Sociology, 12th Edition – Read Now and Download Mobi

dedication

To my newborn granddaughter, Matilda Violet. May she enjoy exploring life’s possibilities.

Published by McGraw-Hill, an imprint of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 1221 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020. Copyright © 2010, 2008, 2007, 2005, 2003, 2001, 1998, 1995, 1992, 1989, 1986, 1983. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written consent of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., including, but not limited to, in any network or other electronic storage or transmission, or broadcast for distance learning.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 QPD/QPD 0 9

ISBN: 978-0-07-340433-2

MHID: 0-07-340433-0

eISBN: 0-07-741361-X

Editor in Chief: Michael Ryan

Senior Sponsoring Editor: Gina Boedeker

Marketing Manager: Caroline McGillen

Director of Development: Rhona Robbin

Developmental Editor: Kate Scheinman

Editorial Coordinator: Daniel Gonzalez

Production Editor: Holly Paulsen

Manuscript Editor: Jan McDearmon

Art Director: Preston Thomas

Design Manager: Andrei Pasternak

Text Designer: Andrei Pasternak, Glenda King

Cover Designer: Andrei Pasternak

Art Editors: Robin Mouat, Rennie Evans

Photo Research Coordinator: Nora Agbayani

Photo Research: Toni Michaels/PhotoFind, LLC.

Media Project Manager: Thomas Brierly

Production Supervisor: Tandra Jorgensen

Composition: 10/12 Minion by Laserwords

Printing: 45# Pub Matte Plus, World Color USA

Front cover: Andersen Ross/Getty Images. Back cover: (park) Travelpix Ltd./Getty

Images; (bag) Image Source/Getty Images

Credits: The credits section for this book begins on Acknowledgments and is considered an extension of the copyright page.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

The Internet addresses listed in the text were accurate at the time of publication. The inclusion of a Web site does not indicate an endorsement by the authors or McGraw-Hill, and McGraw-Hill does not guarantee the accuracy of the information presented at these sites.

about the author

Richard T. Schaefer: Professor, DePaul University B.A. Northwestern University M.A., Ph.D. University of Chicago

Growing up in Chicago at a time when neighborhoods were going through transitions in ethnic and racial composition, Richard T. Schaefer found himself increasingly intrigued by what was happening, how people were reacting, and how these changes were affecting neighborhoods and people’s jobs. His interest in social issues caused him to gravitate to sociology courses at Northwestern University, where he eventually received a BA in sociology.

“Originally as an undergraduate I thought I would go on to law school and become a lawyer. But after taking a few sociology courses, I found myself wanting to learn more about what sociologists studied, and fascinated by the kinds of questions they raised.” This fascination led him to obtain his MA and PhD in sociology from the University of Chicago. Dr. Schaefer’s continuing interest in race relations led him to write his master’s thesis on the membership of the Ku Klux Klan and his doctoral thesis on racial prejudice and race relations in Great Britain.

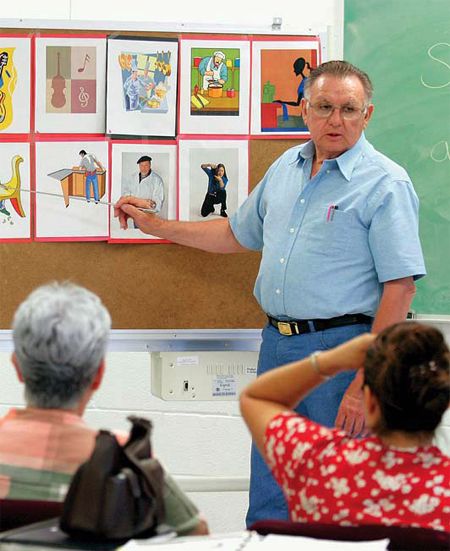

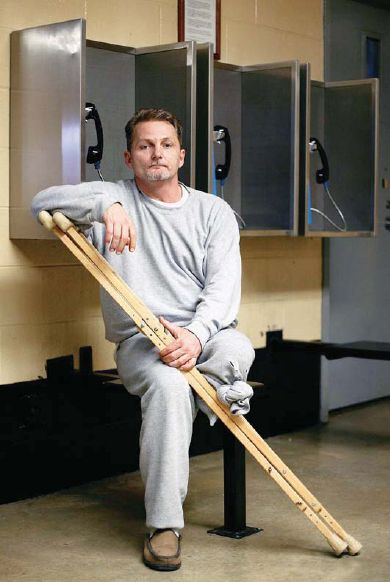

Dr. Schaefer went on to become a professor of sociology, and now teaches at DePaul University in Chicago. In 2004 he was named to the Vincent DePaul professorship in recognition of his undergraduate teaching and scholarship. He has taught introductory sociology for over 35 years to students in colleges, adult education programs, nursing programs, and even a maximum-security prison. Dr. Schaefer’s love of teaching is apparent in his interaction with his students. “I find myself constantly learning from the students who are in my classes and from reading what they write. Their insights into the material we read or current events that we discuss often become part of future course material and sometimes even find their way into my writing.”

Dr. Schaefer is the author of the eighth edition of Sociology: A Brief Introduction (McGraw-Hill, 2009) and of the fourth edition of Sociology Matters (McGraw-Hill, 2009). He is also the author of Racial and Ethnic Groups, now in its twelfth edition, and Race and Ethnicity in the United States, fifth edition, both published by Pearson. Together with William Zellner, he coauthored the eighth edition of Extraordinary Groups, published by Worth in 2007. Dr. Schaefer served as the general editor of the three-volume Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society, published by Sage in 2008. His articles and book reviews have appeared in many journals, including American Journal of Sociology; Phylon: A Review of Race and Culture; Contemporary Sociology; Sociology and Social Re-search; Sociological Quarterly; and Teaching Sociology. He served as president of the Midwest Sociological Society in 1994–1995.

Dr. Schaefer’s advice to students is to “look at the material and make connections to your own life and experiences. Sociology will make you a more attentive observer of how people in groups interact and function. It will also make you more aware of people’s different needs and interests—and perhaps more ready to work for the common good, while still recognizing the individuality of each person.”

brief contents

PART 1 The Sociological Perspective

PART 2 Organizing Social Life

4 Socialization and the Life Course

5 Social Interaction and Social Structure

PART 3 Social Inequality

9 Stratification and Social Mobility in the United States

11 Racial and Ethnic Inequality

PART 4 Social Institutions

14 The Family and Intimate Relationships

19 Health, Medicine, and the Environment

PART 5 Changing Society

20 Population, Communities, and Urbanization

21 Collective Behavior and Social Movements

22 Social Change in the Global Community

contents

PART 1 The Sociological Perspective

Sociology and the Social Sciences

Twentieth-Century Developments

Major Theoretical Perspectives

Applied and Clinical Sociology

Research Today: Looking at Sports from Four Theoretical Perspectives

Developing a Sociological Imagination

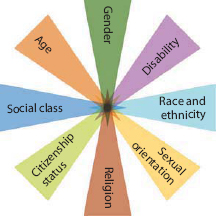

The Significance of Social Inequality

Speaking across Race, Gender, and Religious Boundaries

Sociology in the Global Community: Your Morning Cup of Coffee

Social Policy throughout the World

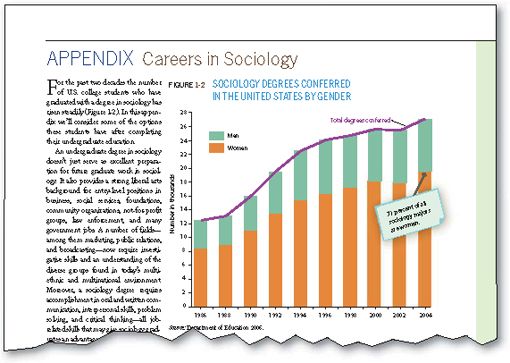

Appendix: Careers in Sociology

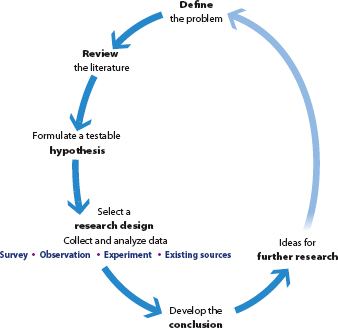

What Is the Scientific Method?

In Summary: The Scientific Method

Research Today: Surveying Cell Phone Users

Research Today: What’s in a Name?

Taking Sociology to Work: Dave Eberbach, Research Coordinator, United Way of Central Iowa

Technology and Sociological Research

SOCIAL POLICY AND SOCIOLOGICAL RESEARCH: STUDYING HUMAN SEXUALITY

Appendix I: Using Statistics and Graphs

Appendix II: Writing a Research Report

PART 2 Organizing Social Life

Development of Culture around the World

Globalization, Diffusion, and Technology

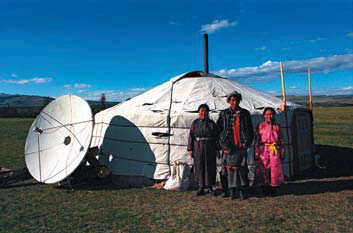

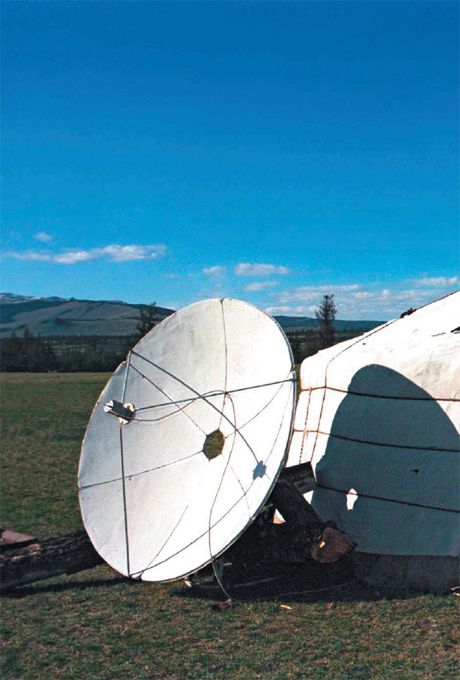

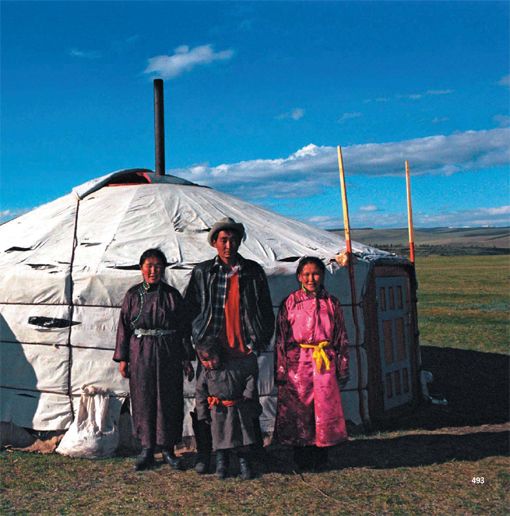

Sociology in the Global Community: Life in the Global Village

Sociology in the Global Community: Cultural Survival in Brazil

Culture and the Dominant Ideology

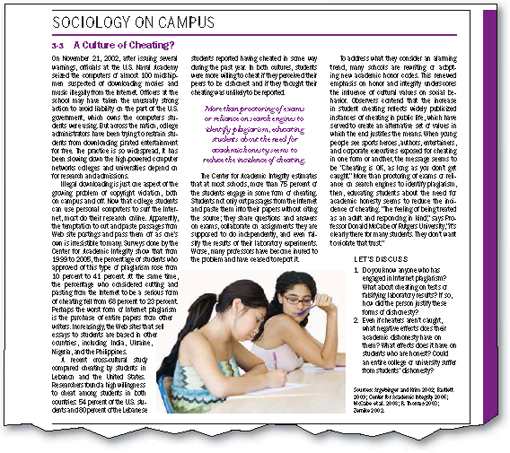

Sociology on Campus: A Culture of Cheating?

Case Study: Culture at Wal-Mart

SOCIAL POLICY AND CULTURE: BILINGUALISM

4 Socialization and the Life Course

Social Environment: The Impact of Isolation

Sociological Approaches to the Self

Sociology on Campus: Impression Management by Students

Psychological Approaches to the Self

Taking Sociology to Work: Rakefet Avramovitz, Program Administrator, Child Care Law Center

Research Today: Online Socializing: A New Agent of Socialization

Socialization throughout the Life Course

Anticipatory Socialization and Resocialization

SOCIAL POLICY AND SOCIALIZATION: CHILD CARE AROUND THE WORLD

5 Social Interaction and Social Structure

Social Interaction and Reality

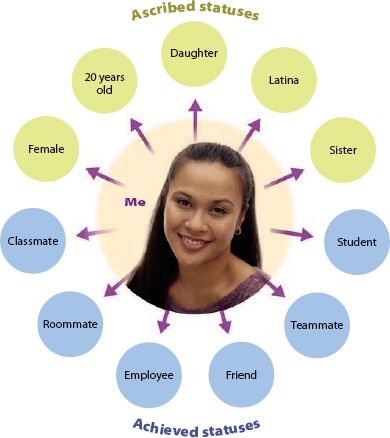

Research Today: Disability as a Master Status

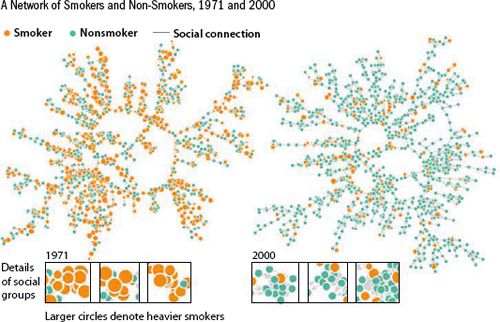

Research Today: Social Networks and Smoking

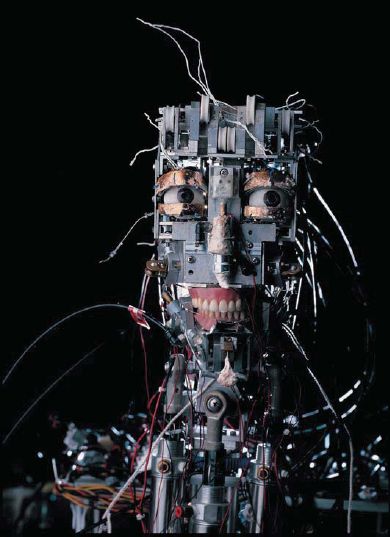

Sociology in the Global Community: The Second Life® Virtual World

Social Structure in Global Perspective

Durkheim’s Mechanical and Organic Solidarity

Tönnies’s Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft

Lenski’s Sociocultural Evolution Approach

SOCIAL POLICY AND SOCIAL INTERACTION: REGULATING THE NET

Research Today: The Drinking Rape Victim: Jury Decision Making

Formal Organizations and Bureaucracies

Characteristics of a Bureaucracy

Bureaucracy and Organizational Culture

Sociology in the Global Community: McDonald’s and the Worldwide Bureaucratization of Society

Case Study: Bureaucracy and the Space Shuttle Columbia

Sociology in the Global Community: Entrepreneurship, Japanese Style

SOCIAL POLICY AND ORGANIZATIONS: THE STATE OF THE UNIONS WORLDWIDE

Sociological Perspectives on the Media

Taking Sociology to Work: Nicole Martorano Van Cleve, Former Brand Planner, Leo Burnett USA

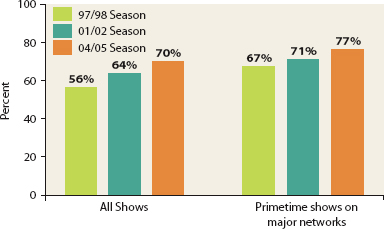

Research Today: The Color of Network TV

Sociology in the Global Community: Al Jazeera Is on the Air

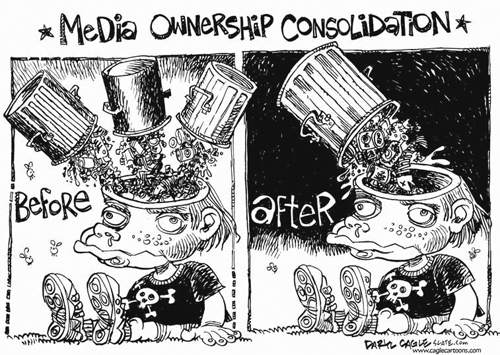

SOCIAL POLICY AND THE MASS MEDIA: MEDIA CONCENTRATION

Informal and Formal Social Control

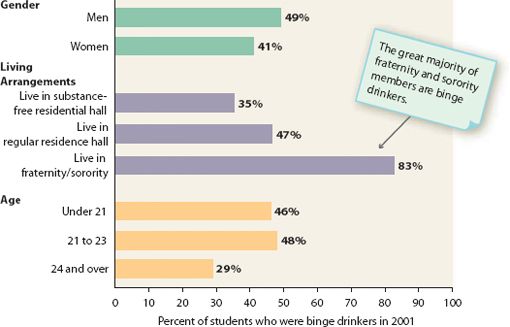

Sociology on Campus: Binge Drinking

Sociological Perspectives on Deviance

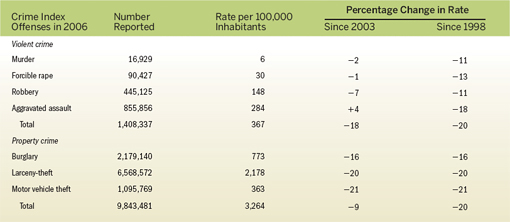

Research Today: Does Crime Pay?

Sociology on Campus: Campus Crime

Taking Sociology to Work: Stephanie Vezzani, Special Agent, U.S. Secret Service

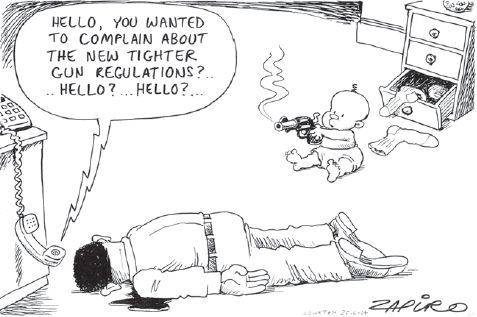

SOCIAL POLICY AND SOCIAL CONTROL: GUN CONTROL

PART 3 Social Inequality

9 Stratification and Social Mobility in the United States

Sociological Perspectives on Stratification

Karl Marx’s View of Class Differentiation

Max Weber’s View of Stratification

Stratification by Social Class

Objective Method of Measuring Social Class

Gender and Occupational Prestige

Research Today: Precarious Work

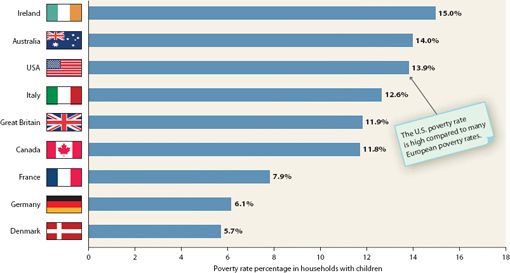

Sociology in the Global Community: It’s All Relative: Appalachian Poverty and Congolese Affluence

Open versus Closed Stratification Systems

Sociology on Campus: Social Class and Financial Aid

Social Mobility in the United States

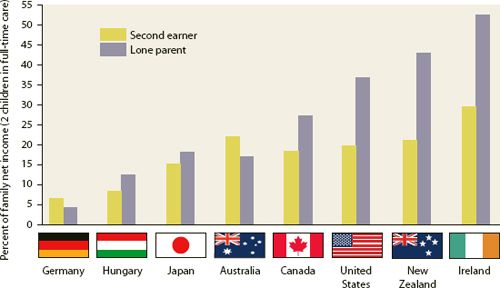

SOCIAL POLICY AND GENDER STRATIFICATION: RETHINKING WELFARE IN NORTH AMERICA AND EUROPE

Stratification in the World System

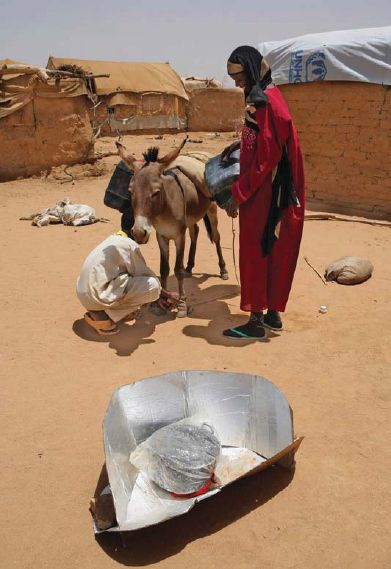

Sociology in the Global Community: Cutting Poverty Worldwide

Sociology in the Global Community: The Global Disconnect

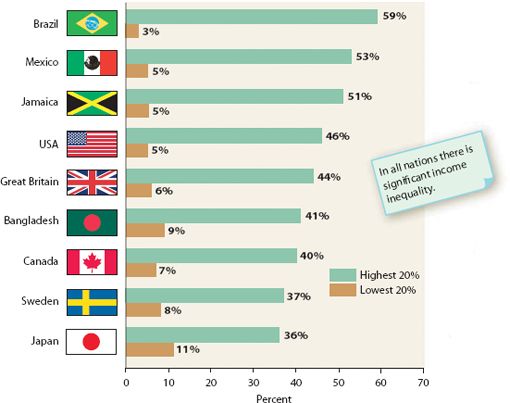

Stratification within Nations: A Comparative Perspective

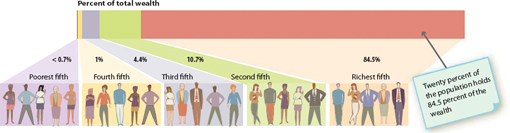

Distribution of Wealth and Income

Sociology in the Global Community: Stratification in Japan

Taking Sociology to Work: Bari Katz, Program Director, National Conference for Community and Justice

Case Study: Stratification in Mexico

Race Relations in Mexico: The Color Hierarchy

SOCIAL POLICY AND GLOBAL INEQUALITY: UNIVERSAL HUMAN RIGHTS

11 Racial and Ethnic Inequality

Minority, Racial, and Ethnic Groups

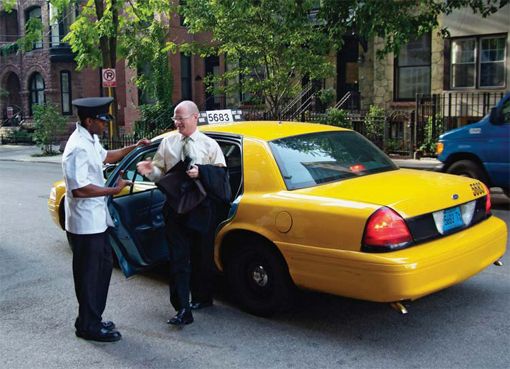

The Privileges of the Dominant

Sociological Perspectives on Race and Ethnicity

Patterns of Intergroup Relations

Race and Ethnicity in the United States

Sociology in the Global Community: The Aboriginal People of Australia

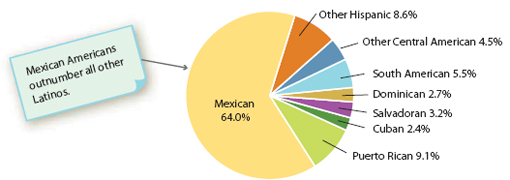

Research Today: Social Mobility among Latino Immigrants

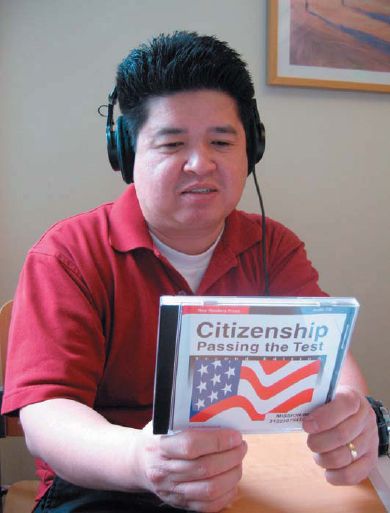

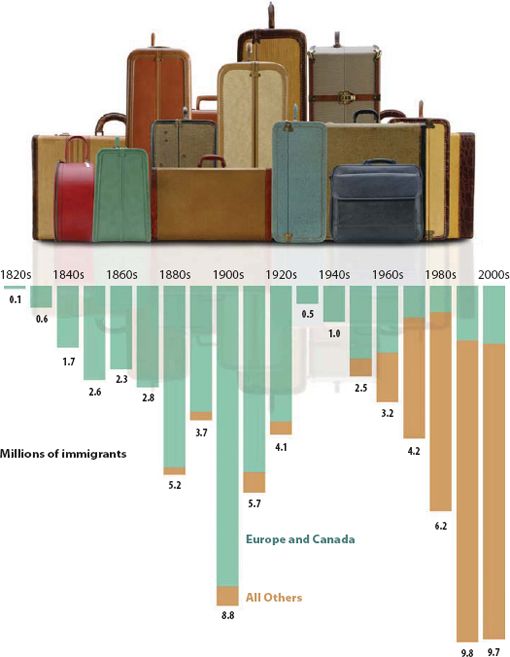

SOCIAL POLICY AND RACIAL AND ETHNIC INEQUALITY: GLOBAL IMMIGRATION

Gender Roles in the United States

Sociology on Campus: The Debate over Title IX

Sociological Perspectives on Gender

Sociology in the Global Community: The Head Scarf and the Veil: Complex Symbols

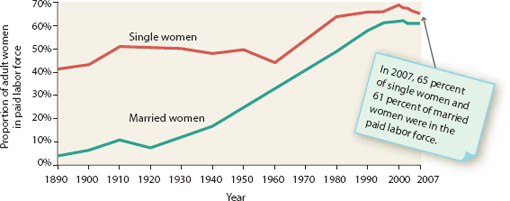

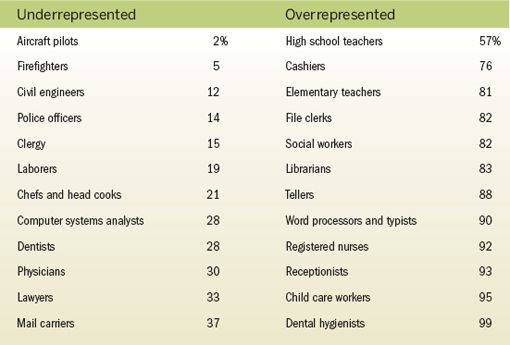

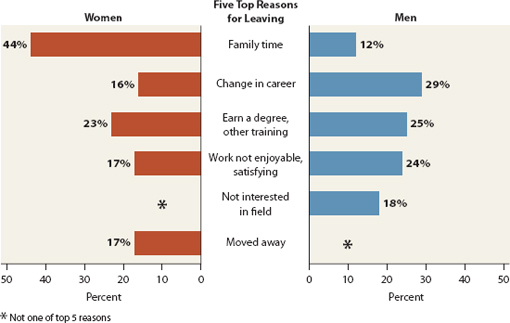

Women in the Workforce of the United States

Social Consequences of Women’s Employment

Emergence of a Collective Consciousness

Taking Sociology to Work: Abigail E. Drevs, Former Program and Volunteer Coordinator, Y-ME Illinois

SOCIAL POLICY AND GENDER STRATIFICATION: THE BATTLE OVER ABORTION FROM A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

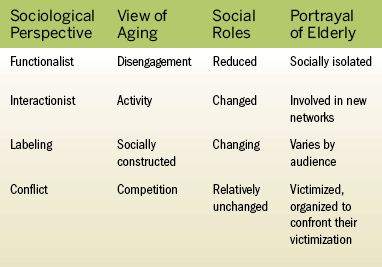

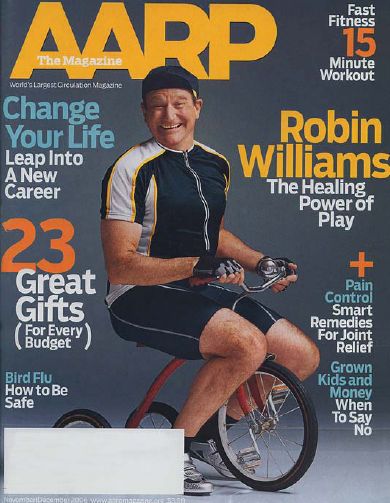

Sociological Perspectives on Aging

Taking Sociology to Work: A. David Roberts, Social Worker

Functionalist Approach: Disengagement Theory

Interactionist Approach: Activity Theory

Role Transitions throughout the Life Course

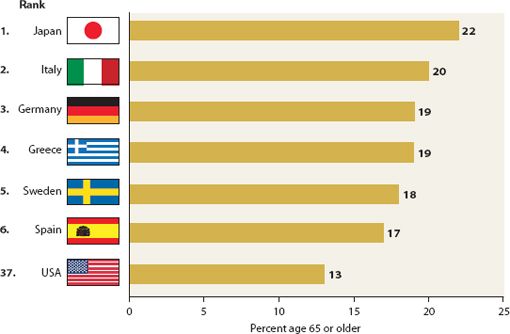

Sociology in the Global Community: Aging, Japanese Style

Age Stratification in the United States

Competition in the Labor Force

The Elderly: Emergence of a Collective Consciousness

Research Today: Elderspeak and Other Signs of Ageism

SOCIAL POLICY AND AGE STRATIFICATION: THE RIGHT TO DIE WORLDWIDE

PART 4 Social Institutions

14 The Family and Intimate Relationships

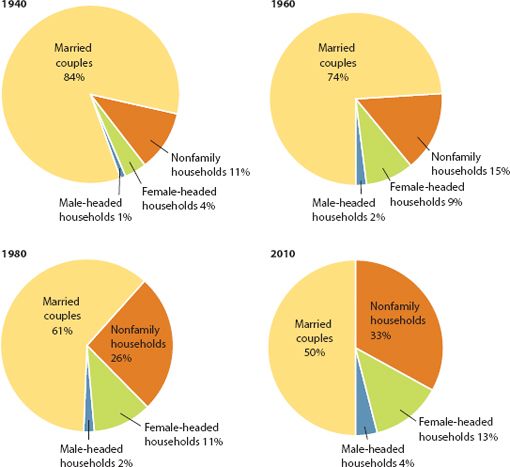

Composition: What Is the Family?

Sociology in the Global Community: One Wife, Many Husbands: The Nyinba

Kinship Patterns: To Whom Are We Related?

Authority Patterns: Who Rules?

Sociological Perspectives on the Family

Variations in Family Life and Intimate Relationships

Research Today: Arranged Marriage, American-Style

Factors Associated with Divorce

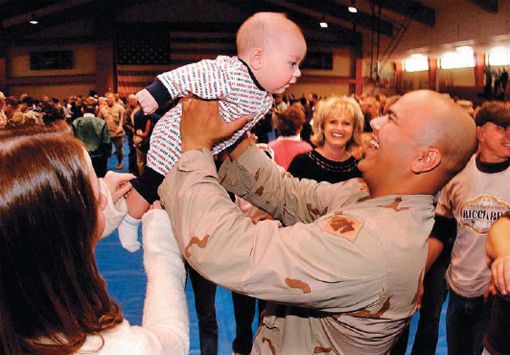

Research Today: Divorce and Military Deployment

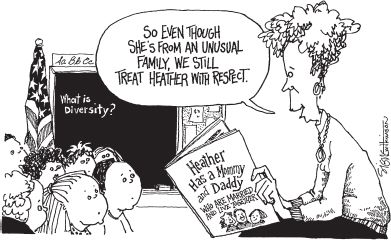

SOCIAL POLICY AND THE FAMILY: GAY MARRIAGE

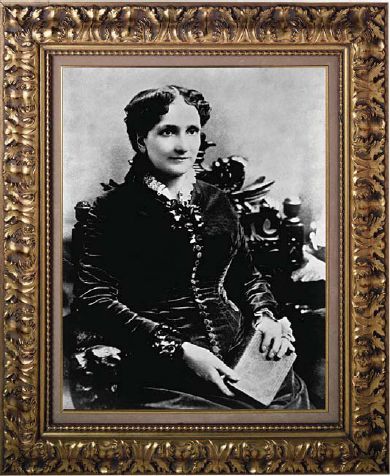

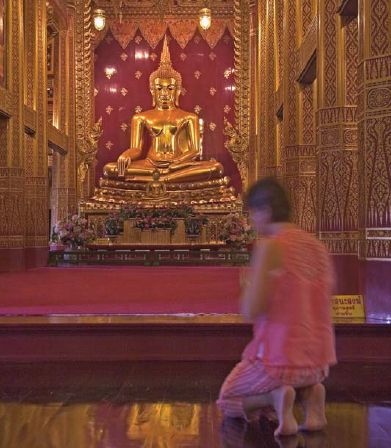

Durkheim and the Sociological Approach to Religion

Sociological Perspectives on Religion

The Integrative Function of Religion

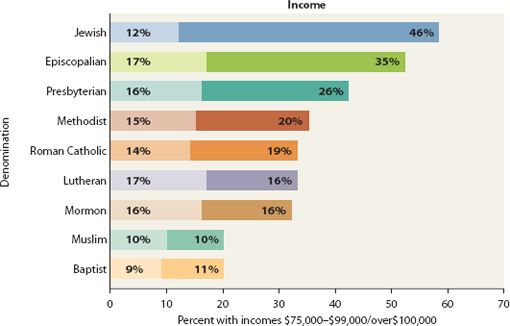

Research Today: Income and Education, Religiously Speaking

Religion and Social Control: A Conflict View

New Religious Movements or Cults

Research Today: Islam in the United States

Research Today: The Church of Scientology: Religion or Quasi-Religion?

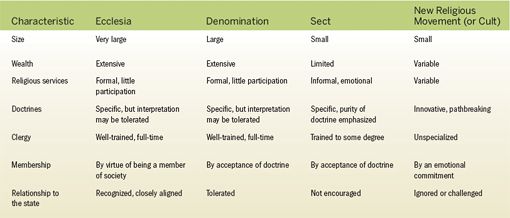

Comparing Forms of Religious Organization

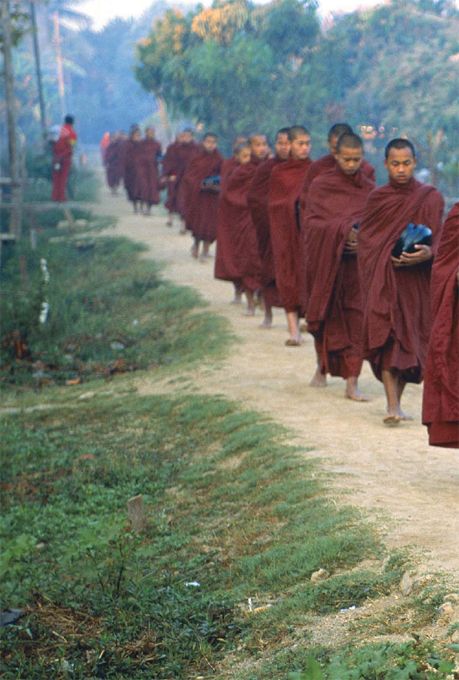

The Religious Tapestry in India

Religion and the State in India

SOCIAL POLICY AND RELIGION: RELIGION IN THE SCHOOLS

Sociological Perspectives on Education

Sociology on Campus: Google University

Taking Sociology to Work: Ray Zapata, Business Owner and Former Regent, Texas State University

Schools as Formal Organizations

Research Today: Violence in the Schools

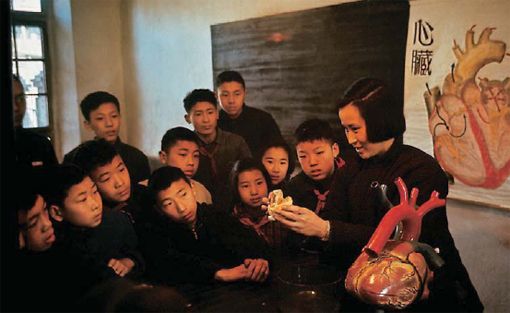

Teachers: Employees and Instructors

SOCIAL POLICY AND EDUCATION: NO CHILD LEFT BEHIND ACT

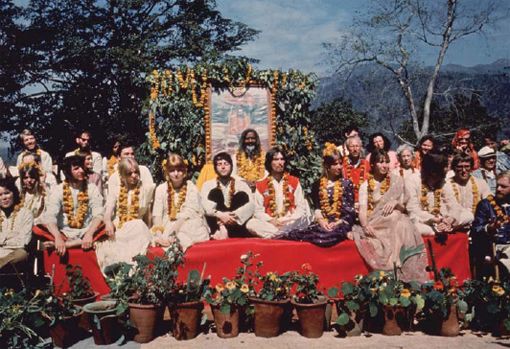

Sociology in the Global Community: Charisma: The Beatles and Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

Dictatorship and Totalitarianism

Political Behavior in the United States

Taking Sociology to Work: Joshua Johnston, Congressional Aide, Office of Congressman Norm Dicks

Research Today: Why Don’t More Young People Vote?

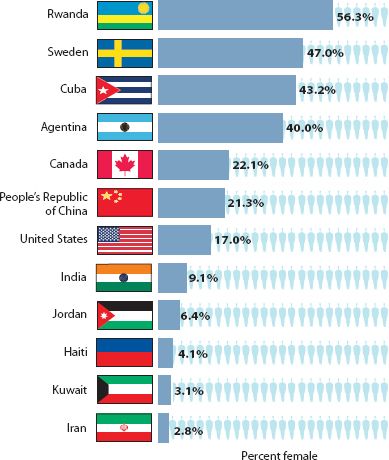

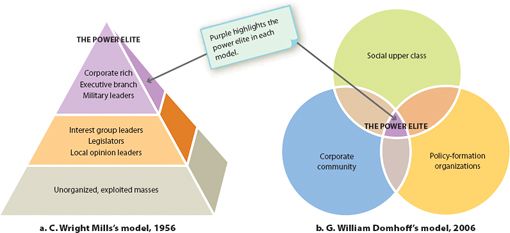

Models of Power Structure in the United States

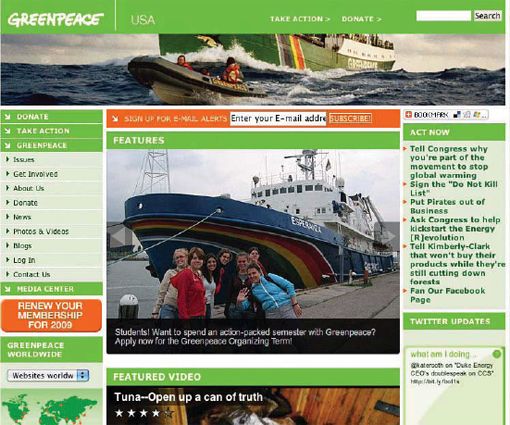

Political Activism on the Internet

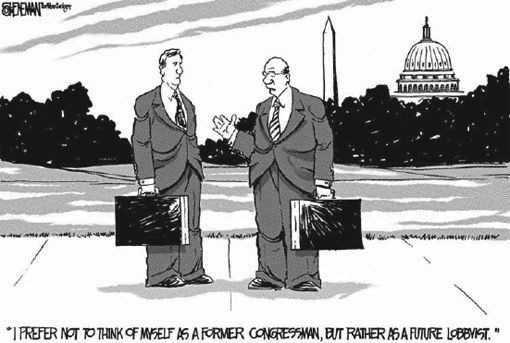

SOCIAL POLICY AND POLITICS: CAMPAIGN FINANCING

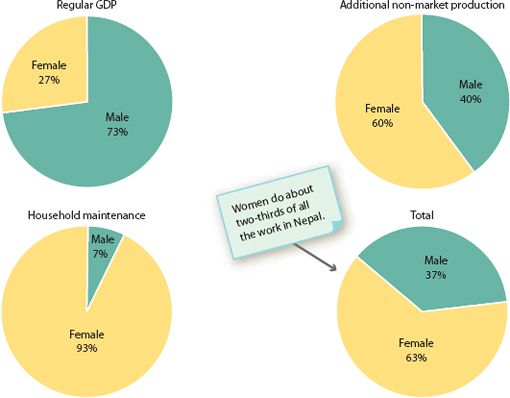

Sociology in the Global Community: Working Women in Nepal

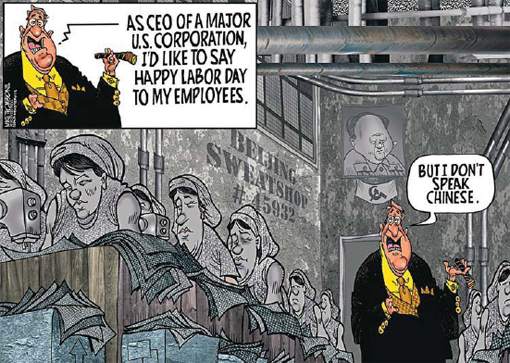

Case Study: Capitalism in China

Chinese Workers in the New Economy

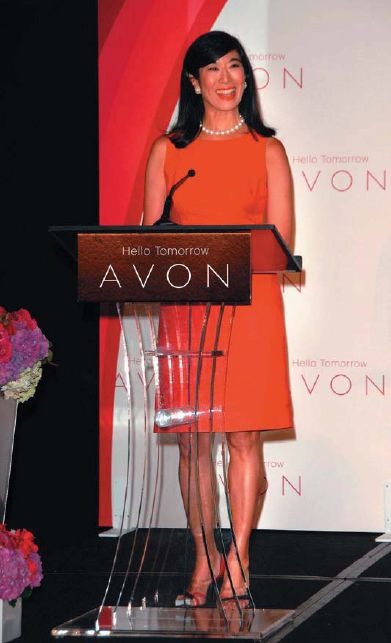

Taking Sociology to Work: Amy Wang, Product Manager, Norman International Company

The Changing Face of the Workforce

Research Today: Affirmative Action

SOCIAL POLICY AND THE ECONOMY: GLOBAL OFFSHORING

19 Health, Medicine, and the Environment

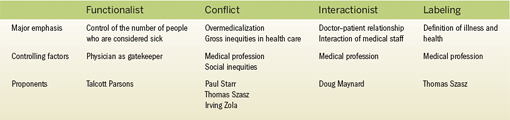

Sociological Perspectives on Health and Illness

Taking Sociology to Work: Lola Adedokun, Independent Consultant, Health Care Research

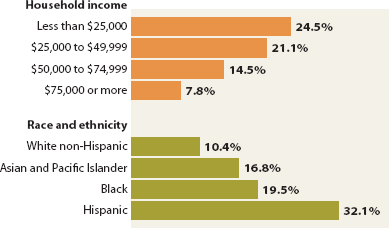

Social Epidemiology and Health

Research Today: The AIDS Epidemic

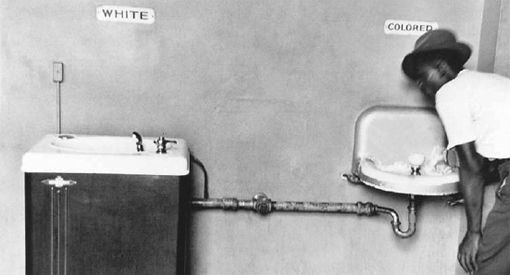

Research Today: Medical Apartheid

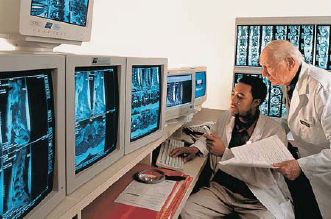

Health Care in the United States

Physicians, Nurses, and Patients

Alternatives to Traditional Health Care

Mental Illness in the United States

Theoretical Models of Mental Disorders

Sociological Perspectives on the Environment

Conflict View of the Environment

Sociology in the Global Community: The Mysterious Fall of the Nacirema

SOCIAL POLICY AND THE ENVIRONMENT: ENVIRONMENTALISM

PART 5 Changing Society

20 Population, Communities, and Urbanization

Demography: The Study of Population

Malthus’s Thesis and Marx’s Response

Fertility Patterns in the United States

Sociology in the Global Community: Population Policy in China

Industrial and Postindustrial Cities

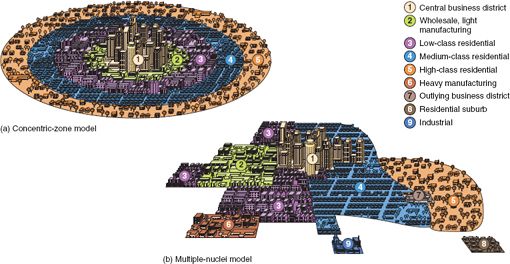

Functionalist View: Urban Ecology

Conflict View: New Urban Sociology

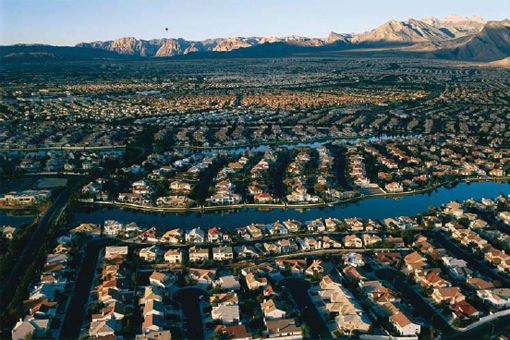

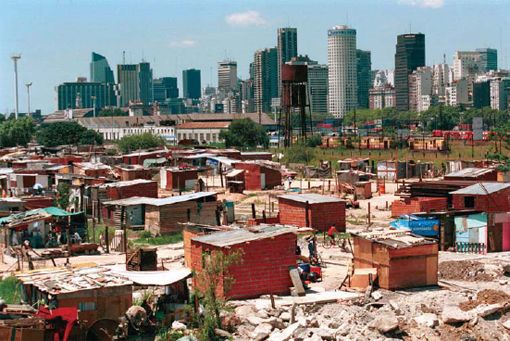

Sociology in the Global Community: Squatter Settlements

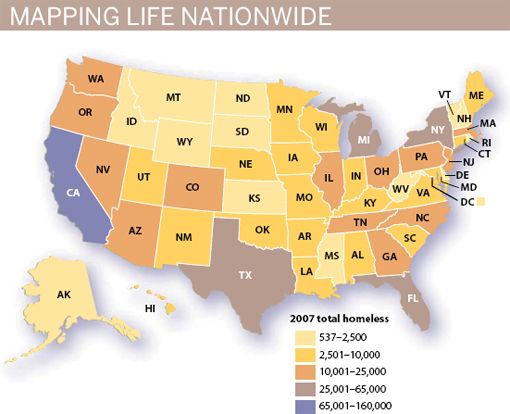

SOCIAL POLICY AND COMMUNITIES: SEEKING SHELTER WORLDWIDE

21 Collective Behavior and Social Movements

Theories of Collective Behavior

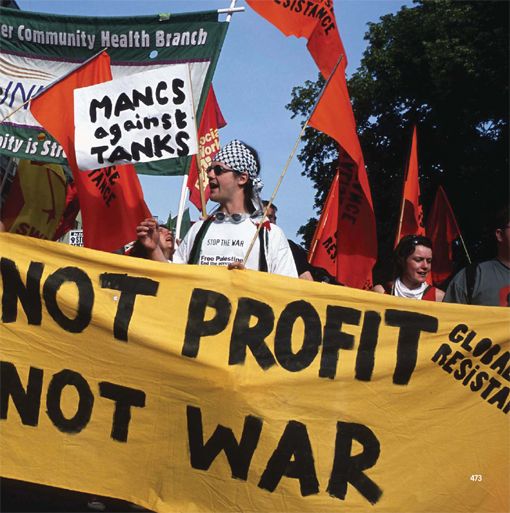

Resource Mobilization Approach

Communications and the Globalization of Social Movements

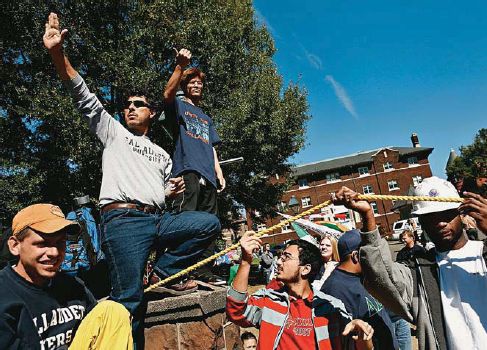

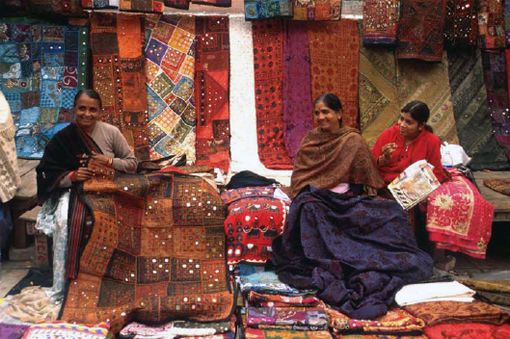

Sociology in the Global Community: Women and New Social Movements in India

Research Today: Organizing for Controversy on the Web

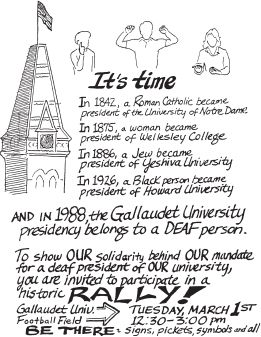

SOCIAL POLICY AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS: DISABILITY RIGHTS

22 Social Change in the Global Community

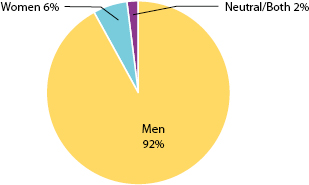

Research Today: The Internet’s Global Profile

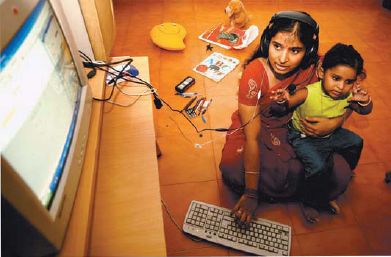

Sociology in the Global Community: One Laptop per Child

Privacy and Censorship in a Global Village

Biotechnology and the Gene Pool

Research Today: The Human Genome Project

SOCIAL POLICY AND GLOBALIZATION: TRANSNATIONALS

Every chapter in this textbook begins with an excerpt from one of the works listed here. These excerpts convey the excitement and relevance of sociological inquiry and draw readers into the subject matter from each chapter.

Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America by Barbara Ehrenreich

“The Demedicalization of Self-Injury” by Patricia A. Adler and Peter Adler

“Body Ritual among the Nacirema” by Horace Miner

Black Picket Fences: Privilege and Peril among the Black Middle Class by Mary Pattillo-McCoy

The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil by Philip Zimbardo

The McDonaldization of Society by George Ritzer

iSpy: Surveillance and Power in the Interactive Era by Mark Andrejevic

Gang Leader for a Day: A Rogue Sociologist Takes to the Streets by Sudhir Venkatesh

Richistan: A Journey through the American Wealth Boom and the Lives of the New Rich by Robert Frank

The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries Are Failing and What Can Be Done About It by Paul Collier

Asian American Dreams: The Emergence of an American People by Helen Zia

Lipstick Jihad: A Memoir of Growing Up Iranian in America and American in Iran by Azadeh Moaveni

Tuesdays with Morrie: An Old Man, a Young Man, and Life’s Greatest Lesson by Mitch Albom

Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life by Annette Lareau

For This Land: Writings on Religion in America by Vine Deloria Jr.

The Shame of the Nation by Jonathan Kozol

Is Voting for Young People? by Martin P. Wattenberg

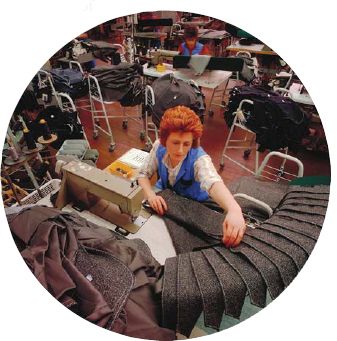

Where Am I Wearing? A Global Tour to the Countries, Factories, and People that Make Our Clothes by Kelsey Timmerman

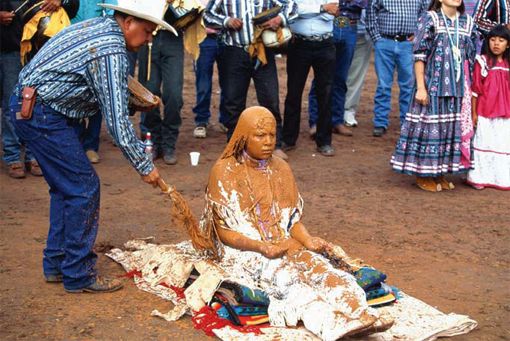

The Scalpel and the Silver Bear: The First Navajo Woman Surgeon Combines Western Medicine and Traditional Healing by Lori Arviso Alvord, M.D., and Elizabeth Cohen Van Pelt

Sidewalk by Mitchell Duneier

Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution by Howard Rheingold

The Pirate’s Dilemma: How Youth Culture Is Reinventing Capitalism by Matt Mason

RESEARCH TODAY

1-1 Looking at Sports from Four Theoretical Perspectives

2-1 Surveying Cell Phone Users

4-2 Online Socializing: A New Agent of Socialization

5-1 Disability as a Master Status

5-2 Social Networks and Smoking

6-1 The Drinking Rape Victim: Jury Decision Making

11-2 Social Mobility among Latino Immigrants

13-2 Elderspeak and Other Signs of Ageism

14-2 Arranged Marriage, American-Style

14-3 Divorce and Military Deployment

15-1 Income and Education, Religiously Speaking

15-2 Islam in the United States

15-3 The Church of Scientology: Religion or Quasi-Religion?

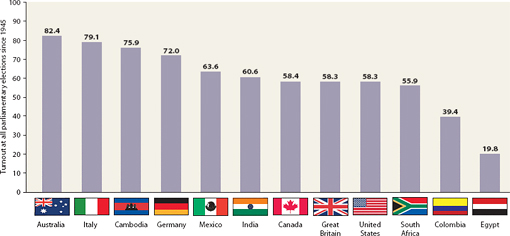

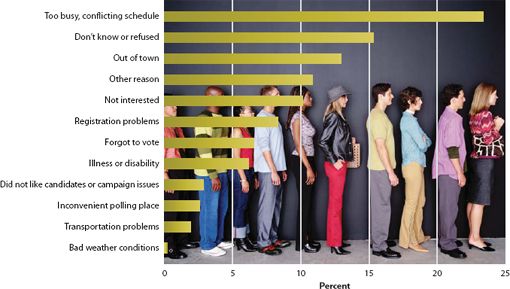

17-2 Why Don’t More Young People Vote?

21-2 Organizing for Controversy on the Web

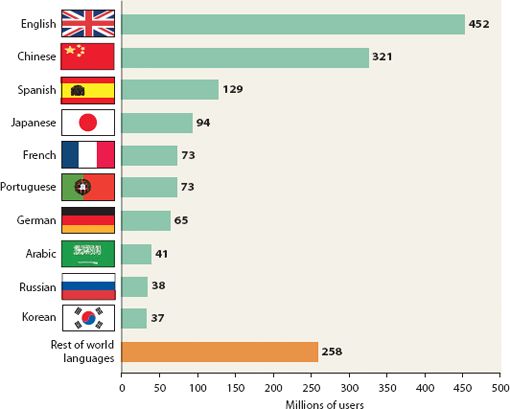

22-1 The Internet’s Global Profile

SOCIOLOGY IN THE GLOBAL COMMUNITY

1-2 Your Morning Cup of Coffee

3-1 Life in the Global Village

3-2 Cultural Survival in Brazil

5-3 The Second Life® Virtual World

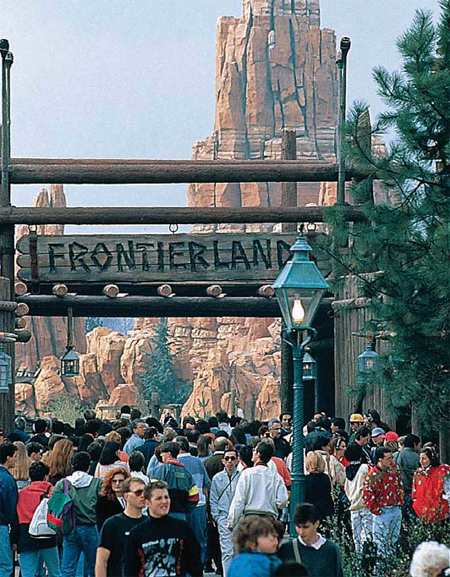

6-2 McDonald’s and the Worldwide Bureaucratization of Society

6-3 Entrepreneurship, Japanese Style

9-2 It’s All Relative: Appalachian Poverty and Congolese Affluence

10-1 Cutting Poverty Worldwide

11-1 The Aboriginal People of Australia

12-2 The Head Scarf and the Veil: Complex Symbols

14-1 One Wife, Many Husbands: The Nyinba

17-1 Charisma: The Beatles and the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

19-3 The Mysterious Fall of the Nacirema

20-1 Population Policy in China

21-1 Women and New Social Movements in India

SOCIOLOGY ON CAMPUS

4-1 Impression Management by Students

9-3 Social Class and Financial Aid

TAKING SOCIOLOGY TO WORK

Dave Eberbach, Research Coordinator, United Way of Central Iowa

Rakefet Avramovitz, Program Administrator, Child Care Law Center

Nicole Martorano Van Cleve, Former Brand Planner, Leo Burnett USA

Stephanie Vezzani, Special Agent, U.S. Secret Service

Jessica Houston Su, Research Assistant, Joblessness and Urban Poverty Research Program

Bari Katz, Program Director, National Conference for Community and Justice

Prudence Hannis, Liaison Officer, National Institute of Science Research, University of Québec

Abigail E. Drevs, Former Program and Volunteer Coordinator, Y-ME Illinois

A. David Roberts, Social Worker

Ray Zapata, Business Owner and Former Regent, Texas State University

Joshua Johnston, Congressional Aide, Office of Congressman Norm Dicks

Amy Wang, Product Manager, Norman International Company

Lola Adedokun, Independent Consultant, Health Care Research

Kelsie Lenor Wilson-Dorsett, Deputy Director, Department of Statistics, Government of Bahamas

Chapter 2

Social Policy and Sociological Research: Studying Human Sexuality

Chapter 3

Social Policy and Culture: Bilingualism

Chapter 4

Social Policy and Socialization: Child Care around the World

Chapter 5

Social Policy and Social Interaction: Regulating the Net

Chapter 6

Social Policy and Organizations: The State of the Unions Worldwide

Chapter 7

Social Policy and the Mass Media: Media Concentration

Chapter 8

Social Policy and Social Control: Gun Control

Chapter 9

Social Policy and Stratification: Rethinking Welfare in North America and Europe

Chapter 10

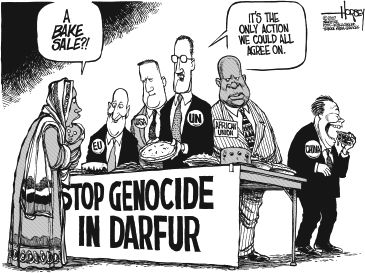

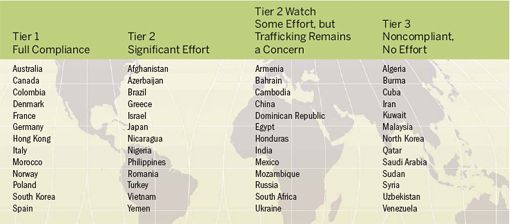

Social Policy and Global Inequality: Universal Human Rights

Chapter 11

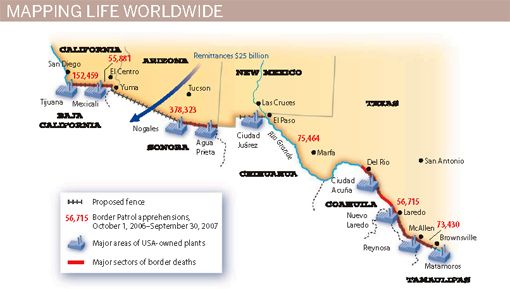

Social Policy and Racial and Ethnic Inequality: Global Immigration

Chapter 12

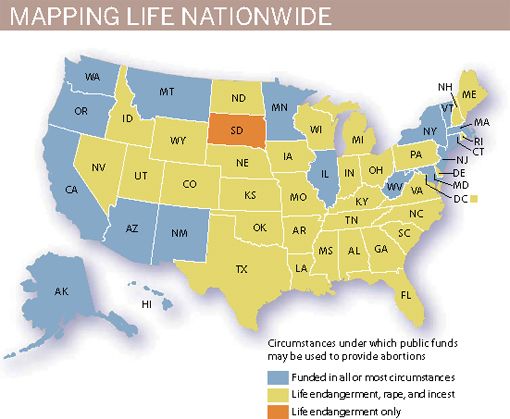

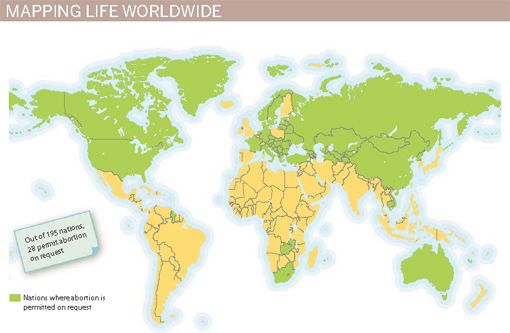

Social Policy and Gender Stratification: The Battle over Abortion from a Global Perspective

Chapter 13

Social Policy and Age Stratification: The Right to Die Worldwide

Chapter 14

Social Policy and the Family: Gay Marriage

Chapter 15

Social Policy and Religion: Religion in the Schools

Chapter 16

Social Policy and Education: No Child Left Behind Act

Chapter 17

Social Policy and Politics: Campaign Financing

Chapter 18

Social Policy and the Economy: Global Offshoring

Chapter 19

Social Policy and the Environment: Environmentalism

Chapter 20

Social Policy and Communities: Seeking Shelter Worldwide

Chapter 21

Social Policy and Social Movements: Disability Rights

Chapter 22

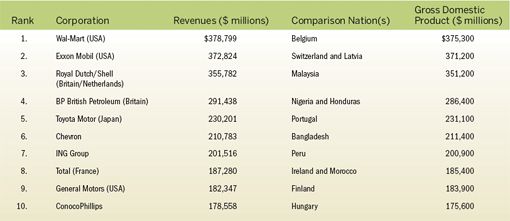

Social Policy and Globalization: Transnationals

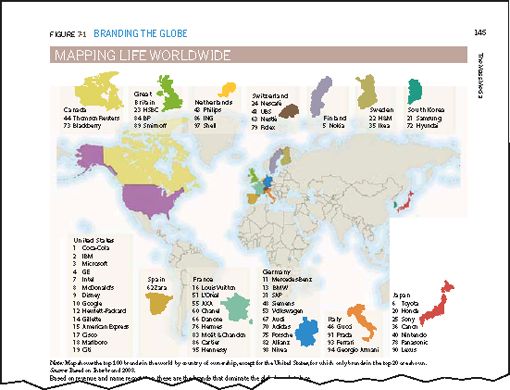

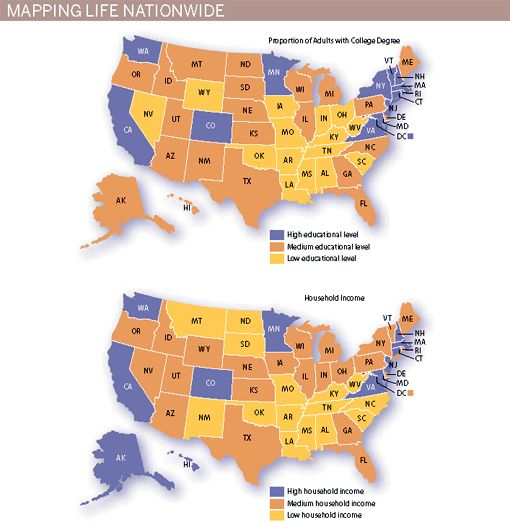

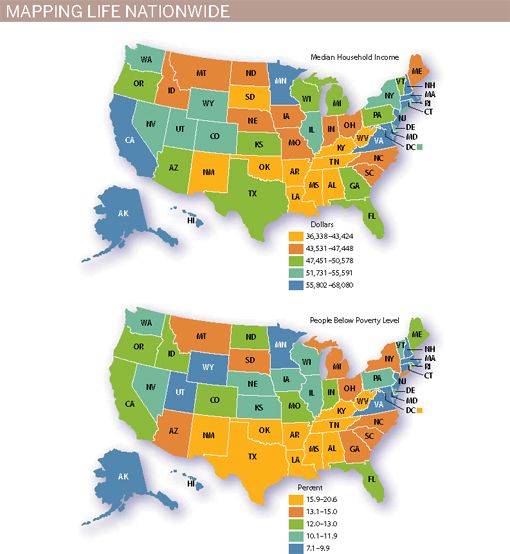

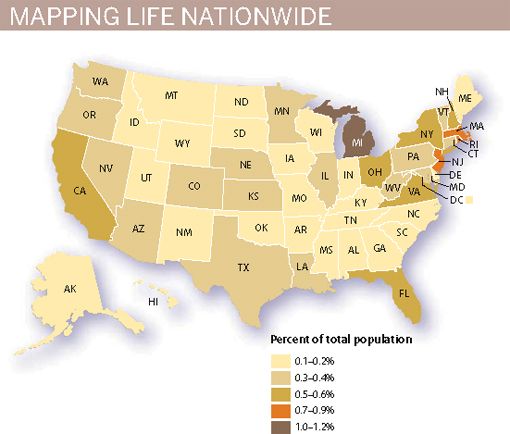

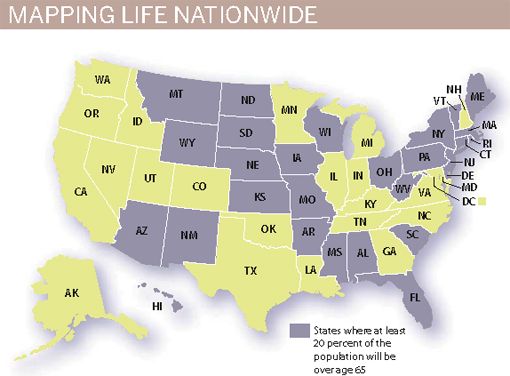

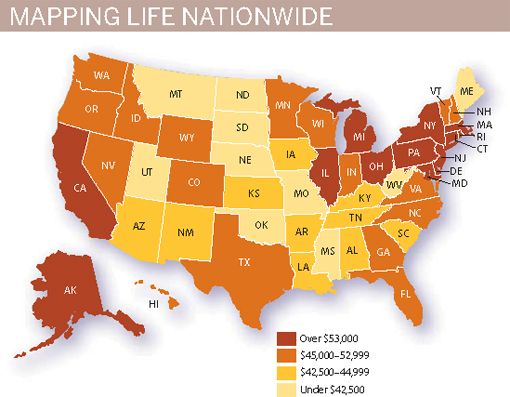

Mapping Life Nationwide

Educational Level and Household Income in the United States

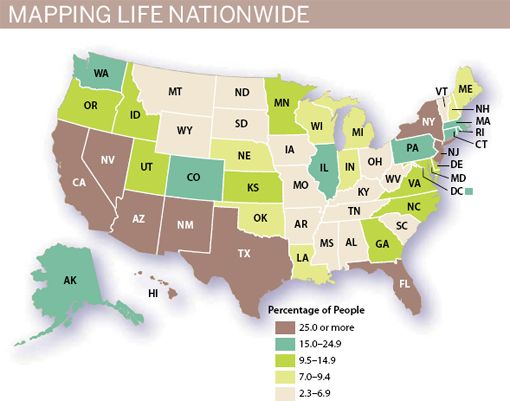

Percentage of People Who Speak a Language Other than English at Home, by State

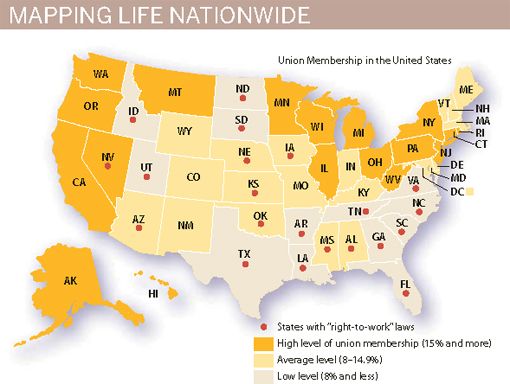

Union Membership in the United States

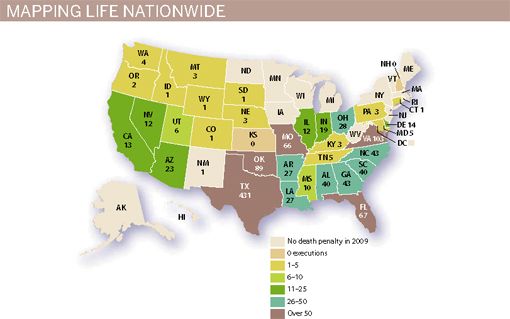

Executions by State since 1976

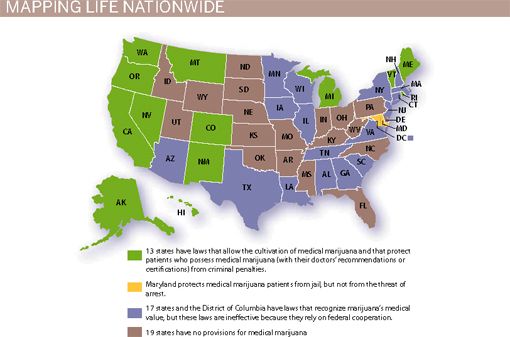

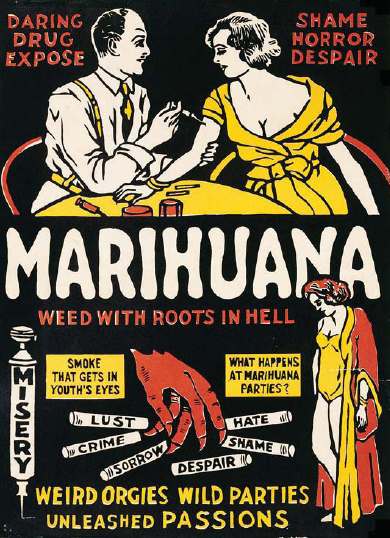

The Status of Medical Marijuana

The 50 States: Contrasts in Income and Poverty Levels

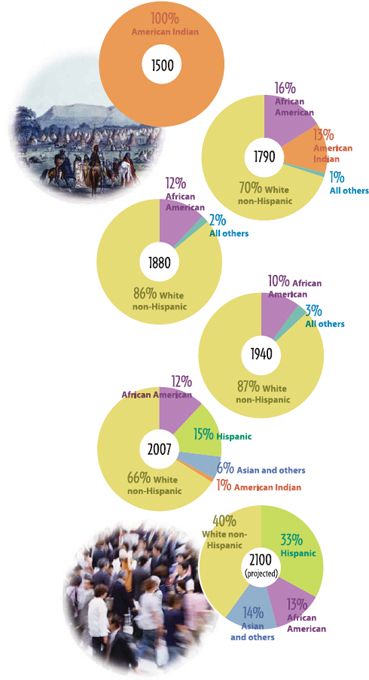

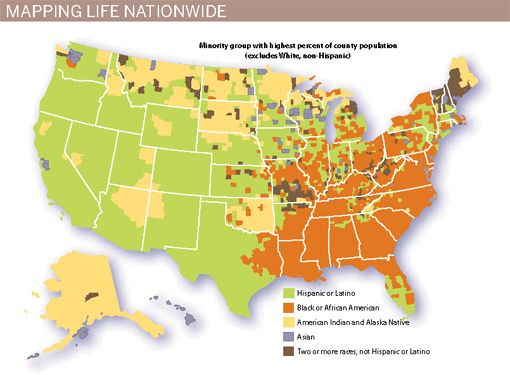

Census 2000: The Image of Diversity

Distribution of the Arab American Population by State

Restrictions on Public Funding for Abortion

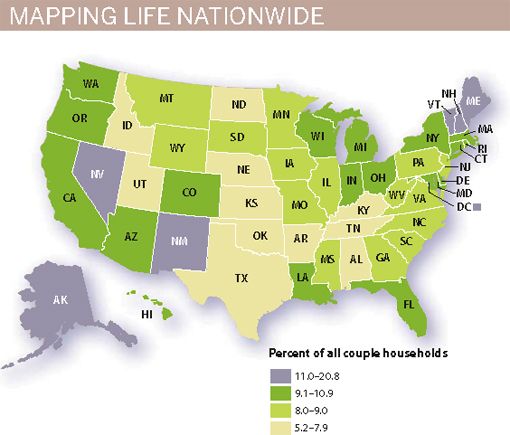

Unmarried-Couple Households by State

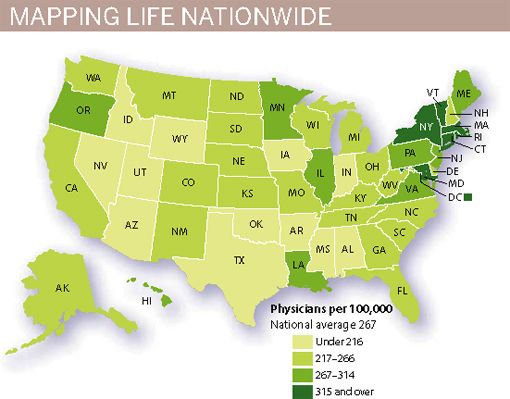

Availability of Physicians by State

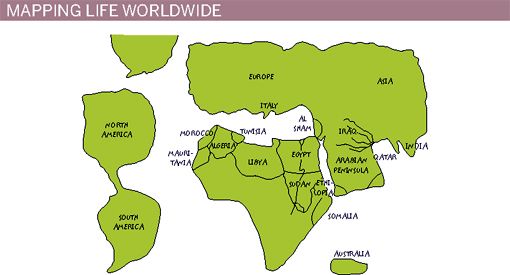

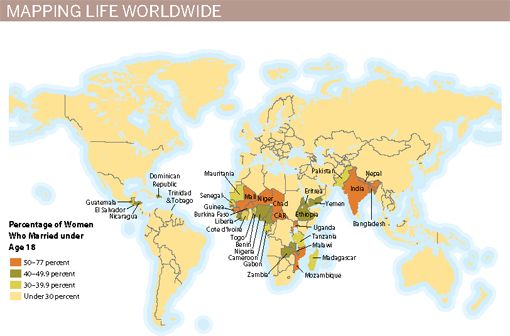

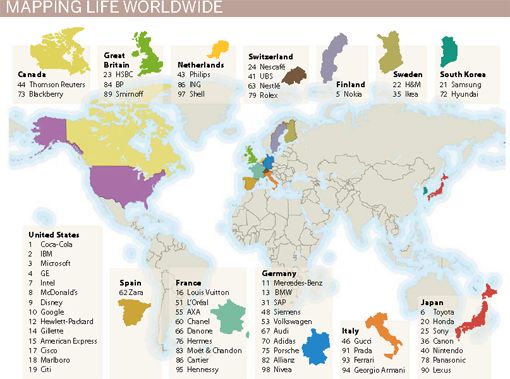

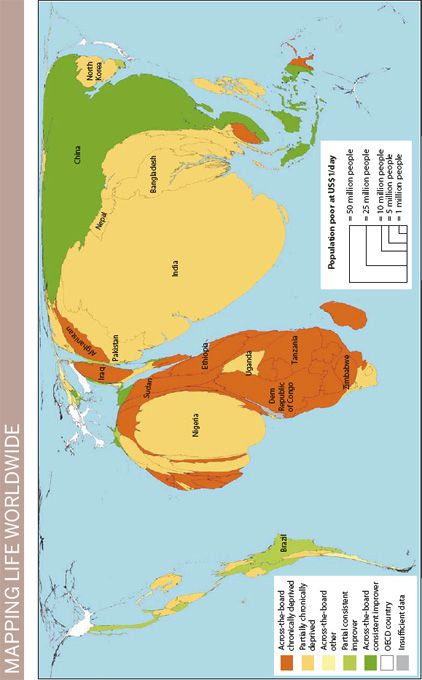

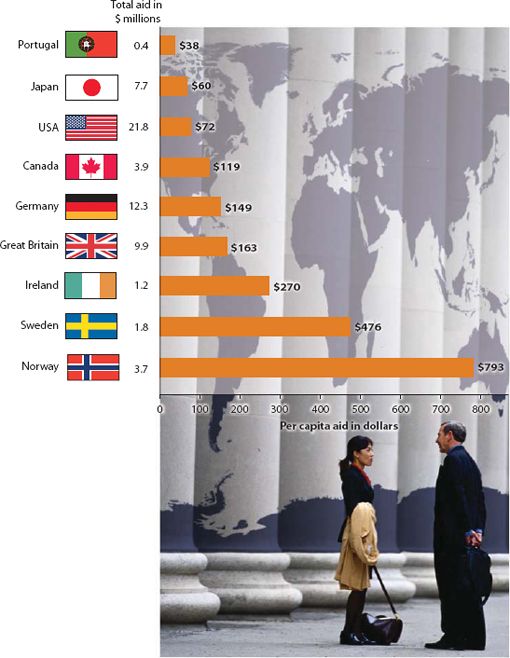

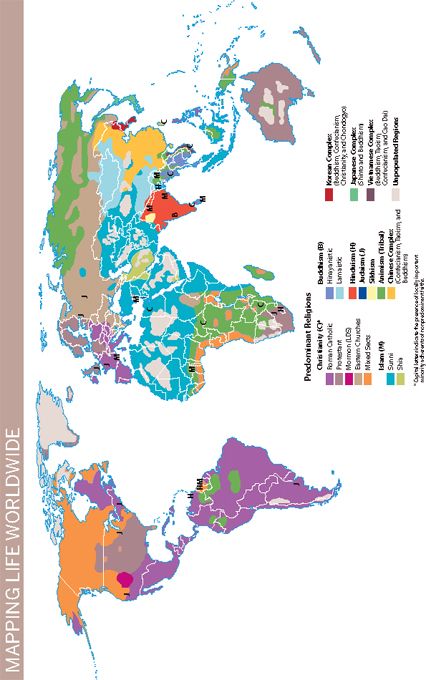

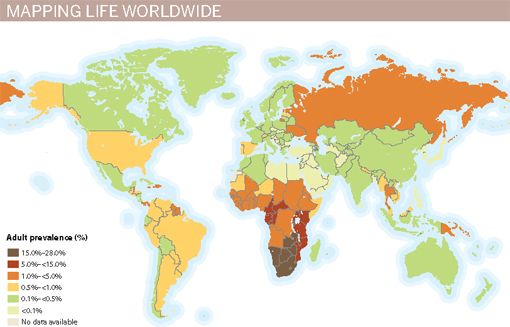

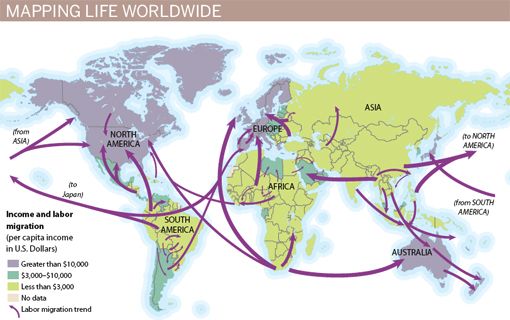

Mapping Life Worldwide

Countries with High Child Marriage Rates

Filtering Information: Social Content

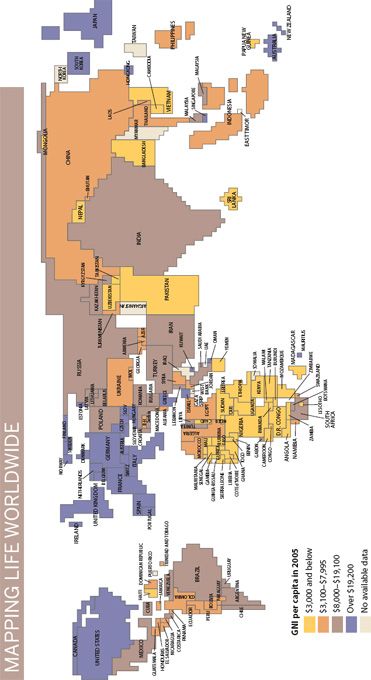

Gross National Income per Capita

Filtering Information: Political Content

Increase in Carbon Dioxide Emissions

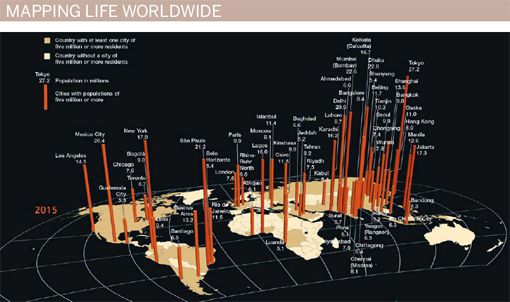

Global Urbanization 2015 (projected)

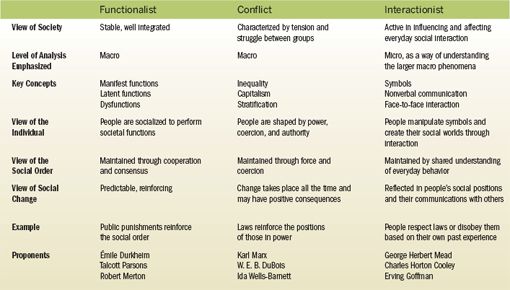

Major Sociological Perspectives

Existing Sources Used in Sociological Research

Sociological Perspectives on Culture

Theoretical Approaches to Development of the Self

Sociological Perspectives on Social Institutions

Comparison of the Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft

Stages of Sociocultural Evolution

Comparison of Primary and Secondary Groups

Characteristics of a Bureaucracy

Sociological Perspectives on the Mass Media

Modes of Individual Adaptation

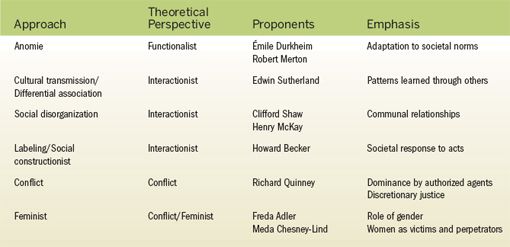

Sociological Perspectives on Deviance

Sociological Perspectives on Social Stratification

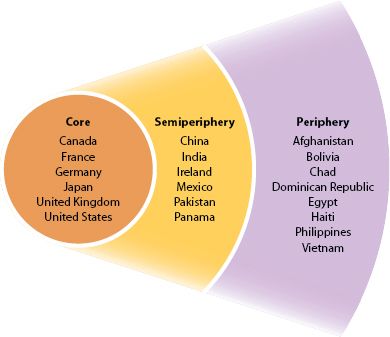

Sociological Perspectives on Global Inequality

Sociological Perspectives on Race and Ethnicity

Sociological Perspectives on Gender

Sociological Perspectives on Aging

Sociological Perspectives on the Family

Sociological Perspectives on Religion

Characteristics of Ecclesiae, Denominations, Sects, and New Religious Movements

Sociological Perspectives on Education

Characteristics of the Three Major Economic Systems

Sociological Perspectives on Health and Illness

Sociological Perspectives on Urbanization

Contributions to Social Movement Theory

Sociological Perspectives on Social Change

After more than 30 years of teaching sociology to students in colleges, adult education programs, nursing programs, an overseas program based in London, and even a maximum-security prison, I am convinced that the discipline can play a valuable role in building students’ critical thinking skills. The distinctive emphasis on social policy found in this text shows students how to use a sociological imagination in examining public policy issues such as welfare reform, economic development, global immigration, gay marriage, and environmentalism.

My hope is that through their reading of this book, students will begin to think like sociologists and will be able to use sociological theories and concepts in evaluating human interactions and institutions. In other words, students will be able to take sociology with them when they graduate from college, pursue careers, and get involved in their own communities and the world at large. Beginning with the introduction of the concept of sociological imagination in Chapter 1, this text highlights the distinctive way in which sociologists examine human social behavior, and how their research findings can be used to understand the broader principles that guide our lives.

The first 11 editions of Sociology have been used in more than 800 colleges and universities. This book is often part of a student’s first encounter with the engaging ideas of sociology. Many who have read it have gone on to make sociology their life’s work. Equally gratifying for me is hearing that Sociology has also made a difference in the lives of other students, who have applied the knowledge they gained in the course to guide their life choices.

The 12th edition of Sociology builds on the success of earlier editions through an emphasis on the following:

• Comprehensive and balanced coverage of theoretical perspectives throughout the text

• Strong coverage of issues pertaining to gender, age, race, ethnicity, and class in all chapters

• Cross-cultural and global content throughout the book

“Students can take sociology with them on campus, in their careers and into the community.”

As with previous editions, the 12th edition explores contemporary issues that students hear about in the media through a sociological lens. From social mobility among Latino immigrants to online social networks to environmental policy issues and health care around the world, this book helps students to develop a sociological perspective as they consider relevant topics and issues. With this objective in mind, coverage of the global economic downturn that began in 2008 and became global in its impact by 2009 is discussed in relevant chapters. Here are some examples of this coverage:

• The impact on labor unions (Chapter 6)

• Increasing numbers of people in the United States living on government support (Chapter 9)

• Scapegoating of Jewish Americans (Chapter 11)

• The social impact on older workers (Chapter 13)

• The social costs of deindustrialization and downsizing (Chapter 18)

• The impact on people’s ability to buy prescription drugs (Chapter 19)

• Rising numbers of people becoming homeless for the first time (Chapter 20)

Taking Sociology with You in College

Chapter-Opening Excerpts:

Each chapter opens with a lively excerpt from the writings of sociologists and others, clearly conveying the excitement and relevance of sociological inquiry.

Sociology on Campus: These boxes apply a sociological perspective to issues of immediate interest to students.

NEW!

Thinking about Movies: Two films that underscore chapter themes are featured at the end of each chapter, along with a set of exercises that encourage students to use their sociological imagination when viewing movies.

Getting Involved: For students who want to become involved in social policy debates, this feature refers students to relevant material on the book’s Online Learning Center.

Self-Quizzes: At the end of every chapter, a 20-question self-quiz allows students to test their comprehension and retention of core information presented in the chapter.

Taking Sociology with You in Your Career

Taking Sociology to Work: These boxes underscore the value of an undergraduate degree in sociology by profiling individuals who majored in sociology and use its principles in their work.

Research Today: These boxes present new sociological findings on topics such as precarious work (how secure is your job?) and affirmative action.

Careers in Sociology: This appendix to Chapter 1 presents career options for students who have their undergraduate degree in sociology, and explains how this degree can be an asset in a wide variety of occupations.

Critical Thinking Questions: Critical thinking questions at the end of each chapter help students to analyze the social world in which they participate.

Use Your Sociological Imagination: These short, thought-provoking sections encourage students to apply the sociological concepts they have learned to the world around them.

Taking Sociology with You into the Community

Case Studies: Applying a sociological lens, our case studies evaluate both the local and the global community—from culture at Wal-Mart and NASA to stratification in Mexico and capitalism in China.

Sociology in the Global Community: These boxes provide a global perspective on topics such as aging, poverty, and the women’s movement.

Social Policy Sections: The end-of-chapter social policy sections play a critical role in helping students to think like sociologists. These sections apply sociological principles and theories to important social and political issues currently being debated by policymakers and the general public.

Maps: The maps titled “Mapping Life Nationwide” and “Mapping Life Worldwide” show the prevalence of social trends in the United States as well as in the global community.

The World as a Village: This new feature, positioned at the beginning of the book, invites students to think about the social world in which they live by figuratively shrinking the world to the size of a small village.

What’s New in Each Chapter?

Chapter 1: Understanding Sociology

• Updated discussion of sociology and common sense, with new examples.

• Discussion of the high suicide rate in Las Vegas as an illustration of Durkheim’s theory of suicide.

• Inclusion of W. E. B. DuBois in the same section and figure as Durkheim, Weber, and Marx, with key term coverage of double consciousness.

• Subsection on Pierre Bourdieu, with key term coverage of cultural capital and social capital.

• Discussion of research on “slugging,” a new form of commuter behavior, as an illustration of the interactionist perspective.

• Expanded coverage of the conflict view of sports in Research Today box, “Looking at Sports from Four Theoretical Perspectives.”

• Inclusion of Burawoy’s concept of public sociology.

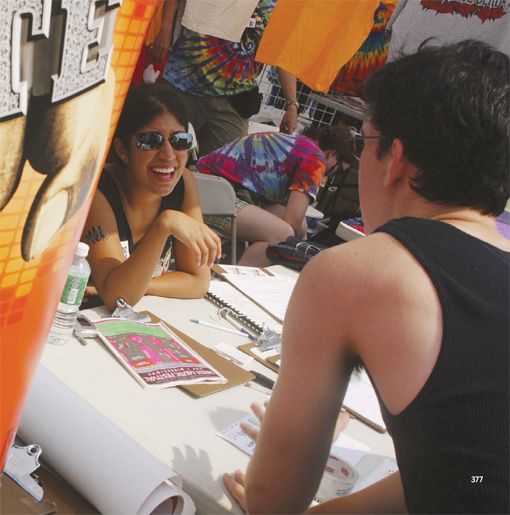

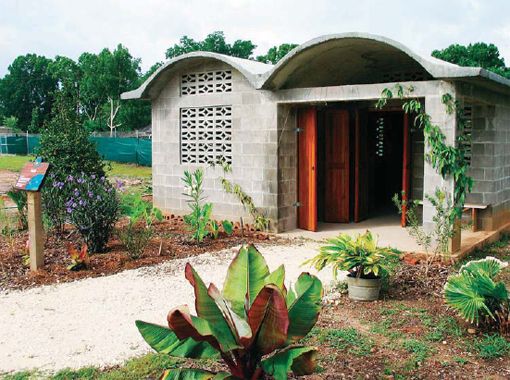

• Discussion of asset-based community development in Arkansas, with photo, as an example of applied sociology.

• Sociology in the Global Community box, “Your Morning Cup of Coffee.”

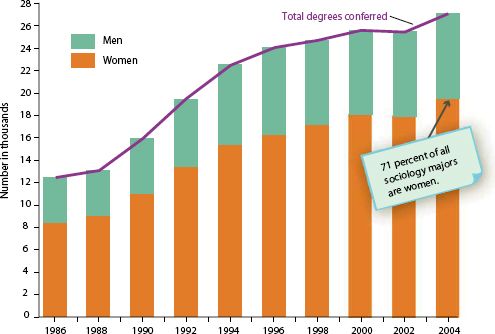

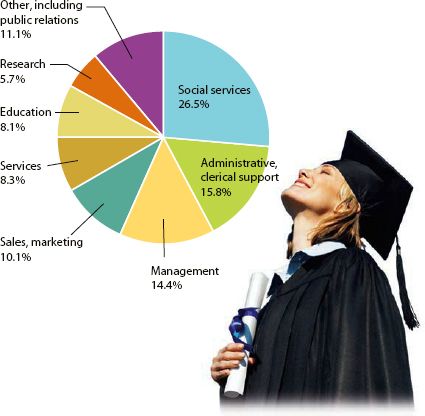

• Figure, “Occupations of Graduating Sociology Majors.”

Chapter 2: Sociological Research

• Chapter-opening excerpt from Patricia A. Adler and Peter Adler, “The Demedicalization of Self-Injury.”

• Coverage of snowball or convenience samples and their uses.

• Research Today box, “Surveying Cell Phone Users.”

• Discussion of undergraduate survey with table, “Top Reasons Why Men and Women Had Sex.”

• Discussion of the controversial embedding of social scientists in the U.S. Army’s Human Terrain System in Iraq, with photo.

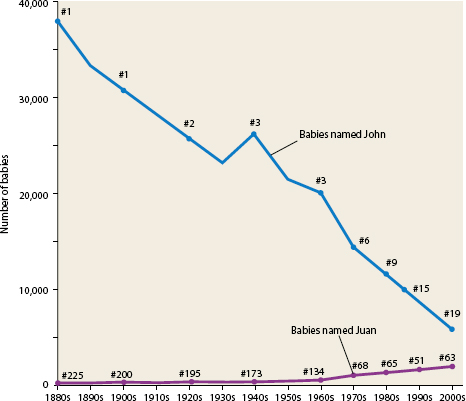

• Updated Research Today box, “What’s in a Name?” including coverage of most common surnames and geographical variations in most popular names.

• Updated discussion of the Exxon Corporation’s use of re-search funding to reduce the $5.3 billion penalty for negligence in the Exxon Valdez disaster to $500 million.

• Section on feminist methodology, with photo of immigrant sex workers.

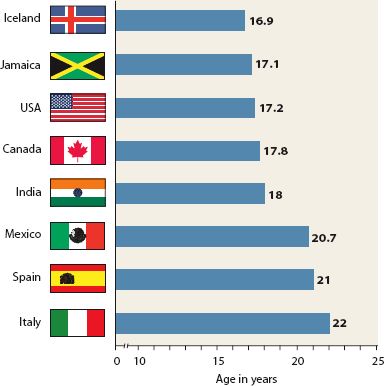

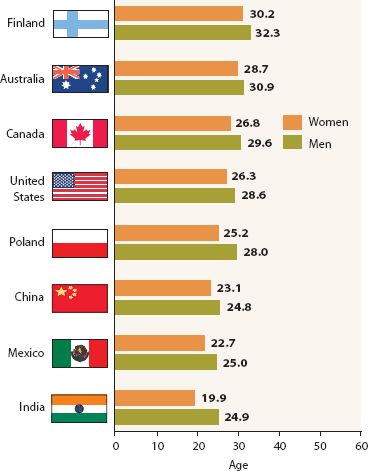

• Figure showing median age of first sex in eight countries.

• Streamlined organization for increased readability.

• Discussion of Theodor Adorno’s concept of the culture industry, with key term treatment.

• Discussion of child marriage as an illustration of cultural relativism, with Mapping Life Worldwide map, “Countries with High Child Marriage Rates.”

• Discussion of McDonald’s move toward local development of menus and marketing strategies at overseas restaurants.

• Discussion of the Navajo word for cancer as an illustration of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.

• Expanded discussion of cultural differences in nonverbal communication.

• Key term treatment of symbol in the section on nonverbal communication.

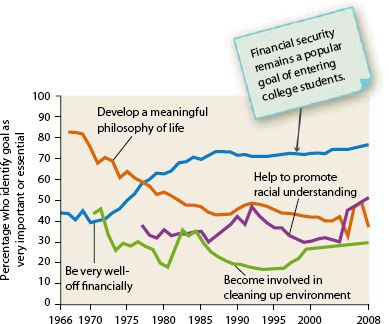

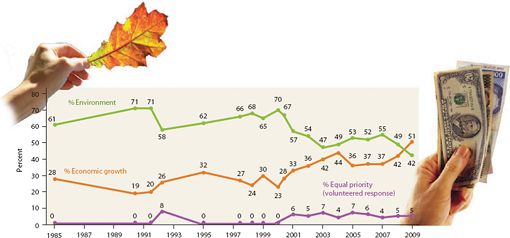

• Discussion of trends in U.S. college students’ environmental values.

• Discussion of cross-cultural research on student cheating.

• Section on global culture war, with key term treatment.

• Mapping Life Nationwide map, “Percentage of People Who Speak a Language Other than English at Home, by State.”

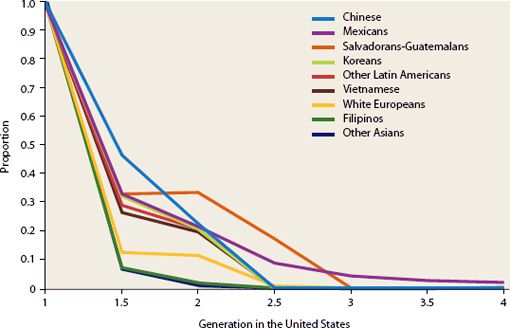

• Discussion of the rapidity with which immigrants to the United States learn English, with figure, “Proportion of Immigrant Group Members in Southern California Who Speak the Mother Tongue, by Generation.”

Chapter 4: Socialization and the Life Course

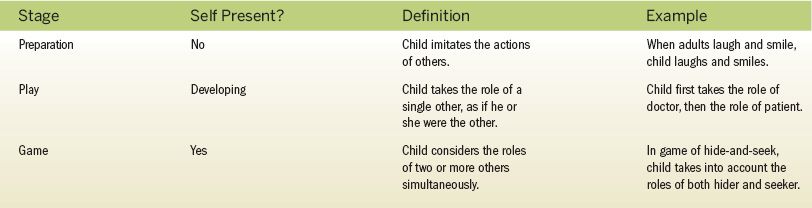

• Summing Up table, “Mead’s Stages of the Self.”

• Discussion of exercise-related impression management among students.

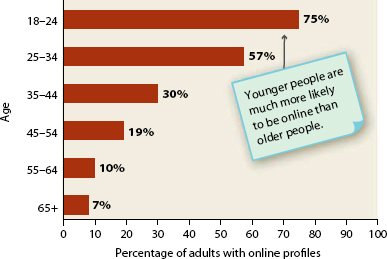

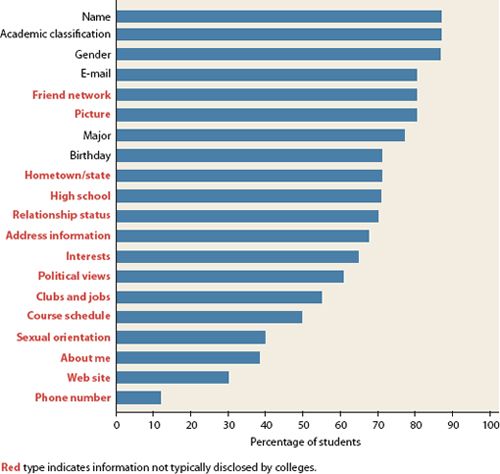

• Research Today box, “Online Socializing: A New Agent of Socialization,” with figures.

• Thinking about Movies exercise on The Departed (Martin Scorsese, 2006).

Chapter 5: Social Interaction and Social Structure

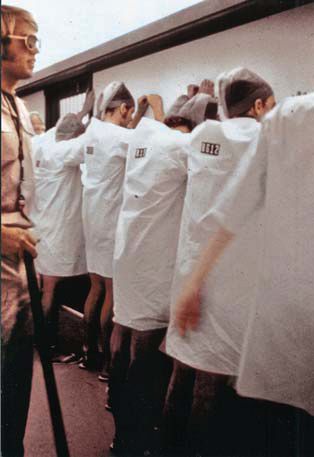

• Chapter-opening excerpt from Philip Zimbardo, The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil.

• Discussion of cross-cultural differences in social interaction and social reality.

• Discussion of the inauguration of President Barack Obama as an example of the institutional function of providing and maintaining a sense of purpose.

• Summing Up table, “Sociological Perspectives on Social Institutions.”

• Research Today box, “Social Networks and Smoking,” with figure.

• Section on virtual worlds, including Sociology in the Global Community box, “The Second Life® Virtual World.”

Chapter 6: Groups and Organizations

• Research Today box, “The Drinking Rape Victim: Jury Decision Making.”

• Discussion of new directions in research on organizations.

• Discussion of societal changes that have weakened the bureaucratization of the workplace.

• Sociology in the Global Community box, “Entrepreneurship, Japanese Style.”

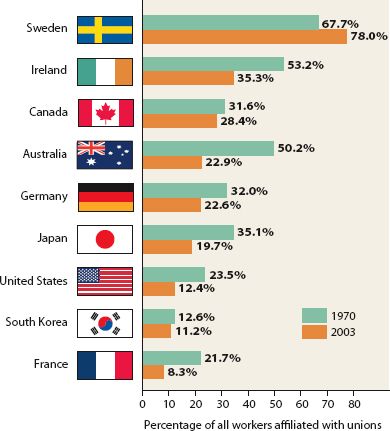

• Revised Social Policy section, “The State of the Unions Worldwide,” including (a) discussion of the effects of the economic downturn of 2008; (b) discussion of the activities of international trade unions; and (c) figure, “Labor Union Membership Worldwide.”

• Chapter-opening excerpt from Mark Andrejevic, iSpy: Surveillance and Power in the Interactive Era.

• Coverage of prominent media events of 2009, including the transition to the Obama administration, street protests in Iran, and Michael Jackson’s death.

• Discussion of cultural convergence, with key term treatment.

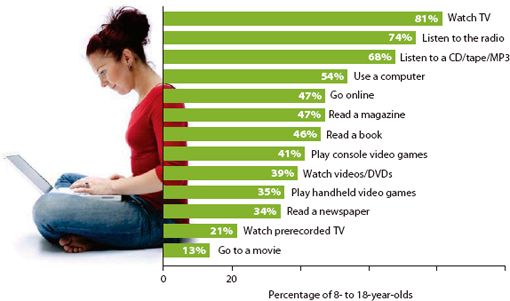

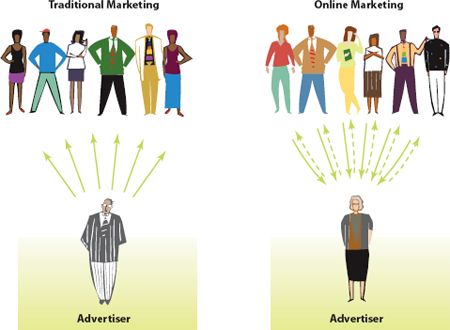

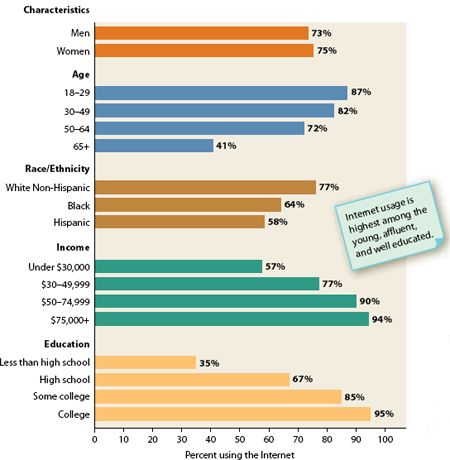

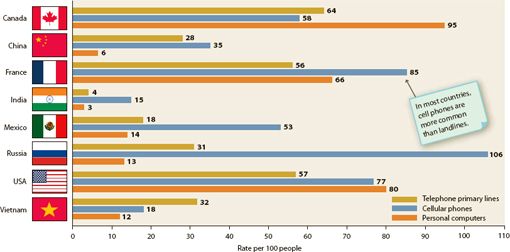

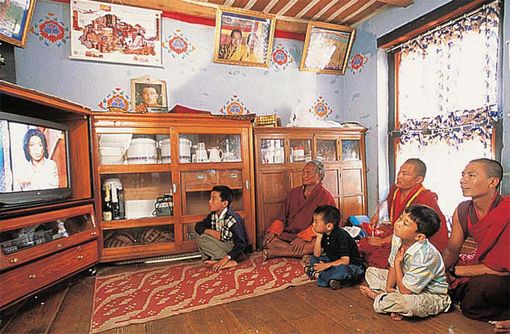

• Discussion of the degree and type of contact U.S. residents have with information and communications technologies, with table.

• Discussion of the media’s role in promoting social norms regarding human sexuality.

• Mapping Life Worldwide map, “Filtering Social Content.”

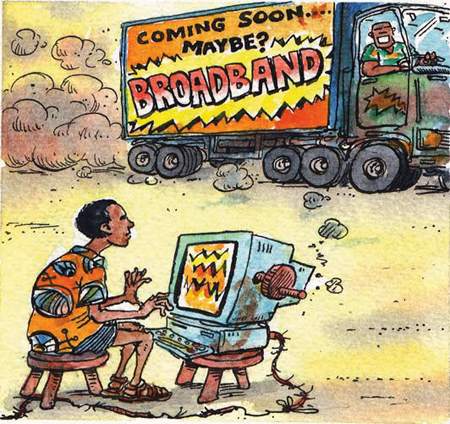

• Section on the “digital divide” that separates low-income groups, racial and ethnic minorities, rural residents, and citizens of developing countries from access to the latest technologies, with cartoon.

• Discussion of the use of online social networks to promote consumption, with figure.

Chapter 8: Deviance and Social Control

• Chapter-opening excerpt from Gang Leader for a Day: A Rogue Sociologist Takes to the Streets by Sudhir Venkatesh.

• Discussion of a recent replication of Milgram’s obedience experiment.

• Research Today box, “Does Crime Pay?”

• Section on social disorganization theory, with key term treatment.

• Section on labeling theory and sexual deviance, with photo.

• Sociology on Campus box, “Campus Crime.”

• Taking Sociology to Work box, “Stephanie Vezzani, Special Agent, U.S. Secret Service.”

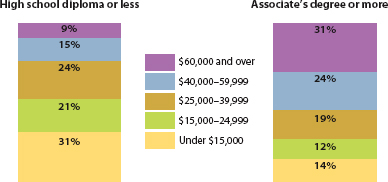

• Social Policy section on gun control, with cartoon.

Chapter 9: Stratification and Social Mobility in the United States

• Chapter-opening excerpt from Richistan: A Journey through the American Wealth Boom and the Lives of the New Rich by Robert Frank.

• Expansion of the discussion of castes to include historical contexts outside India.

• Key term treatment of socioeconomic status (SES) and the feminization of poverty.

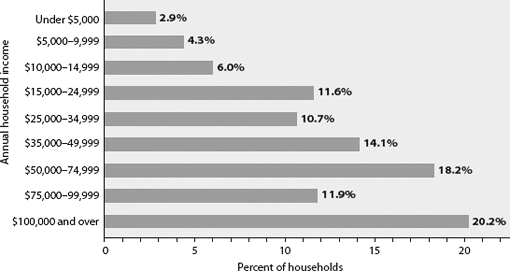

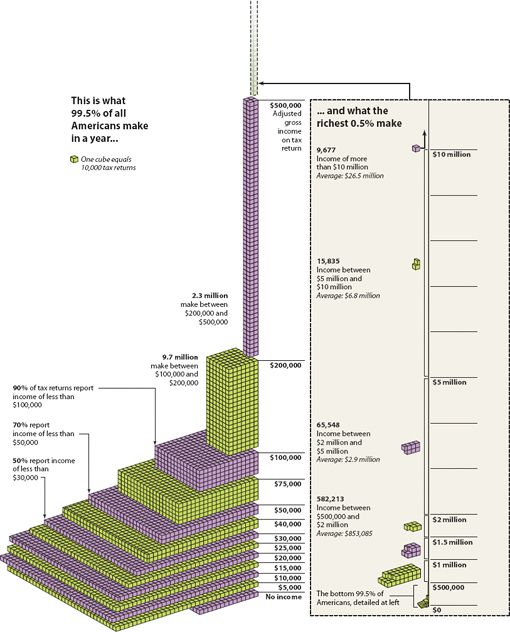

• Expanded discussion of the growing gap in household income between the rich and the poor.

• Research Today box, “Precarious Work,” including coverage of the economic downturn of 2008–2009.

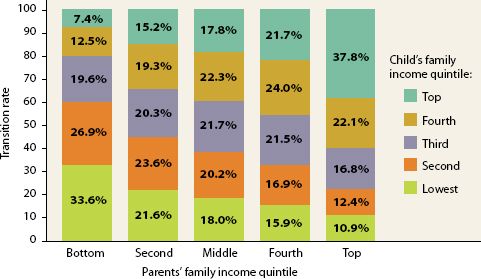

• Expanded discussion of intergenerational mobility, with figure, “Intergenerational Income Mobility.”

• Discussion of the generational change in women’s earnings relative to men’s.

• In the Social Policy section, discussion of the rise in dependence on social security, food stamps, and unemployment insurance during the economic downturn of 2008–2009.

• Chapter-opening excerpt from The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries Are Failing and What Can Be Done About It by Paul Collier.

• Explanation of how social scientists in developing nations measure poverty.

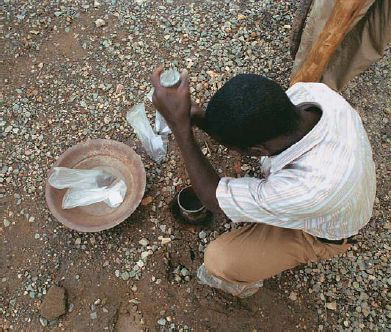

• Description of a microlending program run by the Widows Organization in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

• Updated Sociology in the Global Community box, “Stratification in Japan,” with expanded discussion of gender stratification.

• Discussion of cross-cultural studies of intergenerational mobility over the last half century.

• Discussion of growth of the middle class in some developing nations.

• Description of the effect of the recent economic downturn in the United States on Mexican immigrants and the Mexican economy.

• Discussion of the feminist perspective on human rights.

Chapter 11: Racial and Ethnic Inequality

• Discussion of the process of racial formation, with key term treatment.

• Expanded section on the recognition of multiple identities.

• Explanation of why race and ethnicity are still relevant despite the election or appointment of African Americans to high office in the United States.

• Section on color-blind racism, with key term treatment.

• Key term treatment of White privilege.

• Discussion of public support for the profiling of Arab Americans by airport security personnel.

• Sociology in the Global Community box, “The Aboriginal People of Australia.”

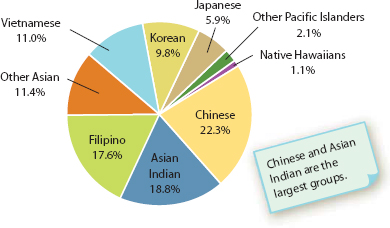

• Comparison of Asian American incomes inside and outside Chinatown in New York City.

• Research Today box, “Social Mobility among Latino Immigrants.”

• Key term treatment of transnationals in Social Policy section on global immigration.

Chapter 12: Stratification by Gender

• Key term coverage of multiple masculinities.

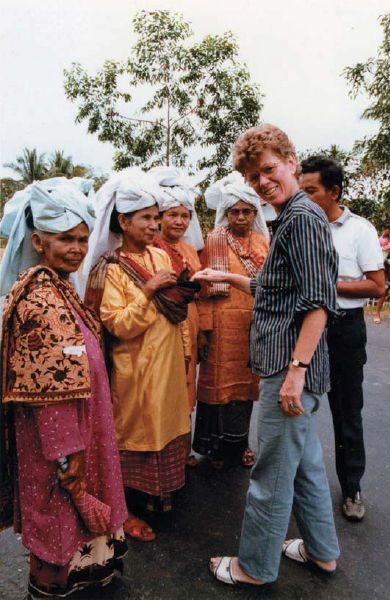

• Discussion of the social construction of gender in West Sumatra, Indonesia, with photo.

• Updated section on the interactionist approach to gender, including new examples of “doing gender” and new research on cross-sex conversations.

• Discussion of the Norwegian law requiring corporations to set aside 40 percent of managerial positions for women.

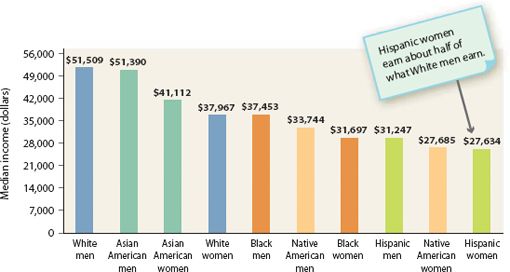

• Discussion of reasons for the pay gap between men and women in the same occupation.

• Discussion of the legal barrier to proving sex discrimination in wage payments.

• Discussion of the debate over abortion in Latin American countries.

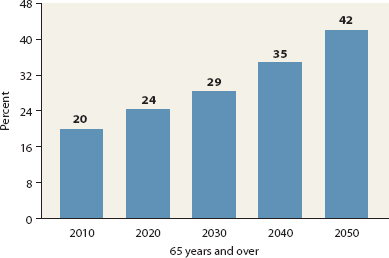

Chapter 13: Stratification by Age

• Discussion of the trend toward the adoption of new technologies by the elderly.

• Section on labeling theory.

• Discussion of the impact of Japan’s aging labor force on Japan’s immigration policy.

• Key term treatment of naturally occurring retirement communities (NORCs).

• Expanded discussion of gender, racial, and ethnic stratification among the elderly, with figure, “Minority Population Aged 65 and Older, Projected.”

• Discussion of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA) and Supreme Court decisions favoring elderly workers.

• Research Today box, “Elderspeak and Other Signs of Ageism.”

• Discussion of research on physician-assisted suicide in Oregon and the Netherlands.

Chapter 14: The Family and Intimate Relationships

• Figure, “Median Age at First Marriage in Eight Countries.”

• Discussion of the impact of new media technologies on dating and mating.

• Discussion of the rise in the number of couples who live apart for reasons other than marital discord, with photo.

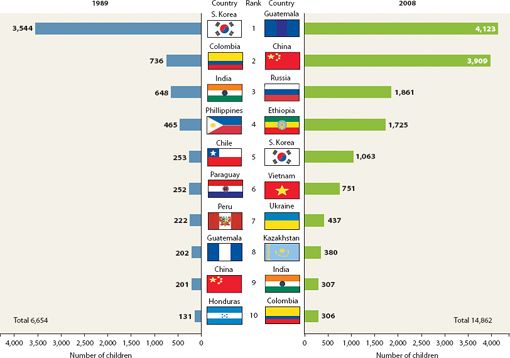

• Table, “Foreign-Born Adoptees by Top Ten Countries of Origin, 1989 and 2008.”

• Comparison of cultural attitudes toward marriage, divorce, and cohabitation in the United States and Europe.

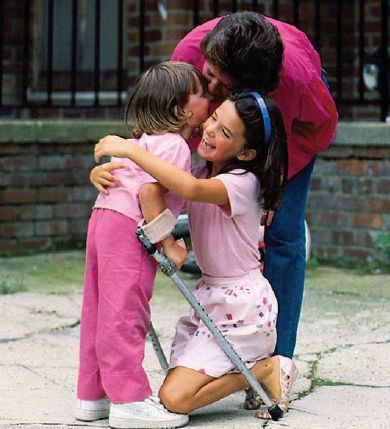

• Updated discussion of the impact of divorce on children.

• Updated coverage of the federal Healthy Marriage Initiative.

• Research Today box, “Divorce and Military Deployment,” with photo.

• Discussion of state legislation and supreme court rulings on gay marriage.

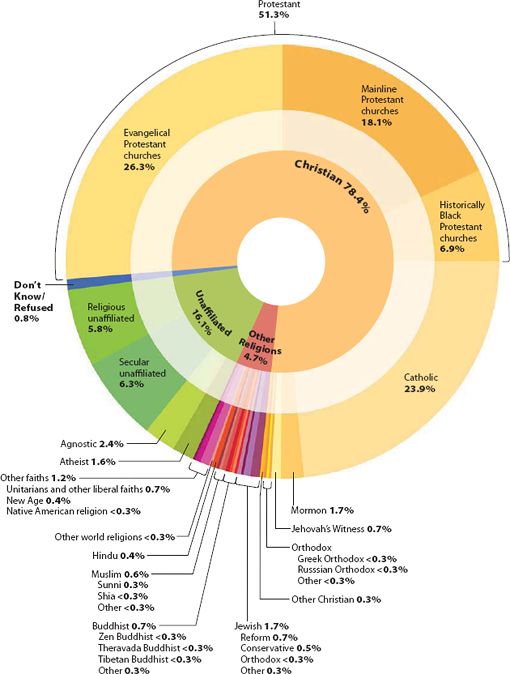

• Figure, “Major Religious Traditions in the United States.”

• Discussion of the goals of the Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships under the Obama administration.

• Discussion of public opinion polls in 143 countries regarding perceptions of religion as a source of oppression or social support.

• Summing Up table, “Components of Religion.”

• Discussion of the fluidity of individual religious adherence.

• Updated discussion of religion on the Internet, including GodTube.com and Second Life®.

• Discussion of changing dress and hairstyle among Sikh men.

• Discussion of the Christian contribution to India’s social safety net.

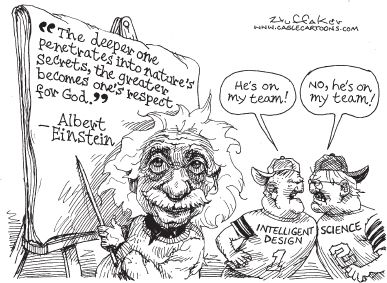

• Discussion of a recent survey of Americans’ beliefs regarding creationism and evolutionary theory.

• Sociology on Campus box, “Google University.”

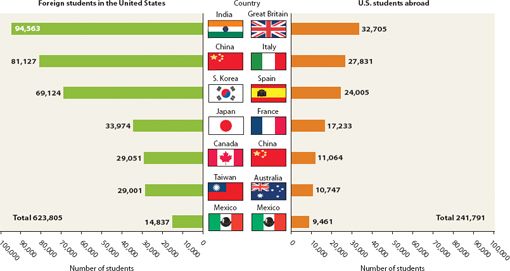

• Table, “Foreign Students by Major Countries of Origin and Destination.”

• Discussion of recent research on tracking of low-income students and their performance on advanced placement exams.

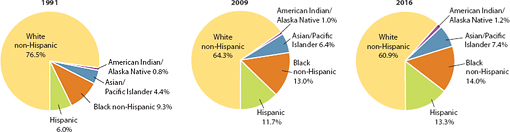

• Figure, “College Campuses by Race and Ethnicity: Then, Now, and in the Future.”

Chapter 17: Government and Politics

• Mapping Life Worldwide map, “Filtering Information: Political Content.”

• Sociology in the Global Community box, “Charisma: The Beatles and Maharishi Mahesh Yogi,” with photo.

• Discussion of the increase in online political activity during the 2008 presidential campaign.

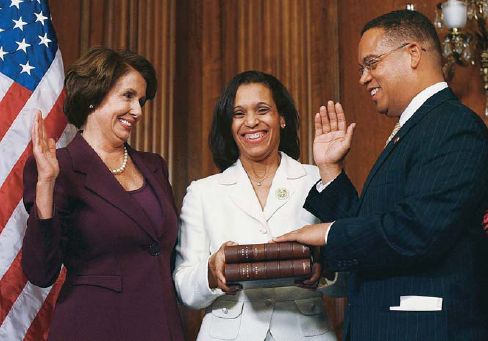

• Figure, “Reasons for Not Voting, 18- to 24-Year-Olds.”

• Coverage of the global power elite.

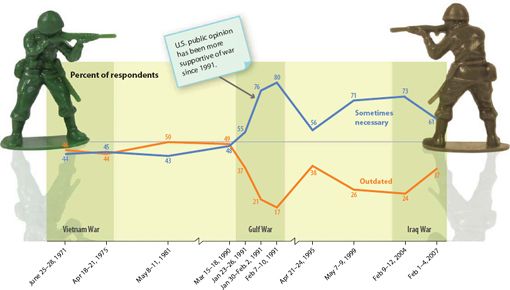

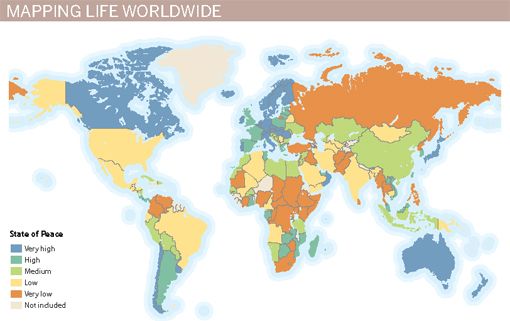

• Mapping Life Worldwide map, “Global Peace Index.”

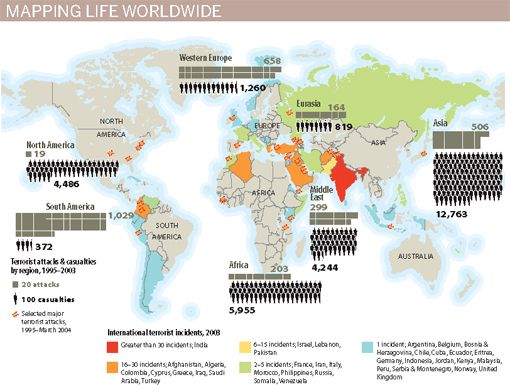

• Discussion of the feminist perspective on terrorism.

• Discussion of e-government, or the online presence of governmental authority.

• Updated Social Policy section on campaign financing, including (a) spending during the 2008 presidential campaign, (b) candidates’ decisions to forgo public funding, and (c) the recent increase in online donations.

Chapter 18: The Economy and Work

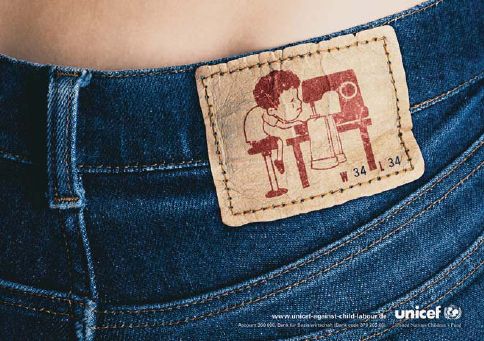

• Chapter-opening excerpt from Kelsey Timmerman, Where Am I Wearing? A Global Tour to the Countries, Factories, and People that Make Our Clothes.

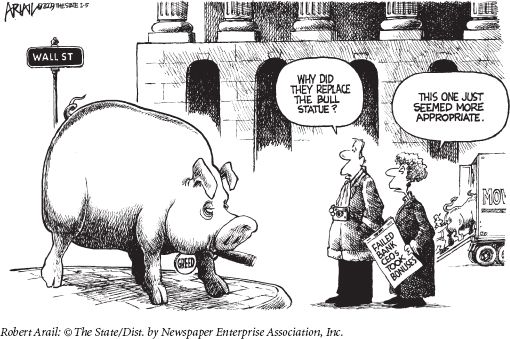

• Discussion of the federal government’s bailout of banking, investment, and insurance companies during the financial crisis of 2008 and its acquisition in 2009 of majority ownership in General Motors.

• Discussion of Karoshi (“death from overwork”) in the section on job satisfaction in Japan.

• Discussion of “color-blind policies” and preferential treatment of children of alumni in Research Today box on affirmative action.

• Discussion of the accelerating effects of the economic downturn of 2008–2009 on the processes of deindustrialization and downsizing.

• Table, “Occupations Most Vulnerable to Offshoring.”

Chapter 19: Health, Medicine, and the Environment

• Combines coverage of health and medicine (Chapter 19 in the 11th edition) with coverage of the environment (Chapter 21 in the 11th edition).

• Mapping Life Worldwide map, “People Living with HIV.”

• Research Today box, “The AIDS Epidemic.”

• Discussion of the effect of the economic downturn of 2008–2009 on the number of people with health insurance and public opinion toward health care reform.

• Discussion of the increased death rate among people without health insurance.

• Discussion of the link between health and economic mobility.

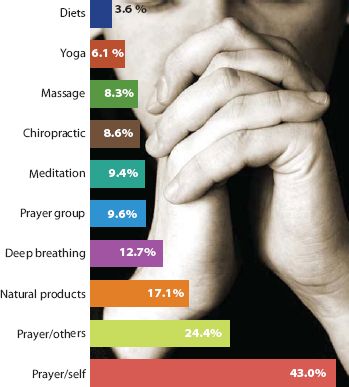

• Figure, “Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine.”

• Discussion of the increasing use of mental health services and the growing public awareness of their necessity.

• Discussion of the higher incidence of mental illness and differential access to treatment among minority groups.

• Discussion of a recent study by the American Lung Association of air quality in U.S. communities.

• Discussion of the Obama administration’s initiative to slow global warming.

• Social Policy section on environmentalism, with figure, “The Environment versus the Economy.”

Chapter 20: Population, Communities, and Urbanization

• Combines coverage of population (Chapter 21 in the 11th edition) with coverage of communities and urbanization (Chapter 20 in the 11th edition).

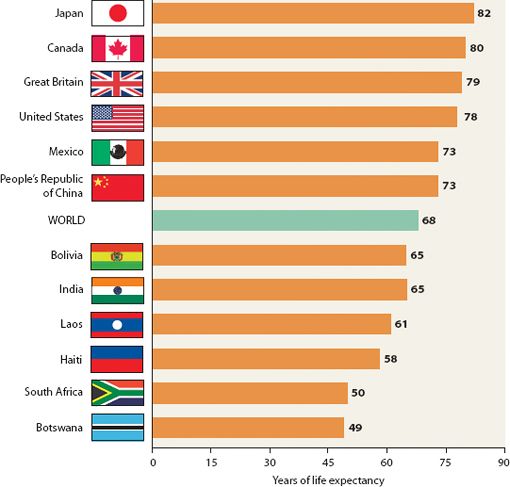

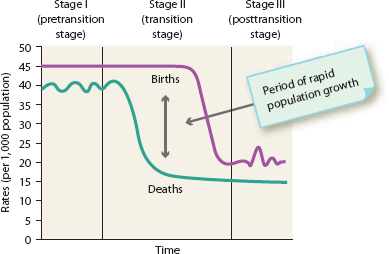

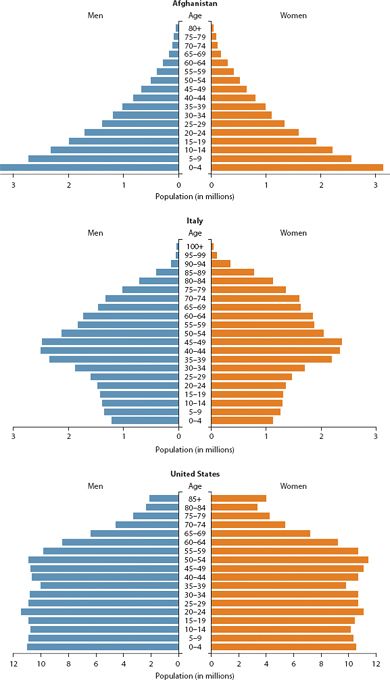

• Figure, “Population Structure of Afghanistan, Italy, and the United States, 2012.”

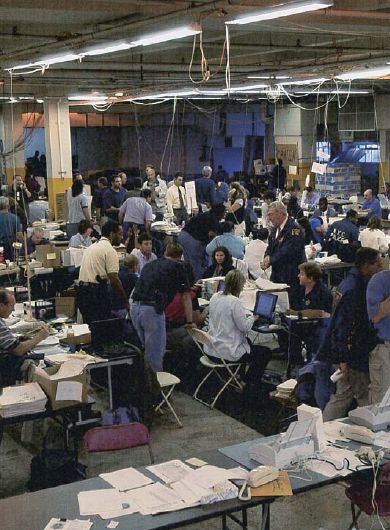

• Updated Social Policy section, “Seeking Shelter Worldwide,” with discussions of the impact of the economic downturn of 2008–2009 on homelessness and on public opinion regarding homelessness.

Chapter 21: Collective Behavior and Social Movements

• Discussion of crowdsourcing, the online practice of asking Internet surfers for ideas or participation in an activity or movement.

• Discussion of the false rumor that Oscar Mayer does not support U.S. troops.

• Summing Up table, “Forms of Collective Behavior.”

Chapter 22: Social Change in the Global Community

• Chapter-opening excerpt from The Pirate’s Dilemma: How Youth Culture Is Reinventing Capitalism by Matt Mason.

• Discussion of the “not on planet Earth” campaign, an antiglobalization movement.

• Discussion of the medical advances made as a result of modern warfare, such as electronically controlled prosthetic devices.

Support for Instructors and Students

Print Resources

Student Study Guide The Study Guide includes a detailed list of key points, key terms and their definitions, true or false self-quizzes, multiple-choice quizzes, fill-in-the-blank questions, and social policy questions.

Primis Customized Readers An array of first-rate readings are available to adopters in a customized electronic database. Some are classic articles from the sociological literature; others are provocative pieces written especially for McGraw-Hill by leading sociologists.

Digital Resources

Online Learning Center The Online Learning Center that accompanies this text (www.mhhe.com/schaefer12e) provides robust resources for both students and instructors.

Students will find video clips, interactive quizzes, diagnostic midterm and final exams, census updates, social policy exercises, chapter glossaries, vocabulary flash cards, and more.

Schaefer’s highly valued instructor resources are available on the password-protected instructor portion of the Online Learning Center. Teaching aids available include the Instructor’s Resource Manual, Test Banks in computerized and Word formats, and PowerPoint slides for the convenience of instructors who choose to give multimedia lectures. The Instructor’s Resource Manual provides sociology instructors with detailed chapter outlines and summaries, learning objectives, additional lecture ideas, class discussion topics, essay questions, topics for student research, critical thinking questions, video resources, and additional readings. The Test Banks include multiple-choice, true or false, and essay questions for every chapter; they will be useful in testing students on basic sociological concepts, application of theoretical perspectives, and recall of important factual information. Correct answers are provided for all questions. The PowerPoint slides include bulleted lecture points, figures, and maps, and instructors are welcome to create overhead transparencies from the slides if they wish to do so.

McGraw-Hill’s EZ Test is a flexible and easy-to-use electronic testing program. The program allows instructors to create tests from book-specific items. It accommodates a wide range of question types, and instructors may add their own questions. Multiple versions of the test can be created, and any test can be exported for use with course management systems such as WebCT, BlackBoard, and PageOut. EZ Test Online is a new service that gives you a place to easily administer your EZ Test—created exams and quizzes online. The program is available for Windows and Macintosh environments.

Also available on the instructor’s portion of the Online Learning Center are book-specific questions created for use with the Classroom Performance System (CPS) by eInstruction, a wireless response system that allows instructors to receive immediate feedback from students. CPS units include easy-to-use software for instructors’ use in creating their own questions and assessments, and delivering them to their students. The units also include individual wireless response pads for students’ use in responding. For further details, go to www.mhhe.com/einstruction.

With the CourseSmart eTextbook version of this title, students can save up to 50 percent off the cost of a print book, reduce their impact on the environment, and access powerful Web tools for learning. Faculty can also review and compare the full text online without having to wait for a print desk copy. CourseSmart is an online eTextbook, which means users need to be connected to the Internet in order to access it. Students can also print sections of the book for maximum portability. For further details, contact your sales representative or go to www.coursesmart.com.

Primis Online Professors can customize this edition of Sociology by selecting from it only those chapters they want to use in their courses. Primis Online allows users to choose and change the order of chapters, as well as add readings from McGraw-Hill’s vast database of content. Both custom-printed textbooks and electronic eBooks are available. To learn more, contact your McGraw-Hill sales representative or visit www.primisonline.com.

Acknowledgments

Since 1999, Elizabeth Morgan has played a most significant role in the development of my introductory sociology books. Fortunately for me, in the 12th edition, Betty has once again been responsible for the smooth integration of all changes and updates.

I deeply appreciate the contributions to this book made by my editors. Developmental editor Kate Scheinman challenged me to make this edition better than its predecessors. Rhona Robbin, director of development, at McGraw-Hill, oversaw the project.

I have received strong support and encouragement from Frank Mortimer, publisher; Gina Boedeker, senior sponsoring editor; and Caroline McGillen, marketing manager. Additional guidance and support were provided by Daniel Gonzalez, editorial coordinator; Holly Paulsen, production editor; Andrei Pasternak, design manager; Nora Agbayani, photo research coordinator; Toni Michaels, photo researcher, Rennie Evans, art editor; Judy Brody, text permissions; and Jan McDearmon, copyeditor.

Academic Reviewers

This edition continues to reflect many insightful suggestions made by reviewers of the eleven hardcover editions and the eight paperback brief editions. The current edition has benefitted from constructive and thorough evaluations provided by sociologists from both two-year and four-year institutions. These include John P. Bartkowski, Mississippi State University; Douglas Forbes, University of Wisconsin—Stevens Point; H. David Hunt, University of Southern Mississippi; Kevin Keating, Broward College; Nelson Kofie, Prince George’s Community College; Richard Leveroni, Schenectady County Community College; Tina Mougouris, San Jacinto College; Gloria Nikolai, Pikes Peak Community College; Sally Raskoff, Los Angeles Valley College; Luis Salinas, University of Houston; and Rebecca Stevens, Mount Union College.

I would also like to acknowledge the contributions of the following individuals: Lynn Newhart, Rockford College, for her work on the Online Learning Center; Martha Warburton, University of Texas at Brownsville and Texas South West College, and Rebecca Matthews, PhD sociology, Cornell University, for their work on the Instructor’s Resource Manual and Study Guide; Gerry Williams, for his work on the PowerPoint presentations; and Jon Bullinger, for his work on the Test Banks and CPS questions. Finally, I would like to thank Peter D. Schaefer, Mary-mount Manhattan College, for developing the new end-of-chapter sections, “Thinking about Movies.”

As is evident from these acknowledgments, the preparation of a textbook is truly a team effort. The most valuable member of this effort continues to be my wife, Sandy. She provides the support so necessary in my creative and scholarly activities.

I have had the good fortune to introduce students to sociology for many years. These students have been enormously helpful in spurring on my own sociological imagination. In ways I can fully appreciate but cannot fully acknowledge, their questions in class and queries in the hallway have found their way into this textbook.

Richard T. Schaefer

inside

Major Theoretical Perspectives

Applied and Clinical Sociology

Developing a Sociological Imagination

Appendix: Careers in Sociology

BOXES

Research Today: Looking at Sports from Four Theoretical Perspectives

Sociology in the Global Community: Your Morning Cup of Coffee

Every day we are influenced by the people with whom we interact.

“I am, of course, very different from the people who normally fill America’s least attractive jobs, and in ways that both helped and limited me. Most obviously, I was only visiting a world that others inhabit full-time, often for most of their lives. With all the real-life assets I’ve built up in middle age—bank account, IRA, health insurance, multiroom home—waiting indulgently in the background, there was no way I was going to “experience poverty” or find out how it “really feels” to be a long-term low-wage worker. My aim here was much more straightforward and objective—just to see whether I could match income to expenses, as the truly poor attempt to do every day. …

In Portland, Maine, I came closest to achieving a decent fit between income and expenses, but only because I worked seven days a week. Between my two jobs, I was earning approximately $300 a week after taxes and paying $480 a month in rent, or a manageable 40 percent of my earnings. It helped, too, that gas and electricity were included in my rent and that I got two or three free meals each weekend at the nursing home. But I was there at the beginning of the off-season. If I had stayed until June 2000 I would have faced the Blue Haven’s summer rent of $390 a week, which would of course have been out of the question. So to survive year-round, I would have had to save enough, in the months between August 1999 and May 2000, to accumulate the first month’s rent and deposit on an actual apartment. I think I could have done this—saved $800 to $1,000—at least if no car trouble or illness interfered with my budget. I am not sure, however, that I could have maintained the seven-day-a-week regimen month after month or eluded the kinds of injuries that afflicted my fellow workers in the housecleaning business.

With all the real-life assets I’ve built up in middle age—bank account, IRA, health insurance, multiroom home—waiting indulgently in the background, there was no way I was going to “experience poverty” or find out how it “really feels” to be a long-term low-wage worker.

In Minneapolis—well, here we are left with a lot of speculation. If I had been able to find an apartment for $400 a month or less, my pay at Wal-Mart—$1,120 a month before taxes—might have been sufficient, although the cost of living in a motel while I searched for such an apartment might have made it impossible for me to save enough for the first month’s rent and deposit. A weekend job, such as the one I almost landed at a supermarket for about $7.75 an hour, would have helped, but I had no guarantee that I could arrange my schedule at Wal-Mart to reliably exclude weekends. If I had taken the job at Menards and the pay was in fact $10 an hour for eleven hours a day, I would have made about $440 a week after taxes—enough to pay for a motel room and still have something left over to save up for the initial costs of an apartment. But were they really offering $10 an hour? And could I have stayed on my feet eleven hours a day, five days a week? So yes, with some different choices, I probably could have survived in Minneapolis. But I’m not going back for a rematch.”

(Ehrenreich 2001:6, 197–198) Additional information about this excerpt can be found on the Online Learning Center at www.mhhe.com/schaefer12e.

In her undercover attempts to survive as a low-wage worker in different cities in the United States, journalist Barbara Ehrenreich revealed patterns of human interaction and used methods of study that foster sociological investigation. This excerpt from her book Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America describes how she left a comfortable home and assumed the identity of a divorced, middle-aged housewife with no college degree and little working experience. She set out to get the best-paying job and the cheapest living quarters she could find, to see whether she could make ends meet. Months later, physically exhausted and demoralized by demeaning work rules, Ehrenreich confirmed what she had suspected before she began: getting by in this country as a low-wage worker is a losing proposition.

Ehrenreich’s study focused on an unequal society, which is a central topic in sociology. Her investigative work, like the work of many other journalists, is informed by sociological research that documents the existence and extent of inequality in our society. Social inequality has a pervasive influence on human interactions and institutions. Certain groups of people control scarce resources, wield power, and receive special treatment.

While it might be interesting to know how one individual is affected by the need to make ends meet, sociologists consider how entire groups of people are affected by these kinds of factors, and how society itself might be altered by them. Sociologists, then, are not concerned with what one individual does or does not do, but with what people do as members of a group or in interaction with one another, and what that means for individuals and for society as a whole.

As a field of study, sociology is extremely broad in scope. You will see throughout this book the range of topics sociologists investigate—from suicide to TV viewing habits, from Amish society to global economic patterns, from peer pressure to genetic engineering. Sociology looks at how others influence our behavior; how major social institutions like the government, religion, and the economy affect us; and how we ourselves affect other individuals, groups, and even organizations.

How did sociology develop? In what ways does it differ from other social sciences? This chapter will explore the nature of sociology as both a field of inquiry and an exercise of the “sociological imagination.” We’ll look at the discipline as a science and consider its relationship to other social sciences. We’ll meet four pioneering thinkers—Émile Durkheim, Max Weber, Karl Marx, and W. E. B. DuBois—and examine the theoretical perspectives that grew out of their work. We’ll note some of the practical applications for sociological theory and research. Finally, we’ll see how sociology helps us to develop a sociological imagination. For those students interested in exploring career opportunities in sociology, the chapter closes with a special appendix.

What has sociology got to do with me or with my life?” As a student, you might well have asked this question when you signed up for your introductory sociology course. To answer it, consider these points: Are you influenced by what you see on television? Do you use the Internet? Did you vote in the last election? Are you familiar with binge drinking on campus? Do you use alternative medicine? These are just a few of the everyday life situations described in this book that sociology can shed light on. But as the opening excerpt indicates, sociology also looks at large social issues. We use sociology to investigate why thousands of jobs have moved from the United States to developing nations, what social forces promote prejudice, what leads someone to join a social movement and work for social change, how access to computer technology can reduce social inequality, and why relationships between men and women in Seattle differ from those in Singapore.

Sociology is, very simply, the scientific study of social behavior and human groups. It focuses on social relationships; how those relationships influence people’s behavior; and how societies, the sum total of those relationships, develop and change.

In attempting to understand social behavior, sociologists rely on a unique type of critical thinking. A leading sociologist, C. Wright Mills, described such thinking as the sociological imagination—an awareness of the relationship between an individual and the wider society, both today and in the past. This awareness allows all of us (not just sociologists) to comprehend the links between our immediate, personal social settings and the remote, impersonal social world that surrounds and helps to shape us. Barbara Ehrenreich certainly used a sociological imagination when she studied low-wage workers (Mills [1959] 2000a).

A key element in the sociological imagination is the ability to view one’s own society as an outsider would, rather than only from the perspective of personal experiences and cultural biases. Consider something as simple as sporting events. On college campuses in the United States, thousands of students cheer well-trained football players. In Bali, Indonesia, dozens of spectators gather around a ring to cheer on well-trained roosters engaged in cockfights. In both instances, the spectators debate the merits of their favorites and bet on the outcome of the events. Yet what is considered a normal sporting event in one part of the world is considered unusual in another part.

The sociological imagination allows us to go beyond personal experiences and observations to understand broader public issues. Divorce, for example, is unquestionably a personal hardship for a husband and wife who split apart. However, C. Wright Mills advocated using the sociological imagination to view divorce not simply as an individual’s personal problem but rather as a societal concern. Using this perspective, we can see that an increase in the divorce rate actually redefines a major social institution—the family. Today’s households frequently include stepparents and half-siblings whose parents have divorced and remarried. Through the complexities of the blended family, this private concern becomes a public issue that affects schools, government agencies, businesses, and religious institutions.

The sociological imagination is an empowering tool. It allows us to look beyond a limited understanding of human behavior to see the world and its people in a new way and through a broader lens than we might otherwise use. It may be as simple as understanding why a roommate prefers country music to hip-hop, or it may open up a whole different way of understanding other populations in the world. For example, in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001, many citizens wanted to understand how Muslims throughout the world perceived their country, and why. From time to time this textbook will offer you the chance to exercise your own sociological imagination in a variety of situations.

use your sociological imagination

You are walking down the street in your city or hometown. In looking around you, you can’t help noticing that half or more of the people you see are overweight. How do you explain your observation? If you were C. Wright Mills, how do you think you would explain it?

Sociology and the Social Sciences

Is sociology a science? The term science refers to the body of knowledge obtained by methods based on systematic observation. Just like other scientific disciplines, sociology involves the organized, systematic study of phenomena (in this case, human behavior) in order to enhance understanding. All scientists, whether studying mushrooms or murderers, attempt to collect precise information through methods of study that are as objective as possible. They rely on careful recording of observations and accumulation of data.

Of course, there is a great difference between sociology and physics, between psychology and astronomy. For this reason, the sciences are commonly divided into natural and social sciences. Natural science is the study of the physical features of nature and the ways in which they interact and change. Astronomy, biology, chemistry, geology, and physics are all natural sciences. Social science is the study of the social features of humans and the ways in which they interact and change. The social sciences include sociology, anthropology, economics, history, psychology, and political science.

Sociology is the scientific study of social behavior and human groups.

These social science disciplines have a common focus on the social behavior of people, yet each has a particular orientation. Anthropologists usually study past cultures and preindustrial societies that continue today, as well as the origins of humans. Economists explore the ways in which people produce and exchange goods and services, along with money and other resources. Historians are concerned with the peoples and events of the past and their significance for us today. Political scientists study international relations, the workings of government, and the exercise of power and authority. Psychologists investigate personality and individual behavior. So what do sociologists focus on? They study the influence that society has on people’s attitudes and behavior and the ways in which people interact and shape society. Because humans are social animals, sociologists examine our social relationships with others scientifically. The range of the relationships they investigate is vast, as the current list of sections in the American Sociological Association suggests (Table 1-1).

TABLE 1-1 SECTIONS OF THE AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

| Aging and the Life Course | Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis | Peace, War, and Social Conflict |

| Alcohol, Drugs, and Tobacco | Evolution, Biology and Society | Political Economy of the World-System |

| Animals and Society | Family | Political Sociology |

| Asia and Asian America | History of Sociology | Population |

| Children and Youth | Human Rights | Race, Gender, and Class |

| Collective Behavior and Social Movements | International Migration | Racial and Ethnic Minorities |

| Communication and Information Technologies | Labor and Labor Movements | Rationality and Society |

| Community and Urban Sociology | Latino/a Sociology | Religion |

| Comparative and Historical Sociology | Law | Science, Knowledge, and Technology |

| Crime, Law, and Deviance | Marxist Sociology | Sex and Gender |

| Culture | Mathematical Sociology | Sexualities |

| Economic Sociology | Medical Sociology | Social Psychology |

| Education | Mental Health | Sociological Practice and Public Sociology |

| Emotions | Methodology | Teaching and Learning |

| Environment and Technology | Organizations, Occupations, and Work | Theory |

The range of sociological issues is very broad. For example, sociologists who belong to the Animals and Society section of the ASA may study the animal rights movement; those who belong to the Sexualities section may study global sex workers or the gay, bisexual, and transgendered movements. Economic sociologists may investigate globalization or consumerism, among many other topics.

Source: American Sociological Association 2009b.

Let’s consider how different social sciences would study the impact of Hurricane Katrina, which ravaged the Gulf Coast of the United States in 2005. Historians would compare the damage done by natural disasters in the 20th century to that caused by Katrina. Economists would conduct research on the economic impact of the damage, not just in the Southeast but throughout the nation and the world. Psychologists would study individual cases to assess the emotional stress of the traumatic event. And political scientists would study the stances taken by different elected officials, along with their implications for the government’s response to the disaster.

Think about It

Which of these topics do you think would interest you the most? Why?

What approach would sociologists take? They might look at Katrina’s impact on different communities, as well as on different social classes. Some sociologists have undertaken neighborhood and community studies, to determine how to maintain the integrity of storm-struck neighborhoods during the rebuilding phase. Researchers have focused in particular on Katrina’s impact on marginalized groups, from the inner-city poor in New Orleans to residents of rural American Indian reservations. The devastating social impact of the storm did not surprise sociologists, for the disaster area was among the poorest in the United States. In terms of family income, for example, New Orleans ranked 63rd (7th lowest) among the nation’s 70 largest cities. When the storm left tens of thousands of Gulf Coast families homeless and unemployed, most had no savings to fall back on—no way to pay for a hotel room or tide themselves over until the next paycheck (Laska 2005).

Sociologists would take a similar approach to studying episodes of extreme violence. In April 2007, just as college students were beginning to focus on the impending end of the semester, tragedy struck on the campus of Virginia Tech. In a two-hour shooting spree, a mentally disturbed senior armed with semi-automatic weapons killed a total of 32 students and faculty at Virginia’s largest university. Observers struggled to describe the events and place them in some social context. For sociologists in particular, the event raised numerous issues and topics for study, including the media’s role in describing the attacks, the presence of violence in our educational institutions, the gun control debate, the inadequacy of the nation’s mental health care system, and the stereotyping and stigmatization of people who suffer from mental illness.

Besides doing research, sociologists have a long history of advising government agencies on how to respond to disasters. Certainly the poverty of the Gulf Coast region complicated the huge challenge of evacuation in 2005. With Katrina bearing down on the Gulf Coast, thousands of poor inner-city residents had no automobiles or other available means of escaping the storm. Added to that difficulty was the high incidence of disability in the area. New Orleans ranked 2nd among the nation’s 70 largest cities in the proportion of people over age 65 who are disabled—56 percent. Moving wheelchair-bound residents to safety requires specially equipped vehicles, to say nothing of handicap-accessible accommodations in public shelters. Clearly, officials must consider these factors in developing evacuation plans (Bureau of the Census 2005f).

Sociological analysis of the disaster did not end when the floodwaters receded. Long before residents of New Orleans staged a massive anticrime rally at City Hall in 2007, researchers were analyzing resettlement patterns in the city. They noted that returning residents often faced bleak job prospects. Yet families who had stayed away for that reason often had trouble enrolling their children in schools unprepared for an influx of evacuees. Faced with a choice between the need to work and the need to return their children to school, some displaced families risked sending their older children home alone. Meanwhile, opportunists had arrived to victimize unsuspecting homeowners. And the city’s overtaxed judicial and criminal justice systems, which had been understaffed before Katrina struck, had been only partially restored. All these social factors led sociologists and others to anticipate the unparalleled rise in reported crime the city experienced in 2006 and 2007 (Jervis 2008; Kaufman 2006).

On August 29, 2005, shortly after Hurricane Katrina swept through the Gulf of Mexico, the U.S. Coast Guard took this aerial photograph of New Orleans. The widespread flooding shown in the photo grew worse as the week wore on, hampering the efforts of rescue teams. Sociologists want to know how the storm affected people from different communities and social classes, as well as how its impact varied with residents’ income, race, and gender.

Throughout this textbook, you will see how sociologists develop theories and conduct research to study and better understand societies. And you will be encouraged to use your own sociological imagination to examine the United States (and other societies) from the viewpoint of a respectful but questioning outsider.

Sociology focuses on the study of human behavior. Yet we all have experience with human behavior and at least some knowledge of it. All of us might well have theories about why people become homeless, for example. Our theories and opinions typically come from common sense—that is, from our experiences and conversations, from what we read, from what we see on television, and so forth.

In our daily lives, we rely on common sense to get us through many unfamiliar situations. However, this commonsense knowledge, while sometimes accurate, is not always reliable, because it rests on commonly held beliefs rather than on systematic analysis of facts. It was once considered common sense to accept that the earth was flat—a view rightly questioned by Pythagoras and Aristotle. Incorrect commonsense notions are not just a part of the distant past; they remain with us today.

Contrary to the common notion that women tend to be chatty compared to men, for instance, researchers have found little difference between the sexes in terms of their talkativeness. Over a five-year period they placed unobtrusive microphones on 396 college students in various fields, at campuses in Mexico as well as the United States. They found that both men and women spoke about 16,000 words per day (Mehl et al. 2007).

Similarly, common sense tells us that in the United States today, military marriages are more likely to end in separation or divorce than in the past due to the strain of long deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan. Yet a study released in 2007 shows no significant increase in the divorce rate among U.S. soldiers over the past decade. In fact, the rate of marital dissolution among members of the military is comparable to that of nonmilitary families. Interestingly, this is not the first study to disprove the widely held notion that military service strains the marital bond. Two generations earlier, during the Vietnam era, researchers came to the same conclusion (Call and Teachman 1991; Karney and Crown 2007).

Like other social scientists, sociologists do not accept something as a fact because “everyone knows it.” Instead, each piece of information must be tested and recorded, then analyzed in relation to other data. Sociologists rely on scientific studies in order to describe and understand a social environment. At times, the findings of sociologists may seem like common sense, because they deal with familiar facets of everyday life. The difference is that such findings have been tested by researchers. Common sense now tells us that the earth is round, but this particular commonsense notion is based on centuries of scientific work that began with the breakthroughs made by Pythagoras and Aristotle.