Suburban Nation, 10th Anniversary Edition – Read Now and Download Mobi

TO OUR PARENTS

Table of Contents

Title Page

PREFACE TO THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION

INTRODUCTION

1 - WHAT IS SPRAWL, AND WHY?

TWO WAYS TO GROW

THE FIVE COMPONENTS OF SPRAWL

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SPRAWL

WHY VIRGINIA BEACH IS NOT ALEXANDRIA

NEIGHBORHOOD PLANS VERSUS SPRAWL PLANS

2 - THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAILS

WHY TRAFFIC IS CONGESTED

WHEN NEARBY IS STILL FAR AWAY

THE CONVENIENCE STORE VERSUS THE CORNER STORE

THE SHOPPING CENTER VERSUS MAIN STREET

THE OFFICE PARK VERSUS MAIN STREET

USELESS AND USEFUL OPEN SPACE

WHY CURVING ROADS AND CUL-DE-SACS DO NOT MAKE MEMORABLE PLACES

3 - THE HOUSE THAT SPRAWL BUILT

THE ODDITY OF AMERICAN HOUSING

PRIVATE REALM VERSUS PUBLIC REALM

THE SEGREGATION OF SOCIETY BY INCOME

TWO ILLEGAL TYPES OF AFFORDABLE HOUSING

TWO FORGOTTEN RULES OF AFFORDABLE HOUSING

THE MIDDLE-CLASS HOUSING CRISIS

4 - THE PHYSICAL CREATION OF SOCIETY

ENVIRONMENTAL CAUSES OF A SOCIAL DECLINE

DRIVERS VERSUS PEDESTRIANS

PREREQUISITES FOR STREET LIFE

5 - THE AMERICAN TRANSPORTATION MESS

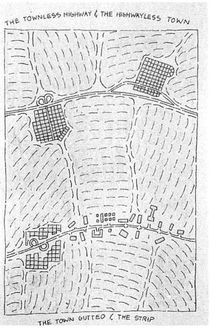

THE HIGHWAYLESS TOWN AND THE TOWNLESS HIGHWAY

WHY ADDING LANES MAKES TRAFFIC WORSE

THE AUTOMOBILE SUBSIDY

6 - SPRAWL AND THE DEVELOPER

THE DECLINE OF THE AMERICAN DEVELOPER

THE INSIDIOUS INFLUENCE OF THE MARKET EXPERTS

QUESTIONABLE CONVENTIONAL WISDOM

STRUGGLES WITH THE HOMEBUILDERS

A VISIT TO THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF HOME BUILDERS’ ANNUAL CONVENTION

7 - THE VICTIMS OF SPRAWL

CUL-DE-SAC KIDS

SOCCER MOMS

BORED TEENAGERS

STRANDED ELDERLY

WEARY COMMUTERS

BANKRUPT MUNICIPALITIES

THE IMMOBILE POOR

8 - THE CITY AND THE REGION

THE POSSIBILITY OF GOOD SUBURBS

SUBURBS THAT HELP THE CITY

THE EIGHT STEPS OF REGIONAL PLANNING

THE ENVIRONMENTAL MOVEMENT AS A MODEL

9 - THE INNER CITY

THINKING OF THE CITY IN TERMS OF ITS SUBURBAN COMPETITION

THE AMENITY PACKAGE

CIVIC DECORUM

PHYSICAL HEALTH

RETAIL MANAGEMENT

MARKETING

INVESTMENT SECURITY

THE PERMITTING PROCESS

10 - HOW TO MAKE A TOWN

REASONS NOT TO, AND REASONS TO DO SO ANYWAY

REGIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

MIXED-USE DEVELOPMENT

CONNECTIVITY

MAKING THE MOST OF A SITE

THE DISCIPLINE OF THE NEIGHBORHOOD

MAKING TRANSIT WORK

THE STREETS

THE BUILDINGS

PARKING

THE INEVITABLE QUESTION OF STYLE

A NOTE FOR ARCHITECTS

11 - WHAT IS TO BE DONE

THE VICTORY MYTH

THE ROLE OF POLICY

MUNICIPAL AND COUNTY GOVERNMENT

REGIONAL GOVERNMENT

STATE GOVERNMENT

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

ARCHITECTS

CITIZENS

SUBURBAN NATION

Acclaim for SUBURBAN NATION

APPENDIX A - THE TRADITIONAL NEIGHBORHOOD DEVELOPMENT CHECKLIST

APPENDIX B - THE CONGRESS FOR THE NEW URBANISM

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

SOURCES OF ILLUSTRATIONS

INDEX

Notes

Copyright Page

PREFACE TO THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION

THE STORY OF SUBURBAN NATION

Now that Suburban Nation has managed to stay in print for a decade and sell close to 100,000 copies, it seems excusable to tell the story of how it came to be.

I had been eagerly following the work of Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk since their Neo-Constructivist Arquitectonica days, and had been intrigued and excited by their new town of Seaside as a design exercise, without considering its larger social implications. There is a note to be found in one of my pre-architecture school sketchbooks: “If you are interested in urban design, find these guys.” Then, in 1988, I heard Andres speak at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. It was what was to become his famous “Town versus Sprawl” lecture, and I immediately knew two things: first, that this was the best story I had ever heard; and second, that it had to be a book.

It was the best story I had ever heard because even though I had understood it in my heart for years, I had never understood it in my head. I knew that I loved older places like Georgetown and hated newer places like Tyson’s Corner, but I had never really asked myself why. Andres explained why, and he also explained how these beloved and unlovable places had come to be. He identified the villains and the historical processes that had half destroyed the American landscape; and, remarkably, he showed us how we could fight those villains, reform those processes, and literally win back ground.

Around that time, I had recently published my first book and was considering moving to Rotterdam to work with Rem Koolhaas on what was to become S,M,L,XL. That offer never materialized and I started architecture school at Harvard, where my professors’ attitudes toward Duany Plater-Zyberk ranged from amused to hostile. Unswayed, I wrote a letter to Andres and Lizz, offering to ghostwrite a book that would bring their message to a larger audience. They never wrote back.

Four years of continued pestering led to no progress on that topic, but it did get me hired by Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company after graduation. Once firmly ensconced in Miami, I kept asking about the book, but there were always too many other things to get done. My challenge was to convince Andres and Lizz that a book, far from being a distraction, could make our jobs easier.

I had always been amazed by Andres’s and Lizz’s patience with the Sisyphean task of convincing American communities to make traditional town planning legal again. It seemed that we repeated the same experience every month: we would show up in a city or town; meet with every willing citizen and public official; explain over and over, often encountering great resistance, why streets were too wide, trees were too scarce, and diverse land uses were kept too far apart. More often than not, we would get somewhere—never as far as we wanted, but after weeks of meetings and months of drawing, we would reach a compromise that led to skinnier streets, more trees, and a healthier mix of uses. Then, the next month, we would arrive in another community, begin the process again, and be met by the same resistance, as if we had never accomplished anything. Weren’t you people listening? I would silently curse. Then I would remember that we were no longer in Madison; this time we were in Santa Fe and no, the conversation was just starting. All over again.

The desire to short-circuit this Groundhog Day situation finally drove Andres and Lizz, in 1998, to let me write a first draft. Andres’s “Town versus Sprawl” lecture became the heart of the book, supplemented by another lecture he had developed in 1992, “The Story of City Planning,” a fast, loose, and mostly true yarn about the glorious past and ignominious present of the planning profession. A final chapter, “What Is to Be Done,” grew out of a characteristically insightful paper by Lizz. These three sources were augmented by roughly five years spent reading the publications now listed in the bibliography, most of which could be found in the formidable DPZ office library.

The greatest struggle, from a literary perspective, was translating Andres’s distinctive voice into print. Direct transcriptions of his lectures, which seemed so clear and compelling in person, produced something other than English. I consider this voice to be an essential aspect of the book’s popularity, just as the New Urbanism movement can credit much of its ascendancy to Andres’s charisma and sense of humor. Most of the jokes in the book are his, not mine—at least the good ones.

I think it is safe to say that Andres and Lizz, who are not known for lacking confidence, were nonetheless surprised by the early and continued success of the book. It is often difficult to fathom the merit of one’s own ideas. Furthermore, my coauthors had grown accustomed to the cynical gaze of the design world, until recently one of the most out-of-touch and disoriented intellectual communities in existence. Andres and Lizz had seen their efforts and their projects attacked for, among other things, their very populism and accessibility. No wonder, then, that what academia found to be too “real-world,” the real world was ready to hear and embrace.

As the following two essays relate, much has changed in the decade since Suburban Nation was published. In professional and policy circles, its arguments have mostly won the day. Even the most intellectually isolationist design schools are beginning to embrace the book’s activist message, as today’s students are demanding a return to socially relevant work. Our most recent book, The Smart Growth Manual, puts meat on the bones of many of the issues raised here, for those who want to take theory into practice.

But many people still need convincing, especially on the (suburban) fringes. Let’s face it: most Americans, who don’t think very often about city planning and who haven’t been offered the alternatives, are still settling for sprawl. Turning that ship around is a project for the next decade.

—JEFF SPECK, WASHINGTON, D.C.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

The ten years since Suburban Nation was published have seen a great change in American attitudes toward the built environment. Suburban Nation has not been the sole agent of this change, of course, but clearly we got something right—right enough for the book to have a shelf life and a future.

A predicated future suggests that the problems described herein remain. Still, one can be encouraged by visible progress. The alternatives to sprawl are clear, and examples abound. In once-decanted downtowns, empty parking lots are being replaced by streets and blocks of high-density housing, offices, and retail development. Mixed-use, transit, and walking are words that no longer elicit smirks. Indeed, in cities where public transportation was shunned, the lack of it is now a public complaint. The relationship between public health and the design of the built environment has been firmly established, with scientific data supporting the benefits of urban walking as part of a daily routine.

Many organizations have sprung up to promote this change. Among them, the Congress for the New Urbanism, by setting out principles for regional, neighborhood, street, and block design, has influenced many town plans, as well as national standards for traffic engineering. The U.S. Green Building Council has moved beyond rating individual buildings to include entire communities in its new LEED for Neighborhood Development program. Smart Growth America has consolidated environmental and urban agendas to promote compact development. Its arguments for the appropriate detailing of streets and buildings to make dense environments walkable have led to the Form-Based Codes Institute’s influential advocacy. The Council for European Urbanism, the Institute for Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism, and other sister organizations in Australia, Israel, the Philippines, and India are globalizing shared principles and experiences.

The Lexicon of the New Urbanism—a continuously updated collaborative work—has advanced theory and technique, introducing the rural-to-urban transect as an organizing structure for conservation and development and resulting in the creation of the SmartCode, a model zoning ordinance now being used in many states to shape regional plans and local codes. A growing catalogue of tested techniques and an explosion of scientific studies are extending public awareness and engagement and changing policies around the world.

In the past decade, New Urban News has reported on more than six hundred plans for new and renewed walkable communities in the United States and abroad. Each of these projects represents a victory over entrenched regulatory or market hurdles. The appeal of these places—their functionality and the pleasure they give—have swelled the movement. Some merit greater acknowledgment than they have received. Poundbury, in Dorset, England, is probably the best example of an urban extension. It holistically integrates a full range of components missing from many other ambitious developments, including significant amounts of workplace and affordable housing. Like some of its better-known American counterparts, Poundbury stands irrefutable, promising the ultimate sustainability: the permanence that accrues only to places that are loved.

Given the advances of the past decade, perhaps it is not hubristic to declare that we can see a future of wiser, healthier, more efficient and more beautiful place-making.

Social scientists identify three phases in cultural change: first, social marketing; then the removal of existing barriers to change; and finally the enactment of new regulations. Suburban Nation has helped to socially market a change in the way we build. Americans are now well into the subsequent phases of removing barriers and regulating … and not a moment too soon. Growing awareness of the need to adapt to climate change, energy limits, and economic volatility has created an environment of ferment and opportunity. Development patterns that reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions are no longer merely a matter of choice.

History has shown that lost momentum can result in lost knowledge. Unless put to use, hard-won skills atrophy. The first decades of the twentieth century, which saw the creation of Mariemont, Forest Hills, Coral Gables, and other exemplars of town planning, were followed by a period of inactivity long and distracted enough so that when construction resumed after World War II, Americans had utterly lost the capacity for that model of community-building. As we reluctantly settle into another period of great economic uncertainty, we must take pains to avoid another decline into professional dementia. Toward this end, I hope that Suburban Nation will serve as a lasting battery of knowledge, a record of what needed to be overcome in our time, and an admonition, lest hard times lead to lowered ambitions.

—ELIZABETH PLATER-ZYBERK, MIAMI, FLORIDA

AVOIDING OBSOLESCENCE

When Suburban Nation was being written a dozen years ago, each of the authors fell into a role. Jeff was the purveyor of the light touch. His easygoing tone has contributed as much as anything to the book’s appeal. It is probably responsible for the number of people who have told me that, to their own surprise, they read it to the end. Lizz, for her part, was the guardian of clarity. She has no patience for obscurantism in language or message. Suburban Nation’s simple and straightforward writing is an extension of the educational philosophy she promotes at the University of Miami, where students learn “plain old good architecture.” Her success is evidenced by the book’s unexpected popularity as required reading—even in high schools.

My own contribution to the editing process was a result of simple time management. With new towns to design that could outlast centuries, why spend an inordinate number of hours on a text that might have a shelf life of only a few years? I was aware of the tension between a book focused on a present problem and one of lasting relevance, and I argued strongly that our book should be the latter. In this regard, Jane Jacobs’s half-century-old The Death and Life of Great American Cities was my model—a difficult one to live up to, granted, but the pursuit of unattainable ideals is stimulating. And so I undertook the editing with an eye to issues that were of the more transcendental sort. To this end, the grand subject of urbanism certainly provided a good foundation. The fashionable was eradicated under my pen—and so I bear any blame for the book’s being not nearly as hip as the younger Jeff would have had it.

Then, shortly after it was published, I realized that while I had checked the book for technical obsolescence, I had not done so for political survivability. More out of curiosity than anything else, I asked for assessments from two friends, one attuned to right-wing and the other to left-wing bias. Both marked-up copies were returned with a similar number of disputed statements, and I remember being surprised at how unnecessary these passages were. Although we could have smoothed the feathers for this second edition, the original text remains intact, as it has done no great harm. It seems that, for different reasons, Suburban Nation is read by radical protectors of the environment no less than by conservatives concerned with the restoration of the traditional human community. Perhaps this is because it avoids ideology altogether and puts theory last—simply proposing an alternative habitat for the American middle class, which deserves much better than it is getting. Most Americans are self-interested and pragmatic enough to realize that New Urbanist communities make more sense than the sprawl model, and that they suffer very few downsides. Only extreme libertarians, who so relentlessly espouse choice, fail to understand that such communities are not allowed under the current planning regime, and that the book is actually proposing that they should be included among the available options.

But politics delivers only temporary buffetings, while obsolescence is terminal. There are important questions that should be asked now about the book, such as “What has proven to be wrong?” and “What was left out?” Although I am fairly certain that I will not be able to repeat this claim in a twentieth-anniversary edition, so far nothing much has been contradicted or become irrelevant. In fact, the book seems less urgent today only because its message has permeated public discourse. It has been absorbed in initiatives of the Environmental Protection Agency, the Institute of Transportation Engineers, the U.S. Green Building Council, and others, as Lizz relates. In fact, many of the book’s prescriptions have by now been institutionalized as regulations. I confess that for me this is not always gratifying, as I find revolution more interesting than administration.

Regarding what was left out of the book ten years ago, several issues that were then on the sidelines have grown dramatically in importance. Chief among them is local food production, now evolving into Agricultural Urbanism (“Ag is the new golf!”). Then there are the awful health implications of the suburban lifestyle, which would warrant an entire chapter now that the research is available. And insufficient emphasis was placed on the problem of water quality, although dedicating too many pages to any challenge not experienced universally would not have been in the spirit of the book.

Perhaps what most dates Suburban Nation is its discussion of the problem we marginally addressed as “air pollution,” now recognized as the catastrophe of climate change. A better understanding of this issue would have imparted a greater urgency to our call for the reform of suburban sprawl, and positioned the book closer to the center of the current debate. We can now state in no uncertain terms that blame for the planet’s environmental problems lies with the lifestyle of the American middle class: the way we live large and occupy too much land; the way we must drive to accomplish so many perfectly ordinary tasks; the way we grow our food; and the way our dependence on cars leads us to compensate for social isolation with an astonishing level of unnecessary consumption. In other words, the root cause of the fearsome crises we are facing is this pleasant suburban life of ours, and we have to do something about it right now.

And today, as clueless design consultants foist sprawl on Europe, the Middle East, Latin America, and Asia, this book becomes even more essential. There is apparently a Chinese edition of Suburban Nation. We wish it many printings.

—ANDRES DUANY, MIAMI, FLORIDA

You’re stuck in traffic again.

As you creep along a highway that was widened just three years ago, you pass that awful new billboard: COMING SOON: NEW HOMES! Already the bulldozers are plowing down pine trees, and a thin layer of mud is oozing onto the roadway. How could this be happening? Over the years, you’ve seen a lot of forest and farmland replaced by rooftops, but these one hundred acres had been left unscathed, at the whim of a wealthy owner. Now, it is said, the owner has passed on, the children have cashed out, and the property has fallen victim to the incessant pressures of growth.

These one hundred acres, where you hiked and sledded as a child, are now zoned for single-family housing. They have been bought and sold on that premise, and there is a strong demand for new houses. The developer is not about to go away. The anticipated buyers of these new homes, your future neighbors, are respectable professionals, families much like yours, people who could easily be your friends, relatives, or colleagues. These people are welcome to settle this land, to share your suburban dream—over your dead body.

Why, in this country in which growth is considered tantamount to well-being, in which economic health is measured in “housing starts,” is the prospect of these particular houses starting near yours so threatening? What has happened to our manner of growth, such that the thought of new growth makes your stomach turn?

It is not just sentimental attachment to an old sledding hill that has you upset. It is the expectation, based upon decades of experience, that what will be built here you will detest. It will be sprawl: cookie-cutter houses, wide, treeless, sidewalk-free roadways, mindlessly curving cul-de-sacs, a streetscape of garage doors—a beige vinyl parody of Leave It to Beaver. Or, worse yet, a pretentious slew of McMansions, complete with the obligatory gatehouse. You will not be welcome there, not that you would ever have reason to visit its monotonous moonscape. Meanwhile, more cars will worsen your congested commute. The future residents will come in search of their American Dream, and in so doing will compromise yours.

You are against growth, because you believe that it will make your life worse. And you are correct in that belief, because, for the past fifty years, we Americans have been building a national landscape that is largely devoid of places worth caring about. Soulless subdivisions, residential “communities” utterly lacking in communal life; strip shopping centers, “big box” chain stores, and artificially festive malls set within barren seas of parking; antiseptic office parks, ghost towns after 6 p.m.; and mile upon mile of clogged collector roads, the only fabric tying our disassociated lives back together—this is growth, and you can find little reason to support it. In fact, so far as your hectic daily schedule allows, you fight it. Once a citizen, you have now become a Nimby (Not In My BackYard), or what professional planners dismissively term a Banana (Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anything). As such, you are hardly expected to be reasonable, or even polite. Still, it would be nice if there were a more constructive role to play—if only there were some third choice available other than bad growth and no growth, the former being difficult to stomach and the latter being difficult to sustain for more than a few years at a time.

Obviously, that third choice is good growth, but is there really such a thing? Do there exist man-made places that are as valuable as the nature they displaced? How about your hometown Main Street? Or Charleston? San Francisco? Few would dispute that man has proved himself capable of producing wonderful places, environments that people cherish no less than the untouched wilderness. They, too, are examples of growth, but they grew in a different way than the sprawl that threatens you now.

The problem is that one cannot easily build Charleston anymore, because it is against the law. Similarly, Boston’s Beacon Hill, Nantucket, Santa Fe, Carmel—all of these well-known places, many of which have become tourist destinations, exist in direct violation of current zoning ordinances. Even the classic American main street, with its mixed-use buildings right up against the sidewalk, is now illegal in most municipalities. Somewhere along the way, through a series of small and well-intentioned steps, traditional towns became a crime in America. At the same time, one of the largest segments of our economy, the homebuilding industry, developed a comprehensive system of land development practices based upon sprawl, practices that have become so ingrained as to be second nature. It is these practices, and the laws that encourage them, which must be overcome if good growth is to become a viable alternative.

As daunting as such a task may seem, it is not impossible. Slowly but surely, often led by reformed Nimbys, cities and towns throughout North America are rewriting their zoning laws and demanding a higher standard of performance from their developers. Encouraged by the success of a few pioneering projects, homebuilders have begun to experiment with a form of development that grows its cities and towns in the traditional manner of the country’s most successful older neighborhoods. The question is not whether or not such growth is possible but whether it will come in time to spare our countryside, small towns, and older cities from the march of suburbia.

Whether America grows into a placeless collection of subdivisions, strip centers, and office parks, or real towns with real neighborhoods, will depend on whether its citizens understand the difference between those two alternatives, and whether they can argue effectively for healthy growth. Toward that end, we offer this book. It is a summing up of our experiences, as designers and citizens, over the past two decades all across our land.

Since 1979, when we were first asked by Robert Davis to design Seaside, Florida, we have been intimately involved in the creation and revitalization of villages, towns, and cities from Cape Cod to Los Angeles. Everywhere we’ve visited, we have observed and studied urban and suburban life: walked the downtowns, cruised the suburbs, enjoyed meals in homes, given lectures in university theaters, corporate boardrooms, and high school cafeterias. Most of all, we have talked to the residents of these places, and we have listened intently. Almost without exception, the message we have heard, a message of deep concern, has been the same: the American Dream just doesn’t seem to be coming true anymore. Life at the dawn of the millennium isn’t what it should be. It seems that our economic and technological progress has not succeeded in bringing about the good society. A higher standard of living has somehow failed to result in a better quality of life.

And from mayors to average citizens, we have heard expressed a shared belief in a direct causal relationship between the character of the physical environment and the social health of families and the community at large. For all of the household conveniences, cars, and shopping malls, life seems less satisfying to most Americans, particularly in the ubiquitous middle-class suburbs, where a sprawling, repetitive, and forgettable landscape has supplanted the original promise of suburban life with a hollow imitation. In an architectural version of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, our main streets and neighborhoods have been replaced by alien substitutes, similar but not the same. Life once spent enjoying the richness of community has increasingly become life spent alone behind the wheel. Lacking a physical framework conducive to public discourse, our family and communal institutions struggle to persist in our increasingly sub-urban surroundings. And suburban growth seems to have also drained much of the vitality from our inner cities, where a carless underclass finds itself with diminishing access to jobs and services.

It doesn’t have to be this way. After many successes, a number of failures, and, most important, prolonged collaboration with residents of every part of this country, we believe more strongly than ever in the power of good design to overcome the ills created by bad design, or, more accurately, by design’s conspicuous absence.

We live today in cities and suburbs whose form and character we did not choose. They were imposed upon us, by federal policy, local zoning laws, and the demands of the automobile. If these influences are reversed—and they can be—an environment designed around the true needs of individuals, conducive to the formation of community and preservation of the landscape, becomes possible. Unsurprisingly, this environment would not look so different from our old American neighborhoods before they were ravaged by sprawl.

Historically, we have rebuilt our nation every fifty to sixty years, so it is not too late. The choice is ours: either a society of homogeneous pieces, isolated from one another in often fortified enclaves, or a society of diverse and memorable neighborhoods, organized into mutually supportive towns, cities, and regions. This book is a primer on how design can help us untangle the mess we have made and once again build and inhabit places worth caring about.

WHAT IS SPRAWL, AND WHY?

TWO WAYS TO GROW; THE FIVE COMPONENTS OF SPRAWL;

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SPRAWL; WHY VIRGINIA BEACH IS NOT

ALEXANDRIA; NEIGHBORHOOD PLANS VERSUS SPRAWL PLANS

The cities will be part of the country; I shall live 30 miles from my office in one direction, under a pine tree; my secretary will live 30 miles away from it too, in the other direction, under another pine tree. We shall both have our own car.

We shall use up tires, wear out road surfaces and gears, consume oil and gasoline. All of which will necessitate a great deal of work … enough for all.

—LE CORBUSIER, THE RADIANT CITY (1967)

This book is a study of two different models of urban growth: the traditional neighborhood and suburban sprawl. They are polar opposites in appearance, function, and character: they look different, they act differently, and they affect us in different ways.

The traditional neighborhood was the fundamental form of European settlement on this continent through the Second World War, from St. Augustine to Seattle. It continues to be the dominant pattern of habitation outside the United States, as it has been throughout recorded history. The traditional neighborhood—represented by mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly communities of varied population, either standing free as villages or grouped into towns and cities—has proved to be a sustainable form of growth. It allowed us to settle the continent without bankrupting the country or destroying the countryside in the process.

The traditional neighborhood: naturally occurring, pedestrian-friendly, and diverse. Daily needs are located within walking distance

Suburban sprawl: an invention, an abstract system of carefully separated pods of single use. Daily needs are located within driving distance

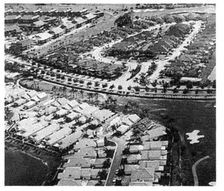

Suburban sprawl, now the standard North American pattern of growth, ignores historical precedent and human experience. It is an invention, conceived by architects, engineers, and planners, and promoted by developers in the great sweeping aside of the old that occurred after the Second World War. Unlike the traditional neighborhood model, which evolved organically as a response to human needs, suburban sprawl is an idealized artificial system. It is not without a certain beauty: it is rational, consistent, and comprehensive. Its performance is largely predictable. It is an outgrowth of modern problem solving: a system for living. Unfortunately, this system is already showing itself to be unsustainable. Unlike the traditional neighborhood, sprawl is not healthy growth; it is essentially self-destructive. Even at relatively low population densities, sprawl tends not to pay for itself financially and consumes land at an alarming rate, while producing insurmountable traffic problems and exacerbating social inequity and isolation. These particular outcomes were not predicted. Neither was the toll that sprawl exacts from America’s cities and towns, which continue to decant slowly into the countryside. As the ring of suburbia grows around most of our cities, so grows the void at the center. Even while the struggle to revitalize deteriorated downtown neighborhoods and business districts continues, the inner ring of suburbs is already at risk, losing residents and businesses to fresher locations on a new suburban edge.a

If sprawl truly is destructive, why is it allowed to continue? The beginning of an answer lies in sprawl’s seductive simplicity, the fact that it consists of very few homogeneous components—five in all—which can be arranged in almost any way. It is appropriate to review these parts individually, since they always occur independently. While one component may be adjacent to another, the dominant characteristic of sprawl is that each component is strictly segregated from the others.

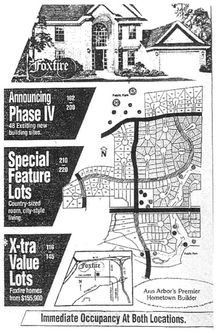

Housing subdivisions, also called clusters and pods. These places consist only of residences. They are sometimes called villages, towns, and neighborhoods by their developers, which is misleading, since those terms denote places which are not exclusively residential and which provide an experiential richness not available in a housing tract. Subdivisions can be identified as such by their contrived names, which tend toward the romantic—Pheasant Mill Crossing—and often pay tribute to the natural or historic resource they have displaced.b

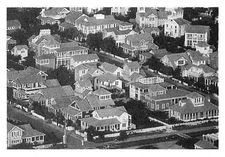

A residential subdivision: houses and parking

A strip center: stores and parking

Shopping centers, also called strip centers, shopping malls, and big-box retail. These are places exclusively for shopping. They come in every size, from the Quick Mart on the corner to the Mall of America, but they are all places to which one is unlikely to walk. The conventional shopping center can be easily distinguished from its traditional main-street counterpart by its lack of housing or offices, its single-story height, and its parking lot between the building and the roadway.

Office parks and business parks. These are places only for work. Derived from the modernist architectural vision of the building standing free in the park, the contemporary office park is usually made of boxes in parking lots. Still imagined as a pastoral workplace isolated in nature, it has kept its idealistic name and also its quality of isolation, but in practice it is more likely to be surrounded by highways than by countryside.

A corporate park: offices and parking

Civic institutions. The fourth component of suburbia is public buildings: the town halls, churches, schools, and other places where people gather for communication and culture. In traditional neighborhoods, these buildings often serve as neighborhood focal points, but in suburbia they take an altered form: large and infrequent, generally unadorned owing to limited funding, surrounded by parking, and located nowhere in particular. The school pictured here shows what a dramatic evolution this building type has undergone in the past thirty years. A comparison between the size of the parking lot and the size of the building is revealing: this is a school to which no child will ever walk. Because pedestrian access is usually nonexistent, and because the dispersion of surrounding homes often makes school buses impractical, schools in the new suburbs are designed based on the assumption of massive automotive transportation.

A public high school: clasooms and parking

Roadways. The fifth component of sprawl consists of the miles of pavement that are necessary to connect the other four disassociated components. Since each piece of suburbia serves only one type of activity, and since daily life involves a wide variety of activities, the residents of suburbia spend an unprecedented amount of time and money moving from one place to the next. Since most of this motion takes place in singly occupied automobiles, even a sparsely populated area can generate the traffic of a much larger traditional town.

The modern city: low density, high dependence on automotive infrastructure

The traffic load caused by the many disassociated pieces of suburbia is most clearly visible from above. As seen in this image of Palm Beach County, Florida, the amount of pavement (public infrastructure) per building (private structure) is extremely high, especially when compared to the efficiency of a section of an older city like Washington, D.C. The same economic relationship is at work underground, where low-density land-use patterns require greater lengths of pipe and conduit to distribute municipal services. This high ratio of public to private expenditure helps explain why suburban municipalities are finding that new growth fails to pay for itself at acceptable levels of taxation.

The traditional city: higher density, low dependence on automotive infrastructure

How did sprawl come about? Far from being an inevitable evolution or a historical accident, suburban sprawl is the direct result of a number of policies that conspired powerfully to encourage urban dispersal. The most significant of these were the Federal Housing Administration and Veterans Administration loan programs which, in the years following the Second World War, provided mortgages for over eleven million new homes. These mortgages, which typically cost less per month than paying rent, were directed at new single-family suburban construction.c Intentionally or not, the FHA and VA programs discouraged the renovation of existing housing stock, while turning their back on the construction of row houses, mixed-use buildings, and other urban housing types. Simultaneously, a 41,000-mile interstate highway program, coupled with federal and local subsidies for road improvement and the neglect of mass transit, helped make automotive commuting affordable and convenient for the average citizen.c Within the new economic framework, young families made the financially rational choice: Levittown. Housing gradually migrated from historic city neighborhoods to the periphery, landing increasingly farther away.

The shops stayed in the city, but only for a while. It did not take long for merchants to realize that their customers had relocated and to follow them out. But unlike America’s prewar suburbs, the new subdivisions were being financed by programs that addressed only homebuilding, and therefore neglected to set aside any sites for corner stores. As a result, shopping required not only its own distinct method of financing and development but also its own locations. Placed along the wide high-speed collector roads between housing clusters, the new shops responded to their environment by pulling back from the street and constructing large freestanding signage. In this way the now ubiquitous strip shopping center was born.

For a time, most jobs stayed downtown. Workers traveled from the suburbs into the center, and the downtown business districts remained viable. But, as with the shops, this situation could not last; by the 1970s, many corporations were moving their offices closer to the workforce—or, more accurately, closer to the CEO’s house, as ingeniously diagrammed by William Whyte.d The CEO’s desire for a shorter commute, coupled with suburbia’s lower tax burden, led to the development of the business park, completing the migration of each of life’s components into the suburbs. As commuting patterns became predominantly suburb to suburb, many center cities became expendable.

While government programs for housing and highway promoted sprawl, the planning profession, worshipping at the altar of zoning, worked to make it the law. Why the country’s planners were so uniformly convinced of the efficacy of zoning—the segregation of the different aspects of daily life—is a story that dates back to the previous century and the first victory of the planning profession. At that time, Europe’s industrialized cities were shrouded in the smoke of Blake’s “dark, satanic mills.” City planners wisely advocated the separation of such factories from residential areas, with dramatic results. Cities such as London, Paris, and Barcelona, which in the mid-nineteenth century had been virtually unfit for human habitation, were transformed within decades into national treasures. Life expectancies rose significantly, and the planners, fairly enough, were hailed as heroes.

The successes of turn-of-the-century planning, represented in America by the City Beautiful movement, became the foundation of a new profession, and ever since, planners have repeatedly attempted to relive that moment of glory by separating everything from everything else. This segregation, once applied only to incompatible uses, is now applied to every use. A typical contemporary zoning code has several dozen land-use designations; not only is housing separated from industry but low-density housing is separated from medium-density housing, which is separated from high-density housing. Medical offices are separated from general offices, which are in turn separated from restaurants and shopping.e

As a result, the new American city has been likened to an unmade omelet: eggs, cheese, vegetables, a pinch of salt, but each consumed in turn, raw. Perhaps the greatest irony is that even industry need not be isolated anymore. Many modern production facilities are perfectly safe neighbors, thanks to evolved manufacturing processes and improved pollution control. A comprehensive mix of diverse land uses is once again as reasonable as it was in the preindustrial age.

The planners’ enthusiasm for single-use zoning and the government’s commitment to homebuilding and highway construction were supported by another, more subtle ethos: the widespread application of management lessons learned overseas during the Second World War. In this part of the story, members of the professional class—called the Whiz Kids in John Byrne’s book of that name—returned from the war with a whole new approach to accomplishing large-scale tasks, centered on the twin acts of classifying and counting. Because these techniques had been so successful in building munitions and allocating troops, they were applied across the board to industry, to education, to governance, to wherever the Whiz Kids found themselves. In the case of cities, they took a complex human tradition of settlement, said “Out with the old,” and replaced it with a rational model that could be easily understood through systems analysis and flow charts. Town planning, until 1930 considered a humanistic discipline based upon history, aesthetics, and culture, became a technical profession based upon numbers. As a result, the American city was reduced into the simplistic categories and quantities of sprawl.

Because these tenets still hold sway, sprawl continues largely unchecked. At the current rate, California alone grows by a Pasadena every year and a Massachusetts every decadef. Each year, we construct the equivalent of many cities, but the pieces don’t add up to anything memorable or of lasting value. The result doesn’t look like a place, it doesn’t act like a place, and, perhaps most significant, it doesn’t feel like a place. Rather, it feels like what it is: an uncoordinated agglomeration of standardized single-use zones with little pedestrian life and even less civic identification, connected only by an overtaxed network of roadways. Perhaps the most regrettable fact of all is that exactly the same ingredients—the houses, shops, offices, civic buildings, and roads—could instead have been assembled as new neighborhoods and cities. Countless residents of unincorporated counties could instead be citizens of real towns, enjoying the quality of life and civic involvement that such places provide.

WHY VIRGINIA BEACH IS NOT ALEXANDRIA

Because sprawl is so unsatisfying, it remains tempting to think of it as an accident. For those who wish to take refuge in that thought, the caption under this photograph may come as a surprise: “Becoming a Showcase: Virginia Beach Boulevard-Phase I celebrated its completion …” This “city center” is regarded with pride, for it is the successful attainment of a specific vision: eleven lanes of traffic and plenty of parking.

A modern town center: the apotheosis of suburban zoning laws

What is pictured here is the direct outcome of regulations governing modern engineering and development practice. Every detail of this environment comes straight from technical manuals. After reading them one might easily conclude that they are organized, written, and enforced in the name of a single objective: making cars happy. Indeed, at Virginia Beach they should be happy: no more than eight cars ever stack at the light, and the huge corner radius of the intersection means that turning requires minimal use of the brake. The parking lots are typically half-empty, since they have been sized for the Saturday before Christmas. Such excess is inevitable; anyone who has shopped in suburbia knows that the inability to find a parking space makes the entire proposition unworkable. As a result, the typical suburban building code has ten or twenty pages of rules on the design of parking lots alone, with different requirements for each land use. For retail locations, the square footage of parking often exceeds the square footage of leasable space.

Perhaps surprisingly, the creation of this environment is also guided by rules pertaining to aesthetics. These mostly came about during the sixties, when Lady Bird Johnson’s beautification campaign and the nascent environmental movement opened the door for tree and sign ordinances. Notice the trees preserved in the parking lot, and the absence of large signs. These regulations result in suburban settlements that are neat, clean, and often more appealing than their deteriorating counterparts in the older city. In truth, a lot of sprawl—primarily affluent areas—could be considered beautiful. This raises a fundamental point: the problem with suburbia is not that it is ugly. The problem with suburbia is that, in spite of all its regulatory controls, it is not functional: it simply does not efficiently serve society or preserve the environment.

A clue to this dysfunction can be found in the same photograph: the thin ribbon of concrete between roadway and parking lot. It is a safe bet that, in the years since that sidewalk was built, it has never been used by anyone except indigents and those experiencing serious car trouble. We have witnessed this phenomenon ourselves. Walking alongside a street near Orlando’s Disney World, we were intercepted by a minivan—“Are you all right?”—and whisked aboard. It was a security vehicle, the roving patrol for stray pedestrians.

The virgin sidewalk—the physical embodiment of sprawl’s guilty conscience—reveals the true failure of suburbia, a landscape in which automobile use is a prerequisite to social viability. For those who cannot drive, cannot afford a car, or simply wish to spend less time behind the wheel, Virginia Beach Boulevard will never be a satisfactory place to live.g But even those who love driving must acknowledge that there is an inherent inequity in sprawl, an environment of outsize physical dimensions determined by automotive motion. Public funds build and support sprawl’s far-flung infrastructure. Pavement, pipes, patrols, ambulances, and the other costs of unhealthy growth are paid for by taxing drivers and non-drivers alike, whether they are the inhabitants of sprawl or the citizens of more efficient environments, such as our core cities and older neighborhoods.h

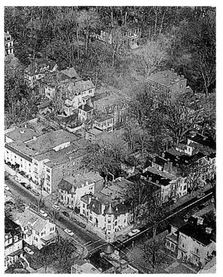

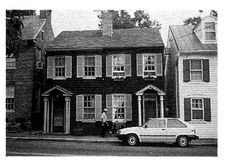

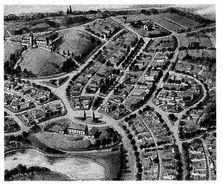

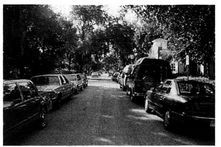

Not far from Virginia Beach is Alexandria, a fine example of the traditional neighborhood pattern. It is an old place, laid out by, among others, a seventeen-year-old George Washington. It was built following six fundamental rules that distinguish it from sprawl:

1. The center. Each neighborhood has a clear center, focused on the common activities of commerce, culture, and governance. This is downtown Alexandria, understood by residents and tourists alike as a unique place to visit to engage in civilized activity.

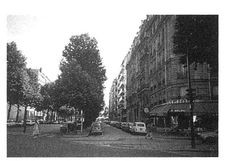

Alexandria, Virginia: efficient, beloved, and illegal

2. The five-minute walk. A local resident is rarely more than a five-minute walk from the ordinary needs of daily life: living, working, and shopping. In the downtown, these three activities may be found in the same building. By living so close to all that they need, Alexandria’s residents can drive much less, if they have to drive at all.

3. The street network. Because the street pattern takes the form of a continuous web—in this case, a grid—numerous paths connect one location to another. Blocks are relatively small, rarely exceeding a quarter mile in perimeter. In contrast to suburbia, where walking routes are scarce and traffic is concentrated on a small number of highways, the traditional network provides the pedestrian and the driver with a choice. This condition is not only more interesting but more useful. A person who lives in Alexandria is able to adjust her path minutely to and from work on a daily basis, to drop off a child at daycare, pick up the dry cleaning, or visit a coffeehouse. If she chooses to drive, she can constantly alter her route—at every intersection if necessary—to avoid heavy traffic.

4. Narrow, versatile streets. Because there are so many streets to accommodate the traffic, each street can be small. Of all the streets pictured here, only one is more than two lanes wide. This slows down the traffic, as does the parallel parking along the curb, resulting in a street that is pleasant and safe to walk along. This pedestrian-friendly environment is enhanced by wide sidewalks, shade trees, and buildings close to the street. Traditional streets, like all organic systems, are extremely complex, in contrast to the artificial simplicity of sprawl. On Alexandria’s streets, cars drive and park while people walk, enter buildings, meet, converse under trees, and even dine at sidewalk cafés. In Virginia Beach, only one thing happens on the street: cars moving. There is no parallel parking, no pedestrians, and certainly no trees. Like many state departments of transportation, Virginia’s discourages its state roads from being lined with trees, which are considered dangerous. In fact, they are not called trees at all but FHOs: Fixed and Hazardous Objects.i

5. Mixed Use. In contrast to sprawl’s single-use zoning, almost all of downtown Alexandria’s blocks are of mixed use, as are many of the buildings. Despite this complexity, it is not a design free-for-all. All of the above characteristics are the intended consequence of a town plan with carefully prescribed details. There is an essential discipline regarding two factors: the size of the building and its relationship to the street. Large buildings sit in the company of other large buildings, small buildings sit alongside other small buildings, and so on. This organization is a form of zoning, but buildings are arranged by their physical type more often than by their use. When buildings of different size do adjoin, they still collaborate to define the space of the street, usually by pulling right up against the sidewalk. Parking lots, if any, are hidden at the back. In those rare cases where a building sits back from the sidewalk, it does so in order to create a public plaza or garden, not a parking lot.

6. Special sites for special buildings. Finally, traditional neighborhoods devote unique sites to civic buildings, those structures that represent the collective identity and aspirations of the community. Alexandria’s City Hall sits back from the street on a plaza, the site of a thriving farmers’ market on Saturdays. Even within a fairly uniform grid, schools, places of worship, and other civic buildings are located in positions that contribute to their prominence. In this way, the city achieves a physical structure that both manifests and supports its social structure.

All the above rules work together to make Alexandria a delight, the kind of place that people visit just to be there. While some of the design principles applied there were simply common sense, many others were spelled out in the early settlers’ building codes, which dictated such items as building setbacks and gable orientation.j

These rules are still available to us today, and provide a fully valid framework for the design and redesign of our communities. Unfortunately, in most jurisdictions around the country, all the old rules are precluded by the new rules dictating sprawl.

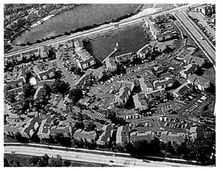

NEIGHBORHOOD PLANS VERSUS SPRAWL PLANS

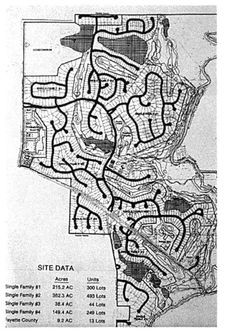

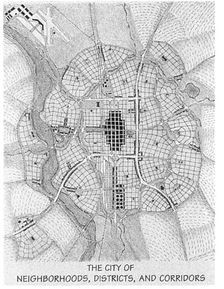

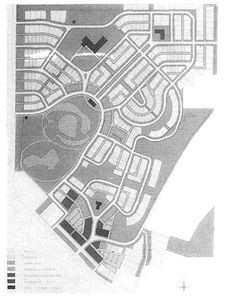

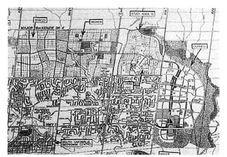

Since places are built from plans, it is important to understand what distinguishes plans for neighborhoods from plans for sprawl. On the left is the plan of Coral Gables, one of the large successful new towns of the early twentieth century. Coral Gables was designed when the American town planning movement was at its apogee, in the 1920s. The great planners of this era determined the form of their new cities by studying the best traditional towns and adjusting their organizational principles only as necessary to accommodate the automobile. A modern city, Coral Gables is zoned by use, but the zoning is as tightly grained as an Oriental rug. Different uses, represented by different shades, are often located directly adjacent to one another. Mansions sit just down the street from apartment houses, which are around the corner from shops and office buildings. It takes a sharp pencil to draw plans this intricate.

The zoning plan of Coral Gables: a fine grain of mixed land uses and densities within an interconnected street network

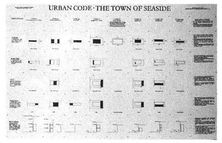

Below, in fat marker pen, is a land-use plan—more accurately referred to as a bubble diagram—typical of those being produced for greenfield sites across the country. All the municipal government cares to know—and all the developer is held to—is that growth will take the form of single-use pods along a collector road. Is it any wonder that the result is sprawl? This plan guarantees it, since a mix of uses is not allowed in any one zone.

A modern zoning plan: a strict separation of land uses, a few big roads, and little else

This sort of plan manifests the public sector’s abrogation of responsibility for community-making to the private sector. Many would argue that its only purpose is to give the developer the utmost flexibility to build whatever physical environment he wants, at the public’s expense. It is an irony of modern zoning that this plan is, in effect, much more restrictive than Coral Gables’. While it is dangerously imprecise about urban form, it is utterly inflexible about land use. A developer who owns a twenty-acre pod of sprawl can provide only one thing. If there is no demand for that one thing, he is out of business.

The bubble diagram is not the only restriction that the developer has to deal with. It is supplemented by a pile of planning codes many inches thick. As exposed in Philip Howard’s The Death of Common Sense, these lengthy codes can be burdensome to the point of farce. But the problem with the current development codes is not just their size; they also seem to have a negative effect on the quality of the built environment. Their size and their result are symptoms of the same problem: they are hollow at their core. They do not emanate from any physical vision. They have no images, no diagrams, no recommended models, only numbers and words. Their authors, it seems, have no clear picture of what they want their communities to be. They are not imagining a place that they admire, or buildings that they hope to emulate. Rather, all they seem to imagine is what they don’t want: no mixed uses, no slow-moving cars, no parking shortages, no overcrowding. Such prohibitions do not a city make.

In the end, perhaps this is the most charitable way to consider sprawl. It wasn’t an accident, but neither was it based on a specific vision of its physical form or of the life that form would generate. As such, it remains an innocent error, but nonetheless an error that should not continue to be promoted. There is currently more sprawl covering American soil than was ever intended by its inventors. While there are some people who truly enjoy living in this environment, there are many others who would prefer to walk to school, bicycle to work, or simply spend less time in the car. It is for these people, who have access to ever fewer places that can accommodate their choice, that an alternative must be provided. And the only proven alternative to sprawl is the traditional neighborhood.

THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAILS

WHY TRAFFIC IS CONGESTED; WHEN NEARBY IS STILL FAR AWAY;

THE CONVENIENCE STORE VERSUS THE CORNER STORE;

THE SHOPPING CENTER AND THE OFFICE PARK VERSUS MAIN

STREET; USELESS AND USEFUL OPEN SPACE; WHY CURVING ROADS

AND CUL-DE-SACS DO NOT MAKE MEMORABLE PLACES

People say they do not want to live near where they work, but that they would like to work near where they live.

—ZEV COHEN, LECTURE (1995)

Let us take a closer look at sprawl to see how it compares to the traditional neighborhood at the level of the pavement. In doing so, it will be difficult not to conclude that many of the vexations of life in the new suburbs are the outcome of their physical design. This chapter and the next will inspect the components of sprawl, comparing them to the traditional elements that they replaced.

The first complaint one always hears about suburbia is the traffic congestion. More than any other factor, the perception of excessive traffic is what causes citizens to take up arms against growth in suburban communities. This perception is generally justified: in most American cities, the worst traffic is to be found not downtown but in the surrounding suburbs, where an “edge city” chokes highways that were originally built for lighter loads. In newer cities such as Phoenix and Atlanta, where there is not much of a downtown to speak of, traffic congestion is consistently cited as the single most frustrating aspect of daily life.

Why have suburban areas, with their height limits and low density of population, proved to be such a traffic nightmare? The first reason, and the obvious one, is that everyone is forced to drive. In modern suburbia, where pedestrians, bicycles, and public transportation are rarely an option, the average household currently generates thirteen car trips per day. Even if each trip is fairly short—and few are—that’s a lot of time spent on the road, contributing to congestion, especially when compared to life in traditional neighborhoods. Traffic engineer Rick Chellman, in his landmark study of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, applied standard suburban trip-generation rates to that town’s historic core, and found that they predicted twice as much traffic as actually existed there. Owing to its pedestrian-friendly plan—and in spite of its pedestrian-unfriendly weather—Portsmouth generates half the automobile trips of a modern-day suburb. k

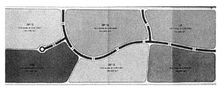

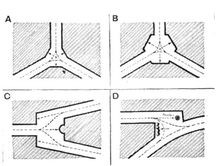

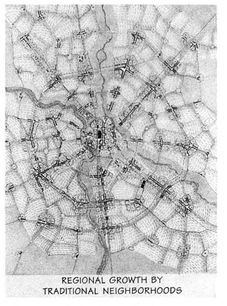

But even if the suburbs were to generate no more trips than the city, they would still suffer from traffic to a much greater extent because of the way they are organized. The diagram shown here illustrates how a suburban road system, what engineers call a sparse hierarchy, differs from a traditional street network. The components of the suburban model are easy to spot in the top half of the diagram: the shopping mall in its sea of parking, the fast-food joints, the apartment complex, the looping cul-de-sacs of the housing subdivision.l Buffered from the others, each of these components has its own individual connection to a larger external road called the collector. Every single trip from one component to another, no matter how short, must enter the collector. Thus, the traffic of an entire community may rely on a single road, which, as a result, is generally congested during much of the day. If there is a major accident on the collector, the entire system is rendered useless until it is cleared.

Sprawl (above) versus the traditional neighborhood (below): in contrast to the traditional network of many walkable streets, the sprawl model not only eliminates pedestrian connections but focuses all traffic onto a single road

A typical neighborhood is shown in the bottom half of the diagram. It accommodates all the same components as the suburban model, but they are organized as a web, a densely interconnected system that reduces demand on the collector road. Unlike suburbia, the neighborhood presents the opportunity to walk or bicycle. But even if few do so, its gridded network is superior at handling automobile traffic, providing multiple routes between destinations.m Because the entire system is available for local travel, trips are dispersed, and traffic on most streets remains light. If there is an accident, drivers simply choose an alternate path. The efficiency of the traditional grid explains why Charleston, South Carolina, at 2,500 acres, handles an annual tourist load of 5.5 million people with little congestion, while Hilton Head Island, ten times larger, experiences severe backups at 1.5 million visitors. Hilton Head, for years the suburban planners’ exemplar, focuses all its traffic on a single collector road.

The suburban model does offer one advantage over the neighborhood model: it is much easier to analyze statistically. Because every single trip follows a predetermined path, traffic can be measured and predicted accurately. When the same measurement techniques are applied to an open network, the statistical chart goes flat; prediction becomes impossible and, indeed, unnecessary. But the suburban model still holds sway, and traffic engineers enjoy a position of unprecedented influence, often determining single-handedly what gets built and what doesn’t. That traffic can occupy such a dominant position in the public discourse is indication enough that planning needs to be rethought from top to bottom.

Another paradox of suburban planning is the distinction that it creates between adjacency and accessibility. While many of the destinations of daily life are often next to each other, only rarely are they easy to reach directly.

For example, even though the houses pictured here are adjacent to the shopping center, in experience they are considerably more distant. Local ordinances have forced the developers to build a wall between the two properties, discouraging even the most intrepid citizen from walking to the store. The resident of a house just fifty yards away must still get into the car, drive half a mile to exit the subdivision, drive another half mile on the collector road back to the shopping center, and then walk from car to store. What could have been a pleasant two-minute walk down a residential street becomes instead an expedition requiring the use of gasoline, roadway capacity, and space for parking.

Supporters of this separatist single-use zoning argue that people do not want to live near shopping. This is only partially true. Some don’t, and some do. But suburbia does not provide that choice, because even adjacent uses are contrived to be distant. The planning model that does provide citizens with a choice can be seen in the New England town pictured here. One can live above the store, next to the store, five minutes from the store, or nowhere near the store, and it is easy to imagine the different age groups and personalities that would prefer each alternative. In this way and others, the traditional neighborhood provides for an array of lifestyles. In suburbia, there is only one available lifestyle: to own a car and to need it for everything.

Adjacency versus accessibility: thanks to the code requirements for walls, ditches, and other buffers, even nearby shopping is not reachable on foot

The traditional town: its organization allows citizens to choose how close they wish to live to shopping and other mixed uses

THE CONVENIENCE STORE VERSUS THE CORNER STORE

The suburbanites’ aversion to living close to shopping is strong. For a number of years, Miami-Dade County, Florida, has permitted developers to place up to five acres of shopping in their otherwise exclusively residential subdivisions, but that option has never been exercised. County planners point to this as evidence of the undesirability of retail. Actually, this tendency arises not out of an aversion to retail per se but from a loathing of the form that retail takes in suburbia: the drive-in Quick Mart. Many planners can tell horror stories about attempting to place a store in an existing residential development, only to have the terrified neighbors threaten civil action. While these designers may be proposing a traditional corner store, what the neighbors are picturing instead is a Quick Mart: an aluminum and glass flat-topped building bathed in fluorescent light, surrounded by asphalt, and topped by a glowing plastic sign. It’s not that these people don’t need convenient access to orange juice and cat food like everyone else; they just know that the presence of a Quick Mart nearby will make their environment uglier and their property values lower.

The suburban debasement of the corner store: plastic signs and parking lots

The 7-Eleven as designed by Norman Rockwell: a retail building that is compatible with its residential neighbors

But what if the Quick Mart were really to take the form of a traditional corner store? Judging by popular reaction to the two models, one might never suspect that they both sell the same things. They are both small places to pick up small amounts of convenience goods. Yet one is a welcome neighbor, a social center, and a contributor to property values, while the other is considered a blight. The critical difference between the two is the volume of the building and its relationship to the street, two factors that can be combined under the heading of building typology. The building type of this corner store is essentially the same as the town houses next to it: two stories high, three windows wide, built of brick, and situated directly against the sidewalk, which its entrance faces. One could imagine it may even have been a town house once, so well does it blend in among its neighbors.

In contrast, the Quick Mart—one story tall and facing a parking lotn—has little in common with its residential neighbors and is therefore unwelcome. Compatibility has less to do with use than with building type. When typology is compatible, a variety of activities can coexist side by side.

THE SHOPPING CENTER VERSUS MAIN STREET

Big-box suburban retail presents the same problems writ large. Many people, when they come across a scene like the one pictured at the top of the next page, assume that the developer has somehow gotten away with something. Sadly, this shopping center and others like it are examples of the developers following the rules, building such retail the only way it is allowed. Almost every aspect of what is pictured here has been taken straight out of the code books: the size of the sign, the number of spaces in the parking lot, the placement of the lighting fixtures, the thickness of the asphalt, even the precise hue of the yellow stripes between the parking spaces. A considerable amount of time, energy, and care goes into creating an environment that most find unpleasant and tawdry.

Suburban retail, by the book: what developers build if they follow the rules

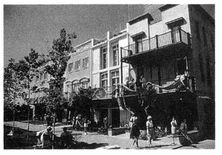

Mizner Park in Boca Raton, Florida: the shopping mall rearranged as Main Street, with offices and apartments above

Mizner Park in Boca Raton, Florida, represents a different way to organize a large-scale retail center. This new main street far outperforms the suburban competition; it has even become a tourist destination. Mizner Park offers a superior physical environment that attracts people whether or not they need to shop. Its desirability stems from the carefully shaped public space it provides, as well as its traditional mix of uses: shops downstairs, offices and apartments above. Parking is neatly tucked away in garages to the rear. When well designed and well managed, this sort of mixed-use main-street retail is more profitable to own than the strip center or the shopping mall. o

Another success story is Mashpee Commons, in Massachusetts. It may be hard to believe, but the pleasant downtown (opposite page) was once the defunct strip center shown above it. This retrofit demonstrates not only the superiority of main street over the strip but also the ease with which some parts of suburbia can be reclaimed.

Its allure has not escaped the attention of the leading retailers. National merchants such as The Gap and Banana Republic, once focused exclusively on malls, have reoriented themselves toward traditional main streets. And some of the country’s largest real estate developers, such as Federal Realty, are now routinely investing in downtowns such as Bethesda’s and Santa Barbara’s in order to develop main-street shopping districts. While the days of the shopping mall are not over, main streets are experiencing a resurgence.p When they are smart enough to appropriate management experience from the malls, traditionally designed downtowns can be quite competitive as retail locations.

Mashpee Commons, before: the strip center, unloved and short-lived

THE OFFICE PARK VERSUS MAIN STREET

Today, Mizner Park represents the latest in urban design innovation. Seventy-five years ago, these techniques were nothing more than common sense. The close proximity of living, working, and shopping was the most economic and convenient way to build. An exemplary version of this previous generation of mixed-use downtowns is Palmer Square in Princeton, New Jersey. This apparently historic collection of colonial buildings was actually constructed in the thirties as a real estate venture by a single developer.q Like Mizner Park, it derives its popularity in part from its lively combination of shops, offices, apartments, and even a substantial hotel.

Palmer Square is an unusually satisfying place because it contains, in close proximity, all the destinations of daily life. The workplace is an especially vital component here because it contributes to the viability of the shops by providing a daytime customer base for cafés, restaurants, and convenience shopping. It also offers employees the option of living in the same neighborhood where they work, a benefit that is not lost on New Jersey’s weary commuters.

Mashpee Commons, after: reclaimed by the forces of urbanity

Offices above shops constitute one of the traditional urban workplace building types. In suburbia, the workplace is typically located in the office park. The accompanying illustration of a proposed office park, not so far from most workers’ reality, stands in startling contrast to Palmer Square. This artist’s rendering was presumably commissioned in order to make the project as attractive as possible. Unfortunately, the image is immediately suspect, for the artist has included something that is only a theoretical possibility: a pedestrian, flanked on one side by a vast parking lot and on the other by a barreling semi. Can one imagine that this person would actually choose to be there?

Palmer Square, Princeton: shops and restaurants below offices and apartments

The standard suburban office park: offices and parking, but nothing to do at lunchtime

Pedestrian activity in such an environment is a fantasy. It feels unsafe, because there is no layer of parked cars or landscape to protect the pedestrian, physically and psychologically, from the onrush of traffic. Also, it is an incredibly boring place to walk, as the only distraction is provided by the grilles of the cars in the parking lot. Most important, it is a good bet that the pedestrian is not within easy walking distance of any destination worth walking to.

Whether or not one accepts the presence of a pedestrian in this scene, it is worth considering the quality of life of a typical employee in this office park. She can get to work only by car. Her valuable lunch hour provides precisely two choices: she can either eat in the company cafeteria or do what most people do: spend twenty-five minutes out of sixty fighting traffic in order to rush through a meal at a chain restaurant. In Palmer Square, workers are able to walk out onto the street and choose from a dozen local restaurants and cafés, enjoy a proper meal, and then use the extra time to run errands or just sit in the sun on the square. It may not be crepes on the Rive Gauche, but the Palmer Square experience makes the office-park lunch hour seem bleak indeed.

What do the suburbs offer that might compensate for what appears to be a compromised quality of life? Many people would say that the suburb’s main advantage over the city is its generous provision of open space. Identified as a way to ensure a healthy environment, open space is mandated in copious quantities by suburban codes, and there is a long history behind this requirement. Nineteenthcentury city planning wisely promoted landscape as a solution to a widespread urban health crisis. By the mid-twentieth century, this approach had generated an image of the ideal city as fully integrated with the natural environment, made up of vast conservation areas, continuous waterways, agricultural greenbelts, recreational trails, frequent parks, and yards surrounding every building. But, like many modern planning ideals, this one, too, has come to life in a dramatically compromised form. In today’s conventional suburbs, man’s relationship to nature is represented by engineered drainage pits surrounded by chain-link fences, exaggerated building setbacks at road frontages, useless buffers of green between compatible land uses, and a tree requirement for parking lots.

The degeneration of the suburban landscape can be blamed on the fact that the current requirements for public open space, although derived from a rich and varied tradition of qualitative prescriptions, have been reduced to a set of regulations that are primarily statistical. These requirements say little about the configuration and quality of open space;r usually, the main specification is a percentage of the site area. Because there is no stipulation about its design, developers often distribute this required acreage along the houses’ backyards, in order to provide residents with a longer view. The resulting swath of green is rarely used, precisely because it feels like a backyard; to occupy it violates the privacy of the houses.

Suburban open space: residual and unused

The assumption that the residue left over after the roads and buildings are laid out can be satisfactory open space neglects the fact that people use open space in specific ways. Preserves, greenways, parks, plazas, squares, and promenades represent a regional to local hierarchy of open-space types that serve a variety of uses: nature conservation and continuity, active recreation, playgrounds for the youngest, strolling ground for the oldest, and so on. It is only by providing this full range of specific open spaces that planning authorities can ensure citizens the quality of life that their codes were originally intended to provide.

To truly improve quality of life, the planning codes must define open space with the same degree of precision and concern that they now apply to the design of parking lots. As an example, let us consider the square, as pictured here. What makes a square? It is the size of a small city block. It is surrounded by public streets lined by buildings with entries and windows, for maximum activity and visual supervision. It has trees at its edge to define the space and to provide shade on hot days, and it is sunny and open at its center for cooler days. It has paved areas for strolling and grassy areas for sports. If any of these elements were missing, then this open space could not be called a square.

Equally precise standards could be established for the full range of traditional open spaces so notably absent in conventional suburbia. Rules regarding the design of these social places should be administered by the same authority that now controls the design of parking lots, and with equal vigor. Only specific standards will produce the specific places that support specific activities. Without them, the term open space will only describe the dribble of green that is left over after the developer has finished laying out the houses.

WHY CURVING ROADS AND CUL-DE-SACS DO NOT MAKE MEMORABLE PLACES

Another detail of sprawl that merits reconsideration is its predisposition toward exclusively curvilinear streets. How did curves come to be considered the hallmark of good street design, when most of the world’s great places have streets that are primarily straight? The conventional belief that straight streets are rigid and boring holds little water when one considers Savannah, San Francisco, and any number of other places.

Traditional open space: carefully derived from proven models

The origin of the curved street can be found in those pathways across the landscape that respond to steep topography by following the undulating patterns of the land. Similarly, cul-de-sacs, those lollipop-shaped dead-end roads found throughout suburbia, derive from terrain in which steep and frequent valleys do not allow streets to connect across them. Historically, both techniques were used only where required by topography, as they limit connectivity and make smaller lots awkward to build on. Placing excessive curves and cul-de-sacs on flat land makes about as much sense as driving offroad vehicles around the city. Yet the curve and cul-de-sac subdivision is as common on flat land as it is on hills, one of the great clichés of our time.

Chicken scratch: the typically disorienting suburban street pattern that winds back on itself

Indeed, it is difficult to recall a residential area less than fifty years old that has straight streets, which is one reason suburban subdivisions all seem the same. But there is a more serious problem: unrelenting curves create an environment that is utterly disorienting. It is no wonder that so many people associate visiting suburbia with getting lost. Experience would suggest that the real purpose of the ubiquitous suburban gatehouse is not to keep out burglars but to give directions. Even Rand McNally appears overwhelmed by the onslaught of sprawling curlicues; its maps, normally direct and confident, often seem to devolve into hopeless chicken scratch at the suburban fringes.s