The Complete Alice in Wonderland (Wonderland Imprints Master Editions) – Read Now and Download Mobi

THE COMPLETE ALICE IN WONDERLAND

Volume I

Comprising the Unabridged Texts of:

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There

Alice’s Adventures Under Ground

The Nursery “Alice”

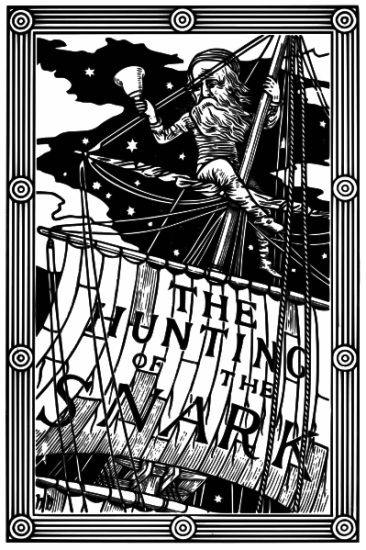

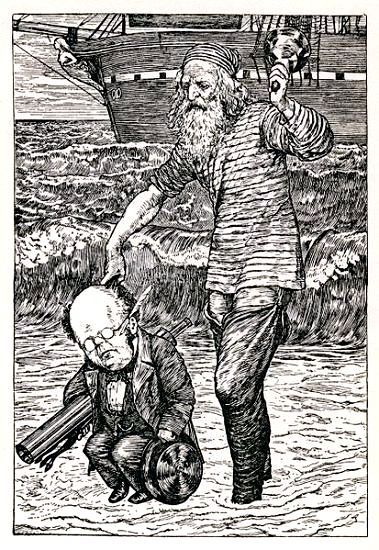

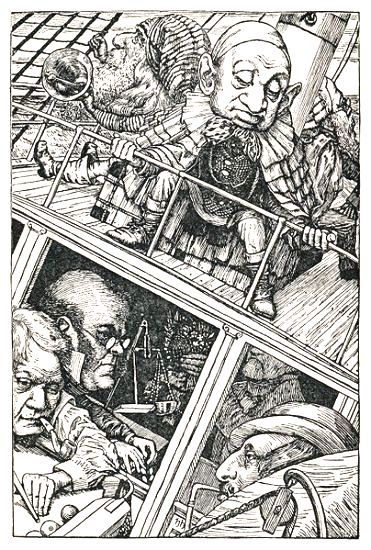

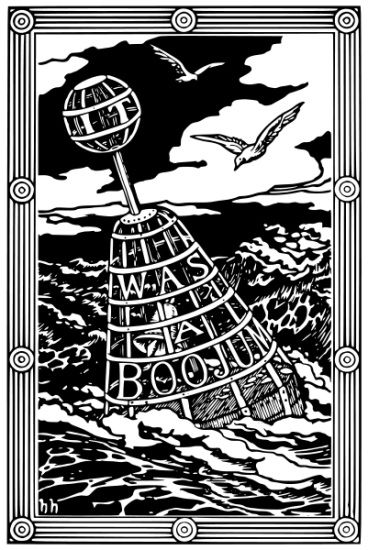

The Hunting of the Snark

By Lewis Carroll

With Kent David Kelly

A collection of the works of Lewis Carroll, uniquely annotated. This collection and all essays are copyright 2010 by Kent David Kelly.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the author.

Printed in the United States of America

Distributed by Wonderland Imprints

Attn: Kent David Kelly

http://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100000867874518

Return to the Beginning of the Book

Introduction to the Master Edition

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

Reflections on Alice in Wonderland

Reflections on the Looking-Glass

Alice's Adventures Under Ground

Reflections on the Under Ground

Reflections on the Nursery “Alice”

INTRODUCTION TO THE MASTER EDITION

By Kent David Kelly

ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND is—deservedly—one of the best-loved books in all the world. It is a triumph not only of the imagination, but also of wit, humor, logical paradox, and the ageless appeal of Victorian charm. Excellent editions of this most excellent book are to be discovered everywhere. Finding a quality electronic version of Alice is, however, a confounding exercise in futility.

Many of the electronic editions are hastily produced, poorly formatted, unedited, or even incomplete. Worse, the abbreviated title Alice in Wonderland can refer to both Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There; or, only the first book; or, incomplete excerpts of each (and often without any publisher clarification on the matter). Due to these well-intentioned yet oddly universal mistakes in the world of electronic publishing, a need was seen for one definitive Kindle Master Edition of the Alice works, created and formatted specifically for the Kindle.

As a Kindle owner and devotee myself, I am very sympathetic to the peculiar woes which readers suffer as a result of over-exposure to amateurish electronic documents. The problems in such works often include (but are by no means limited to): spelling errors; font size issues; character identification issues (such as “w” appearing as “vv,” or the word “corner” as “comer”); forced hyphenation breaks; indentation and spacing issues; spurious pagination; nonexistent tables of contents; a lack of uniquely-created backing matter (glossaries, research essays, endnotes, etc.); incomplete front matter; footnote errors; illustration errors (or no illustrations at all); missing poetry or paragraphs; absent or profligate italics, and much, much more. “Curiouser and curiouser” indeed! In the interests of reader sanity, I have endeavored to make The Complete Alice in Wonderland as correct, complete, user friendly, and simply enjoyable as possible.

Beyond such assuaged frustrations, of course, good readers also demand Master Editions of the texts themselves! In this regard, I have offered not only Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, but also Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There. Further, this edition includes Alice’s Adventures Under Ground (the first draft of Wonderland), The Wasp in a Wig (a long-lost chapter of Through the Looking-Glass), The Nursery “Alice” (an abridged but enlightening supplementary text of the original story), and The Hunting of the Snark (with explanatory notes from Lewis Carroll, revealing its relevance to Wonderland). I trust that the inclusion of these rarer works will provide the Alice devotee with a fascinating and far more inclusive understanding of Wonderland, Lewis Carroll and Alice Liddell herself, which the two common “core” books alone cannot hope to satisfy.

Of course, these works in and of themselves do not tell the entire story. I have also specially written many essays and background articles to support and illuminate Carroll’s masterpieces. These essays include chronologies, biographies, explanatory notes, and a complete glossary of unfamiliar Carrolliana and Victoriana. Additional relevant materials, such as diary entries, letters, period articles and quotations (from Carroll, Alice and others) are included as well. I can certainly guarantee that any Alice fan or Carrollian scholar reading this edition—regardless of their age or their own adventures—will find a muchness of treasures they have never seen before!

Considering the magnitude of this research, writing and editing project, mistakes are certain to creep in. (Perfection, Carroll himself might say, is our unreachable destination; but error is our ongoing journey.) If you, the reader, have any corrections, recommended additions, or simply a comment concerning this work and its supporting materials, your feedback is always welcome! I will be more than happy to attribute those who assist in this

“perfecting” endeavor (by name or username, as you prefer) in a future edition of this work.

In this regard, please feel free to visit me at my author page on Amazon (http://www.amazon.com/-/e/B004AO4O36), my Facebook site (http://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100000867874518), or the page specifically crafted for The Complete Alice in Wonderland. I am also the author of the Carrollian-Lovecraftian “mash-up,” Cthulhu in Wonderland: The Madness of Alice, for those who are interested in further exploration of the darkly humorous nature of insanity (http://www.amazon.com/Cthulhu-Wonderland-Dreadful-Mash-Ups-ebook/dp/B0049H8WSC/). You can of course also reach me personally at any time via e-mail, at [email protected].

An electronic text, of course, will always have its own advantages and disadvantages—all of them considerable. For those Alice fanatics (like me!) who would prefer to own the finest hardcopy versions as well, I can unreservedly recommend The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition, and The Annotated Hunting of the Snark, both written by Martin Gardner. Mister Gardner’s insights into Carroll’s texts are meticulous, brilliant and fascinating. Even better, he has a tremendous respect for Carroll’s favored illustrators, John Tenniel and Henry Holiday. These annotated editions are beautiful and are wonderful additions to any library.

Proper editions of The Nursery “Alice” and Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, however, are much harder to come by, but can occasionally be discovered in quality used bookstores. Another good (but not excellent) book, The Complete Illustrated Works of Lewis Carroll, is of use, but it is far from perfect, and misleading in its title. To my knowledge, The Complete Alice in Wonderland you are now reading is the only work in existence which compiles, supports and annotates all of the “Alice” stories in a single source.

With all that said, I have only one more e-text peeve to confide to you: that of long introductions! And so, without further ado, I welcome you to The Complete Alice in Wonderland. Enjoy your adventures alongside Alice, and do remember:

“Of course you’re mad. Or else you wouldn’t have come here.”

Onward and downward, into Wonderland!

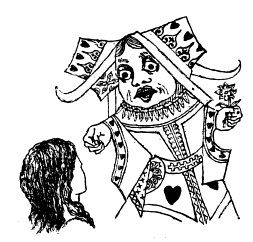

ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND

Introduction: The Creation of Alice

By Kent David Kelly

ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND is a beloved and ageless classic. Indeed, it is one of the most popular, enduring and fondly-quoted books in all the world. Its beginnings, however, were exceedingly humble. If not for the stubborn insistence of a very intelligent and endearing little girl—one Alice Pleasance Liddell—we would not possess this treasury of Victorian wit and humor at all!

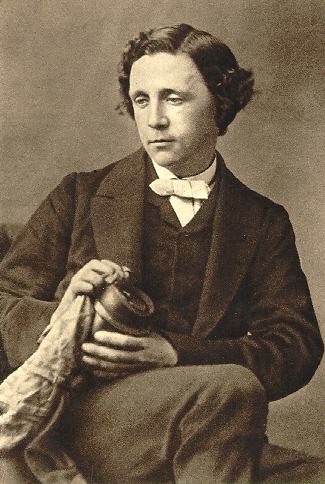

The story of Alice was first improvised as it was spoken, in 1862, by Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (who we know today by his pen name, Lewis Carroll). One summer day, Carroll was out on a boating jaunt with his good friend Robinson Duckworth, and three “Liddell” girls: Lorina, Edith and Alice Pleasance.

On July 4, Carroll made the following entry in his diary:

“Duckworth and I made an expedition up the river to Godstow with the 3 Liddells: we had tea on the bank there, and did not reach Christ Church again till 1/2 past 8, when we took them on to my rooms to see my collection of micro-photographs, and restored them to the Deanery [their home], just before 9.”

Robinson Duckworth’s own reminiscences of that fateful day were as follows:

“I was very closely associated with him [Lewis Carroll] in the production and publication of Alice in Wonderland. I rowed stroke and he rowed bow in the famous Long Vacation voyage to Godstow, when the three Miss Liddells were our passengers, and the story was actually composed and spoken over my shoulder for the benefit of Alice Liddell, who was acting as ‘cox’ of our gig. I remember turning round and saying, ‘Dodgson, is this an extempore romance of yours?’ And he replied, ‘Yes, I’m inventing as we go along.’ I also well remember how, when we had conducted the three children back to the Deanery, Alice said, as she bade us good-night, ‘Oh, Mr. Dodgson, I wish you would write out Alice’s adventures for me.’ He said he should try, and he afterwards told me that he sat up nearly the whole night, committing to a MS. book his recollections of the drolleries with which he had enlivened the afternoon. He added illustrations of his own, and presented the volume, which used often to be seen on the drawing-room table at the Deanery.”

In retrospect, Alice’s memories of those golden summer days may be the most important of all. Later in life, she explained the secret of her stories in this way:

“Most of Mr. Dodgson’s stories were told to us on river expeditions to Nuneham or Godstow, near Oxford. My eldest sister, now Mrs. Skene, was ‘Prima,’ [Latin, roughly translated as ‘first daughter,’ or ‘eldest’] I was ‘Secunda,’ [‘second’] and ‘Tertia’ [‘third’] was my sister Edith. I believe the beginning of Alice was told one summer afternoon when the sun was so burning that we had landed in the meadows down [sic] the river, deserting the boat to take refuge in the only bit of shade to be found, which was under a new-made hayrick. Here from all three came the old petition of ‘tell us a story,’ and so began the ever-delightful tale.

“Sometimes to tease us—and perhaps being really tired—Mr. Dodgson would stop suddenly and say, ‘And that’s all till next time.’ ‘Ah, but it is next time,’ would be the exclamation from all three; and after some persuasion the story would start afresh.

“Another day, perhaps the story would begin in the boat, and Mr. Dodgson, in the middle of telling a thrilling adventure, would pretend to go fast asleep, to our great dismay.”

Carroll, we know now, was indeed growing weary of the endless storytelling, as he wrote this aside in his diary on August 6, 1862: “... Had to go on with my interminable fairy-tale of ‘Alice’s Adventures.’” We are fortunate that he did so, and that Alice persisted in asking for more stories!

Surely, the tale would have died if Alice had not insisted on its immortality. Captain Caryl Hargreaves (Alice’s son), sharing his mother’s memoirs with the world in 1932, revealed the following additional secrets which bring us fuller understanding:

“Nearly all of Alice’s Adventures Under Ground [the first draft of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland] was told on that blazing summer afternoon with the heat haze shimmering over the meadows where the party landed to shelter for a while in the shadow cast by the haycocks near Godstow. I [Alice] think the stories he told us that afternoon must have been better than usual, because I have such a distinct recollection of the expedition, and also, on the next day I started to pester him to write down the story for me, which I had never done before. It was due to my ‘going on, going on’ and importunity that, after saying he would think about it, he eventually gave the hesitating promise which started him writing it down at all.

It was only long after Carroll and Alice became famous—indeed, timeless and unforgettable—that Carroll set forth his own full awareness of the importance of those lost summer days. It is with his most heartfelt and revelatory words that our understanding comes to its fulfillment:

“Many a day had we rowed together on that quiet stream—the three little maidens and I—and many a fairy tale had been extemporised for their benefit—whether it were at times when the narrator was ‘i’ the vein,’ and fancies unsought came crowding thick upon him, or at times when the jaded Muse was goaded into action, and plodded meekly on, more because she had to say something than that she had something to say—yet none of these many tales got written down: they lived and died, like summer midges, each in its own golden afternoon until there came a day when, as it chanced, one of my little listeners petitioned that the tale might be written out for her. That was many a year ago, but I distinctly remember, now as I write, how, in a desperate attempt to strike out some new line of fairy-lore, I had sent my heroine straight down a rabbit-hole, to begin with, without the least idea what was to happen afterwards. And so, to please a child I loved (I don’t remember any other motive), I printed in manuscript, and illustrated with my own crude designs—designs that rebelled against every law of Anatomy or Art (for I had never had a lesson in drawing)—the book which I have just had published in facsimile. In writing it out, I added many fresh ideas, which seemed to grow of themselves upon the original stock; and many more added themselves when, years afterwards, I wrote it all over again for publication: but (this may interest some readers of ‘Alice’ to know) every such idea and nearly every word of the dialogue, came of itself. Sometimes an idea comes at night, when I have had to get up and strike a light to note it down—sometimes when out on a lonely winter walk, when I have had to stop, and with half-frozen fingers jot down a few words which should keep the new-born idea from perishing—but whenever or however it comes, it comes of itself. I cannot set invention going like a clock, by any voluntary winding up: nor do I believe that any original writing (and what other writing is worth preserving?) was ever so produced. ... ‘Alice’ and the ‘Looking-Glass’ are made up almost wholly of bits and scraps, single ideas which came of themselves. Poor they may have been; but at least they were the best I had to offer ...”

“Stand forth, then, from the shadowy past, ‘Alice,’ the child of my dreams. Full many a year has slipped away, since that ‘golden afternoon’ that gave thee birth, but I can call it up almost as clearly as if it were yesterday—the cloudless blue above, the watery mirror below, the boat drifting idly on its way, the tinkle of the drops that fell from the oars, as they waved so sleepily to and fro, and (the one bright gleam of life in all the slumberous scene) the three eager faces, hungry for news of fairy-land, and who would not be said ‘nay’ to: from whose lips ‘tell us a story, please,’ had all the stern immutability of Fate!”

ALICE’S ADVENTURES

IN WONDERLAND

By

LEWIS CARROLL

With Illustrations By

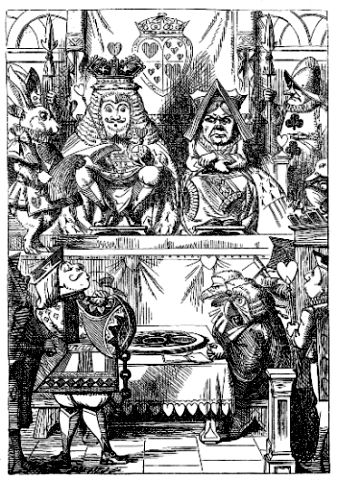

JOHN TENNIEL

Preface to the Seventy-Ninth Thousand

AS ALICE is about to appear on the Stage, and as the lines beginning: “’tis the voice of the Lobster” were found to be too fragmentary for dramatic purposes four lines have been added to the first stanza and six to the second, while the Oyster has been developed into a Panther.

Christmas, 1886

Preface to the Eighty-Sixth Thousand

ENQUIRIES have been so often addressed to me, as to whether any answer to the Hatter’s Riddle can be imagined, that I may as well put on record here what seems to me to be a fairly appropriate answer, vis. “Because it can produce a few notes, though they are very flat; and it is nevar (sic, intentional by the author as “raven” written backwards) put with the wrong end in front! This, however, is merely an afterthought: the Riddle, as originally invented, had no answer at all.

For this eighty-sixth thousand, fresh electrotypes have been taken from the wood-blocks (which, never having been used for printing from, are in as good condition as when first cut in 1865), and the whole book has been set up afresh with new type. If the artistic qualities of this re-issue fall short, in any particular, of those possessed by the original issue, it will not be for want of painstaking on the part of author, publisher, or printer.

I take this opportunity of announcing that the Nursery “Alice,” hitherto priced at four shillings, net, is now to be had on the same terms as the ordinary shilling picture-books—although I feel sure that it is, in every quality (except the text itself, on which I am not qualified to pronounce), greatly superior to them. Four shillings was a perfectly reasonable price to charge, considering the very heavy initial outlay I had incurred: still, as the Public have practically said “We will not give more than a shilling for a picture-book, however artistically got-up,” I am content to reckon my outlay on the book as so much dead loss, and, rather than let the little ones, for whom it was written, go without it, I am selling it at a price which is, to me, much the same thing as giving it away.

Christmas, 1896

A Note on the Text

DUE TO the limitations of electronic formatting—and the difficulties caused by the framing of customizable font sizes—the poem “The Mouse’s Tale” does not appear in the shape of a tail (as it originally appeared in the book). The remainder of the text of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, however, has been meticulously prepared with full respect toward the author’s own intentions.

Prefatory Poem

All in the golden afternoon

Full leisurely we glide;

For both our oars, with little skill,

By little arms are plied,

While little hands make vain pretence

Our wanderings to guide.

Ah, cruel Three! In such an hour,

Beneath such dreamy weather,

To beg a tale of breath too weak

To stir the tiniest feather!

Yet what can one poor voice avail

Against three tongues together?

Imperious Prima flashes forth

Her edict “to begin it”;

In gentler tones Secunda hopes

“There will be nonsense in it!”

While Tertia interrupts the tale

Not more than once a minute.

Anon, to sudden silence won,

In fancy they pursue

The dream-child moving through a land

Of wonders wild and new,

In friendly chat with bird or beast—

And half believe it true.

And ever, as the story drained

The wells of fancy dry,

And faintly strove that weary one

To put the subject by,

“The rest next time—” “It is next time!”

The happy voices cry.

Thus grew the tale of Wonderland:

Thus slowly, one by one,

Its quaint events were hammered out—

And now the tale is done,

And home we steer, a merry crew,

Beneath the setting sun.

Alice! A childish story take,

And, with a gentle hand,

Lay it where Childhood’s dreams are twined

In Memory’s mystic band,

Like pilgrim’s wither’d wreath of flowers

Pluck’d in a far-off land.

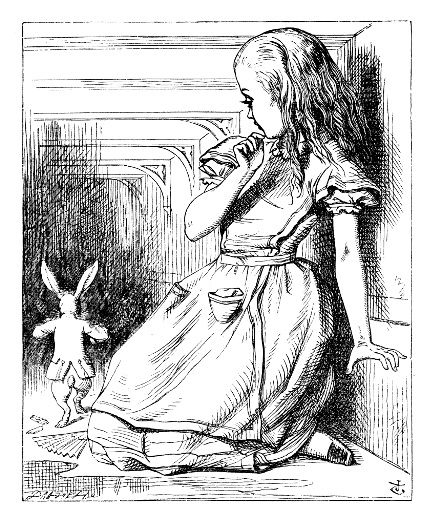

Chapter I

Down the Rabbit-Hole

ALICE WAS beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations in it, “and what is the use of a book,” thought Alice, “without pictures or conversations?”

So she was considering, in her own mind (as well as she could, for the hot day made her feel very sleepy and stupid), whether the pleasure of making a daisy-chain would be worth the trouble of getting up and picking the daisies, when suddenly a White Rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her.

There was nothing so very remarkable in that; nor did Alice think it so very much out of the way to hear the Rabbit say to itself “Oh dear! Oh dear! I shall be too late!” (when she thought it over afterwards, it occurred to her that she ought to have wondered at this, but at the time it all seemed quite natural); but, when the Rabbit actually took a watch out of its waistcoat-pocket, and looked at it, and then hurried on, Alice started to her feet, for it flashed across her mind that she had never before seen a rabbit with either a waistcoat-pocket, or a watch to take out of it, and, burning with curiosity, she ran across the field after it, and was just in time to see it pop down a large rabbit-hole under the hedge.

In another moment down went Alice after it, never once considering how in the world she was to get out again.

The rabbit-hole went straight on like a tunnel for some way, and then dipped suddenly down, so suddenly that Alice had not a moment to think about stopping herself before she found herself falling down what seemed to be a very deep well.

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her, and to wonder what was going to happen next. First, she tried to look down and make out what she was coming to, but it was too dark to see anything: then she looked at the sides of the well, and noticed that they were filled with cupboards and book-shelves: here and there she saw maps and pictures hung upon pegs. She took down a jar from one of the shelves as she passed: it was labeled “ORANGE MARMALADE,” but to her great disappointment it was empty: she did not like to drop the jar, for fear of killing somebody underneath, so managed to put it into one of the cupboards as she fell past it.

“Well!” thought Alice to herself. “After such a fall as this, I shall think nothing of tumbling downstairs! How brave they’ll all think me at home! Why, I wouldn’t say anything about it, even if I fell off the top of the house!” (Which was very likely true.)

Down, down, down. Would the fall never come to an end? “I wonder how many miles I’ve fallen by this time?” she said aloud. “I must be getting somewhere near the centre of the earth. Let me see: that would be four thousand miles down, I think—” (for, you see, Alice had learnt several things of this sort in her lessons in the school-room, and though this was not a very good opportunity for showing off her knowledge, as there was no one to listen to her, still it was good practice to say it over) “—yes, that’s about the right distance—but then I wonder what Latitude or Longitude I’ve got to?” (Alice had not the slightest idea what Latitude was, or Longitude either, but she thought they were nice grand words to say.)

Presently she began again. “I wonder if I shall fall right through the earth! How funny it’ll seem to come out among the people that walk with their heads downwards! The antipathies, I think—” (she was rather glad there was no one listening, this time, as it didn’t sound at all the right word) “—but I shall have to ask them what the name of the country is, you know. Please, Ma’am, is this New Zealand? Or Australia?” (and she tried to curtsey as she spoke—fancy, curtseying as you’re falling through the air! Do you think you could manage it?) “And what an ignorant little girl she’ll think me for asking! No, it’ll never do to ask: perhaps I shall see it written up somewhere.”

Down, down, down. There was nothing else to do, so Alice soon began talking again. “Dinah’ll miss me very much to-night, I should think!” (Dinah was the cat.) “I hope they’ll remember her saucer of milk at tea-time. Dinah, my dear! I wish you were down here with me! There are no mice in the air, I’m afraid, but you might catch a bat, and that’s very like a mouse, you know. But do cats eat bats, I wonder?” And here Alice began to get rather sleepy, and went on saying “Do cats eat bats? Do cats eat bats?” and sometimes “Do bats eat cats?” for, you see, as she couldn’t answer either question, it didn’t much matter which way she put it. She felt that she was dozing off, and had just begun to dream that she was walking hand in hand with Dinah, and was saying to her, very earnestly, “Now, Dinah, tell me the truth: did you ever eat a bat?” when suddenly, thump! thump! down she came upon a heap of sticks and dry leaves, and the fall was over.

Alice was not a bit hurt, and she jumped up on to her feet in a moment: she looked up, but it was all dark overhead: before her was another long passage, and the White Rabbit was still in sight, hurrying down it. There was not a moment to be lost: away went Alice like the wind, and was just in time to hear it say, as it turned a corner, “Oh my ears and whiskers, how late it’s getting!” She was close behind it when she turned the corner, but the Rabbit was no longer to be seen: she found herself in a long, low hall, which was lit up by a row of lamps hanging from the roof.

There were doors all round the hall, but they were all locked; and when Alice had been all the way down one side and up the other, trying every door, she walked sadly down the middle, wondering how she was ever to get out again.

Suddenly she came upon a little three-legged table, all made of solid glass: there was nothing on it but a tiny golden key, and Alice’s first idea was that this might belong to one of the doors of the hall; but, alas! either the locks were too large, or the key was too small, but at any rate it would not open any of them. However, on the second time round, she came upon a low curtain she had not noticed before, and behind it was a little door about fifteen inches high: she tried the little golden key in the lock, and to her great delight it fitted!

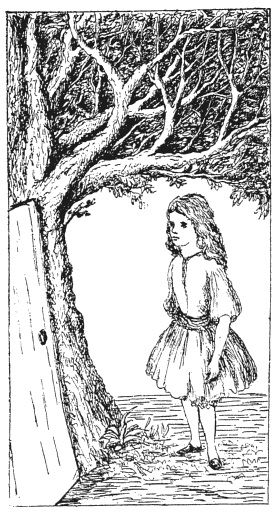

Alice opened the door and found that it led into a small passage, not much larger than a rat-hole: she knelt down and looked along the passage into the loveliest garden you ever saw. How she longed to get out of that dark hall, and wander about among those beds of bright flowers and those cool fountains, but she could not even get her head through the doorway; “and even if my head would go through,” thought poor Alice, “it would be of very little use without my shoulders. Oh, how I wish I could shut up like a telescope! I think I could, if I only knew how to begin.” For, you see, so many out-of-the-way things had happened lately, that Alice had begun to think that very few things indeed were really impossible.

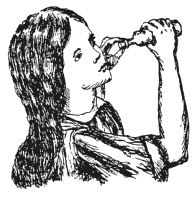

There seemed to be no use in waiting by the little door, so she went back to the table, half hoping she might find another key on it, or at any rate a book of rules for shutting people up like telescopes: this time she found a little bottle on it (“which certainly was not here before,” said Alice), and tied round the neck of the bottle was a paper label, with the words “DRINK ME” beautifully printed on it in large letters. It was all very well to say “Drink me,” but the wise little Alice was not going to do that in a hurry. “No, I’ll look first,” she said, “and see whether it’s marked ‘poison’ or not”; for she had read several nice little stories about children who had got burnt, and eaten up by wild beasts, and other unpleasant things, all because they would not remember the simple rules their friends had taught them: such as, that a red-hot poker will burn you if you hold it too long; and that, if you cut your finger very deeply with a knife, it usually bleeds; and she had never forgotten that, if you drink much from a bottle marked “poison,” it is almost certain to disagree with you, sooner or later.

However, this bottle was not marked “poison,” so Alice ventured to taste it, and, finding it very nice (it had, in fact, a sort of mixed flavour of cherry-tart, custard, pine-apple, roast turkey, toffy, and hot buttered toast), she very soon finished it off.

* * * * *

* * * * *

* * * * *

“What a curious feeling!” said Alice. “I must be shutting up like a telescope!”

And so it was indeed: she was now only ten inches high, and her face brightened up at the thought that she was now the right size for going through the little door into that lovely garden. First, however, she waited for a few minutes to see if she was going to shrink any further: she felt a little nervous about this; “for it might end, you know,” said Alice to herself; “in my going out altogether, like a candle. I wonder what I should be like then?” And she tried to fancy what the flame of a candle looks like after the candle is blown out, for she could not remember ever having seen such a thing.

After a while, finding that nothing more happened, she decided on going into the garden at once; but, alas for poor Alice! when she got to the door, she found she had forgotten the little golden key, and when she went back to the table for it, she found she could not possibly reach it: she could see it quite plainly through the glass, and she tried her best to climb up one of the legs of the table, but it was too slippery; and when she had tired herself out with trying, the poor little thing sat down and cried.

“Come, there’s no use in crying like that!” said Alice to herself rather sharply. “I advise you to leave off this minute!” She generally gave herself very good advice (though she very seldom followed it), and sometimes she scolded herself so severely as to bring tears into her eyes; and once she remembered trying to box her own ears for having cheated herself in a game of croquet she was playing against herself, for this curious child was very fond of pretending to be two people. “But it’s no use now,” thought poor Alice, “to pretend to be two people! Why, there’s hardly enough of me left to make one respectable person!”

Soon her eye fell on a little glass box that was lying under the table: she opened it, and found in it a very small cake, on which the words “EAT ME” were beautifully marked in currants. “Well, I’ll eat it,” said Alice, “and if it makes me grow larger, I can reach the key; and if it makes me grow smaller, I can creep under the door: so either way I’ll get into the garden, and I don’t care which happens!”

She ate a little bit, and said anxiously to herself “Which way? Which way?”, holding her hand on the top of her head to feel which way it was growing; and she was quite surprised to find that she remained the same size. To be sure, this is what generally happens when one eats cake; but Alice had got so much into the way of expecting nothing but out-of-the-way things to happen, that it seemed quite dull and stupid for life to go on in the common way.

So she set to work, and very soon finished off the cake.

* * * * *

* * * * *

* * * * *

Chapter II

The Pool of Tears

“CURIOUSER and curiouser!” cried Alice (she was so much surprised, that for the moment she quite forgot how to speak good English); “now I’m opening out like the largest telescope that ever was! Good-bye, feet!” (for when she looked down at her feet, they seemed to be almost out of sight, they were getting so far off). “Oh, my poor little feet, I wonder who will put on your shoes and stockings for you now, dears? I’m sure I sha’n’t be able! I shall be a great deal too far off to trouble myself about you: you must manage the best way you can—but I must be kind to them,” thought Alice, “or perhaps they wo’n’t walk the way I want to go! Let me see: I’ll give them a new pair of boots every Christmas.”

And she went on planning to herself how she would manage it. “They must go by the carrier,” she thought; “and how funny it’ll seem, sending presents to one’s own feet! And how odd the directions will look!

Alice’s Right Foot, Esq.

Hearth-rug,

near the Fender,

(with Alice’s love).

Oh dear, what nonsense I’m talking!”

Just then her head struck against the roof of the hall: in fact she was now more than nine feet high, and she at once took up the little golden key and hurried off to the garden door.

Poor Alice! It was as much as she could do, lying down on one side, to look through into the garden with one eye; but to get through was more hopeless than ever: she sat down and began to cry again. “You ought to be ashamed of yourself,” said Alice, “a great girl like you,” (she might well say this), “to go on crying in this way! Stop this moment, I tell you!” But she went on all the same, shedding gallons of tears, until there was a large pool all round her, about four inches deep and reaching half down the hall.

After a time she heard a little pattering of feet in the distance, and she hastily dried her eyes to see what was coming. It was the White Rabbit returning, splendidly dressed, with a pair of white kid-gloves in one hand and a large fan in the other: he came trotting along in a great hurry, muttering to himself as he came, “Oh! The Duchess, the Duchess! Oh! Wo’n’t she be savage if I’ve kept her waiting!” Alice felt so desperate that she was ready to ask help of any one: so, when the Rabbit came near her, she began, in a low, timid voice, “If you please, Sir—” The Rabbit started violently, dropped the white kid-gloves and the fan, and scurried away into the darkness as hard as he could go.

Alice took up the fan and gloves, and, as the hall was very hot, she kept fanning herself all the time she went on talking: “Dear, dear! How queer everything is to-day! And yesterday things went on just as usual. I wonder if I’ve been changed in the night? Let me think: was I the same when I got up this morning? I almost think I can remember feeling a little different. But if I’m not the same, the next question is, ‘Who in the world am I?’ Ah, that’s the great puzzle!” And she began thinking over all the children she knew that were of the same age as herself, to see if she could have been changed for any of them.

“I’m sure I’m not Ada,” she said, “for her hair goes in such long ringlets, and mine doesn’t go in ringlets at all; and I’m sure I ca’n’t be Mabel, for I know all sorts of things, and she, oh, she knows such a very little! Besides, she’s she, and I’m I, and—oh dear, how puzzling it all is! I’ll try if I know all the things I used to know. Let me see: four times five is twelve, and four times six is thirteen, and four times seven is—oh dear! I shall never get to twenty at that rate! However, the Multiplication Table doesn’t signify: let’s try Geography. London is the capital of Paris, and Paris is the capital of Rome, and Rome—no, that’s all wrong, I’m certain! I must have been changed for Mabel! I’ll try and say ‘How doth the little—’,” and she crossed her hands on her lap, as if she were saying lessons, and began to repeat it, but her voice sounded hoarse and strange, and the words did not come the same as they used to do:—

“How doth the little crocodile

Improve his shining tail,

And pour the waters of the Nile

On every golden scale!

“How cheerfully he seems to grin,

How neatly spread his claws,

And welcome little fishes in,

With gently smiling jaws!”

“I’m sure those are not the right words,” said poor Alice, and her eyes filled with tears again as she went on, “I must be Mabel after all, and I shall have to go and live in that poky little house, and have next to no toys to play with, and oh, ever so many lessons to learn! No, I’ve made up my mind about it: if I’m Mabel, I’ll stay down here! It’ll be no use their putting their heads down and saying ‘Come up again, dear!’ I shall only look up and say ‘Who am I then? Tell me that first, and then, if I like being that person, I’ll come up: if not, I’ll stay down here till I’m somebody else’—but, oh dear!” cried Alice, with a sudden burst of tears, “I do wish they would put their heads down! I am so very tired of being all alone here!”

As she said this she looked down at her hands, and was surprised to see that she had put on one of the Rabbit’s little white kid-gloves while she was talking. “How can I have done that?” she thought. “I must be growing small again.” She got up and went to the table to measure herself by it, and found that, as nearly as she could guess, she was now about two feet high, and was going on shrinking rapidly: she soon found out that the cause of this was the fan she was holding, and she dropped it hastily, just in time to avoid shrinking away altogether.

“That was a narrow escape!” said Alice, a good deal frightened at the sudden change, but very glad to find herself still in existence. “And now for the garden!” And she ran with all speed back to the little door; but, alas! the little door was shut again, and the little golden key was lying on the glass table as before, “and things are worse than ever,” thought the poor child, “for I never was so small as this before, never! And I declare it’s too bad, that it is!”

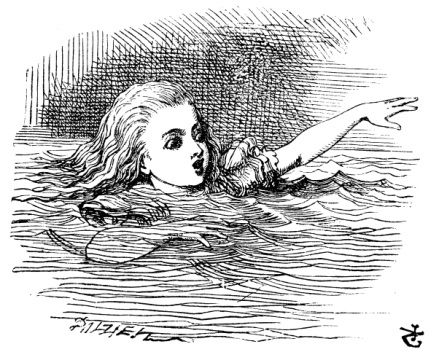

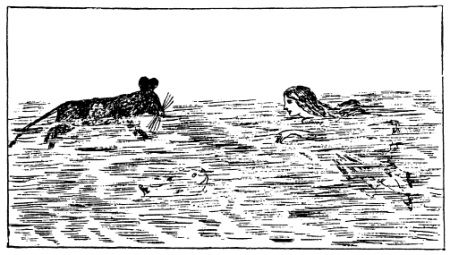

As she said these words her foot slipped, and in another moment, splash! she was up to her chin in salt water. Her first idea was that she had somehow fallen into the sea, “and in that case I can go back by railway,” she said to herself. (Alice had been to the seaside once in her life, and had come to the general conclusion that, wherever you go to on the English coast, you find a number of bathing-machines in the sea, some children digging in the sand with wooden spades, then a row of lodging-houses, and behind them a railway station.) However, she soon made out that she was in the pool of tears which she had wept when she was nine feet high.

“I wish I hadn’t cried so much!” said Alice, as she swam about, trying to find her way out. “I shall be punished for it now, I suppose, by being drowned in my own tears! That will be a queer thing, to be sure! However, everything is queer to-day.”

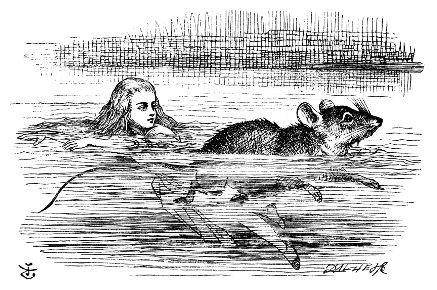

Just then she heard something splashing about in the pool a little way off, and she swam nearer to make out what it was: at first she thought it must be a walrus or hippopotamus, but then she remembered how small she was now, and she soon made out that it was only a mouse that had slipped in like herself.

“Would it be of any use, now,” thought Alice, “to speak to this mouse? Everything is so out-of-the-way down here, that I should think very likely it can talk: at any rate, there’s no harm in trying.” So she began: “O Mouse, do you know the way out of this pool? I am very tired of swimming about here, O Mouse!” (Alice thought this must be the right way of speaking to a mouse: she had never done such a thing before, but she remembered having seen in her brother’s Latin Grammar, “A mouse—of a mouse—to a mouse—a mouse—O mouse!”) The Mouse looked at her rather inquisitively, and seemed to her to wink with one of its little eyes, but it said nothing.

“Perhaps it doesn’t understand English,” thought Alice; “I daresay it’s a French mouse, come over with William the Conqueror.” (For, with all her knowledge of history, Alice had no very clear notion how long ago anything had happened.) So she began again: “Où est ma chatte?” which was the first sentence in her French lesson-book. The Mouse gave a sudden leap out of the water, and seemed to quiver all over with fright. “Oh, I beg your pardon!” cried Alice hastily, afraid that she had hurt the poor animal’s feelings. “I quite forgot you didn’t like cats.”

“Not like cats!” cried the Mouse in a shrill, passionate voice. “Would you like cats, if you were me?”

“Well, perhaps not,” said Alice in a soothing tone: “don’t be angry about it. And yet I wish I could show you our cat Dinah. I think you’d take a fancy to cats, if you could only see her. She is such a dear quiet thing,” Alice went on, half to herself, as she swam lazily about in the pool, “and she sits purring so nicely by the fire, licking her paws and washing her face—and she is such a nice soft thing to nurse—and she’s such a capital one for catching mice—oh, I beg your pardon!” cried Alice again, for this time the Mouse was bristling all over, and she felt certain it must be really offended. “We wo’n’t talk about her any more, if you’d rather not.”

“We indeed!” cried the Mouse, who was trembling down to the end of his tail. “As if I would talk on such a subject! Our family always hated cats: nasty, low, vulgar things! Don’t let me hear the name again!”

“I wo’n’t indeed!” said Alice, in a great hurry to change the subject of conversation. “Are you—are you fond—of—of dogs?” The Mouse did not answer, so Alice went on eagerly: “There is such a nice little dog, near our house, I should like to show you! A little bright-eyed terrier, you know, with oh, such long curly brown hair! And it’ll fetch things when you throw them, and it’ll sit up and beg for its dinner, and all sorts of things—I ca’n’t remember half of them—and it belongs to a farmer, you know, and he says it’s so useful, it’s worth a hundred pounds! He says it kills all the rats and—oh dear!” cried Alice in a sorrowful tone. “I’m afraid I’ve offended it again!” For the Mouse was swimming away from her as hard as it could go, and making quite a commotion in the pool as it went.

So she called softly after it, “Mouse dear! Do come back again, and we wo’n’t talk about cats, or dogs either, if you don’t like them!” When the Mouse heard this, it turned round and swam slowly back to her: its face was quite pale (with passion, Alice thought), and it said, in a low trembling voice, “Let us get to the shore, and then I’ll tell you my history, and you’ll understand why it is I hate cats and dogs.”

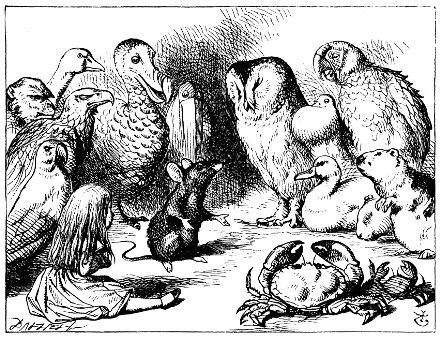

It was high time to go, for the pool was getting quite crowded with the birds and animals that had fallen into it: there were a Duck and a Dodo, a Lory and an Eaglet, and several other curious creatures. Alice led the way, and the whole party swam to the shore.

Chapter III

A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale

THEY WERE indeed a queer-looking party that assembled on the bank—the birds with draggled feathers, the animals with their fur clinging close to them, and all dripping wet, cross, and uncomfortable.

The first question of course was, how to get dry again: they had a consultation about this, and after a few minutes it seemed quite natural to Alice to find herself talking familiarly with them, as if she had known them all her life. Indeed, she had quite a long argument with the Lory, who at last turned sulky, and would only say “I am older than you, and must know better.” And this Alice would not allow, without knowing how old it was, and, as the Lory positively refused to tell its age, there was no more to be said.

At last the Mouse, who seemed to be a person of some authority among them, called out “Sit down, all of you, and listen to me! I’ll soon make you dry enough!” They all sat down at once, in a large ring, with the Mouse in the middle. Alice kept her eyes anxiously fixed on it, for she felt sure she would catch a bad cold if she did not get dry very soon.

“Ahem!” said the Mouse with an important air. “Are you all ready? This is the driest thing I know. Silence all round, if you please! ‘William the Conqueror, whose cause was favoured by the pope, was soon submitted to by the English, who wanted leaders, and had been of late much accustomed to usurpation and conquest. Edwin and Morcar, the earls of Mercia and Northumbria—’”

“Ugh!” said the Lory, with a shiver.

“I beg your pardon!” said the Mouse, frowning, but very politely. “Did you speak?”

“Not I!” said the Lory, hastily.

“I thought you did,” said the Mouse. “I proceed. ‘Edwin and Morcar, the earls of Mercia and Northumbria, declared for him; and even Stigand, the patriotic archbishop of Canterbury, found it advisable—’”

“Found what?” said the Duck.

“Found it,” the Mouse replied rather crossly: “of course you know what ‘it’ means.”

“I know what ‘it’ means well enough, when I find a thing,” said the Duck: “it’s generally a frog, or a worm. The question is, what did the archbishop find?”

The Mouse did not notice this question, but hurriedly went on, “‘—found it advisable to go with Edgar Atheling to meet William and offer him the crown. William’s conduct at first was moderate. But the insolence of his Normans—’ How are you getting on now, my dear?” it continued, turning to Alice as it spoke.

“As wet as ever,” said Alice in a melancholy tone: “it doesn’t seem to dry me at all.”

“In that case,” said the Dodo solemnly, rising to its feet, “I move that the meeting adjourn, for the immediate adoption of more energetic remedies—”

“Speak English!” said the Eaglet. “I don’t know the meaning of half those long words, and, what’s more, I don’t believe you do either!” And the Eaglet bent down its head to hide a smile: some of the other birds tittered audibly.

“What I was going to say,” said the Dodo in an offended tone, “was, that the best thing to get us dry would be a Caucus-race.”

“What is a Caucus-race?” said Alice; not that she wanted much to know, but the Dodo had paused as if it thought that somebody ought to speak, and no one else seemed inclined to say anything.

“Why,” said the Dodo, “the best way to explain it is to do it.” (And, as you might like to try the thing yourself, some winter-day, I will tell you how the Dodo managed it.)

First it marked out a race-course, in a sort of circle, (“the exact shape doesn’t matter,” it said,) and then all the party were placed along the course, here and there. There was no “One, two, three, and away!” but they began running when they liked, and left off when they liked, so that it was not easy to know when the race was over. However, when they had been running half an hour or so, and were quite dry again, the Dodo suddenly called out “The race is over!” and they all crowded round it, panting, and asking “But who has won?”

This question the Dodo could not answer without a great deal of thought, and it sat for a long time with one finger pressed upon its forehead (the position in which you usually see Shakespeare, in the pictures of him), while the rest waited in silence. At last the Dodo said “Everybody has won, and all must have prizes.”

“But who is to give the prizes?” quite a chorus of voices asked.

“Why, she, of course,” said the Dodo, pointing to Alice with one finger; and the whole party at once crowded round her, calling out in a confused way, “Prizes! Prizes!”

Alice had no idea what to do, and in despair she put her hand in her pocket, and pulled out a box of comfits (luckily the salt water had not got into it), and handed them round as prizes. There was exactly one a-piece, all round.

“But she must have a prize herself, you know,” said the Mouse.

“Of course,” the Dodo replied very gravely. “What else have you got in your pocket?” it went on, turning to Alice.

“Only a thimble,” said Alice sadly.

“Hand it over here,” said the Dodo.

Then they all crowded round her once more, while the Dodo solemnly presented the thimble, saying “We beg your acceptance of this elegant thimble”; and, when it had finished this short speech, they all cheered.

Alice thought the whole thing very absurd, but they all looked so grave that she did not dare to laugh; and, as she could not think of anything to say, she simply bowed, and took the thimble, looking as solemn as she could.

The next thing was to eat the comfits: this caused some noise and confusion, as the large birds complained that they could not taste theirs, and the small ones choked and had to be patted on the back. However, it was over at last, and they sat down again in a ring, and begged the Mouse to tell them something more.

“You promised to tell me your history, you know,” said Alice, “and why it is you hate—C and D,” she added in a whisper, half afraid that it would be offended again.

“Mine is a long and a sad tale!” said the Mouse, turning to Alice, and sighing.

“It is a long tail, certainly,” said Alice, looking down with wonder at the Mouse’s tail; “but why do you call it sad?” And she kept on puzzling about it while the Mouse was speaking, so that her idea of the tale was something like this:—

“Fury said to a mouse,

That he met in the house,

‘Let us both go to law:

I will prosecute you.

—Come, I’ll take no denial:

We must have the trial;

For really this morning

I’ve nothing to do.’”

Said the mouse to the cur,

‘Such a trial, dear sir,

With no jury or judge,

Would be wasting our breath.’

‘I’ll be judge, I’ll be jury,’

Said cunning old Fury:

‘I’ll try the whole cause,

And condemn you to death.’”

“You are not attending!” said the Mouse to Alice severely. “What are you thinking of?”

“I beg your pardon,” said Alice very humbly: “you had got to the fifth bend, I think?”

“I had not!” cried the Mouse, sharply and very angrily.

“A knot!” said Alice, always ready to make herself useful, and looking anxiously about her. “Oh, do let me help to undo it!”

“I shall do nothing of the sort,” said the Mouse, getting up and walking away. “You insult me by talking such nonsense!”

“I didn’t mean it!” pleaded poor Alice. “But you’re so easily offended, you know!”

The Mouse only growled in reply.

“Please come back and finish your story!” Alice called after it. And the others all joined in chorus “Yes, please do!” But the Mouse only shook its head impatiently, and walked a little quicker.

“What a pity it wouldn’t stay!” sighed the Lory, as soon as it was quite out of sight. And an old Crab took the opportunity of saying to her daughter “Ah, my dear! Let this be a lesson to you never to lose your temper!” “Hold your tongue, Ma!” said the young Crab, a little snappishly. “You’re enough to try the patience of an oyster!”

“I wish I had our Dinah here, I know I do!” said Alice aloud, addressing nobody in particular. “She’d soon fetch it back!”

“And who is Dinah, if I might venture to ask the question?” said the Lory.

Alice replied eagerly, for she was always ready to talk about her pet: “Dinah’s our cat. And she’s such a capital one for catching mice, you ca’n’t think! And oh, I wish you could see her after the birds! Why, she’ll eat a little bird as soon as look at it!”

This speech caused a remarkable sensation among the party. Some of the birds hurried off at once: one the old Magpie began wrapping itself up very carefully, remarking, “I really must be getting home; the night-air doesn’t suit my throat!” and a Canary called out in a trembling voice, to its children, “Come away, my dears! It’s high time you were all in bed!” On various pretexts they all moved off, and Alice was soon left alone.

“I wish I hadn’t mentioned Dinah!” she said to herself in a melancholy tone. “Nobody seems to like her, down here, and I’m sure she’s the best cat in the world! Oh, my dear Dinah! I wonder if I shall ever see you any more!” And here poor Alice began to cry again, for she felt very lonely and low-spirited. In a little while, however, she again heard a little pattering of footsteps in the distance, and she looked up eagerly, half hoping that the Mouse had changed his mind, and was coming back to finish his story.

Chapter IV

The Rabbit Sends in a Little Bill

IT WAS THE White Rabbit, trotting slowly back again, and looking anxiously about as it went, as if it had lost something; and she heard it muttering to itself. “The Duchess! The Duchess! Oh my dear paws! Oh my fur and whiskers! She’ll get me executed, as sure as ferrets are ferrets! Where can I have dropped them, I wonder?” Alice guessed in a moment that it was looking for the fan and the pair of white kid-gloves, and she very good-naturedly began hunting about for them, but they were nowhere to be seen—everything seemed to have changed since her swim in the pool; and the great hall, with the glass table and the little door, had vanished completely.

Very soon the Rabbit noticed Alice, as she went hunting about, and called out to her, in an angry tone, “Why, Mary Ann, what are you doing out here? Run home this moment, and fetch me a pair of gloves and a fan! Quick, now!” And Alice was so much frightened that she ran off at once in the direction it pointed to, without trying to explain the mistake it had made.

“He took me for his housemaid,” she said to herself as she ran. “How surprised he’ll be when he finds out who I am! But I’d better take him his fan and gloves—that is, if I can find them.” As she said this, she came upon a neat little house, on the door of which was a bright brass plate with the name “W. RABBIT” engraved upon it. She went in without knocking, and hurried upstairs, in great fear lest she should meet the real Mary Ann, and be turned out of the house before she had found the fan and gloves.

“How queer it seems,” Alice said to herself, “to be going messages for a rabbit! I suppose Dinah’ll be sending me on messages next!” And she began fancying the sort of thing that would happen: “‘Miss Alice! Come here directly, and get ready for your walk!’ ‘Coming in a minute, nurse! But I’ve got to watch this mouse-hole till Dinah comes back, and see that the mouse doesn’t get out.’ Only I don’t think,” Alice went on, “that they’d let Dinah stop in the house if it began ordering people about like that!”

By this time she had found her way into a tidy little room with a table in the window, and on it (as she had hoped) a fan and two or three pairs of tiny white kid-gloves: she took up the fan and a pair of the gloves, and was just going to leave the room, when her eye fell upon a little bottle that stood near the looking-glass. There was no label this time with the words “DRINK ME,” but nevertheless she uncorked it and put it to her lips. “I know something interesting is sure to happen,” she said to herself, “whenever I eat or drink anything: so I’ll just see what this bottle does. I do hope it’ll make me grow large again, for really I’m quite tired of being such a tiny little thing!”

It did so indeed, and much sooner than she had expected: before she had drunk half the bottle, she found her head pressing against the ceiling, and had to stoop to save her neck from being broken. She hastily put down the bottle, saying to herself “That’s quite enough—I hope I sha’n’t grow any more—As it is, I ca’n’t get out at the door—I do wish I hadn’t drunk quite so much!”

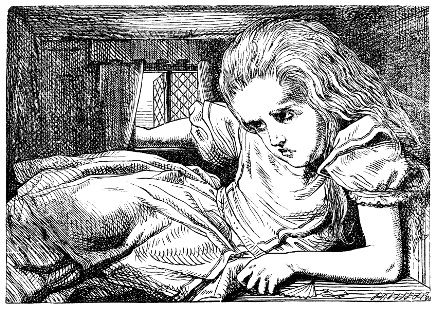

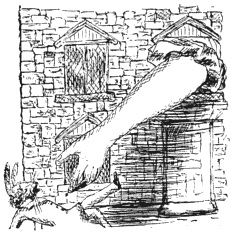

Alas! It was too late to wish that! She went on growing, and growing, and very soon had to kneel down on the floor: in another minute there was not even room for this, and she tried the effect of lying down with one elbow against the door, and the other arm curled round her head. Still she went on growing, and, as a last resource, she put one arm out of the window, and one foot up the chimney, and said to herself “Now I can do no more, whatever happens. What will become of me?”

Luckily for Alice, the little magic bottle had now had its full effect, and she grew no larger: still it was very uncomfortable, and, as there seemed to be no sort of chance of her ever getting out of the room again, no wonder she felt unhappy.

“It was much pleasanter at home,” thought poor Alice, “when one wasn’t always growing larger and smaller, and being ordered about by mice and rabbits. I almost wish I hadn’t gone down that rabbit-hole—and yet—and yet—it’s rather curious, you know, this sort of life! I do wonder what can have happened to me! When I used to read fairy-tales, I fancied that kind of thing never happened, and now here I am in the middle of one! There ought to be a book written about me, that there ought! And when I grow up, I’ll write one—but I’m grown up now,” she added in a sorrowful tone: “at least there’s no room to grow up any more here.”

“But then,” thought Alice, “shall I never get any older than I am now? That’ll be a comfort, one way—never to be an old woman—but then—always to have lessons to learn! Oh, I shouldn’t like that!”

“Oh, you foolish Alice!” she answered herself. “How can you learn lessons in here? Why, there’s hardly room for you, and no room at all for any lesson-books!”

And so she went on, taking first one side and then the other, and making quite a conversation of it altogether; but after a few minutes she heard a voice outside, and stopped to listen.

“Mary Ann! Mary Ann!” said the voice. “Fetch me my gloves this moment!” Then came a little pattering of feet on the stairs. Alice knew it was the Rabbit coming to look for her, and she trembled till she shook the house, quite forgetting that she was now about a thousand times as large as the Rabbit, and had no reason to be afraid of it.

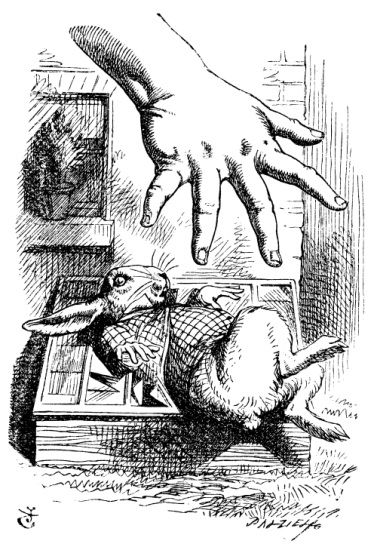

Presently the Rabbit came up to the door, and tried to open it; but, as the door opened inwards, and Alice’s elbow was pressed hard against it, that attempt proved a failure. Alice heard it say to itself “Then I’ll go round and get in at the window.”

“That you wo’n’t!” thought Alice, and, after waiting till she fancied she heard the Rabbit just under the window, she suddenly spread out her hand, and made a snatch in the air. She did not get hold of anything, but she heard a little shriek and a fall, and a crash of broken glass, from which she concluded that it was just possible it had fallen into a cucumber-frame, or something of the sort.

Next came an angry voice—the Rabbit’s—“Pat! Pat! Where are you?” And then a voice she had never heard before, “Sure then I’m here! Digging for apples, yer honour!”

“Digging for apples, indeed!” said the Rabbit angrily. “Here! Come and help me out of this!” (Sounds of more broken glass.)

“Now tell me, Pat, what’s that in the window?”

“Sure, it’s an arm, yer honour!” (He pronounced it “arrum.”)

“An arm, you goose! Who ever saw one that size? Why, it fills the whole window!”

“Sure, it does, yer honour: but it’s an arm for all that.”

“Well, it’s got no business there, at any rate: go and take it away!”

There was a long silence after this, and Alice could only hear whispers now and then; such as, “Sure, I don’t like it, yer honour, at all, at all!” “Do as I tell you, you coward!” and at last she spread out her hand again, and made another snatch in the air. This time there were two little shrieks, and more sounds of broken glass. “What a number of cucumber-frames there must be!” thought Alice. “I wonder what they’ll do next! As for pulling me out of the window, I only wish they could! I’m sure I don’t want to stay in here any longer!”

She waited for some time without hearing anything more: at last came a rumbling of little cart-wheels, and the sound of a good many voices all talking together: she made out the words: “Where’s the other ladder?—Why, I hadn’t to bring but one. Bill’s got the other—Bill! Fetch it here, lad!—Here, put ’em up at this corner—No, tie ’em together first—they don’t reach half high enough yet—Oh! they’ll do well enough. Don’t be particular—Here, Bill! catch hold of this rope—Will the roof bear?—Mind that loose slate—Oh, it’s coming down! Heads below!” (a loud crash)—“Now, who did that?—It was Bill, I fancy—Who’s to go down the chimney?—Nay, I sha’n’t! You do it!—That I wo’n’t, then!—Bill’s got to go down—Here, Bill! The master says you’re to go down the chimney!”

“Oh! So Bill’s got to come down the chimney, has he?” said Alice to herself. “Why, they seem to put everything upon Bill! I wouldn’t be in Bill’s place for a good deal: this fireplace is narrow, to be sure; but I think I can kick a little!”

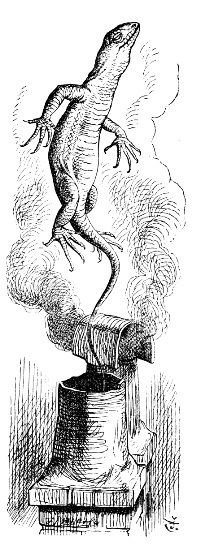

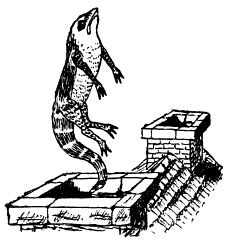

She drew her foot as far down the chimney as she could, and waited till she heard a little animal (she couldn’t guess of what sort it was) scratching and scrambling about in the chimney close above her: then, saying to herself “This is Bill,” she gave one sharp kick, and waited to see what would happen next.

The first thing she heard was a general chorus of “There goes Bill!” then the Rabbit’s voice alone—“Catch him, you by the hedge!” then silence, and then another confusion of voices—“Hold up his head—Brandy now—Don’t choke him—How was it, old fellow? What happened to you? Tell us all about it!”

Last came a little feeble, squeaking voice, (“That’s Bill,” thought Alice), “Well, I hardly know—No more, thank ye; I’m better now—but I’m a deal too flustered to tell you—all I know is, something comes at me like a Jack-in-the-box, and up I goes like a sky-rocket!”

“So you did, old fellow!” said the others.

“We must burn the house down!” said the Rabbit’s voice. And Alice called out, as loud as she could, “If you do, I’ll set Dinah at you!”

There was a dead silence instantly, and Alice thought to herself “I wonder what they will do next! If they had any sense, they’d take the roof off.” After a minute or two, they began moving about again, and Alice heard the Rabbit say “A barrowful will do, to begin with.”

“A barrowful of what?” thought Alice. But she had not long to doubt, for the next moment a shower of little pebbles came rattling in at the window, and some of them hit her in the face. “I’ll put a stop to this,” she said to herself, and shouted out “You’d better not do that again!”, which produced another dead silence.

Alice noticed, with some surprise, that the pebbles were all turning into little cakes as they lay on the floor, and a bright idea came into her head. “If I eat one of these cakes,” she thought, “it’s sure to make some change in my size; and, as it ca’n’t possibly make me larger, it must make me smaller, I suppose.”

So she swallowed one of the cakes, and was delighted to find that she began shrinking directly. As soon as she was small enough to get through the door, she ran out of the house, and found quite a crowd of little animals and birds waiting outside. The poor little Lizard, Bill, was in the middle, being held up by two guinea-pigs, who were giving it something out of a bottle. They all made a rush at Alice the moment she appeared; but she ran off as hard as she could, and soon found herself safe in a thick wood.

“The first thing I’ve got to do,” said Alice to herself, as she wandered about in the wood, “is to grow to my right size again; and the second thing is to find my way into that lovely garden. I think that will be the best plan.”

It sounded an excellent plan, no doubt, and very neatly and simply arranged: the only difficulty was, that she had not the smallest idea how to set about it; and, while she was peering about anxiously among the trees, a little sharp bark just over her head made her look up in a great hurry.

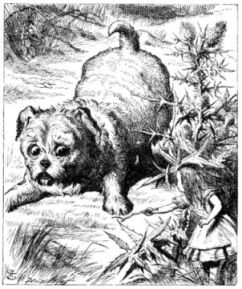

An enormous puppy was looking down at her with large round eyes, and feebly stretching out one paw, trying to touch her. “Poor little thing!” said Alice, in a coaxing tone, and she tried hard to whistle to it; but she was terribly frightened all the time at the thought that it might be hungry, in which case it would be very likely to eat her up in spite of all her coaxing.

Hardly knowing what she did, she picked up a little bit of stick, and held it out to the puppy: whereupon the puppy jumped into the air off all its feet at once, with a yelp of delight, and rushed at the stick, and made believe to worry it: then Alice dodged behind a great thistle, to keep herself from being run over; and the moment she appeared on the other side, the puppy made another rush at the stick, and tumbled head over heels in its hurry to get hold of it: then Alice, thinking it was very like having a game of play with a cart-horse, and expecting every moment to be trampled under its feet, ran round the thistle again: then the puppy began a series of short charges at the stick, running a very little way forwards each time and a long way back, and barking hoarsely all the while, till at last it sat down a good way off, panting, with its tongue hanging out of its mouth, and its great eyes half shut.

This seemed to Alice a good opportunity for making her escape: so she set off at once, and ran till she was quite tired and out of breath, and till the puppy’s bark sounded quite faint in the distance.

“And yet what a dear little puppy it was!” said Alice, as she leant against a buttercup to rest herself, and fanned herself with one of the leaves. “I should have liked teaching it tricks very much, if—if I’d only been the right size to do it! Oh dear! I’d nearly forgotten that I’ve got to grow up again! Let me see—how is it to be managed? I suppose I ought to eat or drink something or other; but the great question is ‘What?’”

The great question certainly was “What?” Alice looked all round her at the flowers and the blades of grass, but she could not see anything that looked like the right thing to eat or drink under the circumstances. There was a large mushroom growing near her, about the same height as herself; and, when she had looked under it, and on both sides of it, and behind it, it occurred to her that she might as well look and see what was on the top of it.

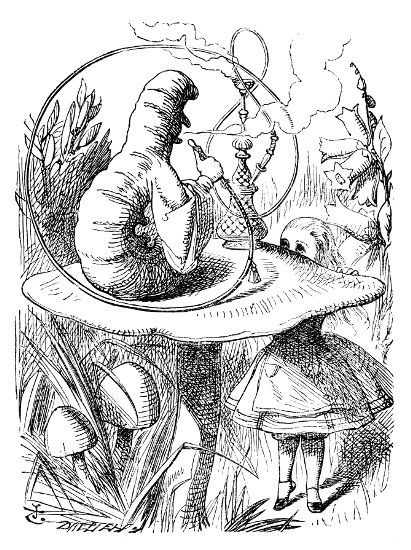

She stretched herself up on tiptoe, and peeped over the edge of the mushroom, and her eyes immediately met those of a large caterpillar, that was sitting on the top with its arms folded, quietly smoking a long hookah, and taking not the smallest notice of her or of anything else.

Chapter V

Advice from a Caterpillar

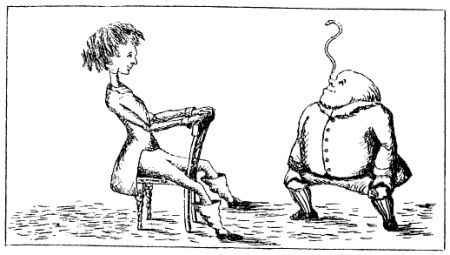

THE CATERPILLAR and Alice looked at each other for some time in silence: at last the Caterpillar took the hookah out of its mouth, and addressed her in a languid, sleepy voice.

“Who are you?” said the Caterpillar.

This was not an encouraging opening for a conversation. Alice replied, rather shyly, “I—I hardly know, Sir, just at present— at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then.”

“What do you mean by that?” said the Caterpillar, sternly. “Explain yourself!”

“I ca’n’t explain myself, I’m afraid, Sir,” said Alice, “because I’m not myself, you see.”

“I don’t see,” said the Caterpillar.

“I’m afraid I ca’n’t put it more clearly,” Alice replied, very politely, “for I ca’n’t understand it myself to begin with; and being so many different sizes in a day is very confusing.”

“It isn’t,” said the Caterpillar.

“Well, perhaps you haven’t found it so yet,” said Alice; “but when you have to turn into a chrysalis—you will some day, you know—and then after that into a butterfly, I should think you’ll feel it a little queer, wo’n’t you?”

“Not a bit,” said the Caterpillar.

“Well, perhaps your feelings may be different,” said Alice: “all I know is, it would feel very queer to me.”

“You!” said the Caterpillar contemptuously. “Who are you?”

Which brought them back again to the beginning of the conversation. Alice felt a little irritated at the Caterpillar’s making such very short remarks, and she drew herself up and said, very gravely, “I think, you out to tell me who you are, first.”

“Why?” said the Caterpillar.

Here was another puzzling question; and, as Alice could not think of any good reason, and as the Caterpillar seemed to be in a very unpleasant state of mind, she turned away.

“Come back!” the Caterpillar called after her. “I’ve something important to say!”

This sounded promising, certainly. Alice turned and came back again.

“Keep your temper,” said the Caterpillar.

“Is that all?” said Alice, swallowing down her anger as well as she could.

“No,” said the Caterpillar.

Alice thought she might as well wait, as she had nothing else to do, and perhaps after all it might tell her something worth hearing. For some minutes it puffed away without speaking; but at last it unfolded its arms, took the hookah out of its mouth again, and said “So you think you’re changed, do you?”

“I’m afraid I am, Sir,” said Alice; “I ca’n’t remember things as I used—and I don’t keep the same size for ten minutes together!”

“Ca’n’t remember what things?” said the Caterpillar.

“Well, I’ve tried to say ‘How doth the little busy bee,’ but it all came different!” Alice replied in a very melancholy voice.

“Repeat, ‘You are old, Father William,’” said the Caterpillar.

Alice folded her hands, and began:—

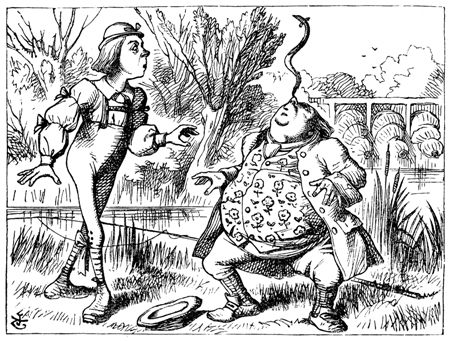

“‘You are old, Father William,’ the young man said,

‘And your hair has become very white;

And yet you incessantly stand on your head—

Do you think, at your age, it is right?’

‘In my youth,’ Father William replied to his son,

‘I feared it might injure the brain;

But, now that I’m perfectly sure I have none,

Why, I do it again and again.’

‘You are old,’ said the youth, ‘as I mentioned before,

And have grown most uncommonly fat;

Yet you turned a back-somersault in at the door—

Pray, what is the reason of that?’

‘In my youth,’ said the sage, as he shook his grey locks,

‘I kept all my limbs very supple

By the use of this ointment—one shilling the box—

Allow me to sell you a couple?’

‘You are old,’ said the youth, ‘and your jaws are too weak

For anything tougher than suet;

Yet you finished the goose, with the bones and the beak—

Pray, how did you manage to do it?’

‘In my youth,’ said his father, ‘I took to the law,

And argued each case with my wife;

And the muscular strength, which it gave to my jaw

Has lasted the rest of my life.’

‘You are old,’ said the youth, ‘one would hardly suppose

That your eye was as steady as ever;

Yet you balanced an eel on the end of your nose—

What made you so awfully clever?’

‘I have answered three questions, and that is enough,’

Said his father: “Don’t give yourself airs!

Do you think I can listen all day to such stuff?

Be off, or I’ll kick you down stairs!’”

“That is not said right,” said the Caterpillar.

“Not quite right, I’m afraid,” said Alice, timidly: “some of the words have got altered.”

“It is wrong from beginning to end,” said the Caterpillar, decidedly; and there was silence for some minutes.

The Caterpillar was the first to speak.

“What size do you want to be?” it asked.

“Oh, I’m not particular as to size,” Alice hastily replied; “only one doesn’t like changing so often, you know.”

“I don’t know,” said the Caterpillar.

Alice said nothing: she had never been so much contradicted in all her life before, and she felt that she was losing her temper.

“Are you content now?” said the Caterpillar.

“Well, I should like to be a little larger, Sir, if you wouldn’t mind,” said Alice: “three inches is such a wretched height to be.”

“It is a very good height indeed!” said the Caterpillar angrily, rearing itself upright as it spoke (it was exactly three inches high).

“But I’m not used to it!” pleaded poor Alice in a piteous tone. And she thought of herself “I wish the creatures wouldn’t be so easily offended!”

“You’ll get used to it in time,” said the Caterpillar; and it put the hookah into its mouth, and began smoking again.

This time Alice waited patiently until it chose to speak again. In a minute or two the Caterpillar took the hookah out of its mouth and yawned once or twice, and shook itself. Then it got down off the mushroom, and crawled away into the grass, merely remarking, as it went, “One side will make you grow taller, and the other side will make you grow shorter.”

“One side of what? The other side of what?” thought Alice to herself.

“Of the mushroom,” said the Caterpillar, just as if she had asked it aloud; and in another moment it was out of sight.

Alice remained looking thoughtfully at the mushroom for a minute, trying to make out which were the two sides of it; and, as it was perfectly round, she found this a very difficult question. However, at last she stretched her arms round it as far as they would go, and broke off a bit of the edge with each hand.

“And now which is which?” she said to herself, and nibbled a little of the right-hand bit to try the effect: the next moment she felt a violent blow underneath her chin: it had struck her foot!

She was a good deal frightened by this very sudden change, but she felt that there was no time to be lost, as she was shrinking rapidly: so she set to work at once to eat some of the other bit. Her chin was pressed so closely against her foot, that there was hardly room to open her mouth; but she did it at last, and managed to swallow a morsel of the left-hand bit.

* * * * *

* * * * *

* * * * *

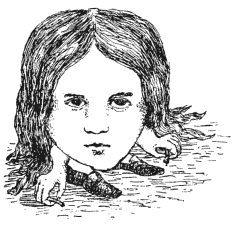

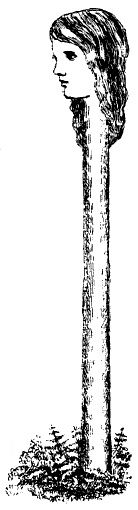

“Come, my head’s free at last!” said Alice in a tone of delight, which changed into alarm in another moment, when she found that her shoulders were nowhere to be found: all she could see, when she looked down, was an immense length of neck, which seemed to rise like a stalk out of a sea of green leaves that lay far below her.

“What can all that green stuff be?” said Alice. “And where have my shoulders got to? And oh, my poor hands, how is it I ca’n’t see you?” She was moving them about, as she spoke, but no result seemed to follow, except a little shaking among the distant green leaves.

As there seemed to be no chance of getting her hands up to her head, she tried to get her head down to them, and was delighted to find that her neck would bend about easily in any direction, like a serpent. She had just succeeded in curving it down into a graceful zigzag, and was going to dive in among the leaves, which she found to be nothing but the tops of the trees under which she had been wandering, when a sharp hiss made her draw back in a hurry: a large pigeon had flown into her face, and was beating her violently with its wings.

“Serpent!” screamed the Pigeon.

“I’m not a serpent!” said Alice indignantly. “Let me alone!”

“Serpent, I say again!” repeated the Pigeon, but in a more subdued tone, and added, with a kind of sob, “I’ve tried every way, and nothing seems to suit them!”

“I haven’t the least idea what you’re talking about,” said Alice.

“I’ve tried the roots of trees, and I’ve tried banks, and I’ve tried hedges,” the Pigeon went on, without attending to her; “but those serpents! There’s no pleasing them!”

Alice was more and more puzzled, but she thought there was no use in saying anything more till the Pigeon had finished.

“As if it wasn’t trouble enough hatching the eggs,” said the Pigeon; “but I must be on the look-out for serpents, night and day! Why, I haven’t had a wink of sleep these three weeks!”

“I’m very sorry you’ve been annoyed,” said Alice, who was beginning to see its meaning.

“And just as I’d taken the highest tree in the wood,” continued the Pigeon, raising its voice to a shriek, “and just as I was thinking I should be free of them at last, they must needs come wriggling down from the sky! Ugh, Serpent!”

“But I’m not a serpent, I tell you!” said Alice. “I’m a—I’m a—”

“Well! What are you?” said the Pigeon. “I can see you’re trying to invent something!”

“I—I’m a little girl,” said Alice, rather doubtfully, as she remembered the number of changes she had gone through, that day.

“A likely story indeed!” said the Pigeon, in a tone of the deepest contempt. “I’ve seen a good many little girls in my time, but never one with such a neck as that! No, no! You’re a serpent; and there’s no use denying it. I suppose you’ll be telling me next that you never tasted an egg!”

“I have tasted eggs, certainly,” said Alice, who was a very truthful child; “but little girls eat eggs quite as much as serpents do, you know.”

“I don’t believe it,” said the Pigeon; “but if they do, why, then they’re a kind of serpent: that’s all I can say.”

This was such a new idea to Alice, that she was quite silent for a minute or two, which gave the Pigeon the opportunity of adding “You’re looking for eggs, I know that well enough; and what does it matter to me whether you’re a little girl or a serpent?”

“It matters a good deal to me,” said Alice hastily; “but I’m not looking for eggs, as it happens; and, if I was, I shouldn’t want yours: I don’t like them raw.”

“Well, be off, then!” said the Pigeon in a sulky tone, as it settled down again into its nest. Alice crouched down among the trees as well as she could, for her neck kept getting entangled among the branches, and every now and then she had to stop and untwist it. After a while she remembered that she still held the pieces of mushroom in her hands, and she set to work very carefully, nibbling first at one and then at the other, and growing sometimes taller, and sometimes shorter, until she had succeeded in bringing herself down to her usual height.

It was so long since she had been anything near the right size, that it felt quite strange at first; but she got used to it in a few minutes, and began talking to herself, as usual, “Come, there’s half my plan done now! How puzzling all these changes are! I’m never sure what I’m going to be, from one minute to another! However, I’ve got back to my right size: the next thing is, to get into that beautiful garden—how is that to be done, I wonder?” As she said this, she came suddenly upon an open place, with a little house in it about four feet high. “Whoever lives there,” thought Alice, “it’ll never do to come upon them this size: why, I should frighten them out of their wits!” So she began nibbling at the right-hand bit again, and did not venture to go near the house till she had brought herself down to nine inches high.

Chapter VI

Pig and Pepper

FOR A MINUTE or two she stood looking at the house, and wondering what to do next, when suddenly a footman in livery came running out of the wood—(she considered him to be a footman because he was in livery: otherwise, judging by his face only, she would have called him a fish)—and rapped loudly at the door with his knuckles. It was opened by another footman in livery, with a round face, and large eyes like a frog; and both footmen, Alice noticed, had powdered hair that curled all over their heads. She felt very curious to know what it was all about, and crept a little way out of the wood to listen.

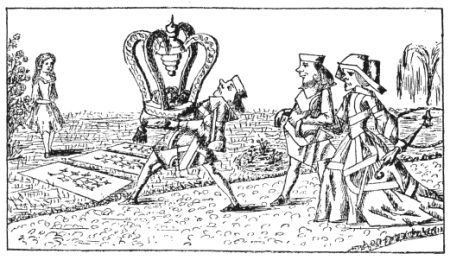

The Fish-Footman began by producing from under his arm a great letter, nearly as large as himself, and this he handed over to the other, saying, in a solemn tone, “For the Duchess. An invitation from the Queen to play croquet.” The Frog-Footman repeated, in the same solemn tone, only changing the order of the words a little, “From the Queen. An invitation for the Duchess to play croquet.”

Then they both bowed low, and their curls got entangled together.

Alice laughed so much at this, that she had to run back into the wood for fear of their hearing her; and, when she next peeped out, the Fish-Footman was gone, and the other was sitting on the ground near the door, staring stupidly up into the sky.

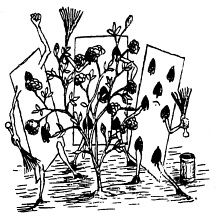

Alice went timidly up to the door, and knocked.