The Merchant of Venice – Read Now and Download Mobi

The RSC Shakespeare

Edited by Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen

Chief Associate Editors: Héloïse Sénéchal and Jan Sewell

Associate Editors: Trey Jansen, Eleanor Lowe, Lucy Munro,

Dee Anna Phares

The Merchant of Venice

Textual editing: Eric Rasmussen

Introduction and Shakespeare’s Career in the Theater: Jonathan Bate

Commentary: Eleanor Lowe and Héloïse Sénéchal

Scene-by-Scene Analysis: Esme Miskimmin

In Performance: Karin Brown (RSC stagings), Peter Kirwan (overview)

The Director’s Cut and Playing Shylock (interviews by Jonathan Bate

and Kevin Wright):

David Thacker, Darko Tresnjak; Antony Sher, Henry Goodman

Editorial Advisory Board

Gregory Doran, Chief Associate Director,

Royal Shakespeare Company

Jim Davis, Professor of Theatre Studies, University of Warwick, UK

Charles Edelman, Senior Lecturer, Edith Cowan University,

Western Australia

Lukas Erne, Professor of Modern English Literature,

Université de Genève, Switzerland

Jacqui O’Hanlon, Director of Education, Royal Shakespeare Company

Akiko Kusunoki, Tokyo Woman’s Christian University, Japan

Ron Rosenbaum, author and journalist, New York, USA

James Shapiro, Professor of English and Comparative Literature,

Columbia University, USA

Tiffany Stern, Professor and Tutor in English, University of Oxford, UK

CONTENTS

“Which Is the Merchant Here?”

“In Belmont Is a Lady Richly Left”

“… And Which the Jew?”

The Merchant of Venice in Performance: The RSC and Beyond

Four Centuries of The Merchant: An Overview

At the RSC

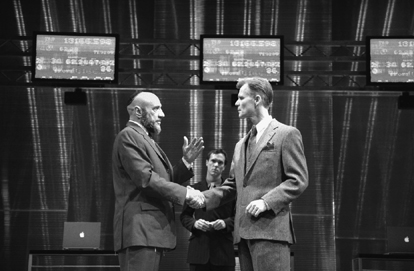

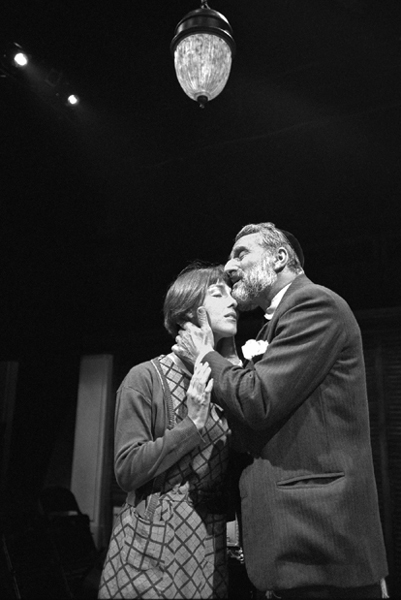

The Director’s Cut: Interviews with David Thacker and Darko Tresnjak

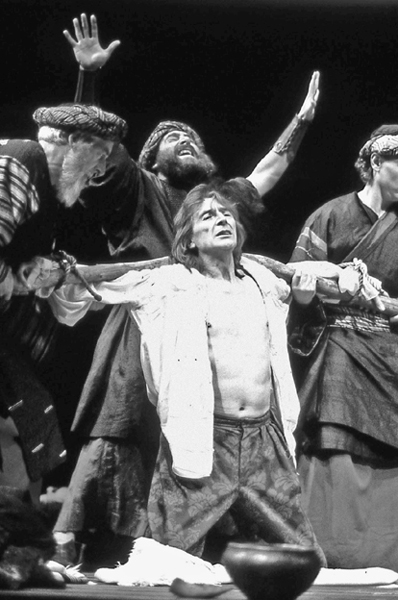

Playing Shylock: Interviews with Antony Sher and Henry Goodman

Shakespeare’s Career in the Theater

Beginnings

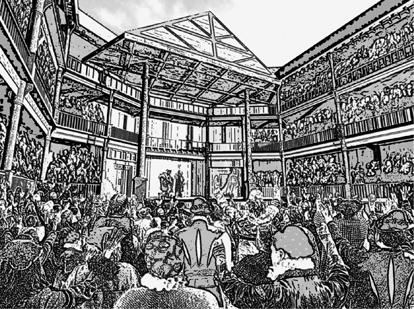

Playhouses

The Ensemble at Work

The King’s Man

INTRODUCTION

“WHICH IS THE MERCHANT HERE?”

In the summer of 1598, Shakespeare’s acting company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, registered their right to allow or disallow the printing of “a book of the Merchant of Venice or otherwise called the Jew of Venice.” They seem to have been a little bit uncertain as to what they should call their new play. Or perhaps they were anxious to forestall any unauthorized publisher from producing a volume called “The Jew of Venice” and passing it off as their play. Christopher Marlowe’s comi-tragic farce The Jew of Malta had been one of the biggest box-office hits of the age, so an echo of its title would have been an attractive proposition.

Fourteen comedies were collected by Shakespeare’s fellow actors in the First Folio of his complete plays, published after his death. The majority of them had titles evocative of an idea (All’s Well That Ends Well, Love’s Labour’s Lost, Much Ado About Nothing) or a time of year (Twelfth Night, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Winter’s Tale). Two of them indicate a group of characters in a particular place: gentlemen of Verona in one case, merry wives of Windsor in the other. One suggests a character type: The Taming of the Shrew. In the light of these patterns, it would have been reasonable to name the comedy registered in 1598 after an idea—Bassanio’s successful quest for Portia is a case of “Love’s Labour’s Won,” Portia’s judgment on Shylock metes out “Measure for Measure.” It would also have been reasonable to indicate a group of characters in a particular place: “The Merchants of Venice” (Bassanio, Lorenzo, Gratiano, Salerio, and Solanio are all merchants of one kind or another). Or it would have been possible to suggest a character type: “The Taming of the Jew.”

In 1600 the play was published with a title page intended to whet the prospective reader’s appetite: The most excellent History of the Merchant of Venice. With the extreme cruelty of Shylock the Jew towards the said Merchant, in cutting a just pound of his flesh, and the obtaining of Portia by the choice of three chests. The character of Shylock and the courtship of Portia by Bassanio were clearly considered to be the play’s principal selling points, and yet it is “the merchant,” Antonio, who gets the top line of the title to himself, a unique distinction in the Folio corpus of Shakespearean comedy (his only rival in this regard is “the shrew” in her play, but “the taming” implicitly gives equal weight to her antagonist, the tamer). Given that Antonio has this unique distinction, one would have expected him to be the central focus of the action. Yet in no other Shakespearean play does the titular character have such a small role: Portia’s is much the largest part, followed by Shylock and then Bassanio. Antonio is no more prominent in the dialogue than his friends Gratiano and Lorenzo. Ask a class of students “Who is the merchant of Venice?” and they will hesitate a moment—as they will not when asked who is the Prince of Denmark or the Moor of Venice.

The part almost seems to be deliberately underwritten. “In sooth I know not why I am so sad,” says Antonio in the very first line of the play. His friends suggest some possible reasons: he is worried about his merchandise, or perhaps he is in love. Antonio denies both, proposing instead that to play the melancholy man is simply his given role in the theater of the world. Intriguingly, Shakespeare gives the name “Antonio” to discontented characters in two other plays. One is Sebastian’s nautical companion in Twelfth Night, who keeps company with his friend day and night, even risks his own life for him, only to be ignored when Sebastian finds the love of a good woman. The other is Prospero’s usurping brother in The Tempest, who has no wife or child of his own and who is again marginalized at the end of the play.

Some productions have explored the sense of exclusion associated with the Antonio figures by suggesting that they are made melancholy by unrequited homoerotic desire. Probably the first critic to identify this possibility as a hidden key to The Merchant of Venice was the (homosexual) poet W. H. Auden. In a dazzling essay called “Brothers and Others” (included in his volume of criticism The Dyer’s Hand, 1962), Auden deftly identified Antonio as “a man whose emotional life, though his conduct may be chaste, is concentrated upon a member of his own sex.” Auden wondered if Antonio’s feelings for Bassanio were somewhat akin to those suggested by the closing couplet of Shakespeare’s twentieth sonnet, addressed to a beautiful young man: “But since she [Nature] pricked thee out for women’s pleasure, / Mine be thy love, and my love’s use their treasure.” The idea that the love of man for man may have an unrivaled spiritual intensity, whereas the congress of man and woman is bound up with breeding and property, has a long history.

It is Antonio rather than Bassanio, Auden suggests, who embodies the words on Portia’s leaden casket: “‘Who chooseth me must give and hazard all he hath.’” Antonio is prepared to give and hazard his own flesh as bond in the deal with Shylock that will provide Bassanio with the financial capital he needs in order to speculate on the marriage market. In Auden’s view, this creates a strange correspondence between the merchant and the Jew: “Shylock, however unintentionally, did, in fact, hazard all for the sake of destroying the enemy he hated; and Antonio, however unthinkingly he signed the bond, hazarded all to secure the happiness of the man he loved.” By setting Antonio’s life as a forfeit, Antonio and Shylock enter into a bond that places them outside the normative rule of law that regulates society. Auden speculatively notes the “association of sodomy with usury” that can be traced back to Dante’s Inferno.

Whether or not it is appropriate to invoke the idea of sexual transgression, Shakespeare often returned to a triangular structure of relationships in which close male friendship is placed at odds with desire for a woman. The pattern recurs not only in several of the plays but also as the implied narrative of the Sonnets. The Merchant of Venice begins with Bassanio seeking to borrow from his friend in order to finance the pursuit of a wealthy lover. He sets himself up as a figure from classical mythology: Jason in pursuit of the Golden Fleece. The analogy establishes Gratiano and Lorenzo as fellow Argonauts. Jason was renowned for being clever and brave, but also selfish and materialistic. His pattern of behavior was to gain the assistance of a woman—Ariadne, Medea—in realizing his ambitions, to become her lover and then to desert her and move on to a new adventure. With Jason as his role model, Bassanio has the potential to join the company of those other lovers in Shakespearean comedy—Claudio in Much Ado About Nothing, Bertram in All’s Well That Ends Well—who are not worthy of the women they obtain.

To make such comparisons is to see that The Merchant of Venice is one of Shakespeare’s darker comedies. The blurring of perspectives between the romantic and the sinister is especially apparent in the beautiful but ironic love-duet of Lorenzo and Jessica at the beginning of the final act. They compare themselves to some oft-sung partners from the world of classical mythology. But what kind of exemplary figures are these? Cressida, who was unfaithful to Troilus; Medea the poisoner; Thisbe, whose tragical fate, though comically represented in the Mechanicals’ play in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, was identical to Juliet’s; and Dido, whom Aeneas deserted in his quest for imperial glory. They are all figures in the pantheon of tragedy, not comedy.

The cleverness that Bassanio shares with the mythological figure of Jason is apparent from his choice of casket. Portia’s late father has devised a simple test to find her the right husband: those suitors who choose the golden or silver caskets are clearly motivated by desire for wealth and must therefore want to marry her for her money. The man who chooses lead obviously does not care about cash, so he is likely to love Portia for herself alone. Bassanio, however, recognizes that appearances are not to be trusted. Venice, sixteenth-century Europe’s preeminent city of commercial exchange and conspicuous consumption, has taught him that credit allows a man to display himself above his means. He does not want to look like a fortune hunter when wooing Portia, so he borrows from Antonio in order to dress like a wealthy man: “By something showing a more swelling port / Than my faint means would grant continuance.” He chooses the lead casket because he knows from his own example that “outward shows” may be least themselves and that the world is easily deceived “with ornament.” Gold, he reasons, is for greedy Midas, so he spurns it—this is what he imagines Portia wants to hear. He is, of course, assisted by the hint she drops for his benefit; whereas Morocco and Aragon had to make their choice in silence, Bassanio’s is heralded by a song that warns against trusting what appears to “the eyes.” And yet the fact remains that Bassanio is driven by the quest for a wealthy spouse. Antonio is the one who really cares about love more than money, about the “bond” of friendship more than the legal and financial bond, about what is “dear” to his heart more than what is “dear” in the sense of expensive. For Shakespeare’s audience, the words “merchant” and “Venice” were both synonymous with the pursuit of money, but paradoxically, Antonio is, of all the characters in the play, the one who is least bound to material possessions.

“IN BELMONT IS A LADY RICHLY LEFT”

Shortly after the Second World War, the Canadian literary critic Northrop Frye published a short essay that inaugurated the modern understanding that Shakespeare’s comedies, for all their lightness and play, are serious works of art, every bit as worthy of close attention as his tragedies. Entitled “The Argument of Comedy,” it proposed that the essential structure of Shakespearean comedy was ultimately derived from the “new comedy” of ancient Greece, which was mediated to the Renaissance via its Roman exponents Plautus and Terence. The “new comedy” pattern, described by Frye as “a comic Oedipus situation,” turned on “the successful effort of a young man to outwit an opponent and possess the girl of his choice.” The girl’s father, or some other authority figure of the older generation, resists the match, but is outflanked, often thanks to an ingenious scheme devised by a clever servant, perhaps involving disguise or flight (or both). Frye, writing during Hollywood’s golden age, saw an unbroken line from the classics to Shakespeare to modern romantic comedy: “The average movie of today is a rigidly conventionalized New Comedy proceeding toward an act which, like death in Greek tragedy, takes place offstage, and is symbolized by the final embrace.”

The union of the lovers brings “a renewed sense of social integration,” expressed by some kind of festival at the climax of the play—a marriage, a dance, or a feast. All right-thinking people come over to the side of the lovers, but there are others “who are in some kind of mental bondage, who are helplessly driven by ruling passions, neurotic compulsions, social rituals, and selfishness.” Malvolio in Twelfth Night, Don John in Much Ado About Nothing, Jaques in As You Like It, Shylock in The Merchant of Venice: Shakespearean comedy frequently includes a party pooper, a figure who refuses to be assimilated into the harmony.

Frye’s “The Argument of Comedy” pinpoints a pervasive structure: “the action of the comedy begins in a world represented as a normal world, moves into the green world, goes into a metamorphosis there in which the comic resolution is achieved, and returns to the normal world.” But for Shakespeare, the green world, the forest and its fairies, is no less real than the court. Frye, again, sums it up brilliantly:

This world of fairies, dreams, disembodied souls, and pastoral lovers may not be a “real” world, but, if not, there is something equally illusory in the stumbling and blinded follies of the “normal” world, of Theseus’ Athens with its idiotic marriage law, of Duke Frederick and his melancholy tyranny [in As You Like It], of Leontes and his mad jealousy [in The Winter’s Tale], of the Court Party with their plots and intrigues. The famous speech of Prospero about the dream nature of reality applies equally to Milan and the enchanted island. We spend our lives partly in a waking world we call normal and partly in a dream world which we create out of our own desires. Shakespeare endows both worlds with equal imaginative power, brings them opposite one another, and makes each world seem unreal when seen by the light of the other.*

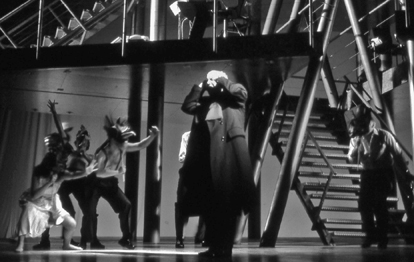

The Merchant of Venice offers an exceptionally interesting set of variations on this pattern. The “new comedy” pattern of the lover getting his girl against the will of her father is there in the Lorenzo and Jessica plot. There is a (not so clever) servant in the form of Lancelet Gobbo. And there is a striking structural movement between two worlds. However, instead of the usual court or paternal household, the normative world, represented by Venice, is that of money and commercial exchange. Portia’s rural estate in “Belmont,” which means “beautiful mountain,” stands in for the “green” world of wood or forest or pastoral community. Productions often portray it as an Arcadian realm of ease, integrity, and self-discovery that stands in contrast to the hard-nosed commerce of the duplicitous city. But although Belmont has an aura of magic and of music, it is not really a dream world.

Portia has been attracted to Bassanio for some time: he has previously visited Belmont in the guise of “a scholar and a soldier” in the retinue of another suitor. But it is when he reasons against gold that love takes her over, banishing all other emotions. She responds with a beautifully articulated self-revelation: ignore my riches, virtues, beauty, status, she says: “the full sum of me / Is sum of nothing, which to term in gross / Is an unlessoned girl, unschooled, unpractisèd.” Yet even in rejecting the notion that people should be measured by the size of their bank balances, she cannot avoid using the language of money that suffuses the whole play (“sum,” “gross”). The lesson of Belmont is actually a cynical one: choose wealth and you won’t get it, appear to reject it and it will be yours. The Prince of Morocco, who takes things at face value, is roundly rejected. It will not be the last time that Shakespeare pits an honest Moor against a world of Italian intrigue.

For all their fine words, both Bassanio and Portia are engaged in “practice,” a word that the Elizabethans associated with the figure of Machiavelli, archetypal Italianate schemer for self-advancement. Bassanio is the gold-digger he pretends not to be, while Portia has no intention of letting any man become “her lord, her governor, her king” in the way that she says she will. At the end of her submission speech, she gives Bassanio the ring (symbol of both wealth and marital union) that will later be the device whereby she tricks him and thus establishes her position as the dominant partner in the relationship. She may speak about giving him all her property—which is what marriage meant according to the law of the time—but when she returns from Venice to Belmont at the end of the play she continues to speak of “my house” and the light “burning in my hall.”

As for Portia’s claim that she is “unlessoned” and “unschooled,” this is wholly belied by her bravura performance in the cross-dressed role of Balthasar, interpreting the laws of Venice with forensic skill that reduces the duke and his magnificoes to amazement. On leaving Belmont, she says that she and Nerissa will remain in a nunnery, the ultimate place of female confinement, until Bassanio’s financial difficulties are resolved. She actually goes to the public arena of the Venetian court, moving from passive (the woman wooed) to active (the problem solver). In the robes of a lawyer instead of those of a nun, she excels in the art of debate, deploying a rhetorical art calculated to delight Queen Elizabeth, who loved nothing more than to outmaneuver courtiers, diplomats, and suitors in the finer points of jurisprudence and theology.

“The quality of mercy is not strained”: the quality of Portia’s argument (and Shakespeare’s writing) unfolds from the several meanings of “strained.” Mercy is not constrained or forced, it must be freely given; nor is it partial or selective—it is a pure distillation like “the gentle rain from heaven,” not the kind of liquid from which impure particles can be strained out. As in Measure for Measure, Shakespeare explores the tension between justice and mercy, here interpreted in terms of the opposition between the Old Testament Jewish law of “an eye for an eye” and Christ’s New Testament covenant of forgiveness. When Shylock refuses to show mercy and stands by the old covenant, Portia’s art is to throw his legal literalism back in his face: the corollary of his demand for an exact pound of flesh is that he should not spill a drop of Venetian blood. But if the quality of mercy is not strained, then neither should be that of conversion: a bitter taste is left when Shylock is constrained to become a Christian.

“… AND WHICH THE JEW?”

Commerce, with which Venice was synonymous, depends on borrowing to raise capital. Christianity, however, disapproved of usury, the lending of money with interest. The Jewish moneylender was early modern Europe’s way out of this impasse. Venice was famous for its ghetto in which the Jews were constrained to live, even as they oiled the wheels of the city’s economy. Shakespeare does not mention the ghetto, but he reveals a clear understanding of how the system worked when Shylock refuses Antonio’s invitation to dinner: “I will buy with you, sell with you, talk with you, walk with you, and so following, but I will not eat with you, drink with you, nor pray with you.” There is sociability and commerce between different ethnic and religious groups, but spiritual practices and customs are kept distinct. Shylock will not go to dinner because his religion prevents him from eating pork, but ultimately he regards questions of business as more important than those of faith: he hates Antonio “for he is a Christian, / But more, for that in low simplicity / He lends out money gratis and brings down / The rate of usance here with us in Venice.”

The historical reality in the age of Shakespeare was that Christians did lend money to each other with interest, while Judaic law as well as Christian frowned upon extortion. What one person regards as immoral exploitation another may regard as legitimate business practice. Shylock makes exactly this point when referring to “my bargains and my well-won thrift, / Which he [Antonio] calls interest.” There are Christian usurers in other plays of the time. Besides, Shylock does not charge interest on the three thousand ducats he lends Antonio: instead, he takes out a bond, albeit of a rather unusual kind, as his insurance policy. One of the play’s key puns, alongside those on terms that are both commercial and emotional such as “dear” and “bond,” is “rate,” which in the dialogue between Bassanio and Shylock about Antonio refers first to the question of interest rates and then to berating in the sense of abuse. The berating of Jew by Christian, and vice versa, is a screen for the real issue, which is the question of who has money and hence power (including the power to win a wealthy, clever, and beautiful wife).

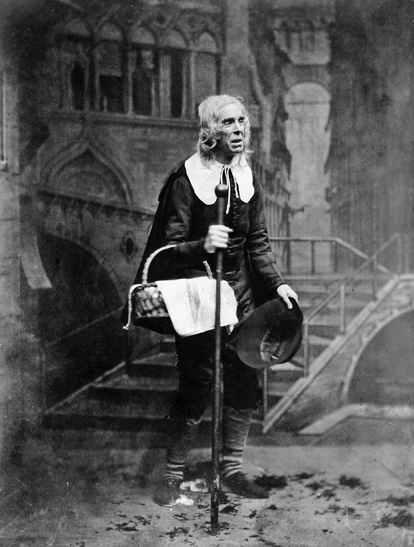

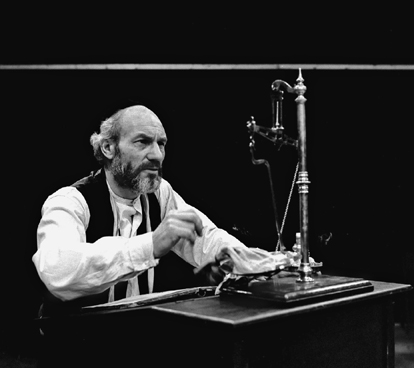

We should therefore be wary of crude generalizations about the anti-Semitism of the play or of the age. It is often said that the original stage Shylock would have had a wig of red hair and a long bottle-like nose, making him into a stereotypical Jew. He was certainly represented thus when the play was revived after the theaters reopened following the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, but there is no evidence that this is how he looked in Shakespeare’s own theater. Portia’s line on arriving in the courtroom, “Which is the merchant here, and which the Jew?,” suggests that in terms of superficial appearance Antonio and Shylock are not readily distinguishable. It is not easily compatible with a caricature Jew. Nor does the dialogue at any point allude to the anti-Semitic propaganda that has defiled the centuries. There are no allusions to the story of Hugh of Lincoln, to poisoning wells, desecrating the host, ritual murder, crucified children. Shylock speaks of his “sacred nation,” but no one replies with the old anti-Semitic accusation that the Jews are to be hated because they murdered Christ. There are, then, different degrees of prejudice in the play, just as there were different degrees of respect and disrespect for Jews in Shakespeare’s Europe. Some, but not all, of the Christians in the play spit upon Shylock simply because he is a Jew. They are the same Christians who don’t spend much time going to church, giving money to the poor, or turning the other cheek.

Barabas, the Jew of Malta in the play written by Marlowe a few years before, answers to the stereotype of the Jew in love with his moneybags (though he does also love his daughter), whereas Shylock famously appeals to a common humanity that extends across the ethnic divide:

He hath disgraced me, and hindered me half a million, laughed at my losses, mocked at my gains, scorned my nation, thwarted my bargains, cooled my friends, heated mine enemies, and what’s the reason? I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die?

In Elizabethan England the test for a witch was the pricking of her thumb: if it did not bleed, the woman was in league with the devil. Shylock’s “If you prick us, do we not bleed” is a way of saying “do not demonize the Jews—we are not like witches.” “The villainy you teach me I will execute,” he continues: if you do demonize me, then I will behave diabolically. The alien, the oppressed minority, sees no alternative but to fight back: “And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?” This is the point of parting between the Jewish law of “an eye for an eye” and the Christian notion of turning the other cheek and showing the quality of mercy. The consequence of Shylock’s insistence on the law of revenge, his failure to show mercy when Portia gives him the opportunity to do so, is his forced conversion. This sticks in the throat of the modern audience because it shows a lack of respect for religious difference, but for most of Shakespeare’s original audience it would have seemed like an act of mercy. Despite his willingness to murder Antonio, he is still given the opportunity of salvation.

The representation of Shylock as monstrous villain has played a part in the appalling history of European anti-Semitism. But such a representation necessarily occludes the subtler moments of Shakespeare’s characterization. A ring is not only the device whereby Portia and Nerissa assert their moral and verbal superiority over their husbands, but also the means by which Shylock is humanized:

TUBAL One of them showed me a ring that he had of your daughter for a monkey.

SHYLOCK Out upon her! Thou torturest me, Tubal. It was my turquoise, I had it of Leah when I was a bachelor. I would not have given it for a wilderness of monkeys.

The role of Shylock has been a gift to great actors down the ages because it gives them the opportunity not only to rage and to be outrageous, but also to turn the mood in an instant, to be suddenly quiet and hurt and sorrowful. When Shylock gleefully whets his knife in the trial scene, he presents the very image of a torturer. But he is tortured himself, simply through the memory of a girl called Leah whom he loved and married, and who bore his daughter (who has deserted both him and his faith) and who died and of whom all that remained was a ring that he would not have given for a wilderness of monkeys.

* “The Argument of Comedy” originally appeared in English Institute Essays 1948, ed. D. A. Robertson (1949), and has often been reprinted in critical anthologies. Frye himself adapted it for inclusion in his classic study, Anatomy of Criticism (1957).

ABOUT THE TEXT

Shakespeare endures through history. He illuminates later times as well as his own. He helps us to understand the human condition. But he cannot do this without a good text of the plays. Without editions there would be no Shakespeare. That is why every twenty years or so throughout the last three centuries there has been a major new edition of his complete works. One aspect of editing is the process of keeping the texts up to date—modernizing the spelling, punctuation, and typography (though not, of course, the actual words), providing explanatory notes in the light of changing educational practices (a generation ago, most of Shakespeare’s classical and biblical allusions could be assumed to be generally understood, but now they can’t).

Because Shakespeare did not personally oversee the publication of his plays, with some plays there are major editorial difficulties. Decisions have to be made as to the relative authority of the early printed editions, the pocket format “quartos” published in Shakespeare’s lifetime and the elaborately produced “First Folio” text of 1623, the original “Complete Works” prepared for the press after his death by Shakespeare’s fellow actors, the people who knew the plays better than anyone else.

The Merchant of Venice is one of three comedies where the Folio text was printed from a marked-up copy of a First Quarto (the others are Love’s Labour’s Lost and Much Ado About Nothing). The standard procedure for the modern editor is to use the First Quarto as the copy text but to import stage directions, act divisions, and some corrections from Folio. Our Folio-led policy means that we follow the reverse procedure, using Folio as copy text, but deploying the First Quarto as a “control text” that offers assistance in the correction and identification of compositors’ errors. Differences are for the most part minor.

The following notes highlight various aspects of the editorial process and indicate conventions used in the text of this edition:

Lists of Parts are supplied in the First Folio for only six plays, not including The Merchant of Venice, so the list here is editorially supplied. Capitals indicate that part of the name which is used for speech headings in the script (thus “Prince of ARAGON, suitor to Portia”).

Locations are provided by the Folio for only two plays, of which The Merchant of Venice is not one. Eighteenth-century editors, working in an age of elaborately realistic stage sets, were the first to provide detailed locations (“another part of the city”). Given that Shakespeare wrote for a bare stage and often an imprecise sense of place, we have relegated locations to the explanatory notes at the foot of the page, where they are given at the beginning of each scene where the imaginary location is different from the one before. In the case of The Merchant of Venice, the action is divided between Venice and Portia’s country estate of Belmont.

Act and Scene Divisions were provided in the Folio in a much more thoroughgoing way than in the Quartos. Sometimes, however, they were erroneous or omitted; corrections and additions supplied by editorial tradition are indicated by square brackets. Five-act division is based on a classical model, and act breaks provided the opportunity to replace the candles in the indoor Blackfriars playhouse which the King’s Men used after 1608, but Shakespeare did not necessarily think in terms of a five-part structure of dramatic composition. The Folio convention is that a scene ends when the stage is empty. Nowadays, partly under the influence of film, we tend to consider a scene to be a dramatic unit that ends with either a change of imaginary location or a significant passage of time within the narrative. Shakespeare’s fluidity of composition accords well with this convention, so in addition to act and scene numbers we provide a running scene count in the right margin at the beginning of each new scene, in the typeface used for editorial directions. Where there is a scene break caused by a momentary bare stage, but the location does not change and extra time does not pass, we use the convention running scene continues. There is inevitably a degree of editorial judgment in making such calls, but the system is very valuable in suggesting the pace of the plays.

Speakers’ Names are often inconsistent in Folio. We have regularized speech headings, but retained an element of deliberate inconsistency in entry directions, in order to give the flavor of Folio. Thus LANCELET is always so-called in his speech headings, but is “Clown” in entry directions.

Verse is indicated by lines that do not run to the right margin and by capitalization of each line. The Folio printers sometimes set verse as prose, and vice versa (either out of misunderstanding or for reasons of space). We have silently corrected in such cases, although in some instances there is ambiguity, in which case we have leaned toward the preservation of Folio layout. Folio sometimes uses contraction (“turnd” rather than “turned”) to indicate whether or not the final “-ed” of a past participle is sounded, an area where there is variation for the sake of the five-beat iambic pentameter rhythm. We use the convention of a grave accent to indicate sounding (thus “turnèd” would be two syllables), but would urge actors not to overstress. In cases where one speaker ends with a verse half line and the next begins with the other half of the pentameter, editors since the late eighteenth century have indented the second line. We have abandoned this convention, since the Folio does not use it, nor did actors’ cues in the Shakespearean theater. An exception is made when the second speaker actively interrupts or completes the first speaker’s sentence.

Spelling is modernized, but older forms are very occasionally maintained where necessary for rhythm or aural effect.

Punctuation in Shakespeare’s time was as much rhetorical as grammatical. “Colon” was originally a term for a unit of thought in an argument. The semicolon was a new unit of punctuation (some of the Quartos lack them altogether). We have modernized punctuation throughout, but have given more weight to Folio punctuation than many editors, since, though not Shakespearean, it reflects the usage of his period. In particular, we have used the colon far more than many editors: it is exceptionally useful as a way of indicating how many Shakespearean speeches unfold clause by clause in a developing argument that gives the illusion of enacting the process of thinking in the moment. We have also kept in mind the origin of punctuation in classical times as a way of assisting the actor and orator: the comma suggests the briefest of pauses for breath, the colon a middling one, and a full stop or period a longer pause. Semi-colons, by contrast, belong to an era of punctuation that was only just coming in during Shakespeare’s time and that is coming to an end now: we have accordingly only used them where they occur in our copy texts (and not always then). Dashes are sometimes used for parenthetical interjections where the Folio has brackets. They are also used for interruptions and changes in train of thought. Where a change of addressee occurs within a speech, we have used a dash preceded by a period (or occasionally another form of punctuation). Often the identity of the respective addressees is obvious from the context. When it is not, this has been indicated in a marginal stage direction.

Entrances and Exits are fairly thorough in Folio, which has accordingly been followed as faithfully as possible. Where characters are omitted or corrections are necessary, this is indicated by square brackets (e.g. “[and Attendants]”). Exit is sometimes silently normalized to Exeunt and Manet anglicized to “remains.” We trust Folio positioning of entrances and exits to a greater degree than most editors.

Editorial Stage Directions such as stage business, asides, indications of addressee and of characters’ position on the gallery stage are only used sparingly in Folio. Other editions mingle directions of this kind with original Folio and Quarto directions, sometimes marking them by means of square brackets. We have sought to distinguish what could be described as directorial interventions of this kind from Folio-style directions (either original or supplied) by placing them in the right margin in a different typeface. There is a degree of subjectivity about which directions are of which kind, but the procedure is intended as a reminder to the reader and the actor that Shakespearean stage directions are often dependent upon editorial inference alone and are not set in stone. We also depart from editorial tradition in sometimes admitting uncertainty and thus printing permissive stage directions, such as an Aside? (often a line may be equally effective as an aside or as a direct address—it is for each production or reading to make its own decision) or a may exit or a piece of business placed between arrows to indicate that it may occur at various different moments within a scene.

Line Numbers in the left margin are editorial, for reference and to key the explanatory and textual notes.

Explanatory Notes at the foot of each page explain allusions and gloss obsolete and difficult words, confusing phraseology, occasional major textual cruces, and so on. Particular attention is given to non-standard usage, bawdy innuendo, and technical terms (e.g. legal and military language). Where more than one sense is given, commas indicate shades of related meaning, slashes alternative or double meanings.

Textual Notes at the end of the play indicate major departures from the Folio. They take the following form: the reading of our text is given in bold and its source given after an equals sign, with “Q” indicating a Quarto reading, Q2 a reading from the Second Quarto of 1619, “F2” a reading from the Second Folio of 1632, and “Ed” one that derives from the subsequent editorial tradition. The rejected Folio (“F”) reading is then given. Thus for Act 2 Scene 9 line 45: “peasantry = Q. F = pleasantry” means that the Folio text’s “pleasantry” has been rejected in favor of the Quarto reading “peasantry,” which seems to make better sense of the line.

KEY FACTS

MAJOR PARTS: (with percentage of lines/number of speeches/scenes on stage) Portia (22%/117/9), Shylock (13%/79/5), Bassanio (13%/73/6), Gratiano (7%/58/7), Lorenzo (7%/47/7), Antonio (7%/47/6), Lancelet Gobbo (6%/44/6), Salerio (5%/31/7), Morocco (4%/7/2), Nerissa (3%/36/7), Jessica (3%/26/7), Solanio (2%/20/5), Duke (2%/18/1), Aragon (2%/4/1), Old Gobbo (1%/19/1).

LINGUISTIC MEDIUM: 80% verse, 20% prose.

DATE: Registered for publication July 1598 and mentioned in Francis Meres’ 1598 list of Shakespeare’s comedies; reference to a ship called the Andrew suggests late 1596 or early 1597, when the Spanish vessel St. Andrew, which had been captured at Cadiz after running aground, was much in the news.

SOURCES: There are many ancient and medieval folk variations on the motif of a body part demanded as surety for a bond. The setting of the story in Venice, the pursuit of “the lady of Belmonte” as the reason the hero needs the money, the bond being made by a friend rather than the hero himself, the identification of the moneylender as a Jew, and the lady disguising herself as a male lawyer, coming to Venice and arguing that the bond does not allow for the shedding of blood all come from a tale in Ser Giovanni Fiorentino’s collection Il Pecorone (“The Dunce,” in Italian, published 1558—no English translation). A lost English play of the 1570s called The Jew may have been an intervening source. The character of Shylock and the elopement of his daughter with a Christian are strongly shaped by Christopher Marlowe’s highly successful play The Jew of Malta (c.1590). The choice between three caskets as a device to identify a worthy marriage partner is another ancient motif; the closest surviving precedent is a story in the medieval Gesta Romanorum (translated by Richard Robinson, 1577, revised 1595 with use of the rare word “insculpt,” which is echoed in Morocco’s speech).

TEXT: Quarto 1600: a good quality text, apparently set from a fair copy of the dramatist’s manuscript; reprinted 1619, with some errors and some corrections. Folio text was set from a copy of the first Quarto, making some corrections, introducing some errors, and apparently drawing on a theatrical manuscript for stage directions, including music cues. We follow Folio where it corrects or modernizes Quarto, but restore Quarto where Folio changes appear to be printers’ errors. The only serious textual problem concerns the Venetian gentlemen known in the theatrical profession as the “Salads.” They are initially identified in entry directions and speech headings as “Salarino” and “Solanio” (variously abbreviated, most commonly to “Sal.” and “Sol.”), but never named in the dialogue, so are unidentified from the point of view of a theater audience. Folio reverses their speech headings at the beginning of the opening scene, probably erroneously. In Act 3 Scene 2 “Salerio” arrives in Belmont as “a messenger from Venice”; he is named in the dialogue, so identifiable to the audience. Is this a third character, a composite of the first two, or—more probably—has Shakespeare forgotten that he began with “Salarino”? In the following scene, Quarto has “Salerio” back in Venice with Antonio and Shylock, which must be an error—he has only just exited from Belmont with Bassanio. Folio intelligently corrects the Act 3 Scene 3 entry direction to “Solanio.” In Act 4 Scene 1, “Salerio” has returned with Bassanio. Some editions and productions have retained Salarino, Solanio, and Salerio, but it seems more likely that Salarino and Salerio are intended to be the same character: we have followed this assumption.

LIST OF PARTS

ANTONIO, a merchant of Venice

BASSANIO, his friend, suitor to Portia

LORENZO, friend of Antonio and Bassanio, in love with Jessica

GRATIANO, friend of Antonio and Bassanio

Friends of Antonio and Bassanio:

SALERIO

SOLANIO

LEONARDO, servant to Bassanio

PORTIA, an heiress

NERISSA, her gentlewoman-in-waiting

BALTHASAR, servant to Portia

STEPHANO, servant to Portia

Prince of ARAGON, suitor to Portia

Prince of MOROCCO, suitor to Portia

SHYLOCK, a Jew of Venice

JESSICA, his daughter

TUBAL, a Jew, Shylock’s friend

LANCELET GOBBO, the clown, servant to Shylock and later Bassanio

OLD GOBBO, Lancelet’s father

DUKE of Venice

Magnificoes of Venice

A Jailer, Attendants and Servants

Act 1 [Scene 1]

running scene 1

Location: Venice

Enter Antonio, Salerio and Solanio

ANTONIO In sooth1 I know not why I am so sad.

It wearies me, you say it wearies you;

But how I caught it, found it, or came by it,

What stuff4 ’tis made of, whereof it is born,

I am to learn5:

And such a want-wit6 sadness makes of me

That I have much ado7 to know myself.

SALERIO Your mind is tossing on8 the ocean,

There where your argosies9 with portly sail

Like signiors10 and rich burghers on the flood,

Or as it were the pageants11 of the sea,

Do overpeer12 the petty traffickers

That curtsy13 to them, do them reverence,

As they fly14 by them with their woven wings.

SOLANIO Believe me, sir, had I such venture15 forth,

The better part16 of my affections would

Be with my hopes17 abroad. I should be still

Plucking the grass to know where sits18 the wind,

Peering in maps for ports and piers and roads19,

And every object that might make me fear

Misfortune to my ventures out of doubt

Would make me sad.

SALERIO My wind cooling my broth

Would blow me to an ague24, when I thought

What harm a wind too great might do at sea.

I should26 not see the sandy hour-glass run,

But I should think of shallows and of flats27,

And see my wealthy Andrew28 docked in sand,

Vailing29 her high top lower than her ribs

To kiss her burial30; should I go to church

And see the holy edifice of stone,

And not bethink me straight32 of dang’rous rocks,

Which touching but33 my gentle vessel’s side,

Would scatter all her spices on the stream34,

Enrobe the roaring waters with my silks35,

And in a word, but even36 now worth this,

And now worth nothing? Shall I have the thought

To think on this, and shall I lack the thought

That such a thing bechanced39 would make me sad?

But tell not me, I know, Antonio

Is sad to think upon his merchandise.

ANTONIO Believe me, no. I thank my fortune for it,

My ventures are not in one bottom43 trusted,

Nor to one place; nor is my whole estate44

Upon45 the fortune of this present year:

Therefore my merchandise makes me not sad.

SALERIO Why, then you are in love.

ANTONIO Fie48, fie!

SOLANIO Not in love neither: then let us say you are sad

Because you are not merry; and ’twere as easy

For you to laugh and leap, and say you are merry

Because you are not sad. Now, by two-headed Janus52,

Nature hath framed53 strange fellows in her time:

Some that will evermore peep54 through their eyes

And laugh like parrots at a bagpiper55,

And other56 of such vinegar aspect

That they’ll not show their teeth in way of smile,

Though58 Nestor swear the jest be laughable.

Enter Bassanio, Lorenzo and Gratiano

SOLANIO Here comes Bassanio, your most noble kinsman,

Gratiano and Lorenzo. Fare ye well,

We leave you now with better company.

SALERIO I would have stayed till I had made you merry,

If worthier friends had not prevented63 me.

ANTONIO Your worth is very dear64 in my regard.

I take it your own business calls on you,

And you embrace66 th’occasion to depart.

SALERIO Good morrow, my good lords.

BASSANIO Good signiors both, when shall we laugh68? Say, when?

You grow exceeding strange69. Must it be so?

SALERIO We’ll make our leisures to attend on yours70.

Exeunt Salerio and Solanio

LORENZO My lord Bassanio, since you have found Antonio,

We two will leave you, but at dinnertime

I pray you have in mind73 where we must meet.

BASSANIO I will not fail you.

GRATIANO You look not well, Signior Antonio.

You have too much respect upon the world76:

They lose it77 that do buy it with much care.

Believe me, you are marvellously78 changed.

ANTONIO I hold79 the world but as the world, Gratiano,

A stage where every man must play a part,

And mine a sad one.

GRATIANO Let me play the fool:

With mirth and laughter let old83 wrinkles come,

And let my liver84 rather heat with wine

Than my heart cool with mortifying groans85.

Why should a man whose blood is warm within,

Sit like his grandsire87 cut in alabaster?

Sleep when he wakes and creep into the jaundices88

By being peevish89? I tell thee what, Antonio—

I love thee, and it is my love that speaks—

There are a sort of men whose visages91

Do cream and mantle92 like a standing pond,

And do a wilful93 stillness entertain,

With purpose to be dressed in an opinion94

Of wisdom, gravity, profound conceit95,

As who should say96, ‘I am, sir, an oracle,

And when I ope97 my lips, let no dog bark!’

O my Antonio, I do know of these

That therefore only are reputed wise

For saying nothing; when I am very sure

If they should speak, would almost damn those ears

Which, hearing them, would call their brothers fools101.

I’ll tell thee more of this another time.

But fish not with this melancholy bait104

For this fool105 gudgeon, this opinion.

Come, good Lorenzo. Fare ye well awhile,

I’ll end my exhortation107 after dinner.

LORENZO Well, we will leave you then till dinnertime.

To Antonio and Bassanio

I must be one of these same dumb109 wise men,

For Gratiano never lets me speak.

GRATIANO Well, keep me company but two years more,

Thou shalt not know the sound of thine own tongue.

ANTONIO Fare you well, I’ll grow113 a talker for this gear.

GRATIANO Thanks, i’faith, for silence is only commendable

In a neat’s tongue dried115 and a maid not vendible.

Exit [Gratiano with Lorenzo]

ANTONIO Is that anything now?116

BASSANIO Gratiano speaks an infinite deal of nothing, more

than any man in all Venice. His reasons118 are two grains of

wheat hid in two bushels of chaff: you shall seek all day ere119

you find them, and when you have them, they are not worth

the search.

ANTONIO Well, tell me now, what lady is the same122

To whom you swore a secret pilgrimage

That you today promised to tell me of?

BASSANIO ’Tis not unknown to you, Antonio,

How much I have disabled126 mine estate

By something127 showing a more swelling port

Than my faint128 means would grant continuance.

Nor do I now make moan129 to be abridged

From such a noble rate130, but my chief care

Is to come fairly off from131 the great debts

Wherein my time132 something too prodigal

Hath left me gaged133. To you, Antonio,

I owe the most in money and in love,

And from your love I have a warranty135

To unburden136 all my plots and purposes

How to get clear of all the debts I owe.

ANTONIO I pray you good Bassanio, let me know it,

And if it stand as you yourself still do,

Within the eye of honour140, be assured

My purse, my person, my extremest means,

Lie all unlocked to your occasions142.

BASSANIO In my schooldays, when I had lost one shaft143,

I shot his fellow of the selfsame flight144

The selfsame way with more advisèd145 watch

To find the other forth146, and by adventuring both

I oft found both. I urge147 this childhood proof

Because what follows is pure innocence148.

I owe you much and, like a wilful youth,

That which I owe is lost. But if you please

To shoot another arrow that self151 way

Which you did shoot the first, I do not doubt,

As I will watch the aim, or153 to find both,

Or bring your latter hazard154 back again,

And thankfully rest155 debtor for the first.

ANTONIO You know me well, and herein spend but156 time

To wind about my love with circumstance157,

And out of158 doubt you do me now more wrong

In making question of my uttermost159

Than if you had made waste160 of all I have.

Then do but161 say to me what I should do

That in your knowledge may by me be done,

And I am pressed163 unto it: therefore speak.

BASSANIO In Belmont is a lady richly left164,

And she is fair and, fairer than that word,

Of wondrous virtues. Sometimes166 from her eyes

I did receive fair speechless messages.

Her name is Portia, nothing undervalued

To168 Cato169’s daughter, Brutus’ Portia.

Nor is the wide world ignorant of her worth,

For the four winds blow in from every coast

Renownèd suitors, and her sunny locks

Hang on her temples like a golden fleece173,

Which makes her seat174 of Belmont Colchos’ strand,

And many Jasons come in quest of her.

O my Antonio, had I but the means

To hold a rival place with one of them,

I have a mind presages178 me such thrift,

That I should questionless179 be fortunate.

ANTONIO Thou know’st that all my fortunes are at sea,

Neither have I money, nor commodity181

To raise a present182 sum: therefore go forth.

Try183 what my credit can in Venice do,

That shall be racked184, even to the uttermost,

To furnish thee185 to Belmont, to fair Portia.

Go presently186 inquire, and so will I,

Where money is, and I no question make

To have it of my trust188 or for my sake.

Exeunt

[Act 1 Scene 2]

running scene 2

Location: Belmont

Enter Portia with her waiting woman, Nerissa

PORTIA By my troth1, Nerissa, my little body is aweary of this

great world.

NERISSA You would be3, sweet madam, if your miseries were

in the same abundance as your good fortunes are, and yet,

for aught5 I see, they are as sick that surfeit with too much, as

they that starve with nothing; it is no small happiness,

therefore, to be seated in the mean7. Superfluity comes sooner

by white hairs, but competency8 lives longer.

PORTIA Good sentences9 and well pronounced.

NERISSA They would be better if well followed.

PORTIA If to do were as easy as to know what were good to

do, chapels had been churches and poor men’s cottages

princes’ palaces. It is a good divine13 that follows his own

instructions; I can easier teach twenty what were good to be

done than be one of the twenty to follow mine own teaching.

The brain may devise laws for the blood16, but a hot temper

leaps o’er a cold decree17—such a hare is madness the youth,

to skip o’er the meshes18 of good counsel the cripple; but this

reason is not in fashion19 to choose me a husband. O me, the

word ‘choose!’ I may neither choose whom I would20, nor

refuse whom I dislike, so is the will21 of a living daughter

curbed by the will22 of a dead father. Is it not hard, Nerissa,

that I cannot choose one nor refuse none?

NERISSA Your father was ever virtuous, and holy men at

their death have good inspirations: therefore the lottery25 that

he hath devised in these three chests of gold, silver and lead,

whereof who27 chooses his meaning chooses you, will no

doubt never be chosen by any rightly28 but one who you shall

rightly love. But what warmth is there in your affection

towards any of these princely suitors that are already come?

PORTIA I pray thee overname31 them, and as thou namest

them, I will describe them, and according to my description

level at33 my affection.

NERISSA First, there is the Neapolitan34 prince.

PORTIA Ay, that’s a colt35 indeed, for he doth nothing but talk

of his horse, and he makes it a great appropriation36 to his

own good parts37 that he can shoe him himself. I am much

afraid my lady his mother played false38 with a smith.

NERISSA Then is there the County39 Palatine.

PORTIA He doth nothing but frown, as who40 should say, ‘An

you will not have me, choose41.’ He hears merry tales and

smiles not. I fear he will prove42 the weeping philosopher when

he grows old, being so full of unmannerly43 sadness in his

youth. I had rather to be married to a death’s-head44 with a

bone in his mouth than to either of these. God defend me

from these two!

NERISSA How47 say you by the French lord, Monsieur Le Bon?

PORTIA God made him, and therefore let him pass for a

man. In truth, I know it is a sin to be a mocker, but he! Why,

he hath a horse better than the Neapolitan’s, a better bad50

habit of frowning than the Count Palatine. He is every man51

in no man. If a throstle52 sing, he falls straight a capering, he

will fence with his own shadow. If I should marry him, I

should marry twenty husbands. If he would despise me, I

would forgive him, for if55 he love me to madness, I should

never requite him.

NERISSA What say you then to Falconbridge, the young

baron of England?

PORTIA You know I say59 nothing to him, for he understands

not me, nor I him: he hath neither Latin, French, nor Italian,

and you will come into the court and swear61 that I have a

poor pennyworth in the62 English. He is a proper man’s

picture, but alas, who can converse with a dumb show63? How

oddly he is suited64. I think he bought his doublet in Italy, his

round hose65 in France, his bonnet in Germany, and his

behaviour everywhere.

NERISSA What think you of the other lord, his neighbour?

PORTIA That he hath a neighbourly charity in him, for he

borrowed69 a box of the ear of the Englishman and swore he

would pay him again when he was able. I think the

Frenchman became his surety71 and sealed under for another.

NERISSA How like you the young German, the Duke of

Saxony73’s nephew?

PORTIA Very vilely in the morning when he is sober, and

most vilely in the afternoon when he is drunk: when he is

best, he is a little worse than a man, and when he is worst, he

is little better than a beast77. An the worst fall that ever fell, I

hope I shall make shift78 to go without him.

NERISSA If he should offer to choose, and choose the right

casket, you should80 refuse to perform your father’s will, if you

should refuse to accept him.

PORTIA Therefore, for fear of the worst, I pray thee set a

deep glass of Rhenish wine83 on the contrary casket, for if the

devil be within, and that temptation without84, I know he will

choose it. I will do anything, Nerissa, ere I will be married to

a sponge86.

NERISSA You need not fear, lady, the having any of these

lords. They have acquainted me with their determinations88,

which is indeed to return to their home, and to trouble you

with no more suit90, unless you may be won by some other sort

than your father’s imposition91, depending on the caskets.

PORTIA If I live to be as old as Sibylla92, I will die as chaste as

Diana93, unless I be obtained by the manner of my father’s

will. I am glad this parcel94 of wooers are so reasonable, for

there is not one among them but I dote on his very absence,

and I wish them a fair departure.

NERISSA Do you not remember, lady, in your father’s time, a

Venetian, a scholar and a soldier, that came hither in

company of the Marquis of Montferrat99?

PORTIA Yes, yes, it was Bassanio, as I think, so was he called.

NERISSA True, madam. He, of all the men that ever my

foolish102 eyes looked upon, was the best deserving a fair lady.

PORTIA I remember him well, and I remember him worthy

of thy praise.

Enter a Servingman

SERVANT The four strangers105 seek you, madam, to take their

leave. And there is a forerunner106 come from a fifth, the Prince

of Morocco, who brings word the prince his master will be

here tonight.

PORTIA If I could bid the fifth welcome with so good heart as

I can bid the other four farewell, I should be glad of his

approach. If he have the condition111 of a saint and the

complexion of a devil112, I had rather he should shrive me than

wive113 me. Come, Nerissa.—Sirrah, go before; whiles

To the Servingman

we shut the gate upon one wooer, another knocks

at the door.

Exeunt

[Act 1 Scene 3]

running scene 3

Location: Venice

Enter Bassanio with Shylock the Jew

SHYLOCK Three thousand ducats1, well.

BASSANIO Ay, sir, for three months.

SHYLOCK For three months, well.

BASSANIO For the which, as I told you, Antonio shall be

bound5.

SHYLOCK Antonio shall become bound, well.

BASSANIO May you stead7 me? Will you pleasure me? Shall I

know your answer?

SHYLOCK Three thousand ducats for three months and

Antonio bound.

BASSANIO Your answer to that.

SHYLOCK Antonio is a good man.

BASSANIO Have you heard any imputation13 to the contrary?

SHYLOCK Ho, no, no, no, no! My meaning in saying he is a

good man is to have you understand me that he is sufficient15.

Yet his means are in supposition16: he hath an argosy bound to

Tripolis17, another to the Indies, I understand moreover, upon

the Rialto18, he hath a third at Mexico, a fourth for England,

and other ventures he hath squandered19 abroad. But ships are

but boards, sailors but men. There be land-rats and water-

rats, water-thieves and land-thieves—I mean pirates21—and

then there is the peril of waters, winds and rocks. The man is,

notwithstanding23, sufficient. Three thousand ducats. I think I

may take his bond.

BASSANIO Be assured you may.

SHYLOCK I will be assured26 I may. And that I may be assured, I

will bethink me27. May I speak with Antonio?

BASSANIO If it please you to dine with us.

SHYLOCK Yes, to smell pork, to eat of the habitation29 which

your prophet the Nazarite30 conjured the devil into. I will buy

with you, sell with you, talk with you, walk with you, and so

following32, but I will not eat with you, drink with you, nor

pray with you. What news on the Rialto? Who is he comes

here?

Enter Antonio

BASSANIO This is Signior Antonio.

SHYLOCK How like a fawning publican36 he looks!

Aside

I hate him for he is a Christian,

But more, for that in low simplicity38

He lends out money gratis39 and brings down

The rate of usance40 here with us in Venice.

If I can catch him once upon the hip41,

I will feed fat42 the ancient grudge I bear him.

He hates our sacred nation43, and he rails—

Even there where merchants most do congregate44—

On me, my bargains and my well-won thrift45,

Which he calls interest. Cursèd be my tribe46,

If I forgive him!

BASSANIO Shylock, do you hear?

SHYLOCK I am debating of my present store49,

And by the near guess of my memory,

I cannot instantly raise up the gross51

Of full three thousand ducats. What of that?

Tubal53, a wealthy Hebrew of my tribe,

Will furnish54 me; but soft! How many months

Do you desire?—Rest you fair55, good signior.

To Antonio

Your worship was the last man in our mouths56.

ANTONIO Shylock, albeit I neither lend nor borrow

By taking nor by giving of excess58,

Yet to supply the ripe wants59 of my friend,

I’ll break a custom.—Is he yet possessed60

To Bassanio

How much ye would61?

SHYLOCK Ay, ay, three thousand ducats.

ANTONIO And for three months.

SHYLOCK I had forgot—three months—you told me so.

Well then, your bond65. And let me see, but hear you,

Methoughts you said you neither lend nor borrow

Upon advantage67.

ANTONIO I do never use68 it.

SHYLOCK When Jacob grazed his uncle Laban’s sheep69—

This Jacob from70 our holy Abram was,

As his wise mother wrought71 in his behalf,

The third possessor72; ay, he was the third—

ANTONIO And what of him? Did he take interest?

SHYLOCK No, not take interest, not, as you would say,

Directly interest. Mark75 what Jacob did:

When Laban and himself were compromised76

That all the eanlings77 which were streaked and pied

Should fall as78 Jacob’s hire, the ewes, being rank,

In end of autumn turnèd to the rams,

And, when the work of generation80 was

Between these woolly breeders in the act,

The skilful shepherd peeled me certain wands82,

And in the doing of the deed of kind83,

He stuck them up before the fulsome ewes84,

Who then conceiving, did in eaning85 time

Fall86 parti-coloured lambs, and those were Jacob’s.

This was a way to thrive87, and he was blest:

And thrift is blessing, if men steal it not.

ANTONIO This was a venture89, sir, that Jacob served for,

A thing not in his power to bring to pass,

But swayed and fashioned91 by the hand of heaven.

Was this inserted92 to make interest good?

Or is your gold and silver ewes and rams?

SHYLOCK I cannot tell, I make it breed as fast.

But note me, signior—

ANTONIO Mark you this, Bassanio,

The devil can cite Scripture for his purpose.

An evil soul producing holy witness

Is like a villain with a smiling cheek,

A goodly100 apple rotten at the heart.

O, what a goodly outside falsehood hath!

SHYLOCK Three thousand ducats, ’tis a good round sum.

Three months from twelve, then let me see, the rate—

ANTONIO Well, Shylock, shall we be beholding104 to you?

SHYLOCK Signior Antonio, many a time and oft

In the Rialto you have rated106 me

About my moneys and my usances.

Still have I borne it with a patient shrug,

For sufferance109 is the badge of all our tribe.

You call me misbeliever, cut-throat dog,

And spit upon my Jewish gaberdine111,

And all for use112 of that which is mine own.

Well then, it now appears you need my help.

Go to114, then. You come to me and you say

‘Shylock, we would have moneys’—you say so,

You that did void116 your rheum upon my beard,

And foot117 me as you spurn a stranger cur

Over your threshold. Moneys is your suit118.

What should I say to you? Should I not say,

‘Hath a dog money? Is it possible

A cur should lend three thousand ducats?’ Or

Shall I bend low and in a bondman’s key122,

With bated123 breath and whisp’ring humbleness,

Say this: ‘Fair sir, you spat on me on Wednesday last;

You spurned me such a day; another time

You called me dog, and for these courtesies

I’ll lend you thus much moneys’?

ANTONIO I am as like128 to call thee so again,

To spit on thee again, to spurn thee too.

If thou wilt lend this money, lend it not

As to thy friends, for when did friendship take

A breed of barren metal132 of his friend?

But lend it rather to thine enemy,

Who, if he break134, thou mayst with better face

Exact the penalties.

SHYLOCK Why, look you how you storm!

I would be friends with you and have your love,

Forget the shames that you have stained me with,

Supply your present wants and take no doit139

Of usance for my moneys, and you’ll not hear me:

This is kind141 I offer.

BASSANIO This were142 kindness.

SHYLOCK This kindness will I show:

Go with me to a notary144, seal me there

Your single145 bond, and in a merry sport

If you repay me not on such a day,

In such a place, such sum or sums as are

Expressed in the condition148, let the forfeit

Be nominated for149 an equal pound

Of your fair flesh, to be cut off and taken

In what part of your body it pleaseth me.

ANTONIO Content, in faith, I’ll seal to such a bond

And say there is much kindness in the Jew.

BASSANIO You shall not seal to such a bond for me.

I’ll rather dwell155 in my necessity.

ANTONIO Why, fear not, man, I will not forfeit it.

Within these two months—that’s a month before

This bond expires—I do expect return

Of thrice three times the value of this bond.

SHYLOCK O father Abram, what these Christians are,

Whose own hard dealings teaches them suspect161

The thoughts of others! Pray you tell me this:

If he should break his day163, what should I gain

By the exaction164 of the forfeiture?

A pound of man’s flesh taken from a man

Is not so estimable166, profitable neither,

As flesh of muttons, beefs or goats. I say

To buy his favour, I extend this friendship:

If he will take it, so169, if not, adieu.

And for my love, I pray you wrong me not.

ANTONIO Yes Shylock, I will seal unto this bond.

SHYLOCK Then meet me forthwith172 at the notary’s,

Give him direction173 for this merry bond,

And I will go and purse174 the ducats straight,

See175 to my house, left in the fearful guard

Of an unthrifty176 knave, and presently

I’ll be with you.

ANTONIO Hie178 thee, gentle Jew.

Exit

This Hebrew will turn Christian, he grows kind179.

BASSANIO I like not fair terms and a villain’s mind.

ANTONIO Come on, in this there can be no dismay.

My ships come home a month before the day.

Exeunt

Act 2 [Scene 1]

running scene 4

Location: Belmont

Enter Morocco, a tawny Moor, all in white, and three or four followers accordingly, with Portia, Nerissa and their train. Flourish cornets

MOROCCO Mislike me not for my complexion,

The shadowed livery2 of the burnished sun,

To whom I am a neighbour and near bred3.

Bring me the fairest creature northward born,

Where Phoebus5’ fire scarce thaws the icicles,

And let us make incision6 for your love,

To prove whose blood is reddest7, his or mine.

I tell thee, lady, this aspect8 of mine

Hath feared9 the valiant. By my love I swear,

The best-regarded virgins of our clime10

Have loved it too: I would not change this hue11,

Except to steal your thoughts, my gentle queen.

PORTIA In terms of choice I am not solely led

By nice14 direction of a maiden’s eyes.

Besides, the lott’ry of my destiny

Bars me the right of voluntary choosing.

But if my father had not scanted17 me,

And hedged18 me by his wit to yield myself

His19 wife who wins me by that means I told you,

Yourself, renownèd prince, then20 stood as fair

As any comer I have looked on yet

For22 my affection.

MOROCCO Even for that I thank you:

Therefore, I pray you lead me to the caskets

To try my fortune. By this scimitar25

That slew the Sophy26 and a Persian prince

That won three fields27 of Sultan Solyman,

I would o’erstare28 the sternest eyes that look,

Outbrave the heart most daring on the earth,

Pluck the young sucking cubs from the she-bear,

Yea, mock the lion when he roars for prey

To win thee, lady. But alas the while!

If Hercules33 and Lichas play at dice

Which is the better man, the greater throw

May turn by fortune from the weaker hand:

So is Alcides36 beaten by his page,

And so may I, blind fortune leading me,

Miss that which one unworthier may attain,

And die with grieving.

PORTIA You must take your chance,

And either not attempt to choose at all

Or swear before you choose, if you choose wrong

Never to speak to lady afterward

In way of marriage: therefore be advised44.

MOROCCO Nor will not45. Come, bring me unto my chance.

PORTIA First, forward to the temple. After dinner

Your hazard47 shall be made.

MOROCCO Good fortune then!

To make me blest or cursed’st among men.

Cornets [and] exeunt

[Act 2 Scene 2]

running scene 5

Location: Venice

Enter the Clown [Lancelet] alone

LANCELET Certainly my conscience will serve1 me to run from

this Jew my master. The fiend is at mine elbow and tempts me,

saying to me, ‘Gobbo3, Lancelet Gobbo, good Lancelet’, or

‘Good Gobbo’, or ‘Good Lancelet Gobbo, use your legs, take the

start5, run away.’ My conscience says, ‘No; take heed, honest

Lancelet, take heed, honest Gobbo’, or, as aforesaid, ‘Honest

Lancelet Gobbo, do not run, scorn running with thy heels7.’

Well, the most courageous8 fiend bids me pack: ‘Fia!’ says the

fiend, ‘Away!’ says the fiend, ‘For the heavens9, rouse up a brave

mind’, says the fiend, ‘and run.’ Well, my conscience, hanging

about the neck of my heart, says very wisely to me, ‘My honest

friend Lancelet, being an honest12 man’s son’, or rather an

honest woman’s son—for indeed my father did something13

smack14, something grow to, he had a kind of taste—well, my

conscience says ‘Lancelet, budge not.’ ‘Budge’, says the fiend.

‘Budge not’, says my conscience. ‘Conscience,’ say I, ‘you

counsel well.’ ‘Fiend,’ say I, ‘you counsel well.’ To be ruled by

my conscience, I should stay with the Jew my master, who,

God bless the mark19, is a kind of devil; and to run away from the

Jew, I should be ruled by the fiend, who, saving your reverence20,

is the devil himself. Certainly the Jew is the very devil

incarnation22, and in my conscience, my conscience is a kind of

hard conscience to offer to counsel me to stay with the Jew; the

fiend gives the more friendly counsel. I will run, fiend. My

heels are at your commandment. I will run.

Enter Old Gobbo, with a basket

GOBBO Master young man, you, I pray you which is the

way to Master Jew’s?

LANCELET O heavens, this is my true-begotten28 father,

Aside

who, being more than sand-blind29, high-gravel-blind, knows

me not. I will try confusions30 with him.

GOBBO Master young gentleman, I pray you which is the

way to Master Jew’s?

LANCELET Turn upon your right hand at the next turning, but

at the next turning of all, on your left; marry, at the very

next turning, turn of no hand35, but turn down indirectly to

the Jew’s house.

GOBBO By God’s sonties37, ’twill be a hard way to hit. Can you

tell me whether one Lancelet, that dwells with him, dwell

with him or no?

LANCELET Talk you of young Master Lancelet?—

Aside

Mark me now, now will I raise the waters41.—Talk you of

young Master Lancelet?

GOBBO No master43, sir, but a poor man’s son. His father,

though I say’t, is an honest exceeding poor man and, God be

thanked, well to live45.

LANCELET Well, let his father be what a46 will, we talk of young

Master Lancelet.

GOBBO Your worship’s friend and Lancelet48.

LANCELET But I pray you ergo49, old man, ergo, I beseech you talk

you of young Master Lancelet?

GOBBO Of Lancelet, an’t51 please your mastership.

LANCELET Ergo, Master Lancelet. Talk not of Master Lancelet,

father53, for the young gentleman—according to fates and

destinies and such odd sayings, the Sisters Three54 and such

branches of learning—is indeed deceased, or as you would

say in plain terms, gone to heaven.

GOBBO Marry, God forbid! The boy was the very staff of my

age, my very prop.

LANCELET Do I look like a cudgel or a hovel-post59, a staff or a

prop? Do you know me, father?

GOBBO Alack the day, I know you not, young gentleman,

but I pray you tell me, is my boy, God rest his soul, alive or

dead?

LANCELET Do you not know me, father?

GOBBO Alack, sir, I am sand-blind. I know you not.

LANCELET Nay, indeed if you had your eyes you might fail of

the knowing66 me: it is a wise father that knows his own

child67.

Well, old man, I will tell you news of your son. Give

He kneels

me your blessing. Truth will come to light, murder cannot be

hid long, a man’s son may, but in the end truth will out.

GOBBO Pray you, sir, stand up. I am sure you are not

Lancelet, my boy.

LANCELET Pray you let’s have no more fooling about it, but

give me your blessing. I am Lancelet, your boy that was, your

son that is, your child that shall be74.

GOBBO I cannot think you are my son.

LANCELET I know not what I shall think of that. But I am

Lancelet, the Jew’s man, and I am sure Margery your wife is

my mother.

GOBBO Her name is Margery80, indeed. I’ll be sworn, if thou

be Lancelet, thou art mine own flesh and blood. Lord

worshipped might he be! What a beard hast thou got! Thou

hast got more hair on thy chin than Dobbin my fill-horse83 has

on his tail.

LANCELET It should seem, then, that Dobbin’s tail

He rises

grows backward86. I am sure he had more hair of his tail than

I have of my face when I last saw him.

GOBBO Lord, how art thou changed! How dost thou and thy

master agree89? I have brought him a present. How ’gree you

now?

LANCELET Well, well. But for mine own part, as I have set up

my rest91 to run away, so I will not rest92 till I have run some

ground; my master’s a very93 Jew. Give him a present? Give

him a halter94! I am famished in his service. You may tell every

finger I have with my ribs95. Father, I am glad you are come.

Give me96 your present to one Master Bassanio, who, indeed,

gives rare97 new liveries. If I serve not him, I will run as far as

God has any ground. O rare fortune! Here comes the man. To

him, father, for I am a Jew99 if I serve the Jew any longer.

Enter Bassanio, with a follower or two [including Leonardo]

BASSANIO You may do so, but let it be so hasted100

To a Servant

that supper be ready at the farthest101 by five of the clock. See

these letters delivered, put the liveries to making, and desire

Gratiano to come anon103 to my lodging.

[Exit a Servant]

LANCELET To him, father.

GOBBO God bless your worship!

Comes forward

BASSANIO Gramercy106! Wouldst thou aught with me?

GOBBO Here’s my son, sir, a poor boy—

LANCELET Not a poor108 boy, sir, but the rich Jew’s man, that

would, sir, as my father shall specify—

GOBBO He hath a great infection110, sir, as one would say, to

serve—

LANCELET Indeed, the short and the long is, I serve the Jew and

have a desire, as my father shall specify—

GOBBO His master and he, saving your worship’s reverence,

are scarce115 cater-cousins—

LANCELET To be brief, the very truth is that the Jew, having

done me wrong, doth cause me, as my father, being, I hope,

an old man, shall frutify118 unto you—

GOBBO I have here a dish of doves that I would bestow upon

your worship, and my suit is—

LANCELET In very brief, the suit is impertinent121 to myself, as

your worship shall know by this honest old man, and though

I say it, though old man, yet poor man, my father.

BASSANIO One speak for both. What would you?

LANCELET Serve you, sir.

GOBBO That is the very defect126 of the matter, sir.

BASSANIO I know thee well, thou hast obtained thy suit.

Shylock thy master spoke with me this day,

And hath preferred129 thee, if it be preferment

To leave a rich Jew’s service, to become

The follower of so poor a gentleman.

LANCELET The old proverb132 is very well parted between my

master Shylock and you, sir: you have the grace of God, sir,

and he hath enough.

BASSANIO Thou speak’st it well. Go, father, with thy son.

Take leave of thy old master and inquire

My lodging out136.—Give him a livery

To a Servant

More guarded138 than his fellows’. See it done.

LANCELET Father, in. I cannot get a service, no. I have ne’er a

tongue in my head. Well, if any man in Italy have a

Points to his palm

fairer table141 which doth offer to swear upon a book,

I shall have good fortune. Go to, here’s a simple142 line of life,

here’s a small trifle143 of wives. Alas, fifteen wives is nothing!

Eleven widows and nine maids is a simple144 coming-in for one

man, and then to scape145 drowning thrice, and to be in peril

of my life with the edge of a feather-bed146. Here are simple

scapes147. Well, if Fortune be a woman, she’s a good wench for

this gear148. Father, come; I’ll take my leave of the Jew in the

twinkling.

Exit Clown [Lancelet with Old Gobbo]

BASSANIO I pray thee good Leonardo, think on this.

Gives a list

These things being bought and orderly bestowed151,

Return in haste, for I do feast152 tonight

My best-esteemed acquaintance. Hie thee, go.

LEONARDO My best endeavours shall be done herein154.

Enter Gratiano

GRATIANO Where’s your master?

LEONARDO Yonder, sir, he walks.

Exit

GRATIANO Signior Bassanio!

BASSANIO Gratiano!

GRATIANO I have a suit to you.

BASSANIO You have obtained it160.

GRATIANO You must not deny me. I must go with you to

Belmont.

BASSANIO Why then you must. But hear thee, Gratiano,

Thou art too wild, too rude164 and bold of voice,

Parts165 that become thee happily enough

And in such eyes as ours appear not faults;

But where they are not known, why, there they show167

Something too liberal168. Pray thee take pain

To allay169 with some cold drops of modesty