Star Wars: The New Jedi Order 08: Edge of Victory 01: Conquest – Read Now and Download Mobi

Comments

A Del Rey® Book

Published by The Random House Ballantine Publishing Group

Copyright © 2001 by Lucasfilm Ltd. & ™.

All Rights Reserved. Used Under Authorization.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by The Random House Ballantine Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Del Rey is a registered trademark and the Del Rey colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

www.starwars.com

www.starwarskids.com

www.delreydigital.com

Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 2001116216

eISBN: 978-0-307-79554-0

v3.1

For Charlie Sheffer

And all of my friends at Salle Auriol Seattle

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many thanks to Shelly Shapiro, Sue Rostoni, Jim Luceno, and Troy Denning for their help during the writing of the manuscript. To Mike Stackpole, for his advice and assurance this would be a fun ride, and Kris Boldis who gave that a strong second. Thanks to Chris Cerasi, Leland Chee, Ben Harper, Enrique Guerrero, and Lisa Collins for meticulous fact-checking and editing.

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Part Two: The Shamed and the Shapers

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Introduction to the Star Wars Expanded Universe

Excerpt from Star Wars: The New Jedi Order: Edge of Victory II: Rebirth

Introduction to the Old Republic Era

Introduction to the Rise of the Empire Era

Introduction to the Rebellion Era

Introduction to the New Republic Era

Introduction to the New Jedi Order Era

Introduction to the Legacy Era

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

Anakin Solo; Jedi Knight (male human)

Ikrit; Jedi Master (male unknown)

Imsatad; Peace Brigade captain (male human)

Jacen Solo; Jedi Knight (male human)

Jaina Solo; Jedi Knight (female human)

Kam Solusar; Jedi Master (male human)

Luke Skywalker; Jedi Master (male human)

Mara Jade Skywalker; Jedi Master (female human)

Mezhan Kwaad; master shaper (female Yuuzhan Vong)

Nen Yim; shaper adept (female Yuuzhan Vong)

Remis Vehn; Peace Brigade pilot (male human)

Sannah; Jedi student (female Melodie)

Shada D’ukal; Talon Karrde’s business associate (female human)

Tahiri Veila; Jedi student (female human)

Talon Karrde; Independent Information Broker (male human)

Tionne; Jedi Knight (female human)

Tsaak Vootuh; commander (male Yuuzhan Vong)

Tsavong Lah; warmaster (male Yuuzhan Vong)

Uunu; Shamed One (female Yuuzhan Vong)

Valin Horn; Jedi student (male human)

Vua Rapuung; warrior (male Yuuzhan Vong)

Yal Phaath; master shaper (male Yuuzhan Vong)

PROLOGUE

Dorsk 82 ducked behind the stone steps of the quay, just in time to dodge a blaster bolt from across the water.

“Hurry on board my ship,” he told his charges. “They’ve found us again.”

That was an understatement. Approaching along the tide embankment was a mob of around fifty Aqualish, jostling each other and shouting hoarsely. Most carried makeshift weapons—clubs, knives, rocks—but a few had force pikes and at least one had a blaster, as the smoking score on the quay testified.

“Join us, Master Dorsk,” The 3D-4 protocol droid close behind him pleaded.

Dorsk nodded his bald yellow-and-green mottled head. “Soon. I have to slow their progress across the causeway, to give everyone time to board.”

“You can’t hold them off yourself, sir.”

“I think I can. Besides, I need to try to talk to them. This is senseless.”

“They’ve gone mad,” the droid said. “They’re destroying droids all over the city!”

“They aren’t mad,” Dorsk averred. “They’re just frightened. The Yuuzhan Vong are on Ando, and may well conquer the planet.”

“But why destroy droids, Master Dorsk?”

“Because the Yuuzhan Vong hate machines,” the Khommite clone answered. “They consider them to be abominations.”

“How can that be? Why would they believe that?”

“I don’t know,” Dorsk replied. “But it is a fact. Go, please. Help the others board. My pilot is already at the controls with the flight instructions, so even if something happens to me, you’ll be okay.”

Still the droid hesitated. “Why are you helping us, sir?”

“Because I am a Jedi and I can. You don’t deserve destruction.”

“Neither do you, sir.”

“Thank you. I do not intend to be destroyed.”

He raised his head up again as the droid finally followed its clattering, whirring comrades to the waiting ship.

The crowd had reached the ancient stone causeway connecting the atoll-city of Imthitill to the abandoned fishing platform Dorsk now crouched on. It seemed they were all on foot, which meant all he had to do was prevent them from crossing the causeway.

With a single bound, Dorsk propelled his thin body up onto the causeway, forsaking the cover of the step down to the fishing platform. Lightsaber held at his side, he watched the mob approach.

I am a Jedi, he thought to himself. A Jedi knows no fear.

Almost surprisingly, he didn’t. His training with Master Skywalker had been fretted with attacks of panic. Dorsk was the eighty-second clone of the first Khommite to bear his name. He’d grown up on a world well satisfied with its own peculiar kind of perfection, and that hadn’t prepared him for danger, or fear, or even the unexpected. There were times when he believed he could never be as brave as the other Jedi students or live up to the standard set by his celebrated predecessor, Dorsk 81.

But watching the large, dark eyes of the crowd that was drawing close, he felt nothing but a gentle sadness that they had been driven to this. They must fear the Yuuzhan Vong terribly.

The destruction of droids had begun small, but in a few days had become a planetwide epidemic. The government of Ando—such as it was—neither condoned nor condemned the brutality, so long as no nondroids were killed or injured in the mess. Without help from the police, Dorsk 82 was the only chance the droids had, and he didn’t plan to fail them. He had already failed too many.

He ignited his lightsaber and for an instant saw everything around him at once. The setting sun had spilled a glorious slick of orange fire into the ocean and lit the high-piled clouds on the horizon into castles of flame. Higher, the sky faded to gold-laced jade and aquamarine and then the pale of night. The lights in the cylindrical white towers of Imthitill were winking on, one by one, and so, too, were the lights of the fishing platforms floating in the deeps, spangling the ocean with lonely constellations.

His own planet hadn’t any such untamed spectacles. Khomm’s weather was as predictable and homogenous as its people. Likely he, Dorsk 82, was the only person of his entire species who could appreciate this sky, or the iron-dressed waves of the sea.

Salt air buffeted around him. He lifted his chin. Somehow, after all of these years, he felt he was doing the thing he had dreamed about at last.

One of the Aqualish stepped before the rest. He was smaller than many, his tusks incised in the local style. He wore the dappled slicksuit of a tug worker.

“Move, Jedi,” he commanded. “These droids are none of your business.”

“These droids are under my protection,” Dorsk replied calmly.

“They are not yours to protect, Jedi,” the Aqualish shouted back. “If their owners do not object, you have no say in the matter.”

“I must disagree,” Dorsk replied. “I also plead with you to see reason. Destroying the droids will not appease the Yuuzhan Vong. They are beyond appeasing.”

“That’s our business,” the self-appointed spokesman of the group shouted. “This isn’t your planet, Jedi. It’s ours. Didn’t you hear? The Yuuzhan Vong just took Duro.”

“I had not heard,” Dorsk replied. “Nor does it matter. Go back to your homes in peace. I don’t want to hurt any of you. I’m taking these droids with me. You will not see them on Ando again. I swear it.”

This time he saw the blaster lift—held by an Aqualish deep in the crowd. Dorsk grasped it with the Force and whisked it through the air until it came to rest in his left hand.

“Please,” he said.

For a long moment, neither side moved. Dorsk felt them wavering, but the Aqualish were a stubborn and violent lot. It was easier to stop a nova once it had started than to calm a whole mob of Aqualish.

He heard a sudden hum and saw a security speeder approaching. He stepped back and allowed it to settle between him and the crowd. He did not relax his guard, even when eight Aqualish troopers in bright yellow body armor piled out and started motioning the crowd back.

The officer stepped forward. “What’s going on here?” he asked.

Dorsk motioned slightly with his head. “These people are intent on destroying a group of droids. I am protecting them.”

“I see,” the officer said. “That’s your ship?”

“Yes.”

“Are there any other Jedi on board?”

“No.”

“Very well.” The officer spoke into a small comlink, too low for Dorsk to hear, but the clone suddenly sensed what was about to happen.

“No!” he shouted. He spun on his heel and ran toward the ship, but even as he did so, several flares of light too bright to look upon struck it. A column of white flame leapt toward the sky, carrying with it the fragments and ions that had once been his ship, his pilot Hhen, and thirty-eight droids.

Dorsk was still watching, mouth working soundlessly at the pointless destruction, when the stun baton hit him.

He fell, turning that same uncomprehending stare on his attackers. The officer he’d been speaking to stood there, holding the baton.

“Stay down, Jedi, and you’ll live.”

“What? Why?…”

“I suppose you haven’t heard. The Yuuzhan Vong have proposed a peace. They will stop their conquest with Duro, and leave Ando, so long as we turn you Jedi over to them. They will take you dead, but they would rather have you alive.”

Dorsk 82 summoned the Force, washed away the pain and paralysis of the blast, and stood.

“Drop your lightsaber, Jedi,” the officer said.

Dorsk straightened himself and looked into the muzzles of the blasters. He dropped the one he had taken from the crowd. He hooked his lightsaber onto his belt.

“I will not fight you,” he said.

“Fine. Then you won’t mind surrendering your weapon.”

“The Yuuzhan Vong will not keep their word. Their only desire is that you rid them of their worst enemies for them. With the Jedi out of the way, they will come for you. If you betray me, you betray yourselves.”

“We’ll take that chance,” the officer said.

“I’m walking away from here,” Dorsk said with a slight wave of his hand. “You will not stop me.”

“No,” the officer said. “I won’t stop you.”

“Nor will any of the rest of you.”

Dorsk 82 started forward. One of the troopers, more strong willed than the others, lifted his blaster in a shaking hand.

“Don’t,” Dorsk pleaded. He held out his hand.

The blaster bolt grazed Dorsk in the palm, and he stepped back, but the action shook the other troopers from the suggestion he had placed in their minds. The next shot seared a hole through his thigh. He dropped to his knees.

“Stop,” the officer said. “No more mind tricks.”

Dorsk torturously pushed himself back to his feet. He took another step forward.

I am a Jedi. A Jedi knows no fear.

The dusk lit with blasterfire.

Help.

The automated signal was weak but faint.

“Got ’em,” Uldir said. “I told you, didn’t I?”

Dacholder, his copilot, clapped him on the back. “No doubt about it, lad. You’re the best rescue flier in the unit.”

“I have good hunches, that’s all,” Uldir replied. “See if you can contact them.”

“Sure thing.” Dacholder activated the comm unit. “Pride of Thela to injured vessel. Injured vessel, can you hear me?”

The answer was static—but modulated static.

“They’re trying to answer,” Uldir said. “Their comm unit must be damaged. Maybe when we get closer. Hey, there they are now.”

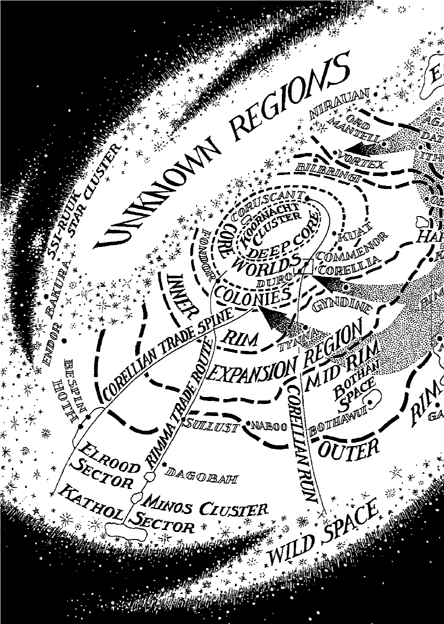

Long-range sensors showed a craft dead in space, medium transport–sized. It ought to be the Winning Hand, a pleasure craft that had made a jump from the Corellian sector and vanished somewhere en route. The Hand’s jump had taken her dangerously near Obroa-skai, which was now in Yuuzhan Vong space. Though they hadn’t moved overtly on any planets since the fall of Duro, the Yuuzhan Vong had been setting up occasional dovin basal interdictors near their space, yanking from hyperspace ships bold or careless enough to approach their somewhat fuzzy borders. Most were never found again, but the Winning Hand had managed to get off a garbled transmission placing them along the Perlemian Trade Route not far from the Meridian sector. That was still a lot of space, but search and rescue had been Uldir’s business for the past six years. At the ripe old age of twenty-two, he was one of the best fliers in the corps.

“Dead-on,” Dacholder said. “Congratulations. Again.”

“Thanks, Doc.”

Dacholder was a little older than Uldir, his hair prematurely shot with gray and receding from his forehead so fast Uldir could almost see it redshifting. He wasn’t a great pilot, but he was competent enough, and Uldir liked him.

“Say, Uldir,” Dacholder began, in an inquisitive tone, “I never asked you—when the Vong came along, why didn’t you request transfer to a military unit? The way you fly, you could be an ace.”

“Too hot for me,” Uldir replied.

“Carbon flush. Rescue is twice the danger with a tenth of the firepower. During the fall of Duro I heard you picked up three stranded pilots under fire from four coralskippers with no backup at all.”

“I was pretty lucky,” Uldir demurred.

“You sure it’s not something else?”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, I heard you attended that Jedi academy of Skywalker’s.”

Uldir could only laugh at that. “Attended isn’t the right word. I was there, caused a systemful of trouble in a real short time, and had no talent for the Jedi thing at all. Still, maybe you’re right. I guess I figured if I couldn’t be a Jedi, I could at least emulate ’em. Search and rescue seemed like the best way. And we’re needed in wartime just as much as the flyboys.”

“And you don’t have to kill.”

Uldir shrugged. “That sounds about right. When did you start thinking about me so much, Doc?” He flipped the magnification up on the visual. “Look there,” he said, as the derelict ship came on-screen. “She doesn’t look half bad. Maybe they didn’t have any casualties.”

“We can only hope,” Dacholder said.

“See anything else out there?”

“Not a thing,” Dacholder replied.

“That’s good. We’re outside of Yuuzhan Vong space, but not that far outside. Even with all the tinkering I’ve done on this baby, I don’t want to run up against one of their interdictors.”

“I noticed you coaxed another twenty percent from the inertial dampeners. Good work.”

“Shows what you can do when you’ve got no life but the service, I guess,” Uldir replied. He adjusted their trajectory a bit. “Looks like they’re limping, but life support seems to be okay.”

“Yeah.”

Uldir gave his copilot a sidewise glance. Doc seemed a little nervous, which was odd. Not that he had the steadiest nerves in the unit, but he was no coward. Maybe it was because they were out so far without backup. The war had forced everyone to spread resources thin.

“Uldir,” Dacholder asked suddenly.

“Uh-huh?”

“Do you think we can beat them? The Vong?”

“That’s a crazy question,” Uldir replied. “Of course we can. They just got a jump on us, that’s all. You’ll see. Once the military gets its act together and brings the Jedi into the equation, the Yuuzhan Vong will be on the run soon enough.”

Dacholder was silent for a moment, watching the ship grow larger.

“I don’t think we can beat them,” he said softly. “I don’t think we ought to be fighting them in the first place.”

“What do you mean?”

“Look, they’ve kicked our butts right from the start. If they make another push, they’ll have Coruscant before you can blink.”

“That’s pretty defeatist.”

“It’s pretty realistic.”

“Then what?” Uldir asked, a little heatedly. “You think we ought to surrender?”

“We don’t have to do that, either. Look, there aren’t that many Vong. They already have as many planets as they need, they’ve said so themselves. They haven’t made a move since Duro, and they won’t—”

The console got Uldir’s attention, so he didn’t hear the rest of what Dacholder was saying. “Hold that thought,” he snapped, “and hail that ship.”

“Why?”

“Because she’s playing dead, that’s why. All her systems just came on, and she’s trying for a tractor lock.” He quickly began evasive maneuvers.

“Let her have us, Uldir,” Dacholder said. “Don’t make me use this.”

To Uldir’s astonishment, this was a blaster his copilot had pointed at his head.

“Doc? What are you doing?”

“Sorry, lad. I like you, I really do. I hate doing this like drinking acid, but it has to be done.”

“What has to be done?”

“The Yuuzhan Vong warmaster was very specific. He wants all of the Jedi.”

“Doc, you fool, I’m not a Jedi.”

“There’s a list, Uldir, and you’re on it.”

“List? What list? Whose list? Not a Yuuzhan Vong list, because they couldn’t possibly know who went to the academy and who didn’t.”

“That’s right. Some of us are in high places.”

Uldir narrowed his eyes. “Us? You’re Peace Brigade, Doc?”

“Yes.”

“Of all the—” Uldir stopped. “And that ship. That’s what’s going to take me to the Yuuzhan Vong, isn’t it?”

“It wasn’t my idea, lad. I’m just following orders. Now, slow her down like a good boy, and let them have their lock.”

“I’m not a Jedi,” Uldir repeated.

“No? I always thought your hunches were a little too good. You seem to see things before they come.”

“Right. Like this, you mean?”

“Doesn’t matter anyway. What matters is they think you’re Jedi. And I’ll bet you know things they would be interested in.”

“Don’t do this, Doc, I’m begging you. You know what the Yuuzhan Vong do to their victims. How can you even think of making deals with them? They destroyed Ithor, for space’s sake!”

“The way I hear it, a Jedi named Corran Horn was responsible for that.”

“Bantha fodder.”

Dacholder sighed. “I’m giving you a three-count, Uldir.”

“Don’t, Doc.”

“One.”

“I won’t go with them.”

“Two.”

“Please.”

“Thr—”

He never got it out. By the time he got to the end of the word, Dacholder was in vacuum, twenty meters away and still accelerating. Uldir sealed the cockpit back up, ears popping and face tingling from his brief brush with nothingness. He glanced at the missing acceleration couch.

“I’m sorry, Doc,” he said. “You didn’t leave me much of a choice. I guess it’s just as well I never told you about all of my modifications.”

He opened the throttle, gaining quick ground on the yacht. By the time they overcame their inertia and started to gain, Uldir had punched into lightspeed and was gone.

To where, he didn’t know. If he survived the hyperspace jump, would he be safe?

And if he wasn’t safe, what about the real Jedi? His friends from the academy?

He couldn’t hide from this. Master Skywalker had to know what was happening. He could think about himself after that was done.

Swilja Fenn tried to stay on her feet. Such a basic thing, standing. One rarely gave it a thought. But the long pursuit on Cujicor, copious blood loss, and a foul, cramped incarceration on a Peace Brigade ship rendered even such basic things a struggle. She drew on the Force for her strength and lashed her lekku in helplessness.

The Peace Brigade goons had dumped her, bound and half senseless, on some nameless moon and hauled gravity out of there. Not much later, the Yuuzhan Vong had shown up. They had cut away her bonds and then replaced them with a living, jellylike substance, all the while spitting at her in a language that seemed made entirely of curses.

After that, more travel in dark places and finally here, barely able to keep her feet under her, in a vast chamber that looked as if it had been carved inside of a chunk of raw meat. Smelled that way, too.

Swilja squinted at someone approaching from the murk and shadows at the far end of the room.

“What do you lylek-dung-grubbers want with me?” she snarled, momentarily forgetting her Jedi training.

The lapse got her a cuff in the face hard enough to knock her off her feet.

When she rose, he was standing over her.

The Yuuzhan Vong liked to scar themselves. They liked cut-up faces and tattoos, severed fingers and toes. The higher up the food chain they were, it seemed the less there was of them. Or at least, what had started as them, because they liked implants, too.

The Yuuzhan Vong standing above her must have been way up the food chain, because he looked like he had fallen into a bin of vibroblades. Scales the color of dried blood covered most of his body, and some sort of cloak hung from his shoulders. The latter twitched, slowly.

And like the other Yuuzhan Vong, he wasn’t there. If he had been Twi’lek or human or Rodian, she might have stopped his heart with the Force or snapped his neck against the ceiling. Dark side or not, she would have done it and rid the galaxy of him forever.

She tried to do the next best thing—hurl herself at him and claw his eyes out. He was only a meter away; surely she could take just one of these gravel-maggots with her.

Unfortunately, the next best thing was exponentially less effective than the best. The same guard who had struck her a moment before lashed out faster than lightning, grabbing her by the lekku and yanking her back. He held her up to the monster confronting her.

“I know you,” Swilja said, spitting out teeth and blood. “You’re the one who called for our heads. Tsavong Lah.”

“I am Warmaster Tsavong Lah,” the monster confirmed.

She spat at him. The spittle struck his hand, but he ignored it, denying her even the minor victory of irritating him.

“I congratulate you on proving yourself worthy of honored sacrifice,” Tsavong Lah said. “You are far more admirable than the cowering scum who delivered you to us. They will merely perish, when their time comes. We will not mock the gods by offering them in sacrifice.” He suddenly showed more of the inside of his mouth than Swilja ever wanted to see. It might have been a grin or a sneer.

“If you know who I am,” Tsavong Lah said, “you know what I want. You know who I want.”

“I have no idea what you want. Given what I know of you it would probably make even a Hutt sick.”

Tsavong Lah licked his lip and twisted his neck slightly. His eyes drilled at her.

“Help me find Jacen Solo,” he said. “With your help, I will find him.”

“Eat poodoo.”

Tsavong Lah shredded a laugh through his teeth.

“It is not my job to convince you,” he said. “I have specialists for that. And if you still cannot be convinced, there are others, many others. One day you will all embrace the truth—or death.” With that he seemed to forget she existed. His eyes emptied of any sign that he saw her or had ever seen her, and he walked slowly away.

“You’re wrong!” she screamed, as they dragged her from the chamber. “The Force is stronger than you. The Jedi will be your end, Tsavong Lah!”

But the warmaster didn’t turn. His stride never broke.

An hour later, even Swilja didn’t believe her brave words. She didn’t even remember them. Nothing existed for her but pain, and eventually, not even that.

PART ONE

PRAXEUM

CHAPTER ONE

Luke Skywalker stood steady and straight before the gathered Jedi, his face composed and stronger than durasteel. The set of his shoulders, his precise gestures, the weight and timbre of each word he spoke all confirmed his confidence and control.

But Anakin Solo knew it was a lie. Anger and fear filled the chamber like a hundred atmospheres of pressure, and beneath that weight something in Master Skywalker crumpled. It felt like hope breaking. Anakin thought it was the worst thing he had ever felt, and he had felt some very bad things in his sixteen years.

The perception didn’t last long. Nothing was broken, only bent, and whatever it was straightened, and Master Skywalker was again as strong and confident in the Force as to the eye. Anakin didn’t think anyone else had noticed it.

But he had. The unshakable had shaken. It was something Anakin would never forget, another of the many things that had seemed eternal to him suddenly gone, another speeder zooming out from underneath his feet, leaving him flat on his back wondering what had happened. Hadn’t he learned yet?

He forced himself to focus his ice-blue eyes on Master Skywalker, on that familiar age- and scar-roughened face. Beyond him, through a huge transparisteel window, flowed the never-ending light and life of Coruscant. Against those cyclopean buildings and streaming trails of light, the Master seemed somehow frail or distracted.

Anakin distanced himself from his heartsickness by concentrating on his uncle’s words.

“Kyp,” Master Skywalker was saying, “I understand how you feel.”

Kyp Durron was more honest than Master Skywalker, in some ways. The anger in his heart was no stranger to the expression on his face. If the Jedi were a planet, Master Skywalker stood at one pole, radiating calm. Kyp Durron stood at the other, fists clenched in fury.

Somewhere near the equator the planet was starting to pull apart.

Kyp took a step forward, running his hand through dark hair shot with silver. “Master Skywalker,” he said, “I submit that you do not know how I feel. If you did, I would sense it in the Force. We all could. Instead, you hide your feelings from us.”

“I never said I felt as you do,” Luke said gently, “only that I understand.”

“Ah.” Kyp nodded, raising one finger and shaking it at Skywalker as if suddenly comprehending his point. “You mean you understand intellectually, but not with your heart! The Jedi you trained and inspired are hunted and killed throughout the galaxy, and you ‘understand’ it the way you might an equation? Your blood doesn’t burn to do something about it?”

“Of course I want to do something about it,” Luke said. “That’s why I’ve called this meeting. But anger is not the answer. Attack is not the answer, and retribution most certainly is not. We are Jedi. We defend, we support.”

“Defend who? Support what? Defend those beings you rescued from the atrocities of Palpatine? Support the New Republic and its good people? Shield the ones we have all shed blood for, time and again in the cause of peace and the greater good? These same cowardly beings who now defame us, deride us, and sacrifice us to their new Yuuzhan Vong masters? No one wants our help. They want us dead and forgotten. I say it’s time we defend ourselves. Jedi for the Jedi!”

Applause smacked around the chamber—not deafening, but not trivial either. Anakin had to admit, Kyp made a certain amount of sense. Who could the Jedi trust now? Only other Jedi, it seemed.

“What would you have us do, then, Kyp?” Luke asked mildly.

“I told you. Defend ourselves. Fight evil, in whatever guise it takes. And we don’t let the fight come to us, to catch us in our homes, asleep, with our children. We go out and find the enemy. Offense against evil is defense.”

“In other words, you would have us all emulate what you and your dozen have been doing.”

“I would have us emulate you, Master Skywalker—when you were battling the Empire.”

Luke sighed. “I was young, then,” he pointed out. “There was much I did not understand. Aggression is the way of the dark side.”

Kyp rubbed his jaw, then smiled briefly. “And who should know better, Master Skywalker, than one who did turn to the dark side.”

“Exactly,” Luke replied. “I fell, though I knew better. Like you, Kyp. We both, in our own way, thought we were wise enough and nimble enough to walk on the laser beam and not get burned. We were both wrong.”

“And yet we returned.”

“Barely. With much help and love.”

“Granted. But there were others. Kam Solusar, for instance, not to forget your own father—”

“What are you saying, Kyp? That it is easy to return from the dark side, and that justifies the risk?”

Kyp shrugged. “I’m saying the line between dark and light isn’t as sharp as you’re trying to make it, or exactly where you want to put it.” He steepled his fingers beneath his chin, then shook them with an air of contemplation. “Master Skywalker, if a man attacks me with a lightsaber, may I defend with my own blade, that he not take my head off? Is that too aggressive?”

“Of course you may.”

“And after I defend, may I press my attack? May I return the blow? If not, why are we Jedi taught lightsaber battle techniques? Why don’t we learn only how to defend, and back off until the enemy has us in a corner and our arms grow tired, until an attack finally slips through our guard? Master Skywalker, sometimes the only defense is an attack. You know this as well as anyone.”

“That’s true, Kyp. I do.”

“But you back down from the fight, Master Skywalker. You block and defend and never return the blow. Meanwhile the blades directed against you multiply. And you have begun to lose, Master Skywalker. One opportunity lost! And there lies Daeshara’cor, dead. Another slip in your defense, and Corran Horn is slandered as the destroyer of Ithor and driven to seclusion. Again an attack is neglected, and Wurth Skidder joins Daeshara’cor in death. And now a flurry of failures as a million blades swing at you, and there go Dorsk 82, and Seyyerin Itoklo, and Swilja Fenn, and who can count those we do not know of yet, or who will die tomorrow? When will you attack, Master Skywalker?”

“This is ridiculous!” a female voice exploded half a meter from Anakin’s ear. It was his sister, Jaina, her face gone red with internal heat. “Maybe you don’t hear all the news, running around playing hero with your squadron, Kyp. Maybe you’ve started feeling so self-important that you think your way is the only way. While you’ve been out there blazing your guns, Master Skywalker has been working quietly and hard to make sure things don’t fall apart.”

“Yes, and see how well that’s gone,” Kyp said. “Duro, for instance. How many Jedi were involved there? Five? Six? And yet not one of you—Master Skywalker included—smelled the rank treachery of the situation until it was too late. Why didn’t the Force guide you?” He paused and then smacked a fist into his palm for emphasis. “Because you were acting like nursemaids, not Jedi warriors! I’ve heard one of you even refused to use the Force.” He looked significantly at Jaina’s twin, who sat stone-faced halfway around the hall.

“You leave Jacen out of this,” Jaina snarled.

“At least your brother was honest in his refusal to use his power,” Kyp said. “Wrong, but honest, and in the end when he had to use it, he did. The rest of this group has no excuse for its ambivalence. If saving our galaxy from the Yuuzhan Vong is not a good enough cause to flex our true might, let self-preservation be!”

“Jedi for Jedi!” Octa Ramis shouted, still in the clutches of renewed grief over losing Daeshara’cor.

“It’s both ourselves and the galaxy I’m trying to preserve,” Luke said. “If we win the fight against the Yuuzhan Vong at the price of using dark-side powers, it will be no victory.”

Kyp rolled his eyes and crossed his arms. “I knew it was a mistake to come here,” he said. “Every second I waste talking with you is a torpedo I might be firing at the Yuuzhan Vong.”

“If you knew that, why did you come?”

“Because I thought even you must see the pattern on the Huj mat by now, Master Skywalker. After months of doing nothing, of watching our numbers dwindle, of listening to the lies circulating about the Jedi from the Rim to the Core, I thought now, at last, you had decided it was time to act. I came, Master Skywalker, to hear you say enough is enough, to lead the Jedi, united, in a just cause. Instead I hear only the same vacillating I’ve grown tired of.”

“On the contrary, Kyp. I called this meeting to make some real decisions about how we should face this crisis.”

“This isn’t a crisis,” Kyp sputtered. “It’s a massacre. And I already know what to do. I’ve been doing it.”

“The people are frightened, Kyp. They’re living in a nightmare, just as we are. They only want to wake up.”

“Yes. And in hopes of waking up, they feed the dream monsters whatever they ask for. Droids. Cities. Planets. Refugees. Now Jedi. By refusing to act against this treachery, Master Skywalker, you come dangerously near condoning it.”

“Bantha fodder!” Jacen snapped, finally breaking his silence. “Master Skywalker hasn’t been complacent. None of us has. But the sort of naked aggression you condone is—”

“Effective?” Kyp sneered.

“Is it?” Jacen challenged. “What have you and your squadron really accomplished? Harried a few Yuuzhan Vong supply ships? Meanwhile we’ve saved tens of thousands—”

“Saved them for what? So they can flee from planet to planet until there’s nowhere else to go? Jacen Solo, who denied the Force, are you lecturing me on what is and isn’t effective?”

“What isn’t effective is this argument,” Luke interjected. “We need calm. We need to think rationally.”

“I’m not sure that’s what we need at all,” Kyp shot back. “Look where your rational policies have gotten us. We’re alone, now, don’t you all see that? Everyone has turned against us.”

“You’re overstating.”

Anakin switched his gaze to the new speaker, Cilghal. The Mon Calamari’s fishlike head bobbed as her bulbous eyes searched around the chamber.

“We still have many allies,” Cilghal said, “in the senate and among the peoples of the New Republic.”

“If by allies you mean people without the guts to actually turn us in, yes,” Kyp said. “But wait a bit. More Jedi will be killed or captured. Stay here, meditate, and wait for them. I won’t. I know what the fight is and where it is.” With that he turned on his heel and started from the chamber.

“No!” Jaina whispered to Anakin. “If Kyp leaves, he’ll take too many with him.”

“So?” Anakin said. “Are you so sure he’s wrong?”

“Of course I—” She stopped, paused, started again. “It won’t help any of us if the Jedi split. We have to try to help Uncle Luke. Come on.”

Jaina followed Kyp from the chamber. After a second or two, Anakin followed. The debate began again behind them, in much more muted terms.

Kyp turned as they approached. “Anakin, Jaina. What do you want?”

“To talk some sense into you,” Jaina said.

“I have plenty of sense,” Kyp said. “You two ought to know better. When did either of you flinch from battle? It’s not like you two to sit while others fight.”

“I haven’t been,” Jaina flared. “Neither has Anakin, or Uncle Luke, or—”

“Spare me. Jaina, I have the greatest respect for Master Skywalker. But he is wrong. I can’t see the Yuuzhan Vong in the Force any more than he can, but I don’t need that to know they’re evil. To know they have to be stopped.”

“Couldn’t you just hear Uncle Luke out?”

“I did. He didn’t say anything I was interested in, and he wasn’t going to.” Kyp shook his head. “Your uncle has changed. Something happens to Jedi Masters as they grow older in the Force. Something that isn’t going to happen to me. They become so concerned with light and dark they can’t act, but can only be acted upon. Like Obi-Wan Kenobi—rather than act himself, he allowed himself to be struck down, become one with the Force, so Luke could then take all of the moral risks.”

“That’s not how Uncle Luke tells it.”

“Your uncle is too close to it. And now he’s become Kenobi.”

“What are you saying, exactly?” Jaina said. “That Uncle Luke is a coward?”

Kyp shrugged and flashed a little smile. “When it comes to his life, no. But when it comes to the Force …” He gestured with the back of his hand. “Ask your brother Jacen—seems to me he’s going gray early, in that respect. The whole galaxy is falling apart around him, and he’s dithering over theoretical philosophy.”

“He did use the Force, though, as you pointed out,” Jaina retorted.

“To save his mother’s life, from what I heard, and almost not then. How long was she in a bacta tank?”

“But he did save her, and me, too.”

“Of course. But would he have called on the Force to save some Duros he didn’t know? Given the fact that he had ample opportunity to do so before that, the answer is self-evidently no. So it wasn’t some universal respect for preserving life or anything of that sort that led him to break his self-imposed ban, was it?”

“No,” Anakin murmured.

“Anakin!” Jaina snapped.

“It’s true,” Anakin replied. “I’m glad he did it, and I’m glad he hurt the warmaster, even if he did call for the heads of all the Jedi, but Kyp’s right. If you and Mom hadn’t been there …”

“Jacen was going through a hard time,” Jaina said.

“Like the rest of us aren’t,” Anakin returned.

“I’ve got to go,” Kyp told them. “Any time either of you wants to fly with me, find me. Other than that, I sincerely hope Master Skywalker comes around. I just can’t wait for it. May the Force be with you.”

They watched him go.

“I wish I didn’t more than half think he was right,” Jaina whispered. “I feel like I’m somehow betraying Uncle Luke.”

Anakin nodded. “I know what you mean. But Kyp is right, about one thing anyway. Whatever else we do, we’re going to have to look out for our own.”

“Jedi for Jedi?” Jaina snorted. “Uncle Luke knows that. I’m not sure where he sent Mom, Dad, Threepio, and Artoo, but it’s got something to do with setting up a network to help Jedi escape before being turned over to the Yuuzhan Vong.”

Anakin shook his head. “Fine, but that’s what Kyp meant by only defending. We’ll never win this war by being reactive. We have to be proactive. We need intelligence. We need to know which Jedi are at risk before they come for us.”

“How can we know that?”

“Think logically. Any planet already taken by the Yuuzhan Vong is obviously dangerous. The planets near occupied space are the next most dangerous, because they’re desperate to strike a deal.”

“The warmaster said he would spare the rest of the galaxy, but only if they turn all of us over to them. That sort of spreads the desperation out, at least for people dumb enough to believe him. We saw what Yuuzhan Vong promises meant on Duro. Don’t cooperate with them and they mow you down. If you do cooperate with them, they mow you down, laughing about how stupid you’ve been.”

Anakin shrugged. “Obviously a lot of people would rather believe Yuuzhan Vong lies than take their chances. The point is—”

“The point is, what are you two doing out here rather than in the meeting?” Jacen Solo asked from the end of the corridor.

“We were trying to talk Kyp into staying,” Anakin told his older brother.

“It’d be easier talking a siringana into a box.”

“True,” Jaina said, “but we had to try. I guess we ought to go back in now.”

“Don’t bother. A few minutes after Kyp walked out, Uncle Luke called a recess. Too much angst and confusion.”

“It’s not going well,” Jaina said.

“No. Too many people think Kyp is right.”

“What do you think?” Anakin asked.

“He’s wrong,” Jacen said without hesitation. “Answering naked aggression with naked aggression can’t be the solution.”

“No? If you hadn’t used that particular solution, you, Mom, and Jaina would be dead right now. Would the universe be better off?”

“Anakin, I’m not proud of—” Jacen began.

Jaina cut him off. “Don’t you two start again. Anakin and I were talking about something constructive when you joined us. Let’s not degenerate into bickering, like the others. We’re siblings, after all. If we can’t talk through this without losing it, how can we expect anyone else to?”

Jacen held his gaze on Anakin for another few heartbeats, waiting to see who would flinch first.

It was Jacen.

“What were you discussing?” he asked softly.

Jaina looked relieved. “How to figure out where the worst hot spots are, which Jedi are in the most immediate danger,” she said.

Jacen quirked his mouth as if tasting a Hutt appetizer. “With the Peace Brigade out there, that’s an open question. They aren’t tied to the interests of a single system. They’ll hunt us from the Rim to the Core if they think it’ll appease the Yuuzhan Vong.”

“The Peace Brigade can’t be everywhere at once. They can’t follow every rumor they’ve heard about Jedi.”

“The Peace Brigade has plenty of allies, and good intelligence,” Jacen countered. “Given what they’ve managed already, they must have more than a few insiders, maybe even in the senate. They don’t have to chase rumors. More often than not, from what I can tell, they don’t even make half the captures they boast about. They’re just the flesh merchants who turn Jedi over to the Yuuzhan Vong.”

“I still have a bad feeling about the senator from Kuat, Viqi Shesh,” Jaina muttered.

“My point is this,” Anakin said. “It’s hard to predict which single Jedi might be next on their list. But if they could get a package deal, wouldn’t they jump at it?”

Jaina’s eyes widened. “You think they’ll move against us while we’re gathered here?”

Anakin drew a negative arc with his chin. “Things aren’t that bad yet, and who would want to face all of the most powerful Jedi in the galaxy at once? That would be crazy—us they’ll pick off one at a time. But—”

“The praxeum!” Jacen interrupted.

“Yes,” Anakin agreed. “The Jedi academy!”

“But they’re just kids!” Jaina said.

“Have you noticed that makes any difference to the Yuuzhan Vong, or to the Peace Brigade, for that matter?” Jacen asked. “Besides, Anakin’s only sixteen, and he’s killed more Yuuzhan Vong in hand-to-hand combat than any of us. The Yuuzhan Vong know that.”

“What about the illusion the Jedi have been maintaining around Yavin Four? That’s been keeping strangers away.”

“Not since almost all of the Jedi Knights have left,” Anakin said. “They’ve either come to Coruscant to this meeting, or gone off to try to help comrades who’ve disappeared. Last I heard, only the students Kam and Tionne are left, with maybe Streen, and Master Ikrit. They might not be strong enough. Where did Uncle Luke go? We should talk to him about this, right away. It may already be too late.”

“That’s a good call, Anakin,” Jacen admitted.

“Thanks.”

What Anakin didn’t mention to his siblings was how he had awakened in the night, heart thrumming, gripped by a nameless dread. And though he couldn’t remember the dream that had torn him from sleep, one image had remained with him: the blond hair and green eyes of Tahiri, his best friend.

And Tahiri was at the academy.

CHAPTER TWO

Luke Skywalker sank into a chair in his study, ran his hand across his brow, and stared out at the night, or what passed for it on Coruscant, the hundred shades of nightglow, shimmering lanes of aircars and transports, bright-studded skyhook tethers lancing toward the unseeable stars. How many thousands of years had passed since anyone had seen a star in the night sky of this city world?

On Tatooine the stars had been hard, glittering promises to a boy who wanted more from life than to be a moisture farmer. They had been everything, and yearning toward them was the seed of everything Luke had become. Now, at the heart of the galaxy he had fought so long to save, he couldn’t even see them.

Something drifted in the Force, an embrace waiting to happen. Waiting for permission to happen.

“Come in, Mara,” he said, rising.

“Stay there,” his wife answered. “I’ll join you.”

She settled into the chair next to him and took his hand. He felt her touch move closer, and found himself flinching away.

“Hey, Skywalker,” she said. “It’s not like I’m here to kill you.”

“That’s a comforting thing to say.”

“Yeah?” Her voice took on an edge. “Don’t think it hasn’t occurred to me. Like when I couldn’t hold down breakfast, or when I take one of these twenty-minute lightspeed tours of every emotion I’ve ever had plus a few that I never knew really existed—and then start over. When my ankles start ballooning up like a Gamorrean boar’s and I’m well on my way to Hutthood, I’d advise any responsible parties to start watching their backs.”

“Hey, wait a minute. I don’t recall the two of us conspiring in this matter. I was just as surprised as you. Besides, your last plan to kill me started this whole thing, pregnancy included. Keep it up, and we’ll be ahead of Han and Leia in no time.”

Mara clucked. “Darling,” she said in disingenuous tones. “I love you, you are my life and my light. If you ever do this to me again, I will vape you where you stand.” She squeezed his hand fondly.

“As I was saying,” Luke said. “How can I please you, sweetheart?”

“Tell me what’s wrong.”

He shrugged and turned his face back to the cityscape. “The Jedi, of course. We’re breaking apart. First the galaxy turns against us, then we turn against each other.”

“It’s too bad I didn’t take care of Kyp years ago,” Mara said.

“Don’t even joke about that. And it isn’t Kyp’s fault—ultimately it’s mine. You explained as much to me once, remember?”

“I remember setting you straight about a few things. That doesn’t make Kyp right now.”

“No, he isn’t right. But when children stray, doesn’t that say something about the parents?”

“This is a fine time to tell me you’re going to be a lousy father. Or maybe you don’t think I’ll be a good mother?”

She was joking, but he felt a sudden wave of fear, depression, and anger from his wife.

“Mara?” he asked. “It was just a metaphor.”

“I know. It’s nothing. Just go on.”

“It’s not nothing.”

“It is nothing. Hormones. Mood swings. Very annoying, being jerked around by chemicals, and not your problem, Skywalker. Go on with what you were saying. Sans the parenthood metaphor.”

“Fine. What I mean is, my teachings weren’t durable enough, or strong enough, or satisfying enough, if the others look to Kyp for their answers.”

“We’ve been betrayed and we’re being slaughtered,” Mara said. “Kyp’s given them an answer to that. You haven’t.”

“Wait. Now you agree with Kyp?”

“I agree we can’t just sit and wait. I know you don’t want to do that either, but you aren’t expressing it well enough. Kyp has given the Jedi a vision, as clear and simple as it is wrong. All we’ve done is give a muddy jumble of assurances and prohibitions. We need to tell them what to do, not what not to do.”

“We?”

“Of course we, Skywalker. You and me. Where you go I go.”

Her Force presence kissed lightly against his again, and for an instant he trembled. It felt good, a warmth against the cold hard nest of his doubts and pain. How could he afford to doubt? How could he let anyone else see it, when it might mean the end of everything?

The touch eased, as if retreating, and he relaxed, and it came again, stealthier and stronger. He gave up, opening himself to her so they mingled in a bright stream. He took her in his arms and let her stroke away the worst of his doubts with her hand and the radiance within her.

“I love you, Mara,” he breathed, after a time.

“I love you, too,” she replied.

“It’s hard to watch it all fall apart.”

“It’s not falling apart, Luke. You have to believe that.”

“I have to be strong for them. I have to be an example. But today—”

“Yes, I saw it. You had a moment of weakness. I think I’m the only one who noticed.”

“No. Anakin noticed. It upset him, a lot.”

“You’re worried about Anakin?” she asked, picking up on the subtext of his spoken word. “He adores you. If there is someone he’s always wanted to be, it’s you. He wouldn’t side with Kyp.”

“That’s not my worry. He’s more like Kyp than he thinks, but he doesn’t see it. He’s been through so much, Mara, and he’s too young to easily absorb what he’s had to deal with. He still carries the blame for Chewbacca’s death with him, and in the back of his mind part of him still thinks Han blames him, too. He watched Daeshara’cor die. He blames himself for the destruction of the Hapan fleet at Fondor. He’s carrying around all that pain, and some day that’s bound to add up to something he’s not experienced enough to handle. Grief and guilt are only a micron away from anger and hatred. And he’s still reckless, still thinks he’s immortal despite all of the death he’s seen.”

“That’s what upset him about your weakness today,” Mara guessed. “He thinks you’re immortal, too.”

“He did believe that. But now he knows if he can lose Chewie, he can lose anyone. That’s not making things better. He’s losing faith in everything he’s counted on his whole life.”

“I didn’t have exactly a normal childhood,” Mara said, “but doesn’t that happen to most children at a certain point?”

“Yes. But most children aren’t Jedi adepts. Most children aren’t as strong in the Force as Anakin, or as inclined to use it. Did you know when he was a boy, he once killed a giant snake by stopping its heart with the Force?”

Mara blinked. “No.”

“Yes. He was defending himself and his friends. It probably seemed like the only thing to do at the time.”

“Anakin is a pragmatic lad.”

“That’s the problem,” Luke sighed. “He grew up around Jedi. Using the Force is like breathing for him, and for Anakin there is nothing very mystical about it. It’s a tool he can do things with.”

“Jacen on the other hand—”

“Jacen is older, but he grew up like Anakin. It’s two different reactions to the same situation. What they have in common is that neither of them thinks I really have it right. And what’s worse, I think at least one of them is correct. I’ve seen—” He broke off.

“What?” Mara gently urged.

“I don’t know. I’ve seen a future. Several futures. However this ends with the Yuuzhan Vong, it won’t be me that ends it, or Kyp, or any of the older Jedi. It will be someone new.”

“Anakin?”

“I don’t know. I’m afraid to even talk about it. Every word spreads, puts ripples in the Force for every person who hears it, changes things. I’m starting to know how Yoda and Ben felt. Watching, trying to guide, hoping I’m not wrong, that I’m seeing clearly, that there is such a thing as wisdom and that I’m not just fooling myself.”

She laughed softly and kissed his cheek. “You worry too much.”

“Sometimes I don’t think I worry enough.”

“Worry?” Mara said softly. She took his hand and placed it against her belly. “You want worry? Listen.”

Once more she enfolded him in the Force, and once more they merged toward one another and the third life in the room, the one growing inside of Mara. Tentatively, hesitantly, Luke reached in to touch his son.

The heart was beating, a simple beautiful rhythm, and around it drifted something like a melody, an awareness both alien and familiar, sensations like taste and smell and sight but not like them at all, a universe with no light but with all of the warmth and security in the world.

“Amazing,” he murmured. “That you can give him that. That you can be that for him.”

“It’s humbling,” she said. “It’s worrisome. What if I make a mistake? What if my sickness comes back? And worst of all—” She paused, and he waited, knowing she would get to it in time. “It’s easy, in a way. To protect him now, all I have to do is protect myself, and I’ve been doing that my whole life. Right now, my life is his life. But after he’s born, it will never be like that again. That’s the part that worries me.”

Luke wrapped his arm around her and hugged. “You’ll do fine,” he said. “I promise you.”

“You can’t promise that, any more than you can hold the young Jedi inside of you or keep them safe. It’s the same. It’s the same fear, Luke.”

“Of course,” he replied. “Of course it is.”

They sat and watched the skies of Coruscant, and spoke no more until someone came to their door.

“Speak and they will come,” Luke murmured. “It’s the Solo children.”

“I can send them away.”

“No. They need to talk to me.” He raised his voice. “Come on in.”

He stood and brightened the lights. Anakin, Jaina, and Jacen entered.

“Sorry we left the meeting,” Jaina said.

“I knew what you were doing, and I thank you for trying. Kyp—Kyp must walk his own path for a while. But that’s not why you came, is it?”

“No,” Jacen said. “We’re worried about the Jedi academy.”

“Right,” Anakin joined in. “It occurred to me that if I were Peace Brigade, and wanted to catch a bunch of Jedi all at once—”

“You’d go to Yavin Four. Good thinking.”

Anakin’s face fell visibly. “You already thought of it.”

Luke nodded. “Don’t feel bad. It was only a few days ago that we had enough reports to spot the trend and realize just how seriously the warmaster’s promise has been taken. Trying to deal with all the local fires, trying to find government support to put a stop to this or at least slow it down, I didn’t realize that there are no longer enough mature Jedi in the system to maintain the illusion we were projecting.”

“So what do we do?” Jacen asked.

“I requested the New Republic send a ship to evacuate them, but they’re dragging their heels. They might continue to for weeks.”

“We can’t wait that long!” Jaina said.

“No,” Luke agreed. “I’ve been trying to find Booster Terrik. I think the best thing for the moment would be to not only evacuate the academy but keep the kids on the move, in the Errant Venture. If we just move them to another planet, we don’t really solve the problem.”

“So they’re with Booster?” Anakin said.

“I can’t locate him, unfortunately. I’m still working on it.”

“Talon Karrde,” Mara said softly.

“Perfect,” Luke said. “You know where to find him?”

“What do you think?” Mara said, smirking.

“But what if the Peace Brigade is already at Yavin Four, or on the way?” Anakin asked.

“It’s the best we can do, for the moment,” Luke told him. “Besides, the danger is still hypothetical. The Peace Brigade might not even know about Yavin Four. And even if they did, Kam and Tionne and Master Ikrit are there. They aren’t exactly defenseless.”

“It’s not the best-kept secret in the galaxy,” Jacen said. “And with the illusion gone, what could Kam do against a warship? Let us go.”

“Out of the question,” Luke replied. “I need you all here, and with the bounty on our heads—especially your head, Jacen—it’s too dangerous for you to go off alone. Your parents would never forgive me if I sent you into that with them away.”

“Ask them, then,” Jaina said.

“I can’t. They’re out of contact now, and could be for some time.”

“Shouldn’t we at least go check on the praxeum?” Jaina persisted. “We could just hide at the edge of the system until Karrde shows up, keep an eye on things, run back here to report if things go wrong.”

Luke shook his head. “I know you’re all restless, especially you, Jaina. But your eyes still haven’t fully healed—”

“Not to Rogue Squadron specs, maybe,” Jaina protested, “but I can see well enough to fly.”

“Even if your vision were fully restored,” Luke went on, “I still don’t think sending any or all of you to Yavin Four is the most productive course. There’s important work to do here. Weren’t you just telling Kyp that, Jaina, Jacen?”

“Yes, Uncle Luke,” Jacen said. “We were.”

“Anakin? You haven’t said much.”

Anakin shrugged. “There isn’t much to say, is there?”

Luke detected something a bit dangerous in that, but it quickly passed.

“I’m glad the three of you are thinking about the situation. We agree that the academy is one of our most vulnerable spots. Help me find the rest. Don’t think for a second I’ve thought of everything, because obviously I haven’t. And don’t forget, we’ll reconvene the meeting tomorrow morning.”

The three of them nodded and left.

When they were gone, Mara clucked. “They might be right.”

Luke sighed again. “They might be. But I have a feeling that whoever goes to Yavin Four must go in force, or they won’t be leaving it again. I’ve learned to trust feelings like this.”

“You should have told them that, then,” Mara said.

He flashed her a sardonic smile. “Then they would have gone for sure.”

Mara took his hand. “No rest for the weary. I’ll contact Karrde.” She touched her belly again. “Meanwhile, Skywalker, find me something to eat. Something big and still bleeding.”

Anakin checked over the systems indicators.

“How do we look, Fiver?” he asked quietly, studying the cockpit readout display.

SYSTEMS WITHIN OPTIMUM VARIANTS, the R7 unit assured him.

“Good. Just hang on while I get clearance. Meanwhile calculate the first jump in the series to get me to the Yavin system.”

That took a certain amount of finagling, including forging a code that would allow him to fly without a check that might alert Uncle Luke or anyone else who would try to stop him.

Because Uncle Luke was wrong, this time. Anakin could feel it in his very center. The Jedi trainees were in grave danger; Talon Karrde would not get there in time. It might already be too late.

It was strange that Uncle Luke still insisted on thinking of Anakin as a child. Anakin had killed Yuuzhan Vong. He had seen friends die and caused the deaths of others. He was responsible for the destruction of countless ships and the beings who crewed them, and that only scratched the most recent skin of the matter.

It was a blind spot the adults in his life had, an ambivalence and a denial. They didn’t understand who he really was, only what he appeared to be. Even his mother and Uncle Luke, who had the Force to help them.

Aunt Mara probably understood—she had never really been a child, either—but even she was blinkered by her relationship with Uncle Luke; she had to take his feelings into account, as well as her own.

Well, there would be anger. He could explain to Uncle Luke about the feeling he had in the Force, but that might only alert the Master to Anakin’s certainty in this matter. Even if Uncle Luke could be convinced to send someone now, it might be someone else, someone older. But Anakin knew it had to be him, he had to go. If he didn’t, his best friend was doomed to a fate much worse than death.

It was the only thing in his life he was really sure of right now.

“Cleared for takeoff,” the port control said.

“Power it up, Fiver,” Anakin murmured. “We’ve got someplace to be.”

CHAPTER THREE

When the stars rushed back into existence, Anakin put his XJ X-wing into a lazy tumble and cut power to everything but sensors and minimal life support. Ordinarily he wouldn’t play it so cautious; after all, someone would almost have to be watching for the hyperwave ripples of an X-wing entering the system to have any chance of detecting it. But given the feeling in his gut, there might just be someone doing that.

The roll and yaw he’d put the X-wing in wasn’t random, but was designed to give his instruments a full accounting of the surrounding space in the least possible time. While the sensors did their job, Anakin reached out with the sense he trusted most—the Force.

The planet Yavin filled most of his view, its vast orange oceans of gas boiling into fractal, elusive patterns. Its familiar face had marked the days and nights of much of his childhood. The praxeum—his uncle Luke’s Jedi academy—was located on Yavin 4, a moon of the gas giant. He could remember watching Yavin in the night sky, a colossal mirage of a planet, wondering what could be there, pushing his evolving Force senses to explore it.

He’d found clouds of methane and ammonia deeper than oceans, hydrogen so stressed by pressure it became metal, life crushed thinner than paper but still thriving, cyclones heavier than lead but faster than the winds of any world habitable by humans. And crystals, sparkling Corusca gems climbing those titan winds, spinning in an ancient dance, capturing what light they could find in the thinner upper atmosphere and gripping it tight in their molecules.

He saw none of this as one might with eyes, of course, but over the nights, through the Force he had felt them, and with references to the library gradually understood them.

In his imagination he had seen more. Pieces of the first Death Star, which had met its end in these very skies, pounded into monomolecular foil by fierce pressure and gravity. Older things, relics of Sith, and species even more lost and distant in time. Once a planet like Yavin swallowed a secret, it wasn’t likely to give it up again. Given the other secrets that had turned up in the Yavin system—and the Sun Crusher Kyp Durron himself had once managed to pull from the belly of the orange giant—that was for the best.

Just beyond the vast rim of Yavin, a bright yellowish star winked—Yavin 8, one of the three moons in the system blessed with life. Anakin had a friend there, a native of that world who had trained briefly at the academy and returned home. He could feel her, very faintly. Yavin 4 was just around the rim, where he had other friends. In a way, the whole system was like a familiar room to Anakin, the sort he could walk into and immediately know if something was out of place.

And something felt very out of place.

In the Force he could feel the Jedi candidates, for they were all strong with it. He could feel Kam Solusar and his wife Tionne, and the ancient Ikrit, not students but full-fledged Jedi. These were seen as through a cloud, suggesting they were at least trying to maintain the illusion that hid Yavin 4 from the casual eye.

But even through that, one presence shone brilliant, made brighter by familiarity and friendship. Tahiri.

She felt him, too, and though he could not quite hear any actual words she might be trying to send, he did feel a sort of rhythm, as of someone talking quickly, excitedly, without pause for breath.

One corner of Anakin’s mouth turned up. Yes, that was Tahiri, all right.

What felt wrong was a little nearer and much weaker. Not Yuuzhan Vong, for they could not be felt in the Force, but someone who shouldn’t be there. Someone slightly confused, but with a growing sense of confidence.

“Hang on, Fiver,” he told his astromech. “Get ready to run or fight in a hurry. It might just be Talon Karrde and his crew here ahead of schedule, but I’d sooner bet against Lando Calrissian in sabacc than to count on it.”

AFFIRMATIVE, the display blinked.

They tumbled into sensor range, and his computer built a silhouette from the magnified image.

“That’s not so bad,” he murmured. “One Corellian light transport. Maybe it is one of Karrde’s bunch.” Or maybe not. And maybe there were a hundred Yuuzhan Vong ships on the other side of the gas giant or Yavin 4, invisible to his Jedi senses and hidden from his sensors. Whatever the case, waiting around wasn’t going to improve matters. He powered up, corrected his tumble, and engaged the ion engines.

He activated his comm system and hailed the stranger. “Transport, acknowledge.”

For a few moments, he got nothing, then the audio crackled. “Who is this?”

“My name is Anakin Solo. What are you doing in the Yavin system?”

“We’re Corusca gem miners.”

“Really. Where’s your trawler?”

Another pause, then words underlined with a bit of anger.

“We can see the moon now. We knew it was here all along. Your Jedi sorcery has failed you.”

THE TRANSPORT IS ARMING WEAPONS SYSTEMS, Fiver noticed. Anakin nodded grimly as the other vessel swung toward him.

“I’m only warning you once,” Anakin said. “Stand down.”

For an answer, he got a blast from a laser cannon, which at that distance he managed to avoid as easily as he might deflect a blaster shot with his lightsaber.

“Gee,” Anakin muttered. “I suppose that says it all.” He opened his S-foils. “Fiver, give me evasive approach six, but I still want the stick just in case.”

ACKNOWLEDGED.

He dropped toward Yavin 4 and the transport at full thrust, spinning and dancing as he went, and when he felt his target firmly enough in the Force, he sliced the night of vacuum with ruby red. The transport returned fire and began its own evasive maneuvers, but that was like a bantha trying to dodge a mace fly.

They had good shields, though. As Anakin completed his first pass, his opponent was still essentially untouched. To make matters more interesting, four winks of blue flame and his instruments agreed that the transport had just fired proton torpedoes at him. Anakin had been preparing to turn for another pass; instead he continued his noseward plunge toward the moon.

“Four proton torpedoes. These guys really don’t like us, Fiver.”

THE TRANSPORT SEEMS HOSTILE, Fiver acknowledged. Anakin sighed. Fiver was a more advanced astromech than R2-D2, but he missed his uncle’s droid’s personality at times. Maybe he ought to do something about that.

Two laser blasts hit his shields in quick succession, but they did their job. On his tracker, the proton torpedoes continued to close as Anakin met resistance from the atmosphere. He plunged on, and the ship began to vibrate faintly. His nose and wings were starting to heat up from the upper atmosphere. If he didn’t time this exactly right, he would scatter all over the jungle kilometers below.

When the lead torp was almost on him, he cut his engines and yanked the nose up. The atmosphere, still thin, was nevertheless able to give the XJ X-wing a good strong slap, hurling him away from the moon. Servos whined and something somewhere made a startling ping. Using the momentum from the atmospheric skip, Anakin turned further spaceward, blood rushing from his head as the g’s mounted, then he kicked in the engines again.

Behind him, the proton torpedoes didn’t fare as well. They tried to turn after him, of course. Two didn’t make it, and continued plunging moonward. The other two skipped along wildly different courses than Anakin and would never find him again before running out of fuel.

“Nice try,” Anakin said grimly. Now he was climbing uphill, out of the gravity well, his lasers pumping a steady rhythm. He took another hit from the enemy’s more powerful gun, and for an instant the lights dimmed in the cockpit. Then they flared back to life as Fiver rerouted, and Anakin took a hammer to the transport. Their shields faltered, and he slagged their primary generator. Looping around them nose to tail, he drilled laser turrets, torpedo ports, and engines.

Then he tried the comm again. “Ready to talk now?” he asked.

“Why not?” the voice from the other end replied. “You can still surrender if you want.”

“That’s—” Anakin began, but Fiver interrupted.

HYPERSPACE JUMP DETECTED. 12 VESSELS HAVE ARRIVED, DISTANCE 100,000 KILOMETERS.

“Sith spit!” Anakin muttered, bringing his sensors to bear.

They weren’t Yuuzhan Vong ships, he saw that immediately, just a motley collection of E-wings, transports, and corvettes.

They were hailing him. He opened the link.

“Unidentified vessel, this is the Peace Brigade,” a voice crackled. “Stand down and surrender, and you won’t be harmed.”

They were too far away to hit him. Soon they wouldn’t be. Anakin closed his S-foils, rolled, opened the throttle, and raced toward the distant viridian of Yavin 4.

Anakin vaulted from the cockpit of the X-wing into silent near darkness. A twilight line of illumination in the distance was the entrance he had flown through into what had once been a part of an ancient Massassi temple complex, much later the central hangar for the Rebel fleet, and which now saw little use at all, since most ships landing at the academy set down outside.

Anakin’s flight boots scuffed the ancient stone surface, and the sound grew around him into the hushed beating of enormous wings. He smelled stone and lubricant and more faintly the musky jungle outside.

Someone was watching Anakin from the darkness.

“Who is that?” a voice asked, each word stretching to fill the abyss.

“It’s me, Kam. Anakin.”

A faint glow appeared, and then a bank of light panels came on. Some ten meters away Kam Solusar stood, hooking his lightsaber back into his belt.

“I thought it felt like you,” Kam said. “But there’s been an unknown ship in orbit for several standard days now. We’ve been trying to keep them confused.”

“Peace Brigade,” Anakin explained. “And the one ship has friends now, about twelve of them. And they aren’t confused anymore.”

He’d been walking toward Kam while he spoke, and suddenly his old teacher swept forward, clasping his arm. “It’s good to see you, Anakin. And you? You’re alone?”

Anakin nodded. “Talon Karrde is on the way with a flotilla. He’s supposed to evacuate you and the students. Uncle Luke wasn’t expecting the Peace Brigade to show up so soon, I guess.”

Kam’s eyes narrowed. “But you were, weren’t you? You came here without permission.”

“I came against orders, actually,” Anakin corrected. “That’s not important now. Getting the students to safety, that is.”

“Of course,” Kam agreed. “How long before the Peace Brigade can land?”

“An hour? Not long.”

“And Karrde?”

“He could be days.”

Kam grimaced. “We can’t hold out here that long.”

“We might. We’re all Jedi.”

Kam snorted. “You need a sense of your limitations. I have a sense of mine. We might do very well, but we’ll lose kids. I have to think of them first.”

They were approaching the turbolift when the door hissed open and ejected a blond-and-orange blur. The blur smacked Anakin at chest height, and he suddenly found surprisingly strong arms wrapped around him in a fierce embrace. Bright green eyes danced centimeters from his own.

He felt his face go warm.

“Hi, Tahiri,” he said.

She pushed back from him. “Hi, yourself, great hero-from-the-stars who’s too good to keep in touch with his best friend.”

“I’ve—”

“Been busy. Right. I know all about it—well, not all about it because we get the news so late here, but I heard about Duro, and Centerpoint, and—”

She stopped suddenly, either because she saw it in his face or felt it in the Force. Centerpoint Station was a sensitive subject.

“Anyway,” she went on, “you won’t believe how boring it’s been without you. All the apprentices have gone off, and that just leaves these kids—” She stepped away, and for the first time, he really saw her.

Whatever she detected in his eyes cut her off in midsentence. “What?” she asked instead. “What are you looking at?”

“I—” Now his face felt like it had been grazed by blasterfire. “You look … different.”

“Older maybe? I’m fourteen now. Last week.”

“Happy birthday.”

“You should have thought of it then, but thanks anyway. Dummy.”

Anakin found himself suddenly unable to meet her eyes. He dropped his gaze. “You’re, uh, still barefoot, I see.”

“What did you expect? I hate shoes. I only wear them when I have to. Shoes were invented by the Sith to keep our delicate toes in anguish and misery, I’m sure of it. Did you think just because I grew a centimeter or two I’d start torturing my feet?”

She looked up at Kam suspiciously. “What’s he doing here, anyway? I know he didn’t come to see me.”

Anakin flinched at the hurt he heard in that.

“Anakin’s come to warn us of trouble,” Kam replied. “In fact, you’ll need to do your catching up later.”

“Really? Trouble?”

“Yes,” Anakin said.

Tahiri put her hands on her hips. “Well, why didn’t you say so? What’s going on?”

“We need to talk to Tionne and Ikrit,” Kam told her, continuing forward into the turbolift.

“Now,” Anakin added, following him.

“But what’s going on?” Tahiri shouted at their suddenly retreating backs.

“I’ll explain on the way,” Anakin promised.

“Fine.” She ducked into the lift just as the door was closing.

“The Yuuzhan Vong warmaster basically put a price on our heads,” Anakin said. “On all our heads, all the Jedi. He announced that if what’s left of the New Republic will turn over all of its Jedi to him—and Jacen especially—he won’t take any more planets.”

“Boy, that sounds like a lie,” Tahiri said.

“Doesn’t matter. People believe him. Like the people in the ships approaching right now.”

“They want to turn us over to the Yuuzhan Vong? Let them try!”

“Don’t worry, they will.”

The door opened and they emerged onto the second level. Kam started down the main corridor and then through a series of passages that were utterly familiar to Anakin, though they all seemed somehow narrower than when he had last seen them. The Massassi temple that housed the academy had once seemed impossibly huge. Now it seemed merely large.

They reached the central area, and twenty-odd faces turned toward them. Human, Bothan, Twi’lek, Wookiee—more than a dozen species were represented. All were quite young except one—Tionne, Kam’s wife, a graceful silver-haired woman with pearl-white eyes. Her eyebrows lifted in surprise and her lips in pleasure.

“Anakin!” she said.

“Tionne,” Kam said gently but urgently, “we need to talk.”

“Anakin!” Sannah, a girl of thirteen with brown hair and yellow eyes, waved at him. Even younger Valin Horn was waving, though he wasn’t shouting.

“He’s busy!” Tahiri told them. But when Anakin went to talk with Kam and Tionne, Tahiri came along.

“Tahiri—” Kam began.

“Oh, no,” she said. “You aren’t leaving me out of this.”

“I wasn’t going to,” Kam said gently. “I was going to ask you to find Master Ikrit and meet us in the conference room.”

“Oh. Okay.”

She whirled off down the corridor on bare feet.

* * *

Tahiri was back with Ikrit only moments later. The old Jedi Master padded into the room on all fours, his long floppy ears dragging the ground. His normally bright eyes seemed a little dull to Anakin, and he felt an inexplicable pang.

“Master Ikrit.”

“Young Anakin. It is good to see you,” Ikrit replied. “Though you bring troubling news.”

“Yes.” He raced through the details once again, for Ikrit and Tionne.

“They would take our children?” Tionne murmured, more darkly than was her wont.

“The Peace Brigade? Absolutely. Tionne, it’s bad for Jedi out there right now.”

“I understand,” she said, then clenched her fist. “No, I don’t understand. Has the galaxy gone mad?”

“Yes,” Kam said softly. “It’s an old madness, war.”

“You don’t have any ships, do you?”

“No. Streen went with Peckhum in the supply ship.”

“Where to?”

“Corellia. He should be back soon. Though I suppose they won’t, now.”

“We’ll have to hide them here, then,” Anakin said. “Where?”

“Down the river! The cave beneath the Palace of the Woolamander,” Tahiri offered. “Master Ikrit’s cave.”

Anakin raised his eyebrows. “That’s a good idea. They’d be really hard to find there, especially if the Peace Brigade doesn’t start looking right away.”

“What do you mean by that?” Kam said, his voice suddenly cautious. “Why would they delay the search?”

“I’ll stay behind,” Anakin said. “I’ll make it look as if we’re still in the temple trying to make a stand. They’ll waste time shooting their way through while you and Tionne get the kids to safety.”

“You’re leaving out one little detail,” Tahiri said. “What about you? What keeps you safe?”

“I’ll hide the X-wing. I know a good place. I can slip through them. Then I’ll play hide-and-seek until Talon Karrde shows up. Once he’s mopped up the Peace Brigade, I’ll lead him to you.”

“You’ve been thinking about this,” Tionne said.

“All the way down,” Anakin admitted. “It’s the best way.”

“He’s right,” Kam said.

“Kam—” Tionne began.

“He’s right,” Kam went on, “except that he’s not the one staying behind—I am.”

“I’m the better pilot,” Anakin said bluntly. “I’m the only one who can pull it off.”

“Anakin is correct,” Ikrit said in his scratchy voice. “It is part of his destiny. And mine.”

“Master Ikrit—”

“You will say I am no warrior. That may be true—it has been long since I wielded a lightsaber, and it was not what I preferred even then. But it is not lightsabers that will prevail here today, not weapons. Not all uses of the Force are aggressive.”

Anakin pursed his lips, but he couldn’t bring himself to contradict the ancient Master.

Kam gnawed his lip for a moment. “Very well,” he said at last. “I don’t like it, but we don’t have time for a debate. Tahiri, come along. Help me and Tionne get the students on the boats.”

“Fine,” Tahiri said, “but I’m staying with Anakin.”

“No,” Anakin said.

“Yes!” Tahiri retorted. “I’ve been stuck on this mud-ball while you’ve been out fighting the Yuuzhan Vong. I’m sick of it! I’m ready to do something!”

“You’re too young for this,” Tionne said.

“Anakin’s only two years older than me! He was fifteen at Sernpidal!”

“That’s right,” Anakin said, “and I got Chewbacca killed. Tahiri, please go with Kam.”

Her eyes widened in shocked betrayal. “You don’t want me with you! After all we—you think I’m a kid, just like they do!”

No, Anakin thought. I just don’t want to see you killed, too.

“Come on, Tahiri,” Tionne said gently. “There’s no time to lose.”

“Fine. That’s just fine,” she said, and without another glance at Anakin she darted from the room.

Kam placed his hand on Anakin’s shoulder. “It’s been hard on her without you here.”

Anakin nodded. “Anyway,” he said gruffly, “I’d better get to work.”