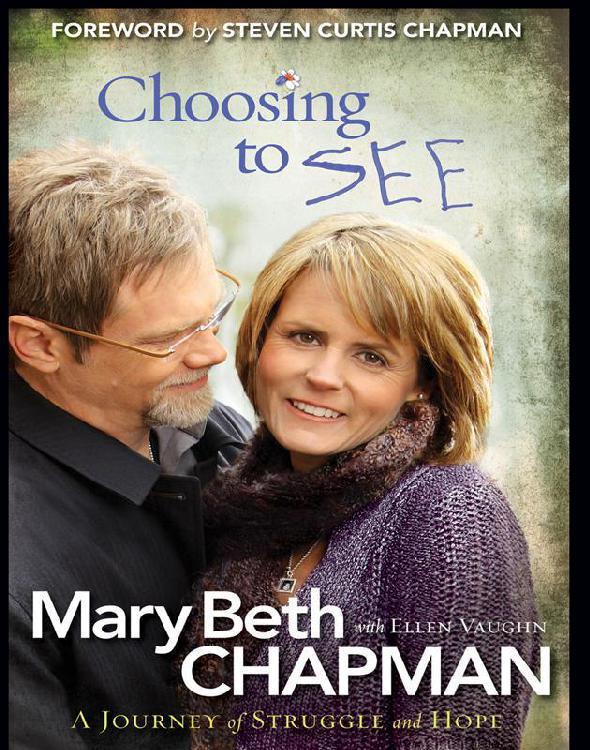

Single Voice

Cathy Ytak

Nothing but

Your

Skin

Shh, listen, there are people walking on the shore. They have dogs. Did you tell anyone? No, no one. They won’t find us, we’re too far from the edge. All I can hear is your heart echoing in my chest. I feel the sweat on our stomachs, and on your forehead, too.

Shh, listen! All I’m listening to is the two of us, the ice crackling, and the water of the lake flowing far below. When we were rolling around, the wrapper from the condom got stuck on my bum. I don’t want to take it off. There’s not enough room to move in our sleeping bags, zipped together to make only one. They’re heavy sleeping bags for camping in the mountains, and you were right, they’re very warm.

Listen, I hear voices and footsteps, and I can see the beams from their flashlights. It’s true, Matt, it seems like they’re getting close.

You tell me that we have to hurry, that they can’t find us together like this, naked, that we have to get dressed. But I’m with you, I don’t want it to stop, and I don’t know where my sweater is. I took it off so quickly that I heard a rip. It might be torn. It’s blue, with a white stripe.

Where did the moon go? Isn’t it shining on us anymore? Matt, what color do you think the moon is?

The ice of the lake is beneath us, and above us is your voice, your voice that sounds anxious. Lou, they’re coming…Lou, shit! Hurry up! But I don’t know how to hurry up. When things happen too fast, I get confused.

I hear them now. They’re crushing the frost under their feet. We’re trapped, lost in the middle of a frozen lake. We’ve been caught! Do they have guns?

I slide my hand between my thighs to dry myself a bit before pulling up my pants, they’re tangled around one of my ankles, I don’t have time to…

I hear my mother first, and behind her I hear dogs barking, and then two men, at least, yelling at us to get out of there, get out of there. But we don’t get out of there. We don’t get out of there fast enough. So they start kicking the sleeping bag. So I get scared. Don’t shake, don’t shake. Why, Matt, why? They don’t have the right. Your lips on my lips and your tongue in my mouth… Be quiet, don’t ask questions, don’t be scared, I’m here. You won’t say anything, I won’t say anything, it’s our story. They can’t take it away from us. Hands grab the sleeping bag and pull in every direction. They tear at everything. The dogs jump in; the sleeping bag rips and feathers come out. My mother screams like a mother and calls me my daughter. I hate her.

They make us stand up and their hands pull us apart. They want to know what the hell we were doing, and what that bastard did. It’s my father’s voice and it’s you he’s talking about. He’s taller than you, he threatens you, he yells louder and louder, asking what you did to her, to his daughter, saying you’re despicable, you’re scum.

I see my mother hunting through the ripped sleeping bag, she searches and searches and she finds a condom, used and tied up. She stands up under the almost-full moon and she points at you, yelling that you assaulted me. That’s what she says: “He assaulted her!”

I see my mother pushing the men aside and walking toward you. She still wears that ring my father gave her on her little finger. She slaps you so hard that your head goes back, and you slip and fall on the ice. The ice shakes and echoes as if the whole lake was going to split in two. The ring hit your cheekbone and cut your skin. You struggle to get up, you have your hand on your cheek, you’re bleeding. In your eyes I see the fear, and I hear all the noise: the dogs barking, the men yelling, our beautiful silence shattered, dirtied. You assaulted—assaulted—me? And I don’t exist, I don’t exist anymore. They gave me a sweater but I’m cold. Blood is running down your cheek, your face is gray. My body is gray, too, like stone.

Suddenly I’m in so much pain that I want to howl. Howl like I howled when I was a baby, like I howled when I was a kid, like I howl every time someone comes near me and I’m not sure if it’s to hurt me or to comfort me. Howling is worse than talking, it makes everything more confused, and the dogs won’t like it. But I’m going to howl because there’s no place for words, for explanations, and because I don’t know how to cry.

I let my head fall back toward the starry sky, toward the moon that’s almost full, long enough to take a gulp of frozen air and let it drop all the way down to my heart. This is for you, Matt. It’s my gift. It’s filled with me and you, multiplied by ten. The dogs growl, sniff me, then lay their snouts on the ground, whimpering. My mom has her head buried in her hands; the men are frozen. Now they’ll all know that I’m the one who howls at night, in the valley. Or maybe they knew that already.

I’m not breathing anymore. I’m drawing out the strength and the softness from your eyes as they stare into mine. I howl again for your lips and your hands, for the blood flowing down your cheek and the blood that just flowed from my body, just a few drops, pink. I howl, most of all, so I’ll never forget.

When I come back to myself, there’s nothing but silence on the frozen lake. I see a man push you roughly into his car while my parents wrap a coat around my exhausted body. Before the car doors close, my eyes meet yours, one last time. You’re crying. Tears slide down your cheeks, turning red from the blood of your cut. The dogs stay back, far behind me. I can see on the ice that they’ve peed out of fear.

Since then, Matt, the hours go by slowly, matching my own slowness. All I have left is the memory of what there was, before. I hurt my vocal cords when I howled. The doctor said it will be weeks or maybe months until I can talk again. I don’t care. I caught a cold, too; I’m in bed, I don’t want to get out. My mother brings me something to eat a few times a day, and herbal tea, and orange juice. She doesn’t look at me; her eyes shift away and look at the blanket so they won’t meet mine. My father never comes into my room. I hear his heavy steps in the hallway. They don’t speak to me, not even to scold me or ask me questions. They called the gynecologist. She was a tall, skinny woman with frozen hands. When she put them on my skin, they felt like ice cubes. She wanted to check something, and I didn’t want her to. She spoke to me gently so I would trust her, but since that night, I don’t trust anyone. She wanted to know what happened between you and me. She put on a clear plastic glove, then slid her hand between my open thighs.

She said, “Excuse me, I always have cold hands, but it won’t take long.” I didn’t like what she was doing to me. But she was quick, and she didn’t hurt me. She pulled out her glove and on the tip there was a bit of red. “You’re not a virgin anymore, are you?” I made a sign to her to lower her ear to my mouth. I murmured in a hoarse wisp of a voice, “No, I have my period.”

And it’s true, because it’s the full moon and my period always comes on the full moon. So I didn’t really answer her question. She didn’t ask again, she was sure that she had the answer on her fingertips. I’m not a virgin anymore and I have my period. Yes, that’s right.

I huddled up under my covers and pretended to sleep. Then I fell asleep for real, and then the psychologist came. He asked me questions, too. He asked if you forced me, and I said no by shaking my head. No, no, no.

“So, you consented?”

I didn’t understand what that meant. Consenting means I said yes to you. But that wasn’t right, because you were the one who said yes to me, so I wasn’t sure. I said no to the psychologist, then yes. So he asked again, “Did he force you?” No. “So, you were okay with it?” Yes. And then I waited for him to ask, “Were you the one who wanted to do it?” And then I would have said YES. But he didn’t ask me that question. That’s how it went, Matt.

“As strange as it may seem,” the psychologist said to my parents, who were waiting in the kitchen, “I believe that Louella agreed to go with this boy and to have sexual relations with him.” My mother said that it wasn’t possible, that I wasn’t mature enough, that I was incapable of making even a simple decision. So, no. It wasn’t possible.

“Louella’s intellectual and decision-making abilities are limited,” he said. “However, she yells less than before and seems to be acclimatizing socially little by little. Her obsession with colors, which we’ve observed for several years, is nothing to be concerned about. At the special needs school, her behavior doesn’t cause any major problems. We know that she is very impressionable. It’s possible that she agreed to go with this boy and to have sexual relations with him. You know, normal or not…we never notice our children growing up.”

My mother didn’t agree with what the psychologist said. She told him that he was wrong, that she knew me because she was my mother. I buried my head under the covers and didn’t listen to the rest. It was dark, and hot. It was almost like the sleeping bag on the lake.

That memory makes me jump up inside, in my bed. I don’t care what other people say. I just remember us, us, us.

I’m going to play back my memory. I’ll rewind to the beginning, because that’s how stories are told, from the beginning. They took away my right to play a part, so I’m going to take it back. I know that wherever you are, you’re doing the same thing, too, every night.

The first time… I really like those words, the first time… The first time I saw you…see, my heart is already starting to beat again. The first time, you never know it’s the first time. You only realize it after, a little later on. The first time I saw you was in the evening, when the bus was taking me home, just like every day of the week when I go to the place I call the school for retards. I had on my mauve jacket and black pants, and my beige hat with two maroon stripes around the edge. You were getting off the bus. I hadn’t seen you get on, and normally, I’m the only one who gets off at that stop. I have to walk from the bus stop down a path that winds through the forest to our farm in the valley. Normally, it’s just me on the path.

Actually, the first time I saw you, I didn’t see you right away—I just heard you. You were getting off the bus, behind me. I had said good night to the driver, and then I heard another voice say good night, and that’s how I knew there were two of us getting off the bus. I didn’t turn around. I put my backpack on my shoulders and I adjusted the straps because I don’t like it when the straps are too loose. I checked that my shoelaces were tied well, because it’s hard to retie them when it’s dark and you can’t see much. And I took the path, like I do every night, but this time, you were behind me. There was some hard snow and our shoes crunched on it. I heard you walking with big, sure strides, crack, crack, and I thought you would pass me. But you stayed behind me. I knew you were a man, and young, because I had heard your voice when you said good night to the bus driver. I’ve never liked people following me, so I turned around. You were walking a dozen steps behind me and you stopped, you looked at me, and then you looked at your feet, as if you didn’t know where to put your eyes. I started walking again, and you started walking, and we went another twenty steps like that. I stopped again because I really didn’t like a man I didn’t know, a young and tall and strong man, following me at night on the path going to the valley.

Then you said, very quietly, “I’m not following you. If you like, I’ll go ahead.” I nodded yes. You passed in front of me, without lifting your head. You looked annoyed. We started walking again, you in front and me behind. But it wasn’t working, and you stopped.

I said, “What is it now?”

You answered, very quietly, “I don’t like being followed either.”

I listened to what you said, I thought for a moment—probably for too long but you didn’t seem to notice—and I said, “Then walk beside me.”

I was standing on one side of the path and you came over to the other side, and we started walking again. I could see that you were shy. I didn’t know what to say either. I’m not good at talking to people, it always takes me time, and this was happening too fast, so I didn’t say anything and neither did you. You were walking at the same pace as me. Once in a while, you kicked a half-eaten pine cone that had fallen out of a tree. I didn’t dare to, even though I like kicking pine cones for fun, too. Ten minutes later, we got to the spot where I turn off the path to get to our farm. You kept walking straight. You didn’t say goodbye and I didn’t either. I heard your steps on the snow getting farther away, crack, crack, quieter and quieter.

I tapped my feet against the wall of the house to get the snow off my shoes and I went into the kitchen. I heard the dogs moving around in the garage. I was the first one home, just like every night. I turned on all the lights, I put two logs in the fireplace, because I like the smell and the color of the flames, and I sat in front of it. Then my mother came home, then my father, and they started talking, both of them at the same time, just like every night. The same words, the same routine—work, the animals, the people at the hospital—my mother is a nurse, my father is a farmer. There were two little sick calves and an old cow that died when it tried to get up to go home, you know, the old ones always want to die at home. My dad shook his head, and I stared at my bowl, watching the butter melt in my vegetable soup, until my dad said to me, “Good Christ, can’t you just eat your soup instead of daydreaming? Do you like it better cold?” My mother probably said, like she did every night, “Leave her alone, you know Louella’s slow.” And I probably winced, because I hate that name, even though it’s been mine for almost seventeen years now. After, there was the sound of dishes in the kitchen sink when I washed them, banging them together a little too much, which always annoys my dad when he’s watching TV, so he grouches, and then I probably make a bit more noise because of it.

That night, under my covers, I dreamed about the path that goes to the farm. There was a shadow on the other side of the path. Whenever I turned my head to look at it, the shadow would disappear under the snow. I kept dreaming the same thing until the grandfather clock sounding three o’clock in the morning…bong, bong, bong…woke me up. And then I fell asleep again. So that was it—the first time we met. The next evening, when I left the school for retards, I went straight to the back of the bus. But the driver called back, “Did you lose something?” so I told him no, then I went to my usual spot and looked straight ahead, at the driver’s back, because I always sit just behind him. When we got to the village, I got up, I said good night to the driver, and I waited a few seconds. I didn’t hear you say good night so I thought I must be alone, as usual, and I walked home, shuffling my feet. The next day, it was the same thing. After that, I lost count—well, I didn’t count the days, you know I’m not good at math, but I think there was a weekend, and then a Monday, and a Tuesday…and then one night, when I was getting off the bus, after I said good night, I heard someone saying good night behind me, and I knew you had come back.

From that moment, my life started to change, slowly. So slowly that at first, I didn’t even notice it was changing.

One night, you got off the bus, you said good night to the driver, and you came up and walked beside me without asking. It was cold; it was only September and everyone was already saying that winter this year would be longer and colder than usual. That’s always what people say when it snows like that in September. But, twenty-four hours later, the snow melts and it starts raining, and they always forget what they said before.

We live in the mountains. Sometimes it’s really cold in the fall, sometimes really mild, sometimes really warm, and sometimes even really hot. I like the fall because of the color of the trees and because it’s so close to winter. I don’t like it because of the dogs that get all excited by the hunting and the gunshots in the forest. I don’t know anymore how many days we walked along the path together without saying anything but good night. Or sometimes not even that. It’s like you were scared of me. And I was a bit scared of you, too. So we each stayed on our own side of the path, kicking our pine cones. Sometimes, one of yours came over to my side and I kicked it back to you. Once, the pine cone that you kicked over to me bounced and did a little spin. I started laughing, and you started laughing. And something moved in my stomach. I didn’t really understand what was happening. I wondered if it was my period, but it wasn’t anywhere near the full moon, only the first quarter. Later, I figured out that it was your laugh that made something move in my stomach, and little by little I got used to that nice, gentle feeling. So you walked closer beside me, and after that, we didn’t need to talk using pine cones anymore.

You said, “My name is Matt.”

I said, “I like that.” But I didn’t tell you right away what my name was, because I hate my name. I thought about it, probably for too long, and then I murmured, “Call me Lou.”

It came to me just like that. Lou. Because it sounds like Louella. And it sounds like “lupine,” which a teacher at school told me means like a wolf. I thought that since we were talking, maybe I should tell you that I was the one who howled sometimes in the valley. But I kept quiet.

“Lou? That’s not very common,” you answered. And I don’t think we said anything else that night. On another night, I apologized. “I don’t talk much, Matt. People say I’m stupid. But if you talk, I’ll listen.” You seemed surprised. You stayed silent for a moment, then you just mumbled that you didn’t talk much either… But actually, you can be a chatterbox. I’ve noticed it. It’s just that you were shy. And that, I understood.

How do people talk to each other? And what do they talk about? I didn’t know anything about you, or you about me. I didn’t know where you had come from or where you were going. I didn’t ask you those questions. But the night you stopped on the path, when you made a sign to me to stop walking and be quiet, and you pointed at a tree where a robin was singing, I understood. I understood that you liked birds, that you liked the forest, that you weren’t one of those guys who go chasing after animals on the weekends with a rifle. I wanted to laugh and cry at the same time. I hadn’t known, until then, that any other kind of guy existed! I remember that day really well because that afternoon, at school, I had a “traumatic incident” or, at least, something really horrible happened. I got trapped in the hallway by a boy who wanted to kiss me. A big boy, with hands like tennis rackets. He pushed me up against the lockers where we keep our gym clothes. He managed to force his tongue into my mouth. I struggled, I freed myself, and as soon as I got far enough away, I slapped him.

He whined, “I’m going to tell the supervisor.”

I said, “Go ahead and I’ll tell him what you did to me.” I grabbed my things and I went outside to wait for the bus, not saying anything to anyone. I was amazed that I had reacted so quickly.

Because they always say to me, “Hurry up, hurry up.”

My dad says, “Make up your mind, you’re driving me nuts dithering like that.”

My mom says, “It doesn’t matter if you wear the blue one or the red one. Just decide which color sweater you want to wear today and stick with it, I’ve got other things to do.”

My grandmother says, “Good lord, that girl is indecisive! She’ll never be able to pick someone to marry.”

My mom says, “Well, she’ll have lots of time to think about that.”

I don’t like it when my family talks about me. It always ends with my dad yelling, “It’s not my fault I have an idiot for a daughter!” And my mom replying, “Oh, are you saying that for my benefit? You know very well that we don’t know if…” She doesn’t finish her sentence, and I don’t know if she wants to say “if she’s an idiot” or “if it’s my fault.” One day, I told you the whole story, Matt. When my mom was pregnant, the cat scratched her arm and she got a little sick from it. When they told her I wouldn’t be very normal when I was born, my dad was sure it was because of the cat, and he kicked the cat and he killed it. My mom never forgave him. And now, when they fight, they always talk about that—the cat, and how I’m an idiot, or slow, it’s the same thing. Matt, you’re the only one who says it’s not the same thing, that just because I can’t do things quickly doesn’t mean I’m an idiot. It’s true, Matt. You’ve never yelled at me to hurry up, except for the night on the lake, because we heard them walking on the shore and they were going to come and surprise us.

The night I told you about my family, I was wearing my black pants and a pale green T-shirt under my dark-green sweater. I wasn’t very happy because I thought my blue gloves didn’t match the green. But then you showed me the tree and the bird singing in the tree, and I wanted that bird to sing for a long time, just for us. Later, you told me that you used to dream of studying birds—an ornithologist is what you called it. And later, I understood why it could only be a dream.

But you weren’t just watching the robin. You were watching me, too. And I thought it was nice to be looked at that way. So I started taking even longer than usual to pick out my clothes, and that made my mother mad. “Louella, are you ready?” No. “Well, what the heck are you doing in there?” She’d come into my room. “What? You’re still in your underwear? What difference does it make if your T-shirt is red or white? You’re putting a sweater on top. No one will even see it!” Yes, but I don’t like it when one color doesn’t go with another. All day I would feel like I was forcing the blue to live with the red…and how would that red get along with this pink—so pale, so delicate? It would hurt it, it would snuff it out. I have a complicated relationship with colors, it’s true. The more I struggle to decide, the more I think I shouldn’t, that it isn’t normal to take this long. So I lose my train of thought, I get confused, and then I don’t even want to get dressed anymore. It always ends the same way: my mom is in a hurry, she’s worried that I’ll miss the bus and she’ll have to drive me to school, and she chooses my outfit for me. “This is what you’re wearing and that’s it! Louella, you’re worse than a baby!” So she thinks, like everyone else does, that I can’t make a decision.

One night I told you about that, Matt. You said, “Colors, for me…” At first, you just told me that you didn’t see them exactly the way I did and that’s why you liked winter, when there was snow everywhere, because white was a “sure” color. That’s what you said to me, “a sure color,” and I was too shy to ask you what you meant. Then you explained it to me. You’re colorblind. There are colors that you don’t see the way I see them. Which ones? Red and green. They look kind of the same to you. Ripe strawberries look the same color as the leaves on the strawberry plant. I thought that was strange. I asked you if it was hard to live like that, and you stopped a moment before saying, “Hard? No, it’s not usually hard. I ask my brother when I’m not sure about the color of clothes. But for certain jobs, it is hard. When you have to work with precise colors, when you have to know if something is red or green, for example. When you want to describe a…” You stopped there. I looked at you and I thought you were going to cry. But maybe it was just that it was so cold and the north wind was blowing into our eyes. But your mouth was sad, too, and I couldn’t explain that away. I thought about the last thing you said: “When you want to describe a…” Describe a bird? Describe the color of its feathers? Is that what you wanted to say, Matt? Because you’re colorblind, you can never be an ornithologist? You told me that you were doing a certificate in carpentry. That your uncle had just moved near here and you were staying with him, but that you were going to leave to do your apprenticeship soon, before the end of the year.

That night, we didn’t talk about anything else. You stayed on your path and I watched you disappear into the night. Your steps were slow, like the sound of our grandfather clock…bong, bong, bong…the same rhythm as my heart when it beats quietly.

Later that night, I stood in front of my mirror and I wondered out loud, “How does Matt see me?” I put on my orange parka, my blue gloves, my black hat, and my brown shoes. Would I look all black and brown to you? I thought that autumn in the mountains was not a very good time for us to really get to know each other—you couldn’t see any of my bare skin under all my clothes. But what brought us closer was something a bit hidden, deep within the two of us, something maybe a bit broken. I yell when someone comes up to me too quickly, and you can’t tell the difference between the color of a zucchini and the color of a carrot. Also, we both liked winter, and snow, too. Because it was cold and it was white. And we were burning up inside, but nobody knew it, except you and me. You had come closer to me, slowly, and everything had changed. The snow was a sure color, and the world seemed sure, too.

Now, in the morning, it’s like waking up after a storm. Everything is wrecked and I don’t know if anything’s left. So, lying under my covers, I search my memory. I try to find everything we said, and even everything we didn’t say. The first times, the thousand first times. The first time you really talked to me, when you stopped to show me the bird. The first time you left your side of the path to come walk next to me. The first time you touched my gloves, without meaning to, to help me hold up my big umbrella that was protecting us from the rain and wind. The first time your lips brushed my hat, and my ear under my hat, one night when it was so foggy and I put my hand in yours.

The first time you took off your gloves so you could touch my skin better. The first time my lips found themselves pressed to yours, in one breath. We’ll always have our first times, Matt, no matter what. I have to find them, one by one, and not forget any. I won’t sleep until I’ve found them all.

The first time we kissed, Matt, it was like a door opening. I had talked to you for a long time. I had told you everything. That I was a difficult child, that as a baby I bit myself until I bled—you can still see the scars on my wrists—and that, most of all, I howled. Like a wolf. I told you that my howling even scares dogs, and that’s why dogs don’t like me and I don’t like them either. I told you my parents dragged me from specialist to specialist, secretly, because they were ashamed that up in the town people were starting to gossip that their girl was howling at the full moon. I told you that, and I was afraid you’d make fun of me. But you placed your lips on mine and your kiss was real.

One night, you took me in your arms. “I have something for you. Close your eyes.” You kissed me. I laughed. I didn’t need to close my eyes just for that. You reached into your pocket and you pulled out a wooden object. “Here, this is for you, it’s a present.” Your outstretched hand held a little carved turtle. Suddenly, it made me sad that you were giving me a turtle. “You don’t like it? I carved it for you.”

I didn’t know what to say. I liked it, but it was still a turtle. I mumbled, “It’s a turtle…”

You looked surprised, and you said, “Yeah! Turtles are strong and tough—that’s why it reminded me of you. I sculpted it out of boxwood, it’s a very hard wood. You don’t like it?”

I told you yes, of course I liked it, and I thanked you. But deep down, I said to myself that maybe you were making fun of me for being slow. I didn’t admit that to you until two days later. You were upset that I could think such a thing. I could see how unhappy you were. I hugged you to try to erase all that.

So I made the little turtle into a pendant and wore it around my neck. The next day, my mother asked me where it came from. I said they gave it to me at the school. “A turtle! It suits you.”

I pretended not to know what she meant. I just knew that the turtle made me feel prettier, because it reminded me of us.

Matt, do you know what drew me to you? Do you know what made up my mind? It wasn’t your hands on my face. It wasn’t your lips on my lips, or your caresses over my clothes, or even the little turtle. It was the injured bird…do you remember? One night, when the moon was shining on the snow, lighting it up like a streetlamp, you found a bird by the side of the path. His wing was broken and he would have died of cold, or else been eaten by another animal. You picked him up. He thrashed around a bit in your hands and you started talking to him, very softly. You said to him, “You have nothing to fear from me. I have big hands, but they’re warm and they won’t hurt you. You were afraid, you were getting numb from the cold, but that’s over, I found you, I won’t leave you alone. I can’t fix your wing here, so I’m going to take you with me. But you’ll see, everything will be okay. And you’ll be able to fly again, soon.” And with your free hand you stroked his little head very gently, and he relaxed, like he had understood. And that’s why I said yes to you. Because you were so gentle with the bird. I knew that you’d be the same with me. That night, we didn’t kiss or hold each other, because there was the bird. But that night, I made my decision.

From then on, we saw each other every night. We waited for the bus to leave before taking each other’s hand. In the town, people are always watching. But on the path leading to the valley, there’s never anyone. So you would come close to me and I would come close to you, and I had waited all day for that moment and you had, too. I would take off the glove on my left hand, and you’d take off the glove on your right hand, and our hands would touch; they were hot. After that, we’d kiss—quickly, or for a long time, it depended on the weather. It was cold outside, and warm between us. Between kisses, you wouldn’t speak much. The day after the injured bird, or maybe the day after that, I asked you, “Have you ever made love with a girl?” You answered yes, turning your eyes away, and I thought I saw something a little sad, a memory that wasn’t very happy. “It wasn’t good?”

“The first time, it can be a disaster.” Your voice was just a murmur, and a little river started flowing in my stomach, between my thighs. I shivered. I thought that you would be the first for me, and I was happy about that, and I thought with you it wouldn’t be a disaster and you would never have sad eyes when you thought about it. At night, under my covers, I’d see your eyes in mine, and you were saying, “Yes.” But the question I was asking you wasn’t, “Have you ever made love with a girl?” The question I was asking you was, “Do you want to make love with me?”

I knew that I wanted to, and I knew that you did, too. It made me dizzy to realize that I could make my own decision. It just took me some time, that’s all! Before going to bed, I’d lock myself in the bathroom. I’d let the warm water run over my skin and imagine it was your hands on my body. I’d write your name on the bathroom tiles, in the steam: Matt, Matt, Matt. Then I’d wipe it so it wouldn’t leave a trace. I dreamed about making love with you, and I knew that dream would come true soon.

The days went by, not very quickly. You told me, “I wish it was summer.” And even though I love winter so much, I whispered, “Me, too.” Because then we wouldn’t have to keep guessing everything about each other, guessing about your skin and my skin under our layers of clothes. One night in November, you had an idea. “We can go to the hunters’ cabin. We can make a fire. We’ll be warm.”

“I don’t like that place, the hunters come there with the animals they’ve killed, they bleed them, they drink and shout…”

“I know, but we can make a fire there.”

I said yes to the hunters’ cabin because it was night and no one would be there. We didn’t have much time. Making a fire would take too long. And what if a hunter saw the smoke coming out of the chimney? We went inside the cabin; I took off my jacket and you took off yours. You lifted up your sweater, then took my hands and slid them under. I had cold hands, or else your stomach was burning. My hands warmed up very quickly, and then you did the same thing with me, and that was it. That was all we did that night, but it was nice to feel my body pulsing under your fingers, all the way down to my thighs.

“We have to go back.” I was shaking, and so were you. It was the cold, right? Or maybe it was something else. Yes, I want to. Do you? I don’t know who said it first. Me, you. We both wanted to, and you would be my first. Those days, I felt like I was keeping a little bit of skin inside me, a piece of childhood that wanted to be erased.

We talked and talked about what we should do, and at night I replayed our words over and over in my head.

What about your place? Could we go to your place? No, we can’t go to my place, Matt, because of the dogs. They’ll smell you, they’ll get all worked up. My parents will know that someone else was there. They’ll ask questions, they’ll accuse me, they’ll look for traces, and they’ll spy on me. All because of the dogs. I don’t like the dogs, Matt, they’ll give us away. What about at your uncle’s? It’s too far, Lou, we’ll never have enough time. We have no car, no place to go…in the spring, in the forest, we can go anywhere… But spring is far away, and it’s especially far away here. Matt, do you remember the year it snowed in May? Yes, I remember. Everywhere else it was almost summer, and here it was still winter. We live in a funny place, Lou. Yes, but it’s ours and I love it and I love winter, too, even though it makes things complicated. And in the spring, you and I won’t see things the same color anymore. Then we’ll find a place for the two of us, where no one will find us, where there won’t be a dog or a human, nothing but us, and our love, and your body and mine and my hands, and no more words… Nothing but your skin, nothing but mine. You know, Lou, the words to talk about love are really disgusting.

I know. One day at school, a boy obsessed with sex listed them off: masturbation, intercourse, testicles, vagina… I don’t know why, maybe it excited him. I thought those words were so ugly. But the slang words aren’t much better. I know a few: screwing, dick, balls…that makes you laugh! We need other words…we need words for the two of us, Matt, that aren’t ugly or cold. Words that are like your skin and mine, words like our hands. Words full of sure colors. Words of love that we’ll both see the same way.

One Saturday, I asked my mom to drive me into town to buy a new bra. She said yes, sighing. She hates going shopping with me because I don’t know how to choose. But that time, I knew what I wanted and I showed it to her: “That one, there.” It closed in front with a hook, and I thought it would be easier to undo if we ever went back to the hunters’ cabin. My mom said okay and then begged me not to take three hours to decide on the color. There was white, beige, burgundy, and black. I picked the beige right away, and my mom looked stunned. That night, she told my dad that my obsession with colors was passing. He didn’t understand what she said because he was watching TV, and my mom repeated, louder, “I think Louella’s not obsessed with colors anymore.” My dad probably shrugged his shoulders to say he didn’t care; anyway, he didn’t answer. I was washing the dishes and I didn’t see them, and I pretended not to hear them either. I thought my beige bra was beautiful, Matt, because you’d see that color the same as me.

But in the end, it didn’t matter. When we went back to the hunters’ cabin, just that once, you passed your hand under my bra, without unhooking it or looking at the color, and that was fine, too. You have a nice voice, Matt, and I liked listening to you talk. You said, “Soon the lake will freeze over, did you see? For a few days now, there’s been ice on the surface. If the cold keeps up, the lake will freeze, and when the ice is thick enough, we can skate on it. Hand in hand. Body to body.”

“Matt! Are you serious?”

I remember the night you first talked to me about the frozen lake. And about your two big sleeping bags for sleeping in the cold that your father had brought back from a camping trip in the mountains. “You can sleep in the snow, and you’re not even cold. Why are you smiling, Lou?”

“Because I don’t want to sleep!”

Your laugh made a night bird fly from one tree to the next. I laughed, too, and I realized that, before you, I never laughed. Everything was sad: my dad’s footsteps in the hallway, my mom’s nagging, and the whole angry world around me. “Hurry up, make up your mind! You’re driving everyone crazy! Quick, Louella, quick!” Nothing made me smile or made me happy. I was surrounded by colors that didn’t get along. Only the snow made me feel calm. But I never laughed. You made me laugh, Matt, and that night in the cabin, I felt like a bird, flying from one tree to another, from a frozen lake to a mountain sleeping bag. I said, “It’s a good idea, we’ll have to wait until the ice is solid. And until the moon is full…well, not totally.” I waited a moment, then I came up close to you and I whispered, “Not totally because when the moon is full, I have my…” It’s hard to say that to a boy, he might be embarrassed, or disgusted, or…I don’t know. Does a boy know that about girls? “I’ll have…um, my period.” I must have turned red, but it was so cold that my face was already red and it wouldn’t have shown.

You said to me, “Having your period doesn’t mean you can’t make love, but…what about a few days before the full moon? Would that be okay?”

“Yes. A few days before, yes. Will the lake be frozen enough?”

“I hope so.”

“Will it be nice out?”

“I hope so.”

And at night, under the covers, in my bed, in my room, I thought about your words, and your words touched my skin, became fingers, lips. I thought of you, I felt you on me, and the pleasure I gave myself was already ours.

And the day came. Just like that. You said to me, “Tonight would be perfect. Because, you know, I’m going to leave on my apprenticeship and I’ll be away for three weeks. Three weeks is a long time. The lake could melt all of a sudden. Or the weather could turn bad. So tonight would be perfect.”

And I replied, “Yes, tonight would be perfect.”

We didn’t talk much on the path through the forest. It was a dry cold, very dry. I kept my gloves on, and you did, too. Our shoes crunched on the snow and seemed to be saying tonight, tonight, tonight. Tonight we’ll have time to love each other, tonight we’ll have time to touch, tonight we’ll take our gloves off…

“Are you sure it will be warm enough in your sleeping bags? What if they get wet from the ice? And if we make it melt?”

“Don’t worry, I’ll bring a big plastic tarp to put under us, and we won’t get cold, that’s for sure. We’ll be hot, very hot. Hotter than you can imagine, Lou.”

“What time will we meet? I’ll have to sneak out. And I can’t let the dogs hear me.”

“Do you think you can do that?”

“Yes, if I’m careful. I’ll open the window quietly, I’ll slide out, I won’t need to take my skis or my snowshoes, the snow is hard enough that you can walk on it without sinking. I’ll come to the edge of the lake.”

“Yes, Lou, and I’ll be waiting for you.”

“With your big sleeping bags?”

“Yes, with my big sleeping bags, a tarp to put on the ice, and a condom.”

“You won’t forget the condom.”

“No, I won’t forget.”

Night came, and I snuck out of the house. The dogs didn’t bark; they didn’t hear anything. The moon was almost full, but not completely. It lit up the snow and the snow sparkled. When I got to the edge of the lake, I saw you, and my heart started to beat stronger. The sleeping bags were thick, you had zipped them together, they fit perfectly. We took them under our arms and walked onto the lake. There was a light dusting of frost on the ice that kept us from slipping. You could see the moon’s reflection in places, and the whole night wrapped around us. We walked silently all the way to the middle of the lake, far from the shore.

“Will anyone be able to see us from the shore?”

“I don’t think so.”

“What if the ice melts?”

“It’s way too thick.”

Then my questions disappeared, and the world outside disappeared, too. We slid into the sleeping bags, we zipped them up, and, in the dark, we let our bodies tell their story. Sometimes, the frozen lake cracked and shook underneath, but we weren’t scared. I said to you, “My body is talking under your hands.” That’s what it felt like. You were right, it was hot all of a sudden, hot like I’ve never been hot before, even in summer. Sweat slid down my arms, my breasts, and where our stomachs met. You weren’t in a hurry, I wasn’t in a hurry. We had all the time in the world and we were a man and a woman, not children anymore. I wanted to bite you, like a puppy, but without hurting you. And you slid into me.

You pushed that little bit of childhood skin, gently. Before I even felt pleasure, I wanted to howl out in joy. It was good, it was good. There was nothing around us except a frozen lake, and our bodies burning on top of it. You weren’t saying anything, you were breathing hard, softly, hard. I followed your breaths and got into a rhythm. I felt you inside me, it didn’t hurt. We were a patch of color on the dark ice of the lake. You came, but not me, not totally, it was a bit quick. You said, “It’s okay, we have the night ahead of us, I have my hands, I have my mouth, there are a thousand and one ways, you’ll have your turn.” And we took our time loving each other, again, again, again.

Until the moment we heard the dogs barking in the distance, and the people walking on the shore.

“As strange as it seems,” the psychologist said to my parents, “I think Louella agreed to go with this boy and to have sexual relations with him.”

My mom took some time to think about what he said. But for a few days now, when she comes into my room, she almost looks me in the eyes. She talks to me, mostly about you. She says that you haven’t come back, that you haven’t tried to see me. That even if you didn’t force me, which has yet to be proven, you haven’t come to see how I am, you haven’t even phoned. She says that I was stupid to trust you and that even if I did say yes, you took advantage of my gullibility. She says that you’ll never come back, that you’ve already forgotten me, and that I should do the same with you. Then she asks if I’m still thinking about you and I shake my head no, because I’m not going to say yes. But I know that you’ve gone on your apprenticeship for three weeks, and that those three weeks have almost gone by. I managed to keep track of all the days, I haven’t missed one. My mom says that you’ve ditched me, but I know that you’re going to come back. I keep quiet, my hand on my throat. Because it’s our secret. And I know you’re coming back tonight, or tomorrow night. I’m not allowed to take the bus anymore, but you’ll wait until it’s really dark at night and you’ll come around to the back of the house, so you won’t disturb the dogs.

You’ll tap on my window. You’ll leave a little note, or just the traces of your steps. If the dogs don’t bark, I’ll open the window. If they do, we’ll wait for the right moment. And one night, one night when the moon is almost full, a very cold night with lots of stars in the sky, we’ll start again. We’ll find each other on the lake and you’ll have two sleeping bags zipped together. My body will be like brand new under yours. You’ll touch my skin, I’ll touch your earlobe, and nothing will happen to wreck our story. We’ll make love as much as we want. And if I hear people walking on the shore, you’ll just say, “You have nothing to be scared of, you’re with me. We’ll survive everything because we love each other. Lou, the dogs will never find us here.” And I’ll believe you, Matt, I’ll believe you.

First published in France as Rien que ta peau, ©Actes Sud, 2008

English translation ©2009 Annick Press

Annick Press Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyrights hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical—without prior written permission of the publisher.

Series editor: Melanie Little

Translated by Paula Ayer

Copyedited by Geri Rowlatt

Proofread by Elizabeth Salomons

Cover design by David Drummond/Salamander Hill Design

Interior design by Monica Charny

Cover photo ©istockphoto.com

To Éric, the rebel.

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) for our publishing activities.

Distribution of this electronic edition without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. Annick Press ebooks are distributed through Kobo, Sony, Barnes & Noble, and other major online retailers. We appreciate your support of our authors’ rights.

Cataloging in Publication

Ytak, Cathy

Nothing but your skin / Cathy Ytak.

(Single voice series)

Translations of: Rien que ta peau and La piscine était vide.

Title on added t.p., inverted: The pool was empty / Gilles Abier.

ISBN 978-1-55451-233-1 (pbk.).—ISBN 978-1-55451-238-6 (bound)

I. Abier, Gilles, 1970- II. Title. III. Series: Single voice series

PZ7.Y73No 2010 j843'.92 C2009-906402-2

Visit our website at www.annickpress.com

For a complete listing of all the titles in the Single Voice series, along with excerpts, please visit www.annickpress.com/singlevoice

Table of Contents

Louella hates her name. She’s obsessed with colors and when she gets upset, she yells herself hoarse. People call her “slow,” but Lou knows one thing for sure: she wants to be with her boyfriend—no matter what her parents or doctors think. Poignantly and sensitively told, NOTHING BUT YOUR SKIN chronicles the aftermath of a mentally challenged girl’s decision to have sex.