VASILY SEMYONOVICH GROSSMAN was born on December 12, 1905, in Berdichev, a Ukrainian town that was home to one of Europe’s largest Jewish communities. In 1934 he published both “In the Town of Berdichev”—a short story that won the admiration of such diverse writers as Isaak Babel, Maksim Gorky, and Boris Pilnyak—and a novel, Glyukauf, about the life of the Donbass miners. During the Second World War, Grossman worked as a war correspondent for the army newspaper Red Star, covering nearly all of the most important battles from the defense of Moscow to the fall of Berlin. His vivid yet sober “The Hell of Treblinka” (late 1944), one of the first articles in any language about a Nazi death camp, was translated and used as testimony in the Nuremberg Trials. His novel For a Just Cause (originally titled Stalingrad) was published in 1952 and then fiercely attacked. A new wave of purges—directed against the Jews—was about to begin; if not for Stalin’s death, in March 1953, Grossman would almost certainly have been arrested. During the next few years Grossman, while enjoying public success, worked on his two masterpieces, neither of which was to be published in Russia until the late 1980s: Life and Fate and Everything Flows. The KGB confiscated the manuscript of Life and Fate in February 1961. Grossman was able, however, to continue working on Everything Flows, a novel even more critical of Soviet society than Life and Fate, until his last days in the hospital. He died on September 14, 1964, on the eve of the twenty-third anniversary of the massacre of the Jews of Berdichev, in which his mother had died.

The Road

Stories, Journalism, and Essays

Vasily Grossman

Translated from the Russian by

Robert and Elizabeth Chandler

with Olga Mukovnikova

Commentary and notes by

Robert Chandler

with Yury Bit-yunan

Afterword by

Fyodor Guber

New York Review Books

New York

Contents

A Young Woman and an Old Woman

1. Grossman and “The Hell of Treblinka”

Part One*

The 1930s

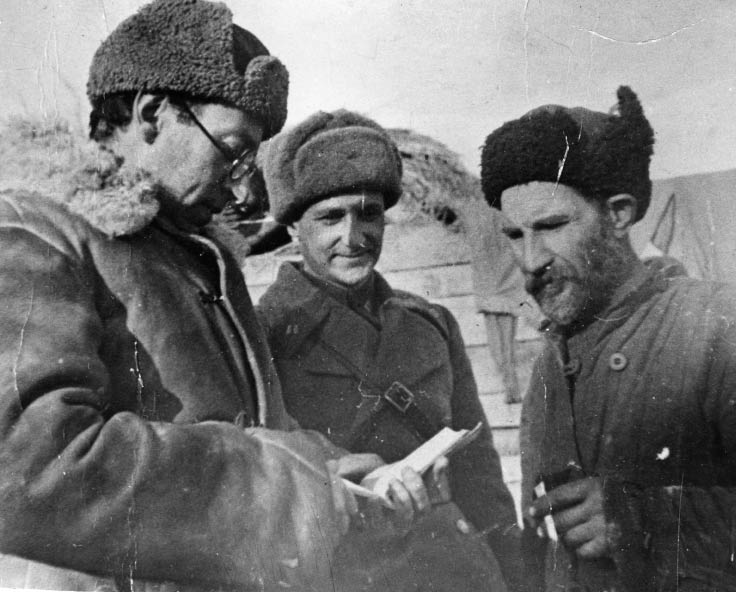

Koktebel' (on the Black Sea), September 1935. Grossman (with glasses) is farthest left of the men sitting.

VASILY Semyonovich Grossman was born on December 12, 1905, in Berdichev, a Ukrainian town that was home to one of Europe’s largest Jewish communities. In 1897, not long before Grossman’s birth, the overall population had been nearly fifty-four thousand, of whom more than forty-one thousand were Jews. At one time there had been eighty synagogues, and in the first half of the nineteenth century, before being supplanted by Odessa, Berdichev had been the most important banking center in the Russian empire.

Both of Grossman’s parents were Jewish and they originally named their son Iosif. Being highly Russified, however, they usually called him Vasily or Vasya—and this is how he has always been known. Grossman himself once said to his daughter, Yekaterina Korotkova, “We were not like the poor shtetl Jews described by Sholem Aleichem, the type that lived in hovels and slept side by side on the floor packed like sardines. No, our family comes from a quite different Jewish background. They had their own carriages and trotters. Their women wore diamonds, and they sent their children abroad to study.” It is unlikely that Grossman knew Yiddish.

According to Yekaterina Korotkova, Grossman’s parents met in Switzerland, where they were both students. Like many Jewish students living abroad, Semyon Osipovich was active in the revolutionary movement. He joined the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (as the Communist Party was then called) in 1902. When the Party split in 1903, he joined the Menshevik faction, which was opposed to Lenin and the Bolsheviks. We also know that Semyon Osipovich played an active role in the 1905 Revolution, helping to organize an uprising in Sebastopol.

At some point in his early childhood Vasily’s parents separated, though they seem to have remained on friendly terms throughout their lives. Vasily was brought up by his mother, Yekaterina Savelievna; they were helped by David Sherentsis, the wealthy husband of his mother’s sister. From 1910 to 1912 Vasily and his mother lived in Geneva; they then returned to Berdichev, to live with the Sherentsis family. His mother worked as a French teacher, and Vasily would retain a good knowledge of French throughout his life; his stepson Fyodor Guber remembers that the family copy of War and Peace did not include any Russian translation of the passages written in French. From 1914 to 1919 Vasily attended secondary school in Kiev. Between 1921 and 1923 he attended the Kiev Higher Institute of Soviet Education, sharing an apartment in Kiev with his father, and from 1923 to 1929 he studied chemistry at Moscow State University, while also working part-time in a home for street children. He soon realized that his true vocation was literature, but he had to continue studying for his degree. His father, a chemical engineer himself, had worked hard to support him, and he wanted his son to be properly qualified. The family’s financial difficulties were compounded by Vasily’s marriage, in January 1928, to Anna Matsuk and the birth of Yekaterina, his only child, in January 1930.

After graduating from the university, Grossman spent two years in the coal-mining area of the Ukraine known as the Donbass, or Donets Basin, working first as a safety engineer in a mine and then as a chemistry teacher in a medical institute. In 1931, after being diagnosed with tuberculosis, he managed to obtain permission to return to Moscow; it seems likely that he was misdiagnosed, although his daughter believes that he had incipient tuberculosis and that this was successfully treated. For two years he worked as an engineer in a factory—with a strange appropriateness, it was a pencil factory—but after that he managed to make his living as a professional writer. He never, however, lost his interest in science.

On returning to Moscow, Grossman went to live with Nadya Almaz, a first cousin on his mother’s side. Five years older than Grossman, she was intelligent and ambitious, a woman of strong moral and political convictions. By the late 1920s, she was working as the personal assistant to Solomon Lozovsky, the head of the Profintern (Trade Union International), an organization whose role was to liaise with trade unions in other countries. For Grossman, Nadya Almaz was both an inspiration and a source of crucial practical help. She encouraged him to write about mines and industrial projects, and she arranged for his manuscripts to be typed. With her many connections in Party circles, she enabled Grossman to join a group of young activists on a trip to Uzbekistan in May and June 1928, and she also helped him to get two of his first articles published, one of them in Pravda—the Communist Party’s main newspaper.

In April 1933, however, Nadya Almaz was arrested, charged with “anti-Soviet activities.” She was expelled from the Party and exiled to Astrakhan. Like many other members of internationalist organizations such as the Profintern and the Comintern (Communist International), she was accused of being in contact with foreign Trotskyists. Later in the 1930s such charges were made all too often and were usually false; Nadya Almaz, however, truly had remained in contact with Trotskyists. She was certainly in communication with Viktor Kibal'chich (the writer and former associate of Trotsky better known by his pseudonym of Victor Serge); her OGPU file records that two “extremely counterrevolutionary letters from Viktor Kibal'chich were found in her possession.” Grossman was still living with Nadya at this time, and he was questioned during the search of her room. He does not appear to have said anything in her defense either then or during the period of her detainment; he did, however, write to her and send her money, and in September 1934 he visited her in Astrakhan.

The years immediately after this seem to have gone well for Grossman—at least in regard to practical and professional matters. In April 1933, after a long struggle, he obtained a permanent Moscow residence permit, and in the summer of 1933 his first novel, Glyukauf, about the life of the Donbass miners, was recommended for publication; this led to his being able to join two important organizations: the Moscow Writers Friendship Society and the Literary Fund. Around this time Grossman also became friends with three former members of the literary group Pereval. Aleksandr Voronsky, the group’s leading figure, had been a supporter of Trotsky, and Pereval had been officially disbanded in 1932. Nevertheless, its members were still playing an active role in Moscow literary life, and these three writers—Boris Guber, Ivan Kataev, and Nikolay Zarudin—were able to offer Grossman both practical help and encouragement. It was Kataev and Zarudin who, in 1934, took Grossman’s story “In the Town of Berdichev” to the editors of the prestigious Literaturnaya gazeta. The story was published promptly, and it won the admiration of such diverse writers as Isaak Babel, Maksim Gorky, and Boris Pilnyak. Glyukauf was also published in 1934. In the following three years Grossman published three small collections of short stories: Happiness (1935), Four Days (1936), and Stories (1937). In 1937 he was admitted to the recently established Union of Soviet Writers, and he also published the first volume of his long novel Stepan Kolchugin. Set in the early twentieth century, it is about a young coal miner who becomes a revolutionary. Grossman’s own experience of the Donbass mines, along with the stories he had heard from his father about the revolutionary movement, enabled him to write about this world from the inside. Like Grossman’s later, more famous novels, this is fiction with a firm basis in fact and imbued with a deep concern for both public and private morality.

***

In 1937 Boris Guber was arrested and shot—as were Kataev, Zarudin, and several other former members of Pereval. Grossman’s first marriage had ended in 1933 and in the summer of 1935 he had begun an affair with Guber’s wife, Olga Mikhailovna. Grossman and Olga Mikhailovna had begun living together in October 1935, and they had married in May 1936, a few days after Olga Mikhailovna and Boris Guber had divorced. Grossman was clearly in danger himself; 1936–37 was the peak of the Great Terror. In 1938 Olga Mikhailovna was arrested for failing to denounce her previous husband, an “enemy of the people.” Grossman quickly had himself registered as the official guardian of Olga’s two sons by Boris Guber, thus saving them from being sent to orphanages or camps. He then wrote to Nikolay Yezhov, the head of the NKVD, pointing out that Olga Mikhailovna was now his wife, not Guber’s, and that she should not be held responsible for a man from whom she had separated long before his arrest. Grossman’s friend, Semyon Lipkin, has commented, “In 1937 only a very brave man would have dared to write a letter like this to the State’s chief executioner.” Later that year—astonishingly—Olga Mikhailovna was released.

The true nature of Grossman’s, or anyone else’s, political beliefs in the 1930s is almost impossible to ascertain; no evidence—no letter, diary, or even report by an NKVD informer—can ever be considered entirely reliable. It is likely, however, that Grossman felt pulled in different directions. On the one hand, many people close to him were arrested or executed in the 1930s, and his father, with whom he had lived for two years when he was in his late teens, had been a committed member of the Menshevik Party, most of whose members had ended up in prison or exile. And it seems that Grossman had at least some sense, at the time it was happening, of the magnitude of the Terror Famine in the Ukraine in 1932–33. On the other hand, he was an ambitious young writer; he wanted to make his mark in the world and he was, therefore, dependent on the Soviet regime. Under the tsars, even in the absence of pogroms, Jews had been the object of discrimination; in the early Soviet Union, by contrast, they constituted a disproportionately large part of the political, professional, and intellectual elite. Whatever his innermost thoughts as he was writing it, this sentence from Grossman’s 1937 letter to Yezhov is objectively true: “All that I possess—my education, my success as a writer, the high privilege of sharing my thoughts and feelings with Soviet readers—I owe to the Soviet government.” And Grossman retained at least some degree of revolutionary romanticism until his last days. It is possible that—like many other members of the intelligentsia—he may have continued, throughout the 1930s, to hope that the Soviet system might, in time, fulfill its revolutionary promise.

All that can be said with certainty is that the distinction between the “establishment” writer of the 1930s and 1940s and the “dissident” who wrote Life and Fate and Everything Flows in the last fifteen years of his life is essentially one of degree. There is no single moment—or even year—that can be seen as having marked a political “conversion.” Even Grossman’s first novel, Glyukauf, little read today, evidently once had some power to shock; in 1932 Gorky criticized a draft for “naturalism”—a Soviet code word for presenting too much unpalatable reality. At the end of his report Gorky suggested that the author should ask himself: “Why am I writing? Which truth am I confirming? Which truth do I wish to triumph?” What Gorky meant by this is that Grossman was showing too little concern for ideology and too much concern for reality. It is hard not to be impressed by Gorky’s intuition; he seems to have sensed where Grossman’s love of truth might lead him.

***

Grossman wrote better with each decade, and it is his last stories that are his greatest. From the twenty or so stories he wrote during the 1930s we have included only one story that was published at the time and two that were first published in the 1960s.

“In the Town of Berdichev” is set at the time of the Polish-Soviet War (February 1919 to March 1921), a war fought against Poland by Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine. It is not difficult to see why this story was received so enthusiastically. Grossman writes vividly, and he performs a skillful balancing act, neither praising nor damning his heroine, Vavilova, a commissar who has to choose between deserting her newborn baby and deserting her Red Army comrades.

In both style and subject matter the story owes much to Isaak Babel, whose story cycle Red Cavalry is set against the background of the same war. In some respects Grossman seems to be trying to outdo Babel, to show that he is no less inventive than him in finding ways to startle the reader: “At first she had blamed everything [i.e., her pregnancy] on him—on the sad, taciturn man who had proved stronger than her and had found a way through her thick leather jacket and the coarse cloth of her tunic and into her woman’s heart.” At a deeper level, however, the story can be read as a profound criticism of Babel. Many of the finest stories in Red Cavalry are about initiations into a world of male violence. Fascinated as he is by violence, Babel does, on the whole, appear to see this initiation as something to be desired. “In the Town of Berdichev,” on the other hand, is about a woman being initiated, or almost initiated, into a feminine world—a world she rejects, then accepts, then rejects again.

Babel was ten years older than Grossman, and he came to fame not long after Grossman began his studies at Moscow State University. Like Grossman, Babel was a Ukrainian Jew, an intellectual with a good knowledge of French literature and a love of Maupassant. It is not surprising that Grossman, as an aspiring writer, should have measured himself against Babel. More important, however, is the degree to which he seems to have defined himself by opposition to Babel. Like Babel, Grossman wrote a great deal about violence. Unlike Babel, he was in no way fascinated by it; he wrote about violence simply because he was thrown up against a number of the most terrible acts of violence of the last century. The theme that fascinated Grossman, the theme to which he repeatedly returns, often in the most unexpected of contexts, is that of maternal love.

***

“A Small Life,” written only two years later, in 1936, is immediately recognizable as the work of the mature Grossman; it is as low-key, as unshowy as “In the Town of Berdichev” is showy. Here too, however, Grossman takes risks—though we do not know whether he tried to publish the story at the time. The hero, Lev Orlov, is timid and depressive; even though his first name means “Lion” and his last name means “Eagle,” he is the antithesis of the positive hero of socialist realist doctrine. In November 1935 Stalin had declared that “Life has become better, life has become merrier,” and these words were repeated again and again—on banners and posters, in radio programs and newspaper articles, and in speeches at May Day parades and other public events. Against this background, Grossman’s use of the words “merrily” and “merriment” and Orlov’s lack of interest in May Day festivities are provocative. During the 1930s the radio was the most important medium for State propaganda; Orlov’s lack of a radio demonstrates his alienation from Soviet life. Grossman does not, of course, overtly sympathize with Orlov, nor does he explicitly condemn him.

With its delicate irony and apparent inconsequentiality, “A Small Life” owes much to Chekhov, who was evidently of central importance to Grossman at least from the beginning of his professional career. “A Young Woman and an Old Woman” is no less Chekhovian. There is painful irony in the contrast between some of our first glimpses of Gagareva, the older of the two women. First we hear her mouthing wooden platitudes about the attention being given by the authorities to “maintaining the health of the country’s citizens”; soon afterward we hear her sobbing, loudly and hoarsely, because her daughter is in the Gulag. Grossman does, admittedly, make a concession to Soviet orthodoxy by allowing a series of arrests on a State farm to end positively, with the triumph of justice, but the story’s Chekhovian musical structure—the various repeated words and images, the way the story both begins and ends with a description of speeding cars—leads the reader to a very different understanding. As Goryacheva is being driven to her dacha in the first scene, she is struck “by this troubling swiftness, by the ease with which objects, people, and animals appeared, grew bigger, and then disappeared in a flash.” In the story’s last lines, Gagareva looks down from the window of her Moscow office at the city below: “Precipitately, as if out of nowhere, [bright automobile headlights] arose out of the fog and gloom, then swiftly traversed the square.” The impression left by the story is of the randomness of Soviet life in the 1930s, the “precipitateness” (this word and its cognates are repeated even more times in the original) with which people are elevated to positions of great authority or cast out into darkness.

In the Town of Berdichev*

VAVILOVA’S face was dark and weather-beaten, and it was odd to see it blush.

“Why are you laughing?” she said finally. “It’s all so stupid.”

Kozyrev took the paper from the table, looked at it, and, shaking his head, burst out laughing again.

“No, it’s just too ridiculous,” he said through his laughter. “Application for leave...from the commissar of the First Battalion...for forty days for reasons of pregnancy.” Then he turned serious. “So what should I do? Who’s going to take your place? Perelmuter from the Divisional Political Section?”

“Perelmuter’s a sound Communist,” said Vavilova.

“You’re all sound Communists,” said Kozyrev. Lowering his voice, as though he were talking about something shameful, he asked, “Is it due soon, Klavdiya?”

“Yes,” said Vavilova. She took off her sheepskin hat and wiped the sweat from her brow.

“I’d have got rid of it,” she said in her deep voice, “but I wasn’t quick enough. You know what it was like—down by Grubeshov there were three whole months when I was hardly out of the saddle. And when I got to the hospital, the doctor said no.” She screwed up her nose, as if about to cry. “I even threatened the bastard with my Mauser,” she went on, “but he still wouldn’t do anything. He said it was too late.”

She left the room. Kozyrev went on staring at her application. “Well, well, well,” he said to himself. “Who’d have thought it? She hardly seems like a woman at all. Always with her Mauser, always in leather trousers. She’s led the battalion into the attack any number of times. She doesn’t even have the voice of a woman...But it seems you can’t fight Nature...”

And for some reason he felt hurt, and a little sad.

He wrote on the application, “The bearer...” And he sat there and frowned, irresolutely circling his pen nib over the paper. How should he word it? Eventually he went on: “to be granted forty days of leave from the present date...” He stopped to think, added “for reasons of health,” then inserted the word “female,” and then, with an oath, deleted the word “female.”

“Fine comrades they make!” he said, and called his orderly. “Heard about our Vavilova?” he asked loudly and angrily. “Who’d have thought it!”

“Yes,” said the orderly. He shook his head and spat.

Together they damned Vavilova and all other women. After a few dirty jokes and a little laughter, Kozyrev called for his chief of staff and said to him, “You must go around tomorrow, I suppose. Find out where she wants to have it—in a hospital or in a billet—and make sure everything’s generally all right.”

The two men then sat there till morning, poring over the one-inch-to-a-mile map and jabbing their fingers at it. The Poles were advancing.

A room was requisitioned for Vavilova. The little house was in the Yatki—as the marketplace was called—and it belonged to Haim-Abram Leibovich-Magazanik, known to his neighbors and even his own wife as Haim Tuter, that is, Haim the Tatar.

Vavilova’s arrival caused an uproar. She was brought there by a clerk from the Communal Department, a thin boy wearing a leather jacket and a pointed Budyonny helmet. Magazanik cursed him in Yiddish; the clerk shrugged his shoulders and said nothing.

Magazanik then switched to Russian. “The cheek of these snotty little bastards!” he shouted to Vavilova, apparently expecting her to share his indignation. “Whose clever idea was this? As if there weren’t a single bourgeois left in the whole town! As if there weren’t a single room left for the Soviet authorities except where Magazanik lives! As if there weren’t a spare room anywhere except one belonging to a worker with seven children! What about Litvak the grocer? What about Khodorov the cloth maker? What about Ashkenazy, our number-one millionaire?”

Magazanik’s children were standing around them in a circle—seven curly-headed angels in ragged clothes, all watching Vavilova through eyes black as night. She was as big as a house, she was twice the height of their father. All this was frightening and funny and very interesting indeed.

In the end Magazanik was pushed out of the way, and Vavilova went through to her room.

From the sideboard, from the chairs with gaping holes and sagging seats, from bedclothes now as flat and dark and flaccid as the breasts of the old women who had once received these blankets as part of their wedding dowries, there came such an overpowering smell of human life that Vavilova found herself taking a deep breath, as if about to dive deep into a pond.

That night she was unable to sleep. Behind the partition wall—as if they formed a complete orchestra, with everything from high-pitched flutes and violins to the low drone of the double bass—the Magazanik family was snoring. The heaviness of the summer night, the dense smells—everything seemed to be stifling her.

There was nothing the room did not smell of.

Paraffin, garlic, sweat, fried goose fat, unwashed linen—the smell of human life, of human habitation.

Now and then she touched her swollen, ripening belly; the living being there inside her was kicking and moving about.

For many months, honorably and obstinately, she had struggled against this being. She had jumped down heavily from her horse. During voluntary working Saturdays in the towns she had heaved huge pine logs about with silent fury. In villages she had drunk every kind of herbal potion and infusion. In bathhouses, she had scalded herself until she broke out in blisters. And she had demanded so much iodine from the regimental pharmacy that the medical assistant had been on the point of penning a complaint to the brigade medical department.

But the child had obstinately gone on growing, making it hard for her to move, making it hard for her to ride. She had felt nauseous. She had vomited. She had felt dragged down, dragged toward the earth.

At first she had blamed everything on him—on the sad, taciturn man who had proved stronger than her and had found a way through her thick leather jacket and the coarse cloth of her tunic and into her woman’s heart. She had remembered him at the head of his men, leading them at a run across a small and terrifyingly simple wooden bridge. There had been a burst of Polish machine-gun fire—and it was as if he had vanished. An empty greatcoat had flung up its arms, fallen, and then hung there over the stream.

She had galloped over him on her maddened stallion and, behind her, as if pushing her on, the battalion had hurtled forward.

What had remained was it. It, now, was to blame for everything. And Vavilova was lying there defeated, while it kicked its little hoofs victoriously. It was living inside her.

Before Magazanik went out to work in the morning, when his wife was serving him breakfast and at the same time trying to drive away the flies, the children, and the cat, he said quietly, with a sideways glance at the wall of the requisitioned room, “Give her some tea—damn her!”

It was as though he were bathing in the sunlit pillars of dust, in all the smells and sounds—the cries of the children, the mewing of the cat, the muttering of the samovar. He had no wish to go off to the workshop. He loved his wife, his children, and his old mother; he loved his home.

Sighing, he went on his way, and there remained in the house only women and children.

The cauldron of the Yatki went on bubbling all through the day. Peasant men traded birch logs as white as chalk; peasant women rustled strings of onions; old Jewish women sat above downy hillocks of geese tied together by their legs. Every now and then a seller would pluck from one of these splendid white flowers a living petal with a snaking, twisting neck—and the buyer would blow on the tender down between its legs and feel the fat that showed yellow beneath the soft warm skin.

Dark-legged lasses in colorful kerchiefs carried tall red pots brimming with wild strawberries; as if about to run away, they cast frightened looks at the buyers. People on carts sold golden, sweating balls of butter wrapped in plump burdock leaves.

A blind beggar with the white beard of a wizard was stretching out his hands and weeping tragically and imploringly, but no one was touched by his terrible grief. Everyone passed by indifferently. One woman, tearing the very smallest onion off her string, threw it into the old man’s tin bowl. He felt it, stopped praying, and said angrily, “May your children be as generous to you in your old age!” And he again began intoning a prayer as ancient as the Jewish nation.

People bought and sold, poked and prodded, raising their eyes as if expecting someone from the tender blue sky to offer them counsel: Should they buy the pike or might they be better off with a carp? And all the time they went on cursing, screeching, scolding one another, and laughing.

Vavilova tidied and swept her room. She put away her greatcoat, her sheepskin hat, and her riding boots. The noise outside was making her head thump, while inside the apartment the little Tuters were all shouting and screaming, and she felt as though she were asleep and dreaming somebody else’s bad dream.

In the evening, when he came back home from work, Magazanik stopped in the doorway. He was astounded: his wife, Beila, was sitting at the table—and beside her was a large woman in an ample dress, with loose slippers on her bare feet and a bright-colored kerchief around her head. The two women were laughing quietly, talking to each other, raising and lowering their large broad hands as they sorted through a heap of tiny undershirts.

Beila had gone into Vavilova’s room during the afternoon. Vavilova had been standing by the window, and Beila’s sharp feminine eye had made out the swollen belly partly concealed by Vavilova’s height.

“Begging your pardon,” Beila had said resolutely, “but it seems to me that you’re pregnant.”

And Beila had begun fussing around her, waving her hands about, laughing and lamenting.

“Children,” she said, “children—do you have any idea what misery they bring with them?” And she squeezed the youngest of the Tuters against her bosom. “Children are such a grief, such a calamity, such never-ending trouble. Every day they want to eat, and not a week passes by but one of them gets a rash and another gets a boil or comes down with a fever. And Doctor Baraban—may God grant him health—expects ten pounds of the best flour for every visit he makes.”

She stroked little Sonya’s head. “And every one of my lot is still living. Not one of them’s going to die.”

Vavilova had turned out to know nothing at all; she did not understand anything, nor did she know how to do anything. She had immediately subordinated herself to Beila’s great knowledge. She had listened, and she had asked questions, and Beila, laughing with pleasure at the ignorance of this woman commissar, had told her everything she needed to know.

How to feed a baby; how to wash and powder a baby; how to stop a baby crying at night; how many diapers and babies’ shirts she was going to need; the way newborn babies can scream and scream until they’re quite beside themselves; the way they turn blue and your heart almost bursts from fear that your child is about to die; the best way to cure the runs; what causes diaper rash; how one day a teaspoon will make a knocking sound against a child’s gums and you know that it’s started to teethe.

A complex world with its own laws and customs, its own joys and sorrows.

It was a world about which Vavilova knew nothing—and Beila indulgently, like an elder sister, had initiated her into it.

“Get out from under our feet!” she had yelled at the children. “Out you go into the yard—quick march!” The moment they were alone in the room, Beila had lowered her voice to a mysterious whisper and begun telling Vavilova about giving birth. Oh no, childbirth was no simple matter—far from it. And like an old soldier talking to a new recruit, Beila had told Vavilova about the great joys and torments of labor.

“Childbirth,” she had said. “You think it’s child’s play, like war. Bang, bang—and there’s an end to it. No, I’m sorry, but that’s not how it is at all.”

Vavilova had listened to her. This was the first time in all the months of her pregnancy that she had met someone who spoke of the unfortunate accident that had befallen her as if it were a happy event, as if it were the most important and necessary thing in her life.

Discussions, now including Magazanik, continued into the evening. There was no time to lose. Immediately after supper, Magazanik took a candle, went up into the attic, and with much clattering brought down a metal cradle and a little tub for bathing the new person.

“Have no fears, comrade Commissar,” he said. He was laughing and his eyes were shining. “You’re joining a thriving business.”

“Shut your mouth, you rascal!” said his wife. “No wonder they call you an ignorant Tatar.”

That night Vavilova lay in her bed. The dense smells no longer felt stifling, as they had during the previous night. She was used to them now; she was not even aware of them. She no longer wanted to have to think about anything.

It seemed to her that there were horses nearby and that she could hear them neighing. She glimpsed a long row of horses’ heads; the horses were all chestnut and each had a white blaze on its forehead. The horses were constantly moving, nodding, snorting, baring their teeth. She remembered the battalion; she remembered Kirpichov, the political officer of the Second Company. There was a lull in the fighting at present. Who would give the soldiers their political talks? Who would tell them about the July days? The quartermaster should be hauled over the coals for this delay in the issue of boots. Once they had boots, the soldiers could make themselves footcloths. There were a lot of malcontents in the second company, especially that curly-headed fellow who was always singing songs about the Don. Vavilova yawned and closed her eyes. The battalion had gone somewhere far, far away, into the pink corridor of the dawn, between damp ricks of hay. And her thoughts about it were somehow unreal.

It gave an impatient push with its little hoofs. Vavilova opened her eyes and sat up in bed.

“A boy or a girl?” she asked out loud.

And all of a sudden her heart felt large and warm. Her heartbeats were loud and resonant.

“A boy or a girl?”

In the afternoon she went into labor.

“Oy!” she screamed hoarsely, sounding more like a peasant woman than a commissar. The pain was sharp, and it penetrated everywhere.

Beila helped her back to her bed. Little Syoma ran off merrily to fetch the midwife.

Vavilova was clutching Beila’s hand. She was speaking quickly and quietly: “It’s started, Beila. I’d thought it would be another ten days. It’s started, Beila.”

Then the pains stopped, and she thought she’d been wrong to send for the midwife.

But half an hour later the pains began again. Vavilova’s tan now seemed separate from her, like a mask; underneath it her face had gone white. She lay there with her teeth clenched. It was as if she were thinking about something tormenting and shameful, as if, any minute now, she would jump up and scream, “What have I done! What have I gone and done!” And then, in her despair, she would hide her face in her hands.

The children kept peeping into the room. Their blind grandmother was by the stove, boiling a large saucepan of water. Alarmed by the look of anguish on Vavilova’s face, Beila kept looking toward the street door. At last the midwife arrived. Her name was Rosalia Samoilovna. She was a stocky woman with a red face and close-cropped hair. Soon the whole house was filled by her piercing, cantankerous voice. She shouted at Beila, at the children, at the old grandmother. Everyone began bustling about. The Primus stove in the kitchen began to hum. The children began dragging the table and chairs out of the room. Looking as if she were trying to put out a fire, Beila was hurriedly mopping the floor. Rosalia Samoilovna was driving the flies away with a towel. Vavilova watched her and for a moment thought they were in the divisonal headquarters and that the army commander had just arrived. He too was stocky, red-faced, and cantankerous, and he used to show up at times when the Poles had suddenly broken through the front line, when everyone was reading communiqués, whispering, and exchanging anxious looks as though a dead body or someone mortally ill were lying in the room with them. And the army commander would slash through this web of mystery and silence. He would curse, laugh, and shout out orders: What did he care about supply trains that had been cut off or entire regiments that had been surrounded?

Vavilova subordinated herself to Rosalia Samoilovna’s powerful voice. She answered her questions; she turned onto her back or her side; she did everything she was told. Now and then her mind clouded. The walls and the ceiling lost their outlines; they were breaking up and moving in on her like waves. The midwife’s loud voice would bring her back to herself. Once again she would see Rosalia Samoilovna’s red, sweating face and the ends of the white kerchief tied over her hair. Her mind was empty of thoughts. She wanted to howl like a wolf; she wanted to bite the pillow. Her bones were cracking and breaking apart. Her forehead was covered by a sticky, sickly sweat. But she did not cry out; she just ground her teeth and, convulsively jerking her head, gasped in air.

Sometimes the pain went away, as if it had never been there at all, and she would look around in amazement, listening to the noise of the market, astonished by a glass on a stool or a picture on the wall.

When the child, desperate for life, once again began fighting its way out, she felt not only terror of the pain to come but also an uncertain joy: there was no getting away from this, so let it be quick.

Rosalia Samoilovna said quietly to Beila, “If you think I’d wish it upon myself to be having my first child at the age of thirty-six, then you’re wrong, Beila.”

Vavilova had not been able to make out the words, but it frightened her that Rosalia Samoilovna was speaking so quietly.

“What?” she asked. “Am I going to die?”

She did not hear Rosalia Samoilovna’s answer. As for Beila, she was looking pale and lost. Standing in the doorway, shrugging her shoulders, she was saying, “Oy, oy, who needs all this? Who needs all this suffering? She doesn’t need it. Nor does the child. Nor does the father, drat him. Nor does God in his heaven. Whose clever idea was it to torment us like this?”

The birth took many hours.

When he got back from work, Magazanik sat on the front steps, as anxious as if it were not Vavilova but his own Beila who was giving birth. The twilight thickened; lights appeared in the windows. Jews were coming back from the synagogue, their prayer garments rolled up under their arms. In the moonlight the empty marketplace and the little streets and houses seemed beautiful and mysterious. Red Army men in riding breeches, their spurs jingling, were walking along the brick pavements. Young girls were nibbling sunflower seeds, laughing as they looked at the soldiers. One of them was gabbling: “And I was eating sweets and throwing the wrappers at him, eating sweets and tossing the wrappers at him...”

“Yes,” Magazanik said to himself. “It’s like in the old tale...So little work to do in the house that she had to go and buy herself a clutch of piglets. So few cares of my own that I have to have a whole partisan brigade giving birth in my house.” All of a sudden he pricked up his ears and stood up. Inside the house he had heard a hoarse male voice. The oaths and curses this voice was shouting were so foul that Magazanik could only shake his head and spit. The voice was Vavilova’s. Crazed with pain, and in the last throes of labor, she was wrestling with God, with woman’s accursed lot.

“Yes,” said Magazanik. “You can tell it’s a commissar giving birth. The strongest words I’ve ever heard from my own dear Beila are ‘Oy, Mama! Oy, Mama! Oy, dearest Mama of mine!’ ”

Rosalia Samoilovna smacked the newborn on its damp, wrinkled bottom and declared, “It’s a boy!”

“What did I say!” cried Beila. Half opening the door, she cried out triumphantly, “Haim, children, it’s a boy!”

And the entire family clustered in the doorway, excitedly talking to Beila. Even the blind grandmother had managed to find her way over to her son and was smiling at the great miracle. She was moving her lips; her head was shaking and trembling as she ran her numb hands over her black kerchief. She was smiling and whispering something no one could hear. The children were pushing her back from the door, but she was pressing forward, craning her neck. She wanted to hear the voice of ever-victorious life.

Vavilova was looking at the baby. She was astonished that this insignificant ball of red-and-blue flesh could have caused her such suffering.

She had imagined that her baby would be large, snub-nosed, and freckled, that he would have a shock of red hair and that he would immediately be getting up to mischief, struggling to get somewhere, calling out in a piercing voice. Instead, he was as puny as an oat stalk that had grown in a cellar. His head wouldn’t stay upright; his bent little legs looked quite withered as they twitched about; his pale blue eyes seemed quite blind; and his squeals were barely audible. If you opened the door too suddenly, he might be extinguished—like the thin, bent little candle that Beila had placed above the edge of the cupboard.

And although the room was as hot as a bathhouse, she stretched out her arms and said, “But he’s cold—give him to me!” The little person was chirping, moving his head from side to side. Vavilova watched him through narrowed eyes, barely daring to move. “Eat, eat, my little son,” she said, and she began to cry. “My son, my little son,” she murmured—and the tears welled up in her eyes and, one after another, ran down her tanned cheeks until they disappeared into the pillow.

She remembered him, the taciturn one, and she felt a sharp maternal ache—a deep pity for both father and son. For the first time, she wept for the man who had died in combat near Korosten: never would this man see his own son.

And this little one, this helpless one, had been born without a father. Afraid he might die of cold, she covered him with the blanket.

Or maybe she was weeping for some other reason. Rosalia Samoilovna, at least, seemed to think so. After lighting a cigarette and letting the smoke out through the little ventilation pane, she said, “Let her cry, let her cry. It calms the nerves better than any bromide. All my mothers cry after giving birth.”

Two days after the birth, Vavilova got up from her bed. Her strength was returning to her; she walked about a lot and helped Beila with the housework. When there was no one around, she quietly sang songs to the little person. This little person was now called Alyosha, Alyoshenka, Alyosha...

“You wouldn’t believe it,” Beila said to her husband. “That Russian woman’s gone off her head. She’s already rushed to the doctor with him three times. I can’t so much as open a door in the house: he might catch a cold, or he’s got a fever, or we might wake him up. In a word, she’s turned into a good Jewish mother.”

“What do you expect?” replied Magazanik. “Is a woman going to turn into a man just because she wears a pair of leather breeches?” And he shrugged his shoulders and closed his eyes.

A week later, Kozyrev and his chief of staff came to visit Vavilova. They smelled of leather, tobacco, and horse sweat. Alyosha was sleeping in his cradle, protected from the flies by a length of gauze. Creaking deafeningly, like a pair of brand-new leather boots, the two men approached the cradle and looked at the sleeper’s thin little face. It was twitching. The movements it made—although no more than little movements of skin—imparted to it a whole range of different expressions: sorrow, anger, and then a smile.

The soldiers exchanged glances.

“Yes,” said Kozyrev.

“No doubt about it,” said the chief of staff.

And they sat down on two chairs and began to talk. The Poles had gone on the offensive. Our forces were retreating. Temporarily, of course. The Fourteenth Army was regrouping at Zhmerinka. Divisions were coming up from the Urals. The Ukraine would soon be ours. In a month or so there would be a breakthrough, but right now the Poles were causing trouble.

Kozyrev swore.

“Sh!” said Vavilova. “Don’t shout or you’ll wake him.”

“Yes, we’ve been given a bloody nose,” said the chief of staff.

“You do talk in a silly way,” said Vavilova. In a pained voice she added, “I wish you’d stop smoking. You’re puffing away like a steam engine.”

The soldiers suddenly began to feel bored. Kozyrev yawned. The chief of staff looked at his watch and said, “It’s time we were on our way to Bald Hill. We don’t want to be late.”

“I wonder where that gold watch came from,” Vavilova thought crossly.

“Well, Klavdiya, we must say goodbye to you!” said Kozyrev. He got to his feet and went on: “I’ve given orders for you to be delivered a sack of flour, some sugar, and some fatback. A cart will come around later today.”

The two men went out into the street. The little Magazaniks were all standing around the horses. Kozyrev grunted heavily as he clambered up. The chief of staff clicked his tongue and leaped into the saddle.

When they got to the corner, the two men abruptly, as though by prior agreement, pulled on the reins and stopped.

“Yes,” said Kozyrev.

“No doubt about it,” said the chief of staff. They burst into laughter. Whipping their horses, they galloped off to Bald Hill.

The two-wheeled cart arrived in the evening. After dragging the provisions inside, Magazanik went into Vavilova’s room and said in a conspiratorial whisper, “What do you make of this, comrade Vavilova? We’ve got news—the brother-in-law of Tsesarsky the cobbler has just come to the workshop.” He looked around and, as if apologizing for something, said in a tone of disbelief, “The Poles are in Chudnov, and Chudnov’s only twenty-five miles away.”

Beila came in. She had overheard some of this, and she said resolutely, “There’s no two ways about it—the Poles will be here tomorrow. Or maybe it’ll be the Austrians or the Galicians. Anyway, whoever it is, you can stay here with us. And they’ve brought you enough food—may the Lord be praised—for the next three months.”

Vavilova said nothing. For once in her life she did not know what to do.

“Beila,” she began, and fell silent.

“I’m not afraid,” said Beila. “Why would I be afraid? I can manage five like Alyosha—no trouble at all. But whoever heard of a mother abandoning a ten-day-old baby?”

All through the night there were noises outside the window: the neighing of horses, the knocking of wheels, loud exclamations, angry voices. The supply carts were moving from Shepetovka to Kazatin.

Vavilova sat by the cradle. Her child was asleep. She looked at his little yellow face. Really, nothing very much was going to happen. Kozyrev had said that they would be back in a month. That was exactly the length of time she was expecting to be on leave. But what if she were cut off for longer? No, that didn’t frighten her, either.

Once Alyosha was a bit stronger, they’d find their way across the front line.

Who was going to harm them—a peasant woman with a babe in arms? And Vavilova imagined herself walking through the countryside early on a summer’s morning. She had a colored kerchief on her head, and Alyosha was looking all around and stretching out his little hands. How good it all felt! In a thin voice she began to sing, “Sleep, my little son, sleep!” And, as she was rocking the cradle, she dozed off.

In the morning the market was as busy as ever. The people, though, seemed especially excited. Some of them, watching the unbroken chain of supply carts, were laughing joyfully. But then the carts came to an end. Now there were only people. Standing by the town gates were just ordinary townsfolk—the “civilian population” of decrees issued by commandants. Everybody was looking around all the time, exchanging excited whispers. Apparently the Poles had already taken Pyatka, a shtetl only ten miles away. Magazanik had not gone out to work. Instead, he was sitting in Vavilova’s room, philosophizing for all he was worth.

An armored car rumbled past in the direction of the railway station. It was covered in a thick layer of dust—as if the steel had gone gray from exhaustion and too many sleepless nights.

“To be honest with you,” Magazanik was saying, “this is the best time of all for us townsfolk. One lot has left—and the next has yet to arrive. No requisitions, no ‘voluntary contributions,’ no pogroms.”

“It’s only in the daytime that he’s so smart,” said Beila. “At night, when there are bandits on every street and the whole town’s in uproar, he sits there looking like death. All he can do is shake with terror.”

“Don’t interrupt,” Magazanik said crossly, “when I’m talking to someone.”

Every now and then he would slip out to the street and come back with the latest news. The Revolutionary Committee had been evacuated during the night, the district Party Committee had gone next, and the military headquarters had left in the morning. The station was empty. The last army train had already gone.

Vavilova heard shouts from the street. An airplane in the sky! She went to the window. The plane was high up, but she could see the white-and-red roundels on its wings. It was a Polish reconnaissance plane. It made a circle over the town and flew off toward the station. And then, from the direction of Bald Hill, cannons began firing.

The first sound they heard was that of the shells; they howled by like a whirlwind. Next came the long sigh of the cannons. And then, a few seconds later, from beyond the level crossing—a joyful peal of explosions. It was the Bolsheviks—they were trying to slow the Polish advance. Soon the Poles were responding in kind; shells began to land in the town.

The air was torn by deafening explosions. Bricks were crumbling. Smoke and dust were dancing over the flattened wall of a building. The streets were silent, severe, and deserted—now no more substantial than sketches. The quiet after each shell burst was terrifying. And from high in a cloudless sky the sun shone gaily down on a town that was like a spread-eagled corpse.

The townsfolk were all in their cellars and basements. Their eyes closed, barely conscious, they were holding their breath or letting out low moans of fear.

Everyone, even the little children, knew that this bombardment was what is known as an “artillery preparation” and that there would be another forty or fifty explosions before the soldiers entered the town. And then—as everyone knew—it would become unbelievably quiet until, all of a sudden, clattering along the broad street from the level crossing, a reconnaissance patrol galloped up. And, dying of fear and curiosity, everyone would be peeping out from behind their gates, peering through gaps in shutters and curtains. Drenched in sweat, they would begin to tiptoe out to the street.

The patrol would enter the main square. The horses would prance and snort; the riders would call out to one another in a marvelously simple human language, and their leader, delighted by the humility of this conquered town now lying flat on its back, would yell out in a drunken voice, fire a revolver shot into the maw of the silence, and get his horse to rear.

And then, pouring in from all sides, would come cavalry and infantry. From one house to another would rush tired dusty men in blue greatcoats—thrifty peasants, good-natured enough yet capable of murder and greedy for the town’s hens, boots, and towels.

Everybody knew all this, because the town had already changed hands fourteen times. It had been held by Petlyura, by Denikin, by the Bolsheviks, by Galicians and Poles, by Tyutyunik’s brigands and Marusya’s brigands, and by the crazy Ninth Regiment that was a law unto itself. And it was the same story each time.

“They’re singing!” shouted Magazanik. “They’re singing!”

And, forgetting his fear, he ran out onto the front steps. Vavilova followed him. After the stuffiness of the dark room, it was a joy to breathe in the light and warmth of the summer day. She had been feeling the same about the Poles as she had felt about the pains of labor: they were bound to come, so let them come quick. If the explosions scared her, it was only because she was afraid they would wake Alyosha; the whistling shells troubled her no more than flies—she just brushed them aside.

“Hush now, hush now,” she had sung over the cradle. “Don’t go waking Alyosha.”

She was trying not to think. Everything, after all, had been decided. In a month’s time, either the Bolsheviks would be back or she and Alyosha would cross the front line to join them.

“What on earth’s going on?” said Magazanik. “Look at that!”

Marching along the broad empty street, toward the level crossing from which the Poles should be about to appear, was a column of young Bolshevik cadets. They were wearing white canvas trousers and tunics.

“Ma-ay the re-ed banner embo-ody the workers’ ide-e-als,” they sang, drawing out the words almost mournfully.

They were marching toward the Poles.

Why? Whatever for?

Vavilova gazed at them. And suddenly it came back to her: Red Square, vast as ever, and several thousand workers who had volunteered for the front, thronging around a wooden platform that had been knocked together in a hurry. A bald man, gesticulating with his cloth cap, was addressing them. Vavilova was standing not far from him.

She was so agitated that she could not take in half of what he said, even though, apart from not quite being able to roll his r’s, he had a clear voice. The people standing beside her were almost gasping as they listened. An old man in a padded jacket was crying.

Just what had happened to her on that square, beneath the dark walls, she did not know. Once, at night, she had wanted to talk about it to him, to her taciturn one. She had felt he would understand. But she had been unable to get the words out...And as the men made their way from the square to the Bryansk Station, this was the song they had been singing.

Looking at the faces of the singing cadets, she lived through once again what she had lived through two years before.

The Magazaniks saw a woman in a sheepskin hat and a greatcoat running down the street after the cadets, slipping a cartridge clip into her large gray Mauser as she ran.

Not taking his eyes off her, Magazanik said, “Once there were people like that in the Bund. Real human beings, Beila. Call us human beings? No, we’re just manure.”

Alyosha had woken up. He was crying and kicking about, trying to kick off his swaddling clothes. Coming back to herself, Beila said to her husband, “Listen, the baby’s woken up. You’d better light the Primus—we must heat up some milk.”

The cadets disappeared around a turn in the road.

A Small Life*

MOSCOW spends the last ten days of April preparing for May Day. The cornices of buildings and the little iron railings along boulevards are repainted, and in the evenings mothers throw up their hands in despair at the sight of their sons’ trousers and coats. On all the city’s squares carpenters merrily saw up planks that still smell of pine resin and the damp of the forest. Supplies managers use their directors’ cars to collect great heaps of red cloth.

Visitors to different government institutions find that their requests all meet with the same answer: “Yes, but let’s leave this until after the holiday!”

Lev Sergeyevich Orlov was standing on a street corner with his colleague Timofeyev. Timofeyev was saying, “You’re being an old woman, Lev Sergeyevich. We could go to a beer hall or a restaurant. We could just wander about and watch the crowds. So what if it upsets your wife? You’re an old woman, the most complete and utter old woman!”

But Lev Sergeyevich said goodbye and went on his way. Morose by nature, he used to say of himself, “I’m made in such a way that I see what is tragic, even when it’s covered by rose petals.”

And Lev Sergeyevich truly did see tragedy everywhere.

Even now as he made his way through the crowds he was thinking how awful it must feel to be stuck in a hospital during these days of merriment, how miserable these days must be for pharmacists, engine drivers, and train crews—people who have to work on the First of May.

When he got home, he said all this to his wife. She began to laugh at him, but he just shook his head and carried on being upset.

Still turning over the same thoughts, he continued to let out loud sighs until late into the night. His wife said angrily, “Lyova, why do you have to feel so sorry for the pharmacists? Why not feel sorry for me for a change and let me sleep? You know I’ve got to be at work by eight o’clock.”

And, the next day, she did indeed leave for work while Lev Sergeyevich was still asleep.

In the mornings he was usually in a good mood at the office, but by two in the afternoon he would be missing his wife, feeling anxious and fidgety and constantly watching the clock. His colleagues understood all this and used to make fun of him.

“Lev Sergeyevich is already looking at the clock,” someone would say—and everyone would laugh except for Agnessa Petrovna, the elderly head accountant, who would pronounce with a sigh: “Orlov’s wife is the luckiest woman in all Moscow.”

This day was no different. As the afternoon wore on, he grew fidgety, shrugging his shoulders in disbelief as he watched the minute hand of the clock.

“Someone to speak to you, Lev Sergeyevich,” a voice called from the adjoining room. It turned out to be his wife—phoning to say that she would have to stay on at work for an extra hour and a half to retype the director’s report.

“All right then,” Lev Sergeyevich replied in a hurt voice, and he hung up.

He did not hurry home. The city was buzzing, and the buildings, streets, and sidewalks all seemed somehow special, not like themselves at all. And this intangible something, born of the May Day sense of community, took many forms. It could be sensed even in the way a policeman was dragging away a drunk. It was as though all the men wandering about the street were related—as though they were all cousins, or uncles and nephews.

Today he would have been only too glad to saunter about with Timofeyev. It was unpleasant being the first to get back home. The room always seems empty and unwelcoming, and there is no getting away from frightening thoughts: What if something had happened to Vera Ignatyevna? What if she had twisted her ankle jumping off a tram?

Lev Sergeyevich would start to imagine that some hulking trolley car had knocked Vera Ignatyevna down, that people were crowding around her body, that an ambulance was tearing along, wailing ominously. He would be seized with terror; he would want to phone friends and family; he would want to rush to the Emergency First-Aid Institute or to the police.

Every time his wife was ten or fifteen minutes late it was the same. He would feel the same panic.

What a lot of people there were on the street now! Why were they all sauntering up and down the boulevard, sitting idly on benches, stopping in front of every illuminated shop window? But then he came to his own building, and his heart leaped for joy. The little ventilation pane was open—his wife was already back.

He kissed Vera Ignatyevna several times. He looked into her eyes and stroked her hair.

“What a strange one you are!” she said. “It’s the same every time. Anyone would think I’ve come back from Australia, not from the Central Rubber Office.”

“If I don’t see you all day,” he replied, “you might just as well be in Australia.”

“You and your eternal Australia!” said Vera Ignatyevna. “They ask me to help type the wall newspaper—and I refuse. I skip Air-Chem Defense Society meetings and come rushing back home. Kazakova has two little children—but Kazakova has no trouble at all staying behind. And that’s not all—she’s a member of the automobile club as well!”

“What a silly darling goose you are!” said Lev Sergeyevich. “Who ever heard of a wife giving her husband a hard time for being too much of a stay-at-home?”

Vera Ignatyevna wanted to answer back, but instead she said in an excited voice, “I’ve got a surprise for you! The Party committee’s been asking people to take in orphanage children for a few days over the holiday. I volunteered—I said we’d like a little girl. You won’t be cross with me, will you?”

Lev Sergeyevich gave his wife a hug.

“How could I be cross with my clever girl?” he said. “It scares me even to think about what I’d be doing and how I’d be living now if chance hadn’t brought us together at that birthday party at the Kotelkovs.”

On the evening of April 29, Vera Ignatyevna was brought back home in a Ford. As she went up the stairs, pink with pleasure, she said to the little girl who had come with her, “What a treat to go for a ride in a car. I could have carried on riding around for the rest of my life!”

It was the second time Vera Ignatyevna had been in a car. Two years before, when her mother-in-law had come to visit, they had taken a taxi from the station. True, that first ride had not been all it might have been—the driver had never stopped cursing, saying his tires would probably collapse and that, with such a mountain of luggage, they should have taken a three-ton truck.

Vera Ignatyevna and her little guest had barely entered the room when the doorbell rang.

“Ah, it must be Uncle Lyova,” said Vera Ignatyevna. She took the little girl by the hand and led her toward the door.

“Let me introduce you,” she said. “This is Ksenya Mayorova, and this is comrade Orlov, Uncle Lyova, my husband.”

“Greetings, my child!” said Orlov, and patted the little girl on the head.

He felt disappointed. He had imagined the little girl would be tiny and pretty, with sad eyes like the eyes of a grown-up woman. Ksenya Mayorova, however, was plain and stocky, with fat red cheeks, lips that stuck out a little, and eyes that were gray and narrow.

“We came by car,” she boasted in a deep voice.

While Vera Ignatyevna was preparing supper, Ksenya wandered about the room examining everything.

“Auntie, have you got a radio?” she asked.

“No, darling. But come here—there’s something we have to do.”

Vera Ignatyevna took her into the bathroom. There they talked about the zoo and the planetarium.

During supper Ksenya looked at Lev Sergeyevich, laughed, and said pointedly, “Uncle didn’t wash his hands!”

She had a deep voice, but her laugh was thin and giggly.

Vera Ignatyevna asked Ksenya how much seven and eight came to, and what was the German word for a door. She asked her if she knew how to skate. They argued about what was the capital of Belgium; Vera Ignatyevna thought it was Antwerp. “No, it’s Geneva,” Ksenya insisted, pouting and stubbornly shaking her head.

Lev Sergeyevich took his wife aside and whispered, “Put her to bed. Then I’ll sit with her and tell her a story—she doesn’t feel at home with us yet.”

“Why don’t you go out into the corridor and have a smoke?” answered his wife. “In the meantime we can air the room.”

Lev Sergeyevich walked up and down the corridor and struggled to recall a fairy tale. Little Red Riding Hood? No, she probably knew it already. Maybe he should just tell her about the quiet little town of Kasimov, about the forests there, about going for walks on the bank of the Oka—about his grandmother, about his brother, about his sisters?

When his wife called him back, Ksenya was already in bed. Lev Sergeyevich sat down beside her and patted her on the head.

“Well,” he asked, “how do you like it here?”

Ksenya yawned convulsively and rubbed her eyes with one fist.

“It’s all right,” she said. “But it must be very hard for you without a radio.”

Lev Sergeyevich began recounting stories from his childhood. Ksenya yawned three times in quick succession and said, “You shouldn’t sit on someone’s bed if you’re wearing clothes. Microbes can crawl off you.”

Her eyes closed. Half asleep, she began mumbling incoherently, telling some crazy story.

“Yes,” she whined. “They didn’t let me go on the excursion. Lidka saw when we were still in the garden...Why didn’t she say anything...?And I carried it twice in my pocket...I’ve been pricked all over...but it wasn’t me who told them about the glass, she’s a sneak...”

She fell asleep. Lev Sergeyevich and his wife went on looking at her face in silence. She was sleeping very quietly, her lips sticking out more than ever, her reddish pigtails moving very slightly against the pillow.

Where was she from? The Ukraine, the north Caucasus, the Volga? Who had her father been? Perhaps he had died doing some glorious work in a mine or in the smoke of some huge furnace? Perhaps he had drowned while floating timber down a river? Who had he been? A mechanic? A porter? A housepainter? A shopkeeper? There was something magnificent and touching about this peacefully sleeping little girl.

In the morning Vera Ignatyevna went off to do some shopping. She needed to stock up for the three days of the holiday. She also wanted to go to the Mostorg Department Store and buy some silk for a summer dress. Lev Sergeyevich and Ksenya stayed behind.

“Listen, mein liebes Kind,” he said. “We’re not going out anywhere today, we’re going to stay at home.”

He sat Ksenya down on his knee, put an arm around her shoulder, and began telling her stories.

“Sit still now, be a good girl,” he would say every time she tried to get down. In the end Ksenya sat still, snuffling occasionally as she watched this talking uncle.

By the time Vera Ignatyevna got back, it was already four o’clock. There had been a lot of people in the shops.

“Why are you looking so sulky, Ksenya?” she asked in a startled voice.

“Why shouldn’t I look sulky?” Ksenya answered. “Maybe I’m hungry.”

Vera Ignatyevna hurried into the kitchen to prepare supper; Lev Sergeyevich carried on entertaining their little guest.

After supper, Ksenya asked for a pencil and some paper, so she could write a letter. “But I don’t need a stamp,” she added. “I’ll give it to Lidka myself.”

While Ksenya was writing, Vera Ignatyevna suggested to her husband that they all go out to the cinema, but Lev Sergeyevich did not like this idea. “What on earth are you thinking of, Vera? The crowds tonight will be terrible. In the first place we won’t be able to get tickets. In the second place, it’s the kind of evening one wants to spend at home.”

“It’s our good fortune to spend all our evenings at home,” retorted Vera Ignatyevna.

“Please don’t start an argument,” snapped Lev Sergeyevich.

“The girl’s bored. She’s used to being with other people all the time. She’s used to being with her friends.”

“Oh, Vera, Vera,” he replied.

Later in the evening they all had tea with cornel jam, and they ate a cake and some pastries. Ksenya enjoyed the cake very much indeed; Vera Ignatyevna felt worried, put her hand on the little girl’s tummy, and shook her head. Soon afterward the girl’s tummy did indeed start to ache. She turned very sullen and stood for a long time by the window, pressing her nose to the cold glass. When the glass became warm, she moved along a little and began to warm another patch of glass with her nose.

Lev Sergeyevich went up to her and asked, “What are you thinking about?”

“Everything,” the girl answered crossly, and went back to squashing her nose into the glass.

In the orphanage they were probably about to have supper. There hadn’t been time for her to receive her present, and she was sure to be left something boring, like a book about animals. She already had one of those. Still, she’d be able to do a swap. This Auntie Vera was really nice. A pity she wasn’t one of the staff. The girls who’d stayed behind in the orphanage were going to spend all day riding about in a truck. As for herself, she was going to become a pilot and drop a gas bomb on this strange Uncle Lyova...There were some quite big girls out in the yard...they were probably from group seven.

She dozed off on her feet and banged her forehead against the glass.

“Go to bed, Ksenka!” said Vera Ignatyevna.

“I butted the glass just like a ram,” said Ksenya.

Lev Sergeyevich woke up in the night. He put out a hand to touch his wife’s shoulder, but she wasn’t there.

“What’s up? Where’s my darling Verochka?” he thought in alarm.

He could hear a quiet voice coming from the sofa, and sobs.

“Calm down now, you silly thing,” Vera Ignatyevna was saying. “How can I take you back at night? There aren’t any trams, and we’d have to walk all the way across Moscow.”

“I kno-o-o-w,” answered a deep voice, in between sobs. “But he’s so very dismable.”

“Never mind, never mind. He’s kind, he’s good. You can see I’m not crying!”

Lev Sergeyevich covered his head with the blanket, so as not to hear any more. Pretending he was asleep, he began quietly snoring.

A Young Woman and an Old Woman*

STEPANIDA Yegorovna Goryacheva, head of a department of an All-Union People’s Commissariat, was leaving for the Crimea that evening. Her vacation began on August 1, but since July 30 was a Saturday, she had decided to leave early, on the evening of the twenty-ninth.

First, however, she had to hurry straight from her office to her dacha in Kuntsevo. Her car was being serviced; afraid of being late, she telephoned her old comrade Cheryomushkin. In 1932 they had worked in the same brigade on a State grain farm; they had both been assistants to the operator of the combine harvester. Cheryomushkin immediately sent over a car—an M-1.

Now she was being driven down the broad new highway to Kuntsevo.

“What’s that knocking?” Goryacheva asked the driver.

The driver gave her a sideways look, licked his upper lip, and by way of reply, asked a question himself: “Will you be needing me long?”

“I shall be needing you for as long as I need you.”

“The car should have gone in for a service today. I told Cheryomushkin.”

“I have to be at the station by eleven. I can’t let you go until then.”

Goryacheva glanced at the driver several times, but she did not say any more to him; he really did look very sullen. They continued along the road. Coming from the opposite direction were other M-1s, their paintwork gleaming, and long ZIS’s—beige, green, or black. At intervals along the highway, which was delineated by a broken white line, were benches with awnings, so that people could wait for buses in comfort, and smart, brightly colored little bridges at places where pedestrians needed to cross over. There were also policemen in white gloves, patrolling the highway with the unhurried calm of men aware of their power. None of the cars was traveling at a speed of less than seventy kilometers an hour—barely had Goryacheva noticed a black point on the gray, matte roadway than this point began to increase in size with precipitate swiftness. And only a few seconds later she glimpsed people’s faces, shining glass, and then the oncoming car was gone—as if it had never been there at all, as if she had simply imagined a forage cap, a heap of wildflowers, a woman’s head below a broad hat. Equally swift, equally precipitate in their appearance and disappearance were a wooden shelter, little wooden houses with little windows crowded with flowerpots, and a woman in a black dress who was grazing a goat.

Goryacheva had driven to the dacha many times, and she was still always struck by this troubling swiftness, by the ease with which objects, people, and animals appeared, grew bigger, and then disappeared in a flash. In the dacha lived her mother, Marya Ivanovna, and her two nieces—Vera and Natashka, the daughters of her late sister. It was a big luxurious dacha, and she and her family shared the eight rooms with the family of another senior official. Until 1937 a certain Yezhegulsky, a man without any children, had lived there with his wife and his old father. Yezhegulsky had been arrested as an enemy of the people; it was over a year now since Goryacheva had moved in, and there was nothing left to recall Yezhegulsky’s existence except for the yellow lilies his father had planted outside the windows. And her fellow occupant, Senyatin—a director of the People’s Commissariat of State Farms—had once shown her a large chest he had found in a shed. It was filled with pinecones, each one wrapped in its own piece of white paper and surrounded by cotton wool. Some of the cones were huge, like strange birds whose wooden feathers, adorned with drops of amber resin, were all standing on end; some were tiny, smaller than acorns. There were pinecones from the Mediterranean and pinecones from the far north of Siberia. These hundreds of pinecones had been collected by the former occupant of their dacha. There was something comical about all these pinecones of different sizes, all so decorous and self-important, all of them wrapped like little dolls in paper and cotton wool. Goryacheva and Senyatin had looked at each other, shaken their heads, and smiled.

“We’ll just have to burn them in the stove,” she had said. “We can’t even use them for the samovar—hand grenades like these are too big!”

“What do you mean, comrade Goryacheva?” Senyatin had answered. “You’re lacking in consciousness. To a botanist they could be of real value. I’ll take the box to the Young Naturalists—or else to a museum.”

The car drew up outside the dacha. While Goryacheva was still talking to the driver, discussing what time they’d need to leave for the station, Vera and Natashka came running to meet her. Their grandmother, Marya Ivanovna, followed them out of the house. The driver parked the car in the shade, on some grass near the gate, as if it were nicer and more fun for the car to stand on fresh grass and in the shade of tall trees. He walked slowly around the car, admired the pneumatic tires, kicked one of them with his boot—not to check its condition but simply for his own satisfaction—wiped the windscreen with his sleeve, shook his head a little, walked over toward the fence, and lay down on the grass. The car smelled of gasoline and hot oil. He breathed this in with delight and thought, “She’s had a good run, she’s worked up a sweat.”

He was dozing off when old Marya Ivanovna walked by with a bucket.

“Our water’s no good, it’s stagnant,” she said, stopping beside him. “We can’t even use it for cooking.” He did not say anything himself, but she began telling him how their water would be fine too if it weren’t for their neighbor’s vicious dog. The dog didn’t let anyone near the well, so the water stagnated. “The well is sick,” she said, “it’s like a cow that isn’t being milked.”

“Why are you having to fetch water yourself?” he said, with a blend of mockery and reproach. Looking at her thin brown face and her gray hair, he went on: “Sending an old woman out to fetch water—important cadres ought to know better! You must be about sixty, yes?”

The old woman could not remember her age. When she wanted the women in the neighboring dachas to express surprise at her readiness to fetch water, scrub floors, and do the laundry, she would say that she was seventy-one. In the polyclinic, however, she had registered herself as being fifty-nine, and that was what she had said to her daughter. She wanted her daughter to feel sorry for her when she died, not to be saying, “Oh well, she had a good long life.” She sighed and said to the driver, “I’m into my seventies. Yes, my dear, well into my seventies.”

“Your daughter should be fetching the water herself,” said the driver. “Or she should send the girls. No, an old woman like you shouldn’t be having to fetch water.”

“You don’t understand,” said Marya Ivanovna. “It’s only today she’s here so early. It’s because she’s going on leave. Normally she doesn’t get back here until nighttime. The girl’s completely worn out. It’s getting better now, she’s calming down, but last winter, when she’d only just started working in Moscow, she’d get back here in her car—and burst into tears. ‘What’s the matter, darling?’ I’d ask. ‘Has someone upset you?’ ‘No,’ she’d reply, ‘it’s just that everything’s so new and strange.’ No, she’s certainly not going to start fetching water! As for the little girls, to be honest with you, they’re bitches, right little bitches. Yes, they tell lies and they use foul words. The older one’s not too bad—she just lies there and reads—but Natashka’s a horror. This morning she said to me, ‘Granny, you’ve guzzled all the sweets that my auntie left me. I’m going to punch you in the teeth.’ Yes, that’s Natashka for you.”

“Insulting the aged is a criminal offense. She should be tried in a people’s court,” said the driver. A moment later, he went on to ask, “So they’re not her own daughters?”

“They’re her nieces, they’re the children of my eldest daughter, Shura. Shura died in 1931, during the famine. Yes, she just swelled up and died. And my old man—he was such a hard worker—he died the same year. He was so swollen his heart could barely keep beating, but all he could think about was the house and the yard. I wanted to bake some flatbreads from thorn apple and I needed wood for the fire, but he wouldn’t let me break up the fence. Then Stepanida took charge of us all. Her State farm gave her eight hundred grams of bread a day and so the four of us stayed alive. At the time she was just a little scrap of a girl—but look where she’s got now!”

“So everything’s all right now?” said the driver, pointing at the dacha and its tall windows.

“Yes, of course,” said the old woman. “Only I feel sad, there are things I’ll never forget. Shura, my eldest one, went out of her mind. She kept wailing, ‘Mama, the whole world’s on fire! Mama, our wheat’s all burning!’ No, I won’t be forgetting that. My old man was so gentle...Heavens!” she exclaimed all of a sudden. “I’ve been talking and talking, but who’s going to give Stepanida her tea? She’s got a train to catch. And she’s still got to call at her apartment in town.”

“There’s time enough,” said the driver. “After all, we do have a car.”

Goryacheva was glad to be going away.