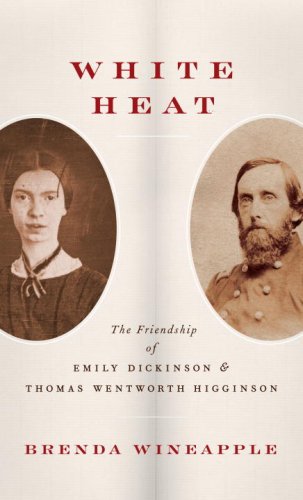

White heat: the friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson – Read Now and Download Mobi

Comments

Contents

Two: Thomas Wentworth Higginson: Without a Little Crack Somewhere

Three: Emily Dickinson: If I Live, I Will Go to Amherst

Four: Emily Dickinson: Write! Comrade, Write!

Five: Thomas Wentworth Higginson: Liberty Is Aggressive

Six: Nature Is a Haunted House

Thirteen: Things That Never Can Come Back

Part Three: Beyond the Dip of Bell

Seventeen: Poetry of the Portfolio

Eighteen: Me—Come! My Dazzled Face

Nineteen: Because I Could Not Stop

Emily Dickinson Poems Known to Have Been Sent to Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Illustrations

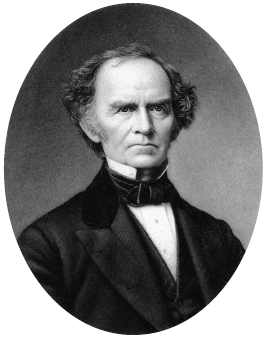

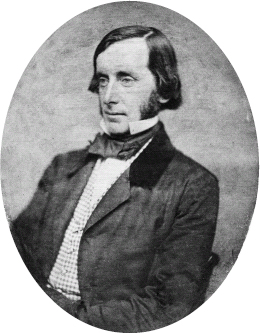

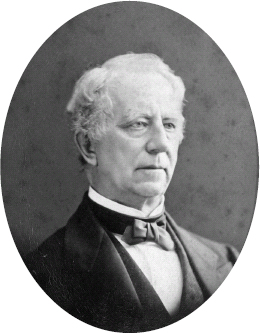

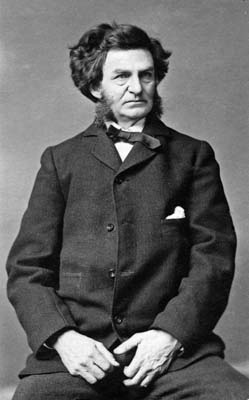

Samuel Bowles. (MS Am 111899b [6]. By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University)

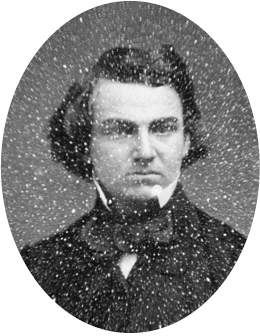

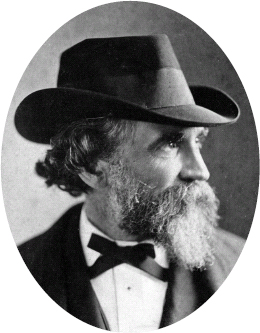

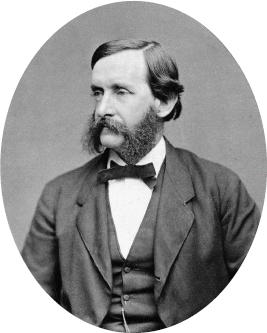

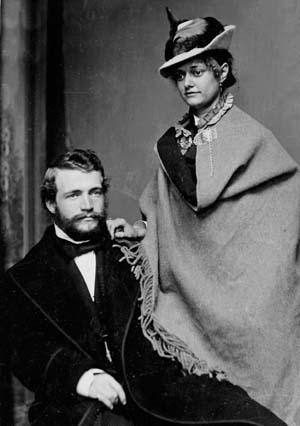

Thomas Wentworth Higginson, 1857. (Courtesy of the Rare Book Department, Boston Public Library)

The Evergreens. (By permission of the Jones Library, Inc.; Amherst, Massachusetts)

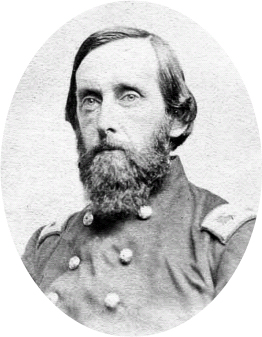

Robert Gould Shaw, 1863. (Boston: John Adams Whipple, 1863. Courtesy of the Boston Athenaeum)

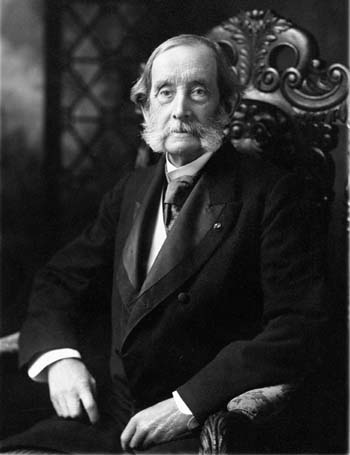

Judge Otis Lord. (MS Am 1118.99b [55]. By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University)

ONE

The Letter

This is my letter to the World

That never wrote to Me—

The simple News that Nature told—

With tender Majesty

Her Message is committed

To Hands I cannot see—

For love of Her—Sweet—countrymen—

Judge tenderly—of Me

Reprinted by Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mabel

Loomis Todd in Emily Dickinson, Poems (1890)

Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?”

Thomas Wentworth Higginson opened the cream-colored envelope as he walked home from the post office, where he had stopped on the mild spring morning of April 17 after watching young women lift dumbbells at the local gymnasium. The year was 1862, a war was raging, and Higginson, at thirty-eight, was the local authority on physical fitness. This was one of his causes, as were women’s health and education. His passion, though, was for abolition. But dubious about President Lincoln’s intentions—fighting to save the Union was not the same as fighting to abolish slavery—he had not yet put on a blue uniform. Perhaps he should.

Yet he was also a literary man (great consolation for inaction) and frequently published in the cultural magazine of the moment, The Atlantic Monthly, where, along with gymnastics, women’s rights, and slavery, his subjects were flowers and birds and the changing seasons.

Out fell a letter, scrawled in a looping, difficult hand, as well as four poems and another, smaller envelope. With difficulty he deciphered the scribble. “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?”

This is the beginning of a most extraordinary correspondence, which lasts almost a quarter of a century, until Emily Dickinson’s death in 1886, and during which time the poet sent Higginson almost one hundred poems, many of her best, their metrical forms jagged, their punctuation unpredictable, their images honed to a fine point, their meaning elliptical, heart-gripping, electric. The poems hit their mark. Poetry torn up by the roots, he later said, that took his breath away.

Today it may seem strange she would entrust them to the man now conventionally regarded as a hidebound reformer with a tin ear. But Dickinson had not picked Higginson at random. Suspecting he would be receptive, she also recognized a sensibility she could trust—that of a brave iconoclast conversant with botany, butterflies, and books and willing to risk everything for what he believed.

At first she knew him only by reputation. His name, opinions, and sheer moxie were the stuff of headlines for years, for as a voluble man of causes, he was on record as loathing capital punishment, child labor, and the unfair laws depriving women of civil rights. An ordained minister, he had officiated at Lucy Stone’s wedding, and after reading from a statement prepared by the bride and groom, he distributed it to fellow clergymen as a manual of marital parity.

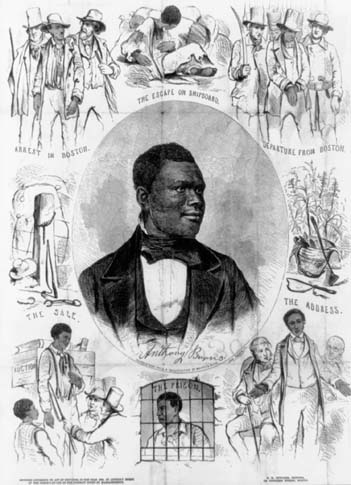

Above all, he detested slavery. One of the most steadfast and famous abolitionists in New England, he was far more radical than William Lloyd Garrison, if, that is, radicalism is measured by a willingness to entertain violence for the social good. Inequality offended him personally; so did passive resistance. Braced by the righteousness of his cause—the unequivocal emancipation of the slaves—this Massachusetts gentleman of the white and learned class had earned a reputation among his own as a lunatic. In 1854 he had battered down a courthouse door in Boston in an attempt to free the fugitive slave Anthony Burns. In 1856 he helped arm antislavery settlers in Kansas and, a loaded pistol in his belt, admitted almost sheepishly, “I enjoy danger.” Afterward he preached sedition while furnishing money and morale to John Brown.

All this had occurred by the time Dickinson asked him if he was too busy to read her poems, as if it were the most reasonable request in the world.

“The Mind is so near itself—it cannot see, distinctly—and I have none to ask—” she politely lied. Her brother, Austin, and his wife, Susan, lived right next door, and with Sue she regularly shared much of her verse. “Could I make you and Austin—proud—sometime—a great way off—’twould give me taller feet—,” she confided. Yet Dickinson now sought an adviser unconnected to family. “Should you think it breathed—and had you the leisure to tell me,” she told Higginson, “I should feel quick gratitude—.”

Should you think my poetry breathed; quick gratitude: if only he could write like this.

Dickinson had opened her request bluntly. “Mr. Higginson,” she scribbled at the top of the page. There was no other salutation. Nor did she provide a closing. Almost thirty years later Higginson still recalled that “the most curious thing about the letter was the total absence of a signature.” And he well remembered that smaller sealed envelope, in which she had penciled her name on a card. “I enclose my name—asking you, if you please—Sir—to tell me what is true?” That envelope, discrete and alluring, was a strategy, a plea, a gambit.

Higginson glanced over one of the four poems. “I’ll tell you how the Sun rose—/ A Ribbon at a time—.” Who writes like this? And another: “The nearest Dream recedes—unrealized—.” The thrill of discovery still warm three decades later, he recollected that “the impression of a wholly new and original poetic genius was as distinct on my mind at the first reading of these four poems as it is now, after thirty years of further knowledge; and with it came the problem never yet solved, what place ought to be assigned in literature to what is so remarkable, yet so elusive of criticism.” This was not the benign public verse of, say, John Greenleaf Whittier. It did not share the metrical perfection of a Longfellow or the tiresome “priapism” (Emerson’s word, which Higginson liked to repeat) of Walt Whitman. It was unique, uncategorizable, itself.

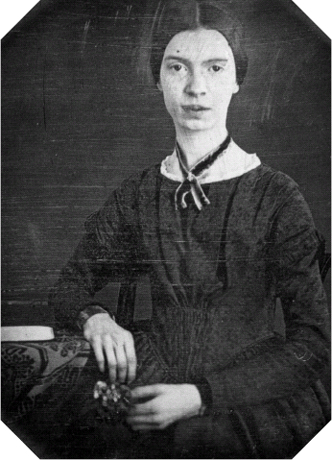

The Springfield Republican, a staple in the Dickinson family, regularly praised Higginson for his Atlantic essays. “I read your Chapters in the Atlantic—” Dickinson would tell him. Perhaps at Dickinson’s behest, her sister-in-law had requested his daguerreotype from the Republican’s editor, a family friend. As yet unbearded, his dark, thin hair falling to his ears, Higginson was nice looking; he dressed conventionally, and he had grit.

Dickinson mailed her letter to Worcester, Massachusetts, where he lived and whose environs he had lovingly described: its lily ponds edged in emerald and the shadows of trees falling blue on a winter afternoon. She paid attention.

He read another of the indelible poems she had enclosed.

Safe in their Alabaster Chambers—

Untouched by Morning—

And untouched by noon—

Sleep the meek members of the Resurrection,

Rafter of Satin and Roof of Stone—

Grand go the Years,

In the Crescent above them—

Worlds scoop their Arcs—

And Firmaments—row—

Diadems—drop—

And Doges—surrender—

Soundless as Dots,

On a Disc of Snow.

White alabaster chambers melt into snow, vanishing without sound: it’s an unnerving image in a poem skeptical about the resurrection it proposes. The rhymes drift and tilt; its meter echoes that of Protestant hymns but derails. Dashes everywhere; caesuras where you least expect them, undeniable melodic control, polysyllabics eerily shifting to monosyllabics. Poor Higginson. Yet he knew he was holding something amazing, dropped from the sky, and he answered her in a way that pleased her.

That he had received poems from an unknown woman did not entirely surprise him. He’d been getting a passel of mail ever since his article “Letter to a Young Contributor” had run earlier in the month. An advice column to readers who wanted to become Atlantic contributors, the essay offered some sensible tips for submitting work—use black ink, good pens, white paper—along with some patently didactic advice about writing. Work hard. Practice makes perfect. Press language to the uttermost. “There may be years of crowded passion in a word, and half a life in a sentence,” he explained. “A single word may be a window from which one may perceive all the kingdoms of the earth…. Charge your style with life.” That is just what he himself was trying to do.

The fuzzy instructions set off a huge reaction. “I foresee that ‘Young Contributors’ will send me worse things than ever now,” Higginson boasted to his editor, James T. Fields, whom he wanted to impress. “Two such specimens of verse came yesterday & day before—fortunately not to be forwarded for publication!” But writing to his mother, whom he also wanted to impress, Higginson sounded more sympathetic and humble. “Since that Letter to a Young Contributor I have more wonderful expressions than ever sent me to read with request for advice, which is hard to give.”

Higginson answered Dickinson right away, asking everything he could think of: the name of her favorite authors, whether she had attended school, if she read Whitman, whether she published, and would she? (Dickinson had not told him that “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers” had appeared in The Republican just six weeks earlier.) Unable to stop himself, he made a few editorial suggestions. “I tried a little,—a very little—to lead her in the direction of rules and traditions,” he later reminisced. She called this practice “surgery.”

“It was not so painful as I supposed,” she wrote on April 25, seeming to welcome his comments. “While my thought is undressed—I can make the distinction, but when I put them in the Gown—they look alike, and numb.” As to his questions, she answered that she had begun writing poetry only very recently. That was untrue. In fact, she dodged several of his queries, Higginson recalled, “with a naive skill such as the most experienced and worldly coquette might envy.” She told him she admired Keats, Ruskin, Sir Thomas Browne, and the Brownings, all names Higginson had mentioned in his various essays. Also, the book of Revelation. Yes, she had gone to school “but in your manner of the phrase—had no education.” Like him, she responded intensely to nature. Her companions were the nearby Pelham Hills, the sunset, her big dog, Carlo: “they are better than Beings—because they know—but do not tell.”

What strangeness: a woman of secrets who wanted her secrets kept but wanted you to know she had them. “In a Life that stopped guessing,” she once told her sister-in-law, “you and I should not feel at home.”

Her mother, she confided, “does not care for thought,” and although her father has bought her many books, he “begs me not to read them—because he fears they joggle the Mind.” She was alone, in other words, and apart. Her family was religious, she continued, “—except me—and address an Eclipse, every morning—whom they call their ‘Father.’” She would require a guidance more perspicacious, more concrete.

As for her poetry, “I sing, as the Boy does by the Burying Ground—because I am afraid.” Such a bald statement would be hard to ignore. “When far afterward—a sudden light on Orchards, or a new fashion in the wind troubled my attention—I felt a palsy, here—the Verses just relieve—.”

In passing, she dropped an allusion to the two literary editors—she was no novice after all—who “came to my Father’s House, this winter—and asked me for my Mind—and when I asked them ‘Why,’ they said I was penurious—and they, would use it for the World—.” It was not worldly approval that she sought; she demanded something different. “I could not weigh myself—Myself,” she promptly added, turning slyly to Higginson. This time she signed her letter as “your friend, E—Dickinson.”

Bewildered and flattered, he could not help considering that next to such finesse, his tepid tips to a Young Contributor were superfluous. What was an essay, anyway; what, a letter? Her phrases were poems, riddles, lyric apothegms, fleeing with the speed of thought. Her imagination boiled over, spilling onto the page. His did not, no matter how much heat he applied, unless, that is, he lost himself, as he occasionally did in his essays on nature—some are quite magical—or in his writing on behalf of the poor and disenfranchised, when he tackled his subject in clear-eyed prose and did not let it go. Logic and empathy were special gifts. Yet by dispensing pellets of wisdom about how to publish, as he did, in the most prestigious literary journal of the day, he presented himself as a professional man of letters, worth taking seriously, which is just what he hoped to become.

This skilled adviser was not as confident as he tried to appear. Perhaps Dickinson sensed this. In the aftermath of Harpers Ferry, Higginson had more or less packed away his revolver and retired to the lakes around his home, where he scoured the woods after the manner of his favorite author, Henry Thoreau. “I cannot think of a bliss as great as to follow the instinct which leads me thither & to wh. I never yet dared fully to trust myself,” Higginson confided to his journals. He wrote all the time—about slave uprisings and Denmark Vesey and Nat Turner and also about boating, snowstorms, woodbines, and exercise. Fields printed whatever Higginson gave him and suggested he gather his nature essays into a book.

But the Confederates had fired on Fort Sumter, and all bets were off. Then thirty-seven years old (Dickinson was thirty), he unsuccessfully tried to organize a military expedition headed by a son of John Brown’s, assuming that the mere sound of Brown’s name would wreak havoc in the South. He tried to raise a volunteer regiment in Worcester. That, too, failed. “I have thoroughly made up my mind that my present duty lies at home,” he rationalized.

By his “present duty” he meant his wife, an invalid who in recent years could not so much as clutch a pen in her gnarled fingers. She needed him. “This war, for which I long and for which I have been training for years, is just as absolutely unobtainable for me as a share in the wars of Napoleon,” he confided to his diary. To console himself, he wrote the “Letter to a Young Contributor” in which he declared one need not choose between “a column of newspaper or a column of attack, Wordsworth’s ‘Lines on Immortality’ or Wellington’s Lines of Torres Vedras; each is noble, if nobly done, though posterity seems to remember literature the longest.” No doubt Dickinson agreed. “The General Rose—decay—/ ,” she would write, “But this—in Lady’s Drawer / Make Summer—When the Lady lie / In Ceaseless Rosemary—.”

South Winds jostle them—

Bumblebees come

Hover—Hesitate—Drink—and are gone—

Butterflies pause—on their passage Cashmere—

I, softly plucking,

Present them—Here—

Hover. Hesitate. Drink. Gone: the elusive Dickinson enclosed three more poems in her second letter to Higginson, along with a few pressed flowers. He must have acknowledged the gift quickly, for in early June she wrote him again. “Your letter gave no Drunkenness,” she replied, “because I tasted Rum before—Domingo comes but once—yet I have had few pleasures so deep as your opinion.”

That initial taste of rum had come from an earlier “tutor,” who had said he would like to live long enough to see her a poet but then died young. As for Higginson’s opinion of her poetry, she took it under ironic advisement. “You think my gait ‘spasmodic’—I am in danger—Sir—,” she wrote in June as if with a grin. “You think me ‘uncontrolled’—I have no Tribunal.” To be sure, Higginson could not have been expected to understand all she meant; who could? No matter. She did not enlist him for that, or at least not for that alone. She wanted understanding and friendship, both of which he offered, all-important to her even if his advice proved superfluous. “The ‘hand you stretch me in the Dark,’” she said, “I put mine in.”

Nor would she admit to being put off by his apparent suggestion that she “delay” publishing. She smiled archly. “‘To publish’—,” she shot back, “that being foreign to my thought, as Firmament to Fin—.” Yet “if fame belonged to me,” she also observed, “I could not escape her—.” Perhaps he had mentioned The Atlantic Monthly, where he often recommended new talent—particularly women—to Fields. He need only dispatch one of her poems.

He did not.

That he told her to be patient seems paradoxical. This was the man who urged immediate, even violent action in the political sphere. Yet he did not say she should never print her poems. He had said “delay.” He needed to find his bearings. Her poetry shocked him, violating as it did the canonical forms of meter and rhyme, and it stunned him with well-shaped insights that thrust him into the very process of writing itself—the difficult transition from idea to page, the repeated attempts to get it right:

We play at Paste—

Till qualified, for Pearl—

Then, drop the Paste—

And deem ourself a fool—

The Shapes—though—were similar—

And our new Hands

Learned Gem-tactics—

Practising Sands—

Having reminisced about her former tutor, Dickinson concluded her third letter with the suggestion that Higginson replace him. “Would you have time to be the ‘friend’ you should think I need?” she wondered with shy charm. “I have a little shape—it would not crowd your Desk—.” And though she did not enclose any poems in this letter, she concluded with a verse:

As if I asked a common Alms,

And in my wondering hand

A Stranger pressed a Kingdom,

And I, bewildered, stand—

As if I asked the Orient

Had it for me a Morn—

And it should lift it’s purple Dikes,

And shatter Me with Dawn!

“But, will you be my Preceptor, Mr. Higginson?”

He could not say no.

EARLY IN HIS CAREER, Higginson had planned to write a sermon, “the Dreamer & worker—the day & night of the soul.” “The Dreamer shld be worker, & the worker a dreamer,” he jotted in his notebook. In a country that measures success in terms of profit rather than poetry, dreamers are an idle lot, inconsequential and neglected. But inside every worker there’s a dreamer, Higginson hopefully insisted, and by the same token dreamers can turn their fantasies to Yankee account: “do not throw up yr ideas, but realize them. The boy who never built a castle in the air will never build one on earth.”

Fragmentary, incomplete, disconsonant—these terms—dreamer and worker, poet and activist—recur with frequency in his later writing. Back and forth he swerved, between a life devoted to dreams and one committed to practical action. The themes are clear, too, in his “Letter to a Young Contributor,” where he incorporated whole sentences from his “Dreamer and Worker” journal to come to a propitious conclusion: “I fancy that in some other realm of existence we may look back with some kind interest on this scene of our earlier life, and say to one another,—‘Do you remember yonder planet, where once we went to school?’ And whether our elective study here lay chiefly in the fields of action or of thought will matter little to us then, when other schools shall have led us through other disciplines.”

Fields of action, fields of thought; the active life or seclusion—twin chambers of a divided American heart. This was Higginson’s conflict. He who would risk his life to end chattel slavery nonetheless fantasized about a cabin in the woods where, like his idol Thoreau, he might front only the essential facts of life. But Higginson had already run for Congress, and would later serve in the Massachusetts legislature and co-edit The Woman’s Journal for the National American Woman Suffrage Association. And he would command the first regular Union army regiment made up exclusively of freed slaves (mustered far earlier than Robert Gould Shaw’s fabled Massachusetts Fifty-fourth). You could not do this from a cabin in the woods.

Opting for the seclusion he could not sustain, Dickinson had walked away from public life, informing Higginson that she did not “cross her Father’s ground to any House or town,” and for many years, as she told him, her lexicon had been her only companion. “The Soul selects her own Society—/ Then—shuts the Door—.” Yet she did not choose unequivocally. No one can who writes.

Emily Dickinson and Thomas Higginson, seven years apart, had been raised in a climate where old pieties no longer sufficed, the piers of faith were brittle, and God was hard to find. If she sought solace in poetry, a momentary stay against mortality, he found it for a time in activism, and for both friendship was a secular salvation, which, like poetry, reached toward the ineffable. This is why he answered her, pursued her, cultivated her, visited her, and wept at her grave. He was not as bullet-headed as many contemporary critics like to think. Relegated to the dustbin of literary history, a relic of Victoriana cursed with geniality and an elegant prose style, Higginson has been invariably dismissed by critics fundamentally uninterested in his radicalism; after all, not until after Dickinson’s death, when the poet’s family contacted him, did he consent to reread the poems and edit them for publication, presumably to appeal to popular taste. Yet he tried hard to prepare the public for her—“The Truth must dazzle gradually / Or every man be blind—,” as she had written—and in his preface to the 1890 volume frankly compared her to William Blake.

Dickinson responded fully to the man he thought—and she thought—he was: courtly and bold, stuffy and radical, chock-full of contradictions and loving. For not only did she initiate the correspondence, but as far as we know she gave no one except Sue more poems than she sent to him. She trusted him, she liked him, she saw in him what it has become convenient to overlook. And he reciprocated in such a way that she often said he saved her life. “Of our greatest acts,” she would later remind him, “we are ignorant—.”

To neglect this friendship reduces Dickinson to the frail recluse of Amherst, extraordinary but helpless and victimized by a bourgeois literary establishment best represented by Higginson. Gone is the Dickinson whose flinty perceptions we admire and whose shrewd assessment of people and things informed her witty, half-serious choice of him as Preceptor, a choice she did not regret. Gone is the woman loyal to those elect few whom she truly trusted. Gone is the sphere of action in which she performed, choosing her own messengers. Gone, too, is Higginson.

Sometimes we see better through a single window after all: this book is not a biography of Emily Dickinson, of whom biography gets us nowhere, even though her poems seem to cry out for one. Nor is it a biography of Colonel Higginson. It is not conventional literary criticism. Rather, here Dickinson’s poetry speaks largely for itself, as it did to Higginson. And by providing a context for particular poems, this book attempts to throw a small, considered beam onto the lifework of these two unusual, seemingly incompatible friends. It also suggests, however lightly, how this recluse and this activist bear a fraught, collaborative, unbalanced and impossible relation to each other, a relation as symbolic and real in our culture as it was special to them. After all, who they were—the issues they grappled with—shapes the rhetoric of our art and our politics: a country alone, exceptional, at least in its own romantic mythology—even warned by its first president to steer clear of permanent alliances—that regularly intervenes on behalf, or at the expense, of others. The fantasy of isolation, the fantasy of intervention: they create recluses and activists, sometimes both, in us all. “The Soul selects its own Society” is a beloved poem; so, too, the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

Though Higginson preserved a large number of Dickinson’s letters to him, most of his to her have mysteriously vanished. Before she died, in 1886, Emily instructed her sister, Lavinia, to burn her papers, a task Lavinia dutifully performed until, about a week after the funeral, she happened upon a boxful of poems (about eight hundred of them) in a bureau drawer. (It seems Dickinson had not instructed Lavinia to burn these.) Lavinia, who wanted these poems published, suddenly realized the literary significance of her sister’s correspondence, but by then she had unthinkingly tossed much of it—Higginson’s letters included—into the blaze. That’s the standard tale. Yet when Higginson, along with Mabel Loomis Todd, Austin’s mistress, was preparing the first edition of Dickinson’s poems, Todd noted in her diary that Lavinia had stumbled across Higginson’s letters to the poet. “Thank Heaven!” she sighed.

At a later date, however, Todd jotted in the margins of her diary: “Never gave them to me.” Today no one knows what became of them: whether Higginson asked that they be destroyed—he seems to have purged as much as he saved—or whether for some inexplicable reason Lavinia intentionally lost them.

Because these letters are missing, one has to infer a good deal: his dependence on her, his infatuation, his downright awe of her strange mind. But not that she sought his friendship.

Yes, she sought him. And the two of them, unlikely pair, drew near to each other with affection as fresh as her poems, as real and as rare.

TWO

Thomas Wentworth Higginson: Without a Little Crack Somewhere

Don’t you think it rather a pity that all the really interesting Americans seem to be dead?” an Englishwoman once asked the aging Colonel Higginson, who, slightly startled by the insult, sadly agreed.

There was a belated quality about Thomas Wentworth Higginson. Born in 1823, almost two decades after Emerson and Garrison and Theodore Parker, he was of a generation fated to admire and emulate but never outshine them. For they were the giants of what Higginson called the sunny side of the transcendental period, spawned by a German philosophical idealism in which the love of nature and humanity routed out the bogey of Puritan gloom, substituting idealism for depravity and sin.

Yet Thomas Wentworth Higginson, their beneficiary, had been at the banquet, unbelievable as that might be to future chroniclers. “It would seem as strange to another generation for me to have sat at the same table with Longfellow or Emerson,” Higginson admitted with characteristic modesty, “as it now seems that men shld hv. sat at the table with Wordsworth or with Milton.”

Perhaps; but perhaps not.

DESCENDED FROM SEVEN GENERATIONS of Higginsons in America, Thomas Wentworth bore the mixed blessing of a long New England lineage. His ancestor the Reverend Francis Higginson had sailed to the New World from England in the spring of 1629 along with six goats, about two hundred other passengers (not including servants), his eight children (one of whom died during the voyage), and his wife, Higginson’s fare on the Talbot paid by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. For one hundred acres of land and thirty pounds per annum, Reverend Francis had been commissioned to save souls in Naumkeag, and he would perform so conscientiously—changing the name of the village to Salem and establishing its first church—that Cotton Mather would dub him the Noah of New England.

When the Reverend Higginson died, just a year after setting foot on Massachusetts soil, his son John took up his mantle by promptly banishing Quakers and then signing a nefarious share of arrest warrants during the witchcraft hysteria of 1692. But John’s rather lackluster commitment to killing witches compromised his own daughter, who was soon accused of the dark art. Not surprisingly, in later years he apologized in public for the terrible delusion he had helped incite and, always one to admit a mistake, at age ninety backed Judge Samuel Sewall’s efforts to abolish slavery and the slave trade, the foundation of much of Salem’s wealth. The local historian Charles Upham, who approved of very few, called Higginson a man of sterling character.

Conscience was a Higginson inheritance, or at least the legacy insisted on by its nineteenth-century descendant Thomas Wentworth. Of course the family had by then distinguished itself in commerce. Higginson’s paternal grandfather, Stephen, shipowner, merchant, and soldier, was the Massachusetts delegate to the Continental Congress in 1783 and the reputed author of The Writings of Laco, published in 1789, which, arguing for freedom of the press, scathingly denounced John Hancock. A member of what was called the Essex Junto, a group of well-to-do Federalist merchants who, despising Jefferson, considered seceding from the United States to protect their interests, he opposed the Embargo Act of 1807, which choked off trade in the port of Salem, but he managed to turn a profit during the War of 1812. No wonder his grandson Wentworth (as Thomas was called) long remembered this imposing specter, attired in black, as wielding a gold-headed cane.

Wentworth Higginson would write laudatory biographies of his ancestor Francis and his grandfather but kept largely silent on the subject of his own father. An improvident investor and lavish spender, Stephen Higginson Jr. had to liquidate most of his colossal library after the War of 1812 and move his family from Boston’s fashionable Mount Vernon Street to a sheep farm in Bolton, where they remained until well-placed friends landed him a job as steward of Harvard College. He immediately built a house on Kirkland Street, then a sandy plain, but doubtless the good-hearted profligate was not the best man to guard the Harvard treasury.

By then his family was quite large. After his first wife died, leaving him five children, Stephen wed his daughters’ governess, Louisa Storrow, a New England Jane Eyre with a pedigree eminently respectable (Appletons, Wentworths, and Storrows) as well as swashbuckling (she was also descended from an English officer who had been imprisoned in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, during the Revolution). Stephen Higginson’s ward since her eleventh year and his wife at nineteen, she bore ten children, six of whom lived to adulthood. Named for her forebears, Thomas Wentworth Storrow Higginson was her last, “the star that gilds the evening of my days—and he must shine bright and clear,” she ominously continued, “or my path will be darkened.” Later in life, Higginson identified his mother as the woman who influenced him most, particularly since he had been a feeble, sickly infant “half dead,” as she had liked to remind him.

Higginson’s childhood was comfortable, privileged, and difficult. A charitable man who helped organize the Harvard Divinity School, his father had not mended his ways. “I think sometimes he will offer his wife and children to somebody who has not got any,” Mrs. Higginson grumbled, and Wentworth would comment, with some aspersion, that “his hospitality was inconveniently unbounded.” When the Republicans in the state legislature (along with Emily Dickinson’s grandfather) chartered the Congregationalist Amherst College in protest against Harvard’s balmy Unitarianism, Harvard lost its annual appropriation, and Stephen Higginson Jr. faced a crisis he could not contain. (The families of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Higginson were thus linked, and though they sat on different sides of the theological fence, each was intimately connected to the way in which that fence had been built.) The deficit mounted, salaries were cut, students were charged for the wine they drank in chapel, and the college sloop was sold. He resigned his post in disgrace, and the Harvard Corporation held him personally responsible for the bills.

The family crated their household goods, auctioned much of their furniture, and took up residence on the far side of Cambridge Common, where Mrs. Higginson could support her brood with boarders in a house built by her eldest son, Francis, now a physician. Another son began to tutor, and yet Stephen Higginson sank deeper into debt, squandering what remained of his own father’s legacy until, at age sixty-four, he suddenly died.

“In works of Love he found his happiness,” read his double-edged epitaph, hinting at promises left unfulfilled. By this time, Wentworth was ten.

HIS HEALTH HAD IMPROVED, he learned to read and recite at four, and as a docile child, good-natured and by many accounts good-looking, he soaked up the scholarly, status-minded standards of the neighborhood, which happened to be Harvard College. Boyhood memories were bookish: he recalled a good set of Dr. Johnson’s works, an early edition of Boswell, the writing of Fanny Burney, and his mother reading Walter Scott. Harvard professors brought by volumes of Collins, Goldsmith, and Campbell to woo his brilliant aunt, Ann Gilliam Storrow, who lived with them; Jared Sparks, later Harvard’s president, entertained the family with portfolios of Washington’s letters to his mother; John G. Palfrey, dean of the divinity school and the historian of New England subsequently adored by Henry Adams, recited aloud all of Hawthorne’s Twice-Told Tales.

At the private school run by William Wells, a place to “fit” for Harvard College, Wentworth hopefully memorized the list of undergraduate classes and at thirteen, well versed in Latin grammar and something of a prodigy, entered the freshman class. “Born in the college, bred to it,” as he later said. (His three elder brothers had also attended Harvard, and each remained involved with it during their lives.) But Wentworth was a lonely, awkward boy who had spurted up to six feet and, desperate to excel, worried lest he be fated for second place.

He studied Greek with the poet Jones Very, French literature with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and chemistry with John Webster, soon notorious for the gruesome murder of George Parkman. He enrolled in a class in entomology, which he adored, and he helped form a makeshift natural history society. He long remembered Edward Tyrrel Channing’s courses in rhetoric. “I rarely write for three hours without half consciously recalling some caution or suggestion of his,” Higginson later recollected of Channing, who also taught Emerson, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Charles Sumner, Wendell Phillips, and Charles Eliot Norton.

At Harvard his friend Levi Thaxter (future husband of the poet Celia Laighton Thaxter) introduced him to the writings of Emerson, Browning, and Hazlitt. Another acquaintance, if not quite a friend, was James Russell Lowell, with whom he felt rivalrous, particularly since he adored Lowell’s fiancée, Maria White, a grand woman flushed with consumption, poetry, and abolition. (Years later Higginson would print her poems whenever he could.) Mainly, though, in the presence of women outside the family, Wentworth was clumsy and tongue-tied until, fed up, he scribbled out topics of conversation on scraps of paper, which he would pull out of his pocket whenever the banter between him and a pretty young woman lagged. Even in flirtation he was something of a pedant.

Emotionally unprepared for college, in 1841 he was equally unready to leave it. Though he toyed with the idea of growing peaches—the communal living experiment at Brook Farm, then in its halcyon days, stirred his suggestible imagination—he took a job teaching in nearby Jamaica Plain, his mother and two sisters having decamped to Vermont, where his brother Francis had opened a medical practice. Wentworth lasted just six months in Jamaica Plain. Fortunately, a rich older cousin, Stephen Perkins, rescued him with an offer to tutor his three sons, one of whom would be cut down at Cedar Mountain in the summer of 1862.

At the Perkins estate in rural Brookline, Higginson entered a world of cultured, self-conscious wealth. Cousin Perkins owned paintings by Sir Joshua Reynolds and Benjamin West, eventually bequeathed to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts; he avidly read Continental literature and talked volubly about the need for social change. For this was the period of what Higginson would call the Newness, when the skies of New England rained reform. The estimable Ralph Waldo Emerson had himself resigned the pulpit in 1832, yearning for a more humane form of belief, one that squarely put divinity in the soul of the individual. Four years later, when Higginson was an impressionable twelve-year-old, Emerson published the very bible of Newness, Nature, which asked, “Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe?” (“God incarnates himself in man,” Emerson declared at the Harvard Divinity School in 1838 and was not to be invited back for thirty years.) In 1840, Elizabeth Peabody opened her atom of a foreign bookshop (Higginson’s description) on West Street in Boston, where she talked up Brook Farm and in the back room printed the transcendentalist organ, The Dial, while so-called transcendentalists—like Emerson and Bronson Alcott—snatched French or German volumes from her shelves. And Higginson’s sister Anna was friends with the peerless Margaret Fuller, the bookstore’s resident sibyl, who organized a series of “Conversations” for Boston women. Fuller sat on a tripod in a velvet gown, demanding no less of herself than of the women assembled before her: What are we, as women, born to do, she asked, and how do we intend to do it?

James Russell Lowell and William Story quit the legal profession to give their all to art, and women writers from George Sand to Lydia Maria Child sympathized with the downtrodden poor. And the slaves. In 1833, Child published her abolitionist Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans, and in 1834, Wentworth’s brother Francis published Remarks on Slavery and Emancipation, a rational argument demolishing any and all excuses for chattel slavery. In 1841 the courts ruled that the Africans who had staged a revolt aboard the Amistad were but kidnapped people unlawfully traded, and Frederick Douglass spoke at the antislavery convention in Nantucket about the abominations he himself had endured.

Buoyed by the Newness, Higginson disdained the predictable professions of law and medicine, and though shaken by the phrenologist who told him he had “splendid talents but no application,” he dreamed of the ideal, inchoate as it was. “I feel overflowing with mental energies,” he told his mother; “I will be Great if I can.” But the only thing he knew how to do was study, so in 1843 he returned to Harvard, where he could dabble in an institutionally sanctioned way, letting greatness find him. (The college permitted resident graduates to take courses without working toward a degree.) “If I have any genius, I must have a fair chance to cherish it,” he pleaded with his dubious mother. “The point I wish to insist upon about all this you see is that it is sensible & rational—not at all utopia.” For money, he applied for a proctorship, and when denied he earned a pittance by tutoring and copying. “I have been brought up poor & am not afraid to continue so,” he declared, more vehement than ever, “and certainly I shall be glad to do it, if it is a necessary accompaniment to a life spent as I wish to spend it.”

Renting a room with a view on the third floor of the College House, he could see pigs and cows meandering on the muddy streets. He was nineteen. He was free. Living on his own, he could redo his college years with no mother waiting up nights for the sound of the latch. And he had at last decided on a profession. He would be a poet. There was no higher calling.

The Higginson household had for years consumed Byron with delight, and the great Emerson had himself said that “all the argument and all the wisdom is not in the encyclopaedia, or the treatise on metaphysics, or the Body of Divinity, but in the sonnet or the play.” Poets unfix the world, banish our habits, dwell in possibilities of change and daring action. They make the world whole; they allow us to catch what we ordinarily miss. “What I would not give to know whether I really have that in me which will make a poet,” he mused, “or whether I deceive myself and only possess a mediocre talent.”

But the latter seemed the case. When the boy’s verses had been summarily rejected by The Dial, Emerson let him down with a thud. “They have truth and earnestness,” the Concord philosopher told him, “and a happier hour may add that external perfection which can neither be commanded nor described.”

Reading De Quincey and Coleridge, Wentworth experimented with opium, hoping for a New England version of “Kubla Khan,” but with no visions forthcoming, he threw himself back into his books, sowing intellectual wild oats, as he later said: Newton, Homer, Hesiod, Chaucer, George Sand, Linnaeus, and more Emerson. He learned German in order to read Jean Paul Richter, whom he worshipped, and Goethe, whom everyone did; he kept up his Greek, and one of his first projects after the Civil War would be a translation of Epictetus, the Stoic philosopher, born a slave, who taught that all souls were equal.

“I did not know exactly what I wished to study in Cambridge,” Higginson would later reminisce. “Indeed, I went there to find out.” At the time, though, he figured his scheme of promiscuous apprenticeship would take ten to fifteen years. “I think I have a fair right to expect, in the then state of my powers, to make my living as a literary man without a profession,” he calculated. Yet something was missing. “I cannot live alone,” he informed his family. “Solitude may be good for study sometimes, but not solitude in a crowd for a social-hearted person like me.”

Actually, with statements like these Wentworth was trying to brace his family for news of his precipitous and wholly unexpected engagement to Mary Channing. A second cousin two years his senior (she was twenty-one) and neither wealthy nor submissive, Miss Channing was not the woman Mrs. Higginson would have chosen for her gilded boy. Intelligent and tart—a real conversational gymnast—she was also pert, churlish, and frequently abrupt. “Whatever be her faults of manner,” Higginson gallantly defended her, “I do like her very much.”

Perhaps Mary Channing was his first rescue mission. Her mother had died when Mary was two, and though her father, an obstetrician esteemed in Boston, had happily remarried, his second wife died in childbirth when Mary was but twelve. This second loss and her father’s inadvertent hand in it devastated her, and as Higginson would later learn, Mary had concluded then and there not to have children herself. The decision predated the onset of a chronic malady that would grip her in her twenties, never to let her go, crippling her limbs and scarring her soul. “Mrs. Higginson is very queer, a great invalid from rheumatism,” an acquaintance once remarked, “a perfect mistress in the art of abuse, in which she indulges frequently with peculiar zest & enthusiasm.”

If Higginson’s mother had not been pleased by her son’s precipitous engagement, the name of Channing had calmed her. Channings occupied the upper reaches of Brahmin Boston, their intellectual and cultural influence radiating from the golden dome of the new State House to the clatter at Quincy Market—and this despite their commitment to such outré causes as women’s rights, prison reform, and abolition. Mary’s own uncle was the celebrated Unitarian preacher William Ellery Channing, who had liberated an entire generation from old-line Congregationalism, and Mary’s brother (William) Ellery, the poet with the orange shoes, had married Margaret Fuller’s sister. Then there was William Henry Channing (who happened to be Higginson’s cousin), the Christian socialist with the honeyed voice who dared scold Emerson for his asocial individualism. (Ironically Channing served as one of the models for Hawthorne’s Hollingsworth, the egomaniacal reformer in The Blithedale Romance.)

As for Higginson, it was Mary herself and her prickliness that pleased him. Besides, he might help with her grief. Hadn’t he lost his own father at a tender age? Certainly both of them were lonely. But Higginson sheepishly admitted that while he could dally at Harvard, picking and choosing courses of study, women were slated for marriage, caretaking, and the so-called domestic arts. Yet his sisters, his mother, and his exceptional aunt demonstrated every day that there was no distinction of sex in intellect, and his sister Anna, as he noted, had written the part of his commencement speech that received the most applause.

“I don’t care about outside show, but I do go for the Rights of Women,” he bolstered Mary, “as far as an equal education & an equal share in government goes.” He meant every word.

He and Mary attended James Freeman Clarke’s liberal Church of the Disciples, the ecumenical congregation that she had helped organize, and together they discussed religion and reform. But Higginson referred to Theodore Parker, not Freeman Clarke, as his spiritual guide. A polymath contemptuous of the status quo, a transcendentalist long before the group rated a name, and the most blasphemous of all preachers in the public’s eye, Parker had the audacity to doubt miracles and champion the enslaved, a bad combination. “God’s fanatic,” Higginson later called him, “pompous, annoying, and eminently good.” (A book by Parker was given to Emily Dickinson, though not by Higginson, some years after the preacher’s untimely death. “I heard that he was ‘poison,’” Dickinson thanked her donor. “Then I like poison very well.”) In old age, Higginson still dreamed about hearing him preach.

Parker’s fire-and-brimstone sermons damning the sin of slavery; William Henry Channing’s dulcet oratory sketching out the shape of a better world; Margaret Fuller, intrepidly insisting it belonged to woman; the cantankerous tongue of Mary Channing taking nothing for granted; and in the Concord distance, Emerson counseling self-trust, self-reliance, and the triumph of good—together they swept Higginson forward into the Newness. He might become Great after all.

POETRY ASIDE, he still needed a paying profession.

Maybe he could be a preacher. Yet as one of his biographers observes, though Higginson assumed the goodness of people, he was far less certain about the nature of God. To him Jesus was a brother, the Bible a book, and all religion an activity shared by all humans regardless of creed; the latter belief he traced to an event in his boyhood, when in 1834 he watched flames demolish the Ursuline convent, on Mount Benedict in Charlestown, torched by an anti-Catholic mob. The rioters were acquitted of arson, and the ringleader, also acquitted, later became head of the anti-Catholic Know-Nothing party. Higginson never got over it.

Warmed by an inner light “not infallible but invaluable,” Higginson read Emerson as if the Concord sage wrote to him alone, and he staked his future on a democracy of perfectible love, what Emerson had called a “just and even fellowship, or none.” “The career of man has grown large, conscious, cultivated, varied, full,” Higginson wrote in later years. “He needs India and Judaea, Greece and Rome; he needs all types of spiritual manhood, all teachers.”

In 1844 he enrolled halfheartedly in the Harvard Divinity School, a court of last resort, but within months scoffed at his teachers, whose theology he considered as weak as the spines of his fellow students. “Any man with some Yes in him would be a blessing,” Higginson loudly complained, feeling belated once again. Gone, he feared, was the heyday of the divinity school, when his father had charge of a crop of superior young men, like Emerson himself.

And besides, events taking place outside the cloistered halls of Harvard concerned him more: Texas, for instance, and its possible admission to the Union as a slave state. “In Cambridge we are in peace,” he wrote in some relief, “since the Texas petition—764 names, 13 ft. long, double column—went off.” Abolition had rapidly become the focus of his frustration, his sense of injustice, his desire to accomplish something tangible. “I crave action…, unbounded action,” he burst out. “I love men passionately, I feel intensely their sufferings and short-comings and yearn to make all men brothers.”

Years later Higginson traced his abolitionist leanings not just to Emerson or his brother’s book (which he hardly mentioned) or Lydia Child’s treatise, all formative, but to his mother and an incident in her life, which trifling though it seems, also associates the abolition of slavery with the emancipation of women, as he and many others would do. Mrs. Higginson had visited cousins in Virginia, who provided her with a male slave to drive her about, and as she’d never encountered a slave before, she asked him if he was satisfied with his life, since, it seemed, he was well fed, well treated, well cared for. Life is good, she prompted. Without hesitation he shot back, “Free breath is good.” So it was, for her too.

Dissatisfied and impatient, Higginson withdrew from divinity school within a year of his enrollment, for despite his failure at getting The Dial to recognize him as a writer, he still guiltily craved literature. “I have repented of many things,” he justified himself to his mother, “but I never repented of my first poetical Effusion.” Again he presented his verse to various magazines but this time chose more hospitable editors. “La Madonna di San Sisto” went to his activist cousin William Henry Channing, who published it in The Present in 1843; Channing then published Wentworth’s poem “Tyrtaeus” in his Brook Farm magazine, The Harbinger.

Tyrtaeus appealed to Higginson: his martial poems had allegedly inspired Spartan soldiers during the Second Messenian War, and Higginson himself hoped to sing on the barricades:

Times change,

And duties with them; now no longer

We summon brothers to take brothers’ lives;

But rouse to conflict higher, holier, stronger

…Against the seeds of ruin now upsurging

Here in this sunny land we call the Free.

Poetry: one might take up the pen for a cause and infuse “a higher element” (Higginson’s term) into, say, the entire antislavery movement, much as the abolitionist poet John Greenleaf Whittier had done. Isn’t this what Emerson meant by a just and even fellowship—though Emerson’s antislavery views were as yet ill-formed. And although antislavery verse encumbered Whittier’s literary career, at least initially (he was scolded by the important literary magazine The North American Review), by lashing poetry to politics, Higginson might still be a poet and yet take action, use himself, say something that could move or change people. In 1846 he dedicated a sonnet to William Lloyd Garrison, abolitionist editor of the staunch antislavery paper The Liberator, and composed a hymn for an antislavery picnic in Dedham. “The land our fathers left to us / Is foul with hateful sin,” the crowd sang; “When shall, O Lord, this sorrow end, / And hope and joy begin?”

“The idea of poetic genius is now utterly foreign to me,” Higginson informed his mother. Instead he had a gospel to sing, its providential ends consistent with his reading of scripture, its goals to be realized on earth. If it brought him some measure of the fame he sought, so much the better.

Higginson applied for readmission to the divinity school in the fall of 1846, oddly explaining his decision in a clumsy third person: “He has abandoned much that men call belief, but seems to himself to have only won former ground to believe more deeply than ever.” That is, he would shuck poetry for the moment but not forgo the brass ring: he intended to reform America to make it, and himself, great.

Mary should be warned. “Setting out, as I do, with an entire resolution never to be intimidated into shutting either my eyes or my mouth,” Higginson told her, “it is proper to consider the chance of my falling out with the world.”

Mary did not blink. She never would through all the trials ahead, and the couple was married on September 22, 1847, James Freeman Clarke presiding.

IF HIGGINSON DID NOT YET KNOW the extent of his agenda, neither did the congregation of the First Religious Society of Newburyport, thirty-eight miles north of Boston, a staid port community that in its salad days was a hub of maritime trade and shipbuilding. The gracious homes of the old shipowners still lined High Street, the main thoroughfare, but by 1847 only their ghosts strolled on the decaying wharves, where they were joined by the factory workers, mostly women, who kept spindles running dawn to dusk for the rich textile men—a poor match all around.

The Higginsons adjusted slowly. Mary found the congregants dull and uncouth. Wentworth hated their materialism, their intolerance, their complacency. Since he also deplored the Mexican War as a means to extend the reach of slavery, he alienated his conservative parishioners, merchants and bankers mostly, who regarded him as a crank. “There are times and places where Human Feeling is fanaticism,” he archly reminded them, “times and places where it seems that a man can only escape the charge of fanaticism by being a moral iceberg.”

With human feeling flowing from every principled pore, Higginson lambasted the Whig candidate for president, Zachary Taylor, as a slaveholder; he invited the abolitionist William Wells Brown, a former slave, to speak at his church. He established a newspaper column to agitate for higher wages, and when the town’s clergy tried to prevent Emerson from lecturing at the Newburyport Lyceum, Higginson chastised them in print. He argued for women’s rights and set up more than one night school for factory workers, particularly women. “Mr. Higginson was like a great archangel to all of us then,” recalled the writer Harriet Prescott Spofford, a protégé from those days. “And there were so many of us!”

And he entered politics. Though pledged, at least in his private journal, to disunion—he could not endorse a constitution that sanctioned slavery—in 1850 he ran for Congress as a Free-Soil candidate in this Whig stronghold. “It will hurt my popularity in Newburyport for they will call it ambition &c,” he shrugged.

Enthusiastic and naive, Higginson innocently assumed he was invincible. Certainly no harm could come to him for advocating fair wages, literacy, temperance, generosity, and above all, abolition in this, the birthplace of Garrison. “They are so much more dependent on me than I on them that I am in no danger,” he informed his family with nonchalance. Yet this was also the town that had clobbered Whittier with sticks, stones, and rotten eggs when the Quaker tried to address an antislavery rally.

Higginson lasted in Newburyport just two years. “My position as an Abolitionist they could not bear,” he concluded when his congregation asked him to resign in 1849. “This could not be altered.”

He took his dismissal with composure, and years later, when he chalked it up to the inexperience of youth, he also admitted that even if he had been more tactful, “I think I would have come to the same thing in the end.”

Leaving Newburyport, he and Mary moved into the home of a relative in nearby Artichoke Mills, a rural retreat deep in the piney woods, and seeking the like-minded, he befriended the gentle Whittier, who lived in Amesbury, just four miles away. For fifteen years, Whittier had been an outspoken abolitionist, publishing (at his own expense) in 1833 the polemical Justice and Expediency; or, Slavery Considered with a View to Its Rightful and Effectual Remedy, Abolition. “Slavery has no redeeming qualities, no feature of benevolence, nothing pure, nothing peaceful, nothing just,” Whittier said, calling for immediate emancipation. A shy Quaker most comfortable operating behind the scenes, he had helped found the Liberty party (precursor of the Republican party), and it was he who insisted Higginson run for United States Congress. (Higginson lost by a wide margin.)

But Higginson was already growing skeptical about politics. The Free-Soilers mainly wanted to keep slavery out of the territories, not abolish it altogether, as he did. And the Fugitive Slave Act, recently passed, permitted slave catchers to pursue escaped slaves into the free states—all the way to Massachusetts, for instance. Plus, the reprehensible law was a rider to the Compromise of 1850, which presumably maintained a balance between slave and free states—and in so doing preserved the status quo, which was slavery itself. “There are always men,” Higginson observed with disgust, “who if anyone claims that two and two make six, will find it absolutely necessary to go half way, and admit that two and two make five.”

To Higginson, armed resistance, not civil disobedience, more and more seemed the only alternative to such legalized inhumanity, and his increasingly militant rhetoric was put to the test when a seventeen-year-old black man, Thomas Sims, was arrested in Boston in the spring of 1851.

Higginson rushed to the city. As a member of the Vigilance Committee, an organization of blacks and whites established several years earlier to assist fugitive slaves, he went straight to the grimy offices of Garrison’s Liberator for a meeting but found to his dismay that only he and two other men—Lewis Hayden and Leonard Grimes, black community leaders—advocated taking action on Sims’s behalf. (Hayden had famously hidden Ellen and William Craft, two fugitive slaves, in his home on Phillips Street, threatening to blow it up rather than surrender the couple.) Garrison, a committed pacifist whose preferred weapon was moral suasion, typically disputed the long-term results of overt action, or violence; his reasoning, Higginson later recalled, “marched like an army without banners.” Others wanted to argue the case in court. This seemed to Higginson to legitimate the very system he believed perfidious: in fact the gloomy granite Court House in which Sims now sat, manacled, was itself a symbol of judicial failure.

Arguing for legal redress, the political abolitionists won the day, and while the case dragged on, Higginson addressed a massive crowd gathered to protest at the Tremont Temple, urging them to do something. No one did. Discouraged, Higginson and his two coconspirators hatched a plot: Sims would leap out of the third-floor Court House window onto a mattress, placed below, and then jump into a carriage waiting to whisk him to the docks, where a sloop stood ready to take him to Canada. But someone must have leaked the plans because on the evening of the intended rescue, fierce iron gratings were installed in the windows of the Court House.

Higginson was livid.

On April 13, Thomas Sims, in tears, was paraded through Boston in chains. Placed on the brig Acorn, he was deported to Savannah, where he was publicly whipped until he bled. Two hundred fifty armed federal deputies had stood at the Boston wharves, their faces impassive, while witnesses chanted “Shame! Shame!”—themselves ashamed for not having done more.

WITH MERRY CONDESCENSION, Henry James once said that Thomas Wentworth Higginson reflected almost everything in the New England air—those agitations, that is, “on behalf of everything, almost, but especially of the negroes and the ladies.” Yet it would be a mistake to dismiss Higginson’s commitment to abolition or woman suffrage as faddishness—or, equally, to disparage it as a calculated scramble for la gloire once he realized poetry was not his métier. Of course reform was in the New England air. Of course Higginson was ambitious. He sought approval, no doubt. He liked to move large audiences. And he was in awe of men like Emerson, Parker, and Channing, who, commanding platform, pulpit, and pen, swayed minds and warmed hearts: what better way to satisfy personal vanity and at the same time salve one’s own conscience for being vain in the first place.

But Higginson was also a true believer and, to put it in unfashionable terms, a very good man.

It would also be a mistake to ignore the sacrifice a man like Higginson was willing to make for his convictions. “Remember that to us, Anti-Slavery is a matter of deadly earnest, which costs us our reputations today, and may cost our lives tomorrow,” he told a friend less exercised about the issue than he. This was not braggadocio. Abraham Lincoln, the most successful antislavery politician of his day, regarded the word abolitionist as odious. At best an abolitionist was a foggy-headed dreamer; at worst, a zealot rabble-rouser, even an atheist willing to abolish churches, the Bible, Christianity. (“Assent—and you are sane—/ ,” Dickinson would write. “Demur—you’re straightway dangerous—/ And handled with a Chain—.”)

“Without a little crack somewhere,” Higginson sharply agreed, “a man could hardly do his duty to the times.”

Lacking a formal pulpit once he lost his Newburyport congregation, Higginson frequently traveled whatever distance it took to speak at abolitionist or women’s rights or Free-Soil rallies. Committed to all three often-overlapping movements, he was still uncertain about the efficacy of Free-Soil. Politics was a stopgap measure more than a real solution to the problem of slavery, he reasoned. And in 1850, when the Whigs split over slavery, he was particularly chary of a proposed Free-Soil coalition with Democrats, which meant to him compromising the party’s antislavery platform. “I hope, however, that there is less real danger of our being corrupted than of our being deluded; deluded by too sanguine hopes of a sudden regeneration of the Democratic Party,” he wrote to a Free-Soil newspaper. When the editor refused to publish his letter, calling it impolitic, Higginson brought it to The Liberator, which did print it. He would not be silent. He would not be silenced. He had joined the Free-Soilers because he thought there he could speak his mind. Now, he noted with contempt, it was said he “‘might damage the cause.’”

At home in Artichoke Falls, his life veered in a different direction. He was quiet, helpful, considerate, and depressed, for Mary was slowly losing control of her muscles. She sat in a special chair and walked with such difficulty that in later years Higginson had to carry her up and down the stairs. Today a diagnosis might reveal rheumatoid arthritis or multiple sclerosis; then, there was nothing known, nothing to do. And though her symptoms occasionally remitted, as is the case with multiple sclerosis, their recurrence left her weaker and more querulous than ever.

But it wasn’t illness alone that tugged at her husband’s heart. The couple had no children, a cruel blow to Higginson, who loved them so unabashedly that he was constantly on the lookout for excuses to bring them into his home. For many years the couple took care of Mary’s niece, a daughter of Ellery and Ellen Fuller Channing, after Ellen Channing died. Mary, however, preferred to avoid children—and, it seems, sex with her husband.

He bore the rebuff with outward equanimity, assuming he had been asked to renounce that which he had no right to claim. For he believed a woman should be able to choose to live as she wished. Mainly, of course, he referred (at least in public) not to sex, though he hinted as much, but to a woman’s right to educational and professional opportunities, signing (along with Mary) the petition for the first national women’s rights convention and urging the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention to reform qualifications for voting. “If Maria Mitchell can discover comets, and Harriet Hosmer carve statues; if Appolonia Jagiello can fight in European revolution…,” he insisted, “then the case is settled so far—…Nor can any one of these be set aside as an exceptional case, until it is shown that it is not, on the other hand, a test case; each person being a possible specimen of a large class who would, with a little less discouragement, have done the same things.”

In his address to that convention, Higginson eloquently spoke on behalf of suffrage and professional opportunities for women: A woman “must be a slave or an equal; there is no middle ground,” he bluntly declared. “If it is plainly reasonable that the two sexes shall study together in the same high school, then it cannot be hopelessly ridiculous that they should study together in college also. If it is common sense to make a woman deputy postmaster, then it cannot be the climax of absurdity to make her postmaster general, or even the higher officer who is the postmaster’s master.” And what of the men who stand in her way? They are primarily anxious, he said, about whether an educated woman, happy and productive, would still make them dinner.

“I, too, wish to save the dinner,” he concluded. “Yet it seems more important, after all, to save the soul.”

Printed as a pamphlet, the speech was considered so alarming that Harper’s New Monthly Magazine immediately ran a rebuttal. “A woman such as you would make, her teaching, preaching, voting, judging, commanding a man-of-war, and charging at the head of a battalion would be simply an amorphous monster not worth the little finger of the wife we would all secure if we could.” Higginson, as usual, was unperturbed. He continued to support the rights of women, his enthusiasm tempered by good humor and rational argument. For like a carefully swept and sunlit room, Higginson’s mind was free of cobwebs and clutter, and while he was heir to the Enlightenment in his thought, his heart throbbed with the idealism of the New. In his superb “Ought Women to Learn the Alphabet?” an article printed in 1859 in The Atlantic, he summarized his argument with characteristic and unassailable intelligence: “What sort of philosophy is that which says, ‘John is a fool; Jane is a genius: nevertheless, John, being a man, shall learn, lead, make laws, make money; Jane, being a woman, shall be ignorant, dependent, disfranchised, underpaid’?” James Russell Lowell, then editor of The Atlantic, shuddered.

When Isabelle Beecher Hooker wrote to Higginson to praise his stand, he answered with some annoyance: “Nothing makes me more indignant than to be thanked by women for telling the truth—thanked as a man—when those same persons are recreant to the women who, at infinitely greater cost, have said the same thing. It costs a man nothing to defend woman—a few sneers, a few jokes, that is all—but for women to defend themselves, have in times past cost almost everything. Without the personal knowledge & influence of such women as Lucretia Mott, Lucy Stone, and Antoinette Brown, I should be nothing.”

Some might say he spoke more truly than he knew, for the most amazing of them all, Emily Dickinson, was not yet on his horizon.

THREE

Emily Dickinson: If I Live, I Will Go to Amherst

Biography first convinces us of the fleeing of the Biographied—,” Emily Dickinson would tell Thomas Wentworth Higginson, as if already flouting the scholars—and busybodies—who might in future years try to dig beneath the surface of her life. For of all people, she is the biographied par excellence: elusive, inexplicable, inscrutable, like the light that exists in spring: “It passes and we stay—.”

Even so, one can’t help pummeling her with questions: Why retire so completely from the public world, never even to cross her father’s lawn, as she told Higginson? Why dress in white? Not want her poems published? And why write to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, of all people, when she could have contacted any number of the luminaries she admired: Emerson, Hawthorne, Dickens, the Brownings, George Eliot?

Yet she did confide in Higginson, and we are grateful—or should be—for only to him, outside her family, did she reveal herself, sharing with him revelations that still puzzle and intrigue us. Coy but not capricious, she was the “only Kangaroo among the Beauty,” as she told him, referring not so much to her looks as to her work, and then purposely warning us, again by means of Higginson, that “when I state myself, as the Representative of the Verse—it does not mean—me—but a supposed person.”

Convinced regardless that the key to her poetry lies in her life, generations of biographer-critics have scurried to their desks, her cryptic letters in hand. The best of these is Richard Sewall, whose scrupulous and standard two-volume biography of Dickinson appeared in 1974. Amassing a huge archive on the poet’s family and friends in order to glimpse her, as he says, through Jamesian reflectors, Sewall handles her reticence by circumventing it; as a matter of fact, the poet herself isn’t born until the first chapter of his second volume. The result is astonishing and reliably balanced in all things—except the matter of Higginson, whom Sewall unfailingly dismisses with a presumption typical of his generation.

Since Sewall’s biographical feat appeared, scholars as talented or dogged as Cynthia Griffin Wolff, Polly Longsworth, Vivian Pollak, Susan Howe, Judith Farr, Christopher Benfey, and Alfred Habegger—to name a very few—have probed Dickinson’s religiosity, her family, her artistry, and her ravishing, often blistering verse. Yet Dickinson teases us, winks at us, and escapes, leaving us begging for more.

What, then, is known of her, particularly in the days before she wrote to Thomas Higginson? Like him, she was the beneficiary of a long line, her paternal ancestor having arrived on one of John Winthrop’s vessels in the port of Salem in 1630. But the Dickinsons settled in the fertile Connecticut River Valley, not in the bustling suburbs of Boston or Cambridge, and, mostly farmers, they did not own ships or command markets or aspire to adventure on high seas and to the gratifications of high office—except in the case of the poet’s grandfather, Samuel Fowler Dickinson, a man well educated, devout, and long remembered in his native village of Amherst as a leading citizen of “unflagging zeal.” That was an understatement.

Samuel was a generous, idealistic, and prominent attorney with a flair for civil service, Calvinism, windy speeches, and debt. Educated at Dartmouth, admitted to the Massachusetts bar, a member of the legislature (both branches), he was also ordained a deacon and remained a deacon for forty years, his deeply religious vision woven into the founding of Amherst College. For without an orthodox institution of higher education in their own backyard, he and his cohorts fretted lest their children slide into that pool of watery theology preached at Harvard and known as Unitarianism.

And with Harvard Unitarians disdaining what they called a new “priest factory,” Squire Dickinson redoubled his efforts. Lobbying to win a charter from the Massachusetts legislature—the same charter that, decreasing Harvard’s stipend, precipitated the ignominious fall of Higginson’s father—Dickinson argued that the new college be located in Amherst. To this end he pledged his own property to defray costs, and paying out of pocket, he depleted so much of his savings that, as his wife reported, “they have compleated the College our affairs are still in a crazy situation.”

But it wasn’t the college that ruined Dickinson. A litigious man, he sued far too often, liquefying great sums; crisis followed financial crisis. Yanked out of Yale, his eldest son, Edward (Emily’s father), was forced to take classes at the Amherst Collegiate Charity Institution, as the college was at first known, until he could go back to New Haven. Then his father hauled him out again. It could not have been easy. Edward, managing finally to graduate from Yale in 1823, desired above all to be free of his father’s embarrassing affairs. “My life,” he sternly warned the woman he loved, “must be a life of business—of laborious application to the study of my profession.”

After studying law in his father’s office and at the Northampton Law School, Edward opened his own practice in Amherst in 1826, the very same year he proposed marriage by mail to Emily Norcross, whom he met in nearby Monson during a lecture on chemistry. But though he plotted his romantic course with the precision of a watchmaker, the two-year courtship lasted far longer than he intended, and despite her poet-daughter’s later characterization of her mother as possessing “unobtrusive faculties,” Emily Norcross was as stubborn as Edward, pulling when he pushed. If he pelted her with letters, she replied infrequently, sometimes not at all. “There is a vast field for enterprise open before us, and all that can excite the ambitious—kindle the zeal—rouse to emulation, & urge us on to glorious deeds is presented to view,” he tried wooing her with his prospects. “A man’s success must depend on himself,” he said over and over, trotting out his attributes—diligence, industry, loyalty, rectitude—so regularly one wonders about the untold depth of the man’s insecurities. And flinging out the last arrow in his odd quiver, he suggested Norcross examine his references.

Norcross delayed answering Edward’s offer of marriage with her roundabout reply: “Your proposals are what I would wish to comply with, but without the advise and consent of my father I cannot consistantly [sic] do it.” Edward duly wrote to her father, a prosperous farmer and entrepreneur in Monson. Again he heard nothing. Ambivalent about marriage, about Edward, about leaving her home, the poet’s mother exercised power in refusal, as her daughter later would; she hardly visited Amherst and did not explain her behavior or her silences. That, too, would become a family trait.

As for Edward, his references were good. A chip off the Puritan block, he neither drank nor smoked nor swore but beat his horse when it displeased him; daughter Emily screamed in protest. Yet he rang the village bell so everyone in town might see the northern lights, and though he read the Bible every morning to his assembled family, he easily laughed at the tedious sermon. Still, he was exacting and cranky, and he typically exempted himself from the rules he made, whether at home or in government. A good temperance man, he backed strict prohibitions against the sale of liquor, but when he asked the apothecary to fill his flask with brandy—though he didn’t have the necessary prescription for it—the shopkeeper reminded him of the regulation. “That rule was not made for me,” Dickinson presumably thundered, adding that he would send to Northampton for his drink.

Edward Dickinson, 1853. “His Heart was pure and terrible.”

Emily Norcross Dickinson. “We were never intimate Mother and Children.”

Raw emotion displeased him. He rarely smiled, and though he read Shakespeare, he frowned at poetry, preferring, as his daughter Emily noted, actualities. “Fathers real life and mine sometimes come into collision,” she would tell her brother, “but as yet, escape unhurt!” An oft-repeated anecdote (likely apocryphal) reveals his histrionic need for control—and affords a glimpse into his daughter Emily’s equally dramatic response to him. At dinner one day, when Edward sputtered about a nicked plate at his setting, Emily sprang from the table, grabbed the offending dish, and marched to the garden, where she smashed it on a stone, saying she was reminding herself not to give it to her father ever again.

But Higginson would find Edward more remote than harsh, and Emily agreed. “Father was very severe to me,” she would typically chuckle to Austin. “He gave me quite a trimming about ‘Uncle Tom’ and ‘Charles Dickens’ and these ‘modern Literati’ who he says are nothing, compared to past generations, who flourished when he was a boy.” Deftly outmaneuvering him, or so the incident of the plate suggests, she similarly humored him when, deciding she was spiritually deficient, he asked the Reverend Jonathan Jenkins to interview her. Emily was by that time in her early forties, and outwardly compliant, sat in the parlor with the fidgeting reverend, a good friend of Austin’s and not much older than she. “There must have lurked in her expressive face a faint suggestion of amusement at the utter incongruity of the situation,” the reverend’s son recalled many years later, “but she was far too urbane a person to have betrayed it.” Jenkins pronounced her “sound,” and that was the end of that.

Edward also huffed and puffed about the education of women, although, as with many things, his timing was slightly off. While courting his reluctant fiancée, he had unsentimentally pontificated about what sort of education women should have, writing under the pseudonym Coelebs (bachelor) in the New-England Inquirer, a short-lived local newspaper. “They do not need a severe course of mathematical discipline,” he claimed. “They are not improved by a minute acquaintance with foreign languages; it is of no use that they are instructed in the laws of mechanical Philosophy. Their sphere is different. They were intended for wives—for mothers.”

The unsettling prospect of marriage evidently inspired a diatribe so anachronistic even one of Edward’s sisters objected. Still, his fiancée’s grammatical infelicities troubled him. “How does it affect us,” he disingenuously wondered, “to receive an epistle from a valued friend, with half the words mis-spelled—in which capitals & small letters have changed positions—where a plural noun is followed by a singular verb?” (He might have been forecasting his daughter’s orthographic style.) Though Emily Norcross’s father had funded the local academy, where she was educated (she also briefly attended the Reverend Claudius Herrick’s school in New Haven), she remained stubbornly unlettered. Her spelling is atrocious. Edward thus plied his fiancée with copies of The Spectator (on which he based his Coelebs essays), as well as several novels by women, noting he admired America’s female literati even though, of course, education was of no great concern to females. It diverted them from their duties as wives and mothers or, worse yet, made them think such duties didn’t matter.