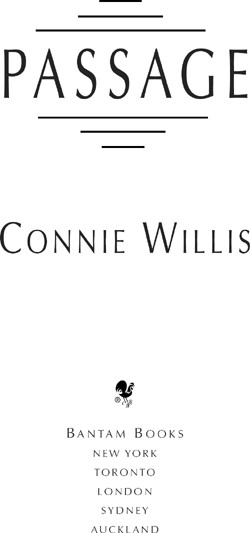

Passage – Read Now and Download Mobi

Contents

Chapter 1

Dag was riding up the lane thinking only of the…

Chapter 2

In the pressure of a short-handed harvest and a run…

Chapter 3

While Sorrel and Tril might have been dubious about letting…

Chapter 4

Even in the late afternoon, the straight road approaching Glassforge…

Chapter 5

Back aboard Copperhead, Dag rode close to the second wagon…

Chapter 6

Fifty paces up the slope from the Pearl Bend wharf…

Chapter 7

The afternoon was waning when Dag at last caught up…

Chapter 8

Dag had the most unsettled look on his face, downright…

Chapter 9

Fawn kept an eye out, but Dag did not return…

Chapter 10

The oil lantern burning low on the kitchen table was…

Chapter 11

The Fetch made thirty river miles before the dank autumn…

Chapter 12

Despite the delay from Dag’s fruitless errand, the Fetch made…

Chapter 13

To the excitement of everyone aboard—although Fawn thought that Dag…

Chapter 14

To Fawn’s bemusement, Remo tagged along on the trip to…

Chapter 15

Dag was reassured early the next morning of the health…

Chapter 16

Fawn watched in alarm as Remo took up the lantern…

Chapter 17

Though the weather stayed cloudy and chilly, the Fetch made…

Chapter 18

During an easy stretch of river in the morning, Berry…

Chapter 19

Berry’s radiant joy seemed to light up the air around…

Chapter 20

Dag braced one knee on a fallen log, checked the…

Chapter 21

What Dag most wanted to do was question Crane: Fawn…

Chapter 22

Flanked by Remo, Dag exited the cave and dragged his…

Chapter 23

Her face carefully held stiff to hide how her stomach…

Chapter 24

The next day the Fetch floated through yet more of…

Dag was riding up the lane thinking only of the chances of a Bluefield farm lunch, and his likelihood of needing a nap afterwards, when the arrow hissed past his face.

Panic washing through him, he reached out his right arm and snatched his wife from her saddle. He fell left, dragging them both off and behind the shield of their horses, snapping his sputtering ground-sense open wide—range still barely a hundred paces, blight it—torn between thoughts of Fawn, of the knife at his belt, of the unstrung bow at his back, of how many, where? All of it was blotted out in the lightning flash of pain as he landed with both their weights on his healing left leg. His cry of “Spark, get behind me!” transmuted to “Agh! Blight it!” as his leg folded under him. Fawn’s mare bolted. His horse Copperhead shied and jerked at the reins still wrapped around the hook that served in place of Dag’s left hand; only that, and Fawn’s support under his arm as she found her feet, kept him upright.

“Dag!” Fawn yelped as his weight bent her.

Dag straightened, abandoning his twisting reach for his bow, as he at last identified the source of the attack—not with his groundsense, but with his eyes and ears. His brother-in-law Whit Bluefield came running across the yard below the old barn, waving a bow in the air and calling, “Oh, sorry! Sorry!”

Only then did Dag’s eye take in the rag target tacked to a red oak tree on the other side of the lane. Well…he assumed it was a target, though the only arrow nearby was stuck in the bark about two feet below it. Other spent arrows lay loose on the ground well beyond. The one that had nearly clipped off his nose had plowed into the soil a good twenty paces downslope. Dag let out his pent breath in exasperation, then inhaled deeply, willing his hammering heart to slow.

“Whit, you ham-fisted fool!” cried Fawn, rising on tiptoe to peer over her restive horse-fort. “You nearly shot my husband!”

Whit arrived breathless, repeating, “Sorry! I was so surprised to see you, my hand slipped.”

Fawn’s mare Grace, who had skittered only a few steps before getting over her alarm at this unusual dismount, put her head down and began tearing at the grass clumps. Whit, familiar with Copperhead’s unsociable character, made a wide circle around the horse to his sister’s side. Dag let the reins unwrap from his hook and allowed Copperhead to go join Grace, which the chestnut gelding did after a few desultory bucks and cow-kicks, just to register his opinion of the proceedings. Dag sympathized.

“I wasn’t aiming at you!” Whit declared anxiously.

“I’m right glad to hear that,” drawled Dag. “I know I annoyed a few people around here when I married your sister, but I didn’t think you were one of ’em.” His lips compressed in a grimmer line. Whit might well have hit Fawn.

Whit flushed. A head shorter than Dag, he was still a head taller than Fawn, whom, after an awkward hesitation, he now embraced. Fawn grimaced, but hugged him back. Both Bluefield heads were crowned with loosely curling black hair, both faces fair-skinned, but while Fawn was nicely rounded, with a captivating sometimes-dimple when she smirked, Whit was skinny and angular, his hands and feet a trifle too big for his body. Still growing into himself even past age twenty, as the length of wrist sticking from the sleeve of his homespun shirt testified. Or perhaps, with no younger brother to hand them down to, he was just condemned to wear out his older clothes.

Dag took a step forward, then hissed, hook-hand clapping to his buckling left thigh. He straightened again with an effort. “Maybe I want my stick after all, Spark.”

“Of course,” said Fawn, and darted across the lane to retrieve the hickory staff from under Copperhead’s saddle flap.

“Are you all right? I know I didn’t hit you,” Whit protested. His mouth bent down. “I don’t hit anything, much.”

Dag smiled tightly. “I’m fine. Don’t worry about it.”

“He is not fine,” Fawn amended sternly, returning with the stick. “He got knocked around something fearsome last month when his company rode to put down that awful malice over in Raintree. He hasn’t nearly healed up yet.”

“Oh, was that your folks, Dag? Was it really a blight bogle—malice,” Whit corrected himself to the Lakewalker term, with a duck of his head at Dag. “We heard some pretty wild rumors about a ruckus up by Farmer’s Flats—”

Fawn overrode this in concern. “That scar didn’t break open when you landed so hard, did it, Dag?”

Dag glanced down at the tan fabric of his riding trousers. No blood leaked through, and the flashes of pain were fading out. “No.” He took the stick and leaned on it gratefully. “It’ll be fine,” he added to allay Whit’s wide-eyed look. He squinted in new curiosity at the bow still clutched in Whit’s left hand. “What’s this? I didn’t think you were an archer.”

Whit shrugged. “I’m not, yet. But you said you would teach me when—if—you came back. So I was getting ready, getting in some practice and all. Just in case.” He held out his bow as if in evidence.

Dag blinked. He had quite forgotten that casual comment from his first visit to West Blue, and was astonished that the boy had apparently taken it so to heart. Dag stared closely, but not a trace of Whit’s usual annoying foolery appeared in his face. Huh. Guess I made more of an impression on him than I’d thought.

Whit shook off his embarrassment over his straying shaft, and asked cheerfully, “So, why are you two back so soon? Is your patrol nearby? They could all come up too, you know. Papa wouldn’t mind. Or are you on a mission for your Lakewalkers, like that courier fellow who brought your letters and the horses and presents?”

“My bride-gifts made it? Oh, good,” said Dag.

“Yep, they sure did. Surprised us all. Mama wanted to write a letter back to you, but the courier had gone off already, and we didn’t know how to get in touch with your people to send it on.”

“Ah,” said Dag. There’s a problem. There was the problem, or one aspect of it: farmers and Lakewalkers who couldn’t talk to each other. Like now? For all his mental rehearsal, Dag found it suddenly difficult to spit out the tale of his exile, just off the cuff like this.

Fortunately, Fawn filled in. “We’re just visitin’. Dag’s sort of off-duty for a time, till his hurts heal up.”

True in a sense—well, no, not really. But there would be time to explain further—maybe when everyone was together, so he wouldn’t have to repeat it all over and over, a prospect that made him wince even more than the vision of explaining it to a crowd.

They strolled to recapture the horses, and Whit waved toward the old barn. “The stalls you used before are empty. You still got that man-eating red nag, I see.” He skirted Copperhead to gather up Grace’s reins; from the way the bay mare resisted his tugging to snatch a few last mouthfuls of grass, one would take her for starved—clearly not the case.

“Yep,” said Dag, stooping with a grunt to scoop up the gelding’s reins in turn. “I still haven’t met anyone I disliked enough to give him to.”

“And he’s been ridin’ Copperhead for eight straight years. It’s a wonder, that.” Fawn dimpled. “Admit it, Dag, you like that dreadful horse.” She went on to her brother, in a tone of bright diversion, “So, what’s been happening here at West Blue since I left?”

“Well, Fletch and Clover was married a good six weeks ago. Mama was sorry you two couldn’t be here for the wedding.” Whit cast a nod at the solid stone farmhouse, sited on the ridge overlooking the wooded valley of the rocky river. The newlyweds’ addition of two rooms off the near end, still in progress when Dag had last seen it, seemed entirely complete, with glass windows, a wood-shingle roof, and even some early-autumn flowers planted around the foundation, softening the fresh scars in the soil. “Clover’s all moved in, now. Ha! It didn’t take her long to shift the twins. They lit out about twenty miles west to break land with a friend of theirs, only last week. You just missed ’em.”

Dag couldn’t help reflecting that of all his Bluefield in-laws, the inimical twins Reed and Rush were probably the ones he’d miss the least; judging from the sudden smile on Fawn’s face, she shared the sentiment. He said affably, “I know they’d been talking about it for a long time.”

“Yeah, Papa and Mama wasn’t too pleased that they picked just before harvest to finally take themselves off, but everyone was so glad of it they didn’t hardly complain. Fletch came in on Clover’s side whenever they clashed, naturally, which was pretty much every day, and they didn’t take any better to him telling them what to do than to her. So it’s a lot more peaceable in the house, now.” He added after a reflective moment, “Dull, really.”

Whit continued an amiable account of the small doings of various cousins, uncles, and aunts as they unsaddled the horses and turned them into the box stalls in the cool old barn. With a glance at Dag’s stick, Whit actually helped them put up their gear without being asked and hoisted Dag’s saddlebags over his shoulder. Feeling that such an apologetic impulse should be encouraged, Dag let him take them. As they made their way back out to climb the hill to the house, Fawn refused to give up her own bags to Dag, telling him to mind himself, and thumped along under the weight with her usual air of determination. Despite their late difficulties, she seemed far less troubled than at her previous homecoming, judging from the smile she cast over her shoulder at him, and he couldn’t help smiling back. Yeah, we’ll get through this somehow, Spark. Together.

The farmhouse kitchen was fragrant with cooking—ham and beans, cornbread, squash, biscuits, applesauce, pumpkin pie, and a dozen familiar go-withs—and the moist perfume of it all made Fawn weirdly homesick even though she was home. Mama and Clover, both be-aproned, were bustling around the kitchen as they stepped through the back door, and Mama, at least, fell on Fawn with shrieks of delighted surprise. Blind Aunt Nattie lumbered up from her spinning wheel just beyond the doorway to her weaving room, hugged Fawn hard, and spared an embrace for Dag as well. Her hand lingered a moment on the wedding cord circling Dag’s left arm, below his rolled-up shirt sleeve and above the arm harness for his hook, and her smile softened. “Glad to see this is still holdin’,” she murmured, and “Aye,” Dag murmured back, giving her in return a squeeze that lifted her off her feet and made her grin outright.

Papa and Fletch clumped in from wherever they’d been working—with the sheep, from the smell—when the greetings were all still at the babbling stage. Plump Clover, announcing that the food wouldn’t wait, sent Fawn and Dag off to put down their bags and wash up. She hurried to set extra places, and wouldn’t let Fawn help serve—“Sit, sit! You two must be tired from all that ridin’. You’re a guest now, Fawn!” Aren’t you? her worried eyes added silently. Fletch looked as if he were wondering the same thing, though he greeted his sister and her unlikely husband affably enough.

They sat eight around the long kitchen table, filled with the variety and abundance of farm fare that Fawn had always taken for granted but that still seemed to take Dag aback; having seen the austerity of life in a Lakewalker camp, Fawn now understood why. Dag certainly did not disapprove, praising the cooks and filling his plate in a way that demonstrated the ultimate compliment of a good appetite.

Fawn was glad for his returning appetite, worn thin as he’d been by this past summer’s gruesome campaign. And he’d been pretty lean to start with. With his height, coppery skin, striking bony face, tousled dark hair, and strange metallic-gold eyes, Dag looked as out of place at a table full of farmers as a heron chick set down in a hen’s nest, even without the faint air of menace and danger from his missing hand and the enigmatic fact of his being a Lakewalker sorcerer. Or Lakewalker necromancer as the bigoted—or frightened—would have it. Not without cause, she admitted to herself.

Fletch, possibly in response to the penetrating looks he was getting from his bride, was the first to ask the question, “I’m surprised to see you two back so soon. You’re not, um…planning to stay, are you?”

Fawn chose to ignore the wary tone. “Just a visit. We’re traveling through. Though I admit, it would be good to rest up for a few days.”

“Oh, of course you can,” cried Clover, brightening with relief.

“That’ll be a treat. I’d love to hear all about your new place.” She added in an arch voice, “So do you two have any good news yet?”

“Beg pardon?” said Dag blankly.

Fawn, who decoded this without effort as Aren’t you pregnant yet?, returned the correct response: “No, not yet. How about you and Fletch?”

Clover smirked, touching her belly. “Well, it’s early days yet. But we’re sure tryin’. Our betrothal ran so long, what with one thing and another, there seemed no reason not to start a family right away.”

Fletch gave his bride a fond, possessive smile, as a farmer might regard his prize broodmare, and Clover looked smug. Fawn didn’t always hit it off with Clover, but she had to admit that the girl was the perfect wife for stodgy Fletch, even without her dowry of a forty-acre field and large woodlot, linked to Bluefield land by a quite short footpath. Fletch put in, “We hope for news by winter, anyhow.”

Fawn glanced at Dag. Despite the unhealed damage to his ground-sense, at this range he would surely know if Clover were pregnant already. He gave Fawn a wry smile and a short headshake. Fawn touched the malice scars on her neck, darkening now to carmine, and thought, Leave it be.

Mama asked, in a more cautious tone, “So…how did things go with your new people at Hickory Lake, Fawn? With your new family?”

Dag’s family. After a perhaps too-revealing hesitation, Fawn chose, “Mixed.”

Dag glanced down at her and swallowed, not only to clear his mouth of his last bite, but said plainly enough: “Truth to tell, not well, ma’am. But that’s not why we’re on this road.”

Nattie said anxiously, “Those Lakewalker wedding cords we made up—didn’t they work?”

“They worked just fine, Aunt Nattie,” Dag assured her. He glanced up and down the table. “I should likely explain to the rest of you something that only Nattie knew when Fawn and I were wed here. Our binding strings”—he touched the dark braid above his left elbow and nodded to Fawn’s, wrapping her left wrist—“aren’t just fancy cords. Lakewalkers weave our grounds into them.”

Five blank stares greeted this statement, and Fawn wondered how he was going to explain ground and groundsense in a way that would make them all understand when they hadn’t seen what she’d seen. When he also had to overcome a lifetime of deep reserve and the habit—no, imperative—of secrecy. It seemed by his long intake of breath that he was about to try.

“Only you farmers use the term magic. Lakewalkers just call it groundwork. Or making. We don’t think it’s any more magic than, than planting seed to get pumpkins or spinning thread to get shirts. Ground is…it’s in everything, underlies everything. Live or un-live, but live ground is brightest, all knotty and shifting. Un-live sits and hums, mainly. You all have ground in you, but you don’t sense it. Lakewalkers perceive it direct. You can think of groundsense as like seeing double, except that seeing doesn’t quite cover—no.” He muttered to his lap, “Keep it simple, Dag.” His eyes and voice rose again. “Just think of it as like seeing double, all right?” He stared hopefully around.

Taking the uncharacteristic quiet that had fallen for encouragement, he went on, “So, just as we can sense ground in things, we can, most of us—sometimes—move things through their grounds. Change them, augment them. That’s groundwork.”

Mama wet her lips. “So…when you mended that glass bowl the twins broke, whistled it back together, was that what you’d call groundwork?”

Stunning the entire Bluefield clan to silence at that time, too, as Fawn vividly recalled—now that had been magic.

Dag, beaming, shot Mama a look of gratitude. “Yes, ma’am. Exactly! Well, it wasn’t the whistling that—well, close enough. That was probably the best groundwork I’d ever done.”

Second best, now, thought Fawn, remembering Raintree. But Raintree had come later, and cost more: very nearly Dag’s life. Did they understand that this wasn’t trivial trickery?

“Lakewalkers like to think that only we have groundsense, but I’ve met a lot of farmers with a trace. Sometimes more than a trace. Nattie’s one.” Dag nodded across the table at Nattie, who grinned in his general direction, though her pearl-colored eyes could not see him. Fletch and Clover and Whit looked startled; Mama, less so. “I don’t know if her blindness sharpened it, or what. But with Nattie’s helping, Fawn and I wove our grounds into our wedding cords as sound as any Lakewalker’s.”

He left out the alarming part about the blood, Fawn noted. He was picking his way through the truth as cautiously as a blindfolded man crossing a floor studded with knives.

Dag went on, “So when we got up to camp, every Lakewalker there could see that they were valid cords. Which threw everyone into a puzzle. Folks had been relying on the cord-weaving to make Lakewalker marriages to farmers impossible, d’you see. To keep bloodlines pure and our groundsense strong. They were still arguin’ about what it meant when we left.”

Papa had been staring at Nattie, but this last drew his frown back to Dag. “Then did your people throw you out for marrying Fawn, patroller?”

“Not exactly, sir.”

“So…what? Exactly?”

Dag hesitated. “I hardly know where to start.” A longer pause. “What all have you folks here in Oleana heard about the malice that emerged over in Raintree?”

Papa said, “There was supposed to have been a blight bogle pop up somewheres north of Farmer’s Flats, that killed a lot of folks, or drove them mad.”

Whit put in, “Or that it was a nerve-ague or brain-worms, that made folks there run around attacking one another. It’s bog country up that way, they say, bad for strange fevers.”

Fletch added, “Down at Millerson’s alehouse, I heard someone say it was an excuse got up by the Lakewalkers to drive farmers back south out of their hunting country. That there never was any blight bogle, and it wasn’t bogle-maddened farmers attacking Lakewalkers, but the other way around.”

Dag squeezed his eyes shut and rubbed his mouth. “No,” he said into his hand, and lowered it.

Clover sat back with a sort of flounce; she didn’t voice it, but her face said it for her: Well, you’d naturally say that, wouldn’t you? Mama and Nattie said nothing, but they seemed to be listening hard.

Dag said, “There was a real malice. We first heard about it when the Raintree Lakewalkers, who were being overwhelmed, sent a courier to Hickory Lake Camp for help. My company was dispatched. We circled, managed to come up on the malice from behind while it was driving its mind-slaves and mud-men south to attack Farmer’s Flats. One of my patrol got a sharing knife into it—killed it. I saw it”—he held out his left arm—“that close. It was very advanced, very, um…advanced.” He paused, glanced around, and tried, “Strong, smart. Almost human-looking.”

Leaving out how the malice had nearly slain him, or that he’d been captain of that company and source of its successful plan…Fawn bit her lip in impatience.

“Here’s the thing, the important thing. No…back up a step, Dag.” He pinched the bridge of his nose. “I’m sorry. There’s too much all at once, and I’m explaining this all backwards, I’m sorry. Try this. Malices have groundsense too, only very much stronger than any human’s. They’re made of ground. They consume ground, to live, to make their—their magery, their mud-men, their own bodies, everything they do. They’re quite mad, in their way.” His face looked suddenly drawn in some memory Fawn did not share and could not guess at. “But that’s what blight is. It’s where some emergent malice has drawn all the ground out of the world, leaving, well, blight. It’s very distinctive.”

“Well, what does it look like?” asked Whit reasonably.

“It doesn’t look like anything else,” said Dag, which netted him some pretty dry looks from around the table.

Fawn pitched in: “It’s not like burnt fields, or rust, or rot, or a killing frost, though it reminds you of all those things. It has a funny gray tinge, like all the color has been sucked out of things. First things die, if they’re alive, and then they fall apart at the seams, and then they dissolve all through. Once you’ve seen that drained-out gray, you can’t ever mistake it. It looks even worse to someone with groundsense, I gather.”

“Yes,” said Dag gratefully.

Mama said faintly, “You’ve seen it, then, Fawn?”

“Yes, twice. Once at that malice’s lair near Glassforge, when Dag and I first met, and once in Raintree. I rode over, after. Dag was hurt on his patrol, which part he didn’t tell you, I notice.” She glowered at him in reproof. “He’d still be on sick leave if we were back at Hickory Lake.”

“You got to go to Raintree?” said Whit, sounding indignantly envious.

Fawn tossed her head. “I saw all that country the malice had torn through. I saw where it got started.” She glanced back to Dag, to check if he was ready to go on.

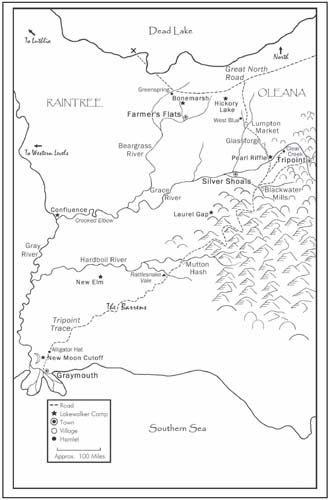

He nodded at her and picked up his tangled thread again. “Here’s the thing. For the past twenty or thirty years, farmers have been breaking land in Raintree north of the old cleared line—that is, north of where the local Lakewalkers had deemed it safe. Or less unsafe, leastways. Lakewalker patrol records show malice emergences get thicker—more frequent—north toward the Dead Lake, see, and thinner south and away. South of the Grace River, they’re very rare. Although unfortunately not all gone, so we can’t stop patrolling those regions. It was at a north Raintree squatter town named Greenspring that this latest malice emerged. Practically under it.”

Fawn nodded. “It hatched out down in a ravine in the town woodlot, by the signs.”

Dag went on, “See, there was a lot of bad blood between the local Lakewalkers and the Greenspring settlers, on account of the arguments about the old cleared line. So when the malice started, none of the squatters knew how to recognize the early signs, or to pick up and run, or how or where to ride for help. Or they’d been told but didn’t believe. Not that they wouldn’t have needed to be lucky as well, because by the time a farmer can see the blight near a lair, there’s a good chance he’s just about to be ground-ripped or mind-slaved anyway. Like stumbling into a spider web. But with that many folks, if they’d all known, someone might have got out to spread the warning. Instead, the malice pretty much ate them. And grew strong way too fast. I think that a whole lot more people died in north Raintree than needed to this summer just because Lakewalkers and farmers weren’t talking to each other.”

“I hadn’t ever seen a mass grave before,” said Fawn quietly. “I don’t ever want to again.”

Papa gave her a sharp glance from under his gray brows. “I did, once, long time ago,” he said unexpectedly. “It was after a flood.”

Fawn looked at him in surprise. “I never knew that.”

“I never talked about it.”

“Hm,” said Aunt Nattie.

Papa sat back and looked at Dag. “Your people aren’t exactly forthcomin’ about these things, you know. In Raintree or Oleana.”

“I know.” Dag ducked his head. “Back when there were few farmers north of the Grace, it scarcely mattered. To the Lakewalkers in the hinterlands north of the Dead Lake—I’ve walked up that way, twice—there’s still no need to do anything differently, because there are no farmers there. Where it matters is in the border country, where things are changing out from under us—like Greenspring. And like West Blue.” He glanced around the table. The food on his plate had all gone cold, Fawn noticed.

Fletch said, “I never got the sense Lakewalkers wanted farmer help.”

“They don’t, mostly,” Dag admitted. “No farmer can fight a malice directly. You can’t close your grounds in defense, for one, you can’t make…certain tools.” He blinked, frowned, seemed to take aim like a rider trying to clear a fence on a balky horse, and blurted out, “Sharing knives. You can’t make sharing knives to kill malices.” Swallowing, he went on, “But even if you can’t be fighters, you might find better ways to avoid being fodder. Everyone alive should be taught how to recognize blight-sign, for one—as routinely as how to identify poison ivy or rattlesnakes or, or how not to stand on the wrong side of the tree you’re felling.”

“How would you go about teaching everyone alive, patroller?” asked Aunt Nattie, in a curious voice.

“I don’t know,” sighed Dag. “Laid out like that, it sounds pretty crazy. We came upon the Glassforge malice early, this past spring, only because of the chance of Chato’s patrol stopping there and gossiping with the local folks about their bandit problem enough for Chato to realize there was something strange going on. If I could only show folks, somehow…I wouldn’t have to talk.” Dag smiled wanly. “I never was much of a talkin’ man.”

“Eat, Dag,” Fawn put in, and pointed to his plate. Everyone else’s was empty. He took an obedient bite.

“Folks could show off that patch of blight you say is by Glassforge,” Whit suggested. “Then they’d all know what it looks like.”

Clover eyed him. “Why would anybody want to go look at a thing like that? It just sounds ugly.”

Whit sat back and rubbed his nose, then brightened. “Then you should charge ’em money.”

Dag stopped chewing and stared. “What?”

“Sure!” Whit sat up. “If they had to pay, they’d think it was something special. You could get up wagon excursions from Glassforge. Charge five copper crays for the ride, and ten for the box lunch. And the lecture for free. It would get folks talking when they got home, too—What did you see in Glassforge, dear? It could be a nice little business, driving the wagon, making the lunches—it would sure beat pulling stumps, anyways. If I had the cash I’d buy that blight, I would. It’d be better ’n a forty-acre field.”

Fawn didn’t think she’d ever seen Dag look so flummoxed. It was all she could do not to giggle, though she mainly wanted to hit Whit.

“Well, you don’t have any cash,” Fletch pointed out dauntingly.

“Thank the stars,” added Clover, fanning herself with her hand.

“You’d likely throw it down a well.”

“Quit your fooling, Whit,” said Papa impatiently. “Nobody thinks it’s amusin’.”

Whit shrugged, kicked back his chair, and rose to carry off his plate to the sink. Dag, slowly, started chewing again. His eyes, following Whit, had an odd look in them—not angry, though, which surprised Fawn, knowing how seriously Dag took all this. With afternoon chores looming, lunch broke up.

Later, putting their things away in the twins’ old bedroom upstairs, Dag folded Fawn to him and sighed.

“Well, I sure made a hash of that. Absent gods. If I can’t talk to my own tent-family and make them understand, how am I ever going to talk to strangers?”

“I didn’t think you did so badly. It was a lot for them to get around, all at once like that.”

“It was all out of order, I never explained sharing knives, they didn’t half believe me—or else half of ’em didn’t believe me, I wasn’t sure which—it was all—oh, Spark, I don’t know what I’m doing on this road. I’m just an old patroller. I’m surely not the man for this.”

“It was your first try. Who gets everything right the first try?”

“Anyone who wants to live for a second try.”

“That’s for things that’ll kill you if you miss, like…like slaying malices, I suppose. People don’t die of stumbling over a few words.”

“I thought I was going to strangle on my tongue.”

About to hug him around the waist, she pushed off and looked up instead. She said shrewdly, “This isn’t just hard because it’s complicated, or new, is it? Lakewalkers aren’t supposed to talk about these secrets to farmers—are they?”

“Indeed, we are not.”

“How much trouble would you be in with your own folks, if they knew?”

He shrugged. “Hard to say.”

That wasn’t too helpful. Fawn narrowed her eyes in worry, but then just gave up and hugged him tight, because he’d never looked like he needed it more. The breath of his laugh stirred her curls as he dropped a kiss atop her head.

In the pressure of a short-handed harvest and a run of dry weather, Fawn and Dag lost their sitting-guest status almost immediately. Dag didn’t seem to mind, showing both willing and a keen and practical interest in the farm and all its doings. It was all as strange and new to him, Fawn realized, as the very different rhythms of a Lakewalker camp had been to her. She wondered if he was homesick yet.

As usual, the Bluefields combined forces for the ingathering with the Ropers, Aunt Roper being Papa’s sister. The Ropers’ place lay just northwest of their own. Two of their sons and Fawn’s closest cousin, Ginger, were still at home to help out, and amongst them all, they cleared Uncle Roper’s big cornfield in three days. Next was the Bluefield late wheat. Dag proved unexpectedly adept with the long scythe. His arm harness held a wooden wrist-cap over his stump, and besides the hook he possessed an array of clever tools on bolts that he swapped in and out of it, including his specially adapted bow. The tool he usually used for clasping the paddle of a narrow boat on the lake also served to aid his grip on the scythe, and after a little experimentation he seemed to find his way into the swing of the task quite contentedly, so Papa left him to it.

Gleaning had been one of the first chores little hands had been put to, back when Fawn and Ginger and Whit had been only hip-high. They were all bigger now, but the gleaning still had to be done. Fawn crouched and shuffled her way across the bright gold stubble, and thought Clover and Fletch could well stand to be prompt in producing the next generation of shorter harvesters. Along the split-rail fence of the pasture, the farm’s horses lined up in mild-eyed curiosity to watch the strange behavior of their people.

At the end of her row, Fawn stood up to stretch her back and check on Dag, working at the far end of the field with Papa, Uncle Roper and his boys, and Fletch to scythe and bundle sheaves and load them into a waiting cart. Dag looked very tall beside the others, though the sleeves of his homespun shirt were rolled up over a coppery suntan not that much deeper than the men’s, and the hat shading his head, woven of lake reeds, was fringed around the rim just like their straw ones. Whit rose beside her, adjusted the strap of the cloth bag across his shoulder, and followed her gaze.

“I must warn Papa to watch and not let Dag overdo,” said Fawn in worry. “He won’t stop on his own.”

“Just exactly how was he hurt, again?” said Whit. “’Cause when we went down to wash up in the river last night, all I saw new was that little bitty cut on his left thigh.”

“It’s not long, but it’s deep,” said Fawn. “The knife blade that did it went straight to the bone and shattered. The Lakewalker medicine maker had an awful time getting all the pieces fished back out. But that’s not what’s dragging him down so.” Taking her lead from Dag, Fawn decided to stick with a much-simplified version of the truth. “The Raintree malice halfway ground-ripped him in the fight, tore up his ground all down his left arm and side. It nearly killed him. It’s like he’s walking around recovering from his own personal blight.”

“Well, how long does that take?”

“I’m not sure. I’m not sure he’s sure. Most folks who get ground-ripped just die on the spot. But Dag says when the Glassforge malice put these marks on my neck”—she rubbed at the ugly red dimples, one on the right side, four on the left—“it injured both flesh and ground. If the bruises had been just from a man’s hand, they’d have cleared up two or three months back, with nothing to show. Ground damage is nasty stuff.” Her hand crept to rub her belly as well, but she halted it, burying it in her skirt instead. Dag wasn’t the only one to carry the worst damage hidden inside.

“Huh,” said Whit, squinting at her neck. “I guess so!”

“The weakness and pain in his body don’t bother him near as much as the harm the ripping did to his groundsense, though.”

“That seeing-double thing he talks about?”

“Yes. Usually he can sense things out for near a mile away, which I gather is pretty amazing even for a Lakewalker. He says it’s down to less ’n a hundred paces right now. The medicine maker said that’s how he’ll know when his ground is better, when he can sense out far again.”

Whit blinked. “So…can he still do his groundwork? Like that bowl?”

Whit had been impressed by the bowl. Rightfully, Fawn thought. “Not yet. Not real well.” She thought of some of Dag’s other marvelous ground-tricks, still not regained, and sighed. When Lakewalkers made love they did it body and ground, with an ingenuity farmers never dreamed of, but she wasn’t about to explain that part to Whit.

Whit shook his head, frowning again at the reapers. “He looks so wrong.”

Fawn shaded her eyes with the edge of her hand. “Why? I think he’s doing pretty good with that scythe.”

“There’s that hat, for one.”

“I wove him that hat! Same as yours.”

“Ah, that explains why he won’t be parted from it. What that man does for you…! But—” Whit gestured inarticulately. “Dag looks all right up on his evil horse. He looks right with that bow of his, anyone can see—you’d think it grew there on his arm, even without how his arrows fly just where he wants. I’ve never seen him draw that big knife of his, but I sure wouldn’t want to be on the other side when he does.”

“No. You wouldn’t,” Fawn agreed.

“But stick him with a scythe or a pitchfork or a bucket, he looks as out of place as—as if you’d hitched that leggy silver mare to a plow.” He jerked his head toward the pasture fence.

Swallow, the dappled gray mare Dag had sent to West Blue as his Lakewalker-style bride-gift, pricked her curving ears alertly. She looked as elegant as moonlight on water, and as swift as a rippling stream even when she was standing still. Beyond, her black colt Darkling, as if proudly aware of collecting his due-share of admiration, kicked up his heels and danced past, tail flicking.

Grace was standing hipshot and bored along the fence line, dark bay coat looking warm and shiny in the sun. Copperhead of the uncertain temper had been left in exile in the small paddock below the old barn, but the two young plow horses Whit was bringing along, and known therefore as Whit’s team, cropped grass placidly a few paces off. Warp and Weft were nice, sturdy, useful-looking beasts, but…you would never imagine them with wings.

“Swallow was supposed to be a gift to Mama.” Fawn sighed. “I don’t suppose Mama rides her.”

Whit snorted. “Not hardly! She’s too terrified. Me, I’ve only taken that mare a few turns around the pasture, but the way she moves sure does make it look a long way to the ground.”

“Dag didn’t mean her to be idle. I thought you might train her to the cart.”

“Well, maybe. Papa means to breed her again, for sure. If we can find a stud around here worthy of her. He was talkin’ about Uncle Hawk’s Trustful, or maybe that flashy stallion of Sunny Sawman’s.”

Fawn said neutrally, “Trustful would be good.” She added, “Papa and Mama aren’t planning to cut Darkling, are they? Dag’s tent-sister Omba was worried about that.”

“Geld that colt? You’d have to be mad!” said Whit. “Just think of the stud fees, in a couple of years! He’ll support his mama in her old age, sure enough—and our mama, too.”

Fawn nodded in satisfaction on Omba’s behalf. “That’s all right, then.” She added, “Grace was bred to a real fine Lakewalker stallion named Shadow before we left.” Somewhat by accident, but that was another tale. “Dag expects her to throw a right lovely foal next spring, with his lines and her temper.”

Whit grinned. “As long as it’s not the other way around.”

“Hey! Grace is a very pretty horse, too, in her own way!”

“If you like ’em short and plump, which I admit is a popular style around here.”

Fawn gave him a suspicious scowl, but deciding he was referring to Clover and not herself, let the dig pass.

Whit lifted his brows and sniggered. “We’ll have to tell Clover your mare is going to beat her to the finish line in the baby race. I want to see the look on her face.”

I’m not in any baby race! Fawn was about to snap, but a loud, sharp whistle from the other end of the wheat field interrupted her. Papa took his hand from his mouth and jerked his thumb firmly toward the ground. His children, interpreting this without difficulty, shrugged in reply and crouched to their gleaning again.

When Mama, Clover, and Aunt Roper lugged lunch up to the wheat field, everyone took a break under the nearby apple trees. Fawn collected a skirt-load of the wormier groundfalls and carried them across to the pasture fence as a treat for the horses. They all clustered up, making the fence creak as they leaned over it, and nuzzled the aromatic fruit out of her hands, their thick, mobile lips tickling her palms. She liked watching the happy way their jaws moved beneath their sliding skins as they munched and crunched and sighed in appreciation, and how they rounded their big nostrils and blinked their deep brown eyes.

She wiped the mess of apple bits and horse slobber from her hands onto her skirt, and started back toward the orchard. Dag was sitting with Uncle and Aunt Roper and Fawn’s cousins, talking and gesturing. Trying to explain ground and groundsense to them, she guessed, partly from the way his hand touched the cord circling his left arm, and waved and closed and opened, but mostly by the way his desperately smiling listeners leaned back as if wishful to edge away, even while sitting cross-legged. Aunt Roper spotted Fawn, waved, and patted the ground beside her invitingly—come protect us from your wild patroller! Fawn sighed and trudged toward them.

The planned few days of rest in West Blue had slid instead into a few weeks of hard work, but Dag found himself oddly at ease despite the delay. The long days outdoors with the harvest-patrol had been laborious—that bean field, for one, had turned out to be much bigger than it looked, and before it was cleared Dag had started seeing cascades of beans in his sleep—but he was sleeping, and well, too. Indoors, every night, in a real bed, wrapped around Fawn. The food was not all dried-out to carry light, painstakingly rationed to the length of a pattern-walk, but gloriously, weightily abundant. There was no worse source of tension than an occasional clash of tempers, no deeper fear than of a splash of untimely rain.

This break in their journey had been good for him. The dark, sick pain in his bones from the blight was giving way to mere clean fatigue from well-used muscles. His left leg was not as weak—he hadn’t needed his stick for days. He felt less…unbalanced. He had not, admittedly, attempted to stray off the Bluefield acres to the village, where he might risk encountering certain young men who had reason to remember his last visit with disfavor. But however Dag was now discussed in village gossip, the bad boys dared not stray up here, either, and Dag was content to be surrounded wholly by farmers who wished him well for Fawn’s sake.

“So, patroller.”

Sorrel’s voice broke into Dag’s drift of thought, and he tilted his head forward, closed his mouth, and opened his eyes, hoping he hadn’t started to snore in his chair. As was their custom, the Bluefield clan had gathered in the parlor after dinner to share the working lights. Clover and Fletch had gone off to her folks this evening, but Tril sat in her usual place sewing; Nattie, though not needing the oil lamp, kept company plying her drop spindle; and Fawn and Whit had set up a table to make arrows, a skill Fawn had mastered this past summer.

Whit’s awful marksmanship had turned out not to be merely from his complete lack of training; his little hoard of arrows, picked up for free somewhere, was ill-made and ill-balanced. When Whit had asked plaintively if Dag couldn’t fix them the way a Lakewalker would, Dag had thought about it, nodded, and, to Whit’s temporary horror, broken them over his knee. He’d then donated Fawn and a dozen old flint points to their replacement, being wishful to conserve his best steel-tipped shafts for more urgent uses than target practice. Besides, it was good for Whit to suffer some instruction from his younger sister. He was still, in Dag’s view, too inclined to discount Fawn.

Now Dag raised his brows, tried to look awake, and answered Fawn’s papa—my tent-father?—“Sir?”

Sorrel was studying him. “I don’t believe I’ve said thank you for staying on through the harvest. You do more work with one hand than most men do with two.”

Fawn, squinting to wrap a carefully cut trio of feathers to a shaft with fine thread, dimpled in an I-told-you-so sort of way.

Sorrel continued, “I never thought much before about what Lakewalker patrollers do, but I suppose it is hard work, in its way. Harder than I rightly imagined, maybe, and not much comfort in it.”

Dag tilted his head in acknowledgment. Sorrel seemed clumsy but sincere, sorting through these new notions.

“But the thing is…I can’t help but wonder…have you ever worked for a living?”

Fawn sat up indignantly, but Dag waved her back down. “It’s not an insult, love. I know what he means. Because in a sense, the answer’s no. Out on patrol, we might hunt, cure skins, collect medicines, trade a little, keep the trails clear, but that’s all second place to hunting malice. Patrollers don’t make and save like farmers do. My camp kin did that part. At home, my bed was always made for me. Not that I ever spent long in it.”

Sorrel nodded. “But you don’t have your camp anymore.”

“…No.”

“So…how are you and Fawn planning to go on, then? Do you think to farm? Or something else?”

“I’m not sure,” said Dag slowly—honestly. “I figured I was too old to learn a whole new way of life, but I will say, these past weeks have given me more to chew on than Tril’s good cooking. I guess I never pictured having friendly folks to show me the trail.”

“A farmer Lakewalker?” murmured Tril, raising her brows. Whit made a face, though Dag was not sure why.

“By myself, no, but Fawn knows her part. Maybe together, it wouldn’t be so unlikely as it once seemed.” His other potential skill, medicine maker, was far too dangerous to attempt in farmer country, he’d been told. Repeatedly. In any case, his weakened ground made the notion futile, for now.

Sorrel said cautiously, “Would you be thinking to take up land here in West Blue?”

Dag glanced at Fawn, who gave him a slight, urgent headshake. No, she had no desire to settle a mere three miles up the road from her disastrous first love, and first hate. Dag wasn’t the only one of them who had been avoiding the village. “It’s too early to say.”

Tril looked up from her sewing, and said, “So what do you plan to do when a child comes along? They don’t keep to schedule, in my experience.” Her penetrating maternal look plainly wondered if he was simply being a male idiot, or if there was something he wasn’t saying.

He wasn’t about to go into the variety of methods available to Lakewalkers for not having children till wanted, some of which he was fairly sure—make that, entirely certain—Fawn’s parents would not approve of. The secret of the malice-damage to Fawn’s womb, as slowly healing as his own inner blight, she had elected to keep to herself, a choice he respected, and—what was that farmer phrase for letting go of a regretted past? Water over the dam. He offered instead, weakly, “Lakewalker women have children on the move.”

Tril gave that the fishy stare it deserved. “But it seems Fawn is not to be a Lakewalker woman, after all. And from what you say, Lakewalker mamas have kin and clan and camp to back ’em, in their need, even if their men are off chasing bogles.”

He wanted to declaim indignantly, I will take care of her! But even he wasn’t that much of a fool. His eyelids lowered, opened; he said instead, merely, “That’s so, ma’am.”

“We plan to travel, before we decide where to settle,” Fawn put in firmly. “Dag promised to show me the sea, and I mean to hold him to his word.”

“The sea!” said Tril, sounding shocked. “You didn’t say you were fixing to go all that way! I thought you were just going to the Grace Valley. Lovie, it’s dangerous!”

“The sea?” said Whit in an equally shocked but very different tone.

“Fawn gets to go to the sea? And Raintree? I’ve never been past Lumpton Market!”

Dag regarded him, trying to imagine a whole life confined to a space scarcely larger than a single day’s patrol-pattern. “By your age, I’d quartered two hinterlands, killed my first malice, and been down the Grace and the Gray both.” He added after a moment, “Didn’t see the sea for the first time till a couple years later, though.”

Whit said eagerly, “Can I go with you?”

“Certainly not!” Fawn cried.

Whit looked taken aback. Dag muffled a heartless smile. In a lifetime of relentlessly heckling his sister, Whit had clearly never once imagined needing her goodwill for any aim of his own. So do our sins bite us, boy.

“We’re not done harvest,” said Sorrel sternly. “You have work here, Whit.”

“Yes, but they’re not leaving tomorrow. Are you?” He looked wildly at Dag.

Dag did some rapid mental calculating. Fawn’s monthly would be coming on shortly, bloodily debilitating since her injuries, though slowly improving as she healed inside. They must certainly wait that out in the most comfortable refuge possible. “We’ll linger and help out for another week, maybe. But we can’t stay much longer. It’ll be near a week’s ride down to the Grace. If we want any choice of boats we have to get there in time to catch the fall rise, and not so late as to be caught by the winter freeze-up. Or just by the cold and wet and misery.”

A daunted silence fell, for a while. Nattie’s spindle whirred, Whit went back to sanding a shaft smooth, and Dag considered the attractions of his bed upstairs, compared to dozing off and falling out of his chair onto his chin.

Whit said suddenly, “What are you planning to do with your horses?”

“Take ’em along,” said Dag.

“On a keelboat? There’s hardly room.”

“No, on a flatboat.”

“Oh.”

More busy silence. Whit set down the shaft with a click, and Dag opened one wary eye.

Whit said, “But Fawn’s mare’s in foal. You wouldn’t want her to drop her foal along the trail somewheres. I mean…wolves. Catamounts. Delay. Wouldn’t it be better to leave her here all comfy at West Blue and pick her up when you got back?”

“And what am I supposed to do, walk?” said Fawn in scorn.

“No, but see…suppose you left her here for Mama to ride, since she can’t ride Swallow. And suppose we each rode one of my team, instead. I’d been meaning to sell them in Lumpton next spring, but I bet down by those rivertowns I’d get a better price. Also Papa and Fletch wouldn’t be put to the trouble of feedin’ them all winter. And you’d save the cost of taking your pregnant horse on a boat ride she wouldn’t hardly appreciate anyhow.”

“How would I get back? Copper can’t carry us double, and my bags!”

“You could pick up another horse when you get down there to Graymouth.”

“Oh, so Dag’s supposed to pay for this, is he?”

“You could sell it again when you got back. That, plus the savings for not shipping your mare, you’d likely come out pretty near even. Or even ahead!”

Fawn huffed in exasperation. “Whit, you can’t come with us.”

“Only as far as the river!” His voice went wheedling. “And see, Mama, I wouldn’t be going off by myself—I’d be with Dag and all. Going out, anyhow, and coming back I’d know how to find my way home again.”

“With money burning a hole in your pocket till it dropped through onto the road, I suppose,” said Sorrel.

“Unless you met up with bandits like Fawn did,” said Tril. “Then you’d lose your money and your life.”

“Fawn’s going. No, worse—Fawn’s going again.”

Sorrel looked as if he wanted to say something like Fawn’s her husband’s business, now, but in light of his prior prying, couldn’t quite work up to it.

His drowsy brain forced into motion, Dag found himself considering not money matters, but safety. A Lakewalker husband and his farmer wife, alone in farmer country, made an odd couple indeed, and they’d already met more than one offended observer who might, had there been time, have taken stronger exception to the pairing. But suppose it were a Lakewalker husband, a farmer wife, and her farmer brother? Might Whit be a buffer for Dag, as well as another pair of eyes to watch out for Fawn? Because absent gods knew Dag couldn’t stay awake all the time. Or even another half-hour. He swallowed a yawn.

“You could fall into bad company, down on that big river,” Tril worried.

“Worse ’n Dag?” Whit inquired brightly.

Tactless, but telling. Sorrel and Tril gave Dag an appraising look; Dag shifted uncomfortably.

He had been brooding about the problems of Lakewalker-farmer divisions for months, without results that he could see, and here was Whit practically volunteering to be a patrol partner and tent-brother. If Dag turned the boy down, would he ever get another such offer? Whit hasn’t the first idea what it would entail.

Of course, neither do I.

“Dag…” said Fawn uneasily.

“Fawn and I will talk about it. As you say, we’re not leaving tomorrow.”

“Dag could show me his blight patch, on the way past Glassforge,” Whit offered eagerly. “I could be—”

Dag raised and firmed his voice. “Fawn and I will talk it over. We’ll talk to you after.”

Whit subsided, with difficulty.

Fawn eyed Dag in deepening curiosity. When he rose to go upstairs, she set aside her arrow-making and followed.

She closed the door of their room behind her, and he took her hand and swung her to a seat on the edge of the twins’ beds, now pushed together. There was still a sort of padded ridge down the middle, but on the soft, clean linens, it wasn’t at all hard to slide over in the night. Rather like a miniature snowbank, but warmer. Much warmer.

“Dag,” Fawn began in dismay, “what in the world were you thinking? You give Whit the least encouragement, and he’ll be badgering us to death to be let tail along.”

He put his arm around her and hugged her up close to his right side. “I’m thinking…I took this road to learn how to talk to farmers. To try some other way of being than lords and servants—or malices and slaves—or kept apart. Tent-brother is sure another way.”

Her fair brow furrowed. “You’re doing that Lakewalker thing again. Trying to join your bride’s tent, be a new brother to her kin.”

He tilted his head. “I suppose I am. You know I mean to style myself Dag Bluefield.”

She nodded. “Your family at Hickory Lake—what’s left of ’em—I didn’t get the sense they exactly nourished your heart even before you sprung me on ’em. Your brother acted like giving you one good word would cost him cash money. And you acted like it was normal.”

“Hm.” He half-lidded his eyes and lowered his head to nibble at her hair. He pressed a stray strand between his lips, rubbing its fine grain.

“Are you that family-hungry, Dag? ’Cause I admit I’m close to full-up, just now.”

He pulled her down so that they lay face-to-face, smiling seriously. “Then you shouldn’t mind sharing.”

“Oh, many’s the time I wished I could give Half-Whit away!”

His lips twitched. He brushed the dark curls from her forehead and kissed along her eyebrows.

“And there’s another thing,” she added severely, although her hand strayed to map his jaw. “Camping in the evening, have you thought how fast it would blight the mood to have him sitting there on the other side of the fire, leering and cracking jokes?”

Dag shrugged. “Camp privacy’s not a new problem for patrollers.”

“Collecting firewood, bathing in the river, scouting for squirrels? So you told me. There’s a whole code, but Whit doesn’t know it.”

“Then I’ll just have to teach him Lakewalker.”

“Yeah? Best bring your hickory stick, for rapping on his skull.”

“I’ve trained denser young patrollers.”

“There are denser young patrollers?” She leaned back, so her eyes would bring his face into focus, likely. “How do they walk upright?”

He sniggered, but answered, “Their partners help ’em along. Feels sort of like a three-legged race some days, I admit. The idea is to keep ’em alive long enough to learn better. It works.” His smile faded a little. “Mostly.”

Her slim fingers combed back his hair, side and side, and pressed his head between them in a little shake. “You’re still thinking Lakewalker. Not farmer.”

“This walk we’re on is for changing that, though. I figure if I can practice on Whit…I might have more margin for mistakes.”

“We say two’s company, three’s a crowd. I swear with you it’s two’s partners, three’s a patrol.”

The fingers moved down to his shirt buttons; he aimed kisses at them in passing, and said, “I’ve been watching and listening, these past weeks, and not just all about how to herd beans. There’s no more head-space for Whit in this house than there was for you. It’s all for Fletch and Clover, and their children. Maybe if he was let out under a higher ceiling, he could straighten up a bit. With help, even grow—less wrenchingly than you had to.”

She shivered. “I wouldn’t wish that even on Whit.” Her smile crept back. “So are you picturing yourself as a tent-brother—or a tent-father? Old patroller.”

“Behave, child,” he returned, mock-sternly. He tried to pay back the favor with the buttons, one-handed, and, benefiting from much recent practice, succeeded.

“With your hand there?”

His only hand was gifting him the most lovely sensations, as his fingers slid and stretched. Silk was a poor weak comparison, for skin so breathing-soft. “I didn’t say what…” He groped for some wordplay on behave, but he was losing language as their bodies warmed each other.

The scent of her hair filled his mouth as she shook her head, and he breathed her in. She murmured muzzily, “Trust me. He will be the most awful pain.”

He drew his head back a little, to be sure of her expression. “Will be? Not would be? Was that a decision, slipped past there?”

She sighed. “I suppose so.”

“Well, he’ll not pain you, or he’ll be answering to me.”

Her eyebrows drew in. “He sneaks it in as jokes. Makes it hard to fight. Especially infuriating when he makes you laugh.”

“If I can run a company of pig-headed patrollers, I can run your brother. Trust me, too.”

“I’d pay money to watch that.”

“For you, the show is free.”

Her lips curved; her great brown eyes were dark and wide. The little hands descended to the next set of buttons. All farmers but one faded from his concern. At this range, opening his ground to her ground was no effort at all. It was like nocking star fire in the bow of his body. She whispered, “Show me…everything.”

Igniting, he rolled her over him, and did.

While Sorrel and Tril might have been dubious about letting their youngest son out on the roads of Oleana even under the escort of their alarming Lakewalker son-in-law, Fletch and Clover, once the idea was broached, were very amenable. Sorrel and Fletch did unite in extracting the most possible labor from Whit during the next week. With his precious permission hanging in the balance, Whit worked if not willingly then without audible protest. In any remaining spare moments, his bow lessons with Dag were set aside in favor of chopping cordwood for winter, a chore normally not due for another month. Though not discussed, the permission became tacit in the face of the mounting woodpile, as, Dag thought, not even Fletch would be capable of such a cruel betrayal.

Fawn’s parents were unexpectedly favorable to the idea of housing Grace. Dag eventually realized it wasn’t just because the mare was a sweet-tempered mount that not only Tril but even Nattie might ride—though Nattie, when this was pointed out, snorted and muttered something about The cart will do for me, thanks—but because she was a sort of equine hostage. That Fawn would need to return to collect her horse—or, by that time, possibly horses—seemed to give Tril some comfort. Though over the next several evening meals Tril did recall and recount every drowning accident that had occurred within a hundred miles of West Blue within living memory. Recognizing maternal nerves, Dag nonetheless quietly resolved to take Whit aside at some less ruffled moment and find out if he could swim any less like a rock than Fawn had, before Dag had done his best to drown-proof her. Even if it was growing a bit chilly for swimming lessons.

A light rain the night before their departure turned the dawn air gray and cool, muting the blush of autumn colors. As the three rode down the farm lane a few damp yellow leaves eddied past, along with farewells, blessings, and a deal of unsolicited advice ignored by both Bluefield siblings with much the same shoulder hunchings. Dag found it pleasant enough to be back aboard Copperhead and moving once more. Along the river road south, Dag tested his groundsense range and fancied it improved. A hundred and fifty paces now, maybe? Whit was temporarily too exhausted to squabble with his sister, so the day’s ride was largely peaceful. And Dag would have his wife to himself tonight, in a cozy inn chamber in Lumpton Market; a touch, an exchange of smiles, a promissory gleam, that furtive dimple, left him riding in a warm glow of expectation as the afternoon drew to a close.

At the shabby little inn off the old straight road north of town, these comfortable plans received an unexpected check. A chance crowd of drivers, drovers, and traveling farm families had nearly filled the place, and Dag’s party was lucky to secure a single small chamber up under the eaves. Looking it over with disfavor, Dag was inclined to think a bedroll in the stable loft would be better, except that the loft had been let out already. But the falling dark, the threat of renewed rain, the fatigue of a twenty-mile ride, and the smells of good cooking from the inn’s kitchen cured them all of ambition to seek farther tonight, and the debate devolved merely as to who was going to get the bed and who was going to put their bedrolls on the floor. It ended with Fawn in the bed, which was too short for Dag as well as too narrow for a couple, Dag down beside it, and Whit crosswise beyond the foot. Even a chaste cuddle was denied, though Fawn did hang her arm over the side and interlace her fingers with Dag’s for a while after she’d turned down the bedside lamp.

Peace did not descend. Before they’d gone down to supper Whit had forced open the window to combat the room’s mustiness; unfortunately, he had thus admitted a patrol of late mosquitoes, roused by the afternoon’s unseasonably warm damp. Every time anyone began to doze off, the thin, threatening whines induced more arm-waving, blanket-ducking, and irate mutters from one of the others, thwarting sleep for all. Dag instinctively bounced the pests away from himself and Fawn through their tiny grounds. Unfortunately, that concentrated the attack on Whit.

Some more rustling, scratching, and swearing, and Whit rose in the dark to try to hunt the bloodthirsty marauders by sound. After he bumped into the bed frame twice and stepped on Dag, Fawn sat up, turned up the oil lamp, and snapped, “Whit, will you settle? You’re worse ’n they are!”

“The buggers have bit me three times already. Wait, there—” Whit’s eyes narrowed to a gray gleam, and his hands rose in an attempt to cup a flying speck. Two quick claps missed, and he lurched over Dag again in pursuit, peering and trying to corner the insect against the whitewashed walls. His hands rose again, wavering with the target’s erratic flight. Muzzy with annoyance and the first confusion of dream sleep, Dag sat up, reached out his left arm, extended his ghost hand like a strand of smoke, and ripped the ground from the mosquito.

The whine abruptly stopped. A puff of gray powder sifted down into Whit’s outstretched palm. His eyes widened as he stared down at Dag. He gulped. “Did you just do that?”

Dag supposed he should say something useful like, Yes, and if you don’t go lie down and hush, you’re next, but he had shocked himself rather worse than he’d shocked Whit.

It’s coming back, like my groundsense range!

And—gone again. He folded his left arm, freed of the hook harness for the night, protectively against his chest, and twitched the blanket over his stump, for all that Whit had seen it several times before. And tried to breathe normally.

Dag’s ghost hand had first appeared to him back when he’d mended that glass bowl so spectacularly last summer, and had been intermittently useful thereafter. It was just a ground projection, the medicine maker had assured him, if an unusually strong and erratic one. Not some uncanny blessing or curse. A ground projection such as powerful makers sometimes used, but haunting his wrist in that unsettling form like a memory of pain and loss, hence the name he’d given it back when he hadn’t yet understood what it was. Invisible to ordinary eyes, dense and palpable to groundsense. And then it had been destroyed, he’d thought—sacrificed in the complex aftermath of the fight with the malice in Raintree.

Where, in an utter extremity of panic and need, he’d ground-ripped the malice, and nearly killed himself doing so.

“Whit, just go lie down.” Fawn’s voice had an edge distinct enough from her earlier grumbling that even Whit heard it.

“Um, yeah. Sure.” He picked his way much more carefully back over Dag, and grunted down to his bedroll once more.

Dag looked up to find Fawn propped on her elbow, frowning over the side of the bed at him. She lowered her voice. “Are you all right, Dag?”

He opened his mouth, paused, and settled on, “Yeah.”

Her eyes narrowed in suspicion. “You have a funny look on your face.”

He didn’t doubt it. He tried to substitute a smile, which didn’t seem to reassure her much. He felt a peculiar sharp throbbing in the ground of his left arm, as if a campfire spark had landed on his skin, or under it—a spark he could not brush away, though his fleshly fingers made a futile effort to, rubbing under his blanket.

She started to settle back, but added, “What did you do to that poor mosquito?”

“Ground-ripped it. I guess.” Except it was no guess. He could feel the creature’s lost ground stuck in his own, as those deadly malice-spatters had once been. Tinier, less toxic, not blighted, not a spreading death—but also not anything like a medicine maker’s gift of ground reinforcement, warm and welcome and healing. This felt uncomfortable and sticky, like a spot of hot tar. Painful. Wrong?

Fawn rolled up on her elbow again. She knew, if Whit clearly did not, just how far outside the usual range of Dag-doings this was. “Really?”

“I probably shouldn’t have,” he muttered.

Her eyes pinched in doubt. “But—it was only a mosquito. You must have killed hundreds by hand, in your time.”

“Thousands, likely,” he agreed. “But…it itches. In my ground.” He rubbed again.

Her brows flew up; her face relaxed in amused relief. “Oh, dear.”

He made no attempt to correct that relief. He captured her trailing hand, kissed it, and nodded to the oil lamp; she stretched up and doused it once again. As the bed creaked, he murmured, “Good night, Spark.”

“G’night, Dag,” she returned, already muffled by her pillow. “Try’n sleep.” A slight snicker. “Don’t scratch.”

He listened to her breathing till it slowed and eased, then, his arms crossed on his chest, turned his groundsense in upon himself.

The tiny coal of alien ground still throbbed within his own. He tried to divest it, to lay it as a ground reinforcement in the floor, or his sheet, or even his own hair. It remained stubbornly stuck. Neither did it seem to be starting to melt into his own ground, converted from mosquito-ground to Dag-ground as a man might digest food—or at least, not yet. He wondered if he had, in that moment of sleepy irritation, planted a permanent infliction upon himself.

Careless irritation. Not mortal panic. Not an overstretched, once-in-a-lifetime heroic reach, out of a heart, body, and ground pushed for an instant beyond human limits. Ground-ripping a mosquito was hardly a great act, nor of grave moral weight.

Except that ground-ripping anything wasn’t a human act at all. It was malice magic, the very heart of malice magic. Wasn’t it?

Lakewalker makers used two kinds of groundwork, in a thousand variations. They might persuade, push, or reorder ground within an object, to subtly alter or augment its nature. And so produce cloth that scarcely frayed, or steel that did not rust, or rope that was nearly impossible to break, or leather that repelled rain—or turned arrows. Or they might gift ground out of their own bodies; most commonly, into their wedding cords, but also as shaped or unshaped reinforcements laid in the matching region of another person’s ground, to speed healing, slow blood loss, fight shock or infection. But always, the limits of the groundwork were in the limits of the maker doing it.

A malice stole ground from the world around it—limited, Dag swore, by nothing but its attention. And its attention ranged somewhere well beyond human, too. But while a person altered gifted ground into their own as slowly as a healing wound, malices seemed to do so almost instantaneously, not by persuasion but by simple, brute, and overwhelming force. Powered by yet more ground-ripping, in a widening spiral.

Perhaps such transformative power was not a human capacity. Even from the malice, Dag had only snatched deadly fragments. Anyone trying to ground-rip something whole the way a malice did might simply burst, like a man trying to drink a lake.

But a man might drink a cup of lake water…

Was a mosquito like a cup of water?

Dag considered the question, and then considered, more dubiously, the sanity of the mind that could even frame it. Or maybe he was coming down with brain-worms, like Whit’s fabulous rumor. Maybe he simply needed to sleep it off. Surely the splotch would go down overnight like any other mosquito bite, absorbed by Dag’s ground just as his body healed more purely physical welts. He snorted and rolled over, firmly shutting his eyes.

It still itched, though.

By the next morning Dag’s whole left arm was so swollen he couldn’t get his arm harness on.

Fawn was inclined to declare a day of rest in Lumpton Market, but Dag insisted he could ride one-handed, and Whit, anxious to pass at last beyond the places he knew, was not much help on the side of reason. By mid-afternoon Fawn was not happy to have her judgment confirmed when Dag fell into a fever. As if she needed any more evidence, he settled on a blanket and watched without protest as she and Whit set up their camp just off the old straight road south. A chill mist rose from the damp ground in the gathering dusk, but at least no more rain threatened.

“All this from a mosquito bite?” she murmured, sliding in beside him as he drew up his knees and hunched around the swollen arm.

He shrugged. “I don’t think it’s going to kill me. That spot in my ground is already starting to feel less hot.”

She felt his forehead in doubt. But his skin was merely over-warm, not burning-dry, and he ate and drank, if with an indifferent appetite. When they rolled up to sleep she filched her brother’s spare blanket away from him to drape on Dag, ruthlessly ignoring Whit’s yelp of protest.

But by the following day, the swelling had gone down, and Dag claimed the ground-welt was being absorbed much like a normal ground reinforcement, if more slowly. He nevertheless grew flushed and silent in the afternoon; by his pinched brows and glazed eyes Fawn suspected a thumping headache.

As unshakable as Fawn felt in the lee-side of Dag’s full strength, she hated her sense of helplessness when he was laid up. He had a store of uncanny Lakewalker healing knowledge in his head and a host of patroller tricks at his fingertips, impressive enough that Hickory Lake’s chief medicine maker had tried to recruit him into her craft. But who cured the medicine maker? A farmer midwife or bonesetter would not be much help in some strange ground-illness, and Fawn realized that despite all this summer’s experiences, she didn’t actually know how to find a Lakewalker at need. It was too far back to Hickory Lake, and still several days ride to the Lakewalker ferry camp on the Grace River. Patrols or couriers did stop now and then at the inn at Lumpton Market or that hotel in Glassforge, but it could be days or even weeks till any chanced along.

The camp that Chato’s patrol had hailed from was closer, she was fairly sure, but she didn’t even know how to find that. That at least had a cure; she asked Dag that night where it was to be found, and he described it to her. For the first time, she began to see the point of their little patrol of three: not only because it would take two Bluefields to even lift Dag, but because one of them could stay with him while the other rode for help.

If strange Lakewalkers would even give help to Dag, half-exiled as he was. Which was a new and ugly thought.

But by the next day, Dag seemed much recovered. At noon they stopped at the roadside farm with the public well where they had first encountered each other, and reminisced happily over small details of shared memory while stocking up on the farmwife’s good provender. That evening found them quite near to Glassforge. Dag opined they could detour off the straight road tomorrow to show Whit the blight and still make town before dark.

They could not have chanced on a prettier day for a ride up into the unpeopled hills east of the old straight road. The sky was the dry deep blue that only the northwest winds brought to Oleana, the air as cool and tangy as apple cider. The trees here were mostly holding their leaves, and the brilliant sun turned their colors blinding: bright crimson edged with blood maroon, yellow gold, a startling flash of nightshade-purple here and there in the drying weeds. Dag’s eyes grew coin-gold in this light, like autumn distilled. Fawn was glad it was Dag leading them up into these game-tracked humps and hollows, because she’d have lost her way as soon as their turn-off was out of sight. If not really been lost; she’d only to strike west to find the road again. But the blight was a smaller target—thankfully—some ten or twelve miles in.

The sun was climbing toward noon when Dag halted Copperhead on the beaten trail they’d been following. A frown tensed his mouth. Fawn kicked her mount Weft alongside, though Copperhead laid his ears back for show.

“Are we close?”

“Yes.”

Her own recall of the place was too dizzied to permit recognition. She’d been carried in head-down and ears ringing, a prisoner, retching from blows and terror. And carried out…her memory shied from that.

Dag pointed up the trail. “This path goes to the ravine on the same side I came down. The visible blight should start about two hundred paces along.”

“And the blight you can’t see?”

He shrugged, though his face stayed strained. “I’ve been feeling the outer shadow for the past half-mile.”

“Healing as you still are, should you go any closer?”

He grimaced. “Likely not.”

“Suppose you wait here, then. Or better, back down the trail a ways. And I’ll just take Whit in for a quick peek.”

He couldn’t argue with the logic of that. A hesitation, a short nod. “Don’t linger, Spark.”

She nodded and waved Whit on in her wake. He looked a trifle confused as he pressed his sturdy horse up next to hers. As Warp and Weft fell into a well-matched pace, he asked, “What was that all about?”

“Being on blight makes Lakewalkers sick. Well, it makes anybody sick, but I was afraid it would send Dag into an awful relapse like after Greenspring. Glory be that he saw the sense of waiting for us.”

Whit glanced around. “But everything is drying up and dying back right now. How do you spot blight in winter? How is it that you’re supposed to tell this here blight from…oh.”

They reined in at the lip of the ravine. They must be very near to what had been Dag’s vantage, that day. The cave was a deep hollow halfway up the ravine’s far side, with a long outcrop of rock shielding the opening almost like a wall. The ravine itself was a dusty gray, devoid of vegetation but for a few skeletal tree trunks. The glimmering creek flowing through in an S-curve was the only movement, the only source of sound. No birds, no insects, no small rustles in the dead weeds. Even the breeze seemed stilled. The peculiar dry cellar-odor of malice habitation wafted faintly up to Fawn, and she swallowed, feeling sickened despite the sun on her back.

“That is the weirdest color I ever did see,” Whit allowed slowly. “It’s not hardly a color at all. Dag was right. It doesn’t look like…anything.”

Fawn nodded, glad Whit seemed to have his wits with him today, because she didn’t think she could have borne stupid jokes right now. “Dag thinks that malice came up from the ground and hatched out right here. Malices all seem to start out pretty much the same, but then they change depending on what they eat. Ground-snatch, that is. If they catch a lot of people, they get to looking more human, but there was one up in Luthlia that mostly ate wolves, that they say grew pretty strange. Dag thinks the first human this one caught must have been a road bandit, hiding out up here, because after it grew its mud-men and caught more folks, it made them all be its bandit gang, at first.” Though some of the men might not have been as mind-slaved as all that, which was in its way an even more disturbing notion. “The bandits who kidnapped me off the road brought me here. Dag was tracking them, and saw.” From here, Dag would certainly have had a clear view of the mud-men carting her in like a sack of stolen grain. “He went in after them—after me—all by himself. No time to wait for his patrol. It wasn’t good odds. But he tossed me his sharing knife, and I managed to get it in the malice. And the malice…” She swallowed again. “Melted. I guess you could say. Malices are immortal, the Lakewalkers claim, but the sharing knives kill them. Kill them in their ground.”

“What are sharing knives, anyhow? Dag keeps mentioning them and then stopping.”

“Yes, well. There are reasons. Lakewalkers make them. Out of Lakewalker bones.”

“So it’s true they rob graves!”

“No! They’re not stolen. Dag—any Lakewalker would get mighty offended to hear you say that. People will their thighbones to their kin to be, be, like, harvested after they die. It’s part of the funeral. Then a Lakewalker knife maker—Dag’s brother Dar is one—cleans and carves and shapes the bone into a knife. They don’t use sharing knives for any other purpose than killing malices.”

“So that’s what you stuck in the malice? Whose thighbone was it, d’you know? Does Dag?”

Fawn supposed gruesome interest was better than none. “Yes, but it’s more complicated than that. Carving the bone itself is only the first step. Then the knife has to be primed. With…with a heart’s death.” She took a breath, not looking at Whit. “That’s the hardest part. Each knife, when it’s made, is bonded to its Lakewalker owner. Someone who has volunteered to share—to donate his or her own death to the knife. When such Lakewalkers think they’re dying, either old and sick or hurt mortal bad, they, they put the knife through their own hearts and capture their deaths. Which are trapped in the knives. So every primed knife costs two Lakewalker lives, one for the bone and the other for the heart’s priming. Ownership is…you can’t buy such a knife. It can only be given to you.”

She glanced up to see Whit squinting and frowning. He said slowly, “So, it’s sort of like…a human sacrifice stuck in a canning jar and preserved, to take out and use later?”