PENGUIN BOOKS

RESTORATION

Tim Harris has spent much of his teaching life rethinking and re-imagining late Stuart Britain. His fascination with the growth of popular politics, mass journalism and crowds has been expressed in a number of groundbreaking books, including London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II and Politics under the Late Stuarts. He taught for some years at Emmanual College, Cambridge, but has since 1986 taught at Brown University, Rhode Island, where he is now Munro-Goodwin-Wilkinson Professor of European History.

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen's Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, Johannesburg, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published by Allen Lane 2005

Published in Penguin Books 2006

4

Copyright © Tim Harris, 2005

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

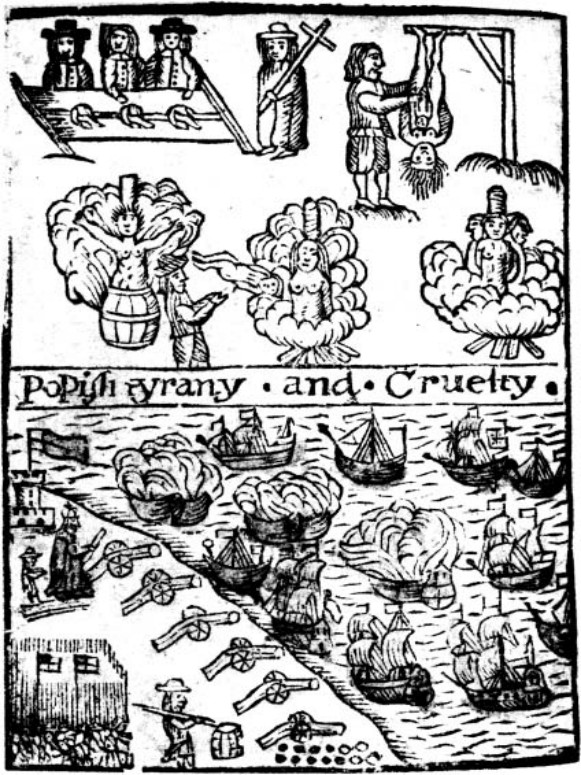

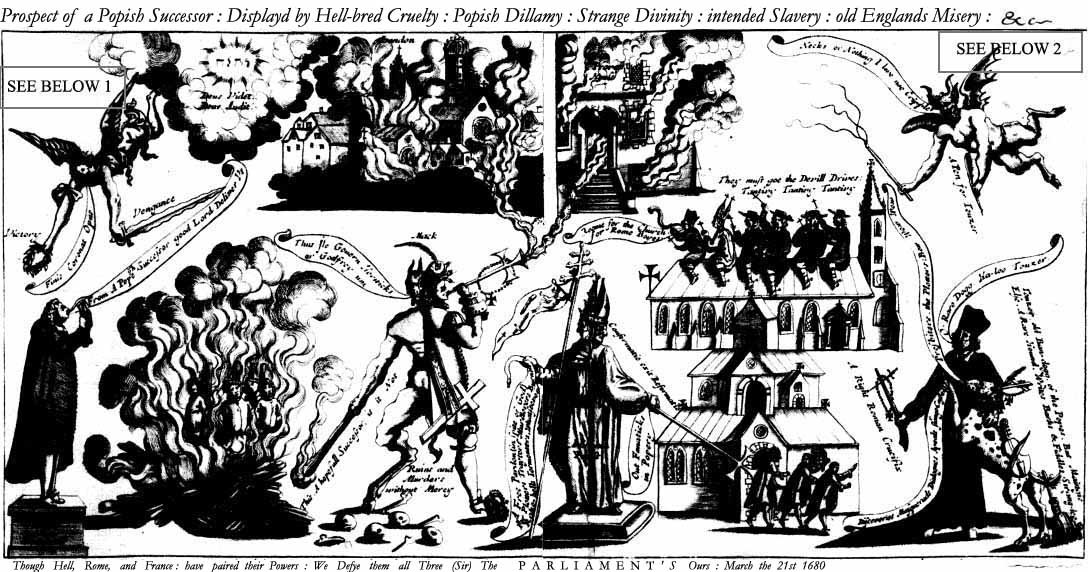

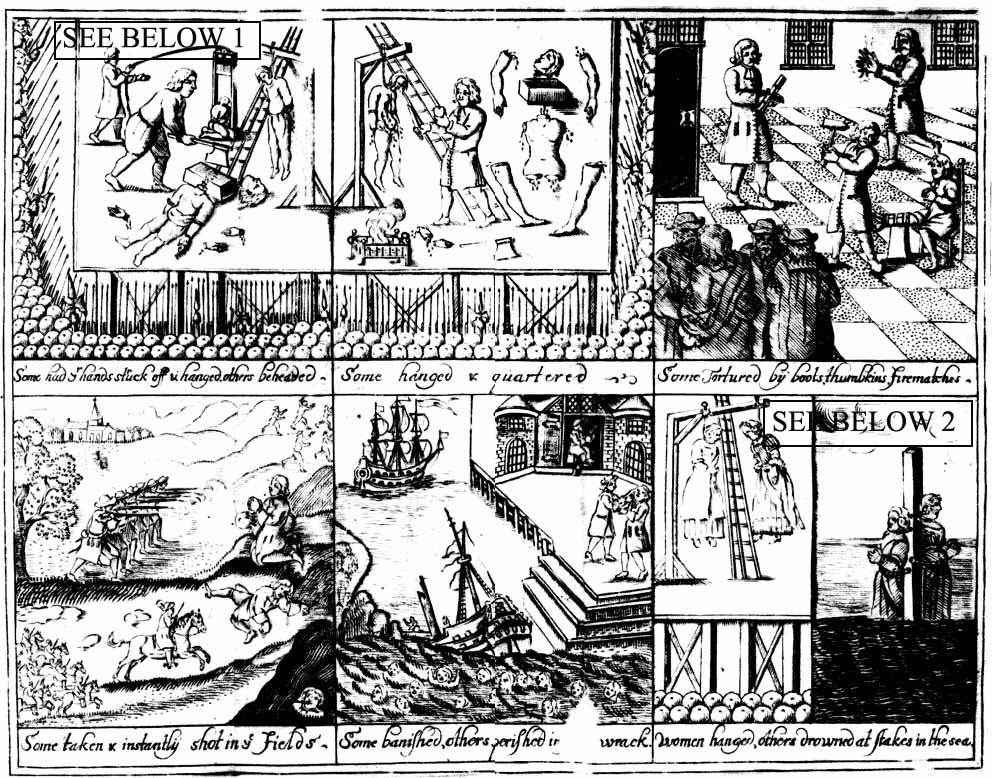

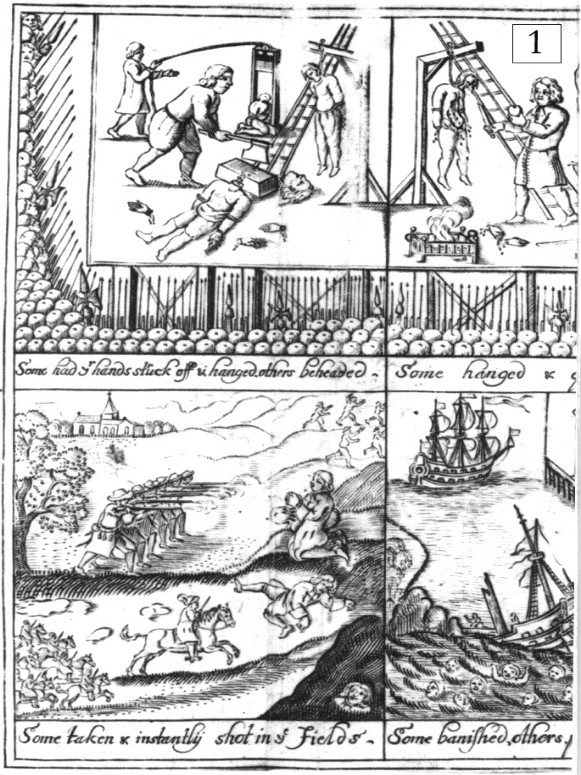

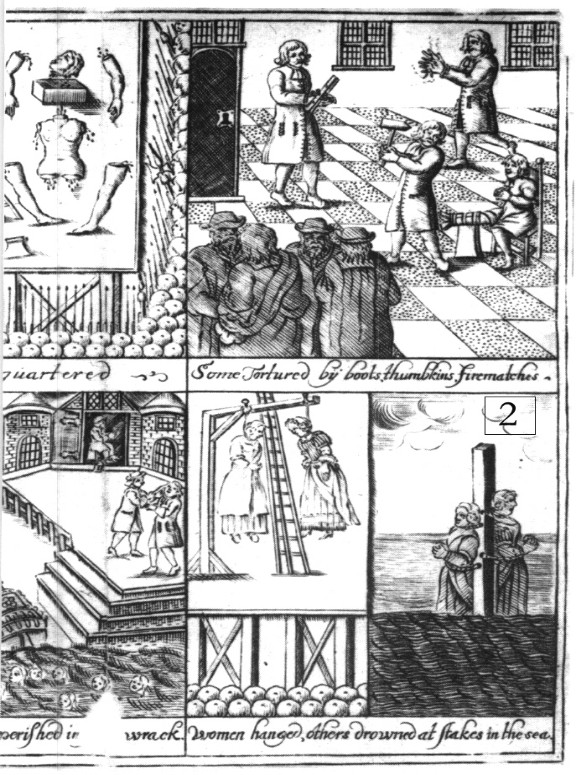

Frontispiece Popish Tyranny and Cruelty: Whig woodcut depicting alleged acts of Catholic cruelty against Protestants, and the Spanish Armada.

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-192674-2

Contents

List of Illustrations

Preface

Introduction

From Restoration to Crisis, c. 1660 – 1681

1. The Nation Would Not Stand Long: Weaknesses of the Restoration Monarchy in England

2. Popery and Arbitrary Government: The Restoration in Ireland and Scotland and the Makings of the British Problem

3. Fearing for the Safety of the People: The Popish Plot, Exclusion and the Nature of the Whig Challenge, c. 1678–1681

Conclusion to Part I

The Royalist Reaction, c. 1679–1685

4. The Remedy for the Disease: The Ideological Response to the Exclusionist Challenge

5. Keeping the Reins of Government Straight: The Tory Reaction in England

6. From Bothwell Bridge to Wigtown: Scotland and the Stewart Reaction

7. Malcontents and Loyalists: The Troubles and Disquiets in Ireland from the Popish Plot to the Royalist Reaction

Conclusion

Notes

Index

List of Illustrations

Frontispiece: Whig woodcut depicting alleged acts of Catholic cruelty against Protestants, and the Spanish Armada of 1588, from The Protestant Tutor, 1679 (British Library)

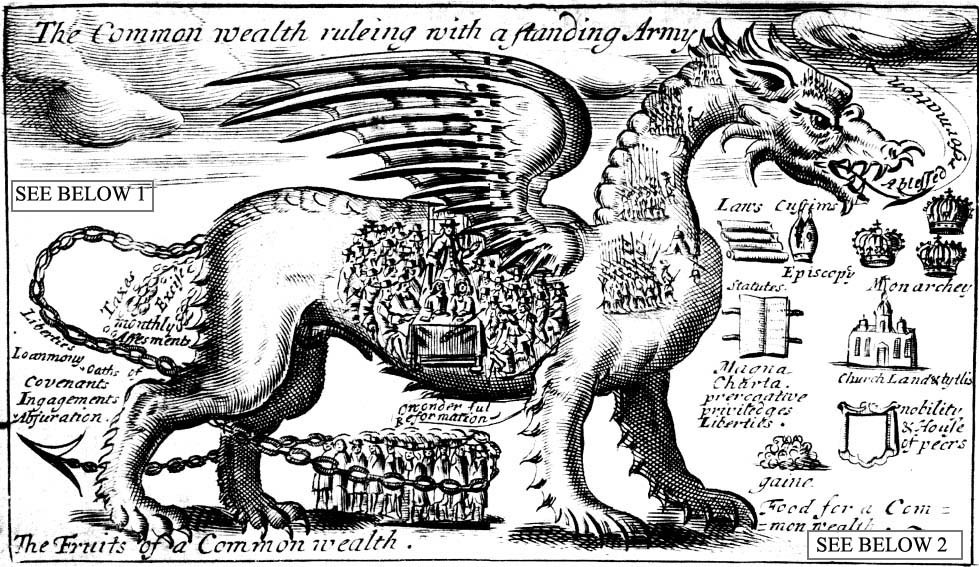

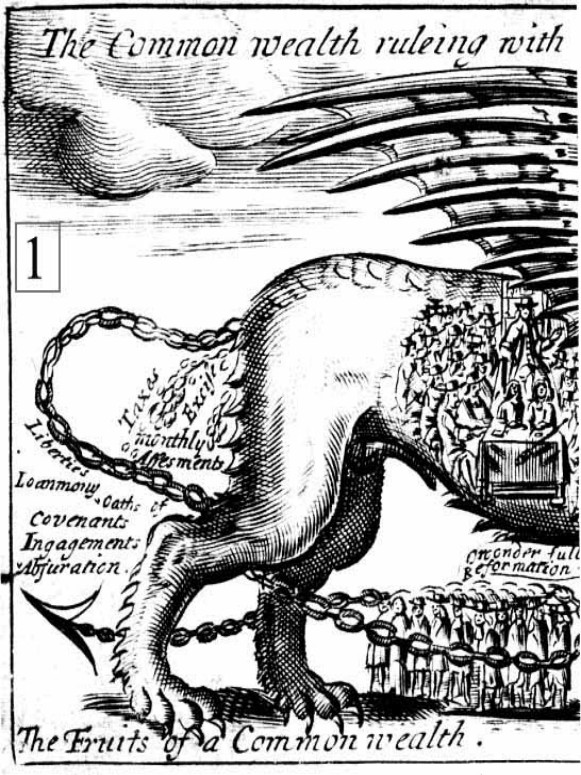

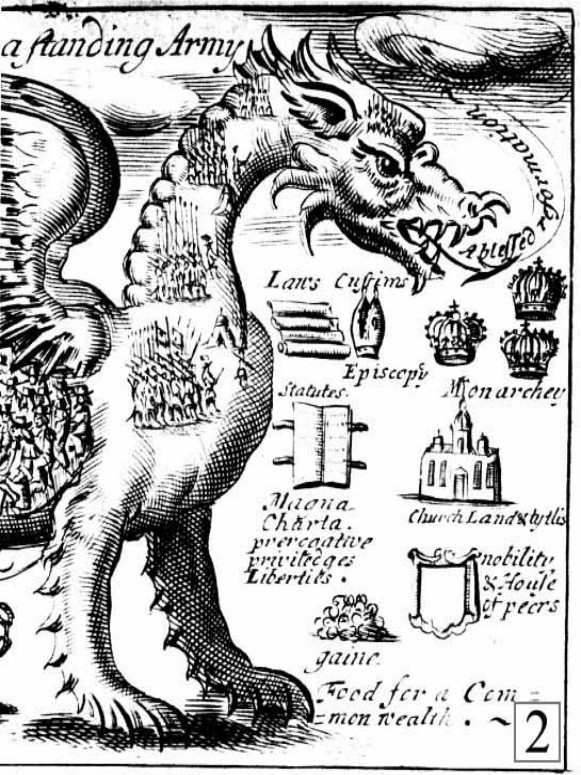

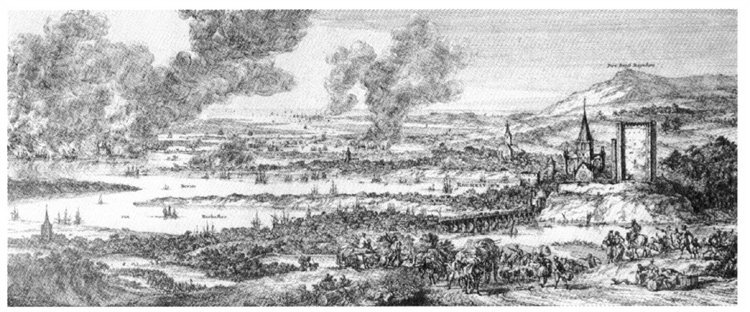

Introduction (pp. 2–3): Tory print representing the tyranny of republican rule in the 1650s (British Museum)

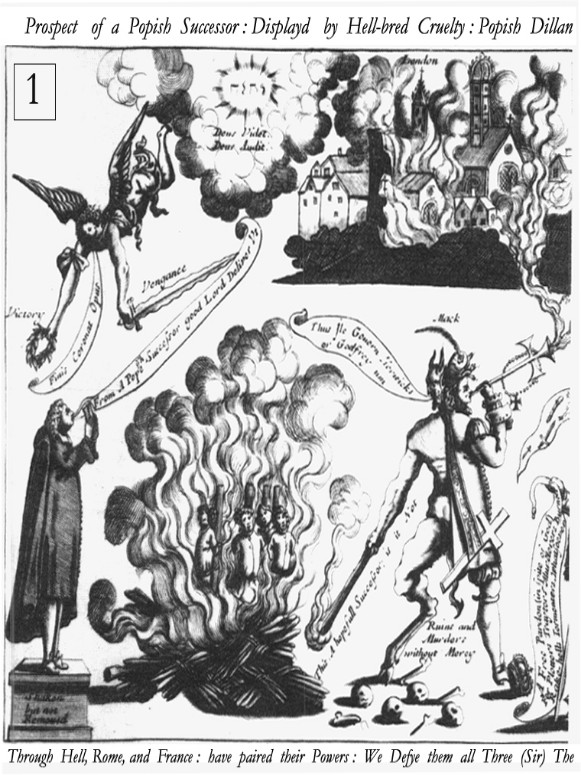

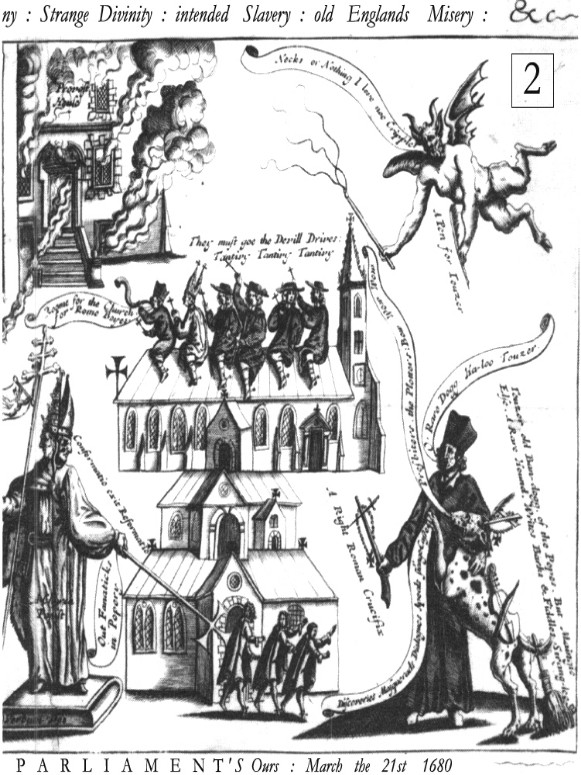

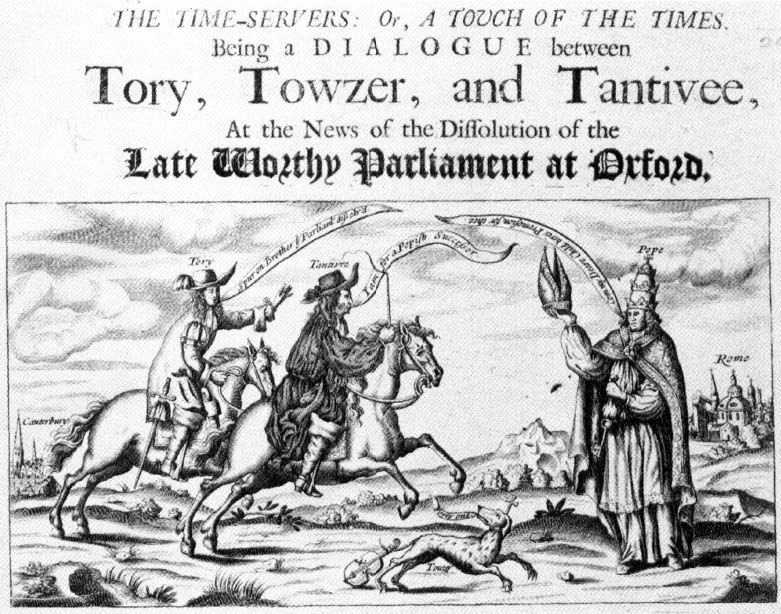

Part One (pp. 40–41): Whig print from the Exclusion Crisis, 1681 (British Museum)

Part Two (pp. 208–9): Woodcut illustrating punishments meted out to Presbyterian dissidents in Scotland during the reign of Charles II. From Alexander Shields' A Hind Let Loose, 1687 (British Library)

Plate Section

1 Charles I and James, Duke of York, by Sir Peter Lely, 1647 (Bridgeman Art Library/Syon House, Middlesex)

2 Drawing of James II, by Robert White, pencil on vellum (Bridgeman Art Library)

3 Louise de Kéroualle, The Duchess of Portsmouth, by the studio of Sir Peter Lely (Bridgeman Art Library/Royal Hospital Chelsea)

4 Dutch attack on the River Medway, June 1667, engraving after Romeyn de Hooghe (Bridgeman Art Library)

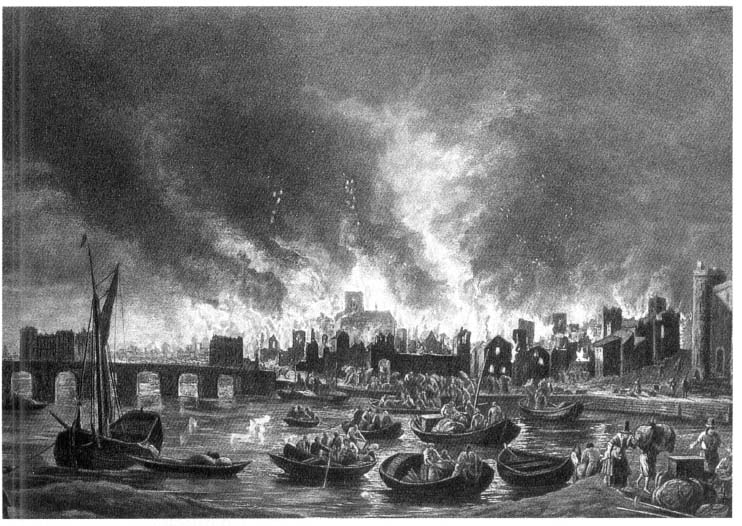

5 The Great Fire of London, in a seventeenth-century print by Lieve Verschuier (Bridgeman Art Library)

6 James Butler, First Duke of Ormonde, by Sir Peter Lely, c. 1665 (by courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery)

7 The Duke and Duchess of Lauderdale, by Sir Peter Lely, c. 1670s (National Trust)

8 Portrait of Thomas Osborne, 1st Earl of Danby, by Sir Godfrey Kneller, c. 1670s (Bridgeman Art Library)

9 Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, in a miniature by Samuel Cooper, c. 1670 (Philadelphia Museum of Art/CORBIS)

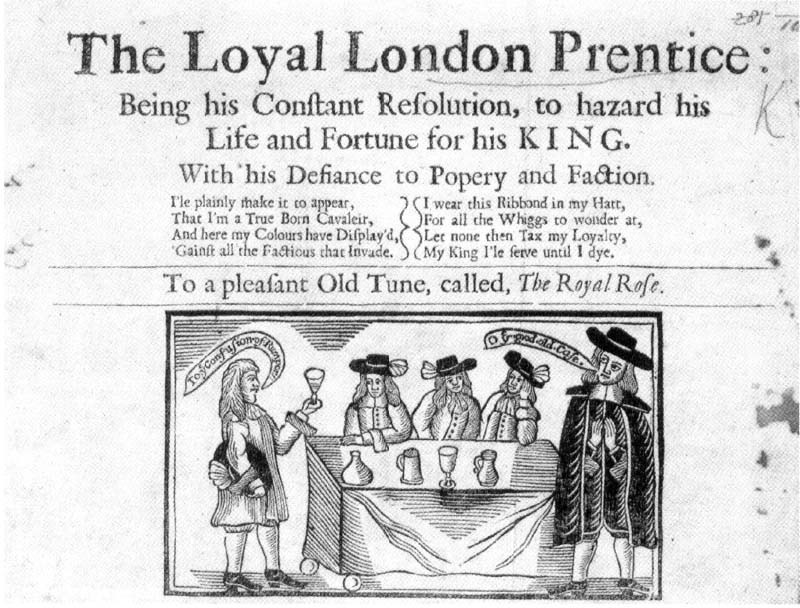

10 ‘The Loyal London Prentice’, Tory broadside, 1681 (British Library)

11 ‘Tory, Towzer and Tantivee’, Whig print form the Exclusion Crisis, 1681 (British Library)

12 Titus Oates, by Thomas Hawker, c. 1678 (by courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery)

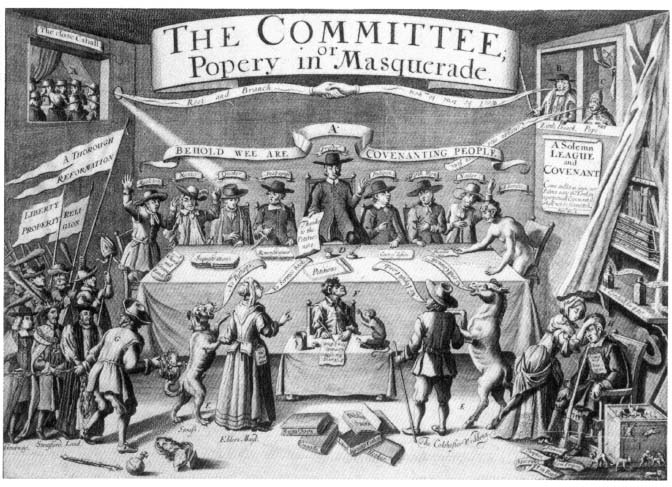

13 ‘The Committee, or popery in masquerade’, Tory print, 1680 (British Museum)

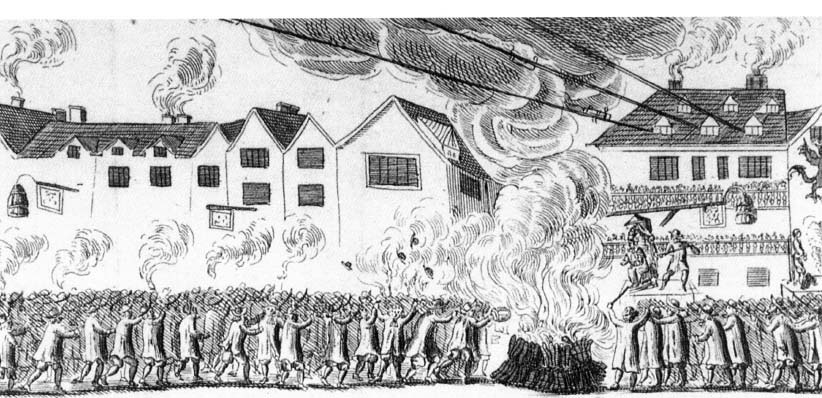

14 The Solemn Mock Procession', 1680 (British Library)

Preface

This book has been a long time in the making. I was advised several years ago by my colleague Gordon Wood that I should take my time and write a big book. I took him at his word, and ended up producing something that was too big to be published as one, and so it has now become two (still quite big) books. What is on offer here is the first.

My original aim had been to write a book which picked up where my study of London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II (Cambridge, 1987) had left off (roughly towards the end of 1682) and carry the story through to the Glorious Revolution, but to make my account a national one rather than focused on just the capital. This would therefore have been a study of the Tory Reaction, the reign of James II and the Revolution of 1688–9, and would have combined high politics with low politics and attempted to answer the call I had made in the introduction to my Politics of Religion in Restoration England (Oxford, 1990 – co-edited with Paul Seaward and Mark Goldie) for a social history of politics for this period. My project, I believed, would cause us fundamentally to rethink the 1680s and the nature of the Glorious Revolution – an event which I felt had been mischaracterized as a mere dynastic coup imposed from above and outside, but which to me seemed more like a genuine revolution and one brought about from below. Several years ago one of my students at Brown, after recognizing the elitist bias in traditional secondary accounts of 1688–9, had poignantly raised the question in class: ‘Where was the crowd?’ My desire was to write an account which would put the crowd back in, which would be people-focused as much as it was politician-focused, and which would recognize the vital contribution which those below the level of the elite made to the political history of this period, through either their sufferings or their activism. However, the study became international rather than national, as it soon became apparent that the story of Scotland and Ireland would need to be told as well. It therefore also grew in scope – considerably so, as it turned out, since I was determined to do justice to the Scottish and Irish pasts for their own sakes, and not just bring them in for cameo appearances to help flesh out an Anglocentric narrative. In the process, the chronological boundaries of the book grew, to cover the years from 1660 to 1720, although with the focus remaining firmly on the 1680s.

It is important to be aware that the project has been conceived all along as an integrated whole. This influenced its organizational logic. The basic questions I sought to address were: how did a regime that had been so popular when it was restored in 1660 fall into crisis by 1680? how did it manage to recover from that crisis by 1685? and how did it sink back so dramatically into crisis by 1688 so that a reigning monarch could be toppled from his throne in England (Scotland and Ireland were very different stories) without being able to offer any significant resistance? The book, as originally conceived, was therefore divided into four parts: from Restoration to crisis, c. 1660–81; royal recovery under Charles II, c. 1681–85; the reign of James II, 1685–8; and the Revolutions and their outcomes, c. 1688–1720. Only after my editor at Penguin, Simon Winder, had read a complete draft of the whole was the decision taken to make it two books–with the first two parts (on the reign of Charles II) forming book one, and the last two book two. I might have thought about the structure somewhat differently had I started with the intention of writing two separate books. There is not a great deal, for example, on Restoration politics in England, in part because this is a story that has been told by others already, and in part because, given the conception of the project as a whole, an analytical discussion of the problems facing the Restoration polity in England seemed a more compelling way of guiding the reader about what was going wrong at this time and why the regime was to fall into crisis by the late 1670s. Moreover, there are certainly things that are explained at length in this first book because they provide a vital context for understanding developments traced in book two. I began writing this book from 1685 onward; only when I had finished the chapters on the Revolutions did I go back and draft the chapters for the years 1660–85, with the aim of setting the context for what was to come thereafter. Nevertheless, in splitting the project into two I have made every effort to produce two stand-alone books – ones which are self-sufficient in the sense that each can be read on its own and does not require familiarity with its companion volume to be intelligible.

Many will no doubt see this study as an exercise in the new British history. Problems nevertheless remain over the use of the adjective ‘British’ to describe an integrated history of the three constituent kingdoms of the Stuart monarchy. Ireland was not part of Britain, in the literal geographical sense, since Britain was the island which comprised England, Scotland and Wales. It is true that Ireland was occasionally called West Britain or Lesser Britain, but that in itself was an imperialist usage, a view from the British mainland rather than an accurate geographical designation or a term used by the inhabitants of Ireland themselves. Politically, the island of Ireland as a whole was to be part of the British state for only a little over a century, between 1801 and 1922. Ethnically, the indigenous Irish population were Gaelic rather than British, although there were also many British peoples (English, Welsh and Scots) living in Ireland. On the other hand, there were also many non-British peoples living in Scotland and Wales. Strictly speaking, this study deals not with Britain nor with the British (exclusively), but with the various peoples who inhabited the Britannic archipelago in the North Atlantic off the coast of north-west Europe and who happened to be ruled over by the same monarch. Indeed, the style ‘his Britannick majesty’ was frequently used by contemporaries to refer to either Charles II or James II in his capacity as king of England, Scotland and Ireland.

Care is clearly needed over terminology. However, it seems both undesirable and unnecessary to outlaw the term ‘British’ in the context of this particular study. Undesirable because we would be forced to employ some rather cumbersome language if we were determined to avoid it; my editor cringed at my references to ‘the Britannic archipelago’, which he asked me to excise from the final version – and, besides, how does one make an adjective from that term? Unnecessary because this study is about revolutions that affected three kingdoms which, whatever the complexion of their indigenous populations, were controlled and run by people who came from Britain. The monarchy itself was genuinely British: the Stewarts were originally a Scottish dynasty who inherited the English (and hence also Irish) crown in 1603 and subsequently anglicized their name. Those in positions of power under the British monarchy were invariably of British – English or Scottish – extraction themselves. Although there was a significant Gaelic culture in Scotland, it was the Lowland Scots, of Anglo-Saxon extraction themselves, who dominated the government of the country, whether under Charles II or James VII (as James II was styled in Scotland) or in the post-revolutionary regimes. Similarly, despite its sizeable Gaelic population, Ireland was under the suzerainty of a British monarch and was ruled at home by people who hailed (either immediately or ultimately) from the British mainland, and one can legitimately talk of it as being a British state at this time in the sense that it was ruled by people of British extraction – primarily English. Even the attempted Catholic revolution in Ireland under James II would have resulted in power being kept largely within the hands of the British, albeit Catholics of Old English (or Anglo-Norman) extraction. Moreover, Irish Catholics at the time used the term ‘the British Monarchy’ to describe the lands (including Ireland) over which the Stuarts ruled. This study, in other words, is a British history in the sense that it offers an examination of the fortunes of British rule across the three kingdoms that comprised the North Atlantic archipelago of Britain and Ireland. Having said that, this work makes every effort to do justice to the struggles, concerns and experiences of the non-British peoples who inhabited this Britannic archipelago, and to avoid terminology that might seem either misleading or unduly imperialistic.

In a project of this size, one inevitably accumulates numerous debts over the years. It was John Morrill who first encouraged me in my plans to write a book on the 1680s and suggested that I should also look at Scotland and Ireland; once I started to look at Scotland and Ireland, however, I realized that the book could not be just about the 1680s, but would have to start much earlier and finish much later. It was an invitation from Mark Goldie to become involved in editing the Roger Morrice Ent'ring Book, a political journal covering the years 1677–91, which confirmed me in my idea that the project was worthwhile, especially when it became apparent that Morrice, like myself, thought in three-kingdoms terms. Mark Kishlansky and David Underdown contributed more to the conceptualization of this project than they perhaps realize, not least through various critical remarks the two of them made to me about the value of British history. The end result might not convince them, but their observations certainly made this a better piece of scholarship than it would otherwise have been. It seemed too much of an imposition to burden friends and colleagues with endless drafts of what seemed to be an endlessly growing manuscript; rather, I sought the necessary critical feedback by delivering discrete sections of what I was working on at conferences, lectures and colloquia across Britain and North America over the last decade or so. For their invaluable input, I would like to thank everyone who has attended whatever presentations I have given about different aspects of this work; they have had a much greater influence on shaping the final outcome than they would ever have realized. Certain individuals who have offered constructive advice, criticism, support and guidance over the years, in addition to those mentioned above, include Charles Carlton, Tom Cogswell, Brian Cowan, Adam Fox, Peter Lake, Allan Macinnes, Steve Pincus, Bill Speck, Stephen Taylor and the participants in a seminar I taught at the Folger Shakespeare Library in the autumn of 2003: Bill Carpenter, D'Maris Coffman, John Cramsie, Erin Kidwell and Joanne Tetlow. As ever, my students at Brown, many of whom have taken classes which in various ways have explored many of the themes explored here, have been a constant source of inspiration. One particular Brown student, Victoria Harris, a budding historian in her own right, conducted research for me on the loyal addresses of 1683, in the process learning the true meaning of the old methodological adage il faut compter. Above all, I have to express my immense debt to Simon Winder, who encouraged this project from the beginning, who patiently awaited the fruits of my labour amid my repeated complaints of disc problems (of the spinal rather than the computer kind), and who read everything in draft and offered a tremendous amount of constructive critical feedback. The project has taken a shape that it would not otherwise have done without Simon's influence. I would also like to thank Helen Dewen, who read the penultimate draft and gave me a valuable independent critical perspective while also encouraging me to believe that what I had to say was worthwhile; Alison Hennessy for help with the illustrations; and Caroline Wilding for compiling the index. I am extremely fortunate to have worked with a very thorough and highly efficient copyeditor, Bob Davenport, who did his best to rescue me from stylistic infelicities, grammatical mistakes, internal inconsistencies, and various other errors. It goes without saying that any mistakes that remain are mine. Special thanks must also go to my agent, Clare Alexander, whom I initially approached with the idea of her helping me place my next project, but who proved of immeasurable assistance once it became apparent that the present one would need to be split into two.

Neither my wife (Beth) nor my children (Victoria and James) read any of this book in draft, but they supported me in innumerable ways during the lengthy time it took to complete it, helping to sustain my sanity in the process. Words cannot convey how much I owe to them – for their forbearance and for their love. For a British historian based in the States, relatives and friends who are prepared to host one's trips to the archives are an invaluable resource. My parents, Audrey and Ron, whose home is conveniently located just off the M25 somewhere between Heathrow and Gatwick airports, made possible much of the research for this book by providing me with a home away from home when I needed to visit the English archives. My brother and his wife, Kevin and Tina, housed me when I undertook research in the Leicestershire Record Office, as did my parents-in-law, John and Grace, when I did research in the West Country, while my sister and her husband, Sarah and Matt, also provided support on my trips to England. Christine Macleod let me and my family stay in her flat overlooking Arthur's Seat in Edinburgh, while Adam Fox and his wife, Carolyn, hosted me on another trip to the Scottish capital. I am indebted to them all, and I hope I never outstayed my welcome.

Research for this project would not have been possible without the financial support of a number of institutions. In particular, I would like to record my gratitude for the receipt of fellowships from the National Endowment of the Humanities, the Huntington Library, and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, as well as research support and leave time from Brown University.

This book is dedicated to Mark Goldie, who first taught me in the late 1970s, who inspired me to become a later-Stuart historian and nurtured whatever talent he saw in me as an undergraduate and graduate student, and who has been a valued mentor, collaborator and friend for many years. I promised him this book a long time ago. Now it has finally arrived, I hope it does not disappoint.

In quoting from original sources, I have extended contemporary contractions but have otherwise adhered to the original spelling and capitalization, though I have very occasionally provided modern punctuation to assist in readability. Dates are in old style, although with the new year taken as having started on 1 January (rather than 25 March, as at the time).

Introduction

On 29 May 1660 Charles II made his triumphant royal entry into London to reclaim the thrones of his three kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland after more than eleven years of republican experimentation in government. The specially called Convention Parliament had voted to restore the Stuart monarchy on 1 May, and Charles was solemnly proclaimed king in London and the suburbs on the 8th. He actually arrived in England on the 25th, landing at Dover at about 1 p.m. Even given the condition of seventeenth-century roads, it would not normally have taken four days to make the journey of some 70 miles from the south-Kent coast to the nation's capital. The slowness of the pace was deliberate, however, so that Charles's entry and Restoration day would coincide with his thirtieth birthday.

The mood was certainly festive. According to contemporary accounts, great concourses of people gathered in all the towns through which the King passed as he made his way from Dover. When he reached Blackheath, just outside the capital, on the morning of the 29th, there were some 120,000 men, women and children who had assembled from 30 miles around ‘to see his Majestie's princely march towards London’. The King's party comprised above 20,000 men on horse and foot, ‘brandishing their swords and shouting with inexpressible joy’ as they progressed the final few miles into the metropolis. The streets all along the way were ‘straw'd with flowers’ and hung with tapestries, the parish church bells rang, and the fountains ran with wine. The Lord Mayor and aldermen came out to meet the restored monarch on his entrance into London and, after performing ‘those obedient ceremonies due in such cases’, rode bareheaded before Charles and his two brothers, the dukes of York and Gloucester, escorting the royals ‘all along the City’

The Common wealth ruleing with a Standing Army: Tory print representing the tyranny of republican rule in the 1650s. The republic is represented as a dragon which has swallowed parliament and is covered with armed troops; it feeds on monarchy, episcopacy, nobility and the laws of the land, and excretes taxes, excises and religious oaths and covenants.

and through to Whitehall. The liverymen of the City companies together with numerous lords and nobles were there in their splendid ceremonial attire, and huge throngs of people lined the streets as far back as Rochester, 25 miles to the south-east. The noise was tremendous: trumpets sounded from the windows and balconies and, according to one observer, there was ‘such shouting as the oldest man alive never heard the like’. Indeed, so large were the crowds that it took seven hours for the royal entourage to pass through the City – from two o'clock in the afternoon until nine at night. The day concluded with bonfires at almost every house, and a spectacular one at Westminster which saw the burning of effigies of Oliver Cromwell and his wife.1

Less than three decades later, in the second week of December 1688, Charles II's younger brother, the Duke of York, made a journey in the opposite direction, under somewhat less auspicious circumstances. York was a Catholic convert who had come to the throne in February 1685 as James II (James VII in Scotland), but his desire as king to promote the civil and religious interests of his co-religionists had proven controversial, to say the least, and by the autumn of 1688 he faced an invasion from Holland by his son-in-law and nephew, William of Orange, purportedly to rescue Protestant liberties across England, Scotland and Ireland from Catholic tyranny. Uncertain of the loyalty of his army, James panicked, dispatched his wife and newborn son to France, and planned to follow them himself. He left the capital in the early hours of 11 December, making his way through the back roads of Kent towards the Isle of Sheppey, where a small custom-house boat was taking on ballast ready for the Channel crossing. At about eleven o'clock that night a group of seamen from Faversham on the search for Catholic fugitives arrived and detained the party. James was with two fellow Catholics, Ralph Sheldon and Sir Edward Hales, but, although the seamen recognized Hales, who was a local man, they failed to recognize the King, who was sporting a short black wig and a patch on his upper lip as a disguise. Taking James to be Hales's Jesuit confessor, they began hurling insults, calling him ‘old Rogue, ugly, lean-jawed hatchet faced Jesuite, popish dog etc.’. If the King had been prepared to reveal himself immediately, he undoubtedly would have saved himself the indignities that followed, for, without knowing whom exactly they had on their hands, the seamen decided to seize all the valuables from their detainees, taking nearly £200 in gold (most of which was on the King himself), before undertaking a strip-search of the man they took to be the Jesuit – that is, they undid his ‘very breeches… and examined for secret treasure, so indecently, as even to the discovery of his nudities’, as our contemporary account delicately phrases it. It was not until the King was eventually brought to the Queen's Arms in Faversham several hours later that his true identity was discovered.2 On this occasion James was to be brought back to London, but William of Orange had no desire to allow his father-in-law/uncle to remain in the country, and encouraged him to flee once again for France, which James this time successfully did on the 23rd. In February 1689 another specially called Convention Parliament was to declare William and his wife, Mary (James II's daughter), king and queen of England and Ireland in James's stead, and a Scottish Convention was to confer the Scottish crown upon them shortly thereafter.

The troubles of the mid seventeenth century had seen England, Scotland and Ireland torn apart by civil war; had led to the overthrow of the existing order in Church and state and the execution of the king, Charles I, outside his own Banqueting House on 30 January 1649; and had culminated in a series of unsuccessful experiments with various non-monarchical forms of government in a desperate but elusive quest for stability until everything began to fall apart following the death of Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell in September 1658. By the winter of 1659–60 the return of the Stuarts, and with them the old order, seemed the only viable solution, and was much longed for by a population who had never really warmed to republicanism. It was a solution that within less than three decades had proved not to be viable. This time, however, the offending Stuart monarch was not to be hauled before a revolutionary court of justice and condemned to death for committing treason against his own people, but was allowed to slip away quietly in the dead of night in a political coup that has come to be known ever since as England's ‘Glorious’ Revolution – even as the ‘Bloodless’ Revolution. William and Mary became joint monarchs (though with the exercise of regal power vested in William alone) in a dynastic settlement that was accompanied by a Declaration of Rights (later enacted as the Bill of Rights) in England and a Claim of Right in Scotland, both of which were intended to vindicate and assert ancient rights and liberties. Affairs in Scotland were to be far from bloodless, however, while the Irish were to lose out in a bloody war of conquest. This was to be the last political revolution in English and Scottish history; moreover, in contrast to the upheavals of the middle of the century, it was actually styled a revolution by those who lived through it.

With the vantage of hindsight, we can see that the Restoration period was the last gasp for the Stuart monarchy. It would not have appeared that way to people at the time. There was a widespread belief after 1660 that the old order could be successfully restored – witness gestures such as tearing the pages out of council minute books for the intervening period, as if destroying the record of the past would be enough to effectively eradicate it. The restored regime certainly did not have things easy, but was it necessarily doomed to fail?

It cannot be denied that the Restoration regime faced serious difficulties. Indeed, by the late 1670s these had grown so severe that many contemporaries – including the King himself – genuinely came to fear the possibility of renewed civil war. Healing the divisions that had caused the outbreak of civil war in 1642, and which in turn had been exacerbated by the political experiences of the 1640s and '50s, proved no easy task, and political tensions soon began to reappear. In addition, new problems arose – not helped by Charles II's own political failings and by a crisis over the succession which developed once the Duke of York's conversion to Catholicism became publicly acknowledged in 1673. York stood as next in line to the throne, owing to Charles's inability to father any legitimate offspring, and his conversion gave rise to fears that the three kingdoms were drifting back along the path towards popery and arbitrary government. This combination of revived tensions and new anxieties caused the growth of considerable disaffection, both inside parliament and ‘out-of-doors’. All that was needed was some form of trigger, a spark to ignite the wealth of combustible material that already existed, and this was provided by the revelations in the summer of 1678 of a supposed Popish Plot to murder Charles II and massacre English Protestants. With the heir to the throne an acknowledged Catholic, the situation seemed alarming, especially to those who already felt unhappy with the restored Stuart regime. By 1679–81 the restored monarchy had been plunged into renewed crisis, as an organized parliamentary opposition with seemingly considerable support among the mass of the population came to demand the exclusion of the Catholic heir from the succession and pressed for further reforms in Church and state. To many political observers the tactics of the Whigs, as this political opposition soon came to be known, appeared very similar to the those pursued by the parliamentary opposition to Charles I on the eve of the Civil War. It seemed as if '41 was come again, and thus that it was all but inevitable that '42 would follow.

Yet the monarchy managed to extricate itself from this crisis. Charles II not only survived the threat but was even able to rebuild the authority and prestige of the crown, so much so that in the final four years of his reign England appeared to be moving towards a style of monarchical absolutism similar to that which had developed on the Continent, especially in France. Indeed, France itself had successfully escaped from its own mid-century crisis, the ‘Fronde’, to emerge as the world's major superpower under le roi soleil, Louis XIV; perhaps England was destined to go the same way. Moreover, by the mid-1680s the Stuart monarchy had managed to consolidate its authority over Scotland, while Ireland seemed to be more prosperous and stable than it had been for a long time. Such was the nature of the royal recovery in the final years of Charles II's reign that when James II came to the throne, in 1685, he enjoyed the strongest position of any English monarch certainly since the accession of the Stuarts in 1603 and arguably since the accession of Henry VIII in 1509. Furthermore, he was not only powerful, but also popular, since Charles II and his Tory allies (as the opponents of the Whigs were called) had done a magnificent job in rallying public opinion behind the Stuart monarchy and the hereditary succession in opposition to the Whig challenge in the years after 1681.

However, everything was to fall apart dramatically within less than four years. It has been said of Charles I that he was an incompetent ruler, ‘but not quite incompetent enough to leave the kingdom free from civil war’; he was, at least, able to muster a royalist party that would enable him to try to defend his cause by force of arms.3 Yet, unlike his ill-fated father in 1642, by late 1688 James II was not even in a position to fight those who sought to bring him down, such had been the nature of his political collapse, with the result that flight – in the hope of enlisting the military support of Louis XIV to recapture his crowns – became his only realistic option. With the collapse of James's regime went the old political system. England and its dependent monarchies of Scotland and Ireland were to develop in very different ways after 1688–9 – different, that is, from how they would have developed otherwise, and different also from the way most of the Continent was to go. England was to get a Bill of Rights and begin the slow evolution towards its modern system of parliamentary monarchy; the Continent was to see the consolidation and enhancement of monarchical absolutism which it would take the bloody revolutions of the late eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries to overthrow.

On the face of it, then, the Glorious Revolution might seem to deserve a significant place in the nation's historical consciousness, akin perhaps to that enjoyed by the American Revolution, the French Revolution or the European revolutions of the nineteenth century in their respective national historiographies. After all, was not the Glorious Revolution the last major political landmark event before England's emergence as a modern political nation – an event which, to quote one modern-day scholar, made ‘possible the emergence of England, and eventually Britain, as a great power’?4 Indeed, was it not the Glorious Revolution, as Lord Hailsham claimed in the House of Lords in March 1986, which laid the ‘foundations from which evolved, peacefully, the system of parliamentary democracy under a constitutional monarch which we enjoy today’?5 Certainly the implications of the revolutionary settlements in Scotland and Ireland have remained with us until the present day – although it has proved much more difficult to put a positive gloss on these. The Revolution was ultimately to cost the Scots their political independence; when they threatened not to follow the English in settling the succession on the electors of Hanover once it became apparent that the Protestant Stuart line brought to power by the dynastic coup of 1688–9 would die out, they had to be brought into line by an incorporating union of 1707 which created the state of Great Britain and under the terms of which the Scots were granted limited representation in what hitherto had been the English parliament at Westminster. It was not until devolution in 1999 that Scotland was to regain a parliament of its own. Few readers will need to be reminded that the seemingly intractable troubles in Northern Ireland have in large part fed off the historical memory of events that happened in Ireland in the Jacobite war of 1689–91, such as the siege of Derry of 1689 or the Battle of Boyne of 1690. It might seem, then, that without a proper understanding of the so-called Glorious Revolution the inhabitants of the British Isles have no chance of fully understanding their own modern world.

Nevertheless, the Glorious Revolution has occupied a somewhat ambiguous place within the British historical imagination. It has proved difficult to know how to relate to it, as the tercentenary commemorations of 1988–9 testified. What exactly was there to commemorate? To those on the left it seemed nowhere near revolutionary enough; to most liberal-minded people it appeared to be an episode fuelled by anti-Catholic religious bigotry (hardly to be lauded in the multicultural Britain of the late twentieth century); while to ultra-conservatives clinging to a sentimental Jacobitism it had merely served to overthrow Britain's legitimate dynasty by an act of infamous treachery. Moreover, how could one commemorate the event without offering an affront to Scottish and Irish sensibilities?6 Furthermore, however it might have been seen in the past, modern-day scholars have had the discomforting habit of reminding us that the so-called Revolution of 1688 was, in fact, essentially a successful invasion of England by a foreign power – by the Dutch, of all people, a nation with whom England had fought three exhausting wars in the 1650s, '60s and '70s. Indeed, 1688 was the last time that England was successfully conquered! William of Orange did not arrive with a team of diplomats and skilled negotiators in his attempt to rescue Protestant liberties in his father-in-law's kingdoms; he landed at Torbay on 5 November 1688 with a professional army of some 15,000 men. James's flight may have meant that William did not need to engage the King's army in major battle, but that does not detract from the fact that what happened was a foreign conquest. And, although civil war was avoided in England, this was not the case in Scotland, where several thousands died in the ensuing Highland War, while Ireland fell victim to a brutal war between the two kings, James and William, in which nearly 25,000 men died in conflict and thousands more of disease.7

If one focused less on the invasion aspect of 1688 and paid more attention to the settlement that was achieved in 1689, then it became much easier to cast the Revolution as an episode in which the English, at least, might deserve to take some pride. The great Whig historians of the past – from the late eighteenth century through to the eve of the Second World War – certainly believed that the Revolution merited a glorious place in the national (English) historical narrative. They nevertheless tended to see it in conservative terms, as a sanitized revolution which exemplified the moderate English way of doing things, in contrast to the excesses of the European revolutions of the late eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries. Thus Edmund Burke, speaking and writing at the time of the French Revolution, saw the Glorious Revolution as ‘a revolution, not made, but prevented’; its intent had been ‘to preserve our ancient and indisputable laws and liberties’ against ‘the fundamental subversion of the antient constitution’ attempted by James II.8 For the great Whig historian of the mid nineteenth century, Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1688–9 was ‘a revolution strictly defensive’, ‘a vindication of ancient rights’, ‘of all revolutions the least violent’. Indeed, Macaulay believed that ‘the highest eulogy’ that could be pronounced on the Glorious Revolution was ‘that it was our last revolution… It was because we had a preserving revolution in the seventeenth century that we have not had a destroying revolution in the nineteenth.’9 For G. M. Trevelyan in 1938, although the expulsion of James II may have been ‘a revolutionary act… the spirit of this strange Revolution was the opposite of revolutionary. It came not to overthrow the law but to confirm it against a law-breaking king.’ Indeed, Trevelyan thought it might more aptly be styled ‘The Sensible Revolution’, which would distinguish it ‘more clearly as among other revolutions’. It is a view that has continued to be endorsed by historians up to the present day.10

The result of such characterizations was to lead twentieth-century scholars to grow more interested in the mid-century crisis in England, attracted by the lure of what seemed much more like a genuine revolution, albeit a failed one. Thus Christopher Hill, a towering figure in seventeenth-century English historiography from 1940 through to the end of the twentieth century, saw the English Civil War as the first of the modern revolutions.11 Similarly Lawrence Stone was convinced that the upheavals of the 1640s and '50s constituted ‘the first “Great Revolution” in the history of the world’ – indeed ‘England's only “Great Revolution” – and ‘an event of fundamental importance in the evolution of Western civilization’.12 Even revisionist historians, who believe that there was no high road to civil war and that early Stuart England was a most unrevolutionary place, seem to agree that what eventually came to pass in the 1640s and '50s was not only a revolution but also ‘the Revolution’ (albeit ‘the product of the traumas of civil war’), which had ‘profound effects on the subsequent history of the British Isles’.13 As one influential recent textbook has put it, summarizing conventional wisdom, 1648–9 was ‘the only revolution in English history’.14 The events of 1688–9 have been seen, by most, as either a postscript or a tidying-up operation – an after-tremor, not the ‘major earthquake itself’15 – or even as something that was essentially conservative and backward-looking.16 Though there have been some attempts, of late, to reinvest the Glorious Revolution in England with more radical credentials, these accounts still leave us with the impression of an episode that was much less revolutionary than what transpired in the 1640s and '50s.17

Such ways of thinking have affected the way historians have tended to study the Glorious Revolution. If it was primarily a defensive revolution, against the innovations of James II, then no long-term causes need to be sought. Our accounts can start with the accession of James II in 1685; at most, perhaps, they need to go back to the final years of Charles II's reign and the so-called Tory Reaction which set in following the defeat of the parliamentary campaign for Exclusion in 1681. Many works, indeed, have concentrated on just the year of revolution itself. This short-term approach has caused a certain myopia, an inability to perceive the underlying problems which undermined the stability of the restored Stuart regime. The oft-repeated assertion that the Glorious Revolution was bloodless and largely non-violent has tended to deflect attention from the bloodiness and violence that did occur, even in England. Whether this was really as sanitized a revolution as is often implied is clearly open to question. And the illusion that it was has been sustained only by ignoring Scotland and Ireland, whose revolutions were both violent and bloody. Finally, the marginalization of the Glorious Revolution vis-à-vis its supposedly more important elder brother of the mid seventeenth century has served to perpetuate further the view that 1688–9 was not much of a revolutionary moment at all. Yet why should a revolt that failed be thought to have had a greater impact on Britain's subsequent historical evolution than one which succeeded?

This study aims to invite a fundamental rethinking of the way we approach the study of the Glorious Revolution and the significance we attach to its outcome. It is concerned, at a basic level, with the origins, nature and outcome of the Glorious Revolution in all three of the kingdoms over which the Stuarts ruled. But its objectives go much further. More generally, it seeks to explore the nature and reality of political power in Restoration England, Scotland and Ireland – how royal authority was made effective, and how it could be undermined. It investigates the root causes of instability in the Restoration period, and why, when monarchy had been so enthusiastically welcomed back in 1660, the restored regime seemed on the verge of collapse less than two decades later. It examines how this regime then managed to extricate itself from this crisis and rebuild the powers of the monarchy in the first half of the 1680s. Finally, it considers why the Stuart regime collapsed so precipitously under James II, how that collapse was brought about, the nature of the solutions devised in 1689, and the longer-term significance of those solutions. A major sub-theme is a consideration of whether there truly was a potential for monarchical absolutism in the Stuart kingdoms in the 1680s and, if so, how and why Britain and Ireland's absolutist turn during this decade was eventually defeated. Broadly speaking, this study is a work of political history. Yet it is also a work of legal–constitutional history and of intellectual history; a study of propaganda, public opinion and popular politics; a work that deals with the localities as well as the centre, and with the concerns of ordinary men and women as well as those of the great and powerful.

This project has been shaped by a belief that the period from the Restoration through to the Glorious Revolution and its aftermath needs to be treated as a whole. However, it grew so large that it became necessary to split it into two volumes. The present book deals with the monarchy under Charles II, from the joyful enthusiasm with which Charles was welcomed back in 1660, through to the crisis the restored regime faced by 1679–81, and on to the rebuilding of the monarchy during the years of the Tory Reaction from 1681 to 1685. A sequel deals with the Revolutions of 1688–9 and their aftermaths, tracing the story from the accession of James II in 1685 through to the early eighteenth century. Both volumes are intended to stand alone and thus to be self-contained. Nevertheless, the study has been conceived as a whole, and together the two books do tell a larger story.

There are a number of deficiencies within the existing corpus of scholarship on the Glorious Revolution, of both a conceptual and an empirical nature, which this study seeks to address. First, most works on the Glorious Revolution have focused on the political elite, concentrating either on events at court or at Westminster, the machinations of the key actors involved in the resistance to James, and the framing of the eventual Revolution settlement, or else on those political ideologues who published treatises and pamphlets seeking to offer intellectual justifications (or alternatively condemnations) of the dynastic shift and the accompanying reforms in Church and state. Less attention has been paid to the role of the middling and lower sorts, or those out-of-doors. Historians have, of course, always been aware that there was a certain amount of crowd unrest at the time of the Glorious Revolution; nevertheless, they have seemed unsure about how to integrate high and low politics in their analyses. The result has been that the crowd has tended to get pushed to one side, or even left out of the picture altogether.18 The frequently encountered characterizations of the Glorious Revolution in England as a mere palace coup or a dynastic revolution highlight the extent to which those out-of-doors have been marginalized within the dominant interpretative paradigm. This seems at odds, however, with recent scholarship on the Restoration, which has emphasized the vitality of politics out-of-doors during the reign of Charles II, the importance of crowd agitation and public demonstrations (not just in London, but also in the provinces) and the vital role of mass petitioning campaigns. Indeed, Restoration scholarship has pointed to the need for a social history of politics: one that does justice to high politics, at the centre, but also sets the operation of politics in its appropriate social context, examining the impact the policies of the rulers had on those they ruled, and considering the extent to which those out-of-doors may have been involved in the political process and actively pursued political agendas of their own.19 In short, the new approaches that have been developed for the Restoration period suggest the need to rethink our approach to the Glorious Revolution; we need an account of the period as a whole that can show the ways in which our understanding of the dynamics of politics out-of-doors for the reign of Charles II can in turn shape our perspective on the reign of James II and the revolution which brought about his downfall.

Second, we have no major modern study of the Glorious Revolution – nor, indeed, of the later Stuart period as a whole – that provides an integrated analysis of developments in all three Stuart kingdoms. Scotland, Ireland and England have typically been treated in isolation, even though the overthrow of James II (or James VII as he was in Scotland) and his replacement by William III (William II in Scotland) had ramifications throughout all three kingdoms of the Stuart composite monarchy. Three kingdoms lost their reigning monarch in 1688–9 as a result of the Dutch intervention in England. Not only did each of three kingdoms experience the Revolution, but there were also three very different revolutions in the respective kingdoms, albeit that they ultimately had the same trigger. Indeed, there seem to be compelling reasons for examining the entire period from the Restoration to the Glorious Revolution in a three-kingdoms context.20 The restoration of monarchy was, in itself, a quintessentially three-kingdoms event, even if each individual kingdom was then to have its own respective Restoration settlement. When Charles II was restored in the spring of 1660, he was restored as king of all three of his kingdoms, and all three kingdoms had played a crucial role in helping to bring about the return of the Stuart monarchy. Ireland was the first to act, when conservatives in the army seized control of Dublin Castle in December 1659 and paved the way for the meeting of the Irish Convention which would ultimately declare for Charles II. It was the intervention in English affairs by the Scottish army under General George Monck from January 1660 that secured the final demise of the Rump Parliament (the rump of the Long Parliament which had declared war on Charles I in 1642, been purged by Colonel Thomas Pride in December 1648, dismissed by Oliver Cromwell in 1653, and recalled to power in 1659) and the calling of the English Convention which would formally restore Charles Stuart. Similarly, the Exclusion Crisis of 1679–81 was not an episode solely in English history, since the attempt in England to exclude the Catholic heir from the succession inevitably had repercussions for Scotland and Ireland, where the same man was also heir to the throne. However, for Scotland and Ireland the period from the Restoration to the Glorious Revolution remains seriously understudied, and is in desperate need of new research if we are to develop a full appreciation of the nature of Stuart rule in these two kingdoms, of the problems it created, and of the true significance of the respective revolutions in each.21 This study therefore aims to fill a major gap by providing the type of contextualized study of the Glorious Revolution in both Scotland or Ireland that was previously lacking, hoping to generate new insights into the Scottish and Irish pasts in the process, while at the same time providing a fresh conceptual framework from which to re-evaluate the nature and significance of the developments within England itself as well as within the Stuart multiple-kingdom inheritance as a whole.

Third, the scholarly community has, on the whole, failed to appreciate the revolutionary significance of 1688–91. It is the contention of this two-volume study that it is in the later Stuart period that the true revolutions of the seventeenth century were located – revolutions, that is, both as contemporaries would have understood the term and also in the modern meaning of the word – involving fundamental and irreversible changes that transformed the way the world was for the inhabitants of England, Scotland and Ireland. The modern British state, and even many of the problems that bedevil the relationships between England, Scotland and Ireland today, is much more a product of the ‘successful’ revolutions that followed in the wake of the dynastic coup of 1688–9 than of the failed (or successfully undone) revolutions of the middle decades of the seventeenth century. Again, this is a point that can be fully grasped only by studying the period from the Restoration to the Glorious Revolution as a whole: we can appreciate how much was changed after 1688 only by understanding exactly what was restored in 1660. These are bold claims. Before we proceed any further, then, more needs to be said about the particular conceptual framework in which this study will be set.

A SOCIAL HISTORY OF POLITICS

A major theme of this study will be that the fortunes of the crown in the years between 1660 and 1688 were intimately linked to the climate of public opinion. Charles II got into trouble by the late 1670s because too many people had become alienated from his regime. Royal recovery in the early 1680s, by contrast, was related in crucial ways to the crown's ability to win back public opinion, while royal collapse under James II was tied up with the crown's failure to carry public opinion behind its ambitious and controversial policies. The emphasis offered here on the importance of public opinion will bear significant implications for our understanding of the Revolution itself, and whether it should be seen merely as a dynastic coup imposed from above (and even outside) or as a revolution wrought from below. It also necessitates setting politics in a broader social context. If this is to be done, however, we need to reflect at the outset on how politicized those below the level of the elite might have been. Did the people have any politics worth talking about? If so, how did they obtain a political education?22

One way, obviously, was through the media. There was a dramatic expansion of the output of the printed press in the seventeenth century, starting with the breakdown in censorship on the eve of the Civil War. Although restrictions were reimposed in the 1650s and at the Restoration, they were never fully effective, and broke down again with the temporary lapsing of the Licensing Act in 1679. During the Exclusion Crisis, and again at the time of the Glorious Revolution, members of the political elite (of all political persuasions) certainly made every effort to exploit the medium of print in order to woo public opinion.23 Printed materials, especially the shorter pamphlets, news-sheets and broadsides, enjoyed a wide circulation, often being deposited in coffee houses and other public places so that they could be read by those who could not afford to buy their own copy. There may have been as many as 2,000 coffee houses in the greater London area alone by the end of the century, although they were far from being a metropolitan phenomenon, since coffee houses could be found throughout the country, in smaller towns as well as in larger urban areas, and also in Scotland and Ireland.24 Though printed media were available, many people continued to learn their news from traditional scribal forms of publication, such as manuscript newsletters, and, while it could be expensive to subscribe to a newsletter service, newsletters were likewise frequently deposited at coffee houses and alehouses for more general consumption. Indeed, it was claimed that in Restoration England newsletters were to be found in every village inn, with the local squire often expounding upon their contents ‘like a little newsmonger’; they were even on occasion posted up in the streets for public perusal, and there they could not only be read but also be recopied for further distribution.25 In Scotland in the late 1670s and early 1680s the minister of Hamilton (on the outskirts of Glasgow) was receiving regular newsletters from a correspondent in Edinburgh, who reported not just Scottish news but also English news which he had presumably picked up from newsletters circulating in the Scottish capital.26 In Ireland, newsletters were reaching not just the capital, Dublin, but also provincial towns, such as Kinsale and Youghall.27

But what impact would printed or written media probably have had on the people at large? After all, was not this a society with relatively low levels of literacy? There are, in fact, compelling reasons why we should not have too pessimistic a view of the political awareness of the mass of the population. In the first place, literacy levels were not as low as we were once led to believe. One important modern study has calculated that only 30 per cent of English men and 30 per cent of English women were literate in the early 1640s (as measured by the ability to sign one's name) – fairly low figures, one might think, though these had risen to 45 per cent and 25 per cent respectively by the accession of George I in 1714. These percentages are somewhat deceptive, however. National averages are not particularly meaningful, because there were marked regional and occupational variations in literacy profiles. The sample from which these totals were derived was biased towards rural communities, but town-dwellers tended to be more literate than those who lived in the countryside. Literacy rates were highest in London, where by 1641 –4 nearly 80 per cent of the adult male population could sign their names. Furthermore, the middling sorts tended to be more literate than the lower orders: yeomen, craftsmen and apprentices were much more likely to be able to sign their names than were husbandmen, labourers and servants. Moreover, the signature test clearly underestimates literacy levels for early modern England, for the simple reason that reading was taught before writing: there were many more people who could read than had learned to sign their name – perhaps as much as half as many again. And, since females tended to be educated up until the point when they could read, but to leave school before they learned to write, there are reasons for suspecting that women were just as likely to be able to read as men.28 Research on Scotland has shown that in the 1670s and '80s about two-thirds of Scottish males were literate, though here the sample was biased towards urban centres and the Lowlands, where literacy was more widespread. In fact Scotland evinced the same marked occupational and regional variations as England, with 82 per cent of labourers illiterate in the period 1640–99 and illiteracy rates much higher in rural areas and in the Highlands.29 So, too, did Ireland, where literacy was again highest among the middle and upper classes and in the towns. One study of debt cases in Dublin for 1651–2, for example, has shown that 66 per cent of sureties could sign their names; by the 1690s the corresponding figure was nearly 80 per cent. All the obvious members of the local Dublin elite were literate, while between 70 and 80 per cent of craftsmen and those involved in the drink trades were too. Butchers and bakers, by contrast, were predominantly illiterate. The more prosperous tenant farmers could read: over 73 per cent of those who signed leases on the Herbert estate at Castleisland in Kerry between 1653 and 1687 could sign their names (66 per cent of the native Irish, 83 per cent of the settlers), as could 85 per cent on the Hill estate in County Down, though here we are dealing with people mainly from the middle ranks of society. In general, literacy was less needed, and also less likely to be obtained, if one were engaged in farming. Thus on the Adair estates around Ballymena, County Antrim, in the later seventeenth century, only 33 per cent of farmers and yeomen could sign their names, whereas 94 per cent of those engaged in trade could.30

In short, literacy was more widespread than once thought. Yet, even if one were illiterate, this was not necessarily a bar to gaining a political education. People did not have to be told what the government was up to by the press; they lived under government, and therefore experienced the implications of government policy directly themselves. Economic regulation, the imposition of taxes, the policing of religious conformity, and the ways in which law and order were enforced all helped shape people's attitudes towards those who held the reins of power. These attitudes, it is true, would be refined, modified, reshaped or even redirected by exposure to the media. And, when we talk about the media, we should not think just about the printed press. Traditional forms of oral communication remained vitally important. One of the most powerful tools for the dissemination of political information and ideas was the sermon, which is why both Charles II and James II sought to clamp down on the expression of hostile political opinions from the pulpit while doing their best to encourage clergy to propagate views favourable to the monarchy. Even when we are dealing with written materials, we have to recognize that often their content came to be transmitted orally. Inability to read did not necessarily prevent people from gaining access to political news conveyed in print or writing, since those who could not read could gather around someone who could and hear extracts of the latest political squibs read aloud. We can even find examples of party activists in the provinces reading pamphlets out for the edification of passers-by, or going into pubs and ‘holding forth to a parcel of apron men’ about the due bounds of political authority.31 Word of mouth remained an essential way of spreading the latest news and gossip. People would typically greet travellers or those who had returned from a journey (particularly those who had come from the capital) with the question ‘What news?’, and the news obtained quickly spread through traditional local communication networks – whether the church, the market, the alehouse or the coffee house. People reacted as much to what they heard as to what they read, and this provided a fertile environment for the spreading of rumours;32 indeed, time and again rumour was to play a crucial role in helping to destabilize the Restoration polity.

Public demonstrations were another form of political communication. An eyewitness could ‘read’ public rituals, such as the elaborate pope-burning processions staged by the supporters of Exclusion in London during the height of the Exclusion Crisis, rather as one could read a Whig anti-Catholic broadside. Here was another medium (like rumour) that the masses could exploit for themselves. And if processions could be read like pamphlets, people could in a sense write their own pamphlets by staging a dramatic ritual which observers could witness, and which the writers of news or political commentary could then carry accounts of in their manuscript newsletters or printed broadsides.

What we have, then, is a more complicated picture than that of the elite simply reaching out to the people and trying to politicize them through printed media – with those who were unable to read (or to read well enough) being left behind in some sort of apolitical void. People were politicized in a variety of other ways as well, particularly by how they came to experience the effects of government policy, and they had their knowledge, expectations, identities, ideals, perspectives and attitudes organized, shaped and mobilized not just by what they read in pamphlets or news periodicals, but also by what they heard in sermons or saw in public demonstrations, what was spread by word of mouth, and what they had been led to believe was true by rumours that were circulating at the time.

THE THREE-KINGDOMS APPROACH

We have suggested that our understanding of the Revolutions of the later seventeenth century would be enhanced by taking a three-kingdoms approach. Some of the reasons have been alluded to already. At the very basic level, given that the Stuart monarchs ruled Scotland and Ireland as well as England, any event or crisis that had implications for the succession of the crown had implications for all three kingdoms. This was true of the Restoration of 1660 itself, as well as of the Exclusion Crisis of 1679–81 and the Glorious Revolution of 1688–9. Further than this, many of the problems that beset the Restoration polity were related to difficulties in managing the multiple-kingdom inheritance and the different legacies bequeathed by the upheavals of the 1640s and 1650s in England, Scotland and Ireland. Thus what Charles II tried to do to stabilize royal authority in one kingdom often had the effect of destabilizing politics in one of his other kingdoms. Contemporaries recognized that there were certain problems or issues facing them that operated on a three-kingdoms level, and not on separate national levels. The concern expressed by the Whigs in England in the late 1670s and early 1680s about the threat of popery and arbitrary government, for example, reflected not just a fear of what might happen, in the future, should the Catholic heir succeed to the English throne; it was also a reaction, in part, against what was going on in the present under Charles II, in Ireland and Scotland. Likewise, Tory fears about the threat posed by the English Whigs and their nonconformist allies were in part conditioned by the Tories' reaction to the subversive challenge offered by the radical Presbyterians north of the border. The extent to which contemporaries thought of the emerging crisis in a three-kingdoms context is evident from the very terms adopted to designate the competing factions or parties: the term ‘Whig’ referred originally to a radical Scottish Presbyterian; ‘Tory’, to an Irish-Catholic cattle thief. Both Charles II and James II frequently sought to play the three-kingdoms card, pursuing particular strategies in one kingdom in order to make political points to another: Charles did this with considerable success in his final years; James's efforts served only to provoke further alarm among his Protestant subjects in all three kingdoms. Indeed, it has long been recognized by Scottish and Irish historians that James would not have fallen in Scotland and Ireland had he not fallen in England; it also needs to be recognized that what James did in Scotland and Ireland goes a long way towards explaining why he lost the support of both the political elite and the mass of the population in England, and thus why he succumbed to the invasion of William of Orange.

Yet, although some factors operated on a three-kingdoms level, others did not. The separate national histories of the three constituent kingdoms of the Stuart composite monarchy also need to be treated on their own terms. We must guard against an Anglocentric approach – one that draws on Scotland and Ireland merely to explain developments within England; three-kingdoms history must not become an excuse for marginalizing those aspects of the Scottish or Irish past which seem irrelevant from an Anglo-imperialist perspective. Hence, in addition to exploring the interplay of events in England, Scotland and Ireland at this time, this book and its sequel devote separate chapters to analysing developments in each of the constituent kingdoms individually. Such a strategy also helps highlight another advantage of pursuing a three-kingdoms approach, namely the comparative perspective it can offer. What it was possible to achieve in one of the three kingdoms can set in sharp relief the significance of what transpired in the others.33

This is not intended to marginalize the Welsh. Scotland and Ireland need to be treated independently for analytical purposes in order to explore the interaction between separate kingdoms that happened to share the same king. The principality of Wales, by contrast, had been incorporated into the English state with Henry VIII's acts of union of 1536 and 1543, and, although political and religious developments could take on distinctive Welsh hues, administratively Wales was part of England. For that reason, developments in the principality will be treated in those chapters that deal with England.

It will be helpful here to say something more about the nature of the political relationship between the three constituent kingdoms of the Stuart monarchy. Scotland and England were two independent kingdoms; James VI of Scotland had simply inherited the English crown back in 1603, but his attempts as James I of England to bring a closer union of the two countries had foundered. Although Oliver Cromwell's conquests of Scotland and Ireland had brought about a temporary political union in the 1650s, this was dissolved at the Restoration. Scotland and England had separate constitutions, separate legal systems and laws, separate administrative and ecclesiastical structures.34

Each kingdom had its own parliament, but the bodies were very different in nature. The English parliament was bicameral, comprising an upper house of lay and ecclesiastical lords and an elected House of Commons. Following the passage of the second Test Act in 1678, which excluded Catholics from sitting in the Lords, there were 147 peers eligible to sit in the upper house (including 24 bishops and 2 archbishops); on average, however, only about half this number were ever in attendance. After the enfranchisement of the county and city of Durham and of Newark (Nottinghamshire) in 1673, the Commons comprised 513 members, the elected representatives of 52 counties and 217 boroughs across England and Wales. Most constituencies returned two members; London was unique in returning four; the Welsh constituencies and five English boroughs returned just one. In some areas the franchise was quite broad. Given inflation, the 40-shilling-freehold requirement was no longer particularly restrictive by the later seventeenth century; in Yorkshire, for example, some 8,000 could vote. The franchises in the boroughs varied considerably, and although some were quite restrictive in Buckingham, for example, only the thirteen town councillors could vote others were extremely broad: in the populous borough of Westminster, where the franchise was invested in the inhabitant householders, the electorate numbered some 25,000 in 1679.35 Indeed, it has been estimated that perhaps as many as one in four of the adult male population had the right to vote in parliamentary elections in the later Stuart period.36 The precise position of parliament within the constitution was vague. Whigs tended to see parliament as a coordinate power, which shared in the king's sovereignty. Tories denied this, and emphasized parliament's subordination to the sovereign monarch. Certainly the king determined when parliament should meet; parliament was not an independent body in that sense. However, the king could neither collect taxes nor enact legislation without parliamentary consent.

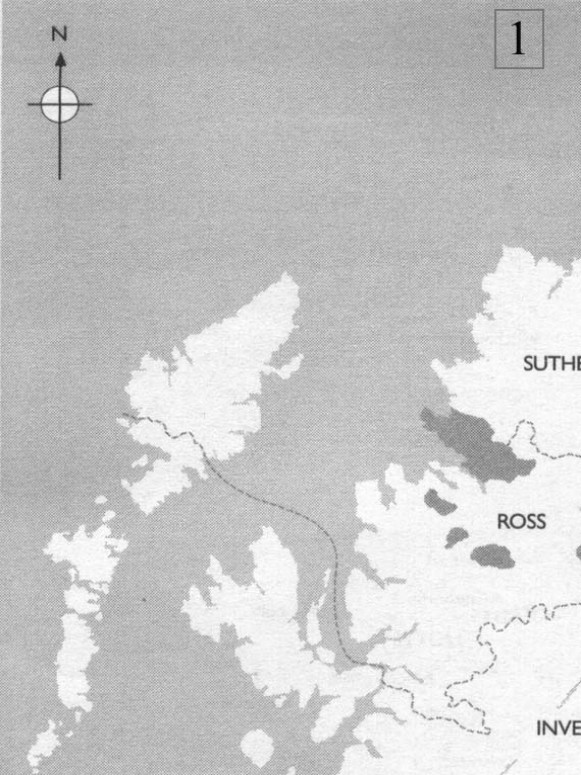

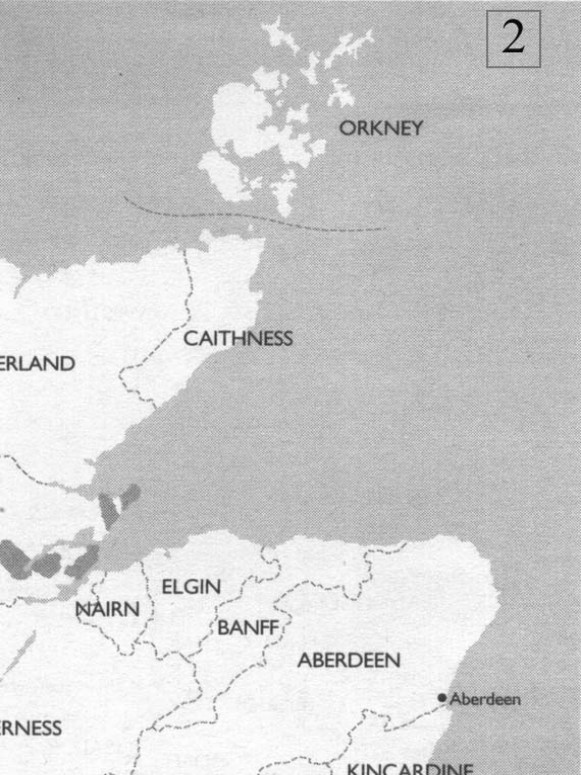

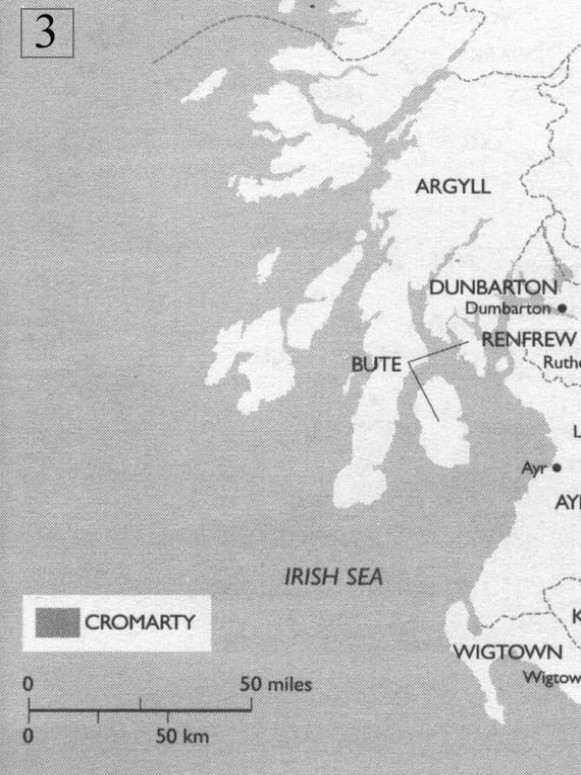

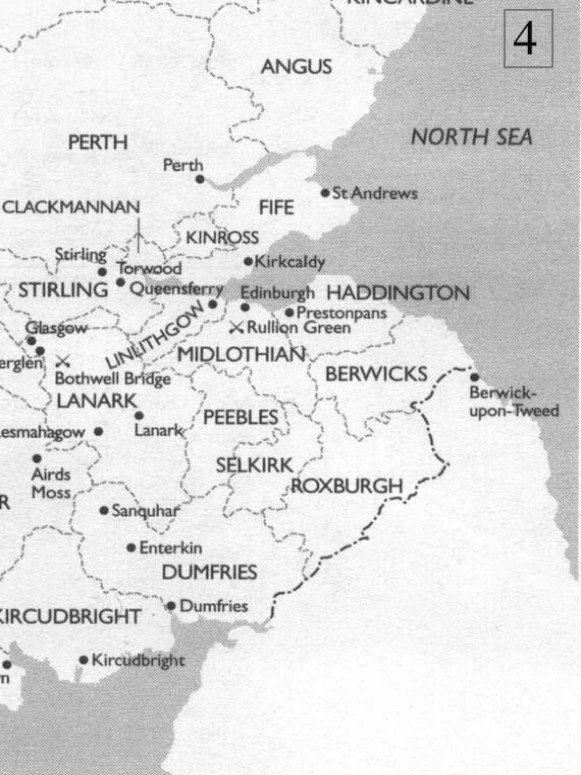

The Scottish parliament, by contrast, was a unicameral body, where the three estates of clergy, tenants-in-chief (comprising both hereditary lords and elected shire representatives) and burgesses sat together. The shires had the right to return two commissioners to parliament, with the exception of Clackmannan and Kinross, which could send just one. The royal burghs sent just one commissioner, though the capital, Edinburgh, sent two. The electorate was small. In the shires the right to vote was restricted to the tenants-in-chief who held lands with an annual value of 40 shillings, although acts of 1661 and 1681 subsequently extended this to include some of the wealthier feuars or feuholders (those who held their land in perpetuity on condition of a substantial yearly payment to the crown). One historian has calculated that the average number of voters in shire elections in the Restoration period was 16. In the burghs the electorate was typically the members of the town council. There was some fluctuation in the composition of the representative element. The number of shires with the right to return commissioners did not become fixed at 33 until 1681, and even then they did not always return their full quota; the number of parliamentary burghs fluctuated between 58 and 68 over the course of the seventeenth century. The 1681 parliament comprised a total of 195 members: 2 archbishops and 10 bishops; 62 lay peers, together with 4 officers of state; 57 shire commissioners representing 33 shires; and 60 burgh commissioners for 59 burghs.37

In Scotland, parliament had to be called if the king wanted to enact legislation; if he sought only money, however, he could call a convention of estates. This meant that, unlike in England, the issue of supply could be kept divorced from the redress of grievances. Moreover, legislative initiatives in the Scottish parliament were managed by a select steering committee known as the Lords of the Articles, comprising eight bishops, eight nobles, eight shire and eight burgh commissioners, and eight officers of state. The original logic behind the Lords of the Articles had been to address some of the problems inherent in having a unicameral parliament. In the first place, the committee was designed to ensure that the different estates had equal representation ‘in the Projecting, and Framing of the Laws’; otherwise, in an open vote in the house, ‘the Estates not being equal in number, a greater State Combining, might overthrow the Interest of another.’ (In England, where both houses had a negative voice, this situation could not arise.) Moreover, since the king could increase the number of nobles and royal burghs at pleasure, he could easily pack the parliament to the disadvantage of the shires, should he so desire. In the second place, it was intended to guarantee that due deliberation took place before any legislation was placed, for in Scotland, where ‘the Procedure [was] quick, and the Forms of Parliament… Expedit and Summar’, a sudden vote in favour of a piece of legislation could put the king info a quandary as to whether or not to assent to the bill, since he might still be ignorant of the design of the law framed; the fact that in England legislation had to go through both houses meant that the crown had more time to evaluate it. However, since 1633 the bishops had chosen the eight noblemen to serve on the Articles, and these eight noblemen had in turn chosen the eight bishops, with the sixteen nobles and bishops then choosing the shire and burgh representatives. Given that the king appointed the bishops (as well as the officers of state), this meant that the crown could effectively determine the complexion of the Articles. And, instead of the Articles being merely a preparatory committee, as originally intended, it came to be established practice that any proposals for legislation which the Articles rejected could not be brought before parliament. Scottish parliaments were thus relatively weak institutions, unable to offer the same sort of counterbalance to the political authority of the crown as their English counterparts.38

The nature of the relationship between Ireland and England was rather different. The English claim to suzerainty over Ireland dated back to the second half of the twelfth century, and stemmed from a papal grant of 1155 by Pope Adrian IV to allow Henry II ‘to enter into the island’ for the purpose of extending the boundaries of the Church, restraining vice, implanting virtues, promoting the growth of the Christian religion, and subjecting the native population to the rule of law. Whether the pope had had the right to give Ireland away in this manner was questionable. The papacy's original claim to the island rested on the Donation of Constantine – whereby in 337 the emperor Constantine had supposedly granted Rome and all the western regions to the pope following his decision to administer his empire from Byzantium – but this had long since been proved a forgery dating from the eighth century. Besides, seventeenth-century English Protestants would have been quick to deny that the popes had ever enjoyed any right to temporal jurisdiction.39 The English therefore chose to base their claim to Ireland ultimately on the right of conquest, which had begun with the Anglo-Norman invasion of 1169 – although it was not to be until 1603 that effective English rule was extended over the whole isle. Henry II had set himself up as feudal overlord of the isle; it was only in Henry VIII's reign that the English king also took on the title of king of Ireland. By an act of 1541 the Irish crown was established as an ‘imperial crown’, possessing ‘all maner honours, prerogatives, dignities and other things whatsoever’ belonging ‘to the estate and majestie of a King imperiall’, but one which was nevertheless ‘united and knit to the imperial crown of England’. It was, in other words, an independent crown that went with the job of being king of England.40

The act of 1541 embodied the crucial ambiguity that underlay the nature of the relationship between England and Ireland throughout the early modern period: were they two independent kingdoms, or was Ireland merely a colonial dependency of England, rather like Virginia? At first glance, the colonial analogy seems to fit well: Ireland was settled by people from the English mainland who expropriated the land from the natives, and it was ruled by the English in the interests of England, who treated Ireland in much the same way as they treated the American colonies. Yet Ireland was not strictly speaking a colony. The native Irish, unlike their American counterparts, were full subjects of the crown, and were even given feudal titles.41 Moreover, Ireland possessed its own government and had its own parliament, though Poynings’ Law of 1494, most famously, had established that the Irish parliament could not enact legislation unless this had been first approved by the English king and council.42

The Irish parliament itself was modelled on the English one: it was bicameral, with a House of Lords (lay and ecclesiastical) and a House of Commons elected by the counties and boroughs, which returned two members each. There were 22 lords spiritual (18 bishops and 4 archbishops), and in 1681 some 119 Irish temporal peers. There were 32 counties, but the crown increased the number of borough seats dramatically over the course of the seventeenth century, in order to assure a Protestant ascendancy in the Commons. Thus the Commons grew in size from 76 in 1560 (when only 10 of the then 20 counties received writs of election), to 232 by 1613, to 276 by 1666 and to 300 after the Glorious Revolution.43 Like England, Ireland had a 40-shilling-freeholder franchise in the counties and a variety of franchises in the boroughs. By 1692 there were 117 borough constituencies; in 55 of these the right to return MPs lay with members of the corporation; in 36 with the freemen; while there were 12 potwalloper boroughs (a potwalloper being anyone not in receipt of arms or charity), 8 county boroughs and 6 manor boroughs. Trinity College, Dublin, also returned two MPs, elected by the fellows and scholars.44