put it this way. If one of the perfectly laid green tiles from my bathroom floor was broken, this lot would come around, affix a slightly smaller brown tile of half the thickness, fill in the gaps with the wrong colour grout and then stand back and say, 'Yep, that looks pretty good.'

It's not even an isolated case. Since noting this, I have been walking around with my head bowed, ignoring the cheery greetings of my neighbours, totally absorbed in studying the road surface. Everywhere I look it's a patchwork of cack-handed repairs completed so shoddily that it's a mystery the place isn't littered with spilled bicyclists. Why is this? It can't be any harder or more expensive to repair a road properly than it is to do it badly.

Tadek, Jarek and Marik have shown that first-class road repairs are possible in Britain. Yet, for some reason, we don't seem to think it matters beyond the main thoroughfares. The people around here studiously mend their window frames, grow brightly coloured shrubs and flowers in their front gardens and paint their front doors in amusing colours. Yet this model of English urban splendour faces a road that appears to have been imported from 1990s Bosnia.

The side roads of England are a disgrace. Can somebody please explain why?

MY CUP RUNNETH OVER AND INTO THE CENTRE CONSOLE

Some time ago, the national press published the findings of a report in which continental Europeans denounced the British as 'a nation of coffee philistines'.

An important point was missed in all this. We are not coffee philistines at all; we have become philistines because of coffee. There is now barely a corner of a British high street that hasn't been commandeered by a bean-bashing multinational of some kind, and within them can be found people talking in a strange and subversive code. You'd be forgiven for wondering how the nation had survived until now without a regular double skinny latte mocha choca top before work.

For confirmation of this, look no further than our obsession with in-car cup holders. Over its brief history, the cup holder as found in European and Japanese cars has evolved from a token fixture intended to persuade Americans to buy the car (US sales of the Jaguar XJ once suffered for the car's want of one) to a device of such cunning and complexity that it can embody more engineering and design expertise than once went into a whole vehicle. And yet the only thing that will fit safely into a cup holder is a cardboard cup from a coffee-shop chain.

Meanwhile, tea – the drink that made Britain great – has been virtually forgotten. Tea is the sustainer of honest toil and remains the second most important commodity of the British building trade after sugar. Some historians believe that the mildly medicinal quality of tea actually encouraged industrialisation, because it allowed our manufacturing centres to proliferate quicker than the bowel disorders that would otherwise have destroyed their populations. Apart from anything else, a Frenchman or Italian, fuelled by espresso that could be used to build roads, would have been far too jittery to sit down patiently and invent the steam engine or the flying shuttle.

Of course, a nominal cup of tea can be bought from Cafe Nation or Buckstars or whatever these left-wing chattering houses are called, but it is a dismal offering in which bag, tepid water and milk have all been introduced to the vessel simultaneously. Furthermore, tea cannot really be enjoyed out of cardboard. It should be served in a chipped ceramic mug (if engaged in something manly, such as roofing or restoring an old sports car) or a bone china cup and saucer (if there is any risk, however slight, of a visit from your mother). Curiously, neither of these things will fit in a car's cup holder.

The cup holder, then, can be regarded at best as the perpetrator of a dangerous fad; at worst as the cradle of the enemies of Britishness.

The problem becomes even more acute if you fancy a proper drink. The instant I joined Salim Khoury at the Telegraph Motor Show, I sensed that he would go home a disappointed man. We had come to test the versatility of cup holders.

Khoury is manager of the American Bar at The Savoy, where he has worked since 1969. He came to Britain from his native Beirut, where he learned the subtleties of cocktail making in response to the demands of a then enormous American hotel clientele. Yet despite the predominantly American image of drinks such as the Manhattan and the Cosmopolitan, he maintains that 'Britain really comes top of the world in cocktails; in making them and in creating them.' His most recent invention is the Telesuite, a new cocktail to celebrate the inauguration of the Savoy's electronic virtual-conferencing arrangement with New York's Waldorf Astoria. The ingredients include absinthe, which is known to be conducive to brainstorming.

Khoury comes equipped as a sort of roving international ambassador of correct cocktail etiquette. His briefcase is a beautiful wood-inlaid aluminium job divided into foam-lined compartments for measuring jug, log-handled stirring spoon, fruit knife, ice bucket, a strainer for taking the pith, ice tongs, a champagne stopper and, of course, the silver shaker itself. 'I stir my Martinis. I never shake,' he says, in response to the inevitable comparison with Bond.

He also brings a selection of glasses, some of them traditional, such as the typical champagne flute, and some of them the trademarks of his bar, such as the Savoy's own more generous champagne goblet, the Martini glass that has been an unassailable feature of the hotel since the '20s, and a huge cut-glass balloon suitable for cognac – a particular favourite of Churchill, apparently.

Sadly, none of them fit in a cup holder.

Cup holders can be divided into two basic types. There is the first phase of development, where they took the simple form of a tapered cup-shaped hollow somewhere on the facia, there to satisfy the supposed demand for cup holders at minimum expense. The most pathetic example of Phase One cup holders probably occurred on a Seat Arosa I once owned, in which the inside of the glovebox lid boasted two vague circular indentations. They were little more than a desperate grasp at cup-holder credibility, a sort of visual indication to Place Cups Here, nothing more. But that was in the mid-'90s, a time when it was suddenly believed that not having a cup holder was like admitting to still having drum brakes at the front.

Phase One cup holders still survive on plenty of cars and are at least suitable for storing mobile phones. They might even accept the base of a champagne flute or wine glass, but a lot depends on location. In the VW Beetle, for example, the diameter of the cup holes is slightly smaller than that of the base of Khoury's Martini glass, and in any case the Martini would have to be tipped on to its side in order to clear the bottom of the dashboard's central binnacle before final insertion. The only drink that can safely be turned on its side is one with a lid on it, which immediately puts us back in the hands of Cafe Nero.

The service is rather better on the Rolls-Royce stand, and especially in the rear of the Phantom, which is a good venue for a drink. Here, the cup-holder tray – essentially still a Phase One type – extends from beneath the seat and will at least accept the pint pot Khoury brought along at my personal insistence (pints not actually being available in the American Bar), since it has sufficient headroom. Rolls-Royce will also supply a proper drinks cabinet, complete with glasses, if desired. But at £240,000 one has to wonder why it isn't standard. You can find a mini bar in a £50 hotel room these days.

Phase Two cup holders are much more fatuous. These are the spring-loaded, extending and retracting type that testify to cup-holder oneupmanship on the part of car manufacturers. Once the novelty of simply having a cup holder wore off – and that happened pretty quickly – it became important for car owners to be able to impress passengers with cup-holder complexity. Top speeds and 0-60mph times have clearly been usurped by the number of stages in your cup holder's deployment. Some of them emerge like time-lapsed film of a daffodil opening, or expand into a sort of plastic balletic first position.

Especially idiotic examples of Phase Two cup holders – but there are many more – occur in the new BMW 5-Series and the Saab 9-3. In the BMW, the central holder not only sprouts from the dashboard, it actually follows a curved path towards the driving seat, as if reaching an extra inch or two for your cappuccino grande might be too much effort.

But Saab can beat that. Its offering is so geometrically baffling that it stands as a testimony to the lifetime's work of Euclid. And you thought the electric hood was clever. The whole assembly collapses into a slot no broader than a disposable biro and is, in purely mechanical terms, a brilliant achievement.

But for what? Khoury's Cosmopolitan, a fine drink in which 'flavour is more important than alcoholic content, absolutely', will either fall out or snap the device clean off. In the BMW, the base of the White Lady glass can be coaxed past the sprung lip intended to hold your king-size Americano in check, but then, because the lip is like a barb, cannot be extracted unless it is turned on its side. It can't be turned on its side until the contents have been drunk. We are now in a cup-holder Catch 22 situation, and the only answer seems to be to turn the car upside down and empty the peerless beverage into a bucket.

This whole cup-holder thing really hasn't been thought through properly. All credit is due to Citroen, then, for maintaining, with the Pluriel, an immutable that was established with the Mini – namely, that the door pockets should be broad enough to accommodate a wine bottle. But for the glasses? Nothing.

There are two conclusions to be drawn from this impromptu investigation into cup holders. The first is that the amount of wit and ingenuity being discharged in the design of them is out of all proportion to the import of their function. There isn't a car out there, no matter how good, in which the same effort couldn't be applied to something more important.

But the second is more encouraging, especially to those who, rightly, are engaged in campaigning against drink driving.

Relax. It's pretty much impossible anyway.

BROWN'S GREEN TAX – A BIT OF A GREY AREA

There are a few simple things I require of government ministers. Taking a broad view, I would be quite interested to know what they are going to do about the funding of the NHS, since it's a very complicated business and I won't pretend for a moment to understand it. A few of them have made it their lives' work, so I'm prepared to defer to them on that one.

On a more personal level, and since they are ultimately responsible for the people who might possibly be able to help me, I'd like to know what government is proposing to do about the bloke who climbed through my window and nicked my portable telly.

There are other issues that are no doubt their concern: the pensions crisis, benefit fraud, the war in Iraq, gay vicars (no, not gay vicars) and what the Monty Python team called the baggage retrieval system at Heathrow. These are all worthy of detailed study by suitably qualified people.

But what I don't need is politicians setting me an example, unless it's Charles Kennedy, since he likes a drink and so do I. I especially don't want them wasting valuable Commons time worrying about what sort of car I should drive, because I can work that one out for myself.

Apparently, some of these people are being offered the option of a ministerial Toyota Prius or a bio-fuelled Jaguar, while at the same time supporting a special tax on 4 x 4 cars in the interests of the environment. Nothing could be more irrelevant.

Let's assume, for the purposes of argument, that global warming is a real threat and that energy consumption is at the root of it. So that would make big, overweight and thirsty 4 x 4s a bad thing, obvious-ly.

And what difference, exactly, is a tax going to make to that? If you're rich enough to run a big 4 x 4, a bit of extra tax isn't going to bother you. More to the point, how does tax save the planet? If 4 x 4s are such a bad thing, why doesn't the government simply ban them? I conclude that they don't want us to stop driving them at all. They just want some more money.

And the same goes for smoking. If lung disease is such an issue, and the government feels duty bound to do something about it, why isn't smoking illegal? Taking heroin is illegal, after all. The answer must surely be that smoking is ultimately good for the nation's coffers, and that nobody really wants us to stop. Same goes for binge drinking and driving around in cars.

I was asked to take part in a radio debate about this 4 x 4 tax business, and I dearly wish I'd been available to do so. On the panel was a man from an organisation called something like the Federation Against All-Wheel Drive; that's not quite right but I'm buggered if I'm going to dignify their mealy-mouthed cause by looking it up and getting it right. What I would say to this man is this: if you want to do something good for the world, can't you think of something better than preaching to us about the exact technical specification of the cars we're driving? Can't you go and make some soup for the poor, or mend some old dear's central heating boiler?

I'm not here to defend the motor industry, since it's big and ugly enough to do that for itself. But I will say this. In the 10 years or so that I have been writing about cars, it has made an unparalleled effort to clean up its act. My car today is between 20 and 50 times less polluting than the ones I struggled to own as a student. It caused less pollution during its manufacture, it causes less pollution in use, and it will cause less when it's thrown away.

What other industry or area of commerce has made a similar effort? Fashion? Construction? Other modes of transport? Publishing? Consumer electronics? I can't name one. Every now and then someone comes up with a totally fatuous statistic that shows, for example, how much less CO2 would be produced if we turned our stereos off instead of leaving them on standby. Is that it?

Well, you might be thinking, the car was always a big culprit. But I'm not so sure. Figures I've heard state that road transport (and remember – that includes stinky Latvian tour buses as well as your Vectra) accounts for anything between 11 and 20 per cent of all so-called greenhouse gases. Even if it's 20 per cent, I'm left wondering about where the other four-fifths are coming from, and yet I hear nothing – nothing – about this in any populist debate about the environment. All I hear is some sanctimonious cant about how if I buy a slightly smaller car everything will be all right.

If I were in power, and I thought taxation was the sovereign salve for all environmental ills, here are a few of the things that would suddenly start costing you a lot more: vegetables grown in Israel and flown to your supermarket, when the same ones are growing just as well in England; replacement kitchens, since the one you have undoubtedly works perfectly well; bottled water from France, since there's perfectly good stuff in the tap; plastic carrier bags, which aren't even made here but are produced in places like China, and even if we recycle them they're sent back to China to be made into more carrier bags and then transported here in ships that burn thousands of litres of heavy fuel oil every day; and so on. These are real-world concerns at least the equal of the Volvo XC-90's fuel consumption. Yet the only person I know who talks intelligently on these matters is, remarkably, a car enthusiast.

I'm not going to be lectured about my driving habits by people who probably haven't bothered to check their loft insulation in the last decade. I have, as it happens, and I've improved it. Leave us alone, and leave our cars alone as well.

Still no news on the stolen telly, by the way.

ANY COLOUR YOU LIKE AS LONG AS IT'S AVAILABLE FROM DULUX

I've got the builders in this week. It's quite a big job – two new bathrooms, decorating throughout, plus a few structural alterations. The whole lot will probably take a couple of months to complete and after one week I'm already over budget, because I hadn't factored in the cost of sugar.

I favour a sort of post-modernist school lavatory chic look for the bachelor household, so on the whole have gone for white stuff. White walls, for example, and white porcelain. Wall tiles look suitably municipal in white and I only ever buy pure white bog roll.

But then we come to the question of the stairs, which have gone uncarpeted for years, the money allotted for the job going to Moto Guzzi. But this time I have studiously binned the Guzzi brochure and immersed myself in the John Lewis website instead. I was going to cover the entire floor in seagrass or some other form of monastic rush matting, but then I had a thought.

How would it look, I wondered, if the stair treads were alternately orange and lemon? That way I could start from a lemon hallway and arrive, purged by the acetic, at an orange landing. John Lewis sell both orange and lemon carpet, so it must be possible.

And then I thought a bit harder about the bathroom floors. White is all very well, and suitably redolent of those hotels situated on roundabouts in which I seem to spend so much of my life these days, but would a riot of terrazzo look better? Curiously, there is a shop just up the road specialising in the stuff, and they do a particularly nice lime-green version. Perhaps we have arrived at that apocalyptic moment in time when the avocado bathroom suite has once again become acceptable, too.

But that's the great thing about renovating the home. As Walt Disney said of animation, you can portray anything that the mind can conceive. There is a massive industry devoted to humouring your bad judgement and several TV programmes inspired by the idea of amateur designers ruining perfectly good houses through the medium of power tools.

No such indulgence from the motor trade. Most new cars come with perhaps half-a-dozen choices of standard interior trim, all of them very, very boring.

Even Porsche are guilty of this. My Boxster was available with just five standard interior colours. The options list featured another five. I went for a special dark-brown leather at huge expense and then paid more to have some panels in the black they would have been in had I not said anything. Yet when I look at it – monument to good taste though it is – I can't help thinking that it still has a leather interior like every other Porsche. I've only meddled in the colour scheme.

Meanwhile Jeremy, who has roundly denounced the Porsche and has spent two years proclaiming that the Honda S2000 is the best roadster money can buy, has bought a Mercedes SLK. Seven standard interior colours were available and in order to break free from the tyranny of German taste he had to resort to the bespoke and very costly 'Designo' range of hues. He now has black seats with red inserts. It looks quite good (though not as good as my Porsche, obviously) but why is it such a big deal? Red and black are hardly the new magnolia. Cars in the '50s had red and black interiors.

I wouldn't mind, but down at my local DIY superstore literally thousands of shades of emulsion are available, and all of them can be produced for you in a few minutes by a youth who wasn't charismatic enough to become an estate agent. The tile shop offers so much choice that I could tile the whole of my road without using any one design twice. Modern manufacturing methods should mean that the same freedom is available to people specifying the seats, floor mats and facia of a new car. But what do we get? Biscuit beige, black and elephant-arse grey. Why? You wouldn't have that at home.

I do get the impression that the motor industry thinks we all need its guidance on matters of interior design. But this is ludicrous. Next time you're in a showroom, have a look at the salesman's tie. Would you let this man choose your new kitchen?

I've ordered the orange and lemon carpet, by the way. And the terrazzo. And I know what some of you are thinking: you're thinking that all this would look revolting. And you may be right, but since it's my house it's my business.

And if you don't like it you don't have to come and stay here.

PORSCHE OUTPERFORMS DESKTOP PRINTER – SHOCK

I spent this morning swearing at my computer printer. I'm no technophobe, but we have here one of those consumer devices assembled with superglue, inside which there are apparently 'no user-serviceable parts', so the only tool left in the engineer manque's box is his 99-piece precision profanity set.

Here's the problem: it doesn't work. So I took it to the local computer shop, slapped it on the counter and explained as much to a man who should have been born with just two fingers. 'Ha ha ha,' he exclaimed, knowingly. 'How long have we had this, then?'

I have had it for five years.

'Well, that's pretty old tech now,' he explained patiently. 'You really need to upgrade.' Now, at this point a lesser man than me might have forked out for the new Epson Stylus Multijet 4.0 Megapixies and gone home happy. But not me. I wanted it mended. 'It's not economical,' he declared.

I appreciate, as everyone keeps telling me, that printers are remarkably cheap these days, but we're still talking about over £100 and that buys a lot of American Hard Gums. Furthermore, how much would my life be advanced by a new printer? Not a jot. I'd be back where I started, trying to print out a simple letter in response to an enquiry from a Mr Graham about music and motoring.

And it gets worse. Because I've had the computer for eight years it seems there is no longer a printer compatible with its old operating system. That means that in order to run the new printer, I'd have to buy a new computer as well, and learn how to use it. That would probably also mean buying a new 'docking station' for my infernal digital diary thing and probably some new upgraded miniature speakers for the CD player as well.

That would be a bit like going to Kwik-Fit for some new tyres and being browbeaten into buying a whole new car. Before you know it I'd have spent something like £1,500 on computer kit, and where would I be? Still sitting in front of an over-specified typewriter, still trying to send a letter to Mr Graham.

Things wear out, but it's not as if the old printer has had a hard life. It's probably produced a dozen pages a week since I've had it. 'Think how many pages that is,' said the computer man, triumphantly. Clearly, neither of us could in the heat of the moment but I've since worked it out and it's around 3,200, or perhaps 48,000 lines of type. Now think how many times the engine in my 106,000-mile 911 has rotated. I've worked that out as well and I think it's something like 6 x 109. One revolution of the flat six is one cycle of operation, like one complete sweep of the printer head, and yet the Porsche STILL WORKS PERFECTLY.

People bemoan the supposed built-in obsolescence of the car, but a better exemplar can be found in the world of digital tech. Those who promised that this stuff would be 'future safe' were simply driving us further into the hideous clutches of PC World and cluttering our lives with redundant plug-in transformers. In fact, the car always was future safe. You could pick any one from the collection in the Beaulieu museum and use it today on today's roads. Even the Stanley Steamer is yours for the driving, so long as you can find a Welshman to dig up a bit more coal for you.

It's undoubtedly true that before the war the motor industry sold you a car, then after the war it started selling you fashion. The difference, though, is that we had a choice. You could embrace the new-fangled Ford Cortina, with its exotic foreign name and faux American styling, or you could do what my dad did and stick with the Morris Eight. The car has been good to us. The computer industry has simply filled my attic with old boxes.

You may be pleased to know that I eventually prised the lid from the bubblejet device and set to it with the little screwdriver from my Hornby train set. A few hours later and – hey printo! It whirred back into life and now sits on the desk in open defiance of Bill Gates and his evil henchmen.

I was very pleased with myself. But I couldn't help thinking that none of this would have been necessary if it had been made by someone like Vauxhall.

(Mr Graham has since received one side of A4 with about a dozen lines on it.)

MEN, RISE UP AND EMBRACE THE WHEELBRACE

As I've said before, there are no real gender issues in motoring. I don't doubt that the tastes of men and women differ slightly, but in an age when women run merchant banks and more and more men have handbags, their requirements are pretty much the same.

I do not believe, for example, that there is a specifically woman's view on motoring. I know some women who are as enthusiastic about motors as I am, and for the same reasons. I also know men who don't have a car at all because they think them the work of Beelzebub. Obviously these so-called 'men' are traitors to their sex, but that's the way it is.

And so to Drivesafe, a new initiative aimed at women motorists and accompanied by the inevitable 'handy pack' of helpful hints. Its authors point out that women do more town miles than men, and are therefore more at risk from threats such as road rage and car-jacking. Many of them, it is believed, lack the self-assurance needed to change a wheel. Drivesafe will show them how.

And on the face of it, that's a good thing. Men go shopping for clothes in the modern world, so it follows that women should be able to change wheels. What bothers me, however, is the suggestion that there won't be men on hand to do it for them.

If a woman suffers a puncture somewhere around town, then surely there will be a man somewhere – in another car, walking along the pavement, looking out of a window – who will put the spare on for her; a man who, denied by social development the opportunity to wear a lady's embroidered favour around his wrist as he rides into a jousting tournament against ye black knight on ye black horse, will relish the opportunity to wield the latter-day Excalibur that is the wheelbrace.

It seems not.

Cry sexist if you must, but this sort of thing really worries me. I'm not suggesting for a moment that a woman shouldn't be able to change a wheel, any more than I think some of my male friends should stop mincing around in the kitchen with tiger prawns and put some bloody shelves up. It's just that today's Guinevere of the road should be able to rely on Gawain in her moment of peril.

In any case, my quarrel is actually with the chaps. In the past few weeks I've watched three men attempt to change a wheel, and they all made a complete Horlicks of it. Cars fell off jacks, nuts were cross-threaded, and everyone had a good laugh. This is deeply symptomatic of a hideous blight affecting the modern British male; namely, that being a bit useless is perceived as being somehow endearing and 'blokeish'. Nothing could be further from the truth.

I keep meeting men who say things like 'Ha ha ha, I can't even wire a plug!' Why not? The instructions are usually moulded into the plug itself, or on a piece of paper pushed over the pins. If you can't wire a plug it's not because you are creative or because you have a left-hemisphere brain or because you're a bit of a bloke. It's because you are an imbecile.

Another man I met recently had employed a builder to screw a wine rack to the wall. Why he wants a wine rack anyway is a bit of a mystery, since he lives only a few doors from a pub that sells proper beer. Even more unfathomable is how he could bear the shame of standing by while another man drilled four holes in some brickwork and inserted some rawlplugs. He can regard himself as little more than a receptacle for keeping sperm at the right temperature until it's needed.

British men are facing a crisis. There are no world wars to fight, very little coal to be dug, no massive programme of railway expansion to feed. The forge is cold and the instruments of duelling are rusting above the fireplace in a country house experience somewhere. Poetry is unfashionable, as is serenading. Ballad-writers are noticeably thin on the ground. The attributes that once defined manliness are receding fast, already at such a low ebb that we can't even be relied upon to sort out a puncture for a distressed damsel. The roads are the last arena in which chivalry can be upheld.

I therefore wholly commend the Drivesafe initiative and in particular the handy pack that comes with it. I haven't seen it yet, but it sounds as if it's full of really useful advice on, among other things, changing wheels on cars.

I therefore think it should be distributed to all males over the age of 12.

HOW THE PEACE AND QUIET OF ENGLAND WAS RUINED BY THE NOISE OF PEOPLE COMPLAINING

As some of you may know, I've spent the last year learning to fly a light aircraft. Very satisfying it is too. It's something I dreamed about as a boy, ever since I picked up my first Air Ace Picture Library comic book and learned to draw something approximating to a Spitfire in the back of my maths exercise book.

But small aeroplanes aren't to everyone's liking. Richard Hammond, for example, whose crashing impatience renders him unable to appreciate the value of pre-flight safety checks, and who is not man enough to thank me when the wings haven't fallen off at the end of a journey.

And then there are the residents of the villages around my flying club's airfield, White Waltham in Berkshire. Some of them hate small aeroplanes because, apparently, they're noisy.

A bit of explanation is required here. A typical small airfield will have several runways – White Waltham has three – pointing in different directions to allow for changes in the wind. Each runway forms one leg of an aerial rectangle, around which the aeroplanes fly while preparing to land. These are called 'circuits', and those of us new to aviation spend a lot of time flying around them practising landings and take-offs. Given that each runway can be used in two directions, there are six circuits in operation at my airfield.

And the circuits are carefully designed to avoid overflying of the local villages, so that the residents won't be annoyed. However, there are a lot of villages and you don't have to stray very far outside the circuit before some old trout rings up the ops room with a complaint. This has happened to me.

People have rung up and, in effect, said, 'James May is flying his noisy little aeroplane over my garden, when he should be to the west a bit.' Well, what did they expect with my sense of direction? They should be grateful I haven't flown straight through the sitting room window or into the local orphanage.

But here's what really gets my goat. The airfield has been there since the '30s, when it was part of the vital Air Transport Auxiliary unit – the organisation that ferried newly built and repaired military aircraft to their operational bases. A lot of the ferry pilots were women, and you may have seen the famous picture, taken at the airfield, of a ripping brunette gal in flying kit standing under the nose of a gigantic Short Stirling. It's almost pornography.

So anyone who can remember when it was all trees would be over 90 and therefore deaf anyway. I doubt there are many people in the surrounding villages who bought their houses before the airfield was built.

In which case, people must have moved in knowing that there would be small aeroplanes flying around. But still they complain about it. This is like buying a house on a Barratt estate and complaining that there are people living next door. It's like me complaining about the sound of bells from the church down the end of my road. The church has been there for several hundred years, and it's not as if I wouldn't have noticed it when I viewed the house. There's a bloody great bell tower sticking out of it.

But no matter – I could probably complain to the authorities and someone would be obliged to look into it, when really Britain would be better served by someone coming around to tell me to stop whining and be grateful that the bells are there, ready to be rung when the EU invades.

Road noise? Well, everyone I know lives on a road of some sort, and they all either own a car or use taxis. A certain amount of noise is therefore to be expected. I would agree wholeheartedly that cars and bikes with wantonly loud exhaust pipes are an unnecessary evil, but that general thrum of traffic is just part of the sonic backdrop of modern life, like Radio 2.

And so, finally, to the Top Gear studio, which is based – da daah! – on an old airfield. It's the one where they used to build and test the Hawker Harrier, which you may know as a particularly noisy aeroplane. Those days are gone, and you'd think the locals would be glad, but you'd think wrongly. Some of them are now complaining that Top Gear is making too much noise.

Really? We're there, on average, about once a week. The airfield is very large, and we occupy the bit right in the middle with our test track. The nearest house is a long way away. I can accept that the steady drone of Clarkson shouting 'poweeeer!' would be quite irksome if you were relaxing in the garden of an afternoon, but the occasional and distant squeal of tyres around the Hammerhead is surely no more intrusive than the chirp of a randy blackbird.

But we live in an era when a single complaint has the weight of a 20,000,000-signature petition delivered to Downing Street. Consider the programme itself. If one person rings or writes to complain that Jeremy has been rude about the Liberal Democrats or that I've said 'cock', the producer is obliged to investigate it and do something about it. Why? Important work is being done at Top Gear. It's thanks to Top Gear that the new Koenigsegg has a rear wing, and that the motor industry knows not to waste its time and money trying to develop a convertible people carrier. If people had complained about Barnes Wallis's bomb bouncing through their back yards, or the Flying Scotsman making an irritating whistling noise, nothing would ever have been achieved and Britain would be renowned the world over only for being very quiet.

It's the same story with the flying club. The people who complain about the aeroplane noise forget that the person flying the airliner that takes them on holiday to Spain will most likely have started flying at a local airfield, often at great personal expense. If people like me weren't there supporting it by flying a wonky circuit over the village, everyone would have to go to Whitby on the train instead.

What else do these people complain about? Talking in restaurants? Babies crying at feeding time? Long grass rustling in the wind? Velcro? They could make a bigger contribution to the fight against noise pollution if they all simultaneously piped down.

Everybody shut up. You're beginning to get on my nerves.

IN CASE YOU'RE READING THIS ON THE BOG, HERE ARE SOME EQUATIONS OF MOTION

Professor Stephen Hawking once averred that for every mathematical equation he included in his book A Brief History of Time, the readership would be halved. This gives us:

(Where Ra is the actual readership, Rp is the potential readership, and N is the number of mathematical quotations. And if you think I'm making this up, it's all been checked by Yan-Chee Yu of the Oxford University Mathematical Institute. So there.)

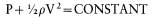

This leads every other one of us rather neatly to the work of the Swiss scientist Daniel Bernoulli (1700-82), whose work on fluid flow showed us, in simplified form at least, that:

(Where P is the static pressure, p is the density, and V is the velocity.)

What Bernoulli was saying, in essence, is that when the pressure in a fluid system is reduced (by a constriction, for example), the velocity must increase, and vice versa. The rate at which the fluid flows will remain the same. It's hugely useful stuff if you design the air intakes for racing cars.

If, however, you are simply annoyed at being stuck in traffic jams at roadworks, you may prefer Bernoulli in its layman's form, which is known as May's Motorway and Dual Carriageway Jam Avoidance Velocity Modulation Principle. This states that when one or more lanes of a busy multi-lane road are closed, the speed limit in the remaining lanes must be increased if the traffic is to keep flowing smoothly.

But here we arrive at a socio-political problem. For years it has been accepted that the most dangerous job in Britain is that of trawlerman. Recent research shows that a trawlerman is some 50 times more likely to be killed or injured at work than, say, me. If he is not despatched by the cold, the cruel sea or a rusty chain, he will be starved to death by the iniquities of EU fishing regulations.

A few years back he was briefly usurped by elephant handlers, since they are few in number but two had been trampled in quick succession, making the profession statistically unsurvivable. Roofers and glaziers are at considerable risk and aircraft carrier flight-deck crew should ensure that their children are well provided for. And surely no working man is in greater peril than the fitted-kitchen salesman who arrived uninvited at my door a few weeks ago just as I had finished reassembling (following a thorough clean) my Beretta.

But here are British road workers, suddenly at number 16 in the hit parade of hazardous jobs. In the last few years the number of deaths and serious injuries sustained by these people has risen sharply, from only one fatality in 2004 to four in the first half of 2005 alone. The Highways Agency is pretty sore about it, which is why motorways and dual carriageways are now strangled by sudden 30mph limits and all that 'lane closed to protect workforce' malarkey.

Quite right, too. No civilised society could possibly want to see its road workers in hospital. We'd quite like to see them mending the roads. By now you're thinking what workforce? and you may have a point. Over the last few weeks I have been monitoring these roadworks, and I have driven just over 26 miles at temporary speed limits past lanes closed supposedly to protect the workforce but without seeing so much as an endangered wheelbarrow. It would appear to be more a case of workforce staying at home to protect workforce. But I don't blame them. It's bloody dangerous.

So here is the solution. Roadwork should only be practised at night, when the traffic flow is light. Slowing to a constant 30 or 40mph for a few miles is really neither here nor there as far as total journey times are concerned. You can even calculate the difference it makes yourself:

(Where T is the extra time taken, D is the length of the roadworks in miles and S is the temporary speed limit.)

During the day, when the traffic is very dense, the workforce should stay away, since the traffic has to keep moving fast to prevent a total jam. At the same time, we can't really expect them to put all those bollards away every morning and so, in accordance with May's principle, the cars should actually speed up through the roadworks. For example, if only one lane is still open on a busy three-lane motorway, the speed limit should be 210mph. Or:

(Where S is the new temporary speed limit, E is the existing speed limit, L is the number of lanes normally available and O is the number of lanes still open.)

I'd be amazed if anyone is still reading this.

IT'S A CAR, JIMMY, BUT NOT AS WE KNOW IT

It must be 20 years since Jimmy Savile told us that this is the age of the train, but maybe, finally, it is. Just as the last of the InterCity 125s he trumpeted so memorably terminates in the long rusty siding at the side of a scrapyard somewhere, things are looking pretty good on the permanent way.

I've been on three trains in the last month. Two between London and Manchester operated by Virgin Trains, and one from there to Hull operated by Northern Rail or something like that. I must admit that I preferred the era when one simply turned up at 'the station' and got on 'the train' instead of arriving at a retail and dining complex with some rails attached and then standing for an hour in front of a massive flickering monitor trying to work out which of a countless number of operators will accept the brightly coloured £135 stub in your hand. But still.

Apart from that, the whole experience was rather good. These were the new Pendolino trains; sleek, stylish and very cool. I know some railway commentators have criticised them for their weight and thirst, but they strike me as a Lexus amongst rolling stock. They are quiet, draught-free, smooth riding and very fast in an unflustered sort of way. The seats are very good, the upholstery subdued, the announcements intelligible. It's some years since I've been on a proper train and I was very pleasantly surprised.

For example, I'd reserved a seat. In the olden days this would mean there was a bit of cardboard wedged under the antimacassar, or was until some pissed pikey removed it, chucked it on the floor and then filled the table with empty Carlsberg cans so you felt better off in the concertina bit between the coaches.

Not any more. A little dot-matrix display above my place read 'Reserved, Mr May' so there was no argument about that.

There was still a chance that a zealous vicar or malodorous railway enthusiast would sit next to me but, again, I was lucky. For two of the journeys I had two seats to myself, and on the third I was joined by a woman who not only smelled rather nice but didn't speak to me at all, which was marvellous.

Crikey, even the buffet has improved. Once there was a slimy carriage offering the following range of sandwich fillings: cheese. Now there is a trolley piled high with fruit cake and pies and a big samovar thing for making hot drinks, a sort of wheeled five-star-hotel tea-and-coffee-making-facilities facility. Any more wine at all with your meal for yourself, sir? Why, yes.

What a pleasant and, as widely claimed, efficient way to travel up the sceptered isle. London to Manchester takes just two and a quarter hours, during which one may of course work on a laptop, read important documents or hold an impromptu meeting with colleagues. Obviously I did none of these things. I looked out of the window for a bit and then fell asleep with my head resting on the seat in front, dribbling on my trousers. But if you did work in IT or a customer relations role, you could annoy everyone else on the train by talking in a loud voice about managing expectations or tapping noisily on your strawberry personal organiser. You can't do that in the car.

However.

I said London to Manchester takes two and a half hours. Unfortunately, it's a place in London where I don't live to a place in Manchester where I don't want to be. And here we arrive at the crux of the public transport conundrum.

Obviously, long-distance communal travel makes sense. You wouldn't fly yourself to America in your own Cessna – you'd get on a big aeroplane with lots of other people and complete the bulk of the journey very rapidly. You wouldn't sail your own dinghy across the North Sea to Norway. You'd get on a ferry and stand around a bar with a load of lorry drivers and pimps. Lots of people seem to want to go from London to Manchester at any time, so they can all go together.

It's the little bits at either end of the journey that cause a problem, yet it's in the towns and cities that public transport is presented as the solution to all our woes. It's rubbish. If I'd had to find my way from Manchester Station to whichever hotel I was staying in using the local buses, I'd have given up and gone home again.

You can bang on all you like about trams, light rail, bendy buses and maglev, but until such things stop outside my front door in the space where I keep my car, they're not really any good. My local underground station – and the estate agent told me I was buying a property ideally situated for local transport facilities – is still 10 minutes' walk away, and with a big suitcase it's just too much trouble. No matter how comprehensive the public transport network becomes, there's always going to be a little bit of the journey requiring something personal.

And let's be honest here. Posh InterCity trains are generally full of respectable people, but local public transport isn't. I'm sure London tube commuters are largely upstanding pillars of society, but there are still enough of them that smell of old pants to make the journey unsavoury.

I have the solution. In my vision I step outside to find something like a Fiat Panda or Smart Car that doesn't belong to me but is open and starts with a simple button. There are no keys. I drive it to the station and leave it. Someone coming from Manchester then uses it to get to the offices around the corner from my house. Then someone else uses it to go to the shops. Occasionally they might pile up in one place or another, but in that case the people who we currently employ as traffic wardens are used to redistribute them a bit. It can't be any harder than running a bus service.

And you can't nick them, because they are electronically tagged to prevent them straying beyond a radius of a few miles. This is a simple matter, one of utilising the technology so readily used to punish us as a means of liberating us instead.

I can't really see why it wouldn't work. This is the age of the true city car – a car owned by the city.

PART 2 – THE FUZZY EDGE OF

AUTOMOTIVE UNDERSTANDING

CHARLES DARWIN MAY BE ON TO SOMETHING

I'm always slightly surprised that my cat, Fusker, can't speak. I spend many hours talking to him, but it's always a totally one-sided conversation and the chances are that the only word he vaguely understands is 'Fusker'. And he can't even say that.

My other dependant, Woman, reckons he can't talk because he's only a cat, and that the evolution of cat technology is such that he just isn't capable of speech and for complex zoological reasons. But I'm not so sure.

In terms of the mechanics of speaking, the cat is as well equipped as I am. He has a voice box of sorts: a mouth, a tongue, teeth. These are what we use to form words. And yet still nothing of any consequence comes out of his witless furry face. Why?

I have been forced to conclude that Fusker remains speechless not because he is incapable of it, but because he has nothing to say. He has nothing to say because he hasn't done anything worth talking about. All he aspires to is another bowl of Munchies or the chance to go outside and look for a lady cat (even though he has no nuts, although he's too thick to realise this). He can communicate either of these desires with a simple bleat.

I suppose it's possible that some distant ancestor of Fusker, while chomping away at his cat food, came up with the design for a separate-condenser steam engine long before James Watt did. However, he could do nothing about it, so the idea went unrecorded. He could do nothing about it because he didn't have opposed thumbs, the very attribute that allowed humankind to fashion a pointy piece of flint into a farming tool and shake off the shackle of being a hunter/gatherer. It was a relatively small step from there to variable valve timing.

Since we're on the subject of tools I'd now like to talk about Mr Stanley and his famous knife. Any man who has owned a Stanley knife – and any man who hasn't is unworthy of his sex – will, at some point during the trimming of some linoleum or the assembly of a l/72nd-scale Messerschmitt 109, have stuck the eponymous craft instrument into his body somewhere. This week, I drove mine into the fleshy end of the thumb of my left hand.

To all intents and purposes, I now have only one arm.

If you'd like to go and stick your own Stanley knife into your own thumb, you will discover how difficult many straightforward life skills can become. Grating cheese, for example, or playing Scott Joplin's 'Maple Leaf Rag' upon the piano. This is what separates us from the beasts of the field and hearth.

Consider driving. I hadn't realised, until it was clad in a Beano-style comedy bandage, just how crucial a role my left thumb plays in this everyday activity. Denied the use of this vital receptor, driving becomes notably more difficult. Even in my old Bentley, which, as a slovenly automatic, does more than pretty much any other car to relieve its owner of the tiresome duty of operating it, I find my finer points of car control slightly compromised.

All of which brings me, eventually, to modern car technology and driver aids, most of which have their basis in micro-electronics. They are amazing things. The injection system of a modern diesel engine can provide five separate squirts of fuel, each minutely timed and of minutely different volume, in the space of one ignition stroke – an event which, at 4,000rpm, occupies just under 0.004 seconds by my calculations. I couldn't do that.

A drive-by-wire throttle, when you depress it in anger at the exit of a corner, will garner information from sensors monitoring, among other things, air density and temperature, limits of traction and perhaps even the steering angle. At the same time, a disposable plug-in module will be deciphering the ignition requirements in three dimensions. I couldn't begin to sort this lot out even given three hours in a silent examination room with a calculator and my lucky pencil sharpener.

In fact, whatever computerised systems are responsible for these things are much, much better than me at punctuality, long division, data management and spatial logic. But I bet they couldn't catch a tennis ball.

I can. I can also ride a bicycle, swim, shoot clay pigeons and pat my head while rubbing my stomach. Bosch Motronic can't do any of these things. I could even, theoretically at least, compete in the triple-jump, and I bet I'd beat that robot Honda keeps banging on about.

So when people tell me that electronic controls are coming between the driver and the modern car, I say cobblers. Yes, the right-hand pedal in the new Golf GTi may seem a bit vicious at times, and perhaps the traction control in this or that supercar is too intrusive. I've no doubt that some electric power-steering systems are placing a barrier between the steering wheel and what the driving wheels are ultimately doing, and brake assist sometimes seems to make a mockery of the relationship between what we do with the middle pedal and what actually happens to the car. But to suggest that these things are usurping the driver is absolute nonsense.

Electronics are merely cussed and logical, as your desktop computer will ultimately prove to be. Meanwhile, the human computer is supreme, the most remarkable electro-mechanical device ever conceived and one as yet barely understood. I now realise that when I drive my old 911 down a winding country road, pretty much every last bit of my body save perhaps my hair is toiling away at the man/machine interface, deciphering the incomprehensible mass of information coming at it and translating it through the brain into a multitude of decisions and inputs. If you don't believe me, try it for yourself without one thumb, a big toe, an eye or a buttock. We are no closer to finding a substitute for the driver than we are to finding an alternative to sperm in the reproductive process.

The greatest driving aid in the history of motoring was fitted to the Benz Motorwagen when it was rolled out of its shed for the very first time, and it has been included in the design of every single car built since. It was you.

And it's still you.

NAKED MOTORCYCLE PORN SHOWING NOW

The late and still sadly missed LJK Setright had a rather pessimistic view of bike shows. He once described them as being 'full of people on crutches looking to buy their next accident'.

Personally, I rather like a good bike show. For a start, experience in my own garage proves that you can fit three or four bikes into the space occupied by one car, which means you don't have to walk as far as you do at the motor show. The fact that the biggest physical workout the average motoring journalist ever takes is three laps of the NEC while looking at cars strikes me as strangely ironic.

Secondly, the atmosphere is better at a bike show. Motorcycling is still largely a hobby, and has yet to be infected with much of the glitz and fatuous marketing cant that accompany the latest launch of a sporty lifestyle vehicle for the active-minded urban sophisticate. There's rather less carpet on the stands, rather more tepid lager in cracked plastic glasses.

And then there are the bikes. I admit that often, when I'm at home alone, I think I should give up motorcycling. I'm getting too old, too cautious, and I'm just not very good at it. I believe that 'waterproof motorcycle clothing' remains an oxymoron, and often, in the middle of a tight, greasy bend, I worry that Newton may have made a mistake, and there's some dark corner of physics where there is no equal and opposite reaction, and I'll fall off. But then I go to a bike show.

Nothing, and I mean nothing, tugs at the strings of my Neanderthal man-being quite like an array of new bikes, and especially the type of big-bore naked motorcycles that I like. It's something to do with the way engineering, styling and the dynamic considerations are required to collaborate in the design; their utter interdependence. A motorcycle really is an extension of your being on the road, and your own mass and dimensions are a critical aspect of the way the whole thing works. There is little room for conceit on the part of its maker, and it shows.

Because, on a naked bike especially, you can see it all. You can see the way the stylist and the mechanic have been forced to collude, to give and take, to work constructively together. Engineering considerations temper the excesses of artistry, artistry dignifies the metalworking. And it all chimes instantly with some need to climb aboard and imagine how the thing might feel, which is why bike shows are full of people sitting astride new machines and gazing blankly into the distance.

Take Yamaha's MT01 muscle bike. One side of the engine looks like the work of dour technologists with Rotring propelling pencils wedged into spring clips in their breast pockets; the other like the fantasies of some blokes in polo-necks who would be as happy doing fashionable kitchen appliances. It appears to have a fish poacher on that side; actually, I believe it's the cover for a filter. Marvellous.

This is why motorbikes make a better static statement than cars. Aston Martin boasts of 'power, beauty, soul', and the new V8 has it all. The power is in the superb engine, the beauty is in the sculpture of its bodywork, and the soul comes from the physical properties – the suspension set-up, the distribution of weight, all that impenetrable stuff – that make it drive the way it does. But on a motorshow stand we sense only the beauty, and feel only a distant longing inspired by some faint carnal promise. Meanwhile, the Ducati Monster is flashing its knickers at you like some metal harlot.

It was Dr Johnson, I believe, who said something to the effect that all men feel slightly inadequate who have not at some time been a soldier. Today, he might say that all men feel cheated who have not at some time owned a motorcycle. They have somehow resisted the silent siren cry it emits even when stationary; they have not succumbed to that visceral urge to crack open the throttle and feel the beast tremble, to quest alone and armoured like some latter-day knight of Arthur's circle.

It's there in all of us, which probably explains why bike-show exhibitors never really bother with the tiresome live-band and rollerblading displays that dog the car show. They know that there's still only one tune that really works for motorcycling, and that it will, whether we like it or not, be playing on a loop in the back of our minds, from the moment we arrive to the moment we leave with a bulging bag of brochures.

Stop fighting it. And get your motor running.

SOME OBSERVATIONS ON REAR-END HANDLING

We've had the Kyoto Summit, we've had the Good Friday Agreement, and we've had a United Nations resolution. And now I'd like all car manufacturers to sign an international gentlemen's agreement promising to leave my bottom alone.

I'm as liberal as the next man etc. etc. but this has now gone too far. What consenting individuals get up to in the privacy of their own homes is one thing; the dead hand of a multinational directed at my buttocks is something else altogether and, to my mind, wholly unacceptable. Is nothing sacred any more?

Now I think about it, I realise that the world's car makers have been showing an unhealthy interest in my plum duff for quite a long time. It started well over a decade ago with the widespread introduction of the heated seat, which for years has been hailed as a great thing on a cold morning. Even my 13-year-old Range Rover has seat heaters.

But here's a thing. It's been very cold for the few days prior to my writing this, and I've been doing quite a bit of driving. Yet at no point have I walked out of my front door into the frosts and hoars and thought, 'God in heaven, my arse is cold.' It never is. My buttocks are the second biggest muscles on my body and therefore retain a huge amount of warmth. I have cold toes, cold fingers, a cold nose, cold ears and cold hair, but none of these things are catered for in the cabin of the car. I suppose Mercedes has made some effort with that Scarftronic neck-warmer fitted to the new SLK, but otherwise it's hot cross buns as usual.

It didn't stop with the seat heater, of course. Some time in the mid-'90s I drove the first BMW 7-series fitted with the 'active seat'. The base of this 'stimulating innovation' could be set to gently rock your pelvis from side to side, supposedly in the interests of reducing backache and encouraging circulation. I tried it on a very long journey and it seemed to work, but I was very uncomfortable with the idea of a German technologist called something like Jurgen fondling my chuff at a distance.

Mercedes responded with that massage seat thing, which incorporates some fans to extract the wurst effects of the corporate lunch. But again, I have the feeling that Herr Doktor is taking an unhealthy interest in my tradesman's.

So far this has been a distinctly German thing, and I suppose it could be worse. It could be the British. Then the new Aston V8 would be fitted with a couple of spring-loaded horsewhips and you'd be scouring the cabin for a suitable piece of leather to bite on. Instead, it's the French who are now at it.

I've been driving the new Citroen C4 VTS, and I have to say there's quite a lot I like about it. It's a great-looking car, it has a sweet motor, it steers quickly and it's even reasonably quick. Obviously it's a bit sporty for my tastes but I imagine it would be ideal for the sort of people who regard trainers as shoes.

What I didn't like was the preponderance of buttons and knobs in the cabin. This sort of thing makes me nervous in a French car, since I've always believed the French to be poor at gadgetry and much better suited to pre-industrial activities such as cheese-making and erecting lavatories that don't flush.

You may remember, if you were watching Top Gear, that the C4 features a novel steering wheel on which the rim rotates but the middle remains stationary. As well it should, since I counted 17 buttons on it and even then I'm not sure I remembered to include the horn. If it went round and round as well you'd be in big trouble.

In fact I was so preoccupied with the steering wheel that I completely forgot about the C4's vibrating seat. Then I joined a motorway and the French got to work on my jacquesie.

This car is fitted with a device that senses the white lines of your motorway lane, and if you stray beyond them the seat performs a brief drum-roll on your bum. Not only that, but it's buttock-specific. Stray right and your right cheek gets a drubbing, stray left and so on. Unless you indicate, in which case the system reasons that you meant to change lane and leaves your derriere mercifully alone.

It sounds like a good idea, and in many ways it is. If you'd nodded off it would wake you up, certainly. For the lady motorist it may be a safer and more comfortable alternative to the vibrations that are apparently to be enjoyed on the pillion seat of any V-twin Italian motorcycle. Trouble is, I'm a chap and there are times when I don't actually need to signal to change lanes on a motorway, such as when I enter an empty contraflow in the middle of the night. Then it's a right pain in the butt.

I can't keep indicating for no obvious reason, or I'll end up looking like my mate Paul, who indicates even when he's turning out of a supermarket car-parking space. Or someone from the Institute of Advanced Motorists. Maybe you can turn the thing off using one of the buttons on the steering wheel, but at this point I was still trying to retune the radio.

I have to say I'm disappointed. I saw the genesis of this technology years ago on something called the Prometheus Project, a sort of non-competitive multi-manufacturer initiative to develop the driving aids of the future. This gave us sat-nav, intelligent cruise control, head-up displays, swivelling headlights and the lane-sensing system at the core of the Citroen's vibra-seat.

By my reckoning, all these things could be combined to allow me to join the motorway in London and then climb into the back for a kip until I arrive in Scotland. Instead, I've been given something to keep me awake. The motor industry has, as usual, aimed low, and humankind has been reduced to fiddling with each other's bottoms like the apes of the trees from which we have supposedly descended.

I think these people should stop arsing around and do something useful.

THE FUTURE OF IN-CAR ENTERTAINMENT

Some years ago I attended the launch of a new Daewoo MPV people-carrier type recreational vehicle, and realised immediately that I was at the dawn of a new era made dark by the lights of a perverted science.