Contents

Return to beginning of chapter

Destination Russia

‘Oh, what a glittering, wondrous infinity of space the world knows nothing of ! Rus!’

Nikolai Gogol, Dead Souls (1842)

For centuries the world has wondered what to believe about Russia. The country has been reported variously as a land of unbelievable riches and indescribable poverty, cruel tyrants and great minds, generous hospitality and meddlesome bureaucracy, beautiful ballets and industrial monstrosities, pious faith and unbridled hedonism. These eternal Russian truths coexist in equally diverse landscapes of icy tundra and sun-kissed beaches, dense silver birch and fir forests and deep and mysterious lakes, snow-capped mountains and swaying grasslands – those famous steppes. Factor in ancient fortresses, luxurious palaces, swirly spired churches and lost-in-time wooden villages and you’ll begin to see why Russia is simply amazing.

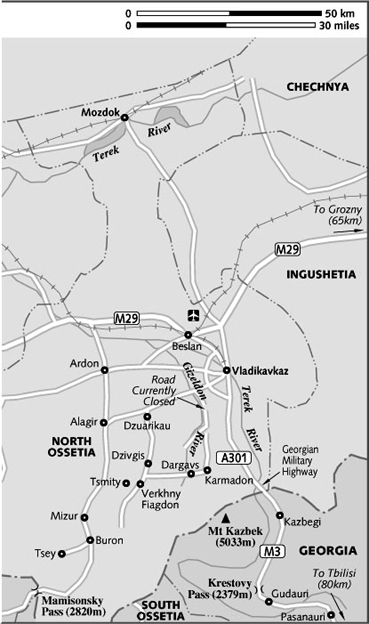

To get the most from Russia, head way off the beaten track. After taking in old favourites such as dynamic Moscow, historic St Petersburg and beautiful Lake Baikal, dive further and deeper into the largest country in the world. Visit the soft, golden sands of the old Prussian resort of Kranz, now known as Zelenogradsk, in the far western Kaliningrad Region; the charming Volga river village of Gorodets, home to folk artists and honey-cake bakers; fascinating Elista, Europe’s sole Buddhist enclave and location of the wacky Chess City; the 400-year-old mausoleums of Dargavs, a North Ossetian ‘city of the dead’ or the hot springs of Kamchatka’s Nalychevo Valley in the Russian Far East.

FAST FACTS

Population: 141.4 million

Surface area: 17 million sq km

Time zones: 11

National symbol: double-headed eagle

Extent of the Russian rail network: 87,000km

Gazprom profits in 2007: R658 billion (US$27.8 billion)

Rate of income tax: 13% flat

Number of deaths per year from alcohol poisoning: 40,000

Number of languages spoken (other than Russian): more than 100

Number of Nobel Prize winners: 20

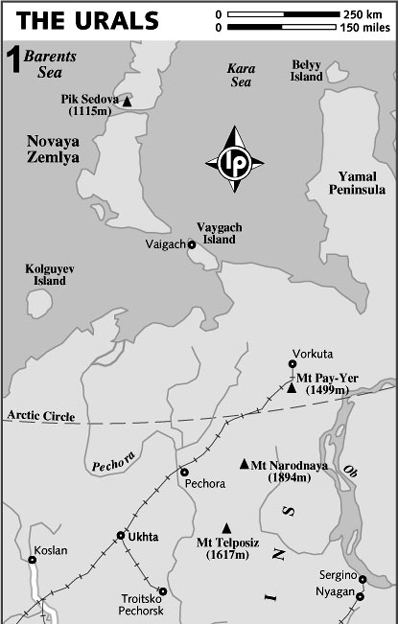

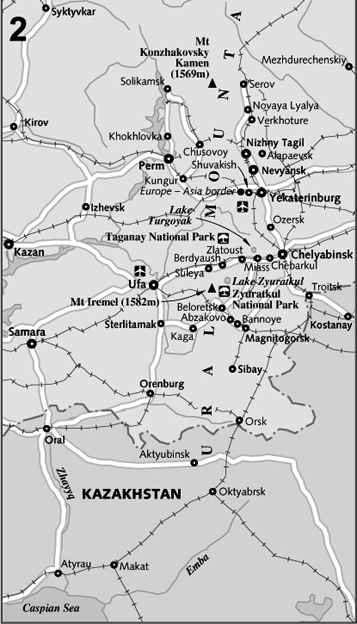

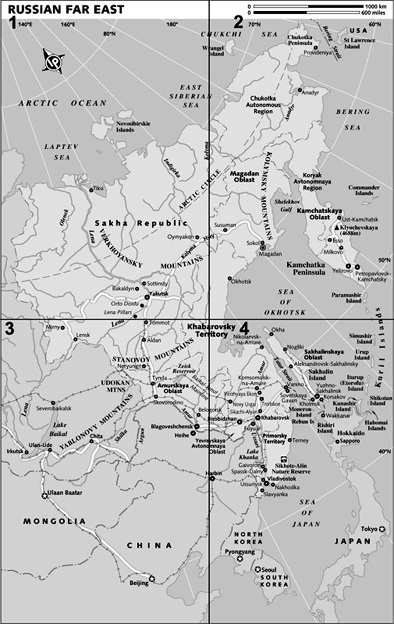

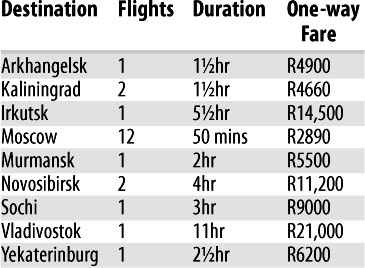

Russia’s vast geographical distances and cultural differences mean you don’t tick off its highlights in the way you might those of a smaller country; the Russian Far East, for example, is the size of Europe. A more sensible approach is to view Russia as a collection of countries, each one deserving exploration. Rather than transiting via Moscow, consider flying direct to a regional centre such as Irkutsk to have an Eastern Siberian vacation, or to Yekaterinburg to explore the Urals mountain range.

If cultural and architectural highlights are what you’re after, stick to European Russia, which is all of the country west of the Urals. If you don’t mind occasionally roughing it and are in search of Russia’s great outdoors, train your eye on the vast spaces of Siberia and the Far East. Alternatively, boost your adrenaline on the country’s top ski resorts and raft-friendly rivers. You can also get a bird’s-eye view of it all from the cockpit of a MiG-25 or even from outer space, as well as unique experiences such as getting a beating in a banya (traditional steam bath).

In the past decade Russia has evolved from the economically jittery, inefficient and disorganised basket case that Vladimir Putin inherited from Boris Yeltsin to a relatively slick petrodollar mover and shaker, the world’s No 1 luxury goods market. Off the back of oil and gas sales, the world’s biggest energy exporter has paid off its debts and stashed away reserves of R3.84 trillion (US$162.5 billion). With the economy growing at an average 7% per year, the National Statistics Agency reported that the average monthly salary rose by 27% in 2007 to R13,500 (US$550) and that unemployment was down to 6%. According to Forbes magazine in 2007, 19 of the 100 richest people in the world were Russians, while the country’s tally of 87 US$ billionaires makes it second only to the US. Lenin is surely spinning in his mausoleum!

The global financial turmoil of late 2008 may have put a significant dent in their bank balances, but it remains true that the lyux life enjoyed by the likes of aluminium mogul Oleg Deripaska or Roman Abramovich might as well be on an different planet from that of the 20 million or so Russians who subsist on less than R4500 a month. Luxury is hardly common to the growing Russian middle class, either, who nevertheless enjoy lives undreamed of by the vast majority of Soviet citizens less than two decades ago. Under such circumstances they have supported Putin and continue to support his successor Dmitry Medvedev, at the same time as gritting their teeth and tightening their purses to deal with steadily rising inflation, counted at 15% in the year to May 2008.

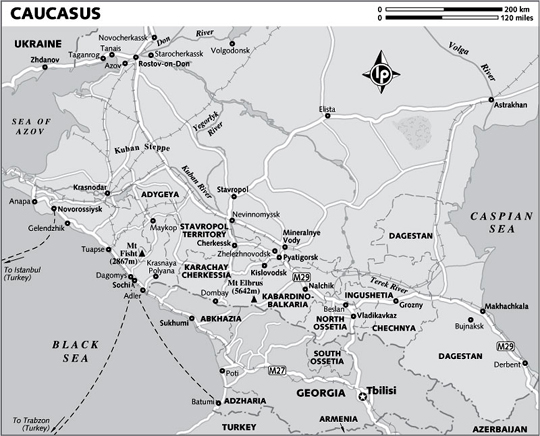

With no credible opponent, Medvedev’s election to president in March 2008 was never in doubt, the only intangibles being how big his majority might be (71.25%) and how many Russians would bother to vote at all (73.73 million). Non-Russian observers worried about how democratic the outcome really was, and fretted even more in August of the same year when Russia came to blows with Georgia over the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

While the controversy inevitably stirred up extreme reactions, a more sober analysis would have that Russia – however heavy-handedly – is fumbling to find a way to deal with its sense of encirclement by NATO-leaning neighbours, such as Georgia, Ukraine and the Baltic States, who were once part of its ‘sphere of influence’ and whose borders continue to harbour Russian nationals. While claiming to not want to defy the international community, Medvedev has said, ‘We are not afraid of anything, including the prospect of a new Cold War.’

Under such circumstances you may be understandably wary about visiting Russia. It would be a lie to say that travel here is all plain sailing. On the contrary, for all the welcome that its people will show you once you’re there, Russia’s initial face can be frosty. Tolerating bureaucracy, an insidious level of corruption and some discomfort, particularly away from the booming urban centres, remains an integral part of the whole Russian travel experience. However, a small degree of perseverance will be amply rewarded.

In 1978, in his commencement address at Harvard, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn talked about Russia’s ‘ancient, deeply rooted autonomous culture…full of riddles and surprises to Western thinking’. From the power machinations of the Kremlin and a resurgent Russian Orthodox Church to the compelling beauty of its arts and the quixotic nature of its people, whose moods tumble between melancholy, indifference and exuberance in the blink of an eye, Russia remains its own unique and fascinating creation that everyone should see for themselves.

Return to beginning of chapter

Getting Started

WHEN TO GO

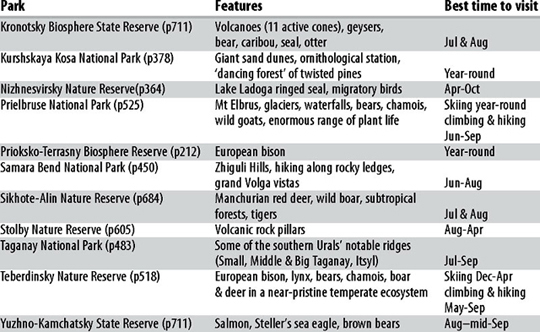

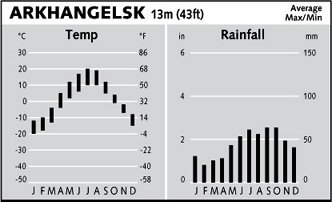

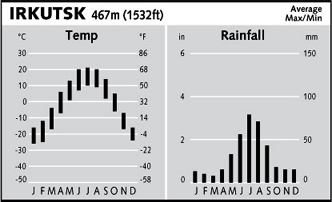

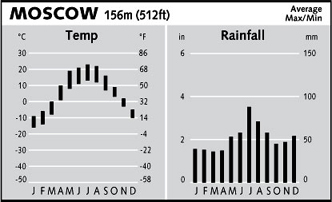

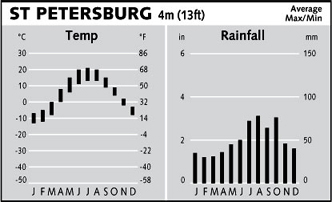

Early summer and autumn are many people’s favourite periods for visiting Russia. By May the snow has usually disappeared and temperatures are pleasant, while the golden autumnal colours of September and early October can be stunning.

July and August are the warmest months and the main holiday season for both foreigners and Russians (which means that securing train tickets at short notice can be tricky). They’re also the dampest months in much of European Russia, with as many as one rainy day in three. In rural parts of Siberia and the Russian Far East, May and June are peak danger periods for encephalitis-carrying ticks, though June and July are worse for biting insects. By September the air has cleared of mosquitoes.

Winter brings the Russia of popular imagination to life. If you’re prepared for it, travel in this season is recommended: the snow makes every-thing picturesque, and the insides of buildings are kept warm. Avoid, however, the first snows (usually in late October) and the spring thaw (March and April), which turn everything to slush and mud.

Return to beginning of chapter

COSTS & MONEY

See Climate Charts (Click here) for more information.

Start saving up! Avoid the major cities and use the platskartny (‘hard’ class, or 3rd class) carriages of overnight trains as an alternative to hotels and it’s possible – just! – to get by on US$50 per day. However, if you visit the main cities, eat meals in restaurants and travel on kupeyny (2nd class) trains, US$150 to $US200 per day is a more realistic figure. Prices drop away from the metropolises, but not significantly, while in remote areas, such as the Russian Far East, everything can cost considerably more.

Dual pricing is also an issue (see the boxed text, opposite). As a foreigner you’ll sometimes be charged more at hotels, too, although not in Moscow or St Petersburg where hotel prices are the same for everyone. It’s often fair game for taxi drivers and sometimes market sellers to try to charge foreigners more – check with locals for prices, but don’t expect that knowledge to be much use unless you can bargain in Russian. You’ll rarely be short-changed by staff in restaurants, cafés and bars, though.

DON’T LEAVE HOME WITHOUT…

- Getting a visa – we’ll guide you through the paperwork (Click here)

- Checking the security situation – travel to parts of the Caucasus is dangerous and not recommended

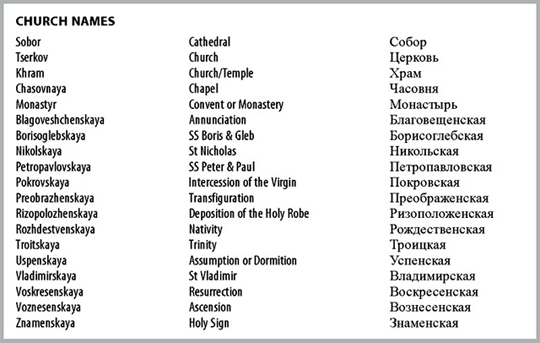

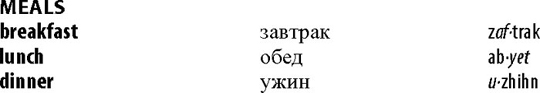

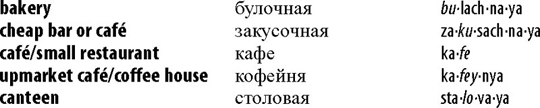

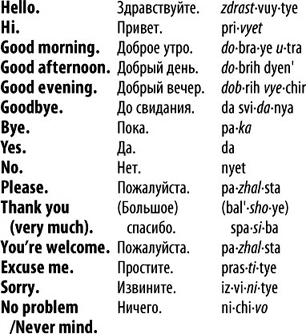

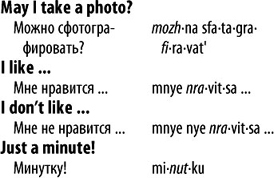

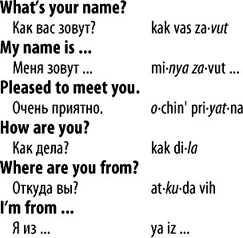

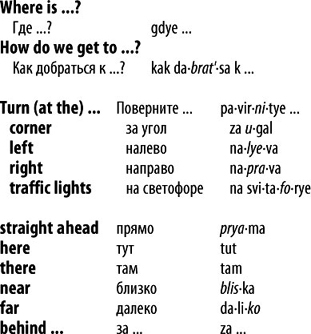

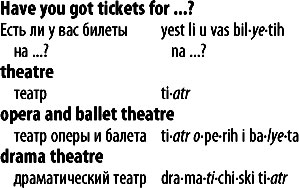

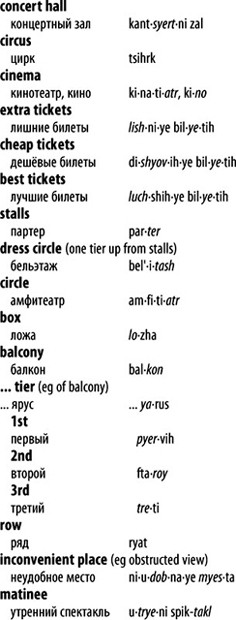

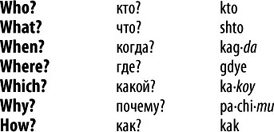

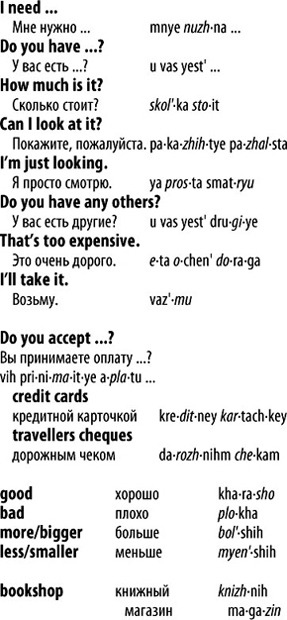

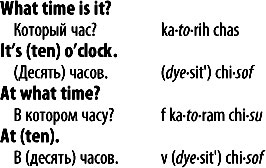

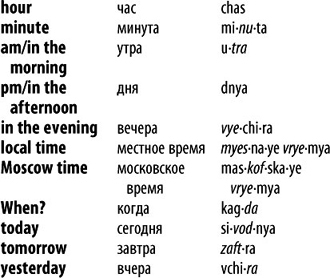

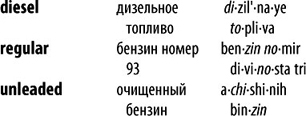

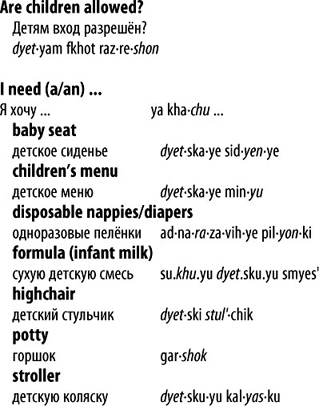

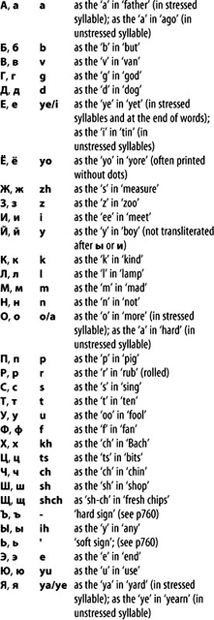

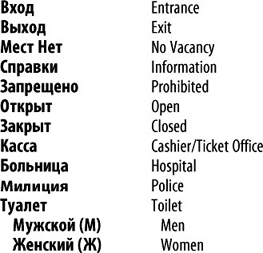

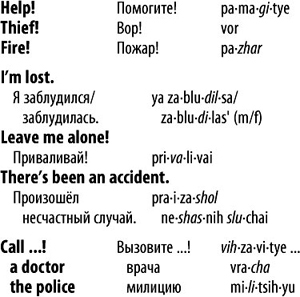

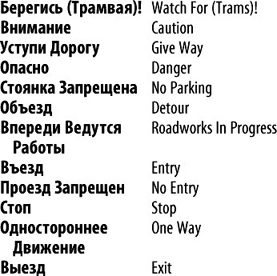

- Learning Cyrillic and packing a phrasebook or mini-dictionary – having a handle on the Russian language will improve your visit immeasurably

- Very warm clothes and a long, windproof coat for winter visits

- Thick-soled, waterproof, comfortable walking shoes

- Effective insect repellent for summer

- A sense of humour and bucket load of patience

- A stash of painkillers or other decent hangover cure

ABOUT MUSEUMS (AND OTHER TOURIST ATTRACTIONS)

Much may have changed in Russia since Soviet times, but one thing remains the same: foreigners typically being charged up to 10 times more than locals at museums and other tourist attractions. Higher foreigner fees generally go towards preserving works of art and cultural treasures that might otherwise receive minimal state funding.

Some major Moscow attractions, such as the Kremlin, State History Museum and St Basil’s, have ditched foreigner prices. All adults pay whatever the foreigner price used to be; all students, children and pensioners pay the low price. However, in St Petersburg foreigner prices rule.

Moscow and St Petersburg apart, non-Russian labels, guides or catalogues in museums are fairly uncommon. In our reviews we mention if there is good English labelling at a museum. Otherwise assume that you’ll need a dictionary to work out the precise details of what you’re seeing, or be prepared to pay even more for a guided tour – particularly if you wish that tour to be in a language you understand.

A few more working practices of Russian museums to keep in mind are:

- Admittance typically stops one hour before the official closing time.

- If you wish to take photos or film a video there will be a separate fee for this, typically an extra R100 for a still camera and R200 for video camera.

- Once a month many places close for a ‘sanitary day’, in theory to allow the place to be thoroughly cleaned; if you specially want to see a museum, call ahead to check it’s open.

Return to beginning of chapter

TRAVELLING RESPONSIBLY

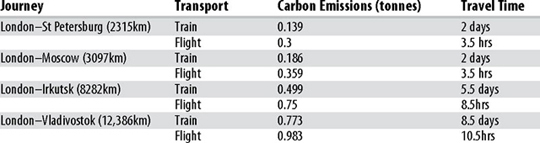

Ease your impact on the environment by travelling overland between Russia and Europe or Asia, as well as using trains to get around the country itself. Sure, it takes more time, but overland travel allows you to see plenty of interesting places en route and meet locals – far more fun than a boring flight. International trains and buses (Click here) are plentiful, and, as our Carbon Emissions Comparison Table shows (Click here), it’s possible in some cases to make more than a 50% cut in your environmental footprint by using them.

Interestingly, when we calculated the emissions that would be generated by taking a (non-existent) bus from London to Vladivostok (1.104 tonnes), we found that this was actually more polluting than a flight – take note, trans-Siberian drivers! For further details on overland travel options see the websites The Man in Seat Sixty-One (www.seat61.com/Russia.htm) and Way to Russia (www.waytorussia.net/Transport/International/Bus.html).

Once in Russia you’ll not fail to notice that as closely as some Russians live with nature, they don’t always respect it: littering, hunting and poaching are common pastimes. Responsible travellers will be appalled by the mess left in parts of the countryside and at how easily rubbish is chucked out of train windows. Accept that you’re not going to change how Russians live, but that you might be able to make a small impression by your own thoughtful behaviour.

It’s obvious to not litter yourself, but also try to minimise waste by avoiding excess packaging. Rather than relying on bottled water, consider using purification tablets or iodine in tap water. Also avoid buying items made from endangered species, such as exotic furs and caviar (Click here) that isn’t from legal sources.

Support local enterprises, environmental groups and charities that are trying to improve Russia’s environmental and social scorecard. A good example is the Great Baikal Trail project helping to construct a hiking trail around Lake Baikal (Click here). Other possibilities include:

Calculations made on www.carbonfootprint.com.

Cross-Cultural Solutions (www.crossculturalsolutions.org) Runs volunteer programs in a range of social services out of Yaroslavl.

Dersu Uzala Ecotours (www.ecotours.ru/english) Works in conjunction with several major nature reserves across Russia on tours and projects.

EcoSiberia (www.ecosiberia.org) Has information on eco attractions, projects and tours in Siberia.

International Cultural Youth Exchange (www.icye.org) Offers a variety of volunteer projects, mostly in Samara.

Language Link Russia (www.jobs.languagelink.ru) Volunteer to work at language centres in Moscow, St Petersburg, Volgograd and Samara.

World 4U (www.world4u.ru/english.html) Russian volunteer association.

World Wise Ecotourism Network (www.traveleastrussia.com) Ecoadventure tour company specialising in Far East Russia and Siberia.

Return to beginning of chapter

TRAVEL LITERATURE

Russia: A Journey to the Heart of a Land and its People by Jonathan Dimbleby – the hefty side product of a 16,000km journey the British journalist made for a BBC documentary across the country in 2007 – is a revealing snapshot of a multifaceted country.

Lost Cosmonaut and Strange Telescopes by Daniel Kalder are both blackly comic and serious explorations of some of Russia’s quirkiest and least visited locations. In the former book, the ‘anti-tourist’ author puts Kalmykia, Tatarstan, Mary-El and Udmurtia under the microscope. In the latter, Kalder goes underground in Moscow, hangs out with an exorcist and extends his travels into Siberia to meet the religious prophet Vissarion (Click here).

Motherland(www.motherlandbook.com) by Simon Roberts depicts in inspirational words and stark pictures the photographer’s year-long journey from Kamchatka to Kaliningrad.

Black Earth: A Journey Through Russia after the Fall by Andrew Meier is acutely observed and elegiac. In dispatches from Chechnya, Moscow, Norilsk, Sakhalin and St Petersburg, he paints a bleak picture of the country.

Black Earth City by Charlotte Hobson is an eloquent account of the author’s year studying in Voronezh in the turbulent period following the dissolution of the USSR. The book captures eternal truths about the Russian way of life.

Through Siberia by Accident and Silverland by Dervla Murphy are affectionate, opinionated discourses on the forgotten towns along Siberia’s BAM rail route by one of the world’s best travel writers.

MUST-SEE MOVIES

Hollywood did Russia proud in David Lean’s romantic epic Doctor Zhivago and spy thrillers such as Gorky Park and The Russia House, but otherwise its interest in the country as a location has been limited. No matter, as Russia has its own illustrious movie-making record. Check out the following classics, listed in chronological order. For more on Russian cinema Click here.

- The Cranes are Flying (1957) Mikhail Kalatozov

- Irony of Fate (1975) Eldar Ryazanov

- Moscow Doesn’t Believe in Tears (1979) Vladimir Menshov

- Stalker (1980) Andrei Tarkovsky

- My Friend Ivan Lapshin (1982) Alexey German

- Burnt by the Sun (1994) Nikita Mikhalkov

- Prisoner of the Mountains (1996) Sergei Bodrov

- Russian Ark (2002) Alexander Sokurov

- The Return (2003) Andrei Zvyagintsev

- 12 (2007) Nikita Mikhalkov

GREAT READS

Russian literature flourished in the 19th century when leviathans such as Pushkin, Gogol, Chekhov and Dostoevsky were wielding their pens. However, 20th- and 21st-century Russia has also bred several notable wordsmiths whose works afford a glimpse of the country’s troubled soul. For more on Russian literature go to Click here.

- War and Peace Leo Tolstoy

- Dr Zhivago Boris Pasternak

- The Master and Margarita Mikhail Bulgakov

- Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov

- Crime and Punishment Fyodor Dostoevsky

- Eugene Onegin Alexander Pushkin

- Dead Souls Nikolai Gogol

- Fathers and Sons Ivan Turgenev

- Kolyma Tales Varlam Shalamov

- Ice Vladimir Sorokin

FANTASTIC FESTIVALS

When Russians throw a party they seldom hold back. Time your trip to coincide with one of these top events and festivals, most showcasing local music, and you’re sure to have a ball.

- Sergei Kuryokhin International Festival (SKIF), late April, St Petersburg (Click here)

- Victory Day, 9 May: most places celebrate this day but St Petersburg (Click here) puts on a great parade

- Glinka Festival, 1-10 June, Smolensk (Click here)

- Sabantuy, mid-June, Tatarstan (Click here)

- Grushinsky festivals, early July, Samara (Click here)

- Naadym, mid-August, Tuva (Click here)

- Ysyakh, 21-22 June, Yakutsk (Click here)

- Sayan Ring International Ethnic Music Festival, mid-July, Shushkenskoe, (Click here)

- Dzhangariada, mid-September, Elitsa (Click here)

- Ded Moroz’s Birthday, 18 November, Veliky Ustyug (Click here)

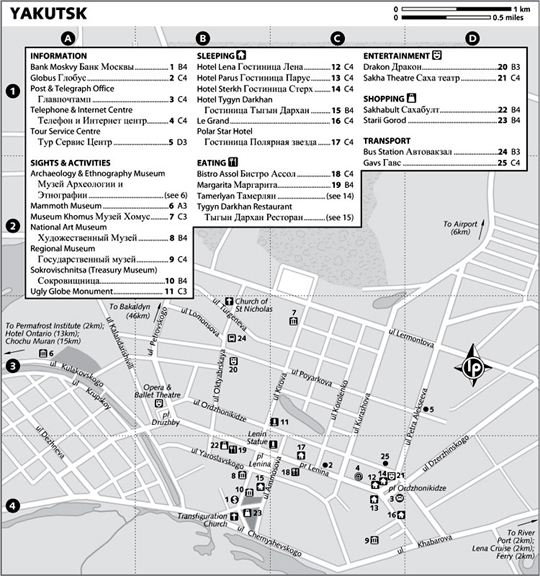

In Siberia by Colin Thubron is a fascinating, frequently sombre account of the author’s journey from the Urals to Magadan in post-Soviet times; it’s worth comparing with his Among the Russians about a journey taken in 1981 from St Petersburg to the Caucasus.

Journey into Russia by Laurens van der Post might have been written 60 years ago, but many of the observations made by the author about Soviet life still seem pertinent today, particularly those about the Russian character.

Return to beginning of chapter

INTERNET RESOURCES

CIA World Factbook (https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rs.html) Read what the US spooks have on the Russkies.

English Russia (www.englishrussia.com) Daily entertainment blog that exists, as its strapline says, ‘just because something cool happens daily on 1/6th of the world’s surface’.

Lonely Planet (www.lonelyplanet.com) Russian travel tips and blogs, plus the Thorn Tree bulletin board.

Moscow Times (www.moscowtimes.ru) All the latest breaking national news, plus links to sister paper the St Petersburg Times and a good travel section.

Russia! (www.readrussia.com) There’s more to Russia than ballet, Leo Tolstoy or Maria Sharapova, as the website of this groovy quarterly magazine sets out to prove with its hip features on contemporary Russky culture.

Russia Beyond the Headlines (www.rbth.rg.ru) Wide-ranging online magazine, with interesting features, sponsored by the daily paper Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Russia Prolife (www.russiaprofile.org) Expert analysis of Russian politics, economics, society and culture that promises to unwrap ‘the mystery inside the enigma’.

Seven Wonders of Russia (www.ruschudo.ru, in Russian) A 2008 project in which Russians nominated and voted for their local wonders both natural and built. Even if you don’t read Russian, the photos are inspirational.

Trans-Siberian Railway Web Encyclopedia (www.transsib.ru/Eng) It’s not been fully updated for several years, but this site still has tonnes of useful information and a huge photo library. (There’s also a German-language version at www.trans-sib.de.)

Way to Russia (www.waytorussia.net) Written and maintained by Russian backpackers, this site is highly informative and on the ball. However, please note that we’ve received complaints about buying train tickets through third parties associated with the site.

Return to beginning of chapter

Itineraries

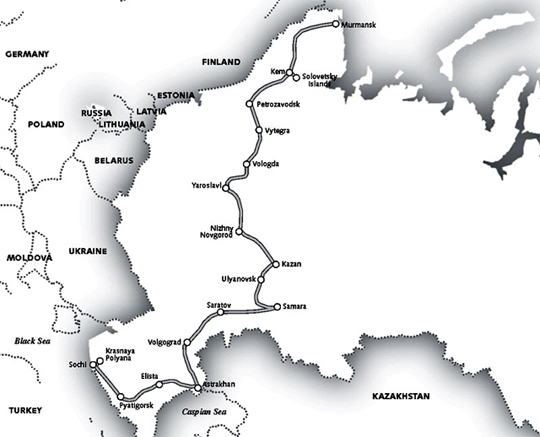

THE AMBER–CAVIAR ROUTE Three Weeks

THE BIG TRANS-SIBERIAN TRIP Two to Four Weeks

RUSSIAN FAR EAST CIRCUIT One Month

TYUMEN TO TUVA: SIBERIA OFF THE BEATEN TRACK One to Two Months

FROM THE WHITE SEA TO THE BLACK SEA One to Two Months

CLASSIC ROUTES

Return to beginning of chapter

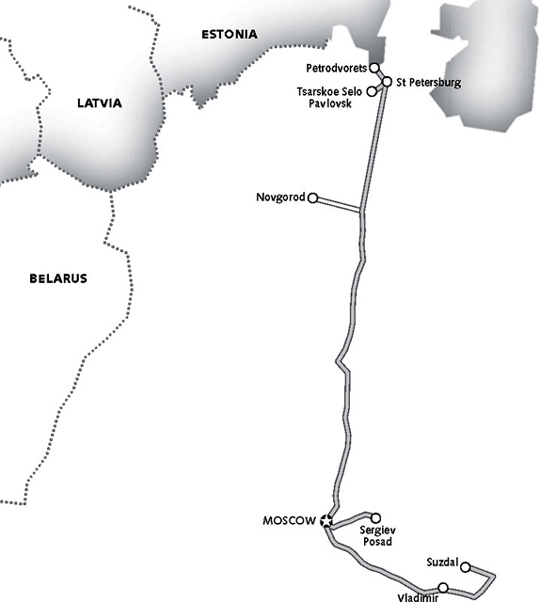

RUSSIAN CAPITALS Two Weeks

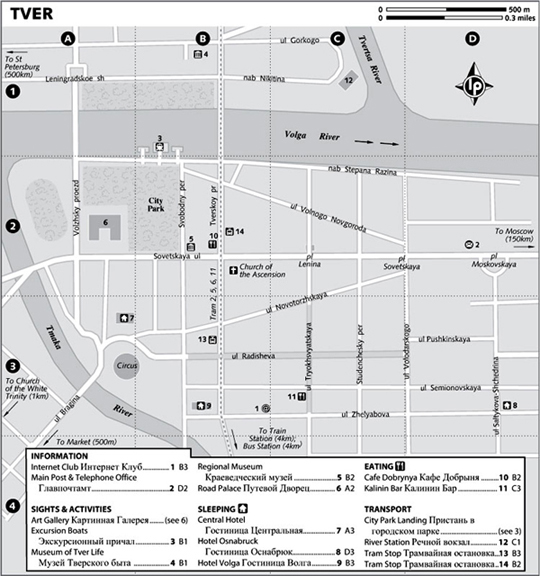

Moscow and St Petersburg are linked by a 650km-long railway. A week is the absolute minimum needed if you want to experience the cream of both cities. Add on another week if you plan on visiting the Golden Ring towns, the palaces around St Petersburg, and Novgorod, where it’s best to stay at least one night.

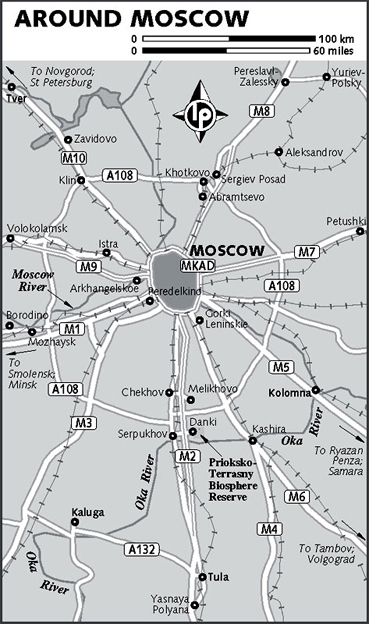

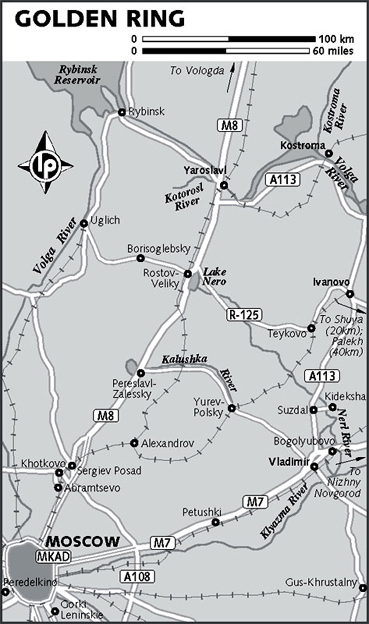

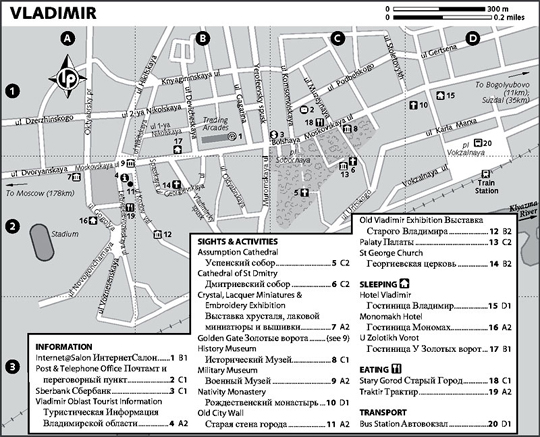

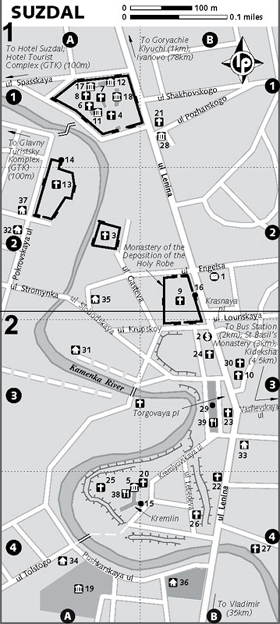

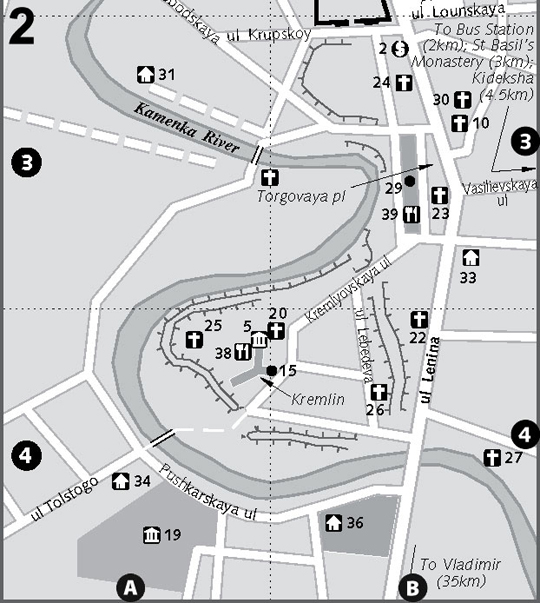

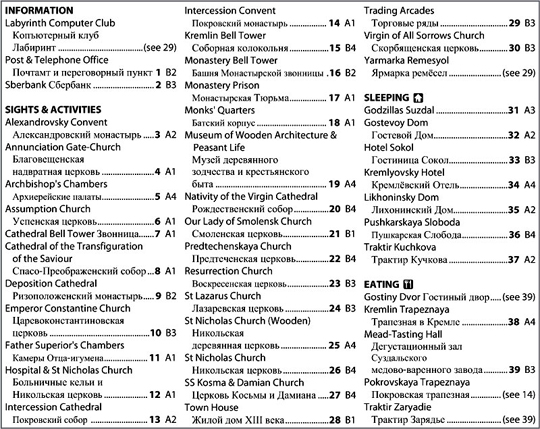

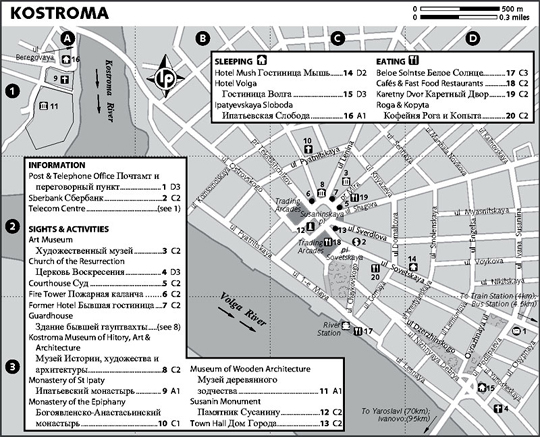

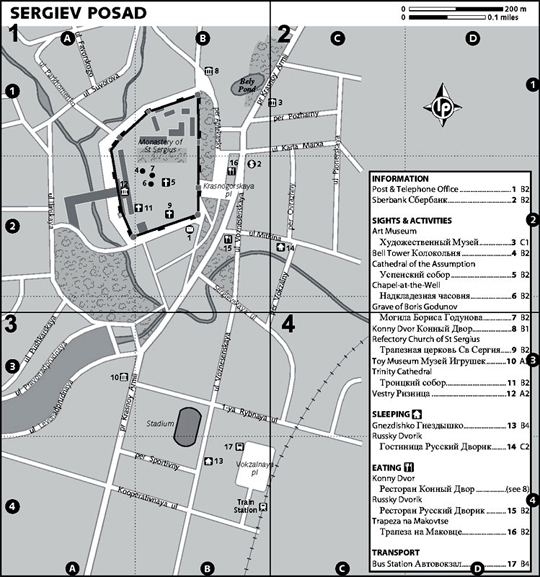

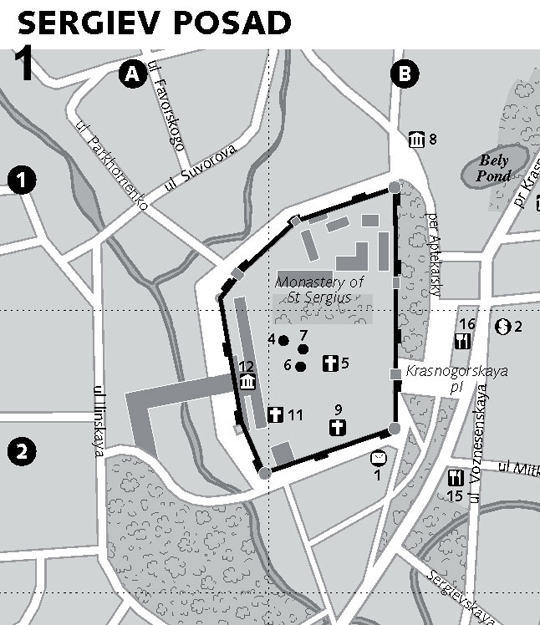

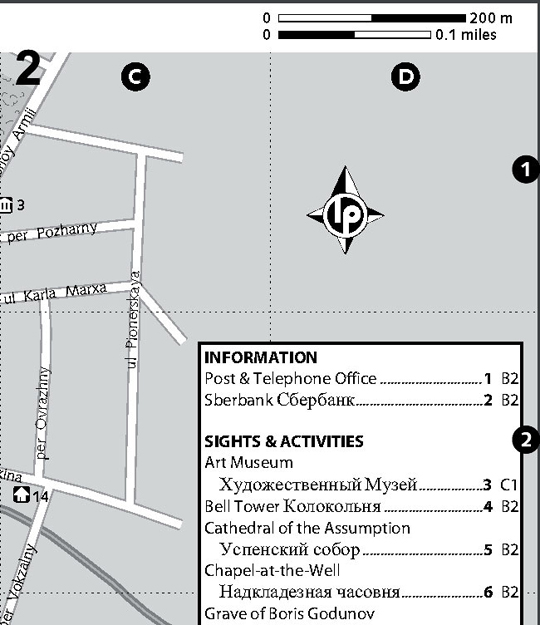

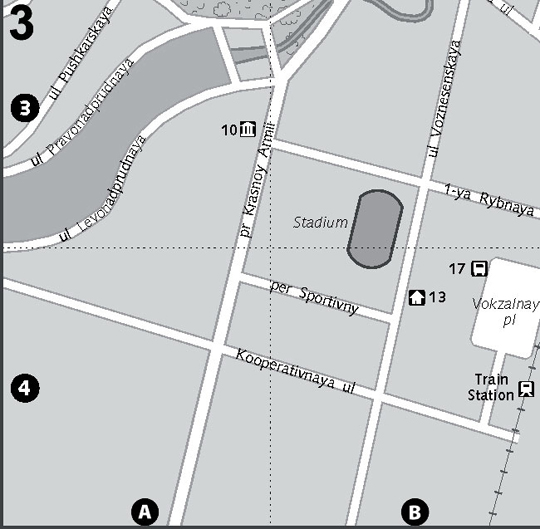

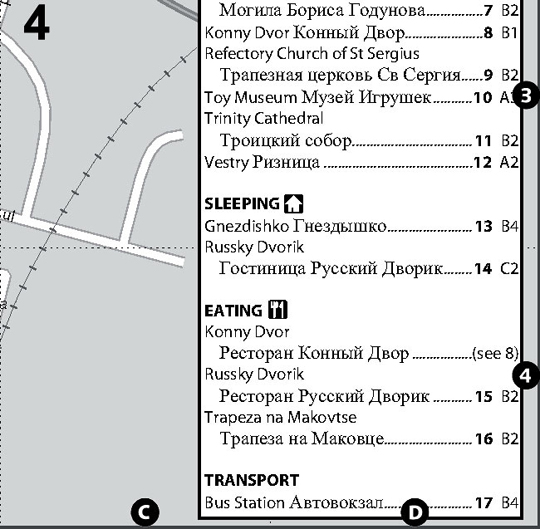

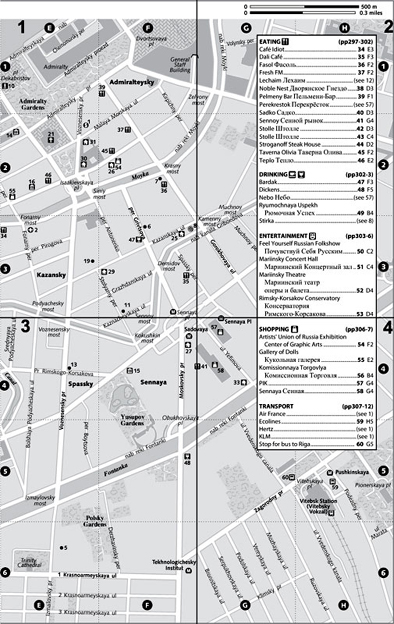

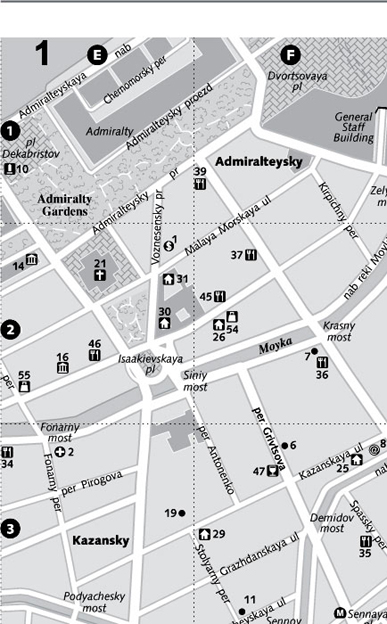

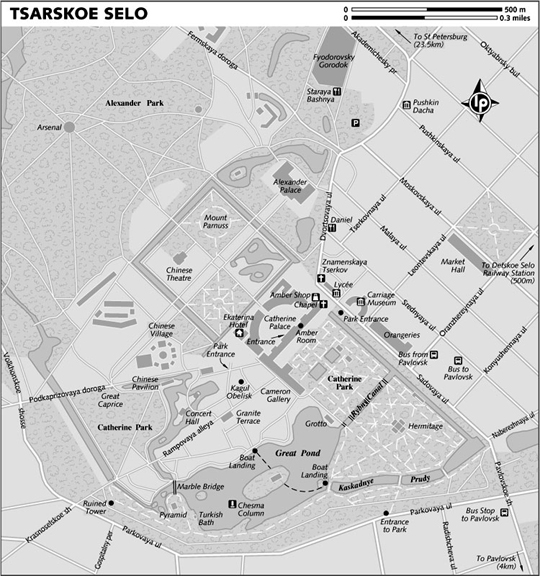

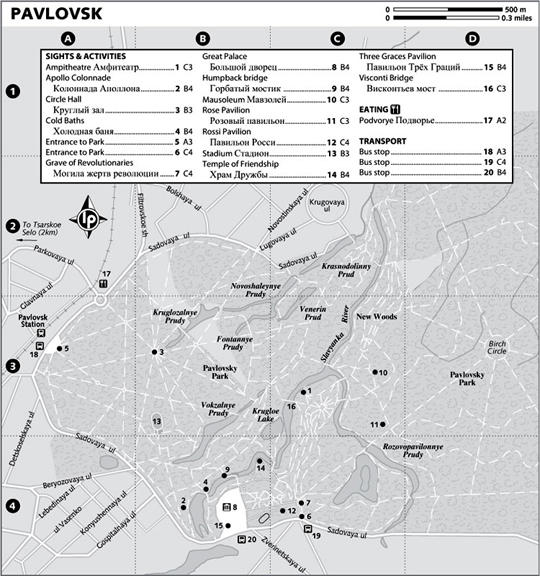

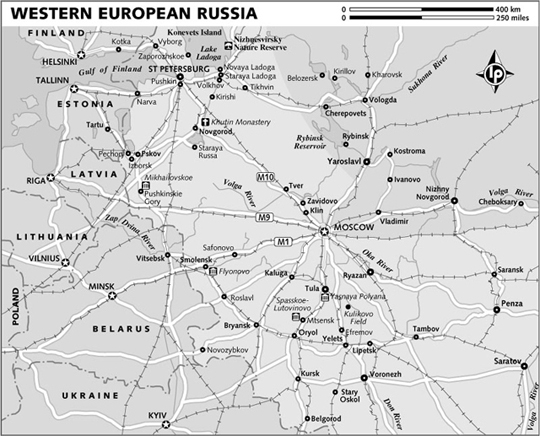

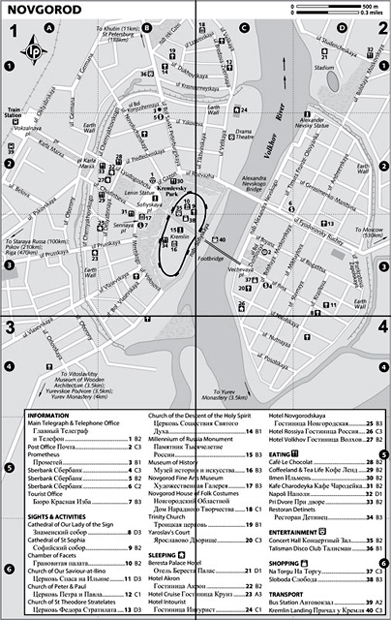

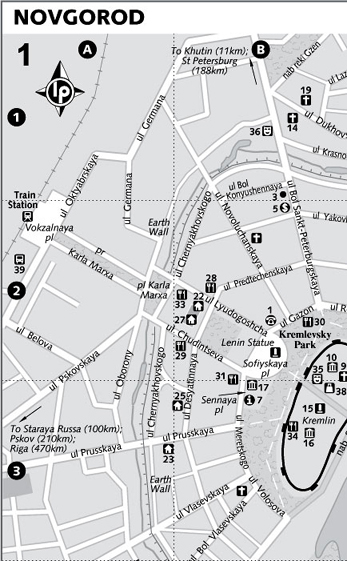

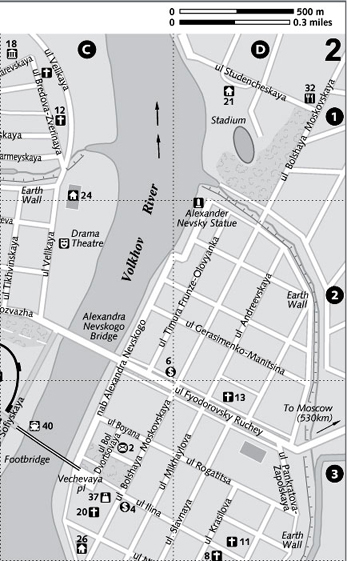

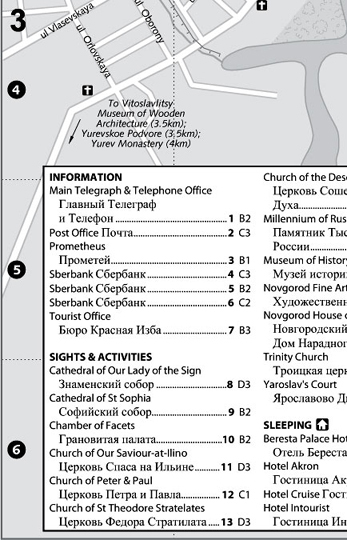

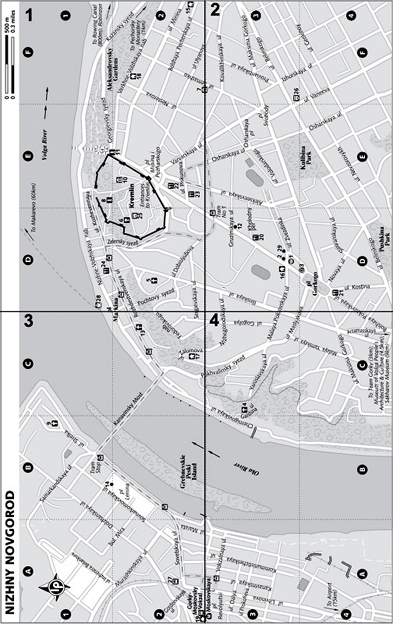

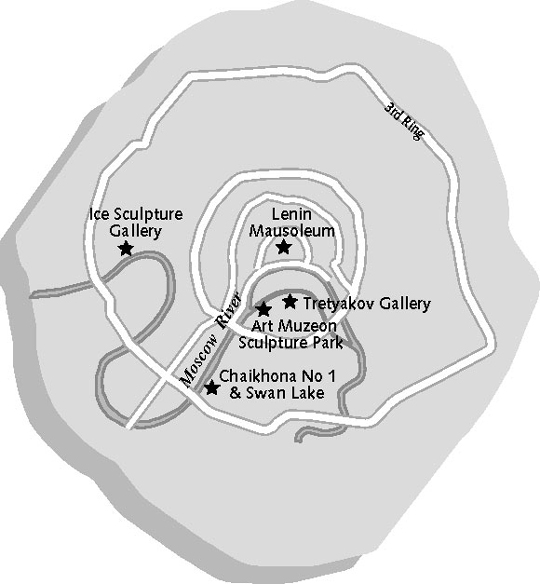

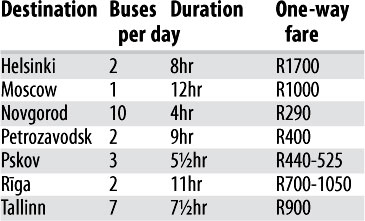

First time in Russia? Then start at the top with the awe-inspiring capital Moscow (Click here) and the spellbinding imperial capital St Petersburg (Click here); both encompass the best elements of the country’s turbulent past and glittering present. Moscow highlights include the historic Kremlin (Click here), glorious Red Square (Click here) and classic Tretyakov Gallery (Click here), while in St Petersburg do not miss the incomparable Hermitage (Click here) and the Russian Museum (Click here), or cruising the city’s rivers and canals (Click here). Enjoy nights dining and drinking at some of the best restaurants and bars in Russia, witnessing first-rate performances at the Bolshoi (Click here) or Mariinsky Theatres (Click here), or relaxing in a banya such as Moscow’s luxury Sanduny Baths (Click here). St Petersburg is ringed by grand palaces set in beautifully landscaped grounds such as Petrodvorets (Click here), Pushkin (Tsarskoe Selo) (Click here) and Pavlovsk (Click here). From Moscow you have easy access to the historic Golden Ring towns of Sergiev Posad (Click here), Suzdal (Click here) and Vladimir (Click here), where you will be rewarded with a slice of rural Russian life far from the frenetic city pace. Also leave time for ancient Novgorod (Click here), home to an impressive kremlin, the Byzantine Cathedral of St Sophia and the riverside Yurev Monastery.

Return to beginning of chapter

THE AMBER–CAVIAR ROUTE Three Weeks

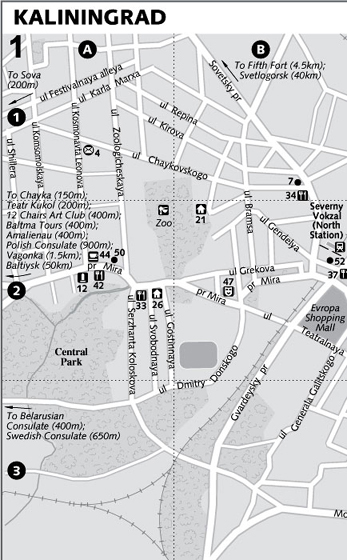

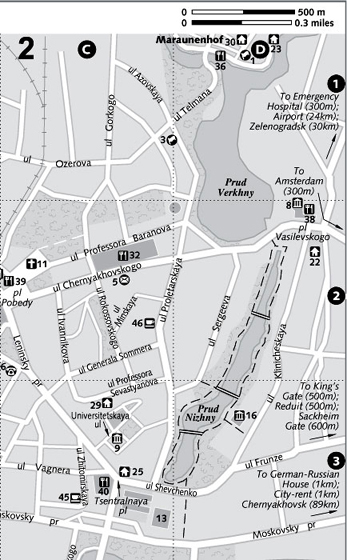

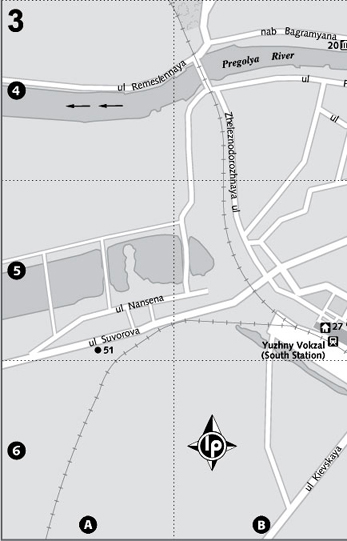

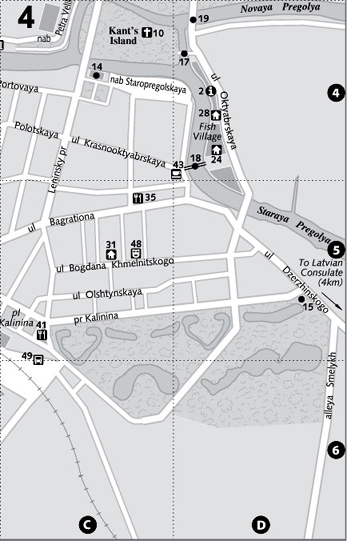

Combining travel by road, rail and river, this 2500km route takes you from the Baltic coast to the Caspian Sea. Avoid the need for a Russian multiple-entry visa and visas to Belarus and Lithuania by flying direct from Kaliningrad to either St Petersburg or Moscow and picking up the route from there.

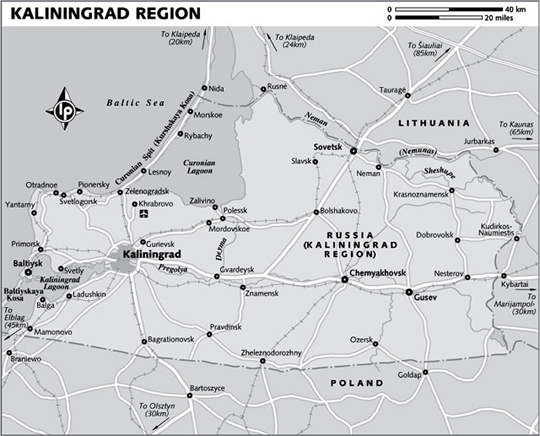

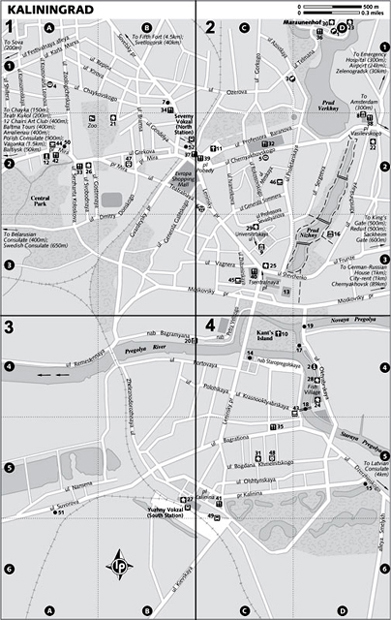

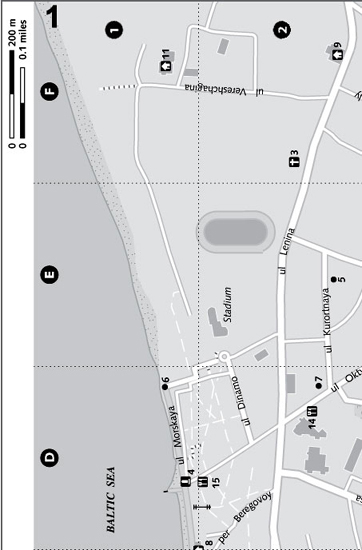

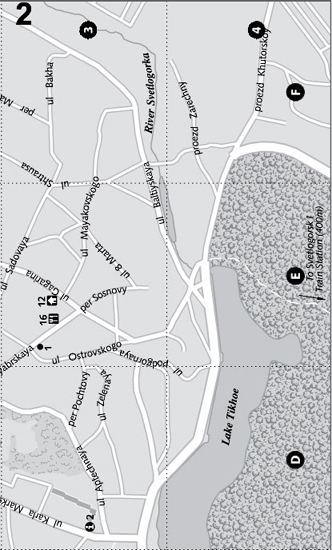

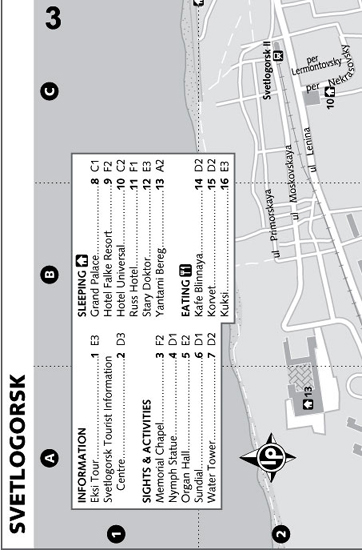

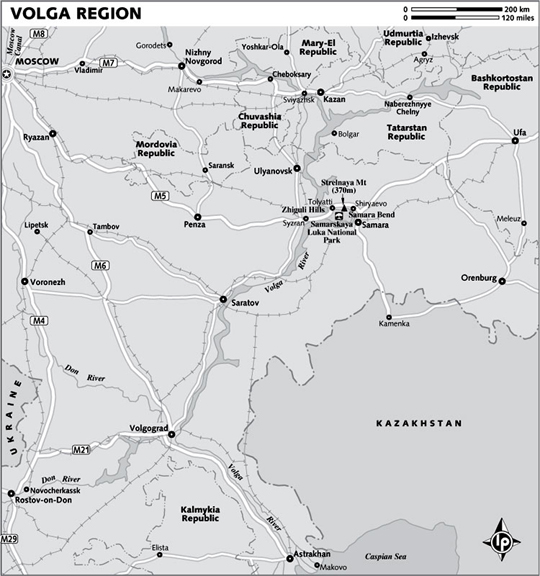

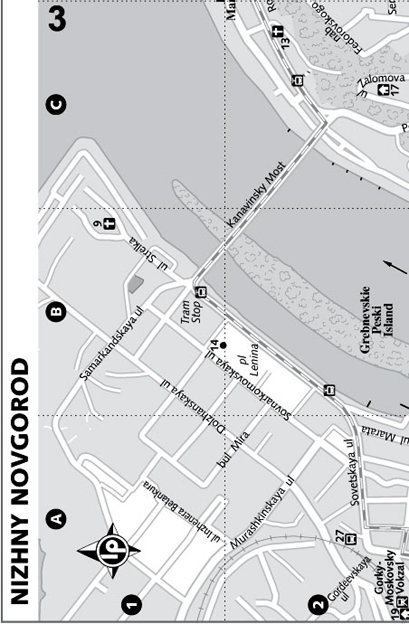

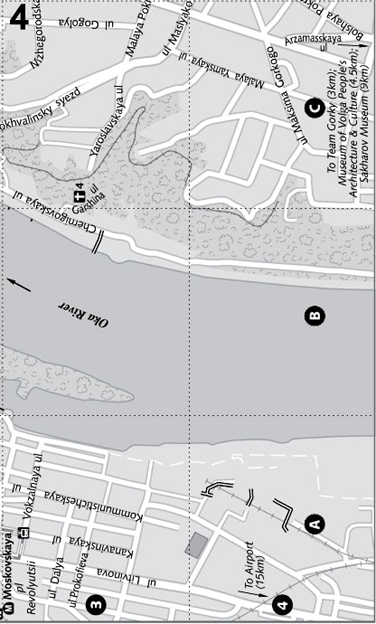

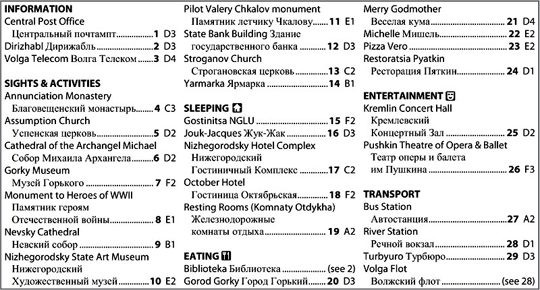

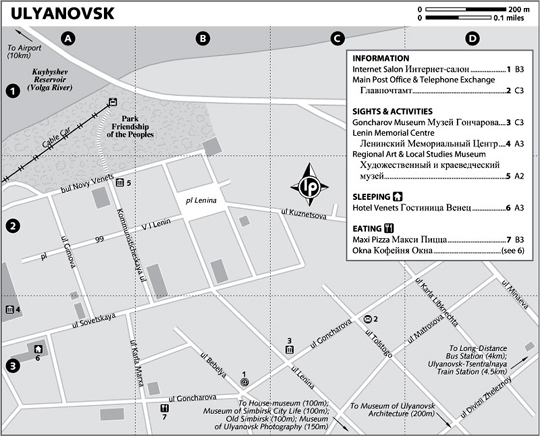

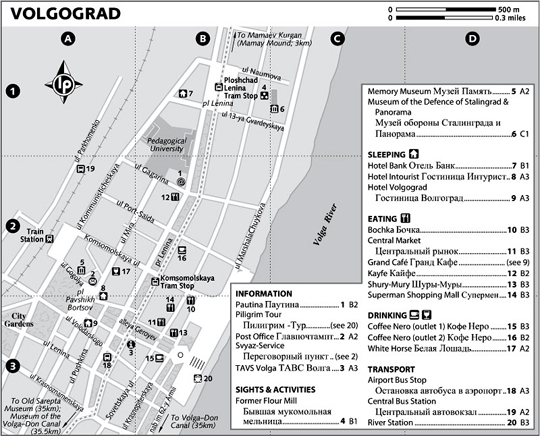

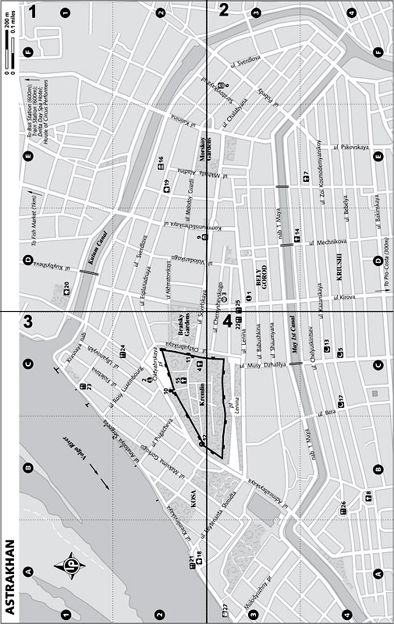

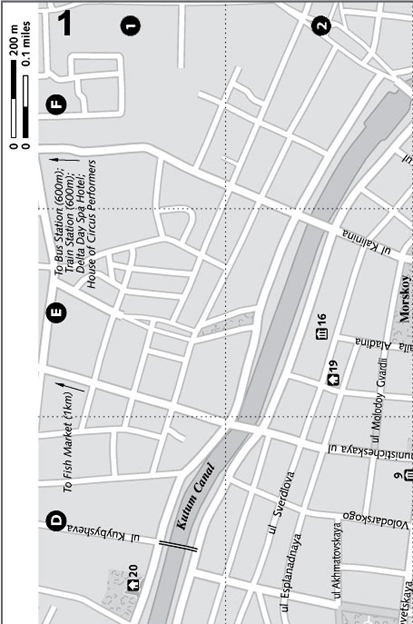

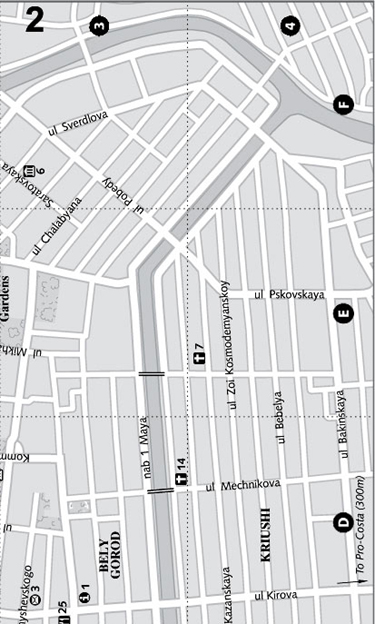

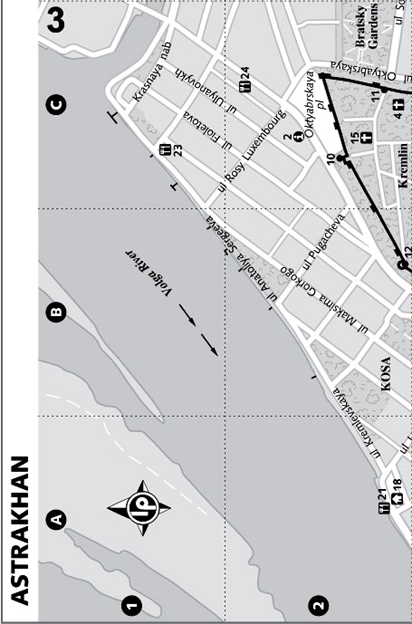

Ease yourself into Russia by exploring the geographically separate Kaliningrad region, Russia’s far west outpost, sandwiched between Poland and Lithuania, and source of 90% of the world’s amber. Four to five days is sufficient to get a taste of the historic city of Kaliningrad (Click here), the delightful seaside resort of Svetlogorsk (Click here) and the ‘dancing forest’ and sand dunes of the Kurshskaya Kosa (Click here), a World Heritage–listed national park. Take a train through Lithuania and Belarus to re-enter ‘big Russia’, pausing in the charming walled city of Smolensk (Click here), which has a connection to the composer Mikhail Glinka, before indulging in the bright lights and big nights of Moscow (Click here). If it’s summer, consider booking a berth on one of the cruise ships that frequently sail down Mother Russia’s No 1 waterway, the Volga River (Click here). Possible stops along the route include Russia’s ‘third capital’ Nizhny Novgorod (Click here), with its mighty kremlin and the Sakharov Museum; the Tatar capital Kazan (Click here), also with a World Heritage–listed kremlin; and Volgograd (Click here), sacred site of Russia’s bloodiest battle of WWII. Follow the river to its mouth into the Caspian Sea to end your journey at the east-meets-west city of Astrakhan (Click here), jumping-off point for exploring the glorious natural attractions, including rare flamingos, of the Volga delta, source of the endangered Beluga sturgeon and its caviar.

Return to beginning of chapter

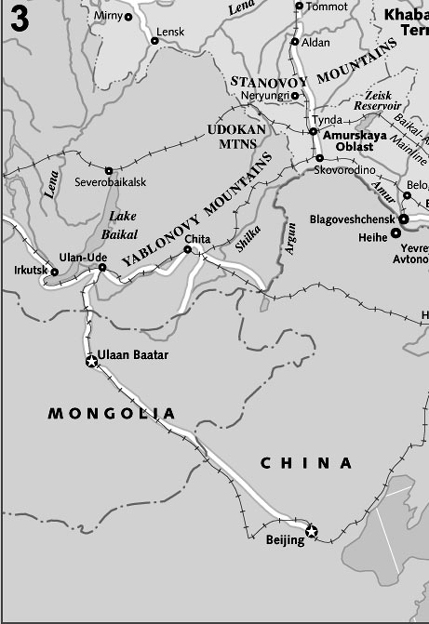

THE BIG TRANS-SIBERIAN TRIP Two to Four Weeks

The 9289km journey between Moscow and Vladivostok can be done, nonstop, in a week, but unless you’re into extreme relaxation we recommend hopping on and off the train, making more of an adventure of it. Spend time seeing the sights in Moscow and St Petersburg and you could easily stretch this trip to a month.

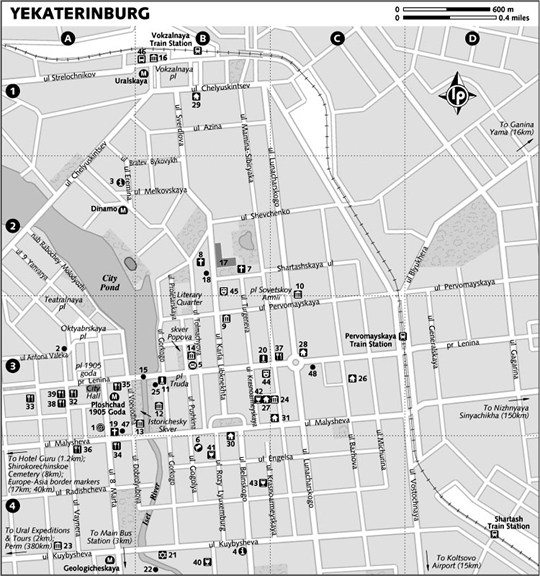

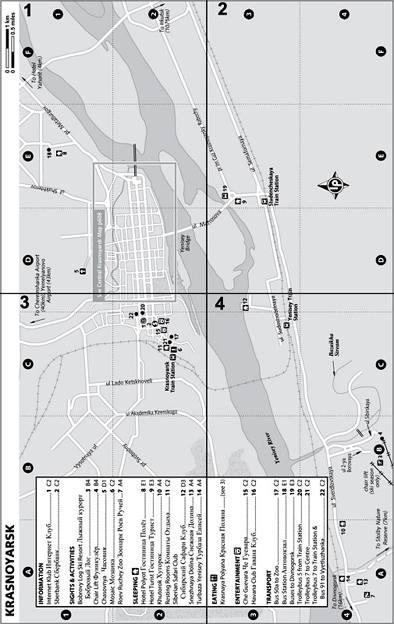

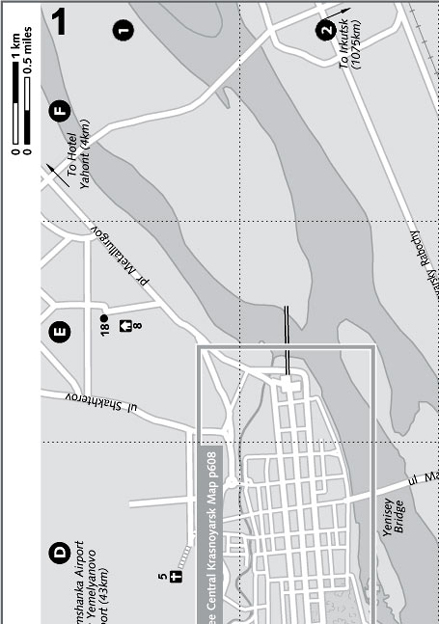

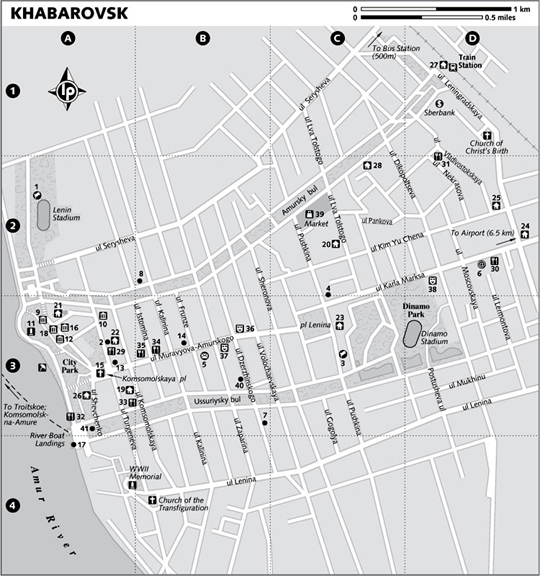

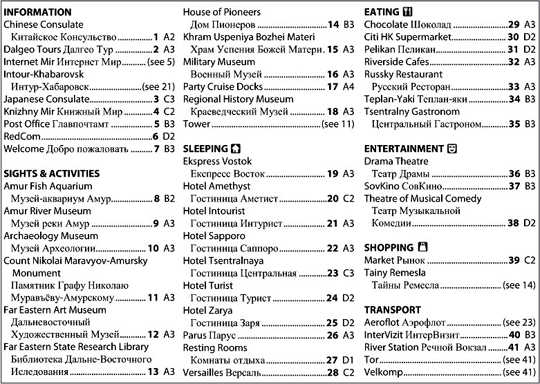

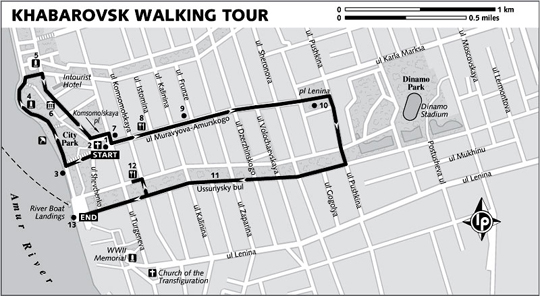

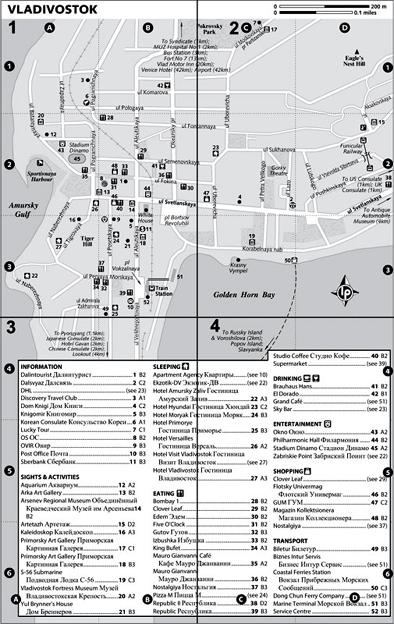

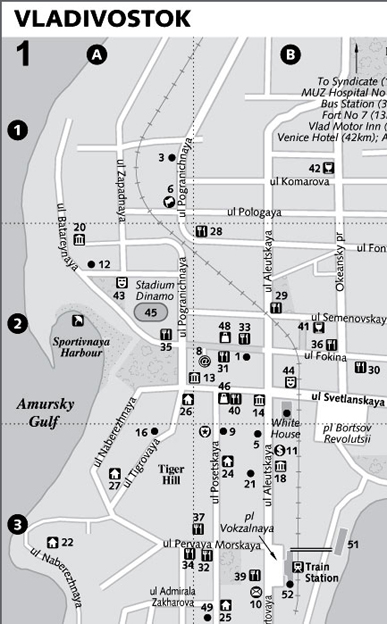

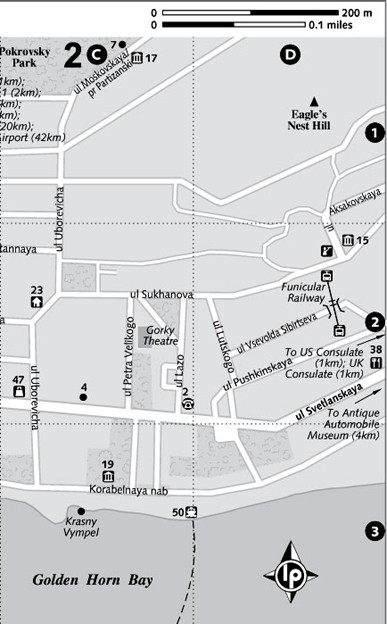

The classic Russian adventure is travelling the Trans-Siberian Railway (Click here), one of the 20th century’s engineering wonders and a route that holds together the world’s largest country. We suggest going against the general flow by boarding the train in the port of Vladivostok (Click here), at the far eastern end of Russia, so you can finish up with a grand party in either Moscow (Click here) or, better yet, St Petersburg (Click here). Vladivostok, situated on a stunningly attractive natural harbour, merits a couple of days of your time, and it’s also worth considering a stop off at Khabarovsk (Click here), a lively city of some charm on the banks of the Amur River – it’s just an overnight hop to the west. Save a couple of days for Ulan-Ude (Click here), a fascinating city where Russian, Soviet and Mongolian cultures coexist, and from where you can venture into the steppes to visit Russia’s principal Buddhist monastery, Ivolginsk Datsan (Click here). Just west of Ulan-Ude the railway hugs the southern shores of magnificent Lake Baikal (Click here). Allow at least three days (preferably longer) to see this beautiful lake, basing yourself on beguiling Olkhon Island (Click here); also check out historic Irkutsk (Click here) on the way there or back. Krasnoyarsk (Click here), on the Yenisey River, affords the opportunity for scenic cruises along one of Siberia’s most pleasant waterways. Crossing the Urals into European Russia, the first stop of note is Yekaterinburg (Click here), a historic, bustling city well stocked with interesting museums and sites connected to the murder of the last tsar and his family. Your last stop before Moscow could be of either the Golden Ring towns of Yaroslavl (Click here) or Vladimir (Click here), both packed with ancient onion-domed churches.

Return to beginning of chapter

ROADS LESS TRAVELLED

Return to beginning of chapter

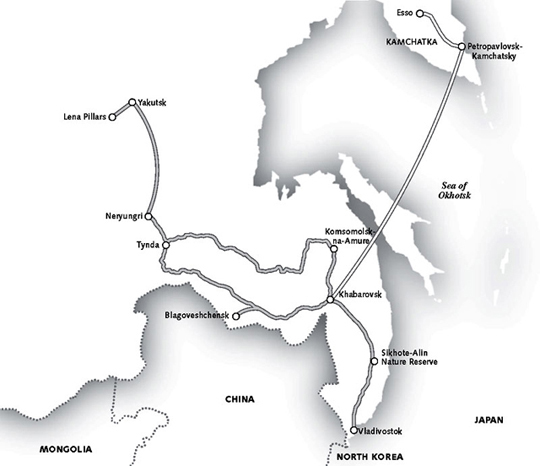

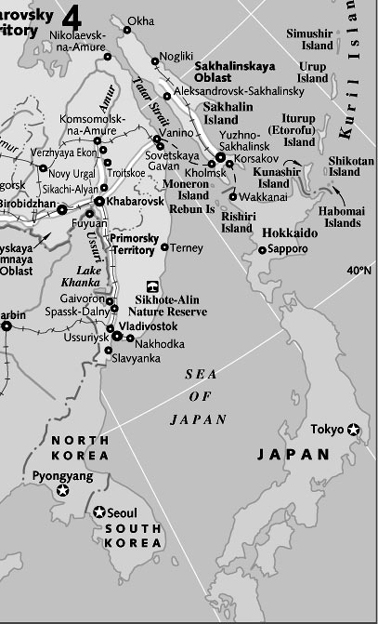

RUSSIAN FAR EAST CIRCUIT One Month

Travel junkies will relish this off-beat trip involving overnight train journeys, hopping around on planes and helicopters, and possibly a bumpy ride by bus through forbidding stretches of taiga and tundra. In summer there’s also the chance to relax on a languid river cruise between Khabarovsk and Komsomolsk-na-Amure.

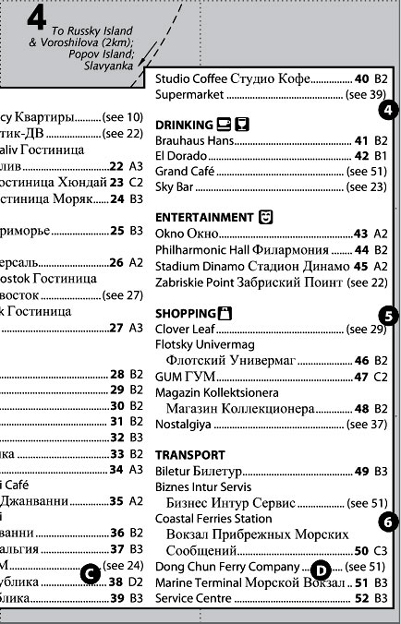

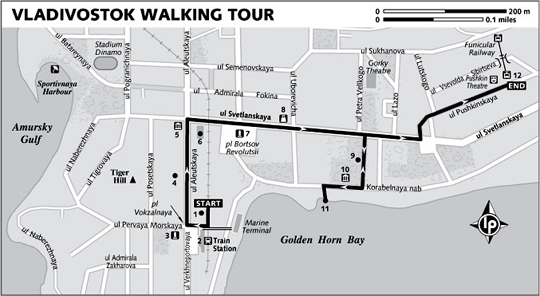

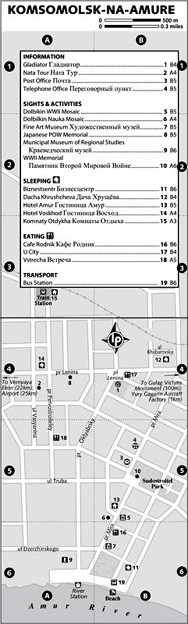

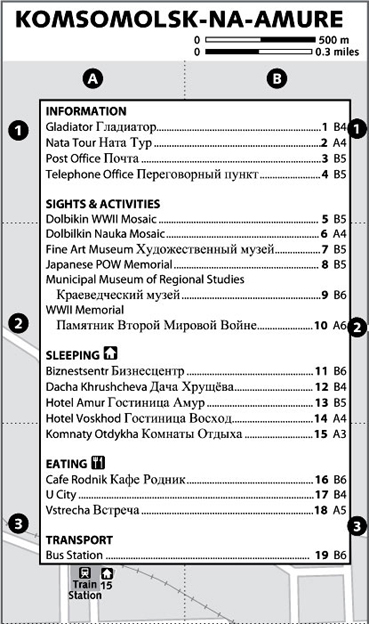

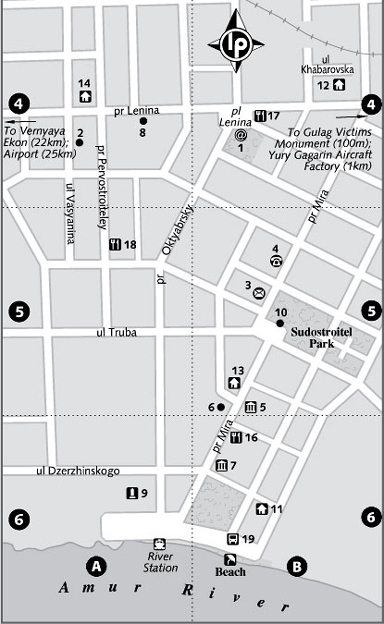

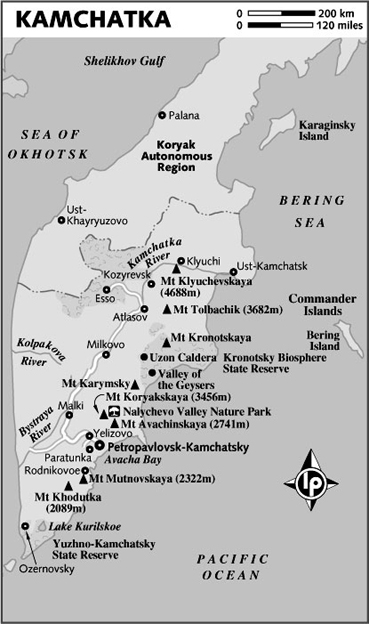

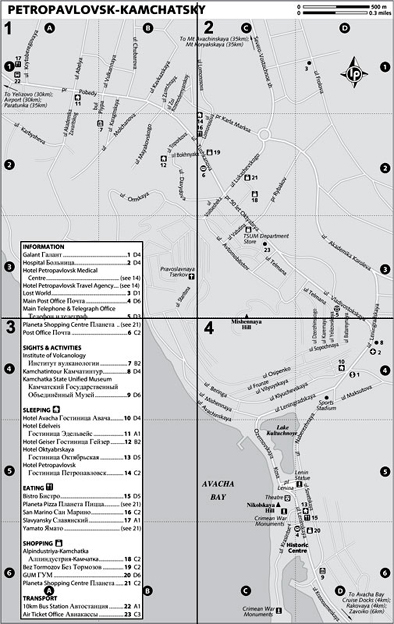

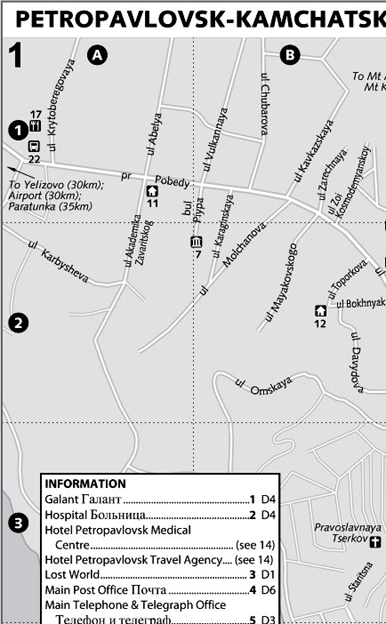

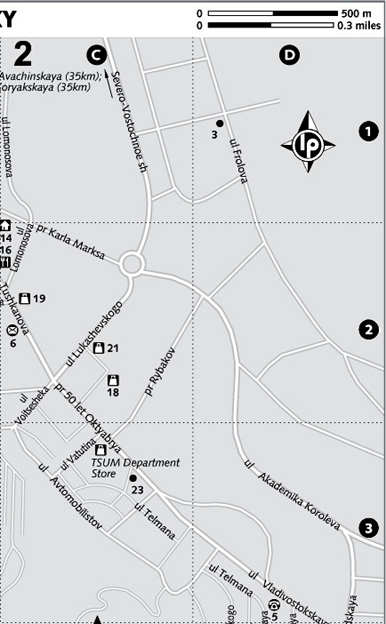

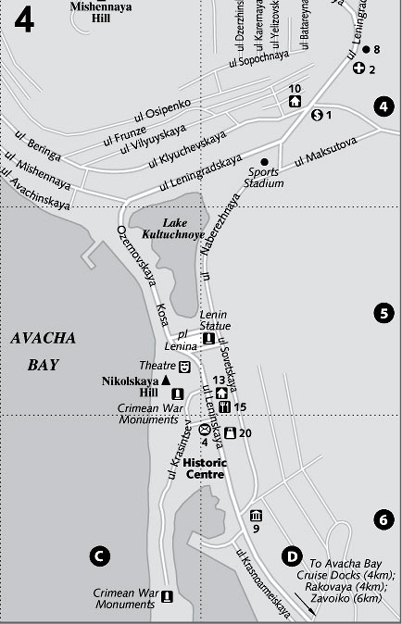

Travel in the Russian Far East isn’t so much a holiday as an expedition. From the ‘wild east’ port of Vladivostok (Click here) head north to Khabarovsk (Click here), with a possible detour to the World Heritage–listed Sikhote-Alin Nature Reserve (Click here). An overnight train from Khabarovsk heads to the lively border town Blagoveshchensk (Click here) – China is on the opposite bank of the Amur River. Another overnight train from here will transport you to Tynda (Click here), headquarters of the Baikal-Amur Mainline (BAM) construction company and a great place to refresh at the local banya. From here there’s a choice. Train and hard-travel fanatics should head to Neryungri (Click here) from where there’s a very bumpy and erratic bus to Yakutsk (Click here), the extraordinary permafrost-bound capital of the Sakha Republic. Alternatively, stick with the BAM route through to the proudly Soviet city of Komsomolsk-na-Amure (Click here) and back to Khabarovsk, from where there are flights to Yakutsk. Once in Yakutsk, make time to cruise to the scenic Lena Pillars (Click here) and to visit the city’s fascinating Permafrost Institute (Click here). A flight from either Khabarovsk or Vladivostok will take you over the Sea of Okhotsk to the highlight of this Far Eastern odyssey: Kamchatka (Click here). Cap off your adventures by climbing one of the snowcapped volcanoes rising behind the rugged peninsula’s capital, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky (Click here), which hugs breathtakingly serene Avacha Bay, and by visiting Esso (Click here), as charming an alpine village as you could wish for at the end of a long bumpy road.

Return to beginning of chapter

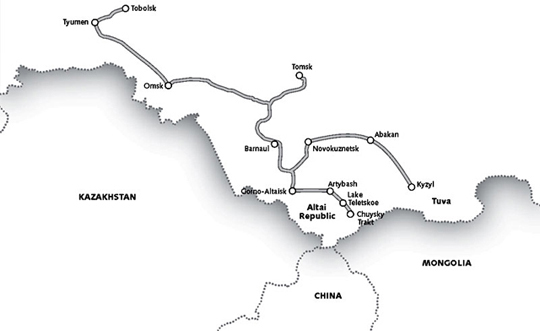

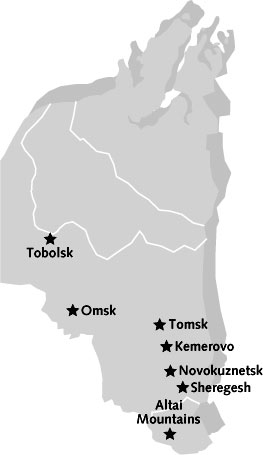

TYUMEN TO TUVA: SIBERIA OFF THE BEATEN TRACK One to Two Months

Direct overnight trains link the major cities on this Siberia-wide itinerary, save Kyzyl, which is best reached either by flight from Barnaul or by a shared taxi from Abakan along the spectacular mountain route, the Usinsky Trakt. In summer a three-day boat trip between Tobolsk and Omsk is also possible.

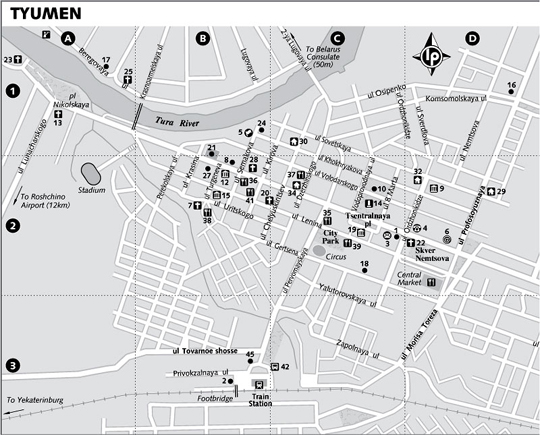

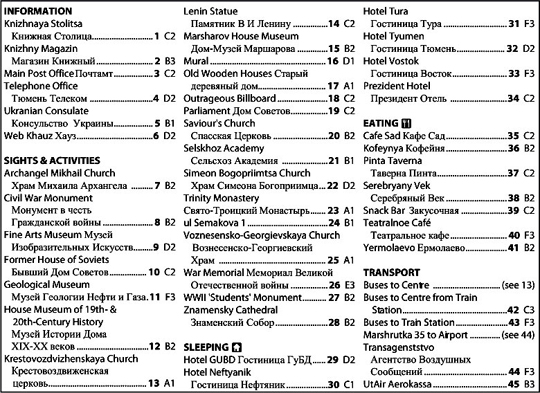

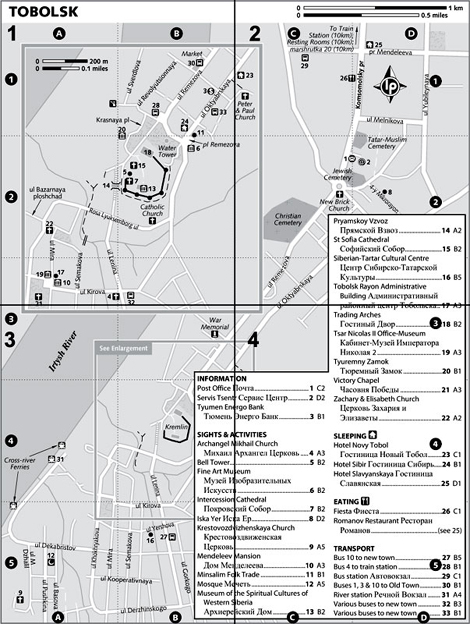

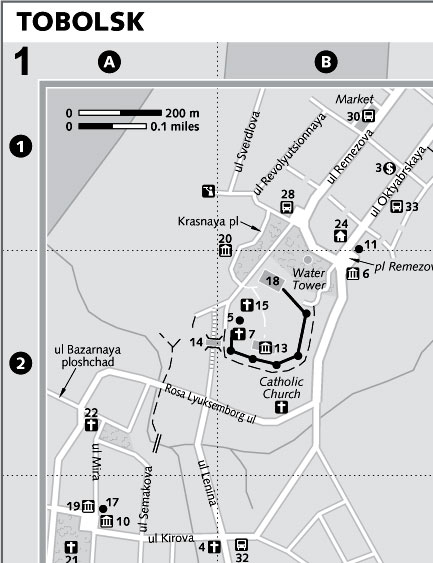

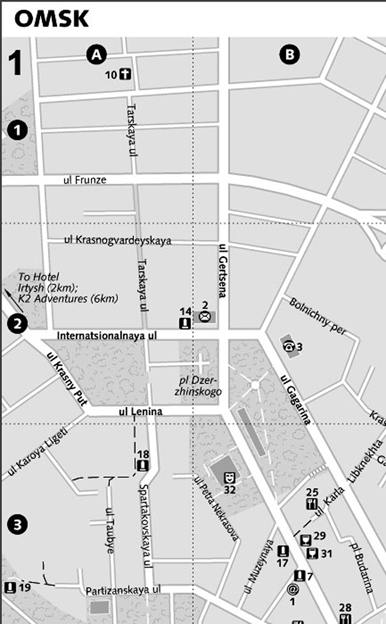

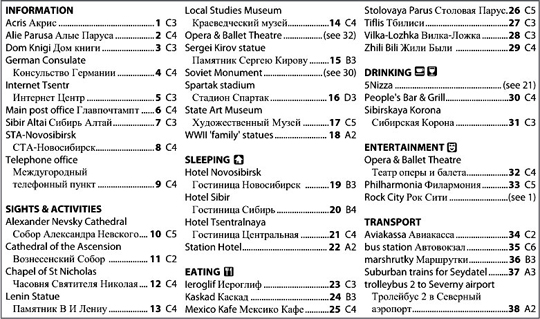

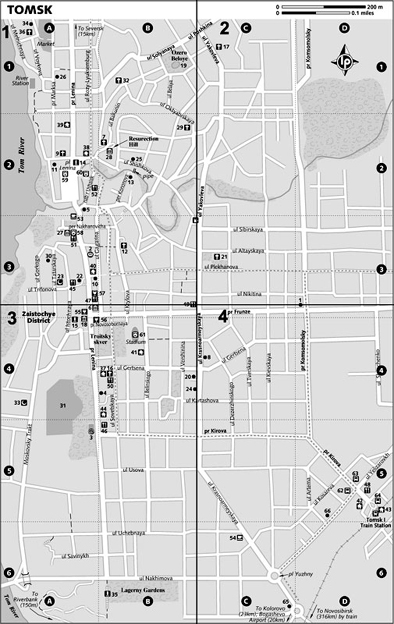

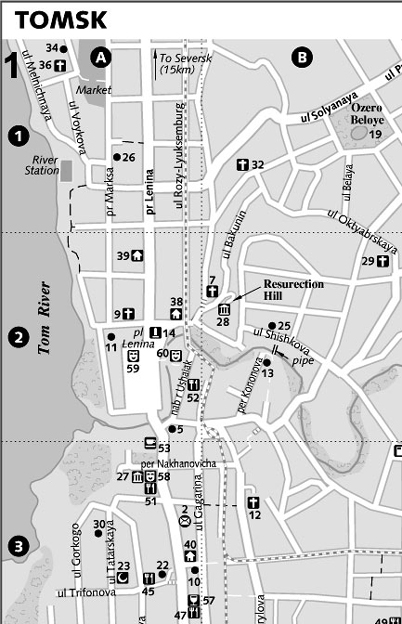

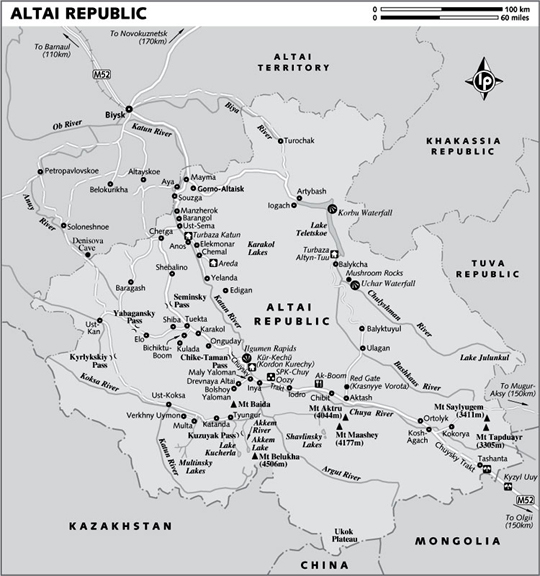

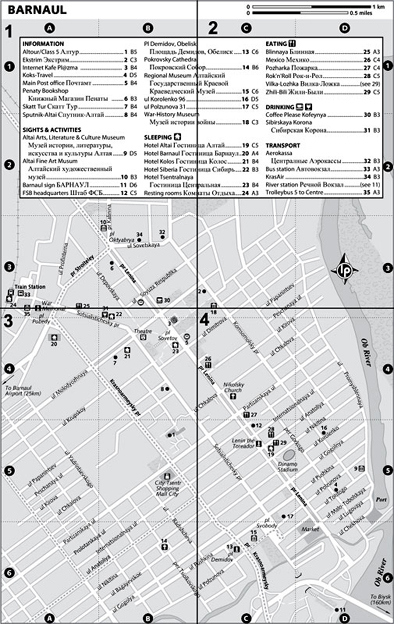

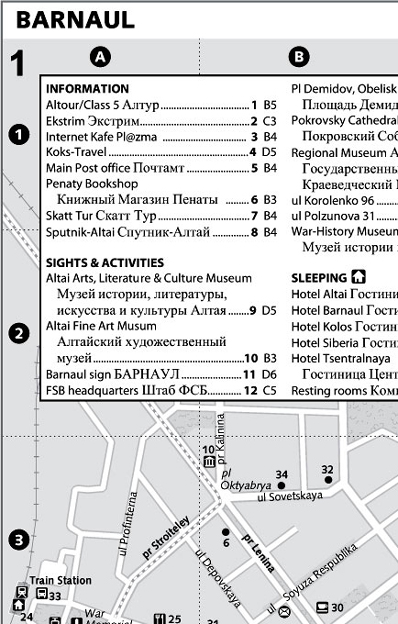

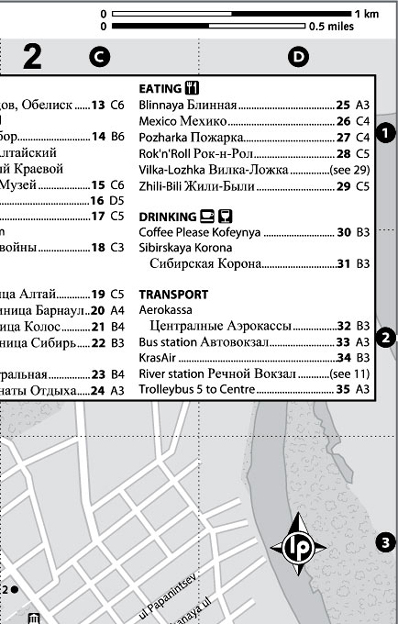

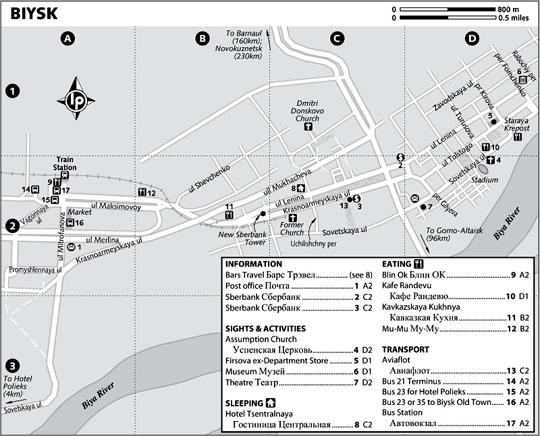

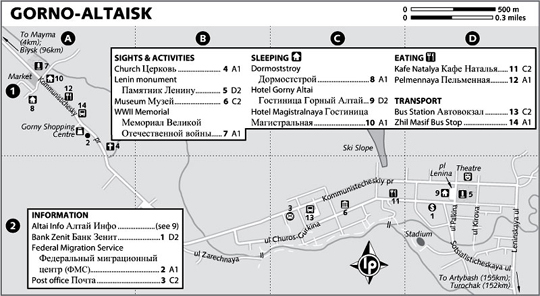

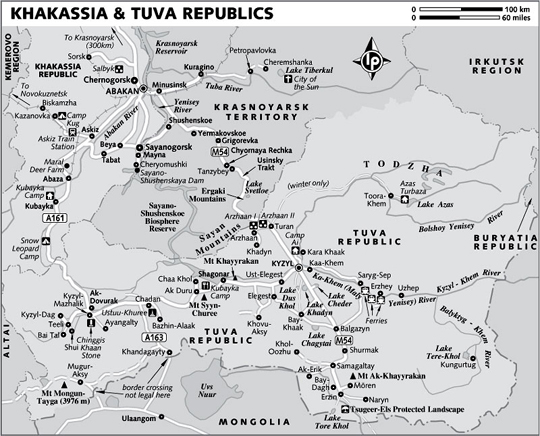

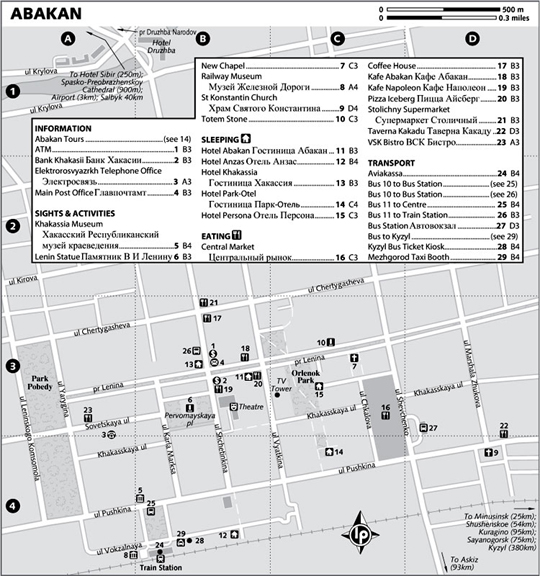

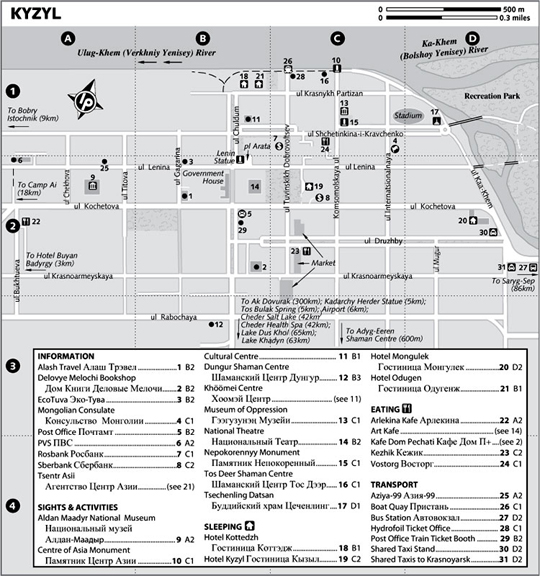

Far from being the forbidding land of the popular imagination, Siberia is a vast, glorious, adventure-travel playground where you could spend months happily exploring areas away from the well-travelled trans-Siberian route. For a journey covering some of Siberia’s lesser-known locations begin in the oil-rich city of Tyumen (Click here), which for all its contemporary bustle includes several picturesque areas of traditional architecture. Journey northeast in the footsteps of the Siberian conqueror Yermak Timofeevich, the exiled writer Fyodor Dostoevsky and the last tsar to Tobolsk (Click here), whose splendid kremlin lords it over the Tobol and Irtysh Rivers. Upriver and back on the main trans-Sib route is Omsk (Click here), a pleasant, thriving city, from where you can head directly to the backwater of Tomsk (Click here), a convivial university town dotted with pretty wooden gingerbread-style houses. Journey south next to Barnaul (Click here), gateway to the mountainous Altai Republic (Click here). Here you can arrange a white-water rafting expedition or plan treks out to Lake Teletskoe and the arty village of Artybash (Click here), or along the panoramic Chuysky Trakt (Click here), a helter-skelter mountain road leading to yurt-dotted grasslands, first stopping in Gorno-Altaisk (Click here) where you’ll have to register your visa. A train journey via Novokuznetsk (Click here) will get you to Abakan (Click here), where you can arrange onward travel to the wild republic of Tuva (Click here). This remote and little-visited region, hard up against Mongolia (with which it shares several cultural similarities), is famed for its throat-singing nomads and mystic shamans. Use the uninspiring capital Kyzyl (Click here) as a base for expeditions to pretty villages and the vast Central Asian steppes.

Return to beginning of chapter

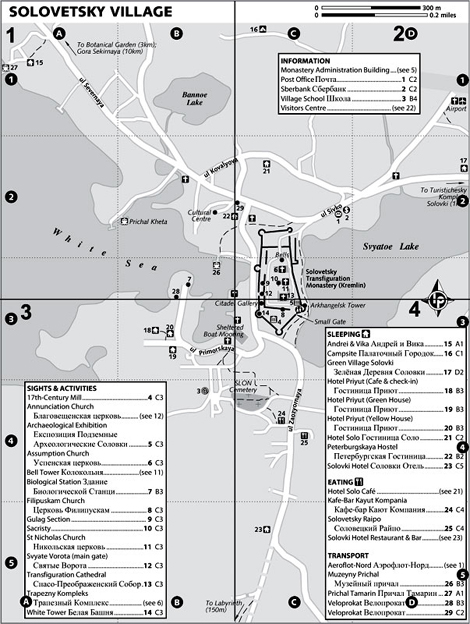

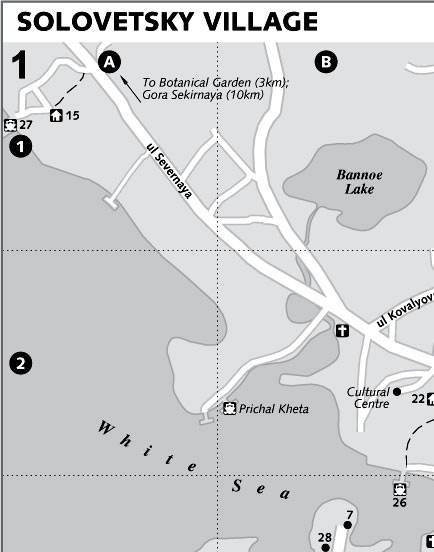

FROM THE WHITE SEA TO THE BLACK SEA One to Two Months

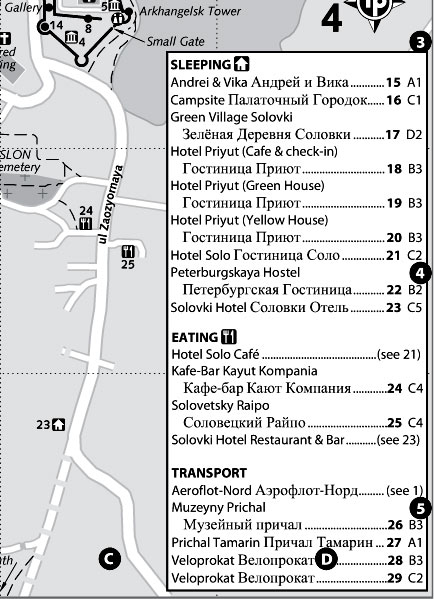

Connecting two of Russia’s least visited (by foreigners) regions, this 3000km route is best travelled in May or June when access to the Solovetsky Islands is possible, Volga River cruises start running and the Black Sea beaches are warm enough for sunbathing.

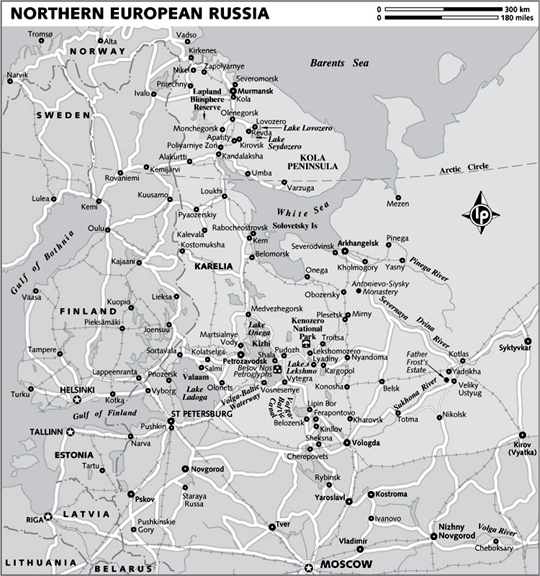

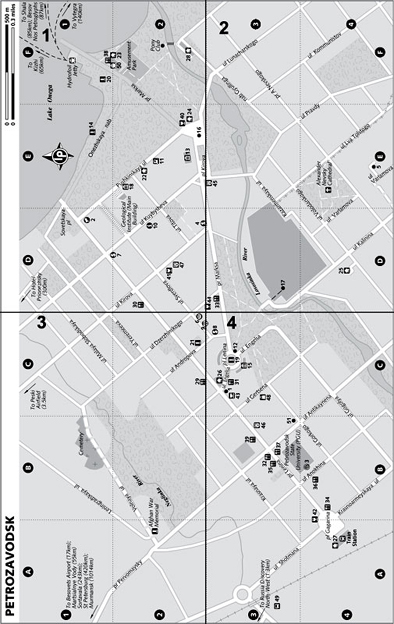

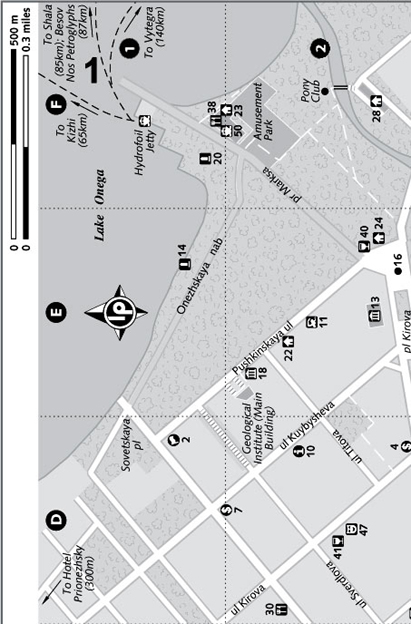

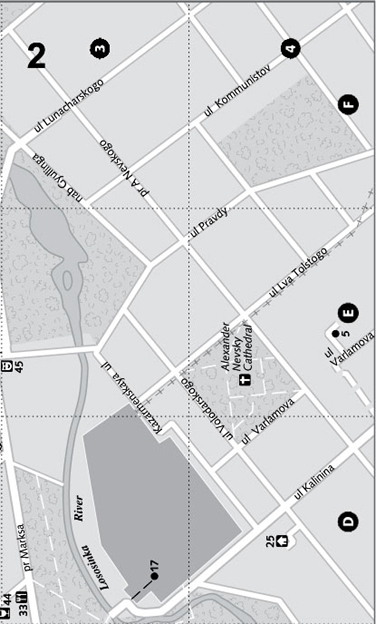

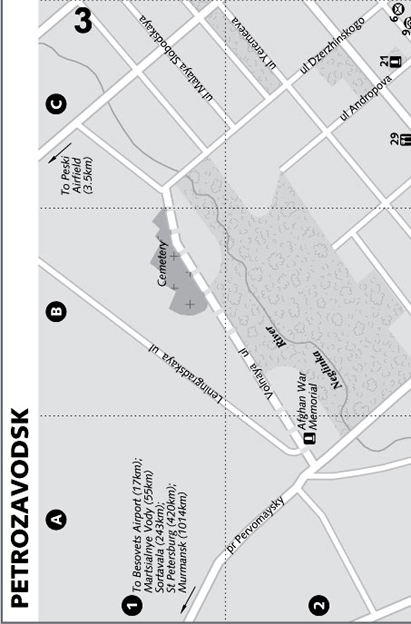

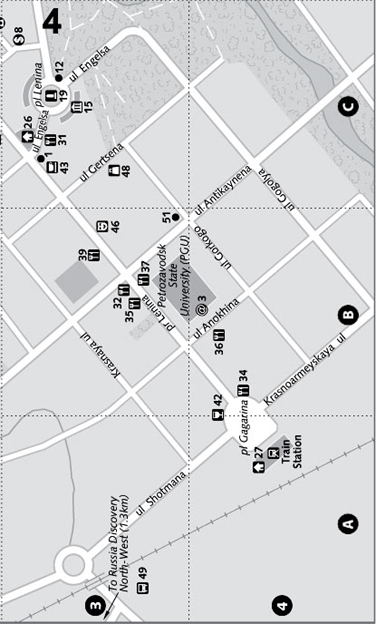

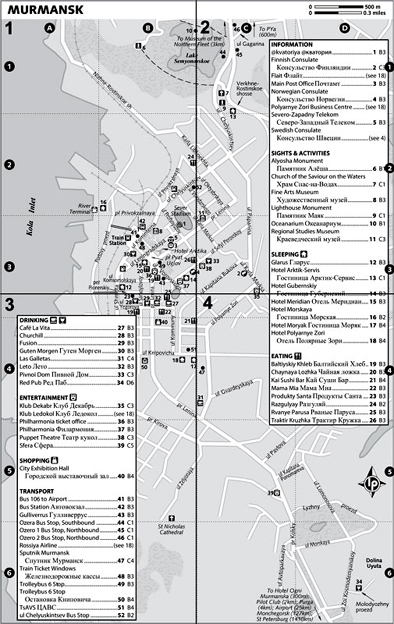

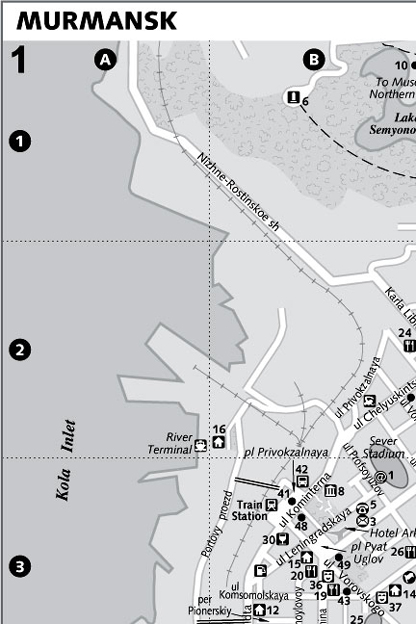

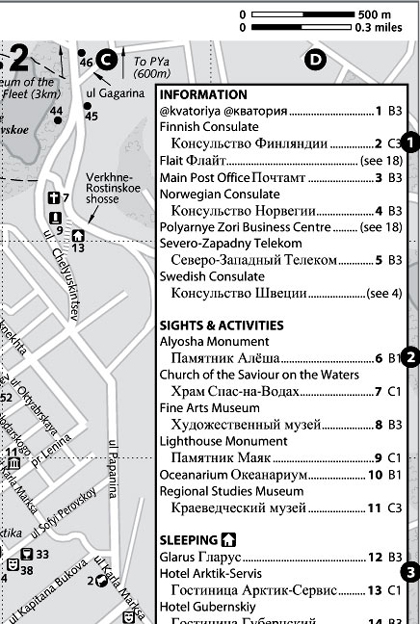

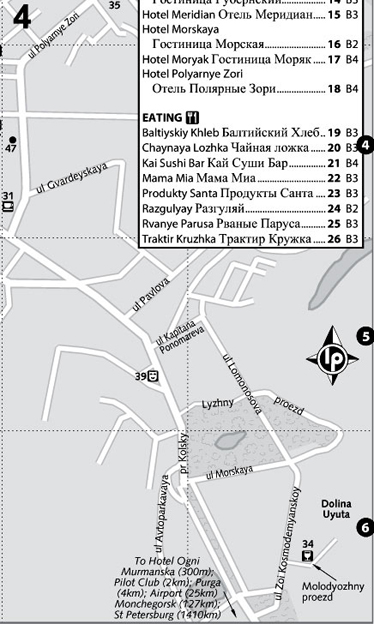

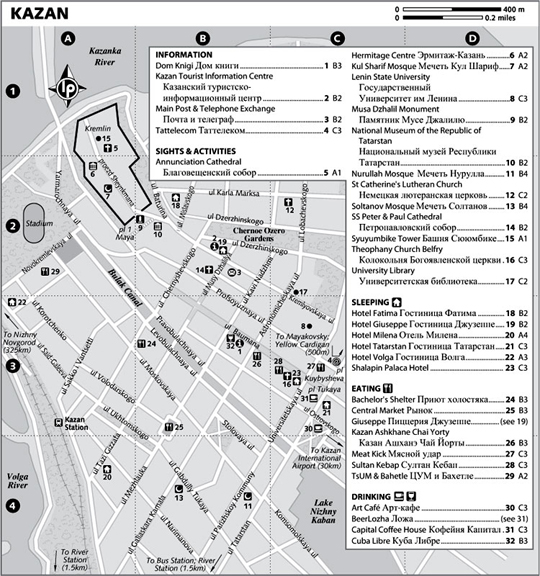

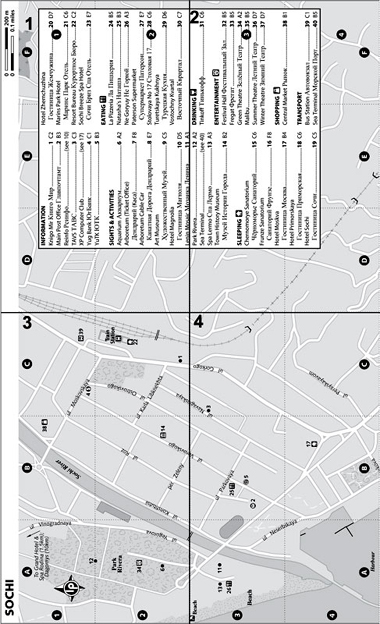

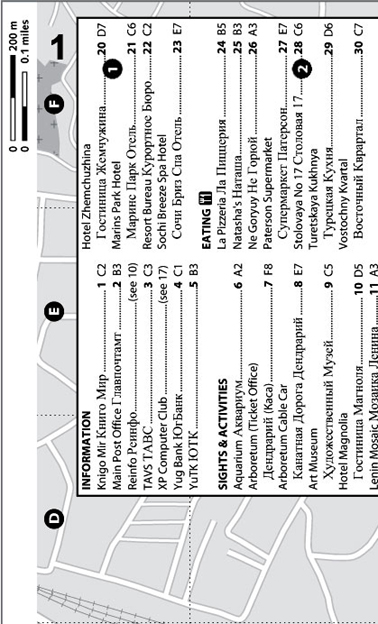

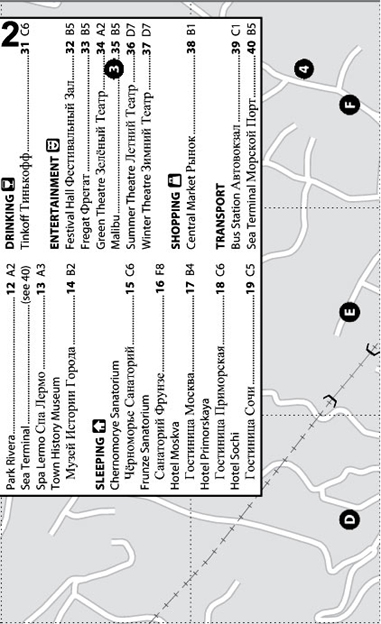

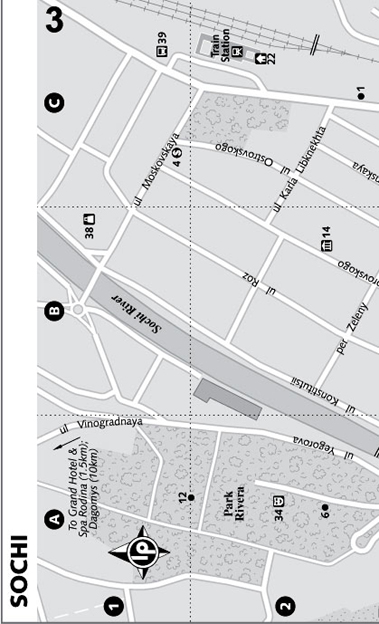

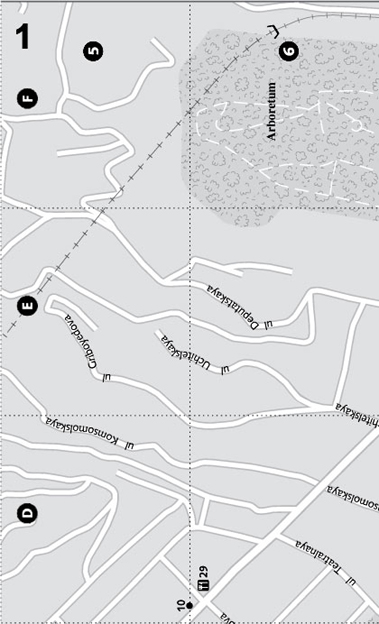

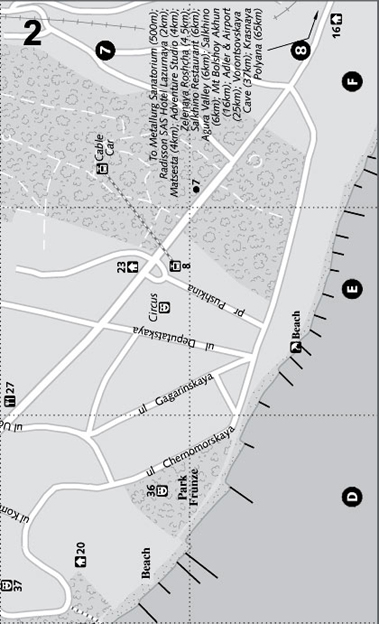

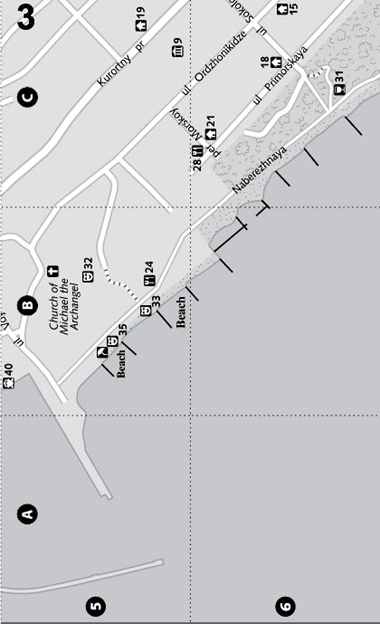

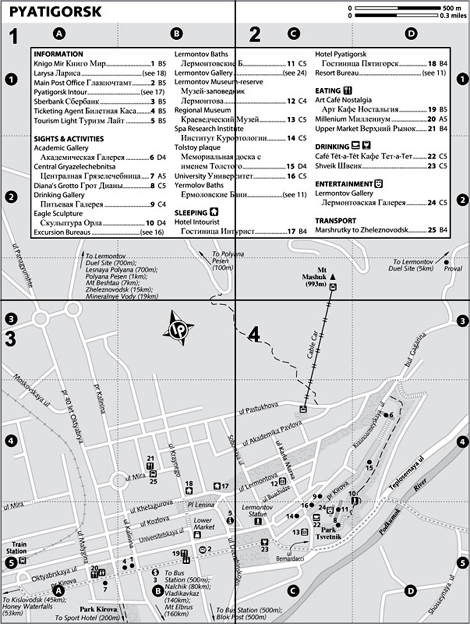

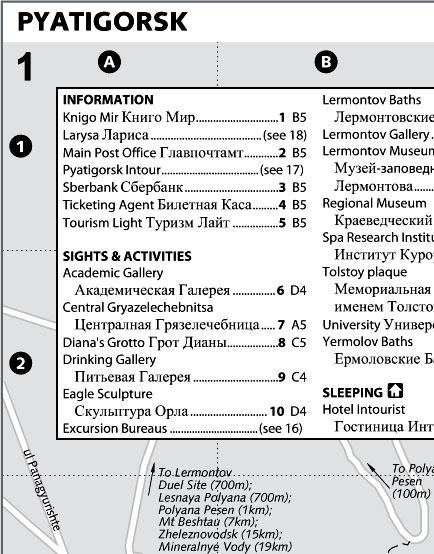

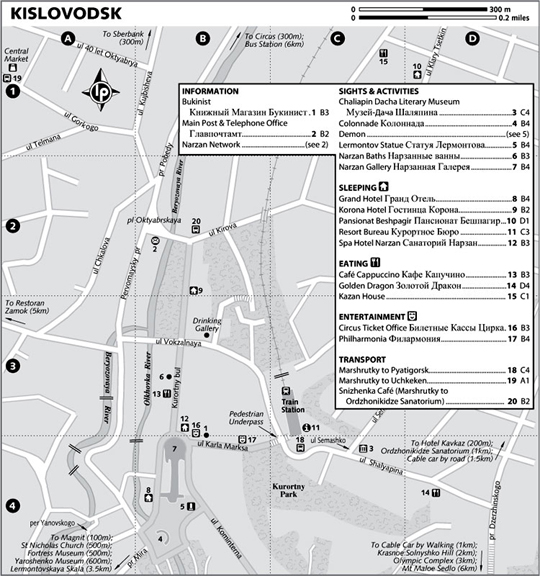

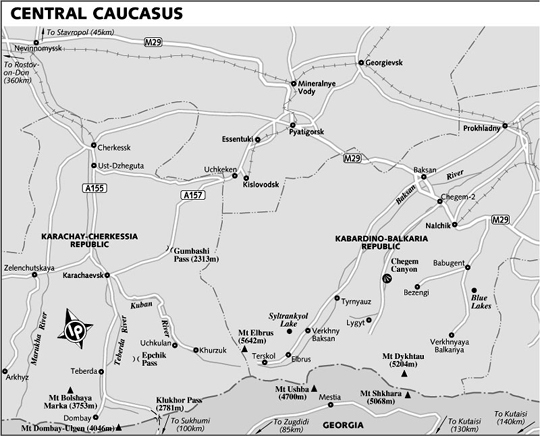

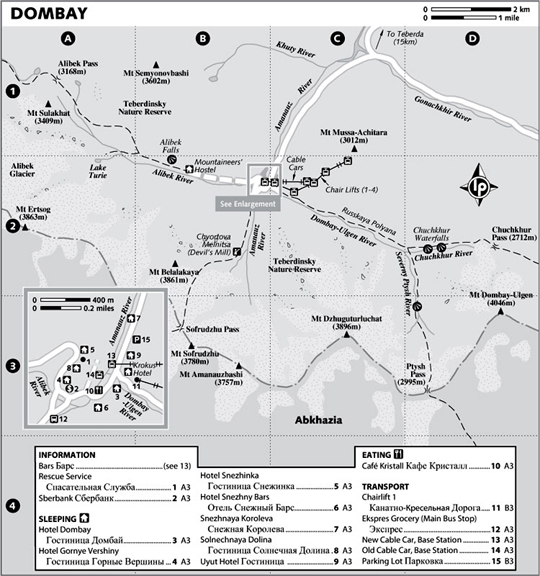

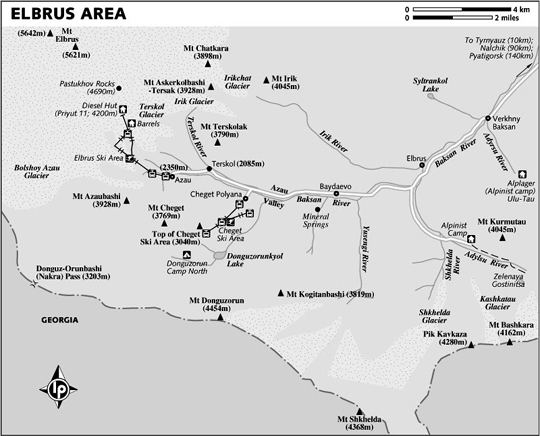

Experience climatic and environmental extremes in this adventurous itinerary running from the frigid White Sea within the Arctic Circle to the sun-kissed Black Sea lapping at the foothills of the Caucasus. Start in Murmansk (Click here), something of a boom town from its offshore gas fields; time your visit right and you might even witness the famous northern lights here. Take a train directly south through the Kola Peninsula, heading for Kem (Click here), access point for the remote Solovetsky Islands (Click here), infamous as the location of Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago but also known for their beautiful landscapes and evocative monastery. Back on the mainland keep on towards appealing Petrozavodsk (Click here) where you can connect, either by hydrofoil across Lake Onega or by bus, to Vytegra (Click here), which has a fascinating submarine museum, before continuing on to historic Vologda (Click here), dotted with old churches and wooden houses. Trains chug on to lovely Yaroslavl (Click here) from where you could take a short cruise on a river boat down to Nizhny Novgorod (Click here) or even further along the Volga to the Tatarstan capital of Kazan (Click here). The Volga continues to guide you south past Lenin’s birthplace of Ulyanovsk (Click here) and Samara (Click here) from where you could go hiking in the rocky Zhiguli Hills. Ultimately you’ll reach Astrakhan (Click here) where you could dip your toe in the Caspian Sea before turning west to the fascinating Buddhist enclave of Elista (Click here), a convenient breaking point en route to the Caucasus mineral-water spa region centred around attractive Pyatigorsk (Click here). From here it’s a straight shot to Sochi (Click here), the Black Sea’s premier resort and host city for the 2014 Winter Olympics, which will be mainly held up at the ski centre of Krasnaya Polyana (Click here).

Return to beginning of chapter

TAILORED TRIPS

Return to beginning of chapter

LITERARY RUSSIA

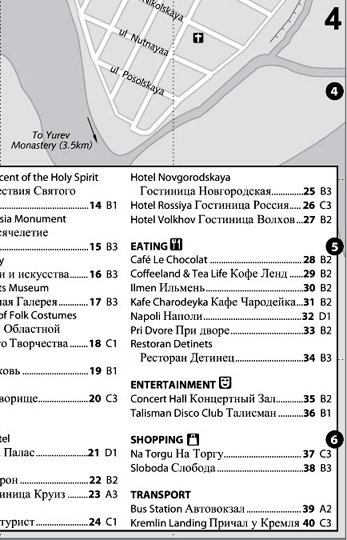

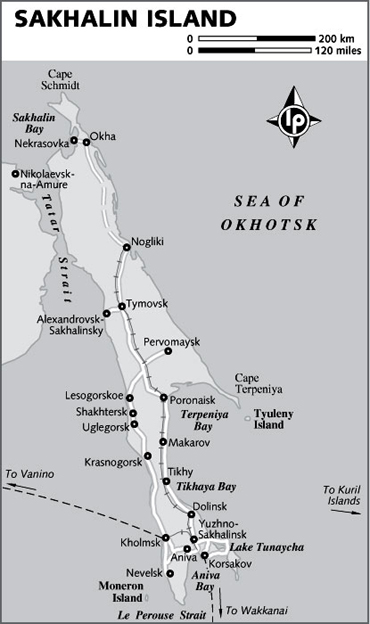

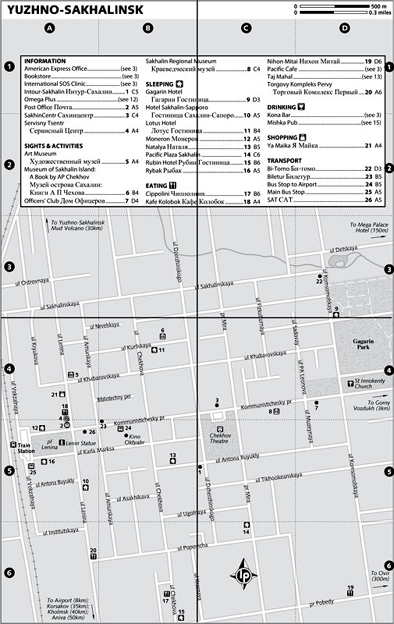

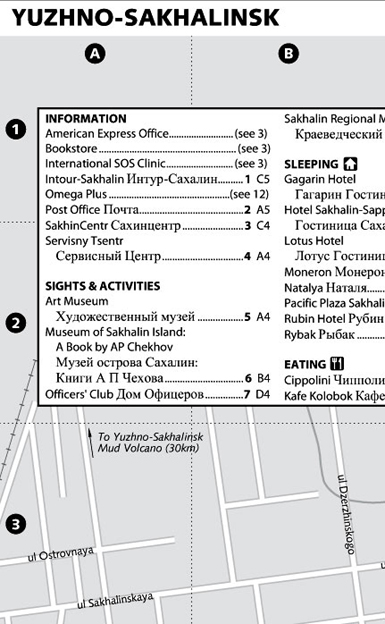

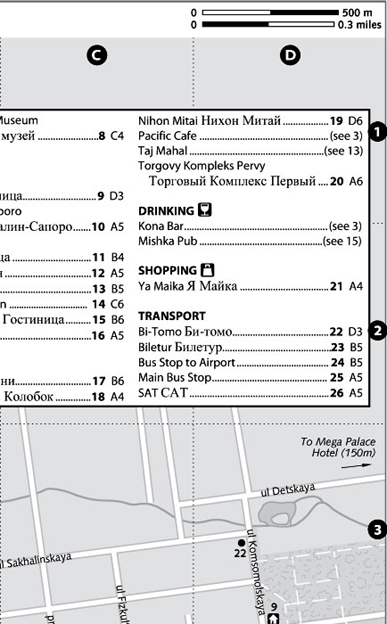

A tour of the locations associated with Russia’s literary giants gives you an insight into what inspired their work, and makes for an offbeat trip across Russia, from the Baltic to the Pacific and back to the Black Sea. St Petersburg (Click here) is arguably Russia’s city of letters, with museums in the former homes of Fyodor Dostoevsky, Alexander Pushkin and the poet Anna Akhmatova. You can also pay your respects at Dostoevsky’s summer hideaway in Staraya Russa (Click here) and the Siberian prisons in which he languished in Tobolsk (Click here) and Omsk (Click here). In contrast Anton Chekhov, whose country estate is at Melikhovo (Click here), made a voluntary trip across Siberia ending up on Sakhalin; a small museum in the island’s capital, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk (Click here), commemorates the writer’s epic journey as does one in Aleksandrovsk-Sakhalinsky (Click here). Boris Pasternak’s dacha in the writers’ colony of Peredelkino (Click here) is open for inspection, as is Yasnaya Polyana (Click here), Leo Tolstoy’s estate, which is surrounded by apple orchards, and Spasskoe-Lutovinovo (Click here), the family manor of Ivan Turgenev. Recite your favourite Pushkin verses at his home in Mikhailovskoe (Click here) before heading south, as the poet did in exile, to the romantic, troubled Caucasus and the resort of Pyatigorsk (Click here), where fellow poet Mikhail Lermontov is commemorated all over town at a grotto, gallery, museum and gardens.

Return to beginning of chapter

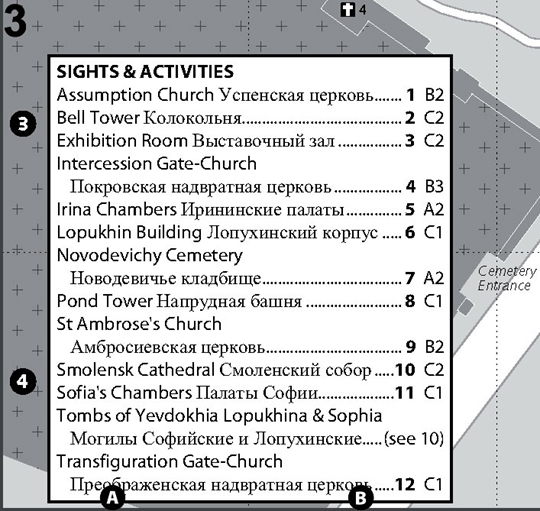

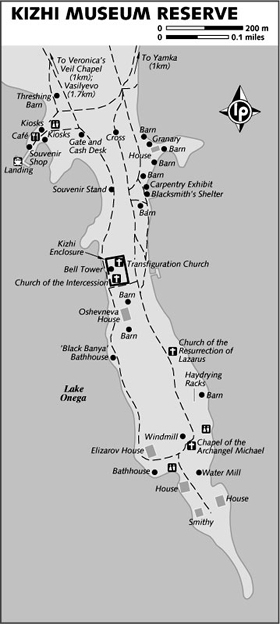

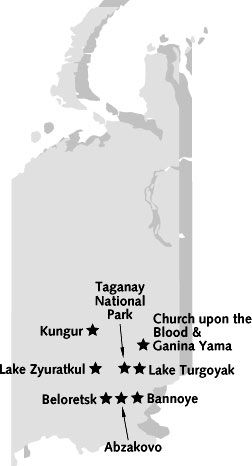

WORLD HERITAGE RUSSIA

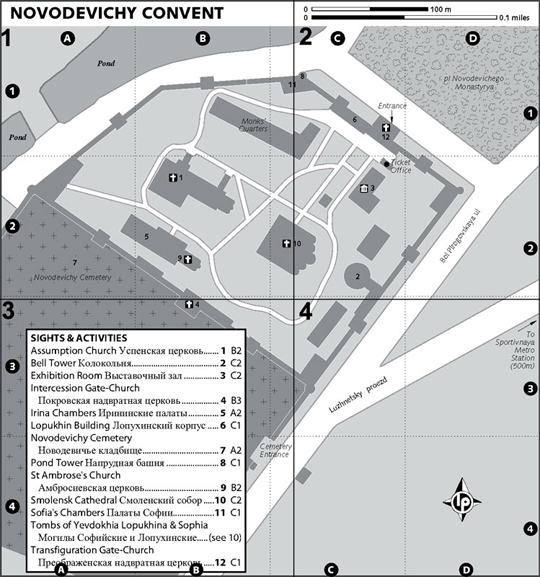

There are 21 Unesco World Heritage sites in Russia. To visit many of them, from the Kurshskaya Kosa (Click here) in Kaliningrad in the west to the volcanoes of Kamchatka (Click here) in the Far East, could easily swallow up a couple of months but would also make an unparalleled tour of the nation’s cultural and geographical highlights. From Kaliningrad head to imperial St Petersburg (Click here), then continue to the fairy-tale churches on Kizhi (Click here) in Lake Ladoga. Journey to the edge of the Arctic Circle to the beautiful Solovetsky Islands (Click here), and on the way back south pause at ancient Novgorod (Click here). In Moscow (Click here), you can tick off the Kremlin, Red Square, Novodevichy Convent and Church of the Ascension at Kolomenskoe. The Golden Ring towns of Vladimir (Click here), Suzdal (Click here) and Sergiev Posad (Click here) are all on the list, as are the spectacular mountains of the Western Caucasus such as Mt Elbrus (Click here). Turning eastward, stop off at Kazan (Click here) for its kremlin before making your assault on the Altai Mountains (Click here). Beguiling Lake Baikal (Click here) and the Sikhote-Alin Nature Reserve (Click here) on the Pacific coast bring up the rear.

Return to beginning of chapter

History

ALEXANDER NEVSKY & THE RISE OF MOSCOW

BORIS GODUNOV & THE TIME OF TROUBLES

DECEMBRISTS & OTHER POLITICAL EXILES

FIVE-YEAR PLANS & FARM COLLECTIVISATION

Russia’s epic history is stacked with larger-than-life characters, such as Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, Stalin and Boris Yeltsin – rulers who run the gamut from enlightened reformers to murderous despots. From its very beginnings it has been a multiethnic country, its inhabitants a colourful and exhausting list of native peoples and invaders, the descendants of whom are still around today.

EARLY HISTORY

Human activity in Russia stretches back a million years, with evidence of Stone Age hunting communities in the region from Moscow to the Altai and Lake Baikal. By 2000 BC a basic agriculture, relying on hardy cereals, had penetrated from the Danube region as far east as the Moscow area and the southern Ural Mountains. At about the same time, peoples in Ukraine and southern areas of European Russia domesticated the horse and developed a nomadic, pastoral lifestyle.

While central and northern European Russia remained a complete back-water for almost 3000 years, the south was subject to a succession of invasions by nomads from the east. The first written records, by the 5th-century-BC Greek historian Herodotus, concern a people called the Scythians, who probably originated in the Altai region of Siberia and Mongolia and were feared for their riding and battle skills. They spread as far west as southern Russia and Ukraine by the 7th century BC. The Scythian empire ended with the arrival of another people from the east, the Sarmatians, in the 3rd century BC.

In the 4th century AD came the Huns of the Altai region, followed by their relations the Avars, then by the Khazars, a Turkic tribe from the Caucasus, who occupied the lower Volga and Don Basins and the steppes to the east and west between the 7th and 10th centuries. The crafty and talented Khazars brought stability and religious tolerance to areas under their control. In the 9th century they converted to Judaism, and by the 10th century they had mostly settled down to farming and trade.

Geoffrey Hosking’s Russia and the Russians is a definitive one-volume trot through 1000 years of Russian history by a top scholar.

Return to beginning of chapter

SLAVS

The migrants who were to give Russia its predominant character were the Slavs. There is some disagreement about where the Slavs originated, but in the first few centuries AD they expanded rapidly to the east, west and south from the vicinity of present-day northern Ukraine and southern Belarus. The Eastern Slavs were the ancestors of the Russians; they were still spreading eastward across the central Russian woodland belt in the 9th century. From the Western Slavs came the Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and others. The Southern Slavs became the Serbs, Croats, Slovenes and Bulgarians.

The Slavs’ conversion to Christianity in the 9th and 10th centuries was accompanied by the introduction of an alphabet devised by Cyril, a Greek missionary (later St Cyril), which was simplified a few decades later by a fellow missionary, Methodius. The forerunner of Cyrillic, it was based on the Greek alphabet, with a dozen or so additional characters. The Bible was translated into the Southern Slav dialect, which became known as Church Slavonic and is the language of the Russian Orthodox Church’s liturgy to this day.

Return to beginning of chapter

VIKINGS & KYIVAN RUS

The first Russian state developed out of the trade on river routes across Eastern Slavic areas – between the Baltic and Black Seas and, to a lesser extent, between the Baltic Sea and the Volga River. Vikings from Scandinavia – the Varangians, also called Varyagi by the Slavs – had been nosing east from the Baltic since the 6th century AD, trading and raiding for furs, slaves and amber, and coming into conflict with the Khazars and with Byzantium, the eastern centre of Christianity. To secure their hold on the trade routes, the Vikings made themselves masters of settlements in key areas – places such as Novgorod, Smolensk, Staraya Ladoga and Kyiv (Kiev) in Ukraine. Though by no means united themselves, they created a loose confederation of city-states in the Eastern Slavic areas.

Ex-diplomat Sir Fitzroy Maclean wrote several entertaining, intelligent books on the country. Holy Russia is a good, short Russian history, while All the Russias: The End of an Empire covers the whole of the former USSR.

The 9th-century legendary figure Rurik of Jutland is the founder of the Rurik dynasty, the ruling family of the embryonic Russian state of Kyivan Rus and the dominant rulers in Eastern Slavic areas until the end of the 16th century. The name Rus may have been that of the dominant Kyivan Viking clan, but it wasn’t until the 18th century that the term Russian or Great Russian came to be used exclusively for Eastern Slavs in the north, while those to the south or west were identified as Ukrainians or Belarusians.

Prince Svyatoslav I made Kyiv the dominant regional power by campaigning against quarrelling Varangian princes and dealing the Khazars a series of fatal blows. After his death in 972, his son Vladimir made further conquests, baptised Kyivan Rus as a Christian state and introduced the beginnings of a feudal structure to replace clan allegiances. However, some principalities – including Novgorod, Pskov and Vyatka (north of Kazan) – were ruled democratically by popular vechi (assemblies).

Kyiv’s supremacy was broken by new invaders from the east – first the Pechenegs, then in 1093 the Polovtsy sacked the city – and by the effects of European crusades from the late 11th century onwards, which broke the Arab hold on southern Europe and the Mediterranean, reviving west–east trade routes and making Rus a commercial backwater.

NAMING RUSSIAN RULERS

In line with common usage, names of pre-1700 rulers are directly transliterated, anglicised from Peter the Great until 1917, and again transliterated after that – thus Andrei Bogolyubov not Andrew, Vasily III not Basil; but Peter the Great not Pyotr, Catherine the Great not Yekaterina etc.

Ivan the Great was the first ruler to have himself formally called tsar. Peter the Great began using emperor, though tsar remained in use. In this book we use empress for a female ruler; a tsar’s wife who does not become ruler is a tsaritsa (in English, tsarina). A tsar’s son is a tsarevitch and his daughter a tsarevna.

Return to beginning of chapter

NOVGOROD & ROSTOV-SUZDAL

The northern Rus principalities began breaking from Kyiv after about 1050. The merchants of Novgorod joined the emerging Hanseatic League, a federation of city-states that controlled Baltic and North Sea trade. Novgorod became the league’s gateway to the lands east and southeast.

As Kyiv declined, the Russian population shifted northwards and the fertile Rostov-Suzdal region northeast of Moscow began to be developed. Vladimir Monomakh of Kyiv founded the town of Vladimir there in 1108 and gave the Rostov-Suzdal principality to his son Yury Dolgoruky, who is credited with founding the little settlement of Moscow in 1147.

Sergei Bodrov’s Mongol, nominated for an Oscar as best foreign film in 2008, focused on the dramatic early life of Chinggis Khaan, whose forces would go on to conquer Russia.

Rostov-Suzdal grew so rich and strong that Yury’s son Andrei Bogolyubov tried to use his power to unite the Rus principalities. His troops took Kyiv in 1169, after which he declared Vladimir his capital, even though the Church’s headquarters remained in Kyiv until 1300. Rostov-Suzdal began to gear up for a challenge against the Bulgars’ hold on the Volga–Ural Mountains region. The Bulgar people had originated further east several centuries before and had since converted to Islam. Their capital, Bolgar, was near modern Kazan, on the Volga.

Return to beginning of chapter

TATARS & THE GOLDEN HORDE

Meanwhile, over in the east, a confederation of armies headed by the Mongolian warlord Chinggis (Genghis) Khaan (1167–1227) was busy subduing most of Asia, except far northern Siberia, eventually crossing Russia into Europe to create history’s largest land empire. Russians often refer to these mainly Mongol invaders as Tatars, when in fact the Tatars were simply one particularly powerful tribe that joined the Mongol bandwagon. The Tatars of Tatarstan actually descended from the Bulgars and are related to the Bulgarians of the Balkans.

In 1223 Chinggis’ forces met the armies of the Russian princes and thrashed them at the Battle of Kalka River. This push into European Russia was cut short by the death of the warlord, but his grandson Batu Khaan returned in 1236 to finish the job, laying waste to Bolgar and Rostov-Suzdal, and annihilating most of the other Russian principalities, including Kyiv, within four years. Novgorod was saved only by spring floods that prevented the invaders from crossing the marshes around the city.

Batu and his successors ruled the Golden Horde (one of the khanates into which Chinggis’ empire had broken) from Saray on the Volga, near modern Volgograd. At its peak the Golden Horde’s territory included most of eastern Europe stretching from the banks of the Dnieper River in the west to deep into Siberia in the east and south to the Caucasus. The Horde’s control over its subjects was indirect: although its armies raided them in traditional fashion if they grew uppity, it mainly used collaborative local princes to keep order, provide soldiers and collect taxes.

Jack Weatherford’s informative book Ghengis Khan and the Making of the Modern World includes some details on the Mongol invasion and occupation of western Russia.

Return to beginning of chapter

ALEXANDER NEVSKY & THE RISE OF MOSCOW

One such ‘collaborator’ was the Prince of Novgorod, Alexander Nevsky, a Russian hero (and later a saint of the Russian Church) for his resistance to German crusaders and Swedish invaders. In 1252, Batu Khaan put him on the throne as Grand Prince of Vladimir.

Sergei Eisenstein’s 1938 movie Alexander Nevsky, focusing on the saviour of Russia’s epic battle with the Teutonic knights, had a music score by Sergei Prokofiev.

Nevsky and his successors acted as intermediaries between the Tatars and other Russian princes. With shrewd diplomacy, the princes of Moscow obtained and hung on to the title of grand prince from the early 14th century while other princes resumed their feuding. The Church provided backing to Moscow by moving there from Vladimir in the 1320s, and was in turn favoured with exemption from Tatar taxation.

But Moscow proved to be the Tatars’ nemesis. With a new-found Russian confidence, Grand Prince Dmitry put Moscow at the head of a coalition of princes and took on the Tatars, defeating them in the battle of Kulikovo Pole on the Don River in 1380. For this he became Dmitry Donskoy (of the Don) and was canonised after his death.

The Tatars crushed this uprising in a three-year campaign but their days were numbered. Weakened by internal dissension, they fell at the end of the 14th century to the Turkic empire of Timur (Tamerlane), which was based in Samarkand (in present-day Uzbekistan). Yet the Russians, themselves divided as usual, remained Tatar vassals until 1480.

Masha Holl’s Russian History site (http://history.mashaholl.com/history.php) abounds with intriguing details, such as the fact that surnames didn’t exist in Russia for most of the Middle Ages.

Return to beginning of chapter

MOSCOW VS LITHUANIA

Moscow (or Muscovy, as its expanding lands came to be known) was champion of the Russian cause after Kulikovo, though it had rivals, especially Novgorod and Tver. More ominous was the rise of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which had started to expand into old Kyivan Rus lands in the 14th century. The threat became real in 1386 when the Lithuanian ruler Jogaila married the Polish queen Jadwiga and became king of Poland, thus joining two of Europe’s most powerful states.

With Jogaila’s coronation as Wladyslaw II of Poland, the previously pagan Lithuanian ruling class embraced Catholicism. The Russian Church portrayed the struggle against Lithuania as one against the pope in Rome. After Constantinople (centre of the Greek Orthodox Church) was taken by the Turks in 1453, the metropolitan – head of the Russian Church – declared Moscow the ‘third Rome’, the true heir of Christianity.

Meanwhile, with the death of Dmitry Donskoy’s son Vasily I in 1425, Muscovy suffered a dynastic war. The old Rurikids got the upper hand – ironically with Lithuanian and Tatar help – but it was only with Ivan III’s forceful reign from 1462 to 1505 that the other principalities ceased to oppose Muscovy.

Return to beginning of chapter

IVAN THE GREAT

In 1478 Novgorod was first of the Great Russian principalities to be brought to heel by Ivan III. To secure his power in the city he installed a governor, deported the city’s most influential families (thus pioneering a strategy that would be used with increasing severity by Russian rulers right up to Stalin) and ejected the Hanseatic merchants, turning Russia’s back on Western Europe for two centuries.

Ivan III was the first Russian emperor to adopt the use of the double-headed eagle as the symbol of state.

The exiles were replaced with Ivan’s administrators, whose good performance was rewarded with temporary title to confiscated lands. This new approach to land tenure, called pomestie (estate), characterised Ivan’s rule. Previously, the boyars (feudal landholders) had held land under a votchina (system of patrimony) giving them unlimited control and inheritance rights over their lands and the people on them. The freedom to shift allegiance to other princes had given them political clout, too. Now, with few alternative princes left, the influence of the boyars declined in favour of the new landholding civil servants. This increased central control spread to the lower levels of society with the growth of serfdom (see the boxed text, opposite).

In 1480 at the Ugra River, southwest of Moscow, Ivan’s armies faced down those of the Tatars who had come to extract tributes withheld by Muscovy for the previous four years. They parted without a fight, Russia free at last of the Tatar yoke.

Tver fell to Moscow in 1485, and far-flung Vyatka fell in 1489. Pskov and Ryazan, the only states still independent at the end of Ivan’s reign, were mopped up by his successor, Vasily III. Lithuania and Poland, however, remained thorns in Russia’s side.

Return to beginning of chapter

IVAN IV (THE TERRIBLE)

Vasily III’s son, Ivan IV, took the throne in 1533 at the age of three, with his mother as regent. After 14 years of court intrigue he had himself crowned ‘Tsar of all the Russias’. The word ‘tsar’, from the Latin caesar, had previously been used only for a great khan or for the emperor of Constantinople.

DEAD SOULS: SERFS IN RUSSIA

During many centuries of feudalism right up to the turn of the 20th century, Russia had serfs: peasants and servants who were tied to their master’s estates. The value of those estates was determined not by their size or output but by the number of such indentured souls.

Before the 1500s peasants could work for themselves after meeting their master’s needs, and had the right to change homes and jobs during the two weeks around 26 November, St George’s Day, when the annual harvest was complete. However, laws introduced by Ivan III in 1497 began to restrict these limited rights to free movement and by 1590 peasants were permanently bound to the lands in which they lived.

Some peasants, of course, still chose to run away, and authority in the countryside collapsed during the Time of Troubles (1606–1613), with thousands absconding south to Cossack areas or east to Siberia, where serfdom was unknown. Despairing landlords found support from the government, which cracked down further on peasants’ personal freedoms. By 1675 they had lost all land rights and, in a uniquely Russian version of serfdom, could be sold separately from the estates on which they worked – slavery, in effect.

In 1842 Nikolai Gogol, one of Russia’s greatest writers, highlighted the trade in serfs, both dead and alive, in his novel Dead Souls. The Russian census of 1857 accounted for over 46 million serfs out of a total population of 62.5 million; around half of these were peasants working state lands who were considered free but in reality still had their movements restricted. As serfdom and slavery were being abolished across Europe and in the USA, it became recognised that changes to Russia’s system also had to be made if its economy was to compete in the age of industrialisation.

The emancipation of March 1861 immediately set serfs free of their masters, but in reality liberation was a much more drawn-out affair. Of the land serfs had worked, roughly a third was kept by established landholders. The rest went to village communes, which assigned it to the individual ex-serfs in return for ‘redemption payments’ to compensate former landholders – a system that pleased nobody and took several decades to sort out completely.

Legally serfdom may have ended in Russia but its practice, according to some, certainly didn’t go away. In his book The Road to Serfdom, Friedrich Hayek argued that the collective farm system of Soviet Russia, in which workers were tied to specified farms and had their work quotas dictated by central government, amounted to state-sponsored serfdom.

Ivan IV’s marriage to Anastasia, from the Romanov boyar family, was a happy one – unlike the five that followed her death in 1560, a turning point in his life. Believing her to have been poisoned, Ivan instituted a reign of terror that earned him the sobriquet grozny (literally ‘awesome’ but commonly translated as ‘terrible’) and nearly destroyed all his earlier good works.

Only parts 1 and 2 of Sergei Eisenstein’s powerful movie trilogy Ivan the Terrible were in the can when the director died in 1948. Just 20 minutes of the third episode were shot.

His subsequent career was indeed terrible, though he was admired for upholding Russian interests and tradition. His military victories in the Volga region, down to the Caspian Sea coast and across into Siberia helped transform Russian into the multiethnic, multireligious state it is today. However, his campaign against the Crimean Tatars nearly ended with the loss of Moscow, and a 24-year war with the Lithuanians, Poles, Swedes and Teutonic knights to the west also failed to gain any territory for Russia.

Ivan’s growing paranoia led him to launch a savage attack on Novgorod in 1570 that finally snuffed out that city’s golden age. An argument about Ivan’s beating of his son’s wife (possibly causing her miscarriage) ended with the tsar accidentally killing his heir in 1581 with a blow to the head. Ivan himself died three years later during a game of chess in 1584. The later discovery of high amounts of mercury in his remains indicated that he had most likely been poisoned – possibly by his own hand, as he had habitually used mercury to ease the pain of a fused spine.

Benson Bobrick’s book, East of the Sun, is a rollicking history of the conquest and settlement of Siberia and the Russian Far East, and is packed with gory details.

Return to beginning of chapter

BORIS GODUNOV & THE TIME OF TROUBLES

Ivan IV’s official successor was his mentally enfeebled son Fyodor, who left the actual business of government to his brother-in-law, Boris Godunov, a skilled ‘prime minister’ who repaired much of the damage done by Ivan. Fyodor died childless in 1598, ending the 700-year Rurikid dynasty, and Boris ruled as tsar for seven more years.

Shortly after Boris’s death a Polish-backed Catholic pretender arrived on the scene claiming to be Dmitry, another son of Ivan the Terrible (who had in fact died in obscure circumstances in Uglich in 1591, possibly murdered on Boris Godunov’s orders). This ‘False Dmitry’ gathered a huge ragtag army as he advanced on Moscow. Boris Godunov’s son was lynched and the boyars acclaimed the pretender tsar.

The story of Boris Godunov inspired both a play by Alexander Pushkin in 1831 and an opera by Modest Mussorgsky in 1869.

Thus began the Time of Troubles (the Smuta), a spell of anarchy, dynastic chaos and foreign invasions. At its heart was a struggle between the boyars and central government (the tsar). The False Dmitry was murdered in a popular revolt and succeeded by Vasily Shuysky (1606–10), another boyar puppet. Then a second False Dmitry challenged Shuysky. Swedish and Polish invaders fought each other over claims to the Russian throne, Shuysky was dethroned by the boyars, and from 1610 to 1612 the Poles occupied Moscow.

Eventually a popular army rallied by merchant Kuzma Minin and noble Dmitry Pozharsky, both from Nizhny Novgorod, with support from the Church, removed the Poles. In 1613 a Zemsky Sobor (Assembly of the Land), with representatives of the political classes of the day, elected 16-year-old Mikhail Romanov tsar, the first of a new dynasty that was to rule until 1917.

Vladimir Khotinenko’s 2007 movie 1612: Chronicle of the Time of Troubles is a big-budget historical epic that plays fast and loose with the events leading up to Russia’s ousting of the Poles from Moscow in 1612.

Return to beginning of chapter

SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY RUSSIA

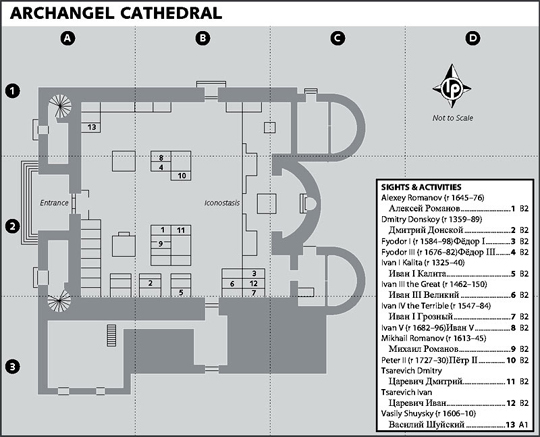

Though the first three Romanov rulers – Mikhail I (1613–45), Alexey I (1645–76) and Fyodor III (1676–82) – provided continuity and stability, there were also big changes that foretold the downfall of ‘old’ Russia.

THE COSSACKS

The word ‘Cossack’ (from the Turkic kazak, meaning free man, adventurer or horseman) was originally applied to residual Tatar groups and later to serfs, paupers and dropouts who fled south from Russia, Poland and Lithuania in the 15th century. They organised themselves into self-governing communities in the Don Basin, on the Dnepr River in Ukraine, and in western Kazakhstan. Those in a given region, eg the Don Cossacks, were not just a tribe; the men constituted a voysko (army), within which each stanitsa (village-regiment) elected an ataman (leader).

Mindful of their skill as fighters, the Russian government treated the Cossacks carefully, offering autonomy in return for military service. Cossacks such as Yermak Timofeevich were the wedge that opened Siberia in the 17th century. By the 19th century there were a dozen Cossack armies from Ukraine to the Russian Far East and, as a group, they numbered 2.5 million people.

The Cossacks were not always cooperative with the Russian state. Three peasant uprisings in the Volga–Don region ‒ 1670, 1707 and 1773 – were Cossack-led. After 1917 the Bolsheviks abolished Cossack institutions, though some cavalry units were revived in WWII. Since 1991 there has been a Cossack revival particularly in the Don region. Cossack regiments have been officially recognised, there is a presidential adviser on Cossacks, and some Cossacks demand that the state recognise them as an ethnic group.

The 17th century saw a huge growth in the Russian lands. In 1650 Tsar Alexey commissioned the Cossack trader Yerofey Khabarov (after whom Khabarovsk is named) to open up the far-eastern region. By 1689 the Russians occupied the northern bank of the Amur. The Treaty of Nerchinsk sealed a peace with neighbouring China that lasted for more than 150 years.

Additionally, when Cossacks in Ukraine appealed for help against the Poles, Alexey came to their aid, and in 1667 Kyiv, Smolensk and lands east of the Dnepr came under Russian control.

In 1648 the Cossack Semyon Dezhnev sailed round the northeastern corner of Asia, from the Pacific Ocean into the Arctic, 80 years before Vitus Bering.

Conflicts within the Church resulted in its transformation into an ally of the authoritarian government, equally distrusted by the people. In the mid-17th century, Patriarch Nikon tried to bring rituals and texts into line with the ‘pure’ Greek Orthodox Church, horrifying those attached to traditional Russian forms, and causing a bitter divide in Russian Orthodoxy (see boxed text, Click here).

Return to beginning of chapter

PETER THE GREAT

Peter I, known as ‘the Great’ for his commanding 2.24m frame and his equally commanding victory over the Swedes, dragged Russia kicking and screaming into Europe, and made it a major world power.

Born to Tsar Alexey’s second wife, Natalia, in 1672, Peter was an energetic and inquisitive youth who often visited Moscow’s European district to learn about the West. Dutch and British ship captains in Arkhangelsk gave him navigation lessons on the White Sea.

THE RISE, FALL AND RISE AGAIN OF THE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

Legend has it that, while preaching the gospel, the apostle Andrew paused in what would later become Kyiv (Kiev) and predicted the founding of a Christian city. In AD 988 Vladimir I fulfilled the prophesy by adopting Christianity from Constantinople (Istanbul today), the eastern centre of Christianity in the Middle Ages, effectively starting the Russian Orthodox Church. The Church’s headquarters stayed at Kyiv until 1300, when it moved north to Vladimir. In 1326 it moved again, from Vladimir to Moscow.

The church flourished until 1653 when it was split by the reforms of Patriarch Nikon. Thinking that the Church had departed from its roots, Nikon insisted, among other things, that the translation of the Bible be altered to conform with the Greek original, and that the sign of the cross be made with three fingers, not two. Even though Nikon was subsequently sacked by Tsar Alexey, his reforms went through and those who refused to accept them became known as Starovery (Old Believers) and were persecuted. Some fled to Siberia or remote parts of Central Asia, where in the 1980s one group was found who had never heard of Vladimir Lenin, electricity or the revolution. Only from 1771 to 1827, from 1905 to 1918 and again recently have Old Believers had real freedom of worship. Estimates put the number of Old Believers worldwide at anything from one to 10 million, but in 1917 there were as many as 20 million.

Another blow to Church power came with the reforms of Peter the Great, who replaced the self-governing patriarchate with a holy synod subordinate to the tsar, who effectively became head of the Church. When the Bolsheviks came to power Russia had over 50,000 churches. Lenin adopted Karl Marx’s view of religion as ‘the opium of the people’. Atheism was vigorously promoted and Josef Stalin seemed to be trying to wipe out religion altogether until 1941, when he decided the war effort needed the patriotism that the church could stir up. Nikita Khrushchev renewed the attack in the 1950s, closing about 12,000 churches. By 1988 fewer than 7000 churches were active.

Since the end of the Soviet Union, the Church has seen a huge revival with around 90% of Russians identifying themselves as Russian Orthodox. New churches are being built and many old churches and monasteries – which had been turned into museums, archive stores and even prisons – have been returned to Church hands and are being restored.

When Fyodor III died in 1682, Peter became tsar, along with his feeble-minded half-brother Ivan V, under the regency of Ivan’s ambitious sister, Sophia. She had the support of a leading statesman of the day, Prince Vasily Golitsyn. The boyars, annoyed by Golitsyn’s institution of a stringent ranking system, schemed successfully to have Sophia sent to a convent in 1689 and replaced as regent by Peter’s unambitious mother.

http://artsci.shu.edu/reesp/documents/index.html is Seton Hall University’s online source book of primary documents on Russia, including proclamations by the tsars and speeches by Lenin and Stalin.

Few doubted Peter as the true monarch, and when he became sole ruler, after his mother’s death in 1694 and Ivan’s in 1696, he embarked on a modernisation campaign, symbolised by his fact-finding mission to Europe in 1697–98; he was the first Muscovite ruler ever to go there and in the process hired a thousand experts for service in Russia.

He was also busy negotiating alliances. In 1695 he had sent Russia’s first navy down the Don River and captured the Black Sea port of Azov from the Crimean Tatars, vassals of the Ottoman Turks. His European allies weren’t interested in the Turks but shared his concern about the Swedes, who held most of the Baltic coast and had penetrated deep into Europe.

Peter’s alliance with Prussia and Denmark led to the Great Northern War against Sweden (1700–21). The rout of Charles XII’s forces at the Battle of Poltava (1709) heralded Russia’s power and the collapse of the Swedish empire. The Treaty of Nystadt (1721) gave Peter control of the Gulf of Finland and the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea, and in the midst of this (in 1707) he put down another peasant rebellion, led by Don Cossack Kondraty Bulavin.

On land taken from the Swedes, Peter founded St Petersburg and in 1712 he made it the capital, symbol of a new, Europe-facing Russia.

Return to beginning of chapter

PETER’S LEGACY

Peter’s lasting legacy was mobilising Russian resources to compete on equal terms with the West. His territorial gains were small, but the strategic Baltic territories added ethnic variety, including a new upper class of German traders and administrators who formed the backbone of Russia’s commercial and military expansion.

Peter the Great – His Life and World, by Robert K Massie, is a good read about one of Russia’s most influential rulers, and provides much detail about how he created St Petersburg.

Peter was also to have the last word on the authority of the Church. When it resisted his reforms he simply blocked the appointment of a new patriarch, put bishops under a government department and in effect became head of the Church himself. Among other modernising measures, he ordered all his administrators and soldiers to shave off their beards.

Vast sums of money were needed to build St Petersburg, pay a growing civil service, modernise the army and launch naval and commercial fleets. But money was scarce in an economy based on serf labour, so Peter slapped taxes on everything from coffins to beards, including an infamous ‘Soul Tax’ on all lower-class adult males. The lot of serfs worsened, as they bore the main tax burden.

Even the upper classes had to chip in: aristocrats could serve in either the army or the civil service, or lose their titles and land. Birth counted for little, with state servants being subject to Peter’s Table of Ranks, a performance-based ladder of promotion, in which the upper grades conferred hereditary nobility. Some aristocrats lost all they had, while capable state employees of humble origin, and thousands of foreigners, became Russian nobles.

Return to beginning of chapter

AFTER PETER

Peter died in 1725 without naming a successor. His wife Catherine, a former servant and one-time mistress of the tsar’s right-hand man Alexander Menshikov, became the first woman to rule Imperial Russia. In doing so, she blazed a path for other women, including her daughter Elizabeth and, later, Catherine the Great, who, between them, held on to the top job for the better part of 70 years.

RUSSIANS IN AMERICA

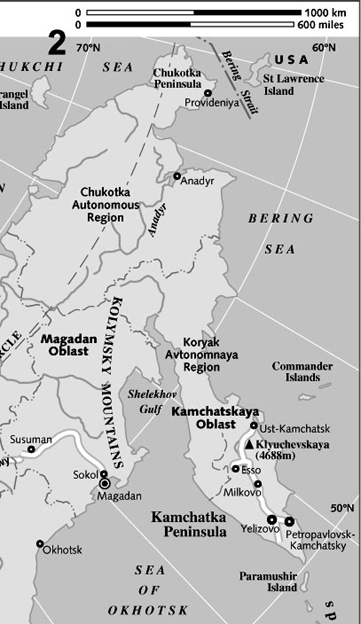

Peter the Great commissioned Vitus Bering, a Danish officer in the Russian navy, to head the Great Northern Expedition, which was ostensibly a scientific survey of Kamchatka (claimed for the tsar in 1697 by the explorer Vladimir Atlasov) and the eastern seaboard. In reality the survey’s aim was to expand Russia’s Pacific sphere of influence as far south as Japan and across to North America.

On his second expedition Bering succeeded in discovering Alaska, landing in 1741. The Bering Straits separating Alaska from the Russian mainland are named after him. Unfortunately, on the return voyage his ship was wrecked off an island just 250km east of the Kamchatka coast. Bering died on the island and it, too, now carries his name.

Survivors of Bering’s crew brought back reports of an abundance of foxes, fur seals and otters inhabiting the islands off the mainland, triggering a fresh wave of fur-inspired expansion. An Irkutsk trader, Grigory Shelekhov, landed on Kodiak Island (in present-day Alaska) in 1784 and, 15 years later, his successor founded Sitka (originally called New Archangel), the capital of Alaska until 1900.

In 1804 the Russians reached Honolulu, and in 1806 Russian ships sailed into San Francisco Bay. Soon afterwards a fortified outpost was established at what is now called Fort Ross, California. Here the imperial flag flew and a marker was buried on which was inscribed ‘Land of the Russian Empire’.

Catherine left day-to-day administration of Russia to a governing body called the Supreme Privy Council, staffed by many of Peter’s leading administrators. Following her death in 1727, and that of her nominated heir, Peter II (grandson of Peter I) just three years later from smallpox, the council elected Peter’s niece Anna of Courland (a small principality in present-day Latvia) to the throne, with a contract stating that the council had the final say in policy decisions. Anna ended this experiment in constitutional monarchy by disbanding the council.

Anna ruled from 1730 to 1740, appointing a Baltic German baron, Ernst Johann von Bühren, to handle affairs of state. His name was Russified to Biron, but his heavy-handed, corrupt style came to symbolise the German influence on the royal family that had begun with Peter the Great.

During the reign of Peter’s daughter, Elizabeth (1741–61), German influence waned and restrictions on the nobility were loosened. Some aristocrats began to dabble in manufacture and trade.

Catherine the Great: Life and Legend, by John T Alexander, is a lively account of the famous empress, making a case for the veracity of some of the more salacious tales of her life.

Return to beginning of chapter

CATHERINE II (THE GREAT)

Daughter of a German prince, Catherine came to Russia at the age of 15 to marry Empress Elizabeth’s heir apparent, her nephew Peter III. Intelligent and ambitious, Catherine learned Russian, embraced the Orthodox Church and devoured the writings of European political philosophers. This was the time of the Enlightenment, when talk of human rights, social contracts and the separation of powers abounded.

Catherine later said of Peter III, ‘I believe the Crown of Russia attracted me more than his person.’ Six months after he ascended the throne she had him overthrown in a palace coup led by her current lover (it has been said that she had more lovers than the average serf had hot dinners); he was murdered shortly afterwards.

Catherine embarked on a program of reforms, though she made it clear that she had no intention of limiting her own authority. She drafted a new legal code, limited the use of torture and supported religious tolerance. But any ideas she might have had of improving the lot of serfs went overboard with the violent peasant rebellion of 1773–74, led by the Don Cossack Yemelyan Pugachev, which spread from the Ural Mountains to the Caspian Sea and along the Volga. Hundreds of thousands of serfs responded to Pugachev’s promises to end serfdom and taxation, but were beaten by famine and government armies. Pugachev was executed and Catherine put an end to Cossack autonomy.

Vincent Cronin’s book, Catherine, Empress of all the Russias, paints a more sympathetic portrait than usual of a woman traditionally seen as a scheming, power-crazed sexpot.

In the cultural sphere, Catherine increased the number of schools and colleges and expanded publishing. Her vast collection of paintings forms the core of the present-day Hermitage collection. A critical elite gradually developed, alienated from most uneducated Russians but also increasingly at odds with central authority – a ‘split personality’ common among future Russian radicals.

RUSSIA’S SCIENTIFIC LEGACY

The Russian Academy of Sciences was established in 1726 and has since produced great results. Students the world over learn about the conditional reflex experiments on Ivan Pavlov’s puppies, and about Dmitry Mendeleyev’s 1869 discovery of the periodic table of elements. Yet you may be surprised to hear from locals about Russia’s invention of the electric light and radio (didn’t you know?).

During the Soviet period, Russian advances in science, hampered by secrecy, bureaucracy and a lack of technology, were dependent on the ruling party. Funding was sporadic, often coming in great bursts for projects that served propaganda or militaristic purposes. Thus the space race received lots of money, and even though little of real scientific consequence was achieved during the first missions, the PR was priceless. In other fields, however, the USSR lagged behind the West; genetics, cybernetics and the theory of relativity were all at one point deemed anathema to communism.

Physics – especially theoretical and nuclear – was supported, and Russia has produced some of the world’s brightest scientists in the field. Andrei Sakharov (1921–89), ‘father of the H-bomb’, was exiled to Gorky (now Nizhny Novgorod) in 1980, five years after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize for his vocal denunciations of the Soviet nuclear program and the Afghan War. He was one of the most influential dissidents of his time.

Return to beginning of chapter

TERRITORIAL GAINS

Catherine’s reign saw major expansion at the expense of the weakened Ottoman Turks and Poles, engineered by her ‘prime minister’ and foremost lover, Grigory Potemkin (Potyomkin). War with the Turks began in 1768, peaked with the naval victory at Çesme and ended with a 1774 treaty giving Russia control of the north coast of the Black Sea, freedom of shipping through the Dardanelles to the Mediterranean, and ‘protectorship’ of Christian interests in the Ottoman Empire – a pretext for later incursions into the Balkans. Crimea was annexed in 1783.

Read about the fascinating life of Grigory Potemkin, lover of Catherine the Great and mover and shaker in 18th-century Russia, in Simon Sebag Montefiore’s Prince of Princes: The Life of Potemkin.

Poland had spent the previous century collapsing into a set of semi-independent units with a figurehead king in Warsaw. Catherine manipulated events with divide-and-rule tactics and even had another former lover, Stanislas Poniatowski, installed as king. Austria and Prussia proposed sharing Poland among the three powers, and in 1772, 1793 and 1795 the country was carved up, ceasing to exist as an independent state until 1918. Eastern Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania – roughly, present-day Lithuania, Belarus and western Ukraine – came under Russian rule.

The roots of the current Chechen war began when Catherine sought to expand her empire into the Caucasus.

After wrapping up the periodic table, Mendeleyev devoted much of his remaining 38 years of life to searching for the universal ethers and rarefied gases that allegedly rule interactions between all bodies.

Return to beginning of chapter

ALEXANDER I

When Catherine died in 1796 the throne passed on to her son, Paul I. A mysterious figure in Russian history (often called the Russian Hamlet by Western scholars), he antagonised the gentry with attempts to reimpose compulsory state service, and was killed in a coup in 1801.

Paul’s son and successor was Catherine’s favourite grandson, Alexander I, who had been trained by the best European tutors. Alexander kicked off his reign with several reforms, including an expansion of the school system that brought education within reach of the lower middle classes. But he was soon preoccupied with the wars against Napoleon, which were to dominate his career.

Under the Treaty of Tilsit in 1807, Alexander agreed to be Emperor of the East while Napoleon was declared Emperor of the West. This alliance, however, lasted only until 1810, when Russia’s resumption of trade with England provoked the French leader to raise an army of 700,000 – the largest force the world had ever seen for a single military operation – to march on Moscow.

Return to beginning of chapter

1812 & AFTERMATH

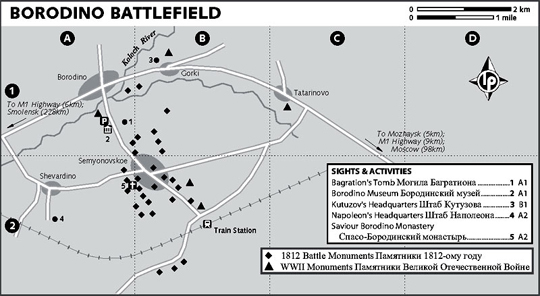

The Russian forces, who were vastly outnumbered, retreated across their own countryside throughout the summer of 1812, scorching the earth in an attempt to deny the French sustenance and fighting some successful rearguard actions. In September, with the lack of provisions beginning to affect he French, the Russian general Mikhail Kutuzov finally decided to turn and fight back at Borodino, 130km outside Moscow. The battle was extremely bloody, but inconclusive, with the Russians withdrawing in good order.

Before the month was out, Napoleon entered a deserted Moscow; the same day, the city began to burn down around him (by whose hand has never been established). Alexander ignored his overtures to negotiate. With winter coming and his supply lines overstretched, Napoleon was forced to retreat. His starving troops were picked off by Russian partisans. Only one in 20 made it back to the relative safety of Poland, and the Russians pursued them all the way to Paris.

At the Congress of Vienna, where the victors met in 1814–15 to establish a new order after Napoleon’s final defeat, Alexander championed the cause of the old monarchies. His legacies were a hazy Christian fellowship of European kings, called the Holy Alliance, and a system of pacts to guard against future Napoleons – or any revolutionary change.

Meanwhile Russia was expanding its territory on other fronts. The kingdom of Georgia united with Russia in 1801. After a war with Sweden in 1807–09, Alexander became Grand Duke of Finland. Russia argued with Turkey over the Danube principalities of Bessarabia (covering modern Moldova and part of Ukraine) and Wallachia (now in Romania), taking Bessarabia in 1812. Persia ceded northern Azerbaijan a year later and Yerevan (in Armenia) in 1828.

Return to beginning of chapter

DECEMBRISTS & OTHER POLITICAL EXILES

Alexander died in 1825 without leaving a clear heir, sparking the usual crisis. His reform-minded brother Constantine, married to a Pole and living happily in Warsaw, had no interest in the throne.