GRAHAM BURGESS achieved the FIDE Master title at the age of twenty following his first place at the international open tournament at Val Thorens, France, in 1988. Since then he has been a regular international competitor, and is the veteran of several chessboard battles with World Championship Candidates. He is the author of twenty highly acclaimed books on chess, and editor of more than two hundred and fifty.

He graduated from the University of Cambridge with a degree in Mathematics in 1989. Since then he has worked as a chess writer, for two years based in Denmark as a club trainer, and later as a commissioning editor in London. Now he is Editorial Director of Gambit Publications Ltd, a chess publishing company founded in 1997. In 1994 he established a new world record for marathon blitz chess playing, scoring a remarkable 87% in 510 games over three days and nights.

In 1997, the first edition of The Mammoth Book of Chess won the prestigious British Chess Federation Book of the Year Award.

Also available

The Mammoth Book of 20th Century Science Fiction

The Mammoth Book of Brain Teasers

The Mammoth Book of Best British Crime/Mysteries

The Mammoth Book of Best Horror Comics

The Mammoth Book of Best of Best New SF

The Mammoth Books of Best New Manga 1, 2 and 3

The Mammoth Books of Best New SF 20, 21 and 22

The Mammoth Book of Best War Comics

The Mammoth Book of Bikers

The Mammoth Book of Boys’ Own Stuff

The Mammoth Book of Brain Workouts

The Mammoth Book of Chess

The Mammoth Book of Comic Fantasy

The Mammoth Book of Comic Quotes

The Mammoth Book of Cover-Ups

The Mammoth Book of CSI

The Mammoth Book of the Deep

The Mammoth Book of Dickensian Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Egyptian Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Extreme Fantasy

The Mammoth Book of Funniest Cartoons of All Time

The Mammoth Book of Hard Men

The Mammoth Book of Historical Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Inside the Elite Forces

The Mammoth Book of Irish Romance

The Mammoth Book of Jack the Ripper

The Mammoth Book of Jacobean Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of King Arthur

The Mammoth Book of Maneaters

The Mammoth Book of Men O’ War

The Mammoth Book of Merlin

The Mammoth Book of Mindblowing SF

The Mammoth Book of Modern Battles

The Mammoth Book of Modern Ghost Stories

The Mammoth Book of Monsters

The Mammoth Book of Mountain Disasters

The Mammoth Book of New Sherlock Holmes Adventures

The Mammoth Book of On the Road

The Mammoth Book of Paranormal Romance

The Mammoth Book of Pirates

The Mammoth Book of Prophecies

The Mammoth Book of Quick Puzzles

The Mammoth Book of Roaring Twenties Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Short SF Novels

The Mammoth Book of Short Spy Novels

The Mammoth Book of Sorcerers’ Tales

The Mammoth Book of The Beatles

The Mammoth Book of Time Travel Romance

The Mammoth Book of True War Stories

The Mammoth Book of Unsolved Crimes

The Mammoth Book of Vampire Romance

The Mammoth Book of Vampire Romance 2 (Love Bites)

The Mammoth Book of Vintage Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Wolf Men

Constable & Robinson Ltd

3 The Lanchesters

162 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 9ER

www.constablerobinson.com

First edition published in the UK in 1997 by Robinson

This revised and updated edition published by Robinson,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2009

Copyright © Graham Burgess 2009

The right of Graham Burgess to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication

Data is available from the British Library

UK ISBN 978-1-84529-931-6

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

First published in the United States in 2009 by Running Press Book Publishers All rights reserved under the Pan-American and International Copyright Conventions This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or hereafter invented, without written permission from the publisher.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Digit on the right indicates the number of this printing

US Library of Congress number: 2008944134

US ISBN 978-0-7624-3726-9

Running Press Book Publishers

2300 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19103-4371

Visit us on the web!

www.runningpress.com

Typeset by Graham Burgess

Printed and bound in the EU

CONTENTS

Foreword by Grandmaster John Nunn

Introduction to the Second Edition

Introduction to the Third Edition

Part One: Mastering Chess

Solutions to Endgame Challenges

Flank Openings and Miscellaneous Systems

Solutions to Attack and Defence Tests

Part Two: The World of Chess

Women’s, Veterans’, Junior and Correspondence Chess

Part Three: Essential Chess Information

A Brief History of the World Chess Championship

Foreword by John Nunn

The origins of chess are shrouded in mystery. Board games were certainly played by the ancient Egyptians and Romans, but nobody knows the rules of these games or whether they were the ancestors of any games played today. The earliest date to which a definite precursor of chess can be traced is about AD 600. Travelling from India via the Arab world to Europe, chess has exerted its peculiar fascination over a wide range of cultures. This universal appeal, stretching for a span of 1400 years, surely indicates that chess taps some deep-rooted elements of the human mind. Chess almost certainly had its origins in a type of war game, and the sporting or competitive element is still one of its most seductive features. The urge to compete is undoubtedly a fundamental part of the human psyche, and while one may argue as to how much of this urge is a result of upbringing and how much is genetically based, the fact is that it exists and is likely to do so for the foreseeable future.

However, chess does not appeal only to the basic desire to win. It also exerts its pull on another important psychological element, the desire to detect patterns and to impose order on chaos. A human playing chess depends not only on memory and ability to calculate sequences of moves, but also on pattern recognition. This often manifests itself on a subconscious level. Somehow, deep within the brain, all the games of chess one has ever seen have made a mark, and the position on the board at any given moment is compared with all these pre-existing patterns. A close match will result in a sudden “feeling” that one knows what the correct plan should be. A skilled human player will know when to trust these mysterious hunches and when to show a healthy scepticism. Often, when a grandmaster is asked why he played a particular move, he will struggle to explain exactly how he came to a decision. It may appear as though he is trying to keep his secrets to himself, but more often it is simply because he does not himself understand the subconscious processes that led him to play a particular move.

This type of process is one of the highest mental faculties of which human beings are capable. By contrast, purely mechanical reasoning, based on calculation, is less distinctive. Suppose, for example, that a businessman makes decisions about whether to invest money in a particular endeavour purely on the basis of financial calculation. Then he might just as well be replaced by a computer, which would be faster and perform the calculations with less chance of error. A real talent for business goes far beyond routine calculations, into the area of judgement and intuition. Just as in chess, a talented businessman will have a lifetime’s experience in his subconscious and this will enable him to make a reasonably accurate decision, even when the information available would result in an “insufficient data” error from a computer. Indeed, his main problem will probably be to try to convince his colleagues of the correctness of his decision. When playing chess, one is alone. There are no colleagues or meetings. One has total authority to implement one’s decisions, and conversely one has to accept full responsibility for the consequences, good or bad. This, too, is one of the appeals of chess. There are few areas in life where decisions can be made without consultation and at a moment’s notice, and there are few areas where the effects are visible so quickly.

The history of chess is one of very gradual development. The rules have evolved over the centuries but have been more or less static for the past 500 years. For half a millennium, chess knowledge has gradually accumulated, but today’s grandmasters still find that much about the game is totally baffling. Now, however, after 1400 years, chess is facing a new challenge from the computer. It is far from clear whether the strongest chess-playing entity on the planet is based on carbon or on silicon. It often seems remarkable to non-chess players that a human has any chance of beating a computer at chess. This arises because of the common misconception that playing chess is all about calculating sequences of moves. The logic then is that since computers are much better at calculating than humans, a computer should normally beat a human. The fallacy here is that, as mentioned above, calculating moves is just one part of playing chess. The mysterious processes of the subconscious are just as important, and these cannot, as yet, be programmed into a machine.

In the 1970s, a human vs computer contest was just a joke, as the poor machines stood no chance at all. Even though they could calculate hundreds of times faster than a human being, the result was a foregone conclusion. At the time, in the artificial intelligence departments of universities all round the world, a great deal of effort was expended on chess programming. The reason was that it was felt that a computer would only play chess successfully when it had been programmed to think like a human being, at least in the limited area of chess. And if it was possible to do it in chess, then why not in other areas of human mental activity? Now, however, the academic interest in chess programming has more or less vanished. Nobody ever succeeded in programming a computer to think like a human being, and all the progress in chess programming has been made by concentrating on what computers do best – calculation. Over the past twenty years the speed of computers has increased enormously and now they can calculate millions of times faster than a human being. What the human does elegantly and with little effort by subconscious pattern recognition, the computer does by “brute force”, i.e. by examining millions of possible continuations and finding the right move by an exhaustive analysis probing many moves ahead. Today’s computers are so fast that the fact that this method is very inefficient doesn’t matter – the computer has megahertz to spare and can afford to waste 99% of its time looking at irrelevant variations that a human would never consider, provided the remaining 1% is spent on the critical lines.

In 1996 the human World Champion, Garry Kasparov, faced the world’s leading computer, Deep Blue, in a six-game match. Most commentators imagined that Kasparov would see off the silicon challenge with little difficulty. There was palpable shock when Kasparov lost the first game. Perhaps Kasparov had underestimated the powers of his opponent; in any event, Kasparov played much better in the remaining games and ended up winning by 4

2. However, Kasparov fared less well in the 1997 rematch and the numbercruncher came out ahead by 3½-2½. Since then, the machines have steadily advanced, and Deep Fritz’s 4-2 win against Vladimir Kramnik in 2006, in which the then world champion failed to win a single game, indicated that the computers had pushed ahead of the top humans. After this, interest in man-machine contests faded since it was apparent that an interesting contest could only be obtained by handicapping the computer in some way.

The lessons of computer chess may have wider implications. Even though the efforts of computer scientists to make computers think like human beings have not been very successful, perhaps this should not be a cause for regret. In chess, at any rate, computers have achieved their current level of performance precisely by not thinking like human beings. The result of this has been a new perspective on chess which has not been provided by 1400 years of human development. Because the processes by which computers select a move are totally different to those employed by humans, computers sometimes come up with an astonishing move which a human would never even consider. Many times in recent years a computer has played a move which the watching humans have dismissed as the result of a programming bug, only for further analysis to reveal the concealed idea behind the move. In other words, the differing perspective of the computer has provided insights which would probably never have been obtained by human analysis. The simple fact is that nobody knows what human beings are missing, and this applies not only to chess.

The limitations of human thought must be there, but little can be said about them because it is impossible to measure the unknown. First of all, our brains are undoubtedly limited by our evolution. Intelligence evolved as a survival characteristic in a world very different from the one we now inhabit. The slow million-year crawl of evolution may have fitted us well for the world in which humanity first appeared, but by comparison the social and technological changes taking place today are lightning-fast. The fact that slightly intelligent apes have developed world-destroying weapons does not imply an ability to manage that same world in a positive way. Moreover, there are probably culturally-based limitations. Human development tends to build gradually from one generation to the next, and only very rarely does it suddenly shoot off at a tangent. Perhaps thousands of years ago there was a fork in the road of knowledge; humanity sped off along one branch, never suspecting that the other existed.

In the absence of any external perspective, we cannot tell how limited our thinking processes are. If we suddenly make contact with extra-terrestrial intelligences, will their thoughts prove to be along utterly different lines to ours, perhaps even to the point of making communication impossible, or will there be enough common ground to make meaningful contact? Nobody can say. However, the progressive development of computers suggests that one day we may be able to create another viewpoint ourselves. Just as the primitive computers of today have shown us new concepts in chess, perhaps one day their successors may show us what we are missing elsewhere. And the first clue will have been provided by a game from sixth-century India.

Symbols and Abbreviations

+ | Check |

++ | Double check |

# | Checkmate |

x | Capture |

!! | Brilliant move |

! | Good move |

!? | Interesting move |

?! | Dubious move |

? | Bad move |

?? | Blunder |

Ch | Championship |

Cht | Team championship |

OL | Olympiad |

Ech | European championship |

Wch | World championship |

Z | Zonal event |

IZ | Interzonal event |

Ct | Candidates’ event |

jr | junior event |

tt | team tournament |

mem | memorial event |

wom | women’s event |

Corr. | Correspondence chess |

(n) | nth match game |

GM | Grandmaster |

IM | International Master |

FM | FIDE Master |

FIDE | Fédération Internationale des |

Echecs (World Chess Federation | |

PCA | Professional Chess Association |

GMA | Grandmasters Association |

USCF | United States Chess Federation |

ECF | English Chess Federation |

When a game mentioned is annotated in The Mammoth Book of the World’s Greatest Chess Games, this is indicated by WGG followed by the game number.

Introduction

Although this is entirely appropriate to be read as a first or second course in chess, it is not a beginners’ chess book in the traditional sense. Likewise, although it contains plenty of high-level material and some truly mind-bending chess puzzles, it is not an experts’ manual. I have written this book in such a way that it provides inspiration and useful information for everyone with an interest in chess, from total beginners to grandmasters.

The result of this, I hope, is a book that you will refer to and dip into for many years to come; a book you will not outgrow as you become an accomplished player.

Why play chess?

Everyone who plays chess has their own answer to this question, and since you have at least picked this book up off the shelf, the game must have an attraction to you.

To children, chess is a cool way to beat other children (or, better still, adults). Winning at chess is far more satisfying than winning in any more primitive type of battle, and has more street-cred than coming top in a maths test (though that is the sort of thing children who play chess tend to do!).

Parents of chess-playing children delight in the mental training the game provides. Children who excel over the chessboard have an uncanny ability to succeed in other fields too.

For adults playing chess at a high level, the thrill of the game is just as great. Adrenaline flows freely during a tense chess game, and a good win feels better than, well, just about anything.

For adults who play chess at less exulted levels, it is a fun pastime, an enjoyable way to spend time with friends or a way to meet people with similar interests at a club. And yes, everyone gets a kick out of winning, no matter how or who against.

These are mainly the external reasons for playing chess. What is it about the game itself that players like? Simply put, the game is beautiful. For all of the supposed complexity of chess, the geometry is simple and elegant. A well-played game has a certain logical crispness about it. Simply seeing a good move on a board can give chess players pleasure. It is a glorious feeling to play a great game, flowing from start to finish.

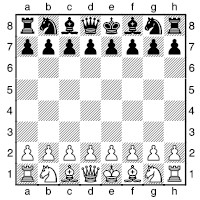

A chapter-by-chapter walk-through of this book

I am assuming that readers already know how to play chess and understand chess notation. If you do not know how the pieces move, I recommend that you learn from a friend or relative, face-to-face across a chessboard. This is by far the best way to learn how to play chess. If this is not possible, then Appendix A, near the end of the book, is the place to start. Then Appendix B explains how chess games are written down, while the next stage in the traditional programme for newcomers to chess is to learn the basic mates: Appendix C.

If you are up to speed with these basics, then the rest of the book beckons. If your main aim is to improve your chess-playing, then proceed to Part One. There you will find tips, examples and positions for solving. Inexperienced players should work through these chapters in turn from the start of the section on delivering mate, while more experienced players can dip in according to taste; the mates in two should provide entertainment, and the combinations a real challenge. I guarantee that no matter how good you are, you will meet your match somewhere in these positions for solving, although for masters this may not be until the tougher combinations.

Seeing tactics is really the key to playing chess successfully, since they are the building blocks from which everything else in chess is made. Therefore, it is especially important to study and understand these early chapters. Once you have got a good feel for the tactical properties of the pieces, it is time to move on to the section on endgames, openings or attack and defence.

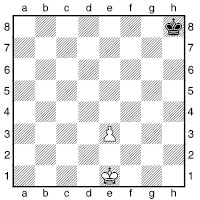

The discussion of endgames is quite brief. My aim here was to present a few of the key positions that will be of most use in practice and to explain the basic concepts of endgame play. There are many weighty tomes of detailed analysis of all manner of endgame positions. My experience is that since the exact positions in the endgame manuals will almost never arise in actual play, it is not so much the specifics of the analysis that are important, but rather the concepts. Playing endgames well is about knowing a few key positions well, knowing what to aim for and analysing a great deal at the board.

In the section on openings my aim has been to explain the spirit of each opening and give you some idea of the typical plans and strategies available to both sides. I feel this is far more useful than presenting a lot of detailed analysis. Once you have identified openings that appeal, you will be in a better position to understand detailed monographs on the individual openings, should you decide further study is needed. I have also indicated a great many traps in the openings.

Even if you have no great interest in studying openings, there is much of interest in the openings section. The strategic examples are all highly instructive illustrative games that will repay close examination.

The chapter “Attack and Defence” was a lot of fun to write. Here we see standard sacrifices (sometimes successful, sometimes not) and plenty of examples of creative attacking, defensive and counterattacking chess. It is in attacking play that tactics and strategy come together.

Talking of strategy, you may be wondering where the section on chess strategy has gone. I decided that it was too important a subject to be compartmentalized, and so the discussion of strategy runs throughout the sections on openings, and attack and defence. The glossary also provides a wealth of information on strategic concepts and could very well be read as a course in the basics of chess strategy.

The second part of the book takes a general look at the chess world and is the place to go if you wish to discover more about how you can pursue your interest in chess, whether by playing club or tournament chess, using computers or by getting online. These are exciting times for chess, since the game is so well suited for playing online, and chess data can be transmitted so efficiently in electronic format. For a time in the 1990s, the battle for chessboard supremacy between the strongest human players and the most powerful computers raged, but now the emphasis is more on cooperation between the two. The puzzles chapter allows you, amongst many other things, to test how well you can cooperate with your own computer.

The glossary in the third part of the book is as detailed as I could make it, with just about every significant chess term I could think of defined and discussed. It is worth taking a look at the glossary even if you don’t have anything specific you need to look up, since a lot of the entries are entertaining or instructive.

There are many people I should thank for, in one way or another, making this book possible. Firstly, Mark Crean at Robinson Publishing, who first approached me with the idea of a big-value general chess book, and all the other staff at Constable & Robinson deserve thanks, notably Mark’s successors, Krystyna Green, Pete Duncan and Duncan Proudfoot. It has been a pleasure to work with such a highly professional publishing company. John Nunn has been a great help; I would like to thank him for his thought-provoking foreword (“I’ve never before seen a foreword containing Indians, aliens and computers” – Mrs Petra Nunn) and general technical assistance. John also provided plenty of ideas, directly and indirectly, for the content of the book. Indeed, a great many of the people I have met since I first learned how the pieces move thirty-eight years ago have in some way provided ideas for the book or helped clarify what my aims should be. In particular I would like to mention Frederic Friedel, Yasser Seirawan, Jonathan Levitt, Reg Burgess, Andrew Savage, Gary Quillan, Sean Elliott, Tyson Mordue, Natasha Regan, Dr Heather Walton, Niels Højgård, Jakob Bjerre Jensen, Steffen Pedersen, David Norwood and Steve Davis. I should also thank my mother and sister who proof-read some sections of the book. I apologize to anyone I have forgotten to mention.

To conclude, I wish you many years of pleasure using this book, and hope that it provides you with a deep understanding of chess and the people who play it.

Graham Burgess

London 1997

(minor updates to this introduction, 2000 and 2009)

Dedication

This third edition is dedicated to my fiancée, June Mary Stengel.

Introduction to the Second Edition

In this new edition, I have sought to bring the book fully up to date in a number of respects. Firstly, I attended to any typos that had found their way into the first edition. Next, I employed a new automated procedure (developed in 1997) to check all the moves for legality and accuracy of notation, and then ran a computer-check over all the analysis. This threw up a number of points, which led to a good deal of new analysis, and in some cases made it necessary to replace games and positions entirely. For the most part though, the analysis stood up to scrutiny, and remains unchanged, but may now be considered computer-approved.

The next task was to bring the content up to date by addressing developments in the fields of computer chess and online chess. In particular, there is a completely new section in the chapter on Computer Chess, discussing the abilities of the latest generation of chess-playing computer engines. Finally, it was necessary to update any topical content, such as the state of play (or non-play) in the world championship.

Graham Burgess

Bristol, England 2000

Introduction to the Third Edition

Enough time has passed since the first edition of The Mammoth Book of Chess that I have now had the experience of players telling me that it was their first book, and even their favourite book, before sitting down at the board – and defeating me. Naturally, I have mixed feelings about this, but I am pleased that this book has made such an impact.

This third edition features a completely new chapter on computer and Internet chess, given how drastically these aspects of chess have changed in the intervening time. I have also added an extra chapter of 60 puzzles which I hope readers will have many hours of pleasure attempting to solve. If they prove too difficult (always an author’s main fear when setting puzzle positions), then please view them as additional examples to complement those in the earlier chapters of the book. Naturally, I have also taken the opportunity to update the book in a number of other respects (particularly the opening coverage), but most of the other material remains largely unaltered.

Finally, I would like to thank the staff at Constable & Robinson for their enthusiasm for this project, their generous allocation of an extra 32 pages, and for their patience when some unexpected changes in my personal situation led to a delay in delivering the new text.

Graham Burgess

Woodbury, Minnesota 2009

Frequently Asked Questions

There follow some of the typical questions that chess players get asked by non-players or casual players, with typical answers – or at least my answers.

How far ahead do you look?

Ah, that old chestnut! It varies a lot. In some positions it is possible to look ahead many moves, generally when there is very little material left on the board, or when many of the moves are totally forced. In other positions there is no point calculating – when there are no forcing variations it can be better to think generally about the position and find simple ways to improve it. In some sharp positions where it is not possible to get to the bottom of the tactical variations, chess players will often let their intuition be the main guide in their choice of move.

That isn’t the sort of answer you wanted though. In a typical middle-game position (if such a thing exists) with some possibility of sharp tactics, but nothing too forcing or complicated, then a good player will typically look ahead three to five moves by both sides, concentrating solely on the plausible moves – this is where intuition comes in. How many positions this amounts to is hard to judge. Consciously, a player may be aware of looking only at a few dozen positions that arise in the variations he looks at. Subconsciously, hundreds of positions will flash past his mind’s eye, but little conscious thought is needed to dismiss those that embody dreadful ideas. Throughout this process, the player will be looking to identify any particularly critical variations that demand more searching analysis.

How do you become a grandmaster?

This is far easier to explain than to do! There are some events (e.g. world junior championship) in which the winner is awarded the title automatically, but most grandmasters gain their title by achieving grandmaster norms. These are exceptional results in international events. If a player scores enough points against sufficiently strong opposition, then he achieves a norm. When he has achieved norms equivalent to a total of 24 games, then if his rating is sufficiently high, he is eligible to receive the title. Most grandmasters achieve their title by scoring three norms of 9 to 11 games, but there is nothing to stop a player gaining the title in one 24-round event!

Does chess require a great deal of patience?

No. In appearance the game may look like one in which patience is essential, but the thinking behind it is mostly violent. Each side is trying to destroy the other. This is not a game of peaceful coexistence, where one tries to coexist slightly better than the other. True, once a high level of skill has been reached, some games can reach technical positions, which become a war of attrition, but even then it is often a slow build-up to a violent finish.

Do the games take a very long time to finish?

Not necessarily. It is entirely possible to play a game of chess in just a few minutes when using a chess clock. When playing for fun (or perhaps for a stake of some sort), one of the standard time limits is five minutes for all the moves – so the game lasts a maximum of ten minutes. Some players prefer even faster time limits – for instance one minute for all the moves. True, the quality of such games is not too good normally! Another way of playing fast games is to use a “lightning buzzer”. This makes a noise every ten seconds (or whatever), and the player whose turn it is to move must make his move at that moment. As for tournament chess, there are plenty of quickplay events, in which each player is allotted twenty to forty minutes for all the moves in each game. In standard tournament play each player has two hours for the first forty moves, and an extra hour to reach move sixty. This does not seem slow if you are playing a tense game! It is true, however, that some forms of chess do take a long time. Postal games can take months or even years, while there is the story of one postal game being played at the rate of one move every year.

How can humans hope to play successfully against powerful computers?

Hmm. A few years ago this question would have been “how can computers hope to play successfully against powerful humans?” In purely calculating terms, computers have a huge advantage. Even the primitive chess computers of the mid-1980s were strong enough to see some intricate tactics. However, computers have no real concept of long-term planning, and no intuition. Put a human up against a strong computer in a position with the pieces randomly scattered over the board, with nothing from which the human can take any bearings, and silicon will come out on top. However, such positions don’t occur very often in chess games. A skilful human chess-player can guide the play along more intuitively graspable lines, and so give the computer more problems. However, even this is becoming too hard, and as of 2009, even the best players in the world struggle to take many points off the best computers; indeed, this type of match is becoming a rarity. That is not to say that computers comprehensively outclass humans though. Computers still miss ideas that humans see readily, and sometimes choose moves that are obviously bad. A computer working with human guidance will play and analyse far better than either in isolation, and this human-computer cooperation has been one of the major driving forces behind the sharp change in playing style at the top levels of modern chess – see the chapter on Computer Chess for more in this topic.

Why don’t more women play chess?

Good question. The reasons generally advanced are social conditioning, or women tending to be less aggressive by nature. I tend to think that most women are much too sensible to persist in playing a board game unless they can become really good at it. Men are perhaps more obsessive. Quite simply, I don’t think anyone really knows why chess doesn’t appeal to more women, or has even advanced a particularly good explanation.

How come there are so many chess books? What is there to write about?

The market for chess books is substantial since there are many ambitious chess players to whom it is important to be up to date with chess theory, since this gives them an edge over their opponents. If you’re spending a lot of time studying chess, there is nothing more annoying than losing a game simply because the opponent is better read. Many books are about openings. Ambitious players tend to specialize in particular ways of starting the game. In a major chess opening, of which there are many, there are hundreds or even thousands of important new master-level games each year. Reading a recent book on the opening in question is the best way to keep up to date. There is also a good market for general books. The understanding of chess strategy does not stand still, and while one could reach a certain level by studying only the games of the “old masters”, one would also be missing out on a lot of new dynamic ideas.

Isn’t chess getting played out? Don’t the top players play most of the game from memory?

This is a common misconception. There are far more possible games of chess than there are particles in the known universe, and the number of possible chess positions, though far fewer, is still astronomical. While it is true that in some openings there are main lines that extend past move twenty, this is not a sign that chess is being played out – just that some of the main highways have been extensively explored. That does not imply that there isn’t a great deal of unexplored territory. And once the known territory is left behind, the players are on their own.

I’m just an ordinary social player. How long would it take a grandmaster to beat me?

If you play sensible moves, then no matter how strong your opponent may be, he will not be able to force a quick checkmate. Expect any mistakes to be punished quickly, and to come under pressure if you play passively. Against a grandmaster, a player below club level would be doing well to avoid serious mishaps in the first twenty moves, and could be proud of reaching move thirty alive. In terms of time taken over the moves, a top-class player could play more or less instantly under these circumstances. It is only when the players are evenly matched that the course of the game depends on strategic subtleties or long-term plans.

Can anyone who didn’t learn chess when they were a young child hope to become any good?

It depends what you mean by “any good”! Most players who go on to join the world élite took up the game when they were very young, but it is not unknown for those who started to play chess in their late teens to become good international-level players or grandmasters. However, I’m not aware of anyone who started to play chess as an adult becoming a grandmaster. However, if your ambitions are to reach a good club or county level, then whatever your age, this is an entirely feasible aim. Get hold of a few books, a reasonable chess computer and visit your local club, and don’t get too upset if you lose a lot of games to start with. Those who take up chess relatively late in life can often become successful in correspondence chess, since in the slower form of the game, speed of thought is not so critical as when playing against the clock – positional understanding, which can be learnt, and a methodical approach count for a great deal. And you can verify everything with a computer, but check the rules of the individual event if you want to have a clear conscience...

Who is really the World Champion, and what’s all this business with FIDE and the PCA, BGN, WCC, etc.? I’m interested in the details.

From 1993 to 2008 it was a rather complicated mess, and there are still some loose ends that could easily become frayed over the next few years. But the good news for chess as a whole is that there is now (as I write in late 2009) a single, undisputed World Champion: Viswanathan An-and from India. But before then...

Garry Kasparov had been the “official” FIDE (Fédération Internationale des Echecs – World Chess Federation) Champion up to 1993, when he broke away to form a new organization, the PCA (Professional Chess Association). Under the auspices of the PCA, he defended his title against the challenger who had won FIDE’s candidates cycle, Nigel Short. Thus the formal legitimacy of both players was obtained by successes in FIDE events. Following the breakaway, FIDE disqualified both players. Under FIDE’s rules, Karpov and Timman, the two highest placed men in the candidates’ events who had neither been disqualified nor had lost a match to anyone still involved in the cycle, contested the then vacant “official” FIDE World Championship. It did little for the credibility of the FIDE match that both these players had lost matches against Short, who in turn was comfortably defeated by Kasparov. Karpov, who had been FIDE Champion 1975–85, won the match.

Most players tended to accept Kasparov as the real champion, but several factors clouded the issue greatly. Kasparov’s organization, the PCA, lost the sponsorship that it had secured from the microprocessor producers Intel. The PCA then ceased operations after just one more title match, Kasparov’s successful defence against Anand in 1995. FIDE’s own championship was plagued with delays in holding Karpov’s next defence, against Kamsky. The match eventually took place in 1996 in Elista, after plans to play in Baghdad had caused outrage around the chess world. FIDE subsequently adopted a knockout format for its world championship, which, while an interesting event in itself, held little credibility as a World Championship. Several key players didn’t take part, and the format tended to produce a new champion each year (generally, but not always, from the world’s top 20 players), as the statistical probability of even a clearly superior player coming through a whole series of mini-match victorious is extremely small.

Meanwhile Kasparov’s attempts to organize a credible world championship had gone further awry. In 1998, Kramnik and Shirov (taking Anand’s place, who declined to take part for contractual reasons) were “appointed” to play a match, with the winner to challenge Kasparov. After Shirov unexpectedly beat Kramnik, it proved difficult to find adequate sponsorship for a Kasparov–Shirov match. At the end of 1998, Shirov was left out in the cold, with Kasparov inviting Anand, who had by then established himself as clearly World No. 2, to challenge him directly. Even for this match, sponsorship proved difficult to find. Russia’s Vladimir Kramnik was then reappointed challenger, and he unexpectedly defeated Kasparov in a match in London in 2000, largely by stifling Kasparov’s creativity with very solid chess.

This was to be Kasparov’s last world championship match, as he was granted no rematch.

Various plans and organizations came and went, before Peter Leko qualified through a different cycle again to face Kramnik, and narrowly failed to lift the crown.

Until his retirement in 2005, Kasparov remained the dominant figure in world chess, and no championship that didn’t involve him in some capacity was going to have much credibility. Once he was out of the picture, a reunification plan had a chance to become reality, despite the many aggrieved parties that both world championship cycles had left in their wake, and the obvious difficulties involved in getting two men to sit down to contest a title that they both believed they had already earned, and with FIDE never admitting that their championship had ever been anything other than the “real” one. But the damage to chess as a whole from its highest-profile event being diluted into two rival cycles was evident to all, and the impetus for reunification looked set to sweep all obstacles from its path.

Without going into all the ins-and-outs, Veselin Topalov from Bulgaria won a world championship tournament in 2005. This had been intended as the reunification event, but Kramnik refused to play, still leaving two rival champions. Kramnik and Topalov contested a bitter match in 2006 (so bitter that the reunification process nearly failed), with Kramnik winning eventually. In 2007, the process called for a further world championship tournament, which was won by Anand, ahead of Kramnik. Those of a traditional frame of mind were disappointed that what had generally been a matchplay title had been decided in a tournament. They could finally be content when in 2008, An-and defended his title with a decisive match victory over Kramnik: the line of succession was intact, and the title was reunified to the satisfaction of all. Or most, at any rate.

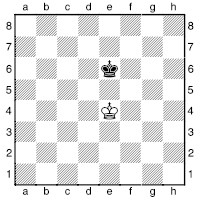

Delivering Mate

The king is not a very fast moving piece. He can move only one square at a time, and so, even on an open board, has a maximum of only eight squares at his disposal, and at the edge of a board a mere five, while in the corner, he can move to at most three squares.

Checkmate occurs when the king is attacked and there is no way of stopping the attack (whether by taking the attacking piece or putting something in the way), and all of the king’s possible flight squares are either attacked by enemy pieces or blocked by “friendly” pieces.

It is not difficult to mate a king. If you have several pieces near your opponent’s king, and his defences are not in order, you should expect to find a mate. Likewise, make sure your own king has protection when he needs it – but more on that in the later chapter on attack and defence.

If you are an experienced player, I suggest you skip this introduction and the 25 novice warm-up positions.

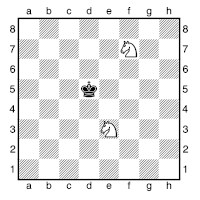

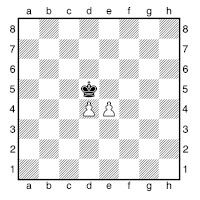

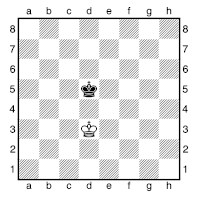

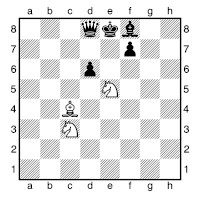

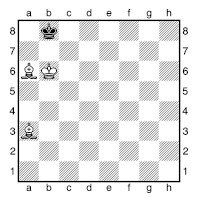

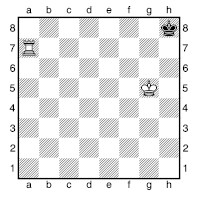

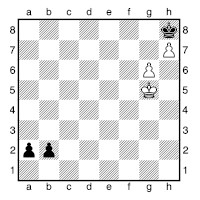

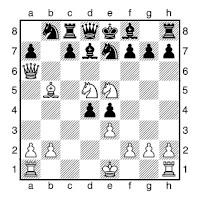

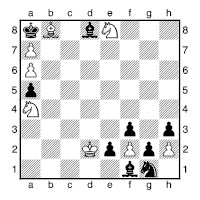

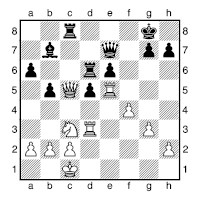

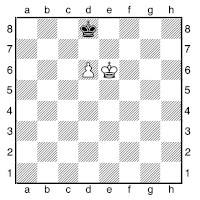

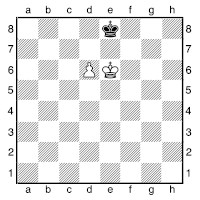

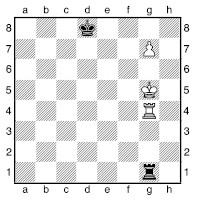

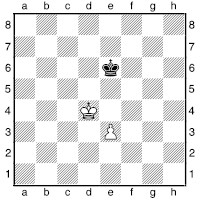

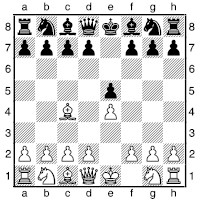

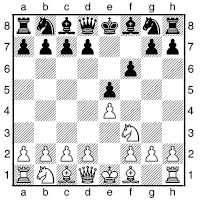

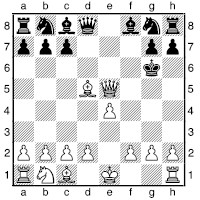

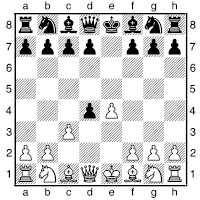

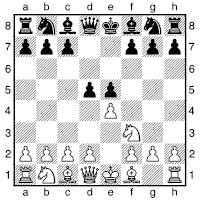

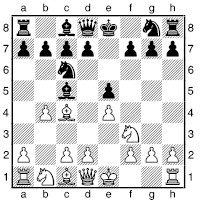

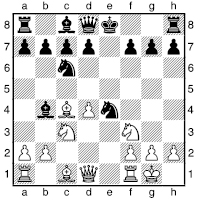

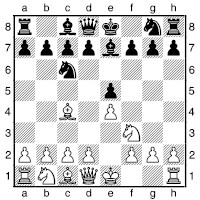

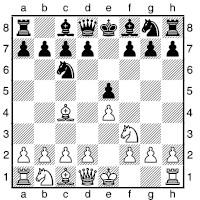

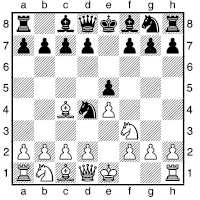

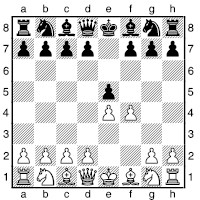

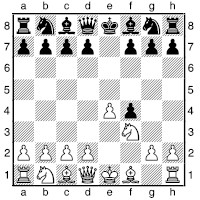

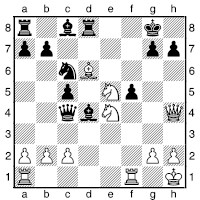

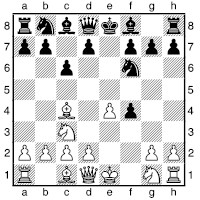

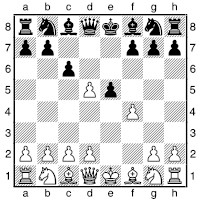

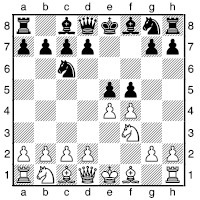

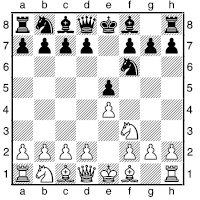

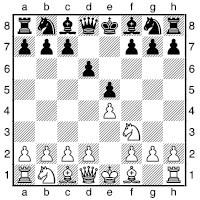

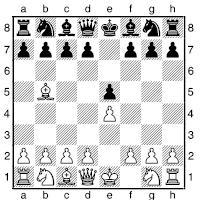

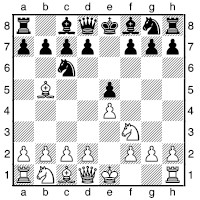

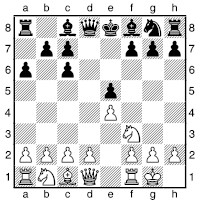

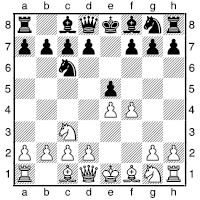

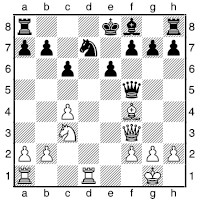

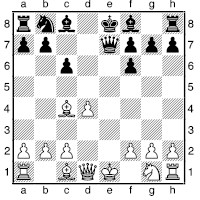

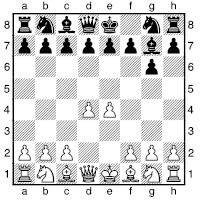

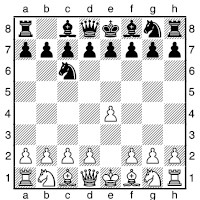

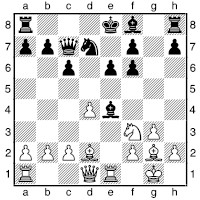

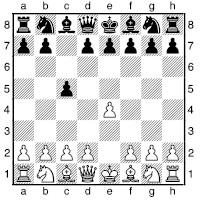

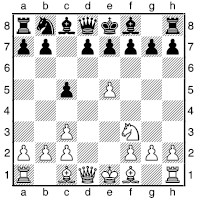

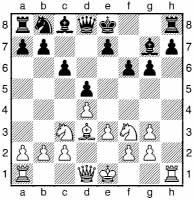

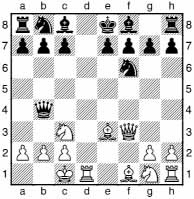

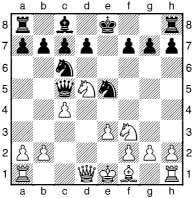

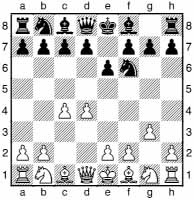

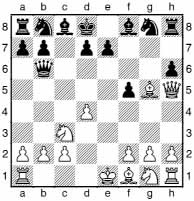

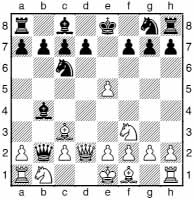

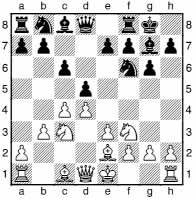

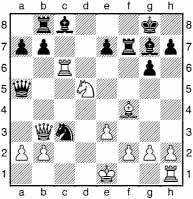

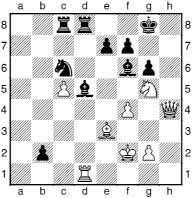

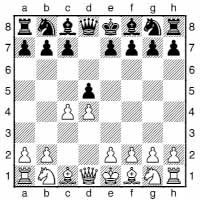

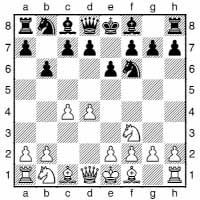

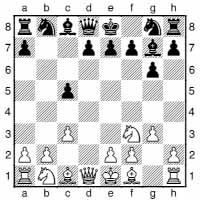

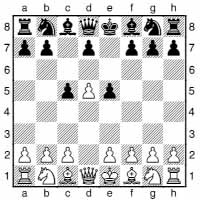

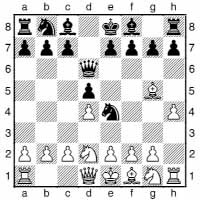

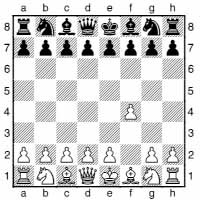

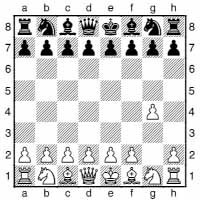

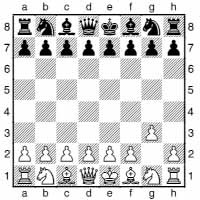

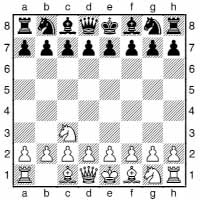

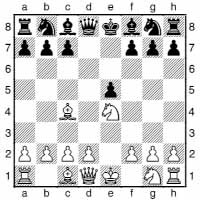

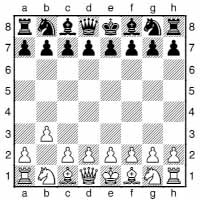

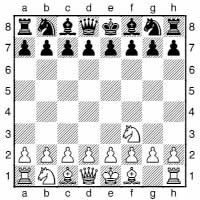

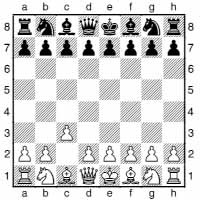

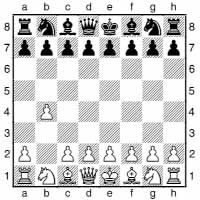

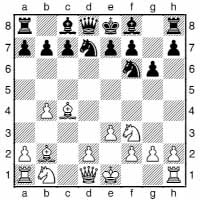

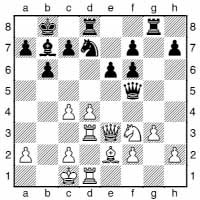

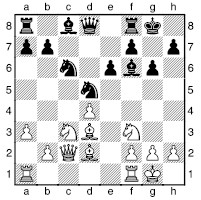

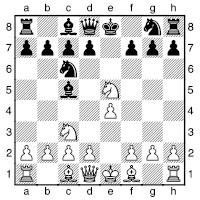

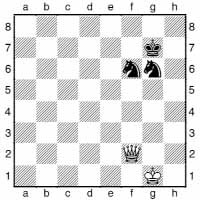

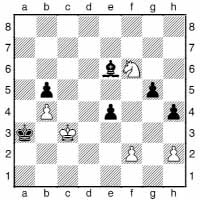

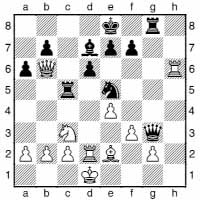

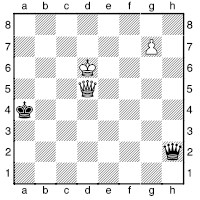

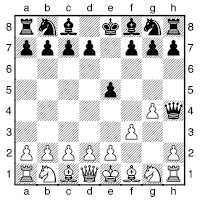

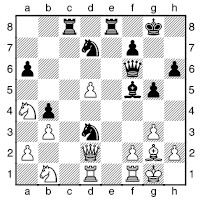

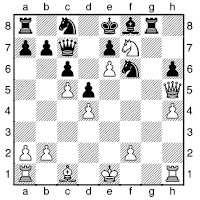

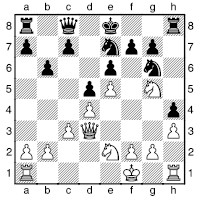

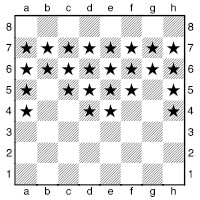

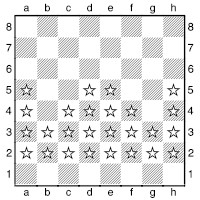

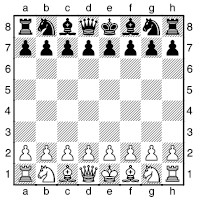

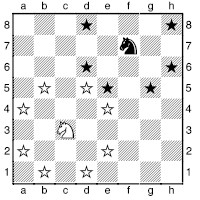

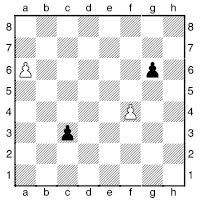

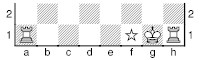

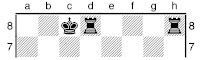

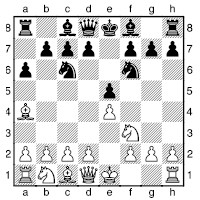

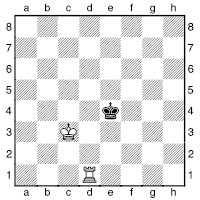

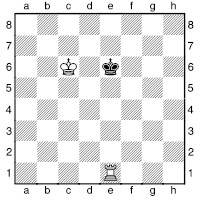

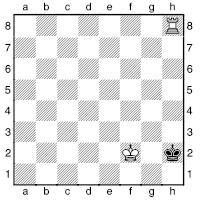

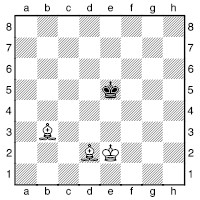

To introduce you to a systematic way of thinking about checkmate, let’s consider how many squares in the king’s field (i.e. the square he is on, and those he might be able to go to) each piece can attack – see the following diagrams.

First, let’s consider the most powerful piece, the queen.

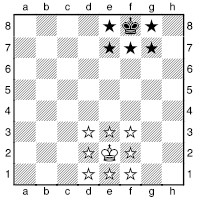

A queen can attack six squares in the king’s field (only five if not giving check). This leaves only three to be covered by other pieces.

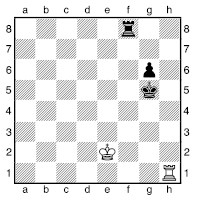

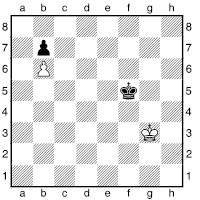

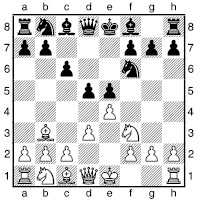

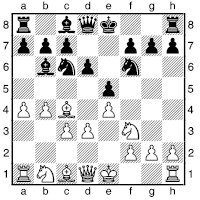

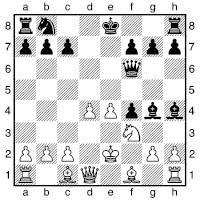

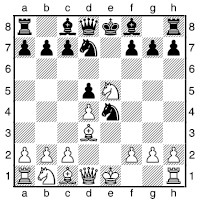

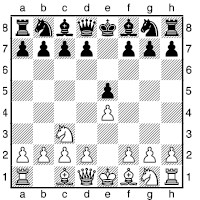

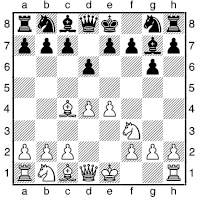

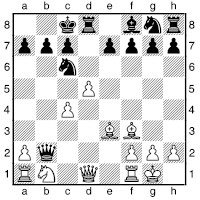

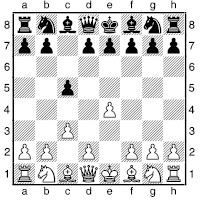

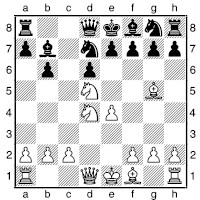

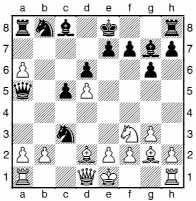

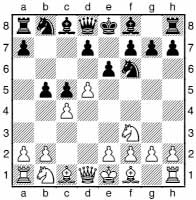

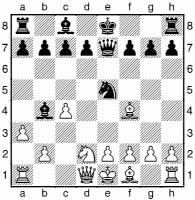

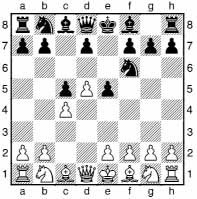

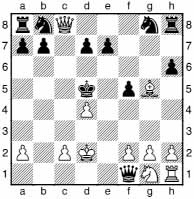

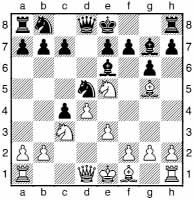

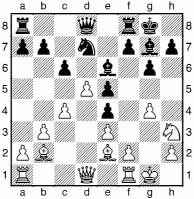

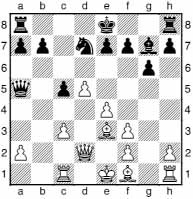

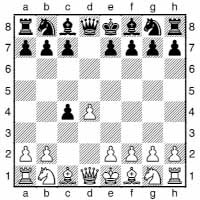

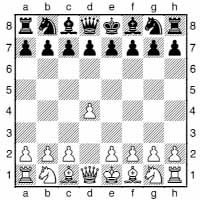

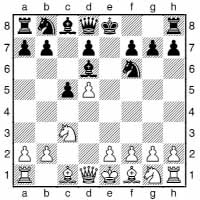

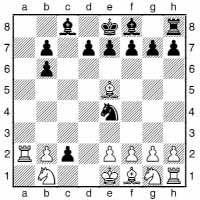

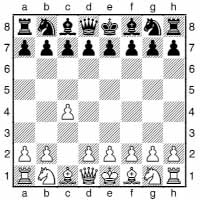

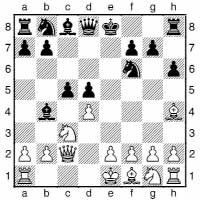

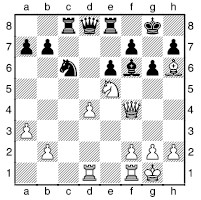

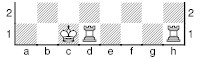

A rook can attack four squares in the king’s field, or only three if it is giving check.

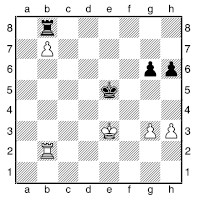

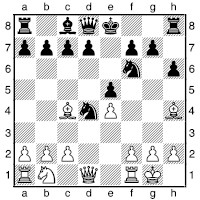

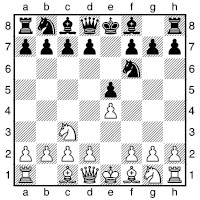

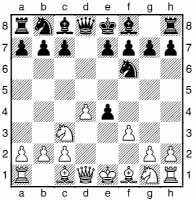

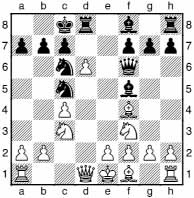

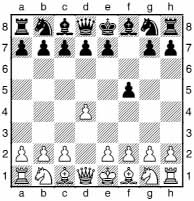

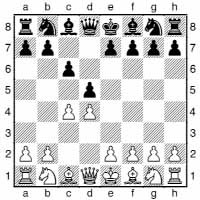

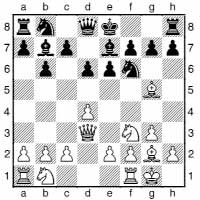

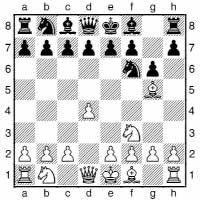

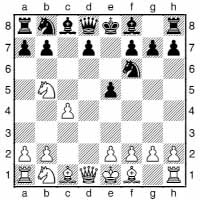

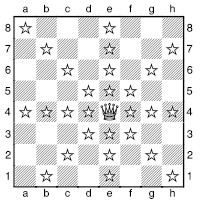

A bishop can attack three squares in the king’s field (only two if not giving check). All of these squares are of the same colour.

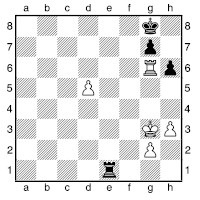

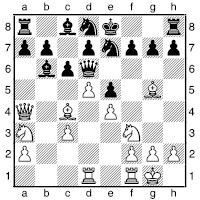

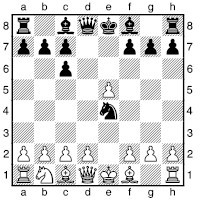

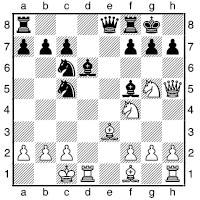

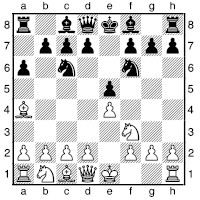

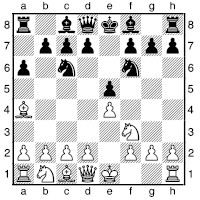

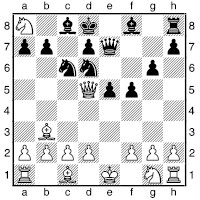

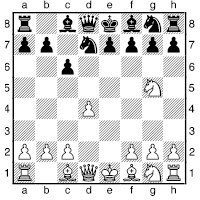

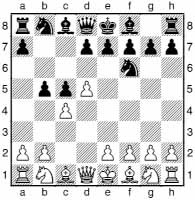

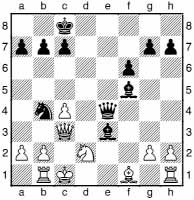

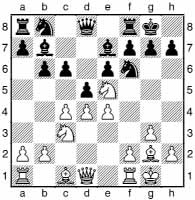

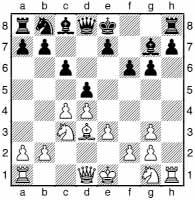

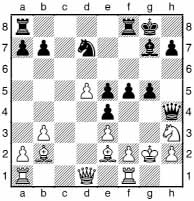

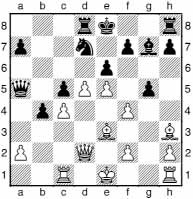

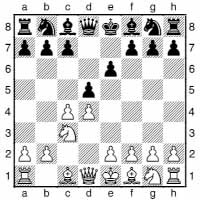

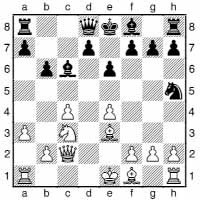

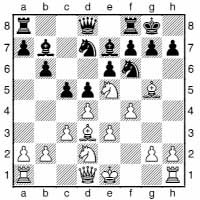

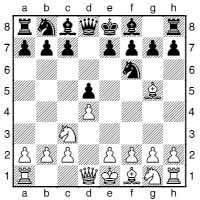

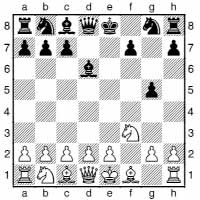

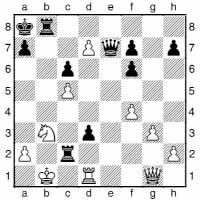

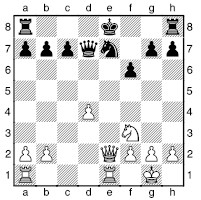

Next we consider the knight, which makes up for its short-range move by moving in a way that no other pieces can.

A knight can attack two squares in the king’s field. Like the bishop, all the squares are of the same colour, though the colour squares that a knight attacks changes each time it moves.

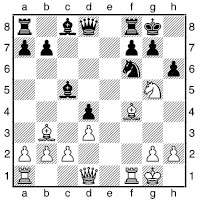

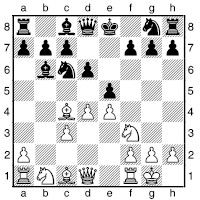

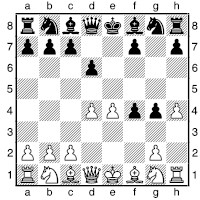

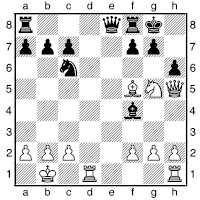

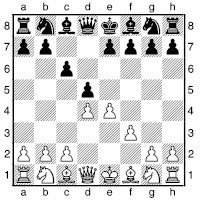

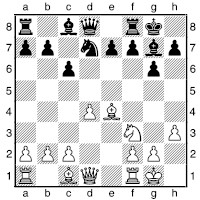

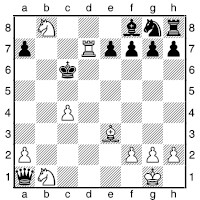

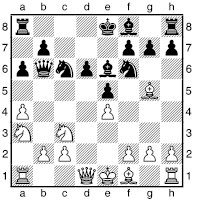

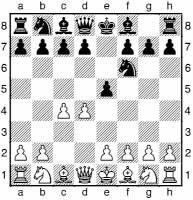

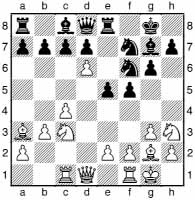

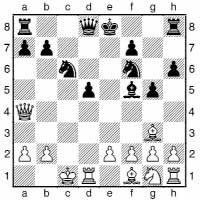

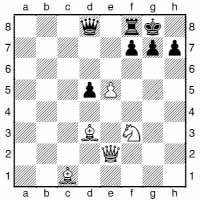

It is all too easy to forget that the humble pawn can also participate in mating attack. A pawn can attack two squares in the king’s field (only one if giving check).

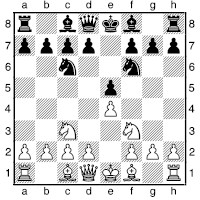

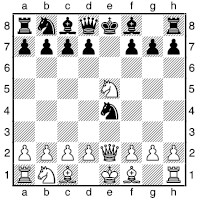

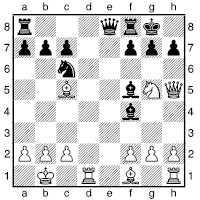

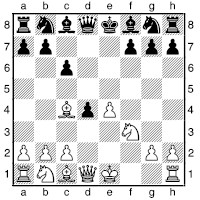

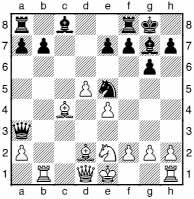

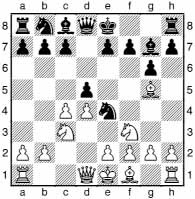

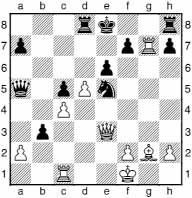

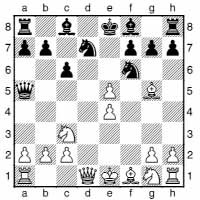

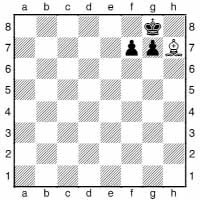

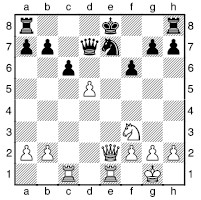

Let us also not forget that the king itself can also help to deliver mate to his opposite number.

A king can attack three squares in the enemy king’s field (and cannot of course give check).

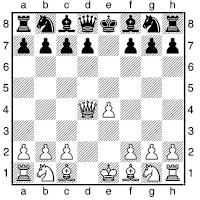

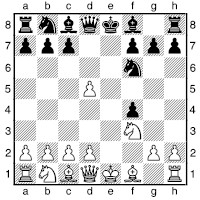

If in each case the above comments are not immediately clear, then I suggest you write down a list of the squares attacked by each white piece in the diagrams. Answers are given on this page.

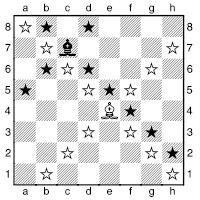

One conclusion we can draw immediately is that the queen is a very powerful mating force in itself, and needs only a little help to deliver mate. A single piece attacking a square next to the enemy king is often all the queen needs. If you think of chess as a medieval war game, then this is the equivalent of needing only the most menial spy in the enemy palace – then a state visit by the queen (see here) wins the war in itself!

Since the rook attacks squares in a straight line, it can be particularly deadly against a king at the edge of the board.

The knight should not be underestimated. Since it moves in a different way from the other pieces, it is the perfect complement to them. Indeed a queen and knight work together so well that when they are buzzing around a king, there is more often than not a mate.

Two bishops also complement each other well, whether attacking along parallel diagonals or at right angles to each other.

This chapter features a series of positions that test your ability to deliver mate. First, here’s a brief look at some standard mating patterns.

Note that in many of the diagrams that follow, only the pieces relevant to the mating idea are shown; in a real game situation there would be plenty of other pieces present.

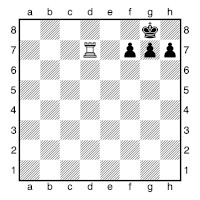

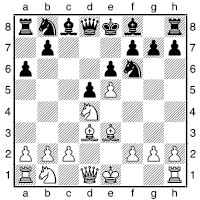

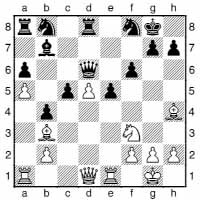

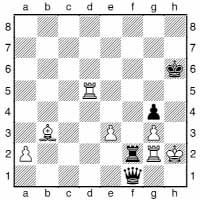

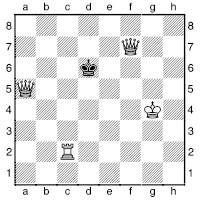

The Back-rank Mate

This is one of the simplest mating ideas, but a tremendously important one. A rook (a queen is also ideal for the purpose) attacks all the squares along the king’s first rank, while a row of pawns prevents the king from advancing to avoid the mate.

White plays 1  d8#.

d8#.

In games between inexperienced players, it is all too common a sight for the player who has been winning to fall victim to a back-ranker. “How can they mate with just a rook?” It is a cruel and bitter blow to lose a game in this way. The simplest way to avoid all risk of a back-ranker is to move one of the pawns in front of the king one square forward. However, I would recommend this precaution only when the game is fully under control and you can spare the time. While the game is still tense, to play any of the moves ...f6, ...g6 and ...h6 not only wastes time, but may also constitute a weakness that invites an attack.

At top level, back-rankers are important too. Not generally as a one-move mating attack, but the value of a complex tactical sequence may hinge on a back-rank trick. (See the glossary entry for Back-rank Mate.)

The back-ranker is also known as the Corridor Mate, though this term also incorporates rare cases (generally in problems) where “friendly” pieces block the king’s movement forwards and backwards, or else on both sides.

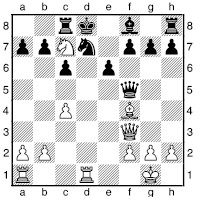

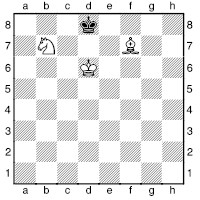

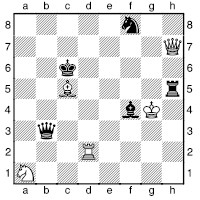

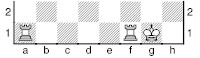

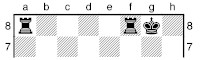

Smothered Mate

If you thought “friendly” pieces didn’t live up to their name in the back-rank mate, here they are positively evil! In a smothered mate, a knight gives check, but this is enough to mate, since all of the king’s possible escape squares are occupied.

It is a bit much to expect that the opponent will block off all of his king’s escape squares and allow a knight to hop in and give mate, so generally a sacrifice will be necessary. Here is a very simple example to set up a smothered mate:

The black king has only the g8-square to which it might flee, so White lures the black queen onto that square: 1  g8+

g8+  xg8 (there is no other way to get out of check) and then 2

xg8 (there is no other way to get out of check) and then 2  g6# finishes off nicely.

g6# finishes off nicely.

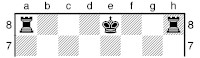

The idea of smothered mate is by no means new. The earliest recorded example is from half a millennium ago, in 1497, not long after the queen’s powers had been extended:

1  e6+

e6+  h8

h8

1... f8 allows instant mate by either

f8 allows instant mate by either

2  f7# or 2

f7# or 2  d7#.

d7#.

2  f7+

f7+  g8 3

g8 3  h6++

h6++

3  d8+ also forces mate – by modern standards an alternative solution is a major flaw in a composition.

d8+ also forces mate – by modern standards an alternative solution is a major flaw in a composition.

3... h8 4

h8 4  g8+!

g8+!  xg8 5

xg8 5  f7#

f7#

This position was published by Lucena in his chess manual. It is therefore rather rough on him that in common chess parlance the name Philidor is generally associated with this idea. To compensate for this, a standard, and very important, position in the theory of rook and pawn versus rook, first published by Salvio in 1634 is generally known as the “Lucena Position” (see the chapter on endgames, here).

Mate with the Queen

The simplest way to give mate is to put your queen right next to the opponent’s king, provided your queen is defended, of course. Then only a few squares need to be denied to the king for it to be mate; none if the king is at the edge of the board. The following are a few examples.

Here a pawn provides the support, and the edge of the board prevents the king from running, so...

1  g7#

g7#

Here’s another, which should be very familiar.

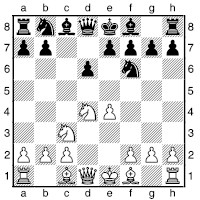

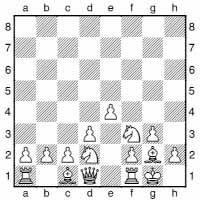

This position has arisen after the moves 1 e4 e5 2  c4

c4  c5 3

c5 3  h5 (a bad move played millions of times by novices) 3...

h5 (a bad move played millions of times by novices) 3... f6 (an even worse move, also unfortunately played millions of times by other novices). Black’s last move was a blunder; instead 3...

f6 (an even worse move, also unfortunately played millions of times by other novices). Black’s last move was a blunder; instead 3... e7 gives Black an excellent position. White now plays:

e7 gives Black an excellent position. White now plays:

4  xf7#

xf7#

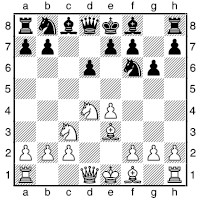

Here’s a more sophisticated idea, often relevant when the king has been dragged out into the open, and the queen is chasing it towards hostile pawns:

1  f6#

f6#

A very economical mate. One pawn covers the two squares the queen cannot reach, while the other pawn defends the queen.

Mate with Several Minor Pieces

Here are some of the most important patterns:

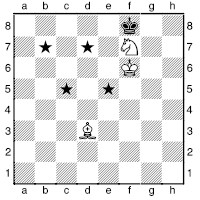

White’s minor pieces dive in and mate the king:

1  xf7+

xf7+  e7 2

e7 2  d5#

d5#

This finish is characteristic of Legall’s Mate, which is a drastic tactical method of breaking a pin.

Two knights can suffice to mate a king when he is short of squares:

1  f7# finishes off nicely. Note that in general knights are more effective when standing next to each other than when defending one another.

f7# finishes off nicely. Note that in general knights are more effective when standing next to each other than when defending one another.

Here are two examples of a pair of bishops delivering mate:

1  g6# is very light compared to some of the mates we have seen. It’s very easy to miss such ideas at the board.

g6# is very light compared to some of the mates we have seen. It’s very easy to miss such ideas at the board.

1  d5# is the finish this time.

d5# is the finish this time.

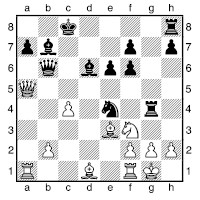

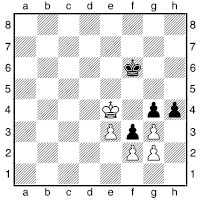

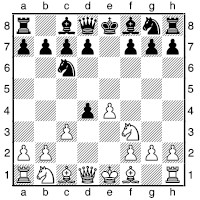

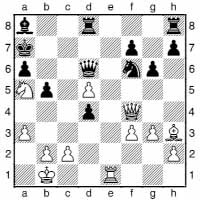

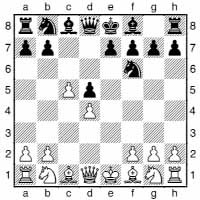

Now we move on to the positions for solving. The first twenty-five positions are intended as warm-ups for novices, and should not take too long to solve, but don’t worry if you get stuck on a few – we all have mental blocks now and then. I have provided some rather generous clues, to some of the positions, in the above diagrams. If all else fails, consider every legal move.

As a rough guide, strong players should solve each position in just a second or two, while ordinary club players should not take long either.

If you have problems solving them, set the position up on a board and concentrate as though you were playing a game.

In the solutions, I note any tactical themes that occur in the positions. These ideas constitute an armoury of checkmating ideas that will help you throughout your chess career.

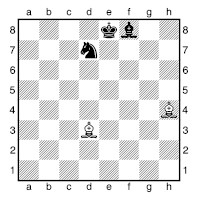

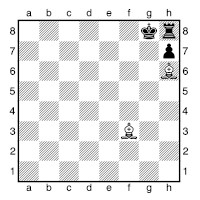

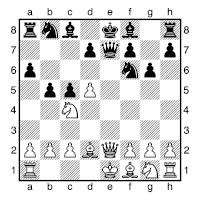

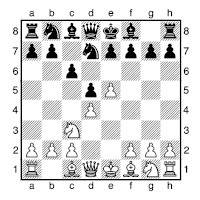

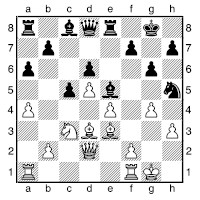

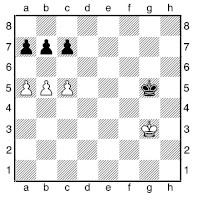

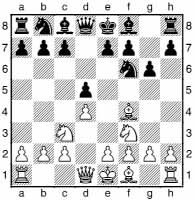

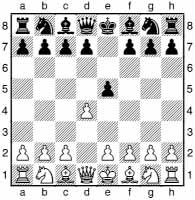

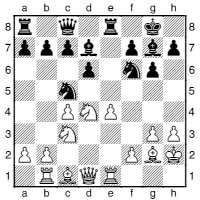

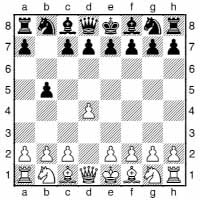

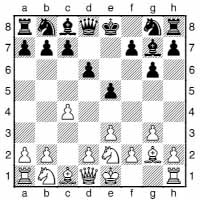

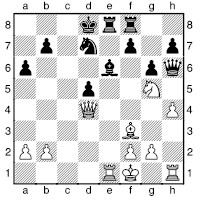

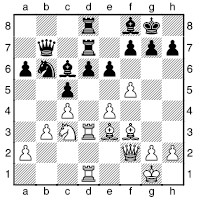

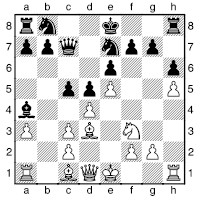

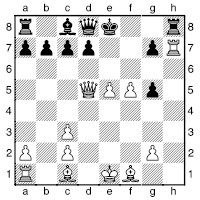

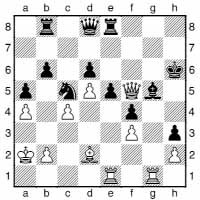

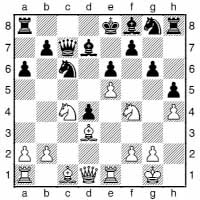

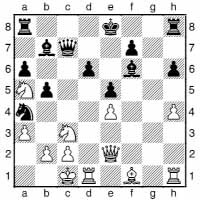

25 Novice Warm-ups

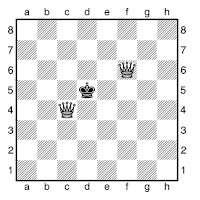

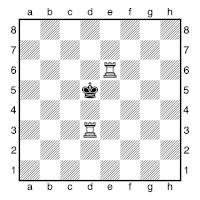

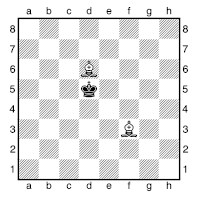

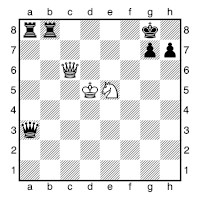

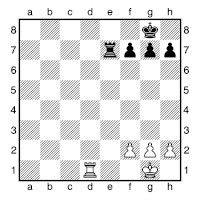

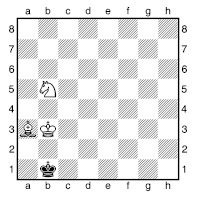

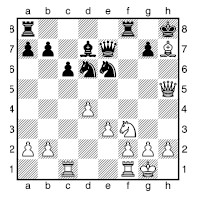

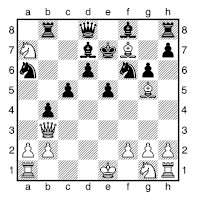

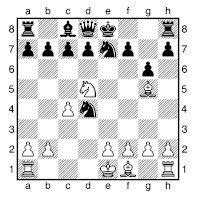

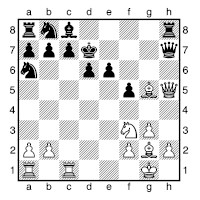

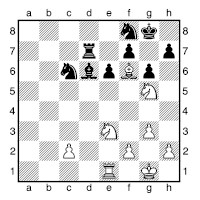

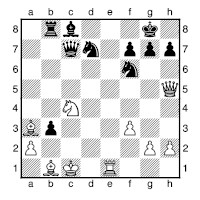

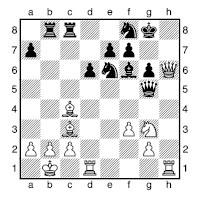

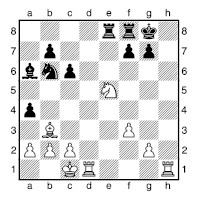

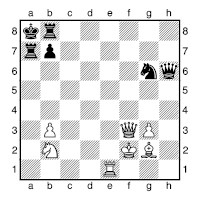

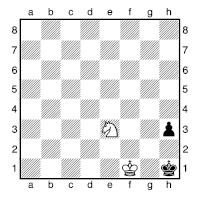

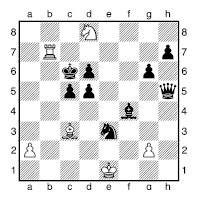

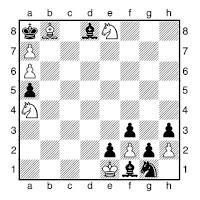

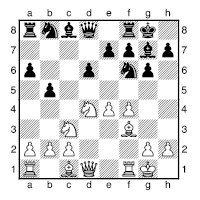

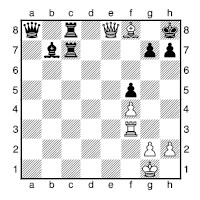

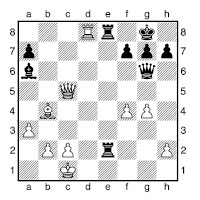

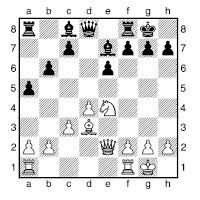

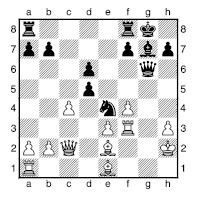

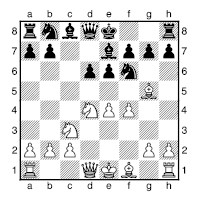

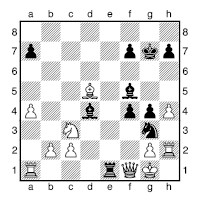

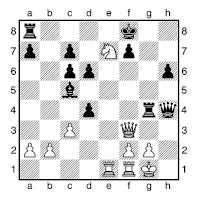

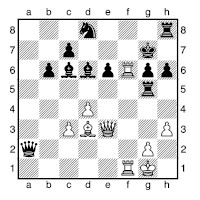

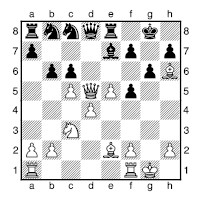

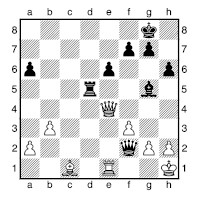

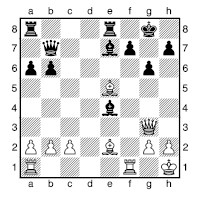

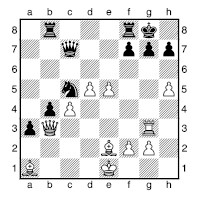

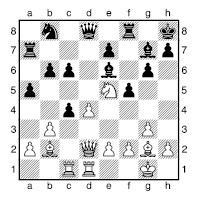

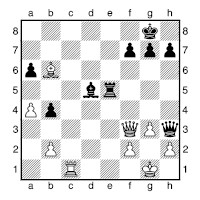

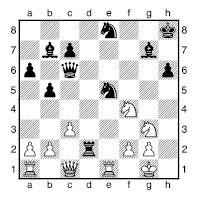

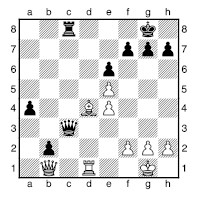

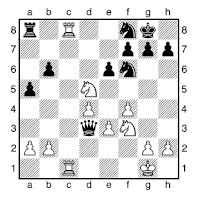

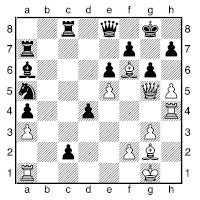

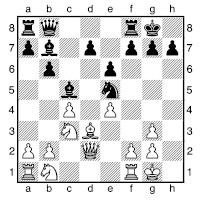

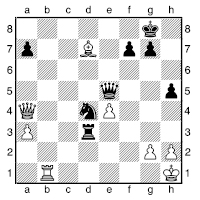

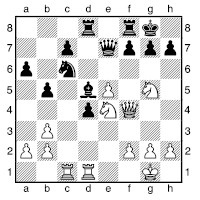

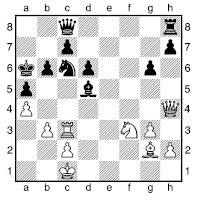

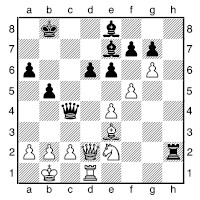

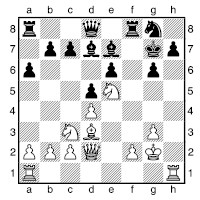

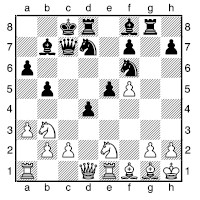

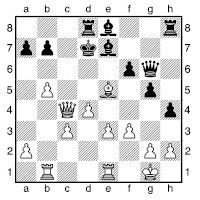

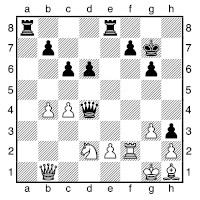

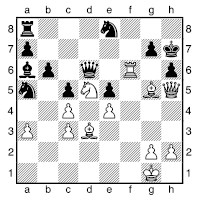

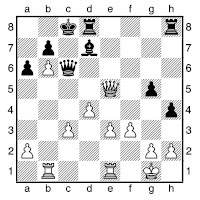

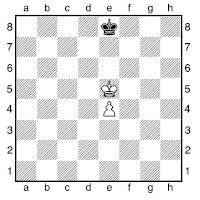

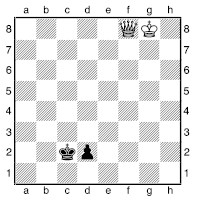

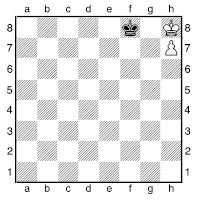

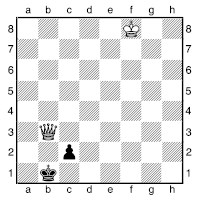

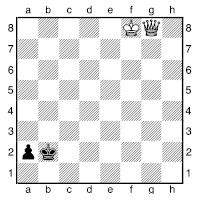

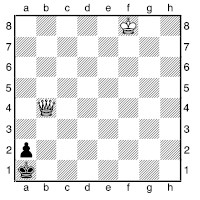

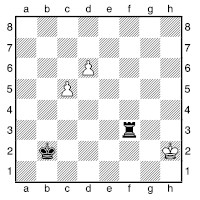

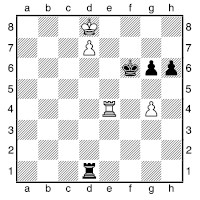

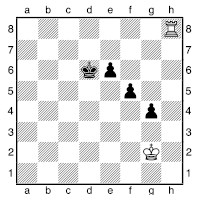

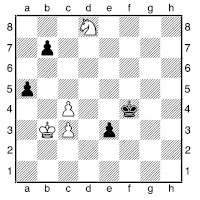

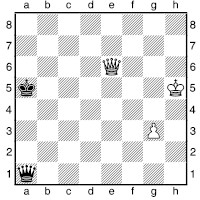

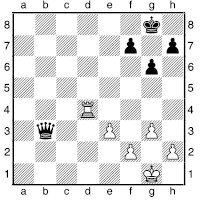

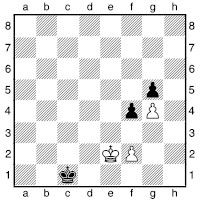

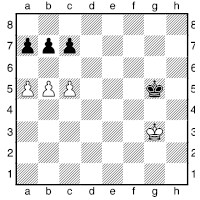

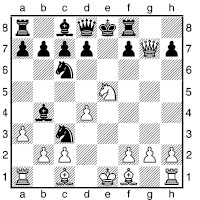

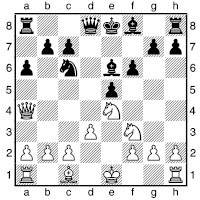

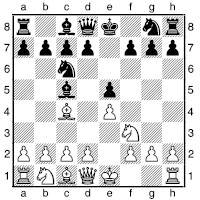

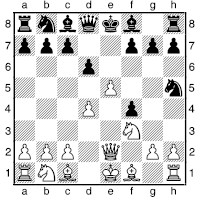

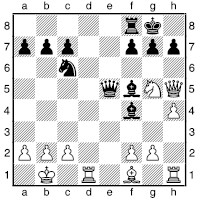

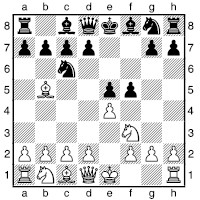

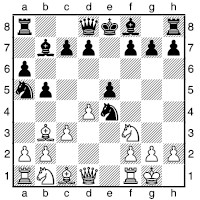

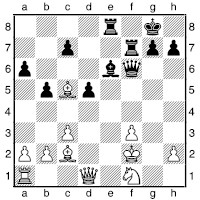

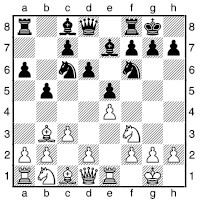

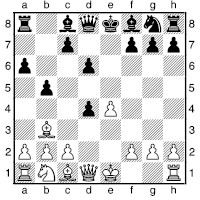

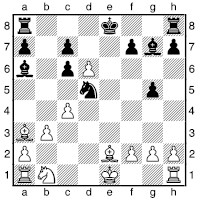

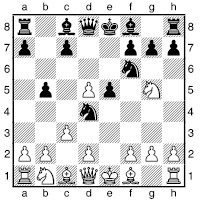

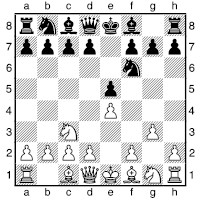

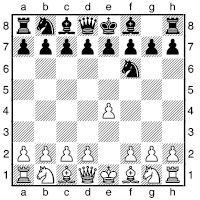

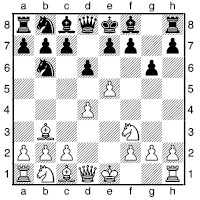

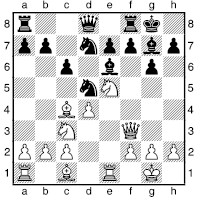

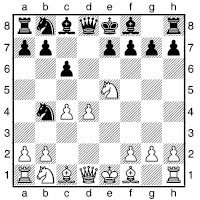

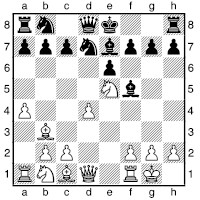

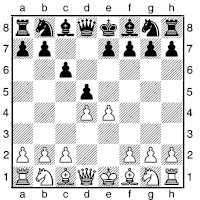

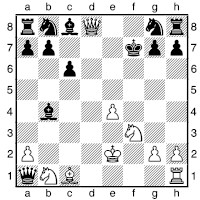

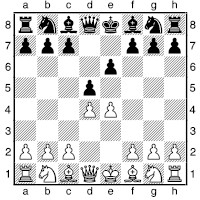

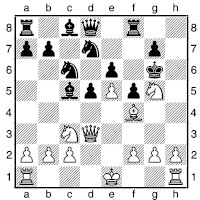

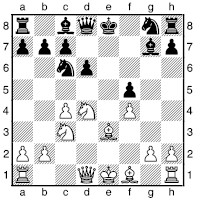

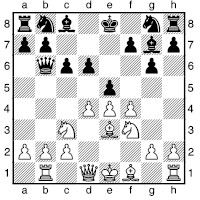

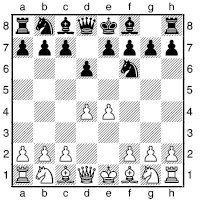

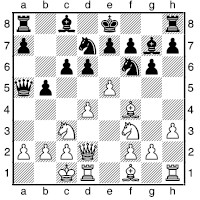

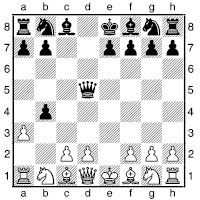

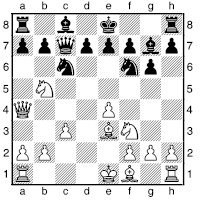

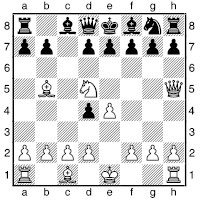

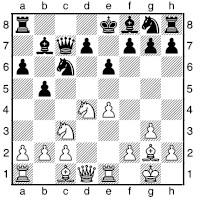

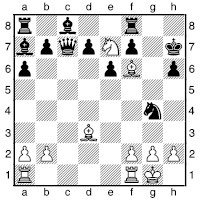

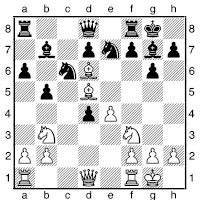

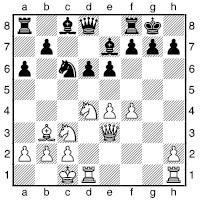

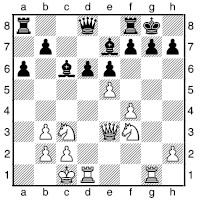

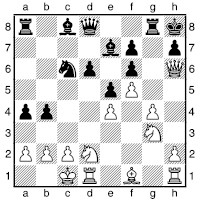

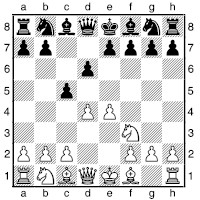

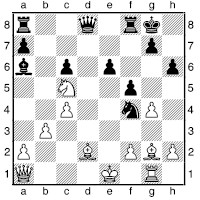

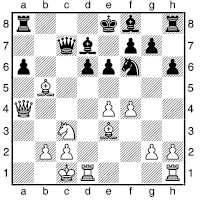

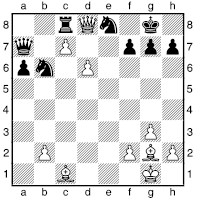

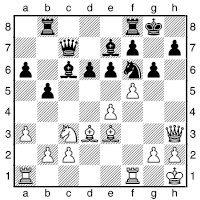

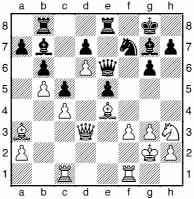

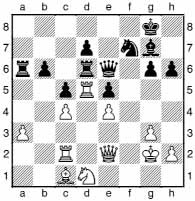

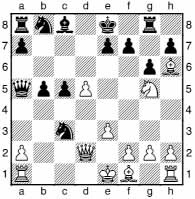

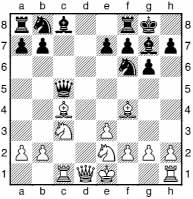

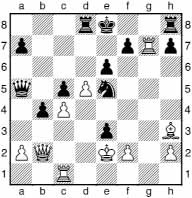

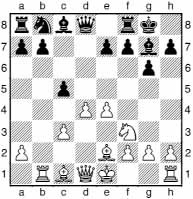

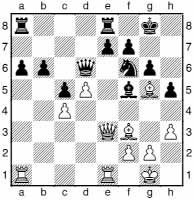

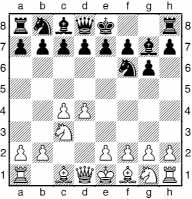

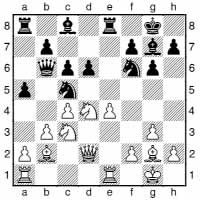

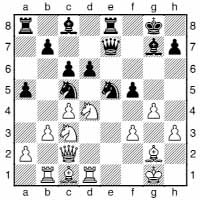

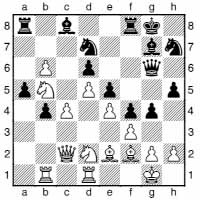

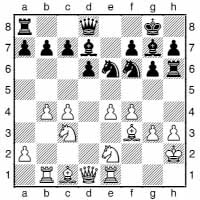

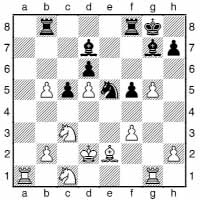

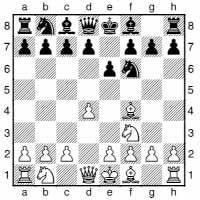

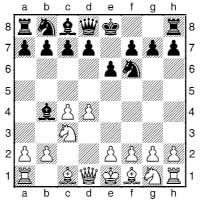

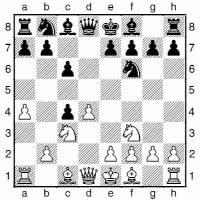

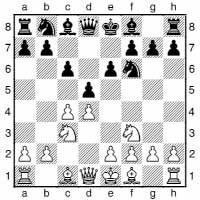

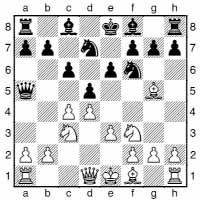

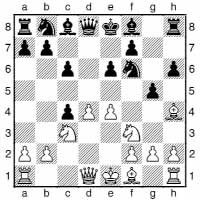

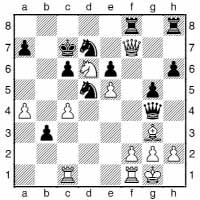

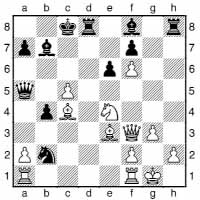

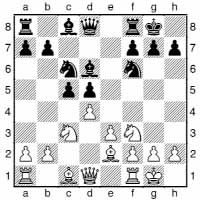

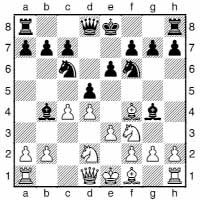

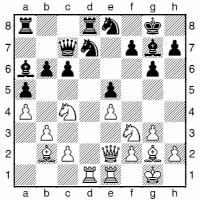

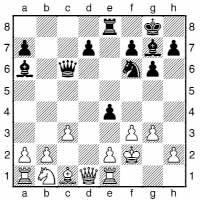

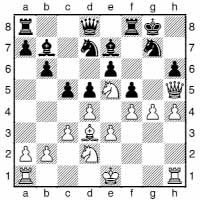

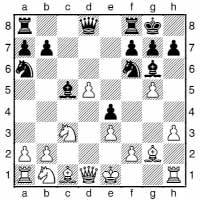

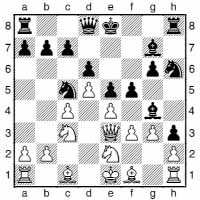

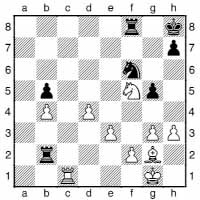

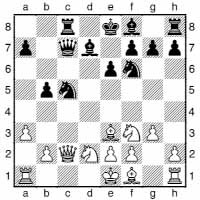

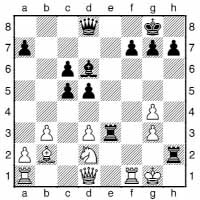

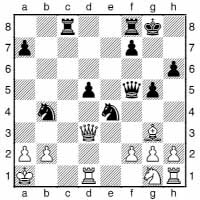

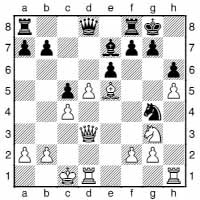

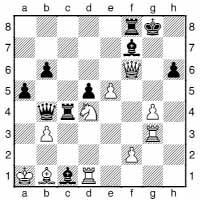

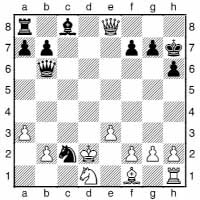

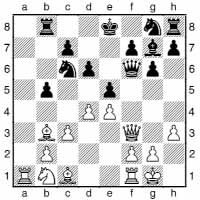

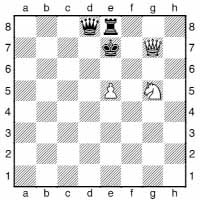

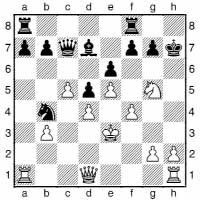

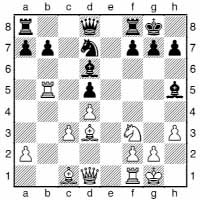

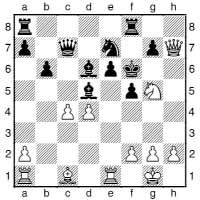

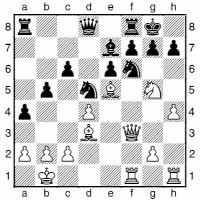

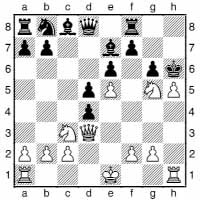

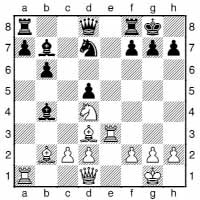

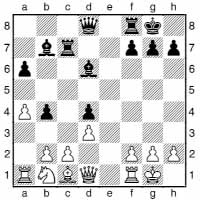

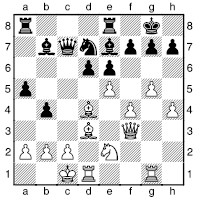

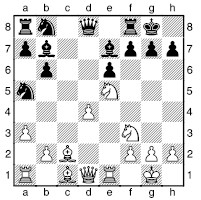

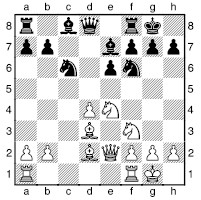

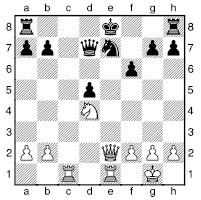

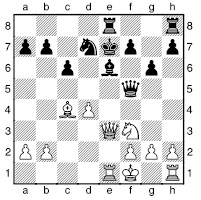

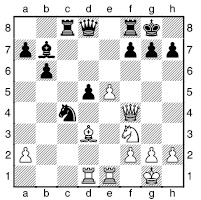

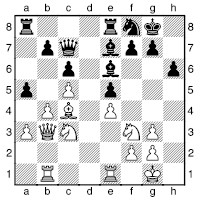

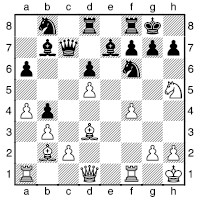

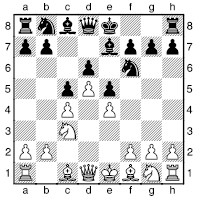

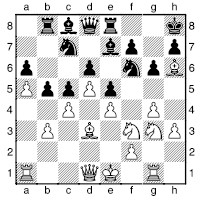

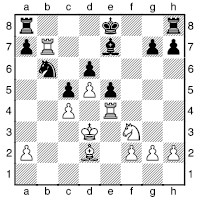

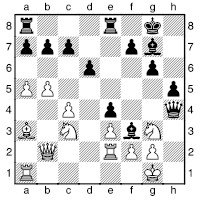

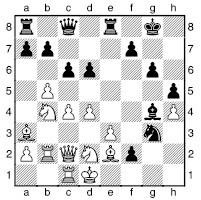

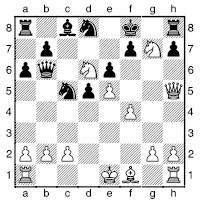

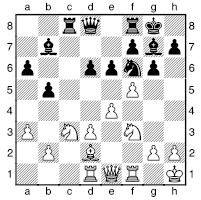

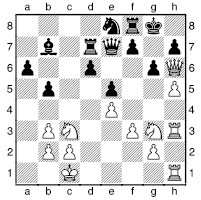

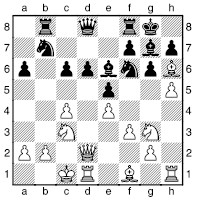

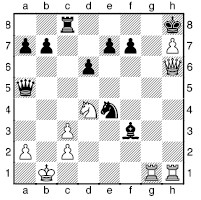

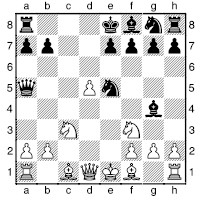

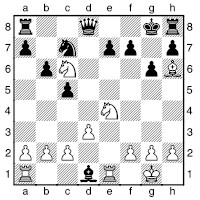

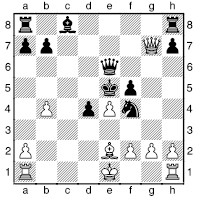

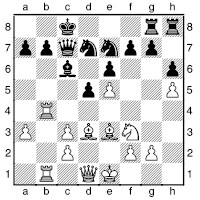

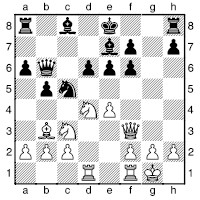

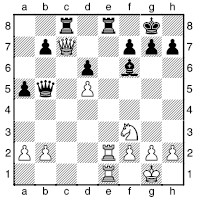

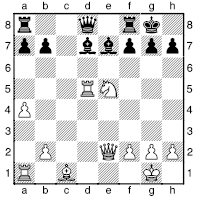

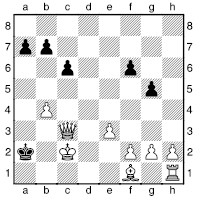

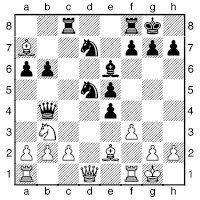

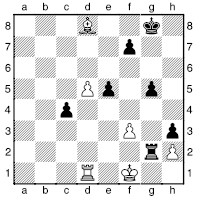

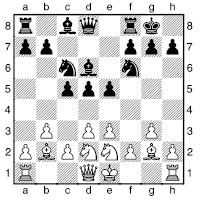

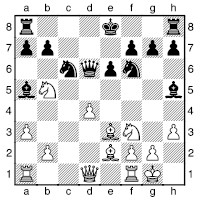

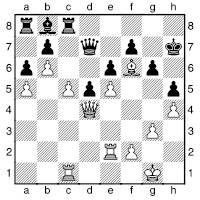

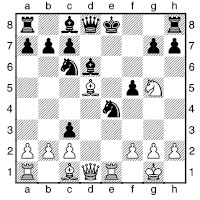

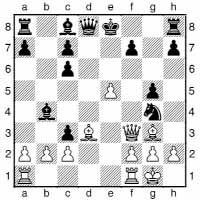

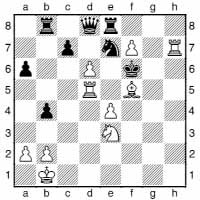

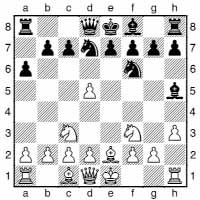

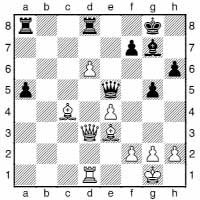

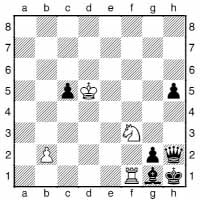

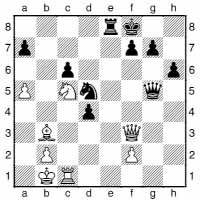

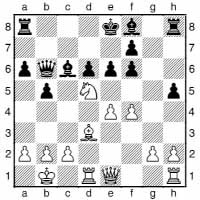

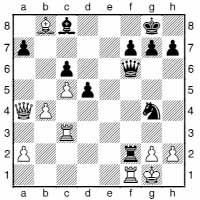

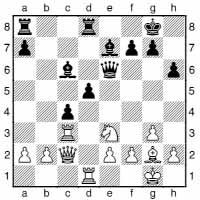

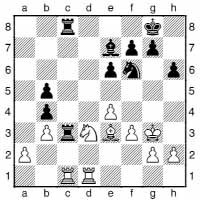

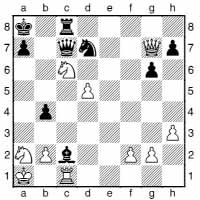

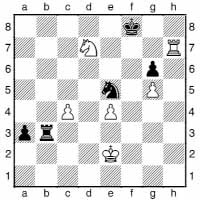

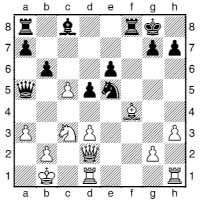

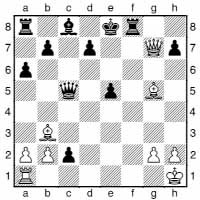

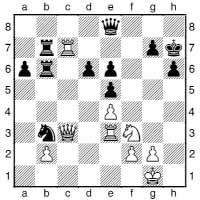

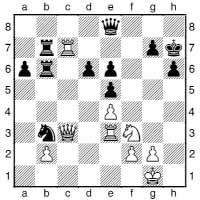

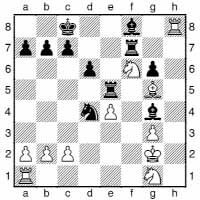

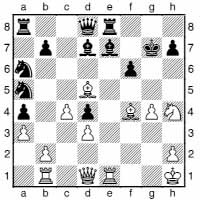

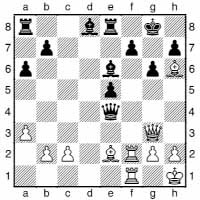

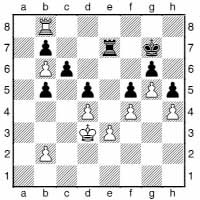

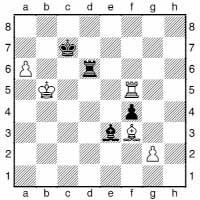

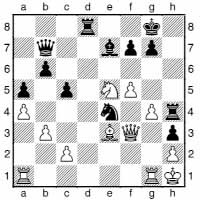

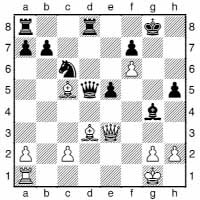

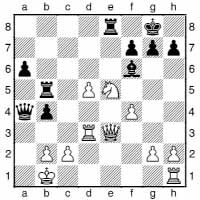

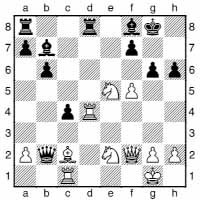

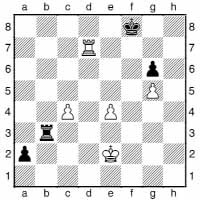

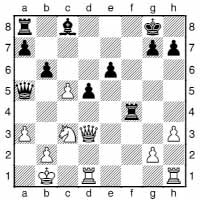

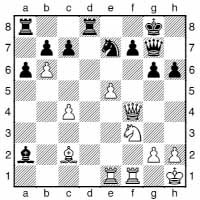

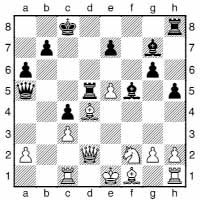

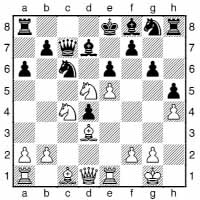

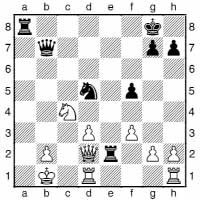

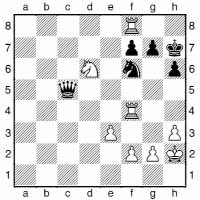

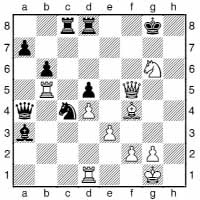

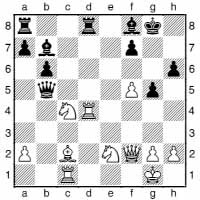

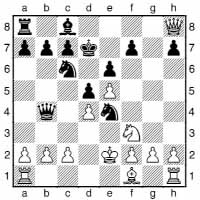

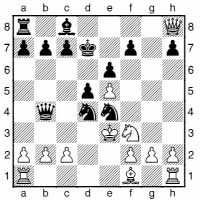

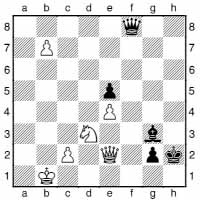

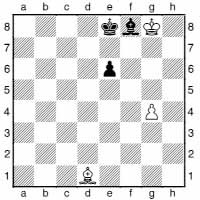

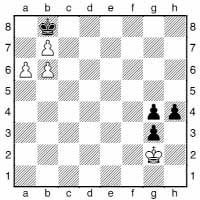

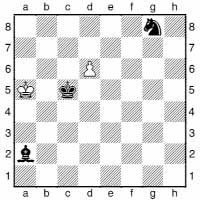

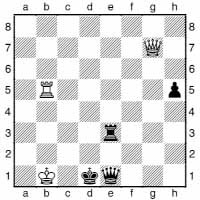

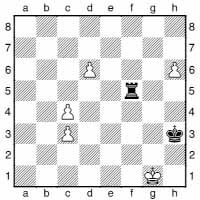

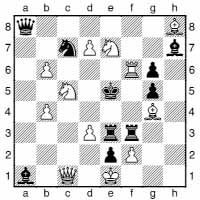

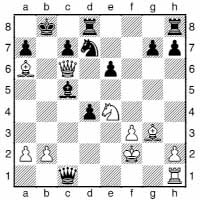

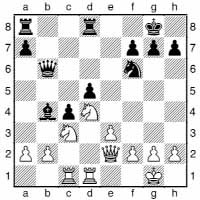

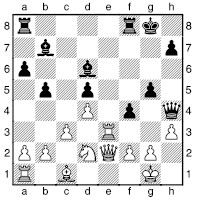

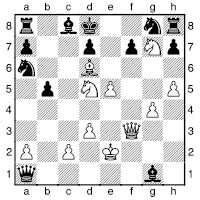

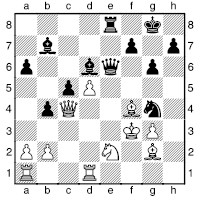

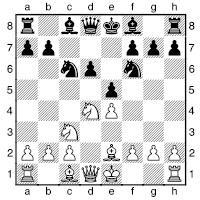

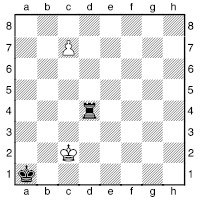

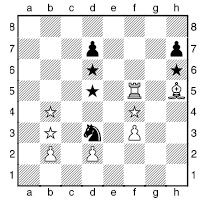

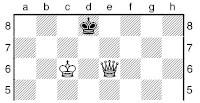

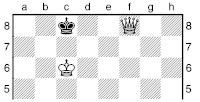

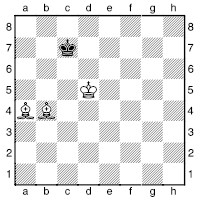

1) White to play and force mate in two moves

2) White to play and force mate in two moves

3) White to play and force mate in two moves

4) White to play and force mate in two moves

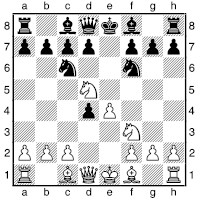

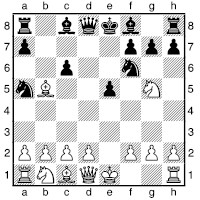

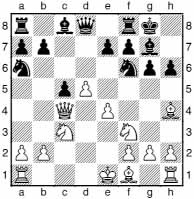

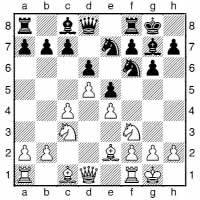

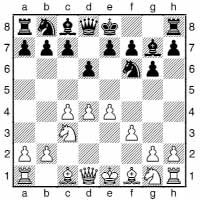

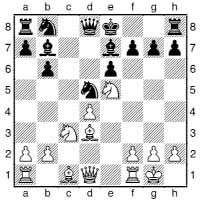

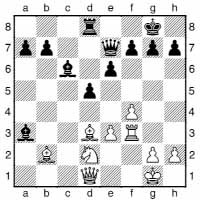

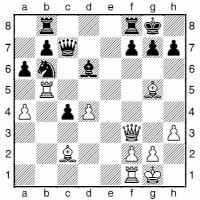

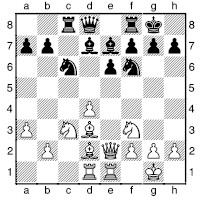

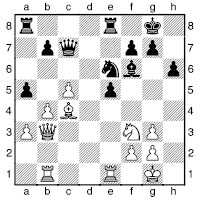

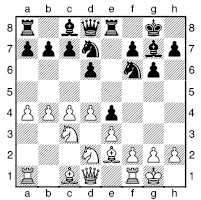

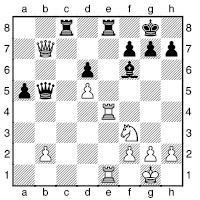

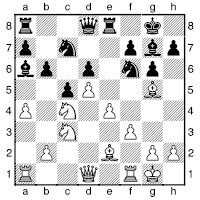

5) White to play and force mate in two moves

6) White to play and force mate in two moves

7) White to play and force mate in two moves

8) White to play and force mate in two moves

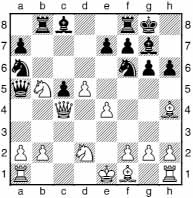

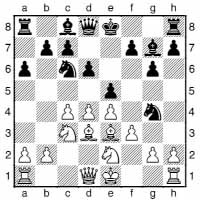

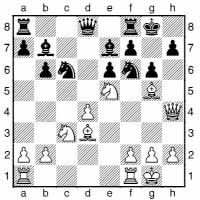

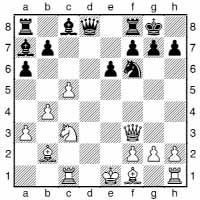

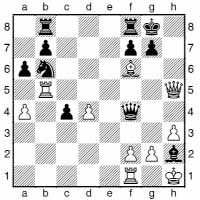

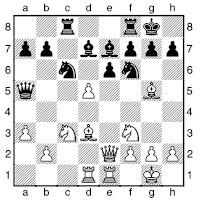

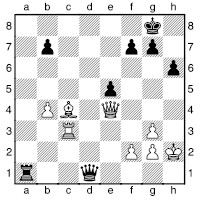

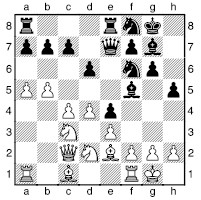

9) White to play and force mate in two moves

10) White to play and force mate in two moves

11) White to play and force mate in two moves

12) White to play and force mate in two moves

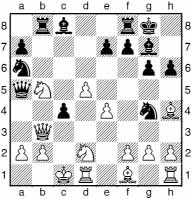

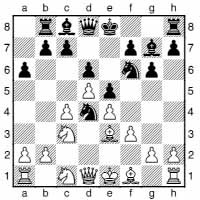

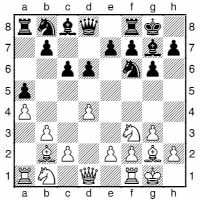

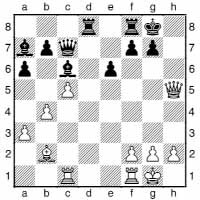

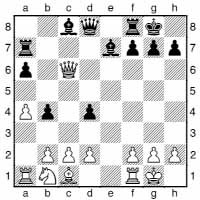

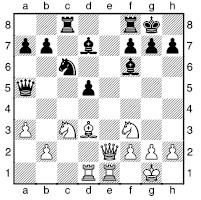

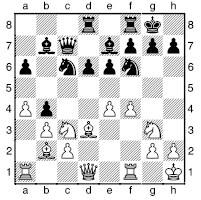

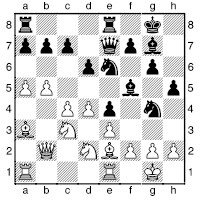

13) White to play and force mate in two moves

14) White to play and force mate in two moves

15) White to play and force mate in two moves

16) White to play and force mate in two moves

17) White to play and force mate in two moves

18) White to play and force mate in two moves

19) White to play and force mate in two moves

20) White to play and force mate in two moves

21) White to play and force mate in two moves

22) White to play and force mate in two moves

23) White to play and force mate in two moves

24) White to play and force mate in two moves

25) White to play and force mate in two moves

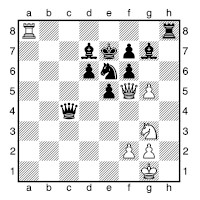

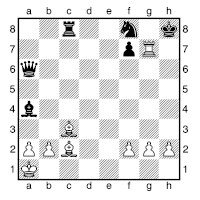

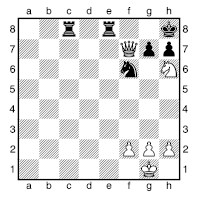

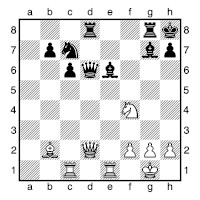

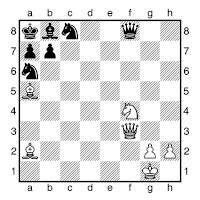

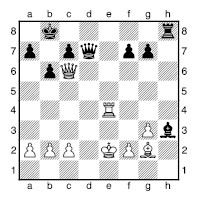

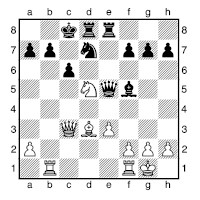

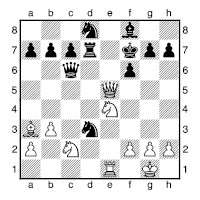

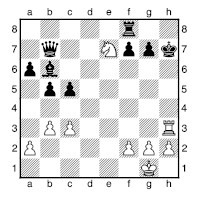

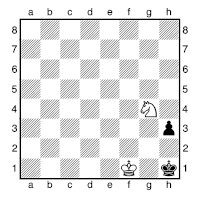

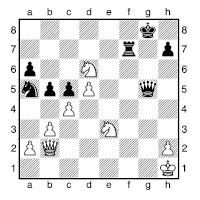

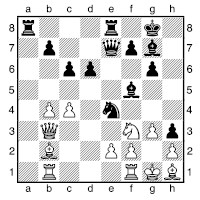

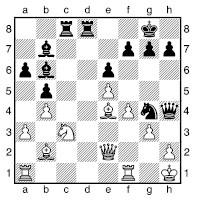

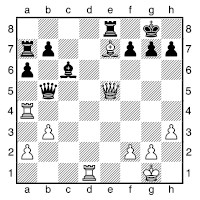

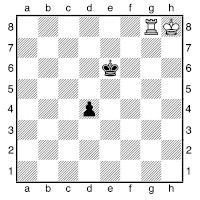

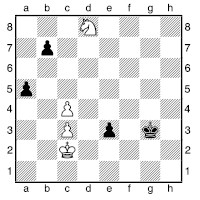

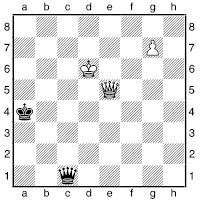

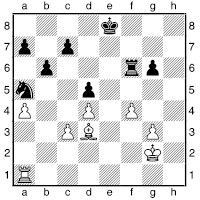

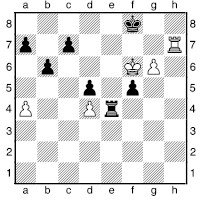

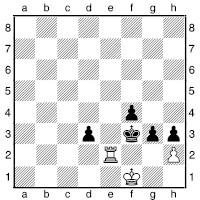

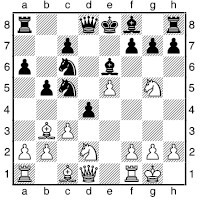

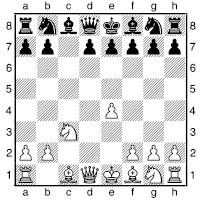

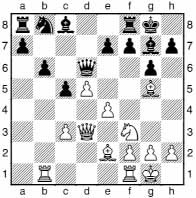

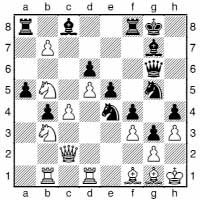

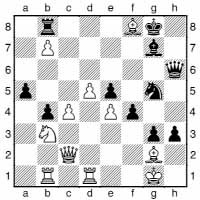

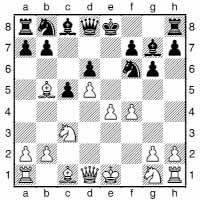

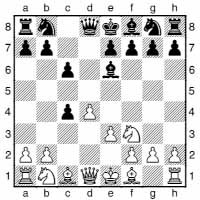

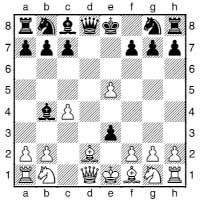

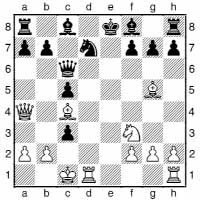

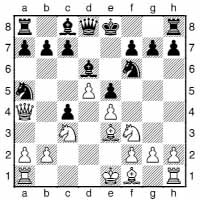

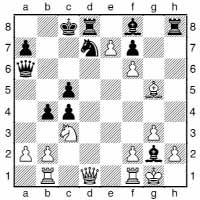

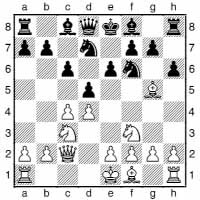

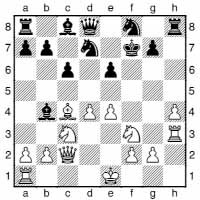

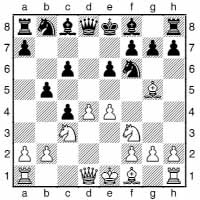

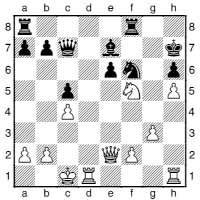

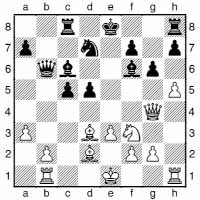

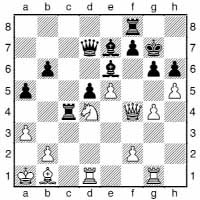

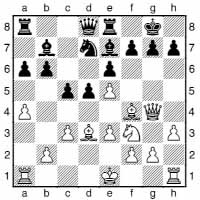

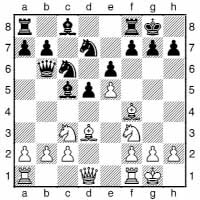

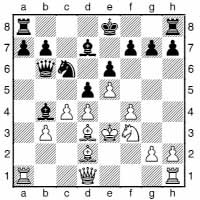

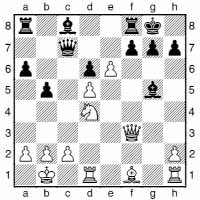

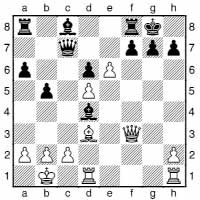

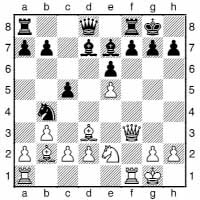

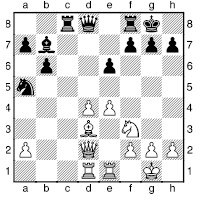

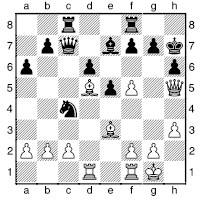

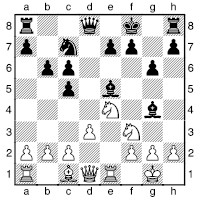

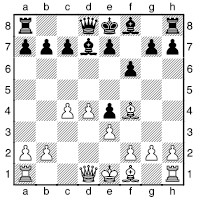

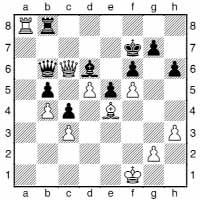

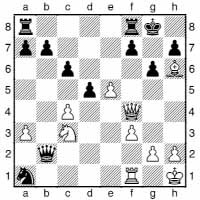

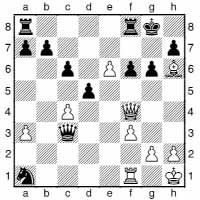

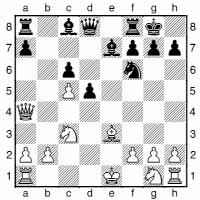

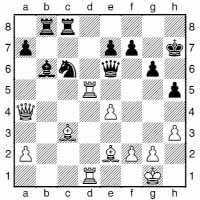

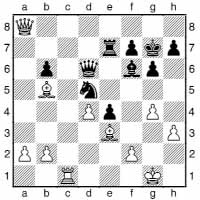

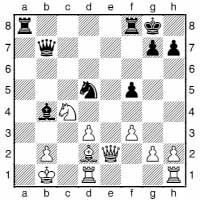

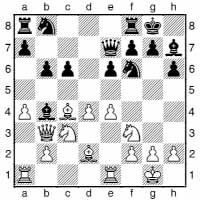

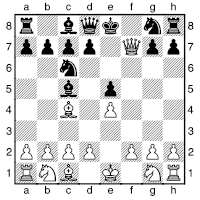

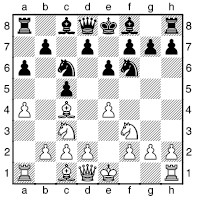

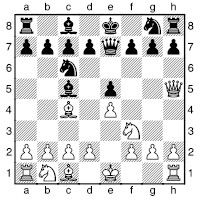

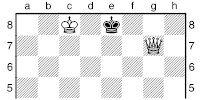

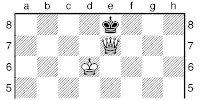

25 Trickier Mates in Two

I hope you didn’t have too many problems with those positions. Here are twenty-five rather more complex mates in two. The ideas tend to follow on logically from those we have seen, but are more deeply hidden, or combine various ideas. Nevertheless, experienced players should sail through this test as well.

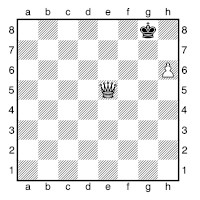

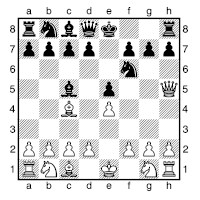

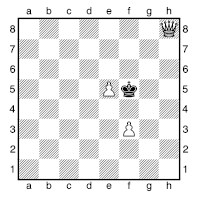

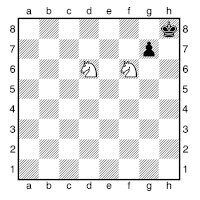

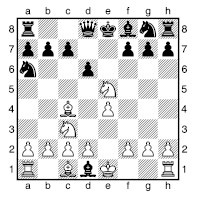

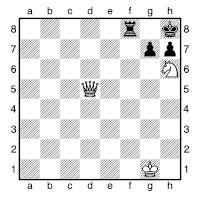

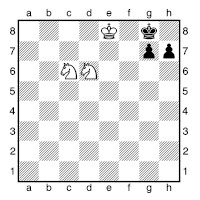

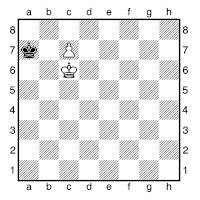

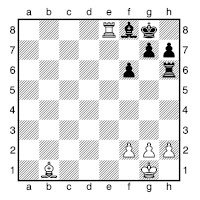

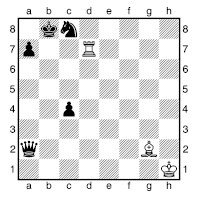

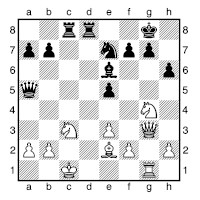

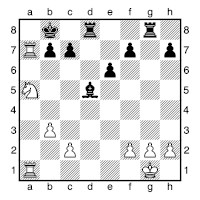

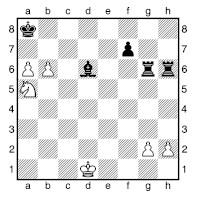

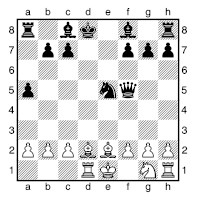

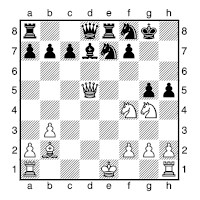

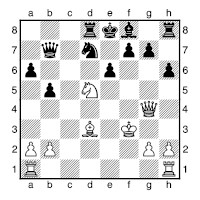

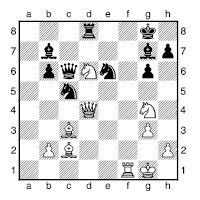

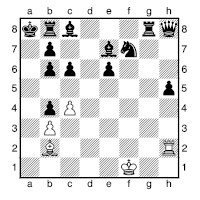

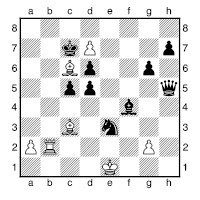

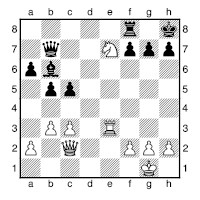

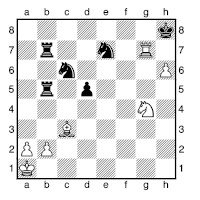

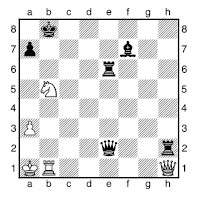

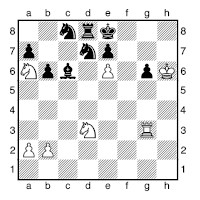

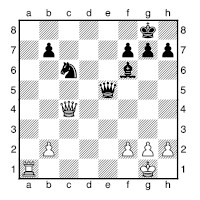

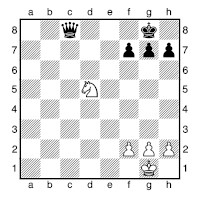

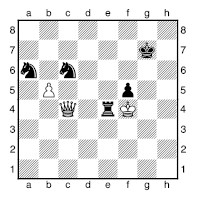

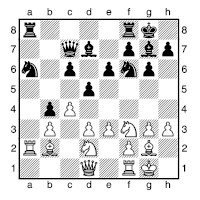

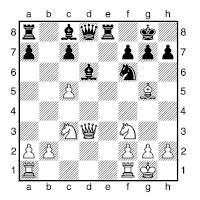

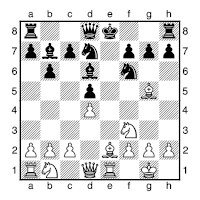

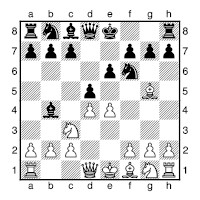

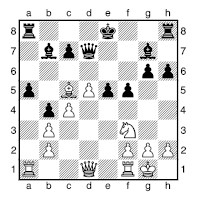

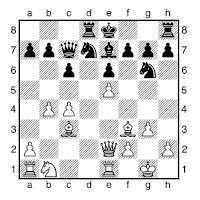

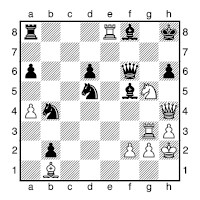

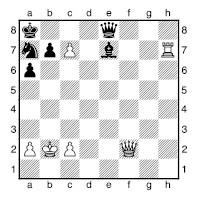

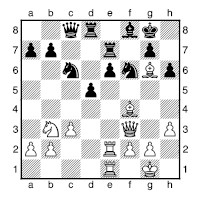

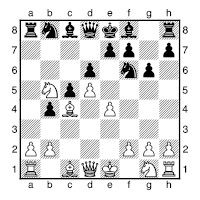

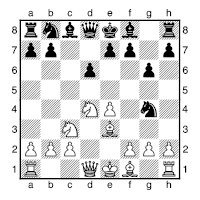

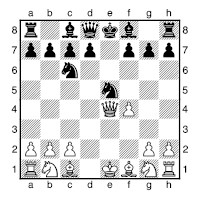

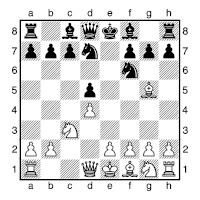

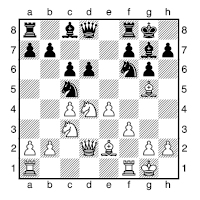

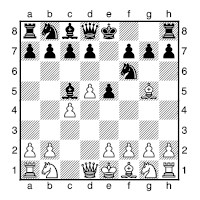

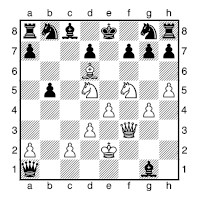

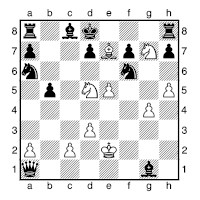

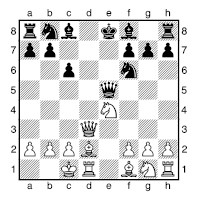

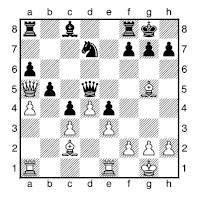

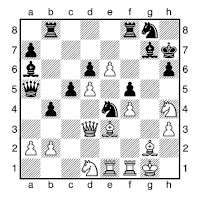

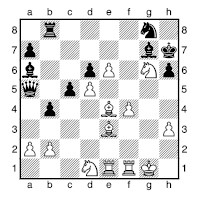

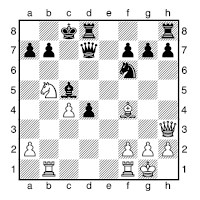

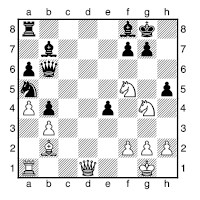

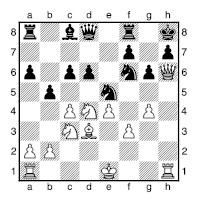

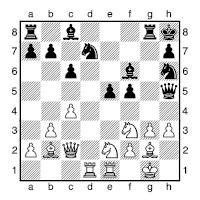

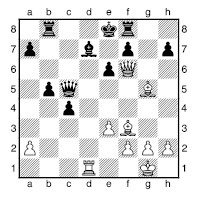

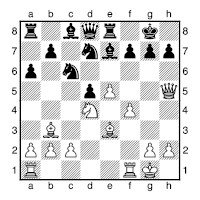

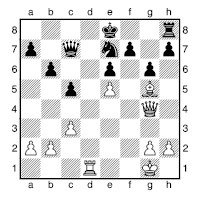

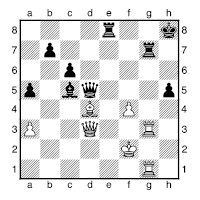

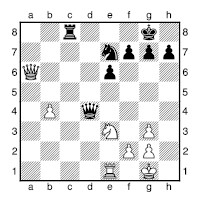

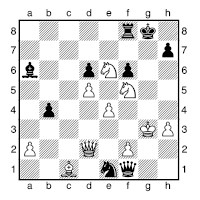

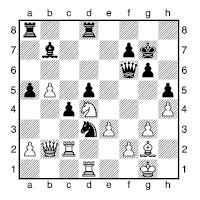

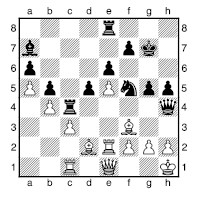

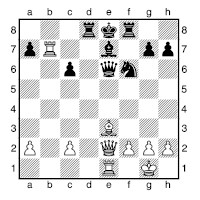

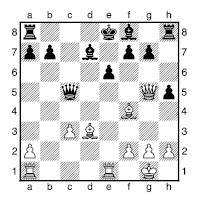

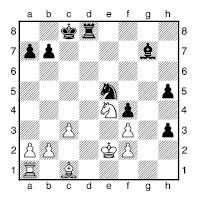

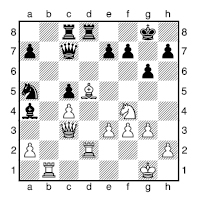

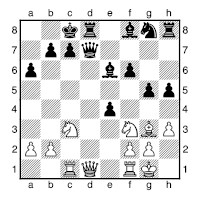

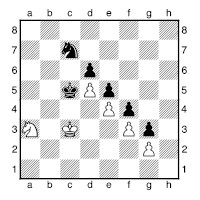

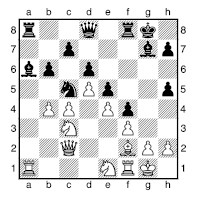

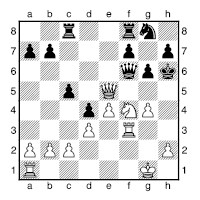

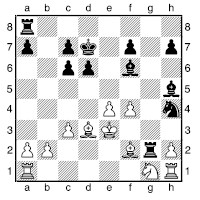

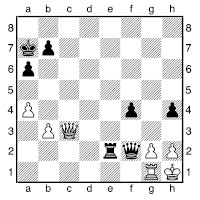

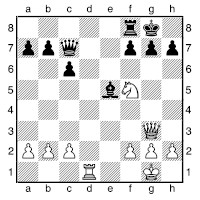

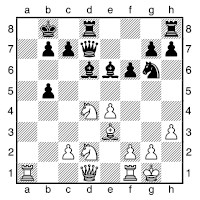

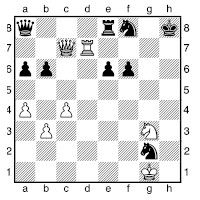

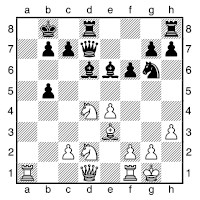

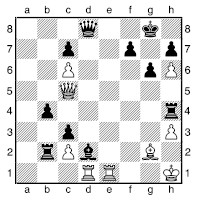

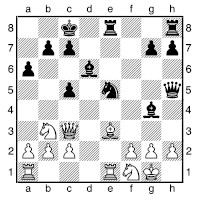

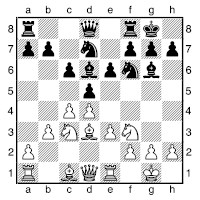

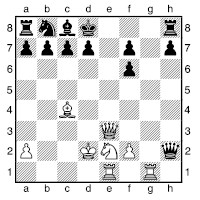

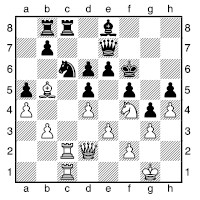

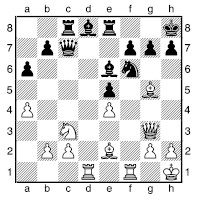

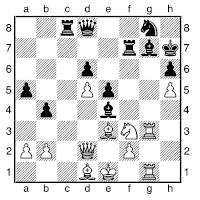

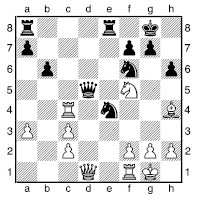

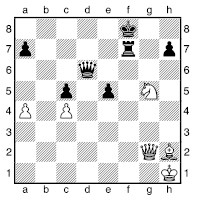

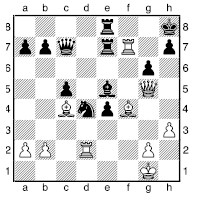

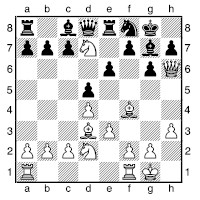

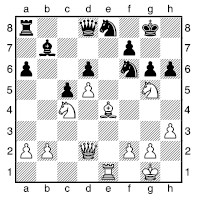

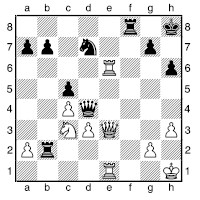

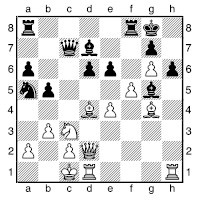

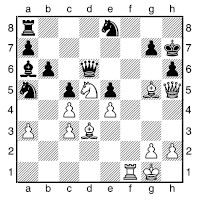

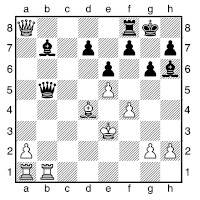

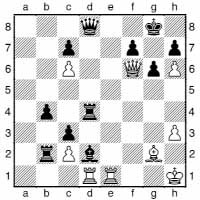

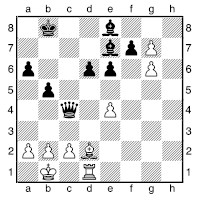

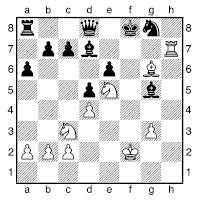

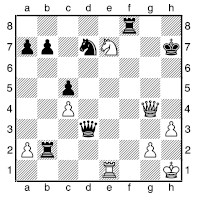

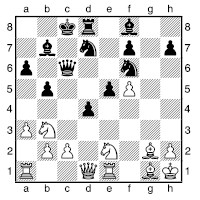

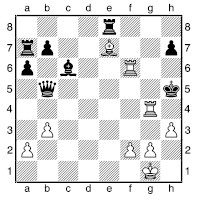

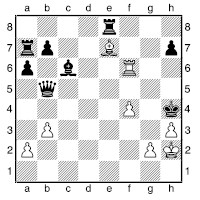

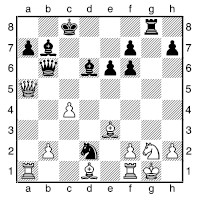

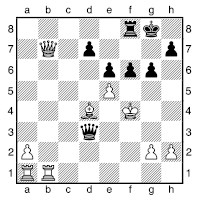

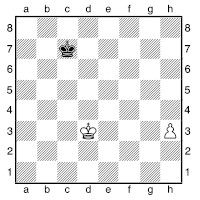

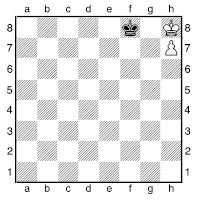

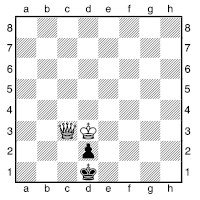

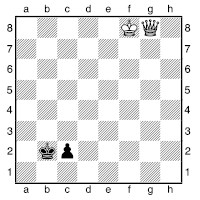

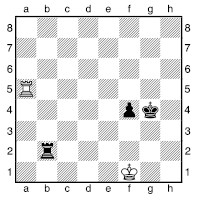

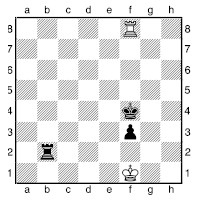

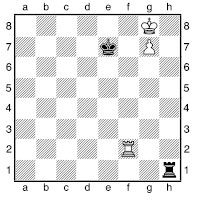

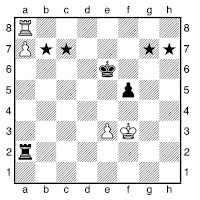

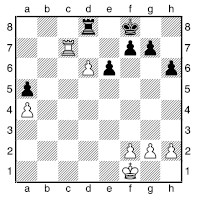

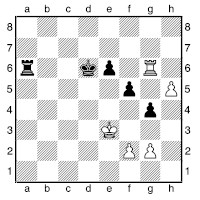

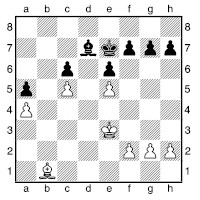

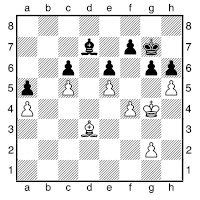

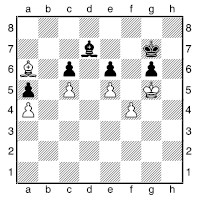

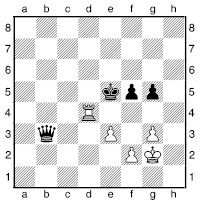

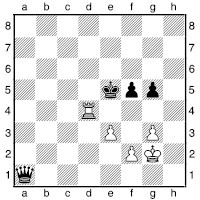

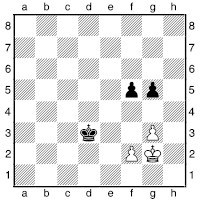

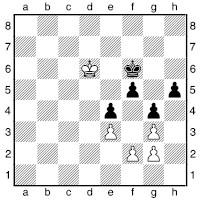

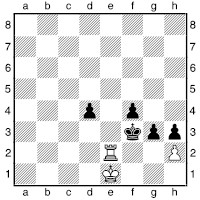

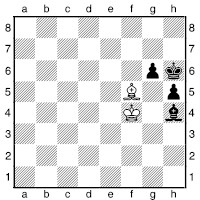

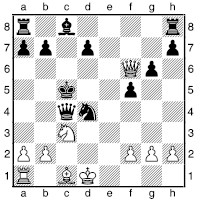

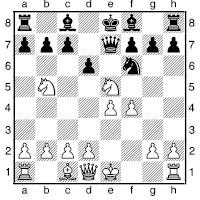

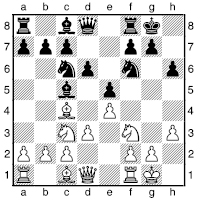

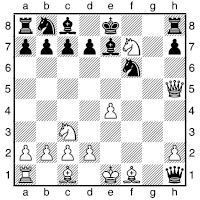

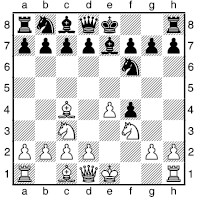

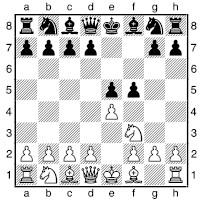

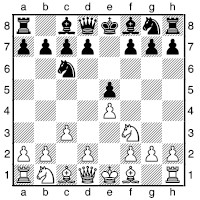

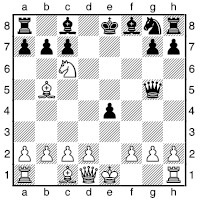

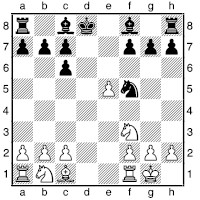

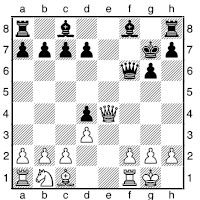

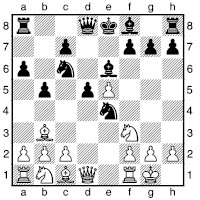

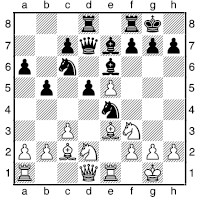

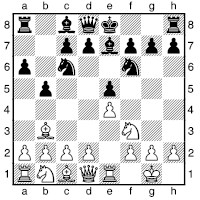

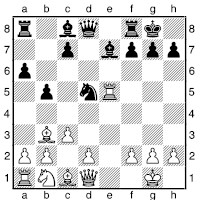

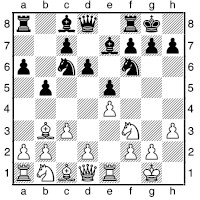

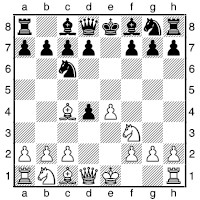

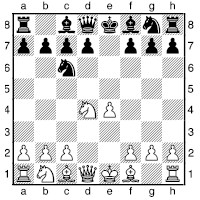

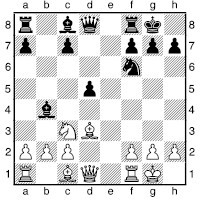

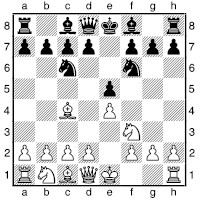

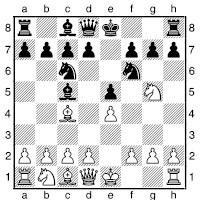

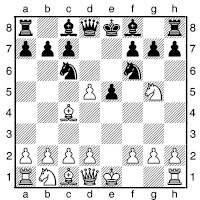

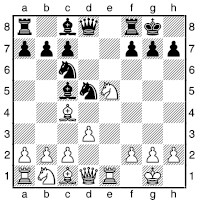

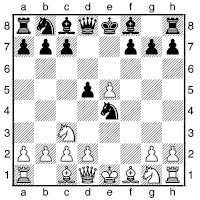

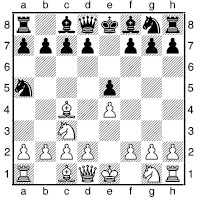

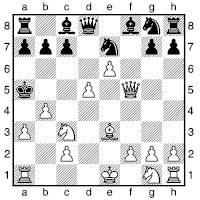

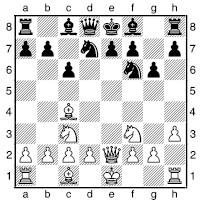

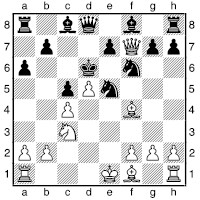

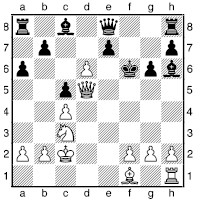

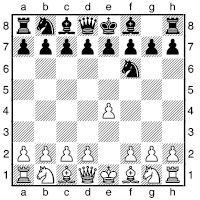

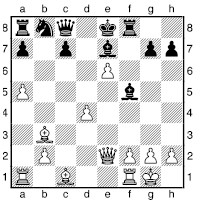

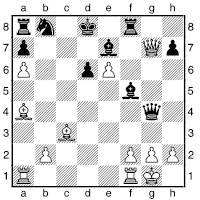

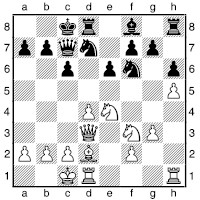

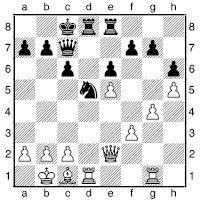

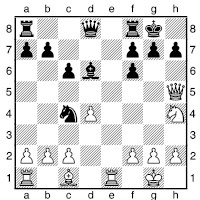

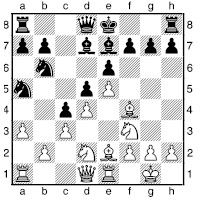

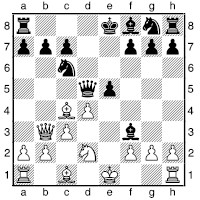

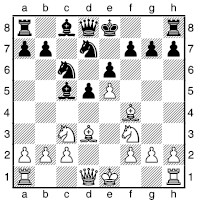

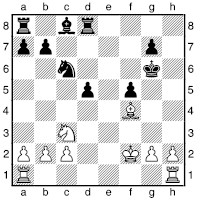

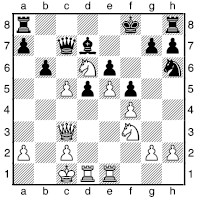

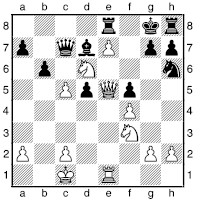

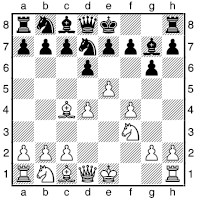

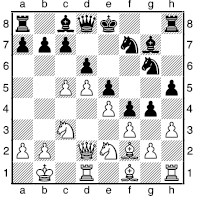

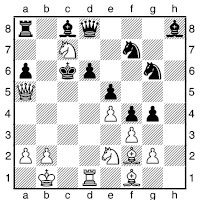

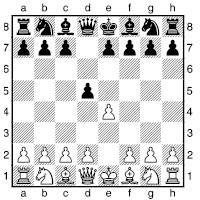

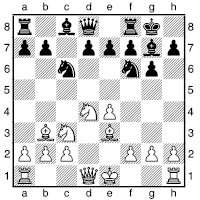

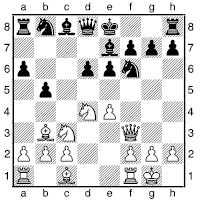

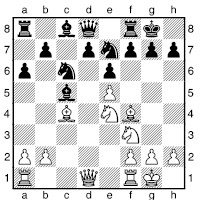

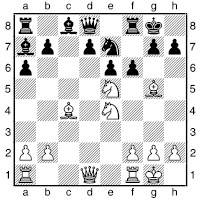

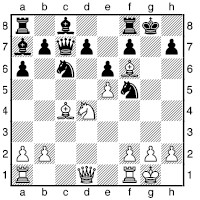

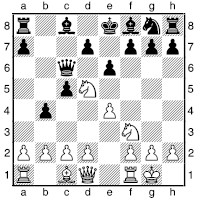

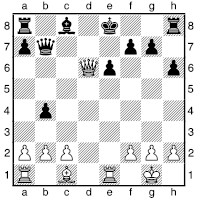

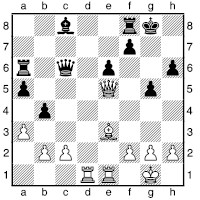

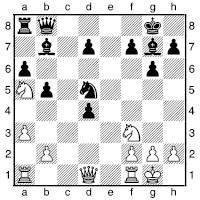

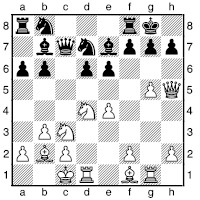

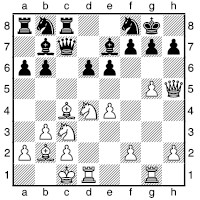

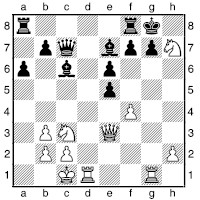

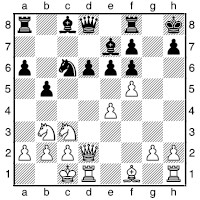

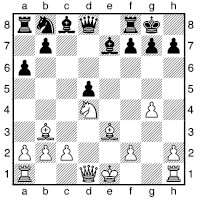

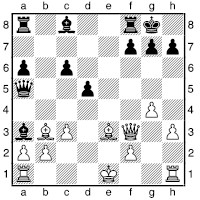

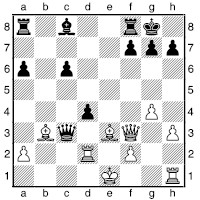

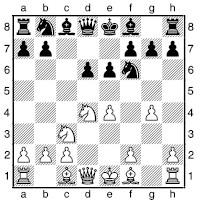

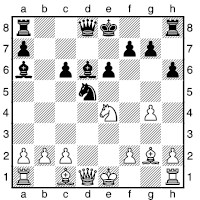

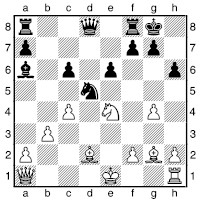

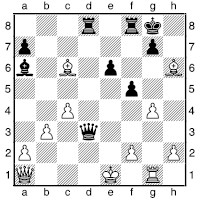

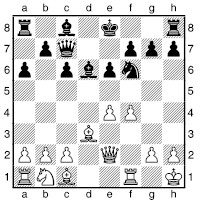

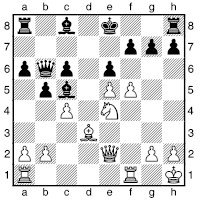

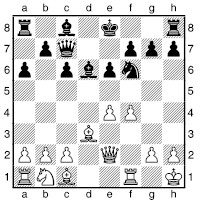

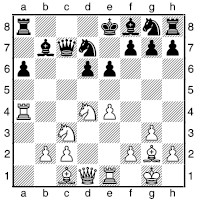

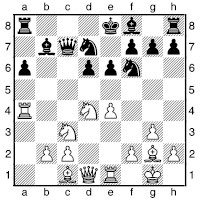

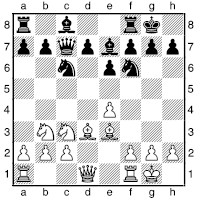

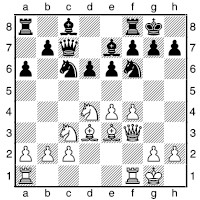

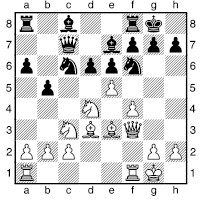

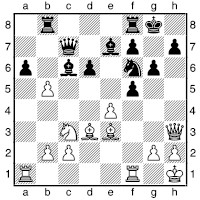

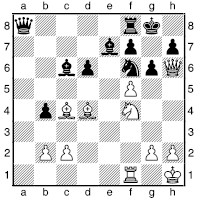

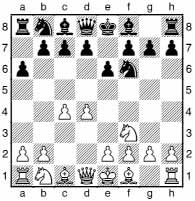

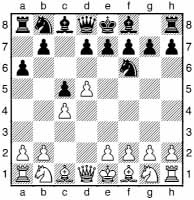

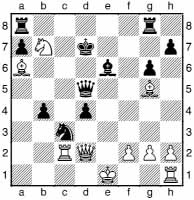

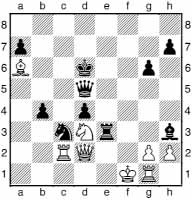

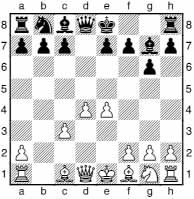

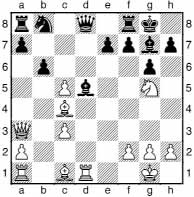

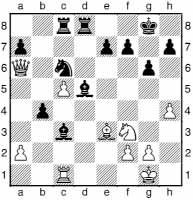

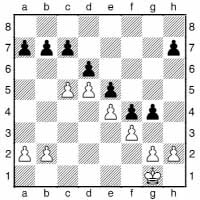

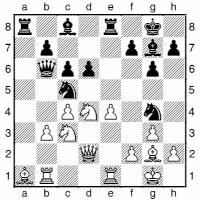

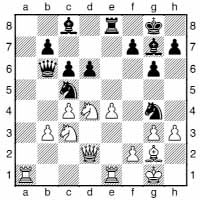

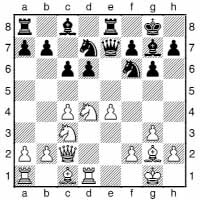

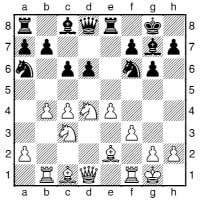

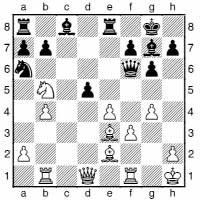

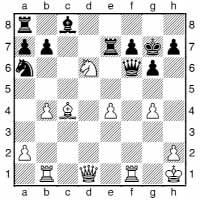

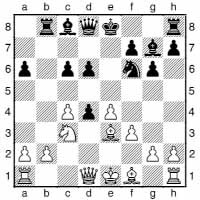

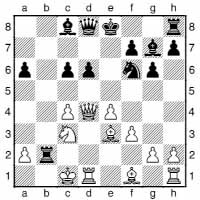

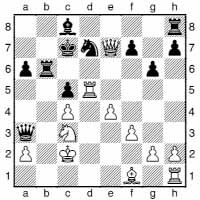

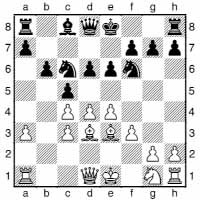

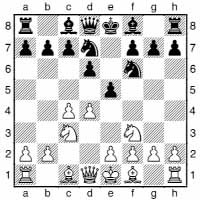

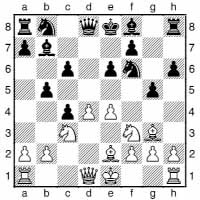

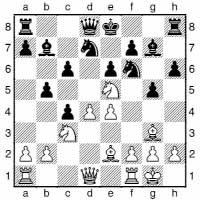

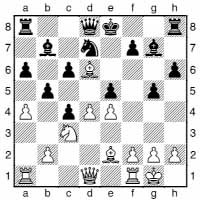

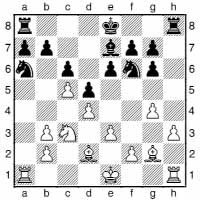

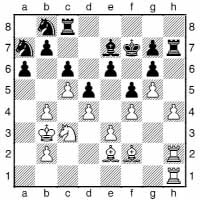

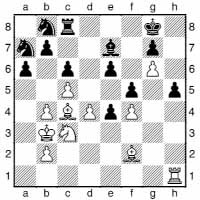

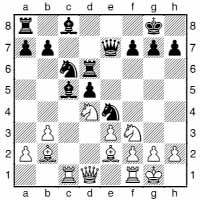

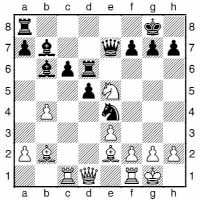

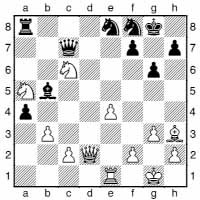

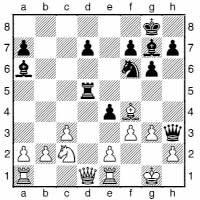

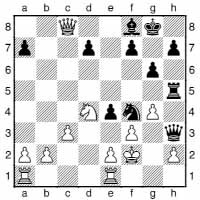

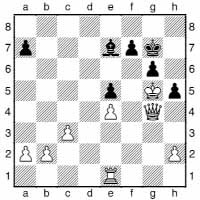

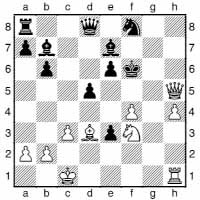

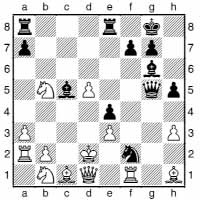

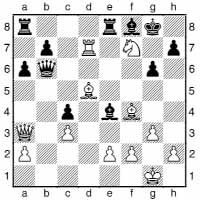

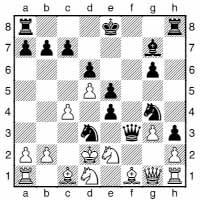

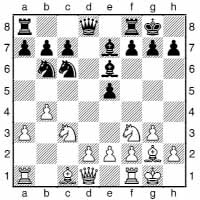

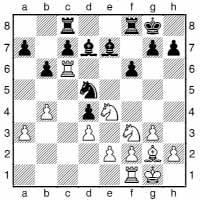

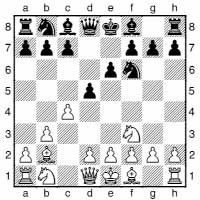

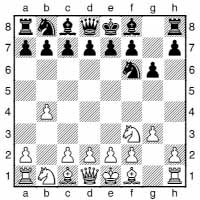

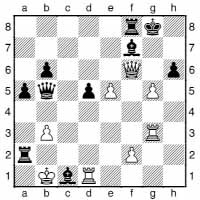

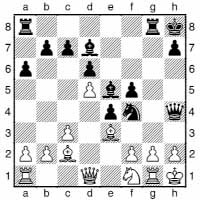

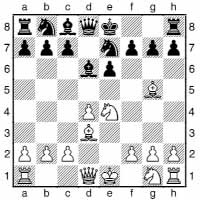

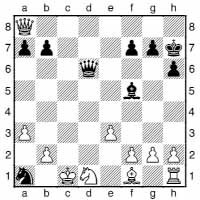

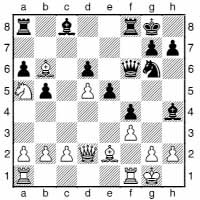

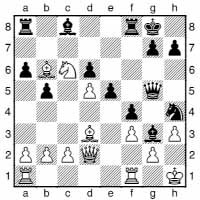

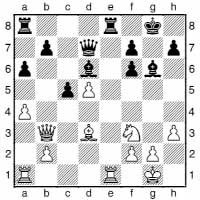

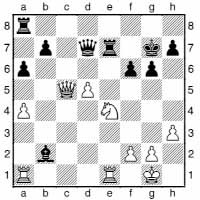

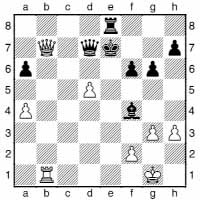

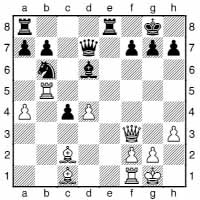

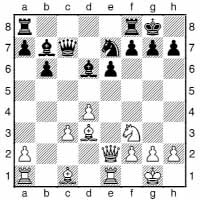

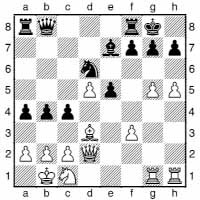

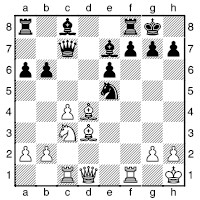

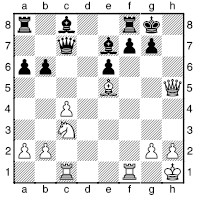

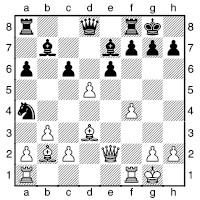

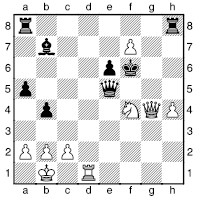

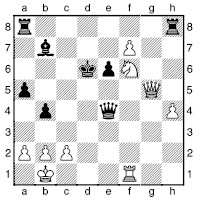

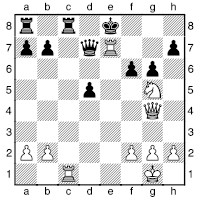

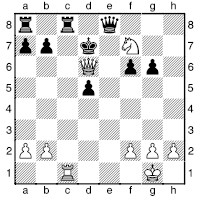

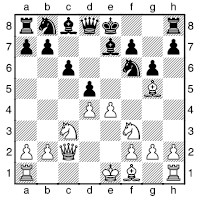

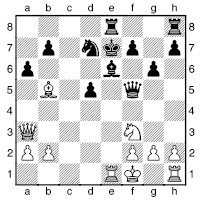

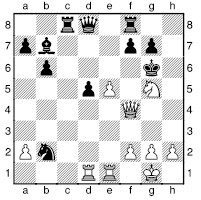

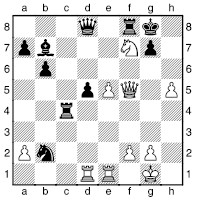

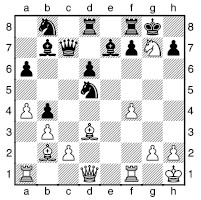

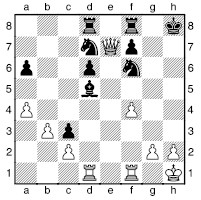

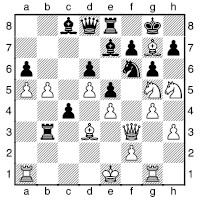

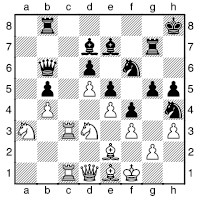

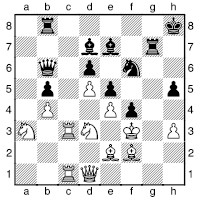

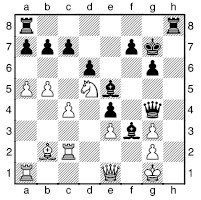

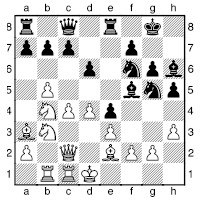

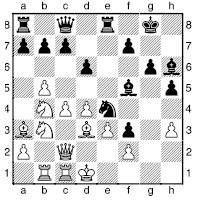

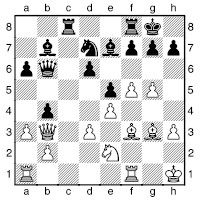

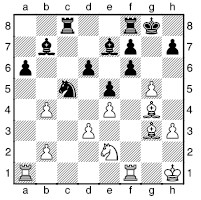

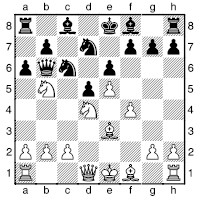

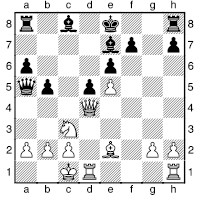

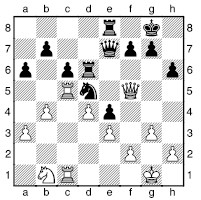

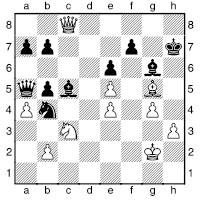

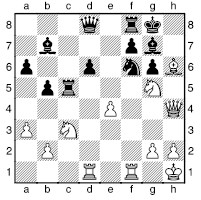

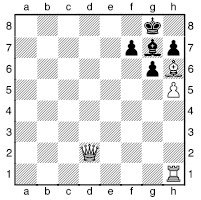

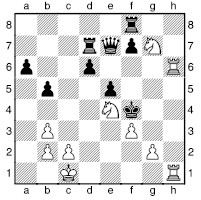

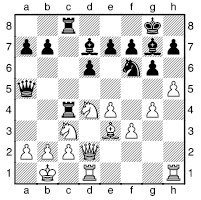

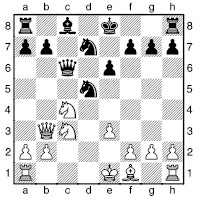

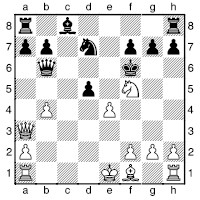

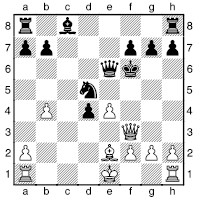

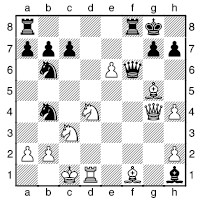

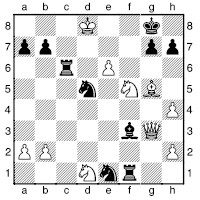

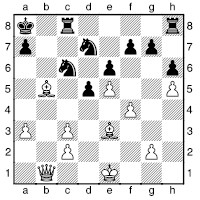

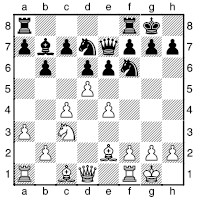

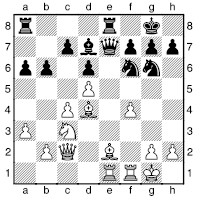

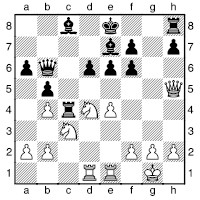

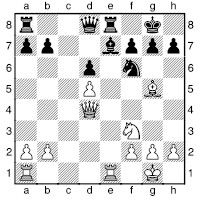

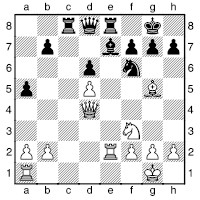

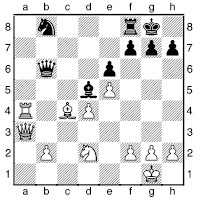

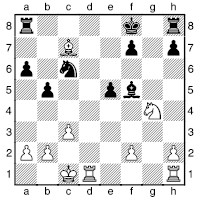

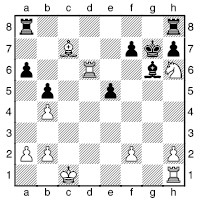

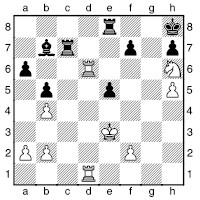

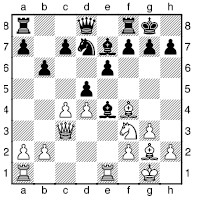

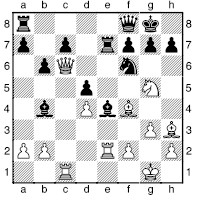

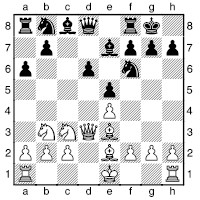

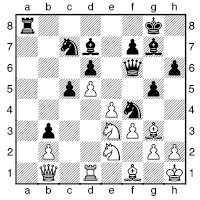

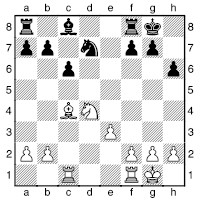

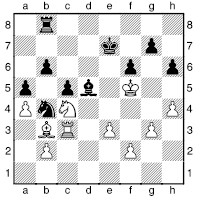

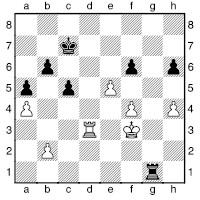

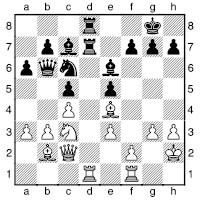

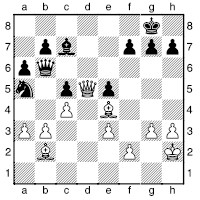

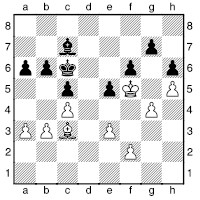

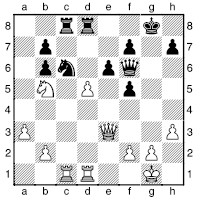

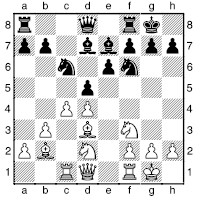

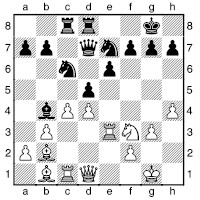

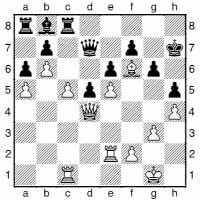

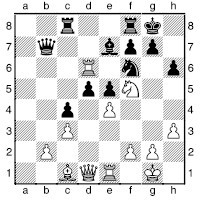

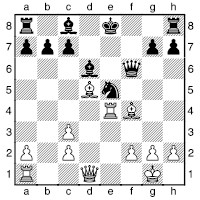

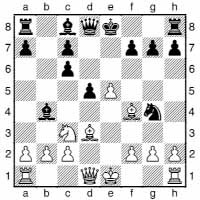

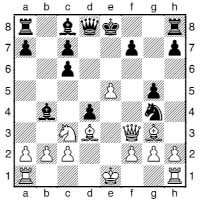

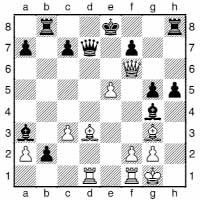

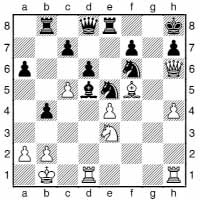

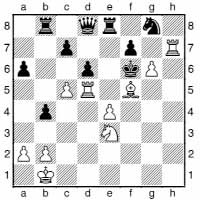

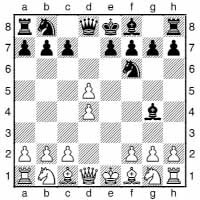

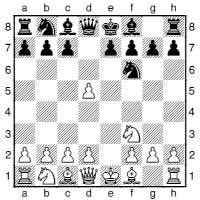

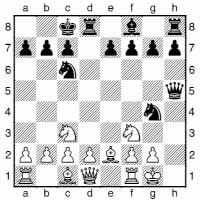

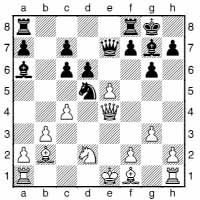

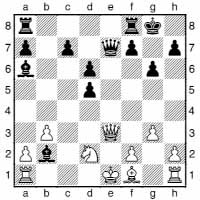

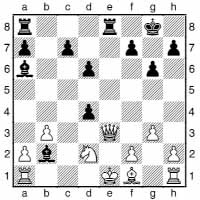

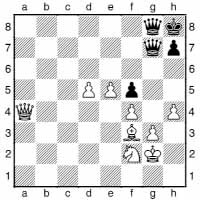

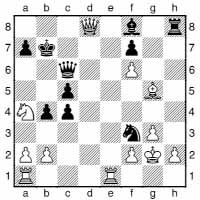

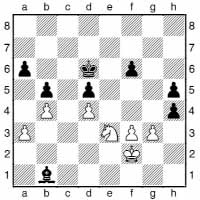

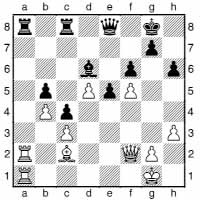

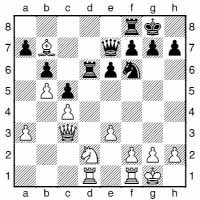

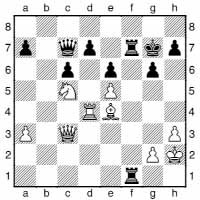

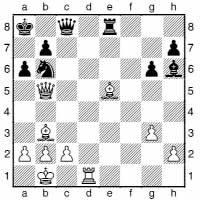

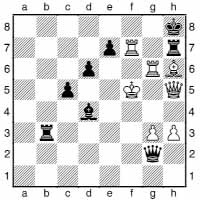

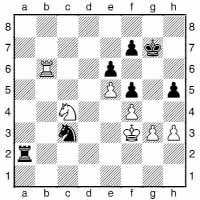

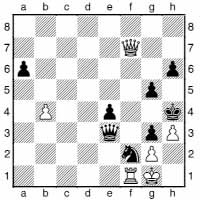

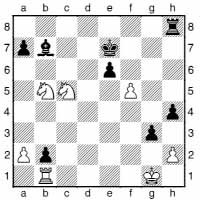

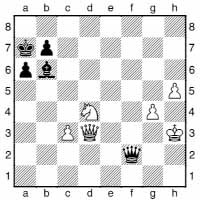

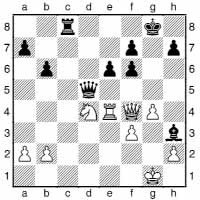

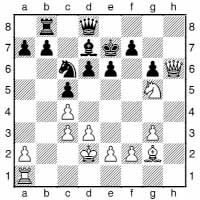

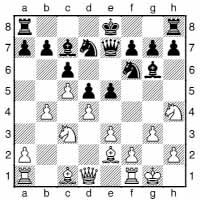

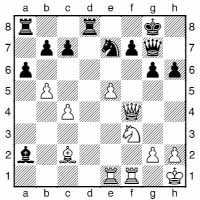

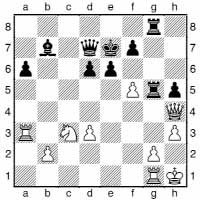

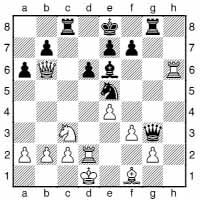

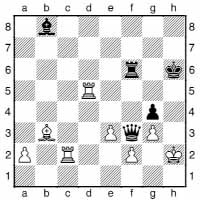

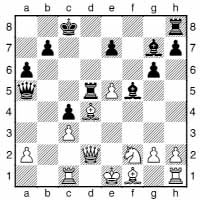

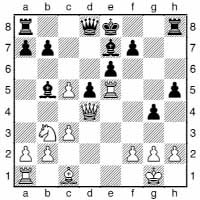

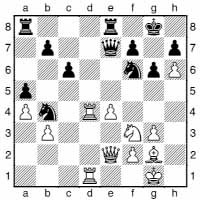

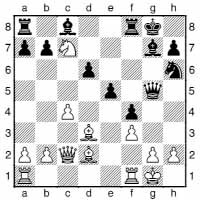

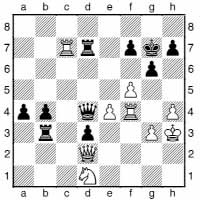

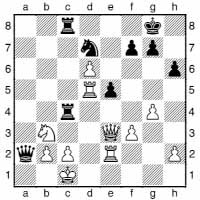

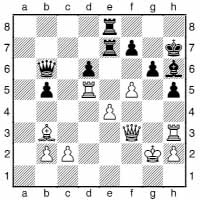

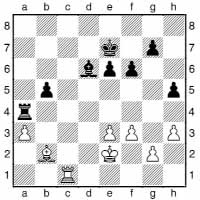

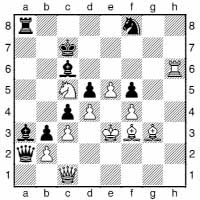

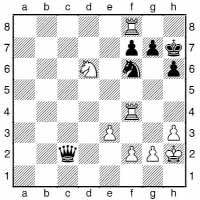

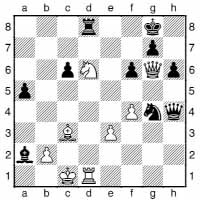

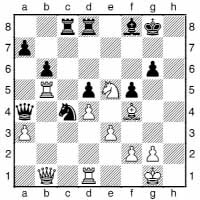

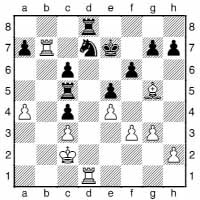

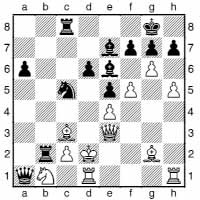

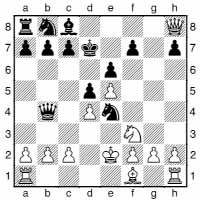

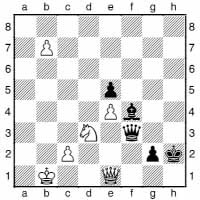

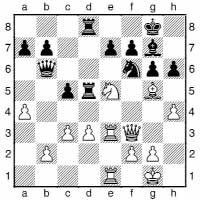

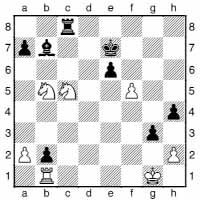

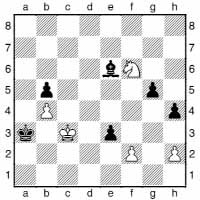

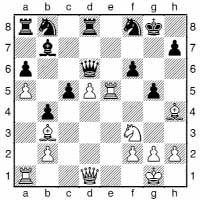

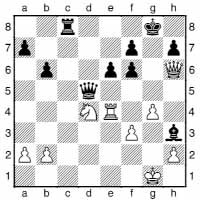

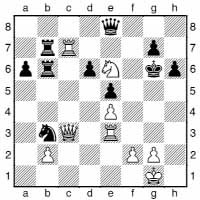

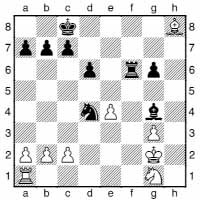

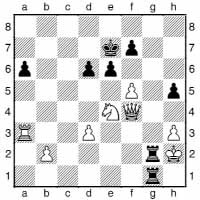

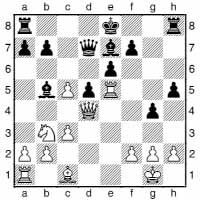

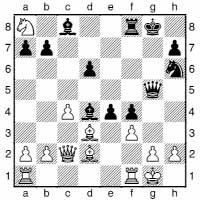

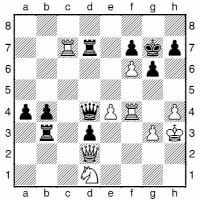

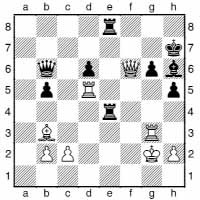

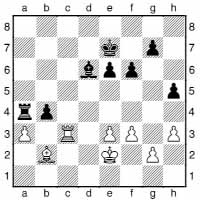

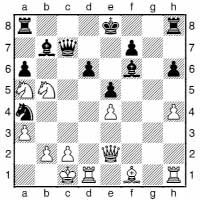

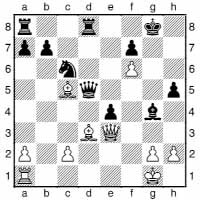

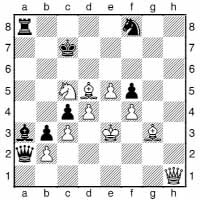

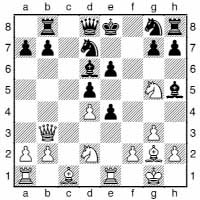

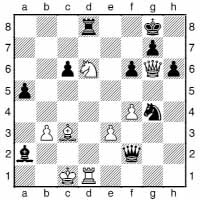

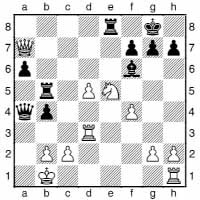

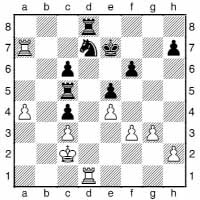

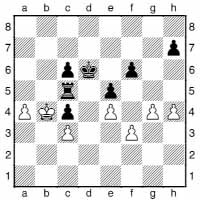

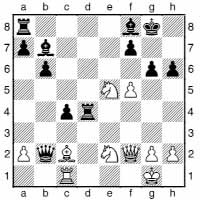

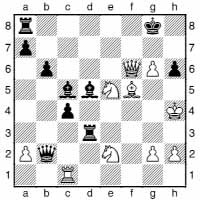

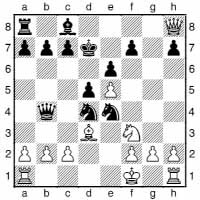

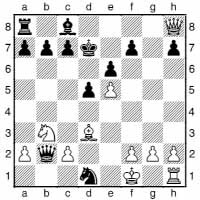

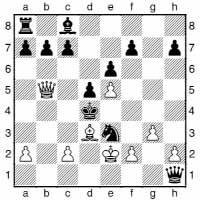

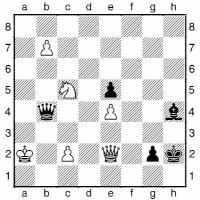

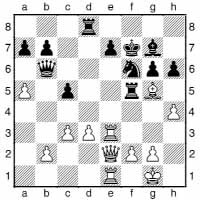

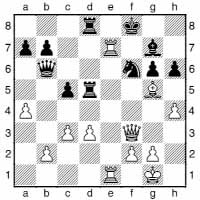

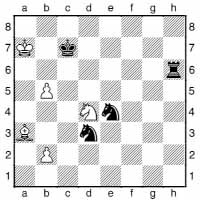

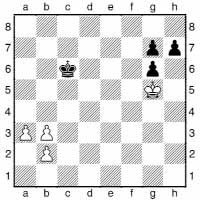

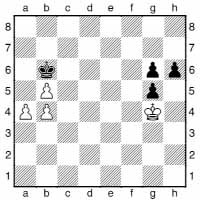

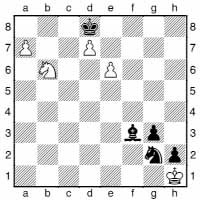

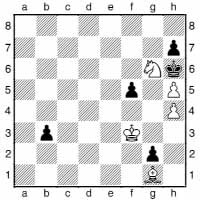

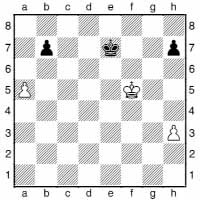

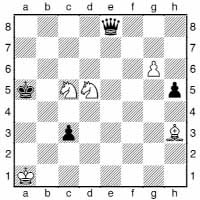

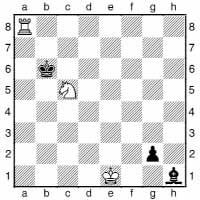

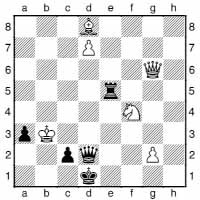

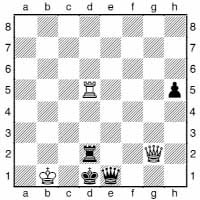

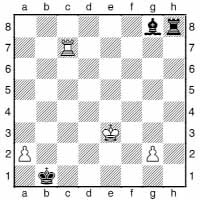

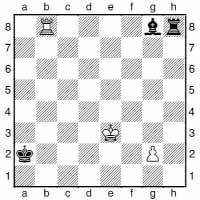

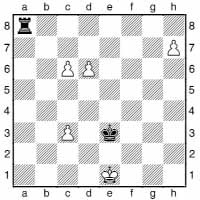

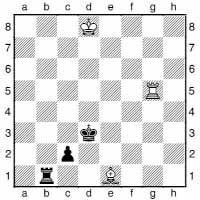

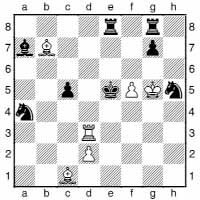

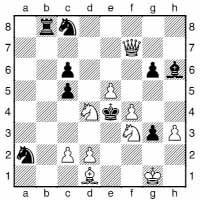

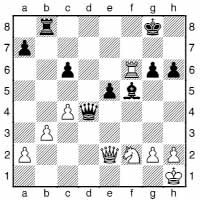

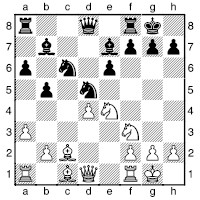

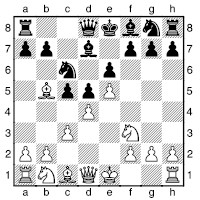

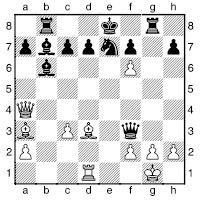

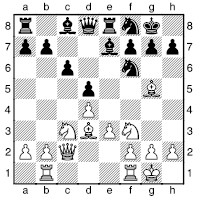

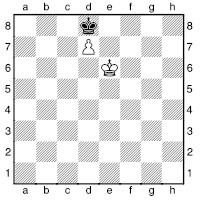

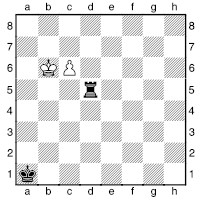

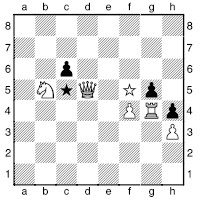

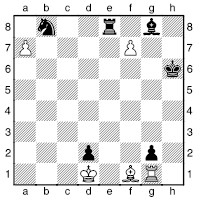

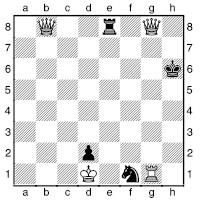

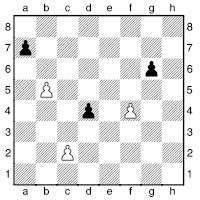

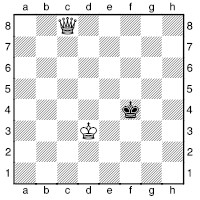

1) White to play and force mate in two moves

2) White to play and force mate in two moves

3) White to play and force mate in two moves

4) White to play and force mate in two moves

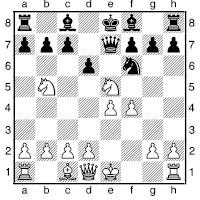

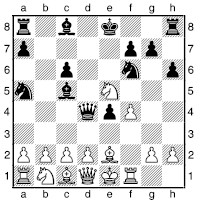

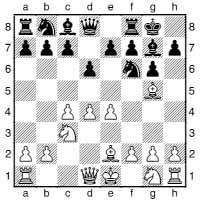

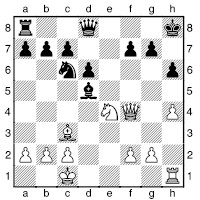

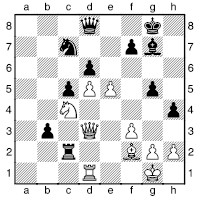

5) White to play and force mate in two moves

6) White to play and force mate in two moves

7) White to play and force mate in two moves

8) White to play and force mate in two moves

9) White to play and force mate in two moves

10) White to play and force mate in two moves

11) White to play and force mate in two moves

12) White to play and force mate in two moves

13) White to play and force mate in two moves

14) White to play and force mate in two moves

15) White to play and force mate in two moves

16) White to play and force mate in two moves

17) White to play and force mate in two moves

18) White to play and force mate in two moves

19) White to play and force mate in two moves

20) White to play and force mate in two moves

21) White to play and force mate in two moves

22) White to play and force mate in two moves

23) White to play and force mate in two moves

24) White to play and force mate in two moves

25) White to play and force mate in two moves

Solutions to Delivering Mate

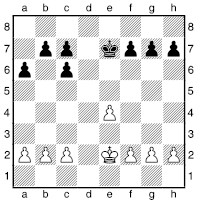

Explanation of diagrams on pages 14–15:

Queens: the f6-queen attacks c6, d4, d6, e5 and e6. The c4-queen attacks c5, c6, d4, d5, e4 and e6.

Rooks: the e6-rook attacks c6, d6, e4 and e5. The d3-rook attacks d4, d5 and d6.

Bishops: the f3-bishop attacks c6, d5 and e4. The d6-bishop attacks c5 and e5.

Knights: the f7-knight attacks d6 and e5. The e3-knight attacks c4 and d5.

Pawns: the e4-pawn attacks d5. The d4-pawn attacks c5 and e5.

King: the white king attacks c4, d4 and e4.

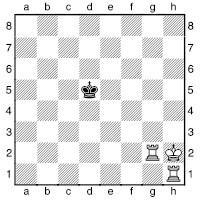

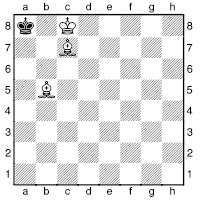

25 Novice Warm-ups – Solutions

1) 1  d8+

d8+  e8 2

e8 2  xe8#

xe8#

The simple back-rank mate has claimed countless victims. Related ideas can decide games at international level, so look out for them!

2) 1  xf7+

xf7+  e7 2

e7 2  d5#

d5#

White’s minor pieces cooperate very well here. This is the finish of Legall’s Mate.

3) 1  g8+

g8+  xg8 2

xg8 2  f7#

f7#

This is perhaps the simplest mating combination involving a queen sacrifice, but also a beautiful and striking one. It is named Philidor’s Legacy, after the great French champion of the eighteenth century, André Danican Philidor, although the idea dates all the way back to Lucena’s 1497 manuscript.

4) 1  e7+

e7+  h8 2

h8 2  f7#

f7#

A simple mate with two knights. One knight forces the king into the corner, and the other delivers the killer blow.

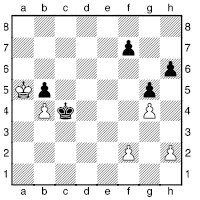

5) 1  c3+

c3+  a1 2

a1 2  b2#

b2#

A typical finish to the mating procedure with bishop and knight versus king. Note that the king must be mated in a corner on which the bishop can cover the corner square, and that White must be careful not to give stalemate.

6) 1 c8

1 c8 is stalemate, and only a draw!

is stalemate, and only a draw!

1... a6 2

a6 2  a8#

a8#

Remember to look out for stalemates and that when you promote a pawn you do not have to take a queen. White could also have won here (though not given mate in two) by playing 1  d7 and then 2 c8

d7 and then 2 c8 .

.

7) 1  a2+

a2+  h8 2

h8 2  xf8#

xf8#

The bishop check forces the king away from the defence of the bishop, so the rook can finish the job with a standard back-ranker.

8) 1  b7+

b7+  a8 2

a8 2  b2#

b2#

This is a typical mating finish to a “Windmill” combination, of which we shall see more in the chapter on tactics. Note that the rook must go to b2 in order to prevent the black queen from taking the bishop.

9) 1  d6+

d6+  a8 2

a8 2  b7#

b7#

A typical finish when forcing mate with two bishops against a bare king.

10) 1  g6

g6  g8 2

g8 2  a8#

a8#

A typical finish when mating with rook against a bare king. It is characteristic of the whole procedure for the white king to place itself a “knight’s move” away from the black king when the rook controls the line separating them. Then, if after Black’s reply the two kings face each other directly, a rook check will force back the sole king or, as here, be checkmate.

11) 1  h6 a1

h6 a1

Or 1...b1 2 g7#.

2 g7#.

2 g7#

It doesn’t matter that Black promotes first – White gives mate! When pawns are racing to promote, it is generally good to have your king in front of the enemy pawns – but only if he slows them down or stops them advancing! Otherwise, he might just encourage them to advance at double speed, with checks or even mate.

12) 1  f6+ and no matter what Black plays, 2

f6+ and no matter what Black plays, 2  xh7# follows. Black has left it a little late in playing the defensive move ...

xh7# follows. Black has left it a little late in playing the defensive move ... g6! This is a typical attacking ploy by White in queen’s pawn openings.

g6! This is a typical attacking ploy by White in queen’s pawn openings.

13) 1  g6+

g6+  g8 2

g8 2  h7#

h7#

This is a standard attacking idea, which may escape a player’s attention, especially when this type of situation arises a few moves into a variation. One sees a perpetual check, with the bishop moving between h7 and some other square on the b1–h7 diagonal, forgetting that this “other square” could be g6, preventing the black king from escaping from the mating net.

14) 1  f6 +

f6 +

1  xh6+?

xh6+?  f8 2

f8 2  xg7+

xg7+  e8 allows the king to sneak out.

e8 allows the king to sneak out.

1... f8 2

f8 2  xg7#

xg7#

A simple forced mate, illustrating, if nothing else, the value of an open file towards the opponent’s king – and of course the right to move!

15) 1  a8+

a8+

1  c6+? bxc6 (and not 1...

c6+? bxc6 (and not 1... xc6? 2

xc6? 2  a8#) permits the king to run out via b7.

a8#) permits the king to run out via b7.

1... xa8 2

xa8 2  c6#

c6#

Rook and knight are very effective at mating kings in corners!

16) 1  c6 and 2 b7# follows. Here we see the vulnerability of the king in the corner, and the power of advancing pawns, even when promotion is not on the cards.

c6 and 2 b7# follows. Here we see the vulnerability of the king in the corner, and the power of advancing pawns, even when promotion is not on the cards.

17) 1  c6+

c6+  xc6 2

xc6 2  e6#

e6#

The knight sacrifice simply diverts the bishop from covering the e6-square. I hope the rather irrational nature of the position did not distract you from this essentially straightforward idea.

18) 1  xf6+

xf6+  xf6 2

xf6 2  f5#

f5#

The thought “if only the queen weren’t there” should have helped you find this move. The queen just needs to vacate f5 in such as way as to avoid disturbing things too much. Then the knight hops in and finishes the job.

19) 1  h7++

h7++  g8 2

g8 2  h8#

h8#

This is the end of a so-called “staircase” mate. Everything is done with double checks, so the attacking pieces being en prise is irrelevant.

20) 1  d6+

d6+  d8 2

d8 2  a5#

a5#

This is the sort of thing that might happen in the early stages of a game, though Black would have had to have been exceedingly incautious. Having said that, I caught a strong county-standard player with something almost as bad in a match once!

21) 1  f6+

f6+  f8 2

f8 2  h6#

h6#

A pleasant geometrical mate, and an illustration that it is occasionally even worth sacrificing a whole queen to get rid of a fianchettoed bishop!

22) 1  g5++

g5++  e8 2

e8 2  d8#

d8#

A double check forces the king back home to e8, where White gives mate rather economically. This is a simplified version of an idea that we will see in various traps in the chapters on chess openings.

23) 1  xh5+

xh5+  xh5 2

xh5 2  g6#

g6#

Essentially, this is a variation on Fool’s Mate, with a decoy of the black rook thrown in. It is also the final sequence of the short game featured in the children’s chess book The Amazing Adventures of Dan the Pawn! The serious point is, of course, that one must be extremely careful when advancing kingside pawns when undeveloped.

24) 1  xa7+

xa7+  xa7

xa7

Or 1... xa7 2

xa7 2  b6#.

b6#.

2  c7#

c7#

This sort of thing should become second nature. The bishop is the only piece stopping  c7 being mate, so any means of diverting it must be examined. When one sees that the knight cannot capture on a7, the picture is complete.

c7 being mate, so any means of diverting it must be examined. When one sees that the knight cannot capture on a7, the picture is complete.

25) 1  e5+ dxe5 2

e5+ dxe5 2  d1#

d1#

A surprisingly abrupt finish, until you consider that the black pieces are doing everything but defend in numbers.

25 Trickier Mates in Two – Solutions

1) 1  g8+

g8+  xg8

xg8

Or 1... xg8 2

xg8 2  f7#.

f7#.

2  f7#

f7#

This is of course the simple Philidor’s Mate (see here), but with the knight also covering g8. It makes no difference here, but I once discovered to my cost in a lightning game that if the rook is on f8 and the knight on f6, there is no mate!

2) 1  g6+

g6+

The knight opens the queen’s line and diverts the key defensive pawn.

1...hxg6 2  h6#

h6#

The clue here was that the black king was extremely short of squares, and so virtually any checks are going to be forcing moves, and should be examined if a mate seems plausible.

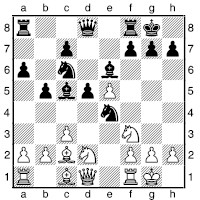

3) 1  xb7+

xb7+  xb7 2

xb7 2  d5#

d5#

As we see, having plenty of pieces around a king does not mean that he is defended! Quite the contrary if all they do is box him in.

4) 1  g4 and 2

g4 and 2  h6# is unstoppable. This is a fairly typical mating net, and shows a potential problem if a bishop abandons its fianchetto position.

h6# is unstoppable. This is a fairly typical mating net, and shows a potential problem if a bishop abandons its fianchetto position.

5) 1  e8+

e8+  xe8

xe8

Or 1... f8 2

f8 2  xf8#.

xf8#.

2  xh7#

xh7#

A simple piece of diversion, but note the long-range power of the bishops!

6) 1  xf7+

xf7+  xf7 2

xf7 2  h6#

h6#

Black’s bunched pieces are worse than useless here, as White’s minor pieces cover all the right squares. Of course, in a real game it would be just as good to give mate in three by the simpler 1  h6+

h6+  h7 2

h7 2  xf7+

xf7+  xh6 3

xh6 3  g7#.

g7#.

7) 1  xe6+ fxe6

xe6+ fxe6

Or 1... e7 2

e7 2  xe7#.

xe7#.

2  g6#

g6#

This type of mate is one that Black must look out for in some of the sharper lines of the Sicilian (see here) where Black delays his kingside development in favour of pursuing arguably greater strategic aims.

8) 1  h8+

h8+  xh8 2

xh8 2  xh8#

xh8#

This is an X-ray combination. In the start position, White covers the h8-square twice (queen and h1-rook) while Black is also on it twice (king and bishop). Nevertheless, White can sacrifice his queen on this square with decisive effect since the c3-bishop “X-rays” through the f6-bishop to h8.

9) 1  a8+

a8+  xa8 2

xa8 2  e8#

e8#

The white queen decoys the black king into a double check that just happens to be mate. It matters not that both checking pieces are attacked; they cannot both be taken at once.

10) 1  xc6+ bxc6

xc6+ bxc6

Other possibilities are 1... c7 2

c7 2  xc7# and 1...

xc7# and 1... b8 2

b8 2  xb7#.

xb7#.

2  a6#

a6#

This is a fairly standard queen sacrifice to open up an apparently secure queenside. A variation on this theme has a white bishop controlling the h2-b8 diagonal, mate being delivered by the two bishops alone.

11) 1  e8+

e8+  xe8

xe8

Or 1... g8 2

g8 2  xf8#.

xf8#.

2  d6#

d6#

Again, a queen sacrifice lures a king into a double check, which, thanks to the unfortunate disposition of the black pieces, happens to be mate.

12) 1  g6 and 2

g6 and 2  h8# follows inevitably. This idea is important in practice, as an important defensive idea is to eliminate a bishop attacking along the a2-g8 diagonal. If the battle is close-fought, the attacker will need to seek ways to keep this bishop alive long enough to help land the decisive blow.

h8# follows inevitably. This idea is important in practice, as an important defensive idea is to eliminate a bishop attacking along the a2-g8 diagonal. If the battle is close-fought, the attacker will need to seek ways to keep this bishop alive long enough to help land the decisive blow.

13) 1

h6+

h6+

The knight sacrifice diverts the bishop off the long diagonal.

1... xh6

xh6

Instead 1... h8 2

h8 2  df7# is a simple knight mate.

df7# is a simple knight mate.

2  h8#

h8#

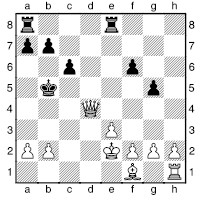

14) 1  g7 and Black can do nothing about 2

g7 and Black can do nothing about 2  a2#. This is, I admit, a rather unnatural position, but then the idea embodied in it is a spectacular one. Indeed, the simultaneous opening of the line for the white rook, and blocking of lines for the black queen and g8-rook is the sort of theme one finds in chess problems. Note that 1

a2#. This is, I admit, a rather unnatural position, but then the idea embodied in it is a spectacular one. Indeed, the simultaneous opening of the line for the white rook, and blocking of lines for the black queen and g8-rook is the sort of theme one finds in chess problems. Note that 1  xh8 not only fails to force mate in two, but also loses: Black plays 1...

xh8 not only fails to force mate in two, but also loses: Black plays 1... g5 or 1...

g5 or 1... g1+ 2

g1+ 2  xg1

xg1  c5+ 3

c5+ 3  f1 b5.

f1 b5.

15) 1  b7+

b7+  xc6

xc6

Or 1... d8 2

d8 2  f6#.

f6#.

2 d8 #

#

A beautiful finish, which I must admit is based upon the game Runau–Schmidt, which you can find as a trap in the Openings section (see here).

16) 1  xb7+

xb7+

Whichever rook captures the queen, it is walking into a pin, and so cannot parry a check from the white rook.

1... bxb7

bxb7

Or 1... axb7 2

axb7 2  a1#.

a1#.

2  e8#

e8#

17) 1  xh7+

xh7+  xh7 2

xh7 2  h3#

h3#

This is quite a standard mating pattern, which often occurs in practice. It is worth watching out for knight checks on e7 (or by Black on e2), since the queen and rook can easily be in the right positions to give this mate.

18) 1  f6

f6

A truly spectacular move, threatening mate on f7.

1...gxf6

Otherwise White carries out his threat: 1... xd5 2

xd5 2  xf7# or else 1...

xf7# or else 1... xb5 2

xb5 2  xf7#.

xf7#.

2  xf6#

xf6#

Another smothered mate. This is reminiscent of a trick Black can pull off in the Grünfeld Defence – see the traps in the Openings section.

19) 1  xf8+

xf8+  xf8 2

xf8 2  h8#

h8#

Essentially, this is just a simple back-ranker, set up by a queen sacrifice.

20) 1  g4

g4

Note that this move carries no threat at all, but puts Black in zugzwang.

1...h2

Black’s only legal move sets up a mate in one by denying the black king its only flight square.

2  f2#

f2#

21) 1  a8+

a8+

1  c7+? is no good since 1...

c7+? is no good since 1... xa2+ is check.

xa2+ is check.

1... xa8 2

xa8 2  c7#

c7#

Double check, and mate. The black king had to be decoyed onto a8 so that when the knight discovered check from the white queen, it also gave check itself.

22) 1  f6 and 2

f6 and 2  h7# follows, unless Black moves his e7-knight, whereupon 2

h7# follows, unless Black moves his e7-knight, whereupon 2  g8# is the finish. The battery from the c3-bishop doesn’t come into the solution at all here – it was just a red herring. In real games you will also need to decide what is relevant and what isn’t!

g8# is the finish. The battery from the c3-bishop doesn’t come into the solution at all here – it was just a red herring. In real games you will also need to decide what is relevant and what isn’t!

23) 1  a8+

a8+

Decoying the black king into the corner. Instead, 1  xa7+ is not so good, since the king does not have to take the knight: 1...

xa7+ is not so good, since the king does not have to take the knight: 1... c7 and the king walks.

c7 and the king walks.

1... xa8 2

xa8 2  c7#

c7#

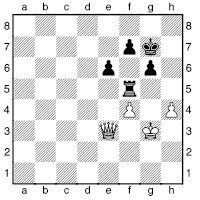

24) 1  g7 and no power in the world can prevent 2

g7 and no power in the world can prevent 2  c7#. Black’s pieces are just too badly placed.

c7#. Black’s pieces are just too badly placed.

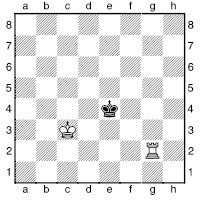

25) 1  e1

e1

Zugzwang – White does not threaten mate on the move, but Black now has no decent move. I ought to apologize for the somewhat unnatural position, but it was mainly to test whether you were sparing a thought for what the opponent could do, rather than just what you can achieve by force.

1... b6

b6

Or 1... c7 2

c7 2  xc7#.

xc7#.

Other bishop moves give White a choice of mates.

2  xb6#

xb6#

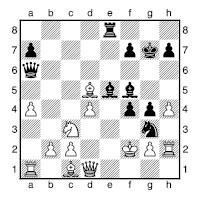

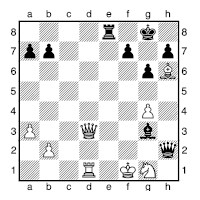

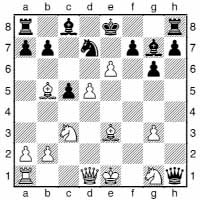

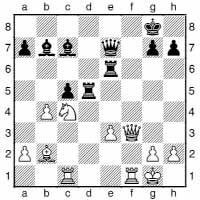

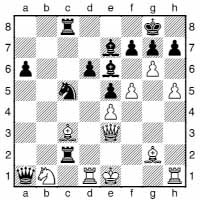

Tactics

In many sports, the word “tactics” refers to the aspects that involve the deepest thought: out-psyching the opponent, or the long-term planning, for instance in pool or snooker. The fact that tactics in chess are the shortest term factors, upon which the medium-term planning and strategy are based, reflects two things: that chess is quite deep, and that it is a game of complete information, in which executing each move is not a problem. If, for instance, pool and snooker were not played using cues and balls, but on a computer that executed the chosen shot exactly as it was intended, then the tactics (e.g. snookering the opponent, safety shots, etc.) would soon become the building-blocks upon which the real strategy of the game was based.

Tactics in chess are the interactions between the pieces that are any deeper than simply capturing material that the opponent has blundered away.

The purpose of this short chapter is to provide an introduction to the main tactical methods that are important in practical chess. The main thing to bear in mind is that it is not so vital to know the precise names of individual tactical devices, but rather to know how to use them to further one’s plans at the board and to put them together to produce combinations. That’s why this chapter is short, while the next, where we get to the interesting stuff, is long.

Checkmate

This, of course, is the most important tactical device of all!

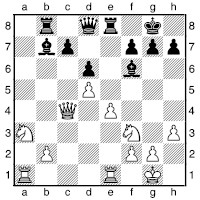

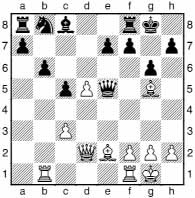

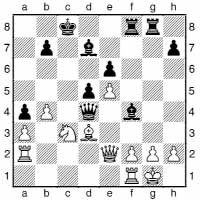

Destruction

A very simple idea: if a key piece is holding the opponent’s position together, it makes sense to remove it, even at a considerable material cost.

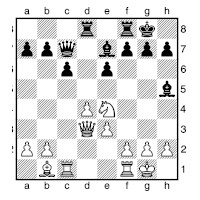

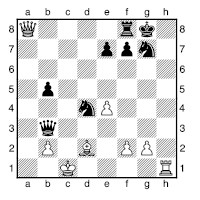

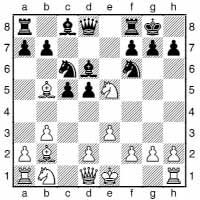

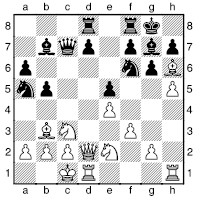

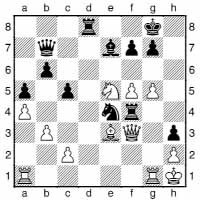

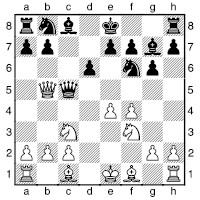

Now 1  a8+ would have no impact: Black could reply 1...

a8+ would have no impact: Black could reply 1... d8. So White plays 1

d8. So White plays 1  xc6!, destroying the knight that is enabling Black to defend against back-rank mates. Then after 1...bxc6 comes 2

xc6!, destroying the knight that is enabling Black to defend against back-rank mates. Then after 1...bxc6 comes 2  a8+, mating.

a8+, mating.

Another very typical destructive theme is a sacrifice to shatter the pawn cover in front of a king. We shall encounter this many times throughout the book.

Tip: try to visualize what might happen if a particular piece did not exist on the board. If you like what you’re seeing, look for ways to destroy the piece in question!

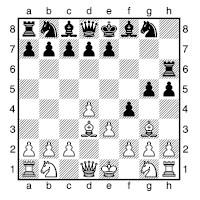

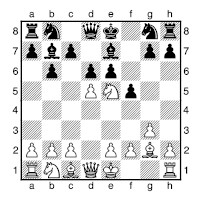

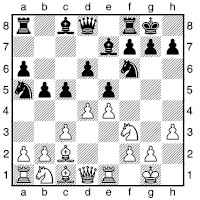

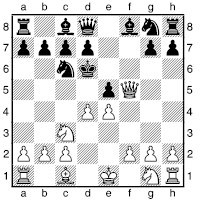

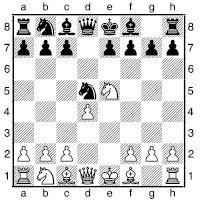

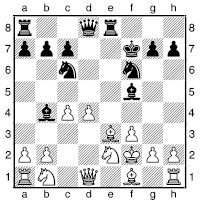

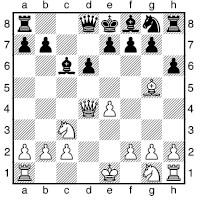

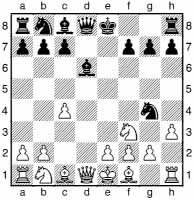

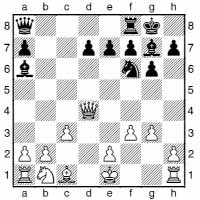

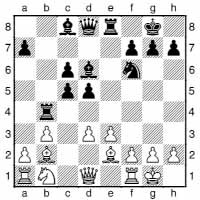

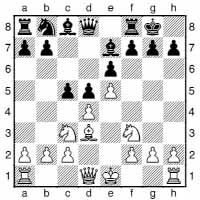

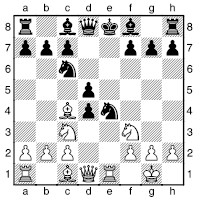

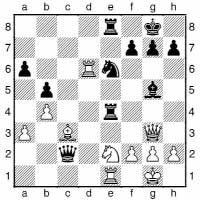

The Fork

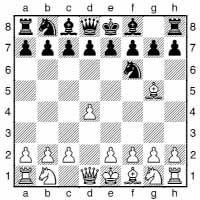

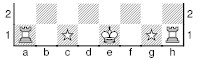

This is one of the simplest and most effective tactical devices. One piece directly attacks two or more enemy pieces simultaneously. Typically a knight is effective for this purpose.

In this very simple example White plays  e7+, attacking both king and queen. Black must move his king out of check, so White’s next move will be

e7+, attacking both king and queen. Black must move his king out of check, so White’s next move will be  xc8, winning a whole queen.

xc8, winning a whole queen.

Between beginners who have reached the level at which they can avoid getting mated in the first few moves, and do not blunder pieces gratuitously, I would reckon that losing material to a knight fork must be the most common single reason for losing a game. The unusual way in which these pesky horses move means that their tricks are often overlooked, even by fairly experienced players.

Forks can also be made by other pieces. Consider the position at the top of the next column. The white b5-pawn is forking the black knights, and the black rook is forking the white king and queen. White wins a knight, but Black a queen for a rook.

Tip for inexperienced players: if your opponent’s knights are at all active, then just before making a move, have a last look to be sure you’re not allowing a knight fork. Remember too that for a knight to fork two pieces, they must stand on the same coloured squares.

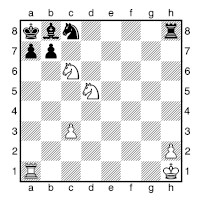

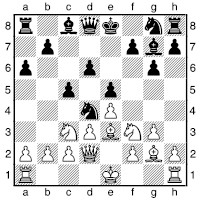

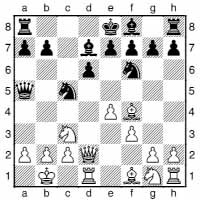

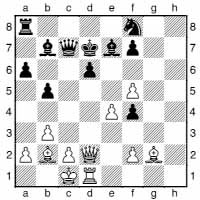

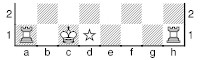

Double Attack

Whereas in a fork, one piece attacks more than one enemy unit, in a double attack, two or more pieces are responsible for creating the multiple attacks.

This may come about when a piece moving to make a discovered attack also makes an attack of its own, as in the diagram.

Here White now plays 10 e5. The pawn attacks the f6-knight directly (an exchange of pawns on e5 would not change this) while, by moving from e4, the pawn has discovered an attack from the f3-bishop onto the black queen’s rook. Experienced players would know to look out for this sort of thing.

A double attack can also arise from a piece moving so as to add to or reinforce the action of others.

In this position, the move 1  a1 opens up a double attack on the two black knights: suddenly, from being attacked once and defended once, they are both attacked twice, and it turns out there is no way to save them both.

a1 opens up a double attack on the two black knights: suddenly, from being attacked once and defended once, they are both attacked twice, and it turns out there is no way to save them both.

Discovered Attack

This occurs when a piece moves off a line, opening up an attack from a piece that had been behind it. In itself, this is no more difficult to deal with than any normal attack on a piece, except maybe that it is a little harder to see. The real problem is that the piece that has moved may be able to create some other problem, perhaps giving check and so making it impossible to deal with the discovered attack.

This position comes from a game Ghitescu–Fischer, Leipzig OL 1960. White has just made a horrible blunder by capturing a pawn on c5. Fischer now played 14... xh2+ whereupon Ghitescu resigned. After the bishop is taken, the black queen will capture her white counterpart.

xh2+ whereupon Ghitescu resigned. After the bishop is taken, the black queen will capture her white counterpart.

Tip: always take note of any potential attacks like this. There may be several pieces in the way, but it is amazing how quickly the rubble can sometimes be cleared.

Discovered Check

This is similar to discovered attack, except that the attack is a check to the king itself. This means that the piece that is moving is free to do pretty much what it likes with complete invulnerability.

In the following diagram Black has carelessly allowed White to give a discovered check from the e1-rook.

For one move the e2-bishop can go to squares that would normally be unthinkable, since Black must deal with the check. The bishop can do most damage by going to a6, and then taking the b7-bishop:  a6+ wins a piece.

a6+ wins a piece.

Tip: allow a discovered check only if you are absolutely certain it is safe to do so, and if you are able to give a discovered check, be sure to extract the maximum value from it.

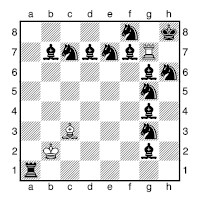

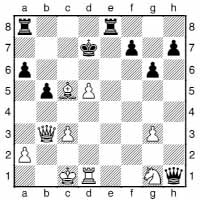

Double Check