FROM THE PAGES OF REPUBLIC

... but as concerning justice, what is it?—to speak the truth and pay your debts—no more than this? And even to this are there not exceptions? (1.331c)

Is the attempt to determine the way of man’s life so small a matter in your eyes—to determine how life may be passed by each one of us to the greatest advantage? (1.344d)

For my own part I openly declare that I am not convinced, and that I do not believe injustice to be more gainful than justice, even if uncontrolled and allowed to have free play. (1.345a)

I propose therefore that we inquire into the nature of justice and injustice, first as they appear in the State, and secondly in the individual, proceeding from the greater to the lesser and comparing them. (2.368e—369a)

... I am myself reminded that we are not all alike; there are diversities of nature among us which are adapted to different occupations. (2.370a—b)

Then it will be our duty to select, if we can, natures which are fitted for the task of guarding the city? (2.374e)

But in reality justice was such as we were describing, being concerned, however, not with the outward man, but with the inward, which is the true self and concernment of man: for the just man does not permit the several elements within him to interfere with one another, or any of them to do the work of the others—he sets in order his own inner life, and is his own master and his own law, and at peace within himself ... (4.443c—d)

“Until philosophers are kings, or the kings and princes of this world have the spirit and power of philosophy, and political greatness and wisdom meet in one, and those commoner natures who pursue either to the exclusion of the other are compelled to stand aside, cities will never have rest from their evils—no, nor the human race, as I believe—and then only will this our State have a possibility of life and behold the light of day.” (5.473d—e)

... for you have often been told that the idea of good is the highest knowledge, and that all other things become useful and advantageous only by their use of this. (6.505a)

—You have shown me a strange image, and they are strange prisoners.—Like ourselves, I replied; and they see only their own shadows, or the shadows of one another, which the fire throws on the opposite wall of the cave. (7.515a)

He who is the real tyrant, whatever men may think, is the real slave, and is obliged to practise the greatest adulation and servility, and to be the flatterer of the vilest of mankind. He has desires which he is utterly unable to satisfy, and has more wants than anyone, and is truly poor, if you know how to inspect the whole soul of him: all his life long he is beset with fear and is full of convulsions and distractions, even as the State he resembles: and surely the resemblance holds ... (9.579d—e)

These, then, are the prizes and rewards and gifts which are bestowed upon the just by gods and men in this present life, in addition to the other good things which justice of herself provides ... And yet, I said, all these are as nothing either in number or greatness in comparison with those other recompenses which await both just and unjust after death. ( 10.613e—614a)

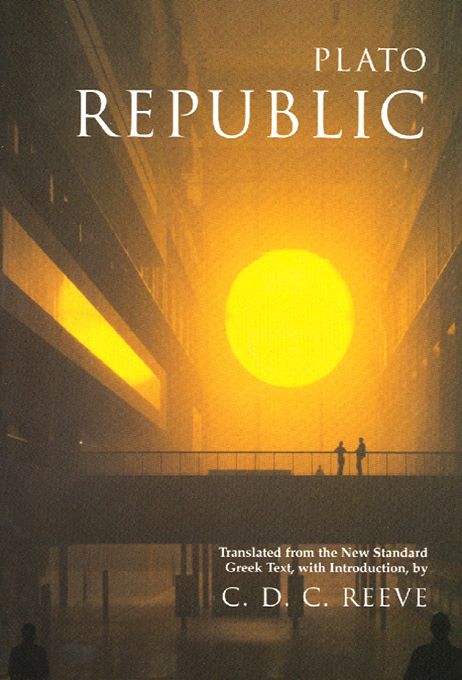

Published by Barnes & Noble Books

122 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10011

www.barnesandnoble.com/classics

Plato is thought to have composed Republic sometime

during the 380s to the 350s B.C.E.

Benjamin Jowett’s translation first appeared in 1871.

Published in 2004 by Barnes & Noble Classics with new Introduction,

Notes, Biography, Chronology, A Note on Conveyances, Comments & Questions,

and For Further Reading.

Introduction, Note on the Translation, Notes, and For Further Reading

Copyright @ 2004 by Elizabeth Watson Scharffenberger.

Note on Plato, The World of Plato and Republic, Inspired By, and

Comments & Questions Copyright © 2004 by Barnes & Noble, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and

retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Barnes & Noble Classics and the Barnes & Noble Classics colophon are

trademarks of Barnes & Noble, Inc.

Republic

ISBN-13: 978-1-59308-097-6 ISBN-10: 1-59308-097-2

eISBN : 978-1-411-43303-8

LC Control Number 2003116604

Produced and published in conjunction with:

Fine Creative Media, Inc.

322 Eighth Avenue

New York, NY 10001

Michael J. Fine, President and Publisher

Printed in Mexico

QM

3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4

PLATO

Plato was born into a wealthy, aristocratic Athenian family in 428 or 427 B.C.E., and he lived until 348 or 347. He had kinship ties on both sides of his family with many prominent men in Athens. His father, Ariston, died when he was a child, and his mother, Perictione, was subsequently married to Pyrilampes. Plato was raised in Pyrilampes’ household along with his older brothers (Glaucon and Adeimantus), a stepbrother (Demos), and a half-brother (Antiphon). As young men, Plato and his brothers were close to Socrates.

Plato’s familial connections and wealth would have made it easy for him to embark on a political career in Athens. But he did not become politically active, perhaps because he became disillusioned with politics after witnessing, first, the brutal oligarchic regime of the Thirty Tyrants, who seized control of Athens at the end of the Peloponnesian War in 404 B.C.E., and then the execution of Socrates, who was condemned to die in 399 under the restored democratic government for “not recognizing the gods recognized by the city and corrupting the youth.”

Plato traveled in the years after Socrates’ death, and he almost certainly spent time in Megara (near Corinth) and Syracuse (on Sicily). He became close friends with Dion, a kinsman of the tyrant of Syracuse, Dionysius I. Plato probably traveled to Syracuse three times during the period from the early 380s to the late 360s. He and Dion evidently planned to educate the tyrant’s son, Dionysius II, in the hopes that, upon succeeding his father, he would put into practice the political ideals they cherished. But these hopes were never fulfilled. Upon taking power in the early 360s, Dionysius II broke with both his kinsman and his tutor.

In the early 380s, Plato began teaching what he called “philosophy” at a place near the grove of the hero Academus on the outskirts of Athens. The school came to be called the “Academy” because of its location, and Plato remained at its head until his death, when his nephew Speusippus took over its administration. After Plato’s death, the Academy continued to be an important center of research and study for many centuries, attracting students from all over the Mediterranean world.

Plato probably started to compose dialogues before he established the Academy. All but a few of his dialogues feature Socrates as the main interlocutor, and most are peopled with figures who would have been well known, especially in Athens’ elite circles, during the fifth century. A large body of writing attributed to Plato survives from antiquity, including Apology (a recreation of Socrates’ defense speech), numerous dialogues, and a series of letters. Most of these works are considered to be truly by Plato, although the authenticity of some texts (including some of the letters and a handful of dialogues) has been doubted at various points in the last 2,400 years.

THE WORLD OF PLATO AND REPUBLIC

| 508 | Cleisthenes, son of Megacles, introduced sweeping polit |

| B.C.E. | ical reforms to the Athenian constitution, marking the beginning of democratic government in Athens. |

| 490 | At the battle of Marathon (26.3 miles from Athens in At tica), Greek land forces, under the command of the Athe nian Miltiades, son of Cimon, defeated an invading army of Persians. Most of the Greek troops who fought at Marathon came from Athens. |

| 480 | At the battle of Thermopylae (a mountain pass in northeast ern Greece), Persian land forces fought against elite Spartan soldiers under the command of Leonidas, one of the Spar tan kings. The entire Spartan force was killed in the battle. |

| 480 | At the battle of Salamis (an island near the port city Piraeus in Attica), Greek naval forces, under the leadership of the Athenian Themistocles, son of Neocles, defeated the Persian navy. |

| 479 | In the battle of Plataea (in Boeotia), Greek land forces deci sively defeated the Persian army, which subsequently with drew from Greece. Under the leadership of the Spartans and then the Athenians, city-states in Greece banded to gether in the fight to free Hellenic city-states on the coast of Asia Minor from Persian dominion. This alliance was soon called the Delian League, because its treasury was kept on the sacred island of Delos; it eventually came un der the total control of the Athenians. |

| c.469 | Socrates, son of Sophroniscus, was born. |

| 462 | Ephialtes, son of Sophronides, and Pericles, son of Xan thippus, introduced reforms to the democratic constitu tion, which expanded the franchise of Athenian citizens and provided more opportunities for political involvement to greater numbers of men, regardless of economic class. |

| 458 | Aeschylus of Eleusis (in Attica) produced his Oresteia tetralogy (the tragedies Agamemnon, Libation Bearers, and Eumenides, and the satyr-drama Proteus) in the annual theatrical competition held at the Greater Dionysia festival in the Theater of Dionysus on the southern slope of the Athenian Acropolis. |

| 454 | The treasury of the Delian League was transferred from the island of Delos to Athens. Under the leadership of Pericles, funds from the treasury were used to finance the construction of buildings on the Acropolis, including the Parthenon, which had been destroyed by the Persian inva sion of 480. |

| 450s—440s | The relationships between Athens and other prominent city-states (notably Sparta, Corinth, and Thebes) dete riorated as Athens expanded its influence throughout the Aegean area. |

| c.450 | The astronomer and natural scientist Anaxagoras (from Clazomenae), who was closely associated with Pericles, is said to be prosecuted on the charge of impiety. Sources reporting this event claim that Anaxagoras fled Athens with Pericles’s assistance and went to Lampsacus (on the eastern entrance to the Hellespont). |

| c.432 | Protagoras of Abdera (in Thrace), a “sophist” and profes sional teacher of rhetoric, visited Athens. |

| 431 | Full-scale hostilities broke out between the Pelopon nesian alliance, led by Sparta, and Athens and its allies, marking the beginning of the Peloponnesian War. Euripi des, son of Mnesarchides (or Mnesarchos), produced Medea in a tetralogy with two other tragedies (Philoctetes and Dictys) and a satyr-drama (Theristai) at the Greater Dionysia festival in Athens. |

| c.429? | Sophocles, son of Sophilus, produced Oedipus Tyrannus (Oedipus the King) in a tragic tetralogy at the Greater Dionysia festival in Athens. |

| 429 | Pericles dies during the plague that falls upon Athens in the first years of the Peloponnesian War. Cleon, son of Cleaenetus, became the leading politician in Athens until his death in battle at Amphipolis in 422. |

| 428 or 427 | Plato was born into a wealthy and influential family. His father, Ariston, died when Plato was a boy; his mother, Perictione, was subsequently married to her uncle Pyril ampes, who was politically prominent and closely associ ated with Pericles. |

| 427 | Gorgias (from Leontini on Sicily), a professional teacher of rhetoric, visited Athens. |

| 423 | At the Greater Dionysia festival, Aristophanes, son of Philippus, produced his comedy Clouds, in which Socrates is portrayed as a professional teacher of rhetoric and natu ral science who runs a “Think Factory.” The comedy was awarded third prize (out of three). |

| 415—413 | Under the leadership of Alcibiades, son of Clinias and former ward of Pericles, Athens sent an armada to attack the city of Syracuse on Sicily. After Alcibiades’ defection to Sparta and other major setbacks, the Athenian forces were defeated and the Sicilian expedition ends with many lives lost and almost all ships in the armada destroyed. |

| 411—410 | During an oligarchic coup in Athens, democratic political in stitutions were temporarily dissolved. Resistance by loyalists led to the restoration of the democratic constitution in 410. |

| 405 | The Spartans defeated the Athenian navy at Aegospotami off the coast of Asia Minor. |

| 404 | The Peloponnesian War ended as Athens surrendered to the Spartans. The Spartans imposed strict terms of surren der upon the Athenians, including the destruction of the Long Walls connecting Athens to the port city Piraeus. They also fomented another oligarchic coup and installed in power a group of men, led by Plato’s kinsman Critias, who came to be known as the Thirty Tyrants. |

| 403 | Democratic loyalists, who took refuge in Piraeus, defeated the Thirty Tyrants and their supporters, and the demo cratic constitution was once again restored. To reduce lin gering factional strife between loyal “democrats” and those who supported the second coup, a general amnesty was declared in 403. Only those deemed directly involved with the Thirty Tyrants were liable for prosecution for crimes against the demos (people). |

| 399 | Socrates, who had been closely associated with Alcibiades and other men known for their hostility to the democratic constitution, was charged with impiety and corrupting youth. He was convicted of both charges and ordered to commit suicide by drinking hemlock. |

| 390s | Plato, along with other members of the Socratic circle (An tisthenes, Phaedo, Eucleides, Aristippus, Aeschines, and Xenophon) began to write “Socratic dialogues.” Athens reemerged as an important naval power in the Aegean area. |

| early 380s | Plato traveled to Syracuse in or around 387, when he be friended Dion, a kinsman of Dionysius I, the tyrant of Syra cuse. It was probably upon his return to Athens from this trip that he began teaching “philosophy” near the grove of the hero Academus on the outskirts of Athens, in a school that came to be known as the Academy. |

| 384 | Aristotle, son of Nicomachus, was born at Stageira (in Chalcidice). He studied at the Academy from 367 until Plato’s death. |

| 378 | In Thebes, the general Gorgidas formed an elite force of 300 men that legendarily comprised pairs of lovers. The corps, known as the Sacred Band, reportedly remained un defeated until the battle at Chaeronea in 338. |

| 360s | After the death of Dionysius I of Syracuse (in 367), Plato is said to have made two trips to Sicily in order to facili tate the restoration of Dion, who had been exiled by Dionysius I. He and Dion apparently hoped to exert po litical influence on Dionysius II, the tyrant’s son and suc cessor. Plato probably visited Syracuse for the last time in 361 or 360. |

| 354 | Dion was assassinated. |

| 348 or 347 | Death of Plato. Speusippus (the son of Plato’s sister Potone) became head of the Academy, and Aristotle left Athens, eventually arriving at the court of King Philip II of Mace don, where he served for a few years as the tutor to Philip’s son, Alexander. |

| 344 | Dionysius II was exiled to Corinth. |

| 339 | Speusippus died. |

| 338 | In the battle of Chaeronea (in Boeotia), the Macedonians under the leadership of Philip II defeated the combined forces of the Athenians and Thebans. The defeat brought Athens, Thebes, and other Greek city-states under the sway of Macedon. |

| 335 | Aristotle returned to Athens and founded a school near a grove outside the city that was sacred to Apollo Lyceius. The school will come to be known as the Lyceum. |

| 323 | Alexander the Great died in Babylon. Anti-Macedonian feeling ran high in Athens after Alexander’s death, causing Aristotle to leave the city and take up residence in Chalcis (on Euboea). Upon his departure, his pupil Theophrastus took over leadership of the Lyceum. |

| 322 | Aristotle died in Chalcis. |

INTRODUCTION

Plato’s Republic has long been recognized as a timeless philosophical masterpiece. Its timelessness results from many factors: its artful composition, its vivid characterizations, its thematic sophistication, and—perhaps most important—the breadth of its interests. As it seeks a definition of “justice” and inquires into the relationship between “right behavior” and “happiness,” the work delves into basic questions of ethics and psychology. In the course of this inquiry, it offers up a striking blueprint for an ideal city-state and thus makes a significant contribution to political philosophy. While making the case for the rule of “philosopher-kings,” it presents influential arguments concerning the very nature of reality and the means by which we human beings might apprehend what is real and distinguish it from what we see and experience in the world around us; with compelling logic and arresting images, it encourages our interest in the fields of metaphysics and epistemology.

It also explores the psychological and social impact of popular forms of cultural discourse and, as part of its delineation of the ideal state, makes a strong—and controversial—case for the censorship of the arts and the tight control of entertainments. Lastly, it paints an awe-inspiring picture of what happens to the soul after the body’s death.

Plato himself was well aware of the fundamental importance of the subjects in his dialogue. He has its interlocutors assert more than once that their conversation, whatever its shortcomings, deals with the most significant issues that human beings can discuss. Yet, timeless as Republic’s concerns are, it is nonetheless the product of a particular era and a particular place. The era is the fourth century B.C.E., and the place is the city-state (polis) of Athens, where Plato was born (most likely in 428 or 427 B.C.E.) and lived most of his life, and also where he founded his philosophical school, the Academy. To appreciate the scope and contours of the far-ranging conversation represented in Republic, it helps to know something about the city in which Plato lived and the cultural milieu in which he composed his dialogues.

Athens in the Fifth and Fourth Centuries B. C. E.:

A Political Overview

Until 338 B.C.E. (about ten years after Plato’s death), Athens was an independent city-state, as were the other major cities of Greece (or Hellas, as it was known in antiquity), such as Sparta, Thebes, Corinth, and Argos. For centuries, each community issued its own currency, used its own calendar, and developed its own system of government and social institutions. Territorial disputes and similar grievances frequently caused wars between city-states and their neighbors; the history of such wars and alliances is long and complicated. Yet, despite their differences, Greeks (Hellenes) throughout the Mediterranean were united by a common language and culture and system of religious beliefs and practices that, they felt, made them distinct from other peoples, whom they commonly called “barbarians.”

Athens resembled other Greek city-states in that it had a predominantly agricultural economy. As in most communities in the ancient world, the work force in Athens and its surrounding territory (Attica) consisted largely of slaves who were either prisoners of war, captives bought from pirates, or their descendants. Political enfranchisement in Athens, as in all other Greek city-states, was limited to sons of enfranchised men. Participation in the government and legal system was completely closed to women. It was virtually impossible for foreigners to become naturalized citizens of Athens, although resident aliens, who were called metics and were almost always from other Greek city-states, were liable for military service and were generally expected to contribute, financially and otherwise, to the community. Women (that is, the wives, daughters, and sisters of citizens) and slaves, both male and female, lived totally under the control of the male head of the household.

Moreover, many of the public institutions that we take for granted, such as hospitals and law enforcement agencies, did not exist in the ancient world generally or in Athens particularly. The cultivation of homoerotic attachments between men (as “lovers,” or erastai) and youths (as “beloveds,” or erômenoi) in the upper echelons of Athenian society—an important backdrop to several Platonic dialogues (notably Symposium and Phaedrus)—further indicates the cultural differences between Athens and contemporary Western civilizations.

Athens differed from other Hellenic city-states in certain important social and political institutions. Unique policies implemented in the sixth century B.C.E. had far-reaching consequences for the development of the city’s famous democratic form of government. Unlike in many Greek communities, the rules determining citizenship in Athens did not require a free-born native man to own land in order to be considered a citizen with some political rights. All citizens, no matter how modest their means, were eligible to attend meetings of the Assembly and scrutinize the performance of magistrates.

In 508 B.C.E., after a difficult period in the late sixth century when men who held power illegitimately (the “tyrant” Peisistratus and his sons Hippias and Hipparchus) controlled Athens, the democratic government was officially established. Its constitution was liberalized during the fifth century so that opportunities to participate directly in the political system were gradually made available to larger numbers of men. Citizens were still divided, as they were in the early sixth century, into four economic classes determined by the amount of property they owned, and they were also divided into ten “tribes.”

Every year men from the highest economic classes were chosen as magistrates, some by lot and some by election. The ten elected magistrates (called strategoi, or “generals”) exercised authority in military as well as civic matters and assumed the political leadership of the polis; most of Athens’ famous statesmen—Pericles, Themistocles, Miltiades, Aristides, Cimon, Cleon, and Alcibiades—were strategoi. The Assembly retained the power to hear debates and vote on all domestic and foreign policies, and it scrutinized magistrates at the end of their terms in office. In addition, fifty men were chosen from each tribe every year by lot to form the Council of 500, the body that prepared business for the Assembly and in essence ran the government on a daily basis.

The average Athenian citizen, especially in the later years of the fifth century, could also exercise political power through the system of courts that tried cases ranging from murder to treason to private suits. These courts always had large juries (a minimum of 250 men, again chosen by lot), and all citizens were eligible for service. Jury duty became especially attractive to many poorer citizens after payment for such service was instituted. Since prominent men were often embroiled in legal disputes, sitting in the courts became an effective way for average people to influence the fortunes of the powerful.

As its democracy developed in the fifth century, Athens was also becoming powerful and cosmopolitan. Indeed, the development of its democracy was inextricably linked to the growth of its military influence in the Aegean Sea. This brought great wealth to the city and empowered its lower economic classes, since they furnished the majority of rowers and soldiers on warships.

Success in the Persian Wars (at the battle of Marathon in 490 B.C.E. and the battle of Salamis in 480) put Athens at the head of the Delian League, an alliance of Greek city-states that was formed to further weaken the influence of the Persians in the Mediterranean. The Athenians, however, gradually monopolized power in the League and used it to advance their own commercial and strategic interests. In the 460s, to protect the maritime trade routes vital to the growing city, Athens began to treat allies on the islands and coasts of the Aegean Sea as if they were subjects, not partners, and interfered in their affairs.

In 454, the League’s treasury was transferred from the island of Delos to Athens, and allies were subsequently required to bring tribute directly to the city. In the 440s, the Athenians, led by Pericles, began using this treasury to finance buildings and extensive public works, including the Parthenon and other edifices on the Athenian Acropolis that are still standing today.

Other leading city-states in Greece, particularly Sparta, Corinth, and Thebes, became alarmed by the development of the Athenian “empire” in the Aegean Sea. Throughout the mid-fifth century, the Athenians clashed with those who opposed their maritime hegemony. In 431, the Spartans and their allies from the Peloponnese (the southern portion of Greece, then dominated by Sparta) declared war on Athens to end its control over the island city-states and coastal areas in northern Greece and Asia Minor. In the series of wars that came to be known as the Peloponnesian War, both sides gained and lost ground over several years, until the defeat of Athens in 404. As a consequence of its defeat by the Peloponnesian alliance, Athens permanently lost its exclusive influence over the Aegean islands. It had to contend for power with other city-states, particularly Thebes and Corinth, throughout the fourth century. Nonetheless, Athens remained the preeminent cultural center of Greece, and when Plato founded his Academy in the 380s, he was able to attract students from all over the Aegean area.

Democracy in Athens also survived the Peloponnesian War, but not without serious challenges. Most Athenians doubtless looked on the wealth and power of their city-state as great assets and saw themselves as the liberators and protectors, and not the oppressors, of their allies. They were also proud of their city’s culture, especially of the freedom of speech and opportunities for political involvement that their constitution notionally afforded to every citizen. Even so, a small but significant percentage of men from Athens’ wealthy aristocratic families considered themselves wrongly dispossessed of political power that, in their view, ought to have been their exclusive prerogative. They felt the democratic constitution left them vulnerable to exploitation and extortion, especially in the courts, where informers (“sycophants”) seeking to get rich constantly threatened to bring them to trial. They also resented the prominence of politicians such as Cleon, who did not use the established “old boy” network of connections and appealed directly to the demos, or common people, for his power.

Wealthy Athenians also tended to disagree with the aggressive military policies that the democratic government pursued, especially the disastrous Sicilian expedition of 415-413 B.C.E., in which a good part of the Athenian navy was destroyed. While many disaffected aristocrats sought to withdraw as much as possible and live quiet lives of “noninvolvement” (apragmosyne), the conflict between oligarchic and populist ideologies caused increasing friction as the Peloponnesian War continued, and the disaster in Sicily galvanized some malcontents and set the stage for radical action. In 411 a short-lived oligarchic coup suspended the constitution and dissolved the Council of 500 and the Assembly. Resistance by loyalists led to the relatively quick and bloodless restoration of both institutions in 410.

After the Athenians surrendered to the Peloponnesian alliance in 404, the Spartans helped the surviving leaders of the coup of 411 overthrow the democracy once again and install another oligarchic government. This new regime suspended the constitution once again, dissolved democratic political institutions, and severely limited political franchise. It also gained renown for its brutality, and, like the government that came into power in 411, lasted only a year. Many men loyal to the democratic constitution took refuge in the port city of Piraeus, which was only a few miles from Athens and a populist stronghold. After a series of battles with supporters of the coup, the loyalists restored democracy to Athens in 403.

To reduce lingering factional strife between loyal “democrats” and those who had supported the second coup, a general amnesty was declared in 403. Only those deemed directly involved with the Thirty Tyrants, as the leaders of the coup of 404 came to be called, were liable for prosecution. Tensions and suspicions remained elevated for many years afterward, however. Although there were no further coup attempts in the fourth century, Athenian democracy continued to generate and, to its credit, tolerate critics. Among these critics, Plato is often counted as the most forceful and articulate.

Religion and Religious Traditions

Athenians were fully invested in the established traditions of Hellenic culture. Religion, and therefore religious rituals and celebrations, were central to this culture. Like other Greeks, the Athenians believed in an array of divinities, from the Olympian gods and goddesses who had Zeus as their king, to the chthonic powers of the underworld, such as the Furies, to local deities, such as river gods. They also deified phenomena that we would consider abstractions, such as Justice, Persuasion, Fear, Madness, and Necessity. The sustained welfare of the community was thought to reside in divine favor, which could be withdrawn if the gods were slighted in any way. Accordingly, every resident was expected to participate in rituals and celebrations in honor of the gods.

In addition to the festivals of individual city-states, Greeks also participated in major biennial and quadrennial religious festivals, such as those at Delphi (the oracular shrine of Apollo) and Olympia (the shrine of Zeus). Even in times of war, men from all over the Hellenic world attended these festivals and competed in their well-known athletic contests. Mystery cults whose members worshiped particular deities—such as the cults devoted to the grain-goddess Demeter and her daughter Persephone at Eleusis in Attica—required their participants to undertake special rites of initiation and keep cultic rituals secret from non-initiates.

The Greeks envisioned the principal Olympian gods and goddesses as members of an extended family who were virtually omnipotent and, although capable of disguise, looked like human beings and were frequently influenced by jealousy and other strong passions. Overall, the gods were thought of as guarantors of justice, rewarding those who uphold laws and customs and punishing those who transgress. But they were also considered capable of adversely affecting human lives in what might strike us as capricious, cruel, and unfair ways. This ambivalent understanding of divine behavior is reflected in Greek poetry and literature, beginning with the Homeric epics (Iliad and Odyssey). In these, deities interfere freely in human affairs and regularly assist their favorite mortal men and women while wreaking havoc upon their “enemies” and competing with their fellow deities.

Religious life was centered on the proper fulfillment of rites in the home and in official public ceremonies. The Greeks put comparatively little emphasis on orthodoxy beyond the very basics of belief, and they had no sacred scriptures equivalent to the Bible or Qur‘an. This lack of orthodoxy accounts in part for the variety in the myths about the gods that have been handed down, often with contradictory details. In the absence of orthodoxy, the Greeks were generally tolerant of special religious sects and schools, such as those of the Pythagoreans and Orphics, and sometimes of foreign religious rites, as long as these could be accommodated to existing beliefs and practices. Because of such tolerance, the poet Xenophanes was able in the late sixth century B.C.E. to question with impunity the accuracy of the representation of the gods in the Homeric epics, and to suggest that popular anthropomor phized conceptions of the gods were mere projections of the human imagination.

As Athens grew in power and prominence during the fifth century, the city attracted intellectually active individuals who sometimes entertained skeptical attitudes toward traditional understandings of the gods. But such attitudes never became popular. Even as Athenians grew more sophisticated and self-conscious about the constructs of their society and culture, most seem to have remained attached to the beliefs and practices of their ancestors. Throughout the classical period (that is, the fifth and fourth centuries B.C.E.), it remained possible to prosecute individuals for “impiety” and “not recognizing the gods recognized by the city.” Such was one of the charges faced in 399 B.C.E. by Socrates, Plato’s friend and mentor and the chief interlocutor of most of the Platonic dialogues.

Poetry and Poetic Traditions

By the fifth century, several poetic works enjoyed enormous popularity and achieved quasi-canonical status. Foremost among these were Iliad and Odyssey, two of the epic poems that the Greeks attributed to Homer, although most modern scholars view them as results of centuries of oral storytelling and poetic improvisation rather than as the work of one person. The epics Cypria, Iliupersis (“The Destruction of Troy”), and a series of poems collectively referred to as Returns (Nostoi), which all dealt with the Trojan War and its aftermath and which survive only in fragments, were widely known as well, as were Theogony, an epic dealing with the origins of the gods, and the didactic poem Works and Days, both composed by Hesiod in the late eighth century B.C.E. Memorizing extensive passages of poetry was a standard educational practice in the classical period. Most Athenians would have thus been well acquainted not only with the works of Homer and Hesiod, but also with those by such lyric poets as Sappho, Simonides, Pindar, and Stesichorus, and they would have known other poems in a variety of styles.

Choruses performed hymns and songs at familial rites, such as marriages, and at public festivals throughout the Hellenic world. In Athens, choral performances in honor of Dionysus gave rise during the sixth century to more sophisticated presentations featuring solo respondents. These were the precursors to the tragedies and comedies performed during the classical period at festivals in the Theatre of Dionysus on the southern slope of the Acropolis. The Dionysian festivals were “high holidays” when public and private business was suspended, and the dramas produced in them were of enormous cultural importance in democratic Athens. Although modern scholars debate whether playwrights attempted directly to influence decision-making by their fellow citizens, there is no doubt that these festivals, which intertwined civic and religious functions, helped create a sense of political identity for the Athenians.

Dramas were composed for a single performance. Nonetheless, many were circulated and memorized, and some quickly achieved quasi-canonical status in their own right. It is not surprising, then, that Plato liberally quotes passages from tragedies by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides as well as other poetic works, most notably Iliad and Odyssey. He cites comedies far less often, but this does not mean that they did not interest him. Plato was particularly concerned with Aristophanes’ Clouds, which was performed in 423 B.C.E. and featured Socrates as a main character; even though Clouds was not the only comedy in which a “Socrates” appeared, Apology 18d-19d indicates that, in Plato’s view, it fostered particularly insidious prejudices against his mentor.

As readers of Republic and other dialogues discover, Plato has Socrates express deep reservations about relying on poetry to educate children and to foster senses of community and social identity among adults. In Republic especially, Socrates repeatedly professes his fondness for the Homeric poems while voicing serious criticism of their contents and ethical and social effects. His refrain concerning tragedy and lyric poetry is similar; they are said to be “charming” and “pleasing” but also dangerous. Comedy, as might be expected, receives almost no compliments in the Platonic dialogues. Yet Republic’s critique of poetry—especially dramatic poetry—is not free of ironies, since Plato is himself something of a dramatist whose dialogues are masterfully constructed “plays” in prose. Moreover, as Jacob Howland observes (The Republic: The Odyssey of Philosophy, pp. 28-29), he is also something of a comedian who delights, just as Aristophanes does, in exposing the foibles of prominent and self-important men.

Intellectual Innovations:

“Scientists,” “Sophists,” and Rhetoricians

The most self-important person we meet in Republic is Thrasymachus, a diplomat and professional rhetorician from the Greek city-state of Chalcedon on the Bosporus near the Black Sea. He does not play much of a role in the dialogue beyond its first book, but his activities as a rhetorician and, as some would say, a “sophist” lead us to consider another set of cultural, intellectual, and political phenomena that are significant in Plato’s work. The systematic study of effective public speaking, and the teaching of the theory as well as the practice of rhetoric, were innovations of the fifth century; they were impelled in part by the demands that democratic institutions such as public assemblies and courts, first in Athens and then elsewhere in the Hellenic world, created. To attain political prominence and power in a democratic setting, men had to be able to persuade large crowds and hold their own in heated debates. Even those who had more modest ambitions could find themselves needing the services of a teacher of rhetoric or a professional speechwriter when they went to court, whether as plaintiffs or defendants. Thus Athenian men—especially young and wealthy ones—began to study rhetoric and techniques of argumentation in ad hoc arrangements with professional and at times highly paid instructors.

The formal study of rhetoric and argumentation was also linked to a broader set of intellectual trends that originated in the Greek city-states of Ionia (the coastal area of Asia Minor) during the seventh and sixth centuries B.C.E. The driving force behind these trends was the desire to comprehend the workings of the cosmos and all its constituent parts in systematic terms, which was fueled by a spirit of inquiry and skepticism about received truths. Xenophanes, an Ionian émigré to the Greek colonies in Italy, challenged Homer’s and Hesiod’s conceptions of the gods, and Pythagoras, another Ionian emigre to Italy, studied the mathematical bases of music and theorized about the reincarnation of the human soul. Others in Ionia and elsewhere became interested in studying the movements of celestial bodies and explaining astronomical phenomena such as eclipses, in discovering the causes for change and movement in physical objects, and in speculating about the nature of matter. By the fifth century, there were many “pre-Socratic philosophers,” as they are known today, active throughout the Greek world. Among them were Heraclitus, Empedocles, Zeno, Anaxagoras, Democritus, Leucippus, and—especially important to the development of Plato’s thought—Parmenides of Elea (in the northwest Peloponnese). In the early fifth century, Parmenides posited proto-metaphysical concepts of “Being” (or “That Which Is”—to on in Greek) that challenged the assumption that any physical object in the phenomenal world “is” in the absolute sense of the verb.

Although these sorts of speculation never became popular among ordinary people, they were nonetheless culturally influential in the fifth century. This was especially true in Athens, because the city’s prosperity and relative openness to foreign visitors and residents attracted itinerant teachers and intellectuals. Theorizing about natural phenomena gave rise to speculation in other fields, and human society, human behavior, and human nature were among the subjects of such observation and speculation. The development of social institutions, laws, customs, belief systems, and other cultural practices was of particular interest; the Athenian experiment with democracy arguably contributed to an increasing self-consciousness about the roles that human perception and choice, on both individual and communal levels, played in shaping society. In addition to theories about the development of civilization and the degrees of its success in molding human nature, there arose ideas about how the model society should be formed, as well as formulations concerning the correct responses by individuals to the pressures and demands of their societies.

Some of these theories seem quite bold. At the end of the fifth century, a rhetorician named Antiphon wrote a treatise titled “On Truth,” in which he asserts that the laws and customs of society are by nature’s standards “unjust,” and that it is consequently “just”—by nature’s standards—to disregard them, provided one is able to do so without being punished. Rational theories concerning the organization of the cosmos inevitably challenged traditional understanding of the roles played by the gods in ordering the world. These theories gave rise to speculation about the role of the gods in human affairs and, in turn, led some individuals to ponder whether the truth about the gods can be apprehended by the human mind. Less daring but still important were experiments with city planning undertaken in communities such as Thurii, the Athenian colony in southern Italy founded under the leadership of Pericles in 444 B.C.E., which drew on the skills of geometers (literally, “earth measurers”) as well as experts on law and social relationships.

Most of the itinerant intellectuals who gravitated to Athens during and after Pericles’ day—including famous figures such as Protagoras, Hippias, Prodicus, and Gorgias—integrated their study and instruction of rhetoric with broader interests in fields that we today might label psychology, sociology, social theory, anthropology, linguistics, language theory, epistemology, music theory, theology, and cosmology. Many of them also investigated astronomy, physics, and the other sciences, as well as mathematics and medicine. These men and their homegrown Athenian counterparts became known as “sophists” (that is, “men who profess wisdom”), although it is not clear that the term was commonly used in the fifth century.

In some regards, the sophists were not wholly unlike the traveling poets and professional performers of Homeric epic (“rhapsodes”) who had been received in Greek city-states for generations. Many of them performed official services for their home cities and, like Thrasymachus and the Sicilian rhetorician Gorgias (from Leontini in Sicily), served as ambassadors to Athens. Yet the presence of these intellectually adventurous and personally ambitious men would have inevitably struck many Athenians as an alarming sign that times were changing, and not necessarily for the better. Indeed, the activities of the sophists seem to have compounded anxieties about economic and social changes that the developments of democracy and “empire” had brought about. The sophists’ fees were typically so high that only wealthy men could afford to hire them to instruct their sons, and their direct influence was thus limited. Their ideas and modi operandi were generally if vaguely known, however, and the public tended to see their activities, not always fairly, as threats to the traditional norms and practices that were thought to guarantee stability and prosperity in Athenian society.

The fact that the sophists appropriated the family’s role in preparing young men for adult life and, moreover, charged fees for their efforts, very likely made them appear all the more suspect in the eyes of average Athenians. If Aristophanes’ comedy Clouds can be trusted for this kind of information, the lightning rod for popular misgivings about the sophists’ activities was the teaching of rhetoric. Rhetorical education, in the worst-case scenario presented by Clouds, could supply the means for young men to “make the weaker argument stronger” and justify their antisocial behavior; it could enable them to cast out all the received wisdom they had absorbed about the gods, society, and family.

Nonetheless, for all this apparent controversy and anxiety concerning the sophists’ newfangled ideas, the changes and upheavals of Athenian society in the late fifth century had less to do with their influence than we might suppose. These upheavals, leading up to the oligarchic coups of 411-410 and 404-403, are better understood as consequences of the Peloponnesian War and the ongoing transformation of the institutions and practices of democracy. Modern scholars are in a position to see how various theories expounded by intellectuals valorized the positions taken by both proponents and detractors of Athenian democracy, but it is unclear how frequently or how keenly average Athenians concerned themselves with the ideological implications, per se, of the sophists’ ideas. In addition, even though sophists were not popular in fifth-century Athens, there was relatively little backlash against them. It is true that the astronomer Anaxagoras was prosecuted on the charge of impiety in, perhaps, 450 B.C.E., and that Socrates was convicted on the charges of impiety and “corrupting the youth” in 399. Anaxagoras, however, was likely attacked because of his closeness to Pericles, and, as we shall soon discuss, there were probably political motivations behind the charges brought against Socrates as well.

The market for the higher education of young men with wealth and aspirations to political prominence did not abate in the fourth century. Various individuals, some of them native Athenians like Isocrates (436-338 B.C.E.), established schools in which rhetoric and other subjects were taught. Thus, after only a generation or so, the novel and at times controversial educational offerings of the fifth-century sophists and rhetoricians were well on their way to becoming institutionalized and mainstreamed. Plato was a direct beneficiary of this process of institutionalization and, in something of a paradox, he was indirectly beholden to the sophists. To be sure, Plato’s portrayals of men like Protagoras, Hippias, and Prodicus (in Protagoras), Polus and Gorgias (in Gorgias), Euthydemus and Dionysodorus (in Euthydemus), and Thrasymachus (in Republic) are not flattering. He dismisses the claims to knowledge and expertise and educational proficiency that such “professors of wisdom” had staked for themselves, and discredits the ways in which these men and their successors—notably Isocrates—taught rhetoric and the “art” of public persuasion. Nonetheless, Plato’s Academy capitalized upon the desire and demand for higher education that Protagoras, Gorgias, and others had cultivated during the preceding decades. Without the fertile field the sophists planted, Plato might never have had the opportunity to found his Academy—or write his dialogues.

Socrates

It is impossible to conceive of Plato apart from Socrates. A native Athenian who lived from approximately 470 B.C.E. until his execution in 399, Socrates committed nothing to writing. What we know of his activities comes largely from the dialogues of Plato and Xenophon, in which Socrates is very often the primary interlocutor. The other intact source—and the sole one dating to Socrates’ lifetime—is Aristophanes’ Clouds, which antedates Plato’s and Xenophon’s works by twenty-five years at the minimum and was composed when Socrates was not yet fifty years old. There are fragments of other comedies from the 420s that mention Socrates, and a very few fragments of works by other “Socratics” who, like Plato and Xenophon, took to writing about the man after his death and using him as a figure in dialogues.

Aristophanes presents an image of Socrates very different from those of Plato and Xenophon. In Clouds, Socrates is portrayed as a professional sophist running a “Think Factory.” His students pay to learn rhetoric (that is, how to “make the weaker argument the stronger”) and other language arts, as well as absurd “scientific” techniques (for example, how to measure the leaps of fleas) and a novel cosmology positing that Zeus “is not.” This Socrates has no scruple about taking on a pupil who wants to cheat his creditors in court, and he is indirectly responsible for a young man’s beating of his aged father.

According to Plato and Xenophon, however, Socrates was in no way a professional; he had no pupils and took no fees. Plato takes particular pains to distance Socrates from Aristophanes’ caricature and from the sophists. He has him disavow all interest in rhetoric and admit to only a youthful and unsatisfying flirtation with the cosmological theories of Anaxagoras (for example, in Phaedo 96a-100a). The Socrates of Plato’s works professes an exclusive commitment to making his fellow Athenians “better” by urging them to examine their values and actions systematically, on the grounds that “the unexamined life is not worth living” (Apology 38a). He exhorts them to think and act in consistently virtuous, just, temperate, and courageous ways, even if such behavior endangers material prosperity and life itself (for example, Apology 29c-30b); he argues that the welfare and health of the soul are more important than any consideration of material comfort. The Platonic Socrates is depicted, moreover, as a paragon of this consistently virtuous way of life, always electing to do what is truly beneficial over what is immediately convenient and gratifying. So consistent is his devotion to the pursuit of the “good life,” for himself and others, that he is willing to permit himself to be killed for its sake (Apology 35c; Gorgias 522d-e).

Plato may well have crafted his representations of Socrates to suit his own purposes, just as Aristophanes doubtless shaped the portrayal in Clouds in accordance with his comic agenda. If we prefer to believe that Plato’s depiction is the more accurate, it is still possible to understand how Aristophanes could have proffered such a disparate perspective on Socrates’ activities. According to Plato, Socrates’ self-appointed mission of spurring his fellow citizens toward self-examination—he describes himself as a gadfly sent to “rouse” Athens, as if it were a large and lazy horse, in Apology 30e—necessitated challenges to their most cherished values and assumptions—including their own presumptions to wisdom. As a result, he may well have irritated, infuriated, and at times humiliated them. For all the distance that Plato strives to create between his mentor and the sophists, we may imagine that, to the average Athenian, the differences between the challenges to traditional conceptions of just behavior offered by Socrates and someone like Antiphon might not have seemed so great. Socrates could have come across as just another sophist who was relentlessly critical of the traditional and the time-honored.

If Plato’s depiction is reliable, Socrates was also highly critical of Athens’ democratic government. We know that he traveled in the elite circles of Athenian society and was closely linked to prominent men from aristocratic families. He was particularly friendly with Pericles’ ward, the charismatic and ambitious Alcibiades (450-404 B.C.E.), whose extravagant behavior and defection to the Peloponnesian alliance in 415 left his associates under a cloud of suspicion. He also knew Critias, the infamous leader of the Thirty Tyrants of 404-403, and other men who harbored open hostilities to democracy. Socrates was almost certainly not actively involved with the Thirty, but his past associations with Critias and Alcibiades may have caused unease in the tense years immediately after the democratic government was restored in 403. The general amnesty obviated his prosecution on political charges, and it is likely that the charges of impiety and corrupting youth that were officially laid against him in 399 were efforts to drive him into exile because of his political associations and views.

Socrates, however, did not go into exile, even though he could have done so after his conviction. On orders from the court that convicted him, he committed suicide by drinking hemlock. He left behind a band of friends and followers who, because of their dedication to preserving Socrates’ legacy, came to be known as “Socratics.” By the late 390s B.C.E., several texts purporting to contain the speeches of prosecution and defense given at Socrates’ trial were in circulation; two texts by Plato and Xenophon, both titled Apology (which literally means “Defense”), are the only extant examples of the latter, and none of the former survives. Dialogues featuring Socrates as an interlocutor remained popular throughout the fourth century, so much so that Aristotle’s Poetics identifies Socratic dialogues as “examples of imitation.” How scrupulously any of these works—including those of Plato—aimed to represent the actual views and activities of Socrates remains an open question.

Plato

We know the names of several Socratics active during the fourth century B.C.E. in Athens and elsewhere: Antisthenes, Phaedo, Eucleides, Aristippus, Aeschines, as well as Plato and Xenophon. Only works by Plato and Xenophon survive intact, and, of these two authors, Plato is by far the more philosophically significant.

Plato was born into a wealthy, aristocratic Athenian family in 428 or 427 B.C.E., and he lived until 348 or 347. (A note in passing: “Plato” was a nickname according to one tradition, but it is now generally accepted as his given name.) He had kinship ties with many prominent men, including the notorious Critias. A large body of writing attributed to Plato survives from antiquity, including Apology (a recreation of Socrates’ defense speech), Republic and a number of other dialogues, and a series of letters. Most of these works are considered genuinely Platonic, although the authenticity of some texts (including some of the letters and a handful of dialogues) has been doubted at various points in the past 2400 years.

The Seventh Letter, which many scholars today view as authentic, offers an autobiographical account explaining how the vicious abuse of power by the Thirty Tyrants and the subsequent trial and execution of Socrates under the restored democracy persuaded Plato to eschew a political career in Athens. It also details his association with the rulers of the Sicilian city of Syracuse, Dionysius I and his son Dionysius II, and their kinsman Dion, who was Plato’s close friend and student. Plato visited Sicily three times during the period from the early 380s to the late 360s. He and Dion evidently planned to educate the younger Dionysius in the hopes that, upon succeeding his father, he would put into practice the political ideals they cherished. Several scholars have speculated that these political ideals were something like the proposals for the ideal state and the government of philosopher-rulers that Socrates advances in Republic. Whatever their aspirations were, Plato and Dion were disappointed when Dionysius II took power in the early 360s and quickly broke with his kinsman and his tutor.

Soon after Plato returned to Athens from his first visit to Syracuse in the early 380s, he began teaching at a place near the grove of the hero Academus on the city’s outskirts. The school came to be called the “Academy” because of its location, and its original mission, like that of Isocrates’ school, may have been to train young men for civic leadership. Plato taught what he called “philosophy” (philosophia) and subjects he deemed essential to its study, notably mathematical sciences.

Plato probably started to compose dialogues before he established the Academy. In all but a few of his dialogues Socrates is the main interlocutor, and most are peopled with figures who would have been well known in Athens’ elite circles during the fifth century. Plato’s older brothers, Glaucon and Adeimantus, play prominent parts in Republic and figure briefly in Parmenides’ introduction. Several dialogues have identifiable “dramatic dates,” at least in approximate terms. The gathering of sophists and their followers at Callias’ house in Protagoras, for example, is set sometime around 432 B.C.E., and the party at Agathon’s house described in Symposium would have taken place in the spring of 416. Most of these works also contain anachronistic details, which seem deliberately planted in order to underscore their inherent fictionality. It is important for readers to keep in mind that the dialogues are not historically accurate accounts of actual conversations, although they may aim to suggest the kinds of conversations that Socrates could have had with Protagoras, Agathon, Plato’s brothers, and other men. Interestingly and importantly, Plato never represents himself as a speaker, although he is mentioned by Socrates in Apology and by Phaedo in Phaedo.

Many scholars have speculated about the dating of Plato’s works, and at times the speculation has inspired heated controversy. Relative dating of the dialogues is complicated by the fact that there is little external evidence corroborating when any of them was composed. One long-popular approach has been to classify the texts as “early,” “middle,” and “late,” on the grounds that there is a development in styles and concerns that reflects the maturation of Plato’s thought. Apology and the “Socratic” dialogues, which feature Socrates in conversation with various men about basic ethical questions and tend to end “aporetically” (without reaching satisfactory resolutions), are thus thought to date to the early years of Plato’s career, when he was still more or less a “Socratic.” “Middle” dialogues in which Socrates is made to advance positive theories, most importantly the theory of the metaphysical “ideas,” are viewed as reflecting the fruition of Plato’s own philosophical inquiries. Those dialogues that reflect less interest in the theory of the ideas and deal instead with other concerns and analyses (for example, the method of “collection and division”) are grouped together as “late.”

According to this interpretation, Republic is categorized among the “middle” dialogues because, among other things, it contains one of the most detailed expositions of the theory of the ideas, which Plato almost certainly derived independently of Socrates from Parmenides’ theory of “Being.” Some critics accordingly estimate that it was composed during the 370s B.C.E. Yet, once again, readers should be aware that such dating is purely speculative, since it depends upon subjective estimations of the developmental stages in Plato’s thought and style.

The past few decades have witnessed an explosion of interest in Plato’s reliance on the dialogue format, and readers can find overviews of the topic in John M. Cooper’s introduction to Plato: Complete Works (pp. xviii-xxi) and Ruby Blondell’s The Play of Character in Plato’s Dialogues (pp. 1-52). The fact that he chose to write not treatises, but dialogues in which different points of view compete, coupled with the fact that he never presents himself as an interlocutor, raises important questions about the relationships among written texts, Plato’s actual thoughts, and his teachings at the Academy. Passages such as Phaedrus 274e-278b, in which Socrates asserts that a sensible and noble man treats written discourse as a mere “amusement,” further complicate interpretation of all the dialogues, including Republic. Readers of Republic will note that, at a crucial moment (7.536b-c), Socrates reminds Glaucon that they are “not serious.” And, although Socrates remarks more than once on the importance of the issues he and his companions are discussing, he repeatedly draws attention to their conversation’s incomplete and provisional qualities.

These factors lead some scholars to argue that the dialogues cannot provide reliable guides to what Plato thought. According to this school of interpretation, Republic and its counterparts showcase the Socratic method of inquiry; they are intended to stimulate readers’ interest in asking their own questions, but do not aim to guide them toward specific points of view, or “theories,” on any given topic. Yet there is a definite set of concerns—about the unreliability of opinions held by “the many,” for example, and their heedless pursuit of pleasure and gratification—that is explored and substantiated in several dialogues. The recurrence of these concerns, and the consistent manner in which they are addressed from dialogue to dialogue, suggest that Plato’s written works are not only advertisements for the Socratic method of inquiry, but also vehicles for a complex agenda that is at once ethical and intellectual, cultural and political.

Succinct summary of this complex agenda is impossible. Readers interested in exploring what scholars have deduced about Plato’s interests and aims are encouraged to consult one or more of the excellent studies available today, including Andrea Wilson Nightingale’s Genres in Dialogue: Plato and the Construct of Philosophy, Angela Hobbs’s Plato and the Hero: Courage, Manliness, and the Impersonal Good, Charles H. Kahn’s Plato and the Socratic Dialogue: The Philosophical Use of a Literary Form, Terence Irwin’s Plato’s Ethics, Debra Nails’s Agora, Academy, and the Conduct of Philosophy, and Josiah Ober’s Political Dissent in Democratic Athens: Intellectual Critics of Popular Rule. This introduction to Republic merits discussion of just a few basic points.

First, the recurrent expose of the unreliability of “what most people think” functions as a weapon that permits a simultaneous attack on traditional ethical understandings (for example, the identification of “justice” with retribution and vengeance) and on the particular ideological assumptions of democracy. (The most important of these assumptions was that, regardless of social position or experience, free-born male citizens were qualified to participate to some extent in political processes.) The critique that Republic and other Platonic texts offer concerning the pervasive materialist tendencies in Greek culture, which are repeatedly said to prioritize appearances and “external” goods (such as wealth, looks, social status, and political power) over “internal” goods and actual conditions, thus complements their more narrowly focused challenge to the soundness of Athenian democracy’s presumptions and practices.

At the heart of this double-sided critique lies the concern that Hellenic culture encouraged a fundamentally childish attachment to pleasure-not just physical and sensual pleasures, but to the psychological pleasures gained through the exercise of power, or through the indulgence of ambition, pride, grief, anger, and other strong emotions. Athenian democracy is represented as exacerbating these childish tendencies, because it maximizes the number of individuals who are permitted to indulge themselves with little real restraint. The ultimate effect of democracy is to render political leaders helplessly incapable of true governance, since they are inevitably forced to gratify and flatter the common people, who can turn on them with impunity as soon as they fail to please (see, for example, Gorgias 500a-519c; Republic 6.492a-493d).

These criticisms run counter to the self-images that most Athenians—and most Greeks—would have nurtured, although the negative assessment of Athenian democracy echoes points made by other upper-class Athenians writing in the fifth and fourth centuries, such as Thucydides, Xenophon, and Isocrates. Plato distinguishes himself, however, by positioning his critique of Athens’ democratic culture within a far broader interrogation of time-honored values and practices that were not specific to Athens. In so doing, he takes aim at the traditional aristocratic ideology cherished by his own social group, which assumed that the well-born and elite few—purportedly endowed with superior intelligence, skill, resources, and “excellence” (aretê)—possessed a natural and god-given right to power. As Andrea Wilson Nightingale argues (Genres in Dialogue, pp. 55-59), the dialogues time and again expose the ignorance and powerlessness of well-born men who presume and are presumed to be “superior.” Even the gifted and privileged Alcibiades is made to concede the “slavishness” of his desire to “please the crowd” in Symposium 215e-216b.

Yet the repeated exposes of how elite individuals like Alcibiades fail to be morally and intellectually “superior” do not overturn the basic presumption that, in a given community, only a few individuals are sufficiently gifted to wield political power. Critical as they are of the conduct and attitudes of contemporary elites, the dialogues ultimately validate the principle of elitism. Against the claims of democracy’s pluralist ideology, Plato’s works seek to reenergize traditional aristocratic views of political power as a special responsibility and privilege reserved for the very few. In the process, however, they completely redefine who the “best men” (hoi aristoi) are, and completely reconfigure the meaning of traditional terms for the qualities of those best men—that is, excellence (aretê), wisdom (sophia), courage (andreia), temperance (sophrosynê), and justice (dikaiosynê).

At its most basic level, Republic is an effort to forge a consistent and meaningful redefinition of “justice” that goes against the grain of much traditional teaching. Readers will see for themselves how its reconfiguration of what is signified by the term goes hand in hand with its argument for an “aristocracy” of men called “philosophers,” whose apprehension of the metaphysical ideas leads them to disdain appearances of all sorts. Their aretê lies in nothing outward, but rests solely in their mature reason and regard for what is beneficial to the soul.

These thoughts could have been conveyed in any number of ways, and in themselves they do not tell us why Plato chose to write dialogues as opposed to treatises. His choice must have been motivated to some extent by the fact that other members of the Socratic circle were composing dialogues, but there might have been additional reasons for his gravitation toward this versatile form. Certainly the dialogue afforded him great flexibility of expression, and with it he was able to craft attractive alternatives to the very forms of discourse (including poetic genres such as tragedy and epic) that Republic and other works expose as the principal carriers of problematic cultural values.

Moreover, even though the dialogues are not philosophical discourses in their own right—since such can never take place in writing (compare Phaedrus 274e-278b)—they are plainly models of the kinds of conversations that thoughtful men can have. They are, in some regards, advertisements for philosophy, and they might have been composed to engage the interest of young Athenian men in the philosophical studies of the Academy.

We should observe here that Isocrates, too, claimed to teach philosophia, using the term to express the dominant cultural values that Socrates and other Platonic interlocutors vigorously criticize. In a work titled Antidosis (354 or 353 B.C.E.), Isocrates explicitly casts doubt on the relevance of the kinds of studies pursued at the Academy—that is, mathematical sciences that aim at the discovery of absolute truths. Isocrates’ skepticism doubtless reflects the long-running competition between his school and the Academy, and it seems likely, as Nightingale maintains (Genres in Dialogue, pp. 21-59), that the dialogues had the additional function of advancing Plato’s far more exclusive definitions of philosophy and the philosopher. Not only do they counter Isocrates’ definition of philosophy, but they also repeatedly strive to demonstrate how Plato’s “brand” of philosophy is useful to both the individuals who practice it and their communities.

At times, as in books 5-10 of Republic, Plato has his interlocutors directly define philosophia and expound on its usefulness. Yet the dialogue form has the additional virtue of permitting Plato to define philosophia indirectly as well as directly, through the very drama of his “plays” in prose. In the dialogues he is able to show—and not merely describe—what philosophy is, and the benefits it brings as well as the challenges it imposes. On the latter score, the give-and-take of the conversations, especially those in which Socrates and his interlocutors reach neither satisfactory conclusion nor mutual understanding, highlight how emotional factors such as ambition, pride, anger, and fear affect the cognitive abilities and powers of reason in even the most intelligent people. These conversations seem designed to bear out what is claimed in book 7 of Republic, that the “whole soul” must be moved in order for the mind to “know,” just as the whole body must be turned from darkness toward light for the eyes to see (7.518c). The rewards, however, are made to seem worth the trouble of this arduous psychological reorientation. Readers have only to contemplate the ease and grace of Socrates, even as he faces death in Crito and Phaedo, to find compelling “advertisements” for the supreme value of Plato’s distinctive brand of philosophy.

The dialogues present Socrates as a paragon of the philosopher’s aretê. They simultaneously permit Plato and his readers to look back at Socrates in a nuanced manner and mark his shortcomings as well as his fine and admirable traits. Socrates may have seen it as his duty to talk to “anyone, young or old” (so Apology 33a), but Plato’s many representations of Socrates’ conversations subtly bring out how such an indiscriminate approach, however commendable in intention, is unrealistic and ultimately self-defeating. Plato himself, we should note, was considerably more selective than Socrates in his contacts; at the Academy he worked only with people eager to study with him, whom he could vet as a condition of their “admission.” In Plato’s hands, then, the Socratic dialogue becomes both homage to a beloved mentor and declaration of intellectual independence.

Republic

In the manuscripts and ancient citations, the title of Republic is given as Politeia (“Constitution”) or Politeiai (“Constitutions”); Peri dikaiou (literally, “concerning that which is just”) is sometimes listed as an alternative title. The book divisions, as those in Laws, are probably not Platonic, but rather the work of scholars in the third and second centuries B.C.E. The sectional numbers (for example, Republic 327b) found in most modern editions refer to the page and section numbers used in one of the first printed texts of Plato’s dialogues, which was published in the late sixteenth century; like the book divisions, they are retained for the sake of convenience.

Again, the date of Republic’s composition is a matter of conjecture. Some scholars argue that it was actually composed in stages, on the grounds that the current text imperfectly marries two (or more) “dramatic” conceptions. Although the physical setting is certain (the house of the metic Polemarchus in Piraeus), there is much disagreement over the dramatic date. Debra Nails (The People of Plato, pp. 324—326) compellingly summarizes the evidence for viewing the current text of Republic as a combination of and expansion upon two earlier works: first, an inconclusive (“aporetic”) Thrasymachus or On Justice, similar to Gorgias and Protagoras and set in the 420s B.C.E., which would have supplied the basis for what is now called book 1, and second, an Ideal State, which would have been the foundation for what is currently in books 2-5. If the latter composition featured Plato’s older brothers Glaucon and Adeimantus as interlocutors, it would have been set in or after 411. This analysis comfortably accounts for the many anachronisms that arise if one attempts, as some critics do, to fix the dramatic date of Republic in a particular year such as 411 or 410, and it also permits some reconciliation with the apparent reference to the discussion of Republic as “yesterday‘s” conversation in Timaeus 17a-19e, which seems to be set in the 420s.

The text that we now possess surely could have been composed in more than one stage. Yet, since anachronisms are present in dialogues that have readily identifiable dramatic dates, the obligation to explain away Republic’s anachronisms by means of theories concerning its composition is less than pressing. Awkward anachronisms and all, Republic is a unified work with a logical and elegant organization, to which we will now direct our attention.

Socrates himself is the narrator of Republic, in which he tells an unknown audience about a conversation that took place “yesterday.” His main interlocutors, from book 2 on, are Glaucon and Adeimantus. His host Polemarchus and Polemarchus’ aged father, Cephalus, are instrumental in getting the conversation going, and the aggressive challenge posed by the rhetorician Thrasymachus in the second part of book 1 is what determines the dialogue’s main interests.

Other men are present in the dialogue: Polemarchus’ half-brother Lysias, a professional speech writer who is discussed in Phaedrus and whose works still survive; another half-brother, Euthydemus; a man named Charmantides, who could be either an elderly man from the rural Attic deme of Paeania or his grandson; and Niceratus, the son of the well-respected political leader and strategos Nicias. These four men are silent witnesses to the conversation, as are the nameless “others” mentioned in 1.327c. Aside from the slave who calls upon Socrates and Glaucon in the first paragraph of book 1, the only other speaker is Cleitophon, an Athenian politician who briefly comes to Thrasymachus’ aid at 1.340b-c.

We do not know much about Glaucon and Adeimantus aside from what Plato shows us. They participated in a battle at Megara, to which Socrates refers at 2.368a. If this was the battle of 409 B.C.E., they could have been only a few years older than Plato, which is the estimate of most scholars; if it was an earlier battle in 424, they would have been much older. Adeimantus, along with Plato, apparently attended Socrates’ trial (Apology 34a), and both he and Glaucon appear on close terms with Socrates in Republic. Cephalus hailed originally from Syracuse on Sicily, and he and his sons were wealthy, well-established foreign residents in Athens. Represented by Plato as an old man, Cephalus was almost certainly dead by 411. Republic’s original readers would have also known that the Thirty Tyrants had Polemarchus executed in 404 so as to seize his property, and this fact puts Thrasymachus’ passionate glamorization of the tyrant’s self-aggrandizing ways ( 1.344a-c) in an especially ironic light. Thrasymachus, as we have already discussed, served as a diplomat in Athens for his native Chalcedon and was also a professional rhetorician, and Plato has Socrates link him to Lysias in Phaedrus. Cleitophon, who is associated with Lysias and Thrasymachus in the pseudo-Platonic dialogue Cleitophon, had become notorious for his political fickleness by the time Aristophanes produced his comedy Frogs in 405 B.C.E.

The conversation in Republic begins simply enough. Socrates, who has plainly been on familiar terms with Polemarchus’ family for a long time, forthrightly asks Cephalus about old age. His response, that aging is not as difficult as it is often reported to be, prompts Socrates to wonder out loud whether Cephalus’ easygoing attitude is in part facilitated by his wealth. The old man’s response is affirmative. The wealthy, he asserts, face death without fear; their resources enable them to satisfy their debts to gods and men and also to avoid lying and cheating, and thus they can die with the confidence that they will not be punished in the afterlife. These remarks are what precipitate the discussion of just behavior and moral conduct, which Socrates introduces as he asks his elderly friend whether “justice” (dikaiosynê) simply consists of paying debts and telling the truth. Cephalus politely bows out of the conversation, leaving his son Polemarchus to argue that justice—meaning “right behavior” in general—does indeed consist of paying debts and giving “what is due,” as poets such as Simonides claim. Socrates, however, quickly leads Polemarchus to realize that there are serious logical problems with this traditional conception of justice, in which “what is due” is defined in terms of “help” to “friends” and “harm” to “enemies,” and the young man is left perplexed.

At this point, Thrasymachus leaps into the discussion, asserting that justice is simply “the advantage of the stronger,” by which he clearly means that “justice” is relative—that is, “right behavior” is whatever those in power determine it to be. With a series of questions that recall those he just posed to Polemarchus, Socrates uncovers logical problems in Thrasymachus’ definition as well. Thrasymachus, however, does not give up. Exploding in frustration at Socrates’ naive assumptions about the responsibilities that the powerful bear to those who are under their control, he reformu lates his ideas with a bold new emphasis evocative of Antiphon’s thinking in “On Truth.” “Justice”—that is, the circumspect avoidance of doing “wrong” to others and obedience to social rules—is doing what is advantageous to another, who is stronger and more powerful than oneself. “Injustice,” on the other hand, is doing what is to one’s own advantage by taking what one wants regardless of social rules and by aggrandizing oneself at the expense of others. It is what leads to “happiness,” provided that one is not penalized for one’s exploitations. Tyrants who kill and confiscate and rape at will, according to Thrasymachus, are the happiest men of all.