The Evolution of Fantasy Role-Playing Games – Read Now and Download Mobi

For my parents,

an active imagination.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Gary Alan Fine for his kind advice on role-playing games of yesterday and today, Nick Montfort for taking time out for my questions about interactive fiction, Alexander Hinkley of Alex’s DBZ RPG for his insights on browser-based games, and Jeff Martin for sharing his thoughts on the creation of True Dungeon.

To the families of the wizards who made fantasy gaming what it is today— J.R.R. Tolkien, Gary Gygax, and Dave Arneson—thank you for the gift that keeps on giving. To the bards who crafted the games I love—Monte Cook, Raph Koster, Erik Mona, and Rose Estes—thank you for your inspiring work. To the paladins who fight the good fight in defending our hobby, including Stephen Colbert, Vin Diesel, Mike Stackpole, Paul Cardwell, and M. Alan Thomas II ... never give up the fight!

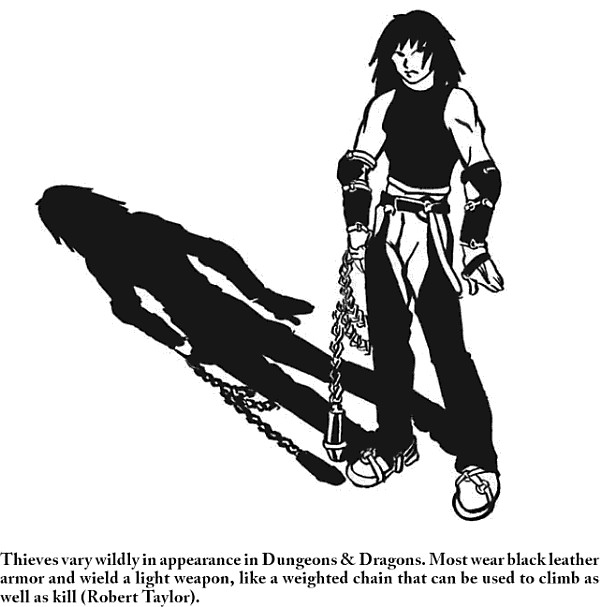

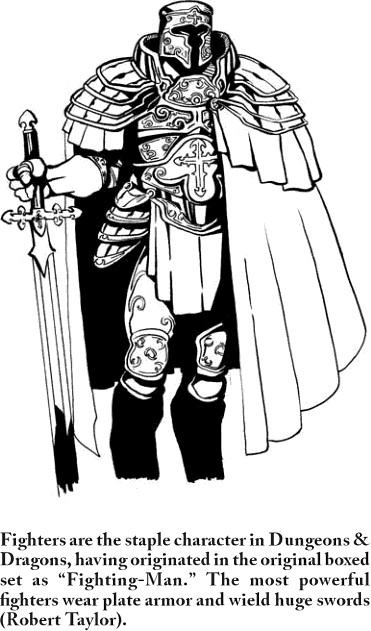

I also want to give a shout-out to my old gaming groups: Kevin Herriman from my very first basic Dungeons & Dragons campaign, Jason Varrone from my 1st edition Advanced Dungeons & Dragons campaign, Bill Jellig from my 2nd edition campaign, and George Webster from my 3rd edition game. I would also like to thank Jeremy Ortiz and Robert Taylor, who participated in my Dungeons & Dragons campaigns and contributed art to this book.

My insights about MUDs came from the many years of working with the outstanding staff of RetroMUD, especially fellow administrator Mazyar Fallah. I’m also thankful for all the players of RetroMUD who taught me volumes about the power of virtual groups, and Arianna Simes and Brandon Smith in particular for sharing their thoughts about gaming in general.

There are plenty of folks whom I didn’t interview for this book but were nevertheless influential in my gaming life. Doug Schonenberg introduced me to Ultima Online. Mike Ettlemyer dragged me kicking and screaming into first-person shooters and now he can’t get rid of me. I blame Chris Bibbs for sharing my thesis with Mike Krahulik and Jerry Holkins of Penny Arcade, which started me on the path of writing this book.

There are also organizations and places online where I lurk that deserve mention: geezergamers.com, enworld.org, RPG.net and Yog-Sothoth.com all provided valuable input over the years on games and gamers of all stripes. ICON has been my home convention for many years. If it wasn’t for me attending the World Fantasy Convention with Fred Durbin, Nick Ozment, and Gabe Dybing this book might not have seen the light of day.

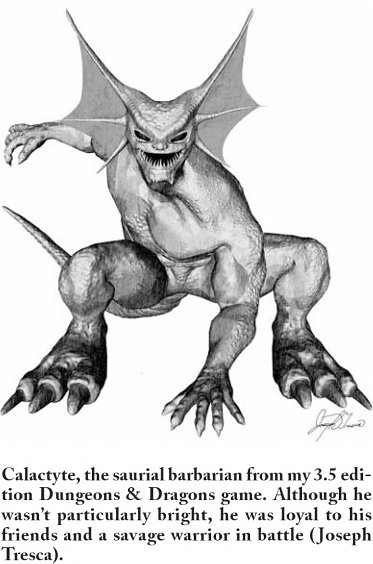

I’ve been particularly blessed by a loving family that supports and encourages my gaming hobbies. My father’s love of science fiction and my mother’s love of reading greatly influenced me as a gamer. I’ve had the amazing good fortune to game with my brother Joe who contributed art to this book, my brother-in-law Eric, and my sister-in-law Melissa.

But the person who deserves the most thanks of all, the inspiration for my master’s thesis, and my constant companion and muse, is my wife. Amber tolerated long nights of writing while keeping up with my gamer-in-training two-year-old son and pregnant with our daughter. Violet will be born by the time this book sees print. I love you!

To my family and friends: Thank you. I look forward to gaming with all of you soon.

PREFACE

When we submitted John Gabriel’s Greater Internet Fuckwad Theory, we were not aware that it already had proponents in centers of higher learning. Except, when they talk about it, they call it The Impact of Anonymity on Disinhibitive Behavior Through Computer-Mediated Communication. Same thing, though [Holkins 2004].

Why write yet another book about role-playing games? There are plenty of authors who have written quite a bit about fantasy gaming in a variety of mediums without having ever actually experienced their evolution firsthand. One of the reasons I chose to write this book is that I was there. I’ve certainly experienced a wider variety of gaming media than some of the developers who created the more popular massive multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) today. There are scholars who have written books on MMORPGs with considerably less gaming experience. The gaming medium is not very old, but there is so much more to gaming than MMORPGs alone.

I was introduced to Dungeons & Dragons at age seven and have been playing it for over twenty years. I snuck into university computer labs to play multi-user dungeons (MUDs) as a teenager long before I could attend college. I’ve played just about every form of fantasy gaming. By the time I went on to graduate school, I was an administrator for a MUD and had published several tabletop gaming supplements for the game I loved.

Every year, I attend I-CON on Long Island and participate in panels on gaming. I grew up with the convention, attending nearly every I-CON since I was twelve. I’ve also participated in discussion panels about gaming at Dragon*Con and Bakuretsu Con.

By the time I went to graduate school at Michigan State University, I was a man on a mission. Scholars were tut-tutting about the marvelous world in which boys played online, while I was facing down death threats, fighting spammers, and grappling with the ugly side that was part of everyday life on the Internet. My masters’ thesis would come full circle when Penny Arcade shared “John Gabriel’s Greater Internet Fuckwad Theory.”

The theory, explained in an online comic in March 2004, explains the unsociable tendencies of online players when combined with anonymity: “Normal Person + Anonymity + Audience = Total Fuckwad.” It was an enlightening lesson about the state of journalism to see the April 2, 2004, Washington Times quote me, as if I had been interviewed, in their column “Watercooler Stories,” where it stated that a “graduate of Michigan State University” had determined that anonymity made people more likely to be offensive. A thesis I had written five years before gained national prominence in a syndicated newspaper because a buddy of mine (Chris Bibbs) mentioned it to a gaming site. It was at that moment that I realized gamers were an international force to be reckoned with.

When I bought my first game console, an Xbox, I wasn’t really keen on many of the first-person shooter games that are so popular today. But a coworker, Mike Ettlemyer, convinced me to join Geezer Gamers (2010). Before I knew it, I was hooked on Halo. And Halo 2. And Halo 3. And Gears of War. And ... you get the idea. I now participate in online games with likeminded Geezers every Wednesday night on Xbox Live. Look for Talien!

I’m also one of the top 1,000 reviewers for Amazon.com, a relationship I’ve cultivated since Amazon.com was launched. I review everything I read, watch, or play, which keeps me pretty busy. In short, I am quite sure there are authors out there who know more about games than I do—but I don’t think they’ve played quite as many games.

When I first considered writing this book, I faced a daunting challenge: How to combine all these different experiences into one book that’s entertaining as well as informative?

Beginning with J.R.R. Tolkien’s Fellowship as envisioned in The Lord of the Rings, I decided to follow the long and twisty thread that is group play inperson and over the Internet. There are echoes of this motley group of races and professions, nationalities and ethos, in every fantasy game created since Dungeons & Dragons. The fingerprints of the tabletop role-playing game are everywhere, and sometimes even the developers don’t realize they’ve been influenced by all the games that have gone before.

Just as the Fellowship helped mold fantasy gaming, it also helped shape how players get together to play. And that’s where my thesis comes in: There are different stages of anonymity that influence how people play together, be it in costume, at a table, over the phone, or on the Internet. In-game and outof-game roles have a powerful effect on the game itself and it is that common thread we will pursue throughout this book.

There is a distressing lack of history knowledge in the gaming community. Tabletop role-players seem entirely disconnected from the miniature wargaming community that spawned Dungeons &Dragons. MUD coders don’t understand where their Dungeons & Dragons–themed rules and assumptions came from. MMORPG developers almost unilaterally ignored what made MUDs successful, making the same mistakes that MUDs made a decade before. Computer role-playing games tout “innovations” that were implemented long before by tabletop gamers and MUD developers. Recently, live action role-playing games started adopting tabletop gaming conventions more formally into their games.

In short, we have a lot to learn from each other. This book is as much about my shared experiences with all these different gaming communities as it is an attempt to encapsulate the history of fantasy gaming. It’s my hope that this book will serve as the foundation for future works, so that authors and developers alike will learn the difference between editions of Dungeons & Dragons and know the heritage of the various races and classes that are commonplace in all forms of gaming today. If you’re a developer who is just starting out, a gaming veteran who wants to reminisce, or you just like games ... this book is for you.

INTRODUCTION

The Company of the Ring shall be Nine; and the Nine Walkers shall be set against the Nine Riders that are evil. With you and your faithful servant, Gandalf will go; for this shall be his great task, and maybe the end of his labours. For the rest, they shall represent the other Free Peoples of the World: Elves, Dwarves, and Men [Tolkien 1954:288].

With those words, J.R.R. Tolkien formed the basic structure of an adventuring party in 1954 that has endured endless fantasy tropes and ever-changing mediums. Although the Fellowship started with elves, dwarves, men, and of course hobbits, it has since expanded to include every race of fantasy imaginable. And where it was once simply enough to define one’s allegiance to a Fellowship by nationality, race and class has come to define each hero in the fantasy gaming genre. One can be a ranger, like Aragorn; a wizard, like Gandalf; or a thief, like Bilbo.

And yet the Fellowship in a gaming experience is fundamentally a gathering of people. Although the players can conceivably control more than one character, the Fellowship is a construct uniquely suited to group play. Characters of diverse backgrounds come together to achieve a common goal, just as a variety of players gather together to play the game. The Fellowship construct is ideally suited to new players. It is independent of previous character relationships, just like the players themselves.

In that light, the Fellowship is both an in- and out-of-game framework on which to hang a gaming experience. This book will examine the archetypes and concepts within the fantasy game and the roles and functions of the players themselves. As the fantasy gaming experience has evolved, so too has the medium in which it is expressed, from novel to tabletop, from imagination to miniatures, from textual descriptions of characters to three-dimensional computer avatars, to the players themselves dressing and acting as the characters.

Media Richness

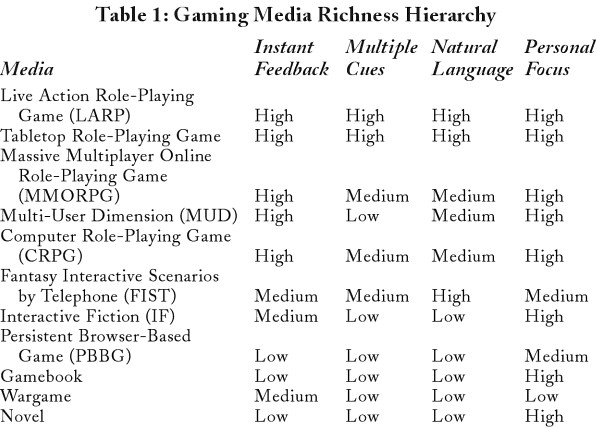

By applying Daft and Lengel’s (1984:191) media richness theory to the fantasy gaming experience, there is much to learn about what constitutes a successful and satisfying game. The media richness theory proposes that communication media have a range of capacity to resolve ambiguity and facilitate understanding. The theory has two main assumptions: that people want to overcome uncertainty in communicating with each other and that different media work best for different situations.

Daft and Lengel’s media richness hierarchy is sorted, from high to low degrees of richness, by the medium’s ability to provide instant feedback; the capacity to transmit multiple cues such as body language, expression, and inflection; the use of natural language; and the personal focus of the medium. We can apply the media richness hierarchy to gaming.

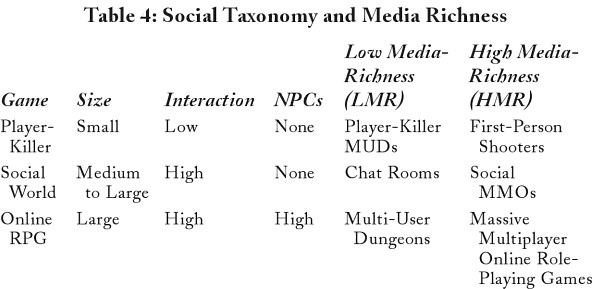

As explained in Table 1, each gaming medium brings with it a level of media richness that conveys something about the character through the player. At one end of the spectrum is the text-based gaming experience, which has no social cues other than what the player types on a keyboard. At the other end is a LARP, where the players dress and act as their characters, blurring the line between the two. In that regard, media richness is a key factor in taking on another role.

This is not to say that a high level of media richness is always desired. Some level of anonymity helps facilitate certain levels of game play. Ambiguity may positively reinforce role-play for a particular gaming medium. Text-based games like MUDs and IF can reveal the mental states of characters and connect to literary traditions and the rhythms, sounds, and shapes of language (Montfort 2010). MMORPGs, which replicate some of the media richness of a LARP through avatars, are successful precisely because of their media richness; the ability to express oneself in a three-dimensional space (Castronova 2005:69) in a way similar to a LARP without any of the physical constraints.

Anonymity of Self and Other

When determining how fantasy games represent a group of gamers, there is another issue to consider: anonymity of self vs. anonymity of other.

Anonymity of self is tightly tied to agency. Players’ ability to control their character, to represent themselves as they wish to be represented, creates a sense of control and engagement. By creating agency, players temporarily forget they’re playing a game and simply play. Characters that are a blank slate may appear anonymous but due to a clunky interface, complex rules, or a lack of believability on the part of the player, fail to provide agency. When agency is achieved, players might be surprised to find that the characters they play take on a life of their own (Sinha 1993:120).

Agency happens on two levels, local and global. On a local level, the player is engaged in a satisfying and believable way by what he does and how the environment responds to him. Global agency happens on a higher level in how the story plays out so that there are logical consequences to the character’s actions as well as the other characters that inhabit the world (Mateas & Stern 2007:206).

Anonymity of other is how much the player knows about the game universe he engages in, including his understanding of the world. This is known as diegesis (Montola 2010). Diegesis is the sum total of knowledge about a universe, including knowledge of the past, present, and future. In a novel this frame of reference is perceived from a single point of origin, the narrator. In role-playing every player interprets the game experience uniquely—the importance of the character’s experience is defined as much as by what is shared about the universe as what isn’t shared. It’s entirely possible for different players to have different or even contrary knowledge within a game universe (Hindmarch 2007:51).

The lack of anonymity in certain types of fantasy gaming, like tabletop and LARPs, alters interpersonal negotiations. The additional layer of sensory knowledge changes the face-to-face interaction (Fine 2009). It is entirely possible for an unattractive male gamer to believe he is playing an attractive female gamer effectively even though his media-richness cues conflict with the character he is attempting to present. Although the hairy gamer might believe he is effectively inhabiting his role, other players interacting with him in the game may disagree. When others express their disagreement, it in turn influences how the gamer sees himself, a feature missing from single-player games. Single-player games that do not involve interactivity with other players are concerned only with making the role believable to the player. Multiplayer games must make the role habitable for the player and also allow the player to inhabit the role for others.

Frame of Reference

The term “role-playing” has come to represent a variety of game forms. A colleague once explained to me when I mentioned that I played Dungeons & Dragons, “I beat that game!” She was referring to computer role-playing games, of course, where it is indeed possible to “beat” the game. The term “role-playing” has now been expanded to include any game in which the player controls a character in a game world and develops him or her throughout the course of play (Hindmarch 2007:47).

Role-playing games differ from other forms of recreation through the act of co-creation. The role-player creates his own experience through personal feelings and emotions. He inhabits a character and feels the character’s experiences in a way that a book or film cannot directly convey. In this way, players interact with a game through a uniquely tailored frame of reference (Mateas 2004:21).

In Shared Fantasy, Gary Alan Fine (1983:188) defines a frame as “a situational definition constructed in accord with organizing principles that govern both the events themselves and participants’ experience of those events.” He breaks down the various frames into levels of the role-playing game experience.

The primary framework is what gamers commonly refer to as real life. It is separate from the game but inextricably part of it. Real life is understood to be outside the rules, and its realities may define or even contradict the game itself (i.e., having to finish a game quickly because the players need to go to work). The membrane between imaginary worlds and real life has become increasingly porous, allowing participants to take the very best elements they enjoy most from each gaming medium (Castronova 2005:158).

The secondary framework is the player framework. Players operate within the game using the rules as they understand them. They operate their characters according to what the game allows, make statistical checks, take damage, and otherwise interact with the variables of the game abstractly, usually through random number generation.

Some players are comfortable interacting with the rules of the game from a purely simulation point of view, focusing exclusively on hit points, character attributes, and the like, rather than providing any narrative structure for their character. Many single-player games that are low on media cues provide these rules as a shortcut to make up for the lack of narrative structure. The intelligence, wisdom, and charisma attributes define the mental characteristics of a character that a player may be unable to provide from a narrative perspective.

The tertiary framework is the role-playing aspect of gaming. Players are their characters, inhabiting a role in a way few games emulate. Most games, like chess, never extend beyond the secondary framework. The tertiary framework is what sets role-playing games apart from other forms of gaming and it is the source of much controversy in the “roll-” vs. “role-” playing debate.

Fine breaks down the tertiary framework further by examining the various forms of engagement by players with the game and their characters.

Character Awareness of Person Reality

The character knows things he would not normally know because the person playing the character knows it. This information can be as esoteric as how to build a flamethrower or as oblique as knowledge of SWAT team tactics. The more removed the setting, the more difficult it becomes for a player to filter his own knowledge when role-playing. This disconnect is a common criticism in fantasy-derived media where the characters use lingo familiar to modern audiences. Although these forms of narrative shortcut are an inaccurate depiction of the universe in question, a certain level of accessibility is required to allow participants to comfortably engage with the setting.

Character Awareness of Player Reality

Characters can take many dynamic actions that are not suitable for players sitting around a table. They can be physically separated. They can be in proximity to each other but not capable of experiencing the same thing—one might be blind or affected by an illusion. It is assumed by many gaming groups that the players will filter this information out of their characters’ knowledge. Some groups pass notes and send players out of the room to prevent player “contamination” of character information.

Characters do not view their universe as a set of game rules, but players do. In systems where there are clear target numbers to perform an action, players may choose their characters’ actions depending on the likelihood of success. Players have become accustomed to having some level of “meta-knowledge” about how the game works, like hit points or ability scores. This is why MMORPGs and CRPGs still display numbers for skill use and damage inflicted even though all the rules can be masked through the game’s interface.

Player Unawareness of Character Reality

Just as players can provide their characters with information they would not normally possess, players inevitably lack information their characters should know. My most recent Dungeons & Dragons character, a fantasy version of a Roman standard bearer named Quintus Aurelius Ignatius, certainly knew more about military protocol and procedures than I did. It is often up to the game master to adjudicate situations in which the character should know something but the player doesn’t. Modern realistic settings and characters that have characteristics in common with their players help reduce this disparity.

Awareness Context of the Game Master

Game worlds are massive universes, fabricated by another game company or by the game master. As such, each game universe is only as detailed as the amount of time and effort invested in it. There’s only so much diegesis a game universe can realistically convey. If players focus on macro- or micro-levels of information, such as the population numbers for a particular race across a continent or the different kinds of microbes that infect a peculiar breed of sheep, the game breaks down. It is up to the game master or coding authority to fill in the blanks, sharing the right information at the right time.

If the information isn’t shared appropriately, the players fail to experience diegesis and the game experience is less engaging. During an investigativestyle tabletop game session, one of my players correctly deduced that a character wasn’t important because I didn’t immediately have the details of her profession at my fingertips. If she was important, he declared, I would immediately know what kind of lawyer she was. He was right.

This analysis of frames helps sheds some light on the “right” way to play a game. A LARP, for example, minimizes character awareness of player reality and increases agency because the player physically inhabits the character’s body through his action. There isn’t necessarily a right or wrong way to game so much as player agreement on which frames they will use to play the game.

Because role-playing isn’t just about inhabiting a role but playing it, narrative inhabitance requires interaction with others. And because there isn’t always a means of determining a player’s level of inhabitance of his role, the only way to discover this is to role-play with the character. This interaction can be jarring for the widely differing levels of inhabitance, because a roleplayer’s diegesis is partially defined by his interaction with other players, while a “roll-player’s” role is defined by his agency. A role-player needs other players to play along with his role. A roll-player does not.

We will define role-playing in this context as not just inhabiting the role but interacting with others. At first blush it might seem that it is not necessary to review the single-player game experience because it does not reflect true social interaction; however, even single-player games attempt to model a group of characters, with the role inhabited by the computer. The effectiveness of the computer’s ability to mimic these characters helps determine the level of interaction within the game. Or, to put it another way, computers are another form of player.

Time

Tim is a currency that all forms of fantasy gaming have in common. Experiencing a role takes time. Because fantasy gaming is a recreational experience, this time commitment requires a player to make a tradeoff by choosing gaming over some other activity.

But fun has a price. It keeps us from doing work and makes us potentially neglect our other responsibilities. Different forms of gaming have different considerations to retain and grow the player base, not the least of which is replayability. The nature of fantasy gaming is experiencing a role, and the shorter the time engaged, the smaller the window for the player experiencing agency (Juul 2004:131).

First-person perspectives that happen in real time require considerably more engagement. One of the common complaints about MMORPGs is that they cannot be easily entered and exited at the player’s whim. MMORPGs happen in real time, so players have to factor in real-life interruptions lest their entire adventuring party die during a bathroom break. Contrast this time commitment with play-by-post games, which by their very nature require limited engagement and interaction (Douglas and Hargadon 2004:203).

MMORPGs and MUDs in particular have a “grind,” performing tasks repeatedly in the hope of gaining some advantage, be it a higher level of experience or acquiring some item. Players spend precious time grinding through these boring tasks to enjoy access to other parts of the game. Even game designers have acknowledged these boring parts by creating mini-games to keep players preoccupied during the necessary downtime (Taylor 2006:85).

Why would anyone create a game that’s boring? Because the progenitor of fantasy gaming, Dungeons & Dragons, was meant to be played in limited but intense chunks of time. In fact, a substantial part of tabletop gaming is taken up in preparation of the game, as Gary Gygax, one of the founders of Dungeons & Dragons, explains:

The most extensive requirement is time. The campaign referee will have to have sufficient time to meet the demands of his players, he will have to devote a number of hours to laying out the maps of his “dungeons” and upper terrain before the affair begins [Gygax 1974:3].

During play, the Dungeon Master skips over the boring parts and emphasizes the action. Early editions of Dungeons & Dragons were nothing but action interspersed with the potential threat of danger. Early parties spent a lot of time searching for traps, mapping, and meticulously performing tasks that others might find boring, but that were an important struggle for survival within the game’s context.

By taking the Dungeons & Dragons framework and applying it to games with thousands of players and a persistent world, the system breaks down. The fourth edition of Dungeons &Dragons addresses precisely this flaw in revising every class so that there are no “boring” levels.

The temporal cost of fun has repercussions for the future of gaming. Modern economies provide workers with much more flexibility than ever before, but as a result of that flexibility, free time is divided into smaller increments (Thom 2010). Games with easier access that accommodate this new structure of free time are likely to survive as a mainstream hobby (Vesna 2004:250).

American Culture

This book primarily focuses on fantasy gaming through the lens of American culture. Although non–Western cultures were influential in gaming, they are beyond the scope of this book.

Comparing the Warhammer Fantasy Role-Playing Game (Fantasy Flight Games 2010) to Dungeons & Dragons illustrates the different approaches to gaming between cultures. Dungeons & Dragons is suffused with hope and power, with gold around every corner. Official campaign worlds for Dungeons & Dragons were slow to come about, instead encouraging game masters to create their own worlds—in keeping with American individualism. Europeaninspired Warhammer, on the other hand, is a world full of rich and ancient history, with a mixture of frail nobility and aging decadence against the backdrop of war. Warhammer captures many of the aspects of The Lord of the Rings that Dungeons &Dragons did not, embracing the heritage of European countries while American fantasy games emphasized pulp-style action.

Japanese CRPGs have influenced fantasy games as well. Adventures can include “cute” (kawaii) elements with cartoon-like characters and silly quests side-by-side with serious and threatening situations. This contrast may be jarring to American audiences, but it’s perfectly in keeping with Japanese culture, which has embraced kawaii in everything from fashion to cartoons (anime) to comics (manga) to role-playing games (Barton 2008:208).

Without the history of wargaming to influence gaming culture like it did in Europe and the United States, Japanese CRPGs are a mix of kawaii, action, fantasy, and science fiction. Japanese CRPGs contributed some important changes to how role-playing games are now played electronically, but we’re chiefly concerned with the heritage of the European Lord of the Rings.

And yet, if The Lord of the Rings is European, why did it become so popular in the United States? Part of the answer is that Dungeons &Dragons acted as a translation of sorts for the fantasy genre. Like Warhammer, Middle-earth is steeped in a world rich with lore and history. Dungeons & Dragons added pulp sensibilities to the fantasy game, an important part of American culture. Pulp fiction featured multitalented heroes, nonstop action, exotic locales, and nefarious villains—it was the genre that spawned the modern comic book industry.

Although Dungeons & Dragons and its ilk are positioned as fantasy roleplaying games limited only by the players’ imagination, they are in fact bound by common principles that make fantasy role-playing games distinctly American. As defined by Fine (1983:76), these elements are a force of unlimited good, a world in opposition with sharply defined sides, an evil that favors only violence to perpetrate its ethos, and the value of hard work.

American culture has some nuances that are unique to it, one being the notion of limitless growth for businesses, consumer buying power, and the economy. In Dungeons & Dragons, this ideology is true of dungeon exploration too. There’s always a monster with treasure around the next corner, always a new area to explore, always a new frontier to conquer.

The very nature of adventure is predicated on an age of expansion and heedless of the results of that expansion. Adventurers are not colonial conquerors but heroes to their homeland, with none of the consequences suffered by the non-dominant societies. When you take treasure from someone, someone else must have lost it, but in Dungeons & Dragons it’s usually an ancient culture that no longer can claim ownership. In MMORPGs perpetual growth borders on parody, as hordes of supposedly unique adventurers camp out in front of dungeons that generate limitless amounts of monsters and treasure. The grind paradigm was parodied in Progress Quest, an application that levels up a character with no player input at all (Grumdrig 2008).

In Dungeons & Dragons, good and evil are axiomatic. There are clearly defined “sides” to which players claim allegiance, and their allegiance influences their characters, from abilities to appearance. In America, this “my way or the highway” philosophy has become an increasingly dominant form of discourse, most ardently in politics and the media. It has spread to the communication channels themselves, with different television networks accusing the other of bias, forming their own “alignment” language.

Dungeons & Dragons’ focus on combat harks back to its wargame roots, with pages of rules centered on conflict. And yet despite the combat rules, Dungeons & Dragons does not focus on senseless violence, torture or depravity. When works like the Book of Erotic Fantasy, by Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel and Duncan Scott were released by a third-party publisher, they caused enough of a stir with D&D owners Wizards of the Coast that the Open Game License was revised to prevent other books like it from being published. Wizards subsequently published the Book of Vile Darkness which addressed similarly “mature” content (Cook 2002).

The Protestant work ethic of toil resulting in great rewards is evident throughout American culture. It informs many reactions to socialism, which, some charge, rewards the lazy who didn’t “earn” their keep. Leveling up, gaining power and experience points provide a very clear path to power in fantasy gaming, rewarding hard work. This ethic is turned on its ear in online roleplaying games where heroes adventure around the clock and it’s possible to “farm” one’s way to power by repeatedly killing creatures that are of no threat to the player’s character.

The Players

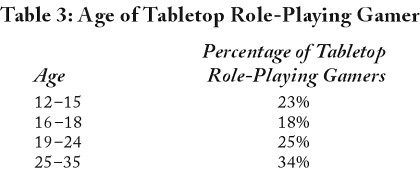

In 2000 Wizards of the Coast conducted one of the largest polls of roleplayers, sending a postcard survey to more than 65,000 respondents in more than 20,000 households of people ages 12 to 35. A follow-up survey was then completed by about 1,000 respondents from the “screener.” In that study Ryan Dancey, then brand manager of Dungeons & Dragons, discovered that six percent of the U.S. population played tabletop role-playing games (about 5.5 million people) and three percent played monthly (about 2.25 million people) (2000).

Role-playing gamers come from diverse backgrounds, but they have enough in common with each other to be grouped into a few distinct categories. As defined by Fine (1983:49), gamers can be grouped into the following categories: military history/wargaming, knowledge of fantasy literature, knowledge of real-world mythology, knowledge of general history/social sciences, knowledge of real-world physical science, and live action role-playing groups like the Society for Creative Anachronism (SCA Webfolk 2010). Interest in any one of these seven categories increases the likelihood a person will be interested in role-playing.

Military history/wargaming now has a distinct fantasy bent thanks to Games Workshop’s Warhammer miniatures game. This category can be further divided into military history buffs and wargamers. In the Wizards of the Coast survey, 17 percent of this population played tabletop role-playing games as well as miniature wargames monthly.

Dungeons & Dragons has strayed far from its original wargaming roots. In the late ’70s, Dungeons & Dragons was still struggling to separate itself from wargaming culture, where it originated, and thus many players came to role-playing from wargaming. Before the advent of Dungeons & Dragons, wargaming was usually a military simulation of a real-life historical event, which attracted military buffs. Given that Fine’s Shared Fantasy was published in 1983, it’s likely that military history buffs no longer see the appeal of roleplaying as much as they once did.

Knowledge of fantasy literature is best exemplified by the surge in popularity of the Lord of the Rings series. The Lord of the Rings movies brought fantasy into the mainstream and had a powerful influence on both role-playing games and fantasy conventions. Decipher published licensed role-playing and collectible card games that took place in Middle-earth. The female population attending genre conventions surged during the release of the three Rings movies. Knowledge of fantasy literature can also encompass horror and science fiction. Many elements from author H.P. Lovecraft’s work are also a part of Dungeons & Dragons (Jacobs 2004).

Interest in mythology and alternative religions can certainly pique one’s interest in gaming. Alternative religions that are connected to mythology, like Asatru and Wicca, help establish a common language that is used in gaming. A wide variety of mythologies has been presented throughout each edition of Dungeons & Dragons.

Knowledge of general history and social sciences is probably most appealing for prospective game masters, who have better insight and more control over how detailed fantasy worlds work. They can use history as a template or actually reconstruct historical events with their own twist, such as Cthulhu Dark Ages or Victorian Age Vampire.

Knowledge of real-world physical science is more relevant to science fiction role-playing games. In a manner similar to history buffs, game masters are likely more interested in constructing a detailed world that operates or warps scientific principles. Surprisingly, there is no one science fiction game that clearly dominates tabletop role-playing like Dungeons & Dragons has dominated the fantasy genre.

Live action role-playing, wherein the players physically inhabit a role, is a natural fit for tabletop role-playing games. Players are able to visualize their fantasy because they performed many of those same actions in another gaming format. Whereas Fine limited this comparison to the Society for Creative Anachronism, the definition can be stretched to include anyone with real-life physical experience who uses that knowledge in a role-playing game, including martial artists, military veterans, and improv actors.

Missing from Fine’s review of gamers was CRPGs and MMORPGs, which have since increased in popularity (Taylor 2006:77). In the Wizards of the Coast survey, 46 percent of tabletop role-players also played computer role-playing games monthly (2000).

Dancey concluded that the mythical “hobby gamer” who played tabletop role-playing games, CRPGs, and miniature wargames comprised a “very, very small portion of the total market.” A minority of gamers played more than one category of hobby game and very few played all three. The largest overlap, though still a minority, was with CRPGs and tabletop role-playing games. This places me in the minority, as I have indeed played all three—but I do not play all three concurrently.

Throughout this book I interview many of the players from my tabletop role-playing game campaigns and from RetroMUD. Through their experiences, I hope to compare and contrast the differences and similarities between each gaming medium.

Gender

However gamers come to tabletop gaming, they all share one thing in common—they are almost uniformly male. Fine (1983:62) estimated that in the early 80s only ten percent of the player population was female. The Wizards of the Coast survey indicated that just 19 percent of female gamers played on a monthly basis (2000).

But it didn’t have to be that way. Studies of children (Child and Child 1973) aged 12 and younger found that girls have more interest in imaginative play than do boys. Role-playing involves many of the attributes that are common in other female-youth-oriented games, including shopping to equip characters, character design and customization, the ability to possess and own pets, and playing a more attractive and mature character. So why aren’t there more women involved in role-playing games?

The answer may lie in the duration of play. Tabletop role-playing involves sitting at a table for long periods of time with a group. Boys’ imaginative play tends to run longer and involve larger groups than girls’. As one of the female players in my 3.5 edition Dungeons & Dragons campaign explained:

I had two traditional D&D experiences at age 16 and then again at 26. I enjoyed puzzle solving, but on both occasions I found the delay in discovering opponents’ weaknesses and strengths lacking in excitement of a visual real-time battle. Therefore a character reaction or statement that might be influenced by adrenaline would be easier to come by in a real-time video game. Sadly traditional RPG was about as exciting as jogging from one end of a pool to another for me [Melissa Tresca 2010].

These challenges can be overcome, of course. However, other forms of role-playing that remove the duration of play and the requirement of sitting at a table for long periods of time seem to be more popular with women. MMORPGs, for example, focus on character and object customization, without the requirement for long stretches with a peer group. Conversely, LARPs include all the imaginative play of tabletop role-playing games, but focus more on interaction between individuals than a group confined to a table.

There are other problems that keep females away from gaming that are endemic to any male-dominated form of entertainment. The self-reinforcing nature of a male-dominated game seems less welcoming to women because there are so many men playing. That females can be portrayed in fantasy literature in as sex objects doesn’t help; chauvinism of male players, who game for the express purpose of getting away from wives and girlfriends, further reinforces the gender barrier (Archer 2004:268).

As Ryan Dancey indicated in the survey, “It is clear that female gamers constitute a significant portion of the hobby gaming audience; essentially a fifth of the total market. This represents a total population of several million active female hobby gamers. However, females, as a group, spend less than males on the hobby” (2000).

The term “girl gamer” is slowly being taken back by women as a badge of pride. As other forms of fantasy gaming developed, many of the barriers that discouraged females from playing have fallen away. Online games are the most promising change of the gamer landscape. We can only hope that a more equally balanced gaming population will continue to transform the pen-andpaper role-playing culture as well.

Evolution of My Fantasy Gaming Experience

The evolution of fantasy gaming took a huge leap forward in 1971, when Gary Gygax translated the epic warfare that took place in The Lord of the Rings into wargame rules through Chainmail. The medieval miniatures wargame had it all: hobbits and elves, wizards and warriors. As befitting the racial preferences of The Lord of the Rings, troop types were identified primarily by race. There was no suggestion that the players inhabit the role of their characters, however (Mona 2007:26).

It wasn’t until 1974 that the real details of each squad were fleshed out. With the advent of the pen-and-paper role-playing game Dungeons &Dragons, players could take the role of individuals. No longer were they a faceless army of elves— they were members of Fellowships on their own quests, just like Legolas, Gimli, and Frodo. Their quests were primarily focused on dungeon delving, a nod to the journey through the Mines of Moria, the first adventuring dungeon filled with monsters to slay, such as cave trolls, orcs, goblins, and Balrogs. It was only fitting that the person who played all of the opponents was the Dungeon Master (DM). This role required quite a bit of responsibility and organization, since the DM handled all the other roles that weren’t performed by other players.

I was introduced to Dungeons & Dragons in elementary school and had been playing it for some time before I became acquainted with The Lord of the Rings. Much to my surprise, all the fantasy tropes were there. Further research unearthed that they were officially present in Dungeons & Dragons until the Tolkien estate asked TSR to remove the copyrighted names of Balrogs and hobbits. The Lord of the Rings series helped me write three book reports in junior high. (Of course, The Lord of the Rings isn’t technically a trilogy—it’s actually six volumes spread amongst three books.)

I started playing Dungeons & Dragons with the “red box” basic set. My mother helped me play the very first game. Once I got the hang of it, I gathered up my neighbors (Kenny, Kevin, and George), and with me in the role of Dungeon Master, we were off.

My aunt Vickie, not understanding the difference between Advanced Dungeons & Dragons and Basic Dungeons & Dragons, bought me all the hardcover books. I read them in wonder, hoping one day to be able to advance to, well, advanced.

By the time I graduated from elementary school, I had access to a larger pool of players. The group increased to four: two Jasons, Doug, and Oren. By the time I reached high school, the group grew larger: Rob, Jeremy, Kurt, Bill, Joe and others who came and went. We played every weekend for hours, sometimes twice a weekend, ignorant that Dungeons & Dragons was primarily popular with college kids. We played two entire campaigns, one using the basic edition rules and one using the first edition rules, before I graduated high school.

With the advent of computers, text-based games like ADVENT and DNGEON mimicked the endless dungeon exploration and battle against monsters. My first computer gaming experience was via a PET computer in elementary school, wherein I had the opportunity to challenge my wits against the great wizard Zot in the game Wizard’s Castle. I found the game too difficult. At age nine I was still grasping the basics of role-playing games.

DNGEON was eventually released by Infocom as Zork. My parents insisted on purchasing a computer system instead of a game console, a decision I disagreed with at the time (I wanted an Odyssey) but one that in retrospect changed my life for the better. It was thanks to our Atari 800 that I was introduced to Zork.

I still remember the struggle to open a locked door in Zork. All we had was a letter opener and a placemat. After days of puzzling over how to get through the door, it hit me in a flash—slide the placemat under the door, push the letter opener into the lock, knock the key out of the lock on the other side, and then pull the placemat back! It’s a triumph that stuck with me decades later. In all my years of gaming, few games have provided as satisfying an experience.

Even Zork couldn’t capture the feel of a party of characters however. Text-based games could handle only one player at a time until the advent of multi-user dungeons (MUDs). In 1978, Roy Trubshaw and Richard Bartle at Essex University created the first MUD, a nod to its dungeon-crawling predecessors (Glenday 2008: 170). Following in the footsteps of the single-player computer games, MUDs allowed players to adventure together in groups just like the Fellowship. The goal was to accumulate enough points to become a wizard, like Gandalf, and thereby be granted powers that mere mortals did not possess.

My experience with MUDs began with Ivory Towers. In Ivory Towers two different-aligned cities, one chaotic and the other lawful, battled in an endless struggle against each other. My character, Lamech, ascended in the ranks of a tight hierarchy of chaotic priests. Lamech was a noncombatant, a novelty in a bloodthirsty world where killing other player characters was the norm.

It’s noteworthy that I was playing Ivory Towers at the same time Indra Singh was playing Shades, a rival MUD (1999). Shades players were reviled across Ivory Towers, who would invade when Shades was down (or they were bored), gleefully committing mass murder in a bloody invasion that ended as quickly as it started.

Eventually, I switched to the Finnish LPMUD BatMUD. I made and lost friends on BatMUD, and even met my spouse Amber there. After a long and storied history as a satyr paladin known as Talien Radisgad, I left BatMUD to join the coding staff of another LPMUD, RetroMUD.

Over a decade of experience as an administrator on RetroMUD led to my master’s thesis, The Impact of Anonymity on Disinhibitive Behavior through Computer-Mediated Communication. I also became a staff reviewer for the MUD section of Gamers.com, which gave me an opportunity to view the breadth and depth of MUDs at the height of their popularity.

Given the popularity of Dungeons & Dragons across campuses in America, it was ironic that I had difficulty finding pen-and-paper gamers in college. When I moved to Michigan to pursue my master’s degree, I ran a brief second edition campaign with players from RetroMUD: Darren, Damien, Amber, and Chris.

In 1980, computer technology had advanced enough to make graphic visualizations feasible. Rogue, created by Michael Toy, Glenn Wichman, and Ken Arnold, bridged the gap between the old text-based games and the new graphics, exchanging text symbols for dungeon icons.

Rogue was a solitary dungeon crawl with randomly generated obstacles. The goal was to retrieve the Amulet of Yendor from the lowest level of the dungeon and escape with it. I played Rogue extensively on the Atari 520 ST, but never made it to the bottom level. The Ur-viles inevitably showed up and all was lost.

As computers advanced, MUDs advanced along with them. When graphics became detailed enough to represent characters in much the same way that miniatures were used for Chainmail, MMORPGs became feasible. The first MMORPG was Neverwinter Nights, which debuted on America Online in 1991 (Glenday 2008: 156). It had a two-dimensional graphical interface, granting players a top-down view of the universe. Parties were formed, dungeons were delved, and the rich tradition of the Fellowship continued.

In the late 1990s, I became a staff reviewer for All Game Guide. There were so many computer games that it was difficult to keep up. It gave me an appreciation for the wide range of games available for the PC.

By 1997, the MMORPG scene exploded with Ultima Online. Created by Richard Garriot, Starr Long, Rick Delashmit and later Raph Koster, Ultima Online took on the challenge of creating a fully realized universe outside the dungeon that could support an entire population of adventurers, villagers, and monsters. Ultima Online was an improvement over Neverwinter Nights with its three-quarters view from above. I played Ultima Online on a trial basis.

I was an active member of the MUD-Dev mailing list, on which MUD creators and MMORPG collaborators spoke as equals. During that time, the MMORPG coders shared the challenges they faced, challenges that MUD coders had been dealing with for years. I had several constructive conversations with some of the founders of MMORPGs, including Koster (2010). Despite the change in format, the issues bringing people together for a grand old fantasy adventure were still the same.

In 1999, EverQuest provided a three-dimensional graphical environment that went beyond tile-based representation (Glenday 2008: 170). Characters walked, ran, jumped, swam, and later rode mounts. EverQuest was rapidly followed by Asheron’s Call in 1999 and Dark Age of Camelot in 2001. I played the free three-month trial of Asheron’s Call.

The open game license (OGL) movement arrived in 2000. The OGL was an open content license published by Wizards of the Coast for role-playing games. The OGL movement, spearheaded by Ryan Dancey, gave hundreds of small businesses the chance to contribute rules and adventures to Dungeons & Dragons. It also gave struggling writers an opportunity to get published (Archer 2004:273). I authored several game accessories compatible with Dungeons & Dragons under the OGL, published by Alderac Entertainment Group, Goodman Games, Malladin’s Gate, MonkeyGod Enterprises, Otherworld Creations, Paradigm Concepts, Privateer Press, Reality Deviant Publications, RPG Objects, and Ronin Arts. I also wrote articles for a variety of periodicals, including D20 Filtered, Dragon Magazine, Pyramid, and the RPG Times. My ongoing love affair with Dungeons & Dragons continues to this day; I am an action horror columnist for RPG.net and the National RPG Examiner for Examiner.com (Tresca 2010).

I returned to the East Coast to co–DM a third edition Dungeons & Dragons campaign with Robert Taylor for Amber, Matt, Jeremy, George, two Joes, Melissa, and Mike. After my son was born, Jeremy, George, the same two Joes, and Bill now play a d20 Modern/Delta Green game once a month on Long Island.

D&D evolved as well, experiencing several revisions throughout the decades. Given that Dungeons & Dragons inspired the very first text-based adventure games, it was only a matter of time before parent met child. Dungeons & Dragons Online was launched in 2006 with the goal of bringing the Fellowship experience to the MMORPG. I played Dungeons & Dragons Online with Chris, Rob, Joe, Melissa, and Amber for about six months.

Every year at I-CON, I participate in seminars on both pen-and-paper and electronic gaming (I-CON Staff 2006). I’ve witnessed some enthralling conversations dealing with the differences across mediums and also spoken to audiences ranging from over sixty people to just one person. It’s this merging of electronic and print that encouraged me to write this book.

In 2007, the fourth edition of Dungeons & Dragons was announced. The latest version of the original pen-and-paper role-playing game promised a digital initiative that would eventually allow players to game with each other online. Years after this possibility was promised, we’re still waiting for D&D to come full circle, embracing the adventuring medium that it inspired and allowing players from all over the world to become part of the largest Fellowship of all ... the Internet.

But there is one additional level of immersion. Rather than using imagination alone to create a character or computer graphics to depict one, why not dress up as the character? In a LARP, the player IS the character. The player is playing a role, but his features, attire, and actions all translate to some ingame effect. With LARPing, there is a delicate balance between character and player, just as actors struggle with their roles. That intersection means less control over the game’s presentation. A fact I learned all too well in my first LARP experience.

Structure

This book is structured in order of fantasy inspiration. Beginning with Tolkien’s works, we follow the path of gaming evolution to miniature wargames, which in turn birthed tabletop role-playing games. From there multiple paths diverge into interactive fiction, play-by-post, and CRPGs. MUDs and MMORPGs follow. We finally end with LARPs, which have developed along their own divergent path.

Throughout, I attempt to trace a common historical narrative and compare it to my own personal experiences. Although I have played many different games, I have not participated in every piece of gaming history in this book. Whenever possible, I have asked players, designers, and game scholars to fill in my gaps of experience. Each chapter is broken down into the following sections: History, Fellowship, Narrative, Personalization, Risk, Roles, and Status.

The history section provides a necessarily brief overview of the history of each gaming medium. The murky history of gaming is fraught with contradictions for many reasons, not the least of which that it is in designers’ best interests to “be first” to protect their intellectual property. When a game is published, when its manual was published, and who exactly owns what elements of a game’s intellectual property are beyond the scope of this book. Each history section is by no means the final word on gaming. Other authors have devoted entire works to just one gaming medium, like Barton’s Dungeons & Desktops, an extensive overview of computer role-playing games, and Nick Montfort’s exploration of interactive fiction in Twisty Little Passages. My goal is to show the commonality amongst the various gaming mediums.

The fellowship section covers how teamwork is a fundamental part of role-playing games. We review how players find each other in the game, how they work together as a team, and the support that each game provides for team play.

Narrative focuses on the overall message that games convey through ingame influences and the game’s interface. Games that claim to be about story might undermine that goal by giving players endless opportunities to just kill monsters. Role-playing games that promise an immersive experience but offer “+1 swords of fire” are falling short of their promise. Narrative encompasses the world, the key concepts as outlined by developers, inherited by the cultures they live in real life, and influenced by popular tropes laid down by Tolkien and other early fantasy authors.

The personalization section reviews the extent to which the game is modified to suit the players’ needs. In a novel this doesn’t happen at all, but in interactive games it is one of the defining characteristics. CRPGs cater exclusively to the player, personalizing the game to his needs. On a more dynamic scale, tabletop game masters provide personalized content as appropriate for their group, balancing a huge variety of variables to find a common ground between all participants.

The risk section provides the motivation for characters to exist in the world. It binds them together and encourages them to work in groups; provides a common foe for them to defeat and a means of advancing through successive wins against said foe. We focus primarily on heroic fantasy, which by necessity involves violent conflict.

The roles section covers a wide variety of topics, including the gender, race, and class of a player’s character. These roles can be strictly or loosely defined, determined by the narrative or by the player. They are divided into creator roles, participant roles, and character roles. The depth of a role tells as much about the game as it does about the player. Roles with more extensive information about the character require more of an investment by the player— those that provide very little information rely almost exclusively on the player to fill in the blanks. I also cover the demographics of the players themselves and the meta-game roles they take on to play the game.

The status section also includes levels, social status, and advancement. Leveling and advancing in power is a distinctly American concept that we’ll explore in more detail later. Status is associated with this increase in power in multiplayer games, as it provides a pecking order of sorts that is overtly and subtly encouraged by the game itself.

Gaming has taken some surprising turns over the years. The goal of this book is to trace the origins of the Fellowship and its application for characters and players in a text-based, graphical, online, and in-person medium. By examining how fantasy gaming has evolved across mediums, much can be learned about what the future holds in store for our own Fellowships, be they in fantasy lands or around dining room tables.

ONE

THE LORD OF THE RINGS

How did it influence the D&D game? Whoa, plenty, of course. Just about all the players were huge JRRT fans, and so they insisted that I put as much Tolkien-influenced material into the game as possible. Anyone reading this that recalls the original D&D game will know that there were Balrogs, Ents, and Hobbits in it. Later those were removed, and new, non–JRRT things substituted—Balor demons, Treants, and Halflings [Gygax 2007].

Introduction

The structure of John Ronald Reuel (J.R.R.) Tolkien’s Fellowship was first established in The Lord of the Rings. The Fellowship consisted of nine individuals and it encompassed elves, humans, hobbits, dwarves, and a being that might be considered an angel of sorts (Gandalf). The number was chosen to counter the nine Ringwraiths who opposed them.

Each member of the Fellowship represented their race. Legolas embodied the typical elvish traits of archery and stealth, Gimli represented the raging dwarvish warrior, and Boromir was an analogue for humanity in all its selfishness and nobility. These characters established archetypes that would shape the fantasy games that followed.

In gaming, the term “Fellowship” is archaic. The more common reference is “party,” short for “adventuring party.” “Group” is also commonly used in massive multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs). Though they vary in composition, the party is a fantasy staple that has been consistent across gaming mediums. And all of them have their roots in Tolkien’s Middle-earth.

The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings helped shape fantasy games through Tolkien’s obsessive attention to detail and world building. Unlike typical “sword and sorcery” novels, Tolkien’s works spanned epic struggles, incorporating realworld languages and mythologies. This is not to lessen the contributions of other authors to fantasy gaming—Robert E. Howard, Michael Moorcock, Fritz Leiber, and H.P. Lovecraft are all major contributors—but rather to emphasize the importance of Tolkien’s contribution to what would later be termed “high fantasy” (Barton 2008:18).

Although Dungeons & Dragons largely emulated Middle-earth and its peoples, two game companies had explicit rights to the world’s license: the Middle-earth Role Playing (MERP) game from Iron Crown Enterprises (1997) and Decipher’s The Lord of the Rings Roleplaying Game (2002). Middleearth Role Playing used a streamlined version of the Rolemaster rules. Of the two, The Lord of the Rings Roleplaying Game has more in common with the latest iterations of Dungeons & Dragons. Despite both games being created long after Dungeons & Dragons, the two systems provide an insightful filter in translating Tolkien’s vision to a game world.

I am not a Tolkien scholar. My knowledge of Tolkien is limited to reading The Hobbit, the Lord of the Rings trilogy, seeing Peter Jackson’s films many times, and role-playing games that have incorporated Tolkien’s world into their system and setting. My goal in this book is to draw a connection between roleplaying games and their ilk from Tolkien’s vision, not to provide an expansive analysis of his work—a task left to far more qualified scholars.

Fellowship

Although the lone hero is popular in fiction and simplifies plotlines, roleplaying games create heroic narratives through cooperation. The Fellowship created the foundation of what great tales are made of: a community of diverse races, cultures, professions, and aims brought together for the greater good.

As mentioned previously, the number of members of the Fellowship was created to counter the number of Ringwraiths. And yet this trope has not carried over to the traditional fantasy adventuring party. Traditional Dungeons & Dragons suggests two to six characters (Slavicsek 2005:12). The Middleearth Role Playing game features four players in its example of play. The Lord of the Rings Roleplaying Game features just two players in its example, considerably less than the Fellowship’s nine, but counsels having separate and distinct characters to avoid overlap (Long 2002:76).

The Fellowship number of nine doesn’t translate well across fantasy genres. Even Tolkien broke the Fellowship up into smaller, more manageable groups. Older Dungeons & Dragons adventures detailed up to ten members of the adventuring party as sample characters, implying that all ten might be played at once.

The number of characters played in a Dungeons & Dragons game is often restricted by the number of players available. Nine players are hard to find, much less cram into one room. A survey of gamers at ENWorld indicated that 62 percent played with five or six players (Lorne 2007). Less than 2 percent numbered over eight members, a far cry from Tolkien’s original vision. In comparison, World of Warcraft limits the maximum party to five (WoWWiki Staff 2010).

Narrative

What Tolkien achieved in his epic works stretched the boundaries of standard novels and plot structure. The world was as much an important part of the action as the characters that lived in it. Game developers are attracted to this form of world-building because it enables spatial storytelling, which in turn lends itself well to multiple entry points in the narrative—an important part of multiplayer gaming in particular. These fleshed-out worlds provide a stage for game developers to perform their art (Jenkins 2004:122).

The Lord of the Rings established the basic outlines of a quest: disparate characters with a foe in common come together to destroy him by retrieving an object that represents his power (Harrigan and Wardrip-Fruin 2007:3). This standard quest is sometimes known as a “fetch” quest in computer gaming parlance. There are usually weaker but no less formidable minions defending the evil nemesis and his object, sometimes numbering nine, sometimes less. Other quests involve defeating each of them in turn, descending through dungeons or progressively more dangerous areas until the final climax. Sometimes this is a two-step process; retrieve the item, then destroy the villain with it (Barton 2008:32).

Middle-earth’s narrative includes a strong sense of history, respect for nature, clearly defined forces of good and evil, and fear of power, death and corruption.

Tolkien’s world is suffused with history. It is present in every scene, every character, every conflict. The setting beyond ancient; it is a world that has been long lived in, with all characters keenly aware of their lineage and their place within it (Long 2002:256).

Middle-earth is also very much in touch with nature. It is filled with natural, breathtaking settings, and the land is as much a character as the protagonists. The world physically responds to morality, flowering in the presence of good and withering in the presence of evil.

These dichotomies of good and evil clearly designate which side is which, a theme that has continued throughout the Dungeons & Dragons alignment system (Buck 2003). Orcs are the opposite of elves. Minas Morgul and the Nazgul oppose Minas Tirith and Gondor. Gandalf opposes the Balrog.

Middle-earth has a clearly defined evil power that can only be defeated by great force (Smith 2007:155). This tradition, steeped in Tolkien’s work, has been criticized by M.A.R. Barker, author of the Empire of the Petal Throne game, as a “gentlemanly evil.” At heart, the conflict between good and evil is also governed by a sense of fair play, whereby force can be combated by equal force and terrorism is not utilized (Fine 1983:78).

The force of evil is an inherent trait. Once someone turns to evil, he is irrevocably corrupt. There are no good orcs or nice dragons in Middle-earth, and that’s on purpose. As The Lord of the Rings Roleplaying Game puts it, “They aren’t misunderstood, the victims of non-nurturing cultures, downtrodden and oppressed members of the lower class, or anything like that.” (Long 2002:259).

Death is a key part of The Lord of the Rings, a recurring theme that becomes humanity’s obsession. The loss of a child, embodied by a parent’s grief as well as the death of the future, is a plot device Tolkien uses to powerful effect (Crawford 2007:169). Death is an ever-present threat, embodied by the “undead” that are so ubiquitous in role-playing games. In The Lord of the Rings death is greatly feared and that fear drives much of the selfish acts of humanity (Fahraeus 2007:273). Even immortal beings like elves see a decline in their civilization. Contrast this with games where player character death is a minor inconvenience at best.

Another recurring theme is the contrast between fate and free will. Gandalf makes pronouncements about choice throughout the story, which ultimately leads to the destruction of the Ring, reinforcing the importance of the hand of fate. Similarly, Frodo and Bilbo’s decisions to keep or give away the ring are signs of their ability to exercise free will (Long 2002:50).

Curiously, another major theme lacking in most fantasy descendants of Tolkien’s legacy is the corruption of power. Gandalf, Elrond, and Galadriel all reject the power of the ring. Few fantasy games have penalties for a rise in power; instead, they reward it. A player with an all-powerful ring would be envied rather than considered a threat.

The two aspects of standard fantasy gaming tropes that clash considerably with Middle-earth sensibilities are the endless quests for treasure and the use of magic. Treasure-seeking is a holdover from Robert E. Howard’s Conan (Paradox 2010) and Fritz Leiber’s Gray Mouser (Crawford 2010). While treasure is an important part of The Lord of the Rings and specifically The Hobbit, it is not the only reason to adventure.

Magic, on the other hand, poses a challenge in translating Middle-earth into fantasy gaming. It is not meant to be used lightly, and certainly not by weak-willed humanity. As demonstrated by the corrupting power of the One Ring, men are entirely unsuited to wield magic in its most powerful forms; powerful magic is a particularly strong temptation (Riga 2007:211). Gandalf exhibits great restraint precisely because using magic is dangerous. The fear of corruption is entirely at odds with the standard fantasy gaming wizard. The fireball-hurling wizard was heavily inspired by Jack Vance’s Dying Earth series (Wetzels 2002). Today’s adventurers have no such compunctions.

Personalization

At first blush, it may seem that The Lord of the Rings has little in common with tabletop role-playing games except for fantasy elements like elves, dwarves, and wizards. As Nick Montfort states in Twisty Little Passages (2003:75), “The extent to which Dungeons & Dragons is inspired by J.R.R. Tolkien’s work has frequently been misunderstood and overstated.” Officially, “D&D was not written to recreate or in any collective way simulate Professor Tolkien’s world or beings ... this system works with the worlds of R.E. Howard, Fritz Leiber, and L.S. de Camp and Fletcher Pratt much better than that of Tolkien” (Kuntz 1980:22).

And yet Dungeons & Dragons and The Lord of the Rings share a common heritage that goes beyond the attributes of certain fantasy races. Although Gygax admitted that Dungeons & Dragons was not designed with Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces in mind, he also recognized that the monomyth is strongly present in fantasy role-playing games (Office of Resources for International and Area Studies [ORIAS]).

In the monomyth, the hero receives a call to adventure, usually at the behest of a guide. The threshold of adventure takes place in a particular setting where the hero faces a difficult task. He overcomes it with some supernatural assistance. During his adventure, he makes “father atonement”—usually to a father-like figure or government authority.

In return, the hero receives a token of his heroism, monetary or honorific. His triumph, or apotheosis, is the climax of the adventure. The hero returns home to rest and recuperate. The adventure has been completed, his heroism acknowledged, and the cycle begins again. All these elements are present in The Lord of the Rings and fantasy literature in general (1989:166).

Risk

The novel and the role-playing game share more than just fantastical literary artifacts. As Janet Murray explained in First Person (2004:2), novels and games share two structures, the contest and the puzzle.

The War of the Ring provides the backdrop for a multitude of contests. A key staple of Dungeons & Dragons and its successors is a strong combat element, such that a new player could be forgiven for assuming that the games constitute nothing but battles.

The riddle, from the Anglo-Saxon “raedan,” which means to advise, guide, or explain (Montfort 2003:4) is the literary precursor to ergodic fiction. By posing a riddle, the author challenges the protagonist as well as the reader. Both are invited to solve the problem, although the outcome is inevitable in literature. Specifically, the situational puzzle, in which a situation is described and the listener is challenged to give the full context of the description, is perhaps the closest riddle form to interactive fiction (2003:41).

In The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien frequently uses riddles and prophecies to provide twists in the story. The inscription on the One Ring and the prophecy associated with it is a challenge to the reader to predict the outcome of the tale, and ultimately Tolkien’s to solve. Tolkien included several other riddles in his stories, from “Speak friend and ye shall enter” to “No man will kill the witch king.”

For those systems that either deemphasize combat or provide alternatives to it, the puzzle is a strong element in the various forms of role-playing games. This is most prevalent in systems that do not easily convey combat, like textbased interactive fiction. Zork, for example, consisted almost entirely of riddles and challenges between the game designer and the player, who had to figure out the “right” way to succeed.

The novel and interactive fiction intersect in Choose Your Own Adventure books, which allow the player to read a story usually involving traditional conflict, but resolve it through puzzle solving and trial and error. We will discuss gamebooks and interactive fiction in a subsequent chapter.

Roles

First recorded in English in 1606, the term “role” has its roots in the Old French word “rolle.” It refers to a roll of parchment or a scroll, and more specifically to the text from which an actor learns his part. There are both creator roles, who help invent the narrative that the participants experience, and participant roles, who receive that experience and explore it.

Creator Roles

In fiction, creator roles are limited to the authors. It’s possible for there to be other creators, but the more control a reader has over the fiction—in essence, becoming a co-creator of the work—the more the book can be classified as interactive fiction, which we will discuss in a later chapter.

Author

In Synthetic Worlds, Castronova highlights Tolkien’s conceptions of world builders—the gods—as “subcreators,” who are in turn subservient to one overall creator. They undertake this act as a divine calling of sorts, the urge to create surpassing petty selfish concerns. Castronova postulates that Tolkien’s invention of “subcreators” was the author submitting his own framework for creation as a channel for his beliefs of the One True God (2005:308). In essence, God begat Tolkien, Tolkien begat deities in his fictional universe, who begat other characters, and by knowing these characters the reader gets a better insight up through the lineage of creation in God’s mysterious works. The role of author is not unlike the role of game master in this regard, as even the deities of the universe are merely an extension of the game master’s persona.

Participant Roles

Like the creator role, the participant role is relegated to just one: the reader.

Reader

Unlike the fantasy games that would come later, reading The Lord of the Rings is a solitary experience. The reader is an observer. And yet the reading experience still fits into the media richness scale. It is not mutable; unlike interactive fiction, the text is set on the page. Mackay posits that a player who reads text is transformed by it. The reader’s everyday self is reconfigured into a reading-self through the filtered experience of the reader, but restructured according to the text. The reading self is thus a manifestation of the reader’s imagination, formed through a series of guidelines set down by the author of the text (2001:66).

One important difference between role-playing and reading a novel is the agreement between another reader’s interpretations of the text. Reading is an intensely self-centered experience, an effect mirrored in computer role-playing games that are entirely focused on catering to the player.

Role-playing requires some sharing of vision, imagination, and basics of communication between two or more participants. While a reader may place herself in the shoes of the protagonist, in a role-playing game she encounters other characters that are in turn projections of their players. Even if the character is described in the broadest strokes of race and gender, there must be some agreement for the players to interact. In this shared fantasy, all the players must agree on the basics of interaction.

Character Roles

Unlike role-playing games and other forms of fantasy gaming, there is no distinction between player and nonplayer characters in fiction. There are just characters. There may be a protagonist for whom the narrative is filtered to tell her story, or an omniscient narrator may move from character to character, sharing each character’s perspective in turn. Montfort (2003:33) terms these characters “persons,” as they are a necessary part of the story but cannot be interacted with. They are the cornerstone of the reader’s role in the fantasy universe.

The Lord of the Rings Roleplaying Game from Decipher quantifies the characteristics of the heroes of Middle-earth as compassion, responsible free will, generosity, honesty and fairness, honor and nobility, restraint, self-sacrifice, valor, and wisdom (Long 2002:51).

The struggle over the One Ring in The Lord of the Rings is all about free will. The Ring has the ability to corrupt those who wear it, and only those with strong wills can turn away from its temptation. Free will is an important part of self-sacrifice, the ability to put one’s own personal needs aside for the greater good. Frodo and Boromir sacrifice much in the War of the Ring.

Compassion is demonstrated by Gandalf, who pities Gollum and even spares the foul Saruman’s life. The heroes also exercise restraint of arms, slaying foes only in armed combat and meeting them head on.

Other characteristics epitomize the true hero: speaking truthfully and honestly, standing by one’s word, and treating others fairly regardless of station. Generosity is demonstrated by Theoden’s gift of Shadowfax to Gandalf in a time of need. Although the acquisition of treasure is a recurring theme in The Lord of the Rings, the heroes don’t seek wealth out of greed—a sharp contrast from the Conan series and a major diverging element from Dungeons & Dragons. Finally, the members of the Fellowship possess wisdom, understanding powers beyond their ken—the refusal by several powerful beings to use the Ring against Sauron being a prime example.

Races

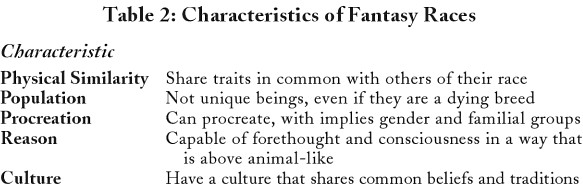

Unlike its usage in modern times, the term “race” in gaming represents a species. Race is one of the most basic attributes in defining a character in fantasy literature. Andrew P. Miller and Daniel Clark (1998:155) distinguish fantasy races from fantasy creatures by the following list:

The simplification of racial archetypes in The Lord of the Rings is understandable. Identifying members of the Fellowship by race helps identify their origins, clearly delineating their political and national allegiance. The Fellowship is as much a League of Nations as it is an adventuring party, dedicated to achieving a common goal that has far-reaching political ramifications. They are not merely after loot and prestige. These adventurers are out to save the world.