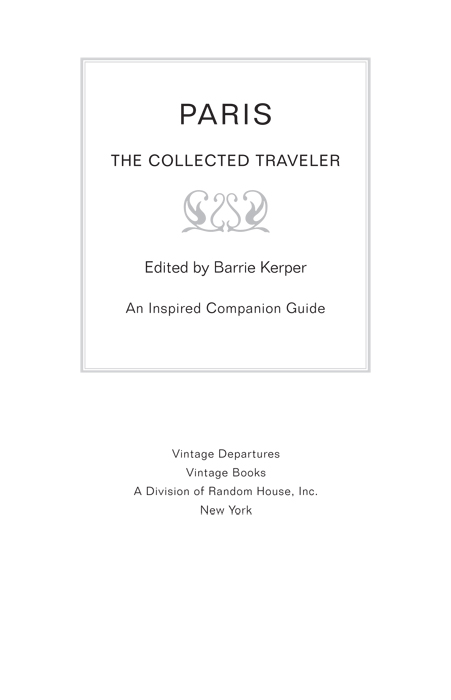

Paris – Read Now and Download Mobi

CONTENTS

THE AUTHORS

Steve Fallon

Steve, who has worked on every edition of Paris and France except the first, visited the ‘City of Light’ for the first time at age 16 with his half-French best friend, where they spent a week drinking vin ordinaire from plastic bottles, keeping several paces ahead of irate café waiters demanding to be paid, and learning French swear words that shocked even them. Despite this inexcusable behaviour, the PAF (border police) let him back in five years later to complete a degree in French at the Sorbonne. Now based in East London, Steve will be just one Underground stop away from Paris when Eurostar trains begin departing from Stratford in 2010. C’est si bon… Steve was the coordinating author and wrote the Introducing Paris, Getting Started, Background, Sleeping, Gay & Lesbian Paris and Directory chapters. He also cowrote the Neighbourhoods, Shopping, Eating, Drinking and Nightlife & the Arts chapters.

Nicola Williams

For Nicola, a British journalist living and working in France for the past 12 years (home is a hillside house with Lake Geneva view in Haute Savoie), it is an easy flit to Paris where she has spent endless amounts of time eating her way around and revelling in the city’s extraordinary art and architecture. When she’s not working for Lonely Planet, she can be found in the Alps skiing or hiking, strolling around Florence or having fun with family in Britain and Germany. Nicola has worked on numerous other Lonely Planet titles including France, Provence & the Côte d’Azur and The Loire. Nicola wrote the Sports & Activities, Excursions and Transport chapters. She also cowrote the Neighbourhoods, Shopping, Eating, Drinking and Nightlife & the Arts chapters.

PHOTOGRAPHER

Will Salter

In the last 12 years, Will has worked on assignment in over 50 countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Pacific region as well as Antarctica. He has produced a body of award-winning work that includes evocative images of travel, portraits and sport. He sees photography as a privilege, a rare opportunity to become intimately involved in people’s lives. Will is based in Melbourne, Australia, with his wife and two children. His website is www.willsalter.com.

LONELY PLANET AUTHORS

Why is our travel information the best in the world? It’s simple: our authors are passionate, dedicated travellers. They don’t take freebies in exchange for positive coverage so you can be sure the advice you’re given is impartial. They travel widely to all the popular spots, and off the beaten track. They don’t research using just the internet or phone. They discover new places not included in any other guidebook. They personally visit thousands of hotels, restaurants, palaces, trails, galleries, temples and more. They speak with dozens of locals every day to make sure you get the kind of insider knowledge only a local could tell you. They take pride in getting all the details right, and in telling it how it is. Think you can do it? Find out how at lonelyplanet.com.

GETTING STARTED

WHEN TO GO

FESTIVALS & EVENTS

COSTS & MONEY

INTERNET RESOURCES

BLOGS

Paris is a dream destination for countless reasons, but among the most obvious is that it requires so very little advance planning. Tourist literature abounds, maps are excellent and readily available, and the staff at tourist offices are usually helpful and efficient. Paris is so well developed and organised that you don’t have to plan much of anything before your trip.

But this is fine only if your budget is unlimited, you don’t have an interest in any particular period of architecture or type of music, and you’ll eat or drink anything put down in front of you. This is Paris, one of the most visited cities of the world, and everyone wants a piece of the action. First and foremost, book your accommodation well ahead. And if you have specific interests – live big-name jazz, blockbuster art exhibitions, top-end restaurants – you’ll certainly want to make sure that the things you expect to see and do will be available or open to you when you arrive. The key here is advance planning (Click here).

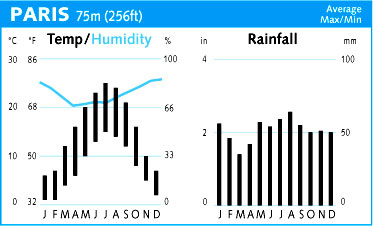

WHEN TO GO

As the old song says, Paris is lovely in springtime – though winterlike relapses and heavy rains are not uncommon in the otherwise beautiful month of April. The best months are probably May and June – but early, before the hordes of tourists descend. Autumn is also pleasant – some people say the best months of the year to visit are September and October – but of course the days are getting shorter and in October hotels are booked solid by businesspeople attending conferences and trade shows. In winter Paris has all sorts of cultural events going on, while in summer the weather is warm – sometimes sizzling. In any case, in August Parisians flee for the beaches to the west and south, and many restaurateurs and café owners lock up and leave town too. It’s true that you will find more places open in August than even a decade ago, but it still can feel like a ghost town in certain districts. For more information on Paris’ climate, Click here.

To ensure that your trip does (or perhaps does not) coincide with a public holiday, Click here. For a list of festivals and other events to plan around, see below.

DON’T LEAVE HOME WITHOUT…

- an adaptor plug for electrical appliances

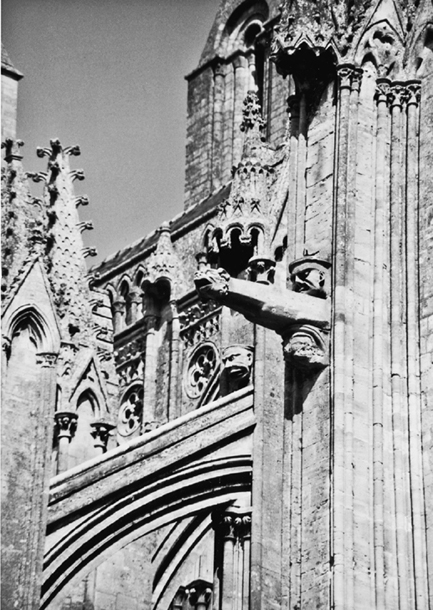

- binoculars for viewing detail on churches and other buildings

- an immersion water heater or small kettle for an impromptu cup of tea or coffee

- tea bags if you need that cuppa since the French drink buckets of the herbal variety but not much of the black stuff

- premoistened towelettes or a large cotton handkerchief to soak in fountains and use to cool off in the hot weather

- sunglasses and sun block, even in the cooler months

- swimsuit and thongs (flip-flops) for Paris Plages or swimming pool

- a Swiss Army knife, with such essentials as a bottle opener and strong corkscrew

Return to beginning of chapter

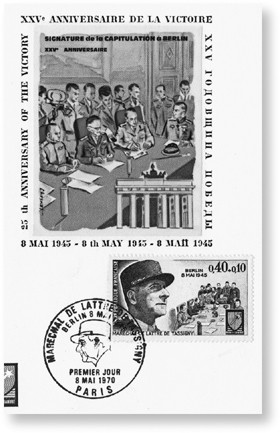

FESTIVALS & EVENTS

Innumerable festivals, cultural and sporting events and trade shows take place in Paris throughout the year; weekly details appear in Pariscope and L’Officiel des Spectacles Click here. You can also find them listed under ‘What’s On’ on the website of the Paris Convention & Visitors Bureau (www.parisinfo.com). The following abbreviated list gives you a taste of what to expect throughout the year.

January & February

FESTIVAL DES MUSIQUES DU NOVEL AN

The New Year Music Festival, relatively subdued after the previous night’s shenanigans Click here with marching and carnival bands, dance acts and so on, takes place on the afternoon of New Year’s Day at the Palais de Chaillot at Trocadéro.

LOUIS XVI COMMEMORATIVE MASS

On the Sunday closest to 21 January, royalists and right-wingers attend a mass at the Chapelle Expiatoire (Click here marking the execution by guillotine of King Louis XVI in 1793.

FASHION WEEK

Prêt-à-Porter, the ready-to-wear fashion salon that is held twice a year in late January and again in September, is a must for fashion buffs and is held at the Parc des Expositions at Porte de Versailles in the 15e arrondissement (metro Porte de Versailles), southwest of the city centre.

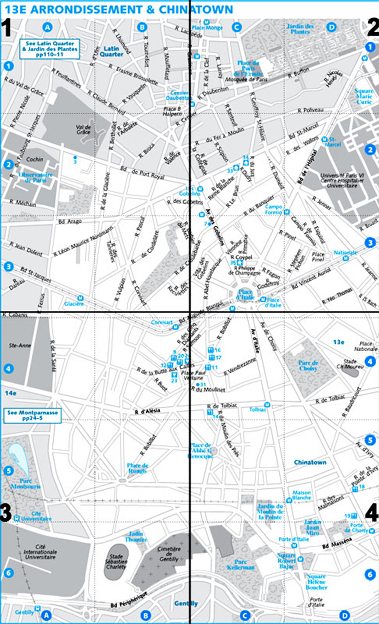

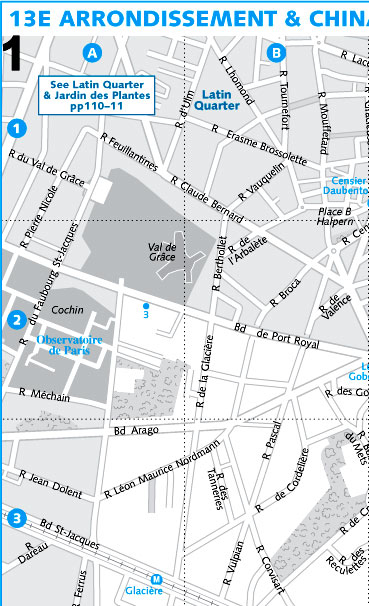

CHINESE NEW YEAR

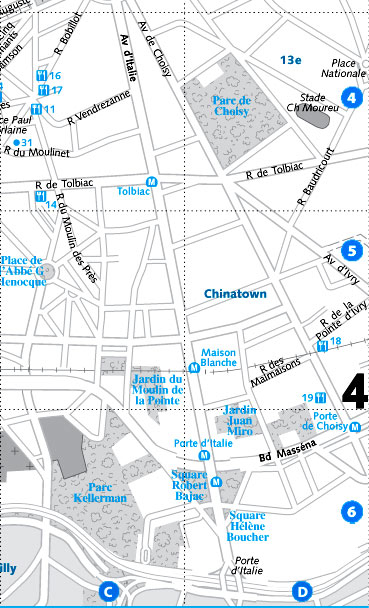

Dragon parades and other festivities are held in late January or early February in two Chinatowns: the smaller, more authentic one in the 3e, taking in rue du Temple, rue au Maire and rue de Turbigo (metro Temple or Arts et Métiers); and the larger, flashier one in the 13e in between porte de Choisy, porte d’Ivry and blvd Masséna (metro Porte de Choisy, Port d’Ivry or Tolbiac).

SALON INTERNATIONAL DE L’AGRICULTURE

A 10-day international agricultural fair with produce and animals turned into dishes from all over France, held at the Parc des Expositions at Porte de Versailles in the 15e (metro Porte de Versailles) from late February to early March.

March–May

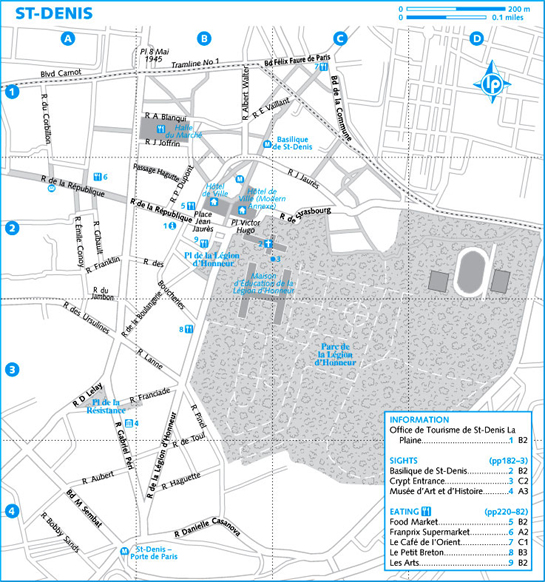

BANLIEUES BLEUES

www.banlieuesbleues.org, in French

The ‘Suburban Blues’ jazz and blues festival is held over five weeks in March and April in the northern suburbs of Paris, including St-Denis, and attracts some big-name talent.

PRINTEMPS DU CINÉMA

www.printempsducinema.com, in French

Cinemas across Paris offer filmgoers a unique entry fee of €3.50 over three days (usually Sunday, Monday and Tuesday) sometime around 21 March.

FOIRE DU TRÔNE

www.foiredutrone.com, in French

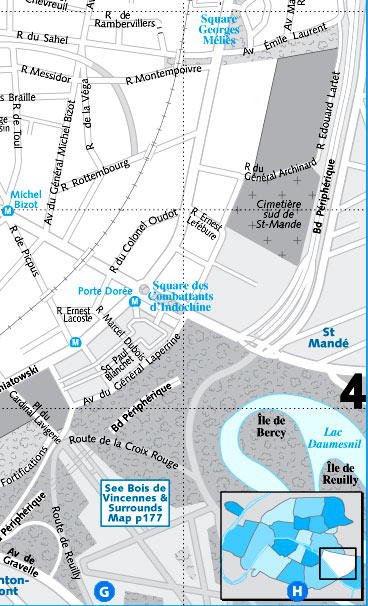

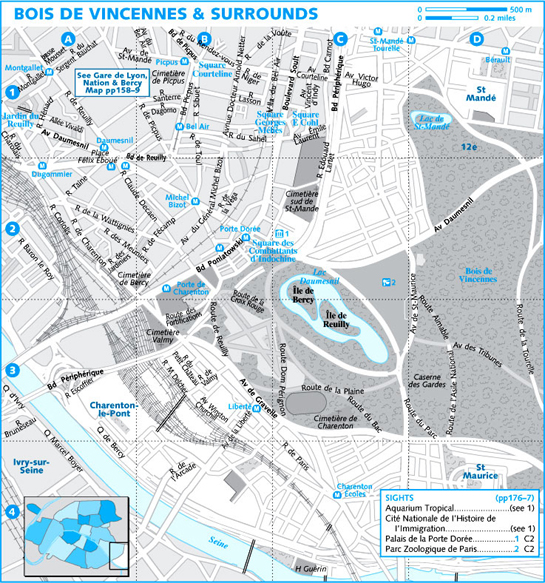

This huge funfair, with 350 attractions spread over 10 hectares, is held on the pelouse de Reuilly of the Bois de Vincennes (metro Porte Dorée) for eight weeks from late March to mid-May.

MARATHON INTERNATIONAL DE PARIS

The Paris International Marathon, usually held on the first Sunday of early April, starts on the av des Champs-Élysées, 8e, and finishes on av Foch, in the 16e. The Semi-Marathon de Paris is a half-marathon held in early March; see the website for map and registration details.

FOIRE DE PARIS

This huge modern-living fair, including crafts, gadgets and widgets, and food and wine, is held from late April to early May at the Parc des Expositions at Porte de Versailles in the 15e (metro Porte de Versailles).

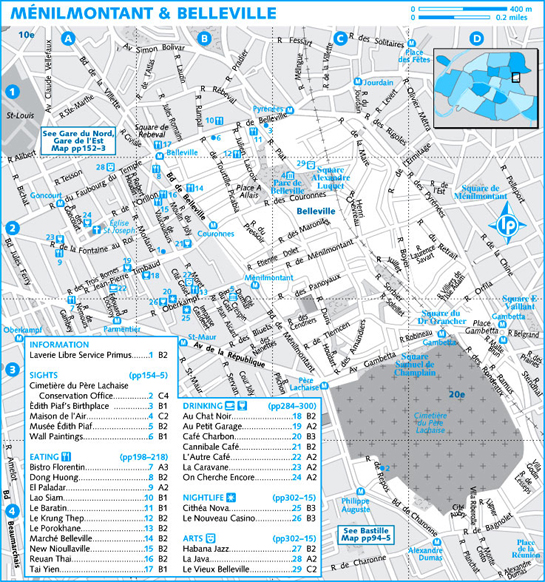

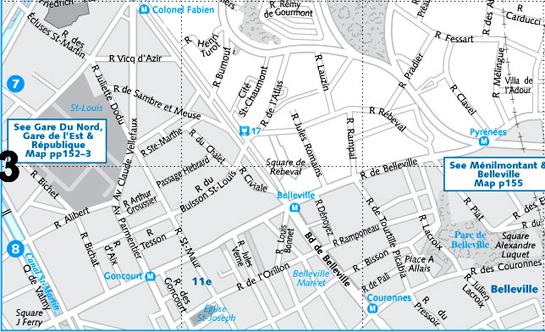

ATELIERS D’ARTISTES DE BELLEVILLE: LES PORTES OUVERTES

www.ateliers-artistes-belleville.org, in French

More than 200 painters, sculptors and other artists in Belleville (metro Belleville) in the 10e open their studio doors to visitors over four days (Friday to Monday) in mid-May in an event that has now been going for two decades.

LA NUIT DES MUSÉES

www.nuitdesmusees.culture.fr, in French

Key museums across Paris throw open their doors at 6pm for one Saturday night in mid-May on ‘Museums Night’ and don’t close till late. Some also organise special events.

FRENCH TENNIS OPEN

The glitzy Internationaux de France de Tennis – the Grand Slam – takes place from late May to mid-June at Stade Roland Garros (metro Porte d’Auteuil) at the southern edge of the Bois de Boulogne in the 16e.

June–August

FOIRE ST-GERMAIN

www.foiresaintgermain.org, in French

This month-long festival of concerts and theatre from early June to early July takes place on the place St-Sulpice, 6e (metro St-Sulpice) and various other venues (see website) in the quartier St-Germain.

FÊTE DE LA MUSIQUE

www.fetedelamusique.fr, in French

This national music festival welcomes in summer on Midsummer’s Night (21 June) and caters to a great diversity of tastes (including jazz, reggae and classical) and features staged and impromptu live performances all over the city.

GAY PRIDE MARCH

www.gaypride.fr, in French

This colourful Saturday-afternoon parade in very late June through the Marais to Bastille celebrates Gay Pride Day, with various bars and clubs sponsoring floats, and participants in some pretty outrageous costumes.

PARIS JAZZ FESTIVAL

www.parcfloraldeparis.com; www.paris.fr

There are free jazz concerts every Saturday and Sunday afternoon in June and July in the Parc Floral de Paris (metro Château de Vincennes).

LA GOUTTE D’OR EN FÊTE

www.gouttedorenfete.org, in French

This week-long world-music festival (featuring rai, reggae and rap) is held at square Léon, 18e (metro Barbès Rochechouart or Château Rouge) from late June to early July.

PARIS CINÉMA

This two-week festival in the first half of July sees rare and restored films screened in selected cinemas across Paris.

BASTILLE DAY (14 JULY)

Paris is the place to be on France’s national day. Late on the night of the 13th, bals des sapeurs-pompiers (dances sponsored by Paris’ firefighters, who are considered sex symbols in France) are held at fire stations around the city. At 10am on the 14th, there’s a military and fire-brigade parade along av des Champs-Élysées, accompanied by a fly-past of fighter aircraft and helicopters. In the evening, a huge display of feux d’artifice (fireworks) is held at around 11pm on the Champ de Mars, 7e.

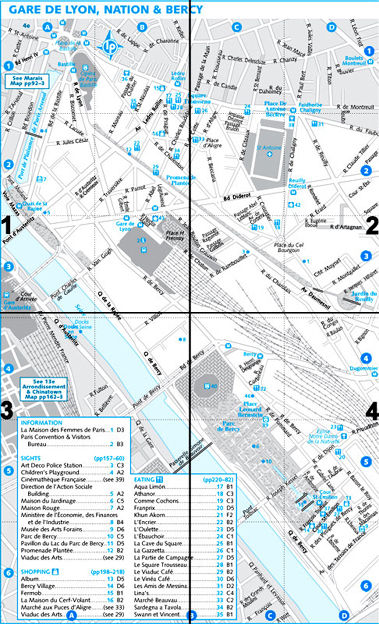

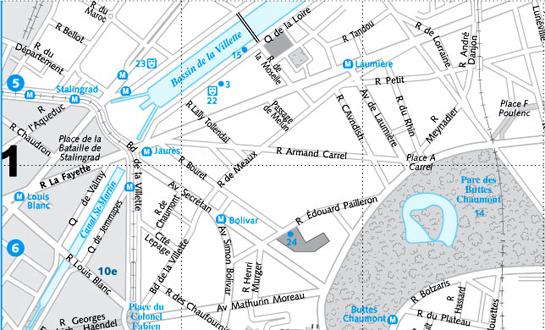

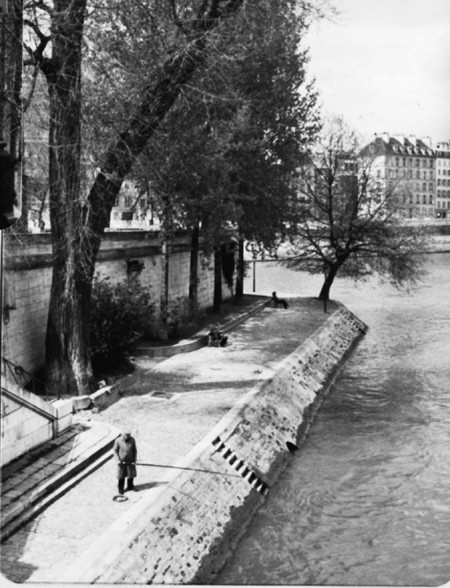

PARIS PLAGES

Initiated in 2002, ‘Paris Beaches’ is one of the most inspired and successful city recreational events in the world. Across four weeks, from mid-July to mid-August, three waterfront areas are transformed into sand and pebble ‘beaches’, complete with sun beds, beach umbrellas, atomisers, lounge chairs and palm trees. They make up the 3km-long stretch along the Right Bank embankment from the quai Henri IV at the Pont de Sully (metro Sully Morland) in the 4e to the quai des Tuileries (metro Tuileries) below the Louvre in the 1er; a 1km-long ‘beach’ below the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and across from the Parc de Bercy in the 13e on the Left Bank; and the area around the Bassin de la Villette in the 19e (metro Jaurès). The beaches are open from 8am to midnight daily.

TOUR DE FRANCE

The last of 21 stages of this prestigious, 3500km-long cycling event finishes with a race up av des Champs-Élysées on the third or fourth Sunday of July, as it has done since 1975.

September & October

JAZZ À LA VILLETTE

www.villette.com, in French

This super 10-day jazz festival in early September has sessions in Parc de la Villette, at the Cité de la Musique and in surrounding bars.

FESTIVAL D’AUTOMNE

The Autumn Festival of arts has painting, music, dance and theatre at venues throughout the city from mid-September to mid-December.

EUROPEAN HERITAGE DAYS

www.journeesdupatrimoine.culture.fr, in French

As elsewhere in Europe on the third weekend in September, Paris opens the doors to buildings (eg embassies, government ministries, corporate offices – even the Palais de l’Élysée) normally off-limits to outsiders.

TECHNOPARADE

www.technopol.net, in French

Part of the annual festival called Rendez-vous Électroniques (Electronic Meeting), this parade involving some 20 floats and carrying 150 musicians and DJs wends its way on the periphery of the Marais on the third Saturday of September, starting and ending at place de la Bastille, 12e.

NUIT BLANCHE

‘White Night’ (or more accurately ‘All Nighter’) is when Paris ‘does’ New York and becomes ‘the city that doesn’t sleep at all’. It’s a cultural festival that lasts from sundown until sunrise on the first Saturday and Sunday of October, with museums and recreational facilities in town joining bars and clubs and staying open till the very wee hours.

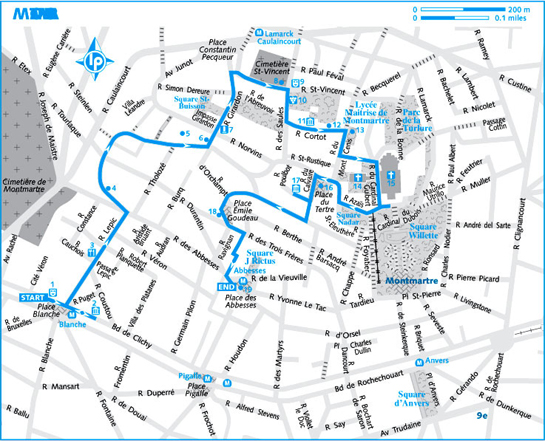

FÊTE DES VENDANGES DE MONTMARTRE

www.fetedesvendangesdemontmartre.com, in French

This festival is held over the second weekend in October following the harvesting of grapes from the Close du Montmartre, with costumes, speeches and a parade.

FOIRE INTERNATIONALE D’ART CONTEMPORAIN

Better known as FIAC, this huge contemporary art fair is held over five days in late October, with some 160 galleries represented at the Louvre and the Grand Palais.

November & December

AFRICOLOR

www.africolor.com, in French

This African music festival is held for the most part in venues in the suburbs surrounding Paris from late November to late December.

JUMPING INTERNATIONAL DE PARIS

www.salon-cheval.com, in French

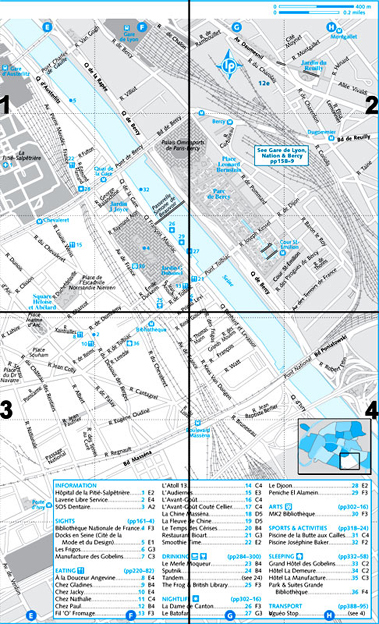

This annual showjumping tournament features the world’s most celebrated jumpers at the Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy in the 12e arrondissement (metro Bercy) in the first half of December. The annual International Showjumping Competition forms part of the Salon du Cheval at the Parc des Expositions at Porte de Versailles in the 15e (metro Porte de Versailles).

top picks

UNUSUAL EVENTS

- Paris Plages (opposite) – the next best thing to the seaside along France’s smallest urban beaches

- Gay Pride March (opposite) – feathers and beads and participants in and out of same

- Fête des Vendanges de Montmartre (left) – lots of noise for a bunch of old (and some say sour) grapes

- Louis XVI Commemorative Mass – right-wing sob-fest for aristocrats, pretenders and hangers-on

- Salon Internationale de l’Agriculture – lots to smell (cowpats) and hear (braying donkeys) and see (lambs gambolling) and eat and drink at Europe’s largest agricultural fair

CHRISTMAS EVE MASS

Mass is celebrated at midnight on Christmas Eve at many Paris churches, including Notre Dame, but get there by 11pm to find a place.

NEW YEAR’S EVE

Blvd St-Michel (5e), place de la Bastille (11e), the Eiffel Tower (7e) and especially av des Champs-Élysées (8e) are the places to be to welcome in the New Year.

Return to beginning of chapter

COSTS & MONEY

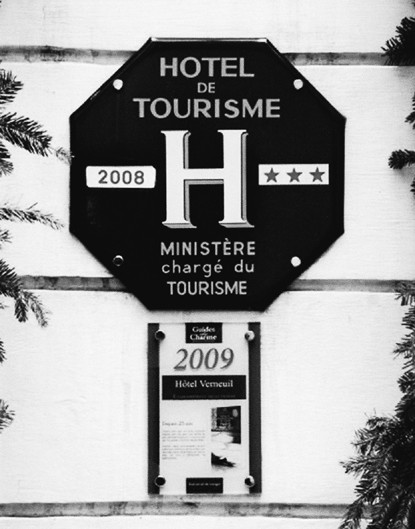

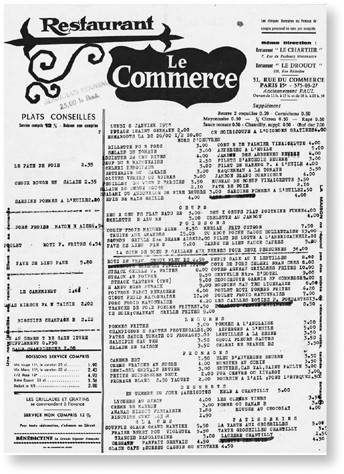

If you stay in a hostel or in a showerless, toiletless room in a bottom-end hotel and have picnics rather than dining out, it is possible to stay in Paris for €50 a day per person. A couple staying in a two-star hotel and eating one cheap restaurant meal each day should count on spending at least €75 a day per person. Eating out frequently, ordering wine and treating yourself to any of the many luxuries on offer in Paris will increase these figures considerably.

If greater Paris were a country, its economy would rank as one of the world’s largest (in fact, placing at No 17). The 617,000 companies employing just over five million people in Île de France contribute to the region’s €415 billion GDP, which accounts for upwards of a third of the total for all of France. The service industries employ the most people – almost 82% of the workforce, of which 4% are in tourism. Not surprisingly, only 0.5% of Parisians are involved in the primary industries of agriculture, forestry or fishing.

Manufacturers – software developers, electronic industries, pharmaceuticals, publishers – employ about 18% of the workforce. As most industry is located outside the Périphérique Click here, about the only factories you’re likely to see during your visit are those lining the highway from Charles de Gaulle airport. As a result, 50% of Parisians commute out of – rather than into – the city every day to work.

That is, those who have a job to commute to do. Unemployment is currently at a low of around 7.5% nationally, and the jobless rate for Paris is about half that figure. However, for youths living in the dire housing estates surrounding the city, the figure reaches more than 20%, one of the reasons that the banlieues (suburbs) erupted into violence at the end of 2005 Click here. Bids by the previous government to reduce the number of jobless youth through its controversial CPE plan Click here were stymied early the following year when a million workers and students took to the streets in protest. They argued that the law, which would allow companies with more than 20 employees to fire workers under 26 within the first two years of employment with no severance pay, encouraged a regular turnover of cut-rate staff and did not allow young people to build careers. The French government decided to withdraw the CPE altogether later in 2006.

To a certain extent the government’s ability to boost employment through training and aid is crimped: it simply doesn’t have the money. First and foremost is the need to reduce debt, which stood at almost 67% of GDP in 2007. The country was also in danger of breaching EU rules regulating national debt – again – if it didn’t cut its spending. The national public deficit was expected to rise to over 3% of GDP in 2008, which is above the EU limit.

To fill the national coffers, France has raised billions of euros by selling stakes in state-owned companies. In late 2007 and early 2008 it sold a stake of 2.5% in the power company Électricité de France and one of 3.3% in Aéroports de Paris, the company that manages Charles de Gaulle and Orly airports. It’s not the first time that the government has flogged the family silver.

HOW MUCH?

An hour’s car parking: from €1 (street), €2.40 (garage)

Average fair/good seat at the opera: €40/60

Cinema ticket: €5.90 to €9.90 (adult)

Copy of Le Monde newspaper: €1.30

Coffee at a café bar: from €1.20

Grand crème at Champs-Élysées café terrace: €4.50

Metro/bus ticket: €1.50 (€10 for 10)

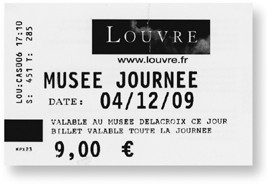

Entry to the Louvre: €9 (adult)

Litre of bottled mineral water: from €0.70 (supermarket), €1 (corner shop)

Pint of local beer: from €6.50 (€5 at happy hour)

Pop music CD: €13 to €18

Street snack: from €2.50 (basic crêpe or galette)

Return to beginning of chapter

INTERNET RESOURCES

Wi-fi is widely available at midrange and top-end hotels in Paris (sometimes for free but more usually for something like €5 per one-off connection) and occasionally in public spaces such as train stations and tourist offices. For a list of almost 100 free-access wi-fi cafés in Paris, visit www.cafes-wifi.com (in French).

If you don’t have a laptop or wi-fi access, don’t fret: Paris is awash with internet cafés with their own computers, and you’ll probably find at least one in your immediate neighbourhood.

In terms of websites to consult before you go, Lonely Planet (www.lonelyplanet.com) is a good start for many of the city’s more useful links. The following English-language websites are useful when wanting learn more about Paris (and France).

Expatica (www.expatica.com) Lifestyle website for internationals living in countries worldwide, including France, with regularly updated news, features and blogs.

French Government Tourism Office (www.francetourism.com) Official tourism site with all manner of information on and about travel in France, with lots and lots on Paris too.

Go Go Paris! Culture! (www.gogoparis.com) Clubs, hangouts, art gigs, dance around town, eat and drink – everything a culture vulture living in Paris needs.

Mairie de Paris (www.paris.fr) Your primary source of information about Paris, with everything from opening times and what’s on to the latest statistics direct from the Hôtel de Ville.

Paris Convention & Visitors Bureau (www.parisinfo.com) The official site of the Office de Tourisme et de Congrès – the city’s tourist office – is super, with more links than you’ll ever need.

Paris Digest (www.parisdigest.com) Useful site for making pretravel arrangements and for its forum.

Paris Pages (www.paris.org) Has good links to museums and cultural events.

Paris Woman (www.pariswoman.com) Deals with news and issues and events affecting expatriate women in Paris.

RATP (www.ratp.com) This invaluable (and easy to use) website from the city’s transport network will help you negotiate your way around town.

ADVANCE PLANNING

A couple of months before you go Try to book your accommodation months ahead, especially if it’s high season and you want to stay in a boutique hotel like the Hôtel Caron de Beaumarchais, a ‘find’ such as the Hôtel Jeanne d’Arc or some place offering exceptional value for money like the Hôtel du Champ-du-Mars. Take a look at some of the ‘what’s on’ websites listed on opposite or the entertainment magazines Pariscope and L’Officiel des Spectacles Click here.

A month before you go If you’re interested in serious fine dining at places like Le Grand Véfour Click here or the Casa Olympe and there’s more than one of you, book a table now. Now is also the time to visit the Fnac and/or Virgin Megastore websites Click here to get seats for a big-ticket concert, musical or play.

Two weeks before you go Blockbuster exhibitions at venues such as the Grand Palais or Centre Pompidou – or even a visit to the Louvre – can be booked in advance via Fnac or Virgin Megastore for a modest fee. Sign up for an email newsletter via Expatica (opposite) and read some up-to-date blogs.

A day or two before you go Make sure your bookings are in order and you’ve followed all the instructions outlined in this chapter.

Return to beginning of chapter

BLOGS

If there’s one country in Europe where blogging is a national pastime (so that’s what they do outside their 35-hour work week) it’s France. The underbelly of what French people think right now, the French blogosphere is gargantuan, with everyone and everything from streets and metro stops to bands, bars and the president having their own blog. For an informative overview (did someone say three million bloggers in France and counting?) see LeMondeduBlog.com (www.lemondedublog.com in English & French). Parisian star du blog Loïc Le Meur (www.loiclemeur.com in English & French) – one of France’s most widely read and watched (this serial entrepreneur vid-blogs like mad at www.loic.tv) – considerately blogs a best-of-blog list at www.eu.socialtext.net/loicwiki/index.cgi?french_blogosphere.

For clubbing, music and nightlife links Click here. Blogroll to tune into politics, fashion/kitchen gossip, happenings and bags more in the capital (in English):

Chocolate & Zucchini (http://chocolateandzucchini.com) Food-driven blog by a 28-year-old foodie called Clotilde from Montmartre.

Le Blageur à Paris (www.parisblagueur.blogspot.com) On-the-ball, engaging and inspirational snapshots of Parisian life from one of the city’s most enigmatic bloggers, a 32-year-old French fille called Meg Zimbeck.

Paris Daily Photo (www.parisdailyphoto.com) An image a day with detailed comment, enjoyed by 2000-odd a day, from friendly Eric in the 9e arrondissement.

Petite Brigitte (http://petitebrigitte.com) ‘Inside Paris: Gossip, News, Fashion’ with a savvy Parisian gal in St-Germain des Prés.

Secrets of Paris (www.secretsofparis.com) OK, OK, she writes for lots of our competitors but this site is a great resource, full of venue recommendations, lots of great bar/nightlife info.

The Paris Blog (www.theparisblog.com) Insightful portrait of Parisian life by a blogger collective.

Voice of a City (www.voiceofacity.com) Eurostar-vetted voices blog about their Paris.

BACKGROUND

HISTORY

EARLY SETTLEMENT

INVASIONS & DYNASTIES

CONSOLIDATION OF POWER

A CULTURAL ‘REBIRTH’

REFORM & REACTION

ANCIEN RÉGIME & ENLIGHTENMENT

COME THE REVOLUTION

LITTLE BIG MAN & EMPIRE

THE RETURN OF THE MONARCHY

FROM PRESIDENT TO EMPEROR

THE COMMUNE & THE ‘BEAUTIFUL AGE’

THE GREAT WAR & ITS AFTERMATH

WWII & OCCUPATION

POSTWAR INSTABILITY

CHARLES DE GAULLE & THE FIFTH REPUBLIC

POMPIDOU TO CHIRAC

PARIS TODAY

ARTS

LITERATURE

PHILOSOPHY

PAINTING

SCULPTURE

MUSIC

CINEMA

THEATRE

DANCE

ARCHITECTURE

GALLO-ROMAN

MEROVINGIAN & CAROLINGIAN

ROMANESQUE

GOTHIC

RENAISSANCE

BAROQUE

NEOCLASSICISM

ART NOUVEAU

MODERN

CONTEMPORARY

ENVIRONMENT & PLANNING

THE LAND

GREEN PARIS

URBAN PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT

GOVERNMENT & POLITICS

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

NATIONAL GOVERNMENT

MEDIA

FASHION

LANGUAGE

TIMELINE

HISTORY

With upwards of 12 million inhabitants, the greater metropolitan area of Paris is home to almost 19% of France’s total population (central Paris counts just under 2.2 million souls). Since before the Revolution, Paris has been what urban planners like to call a ‘hypertrophic city’ – the enlarged ‘head’ of a nation-state’s ‘body’. The urban area of the next biggest city – Marseilles – is just over a third the size of central Paris.

As the capital city, Paris is the administrative, business and cultural centre; virtually everything of importance in the republic starts, finishes or is currently taking place here. The French have always said ‘Quand Paris éternue, la France s’en rhume’ (When Paris sneezes, France catches cold) but there have been conscious efforts – going back at least four decades – by governments to decentralise Paris’ role, and during that time the population, and thus to a certain extent the city’s authority, has actually shrunk. The pivotal year was 1968, a watershed not just in France but throughout Western Europe.

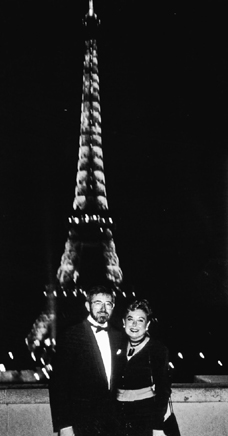

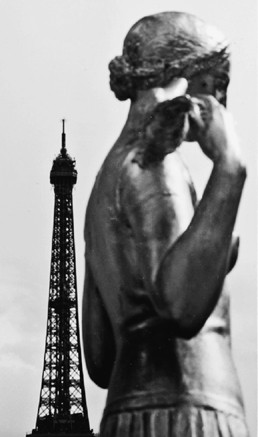

Paris has a timeless quality, a condition that can often be deceiving. And while the cobbled backstreets of Montmartre, the terraced cafés of Montparnasse, the iconic structure of the Eiffel Tower and the placid waters of the Seine may all have some visitors believing that the city has been here since time immemorial, that’s hardly the case.

Return to beginning of chapter

EARLY SETTLEMENT

The early history of the Celts is murky, but it is thought that they originated somewhere in the eastern part of central Europe around the 2nd millennium BC and began to migrate across the continent, arriving in France sometime in the 7th century BC. In the 3rd century a group of Celtic Gauls called the Parisii settled here.

Centuries of conflict between the Gauls and Romans ended in 52 BC, with the latter taking control of the territory. The settlement on the Seine prospered as the Roman town of Lutetia (from the Latin for ‘midwater dwelling’, in French, Lutèce), counting some 10,000 inhabitants by the 3rd century AD.

The Great Migrations, beginning around the middle of the 3rd century AD with raids by the Franks and then by the Alemanii from the east, left the settlement on the south bank scorched and pillaged, and its inhabitants fled to the Île de la Cité, which was subsequently fortified with stone walls. Christianity (as well as Mithraism; see opposite) had been introduced early in the previous century, and the first church, probably made of wood, was built on the western part of the island.

Return to beginning of chapter

INVASIONS & DYNASTIES

The Romans occupied what would become known as Paris (after its first settlers) from AD 212 to the late 5th century. It was at this time that a second wave of Franks and other Germanic groups under Merovius from the north and northeast overran the territory. Merovius’ grandson, Clovis I, converted to Christianity, making Paris his seat in 508. Childeric II, Clovis’ son and successor, founded the Abbey of St-Germain des Prés a half-century later, and the dynasty’s most productive ruler, Dagobert, established an abbey at St-Denis. This abbey soon became the richest, most important monastery in France and became the final resting place of its kings.

The militaristic rulers of the Carolingian dynasty, beginning with Charles ‘the Hammer’ Martel (688–741) were almost permanently away fighting wars in the east, and Paris languished, controlled mostly by the counts of Paris. When Charles Martel’s grandson, Charlemagne (768–814), moved his capital to Aix-la-Chapelle (today’s Aachen in Germany), Paris’ fate was sealed. Basically a group of separate villages with its centre on the island, Paris was badly defended throughout the second half of the 9th century and suffered a succession of raids by the ‘Norsemen’ (Vikings).

MITHRA & THE GREAT SACRIFICE

Mithraism, the worship of the god Mithra, originated in Persia. As Roman rule extended into the west, the religion became extremely popular with traders, imperial slaves and mercenaries of the Roman army and spread rapidly throughout the empire in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD. In fact, Mithraism was the principal rival of Christianity until Constantine came to the throne in the 4th century.

Mithraism was a mysterious religion with its devotees (mostly males) sworn to secrecy. What little is known of Mithra, the god of justice and social contract, has been deduced from reliefs and icons found in sanctuaries and temples, particularly in Eastern and Central European countries. Most of these portray Mithra clad in a Persian-style cap and tunic, sacrificing a white bull in front of Sol, the sun god. From the bull’s blood sprout grain and grapes and from its semen animals. Sol’s wife Luna, the moon, begins her cycle and time is born.

Mithraism and Christianity were close competitors partly because of the striking similarity of many of their rituals. Both involve the birth of a deity on winter solstice (25 December), shepherds, death and resurrection, and a form of baptism. Devotees knelt when they worshipped and a common meal – a ‘communion’ of bread and water – was a regular feature of both liturgies.

Return to beginning of chapter

CONSOLIDATION OF POWER

The counts of Paris, whose powers had increased as the Carolingians feuded among themselves, elected one of their own, Hugh Capet, as king at Senlis in 987. He made Paris the royal seat and resided in the renovated palace of the Roman governor on the Île de la Cité (the site of the present Palais de Justice). Under Capetian rule, which would last for the next 800 years, Paris prospered as a centre of politics, commerce, trade, religion and culture. By the time Hugh Capet had assumed the throne, the Norsemen (or Normans, descendants of the Vikings) were in control of northern and western French territory. In 1066 they mounted a successful invasion of England from their base in Normandy.

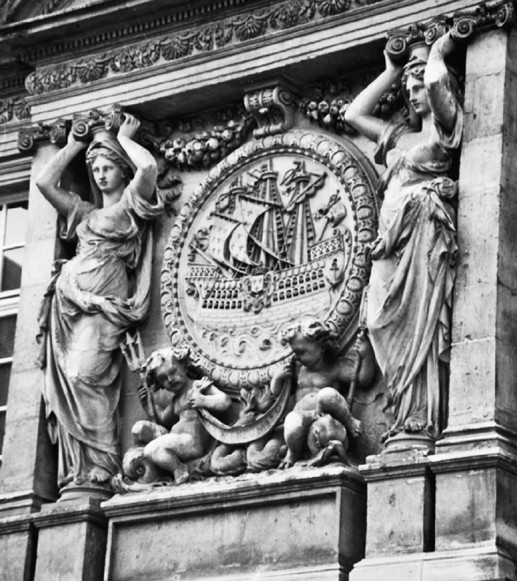

Paris’ strategic riverside position ensured its importance throughout the Middle Ages, although settlement remained centred on the Île de la Cité, with the rive gauche (left bank) to the south given over to fields and vineyards; the Marais area on the rive droite (right bank) to the north was a waterlogged marsh. The first guilds were established in the 11th century, and rapidly grew in importance; in the mid-12th century the ship merchants’ guild bought the principal river port, by today’s Hôtel de Ville (city hall), from the crown.

GOING UP & UP

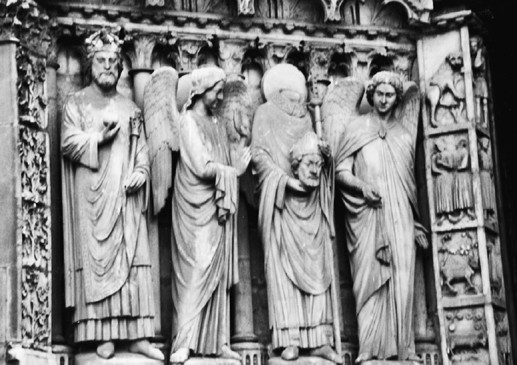

The 12th and 13th centuries were a time of frenetic building activity in Paris. Abbot Suger, both confessor and minister to several Capetian kings, was one of the powerhouses of this period; in 1136 he commissioned the basilica at St-Denis. Less than three decades later, work started on the cathedral of Notre Dame, the greatest creation of medieval Paris. At the same time Philippe-Auguste (r 1180–1223) expanded the city wall, adding 25 gates and hundreds of protective towers.

The Marais, whose name means ‘swamp’, was drained for agricultural use and settlement moved to the north (or right) bank of the Seine. this would soon become the mercantile centre, especially around place de Grève (today’s place de l’Hôtel de Ville). The food markets at Les Halles first came into existence in 1183 and the Louvre began its existence as a riverside fortress in the 13th century. In a bid to do something about the city’s horrible traffic congestion and stinking excrement (the population numbered about 200,000 by the year 1200), Philippe-Auguste paved four of Paris’ main streets for the first time since the Roman occupation, using metre-square sandstone blocks. By 1292 Paris counted 352 streets, 10 squares and 11 crossroads.

The area south of the Seine – today’s Left Bank – was by contrast developing not as a trade centre but as the centre of European learning and erudition, particularly in the so-called Latin Quarter. The ill-fated lovers Pierre Abélard and Héloïse (boxed text) wrote the finest poetry of the age and their treatises on philosophy, and Thomas Aquinas taught at the new University of Paris. About 30 other colleges were established, including the Sorbonne.

In 1337 some three centuries of hostility between the Capetians and the Anglo-Normans degenerated into the Hundred Years’ War, which would be fought on and off until the middle of the 15th century. The Black Death (1348–49) killed more than a third (an estimated 80,000 souls) of Paris’ population but only briefly interrupted the fighting. Paris would not see its population reach 200,000 again until the beginning of the 16th century.

The Hundred Years’ War and the plague, along with the development of free, independent cities elsewhere in Europe, brought political tension and open insurrection to Paris. In 1358 the provost of the merchants, a wealthy draper named Étienne Marcel, allied himself with peasants revolting against the dauphin (the future Charles V) and seized Paris in a bid to limit the power of the throne and secure a city charter. But the dauphin’s supporters recaptured it within two years, and Marcel and his followers were executed at place de Grève. Charles then completed the right-bank city wall begun by Marcel and turned the Louvre into a sumptuous palace for himself.

After the French forces were defeated by the English at Agincourt in 1415, Paris was once again embroiled in revolt. The dukes of Burgundy, allied with the English, occupied the capital in 1420. Two years later John Plantagenet, duke of Bedford, was installed as regent of France for the English king, Henry VI, who was then an infant. Henry was crowned king of France at Notre Dame less than 10 years later, but Paris was almost continuously under siege from the French for much of that time.

Around that time a 17-year-old peasant girl known to history as Jeanne d’Arc (Joan of Arc) persuaded the French pretender Charles VII that she’d received a divine mission from God to expel the English from France and bring about Charles’ coronation. She rallied French troops and defeated the English at Patay, north of Orléans, and Charles was crowned at Reims. But Joan of Arc failed to take Paris. In 1430 she was captured, convicted of witchcraft and heresy by a tribunal of French ecclesiastics and burned at the stake.

Charles VII returned to Paris in 1436, ending more than 16 years of occupation, but the English were not entirely driven from French territory (with the exception of Calais) for another 17 years. The occupation had left Paris a disaster zone. Conditions improved while the restored monarchy moved to consolidate its power under Louis XI (r 1461–83), the first Renaissance king under whose reign the city’s first printing press was installed at the Sorbonne. Churches were rehabilitated or built in the Flamboyant Gothic style (Click here) and a number of hôtels particuliers (private mansions) such as the Hôtel de Cluny (now the Musée National du Moyen Age, Click here) and the Hôtel de Sens (now the Bibliothèque Forney, Click here) were erected.

Return to beginning of chapter

A CULTURAL ‘REBIRTH’

The culture of the Italian Renaissance (French for ‘rebirth’) arrived in full swing in France during the reign of François I in the early 16th century partly because of a series of indecisive French military operations in Italy. For the first time, the French aristocracy was exposed to Renaissance ideas of scientific and geographical scholarship and discovery as well as the value of secular over religious life. The population of Paris at the start of François’ reign in 1515 was 170,000 – still almost 20% less than it had been some three centuries before, when the Black Death had decimated the population.

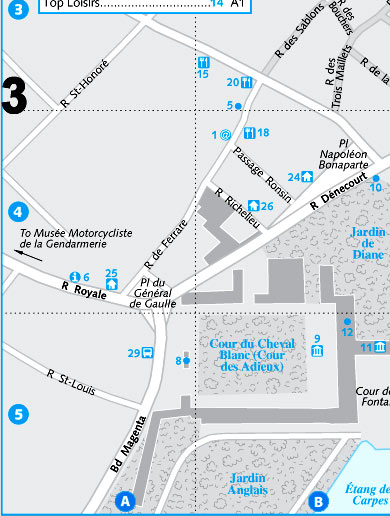

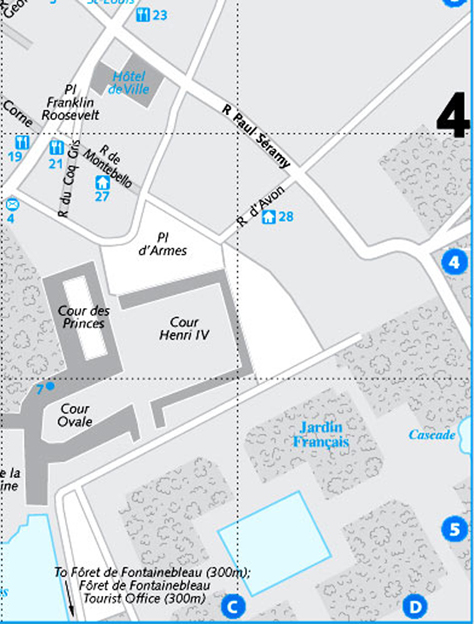

Writers such as François Rabelais, Clément Marot and Pierre de Ronsard of La Pléiade were influential at this time, as were the architectural disciples of Michelangelo and Raphael. Evidence of this architectural influence can be seen in François I’s chateau at Fontainebleau and the Petit Château at Chantilly. In the city itself, a prime example of the period is the Pont Neuf, the ‘New Bridge’ that is, in fact, the oldest span in Paris. This new architecture was meant to reflect the splendour of the monarchy, which was fast moving towards absolutism, and of Paris as the capital of a powerful centralised state. But all this grandeur and show of strength was not enough to stem the tide of Protestantism that was flowing into France.

Return to beginning of chapter

REFORM & REACTION

The position of the Protestant Reformation sweeping across Europe in the 1530s had been strengthened in France by the ideas of John Calvin, a Frenchman exiled to Geneva. The edict of January 1562, which afforded the Protestants certain rights, was met by violent opposition from ultra-Catholic nobles whose fidelity to their faith was mixed with a desire to strengthen their power bases in the provinces. Paris remained very much a Catholic stronghold, and executions continued apace up to the outbreak of religious civil war.

The Wars of Religion (1562–98) involved three groups: the Huguenots (French Protestants supported by the English), the Catholic League and the Catholic king. The fighting severely weakened the position of the monarchy and brought the kingdom of France close to disintegration. On 7 May 1588, on the ‘Day of the Barricades’, Henri III, who had granted many concessions to the Huguenots, was forced to flee from the Louvre when the Catholic League rose up against him. He was assassinated the following year.

Henri III was succeeded by Henri IV, who inaugurated the Bourbon dynasty and was a Huguenot when he ascended the throne. Catholic Paris refused to allow its new Protestant king entry into the city, and a siege of the capital continued for almost five years. Only when Henri embraced Catholicism at St-Denis did the capital welcome him. In 1598 he promulgated the Edict of Nantes, which guaranteed the Huguenots religious freedom as well as many civil and political rights, but this was not universally accepted.

Henri consolidated the monarchy’s power and began to rebuild Paris (the city’s population was now about 450,000) after more than 30 years of fighting. The magnificent place Royale (today’s place des Vosges in the Marais) and place Dauphine at the western end of the Île de la Cité are prime examples of the new era of town planning. But Henri’s rule ended as abruptly and violently as that of his predecessor. In 1610 he was assassinated by a Catholic fanatic named François Ravaillac when his coach became stuck in traffic along rue de la Ferronnerie in the Marais. Ravaillac was executed by an irate mob of Parisians (who were mightily sick of religious turmoil by this time) by being quartered – after a thorough scalding.

Henri IV’s son, the future Louis XIII, was too young to assume the throne, so his mother, Marie de Médici, was named regent. She set about building the magnificent Palais du Luxembourg and its enormous gardens for herself just outside the city wall. Louis XIII ascended the throne at age 16 but throughout most of his undistinguished reign he remained under the control of Cardinal Richelieu, his ruthless chief minister. Richelieu is best known for his untiring efforts to establish an all-powerful monarchy in France, opening the door to the absolutism of Louis XIV, and French supremacy in Europe. Under Louis XIII’s reign two uninhabited islets in the Seine – Île Notre Dame and Île aux Vaches – were joined to form the Île de St-Louis, and Richelieu commissioned a number of palaces and churches, including the Palais Royal and the Église Notre Dame du Val-de-Grâce.

Return to beginning of chapter

ANCIEN RÉGIME & ENLIGHTENMENT

Le Roi Soleil (the Sun King) – Louis XIV – ascended the throne in 1643 at the age of five. His mother, Anne of Austria, was appointed regent, and Cardinal Mazarin, a protégé of Richelieu, was named chief minister. One of the decisive events of Louis XIV’s early reign was the War of the Fronde (1648–53), a rebellion by the bourgeoisie and some of the nobility opposed to taxation and the increasing power of the monarchy. The revolt forced the royal court to flee Paris for a time.

When Mazarin died in 1661, Louis XIV assumed absolute power until his own death in 1715. Throughout his long reign, characterised by ‘glitter and gloom’ as one historian has put it, Louis sought to project the power of the French monarchy – bolstered by claims of divine right – both at home and abroad. He involved France in a long series of costly, almost continuous wars with Holland, Austria and England, which gained France territory but terrified its neighbours and nearly bankrupted the treasury. State taxation to fill the coffers caused widespread poverty and vagrancy in Paris, which was by then a city of almost 600,000 people.

But Louis was able to quash the ambitious, feuding aristocracy and create the first truly centralised French state, elements of which can still be seen in France today. While he did pour huge sums of money into building his extravagant palace at Versailles, by doing so he was able to turn his nobles into courtiers, forcing them to compete with one another for royal favour and reducing them to ineffectual sycophants.

Louis mercilessly persecuted his Protestant subjects, whom he considered a threat to the unity of the state and thus his power. In 1685 he revoked the Edict of Nantes, which had guaranteed the Huguenots freedom of conscience.

It was Louis XIV who said ‘Après moi, le déluge’ (After me, the flood); in hindsight his words were more than prophetic. His grandson and successor, Louis XV, was an oafish, incompetent buffoon, and grew to be universally despised. However, Louis XV’s regent, Philippe of Orléans, did move the court from Versailles back to Paris; in the Age of Enlightenment, the French capital had become, in effect, the centre of Europe.

As the 18th century progressed, new economic and social circumstances rendered the ancien régime (old order) dangerously out of step with the needs of the country and its capital. The regime was further weakened by the antiestablishment and anticlerical ideas of the Enlightenment, whose leading lights included Voltaire (François-Marie Arouet), Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Denis Diderot. But entrenched vested interests, a cumbersome power structure and royal lassitude prevented change from starting until the 1770s, by which time the monarchy’s moment had passed.

The Seven Years’ War (1756–63) was one of a series of ruinous military engagements pursued by Louis XV. It led to the loss of France’s flourishing colonies in Canada, the West Indies and India. It was in part to avenge these losses that Louis XVI sided with the colonists in the American War of Independence (1775–83). But the Seven Years’ War cost France a fortune and, more disastrously for the monarchy, it helped to disseminate at home the radical democratic ideas that were thrust upon the world stage by the American Revolution.

Return to beginning of chapter

COME THE REVOLUTION

By the late 1780s, the indecisive Louis XVI and his dominating Vienna-born queen, Marie-Antoinette, known to her subjects disparagingly as l’Autrichienne (the Austrian), had managed to alienate virtually every segment of society – from the enlightened bourgeoisie to the conservatives – and the king became increasingly isolated as unrest and dissatisfaction reached boiling point. When he tried to neutralise the power of the more reform-minded delegates at a meeting of the États-Généraux (States-General) at the Jeu de Paume in Versailles from May to June 1789 (Click here), the masses – spurred on by the oratory and inflammatory tracts circulating at places like the Café de Foy at Palais Royal – took to the streets of Paris. On 14 July, a mob raided the armoury at the Hôtel des Invalides for rifles, seizing 32,000 muskets, and then stormed the prison at Bastille – the ultimate symbol of the despotic ancien régime. The French Revolution had begun.

At first, the Revolution was in the hands of moderate republicans called the Girondins. France was declared a constitutional monarchy and various reforms were introduced, including the adoption of the Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme and du Citoyen (Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen). This document set forth the principles of the Revolution in a preamble and 17 articles, and was modelled on the American Declaration of Independence. A forward-thinking document called Les Droits des Femmes (The Rights of Women) was also published. But as the masses armed themselves against the external threat to the new government – posed by Austria, Prussia and the exiled French nobles – patriotism and nationalism mixed with extreme fervour and then popularised and radicalised the Revolution. It was not long before the Girondins lost out to the extremist Jacobins, led by Maximilien Robespierre, Georges-Jacques Danton and Jean-Paul Marat. The Jacobins abolished the monarchy and declared the First Republic in September 1792 after Louis XVI proved unreliable as a constitutional monarch. The Assemblée Nationale (National Assembly) was replaced by an elected Revolutionary Convention.

In January 1793 Louis XVI, who had tried to flee the country with his family but only got as far as Varennes, was convicted of ‘conspiring against the liberty of the nation’ and guillotined at place de la Révolution, today’s place de la Concorde. His consort, Marie-Antoinette, was executed in October of the same year.

A DATE WITH THE REVOLUTION

Along with standardising France’s – and, later, most of the world’s – system of weights and measures with the almost universal metric system, the Revolutionary government adopted a new, ‘more rational’ calendar from which all ‘superstitious’ associations (ie saints’ days and mythology) were removed. Year 1 began on 22 September 1792, the day the First Republic was proclaimed. The names of the 12 months – Vendémaire, Brumaire, Frimaire, Nivôse, Pluviôse, Ventôse, Germinal, Floréal, Prairial, Messidor, Thermidor and Fructidor – were chosen according to the seasons. The autumn months, for instance, were Vendémaire, derived from vendange (grape harvest); Brumaire, derived from brume (mist or fog); and Frimaire, derived from frimas (wintry weather). In turn, each month was divided into three 10-day ‘weeks’ called décades, the last day of which was a rest day. The five remaining days of the year were used to celebrate Virtue, Genius, Labour, Opinion and Rewards. While the republican calendar worked well in theory, it caused no end of confusion for France in its communications and trade abroad because the months and days kept changing in relation to those of the Gregorian calendar. The Revolutionary calendar was abandoned and the old system was restored in France in 1806 by Napoleon Bonaparte.

In March 1793 the Jacobins set up the notorious Committee of Public Safety to deal with national defence and to apprehend and try ‘traitors’. This body had dictatorial control over the city and the country during the so-called Reign of Terror (September 1793 to July 1794), which saw most religious freedoms revoked and churches closed to worship and desecrated. Paris during the Reign of Terror was not unlike Moscow under Joseph Stalin.

Jacobin propagandist Marat was assassinated in his bathtub by the Girondin Charlotte Corday in July 1793 and by autumn the Reign of Terror was in full swing; by mid-1794 some 2500 people had been beheaded in Paris and more than 14,500 executed elsewhere in France. In the end, the Revolution turned on itself, ‘devouring its own children’ in the words of an intimate of Robespierre, Jacobin Louis Antoine Léon de Saint-Just. Robespierre sent Danton to the guillotine; Saint-Just and Robespierre eventually met the same fate. Paris celebrated for days afterwards.

After the Reign of Terror faded, a five-man delegation of moderate republicans led by Paul Barras, who had ordered the arrests of Robespierre and Saint-Just, set itself up to rule the republic as the Directoire (Directory). On 5 October 1795 (or 13 Vendémaire in year 6 – boxed text), a group of royalist jeunesse dorée (gilded youth) bent on overthrowing the Directory was intercepted in front of the Église St-Roch on rue St-Honoré. They were met by loyalist forces led by a young Corsican general named Napoleon Bonaparte, who fired into the crowd. For this ‘whiff of grapeshot’ Napoleon was put in command of the French forces in Italy, where he was particularly successful in the campaign against Austria. His victories would soon turn him into an independent political force.

Return to beginning of chapter

LITTLE BIG MAN & EMPIRE

The post-Revolutionary government led by the five-man Directory was far from stable, and when Napoleon returned to Paris in 1799 he found a chaotic republic in which few citizens had any faith. In November, when it appeared that the Jacobins were again on the ascendancy in the legislature, Napoleon tricked the delegates into leaving Paris for St-Cloud to the southwest (‘for their own protection’), overthrew the discredited Directory and assumed power himself.

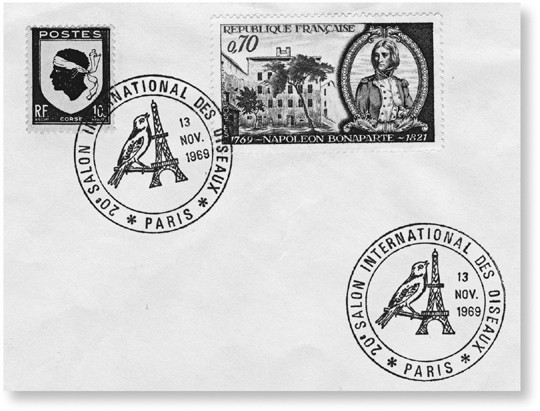

At first, Napoleon took the post of First Consul, chosen by popular vote. In a referendum three years later he was named ‘Consul for Life’ and his birthday became a national holiday. By December 1804, when he crowned himself ‘Emperor of the French’ in the presence of Pope Pius VII at Notre Dame, the scope and nature of Napoleon’s ambitions were obvious to all. But to consolidate and legitimise his authority Napoleon needed more victories on the battlefield. So began a seemingly endless series of wars and victories by which France would come to control most of Europe.

In 1812 Napoleon invaded Russia in an attempt to do away with his last major rival on the Continent, Tsar Alexander I. Although his Grande Armée managed to capture Moscow, it was wiped out by the brutal Russian winter; of the 600,000 soldiers mobilised, only 90,000 – a mere 15% – returned. Prussia and Napoleon’s other adversaries quickly recovered from their earlier defeats, and less than two years after the fiasco in Russia the Prussians, backed by Russia, Austria and Britain, entered Paris. Napoleon abdicated and was exiled to the island of Elba off the coast of Italy. The Senate then formally deposed him as emperor.

At the Congress of Vienna (1814–15), the victorious allies restored the House of Bourbon to the French throne, installing Louis XVI’s brother as Louis XVIII (Louis XVI’s second son, Charles, had been declared Louis XVII by monarchists in exile but he died while under arrest by the Revolutionary government). But in February 1815 Napoleon escaped from Elba, landed in southern France and gathered a large army as he marched towards Paris. On 1 June he reclaimed the throne at celebrations held at the Champs de Mars. But his reign came to an end just three weeks later when his forces were defeated at Waterloo in Belgium. Napoleon was exiled again, this time to St Helena in the South Atlantic, where he died in 1821.

Although reactionary in some ways – he re-established slavery in France’s colonies, for example – Napoleon instituted a number of important reforms, including a reorganisation of the judicial system; the promulgation of a new legal code, the Code Napoléon (or civil code), which forms the basis of the French legal system to this day; and the establishment of a new educational system. More importantly, he preserved the essence of the changes brought about by the Revolution. Napoleon is therefore remembered by many French people as the nation’s greatest hero.

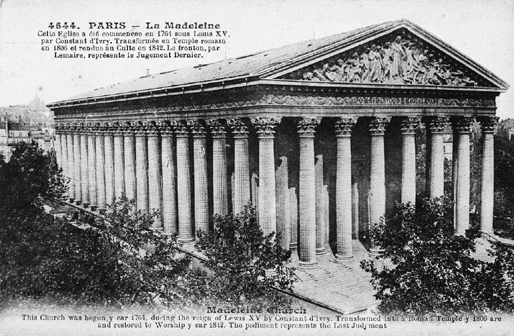

Few of Napoleon’s grand architectural plans for Paris were completed, but the Arc de Triomphe, Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, La Madeleine, Pont des Arts, rue de Rivoli and some buildings within the Louvre complex as well as the Canal St-Martin all date from this period.

Return to beginning of chapter

THE RETURN OF THE MONARCHY

The reign of ‘the gouty old gentleman’ Louis XVIII (1814–24) was dominated by the struggle between extreme monarchists who wanted a return to the ancien régime, liberals who saw the changes wrought by the Revolution as irreversible, and the radicals of the working-class neighbourhoods of Paris (by 1817 the population of Paris stood at 715,000). Louis’ successor, the reactionary Charles X (r 1824–30), handled this struggle with great incompetence and was overthrown in the so-called July Revolution of 1830 when a motley group of revolutionaries seized the Hôtel de Ville. The Colonne de Juillet in the centre of the place de la Bastille honours those killed in the street battles that accompanied this revolution; they are buried in vaults under the column.

Louis-Philippe (r 1830–48), an ostensibly constitutional monarch of bourgeois sympathies and tastes, was then chosen by parliament to head what became known as the July Monarchy. His tenure was marked by inflation, corruption and rising unemployment and was overthrown in the February Revolution of 1848, in whose wake the Second Republic was established. The population of Paris had reached one million by 1844.

Return to beginning of chapter

FROM PRESIDENT TO EMPEROR

In presidential elections held in 1848, Napoleon’s inept nephew, the German-accented Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, was overwhelmingly elected. Legislative deadlock caused Louis Napoleon to lead a coup d’état in 1851, after which he was proclaimed Emperor Napoleon III (Bonaparte had conferred the title Napoleon II on his son upon his abdication in 1814, but the latter never ruled). A plebiscite overwhelmingly approved the motion (7.8 million in favour and 250,000 against), and Napoleon III moved into the Palais des Tuileries.

The Second Empire lasted from 1852 until 1870. During this period France enjoyed significant economic growth, and Paris was transformed by town planner Haussmann (boxed text) into the modern city it now is today. The city’s first department stores were also built at this time – the now defunct La Ville de Paris in 1834 followed by Le Bon Marché in 1852 – as were the passages couverts, Paris’ delightful covered shopping arcades Click here.

Like his uncle before him, Napoleon III embroiled France in a number of costly conflicts, including the disastrous Crimean War (1854–56). In 1870 Otto von Bismarck goaded Napoleon III into declaring war on Prussia. Within months the thoroughly unprepared French army was defeated and the emperor taken prisoner. When news of the debacle reached Paris the masses took to the streets and demanded that a republic be declared.

Return to beginning of chapter

THE COMMUNE & THE ‘BEAUTIFUL AGE’

The Third Republic began as a provisional government of national defence in September 1870. The Prussians were, at the time, advancing on Paris and would subsequently lay siege to the capital, forcing starving Parisians to bake bread partially with sawdust and consume most of the animals on display in the Ménagerie at the Jardin des Plantes. In January 1871 the government negotiated an armistice with the Prussians, who demanded that National Assembly elections be held immediately. The republicans, who had called on the nation to continue to resist the Prussians and were overwhelmingly supported by Parisians, lost to the monarchists, who had campaigned on a peace platform.

As expected, the monarchist-controlled assembly ratified the Treaty of Frankfurt. However, when ordinary Parisians heard of its harsh terms – a huge war indemnity, cession of the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, and the occupation of Paris by 30,000 Prussian troops – they revolted against the government.

Following the withdrawal of Prussian troops on 18 March 1871, an insurrectionary government, known to history as the Paris Commune, was established and its supporters, the Communards, seized control of the capital (the legitimate government had fled to Versailles). In late May, after the Communards had tried to burn the centre of the city, the Versailles government launched an offensive on the Commune known as La Semaine Sanglante (Bloody Week), in which several thousand rebels were killed. After a mop-up of the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, the last of the Communard insurgents – cornered by government forces in the Cimetière du Père Lachaise – fought a hopeless, all-night battle among the tombstones. In the morning, the 147 survivors were lined up against what is now known as the Mur des Fédérés (Wall of the Federalists). They were then shot, and buried in a mass grave. A further 20,000 or so Communards, mostly working class, were rounded up throughout the city and executed. As many as 13,000 were jailed or transported to Devil’s Island penal colony off French Guyana in South America.

HAUSSMANN’S HOUSING

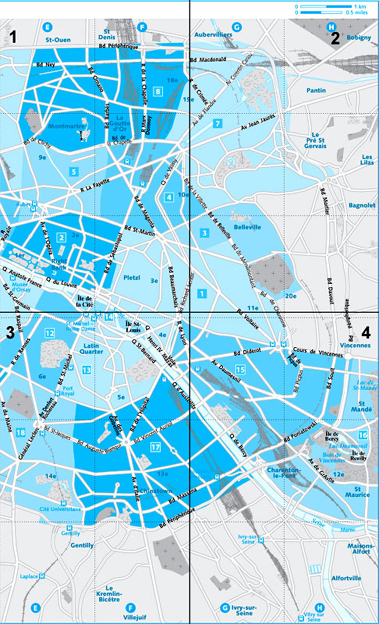

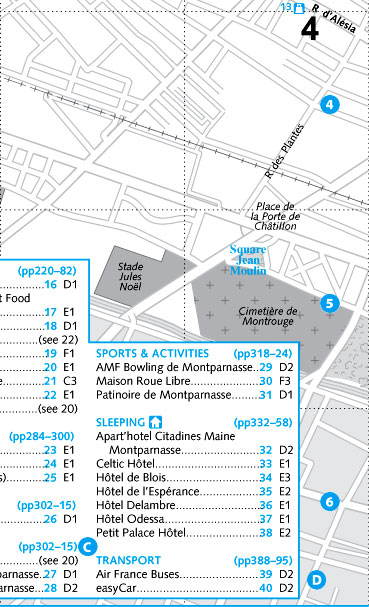

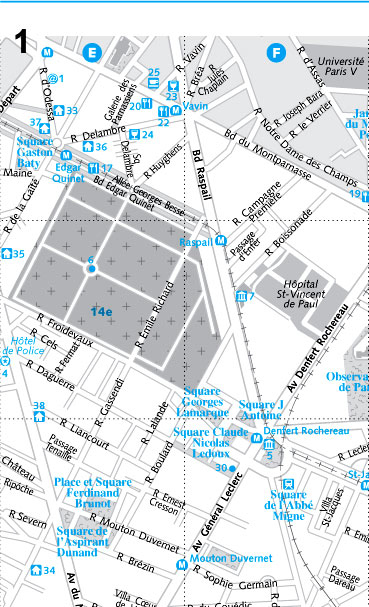

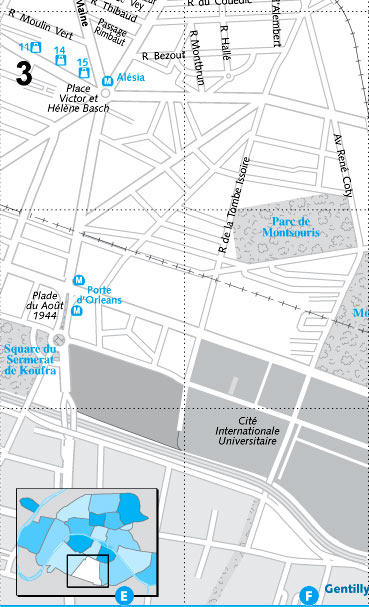

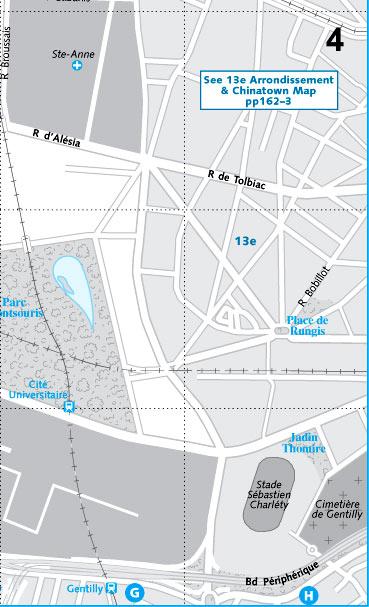

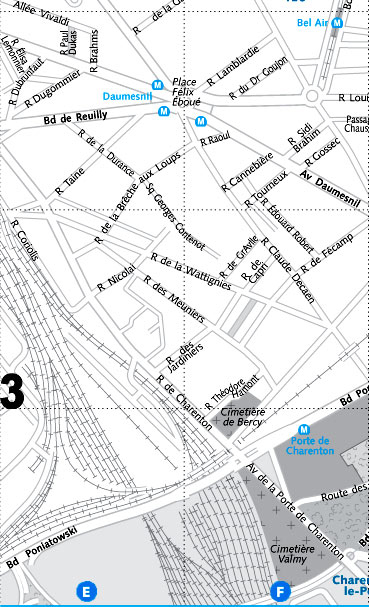

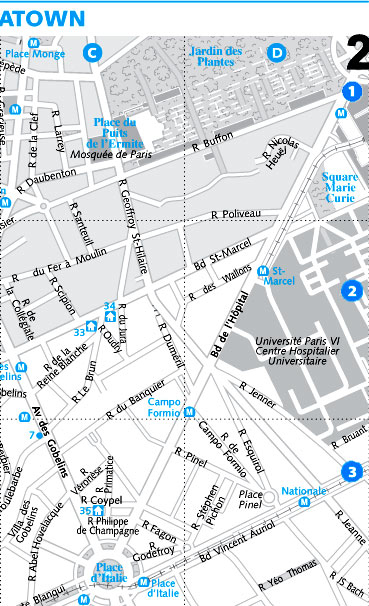

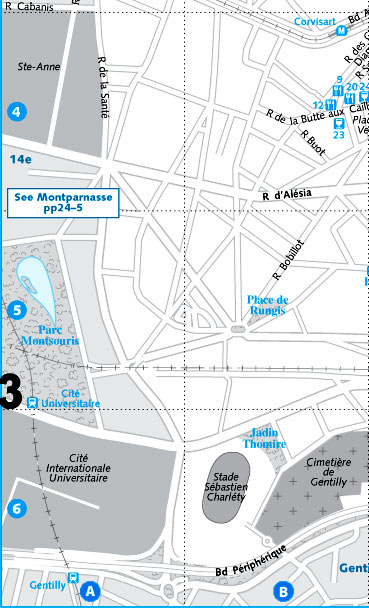

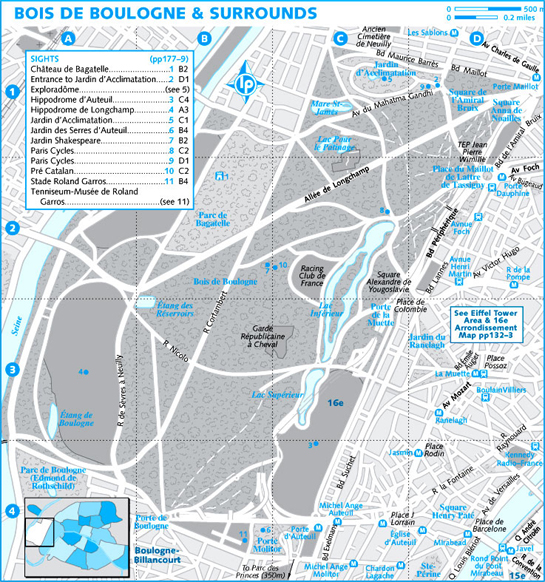

Few town planners anywhere in the world have had as great an impact on the city of their birth as did Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann (1809–91) on Paris. As Prefect of the Seine département under Napoleon III between 1853 and 1870, Haussmann and his staff of engineers and architects completely rebuilt huge swaths of Paris. He is best known (and most bitterly attacked) for having demolished much of medieval Paris, replacing the chaotic narrow streets – easy to barricade in an uprising – with the handsome, arrow-straight thoroughfares for which the city is now celebrated. He also revolutionised Paris’ water-supply and sewerage systems and laid out many of the city’s loveliest parks, including large areas of the Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes as well as the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont and Parc Montsouris (Map). The 12 avenues leading out from the Arc de Triomphe were also his work.

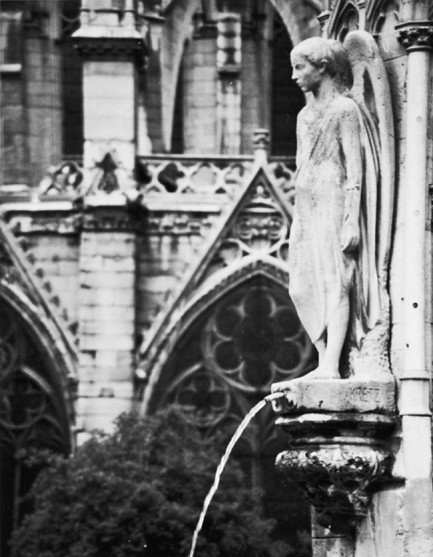

Karl Marx, in his The Civil War in France, interpreted the Communard insurrection as the first great proletarian uprising against the bourgeoisie, and socialists came to see its victims as martyrs of the class struggle. Among the buildings destroyed in the fighting were the original Hôtel de Ville, the Palais des Tuileries and the Cours des Comptes (site of the present-day Musée d’Orsay). Both Ste-Chapelle and Notre Dame were slated to be torched but those in charge apparently had a change of heart at the last minute.

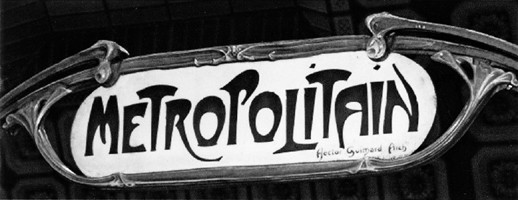

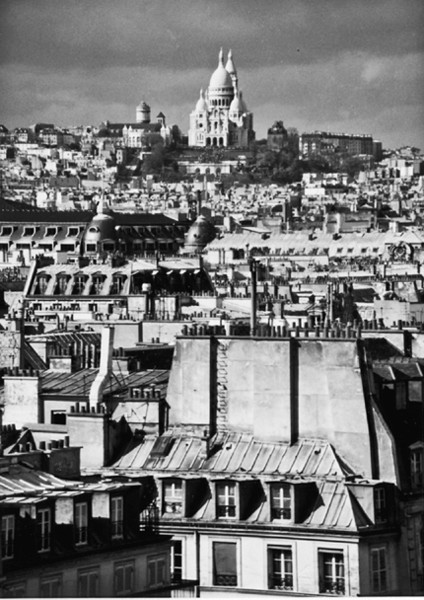

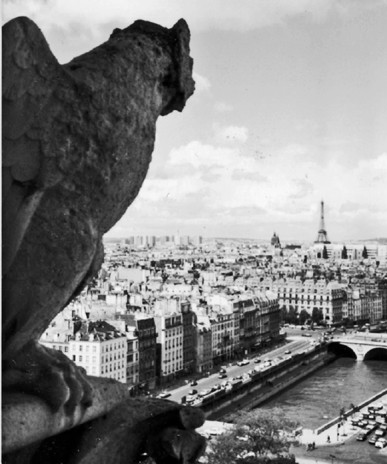

Despite this disastrous start, the Third Republic ushered in the glittering belle époque (beautiful age), with Art Nouveau architecture, a whole field of artistic ‘isms’ from impressionism onwards and advances in science and engineering, including the construction of the first metro line, which opened in 1900. Expositions universelles (world exhibitions) were held in Paris in 1889 – showcasing the then maligned Eiffel Tower – and again in 1900 in the purpose-built Petit Palais. The Paris of nightclubs and artistic cafés made its first appearance around this time, and Montmartre became a magnet for artists, writers, pimps and prostitutes (Click here).

But France was consumed with a desire for revenge after its defeat by Germany, and jingoistic nationalism, scandals and accusations were the order of the day. The most serious crisis – morally and politically – of the Third Republic, however, was the infamous Dreyfus Affair. This began in 1894 when a Jewish army captain named Alfred Dreyfus was accused of betraying military secrets to Germany – he was then court-martialled and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil’s Island. Liberal politicians, artists and writers, including the novelist Émile Zola, who penned his celebrated ‘J’accuse!’ (I Accuse!) open letter in support of the captain, succeeded in having the case reopened – despite bitter opposition from the army command, right-wing politicians and many Catholic groups – and Dreyfus was vindicated in 1900. When he died in 1935 Dreyfus was laid to rest in the Cimetière de Montparnasse. The Dreyfus affair discredited the army and the Catholic Church in France. This resulted in more-rigorous civilian control of the military and, in 1905, the legal separation of the Catholic Church and the French state.

Return to beginning of chapter

THE GREAT WAR & ITS AFTERMATH

Central to France’s entry into WWI was the desire to regain the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, lost to Germany in the Franco-Prussian War. Indeed, Raymond Poincaré, president of the Third Republic from 1913 to 1920 and later prime minister, was a native of Lorraine and a firm supporter of war with Germany. But when the heir to the Austrian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated by a Bosnian Serb in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914, Germany and Austria-Hungary – precipitating what would erupt into the first-ever global war – jumped the gun. Within a month, they had declared war on Russia and France.

By early September German troops had reached the River Marne, just 15km east of Paris, and the central government moved to Bordeaux. But Marshal Joffre’s troops, transported to the front by Parisian taxicabs, brought about the ‘Miracle of the Marne’, and Paris was safe within a month. In November 1918 the armistice was finally signed in a railway carriage in a clearing of the Forêt de Compiègne, 82km northeast of Paris.

The defeat of Austria-Hungary and Germany in WWI, which regained Alsace and Lorraine for France, was achieved at an unimaginable human cost. Of the eight million French men who were called to arms, 1.3 million were killed and almost one million crippled. In other words, two of every 10 Frenchmen aged between 20 and 45 years of age were killed in WWI. At the Battle of Verdun (1916) alone, the French, led by General Philippe Pétain, and the Germans each lost about 400,000 men.

The 1920s and ’30s saw Paris as a centre of the avant-garde, with artists pushing into new fields of cubism and surrealism, Le Corbusier rewriting the textbook for architecture, foreign writers such as Ernest Hemingway and James Joyce drawn by the city’s liberal atmosphere Click here and nightlife establishing a cutting-edge reputation for everything from jazz clubs to striptease.

France’s efforts to promote a separatist movement in the Rhineland, and its occupation of the Ruhr in 1923 to enforce German reparations payments, proved disastrous. But it did lead to almost a decade of accommodation and compromise with Germany over border guarantees, and to Germany’s admission to the League of Nations. The naming of Adolf Hitler as German chancellor in 1933, however, would put an end to all that.

Return to beginning of chapter

WWII & OCCUPATION

During most of the 1930s, the French, like the British, had done their best to appease Hitler. However, two days after the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, Britain and France declared war on Germany. For the first nine months Parisians joked about le drôle de guerre – what Britons called ‘the phoney war’ – in which nothing happened. But the battle for France began in earnest in May 1940 and by 14 June France had capitulated. Paris was occupied, and almost half the population of just under five million fled the city by car, by bicycle or on foot. The British expeditionary force sent to help the French barely managed to avoid capture by retreating to Dunkirk, described so vividly in Ian McEwan’s Atonement (2001) and in a dreamlike sequence in Joe Wright’s 2007 film of the book, and crossing the English Channel in small boats. The Maginot Line, a supposedly impregnable wall of fortifications along the Franco-German border, had proved useless – the German armoured divisions simply outflanked it by going through Belgium.

The Germans divided France into a zone under direct German rule (along the western coast and the north, including Paris), and into a puppet-state based in the spa town of Vichy and led by General Philippe Pétain, the ageing WWI hero of the Battle of Verdun. Pétain’s collaborationist government, whose leaders and supporters assumed that the Nazis were Europe’s new masters and had to be accommodated, as well as French police forces in German-occupied areas (including Paris) helped the Nazis round up 160,000 French Jews and others for deportation to concentration and extermination camps in Germany and Poland. (In 2006 the state railway SNCF was found guilty of colluding in the deportation of Jews during WWII and was ordered to pay compensation to the families of two victims.)

After the fall of Paris, General Charles de Gaulle, France’s undersecretary of war, fled to London. In a radio broadcast on 18 June 1940, he appealed to French patriots to continue resisting the Germans. He set up a French government-in-exile and established the Forces Françaises Libres (Free French Forces), a military force dedicated to fighting the Germans.

The underground movement known as the Résistance (Resistance), whose active members never amounted to more than about 5% of the French population, engaged in such activities as sabotaging railways, collecting intelligence for the Allies, helping Allied airmen who had been shot down, and publishing anti-German leaflets. The vast majority of the rest of the population did little or nothing to resist the occupiers or assist their victims or were collaborators, such as the film stars Maurice Chevalier and Arletty, and the designer Coco Chanel.

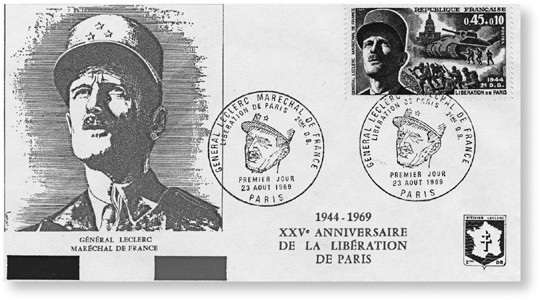

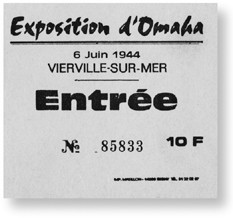

The liberation of France began with the Allied landings in Normandy on D-day (Jour-J in French): 6 June 1944. On 15 August Allied forces also landed in southern France. After a brief insurrection by the Résistance, Paris was liberated on 25 August by an Allied force spearheaded by Free French units – these units were sent in ahead of the Americans so that the French would have the honour of liberating the capital the following day. Hitler, who visited Paris in June 1940 and loved it, ordered that the city be burned toward the end of the war. It was an order that, gratefully, had not been obeyed.

Return to beginning of chapter

POSTWAR INSTABILITY

De Gaulle returned to Paris and set up a provisional government, but in January 1946 he resigned as president, wrongly believing that the move would provoke a popular outcry for his return. A few months later, a new constitution was approved by referendum. De Gaulle formed his own party (Rassemblement du Peuple Française) and would spend the next 13 years in opposition.

The Fourth Republic was a period that saw unstable coalition cabinets follow one another with bewildering speed (on average, one every six months), and economic recovery that was helped immeasurably by massive American aid. France’s disastrous defeat at Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam in 1954 ended its colonial supremacy in Indochina. France also tried to suppress an uprising by Arab nationalists in Algeria, where over one million French settlers lived.

The Fourth Republic came to an end in 1958, when extreme right-wingers, furious at what they saw as defeatism rather than tough action in dealing with the uprising in Algeria, began conspiring to overthrow the government. De Gaulle was brought back to power to prevent a military coup and even possible civil war. He soon drafted a new constitution that gave considerable powers to the president at the expense of the National Assembly.

Return to beginning of chapter

CHARLES DE GAULLE & THE FIFTH REPUBLIC

The Fifth Republic was rocked in 1961 by an attempted coup staged in Algiers by a group of right-wing military officers. When it failed, the Organisation de l’Armée Secrète (OAS) – a group of French colons (colonists) and sympathisers opposed to Algerian independence – turned to terrorism, trying several times to assassinate de Gaulle and nearly succeeding in August 1962 in the Parisian suburb of Petit Clamart. The book and film The Day of the Jackal portrayed a fictional OAS attempt on de Gaulle’s life.

In 1962, after more than 12,000 had died as a result of this ‘civil war’, de Gaulle negotiated an end to the war in Algeria. Some 750,000 pied-noir (black feet), as Algerian-born French people are known in France, flooded into France and the capital. Meanwhile, almost all of the other French colonies and protectorates in Africa had demanded and achieved independence. Shrewdly, the French government began a programme of economic and military aid to its former colonies to bolster France’s waning importance internationally and to create a bloc of French-speaking nations – la francophonie – in the developing world.

Paris retained its position as a creative and intellectual centre, particularly in philosophy and film-making, and the 1960s saw large parts of the Marais beautifully restored. But the loss of the colonies, the surge in immigration, economic difficulties and an increase in unemployment weakened de Gaulle’s government.

In March 1968 a large demonstration in Paris against the war in Vietnam was led by student Daniel ‘Danny the Red’ Cohn-Bendit, who is today copresident of the Green/Free European Alliance Group in the European Parliament. This gave impetus to the student movement, and protests were staged throughout the spring. A seemingly insignificant incident in May 1968, in which police broke up yet another in a long series of demonstrations by students of the University of Paris, sparked a violent reaction on the streets of the capital; students occupied the Sorbonne and barricades were erected in the Latin Quarter. Workers joined in the protests and six million people across France participated in a general strike that virtually paralysed the country and the city. It was a period of much creativity and new ideas with slogans appearing everywhere, such as ‘L’Imagination au Pouvoir’ (Put Imagination in Power) and ‘Sous les Pavés, la Plage’ (Under the Cobblestones, the Beach), a reference to Parisians’ favoured material for building barricades and what they could expect to find beneath them.

The alliance between workers and students couldn’t last long. While the former wanted to reap greater benefits from the consumer market, the latter wanted (or at least said they wanted) to destroy it – and were called ‘fascist provocateurs’ and ‘mindless anarchists’ by the French Communist leadership. De Gaulle took advantage of this division and appealed to people’s fear of anarchy. Just as Paris and the rest of France seemed on the brink of revolution, 100,000 Gaullists demonstrated on the av des Champs-Élysées in support of the government and stability was restored.

Return to beginning of chapter

POMPIDOU TO CHIRAC

There is no underestimating the effect the student riots of 1968 had on France and the French people, and on the way they govern themselves today. After stability was restored the government made a number of immediate changes, including the decentralisation of the higher education system, and reforms (eg lowering the voting age to 18, an abortion law and workers’ self-management) continued through the 1970s, creating, in effect, the modern society that is France today.

President Charles de Gaulle resigned in 1969 and was succeeded by the Gaullist leader Georges Pompidou, who was in turn replaced by Valéry Giscard d’Estaing in 1974. François Mitterrand, long-time head of the Partie Socialiste (PS), was elected president in 1981 and, as the business community had feared, immediately set out to nationalise privately owned banks, large industrial groups and various other parts of the economy. However, during the mid-1980s Mitterrand followed a generally moderate economic policy and in 1988, aged 69, he was re-elected for a second seven-year term.

In the 1986 parliamentary elections the right-wing opposition led by Jacques Chirac, mayor of Paris since 1977, received a majority in the National Assembly; for the next two years Mitterrand was forced to work with a prime minister and cabinet from the opposition, an unprecedented arrangement in French governance known as cohabitation.

In the May 1995 presidential elections Chirac enjoyed a comfortable victory (Mitterrand, who would die in January 1996, decided not to run again because of failing health). In his first few months in office Chirac received high marks for his direct words and actions in matters relating to the EU and the war in Bosnia. His cabinet choices, including the selection of ‘whiz kid’ foreign minister Alain Juppé as prime minister, were well received. But Chirac’s decision to resume nuclear testing on the French Polynesian island of Mururoa and a nearby atoll was met with outrage in France and abroad. On the home front, Chirac’s moves to restrict welfare payments (designed to bring France closer to meeting the criteria for the European Monetary Union; EMU) led to the largest protests since 1968. For three weeks in late 1995 Paris was crippled by public-sector strikes, battering the economy.

In 1997 Chirac took a big gamble and called an early parliamentary election for June. The move backfired. Chirac remained president but his party, the Rassemblement Pour la République (RPR; Rally for the Republic), lost support, and a coalition of Socialists, Communists and Greens came to power. Lionel Jospin, a former minister of education in the Mitterrand government (who, most notably, promised the French people a shorter working week for the same pay), became prime minister. France had once again entered into a period of cohabitation – with Chirac on the other side of the table this time around.

top picks

HISTORICAL READS

- Paris: The Secret History, Andrew Hussey (2006) – a book not unlike Peter Ackroyd’s London: The Biography, this colourful historical tour of Paris opens the door to (but does not solve) many of the city’s mysteries.

- Paris Changing, Christopher Rauschenberg (2007) – modern-day photographer follows in the footsteps of early-20th-century snapper Eugène Atget in this ‘spot the difference’ album of before-and-after photos.

- The Flâneur: A Stroll Through the Paradoxes of Paris, Edmund White (2001) – doyen of American literature and long-term resident (and flâneur – ‘stroller’) of Paris, White notices things rarely noticed by others – veritable footnotes of footnotes – in this loving portrait of his adopted city.

- The Seven Ages of Paris: Portrait of a City, Alistair Horne (2002) – this superb, very idiosyncratic ‘biography’ of Paris divides the city’s history into seven ages – from the 13th-century reign of Philippe-Auguste to President Charles de Gaulle’s retirement in 1969.

- Is Paris Burning? Larry Collins & Dominique Lapierre (1965) – this is a tense and very intelligent reportage of the last days of the Nazi occupation of Paris.

- Paris: The Biography of a City, Colin Jones (2005) – although written by a University of Warwick professor, this one-volume history is not at all academic. Instead, it’s rather chatty, and goes into much detail on the physical remains of history as the author walks the reader through the centuries and the city.

- Cross Channel, Julien Barnes (1997) – This is a witty collection of key moments in shared Anglo-French history – from Joan of Arc to a trip via Eurostar from London to Paris – by one of Britain’s most talented novelists.

For the most part Jospin and his government continued to enjoy the electorate’s approval, thanks largely to a recovery in economic growth and the introduction of a 35-hour working week, which created thousands of (primarily part-time) jobs. But this period of cohabitation, the longest-lasting government in the history of the Fifth Republic, ended in May 2002 when Chirac was returned to the presidency for a second five-year term with 82% of the vote. This reflected less Chirac’s popularity than the fear of Jean-Marie Le Pen, leader of the right-wing Front National, who had garnered nearly 17% of the first round of voting against Chirac’s 20%.

Chirac appointed Jean-Pierre Raffarin, a popular regional politician, as prime minister and pledged to lower taxes with declining revenues from a sluggish economy. But in May 2005 the electorate handed Chirac an embarrassing defeat when it overwhelmingly rejected, by referendum, the international treaty that was to create a constitution for the EU.