Table of Contents

“Nobody Cares What You Do in There”: The Low Road

The Rise of the Creative Class

Innovation Blowback: Disruptive Management Practices from Asia

The Process of Social Innovation

A Conversation with Beth Noveck

A Conversation with Jon Schnur

A Conversation with Tom Kelley

A Conversation with Katie Salen

Also by Steven Johnson

Interface Culture: How New Technology Transforms the Way We Create and Communicate

Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software

Mind Wide Open: Your Brain and the Neuroscience of Everyday Life

Everything Bad Is Good for You: How Today’s Popular Culture Is Actually Making Us Smarter

The Ghost Map: The Story of London’s Most Terrifying Epidemic—and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World

The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution, and the Birth of America

Where Good Ideas Come From

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd.)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty. Ltd.)

Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd., 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi—110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty.) Ltd., 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

THE INNOVATOR’S COOKBOOK

Copyright © 2011 by Steven Johnson

A continuation of this copyright page appears on page 257

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions. RIVERHEAD is a registered trademark of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

The RIVERHEAD logo is a trademark of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

First Riverhead trade paperback edition: October 2011

ISBN : 978-1-101-55038-0

INTRODUCTION

The first step in winning the future is encouraging

American innovation.

—BARACK OBAMA, STATE OF THE UNION ADDRESS, JANUARY 20II

I first began working explicitly on the problem of innovation in the summer of 2006, when I started writing a book about new ideas and the environments that encouraged them. But it wasn’t until I finished that book that I realized I had been wrestling with innovation, in one way or another, for almost two decades. The first articles I published in my twenties as an easily distracted English-lit grad student gravitated toward the digital revolutions coming out of Silicon Valley; all my books since then have focused on new ideas and their transformative power—innovations in science or tech or politics or entertainment, some of them recent headlines and some ancient history.

That long history with the topic may help explain why I assumed almost by default, as I was writing the innovation book, that there was nothing particularly timely about the subject matter, nothing distinct to the zeitgeist of postmillennial culture. Sure, we routinely lavish praise on and pen hagiographies about entrepreneurs like Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg, but we did the same for Thomas Edison and Ben Franklin before them. I had written books that I consciously thought of as zeitgeist-y as I was working on them. Innovation wasn’t like that. This was, in fact, one of the things I found refreshing about the topic. Innovation wasn’t trendy; it was evergreen.

But then something seemed to happen, as the world economy began to climb its way out of the Great Crunch of 2008 to 2009, and we began to probe through the rubble looking for clues to explain what had brought on such a colossal failure, clues that might also, we hoped, suggest ways to avoid similar failures in the future. After a decade of financial pseudo innovation—the creditdefault swaps and collateralized debt obligations that inflated the housing bubble and nearly brought down the world economy when that bubble inevitably burst—it seemed suddenly, viscerally clear that economic growth needed to come from making useful things again, whether those things were electric cars or digital code, and not just creating illusory value out of complex derivative schemes.

I saw this firsthand in the United States, and to a lesser extent in the UK, but I suspect the pattern extends throughout the world. By the time I had finished the final draft of my book, innovation seemed to be on everyone’s lips: public school superintendents, venture capitalists, clean-energy entrepreneurs, op-ed writers. And so when President Obama delivered his State of the Union address in January of 2011, it was not terribly surprising to see him devote nearly a third of the speech to innovation-related initiatives. The speech is worth quoting from in some length, because the way that he frames the issue tells us something important about why innovation seems so central to us today:

The first step in winning the future is encouraging American innovation. None of us can predict with certainty what the next big industry will be or where the new jobs will come from. Thirty years ago, we couldn’t know that something called the Internet would lead to an economic revolution. What we can do—what America does better than anyone else—is spark the creativity and imagination of our people. We’re the nation that put cars in driveways and computers in offices; the nation of Edison and the Wright brothers; of Google and Facebook. In America, innovation doesn’t just change our lives. It is how we make our living.

Our free-enterprise system is what drives innovation. But because it’s not always profitable for companies to invest in basic research, throughout our history, our government has provided cutting-edge scientists and inventors with the support that they need. That’s what planted the seeds for the Internet. That’s what helped make possible things like computer chips and GPS. Just think of all the good jobs—from manufacturing to retail—that have come from these breakthroughs.

Half a century ago, when the Soviets beat us into space with the launch of a satellite called Sputnik, we had no idea how we would beat them to the moon. The science wasn’t even there yet. NASA didn’t exist. But after investing in better research and education, we didn’t just surpass the Soviets; we unleashed a wave of innovation that created new industries and millions of new jobs.

This is our generation’s Sputnik moment. Two years ago, I said that we needed to reach a level of research and development we haven’t seen since the height of the Space Race. And in a few weeks, I will be sending a budget to Congress that helps us meet that goal. We’ll invest in biomedical research, information technology, and especially clean energy technology—an investment that will strengthen our security, protect our planet, and create countless new jobs for our people.

As Obama suggests, the social impact of innovation has a long history to it, one that, it should be said, is hardly as America-centric as Obama implies: think of the British steam engines that powered the first wave of the industrial revolution in the eighteenth century, or the inventions in algebra and double-entry accounting during the Islamic golden age more than a thousand years ago. The history of human progress, worldwide, is the history of new ideas put to wonderful new use.

But the State of the Union address also shed light on what makes our present attitude toward innovation different, in two fundamental ways. The first is this distinct assumption that innovation can—and should—be cultivated; that it wasn’t just something that would magically emerge on its own from the folkloric Entrepreneurial American Spirit. Innovation could be taught, encouraged, supported—or suppressed—thanks to decisions that we made as a society. It wasn’t enough just to lower the capital gains tax and let the entrepreneurs and venture capitalists go wild; innovation required more subtle interventions for it to truly flourish.

The president’s interest in nurturing innovation has its roots in a growing body of research that has accumulated over the past twenty years, some of it written by economists and legal scholars who would become part of Obama’s inner circle. For most of the twentieth century, innovation lived at the margins of most economics scholarship. Thousands of books were written on the efficiency of markets, and the conditions under which governments might correct capitalism’s turbulence or inequities; elaborate mathematical models were built to explain the miracles of price signaling. But the seemingly equally important question of how societies came up with new products in the first place went largely unexamined. Intriguingly, some of the most astute analyses of innovation came from open critics of capitalism: starting with Marx’s famous observation that market-driven economies created a culture of permanent change, where “all that is solid melts into air.” Later, the Austrian socialist Joseph Schumpeter chronicled capitalism’s relentless drive for “creative destruction”—popularizing a phrase that would eventually be embraced by titans of industry and business school seminars, losing its original negative connotations in the process.

But the past two decades have corrected this strange oversight, as a growing number of influential thinkers have begun to investigate the mysteries of innovation, many of whom are represented in this volume. Books with titles like The Innovator’s Dilemma and The Art of Innovation now circulate through business school syllabi and corporate retreats. Creativity consultants do a booming business. Cities around the globe vie to re-create the innovation magic of high-tech hubs like Silicon Valley or Route 128.

The Innovator’s Cookbook is, in part, an attempt to capture the best of that wide-ranging scholarship in a single volume. But it is also an attempt to shine light on a more recent development in the literature of innovation, one that is also evident in Obama’s State of the Union address. And that is the growing sense that governments have an integral role to play in fostering innovative societies—and, perhaps more radically, that they themselves can show some of the inventiveness that has traditionally been the hallmark of the private sector. While the scholarship on innovation that has blossomed over the past twenty years has opened many doors in understanding how new products and services emerge, it has generally worked under the assumption that the most important innovations arose out of the competitive pressure of the marketplace. But the revolutionary impact of the Internet and the Web—the two most transformative innovations of our time, both of which evolved outside traditional market environments and are, effectively, owned and operated collectively—have made it clear that the private sector hardly holds a monopoly on innovation.

I suspect the most important breakthroughs over the next ten years will come from hybrid environments, where the public and private sectors overlap. Consider two examples from the past few years: Kickstarter and SeeClickFix. Kickstarter is a site that allows individuals to fund creative projects, like movies, art installations, albums, and so on. Donors may get special gifts in return for their contributions—signed copies of the final CD or an invitation to the opening—but they do not own the creations they help support. In just two years of existence, Kickstarter has raised more than $60 million for thousands of projects, taking a small cut of each transaction. The economic exchange that Kickstarter enables between donors and creators works outside the traditional logic of markets. People are “investing” in others not for the promise of subsequent financial reward, but rather for the social rewards of supporting important work. The artists, on the other hand, are relying on a decentralized network of support, not government grants. And yet Kickstarter itself is a for-profit company that may well make a nice return for its own investors and founders.

SeeClickFix is a mobile app that allows community members to report open fire hydrants, dangerous intersections, threatening tree limbs, and other pressing local needs. (A related service, FixMyStreet, launched in the UK several years ago.) In proper Web 2.0 fashion, all complaints are visible to the community, and other members can vote to endorse the problem. SeeClickFix has begun offering free dashboards for local governments, with a premium service available for a monthly fee. The service also bundles together its user-generated reports and e-mails them to the appropriate authorities in each market. It’s an intriguing hybrid model: the private sector creates the interfaces for managing and mapping urban issues, while the public sector continues its traditional role of resolving those issues.

What I love about these services is not just the laudable goals they both set out to accomplish, but the inventiveness of the approaches they take. They are each tackling a long-standing social problem: How do we support artists whose work is not yet sustained by the marketplace? How do we monitor all the changing needs of real-world neighborhoods? But their methods are amazingly novel—so novel, in fact, that you might be inclined to suspect that they might never work in practice. But the same skepticism was said of a user-authored encyclopedia that Jimmy Wales launched ten years ago—and now Wikipedia regularly outperforms the Encyclopedia Britannica. That these unlikely projects actually turn out to work in practice is a testament not only to the new technologies of the Web and mobile computing; it’s also a testament to the adventurousness of the general public, the people who actually use and support these services, and in many cases expand their range—a process that Columbia’s Amar Bhidé calls “venturesome consumption.”

This is the great opportunity of our time: we have both extraordinary new tools that allow us to build things like Kickstarter and SeeClickFix and we have a society of consumers and citizens who are willing to experiment with these crazy new schemes, so much so that what seemed crazy two years ago now just seems routine. The ideas assembled in this book—particularly in the conversations with “innovators at work” in the second half—are all, in their different ways, wrestling with the question of how best to capitalize on that opportunity. New ideas have been driving human progress since the Stone Age; what we have now is a growing set of new ideas about how to generate new ideas. Many of those ideas will come out of private-sector start-ups, but just as many will come from outside the marketplace: from universities, and nonprofits, and, yes, even governments. In this sense, The Innovator’s Cookbook is not unlike what you find in the traditional variety of cookbooks: the best recipes draw their flavors from multiple cuisines. The Internet has been the most powerful driver of innovation in our time in large part because it drew upon ideas from university scholarship, military research, visionary start-ups, open-source collaborations—not to mention all those venturesome consumers figuring out amazing new uses for the technology. The ideas that will “win the future”—in the United States, and everywhere else—will no doubt be concocted out of equally diverse ingredients.

Steven Johnson

May 2011

ESSAYS

The Discipline of Innovation

PETER DRUCKER

Despite much discussion these days of the “entrepreneurial personality,” few of the entrepreneurs with whom I have worked during the past thirty years had such personalities. But I have known many people—say salespeople, surgeons, journalists, scholars, even musicians—who did have them without being the least bit entrepreneurial. What all the successful entrepreneurs I have met have in common is not a certain kind of personality but a commitment to the systematic practice of innovation.

Innovation is the specific function of entrepreneurship, whether in an existing business, a public service institution, or a new venture started by a lone individual in the family kitchen. It is the means by which the entrepreneur either creates new wealth-producing resources or endows existing resources with enhanced potential for creating wealth.

Today, much confusion exists about the proper definition of entrepreneurship. Some observers use the term to refer to all small businesses; others, to all new businesses. In practice, however, a great many well-established businesses engage in highly successful entrepreneurship. The term, then, refers not to an enterprise’s size or age but to a certain kind of activity. At the heart of that activity is innovation: the effort to create purposeful, focused change in an enterprise’s economic or social potential.

SOURCES OF INNOVATION

There are, of course, innovations that spring from a flash of genius. Most innovations, however, especially the successful ones, result from a conscious, purposeful search for innovation opportunities, which are found only in a few situations. Four such areas of opportunity exist within a company or industry: unexpected occurrences, incongruities, process needs, and industry and market changes.

Three additional sources of opportunity exist outside a company in its social and intellectual environment: demographic change, changes in perception, and new knowledge.

True, these sources overlap, different as they may be in the nature of their risk, difficulty, and complexity, and the potential for innovation may well lie in more than one area at a time. But together, they account for the great majority of all innovation opportunities.

1. Unexpected Occurrences

Consider, first, the easiest and simplest source of innovation opportunity: the unexpected. In the early 1930s, IBM developed the first modern accounting machine, which was designed for banks. But banks in 1933 did not buy new equipment. What saved the company—according to a story that Thomas Watson Sr., the company’s founder and long-term CEO, often told—was its exploitation of an unexpected success: The New York Public Library wanted to buy a machine. Unlike the banks, libraries in those early New Deal days had money, and Watson sold more than a hundred of his otherwise unsalable machines to libraries.

Fifteen years later, when everyone believed that computers were designed for advanced scientific work, business unexpectedly showed an interest in a machine that could do payroll. Univac, which had the most advanced machine, spurned business applications. But IBM immediately realized it faced a possible unexpected success, redesigned what was basically Univac’s machine for such mundane applications as payroll, and within five years became a leader in the computer industry, a position it has maintained to this day.

The unexpected failure may be an equally important source of innovation opportunities. Everyone knows about the Ford Edsel as the biggest new-car failure in automotive history. What very few people seem to know, however, is that the Edsel’s failure was the foundation for much of the company’s later success. Ford planned the Edsel, the most carefully designed car to that point in American automotive history, to give the company a full product line with which to compete with General Motors. When it bombed, despite all the planning, market research, and design that had gone into it, Ford realized that something was happening in the automobile market that ran counter to the basic assumptions on which GM and everyone else had been designing and marketing cars. No longer was the market segmented primarily by income groups; the new principle of segmentation was what we now call “lifestyles.” Ford’s response was the Mustang, a car that gave the company a distinct personality and reestablished it as an industry leader.

Unexpected successes and failures are such productive sources of innovation opportunities because most businesses dismiss them, disregard them, and even resent them. The German scientist who around 1905 synthesized novocaine, the first nonaddictive narcotic, had intended it to be used in major surgical procedures like amputations. Surgeons, however, preferred total anesthesia for such procedures; they still do. Instead, novocaine found a ready appeal among dentists. Its inventor spent the remaining years of his life traveling from dental school to dental school making speeches that forbade dentists from “misusing” his noble invention in applications for which he had not intended it.

This is a caricature, to be sure, but it illustrates the attitude managers often take to the unexpected: “It should not have happened.” Corporate reporting systems further ingrain this reaction, for they draw attention away from unanticipated possibilities. The typical monthly or quarterly report has on its first page a list of problems—that is, the areas where results fall short of expectations. Such information is needed, of course, to help prevent deterioration of performance. But it also suppresses the recognition of new opportunities. The first acknowledgment of a possible opportunity usually applies to an area in which a company does better than budgeted. Thus genuinely entrepreneurial businesses have two “first pages”—a problem page and an opportunity page—and managers spend equal time on both.

2. Incongruities

Alcon Laboratories was one of the success stories of the 1960s because Bill Conner, the company’s cofounder, exploited an incongruity in medical technology. The cataract operation is the world’s third or fourth most common surgical procedure. During the past three hundred years, doctors systematized it to the point that the only “old-fashioned” step left was the cutting of a ligament. Eye surgeons had learned to cut the ligament with complete success, but it was so different a procedure from the rest of the operation, and so incompatible with it, that they often dreaded it. It was incongruous.

Doctors had known for fifty years about an enzyme that could dissolve the ligament without cutting. All Conner did was to add a preservative to this enzyme that gave it a few months’ shelf life. Eye surgeons immediately accepted the new compound, and Alcon found itself with a worldwide monopoly. Fifteen years later, Nestlé bought the company for a fancy price.

Such an incongruity within the logic or rhythm of a process is only one possibility out of which innovation opportunities may arise. Another source is incongruity between economic realities. For instance, whenever an industry has a steadily growing market but falling profit margins—as say, in the steel industries of developed countries between 1950 and 1970—an incongruity exists. The innovative response: minimills.

An incongruity between expectations and results can also open up possibilities for innovation. For fifty years after the turn of the century, shipbuilders and shipping companies worked hard both to make ships faster and to lower their fuel consumption. Even so, the more successful they were in boosting speed and trimming their fuel needs, the worse the economics of ocean freighters became. By 1950 or so, the ocean freighter was dying, if not already dead.

All that was wrong, however, was an incongruity between the industry’s assumptions and its realities. The real costs did not come from doing work (that is, being at sea) but from not doing work (that is, sitting idle in port). Once managers understood where costs truly lay, the innovations were obvious: the roll-on and roll-off ship and the container ship. These solutions, which involved old technology, simply applied to the ocean freighters what railroads and truckers had been using for thirty years. A shift in viewpoint, not in technology, totally changed the economics of ocean shipping and turned it into one of the major growth industries of the last twenty to thirty years.

3. Process Needs

Anyone who has ever driven in Japan knows that the country has no modern highway system. Its roads still follow the paths laid down for—or by—oxcarts in the tenth century. What makes the system work for automobiles and trucks is an adaptation of the reflector used on American highways since the early 1930s. The reflector lets each car see which other cars are approaching from any one of a half-dozen directions. This minor invention, which enables traffic to move smoothly and with a minimum of accidents, exploited a process need.

What we now call the media had its origin in two innovations developed around 1890 in response to process needs. One was Ottmar Mergenthaler’s Linotype, which made it possible to produce newspapers quickly and in large volume. The other was a social innovation, modern advertising, invented by the first true newspaper publishers, Adolph Ochs of the New York Times, Joseph Pulitzer of the New York World, and William Randolph Hearst. Advertising made it possible for them to distribute news practically free of charge, with the profit coming from marketing.

4. Industry and Market Changes

Managers may believe that industry structures are ordained by the good Lord, but these structures can—and often do—change overnight. Such change creates tremendous opportunity for innovation.

One of American business’s great success stories in recent decades is the brokerage firm of Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette, recently acquired by the Equitable Life Assurance Society. DL&J was founded in 1960 by three young men, all graduates of the Harvard Business School, who realized that the structure of the financial industry was changing as institutional investors became dominant. These young men had practically no capital and no connections. Still, within a few years, their firm had become a leader in the move to negotiated commissions and one of Wall Street’s stellar performers. It was the first to be incorporated and go public.

In a similar fashion, changes in industry structure have created massive innovation opportunities for American health care providers. During the past ten or fifteen years, independent surgical and psychiatric clinics, emergency centers, and HMOs have opened throughout the country. Comparable opportunities in telecommunications followed industry upheavals—in transmission (with the emergence of MCI and Sprint in longdistance service) and in equipment (with the emergence of such companies as Rolm in the manufacturing of private branch exchanges).

When an industry grows quickly—the critical figure seems to be in the neighborhood of 40 percent growth in ten years or less—its structure changes. Established companies, concentrating on defending what they already have, tend not to counterattack when a newcomer challenges them. Indeed, when market or industry structures change, traditional industry leaders again and again neglect the fastest-growing market segments. New opportunities rarely fit the way the industry has always approached the market, defined it, or organized to serve it. Innovators, therefore, have a good chance of being left alone for a long time.

5. Demographic Changes

Of the outside sources of innovation opportunities, demographics are the most reliable. Demographic events have known lead times; for instance, every person who will be in the American labor force by the year 2000 has already been born. Yet because policymakers often neglect demographics, those who watch them and exploit them can reap great rewards.

The Japanese are ahead in robotics because they paid attention to demographics. Everyone in the developed countries around 1970 or so knew that there was both a baby bust and an education explosion going on; about half or more of the young people were staying in school beyond high school. Consequently, the number of people available for traditional blue-collar work in manufacturing was bound to decrease and become inadequate by 1990. Everyone knew this, but only the Japanese acted on it, and they now have a ten-year lead in robotics.

Much the same is true of Club Mediterranee’s success in the travel and resort business. By 1970, thoughtful observers could have seen the emergence of large numbers of affluent and educated young adults in Europe and the United States. Not comfortable with the kind of vacations their working-class parents had enjoyed—the summer weeks at Brighton or Atlantic City—these young people were ideal customers for a new and exotic version of the “hangout” of their teen years.

Managers have known for a long time that demographics matter, but they have always believed that population statistics change slowly. In this century, however, they don’t. Indeed, the innovation opportunities made possible by changes in the numbers of people—and in their age distribution, education, occupations, and geographic location—are among the most rewarding and least risky of entrepreneurial pursuits.

6. Changes in Perception

“The glass is half full” and “The glass is half empty” are descriptions of the same phenomenon but have vastly different meanings. Changing a manager’s perception of a glass from half full to half empty opens up big innovation opportunities.

All factual evidence indicates, for instance, that in the last twenty years, Americans’ health has improved with unprecedented speed—whether measured by mortality rates for the newborn, survival rates for the very old, the incidence of cancers (other than lung cancer), cancer cure rates, or other factors. Even so, collective hypochondria grips the nation. Never before has there been so much concern with or fear about health. Suddenly, everything seems to cause cancer or degenerative heart disease or premature loss of memory. The glass is clearly half empty.

Rather than rejoicing in great improvements in health, Americans seem to be emphasizing how far away they still are from immortality. This view of things has created many opportunities for innovations: markets for new health care magazines, for exercise classes and jogging equipment, and for all kinds of health foods. The fastest-growing new U.S. business in 1983 was a company that makes indoor exercise equipment.

A change in perception does not alter facts. It changes their meaning, though—and very quickly. It took less than two years for the computer to change from being perceived as a threat and as something only big businesses would use to something one buys for doing income tax. Economics do not necessarily dictate such a change; in fact, they may be irrelevant. What determines whether people see a glass as half full or half empty is mood rather than fact, and a change in mood often defies quantification. But it is not exotic. It is concrete. It can be defined. It can be tested. And it can be exploited for innovation opportunity.

7. New Knowledge

Among history-making innovations, those that are based on new knowledge—whether scientific, technical, or social—rank high. They are the superstars of entrepreneurship; they get the publicity and the money. They are what people usually mean when they talk of innovation, although not all innovations based on knowledge are important.

Knowledge-based innovations differ from all others in the time they take, in their casualty rates, and in their predictability, as well as in the challenges they pose to entrepreneurs. Like most superstars, they can be temperamental, capricious, and hard to direct. They have, for instance, the longest lead time of all innovations. There is a protracted span between the emergence of new knowledge and its distillation into usable technology. Then there is another long period before this new technology appears in the marketplace in products, processes, or services. Overall, the lead time involved is something like fifty years, a figure that has not shortened appreciably throughout history.

To become effective, innovation of this sort usually demands not one kind of knowledge but many. Consider one of the most potent knowledge-based innovations: modern banking. The theory of the entrepreneurial bank—that is, of the purposeful use of capital to general economic development—was formulated by the Comte de Saint-Simon during the era of Napoleon. Despite Saint-Simon’s extraordinary prominence, it was not until thirty years after his death in 1825 that two of his disciples, the brothers Jacob and Isaac Pereire, established the first entrepreneurial bank, the Credit Mobilier, and ushered in what we now call finance capitalism.

The Pereires, however, did not know modern commercial banking, which developed at about the same time across the channel in England. The Credit Mobilier, failed ignominiously. A few years later, two young men—one an American, J. P. Morgan, and one a German, Georg Siemens—put together the French theory of entrepreneurial banking and the English theory of commercial banking to create the first successful modern banks: J.P. Morgan & Company in New York, and the Deutsche Bank in Berlin. Ten years later, a young Japanese, Shibusawa Eiichi, adapted Siemens’s concept to his country and thereby laid the foundation of Japan’s modern economy. This is how knowledge-based innovation always works.

The computer, to cite another example, required no fewer than six separate strands of knowledge:

• binary arithmetic

• Charles Babbage’s conception of a calculating machine, in the first half of the nineteenth century

• the punch card, invented by Herman Hollerith for the U. S. census of 1890

• the audion tube, an electronic switch invented in 1906

• symbolic logic, which was developed between 1910 and 1913 by Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead

• concepts of programming and feedback that came out of the abortive attempts during World War I to develop effective antiaircraft guns

Although all the necessary knowledge was available by 1918, the first operational digital computer did not appear until 1946.

Long lead times and the needs for convergence among different kinds of knowledge explain the peculiar rhythm of knowledge-based innovation, its attractions, and its dangers. During a long gestation period, there is a lot of talk and little action. Then, when all the elements suddenly converge, there is tremendous excitement and activity and an enormous amount of speculation. Between 1880 and 1890, for example, almost one thousand electronic-apparatus companies were founded in developed countries. Then, as always, there was a crash and a shakeout. By 1914, only twenty-five were still alive. In the early 1920s, three hundred to five hundred automobile companies existed in the United States; by 1960, only four of them remained.

It may be difficult, but knowledge-based innovation can be managed. Success requires careful analysis of the various kinds of knowledge needed to make an innovation possible. Both J. P. Morgan and Georg Siemens did this when they established their banking ventures. The Wright brothers did this when they developed the first operational airplane.

Careful analysis of the needs—and above all, the capabilities—of the intended user is also essential. It may seem paradoxical, but knowledge-based innovation is more market dependent than any other kind of innovation. De Havilland, a British company, designed and built the first passenger jet, but it did not analyze what the market needed and therefore did not identify two key factors. One was configuration—that is, the right size with the right pay-load for the routes on which a jet would give an airline the greatest advantage. The other was equally mundane: How could the airlines finance the purchase of such an expensive plane? Because de Havilland failed to do an adequate user analysis, two American companies, Boeing and Douglas, took over the commercial jetaircraft industry.

PRINCIPLES OF INNOVATION

Purposeful, systematic innovation begins with the analysis of the sources of new opportunities. Depending on the context, sources will have different importance at different times. Demographics, for instance, may be of little concern to innovators of fundamental industrial processes like steelmaking, although the Linotype machine became successful primarily because there were not enough skilled typesetters available to satisfy a mass market. By the same token, new knowledge may be of little relevance to someone innovating a social instrument to satisfy a need that changing demographics or tax laws have created. But whatever the situation, innovators must analyze all opportunity sources.

Because innovation is both conceptual and perceptual, wouldbe innovators must also go out and look, ask, and listen. Successful innovators use both the right and left sides of their brains. They work out analytically what the innovation has to be to satisfy an opportunity. Then they go out and look at potential users to study their expectations, their values, and their needs.

To be effective, an innovation has to be simple, and it has to be focused. It should do only one thing; otherwise it confuses people. Indeed, the greatest praise an innovation can receive is for people to say, “This is obvious! Why didn’t I think of it? It’s so simple!” Even the innovation that creates new uses and new markets should be directed toward a specific, clear, and carefully designed application.

Effective innovations start small. They are not grandiose. It may be to enable a moving vehicle to draw electric power while it runs along rails, the innovation that made possible the electric streetcar. Or it may be the elementary idea of putting the same number of matches into a matchbox (it used to be fifty). This simple notion made possible the automatic filling of matchboxes and gave the Swedes a world monopoly on matches for half a century. By contrast, grandiose ideas for things that will “revolutionize an industry” are unlikely to work.

In fact, no one can foretell whether a given innovation will end up a big business or a modest achievement. But even if the results are modest, the successful innovation aims from the beginning to become the standard setter, to determine the direction of a new technology or a new industry, to create the business that is—and remains—ahead of the pack. If an innovation does not aim at leadership from the beginning, it is unlikely to be innovative enough.

Above all, innovation is work rather than genius. It requires knowledge. It often requires ingenuity. And it requires focus. There are clearly people who are more talented innovators than others, but their talents lie in well-defined areas. Indeed, innovators rarely work in more than one area. For all his systematic innovative accomplishments, Thomas Edison worked only in the electrical field. An innovator in financial areas, Citibank, for example, is not likely to embark on innovations in health care.

In innovation, as in any other endeavor, there is talent, there is ingenuity, and there is knowledge. But when all is said and done, what innovation requires is hard, focused, purposeful work. If diligence, persistence, and commitment are lacking, talent, ingenuity, and knowledge are of no avail.

There is, of course, far more to entrepreneurship than systematic innovation—distinct entrepreneurial strategies, for example, and the principles of entrepreneurial management, which are needed equally in the established enterprise, the public service organization, and the new venture. But the very foundation of entrepreneurship is the practice of systematic innovation.

“Nobody Cares What You Do in There”: The Low Road

STEWART BRAND

I thas to do with freedom. Or so I surmised from a 1990 conversation with John Sculley, then head of Apple Computer. Sculley was trained in architecture before he started rocketing up corporate ladders. During a break at a conference, we got talking about buildings. Apple had expanded from five buildings into thirtyone in the few years Sculley had been at Apple. I asked him, “Do you prefer moving into old buildings or making new ones?” “Oh, old ones,” he said. “They are much more freeing.”

That statement throws a world of design assumptions upside down. Why are old buildings more freeing? A way to pursue the question is to ask, what kinds of old buildings are the most freeing?

A young couple moves into an old farmhouse or old barn, lit up with adventure. An entrepreneur opens shop in an echoing warehouse, an artist takes over a drafty loft in the bad part of town, and they feel joy at the prospect. They can’t wait to have at the space and put it immediately to work. What these buildings have in common is that they are shabby and spacious. Any change is likely to be an improvement. They are discarded buildings, fairly free of concern from landlord or authorities: “Do what you want. The place can’t get much worse anyway. It’s just too much trouble to tear down.”

Low Road buildings are low-visibility, low-rent, no-style, high-turnover. Most of the world’s work is done in Low Road buildings, and even in rich societies the most inventive creativity, especially youthful creativity, will be found in Low Road buildings taking full advantage of the license to try things.

Take MIT—the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. A university campus is ideal for comparing building effectiveness because you have a wide variety of buildings serving a limited number of uses—dormitories, laboratories, classrooms, and offices, that’s about it. I’m familiar enough with MIT to know which two buildings are regarded with the most affection among the sixty-eight on campus. One, not surprisingly, is a dormitory called Baker House, designed by Alvar Aalto in 1949. Though Modernist and famous, it is warmly convivial and varied throughout, with a sintered-brick exterior that keeps improving with time.

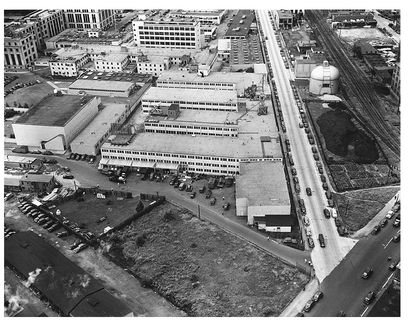

But the most loved and legendary building of all at MIT is a surprise: a temporary building left over from World War II without even a name, only a number: Building 20. It is a sprawling 250,000 square-foota three-story wood structure—“The only building on campus you can cut with a saw,” says an admirer— constructed hastily in 1943 for the urgent development of radar and almost immediately slated for demolition. When I last saw it in 1993, it was still in use and still slated for demolition. In 1978 the MIT Museum assembled an exhibit to honor the perpetual fruitfulness of Building 20. The press release read:

Unusual flexibility made the building ideal for laboratory and experimental space. Made to support heavy loads and of wood construction, it allowed a use of space which accommodated the enlargement of the working environment either horizontally or vertically. Even the roof was used for short-term structures to house equipment and test instruments.

Although Building 20 was built with the intention to tear it down after the end of World War II, it has remained these thirty-five years providing a special function and acquiring its own history and anecdotes. Not assigned to any one school, department, or center, it seems to always have had space for the beginning project, the graduate student’s experiment, the interdisciplinary research center.

Indeed, MIT’s first interdisciplinary laboratory, the renowned Research Laboratory of Electronics, founded much of modern communications science there right after the war. The science of linguistics was largely started there, and forty years later in 1993 one of its pioneers, Noam Chomsky, was still rooted there. Innovative labs for the study of nuclear science, cosmic rays, dynamic analysis and control, acoustics, and food technology were born there. Harold Edgerton developed stroboscopic photography there. New-technology companies such as Digital Equipment Corporation and Bolt, Baranek, and Newman incubated in Building 20 and later took its informal ways with them into their corporate cultures and headquarters. The Tech Model Railroad Club on the third floor, E Wing, was the source in the early 1960s of most of the first generation of computer “hackers,” who set in motion a series of computer technology revolutions (still in progress).

1945: Here photographed from a Navy blimp at the end of World War II, the so-called Radiation Laboratory at Building 20 was one of its unsung heroes. In an undertaking similar in scope to the Manhattan project that created the atomic bomb, the emergency development of radar employed the nation’s best physicists in an intense collaboration that changed the nature of science. Unlike Los Alamos, the MIT radar project was not run by the military, and unlike Los Alamos, no secrets got out. The verdict of scientists afterward was, “The atom bomb only ended the war. Radar won it.” THE MIT MUSEUM. NEG. NO. CC-20-417.

1945: During the war the innocuous building at 18 Vassar Street in Cambridge sprouted odd outgrowths overnight. THE MIT MUSEUM. NEG. NO. CC-20-421.

Like most Low Road buildings, Building 20 was too hot in the summer, too cold in the winter, Spartan in its amenities, often dirty, and implacably ugly. Whatever was the attraction? The organizers of the 1978 exhibit queried alumni of the building and got illuminating answers. “Windows that open and shut at will of the owner!” (Martha Ditmeyer) “The ability to personalize your space and shape it to various purposes. If you don’t like a wall, just stick your elbow through it.” (Jonathan Allan) “If you want to bore a hole in the floor to get a little extra vertical space, you do it. You don’t ask. It’s the best experimental building ever built.” (Albert Hill) “One never needs to worry about injuring the architectural or artistic value of the environment.” (Morris Halle) “We feel our space is really ours. We designed it, we run it. The building is full of small microenvironments, each of which is different and each a creative space. Thus the building has a lot of personality. Also it’s nice to be in a building that has such prestige.” (Heather Lechtman)

In 1991 I asked Jerome Wiesner, retired president of MIT, why he thought that “temporary” Building 20 was still around after half a century. His first answer was practical: “At three hundred dollars a square foot, it would take seventy-five million dollars to replace.” His next answer was aesthetic: “It’s a very matter-of-fact building. It puts on the personality of the people in it.” His final answer was personal. When he was appointed president of the university, he quietly kept a hideaway office in Building 20 because that was where “nobody complained when you nailed something to a door.”

Every university has similar stories. Temporary is permanent, and permanent is temporary. Grand, final-solution buildings obsolesce and have to be torn down because they were too overspecified to their original purpose to adapt easily to anything else. Temporary buildings are thrown up quickly and roughly to house temporary projects. Those projects move on soon enough but they are immediately supplanted by other temporary projects—of which, it turns out, there is an endless supply. The projects flourish in the low-supervision environment, free of turf battles because the turf isn’t worth fighting over. “We did some of our best work in the trailers, didn’t we?” I once heard a Nobel-winning physicist remark. Low Road buildings keep being valuable precisely because they are disposable.

Building 20 raises a question about what are the real amenities. Smart people gave up good heating and cooling, carpeted hallways, big windows, nice views, state-of-the-art construction, and pleasant interior design for what? For sash windows, interesting neighbors, strong floors, and freedom.

Many have noticed that young artists flock to rundown industrial neighborhoods, and then a predictable sequence occurs. The artists go there for the low rents and plenty of room to mess around. They make the area exciting, and some begin to spruce it up. Eventually it becomes fashionable, with trendy restaurants, nightclubs, and galleries. Real estate values rise to the point where young artists can’t afford the higher rents, and the sequence begins again somewhere else. Economic activity follows Low Road activity.

Jane Jacobs explains why:

Only operations that are well-established, high-turnover, standardized or highly subsidized can afford, commonly, to carry the costs of new construction. Chain stores, chain restaurants, and banks go into new construction. But neighborhood bars, foreign restaurants and pawn shops go into older buildings. Supermarkets and shoe stores often go into new buildings; good bookstores and antique dealers seldom do. Well-subsidized opera and art museums often go into new buildings. But the unformalized feeders of the arts—studios, galleries, stores for musical instruments and art supplies, backrooms where the low earning power of a seat and table can absorb uneconomic discussions—these go into old buildings . . .

Old ideas can sometimes use new buildings. New ideas must come from old buildings.b

A related economic sequence happened around houses. People used to store stuff in basements and attics (big tools and toys in the cellar, clothes and memories in the attic). These were the raw, undifferentiated, Low Roadish parts of the house. But after the 1920s, basements and attics were eschewed by new bungalows, Modernist homes, and ranch houses. Basement storage moved into the garage, but then it got displaced again when the garage was converted to a studio, home office, spare bedroom, or rental unit. Where did the storage go next? Economic activity followed Low Road activity. The “self-storage” business took off in the 1970s and 1980s. Windowless clusters of garagelike spaces at the edge of town or edge of industrial districts were thrown together and rented out cheap.c In these spaces you find the damnedest things—a boxer working out, quiet adultery, an old gent in a huge chair enjoying a cigar away from his wife, an entire British barn in pieces, a hydroponic garden, stolen goods, a motorcycle repair shop, an artist’s studio, someone shaping surfboards, lots of very ordinary storage, and, about once a month somewhere in America, a dead body.

Such trends are invisible to high-style architects, but commercial developers watch them closely. They noticed that small businesses often start up in garages, warehouses, and self-storage spaces, sometimes spawning whole Silicon Valley–type local boomtowns.

When my wife, Patty Phelan, started an equestrian mail order catalogue business, she took over one bay of a huge old wood building left over from World War II—part of a shipyard that had built Liberty ships and tankers. Her bay had all the usual amenities—concrete floor, a too-narrow, too-deep space, ill-lit, with a sixty-foot ceiling. She and her staff froze in the winter and baked in the summer. But that space absorbed five years of drastic growth. The company went from one employee to twenty-four, from fifty thousand dollars a year to $3.2 million, while keeping all of its warehousing and shipping on the site. Piece by piece she grew the space, first constructing a second floor, then breaking through a wall into the adjoining bay when that tenant moved out and adding a second floor in there, then cutting through her back wall into some ceilingless interior rooms and roofing them in. Her rent stayed low while she added a skylight, ceiling fans, openable windows, a dutch door, lots more wiring, lots more lighting, and a kitchen.

That’s the patterns that developers thought they might be able to duplicate—long, low, cheap building, a series of bays, each with a garage door, low rent, nothing fancy. Called “incubators,” they were built by the hundreds, and they prospered. By 1990 there was a National Business Incubation Association boosting another Low Road–derivative industry.

The wonder is that Low Road building use has never been studied formally, either for academic or commercial interest or to tease out design principles that might be useful in other buildings. What do people do to buildings when they can do almost anything they want? I haven’t researched the question either, but I’ve lived some of it. [The book in which this essay appears] was assembled and written in two classic Low Road buildings. My writing office was a derelict landlocked fishing boat named the Mary Heartline. Decades ago, after its fishing career was over, a gay couple acquired it for dockside trysts, fixing it up like a Victorian cottage. Then two divorced gentlemen took it over, also for trysts, but it began sinking, so they moved it onto land, ostensibly for repair. It became a real-estate office, a subscriptions-handling office, and then I got it. It was on no property map of the town. If you leaned against the hull in the wrong place, your hand would go through. It’s probably gone by the time you’re reading this.

Thanks to the gay couple’s Victorian tastes, the place was a maze of little niches, drawers, and cupboards. It was like working inside an old-fashioned rolltop desk. One day I acquired a fax machine. There being no convenient place to park it, I used a saber saw to hack out a level place by the old steering wheel, along with a hole for the electrical and phone lines. It took maybe ten minutes and required no one else’s opinion. When you can make adjustments to your space by just picking up a saber saw, you know you’re in a Low Road building.

My research library was in a shipping container twenty yards away—one of thirty rented out for self-storage. I got the steel eight-by-eight-by-forty-foot space for $250 a month and spent all of one thousand dollars fixing it up with white paint, cheap carpet, lights, an old couch, and raw plywood work surfaces and shelves. It was heaven. To go in there was to enter the book-inprogress—all the notes, tapes, 5x8 cards, photos, negatives, magazines, articles, 450 books, and other research oddments laid out by chapters or filed carefully. When the summer sun made it too hot for work, I sawed a vent in the wood floor, put a black-painted length of stovepipe out of the ceiling, and slathered the whole top of the container with brightly reflective aluminum paint—end of heat problem. That’s how Low Road buildings are made livable: just do it.

In fact, weather becomes a perverse attraction. Whereas competent sealed buildings lull us with their “perfect climate,” and incompetent ones drive us crazy with their uncontrollable heats and colds, a drafty old building reminds us what the weather is up to outside and invites us to do something about it—put on a sweater; open a window. Rain is loud on the roof. You smell and feel the seasons. Weather comes in the building a bit. That sort of invasion we would condemn in a new building and blame the architect, but in a ratty old building—designed for some other use after all—there’s no one to blame.

Such buildings leave fond memories of improvisation and sensuous delight. When I lived with an artists’ commune in an old church in New York State, I slept in the steeple in front of the rose window overlooking the stream below. The major problem was being pooped on by pigeons, so I made a canopy from the canvas of a large bad painting (art side up) and thereafter slept in comfort, cooed to my rest by flights of angels.

Low Road buildings are peculiarly empowering.

How to Kill Creativity

TERESA M. AMABILE

When I consider all the organizations I have studied and worked with over the past twenty-two years, there can be no doubt: creativity gets killed much more often than it gets supported. For the most part, this isn’t because managers have a vendetta against creativity. On the contrary, most believe in the value of new and useful ideas. However, creativity is undermined unintentionally every day in work environments that were established—for entirely good reasons—to maximize business imperatives such as coordination, productivity, and control.

Managers cannot be expected to ignore business imperatives, of course. But in acting on these imperatives, they may be inadvertently designing organizations that systematically crush creativity. My research shows that it is possible to develop the best of both worlds: organizations in which business imperatives are attended to and creativity flourishes. Building such organizations, however, requires us to understand precisely what kinds of managerial practices foster creativity—and which kill it.

WHAT IS BUSINESS CREATIVITY?

We tend to associate creativity with the arts and to think of it as the expression of highly original ideas. Think of how Pablo Picasso reworked the conventions of painting or how William Faulkner redefined fiction. In business, originality isn’t enough. To be creative, an idea must also be appropriate—useful and actionable. It must somehow influence the way business gets done—by improving a product, for instance, or by opening up a new way to approach a process.

The associations made between creativity and artistic originality often lead to confusion about the appropriate place of creativity in business organizations. In seminars, I’ve asked managers if there is any place they don’t want creativity in their companies. About 80 percent of the time, they answer, “Accounting.” Creativity, they seem to believe, belongs just in marketing and R&D. But creativity can benefit every function of an organization. Think of activity-based accounting. It was an invention—an accounting invention—and its impact on business has been positive and profound.

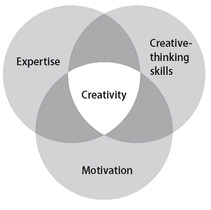

Along with fearing creativity in the accounting department—or really, in any unit that involves systematic processes or legal regulations—many managers also hold a rather narrow view of the creative process. To them, creativity refers to the way people think—how inventively they approach problems, for instance. Indeed, thinking imaginatively is one part of creativity, but two others are also essential: expertise and motivation.

Expertise encompasses everything that a person knows and can do in the broad domain of his or her work. Take, for example, a scientist at a pharmaceutical company who is charged with developing a blood-clotting drug for hemophiliacs. Her expertise includes her basic talent for thinking scientifically as well as all the knowledge and technical abilities that she has in the fields of medicine, chemistry, biology, and biochemistry. It doesn’t matter how she acquired this expertise, whether through formal education, practical experience, or interaction with other professionals. Regardless, her expertise constitutes what the Nobel laureate, economist, and psychologist Herb Simon calls her “network of possible wanderings,” the intellectual space that she uses to explore and solve problems. The larger this space, the better.

Creative thinking, as noted above, refers to how people approach problems and solutions—their capacity to put existing ideas together in new combinations. The skill itself depends quite a bit on personality as well as on how a person thinks and works. The pharmaceutical scientist, for example, will be more creative if her personality is such that she feels comfortable disagreeing with others—that is, if she naturally tries out solutions that depart from the status quo. Her creativity will be enhanced further if she habitually turns problems upside down and combines knowledge from seemingly disparate fields. For example, she might look to botany to help find solutions to the hemophilia problem, using lessons from the vascular systems of plants to spark insights about bleeding in humans.

As for work style, the scientist will be more likely to achieve creative success if she perseveres through a difficult problem. Indeed, plodding through long dry spells of tedious experimentation increases the probability of truly creative breakthroughs. So, too, does a work style that uses “incubation,” the ability to set aside difficult problems temporarily, work on something else, and then return later with a fresh perspective.

Expertise and creative thinking are an individual’s raw materials—his or her natural resources, if you will. But a third factor—motivation—determines what people will actually do. The scientist can have outstanding educational credentials and a great facility for generating new perspectives to old problems. But if she lacks the motivation to do a particular job, she simply won’t do it; her expertise and creative thinking will either go untapped or be applied to something else.

My research has repeatedly demonstrated, however, that all forms of motivation do not have the same impact on creativity. In fact, it shows that there are two types of motivation—extrinsic and intrinsic, the latter being far more essential for creativity. But let’s explore extrinsic first, because it is often at the root of creativity problems in business.

Extrinsic motivation comes from outside a person—whether the motivation is a carrot or a stick. If the scientist’s boss promises to reward her financially should the blood-clotting project succeed, or if he threatens to fire her should it fail, she will certainly be motivated to find a solution. But this sort of motivation “makes” the scientist do her job in order to get something desirable or avoid something painful.

Obviously, the most common extrinsic motivator managers use is money, which doesn’t necessarily stop people from being creative. But in many situations, it doesn’t help either, especially when it leads people to feel that they are being bribed or controlled. More important, money by itself doesn’t make employees passionate about their jobs. A cash reward can’t magically prompt people to find their work interesting if in their hearts they feel it is dull.

But passion and interest—a person’s internal desire to do something—are what intrinsic motivation is all about. For instance, the scientist in our example would be intrinsically motivated if her work on the blood-clotting drug were sparked by an intense interest in hemophilia, a personal sense of challenge, or a drive to crack a problem that no one else has been able to solve. When people are intrinsically motivated, they engage in their work for the challenge and enjoyment of it. The work itself is motivating. In fact, in our creativity research, my students, colleagues, and I have found so much evidence in favor of intrinsic motivation that we have articulated what we call the Intrinsic Motivation Principle of Creativity: people will be most creative when they feel motivated primarily by the interest, satisfaction, and challenge of the work itself—and not by external pressures.

THE CREATIVITY MAZE

To understand the differences between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation, imagine a business problem as a maze.

One person might be motivated to make it through the maze as quickly and safely as possible in order to get a tangible reward, such as money—the same way a mouse would rush through for a piece of cheese. This person would look for the simplest, most straightforward path and then take it. In fact, if he is in a real rush to get that reward, he might just take the most beaten path and solve the problem exactly as it has been solved before.

That approach, based on extrinsic motivation, will indeed get him out of the maze. But the solution that arises from the process is likely to be unimaginative. It won’t provide new insights about the nature of the problem or reveal new ways of looking at it. The rote solution probably won’t move the business forward.

Another person might have a different approach to the maze. She might actually find the process of wandering around the different paths—the challenge and exploration itself—fun and intriguing. No doubt, this journey will take longer and include mistakes, because any maze—any truly complex problem—has many more dead ends than exits. But when the intrinsically motivated person finally does find a way out of the maze—a solution—it very likely will be more interesting than the rote algorithm. It will be more creative.

There is abundant evidence of strong intrinsic motivation in the stories of widely recognized creative people. When asked what makes the difference between creative scientists and those who are less creative, the Nobel Prize–winning physicist Arthur Schawlow said, “The labor-of-love aspect is important. The most successful scientists often are not the most talented, but the ones who are just impelled by curiosity. They’ve got to know what the answer is.” Albert Einstein talked about intrinsic motivation as “the enjoyment of seeing and searching.” The novelist John Irving, in discussing the very long hours he put into his writing, said, “The unspoken factor is love. The reason I can work so hard at my writing is that it’s not work for me.” And Michael Jordan, perhaps the most creative basketball player ever, had a “love of the game” clause inserted into his contract; he insisted that he be free to play pickup basketball games anytime he wished.

Creative people are rarely superstars like Michael Jordan. Indeed, most of the creative work done in the business world today gets done by people whose names will never be recorded in history books. They are people with expertise, good creative-thinking skills, and high levels of intrinsic motivation. And just as important, they work in organizations where managers consciously build environments that support these characteristics instead of destroying them.

MANAGING CREATIVITY

Managers can influence all three components of creativity: expertise, creative-thinking skills, and motivation. But the fact is that the first two are more difficult and time-consuming to influence than motivation. Yes, regular scientific seminars and professional conferences will undoubtedly add to the scientist’s expertise in hemophilia and related fields. And training in brainstorming, problem solving, and so-called lateral thinking might give her some new tools to use in tackling the job. But the time and money involved in broadening her knowledge and expanding her creative-thinking skills would be great. By contrast, our research has shown that intrinsic motivation can be increased considerably by even subtle changes in an organization’s environment. That is not to say that managers should give up on improving expertise and creative-thinking skills. But when it comes to pulling levers, they should know that those that affect intrinsic motivation will yield more immediate results.

More specifically, then, what managerial practices affect creativity? They fall into six general categories: challenge, freedom, resources, work-group features, supervisory encouragement, and organizational support. These categories have emerged from more than two decades of research focused primarily on one question: what are the links between work environment and creativity? We have used three methodologies: experiments, interviews, and surveys. While controlled experiments allowed us to identify causal links, the interviews and surveys gave us insight into the richness and complexity of creativity within business organizations. We have studied dozens of companies and, within those, hundreds of individuals and teams. In each research initiative, our goal has been to identify which managerial practices are definitively linked to positive creative outcomes and which are not.

For instance, in one project, we interviewed dozens of employees from a wide variety of companies and industries and asked them to describe in detail the most and least creative events in their careers. We then closely studied the transcripts of those interviews, noting the managerial practices—or other patterns—that appeared repeatedly in the successful creativity stories and, conversely, in those that were unsuccessful. Our research has also been bolstered by a quantitative survey instrument called KEYS. Taken by employees at any level of an organization, KEYS consists of seventy-eight questions used to assess various workplace conditions, such as the level of support for creativity from top-level managers or the organization’s approach to evaluation.

Taking the six categories that have emerged from our research in turn, let’s explore what managers can do to enhance creativity—and what often happens instead. Again, it is important to note that creativity-killing practices are seldom the work of lone managers. Such practices usually are systemic—so widespread that they are rarely questioned.

Challenge

Of all the things managers can do to stimulate creativity, perhaps the most efficacious is the deceptively simple task of matching people with the right assignments. Managers can match people with jobs that play to their expertise and their skills in creative thinking, and ignite intrinsic motivation. Perfect matches stretch employees’ abilities. The amount of stretch, however, is crucial: not so little that they feel bored but not so much that they feel overwhelmed and threatened by a loss of control.

Making a good match requires that managers possess rich and detailed information about their employees and the available assignments. Such information is often difficult and time-consuming to gather. Perhaps that’s why good matches are so rarely made. In fact, one of the most common ways managers kill creativity is by not trying to obtain the information necessary to make good connections between people and jobs. Instead, something of a shotgun wedding occurs. The most eligible employee is wed to the most eligible—that is, the most urgent and open— assignment. Often, the results are predictably unsatisfactory for all involved.

Freedom

When it comes to granting freedom, the key to creativity is giving people autonomy concerning the means—that is, concerning process—but not necessarily the ends. People will be more creative, in other words, if you give them freedom to decide how to climb a particular mountain. You needn’t let them choose which mountain to climb. In fact, clearly specified strategic goals often enhance people’s creativity.

I’m not making the case that managers should leave their subordinates entirely out of goal- or agenda-setting discussions. But they should understand that inclusion in those discussions will not necessarily enhance creative output and certainly will not be sufficient to do so. It is far more important that whoever sets the goals also makes them clear to the organization and that these goals remain stable for a meaningful period of time. It is difficult, if not impossible, to work creatively toward a target if it keeps moving.

Autonomy around process fosters creativity because giving people freedom in how they approach their work heightens their intrinsic motivation and sense of ownership. Freedom about process also allows people to approach problems in ways that make the most of their expertise and their creative-thinking skills. The task may end up being a stretch for them, but they can use their strengths to meet the challenge.

How do executives mismanage freedom? There are two common ways. First, managers tend to change goals frequently or fail to define them clearly. Employees may have freedom around process, but if they don’t know where they are headed, such freedom is pointless. And second, some managers fall short on this dimension by granting autonomy in name only. They claim that employees are “empowered” to explore the maze as they search for solutions but, in fact, the process is proscribed. Employees diverge at their own risk.

Resources

The two main resources that affect creativity are time and money. Managers need to allot these resources carefully. Like matching people with the right assignments, deciding how much time and money to give to a team or project is a sophisticated judgment call that can either support or kill creativity.

Consider time. Under some circumstances, time pressure can heighten creativity. Say, for instance, that a competitor is about to launch a great product at a lower price than you’re offering or that society faces a serious problem and desperately needs a solution—such as an AIDS vaccine. In such situations, both the time crunch and the importance of the work legitimately make people feel that they must rush. Indeed, cases like these would be apt to increase intrinsic motivation by increasing the sense of challenge.

Organizations routinely kill creativity with fake deadlines or impossibly tight ones. The former create distrust and the latter cause burnout. In either case, people feel overcontrolled and unfulfilled—which invariably damages motivation. Moreover, creativity often takes time. It can be slow going to explore new concepts, put together unique solutions, and wander through the maze. Managers who do not allow time for exploration or do not schedule in incubation periods are unwittingly standing in the way of the creative process.

When it comes to project resources, again managers must make a fit. They must determine the funding, people, and other resources that a team legitimately needs to complete an assignment—and they must know how much the organization can legitimately afford to allocate to the assignment. Then they must strike a compromise. Interestingly, adding more resources above a “threshold of sufficiency” does not boost creativity. Below that threshold, however, a restriction of resources can dampen creativity. Unfortunately, many managers don’t realize this and therefore often make another mistake. They keep resources tight, which pushes people to channel their creativity into finding additional resources, not in actually developing new products or services.

Another resource that is misunderstood when it comes to creativity is physical space. It is almost conventional wisdom that creative teams need open, comfortable offices. Such an atmosphere won’t hurt creativity, and it may even help, but it is not nearly as important as other managerial initiatives that influence creativity. Indeed, a problem we have seen time and time again is managers paying attention to creating the “right” physical space at the expense of more high-impact actions, such as matching people to the right assignments and granting freedom around work processes.

Work-Group Features

If you want to build teams that come up with creative ideas, you must pay careful attention to the design of such teams. That is, you must create mutually supportive groups with a diversity of perspectives and backgrounds. Why? Because when teams comprise people with various intellectual foundations and approaches to work—that is, different expertise and creative thinking styles—ideas often combine and combust in exciting and useful ways.

Diversity, however, is only a starting point. Managers must also make sure that the teams they put together have three other features. First, the members must share excitement over the team’s goal. Second, members must display a willingness to help their teammates through difficult periods and setbacks. And third, every member must recognize the unique knowledge and perspective that other members bring to the table. These factors enhance not only intrinsic motivation but also expertise and creative-thinking skills.

Again, creating such teams requires managers to have a deep understanding of their people. They must be able to assess them not just for their knowledge but for their attitudes about potential fellow team members and the collaborative process, for their problem-solving styles, and for their motivational hot buttons. Putting together a team with just the right chemistry—just the right level of diversity and supportiveness—can be difficult, but our research shows how powerful it can be.

It follows, then, that one common way managers kill creativity is by assembling homogeneous teams. The lure to do so is great. Homogeneous teams often reach “solutions” more quickly and with less friction along the way. These teams often report high morale, too. But homogeneous teams do little to enhance expertise and creative thinking. Everyone comes to the table with a similar mind-set. They leave with the same.

Supervisory Encouragement

Most managers are extremely busy. They are under pressure for results. It is therefore easy for them to let praise for creative efforts—not just creative successes but unsuccessful efforts, too—fall by the wayside. One very simple step managers can take to foster creativity is not to let that happen.

The connection to intrinsic motivation here is clear. Certainly, people can find their work interesting or exciting without a cheering section—for some period of time. But to sustain such passion, most people need to feel as if their work matters to the organization or to some important group of people. Otherwise, they might as well do their work at home and for their own personal gain.

Managers in successful, creative organizations rarely offer specific extrinsic rewards for particular outcomes. However, they freely and generously recognize creative work by individuals and teams—often before the ultimate commercial impact of those efforts is known. By contrast, managers who kill creativity do so either by failing to acknowledge innovative efforts or by greeting them with skepticism. In many companies, for instance, new ideas are met not with open minds but with time-consuming layers of evaluation—or even with harsh criticism. When someone suggests a new product or process, senior managers take weeks to respond. Or they put that person through an excruciating critique.

Not every new idea is worthy of consideration, of course, but in many organizations, managers habitually demonstrate a reaction that damages creativity. They look for reasons not to use a new idea instead of searching for reasons to explore it further. An interesting psychological dynamic underlies this phenomenon. Our research shows that people believe that they will appear smarter to their bosses if they are more critical—and it often works. In many organizations, it is professionally rewarding to react critically to new ideas.