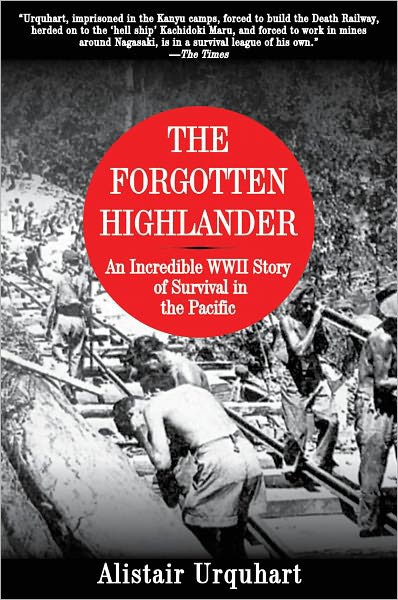

The Forgotten Highlander

An Incredible WWII Story of Survival in the Pacific

Alistair Urquhart

Copyright © 2010 by Alistair Urquhart

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 555 Eighth Avenue, Suite 903, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 555 Eighth Avenue, Suite 903, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

9781616081522

Printed in the United States of America

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Introduction

One - Will Ye No Come Back Again?

Two - Jealousy

Three - Land of Hope and Glory!

Four - Death March

Five - Hellfire Pass

Six - Bridge on the River Kwai

Seven - It’s a Sin to Tell a Lie

Eight - Sentimental Journey

Nine - Back from the Dead

Acknowledgements

Index

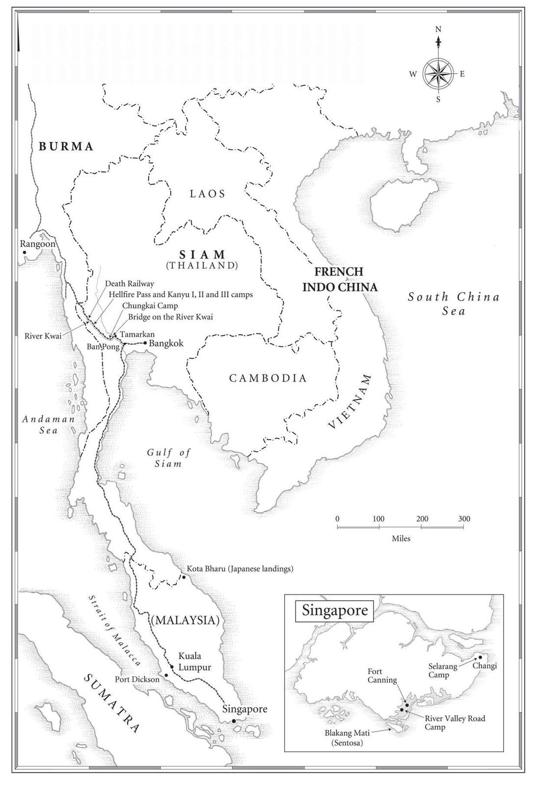

Singapore and the Thai-Malay Peninsula, during the Second World War

Introduction

As one of the last survivors of my battalion of the Gordon Highlanders, the majority of whom were either killed or captured by the Japanese Imperial Army in Singapore, I know that I am a lucky man.

I was lucky to survive capture in Singapore and to come out of the jungle alive after 750 days as a slave on the ‘Death Railway’ and the bridge over the river Kwai. Surviving my ordeal in the hellship Kachidoki Maru and, after we were torpedoed, five days adrift alone in the South China Sea, perhaps stretched my luck. So too my close shave with the atomic bomb, when I was struck by the blast of the A-bomb dropped on Nagasaki.

My story may be remarkable but for over sixty years I have remained silent about my sufferings at the hands of the Japanese. So many of us former prisoners of war did, and all for the same reasons. We did not wish to upset our wives and families, and ourselves, with unsettling tales of unimaginable torments. The memories that made us dread the nightmares which came with sleep were just too horrific. And on our liberation we all signed undertakings to the British government that we would not talk about the war crimes we witnessed or reveal what we saw in the atomic wasteland of Nagasaki.

Now I am breaking my silence to bear witness to the systematic torture and murder of tens of thousands of allied prisoners. After the death of my wife, Mary, I wrote down a personal record of everything that had happened to me as a prisoner. It was a distressing experience and at times writing this book has also been painful.

My business with Japan is unfinished, however, and will remain so until the Japanese government fully accepts its guilt and tells its people what was done in their name.

For as well as being a lucky man I am an angry man. We were a forgotten force in Singapore that vanished overnight into the jungles of Burma and Thailand to become a ghost army of starved slave labourers. During the Cold War those of us who survived became an embarrassment to the British and American governments, which turned a blind eye to Japanese war crimes in their desire to forge alliances against China and Russia.

It was our great misfortune as young soldiers to be swept into the maelstrom of the now largely forgotten Asian holocaust planned and perpetrated by Japan’s militarist leaders. We were not just prisoners but slaves in Japan’s vast South-East Asian gulag, forced to become a vital part of the Emperor’s war effort.

Millions of Asians died at the hands of the Japanese from 1931 to 1945. Like the allied prisoners, the British, Americans, Australians, Dutch and Canadians, they were starved and beaten, tortured and massacred in the most sadistic fashion.

Some time ago I saw a television documentary in which a Japanese railway engineer revisited Hellfire Pass, where we slaved and died on the Death Railway. He claimed that nobody had died and that prisoners had been well cared for. The prisoners and press-ganged natives who worked on the railway died in such vast numbers that to me this was equivalent to Holocaust denial. This book is my answer to those who would doubt the scale and awfulness of Japan’s murderous policies during the war.

Germany has atoned for the holocaust its Nazis conducted in Europe. Young Germans know of their nation’s dreadful crimes. But young Japanese are taught little of their nation’s guilt in the death of millions of Asian people, the enslavement of Korean ‘comfort’ women, the Rape of Nanking, the Bataan Death March, the extermination of allied prisoners on Sandakan, the revolting human ‘experiments’ conducted by the Japanese Army on prisoners in Unit 731 and the use of slave labour on the Death Railway.

Japan’s reluctance to admit its crimes has now become a major issue in the red-hot crucible of South-East Asian politics, and rightly so. Both China and Korea have objected to Japanese school textbooks that underplay war crimes committed by the Japanese Imperial Army.

In September 2008, at the ripe old age of eighty-nine, I travelled to San Francisco to be reunited with an old friend – the USS Pampanito, which torpedoed the hellship Kachidoki Maru. I took part in a remembrance ceremony on Sunday 14 September 2008 exactly sixty-four years to the day after we were sunk in the South China Sea en route to Japan from Singapore. I stood in the control room where Lieutenant Commander Paul Summers, captain of the submarine, had tracked the Kachidoki Maru, moved in for the kill and given the order to fire. I also stood in the forward torpedo room from where five torpedoes were fired at me on that fateful night when so many poor souls lost their lives. As I watched tourists from across the world take snapshots of the grey instrument of war, I tried to make sense of it all. I could not explain why I had wanted to come to San Francisco and put myself through a lengthy flight but I had felt it needed to be done. I felt I had to lay some demons to rest, sink them to the depths like the hundreds who lost their lives in that faraway sea. It was a therapeutic process, much like writing this memoir.

Of course both mentally and physically I have never fully recovered from my experiences. In the early years after the war the nightmares became so bad that I had to sleep in a chair for fear of harming my wife as I lashed out in my sleep. My nose had been broken so often during beatings that I could not breathe through it and required surgery. The tropical diseases that racked my body gave me pain for many years and have made me a guinea pig still for the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. I have never been able to eat properly since those starvation days and the stripping of my stomach lining by amoebic dysentery. All these years later I still crave a bowl of rice. In my seventies I developed an aggressive cancer that doctors believe may have been linked to my exposure to radiation at Nagasaki. The skin cancer I am currently battling is unquestionably the result of slaving virtually naked for months on end in the tropical sun.

My time as a prisoner of the Japanese helped shape and determine my path in life just as much as my childhood did. Like it or not, the horrors did happen to me and to thousands of others. Yet some good has come out of it. My ordeal has made me a much more patient, caring person. Inspired by the devotion of our hard-pressed medics on the Death Railway I was able to care for my young daughter when she was ill and for my late wife, who required twenty-four-hour attention in the last stages of her life. While in Japan, and working with my friend Dr Mathieson, I vowed to spend the rest of my life helping others and I am pleased to say that I have done so. It is where my satisfaction comes from nowadays.

I have tried to use my experiences in a positive fashion and have adopted a motto from them, which I never tire of telling others: ‘There is no such word as “can’t”.’

I have not allowed my life to be blighted by bitterness. At ninety years of age I have lived a long life and continue to live it to the fullest. I enjoyed a long marriage to my wife and I have been fortunate to have a family and to enjoy their success. I have amazed my doctors, my friends, my family and myself by remaining fit and still enjoying my passion for ballroom dancing. I have found companionship too, with Helen, my dancing partner. We run tea dances together and help and support each other. I keep myself alert by painting and teaching my fellow senior citizens how to use the internet. I am grateful for my present way of life, after all the turmoil that life has thrown at me – and thankful to have retained my sense of humour.

Most importantly I now visit schools to tell pupils of what really happened in the Far East during those terrible war years. In my ninety-first year I am fortunate enough, despite the best efforts of the Japanese Imperial Army, to have the vim and vigour required to tell a new generation of how we suffered.

Scandalously our sufferings, which have haunted all of us Far East prisoners of war throughout our lives, were only recognised by the British government in the year 2000, when it offered compensation of £10,000 to the remaining survivors. Unbelievably the British taxpayer had to pay out that paltry sum not the culpable Japanese government.

I hope that this book will stand as an indictment of the criminal regime that ran Japan during the war years and the failure of successive Japanese governments to face up to their crimes.

But I hope too that it will be inspirational and offer hope to those who suffer adversity in their daily lives – especially in these difficult times.

Life is worth living and no matter what it throws at you it is important to keep your eyes on the prize of the happiness that will come. Even when the Death Railway reduced us to little more than animals, humanity in the shape of our saintly medical officers triumphed over barbarism.

Remember, while it always seems darkest before the dawn, perseverance pays off and the good times will return.

May health and happiness be yours.

Alistair Urquhart

Broughty Ferry, Dundee

July 2009

One

Will Ye No Come Back Again?

Everyone remembers how they heard the news. On the morning of 3 September 1939 I was working at the warehouse. As I scuttled around the empty cavern of a building, the sound of my footsteps echoed off the high tin roof. At either end the main doors, which allowed the trucks and carts to drive straight through for loading, were closed. I had the place to myself. It was a Sunday and I wasn’t meant to be working but I was an ambitious young apprentice of nineteen, keen to make my way in the world and to get on. The older men, workers who had been with the firm all of their days, said that if you rolled your sleeves up and kept your mouth shut, you could have a job for life. It sounded good to me. For a lot of people the thirties were still ‘hungry’ and you counted yourself very lucky to have a job ‘with prospects’.

I had been in the warehouse since 8 a.m., making up loads for the lorries, to beat the Monday morning rush. Better to get ahead of the game than to chase your tail later. If a job’s worth doing, it’s worth doing well and all that. At around a quarter to twelve I was searching for crates high on the mezzanine floor that looped around the draughty walls, when I heard footsteps below on the concrete. I tensed up as a voice shouted, ‘Who’s up there?’

The stentorian tones of the managing director were unmistakable. The big boss! He had slipped in unnoticed through the side door.

‘It’s just me, Mr Grassie,’ I said nervously, stepping out of the shadows to peer down at my boss and his furrowed brow.

John Grassie looked at me incredulously. I was wearing my usual work attire, including a sleeveless jumper over my company shirt and tie, even though I wasn’t supposed to be there – Lawson Turnbull & Co. Ltd paid no overtime.

‘What in God’s name are you doing here, laddie?’ demanded Mr Grassie. ‘Get off home. Don’t you know war has been declared? Your family will want you home.’

I did not really appreciate the gravity of those words: ‘war has been declared’. I certainly had no conception of how they would change my life. But there was a strange urgency in his voice that made me obey Mr Grassie instantly. He locked up behind me as I set off on my old bike to make the seven-mile journey home. As I hurtled along the deserted streets my mind raced with the possibilities. Chief among them: Would I be called up?

I lived with my parents, auntie, sister and two brothers in a newly built granite bungalow on the western fringes of Aberdeen, the ‘Silver City of the North’ as it was styled by dint of its glinting granite buildings. When I got home Mum and Dad, Auntie Dossie, my older brother Douglas, younger brother Bill and younger sister Rhoda were all in the living room, grimly gathered around the wireless set.

Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, who only months before had promised ‘peace for our time’, had just announced that Britain was at war with Germany. I was born in 1919, the year that the First World War, ‘the War to End All Wars’, had officially been concluded. Now here we were a mere twenty years later taking up arms against the same foe. The irony was not lost on me.

After the disaster of the First World War, my father never imagined the powers that be would be stupid enough to lead us into another one. But it transpired that Chamberlain was no match for Hitler. When the conversation inevitably came around to conscription, Father turned to me and said, quite straight-faced, ‘At least your surname begins with the letter “U”. You’re at the end of the alphabet and the war will be over when they get to you, son.’ I thought ruefully of the troops in 1914 who were told they would be ‘home by Christmas’ and kept my doubts to myself.

Unlike so many in the north-east of Scotland, the Urquharts were not a military family. Indeed the motto of the ancient Urquharts was curiously unwarlike for a Highland clan and its admonition to ‘Speak well, mean well, do well’ could have been written specially for us. My father George was an exceptional mathematician and a teacher of English and Latin at the private commercial college he had helped to found in Aberdeen. He was a clever man. Born the son of humble textile mill workers in the Angus county town of Forfar, he had won a scholarship to the local academy and for the times his progress was an unusual example of social mobility. He was the only one of fourteen siblings to make it out of the mill. But he was systematically diddled by a business partner and his ambitions were never fulfilled. Accordingly we lived in what were politely referred to at the time as ‘straitened circumstances’.

Dad had started the business school with a fellow teacher called Billy Trail. While Dad headed the general education side of the college, Mr Trail was in charge of the clerical school, which taught typing and office skills. Mr Trail became a very close family friend. It was the third partner, Mr Wishart, the one who looked after the finances – a little too well – who did the diddling. In the early 1930s it became apparent that there was not enough money in the business account to pay the wages. Dad and Mr Trail confronted Mr Wishart. He said he would sort the situation immediately. The books were soon corrected but the thieving had gone on for many years. The police should have been called but neither Father nor Mr Trail was very business-minded and they just got on as best they could.

During the First World War Dad had become the first in our family to enlist in the British Army when he joined Aberdeen’s local regiment, the Gordon Highlanders. Like so many others of his generation, he would know the horrors of the Battle of the Somme and was discharged on medical grounds in 1916, having been gassed and suffering from shellshock. In later life whenever there was a clap of thunder in a storm he would begin to tremble and shake. As a youngster I used to wonder why he did that. It was only years after that I realised the sound brought back the terrors of trench life and the big guns booming overhead, day and night. Like many of his generation he never talked of his wartime experiences. Later, after my own hellish war, I would learn why.

On the very rare occasions the adults did speak of it they did so in hushed tones. The trenches of the Western Front were a vast, industrialised slaughterhouse – where youth was squandered in a way that the old Highlanders, for all of their bloodthirsty ways, could never have imagined. Looking back I wonder now what effect the war had on my father’s life. Perhaps before it he had been an exuberant, outgoing character, full of small talk and fun.

Certainly the father I knew was remote and distant. He had survived the Great War and the Great Depression. He was content to live out ‘a quiet life’, and small boys like me should most definitely be seen and not heard. I pressed him on his wartime experiences but he never encouraged my curiosity. The thousand-yard stare that glazed over his eyes whenever the subject came up, or when he heard the wireless’s news bulletins of faraway battles, spoke volumes.

After the outbreak of the Second World War, I went back to work as usual and waited. It did not take long. On 23 September, just a few days after my twentieth birthday, the dreaded letter from the War Office dropped through the letter box at home.

When I returned from work Mum handed it to me and with nervous fingers I opened one of the few letters that had ever been addressed to me personally. The envelope, stamped ominously ‘On His Majesty’s Service’, was addressed to ‘Mr. Alistair Kynoch Urquhart, 9 Seafield Drive West, Aberdeen’. Its contents informed me that four days hence I was to report to the Gordon Highlanders’ headquarters at the Bridge of Don barracks near the seafront on the northern outskirts of Aberdeen.

With a sinking feeling I looked at the letter again and again. But there was no mistake and no opting out. Far from being the last to be called up, I was one of the first. Suddenly the realisation hit me: ‘I will lose my job!’

Since the age of fourteen I had been working at Lawson Turnbull, plumbers’ merchants and electrical wholesalers, which stretched along most of Mealmarket Street in central Aberdeen. Previously I had attended Robert Gordon College, a well-known and prestigious grammar school, along with my brother Douglas, who was eighteen months my senior.

When my father’s income fell our parents could not afford to keep us both in study. I had a two-year bursary but when that ran out the family simply could not pay for me to attend school. To help my mother out I had to get a job and quickly. I applied for several positions and within a fortnight, even though I was shy of my fifteenth birthday and still wearing short trousers, Mr Grassie took me on as an office boy. I was so proud. Ignoring all of the usual distractions I raced home in exultation to tell Mum the good news. I was elated to start work at a wage of 5/- (25p) per week. The hours were long, 8 a.m. till 5.30 p.m. Monday to Friday, and included Saturdays till 1 p.m.; on Christmas Days we were allowed to go home at 3 p.m. But I was thrilled. It was a good job with the possibility of advancement. And I would be contributing financially at home.

To begin with I never had any one special role in the company. I just did what was required. One day I would be packing crates bound for Wick in the far north of Scotland and on the next my puny teenage arms would be hoisting cast-iron baths on to the back of flatbed trucks. I really enjoyed it apart from the cold. There was no heating in the wide-open warehouse and you still had to wear a collar and tie. I had to buy my own company coat and I would wear my collar and tie over the top. It looked ridiculous but it was better than freezing to death. I also used to stuff straw in my boots, which worked amazingly well.

The bosses believed that every employee should start at the bottom, in the dust. Those who showed any particular potential or aptitude were given the chance to learn each facet of the business, which was wide and varied. One day, after a couple of years running office errands, I was called into the managing director’s office. Full of apprehension and fearful of losing my job (something that was a sin in those days), I gingerly entered the office to be told the amazing news that I was to be offered the job of trainee warehouseman with a wage of fifteen shillings a week. Promoted upstairs to the showroom my first task was wiring and hanging electric light fittings throughout the front room. I worked in the showroom for a year serving customers who came in off the street. I really enjoyed serving the public. I sold them bathroom suites, shower cubicles, light fittings and lamps. We also had a wide selection of Royal Doulton chinaware and were renowned in Aberdeen for being cheaper than the rival shops because of our connections with their bathroom people. After a while they had me making up bathroom suites and partitions myself, so I got to become a joiner as well. After learning the ropes in the showroom I worked in the electrical department for six months. There was so much to learn. Luckily my immediate boss Sandy Anderson knew the trade backwards so I watched and listened, and soaked it all in.

There were no tea breaks and I got an hour for lunch. Most men would bring flasks to work but with no canteen area in which to take lunch communally I preferred to go home. At the lunchtime whistle I would race home on my bike. Mum would have a bowl of steaming-hot soup ready for me to devour, along with an Aberdeen ‘rowie’, the local savoury bread roll made with so much salt and butter that folk sometimes called them ‘butteries’. Then I would pedal back to work, avoiding the speeding trams and not even stopping to watch the hurdy-gurdy man, whose organ and dancing monkey had entertained and mesmerised me for hours as a schoolboy. It was a bit Dickensian but we were just so grateful to have a job.

So it was with some trepidation that I approached conscription. I loved my job and did everything I could to keep it. Around Aberdeen in those days there was not a lot of employment. The shipyards, textile factories and paper mills had all been badly hit by the Depression and we lived in constant fear of becoming ‘idle’. Knots of men, desolate and dejected, gathered at the street corners. The men who had beaten the Kaiser were defeated now – by unemployment. And we were all desperate to avoid their fate.

I was under the impression that the government had given some sort of order to the effect that jobs would be kept for men when they returned from war but these assurances all seemed very vague. There had been terrific scandals after the Great War when men, including police officers, returned home to find that promised jobs had gone. Mr Grassie, however, was adamant that his men would have jobs to return home to. He was a veteran of the 1914 – 18 war and it was important to him that ‘his boys’ go to war. It was equally important that their jobs were kept for them when they came home and he was very sincere in his determination to do this for us.

I had only four days to prepare myself for basic training. In that period my stomach churned and I shook a bit! I had not left home before and the prospect of joining up was very intimidating. In fact the furthest I had travelled was eighty miles south to Dundee, where my grandparents lived. I did not know it at the time but I would not even be allowed out of the barracks for the first six weeks of basic training.

Finally the day of departure dawned. My work colleagues had already wished me well, with some of the older men, veterans of the First World War, offering the sage advice, ‘Remember, Alistair. Keep your heid doon.’ On my last day at work Mr Grassie even shook my hand – for the first time in the six years I had worked for him.

At home Rhoda, Bill and Doug stood back, white-faced and cowed by the sudden emotion of my leaving. The adults knew the reality of war. There were lots of tears from Mum, and Auntie Dossie was inconsolable. They had lost their brother Will at the Somme and my departure brought back terrible memories. Mum sobbed quietly but Auntie Dossie cried uncontrollably and clutched at my arm.

‘Don’t go! Don’t go!’ she pleaded. ‘Oh Alistair, stay a wee while longer.’ It was an awful moment and, try as I might, I could not stop the tears rolling down my cheeks.

‘I’ll be all right, I’ll be OK,’ I replied. ‘Don’t worry, I’ll be home soon.’

Then Father intervened and shook my hand manfully, making me promise that I would ‘look after myself’. As ever he controlled his emotions and overcame whatever dreadful memories he had of earlier partings for the Great War. Doug stepped forward and imitated Dad, shaking my hand firmly. At last I wrenched myself free, swung my rucksack on my back and headed for the tram to the Bridge of Don barracks.

The Gordons had lost nine thousand men in the First World War and suffered a further twenty thousand casualties. Every family in the north-east of Scotland had been affected. Now I was taking the same road my father had taken all those years before. His journey had led him straight to the gates of hell, to the Battle of the Somme, where Britain’s ‘pals’ battalions were decimated and the army suffered sixty thousand casualties on the first day. I could not help wondering what the future held in store for me. But Dad did not offer any advice. He knew by then that I was self-reliant and that I would tackle this challenge in the same head-on manner that I had everything else.

When I got to the main gates of the Bridge of Don barracks I gritted my teeth and strode purposefully through without looking back. I put the tearful departure from home to the back of my mind and reported straight to the guardroom. A sentry volunteered to take me to the looming stone barracks. It was the coldest place imaginable, a stone’s throw from the North Sea and further north than Moscow. In the centre of the vast barracks room, which I was to share with twenty-seven other equally nervous young men, sat a dismally unlit iron stove.

As I was to find out, we would be given a weekly fuel allowance of coal and when it ran out that was it. The only warm place was the NAAFI (Navy, Army and Air Force Institute) canteen, which also sold beer, cigarettes, tea and coffee. I would occasionally relax in there to get some heat but I was not a drinker or a smoker. In fact at the age of twenty I still had not even touched a drop of liquor.

I had been one of the first to arrive in the barracks. Men continued to trickle in as we took stock of our new home and put together the iron bed frames. We were a mixed bunch, made up of farm-workers, servants, labourers, fishermen, apprentice engineers and plumbers. There were no university students or graduates. We were rough and ready. Perhaps that was why we had been selected in the first draft, the expendable? The atmosphere between everyone was a little strained to begin with. There was a lot of grumbling at lives suddenly being turned upside down and becoming regimented, and no gung-ho euphoria about fighting for King and Country. We were quiet and subdued, apprehensive and waiting for something to happen.

On that first day we were issued with our kit at the quartermaster’s store. Rough blankets, kit bag, toiletries, toothbrush, uniform, fatigues, boots, socks, underwear, cap, overcoat and a gas mask were all shoved into our grasp. Rifles came later. Some of the kit was new but most of it was very much second-hand. The uniforms were illfitting and faded, the gear rusted and tired.

After a restless first night we sprang out of bed for roll-call at 6 a.m. and gathered outside on the parade ground for physical training, or PT as it would become known. After energetic exercises on the spot, jumping up and down, and a run around the barracks square, I discovered somewhat to my surprise just how fit I was compared with the others.

I had always been very sporting. From an early age I represented my primary school at football, playing other schools on Saturday mornings and for the Cub Scouts in the afternoons. When I went to grammar school I took up swimming, rugby, cricket and athletics. On Saturdays I played rugby for the school colts in the morning, football for the Scouts in the afternoon, before gymnastics with the Scouts in the evening. I could not have fitted much more in if I had tried but I never thought anything of it.

Sunday mornings were spent at Aberdeen swimming pool, a salt-water pool down at the seafront. I was a member of the Bon Accord Swimming Club and no matter what the weather was like I would be there every Sunday at 6 a.m., shivering and keen to get stuck in. An excellent coach put us through our paces, all the swim strokes, except the butterfly, which was not even thought about at that time. I managed to complete my life-saving badge – and later all the swimming lessons really would be a ‘lifesaver’.

After a Sunday morning doing lengths in the icy water I would cycle back home and make breakfast for my mother and father, who were still in bed. I would cheerfully serve them ham and eggs with fried bread and tomatoes.

Sport and Boy Scout activities took up most of my weekends. I had joined the Cubs when I was seven and then graduated to Scouts, managing to gain my King’s Scout Badge. I took it seriously and was very proud when in 1935 our patrol won the coveted Baden Powell Flag as best troop, in competition with the rest of the Aberdeen Scout groups.

When I left school to start my working career I could not participate with the Scouts as much as I had previously but I still went to meetings on Friday nights and kept up football with them on Saturday afternoons. And I persisted with the summer camping trips, which were always a highlight of the year. We went to spots across Aberdeenshire and quite often down the coast to Montrose in Angus, a favourite for me because the town hall held a dance on Saturday nights. By that time dancing had become a major part of my life.

When I was aged six my parents dragged me off to Highland dancing classes. Reluctant at first, I came to enjoy it and progressed to tap dancing. These classes lasted until I was sixteen, when I thought about getting into ballroom dancing. I hadn’t been in a proper dance hall and wanted to know what I was doing before I went and made a fool of myself. Despite the steep cost of 2/6d (12.5p) for ballroom dance classes, which accounted for around a third of my weekly wage, I bit the bullet and went for it. On Saturday afternoons I cycled to a dance studio in Bridge Street, where the classes were led by Mr J. L. McKenzie, a first-rate professional dancer. He taught waltz, Highland and dance hall steps. He was also a very good ballroom teacher. I threw myself into it and quickly became quite proficient.

My best pal, Eric Bissett, who worked alongside me at the plumbers’ merchants, was one of the few of us who had a girlfriend. But when we went out on Saturday nights Eric and his gal always struggled with the dances and the various steps. After much pestering I relented and offered them some free tuition, asking my parents if we could use our living room as an impromptu dance studio. Dad did not approve but Mum was in favour and won the battle. She always had the final say over Father in such matters. So Eric, his girlfriend and a few other pals would come round to the house on Thursday nights for lessons. We would clear the living room, pushing the furniture to the walls, and I would teach them all to dance. After that we were always out together dancing.

The first time I went to a dance hall was a magical experience. The place was a fantastic, glittering palace with hundreds of young men and women queuing to get in. Inside, the girls were on one side of the hall and the boys were on the other side. We would all be eyeing each other up, with the boys working up the courage to cross the floor to ask for a dance. Quite often you got beaten to the girl of your choice and there would be a spat. After a while I got the hang of it and started to book dance partners. I would give a girl a dance and then ask her for the next slow dance or quickstep. If she agreed and someone else later asked her for that dance, she would politely decline and say she was already booked. I always went for the ones that I knew could dance.

The Palais de Dance was a very popular venue on Diamond Street in Aberdeen. It was a picturesque granite building purpose-built as a dance hall, with a proper floor, seating all round the edges and a balcony that served tea and coffee. It was the posh place to go, with a higher admission price and a middle-class clientele. It did not sell alcohol but most of us were teenagers or just in our early twenties anyway and we did not care for the stuff. Some of the working men would go to the pub first and then go to the dance but it was frowned upon and girls would often refuse to dance with men if they could smell liquor on their breath. If the men complained, they were thrown out.

The Palais was a happening place to be and had a great house band but my favourite venue was the Beach Ballroom on the promenade. It was a much bigger place than the Palais de Dance and the floor was sprung on chains. You could dance all night and not get tired. It was also more working-class and I felt more at home. Dances would start at seven-thirty or eight in the evening and I would usually meet my friends there. I would always say to the girls that I would see them inside – it was a polite way of saying, ‘I’m not paying your admission fee!’

On Friday and Saturday nights there would be a live band at the Ballroom. Since it was such a big venue the operators managed to attract all the big dance bands of the day, including Joe Loss, Oscar Rabin, and Henry Hall and his famous BBC band. If Joe Loss played the Ballroom on a Friday night, he would give a concert on Sunday night. The Ballroom would be filled with rows of chairs and he would play light opera and Gershwin. It was fantastic to see the top acts of the day in my hometown playing music made especially for ballroom dancing. Victor Silvester, a professional dance teacher from London, had his own band and took many tunes of the day and put them to the tempo of the fox-trot and rumba. My favourite dance was the slow fox-trot. Everyone tells me that it is the most difficult but I always found it very easy and girls would line up to dance it with me.

The dances would usually finish at 10.30 p.m. On Fridays they would have late dances, which would last until one in the morning. I had no problem dancing all night and would never sit out a dance. I would dance in my suit and never take off my jacket or tie.

If I had the money, I would sometimes take a girl I had met at the dances to the pictures. Everyone who took girls would try and sit in the back row, in the chummy seats. There was one girl, Hazel Watson, whom I danced with most. I was always trying to pluck up the courage to ask her out. She was a couple of years younger than me. Hazel was a beautiful blonde with sparkling blue eyes and she just loved to dance. She was one of the few that could keep up with me and I got to know her very well. She worked at the paper mill, ‘using her fingers’, and my group of friends would often meet up with her group on Sundays.

On Sunday afternoons Eric, myself and two other pals, Bob, a shipyard worker, and Alec, a shop clerk, would go to Duthie Park. Sometimes a trio would be playing in the Winter Gardens there and we would meet the girls we had danced with the previous night.

On Sunday nights we would go to Union Street and walk ‘The Mat’, a promenade route that took us from Holburn Junction down towards the sea to stop at Market Street, and back up again. There would be hundreds of young people doing the same thing, boys walking one way, girls coming back up the other. We would go up and down four or five times an evening, stopping in shop doorways to talk to bunches of girls whom we knew from the dancing.

My main interest in girls was whether they could dance or not. I rarely had any money to take them out anyway, so I stuck to work, dancing, sport and Scouts. Sadly there were no girlfriends for me. Nonetheless it was a happy time.

Far away dark clouds were gathering. Even in remote Aberdeen there were ominous portents, with local men volunteering to fight against Franco in Spain and violent clashes in the streets when Sir Oswald Mosley’s blackshirted fascists came to town.

When I got into the Army and basic training at Bridge of Don I was super-fit and without doubt the fittest man in my regiment. On the obstacle course I was always way ahead of the pack. If there was a quicker way of doing things, I always found it.

After the officers had put us through PT, a chillingly cold shower was followed by breakfast. Then the commanding officer would give his usual speech. He paced up and down, reciting the King’s regulations and welcoming us into the British Army. When he was done we were ordered back to the parade ground for the regimental sergeant major to have a go at us. He was one of the usual ferocious and special RSM breed to be found within the British Army and had a wonderful command of a spectacular range of foul-mouthed and highly inventive insults to bestow on his hapless new charges.

But he certainly did have grounds for ripping into us. What a right bunch of idiots we must have looked! Some men literally did not know left from right. Some boys on bayonet drill could not even stab the huge straw-filled sack suspended in front of them. Half of them couldn’t run, never mind anything else. Nothing but plodders, I thought. The apoplectic RSM would storm around looking about ready to burst a blood vessel, shouting in their faces. ‘What a shower,’ he would mutter as he shook his head and stomped off. He knew he had his work cut out for him. He was used to dealing with the regular Army. But those soldiers had volunteered for a career in the military – we were all conscripts, not even reluctant volunteers. A big difference.

During bayonet drill the officers were determined we should picture the sack as a real person. ‘It’s him or you! Give him the cold steel!’ they would shout as you charged these men of straw with your rifle jousting out in front of you. Some men would hesitate before the sack and pathetically poke or prod it, much to the fury of the officers. They urged you to ‘put your war face on’ and scream a bloodcurdling war cry as you ran up and thrust your bayonet right through the sack. I really hoped that it would never come to the real thing, face to face, but I trained as if it were ‘do or die’.

In the afternoon we had light-machine-gun drill. We learned to dismantle and put Bren guns together again, and generally get the feel for them and how they worked. The Bren gun was the ‘workhorse’ of the British infantry. Introduced in the mid-thirties, it fired up to five hundred rounds a minute of the same .303 ammunition used in the Lee Enfield rifles that we would carry. It was designed by the Czechs in Brno and manufactured in Enfield, hence it became known as the ‘Bren’ gun.

By four in the afternoon we were usually done for the day and were dismissed to our barracks. I spent the time polishing my boots and blanco-ing (whitening) my webbing and polishing the brass buttons on my tunic. Others played cards, read books and generally dodged. I took to Army life better than most. There had been discipline in the Boy Scouts and I had reached the level of patrol leader before becoming a Rover Scout, so I was used to it. Plus I had had to be disciplined for my job. But others really struggled with it. If anyone stepped out of line, the Army had some inventive punishments lined up for them. They might be given seven days of ‘jankers’, punishment duties such as performing in full kit with their rifle presented in front of them or peeling endless mountains of spuds. The most soul-destroying punishment of all was the mindbending task of painting coal white.

Eventually we received rifles for .22 shooting practice. Once adept with the small-bore rifles we progressed to .303 training in the nearby sand dunes. I had never fired a gun before and was surprised by the powerful kick that the .303 gave you. But I became a reasonable shot.

As well as the bayonet practice and obstacle courses, we trained in hand-to-hand combat. I was coping well, especially at the fitness tasks. There was a level of competition between the men, which the NCOs would try to play up as much as they could. It was more good banter than anything else but it was a healthy way to train. The NCOs were also quite obviously picking out people for the overseas draft.

Of the original twenty-eight of us, eight failed to make the grade. I was one of the unlucky twenty selected to go to war. After being selected for the draft I was immediately given seven days home leave. I had to wear my uniform in public but it was great to get back home. My own bed had never felt so warm and cosy! While I enjoyed Mum’s home cooking and being around loved ones again, I could never fully relax because I knew I would soon be leaving again. I was really leaving home this time. We knew we were being sent somewhere but we never had any inkling as to where it might be. The short stay at home gave me time to reflect on the past six weeks and on what lay ahead.

The Gordon Highlanders had a proud military history dating back to 1794, when the regiment was raised by the 4th Duke of Gordon. Many of the original recruits were drawn from the huge Gordon estates to fight Napoleon’s armies during the French Revolutionary Wars. The first recruitment campaign was assisted by the Duchess of Gordon, who was said to have offered a kiss as an incentive to join her husband’s regiment. Winston Churchill described the Gordons, who helped expand the British Empire with service on the frontiers of India, Afghanistan, Egypt, Sudan and South Africa, as ‘the finest regiment that ever was’. The Gordons were famous in and around Aberdeen and were always at the forefront of battle, a fact highlighted by their terrible losses in the First World War. I would strut around town ramrod-straight and proud to wear the uniform of my local regiment. Both terrified and excited at the prospect of seeing some action, I did my best to keep my emotions in check.

A small clue to our ultimate destination came soon after I returned to the barracks. I was sent straight to the quartermaster’s storeroom and issued with tropical fatigues and a topee. I personally had no idea where we were headed. As far as I was concerned it could have been anywhere around the Mediterranean or the African desert.

We were due to leave immediately but as luck would have it Aberdeen was hit by one of the worst snowstorms in its history. Snow piled up and trains halted. Everyone was well and truly snowed in. The pace of recruitment had picked up and, with the barracks filling up, my ‘shortened’ platoon of twenty marched to Linksfield School hall a few miles away to wait instructions. It was to become our home for a full three weeks as we waited out the snow.

To prevent us going completely stir crazy the bosses allowed us out between 7 p.m. and 10 p.m. We could not go home, even for a visit, but the fresh air did us good. I went to local dances whenever I could, even though I had to dance in my uniform. We had no one in charge of us for most of the day, until a sergeant or corporal would arrive at seven in the evening to check us in and out. I made friends with most of the men in the unit and we all got on pretty well, which helped. Thankfully there was no bullying of weaker members or cliques scheming in corners. One or two men looked to me for some leadership since I was prepared to take charge of situations. But I never really bonded too close to any of the men. I was civil with them all and I got on with my own affairs. Like so much of Army service it was a boring time.

At the end of November the snow finally lifted. We marched the four or five miles into town, down Main Street, to the railway station. On the train there were no seats for us and we had to sit in the corridors on top of our kit bags. It was freezing cold and as the train rattled south it followed the familiar route that I had sometimes taken to cycle to Dundee to see my father’s parents, retired textile workers in the Empire’s great ‘Juteopolis’, where hundreds of smokestacks from the jute mills belched out a thick pall of smoke across the city sarcastically described in postcards of the day as ‘Bonnie Dundee’.

We passed through the fishing town of Stonehaven with its picturesque harbour. Near by spectacular Dunottar Castle towered above sheer cliffs, jutting out defiantly into the grey waters of the North Sea. Here ‘Braveheart’ William Wallace had burned the English garrison alive in the castle chapel and, later, 167 radical protestants had been squeezed into a small dungeon and left to die in Scotland’s own ‘black hole of Calcutta’. I shuddered to think of it and was glad that we had moved on from the cruelty of the Middle Ages, or so I thought. Next we passed through Arbroath. The lofty ruins of the red sandstone abbey dominated the skyline, rising above the cottages of the fisher-folk in the area known as the ‘fit o’ the toon’, where each house seemed to boast a haddock-smoking shed in the backyard, producing the famous Arbroath ‘smokies’.

For a lot of people Arbroath was the spiritual heart of Scotland. In 1320 the Scots had boldly announced their determination to resist English domination. The words of the famous Declaration of Arbroath echo across the ages: ‘It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom – for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.’ Now it was us that were to be fighting for freedom and a more reluctant band of freedom fighters would be hard to imagine. William Wallace and his men may have been warriors. We were most definitely not. A collection of timid, ill-trained clerks and farm boys, we were to be pitched into a conflict that would plumb the depths of medieval barbarism – against a ruthless and blood-drenched foe with a decade of fighting experience.

As we shoogled across the Tay Rail Bridge, the piers of the old bridge poked out of the waters below, serving as an eerie memorial to all those who had drowned in the famous disaster of sixty years before. I was quite literally entering an unknown world. My thoughts turned to home and a happy childhood. Mum, Dad and Auntie Dossie would be hugging the kitchen fire now, and I smiled as I thought of Dad and Auntie Dossie bickering over who should poke the coal fire, the only source of heat in the house.

Dossie was Mum’s sister. Her real name was Kathleen but she was known as Dossie. Mum and Dossie were as thick as thieves, always laughing and joking. They would constantly be ganging up on Father. I don’t know how he managed to put up with the two of them.

My father was a very serious, regimented man. He lived his life wrapped in the security of a grey suit and a rigid routine. Every night when he returned home from work at the college Mother would have the tea ready to put on the table. Father sat at the head of the table and was always served first. Talk was strictly discouraged, as was reading. To us he was the strictest father in the world.

After dinner he would sit in front of the fire. Ignoring the incessant chatter between Mum and Dossie, he would read a library book for half an hour then put it down and pick up his card tray and play patience for half an hour. Then he would read for half an hour, play patience, and so it went on until it was time for bed. It would be the same story every night except on Saturdays, when at nine in the evening he would catch a tramcar to Castlegate. He would pop into the same pub to stand at the bar and drink a half pint of beer. Then he would go to the market, where he could buy unsold produce cheaply, and come back with some discounted fruit or meat. He did that every week – year in, year out. He was a real creature of habit.

Dad stayed an aloof figure in the household. Born in the reign of Queen Victoria, he was a product of his generation and Victorian in many ways. He maintained a stiff upper lip and whenever he went for a walk in the evenings he selected his favourite walking stick. Mum never went with him but his plain willow stick always did. He walked to work but he never used the stick in a business situation, only for pleasure. I can recall seeing a photograph of Father with around a dozen of his friends and they are all clutching walking sticks. I still have his stick and it is one of my great treasures.

My fondest memories of Dad are from the time in 1935 when we moved from rented accommodation into our bungalow in Aberdeen. He decided to convert the attic into two bedrooms and selected me as his labourer and assistant. It was a great time and I was as proud as punch. He was a marvel to watch, a real craftsman with his hands. He was about five foot six inches, slim, with light golden hair, thinning across the top, which I noticed when he crouched down to hammer in the nails. He also sported long sideburns, which both of my brothers would later imitate. He taught me how to swing a hammer properly, install joists, hang wallpaper and decorate.

After completing the conversion I shared an attic room with Bill, who was six years my junior. With such a big age difference we pretty much went our own separate ways – although I did ensure that the local bullies never picked on him when we played in the street. Bill was small and skinny and often hid behind Mother’s dress. Rhoda shared a room downstairs with Auntie Dossie. Doug, as the eldest, enjoyed the largest attic room all to himself – something that was a source of constant irritation to me.

Doug was clever and like a number of such people was rather lazy. He was very laid-back and liked reading and music, both of which were much too sedate for me. He enjoyed cricket and I teased him endlessly over its being a game for softies. Even though he was older than me, and slightly taller, I used to goad him mercilessly. ‘Softie! Softie!’ I would taunt until he snapped. He would become so angry that he would launch himself after me with a ridiculous running action, all uncoordinated arms and legs, shouting, ‘I’m going to kill you!’

But I was always too quick. I would bolt out of the house and run into our neighbour’s house, right through their living room and kitchen and out the back door to safety. The women all knew me and used to scream at me to get out but they were never really too bothered. It was all part of the game; we all got along well in a caring community.

Growing up I was not exactly a bad child but I was in trouble on a regular basis. Discipline at school was very strict. The teachers made liberal use of their ‘attitude adjusters’. Some used the cane while others preferred the fearsome Lochgelly tawse, a thick two- or three-tailed leather strap, named after the Fife mining village where it was produced and which stung for hours after it struck your wrists. I got belted frequently for talking in class but made sure I kept quiet about it when I got home to avoid further punishment. Father liked peace and quiet when he came home from work, and I was so full of energy that I used to drive him up the wall. I would run from room to room, mindlessly slamming doors or rushing past him and knocking his book off its perch. He was the disciplinarian whenever I got into trouble. He would never castigate me verbally, he would just methodically fetch his razor strop and track me down to wherever I was cowering. He would bare my backside and strap me, leaving stinging red marks. If it was a particularly dire offence, I would be sent to my room without dinner. He never shouted. I knew that if I did something wrong and he found out about it, he would punish me for it. Happily most of the time Mum and Auntie Dossie shielded my behaviour from him.

While us kids were at school and Dad at work, the house was left to the sisters. Dossie did the housework while Mum did the cooking. She was a great cook and the kitchen was very much her domain. Cooking smells would emanate from it all day and pots would bubble constantly on the stove. I can never actually remember entering the kitchen in the daytime and her not being there.

My mother, Gertrude, was the best mother I could ever have had. Mum was slightly taller than Dad, around five feet eight inches with a slim build and dark brown eyes and hair that she always wore in buns on each side of her head. She had a great sense of humour and was a terrific conversationalist. Mum’s parents were quite well-to-do. Her father was a sales representative for a big London firm and she had attended Albyn School, a private establishment in Aberdeen, where they had lived in Hamilton Terrace in the posh west end of town. She was also very musical and was a great pianist, just like my brother Doug. Auntie Dossie was musical too and a marvellous singer. On special occasions we would all gather around the piano in the lounge for a sing-song.

Mum was a real Scottish cook. Nothing went to waste and every penny was a prisoner. The Scots have a reputation for thriftiness but most of them would defer to Aberdonians when it comes to frugality. Hearty soups and broths, mince and tatties, dough balls, stovies, pies, crumbles and steam puddings were conjured up from her tight budget. People used to love visiting our house. Aside from the great food, Mum was a wonderful host. Most of the day she went around the house without her teeth in. But as soon as the doorbell rang there would be a frantic scramble to find her gnashers and pop them in – much to our mirth. She had a bubbly personality and a deeply caring side that made her aware of everyone’s existence. She always ensured the conversation flowed and involved everyone. Even when she was serving food or stirring pots she would be engaging with people and making them laugh. She was never flustered. While she had her own opinions – and would fight to make them heard – she never spoke ill of anyone.

Placid and calm, Mum was the polar opposite of her sister. Yet they complemented each other so well. They were always in high spirits when together and kept the house full of warmth and love. Rhoda took after Mother in all respects. She was like a miniature version of Mum and very much a girly girl who loved her dolls and pretty dresses, make-believe and tea parties. She steered well clear of Doug and me, especially when we were up to our rough games.

Auntie Dossie was a very bonnie woman but had never married and always lived with us. She was diminutive, barely touching five feet tall, and walked with a slight stoop. Her extraordinary shock of grey hair was the only hint that she was no ordinary person. There were times when she was more ‘dotty’ than Dossie. She was splendidly eccentric, great with us children and we all loved her.

She did have one boyfriend but after a while she ended the relationship, explaining to my mother, ‘He’s got very hairy legs, I couldn’t possibly marry him.’ Sometimes Dossie did things without first engaging the brain and nothing could encourage her to change gear. She constantly had a cheap Woodbine cigarette hanging from her mouth, even when doing the housework. The thin white fags would stick to her bottom lip and she’d natter and dust without ever removing the cigarette. She lit the next smoke with her last one. But she never smoked in front of the fire. Dad objected to the smell and she respected that.

Dossie also had the habit of rubbing her leg mindlessly while sitting in front of the fire. On one occasion while Mum, Dossie and Dad were sitting at the fire, she was rubbing away at her leg, the action becoming ever more furious. Dossie, who always sat between Mum and Dad, turned to Mother and said, ‘Gertie, I’ve no feeling in my leg.’

Mum replied, ‘You idiot. That’s my leg you’re rubbing!’

They were always laughing hilariously and prattled on for ever. But sometimes Mum was the absent-minded one. On one frosty winter morning, the day that the bin men collected the rubbish, Mum told Dossie that she was going to take the bin from the back door out to the street to be emptied. She went out, bracing herself against the chill, walked down the side path and handed it to the bin man. Back in the house she shivered and said to Dossie, ‘It’s awfully cold out there today, Doss.’

‘No wonder,’ Dossie roared with laughter. ‘You haven’t got your skirt on!’ At the realisation that she had shown her bloomers in all their glory to the bin man, Mum rushed to her room, suffering equal measures of embarrassment and amusement.

All of the kids in our street used to gather on the piece of grass down from our house to play football and cricket. During the ‘lichty nichts’, the long summer evenings of northern Scotland, we could play for hours after dinner and my parents had a job getting me inside. Auntie Dossie would have to come out and shout us in. By contrast the winters in Aberdeen were long, dark, frosty and bitter – trapping us indoors all evening. I was never one to sit and read a book and always had to have something to do with my feet or hands. I think that is why Mum gave me the job of collecting the messages from the Co-operative.

There was no pre-packaging and everything was made up to order. When you bought butter, for instance, whoever was working behind the counter would take it out and pat a golden yellow lump into a rectangle and wrap it in brown paper. All of the rice, tea, coffee, barley, lentils and things were taken out of sacks, weighed and put into paper bags. I used to love their bread. It was pan-baked and would have crusts on five of six sides. The sixth side would be white bread. On my walk back home I would pick at the warm bread and scoff it down, hoping Mum wouldn’t notice. The shop assistants in their yellow aprons were always nice, especially to us kids. There was great banter but they looked out for us, making sure our change was firmly in our grasp before we left, saying sternly, ‘Now go straight home. No dawdling.’

Eighty years later I can still remember our Co-op number – 28915. I would get sent down to buy our food – bread, milk, everything really. We had to quote that number every time we bought something. Every year there was a dividend that was paid out. The payment amounted to two shillings and sixpence in the pound so it accumulated quite well. It arrived just before we broke off for the six-week summer school holidays and Mum would buy us a pair of leather sandals and a pair of khaki shorts, which had to last all summer. We used to slide down rocks at the beach, exploring caves, climbing trees, and when we ripped them or tore holes in them it was a case of tough luck. I spent most of my summers wearing tattered and torn shorts.

I earned my pocket money by going for the groceries. Every Saturday Mum would pay me the princely sum of a penny, which after much deliberation I duly spent at the local sweetie shop, a sparkling Aladdin’s cave boasting shelves groaning with row upon row of gleaming glass jars proudly announcing their sugary contents. Granny Sookers, boilings, horehounds, barley sugar, butterscotch, pineapple chunks, eclairs, bull’s-eyes, pear drops, humbugs, candy twists, aniseed balls, Edinburgh rock, peanut brittle and Turkish delight were all available by the quarter-pound. They had trays too, for us kids, lined with sweets of all colours, shapes and tastes. I usually plumped for liquorice swirls or sometimes McCowan’s Highland Toffee, which I could savour and make last for most of the day.

As we rattled south on the train the thoughts of life in Aberdeen were a useful distraction from the tedium. Our uncomfortable journey through blacked-out England seemed to take for ever, with numerous unexplained stops and detours into sidings where the train shuddered and clanked to a halt. The country was slowly grinding into action, stretching its sinews and mobilising for war.

Eventually, after a day and a half of constant travelling in freezing and cramped conditions, we arrived at Dover early in the evening. The local ‘Betties’, the wonderful ladies of the Women’s Voluntary Service, greeted us with tea to wash down our hard-tack rations. Soon after we were ushered on to an awaiting trawler, which had been commissioned to take us across the English Channel to Cherbourg in the darkness of that very cold winter’s night. Herded on to the deck we had only our kit bags to serve as seats. Slowly the trawler edged out of the harbour and into the Channel. It was a rough crossing and my first experience of sea-sickness. Within an hour the relentless heavy swell had me, along with many others, hanging over the rails being violently sick. I decided to move up near the bridge, thinking if I went higher I might not feel as if I were dying. From out of nowhere a hand grasped my shoulder and a voice said, ‘Here, laddie, get this down you.’ The trawler captain handed me half a mug of brandy and I did my best to gulp down the burning liquid. It was the first time alcohol had passed my lips and it tasted so awful that I could not imagine how anyone could actually enjoy the taste. The captain waited until I had finished then told me to go and sit at the stern. Thanking him, I did so and felt a bit better.

By November 1939 there was a great fear of German U-boats and aircraft patrolling the English Channel so the captain prolonged our misery by zig-zagging for hours to avoid contact with submarines. Dawn was breaking when we arrived at Cherbourg. I was grateful to set foot on foreign soil for the first time. Terra firma never felt so good. At a large hall we had tea and biscuits and a few hours later were shepherded on to a train for the next part of the journey – to where we did not know. If the train down to Dover was uncomfortable, then the third-class coach of the French train was even worse. But at least we had seats this time, albeit hard wooden affairs.

We seemed to travel for days, the train stopping even more often than we had coming down through England. Everything was so different in France. Even the trains. They were more like box carriages. As we watched the endless French countryside roll past, the men became apprehensive and conversation faded away. Compared with Scotland’s majestic mountains, green hills and lochs, this part of France seemed bare and featureless.

Tired and weary, we finally arrived at a large port city that we were told was Marseilles. Billeted overnight in a school hall, we marched the next morning to the harbour and went straight on to a liner that had been converted into a troop ship. It turned out the vessel was the SS Andes, and once at sea we were told it would be taking us all the way to Singapore. I had never expected to travel in my life and now was setting sail for a distant land, one of those coloured pink on the school map of the world – to indicate that it was ‘ours’, a part of the British Empire.

Conditions on board the Andes were much better than we had experienced earlier on in the journey. There were about ten or twelve hammocks to a cabin. For most of us it was the first time we had ever seen hammocks and they took some getting used to. Getting in and out of them was especially tricky. It made for a few comical efforts, with some of the larger men jumping into their hammocks, spinning around and being spat out on to the floor! But once I got used to it, it was heaven compared with what had gone before. At least the weather was warmer, and as we had set sail from the shores of Europe an Army band on the quayside played the haunting Scottish Jacobite song, ‘Will Ye No Come Back Again?’ It brought a lump to my throat. Yet we never imagined that so many of us would not be coming back again.

We ploughed on into the Mediterranean accompanied by destroyers and other vessels in convoy – and, just as the trawler had across the English Channel, we kept changing course. Our first stop was to be Port Said at the head of the Suez Canal – a ten-day voyage away.

During the trip full Army training was in force. The day started with PT, followed by arms drill then weapons training. Between noon and 2 p.m. we had to rest. In the afternoons there was more drill and other warfare activities, with a few sessions of boat drill thrown in. This prepared us for abandoning ship. Sirens and whistles would suddenly fill the air and we had to make our way to the lifeboats, ready them and stand by. It was always a complete shambles. People forgot to bring their life-belts and men would be running all over the place, getting in the wrong positions or ending up with the wrong regiment. I just hoped it never came to the real thing or we would be in dire straits.

Movement about the ship was restricted. You couldn’t just go up on deck whenever you pleased. Much like prison, you were let out for a daily constitutional and, much like prison, there was some homosexual activity too. At first I was shocked by this. It was illegal at the time and aside from the odd joke I had never encountered it in Aberdeen. Those who were ‘that way inclined’ were quite open about it. They never bothered the rest of us and people were fairly tolerant. But we were all starting to get on each other’s nerves.

My group of twenty were the only Gordon Highlanders on board. There were Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders there too, though in truth they were Lowlanders recruited from Glasgow and around their headquarters at Stirling Castle and we did not really get on. Rivalries between regiments were common, with much name-calling and ridiculous insults relating to the Gordons’ alleged fondness for sheep. Sheer boredom led to a lot of bickering on board, even among ourselves. Tempers frayed and insults flew over the most trivial things, especially in our sleeping quarters where the steel walls amplified every sound or movement. There was plenty of petulant kicking of hammocks and cries of, ‘Can you not lie still for five minutes!’

Once we arrived at Port Said approximately half of the forces on board got a twelve-hour pass to go ashore. I was not lucky enough to get one so I stayed on board sun-bathing and by now getting a good tan, looking more like a fit and fighting man every day – or so I told myself.

The following day we sailed through the Suez Canal and into the Red Sea. Going through the canal was quite an experience. We had been taught about this amazing feat of engineering at school but it seemed so narrow that you felt you could reach out and touch both sides. By now, though, the temperature had soared and some of us longed for the snow-covered north of Scotland.

Our next port of call was the British colony of Aden (now Yemen), a strategic port and prized British base in the Gulf of Aden. Shore leave was granted to those who’d had no passes at Port Said and we went ashore in groups of a dozen or so.

It was a real eye-opener. A lot of the men had only ever seen other white people before. Growing up in Aberdeen with a busy harbour, I would often see different nationalities down at the docks but I had seen nothing like this. It was an alien world. Hawkers pestered us endlessly, selling watches and other cheap trinkets. The heat was getting to me. Blond hair, pale skin and blue eyes might have been OK growing up in the cool climes of northern Scotland but in this heat I really struggled. To my untravelled eyes the locals appeared shifty and my nose recoiled at the squalid stench of open drains, strange cooking smells and the foreign spices of the place. I was happy to get back to the ship just as soon as I could.

During our leisure time on board we played deck quoits and cards and read and wrote letters back home. But after Aden life became tenser. There was a lot of activity in the Indian Ocean and we had a number of ‘musters’, fearing that German submarines were operating there. It was the first time that I conceived of any danger and felt under threat. It had all been so unreal up until then. When we arrived safely at Calcutta, the next port of call, I was again granted leave. But I was so repelled by what I saw that I declined to go ashore. It looked a filthy, dirty, poverty-stricken place. Stores were taken on and the next day we sailed out across the Bay of Bengal and down the west coast of Burma and the Malay Peninsula.

Finally on 22 December 1939, three weeks after we had set sail from Marseilles, we arrived at our destination – the colony of Singapore. The diamond-shaped island at the tip of the Malay Peninsula was developed by Sir Stamford Raffles in the early 1820s to become the ‘Emporium of the East’. This trading crossroads was Britain’s greatest fortress east of Suez – and a terrific prize for the expansionist Japanese Empire. Protected by huge fifteen-inch guns that pointed out to sea to deter naval assault, it had become the ‘Gibraltar of the East’ and was believed to be impregnable.

As we pulled into harbour I went up on deck and marvelled at the sight. The docks were busy with ships and teeming with wiry, brown-skinned coolies heaving impossibly huge loads on to their backs to unload into the massive warehouses and go-down sheds. Behind the sheds I caught my first glimpse of Singapore’s impressive skyline, like nothing I had ever seen before. Squinting into the scorching Singapore sun, I could see rows of white buildings and dominating them all were the sleek art deco lines of the Cathay Building skyscraper, its spire reaching into the cloudless sky. I could not help thinking of the grey granite of old Aberdeen, wreathed in the freezing ‘haar’ that rolled in off the chilly North Sea. Home was a world away. But this was it, I thought. My new home. It was an exciting and exotic new beginning.

Two

Jealousy

Our knees wobbled down the gangway and, glad to set foot again on solid ground, we staggered bow-legged along the quayside to a row of Army trucks waiting to take us to the barracks. A gruff transport officer instructed us to hoist our kit bags, which contained all our worldly possessions, into the back of the small pick-up trucks.

We clambered up, eight to each green open-top truck, and sat with our feet on our bags. It was only mid-morning but the sun was high, the city already alive and raucous. I was more than glad to get off the ship. It had become so monotonous and tensions were running high. It felt a whole lot safer to be back on land. We still did not know what was in store for us but we were getting accustomed to that by now. The fear of the unknown had started to lose its edge.

Singapore was a sexy posting for British colonials, who enjoyed a privileged, bungalow-dwelling existence. They had servants to prepare their Singapore sling cocktails, grown men, known as ‘boys’, to run their households, and ayahs, native nannies, to look after their children. During the twenties and thirties the explosive growth in the automotive industry had created a terrific demand for the rubber grown in the vast plantations up-country in Malaya. The material was shipped out to Europe and North America from Singapore’s heaving port. The outbreak of war had further boosted demand for rubber and Malaya’s other great export, tin. Fortunes were being made and Singapore was a boomtown. The island even boasted its own Ford factory, the only car manufacturing plant in the whole of South-East Asia. Symbolic of Singapore’s affluence was the shimmering splendour of the Cathay Building complete with a large air-conditioned cinema. It was an opulent existence for officers and colonials, with no shortage of exotic nightlife at places like Raffles Hotel – all strictly out of bounds to us ORs as the ‘other ranks’, the non-officers, were known.

The sheer diversity of the population was amazing. To us it was a kaleidoscope of humanity. There were Chinese, Javanese, Indians, Tamils, Malayans, lots of Eurasians and even a sizeable Japanese minority, several of whom had been busy spying for their motherland. It was an ethnic melting pot and a political cauldron. Refugees from the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 had flooded in and set up aid organisations to channel arms back to the Chinese resistance.

While louche British expatriates recreated the Home Counties in the tropics and sipped their gin slings in the country club, Singapore was seething with political intrigue among groups who had very different ideas about the future of the British Empire. Malayan nationalists, Chinese nationalists and Indian nationalists vied with Malayan communists, Chinese communists and Indian communists, not to mention Japanese sympathisers. And then there were the Buddhists, Muslims, Jews, Christians, Taoists, Sikhs and Hindus!

The driver told us to hang on. It would be a bumpy eighteen-mile ride to our barracks, situated at Selarang, east of the city, past Changi village on the Changi peninsula. As we bounced along the dusty, unpaved roads, gripping on for dear life, I saw for the first time how poor the place was for the vast majority of people. As we trundled past rickety open-fronted shops and shacks, a heady mixture of tamarind, cinnamon, nutmeg, wisps of incense, frying fish and rotting fruit invaded my nostrils. Groups of Chinese men were hunched over benches clattering down mah-jong tiles with great flourishes, gambling and shouting.

The sights, sounds and above all the heat hit us like a sledgehammer. I looked at my intrepid fellow conscripts who were also soaking up their new surroundings. We had never seen anything like it. Small, tan-skinned men were standing around fires frying green bananas in their skins while others cracked coconuts with machetes, tossed their heads back and drank deeply. After passing through Singapore City and its bordering villages, we were soon in the countryside, and countless rice fields and banana plantations.

Finally at the end of the forty-five-minute journey, we arrived at Selarang, the home of the 2nd Battalion of the Gordon Highlanders. I noticed immediately that the fencing did not extend all the way around the barracks and it seemed a rather sleepy haven. As we approached the parade ground I saw five blocks of two-storey concrete barracks, with open verandas overlooking the square. Little did we realise that this inoffensive-looking complex, designed to house 820 men, would later become the scene of one of the most infamous episodes in the history of the British Army. These blocks were to be our new home and they were certainly modern and a bright change from the grim greyness of our Bridge of Don base.

Joining a regular battalion of time-served soldiers was a daunting prospect to us rookies. We unloaded our kit and were ordered to the dining room for lunch, where Chinese cooks gave us British food. After we had eaten, the commanding officer Lieutenant Colonel W. J. Graham welcomed us to Singapore. He was an authoritative figure, who quite obviously came from a ‘good’ family. He certainly spoke better English than we did. He gave us an informal pep talk right there in the dining room, welcoming us and reading a lot of the King’s regulations from his wee Army book.

He reminded us of our great traditions and the need to uphold the honour of the regiment. The Gordons seemed to have been in so many of the key battles fought by the British Army. The buttons on our white spats were black – in memory of our commander during the Napoleonic Wars. The details of his interment were taught in verse to generations of British schoolboys as ‘The Burial of Sir John Moore after Corunna’. At Waterloo the Gordons had grasped the stirrups of the galloping Scots Greys when they charged into Napoleon’s troops with the cry ‘Scotland Forever!’ – a scene immortalised in Lady Butler’s famous painting. It was certainly a hard act to follow and frankly we hoped that we would never be required to do so.

Colonel Graham then went on to speak about Singapore itself and the dark dangers that lurked therein. Pacing up and down before us innocent recruits he suddenly announced to our surprise: ‘Venereal Disease! I’m sure you all know what it is. I can tell you now that it is rife among the Chinese, Malays and Eurasians. Any soldier contracting the disease will be charged and severely dealt with.’

Talk about being punished twice for one crime!

He warned us to watch our wallets when in the city and also reminded us that the military police would pick us up and bring us in front of him if we were spotted without wearing proper uniform – including our thick, redchecked, woollen Glengarry caps, despite the intense heat.

He finished up by saying, ‘Tomorrow you will rest and draw equipment from the quartermaster’s stores and familiarise yourself with your surroundings.’

After the commanding officer’s speech we were split into our companies – A, B, C and D. I was assigned to D Company, along with three others from my platoon of new arrivals. We joined the barracks and tried to settle in. But we were the new meat and fresh targets. We got some amount of ribbing, most of it good-natured but some below the belt and bordering on bullying. Like a new football club signing entering the changing rooms for the first time, there was plenty of macho posturing and mock sexual advances towards us ‘pretty young things’. I decided to muck right in and do the best I could. I was sure that I could become a good soldier and be better than most of my tormentors anyway.

The following day, after a sleepless night, was spent mostly drawing equipment, clothing and rifle. When the officer in the quartermaster’s store handed me my rifle I thought he was kidding me on. I stared at the antique gun and turned it over and over in my hands. With utter disbelief I saw it was dated 1907 – a bashed-up relic from before the First World War. I realised that the rifle and its accompanying bayonet, along with my webbing and buttons, would require much cleaning, polishing and general elbow grease to bring it up to the standard of regular soldiers, whose long experience in Singapore gave them the edge over us.