The Game

Penetrating The Secret Society of Pick-Up Artists

Neil Strauss

THE GAME

Neil Strauss is a regular contributor to the New York Times and Rolling Stone. He is also the co-author of three New York Times bestsellers—Jenna Jameson’s How to Make Love Like a Porn Star, Mötley Crüe’s The Dirt and Marilyn Manson’s The Long Hard Road Out of Hell—and a Los Angeles Times bestseller, Dave Navarro’s Don’t Try This at Home. He lives in Los Angeles.

Dedicated to the thousands of people I talked to in

bars, clubs, malls, airports, grocery stores, subways,

and elevators over the last two years.

If you are reading this, I want you to know that I

wasn’t running game on you. I was being sincere.

Really. You were different.

“I COULD NOT BECOME ANYTHING:

NEITHER BAD NOR GOOD, NEITHER

A SCOUNDREL NOR AN HONEST MAN,

NEITHER A HERO NOR AN INSECT.

AND NOW I AM EKING OUT MY DAYS

IN MY CORNER, TAUNTING MYSELF

WITH THE BITTER AND ENTIRELY

USELESS CONSOLATION THAT AN

INTELLIGENT MAN CANNOT SERIOUSLY

BECOME ANYTHING; THAT ONLY

A FOOL CAN BECOME SOMETHING.”

FYODOR DOSTOEVSKY,

Notes from Underground

Those who have read early drafts of this book have all asked the same questions:

IS THIS TRUE?

DID IT REALLY HAPPEN?

ARE THESE GUYS

FOR REAL?

Thus, I find it necessary to employ

an old literary device…

THE

FOLLOWING

IS A TRUE

STORY.

IT REALLY HAPPENED.

Men will deny it,

Women will doubt it.

But I present it to you here,

Naked, vulnerable, and

disturbingly real.

I beg you for your forgiveness in advance.

DON’T HATE THE PLAYER…

HATE THE GAME.

MEN WEREN’T REALLY THE ENEMY—

THEY WERE FELLOW VICTIMS

SUFFERING FROM AN OUTMODED

MASCULINE MYSTIQUE THAT MADE

THEM FEEL UNNECESSARILY

INADEQUATE WHEN THERE WERE

NO BEARS TO KILL.

—BETTY FRIEDAN

The Feminine Mystique

The house was a disaster.

Doors were split and smashed off their hinges; walls were dented in the shape of fists, phones, and flowerpots; Herbal was hiding in a hotel room scared for his life; and Mystery was collapsed on the living room carpet crying. He’d been crying for two days straight.

This wasn’t a normal kind of crying. Ordinary tears are understandable. But Mystery was beyond understanding. He was out of control. For a week, he’d been vacillating between periods of extreme anger and violence, and jags of fitful, cathartic sobbing. And now he was threatening to kill himself.

There were five of us living in the house: Herbal, Mystery, Papa, Playboy, and me. Boys and men came from every corner of the globe to shake our hands, take photos with us, learn from us, be us. They called me Style. It was a name I had earned.

We never used our real names—only our aliases. Even our mansion, like the others we had spawned everywhere from San Francisco to Sydney, had a nickname. It was Project Hollywood. And Project Hollywood was in shambles.

The sofas and dozens of throw pillows lining the floor of the sunken living room were fetid and discolored with the sweat of men and the juices of women. The white carpet had gone gray from the constant traffic of young, perfumed humanity herded in off Sunset Boulevard every night. Cigarette butts and used condoms floated grimly in the Jacuzzi. And Mystery’s rampage during the last few days had left the rest of the place totaled and the residents petrified. He was six foot five and hysterical.

“I can’t tell you what this feels like,” he choked out between sobs. His whole body spasmed. “I don’t know what I’m going to do, but it will not be rational.”

He reached up from the floor and punched the stained red upholstery of the sofa as the siren-wail of his despondency grew louder, filling the room with the sound of a grown male who has lost every characteristic that separates man from infant from animal.

He wore a gold silk robe that was several sizes too small, exposing his scabbed knees. The ends of the sash just barely met to form a knot and the curtains of the robe hung half a foot apart, revealing a pale, hairless chest and, below it, saggy gray Calvin Klein boxer shorts. The only other item of clothing on his trembling body was a winter cap pulled tight over his skull.

It was June in Los Angeles.

“This living thing.” He was speaking again. “It’s so pointless.”

He turned and looked at me through wet, red eyes. “It’s Tic Tac Toe. There’s no way you can win. So the best thing to do is not to play it.”

There was no one else in the house. I would have to deal with this. He needed to be sedated before he snapped out of tears and back into anger. Each cycle of emotions grew worse, and this time I was afraid he’d do something that couldn’t be undone.

I couldn’t let Mystery die on my watch. He was more than just a friend; he was a mentor. He’d changed my life, as he had the lives of thousands of others just like me. I needed to get him Valium, Xanax, Vicodin, anything. I grabbed my phone book and scanned the pages for people most likely to have pills—people like guys in rock bands, women who’d just had plastic surgery, former child actors. But everyone I called wasn’t home, didn’t have any drugs, or claimed not to have any drugs because they didn’t want to share.

There was only one person left to call: the woman who had triggered Mystery’s downward spiral. She was a party girl; she must have something.

Katya, a petite Russian blonde with a Smurfette voice and the energy of a Pomeranian puppy, was at the front door in ten minutes with a Xanax and a worried look on her face.

“Do not come in,” I warned her. “He’ll probably kill you.” Not that she didn’t entirely deserve it, of course. Or so I thought at the time.

I gave Mystery the pill and a glass of water, and waited until the sobs slowed to a sniffle. Then I helped him into a pair of black boots, jeans, and a gray T-shirt. He was docile now, like a big baby.

“I’m taking you to get some help,” I told him.

I walked him outside to my old rusty Corvette and stuffed him into the tiny front seat. Every now and then, I’d see a tremor of anger flash across his face or tears roll out of his eyes. I hoped he’d remain calm long enough for me to help him.

“I want to learn martial arts,” he said docilely, “so when I want to kill someone, I can do something about it.”

I stepped on the accelerator.

Our destination was the Hollywood Mental Health Center on Vine Street. It was an ugly slab of concrete surrounded day and night by homeless men who screamed at lampposts, transvestites who lived out of shopping carts, and other remaindered human beings who set up camp where free social services could be found.

Mystery, I realized, was one of them. He just happened to have charisma and talent, which drew others to him and prevented him from ever being left alone in the world. He possessed two traits I’d noticed in nearly every rock star I’d ever interviewed: a crazy, driven gleam in his eyes and an absolute inability to do anything for himself.

I brought him into the lobby, signed him in, and together we waited for a turn with one of the counselors. He sat in a cheap black plastic chair, staring catatonically at the institutional blue walls.

An hour passed. He began to fidget.

Two hours passed. His brow furrowed; his face clouded.

Three hours passed. The tears started.

Four hours passed. He bolted out of his chair and ran out of the waiting room and through the front door of the building.

He walked briskly, like a man who knew where he was going, although Project Hollywood was three miles away. I chased him across the street and caught up to him outside a mini-mall. I took his arm and turned him around, baby talking him back into the waiting room.

Five minutes. Ten minutes. Twenty minutes. Thirty. He was up and out again.

I ran after him. Two social workers stood uselessly in the lobby.

“Stop him!” I yelled.

“We can’t,” one of them said. “He’s left the premises.”

“So you’re just going to let a suicidal man walk out of here?” I couldn’t waste time arguing. “Just have a therapist ready to see him if I get him back here.”

I ran out the door and looked to my right. He wasn’t there. I looked left. Nothing. I ran north to Fountain Avenue, spotted him around the corner, and dragged him back again.

When we arrived, the social workers led him down a long, dark hallway and into a claustrophobic cubicle with a sheet-vinyl floor. The therapist sat behind a desk, running a finger through a black tangle in her hair. She was a slim Asian woman in her late twenties, with high cheekbones, dark red lipstick, and a pinstriped pantsuit.

Mystery slumped in a chair across from her.

“So how are you feeling today?” she asked, forcing a smile.

“I’m feeling,” Mystery said, “like there’s no point to anything.” He burst into tears.

“I’m listening,” she said, scrawling a note on her pad. The case was probably already closed for her.

“So I’m removing myself from the gene pool,” he sobbed.

She looked at him with feigned sympathy as he continued. To her, he was just one of a dozen nutjobs she saw a day. All she needed to figure out was whether he required medication or institutionalization.

“I can’t go on,” Mystery went on. “It’s futile.”

With a rote gesture, she reached into a drawer, pulled out a small package of tissues, and handed it to him. As Mystery reached for the package, he looked up and met her eyes for the first time. He froze and stared at her silently. She was surprisingly cute for a clinic like this.

A flicker of animation flashed across Mystery’s face, then died. “If I had met you in another time and another place,” he said, crumpling a tissue in his hands, “things would have been different.”

His body, normally proud and erect, curved like soggy macaroni in his chair. He stared glumly at the floor as he spoke. “I know exactly what to say and what to do to make you attracted to me,” he continued. “It’s all in my head. Every rule. Every step. Every word. I just can’t…do it right now.”

She nodded mechanically.

“You should see me when I’m not like this,” he continued slowly, sniffling. “I’ve dated some of the most beautiful women in the world. Another place, another time, and I would have made you mine.”

“Yes,” she said, patronizing him. “I’m sure you would have.”

She didn’t know. How could she? But this sobbing giant with the crumpled tissue in his hands was the greatest pickup artist in the world. That was not a matter of opinion, but fact. I’d met scores of the self-proclaimed best in the previous two years, and Mystery could out-game them all. It was his hobby, his passion, his calling.

There was only one person alive who could possibly compete with him. And that man was sitting in front of her also. From a formless lump of nerd, Mystery had molded me into a superstar. Together, we had ruled the world of seduction. We had pulled off spectacular pickups before the disbelieving eyes of our students and disciples in Los Angeles, New York, Montreal, London, Melbourne, Belgrade, Odessa, and beyond.

And now we were in a madhouse.

I am far from attractive. My nose is too large for my face and, while not hooked, has a bump in the ridge. Though I am not bald, to say that my hair is thinning would be an understatement. There are just wispy Rogaine-enhanced growths covering the top of my head like tumbleweeds. In my opinion, my eyes are small and beady, though they do have a lively glimmer, which is doomed to remain my secret because no one can see it behind my glasses. I have indentations on either side of my forehead, which I like and believe add character to my face, though I’ve never actually been complimented on them.

I am shorter than I’d like to be and so skinny that I look malnourished to most people, no matter how much I eat. When I look down at my pale, slouched body, I wonder why any woman would want to sleep next to it, let alone embrace it. So, for me, meeting girls takes work. I’m not the kind of guy women giggle over at a bar or want to take home when they’re feeling drunk and crazy. I can’t offer them a piece of my fame and bragging rights like a rock star or cocaine and a mansion like so many other men in Los Angeles. All I have is my mind, and nobody can see that.

You may notice that I haven’t mentioned my personality. This is because my personality has completely changed. Or, to put it more accurately, I completely changed my personality. I invented Style, my alter ego. And in the course of two years, Style became more popular than I ever was—especially with women.

It was never my intention to change my personality or walk through the world under an assumed identity. In fact, I was happy with myself and my life. That is, until an innocent phone call (it always starts with an innocent phone call) led me on a journey into one of the oddest and most exciting underground communities that, in more than a dozen years of journalism, I have ever come across. The call was from Jeremie Ruby-Strauss (no relation), a book editor who had stumbled across a document on the Internet called the layguide, short for The How-to-Lay-Girls Guide. Compressed into 150 sizzling pages, he said, was the collected wisdom of dozens of pickup artists who have been exchanging their knowledge in newsgroups for nearly a decade, secretly working to turn the art of seduction into an exact science. The information needed to be rewritten and organized into a coherent how-to book, and he thought I was the man to do it.

I wasn’t so sure. I want to write literature, not give advice to horny adolescents. But, of course, I told him it wouldn’t hurt to take a look at it.

The moment I started reading, my life changed. More than any other book or document—be it the Bible, Crime and Punishment, or The Joy of Cooking—the layguide opened my eyes. And not necessarily because of the information in it, but because of the path it sent me hurtling down.

When I look back on my teenage years, I have one major regret, and it has nothing to do with not studying hard enough, not being nice to my mother, or crashing my father’s car into a public bus. It is simply that I didn’t fool around with enough girls. I am a deep man—I reread James Joyce’s Ulysses every three years for fun. I consider myself reasonably intuitive. I am at the core a good person, and I try to avoid hurting others. But I can’t seem to evolve to the next state of being because I spend far too much time thinking about women.

And I know I’m not alone. When I first met Hugh Hefner, he was seventy-three. He had slept with over a thousand of the most beautiful women in the world, by his own account, but all he wanted to talk about were his three girlfriends—Mandy, Brandy, and Sandy. And how, thanks to Viagra, he could keep them all satisfied (though his money probably satisfied them enough). If he ever wanted to sleep with somebody else, he said, the rule was that they’d all do it together. So what I gathered from the conversation was that here was a guy who’s had all the sex he wanted his whole life and, at seventy-three, he’s still chasing tail. When does it stop? If Hugh Hefner isn’t over it yet, when am I going to be?

If the layguide had never crossed my path, I, like most men, would never have evolved in my thinking about the opposite sex. In fact, I probably started off worse than most men. In my preteen years, there were no games of doctor, no girls who charged a dollar to look up their skirts, no tickling classmates in places I wasn’t supposed to touch. I spent most of teenage life grounded, so when my sole adolescent sexual opportunity arose—a drunken freshman girl called and offered me a blow job—I was forced to decline, or else suffer my mother’s wrath. In college I began to find myself: the things I was interested in, the personality I’d always been too shy to express, the group of friends who would expand my mind with drugs and conversation (in that order). But I never became comfortable around women: They intimidated me. In four years of college, I did not sleep with a single woman on campus.

After school I took a job at the New York Times as a cultural reporter, where I began to build confidence in myself and my opinions. Eventually, I gained access to a privileged world where no rules applied: I went on the road with Marilyn Manson and Motley Crue to write books with them. In all that time, with all those backstage passes, I didn’t get so much as a single kiss from anyone except Tommy Lee. After that, I pretty much gave up hope. Some guys had it; other guys didn’t. I clearly didn’t.

The problem wasn’t that I’d never been laid. It was that the few times I did get lucky, I’d turn a one-night stand into a two-year stand because I didn’t know when it was going to happen again. The layguide had an acronym for people like me: AFC—average frustrated chump. I was an AFC. Not like Dustin.

I met Dustin the year I graduated from college. He was friends with a classmate of mine named Marko, a faux-aristocratic Serbian who had been my companion in girllessness since nursery school, thanks largely to his head, which was shaped like a watermelon. Dustin wasn’t any taller, richer, more famous, or better looking than either of us. But he did possess one quality we didn’t: He attracted women.

When Marko first introduced me to him, I was unimpressed. He was short and swarthy with long curly brown hair and a cheesy button-down gigolo shirt with too many buttons undone. That night, we went to a Chicago club called Drink. As we checked our coats, Dustin asked, “Do you know if there are any dark corners in here?”

I asked him what he needed dark corners for, and he replied that they were good places to take girls. I raised my eyebrows skeptically. Minutes after entering the bar, however, he made eye contact with a shy-looking girl who was talking with a friend. Without a word, Dustin walked away. The girl followed him—straight to a dark corner. When they finished kissing and groping, they parted wordlessly, without an obligatory exchange of phone numbers or even a sheepish see-you-later.

Dustin repeated this seemingly miraculous feat four times that night. A new world opened up before my eyes.

I grilled him for hours, trying to determine what sort of magical powers he possessed. Dustin was what they call a natural. He had lost his virginity at age eleven, when the fifteen-year-old daughter of a neighbor used him as a sexual experiment, and he had been fucking nonstop since. One night, I took him to a party on a boat anchored in New York’s Hudson River. When a sultry brown-haired, doe-eyed girl walked by, he turned to me and said, “She’s just your type.”

I denied it and stared at the floor, as usual. I was afraid he’d try to make me talk to her, which he soon did.

When she walked past again, he asked her, “Do you know Neil?”

It was a stupid icebreaker, but it didn’t matter now that the ice was broken. I stammered out a few words, until Dustin took over and rescued me. We met her and her boyfriend at a bar afterward. They had just moved in together. Her boyfriend was taking their dog for a walk. After a few drinks, he took the dog home, leaving the girl, Paula, with us.

Dustin suggested going back to my place to cook a late-night snack, so we walked to my tiny East Village apartment and, instead, collapsed on the bed, with Dustin on one side of Paula and me on the other. When Dustin started kissing her left cheek, he signaled me to do the same on her right cheek. Then, in synchronicity, we moved down her body to her neck and her breasts. Though I was surprised by Paula’s quiet compliance, for Dustin this seemed to be business as usual. He turned to me and asked if I had a condom. I found one for him. He pulled off her pants and moved into her while I continued lapping uselessly at her right breast.

That was Dustin’s gift, his power: giving women the fantasy they never thought they’d experience. Afterward, Paula called me constantly. She wanted to talk about the experience all the time, to rationalize it, because she couldn’t believe what she had done. That’s how it always worked with Dustin: He got the girl; I got the guilt.

I chalked this up to a simple difference of personality. Dustin had a natural charm and animal instinct that I just didn’t. Or at least that’s what I thought, until I read the layguide and explored the newsgroups and websites it recommended. What I discovered was an entire community filled with Dustins—men who claimed to have found the combination to unlock a woman’s heart and legs—along with thousands of others like myself, trying to learn their secrets. The difference was that these men had broken down their methods to a specific set of rules that anybody could apply. And each self-proclaimed pickup artist had his own set of rules.

There was Mystery, a magician; Ross Jeffries, a hypnotist; Rick H., a millionaire entrepreneur; David DeAngelo, a real estate agent; Juggler, a standup comedian; David X, a construction worker; and Steve P., a seductionist so powerful that women actually pay to learn how to give him better head. Put them on South Beach in Miami and any number of better-looking, musclebound bullies will be kicking sand in their pale, emaciated faces. But put them in a Starbucks or Whiskey Bar, and they’ll be taking turns making out with that bully’s girlfriend as soon as his back is turned.

Once I discovered their world, the first thing that changed was my vocabulary. Terms like AFC, PUA (pickup artist), sarging (picking up women), and HB (hot babe)1 entered my permanent lexicon. Then my daily rituals changed as I became addicted to the online locker room these pickup artists had created. Whenever I returned home from meeting or going out with a woman, I sat down at my computer and posted my questions of the night on the newsgroups. “What do I do if she says she has a boyfriend?”; “If she eats garlic during dinner, does it mean she isn’t planning on kissing me?”; “Is it a good or a bad sign when a girl puts on lipstick in front of me?”

And online characters like Candor, Gunwitch, and Formhandle began replying to my questions. (The answers, in order: use a boyfriend-destroyer pattern; you’re overanalyzing this; neither.) Soon I realized this was not just an Internet phenomenon but a way of life. There were cults of wanna-be seductionists in dozens of cities—from Los Angeles to London to Zagreb to Bombay—who met weekly in what they called lairs to discuss tactics and strategies before going out en masse to meet women.

In the guise of Jeremie Ruby-Strauss and the Internet, God had given me a second chance. It wasn’t too late to be Dustin, to become what every woman wants—not what she says she wants, but what she really wants, deep inside, beyond her social programming, where her fantasies and daydreams lie.

But I couldn’t do it on my own. Talking to guys online was not going to be enough to change a lifetime of failure. I had to meet the faces behind the screen names, watch them in the field, find out who they were and what made them tick. I made it my mission—my full-time job and obsession—to hunt down the greatest pickup artists in the world and beg for shelter under their wings.

And so began the strangest two years of my life.

1A glossary has been provided on page 439 with detailed explanations of these and other terms used by the seduction community.

THE FIRST PROBLEM FOR ALL OF US,

MEN AND WOMEN, IS NOT TO LEARN,

BUT TO UNLEARN.

—GLORIA STEINEM,

commencement speech, Vassar College

I withdrew five hundred dollars from the bank, stuffed it into a white envelope, and wrote Mystery on the front. It was not the proudest moment of my life.

But I had dedicated the last four days to getting ready for it anyway buying two hundred dollars worth of clothing at Fred Segal, spending an afternoon shopping for the perfect cologne, and dropping seventy-five bucks on a Hollywood haircut. I wanted to look my best; this would be my first time hanging out with a real pickup artist.

His name, or at least the name he used online, was Mystery. He was the most worshipped pickup artist in the community, a powerhouse who spit out long, detailed posts that read like algorithms of how to manipulate social situations to meet and attract women. His nights out seducing models and strippers in his hometown of Toronto were chronicled in intimate detail online, the writing filled with jargon of his own invention: sniper negs, shotgun negs, group theory, indicators of interest, pawning—all of which had become an integral part of the pickup artist lexicon. For four years, he had been offering free advice in seduction newsgroups. Then, in October, he decided to put a price on himself and posted the following:

Mystery is now producing Basic Training workshops in several cities around the world, due to numerous requests. The first workshop will be in Los Angeles from Wednesday evening, October 10, through Saturday night. The fee is $500 (U.S.). This includes club entry, limo for four evenings (sweet huh?), an hour lecture in the limo each evening with a thirty-minute debriefing at the end of the night, and finally three-and-a-half hours per night in the field (broken up into two clubs per night) with Mystery. By the end of Basic Training you will have approached close to fifty women.

It is no easy feat to sign up for a workshop dedicated to picking up women. To do so is to acknowledge defeat, inferiority, and inadequacy. It is to finally admit to yourself that after all these years of being sexually active (or at least sexually cognizant), you have not grown up and figured it out. Those who ask for help are often those who have failed to do something for themselves. So if drug addicts go to rehab and the violent go to anger management class, then social retards go to pickup school.

Clicking send on my e-mail to Mystery was one of the hardest things I’d ever done. If anyone—friends, family, colleagues, and especially my lone ex-girlfriend in Los Angeles—found out I was paying for live in-field lessons on picking up women, the mockery and recrimination would be instant and merciless. So I kept my intentions secret, dodging social plans by telling people that I was going to be showing an old friend around town all weekend.

I would have to keep these two worlds separate.

In my e-mail to Mystery, I didn’t tell him my last name or my occupation. If pressed, I planned to just say I was a writer and leave it at that. I wanted to move through this subculture anonymously, without either an advantage or extra pressure because of my credentials.

However, I still had my own conscience to deal with. This was, far and away, the most pathetic thing I’d ever done in my life. And unfortunately—as opposed to, say, masturbating in the shower—it wasn’t something I could do alone. Mystery and the other students would be there to bear witness to my shame, my secret, my inadequacy.

A man has two primary drives in early adulthood: one toward power, success, and accomplishment; the other toward love, companionship, and sex. Half of life then was out of order. To go before them was to stand up as a man and admit that I was only half a man.

A week after sending the e-mail, I walked into the lobby of the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel. I wore a blue wool sweater that was so soft and thin it looked like cotton, black pants with laces running up the sides, and shoes that gave me a couple extra inches in height. My pockets bulged with the supplies Mystery had instructed every student to bring: a pen, a notepad, a pack of gum, and condoms.

I spotted Mystery instantly. He was seated regally in a Victorian armchair, with a smug, I-just-bench-pressed-the-world smile on his face. He wore a casual, loose-fitting blue-black suit; a small, pointed labret piercing wagged from his chin; and his nails were painted jet black. He wasn’t necessarily attractive, but he was charismatic—tall and thin, with long chestnut hair, high cheekbones, and a bloodless pallor. He looked like a computer geek who’d been bitten by a vampire and was midway through his transformation.

Next to him was a shorter, intense-looking character who introduced himself as Mystery’s wing, Sin. He wore a form-fitting black crew neck shirt, and his hair was pitch black and gelled straight back. He had the complexion, however, of a man whose natural hair color is red.

I was the first student to arrive.

“What’s your top score?” Sin leaned in and asked as I sat down. They were already assessing me, trying to figure out if I was in possession of a thing called game.

“My top score?”

“Yeah, how many girls have you been with?”

“Um, somewhere around seven,” I told them.

“Somewhere around seven?” Sin pressed.

“Six,” I confessed.

Sin ranked in the sixties, Mystery in the hundreds. I looked at them in wonder: These were the pickup artists whose exploits I’d been following so avidly online for months. They were another class of being: They had the magic pill, the solution to the inertia and frustration that has plagued the great literary protagonists I’d related to all my life—be it Leopold Bloom, Alex Portnoy, or Piglet from Winnie the Pooh.

As we waited for the other students, Mystery threw a manila envelope full of photographs in my lap.

“These are some of the women I’ve dated,” he said.

In the folder was a spectacular array of beautiful women: a headshot of a sultry Japanese actress; an autographed publicity still of a brunette who bore an uncanny resemblance to Liv Tyler; a glossy picture of a Penthouse Pet of the Year; a snapshot of a tan, curvy stripper in a negligee who Mystery said was his girlfriend, Patricia; and a photo of a brunette with large silicone breasts, which were being suckled by Mystery in the middle of a nightclub. These were his credentials.

“I was able to do that by not paying attention to her breasts all night,” he explained when I asked about the last shot. “A pickup artist must be the exception to the rule. You must not do what everyone else does. Ever.”

I listened carefully. I wanted to make sure every word etched itself on my cerebral cortex. I was attending a significant event; the only other credible pickup artist teaching courses was Ross Jeffries, who had basically founded the community in the late 1980s. But today marked the first time seduction students would be removed from the safe environs of the seminar room and let loose in clubs to be critiqued as they ran game on unsuspecting women.

A second student arrived, introducing himself as Extramask. He was a tall, gangly, impish twenty-six-year-old with a bowl cut, overly baggy clothing, and a handsomely chiseled face. With the right haircut and outfit, he would easily have been a good-looking guy.

When Sin asked him what his count was, Extramask scratched his head uncomfortably. “I have virtually zero experience with girls,” he explained. “I’ve never kissed a girl before.”

“You’re kidding,” Sin said.

“I’ve never even held a girl’s hand. I grew up pretty sheltered. My parents were really strict Catholics, so I always had a lot of guilt about girls. But I’ve had three girlfriends.”

He looked at the floor and rubbed his knees in nervous circles as he listed his girlfriends, though no one had asked for the particulars. There was Mitzelle, who broke up with him after seven days. There was Claire, who told him after two days that she’d made a mistake when she agreed to go out with him.

“And then there was Carolina, my sweet Carolina,” he said, a dreamy smile spreading across his face. “We were a couple for one day. I remember her walking over to my house the next afternoon with her friend. I saw her across the street, and I was excited to see her. When I got closer, she yelled, ‘I’m dumping you.’”

All of these relationships apparently took place in sixth grade. Extramask shook his head sadly. It was hard to tell whether he was consciously being funny or not.

The next arrival was a tanned, balding man in his forties who’d flown in from Australia just to attend the workshop. He had a ten-thousand-dollar Rolex, a charming accent, and one of the ugliest sweaters I’d ever seen—a thick cable-knit monstrosity with multi-colored zigzags that looked like the aftermath of a finger-painting mishap. He reeked of money and confidence. Yet the moment he opened his mouth to give Sin his score (five), he betrayed himself. His voice trembled; he couldn’t look anyone in the eye; and there was something pathetic and childlike about him. His appearance, like his sweater, was just an accident that spoke nothing of his nature.

He was new to the community and reluctant to share even his first name, so Mystery christened him Sweater.

The three of us were the only students in the workshop.

“Okay, we’ve got a lot to talk about,” Mystery said, clapping his hands together. He leaned in close, so the other guests in the hotel couldn’t hear.

“My job here is to get you into the game,” he continued, making piercing eye contact with each of us. “I need to get what’s in my head into yours. Think of tonight as a video game. It is not real. Every time you do an approach, you are playing this game.”

My heart began pounding violently. The thought of trying to start a conversation with a woman I didn’t know petrified me, especially with these guys watching and judging me. Bungee jumping and parachuting were a cakewalk compared to this.

“All your emotions are going to try to fuck you up,” Mystery continued. “They are there to try to confuse you, so know right now that they cannot be trusted at all. You will feel shy sometimes, and self-conscious, and you must deal with it like you deal with a pebble in your shoe. It’s uncomfortable, but you ignore it. It’s not part of the equation.”

I looked around; Extramask and Sweater seemed just as nervous as I was. “I need to teach you, in four days, the whole equation—the sequence of moves you need to win,” Mystery went on. “And you will have to play the game over and over to learn how to win. So get ready to fail.”

Mystery paused to order a Sprite with five slices of lemon on the side, then told us his story. He spoke in a loud, clear voice—modeled, he said, on the motivational speaker Anthony Robbins. Everything about him seemed to be a conscious, rehearsed invention.

Since the age of eleven, when he beat the secret to a card trick out of a classmate, Mystery’s goal in life was to become a celebrity magician, like David Copperfield. He spent years studying and practicing, and managed to parlay his talents into birthday parties, corporate gigs, and even a couple of talk shows. In the process, however, his social life suffered. At the age of twenty-one, when he was still a virgin, he decided to do something about it.

“One of the world’s greatest mysteries is the mind of a woman,” he told us grandiosely. “So I set out to solve it.”

He took a half hour bus ride into Toronto every day, going to bars, clothing stores, restaurants, and coffee shops. He wasn’t aware of the online community or any other pickup artists, so he was forced to work alone, relying on the one skill he did know: magic. It took him dozens of trips to the city before he even worked up the guts to talk to a stranger. From there, he tolerated failure, rejection, and embarrassment day and night until, piece by piece, he put together the puzzle that is social dynamics and discovered what he believed to be the patterns underlying all male-female relationships.

“It took me ten years to discover this,” he said. “The basic format is FMAC—find, meet, attract, close. Believe it or not, the game is linear. A lot of people don’t know that.”

For the next half hour, Mystery told us about what he called group theory. “I have done this specific set of events a bazillion times,” he said. “You do not walk up to a girl who’s all by herself. That is not the perfect seduction. Women of beauty are rarely found alone.”

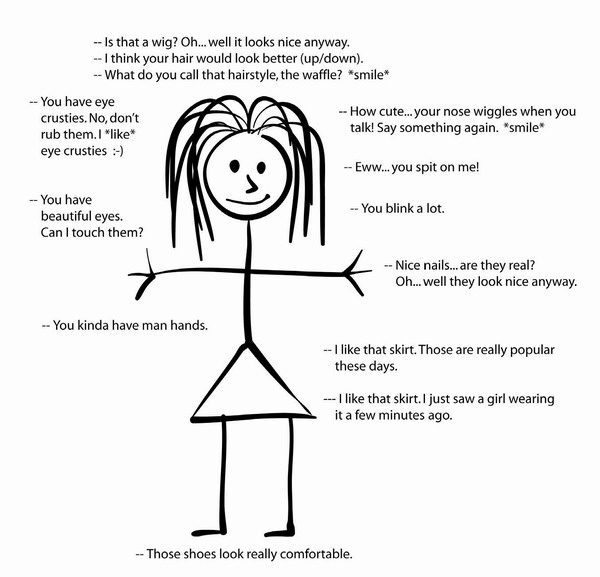

After approaching the group, he continued, the key is to ignore the woman you desire while winning over her friends—especially the men and anyone else likely to cockblock. If the target is attractive and used to men fawning all over her, the pickup artist must intrigue her by pretending to be unaffected by her charm. This is accomplished through the use of what he called a neg.

Neither compliment nor insult, a neg is something in between—an accidental insult or backhanded compliment. The purpose of a neg is to lower a woman’s self esteem while actively displaying a lack of interest in her—by telling her she has lipstick on her teeth, for example, or offering her a piece of gum after she speaks.

“I don’t alienate ugly girls; I don’t alienate guys. I only alienate the girls I want to fuck,” Mystery lectured, eyes blazing with the conviction of his aphorisms. “If you don’t believe me, you will see it tonight. Tonight is the night of experiments. First, I am going to prove myself. You are going to watch me and then we are going to push you to try a few sets. Tomorrow, if you do what I say, you will be able to make out with a girl within fifteen minutes.”

He looked at Extramask. “Name the five characteristics of an alpha male.”

“Confidence?”

“Right. What else?”

“Strength?”

“No.”

“Body odor?”

He turned to Sweater and me. We were also clueless.

“The number one characteristic of an alpha male is the smile,” he said, beaming an artificial beam. “Smile when you enter a room. As soon as you walk in a club, the game is on. And by smiling, you look like you’re together, you’re fun, and you’re somebody.”

He gestured to Sweater. “When you came in, you didn’t smile when you talked to us.”

“That’s just not me,” Sweater said. “I look silly when I smile.”

“If you keep doing what you’ve always done, you’ll keep getting what you’ve always gotten. It’s called the Mystery Method because I’m Mystery and it’s my method. So what I’m going to ask is that you indulge in some of my suggestions and try new things over the next four days. You are going to see a difference.”

Besides confidence and a smile, we learned, the other characteristics of an alpha male were being well-groomed, possessing a sense of humor, connecting with people, and being seen as the social center of a room. No one bothered to tell Mystery that those were actually six characteristics.

As Mystery dissected the alpha male further, I realized something: The reason I was here—the reason Sweater and Extramask were also here—was that our parents and our friends had failed us. They had never given us the tools we needed to become fully effective social beings. Now, decades later, it was time to acquire them.

Mystery went around the table and looked at each of us. “What kind of girls do you want?” he asked Sweater.

Sweater pulled a piece of neatly folded notebook paper out of his pocket. “Last night I wrote down a list of goals for myself,” he said, unfolding the page, which was filled with four columns of numbered items. “And one of the things I’m looking for is a wife. She needs to be smart enough to hold up her end of any conversation and have enough style and beauty to turn heads when she walks into a room.”

“Well, look at you,” Mystery said. “You look average. People think if they look generic, then they can seduce a wide array of women. Not true. You have to specialize. If you look average, you’re going to get average girls. Your khaki pants are for the office. They’re not for clubs. And your sweater—burn it. You need to be bigger than life. I’m talking over the top. If you want to get the 10s, you need to learn peacock theory.”

Mystery loved theories. Peacock theory is the idea that in order to attract the most desirable female of the species, it’s necessary to stand out in a flashy and colorful way. For humans, he told us, the equivalent of the fanned peacock tail is a shiny shirt, a garish hat, and jewelry that lights up in the dark—basically, everything I’d dismissed my whole life as cheesy.

When it came time for my personal critique, Mystery had a laundry list of fixes: get rid of the glasses, shape the overgrown goatee, shave the expensively trimmed tumbleweeds on my head, dress more outrageously, wear a conversation piece, get some jewelry, get a life.

I wrote down every word of advice. This was a guy who thought about seduction nonstop, like a mad scientist working on a formula to turn peanuts into gasoline. The archive of his Internet messages was 3,000 posts long—more than 2,500 pages—all dedicated to cracking the code that is woman.

“I have an opener for you to use,” he said to me. An opener is a prepared script used to start a conversation with a group of strangers; it’s the first thing anyone who wants to meet women must be armed with. “Say this when you see a group with a girl you like. ‘Hey, it looks like the party’s over here.’ Then turn to the girl you want and add, ‘If I wasn’t gay, you’d be so mine.’”

A flash of crimson burned up my face. “Really?” I asked. “How is that going to help?”

“Once she’s attracted to you, it won’t matter whether you said you were gay or not.”

“But isn’t that lying?”

“It’s not lying,” he replied. “It’s flirting.”

To the group, he offered other examples of openers: innocent but intriguing questions like “Do you think magic spells work?” or “Oh my god, did you see those two girls fighting outside?” Sure, they weren’t that spectacular or sophisticated, but all they are meant to do is get two strangers talking.

The point of Mystery Method, he explained, is to come in under the radar. Don’t approach a woman with a sexual come-on. Learn about her first and let her earn the right to be hit on.

“An amateur hits on a woman right away,” he decreed as he rose to leave the hotel. “A pro waits eight to ten minutes.”

Armed with our negs, group theory, and camouflage openers, we were ready to hit the clubs.

We piled into the limo and drove to the Standard Lounge, a velvet-ropeguarded hotel hotspot. It was here that Mystery shattered my model of reality. Limits I had once imposed on human interaction were extended far beyond what I ever thought possible. The man was a machine.

The Standard was dead when we walked in. We were too early. There were just two groups of people in the room: a couple near the entrance and two couples in the corner.

I was ready to leave. But then I saw Mystery approach the people in the corner. They were sitting on opposite couches across a glass table. The men were on one side. One of them was Scott Baio, the actor best known for playing Chachi on Happy Days. Across from him were two women, a brunette and a bleached blonde who looked like she’d stepped out of the pages of Maxim. Her cut-off white T-shirt was suspended so high into the air by fake breasts that the bottom of it just hovered, flapping in the air above a belly tightened by fastidious exercise. This woman was Baio’s date. She was also, I gathered, Mystery’s target.

His intentions were clear because he wasn’t talking to her. Instead, he had his back turned to her and was showing something to Scott Baio and his friend, a well-dressed, well-tanned thirty-something who looked as if he smelled strongly of aftershave. I moved in closer.

“Be careful with that,” Baio was saying. “It cost forty-thousand dollars.”

Mystery had Baio’s watch in his hands. He placed it carefully on the table. “Now watch this,” he commanded. “I tense my stomach muscles, increasing the flow of oxygen to my brain, and…”

As Mystery waved his hands over the watch, the second hand stopped ticking. He waited fifteen seconds, then waved his hands again, and slowly the watch sputtered back to life—along with Baio’s heart. Mystery’s audience of four burst into applause.

“Do something else!” the blonde pleaded.

Mystery brushed her off with a neg. “Wow, she’s so demanding,” he said, turning to Baio. “Is she always like this?”

We were witnessing group theory in action. The more Mystery performed for the guys, the more the blonde clamored for attention. And every time, he pushed her away and continued talking with his two new friends.

“I don’t usually go out,” Baio was telling Mystery. “I’m over it, and I’m too old.”

After a few more minutes, Mystery finally acknowledged the blonde. He held his arms out. She placed her hands in his, and he began giving her a psychic reading. He was employing a technique I’d heard about called cold reading: the art of telling people truisms about themselves without any prior knowledge of their personality or background. In the field, all knowledge—however esoteric—is power.

With each accurate sentence Mystery spoke, the blonde’s jaw dropped further open, until she started asking him about his job and his psychic abilities. Every response Mystery gave was intended to accentuate his youth and enthusiasm for the good life Baio said he had outgrown.

“I feel so old,” Mystery said, baiting her.

“How old are you?” she asked.

“Twenty-seven.”

“That’s not old. That’s perfect.”

He was in.

Mystery called me over and whispered in my ear. He wanted me to talk to Baio and his friend, to keep them occupied while he hit on the girl. This was my first experience as a wing—a term Mystery had taken from Top Gun, along with words like target and obstacle.

I struggled to make small talk with them. But Baio, looking nervously at Mystery and his date, cut me off. “Tell me this is all an illusion,” he said, “and he’s not actually stealing my girlfriend.”

Ten long minutes later, Mystery stood up, put his arm around me, and we left the club. Outside, he pulled a cocktail napkin from his jacket pocket. It contained her phone number. “Did you get a good look at her?” Mystery asked. “That is what I’m in the game for. Everything I’ve learned I used tonight. It’s all led up to this moment. And it worked.” He beamed with selfsatisfaction. “How’s that for a demonstration?”

That was all it took. Stealing a girl right from under a celebrity’s nose has-been or not—was a feat even Dustin couldn’t have accomplished. Mystery was the real deal.

As we took the limo to the Key Club, Mystery told us the first commandment of pickup: the three-second rule. A man has three seconds after spotting a woman to speak to her, he said. If he takes any longer, then not only is the girl likely to think he’s a creep who’s been staring at her for too long, but he will start overthinking the approach, get nervous, and probably blow it.

The moment we walked into the Key Club, Mystery put the threesecond rule into action. Striding up to a group of women, he held out his hands and asked, “What’s your first impression of these? Not the big hands, the black nails.”

As the girls gathered around him, Sin pulled me aside and suggested wandering the club and attempting my first approach. A group of women walked by and I tried to say something. But the word “hi” just barely squeaked out of my throat, not even loud enough for them to hear. As they continued past, I followed and grabbed one of the girls on the shoulder from behind. She turned around, startled, and gave me the withering what-a-creep look that was the whole reason I was too scared to talk to women in the first place.

“Never,” Sin admonished me in his adenoidal voice, “approach a woman from behind. Always come in from the front, but at a slight angle so it’s not too direct and confrontational. You should speak to her over your shoulder, so it looks like you might walk away at any minute. Ever see Robert Redford in The Horse Whisperer? It’s kind of like that.”

A few minutes later, I spotted a young, tipsy-looking woman with long, tangled blonde curls and a puffy pink vest standing alone. I decided that approaching her would be an easy way to redeem myself. I circled around until I was in the ten o’clock position in front of her and walked in, imagining myself approaching a horse I didn’t want to frighten.

“Oh my God,” I said to her. “Did you see those two girls fighting outside?”

“No,” she said. “What happened?”

She was interested. She was talking to me. It was working.

“Um, two girls were fighting over this little guy who was half their size. It was pretty brutal. He was just standing there laughing as the police came and arrested the girls.”

She giggled. We started talking about the club and the band playing there. She was very friendly and actually seemed grateful for the conversation. I had no idea that approaching a woman could be this easy.

Sin sidled up to me and whispered in my ear, “Go kino.”

“What’s kino?” I asked.

“Kino?” the girl replied.

Sin reached behind me, picked up my arm, and placed it on her shoulder. “Kino is when you touch a girl,” he whispered. I felt the heat of her body and was reminded of how much I love human contact. Pets like to be petted. It isn’t sexual when a dog or a cat begs for physical affection. People are the same way: We need touch. But we’re so sexually screwed up and obsessed that we get nervous and uncomfortable whenever another person touches us. And, unfortunately, I am no exception. As I spoke to her, my hand felt wrong on her shoulder. It was just resting there like some disembodied limb, and I imagined her wondering what exactly it was doing there and how she could gracefully extricate herself from under it. So I did her the favor of removing it myself.

“Isolate her,” Sin said.

I suggested sitting down, and we walked to a bench. Sin followed and sat behind us. As I’d been taught, I asked her to tell me the qualities she finds attractive in guys. She said humor and ass.

Fortunately, I have one of those qualities.

Suddenly, I felt Sin’s breath on my ear. “Sniff her hair,” he was instructing.

I smelled her hair, although I wasn’t exactly sure what the point was. I figured Sin wanted me to neg her. So I said, “It smells like smoke.”

“Nooooo!” Sin hissed in my ear. I guess I wasn’t supposed to neg.

She seemed offended. So, to recover, I took another whiff. “But underneath that, there’s a very intoxicating smell.”

She cocked her head to one side, furrowed her brow ever so slightly, scanned me up and down, and said, “You’re weird.” I was blowing it.

Fortunately, Mystery soon arrived.

“This place is dead,” he said. “We’re going somewhere more target rich.” To Mystery and Sin, these clubs didn’t seem to be reality. They had no problem whispering in students’ ears while they were talking to women, dropping pickup terminology in front of strangers, and even interrupting a student during a set and explaining, in front of his group, what he was doing wrong. They were so confident and their talk was so full of incomprehensible jargon that the women rarely even raised an eyebrow, let alone suspected they were being used to train wanna-be ladies’ men.

I bid my new friend good-bye as Sin had taught me, pointing to my cheek and saying, “Kiss good-bye.” She actually pecked me. I felt very alpha.

On the way out, as I stopped to use the bathroom, I found Extramask standing there, twirling an unwashed lock of hair in his fingers. “Are you waiting for the toilet?” I asked.

“Sort of,” he replied nervously. “Go ahead.”

I gave him a quizzical look. “Can I tell you something?” he asked.

“Sure.”

“I have a lot of trouble peeing beside guys in urinals. When there’s another guy standing there, I can’t fucking pee. Even if I’m peeing already and a guy walks up, I stop. And then I just stand there all nervous and shit.”

“No one’s judging you.”

“Yeah,” he said. “I remember about a year ago, a guy and I were trying to piss in these urinals that were right next to each other, but we both just ended up standing there. We stood there for around two minutes, recognizing each other’s pee-shyness, until I zipped up and went to another bathroom.”

He paused. “The guy never thanked me for changing bathrooms that day.”

I nodded, walked to the urinal, and discharged my duties with a distinct lack of self-consciousness. Compared to Extramask, I was going to be an easy student.

As I left the bathroom, he was still standing there. “I always liked urinal dividers,” he said. “But you only seem to find them at the classy places.”

I was in high spirits in the limo to the next bar. “Do you think I could have kissed her?” I asked Mystery.

“If you think you could have, then you could have,” he said. “As soon as you ask yourself whether you should or shouldn’t, that means you should. And what you do is, you phase-shift. Imagine a giant gear thudding down in your head, and then go for it. Start hitting on her. Tell her you just noticed she has beautiful skin, and start massaging her shoulders.”

“But how do you know it’s okay?”

“What I do is, I look for IOIs. An IOI is an indicator of interest. If she asks you what your name is, that’s an IOI. If she asks you if you’re single, that’s an IOI. If you take her hands and squeeze them, and she squeezes back, that’s an IOI. And as soon as I get three IOIs, I phase-shift. I don’t even think about it. It’s like a computer program.”

“But how do you kiss her?” Sweater asked.

“I just say, ‘Would you like to kiss me?’”

“And then what happens?”

“One of three things,” Mystery said. “If she says, ‘Yes,’ which is very rare, you kiss her. If she says, ‘Maybe,’ or hesitates, then you say, ‘Let’s find out,’ and kiss her. And if she says, ‘No,’ you say, ‘I didn’t say you could. It just looked like you had something on your mind.’”

“You see,” he grinned triumphantly. “You have nothing to lose. Every contingency is planned for. It’s foolproof. That is the Mystery kiss-close.”

I furiously scribbled every word of the kiss-close in my notebook. No one had ever told me how to kiss a girl before. It was just one of those things men were supposed to know on their own, like shaving and car repair.

Sitting in the limo with a notebook on my lap, listening to Mystery talk, I asked myself why I was really there. Taking a course in picking up women wasn’t the kind of thing normal people did. Even more disturbing, I wondered why it was so important to me, why I’d become so quickly obsessed with the online community and its leading pseudonyms.

Perhaps it was because attracting the opposite sex was the only area of my life in which I felt like a complete failure. Every time I walked down the street or into a bar, I saw my own failure staring me back in the face with red lipstick and black mascara. The combination of desire and paralysis was deadly.

After the workshop that night, I opened my file cabinet and dug through my papers. There was something I wanted to find, something I hadn’t looked at in years. After a half hour, I found it: a folder labeled “High School Writing.” I pulled out a piece of lined notebook paper covered from top to bottom with my chicken scratching. It was the only poem I’ve ever attempted in my life. It was written in eleventh grade, and I never showed it to anyone. However, it was the answer to my question.

SEXUAL FRUSTRATION

BY NEIL STRAUSS

The only reason you go out,

The only objective in mind,

A glimpse of a familiar pair

Of legs on a busy street or

A squeeze from a female who

You can only call your friend.

A scoreless night fosters hostility.

A scoreless weekend breeds animosity.

Through red eyes all the world is seen,

Angry at friends and family for no

Reason that they can perceive.

Only you know why you are so mad.

There is the ‘just friends’ one who you’ve

Known for so long, who respects you

So much that you can’t do what you want.

And she no longer bothers to put on her

False personality and flirt because she thinks

You like her for who she is when what you

Liked about her was her flirtatiousness.

When your own hand becomes your best lover,

When your life-giving fertilizer is wasted

In a Kleenex and flushed down the toilet

You wonder when you are going to stop

Thinking about what could have happened

That night when you almost got somewhere.

There is the coy one who smiles

And looks like she wants to meet you,

But you can’t work up the nerve to talk.

So instead she will become one of your nighttime

Fantasies, where you could have but didn’t.

Your hand will be substituted for hers.

When you neglect work and meaningful activities,

When you neglect the ones who really love you,

For a shot at a target that you rarely hit.

Does everyone get lucky with women but you,

Or do females just not want it as bad as you do?

In the decade since I’d written that poem, nothing had changed. I still couldn’t write poetry. And, more important, I still felt the same way. Perhaps signing up for Mystery’s workshop had been an intelligent decision. After all, I was doing something proactive about my lameness.

Even the wise man dwells in the fool’s paradise.

On the last night of the workshop, Mystery and Sin took us to a bar called the Saddle Ranch, a country-themed meat market on the Sunset Strip. I’d been there before—not to pick up women, but to ride the mechanical bull. One of my goals in Los Angeles was to master the machine at its fastest setting. But not today. After three consecutive nights of going out until 2:00 A.M. and then breaking down approaches with Mystery and the other students far beyond the allotted half-hour, I was wiped out.

Within minutes, however, our tireless professor of pickup was at the bar, making out with a loud, tipsy girl who kept trying to steal his scarf. Watching Mystery work, I noticed that he used the exact same openers, routines, and lines—and got a phone number or a tongue down nearly every time, even if the woman was with a boyfriend. I’d never seen anything like it. Sometimes a woman he was talking to was even moved to tears.

As I walked toward the mechanical bull ring, feeling foolish in a red cowboy hat Mystery had insisted I wear, I saw a girl with long black hair, a formfitting sweater, and tan legs sticking out of a ruffled skirt. She was talking animatedly to two guys, bouncing around them like a cartoon character.

One second. Two seconds. Three.

“Hey, looks like the party’s over here.” I spoke to the guys, then turned to face the girl. I stuttered for a moment. I knew the next line—Mystery had been pushing it on me all weekend—but I’d been dreading using it.

“If…if I wasn’t gay, you’d be so mine.”

A huge smile spread across her face. “I like your hat,” she screeched, grabbing the brim.

I guess peacocking did work. “Hey, now,” I told her, repeating a line I had heard Mystery use earlier. “Hands off the merchandise.”

She responded by throwing her arms around me and telling me I was fun. Every ounce of fear evaporated with her acceptance. The secret to meeting women, I realized, is simply knowing what to say, and when and how to say it.

“How do you all know each other?” I asked.

“I just met them,” she said. “My name is Elonova.” She curtseyed clumsily.

I took that as an IOI.

I showed Elonova an ESP trick Mystery had taught me earlier that evening, in which I guessed a number she was thinking between one and ten (hint: it’s almost always seven), and she clapped her hands together gleefully. The guys, in the presence of my superior game, wandered off.

When the bar closed, Elonova and I moved outside. Every AFC we walked past gave me the thumbs up and said, “She’s hot” or “You lucky bastard.” What idiots. They were fucking up my game—that is, if I could figure out a way to tell Elonova I was straight. Hopefully, she’d figured it out on her own by now.

I remembered Sin telling me to kino, so I put my arm around her. This time, however, she backed away. That was definitely not an IOI. As I took a step toward her to try again, one of the guys she’d been with in the bar arrived. She flirted with him as I stood there stupidly. When she turned back to me a few minutes later, I told her we should hang out sometime. She agreed, and we exchanged numbers.

Mystery, Sin, and the boys were all in the limo, watching the whole exchange go down. I climbed inside, thinking I was hot shit for numberclosing in front of them all. But Mystery wasn’t impressed.

“You got that number-close,” he said, “because you forced yourself on her. You let her play with you.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Have I ever told you about cat string theory?”

“No.”

“Listen. Have you ever seen a cat play with a string? Well, when the string is dangling above its head, just out of reach, the cat goes crazy trying to get it. It leaps in the air, dances around, and chases it all over the room. But as soon as you let go of the string and it drops right between the cat’s paws, it just looks at the string for a second and then walks away. It’s bored. It doesn’t want it anymore.”

“So…”

“So that girl moved away from you when you put your arm around her. And you ran right back to her like a puppy dog. You should have punished her—turned away and talked to someone else. Let her work to get your attention back. After that, she made you wait while she talked to that dork.”

“What should I have done?”

“You should have said, ‘I’ll let you two be alone,’ and started to walk away, as if you were giving her to him—even though you knew she liked you more. You have to act like you are the prize.”

I smiled. I think I really understood.

“Yeah,” he said. “Be the dancing string.”

I grew silent and thought about it, kicking my legs up against the bar counter of the limousine and slouching into the seat. Mystery turned to Sin, and they talked amongst themselves for several minutes. It felt like they were discussing me.

I tried not to make eye contact with them. I wondered if they were going to tell me that I’d held the workshop up, that I wasn’t yet ready for it, that I should study for another six months and then take it again.

Suddenly, Mystery and Sin ended their huddle. Mystery broke into a wide smile and looked straight at me.

“You’re one of us,” he said. “You’re going to be a superstar.”

MSN GROUP: Mystery’s Lounge

SUBJECT: Sex Magic

AUTHOR: Mystery

My Mystery Method workshop in Los Angeles kicked ass. I’ve decided to teach several impressive ways to demonstrate mind power through magic at my next workshop. After all, some of you need something with which to convey your charming personalities. If you are going in without an edge—like if you say, “Hi, I’m an accountant”—you will not capture your target’s attention and curiosity.

So, since the workshop, I’ve retired the FMAC model and broken down the approach to thirteen detailed steps. Here is the basic format to all approaches:

1. Smile when you walk into a room. See the group with the target and follow the three-second rule. Do not hesitate—approach instantly.

2. Recite a memorized opener, if not two or three in a row.

3. The opener should open the group, not just the target. When talking, ignore the target for the most part. If there are men in the group, focus your attention on the men.

4. Neg the target with one of the slew of negs we’ve come up with. Tell her, “It’s so cute. Your nose wiggles when you laugh.” Then get her friends to notice and laugh about it.

5. Convey personality to the entire group. Do this by using stories, magic, anecdotes, and humor. Pay particular attention to the men and the less attractive women. During this time, the target will notice that you are the center of attention. You may perform various memorized pieces like the photo routine,2 but only for the obstacles.

6. Neg the target again if appropriate. If she wants to look at the pictures, for example, say, “Oh my god, she’s so grabby. How do you roll with her?”

7. Ask the group, “So, how does everyone know each other?” If the target is with one of the guys, find out how long they’ve been together. If it’s a serious relationship, eject politely by saying, “Pleasure meeting you.”

8. If she is not spoken for, say to the group, “I’ve sort of been alienating your friend. Is it all right if I speak to her for a couple of minutes?” They always say, “Uh, sure. If it’s okay with her.” If you’ve executed the preceding steps correctly, she will agree.

9. Isolate her from the group by telling her you want to show her something cool. Take her to sit with you nearby. As you lead her through the crowd, do a kino test by holding her hand. If she squeezes back, it’s on. Start looking for other IOIs.

10. Sit with her and perform a rune reading, an ESP test, or any other demonstration that will fascinate and intrigue her.

11. Tell her, “Beauty is common but what’s rare is a great energy and outlook on life. Tell me, what do you have inside that would make me want to know you as more than a mere face in the crowd?” If she begins to list qualities, this is a positive IOI.

12. Stop talking. Does she reinitiate the chat with a question that begins with the word “So?” If she does, you’ve now seen three IOIs and can…

13. Kiss close. Say, out of the blue, “Would you like to kiss me?” If the setting or circumstances aren’t conducive to physical intimacy, then give yourself a time constraint by saying, “I have to go, but we should continue this.” Then get her number and leave.

—Mystery

The Mystery Method course handout

2 The photo routine involves carrying an envelope of photos in a jacket pocket, as if they’ve just been developed. Each photo, however, is pre-selected to convey a different aspect of the PUA’s personality, such as images of the PUA with beautiful women, with children, with pets, with celebrities, goofing off with friends, and doing something active like roller-blading or skydiving. The PUA should also have a short, witty story to accompany each photo.

Sure, there is Ovid, the Roman poet who wrote The Art of Love; Don Juan, the mythical womanizer based on the exploits of various Spanish noblemen; the Duke de Lauzun, the legendary French rake who died on the guillotine; and Casanova, who detailed his hundred-plus conquests in four thousand pages of memoirs. But the undisputed father of modern seduction is Ross Jeffries, a tall, skinny, porous-faced self-proclaimed nerd from Marina Del Rey, California. Guru, cult leader, and social gadfly, he commands an army sixty thousand horny men strong, including top government officials, intelligence officers, and cryptographers.

His weapon is his voice. After years of studying everyone from master hypnotists to Hawaiian Kahunas, he claims to have found the technology—and make no mistake about it, that’s what it is—that will turn any responsive woman into a libidinous puddle. Jeffries, who claims to be the inspiration for Tom Cruise’s character in Magnolia, calls it Speed Seduction.

Jeffries developed Speed Seduction in 1988, after ending a five-year streak of sexlessness with the help of neuro-linguistic programming (NLP), a controversial fusion of hypnosis and psychology that emerged from the personal development boom of the 1970s and led to the rise of self-help gurus like Anthony Robbins. The fundamental precept of NLP is that one’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior—and the thoughts, feelings, and behavior of others—can be manipulated through words, suggestions, and physical gestures designed to influence the subconscious. The potential of NLP to revolutionize the art of seduction was obvious to Jeffries.

Over the years, Jeffries has either outlasted, sued, or crushed any competitor in the field of pickup to make his school, Speed Seduction, the dominant model for getting a woman’s lips to touch a man’s—that is, until Mystery came along and started teaching workshops.

Thus, the clamor online for an eyewitness account of Mystery’s first workshop was overwhelming. Mystery’s admirers wanted to know if the class was worthwhile; his enemies, particularly Jeffries and his disciples, wanted to tear him apart. So I obliged, posting a detailed description of my experiences.

At the end of my review, I issued a call for wings in Los Angeles, asking only that they be somewhat confident, intelligent, and socially comfortable. I knew that in order to become a pickup artist myself, I would somehow have to internalize everything I had seen Mystery do. This would happen only through practice—through hitting the bars and clubs every night until I became a natural like Dustin, or even an unnatural like Mystery.

The day my report on the workshop hit the Internet, I received an e-mail from someone in Encino nicknamed Grimble, who identified himself as a Ross Jeffries student. He wanted to “sarge” with me, as he put it. Sarging is pickup artist jargon for going out to meet women; the term evidently has its origin in the name of one of Ross Jeffries’s cats, Sargy.

An hour after I sent him my phone number, Grimble called. More than Mystery, it was Grimble who would initiate me into what could only be described as a secret society.

“Hey, man,” he said, in a conspiratorial hiss. “So what do you think of Mystery’s game?”

I gave him my assessment.

“Wow, I like it,” he said. “But you have to hang out with Twotimer and me some time. We’ve been sarging with Ross Jeffries a lot.”

“Really? I’d love to meet him.”

“Listen. Can you keep a secret?”

“Sure.”

“How much technology do you use in your sarges?”

“Technology?”

“You know, how much is technique and how much is just talking?”

“I guess fifty-fifty,” I said.

“I’m up to 90 percent.”

“What?”

“Yeah, I use a canned opener, then I elicit her values and find out her trance words. And then I go into one of the secret patterns. Do you know the October Man sequence?”

“Never heard of it, unless Arnold Schwarzenegger was in it.”

“Oh, man. I had a girl over here last week, and I gave her a whole new identity. I did a sexual value elicitation, and then changed her whole timeline and internal reality. Then I brushed my finger along her face, telling her to notice”—and here he switched to a slow, hypnotic voice—“how wherever I touch…it leaves a trail of energy moving through you…and wherever you can feel this energy spreading…the deeper you want to allow your-self…to feel these sensations…becoming even more…intense.”

“And then what?”

“I brushed my finger along her lips, and she started sucking it,” he exclaimed triumphantly. “Full-close!”

“Wow,” I said.

I had no idea what he was talking about. But I wanted this technology. I thought back to all the times I’d taken women to my house, sat on the bed next to them, leaned in for the kiss, and been deflected with the “let’s just be friends” speech. In fact, this rejection is such a universal experience that Ross Jeffries invented not just an acronym for it, LJBF, but a litany of responses as well.3

I talked to Grimble for two hours. He seemed to know everybody—from legends like Steve P., who supposedly had a cult of women paying cash for the privilege of sexually servicing him, to guys like Rick H., Ross’s most famous student, thanks to an incident that involved him, a hot tub, and five women.

Grimble would make a perfect wing.

3 One such response from Jeffries is, “I don’t promise any such thing. Friends don’t put each other into boxes like that. The only thing I’ll promise is never to do anything unless you and I both feel totally comfortable, willing, and ready.”

I drove to Grimble’s house in Encino the following night to go sarging. This would be my first time in the field since Mystery’s workshop. It would also be my first time hanging out one-on-one with a stranger I’d met online. All I really knew about him was that he was a college student and he liked girls.

When I pulled up, Grimble strode outside and flashed a big smile that I didn’t quite trust. He didn’t seem dangerous or mean. He just seemed slippery, like a politician or a salesman or, I suppose, a seducer. He had the complexion of barley tea, though he was actually German. In fact, he claimed to be a descendent of Otto von Bismarck. He wore a brown leather jacket over a silver floral-print shirt, which was unbuttoned to reveal an eerily hairless chest thrust out further than his nose. In his hands was a plastic bag full of videotapes, which he dumped into the back of my car. He reminded me of a mongoose.

“These are some of Ross’s seminars,” he said. “You’ll really like the DC seminar, because he gets into synesthesia there. The other tapes are from Kim and Tom”—Ross’s ex-girlfriend and her new boyfriend. “It’s their New York seminar, ‘Advanced Anchoring and Other Sneaky Stuff.’”

“What’s anchoring?” I asked.

“My wing Twotimer will show you when you meet him. Ever experienced condiment anchoring before?”

I had so much to learn. Men generally don’t communicate to one another with the same level of emotional depth and intimate detail as most women. Women discuss everything. When a man sees his friends after getting laid, they ask, “How’d it go?” And in return, he gives them either a thumbs up or a thumbs down. That’s how it’s done. To discuss the experience in detail would mean giving your friends mental images they don’t really want to have. It is a taboo among men to picture their best friends naked or having sex, because then they might find themselves aroused—and we all know what that means.

So, ever since I’d first started harboring lustful thoughts in sixth grade, I’d assumed that sex was something that just happened to guys if they went out a lot and exposed themselves to chance—after all, that’s why they called it getting lucky. The only tool they had in their belt was persistence. Of course, there were some men who were sexually comfortable around women, who would tease them mercilessly until they had them eating out of their hands. But that wasn’t me. It took all of my courage to simply ask a woman for the time or where Melrose Avenue was. I didn’t know anything about anchoring, eliciting values, finding trance words, or these other things Grimble kept talking about.

How did I ever get laid without all this technology?

It was a quiet Tuesday night in the Valley, and the only place Grimble knew to go was the local T.G.I. Friday’s. In the car, we warmed up—listening to cassette tapes of sarges by Rick H., practicing openers, faking smiles, and dancing in our seats to get energetic. It was one of the most ridiculous things I’d ever done, but I was entering a new world now, with its own rules of behavior.

We walked in the door of the restaurant—confident, smiling, alpha. Unfortunately, no one noticed. There were two guys at the bar watching a baseball game on television, a group of businesspeople at a corner table, and a mostly male bar staff. We strutted to the balcony. As we pushed the door open, a woman appeared. Time to put what I’d learned to the test.

“Hey,” I said to her. “Let me get your opinion on something.”

She stopped and listened. She was about four foot ten, with short, frizzy hair and a marshmallow body, but she had a nice smile; she would be good practice. I decided to use the Maury Povich opener.

“My friend Grimble there just got a call today from the Maury Povich show,” I began. “And it seems they’re doing a segment on secret admirers. Evidently, someone has a little crush on him. Do you think he should go on the show or not?”

“Sure,” she answered. “Why not?”

“But what if his secret admirer is a man?” I asked. “Talk shows always need to put an unexpected twist on everything. Or what if it’s a relative?”

It’s not lying; it’s flirting.

She laughed. Perfect. “Would you do the show?” I asked.

“Probably not,” she answered.

Suddenly, Grimble stepped in. “So you would make me go on the show, but you wouldn’t do it yourself,” he teased her. “You’re not adventurous at all, are you?” It was great to watch him work. Where I would have let the conversation wane into small talk, he was already leading her somewhere sexual.

“I am,” she protested.

“Then prove it to me,” he said, smiling. “Let’s try a little exercise. It’s called synesthesia.” He took a step closer to her. “Have you ever heard of synesthesia? It will enable you to find all kinds of resources to accomplish and feel the things you want in life.”

Synesthesia is the nerve gas in the arsenal of the speed seducer. Literally, it is an overlapping of the senses. In the context of seduction, however, synesthesia refers to a type of waking hypnosis in which a woman is put into a heightened state of awareness and told to imagine pleasurable images and sensations growing in intensity. The goal: to make her uncontrollably aroused.

She agreed and closed her eyes. I was finally going to get to hear one of Ross’s secret patterns. But as soon as Grimble began, a stocky, red-faced jock wearing a pocket undershirt marched up to him.

“What are you doing?” he asked Grimble.

“I was showing her a self-improvement exercise called synesthesia.”

“Well, that’s my wife.”

I had forgotten to check for a wedding ring, though I doubted minor inconveniences like marriage mattered to Grimble.

“Go disarm the guy,” Grimble turned to me and hissed, “while I work on the girl.”

I had no idea how to disarm him. He didn’t seem quite as laid-back as Scott Baio. “He can show you the exercise, too,” I said wanly. “It’s really cool.”

“I don’t know what the fuck you’re talking about,” the guy said. “What is this thing supposed to do to me?” He took a step closer and leaned his face into mine. He smelled like whiskey and onion rings.

“It tells you whether…whether…” I stammered. “Never mind.”

The guy lifted his hands and pushed me backward. Though I tell girls I’m five feet and eight inches, I’m actually five foot six. The top of my head just reached his shoulders.

“Stop it,” his wife, our former sarge, said. She turned to us. “He’s drunk. He gets like this.”

“Like what?” I asked. “Violent?”

She smiled sadly.

“You seem like a great couple,” I said. My attempt to disarm him had clearly failed, because he was about to disarm me. His red drunken face was two inches from mine and yelling about ripping something.

“Pleasure meeting you both,” I squeaked, slowly backing away.

“Remind me,” Grimble said as we retreated to the car, “to teach you how to handle the AMOG.”

“The AMOG?”