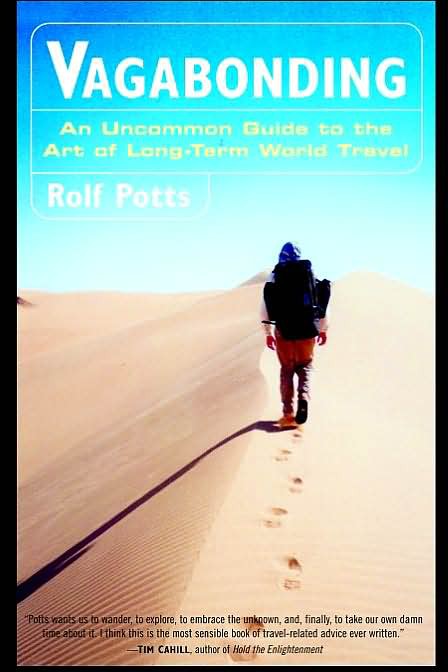

Vagabonding: An Uncommon Guide to the Art of Long-Term World Travel – Read Now and Download Mobi

Comments

Vagabonding

AN UNCOMMON GUIDE

TO THE ART

OF LONG-TERM

WORLD TRAVEL

Rolf Potts

VILLARD  NEW YORK

NEW YORK

Contents | |

| 1. | |

| 2. | |

| 3. | |

| 4. | |

| 5. | |

| 6. | |

| 7. | |

| 8. | |

| 9. | |

| 10. | |

| 11. | |

For two teachers:

GEORGE D. POTTS,

prairie naturalist and

dreamer extraordinaire

And in memory of

JOHN FREDIN,

mentor and friend

(1930–2000)

You air that serves me breath to speak!

You objects that call from diffusion my meanings and give them shape!

You that wraps me and all things in delicate equible showers!

You paths worn in irregular hollows by the roadsides!

I believe you are latent with unseen existences, you are so dear to me.

— WALT WHITMAN, “SONG OF THE OPEN ROAD”

Vagabonding— n. (1) The act of leaving behind the orderly world to travel independently for an extended period of time. (2) A privately meaningful manner of travel that emphasizes creativity, adventure, awareness, simplicity, discovery, independence, realism, self-reliance, and the growth of the spirit. (3) A deliberate way of living that makes freedom to travel possible.

Preface

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

Many travel books can help prepare you for an overseas trip, but this book — in sharing a simple and time-honored ethic — can teach you how to travel for the rest of your life. Some books, in offering encyclopedic (and often redundant) travel information, create the illusion that the best way to plan for an extended trip is to micromanage it. This book, in offering you only the advice you need to prepare for (and adapt to) the road, encourages you to enrich your travels with the vivid joys of uncertainty. And while some travel books become obsolete after one reading, this book will shed new perspectives and resonate in new ways as your travel career progresses.

This book views long-term travel not as an escape but as an adventure and a passion — a way of overcoming your fears and living life to the fullest. In reading it, you will find out how to gain an impressive wealth (of travel time) through simplicity. You will find out how to discover and deal with new experiences and adventures on the road. And, as much as anything, you will find out how to travel the world on your own terms, by overcoming the myths and pretentions that threaten to cheapen your experience.

If you’ve ever felt the urge to travel for extended periods of time but aren’t sure how to find the time and freedom to do it, this is the book for you. If you’ve traveled before but felt something vital was missing from the experience, this book is for you, too.

This book is not for daredevils and thrill seekers but for anyone willing to make an uncommon choice that allows for weeks and months at a time, improvising (and saving money) as you go.

If this sounds like an intriguing possibility, then by all means read on. . . .

INTRODUCTION

All I mark as my own you shall offset it with your own,

Else it were time lost listening to me.

— WALT WHITMAN, “SONG OF MYSELF”

How to Win and Influence Yourself

Not so long ago, as I was taking a slow, decrepit old mail steamer down Burma’s Irrawaddy River, I ran out of things to read. When the riverboat called at a small town called Pyay, I dashed ashore and bought the only English-language book I could find for sale: a beat-up copy of Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People, which I proceeded to read as we slowly steamed toward Rangoon.

Somehow, I’d gone through my entire life without ever having read a self-help book. Carnegie’s advice, as it turned out, was a charming mix of common sense (“be a good listener”), good advice (“show respect for the other man’s opinions”), and antique notions (“don’t forget how profoundly women are interested in clothes”). Having enjoyed the book on the river, I gave it away in Rangoon and temporarily forgot about it.

About a month later, I was approached to write a book about the art and attitude of long-term travel. Since I’d primarily been endorsing this vagabonding ethic through the narrative stories I’d written for Salon.com, I figured I should probably do some research into the structure and format of advice books. Thus, in the process of trying to relocate a copy of How to Win Friends and Influence People, I discovered that the advice and self-help book market has changed a lot since Carnegie’s day. Nearly every human activity, desire, and demographic, it seems, is now catered to by some kind of inspirational book. The Chicken Soup for the Soul and Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff series by themselves nearly required their own section of the bookstore.

Standing there amid the shelves — and bewildered at the variety — I began to imagine a vagabonding publishing empire: not just Vagabonding, but Vagabonding for Teens. Vagabonding for Singles. Vagabonding for Golfers. Vagabonding Your Wardrobe. The Ten-Week Vagabonding Diet. A Vagabonding Christmas. A Baby’s First Vagabonding. 101 Zesty Vagabonding Recipes. All I Ever Really Needed to Know I Learned While Vagabonding. And so on.

In the end, I left the bookstore without picking up a single book. I decided that I would write the book the only way I knew how: from experience, from passion, and from common sense.

If at times this book seems unorthodox, well, good. Vagabonding itself is unorthodox.

As for the word vagabonding, I used to think it was my own invention. This was back in 1998, when I was first pitching an adventure travel column to Salon.com. At the time, I wanted a succinct word to describe what I was doing: leaving the ordered world to travel on the cheap for an extended period of time. Backpacking seemed too vague a description, globe-trotting sounded too pretentious, and touring rang a bit lame. Consequently, I put a playful spin on the word vagabond — the old, Latin-derived term that refers to a wanderer with no fixed home — and came up with vagabonding.

I’d almost convinced myself that I’d given hip new phrasing to a certain attitude of travel when I discovered a dog-eared paperback entitled Vagabonding in Europe and North Africa on the shelf of a used bookstore in Tel Aviv. Written by an American named Ed Buryn, the book had not only been published before my travel column hit the Internet but had been written before I was born. And in spite of its occasional hippie-era phrasing (“avoid your travel agent like he was the cops and go out to find out about the world by yourself”), I found Vagabonding in Europe and North Africa to be a fine collection of advice, a levelheaded and insightful pre–Lonely Planet take on the nuts, bolts, and philosophy of independent travel. Consequently, discovering Ed Buryn’s book was not discouraging so much as it was liberating: It made me realize that, whatever name you give it, the act of vagabonding is not an isolated trend so much as it is (to crib a Greil Marcus phrase) a “spectral connection between people long separated by place and time, but somehow speaking the same language.”

I have since seen reference to the word vagabonding as early as 1871 (in Mark Twain’s Roughing It), but I’ve never found it in any dictionary. In a way, it’s a kind of nonsense word — playfully adapted to describe a travel phenomenon that was already out there when Walt Whitman wrote, “I or you pocketless of a dime may purchase the pick of the earth.”

Thus, a part of me wants to keep the notion of vagabonding partly rooted in nonsense: as indeterminate, slightly slippery, and open to interpretation as the travel experience itself.

So, as you prepare to read the book, just keep in mind what martial arts master Bruce Lee said: “Research your own experiences for the truth. . . . Absorb what is useful. . . . Add what is specifically your own. . . . The creating individual is more than any style or system.”

On the road, the same holds true for vagabonding.

PART I

Vagabonding

CHAPTER 1

From this hour I ordain myself loos’d of limits and imaginary lines,

Going where I list, my own master total and absolute,

Listening to others, considering well what they say,

Pausing, searching, receiving, contemplating,

Gently, but with undeniable will divesting myself of the holds that would hold me.

— WALT WHITMAN, “SONG OF THE OPEN ROAD”

Declare Your Independence

Of all the outrageous throwaway lines one hears in movies, there is one that stands out for me. It doesn’t come from a madcap comedy, an esoteric science-fiction flick, or a special-effects-laden action thriller. It comes from Oliver Stone’s Wall Street, when the Charlie Sheen character — a promising big shot in the stock market — is telling his girlfriend about his dreams.

“I think if I can make a bundle of cash before I’m thirty and get out of this racket,” he says, “I’ll be able to ride my motorcycle across China.”

When I first saw this scene on video a few years ago, I nearly fell out of my seat in astonishment. After all, Charlie Sheen or anyone else could work for eight months as a toilet cleaner and have enough money to ride a motorcycle across China. Even if they didn’t yet have their own motorcycle, another couple months of scrubbing toilets would earn them enough to buy one when they got to China.

The thing is, most Americans probably wouldn’t find this movie scene odd. For some reason, we see long-term travel to faraway lands as a recurring dream or an exotic temptation, but not something that applies to the here and now. Instead — out of our insane duty to fear, fashion, and monthly payments on things we don’t really need — we quarantine our travels to short, frenzied bursts. In this way, as we throw our wealth at an abstract notion called “lifestyle,” travel becomes just another accessory — a smooth-edged, encapsulated experience that we purchase the same way we buy clothing and furniture.

Not long ago, I read that nearly a quarter of a million short-term monastery- and convent-based vacations had been booked and sold by tour agents in the year 2000. Spiritual enclaves from Greece to Tibet were turning into hot tourist draws, and travel pundits attributed this “solace boom” to the fact that “busy overachievers are seeking a simpler life.”

What nobody bothered to point out, of course, is that purchasing a package vacation to find a simpler life is kind of like using a mirror to see what you look like when you aren’t looking into the mirror. All that is really sold is the romantic notion of a simpler life, and — just as no amount of turning your head or flicking your eyes will allow you to unselfconsciously see yourself in the looking glass — no combination of one-week or ten-day vacations will truly take you away from the life you lead at home.

Ultimately, this shotgun wedding of time and money has a way of keeping us in a holding pattern. The more we associate experience with cash value, the more we think that money is what we need to live. And the more we associate money with life, the more we convince ourselves that we’re too poor to buy our freedom. With this kind of mind-set, it’s no wonder so many Americans think extended overseas travel is the exclusive realm of students, counterculture dropouts, and the idle rich.

In reality, long-term travel has nothing to do with demographics — age, ideology, income — and everything to do with personal outlook. Long-term travel isn’t about being a college student; it’s about being a student of daily life. Long-term travel isn’t an act of rebellion against society; it’s an act of common sense within society. Long-term travel doesn’t require a massive “bundle of cash”; it requires only that we walk through the world in a more deliberate way.

This deliberate way of walking through the world has always been intrinsic to the time-honored, quietly available travel tradition known as “vagabonding.”

Vagabonding involves taking an extended time-out from your normal life — six weeks, four months, two years — to travel the world on your own terms.

But beyond travel, vagabonding is an outlook on life. Vagabonding is about using the prosperity and possibility of the information age to increase your personal options instead of your personal possessions. Vagabonding is about looking for adventure in normal life, and normal life within adventure. Vagabonding is an attitude — a friendly interest in people, places, and things that makes a person an explorer in the truest, most vivid sense of the word.

Vagabonding is not a lifestyle, nor is it a trend. It’s just an uncommon way of looking at life — a value adjustment from which action naturally follows. And, as much as anything, vagabonding is about time — our only real commodity — and how we choose to use it.

Sierra Club founder John Muir (an ur-vagabonder if there ever was one) used to express amazement at the well-heeled travelers who would visit Yosemite only to rush away after a few hours of sightseeing. Muir called these folks the “time-poor” — people who were so obsessed with tending their material wealth and social standing that they couldn’t spare the time to truly experience the splendor of California’s Sierra wilderness. One of Muir’s Yosemite visitors in the summer of 1871 was Ralph Waldo Emerson, who gushed upon seeing the sequoias, “It’s a wonder that we can see these trees and not wonder more.” When Emerson scurried off a couple hours later, however, Muir speculated wryly about whether the famous transcendentalist had really seen the trees in the first place.

Nearly a century later, naturalist Edwin Way Teale used Muir’s example to lament the frenetic pace of modern society. “Freedom as John Muir knew it,” he wrote in his 1956 book Autumn Across America, “with its wealth of time, its unregimented days, its latitude of choice . . . such freedom seems more rare, more difficult to attain, more remote with each new generation.”

But Teale’s lament for the deterioration of personal freedom was just as hollow a generalization in 1956 as it is now. As John Muir was well aware, vagabonding has never been regulated by the fickle public definition of lifestyle. Rather, it has always been a private choice within a society that is constantly urging us to do otherwise.

This is a book about living that choice.

PART II

Getting Started

CHAPTER 2

If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.

— HENRY DAVID THOREAU, WALDEN

Earn Your Freedom

There’s a story that comes from the tradition of the Desert Fathers, an order of Christian monks who lived in the wastelands of Egypt about seventeen hundred years ago. In the tale, a couple of monks named Theodore and Lucius shared the acute desire to go out and see the world. Since they’d made vows of contemplation, however, this was not something they were allowed to do. So, to satiate their wanderlust, Theodore and Lucius learned to “mock their temptations” by relegating their travels to the future. When the summertime came, they said to each other, “We will leave in the winter.” When the winter came, they said, “We will leave in the summer.” They went on like this for over fifty years, never once leaving the monastery or breaking their vows.

Most of us, of course, have never taken such vows — but we choose to live like monks anyway, rooting ourselves to a home or a career and using the future as a kind of phony ritual that justifies the present. In this way, we end up spending (as Thoreau put it) “the best part of one’s life earning money in order to enjoy a questionable liberty during the least valuable part of it.” We’d love to drop all and explore the world outside, we tell ourselves, but the time never seems right. Thus, given an unlimited amount of choices, we make none. Settling into our lives, we get so obsessed with holding on to our domestic certainties that we forget why we desired them in the first place.

Vagabonding is about gaining the courage to loosen your grip on the so-called certainties of this world. Vagabonding is about refusing to exile travel to some other, seemingly more appropriate, time of your life. Vagabonding is about taking control of your circumstances instead of passively waiting for them to decide your fate.

Thus, the question of how and when to start vagabonding is not really a question at all. Vagabonding starts now. Even if the practical reality of travel is still months or years away, vagabonding begins the moment you stop making excuses, start saving money, and begin to look at maps with the narcotic tingle of possibility. From here, the reality of vagabonding comes into sharper focus as you adjust your worldview and begin to embrace the exhilarating uncertainty that true travel promises.

In this way, vagabonding is not a merely a ritual of getting immunizations and packing suitcases. Rather, it’s the ongoing practice of looking and learning, of facing fears and altering habits, of cultivating a new fascination with people and places. This attitude is not something you can pick up at the airport counter with your boarding pass; it’s a process that starts at home. It’s a process by which you first test the waters that will pull you to wonderful new places.

During this process, you may even find that you aren’t up for the uncertainties and adaptations that vagabonding requires. “Vagabonding,” as Ed Buryn bluntly put it thirty years ago, “is not for comfort hounds, sophomoric misanthropes or poolside faint-hearts, whose thin convictions won’t stand up to the problems that come along.” In saying this, Buryn wasn’t being a snob. After all, vagabonding involves sacrifices, and its particular sacrifices are not for everyone.

Thus, it’s important to keep in mind that you should never go vagabonding out of a vague sense of fashion or obligation. Vagabonding is not a social gesture, nor is it a moral high ground. It’s not a seamless twelve-step program of travel correctness or a political statement that demands the reinvention of society. Rather, it’s a personal act that demands only the realignment of self.

If this personal realignment is not something you’re willing to confront (or, of course, if world travel isn’t your idea of a good time), you have the perfect right to leave vagabonding to those who feel the calling.

Ironically, the best litmus test for measuring your vagabonding gumption is found not in travel but in the process of earning your freedom to travel. Earning your freedom, of course, involves work — and work is intrinsic to vagabonding for psychic reasons as much as financial ones.

To see the psychic importance of work, one need look no further than people who travel the world on family money. Sometimes referred to as “trustafarians,” these folks are among the most visible and least happy wanderers in the travel milieu. Draping themselves in local fashions, they flit from one exotic travel scene to another, compulsively volunteering in local political causes, experimenting with exotic intoxicants, and dabbling in every non-Western religion imaginable. Talk to them, and they’ll tell you they’re searching for something “meaningful.”

What they’re really looking for, however, is the reason why they started traveling in the first place. Because they never worked for their freedom, their travel experiences have no personal reference — no connection to the rest of their lives. They are spending plenty of time and money on the road, but they never spent enough of themselves to begin with. Thus, their experience of travel has a diminished sense of value.

Thoreau touched on this same notion in Walden. “Which would have advanced the most at the end of a month,” he posited, “the boy who had made his own jackknife from the ore which he had dug and smelted, reading as much as would be necessary for this — or the boy who had . . . received a Rodgers’ penknife from his father? Which would be most likely to cut his fingers?”

At a certain level, the idea that freedom is tied to labor might seem a bit depressing. It shouldn’t be. For all the amazing experiences that await you in distant lands, the “meaningful” part of travel always starts at home, with a personal investment in the wonders to come.

“I don’t like work,” says Marlow in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, “but I like what is in the work — the chance to find yourself.” Marlow wasn’t referring to vagabonding, but the notion still applies. Work is not just an activity that generates funds and creates desire; it’s the vagabonding gestation period, wherein you earn your integrity, start making plans, and get your proverbial act together. Work is a time to dream about travel and write notes to yourself, but it’s also the time to tie up your loose ends. Work is when you confront the problems you might otherwise be tempted to run away from. Work is how you settle your financial and emotional debts — so that your travels are not an escape from your real life but a discovery of your real life.

On a practical level, there are countless ways to earn your travels. On the road, I have met vagabonders of all ages, from all backgrounds and walks of life. I’ve met secretaries, bankers, and policemen who’ve quit their jobs and are taking a peripatetic pause before starting something new. I’ve met lawyers, stockbrokers, and social workers who have negotiated months off as they take their careers to new locations. I’ve met talented specialists — waiters, Web designers, strippers — who find they can fund months of travel on a few weeks of work. I’ve met musicians, truck drivers, and employment counselors who are taking extended time off between gigs. I’ve met semiretired soldiers and engineers and businessmen who’ve reserved a year or two for travel before dabbling in something else. Some of the most prolific vagabonders I’ve met are seasonal workers — carpenters, park service workers, commercial fishermen — who winter every year in warm and exotic parts of the world. Other folks — teachers, doctors, bartenders, journalists — have opted to take their very careers on the road, alternating work and travel as they see fit.

Many vagabonders don’t even maintain a steady job description, taking short-term work only as it serves to fund their travels and their passions. In Generation X, Douglas Coupland defined this kind of work as an “anti-sabbatical” — a job approached “with the sole intention of staying for a limited period of time (often one year) . . . to raise enough funds to partake in another, more personally meaningful activity.” Before I got into writing, a whole slew of antisabbaticals (landscaping, retail sales, temp work) earned me my vagabonding time.

Of all the antisabbaticals that funded my travels, however, no experience was quite as vivid as the two years I spent teaching English in Pusan, South Korea. In addition to learning tons about Asian social customs through my work, I discovered that the simple act of walking to work was itself an exercise in possibility. On a given day in Korea, I was equally likely to be greeted by a Buddhist monk wearing Air Jordans as I was by a woman in a stewardess uniform handing out promotional toilet tissue. I eventually stopped noticing such details as children screaming “hello,” old men urinating in public, and vegetable-truck loudspeakers blasting “Edelweiss.” After two years on the job, I actually found myself fighting boredom as I crooned “California Dreaming” with my salaryman tutees and a roomful of miniskirted seventeen-year-old karaoke “hostesses.” And on top of all this, the pay was pretty good.

However you choose to fund your travel freedom, keep in mind that your work is an active part of your travel attitude. Even if your antisabbatical job isn’t your life’s calling, approach your work with a spirit of faith, mindfulness, and thrift. In such a manner, Thoreau was able to meet all his living expenses at Walden Pond by working just six weeks a year. Since vagabonding is more involved than freelance philosophizing, however, you might have to invest a bit more time in scraping together your travel funds.

Regardless of how long it takes to earn your freedom, remember that you are laboring for more than just a vacation.

A vacation, after all, merely rewards work. Vagabonding justifies it.

Ultimately, then, the first step of vagabonding is simply a matter of making work serve your interests, instead of the other way around. Believe it or not, this is a radical departure from how most people view work and leisure.

A few years ago, Escape magazine editor Joe Robinson spearheaded a petition campaign called Work to Live. The goal of this movement was to pass a law that would increase American vacation time to three weeks after one year on the job, and to four weeks after three years. The rationale was that Americans place too much emphasis on work — that all we have to look forward to from day to day is a long tunnel of eleven and a half months of work every year. “The leading casualty of all this is our time,” said Robinson, “that commodity we seemed to have so much of back in sixth grade, when the clock on the wall never seemed to move.”

Robinson’s campaign was a worthy one, and it found plenty of support at the grassroots level (and a fair amount of antagonism in corporate circles). Amid all this publicity, however, I was amazed that nobody was subversive enough to point out the obvious: As citizens of a stable, prosperous democracy, any one of us has the power to create our own free time, outside the whims of federal laws and private-sector policies. Indeed, if the clock appears to move faster than it did in sixth grade, it’s only because we haven’t actualized our power as adults to set our own recess schedule.

To actualize this power, we merely need to make strategic use (if only for a few weeks or months) of a time-honored personal-freedom technique, popularly known as “quitting.” And, despite its pejorative implication, quitting need not be as reckless as it sounds. Many people are able to create vagabonding time through “constructive quitting” — that is, negotiating with their employers for special sabbaticals and long-term leaves of absence.

Even leaving your job in a more permanent manner need not be a negative act — especially in an age when work is likely to be defined by job specialization and the fragmentation of tasks. Whereas working a job with the intention of quitting it might have been an act of recklessness a hundred years ago, it is more and more often becoming an act of common sense in an age of portable skills and diversified employment options. Keeping this in mind, don’t worry that your extended travels might leave you with a “gap” on your résumé. Rather, you should enthusiastically and unapologetically include your vagabonding experience on your résumé when you return. List the job skills travel has taught you: independence, flexibility, negotiation, planning, boldness, self-sufficiency, improvisation. Speak frankly and confidently about your travel experiences — the odds are, your next employer will be interested and impressed (and a wee bit envious).

As Pico Iyer pointed out, the act of quitting “means not giving up, but moving on; changing direction not because something doesn’t agree with you, but because you don’t agree with something. It’s not a complaint, in other words, but a positive choice, and not a stop in one’s journey, but a step in a better direction. Quitting — whether a job or a habit — means taking a turn so as to be sure you’re still moving in the direction of your dreams.”

In this way, quitting a job to go vagabonding should never be seen as the end of something grudging and unpleasant. Rather, it’s a vital step in beginning something new and wonderful.

Tip Sheet

SABBATICALS, UNPAID LEAVE, AND QUITTING YOUR JOB

Six Months Off: How to Plan, Negotiate, and Take the Break You Need Without Burning Bridges or Going Broke, by Hope Dlugozima, James Scott, and David Sharp (Henry Holt, 1996)

A detailed, action-oriented how-to book about planning and negotiating employee sabbaticals and leaves of absence.

Time Off from Work: Using Sabbaticals to Enhance Your Life While Keeping Your Career on Track, by Lisa Angowski Rogak (John Wiley & Sons, 1994)

A practical guide to planning and implementing sabbaticals. Includes tips on long-term financial planning.

I-Resign.com (http://www.i-resign.com)

Online advice on how to diplomatically quit your job, sample resignation letters, discussion boards about quitting, tips on finding a new job.

FINDING JOBS AND CAREERS OVERSEAS

A fantastic way to earn travel money is to find work overseas. Such work will not only fund your travels but will also teach you intuitive lessons about how to act and react in foreign cultures. Highly recommended as a way to enable and inspire your vagabonding career.

Work Worldwide: International Career Strategies for the Adventurous Job Seeker, by Nancy Mueller (Avalon Travel Publishing, 2000)

Step-by-step advice on how to research, apply for, and get an international job.

Work Abroad: The Complete Guide to Finding a Job Overseas, by Clayton A. Hubbs, Susan Griffith, and William T. Nolting (Transitions Abroad, 2000)

A practical guide for finding jobs overseas. Includes country-by-country listings of employers and organizations.

Overseas Jobs (http://www.overseasjobs.com/)

Online information and resources regarding international jobs, careers, and work. Country-specific online job listings.

Overseas Digest (http://overseasdigest.com/)

Employment tips and cross-cultural information for Americans working abroad.

Teaching English Overseas: A Job Guide for Americans and Canadians, by Jeff Mohamed (English International, 2000)

A comprehensive practical guide for finding jobs teaching English overseas. Includes detailed information and advice on choosing a training program, teaching without training, and how to conduct a successful job search. Useful companion website at http://www.english-inter national.com/.

Dave’s ESL Café (http://eslcafe.com/)

One of the oldest and most useful Internet resources for overseas English teachers and job seekers. Includes discussion forums and job listings.

INTERNATIONAL EMPLOYMENT REFERENCES

International Jobs: Where They Are, How to Get Them, by Eric Kocher and Nina Segal (Perseus Press, 1999)

International Jobs Directory: A Guide to Over 1001 Employers, by Ronald L. Krannich and Caryl Rae Krannich (Impact Publications, 1999)

The Directory of Jobs and Careers Abroad, by Elisabeth Roberts and Jonathan Packer (Vacation-Work, 2000)

OVERSEAS DANGERS

One of the big issues these days among potential vagabonders is whether or not it’s safe to travel overseas anymore.

The short answer to this concern is that traveling around the world is statistically no more dangerous than traveling across your hometown. Indeed, as with home, most dangers and annoyances on the road revolve around sickness, theft, and accidents (see chapter 7) — not political violence or terrorism.

Should political violence or terrorism capture headlines, however, the secret to avoiding it is not to cancel your travel plans but to simply keep yourself informed. Just because the evening news shows unrest in a southern Lebanon refugee camp, for instance, doesn’t necessarily mean it’s dangerous to visit Beirut or Galilee (or, for that matter, other parts of southern Lebanon). By the same token, the evening news might habitually ignore the political situation in West Africa, but that doesn’t mean it’s safe to visit Sierra Leone or Liberia. Obviously, then, planning and monitoring your destinations will require that you look past the evening news. Online resources such as U.S. State Department Travel Warnings and World Travel Watch (see below) make good starting points for assessing the current safety situation in any given part of the world.

Even if you accidentally find yourself in a dangerous area as you travel, the key to keeping safe is knowing and talking to the locals (who can tell you where specific dangers lurk), patronizing mom-and-pop businesses (which are never targeted in political attacks), avoiding a loud or flashy appearance (this includes dogmatic debates of religion and politics), and traveling outside of predictable tourist patterns (which are easier to target by troublemakers). In short, the engaged and humble attitude of vagabonding will naturally lend to a safer journey. Should the security situation seem especially tense in a region, go a step further and avoid hangouts that cater exclusively to foreigners (expat bars, Hard Rock Cafes, and the like), stay away from public demonstrations and crowds (this includes small bands of drunks and rabble-rousers), and don’t share your travel plans or lodging arrangements with strangers.

On a final note, keep in mind that most people in the world will see you not as a political entity or an appendage of the “Great Satan” but as a guest to their country. Even if they vehemently disagree with your country’s policies and practices, they will invariably honor your individuality and regard you with hospitality and respect. You’d never guess this by watching the evening news, of course, but travel allows you to experience the nuances of the world in a way that mass media never will.

U.S. State Department Travel Warnings State Department Consular Information Sheets (found online at http://travel.state.gov/travel__warnings.htm) are available for every country of the world. They describe national entry requirements, currency regulations, unusual health conditions, the crime and security situations, political disturbances, and areas of instability. In the event of a specific and current danger in a country, a special “Travel Warning” is posted alongside the consular information.

World Travel Watch (http://www.worldtravelwatch.com)

Travel publishers Larry Habegger and James O’Reilly have been writing this weekly travel safety and security update since 1985. It includes succinct, current, and useful information about dangers and disturbances (and odd happenings in general) around the world.

“A Safe Trip Abroad” Online Tip Sheet Available online (http://travel.state.gov/asafetripabroad.htm), this Department of State tip sheet has good, basic information for keeping out of danger overseas. Included are tips for staying safe from pickpockets and general crime, as well as from political violence and terrorism. Online links lead to specific tip sheets on travel to the Caribbean, Central and South America, China, Mexico, the Middle East, Russia, and South Asia.

The World’s Most Dangerous Places, by Robert Young Pelton (Harper Resource, 2000)

An extensive guide to the danger zones of the world by journalist Robert Pelton. This book evaluates the danger factor in destinations around the globe (including the United States) and provides relevant historical, cultural, and geographical information. “The message is that travel can be dangerous if you want it to be and it can be very safe if you want it to be,” writes Pelton. “Even in a war zone.”

For a fully updated and linkable online version of this resource guide, surf to http://vagabonding.net/ and follow the “Resources” link.

VAGABONDING VOICES

For me, the experience of travel is not only what I’m seeing but also what I have chosen to leave behind, even for a short time, and the perspective I gain from doing that. The hardest thing about travel is deciding to go. Once you’ve made that commitment, the rest of it is easy. And, despite the anxiety that comes with these issues, my travel experience would not be the same without them. I remember stopping my motorcycle just outside the Bayon complex at Angkor Wat, Cambodia, so I could absorb the scene in front of me. I was overwhelmed with the most awesome feeling of gratitude and pride. I was proud of myself for being there — because I’d worked hard to get there and I knew it. But also for quitting a great job, because I know there is more out there.

— REBECCA MARKEY, 28, EMPLOYMENT COUNSELOR, ONTARIO

————

Don’t wait around. Don’t get old and make excuses. Save a couple thousand dollars. Sell your car. Get a world atlas. Start looking at every page and tell yourself that you can go there. You can live there. Are there sacrifices to be made? Of course. Is it worth it? Absolutely. The only way you’ll find out is to get on the plane and go. And let me tell you something. That first morning, when you are in your country of choice, away from all of the conventions of a typical, everyday lifestyle, looking around at your totally new surroundings, hearing strange languages, smelling strange, new smells, you’ll know exactly what I’m talking about. You’ll feel like the luckiest person in the world.

— JASON GASPERO, 31, NEWSLETTER EDITOR, HAWAII

————

There is a very satisfying feeling I get when I work hard and make my own way. It makes me feel like a conqueror, like I’ve “made it.” I lived for most of a year in Europe pretty much hand-to-mouth, which was stressful at times for sure, but it was very challenging and forced me to be creative. This, to me, was a big part of the experience — I learned a lot about myself and my capabilities.

— JOHN BOCSKAY, 30, TEACHER, NEW YORK

VAGABONDING PROFILE

Walt Whitman

Allons! whoever you are, come travel with me!

— WALT WHITMAN, “SONG OF THE OPEN ROAD”

Should vagabonding have a patron saint, it would be the nineteenth-century poet Walt Whitman — if for no reason other than “Song of the Open Road,” his infectiously joyous ode to the spirit of travel.

Born in 1819 to a working-class family in New York, Whitman entered the working world as an office boy at age eleven. It was here, and at his later employment as a printer’s apprentice, that he developed a passion for self-education — as well as an eye for finding uncommon beauty in the common activity of daily life. Whitman eventually moved on to work as a journalist, but his real life’s work was Leaves of Grass, a collection of free-spirited verse that grew to more than three hundred poems by the time of his death in 1892.

As a youth, Whitman was particularly inspired by his daily ferry trips from Brooklyn to Manhattan, which instilled in him a lasting appreciation for the uncommon joys and vivid details of travel. And while his later travels took him to budding American outposts such as New Orleans and Denver, it is this celebration of simple movement and possibility that gives “Song of the Open Road” its visceral and inclusive energy:

To see nothing anywhere but what you may reach it and pass it,

To conceive no time, however distant, but what you may reach it and pass it,

To look up or down no road but it stretches and waits for you,

To know the universe itself as a road, as many roads, as roads for traveling souls.

CHAPTER 3

From all your herds, a cup or two of milk,

From all your granaries, a loaf of bread,

In all your palace, only half a bed:

Can man use more? And do you own the rest?

— ANCIENT SANSKRIT POEM

Keep It Simple

In March 1989, the Exxon Valdez struck a reef off the coast of Alaska, resulting in the largest oil spill in U.S. history. Initially viewed as an ecological disaster, this catastrophe did wonders to raise environmental awareness among average Americans. As television images of oil-choked sea otters and dying shorebirds were beamed across the country, pop environmentalism grew into a national craze.

Instead of conserving more and consuming less, however, many Americans sought to save the earth by purchasing “environmental” products. Energy-efficient home appliances flew off the shelves, health-food sales boomed, and reusable canvas shopping bags became vogue in strip malls from Jacksonville to Jackson Hole. Credit card companies began to earmark a small percentage of profits for conservation groups, thus encouraging consumers to “help the environment” by striking off on idealistic shopping binges.

Such shopping sprees and health-food purchases did very little to improve the state of the planet, of course — but most people managed to feel a little better about the situation without having to make any serious lifestyle changes.

This notion — that material investment is somehow more important to life than personal investment — is exactly what leads so many of us to believe we could never afford to go vagabonding. The more our life options get paraded around as consumer options, the more we forget that there’s a difference between the two. Thus, having convinced ourselves that buying things is the only way to play an active role in the world, we fatalistically conclude that we’ll never be rich enough to purchase a long-term travel experience.

Fortunately, the world need not be a consumer product. As with environmental integrity, long-term travel isn’t something you buy into; it’s something you give to yourself.

Indeed, the freedom to go vagabonding has never been determined by income level; it’s found through simplicity — the conscious decision of how to use what income you have.

And, contrary to popular stereotypes, seeking simplicity doesn’t require that you become a monk, a subsistence forager, or a wild-eyed revolutionary. Nor does it mean that you must unconditionally avoid the role of consumer. Rather, simplicity merely requires a bit of personal sacrifice: an adjustment of your habits and routines within consumer society itself.

At times, the biggest challenge in embracing simplicity will be the vague feeling of isolation that comes with it, since private sacrifice doesn’t garner much attention in the frenetic world of mass culture.

Jack Kerouac’s legacy as a cultural icon is a good example of this. Arguably the most famous American vagabonder of the twentieth century, Kerouac vividly captured the epiphanies of hand-to-mouth travel in books like On the Road and Lonesome Traveler. In The Dharma Bums, he wrote about the joy of living with people who blissfully ignore “the general demand that they consume production and therefore have to work for the privilege of consuming, all that crap they didn’t really want . . . general junk you always see a week later in the garbage anyway, all of [it] impersonal in a system of work, produce, consume.”

Despite his observance of material simplicity, however, Kerouac found that his personal life — the life that had afforded him the freedom to travel — was soon overshadowed by a more fashionable (and marketable) public vision of his travel lifestyle. Convertible cars, jazz records, marijuana — and, later, Gap khakis — ultimately came to represent the mystical “It” that he and Neal Cassady sought in On the Road. As his Beat cohort William S. Burroughs was to point out years after Jack’s death, part of Kerouac’s mystique became inseparable from the idea that he “opened a million coffee bars and sold a million pairs of Levi’s to both sexes.”

In some ways, of course, coffee bars, convertibles, and marijuana are all part of what made travel appealing to Kerouac’s readers. That’s how marketing (intentional and otherwise) works. But these aren’t the things that made travel possible for Kerouac. What made travel possible was that he knew how neither self nor wealth can be measured in terms of what you consume or own. Even the downtrodden souls on the fringes of society, he observed, had something the rich didn’t: time.

This notion — the notion that “riches” don’t necessarily make you wealthy — is as old as society itself. The ancient Hindu Upanishads refer disdainfully to “that chain of possessions wherewith men bind themselves, and beneath which they sink”; ancient Hebrew scriptures declare that “whoever loves money never has money enough.” Jesus noted that it’s pointless for a man to “gain the whole world, yet lose his very self,” and the Buddha whimsically pointed out that seeking happiness in one’s material desires is as absurd as “suffering because a banana tree will not bear mangoes.”

Despite several millennia of such warnings, however, there is still an overwhelming social compulsion — an insanity of consensus, if you will — to get rich from life rather than live richly, to “do well” in the world instead of living well. And, in spite of the fact that America is famous for its unhappy rich people, most of us remain convinced that just a little more money will set life right. In this way, the messianic metaphor of modern life becomes the lottery — that outside chance that the right odds will come together to liberate us from financial worries once and for all.

Fortunately, we were all born with winning tickets — and cashing them in is a simple matter of altering our cadence as we walk through the world. Vagabonding sage Ed Buryn knew as much: “By switching to a new game, which in this case involves vagabonding, time becomes the only possession and everyone is equally rich in it by biological inheritance. Money, of course, is still needed to survive, but time is what you need to live. So, save what little money you possess to meet basic survival requirements, but spend your time lavishly in order to create the life values that make the fire worth the candle. Dig?”

Dug. And the best part is that, as you cultivate your future with rich fields of time, you are also sowing the seeds of personal growth that will gradually bloom as you travel into the world.

In a way, simplifying your life for vagabonding is easier than it sounds. This is because travel by its very nature demands simplicity. If you don’t believe it, just go home and try stuffing everything you own into a backpack. This will never work, because no matter how meagerly you live at home, you can’t match the scaled-down minimalism that travel requires. You can, however, set the process of reduction and simplification into motion while you’re still at home. This is useful on several levels: Not only does it help you to save up travel money, but it helps you realize how independent you are of your possessions and your routines. In this way, it prepares you mentally for the realities of the road, and makes travel a dynamic extension of the life-alterations you began at home.

As with, say, giving up coffee, simplifying your life will require a somewhat difficult consumer withdrawal period. Fortunately, your impending travel experience will give you a very tangible and rewarding long-term goal that helps ease the discomfort. Over time, as you reap the sublime rewards of simplicity, you’ll begin to wonder how you ever put up with such a cluttered life in the first place.

On a basic level, there are three general methods to simplifying your life: stopping expansion, reining in your routine, and reducing clutter. The easiest part of this process is stopping expansion. This means that in anticipation of vagabonding, you don’t add any new possessions to your life, regardless of how tempting they might seem. Naturally, this rule applies to things like cars and home entertainment systems, but it also applies to travel accessories. Indeed, one of the biggest mistakes people make in anticipation of vagabonding is to indulge in a vicarious travel buzz by investing in water filters, sleeping bags, and travel-boutique wardrobes. In reality, vagabonding runs smoothest on a bare minimum of gear — and even multiyear trips require little initial investment beyond sturdy footwear and a dependable travel bag or backpack.

While you’re curbing the material expansion of your life, you should also take pains to rein in the unnecessary expenses of your weekly routine. Simply put, this means living more humbly (even if you aren’t humble) and investing the difference into your travel fund. Instead of eating at restaurants, for instance, cook at home and pack a lunch for work or school. Instead of partying at nightclubs and going out to movies or pubs, entertain at home with friends or family. Wherever you see the chance to eliminate an expensive habit, take it. The money you save as a result will pay handsomely in travel time. In this way, I ate lot of bologna sandwiches (and missed out on a lot of grunge-era Seattle nightlife) while saving up for a vagabonding stint after college — but the ensuing eight months of freedom on the roads of North America more than made up for it.

Perhaps the most challenging step in keeping things simple is reducing clutter — downsizing what you already own. As Thoreau observed, downsizing can be the most vital step in winning the freedom to change your life: “I have in my mind that seemingly wealthy, but most terribly impoverished class of all,” he wrote in Walden, “who have accumulated dross, but know not how to use it, or get rid of it, and thus have forged their own golden or silver fetters.”

How you reduce your “dross” in anticipation of travel will depend on your situation. If you’re young, odds are you haven’t accumulated enough to hold you down (which, incidentally, is a big reason why so many vagabonders tend to be young). If you’re not so young, you can re-create the carefree conditions of youth by jettisoning the things that aren’t necessary to your basic well-being. For much of what you own, garage sales and online auctions can do wonders to unclutter your life (and score you an extra bit of cash to boot). Homeowners can win their travel freedom by renting out their houses; those who rent accommodations can sell, store, or lend out the things that might bind them to one place.

An additional consideration in life-simplification is debt. As Laurel Lee wryly observed in Godspeed, “Cities are full of those who have been caught in monthly payments for avocado green furniture sets.” Thus, if at all possible, don’t let avocado green furniture sets (or any other seemingly innocuous indulgence) dictate the course of your life by forcing you into ongoing cycles of production and consumption. If you’re already in debt, work your way out of it — and stay out. If you have a mortgage or other long-term debt, devise a situation (such as property rental) that allows you to be independent of its obligations for long periods of time. Being free from debt’s burdens simply gives you more vagabonding options.

And, for that matter, more life options.

As you simplify your life and look forward to spending your new wealth of time, you’re likely to get a curious reaction from your friends and family. On one level, they will express enthusiasm for your impending adventures. But on another level, they might take your growing freedom as a subtle criticism of their own way of life. Because your fresh worldview might appear to call their own values into question (or, at least, force them to consider those values in a new light), they will tend to write you off as irresponsible and self-indulgent. Let them. As I’ve said before, vagabonding is not an ideology, a balm for societal ills, or a token of social status. Vagabonding is, was, and always will be a private undertaking — and its goal is to improve your life not in relation to your neighbors but in relation to yourself. Thus, if your neighbors consider your travels foolish, don’t waste your time trying to convince them otherwise. Instead, the only sensible reply is to quietly enrich your life with the myriad opportunities that vagabonding provides.

Interestingly, some of the harshest responses I’ve received in reaction to my vagabonding life have come while traveling. Once, at Armageddon (the site in Israel, not the battle at the end of the world), I met an American aeronautical engineer who was so tickled at having negotiated five days of free time into a Tel Aviv consulting trip that he spoke of little else as we walked through the ruined city. When I eventually mentioned that I’d been traveling around Asia for the past eighteen months, he looked at me as if I’d slapped him. “You must be filthy rich,” he said acidly. “Or maybe,” he added, giving me the once-over, “your mommy and daddy are.”

I tried to explain how two years of teaching English in Korea had funded my freedom, but the engineer would have none of it. Somehow, he couldn’t accept that two years of any kind of honest work could have funded eighteen months (and counting) of travel. He didn’t even bother sticking around for the real kicker: In those eighteen months of travel, my day-to-day costs were significantly cheaper than they would have been back in the United States.

The secret to my extraordinary thrift was neither secret nor extraordinary: I had tapped into that vast well of free time simply by forgoing a few comforts as I traveled. Instead of luxury hotels, I slept in clean, basic hostels and guesthouses. Instead of flying from place to place, I took local buses, trains, and share-taxis. Instead of dining at fancy restaurants, I ate food from street vendors and local cafeterias. Occasionally, I traveled on foot, slept out under the stars, and dined for free at the stubborn insistence of local hosts.

In what ultimately amounted to over two years of travel in Asia, eastern Europe, and the Middle East, my lodging averaged out to just under five dollars a night, my meals cost well under a dollar a plate, and my total expenses rarely exceeded one thousand dollars a month.

Granted, I have simple tastes — and I didn’t linger long in expensive places — but there was nothing exceptional in the way I traveled. In fact, entire multinational backpacker circuits (not to mention budget-guidebook publishing empires) have been created by the simple abundance of such travel bargains in the developing world. For what it costs to fill your gas tank back home, for example, you can take a train from one end of China to the other. For the price of a home-delivered pepperoni pizza, you can eat great meals for a week in Brazil. And for a month’s rent in any major American city, you can spend a year in a beach hut in Indonesia. Moreover, even the industrialized parts of the world host enough hostel networks, bulk transportation discounts, and camping opportunities to make long-term travel affordable.

Ultimately, you may well discover that vagabonding on the cheap becomes your favorite way to travel, even if given more expensive options. Indeed, not only does simplicity save you money and buy you time; it also makes you more adventuresome, forces you into sincere contact with locals, and allows you the independence to follow your passions and curiosities down exciting new roads.

In this way, simplicity — both at home and on the road — affords you the time to seek renewed meaning in an oft-neglected commodity that can’t be bought at any price: life itself.

Tip Sheet

RESOURCES FOR LIFESTYLE SIMPLICITY

Your Money or Your Life: Transforming Your Relationship with Money and Achieving Financial Independence, by Joe Dominguez and Vicki Robin (Penguin USA, 1999)

This bestselling book uses a nine-step process to demonstrate how most people are making a “dying” instead of a living. Includes practical pointers for achieving financial independence by altering your lifestyle.

Voluntary Simplicity: Toward a Way of Life That Is Outwardly Simple, Inwardly Rich, by Duane Elgin (Quill, 1993)

First published in 1981, this is a popular reference and inspiration for those looking to live a simpler life. Strongly themed toward environmental sustainability.

The Simple Living Guide: A Sourcebook for Less Stressful, More Joyful Living, by Janet Luhrs (Broadway Books, 1997)

Luhrs is the founder and publisher of the Simple Living Journal(companion website at http://www.simpleliving .com/). The book contains tips for living fully and well through simplicity.

Less Is More: The Art of Voluntary Poverty — an Anthology of Ancient and Modern Voices Raised in Praise of Simplicity, edited by Goldian Vandenbroeck (Inner Traditions, 1996)

Quotes and essays on the value of simplicity, from the likes of Socrates, Shakespeare, Saint Francis, Benjamin Franklin, and Mohandas Gandhi, as well as the Bible, The Dhammapada, Tao Te Ching, and The Bhagavad Gita.

Dematerializing: Taming the Power of Possessions, by Jane Hammerslough (Perseus Books, 2001)

An examination of “possession-obsession” and how it negatively affects our personal growth, creativity, and relationships.

Walden, by Henry David Thoreau

The philosophical account of Thoreau’s experiment in antimaterialist living. An American literary classic for over 150 years.

BUDGETING AND MONEY MANAGEMENT

The Pocket Idiot’s Guide to Living on a Budget, by Peter J. Sander and Jennifer Basye Sander (Alpha Books, 1999)

A concise guide to planning and abiding by a day-to-day budget.

The Budget Kit: The Common Cents Money Management Workbook, by Judy Lawrence (Dearborn Trade, 2000)

Easy-to-use tips for managing your finances and getting the most out of your income.

The Complete Tightwad Gazette: Promoting Thrift as a Viable Alternative Lifestyle, by Amy Dacyczyn (Random House, 1999)

Nine hundred pages of tips for frugal living.

The Dollar Stretcher (http://www.stretcher.com/)

An online resource for saving money in day-to-day life. Features weekly columns on thrift and simplicity.

VAGABONDING FOR SENIORS AND FAMILIES

Statistically, most vagabonders are eighteen to thirty-five years old and childless — but this doesn’t mean that youthful independence is a prerequisite for long-term travel. Indeed, some of the most dynamic vagabonders are the adventurous elder and family travelers who defy stereotype and set out to discover the world for themselves.

Senior Vagabonders

On a general level, all of the advice in this book — from choosing a guidebook to interacting with local cultures — applies just as readily to older travelers as to younger ones. Senior vagabonders might occasionally seek out more creature comforts than their younger counterparts, but the same basic rules and freedoms of independent travel apply. And since most cultures treat elders with uncommon interest and respect, older travelers invariably wander into charming adventures and friendships on the road. Naturally, extra care should be taken in tourist zones (see chapter 6), where unscrupulous touts and scam artists often see seniors as easy marks.

Some older vagabonders might feel a little intimidated at the outset of their travels, since independent travel is often cast in a youth-culture vernacular. One way to offset this anxiety is to join up with a brief package tour or “volunteer vacation” program at the outset of your journey. Given a good attitude and a proper level of awareness, you’ll feel much more confident about independent travel after these initial days or weeks in your host culture.

Travel Unlimited: Uncommon Adventures for the Mature Traveler, by Alison Gardner (Avalon Travel Publishing, 2000)

A worldwide menu of active travel opportunities for the older adventurer. The book emphasizes “vacation” travel but is a good starting point for seniors wanting to know about alternative travel opportunities, including volunteering and “eco-tourism.”

Marco Polo Magazine

“Dedicated to adventure travelers over fifty.” Features down-to-earth articles about older travelers making their own way on the road; $10 for a four-issue (one-year) subscription. Companion website at http://www.marcopolo magazine.com.

Elderhostel

The world’s largest educational and travel organization for adults fifty-five and over. Offers ten thousand programs a year in over one hundred countries. A good way for traveling seniors to get a taste of other cultures before striking off on their own. Information online at http://elderhostel.org.

State Department Travel Tips for Older Americans

Posted online (http://travel.state.gov/olderamericans.htm), this tip sheet is a useful primer for older independent travelers. Topics covered include trip preparation, passport and visas, health, money and valuables, safety precautions, and shopping.

Vagabonding with Children

Parenthood may be an adventure in and of itself, but this doesn’t mean that you have to limit the adventure to your hometown. For children of any age (and six- to fourteen-year-olds in particular), an extended journey into the world can be an unparalleled educational experience that inspires new interests and passions. And while the task of parenting on the road can sometimes be a challenge for the grown-ups, the singular adventures (and collective memories) of family vagabonding will more than make up for it.

Lonely Planet Travel with Children, by Cathy Lanigan and Maureen Wheeler (Lonely Planet, 2002)

A practical guide to the challenges and joys of traveling with children, including trip preparation and kid-friendly destinations.

Gutsy Mamas: Travel Tips and Wisdom for Mothers on the Road, by Marybeth Bond (Travelers’ Tales, 1997)

Inspirational and informative advice on staying healthy on the road, traveling to Third World countries (and close to home), and keeping children of all ages entertained and adults energized.

Your Child’s Health Abroad, by Jane Wilson-Howarth and Matthew Ellis (Bradt Publications, 1998)

Accessible and practical health information for parents traveling with children to far-flung areas of the world.

One Year Off: Leaving It All Behind for a Round-the-World Journey with Our Children, by David Elliot Cohen (Simon & Schuster, 1999)

When David Elliot Cohen turned forty, he quit his job, sold his house and car, and left to travel the world — with his wife and three kids (ages eight, seven, and two) in tow. A firsthand account of how vagabonding exotic lands can be a family experience.

Worldhop: One Family, One Year, One World (http://www .worldhop.com/)

Online journals and inspiration from an Alaska family (ages forty-nine, forty-eight, fourteen, and seven) who sold and stored their possessions, quit work and school, and spent a year traveling around the world.

Family Travel Forum (http://familytravelforum.com)

Online information on worldwide destinations for adults and children. Features discussion boards and advice for all manner of family travel issues.

Traveling Internationally with Your Kids

(http://travelwithyourkids.com)

Online resources for traveling overseas with children. Features guidebook recommendations, trip preparation tips, and activity suggestions.

For a fully updated and linkable online version of this resource guide, surf to http://vagabonding.net/ and follow the “Resources” link.

VAGABONDING VOICES

To allow for travel, we spend less money on things at home (new cars, clothes, stuff in general). We have no debt, including credit card debt — in order to remain financially free to leave. We rent out our home each year when we travel. With no debt (except a mortgage), renting our house allows us to leave without sending a dime back home. Most Americans don’t live this way. Their huge debt load would make it awfully difficult to leave. And as an aside, many of our middle-aged friends tell us, “Oh, we’d love to do what you do, but we can’t” — money, debt, obligations, etc. The way I see it is that most folks simply choose their boxes. Any of us do what is fundamentally most important to us.

— LINDA ROSE, 58, RETIRED TEACHER, OREGON

————

My lifestyle sacrifices for travel are mainly in relation to American life, which means I still live quite luxuriously. Riding my bike rather than taking the metro or taxis, and packing my lunch rather than spending eight bucks every day, is hardly much of a sacrifice. I try not to buy much meat and coffee and alcohol, but I still go out for those things occasionally. I don’t go to the mall and buy clothes. Also, I refuse to spend money on haircuts. It’s amazing how much you can save when you don’t mind looking like a schmuck for a few months.

— SAM ENGLAND, 25, STUDENT AND TEMP WORKER, WASHINGTON, D.C.

————

Deal with all material responsibilities of home before you go on your travels. That way you’ll be able to enjoy the experience more fully, not worrying about when exactly you have to come home, or what you’ll have to do when you get there. It is easier to live in the now when all responsibilities are taken care of ahead of time.

— R. J. MOSER, 38, HOME RENOVATOR, WASHINGTON

VAGABONDING PROFILE

Henry David Thoreau

My greatest skill has been to want little.

— HENRY DAVID THOREAU, WALDEN

Although Henry David Thoreau never traveled very far outside of New England, he promoted an uncommon view of wealth that is essential to vagabonding. Considering all material possessions beyond basic necessities to be an obstacle to true living, he espoused the idea that wealth is found not in what you own but in how you spend your time. “A man is rich,” he wrote in Walden, “in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone.”

Born in Concord, Massachusetts, in 1817, Thoreau trained as an engineer at Harvard, although he never could pinpoint his true profession. At various times, he called himself a schoolteacher, a surveyor, a farmer, a house painter, a pencil maker, a writer, and “sometimes a poetaster.” It is as a writer that he is best remembered — particularly for his book Walden, the vivid account of his one-year experiment in antimaterialist living.

At Walden Pond, Thoreau lived in such a way that he only had to work six weeks a year: eating vegetables from his garden and fish from the pond; living in a “tight, light, and clean house” that he built himself; avoiding unnecessary expenses, including fresh meat, fancy clothes, and coffee. This left him with ample time to indulge in the things he loved best: reading, writing, walking, thinking, and observing nature.

In this way — through simplicity — Thoreau was able to find true wealth. “Superfluous wealth can buy superfluities only,” he wrote. “Money is not required to buy one necessity of the soul.”

CHAPTER 4

Reading old travel books or novels set in faraway places, spinning globes, unfolding maps, playing world music, eating in ethnic restaurants, meeting friends in cafes . . . all these things are part of never-ending travel practice, not unlike doing scales on a piano, shooting free-throws, or meditating.

— PHIL COUSINEAU, THE ART OF PILGRIMAGE

Learn, and Keep Learning

One of the best travel parables to come from world history involves a certain Christopher Columbus, who — as we all learned in grade school — sailed the ocean blue in the year 1492. That the legendary Italian navigator ever resolved to seek the East by sailing west says a lot about his gumption, but it also shows that he’d done his homework. Using classic geographical texts written by ancient Greek and Latin authors, as well as a copy of Marco Polo’s Travels, he had good reason to think his westbound quest for Asia might work.

After his initial voyages proved both promising and perplexing, Columbus’s third expedition finally sighted land that was unmistakably continental. Instead of confronting uncertainty, however — instead of wading ashore to verify just what he had found — Columbus rushed back to an outpost on Hispaniola and concocted a triumphant letter to send back to Spain. Rather than using empirical evidence to prove that this was China or India, he went back to the Greek and Latin geographers who’d inspired him in the first place. Quoting passage after passage from the erudite ancients, he confidently concluded that he had at last sighted the elusive Asian mainland.

As any bright eight-year-old will tell you, however, his grand assumption was a good hemisphere off.

The example of Columbus can teach us a couple of vital lessons about vagabonding. First, it shows how doing your pretrip homework — that is, harnessing the knowledge of those who examined the world before you — can lead you to fabulous new horizons. By that same token, however, you will never be able to truly appreciate the unexpected marvels of travel if you rely too heavily on your homework and ignore what is right before your eyes.

Thus, you need to strike a balance between tapping the inspiration that compelled you to hit the road and knowing that nothing short of travel itself can prepare you for the new worlds that await. The reason vagabonding is so appealing is that it promises to show you the destinations and experiences you’ve dreamed about; but the reason vagabonding is so addictive is that, joyfully, you’ll never quite find what you dreamed. Indeed, the most vivid travel experiences usually find you by accident, and the qualities that will make you fall in love with a place are rarely the features that took you there.

In this way, vagabonding is not just a process of discovering the world but a way of seeing — an attitude that prepares you to find the things you weren’t looking for.

The discoveries that come with travel, of course, have long been considered the purest form of education a person can acquire. “The world is a book,” goes a saying attributed to Saint Augustine, “and those who do not travel read only one page.” Vagabonding is all about delving into the thick plots the world promises, and the more you “read” (so to speak), the better you position yourself to keep reading. However, even if you’re stuck on the first paragraph, it’s still important to ready yourself for the pages to come. After all, you don’t stand to grow much from your travels if you just skim your way through the world at random.

Just how extensively you should prepare yourself before vagabonding is a topic of much debate among travelers. Many experienced vagabonders believe that less preparation is actually better in the long run. The naturalist John Muir used to say that the best way to prepare for a trip was to “throw some tea and bread into an old sack and jump over the back fence.” Not only does such bold spontaneity add a spark of adventure to your travels, longtime travelers argue, but it also lessens the kind of prejudices and preconceptions that might jade your experience.

It’s important to keep in mind, however, that experienced vagabonders already possess the confidence, faith, and know-how to make such spontaneous travel work. They know how easy the travel basics are, and — using their passions, instincts, and a little local information — they begin their immersion education the moment they touch down at their destinations.

Personally, while I respect the spontaneous approach, I prefer the hum of excitement that comes with carefully preparing at home for the trip to come. And, as Phil Cousineau pointed out in The Art of Pilgrimage, I tend to believe that “preparation no more spoils the chance for spontaneity and serendipity than discipline ruins the opportunity for genuine self-expression in sports, acting, or the tea ceremony.”

For the first-time vagabonder, of course, preparation is a downright necessity — if for no other reason than to familiarize yourself with the fundamental routines of travel, to learn what wonders and challenges await, and to assuage the fears that inevitably accompany any life-changing new pursuit. The key to preparation is to strike a balance between knowing what’s out there and being optimistically ignorant. The gift of the information age, after all, is knowing your options — not your destiny — and those people who plan their travels with the idea of eliminating all uncertainty and unpredictability are missing out on the whole point of leaving home in the first place.

The goal of preparation, then, is not knowing exactly where you’ll go but being confident nonetheless that you’ll get there. This means that your attitude will be more important than your itinerary, and that the simple willingness to improvise is more vital, in the long run, than research.

After all, your very first day on the road — in making travel immediate and real — could very well revolutionize every idea you ever gleaned in the library.

As John Steinbeck wrote in Travels with Charley, “Once a journey is designed, equipped, and put in process, a new factor enters and takes over. A trip, a safari, an exploration, is an entity . . . no two are alike. And all plans, safeguards, policing, and coercion are fruitless. We find after years of struggle that we do not take a trip; a trip takes us.”

Regardless of how much time you choose to spend in travel planning, the odds are your true preparations began long ago, when you first learned there was a world out there to explore. Over a lifetime, various sources of inspiration — novels, teachers, hobbies — help to stoke the vagabonding urge. Once you’ve made the determined decision to hit the road, of course, this preparation process focuses and intensifies.

The first place many people turn when planning a trip is traditional media (the kind of information you can find at a library), since it represents such a broad variety of resources. However, a lot of media information — especially day-to-day news — should be approached with a healthy amount of skepticism. This is because so many media outlets (especially television and magazines) are more in the business of competing for your attention than giving you a balanced picture of the world. Real people and places become objectified — made unreal — as the news media dotes on wars, disasters, elections, celebrities, and sporting events.

Moreover, what qualifies as “travel coverage” in the mainstream news revolves primarily around stunts, tie-ins, and commerce: rich men racing balloons around the world; sci-fi fans driving hundreds of miles to catch the latest Star Wars premiere; industry insiders comparing air-travel bargains. Personal, long-term travel rarely gets a mention, unless it relates to something moralistic or vaguely alarming (usually in regard to young people). Time magazine in particular has the irksome habit of portraying twenty-something backpackers as drug-addled dimwits.

A good rule of thumb, then, when watching news coverage of other countries, is to think about how the average Hollywood movie exports visions of America to other countries. Just as day-to-day American life is not characterized by car chases, gun battles, and unusually large-breasted women, life overseas is not populated by sinister or melodramatic stereotypes. Rather, it is full of people with values not that much different than your own. Before I went to the Middle East, for example, I’d assumed from media images that Syria was a “rogue state” full of humorless police informants and terrorist training camps. Once I’d drummed up the courage to actually visit Syria, however, this stereotype was shattered by the simple warmth and exuberance of the Arabs, Kurds, and Armenians who lived there. If police informants were indeed trailing my every move in Syria, they witnessed little more than a charming succession of home-cooked dinners, spontaneous neighborhood tours, and tea-shop backgammon games.

Thus, to gain accurate perspective and inspiration for your travels, you need to duck the frenzy of day-to-day news and dig for more relevant sources of information. Fortunately, there are plenty of options: literary travel narratives; specialty magazines covering all manner of travel; English-language foreign newspapers and journals; novels set in distant lands; academic and historical studies of other cultures; foreign-language dictionaries and phrasebooks; maps and atlases; scientific and cultural videos and TV programs; almanacs, encyclopedias, and travel reference books; travelogues and guidebooks.

I’ve listed starting points for various such resources at the end of this chapter, but I’ll elaborate a bit here on travel guidebooks, since they’re particularly important. Guidebooks should never be your only source of travel information, of course, but they deserve a special mention because they’re likely the only resource you’ll bring with you on the road. They also contain the kind of pertinent, specialized information that can help even the most timid homebody gain knowledge and courage about the practical possibilities of vagabonding. Nevertheless, you should carefully consider a guidebook’s advantages and limitations before you use it to dictate your travels.

Too often, travelers adhere far too religiously to the advice and information that guidebooks dispense. And while some critics blame this trend on the current popularity of “independent” travel guidebooks, this certainly isn’t a recent phenomenon. When visiting the Holy Land in the nineteenth century, Mark Twain expressed frequent exasperation at the guidebook fundamentalists in his travel party: “I can almost tell, in set phrase, what they will say when they see Tabor, Nazareth, Jericho, and Jerusalem,” Twain wrote in The Innocents Abroad, “because I have the books they will ‘smouch’ their ideas from. These authors write pictures and frame rhapsodies, and lesser men follow and see with the author’s eyes instead of their own, and speak with his tongue. . . . The pilgrims will tell of Palestine, when they get home, not as it appeared to them, but as it appeared in [the guidebooks] — with the tints varied to suit each pilgrim’s creed.”

Because a guidebook can thus jade your impressions, it’s important to use it as a handy reference during your adventures — not as an all-encompassing holy book. Even professional guidebook writers recommend that you maintain a healthy independence from their advice. “There is no need to treat a Lonely Planet book like a bible,” travel publisher Tony Wheeler once told me in an interview. “Just because we don’t list certain restaurants and hotels doesn’t mean they aren’t any good. Sometimes people even write to say they use our books only to see where not to go. They don’t want to stay with everybody else, so they go to the hotels that aren’t listed in the Lonely Planet. I think that’s great because we encourage travelers to be different.”