“DOES THIS HURT?” HE ASKED.

Because it was hurting him.

Beneath his hands, her breathing quickened. “N-no.” She stared at him, eyes wide but unafraid, and her soft, pink lips parted slightly. “It feels … nice.”

He was braced over her now, his body stretched alongside hers, so that he had only to lower his head to touch his lips to hers. Thoughts of the Heirs, the Primal Source all dissolved like vapor beneath the sun of his and her shared awareness. Her gaze flicked down to his mouth, as well, and the dropping of her lashes and flush spreading across her cheeks revealed that not only had she shared his thought, but wanted it, too. What would she taste like? Both the scientist and the man within him needed to find out.

Slowly, slowly he bent lower, suspended in liquid time. His heart slammed within the cage of his chest, and he was tight and hard everywhere. He cradled the juncture of her neck and jaw, feeling the rush of her pulse at that tender convergence. Such delicacy. Combined with remarkable strength.

“You’re a very courageous woman,” he breathed, close enough to count freckles.

She brought her hand up to curve around the back of his head. “I know,” she answered.

He smiled at that, a small smile. And then he stopped smiling, because he kissed her.

The Blades of the Rose

Warrior

Scoundrel

Rebel

Stranger

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

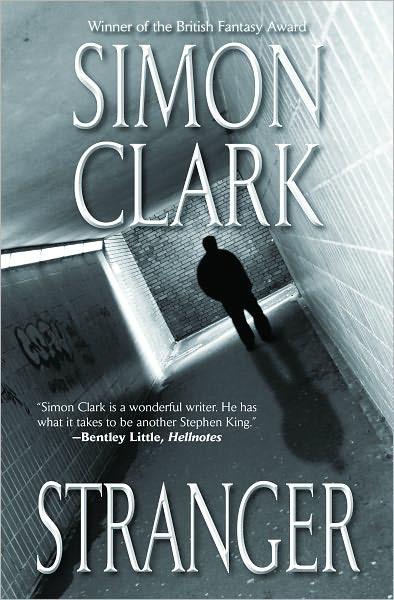

STRANGER

The Blades of the Rose

Zoë Archer

ZEBRA BOOKS are published by

Kensington Publishing Corp.

119 West 40th Street

New York, NY 10018

Copyright © 2010 by Ami Silber

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of the Publisher, excepting brief quotes used in reviews.

If you purchased this book without a cover you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the Publisher and neither the Author nor the Publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.”

All Kensington titles, imprints and distributed lines are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchases for sales promotion, premiums, fund-raising, educational or institutional use.

Special book excerpts or customized printings can also be created to fit specific needs. For details, write or phone the office of the Kensington Special Sales Manager: Attn. Special Sales Department. Kensington Publishing Corp., 119 West 40th Street, New York, NY 10018. Phone: 1-800-221-2647.

Zebra and the Z logo Reg. U.S. Pat. & TM Off.

eISBN-13: 978-1-4201-1986-2

eISBN-10: 1-4201-1986-2

First Printing: December 2010

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

For Zack,

sometimes strange but never a stranger,

my heart will always know yours

CONTENTS

Chapter 3 Miss Murphy Makes the Leap

Chapter 4 Unfamiliar Territory

Chapter 5 Sleeping Arrangements

Chapter 6 Catullus in the Dark

Chapter 8 Rex Quondam, Rexque Futurus

Chapter 10 Mr. Graves Takes Control

Chapter 11 Of Scarabs and Sulfuric Acid

Chapter 12 The King and the Heir

Chapter 14 Crossing the Boundary

Chapter 16 The Hazards and Habits of Otherworld

Chapter 21 The Blades of the Rose

Thank you to superagent Kevan Lyon and wondereditor Megan Records for loving my crazy adventurers as much as I do. And thank you to the many people whose support and encouragement helped make the dream of the Blades of the Rose a reality: Andy and Christina Blaiklock, Lorelie Brown, Pauline DiPego, Jerry DiPego, Gene and Janice Fiskin (hi, Mom!), Kathy Harmening, Carolyn Jewel, Carrie Lofty, Tiffani McCoy, Julia McDermott, Courtney Milan, Martti Nelson, Elyssa Papa, Jeffrey Silber (hi, Dad!), Liz Thurmond, and Lisa Zalokar.

The steamship Antonia, two days from Liverpool, 1875.

Three guns pointed at Gemma Murphy.

She pointed her own derringer right back. Two shots only. Maybe she could get her hands on one of the revolvers aimed at her. Hopefully, it wouldn’t come to that.

A sane person would have fled the cabin. But Gemma wasn’t sane. She was a journalist.

So, instead of running, she confronted three faces ranging in expression from curious to outright hostile. And their guns.

The culmination of weeks of hard travel. On the trail of a story, she had journeyed all the way from a small trading post in the Canadian Rockies, across the United States, to New York, where she boarded the Antonia. Horseback, stagecoach, train. Clapboard boardinghouses with thin mattresses and thinner walls. Food boiled to inedibility. Groping hands, speculative leers. Rats and dogs.

She’d faced them all, pressing onward, always a day behind her quarry—but that was deliberate. She couldn’t let them see her. To be seen was to risk being recognized. Maybe she flattered herself to think that any of the people she followed would remember her. After all, she had only seen them twice, and spoken with one member of their party once. Weeks, thousands of miles, had passed since then.

But there was a strong disadvantage to being a redhead. People with bright copper hair and freckles had a tendency to be remembered—like a flare’s afterimage burned into the eye. Sometimes Gemma used her appearance and gender to her advantage. It always helped a reporter to have an advantage. Other times, her looks and sex were a damned pain in the behind.

As soon as she learned that her quarry had booked passage on the Antonia, bound for Liverpool, Gemma also reserved a cabin on that same ship. To follow at sea, even a day behind, meant the possibility of losing them. So, for the past week onboard the ship, she’d led a nocturnal existence. Staying in her cabin during the day, to avoid being spotted. In those close confines, she wrote articles until her hands cramped. She had little to go on but speculation. That did not stop her from piecing together events with her own prodigious imagination. Night saw her skulking about the ship, getting some much-needed fresh air. And, once the other passengers had retired for the evening, listening at doors.

Her quarry met in one another’s cabins. Often, their conversations held no information. But tonight had been different.

“When did the Heirs activate the Primal Source?” The woman’s voice. Her English accent was refined, but her words were tough and strong.

Gemma pulled from her pocket her notebook and began scribbling furiously in it.

“Some two and a half months ago.” Another English voice. One of the two men. His voice, so impeccably British in its accents, was deep and sonorous. Even now, with a door between them, his voice played havoc with her normally reliable sensibilities. She remembered the impact his voice had on her at the trading post, and ruefully reflected that none of that impact had been lost in the intervening time and distance. “But they haven’t the faintest idea what to do with it.”

“That’s why they came for me in Canada,” said the woman.

“If the Heirs can’t use the Primal Source,” the second man noted, “then there shouldn’t be any danger.” The accents of western Canada marked this man’s voice, yet he held a natural authority in his tone.

“It does not work that way,” the woman answered. “The Primal Source has the power to grant and embody the possessor’s most profound hopes and dreams.”

“Even if said possessor does not actively attempt this?” asked the Canadian.

The woman replied, “All the Primal Source needs is to be in close proximity to the one who possesses it, and it can act on even the most buried desires.”

Good gravy! What could this Primal Source be?

Just then, a sailor on watch walked through the passageway. He looked at Gemma, standing alone outside a cabin door, with a curious frown.

“Can I help you, miss?” he asked.

“Just looking for my key,” she murmured, careful to keep her voice down. Her notebook was concealed in the folds of her skirt. “I’m such a ninny—I can never remember where I put it.”

“The purser can get you another one.”

“Oh, no,” Gemma said. She made some wave of her hand, the universal sign of a woman who doesn’t want to be a bother. “I’ll find it. Please, carry on with whatever you were doing.”

“Are you sure, miss?”

Blast these polite sailors. “Yes, quite sure.” She smiled and, God help her, fluttered her lashes. Gemma never considered herself a beautiful woman—red hair and freckles weren’t often considered the height of female loveliness—but she did know that batting her eyelashes generally worked as a distracting device.

Correct. The sailor, hardly more than a boy, flushed, stammered, and then ambled away. The moment he disappeared down the passageway, Gemma pressed her ear to the cabin door, notebook at the ready.

“And what are the Heirs’ deepest desires?” This was asked by the Canadian. He was the newcomer in the trio, she deduced.

The reply came from the Englishman, an answer arising from long experience. “The supremacy of England. An empire that encompasses the entire world.”

Gemma pressed her hand to her mouth, horrified by the idea. It seemed the stuff of a despotic nightmare, to have one country in control of the whole globe, with one set of laws. One monarch. The American in Gemma rebelled at the idea. Nearly a hundred years ago, her country had been forged in blood, fighting to free itself from the tyranny of oversea rule. Thousands of lives lost to secure freedom for its citizens. And to lose it all again? Just as every other nation would lose its independence?

The woman added, in hard, bleak tones, “Somehow, the Primal Source will embody this. Which means destruction and devastation on a global scale.”

“Unless the Blades stop the Heirs’ dream from manifesting,” said the Englishman.

“I pray to God we aren’t too late.” This, from the woman. A grim hope.

On that somber note, the voices within wished each other a good night. Gemma scurried away, into the shadows, to watch from a safe distance. Peering around the corner of the passageway, she saw the door to the cabin open, yellow lamplight falling into the corridor. A woman and man emerged, holding hands. The woman was fair in coloring, slight of build, but she radiated a steely strength matched by the bronze-skinned man beside her.

When they stepped into the passageway, the man tensed slightly. The change in his posture was so subtle, Gemma barely saw it, but the woman felt the change at once.

“What is it, Nathan?” she asked.

He peered around, much the way a wolf might search for prey. “Thought I sensed something … familiar.” He gazed up and down the passageway with sharp, dark eyes, and Gemma could have sworn he was actually smelling the air.

She flattened herself against the bulkhead, hiding, heart knocking against her ribs. She’d come too far to be found out now, so close to the story.

She heard the man take a step in her direction, then stop. “It’s this damned sea air. Can’t get a bead on anything.”

“We’ll get you on land again soon. Come to bed,” murmured the woman, and Gemma knew from the throaty warmth of the woman’s voice, bed was precisely the destination in mind. Gemma’s own face flushed to hear the husky promise in the woman’s words. Words one would speak to a lover. And it affected the man, most definitely. Gemma thought she heard him literally growl in response, before their footsteps hurriedly disappeared toward their stateroom.

Once they had gone, Gemma poked her head around the corner again. She saw the third man in the group standing outside the cabin, locking the door. He was a tall man, and had to bend a little to keep from knocking his head into the low ceiling. Gemma recognized his long, elegant form immediately, and would have lingered longer to observe him, but she did not want to risk being spotted. So she pushed back into the shadows, listening to him lock his door. It seemed to take rather a long time, but at last he straightened and began walking.

Straight in her direction. On feet well used to keeping silent, Gemma hurried away.

She waited in the stern for several minutes. Once she felt confident she wouldn’t encounter any of her quarry, she jogged quickly back to the cabin. She pressed her ear to the door. No sound within. Bending low, she looked at the small gap between the door and the deck. Dark. The lamps inside were extinguished. He wasn’t inside—unless he’d come back within minutes of leaving and immediately gone to sleep. Unlikely.

Now was her chance to do some investigating. Surely she’d find something of note in his cabin. A fast glance up and down the passageway ensured she was entirely alone.

Gemma opened the cabin door.

And found herself staring at a drawn gun.

Damn. He was in. Working silently at a table by the light of one small lamp. At her entrance, he was out of his chair and drawing a revolver in one smooth motion.

She drew her derringer.

They stared at each other.

In the small cabin, Catullus Graves’s head nearly brushed the ceiling as he faced her. Her reporter’s eye quickly took in the details of his appearance. Even though he was the only black passenger on the ship, more than just his skin color made him stand out. His scholar’s face, carved by an artist’s hand, drew one’s gaze. Arresting in both its elegant beauty and keen perception. A neatly trimmed goatee framed his sensuous mouth. The long, lean lines of his body—the breadth of his shoulders, the length of his legs—revealed a man comfortable with action as well as thought. Though Gemma had not been aware how comfortable. Until she saw the revolver held easily, familiarly in his large hand. A revolver trained on her. She’d have to do something about that.

“Mr. Graves,” she murmured, shutting the door behind her.

Behind his spectacles, Catullus Graves’s dark eyes widened. “Miss Murphy?”

Despite the fact that she was in danger of being shot, it wasn’t until Graves spoke to Gemma that her heart began to pound. And she was absurdly glad he did remember her, for she certainly hadn’t forgotten him. They’d met but briefly. Spoke together only once. Yet the impression of him remained, and not merely because she had an excellent memory.

“I thought you were out,” she said. As if that excused her behavior.

“Wanted to get a barometric reading.” Catullus Graves frowned. “How did you get in?”

“I opened the door,” she answered. Which was only a part of the truth. She wasn’t certain he would believe her if she told him everything.

“That’s not possible. I put an unbreakable lock on it. Nothing can open it without a special key that I made.” He sounded genuinely baffled, convinced of the security of his invention. Gemma glanced around the cabin. Covering all available surfaces, including the table where he had been working moments earlier, were small brass tools of every sort and several mechanical objects in different states of assembly. Graves was an inventor, she realized. She knew her way around a workshop, but the complex devices Graves worked on left her mystified.

She also realized—the same time he did—that they were alone in his cabin. His small, intimate cabin. She tried, without much success, not to look at the bed, just as she tried and failed not to picture him stripping out of his clothes before getting into that bed for the night. She barely knew this man! Why in the name of the saints did her mind lead her exactly where she did not want it to go?

The awareness of intimacy came over them both like an exotic perfume. He glanced down and saw that he was in his shirtsleeves, and made a cough of startled chagrin. He reached for his coat draped over the back of a chair. One hand still training his gun on her, he used the other to don his coat.

“Strange to see such modesty on the other end of a Webley,” Gemma said.

“I don’t believe this situation is covered in many etiquette manuals,” he answered. “What are you doing here?”

One hand gripping her derringer, Gemma reached into her pocket with the other. “Easy,” she said, when he tensed. “I’m just getting this.” She produced a small notebook, which she flipped open with a practiced one-handed gesture.

“Pardon—I’ll have a look at that,” Graves said. Polite, but wary. He stepped forward, one broad-palmed hand out.

A warring impulse flared within Gemma. She wanted to press herself back against the door, as if some part of herself needed protecting from him. Not from the gun in his other hand, but from him, his tall, lean presence that fairly radiated with intelligence and energy. Keep impartial, she reminded herself. That was her job. Report the facts. Don’t let emotion, especially female emotion, cloud her judgment.

And yet that damned traitorous female part of her responded at once to Catullus Graves’s nearness. Wanted to be closer, drawn in by the warmth of his eyes and body. An immaculately dressed body. As he crossed the cabin with only a few strides, Gemma undertook a quick perusal. Despite being pulled on hastily, his dark green coat perfectly fit the breadth of his shoulders. She knew that beneath the coat was a pristine white shirt. His tweed trousers outlined the length of his legs, tucked into gleaming brown boots. His burgundy silk cravat showed off the clean lines of his jaw. And his waistcoat. Good gravy. It was a minor work of art, superbly fitted, the color of claret, and worked all over with golden embroidery that, upon closer inspection, revealed itself to be an intricate lattice of vines and flowers. Golden silk-covered buttons ran down its front, and a gold watch chain hung between a pocket and one of the buttons. Hanging from the chain, a tiny fob in the shape of a knife glinted in the lamplight.

On any other man, such a waistcoat would be dandyish. Ridiculous, even. But not on Catullus Graves. On him, the garment was a masterpiece, and perfectly masculine, highlighting his natural grace and the shape of his well-formed torso. She knew about fashion, having been forced to write more articles than she wanted on the subject. And this man not only defined style, he surpassed it.

But she was through with writing about fashion. That was precisely why she was on this steamship in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

With this in mind, Gemma tore her gaze from this vision to find him watching her. A look of faint perplexity crossed his face. Almost bashfulness at her interest.

She let him take the notebook from her, and their fingertips accidentally brushed.

He almost dropped the notebook, and she felt heat shoot into her cheeks. She had the bright ginger hair and pale, freckled skin of her Irish father, which meant that, even in low lamplight, when Gemma blushed, only a blind imbecile could miss it.

Catullus Graves was not a blind imbecile. His reaction to her blush was to flush, himself, a deeper mahogany staining his coffee-colored face.

A knock on the door behind her had Gemma edging quickly away, breaking the spell. She backed up until she pressed against a bulkhead.

“Catullus?” asked a female voice on the other side of the door. The woman from earlier.

Graves and Gemma held each other’s gaze, weapons still drawn and trained on each other.

“Yes?” he answered.

“Is everything all right?” the woman outside pressed. “Can we come in?”

Continuing to hold Gemma’s stare, Graves reached over and opened the door.

Immediately, the fair-haired woman and her male companion entered.

“Thought it was nothing,” the man said, grim. “But I know I’ve caught that scent before, and—” He stopped, tensing. He swung around to face Gemma, who was plastered against the bulkhead with her little pistol drawn.

Both he and the woman had their own revolvers out before one could blink.

And now Gemma had not one but three guns aimed at her.

“Astrid, Lesperance,” said Catullus Graves as though making introductions at a card party, “you remember Miss Murphy.”

“From the trading post?” demanded the woman. Gemma recalled her name: Astrid Bramfield. She had exchanged her mountain woman’s garb of trousers and heavy boots for a more socially acceptable traveling dress. Yet the woman had lost none of her steely strength. She eyed Gemma with storm-colored eyes cold with suspicion, an enraged Valkyrie. “Following us all the way from the Northwest Territory. She must be working for them.”

Them?

“Let’s give her a chance to explain herself,” said the other man, level. Though he didn’t lower his gun. Nathan Lesperance, Gemma recalled. He wore a sober, dark suit, as befitting his profession as an attorney, but the copper hue of his skin and sharp planes of his face revealed Lesperance’s full Native blood.

A white woman, an Indian man, and a black man. Truly an unusual gathering. One Gemma was glad she’d followed.

“I retrieved this from her,” Graves said, holding up the notebook.

“What does it say?” Astrid Bramfield asked sharply.

Graves glanced down at the notebook. A frown appeared between his brows. Gemma nearly smiled. Her handwriting was deplorable, mostly because she deliberately made it illegible to anyone but her. No sense letting other reporters read her notes. She may as well give those buffoons in the newsroom all of her bylines.

“I don’t know,” he answered.

At this, Astrid Bramfield looked surprised, as though Graves admitting a deficiency in any knowledge was shocking.

“If I may translate,” Gemma said, holding out her hand. She did not miss the careful way in which Graves returned her notebook, avoiding the contact of her skin.

Wanting her own distraction, she looked down at her notes, although she hardly needed them. Every word of the conversation she’d overheard was inscribed permanently on the slate of her memory. She recited everything she had heard.

“Eavesdropping,” snapped Astrid Bramfield. “I prefer to call it ‘unsupervised listening,’” Gemma answered.

A corner of Graves’s mouth twitched, but he forced it down and looked serious.

Gemma closed her notebook and slipped it back into her pocket. “All very strange and bewildering, you must admit.”

“We need not admit anything,” Astrid Bramfield replied.

“You’re a journalist,” Graves said with sudden understanding. His keen, dark eyes took note of her ink-stained fingers, the tiny callus on her right index finger that came from holding a pen for hours at a stretch. “That’s what you were doing at the trading post in the Northwest Territory.”

Gemma nodded. “I had planned on writing a series of articles about life on the frontier. But when you crossed my path, I knew I would find a hell of a story. And I was right.”

“A journalist,” Astrid Bramfield repeated, her tone revealing exactly how she felt about reporters.

No doubt most members of Gemma’s profession deserved their reputation. But Gemma wasn’t like them. For one thing, she was a woman. Not an automatic guarantee of integrity, yet it was a small mark of distinction.

Something that looked suspiciously like disappointment flickered in Catullus Graves’s eyes before being shuttered away. “You’ll find no story here, Miss Murphy.” He took a step back, and she found, oddly, that she missed his nearness. “It is in your best interest, when this ship docks, to turn around and go home.”

Back to Chicago? She would never do that—she had crossed a continent and an ocean for this story.

“Who are the Heirs?” Gemma asked.

Graves, Lesperance, and Astrid Bramfield all tensed. None of them spoke as a sharp silence descended. Very surprising, considering recent developments. Then—

“They’re called the Heirs of Albion,” Lesperance said.

“Nathan!” Astrid Bramfield exclaimed, and Graves looked alarmed.

Yet it couldn’t be stopped now. “A very powerful group of Englishmen,” Lesperance continued. “They want the entire world as part of the British Empire, no matter the cost. But Astrid, Graves, and I are going to stop them. With the help of the other Blades of the Rose.”

“Lesperance, enough,” growled Graves.

Astrid Bramfield was at Lesperance’s side in a heartbeat, alarmed and concerned. Though she still held her pistol pointed at Gemma, her other hand cupped Lesperance’s face with tender anxiety. “What are you doing, revealing such secrets? This woman is a stranger.”

Frowning, Lesperance murmured, “I don’t know. I only know that we can trust her.”

“But she’s a journalist,” was Astrid’s reply. Her words fought against a sense of betrayal by one held so deeply within her heart. As Gemma had seen thousands of miles ago in the Northwest Territory, the connection and bond between Astrid Bramfield and Lesperance was palpable, enviable.

She’d never had that connection, that bond. And never would, given the choices in life she had made.

Gemma shouldered aside that familiar loneliness. “Don’t blame him,” she said quickly. “It’s an … ability I have. To get answers.”

“Ability?” Graves repeated, raising an eyebrow.

She did not want to dwell on something that might derail the entire conversation. “But Mr. Lesperance is right. You can trust me.”

“There is no such thing as a trustworthy reporter,” retorted Astrid Bramfield.

“You did say you were after a story,” Graves added, somewhat more gently.

Gemma thought quickly. “I can write about these Heirs of Albion and expose them. Stop whatever it is they plan on doing.”

Astrid Bramfield, despite her refined English accent, gave a very unladylike snort of disbelief. “It would not be so easy as that.”

If Gemma was to find an ally, it would not be with this tough, guarded woman, so she turned to Catullus Graves. He watched her carefully, commingled caution and interest in his expression.

“Exposure in a national newspaper can bring even the most powerful men down,” she said, meeting his gaze. Even behind the protective glass of his spectacles, his eyes were a dark pull. He observed her as if not entirely certain to what species she belonged.

“Astrid is right,” he answered. “If it was simply a matter of publishing an exposé, such a thing would have been done long ago. A few printed words would not even dent the Heirs’ armor. They are above trifles such as exposure and public opinion.”

“Surely no one is that powerful.”

“Miss Murphy,” he said, holding her gaze, “you have no idea.”

The gravity of his words, the seriousness of his handsome face, shook her like the deep tolling of a bell. Which meant she needed to know more.

“What could they possibly have at their disposal that gives them so much influence?”

Again, that tense silence fell, and Gemma could feel them all struggle against it, against her question.

“Magic,” Astrid blurted, then clapped a hand over her mouth. She stabbed Gemma with an angry scowl.

Over the course of her life and professional career, Gemma had been the recipient of more than one angry scowl, and Astrid Bramfield’s could not upset her. Gemma was much more interested in what the Englishwoman had just revealed. “Magic,” Gemma repeated.

This was not a question, and so no one spoke.

With a deliberate gesture, Gemma put her derringer onto a nearby table, then gave it a small shove so that it moved out of her immediate reach. Now she was entirely unarmed.

Graves saw the move for what it was: a sign of faith. Theatrical, but effective. He tucked his own revolver into his belt, never taking his eyes from hers.

Lesperance followed suit, but Astrid Bramfield put away her gun only with great reluctance. Clearly, some great injury lay in her past, to make her so cautious.

Gemma’s attention moved back to Graves, drawn to him as if by some inescapable force. He had been watching her, assessing her, and she prayed she would not blush again under his scrutiny. God! She was hardly an innocent child, and had seen—and done—rather a lot in her twenty-seven years. Yet nothing and no one made her blush as Catullus Graves could with just a look.

He narrowed his eyes. “Yes, magic, Miss Murphy.” He spoke lowly as though recounting to a child a tale of terror. “There exists in this world actual magic. It is too dangerous for any civilian reporter to confront—and live.”

“I know.”

“You might scoff, but—wait. You know?”

“Yes.”

“About magic?”

“Yes.”

“That it is real?”

“Yes.”

He gaped. As did Astrid and Lesperance, who traded looks of disbelief with one another. Obviously, everyone had anticipated that she would not believe in magic. And, had she been anyone else, perhaps she wouldn’t have.

“How—?”

Gemma turned to Astrid. “Assist me with something.”

Guardedly, the Englishwoman approached.

“Please, stand out in the passageway.”

“Why?”

The Englishwoman’s caution grated. Gemma said, teeth gritted, “Just … please. I promise I won’t seduce or kill anyone while you do.”

With one final, suspicious glance over her shoulder, Astrid opened the cabin door and stood in the passageway. Gemma shut the door in the woman’s face. A yelp of outrage penetrated the door.

Lesperance strode toward Gemma with a dark scowl, as ferocious as a wolf protecting its mate.

“I’m not going to harm her,” Gemma said, raising up her hands. Without question, Lesperance would utterly annihilate anyone foolish enough to try to hurt Astrid. “Just a brief demonstration.”

Barely appeased, Lesperance held himself back. A pulse in her throat proved to Gemma that she had narrowly avoided danger. “Now,” Gemma said, turning to Graves, “lock the door.”

A small frown knitted his brow, but he came closer to do so. His boots brushed past the hem of her skirt, and, even though the gesture could not have been less intimate, Gemma’s heart sped into a gallop. She’d spent months in the Canadian mountain wilderness, living close with trappers and miners and men of every stripe, the raw and the refined. Almost nothing any of them did or said affected her the way a simple brush of Catullus Graves’s boots against her skirt could. And he seemed equally flustered, despite the fact that he was well past boyhood and most definitely a grown man.

Gemma made herself focus on the lock. It wasn’t an ordinary lock on the door, but a small device that clearly was his own invention—an intricate network of metal fittings that looked as if it was assembled by tiny, industrious Swiss watchmakers. Graves’s long, agile fingers worked quickly over the lock, and she heard a click.

“There,” he said, straightening. He cleared his throat and stepped back, and Gemma realized that she had drifted closer to watch him at work.

“Now, Mrs. Bramfield,” Gemma said through the door, “try to come in.”

The doorknob rattled, but the door remained closed. “I can’t,” came the muffled reply.

“Use a little force.”

This time, the knob rattled harder, the door shaking a bit, but it still remained shut. “Still can’t,” Astrid said. “I could try to kick it in.”

“Not necessary.” She turned to Graves, watching avidly. “You agree that I didn’t kick the door open when I came in a short while ago.” When he nodded, Gemma said, “If you would, unlock the door and let Mrs. Bramfield in.”

He did so, and the Englishwoman strode back into the cabin, looking puzzled. “What did that prove?” she asked.

“That, when the door was shut and Mr. Graves’s lock was set, you could not open the door.” Gemma walked to it and opened the door again. “I’m going to stand in the passageway, and I want you to lock the door behind me. Just as you did with Mrs. Bramfield.”

Graves, still frowning, gave a short nod. So Gemma did exactly as she said she would, going out into the passageway and letting Graves close and lock the door.

“All set?” she asked through the thick wood.

“Yes—all set,” he answered.

Gemma placed her hand on the doorknob. And opened the door.

Instead of being met by a gun, three stunned faces greeted her entrance into the cabin.

She shut the door behind her again. “You asked how I might know of magic, Mr. Graves? There it is.”

“Could be a trick,” Lesperance noted.

“No,” said Graves. “Nothing can open that lock except the key that I made.” He gazed at her with a mixture of admiration and surprise. “Nothing, but magic.”

“It’s called the Key of Janus,” Gemma explained. She felt a strange little glow of satisfaction to amaze not just Astrid and Lesperance, but a clearly brilliant mind such as Catullus Graves. “Something that’s been in my mother’s Italian family for generations. Dates back to ancient Rome. With it, we can open any door. Doesn’t matter how strong the lock, how heavy the door. The Key opens them all.” Though lately, even that had changed. But there was no need to mention that now.

“How did your family keep from becoming thieves?” Graves asked.

She grinned. “Many didn’t.” Then sobered. “But even more remained honest, despite the temptations to do otherwise. So you see “—she opened her hands wide—” I know that magic exists, since it’s been in my family for hundreds, if not thousands, of years.”

Astrid muttered something that might have been, “Blimey.”

Graves thoughtfully rubbed his mouth. After staring at her for a few moments, he strode toward the porthole and, bracing his hands on either side of the small window, gazed out at the moon upon the water.

“You can’t scare me with tales of magic, Mr. Graves,” Gemma said to his broad back. “Because I know all about it.”

“Not everything,” he corrected, turning back to face her. “The magic that’s in your family, that is just one small, and relatively innocuous, part of the limitless magic that exists in the world. It can be found everywhere, from the most populous cities, to the farthest reaches of the wilderness.”

“Including the Northwest Territory?” Gemma asked. According to Gemma’s investigations at the trading post, Astrid Bramfield had been living alone in the Canadian mountains, until Catullus Graves and another man—now dead—had come to find her. Graves had returned from the wilderness with Astrid and Lesperance before setting off for England, with Gemma in pursuit.

“Exactly.” His hands clasped behind his back. He had, at that moment, a professorial air, much more comfortable discussing such subjects than being in touching distance of her.

“Is that what those other Englishmen at the trading post were looking for? Magic?”

“You remember them?” he asked, taken aback.

Gemma’s mouth curved, wry. “Hard to forget. A bigger bunch of pompous asses I never met—and, believe me, I’ve known quite a few.” Especially in the newsroom of the Tribune. “They came in the same day that Mr. Lesperance arrived, looking for guides, and managed to insult everyone in the trading post.”

Lesperance stood even straighter. “You,” he said, staring at her. “I saw you there that day, too. Out of the corner of my eye. You were lurking behind some buildings. I went to follow—and then the Heirs grabbed me.”

She did do rather a lot of lurking in her work, but couldn’t feel too embarrassed about it. Being polite and proper never made anyone into a good journalist. “Heirs,” she repeated. “You mentioned them before. Those Englishmen at the trading post were called Heirs?”

“The Heirs of Albion,” Graves said, grim. “As we said, they want everything for England’s empire, and that includes the world’s magic.”

Gemma blanched. “That’s … awful.” A sudden thought struck her. “Does that include my magic?”

His somber expression showed that he had already considered this possibility. “Very likely. Either it will be stripped from you or—” He broke off, frowning deeply.

“Or?” Gemma prompted.

“Or your magic, and you, will be enslaved. At any given moment, you could be summoned and forced to open any lock, any door. A vault holding a nation’s wealth. A chamber guarding royalty, leaving the monarch vulnerable to an assassin’s bullet.”

A whooshing in her ears, the sound of her blood rocketing through the vast network of her body. Saint Francis de Sales, that would make her an accomplice to murder! Her stomach churned in disgust and revulsion.

“The Heirs wouldn’t do that,” she averred, then undermined her own certainty by adding, more faintly, “would they?”

“They have and they will.” Graves’s tone left no room for uncertainty. He stepped closer, his eyes containing experiences beyond Gemma’s substantial imagination. “Which is exactly why you cannot be involved in anything to do with them. Even if the magic they wield is itself benign, their use of it is incredibly dangerous. Especially to someone like you.”

Now that he stood in front of her, Gemma had to tilt her head back to look him in the eye. If the intent was to intimidate her, in that regard, the gesture didn’t work. What his nearness did do, however, was make her aware of his warmth and scent—a mixture of bergamot, tobacco, and the intangible essence of him, his flesh and self.

“I don’t mind a little danger.” Her voice sounded husky to her ears.

His velvet-dark eyes moved over her face, lingering on the freckles dotting the bridge of her nose, before traveling down to idle on her mouth, and then lower. The dress Gemma wore was modest as a schoolmarm, with a high, buttoned collar and not a single bit of flesh exposed, save for her hands. But even in the most demure dress ever sewn, there was no concealing Gemma’s figure. Not only had she inherited her mother’s magic, but her hips and breasts as well. While Gemma had a mind for journalism, fate and family had given her the body of a burlesque dancer. Between her figure and her flaming, bright hair, Gemma’s pursuit of professional legitimacy was an uphill battle.

Sometimes she resented her curvaceous figure and saw it as nothing more than an impediment to being taken seriously. And other times …

To see frank male admiration in Catullus Graves’s face as he looked at her … she couldn’t deny a certain … gratification.

When his gaze met hers again, his voice came out somewhat raspy. “It isn’t a little danger. It’s a lot of danger. And I refuse to imperil you at all by having you anywhere near the Heirs—or us.”

A difference, she sensed, between his protectiveness and the condescension she endured back home. The male reporters at the Trib smirked and told her the life of a journalist was too perilous for a woman—her delicate constitution, her fragile sensibilities. Never mind that she could hold her liquor better than any of them, including Pritchard. Gemma could also swing a mean left hook and shoot a rifle. But, no, as befitting a woman’s disposition and health she was supposed to be writing harmless little articles about putting up summer beans or the best ways to get grape stains out of a baby’s pinafore.

Catullus Graves’s concern for her safety had nothing to do with whether or not he considered her capable, and everything to do with the fact that these Heirs of Albion were ruthless, murderous men. Men hell-bent on controlling the world’s magic for their own selfish desires.

She recognized the danger was real. Just as she understood that she had to write this story. Joseph McCullagh knew reporting on the Civil War from the front lines could cost him his life, but the risk to himself was nothing compared to the need for the public to know about the horrors of war.

“I will still write about this,” she challenged.

“No one will believe a word of it,” he answered.

“Then tell me more! What harm could it do, if no one will believe what I write?”

Graves, still holding Gemma’s gaze, shook his head. “The answer is no. Any more information will only jeopardize you further.” His expression darkened. “Lives will be lost, Miss Murphy. Of that, there is no doubt. And I swear that yours will not be one of them.”

“Will your life be lost, Mr. Graves?”

“Very possibly.” Not a trace of fear or exaggeration in his voice, just a simple statement of fact. He might die soon, violently, and he accepted that.

Her heart plunged to contemplate his death, even though he was a stranger to her.

Gemma started when Catullus Graves’s large, warm hands curved over her shoulders. Even through the layers of her clothing, she felt his touch move in swift, heated currents through her body. Temporarily stunned, she let him gently guide her backward. Then he took one hand from her, opened the door, and then lightly conducted her into the passageway.

“Forget everything you’ve heard here tonight, Miss Murphy,” he advised.

“You know I can’t do that.”

“Much as it pains me to say so,” he said, “that is your concern, not mine. But forget it you must.”

“But—”

“I know you can open any door, but I will trust you not to open mine again.” Regret seemed to cross his handsome, thoughtful face. “Good night, Miss Murphy. And, for the last time, good-bye.”

With that, he closed the door. Leaving her alone in the passageway.

Gemma stood there for a moment before heading back to her cabin and vowing to herself that, whatever the costs, whatever risks to herself, she would have her story. There were still so many questions unanswered, and she would find those answers. Not even the formidable force of Catullus Graves could stand in her way.

It amazed Catullus. He had been on board the ship for over a week and, during that time, not once had he seen Gemma Murphy. Now, he could not take a step outside his cabin without running into her.

Not literally—she maintained a respectable distance. But he had only to turn his head, and there she was. Across the dining room. Striding briskly past deck chairs and their blanket-swathed occupants as he took one of his own daily walks. Peering at him from behind a week-old newspaper in the reading room. Even the smoking lounge, the province exclusively for men. Catullus had gone in to indulge in an occasional pipe, and she entered the room right after him. Took a cheroot from an astounded steward, then lit up and cheerfully smoked, while Catullus and everyone else in the lounge gaped like guppies. No one had ever seen a respectable woman smoke before. It was … disturbing. Alluring.

He thought perhaps she might badger him with questions. Yet she never did. Whenever he saw her, she would smile cordially but preserve the space between them.

He couldn’t tell if he was glad or disappointed that she had not entered his cabin again. Every step outside in the passageway had made his pulse speed. But she never came to him privately. Only hovered in the public parts of the ship like a brilliant phantom.

Catullus now stood upon the prow, watching the ship cleave the gray water as it neared Liverpool. Sailing directly to Southampton hadn’t been an option, since the next steamship traveling to that town wouldn’t depart New York for two weeks. Far too long a wait with so much at stake. So, he and Astrid and Lesperance had booked passage to Liverpool, with the intent to hop immediately on a train heading to the Blades’ Southampton headquarters.

If he could, he would get out and tow the ship in, if only to get them to Liverpool faster. The ship docked tomorrow morning, and he was in a fever of impatience to reach their destination. What Astrid had revealed about the Primal Source—that it could actually embody the dreams and hopes of its possessor—had to be brought to the other Blades’ attention. At headquarters, they could discuss strategies, formulate a plan. Catullus enjoyed plans.

Wind and sea spray blew across the prow. Not as cold as those Canadian mountains, but he took pleasure in the soft black cashmere Ulster overcoat he wore, with its handsome cape and velvet collar. Too windy for a hat—but he was alone and so there wasn’t a breach of propriety.

Or had been alone. Catullus sensed, rather than saw, Gemma Murphy as she stepped onto the prow. His heart gave that peculiar jump it always did whenever he became aware of her. It happened the first time he saw her, at the tatty trading post in the Northwest Territory, and it happened now.

“Don’t be an ass,” he muttered to himself. She had said quite plainly that what she sought was a story. Nothing more.

He tried to make himself focus on the movement of the ship through the water, contemplating its propulsion mechanisms and forming in his mind a better means of water displacement. No use. His thoughts scattered like dropped pins when flaming hair flashed in his peripheral vision.

Bracing his arms on the rail, Catullus decided to be bold. He turned his head and looked directly at her.

She stood not two yards away—closer than she had been since the night in his cabin. That night, they had stood close enough for him to see all the delicious freckles that scattered over her satiny skin, close enough to see those freckles disappear beneath the collar of her prim dress, close enough to wonder if those freckles went all the way down her body.

God, don’t think of that.

Like him, she now had her forearms resting upon the rail, her ungloved hands clasped, and her face turned into the wind, little caring, as other women might, about the unladylike color in her cheeks called forth by the wind. She stared out to sea, watching the waves and the seabirds drafting beside the ship, a little smile playing upon her soft, pink mouth. Something secret amused her.

Him? He told himself he didn’t care if she found him amusing, terrifying, or wonderful. The division between them was clear. He was a Blade of the Rose on the most important mission ever undertaken. The fate of the world’s magic, and freedom, lay in the balance. Pretty redheaded reporters with dazzling blue eyes and luscious figures were entirely, absolutely irrelevant. Dangerous, even.

But he watched her now, just the same. She wore the same sensible traveling dress, a plain gray cotton that had seen several years of service. So thoroughly was it worn that the fabric, as it blew against her legs, revealed that Gemma Murphy had on a very light petticoat and was most likely not wearing a bustle.

He found himself struggling for breath.

Keep moving upward, he told his eyes. And they obeyed him, moving up to see that the truly magnificent bosom of Miss Murphy was, at present, marginally hidden by a short blue jacket of threadbare appearance. The elbows were faded. She must move her arms quite a bit to get that kind of wear. An active woman.

What he wouldn’t do to get that delectable figure and coloring into some decent clothing! Silk, naturally. Greens would flatter her best, but there were also deep, rich blues, luxuriant golds, or even chocolate browns. And he knew just the dressmaker, too, a Frenchwoman who kept a shop off Oxford Street. Madame Celine would be beside herself for the chance to dress a pre-Raphaelite vision such as Miss Murphy. And if he could see Gemma Murphy slipping off one of those exquisite gowns, revealing her slender arms, her corset and chemise … or perhaps underneath the gown, she would wear nothing at all….

Catullus shook himself. What the bloody hell did he think he was doing, mentally dressing and undressing a woman he barely knew? A woman who made no secret of her ambition to expose the world of magic that Catullus, his family, and the Blades had fought so hard to keep hidden.

But instead of marching back to his cabin, as he planned, he simply remained on the prow, close, but not too close, to Miss Murphy.

He glanced over at her sharply, realizing something. Then swore under his breath.

Gemma Murphy blinked in astonishment when Catullus strode over to her. Clearly, she hadn’t anticipated him approaching. He said nothing as he pulled off his plush, warm coat and then draped it over her shoulders. The overcoat was far too big for her, naturally, its hem now grazing the deck.

She also did not speak, but stared up at him. Her slim, pale hands held the lapels close. Catullus cursed himself again when he saw that she was shivering slightly.

“Don’t you have a decent coat to wear?” he demanded, gruff.

“It got lost somewhere between Winnipeg and New York.” Her voice, even out here in the hard wind, resounded low and warm, like American bourbon.

“Then get another.”

Again, that little smile. “Lately, I haven’t had the funds or time to see a dressmaker.”

He had the funds, thanks to the Graves family’s profitable side work providing manufacturers with the latest in production technology. And, even though time was in short supply, Catullus had managed to squeeze in an hour with one of Manhattan’s best tailors, where he’d purchased this Ulster and three waistcoats. He usually avoided ready-made garments, but an exception had been made in these unusual circumstances, and the coat had been modified to his specifications. Catullus didn’t patronize bigots, either, but if the color of his skin had bothered the tailor, the color of Catullus’s money won out.

“Then perhaps you oughtn’t stand out on the coldest part of the ship,” he suggested dryly.

Looking up at him with her bright azure eyes, she said, “But I like the view.”

Did she mean the sea or him? Damn it, he never could tell when a woman was saying something flirtatious or innocuous. Catullus didn’t have his friend Bennett Day’s skill with women—nobody did, except Bennett, and now Bennett was happily married and miles away. So all Catullus could do was blush and clear his throat, wondering how to answer.

Flirting was a skill he never mastered, so he plowed onward. “Why do you keep following me?” he asked.

“That’s cocky,” she answered. “Maybe you keep following me. This isn’t such a large ship.”

“I’ve been followed enough to know when it happens.” And he’d had just as many bids on his life. Though he doubted Miss Murphy would try to stick a knife into his throat, which happened far too regularly.

Her eyes did gleam, though. “Have you been followed before? How many times? By whom? How did you elude them?”

“No one ever forgets you’re a reporter, do they?”

Her laugh was even more low and seductive than her voice. “I never do. Why should anyone else?”

True enough. “As I said before,” he pressed, “you will get no more from me, nor from Astrid or Lesperance. There is no story.”

“There most definitely is a story, Mr. Graves,” she corrected smartly. “And either you tell it to me, or I’ll conduct the investigation on my own. But I will get everything. I’m quite tenacious.”

“So I’ve observed.” In truth, tenacity was a quality he had long prized in others and tried to cultivate in himself. Most inventions took persistence to perfect. Almost nothing came together with merely a whim. If a mechanism wasn’t working precisely right, he kept at it, refining, reassessing, until he created exactly what he intended.

In the case of stubborn American reporters, he could do with a little less tenacity.

This American reporter suddenly sank her hands into the front pockets of the overcoat and sighed with appreciation. “What a lovely coat! I’ve never felt anything so soft. What’s it made of?”

“Persian cashmere.”

“Bless me, how wonderful.” She rubbed one creamy cheek against the velvet collar. “And so many pockets.” She examined the inside of the coat and found that, indeed, it was lined with a multitude of pockets, and all of them holding something.

“I requested them added when I purchased the coat,” Catullus said, watching her slim fingers trail over the pockets in a quick cataloguing.

“It’s so nice and warm—though,” she added with a sparkle in her eyes, followed by a lowering of reddish gold lashes, “you did me a favor by warming it for me.”

With the heat of his body. Now sinking into hers. The idea dried his mouth as a bolt of desire ran straight to his groin.

Catullus clenched his jaw in consternation. Either the woman was an extremely accomplished flirt and manipulator of men, or she simply had a knack for saying things that roused his normally restrained libido. Neither of the possibilities pleased him.

“Keep the coat,” he muttered. “Have it sent to my cabin later.” He started to stalk off.

“Wait, please!”

He turned at her words, knowing he was scowling and being altogether ungentlemanly, but finding it hard to stop himself. Being played with like a puppet on a string did little to coax him into good humor.

The flirtatious cast of Miss Murphy’s face evaporated, leaving behind an expression he suspected was more true to the woman. Instead of deliberate charm, her eyes were alight with intelligence and determination. She gazed at him steadily, not a coquette but a woman with intent.

“I’ve been doing some thinking,” she said, “since the other night in your c-cabin.” She stumbled a bit over that last word, as if remembering the few moments they had been alone together. More playacting?

“I often think,” he replied. “And find it to be a highly underutilized pastime.”

A brief, real smile flashed across her face, and Catullus saw to his dismay a minuscule dimple appear in the right corner of her mouth. Precisely where a man might place the tip of his tongue before moving on to her lips.

“We’re in agreement on that.” She stepped nearer. “But what I’ve been thinking about, and can’t seem to get out of my head, is the Heirs of Albion’s goal.”

The mention of his old foes brought Catullus’s mind fully back into the present, and future. “A British empire that encompasses the globe.”

“You’re British, aren’t you? Wouldn’t such a goal work to your benefit?”

“I don’t believe any nation should have that much power. And I don’t believe one government should dictate how the rest of the world conducts its business.” Warming to his topic, he forgot to be angry with Gemma Murphy, and instead spoke with unguarded feeling. “Further, capturing the world’s magic to ensure that kind of despotism is abominable.”

“And your friends, Mrs. Bramfield and Mr. Lesperance, they and others share your feelings. Mr. Lesperance called them …” She thought back for a moment. “The Blades of the Rose. Are you one of these Blades?”

At her question, he felt a subtle pressure, a force working upon him, coaxing him. Tell her. She’s trustworthy. Just open your mouth and speak the answer. But he shoved that force away. An odd impulse, one he was glad he didn’t give in to.

“This conversation is over, Miss Murphy.” Before he could take a step, she reached out and took hold of his arm with a surprisingly strong grip.

“I’m sorry,” she said quickly. “I won’t ask more about them. Only—don’t go.”

He rather liked hearing her say that. Somewhat too much. Yet, despite his brain telling him to do just that—leave and never speak with her again—he stayed.

“I also think that what the Heirs are doing is horrible,” she continued. “Not just because they might steal or use my magic. My Irish family in America fought against the British in the War of Independence. Some lost their homes. Others died.” Her voice strengthened, grew proud. There was no artifice here. “It’s always been a source of honor for the Murphys, myself included. We stood up and fought for freedom, regardless of the price.”

“A justifiable sense of pride.”

She accepted this with a nod. “I can’t be a soldier— I don’t want to be one. But I can do something to help, something to stop the Heirs.”

“Miss Murphy, your help is not wanted.”

She did not flinch from his hard words, even as he regretted having to say them. She pressed, “Tell me everything. About the exploitation of magic. About the barbarity of the Heirs. Let me write about them.”

With a sharp movement, Catullus turned to go. Yet she dogged him, putting herself in his path.

“You say no one will believe what I write,” she said insistently, “but I don’t think that’s true. The public will believe, Mr. Graves. And they won’t stand for such wickedness. They will rise up and—” She stopped, because he was laughing.

Not an amused laugh, but a harsh and bitter one. “Newspapers mean nothing to these men. They couldn’t care less if you published their home addresses and bank accounts, plus a detailed description of every crime they had ever committed. A fly’s buzzing, nothing more.” He stepped closer, and, judging from the slightly alarmed look on her face, he must have cut a menacing figure. Good. She needed to be afraid.

“And do you know what they do with flies?” He pounded one fist into his own palm. “Crush them. Destroy them utterly.”

“But the public,” she foundered, “the government—” “Can do nothing. Not the president of your United States, and not even the Queen. The Heirs serve her Empire, but neither she nor the prime minister nor all the damned members of Parliament can touch them. They answer to no one but themselves and their greed. And they will take a tender morsel such as yourself and make you wish all the Murphys had died in the Revolution so that you might never have been born.”

The pink in her cheeks was gone entirely. Her freckles stood out like drops of blood upon her chalky face. Catullus realized he had been shouting. He never shouted.

He collected himself, barely. A tug on his jacket, a straightening of his tie. “I do not like yelling at ladies,” he said after a moment. “I don’t like yelling at you. But the moment the Heirs of Albion become aware of your presence is the day you become one of the walking dead.”

“Like you?” Her voice did not tremble.

“Pardon?”

“Are the Heirs aware of your presence?”

“Yes.” More than aware. They hated him and his entire family. Considering that the Graves clan had been supplying the Blades of the Rose with inventions and mechanical assistance for generations, the Heirs would prefer if every single member of the Graves family were cold in their tombs.

“Yet you’re still alive.”

“Because, in this war of magic, I am a professional soldier. And you are a civilian.”

“Civilians can fight. They did in the War of Independence.”

“This isn’t flintlock muskets and single-shot pistols, Miss Murphy. It’s magic that can literally wipe a city off the face of the map. And I am telling you now for the last time “—he jabbed out with a forefinger—” you are not to get involved.”

He spun on his heel and stormed away. This time, she did not try and stop him.

Several hours later, he was bent over the cramped desk in his cabin, adjusting the tension in some steel springs, when a tap sounded at his door. He found a steward outside, holding his coat.

“The lady said I was to give you this, sir,” the young sailor said.

Catullus gave the lad a shilling and, after taking back the overcoat, sent him on his way.

With the door to his cabin closed, Catullus found himself holding the coat up to his face, inhaling. He pictured her in the coat, how deceptively delicate she appeared in its voluminous folds.

There. The scent of lemon blossom and cinnamon. Her scent. He could smell it all day and never grow tired of it. Even this small sense of Gemma Murphy thickened his blood.

A small square of paper was pinned to the lapel. He adjusted his spectacles to peer at handwriting, ruthlessly tamed into a semblance of legibility.

It is a beautiful coat, but you look much more dashing in it than I. Thanks for the loan.—GM

He ran his thumb over the scrap of paper, picturing her ink-stained fingers. Perhaps he should write her a note. Apologize for his rudeness.

No. What he did was for her own protection, whether she believed him or not.

He dropped the beautiful Persian cashmere coat upon the floor and went back to work.

After the relative quiet of life aboard ship, the noise and commotion of the Liverpool docks threatened to knock one down to the floor. Catullus, Astrid, and Lesperance joined the rest of the Antonia’s passengers as the steamship approached the dock. From their vantage at the rail, they saw how the docks seethed with activity. Sailors, stevedores, and passengers all crowded along the waterfront in a chaos of sound and movement. Merchandise of every description was being hauled back and forth—American cotton, Chinese tea, African palm oil.

But slaves had made Liverpool. Not with their hands, but with the sale of their bodies. As Catullus watched the bustling dock draw closer, it didn’t escape him that Liverpool—and England—once grew wealthy from the slave trade. Ships had sailed from the Liverpool docks, laden with guns and beads, to trade for men, women, and children ripped from their West African homes. Those same ships then made the grueling voyage to the Caribbean and the American South, and there sold their surviving human cargo—including Catullus’s own family, generations ago. Then back to Liverpool with sugar, rum, cotton, and profit.

The slave trade had been officially abolished in England almost seventy years past, but Catullus felt its presence as the steamship approached the thriving docks.

All this, built by blood. Blood that ran in his veins.

Yet, despite this, he felt glad to be back in England again. It was, in all its conflicting existence, his homeland. His friends, the Blades, and his family were all here. He missed his workbench, and his tools, and the smell of oil, metal, and electricity. His workshop, nestled in the basement of the Blades’ headquarters, remained his truest home.

He glanced over at Astrid, who was also watching the dock come closer. Her mouth was pressed into a thin, tense line, and her hand was threaded tightly with Lesperance’s, her knuckles showing white.

“Back again,” Catullus said gently.

She gave a tight nod. Four years ago, a grieving Astrid had fled England, and the Blades, after her husband had been killed on a mission. She had exiled herself in the Canadian Rockies, until Catullus had been forced to bring her back. But she wasn’t returning with a broken heart.

Lesperance spared not a look for the bustle of the docks. His focus remained solely on Astrid, a concerned frown between his brows. “You can face this,” Lesperance murmured, knowing what tumult she must feel. “It’s only a pile of rocks. Nothing compared to the strength of you.”

The thin press of her mouth softened as she turned to Lesperance with a small smile. Despite the fact that they stood in full view of everyone on the ship and the docks, Astrid leaned close and kissed Lesperance. Such unguarded warmth and tenderness in that kiss, returned passionately by Lesperance, who clearly didn’t give a damn that anybody was watching.

Catullus looked away, fighting a quick pain, a sudden loneliness. Astrid had somehow been blessed to find love not once but twice, both times with good men. At forty-one years old, love still eluded Catullus.

His gaze alit upon Gemma Murphy, standing some distance down the rail. A group of passengers separated them, but he met her vivid blue eyes across the crowd.

In that crowd, amidst the cacophonous din rising up like a fist from the docks, Catullus found himself aware of only her. The brilliant gleam of her eyes, alive with intelligence and humor and will. A quick, potent flare of desire answered within him. More than desire. Something else, something deeper than a body’s wants. And, in the way she suddenly drew herself up, widening those astonishing eyes, she felt it as well.

“Haunted still by your redheaded ghost,” Astrid said behind him, her voice hard with suspicion.

Catullus came back to himself, who and where he was. He broke from Gemma Murphy’s gaze to watch the dock.

“No amount of silence on my part will exorcise her,” he said.

“Determined,” Lesperance noted, admiring. Astrid shot him a glare.

Catullus made himself shrug with indifference. “We’ll lose her once we come ashore.”

“I wouldn’t be so sure,” said Astrid. “That bloody girl’s resolved to attach herself to us—or rather to you.”

He scrupulously avoided looking at Astrid and her sharp eyes. “I’m the unattached male in our party. For a woman like her, I present the easiest target.”

“For a huntress, she’s damned fond of her prey,” Astrid replied, heated.

The ship finally docking gave Catullus a reprieve. He, Astrid, and Lesperance joined the chattering, excited passengers as they disembarked. Somewhere in the crowd behind him was Gemma Murphy. But ahead of him was the most important mission of his life. He would forget her, as he must.

A few satchels made up their minimal luggage. As soon as it was collected, they started toward the train station. Everywhere was thick with people and voices and heavy drays loaded with cargo. The cheerful chaos of commerce.

Which made for hard going to reach the station on foot. It wasn’t far, a quarter mile, and hiring a cab was impossible in this bedlam. Yet each step found the trio buffeted by movement. At this rate, they would reach the station by nightfall.

“Bugger this,” Catullus muttered under his breath. He signaled Astrid and Lesperance to a narrow side street off the busy dock, blissfully empty.

They both nodded. It might not be a direct route to the station, but they’d reach their destination faster. And, in these circumstances, time was all. They had to reach Southampton as soon as possible.

So the three of them ducked into the side street. The only occupants were a few crates and a dog. The dog noticed Lesperance and trotted forward to him, tail wagging. Lesperance gave the animal a good scratch under the chin before striding briskly onward. The dog scampered away, cheerful in its existence.

“Always making friends,” Astrid murmured.

“They aren’t friends,” Catullus said. He stared ahead, where the large figures of three men swiftly blocked the narrow street. He, Astrid, and Lesperance stopped, tensing. The men loomed nearer. All of them held knives. “Heirs,” growled Lesperance.

“No—they won’t get their hands dirty here,” Catullus said. “Thugs hired by the Heirs to watch the docks. Should have expected this.”

He started to reach for his revolver before checking himself. This was civilized England, where men didn’t wear guns in the streets, including himself. His pistol and shotgun were both packed away in the bags he carried. And, even if he could get to them quickly, firearms were too conspicuous, too noisy, too problematic for close-quarters fighting.

Evasion was a better option than engagement. Only fools raced into battle, if it could be avoided.

Catullus turned, thinking to lead Astrid and Lesperance back to the main dock. They might have a chance to lose their pursuers in the throng.

He cursed as two more men blocked the other end of the street. One of them pulled a cudgel from beneath his heavy coat, and the other, smiling brutally, brandished a dockworker’s hook.

“Hardly ten minutes ashore, and already in a fight.” But Astrid smiled coldly as she spoke, shifting into a ready stance. Meanwhile, Lesperance growled, half in warning, half in frustration. Even this side street was too public for him to truly unleash what he was capable of. His hands curled into fists as a substitute.

“I’ll take the two behind us,” Catullus said lowly.

“We’ve got the other three,” answered Lesperance. A shared, clipped nod, and they broke apart.

Lesperance and Astrid sprang toward the advancing threesome. The thugs stood motionless for a bare second, stunned that those who were supposed to be the victims had, in fact, become aggressors. Catullus had a brief impression of Lesperance’s swinging fists, and Astrid’s own expert fighting skills as she dodged and struck. But Catullus’s attention had its share of distractions and he focused on the two toughs coming at him.

He couldn’t use his guns, but pulled a shotgun shell from a side pocket on a satchel, then dropped the bag. He kicked an empty crate at the advancing men. They ducked, and the crate shattered into planks and splinters. The bloke with the cudgel recovered faster than his comrade, lunging forward and swinging out with his heavy club. Catullus neatly sidestepped the blow. Then the cudgel hit a brick wall lining the street. The bricks exploded with a flash of blue light.

Catullus shielded his eyes from the glare. He leapt back to see a hole the size of a door where the cudgel had hit. The man wielding it laughed, a guttural rasp.

“That’s right, guv,” he chortled with a Liverpudlian roll to his words. “Got me a little something extra, thanks to the gents what hired us.” He held the club up, and Catullus saw a small mark branded into the wood. Catullus had seen that lion brand before on other clubs, knives, and even the wooden handles of guns. It imbued whatever had been branded with the Heirs’ particular variety of dark magic—including a hired tough’s cudgel.

The man swung the club again, this time hitting the ground. Another blast of light. Catullus staggered from the concussion as the pavement split apart into gaping fractures.

As he struggled to gain his footing, the other thug pounced, hook swinging. Catullus blocked the wicked curved gaff, then planted a foot in the man’s gut and shoved him back.

His comrade plowed toward Catullus again.

“I have a little something extra, as well,” Catullus said. Gripping the brass shotgun shell, he slammed its bottom down onto a nail sticking from a shattered crate.

The small blast shook him, ran in shock waves up his arm, but it was enough to shoot a little ball of glinting material from the cap. The ball spread into a wire net, which tangled itself around the advancing thug.

For a few moments, the tough could only flounder and swear, snarled in the net, his cudgel useless against the snare.

“Never tried that by hand before,” Catullus murmured to himself.

His companion shoved past and came at Catullus. The hook swung. Catullus lightly stepped back, then grabbed the man’s arm. It was difficult, since Catullus’s hand still buzzed with the aftereffects of the shell’s blast. They grappled, fighting for footing and control of the gaff. Catullus was taller than the thug, but the man was heavier and furious that the intended target wasn’t going down easily. They wrestled, careening back and forth between the walls lining the street. A hot trail of pain gleamed as the hook caught the top of Catullus’s cheekbone.

With a sudden grunt, the man collapsed against Catullus. Peering over the unconscious man’s shoulder, Catullus saw something rather amazing.

Gemma Murphy held a heavy rope, one end tied into a large, weighty knot. The stain of red and clump of hair attached to the knot testified to how hard she had hit Catullus’s assailant.

“Dead?” she asked.

Catullus shoved at the man heavily against him. The man crumpled to the ground. “No, but he smells like it.” He strode to where the cudgel-wielding tough still struggled against the net. With one quick punch, Catullus knocked the man unconscious. Like his associate, the thug collapsed to the ground.

“Deft,” Catullus murmured, glancing between the rope she held, then up at Miss Murphy.

She looked back at him with a gleam of triumph hidden beneath careful sangfroid, then turned to the net, still covering the insensate thug. “What are you doing with a net inside a shotgun shell?”

“I had planned on using it for fishing. It has a much smaller charge than with a typical shell.” Which had kept him from blowing his own hand up. He shook it out, losing the last traces of the reverberations.

“Diabolical,” she added, eyeing the intricate wire net.

Catullus smiled modestly.

Then Gemma Murphy glanced behind him with a frown. “Your friends—”

Hell. He’d been so amazed at Miss Murphy’s appearance, he had almost forgotten Astrid and Lesperance. He turned to them now. One of their assailants lay upon the ground, unconscious or dead Catullus could not tell. The other two were giving a hell of a fight. Lesperance bared his teeth as he and his attacker traded punches, while Astrid sent a flurry of deliberate kicks toward the stomach and legs of the thug advancing on her.

The man bearing down on Astrid glanced over to see Catullus standing with Gemma Murphy. His watery little eyes took stock of everyone in the alley, as though cataloguing them for a future report to the Heirs. Yet the thug not only saw Catullus, Astrid, and Lesperance, but Gemma Murphy as well, including her in their ranks. Too late did Catullus step in front of her, shielding her from his gaze. Astrid also darted a glance in Catullus’s direction, giving her attacker a tiny opening. But instead of launching an assault, the man spun on his heels and darted away. He’d calculated the odds and found them decidedly not in his favor.

So he fled.

His comrade wasn’t so lucky. Lesperance punished him with punches until the remaining thug slid in a boneless, bloody heap to the grimy pavement.

“Everyone all right?” Catullus asked.

Astrid nodded, and Lesperance grunted an assent, gingerly adjusting his jaw.

“And you?” Catullus turned to Miss Murphy.

She also nodded, though she held up one slim hand, revealing red, chafed fingers “Little bit of rope burn.” She shrugged off this small injury.

“What are you doing here?” Astrid demanded.

Miss Murphy was not fazed by Astrid’s harsh tone. “I had a feeling that trouble might follow you off the ship.” She glanced over at the huge hole and fissures left by the cudgel, and raised a brow. “I see I was right.”

Catullus took advantage of the brief lull to retrieve the cudgel. With a knife, he scratched off the lion brand, rendering it just a piece of heavy wood. He tossed it to the ground and was gratified that it only rolled along the pavement, rather than cleave a gaping hole in the street.

Miss Murphy still had her questions. “How did they know to find you in Liverpool?”

“The Heirs must have hired men to watch all the major ports,” said Catullus. He was all brisk business as he collected his bags. “Bristol, London. Southampton, of course. And Liverpool. We have to leave immediately. Before more Heir hooligans arrive.”

“One of them got away,” Lesperance rumbled. “I can give chase.”

“How?” asked Gemma Murphy. “He’s probably long gone by now, lost in the crowd.”

“I’ve got a few ways of tracking someone,” Lesperance said, with a small, dark smile.

Miss Murphy didn’t understand, but this wasn’t the moment for explanations.

“No time,” Catullus said. “The authorities might be here any minute and we have to get out of Liverpool now. Grab your bags.” He strode toward Gemma Murphy and wrapped a hand around her slender, strong wrist. She glanced down at the sight, then up again, a question in her eyes.

“What are you doing?”

He began to pull her toward the end of the street, toward the train station. “Keeping you alive.”

Chapter 3

Miss Murphy Makes the Leap

Gemma hurried to keep up with Catullus Graves’s longlegged strides as they cut through the streets of Liverpool. She had no idea where he was taking her, but he seemed to know exactly where to go. Gemma darted a quick glance behind. None of the thugs followed, though Astrid and Lesperance remained vigilant as they trailed after her and Graves.

“Those men,” she panted. Damn those weeks of travel, leaving her softer and less conditioned. “They were sent by the Heirs?”

“Yes.” Clipped and alert, he didn’t spare Gemma a glance. But he didn’t release her, either. His hand was an unbreakable hold around her wrist. “And they saw you.” This he said with anger hard in his voice. Anger at her? She had just helped him.

When a train station loomed into view, Gemma tried to dig her heels into the pavement. “Don’t send me away.”

He didn’t slow, her resistance proving useless against his strength. “I’m not,” he growled. “We are taking a train to Southampton, and you’re coming with us.”

So prepared was she to argue her case, she thought she misheard him. “What?”

On the steps leading into the station, he finally did stop, swinging around to face her. Behind his spectacles, his eyes were deepest brown, gleaming with fury and resolve. “I was a damned idiot,” he snarled. “I let one of those bastards see you, and now your life isn’t worth tuppence.”

His anger was for himself, not her. But she couldn’t allow that. “He only saw me for a second. Surely that’s not enough.”

“For the Heirs, it’s all they need. It won’t take much for them to learn who you are, and know that you fought on the side of the Blades. That means your life is imperiled.” He paced up the stairs to the station, with her still in tow. “The safest place for you now is with me.”

A fast chill ran along Gemma’s spine to think that she was now the target of a ruthless band of powerful, magic-wielding men. She’d experienced danger before—including a trio of unruly fur trappers desperate for female company, though they were less inclined to pursue her after she shot one in the hand and nearly emasculated another. There had been many other brushes with risk. But nothing like this. Nothing where she truly felt her life was threatened.

Graves would keep her close, keep her safe. There was no doubt in him. While she was in his care, he would ensure no harm would come to her.

Inside, the station teemed with activity, almost as chaotic as the docks. Gray sunshine poured in from large skylights, illuminating the cavernous station and people swarming along platforms, where huge, shining black trains waited and steamed. None of the thousands of people here had any idea that a war was being fought for the world’s magic. But they might learn, when she wrote of it.

If she lived.

Graves stopped in the middle of this industrial and human maelstrom. Astrid and Lesperance caught up, and the Englishwoman shot Gemma a suspicious glance.

“She’s coming with us, then?”

“One of them saw her.”

Astrid nodded with grim understanding, though it was clear from her severe expression that she didn’t care for Gemma’s presence.

Well, Gemma didn’t much like Astrid Bramfield, either. “You aren’t the only woman who knows how to fight.” She had proved it, minutes ago.

“Good.” But there was no faith or gratitude in the Englishwoman’s silver eyes.

“Miss Murphy’s shown she can be trusted,” Lesperance said.

“She’s demonstrated she can swing a rope,” countered Astrid. “That doesn’t mean she’s trustworthy.”

“She’s still coming with us,” said Graves.

“And standing right here,” added Gemma. She didn’t care for being talked about like a unmatched, smelly shoe.

“I’ll purchase the tickets.” Graves finally released Gemma’s wrist to move toward the ticket counter, and she found she wanted his touch again.

“Wait!”