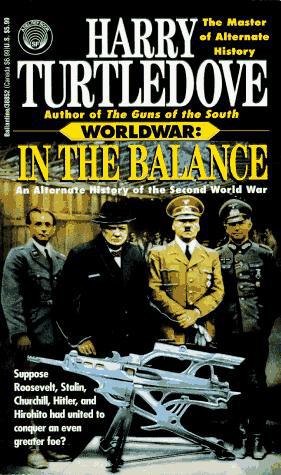

BOOKS BY HARRY TURTLEDOVE

The Guns of the South

THE WORLDWAR SAGA

Worldwar: In the Balance

Worldwar: Tilting the Balance

Worldwar: Upsetting the Balance

Worldwar: Striking the Balance

COLONIZATION

Colonization: Second Contact

Colonization: Down to Earth

Colonization: Aftershocks

THE VIDESSOS CYCLE

The Misplaced Legion

An Emperor for the Legion

The Legion of Videssos

Swords of the Legion

THE TALE OF KRISPOS

Krispos Rising

Krispos of Videssos

Krispos the Emperor

THE TIME OF TROUBLES SERIES

The Stolen Throne

Hammer and Anvil

The Thousand Cities Videssos Besieged

Noninterference

Kaleidoscope

A World of Difference

Earthgrip

Departures

How Few Remain

THE GREAT WAR

The Great War: American Front

The Great War: Walk in Hell

The Great War: Breakthroughs

American Empire: Blood and Iron

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

(Characters with names in CAPS are historical, others fictional)

HUMANS

Aloysius captive in Fiat, Indiana

ANIELEWICZ, MORDECHAI guerrilla leader in the Warsaw ghetto

Arenswald, Michael engineer Heavy Artillery Battalion Dora

Bagnall, George flight engineer in RAF bomber crew

Bauer, Klaus hull gunner in Heinrich Jäger’s tank

Becker, Karl engineer Heavy Artillery Battalion Dora

Bell, Douglas bomb-aimer in RAF bomber crew

BOR-KOMOROWSKI, TADEUSZ general, Polish Home Army

Brodsky, Nathan Jewish laborer at Warsaw airport

Burkett, Dr. biology professor at University of Chicago.

Chase, Otto cement plant worker at Dixon, Illinois

CHURCHILL, WINSTON prime minister of Great Britain

Collins, Colonel U.S. Army officer

COMPTON, ARTHUR supervisor, University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory

Daniels, Pete “Mutt” manager, Decatur Commodores (I-I-I League)

Daphne barmaid at the White Horse Inn, Dover, England

David child of Jewish fighter, Warsaw

Doi, Colonel Japanese interrogator of Teerts

Donlan, Kevin U.S. Army private in Naperville, Illinois

Embry, Ken pilot of RAF bomber crew

FERMI, ENRICO nuclear physicist at the University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory

Finkelstein, Sam doctor

Fiore, Bobby second baseman, Decatur Commodores (I-I-I League)

Fuchs, Stefan loader in Heinrich Jäger’s tank

Goldfarb, David RAF radarman in Dover England

Gorbunova, Ludmila Red Air Force pilot

Gordon captive in Fiat, Indiana

GROVES, LESLIE U.S. Army colonel

HITLER, ADOLF German Führer

Höcker, Maximilian lieutenant colonel, German Army, Paris

HULL, CORDELL U.S. secretary of state

Jacobi, Nathan BBC newsreader

Jäger, Heinrich major Sixteenth Panzer Division

Jones, Jerome RAF radarman in Dover England

Karpov, Feofan Red Air Force colonel

Kasherina, Yevdokia Red Air Force pilot

Kobayashi, Lieutenant-Colonel Japanese interrogator of Teerts

Kraniinov, Viktor Red Army lieutenant colonel in Moscow

Lane, Edward “Ted” radioman in RI4F bomber crew

Larssen, Barbara graduate student in medieval literature; Jens’ wife

Larssen, Jens nuclear physicist, University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory

Leah Jewish fighter in Warsaw

Lejb Jew in Hrubieszów, Poland

Lidov, Boris NKVD lieutenant colonel, Moscow

Liu Han Chinese peasant woman

Marie captive in Fiat, Indiana

MARSHALL, GEORGE U.S. Army Chief of Staff

Max Jew who survived Babi Yar; Soviet partisan

MOLOTOV, VYACHESLAV foreign commissar of the USSR

Okamoto, Major Japanese interpreter and interrogator of Teerts

Old sun tailor in China

PATTON, GEORGE U.S. Army major general

Pavlyuchenko, Kliment kolkhoz (collective farm) headman in the Ukraine

Popova, Yelena Red Air Force major

RIBBENTROP, JOACHIM VON German foreign minister

Riecke, Ernst captain, Sixteenth Panzer Division

Risberg, Buck soldier in Aurora, illinois

Rodney captive in Fiat, Indiana

Russie, Moishe ex-medical student in the Warsaw ghetto

Russie, Reuven Moishe Russie ’s son

Russie, Rivka Moishe Russie’s wife

Sal captive in Fiat, Indiana

Sanders, Charlie black man feeding soldiers in Naperville, Illinois

Schmidt, Dieter driver of Heinrich Jäger’s tank

Schneider, Sergeant U.S. Army recruiting sergeant

Schultz, Georg gunner of Heinrich Jäger’s tank

Sebring, Gerald nuclear physicist, University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory

Simpkin, Joe rear gunner in RAF bomber crew

SKORZENY, OTTO SS Hauptstürmfuhrer

Spiegel, Michael German Army lieutenant colonel in Satu Mare, Romania

Stansfield, Roger Royal Navy commander; CO of HMS Seanymph

Sullivan, Joe pitcher Decatur Commodores (I-I-I League)

Sylvia barmaid at the White Horse Inn, Dover England

SZILARD, LEO nuclear physicist, University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory

THOMSEN, HANS German ambassador to the United States

Thomsen, Pete reporter on the Rockford Courier-Journal

TOGO, SHIGENORI Japanese foreign minister

Tompkins, Charlie mechanic in Strasburg, Ohio

Virgil sailor on the merchant ship Caledonia

Wagner, Eddie U.S. Army private near Delphi, Indiana

Whyte, Alf navigator in RAF bomber crew

Yeager, Sam outfielder Decatur Commodores (I-I-I League)

Yi Min Chinese apothecary

Yossel Jewish fighter in Poland

ZINN, WALT nuclear physicist, University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory

THE RACE

Atvar fleetlord, invasion fleet

Breltan radar technician, 67th Emperor Sohrheb

Drefsab intelligence operator on Atvar’s staff

Erewlo subleader, communications section

Feneress shiplord—member of Straha’s faction

Gefron killercraft pilot, flight leader

Gnik outpost commander at Fiat, Indiana

Hassov shiplord—member of Kirel’s faction

Horrep shiplord—member of Straha’s faction

Kirel shiplord, 127th Emperor Hetto

Krefak missile battery officer

Krentel landcruiser commander

Mozzten shiplord based in U.S.A.

Relek shiplord 16th Emperor Osjess

Relhost assault force commander in attack on Chicago

Ristin soldier captured by U.S. Army

Rolvar killercraft pilot

Shonar shiplord—member of Straha’s faction

Ssofeg prison-camp official in China

Straha shiplord 206th Emperor Yower

Svallah artillery supervisor in the attack on Chicago

Teerts killercraft pilot, flight leader

Telerep landcruiser gunner

Tessrek senior psychologist

Ullhass soldier captured by U.S. Army

Ussmak landcruiser driver

Votal landcruiser commander

Xarol killercraft pilot

Zingiber Northern Flank Commander in the attack on Chicago

Zolraag governor of Warsaw

1

1

Fleetlord Atvar strode briskly into the command station of the invasion fleet bannership 127th Emperor Hetto. Officers stiffened in their seats as he came in. But for the way his eye turrets swiveled in their sockets, one to the left, the other to the right, he ignored them. Yet had any been so foolish as to omit the proper respect, he would have noticed—and remembered.

Shiplord Kirel, his body paint less elaborate only than Atvar’s, joined him at the projector. As Atvar did every morning, he said, “Let us examine the target.” Kirel served the fleetlord by touching the control with his own index claw. A blue and gray and white sphere sprang into being, a perfect representation of a life-bearing world floating in space.

All the officers turned both eyes toward the hologram. Atvar, as was his custom, walked around the projector to view it from all sides: Kirel followed him. When they were back where they had begun, Atvar ran out a bifurcated tongue. “Cold-looking place,” the fleetlord said, as he usually did. “Cold and wet.”

“Yet it will serve the Race and the Emperor,” Kirel replied. When he spoke those words, the rest of the officers returned to their assigned tasks; the morning ritual was over. Kirel went on, “Pity such a hot white star as Tosev has hatched so chilly an egg.”

“Pity indeed,” Atvar agreed. That chilly world revolved around a star more than twice as bright as the sun under which he’d been raised. Unfortunately, it did so toward the outer edge of the biosphere. Not only did Tosev 3 have too much free water, it even had frozen water on the ground here and there. In the Empire’s three current worlds, frozen water was rare outside the laboratory.

Kirel said, “Even if Tosev 3 is colder on average than what we’re used to, Fleetlord, we won’t have any real trouble living there, and parts will be very pleasant.” He opened his jaws slightly to display small, sharp, even teeth. “And the natives should give us no difficulty.”

“By the Emperor, that’s true.” Though his sovereign was light-years away, Atvar automatically cast both eyes down to the floor for a moment. So did Kirel. Then Atvar opened his jaws, too, sharing the shiplord’s amusement. “Show me the picture sequence from the probe once more.”

“It shall be done.” Kirel poked delicately at the projector controls. Tosev 3 vanished, to be replaced by a typical inhabitant: a biped with a red-brown skin, rather taller than a typical male of the Race. The biped wore a strip of cloth round its midsection and carried a bow and several stone-tipped arrows. Black fur sprouted from the top of its head

The biped vanished. Another took its place, this one swaddled from head to foot in robes of dirty grayish tan. A curved iron sword hung from a leather belt at its waist. Beside it stood a brown-furred riding animal with a long neck and a hump on its back.

Atvar pointed to the furry animal, then to the biped’s robes. “Even the native creatures have to protect themselves from Tosev 3’s atrocious climate.” He ran a hand down the smooth, glistening scales of his arm.

More bipeds appeared in holographic projection, some with black skins, some golden brown, some a reddish color so light it was almost pink. As the sequence moved on, Kirel opened his jaws in amusement once more. He pointed to the projector. “Behold—now!—the fearsome warrior of Tosev 3.”

“Hold that image. Let everyone, look closely at it,” Atvar commanded.

“It shall be done.” Kirel stopped the flow of images. Every officer in the command station swiveled one eye toward the image, though most kept the other on the tasks before them.

Atvar laughed silently as he studied the Tosevite fighter. This native belonged to the pinkish race, though only one hand and his face were visible to testify to that. Protective gear covered the rest of him almost as comprehensively as had the earlier biped’s robes. A pointed iron helmet with several dents sat on top of his head. He wore a suit of rather rusty mail that reached almost to his knees, and heavy leather boots below them. A flimsy coat of bluish stuff helped keep the sun off the mail.

The animal the biped rode, a somewhat more graceful relative of the humped creature, looked bored with the whole business. An iron-headed spear projected upward from the biped’s seat. His other armament included a straight sword, a knife, and a shield with a cross painted on it.

“How well do you think his kind is likely to stand up to bullets, armored fighting vehicles, aircraft?” Atvar asked rhetorically. The officers all laughed, looking forward to an easy conquest, to adding a fourth planet and solar system to the dominions of the Emperor.

Not to be outdone in enthusiasm by his commander, Kirel added, “These are recent images, too: they date back only about sixteen hundred years.” He paused to poke at a calculator. “That would be about eight hundred of Tosev 3’s revolutions. And how much, my fellow warriors, how much can a world change in a mere eight hundred revolutions?”

The officers laughed again, more widely this time. Atvar laughed with them. The history of the Race was more than a hundred thousand years deep; the Ssumaz dynasty had held the throne for almost half that time, ever since techniques for ensuring male heirs were worked out. Under the Ssumaz Emperors, the Race took Rabotev 2 twenty-eight thousand years ago, and seized Halless 1 eighteen thousand years after that. Now’ it was Tosev 3’s turn. The pace of conquest was quickening, Atvar thought.

“Carry on, servants of the Emperor,” the fleetlord said. The officers stiffened once more as he left the command station.

He was back in his suite, busy with the infinite minutiae that accompanied command, when his door buzzer squawked. He looked up from the computer screen with a start. No one was scheduled to interrupt him at this time, and the Race did not lightly break routine. Emergency in space was improbable in the extreme, but who would dare disturb him for anything less?

“Enter,” he growled.

The junior officer who came into the suite looked nervous; his tail stump twitched and his eyes swiveled quickly, now this way, now that, as if he were scanning the room for danger. “Exalted Fleetlord, kinsmale of the Emperor, as you know, we draw very near the Tosev system,” he said, his voice hardly louder than a whisper.

“I had better know that,” Atvar said with heavy sarcasm.

“Y-yes, Exalted Fleetlord.” The junior officer, almost on the point’ of bolting, visibly gathered himself before continuing: “Exalted Fleetlord, I am Subleader Erewlo, in the communications section. For the past few ship’s days, I have detected unusual radio transmissions coming from that system. These appear to be artificial in nature, and, and”—now he had to force himself to go on and face Atvar’s certain wrath—“from tiny doppler shifts in the signal frequency, appear to be emanating from Tosev 3.”

In fact, the fleetlord was too startled to be furious. “That is ridiculous,” he said. “How dare you presume to tell me that the animal-riding savages our probes photographed have moved in the historic swivel of an eye turret up to electronics when we required tens of millennia for the same advance?”

“Exalted Fleetlord, I presume nothing,” Erewlo quavered. “I merely report to you anomalous data which may be of import to our mission and therefore to the Race.”

“Get out,” Atvar said, his voice flat and deadly dangerous. Erewlo fled.

The fleetlord glared after him. The report was ridiculous, on the face of it. The Race changed but slowly, in tiny, sensible increments. Though both the Rabotevs and the Hallessi were conquered before they developed radio, they had had comparably long, comparably leisurely developments. Surely that was the norm among intelligent races.

Atvar spoke to his computer. The data the subleader had mentioned came up on his screen. He studied them, asked the machine for their implications. The implications were as Erewlo had said: with a probability that approached one, those were artificial radio signals coming from Tosev 3.

The fleetlord snarled a command the computer was not anatomically equipped to obey. If the natives of Tosev 3 had somehow stumbled across radio, what else did they know?

Just as the hologram of Tosev 3 had looked like a world floating in space, so the world itself, seen through an armorglass window, resembled nothing so much as a holographic image. But to get round to its other side now, Atvar would have to wait for the 127th Emperor Hetto to finish half an orbit.

The fleetlord glared down at the planet below. He had been glaring at it ever since the fleet arrived, one of his own years before. No one in all the vast history of the Race had ever been handed such a poisonous dilemma. The assembled shiplords stood waiting for Atvar to give them their orders. His the responsibility, his the rewards—and the risks.

“The natives of Tosev 3 are more technologically advanced than we believed they would be when we undertook this expedition,” he said, seeing if gross understatement would pry a reaction from them.

As one, they dipped their heads slightly in assent. Atvar tightened his jaws—would that he might bite down on his officers’ necks. They were going to give him no help at all. His the responsibility. He could not even ask the Emperor for instructions. A message Home would take twenty-four Home years to arrive, the reply another twenty-four. The invasion force could go back into cold sleep and wait—but who could say what the Tosevites would have invented by then?

Atvar said, “The Tosevites appear at the moment to be fighting several wars among themselves. History tells us their disunity will work to our advantage.” Ancient history, he thought; the Empire had had a single rule so long that no one, had any practice playing on the politics of disunion. But the manuals said such a thing was possible, and the manuals generally knew what they were talking about.

Kirel assumed the stooping posture of respect, a polite way to show he wished to speak. Atvar turned both eyes on him, relieved someone would say at least part of what he thought. The shiplord of the 127th Emperor Hetto said, “Is it certain we can successfully overcome the Tosevites, Fleetlord? Along with radio and radar, they have aircraft of their own, as well as armored fighting vehicles—our probes have shown them clearly.”

“But these weapons are far inferior to ours of similar types. The probes also show this clearly.” That was Straha, shiplord of the 206th Emperor Yower. He ranked next highest among the shiplords after Kirel, and wanted to surpass him one day.

Kirel knew of Straha’s ambitions, too. He abandoned the posture of respect to scowl at his rival. “A great many of these weapons are in action, however, and more being manufactured all the time. Our supplies are limited to those we have fetched across the light-years.”

“Have the Tosevites atomics?” Straha jeered. “If other measures fail, we can batter them into submission.”

“Thereby reducing the value of the planet to the colonists who will follow us,” Kirel said.

“What would you have us do?” Straha said. “Boost for home, having accomplished nothing?”

“It is within the fleetlord’s power,” Kirel said stubbornly.

He was right; abandoning the invasion was within Atvar’s power. No censure would fall on him if he started back—no official censure. But instead of being remembered through all the ages as Atvar World conqueror, an epithet only two in the long history of the Race had borne before him, he would go down in the annals as Atvar Worldfleer, a title he would be the first to assume, but hardly one he craved.

His the responsibility. In the end, his choice was no choice. “The awakening and orientation of the troops has proceeded satisfactorily?” he asked the shiplords. He did not need their hisses of assent to know the answer to his question; he had been following computer reports since before the fleet took up orbit around Tosev 3. The Emperor’s weapons and warriors were ready.

“We proceed,” he said. The shiplords hissed again.

“Come on, Joe!” Sam Yeager yelled in from left toward his pitcher. “One more to go. You can do it.” I hope, Yeager added to himself.

On the mound, Joe Sullivan rocked into his motion, wound up, delivered. Some days, Sullivan couldn’t find the plate with a map. What do you expect from a seventeen-year-old kid? Yeager thought. Today, though, the big curve bit the outside corner. The umpire’s right hand came up. A couple of people in the crowd of a couple of hundred cheered.

Sullivan fired again. The batter, a big left-handed-hitting first baseman named Kobeski, swung late, lifted a lazy fly ball to left. “Shit!” he said loudly, and threw down his bat in disgust Yeager drifted back a few steps. The ball smacked his glove; his other hand instantly covered it. He trotted in toward the visitors’ dugout. So did the rest of the Decatur Commodores.

“Final score, Decatur 4, Madison 2,” the announcer said over a scratchy, tinny microphone. “Winner, Sullivan. Loser, Kovacs. The Springfield Brownies start a series with the Blues here at Breese Stephens Field tomorrow. Game time will be noon. Hope to see you then.”

As soon as he got into the dugout, Yeager pulled a pack of Camels from the hip pocket of his wool flannel uniform. He lit up, sucked in a deep drag, blew out a contented cloud of smoke. “That’s the way to do it, Joe,” he called to Sullivan, who was ahead of him in the tunnel that led to the visitors’ locker room. “Keep the ball down and away from a big ox like Kobeski and he’ll never put one over that short right field they have here.”

“Uh, yeah. Thanks, Sam,” the winning pitcher said over his shoulder. He took off his cap, wiped his sweaty forehead with a sleeve. Then he started unbuttoning his shirt.

Yeager stared at Sullivan’s back, slowly shook his head in wonder. The kid hadn’t even known what he was up to; he’d just. happened to do the right thing. He’s only seventeen, the left fielder reminded himself again. Most of the Commodores were just like Joe, kids too young for the draft. They made Yeager feel even older than the thirty-five years he actually carried.

His “locker” was a nail driven into the wall. He sat down on a milking stool in front of it, began to peel off his uniform.

Bobby Fiore landed heavily on the stool beside him. The second baseman was a veteran, too, and Yeager’s roommate. “I’m getting too old for this,” he said with a grimace.

“You’re what? Two years younger than I am?” Yeager said. “I guess so. Something like that.” Fiore’s dark, heavily bearded face, full of angles and shadows, was made to be a mask of gloom. It also made him a perfect contrast to Yeager, whose blond, ruddy features shouted farmboy! to the world. Gloomy now, Fiore went on, “What the hell’s the use of playing in a lousy Class B league when you’re as old as we are? You still think you’re gonna be a big leaguer, Sam?”

“The war goes on long enough, who can say? They may draft everybody ahead of me, and they don’t want to give me a rifle. I tried volunteering six months ago, right after Pearl Harbor.”

“You got store-bought teeth, for Christ’s sake,” Fiore said.

“Doesn’t mean I can’t eat, or shoot, either,” Yeager said. He’d almost died in the influenza epidemic of 1918. His teeth, weakened by fever, rotted in his head and came out over the next few years; he’d worn full upper and lower plates since before he started shaving. Ironically, the only teeth of his own he had now were his four wisdom teeth, the ones that gave everyone else trouble. They’d come in fine, long after the rest were gone.

Fiore just snorted and walked naked to the shower. Yeager followed. He washed quickly; the shower was cold. It could have been worse, he thought as he toweled himself dry. A couple of Three-I League parks didn’t even have showers for the visiting team. Walking back to the hotel in a sticky, smelly uniform was a pleasure of bush-league ball he could do without

He tossed his uniform into a canvas duffel bag, along with his spikes and glove. As he started getting into his street clothes, he picked up the conversation with Fiore: “What am I supposed to do, Bobby, quit? I’ve been going too long for that. Besides, I don’t know a lot besides playing ball.”

“What do you need to know to get a job at a defense plant that pays better’n this?” Fiore asked. But he was slinging his jock into his duffel bag, too.

“Why don’t you, if you’re so fed up?” Yeager said.

Fiore grunted. “Ask me on a day when I didn’t get any hits. Today I went two for four.” He slung the blue bag over his shoulder, picked his, way out of the crowded locker room.

Yeager went with him. The cop at the players’ entrance tipped his cap to them as they walked past; by his white mustache, he might have tried volunteering for the Spanish-American War.

Both ballplayers took a long, deep breath at the same time. They smiled at each other. The air was sweet with the smell of the rolls and bread baking at Gardner’s Bakery across the street’ from the park. Fiore said, “I got a cousin who runs a little bakery in Pittsburgh. His place don’t smell half as good as this.”

“Next time I’m in Pittsburgh, I’ll tell your cousin you said that,” Yeager said.

“You ain’t going to Pittsburgh, or any other big-league town, not even if the war goes on till 1955,” Fiore retorted. “What’s the best league you ever played in?”

“I put in half a season for Birmingham in 1933,” Yeager said. “The Southern Association’s Class A-1 ball. Broke my ankle the second game of a Fourth of July doubleheader and I was out for the rest of the year.” He knew he’d lost a step, maybe a step and a half, when he came back the next season. He also knew any real chance he’d had of making the majors had snapped along with the bone in his ankle.

“You’re ahead of me after all. I put in three weeks at Albany—the Eastern League’s Class A—but when I made three errors in one game they shipped me right on out of there. Bastards.” Fiore spoke the word without much heat. If you screwed up, another ballplayer was always ready to grab your place. Anybody who didn’t understand that had no business playing the game for money.

Yeager stopped at a newsstand around the corner from the hotel and bought a magazine. “Something to look at on the train back to Decatur,” he said, handing the fellow at the stand a quarter. The year before, he would have got a nickel back. Now he didn’t. When you got a Three-I league salary, every nickel counted. He didn’t think going from digest size up to bedsheet was worth the extra five cents.

Fiore’s lip curled at his choice of reading matter. “How can you stand that Buck Rogers stuff?”

“I like it.” Yeager hung onto the new Astounding. He added, “Ten years ago, who would have believed the blitz or aircraft carriers or tanks? They were talking about all that’ kind of stuff in here then.”

“Yeah, well, I wish they’d been wrong,” Fiore said, to which Yeager had no good reply.

They came into the hotel lobby a couple of minutes later. The desk clerk had a radio on to catch the afternoon news. H.V. Kaltenborn’s rich, authoritative voice told of fighting in North Africa near Gazala, of fighting in Russia south of Kharkov, of an American landing on the island of Espfritu Santo in the New Hebrides.

Yeager gathered Espfritu Santo lay somewhere in the South Pacific. He had no idea just where. He couldn’t have found Gazala or Kharcov without a big atlas and patience, either. The war had a way of throwing up name after name he’d never learned about in school.

Kaltenborn went on, “Daring Czech patriots have struck at the Reichsprotektor for occupied Bohemia, Nazi butcher Reinhard Heydrich, in Prague. They say they have slain him. German radio blames the assault on the ‘treacherous British,’ and maintains Heydrich still lives. Time will tell.”

“Nice to hear we’re movin’ forward somewhere, even if I can’t pronounce the name of the place,” Yeager said.

“Means ‘Holy Spirit,’” Fiore told him. “Must be Spanish, but it sounds enough like Italian for me to understand it.”

“Okay,” Yeager said, glad to be enlightened. He walked over to the stairs, Fiore trailing after him. The elevator man sneered at them. That always made Yeager feel like a cheapskate, but he was too used to the feeling to let it worry him much. For that matter, the hotel was cheap, too, with a single bathroom down at the end of the hail on each floor.

He used the room key, tossed his duffel onto the bed, picked up suitcases and tossed them beside the duffel, started transferring clothes from the duffel and the closet to the bags as automatically as he hit the cutoff man on a throw from the outfield. If he’d thought about what he was doing, he would have taken twice as long for a worse job. But after half a lifetime checking out of small-town hotels, where was the need for thought?

On the other bed, Fiore was packing with the same effortless skill. They finished within a few seconds of each other, closed their bags, and hauled them downstairs. They were the first ones back to the lobby; for most of their teammates, packing didn’t come so easy yet.

“Another road trip done,” Yeager said. “Wonder how many miles on the train I’ve put in over the years.”

“I dunno,” Fiore answered. “But if I found a secondhand car with that many miles on it, I sure as hell wouldn’t buy it.”

“You go to the devil.” But Yeager had to laugh. A secondhand car with that many miles on it probably wouldn’t even run.

The rest of the Commodores straggled down by ones and twos. A few came over to shoot the breeze, but most formed their own, bigger group; the bonds of youth were stronger than those of the team. That saddened Yeager, but he understood it Back when he started playing pro ball in the long-dead days of 1925, he hadn’t dared go up to the veterans either. The war only made things worse by taking away just about everybody between him and Fiore on the one hand and the kids on the other.

The manager, Pete Daniels (universally called “Mutt”), settled accounts with the desk clerk, then turned to his troops and declared, “Come on, boys, we got us a five o’clock train to catch:” His drawl was as thick and sticky as the Mississippi mud he’d grown up farming. He’d caught for part of two seasons with the Cardinals thirty years before, back in the days when they were always near the bottom of the pack, and then a long time in the minors.

Yeager wondered if Mutt still dreamed of a big-league manager’s job. He’d never had the nerve to ask, but he doubted it: the war hadn’t opened those slots. Most likely, Daniels was here because he didn’t know anything better to do. It gave the two of them something in common.

“Well, let’s go,” Daniels said as soon as the clerk presented him with a receipt. He marched out onto the street, a parade of one. The Decatur Commodores tromped after him. The year before, they would have piled into three or four taxis and gone to the station that way. But with gas and tires in short supply, taxis might as well have been swept off the street. The ballplayers waited on the corner for the crosstown bus, then plopped their nickels into the fare box as they climbed aboard.

The bus rolled west down Washington Avenue. At the intersections with north-south streets, Yeager could see water looking either way; Madison sat on a narrow neck of land between lakes Mendota and Monona. The bus went around Capitol Park before returning to Washington to get to the Illinois Central station. The capitol itself, a granite-domed white marble building in the shape of a Greek cross, dominated the low skyline of the city.

The bus stopped right in front of the station. Mutt Daniels waved train tickets. He’d kept track of things in a four-city swing through Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin; now the Commodores would spend the next month back at Fan’s Field, so he’d only have to worry about lineups for a while.

A colored porter wheeled up a baggage cart. He tipped his cap, grinned to show off a mouthful of gold teeth. “Heah you go, gentlemen,” he said, his accent even richer than the manager’s. Yeager let the fellow heave his bags onto the cart, tipped him a nickel. The gleaming grin got wider.

Sitting beside Yeager in the passenger car, Fiore said, “When my dad first got to New York from the old country, he took the train from there to Pittsburgh, where my uncle Joe already was. First smoke he’s ever seen in his life is the steward, and he’s got gold teeth just like the porter here. For months, my, dad thought all colored folks came that way.”

Yeager laughed, then said, “Hell, I grew up between Lincoln and Omaha, and I never saw anybody who wasn’t white till I went off-to play ball. I’ve barnstormed against colored teams a couple of times, make some extra money during the winter. Some of those boys, if they were white, they could play anywhere.”

“That’s probably true,” Fiore said. “But they ain’t white.” The train started to roll. Fiore twisted in his seat, trying to get comfortable. “I’m gonna sleep for a while, then head back to the dining car after the crowd thins out”

“If you aren’t awake by eight, I’ll give you a shot in the ribs,” Yeager said. Fiore nodded with his eyes closed. He was good at sleeping on trains, better than Yeager, who got out his Astounding and started to read. The newest Heinlein serial had ended the month before, but stories by Asimov, Robert Moore Williams, del Rey, Hubbard, and Clement were plenty to keep him entertained. In minutes, he was millions of miles and thousands of years from the mundane reality of an Illinois Central train rolling south over flat prairie fields between one Midwestern town and another.

A field kitchen rolled up to the tank company somewhere south of Kharkov. After a couple of weeks of motoring this way and that, first to halt a Russian attack and then to trap the attackers, Major Heinrich Jäger couldn’t have said where he was more precisely than that without a call to Sixteenth Panzer’s signal detachment.

The field kitchen didn’t properly belong to the company. Like the other two units that made up the Second Panzer Regiment, it had a motorized kitchen that was supposed to stay with it, while this one was horse-drawn. Jäger didn’t care. He waved the driver to a halt, shouted to rout out his tank crews.

Some of the men kept on sleeping, in their Panzer IIIs or under them. But the magic word “food” and the savory smell that wafted from the stew kettle got a good many up and moving. “What have you got for us?” Jäger asked the driver and the cook.

“Boiled kasha, sir, with onions and meat,” the cook answered.

Jäger had never tasted buckwheat groats till the. panzer division smashed its way into southern Russia the July before. They still weren’t his top choice, or anywhere close to it, but they filled the belly nicely. He knew better than to ask about the meat—horse, donkey, maybe dog? He didn’t want to know. Had it been beef or mutton, the cook would have bragged about it.

He dug out his mess tin, got in line. The cook ladled out a big dollop of steaming stew. He attacked it with gusto. His stomach complained for a moment; it wasn’t used to taking on a heavy load in the wee small hours. Then it decided it liked being full, and shut up.

Somewhere off in the distance, a machine gun started chattering, and a few seconds later another one. A frown twisted Jäger’s stubbly face as he ate. The Russians were supposed to have been kaput around these parts for most of a week. But then, nobody lived to grow old by counting Russians out too soon. The previous winter had proved that.

As if drawn by a magnet, Jäger peered through the darkness toward the hulk of a T-34 that sat, turret all askew, perhaps fifty meters away. The killed tank was only a vague shape in the darkness, but even a glimpse could make fearful sweat start under his arms.

“If only we had panzers like that,” he murmured. He stuck his spoon into the stew still on his tin plate, stroked the black ribbon of his wound badge. Thanks to a T-34, he would have a furrow in his calf till the day he died. The rest of the crew of the Panzer III he’d been in at the time hadn’t been so lucky; only one other man had bailed out, and he was back in Germany getting pieced together one operation at a time.

Simply measured tank against tank, a Panzer III, even, one with the new, long 50mm gun, had no business taking on a T-34. The Russian tank boasted a cannon half again as big, thicker armor cleverly sloped to deflect shells, and an engine that was not only more powerful than a Panzer IIIs but a diesel to boot, so it wouldn’t go up in flames the way the. German machine’s petrol-powered Maybach so often did.

“It’s not so bad as all that, sir.” The cheerful voice at his shoulder belonged to Captain Ernst Riecke, his second-in-command.

“Ha. You heard me muttering to myself, did you?” Jäger said.

“Yes, sir. You ask me, it’s the same in tanks as it is in screwing, sir.”

Jäger raised an eyebrow. “This I have to hear.”

“Well, in both cases knowing what to do with what you’ve got counts for more than how big it is.”

The company commander snorted. Still, no doubt Riecke had a point. Even after almost a year of painful instruction at the hands of the Germans, the Bolsheviks were still in. the habit of committing their armor by dribs and drabs instead of massing it for maximum effect. That was how the dead T-34 had come to grief: rumbling along without support, it had been set upon and destroyed by three Panzer IIIs.

Still…“Think how fine it would be to have a big one and know what to do with it.”

“It is enjoyable, sir,” Riecke said complacently. “Or were you talking about panzers again?”

“You’re incorrigible,” Jäger said, and then wondered if it was just that the captain was still on the sunny side of thirty. Promotion came quickly on the Russian front. Good officers led their troops forward rather than sending up orders from the rear. That meant good officers died in larger numbers, a twisted sort of natural selection that worried Jäger.

He felt every one of his own forty-three years. He’d fought in the trenches in France in 1918, in the last push toward Paris and then in the grinding retreat to the Rhine. He’d first seen tanks then, the clumsy monsters the British used, and knew at once that if he ever went to war again, he wanted them on his Side for a change. But they were forbidden to the postwar Reichswehr. As soon as Hitler took the gloves off and started rearming Germany, Jäger went straight into armor.

He took another couple of mouthfuls of stew, then asked, “How many panzers do we have up and running?”

“Eleven,” Riecke answered. “Maybe we’ll be able to get another one going in the morning, if we scrounge around for some fuel line.”

“Not bad,” Jäger said, as much to console himself as to reassure Riecke. On paper, his company should have had twenty-two Panzer IIIs. In fact, it had had nineteen when the Russians launched their attack. On the eastern front, getting that close to paper strength was no small accomplishment.

“The Reds can’t be in good shape, either,” Riecke said. His voice turned worried, just for a moment: “Can they?”

“We’ve bagged enough of them, the last three weeks,” Jäger said. That was true enough; a couple of hundred thousand Russians had trudged off into captivity when the Germans pinched off the opening through which they’d poured. The enemy threw away more than a thousand tanks and two thousand artillery pieces. Bolshevik losses the summer before had been on an even more colossal scale.

But before he crossed from Romania into Russia, he’d never imagined how immense the country was; how the plains seemed to stretch on and on forever; how thin a division, a corps, an army, could spread just to hold a front, let alone advance. And from those limitless plains sprang seemingly limitless streams of men and tanks. And they all fought, ferociously if without much skill. Jäger knew too well the Wehrmacht was anything but limitless. If every German soldier slew two Red Army men, if every panzer knocked out two T-34s or KVs, the Russians had a net gain.

Riecke lit a cigarette. The flare of the match briefly showed the dirt ground into fatigue lines he’d not had a month before. Yet somehow he still looked boyish. Jäger envied him that; at the rate he himself was going gray, he’d look like a grandfather any day now.

The captain passed him the pack. He took a cigarette, leaned closer to light it from Riecke’s. “Thanks,” he said, shielding the glowing coal with one hand: no point giving a sniper a free target. Riecke also hid his smoke.

After they’d crushed out the cigarettes under their bootheels, Riecke said suddenly, “Are we, going to get new models anytime soon, sir? What does your brother say?”

“Nothing he shouldn’t, which means I don’t know for certain,” Jäger answered. His brother Johann worked as an engineer for Henschel. His letters were always censored with special zeal, lest they fall into enemy hands on the long road between Germany and somewhere south of Kharkov. But brothers had ways with words that censors could not follow. After a moment, Jäger added, “It might be possible, though I thought size didn’t concern you …?”

“Oh, I’ll carry on with what we have,” the younger man said breezily. Not that there’s any choice in the matter, Jäger thought. Riecke’ went on, “Still, as you say, it would be nice to be better and bigger at the same time.”

“So it would.” Jäger splashed a little water onto his mess tin from his water bottle, pulled out some fresh spring grass to wipe it more or less clean. Then he yawned. “I’m going to try to sleep till sunup. Don’t be afraid to wake me if there’s any sign of trouble.” He’d given Riecke that order at least a hundred times. As he always did, the captain nodded.

The drone of the four Merlins made every filling in Flight Lieutenant George Bagnall’s head feel as if it were shaking loose from its tooth. The Lancaster jounced in the air as 88mm flak burst all around it, filling the night with puffs of smoke that absurdly reminded the flight engineer of dumplings.

Searchlights stabbed up from the ground, seeking to impale a bomber like a bug on a collector’s pin. The Lancaster’s belly was a flat matte black, but not black enough to make it safe if one of those skewers of light happened to catch it. Fortunately, Bagnall was too busy monitoring engine temperature and revolutions, fuel consumption, oil pressure, hydraulic lines, and all the other complex systems that had to work if the Lancaster was to keep flying, to be as frightened as he would have been as a mere passenger.

But not even the most mechanically attentive man could have stared at his dials and meters to the exclusion of the spectacle outside the thick Perspex window. Even as Bagnall watched, more flames started in Cologne, some the almost blue-white glare of incendiaries, others spreading red blisters of ordinary fire.

Perhaps half a mile away from Bagnall’s plane and a little lower in the sky, a bomber heeled over and plunged ground-ward, one wing a sheet of flame. The flight engineer’s shiver had nothing to do with the frigid air through which his Lanc flew.

Ken Embry grunted beside him. “We may have flown a thousand bloody bombers to Cologne,” the pilot said. “Now we have to see how bloody many fly back from it.” His voice rang metallically in the intercom earphones.

“Jerry doesn’t seem very pleased with us tonight, does he?” Bagnall answered, not about to let his friend outdo him in cynicism and understatement.

Below them in the nose, Douglas Bell let out a whoop like a red Indian. “There’s the train station! Hold her steady, steady—Now!” the bombaimer shouted. The Lancaster shuddered again, in a new way this time, as destruction tumbled down on the German city by the Rhine.

“That’s for Coventry,” Embry said quietly. He’d lost a sister in the German raid on the English town a year and a half before.

“Coventry and then some,” Bagnall agreed. “The Germans didn’t throw nearly so many aircraft at us, and they don’t have a bomber that can touch the Lanc.” He set an affectionate gloved hand on the instrument panel in front of him.

The pilot grunted again. “They slaughter our civilians and we slaughter theirs. The same with the soldiers in the desert, the same in Russia. The Japanese are still moving against the Yanks in the Pacific, and Jerry is sinking too many ships in the Atlantic. If I didn’t know better, I’d say we were losing the bloody war.”

“I wouldn’t go that far,” Bagnall said after a few seconds of judicious consideration. “But it does rather seem to hang in the balance, doesn’t it? Sooner or later, one side or the other will do something monumentally stupid, and that will tell the tale.”

“Good Lord, we’re doomed if that’s so,” Embry exclaimed. “Can you imagine anyone more monumentally stupid than an Englishman with his blood up?”

Bagnall scratched at his cheek below the bottom edge of his goggles; those few square inches were the only ones not covered by one or more—usually more—layers of clothing. They were also quite numb. He flogged his brain for some sort of comeback, but nothing occurred to him; this time he’d have to yield the palm of cynicism to the pilot.

He had only a few seconds in which to feel rueful. Then shouts from the rear gunner, and the top turret rang in his ears, almost deafening him: “Enemy fighter to starboard and low! Bandit! Bandit! Bloody fucking bandit!” Machine guns began to hammer, although the .303 rounds were not likely to do much good.

Ken Embry heeled the Lancaster over on its side and dove away from the menace, flying his big, unwieldy aircraft as much like a fighter as he could. The frame groaned in protest. Like any sensible pilot, Embry ignored it. The German up there was more likely to kill him than he was to tear off the Lanc’s wings. He piled power onto the engines of one wing, cut it from those of the other. The Lancaster fell through the air like a stone. Bagnall clapped a hand to his mouth, as if to catch the stomach that was trying to crawl up his throat.

The shouts from the gunners rose to a crescendo. All at once drenched in sweat despite the icy air outside, Bagnall felt shells slam—one, two, three—into the wing and side of the fuselage. A twin-engine plane roared above the windscreen and vanished into the blackness, pursued by tracers from the Lanc’s guns.

“Messerschmitt-110,” Bagnall said shakily.

“Good of you to tell me,” Embry answered. “I was rather too occupied to notice.” He raised his voice. “Everyone present and accounted for?” The seven-man crew’s answers came back high and shrill, but they all came back. Embry turned to Bagnall. “And how did our humble chariot fare?”

Bagnall studied the gauges. “Everything appears—normal,” he said, surprised at how surprised he sounded. He rallied gamely: “We might have been a bit more embarrassed had Jerry chosen to shoot us up before we disposed of our cargo.”

“Indeed,” the pilot said. “Having disposed of it, I see no urgent reason to tarry over the scene any longer. Mr. Whyte, will you give us a course for home?”

“With pleasure, sir,” AIf Whyte answered from behind the black curtain that protected his night vision. “I thought for a moment there you were trying to fling me over the side. Fly course two-eight-three. I say again twoeight-three. That should put us on the ground back at Swinderby in about four and a half hours.”

“Or somewhere in England, at any rate,” Embry remarked; long-range navigation at night was anything but an exact science. When Whyte let out an indignant sniff, the pilot added, “Maybe I should have flung you over the side; we’d likely do just as well following a trail of bread crumbs back from Hansel and Gretel Land.”

Despite his ragging, Embry swung the bomber onto the course the navigator had given him. Bagnall kept a close eye on the instrument panel, still worried lest a line had been broken. But all the pointers stayed where they should have; the four Merlins steadily drove the Lancaster through the air at above two hundred miles an hour. The Lanc was a tough bird, especially compared to the Blenheims in which he’d started the war. And—they’d been lucky.

He peered through the windscreen. Other Lancasters, Stirlings, and Manchesters showed up as blacker shapes against the dark sky; engine exhausts glowed red. As burning Cologne receded behind him, he felt the first easing of fear. The worst was over, and he was likely to live to fly another mission—and be terrified again.

The crew’s chatter, full of the same relief he knew himself, rang in his earphones. “Bloody good hiding we gave Jerry,” somebody said. Bagnall found himself nodding. There had been flak and there had been fighters (that Me-110 filled his mind’s eye for a moment), but he’d seen worse with both—the massive bomber force had half paralyzed Cologne’s defenses. Most of his friends—with a little luck, all his friends—would be coming home to Swinderby. He wriggled in his seat, trying to get more comfortable. Downhill now, he thought.

Ludmila Gorbunova bounced through the air less than a hundred meters off the ground. Her U-2 biplane seemed hardly more than a toy; any fighter from the last two years of the previous war could have hacked the Kukuruznik from the sky with ease. But the Wheatcutter was not just a trainer—it had proved itself as a military plane since the first days of the Great Patriotic War. Tiny and quiet, it was made for slipping undetected past German lines.

She pulled the stick back to gain more altitude. It failed to help. No flashes of artillery came from what had been first the Russian assault position, then the Russian defensive position, and finally, humiliatingly, the Russian pocket trapped inside a fascist ring.

No one had reported artillery fire from within the pocket the night before, or the night before that. Sixth Army was surely dead. But, as if unwilling to believe it, Frontal Aviation kept sending out planes in the hope the corpse might somehow miraculously revive.

Ludmila went gladly. Behind her goggles, tears stung her eyes. The offensive had begun with such promise. Even the fascist radio admitted fear that the Soviets would retake Kharkov. But then—Ludmila was vague on what had happened then, although she’d flown reconnaissance all through the campaign. The Germans managed to pinch off the salient the Soviet forces had driven into their position, and then the battle became one of annihilation.

Her gloved hand tightened on the stick as if it were a fascist invader’s neck. She’d got out of Kiev with her mother bare days before the Germans surrounded the city. Both of her brothers and her father were in the army; no letters had come from any of them for months. Sometimes, though it was no proper thought for a Soviet woman born five years after the October Revolution, she wished she knew how to pray. A fire glowed, off in the distance. She turned the plane toward it. From all she had seen, anyone showing lights in the night had to be German. Whatever Soviet troops were still unbagged within the pocket would not dare draw attention to themselves. She brought the Kukuruznik down to treetop height. Time to remind the fascists they did not belong here.

As the fire brightened ahead of her, her gut clenched. She bit down hard on the inside of her lower lip, using pain to fight fear. “I am not afraid, I am not afraid, I am not afraid,” she said. But she was afraid, every time she flew.

No time for the luxury of fear, not any more. The men lounging in the circle of light round the fire swelled in a moment from ant-sized to big as life. Germans sure enough, in dirty field-gray with coal-scuttle helmets. They started to scatter an instant before she thumbed the firing button mounted on top of her stick.

The two ShVAK machine guns attached under the lower wing of the biplane added their roar to the racket of the five-cylinder radial engine. Ludmila let the guns chatter as she zoomed low above the fire. As it dimmed behind her, she looked back over her shoulder to see what she had accomplished.

A couple of Germans lay sprawled in the dirt, one motionless, the other writhing ‘like a fence lizard in the grasp of a cat. “Khorosho,” Ludmila said softly. Triumph drowned terror. “Ochen khorosho.” It was very good. Every blow against the fascists helped drive them back—or at least hindered them from coming farther forward..

Flashes from out of the darkness, from two places, then three—not fire, firearms. Terror came roaring back. Ludmila gave the Kukuruznik all the meager power it had. A rifle bullet cracked past her head, horridly close. The muzzle flashes continued behind her, but after a few seconds she was out of range.

She let the biplane climb so she could look for another target. The breeze that whistled in over the windscreen of the open cockpit dried the stinking, fear-filled sweat on her forehead and under her arms. The trouble with the Germans was that they were too good at their trade of murder and destruction. They could have had only a few seconds’ warning before her plane swooped on them out of the night, but instead of running and hiding, they’d run and then fought back—and almost killed her. She shuddered again, though they were kilometers behind her now.

When they’d first betrayed the treaty of peace and friendship and invaded the Soviet Union, she’d been confident the Red Army would quickly throw them back. But defeat and retreat followed retreat and defeat. Bombers appeared over Kiev, broad-winged Heinkels, Dorniers skinny as flying pencils, graceful Junkers-88s, Stukas that screamed like damned souls as they stooped, hawklike, on their targets. They roamed as they would. No Soviet fighters came up to challenge them.

Once in Rossosh, out of the German grasp, Ludmila happened to mention to a harried clerk that she’d gone through Osoaviakhim flight training. Two days later, she found herself enrolled in the Soviet Air Force. She still wondered whether the man did it for the sake of the country or to save himself the trouble of finding her someplace to sleep.

Too late to worry about that now. Whole regiments of women pilots flew night-harassment missions against the fascist invaders. One day, Ludmila thought, I will graduate to a real fighter instead of my U-2. Several women had become aces, downing more than five German planes apiece.

For now, though, the reliable old Wheatcutter would do well enough. She spotted another fire, off in the distance. The Kukuruznik banked, swung toward it.

Planes roared low overhead. The red suns under their wings and on the sides of their fuselages might have been painted from blood. Machine guns spat flame. The bullets kicked up dust and splashed in the water like the first big drops of a rainstorm.

Liu Han had been swimming and bathing when she heard the Japanese fighters. With a moan of terror, she thrust herself all the way under, until her toes sank deep into the slimy mud bottom of the stream. She held her breath until the need for air drove her to the surface once more, gasped in a quick breath, sank

When she had to come up again, she tossed her head to get the long, straight black hair out of her eyes, then quickly looked around. The fighters had vanished as quickly as they appeared. But she knew the Japanese soldiers would not be far behind. Chinese troops had retreated through her village the day before, falling back toward Hankow.

A few swift strokes and she was at the bank of the stream. She scrambled up, dried herself with a few quick strokes of a rough cotton towel, put on her robe and sandals, and took a couple of steps away from the water.

Another drone of motors, this one higher and farther away than the fighters, a whistle in the air that belonged to no bird…The bomb exploded less than a hundred yards from Liu. The blast lifted her like a toy and flung her back into the stream.

Stunned, half-deafened, she thrashed in the water. She breathed in a great gulp of it. Coughing, choking, retching, she thrust her head up into the precious air, gasped out a prayer to the Buddha: “Amituofo, help me!”

More bombs fell all around. Earth leapt into the air in fountains so perfect and beautiful and transient, they almost made her forget the destruction they represented. The noise of each explosion slapped her in the face, more like a blow, physically felt, than a sound. Metal fragments of bomb casing squealed wildly as they flew. A couple of them splashed into the stream not far from Liu. She moaned again. The year before, a bomb fragment had torn her father in two.

The explosions moved farther away, on toward the village. Awkwardly, robe clinging to, her arms and legs and hindering her every motion, she swam back to the bank, staggered out onto land once more. No point drying herself now, not when her damp towel was covered with earth. She automatically picked it up and started home, praying again to the Amida Buddha that her home still stood.

Bomb craters pocked the fields. Here and there, men and women lay beside them, torn and twisted in death. The dirt road, Liu saw, was untouched; the bombers had left it intact for the Japanese army to use.

She wished for a cigarette. She’d had a pack of Babies in her pocket, but they were soaked now. Water dripped from her hair into her eyes. When she saw columns of smoke rising into the sky, she, began to run. Her sandals went flap-squelch, flap-squelch against her feet. Ahead, in the direction of the village, she heard shouts and screams, but with her ears still ringing she could not make out words.

People stared as she ran up. Even in the midst of disaster, her first thought was embarrassment at the way the wet cloth of her robe molded itself to her body. Even the small swellings of her nipples were plainly visible. “Paying to see a woman’s body” was a euphemism for visiting a whore. No one so much as had to pay to see Liu’s.

But in the chaos that followed the Japanese air attack, a mere woman’s body proved a small concern. Absurdly, some of the people in the village, instead of being terrified and filled with dread like Liu, capered about as if in celebration. She called, “Has everyone here gone crazy, Old Sun?”

“No, no,” the tailor shouted back. “Do you know what the eastern devils’ bombs did? Can you guess?” An enormous grin showed his almosttoothless gums.

“I would say they missed everything, but …” Liu paused, gestured at the rising smoke. “I see that cannot be so.”

“Almost as good.” Old Sun hugged himself with glee. “No, even better—nearly all their bombs fell right on the yamen.”

“The yamen?” Liu gaped, then started to laugh herself. “Oh, what a pity!” The walled enclosure of the yamen housed the county head’s residence, his audience hail, the jail, the court that sent people there, the treasury, and other government departments. Tang Wen Lan, the county head, was notoriously corrupt, as were most of his clerks, secretaries, and servants.

“Isn’t it sad. I think I’ll go home and put on white for Tang’s funeral,” Old Sun said.

“He’s dead?” Liu exclaimed. “I thought a man as wicked as that would live forever.”

“He’s dead,” Old Sun said positively. “The ghost Life-Is-Transient is taking him to the next world right now—if death’s messenger can find enough pieces to carry. One bomb landed square on the office where he was taking bribes. No one will squeeze us any more. How sad, how terrible!” His elastic features twisted into a mask of mirthful mourning that belonged in a pantomime show.

Yi Min, the local apothecary, was less sanguine than Old Sun. “Wait until the eastern dwarfs come. The Japanese will make stupid dead Tang Wen Lan seem like a prince of generosity. He had to leave us enough rice to get through to next year so he could squeeze us again. The Japanese will keep it all for themselves. They don’t care whether we live or die.”

Too much of China had learned that, to its sorrow. However rapacious and inept the government of Chiang Kai-shek had proved itself, places under Japanese rule suffered worse. For one thing, as Yi Min had said, the invaders took for themselves first and left only what they did not want to the Chinese they con-trolled. For another, while they were rapacious, they were not inept. Like locusts, when they swept a province clean of rice, they swept it clean.

Liu said, “Shall we run away, then?”

“A peasant without his plot is nothing,” Old Sun said. “If I am to starve, I would sooner starve at home than somewhere on the road far from my ancestors’ graves.”

Several other villagers agreed. Yi Min said, “But what if it is a choice between living on the road and dying by the graves of your ancestors? What then, Old Sun?”

While the two men argued, Liu Han walked on into the village. Sure enough, it was as Old Sun had said. The yamen was a smoking ruin, its walls smashed down here and there as if by a giant’s kicks. The flagpole had been broken like a broomstraw; the Kuomintang flag, white star in a blue field on red, lay crumpled in the dirt.

Through a gap in the wrecked wall, Liu Han stared in at Tang Wen Lan’s office. If the county head had been in there when the bomb landed, Old Sun was surely right in thinking him dead. Nothing was left of the building but a hole in the ground and some thatch blown off the roof.

Another bomb had landed on the jail. Whatever the crimes for which the prisoners had been confined, they’d suffered the maximum penalty. Shrieks said some were suffering still. Villagers were already going through the yamen, scavenging what they could and dragging out bodies and pieces of bodies. The thick, meaty smell of blood fought with those of smoke and freshly upturned earth. Liu Han shuddered, thinking how easily others might have been smelling her blood right now.

Her own house stood a couple of blocks beyond the yamen. She saw smoke rising from that direction, but thought nothing of it. No one willingly believes disaster can befall her. Not even when she rounded the last corner and saw the bomb crater where the house had stood did she credit her own eyes. Less was left here than at the county head’s office.

I have no home. The thought took several seconds to register, and hardly seemed to mean anything even after Liu formed it. She stared clown at the ground, dully wondering what to do next. Something small and dirty lay by her left foot. She recognized it in the same slow, sluggish way she had realized her house was gone. It was her little sons hand. No sign of the rest of him remained.

She stooped and picked up the band, just as if he were there, not merely a mutilated fragment. The flesh was still warm against hers. She heard a loud cry, and needed a little while to know it came from her own throat. The cry went on and on, seemingly without her: when she tried to stop, she found she couldn’t.

Slowly, slowly, it stopped being the only sound in her universe. Other noises penetrated, cheerful pop-pop-pops like strings of firecrackers going off. But they were not firecrackers. They were rifles. Japanese soldiers were on the way.

David Goldfarb watched the green glow of the radar screen at Dover Station, waiting for the swarm of moving blips that would herald the return of the British bomber armada. He turned to the fellow technician beside him. “I’m sure as hell gladder to be looking for our planes coming back than I was year before last, watching every German in the whole wide world heading straight for London.”

“You can say that again.” Jerome Jones rubbed his weary eyes. “It was a bit dicey there for a while, wasn’t it?”

“Just a bit, yes.” Goldfarb leaned back in his uncomfortable chair, hunched his shoulders. Something in his neck went snap. He grunted with relief, then grunted again as he thought about Jones’s reply. He’d lived surrounded by British reserve all his twenty-three years, even learned to imitate it, but it still seemed unnatural to him.

His newlywed parents had fled to London to escape Polish pogroms a little before the start of the first World War. A stiff upper lip was not part of the scanty baggage they’d brought with them; they shouted at each other, and eventually at David and his brothers and sister, sometimes angrily, more often lovingly, but always at full throttle. He’d never learned at home to hold back, which made the trick all the harder anywhere else.

The reminiscent smile he’d worn for a moment quickly faded. By the news dribbling out, pogroms rolled through Poland again, worse under the Nazis than ever under the tsars. When Hitler swallowed Czechoslovakia, Saul Goldfarb had written to his own brothers and sisters and cousins in Warsaw, urging them to get out of Poland while they could. No one left. A few months later, it was too late to leave.

A blip on the screen snapped him out of his unhappy reverie. “Blimey,” Jones breathed, King’s English cast aside in surprise, “lookit that bugger go.”

“I’m looking,” Goldfarb said. He kept on looking, too, until the target disappeared again. It didn’t take long. He sighed. “Now we’ll have to fill out a pixie report.”

“Third one this week,” Jones observed. “Bloody pixies’re getting busier, whatever he hell they are.”

“Whatever,” Goldfarb echoed. For the past several months, radars in England—and, he gathered unofficially, the United States as well—had been showing phantom aircraft flying impossibly high and even more impossibly fast; 90,000 feet and better than 2,000 miles an hour were the numbers he’d heard most often. He said, “I used to think they came from something. wrong in the circuits somewhere. I’ve seen enough now, though, that I have trouble believing it.

“What else could they be?” Jones still belonged to the circuitry-problem school. He fired off the big guns of its argument: “They aren’t ours. They don’t belong to the Yanks. And if they were Jerry’s they d be dropping things on our heads. What does that leave? Men from Mars?

“Laugh all you like” Goldfarb said stubbornly. “If there’s something wrong in the machinery’s guts, why can t the boffins find it and fix it?”

“Crikey, I don’t think even the blokes who invented this beast know what all it can and can’t do,” Jones retorted.

Since that was unquestionably true Goldfarb didn’t respond to it directly. Instead, he said, “So why has the machinery only started finding pixies now? Why didn’t they show up on the screens from the first day?”

“If the boffins can’t figure it out, how do you expect me to know?” Jones said. “Pull out a bloody pixie report form, will you? With luck, we can get it done before we spot the bombers. Then we won’t have to worry about it tomorrow.”

“Right.” Goldfarb sometimes thought that if the Germans had managed to cross the Channel and invade England, the British could have penned them behind walls of paper and then buried them in more. The pigeonholes under the console at which he sat held enough requisitions, directives, and reports to baffle the most subtle bureaucrat for years.

Nor was the pixie report, blurrily printed on coarse, shoddy paper, properly called by a name anywhere near so simple. The RAF had instead produced.a document titled INCIDENT OF APPARENT ANOMALOUS DETECTION OF HIGH-SPEED, HIGH-ALTITUDE TARGET. Lest the form fall into German hands, it nowhere mentioned that the anomalous detections (apparent detections, Goldfarb corrected himself) took place by means of radar. As if Jerry doesn’t know we’ve got it, he thought.

He found a stub of pencil, filled in the name of the station, the date, time, and bearing and perceived velocity of the contact, then stuck the form in a manila folder taped to the side of the radar screen. The folder, stuck there by the base CO, was labeled PIXIE REPORTS. With an attitude like that, the CO would never see promotion again.

Jones grunted in satisfaction, as if he’d filled out the form himself. He said, “Off it goes to London tomorrow.”

“Yes, so they can compare it to others they’ve got and work out altitude and such from the figures,” Goldfarb said. “They wouldn’t bother with that if it were just in the circuits, now, would they?”

“Don’t ask me what they’ll do in London,” Jones said, an attitude Goldfarb also found sensible. Jones went on, “I’d be happier believing the pixies were real if anyone ever saw one anywhere but there.” He pointed at the radar screen.

“So would I,” Goldfarb admitted, “but look at the trouble we’ve had even with the Ju-86.” The wide-span reconnaissance bombers had been flying over southern England for months, usually above 40,000 feet—so high that Spitfires had enormous trouble climbing up to intercept them.

Jerome Jones remained unconvinced. “The Junkers 86 is just a Jerry crate. It’s got a good ceiling, yes, but it’s slow and easy to shoot down once we get to it. It’s not like that Superman bloke in the Yank funny books, faster than a speeding bullet.”

“I know. I’m just saying we can’t see a plane that high up even if it’s there—and if it’s going that fast, even a spotter with binoculars doesn’t have long to search before it’s gone. What we need are binoculars slaved to the radar, so one could know precisely where to look.” As he spoke, Goldfarb wondered if that was practical, and how to go about setting it up if it was.

He got so lost in his own scheme that he didn’t really notice the blip on the radar screen for a moment. Then Jones said, “Pixies again.” Sure enough, the radar was reporting more of the mysterious targets. Jones’s voice changed. “They’re acting peculiar.”

“Too right they are.” Goldfarb stared at the screen, mentally translating its picture into aircraft (he wondered if Jones, who thought of pixies as something peculiar going on inside the radar set, did the same). “They’re showing up as slower than they ever did before.”

“And there are more of them,” Jones said. “Lots more.” He turned to Goldfarb. No one looked healthy by the green glow of the cathode-ray tube, but now he’ seemed especially pale; the line of his David Niven mustache was the sole color in his thin, sharp-featured face. “David, I think—they must be real.” Goldfarb recognized what was in his voice. It was fear.

2

2

Hunger crackled like fire in Moishe Russie’s belly. He’d thought lean times and High Holy Days fasts had taught him what hunger meant, but they’d no more prepared him for the Warsaw ghetto than a picture of a lake taught a man to swim.

Long black coat flapping about him like a moving piece of the night, he scurried from one patch of deep shadow to the next. It was long past curfew, which had begun at nine. If a German saw him, he would live only so long as he still amused his tormentor. Fear dilated his nostrils at every breath, made him suck in great draughts of the fetid ghetto air.

But hunger drove harder than fear—and after all, he could become the object of a German’s sport at any hour of the day or night, for any reason or none. Only four days before, the Nazis had fallen on the Jews who came to the Leszno Street courthouse to pay their taxes—taxes the Nazis themselves imposed. They robbed the Jews not only of what they claimed was owed, but also of anything else they happened to have on their persons. With the robbery came blows and kicks, as if to remind the Jews in whose clawed grip they lay.

“Not that I needed reminding,” Russie whispered aloud. He was a native of Wolynska Street, and had been in the ghetto since Warsaw surrendered to the Germans. Not many had lasted through two and a half years of hell

He wondered how much longer he would last. He’d been a medical student before September 1939; he could diagnose his own symptoms easily enough. Loose teeth and tender gums warned of the onset of scurvy; poor night vision meant vitamin A deficiency. The diarrhea could have had a dozen fathers. And starvation needed no doctor to give it a name. The hundreds of thousands of Jews packed into four square kilometers had all too intimate an acquaintance with it.

The one advantage of being so thin was that his coat went round him nearly twice. He’d liked it better when it was a proper fit.

His furtive movements became, even more cautious as he, drew near the wall. The red bricks went up twice as high as a man, with barbed wire strung above them to keep the boldest adventurer from climbing over. However much he wanted to, Russie did not aim to try that. Instead, he whirled the sack he carried around and. around like an Olympic hammerthrower, then flung it toward the Polish side of the wall.

The sack flew up and over. Heart pounding, Russie listened to it land. He had padded the silver candlestick with rags, so it bit with a soft, dull thump instead of a clatter. He strained to catch the sound of footfalls on the other side. He was at the Pole’s mercy now. If the fellow simply wanted to steal the candlestick, he could. If he had hope of more, he’d keep the bargain they’d made in Leszno Street.

Waiting stretched like the lengths of wire on the wall and had as many spikes. Try as he would, Russie could hear nothing from the other side. Maybe the Germans had arrested the Pole. Then the precious candlestick would lie abandoned till some passerby came upon it…and Russie would have squandered one of his last remaining resources for nothing.

A soft plop on the cobblestones not far away. Russie sprinted over. The rags that bound up the tattered remnants of his shoes made hardly a sound. He held his hat on with one hand; as he grew thinner, even his head seemed to have shrunk.

He snatched up the bag, dashed back toward darkness. Even as he ran, the rich, intoxicating odor of meat flooded his senses, made his mouth gush with saliva. He fumbled at the drawstring, reached inside. His spidery fingers closed round the chunk, gauged its size and weight. Not the half a kilo he’d been promised, but not far from it. He’d expected the Pole to cheat worse: what recourse did a Jew have? Perhaps he could complain to the SS. Sick and starving though he was, the thought raised black laughter in him.

He drew out his hand, licked the salt and fat that clung to it. Water filled his eyes as well as his mouth. His wife, Rivka, and their son, Reuven (and, incidentally, himself), might live a little longer. Too late for their little Sarah, too late for his wife’s parents and his own father. But the three of them might go on.

He smacked his lips. Part of the sweetness on his tongue came from the meat’s being spoiled (but only slightly; he’d eaten far worse), the rest because it was pork. The rabbis in the ghetto had long since relaxed the prohibitions against forbidden food, but Russie still felt guilty every time it passed his lips. Some Jews chose to starve sooner than break the Law. Had he been alone in the ghetto, Russie might have followed that way. But while he had others to care for, he would live if he could. He’d talk it over with God when he got the chance.

How best to use the meat? he wondered. Soup was the only answer: it would last for several days, that way, and make rotten potatoes and moldy cabbage tolerable (only a tiny part of him remembered the dim dead days before the war, when he would have turned aside in scorn from rotten potatoes and moldy cabbage instead of wolfing them down and wishing for more).

He reached into a coat pocket. Now his spit-wet fist closed on a wad of zlotys, enough to bribe a Jewish policeman if he had to. The banknotes were good for little else; mere money was rarely enough to buy food, not in the ghetto.

“I have to get back,” he reminded himself under his breath. If he was not at his sewing machine in the factory fifteen minutes after curfew lifted, some other scrawny Jew would praise God for having the chance to take his place. And if he was there but too worn to meet his quota of German uniform trousers, he would not keep his sewing machine long. His narrow, clever hands were made for taking a pulse or removing an appendix, but their agility with bobbin and cloth was what kept him and part of his family alive.

He wondered how long he would be allowed to maintain even the hellish life he led. He did not so much fear the random murder that stalked the ghetto on German jackboots. But just that day, whispers had slithered from bench to bench at the factory. The Lublin ghetto, they said, had ceased to be: thousands of Jews taken away and—Everyone filled in his own and, according to his nightmares.

Russie’s and was something like a meat-packing plant, with people going through instead of cattle. He prayed that he was wrong, that God would never allow such an abomination. But too many prayers had fallen on deaf ears, too many Jews lay dead on sidewalks until at last, like cordwood, they were piled up and hauled away.

“Lord of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob,” he murmured softly, “I beg You, give, me a sign that You have not forsaken Your chosen people.”

Like tens of thousands of his fellow sufferers, he sent up that prayer at all hours of the day and night, sent it up because it was the only thing he could do to affect his horrid fate.

“I beg You, Lord,” he murmured again, “give me a sign.”

All at once, noon came to the Warsaw ghetto in the middle of the night. Moishe Russie stared in disbelieving wonder, at the sun-hot point of light blazing in the still-black sky. Parachute flare, he thought, remembering the German bombardment of his city.

But it was no flare. Whatever it was, it was bigger and brighter than any flare, by itself lighting the whole of the ghetto—maybe the whole of Warsaw, or the whole of Poland—bright as day. It hung unmoving in the sky, as no flare could. Slowly, slowly, slowly, the point of light became a smudge, began to fade from eye-searing, actinic violet to white and yellow and orange. The brilliance of noon gave way little by little to sunset and then to twilight. The two or three startled birds that burst into song fell silent again, as if embarrassed at being fooled.”

Their sweet notes were in any case all but drowned by the cries from the ghetto and beyond, cries of wonder and fear. Russie heard German voices with fear in them. He had not heard German voices with fear in them since the Nazis forced the Jews into the ghetto. He had not imagined he could hear such voices. Somehow that made them all the sweeter.

Tears poured from his dazzled eyes, ran down his dirty, hollow cheeks into the curls of his beard. He sagged against a torn poster that said Piwo. He wondered how long it had been since beer came into the ghetto.

But none of that mattered, not in any real sense of the word. He had asked God for a sign, and God gave him one. He did not know how he could pay God back, but he promised to spend the rest of his life finding out.

Fleetlord Atvar stood before the holographic projection of Tosev 3. As he watched, points of light blinked into being here and there above the world’s ridiculously small landmasses. He wondered if, once Tosev 3 came under the dominion of the Race, manipulation of plate tectonics might bring up more usable territory.

That was a question for the future, though, for five hundred years hence, or five thousand, or twenty-five thousand. Eventually, when everything was decided and planned down to the last detail, the Race would act. That way had served it well for centuries piled on centuries.