THE BACKYARD HOMESTEAD

guide to Raising

Raising

FARM ANIMALS

The mission of Storey Publishing is to serve our customers by publishing practical information that encourages personal independence in harmony with the environment.

Edited by Sarah Guare

Art direction by Dan O. Williams

Book design and text production by MacFadden and Thorpe

Cover illustration and illustrations on pages i-vi by © Michael Austin, Jing and Mike Company Interior illustration credits appear on page 340

Indexed by Andrea Chesman

Expert review of the rabbit chapter by Bob Bennett, the sheep chapter by Carol Ekarius, the turkey chapter by Eugene Morton, and the cattle chapter by Mary Sherman

© 2011 by Storey Publishing, LLC

Sections of this book previously appeared in the following books by Storey Publishing: Barnyard in Your Backyard, edited by Gail Damerow; Storey’s Guide to Keeping Honey Bees, by Malcolm T. Sanford and Richard E. Bonney; and Storey’s Guide to Raising Pigs, by Kelly Klober.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages or reproduce illustrations in a review with appropriate credits; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other—without written permission from the publisher.

The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without guarantee on the part of the author or Storey Publishing. The author and publisher disclaim any liability in connection with the use of this information.

Storey books are available for special premium and promotional uses and for customized editions. For further information, please call 1-800-793-9396.

Storey Publishing

210 MASS MoCA Way

North Adams, MA 01247

www.storey.com

Printed in the United States by Versa Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The backyard homestead guide to raising farm animals / edited by Gail Damerow.

p. cm.

Includes index.

Previously published as: Barnyard in your backyard. North Adams, MA : Storey Pub., c2002.

ISBN 978-1-60342-969-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Domestic animals. 2. Food animals. I. Damerow, Gail.

SF61.B23 2011

636—dc22

2010051172

THE BACKYARD HOMESTEAD

guide to Raising

FARM ANIMALS

Edited by Gail Damerow

Contributing Authors:

Richard E. Bonney, Gail Damerow, Kelly Klober, Darrell L. Salsbury, Malcolm T. Sanford, Nancy Searle, Paula Simmons, Heather Smith Thomas

Contents

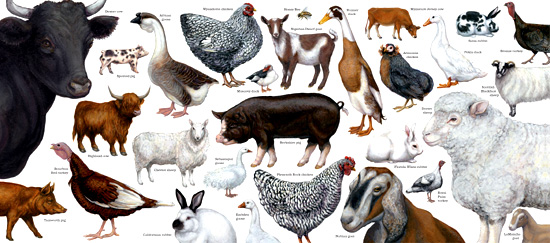

Introducing Backyard Farm Animals

How Many Animals Can You Keep?

Preface

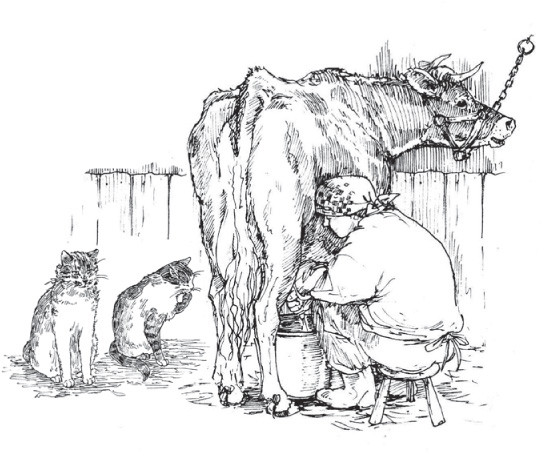

I did not grow up on a farm. My father was a town boy. My mother was raised in the country, left at her first opportunity, and never looked back. I have fond memories of visiting my grandmother and her big flock of laying hens; of watching an uncle milk his cows; of briefly, while my parents built a new house, living in a rented country house with pigs across the road and a goat next door that surprised and delighted me one noon by poking its head through the kitchen window hoping to snatch a bite of my sandwich. These and similar events made me determined to someday have farm animals of my own.

And so when I came of age I started out with chickens, soon followed by ducks and geese and other poultry. Then came rabbits. Then I had to have goats. In the decades that followed I have, at one time or another, raised nearly every species of farm animal. At first I did it just for fun. Before long I realized I had ready access to eggs, milk, and meat that were fresher and better tasting than anything available at the store. I have been grateful for these resources during the several economic crises that have occurred over the years, and especially today in the face of growing concern about the safety of industrially produced food.

I didn’t have any background in farming or raising livestock, and by the time I was ready to seek their advice no farmers were left in my family. I gleaned most of my start-up information from books, and the rest I learned simply by rolling up my sleeves and jumping into what has become a life-long and ongoing learning experience. My point is that you need not have grown up on a farm to raise farm animals. This book is offered as your first step toward enjoying the rewarding experience of keeping livestock of your own and to assure you—you can do it!

Gail Damerow

Introducing Backyard Farm Animals

Food security. The term means different things to different people. One definition involves having a reliable source of basic foods and not having to worry about going hungry. Another requires the food to be of sufficient quantity and quality to meet your dietary needs and satisfy your food preferences. Still other definitions specify that the food be nutritious, safe, and healthful. And some definitions incorporate the concepts of local self-sufficiency and environmental sustainability.

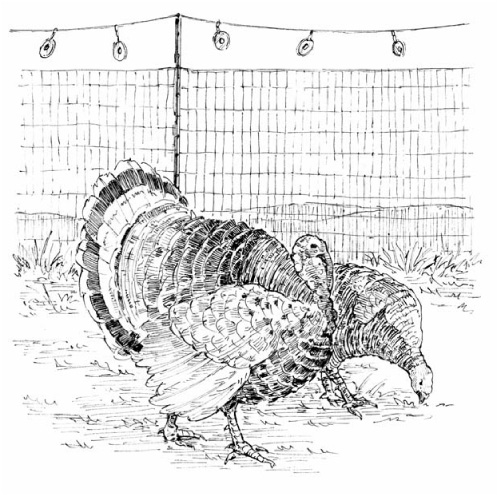

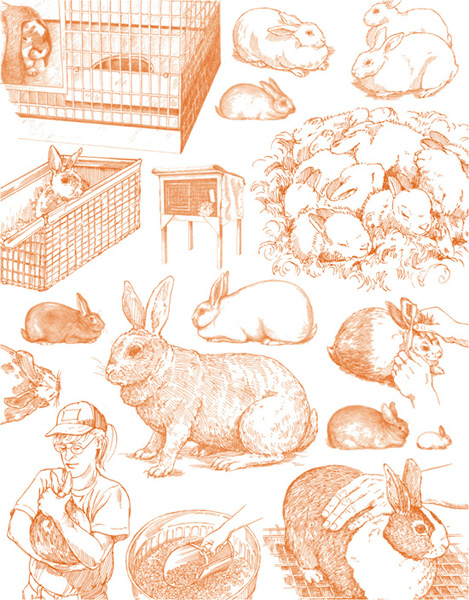

Taken together, these various definitions point in one direction: Grow your own. And unless you are a vegetarian, that means raising livestock. As a lot of people are learning, you don’t need to live on a farm to raise food animals. A pair of rabbits in the carport or on the back porch will provide a year-round supply of meat while taking up hardly any space at all. A beehive or two will give you healthful honey while pollinating your garden. A few hens will provide you with fresh eggs while living happily in one corner of the garden. When I started out with livestock, I lived on approximately one acre on which I raised a variety of rabbits, chickens, turkeys, ducks, and geese, along with a big garden and a small orchard. The garden and orchard benefited from the manure produced by the animals, and the animals benefited from surplus produce gleaned from the garden. Best of all, my family enjoyed food security of the highest order.

Today I live on a farm, where we have space to raise more food animals. We keep dairy goats for their delicious milk, and on occasion use surplus milk to raise a calf for awesomely tasty homegrown burgers or to raise piglets that fill our freezer with succulent pork. But you don’t have to live on a farm, or even on one acre of land, to produce nutritious, safe, healthful eggs, milk, and meat. This book is here to point the way.

Why Raise Food Animals?

Aside from supplying wholesome eggs, milk, meat, and honey, keeping farm animals has another health benefit. Observing the sight and sounds of the animals in your yard offers a refreshing, stress-reducing change from the scurry of modern life. Provided you leave the cell phone behind, doing barnyard chores is a great way to take time out for relaxation and quiet enjoyment. Since livestock must be cared for daily, they pull you away from your indoor activities and force you to get out for a little exercise and fresh air. I often spend long days in the office and look forward to doing evening chores that not only let me stretch my muscles but also help clear my head.

Educational value is another important reason for raising backyard livestock. Too many kids today believe eggs come in plastic cartons and milk comes from a cardboard box. Keeping animals for food helps kids learn, hands on, the basics of producing their food. As any farm family will avow, helping to care for animals at home is a wonderful way for children to learn responsibility, patience, dedication, and compassion. And you could find no better way than raising barnyard animals for children to learn about the natural processes of procreation, birth, and death. As a wonderful bonus, children who grow up around farm animals are generally healthier than children who grow up isolated from the land.

A big question livestock novices frequently ask is, “Can I save money by growing my own _______ (fill in the blank)?” One thing is for certain: It’s not about money. If you take into consideration the cost of building facilities and acquiring stock, as well as feeding and otherwise maintaining your animals, and especially if you include the amount of time you put into the endeavor, you cannot produce your own meat, milk, eggs, and honey as cheaply as you can purchase them from a big-time industrialized producer. If, on the other hand, you are buying quality products from small-scale producers, you can come pretty close to matching or beating their price.

So each chapter of this book includes a discussion on whether or not you can save money by growing your own, taking into consideration mainly the cost of feed, which is the major expense of keeping livestock once your animals have been acquired and their housing established. Even if your chosen endeavor turns out not to be a spectacular financial success, if you take into consideration all the advantages of growing your own—including the satisfaction of putting healthful, wholesome food on the table and the fun you have doing it—you should be able to produce your own food at a reasonable price.

Accentuate the Positive

The marvelous rewards that come from raising your own food animals don’t come without a price, however, and here I’m not referring to money. For one thing, barnyard animals require constant care, day after day, week after week. No matter what else may be going on in your life on a particular day, or how tired you are at day’s end, you must make time to take care of your livestock. Although daily chores don’t involve a lot of time or hard work, they are an important responsibility. If you have trouble finding a substitute caretaker for times when you must be away, you may soon feel tied down by your animals.

But that’s mainly a matter of attitude. Many’s the time I have felt like not doing barnyard chores, only to have my spirits lifted when I got to the barn and was greeted by animals eagerly awaiting my arrival. Sometimes when I turn down an invitation from a friend or relative because I can’t leave my animals for extended periods of time, I’m exhorted to “get rid of all those animals” so I can “be free.” Anyone who could say such a thing doesn’t have livestock of their own; my friends who do have barnyard animals would never consider suggesting anything of the sort. Keeping livestock gives us freedom of a different kind—freedom to eat what we choose, produced by animals raised the way we choose to raise them.

Other downsides that can be part and parcel of keeping backyard livestock include the need to deal with manure, odor, noise, flies, and complaining neighbors. All of these potentially negative factors can be handily dealt with through proper management. I consider manure to be a bonus rather than a disadvantage because I am a gardener, and manure makes outstanding compost that grows a bounty of scrumptious vegetables. My barnyard animals provide me with a constant supply of manure. Odor-free composting techniques are covered in such books as The Complete Compost Gardening Guide, by Barbara Pleasant and Deborah L. Martin. If you are not a gardener, surely you know someone who is who would be delighted to have a source of free, natural fertilizer and more than likely would be happy to clean out your barn to get it.

Properly dealing with manure automatically solves the problems of odor and flies, which leaves us next to consider noise. Barnyard noise is particularly problematic because not everyone considers it a problem. When I hear my neighbor’s cow bellow, I know her calf is being weaned or the cow is ready to be rebred. I once had a neighbor who, when she heard a neighbor’s cow bellow, became so alarmed she called in a vet at her own expense. Now that can get pretty annoying if you are the cow’s owner.

Even if your chosen endeavor turns out not to be a spectacular financial success, if you take into consideration all the advantages of growing your own you should be able to produce your own food at a reasonable price.

A crowing rooster is another noise-maker that not everyone considers to be a problem. I enjoy hearing the sound of a cock crow, but I no longer have to worry about neighbors complaining about it. That’s one of the reasons I moved from one acre to a farm, while some of my chicken-keeping friends have been in constant battles, sometimes ending up in court, over their crowing roosters. Laying hens don’t make nearly as much racket as roosters, although the occasional cranky neighbor may take exception to their cackling. If barnyard noise is a potential problem, consider silent animals, such as honey bees, rabbits, or Muscovy ducks. The latter are sometimes called quackless ducks because their sound is so muted it can be heard only at close range.

Dealing with “The Day”

Unless your interest is in fresh eggs or honey, raising food animals means you must be prepared for the eventuality that one day animals will be butchered. Even a dairy animal involves meat production, since in order to give milk the female must give birth, giving you an annual crop of young ones to deal with. Butchering an animal you raised yourself can be traumatic if you, or especially your child, have become attached to the animal. How well I remember the rabbits our family had when I was little. I had thought they were my pets until the day I came home from school and found them hanging from the basement rafters to be skinned. I can’t tell you how betrayed I felt. I eventually got over it, and today rabbit is one of my favorite meats. But as a child, I would have appreciated knowing the rabbits our family was raising, that I had spent so much time playing with, were destined for the dinner plate. With a tactful approach, no child is too young to learn.

The cardinal rule among those of us who raise animals for meat is to never name one. Well, that’s not quite realistic, especially when you have more than one and need to differentiate between them. But at least avoid giving them affectionate petlike names. Instead use either numbers or names that serve as a reminder of the animal’s purpose in life, such as Finger Lickin’, Hambone, or Sir Loin.

Dealing with butchering involves not only overcoming the emotional aspects, but also following the prescribed procedures that result in safe, tender, tasty meat. Educate yourself by reading a book such as Basic Butchering of Livestock & Game, by John J. Mettler, Jr., and if the process sounds like something you’d rather not get involved with, find out ahead of time if you can count on someone else to do it for you. That someone might be a friend or neighbor raising similar livestock, or perhaps a professional slaughterhouse.

Not all slaughterhouses accept all kinds of livestock. Some take only poultry, whereas others take only larger animals. Even a custom butcher who handles larger stock might have a seasonal schedule: for example, taking in only game animals during the hunting season. When you find a slaughterhouse you plan to use, seek endorsements from past customers. We once had a pig butchered by a shop we had not used before, and they included far too much fat in the ground sausage (which you can understand when you realize that such a shop charges by the pound). As a result, 1 pound of sausage cooked down to less than ½ pound of meat, and—since fat does not keep as well as lean meat—a lot of the sausage went rancid in the freezer before we could use it up.

Perhaps you don’t want to get involved in raising meat at all. Consider that right from the start. If you want a cow or goat for milk, the animal will lactate only as a result of giving birth, so you will have one or more babies to deal with in the future. If you don’t raise them for meat, what you will do with them? If you raise chickens or other fowl for eggs, one of the birds may eventually steal off into some secluded place to lay her eggs and hatch a batch of chicks, thus greatly increasing your backyard population. The offspring might be considered a bonus if raised for meat, a burden if not.

One of the big advantages to raising livestock solely for meat is that the project can be short-term. A batch of broiler chickens, for example, can be raised and butchered all within 8 weeks’ time. A lamb can be ready to turn into chops in six or seven months. These short time frames give you a chance to decide whether you like raising livestock at all. If the answer is yes, you then have the choice of doing another short-term meat project in the future or engaging in a long-term project involving breeding your own animals.

The Value of Networking

Once you’ve decided which animals to keep, educate yourself further about what’s involved. Read not only this book, which provides an overview of each type of food animal, but also some of the books mentioned in the Resources section on page 333, which offer more in-depth details on each specific breed. Subscribe to a periodical dealing with your chosen breed. Network with others who raise the breed by joining a local club, if one exists, and regional or national breed clubs. Visit the fair in your county, and perhaps in surrounding counties, to meet people who have the breed that interests you.

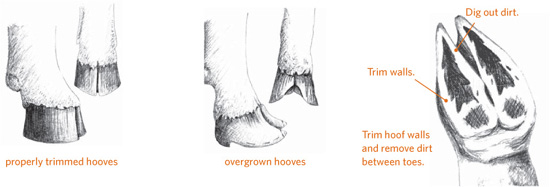

A super place to gather information is at a 4-H show, where the kids involved are well educated about their animals and eager to share their knowledge. Nothing pleases children more than the opportunity to show an adult how smart they are. The people you meet during your networking will become invaluable when you have questions about such things as how to harvest honey, milk a cow, or trim a goat’s hooves.

Finding Stock

The same places that offer good networking opportunities are also excellent sources for locating livestock to purchase. Avoid purchasing stock at an auction or sale barn, where animals are constantly coming and going. You will have no idea where your animal came from, and you can’t tell how healthy or unhealthy it may have been to start with or what kind of diseases it may have been exposed to along the way. The last thing you want is for your first livestock experience to turn into a fiasco involving multiple expensive visits with the veterinarian, administering medications to a reluctant animal, and in the end possibly losing the animal despite your best efforts.

If possible, buy animals from someone who lives nearby. Livestock purchased close to your home already will be adapted to your area, and you will have someone to turn to if you need help later on. When you buy from a local breeder, you can see for yourself whether the animals come from a clean, healthful environment and whether the breeding population has the proper conformation. If you are buying a female breeding animal—a cow, ewe, sow, or doe (goat or rabbit)—the seller may have a male animal to which you could breed her when the time comes. Keeping a rabbit buck for breeding is no big deal, but keeping a bull, ram, boar, or goat buck just to breed one or two females is neither safe nor cost-effective.

Raising a rare breed for food may seem contradictory, but doing so supports breeders and encourages them to perpetuate that breed.

An excellent place to find local sellers of livestock is the farm store. Many farm stores maintain a bulletin board where breeders may advertise livestock for sale, and the clerks can tell you who buys feed for the species you are seeking. The county Extension office is another possible source of information, although some agencies are more active and knowledgeable than others. Larger livestock operations might advertise in the Yellow Pages of your phone book, in the newspaper classified ads, or in the freebie shopper newspapers that abound in every community. The farm store and Extension office can also tell you if your area has a club or other interest group dedicated to your breed. Also check with the national association that promotes your chosen breed or species, most of which maintain a membership list that is available to the public. Some organizations publish their membership list on websites to help you locate members nearest you.

If you are interested in a less common breed, contact the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy or Rare Breeds Canada for their periodically updated list of breeders. Raising a rare breed for food may seem contradictory, but doing so supports breeders and encourages them to perpetuate that breed; if nobody wants these animals, nobody will continue producing them. Besides, taste tests prove time and again that rare breeds are often the best tasting, primarily because they have not been selectively bred for rapid growth.

Getting the Animal Home

If you have difficulty finding what you want locally, cast your net a little farther afield. When purchasing animals from a distance, try to travel to the seller’s location to view the breeder stock and pick up your purchase. No matter how carefully animals are transported, shipping always involves certain risks.

We have occasionally purchased a calf from a dairy in the next county and transported it home in our pickup camper, and we never had a problem until one extremely hot day. During the 45-minute drive home we stopped to offer the calf some water. It was too frightened to drink, so we decided the better plan was to get home fast and get it off the hot truck. By the time we arrived home the calf was nearly prostrate from heat and dehydration. After a good hosing down with cold water and several gallons of Gatorade, the calf was fine, but the incident gave us quite a scare. Since then if we have to transport livestock in the summer, we do so in the cool hours of early morning or late evening.

If you cannot pick up your purchase in person but must arrange to have it shipped, have a clear written understanding with the seller regarding who bears the risk if the animal gets sick or dies. The stress of long-distance travel compromises an animal’s immune system, risking infection during travel or on arrival at its new home.

Preparing a Home

Before bringing home your first animal, have everything ready for it. A little advance preparation will smooth the way.

Ensure family support. Check with all members of your family to see how they feel about having livestock in your backyard. It’s always best to have everyone’s full support, especially when you may need a substitute to do your daily chores whenever you must be away. If not all members are involved in maintaining the livestock, strife can result when the uninterested members feel the others spend too much time at the barn, yet they share in the bounty. By contrast, relations in families in which everyone is involved in some phase of animal care are usually harmonious. In our family, my husband and I normally do chores together; we each have certain responsibilities, but each of us pitches in for the other when need be. We enjoy our time together walking to and from the barn, but at the barn, we devote our full attention to the animals.

Establish caretaking responsibilities. Establish a caretaking schedule and decide who in your family will do what chores daily, weekly, monthly, and seasonally. Children, for instance, can be in charge of the daily routines of feeding, milking, and gathering eggs; these simple tasks will help them learn about responsibility. Adults or older teenagers should probably be involved in the less frequent but more difficult tasks, such as vaccinating, cleaning stalls, or attending births.

Check zoning regulations. Every area has a slightly different set of zoning laws, which may prohibit you from keeping certain species, limit the number of each species you may keep, regulate the distance animal housing must be from nearby human dwellings or your property line, or restrict the use of electric fencing.

I saw firsthand how zoning works on my little one-acre farmstead, which was rezoned after I moved there. Although my poultry activities were grandfathered in—meaning the authorities could not make me get rid of the birds I already had—I was not allowed to increase the population. Now the nature of raising chickens is that after the spring hatch you have more, and as the year progresses and you butcher some, you have fewer. Complying with the new law meant I would not be able to hatch and raise young chickens for meat. I managed to prevail as long as I lived there, but not without hassles from neighbors and occasional visits from the authorities. If you plan to raise livestock on property you have yet to purchase, check not only existing laws but also proposed changes. If existing zoning laws are not livestock friendly, several websites explain how to get the laws changed.

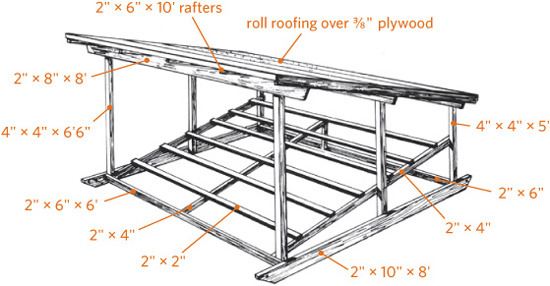

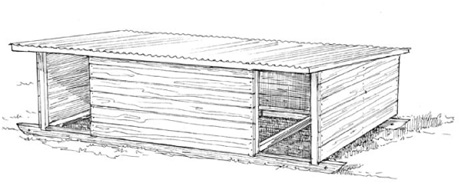

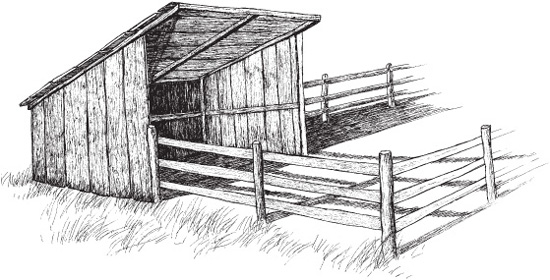

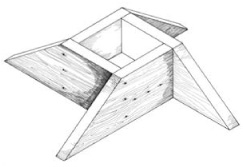

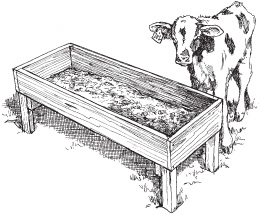

Prepare facilities. Once you learn of any zoning regulations that will influence where on your property you may keep animals, prepare their housing. Most animals require all-weather housing. If your area has particularly hot days or cold days, take those extremes into consideration right from the start, or you may never get around to providing proper housing. If you are starting out with babies, remember they will grow; make sure your facilities are big enough to handle them when they mature. If you wish to breed your stock to raise future babies, chances are pretty good you’ll want to keep one or more of the babies, so allow space for expansion. Since things have a way of taking longer than expected, have your facilities ready and waiting before you bring home your first animal. Provide adequate feed and water stations.

Lay in a supply of feed. Unlike wild animals, which are adept at balancing their own nutritional needs, domestic animals rely on us to furnish all the nutrients they need. The best choice for a beginner is to use bagged feed from the farm store. If you are concerned about what’s in the ration you can opt for an all-natural formula. If you prefer certified organic feed, expect to pay 50 to 100 percent more. After you become knowledgeable about your chosen species’ habits and dietary needs, you will be in a better position to develop an alternative ration, should you so desire. Meanwhile, if the bagged feed you will be using is different from what the animal has been eating, purchase some of its usual feed from the animal’s seller. Gradually mix in greater quantities of new feed with the old to avoid an abrupt change that can cause digestive upset in an animal already stressed from the move.

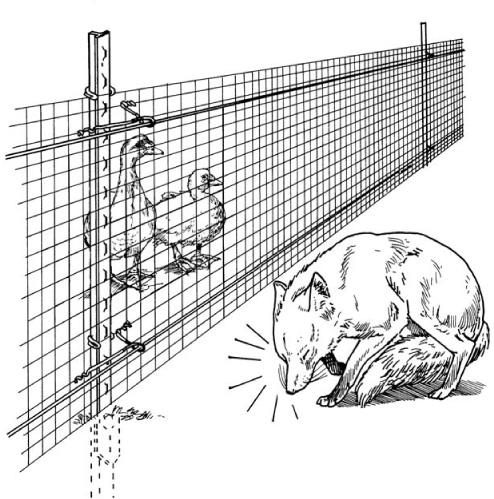

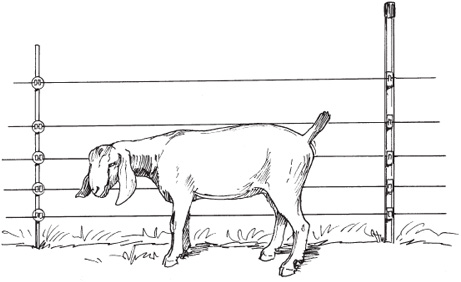

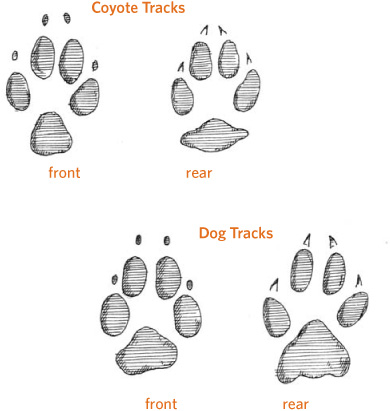

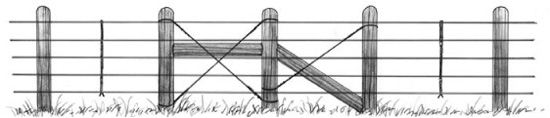

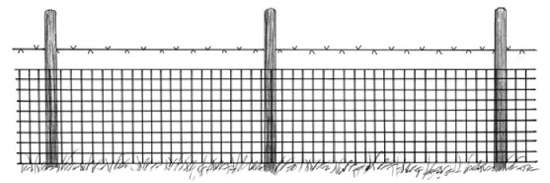

Install sturdy fencing. Secure the livestock area with a stout fence that not only keeps in your livestock but also keeps out predators. When most people hear the word predator, they think of wild animals such as foxes, raccoons, or coyotes. But the number one predators of domestic livestock are dogs. Our neighborhood was once terrorized by a dog that killed countless chickens (including some of mine), a calf, a couple of sheep, and dozens of 4-H rabbits. When the animal-control officer finally caught and euthanized the dog, the owner was furious that her children had been deprived of their beloved pet. Sometimes a predator dog is not the neighbor’s but your own. I’ve heard many a tale of dogs that got along well with poultry, and even guarded them, then for reasons only the dog could know eventually went on a rampage and killed the birds.

Most livestock books recommend farm fencing of one sort or another, which securely confines stock and excludes predators, but may not be legal in more populated areas. The type of fencing you use must be acceptable in your area, both legally and aesthetically. To make your fence animal safe as well as publicly acceptable, you may have to fudge a bit by camouflaging farm fence to look like something else from the outside; for instance, having small-mesh woven wire on the inside with attractive post and rail board fencing on the outside. Attractive fencing that blends well with the neighborhood landscape is more likely to be acceptable to neighbors.

Inform your neighbors. Let your neighbors know about your plan to raise livestock. Explain that you are taking great pains to keep your animals from getting into other people’s yards and to keep other people’s animals out of your yard. Describe what you are doing to maintain clean housing and minimize odors and flies. By letting the neighbors in on your plans, you are less likely to hear complaints from them later. You might even get them involved by asking for their input and advice. Perhaps they’d be willing to help out, for instance when you go on vacation, in exchange for fresh eggs from your chickens, fresh milk from your cow or goat, or barnyard compost for their garden. Who knows—you might pique their interest enough that they’ll want backyard farm animals of their own.

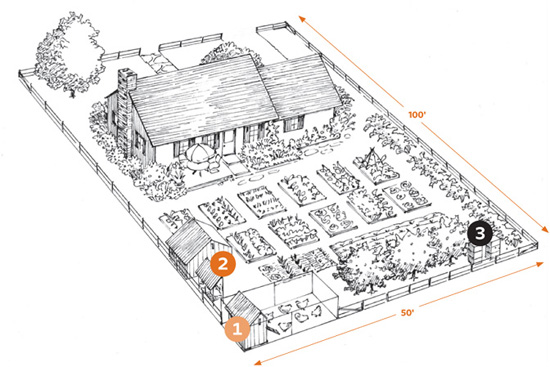

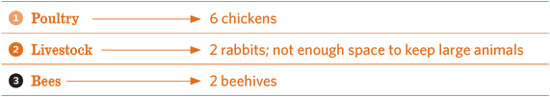

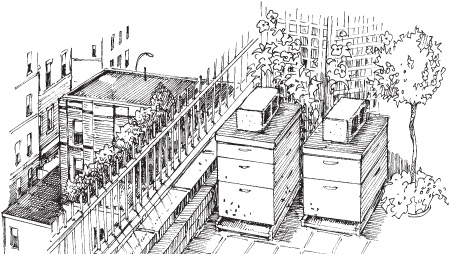

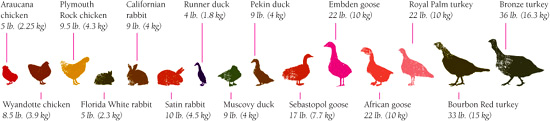

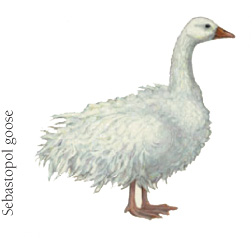

How Many Animals Can You Keep?

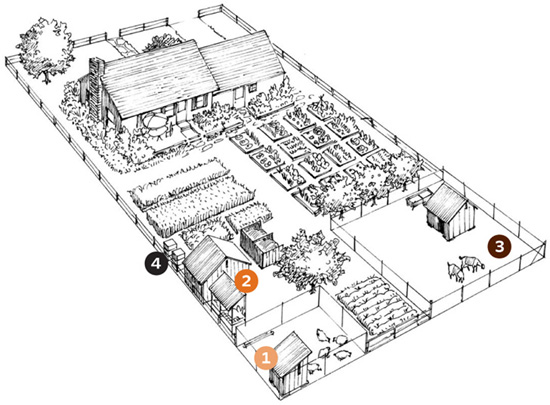

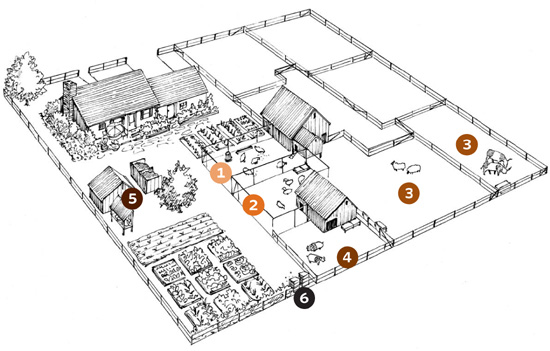

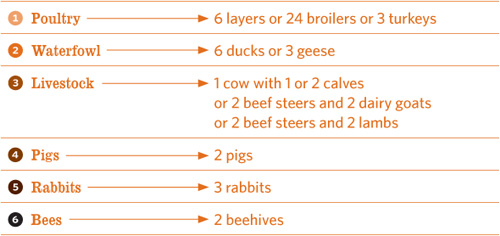

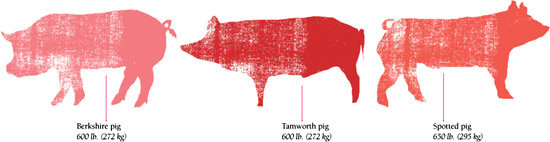

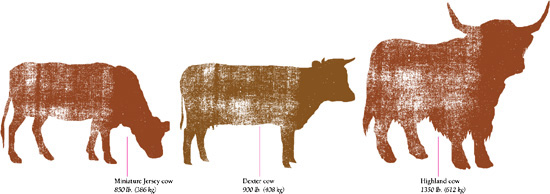

The following illustrations show some of the possibilities for the number of animals that can be kept in an average yard. A quarter-acre lot, planned out well and intensively maintained, can provide milk, meat, honey, and eggs for a small family. Adding another quarter acre allows you to inexpensively raise steers for beef. These examples show what can be done in a given amount of space, but remember: the less living space your animals have, the more time you will have to spend cleaning and maintaining their quarters.

A Homestead on One-Tenth of an Acre

A Homestead on a Quarter Acre

A Homestead on Half an Acre

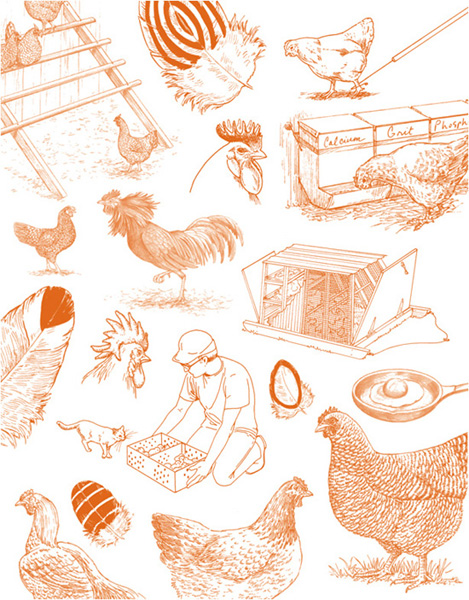

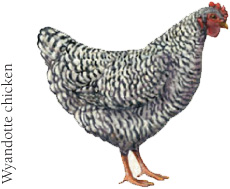

CHAPTER 1 Chickens

If you’ve never raised livestock before, chickens make a great place to start. They’re easy to raise, they don’t need a lot of space, and they don’t cost a lot of money to buy or to feed. Everything you learn about feeding, housing, and caring for your chickens will help you later if you decide to raise some other kind of animal.

All chickens belong to the genus Gallus, the Latin word for cock, or rooster. The English naturalist Charles Darwin traced all breeds of domestic chicken back tens of thousands of years to the wild red jungle fowl of Southeast Asia (Gallus gallus). These fowl look something like today’s brown Leghorns, only smaller. Recent evidence indicates that gray jungle fowl (Gallus sonneratii) may also have been involved in the domestic chickens’ lineage.

Wild jungle fowl are homebodies, preferring to live and forage in one place as long as possible. This trait made taming wild fowl an easy task. All people had to do was provide a suitable place for the chickens to live and make sure they got plenty to eat. As a reward, their keepers had ready access to fresh eggs and meat.

Early chickens didn’t lay many eggs, though, and they made pitifully scrawny meat birds. Over time, chicken keepers selected breeders from those that laid best or grew fastest and developed the most muscle. Different chicken breeders made their selections based on different criteria, and thus came about today’s many different breeds. The Romans called household chickens Gallus domesticus, a term scientists still use.

In 1868, Darwin took inventory of the world’s chicken population and found only 13 breeds. Now we have many times that number. Most of today’s breeds were developed during the twentieth century, when chickens became the most popular domestic food animal.

Getting Started ........................................................................... 12

Choosing the Right Breed ..................................................... 13

Raising Chicks ............................................................................ 20

Raising Broilers ......................................................................... 24

Egg Production ........................................................................... 26

Housing a Flock .......................................................................... 31

Feeding Chickens ...................................................................... 37

Handling Chickens .................................................................. 41

Chicken Health .......................................................................... 44

Getting Started

How much money you spend to get started depends on such factors as the kind of chickens you want and how common they are in your area, how simple or elaborate their housing will be, and whether you already have facilities you can use or modify. Chickens must be protected from wind and harsh weather, but the housing need not be fancy. If your yard isn’t fenced, you’ll need to put one up.

In deciding where to put your chicken yard, consider whether crowing may bother your neighbors. Male chickens—called roosters, or cocks—are well known for their inclination to crow at dawn. Cocks occasionally crow during the day, and if two cocks are within hearing distance, they will periodically engage in an impromptu crowing contest. A rooster rarely crows during the dark of night, unless he is disturbed by a sound or a light.

If keeping a rooster is illegal in your area, or the sound of crowing might cause a problem, consider keeping hens without a rooster. Although the rare persnickety neighbor may complain about hen sounds, the loudest noise a hen makes is a brief cackle upon leaving the nest after she’s laid an egg. Contented hens sing to themselves by making a happy sound that only a grouch could object to. Without a rooster, hens will still lay eggs. The rooster’s function is not to make hens lay eggs but to fertilize the eggs so they can develop into chicks. Without a rooster, you won’t be able to hatch the eggs your hens lay.

Caring for a home flock takes only a few minutes each day to provide feed and water and to collect eggs.

Comparing Benefits and Drawbacks

Raising chickens has some downsides. One is the dust they stir up, which can get pretty unpleasant if they are housed in an outbuilding where equipment is stored. Another is their propensity to scratch the ground and dig dust holes, which can be a big problem if they get into a bed of newly planted seedlings. Chickens also produce plenty of droppings that, if not properly managed, will smell bad and attract flies.

Until you raise your own chickens, it may be hard to believe that people become attached to their chickens and have difficulty letting them go when it’s time to butcher meat birds or replace old layers with younger, more efficient hens. The only alternative, though, is to run a retirement home for chickens, which gets pretty expensive, and the birds will still get old and die eventually. You’ll have to come to grips with the loss.

For many people, the upside of raising chickens far outweighs the downside. Chickens provide wholesome eggs and meat for your family, and you can take pride in knowing that the flock that puts food on your table lives under pleasant conditions.

Caring for a home flock takes only a few minutes each day to provide feed and water and to collect eggs. In hot or cold weather, these jobs must be done twice daily, seven days a week. If you raise chickens for meat, the project will be finished in two to three months. If you raise hens for eggs, you must care for them year-round. As long as you keep in mind that your flock relies on you for its survival, raising chickens is a breeze.

Check First to See If You’re Allergic

Before you set up a chicken farm, make sure that you and your family are not allergic to chicken dander. You can find this out ahead of time by visiting a poultry show at your county fair or spending a few hours helping care for someone else’s chickens. If you discover you have an allergic reaction, you will have avoided the expense and heartache of setting up a flock you immediately have to get rid of.

Choosing the Right Breed

No one knows for certain how many breeds of chicken can be found throughout the world. Some breeds that once existed have become extinct, new ones have been developed, and forgotten ones have been rediscovered. Only a fraction of the breeds known throughout the world are found in North America.

The American Standard of Perfection, published by the American Poultry Association, contains descriptions and pictures of the many breeds and varieties officially recognized by that organization. These breeds are organized according to whether they are large chickens or bantam (miniature chickens suitable for exhibition or as pets), and each group is divided by class. Large chickens are classified according to their place of origin: American, Asiatic, English, Mediterranean, Continental, and Other (including Oriental). Each class is further broken down into breeds and varieties. Chickens of the same breed all have the same general type, or conformation. A chicken that looks similar to the ideal for its breed, as depicted in the Standard, is true to type, or typey.

Most chickens have white or yellow skin. If you are raising chickens for meat, the skin color may make a difference to you. People of Asian cultures tend to prefer chickens with dark skin, Europeans prefer white skin, and most Americans prefer yellow skin.

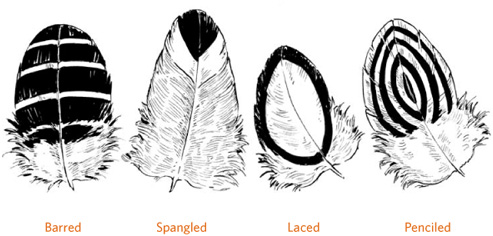

Some breeds come in more than one plumage color; each color constitutes a variety. The colors may be plain—such as red, white, or blue—or they may have a pattern, such as spangled, penciled, or barred. Two varieties of the Plymouth Rock are white and barred.

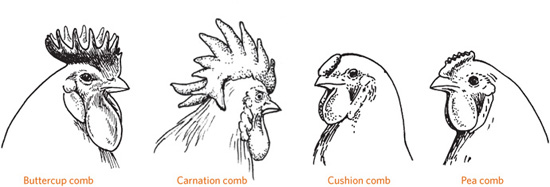

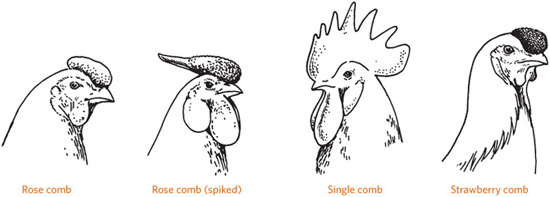

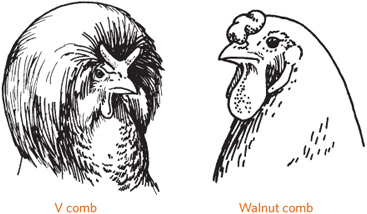

Another feature that can distinguish one variety from another is the style of comb. Most breeds sport the classic single comb, with its series of sawtooth zigzags. The Sicilian Buttercup, by contrast, has two rows of points that meet at the front and back, giving the comb a flowerlike look. Other comb styles are carnation, cushion, pea, rose, and strawberry. Rose comb and single comb are two varieties of Leghorn. Comb style becomes important in areas of weather extremes: Chickens with small combs that lie close to the head are less likely to suffer frostbite than chickens with large combs.

Some breeds come in more than one plumage color; each color constitutes a variety.

With all these different possibilities, how do you choose the breed and variety that is best for you? Narrow your choices by deciding what you want your chickens to do for you:

• Do you primarily want eggs?

• Do you want to raise your own chicken meat?

• Do you want both meat and eggs?

• Do you want to help preserve an endangered breed?

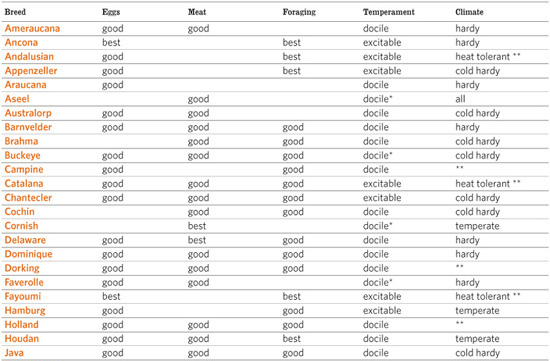

Quick Guide to Chicken Breeds

Egg Breeds

Meat Breeds

Dual-Purpose Breeds

Egg Breeds

All hens lay eggs, but some breeds lay more eggs than others. The best laying hen will yield about 24 dozen eggs per year. The best layers are smallish breeds that produce white-shell eggs. These breeds originated near the Mediterranean Sea, hence their classification as Mediterranean. Examples are Minorca, Ancona, and Leghorn, respectively named after the Spanish island of Minorca and the Italian seaport towns of Ancona and Leghorn (Livorno).

Leghorn is the breed used commercially to produce white eggs for supermarkets. Leghorns are inherently nervous, flighty birds that are unlikely to calm down unless you spend a lot of time taming them. The most efficient layers are crosses between breeds or strains within a breed. The strains used to create commercial layers are often kept secret, and the best production strains are not available to the general public.

While most layers produce white-shell eggs, some lay brown-shell eggs. Brown egg layers are calmer than Leghorns, and therefore most people find them more fun to raise. Brown egg layers are usually dual-purpose breeds or hybrids.

The laying ability of all hens is greatest during their first year. Each year thereafter, the eggs increase slightly in size and decrease in number. At some point you will have to decide if you are getting enough eggs to justify feeding and caring for your hens. Laying hens that don’t lay well enough to earn their keep are called spent hens, and usually end up as stewing hens. Most people who keep hens for eggs replace them with young pullets every two to three years.

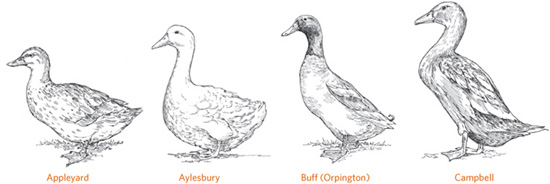

Meat Breeds

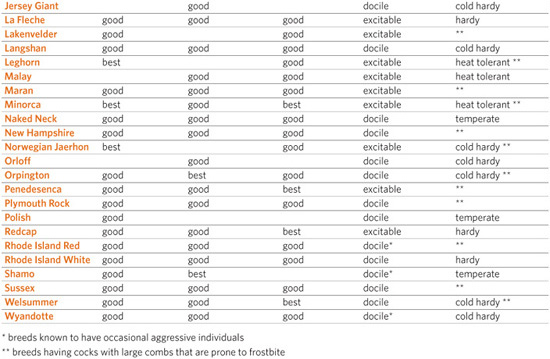

Good layers are scrawny, because they put all their energy into making eggs instead of meat. If you want chickens mainly to have homegrown meat, raise a meat breed. For meat purposes, most people prefer to raise white-feathered breeds, because they look cleaner than dark-feathered birds after plucking. The best breeds for meat grow plump fast. The longer a chicken takes to get big enough to butcher, the more it eats. The more it eats, the more it costs to feed. A slow growing broiler therefore costs more per pound than a faster grower.

Most meat breeds are in the English class, which includes Australorp, Orpington, and Cornish. Of these, the most popular is Cornish, which originated in Cornwall, England. The fastest growing broilers result from a cross between Cornish and New Hampshire or Plymouth Rock. The Rock-Cornish cross is the most popular meat hybrid. Those 1-pound (0.5 kg) Cornish hens you see in the supermarket are actually 4-week-old Rock-Cornish crosses and may not be hens but cockerels (young cocks).

When raising chickens on pasture became popular, growers quickly learned that commercial strain Cornish cross chickens are not active foragers, so to raise pastured poultry, they turned to a cross between the slower growing heritage Cornish and other old-time breeds. Most of these broilers do not have white plumage like industrial broilers, hence some of the trade names for similar hybrids in the United States include a reference to color: Black Broiler, Red Broiler, and Silver Cross to name a few.

A Rock-Cornish eats just 2 pounds (1 kg) of feed for each pound of weight it gains. By comparison, a layer eats three times as much to gain the same weight. You can see, then, why it doesn’t make much sense to raise a laying breed for meat or a meat breed for eggs. If you want both eggs and meat, you could keep a flock of layers and raise an occasional batch of fryers, or you could raise a dual-purpose breed.

Strains

A strain consists of related chickens of the same breed and variety that have been selectively bred for emphasis on specific traits, making the strain readily identifiable to the trained eye. Most strains are named after their breeder, although sometimes a breeder will develop more than one strain and give each a code name.

Two strains may be so different from each other that generalized comparisons about their breed become difficult. Indeed, sometimes more variation occurs among strains than among breeds. To further complicate matters, the farther a strain gets from its source, the more it may change, because the new breeder may not share the vision of the original breeder. When a strain is taken up by several new breeders, chances are good that each will selectively breed in a different direction until the original strain is barely recognizable.

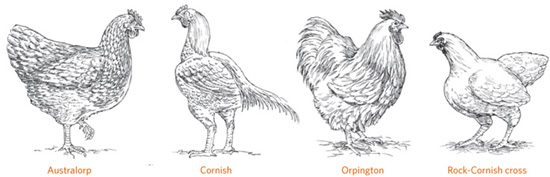

Dual-Purpose Breeds

Dual-purpose breeds kept for both meat and eggs don’t lay quite as well as a laying breed and aren’t quite as fast growing as a meat breed, but they lay better than a meat breed and grow plumper faster than a laying breed. Most dual-purpose chickens are classified as American because they originated in the United States. They have familiar names like Rhode Island Red, Plymouth Rock, Delaware, and New Hampshire. All American breeds lay brown-shell eggs.

Some hybrids make good dual-purpose chickens. One is the Black Sex Link, a cross between a Rhode Island Red rooster and a Barred Plymouth Rock hen. Another is the Red Sex Link, a cross between a Rhode Island cock and a White Leghorn hen. (A sex link is a hybrid whose chicks can be sexed by their color or feather growth.) Red Sex Links lay better than Black Sex Links, but their eggs are smaller and dressed birds weigh nearly 1 pound (0.5 kg) less.

Each hatchery has its favorite hybrid. Although hybrids are generally more efficient at producing meat and eggs than a pure breed, chicks hatched from their eggs will not be the same as the parent stock. If in the future you want more of the same, you will have to buy new chicks from the hatchery. One of the advantages of keeping a nonhybrid is that when you are ready for replacement layers you can hatch your own. Since about half the chicks will be cockerels, you can raise the surplus cockerels for meat.

Endangered Breeds

Many dual-purpose breeds once commonly found on farmsteads are now endangered. Because these chickens have not been bred for factory-like production, they’ve retained their ability to survive harsh conditions, desire to forage, and resistance to disease.

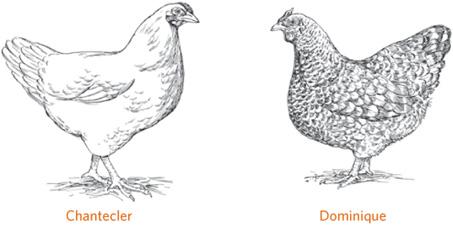

The two organizations American Livestock Breeds Conservancy and Rare Breeds Canada keep track of breeds and varieties they believe are in particular danger of becoming extinct and encourage breeders to engage in poultry conservation. Among the most endangered breeds is the Dominique, sometimes incorrectly called “Dominecker,” the oldest American breed. A few years ago, it almost disappeared, but it is now coming back thanks to the efforts of conservation breeders. Canada’s oldest breed, the Chantecler, experienced a similar turn of fate.

Making the Purchase

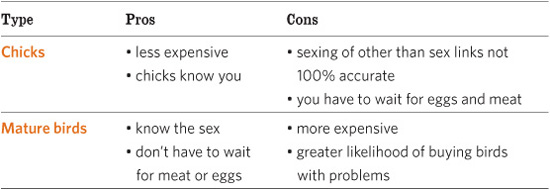

After settling on a breed, variety, and strain, your next decision is whether to purchase newly hatched chicks or grown chickens. Starting with chicks is less expensive than buying the same number of mature birds, and the chicks will grow up knowing you are their keeper. Some breeds and hybrids are sold sexed, meaning you know when you buy them how many are cockerels and how many are pullets (young hens). Sex-link hybrids are easy to sex, because the pullets are a different color from the cockerels. Most breeds must be sexed by examining their private parts, which requires experience and skill to avoid injuring the young birds. Unsexed chicks are sold straight run or as hatched, in which case about half will be cockerels and half pullets. If you want to raise laying hens and no roosters, sexed pullets are the best option. If you want to raise a batch of broilers for the freezer, all cockerels will grow faster and larger.

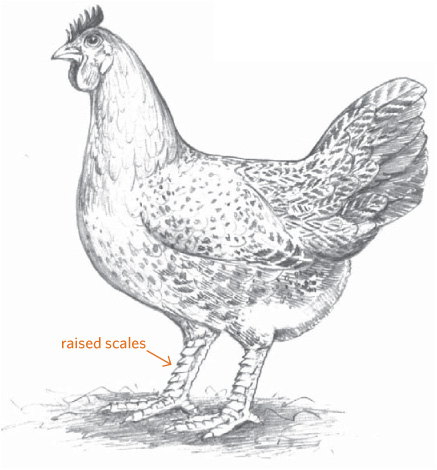

Starting with grown laying hens carries certain risks, among them the greater likelihood of buying diseased or spent hens. To make sure you are getting young hens, look for legs that are smooth and clean, and breastbones that are soft and flexible. Advantages to purchasing grown chickens are that you can easily tell the roosters from the hens, and you won’t have to wait as long to start enjoying fried chicken or fresh eggs.

Starting a Breeder Flock

If you’re happy with hybrid layers or buying an occasional batch of broilers to raise, you don’t need a breeder flock. But if you wish to hatch eggs and raise chicks in the future, you’ll need to maintain a breeder flock. Chicken keepers who hatch eggs include homesteaders who enjoy producing their own meat and eggs and preservationists who work with an endangered breed.

To have consistent results in your chicks year after year, your breeding flock must include chickens only of a single breed. Your results will be inconsistent if you hatch eggs from a flock containing different breeds or commercially crossbred chickens. The birds in your breeding flock should be healthy and free of deformities. They should be reasonably true to type, meaning that each bird is of the correct size, shape, and color for its breed.

You can hatch eggs in two ways: Let a hen hatch them for you or hatch them in a mechanical incubator. Letting a hen handle the hatching is called natural incubation. If you hatch eggs in a mechanical device, the process is called mechanical or artificial incubation. For in-depth details on breeder flock management and egg hatching, see Storey’s Guide to Raising Chickens by Gail Damerow.

Where you buy your chickens depends on what kind you want. If you want a production breed or hybrid, get chicks from a commercial hatchery. If none is nearby, deal with a reputable firm that ships by mail. You may find chicks at a local feed store, although chances are you won’t be able to learn much about what they are or where they came from. Avoid bargain chicks that come free with your first purchase of a sack of feed; they are likely to be excess cockerels of a laying breed.

Dual-purpose breeds are sold by hatcheries, as well as by individuals who advertise in local newspapers. Visiting the seller lets you see what the flock looks like and the conditions under which the birds are raised.

In making your final selection, the main thing to look for is good health. Chicks should be bright-eyed and perky. If they come by mail, open the box in front of the mail carrier, in case something has gone wrong and you need to file a claim. In grown chickens, signs of good health include the following:

• Feathers that are smooth and shiny, not dull or ruffled

• Eyes that are bright, not watery or sunken

• Legs that are smooth and clean, not rough and dirty

• Combs that are full and bright, not shrunken and dull

• Soundless breathing; no coughing, sneezing, or rattling sounds

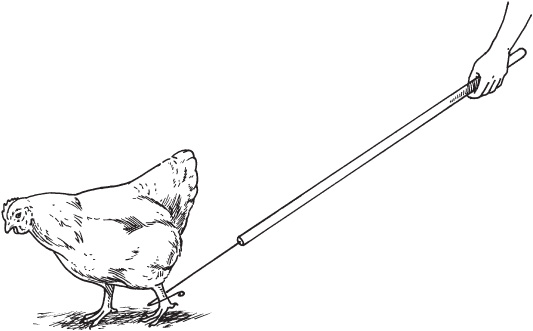

When you visit a seller, whistle as you approach the flock. The chickens will pause to listen, letting you easily hear any unusual breathing sounds. Before taking home your selection, look under each chicken’s wing and around the vent under its tail to make sure it isn’t crawling with body parasites.

How many chickens to get depends, again, on your purpose in keeping them. If you are interested in egg production, determine how many eggs you want per day, divide that number by two, and multiply by three. If you want, for example, six eggs per day, you’ll need at least nine hens. Since hens don’t lay at the same rate all year long, sometimes you’ll have more eggs than you can use, and other times you’ll have too few. It’s the nature of the game. With meat birds the calculation is a bit simpler: Each chicken equals one fryer. You might raise one batch a year, based on how much chicken your family eats in a year, or you might avoid having a whole lot of butchering to do at one time by dividing up the total into several smaller batches and raising them sequentially.

When you order chicks by mail, open the box in front of the mail carrier to verify any claim you may have for losses. Introduce the chicks to household pets to let them know the chicks are yours and shouldn’t be touched.

Should I Buy Chicks or Adult Birds?

How Long Do Chickens Live?

A chicken may live 10 to 15 years. Few chickens live out their full, natural lives. Chickens raised for meat have a short life of only 8 to 12 weeks. Chickens raised for eggs or as breeders are usually kept for 2 or 3 years, until their productivity and fertility decline. A chicken kept in a protective environment may survive as long as 25 years, although geriatric hens lay precious few eggs.

Raising Chicks

When a hen hatches out a brood, she keeps them in the nest until she feels they are ready to venture out into the world. Even after they leave the nest, she keeps them warm and helps them find food. A mother hen gathers her brood under her wings if it rains or she senses danger. She squawks and puffs up, making herself look as big as possible to chase away any dog, cat, or human that might come near.

When you raise chicks yourself, you become their mother hen. No, you needn’t keep your chicks in your pocket or puff yourself up and squawk if something threatens them, but you do need to make sure they are well fed, warm, and safe.

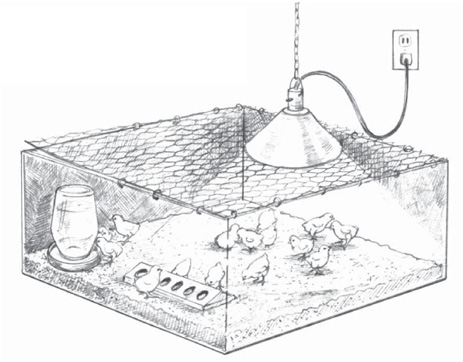

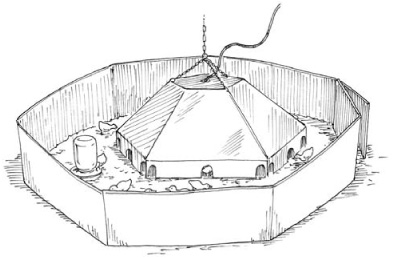

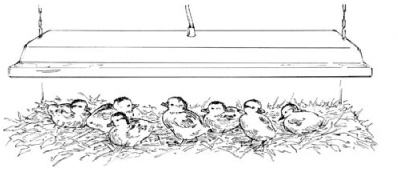

The Brooder Box

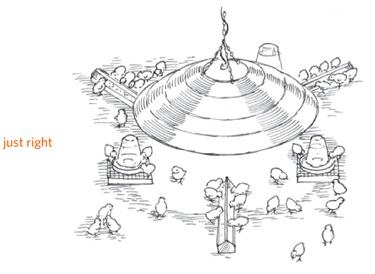

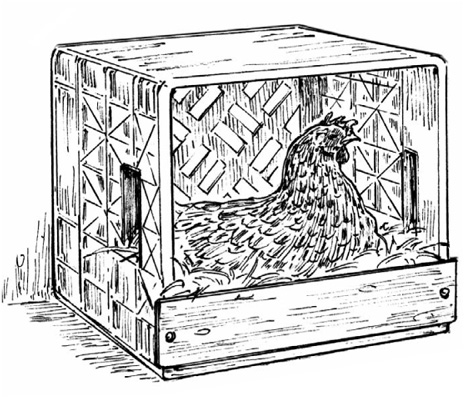

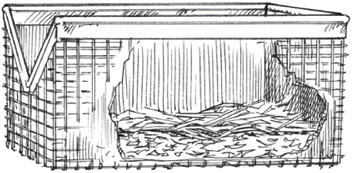

Chicks need a warm, dry, draft-free place where they are protected from dogs, cats, and other animals. Such a place is called a brooder. The simplest brooder is a sturdy cardboard box big enough to hold a feeder and drinker, and still have space so the chicks can move around.

Fasten a piece of chicken wire or hardware cloth to the top of the box so air can get in but pets can’t. Place a piece of cardboard or some newspapers over part of the top if necessary to keep out drafts.

At one end of the box, hang a light-bulb in a reflector; you can purchase this setup at a farm store or hardware store. The heat from the light will keep the chicks warm. To increase the warmth level, lower the light or increase the wattage; to decrease the warmth level, reduce the wattage, raise the light, or use a larger box.

Line the bottom of the box with several layers of newspaper topped with paper toweling. The paper toweling gives the chicks better footing than newspaper, which they would find slippery. After at least a week, when the chicks are walking and eating well, you can use shredded paper, wood shavings (but not cedar, which is toxic), sand, or other bedding at the bottom of the brooder. Bedding absorbs droppings and helps keep the chicks warm and dry but should not be used until they learn to eat chick feed instead of bits of bedding. Each day, sprinkle a little clean bedding over the old bedding.

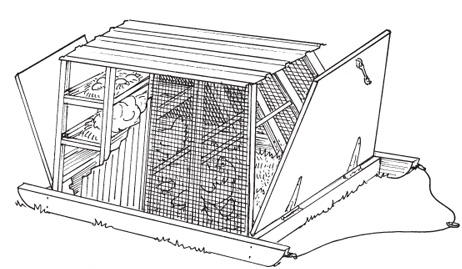

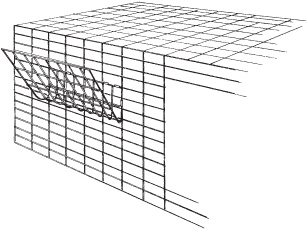

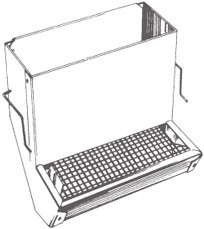

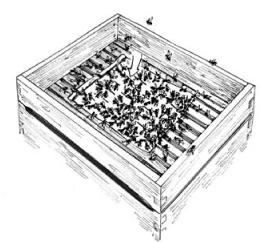

A brooder box has a warming light, good ventilation, clean litter, and plenty of food and water.

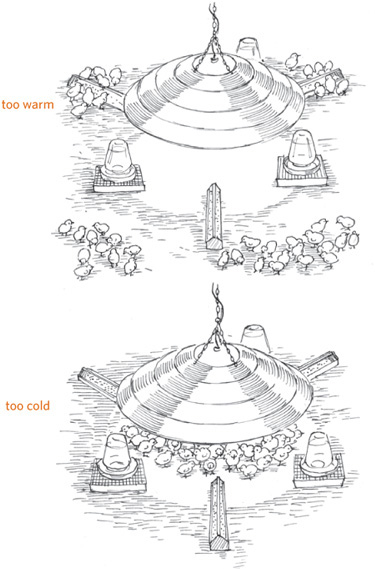

You can tell whether chicks are comfortable in the brooder by the way they act:

• If they are too warm, they will pant and move as far away from the light as they can, crowding into corners and possibly smothering one another.

• If they are not warm enough, they will complain loudly, crowd under the light, sleep in a pile, and possibly smother one another.

• When they are just right, they will move freely around the brooder, make contented sounds, and sleep nicely spread out. The brooder box is the right size if the chicks don’t crowd near the feeder and drinker while sleeping.

The advantage to using cardboard boxes is that they are disposable, so you don’t have to worry about disinfecting and storing them for reuse. A popular brooder used by chicken newbies is a plastic storage tote, which works okay provided the paper and bedding are cleaned out and replaced often to prevent an accumulation of moisture. Moisture leads to moldiness, and moldiness leads to brooder pneumonia.

If you plan to raise a lot of chicks in the future, you may eventually wish to purchase or build a permanent brooder. But it’s a good idea to start with cardboard boxes, which will give you an idea of the features your brooder will need and its appropriate size given the number of chicks you brood at a time and the growth rate of your chosen breed. Whatever style of brooder you use, if your chicks are kept warm, dry, and away from drafts and predators, fed properly, and always have clean water, chances are good they will thrive and grow.

Chicken Development

Feeding Chicks

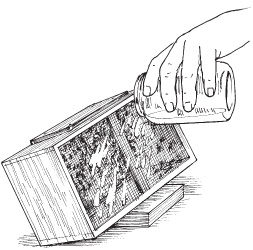

A chick should drink its first water as soon as possible, and the water should be warmed to room temperature. If you set out the water before you go to pick up your chicks, it will be a comfortable temperature by the time you get back. Dip the beak of each chick into the water and make sure it swallows before you release it into the brooder.

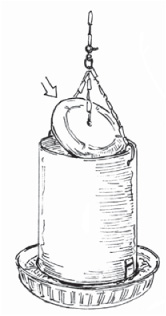

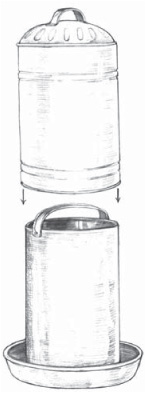

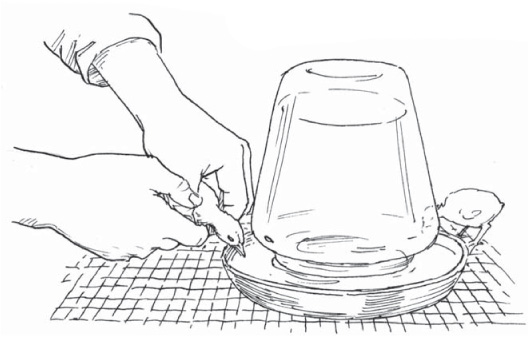

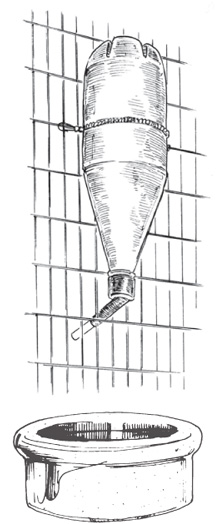

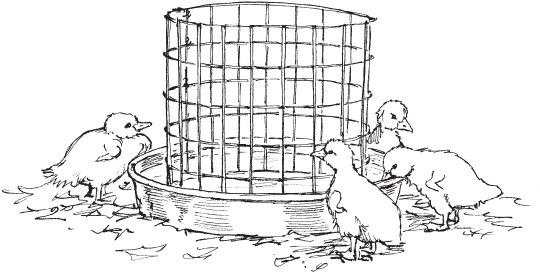

Clean, fresh water must be available at all times thereafter. The easiest way to water chicks is to use a 1-quart (1 L) glass jar fitted with a chick-watering basin from the farm store or poultry supply catalog. Fill the jar with water, place the basin on top, and flip the jar over. Every time a chick takes a drink, water flows out of the jar into the basin. These devices are designed to keep chicks from getting the water dirty by walking in it and from drowning by falling into the water. As the chicks get older and need more water and a larger basin, switch to the 1-gallon (4 L) size.

Feed them a starter ration purchased from the farm store. Starter is higher in protein and lower in calcium than layer ration, which should never be fed to young chickens. Some brands of starter are medicated, some are not. Medicated ration is designed to prevent coccidiosis. If your chicks were vaccinated against coccidiosis at the hatchery, do not feed them medicated starter as it will neutralize the vaccine.

How to Read the Brooder Temperature

Chicks shipped by mail will arrive packed tightly in a well-ventilated box. Their yolk reserves allow them to survive their first few hours out of the incubator without food and water.

In areas where chickens are big business, farm stores sell a variety of rations for chicks. You may find starter ration for newly hatched chicks and grower ration for older chicks. You may find one kind of grower ration for meat birds and another kind for layers. In most parts of the United States, though, you will find only one all-purpose starter or starter-grower.

If you run out of starter, or you forget to pick some up and you have chicks to feed, you can make an emergency starter ration by cracking scratch grains in the blender or, if you have no scratch, by running a little uncooked oatmeal through the blender and mixing it 50/50 with cornmeal. Grains are high in calories and low in the protein, vitamins, and minerals a chick needs for good growth and health, so don’t routinely use this mixture.

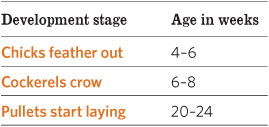

Depending on their breed, chicks will be fully feathered by the time they are 4 to 6 weeks old.

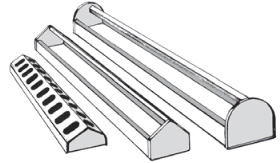

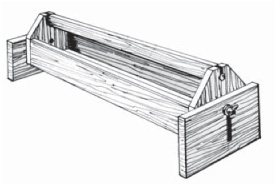

Initially, sprinkle a little feed on the paper towels lining the brooder box and put the rest in a shallow dish or tray. Once the chicks learn where to find chow, switch to a feeder designed especially for chicks. If the feeder has a cover with slots in it, allow one slot per chick. If the feeder is a trough type without a cover, allow 1 inch (2.5 cm) of trough length per chick, or half that if the chicks can eat from both sides.

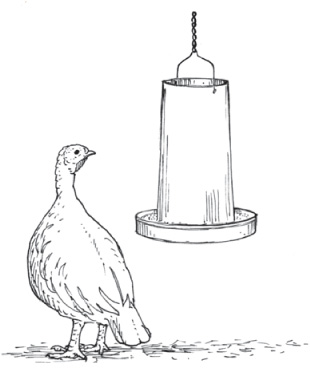

To minimize waste, fill the feeder only two-thirds full. The top of the feeder should be as high as the chicks’ backs. Raise the feeder as the chicks grow, either by using a hanging feeder with an adjustable chain or by putting wooden blocks under the feeder. When your chicks outgrow their baby feeder, switch to a chicken-sized model.

Feeding Layers versus Broilers

If you are raising layers, when they reach 18 weeks of age, gradually mix layer ration into the starter until they are completely switched over to adult ration by the time they start laying. Of the laying breeds, each pullet will eat about 25 pounds (11 kg) of feed by laying age at 20 weeks. Dual-purpose breeds take a bit longer to reach laying age and eat about 27 pounds (12 kg) of feed.

If you raise chicks for eggs, you want them to grow slowly so they are fully developed by the time they start to lay. If you raise broilers, on the other hand, you want them to grow as fast as possible to keep them nice and tender until they get big enough to butcher. The younger the chicken, the more tender it will be. Feed meat chicks often to stimulate their appetite. The more they eat, the faster they grow.

As They Grow

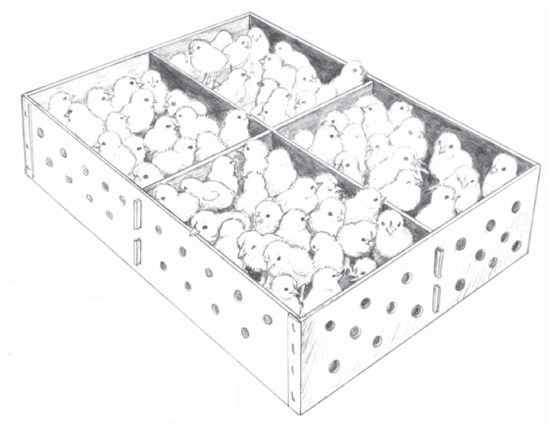

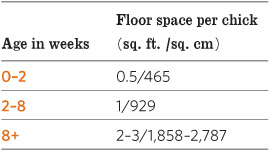

Chicks start growing feathers on their wings within a day or two of hatching. Depending on their breed, they will be fully feathered by the time they are 4 to 6 weeks old. By then, they need at least 1 square foot (30 sq cm) of space each and no longer require artificial heat. They are ready to be moved out of the brooder and into the chicken house.

As the chicks grow, be sure to provide more space and less heat. The rule of thumb is to start them at 95°F (35°C) and reduce the heat 5 degrees a week until ambient temperature is reached. Chicks that are kept too warm or crowded start pecking at one another, causing serious wounds that lead to cannibalism. Cannibalism is a learned habit that usually starts about the time feathers start growing on the lower back. Once cannibalism starts, it’s difficult to stop. Preventive measures include increasing the available space, reducing heat and light, and using a red lightbulb that minimizes the attractiveness of blood and emerging blood-filled feathers.

From Chicks to Chickens

As your chicks grow, you will soon be able to tell the cockerels from the pullets. At 3 to 8 weeks of age, depending on the breed, they will develop reddened combs and wattles. Cockerels have larger, more brightly colored combs and wattles than pullets.

Cockerels will develop spurs on their legs. The older a cock gets, the longer his spurs grow. Hens have no spurs, or tiny spurs, or little round knobs in place of spurs. Game hens are one exception—they may have spurs as long as 1K inches (4 cm).

In some breeds, the cock’s feathers are a different color from the hen’s. In most breeds, the cock’s hackle and saddle feathers are pointed, whereas a hen’s feathers are rounded. The cock also develops long, sweeping tail feathers.

And, of course, the cockerels are the ones that crow. Their first attempts will sound pretty funny, but soon enough they’ll get the hang of it. When the cockerels start chasing the pullets, it’s time to separate them. Select the best cockerels for breeding and fatten the rest for butchering.

Pullets start laying at 20 to 24 weeks, depending on the breed. The first eggs will be small and probably laid on the floor. After a few weeks, you should find regularsize eggs in the nests.

Relieving boredom is another way to prevent cannibalism. Chicks brooded on a wire floor peck each other more readily than chicks brooded on a solid floor covered with litter. The bedding gives chicks an opportunity to engage in normal chicken behavior of pecking, scratching, and dust bathing—things chicks instinctively do when just days old. Lacking the opportunity to engage in these activities, they instead peck each other’s feathers and toes.

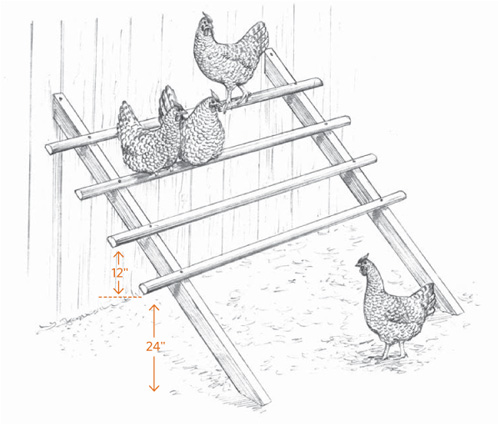

Perches also help relieve boredom by giving chicks a place to play. Given a chance, chicks will practice perching when only a few days old. Pretty soon, they’ll be playing perching games. A chick may jump onto the perch and then jump off the other side, scaring the dickens out of the other chicks. Or one chick may follow another onto the perch, causing the first to lose its balance and hop down. After a few weeks, some chicks will roost on the perch overnight. By the time they are 4 or 5 weeks old, all of the chicks will roost. Allow 4 inches (10 cm) of roosting space per chick.

Don’t use a perch, however, if you’re raising broilers. A perch causes heavy meat birds to get blisters on their breasts. Blisters and calluses may also occur on heavy birds housed on a wire floor or on packed, damp litter. If you raise broilers, forget the perches and freshen the bedding every day.

Chick Health Issues

If you keep your chicks warm, dry, and away from drafts and predators, feed them properly, and make sure they always have clean water, chances are they’ll thrive and grow. Here are three common conditions that affect chicks: pasting, coccidiosis, and brooder pneumonia.

Pasting. Pasting occurs when droppings stick to a chick’s rear end and clog the vent opening. Moisten the wad of dried droppings with warm water and gently pick it off, taking care not to tear the chick’s tender skin. To prevent pasting, make sure your chicks don’t get a chill. If pasting persists, mix a little cornmeal or ground-up raw oatmeal with their starter; or better yet, seek a brand of starter that does not invite pasting. By the time your chicks are 1 week old, pasting should no longer be a problem.

Coccidiosis. Coccidiosis is a parasitic infection that causes droppings to be loose, watery, and sometimes bloody. Chicks raised in the cool weather of early spring are unlikely to get this disease unless they live in filthy conditions or are forced to drink dirty water. Coccidiosis occurs more often during warm humid weather, when the parasites naturally flourish. To prevent this disease, keep drinking water free of droppings and scrub the waterer every time you refill it. Keep the brooder bedding clean and dry by immediately replacing dirty or wet bedding.

As a first-time chicken owner, you would be wise to avoid coccidiosis by either having your chicks vaccinated or feeding them a medicated starter, which contains a coccidiostat. Do not feed medicated starter to chicks that have been vaccinated, as it will neutralize the vaccine, which is simply a low-level dose of the coccidia chicks are most likely to encounter in their environment. Medicated starter is designed as a preventive measure and won’t help chicks that already have coccidiosis. Treating the disease requires stronger medication available from a farm store, poultry supplier, or veterinarian.

Brooder pneumonia. This fungal infection of the lungs causes affected chicks to have difficulty breathing, or they may just sicken and die. To prevent brooder pneumonia, make sure the feed and bedding are always free from moisture, since the combination of moisture and brooder warmth creates an ideal environment for fungal growth.

Raising Broilers

Of all the forms of livestock, chickens put meat on your table with the least amount of time and effort. In a matter of weeks your chicken-keeping chores are over and your freezer is full of tasty, healthful poultry. If, on the other hand, you keep a dual-purpose flock, the availability of poultry meat can be ongoing as you butcher surplus cockerels and spent hens throughout the year.

Meat Classes

Chicken meat can be divided into five basic classes.

Rock-Cornish game hen, Cornish game hen. Not a game bird at all and not necessarily a hen, but an immature (usually 5 to 6 weeks old) Cornish or Cornish cross chicken of no more than 2 pounds (1 kg) dressed weight. This single-serving chicken is typically stuffed and roasted whole.

Broiler, fryer. A tender chicken, usually less than 13 weeks of age, that has soft, pliable, smooth-textured skin and a flexible breastbone. A broiler/fryer is tender enough to be cooked by any method.

Roaster, roasting chicken. A tender chicken, usually between 3 and 5 months of age, that has soft, pliable, smooth-textured skin and a breastbone that is somewhat less flexible than that of a broiler. A roaster is usually stuffed, roasted whole, and sliced for serving.

Hen, fowl, baking chicken, stewing chicken. A mature hen, usually older than 10 months of age, with meat that is less tender than that of a roaster and a nonflexible breastbone. This chicken must be cooked by a moist method such as stewing, braising, or pressure cooking. Stewing hens are generally laying hens that are no longer economically productive.

Cock, rooster. A mature male chicken with coarse skin, a hardened breast-bone tip, and tough, dark meat. Such a chicken is generally not fit to eat, although with long, moist cooking may be made tender enough to chew. A better plan is to butcher surplus cockerels at the fryer stage, which is about the time they begin to crow.

Managing Meat Birds

The trick to growing tender, tasty chickens is to feed them for good growth and ensure they live a healthful life with a minimum of stress. Chickens that don’t have a lot of room for activity will grow more quickly, and their meat will be more tender but less flavorful when compared to chickens that have more opportunity to be active. Methods for raising meat birds fall into three basic categories.

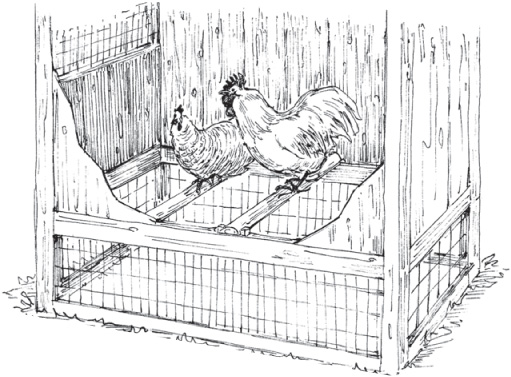

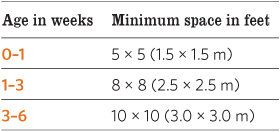

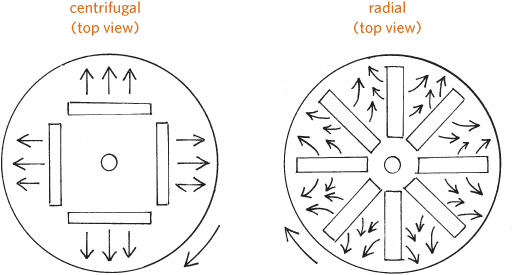

Indoor confinement involves housing chickens indoors on litter and bringing them everything they eat. This method works best where space is limited. The goal of confinement is to get the most meat for the least cost by efficiently converting feed into meat. The standard feed conversion ratio is 2 to 1—each bird averages 2 pounds (1 kg) of feed for every 1 pound (0.5 kg) of weight gain. To get a feed conversion ratio that high, you must raise industrial strain Cornish-cross hybrids, which have been developed for their distinct ability to eat and grow. Efficient feed conversion means allowing birds only enough space to get to feeders and drinkers, and no more. If you don’t like the idea of imitating this industrial production method, give your meat birds more room than the minimums shown in the accompanying chart, but be prepared to feed them a bit longer than the usual eight weeks or less to grow them to target weight.

Range confinement, like indoor confinement, involves keeping broilers in a building, but this building is portable, is kept on pasture, and is moved daily. Range confinement reduces feed costs, especially if you move housing first thing each day to encourage hungry birds to forage for an hour before feeding them their morning ration. On the other hand, you need enough good pasture (or unsprayed lawn) to move the shelter daily, and you must do so each day without fail. As they reach harvest size, the birds will graze faster and deposit a higher concentration of droppings, making it necessary to move them at least twice a day. Chickens raised by this method take longer to reach target weight than do those confined indoors.

Minimum Space for Confined Meat Birds

Breeds by Skin Color

Yellow

Aseel, Barnvelder, Brahma, Buckeye, Chantecler, Cochin, Cornish, Delaware, Dominique, Holland, Java, Jersey Giant, Langshan, Malay, Naked Neck, New Hampshire, Orloff, Plymouth Rock, Rhode Island, Welsummer, Wyandotte

White

Ameraucana, Australorp, Dorking, Faverolle, Houdan, La Fleche, Maran, Minorca, Orpington, Penedesenca, Redcap, Sussex

Pinkish

Catalana

Black

Silkie

Free range lets chickens freely come and go from their range shelter. This method requires more land than either form of confinement, because you need enough space for both a shelter and a pasture for grazing (and trampling), multiplied several times to allow for fresh forage. Figure at least one- quarter acre for 100 birds. Industrial Cornish cross chickens are unsuitable for this method because they are not active foragers. A better option is one of the many heritage Cornish cross strains, sometimes called “Label Rouge” chickens after the French organically grown hybrids they are modeled on. This method requires less labor than range confinement (because you don’t have to move the shelter daily) but more labor than indoor confinement (because you do have to move the shelter occasionally). Allowing the chickens to exercise creates darker, firmer, more flavorful meat but also causes them to eat more and grow more slowly—they don’t reach target weight until about 13 weeks. A typical feed conversion ratio for pastured poultry is 4 to 1—each bird averages 4 pounds (2 kg) of feed for every 1 pound (0.5 kg) of weight gain.

A combination management plan is to raise chickens in confinement for eight weeks, butcher some as fryers, and range feed the rest for another four to five weeks until they reach roaster size. This plan stretches butchering over a longer period of time, making the job more manageable if you grow lots of meat birds but have few helpers when the time comes to harvest them.

Feeding Meat Birds

Young birds convert feed into meat more efficiently than older ones. The most economical meat is a broiler or fryer weighing 2½ to 3½ pounds (1.25 to 1.5 kg). Raising roasters that weigh 4 to 6 pounds (2 to 3 kg) costs more per pound.

A confinement-fed broiler eats about 2 pounds (1 kg) of starter for every pound of weight it gains. If you raise an efficient meat breed or hybrid to 3½ pounds (1.5 kg), each will eat 7 pounds (3.25 kg) of starter by butchering time at 7 to 8 weeks. If you raise a dual-purpose breed, your broilers won’t grow as rapidly. Depending on their breed, by the time they weigh 3½ pounds (1.5 kg), they may eat twice as much as a specialized meat breed. Pastured broilers are typically raised to 5 or 6 pounds (2.5 to 3 kg), during which time they may eat as much as 24 pounds (11 kg) of ration.

The older a chicken is, the less efficiently it converts feed into meat and the costlier it becomes to raise. The conversion ratio starts out below 1 in newly hatched chicks and reaches 2 to 1 at about the fifth or sixth week. During the seventh or eighth week, the cumulative, or average, ratio reaches 2 to 1—the point of diminishing return. From then on, the cumulative ratio has nowhere to go but up. Yet, even though the most economical meat comes from younger, lighter birds, most folks prefer meatier broilers or fryers, which of course cost more per pound to raise.

One way to assess the readiness of a meat bird for butchering is to determine if its shape more closely resembles a rectangle (left), which is preferred, or a triangle.

Can you save money growing your own broilers? That depends on the price of feed, how much the cost can be reduced by pasturing, how efficiently your broilers grow, and the weight at which they are harvested. If you are satisfied with cheap, industrially produced supermarket chicken, all bets are off; growing your own compares in value, if not in price, to broilers purchased from alternative sources. Using averages (and for simplicity’s sake, ignoring the cost of housing, water, electricity, and so forth), do the math: By the time a pastured broiler reaches the live weight of 5 pounds it will have eaten about 20 pounds of feed. At 75 percent of live weight, a 5-pound chicken dresses out to approximately 3¾ pounds. Your break-even cost can be calculated by comparing the purchase price of a broiler with the cost of starter/grower ration. At current rates, a pastured broiler sells for approximately $6.50 per pound, or about $24.00 for a 3¾ pounder. The current rate for one brand of all-natural starter/grower ration is about 25 cents per pound, or about $5.00 for 20 pounds, which is approximately one-fifth the value of the meat. Even if you pay $3.50 for each broiler chick, and 50 to 100 percent extra for certified organic feed, it’s still a pretty good deal.

Water Is Essential

Regardless of your management method, provide free access to fresh water at all times. Chickens that don’t get enough to drink eat less and therefore grow more slowly.

Avoiding Drug Residue

Starter ration comes in medicated and nonmedicated formulas. The medicated version contains a coccidiostat to prevent coccidiosis, an intestinal disease that interferes with nutrient absorption and drastically reduces the growth rate of infected birds. If you choose to start your broiler flock on a medicated ration, you must find a nonmedicated feed to use during the drug’s withdrawal period, which represents the minimum number of days that must pass from the time drug use stops until the drug residue dissipates from the birds’ bodies to a level deemed acceptable for human consumption. If the label does not specify a withdrawal period, ask your feed dealer to look it up for you in his spec book.

If you choose to use nonmedicated feed throughout the growing period, you’ll have to be careful to prevent coccidiosis. This disease is especially problematic in areas where conditions are warm and humid. Keep litter clean and dry for indoor birds, move range-fed birds frequently to prevent a build-up of droppings, and keep drinking water free of droppings. If, despite your best efforts, your chickens should require a coccidiostat or any other medication, observe the specified withdrawal period. For many drugs, the withdrawal period is 30 days.

An alternative for entirely avoiding the issue of drug residue is to have the hatchery vaccinate your chicks. The vaccine stimulates a natural immunity by introducing a low-level infection of the species of coccidia the chicks are most likely to encounter in their environment. Many hatcheries offer the option of having chicks vaccinated, which produces lifetime protection against coccidiosis, provided the chicks are never fed medicated rations, which would neutralize the vaccine.

Butchering

As butchering time draws near, seek out a fellow backyard chicken keeper willing to show you how to clean your broilers, or learn the procedure from a comprehensive chicken-raising book such as Storey’s Guide to Raising Chickens by Gail Damerow. If you prefer not to butcher your own chickens, look for a custom slaughterhouse in your area that handles chickens.

Egg Production

A pullet starts laying when she is about 22 weeks old. Her first eggs are quite small, but by 30 weeks old, her eggs should be of normal size. Each egg takes about 25 hours to develop, causing a hen to lay about an hour later each day. As laying and sleeping time converge, the hen will skip a day, then start a new cycle.

Some hens take more time than normal between eggs and therefore lay fewer eggs per cycle than a hen that lays every 25 hours. Conversely, some hens lay closer to every 24 hours and so lay more eggs per cycle. The laying cycle of individual hens therefore varies, and may be as little as 12 days. Production hens are bred to have the shortest possible interval between eggs so they will lay as many eggs as possible per cycle. The best heavy-breed hens lay about 40 eggs in a cycle; a Leghorn lays closer to 80 eggs.

Can you save money by keeping your own hens? That depends on the price of feed, how much the cost can be reduced by judiciously feeding kitchen or garden scraps, how well your hens lay, and the price you’re paying for eggs now. If you are satisfied with cheap, industrially produced supermarket eggs, all bets are off; growing your own compares in value, if not in price, to eggs from alternative sources. Using averages (and for simplicity’s sake, ignoring the cost of housing, water, electricity, and so forth), do the math: A hen eats 2 pounds of rations per week or about 100 pounds per year, during which she lays maybe 240, or 20 dozen, eggs. The approximate break-even cost can be calculated by multiplying how much you are paying per dozen eggs times 20 dozen, and comparing that figure to what you would pay for 100 pounds of lay ration. At current rates, 1 dozen organic eggs sells for $4.00 or more per dozen. That works out to $80.00 per year for 20 dozen eggs. The current rate for one brand of all-natural lay ration is about $26.00 per 100 pounds, or approximately one-third the value of the eggs. Even if you buy the chick for $3.50, or a laying hen for $15.00, and pay 50 to 100 percent more to purchase certified organic feed, you’re still money ahead.

The Life of a Layer

A good laying hen produces about 20 dozen eggs in her first year. At 18 months of age, she stops laying and goes into a molt, during which her old feathers gradually fall out and are replaced with new ones. Chickens molt once a year, usually in the fall, and the process generally takes 2 to 3 months. Because a hen needs all her energy to grow replacement feathers during the molt, she lays few eggs or none at all. Once her new feathers are in, she looks sleek and shiny, and she begins laying again.