For my father,

who unknowingly kindled the fire decades ago,

and my mother,

who taught me the discipline to sustain the blaze

For whatever cause a country is ravaged, we ought to spare those edifices which do honor to human society, and do not contribute to increase an enemy's strength--such as temples, tombs, public buildings, and all works of remarkable beauty. . . . It is declaring one's self to be an enemy of mankind, thus wantonly to deprive them of these wonders of art.

--Emmerich de Vattel, The Law of Nations, 1758

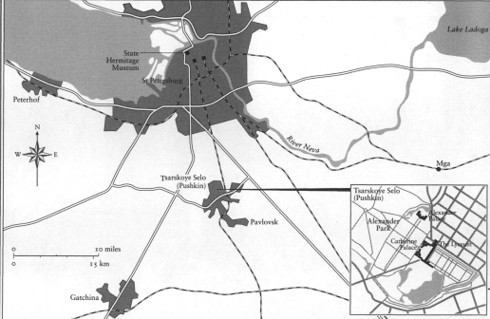

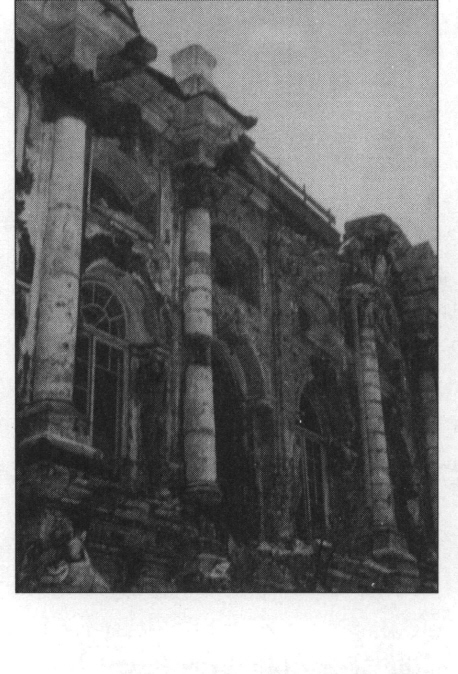

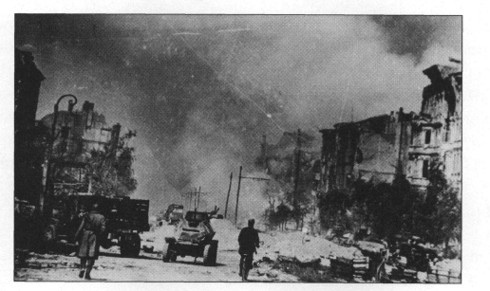

I have studied in detail the state of the historic monuments in Peterhof, Tsarskoe Selo, and Pavlovsk, and in all three towns I have witnessed monstrous outrages against the integrity of these monuments. Moreover, the damage caused--a full inventory of which would be extremely difficult to give because it is so extensive--bears the marks of premeditation.

--Testimony of Iosif Orbeli, director of the Hermitage,

before the Nurnberg tribunal, February 22, 1946

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

i was once told that writing is a lonely endeavor and the observation is correct. But a manuscript is never completed in a vacuum, especially one that is fortunate enough to be published, and in my case there are many who helped along the way.

First, Pam Ahearn, an extraordinary agent who rode out every storm into calm waters. Next, Mark Tavani, a remarkable editor who gave me a chance. Then there are Fran Downing, Nancy Pridgen, and Daiva Woodworth, three lovely women who made every Wednesday night special. I am honored to be "one of the girls." The novelists David Poyer and Lenore Hart not only provided practical lessons, but they led me to Frank Green, who took the time to teach me what I should know. Also, Arnold and Janelle James, my in-laws, who never voiced a discouraging word. Finally, there are all those who listened to me ramble, read my attempts, and offered their opinions. I'm afraid to list names in fear of forgetting someone. Please know that each of you is important and your thoughtful consideration, without question, moved the journey along.

Above all, though, are two special people who mean the most. My wife, Amy, and daughter, Elizabeth, who together make all things possible, including this.

PROLOGUE

Mauthausen Concentration Camp, Austria

April 10, 1945

The prisoners called him Ears because he was the only Russian in Hut 8 who understood German. Nobody ever used his given name, Karol Borya. `Yxo--Ears--had been his label from the first day he entered the camp over a year ago. It was a tag he regarded with pride, a responsibility he took to heart.

"What do you hear?" one of the prisoners whispered to him through the dark.

He was cuddled close to the window, pressed against the frigid pane, his exhales faint as gossamer in the dry sullen air.

"Do they want more amusement?" another prisoner asked.

Two nights ago the guards came for a Russian in Hut 8. He was an infantryman from Rostov near the Black Sea, relatively new to the camp. His screams were heard all night, ending only after a burst of staccato gunfire, his bloodied body hung by the main gate the next morning for all to see.

He glanced quickly away from the pane. "Quiet. The wind makes it difficult to hear."

The lice-ridden bunks were three-tiered, each prisoner allocated less than one square meter of space. A hundred pairs of sunken eyes stared back at him.

All the men respected his command. None stirred, their fear long ago absorbed into the horror of Mauthausen. He suddenly turned from the window. "They're coming."

An instant later the hut's door was flung open. The frozen night poured in behind Sergeant Humer, the attendant for Prisoners' Hut 8.

"Achtung!"

Claus Humer was Schutzstaffel, SS. Two more armed SS stood behind him. All the guards in Mauthausen were SS. Humer carried no weapon. Never did. A six-foot frame and beefy limbs were all the protection he needed.

"Volunteers are required," Humer said. "You, you, you, and you."

Borya was the last selected. He wondered what was happening. Few prisoners died at night. The death chamber remained idle, the time used to flush the gas and wash the tiles for the next day's slaughter. The guards tended to stay in their barracks, huddled around iron stoves kept warm by firewood prisoners died cutting. Likewise, the doctors and their attendants slept, readying themselves for another day of experiments in which inmates were used indiscriminately as lab animals.

Humer looked straight at Borya. "You understand me, don't you?"

He said nothing, staring back into the guard's black eyes. A year of terror had taught him the value of silence.

"Nothing to say?" Humer asked in German. "Good. You need to understand . . . with your mouth shut."

Another guard brushed past with four wool overcoats draped across his outstretched arms.

"Coats?" muttered one of the Russians.

No prisoner wore a coat. A filthy burlap shirt and tattered pants, more rags than clothing, were issued on arrival. At death they were stripped off to be reissued, stinking and unwashed, to the next arrival. The guard tossed the coats on the floor.

Humer pointed. "Mantel anziehen."

Borya reached down for one of the green bundles. "The sergeant says to put them on," he explained in Russian.

The other three followed his lead.

The wool chafed his skin but felt good. It had been a long time since he was last even remotely warm.

"Outside," Humer said.

The three Russians looked at Borya and he motioned toward the door. They all walked into the night.

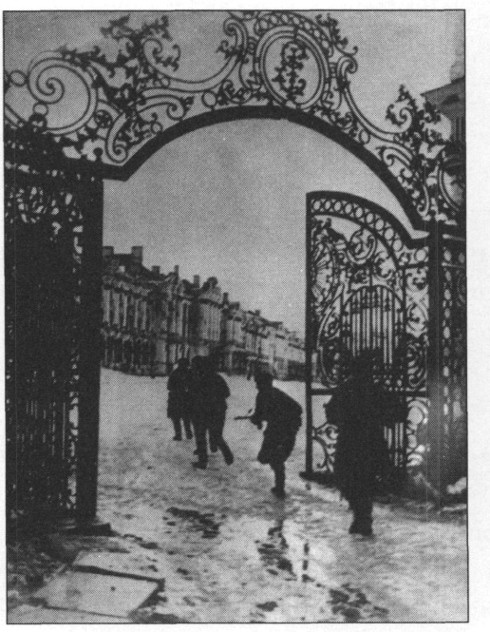

Humer led the file across the ice and snow toward the main grounds, a frigid wind howling between rows of low wooden huts. Eighty thousand people were crammed into the surrounding buildings, more than lived in Borya's entire home province in Belarus. He'd come to think that he would never see that place again. Time had almost become irrelevant, but for his sanity he tried to maintain some sense. It was late March. No. Early April. And still freezing. Why couldn't he just die or be killed? Hundreds met that fate every day. Was his destiny to survive this hell?

But for what?

At the main grounds Humer turned left and marched into an open expanse. More prisoners' huts stood on one side. The camp's kitchen, jail, and infirmary lined the other. At the far end was the roller, a ton of steel dragged across the frozen earth each day. He hoped their task did not involve that unpleasant chore.

Humer stopped before four tall stakes.

Two days ago a detail was taken into the surrounding forest, Borya one of ten prisoners chosen then, as well. They'd felled three aspens, one prisoner breaking an arm in the effort and shot on the spot. The branches were sheared and the logs quartered, then dragged back to camp and planted to the height of a man in the main grounds. But the stakes had remained bare the past couple of days. Now two armed guards watched them. Arc lights burned overhead and fogged the bitterly dry air.

"Wait here," Humer said.

The sergeant pounded up a short set of stairs and entered the jail. Light spilled out in a yellow rectangle from the open door. A moment later four naked men were led outside. Their blond heads were not shaved like the rest of the Russians, Poles, and Jews who constituted the vast majority of the camp's prisoners. No weak muscles or slow movements, either. No apathetic looks, or eyes sunk deep in their sockets, or edema swelling emaciated frames. These men were stocky. Soldiers. Germans. He'd seen their look before. Granite faces, no emotion. Stone cold, like the night.

The four walked straight and defiant, arms at their sides, none evidencing the unbearable cold their milky skin must have been experiencing. Humer followed them out of the jail and motioned to the stakes. "Over there."

The four naked Germans marched where directed.

Humer approached and tossed four coils of rope in the snow. "Tie them to the stakes."

Borya's three companions looked at him. He bent down and retrieved all four coils, handing them to the other three and telling them what to do. They each approached a naked German, the men standing at attention before the rough aspen logs. What violation had provoked such madness? He draped the rough hemp around his man's chest and strapped the body to the wood.

"Tight," Humer yelled.

He knotted a loop and pulled the coarse fiber hard across the German's bare chest. The man never winced. Humer looked away at the other three. He took the opportunity to whisper in German, "What did you do?"

No reply.

He pulled the rope tight. "They don't even do this to us."

"It is an honor to defy your captor," the German whispered.

Yes, he thought. It was.

Humer turned back. Borya knotted the last loop. "Over there," Humer said.

He and the other three Russians trudged across fresh snow, out of the way. To keep the cold at bay he stuffed his hands into his armpits and shifted from foot to foot. The coat felt wonderful. It was the first warmth he'd known since being brought to the camp. It was then that his identity had been completely stripped away, replaced by a number--10901--tattooed onto his right forearm. A triangle was stitched to the left breast of his tattered shirt. An R in his signified that he was Russian. Color was important, too. Red for political prisoners. Green for criminals. Yellow Star of David for Jews. Black and brown for prisoners of war.

Humer seemed to be waiting for something.

Borya glanced to his left.

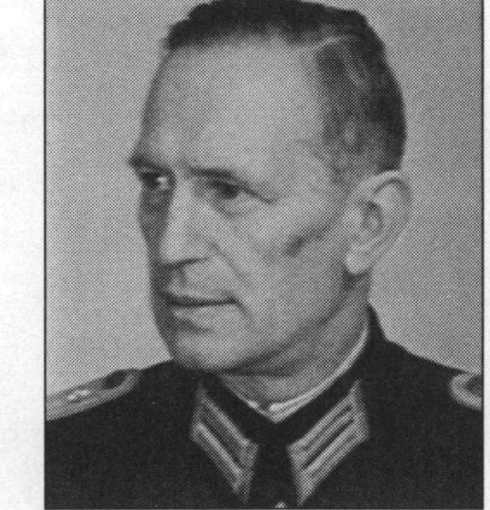

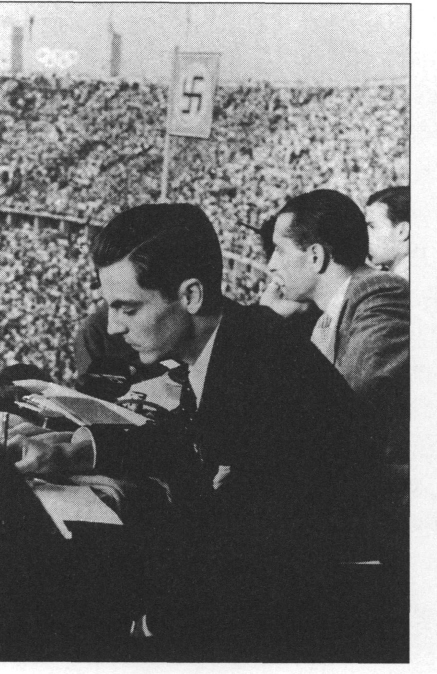

More arc lights illuminated the parade ground all the way to the main gate. The road outside, leading to the quarry, faded into darkness. The command headquarters building just beyond the fence stood unlit. He watched as the main gate swung open and a solitary figure entered the camp. The man wore a greatcoat to his knees. Light trousers extended out the bottom to tan jackboots. A light-colored officer's hat covered his head. Outsize thighs hitched bowlegged in a determined gait, the man's portly belly leading the way. The lights revealed a sharp nose and clear eyes, the features not unpleasant.

And instantly recognizable.

Last commander of the Richthofen Squadron, Commander of the German Air Force, Speaker of the German Parliament, Prime Minister of Prussia, President of the Prussian State Council, Reichmaster of Forestry and Game, Chairman of the Reich Defense Council, Reichsmarschall of the Greater German Reich. The Fuhrer's chosen successor.

Hermann Goring.

Borya had seen Goring once before. In 1939. Rome. Goring appeared then wearing a flashy gray suit, his fleshy neck wrapped in a scarlet cravat. Rubies had adorned his bulbous fingers, and a Nazi eagle studded with diamonds was pinned to the left lapel. He'd delivered a restrained speech urging Germany's place in the sun, asking, Would you rather have guns or butter? Should you import lard or metal ore? Preparedness makes us powerful. Butter merely makes us fat. Goring had finished that oratory in a flurry, promising Germany and Italy would march shoulder to shoulder in the coming struggle. He remembered listening intently and not being impressed.

"Gentlemen, I trust you are comfortable," Goring said in a calm voice to the four bound prisoners.

No one replied.

"What did he say, `Yxo," whispered one of the Russians.

"He's ridiculing them."

"Shut up," Humer muttered. "Give your attention or you'll join them."

Goring positioned himself directly before the four naked men. "I ask each of you again. Anything to say?"

Only the wind replied.

Goring inched close to one of the shivering Germans. The one Borya had bound to the stake.

"Mathias, surely you don't want to die this way? You're a soldier, a loyal servant of the Fuhrer."

"The--Fuhrer--has nothing to do--with this," the German stammered, his body shivering in violet quakes.

"But everything we do is for his greater glory."

"Which is why I--choose to die."

Goring shrugged. A casual gesture, as someone would do if deciding whether to have another pastry. He motioned to Humer. The sergeant signaled two guards, who toted a large barrel toward the bound men. Another guard approached with four ladles and tossed them into the snow. Humer glared at the Russians. "Fill them with water, and go stand by one of those men."

He told the other three what to do and four ladles were picked up, then submerged.

"Spill nothing," Humer warned.

Borya was careful, but the wind buffeted a few drops out. No one noticed. He returned to the German he'd bound to the stake. The one called Mathias. Goring stood in the center, pulling off black leather gloves.

"See, Mathias," Goring said, "I'm removing my gloves so I can feel the cold, as your skin does."

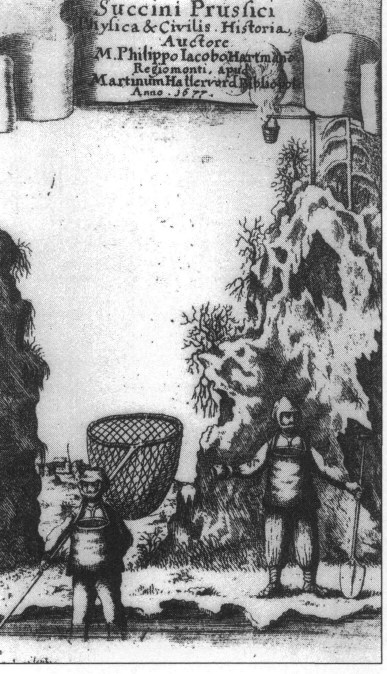

Borya stood close enough to see the heavy silver ring wrapping the third finger of the man's right hand, a clutched mailed fist embossed on it. Goring stuffed his right hand into a trouser pocket and removed a stone. It was golden, like honey. Borya recognized it. Amber. Goring fingered the clump and said, "Water will be showered over you every five minutes until somebody tells me what I want to know, or you die. Either is acceptable to me. But, remember, whoever talks lives. Then one of these miserable Russians will take your place. You can then have your coat back and pour water on him until he dies. Imagine what fun that would be. All you have to do is tell me what I want to know. Now, anything to say?"

Silence.

Goring nodded to Humer.

"Giesse es," Humer said. Pour it.

Borya did, and the other three followed his lead. Water soaked into Mathias's blond mane, then trickled down his face and chest. Shivers accompanied the stream. The German uttered not a sound, other than the chatter of his teeth.

"Anything to say?" Goring asked again.

Nothing.

Five minutes later the process was repeated. Twenty minutes later, after four more dousings, hypothermia started setting in. Goring stood impassive and methodically massaged the amber. Just before another five minutes expired he approached Mathias.

"This is ridiculous. Tell me where das Bernstein-zimmer is hidden and stop your suffering. This is not worth dying for."

The shivering German only stared back, his defiance admirable. Borya almost hated being Goring's accomplice in killing him.

"Sie sind ein lugnerisch diebisch-schwein," Mathias managed in one breath. You are a lying, thieving pig. Then the German spat.

Goring reeled back, spittle splotching the front of his greatcoat. He released the buttons and shook the stain away, then culled back the flaps, revealing a pearl gray uniform heavy with decorations. "I am your Reichsmarschall. Second only to the Fuhrer. No one wears this uniform but me. How dare you think you can soil it so easily. You will tell me what I want to know, Mathias, or you will freeze to death. Slowly. Very slowly. It will not be pleasant."

The German spat again. This time on the uniform. Goring stayed surprisingly calm.

"Admirable, Mathias. Your loyalty is noted. But how much longer can you hold out? Look at you. Wouldn't you like to be warm? Pressing your body close to a big fire, your skin wrapped in a cozy wool blanket." Goring suddenly reached over and yanked Borya close to the bound German. Water splattered from the ladle onto the snow. "This coat would feel wonderful, would it not, Mathias? Are you going to allow this miserable cossack to be warm while you freeze?"

The German said nothing. Only shivered.

Goring shoved Borya away. "How about a little taste of warmth, Mathias?"

The Reichsmarschall unzipped his trousers. Hot urine arched out, steaming on impact, leaving yellow streaks on bare skin that raced down to the snow. Goring shook his organ dry, then zipped his trousers. "Feel better, Mathias?"

"Verrottet in der schweinsholle."

Borya agreed. Rot in hell pig.

Goring rushed forward and backhanded the soldier hard across the face, his silver ring ripping open the cheek. Blood oozed out.

"Pour!" Goring screamed.

Borya returned to the barrel and refilled his ladle.

The German named Mathias started shouting. "Mein Fuhrer. Mein Fuhrer. Mein Fuhrer." His voice grew louder. The other three bound men joined in.

Water rained down.

Goring stood and watched, now furiously fingering the amber. Two hours later, Mathias died caked in ice. Within another hour the remaining three Germans succumbed. No one mentioned anything about das Bernstein-zimmer.

The Amber Room.

ONE

Atlanta, Georgia

Tuesday, May 6, the present, 10:35 a.m.

Judge Rachel Cutler glanced over the top of her tortoiseshell glasses. The lawyer had said it again, and this time she wasn't going to let the comment drop. "Excuse me, counselor."

"I said the defendant moves for a mistrial."

"No. Before that. What did you say?"

"I said, 'Yes, sir.' "

"If you haven't noticed, I'm not a sir."

"Quite correct, Your Honor. I apologize."

"You've done that four times this morning. I made a note each time."

The lawyer shrugged. "It seems such a trivial matter. Why would Your Honor take the time to note my simple slip of the tongue?"

The impertinent bastard even smiled. She sat erect in her chair and glared down at him. But she immediately realized what T. Marcus Nettles was doing. So she said nothing.

"My client is on trial for aggravated assault, Judge. Yet the court seems more concerned with how I address you than with the issue of police misconduct."

She glanced over at the jury, then at the other counsel table. The Fulton County assistant district attorney sat impassive, apparently pleased that her opponent was digging his own grave. Obviously, the young lawyer didn't grasp what Nettles was attempting. But she did. "You're absolutely right, counselor. It is a trivial matter. Proceed."

She sat back in her chair and noticed the momentary look of annoyance on Nettles's face. An expression that a hunter might give when his shot missed the mark.

"What of my motion for mistrial?" Nettles asked.

"Denied. Move on. Continue with your summation."

Rachel watched the jury foreman as he stood and pronounced a guilty verdict. Deliberations had taken only twenty minutes.

"Your Honor," Nettles said, coming to his feet. "I move for a presentence investigation prior to sentencing."

"Denied."

"I move that sentencing be delayed."

"Denied."

Nettles seemed to sense the mistake he'd made earlier. "I move for the court to recuse itself."

"On what grounds?"

"Bias."

"To whom or what?"

"To myself and my client."

"Explain."

"The court has shown prejudice."

"How?"

"With that display this morning about my inadvertent use of sir."

"As I recall, counselor, I admitted it was a trivial matter."

"Yes, you did. But our conversation occurred with the jury present, and the damage was done."

"I don't recall an objection or a motion for mistrial concerning the conversation."

Nettles said nothing. She looked over at the assistant DA. "What's the State's position?"

"The State opposes the motion. The court has been fair."

She almost smiled. At least the young lawyer knew the right answer.

"Motion to recuse denied." She stared at the defendant, a young white male with scraggly hair and a pockmarked face. "The defendant shall rise." He did. "Barry King, you've been found guilty of the crime of aggravated assault. This court hereby remands you to the Department of Corrections for a period of twenty years. The bailiff will take the defendant into custody."

She rose and stepped toward an oak-paneled door that led to her chambers. "Mr. Nettles, could I see you a moment?" The assistant DA headed toward her, too. "Alone."

Nettles left his client, who was being cuffed, and followed her into the office.

"Close the door, please." She unzipped her robe but did not remove it. She stepped behind her desk. "Nice try, counselor."

"Which one?"

"Earlier, when you thought that jab about sir and ma'am would set me off. You were getting your butt chapped with that half-cocked defense, so you thought me losing my temper would get you a mistrial."

He shrugged. "You gotta do what you gotta do."

"What you have to do is show respect for the court and not call a female judge sir. Yet you kept on. Deliberately."

"You just sentenced my guy to twenty years without the benefit of a presentence hearing. If that isn't prejudice, what is?"

She sat down and did not offer the lawyer a seat. "I didn't need a hearing. I sentenced King to aggravated battery two years ago. Six months in, six months' probation. I remember. This time he took a baseball bat and fractured a man's skull. He's used up what little patience I have."

"You should have recused yourself. All that information clouded your judgment."

"Really? That presentence investigation you're screaming for would have revealed all that, anyway. I simply saved you the trouble of waiting for the inevitable."

"You're a fucking bitch."

"That's going to cost you a hundred dollars. Payable now. Along with another hundred for the stunt in the courtroom."

"I'm entitled to a hearing before you find me in contempt."

"True. But you don't want that. It'll do nothing for that chauvinistic image you go out of your way to portray."

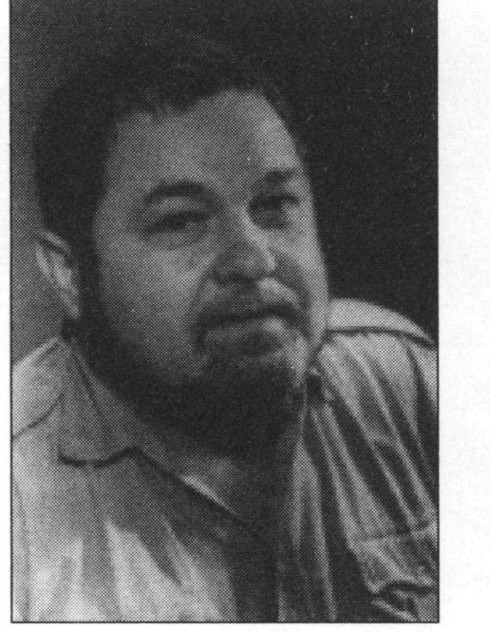

He said nothing, and she could feel the fire building. Nettles was a heavyset, jowled man with a reputation for tenacity, surely unaccustomed to taking orders from a woman.

"And every time you show off that big ass of yours in my court, it's going to cost you a hundred dollars."

He stepped toward the desk and withdrew a wad of money, peeling off two one-hundred-dollar bills, crisp new ones with the swollen Ben Franklin. He slapped both on the desk, then unfolded three more.

"Fuck you."

One bill dropped.

"Fuck you."

The second bill fell.

"Fuck you."

The third Ben Franklin fluttered down.

TWO

Rachel donned her robe, stepped back into the courtroom, and climbed three steps to the oak dais she'd occupied for the past four years. The clock on the far wall read 1:45 P.M. She wondered how much longer she'd have the privilege of being a judge. It was an election year, qualifying had ended two weeks back, and she'd drawn two opponents for the July primary. There'd been talk of people getting into the race, but no one appeared until ten minutes before five on Friday to plunk down the nearly four-thousand-dollar fee needed to run. What could have been an easy uncontested election had now evolved into a long summer of fund-raisers and speeches. Neither of which were pleasurable.

At the moment she didn't need the added aggravation. Her dockets were jammed, with more cases being added by the day. Today's calendar, though, was shortened by a quick verdict in State of Georgia v. Barry King. Less than a half hour of deliberation was fast by any standard, the jurors obviously not impressed with T. Marcus Nettles's theatrics.

With the afternoon free, she decided to tend to a backlog of non-jury matters that had clogged over the past two weeks of jury trials. The trial time had been productive. Four convictions, six guilty pleas, and one acquittal. Eleven criminal cases out of the way, making room for the new batch her secretary said the scheduling clerk would deliver in the morning.

The Fulton County Daily Report rated all the local superior court judges annually. For the past three years she'd been ranked near the top, disposing of cases faster than most of her fellow judges, with a reversal rate in the appellate courts of only 2 percent. Not bad being right 98 percent of the time.

She settled behind the bench and watched the afternoon parade begin. Lawyers hustled in and out, some ferrying clients in need of a final divorce or a judge's signature, others looking for a resolution to pending motions in civil cases awaiting trial. About forty different matters in all. By the time she glanced again at the clock across the room, it was 4:15 and the docket had whittled down to two items. One was an adoption, a task she really enjoyed. The seven-year-old reminded her of Brent, her own seven-year-old. The last matter was a simple name change, the petitioner unrepresented by counsel. She'd specifically scheduled the case at the end, hoping the courtroom would be empty.

The clerk handed her the file.

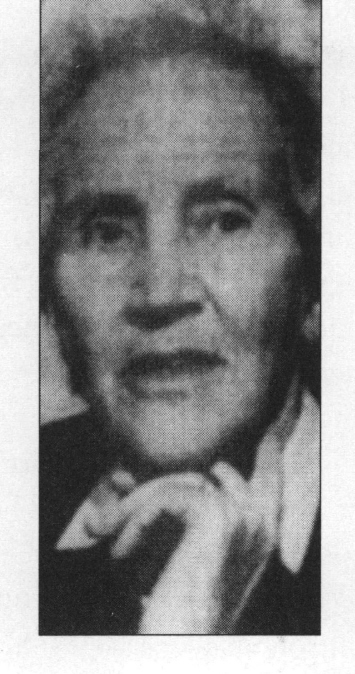

She stared down at the old man dressed in a beige tweed jacket and tan trousers who stood before the counsel table.

"Your full name?" she asked.

"Karl Bates." His tired voice carried an East European accent.

"How long have you lived in Fulton County?"

"Thirty-nine years."

"You were not born in this country?"

"No. I come from Belarus."

"And you are an American citizen?"

He nodded. "I'm an old man. Eighty-one. Almost half my life spent here."

The question and answer was not relevant to the petition, but neither the clerk nor the court reporter said anything. Their faces seemed to understand the moment.

"My parents, brothers, sisters--all slaughtered by Nazis. Many died in Belarus. We were White Russians. Very proud. After the war, not many of us were left when the Soviets annexed our land. Stalin was worse than Hitler. A madman. Butcher. Nothing remained there when he was through, so I leave. This country is the land of promise, right?"

"Were you a Russian citizen?"

"I believe correct designation was Soviet citizen." He shook his head. "But I never consider myself Soviet."

"Did you serve in the war?"

"Only of necessity. The Great Patriotic War, Stalin called it. I was lieutenant. Captured and sent to Mauthausen. Sixteen months in a concentration camp."

"What was your occupation here after immigrating?"

"Jeweler."

"You have petitioned this court for a change of name. Why do you wish to be known as Karol Borya?"

"It is my birth name. My father named me Karol. It means 'strong-willed.' I was youngest of six children and almost die at birth. When I immigrate to this country, I thought, must protect identity. I work for government commissions while in Soviet Union. I hated Communists. They ruin my homeland, and I speak out. Stalin sent many countrymen to Siberian camps. I thought harm would come to my family. Very few could leave then. But before my death, I want my heritage returned."

"Are you ill?"

"No. But I wonder how long this tired body will hold out."

She looked at the old man standing before her, his frame shrunken with age but still distinguished. The eyes were inscrutable and deep-set, hair stark white, voice gravelly and enigmatic. "You look marvelous for a man your age."

He smiled.

"Do you seek this change to defraud, evade prosecution, or hide from a creditor?"

"Never."

"Then I grant your petition. You shall be Karol Borya once again."

She signed the order attached to the petition and handed the file to the clerk. Stepping from the bench, she approached the old man. Tears slipped down his stubbled cheeks. Her eyes had reddened, as well. She hugged him and softly said, "I love you, Daddy."

THREE

4:50 p.m.

Paul Cutler stood from the oak armchair and addressed the court, his lawyerly patience wearing thin. "Your Honor, the estate does not contest movant's services. Instead, we merely challenge the amount he's attempting to charge. Twelve thousand three hundred dollars is a lot of money to paint a house."

"It was a big house," the creditor's lawyer said.

"I would hope," the probate judge added.

Paul said, "The house is two thousand square feet. Not a thing unusual about it. The paint job was routine. Movant is not entitled to the amount charged."

"Judge, the decedent contracted with my client for a complete house painting, which my client did."

"What the movant did, Judge, was take advantage of a seventy-three-year-old man. He did not render twelve thousand three hundred dollars' worth of services."

"The decedent promised my client a bonus if he finished within a week, and he did."

He couldn't believe the other lawyer was pressing the point with a straight face. "That's convenient, considering the only other person to contradict that promise is dead. The bottom line is that our firm is the named executor on the estate, and we cannot in good conscience pay this bill."

"You want a trial on it?" the crinkly judge asked the other side.

The creditor's lawyer bent down and whispered with the housepainter, a younger man noticeably uncomfortable in a tan polyester suit and tie. "No, sir. Perhaps a compromise. Seven thousand five hundred."

Paul never flinched. "One thousand two hundred and fifty. Not a dime more. We employed another painter to view the work. From what I've been told, we have a good suit for shoddy workmanship. The paint also appears to have been watered down. As far as I'm concerned, we'll let the jury decide." He looked at the other lawyer. "I get two hundred and twenty dollars an hour while we fight. So take your time, counselor."

The other lawyer never even consulted his client. "We don't have the resources to litigate this matter, so we have no choice but to accept the estate's offer."

"I bet. Bloody damn extortionist," Paul muttered, just loud enough for the other lawyer to hear, as he gathered his file.

"Draw an order, Mr. Cutler," the judge said.

Paul quickly left the hearing room and marched down the corridors of the Fulton County probate division. It was three floors down from the melange of Superior Court and a world apart. No sensational murders, high-profile litigation, or contested divorces. Wills, trusts, and guardianships formed the extent of its limited jurisdiction--mundane, boring, with evidence usually amounting to diluted memories and tales of alliances both real and imagined. A recent state statute Paul helped draft allowed jury trials in certain instances, and occasionally a litigant would demand one. But, by and large, business was tended to by a stable of elder judges, themselves once advocates who roamed the same halls in search of letters testamentary.

Ever since the University of Georgia sent him out into the world with a juris doctorate, probate work had been Paul's specialty. He'd not gone right to law school from college, summarily rejected by the twenty-two schools he'd applied to. His father was devastated. For three years he labored at the Georgia Citizens Bank in the probate and trust department as a glorified clerk, the experience enough motivation for him to retake the law school admission exam and reapply. Three schools ultimately accepted him, and a third-year clerkship resulted in a job at Pridgen & Woodworth after graduation. Now, thirteen years later, he was a sharing-partner in the firm, senior enough in the probate and trust department to be next in line for full partnership and the department's managerial reins.

He turned a corner and zeroed in on double doors at the far end.

Today had been hectic. The painter's motion had been scheduled for over a week, but right after lunch his office received a call from another creditor's lawyer to hear a hastily arranged motion. Originally it was set for 4:30, but the lawyer on the other side failed to show. So he'd shot over to an adjacent hearing room and taken care of the house painter's attempted thievery. He yanked open the wooden doors and stalked down the center aisle of the deserted courtroom. "Heard from Marcus Nettles yet?" he asked the clerk at the far end.

A smile creased the woman's face. "Sure did."

"It's nearly five. Where is he?"

"He's a guest of the sheriff's department. Last I heard, they've got him in a holding cell."

He dropped his briefcase on the oak table. "You're kidding."

"Nope. Your ex put him in this morning."

"Rachel?"

The clerk nodded. "Word is he got smart with her in chambers. Paid her three hundred dollars then told her to F off three times."

The courtroom doors swung open and T. Marcus Nettles waddled in. His beige Neiman Marcus suit was wrinkled, Gucci tie out of place, the Italian loafers scuffed and dirty.

"About time, Marcus. What happened?"

"That bitch you once called your wife threw me in jail and left me there since this mornin'." The baritone voice carried a strain. "Tell me, Paul. Is she really a woman or some hybrid with nuts between those long legs?"

He started to say something, then decided to let it go.

"She climbs my ass in front of a jury because I called her sir--"

"Four times, I heard," the clerk said.

"Yeah. Probably was. After I move for a mistrial, which she should have granted, she gives my guy twenty years without a presentence hearin'. Then she wants to give me an ethics lesson. I don't need that shit. Particularly from some smart-ass bitch. I can tell you now, I'll be pumpin' money to both her opponents. Lots of money. I'm going to rid myself of that problem the second Tuesday in July."

He'd heard enough. "You ready to argue this motion?"

Nettles laid his briefcase on the table. "Why not? I figured I'd be in that cell all night. Guess the whore has a heart, after all."

"That's enough, Marcus," he said, his voice a bit firmer than he intended.

Nettles's eyes tightened, a penetrating feral stare that seemed to read his thoughts. "The shit you care? You've been divorced--what?--three years? She must gouge a chunk out of your paycheck every month in child support."

He said nothing.

"I'll be fuckin' damned," Nettles said. "You still got a thing for her, don't you?"

"Can we get on with it?"

"Son of a bitch, you do." Nettles shook his bulbous head.

He headed for the other table to get ready for the hearing. The clerk popped from her chair and walked back to fetch the judge. He was glad she'd left. Courthouse gossip blew from ear to ear like a wildfire.

Nettles settled his portly frame into the armchair. "Paul, my boy, take it from a five-time loser. Once you get rid of 'em, be rid of 'em."

FOUR

5:45 p.m.

Karol Borya cruised into his driveway and parked the Oldsmobile. At eighty-one, he was happy to still be driving. His eyesight was amazingly good, and his coordination, though slow, seemed adequate enough for the state to renew his license. He didn't drive much, or far. To the grocery store, occasionally to the mall, and over to Rachel's house at least twice a week. Today he'd ventured only four miles to the MARTA station, where he'd caught a train downtown to the courthouse for the name-change hearing.

He'd lived in northeast Fulton County nearly forty years, long before the explosion of Atlanta northward. The once forested hills of red clay, whose runoff had tracked into the nearby Chattahoochee River, were now covered in commercial development, high-end residential subdivisions, apartments, and roads. Millions lived and worked around him, Atlanta along the way having acquired the designations of metropolitan and "Olympic host."

He ambled out to the street and checked the curbside mailbox. The evening was unusually warm for May, good for his arthritic joints, which seemed to sense the approach of fall and downright hated winter. He walked back toward the house and noticed that the wooden eaves needed painting.

He sold his original acreage twenty-four years ago, garnering enough to pay cash for a new house. The subdivision then was one of the newer developments, the street now evolved into a pleasant nook under a canopy of quarter-century timber. His cherished wife, Maya, died two years after the house was completed. Cancer claimed her fast. Too fast. He hardly had time to say good-bye. Rachel was fourteen and brave, he was fifty-seven and scared to death. The prospect of growing old alone had frightened him. But Rachel had always stayed nearby. He was lucky to have such a good daughter. His only child.

He trudged into the house, and was there only a few minutes when the back door burst open and his two grandchildren rushed into the kitchen. They never knocked and he never locked the door. Brent was seven, Marla six. Both hugged him. Rachel followed them inside.

"Grandpa, Grandpa, where's Lucy?" Marla asked.

"Asleep in the den. Where else?" The stray had wandered into the backyard four years ago and never left.

The children bolted to the front of the house.

Rachel yanked open the refrigerator and found a pitcher of tea. "You got a little emotional in court."

"I know I say too much. But I thought of papa. I wish you knew him. He work the fields every day. A Tsarist. Loyal to end. Hated Communists." He paused. "I was thinking, I have no photo of him."

"But you have his name again."

"And for that I thank you, my darling. Did you learn where was Paul?"

"My clerk checked. He was tied up in probate court and couldn't make it."

"How is he doing?"

She sipped her tea. "Okay, I guess."

He studied his daughter. She was so much like her mother. Pearl white skin, frilly auburn hair, perceptive brown eyes that cast the prepossessing look of a woman in charge. And smart. Maybe too smart for her own good.

"How are you doing?" he asked.

"I get by. I always do."

"You sure, daughter?" He'd noticed changes lately. Some drifting, a bit more distance and fragility. A hesitancy toward life that he found disturbing.

"Don't worry about me, Daddy. I'll be fine."

"Still no suitors?" He knew of no men in the three years since the divorce.

"Like I have time. All I do is work and tend those two in there. Not to mention you."

He had to say it. "I worry about you."

"No need."

But she looked away while answering. Perhaps she wasn't quite so certain of herself. "Not good to be old alone."

She seemed to get the message. "You're not."

"I'm not speaking of me, and you know it."

She moved to the sink and rinsed her glass. He decided not to press and reached over and flicked on the counter television. The station was still set to CNN Headline News from the morning. He turned down the volume and felt he had to say, "Divorce is wrong."

She cut him one of her looks. "You going to start with the lecture?"

"Swallow that pride. You should try again."

"Paul doesn't want to."

His gaze held hers. "You both too proud. Think of my grandchildren."

"I did when I divorced. All we did was fight. You know that."

He shook his head. "Stubborn, like your mother." Or was she like him? Hard to tell.

Rachel dried her hands with the dish towel. "Paul will be by about seven to get the kids. He'll bring them home."

"Where you going?"

"Fund-raiser for the campaign. Going to be a tough summer, and I'm not looking forward to it."

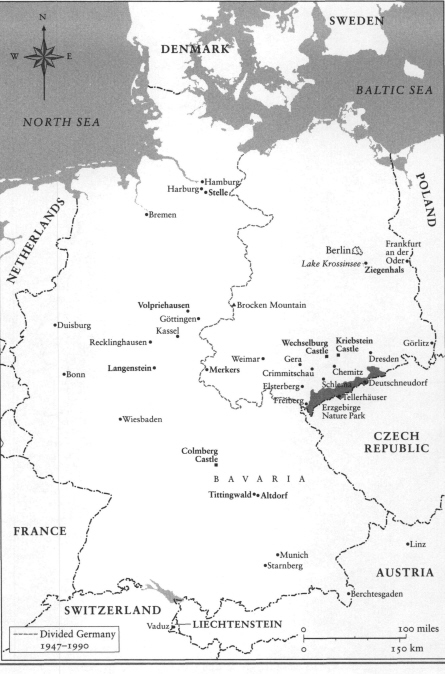

He focused on the television and saw mountain ranges, steep inclines, and rocky crags. The sight was instantly familiar. A caption at the bottom left read STOD, GERMANY. He turned up the volume.

"--millionaire contractor Wayland McKoy thinks this area in central Germany may still harbor Nazi treasure. His expedition begins next week into the Harz Mountains of what was once East Germany. These sites have only recently become accessible, thanks to the fall of Communism and the reunification of East and West Germany." The image switched to a tight view of caves in forested inclines. "It's believed that in the final days of World War Two, Nazi loot was hastily stashed inside hundreds of tunnels crisscrossing these ancient mountains. Some were also used as ammunition dumps, which complicates the search, making the venture even more hazardous. In fact, more than two dozen people have lost their lives in this area since World War Two, trying to locate treasure."

Rachel came close and kissed him on the cheek. "I have to go."

He turned from the television. "Paul be here at seven?"

She nodded and headed for the door.

He immediately returned his attention to the television.

FIVE

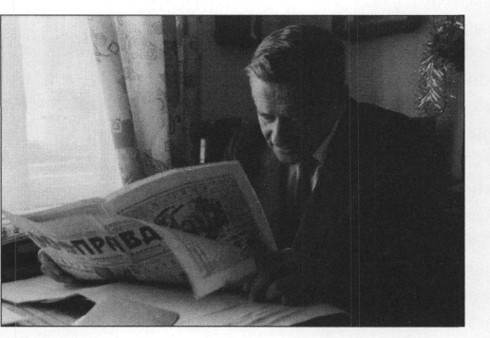

Borya waited until the next half hour, hoping headline news would contain some story repeats. And he was lucky. The same report on Wayland McKoy's search of the Harz Mountains for Nazi treasure appeared at the end of the six-thirty segment.

He was still thinking about the information, twenty minutes later, when Paul arrived. By then he was in the den, a German road map unfolded on the coffee table. He'd bought it at the mall a few years back, replacing the dated National Geographic one he'd used for decades.

"Where are the children?" Paul asked.

"Watering my garden."

"You sure that's safe for your garden?"

He smiled. "It's been dry. They can't hurt."

Paul plopped into an armchair, his tie loosened and collar unbuttoned. "That daughter of yours tell you she put a lawyer in jail this morning?"

He didn't look up from the map. "He deserve it?"

"Probably. But she's running for reelection, and he's not one to mess with. That fiery temper is going to get her in trouble one day."

He looked at his former son-in-law. "Just like my Maya. Run off half-crazy in a moment."

"And she won't listen to a thing anybody says."

"Got from her mother, too."

Paul smiled. "I bet." He gestured to the map. "What are you doing?"

"Checking something. Saw on CNN. Fellow claims art is still in Harz Mountains."

"There was a story in USA Today on that this morning. Caught my eye. Some guy named McKoy from North Carolina. You'd think people would give up on the Nazi legacy thing. Fifty years is a long time for some three-hundred-year-old canvas to languish in a damp mine. It would be a miracle if it wasn't a mass of mold."

He creased his forehead. "The good stuff already found or lost forever."

"I guess you should know all about that."

He nodded. "A little experience there, yes." He tried to conceal his current interest, though his insides were churning. "Could you buy me copy of that USA newspaper?"

"Don't have to. Mine's in the car. I'll go get it."

Paul left through the front door just as the back door opened and the two children trotted into the den.

"Your papa's here," he said to Marla.

Paul returned, handed him the paper, then said to the children, "Did you drown the tomatoes?"

The little girl giggled. "No, Daddy." She tugged at Paul's arm. "Come see Granddaddy's vegetables."

Paul looked at him and smiled. "I'll be right back. That article is on page four or five, I think."

He waited until they left through the kitchen before finding the story and reading every word.

GERMAN TREASURES AWAIT?

By Fran Downing, Staff Writer

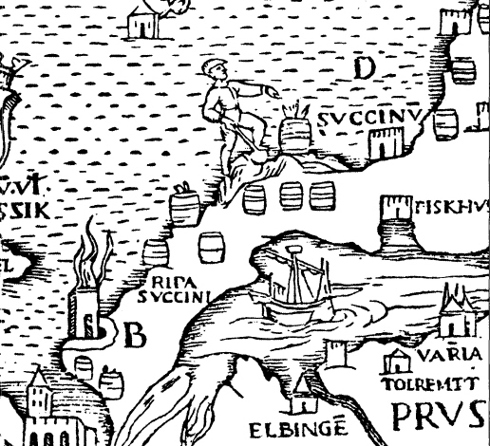

Fifty-two years have passed since Nazi convoys rolled through the Harz Mountains into tunnels dug specifically to secret away art and other Reich valuables. Originally, the caverns were used as weapons manufacturing sites and munitions depots. But in the final days of World War II, they became perfect repositories for pillaged loot and national treasures.

Two years ago, Wayland McKoy led an expedition into the Heimkehl Caverns near Uftrugen, Germany, in search of two railroad cars buried under tons of gypsum. McKoy found the cars, along with several old master paintings, toward which the French and Dutch governments paid a handsome finder's fee.

This time McKoy, a North Carolina contractor, real estate developer and amateur treasure hunter, is hoping for bigger loot. He's been a part of four past expeditions and is hoping his latest, which starts next week, will be his most successful.

"Think about it. It's 1945. The Russians are coming from one end, the Americans from another. You're the curator of the Berlin museum full of art stolen from every invaded country. You've got a few hours. What do you put on the train to get out of town? Obviously, the most valuable stuff."

McKoy tells the tale of one such train that left Berlin in the waning days of World War II, heading south for central Germany and the Harz Mountains. No records exist of its destination, and he's hoping the cargo lies within some caverns found only last fall. Interviews with relatives of German soldiers who helped load the train have convinced him of the train's existence. Earlier this year, McKoy used ground-penetrating radar to scan the new caverns.

"Something's in there," McKoy says. "Certainly big enough to be boxcars or storage crates."

McKoy has already secured a permit from German authorities to excavate. He's particularly excited about the prospects of foraging this new site, since, to his knowledge, no one has yet excavated the area. Once a part of East Germany, the region has been off-limits for decades. Current German law provides that McKoy can retain only a small portion of whatever is not claimed by rightful owners. Yet McKoy is undeterred. "It's exciting. Hell, who knows, the Amber Room could be hidden under all that rock."

The excavations will be slow and hard. Backhoes and bulldozers could damage the treasure, so McKoy will be forced to drill holes in the rocks and then chemically break them apart.

"It's slow going and dangerous, but worth the trouble," he says. "The Nazis had prisoners dig hundreds of caves, where they stored ammunition to keep it safe from the bombers. Even the caves used as art repositories were many times mined. The trick is to find the right cave and get inside safely."

McKoy's equipment, seven employees and a television crew are already waiting in Germany. He plans to head there over the weekend. The nearly $1 million cost is being borne by private investors hoping to cash in on the bonanza.

McKoy says, "There's stuff in the ground over there. I'm sure of it. Somebody's going to find all that treasure. Why not me?"

He looked up from the newspaper. Mother of Almighty God. Was this it? If so, what could be done about it? He was an old man. Realistically, there was little left he could do.

The back door opened and Paul strolled into the den. He tossed the paper on the coffee table.

"You still interested in all that art stuff?" Paul asked.

"Habit of lifetime."

"Would be kind of exciting to dig in those mountains. The Germans used them like vaults. No telling what's still there."

"This McKoy mentions Amber Room." He shook his head. "Another man looking for lost panels."

Paul grinned. "The lure of treasure. Makes for great television specials."

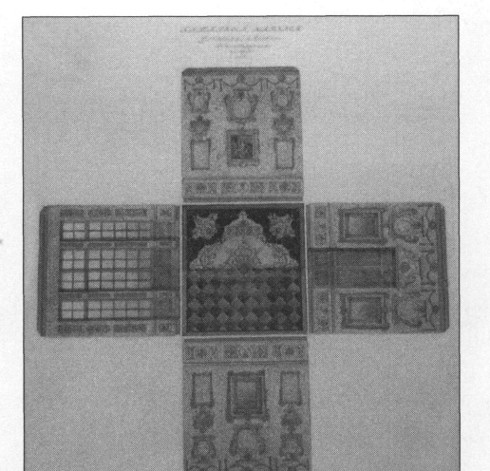

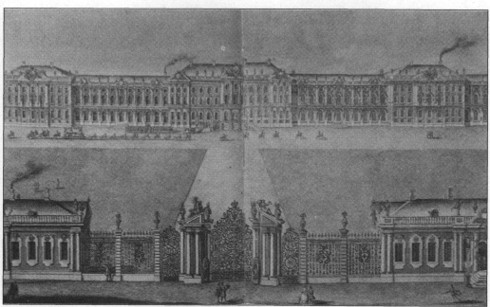

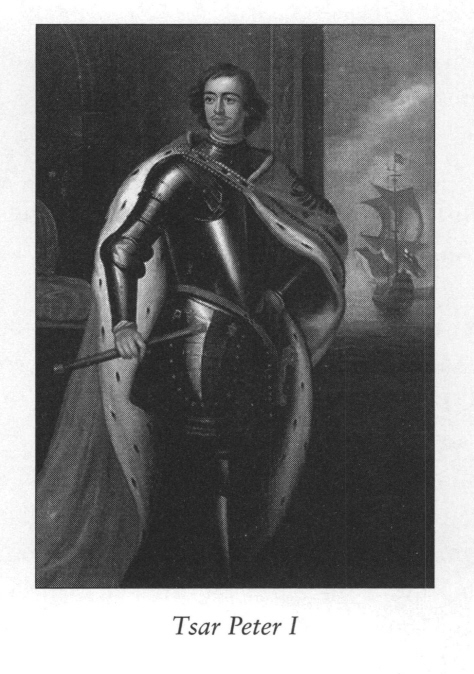

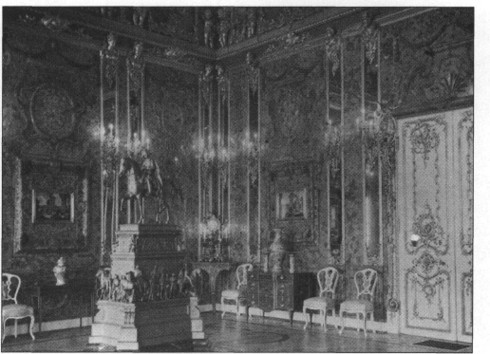

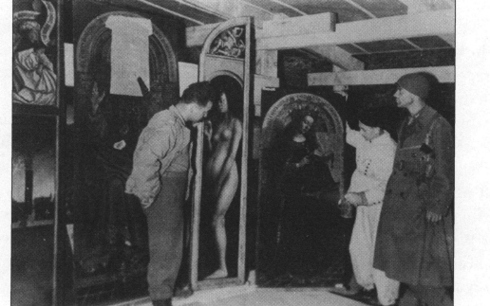

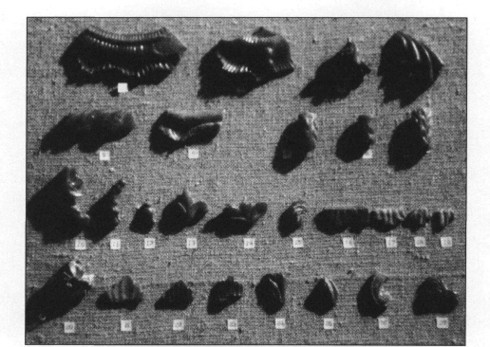

"I saw the amber panels once," he said, giving in to an urge to talk. "Took train from Minsk to Leningrad. Communists had turned Catherine Palace into a museum. I saw the room in its glory." He motioned with his hands. "Ten meters square. Walls of amber. Like a giant puzzle. All the wood carved beautifully and gilded gold. Amazing."

"I've read about it. A lot of folks regarded it as the eighth wonder of the world."

"Like stepping into fairy tale. The amber was hard and shiny like stone, but not cold like marble. More like wood. Lemon, whiskey brown, cherry. Warm colors. Like being in the sun. Amazing what ancient masters could do. Carved figurines, flowers, seashells. The scrollwork so intricate. Tons of amber, all handcrafted. No one ever do that before."

"The Nazis stole the panels in 1941?"

He nodded. "Bastard criminals. Strip room clean. Never seen again since 1944." He was getting angry thinking about it and knew he'd said too much already, so he changed the subject. "You said my Rachel put lawyer in jail?"

Paul sat back in the chair and crossed his ankles on an ottoman. "The Ice Queen strikes again. That's what they call her around the courthouse." He sighed. "Everybody thinks because we're divorced I don't mind."

"It bothers?"

"I'm afraid it does."

"You love my Rachel?"

"And my kids. The apartment gets pretty quiet. I miss all three of 'em, Karl. Or should I say, Karol. That's going to take some getting used to."

"Us both."

"Sorry about not being there today. My hearing got postponed. It was with the lawyer Rachel jailed."

"I appreciate help with petition."

"Any time."

"You know," he said, a twinkle in his eye, "she's seen no man since divorce. Maybe why she's so cranky?" Paul noticeably perked up. He thought he'd read him right. "Claims too busy. But I wonder."

His former son-in-law did not take the bait, and simply sat in silence. He returned his attention to the map. After a few moments, he said, "Braves on TBS."

Paul reached for the remote and punched on the television.

He didn't mention Rachel again, but all through the game he kept glancing at the map. A light green delineated the Harz Mountains, rolling north to south then turning east, the old border between the two Germanies gone. The towns were noted in black. Gottingen. Munden. Osterdode. Warthberg. Stod. The caves and tunnels were unmarked, but he knew they were there. Hundreds of them.

Where was the right cave?

Hard to say anymore.

Was Wayland McKoy on the right track?

SIX

10:25 p.m.

Paul cradled Marla and gently carried her into the house. Brent followed, yawning. A strange feeling always accompanied him when he entered. He and Rachel had bought the two-story brick colonial just after they married, ten years ago. When the divorce came, seven years later, he'd voluntarily moved out. Title remained in both their names and, interestingly, Rachel insisted he retain a key. But he used it sparingly, and always with her prior knowledge, since Paragraph VII of the final decree provided for her exclusive use and possession, and he respected her privacy no matter how much it sometimes hurt.

He climbed the stairs to the second floor and laid Marla in her bed. Both children had bathed at their grandfather's house. He undressed her and slipped her into some Beauty and the Beast pajamas. He'd twice taken the children to see the Disney movie. He kissed her good night and stroked her hair until she was sound asleep. After tucking Brent in, he headed downstairs.

The den and kitchen were messy. Nothing unusual. A housekeeper came twice a week since Rachel was not noted for neatness. That was one of their differences. He was a perfectly in place person. Not compulsive, just disciplined. Messes bothered him, he couldn't help it. Rachel didn't seem to mind clothes on the floor, toys strewn about, and a sinkful of dishes.

Rachel Bates had been an enigma from the start. Intelligent, outspoken, assertive, but alluring. That she'd been attracted to him was surprising, since women were never his strong point. There'd been a couple of steady dates in college and one relationship he thought was serious in law school, but Rachel had captivated him. Why, he'd never really understood. Her sharp tongue and brusque manner could hurt, though she didn't mean 90 percent of what she said. At least that's what he told himself over and over to excuse her insensitivity. He was easygoing. Too easygoing. It seemed far less trouble to simply ignore her than rise to the challenge. But sometimes he felt she wanted him to challenge her.

Did he disappoint her by backing down? Letting her have her way?

Hard to say.

He wandered toward the front of the house and tried to clear his head, but each room assaulted him with memories. The mahogany console with the fossil stone top they'd found in Chattanooga one weekend antiquing. The cream-on-sand conversation sofa where they'd sat many nights watching television. The glass credenza displaying Lilliput cottages, something they both collected with zeal, many a Christmas marked by reciprocal gifts. Even the smell evoked fondness. The peculiar fragrance homes seemed to possess. The musk of life, their life, filtered by time's sieve.

He stepped into the foyer and noticed the portrait of him and the kids still on display. He wondered how many divorcees kept a ten by twelve of their ex around for all to see. And how many insisted that their ex-husband retain a key to the house. They even still possessed a couple of joint investments, which he managed for them both.

The silence was broken by a key scraping the front door lock.

A second later the door opened and Rachel stepped inside. "Kids any trouble?" she asked.

"Never."

He took in the black princess-seamed jacket that cinched her waist and the slim skirt cut above the knee. Long, slender legs led down to low-heeled pumps. Her auburn hair fell in a layered bob, barely brushing the tips of her thin shoulders. Green tiger eyes trimmed in silver dangled from each of her earlobes and matched her eyes, which looked tired.

"Sorry about not making it to the name change," he said. "But your stunt with Marcus Nettles held things up in probate court."

"He's a sexist bastard."

"You're a judge, Rachel, not the savior of the world. Can't you use a little diplomacy?"

She tossed her purse and keys on a side table. Her eyes hardened like marbles. He'd seen the look before. "What do you expect me to do? The fat bastard drops hundred-dollar bills on my desk and tells me to fuck off. He deserved to spend a few hours in jail."

"Do you have to constantly prove yourself?"

"You're not my keeper, Paul."

"Somebody needs to be. You've got an election coming up. Two strong opponents, and you're only a first-termer. Nettles is already talking about bankrolling both of them. Which, by the way, he can afford. You don't need that kind of trouble."

"Screw Nettles."

Last time he'd arranged the fund-raisers, handled advertising, and courted the people needed to secure endorsements, attract the press, and secure votes. He wondered who would run her campaign this time. Organization was not Rachel's strong suit. So far she hadn't asked for help, and he really didn't expect her to. "You can lose, you know."

"I don't need a political lecture."

"What do you need, Rachel?"

"None of your damn business. We're divorced. Remember?"

He recalled what her father said. "Do you? We've been apart three years now. Have you dated anyone during that time?"

"That's also none of your business."

"Maybe not. But I seem to be the only one who cares."

She stepped close. "What's that supposed to mean?"

"The Ice Queen. That's what they call you around the court-house."

"I get the job done. Rated highest of any judge in the county last time the Daily Report checked stats."

"That all you care about? How fast you clear a docket?"

"Judges can't afford friends. You either get accused of bias or are hated for a lack of it. I'd rather be the Ice Queen."

It was late, and he didn't feel like an argument. He brushed past her toward the front door. "One day you may need a friend. I wouldn't burn all my bridges if I were you." He opened the door.

"You're not me," she said.

"Thank God."

And he left.

SEVEN

Northeast Italy

Wednesday, May 7, 1:34 a.m.

His umber jumpsuit, black leather gloves, and charcoal sneakers blended with the night. Even his close-cropped, bottle-dyed chestnut hair, matching eyebrows, and swarthy complexion helped, the past two weeks spent scouring North Africa having left a tan on his Nordic face.

Gaunt peaks rose all around him, a jagged amphitheater barely distinguishable from the pitch sky. A full moon hung in the east. A spring chill lingered in the air that was fresh, alive, and different. The mountains echoed a low peal of distant thunder.

Leaves and straw cushioned his every step, the underbrush thin under gangly trees. Moonlight dappled through the canopy, spotting the trail with iridescence. He chose his steps carefully, resisting the urge to use his penlight, his sharp eyes ready and alert.

The village of Pont-Saint-Martin lay a full ten kilometers to the south. The only way north was a snaking two-lane road that led eventually, after forty more kilometers, to the Austrian border and Innsbruck. The BMW he'd rented yesterday at the Venice airport waited a kilometer back in a stand of trees. After finishing his business he planned to drive north to Innsbruck, where tomorrow an 8:35 A.M. Austrian Airlines shuttle would whisk him to St. Petersburg, where more business awaited.

Silence surrounded him. No church bells clanging or cars screaming past on the autostrada. Just ancient groves of oak, fir, and larch patchworking the mountainous slopes. Ferns, mosses, and wildflowers carpeted the dark hollows. Easy to see why da Vinci included the Dolemites in the background of the Mona Lisa.

The forest ended. A grassy meadow of blossoming orange lilies spread before him. The chateau rose at the far end, a pebbled drive horseshoeing in front. The building was two stories tall, its redbrick walls decorated with gray lozenges. He remembered the stones from his last visit two months ago, surely crafted by masons who'd learned from their fathers and grandfathers.

None of the forty or so dormer windows flickered with light. The oaken front door likewise loomed dark. No fences, dogs, or guards. No alarms. Just a rambling country estate in the Italian Alps owned by a reclusive manufacturer who'd been semiretired for almost a decade.

He knew that Pietro Caproni, the chateau's owner, slept on the second floor in a series of rooms that encompassed the master suite. Caproni lived alone, except for three servants who commuted daily from Pont-Saint-Martin. Tonight, Caproni was entertaining, the cream-colored Mercedes parked out front probably still warm from a drive made earlier from Venice. His guest was one of many expensive working women. They would sometimes come for the night or the weekend, paid for their trouble in euros by a man who could afford the price of pleasure. Tonight's excursion had been timed to coincide with her visit, and he hoped she would be enough of a distraction to cover a quick in and out.

Pebbles crunched with each step as he crossed the drive and rounded the chateau's northeast corner. An elegant garden led back to a stone veranda, Italian wrought iron separating tables and chairs from grass. A set of French doors opened into the house, both knobs locked. He straightened his right arm and twisted. A stiletto slipped off its O-ring and slithered down his forearm, the jade handle nestling firmly in his gloved palm. The leather sheath was his own invention, specially designed for a dependable release.

He plunged the blade into the wooden jamb. One twist, and the bolt surrendered. He resecured the stiletto in his sleeve.

Stepping into a barrel-vaulted salon, he gently closed the glasspaneled door. He liked the surrounding decor of neoclassicism. Two Etruscan bronzes adorned the far wall under a painting, View of Pompeii, one he knew to be a collector's item. A pair of eighteenth-century bibliotheques hugged two Corinthian columns, the shelves brimming with antique volumes. From his last visit he remembered the fine copy of Guicciardini's Storia d'Italia and the thirty volumes of Teatro Francese. Both were priceless.

He threaded the darkened furniture, passed between the columns, then stopped in the foyer and listened up the stairs. Not a sound. He tiptoed across a wheel-patterned marble floor, careful not to scrape his rubber soles. Neapolitan paintings adorned the faux-marble panels. Chestnut beams supported the darkened ceiling two stories above.

He stepped into the parlor.

The object of his quest lay innocently on an ebony table. A match case. Faberge. Silver and gold with an enameled translucent strawberry red over a guilloche ground. The gold collar was chased with leaf tips, the thumbpiece cabochon sapphire. It was marked in Cyrillic initials, N. R. 1901. Nicholas Romanov. Nicholas II. The last Tsar of Russia.

He yanked a felt bag from his back pocket and reached for the case.

The room was suddenly flooded with light, shafts of incandescent rays from an overhead chandelier burning his eyes. He squinted and turned. Pietro Caproni stood in the archway leading to the foyer, a gun in his right hand.

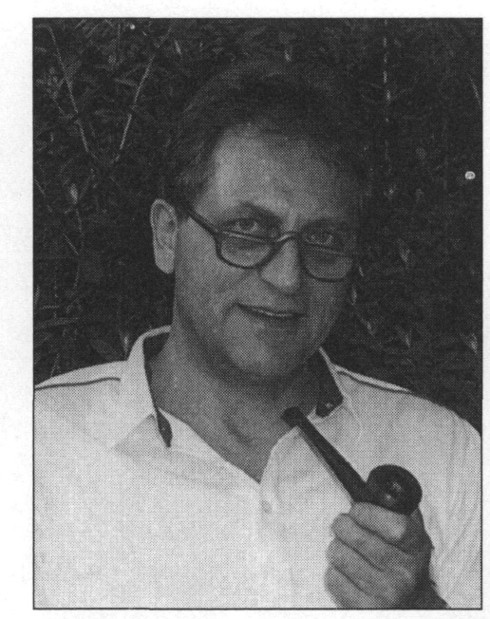

"Buona sera, Signor Knoll. I wondered when you would return."

He struggled to adjust his vision and answered in Italian, "I didn't realize you would be expecting my visit."

Caproni stepped into the parlor. The Italian was a short, heavy-chested man in his fifties with unnaturally black hair. He wore a navy blue terry-cloth robe tied at the waist. His legs and feet were bare. "Your cover story from the last visit didn't check out. Christian Knoll, art historian and academician. Really, now. An easy matter to verify."

His vision settled as his eyes adjusted to the light. He reached for the match case. Caproni's gun jutted forward. He pulled back and raised his arms in mock surrender. "I merely wish to touch the case."

"Go ahead. Slowly."

He lifted the treasure. "The Russian government has been looking for this since the war. It belonged to Nicholas himself. Stolen from Peterhof outside Leningrad sometime in 1944, a soldier pocketing a souvenir from his time in Russia. But what a souvenir. One of a kind. Worth now on the open market about forty thousand U.S. dollars. That's if someone were foolish enough to sell. 'Beautiful loot' is the term, I believe, the Russians use to describe things such as this."

"I'm sure after your liberation this evening it would have quickly found its way back to Russia?"

He smiled. "The Russians are no better than thieves themselves. They want their treasures back only to sell them. Cash poor, I hear. The price of Communism, apparently."

"I am curious. What brought you here?"

"A photograph of this room in which the match case was visible. So I came to pose as a professor of art history."

"You determined authenticity from that brief visit two months ago?"

"I am an expert on such things. Particularly Faberge." He laid the match case down. "You should have accepted my offer of purchase."

"Far too low, even for 'beautiful loot.' Besides, the piece has sentimental value. My father was the soldier who pocketed the souvenir, as you so aptly describe."

"And you so casually display it?"

"After fifty years, I assumed nobody cared."

"You should be careful of visitors and photos."

Caproni shrugged. "Few come here."

"Just the signorinas? Like the one upstairs now?"

"And none of them are interested in such things."

"Only euros?"

"And pleasure."

He smiled and casually fingered the match case again. "You are a man of means, Signor Caproni. This villa is like a museum. That Aubusson tapestry there on the wall is priceless. Those two Roman capriccios are certainly valued collectibles. Hof, I believe, nineteenth century?"

"Good, Signor Knoll. I'm impressed."

"Surely you can part with this match case."

"I do not like thieves, Signor Knoll. And, as I said during your last visit, the item is not for sale." Caproni gestured with the gun. "Now you must leave."

He stayed rooted. "What a quandary. You certainly cannot involve the police. After all, you possess a treasured relic the Russian government would very much like returned--pilfered by your father. What else in this villa fits into that category? There would be questions, inquiries, publicity. Your friends in Rome will be of little help, since you will then be regarded as a thief."

"Lucky for you, Signor Knoll, I cannot involve the authorities."

He casually straightened, then twitched his right arm. It was an unnoticed gesture partially obscured by his thigh. He watched as Caproni's gaze stayed on the match case in his left hand. The stiletto released from its sheath and slowly inched down the loose sleeve until settling into his right palm. "No reconsideration, Signor Caproni?"

"None." Caproni backed toward the foyer and gestured again with the gun. "This way, Signor Knoll."

He wrapped his fingers tight on the handle and rolled his wrist forward. One flick, and the blade zoomed across the room, piercing Caproni's bare chest in the hairy V formed by the robe. The older man heaved, stared down at the handle, then fell forward, his gun clattering across the terrazzo.

He quickly deposited the match case into the felt bag, then stepped across to the body. He withdrew the stiletto and checked for a pulse. None. Surprising. The man died fast.

But his aim had been true.

He cleaned the blood off on the robe, slid the blade into his back pocket, then mounted the stairs to the second floor. More faux marble panels lined the upper foyer, periodically interrupted by paneled doors, all closed. He stepped lightly across the floor and headed toward the rear of the house. A closed door waited at the far end of the hall.

He turned the knob and entered.

A pair of marble columns defined an alcove where a king-size poster bed rested. A low-wattage lamp burned on the nightstand, the light absorbed by a symphony of walnut paneling and leather. The room was definitely a rich man's bedroom.

The woman sitting on the edge of the bed was naked. Long, dramatic red hair framed a pair of pyramid-like breasts and exquisite almond-shaped eyes. She was puffing on a thin black-and-gold cigarette and gave him only a disconcerting glance. "And who are you?" she quietly asked in Italian.

"A friend of Signor Caproni's." He stepped into the bedchamber and casually closed the door.

She finished the cigarette, stood, and strutted close, her thin legs taking deliberate strides. "You're dressed strangely for a friend. You look more like a burglar."

"And you seem unconcerned."

She shrugged. "Strange men are my business. Their needs are no different from anyone else's." Her gaze raked him from head to toe. "You have a wicked gleam in your eyes. German, no?"

He said nothing.

She massaged his hands through the leather gloves. "Powerful." She traced his chest and shoulders. "Muscles." She was close now, her erect nipples nearly touching his chest. "Where is the signor?"

"Detained. He suggested I might enjoy your company."

She looked at him, hunger in her eyes. "Do you have the capabilities of the signor?"

"Monetary or otherwise?"

She smiled. "Both."

He took the whore in his arms. "We shall see."

EIGHT

St. Petersburg, Russia

10:50 a.m.

The cab jerked to a stop and Knoll stepped out onto busy Nevsky Prospekt, paying the driver with two twenty-dollar bills. He wondered what happened to the ruble. It wasn't much better than play money anymore. The Russian government openly banned the use of dollars years ago on pain of imprisonment, but the cabdriver didn't seem to care, eagerly demanding and pocketing the bills before whipping the taxi away from the curb.

His flight from Innsbruck had touched down at Pulkovo Airport an hour ago. He'd shipped the match case from Innsbruck overnight to Germany with a note of his success in northern Italy. Before he too returned to Germany, there was one last errand to be performed.

The prospekt was packed with people and cars. He studied the green dome of Kazan Cathedral across the street and turned to spy the gilded spire of the distant Admiralty off to the right, partially obscured by a morning fog. He imagined the boulevard's past, when traffic was all horse-drawn and prostitutes arrested during the night swept the cobbles clean. What would Peter the Great think now of his "window to Europe"? Department stores, cinemas, restaurants, museums, shops, art studios, and cafes lined the busy five-kilometer route. Flashing neon and elaborate kiosks sold everything from books to ice cream and heralded the rapid advance of capitalism. What had Somerset Maugham described? Dingy and sordid and dilapidated.

Not anymore, he thought.

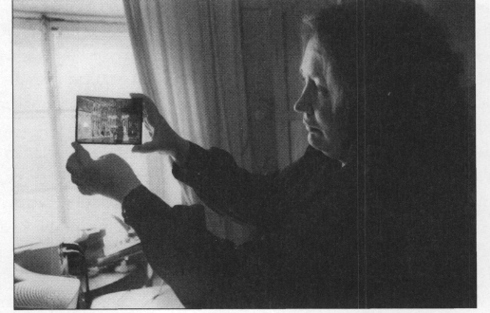

Change was the reason he was able to even come to St. Petersburg. The privilege of scouring old Soviet records had been extended to outsiders only recently. He'd made two previous trips this year--one six months ago, another two months back--both to the same depository in St. Petersburg, the building he now entered for the third time.

It was five stories with a rough-hewn stone facade, grimy from engine exhaust. The St. Petersburg Commercial Bank operated a busy branch out of one part of the ground floor, and Aeroflot, the Russian national airline, filled the rest. The first through third and fifth floors were all austere government offices: Visa and Foreign Citizen's Registration Department, Export Control, and the regional Agricultural Ministry. The fourth floor was devoted exclusively to a records depository. One of many scattered throughout the country, it was a place where the remnants of seventy-five years of Communism could be stored and safely studied.

Yeltsin had opened the documents to the world through the Russian Archival Committee, a way for the learned to preach his message of anti-Communism. Clever, actually. No need to purge the ranks, fill the gulags, or rewrite history as Khrushchev and Brezhnev managed. Just let historians uncover the multitude of atrocities, thievery, and espionage--secrets hidden for decades under tons of rotting paper and fading ink. Their eventual writings would be more than enough propaganda to serve the needs of the state.

He climbed black iron stairs to the fourth floor. They were narrow in the Soviet style, indicating to the knowledgeable, like himself, that the building was post-revolutionary. A call yesterday from Italy informed him that the depository would be open until 3:00 P.M. He'd visited this one and four others in southern Russia. This facility was unique, since a photocopier was available.

On the fourth floor a battered wooden door opened into a stuffy space, its pale green walls peeling from a lack of ventilation. There was no ceiling, only pipes and ducts caked in asbestos crisscrossing beneath the brittle concrete of the fifth floor. The air was cool and moist. A strange place to house supposedly precious documents.

He stepped across gritty tile and approached a solitary desk. The same clerk with wispy brown hair and a horsy face waited. He'd concluded last time the man to be an involuted, self-depreciating, nouveau Russian bureaucrat. Typical. Hardly a difference from the old Soviet version.

"Dobriy den," he said, adding a smile.

"Good day," the clerk replied.

In Russian, he stated, "I need to study the files."

"Which ones?" An irritating smile accompanied the inquiry, the same look he recalled from two months before.

"I'm sure you remember me."

"I thought your face familiar. The Commission records, correct?"

The clerk's attempt at coyness was a failure. "Da. Commission records."

"Would you like me to retrieve them?"

"Nyet. I know where they are. But thank you for your kindness."

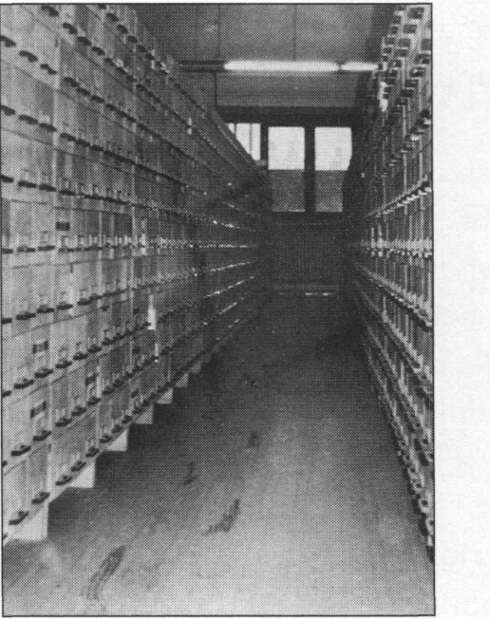

He excused himself and disappeared among metal shelves brimming with rotting cardboard boxes, the stale air heavily scented with dust and mildew. He knew a variety of records surrounded him, many an overflow from the nearby Hermitage, most from a fire years ago in the local Academy of Sciences. He remembered the incident well. "The Chernobyl of our culture," the Soviet press labeled the event. But he'd wondered how unintentional the disaster may have been. Things always had a convenient tendency of disappearing at just the right moment in the USSR, and the reformed Russia was hardly any better.

He perused the shelves, trying to recall where he left off last time. It could take years to finish a thorough review of everything. But he remembered two boxes in particular. He'd run out of time on his last visit before getting to them, the depository having closed early for International Women's Day.

He found the boxes and slid both off the shelf, placing them on one of the bare wooden tables. About a meter square, each box was heavy, maybe twenty-five or thirty kilograms. The clerk still sat toward the front of the depository. He realized it wouldn't be long before the impertinent fool sauntered back and made a note of his latest interest.

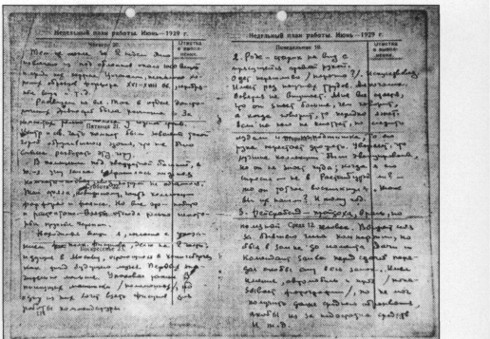

The label on top of both boxes read in Cyrillic, EXTRAORDINARY STATE COMMISSION ON THE REGISTRATION AND INVESTIGATION OF THE CRIMES OF THE GERMAN-FASCIST OCCUPIERS AND THEIR ACCOMPLICES AND THE DAMAGE DONE BY THEM TO THE CITIZENS, COLLECTIVE FARMS, PUBLIC ORGANIZATIONS, STATE ENTERPRISES, AND INSTITUTIONS OF THE UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLIC.

He knew the Commission well. Created in 1942 to resolve problems associated with the Nazi occupation, it eventually did everything from investigating concentration camps liberated by the Red Army to valuing art treasures looted from Soviet museums. By 1945 the commission evolved into the primary sender of thousands of prisoners and supposed traitors to the gulags. It was one of Stalin's concoctions, a way to maintain control, and eventually employed thousands, including field investigators who searched western Europe, northern Africa, and South America for art pillaged by the Germans.

He settled down into a metal chair and started sifting page by page through the first box. The going was slow, thanks to the volume and the heavy Russian and Cyrillic diatribes. Overall, the box was a disappointment, mostly summary reports of various Commission investigations. Two long hours passed and he found nothing of interest. He started on the second box, which contained more summary reports. Toward the middle, he came to a stack of field reports from investigators. Acquisitors, like himself. But paid by Stalin, working exclusively for the Soviet government.

He scanned the reports one by one.

Many were unimportant narratives of failed searches and disappointing trips. There were some successes, though, the recoveries noted in glowing language. Degas's Place de la Concorde. Gauguin's Two Sisters. Van Gogh's last painting, The White House at Night. He even recognized the investigators' names. Sergei Telegin. Boris Zernov. Pyotr Sabsal. Maxim Voloshin. He'd read other field reports filed by them in other depositories. The box contained a hundred or so reports, all surely forgotten, of little use today except to the few who still searched.

Another hour passed, during which the clerk wandered back three times on the pretense of helping. He'd declined each offer, anxious for the irritating little man to mind his own business. Near five o'clock he found a note to Nikolai Shvernik, the merciless Stalin loyalist who had headed the Extraordinary Commission. But this memo was unlike the others. It was not sealed on official Commission stationery. Instead, it was handwritten and personal, dated November 26, 1946, the black ink on onionskin nearly gone:

Comrade Shvernik,

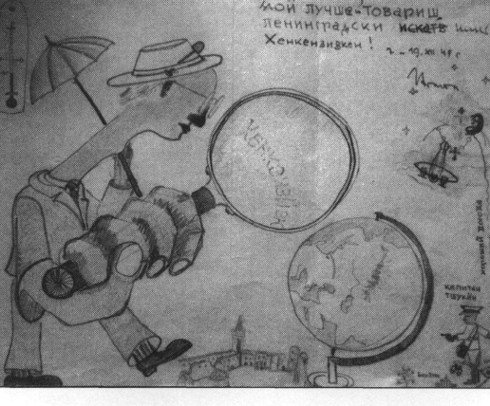

I hope this message finds you in good health. I visited Donnersberg but could not locate any of the Goethe manuscripts thought there. Inquiries, discreet of course, revealed previous Soviet investigators may have removed the items in November 1945. Suggest a recheck of Zagorsk inventories. I met with `Yxo yesterday. He reports activity by Loring. Your suspicions seem correct. The Harz mines were visited repeatedly by various work crews, but no local workers were employed. All persons were transported in and out by Loring. Yantarnaya komnata may have been found and removed. It is impossible to say at this time. `Yxo is following additional leads in Bohemia and will report directly to you within the week.

Danya Chapaev

Clipped to the tissue sheet were two newer sheets of paper, both photocopies. They were KGB information memos dated March, seven years ago. Strange they were there, he thought, tucked indiscriminately among fifty-plus-year-old originals. He read the first note typed in Cyrillic:

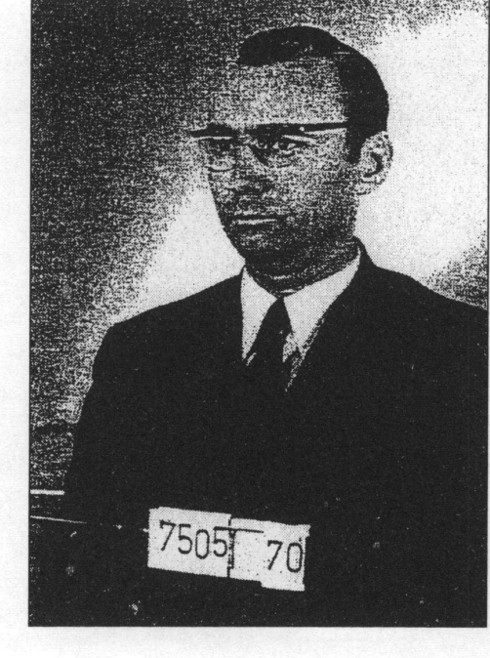

`Yxo is confirmed to be Karol Borya, once employed by Commission, 1946-1958. Immigrated to United States, 1958, with permission of then-government. Named changed to Karl Bates. Current address: 959 Stokeswood Avenue. Atlanta, Georgia (Fulton County), USA. Contact made. Denies any information on yantarnaya komnata subsequent to 1958. Have been unable to locate Danya Chapaev. Borya claimed no knowledge of Chapaev's whereabouts. Request additional instructions on how to proceed.

Danya Chapaev was a name he recognized. He'd looked for the old Russian five years ago but had been unable to find him, the only one of the surviving searchers he hadn't interviewed. Now there may be another. Karol Borya, aka Karl Bates. Strange, the nickname. The Russians seemed to delight in code words. Was it affection or security? Hard to tell. References like Wolf, Black Bear, Eagle, and Sharp Eyes he'd seen. But `Yxo? "Ears." That was unique.

He flipped to the second sheet, another KGB memo typed in Cyrillic that contained more information on Karol Borya. The man would now be eighty-one years old. A jeweler by trade, retired. His wife died a quarter century back. He had a daughter, married, who lived in Atlanta, Georgia, and two grandchildren. Six-year-old information, granted. But still more than he possessed on Karol Borya.

He glanced again at the 1946 document. Particularly the reference to Loring. It was the second time he'd seen that name among reports. Couldn't be Ernst Loring. Too young. More likely the father, Josef. The conclusion was becoming more and more inescapable that the Loring family had long been on the trail, as well. Maybe the trip to St. Petersburg had been worth the trouble. Two direct references to yantarnaya komnata, rare for Soviet documents, and some new information.

A new lead.

Ears.

"Will you be through soon?"

He looked up. The clerk stared down at him. He wondered how long the bastard had been standing there.

"It's after five," the man said.

"I didn't realize. I will be finished shortly."

The clerk's gaze roamed across the page in his hand, trying to steal a look. He nonchalantly tabled the sheet. The man seemed to get the message and headed back to his desk.

He lifted the papers.