The seeker – Read Now and Download Mobi

THE SEEKER

Tribe of One Trilogy

Book Two

Simon Hawke

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

FOR BRIAN THOMSEN

Special acknowledgments to Rob King, Troy Denning, Robert M. Powers, Sandra West, Jennifer Roberson, Deb Lovell, Bruce and Peggy Wiley, Emily Tuzson, Adele Leone, the crew at Arizona Honda, and my students, who keep me on my toes and teach me as much as I teach them.

PROLOGUE

The twin moons of Athas flooded the desert with a ghostly light as the dark sun sank on the horizon. The temperature dropped quickly while Ryana sat warming herself by the campfire, relieved at having left the city.

Tyr held nothing for her but bad memories. As a young girl growing up in a villichi convent, she had dreamt of visiting the city at the foot of the Ringing Mountains. Tyr had seemed like an exotic and exciting place then, when she could only imagine its teeming marketplaces and its tantalizing nightlife. She had heard stories of the city from the older priestesses, those who had been on pilgrimages, and she had longed for the day when she could take her own pilgrimage and leave the convent to see the outside world. Now she had seen it, and it was a far cry from the dreams of her youth.

When in her girlish dreams she had imagined the crowded streets and glamorous marketplaces of Tyr, she had pictured them without the pathetic, scrofulous beggars that crouched in the dust and whined plaintively for coppers, holding out their filthy hands in supplication to every passerby. The colorful images of her imagination had not held the stench of urine and manure from all the beasts penned up in the market square, or the human waste produced by the city’s residents, who simply threw their refuse out the windows into the streets and alleys. She had imagined a city of grand, imposing buildings, as if all of Tyr were as impressive as the Golden Tower or Kalak’s ziggurat. Instead she found mostly aging, blocky, uniformly earth-toned structures of crudely mortared brick covered with cracked and flaking plaster, such as the ramshackle hovels in the warrens. There the poor people of Tyr lived in squalid and pitiful conditions, crowded together like beasts crammed into stinking holding pens.

She had not imagined the vermin and the filth, or the flies and the miasma of decay as garbage rotted in the streets, or the pickpockets and the cutthroats and the vulgar, painted prostitutes, or the rioting mobs of desperate people caught up in the painful transition of a city laboring to shift from a sorcerer-king’s tyranny to a more open and democratic form of government. She had not imagined that she would come to Tyr not as a priestess on a pilgrimage, but as a young woman who had broken her sacred vows and fled the convent in the night, in pursuit of the only male she had ever known and loved. Nor had she imagined that before she left the city, she would learn what it meant to kill.

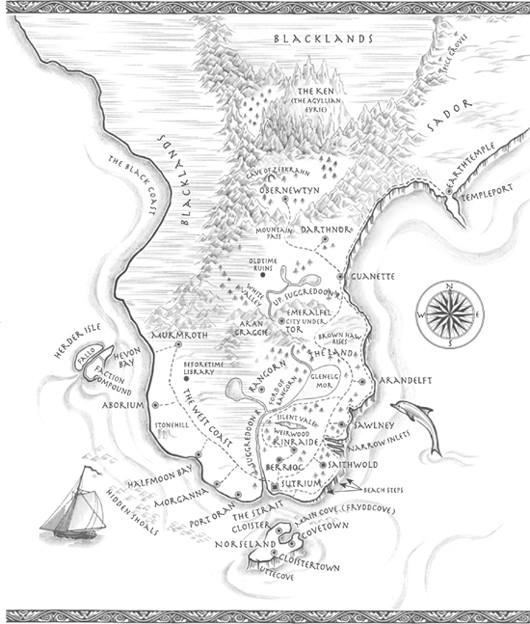

She turned away from the shadowy city in the distance, feeling no regret at leaving it, and gazed across the desert spreading out below. She and Sorak had made camp on the crest of a ridge overlooking the Tyr Valley, just east of the city. Beyond the city, to the west, the foothills rose to meet the Ringing Mountains. To the east, they gradually fell away, almost completely encircling the valley, save for the pass directly to the south, along which the trade route ran from Tyr out across the tablelands. The caravans always took the pass, then headed southeast to Altaruk, or else turned to the northeast toward Silver Spring, before heading north to Urik, or northeast to Raam and Draj. To the east of the oasis known as Silver Spring, there was nothing but rocky, inhospitable desert, a trackless waste known as the Stony Barrens that stretched out for miles before it ended at the Barrier Mountains, beyond which lay the cities of Gulg and Nibenay.

The caravans all have their routes mapped out, Ryana thought, while ours has not yet been determined. She sat alone, huddled in her cloak, her long, silvery white hair blowing gently in the breeze, and wondered when Sorak would return. Or, perhaps more properly, she thought, the Ranger. Shortly before he had left the campsite, Sorak had fallen asleep, and the Ranger had come out to take control of his body. She did not really know the Ranger very well, though she had met him many times before. The Ranger was not much for words. He was a hunter and a tracker, an entity wise in the lore of the mountain forests and desert tablelands.

The Ranger ate flesh, as did the other entities who made up Sorak’s inner tribe. Sorak, like the villichi among whom he was raised, was vegetarian. It was one of the many anomalies of his multiplicity. Though, unlike her, Sorak had not been born villichi, he had been raised in the villichi convent and had adopted many of their ways. And, like all villichi, he had sworn to follow the Way of the Druid and the Path of the Preserver.

Ryana recalled the day when Sorak had been brought to the convent by the pyreen elder, who had found him half dead in the desert. He had been cast out of his tribe and left to die because he had been born a half-breed. Though the human and demihuman races of Athas frequently mixed, and half-breeds such as half-dwarves, half-giants, and half-elves were not uncommon, Sorak was an elfling—perhaps the only one of his kind.

Elves and halflings were mortal enemies, and usually killed one another on sight. Yet, somehow, an elf and a halfling had mated to produce Sorak, giving him the characteristics of both races. Halflings were small, though powerfully built, while elves were extremely tall, lean and long-limbed. Sorak’s proportions, a mixture of the two, were similar to those of humans. In fact, at first glance, he looked completely human.

The differences were slight, though significant. His long black hair was thick and luxuriant, like a halfling’s mane. His eyes were deeply set and dark, with an unsettling, penetrating gaze, and like both elves and halflings, he could see in the dark. His eyes had the same, cat-like lambency that halfling eyes had in the darkness. His facial features had an elvish cast, sharply pronounced, with high, prominent cheekbones; a sharp nose; a narrow, almost pointed chin; a wide, sensual mouth; arched eyebrows; and pointed ears. And, like elves, he could grow no facial hair.

But as unique as his physical appearance was, his mental makeup was even more unusual. Sorak was a ‘tribe of one.’ The condition was exceedingly rare, and so far as Ryana knew, only the villichi truly understood it. She knew of least two cases that had occurred among villichi, though neither during her lifetime. Both priestesses who had been so afflicted had kept extensive journals, and as a girl, Ryana had studied them in the temple library, the better to understand her friend.

She had been only six years old when Sorak had been brought to the villichi convent, and he had been approximately the same age. He had no memory of his past, the time before he was cast out into the desert, so he himself did not know how old he was. The trauma of his experience had not only wiped out his memories, it had divided his mind in such a way that he now possessed at least a dozen different personalities, each with its own unique attributes, not the least of which were powerful psionic powers.

Before Sorak came, there had never been a male in residence at the villichi convent. The villichi were a female sect, not only by choice, but by accident of birth, as well. Villichi, too, were rare, though not as uncommon as tribes of one. Only human females were born villichi, though no one knew why. They were a mutation, marked by such physical characteristics as their unusual height and slenderness, their fairness, and their elongated necks and limbs. In terms of their physical proportions, they had more in common with elves than humans, though elves were taller still. But what truly made them different was that they were born with fully developed psionic abilities. Whereas most humans and many demihumans had a latent potential for at least one psionic power, it usually took many years of training under a psionicist, a master of the Way, to bring it out. Villichi children were born with it in full flower.

Ryana was short for a villichi, though at almost six feet, she was still tall for a human female, and her proportions were closer to the human norm. The only thing that marked her as different was her silvery white hair, like that of an albino. Her eyes were a striking, bright emerald green, and her skin was so fair as to be almost translucent. Like all villichi, she burned easily in the hot Athasian sun if she was not careful.

Her parents were poor and already had four other children when she was born. Things had been hard enough for them without an infant who tossed household objects around with the power of her mind whenever she was feeling hungry or cranky. When a villichi priestess on pilgrimage had come to their small village, they had been relieved to surrender the custody of their troublesome psionic child to an order devoted to the proper care, nurturing, and training of others like her.

Sorak’s situation had been different. Not only was he a male, which was bad enough, he was not even human. His arrival at the convent had stirred up a great deal of heated controversy. Varanna, the high mistress of the order, had accepted him because he was both a tribe of one and gifted with incredible psionic powers, the strongest she had ever encountered. The other priestesses, however, had initially resented the presence of a male in their midst, and an elfling male at that.

Even though he was just a child, they had protested. Males sought only to dominate women, they had argued, and elves were notoriously duplicitous. As for halflings, not only were they feral flesh-eaters, they often ate human flesh as well. Even if Sorak did not manifest any of those loathsome traits, the young villichi felt that the mere presence of a male in the convent would be disruptive. Varanna had stood firm, however, insisting that though Sorak had not been born villichi, he was nevertheless gifted with unusual psionic talent, as were they all. He was also a tribe of one, which meant that without villichi training to adapt him to his rare condition, he would have been doomed to a life of suffering and, ultimately, insanity.

On the day Sorak was first brought to Ryana’s residence hall, the other young priestesses had all protested vehemently. Ryana, alone, stood up for him. Looking back on it now, she was not sure she could remember why. Perhaps it was because they were roughly the same age, and Ryana had no one else her age to be friends with at the convent. Perhaps it was her own natural willfulness and rebelliousness that had caused her to diverge from the others and stand up for the young elfling, or perhaps it was because she had always felt alone and saw that he was alone, too. Perhaps, even then, she had known somehow, on some deeply intuitive, subconscious level, that the two of them were fated to be together.

He had seemed hurt, lost and alone, and her heart went out to him. He had no memory. He did not even know his own name. The high mistress had named him Sorak, an elvish word used to describe a nomad who always walked alone. Even then, Ryana had joined herself to him, and they had grown up as brother and sister. Ryana had always thought she understood him better than anybody else. However, there were limits to her own understanding, as she had discovered on the day, not very long ago, when she had announced her love to Sorak—and been rebuffed, because several of Sorak’s personalities were female, and could not love another woman.

She had first felt shock, and then humiliation, then anger at his never having told her, and then pain… for him and for his loneliness, for the unique and harsh realities of his existence. She had retired to the meditation chamber in the tower of the temple to sort things out in her own mind, and when she came out again, it was only to learn that he had left the convent.

She had blamed herself at first, thinking she had driven him away. But the high mistress had explained that, if anything, she had only been the catalyst for a decision Sorak had been struggling to make for quite some time.

“I have always known that he would leave us one day,” Mistress Varanna had said. “Nothing could have held him, not even you, Ryana. Elves and halflings are wanderers. It is in their blood. And Sorak has other forces driving him, as well. There are questions he hungers to have answered, and he cannot find those answers here.”

“But I cannot believe that he would simply leave without even saying good-bye,” Ryana had said.

Mistress Varanna had smiled. “He is an elfling. His emotions are not the same as ours. You, of all people, ought to know that by now. You cannot expect him to act human.”

“I know, but… It’s just that… I had always thought…”

“I understand,” the high mistress had said in a sympathetic tone. “I have known how you felt about Sorak for quite some time now. I could see it in your eyes. But the sort of partnership you hoped for was never meant to be, Ryana. Sorak is an elfling and a tribe of one. You are villichi, and the villichi do not take mates.”

“But there is nothing in our vows that prohibits it,” Ryana had protested.

“Strictly speaking, no, there is not,” the high mistress had agreed. “I will grant you that the interpretation of the vows we take could certainly be argued on that point. But practically speaking, it would be folly. We cannot bear children. Our psionic abilities and our training, to say nothing of our physical makeup, would threaten most males. It is not for nothing that most of the priestesses choose celibacy.”

“But Sorak is different,” Ryana had protested, and the high mistress held up her hand to forestall any further comment.

“I know what you are going to say,” she said, “and I will not disagree. His psionic powers are the strongest I have yet encountered. Not even I can penetrate his formidable defenses. And since he is a half-breed, he may also be unable to sire offspring. However, Sorak has certain unique problems that he may never be able to overcome. At best, he will only find a way to live with them. His path in life is a solitary one, Ryana. I know that it is hard for you to hear these things right now, and harder still to understand them, but you are young yet, and your best and most productive years are still ahead of you.

“Soon,” she had continued, “you will be taking over Sister Tamura’s training sessions, and you will discover that there is a great measure of satisfaction to be found in molding the minds and bodies of the younger sisters. In time, you will be departing on your first pilgrimage to seek out others like ourselves and bring them into the fold, and to gather information about the state of things in the outside world. When you return, it will help us in our quest to find a way of reversing all the damage that our world has suffered at the hands of the defilers. Our task here is a holy and a noble one, and its rewards can be ever so much greater than the ephemeral pleasures of love.

“I know these things are hard to hear when one is young,” Varanna had said with an indulgent smile. “I was young myself once, so I know, but time brings clarity, Ryana. Time and patience. You gave Sorak what he needed most, your friendship and your understanding. More than anyone else, you helped him gain the strength that he required to go out and find his own way in the world. The time has come for him to do that, and you must respect his choice. You must let him go.”

Ryana had tried to tell herself that the high mistress was right, that the best thing she could do for Sorak was to let him go, but she could not make herself believe it. They had known each other for ten years, since they were both small children, and she had never felt as close to any of her villichi sisters as she had to Sorak. Perhaps she had nurtured unreasonable expectations as to the sort of relationship they could have, but while it was now clear to her that they never could be lovers, she still knew that Sorak loved her as much as he could ever love anyone. For her part, she had never wanted anyone else. She had never even known another male.

The priestesses had frequently discussed the different ways in which physical desire could be sublimated. On occasion, a priestess on a pilgrimage might indulge in the pleasures of the flesh, for it was not expressly forbidden by their vows, but even those who had done so had eventually chosen celibacy. Males, they said, left much to be desired when it came to such things as companionship, mutual respect, and spiritual bonding. Ryana was still a virgin, so she had no personal experience from which to judge, but the obvious implication seemed to be that the physical side of love was not all that important. What was important was the bond that she had shared with Sorak from childhood. With his departure, she had felt a void within her that nothing else could fill.

That night, after everyone had gone to sleep, she had quickly packed her rucksack with her few possessions, then stole into the armory where the sisters kept all the weapons used in their training. The villichi had always followed a philosophy that held the development of the body to be as important as the training of the mind. From the time they first came to the convent, the sisters were all trained in the use of the sword, the staff, the dagger, and the crossbow, in addition to such weapons as the cahulaks, the mace and flail, the spear, the sickle, and the widow’s knife. A one villichi priestess on a pilgrimage was not as vulnerable as she appeared.

Ryana had buckled on an iron broadsword and tucked two daggers into the top of each of her high moccasins. She also took a staff and slung a crossbow across her back, along with a quiver of bolts. Perhaps the weapons were not hers to take, but she had put in her share of time in the workshop of the armory, fashioning bows and arrows and working at the forge, making iron swords and daggers, so in a sense, she felt she had earned a right to them. She did not think Sister Tamura would begrudge her. If anyone would understand, Tamura would.

Ryana then had climbed over the wall so as not to alert the old gatekeeper. Sister Dyona might not have prevented her from leaving, but Ryana was sure she would have tried to talk her out of it and insisted that she first discuss it with Mistress Varanna. Ryana was in no mood to argue or try to justify her actions. She had made her decision. Now she was living with the consequences of that decision, and those consequences were that she had absolutely no idea what lay ahead of her.

All she knew was that they had to find a wizard known only as the Sage, something that was a lot easier said than done. Most people believed the Sage was nothing but a myth, a legend for the common people to keep hope alive, hope that one day the power of the defilers would be broken, the last of the dragons would be slain, and the greening of Athas would begin.

According to the story, the Sage was a hermit wizard, a preserver who had embarked upon the arduous path of metamorphosis into an avangion. Ryana had no idea what exactly an avangion was. There had never been an avangion on Athas, but the ancient books of magic spoke of it. Of all the spells of metamorphosis, the avangion transformation was the most difficult, the most demanding, and the most dangerous. Aside from dangers inherent in the metamorphsis itself, there were dangers posed by defilers, especially the sorcerer-kings, to whom the avangion would be the greatest threat.

Magic had a cost, and that cost was most dramatically visible in the reduction of Athas to a dying, desert planet. The templars and their sorcerer-kings claimed that it was not their magic that had defiled the landscape of Athas. They insisted the destruction of the ecosystem began thousands of years earlier with those who had tried to control nature, and that it was aided by changes in the sun, which no one could control. There may have been some truth to that, but few people believed these claims, for there was nothing that argued against them quite so persuasively as the devastation brought about by the practice of defiler magic.

Preservers did not destroy the land the way defilers did, but most people did not bother to differentiate between defiler and preserver magic. Magic of any form was universally despised for being the agency of the planet’s ruin. Everyone had heard the legends, and there was no shortage of bards who repeated them. “The Ballad of a Dying Land,” “The Dirge of the Dark Sun,” “The Druid’s Lament,” and many others were songs that told the story of how the world had been despoiled.

There had been a time when Athas was green, and the winds blowing across its verdant, flowering plains had carried the song of birds. Once, its dense forests had been rich with game, and the seasons came and went, bringing blankets of virgin snow during the winter and rebirth with every spring. Now, there were only two seasons, as the people said, “summer and the other one.”

During most of the year, the Athasian desert was burning hot during the day and freezing cold at night, but for two to three months during the Athasian summer, the nights were warm enough to sleep outside without a blanket and the days brought temperatures like the inside of an oven. Where once the plains were green and fertile, now they were barren, desert tablelands covered merely with brown desert grasses, scrubby ironwood and pagafa trees, a few drought resistant bushes, and a wide variety of spiny cacti and succulents, many of them deadly. The forests had, for the most part, given way to stony hills, where the winds wailed through the rocky crags, making a sound like some giant beast howling in despair. Only in isolated spots, such as the Forest Ridge of the Ringing Mountains, was there any evidence of the world the way it once had been, but with every passing year, the forests died back a little more. And what did not die was destroyed by the defilers.

Magic required energy, and the source of that energy could be the life-force of the spellcaster or that of other living things such as plants. The magic practiced by defilers and preservers was essentially the same, but preservers had a respect for life, and cast their spells conservatively so that any energy borrowed from plant life was taken in such a way as to allow a full recovery.

Preservers did not kill with their magic.

Defilers, on the other hand, practiced the sorcery of death. When a defiler cast a spell, he sought only to absorb as much energy as he could, the better to increase his power and the potency of his spell. When a defiler drew energy from a plant, it withered and died, and the soil where it grew was left completely barren.

The great lure of defiler magic was that it was incredibly addictive. It allowed the sorcerer to increase his power far more quickly than those who followed the Path of the Preserver, which mandated reverence for life. But as with any addictive drug, the defiler’s boundless lust for power necessitated ever greater doses. In his relentless quest for power, the defiler eventually reached the limit of what he could absorb and contain, beyond which the power would consume him…

Only the sorcerer-kings could withstand the flood of complete defiling power, and they did so by changing. They transformed themselves through painful, time-consuming rituals and gradual stages of development into creatures whose voracious appetites and capacities for power made them the most dangerous life-forms on the planet… Dragons.

Dragons were hideous perversions, thought Ryana, sorcerous mutations that posed a threat to all life on the planet. Everywhere a dragon passed, it laid waste to the entire countryside and took a fearful toll in the human and demihuman lives that it demanded as a tribute.

Once a sorcerer-king embarked upon the magical path of metamorphosis that would transform him into a dragon, there was no return. Merely to begin the process was to pass beyond redemption. With each successive stage of the transformation, the sorcerer changed physically, gradually losing all human appearance and taking on the aspect of a dragon. By then, the defiler would have ceased to care about its own humanity, or lack of it. The metamorphosis brought with it immortality and a capacity for power beyond anything the defiler had ever experienced before. It would make no difference to a dragon that its very existence threatened all life on the planet; its insatiable appetite could reduce the world to a barren, dried out rock incapable of supporting any life at all. Dragons did not care about such things. Dragons were insane.

There was only one creature capable of standing up to the power of a dragon, and that was an avangion. Or at least, so the legends said. An avangion was the antithesis of a dragon, a metamorphosis achieved through following the Path of the Preserver. The ancient books of magic spoke of it, but there had never been an avangion on Athas, perhaps because the process took far longer than did the dragon metamorphosis. According to the legend, the process of avangion transformation was not powered by absorbed life-force, and so the avangion was stronger than its defiler enemies. While the dragon was the enemy of life, the avangion was the champion of life, and possessed a powerful affinity for every living thing. The avangion could counteract the power of a dragon and defeat it, and help bring about the greening of the world.

According to the legend, one man, a preserver—a hermit wizard known only as the Sage—had embarked upon the arduous and lonely path of metamorphosis that would transform him into an avangion. Because the long, painful, and extremely demanding transformation would take many years, the Sage had gone into seclusion in some secret hiding place, where he could concentrate upon the complicated spells of metamorphosis and keep safe from the defilers who would seek to stop him at all costs. Even his true name was unknown, so that no defiler could ever use it to gain power over him or deduce the location of his hiding place.

The story had many different variations, depending on which bard sang the song, but it had been around for years, and no avangion had been forthcoming. No one had ever seen the Sage or spoken to him or knew anything about him. Ryana, like most people, had always believed the story was nothing but a myth… until now.

Sorak had embarked upon a quest to find the Sage, to both discover the truth about his own past and find a purpose for his future. He had first sought out Lyra Al’Kali, the pyreen elder who had found him in the desert and brought him to the convent.

The pyreens, known also as the peace-bringers, were shapechangers and powerful masters of the Way, devoted to the Way of the Druid and the Path of the Preserver. They were the oldest race on Athas, and though their lives spanned centuries, they were dying out. No one knew how many of them were left. It was believed that only a very small number remained. The pryeens were wanderers, mystics who traveled the world and sought to counteract the corrupting influence of the defilers—but they usually kept to themselves and avoided contact with humans and demihumans alike. When the Elder Al’Kali had brought Sorak to the convent, it had been both the first and last time Ryana had ever laid eyes on a pyreen.

Once each year, Elder Al’Kali made a pilgrimage to the summit of the Dragon’s Tooth to reaffirm her vows. Sorak had found her there, and she had told him that the leaders of the Veiled Alliance—an underground network of preservers who fought against the sorcerer-kings—maintained some sort of contact with the Sage. Sorak had gone to Tyr to seek them out. In trying to make contact with the Veiled Alliance, he had inadvertently become involved in political intrigue aimed at toppling the government of Tyr, exposing the members of the Veiled Alliance, and restoring the templars to power under a defiler regime. Sorak had helped to foil the plot and, in return, the leaders of the Veiled Alliance had given him a scroll which, they said, contained all they knew about the Sage.

“But why write it down upon a scroll?” Sorak wondered aloud after they had left. “Why not simply tell me?”

“Perhaps because it was too complicated,” Ryana had suggested, “and they thought you might forget if it were not written down.”

“But they said that I must burn this after I had read it,” Sorak said, shaking his head. “If they were so concerned that this information not fall into the wrong hands, why bother to write it down at all? Why take the risk?”

“It does seem puzzling,” she had agreed.

He had broken the seal on the scroll and unrolled it.

“What does it say?” Ryana asked, anxiously.

“Very little,” Sorak had replied. “It says, ‘Climb to the crest of the ridge west of the city. Wait until dawn. At sunrise, cast the scroll into a fire. May the Wanderer guide you on your quest.’ And that is all.” He shook his head. “It makes no sense.”

“Perhaps it does,” Ryana had said. “Remember that the members of the Veiled Alliance are sorcerers.”

“You mean the scroll itself is magic?” Sorak said. Then he nodded. “Yes, that could be. Or else I have been duped and played for a fool.”

“Either way, we shall know at dawn tomorrow,” said Ryana.

By nightfall, they had reached the crest of the ridge and made camp. She had slept for a while, then woke to take the watch so that Sorak could sleep. No sooner had he closed his eyes than the Ranger came out and took control. He got up quietly and stalked off into the darkness without a word, his eyes glowing like a cat’s. Sorak, she knew, was fast asleep, ducked under, as he called it. When he awoke, he would have no memory of the Ranger going out to hunt.

Ryana had grown accustomed to this unusual behavior back when they were still children at the convent. Sorak, out of respect for the villichi who had raised him, would not eat meat. However, his vegetarian diet went against his elf and halfling natures, and his other personalities did not share his desire to follow the villichi ways. To avoid conflict, his inner tribe had found an unique method of compromise. While Sorak slept, the Ranger would hunt, and the rest of the tribe could enjoy the warm blood of a fresh kill without Sorak’s having to participate. He would awaken with a full belly, but no memory of how it got that way. He would know, of course, but since he would not have been the one to make the kill and eat the flesh, his conscience would be clear.

It was, Ryana thought, a curious form of logic, but it apparently satisfied Sorak. For her part, she did not really care if he ate flesh or not. He was an elfling, and it was natural for him to do so. For that matter, she thought, one could argue that it was natural for humans to eat flesh, as well. Since she had broken her vows by leaving the convent, perhaps there was nothing left to lose by eating meat, but she had never done so. Just the thought was repellent to her. It was just as well that Sorak’s inner tribe went off to make their kill and consume it away from the camp. She grimaced as she pictured Sorak tearing into a hunk of raw, still warm and bloody meat. She decided that she would remain a vegetarian.

It was almost dawn when the Ranger returned. He moved so quietly that even with her trained villichi senses, Ryana didn’t hear him until he stepped into the firelight and settled down on the ground beside her, sitting cross-legged. He shut his eyes and lowered his head upon his chest… and a moment later, Sorak awoke and looked up at her.

“Did you rest well?” she asked, in a faintly mocking tone.

He merely grunted. He looked up at the sky. “It is almost dawn.” He reached into his cloak and pulled out the rolled up scroll. He unrolled it and looked at if once again. “‘At sunrise, cast the scroll into a fire—May the Wanderer guide you on your quest,’” he read.

“It seems simple enough,” she said. “We have climbed the ridge and made a fire. In a short while, we shall know the rest… whatever there may be to know.”

“I have been thinking about that last part,” Sorak said. “‘May the Wanderer guide you on your quest.’ It is a common sentiment often expressed to wish one well upon a journey, but the word ‘quest’ is used instead of ‘journey’ in this case.”

“Well, they knew your journey was a quest,” Ryana said with a shrug.

“True,” said Sorak, “but otherwise, the words written on the scroll are simple and direct, devoid of any sentiment or salutation.”

“You mean you think that something else is meant?”

“Perhaps,” said Sorak. “It would seem to be a reference to The Wanderer’s journal. Sister Dyona gave me her own copy the day I left the convent.”

He opened his pack, rummaged in it for a moment, and then pulled out a small, plain, leather-bound book, stitched together with animal gut. It was not something that would have been produced by the villichi, who wrote their knowledge down on scrolls. “You see how she inscribed it?

“A small gift to help guide you on your journey. A more subtle weapon than your sword, but no less powerful, in its own way. Use it wisely.

“A subtle weapon,” he repeated, “to be used wisely. And now the scroll from the Veiled Alliance seems to refer to it again.”

“It is known that the Veiled Alliance makes copies of the journal and distributes them,” Ryana said thoughtfully. “The book is banned because it speaks truthfully of the defilers, but you think there may be something more to it than that?”

“I wonder,” Sorak said. “I have been reading through it, but perhaps it merits a more careful study. It is possible that it may contain some sort of hidden meaning.” He looked up at the sky again. It was getting light. “The sun will rise in another moment.” He rolled the scroll up once again and held it out over the fire, gazing at it thoughtfully. “What do you think will happen when we burn it?”

She shook her head. “I do not know.”

“And if we do not?”

“We already know what it contains,” she said. “It would seem that there is nothing to be served by holding on to it.”

“Sunrise,” he said again. “It is most specific about that. And on this ridge. On the crest, it says.”

“We have done all else that was required. Why do you hesitate?”

“Because I hold magic in my hand,” he said. “I feel certain of it now. What I am not certain of is what spell we may be loosing when we burn it.”

“The members of the Veiled Alliance are preservers,” she reminded him. “It would not be a defiler spell. That would go against everything that they believe.”

He nodded. “I suppose so. But I have an apprehension when it comes to magic. I do not trust it.”

“Then trust your instincts,” said Ryana. “I will support you in whatever you choose to do.”

He looked up at her and smiled. “I am truly sorry that you broke your vows for me,” he said, “but I am also very glad you came.”

“Sunrise,” she said, as the dark sun peeked over the horizon.

“Well…” he said, then dropped the scroll into the fire.

It rapidly turned brown, then burst into flame, but it was a flame that burned blue, then green, then blue again. Sparks shot from the scroll as it was consumed, sparks that danced over the fire and flew higher and higher, swirling in the rising, blue-green smoke, going around faster and faster, forming a funnel like an undulating dust devil that hung over the campfire and grew, elongating as it whirled around with ever increasing speed. It sucked the flames from the fire, drawing them up into its vortex, which sparked and crackled with magical energy, raising a wind that plucked at their hair and cloaks and blinded them with dust and ash.

It rose high above the now-extinguished fire, making a rushing, whistling noise over which a voice suddenly seemed to speak, a deep and sonorous voice that came out of the blue-green funnel cloud to speak only one word.

“Nibenaaaay…”

Then the glowing funnel cloud rose up and skimmed across the ridge, picking up speed as it swept down toward the desert floor. It whirled off rapidly across the tablelands, heading due east, toward Silver Spring and the desert flats beyond it. They watched it recede into the distance, moving with such amazing speed that it left a trail of blue-green light behind it, as if marking out the way. Then it was gone, and all was quiet once again.

They both stood, gazing after it, and for a moment, neither of them spoke. Then Sorak broke the silence. “Did you hear it?” he asked.

Ryana nodded. “The voice said, ‘Nibenay.’ Do you think it was the Sage who spoke?”

“I do not know,” Sorak replied. “But it went due east. Not southeast, where the trade route runs to Altaruk and from there to Gulg and then to Nibenay, but directly east, toward Silver Spring and then beyond.”

“Then that would seem to be the route that we must take,” Ryana said.

“Yes,” said Sorak, nodding, “but according to The Wanderer’s Journal, that way leads across the Stony Barrens. No trails, no villages or settlements, and worst of all, no water. Nothing but a rocky waste until we reach the Barrier Mountains, which we must cross if we are to reach Nibenay by that route. The journey will be harsh… and very dangerous.”

“Then the sooner we begin it, the sooner it will end,” Ryana said, picking up her rucksack, her crossbow, and her staff. “But what are we to do when we reach Nibenay?”

“Your guess is as good as mine,” said Sorak, “but if we try to cross the Stony Barrens, we may never even reach the Barrier Mountains.”

“The desert tried to claim you once before, and it failed,” said Ryana. “What makes you think that now it will succeed?”

Sorak smiled. “Well, perhaps it won’t, but it is not wise to tempt fate. In any case, there is no need for both of us to make so hazardous a journey. You could return to Tyr and join a caravan bound for Nibenay along the trade route by way of Altaruk and Gulg. I could simply meet you there and—”

“No, we go together,” said Ryana, in a tone that brooked no argument. She slung her crossbow across her back and slipped her arms through the straps of the rucksack. Holding her staff in her right hand, she started off down the western slope. She walked a few paces, then paused, looking back over her shoulder. “Coming?” Sorak grinned. “Lead on, little sister.”

CHAPTER ONE

They traveled due east, moving at a steady but unhurried pace. The oasis at Silver Spring was roughly sixty miles straight across the desert from where they had made camp upon the ridge. Sorak estimated it would take them at least two days to make the journey if they walked eight to ten hours a day. The pace allowed for short, regular rest periods, but did not allow for anything that might slow them down.

Ryana knew that Sorak could have made much better time had he been traveling alone. His elf and halfling ancestry made him much better suited for a journey in the desert. Being villichi, Ryana’s physique was superior to most other humans, and her training at the convent had given her superb conditioning. Even so, she could not hope to match Sorak’s natural powers of endurance. The dark sun could quickly sap the strength of most travelers, but even in the relentless, searing heat of an Athasian summer, elves could run for miles across the open desert at speeds that would rupture the heart of any human who attempted to keep pace. As for halflings, what they lacked in size and speed, they made up for in brute strength and stamina. In Sorak, the best attributes of both races were combined.

As Ryana had reminded him, the desert had tried to claim him once before, and it failed. A human child abandoned in the desert would have had no hope of surviving more than a few hours, at best. Sorak had survived for days without food or water until he had been rescued. Still, it had been a long time since Sorak had seen the desert, and it held a grim fascination for him. He would always regard the Ringing Mountains as his home, but the desert was where he had been born. And where he had almost died.

As Ryana walked beside him, Sorak remained silent, as if oblivious to her presence. Ryana knew that he was not ignoring her; he was immersed in a silent conversation with his inner tribe. She recognized the signs. At such times, Sorak would seem very distant and preoccupied, as if he were a million miles away. His facial expression was neutral, yet it conveyed a curious impression of detached alertness. If she spoke to him, he would hear her—or, more specifically, the Watcher would hear and redirect Sorak’s attention to the external stimulus. She maintained her own silence, however, so as not to interrupt the conversation she was not able to hear.

For as long as she had known Sorak, which had been almost all her life, Ryana had wondered what it must be like for him to have so many different people living inside him. They were a strange and fascinating crew. Some she knew quite well; others she hardly knew at all. And there were some of whom she was not even aware. Sorak had told her he knew of at least a dozen personalities residing within him. Ryana knew of only nine.

There was the Ranger, who was most at home when he was wandering in the mountain forests or hunting in the wild. He had not liked the city and had only come out rarely while Sorak was in Tyr. As children, when Ryana and Sorak had gone out on hikes in the forests of the Ringing Mountains, it was always the Ranger who was in the forefront of Sorak’s consciousness. He was the strong and silent type. So far as Ryana knew, the only one of Sorak’s inner tribe with whom the Ranger seemed to interact was Lyric, whose playfulness and child-like sense of wonder compensated for the Ranger’s dour, introspective pragmatism.

Ryana had met Lyric many times before, but she had liked him much better in her childhood than she did now. While she and Sorak had matured, Lyric had remained essentially a child by nature. When he came out, it was usually to marvel at some wildflower or sing a song or play his wooden flute, which Sorak kept strapped to his pack. The instrument was about the length of his arm and carved from stout, blue pagafa wood. Sorak was unable to play it himself, while Lyric seemed to have the innate ability to play any musical instrument he laid his hands on. Ryana had no idea what Lyric’s age was, but apparently he had been “born” sometime after Sorak came to the convent. She thought, perhaps, that he had not existed prior to that time because Sorak had sublimated those qualities within himself. His early childhood must have been terrible. Ryana could not understand what Sorak could possibly regain if he managed to remember it.

Eyron could not understand, either. If Lyric was the child within Sorak, then Eyron was the world-weary and cynical adult who always weighed the consequences of every action taken by the others. For every reason Sorak had to do something, Eyron could usually come up with three or four reasons against it. Sorak’s quest was a case in point. Eyron had argued in favor of Sorak’s continued ignorance about his past. What difference would it really make, he had asked, if Sorak knew which tribe he came from? At best, all he would learn was which tribe had cast him out. What would it benefit him to know who his parents were? One was an elf; the other was a halfling. Was there any pressing reason to know more? What difference did it make, Eyron had asked, if Sorak never learned the circumstances leading to his birth? Perhaps his parents had met, fallen in love, and mated, against all the beliefs and conventions of their respective tribes and races. If so, then they may both have been cast out themselves, or worse. On the other hand, perhaps Sorak’s mother had been raped during an attack on her tribe, and Sorak had been the issue—not only an unwanted child, but one that was anathema to both his mother and her people. Whatever the truth was, Eyron had insisted, there was really nothing to be gained from knowing it. Sorak had left the convent, and life was now his to start anew. He could live it in any manner that he chose.

Sorak disagreed, believing he could never truly find any meaning or purpose in his life until he found out who he was and where he came from. Even if he chose to leave his past behind, he would first have to know what it was he was leaving.

When Sorak had told Ryana of this discussion, she had realized that, in a way, he had been arguing with himself. It had been a debate between two completely different personalities, but at the same time, it was an argument between different aspects of the same personality. In Sorak’s case, of course, those different aspects had achieved a full development as separate individuals. The Guardian was a prime example, embodying Sorak’s nurturing, empathic, and protective aspects, developed into a maternal personality whose role was not only to protect the tribe, but to maintain a balance between them.

When she had read the journals of the two villichi priestesses who had also been tribes of one, Ryana had learned that cooperation between the different personalities was by no means a given. Quite the opposite. Both women had written that in their younger days, they had no real understanding of their condition, and that they had often experienced “lapses,” as they called them, during which they were unable to remember periods of time lasting from several hours to several days. During those times, one of their other personalities would come out and take control, often acting in a manner that was completely inconsistent with the behavior of the primary personality. At first, neither of them was aware that they possessed other personalities, and while these other personalities were aware of the primary, they were not always aware of one another. It was, the victims wrote, a very confusing and frightening existence.

As with Sorak, the training the women received at the villichi convent enabled them to become aware of their other personalities and come to terms with them. Training in the Way not only saved their sanity, but opened up new possibilities for them to lead full and productive lives.

In Sorak’s case, the Guardian had been the one who had responded first, serving as a conduit between Sorak and the other members of his inner tribe. She possessed the psionic talents of telepathy and telekinesis, while Sorak, contrary to initial perceptions, appeared to possess no psionic talent whatsoever.

This had frustrated him immensely during his training sessions, and when his frustration had reached a peak, the Guardian would always take over. It was Mistress Varanna who had first realized this and prevailed upon the Guardian to acknowledge herself openly, convincing her that it would not be in Sorak’s best interests for her to protect him from the truth about himself. For Sorak, that had been the turning point.

Because the Guardian always spoke with Sorak’s voice, Ryana had never realized that she was female. It was not until Ryana told Sorak she desired him that she discovered the truth about the Guardian’s gender. No less shocking was the discovery that Sorak had at least two other female personalities within him—the Watcher, who never slept and only rarely spoke, and Kivara, a mischievous and sly young girl of a highly inquisitive and openly sensual temperament. Ryana had never spoken with the Watcher, who never manifested externally, nor had she ever met Kivara. When the Guardian came out, she usually manifested in such a manner that there was no visible change in Sorak’s personality or his demeanor. From the way Sorak spoke about Kivara, however, it seemed clear that Kivara could never be that subtle. Ryana could not imagine what Kivara would be like. She was not really sure she wanted to know.

She knew of three other personalities Sorak possessed. Or perhaps it was they who possessed him.

There was Screech, the beast-like entity who was capable of communication only with other wild creatures, and the Shade, a dark, grim, and frightening presence that resided deep within Sorak’s subconscious, emerging only when the tribe was facing a threat to its survival. And finally, there was Kether, the single greatest mystery of Sorak’s complicated multiplicity.

Ryana had encountered Kether only once, though she had discussed the strange entity with Sorak many times. The one time she had seen him, Kether had displayed powers that seemed almost magical, though they must have been psionic, for Sorak had never received any magical training. Still, that was merely a logical assumption, and when it came to Kether, Ryana was not sure that logic would apply. Even Sorak did not quite know what to make of Kether.

“Unlike the others, Kether is not truly a part of the inner tribe,” Sorak told her when she voiced her thoughts. He appeared nervous, attempting to explain the little he understood about the strange, ethereal entity called Kether. “At least, he somehow does not seem to be. The others know of him, but they do not communicate with him, and they do not know where he comes from.”

“You speak as if he comes from somewhere outside yourself,” Ryana said.

“Yes, I know. And yet, that is truly how it seems.”

“But… I do not understand. How can that be? How is it possible?”

“I simply do not know,” Sorak replied with a shrug—“I wish I could explain it better, but I cannot. It was Kether who came out when I was dying in the desert, sending forth a psionic call so powerful that it reached Elder Al’Kali at the very summit of the Dragon’s Tooth. Neither I nor any of the others have ever been able to duplicate that feat. We do not possess such power. Mistress Varanna always believed that the power was within me, but I suspect the power truly lies with Kether and that I am but a conduit through which it sometimes flows. Kether is by far the strongest of us, more powerful even than the Shade, yet he does not truly seem to be a part of us. I cannot feel him within me, as I can the others.”

“Perhaps you cannot feel him because he resides deep beneath your level of awareness, like the infant core of which you spoke,” Ryana said.

“Perhaps,” said Sorak, “though I am aware of the infant core, albeit very dimly. I am also aware of others that are deeply buried and do not come out… or at least have refrained from coming out thus far. I sense their presence; I can feel them through the Guardian. But with Kether, there is a very different feeling, one that is difficult to describe.”

“Try.”

“It is…” He shook his head. “I do not know if I can properly convey it. There is a profound warmth that seems to spread throughout my entire body and a feeling of… dizziness, though perhaps that it not quite the right word. It is a sort of lightness, a spinning sensation, almost as if I am falling from a great height… and then I simply fade away. When I return, there is still that sensation of great warmth, which remains present for a while, then slowly fades. And for however long Kether possessed me, I can usually remember nothing.”

“When you speak of the others manifesting,” said Ryana, “you simply say they ‘come out.’ But when you speak of Kether, you speak of being possessed.”

“Yes, that is how it feels. It is not as if Kether comes out from within me, but as if he… descends upon me somehow.”

“But from where?”

“I only wish I knew. From the spirit world, perhaps.”

“You think that Kether is a fiend?”

“No, fiends are merely creatures of legend. We know that they do not exist. We know that spirits do exist, however. They are the animating core of every living thing. The Way teaches us that the spirit never truly dies, that it survives corporeal death and unites with the greater life-force of the universe. We are taught that elementals are a lower form of spirit, entities of nature bound to the physical plane. But higher spirits exist upon a higher plane, one we cannot perceive, for our own spirits have not yet ascended to it.”

“And you think that Kether is a spirit that has found a way to bridge those planes through you?”

“Perhaps. I cannot say. I only know there is a sense of goodness about Kether, an aura of tranquility and strength. And he does not seem as if he is a part of me, somehow. More like a benevolent visitor, a force from without. I do not know him, but neither do I fear him. When he descends upon me, it is as if I fall asleep, then awake with a pervading sense of calm, and peacefulness, and strength. I cannot explain it any more than that. I truly wish I could.”

I have known him almost all my life, Ryana thought, and yet, there are ways in which I do not know him at all. For that matter, there are ways in which he does not even know himself.

“A copper for your thoughts,” Sorak said, abruptly bringing her back to the present from her reverie. She smiled. “Can you not read them?”

“The Guardian is the telepath among us,” he replied gently, “but she would not presume to read your thoughts unless you gave consent. At least, I do not think she would.”

“You mean you are not sure?”

“If she felt it was important to the welfare of the tribe, then perhaps she might do it and not tell me,” he said.

“I do not fear having my thoughts read by the Guardian. I have nothing to hide from you,” Ryana said. “From any of you. Just now, I was merely thinking how little I truly know you, even after ten years.”

“Perhaps because, in many ways, I do not truly know myself,” Sorak replied wistfully.

“That is just what I was thinking,” said Ryana. “You must have been reading my mind.”

“I told you, I would never knowingly consent to—”

“I was only joking, Sorak,” said Ryana.

“Ah, I see.”

“You really should ask Lyric to loan you his sense of humor. You have always been much too serious.”

She had meant it lightly, but Sorak nodded, taking it as a completely serious comment. “Lyric and Kivara seem to possess all of our humor. And also Eyron, I suppose, although his humor is of a somewhat caustic stripe. I have never been very good at being able to tell when people are joking with me. Not even you. It makes me feel… insufficient.”

Parts of what should have been a complete personality have been distributed among all of the others, thought Ryana with a touch of sadness. When they were younger, she had often played jokes on him because he was always such an easy victim. She wondered whether she should save her jests for Lyric, who could be tiresome because he seemed to have no serious side at all, or try to help Sorak develop the lighter side of his own nature.

“I have never felt that you were insufficient in any way,” she told him. “Merely different.” She sighed. “It’s strange. When we were younger, I simply accepted you the way you were. Now, I find myself struggling to understand you—all of you—more fully. Had I made the effort earlier, perhaps I would have never driven you away.”

He frowned. “You thought you drove me away from the convent?” He shook his head. “I had reasons of my own for leaving.”

“Can you say with honesty that I was not one of those reasons?” she asked directly.

He hesitated a moment, then replied, “No, I cannot,”

“So much for the duplicity of elves,” she said.

“I am only part elf,” Sorak replied. Then he realized she was teasing him a bit and smiled. “I had my own reasons for leaving, it is true, but I also did not wish to remain a source of emotional distress to you.”

“And so you created even more emotional distress by leaving,” she said lightly. “I understand. It must be elfling logic.”

He gave her a sidelong glance. “Am I to suffer your barbs throughout this entire journey?”

“Perhaps only a part of it,” she replied. She held up her hand, thumb, and forefinger about an inch apart.

“A small part.”

“You are almost as bad as Lyric.”

“Well, if you are going to be insulting, then you can just duck under and let Eyron or the Guardian come out. Either one could certainly provide more stimulating conversation.”

“I couldn’t agree more,” Sorak replied, suddenly speaking in an entirely different tone of voice, one that was more clipped, insouciant, and a touch wry. It was no longer Sorak, Ryana realized, but Eyron. Sorak had taken her literally. He had apparently decided that she was annoyed with him, so he had ducked under and allowed Eyron to come forth.

His bearing had undergone a subtle change, as well. His posture went from erect and square-shouldered to slightly slumped and round-shouldered. He altered his pace slightly, taking shorter steps and coming down a bit harder on his heels, the way an older, middle-aged person might walk. A casual observer might not have noticed any difference, but Ryana was villichi, and she had long since become alert to the slightest change in Sorak’s bearing and demeanor. She would have recognized Eyron even if he hadn’t spoken.

“I was only teasing Sorak a little,” she explained. “I was not really insulted.”

“I know that,” Eyron replied.

“I know you know that,” said Ryana. “I meant for you to let Sorak know it. I did not mean for him to go away. I just wish he wouldn’t be so somber and serious all the time.”

“He will always be somber and serious,” said Eyron. He is somber and serious to the point of pain. You are not going to change him, Ryana. Leave him alone.”

“You’d like for me to do that, wouldn’t you?” she said irately. “It would make the rest of you feel more secure.”

“Secure?” Eyron repeated. “You think you present any sort of threat to us?”

“I did not mean it quite that way,” said Ryana.

“Oh? How did you mean it, then?”

“Why must you always be so disputatious?” she countered.

“Because I enjoy a good argument occasionally, just as you enjoy teasing Sorak from time to time. However, the difference between us is that I enjoy the stimulation of a lively debate, while you tease Sorak because you know that he is hopelessly ill equipped to deal with it.”

“That is not true!” she protested.

“Isn’t it? I notice that you never try it with me. Why is that, I wonder?”

“Because teasing is a playful pastime, and your humor is all caustic and bitter.”

“Ah, so you want playful humor? In that case, I will summon Lyric forth.”

“No, wait!”

“Why? I thought that was what you wanted.”

“Stop trying to twist my words!”

“I am merely trying to make you see their import,” Eyron replied dryly. “You never try to bait me with your wit, not because you fear I am your match, but because you bear me no resentment, as you do Sorak.”

She stopped in her tracks suddenly, absolutely astonished at his words. “What?”

Eyron glanced back at her. “You are surprised? Truly, it seems you know yourself even less well than Sorak does.”

“What are you talking about? I love Sorak! I bear no resentment toward him! He knows that! You all know that!”

“Do we, indeed?” Eyron replied, with a wry grimace. “In point of fact, Lyric knows you love Sorak merely because he has heard you say so. But he comprehends nothing of the emotion himself. The Ranger may or may not know it. Either way, it would make no difference to him. Screech? Screech could comprehend the act of mating, certainly, but not the more complex state of love. The Watcher knows and understands, but she is uneasy with the concept of a woman’s love. Kivara is rather titillated by the notion, but for reasons having to do with the senses, not the heart. And the Shade is as far removed from love as the night is from the day. Now the Guardian knows you love Sorak, but I doubt she would disagree with me that you also feel resentment toward him. As for Kether… well, I would not presume to speak for Kether, as Kether does not condescend to speak with me. Nevertheless, the fact remains that beneath your love for Sorak smolders a resentment that you lack the courage or honesty to acknowledge to yourself.”

“That is absurd!” Ryana said, angrily. “If I were to resent anyone, it would be you, for being so contentious all the time!”

“On the contrary, that is precisely why you do not resent me,” Eyron said. “I allow you an outlet for your anger. Deep down, you are angry at Sorak, but you cannot express it. You cannot even admit it to yourself, but it is there, nevertheless.”

“I thought the Guardian was the telepath among you,” said Ryana sourly. “Or have you developed the gift as well?”

“It does not require a telepath to see where your feelings lie,” said Eyron. “The Guardian once called you selfish. Well, you are. I am not saying that is a bad thing, you understand, but by not admitting to yourself that your feelings of anger and resentment stem from your own selfish desires, you are only making matters worse. Perhaps you would prefer to discuss this with the Guardian. You might take it better if you heard it from another female.”

“No, you started this, you finish it,” Ryana said. “Go on. Explain to me how my own selfish desires led me to break my vows and abandon everything I knew and cherished for Sorak’s sake.”

“Oh, please,” said Eyron. “You did absolutely nothing for Sorak’s sake. What you did you did for your own sake, because you wanted to do it. You may have been born villichi, Ryana, but you always chafed at the restrictive life in the convent. You were always dreaming of adventures in the outside world.”

“I left the convent because I wanted to be with Sorak!”

“Precisely,” Eyron said, “because you wanted to be with Sorak. And because with Sorak gone, there was no compelling reason for you to remain. You sacrificed nothing for his sake that you would not have gladly given up, in any case.”

“Well… if that is true, and I have only done what I wanted to do, then what reason would I possibly have for being angry with him?”

“Because you want him, and yet you cannot have him,” Eyron said simply.

Even after knowing him for all those years, and having seen how his personas shifted, it was difficult for her to hear those words coming from his lips. It was Eyron speaking, and not Sorak, but it was Sorak’s face she saw and Sorak’s voice she heard, even though the tone was different.

“That has already been settled,” she said, looking away. It was difficult to meet his gaze. Eyron’s gaze, she reminded herself, but still Sorak’s eyes.

“Has it?”

“You were there when we discussed it, were you not?”

“Simply because a matter was discussed does not mean it has been settled,” Eyron replied. “You grew up with Sorak, and you came to love him, even knowing that he was a tribe of one. You thought you could accept that, but it was not until you forced the issue that Sorak told you it could never be, because three of us are female. It came as quite a shock to you, and Sorak bears the blame for that because he should have told you. There lies the root of your resentment, Ryana. He should have told you. All those years, and you never even suspected, because he kept it from you.”

Ryana was forced to admit to herself that it was true. She had thought she understood, and perhaps she did, but despite that, she still felt angry and betrayed.

“I never kept anything from him,” she said, looking down at her feet. “I would have given anything, done anything. He had but to ask! Yet, he kept from me something that was a vital part of who and what he was. Had I known, perhaps things might have been different. I might not have allowed myself to fall in love with him. I might not have built up my hopes and expectations… Why, Eyron? Why couldn’t he have told me?”

“Has it not occurred to you that he might have been afraid?” said Eyron.

She glanced up at him with surprise, seeing Sorak’s face, his eyes gazing back at her… yet it was not him. “Afraid? Sorak was never afraid of anything. Why would he be afraid of me?”

“Because he is male, and he is young, and because to be a young male is to be awash in insecurities and feelings one cannot fully understand,” Eyron replied. “I speak from experience, of course. I share his doubts and fears. How could I not?”

“What doubts? What fears?”

“Doubts about himself and his identity,” said Eyron. “And a fear that you might think him less of a male for having female aspects.”

“But that is absurd!”

“Nevertheless, it is true. Sorak loves you, Ryana. But he can never make love with you because our female aspects could not countenance it. You think that is not a source of torment for him?”

“No less than it is for me,” she replied. She looked at him, curiously. “What of you, Eyron? You have said nothing of how you feel about me.”

“I think of you as my friend,” said Eyron. “A very close friend. My only friend, in fact.”

“What? Do none of the others—?”

“Oh, no, I did not mean that,” said Eyron, “that is different. I meant my only friend outside the tribe. I do not make friends easily, it seems.”

“Could you countenance me as Sorak’s lover?”

“Of course. I am male, and I consider you my friend. I cannot say that I love you, but I do have feelings of affection for you. Were the decision mine alone to make—mine and Sorak’s, that is—I would have no objections. I think the two of you are good for one another. But, unfortunately, there are others to consider.”

“Yes, I know. But I am grateful for your honesty. And your expression of goodwill.”

“Oh, it is much more than goodwill, Ryana,” Eyron said. “I am very fond of you. I do not know you as well as Sorak does; none of us do, except perhaps the Guardian. And while I must confess that my nature is not the most amenable to love, I think that I could learn to share the love that Sorak feels for you.”

“I am glad to hear that,” she said.

“Well, then, perhaps I am not quite as disputatious as you think,” said Eyron.

She smiled. “Perhaps not. But there are times…”

“When you would like to strangle me,” Eyron completed the statement for her.

“I would not go quite that far,” she said. “Pummel you a bit, perhaps.”

“I am gratified at your restraint, then. I am not much of a fighter.”

“Eyron fears a fee-male! Eyron fears a fee-male!”

“Be quiet, Lyric!” Eyron said, in an annoyed tone.

“Nyaah-nyaah-nyahh, nyaah-nyaah-nayahh!”

Ryana had to laugh at the sudden, rapid changes that flickered across Sorak’s features. One moment, he was Eyron, the mature and self-possessed, articulate adult; in the next instant, he was Lyric, the taunting and irrepressible child. His facial expressions, his bearing, his body language, everything changed abruptly back and forth as the two different personas alternately manifested themselves.

“I am pleased you find it so amusing,” Eyron said to her irritably.

“Nyaah-nyaah-nyaah, nyaah-nyaah-nyaah!” Lyric taunted in a high-pitched, singsong voice.

“Lyric, please,” Ryana said. “Eyron and I were having a conversation. It is not polite to interrupt when grown-ups are speaking.”

“Oh, all-riiight…” Lyric said dejectedly.

“He never listens to me the way he listens to you,” said Eyron, as Lyric’s pouting expression was abruptly replaced on Sorak’s face by Eyron’s wry look of annoyance.

“That is because you are impatient with him,” Ryana said with a smile. “Children always recognize the weak points in adults, and they are quick to play on them.”

“I grow impatient merely because he delights so in annoying me,” said Eyron.

“It is only a ploy to get attention,” said Ryana. “If you were to indulge him more, he would feel less need to provoke you.”

“Females are better at such things,” said Eyron.

“Perhaps. But males could do equally well if they took the time to learn,” Ryana said. “Most of them forget too easily what it was like to be a child.”

“Sorak was a child,” Eyron said. “I never was.”

Ryana sighed. “There are some things about you all that I think I shall never understand,” she said with resignation.

“It is better simply to accept some things without trying to understand them,” replied Eyron.

“I do my best,” Ryana said.

They continued talking for a while as they walked, and it helped to pass the time of their journey, but Eyron soon wearied of the trek and ducked back under, allowing the Guardian to manifest. In a way, however, the Guardian had been there all along. Like the Watcher, she was never very far beneath the surface, always present, even when one of the others had come out. As her name implied, her primary role was to act as the protector of the tribe. She was the strong, maternal figure, sometimes interacting with the others in an active way, sometimes content to remain passive, but always there as a moderating presence, a force for balance in the inner tribe. While she was manifested, Sorak was there too as an underlying presence. If he chose to, he could speak, or else he could simply listen and observe while the Guardian interacted with Ryana. When any of the others were out, things were often slightly different. If Lyric was at the fore of their personas, he and Sorak could both be out at the same time, like two individuals awake in the same body, as was the case with Sorak and the Guardian, or Screech. But if it was Eyron, or the Ranger, or any of the others that were stronger personalities, Sorak often wasn’t there at all. At such times, he faded back into his own subconscious, and his knowledge of what occurred during the times when any of the stronger ones were out depended on the Guardian granting him access to the memories. Kivara seemed to cause him the greatest difficulty. Of all his personalities, she was the most unruly and unpredictable, and the two were frequently in conflict. If Kivara had her way, Sorak had explained, she would come out more often, but the Guardian kept her in line. The Guardian was capable of overriding all the other personalities, Sorak’s included, save for Kether and the Shade. And those two appeared only rarely.

It had taken Ryana ten years to become accustomed to the intricacies of the relationships of Sorak’s inner tribe. She could imagine how it would be for anyone who met Sorak for the first time. And she could understand why Sorak did not trouble to explain his curious condition to others that he met. It would only frighten people and confuse them. Without training in the Way, it would have frightened and confused him, too. She wondered if there was any way that he could ever become normal.

“Guardian,” she said, knowing that the privacy of her own thoughts would be respected unless she invited the Guardian to look into her mind, “I have been wondering about something, but before we speak of it, I wish to make certain you do not take it amiss. It is not my desire to offend.”

“I would never think that of you,” the Guardian replied. “Speak then, and speak frankly.”

“Do you think that there is any chance Sorak could ever become normal?”

“What is normal?” the Guardian replied.

“Well… you know what I mean. Like everybody else.”

“Everybody else is not the same,” the Guardian replied. “What is normal for one person may not be normal for another. But I believe I understand your meaning. You wish to know if Sorak could ever become just Sorak, and not a tribe of one.”

“Yes. Not that I wish you did not exist, you understand. Well… in a sense, I suppose I do, but it is not because of any feeling that I have against you. Any of you. It is just that… if things had been different…”

“I understand,” the Guardian replied, “and I wish that I could answer your question, but I cannot. It goes beyond my realm of knowledge.”

“Well… suppose we find the Sage,” Ryana said, “and suppose he can change things with his magic—make it so that Sorak is no longer a tribe of one, but simply Sorak. If that were possible…” her voice trailed off.

“How would I feel about that?” the Guardian completed the thought for her. “If it were possible, I suppose it would depend on how it were possible.”

“What do you mean?”

“It would depend on how it would be achieved, assuming that it could be achieved,” the Guardian replied. “Imagine yourself in my place, if you can. You are not simply Ryana, but Ryana is merely one aspect of your self. You share your body and your mind with other aspects, who are equally a part of you, though separate. Let us say that you have found a wizard who can make you the same as everybody else—the same, that is, in the sense you mean. Would you not be concerned about how that would be done?

“If this wizard were to say to you, ‘I can make you whole, unite all of your aspects into one harmonious persona,’ well, in that case, you might be inclined to accept such a solution. And accept it eagerly. But what if that same wizard were to say to you, ‘Ryana, I can make it so that you will be like everybody else. I can make it so that only Ryana will exist, and the others will all disappear’? Would you be so eager to accept such a solution then? Would it not be the same as asking you to agree to the deaths of all the others? And if we assume, for the sake of the discussion, that you could accept such a situation, what would be the outcome? If all the others were separate entities who made up a greater whole, what would be gained, and what would be lost? If they were to die, what sort of person would that leave? One who was complete? Or one who was but a fragment of a balanced individual?”

“I see,” Ryana said. “In such a case then, if the choice were mine to make, I would, of course, refuse. But suppose it was the first choice that you mentioned?”

“To unite us all in one persona—Sorak’s?” asked the Guardian.

“In a manner that would preserve you all, though as one individual instead of many,” said Ryana. “What then?”

“If that were possible,” the Guardian replied, “then I think, perhaps, I would have no objection. If it would benefit the tribe to become one instead of many and preserve all those within it as a part of Sorak, then it might indeed be for the best. But again, we must think of what might be gained and what might be lost. What would become of all the powers we have as a tribe? Would they be preserved, or would some be lost as a result? And what would become of Kether? If Kether is, as we suspect, a spirit from another plane, would his ability to manifest through Sorak be preserved? Or would that bridge be forever burned behind us?”

Ryana nodded. “Yes, those are all things that would have to be considered. Still, it was but an idle speculation. Perhaps not even the Sage would have such power.”

“We shall not know that until we find him,” said the Guardian. “And who is to say how long this quest may take? There is still one more thing to consider, so long as we are discussing possibilities. Something that you may have failed to take into account.”

“And that is?”

“Suppose we found the Sage, and he was able to unite us all into one person, with no loss to any of us. Sorak would become the tribe, all blended into one person who was, as you say, ‘normal.’ And the tribe would become Sorak. All the things that I am, all that is Kivara, and Lyric, the Watcher and the Ranger and the Shade, Screech and Eyron and the others, some of whom still lie deeply buried, all would become a part of Sorak. What, then, would become of the Sorak that you know and love? Would he not become someone very different? Would the Sorak that you know not cease to exist?”

Ryana continued walking silently for a while, mulling that over. The Guardian did not impinge upon her contemplation. Finally, Ryana said, “I had never considered the possibility that Sorak might be changed in a manner that would render him completely different. If that were the case, then I suppose my own thoughts on the matter, my own feelings, would be determined by whether or not such a change would be in his best interests. That is to say, in all of your best interests.”

“I do not mean to be harsh,” the Guardian said, “but consider also that it is Sorak as you know him now who loves you. I understand that love, and am capable of sharing it to some degree, but I could not love you that way that Sorak does. Perhaps it is because I am a female and my nature is such that I could not love another female. If Sorak were to change in the way we are discussing, perhaps that love would change, as well. But you must also consider all the others. Eyron is male, yet he thinks of you as a friend, not as a lover. The Watcher does not love you and never could. The Ranger is indifferent to you, not because of any shortcoming on your part, it is just that the Ranger is the Ranger, and he is not given to such emotions. Neither is the Shade. Kivara is fascinated by new sensations and experiences, but while she may not balk at a physical relationship with you, she would be a very fickle and uncaring lover. And there are all the others, whose feelings and modes of thought would all go into creating the new Sorak of whom we speak. It is quite possible that this new Sorak would no longer love you.”

Ryana moistened her lips. “If the change would benefit him—would benefit you all—and make him happy, then I would accept that, despite the pain that it would bring me.”

“Well, we speak of something that may never come to pass,” the Guardian replied. “When we first spoke of your love for Sorak, I called you selfish and accused you of thinking only of yourself. I spoke harshly and I now regret that. I know now that you are nothing of the sort. And what I am about to say, I say not for my sake, but for yours. To long for something that may never be is to build a foundation on a swamp. Your hopes are likely to sink into the quagmire. I know that it is far more easily said than done, but if you could try to learn how to love Sorak as a friend, a brother, then whatever happens in the future, you may save your heart from breaking.”

“You are right,” Ryana said. “It is far more easily said than done. Would it were not so.”

They traveled on throughout the day, stopping occasionally to rest, and their journey was, for the most part, uneventful. As the day wore on, the temperatures climbed steadily, until the dark Athasian sun was beating down on them like a merciless adversary. Sorak came out again and accompanied her for the rest of their journey that day, though the Guardian kept him from remembering the last part of their conversation. They found themselves conversing less and less, conserving their energies for the long trek still ahead of them.