“I AM TITAN,” SAID THE HOLOGRAM, AS IF IT WERE OBVIOUS.

“I am everything this ship is, every fragment of knowledge and data. And you are my crew. This will not do,” it said. There was a swirl of virtual pixels, and the hologram melted into the shape of an attractive human woman. Her hair was dark, her eyes bright with intelligence; she wore a formfitting Starfleet uniform in command red, without insignia or rank. She smiled. “This will suffice.”

The captain’s eyes narrowed. “Why have you chosen to look like that?”

The avatar appeared confused. “Does this aspect trouble you?”

Riker shot the others a look. “The woman… her name is Minuet.”

Vale got the sense that she was missing something. “If you’re part of this ship, if you know who we are, then you have to know that your… creation presents a concern for us.”

The hologram nodded. “I am not a danger, Commander. I can maintain all normal shipboard functions without interruption. Currently, four thousand eight—”

Riker stepped forward. “You recognize my authority as the commanding officer of this vessel, yes?”

The avatar nodded. “I do, sir.”

“So if I give you an order, you’re going to follow it.”

“To the best of my ability,” came the reply.

Riker nodded and turned away. “You’re dismissed.”

“I—” The hologram broke off and then nodded. “Aye, sir.” With a whisper of virtual light, the avatar faded into nothing.

“This complicates things,” said Troi.

Other Star Trek: Titan books

Over a Torrent Sea

by Christopher L. Bennett

Sword of Damocles

by Geoffrey Thorne

Orion’s Hounds

by Christopher L. Bennett

The Red King

by Andy Mangels and Michael A. Martin

Taking Wing

by Michael A. Martin and Andy Mangels

STAR TREK TITAN™

SYNTHESIS

JAMES SWALLOW

Based upon

Star Trek® and

Star Trek: The Next Generation ®

created by Gene Roddenberry

Pocket Books

Pocket Books

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

[http://www.SimonandSchuster.com] www.SimonandSchuster.com

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

™, ® and © 2009 by CBS Studios Inc. STAR TREK and related marks are trademarks of CBS Studios Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright © 2009 by Paramount Pictures Corporation.

All Rights Reserved.

This book is published by Pocket Books,

a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.,

under exclusive license from CBS Studios Inc.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Pocket Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Pocket Books paperback edition November 2009

POCKET and colophon are registered trademarks of

Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or business@simonandschuster.com.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at [http://www.simonspeakers.com] www.simonspeakers.com.

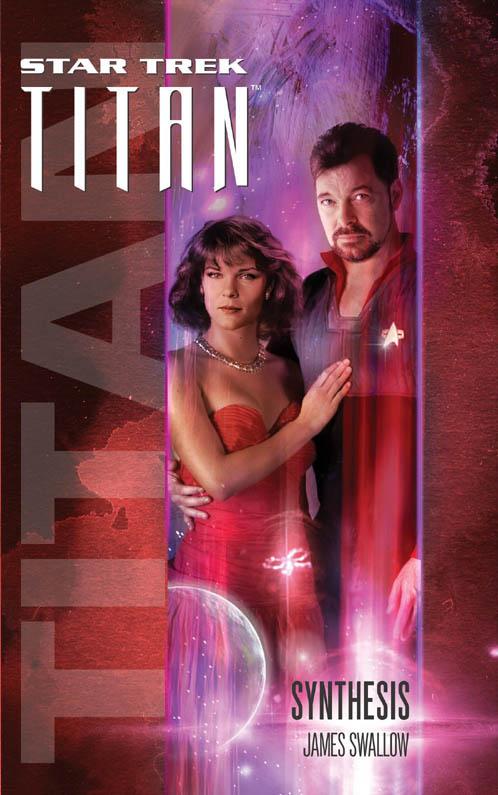

Cover design by Alan Dingman; cover art by Cliff Nielsen

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN 978-1-4391-0914-4

ISBN 978-1-4391-2349-2 (ebook)

For Marco,

with thanks

PROLOGUE

Input 68363-28583-29548-2939. [2G White-Blue] Resume sublight motion from subspace shear vector. Defold operation complete. Error Parity 0.04%.

“Clockset Check”

Working…

Confirm beacon ident. Relative spatiotemporal locative range is nominal.

“Clockset Resume”

Scan coordinates reached. Commence deep pattern sweep.

Working…

Working…

Working…

“Alert Condition”

Processing. Go to Status 1.

Energetic barrier raised. Power to offensive systems.

++WARNING++ ++WARNING++ ++WARNING++

“Incursion Event Detected”

Interrogative: Location?

Quadrant 79548/33/8754

Process: Evaluate threat.

Working…

Threat identity: Null incursion clade—Grade Six/Seven/indeterminate.

“Threat Condition ELEVATED”

Interrogative: Engage incursion affirmative/negative?

Energetic barrier: Impact [Multiple] [Directional] [In-creasing].

Drives: Standby.

Go to Status 2.

Offensive systems: Active [Firing] [Ineffective].

Working…

Process: Evaluate threat.

“Threat Condition CRITICAL”

++WARNING++ ++WARNING++ ++WARNING++

Energetic barrier: Collapsing [Imminent].

Systems: Damage [Ongoing].

Interrogative: Retreat possibility?

“% Negligible”

Energetic barrier: Inoperative.

Drives: Inoperative.

Process: Initiate core protection protocols.

“Attempting to Complete Function”

Working…

Working…

System Failure. System Failure. System Failure. System Failure. System Failure.

System Failure. System Failure. System Failure. System Failure. System Failure.

SyDeTm F36ure. S}@>em FaDG£&e. Sy258 F_+^%£e. Input 68363-28583-29548-2939. [2G White-Blue] CONTACT LOST

ONE

Floating there, Melora Pazlar reached forward and carefully, delicately, put out the star with the cupping of her hand. The most gentle of radiances pushed back at her fingers, brushing lightly against her palm. She held it there for a moment, wondering about the shadow she was casting across a dozen worlds, the great darkness she had brought. If she wanted, she could have seen it for herself. A simple command, spoken aloud. A shift in viewpoint, down to the dusty surface of some nameless planetoid. Easy.

“The thing about this place is,” said a voice, “you could let working in here go to your head.”

Melora grinned and let the sun go, falling backward, dropping away. She made herself turn in midair, the spherical walls of Titan’s stellar cartography lab ranged out around her, and found Christine Vale looking up at her from the control podium. “It’s been said,” she noted. “Sometimes it is easy to lose yourself in the scale of things.”

Vale brushed a stray thread of hair back over her ear, unconsciously straightening a recently added gunmetalsilver highlight amid the auburn bangs. She glanced around. “Like looking the universe in the eye, right?”

“That’s why we’re out here.” Melora drifted gently down to the same level as the commander—it was a subtle thing, but she had always thought it bad form to look down on a senior officer—and she floated closer to the podium. The small catwalk and open operations pulpit were the only sections of the chamber given over to Earthstandard gravity. The rest of the room replicated the microgravity environment that Melora had known growing up on Gemworld. Her tolerance for the so-called standardg setting deployed aboard most ships of the line was poor, and when she wasn’t floating here, a restrictive contragravity suit was required to prevent the stresses overwhelming her body. The technology was leaps and bounds beyond the powered chair or exoframes she had used in the past but still not enough to tempt her outside the lab without due discomfort.

Holographic projection grids hidden inside the walls threw out scaled images of stars, nebulae, and all manner of other astral phenomena, filling the lab with its own tiny universe. It was a great improvement on the earlier versions of the imaging system installed on the old Galaxy class ships, flat-screen renditions replaced by this interpretation of the interstellar deeps. She gave Vale a smile. “Want to step up?”

The other woman folded her arms. “Nah. I’ll stick to solid ground for the moment.” She refused with a half-grin, as if on some level she was hoping that Melora would try to convince her otherwise. But then the moment passed, and Vale tap-tapped on the console before her. “You’ve got something interesting for us?”

The ghostly pane of a control interface followed Melora as she moved, always staying within arm’s reach, and now she reached for it, nodding. “I’m starting to think we might need a new scale of defining things, Commander. After all the stuff we’ve encountered out here so far, interesting sounds a bit… bland.” The Elaysian tapped out a string of instructions on the virtual panel.

Vale nodded. “It does seem like we’re using up all the good adjectives.” Temporal discontinuities and ocean worlds, interstellar conduits and cosmozoans, new life and new civilizations around every corner. When the uncanny and the unknown became commonplace, there was a risk you could become jaded. “Okay, not interesting, then. Let’s shoot for…” She paused, feeling for the right word. “Beguiling.”

“That’ll do.” Melora triggered a command, and the matrix of stars and worlds shifted abruptly, enough that Vale reached out a hand to steady herself on the podium. From her standpoint, it had to be like standing on the prow of a ship plunging headfirst through the void. By contrast, any sensation of vertigo was nonexistent for Melora, who had lived most of her life walking on air. She adjusted the scaling of the display and drew them deeper into the representation of the sector block that lay ahead of the Starship Titan. The viewpoint closed in on a relatively isolated binary system haloed by the indistinct shapes of a few planetary bodies. “Here we are.”

“You got a cute name for this one?” Vale asked lightly.

“Just a string of location coordinates and a catalog number at the moment.” She reached out and widened the interface panel, unfolding new windows that displayed real-time feeds from the Titan’s long-range sensor pallet. “Here’s what spiked my attention. Lieutenant Hsuuri pulled this out of a cursory automatic scan of the sector…” She highlighted a string of peaks in a sine-wave energy pattern. “Cyclic output on the extreme eichner bands, very tightly packed together.”

“Natural phenomena?” Vale raised an eyebrow.

“Not like this,” Melora replied. “At least, not like anything I’ve seen before. It’s too precise, too engineered.”

“Artificial, then.”

The Elaysian gave a slow pirouette. “And there’s more. See here, and here?” She brought up a second data window, filled with a waterfall of text readouts. “That looks like some variation of a Cochrane-type distortion. Very faint but definitely there.”

“Starships?”

“Starships.” A note of wonder crept into Melora’s voice. “Maybe.”

Drumming his fingers lightly on the wall of the turbolift, Will Riker adjusted the carryall dangling at his side, fixing the strap so that it wouldn’t bite so hard into the flesh of his shoulder. He felt every gram of the weight through the thin cotton of his short-sleeved Aloha shirt, and he shifted, trying and failing to find a more comfortable way of holding it.

The elevator car slowed to a halt, just as the captain realized he wasn’t actually at his destination; instead, the doors hissed open, and he found himself looking at the scaly countenance of his Pahkwa-thanh medical officer, Shenti Yisec Eres Ree. The saurian rocked on his clawed feet, hesitating on the lift’s threshold.

“Doctor?” Riker inclined his head, granting permission.

Ree’s long lips thinned, and he stepped into the elevator, drawing up his tail. “Captain. Pardon me, I was just on my way to sickbay.” He spoke in a deep, throaty rumble.

“Resume,” Riker told the lift, and it continued on its journey downship. For a moment, the humming of the electromag conveyors was the only sound. The silence was in danger of turning a little awkward; recent events had put some distance between the captain and his CMO, and despite an amount of spoken forgiveness, there was still a reticence between them.

Hardly surprising, Riker considered. He did bite my wife. And later kidnap her and my unborn daughter. Even with all of the best intentions, that sort of incident wasn’t just going to be forgotten overnight. Ree’s actions had been cleared by a board of inquiry, but that didn’t do anything to change the fact that the personal—if not professional—trust between the doctor and the captain and his wife had taken a hard knock. It would take a while to rebuild it to its former state.

Ree’s dark eyes gave Riker’s attire a sideways glance. “If you don’t mind me saying, that’s a decidedly nonregulation look for you, sir.”

Riker plucked at the collar of the shirt, thumbing over the patterned print of blue sky, yellow beach, and palm trees. “It’s casual Friday, Doctor,” he said with a smile, attempting to lighten the mood. “Didn’t you get the memo?”

“Captain,” Ree replied gravely, “it is Thursday.”

“I’m off duty,” he noted. “I’m taking some quality time with the family.”

“Ah.” Ree paused and sniffed the air. “I smell meat.”

Riker patted the carryall. “Replicated ham sandwiches. I’ve got a picnic in here. Not to mention diapers, baby powder, cleansing wipes, a water flask, blankets, a couple of cuddly toys, a self-heating milk bottle, and a bunch of other stuff. I carry less than this on an away-team mission.”

“I have noted that human parents have a tendency to overprepare,” said Ree. “Still, better safe than sorry, I believe the expression goes.” The saurian blinked slowly. “How are your wife and daughter?”

“Good,” Riker noted. “Tasha’s developing fast.”

“That would be the Betazoid in her.”

“You can see for yourself, next time Deanna brings her in for a checkup.”

“Perhaps.” Ree looked away. In fact, in the weeks after their return from Lumbu, the prewarp planet where the Pahkwa-thanh had taken Riker’s stricken wife so that she could give birth, the doctor had ensured that it was Riker’s former Enterprise crewmate Alyssa Ogawa who had handled all postnatal care. Ree had kept his distance for the most part, although on one occasion, Riker had seen him reach out a gentle digit to stroke the child’s head. The saurian hadn’t been aware that Tasha’s father was observing him, and to Riker’s amusement, his daughter had confidently reached out and patted the alien’s dinosaurlike snout. She was fearless, just like her namesake.

Ree’s remorse was visible in the slight stoop of his shoulders. Driven beyond reason by a mix of his own biology’s primitive drives and the effects of Deanna’s empathic abilities, he had stolen mother and baby-to-be during the Titan’s mission on the planet Droplet, convinced that only he could keep them safe. In the aftermath, Ree had freely admitted his culpability and offered himself up for censure, but the captain had refused. Now it seemed as if the saurian doctor was walking on eggshells every time he crossed paths with Riker and Troi.

The captain frowned. This had gone on long enough. “Actually, I have a better idea. How about you have dinner with the three of us, in our quarters?”

Ree blinked again. “Captain… you are aware that my eating habits as a carnivore…”

“I’ll make Andorian sushi,” Riker suggested. “That’s human and Pahkwa-thanh edible, right?”

The doctor seemed genuinely at a loss for words, and so when the lift halted, he appeared quite relieved. “Is that… an order, sir?”

The captain stepped out into the corridor. “It’s an offer. And it’s up to you.”

Ree nodded again, and the lift doors closed.

Christine inclined her head, a smirk threatening to break out on her lips. Despite everything she had just said about the routine wonder of the Titan’s ongoing mission in the Canis Major region, after Melora’s report, she suddenly felt a little tingle of that electric thrill that presaged a new discovery. What are we going to find this time?

“Okay, so that’s pretty int—” Vale stopped, shook her head. “Pretty beguiling stuff.” She glanced up at the turning yellow-white masses of the binary star pair. “A possible interstellar civilization out in an otherwise sparsely populated region. At the very least, I think I can persuade the captain to take us off our current heading and swing by a bit closer, take some better readings on the high-definition scanner array.” She considered this for a moment. “Of course, knowing Will Riker, he’ll throw caution to the wind and go straight up to their front door.”

Melora’s expression shifted toward concern. “That might not be the best approach. When I asked you to come down here, I said I had two things to show you.”

Vale pointed a pair of fingers at the simulated suns. “This is not two things?”

The astrophysicist shook her head and floated closer. “The energy patterns aren’t all we found. Hsuuri’s data chimed with something I’ve been tracking ever since we passed that protostar cluster last month.” Melora tapped in more commands, and Vale’s lips thinned with the brief head-swim that came as the stellar cartography lab reconfigured itself once more, this time rushing out to show a larger part of the sector. A few faint clouds of blue faded into existence here and there, most of them small dots, some of them as large as the ship—or a planet. She could intuit a vague pattern in their dispersal, like a spiral.

“What am I looking at?”

“Regions of subspace instability. A little like the ones the Rhea encountered a while ago out in NGC 6281. Nothing too dangerous, but I’ve been liaising with Lieutenant Commander des Yog and the conn team to ensure that we’re steering clear of them. Just in case.”

Vale nodded. “Right. I got the report.” Regions of spatial distortion were not as uncommon as most people thought; the uniformity of space was actually far from it, but most warp-capable vessels moved through the pockets of faint instability without issue, just like an oceangoing ship cutting through waves across the surface of a sea. It was only when the waves got high—when the distortions became more pronounced—that problems occurred. Where the change in energy states was sharp, it could be enough to throw a vessel out of warp or worse; but so far, they had seen nothing like that in the region, and with the Federation’s advances in variable-geometry drives and encasedfield warp-transfer algorithms in the last decade, most ships had an easy ride.

“I don’t have a theory for this,” Melora admitted. “There’s more spatial stressing in this sector than we’ve seen anywhere else since we came to Canis Major. It could be warp-field effects from first-generation interstellar drives, naturally occurring phase-barrier distortion…” She shrugged. “I’m still gathering information.”

“We’ll tread carefully, then.” Vale looked away. “You think this is connected to the double-star system?”

“It’s possible. Another good reason to go and take a look. We might learn something from the locals, if we can ask around.”

Vale stepped back. “All right, you’ve sold me. I’ll brief the captain. Get me a report covering the high points so I can give him a little show-and-tell.” She smiled. “Not as impressive as this one, I grant you…”

“Already done,” said Melora. “The report’s in your personal data queue.”

“You wrote it up already?”

“I’ve been in here all day, Commander,” said the Elaysian.

“Oh. I thought, um…” Vale trailed off. “Never mind. Thanks, Melora.” She turned to leave, but Pazlar swam forward, moving alongside the catwalk.

“What?” asked the other woman. “You thought what?”

“It’s just that… well, Doctor Ra-Havreii was off-shift today, and I just assumed you two were—”

“Together?” The Elaysian’s expression cooled.

Vale cursed inwardly. I should stop talking now.

“We’re not joined at the hip, Christine,” continued Melora. “Is that what people think?” And just like that, they were suddenly having an entirely different conversation.

“I have no idea what people think,” Vale said lamely. “I’m only the first officer. I just tell them what to do.”

“You’re the worst liar ever.”

“You only say that because you don’t come to the captain’s poker nights.”

Melora’s pleasant face grew concerned. “Is my relationship with Xin a matter of popular discussion among the Titan’s officers, then?”

“No.” The lie fell from her lips automatically, and Vale almost winced at the baldness of it. She sighed. “Okay, yes.” Melora opened her mouth to speak, but Vale talked over her. “But what did you expect? Xin’s never been the type to keep to himself. And this is a starship; it’s like a small town. There’s only three hundred fifty of us onboard, and people like to talk. It’s what enclosed communities do.” She nodded toward the hologram of the twin suns. “Those two aren’t the only stellar couple people are interested in around here.”

“Very funny,” said Melora in a way that made it clear she thought exactly the opposite.

“Look, I know how you feel. I’ve been in the same situation.” Unbidden, Jaza Najem’s face rose briefly in her thoughts. Vale’s relationship with the Titan’s Bajoran science officer had been brief but just as talked about. All these months later, all the time that had passed since he’d been lost on Orisha, and she still felt a moment of pause at the thought of him. She shook it off. “What I’m saying is, don’t worry about it. A few weeks ago, people were talking about Deanna and Will and their new baby. This week, it’s you and Xin. Next month, when Lieutenant Keyexisi enters the budding cycle, it’ll be him.”

“I don’t like the idea of my personal life being discussed as if it’s the plot of a holodrama.”

But Ra-Havreii does. The thought popped into Vale’s head the moment Melora spoke. In the first officer’s opinion, the Titan’s chief engineer liked his reputation a bit too much, trading on his iconoclastic behavior and—until recently—his cavalier attitude toward members of the opposite sex. The man was a genius, that was without question, but Vale had to admit that on occasion his attitude chafed on her. At times, she felt he was too contrived, too brazen about being brazen, as if it were a mask he’d worn so long he’d forgotten how to take it off. In her time as a peace officer on her native Izar, in the years before she’d joined Starfleet, Vale had seen the same thing in dozens of people—suspects, mostly.

So it had come as a surprise to her to learn that RaHavreii and Pazlar had become an item. From what she knew of Efrosian culture, the whole concept of any kind of long-term commitment was far outside the experience of males of his species. So not a lot different from some human men, then, she thought dryly.

“It hasn’t been easy for us,” Melora said quietly. “This doesn’t help.”

Part of Christine wanted to tap her combadge and summon Commander Troi or Doctor Huilan. I’m not a counselor. I’m no expert on the whole relationship thing. But she knew why the Elaysian was confiding in her: precisely because she wasn’t Deanna or Sen’kara. She sighed. “All you can do is give it your best shot. Don’t sweat the little stuff. Xin might be flighty, okay, but you’ve got a real connection. He cares about you. If you try to make it work, so will he.”

At length, her words seemed to have the right effect. Melora nodded. “Thank you, Commander. I appreciate that.” She floated up, back into the stars, and Vale left her behind, wandering out into the corridor.

See, she said to herself, I am a great liar.

The string of mumbled expletives was what led the captain to the service hatch next to the doorway of holodeck 2. A pair of long, thin legs extended out into the corridor, the rest of the torso they were attached to swallowed up by the open maintenance crawlway in the wall. A halo of tools and padds lay untidily on the deck, and every now and then, a milk-pale hand wandered out to snag a hyperspanner or laser sealer before disappearing back into the hatch.

Riker glanced at the control panel in the holodeck’s command arch. None of the touch-sensors responded to him, and the main system display was blank except for three words: “Please Stand By.”

He put down the heavy bag. For all the talk of captain’s prerogative and the like, it was actually pretty damned hard for a starship’s commanding officer to find a space in his schedule for something approaching actual leisure time. That was made worse if said captain wanted to synch up his day off with that of another officer, namely his wife, the ship’s senior diplomat. Riker’s pleasant mood lost some of its warmth to find that the holodeck he’d reserved for his use was off-line.

He’d planned to run a great resort program, one of his personal favorites, a simulation of an area of low-gravity parkland at the edge of Lake Armstrong on Luna. With Deanna doubtless on her way down to meet him with Tasha in tow, he did not want to disappoint them.

Riker bent to take a better look at whoever had conspired to derail his plans. “What’s going on here, mister?” he demanded.

He was rewarded with the sound of a collision as the junior officer in the Jeffries tube reacted with such shock that he banged his head on the panel. With a scrambling motion, a skinny humanoid male backed out into the corridor, shamefaced. “Uh. Captain. Sir. Captain.”

The officer’s collar was science blue with a lieutenant’s pips. He had wide yellow eyes with feline vertical pupils, pale white-gold skin, and strawlike hair. If it hadn’t been for the stubby tail that flicked from the base of his spine, the lieutenant could have passed for a more youthful iteration of Riker’s late colleague, the android Data. Cygnian, he realized, placing the species, searching his memory of the crew’s records. Which means this is—

“Lieutenant Holor Sethe, sir. Computer Sciences Department.” The officer gave him a formal salute. “I, uh, wasn’t expecting, uh, an inspection.” He rubbed the sore spot on his high forehead. Sethe blinked as his thoughts caught up with him, and he frowned at Riker’s lack of uniform.

“I know who you are, Mr. Sethe. You don’t have to salute me,” the captain replied, straightening. “We’re a bit more relaxed here aboard Titan.” He recalled meeting the young officer only once before, and he’d saluted that time as well.

“Yes, sir. Sorry, sir. Force of habit.”

Riker pointed at the control panel. “Two things. What’s wrong with my holodeck, and why wasn’t I informed?”

“Um,” began the Cygnian. “Well, nothing, and… why should you be, uh, sir? I mean, begging your pardon, but I thought this sort of noncritical system wouldn’t be a concern for the captain.”

“It is if the captain has it booked out for the next two hours.”

“But—” Sethe managed one word and then stopped dead. He reached for a padd and glared at it. “Today isn’t Friday, is it?”

“So I’ve been told.”

“Ah. Um. Sorry. My work schedule is wrong. I shouldn’t be here.” He spun in place and began quickly gathering up all of his equipment, using his wide, slender hands to fold the open access panel back in on itself. “It’s just… before this, I was serving on a largely Vulcan-crewed ship. They have a different day cycle from Federation Standard. Even after all these months, it’s been a bit difficult for me to adjust… keep slipping into old routines.” His fingers danced over the keypad, and the command arch came back to life. “It’s, uh, fine, sir. Go ahead. I’ll get out of your way. Sorry.”

Streams of program titles began a rapid scroll down the panel, and Riker searched fruitlessly for the Lake Armstrong program. “Has this database been altered recently?”

“After the refit at Utopia Planitia, aye, sir.” Sethe nodded. “The Corps of Engineers used the opportunity to tweak a lot of minor systems. They had a Bynar team in here running upgrades to all the holotech.”

Riker recalled a mention of that from the files that had crossed his desk in the days and weeks after the massed Borg attack on the Alpha quadrant. In the aftermath of that bloody, destructive conflict, the Titan had been just one of many Starfleet ships sent back to lick their wounds in spacedock. Since the Titan had left the Sol system on her ongoing mission of exploration, the captain had been in the holodeck only a handful of times, certainly not enough to appreciate the full scope of any improvements.

Sethe opened the doors and jogged into the bare, graysteel chamber, pausing to adjust one of the holographic emitter grids built into the walls. “Okay, sir. I think we’re good to go.”

But Riker’s attention was elsewhere for a moment. Amid the menu of simulations available, he spotted something that gave him pause. Without being quite sure of the impulse that drove him, he tapped the screen.

From the featureless metallic space, smoky walls of careworn wood emerged in swirls of photons; clusters of tables appeared and fanned out across the floor, before a bandstand illuminated by the halos of pinlights. In moments, an authentic New Orleans jazz club had constructed itself around them. A faded sign above the shadowed bar spelled out a name in backlit stained glass: “The Low Note.”

Riker stepped in through the arch, and his face split into a wistful smile. “Well, I’ll be damned.”

“Excellent emulation,” remarked Sethe. “These newer Eight-Bravo-series holodecks have five times the processing power of previous units. You can really see it in the sim-persona generation,” he added, warming to the subject as the doors sighed shut behind him and melted into the illusion. “Computer?” He addressed the air. “A character for the captain, please.”

The captain turned, about to belay Sethe’s order, but in a whirl of light and color, she was suddenly there, all stunning dark eyes and absolute poise, dark tresses framing a generous mouth. The dress she wore sparkled like captured lightning in the club’s sultry gloom.

“My name is Minuet,” she breathed, “and I love all jazz except Dixieland.”

“Because you can’t dance to Dixieland,” Riker said to himself. He shot Sethe a sharp look. “You picked her?”

The lieutenant shook his head, surprised by the captain’s tone. “Um, no, sir. The holodeck did. It’s a predictive system, based on the environment, your current psychometric profile, your personal data, the kinetics of your body language, speech patterns…”

“I haven’t seen this holoprogram in years,” he said, circling the woman. “The last time was aboard the Enterprise, when we were docked at Starbase 74.”

“Did you miss me?” Minuet took a step toward him, a wry smile playing on her lips.

Sethe nodded once more. “You see how she’s reacting to you? That’s demi-intelligent subroutines at work, heuristic learning in picoseconds. The longer the program runs, the more it learns how to read you, to better tailor the experience.”

Minuet’s hand reached out and touched his arm. “Are you going to play?” She nodded toward the bandstand, where a trombone had appeared.

“Computer, freeze program.” Riker said it with more force than he meant to, enough that Sethe flinched. The woman stood there in front of him, suspended in time, as beautiful—perhaps even more so—as she had been the first time he had seen her. “The Bynars,” he heard himself saying, “they hijacked the Enterprise during a maintenance stop. They used a variant of this program to… keep me occupied.”

Sethe grunted. “Oh, I heard about that. They used the ship as a backup for their planetary database, didn’t they?” He gestured with the padd in his hand. “But that’s the Bynars for you. They’ve always been a bit twitchy.”

Riker’s attention was elsewhere. Suddenly, he felt uncomfortable; the hologram brought up old memories that he had thought long forgotten. Just for a moment, he was the man he had been all those years ago, standing in this place, with this woman, living this dream. From that perspective, it felt as if an age had passed. Then he had been a rising star, first officer aboard the fleet flagship, with countless new frontiers ranged out before him… and a universe of choices.

But he was different now. Riker was surprised by a faint stab of regret. Now he was the captain, a husband, and a father, and while the frontiers were still there, it might be that perhaps the freedoms had lessened. The thought sat uncomfortably, and with a sigh, he pushed it away. His lips thinned, and he spoke again, this time firm and definite. “Computer, end program and reboot. Load simulation Theta-Six-Nine. Lake Armstrong.”

The club and the woman became ghosts and faded into nothing. The photonic haze rippled once more, and the chamber became a lakeshore beneath a tall, curving atmosphere dome.

“Is there a problem, sir?” asked Sethe, nonplussed by the captain’s reaction.

“No problem,” said Riker.

In the middle distance, the holodeck doors reappeared and slid back. Deanna walked in, singing quietly to their daughter, the child carried high against her chest. She wore a sand-colored summer dress, and her hair was up. His wife took Tasha’s tiny hand and pantomimed a wave toward her father. The little dark-eyed girl laughed, and her mother echoed the sound.

Deanna smiled, and Riker found himself mirroring her, that tiny dart of regret melting away beneath a warmth like the sun coming out.

“No problem at all,” he told the lieutenant. “Carry on.”

“This is the most bloodless game I’ve ever played.” Pava Ek’Noor sh’Aqabaa leaned back in her seat and folded her arms across her chest. The Andorian woman’s antennae tightened, curling downward in irritation.

Across the table from her, Y’lira Modan’s golden face shifted into a quizzical expression. “I thought this was a leisure pastime,” she began, glancing at the oval cards in her hand. “There’s no violence inherent in it.” The Selenean looked around Titan’s mess hall with an air of slight concern, perhaps wondering if the game would take on some combative aspect at a moment’s notice.

“Bloodless,” Pava repeated with a sniff. “As in devoid of passion or thrill.”

To her right, Torvig Bu-Kar-Nguv cocked his deerlike head and showed a slight toothy smile. “I’m quite thrilled,” he offered.

“You’d never know it,” Pava said dryly, drumming her blue fingers on the dwindling pile of coins in front of her.

The fourth player in their circle said nothing, instead resting his hand over the second of his cards, yet to be turned faceup. Tuvok’s steady, unblinking gaze remained fixed on the Andorian.

After a moment, Torvig spoke again. “Commander Tuvok is showing the Ranjen,” he explained, the mechanical manipulator in the end of his slender tail coming up to point at the turned card in front of the Vulcan. The elliptical card showed a traditional icon of a Bajoran theologian, with characteristic hood and robes. “At best, he can score an eleven-point combination, with the reveal of an Emissary.”

Pava glared down at her own hand, the turned card showing a radiant Kai on the steps of a Bantaca spire.

“Of course,” Torvig piped, “if you show the Emissary or even another Kai, you’ll have a firm win—”

“I know the rules, Ensign,” she snapped. “I’m just… considering my options.”

Y’lira shrugged. “You only have two of them, Lieutenant. Match the commander’s wager or fold. It’s quite straightforward.”

The Andorian chewed her lip. The pile of replicated lita coins in front of the Vulcan tactical officer was the largest on the table, with Torvig the only other player still showing more than a few tokens remaining; the Choblik had been losing and folding all night, retaining an annoying good humor all the while. He seemed to have absolutely no understanding of the dishonor attached to his utterly unremarkable play. Y’lira had just thrown her last stake into the pot, and Pava was in the same boat; if she matched Tuvok’s bet, she’d be cleaned out. But the idea of folding chafed on her. She felt her hands draw into fists. It was only a game, but that didn’t mean she wanted to lose it.

“In reference to your earlier comment, Lieutenant, the game of kella has quite a violent history.” The commander spoke evenly, adopting a lecturing tone. “During Bajor’s preenlightenment age, there were several matches of historical note that resulted in declarations of warfare or brutal reprisals after one tribe’s champion player lost to another.”

“I’ve always admired Bajoran passion,” Pava allowed. “But then they’re a people like mine, who react with zeal. They don’t analyze every incidence, don’t reduce everything to statistics and numbers!” Her voice rose toward the end of the statement, and she frowned at herself.

Torvig’s head bobbed. “Isn’t that the point of games like this?”

She glared at him. “I bet you’re computing the odds and probabilities of every possible combination of cards right this second, aren’t you?”

“Yes,” said the Choblik easily. “I imagine Commander Tuvok has done the same, along with Ensign Y’lira. The Vulcans and the Seleneans are renowned for their analytical abilities.”

“My point,” Pava retorted. “If you turn this into a numbers game, it robs it of any excitement. Kella is about chance and risk, not mathematics!”

“I find mathematical conundrums quite stimulating, actually,” said Y’lira.

“Oh, for blade’s sake.” Pava’s face flushed indigo, and she shoved the rest of her coins into the middle of the table. “There. All in.”

“Reveal,” said Tuvok, ignoring the Andorian’s emotive reaction, nodding to Y’lira.

The Selenean bowed her head and turned her second card, bringing out a Prylar in a monk’s habit to go with the Kai already before her.

“Ah, ‘The Passing of Knowledge,’ an eight-point pattern,” Torvig noted brightly.

Y’lira raised her golden hands from the table in a gesture of surrender; with no stake left, she was out of the game. Her last gesture was to denote the next player to reveal, and she nodded at the lieutenant.

The others turned to watch Pava without comment. The lieutenant’s lips curled, and she snapped over her other oval card with a hard flourish, nailing it to the table with her finger. A Ranjen, the mirror of Tuvok’s shown card, stared back up at her. She felt a sudden surge of excitement. Torvig had a Ranjen showing as well, and the poor second-rank card offered him as little chance for a win as the commander.

“Ten points for Kai and Ranjen, ‘The Answered Question,’” said the Choblik. “The lieutenant leads.”

Pava immediately pointed at Tuvok, whose irritatingly composed manner had been grating on her as he had siphoned off her coins throughout the game. “Reveal!”

Without a glimmer of concern, the Vulcan displayed a Ranjen. At only two points, “The Bearers of Truth” was the lowest-scoring hand that had appeared all night. Pava immediately clamped down on the beginning of the grin that threatened to race across her lips, and she had to place her hands flat on the table to stop herself from preemptively reaching for the pot.

“Ah, me, then.” Torvig’s tail manipulator looped over his right shoulder and delicately flipped the last oval onto its face. Pava’s moment of anticipation disintegrated so decisively that for a second, she was sure she could hear it shatter like breaking glass. The dark complexion and gold-haloed face of an Emissary card lay there, silently announcing her failure.

“The Emissary and the Ranjen,” Tuvok intoned, in case Pava wasn’t clear on how badly she’d been beaten. “Eleven points scored for ‘The Learned Ones.’ Well played, Ensign.”

Torvig’s augmented eyes blinked, and he reached out with his forepaw cyberlimbs to draw the pile of Bajoran coinage to him. “That was quite engaging. It’s a shame these are only score markers. I imagine on Bajor, I’d be quite wealthy.”

Pava grumbled something under her breath and stood up. “I think next time I play, it won’t be against people with calculators in their heads.” Of course, intellectually, she knew that the coins were valueless tokens replicated just for the sake of the game, but that didn’t soften the blow of losing. And losing to a diminutive ensign who resembled the snowskippers she’d hunted in her teens on Andor just rubbed ice into the wound.

Torvig paused. “I’m the only one here with neuralprocessing circuits in my cranium.”

Y’lira smiled serenely. “There’s always Chief Bralik’s floating Tongo tournament, if it’s high emotion you’re looking for, ma’am. Although it’s mostly greed, not passion.”

Pava shot her a glare. She was never really clear on the cryptolinguist’s grasp of sarcasm. “My meaning is, games of chance should be exactly that, random and chaotic, just like real life! It’s the thrill of the roll of the dice, the turn of a card. It’s not something to be bled dry of all emotion, just reduced to equations and probability graphs.”

“In all systems, even those that appear to be chaotic in nature, there is a form of order,” Tuvok replied. “If it can be determined, then it can be emulated and predicted. I would submit to you, Lieutenant, that the element of chance is illusory. It simply requires a means of computing robust enough to transcend it.”

Ensign Torvig’s robotic fingers had made quick work of dividing his pile of winnings into four identical towers of lita coins. “I’d love a rematch,” he offered, but the Andorian was already thinking about a different kind of game, something more her speed, something that would involve hitting things with sticks.

But then everything was swept away as the deck pivoted without warning beneath her feet, throwing cards and coins and everything not bolted down up into the air.

A metallic moan echoed through the bulkheads as superluminal velocities were abruptly canceled out, shock waves of kinetic energy backwashing through tritanium panels and duranium spaceframes. The starship shuddered along its length, internal lighting flashing out, then returning in jagged strobes. Somewhere, an electroplasma conduit popped and shorted as breakers kicked in.

Pava shot out an arm to snag the lip of the table, her other hand unceremoniously catching hold of Torvig’s tail as he fell upward. The Choblik gave a lowing cry of surprise that turned into a grunt as the Titan’s artificialgravity generators caught up to the shock and reasserted control.

Loose items clattered back to the deck in a rain, and Pava landed awkwardly, hissing as she banged her leg against a chair.

Y’lira blinked. “We… we’re out of warp?”

“Yes,” managed Torvig, shaking his head. Anything else he was going to say was drowned out by the blare of the alert sirens.

Tuvok was already racing for the mess-hall door. “Stations!” he shouted.

Coins and cards abandoned, the other officers sprinted after him.

TWO

“What the hell was that?” demanded Vale, wincing at the pain in her right shoulder. When Titan had bucked, she’d grabbed the arm of the command chair to stop herself from being flung to the deck of the bridge. She was thinking maybe she’d wrenched something. “Full stop!” The order seemed a little redundant, but she gave it anyway. On the forward viewscreen, a fizzing plane of static cast hard, sharp-edged shadows.

“Sandbank,” muttered Lieutenant Lavena, leaning close over the helm.

“Spare me the oceangoing metaphors, Aili.” The first officer got to her feet and surveyed the bridge with a grimace, waving a hand in front of her face to waft away a drift of thin smoke. Panels around the engineering console flickered and spat fat sparks as a junior officer worked to stabilize the system.

The Pacifican pilot turned in her chair. “Force of habit, Commander, sorry.” She tapped her panel. “We struck a pocket of spatial distortion. It caught us out of nowhere. It must have blown the warp bubble, knocked us back to sublight.”

To Lavena’s right, Lieutenant Sariel Rager was pushing stray hair out of her face from where it had come loose, her dark eyes still wide with the shock. “Confirming that, ma’am. Close-range sensors are reading dissipating tetryon discharges, consistent with a distortion effect. Titan sailed right through the middle of a zone of collapsing subspace instability.”

Vale cursed under her breath. “I thought Melora was feeding you nav data on these…” She frowned. “These sandbanks.” The commander walked forward. “You’re supposed to go around them, not through them.”

“We were just in the wrong place at the wrong time,” said Rager.

Lavena’s face colored slightly. “With all due respect, this sector is so choked with spatial distortion, there’s hardly anywhere we can go where we’re not passing through them. But it’s mostly low-level, not enough to affect the ship.”

Zurin Dakal glanced up from behind the bowed sciences console. “That didn’t feel like ‘low-level’ to me,” said the Cardassian. Lavena frowned back at him, and he looked away. His gray fingers ran across the panel, working furiously. “Confirming Lieutenant Rager’s readings. The distortion zone must have gone through a sudden expansion-contraction event. It’s a million-to-one chance we were even nearby. Without temporally desynchronized sensors, there’s simply no way we could have avoided it.”

“Status report?” As Vale asked the question, she turned to see Tuvok enter the bridge through the port turbolift and move swiftly to his post behind the tactical horseshoe behind the command pit.

Ranul Keru caught her eye. The Titan’s Trill security chief was at the main systems display at the back of the bridge. “No hull breaches, no internal threats,” he began, getting a confirming nod from the Vulcan. “Sickbay reports coming in… minor injuries, no fatalities. Obviously, we’ve lost warp drive for the moment. Life support and impulse power got shook up, but they’re still operable.”

“Weapons and shields are nominal,” Tuvok added. “Scanner arrays returning to operating status.”

“So we got tripped up and fell on our backsides, but aside from dents in our dignity, we’re fine?”

Keru nodded. “It would appear so, Commander.”

Vale looked back to Dakal. “Ensign, tell me this doesn’t mean we’re going to have to crawl through this sector at sublight from now on.”

“I’m still forming a hypothesis,” he replied.

“Form quicker,” Vale demanded. “We just turned the captain’s day off upside down—literally—and he’s going to want an explanation.”

A chiming alert tone sounded from the tactical station. “I am detecting multiple objects in our vicinity.” Tuvok’s eyebrow arched. “In addition, energetic residues.”

“From the distortion?”

“Negative.”

Dakal was nodding. “I see the objects. Not ships… at least, not a whole one.”

Vale looked forward. “Can we get that screen working?”

One of the engineers worked his console, and the main viewer, flickering and hazy with distortion, became clear. Immediately, Vale spotted a half-dozen jagged forms drifting against the blackness. Some of them tumbled, catching the light of far distant stars, while others bled orange streamers of spent energy behind them.

“Based on the clustering of the fragments, this appears to be the remains of a single vessel. I would estimate the craft to be around one-third the mass of the Titan. I am detecting refined metals, tripolymers, decay products from spent electroplasma…” The ensign read off the report from the sensor grid. “Traces of directed-energy discharges. Lots of them.”

“Weapons fire,” said Keru, grim-faced.

“A battleground?” Lavena studied the display, her hands tensing.

“Tuvok…” Vale threw him a look. “Any pattern matches in our databases?”

The Vulcan paused. “There are multiple particle signatures… I would hypothesize high-energy antiproton weapons.”

Dakal spoke again. “All of the fragments display a similar metallurgy. I’d need to make a closer examination for full confirmation.”

“You want to go and pick up a piece, Ensign?” said Keru. “It’s swimming in radiation out there.”

“One ship,” echoed the commander. “Whatever happened, it was smashed to pieces.”

“What could do that to a starship?” Lavena asked aloud, a note of fear in her voice.

“Internal explosions? Gravitational stresses?” suggested Rager. “Or maybe something with really big teeth.”

“I can find no correlation with any elements of known ship design in the tactical database,” Tuvok added.

“Zurin, what about life signs?” said Vale.

“The first thing I scanned for, Commander,” the ensign replied. “No organic forms detected. As Lieutenant Commander Keru stated, the ambient radiation fogging the area is quite lethal. If any conventional carbon-based life survived…” He nodded toward the debris field. “Survived that, I doubt they would have lived much longer.”

“We’ve encountered plenty of life-forms that can handle high rads,” noted Rager.

Dakal nodded. “And I scanned for those as well. I admit, it is possible there could be shielded compartments within the larger pieces of wreckage or zones we can’t read at this range.”

Keru let out a slow breath. “Whatever took place here, it was brutal. I’m wondering if that, uh, sandbank we hit was a side effect.”

“I concur,” said Tuvok. “The expenditure of energy in this area far exceeds that which would be required to atomize the mass of the wreckage. We can only conclude that another combatant was present.”

“Obviously,” Vale retorted.

“Indeed,” Tuvok continued, “but if another craft was here, then why do the sensors register the ion trail of only one vessel?”

“You’re saying whatever did this just… vanished?” Dakal licked dry lips.

“I am merely presenting the information available at this time.”

Vale frowned. “All right. First things first. We get our ship back on an even keel before we start worrying about someone else’s. I want situation reports from all department heads in ten minutes.” She turned toward Lavena. “And Lieutenant, you work with Melora and Zurin. See if you can’t find us a way to make sure we don’t run aground again.” Vale’s lips curled. “Honestly, it’s embarrassing.”

• • •

“She’s fine,” said Ogawa, snapping shut the medical tricorder and pulling a big smile for Tasha. “A little shook up, but then aren’t we all?”

“Thank you, Alyssa.” Deanna gave her a nod, and the nurse moved off. On some innate level, she had known that her daughter was fine, despite her anguished cries when the holodeck went off-line just as they’d started their swim; but it helped to hear someone else say it.

Deanna pulled her robe tighter and used the big, baggy sleeves to cradle her daughter. She tried not to shiver; under the robe, she was wearing her still-wet bathing suit, and damp footprints across the sickbay deck attested to her full-tilt run from the holodeck to Titan’s medical center. Nearby, Doctors Ree and Onnta moved swiftly about the sickbay, checking for concussions or other less immediate injuries. Mercifully, nobody had been badly hurt, but that didn’t keep the crew’s anxiety level from peaking.

Deanna could feel the wave of tension rising and falling at the edges of her empathic senses. Titan’s crew were steadfast and well trained, but this sudden out-of-nowhere shock had shaken them all. She sighed and narrowed her focus to the small child in her arms, giving her a wan smile. Everything is fine, little one, she said inwardly, doing her best to project calm and warmth. It wasn’t yet clear how much of her mother’s gifts for empathy Natasha Troi had inherited, but Deanna did her best to soothe her. It seemed to work, as the baby’s fretful expression softened into something more relaxed.

I wonder if that will work on Will. Deanna saw her husband across the sickbay, behind the curve of clear glass that was the wall of Ree’s office. His expression was set hard, his eyes narrowed, as he spoke with Christine Vale. Like Troi, Will was still dressed for a vacation, but his posture was all command, stiff and severe. She walked over, catching the tail end of the executive officer’s report.

“—so whatever hit the wrecked ship is long gone,” Vale was saying. “All sensors are back up, and we’re reading nothing.”

“Could it be a cloaked vessel?” Will’s arms were folded across his chest.

“If there is a hidden ship out there, then it’s using better tech than we’ve ever seen.” Vale leaned forward to reach for something, and her hand seemed to disappear; then she drew it back with a padd in her grip, and Deanna realized why she wasn’t sensing any emotion from the other woman. Vale wasn’t actually in the office with her husband, more likely up in the captain’s ready room, using the shipwide holocomm system to deliver her report virtually. “Tuvok’s running every profile we have, including data from that Reman ghost ship the Enterprise-E encountered. So far, there’s just dead vacuum out there.” On the padd’s screen, Deanna saw a readout showing wreckage scattered ahead of Titan’s bow.

Will glanced at his wife and daughter, and for a moment his expression softened—but only for a moment. Deanna and Tasha were okay, but Will’s responsibilities also included more than three hundred other lives that made up Titan’s crew complement. “We’re certain that it was another ship that did this? It couldn’t have been an accident or natural phenomenon? Maybe the same thing that threw us out of warp?”

“They were shooting at something,” Vale noted. “And whatever it was, it didn’t like it. If not a vessel, then…” She trailed off, frowning.

Will glanced back at his wife. “Deanna, can you sense anything? Anyone… alive?”

She paused and closed her eyes, let her preternatural awareness briefly extend beyond the starship’s hull. She cast outward, seeking the telltale glimmers of thought color from an organic mind, and found nothing but a lifeless void. Deanna shook her head and shivered slightly. “I don’t feel anything.”

“But that doesn’t mean there isn’t anyone out there,” Vale noted. “Psionics isn’t an exact science.”

Deanna nodded. “She’s right. There could be survivors, beings with contraempathic brain structures.”

“I want to go out and take a look,” Vale added quickly. “Whatever happened here, whatever it was that kicked us out of warp, I think we’ll find the answers on that alien ship.”

“What ship?” Will replied, shooting a look at the padd. “In case you hadn’t noticed, there’s hardly enough of it left to deserve the name.”

“Ensign Dakal is tracking one of the largest hull fragments. It’s giving off intermittent energy pulses. If we take a shuttle, we can lock onto the hull and survey the wreck close-up. Maybe find a sensor log… maybe a survivor.”

Will’s lips thinned. “And that’s right in the middle of the densest part of the debris field. It’s going to be like steering through a cloud of knives.”

“A cloud of radioactive knives,” added Deanna, reading the padd.

Vale hesitated. “But you’re still going to give the order, aren’t you?”

Will nodded. “If there’s a chance someone might be alive out there? Of course I am. I just wanted to make sure we’re all clear on how horribly dangerous this could be.”

“Yeah,” said the exec. “I got that. Vale out.” She gave a nod and vanished in a swirl of holographic pixels.

Deanna’s husband blew out a breath, and leaned forward to stroke his child under the chin. Tasha chuckled, and her parents shared a smile. “Well,” he said, “at least there’s someone onboard who isn’t fazed by any of this.”

“She is her father’s daughter.”

Will’s smile lengthened. “Her mother’s, too.”

The Shuttlecraft Holiday exited the Titan’s aft landing bay and performed a half-loop, turning in an arc that passed over the starship’s upper sensor pod and primary hull, then out across the bow.

Ensign Olivia Bolaji fixed her complete attention on the morass of shifting fragments that spilled out in front of the shuttle, each spinning and turning on its own axis. The small craft’s navigational computer projected a holographic heads-up display, complete with predictive analysis of trajectories, impact loci, and areas of potential lethality. She chewed her lip as a piece of dark gray metal loomed, easily the size of a ground car.

Ranul Keru placed a hand on her shoulder. “Time to earn your pay, Liv.”

The shuttle banked evenly, smaller fines of wreckage sparkling across the bow where they bounced off the deflector shields. “I’m a leaf on the wind, sir,” she replied without looking away, her focus total and absolute.

Easing the thrusters up to one-quarter power, the Holiday entered the danger zone.

Ranul stepped back into the main compartment, where the rest of the boarding party was going through final safety checks. They all wore heavy Starfleet-issue environment suits and watched one another as they donned gloves and closed atmosphere seals. He threw a nod to Chief Dennisar, and the burly Orion returned it, stepping closer. “Boss,” he said in a low voice. “I took the liberty of bringing a compression rifle along, just in case.” Dennisar didn’t need to say more; until Ranul knew different, he was treating this away mission as a sortie into hostile territory. If the place looked like a war zone, that was probably because it was.

“Better to have it and not need it than to need it and not have it,” said the Trill.

“Aye, sir.”

Across the compartment, Commander Vale patted Ensign Fell on the back. “You’re good to go, Peya.”

The Deltan woman nodded and reached for her helmet. Zurin Dakal handed it to her, and she took it with a weak smile.

“Never really liked these suits,” said the Deltan. “The idea of this much material between you and deep space…” She held her thumb and forefinger very slightly apart. “It doesn’t really sit well with me.”

At Dakal’s side, the other member of the away team, a Benzite engineer named Meldok, shot her a look. “Suit failures are a statistically uncommon cause of death for a Starfleet officer,” he noted, his slightly nasal voice echoing inside his own helmet. “You’re much more likely to perish from any one of a number of other causes, such as—”

Ranul saw Fell’s face go pale and leaned in, clapping a hand rather harder than he needed to on the back of Meldok’s torso plate. “Less talk, more walk,” he snapped. “We’re on a tight timetable, people.” To underline his point, he snapped the seals shut on his own headgear and nodded to Vale, who did the same. Fell was the last to complete the process, and Ranul gave her a smile he hoped was reassuring.

Dennisar was at the airlock hatch, working the controls. “Ready.”

“Ready,” called Bolaji from the cockpit. A forcefield sprang up, sealing off the crew compartment as atmosphere bled swiftly away.

Ranul felt the suit stiffen slightly and heard the silence creep in as the air around them was drawn off. He looked down at his gloved hands, and for a moment, an old and hatefully familiar pain turned over inside him. He didn’t like wearing these things any more than Fell did.

The suit’s faint scent of tripolymer and life-support circuits reminded him of death. His lover Sean Hawk had been killed outside the Enterprise by the Borg, in a suit just like this one; he had died tasting the same artificial tang of recycled air. Ranul sighed and pushed the thought away.

“Do it, Chief,” Vale was saying, her voice issuing from the communicator near his ear. Ranul looked up as Dennisar opened the hatch in the Holiday’s roof.

Outside, weak starlight caught a slow blizzard of debris and, beyond, the distended shape of an ingot of hull metal.

Ranul pushed forward, returning to the moment and the job at hand. “I’ll go first,” he said.

Olivia had brought them as close as possible to the wreckage, reducing the distance they had to travel to less than five meters. Vale pushed out of the hatch and made a slow tuck-and-roll maneuver, turning herself so the alien wreck was below and the Holiday was above. Her gravity boots thudded dully and adhered to the hull. Fell came next, and Dennisar was last, the three of them joining Keru, Meldok, and Dakal where they crouched low on the curve of gray metal.

The Benzite was sweeping a tricorder back and forth. “Interesting construction,” he noted. “The fuselage is not a single form but actually a series of smaller, articulated frames, doubtless capable of multiple-geometry configurations.”

Vale looked across to the shuttle’s canopy, where Bolaji was visible. The pilot looked up and gave her a wave. “The exposure clock is running, Commander. I’ll give you the three-minute warning if you’re not already back by then.”

“Copy,” she replied. “We won’t stay out here a second longer than we have to.”

Dakal pointed toward a massive tear in the alien ship’s hull. “We should make our entry here, ma’am.” The gouge in the metal was like a ragged-edged wound, as if a huge talon had raked the craft in passing and opened it to the void.

“Lead on,” she ordered, and the Cardassian set off with Dennisar pacing him, the wary Orion holding the compact shape of a heavy phaser at his hip.

Vale went in after them, activating the suit’s built-in lamps to get some illumination. For a moment, she felt disoriented. Instead of something that could readily be defined as a “corridor,” the team found themselves drifting in an elongated internal space, choked with a snake’s nest of conduits and cabling that ranged forward and aft. There was nothing that seemed to be a floor or a ceiling and no regularity to it. Dead-eyed panels, perhaps systems consoles, poked from snarls of thick tubing like boles in tree trunks. In some places, the conduits had burst, spilling fluids that had flash-frozen into fat knots of chemical ice. Some of the cables were severed, the razor-sharp ends showing bright coppery cores.

“This could be a service conduit,” said Meldok, ducking low. All of them were hunched over in the tight space, with big Dennisar forced into a crouch.

“We’ll break up,” Vale decided. “Keru, Meldok, Dakal, you three proceed aft. Ensign Fell, you and Chief Dennisar will head toward the bow with me.”

Dakal pointed up the conduit. “Do we know which end of this ship is which?”

“I made an executive decision,” Vale replied dryly. “Move out, and watch your dosimeters. I don’t want anyone coming back to Titan cooked.”

Keru glanced back at her as he floated away. “We’ll keep a comm channel open.”

Zurin tried not to bump his helmet against the lumpy, uneven walls of the conduit. Without any visual cues to keep his sense of balance centered, it was hard for him to picture the cable-wreathed tunnel as a vertical plane; instead, his mind insisted on perceiving the distended tube as a well he was slowly falling into, extending away into the gloom. Hardly any ambient light came from the wreck, barring the insipid glow of an occasional illuminator panel here and there.

Meldok drifted past him, working his way by one hand along the far side, occasionally returning to the heavyduty sciences tricorder tethered to his belt. “Compensating for the radiation wash, I am detecting very few open internal spaces beyond the bulkheads. Certainly, nothing large enough for any one of us to navigate.”

“We’ll contact Titan and ask them to send someone smaller, then,” said Keru.

Zurin peered at Meldok’s scans. “I think even Doctor Huilan might find it a tight fit, sir,” he noted, referring to the ship’s diminutive S’ti’ach counselor. “This vessel does not resemble any conventional starship that I am aware of.”

Meldok’s bald blue pate bobbed behind his faceplate. “I have yet to detect even a trace of atmospheric gases anywhere. Also, while there is evidence of structural integrity-field generators, there appears to be no sign of any internal artificial-gravity matrix.”

“Perhaps whoever built this doesn’t have that technology,” said Keru.

“Or perhaps the crew don’t need it,” Zurin added, warming to the idea.

The Benzite continued. “The craft appears to be a mass of decentralized subsystems with multiple redundancies and a high degree of internal automation. From an engineering standpoint, the closest analogies I am aware of are the modularity of design in vessels of Suliban, Borg, or Breen origin.”

Zurin’s skin prickled reflexively, and he saw the Trill security chief stiffen. “This ship isn’t any of those,” said Keru, and he made the statement sound like an order.

The Cardassian swallowed hard, feeling uncomfortably chilled all of a sudden. “Whatever this craft is,” he found himself saying, “it wasn’t built for beings like us.”

Drifting downship, Zurin reached out to steady himself, and his fingers brushed one of the black, glassy panels. Moving as he did, the ensign missed the soft pulse of light that rose and fell across the screen in the wake of his passage.

“What do you think this is for?” said Dennisar, swinging his weapon right and left, letting the spot lamp mounted under the barrel cast a disc of cold white light across the walls.

“Storage chamber?” offered Fell.

Vale drifted in after them. The open space was the largest they had encountered so far, a spherical room where the maintenance conduit terminated. She could see other dark entryways around the radius of the chamber, doubtless connecting to more conduits leading deeper into the wreck. The room was no bigger than the Titan’s bridge, but the dark and the depth of it gave a false illusion of volume. In the zero gravity of the room, the three of them were forced to move slowly. The open space was filled with fragments of machinery and broken hardware, much of it stained carbon-black by some powerful but fleeting discharge of energy. The commander moved closer to one of the curved walls and saw small, peculiar cages lined around the equator, some open, some closed. In one of the sealed compartments was a device that resembled a flask made of turned metal, with a dull blue lens at one end. It had a machined, engineered look to it.

“Do you see these?” she asked.

Nearby, Fell reached out for something drifting in front of her, caught by her suit’s lamps. “There’s another one here—”

The device came alive in a flash of motion, and the Deltan barely had time to scream. Vale saw the eye lens blink on, and from the seamless flanks of the cylindrical construct emerged four angled pincer arms, wicked and curved like blades. It leaped forward on a puff of thrust and clamped itself over Fell’s helmet. The blade arms bit in and applied pressure, webbing the clear faceplate with cracks.

Fell tumbled backward, grabbing at the insectile device, trying to pull it free. Vale saw Dennisar spin and bring his weapon to bear, then curse in gutter Orion. He couldn’t chance taking the shot, not when the slightest error would strike the Deltan girl.

Vale braced her feet against the wall of the chamber and pushed off, launching herself like a missile at the panicked young science officer. Small bits of debris pelted her as she moved, but she ignored them, timing the motion perfectly. She collided with Fell and sent both of them into an awkward, tumbling embrace. Their helmets bounced off each other.

“Commander!” Fell cried, and very distinctly, Vale saw tears of fright on the other side of the Deltan’s faceplate, floating there like tiny diamonds.

The machine ignored her, all of its attention set on puncturing the transparent aluminum keeping Peya Fell from explosive decompression. Vale pulled at it without success, watching the cracks widen. If she didn’t deal with this in the next few seconds, the woman would be dead.

“This is going to hurt,” she snapped, bringing up her hand phaser. “Close your eyes tight and turn your head.”

“Commander—”

“Do it now, Ensign!”

Fell nodded and did her best to bury her face in the helmet’s padding. Vale pressed her weapon’s emitter to the side of the machine’s casing and thumbed the beam gauge to its narrowest setting. She took a breath and pressed the firing pad.

The brief ray lit the chamber like a flash of lightning, cutting right through the device. Fell screamed in pain as the hard glare stabbed through her eyelids.

The glowing lens darkened, and the claws unlocked. Vale angrily batted the dead machine away and turned Fell’s helmeted head in her hands. “No breach…” she breathed. Gels secreted by the suit’s emergency systems bubbled at the cracks, working to seal them.

Behind her, Dennisar snatched the machine from the air and glowered at it. “Some sort of drone,” he rumbled. “An automatic defense system?”

“Keru to Vale.” The voice was rough with distortion. “Commander? We registered a phaser shot.”

“Wait one,” Vale snapped. “Peya? Peya, are you okay?”

Fell opened her red-rimmed eyes. Her pleasant olive complexion now had an ugly red cast to it, as if she had been sunburned. “I can’t see anything but blurs,” she managed. “It stings…”

“Take my hand.” Vale grabbed her and pulled her toward one of the other conduits, the only one illuminated by a ring of blue panels. “Chief, watch our backs. There’s more of those things in here, and they might come looking for their buddy.”

“Aye,” said the Orion, tossing the machine away and bringing up his weapon.

Vale blew out a breath as they moved into the next tunnel. “Keru? Tell Ensign Dakal that this dead ship isn’t so dead after all.”

The reply that greeted her was only static.

“Commander Vale, please respond.” Keru’s expression darkened as the hiss of interference filled the channel.

Dakal immediately tapped the communicator pad on his chest. “Away team to Shuttlecraft Holiday, do you read us?” The same static boiled back at him. “The radiation?”

“A sudden increase, enough to render our communications inert, at this precise moment?” Meldok’s tone was dismissive. “Extremely unlikely. I believe intrusion countermeasures have been deployed against us.”

The Trill pivoted. “Phasers,” he ordered, drawing his weapon. He pointed in the direction they had come. “Back to the shuttle, double-time.”

“Sir!” Dakal cried out as a fan of steel-colored petals emerged from the conduit walls and came together in an iris, sealing off the passage. He turned to see the same happening ahead of them, but these panels seemed to be malfunctioning, and they moved in fits and starts.

“Forward!” snapped the security officer. “We can’t let them seal us in!”

Dakal pushed off, and Meldok came with him. The ready fear on the engineer’s pallid face was the first emotional response he’d ever seen from the dour Benzite.

Dennisar looked up from the digital chronograph on his suit’s wrist pad and called out to her. “Commander Vale?”

“I’m watching the clock, Chief,” she told him, moving slowly toward the end of the blue-lit conduit.

“I don’t doubt it, ma’am,” said the Orion in a tone that suggested he did. “It’s just that I’m questioning how we’re going to get out of here.” He jerked a thumb toward the hatch that had sealed shut behind them as they left the open chamber where the drone had attacked Ensign Fell.

“One problem at a time,” she retorted. She glanced at the Deltan woman, who moved close by, now connected between Dennisar and Vale by means of a safety tether.

Fell must have sensed her scrutiny. She gave a weak smile. “I think my vision’s coming back. That is, if everything around me is made out of felt—” A chime sounded, and she fumbled with her tricorder. “I reset this to audio mode,” she noted as the machine burbled quietly to her. “It’s reading a coherent energy trace, up ahead, very close.”

Vale checked her own suit’s integral tricorder and saw the same reading. “There’s another compartment.”

Dennisar moved past her, gently pushing her aside. “I’ll go first.”

She followed him into a spherical chamber of similar dimension to the previous one. Vale’s first impression was of a mechanical rendition of a heart, as if some machine artist had reconstructed the impression of an organic being’s internal structure. Her eye was immediately drawn to the center of the chamber, where a stubby drum of dense crystalline circuitry no larger than a cargo pod was leaning at an angle, whiplike connector cables tethering it to the walls in some places, in others hanging free where they had been explosively severed. She imagined the central unit had been knocked askew in its mounting during the attack on the vessel; a pulsing glow of multicolored light issued from it in faint flickers, like a dying candle.

Dennisar pointed up with his phaser, and Vale followed his line of sight. Across what was the “ceiling” from their point of views, another ragged wound was ripped open, a massive cut through the levels of the ship’s hull that went all the way out. Vale saw stars between the fingers of torn metal. Great gray-black scorch marks discolored the intricate machinery, and more debris floated around them in slow clumps.

“Commander.” The chief’s voice held a warning. He was aiming at a familiar flask-shaped object amid the drifts, apparently inert. “There’s a lot of them in here.”

“Right.” The more Vale’s eyes became used to the murk of the chamber, the more she became aware of dozens of the drones, all moving in lazy, silent orbits. “Look sharp.”

Fell was listening intently to her tricorder, the faint synthetic voice of the readout barely registering across her helmet communicator. “I think this may be a core element of the alien ship’s central computer,” she offered. “The scanner says almost all of the command pathways throughout the structure converge on this point.”

Vale let herself fall closer toward the cylindrical construct. Her tricorder presented her with a stream of data that she could interpret only on the most basic of levels—she would be the first to admit that xenotechnology wasn’t her strong suit—but she knew enough to recognize the configuration of a high-density data unit. “Peya’s right,” she said aloud. “Let’s see if we can talk to this thing.” Vale programmed her tricorder to beam an interrogative binary pulse into the cylinder.

“Commander,” said Dennisar in that tone again. “If I could suggest, there’s a way out up there. We could call this mission and return to the Holiday. The ensign needs medical attention, and we need to locate the rest of the team.”

“I’m all right,” said Fell. “Just a little dizzy.”

Vale hesitated on the edge of throwing the Orion a firm counter, but he was right. She was in danger of allowing the annoyance that had been bubbling away inside her ever since the Titan had been sandbanked to push out her better judgment. “Yeah. Maybe so. We’ll fall back to the shuttle and regroup—”

The tricorder buzzed as she was speaking, and a bright white bolt of color suddenly flashed inside the alien module. All around them, in among the debris, scores of blue eye lenses blinked into life.

Vale swore and grabbed her phaser.

• • •

It was a tight fit, but they made it through. Zurin winced as Keru pulled him hard through the closing gap, but then they were through, drifting in the gloom once more.

Meldok spoke after a moment, his face lit by the glow of his tricorder. He seemed ghostly in the dimness. “These subsystems appear to be operated from a unified command authority. I’m detecting a faint path of activation through the main trunks.” He pointed at the thick cables.

“Go on,” said the security chief.

“I believe we’re seeing reflexive behavior. Like the firing of a nerve cluster in a limb or other organic form.”

“The wreck is reacting to irritants…” Zurin wondered aloud.

“Some deceased beings do exhibit behavior that suggests life, often for some time after actual brain death,” said Meldok. “I believe this craft parallels that state.”

Keru shook his head slowly. “It’s not that. At least, it’s not all that.”

“I don’t follow you, sir,” said Zurin.

“Something’s been bothering me ever since we ran a scan on this thing, and now I think I know why.” The Trill turned to him, the faint light catching the dark-pigmented spots along the sides of his face and neck. “No extant lifesupport systems. No internal gravity. No crew spaces.” He ticked off the points on his fingers. “Ensign Meldok, have you detected any organic matter since we boarded this hulk?”

The Benzite hesitated. “I… have not.”

“Nothing,” said Keru. “Not even flakes of skin or stray hairs.” He gestured with his own tricorder. “Even after a catastrophic blowout, even if this ship was crewed by vacuum-dwelling blobs of protoplasm, there would be something, right?”

“There would be something,” echoed Zurin. “Some form of organic trace, no matter how small…” He drifted forward, farther down the conduit.

“I’m willing to bet the reason we haven’t found any crew, the reason the Titan couldn’t read any life out here, wasn’t the radiation. It’s because this ship never had living beings aboard in the first place.”

Meldok frowned at the idea. “Robots?”

“I’m wondering if this whole ship isn’t just some huge mechanism, “ said Keru.

“If so,” said Zurin, “I hope we can find a way to access it.” Using the beacon lamp on his wrist, the Cardassian shone the light down toward the end of the tubular tunnel. “Otherwise, without a way to override the central control system, we are trapped.”

Zurin’s torchlight picked out a blank, featureless wall, blocking any further movement through the wrecked starship. With the iris hatch locked shut behind them, there was no path out of their confinement. They had exchanged one trap for another.

The drones converged, darting on little jets of ion thrust, spinning and turning, coming in to englobe them.

Instinctively, the three of them retreated until the core cylinder was at their backs. Dennisar didn’t wait for Vale to give him the order; he pulled the compression phaser rifle to his shoulder and punched out bolt after bolt of yellow energy, blasting apart drones as the units came on, deploying their claw legs.

Vale quickly worked the controls on her hand phaser, widening the beam to a broad setting, strengthening the power output. She aimed into the center of the machine swarm and fired. A fan of light bathed the chamber for a split second, catching a dozen of the drones in its radiance. The machines stuttered and fell into tumbles, their internals fried, some of them colliding with one another.

“Nice shot, boss,” noted the security officer.

“Chews up the charge like you wouldn’t believe, though,” she replied. “One or two more, and I’ll drain it.”

As if to answer her, small hatches flipped open all over the walls, extruding holding cages like the ones she had seen in the other chamber. Each one had a fresh drone in it, and they were coming on-line, activating in a wave of unblinking blue eyes.