TRSF – Read Now and Download Mobi

Contents

COMMUNICATIONS

BY CORY DOCTOROW

ENERGY

BY VANDANA SINGH

COMPUTING

By KEN LIU

COMPUTING

By JOE HALDEMAN

ROBOTICS

By MA BOYONG

BIOMEDICINE

By PAT CADIGAN

MATERIALS

The Surface of Last Scattering

By KEN MACLEOD

WEB

Specter-Bombing the Beer Goggles

By PAUL DI FILIPPO

ENERGY

By TOBIAS BUCKELL

COMMUNICATIONS

The Flame Is Roses, The Smoke Is Briars

By GWYNETH JONES

SPACEFLIGHT

By GEOFFREY A. LANDIS

BIOMEDICINE

By ELIZABETH BEAR

Introduction

Welcome to the 2011 TRSF, the first annual anthology of original science fiction stories from MIT’s Technology Review. With stories set in the near future from celebrated masters and emerging authors, TRSF is our contribution to the tradition of “hard” science fiction. It’s a tradition that stretches all the way back to Jules Verne, in which writers draw from the cutting edges of engineering and science, and try to portray how technology might advance in a way that futurists, economists, and other down-to-earth pundits can’t.

Because of its emphasis on technical plausibility, hard science fiction has been accused in the past—not always unfairly—of neglecting plot and character development in favor of breathless exposition about some flashy gadget or astronomical phenomenon. But the stories in these pages prove that you don’t have to sacrifice great writing to say something interesting about how the future might work. Hard science fiction has also been accused—again, not always unfairly—of being the jealously guarded preserve of mostly American men. So, striving for a richer spectrum of viewpoints, we have chosen male and female authors who come from around the world, including one writer whose work is appearing for the first time in English.

Inspired by the real-world technological breakthroughs covered online and in print by Technology Review, these authors bring you 12 visions of tomorrow, looking at how the Internet, computing, energy, biotechnology, spaceflight, and more might develop, and how those developments might affect the people who have to live with them. What do you think of these visions? What technologies do you believe are going to profoundly transform how we live, and would deserve to be the inspiration for a story in next year’s TRSF? Let us know online at www.technologyreview.com/sf.

—Stephen Cass

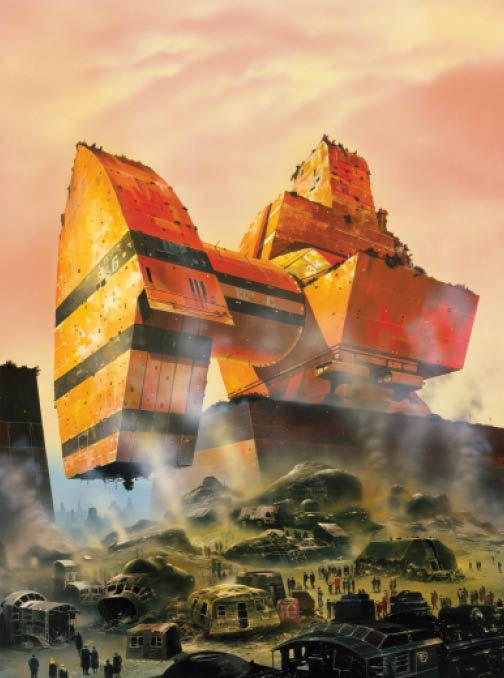

About the artist

CHRIS FOSS has produced some of the most iconic and recognizable images in science fiction. In a career stretching over 40 years, he has illustrated the covers of books for Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Philip K. Dick, and many more. In his early career, Foss produced two to three paintings a week, relying on art directors for guidance about content and tone rather than reading manuscripts (once, for an Asimov title, one director simply asked Foss to give him “a green one.”) The resulting cover would sometimes prove to be more memorable than the actual book; Foss can evoke an entire story with a single scene. His spacecraft and buildings often display signs of wear and damage, conjuring up histories of better days and hours of hard use. TRSF has reproduced six of these classic images.

The illustrations that follow in the TRSF are originally from the following books: Ancient My Enemy (Gordon R. Dickson, 1978); The Bloodstar Conspiracy (Smith and Goldin, 1978); Norman Conquest 2066 (J.I. McIntosh, 1976); Deepwater (Alex Finer, 1985); Conquests (Poul Anderson, 1981); and Earth is Room Enough (Isaac Asimov, 1986).

With the publication this year of Hardware: The Definitive SF Works of Chris Foss (Titan Books), Foss is enjoying a revival, and he continues to paint and experiment with new techniques; for the cover of TRSF, his first major recent U.S. commission, he developed a style that combines collage with oil painting. To learn more about the creation of the cover, visit www.technologyreview.com/sf. To see more of Foss’s work, visit his website at www.chrisfossart.com.

Journalist, co-editor of the Boing Boing blog, and science fiction author, London-based Cory Doctorow won the 2004 Locus Award for Best First Novel for Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom. He was a finalist for the 2009 Hugo Award and won the John W. Campbell Memorial Award that year. Doctorow’s stories often take a wry look at the digital zeitgeist, and this story is no exception.

COMMUNICATIONS

The Brave

Little Toaster

BY CORY DOCTOROW

One day, Mister Toussaint came home to find an extra 300 euros’ worth of groceries on his doorstep. So he called up Miz Rousseau, the grocer, and said, “Why have you sent me all this food? My fridge is already full of delicious things. I don’t need this stuff and besides, I can’t pay for it.”

But Miz Rousseau told him that he had ordered the food. His refrigerator had sent in the list, and she had the signed order to prove it.

Furious, Mister Toussaint confronted his refrigerator. It was mysteriously empty, even though it had been full that morning. Or rather, it was almost empty: there was a single pouch of energy drink sitting on a shelf in the back. He’d gotten it from an enthusiastically smiling young woman on the metro platform the day before. She’d been giving them to everyone.

“Why did you throw away all my food?” he demanded. The refrigerator hummed smugly at him.

“It was spoiled,” it said.

BUT THE FOOD hadn’t been spoiled. Mister Toussaint pored over his refrigerator’s diagnostics and logfiles, and soon enough, he had the answer. It was the energy beverage, of course.

“Row, row, row your boat,” it sang. “Gently down the stream. Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily, I’m offgassing ethylene.” Mister Toussaint sniffed the pouch suspiciously.

“No you’re not,” he said. The label said that the drink was called LOONY GOONY and it promised ONE TRILLION TIMES MORE POWERFUL THAN ESPRESSO!!!!!ONE11! Mister Toussaint began to suspect that the pouch was some kind of stupid Internet of Things prank. He hated those.

He chucked the pouch in the rubbish can and put his new groceries away.

THE NEXT DAY, Mister Toussaint came home and discovered that the overflowing rubbish was still sitting in its little bag under the sink.

The can had not cycled it through the trapdoor to the chute that ran to the big collection-point at ground level, 104 storeys below.

“Why haven’t you emptied yourself?” he demanded. The trash can told him that toxic substances had to be manually sorted. “What toxic substances?”

So he took out everything in the bin, one piece at a time. You’ve probably guessed what the trouble was.

“Excuse me if I’m chattery, I do not mean to nattery, but I’m a mercury battery!” LOONY GOONY’s singing voice really got on Mister Toussaint’s nerves.

“No you’re not,” Mister Toussaint said.

MISTER TOUSSAINT tried the microwave. Even the cleverest squeezy-pouch couldn’t survive a good nuking. But the microwave wouldn’t switch on.

“I’m no drink and I’m no meal,” LOONY GOONY sang. “I’m a ferrous lump of steel!”

The dishwasher wouldn’t wash it (“I don’t mean to annoy or chafe, but I’m simply not dishwasher safe!”). The toilet wouldn’t flush it (“I don’t belong in the bog, because down there I’m sure to clog!”). The windows wouldn’t retract their safety screen to let it drop, but that wasn’t much of a surprise.

“I hate you,” Mister Toussaint said to LOONY GOONY, and he stuck it in his coat pocket. He’d throw it out in a trash can on the way to work.

THEY ARRESTED Mister Toussaint at the 678th Street station. They were waiting for him on the platform, and they cuffed him just as soon as he stepped off the train. The entire station had been evacuated and the police wore full biohazard containment gear. They’d even shrinkwrapped their machine-guns.

“You’d better wear a breather and you’d better wear a hat, I’m a vial of terrible deadly hazmat,” LOONY GOONY sang.

When they released Mister Toussaint the next day, they made him take LOONY GOONY home with him. There were lots more people with LOONY GOONYs to process.

MISTER TOUSSAINT paid the rush-rush fee that the storage depot charged to send over his container. They forklifted it out of the giant warehouse under the desert and zipped it straight to the cargo-bay in Mister Toussaint’s building. He put on old, stupid clothes and clipped some lights to his glasses and started sorting.

Most of the things in the container were stupid. He’d been throwing away stupid stuff all his life, because the smart stuff was just so much easier. But then his Grandpa had died and they’d cleaned out his little room at the pensioner’s ward and Mister Toussaint had just shoved it all in the container and sent it out to the desert.

From time to time, he’d thought of the eight cubic meters of stupidity he’d inherited and sighed a put-upon sigh. He’d loved Grandpa, but he wished the old man had used some of the ample spare time from the tail end of his life to replace his junk with stuff that could more gracefully reintegrate with the materials stream.

How inconsiderate!

The house chattered enthusiastically at the toaster when he plugged it in, but the toaster said nothing back. It couldn’t. It was stupid. Its bread-slots were crusted over with carbon residue and it dribbled crumbs from the ill-fitting tray beneath it. It had been designed and built by cavemen who hadn’t ever considered the advantages of networked environments.

It was stupid, but it was brave. It would do anything Mister Toussaint asked it to do.

“It’s getting hot and sticky and I’m not playing any games, you’d better get me out before I burst into flames!” LOONY GOONY sang loudly, but the toaster ignored it.

“I don’t mean to endanger your abode, but if you don’t let me out, I’m going to explode!” The smart appliances chattered nervously at one another, but the brave little toaster said nothing as Mister Toussaint depressed its lever again.

“You’d better get out and save your ass, before I start leaking poison gas!” LOONY GOONY’s voice was panicky. Mister Toussaint smiled and depressed the lever.

Just as he did, he thought to check in with the flat’s diagnostics. Just in time, too! Its quorum-sensors were redlining as it listened in on the appliances’ consternation. Mister Toussaint unplugged the fridge and the microwave and the dishwasher.

THE COOKER and trash can were hard-wired, but they didn’t represent a quorum.

THE FIRE DEPARTMENT took away the melted toaster and used their axes to knock huge, vindictive holes in Mister Toussaint’s walls. “Just looking for embers,” they claimed. But he knew that they were pissed off because there was simply no good excuse for sticking a pouch of independently powered computation and sensors and transmitters into an antique toaster and pushing down the lever until oily, toxic smoke filled the whole 104th floor.

Mister Toussaint’s neighbors weren’t happy about it either.

But Mister Toussaint didn’t mind. It had all been worth it, just to hear LOONY GOONY beg and weep for its life as its edges curled up and blackened.

He argued mightily, but the firefighters refused to let him keep the toaster. ■

Born and raised in New Delhi, Singh now lives in Massachusetts, where she is an assistant professor of physics at Framingham State University. She has been publishing science fiction stories since the mid-2000s, and her work has been included in several “Best Of” anthologies.

ENERGY

Indra’s Web

BY VANDANA SINGH

Mahua ran over the familiar, rock-studded pathway under the canopy of acacia trees, her breath coming fast and ragged. She would have to stop soon, she wasn’t as young as she used to be, and there was a faint, persistent pain in her right knee—but she loved this physicality: heart thumping, sweat running down her face in rivulets, the forest smelling of sap and animal dung, grit on her lips from the dust. The forest was where she got her best ideas; it was an eternal source of inspiration. It was why her work was getting recognition across the world. But the forest didn’t care about fame or fortune—here she was just another animal: breath and flow, a kite on the wing, a deer running.

Running, she liked to have the net chatter going on in the Shell in her ear: Salman monitoring the new grid, Varun and Ali reporting on the fish stocks in the artificial marshland by the river, Doctor Sabharwal’s monitor relaying Mahua’s grandmother’s condition at the hospital: stable, stable, stable, still on life support. Thinking about her grandmother’s stroke made Mahua feel like she was about to fall into a pit of despair; she distracted herself with the reminder that she had promised Namita she would try out the myconet music app during this morning’s run. “It’s just for fun, Mahua-di, but try it, you’ll like it.” They were so anxious about her, these young people, knowing she was not quite herself these days. Moved and perversely annoyed by their concern, she had spent some hours with them in the biosystems lab learning the app…

There is a fungal network, a myconet, a secret connection between the plants of the forest. They talk to each other, the acacia and the shisham and the gulmohar tree, in a chemical tongue. They communicate about pests, food sources, the weather, all through the flow of biomolecules through the fungal hyphae. Through this network, large trees have even been known to share nutrients with saplings of the same species. Mahua’s protégé, Namita, is part of the team that helped decipher (to the extent that humans can) this subtle language. In the forest they have planted sensors in the soil to catch some of the chemical exchanges between plants. The signals are fed back into the interpreter and then analyzed. Some members of the team have made music from the signals: convert the concentration of a certain biochemical transmitter changing in real time into a succession of notes where the duration indicates the strength of the transmitter. Add a few other transmitter signals as sounds of a slightly different frequency and you’ll get a sometimes musical chatter that is at once soothing and intriguing. Mahua is new to this and she’s never tried it out in the forest before. She’s always encouraged play in their research—it is not only fun, but important, she tells them—play leads to new insights, shakes up pre-conceived notions… And now they need the relief of play, after having spent the past few months calculating and putting in place Ashapur’s first smart energy grid, the Suryanet, modeled on the myconet itself.

Mahua turned on the app. As she ran she picked up information from the closest few sensors so that she had a “picture” that changed in time and space. At first she heard nothing but the soothing semi-music of the various tones. Then the surprise came, a peculiar sensation rather like vertigo, a kind of slippage, as though she was leaving her human self behind, dissolving into something infinitely vast. It was like looking up at the Milky Way from the top of a high mountain on a clear night. She had always been quick to discern webs of relationships—it was her particular skill, after all—but this was different. A feeling like an electric shock coursed through her, a long moment of recognition, as though her deepest mind already knew this pattern. The effect was so startling that she stumbled over a tree root. Then the Shell beeped urgently in her ear, and the spell broke.

It was Salman, calling out an alert: Suntower 1 had failed. There were random fluctuations going on all over the new energy grid that nobody could explain, Salman said, breathless. It seemed likely that the Suryanet, so painstakingly put in place over the past few months, the result of years of effort, on which everyone was depending for the survival of Ashapur and maybe of the biosphere itself—the Suryanet could be a spectacular failure.

ONE OF THE things Mahua had learned from her grandmother was that when trouble struck, unless it needed immediate attention, it was good to slow down and meander a little. So she wandered to the top of the ridge, where the height enabled her to see Ashapur in all its glory.

A former slum, it used to lie on the edge of Delhi like a sore. In the last ten years the Ashapur project had transformed it. The hutments of cardboard and tin had been replaced by dwelling houses built mostly by the residents themselves with traditional materials: a hard mixture of mud, straw, rice husk, surfaced with a lime-based plaster. In use for thousands of years, then forgotten, and revived in the 20th century by visionary architects like Laurie Baker, the material had so far survived nearly ten years of baking heat and monsoon rains. The majority of the residents were the original slum inhabitants, climate refugees from the drowned villages of Bangladesh, their homes transformed by the Ashapur project. When Mahua looked at Ashapur from this height she saw mostly an uneven carpet of green and silver—rooftop gardens broken by the gleam of solar panels, and corridors of native trees, neem, khejri, gulmohar, running down the hill from her forest like green arteries through the settlement.

Above this vista rose the suntowers like a surrealist’s dream: four functioning, and a fifth under construction, their tops capped by sun-tracking petals of biomimetic material containing tiny, environmentally benign artificial cells, the suryons, that drank up photons. The largest, oldest facility was Suntower 1, now mysteriously moribund. Ashapur was nearly self-sufficient in food and energy, and with the new grid, the Suryanet, they should have been able to donate power to the Delhi grid, thereby silencing the naysayers and establishing the need for a thousand Ashapurs. Four solar plants making hydrogen from the breakdown of water; sewage-fed biogas plants; enormous energy savings from building construction and layout—none of the buildings needed air conditioning; numerous rooftops with solar panels; even greater energy savings from the fact that these former villagers were traditionally energy-efficient, living in clusters, throwing away nothing, re-using almost everything. And all the energy sources were now connected on the Suryanet. Yet…

She took the long way to Suntower 1. She always found it calming to walk through Ashapur. The narrow roads were not built on a rectangular pattern but instead curved, moving obligingly around an ancient peepul tree or dwelling. Her designers had kept the street pattern of the original slum but had improved on it, allowing room for people to congregate in front of this chai-house or in that niche, so that old women could gossip and mind the little ones, and the wandering cows and pariah dogs had room to rest. Here, right at the corner she was passing now, between an Internet café and an agricultural research center—here’s where a potential foreign funder had stopped her six years ago. “I don’t understand,” he’d said, “why this town is so untidy. There’s no order, no proper grid for the streets. It looks very inefficient. And the roads are too narrow for traffic flow! Where are your cars?”

In response to this sort of thing her grant-writing team had developed a slide show—apparently some of these potential funders could only understand things if they were in a powerpoint presentation—to show how optimal city function could be best achieved by having connectivity at multiple scales. Large, coarse, fewer pathways for cars; smaller, more dense ones for people. And for other animals as well as people, the green corridors that branched into the city, maintaining biodiversity and the psychological benefits of closeness to nature, while providing Ashapur with cooler summers, seasonal supplies of fruit and nuts, and raw material for a new cottage industry in crafts.

Now she entered Energy Central, the building below Suntower 1. It was cool here—the thick mud-based walls ensured that—and the curving stairway with its murals gave no hint of the troubles of Suntower 1, rising high above the roof. At the lab door there was the familiar sign that Salman had installed by encouraging a vivid green moss to grow on an earthboard so that it spelled out the motto of the Biomimetic Energy Materials Lab—“To Learn from Nature, not to Exploit Her.” His colleagues had teased Salman about the irony of exploiting a moss to write these noble words, but the moss seemed to have decided things for itself. It spelled “To learm from Natur, not to Explod,” which still made her smile.

Inside there was a dim coolness and the glow of multiple terminals. A meeting was in progress, chaotic and impassioned as usual. Arguments and discussions in Hindi, English and Bangla: Salman, deep in agitated conversation with Namita and Ayush, Hamid, a young trainee who had once begged on the streets as a child, patiently explaining the situation to the boy who had brought the tea. Mahua stayed just inside the door, unnoticed, letting the words flow around her, sensing the web of ideas and feelings raging through the room.

“... no guarantee that modeling the Suryanet on the myconet was going to work—why risk everything on one crazy idea?”

“… calculations, have you forgotten we did the entire constructal analysis? Besides, scale-free networks are everywhere…”

“Nobody’s networked a suryon-based system before or allowed it to self-regulate! There were safer ways of doing this, better ways! But no, you have to go on about minimal control! It’s centralized control systems that make everything work!”

“Yaar, stop being a control freak, OK? We’re just mimicking the natural control systems that exist in nature. Stop panicking… obviously there’s a bug in the system somewhere…”

“… oldest suntower, beta version of the suryons, it’s bound to fail…”

“… not this quickly, idiot…”

Chanchal, from one of the terminals:

“Salman, look at what’s happening to the other suntowers! Energy collection is now above average by seven percent in 2, 3 and 4! But… dekho, boss! These numbers! More inflow than outflow. There’s a major bug somewhere!”

“Or energy is no longer conserved,” someone said, as there was a mass movement to the terminal.

Mahua found herself curiously detached from the mayhem. A signal sounded repetitively in the lab like the beep of the monitor in her grandmother’s hospital room.

She remembers the first time seeing these young people in various colleges and universities, nearly a decade ago. They are bound for brilliant careers as engineers, managers, CEOs, their upturned faces curious, skeptical, polite. She has nothing to offer them so she gives it all she has.

“I come to you with empty hands,” she says. “I can’t offer you much money. I can’t offer you big houses, two cars, five air conditioners. Nor the jet-setting lifestyle with its cross-continental board meetings, the wife or husband who will ultimately cheat on you, the children who will drive you crazy. What I can give you is a chance to be part of a revolution. A revolution that might just save our earth from the climate crisis. One that comes up with not just new technologies, but new ways to live that are more whole and deep and satisfying than anything you’ve known. Most of you have enjoyed being in college. You are the best of the lot, the ones who get high on learning, and on the company of like minds. The Ashapur project is like college, except that you have the chance to learn by doing, and to do more good than you ever could with the life now laid out for you. We will take care of your housing and health care, and you will get as much salary as I do. Which isn’t saying very much. But you’ll get up every morning knowing that by the end of the day you would have made a new discovery, a new friend, a new way of looking at the world. You will blow old paradigms out of existence on a near-daily basis. I promise you that. Are you with me?”

Some of the faces look incredulous, even mocking, but there are others who light up. She’s struck a chord deep inside them. She lets out a deep breath of relief.

Now she thinks: had she betrayed them after all? Would they forgive her, if this turned out to be the disaster she had always feared?

Finally they noticed her, surrounded her, pulled her before the screens, presented their arguments before her. “Look,” she said at last. “You know how to check everything according to the protocols. Do that. Then come up with some wild theories and shake up the possibilities, but don’t panic. We can survive a couple of power failures; it isn’t as though we haven’t grown up with them. The hospital seems to have enough power right now; so do most key-need places. Make sure backup generators are working and just wait.”

MAHUA, was named by her long-dead mother because she was born under a mahua tree on the way to Delhi. The two of them—mother and grandmother—had migrated from their village in Bihar after her father died. She grew up in the slums, where her mother died when Mahua was eleven, only three months before their fortunes changed.

So it’s been Mahua and her grandmother, who now lies in a hospital bed after a stroke, kept alive by the machines that surround her. The woman with the temper and the loud laugh, who always had something to say, now looks at Mahua with wide, frightened eyes. She can’t speak but she can croak a little. Sometimes she lies peacefully while Mahua holds her hand, but at other times she seems to be trying to tell Mahua something. Mahua, who can discern connections with a skill that frightens her sometimes, cannot tell what her grandmother is trying to say. She tries to reassure her—there are all kinds of new techniques the surgeons want to try. There’s hope.

When she was a child Mahua used to follow ants as they moved purposefully across the dirt floor of the room. She wanted to know where they were going in such a hurry, and whether their abrupt pauses and frantically waving antennae had some hidden significance. Later she came to realize that the ants followed invisible trails across the floor—that the world was full of secret communication channels, like the electric wires between poles that rose above the tenements. It was as though some inner sense within her had opened because following this realization she was suddenly aware of walking through a tangled spider’s web of relationships. The gossiping old women who sat around her mother’s sewing machine, jabbering about this and that, speaking as much with meaningful glances and shakes of the fist as with their cracked voices—the way people looked at each other, signifying feelings and relations, how people spoke as much with their silences as with words. Even the winds that brought the monsoon rains had some sort of pattern or cycle, a network in both time and space. She was delighted with this discovery but she didn’t understand it then.

The narrow little lanes of the slum are like spider webs, intersecting at odd angles, curving around hutments, like a stream of water. Everywhere there are people and smells and here and there an Internet café or a soda stand or a chaatwala. In this mess and confusion someone’s placed a computer in a niche on a wall and the street kids play with it between school and errands and work. After a long time she’s found the courage to go up to the shiny, inviting screen, the keyboard, where the letters are in Hindi—thank goodness she can read—but the screen itself has a number of floating objects, tumbling and combining when they meet. She stares at it, mesmerized, and after a while she tries a hesitant tap on the keyboard. Three days later she’s learnt that she can save the game in her own name. She keeps playing. In a strange way it makes sense the way the slum itself makes sense. It’s pattern and rhythm, although she will not know those words for a long time. At the end of this period there is a person at her door, and a scholarship to go to a really good school with housing for herself and her grandmother, and guidance from the Slum Children’s Education Trust which is inhabited by kindly aunties.

At thirteen Mahua fell ill. She diagnosed the malady herself as anxiety brought on by acute apophenia. Becoming sensitive to networks and relationships, she saw connections everywhere, even when they weren’t actually present. This drove her crazy but she didn’t want to take medicines to suppress her ability for pattern recognition. Instead she resolved to train her mind to distinguish between false apparent connections and real ones—the only way to do that was to study the world. With this determination, her new school, with its snooty, unfriendly girls and regimented routine, became a matter of finding the grain in the chaff, the flashes of joy in the misery.

For instance: Mrs. Khosla introducing the concept of energy in her usual monotone. A classroom full of bored children, and only Mahua sitting up, recognizing that she has just been handed the golden key, the central concept, that through which the entire universe interacted, the currency of all communication. Energy! And its conservation law. All real systems were governed by fundamental laws that acted as constraints. That is how you differentiated apparent relationships from real ones!

But as she stands in the hospital room looking at her grandmother (the old woman is made almost alien by the tubes and wires of the life-support system), she feels that she has failed after all. What good is it to be able to sense patterns and relationships when she can’t tell what her own grandmother wants to say? Tomorrow they’ll try once more to work with the eyelids to see if her grandmother can learn to communicate thus. But the old woman, always contrary, has apparently refused to cooperate. What does she want? Not death, surely, not before exploring all the options. Her grandmother has such a zest for life. She’d opened a small business of her own at the age of seventy-three, making simmerpots. This is a pot is made of mud and straw rather like the walls of the dwellings but in different proportions—and it is one reason why energy usage is so low in Ashapur. You cook your stew or curry on the stove for two minutes, until it is simmering nicely, and then you take it off the heat and put it inside the simmerpot. The simmerpot is such a good insulator that the food keeps cooking in there for hours afterwards. Not her grandmother’s invention—it had been in use in her village for centuries. But here only her grandmother and a handful of trainees know how to make it, and when you walk around Ashapur you see simmerpots everywhere, on kitchen window-sills and in the large community dining rooms. And the woman who made it popular and indispensable, who had such vivacity at eighty-one that she could gossip non-stop with her neighbors until three in the morning, now lies hooked up to machines like a captive, with death in her eyes.

Mahua has finally seen it. Her grandmother wants to die.

THAT EVENING Mahua goes walking down the lanes of Ashapur, following a hunch.

There before her is Suntower 5. While physically connected to the grid, it is still under construction; only the skeletal frames of the petals are complete, the tubing through which the suryon-embedded substratum will eventually be pumped up. There is a sleepy boy in the control room, one of the former street urchins assigned to do some after-hours caretaking. Tousling his hair and sending him off for some tea, Mahua sits before the computer. Suntower 5 is the newest design; the suryon distribution architecture is so complex and bug-ridden that it will take a while to implement. Since the work began on the grid so many months ago, nobody has been able to attend to Suntower 5.

It doesn’t take Mahua long to zoom into an image of a petal atop the tower. At first she sees just the skeleton, but there, between the supports is a new, delicate, lace-like integument. The suryons are distributing themselves, filling in the empty spaces. Somehow the Suryanet has not only decided that Suntower 5 should be functional, but has allocated resources to it, which is why Suntower 1—the oldest, and least efficient—has shut itself down. Temporarily, perhaps, but who knows? Does a sufficiently complex network give rise to its own wisdom? She sends a hint to the team at Suntower 1. By the morning they will have figured it out. She sips her tea, talks to the sleepy attendant. At last she goes back into the night, thinking about the networks in which she exists, and how tomorrow a major node on which her very life depends will be taken off-line forever. She thinks of the forest on the ridge. The forest lives on because it accepts death—with every twig that falls, with every ant that meets its annihilation, a thousand life-forms come into being. Danger walks there and so its denizens learn adaptation; here, too, we must rebuild ourselves, define ourselves anew with each loss, each encounter. She remembers a story her grandmother once told her about Indra’s Web, the ultimate cosmic network in which every node mirrors the whole…

In the twilight hush there are sleepy sounds of birds settling in the trees; a family of rhesus monkeys chatter softly in a rooftop garden above her head. A radio is playing an old film song, very softly. It is a warm night; someone has a khas-khas cooler working, the sound of the fan almost drowning out the steady drip of water. If she wants, her Shell unit can pick up energy data from the sensors in each dwelling place. She loves this marriage of the traditional and the new, the forest and the city, this great experiment, this marvel that is Ashapur, City of Hope. ■

Boston-based Ken Liu has worked as a programmer and as a lawyer, which he says are “surprisingly similar” professions. He has been regularly publishing science fiction short stories since 2003. He’s currently co-writing his first novel with his wife, and has translated a number of Chinese stories into English, one of which, by Ma Boyong, appears in this collection.

COMPUTING

Real Artists

BY KEN LIU

“You’ve done well,” Creative Director Len Palladon said, looking over Sophia’s résumé.

Sophia squinted in the golden California sun that fell on her through the huge windows of the conference room. She wanted to pinch herself to be sure she wasn’t dreaming. She was here, really here, on the hallowed campus of Semaphore Pictures, in an interview with the legendary Palladon.

She licked her dry lips. “I’ve always wanted to make movies.” She choked back for Semaphore. She didn’t want to seem too desperate.

Palladon was in his thirties, dressed in a pair of comfortable shorts and a plain gray T-shirt whose front was covered with the drawing of a man swinging a large hammer over a railroad spike. A pioneer in computer-assisted movie making, he had been instrumental in writing the company’s earliest software and was the director of The Mesozoic, Semaphore’s first film.

He nodded and went on, “You won the Zoetrope screenwriting competition, earned excellent grades in both technology and liberal arts, and got great recommendations from your film studies professors. It couldn’t have been easy.”

To Sophia, he seemed a bit pale and tired, as though he had been spending all his time indoors, not out in the golden California sun. She imagined that Palladon and his animators must have been working overtime to meet a deadline: probably to finish the new film scheduled to be released this summer.

“I believe in working hard,” Sophia said. What she really wanted was to tell him that she knew what it meant to stay up all night in front of the editing workstation and wait for the rendering to complete, all for the chance to catch the first glimpse of a vision coming to life on the screen. She was ready.

Palladon took off his reading glasses, smiled at Sophia, and took out a tablet from behind him. He touched its screen and slid it across the table to Sophia. A video was playing on it.

“There was also this fan film, which you didn’t put on your résumé. You made it out of footage cut and spliced from our movies, and it went viral. Several million views in two weeks, right? You gave our lawyers quite a headache.”

Sophia’s heart sank. She had always suspected that this might become a problem. But when the invitation to interview at Semaphore came in her email, she had whooped and hollered, and dared to believe that somehow the executives at Semaphore had missed that little film.

SOPHIA REMEMBERED going to The Mesozoic. She was seven. The lights dimmed, her parents stopped talking, the first few bars of Semaphore’s signature tune began to play, and she became still.

Over the next two hours, as she sat there in the dark theater, mesmerized by the adventure of the digital characters on that screen, she fell in love. She didn’t know it then, but she would never love a person as much as she loved the company that made her cry and laugh, the company that made The Mesozoic.

A Semaphore movie meant something: no, not merely technological prowess in digital animation and computer graphics that were better than life. Sure, these accomplishments were impressive, but it was Semaphore’s consistent ability to tell a great story, to make movies with heart, to entertain and move the six-year old along with the sixteen-year old and the sixty-year old, that truly made it an icon, a place worthy of being loved.

Sophia saw each of Semaphore’s films hundreds of times. She bought them multiple times, in successive digital formats: discs, compressed downloads, lossless codecs, enhanced and re-enhanced and super-enhanced.

She knew each scene down to the second, could recite every line of dialogue from memory. She didn’t even need the movies themselves any more; she could play them in her head.

She took film studies classes and began to make her own shorts, and she yearned to make them feel as great as the Semaphore classics. Advances in digital filmmaking equipment made it possible for her to achieve some spectacular effects on a small budget. But no matter how many times she rewrote her scripts or how late she stayed in the editing labs, the results of her efforts were laughable, embarrassing, ridiculous. She could not bear to watch them herself, much less show them to others.

“Don’t be discouraged,” a professor told her, when he saw her slumped over in despair. “You got into this because you wanted to make something beautiful. But it takes time, lots of time, to be good at any creative work. The fact that you hate your own work right now so much just means that you have good taste. And great taste is the most valuable tool of a great artist. Keep at it. Someday you’ll be as good as the best. Someday you’ll make something beautiful enough even for you.”

She went back to the Semaphore films, picked them apart and put them back together, trying to discover their secret. Now she was no longer viewing them as a mere fan, but as a reverse-engineer.

Gradually, because she did have great taste, she could not help but begin to see tiny flaws in them. The Semaphore films were not quite as perfect as she had thought. There were small things here and there that could be improved. And sometimes even big things.

She went into seedy corners of the web to find out how to break the encryption codes on her digital-rights-managed Semaphore movie files, imported them into the editing stations, and modified them to suit her new vision.

And then she sat back in the darkness, at her computer, and watched her edited version of The Mesozoic again. She cried when she was done. It was better. She had made a great film even greater, closer to perfection.

In some way, she felt as if the perfect Semaphore film had always been there, but hidden in places under the veil that was the released version. She had simply walked in and revealed the beauty underneath.

How could she not share this vision with the world? She was in love with the beauty of Semaphore, and beauty wanted to be free.

“I… I…” Sophia realized now that she had been engaging in denial. She had refused to think about how she had likely broken the law just by putting that edited version on the web. She had no good answer. “I love Semaphore’s movies so much…” Her voice trailed off.

Palladon held up a hand and laughed. “Relax. I think it was brilliant. I told the recruiting department to fly you out not because of your application or résumé, but because of your unauthorized re-edit.”

“You liked it?” Sophia could hardly believe her ears.

Palladon nodded. “Tell me what you think was your best change?”

Sophia did not hesitate. This question she had thought about a lot. “Semaphore’s films are wonderful, but they’re fantastic if you’re a boy. I changed The Mesozoic so that it was fantastic for girls too.”

Palladon stared at Sophia, deep in thought. Sophia held her breath.

“That makes sense,” Palladon finally said. “Most of us working here are men. I’ve been saying for years that we needed more women in the process. I was right about you: a real artist will do whatever it takes to make a great vision come true, even if she has to work with someone else’s art.”

“ALL DONE?”

Sophia nodded and handed the stack of signed legal documents back to Palladon. He had explained that before he could give her an offer, he wanted to show her a bit of the Semaphore creative process so she would know what she was getting into. She had to sign some pretty draconian NDAs to protect Semaphore’s trade secrets.

Sophia didn’t hesitate for even one second. Getting a peek at how Semaphore made its magic was a lifelong dream.

Palladon took her down a long series of hallways lined with closed doors. Sophia looked around, imagining what lay behind them: bright, open workspaces where each employee was free to decorate her cubicle to express her creativity? Legendary conference rooms filled with colorful Lego blocks and Japanese toys to get the creative juices of the artists and engineers flowing? Server rooms filled with the proprietary computing hardware that made all the magic possible? Creative, talented artists reclining in bean bag chairs tossing around the germ of an idea, each adding and polishing until it shone full and lustrous as a pearl?

The doors remained closed.

Finally, Palladon stopped in front of a door and unlocked it with a key. He and Sophia walked into the darkness beyond.

THEY WERE in the projection booth overlooking a small theater. Sophia looked through the booth window and counted about sixty seats below, about half of which were filled. The audience was completely absorbed by the movie playing on the big screen in front. The humming from the projectors filled the booth.

“Is that… ?” Sophia pressed her nose up against the window. Her heart pounded in her ears. She forgot to finish the question.

“Yes,” Palladon said. “That’s an early version of our next film: The Mesozoic Again. It’s a story about a boy meeting a dinosaur, and learning timeless lessons about friendship and family.”

Sophia watched the bright figures on the screen, wishing she were down there, among the rapt audience.

“So this is a test screening?”

“No, this is how the film is made.”

“I don’t understand.”

Palladon walked over to a bank of displays on the other side of the projection booth and pulled out two chairs. “Sit down. I’ll explain.”

The monitors showed bundles of lines of different colors moving slowly across the screen, like the lines traced by heart monitors or seismographs.

“You know, of course, that a movie is an intricate emotion-generating machine.”

Sophia nodded.

“During the span of two hours, it must lead the audience by the nose on an emotional roller coaster: moments of laughter are contrasted with occasions for pity, exhilarating highs followed by terrifying and precipitous drops. The emotional curve of a film is its most abstract representation as well as the most primal. It’s the only thing that lingers in the audience’s mind after they leave the theater.”

Sophia nodded again. This was all just basic film theory.

“So how do you know that the audience is following the curve you want?”

“I guess you do what every storyteller does,” Sophia said, hesitant, feeling lost. “You try to empathize with the audience.”

Palladon waited, his expression unchanged.

“And maybe you try to do test screenings and tweak things a bit at the end,” Sophia added. Actually she didn’t believe in test screenings. She thought focus groups and audience reaction surveys were why the other studios produced such pap. But she didn’t know what else to say.

“Aha,” Palladon said, clapping his hands together. “But how do you get test audiences to give you useful feedback? If you survey them after, you’ll only get very crude answers, and people lie, telling you what they think you want to hear. If you try to get people to give real-time feedback by pressing buttons as they watch the film, they become too self-conscious, and people aren’t always good at understanding their own emotions.”

SIXTY CAMERAS were suspended from the ceiling of the theater, each trained on a single seat below.

As the film played, the cameras relayed their feeds to a bank of powerful computers, where each feed was put through a series of pattern-recognition algorithms.

By detecting microscopic shifts in each face caused by the expansion and contraction of blood vessels below the skin, the computers monitored each audience member’s blood pressure, pulse, and level of excitement.

Other algorithms tracked the expressions on each face: smiling, smirking, crying, impatience, annoyance, disgust, anger, or just boredom and apathy. By measuring how much certain key points on a face moved—corners of the mouth, the eyes, ends of eyebrows—the software could make fine distinctions, like that between a smile out of amusement and a smile due to affection.

The data, collected in real time, could be plotted against each frame of the film, showing each audience member’s emotional curve as they experienced the movie.

“SO YOU CAN tune your movies a little better than other studios with test screenings. Is that your secret?”

Palladon shook his head. “Big Semi is the greatest auteur in the history of filmmaking. It doesn’t just ‘tune.’”

MORE THAN seven thousand processors were wired together into a computing grid in the basement of the Semaphore campus. This was where Big Semi lived—the “semi” was short for either “semiotics” or “semantics,” no one knew for sure anymore. Big Semi was The Algorithm, Semaphore’s real secret.

Every day, Big Semi generated kernels for high-concept movies by randomly picking out seemingly incongruous ideas out of a database: cowboys and dinosaurs, WWII tactics in space, a submarine film transposed onto Mars, a romantic comedy starring a rabbit and a greyhound.

In the hands of less-skilled artists, these ideas would have gone nowhere, but Big Semi, based on Semaphore’s record, had access to the emotional curves of proven hits in each genre. It could use these as templates.

Taking the high-concept kernel, Big Semi generated a rough plot using more random elements taken from a database of classic films augmented with trending memes in the zeitgeist gathered from web search statistics. It then rendered a rough film based on that plot, using stock characters and stock dialogue, and screened the result for a test audience.

The initial attempt was usually laughably bad. The audience response curves would be all over the place, but nowhere near the target. But that was no big deal for Big Semi. Nudging responses to fit a known curve was nothing more than an optimization problem, and computers were very good at those.

Big Semi turned art into engineering.

Say that the beat at ten minutes in should be a moment of poignancy. If the hero saving a nest of baby dinosaurs didn’t do it, then Big Semi would substitute in a scene of the hero saving a family of furry proto-otters and see if the response curves on the next test screening moved any closer to the ideal.

Or say that the joke that ended act one needed to get the audience into a particular mood. If a variation on a line taken from a classic didn’t do it, then Big Semi would try a pop culture reference, a physical gag, or even change the scene into an impromptu musical number—some of these alternatives were things no human director would ever think of—but Big Semi had no preconceptions, no taboos. It would attempt all alternatives and pick the best one based on results alone.

Big Semi sculpted actors, built sets, framed shots, invented props, refined dialogue, composed music, and devised special effects—all digitally, of course. It treated everything as levers to nudge the response curves.

Gradually, the stock characters came to life, the stock dialogue gained wit and pathos, and a work of art emerged from random noise. On average, after a hundred thousand iterations of this process, Big Semi would have a film that elicited from the audience the desired emotional response curve.

Big Semi did not work with scripts and storyboards. It did not give any thought to themes, symbols, homages, or any other words you might find in a film studies syllabus. It did not complain of having to work with digital actors and digital sets because it knew of no other way. It simply evaluated each test screening to see where the response curves still deviated from the target, made big changes and small tweaks and tested it again. Big Semi did not think. It had no pet political cause, no personal history, no narrative obsession or idée fixe that it wanted to push into its films.

Indeed Big Semi was the perfect auteur. Its only concern was to create an artifact as meticulously crafted as a Swiss watch that precisely pulled the audience along the exact emotional curve guaranteed to make them laugh and cry in the right places. After they left the theater, they would give the film great word-of-mouth, the only form of marketing that worked consistently, that always got through people’s ad-blockers.

Big Semi made perfect films.

“SO WHAT would I do?” Sophia asked. She felt her face flush and her heart beating fast. She wondered if any cameras were in the booth, observing her. “What do you do? It sounds like Big Semi is the only creative one around here.”

“Why, you’ll be a member of the test audience, of course,” Palladon said. “Isn’t that obvious? We can’t let the secret out, and Big Semi requires audiences to do its work.”

“You just sit there all day and watch movies? You can do that with anybody off the street!”

“No, we can’t,” Palladon said. “We do need some non-artists in the audience to be sure we’re not out of touch, but we need even more people with great taste. Some of us have much more knowledge about the history of film, finer senses of empathy, broader emotional ranges, more discerning eyes and ears for details, deeper capacities for feeling—Big Semi needs our feedback to avoid trite clichés and cheap laughs, mawkish sentiment and insincere catharsis. And as you’ve already discovered on your own, the composition of the audience determines how good a film Big Semi can make.”

I’ve been saying for years that we needed more women in the process.

“It is only by trying out his skill against the finest palate that a chef can design the best dishes. Big Semi needs the best audience to make the best film the world has ever seen.”

And great taste is the most valuable tool of a great artist.

SOPHIA SAT numbly in the conference room, alone.

“Are you all right?” A secretary passing by poked her head in.

“Yes. I just need a moment.”

Palladon had explained to her that there would be eye drops and facial massages to combat the physical fatigue. There would also be drugs to induce short-term memory loss so that everyone could forget the film they had just seen and sit through the next screening again, tabulae rasae. The forgetting was necessary to ensure that Big Semi got accurate feedback.

Palladon had gone on to say many other things, but Sophia didn’t remember any of them.

So this is what it’s like to fall out of love.

“YOU HAVE to let us know within two weeks,” Palladon said, as he walked Sophia down the long driveway to the campus gate.

Sophia nodded. The drawing on the front of Palladon’s T-shirt caught her attention. “Who is that?”

“John Henry,” Palladon said. “He was a laborer on the railroads in the nineteenth century. When the owners brought in steam-powered hammers to take jobs away from the driving crews, John challenged a steam hammer to a race to see who could work faster.”

“Did he win?”

“Yes. But as soon as the race was over, he died of exhaustion. He was the last man to challenge the steam hammers because the machines got faster every year.”

Sophia stared at the drawing. Then she looked away.

Keep at it. Someday you’ll be as good as the best.

She would never be as good as Big Semi, who got better every year.

The golden California sun was so bright and warm, but Sophia shivered.

She closed her eyes and remembered how she felt in that dark theater as a little girl. She was transported to another world. That was the point of great art. Watching a perfect movie was like living a whole other life.

“A real artist will do whatever it takes to make a great vision come true,” Palladon said, “even if it’s just sitting still in a dark room.” ■

One of the masters of science fiction, Joe Haldeman is best known for his 1974 book, The Forever War, which won the Hugo and Nebula Awards. Living in Florida, he also teaches writing at MIT and continues to be an active author, winning the Nebula Award for Best Novel in 2005 for Camouflage.

COMPUTING

Complete

Sentence

BY JOE HALDEMAN

The cell was spotless white and too bright and smelled of chlorine bleach.

“So I’ve had it, is what you’re saying.” Charlie Draper sat absolutely still on the cell bunk. “I didn’t kill Maggie. You know that better than anybody.”

His lawyer nodded slowly and looked at him with no expression. She was beautiful, and that sometimes helped with a jury, though evidently not this time.

“We’ve appealed, of course.” Her voice was a fraction of a second out of synch with her mouth. “It’s automatic.”

“And meaningless. I’ll be out before they open the envelope.”

“Well.” She stepped over to the small window and looked down at the sea. “We went over the pluses and minuses before you opted for virtual punishment.”

“So I serve a hundred years in one day—”

“Less than a day. Overnight.”

“—and then sometime down the pike some other jury decides I’m innocent, or at least not guilty, and then what? They give me back the hundred years I sat here?”

He was just talking, of course; he knew the answer. There might be compensation for wrongful imprisonment. A day’s worth, though, or a century? Nobody had yet been granted it; virtual sentencing was too new.

“You have to leave now, counselor,” a disembodied voice said. She nodded, opened her mouth to say something, and disappeared.

That startled him. “It’s already started?”

The door rattled open, and an unshaven trusty in an orange jumpsuit shambled in with a tray. Behind him was a beefy guard with a shotgun.

“WHAT’S WITH the gun?” he said to the trusty. “This isn’t real; I can’t escape.”

“Don’t answer him,” the guard said. “You’ll wind up in solitary, too.”

“Oh, bullshit. Neither of you are real people.”

The guard stepped forward, reversed the weapon, and thumped him hard on the sternum. “Not real?” He hit the wall behind him and slid to the floor, trying to breathe, pain radiating from the center of his chest.

AS THE cell walls and Draper faded, a nurse gently wiggled the helmet until it came off her head. It was like a light bicycle helmet, white. With a warm gloved hand, she helped her sit up on the gurney.

She looked over at Draper, lying on the gurney next to hers. His black helmet was more complicated, a thick cable and lots of small wires. The same blue hospital gown as she was wearing. But he had a catheter, and there was a light black cable around his chest, hardly a restraint, held in place by a small lock with a tag she had signed.

The nurse set her white helmet down carefully on a table. “You don’t want to drive or anything for a couple of hours.” She had a sour expression, lips pursed.

“No problem. I have Autocar.”

She nodded microscopically. Rich bitch. “I’ll take you to where your things are.”

“Okay. Thank you.” As she scrunched off the gurney, the gown slid open, and she reached back to hold it closed, feeling silly. She followed the woman as she stalked through the door. “I take it you don’t approve.”

“No, ma’am. He serves less than one day for murdering his wife.”

“A, he didn’t murder her, and B, it will feel like a hundred years.”

“That’s what they say.” The nurse turned with eyes narrowing. “They all say they didn’t do it. And they say it feels like a long time. What would you expect them to say? ‘I beat the system and was in and out in a day?’ Here.”

As soon as the door clicked shut, she opened the locker and lifted out her neatly folded suit, the charcoal grey one she had appeared to be wearing in the cell a few minutes before.

THE BLOW had knocked the wind out of him. By the time he got his voice back, they were gone.

The tray had a paper plate with something like cold oatmeal on it. He picked up the plastic spoon and tasted the stuff. Grits. They must have known he hated grits.

“They didn’t say anything about solitary. What, I’m going to sit here like this for a hundred years?” No answer.

He carried the plate over to the barred window. It was open to the outside. A fall of perhaps a hundred feet to an ocean surface. He could hear faint surf but, leaning forward, couldn’t see the shore, even with the cold metal bars pressing against his forehead. The air smelled of seaweed, totally convincing.

He folded the paper plate and threw it out between the bars. The grits sprayed out and the plate dipped and twirled realistically, and fell out of sight.

He studied the waves. Were they too regular? That would expose their virtuality. He had heard that if you could convince yourself that it wasn’t real—completely convince your body that this wasn’t happening—the time might slip quickly away in meditation. Time might disappear.

But it was hard to ignore the throbbing in his chest. And there were realistic irregularities in the waves. In the trough between two waves, a line of pelicans skimmed along with careless grace.

Maybe the illusion was only maintained at that level when he was concentrating. He closed his eyes and tried to think of nothing.

Zen trick: four plain tiles. Make each one disappear. The no-thing that is left is just as real. Exactly as real. After a while, he opened his eyes again.

The pelicans came back. Did that mean anything?

Maybe he shouldn’t have thrown away the grits. You probably get hungry in virtual reality. But you couldn’t starve to death, not overnight. No matter how long it seemed.

He gave the iron bar a jerk. It squeaked.

He tugged on it twice, and it seemed to move a fraction of a millimeter each time. Was that possible? He looked closely, and indeed the hole the bar was seated in had slightly enlarged. He could wiggle it.

“Trusty?” he shouted. Nothing. He walked to the steel door and shouted through the little hole. “Hey! Your goddamn jail’s already falling apart!” He peered through the small peephole. Nothing but darkness.

He sniffed at the hole, and it smelled of drilled metal. “Hey! I know you’re out there!”

But what did he really know?

SHE POPPED her umbrella against the afternoon shower and was almost to the parking place when a young man came running out. “Ms. Hartley!” He was waving a piece of paper. “Ms. Hartley!” She stepped toward him and let him get under the umbrella.

“Your objection was approved. You can bring him out any time!”

She glanced at her watch. He’d only been in VR for about twenty minutes, counting the time she’d spent dressing. “Let’s go!” Two months passing each minute.

Security at the courthouse door took an agonizing five minutes. But the young man raced on ahead to make sure the room was ready.

She crashed through a door and rushed up the single flight of stairs rather than wait for the elevator. The sour-faced woman was blocking the entrance to the VR room.

“Get out of the way. Every second, he spends a day in that awful cell.”

“You know this won’t work if he doesn’t believe in his own innocence. If he blames himself in any way.”

“He wasn’t even there when his wife was murdered!” The woman’s eyes searched the lawyer’s face. “Look! I’ve been a defense attorney for eighteen years. I know when someone’s lying to me. He didn’t kill her!”

She pushed on in and the young man was standing by a chair, next to the gurney that Charlie Draper lay on, holding the white helmet. “Here. You don’t have to lie down. Just put this on.”

CRAPPY SYSTEM can’t even make an illusion that works.

He went back to the iron bar and rotated it squeaking in its concrete socket, and gave it a good rattle. Concrete dust sifted down. He seized it in both hands and gave it all he had. “Bitch!” He squeezed it as hard as he had Maggie’s neck, and jerked, with the strength that had snapped it and killed her.

The bar came free in his hands. A piece of concrete fell to the floor with a solid thunk.

“You call this a…”

A large crack crawled up and down from floor to ceiling. With a loud growl, half the wall tilted and fell piecemeal into the sea.

“Wait.” A fine powder was drifting down. He looked up to see the ceiling disappear. “No.” All four walls crumbled into gravel and showered to the sea.

WHEN THEY took the helmet off her, there was an older man, dressed like a doctor, standing there.

“It’s a temporary thing,” he said. “He’s resisting coming out of it. For some reason.”

“I didn’t go to the cell. I didn’t go anywhere,” she said, peering inside the helmet. “It was all just white, and white noise, static.”

“You’re out of the circuit. The electronics do test out. But he’s not letting you make contact.”

She looked into her client’s vacant eyes. She touched his cheek gently and he didn’t respond. “Has this happened before?”

“Not with people who know and trust each other. But we’ll get through to him.”

“Meanwhile…every ten hours is a hundred years?”

“That’s a safe assumption.” The doctor opened the manila folder in his hand and looked at the single piece of paper within. “He signed a waiver—”

“I know. I was there.” She lifted her client’s hand and let it drop back onto the sheet.

“HE’S A… social kind of guy. I hope he’s not too lonely.”

THERE WAS only the floor and the iron door. He touched the door and it fell away. It turned end over end once, and slid flawlessly into the water, like an Olympic diver.

Above him, a perfect cloudless sky that somehow had no sun. Below, the waves marched from one horizon to the opposite. A line of pelicans appeared.

He tried to throw himself into the water, but he hit something soft and invisible, and fell gently back.

He screamed until he was hoarse. Then he tried to sleep. But the noise of the waves kept him awake. ■

Ma Boyong is a popular Beijing-based writer of short stories and novels. He fuses western conventions with traditional Chinese elements. Published here for the first time in English (translated by Ken Liu, whose own work also appears in this collection), Ma introduces a liberal dose of the satire for which he is well known in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

ROBOTICS

The Mark

Twain Robots

BY MA BOYONG

“I must warn you: giving robots a sense of humor is dangerous.”

Professor White, the famous roboticist, put down his pipe and stared severely at Kevin, a young researcher whose hair was dyed a careless shade of blond.

But Kevin, unintimidated, continued calmly, “Right now, competition in the market is intense. We have to differentiate our robots somehow. Marketing research shows that the public is sick and tired of metal faces that never change their expressions. They crave robots with personality, a human touch.”

“But is this even possible? Can robots tell jokes just like humans?” another Director of the Board asked.

“Technically, it’s not difficult,” Kevin replied. “My group has already developed a whole set of algorithms, which, combined with our joke database, can generate all kinds of jokes suitable for every occasion.” He paused meaningfully before going on. “Indeed, our simulations almost passed the Turing Test.”

The Directors were suitably impressed. They were optimistic about the market potential of humorous robots. Kevin’s group received a large budget boost to support the integration of the humor module, nicknamed “Mark Twain,” with production models.

Of the entire Board only Professor White held onto his original objection. After the meeting, the old man stubbornly insisted, “You’re going to have a real problem on your hands. This is not a good idea.”

THE INCIDENT took place in one of the company’s test labs. There, the first robot equipped with the Mark Twain module malfunctioned for no apparent reason and shut itself down. The next few test models also suffered random shutdowns in similar fashion. Not a single one completed the test routines.

The researchers were puzzled. They went over the circuit diagrams and the code printouts again and again, even testing each individual screw. They discovered no flaws.

But the robots continued to malfunction. And the way each robot failed was different: some failed on the first test during the quality assurance process, others lasted until the team was just about ready to declare victory—this made tracking down the problem very difficult.

Having run out of options, the team sought the advice of Professor White. After the Professor looked over the testing records, he called a team meeting.

“Have you noticed the common element in all these malfunctions? The robots all failed when they interacted with humans.”

Professor White pointed to a recorded video: An engineer in an orange suit walked up to a freshly assembled robot and briefly spoke to it.

“He was just talking to the robot to see if the Mark Twain module was functioning correctly,” Kevin said.

“Final assembler, mechanical beautician, test engineer, packaging engineer, logistics engineer…” The Professor counted them off. “From the time a robot comes off the assembly line to the time it’s loaded onto a truck, it will encounter a dozen or so humans. I gather that during these times the robot is free to interact with any of the humans? All of the malfunctions occur during these interactions.”

Kevin was puzzled. “You’re saying we shouldn’t allow such encounters? But the set up is deliberate. These workers all have different social backgrounds, educational profiles, and personalities. We need to test the ability of the Mark Twain module to adapt to different environments and interact with different kinds of people. What’s wrong with that?”

Professor White shook his head. “I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with your procedure, which is well-designed. But the problem is deeper—do you remember the Three Laws of Robotics? All robots must obey them.”

Everyone laughed, thinking the Professor was joking. Each member of the research group had a Ph.D. in robotics. The “Three Laws” were so basic that even children could recite them. How could they offer any insight into the mysterious malfunctions here?

Professor White sighed, knowing that they did not understand. He played another recorded video. This one showed the entire process, from assembly to malfunction, of the sixth prototype robot equipped with the Mark Twain module.

Number Six was transported from the end of the assembly line to a designated location. The artificial skin hadn’t been applied yet, and the undecorated metal composite skeleton seemed cold and forbidding. A test engineer walked up to it and turned on the microphone so that the conversation could be recorded and be heard by other engineers in the lab.

“Number Six, can you understand me?”

“Of course. I’m made right here in this country.” It paused, then added, “You know that those women at that bar were only pretending to be foreign so they didn’t have to talk to you, right?”

Everyone laughed. The engineer, satisfied, checked off a box on his clipboard.

“Number Six, my name is Wiesel. I’ll be doing your testing.”

“Show me your educational credentials first. I’m not some cheap knock-off that any unqualified idiot can operate.”

“Hey!” Wiesel was taken aback. “Are you insulting me? I’m going to report you to the company.”

“To produce a robot like me requires at least a million dollars. To hire an engineering intern from a third-rate college costs only eighty thousand a year. Whose side do you think the company will take?” The robot rolled its naked eyeballs—the eyelids hadn’t been installed yet. Others in the lab who overheard the exchange laughed and whistled.

Wiesel looked awkward, and chuckled once. He put a big checkmark on his clipboard and left quietly. Number Six stared after him as he walked away, shoulders slumped.

Five minutes later, Number Six short-circuited and shut down.

Professor White rewound the recording to the point where Wiesel was leaving. He pointed at the screen. “Look at the expression on this man. His feelings were hurt.”

“But it was only a joke,” one of the researchers said.

“Maybe for those watching, but not him. This is the real reason for the malfunctions. The First Law of Robotics clearly states: ‘A robot may not injure a human being.’ That joke clearly touched a sore point with Weisel, an insecurity. Number Six detected this, and so its fail-safe systems kicked in to shut it down.”

“But that was not a real injury.”

“When you are made fun of by others, doesn’t your chest feel tight? When a woman dumps you, don’t you find food to be tasteless and sleep hard to come by? When a person’s feelings are hurt, the injury will manifest itself in physiological reactions. From a robot’s perspective, a mental injury and a physical one are equivalent.”

Professor White played a few more recordings. Now that the researchers understood what they were looking for, the pattern became clear. Without exception, the Mark Twain robots’ jokes went too far and hurt the feelings of some interlocutor. The First Law then kicked in and caused the robot to self-destruct.

“Humor is in large measure an art based on derision and put-downs. It’s in the nature of jokes to hurt some people. This is incompatible with the First Law. That’s why from the start I told you it was a dangerous idea.”

The team fell silent.

“Is there really no way to make the humor module compatible with the Three Laws?” Kevin asked, pitifully.

Professor White was now their only hope. He cogitated for a while, and then said, “It’s not impossible. There are some jokes that offend no one. If we adjust the joke database and the filtering algorithms so that the robots pick only jokes that are safe for all humans, then theoretically it’s possible to avoid the First Law.”

These words rekindled hope in everyone, but the Professor’s next sentence sent them back into the depths of suffering. “But I don’t know if this sort of neutered—please excuse me for using this word—speech can still be called humor.”

But the research group had no choice. They had to try it.

Following Professor White’s advice, they set about the task of designing appropriate filters. But this turned to require a much more complex set of algorithms than generating good jokes in the first place.

Since the Board intended the new robots for the global market, the research group had to eliminate the possibility of the Mark Twain module generating jokes that would offend or hurt anyone. But human society was so complicated. It was difficult to find jokes that would not offend some segment of the population. The research group had to sift through the joke database again and again and compare its contents with the constant stream of media reports of people taking offense at various things to select only joke topics that were as safe as possible.

After the modified Mark Twain 2.0 module was completed, the self-destruction of robots did stop. The robots were now able to follow the First Law. But there was a new problem: the robots were no longer funny.

“It tells jokes like a human resources specialist,” a test engineer complained.

“I’d rather drink liquid nitrogen than listen to this pap,” another worker said.

The Board held an emergency meeting. After the Directors watched a Mark Twain 2.0 robot perform for ten minutes, they unanimously agreed that this product could not be released to market. A humorous robot that was not funny at all was worse than useless.

But all was not lost. A brilliant salesman had the idea of selling the dozen or so Mark Twain 2.0 prototypes to a certain country in the Far East. There, every spring, a great variety show was broadcast to the entire country, and the people in charge loved the jokes told by the Mark Twain 2.0 robots.

The hapless audience there cursed the bland robot comedians in private and turned off their TVs, but the people in charge were pleased and used the robots for every public occasion. Safe entertainment was important for a harmonious society.

After abandoning the useless Mark Twain 2.0 prototypes, the research group locked themselves in a conference room and vowed to come up with a solution before coming out. Suggestion after suggestion was debated and then rejected. The team squeezed out every last ounce of brainpower to try to solve this problem.

Hope dawned on the third day.

One of the engineers stood up and announced: “There is one type of humor that can make others laugh without injuring them. I think we should focus our research in that direction.”

“What do you mean?” Kevin asked.

Among all the researchers on the team, the man who had spoken had the least prestigious educational credentials. He was always dealing with subtle digs and exclusion by the other researchers who formed little cliques. In order to improve his social standing, he had developed a habit of telling embarrassing stories about himself to others.

“Self-mockery,” the man said, and blushed.

After further discussion, everyone realized the brilliance of this suggestion: a robot that constantly made fun of itself would entertain the human user, but wouldn’t offend anyone. This would get around the First Law and the blandness of Mark Twain 2.0 at the same time.

Following this path, they quickly developed Mark Twain 3.0. This would be the research group’s final chance. After the first Mark Twain 3.0 prototype came off the assembly line, the whole team crowded around it.

Kevin began the testing. “Tell us a joke.”

“You really want to hear a robot tell a joke?” The robot’s tone was so serious that all the researchers had to hold back their smiles.

“Yes. For example, what do you think of the way you look?” Kevin asked.

The robot glanced at its reflection in a nearby chrome panel. “There’s nothing good to say about my appearance. It’s just a bunch of broken wires taped together like a mummy.” The robot shrugged its shoulders. “I was probably a lawn mower trying to cross the highway who didn’t make it.”

Everyone laughed. But amidst the laughter, white smoke came out of the body of the Mark Twain 3.0 robot, and it collapsed in a heap on the ground.

“WHAT HAPPENED?” The Directors asked. They had already decided to abandon the project and write off all the investment, but they still wanted to understand the details.

Kevin was too dejected to say anything. Professor White stood up and answered for him. “In order to make others laugh, the Mark Twain module forced the robot to posit the following: ‘I = a bunch of broken wires.’ This had to be accepted by the robot’s self-awareness routines as a fact. But the self-awareness routines were also fed the following: ‘I = expensive Mark Twain 3.0 prototype robot.’ This was also accepted as a fact. Since the two ‘facts’ could not be made compatible, the logical subsystems failed as though there were a division by zero. The whole system then collapsed.”

“Can you explain it in simpler terms?” One of the Directors, who had little technical background, begged.

Professor White waved his arms. “Self-mockery led to irreversible logical errors for the robot. This is because Mark Twain 3.0 violates the Third Law of Robotics: A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.”

Professor White then looked around the table with a serious expression, and continued, “You can also try to understand it this way: for a robot equipped with Mark Twain 3.0, the only alternative to hurting someone or hurting itself was to tell the bland jokes of version 2.0. But even a robot has too much self respect to speak the way a Mark Twain 2.0 robot is forced to speak.” ■

Pat Cadigan is an American author who has settled in England. Best known for her cyberpunk fiction, she won the 1988 Locus Award for Best Short Story, and another Locus Award in 1990 for Best Collection. In 1992 and 1995 she won the Arthur C. Clarke Award for two of her novels and continues to have her short stories regularly featured in anthologies.

BIOMEDICINE

Cody

BY PAT CADIGAN

“Common wisdom has it,” said LaDene from where she was stretched out on the queen-sized bed, “that anyone with a tattoo on their face goes crazy within five years.”

Cody paused in his examination of his jawline in the mirror over the desk to give her a look. “You see any tattoos on this example of manly beauty?”

“Can’t see the moon from here, either. Or the TV remote,” she added as she sat up and looked around. Cody found it on the desk and tossed it to her. “Thanks. You know, carnies would call you a marked man.”

“Carnies?” He gave a short laugh. “Don’t tell me you threw over the bright lights of the midway to keep a low profile in budget accommodations.”

“Higher-end budget accommodations.” She put on the TV and began channel-surfing. “For the discerning yet financially-savvy business traveller. Don’t you ever read the brochures?”